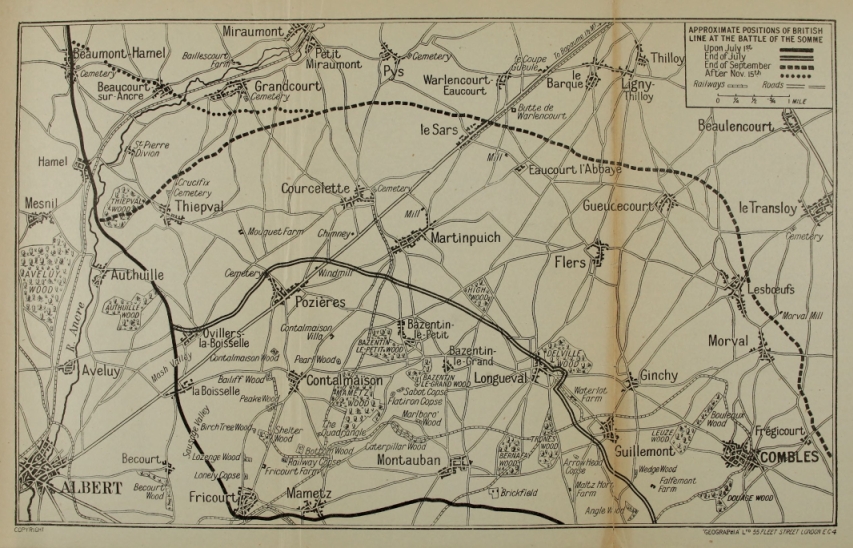

APPROXIMATE POSITIONS OF BRITISH

LINE AT THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME

BY

ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

AUTHOR OF

'THE GREAT BOER WAR,' ETC.

HODDER AND STOUGHTON

LONDON NEW YORK TORONTO

MCMXVIII

SIR ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE'S

HISTORY OF THE WAR

Uniform with this Volume.

THE BRITISH CAMPAIGN IN FRANCE AND FLANDERS

1914

THE BREAKING OF THE PEACE.

THE OPENING OF THE WAR.

THE BATTLE OF MONS.

THE BATTLE OF LE CATEAU.

THE BATTLE OF THE MARNE.

THE BATTLE OF THE AISNE.

THE LA BASSÉE-ARMENTIÈRES OPERATIONS.

THE FIRST BATTLE OF YPRES.

A RETROSPECT AND GENERAL SUMMARY.

THE WINTER LULL OF 1914.

THE BRITISH CAMPAIGN IN FRANCE AND FLANDERS

1915

THE OPENING MONTHS OF 1915.

NEUVE CHAPELLE AND HILL 60.

THE SECOND BATTLE OF YPRES.

THE BATTLE OF RICHEBOURG-FESTUBERT.

THE TRENCHES OF HOOGE.

THE BATTLE OF LOOS.

With Maps, Plans, and Diagrams,

6s. net each Volume.

HODDER AND STOUGHTON

LONDON, NEW YORK, AND TORONTO

PREFACE

In two previous volumes of this work a narrative has been given of those events which occurred upon the British Western Front during 1914, the year of recoil, and 1915, the year of equilibrium. In this volume will be found the detailed story of 1916, the first of the years of attack and advance.

Time is a great toner down of superlatives, and the episodes which seem world-shaking in our day may, when looked upon by the placid eyes of historical philosophers in days to come, fit more easily into the general scheme of human experience. None the less it can be said without fear of ultimate contradiction that nothing approaching to the Battle of the Somme, with which this volume is mainly concerned, has ever been known in military history, and that it is exceedingly improbable that it will ever be equalled in its length and in its severity. It may be said to have raged with short intermissions, caused by the breaking of the weather, from July 1 to November 14, and during this prolonged period the picked forces of three great nations were locked in close battle. The number of combatants from first to last was between {vi} two and three millions, and their united casualties came to the appalling total of at least three-quarters of a million. These are minimum figures, but they will give some idea of the unparalleled scale of the operations.

With the increasing number and size of the units employed the scale of the narrative becomes larger. It is more difficult to focus the battalion, while the individual has almost dropped out of sight. Sins of omission are many, and the chronicler can but plead the great difficulty of his task and regret that his limited knowledge may occasionally cause disappointment.

The author should explain that this volume has had to pass through three lines of censors, suffering heavily in the process. It has come out with the loss of all personal names save those of casualties or of high Generals. Some passages also have been excised. On the other hand it is the first which has been permitted to reveal the exact identity of the units engaged. The missing passages and names will be restored when the days of peace return.

ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE.

February 3, 1918.

CONTENTS

JANUARY TO JULY 1916

General situation—The fight for the Bluff—The Mound of St. Eloi—Fine performance of Third Division and Canadians—Feat of the 1st Shropshires—Attack on the Irish Division—Fight at Vimy Ridge—Canadian Battle of Ypres—Death of General Mercer—Recovery of lost position—Attack of Thirty-ninth Division—Eve of the Somme

THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME

Attack of the Seventh and Eighth Corps on Gommecourt,

Serre, and Beaumont Hamel

Line of battle in the Somme sector—Great preparations—Advance of Forty-sixth North Midland Division—Advance of Fifty-sixth Territorials (London)—Great valour and heavy losses—Advance of Thirty-first Division—Advance of Fourth Division—Advance of Twenty-ninth Division—Complete failure of the assault

THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME

Attack of the Tenth and Third Corps, July 1, 1916

Magnificent conduct of the Ulster Division—Local success but general failure—Advance of Thirty-second Division—Advance of Eighth Division—Advance of Thirty-fourth Division—The turning-point of the line

THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME

The Attack of the Fifteenth and Thirteenth Corps, July 1, 1916

The advance of the Twenty-first Division—Of the 64th Brigade—First permanent gains—50th Brigade at Fricourt—Advance of Seventh Division—Capture of Mametz—Fine work by Eighteenth Division—Capture of Montauban by the Thirtieth Division—General view of the battle—Its decisive importance

THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME

From July 2 to July 14, 1916

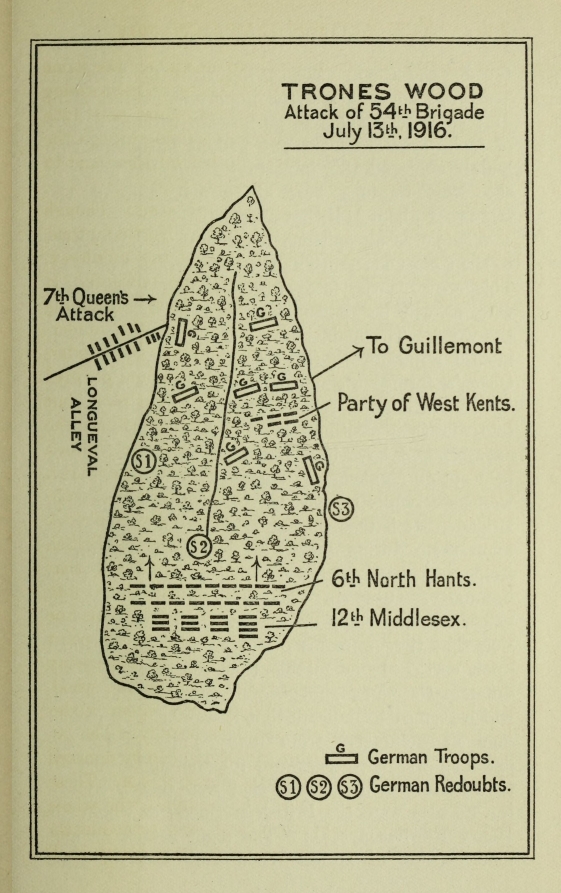

General situation—Capture of La Boiselle by Nineteenth Division—Splendid attack by 36th Brigade upon Ovillers—Siege and reduction of Ovillers—Operations at Contalmaison—Desperate fighting at the Quadrangle by Seventeenth Division—Capture of Mametz Wood by Thirty-eighth Welsh Division—Capture of Trones Wood by Eighteenth Division

THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME

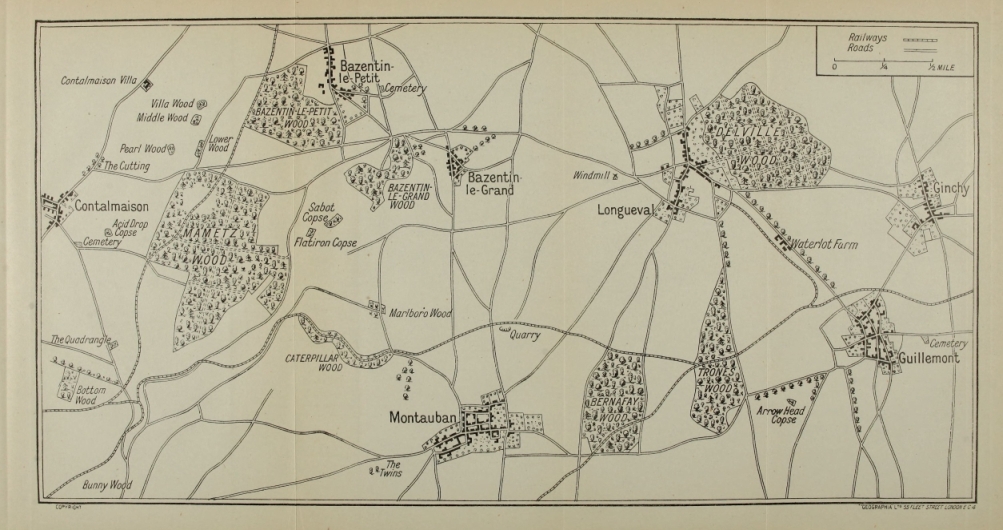

The Breaking of the Second Line. July 14, 1916

The great night advance—The Leicester Brigade at Bazentin—Assault by Seventh Division—Success of the Third Division—Desperate fight of Ninth Division at Longueval—Operations of First Division on flank—Cavalry advance

THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME

July 14 to July 31

Gradual advance of First Division—Hard fighting of Thirty-third Division at High Wood—The South Africans in Delville Wood—The great German counter-attack—Splendid work of 26th Brigade—Capture of Delville Wood by 98th Brigade—Indecisive fighting on the Guillemont front

THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME

The Operations of Gough's Army upon the Northern Flank

up to September 15

Advance, Australia!—Capture of Pozières—Fine work of Forty-eighth Division—Relief of Australia by Canada—Steady advance of Gough's Army—Capture of Courcelette

THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME

August 1 to September 15

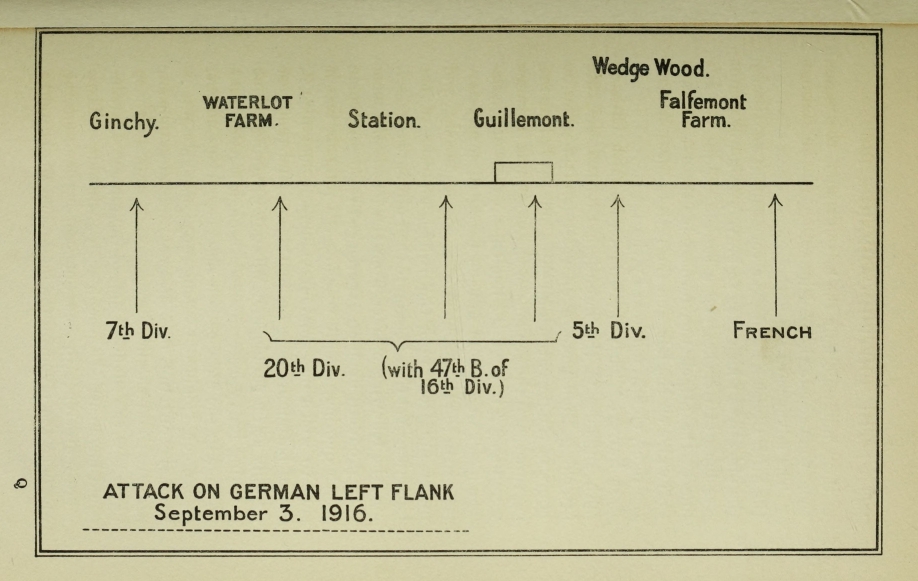

Continued attempts of Thirty-third Division on High Wood—Co-operation of First Division—Operation of Fourteenth Division on fringe of Delville Wood—Attack by Twenty-fourth Division on Guillemont—Capture of Guillemont by 47th and 59th Brigades—Capture of Ginchy by Sixteenth Irish Division

THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME

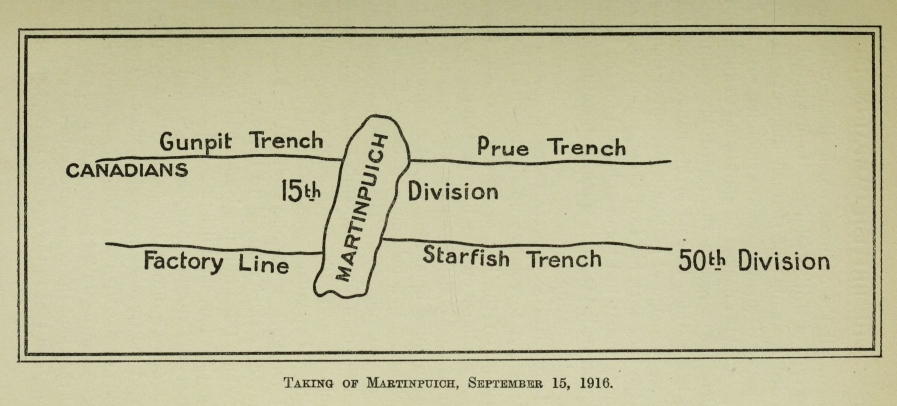

Breaking of the Third Line, September 15

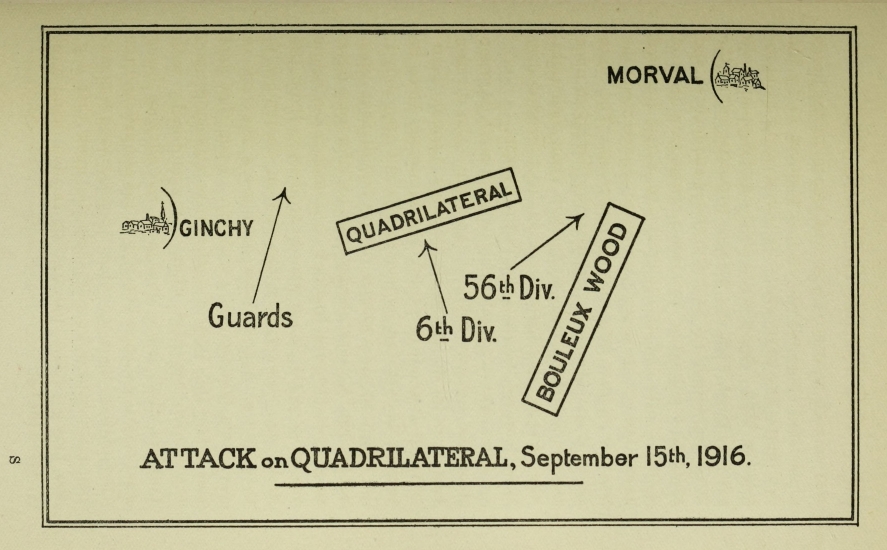

Capture of Martinpuich by Fifteenth Division—Advance of Fiftieth Division—Capture of High Wood by Forty-seventh Division—Splendid advance of New Zealanders—Capture of Flers by Forty-first Division—Advance of the Light Division—Arduous work of the Guards and Sixth Divisions—Capture of Quadrilateral—Work of Fifty-sixth Division on flank—Debut of the tanks

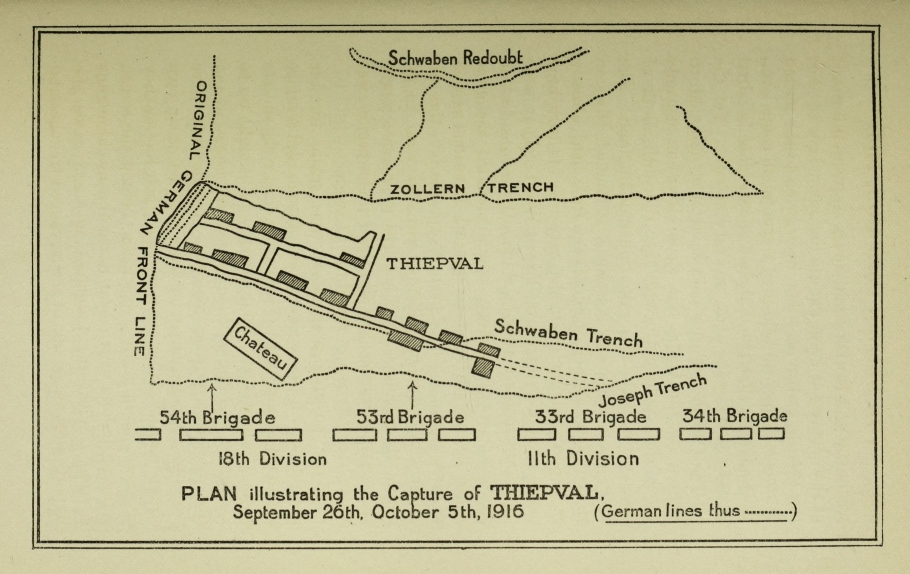

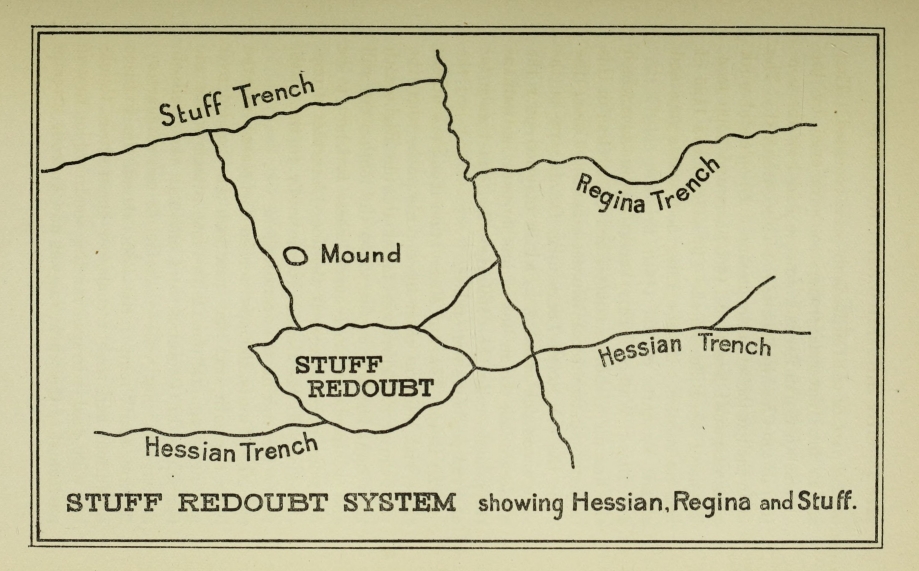

THE GAINING OF THE THIEPVAL RIDGE

Assault on Thiepval by Eighteenth Division—Heavy fighting—Co-operation of Eleventh Division—Fall of Thiepval—Fall of Schwaben Redoubt—Taking of Stuff Redoubt—Important gains on the Ridge

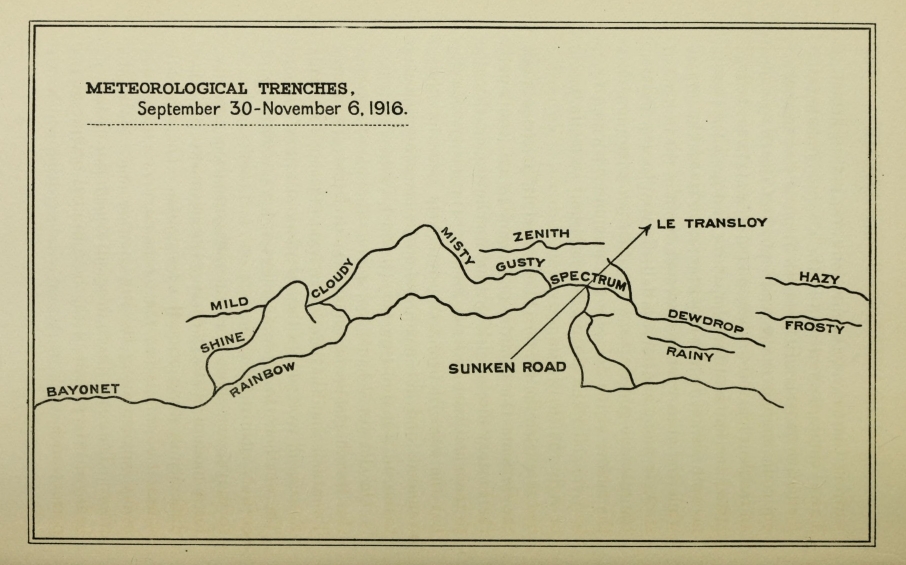

THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME

From September 15 to the Battle of the Ancre

Capture of Eaucourt—Varying character of German resistance—Hard trench fighting along the line—Dreadful climatic conditions—The meteorological trenches—Hazy Trench—Zenith Trench—General observations—General von Arnim's report

THE BATTLE OF THE ANCRE

November 13, 1916

The last effort—Failure in the north—Fine work of the Thirty-ninth, Fifty-first, and Sixty-third Divisions—Surrounding of German Fort—Capture of Beaumont Hamel—Commander Freyberg—Last operations of the season—General survey—"The unwarlike Islanders"

MAPS AND PLANS

Approximate Positions of British Line at the Battle of the Somme

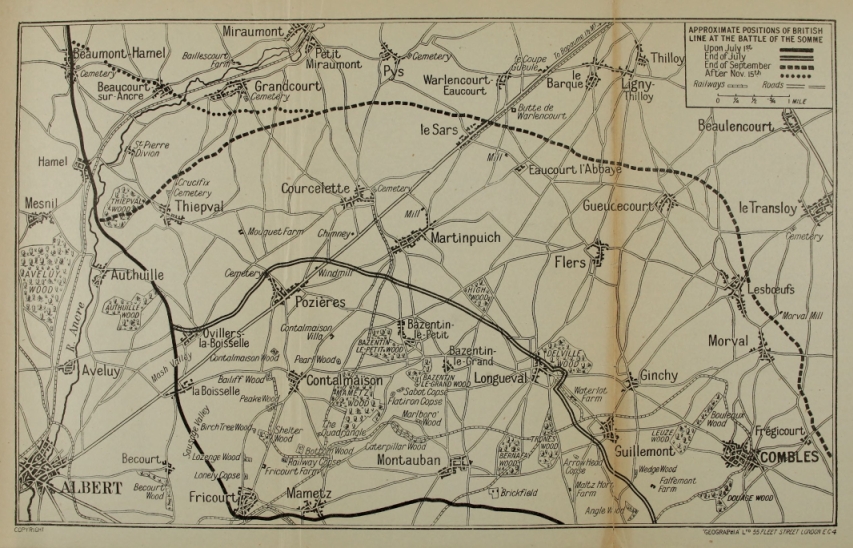

British Battle Line, July 1, 1916

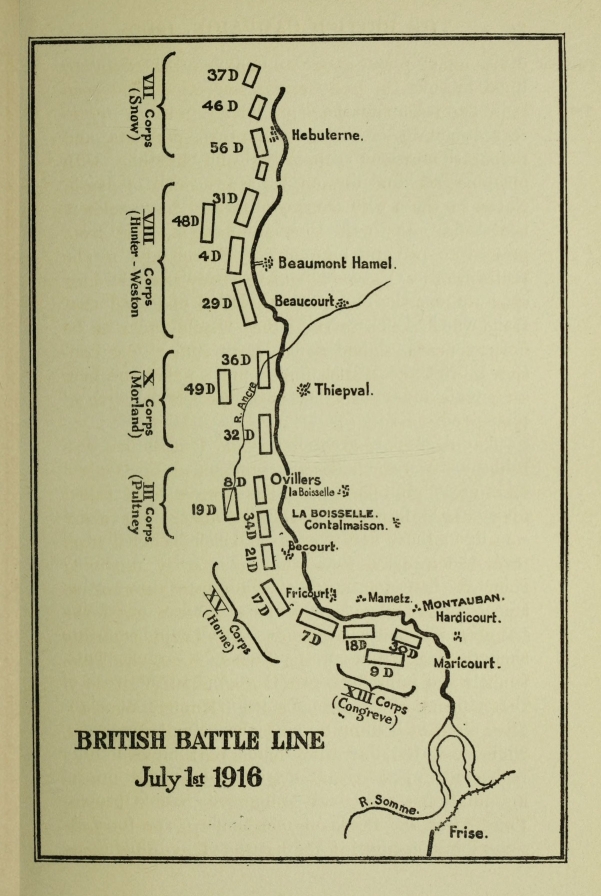

Quadrangle Position, July 5-11, 1916

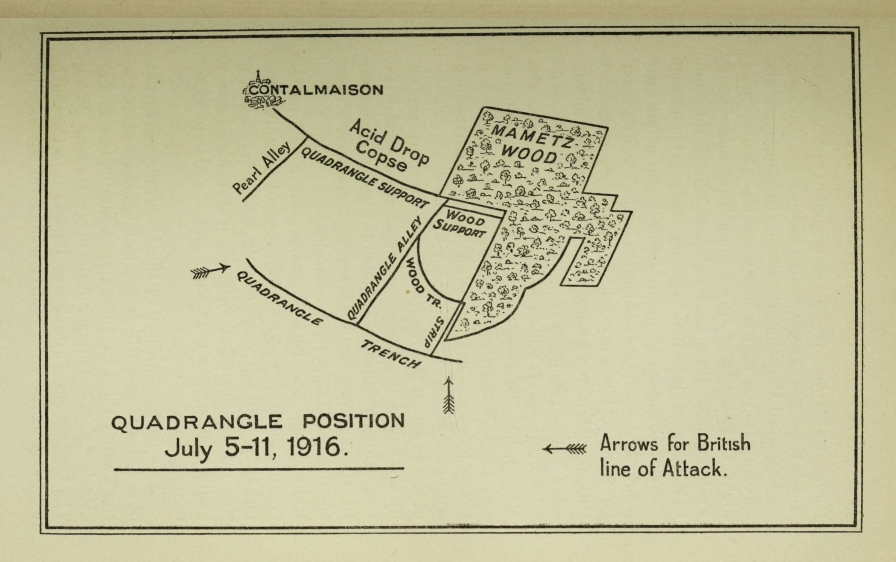

Trones Wood: Attack of 54th Brigade, July 13, 1916

The Second German Line, Bazentins, Delville Wood, etc.

Attack on German Left Flank, September 3, 1916

Final Position at Capture of Martinpuich

Attack on Quadrilateral, September 15, 1916

Plan illustrating the Capture of Thiepval, September 26, October 5, 1916

Stuff Redoubt System, showing Hessian, Regina, and Stuff

Meteorological Trenches, September 30-November 6, 1916

Map to illustrate the British Campaign in France and Flanders [Transcriber's note: this map was omitted from the etext because its size and fragility made it impractical to scan.]

APPROXIMATE POSITIONS OF BRITISH

LINE AT THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME

General situation—The fight for the Bluff—The Mound of St. Eloi—Fine performance of Third Division and Canadians—Feat of the 1st Shropshires—Attack on the Irish Division—Fight at Vimy Ridge—Canadian Battle of Ypres—Death of General Mercer—Recovery of lost position—Attack of Thirty-ninth Division—Eve of the Somme.

The Great War had now come into its second winter—a winter which was marked by an absolute cessation of all serious fighting upon the Western front. Enormous armies were facing each other, but until the German attack upon the French lines of Verdun at the end of February, the infantry of neither side was seriously engaged. There were many raids and skirmishes, with sudden midnight invasions of hostile trenches and rapid returns with booty or prisoners. Both sides indulged in such tactics upon the British front. Gas attacks, too, were occasionally attempted, some on a large scale and with considerable result. The condition of the troops, though it could not fail to be trying, was not so utterly miserable as during the first cold season in the trenches. The British had ceased to be a mere fighting fringe with nothing behind it. The troops were numerous and eager, so that reliefs were frequent. All sorts of devices were {2} adopted for increasing the comfort and conserving the health of the men. Steadily as the winter advanced and the spring ripened into summer, fresh divisions were passed over the narrow seas, and the shell-piles at the bases marked the increased energy and output of the workers in the factories. The early summer found everything ready for a renewed attempt upon the German line.

The winter of 1915-16 saw the affairs of the Allies in a condition which could not be called satisfactory, and which would have been intolerable had there not been evident promise of an amendment in the near future. The weakness of the Russians in munitions had caused their gallant but half-armed armies to be driven back until the whole of Poland had fallen into the hands of the Germanic Powers, who had also reconquered Galicia and Bukovina. The British attempt upon Gallipoli, boldly conceived and gallantly urged, but wanting in the essential quality of surprise, had failed with heavy losses, and the army had to be withdrawn. Serbia and Montenegro had both been overrun and occupied, while the efficient Bulgarian army had ranged itself with our enemies. The Mesopotamian Expedition had been held up by the Turks, and the brave Townshend, with his depleted division, was hemmed in at Kut, where, after a siege of five months, he was eventually compelled, upon April 26, to lay down his arms, together with 9000 troops, chiefly Indian. When one remembers that on the top of this Germany already held Belgium and a considerable slice of the north of France, which included all the iron and coal producing centres, it must be admitted that the Berlin Press had some reason upon its side when it insisted that it had {3} already won the War upon paper. To realise that paper, was, however, an operation which was beyond their powers.

What could the Allies put against these formidable successes? There was the Colonial Empire of Germany. Only one colony, the largest and most powerful, still remained. This was East Africa. General Smuts, a worthy colleague of the noble Botha, had undertaken its reduction, and by the summer the end was in sight. The capture of the colonies would then be complete. The oceans of the world were another asset of the Allies. These also were completely held, to the absolute destruction of all German oversea commerce. These two conquests, and the power of blockade which steadily grew more stringent, were all that the Allies could throw into the other scale, save for the small corner of Alsace still held by the French, the southern end of Mesopotamia, and the port of Salonica, which was a strategic checkmate to the southern advance of the Germans. The balance seemed all against them. There was no discouragement, however, for all these difficulties had been discounted and the Allies had always recognised that their strength lay in those reserves which had not yet had time to develop. The opening of the summer campaign of 1916, with the capture of Erzeroum, the invasion of Armenia, and the reconquest of Bukovina, showed that the Russian army had at last found its second wind. The French had already done splendid work in their classical resistance at Verdun, which had extended from the last weeks of February onwards, and had cost the Germans over a quarter of a million of casualties. The opening of the British campaign in July found the whole {4} army most eager to emulate the deeds of its Allies, and especially to take some of the weight from the splendid defenders of Verdun. Their fight against very heavy odds in men, munitions, and transport, was one of the greatest deeds of arms, possibly the greatest deed of arms of the war. It was known, however, before July that a diversion was absolutely necessary, and although the British had taken over a fresh stretch of trenches so as to release French reinforcements, some more active help was imperatively called for.

Before describing the summer campaign it is necessary to glance back at the proceedings of the winter and spring upon the British line, and to comment upon one or two matters behind that line which had a direct influence upon the campaign. Of the minor operations to which allusion has already been made, there are none between the Battle of Loos and the middle of February 1916 which call for particular treatment. Those skirmishes and mutual raidings which took place during that time centred largely round the old salient at Ypres and the new one at Loos, though the lines at Armentières were also the scene of a good deal of activity. One considerable attack seems to have been planned by the Germans on the north-east of Ypres in the Christmas week of 1915—an attack which was preceded by a formidable gas attack. The British artillery was so powerful, however, that it crushed the advance in the trenches, where the gathered bayonets of the stormers could be seen going down before the scourging shrapnel like rushes before a gale. The infantry never emerged, and the losses must have been very heavy. This was the only considerable attempt made by either side during the winter.

At the time of Lord French's return another change was made at home which had a very immediate bearing upon the direction of the War. Britain had suffered greatly from the fact that at the beginning of hostilities the distinguished officers who composed the central staff had all been called away for service in the field. Lord Kitchener had done wonders in filling their place, but it was impossible for any man, however great his abilities or energy, to carry such a burden upon his shoulders. The more conscientious the man the more he desires to supervise everything himself and the more danger there is that all the field cannot be covered. Already the recruiting service, which had absorbed a great deal of Lord Kitchener's energies with most splendid results, had been relegated to Lord Derby, whose tact and wisdom produced fresh armies of volunteers. Now the immediate direction of the War and the supervision of all that pertained to the armies in the field was handed over to Sir William Robertson, a man of great organising ability and of proved energy. From this time onwards his character and judgment bulked larger and larger as one of the factors which made for the success of the Allies.

In January 1916 Britain gave her last proof of the resolution with which she was waging war. Already she had shown that no question of money could diminish her ardour, for she was imposing direct taxation upon her citizens with a vigour which formed the only solid basis for the credit of the Allies. Neither our foes nor our friends have shown such absolute readiness to pay in hard present cash, that posterity might walk with a straighter back, and many a man was paying a good half of his income {6} to the State. But now a sacrifice more intimate than that of money had to be made. It was of that personal liberty which is as the very breath of our nostrils. This also was thrown with a sigh into the common cause, and a Military Service Bill was passed by which every citizen from 19 to 41 was liable to be called up. It is questionable whether it was necessary as yet as a military measure, since the enormous number of 5,000,000 volunteers had come forward, but as an act of justice by which the burden should be equally distributed, and the shirker compelled to his duty, it was possible to justify this radical departure from the customs of our fathers and the instincts of our race. Many who acquiesced in its necessity did so with a heavy heart, feeling how glorious would have been our record had it been possible to bring forward by the stress of duty alone the manhood of the nation. As a matter of fact, the margin left over was neither numerous nor important, but the energies of the authorities were now released from the incessant strain which the recruiting service had caused.

The work of the trenches was made easier for the British by the fact that they had at last reached an equality with, and in many cases a superiority to, their enemy, in the number of their guns, the quantity of their munitions, and the provision of those smaller weapons such as trench mortars and machine-guns which count for so much in this description of warfare. Their air supremacy which had existed for a long time was threatened during some months by the Fokker machines of the Germans, and by the skill with which their aviators used them, but faster models from England soon restored the balance. {7} There had been a time also when the system and the telescopic sights of the German snipers had given them an ascendancy. Thanks to the labours of various enthusiasts for the rifle, this matter was set right and there were long stretches of the line where no German head could for an instant be shown above the parapet. The Canadian sector was particularly free from any snipers save their own.

The first serious operation of the spring of 1916 upon the British line was a determined German attack upon that section which lies between the Ypres-Comines Canal and the Ypres-Comines railway on the extreme south of the Ypres salient; Hill 60 lies to the north of it. In the line of trenches there was one small artificial elevation, not more than thirty feet above the plain. This was called the Bluff, and was the centre of the attack. It was of very great importance as a point of artillery observation. During the whole of February 13 the bombardment was very severe, and losses were heavy along a front of several miles, the right of which was held by the Seventeenth Division, the centre by the Fiftieth, and the left by the Twenty-fourth. Finally, after many of the trenches had been reduced to dirt heaps five mines were simultaneously sprung under the British front line, each of them of great power. The explosions were instantly followed by a rush of the German infantry. In the neighbourhood of the Bluff, the garrison, consisting at that point of the 10th Lancashire Fusiliers, were nearly all buried or killed. To the north lay the 10th Sherwood Foresters and north of them the 8th South Staffords, whose Colonel, though four times wounded, continued {8} to direct the defence. It was impossible, however, to hold the whole line, as the Germans had seized the Bluff and were able to enfilade all the trenches of the Sherwoods, who lost twelve officers and several hundred men before they would admit that their position was untenable. The South Staffords being farther off were able to hold on, but the whole front from their right to the canal south of the Bluff was in the hands of the Germans, who had very rapidly and skilfully consolidated it. A strong counter-attack by the 7th Lincolns and 7th Borders, in which the survivors of the Lancashire Fusiliers took part, had some success, but was unable to permanently regain the lost sector, six hundred yards of which remained with the enemy. A lieutenant, with 40 bombers of the Lincolns, 38 of whom fell, did heroic work.

The attack had extended to the north, where it had fallen upon the Fiftieth Division, and to the Twenty-fourth Division upon the left of it. Here it was held and eventually repulsed. Of the company of the 9th Sussex who held the extreme left of the line, a large portion were blown up by a mine and forty were actually buried in the crater. Young Lieutenant McNair, however, the officer in charge, showed great energy and presence of mind. He held the Germans from the crater and with the help of another officer, who had rushed up some supports, drove them back to their trenches. For this McNair received his Victoria Cross. The 3rd Rifle Brigade, a veteran regular battalion, upon the right of the Sussex, had also put up a vigorous resistance, as had the central Fiftieth Division, so that in spite of the sudden severity of the attack it was only at the one {9} point of the Bluff that the enemy had made a lodgment—that point being the real centre of their effort. They held on strongly to their new possession, and a vigorous fire with several partial attacks during the next fortnight failed to dislodge them.

Early in March the matter was taken seriously in hand, for the position was a most important one, and a farther advance at this point would have involved the safety of Ypres. The Seventeenth Division still held the supporting trenches, and these now became the starting-point for the attack. A considerable artillery concentration was effected, two brigades of guns and two companies of sappers were brought up from the Third Division, and the 76th Brigade of the same Division came up from St. Omer, where it had been resting, in order to carry out the assault. The general commanding this brigade was in immediate command of the operations.

The problem was a most difficult one, as the canal to the south and a marsh upon the north screened the flanks of the new German position, while its front was covered by shell-holes which the tempestuous weather had filled with water. There was nothing for it, however, but a frontal attack, and this was carried out with very great gallantry upon March 2, at 4.30 in the morning. The infantry left their trenches in the dark and crept forward undiscovered, dashing into the enemy's line with the first grey glimmer of the dawn. The right of the attack formed by the 2nd Suffolks had their revenge for Le Cateau, for they carried the Bluff itself with a rush. So far forward did they get that a number of Germans emerged from dug-outs in their rear, and were organising a dangerous attack when they were pelted back {10} into their holes by a bombing party. Beyond the Bluff the Suffolks were faced by six deep shelters for machine-guns, which held them for a time but were eventually captured. The centre battalion consisted of the 8th Royal Lancasters, who lost heavily from rifle fire but charged home with great determination, flooding over the old German front line and their support trenches as well as their immediate objective. The left battalion in the attack were the 1st Gordon Highlanders, who had a most difficult task, being exposed to the heaviest fire of all. For a moment they were hung up, and then with splendid spirit threw themselves at the hostile trenches again and carried everything before them. They were much helped in this second attack by the supporting battalion, the 7th Lincolns, whose bombers rushed to the front. The 10th Welsh Fusiliers, who were supporting on the right, also did invaluable service by helping to consolidate the Bluff, while the 9th West Ridings on the left held the British front line and repulsed an attempt at a flanking counter-attack.

In spite of several counter-attacks and a very severe bombardment the line now held firm, and the Germans seem to have abandoned all future designs upon this section. They had lost very heavily in the assault, and 250 men with 5 officers remained in the hands of the victors. Some of the German trench taken was found to be untenable, but the 12th West Yorkshires of the 8th Brigade connected up the new position with the old and the salient was held. So ended a well-managed and most successful little fight. Great credit was due to a certain officer, who passed through the terrible {11} German barrage again and again to link up the troops with headquarters. Extreme gallantry was shown also by the brigade-runners, many of whom lost their lives in the all-important work of preserving communications.

Students of armour in the future may be interested to note that this was the first engagement in which British infantry reverted after a hiatus of more than two centuries to the use of helmets. Dints of shrapnel upon their surfaces proved in many cases that they had been the salvation of their wearers. Several observers have argued that trench warfare implies a special trench equipment, entirely different from that for surface operations.

In the middle of March the pressure upon the French at Verdun had become severe, and it was determined to take over a fresh section of line so as to relieve troops for the north-eastern frontier. General Foch's Tenth Army, which had held the sector opposite to Souchez and Lorette, was accordingly drawn out, and twelve miles were added to the British front. From this time forward there were four British armies, the Second (Plumer) in the Ypres district, the First (Monro) opposite to Neuve Chapelle, the Third (Allenby) covering the new French sector down to Arras, the Fourth (Rawlinson) from Albert to the Somme.

A brisk skirmish which occurred in the south about this period is worthy of mention—typical of many smaller affairs the due record of which would swell this chapter to a portentous length. In this particular instance, a very sudden and severe night attack was directed by the Germans against a post held by the 8th East Surreys of the Eighteenth {12} Division at the points where the British and French lines meet just north of the Somme. This small stronghold, known as Ducks' Post, was at the head of a causeway across a considerable marsh, and possessed a strategic importance out of all proportion to its size. A violent bombardment in the darkness of the early morning of March 20 was followed by an infantry advance, pushed well home. It was an unnerving experience. "As the Huns charged," says one who was present, "they made the most hellish screaming row I ever heard." The Surrey men under the lead of a young subaltern stood fast, and were reinforced by two platoons. Not only did they hold up the attack, but with the early dawn they advanced in turn, driving the Germans back into their trenches and capturing a number of prisoners. The post was strengthened and was firmly held.

The next episode which claims attention is the prolonged and severe fighting which took place from March 27 onwards at St. Eloi, the scene of so fierce a contest just one year before. A small salient had been formed by the German line at this point ever since its capture, and on this salient was the rising known as the Mound (not to be confounded with the Bluff), insignificant in itself since it was only twenty or thirty feet high, but of importance in a war where artillery observation is the very essence of all operations. It stood just east of the little village of St. Eloi. This place was known to be very strongly held, so the task of attacking it was handed over to the Third Division, which had already shown at the Bluff that they were adepts at such an attack. After several weeks of energetic preparation, five {13} mines were ready with charges which were so heavy that in one instance 30,000 pounds of ammonal were employed. The assault was ordered for 4.15 in the morning of March 27. It was known to be a desperate enterprise and was entrusted to two veteran battalions of regular troops, the 4th Royal Fusiliers and the 1st Northumberland Fusiliers. A frontal attack was impossible, so it was arranged that the Royals should sweep round the left flank and the Northumberlands the right, while the remaining battalions of the 9th Brigade, the 12th West Yorks and 1st Scots Fusiliers, should be in close support in the centre. At the appointed hour the mines were exploded with deadly effect, and in the pitch darkness of a cloudy rainy morning the two battalions sprang resolutely forward upon their dangerous venture. The trenches on each flank were carried, and 5 officers with 193 men of the 18th Reserve Jaeger fell into our hands. As usual, however, it was the retention of the captured position which was the more difficult and costly part of the operation. The Northumberlands had won their way round on the right, but the Fusiliers had been partially held up on the left, so that the position was in some ways difficult and irregular. The guns of the Third Division threw forward so fine a barrage that no German counter-attack could get forward, but all day their fire was very heavy and deadly upon the captured trenches, and also upon the two battalions in support. On the night of the 27th the 9th Brigade was drawn out and the 8th took over the new line, all access to it being impossible save in the darkness, as no communication trenches existed. The situation was complicated by the fact that although the British {14} troops had on the right won their way to the rear of the craters, one of these still contained a German detachment, who held on in a most heroic fashion and could not be dislodged. On March 30 the situation was still unchanged, and the 76th Brigade was put in to relieve the 8th. The 1st Gordons were now in the line, very wet and weary, but declaring that they would hold the ground at all costs. It was clear that the British line must be extended and that the gallant Germans in the crater must be overwhelmed. For this purpose, upon the night of April 2, the 8th Royal Lancasters swept across the whole debatable ground, with the result that 4 officers and 80 men surrendered at daylight to the Brigade-Major and a few men who summoned them from the lip of the crater. The Divisional General had himself gone forward to see that the captured ground was made good. "We saw our Divisional General mid-thigh in water and splashing down the trenches," says an observer. "I can tell you it put heart into our weary men." So ended the arduous labours of the Third Division, who upon April 4 handed over the ground to the 2nd Canadians. The episode of the St. Eloi craters was, however, far from being at an end. The position was looked upon as of great importance by the Germans, apart from the artillery observation, for their whole aim was the contraction, as that of the British was the expansion, of the space contained in the Ypres salient. "Elbow room! More elbow room!" was the hearts' cry of Plumer's Second Army. But the enemy grudged every yard, and with great tenacity began a series of counter-attacks which lasted with varying fortunes for several weeks.

Hardly had the Third Division filed out of the trenches when the German bombers were buzzing and stinging all down the new line, and there were evident signs of an impending counter-attack. Upon April 6 it broke with great violence, beginning with a blasting storm of shells followed by a rush of infantry in that darkest hour which precedes the dawn. It was a very terrible ordeal for troops which had up to then seen no severe service, and for the moment they were overborne. The attack chanced to come at the very moment when the 27th Winnipeg Regiment was being relieved by the 29th Vancouvers, which increased the losses and the confusion. The craters were taken by the German stormers with 180 prisoners, but the trench line was still held. The 31st Alberta Battalion upon the left of the position was involved in the fight and drove back several assaults, while a small French Canadian machine-gun detachment from the 22nd Regiment distinguished itself by an heroic resistance in which it was almost destroyed. About noon the bombardment was so terrific that the front trench was temporarily abandoned, the handful of survivors falling back upon the supports. The 31st upon the left were still able to maintain themselves, however, and after dusk they were able to reoccupy three out of the five craters in front of the line. From this time onwards the battle resolved itself into a desperate struggle between the opposing craters. During the whole of April 7 it was carried on with heavy losses to both parties. On one occasion a platoon of 40 Germans in close formation were shot down to a man as they rushed forward in a gallant forlorn hope. For three days the struggle went on, at the end of {16} which time four of the craters were still held by the Canadians. Two medical men particularly distinguished themselves by their constant passage across the open space which divided the craters from the trench. The consolidation of the difficult position was admirably carried out by the C.R.E. of the Second Canadian Division.

The Canadians were left in comparative peace for ten days, but on April 19 there was a renewed burst of activity. Upon this day the Germans bombarded heavily, and then attacked with their infantry at four different points of the Ypres salient. At two they were entirely repulsed. On the Ypres-Langemarck road on the extreme north of the British position they remained in possession of about a hundred yards of trench. Finally, in the crater region they won back two, including the more important one which was on the Mound. Night after night there were bombing attacks in this region, by which the Germans endeavoured to enlarge their gains. New Brunswick and Nova Scotia were now opposed to them and showed the same determination as the men of the West. The sector held by the veteran First Canadian Division was also attacked, the 13th Battalion having 100 casualties and the Canadian Scots 50. Altogether this fighting had been so incessant and severe, although as a rule confined to a very small front, that on an average 1000 casualties a week were recorded in the corps. The fighting was carried on frequently in heavy rain, and the disputed craters became deep pools of mud in which men fought waist deep, and where it was impossible to keep rifle or machine-gun from being fouled and clogged. Several of the smaller craters were found {17} to be untenable by either side, and were abandoned to the corpses which lay in the mire.

The Germans did not long remain in possession of the trench which they had captured upon the 19th in the Langemarck direction. Though it was almost unapproachable on account of the deep mud, a storming column of the 1st Shropshires waded out to it in the dark up to their waists in slush, and turned the enemy out with the point of the bayonet. Upon April the 21st the line was completely re-established, though a sapper is reported to have declared that it was impossible to consolidate porridge. In this brilliant affair the Shropshires lost a number of officers and men, including their gallant Colonel, Luard, and Lieutenant Johnstone, who was shot by a sniper while boldly directing the consolidation from outside the parapet without cover of any kind. The whole incident was an extraordinarily fine feat of arms which could only have been carried out by a highly disciplined and determined body of men. The mud was so deep that men were engulfed and suffocated, and the main body had to throw themselves down and distribute their weight to prevent being sucked down into the quagmire. The rifles were so covered and clogged that all shooting was out of the question, and only bombs and bayonets were available for the assault. The old 53rd never did a better day's work.

During the whole winter the Loos salient had been simmering, as it had never ceased to do since the first tremendous convulsion which had established it. In the early part of the year it was held by cavalry brigades, taking turns in succession, and during this time there was a deceptive quiet, which {18} was due to the fact that the Germans were busy in running a number of mines under the position. At the end of February the Twelfth Division took over the north of the section, and for ten weeks they found themselves engaged in a struggle which can only be described as hellish. How constant and severe it was may be gauged from the fact that without any real action they lost 4000 men during that period. As soon as they understood the state of affairs, which was only conveyed to them by several devastating explosions, they began to run their own mines and to raid those of their enemy. It was a nightmare conflict, half above ground, half below, and sometimes both simultaneously, so that men may be said to have fought in layers. The upshot of the matter, after ten weeks of fighting, was that the British positions were held at all points, though reduced to an extraordinary medley of craters and fissures, which some observer has compared to a landscape in the moon. The First Division shared with the Twelfth the winter honours of the dangerous Loos salient.

On April 27 a considerable surface attack developed on this part of the line, now held by the Sixteenth Irish Division. Early upon that day the Germans, taking advantage of the wind, which was now becoming almost as important in a land as it had once been in a sea battle, loosed a cloud of poison upon the trenches just south of Hulluch and followed it up by a rush of infantry which got possession of part of the front and support lines in the old region of the chalk-pit wood. The 49th Brigade was in the trenches. This Brigade consisted of the 7th and 8th Inniskillings, with the 7th and 8th Royal Irish. It was upon the first two battalions that the cloud of {19} gas descended, which seems to have been of a particularly deadly brew, since it poisoned horses upon the roads far to the rear. Many of the men were stupefied and few were in a condition for resistance when the enemy rushed to the trenches. Two battalions of Dublin Fusiliers, however, from the 48th Brigade were in the adjoining trenches and were not affected by the poison. These, together with the 8th Inniskillings, who were in the rear of the 7th, attacked the captured trench and speedily won it back. This was the more easy as there had been a sudden shift of wind which had blown the vile stuff back into the faces of the German infantry. A Bavarian letter taken some days later complained bitterly of their losses, which were stated to have reached 1300 from poison alone. The casualties of the Irish Division were about 1500, nearly all from gas, or shell-fire. Coming as it did at the moment when the tragic and futile rebellion in Dublin had seemed to place the imagined interests of Ireland in front of those of European civilisation, this success was most happily timed. The brunt of the fighting was borne equally by troops from the north and from the south of Ireland—a happy omen, we will hope, for the future.

Amongst the other local engagements which broke the monotony of trench life may be mentioned one upon May 11 near the Hohenzollern Redoubt where the Germans held for a short time a British trench, taking 127 of the occupants prisoners. More serious was the fighting upon the Vimy Ridge south of Souchez on May 15. About 7.30 on the evening of that day the British exploded a series of mines which, either by accident or design, were short of {20} the German trenches. The sector was occupied by the Twenty-fifth Division, and the infantry attack was entrusted to the 11th Lancashire Fusiliers and the 9th North Lancashires, both of the 74th Brigade. They rushed forward with great dash and occupied the newly-formed craters, where they established themselves firmly, joining them up with each other and cutting communications backwards so as to make a new observation trench.

The Twenty-fifth Division lay at this time with the Forty-seventh London Division as its northern neighbour, the one forming the left-hand unit of the Third Army, and the other the extreme right of the First. Upon the 19th the Londoners took over the new position from the 74th, and found it to be an evil inheritance, for upon May 21, when they were in the very act of relieving the 7th and 75th Brigades, which formed the front of the Twenty-fifth Division, they were driven in by a terrific bombardment and assault from the German lines. On the front of a brigade the Germans captured not only the new ground won but our own front line and part of our supporting line. Old soldiers declared that the fire upon this occasion was among the most concentrated and deadly of the whole War. With the new weapons artillery is not needed at such short range, for with aerial torpedoes the same effect can be produced as with guns of a great calibre.

In the early morning of April 30, there was a strong attack by the Germans at Wulverghem, which was the village to the west of Messines, to which our line had been shifted after the attack of November 2, 1914. There is no doubt that all this bustling upon the part of the Germans was partly for the purpose {21} of holding us to our ground while they dealt with the French at Verdun, and partly to provoke a premature offensive, since they well knew that some great movement was in contemplation. As a matter of fact, all the attacks, including the final severe one upon the Canadian lines, were dealt with by local defenders and had no strategic effect at all. In the case of the Wulverghem attack it was preceded by an emission of gas of such intensity that it produced much sickness as far off as Bailleul, at least six miles to the west. Horses in the distant horse lines fell senseless under the noxious vapour. It came on with such rapidity that about a hundred men of the Twenty-fourth Division were overcome before they could get on their helmets. The rest were armed against it, and repelled the subsequent infantry attacks carried out by numerous small bodies of exploring infantry, without any difficulty. The whole casualties of the Fifth Corps, whose front was attacked, amounted to 400, half by gas and half by the shells.

In May, General Alderson, who had commanded the Canadians with such success from the beginning, took over new duties and gave place to General Sir Julian Byng, the gallant commander of the Third Cavalry Division.

Upon June 2 there began an action upon the Canadian front at Ypres which led to severe fighting extending over several weeks, and put a very heavy strain upon a corps the First Division of which had done magnificent work during more than a year, whilst the other two divisions had only just eased up after the fighting of the craters. Knowing well that the Allies were about to attack, the Germans were exceedingly anxious to gain some success which would {22} compel them to disarrange their plans and to suspend that concentration of troops and guns which must precede any great effort. In searching for such a success it was natural that they should revert to the Ypres salient, which had always been the weakest portion of the line—so weak, indeed, that when it is seen outlined by the star shells at night, it seems to the spectator to be almost untenable, since the curve of the German line was such that it could command the rear of all the British trenches. It was a region of ruined cottages, shallow trenches commanded by the enemy's guns, and shell-swept woods so shattered and scarred that they no longer furnished any cover. These woods, Zouave Wood, Sanctuary Wood, and others lie some hundred yards behind the front trenches and form a rallying-point for those who retire, and a place of assembly for those who advance.

The Canadian front was from four to five miles long, following the line of the trenches. The extreme left lay upon the ruined village of Hooge. This part of the line was held by the Royal Canadian Regiment. For a mile to their right, in front of Zouave and Sanctuary Woods, the Princess Patricia's held the line over low-lying ground. In immediate support was the 49th Regiment. These all belonged to the 7th Canadian Brigade. This formed the left or northern sector of the position.

In the centre was a low hill called Mount Sorel, in which the front trenches were located. Immediately in its rear is another elevation, somewhat higher, and used as an observing station. This was Observatory Hill. A wood, Armagh Wood, covered the slope of this hill. There is about two hundred yards {23} of valley between Mount Sorel and Observatory Hill, with a small stream running down it. This section of the line was essential for the British, since in the hands of the enemy it would command all the rest. It was garrisoned by the 8th Brigade, consisting of Canadian Mounted Rifles.

The right of the Canadian line, including St. Eloi upon the extreme limit of their sector, was held by troops of the Second Canadian Division. This part of the line was not involved in the coming attack. It broke upon the centre and the left, the Mount Sorel and the Hooge positions.

The whole operation was very much more important than was appreciated by the British public at the time, and formed a notable example of anticipatory tactics upon the part of the German General Staff. Just as they had delayed the advance upon the west by their furious assault upon Verdun on the east, so they now calculated that by a fierce attack upon the north of the British line they might disperse the gathering storm which was visibly banking up in the Somme Valley. It was a bold move, boldly carried out, and within appreciable distance of success.

Their first care was to collect and concentrate a great number of guns and mine-throwers on the sector to be attacked. This concentration occurred at the very moment when our own heavy artillery was in a transition stage, some of it going south to the Somme. Hardly a gun had sounded all morning. Then in an instant with a crash and a roar several mines were sprung under the trenches, and a terrific avalanche of shells came smashing down among the astounded men. It is doubtful if a more hellish {24} storm of projectiles of every sort had ever up to that time been concentrated upon so limited a front. There was death from the mines below, death from the shells above, chaos and destruction all around. The men were dazed and the trenches both in front and those of communication were torn to pieces and left as heaps of rubble.

One great mine destroyed the loop of line held by the Princess Patricia's and buried a company in the ruins. A second exploded at Mount Sorel and did great damage. At the first outburst Generals Mercer and Williams had been hurried into a small tunnel out of the front line, but the mine explosion obliterated the mouth of the tunnel and they were only extricated with difficulty. General Mercer was last seen encouraging the men, but he had disappeared after the action and his fate was unknown to friend or foe until ten days later his body was found with both legs broken in one of the side trenches. He died as he had lived, a very gallant soldier. For four hours the men cowered down in what was left of the trenches, awaiting the inevitable infantry attack which would come from the German lines fifty yards away. When at last it came it met with little resistance, for there were few to resist. Those few were beaten down by the rush of the Würtembergers who formed the attacking division. They carried the British line for a length of nearly a mile, from Mount Sorel to the south of Hooge, and they captured about 500 men, a large proportion of whom were wounded. General Williams, Colonel Usher, and twelve other officers were taken.

When the German stormers saw the havoc in the trenches they may well have thought that they had {25} only to push forward to pierce the line and close their hands at last upon the coveted Ypres. If any such expectation was theirs, they must have been new troops who had no knowledge of the dour tenacity of the Canadians. The men who first faced poison gas without masks were not so lightly driven. The German attack was brought to a standstill by the withering rifle-fire from the woods, and though the assailants were still able to hold the ground occupied they were unable to increase their gains, while in spite of a terrific barrage of shrapnel fresh Canadian battalions, the 14th and 15th from the 3rd Canadian Brigade, were coming up from the rear to help their exhausted companions.

The evening of June 2 was spent in confused skirmishing, the advanced patrols of the Germans getting into the woods and being held up by the Canadian infantry moving up to the front. Some German patrols are said to have got as far as Zillebeke village, three-quarters of a mile in advance of their old line. By the morning of June 3 these intruders had been pushed back, but a counter-attack before dawn by the 9th Brigade was held up by artillery fire, Colonel Hay of the 52nd (New Ontario) Regiment and many officers and men being put out of action. The British guns were now hard at work, and the Würtembergers in the captured trenches were enduring something of what the Canadians had undergone the day before. About 7 o'clock the 2nd and 3rd Canadian Brigades, veterans of Ypres, began to advance, making their way through the woods and over the bodies of the German skirmishers. When the advance got in touch with the captured trenches it was held up, for the Würtembergers stood to it {26} like men, and were well supported by their gunners. On the right the 7th and 10th Canadians got well forward, but had not enough weight for a serious attack. It became clear that a premature counter-attack might lead to increased losses, and that the true method was to possess one's soul in patience until the preparation could be made for a decisive operation. The impatience and ardour of the men were very great, and their courage had a fine edge put upon it by a churlish German official communiqué, adding one more disgrace to their military annals, which asserted that more Canadian prisoners had not been taken because they had fled so fast. Canadians could smile at the insult, but it was the sort of smile that is more menacing than a frown. The infantry waited grimly while some of the missing guns were recalled into their position. Up to this time the losses had been about 80 officers and 2000 men.

The weather was vile, with incessant rain which turned the fields into bogs and the trenches into canals. For a few days things were at a standstill, for the clouds prevented aeroplane reconnaissance and the registration of the guns. The Corps lay in front of its lost trenches like a wounded bear looking across with red eyes at its stolen cub. The Germans had taken advantage of the lull to extend their line, and on June 6 they had occupied the ruins of Hooge, which were impossible to hold after all the trenches to the south had been lost. In their new line the Germans awaited the attack which they afterwards admitted that they knew to be inevitable. The British gunfire was so severe that it was very difficult for them to improve their new position.

On the 13th the weather had moderated and all {27} was ready for the counter-attack. It was carried out at two in the morning by two composite brigades. The 3rd (Toronto) and 7th Battalions led upon the right, while the 13th (Royal Highlanders) and 16th (Canadian Scots) were in the van of the left, with their pipers skirling in front of them. Machine-guns supported the whole advance. The right flank of the advance, being exposed to the German machine-guns, was shrouded by the smoke of 200 bombs. The night was a very dark one and the Canadian Scots had taken advantage of it to get beyond the front line, and, as it proved, inside the German barrage zone, so that heavy as it was it did them no scathe. The new German line was carried with a magnificent rush, and a second heave lifted the wave of stormers into the old British trenches—or the place where they had been. Nine machine-guns and 150 prisoners from the 119th, 120th, 125th, and 127th Würtemberg Regiments were captured. To their great joy the Canadians discovered that such munitions as they had abandoned upon June 2 were still in the trenches and reverted into their hands. It is pleasant to add that evidence was found that the Würtembergers had behaved with humanity towards the wounded. From this time onwards the whole Canadian area from close to Hooge (the village still remained with the enemy) across the front of the woods, over Mount Sorel, and on to Hill 60, was consolidated and maintained. Save the heavy reciprocal losses neither side had anything to show for all their desperate fighting, save that the ruins of Hooge were now German. The Canadian losses in the total operations came to about 7000 men—a figure which is eloquent as to the severity of the fighting. They emerged {28} from the ordeal with their military reputation more firmly established than ever. Ypres will surely be a place of pilgrimage for Canadians in days to come, for the ground upon the north of the city and also upon the south-east is imperishably associated with the martial traditions of their country. The battle just described is the most severe action between the epic of Loos upon the one side, and that tremendous episode in the south, upon the edge of which we are now standing.

There is one other happening of note which may in truth be taken as an overture of that gigantic performance. This was the action of the Seventeenth Corps upon June 30, the eve of the Somme battle, in which the Thirty-ninth Division, supported by guns from the Thirty-fifth and Fifty-first Divisions upon each side of it, attacked the German trenches near Richebourg at a spot known as the Boar's Head. The attack was so limited in the troops employed and so local in area that it can only be regarded as a feint to take the German attention from the spot where the real danger was brewing.

After an artillery preparation of considerable intensity, the infantry assault was delivered by the 12th and 13th Royal Sussex of the 116th Brigade. The scheme was that they should advance in three waves and win their way to the enemy support line, which they were to convert into the British front line, while the divisional pioneer battalion, the 13th Gloster, was to join it up to the existing system by new communication trenches. For some reason, however, a period of eleven hours seems to have elapsed between the first bombardment and the actual attack. The latter was delivered at three {29} in the morning after a fresh bombardment of only ten minutes. So ready were the Germans that an observer has remarked that had a string been tied from the British batteries to the German the opening could not have been more simultaneous, and they had brought together a great weight of metal. Every kind of high explosive, shrapnel, and trench mortar bombs rained on the front and support line, the communication trenches and No Man's Land, in addition to a most hellish fire of machine-guns. The infantry none the less advanced with magnificent ardour, though with heavy losses. On occupying the German front line trenches there was ample evidence that the guns had done their work well, for the occupants were lying in heaps. The survivors threw bombs to the last moment, and then cried, "Kamerad!" Few of them were taken back. Two successive lines were captured, but the losses were too heavy to allow them to be held, and the troops had eventually under heavy shell-fire to fall back on their own front lines. Only three officers came back unhurt out of the two battalions, and the losses of rank and file came to a full two-thirds of the number engaged. "The men were magnificent," says one who led them, but they learned the lesson which was awaiting so many of their comrades in the south, that all human bravery cannot overcome conditions which are essentially impossible. A heavy German bombardment continued for some time, flattening out the trenches and inflicting losses, not only upon the 39th but upon the 51st Highland Territorial Division. This show of heavy artillery may be taken as the most pleasant feature in the whole episode, since it shows that its object was attained at least to the very important {30} extent of holding up the German guns. Those heavy batteries upon the Somme might well have modified our successes of the morrow.

A second attack made with the same object of distracting the attention of the Germans and holding up their guns was made at an earlier date at a point called the triangle opposite to the Double Grassier near Loos. This attack was started at 9.10 upon the evening of June 10, and was carried out in a most valiant fashion by the 2nd Rifles and part of the 2nd Royal Sussex, both of the 2nd Brigade. There can be no greater trial for troops, and no greater sacrifice can be demanded of a soldier, than to risk and probably lose his life in an attempt which can obviously have no permanent result, and is merely intended to ease pressure elsewhere. The gallant stormers reached and in several places carried the enemy's line, but no lasting occupation could be effected, and they had eventually to return to their own line. The Riflemen, who were the chief sufferers, lost 11 officers and 200 men.

A word should be said as to the raids along the line of the German trenches by which it was hoped to distract their attention from the point of attack, and also to obtain precise information as to the disposition of their units. It is difficult to say whether the British were the gainers, or the losers on balance in these raids, for some were successful, while some were repelled. Among a great number of gallant attempts, the details of which hardly come within the scale of this chronicle, the most successful perhaps were two made by the 9th Highland Light Infantry and by the 2nd Welsh Fusiliers, both of the Thirty-third Division. In both of these cases very extensive damage was done and numerous prisoners were taken. {31} When one reads the intimate accounts of these affairs, the stealthy approaches, the blackened faces, the clubs and revolvers which formed the weapons, the ox-goads for urging Germans out of dug-outs, the dark lanterns and the knuckle-dusters—one feels that the age of adventure is not yet past and that the spirit of romance was not entirely buried in the trenches of modern war. There were 70 such raids in the week which preceded the great attack.

Before plunging into the huge task of following and describing the various phases of the mighty Battle of the Somme a word must be said upon the naval history of the period which can all be summed up in the Battle of Jutland, since the situation after that battle was exactly as it had always been before it. This fact in itself shows upon which side the victory lay, since the whole object of the movements of the German Fleet was to produce a relaxation in these conditions. Through the modesty of the British bulletins, which was pushed somewhat to excess, the position for some days was that the British, who had won everything, claimed nothing, while the Germans, who had won nothing, claimed everything. It is true that a number of our ships were sunk and of our sailors drowned, including Hood and Arbuthnot, two of the ablest of our younger admirals. Even by the German accounts, however, their own losses in proportion to their total strength were equally heavy, and we have every reason to doubt their accounts since they not only do not correspond with reliable observations upon our side, but because their second official account was compelled to admit that their first one had been false. The whole affair may be summed up by saying that after making an excellent {32} fight they were saved from total destruction by the haze of evening, and fled back in broken array to their ports, leaving the North Sea now as always in British keeping. At the same time it cannot be denied that here as at Coronel and the Falklands the German ships were well fought, the gunnery was good, and the handling of the fleet, both during the battle and especially under the difficult circumstances of the flight in the darkness to avoid a superior fleet between themselves and home, was of a high order. It was a good clean fight, and in the general disgust at the flatulent claims of the Kaiser and his press the actual merit of the German performance did not perhaps receive all the appreciation which it deserved.

Attack of the Seventh and Eighth Corps on

Gommecourt, Serre, and Beaumont Hamel

Line of battle in the Somme sector—Great preparations—Advance of Forty-sixth North Midland Division—Advance of Fifty-sixth Territorials (London)—Great valour and heavy losses—Advance of Thirty-first Division—Advance of Fourth Division—Advance of Twenty-ninth Division—Complete failure of the assault.

The continued German pressure at Verdun which had reached a high point in June called insistently for an immediate allied attack at the western end of the line. With a fine spirit of comradeship General Haig had placed himself and his armies at the absolute disposal of General Joffre, and was prepared to march them to Verdun, or anywhere else where he could best render assistance. The solid Joffre, strong and deliberate, was not disposed to allow the western offensive to be either weakened or launched prematurely on account of German attacks at the eastern frontier. He believed that Verdun could for the time look after herself, and the result showed the clearness of his vision. Meanwhile, he amassed a considerable French army, containing many of his best active troops, on either side of the Somme. General Foch was in command. They formed the right wing of the {34} great allied force about to make a big effort to break or shift the iron German line, which had been built up with two years of labour, until it represented a tangled vista of trenches, parapets, and redoubts mutually supporting and bristling with machine-guns and cannon, for many miles of depth. Never in the whole course of history have soldiers been confronted with such an obstacle. Yet from general to private, both in the French and in the British armies, there was universal joy that the long stagnant trench life should be at an end, and that the days of action, even if they should prove to be days of death, should at last have come. Our concern is with the British forces, and so they are here set forth as they stretched upon the left or north of their good allies.

The southern end of the whole British line was held by the Fourth Army, commanded by General Rawlinson, an officer who has always been called upon when desperate work was afoot. His army consisted of five corps, each of which included from three to four divisions, so that his infantry numbered about 200,000 men, many of whom were veterans, so far as a man may live to be a veteran amid the slaughter of such a campaign. The Corps, counting from the junction with the French, were, the Thirteenth (Congreve), Fifteenth (Horne), Third (Pulteney), Tenth (Morland), and Eighth (Hunter-Weston). Their divisions, frontage, and the objectives will be discussed in the description of the battle itself.

BRITISH BATTLE LINE July 1st 1916

North of Rawlinson's Fourth Army, and touching it at the village of Hébuterne, was Allenby's Third Army, of which one single corps, the Seventh (Snow), was engaged in the battle. This added three {36} divisions, or about 30,000 infantry, to the numbers quoted above.

It had taken months to get the troops into position, to accumulate the guns, and to make the enormous preparations which such a battle must entail. How gigantic and how minute these are can only be appreciated by those who are acquainted with the work of the staffs. As to the Chief Staff of all, if a civilian may express an opinion upon so technical a matter, no praise seems to be too high for General Kiggell and the others under the immediate direction of Sir Douglas Haig, who had successively shown himself to be a great Corps General, a great Army leader, and now a great General-in-Chief. The preparations were enormous and meticulous, yet everything ran like a well-oiled piston-rod. Every operation of the attack was practised on similar ground behind the lines. New railheads were made, huge sidings constructed, and great dumps accumulated. The corps and divisional staffs were also excellent, but above all it was upon those hard-worked and usually overlooked men, the sappers, that the strain fell. Assembly trenches had to be dug, double communication trenches had to be placed in parallel lines, one taking the up-traffic and one the down, water supplies, bomb shelters, staff dug-outs, poison-gas arrangements, tunnels and mines—there was no end to the work of the sappers. The gunners behind laboured night after night in hauling up and concealing their pieces, while day after day they deliberately and carefully registered upon their marks. The question of ammunition supply had assumed incredible proportions. For the needs of one single corps forty-six miles of motor-lorries were engaged in bringing up {37} the shells. However, by the end of June all was in place and ready. The bombardment began about June 23, and was at once answered by a German one of lesser intensity. The fact that the attack was imminent was everywhere known, for it was absolutely impossible to make such preparations and concentrations in a secret fashion. "Come on, we are ready for you," was hoisted upon placards on several of the German trenches. The result was to show that they spoke no more than the truth.

There were limits, however, to the German appreciation of the plans of the Allies. They were apparently convinced that the attack would come somewhat farther to the north, and their plans, which covered more than half of the ground on which the attack actually did occur, had made that region impregnable, as we were to learn to our cost. Their heaviest guns and their best troops were there. They had made a far less elaborate preparation, however, at the front which corresponded with the southern end of the British line, and also on that which faced the French. The reasons for this may be surmised. The British front at that point is very badly supplied with roads (or was before the matter was taken in hand), and the Germans may well have thought that no advance upon a great scale was possible. So far as the French were concerned they had probably over-estimated the pre-occupation of Verdun and had not given our Allies credit for the immense reserve vitality which they were to show. The French front to the south of the Somme was also faced by a great bend of the river which must impede any advance. Then again it is wooded, broken country down there, and gives good concealment for masking an operation. These {38} were probably the reasons which induced the Germans to make a miscalculation which proved to be an exceedingly serious one, converting what might have been a German victory into a great, though costly, success for the Allies, a prelude to most vital results in the future.

It is, as already stated, difficult to effect a surprise upon the large scale in modern warfare. There are still, however, certain departments in which with energy and ingenuity effects may be produced as unforeseen as they are disconcerting. The Air Service of the Allies, about which a book which would be one long epic of heroism could be written, had been growing stronger, and had dominated the situation during the last few weeks, but it had not shown its full strength nor its intentions until the evening before the bombardment. Then it disclosed both in most dramatic fashion. Either side had lines of stationary airships from which shell-fire is observed. To the stranger approaching the lines they are the first intimation that he is in the danger area, and he sees them in a double row, extending in a gradually dwindling vista to either horizon. Now by a single raid and in a single night, every observation airship of the Germans was brought in flames to the earth. It was a splendid coup, splendidly carried out. Where the setting sun had shone on a long German array the dawn showed an empty eastern sky. From that day for many a month the Allies had command of the air with all that it means to modern artillery. It was a good omen for the coming fight, and a sign of the great efficiency to which the British Air Service under General Trenchard had attained. The various types for scouting, for artillery work, {39} for raiding, and for fighting were all very highly developed and splendidly handled by as gallant and chivalrous a band of heroic youths as Britain has ever enrolled among her guardians. The new F.E. machine and the de Haviland Biplane fighting machine were at this time equal to anything the Germans had in the air.

The attack had been planned for June 28, but the weather was so tempestuous that it was put off until it should moderate, a change which was a great strain upon every one concerned. July 1 broke calm and warm with a gentle south-western breeze. The day had come. All morning from early dawn there was intense fire, intensely answered, with smoke barrages thrown during the last half-hour to such points as could with advantage be screened. At 7.30 the guns lifted, the whistles blew, and the eager infantry were over the parapets. The great Battle of the Somme, the fierce crisis of Armageddon, had come. In following the fate of the various British forces during this eventful and most bloody day we will begin at the northern end of the line, where the Seventh Corps (Snow) faced the salient of Gommecourt.

This corps consisted of the Thirty-seventh, Forty-sixth, and Fifty-sixth Divisions. The former was not engaged and lay to the north. The others were told off to attack the bulge on the German line, the Forty-sixth upon the north, and the Fifty-sixth upon the south, with the village of Gommecourt as their immediate objective. Both were well-tried and famous territorial units, the Forty-sixth North Midland being the division which carried the Hohenzollern Redoubt upon October 13, 1915, while the Fifty-sixth was made up of the old London territorial battalions, {40} which had seen so much fighting in earlier days while scattered among the regular brigades. Taking our description of the battle always from the north end of the line we shall begin with the attack of the Forty-sixth Division.

The assault was carried out by two brigades, each upon a two-battalion front. Of these the 137th Brigade of Stafford men were upon the right, while the 139th Brigade of Sherwood Foresters were on the left, each accompanied by a unit of sappers. The 138th Brigade, less one battalion, which was attached to the 137th, was in reserve. The attack was covered so far as possible with smoke, which was turned on five minutes before the hour. The general instructions to both brigades were that after crossing No Man's Land and taking the first German line they should bomb their way up the communication trenches, and so force a passage into Gommecourt Wood. Each brigade was to advance in four waves at fifty yards interval, with six feet between each man. Warned by our past experience of the wastage of precious material, not more than 20 officers of each battalion were sent forward with the attack, and a proportional number of N.C.O.'s were also withheld. The average equipment of the stormers, here and elsewhere, consisted of steel helmet, haversack, water-bottle, rations for two days, two gas helmets, tear-goggles, 220 cartridges, two bombs, two sandbags, entrenching tool, wire-cutters, field dressings, and signal-flare. With this weight upon them, and with trenches which were half full of water, and the ground between a morass of sticky mud, some idea can be formed of the strain upon the infantry.

Both the attacking brigades got away with splendid steadiness upon the tick of time. In the case of the 137th Brigade the 6th South Staffords and 6th North Staffords were in the van, the former being on the right flank where it joined up with the left of the Fifty-sixth Division. The South Staffords came into a fatal blast of machine-gun fire as they dashed forward, and their track was marked by a thick litter of dead and wounded. None the less, they poured into the trenches opposite to them but found them strongly held by infantry of the Fifty-second German Division. There was some fierce bludgeon work in the trenches, but the losses in crossing had been too heavy and the survivors were unable to make good. The trench was held by the Germans and the assault repulsed. The North Staffords had also won their way into the front trenches, but in their case also they had lost so heavily that they were unable to clear the trench, which was well and stoutly defended. At the instant of attack, here as elsewhere, the Germans had put so terrific a barrage between the lines that it was impossible for the supports to get up and no fresh momentum could be added to the failing attack.

The fate of the right attack had been bad, but that of the left was even worse, for at this point we had experience of a German procedure which was tried at several places along the line with most deadly effect, and accounted for some of our very high losses. This device was to stuff their front line dug-outs with machine-guns and men, who would emerge when the wave of stormers had passed, attacking them from the rear, confident that their own rear was safe on account of the terrific barrage between the lines. {42} In this case the stormers were completely trapped. The 5th and 7th Sherwood Foresters dashed through the open ground, carried the trenches and pushed forward on their fiery career. Instantly the barrage fell, the concealed infantry rose behind them, and their fate was sealed. With grand valour the leading four waves stormed their way up the communication trenches and beat down all opposition until their own dwindling numbers and the failure of their bombs left them helpless among their enemies. Thus perished the first companies of two fine battalions, and few survivors of them ever won their way back to the British lines. Brave attempts were made during the day to get across to their aid, but all were beaten down by the terrible barrage. In the evening the 5th Lincolns made a most gallant final effort to reach their lost comrades, and got across to the German front line which they found to be strongly held. So ended a tragic episode. The cause which produced it was, as will be seen, common to the whole northern end of the line, and depended upon factors which neither officers nor men could control, the chief of which were that the work of our artillery, both in getting at the trench garrisons and in its counter-battery effects had been far less deadly than we had expected. The losses of the division came to about 2700 men.

The attack upon the southern side of the Gommecourt peninsula, though urged with the utmost devotion and corresponding losses, had no more success than that in the north. There is no doubt that the unfortunate repulse of the 137th Brigade upon their left, occurring as it did while the Fifty-sixth Division was still advancing, enabled the {43} Germans to concentrate their guns and reserves upon the Londoners, but knowing what we know, it can hardly be imagined that under any circumstances, with failure upon either side of them, the division could have held the captured ground. The preparations for the attack had been made with great energy, and for two successive nights as many as 3000 men were out digging between the lines, which was done with such disciplined silence that there were not more than 50 casualties all told. The 167th Brigade was left in reserve, having already suffered heavily while holding the water-logged trenches during the constant shell-fall of the last week. The 7th Middlesex alone had lost 12 officers and 300 men from this cause—a proportion which may give some idea of what the heavy British bombardment may have meant to the Germans. The advance was, therefore, upon a two-brigade front, the 168th being on the right and the 169th upon the left. The London Scottish and the 12th London Rangers were the leading battalions of the 168th, while the Westminsters and Victorias led the 169th with the 4th London, 13th Kensingtons, 2nd London and London Rifle Brigade in support. The advance was made with all the fiery dash with which the Cockney soldiers have been associated. The first, second, and third German lines of trench were successively carried, and it was not until they, or those of them who were left, had reached the fourth line that they were held. It was powerfully manned, bravely defended, and well provided with bombs—a terrible obstacle for a scattered line of weary and often wounded men. The struggle was a heroic one. Even now had their rear been clear, or had there been a shadow of support {44} these determined men would have burst the only barrier which held them from Gommecourt. But the steel curtain of the barrage had closed down behind them, and every overrun trench was sending out its lurking occupants to fire into their defenceless backs. Bombs, too, are essential in such a combat, and bombs must ever be renewed, since few can be carried at a time. For long hours the struggle went on, but it was the pitiful attempt of heroic men to postpone that retreat which was inevitable. Few of the advanced line ever got back. The 3rd London, particularly, sent forward several hundred men with bombs, but hardly any got across. Sixty London Scots started on the same terrible errand. In the late afternoon the remains of the two brigades were back in the British front line, having done all, and more than all, that brave soldiers could be expected to do. The losses were very heavy. Never has the manhood of London in one single day sustained so grievous a loss. It is such hours which test the very soul of the soldier. War is not all careless slang and jokes and cigarettes, though such superficial sides of it may amuse the public and catch the eye of the descriptive writer. It is the most desperately earnest thing to which man ever sets his hand or his mind. Many a hot oath and many a frenzied prayer go up from the battle line. Strong men are shaken to the soul with the hysteria of weaklings, and balanced brains are dulled into vacancy or worse by the dreadful sustained shock of it. The more honour then to those who, broken and wearied, still hold fast in the face of all that human flesh abhors, bracing their spirits by a sense of soldierly duty and personal honour which is strong enough to prevail over death itself.