He stared at the girl in amazement, for he had never seen such brazen nakedness in all his life—and such real beauty....

The Pig and Whistle of 1789 was a far cry from

Central Park in 1950. And Ephraim Hale was certain

that more than rum had been used to get him there!

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Imagination Stories of Science and Fantasy

December 1950

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Ephraim Hale yawned a great yawn and awakened. He'd expected to have a headache. Surprisingly, considering the amount of hot buttered rum he'd consumed the night before, he had none. But where in the name of the Continental Congress had he gotten to this time? The last he remembered was parting from Mr. Henry in front of the Pig and Whistle. A brilliant statesman, Mr. Henry.

"Give me liberty or give me death."

E-yah. But that didn't tell him where he was. It looked like a cave. This sort of thing had to stop. Now he was out of the Army and in politics he had to be more circumspect. Ephraim felt in his purse, felt flesh, and every inch of his six feet two blushed crimson. This, Martha would never believe.

He sat up on the floor of the cave. The thief who had taken his clothes had also stolen his purse. He was naked and penniless. And he the representative from Middlesex to the first Congress to convene in New York City in this year of our Lord, 1789.

He searched the floor of the cave. All the thief had left, along with his home-cobbled brogans, his Spanish pistol, and the remnants of an old leather jerkin, was the post from Sam Osgood thanking him for his support in helping to secure Osgood's appointment as Postmaster General.

Forming a loin cloth of the leather, Ephraim tucked the pistol and cover in it. The letter could prove valuable. A man in politics never knew when a friend might need reminding. Then, decent as possible under the circumstances, he walked toward the distant point of light to reconnoiter his position. It was bad. His rum-winged feet had guided him into a gentleman's park. And the gentleman was prolific. A dozen boys of assorted ages were playing at ball on the greensward.

Rolling aside the rock that formed a natural door to the cave, Ephraim beckoned the nearest boy, a cherub of about seven. "I wonder, young master, if you would tell me on whose estate I am trespassing."

The boy grinned through a maze of freckles. "Holy smoke, mister. What you out front for? A second Nature Boy, or Tarzan Comes To Television?"

"I beg your pardon?" Ephraim said puzzled.

"Ya heard me," the boy said.

Close up, he didn't look so cherubic. He was one of the modern generation with no respect for his elders. What he needed was a beech switch well applied to the seat of his britches. Ephraim summoned the dignity possible to a man without pants. "I," he attempted to impress the boy, "am the Honorable Ephraim Hale, late officer of the Army of The United States, and elected representative from Middlesex to Congress. And I will be beholden to you, young sir, if you will inform your paternal parent a gentleman is in distress and wouldst have words with him."

"Aw, ya fadder's mustache," the boy said. "Take it to the V.A. I should lose the old man a day of hackin'." So saying, he returned to cover second base.

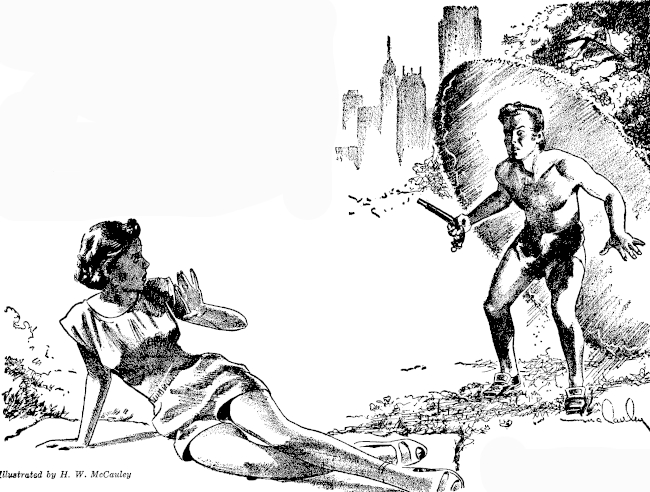

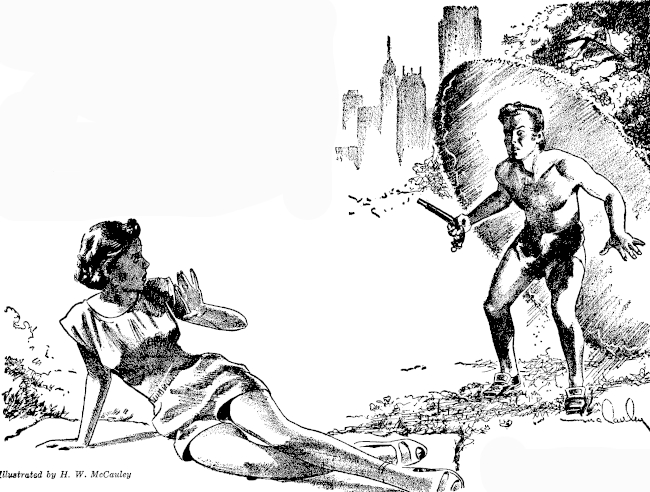

Ephraim was tempted to pursue and cane him. He might if it hadn't been for the girl. While he had been talking to the boy she had strolled across the greensward to a sunny knoll not far from the mouth of the cave. She was both young and comely. As he watched, fascinated, she began to disrobe. The top part of her dress came off revealing a bandeau of like material barely covering her firm young breasts. Then, stepping out of her skirt, she stood a moment in bandeau and short flared pants, her arms stretched in obeisance to the sun before reclining on the grass.

He stared at the girl in amazement, for he had never seen such brazen nakedness in all his life—and such real beauty....

Ephraim blushed furiously. He hadn't seen as much of Martha during their ten years of marriage. He cleared his throat to make his presence known and permit her to cover her charms.

The girl turned her head toward him. "Hello. You taking a sun bath, too? It's nice to have it warm so oily, ain't it?"

Ephraim continued to blush. The girl continued to look, and liked what she saw. With a pair of pants and a whiskey glass the big man in the mouth of the cave could pass as a man of distinction. If his hair was long, his forehead was high and his cheeks were gaunt and clean shaven. His shoulders were broad and well-muscled and his torso tapered to a V. It wasn't every day a girl met so handsome a man. She smiled. "My name's Gertie Swartz. What's yours?"

Swallowing the lump in his throat, Ephraim told her.

"That's a nice name," she approved. "I knew a family named Hale in Greenpernt. But they moved up to Riverside Height. Ya live in the Heights?"

Ephraim tried to keep from looking at her legs. "No. I reside on a farm, a league or so from Perth Amboy."

"Oh. Over in Joisey, huh?" Gertie was mildly curious. "Then what ya doin' in New York in that Johnny Weismuller outfit?"

"I," Ephraim sighed, "was robbed."

The girl sat up, clucking sympathetically. "Imagine. Right in Central Park. Like I was saying to Sadie just the other night, there ought to be a law. A mugger cleaned you, huh?"

A bit puzzled by her reference to a crocodilus palustris, but emboldened by her friendliness, Ephraim came out of the cave and sat on the paper beside her. Her patois was strange but not unpleasant. Swartz was a German name. The blond girl was probably the offspring of some Hessian. Even so she was a pretty little doxy and he hadn't bussed a wench for some time. He slipped an experimental arm around her waist. "Haven't we met before?"

Gertie removed his arm and slapped him without heat. "No. And no hard feelings, understand. Ya can't blame a guy for trying." She saw the puckered white scars on his chest, souvenirs of King's Mountain. "Ya was in the Army, huh?"

"Five years."

She was amazed and pleased. "Now ain't that a coincidence? Ya probably know my brother Benny. He was in five years, too." Gertie was concerned. "You were drinking last night, huh?"

"To my shame."

Gertie made the soft clucking sound again. "How ya going to get home in that outfit?"

"That," Ephraim said, "is the problem."

She reached for and put on her skirt. "Look. I live just over on 82nd. And if ya want, on account of you both being veterans, I'll lend you one of Benny's suits." She wriggled into the top part of her four piece sun ensemble. "Benny's about the same size as you. Wait."

Smiling, Ephraim watched her go across the greensward to a broad turnpike bisecting the estate, then rose in sudden horror as a metallic-looking monster with sightless round glass eyes swooped out from behind a screen of bushes and attempted to run her down. The girl dodged it adroitly, paused in the middle of the pike to allow a stream of billings-gate to escape her sweet red lips, then continued blithely on her way.

His senses alerted, Ephraim continued to watch the pike. The monsters were numerous as locusts and seemed to come in assorted colors and sizes. Then he spotted a human in each and realized what they must be. While he had lain in a drunken stupor, Mother Shipton's prophecy had come true—

'Carriages without horses shall go.'

He felt sick. The malcontents would, undoubtedly, try to blame this on the administration. He had missed the turning of an important page of history. He lifted his eyes above the budding trees and was almost sorry he had. The trees alone were familiar. A solid rectangle of buildings hemmed in what he had believed to be an estate; unbelievable buildings. Back of them still taller buildings lifted their spires and Gothic towers and one stubby thumb into the clouds. His pulse quickening, he looked at the date line of a paper on the grass. It was April 15, 1950.

He would never clank cups with Mr. Henry again. The fiery Virginian, along with his cousin Nathan, and a host of other good and true men, had long since become legends. He should be dust. It hadn't been a night since he had parted from Mr. Henry. It had been one hundred and sixty-one years.

A wave of sadness swept him. The warm wind off the river seemed cooler. The sun lost some of its warmth. He had never felt so alone. Then he forced himself to face it. How many times had he exclaimed:

"If only I could come back one hundred years from now."

Well, here he was, with sixty-one years for good measure.

A white object bounded across the grass toward him. Instinctively Ephraim caught it and found it was the hard white sphere being used by the boys playing at ball.

"All the way," one of them yelled.

Ephraim cocked his arm and threw. The sphere sped like a rifle ball toward the target of the most distant glove, some seventeen rods away.

"Wow!" the youth to whom he had spoken admired. The young voice was so shocked with awe Ephraim had an uneasy feeling the boy was about to genuflect. "Gee. Get a load of that whip. The guy's got an arm like Joe DiMaggio...."

Supper was good but over before Ephraim had barely got started. Either the American stomach had shrunk or Gertie and her brother, despite their seeming affluence, were among the very poor. There had only been two vegetables, one meat, no fowl or venison, no hoe cakes, no mead or small ale or rum, and only one pie and one cake for the three of them.

He sat, still hungry, in the parlor thinking of Martha's ample board and generous bed, realizing she, too, must be dust. There was no use in returning to Middlesex. It would be as strange and terrifying as New York.

Benny offered him a small paper spill of tobacco. "Sis tells me ya was in the Army. What outfit was ya with?" Before Ephraim could tell him, he continued, "Me, I was one of the bastards of Bastogne." He dug a thumb into Ephraim's ribs. "Pretty hot, huh, what Tony McAuliffe tells the Krauts when they think they got us where the hair is short and want we should surrender."

"What did he tell them?" Ephraim asked politely.

Benny looked at him suspiciously.

"'Nuts!' he tol' 'em. 'Nuts.' Ya sure ya was in the Army, chum?"

Ephraim said he was certain.

"E.T.O. or Pacific?"

"Around here," Ephraim said. "You know, Germantown, Monmouth, King's Mountain."

"Oh. State's side, huh?" Benny promptly lost all interest in his sister's guest. Putting his hat on the back of his head he announced his bloody intention of going down to the corner and shooting one of the smaller Kelly Pools.

"Have a good time," Gertie told him.

Sitting down beside Ephraim she fiddled with the knobs on an ornate commode and a diminutive mule-skinner appeared out of nowhere cracking a bull whip and shouting something almost unintelligible about having a Bible in his pack for the Reverend Mr. Black.

Ephraim shied away from the commode, wide-eyed.

Gertie fiddled with the knobs again and the little man went away. "Ya don't like television, huh?" She moved a little closer to him. "Ya want we should just sit and talk?"

Patting at the perspiration on his forehead with one of Benny's handkerchiefs, Ephraim said, "That would be fine."

As with the horseless carriages, the towering buildings, and the water that ran out of taps hot or cold as you desired, there was some logical explanation for the little man. But he had swallowed all the wonders he was capable of assimilating in one night.

Gertie moved still closer. "Wadda ya wanna talk about?"

Ephraim considered the question. He wanted to know if the boys had ever been able to fund or reduce the national debt. Seventy-four million, five hundred and fifty-five thousand, six hundred and forty-one dollars was a lot of money. He wanted to know if Mr. Henry had been successful in his advocation of the ten amendments to the Constitution, here-in-after to be known as the Bill Of Rights, and how many states had ratified them. He wanted to know the tax situation and how the public had reacted to the proposed imposition of a twenty-five cent a gallon excise tax on whiskey.

"What," he asked Gertie, "would you say was the most important thing that happened this past year?"

Gertie considered the question. "Well, Rita Hayworth had a baby and Clark Gable got married."

"I mean politically."

"Oh. Mayor O'Dwyer got married."

Gertie had been very kind. Gertie was very lovely. Ephraim meant to see more of her. With Martha fluttering around in heaven exchanging receipts for chow chow and watermelon preserves, there was no reason why he shouldn't. But as with modern wonders, he'd had all of Gertie he could take for one night. He wanted to get out into the city and find out just what had happened during the past one hundred and sixty-one years.

Gertie was sorry to see him go. "But ya will be back, won't you, Ephraim?"

He sealed the promise with a kiss. "Tomorrow night. And a good many nights after that." He made hay on what he had seen the sun shine. "You're very lovely, my dear."

She slipped a bill into the pocket of his coat. "For the Ferry-fare back to Joisey." There were lighted candles in her eyes. "Until tomorrow night, Ephraim."

The streets were even more terrifying than they had been in the daytime. Ephraim walked east on 82nd Street, south on Central Park West, then east on Central Park South. He'd had it in mind to locate the Pig and Whistle. Realizing the futility of such an attempt he stopped in at the next place he came to exuding a familiar aroma and laying the dollar Gertie had slipped into his pocket on the bar, he ordered, "Rum."

The first thing he had to do was find gainful employment. As a Harvard graduate, lawyer, and former Congressman, it shouldn't prove too difficult. He might, in time, even run for office again. A congressman's six dollars per diem wasn't to be held lightly.

A friendly, white-jacketed, Mine Host set his drink in front of him and picked up the bill. "I thank you, sir."

About to engage him in conversation concerning the state of the nation, Ephraim looked from Mine Host to the drink, then back at Mine Host again. "E-yah. I should think you would thank me. I'll have my change if you please. Also a man-sized drink."

No longer so friendly, Mine Host leaned across the wood. "That's an ounce and a half. What change? Where did you come from Reuben? What did you expect to pay?"

"The usual price. A few pennies a mug," Ephraim said. "The war is over. Remember? And with the best imported island rum selling wholesale at twenty cents a gallon—"

Mine Host picked up the shot glass and returned the bill to the bar. "You win. You've had enough, pal. What do you want to do, cost me my license? Go ahead. Like a good fellow. Scram."

He emphasized the advice by putting the palm of his hand in Ephraim's face, pushing him toward the door. It was a mistake. Reaching across the bar, Ephraim snaked Mine Host out from behind it and was starting to shake some civility into the publican when he felt a heavy hand on his shoulder.

"Let's let it go at that, chum."

"Drunk and disorderly, eh?" a second voice added.

The newcomers were big men, men who carried themselves with the unmistakable air of authority. He attempted to explain and one of them held his arms while the other man searched him and found the Spanish pistol.

"Oh. Carrying a heater, eh? That happens to be against the law, chum."

"Ha," Ephraim laughed at him. "Also ho." He quoted from memory Article II of the amendments Mr. Henry had read him in the Pig and Whistle:

"'A well-regulated militia being necessary to the security of a free state the right of the people to keep and bear Arms shall not be infringed'."

"Now he's a militia," the plain-clothes man said.

"He's a nut," his partner added.

"Get him out of here," Mine Host said.

Ephraim sat on the bunk in his cell, deflated. This was a fine resurrection for a member of the First Congress.

"Cheer up," a voice from the upper bunk consoled. "The worst they can do is burn you." He offered Ephraim a paper spill of tobacco. "The name is Silovitz."

Ephraim asked him why he was in gaol.

"Alimony," the other man sighed. "That is the non-payment thereof."

The word was new to Ephraim. He asked Silovitz to explain. "But that's illegal, archaic. You can't be jailed for debt."

His cell mate lighted a cigarette. "No. Of course not. Right now I'm sitting in the Stork Club buying Linda Darnell a drink." He studied Ephraim's face. "Say, I've been wondering who you look like. I make you now. You look like the statue of Nathan Hale the D.A.R. erected in Central Park."

"It's a family resemblance," Ephraim said. "Nat was a second cousin. They hung him in '76, the same year I went into the Army."

Silovitz nodded approval. "That's a good yarn. Stick to it. The wife of the judge you'll probably draw is an ardent D.A.R. But if I were you I'd move my war record up a bit and remove a few more cousins between myself and Nathan."

He smoked in silence a minute. "Boy. It must have been nice to live back in those days. A good meal for a dime. Whiskey, five cents a drink. No sales or income or surtax. No corporate or excise profits tax. No unions, no John L., no check-off. No tax on diapers and coffins. No closed shops. No subsidies. No paying farmers for cotton they didn't plant or for the too many potatoes they did. No forty-two billion dollar budget."

"I beg your pardon?" Ephraim said.

"Ya heard me." Swept by a nostalgia for something he'd never known, Silovitz continued. "No two hundred and sixty-five billion national debt. No trying to spend ourselves out of the poor house. No hunting or fishing or driving or occupational license. No supporting three-fourths of Europe and Asia. No atom bomb. No Molotov. No Joe Stalin. No alimony. No Frankie Sinatra. No video. No be-bop."

His eyes shone. "No New Dealers, Fair Dealers, Democrats, Jeffersonian Democrats, Republicans, State's Righters, Communists, Socialists, Socialist-Labor, Farmer-Labor, American-Labor, Liberals, Progressives and Prohibitionists and W.C.T.U.ers. Congress united and fighting to make this a nation." He quoted the elderly gentleman from Pennsylvania. "'We must all hang together, or assuredly we shall all hang separately.' Ah. Those were the days."

Ephraim cracked his knuckles. It was a pretty picture but, according to his recollection, not exactly correct. The boys had hung together pretty well during the first few weeks after the signing of the Declaration Of Independence. But from there on in it had been a dog fight. No two delegates had been able to agree on even the basic articles of confederation. The Constitution itself was a patch work affair and compromise drafted originally as a preamble and seven Articles by delegates from twelve of the thirteen states at the May '87 convention in Philadelphia. And as for the boys hanging together, the first Congress had convened on March 4th and it had been April 6th before a quorum had been present.

Silovitz sighed. "Still, it's the little things that get ya. If only Bessie hadn't insisted on listening to 'When A Girl Marries' when I wanted to hear the B-Bar-B Riders. And if only I hadn't made that one bad mistake."

"What was that?" Ephraim asked.

Silovitz told him. "I snuck up to the Catskills to hide out on the court order. And what happens? A game warden picks me up because I forgot to buy a two dollar fishing license!"

A free man again, Ephraim stood on the walk in front of the 52nd Street Station diverting outraged pedestrians into two rushing streams as he considered his situation. It hadn't been much of a trial. The arresting officers admitted the pistol was foul with rust and probably hadn't been fired since O'Sullivan was a gleam in his great-great grandfather's eyes.

"Ya name is Hale. An' ya a veteran, uh?" the judge had asked.

"Yes," Ephraim admitted, "I am." He'd followed Silovitz's advice. "What's more, Nathan Hale was a relation of mine."

The judge had beamed. "Ya don' say. Ya a Son Of The Revolution, uh?"

On Ephraim admitting he was and agreeing with the judge the ladies of the D.A.R. had the right to stop someone named Marion Anderson from singing in Constitution Hall if they wanted to, the judge, running for re-election, had told him to go and drink no more, or if he had to drink not to beef about his bill.

"Ya got ya state bonus and ya N.S.L.I. refund didncha?"

Physically and mentally buffeted by his night in a cell and Silovitz's revelation concerning the state of the nation, Ephraim stood frightened by the present and aghast at the prospect of the future.

Only two features of his resurrection pleased him. Both were connected with Gertie. Women, thank God, hadn't changed. Gertie was very lovely. With Gertie sharing his board and bed he might manage to acclimate himself and be about the business of every good citizen, begetting future toilers to pay off the national debt. It wasn't an unpleasing prospect. He had, after all, been celibate one hundred and sixty-one years. Still, with rum at five dollars a fifth, eggs eighty cents a dozen, and lamb chops ninety-five cents a pound, marriage would run into money. He had none. Then he thought of Sam Osgood's letter....

Mr. Le Duc Neimors was so excited he could hardly balance his pince-nez on the aquiline bridge of his well-bred nose. It was the first time in the multi-millionaire's experience as a collector of Early Americana he had ever heard of, let alone been offered, a letter purported to have been written by the First Postmaster General, franked by the First Congress, and containing a crabbed foot-note by the distinguished patriot from Pennsylvania who was credited with being the founding father of the postal system. He read the foot-note aloud:

Friend Hale:

May I add my gratitude to Sam's for your help in this matter. I have tried to convince him it is almost certain to degenerate into a purely political office as a party whip and will bring him as many headaches as it will dollars or honors. However, as 'Poor Richard' says, 'Experience keeps a dear school, but fools will learn in no other'.

Cordially, Ben

The multi-millionaire was frank. "If this letter and cover are genuine, they have, from the collector's viewpoint, almost incalculable historic and philatelic value." He showed the sound business sense that, along with marrying a wealthy widow and two world wars, he had been able to pyramid a few loaves of bread and seven pounds of hamburger into a restaurant and chain-grocery empire. "But I won't pay a penny more than, say, two hundred and twenty-five thousand dollars. And that only after an expert of my choice has authenticated both the letter and the cover."

Weinfield, the dealer to whom Ephraim had gone, swallowed hard. "That will be satisfactory."

"E-yah," Ephraim agreed.

He went directly to 82nd Street to press his suit with Gertie. It wasn't a difficult courtship. Gertie was tired of reading the Kinsey Report and eager to learn more about life at first hand. The bastard of Bastogne was less enthusiastic. If another male was to be added to the family he would have preferred one from the Eagle or 10th Armored Division or the 705th Tank Destroyer Battalion. However on learning his prospective brother-in-law was about to come into a quarter of a million dollars, minus Weinfield's commission, he thawed to the extent of loaning Ephraim a thousand dollars, three hundred and seventy-five of which Gertie insisted Ephraim pay down on a second-hand car.

It was a busy but happy week. There was the matter of learning to drive. There were blood tests to take. There was an apartment to find. Ephraim bought a marriage license, a car license, a driver's license, and a dog license for the blond cocker spaniel that Gertie saw and admired. The principle of easy credit explained to him, he paid twenty-five dollars down and agreed to pay five dollars a week for four years, plus a nominal carrying charge, for a one thousand five hundred dollar diamond engagement ring. He paid ten dollars more on a three-piece living room suite and fifteen dollars down on a four hundred and fifty dollar genuine waterfall seven-piece bedroom outfit. Also, at Gertie's insistence, he pressed a one hundred dollar bill into a rental agent's perspiring palm to secure a two room apartment because it was still under something Gertie called rent control.

His feet solidly on the ground of the brave new America in which he had awakened, Ephraim, for the life of him, couldn't see what Silovitz had been beefing about. E-yah. Neither a man nor a nation could stay stationary. Both had to move with the times. They'd had Silovitz's at Valley Forge, always yearning for the good old days. Remembering their conversation, however, and having reserved the bridal suite at a swank Catskill resort, Ephraim, purely as a precautionary measure, along with his other permits and licenses, purchased a fishing license to make certain nothing would deter or delay the inception of the new family he intended to found.

The sale of Sam Osgood's letter was consummated the following Monday at ten o'clock in Mr. Le Duc Neimors' office. Ephraim and Gertie were married at nine in the City Hall and after a quick breakfast of dry martinis she waited in the car with Mr. Gorgeous while Ephraim went up to get the money. The multi-millionaire had it waiting, in cash.

"And there you are. Two hundred and twenty-five thousand dollars."

Ephraim reached for the stacked sheaves of bills, wishing he'd brought a sack, and a thin-faced man with a jaundice eye introduced himself. "Jim Carlyle is the name." He showed his credentials. "Of the Internal Revenue Bureau. And to save any possible complication, I'll take Uncle Sam's share right now." He sorted the sheaves of bills into piles. "We want $156,820 plus $25,000, or a total of $179,570, leaving a balance of $45,430."

Ephraim looked at the residue sourly and a jovial man slapped his back and handed him a card. "New York State Income Tax, Mr. Hale. But we won't be hogs. We'll let you off easy. All we want is 2% up to the first $1,000, 3% on the next $2,000, 4% on the next $2,000, 5% on the next $2,000, 6% on the next $2,000, and 7% on everything over $9,000. If my figures are correct, and they are, I'll take $2,930.10." He took it. Then, slapping Ephraim's back again, he laughed. "Leaving, $42,499.90."

"Ha ha," Ephraim laughed weakly.

Mr. Weinfield dry-washed his hands. "Now we agreed on a 15% commission. That is, 15% of the whole. And 15% of $225,000 is $32,750 you owe me."

"Take it," Ephraim said. Mr. Weinfield did and Ephraim wished he hadn't eaten the olive in his second martini. It felt like it had gone to seed and was putting out branches in his stomach. In less than five minutes his quarter of a million dollars had shrunk to $9,749.90. By the time he paid for the things he had purchased and returned Benny's $1,000 he would be back where he'd started.

Closing his case, Mr. Carlyle asked, "By the way, Mr. Hale. Just for the record. Where did you file your report last year?"

"I didn't," Ephraim admitted. "This is the first time I ever paid income tax."

Mr. Le Duc Neimors looked shocked. The New York State man looked shocked. Mr. Weinfield looked shocked.

"Oh," Carlyle said. "I see. Well in that case I'd better take charge of this too." He added the sheaves remaining on the desk to those already in his case and fixed Ephraim with his jaundiced eye. "We'll expect you down at the bureau as soon as it's convenient, Mr. Hale. If there was no deliberate intent on your part to defraud, it may be that your lawyers still can straighten this out without us having to resort to criminal prosecution."

Gertie was stroking the honey-colored Mr. Gorgeous when Ephraim got back to the car. "Ya got it, honey?"

"Yeah," Ephraim said shortly. "I got it."

He jerked the car away from the curb so fast he almost tore out the aged rear end. Her feelings hurt, Gertie sniveled audibly until they'd crossed the George Washington Bridge. Then, having suffered in comparative silence as long as she could, she said, "Ya didn't need to bite my head off, Ephraim. And on our honeymoon, too. All I done was ast ya a question."

"Did," Ephraim corrected her.

"Did what?" Gertie asked.

Ephraim turned his head to explain the difference between the past tense and the participle "have done" and Gertie screamed as he almost collided head on with a car going the other way. Mr. Gorgeous yelped and bit Ephraim on the arm. Then, both cars and excitement being new to the twelve week old puppy, he was most inconveniently sick.

On their way again, Ephraim apologized. "I'm sorry I was cross." He was. None of this was Gertie's fault. She couldn't help it if he'd been a fool. There was no need of spoiling her honeymoon. The few hundred in his pockets would cover their immediate needs. And he'd work this out somehow. Things had looked black at Valley Forge, too.

Gertie snuggled closer to him. "Ya do love me, don't ya?"

"Devotedly," Ephraim assured her. He tried to put his arm around her. Still suspicious, Mr. Gorgeous bit him again. Mr. Gorgeous, Ephraim could see, was going to be a problem.

His mind continued to probe the situation as he drove. Things had come to a pretty pass when a nation this size was insolvent, when out-go and deficit spending so far exceeded current revenue, taxes had become confiscatory. There was mismanagement somewhere. There were too many feet under the table. Too many were eating too high off the hog. Perhaps what Congress needed was some of the spirit of '76 and '89. A possible solution of his own need for a job occurred to him. "How," he asked Gertie, "would you like to be the wife of a Congressman?"

"I think we have a flat tire," she answered. "Either that, honey, or one of the wheels isn't quite round on the bottom."

She walked Mr. Gorgeous while he changed the tire. It was drizzling by the time they got back in the car. Both the cowl and the top leaked. A few miles past Bear Mountain, it rained. It was like riding in a portable needle-shower. All human habitation blotted out by the rain, the rugged landscape was familiar to Ephraim. He'd camped under that great oak when it had been a young tree. He'd fought on the crest of that hill over-looking the river. But what in the name of time had he been fighting for?

He felt a new wave of tenderness for Gertie. This was the only world the child had ever known. A world of video and installment payments, of automobiles and war, of atom bombs and double-talk and meaningless jumbles of figures. A world of confused little men and puzzled, barren, women.

"I love you, Gertie," he told her.

She wiped the rain out of her eyes and smiled at him. "I love you, too. And it's all right with me to go on. But I think we'd better stop pretty soon. I heard Mr. Gorgeous sneeze and I'm afraid he's catching cold."

Damn Mr. Gorgeous, Ephraim thought. Still, there was sense in what she said. The rain was blinding. He could barely see the road. And somewhere he'd made a wrong turning. They'd have to stop where they could.

The hotel was small and old and might once have been an Inn. Ephraim got Gertie inside, signed the yellowed ledger, and saw her and Mr. Gorgeous installed in a room with a huge four poster bed before going back for the rest of the luggage.

A dried-up descendant of Cotton Mather, the tobacco chewing proprietor was waiting at the foot of the stairs when he returned sodden with rain and his arms and hands filled with bags.

"Naow, don't misunderstand me, Mr. Hale," the old witch-burner said, "I don't like t' poke m' nose intuh other people's business. But I run a respectable hotel an I don't cater none t' fly-b'-nights or loose women." He adjusted the glasses on his nose. "Y' sure y' an' Mrs. Hale are married? Y' got anythin' t' prove it?"

Ephraim counted to ten. Then still half-blinded by the rain dripping from the brim of his Homburg he set the bags on the floor, took an envelope from his pocket, selected a crisp official paper, gave it to the hotel man, picked up the bags again and climbed the stairs to Gertie.

She'd taken off her wet dress and put on a sheer negligee that set Ephraim's pulse to pounding. He took off his hat, eased out of his sodden coat and tossed it on a chair.

"Did I ever tell you I loved you?"

Gertie ran her fingers through his hair. "Go ahead. Tell me again."

Tilting her chin, Ephraim kissed her. This was good. This was right. This was all that mattered. He'd make Gertie a good husband. He—

A furtive rap on the door side-tracked his train of thought. He opened it to find the old man in the hall, shaking as with palsy. "Now a look a yere, Mister," he whispered. "If y' ain't done it, don't do it. Jist pack yer bags and git." One palsied hand held out the crisp piece of paper Ephraim had given him. "This yere fishin' license ain't for it."

Ephraim looked from the fishing license to his coat. The envelope had fallen on the floor, scattering its contents. A foot away, under the edge of the bed, his puppy eyes sad, Mr. Gorgeous was thoughtfully masticating the last of what once had been another crisp piece of paper. As Ephraim watched, Mr. Gorgeous burped, and swallowed. It was, as Silovitz had said, the little things.

It was three nights later, at dusk, when Mickey spotted the apparition. For a moment he was startled. Then he knew it for what it was. It was Nature Boy, back in costume, clutching a jug of rum to his bosom.

"Hey, Mister," Mickey stopped Ephraim. "I been looking all over for you. My cousin's a scout for the Yankees. And when I told him about your whip he said for you to come down to the stadium and show 'em what you got."

Ephraim looked at the boy glass-eyed.

Mickey was hurt by his lack of enthusiasm. "Gee. Ain't you excited? Wouldn't you like to be a big league ball player, the idol of every red-blooded American boy? Wouldn't you like to make a lot of money and have the girls crazy about you?"

The words reached through Ephraim's fog and touched a responsive chord. Drawing himself up to his full height he clutched the jug still tighter to his bosom with all of the dignity possible to a man without pants.

"Ya fadder's mustache," he said.

Then staggering swiftly into the cave he closed the rock door firmly and finally behind him.