The Project Gutenberg eBook of Inheritance, by Edward W. Ludwig

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online

at

www.gutenberg.org. If you

are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the

country where you are located before using this eBook.

Title: Inheritance

Author: Edward W. Ludwig

Release Date: April 09, 2021 [eBook #65035]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

Produced by: Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK INHERITANCE ***

He had been in the cave for only a short time it

seemed. But when he finally emerged the world he

knew was gone. And it had left him with a strange—

INHERITANCE

By Edward W. Ludwig

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Imagination Stories of Science and Fantasy

October 1950

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

It shone as a pin-point of silver far away in the midnight-blackness of

the cave. It shone as a tiny island of life in a sea of death. It shone

as a symbol of His mercy.

Martin stood swaying, staring wide-eyed at that wonderful light and

letting its image sink deep into his vision. His eyes lidded as

consciousness faded for an instant, then opened.

"We've almost made it," he gasped. "We've almost made it, Sandy, you

and me and the pup!"

His hand passed tenderly over the puppy, a soft, hairy ball of living

warmth cradled in his arm. And from out of the darkness at his feet

came a feeble bark.

Martin choked on the ancient, tomb-stale air. "We can't stop now,

Sandy," he wheezed. "We're almost there, almost at the entrance!"

He shuffled forward over the cold stone floor of the little cave, the

thick, dead air a solid thing, a wall that pressed him back, back, back.

But the light grew larger, expanding like a balloon, and suddenly

there was a skittering of dog-paws over stone and a joyous, frantic

barking.

"That's right, Sandy, go ahead. Breathe that air, that fresh air!"

Martin staggered once, his lean, tall body thudding against sharp rock

in the side of the cave. Then a draft of air blew cool and fresh into

his face, and a strength returned to him.

Abruptly, he was at the source of the light, at the cave's entrance, a

hole barely large enough for him to squeeze through. The blinding light

of day fell upon him like a gigantic, crashing sea wave. He closed his

aching eyes and fell to the side of the rock-strewn hill, sucking the

clean sweet air deep into his lungs.

At length he sat up, holding the pup in his arms. "Two days in that

hole of hell," he murmured, "and it's all your fault. A month old, and

you have to start exploring caves."

He cocked his head. "Still, I guess it's partly my fault. After all, I

got lost, too."

Sandy, a black and white fox terrier, barked impatiently.

"Okay, Sandy, okay. We'll go home."

Shakily, Martin rose. His mind was clear now, the fogginess washed away

by the cool morning air. There was only hunger, that great gnawing

hunger, and thirst that made his throat and mouth seem as dry as

ancient parchment.

As he stood overlooking the valley below with its green fields and

little groves of trees, a realization came to him. The world wasn't

so bad after all! Up to this moment, he'd almost hated the world

with its wars, its threats of mass destruction, its warnings of

atomic dusts and plagues that could wipe out humanity within an hour.

He'd most certainly hated the cities with their blaring, rumbling

automobile-monsters, with their mad rushing, their greedy, frantic,

senseless, superficial living that was really not living at all.

That was why he had chosen to live in the hill country, on the

outskirts of the village, raising his few vegetables and making a trip

every few days to the village store to purchase other necessities with

his pension check from World War II.

But now, he realized, it was good to be alive and to be a part of the

green, growing things of Earth.

Sandy barked again.

"Okay, okay, Sandy. We'll go."

But Sandy came sidling up to him now, tail between his legs. His

barking faded to a low, shrill whimper.

"Sandy! What's the matter? What's wrong?"

Even the whimpering ceased, and there was silence. Martin stared at

the dog, not understanding. To him came a feeling. Something was

wrong. A nameless fear rose within him, but the cause of that fear was

intangible, locked just below the surface of consciousness.

He took the fear, crushed it, pushed it back into the caverns of his

mind that held only forgotten things. "Nothing's wrong," he declared

boldly. "We're just tired and hungry, that's all."

He strode down the quiet hillside toward the broad highway that

stretched across the valley. He sang:

"We're happy, so happy,

Don't want to reach a star;

We're happy, always happy,

Just the way we are."

Strange about that tune, he thought. He hated popular music, but in

a regrettable moment of optimism he'd once purchased a second-hand

battery video. After a three-day saturation with tooth paste and soap

commercials he'd consigned the monstrosity to a remote corner of the

woods, but that tune—of all the dubious products of civilization—had

somehow stuck in his memory.

Suddenly he stopped singing, as if some inexplicable pressure had

seized his throat, stopping the flow of words. It was quiet—so

incredibly, alarmingly, terrifyingly quiet. Just ahead of him was the

highway, its gray smooth ribbon clearly visible through a thin wall of

elms. But there was no swish-swish of speeding cars.

And there were no bird twitterings and no insect hummings and no

skitterings of squirrels at the bases of trees and no droning of

gyro-planes. There was only silence.

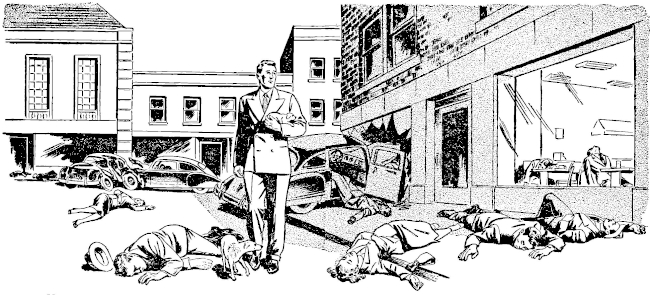

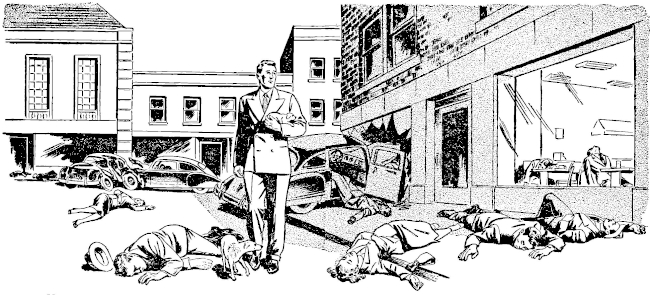

He broke out onto the highway which was dotted with cars, and the cars

were motionless. Some of them were crushed, charred wrecks on the side

of the road; some had collided in the center of the road to become ugly

little mountains of twisted metal, and others were simply parked. But

all were motionless.

"Come on, Sandy. Something's happened!"

Sandy wouldn't come. He arched his trembling body across Martin's legs,

whimpering. Martin picked him up. Sandy in one arm, the drowsy-eyed pup

in the other, he walked to the nearest car, which appeared undamaged.

There were three occupants. A man, a woman, a girl-child, and they were

as if sleeping. No wounds, no discolorations were on their flesh. But

their flesh was cold, cold, and there were no heart beats. They were

dead.

"We—We won't go home yet," Martin said softly. "We'll go to the

village."

He walked. He walked past a hundred, a thousand silent cars with silent

occupants, past green meadows that were dotted with silent, fallen

cattle and sheep and horses.

There was a new fear within him now, but even greater than the fear was

a numbness that like a sleep-producing drug had dulled mind and vision

and hearing. He walked stiffly, automatically. He was afraid to think

and reason, for thought and reason could bring only—madness.

"At the village we'll find out what happened," he mumbled.

At the village he found out—nothing. Because there, too, was only a

silence and the white, still people.

"Perhaps in the city—" he murmured. "Yes, the city."

The City was 20 miles away, and he selected an automobile, one in which

there were no still people. It had been a long time since he'd driven,

nearly ten years, but after a few moments of fumbling, remembrance

came easily. With Sandy and the pup on the front seat beside him, he

drove....

The City was as empty as an ancient skull. There was no life and no

reminder of life. There were no still people and no automobiles and no

movement and no sound. The towering white office buildings, the broad

avenues, the theatres, the parks—all seemed hollow and unreal, like a

desert mirage that would dissolve into nothingness at the whispering

touch of a breeze.

Martin mumbled, "I reckon, Sandy, that everybody left the City. They

headed for the country. That's why we passed so many cars."

He spied the office of The Times. "Maybe we can find out something in

there," he said. "Come on, Sandy. Pup, you stay here."

He parked the car and strode into the building, past desks, cabinets,

typewriters, stacked bundles of newspapers.

Then he saw the man. He was one of the silent men, sprawled back in a

chair, a typewriter before him. He had been writing, evidently, for one

stiff, white hand was still poised over the keys.

Martin read the typewritten words aloud:

"The enemy had apparently underestimated the power of the odorless,

tasteless gas. A Nitrogen compound of extreme volutility, it has

reached virtually every inch of the Earth. The enemy is destroyed as we

are destroyed. Gas masks and air filters have proved useless. The gas

is highly unstable and should disintegrate within 48 hours, yet because

of the suddenness of the attack, we can conclude only that humanity

is—" The message broke off.

Suddenly the newsroom was like a tomb, a burial of all mankind's

accomplishments and frustrations, his good-doings and evil-doings. Here

into this room had flowed, ceaseless as a river, the stories of man's

love, hate, struggle, fear, grasping, success, and disappointment. Side

by side they lay in the labyrinth of files, the stories of Mrs. Smith's

divorce and a dictator's defeat, the sagas of a child losing a pet and

a scientist discovering a star. All equal now, as skeletons of great

men and little men are equal, all buried in steel drawers and sealed by

silence.

Martin looked at the stiffened figure of the reporter. "I wonder

why you stayed," he mused. "I wonder why you didn't flee like the

others. Maybe, maybe you wanted to write the last news story ever

written—and the most important one. Yes, I reckon that was it."

Slowly, Martin walked out of the building and slid into the car. Sandy

welcomed him with a joy-filled barking and tail-wagging and tried to

lick his face, and the pup attempted to waddle across his legs.

"No, Sandy, don't." He stared unseeingly through the windshield.

"Everybody's gone, Sandy, everybody on Earth, except me." His eyes

widened slightly. "Course, there might be somebody else, somewhere.

The gas never got to us in the cave. Maybe somebody else escaped,

somehow."

He shook his head. "Nope, no use hoping for that. Odds'd be a thousand

to one 'gainst my finding 'em. No, we just got to make up our minds

that we're the last ones alive."

The last ones alive. The thought was like flame in his mind. The

numbness was gone now, as coldness thaws from a warmed body, but there

came to him a second thought, a horrible, fear-born thought which he

dared not say aloud, even to Sandy.

A man can't live alone, without hearing another human voice, without

seeing another human form. A man isn't made that way. You've got two

choices now, just two: Suicide or madness. Which will it be? Suicide or

madness, suicide or madness....

He sat for a long, long time, his mind a jumble of indecision. Then at

last he thought, I don't want to go mad, the other way is best. We'll

make it easy. Carbon monoxide would be the easiest way.

But suddenly there was a churning and a twisting in his stomach, as

though it were being squeezed by a giant hand.

"Golly, Sandy, we forgot to eat. And we haven't eaten for two days."

And to himself he said, This'll be our last meal, the last we'll ever

have.

He took the pup in his arms and Sandy followed. He spied a huge sign

not far away—Cafe Royale. It was a magnificent restaurant, the

carpeted, canopied entrance reminding him of the front of a sultan's

palace. Three days ago—if he'd been foolish enough to come to the City

then—he'd have rushed past it with his hand protecting his pocketbook,

hardly daring to look within lest the stiff-shirted, high-chinned

waiters and patrons think him a country bumpkin.

But now—well, why not?

He ambled through the vast dining hall with its multitude of

white-clothed tables, its potted palms, its modernistic, chromium bar.

The high walls were decorated with soft-hued, multi-colored murals

depicting the rise of Western Civilization—first, the pioneers, the

cowboys, then a factory scene and a war scene, and finally a group of

spacemen entering a moon-bound rocket.

Martin made a wheezing sound of admiration. "What a place, eh, Sandy?

We should have come here a long time ago."

Then he spied the juke box. "There's one of them music machines—and

it's lit up. Reckon the power's still on."

Martin had always wanted to play a juke box, but nickels, back home,

were scarce. He pursed his lips. "Why not, Sandy? Nickels don't mean

much now, and if this is going to be our last meal, we might as well

enjoy it."

He inserted a quarter, and after a few moments of pushing this and

that button, music played. It was "Song of The Stars," the latest

hit, vibrant, full, rhythmic—not at all like the screeching from the

second-hand video he'd owned once.

While he listened, he strode to the bar. Not that he was a drinking

man. He occasionally had a cold beer on Saturday evening; that was

all. But now, with that dazzling array of bottles glittering before

him—"Nobody'll miss it now," he told Sandy.

He poured himself three fingers of Scotch and downed it thirstily.

"Ahhhh! Been a long time since I had anything like that. Now let's see

what's in that kitchen."

Electricity was still on. Refrigerators were humming, and Martin's gaze

wandered appraisingly over red, juicy T-bones, over dressed chickens,

turkeys, rabbits, hams.

"Reckon we're too hungry to wait for chicken," he drawled. "Guess

T-bones'd be nice for a last meal. How about it, Sandy?"

Sandy barked.

Dinner was soon ready. Fried T-bone, mashed potatoes and dark

gravy, caviar, some kind of soup with a fishy taste, apple pie with

strawberry ice cream, chocolate cake with vanilla ice cream, maple nut,

tuiti-fruiti and pineapple ice cream, and coffee.

Martin settled back and puffed on a 50c cigar. "You know, Sandy, it

wouldn't always be like this. In a couple of weeks there won't be any

more power. Food will spoil, there'll be only canned stuff."

He frowned thoughtfully. Perhaps he'd been wrong. Perhaps suicide was

not the best way. He could have a few pleasures in the next day or

two—if madness didn't come. And if madness did start to come, well....

It was a sleek, streamlined jet job, the automobile of automobiles. Not

an antiquated monstrosity like the '51 coupe he'd been driving.

He stared through the window at its tear-drop lines, at its broad,

transparent top, at the shiny chrome and gold.

"We shouldn't be thinking about such things, Sandy. We should be

thinking about all those people, those poor people who died. All the

men and women and children—"

For an instant, grief welled up within him, a cold, almost sickening

grief. But abruptly, it became an impersonal, remote kind of grief.

It was like a Fourth of July rocket shooting out a blinding tail of

crimson and then bursting, its body crumbling into a thousand pieces, a

thousand tiny sparks falling and fading and dying.

"Still, they knew it was coming, didn't they, Sandy? And they didn't

try very hard to stop it."

He looked again at the car. "Reckon it won't do any harm to see how it

runs. After all, if we're goin' mad, we might as well enjoy ourselves

first."

The window display in the sport shop fascinated him. There were guns

and fishing rods and fur-lined jackets and shiny boots and bright

woolen shirts and sun goggles and camp stoves and—

"Don't reckon the guns'd do us much good," Martin murmured, "seein' as

how there's nothing left alive—'cept us. Might be fun to shoot 'em

though. I remember when I was a kid, how I used to shoot windows out of

old houses." He chuckled softly.

His gaze traveled to the fishing equipment. "Golly, Sandy, I'll bet

there's fish left in the oceans! The gas never touched us there in the

cave. I'll bet the fish—or a lot of 'em—escaped, too!"

He glanced disapprovingly at his thin, faded shirt, dirty khaki

trousers, and worn, scuffed shoes. Those clean, bright, woolen clothes

in the window would be nice, very nice, on cool nights.

"Might even have dog clothes in there," he said. "Maybe a dog sweater.

How'd you like that, Sandy?"

Sandy barked eagerly.

He squatted on the floor of the travel office, surrounded by a sea

of crisp, gaudy-colored posters and pamphlets. What a place this old

Earth was! The pyramids of Egypt, the Tower of London, the Washington

Monument, the Florida Everglades, the Arch of Triumph, the Eiffel

Tower, Yosemite Valley, Boulder Dam, the Wall of China, Yellowstone

Park, Suez Canal, Panama Canal, Niagara. Why, it would take a lifetime

to see them all!

"You know, Sandy, if a man didn't go mad from being alone, he could

see a lot of things. He could travel anywhere on this continent in a

car. If something went wrong, he could get parts out of other cars,

get gas out of other tanks. There's plenty of canned food everywhere,

'nough to last a lifetime—a dozen lifetimes. Why, he could walk right

into Washington, right into the White House and see how the President

lived, or go to Hollywood and see how they used to make pictures, or

go to them telescope places and look at the stars. Course, there'd be

bodies almost everywhere, but in a year or so they'd be gone, all 'cept

the bones which never hurt nobody."

He scratched his neck thoughtfully. "Why, you wouldn't have to stay on

this continent even. You could find a little boat and sail up the coast

to Alaska and then cut across to Asia. It's only fifty miles, they say.

And then you could go down to China and India and Africa and Europe.

Why, a man could go any place in the world alone!"

Sandy began to lick his face and the pup released a nervous, eager bark

that was more like "Yip! Yip!" than a bark.

"That's right, Sandy. I'm not alone, am I? No more than I ever was,

really. Never liked to talk to people anyway. You're only two years

old, you'll live for ten, maybe twelve years yet, you and the pup.

Maybe longer than I will."

He rose, frowning. It was strange. There was a grief and a loneliness

within him and he knew they would be within him forever. But, too,

there was an ever-growing peace and contentment and a satisfaction, and

a sense of still belonging to Earth and being a part of it. Strangest

of all, he realized that there was no madness in his mind and no seed

of madness. He felt like a boy again, about to begin a wondrous journey

through unexplored and enchanted lands to discover new marvels.

He left the travel office, Sandy and the pup barking and clammering at

his heels, and he was singing:

"We're happy, so happy,

Don't want to reach a star;

We're happy, always happy,

Just the way we are...."

*** END OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK INHERITANCE ***

Updated editions will replace the previous one—the old editions will

be renamed.

Creating the works from print editions not protected by U.S. copyright

law means that no one owns a United States copyright in these works,

so the Foundation (and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United

States without permission and without paying copyright

royalties. Special rules, set forth in the General Terms of Use part

of this license, apply to copying and distributing Project

Gutenberg™ electronic works to protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG™

concept and trademark. Project Gutenberg is a registered trademark,

and may not be used if you charge for an eBook, except by following

the terms of the trademark license, including paying royalties for use

of the Project Gutenberg trademark. If you do not charge anything for

copies of this eBook, complying with the trademark license is very

easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose such as creation

of derivative works, reports, performances and research. Project

Gutenberg eBooks may be modified and printed and given away--you may

do practically ANYTHING in the United States with eBooks not protected

by U.S. copyright law. Redistribution is subject to the trademark

license, especially commercial redistribution.

START: FULL LICENSE

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg™ mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase “Project

Gutenberg”), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full

Project Gutenberg™ License available with this file or online at

www.gutenberg.org/license.

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg™ electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg™

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or

destroy all copies of Project Gutenberg™ electronic works in your

possession. If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a

Project Gutenberg™ electronic work and you do not agree to be bound

by the terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person

or entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. “Project Gutenberg” is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg™ electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg™ electronic works if you follow the terms of this

agreement and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg™

electronic works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation (“the

Foundation” or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection

of Project Gutenberg™ electronic works. Nearly all the individual

works in the collection are in the public domain in the United

States. If an individual work is unprotected by copyright law in the

United States and you are located in the United States, we do not

claim a right to prevent you from copying, distributing, performing,

displaying or creating derivative works based on the work as long as

all references to Project Gutenberg are removed. Of course, we hope

that you will support the Project Gutenberg™ mission of promoting

free access to electronic works by freely sharing Project Gutenberg™

works in compliance with the terms of this agreement for keeping the

Project Gutenberg™ name associated with the work. You can easily

comply with the terms of this agreement by keeping this work in the

same format with its attached full Project Gutenberg™ License when

you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are

in a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States,

check the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this

agreement before downloading, copying, displaying, performing,

distributing or creating derivative works based on this work or any

other Project Gutenberg™ work. The Foundation makes no

representations concerning the copyright status of any work in any

country other than the United States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other

immediate access to, the full Project Gutenberg™ License must appear

prominently whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg™ work (any work

on which the phrase “Project Gutenberg” appears, or with which the

phrase “Project Gutenberg” is associated) is accessed, displayed,

performed, viewed, copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online

at

www.gutenberg.org. If you

are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws

of the country where you are located before using this eBook.

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg™ electronic work is

derived from texts not protected by U.S. copyright law (does not

contain a notice indicating that it is posted with permission of the

copyright holder), the work can be copied and distributed to anyone in

the United States without paying any fees or charges. If you are

redistributing or providing access to a work with the phrase “Project

Gutenberg” associated with or appearing on the work, you must comply

either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 or

obtain permission for the use of the work and the Project Gutenberg™

trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg™ electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any

additional terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms

will be linked to the Project Gutenberg™ License for all works

posted with the permission of the copyright holder found at the

beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg™

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg™.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg™ License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including

any word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access

to or distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg™ work in a format

other than “Plain Vanilla ASCII” or other format used in the official

version posted on the official Project Gutenberg™ website

(www.gutenberg.org), you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense

to the user, provide a copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means

of obtaining a copy upon request, of the work in its original “Plain

Vanilla ASCII” or other form. Any alternate format must include the

full Project Gutenberg™ License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg™ works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg™ electronic works

provided that:

• You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg™ works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is owed

to the owner of the Project Gutenberg™ trademark, but he has

agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments must be paid

within 60 days following each date on which you prepare (or are

legally required to prepare) your periodic tax returns. Royalty

payments should be clearly marked as such and sent to the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the address specified in

Section 4, “Information about donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation.”

• You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg™

License. You must require such a user to return or destroy all

copies of the works possessed in a physical medium and discontinue

all use of and all access to other copies of Project Gutenberg™

works.

• You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of

any money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days of

receipt of the work.

• You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg™ works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project

Gutenberg™ electronic work or group of works on different terms than

are set forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing

from the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the manager of

the Project Gutenberg™ trademark. Contact the Foundation as set

forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

works not protected by U.S. copyright law in creating the Project

Gutenberg™ collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg™

electronic works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may

contain “Defects,” such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate

or corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other

intellectual property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or

other medium, a computer virus, or computer codes that damage or

cannot be read by your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the “Right

of Replacement or Refund” described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg™ trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg™ electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium

with your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you

with the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in

lieu of a refund. If you received the work electronically, the person

or entity providing it to you may choose to give you a second

opportunity to receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If

the second copy is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing

without further opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you ‘AS-IS’, WITH NO

OTHER WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT

LIMITED TO WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of

damages. If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement

violates the law of the state applicable to this agreement, the

agreement shall be interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or

limitation permitted by the applicable state law. The invalidity or

unenforceability of any provision of this agreement shall not void the

remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg™ electronic works in

accordance with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the

production, promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg™

electronic works, harmless from all liability, costs and expenses,

including legal fees, that arise directly or indirectly from any of

the following which you do or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this

or any Project Gutenberg™ work, (b) alteration, modification, or

additions or deletions to any Project Gutenberg™ work, and (c) any

Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg™

Project Gutenberg™ is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of

computers including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It

exists because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations

from people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg™’s

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg™ collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg™ and future

generations. To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation and how your efforts and donations can help, see

Sections 3 and 4 and the Foundation information page at www.gutenberg.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non-profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation’s EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent permitted by

U.S. federal laws and your state’s laws.

The Foundation’s business office is located at 809 North 1500 West,

Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887. Email contact links and up

to date contact information can be found at the Foundation’s website

and official page at www.gutenberg.org/contact

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg™ depends upon and cannot survive without widespread

public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine-readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To SEND

DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any particular state

visit

www.gutenberg.org/donate.

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations. To

donate, please visit: www.gutenberg.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg™ electronic works

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project

Gutenberg™ concept of a library of electronic works that could be

freely shared with anyone. For forty years, he produced and

distributed Project Gutenberg™ eBooks with only a loose network of

volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg™ eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as not protected by copyright in

the U.S. unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not

necessarily keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper

edition.

Most people start at our website which has the main PG search

facility:

www.gutenberg.org.

This website includes information about Project Gutenberg™,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.