Michigan Avenue, Chicago, from the steps of the Art Institute.

THE

VALLEY OF DEMOCRACY

BY

MEREDITH NICHOLSON

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY

WALTER TITTLE

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

1919

Copyright, 1917, 1918, by

Charles Scribner’s Sons

Published September, 1918

Reprinted November, December 1918

TO MY CHILDREN

ELIZABETH, MEREDITH, AND LIONEL

IN TOKEN OF MY AFFECTION

AND WITH THE HOPE THAT THEY MAY BE FAITHFUL TO THE

HIGHEST IDEALS OF AMERICAN CITIZENSHIP

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Folks and Their Folksiness | 1 |

| II. | Types and Diversions | 39 |

| III. | The Farmer of the Middle West | 83 |

| IV. | Chicago | 135 |

| V. | The Middle West in Politics | 181 |

| VI. | The Spirit of the West | 235 |

In the reprintings of a book of this character it would be possible to revise and rewrite in such manner as to conceal the errors or misjudgments of the author. It seems, however, more honest to permit these impressions to stand practically as they were written, with only a few minor corrections. It was my aim to make note of conditions, tendencies, and needs in the Valley of Democracy, and the conclusion of the war has affected my point of view with reference to these matters very little.

The first months of the present year have been so crowded with incidents affecting the whole world that we recall with difficulty the events of only a few years ago. We have met repeated crises with an inspiring exhibition of unity and courage that should hearten us for the new tasks of readjustment that press for attention, and for the problems of self-government that are without end. I shall feel that these pages possess some degree of vitality if they quicken in the[x] mind and heart of the reader a hope and confidence that we of America do not walk blindly, but follow a star that sheds upon us a perpetual light.

M. N.

Indianapolis, June 1, 1919.

| Michigan Avenue, Chicago, from the steps of the Art Institute | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| “Ten days of New York, and it’s me for my home town” | 6 |

| Art exhibits ... now find a hearty welcome | 20 |

| The Municipal Recreation Pier, Chicago | 66 |

| Types and Diversions | 74 |

| On a craft plying the waters of Erie I found all the conditions of a happy outing and types that it is always a joy to meet | 78 |

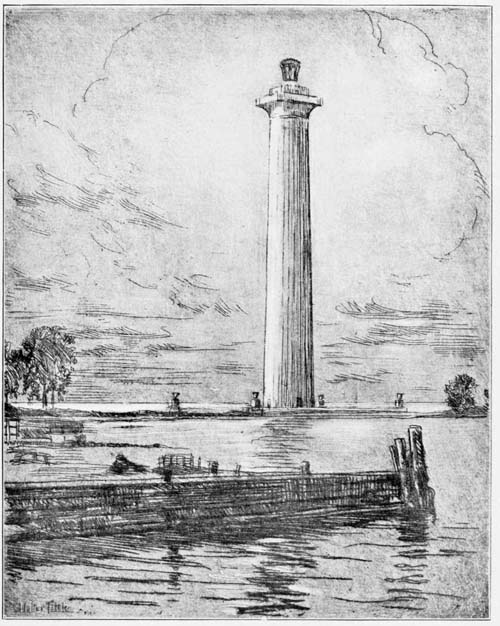

| The Perry Monument at Put-in Bay | 80 |

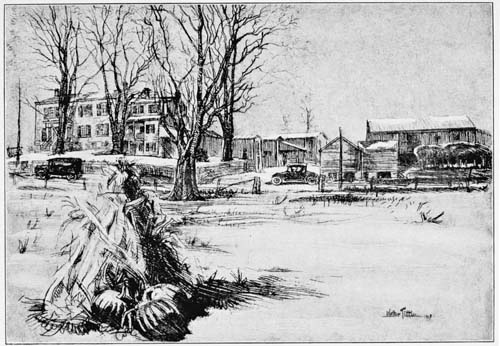

| A typical old homestead of the Middle West | 100 |

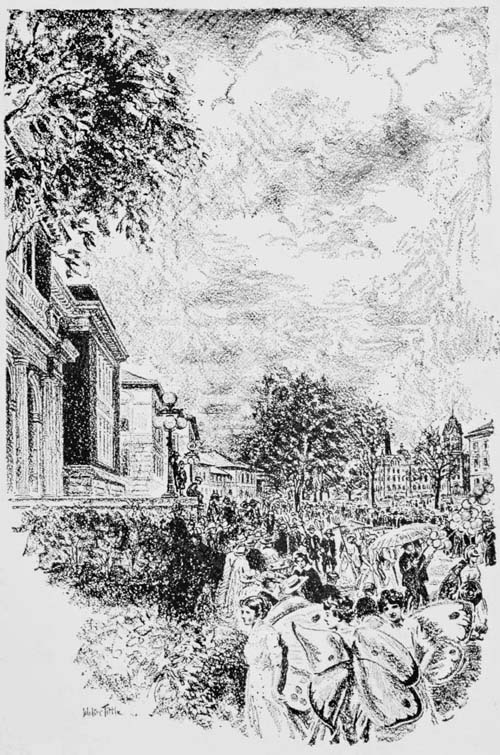

| Students of agriculture in the pageant that celebrated the fortieth anniversary of the founding of Ohio State University | 114 |

| A feeding-plant at “Whitehall,” the farm of Edwin S. Kelly, near Springfield, Ohio | 120 |

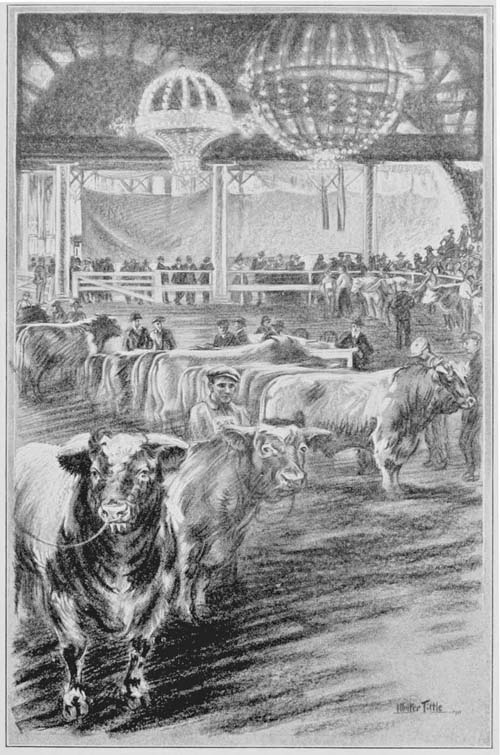

| Judging graded shorthorn herds at the American Royal Live Stock Show in Kansas City | 132 |

| Chicago is the big brother of all lesser towns | 142 |

| The “Ham Fair” in Paris is richer in antiquarian loot, but Maxwell Street is enough; ’twill serve! | 152 |

| Banquet given for the members of the National Institute of Arts and Letters | 176[xii] |

| There is a death-watch that occupies front seats at every political meeting | 194 |

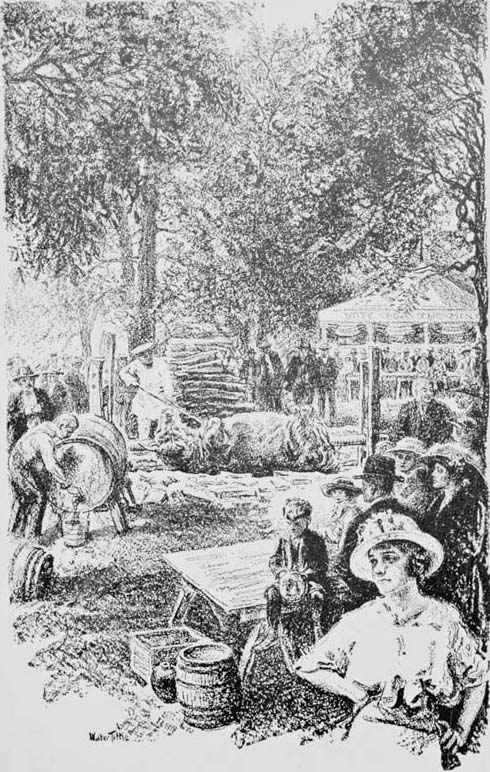

| The Political Barbecue | 198 |

THE VALLEY OF DEMOCRACY

France evoked from the unknown the valley that may, in more than one sense, be called the heart of America.... The chief significance and import of the addition of this valley to the maps of the world, all indeed that makes it significant, is that here was given (though not of deliberate intent) a rich, wide, untouched field, distant, accessible only to the hardiest, without a shadowing tradition or a restraining fence, in which men of all races were to make attempt to live together under rules of their own devising and enforcing. And as here the government of the people by the people was to have even more literal interpretation than in that Atlantic strip which had traditions of property suffrage and church privilege and class distinctions, I have called it the “Valley of the New Democracy.”

—John H. Finley: “The French in the Heart of America.”

THE VALLEY OF DEMOCRACY

“THE great trouble with these fellows down here,” remarked my friend as we left the office of a New York banker—“the trouble with all of ’em is that they forget about the Folks. You noticed that when he asked in his large, patronizing way how things are going out West he didn’t wait for us to answer; he pressed a button and told his secretary to bring in those tables of railroad earnings and to-day’s crop bulletins and that sort of rubbish, so he could tell us. It never occurs to ’em that the Folks are human beings and not just a column of statistics. Why, the Folks——”

My friend, an orator of distinction, formerly represented a tall-corn district in Congress. He drew me into Trinity churchyard and discoursed in a vein with which I had long been familiar upon a certain condescension in Easterners,[2] and the East’s intolerable ignorance of the ways and manners, the hopes and aims, of the West, which move him to rage and despair. I was aware that he was gratified to have an opportunity to unbosom himself at the brazen gates of Wall Street, and equally conscious that he was experimenting upon me with phrases that he was coining for use on the hustings. They were so used, not without effect, in the campaign of 1916—a contest whose results were well calculated to draw attention to the “Folks” as an upstanding, independent body of citizens.

Folks is recognized by the lexicographers as an American colloquialism, a variant of folk. And folk, in old times, was used to signify the commonalty, the plain people. But my friend, as he rolled “Folks” under his tongue there in the shadow of Trinity, used it in a sense that excluded the hurrying midday Broadway throng and restricted its application to an infinitely superior breed of humanity, to be found on farms, in villages and cities remote from tide-water. His passion for democracy, his devotion to the commonweal, is not wasted upon New Englanders or Middle States people. In the South there are Folks, yes; his own people had come out of North Carolina, lingered a while in Kentucky, and lodged finally in Indiana, whence,[3] following a common law of dispersion, they sought new homes in Illinois and Kansas. Beyond the Rockies there are Folks; he meets their leaders in national conventions; but they are only second cousins of those valiant freemen who rallied to the call of Lincoln and followed Grant and Sherman into battles that shook the continent. My friend’s point of view is held by great numbers of people in that region we now call the Middle West. This attitude or state of mind with regard to the East is not to be taken too seriously; it is a part of the national humor, and has been expressed with delightful vivacity and candor in Mr. William Allen White’s refreshing essay, “Emporia and New York.”

A definition of Folks as used all the way from Ohio to Colorado, and with particular point and pith by the haughty sons and daughters of Indiana and Kansas, may be set down thus:

Folks. n. A superior people, derived largely from the Anglo-Saxon and Celtic races and domiciled in those northern States of the American Union whose waters fall into the Mississippi. Their folksiness (q. v.) is expressed in sturdy independence, hostility to capitalistic influence, and a proneness to social and political experiment. They are strong in the fundamental virtues, more or less sincerely averse to conventionality, and believe themselves possessed of a breadth of vision and a devotion to the common good at once beneficent and unique in the annals of mankind.

[4]We of the West do not believe—not really—that we are the only true interpreters of the dream of democracy. It pleases us to swagger a little when we speak of ourselves as the Folks and hint at the dire punishments we hold in store for monopoly and privilege; but we are far less dangerous than an outsider, bewildered or annoyed by our apparent bitterness, may be led to believe. In our hearts we do not think ourselves the only good Americans. We merely feel that the East began patronizing us and that anything we may do in that line has been forced upon us by years of outrageous contumely. And when New York went to bed on the night of election day, 1916, confident that as went the Empire State so went the Union, it was only that we of the West might chortle the next morning to find that Ah Sin had forty packs concealed in his sleeve and spread them out on the Sierra Nevadas with an air that was child-like and bland.

Under all its jauntiness and cocksureness, the West is extremely sensitive to criticism. It likes admiration, and expects the Eastern visitor to be properly impressed by its achievements, its prodigious energy, its interpretation and practical application of democracy, and the earnestness with which it interests itself in the[5] things of the spirit. Above all else it does not like to appear absurd. According to its light it intends to do the right thing, but it yields to laughter much more quickly than abuse if the means to that end are challenged.

The pioneers of the older States endured hardships quite as great as the Middle Westerners; they have contributed as generously to the national life in war and peace; the East’s aid to the West, in innumerable ways, is immeasurable. I am not thinking of farm mortgages, but of nobler things—of men and women who carried ideals of life and conduct, of justice and law, into new territory where such matters were often lightly valued. The prowler in these Western States recognizes constantly the trail of New Englanders who founded towns, built schools, colleges, and churches, and left an ineffaceable stamp upon communities. Many of us Westerners sincerely admire the East and do reverence to Eastern gods when we can sneak unobserved into the temples. We dispose of our crops and merchandise as quickly as possible, that we may be seen of men in New York. Western school-teachers pour into New England every summer on pious pilgrimages to Concord and Lexington. And yet we feel ourselves, the great body of us, a peculiar people. “Ten days[6] of New York, and it’s me for my home town” in Ohio, Indiana, Kansas, or Colorado. This expresses a very general feeling in the provinces.

It is far from my purpose to make out a case for the West as the true home of the Folks in these newer connotations of that noun, but rather to record some of the phenomena observable in those commonwealths where we are assured the Folks maintain the only true ark of the covenant of democracy. Certain concessions may be assumed in the unconvinced spectator whose path lies in less-favored portions of the nation. The West does indubitably coax an enormous treasure out of its soil to be tossed into the national hopper, and it does exert a profound influence upon the national life; but its manner of thought is different: it arrives at conclusions by processes that strike the Eastern mind as illogical and often as absurd or dangerous. The two great mountain ranges are barriers that shut it in a good deal by itself in spite of every facility of communication; it is disposed to be scornful of the world’s experience where the experience is not a part of its own history. It believes that forty years of Illinois or Wisconsin are better than a cycle of Cathay, and it is prepared to prove it.

“Ten days of New York, and it’s me for my home town.”

The West’s philosophy is a compound of[7] Franklin and Emerson, with a dash of Whitman. Even Washington is a pale figure behind the Lincoln of its own prairies. Its curiosity is insatiable; its mind is speculative; it has a supreme confidence that upon an agreed state of facts the Folks, sitting as a high court, will hand down to the nation a true and just decision upon any matter in controversy. It is a patient listener. Seemingly tolerant of false prophets, it amiably gives them hearing in thousands of forums while awaiting an opportunity to smother their ambitions on election day. It will not, if it knows itself, do anything supremely foolish. Flirting with Greenbackism and Free Silver, it encourages the assiduous wooers shamelessly and then calmly sends them about their business. Maine can approach her election booths as coyly as Ohio or Nebraska, and yet the younger States rejoice in the knowledge that after all nothing is decided until they have been heard from. Politics becomes, therefore, not merely a matter for concern when some great contest is forward, but the year round it crowds business hard for first place in public affection.

[8]

The people of the Valley of Democracy (I am indebted for this phrase to Dr. John H. Finley) do a great deal of thinking and talking; they brood over the world’s affairs with a peculiar intensity; and, beyond question, they exchange opinions with a greater freedom than their fellow citizens in other parts of America. I have travelled between Boston and New York on many occasions and have covered most of New England in railway journeys without ever being addressed by a stranger; but seemingly in the West men travel merely to cultivate the art of conversation. The gentleman who borrows your newspaper returns it with a crisp comment on the day’s events. He is from Beatrice, or Fort Collins, perhaps, and you quickly find that he lives next door to the only man you know in his home town. You praise Nebraska, and he meets you in a generous spirit of reciprocity and compliments Iowa, Minnesota, or any other commonwealth you may honor with your citizenship.

The West is proud of its talkers, and is at pains to produce them for the edification of the visitor. In Kansas a little while ago my host summoned a friend of his from a town eighty[9] miles away that I might hear him talk. And it was well worth my while to hear that gentleman talk; he is the best talker I have ever heard. He described for me great numbers of politicians past and present, limning them with the merciless stroke of a skilled caricaturist, or, in a benignant mood, presented them in ineffaceable miniature. He knew Kansas as he knew his own front yard. It was a delight to listen to discourse so free, so graphic in its characterizations, so colored and flavored with the very soil. Without impropriety I may state that this gentleman is Mr. Henry J. Allen, of the Wichita Beacon; the friend who produced him for my instruction and entertainment is Mr. William Allen White of the Emporia Gazette. Since this meeting I have heard Mr. Allen talk on other occasions without any feeling that I should modify my estimate of his conversational powers. In his most satisfying narrative, “The Martial Adventures of Henry and Me,” Mr. White has told how he and Mr. Allen, as agents of the Red Cross, bore the good news of the patriotism and sympathy of Kansas to England, France, and Italy, and certainly America could have sent no more heartening messengers to our allies.

I know of no Western town so small that it[10] doesn’t boast at least one wit or story-teller who is exhibited as a special mark of honor for the entertainment of guests. As often as not these stars are women, who discuss public matters with understanding and brilliancy. The old superstition that women are deficient in humor never struck me as applicable to American women anywhere; certainly it is not true of Western women. In a region where story-telling flourishes, I can match the best male anecdotalist with a woman who can evoke mirth by neater and defter means.

The Western State is not only a political but a social unit. It is like a club, where every one is presumably acquainted with every one else. The railroads and interurbans carry an enormous number of passengers who are solely upon pleasure bent. The observer is struck by the general sociability, the astonishing amount of visiting that is in progress. In smoking compartments and in day coaches any one who is at all folksy may hear talk that is likely to prove informing and stimulating. And this cheeriness and volubility of the people one meets greatly enhances the pleasure of travel. Here one is reminded constantly of the provincial confidence in the West’s greatness and wisdom in every department of human endeavor.

[11]In January of last year it was my privilege to share with seven other passengers the smoking-room of a train out of Denver for Kansas City. The conversation was opened by a vigorous, elderly gentleman who had, he casually remarked, crossed Kansas six times in a wagon. He was a native of Illinois, a graduate of Asbury (Depauw) College, Indiana, a Civil War veteran, and he had been a member of the Missouri Legislature. He lived on a ranch in Colorado, but owned a farm in Kansas and was hastening thither to test his acres for oil. The range of his adventures was amazing; his acquaintance embraced men of all sorts and conditions, including Buffalo Bill, whose funeral he had just attended in Denver. He had known General George A. Custer and gave us the true story of the massacre of that hero and his command on the Little Big Horn. He described the “bad men” of the old days, many of whom had honored him with their friendship. At least three of the company had enjoyed like experiences and verified or amplified his statements. This gentleman remarked with undisguised satisfaction that he had not been east of the Mississippi for thirty years!

I fancied that he acquired merit with all the trans-Mississippians present by this declaration.[12] However, a young commercial traveller who had allowed it to become known that he lived in New York seemed surprised, if not pained, by the revelation. As we were passing from one dry State to another we fell naturally into a discussion of prohibition as a moral and economic factor. The drummer testified to its beneficent results in arid territory with which he was familiar; one effect had been increased orders from his Colorado customers. It was apparent that his hearers listened with approval; they were citizens of dry States and it tickled their sense of their own rectitude that a pilgrim from the remote East should speak favorably of their handiwork. But the young gentleman, warmed by the atmosphere of friendliness created by his remarks, was guilty of a grave error of judgment.

“It’s all right for these Western towns,” he said, “but you could never put it over in New York. New York will never stand for it. London, Paris, New York—there’s only one New York!”

The deep sigh with which he concluded, expressive of the most intense loyalty, the most poignant homesickness, and perhaps a thirst of long accumulation, caused six cigars, firmly set in six pairs of jaws, to point disdainfully at the[13] ceiling. No one spoke until the offender had betaken himself humbly to bed. The silence was eloquent of pity for one so abandoned. That any one privileged to range the cities of the West should, there at the edge of the great plain, set New York apart for adoration, was too impious, too monstrous, for verbal condemnation.

Young women seem everywhere to be in motion in the West, going home from schools, colleges, or the State universities for week-ends, or attending social functions in neighboring towns. Last fall I came down from Green Bay in a train that was becalmed for several hours at Manitowoc. I left the crowded day coach to explore that pleasing haven and, returning, found that my seat had been pre-empted by a very charming young person who was reading my magazine with the greatest absorption. We agreed that the seat offered ample space for two and that there was no reason in equity or morals why she should not finish the story she had begun. This done, she commented upon it frankly and soundly and proceeded to a brisk discussion of literature in general. Her range of reading had been wide—indeed, I was embarrassed by its extent and impressed by the shrewdness of her literary appraisements. She was bound for a normal school where she was receiving instruction,[14] not for the purpose of entering into the pedagogical life immediately, but to obtain a teacher’s license against a time when it might become necessary for her to earn a livelihood. Every girl, she believed, should fit herself for some employment.

Manifestly she was not a person to ask favors of destiny: at eighteen she had already made terms with life and tossed the contract upon the knees of the gods. The normal school did not require her presence until the day after to-morrow, and she was leaving the train at the end of an hour to visit a friend who had arranged a dance in her honor. If that species of entertainment interested me, she said, I might stop for the dance. Engagements farther down the line precluded the possibility of my accepting this invitation, which was extended with the utmost circumspection, as though she were offering an impersonal hospitality supported by the sovereign dignity of the commonwealth of Wisconsin. When the train slowed down at her station a commotion on the platform announced the presence of a reception committee of considerable magnitude, from which I inferred that her advent was an incident of importance to the community. As she bade me good-by she tore apart a bouquet of fall flowers she had been[15] carrying, handed me half of them, and passed from my sight forever. My exalted opinion of the young women of Wisconsin was strengthened on another occasion by a chance meeting with two graduates of the State University who were my fellow voyagers on a steamer that bumped into a riotous hurricane on its way down Lake Michigan. On the slanting deck they discoursed of political economy with a zest and humor that greatly enlivened my respect for the dismal science.

The listener in the West accumulates data touching the tastes and ambitions of the people of which local guide-books offer no hint. A little while ago two ladies behind me in a Minneapolis street-car discussed Cardinal Newman’s “Dream of Gerontius,” with as much avidity as though it were the newest novel. Having found that the apostles of free verse had captured and fortified Denver and Omaha, it was a relief to encounter these Victorian pickets on the upper waters of the Mississippi.

One is struck by the remarkable individuality of the States, towns, and cities of the West. State boundaries are not merely a geographical[16] expression: they mark real differences of opinion, habit, custom, and taste. This is not a sentimental idea; any one may prove it for himself by crossing from Illinois into Wisconsin, or from Iowa into Nebraska. Kansas and Nebraska, though cut out of the same piece, not only seem different but they are different. Interest in local differentiations, in shadings of the “color” derived from a common soil, keep the visitor alert. To be sure the Ladies of the Lakes—Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, Milwaukee, Toledo, Duluth—have physical aspects in common, but the similarity ends there. The literature of chambers of commerce as to the number of freight-cars handled or increases of population are of no assistance in a search for the causes of diversities in aim, spirit, and achievement.

The alert young cities watch each other enviously—they are enormously proud and anxious not to be outbettered in the struggle for perfection. In many places one is conscious of an effective leadership, of a man or a group of men and women who plant a target and rally the citizenry to play for the bull’s-eye. A conspicuous instance of successful individual leadership is offered by Kansas City, where Mr. William R. Nelson, backed by his admirable newspaper,[17] The Star, fought to the end of his life to make his city a better place to live in. Mr. Nelson was a remarkably independent and courageous spirit, his journalistic ideals were the highest, and he was deeply concerned for the public welfare, not only in the more obvious sense, but equally in bringing within the common reach enlightening influences that are likely to be neglected in new communities. Kansas City not only profited by Mr. Nelson’s wisdom and generosity in his lifetime, but the community will receive ultimately his entire fortune. I am precluded from citing in other cities men still living who are distinguished by a like devotion to public service, but I have chosen Mr. Nelson as an eminent example of the force that may be wielded by a single citizen.

Minneapolis offers a happy refutation of a well-established notion that a second generation is prone to show a weakened fibre. The sons of the men who fashioned this vigorous city have intelligently and generously supported many undertakings of highest value. The Minneapolis art museum and school and an orchestra of widening reputation present eloquent testimony to the city’s attitude toward those things that are more excellent. Contrary to the usual history, these were not won as the result of laborious[18] effort but rose spontaneously. The public library of this city not only serves the hurried business man through a branch in the business district, equipped with industrial and commercial reference books, but keeps pace with the local development in art and music by assembling the best literature in these departments. Both Minneapolis and Kansas City are well advertised by their admirably managed, progressive libraries. More may be learned from a librarian as to the trend of thought in his community than from the secretary of a commercial body. It is significant that last year, when municipal affairs were much to the fore in Kansas City, there was a marked increase in the use of books on civic and kindred questions. The latest report of the librarian recites that “as the library more nearly meets the wants of the community, the proportion of fiction used grows less, being but 34 per cent of the whole issue for the year.” Similar impulses and achievements are manifested in Cleveland, a city that has written many instructive chapters in the history of municipal government. Since her exposition of 1904 and the splendid pageant of 1914 crystallized public aspiration, St. Louis has experienced a new birth of civic pride. Throughout the West American art has found cordial support.[19] In Cleveland, Toledo, Detroit, Cincinnati, Indianapolis, St. Louis, Chicago, Minneapolis, Omaha, and Kansas City there are noteworthy specimens of the best work of American painters. The art schools connected with the Western museums have exercised a salutary influence in encouraging local talent, not only in landscape and portraiture, but in industrial designing.

By friendly co-operation on the part of Chicago and St. Louis smaller cities are able to enjoy advantages that would otherwise be beyond their reach. Lectures, orchestras, and travelling art exhibits that formerly stopped at Chicago or jumped thence to California, now find a hearty welcome in Kansas City, Omaha, and Denver. Thus Indianapolis was among the few cities that shared a few years ago in the comprehensive presentation of Saint Gaudens’s work. The expense of the undertaking was not inconsiderable, but merchants and manufacturers bought tickets for distribution among their employees and met the demand with a generosity that left a balance in the art association’s treasury. These Western cities, with their political and social problems, their rough edges, smoke, and impudent intrusions of tracks and chimneys due to rapid development and phenomenal[20] prosperity, present art literally as the handmaiden of industry—

“All-lovely Art, stern Labor’s fair-haired child.”

If any one thing is quite definitely settled throughout this territory it is that yesterday’s leaves have been plucked from the calendar: this verily is the land of to-morrow. One does not stand beside the Missouri at Omaha and indulge long in meditations upon the turbulent history and waywardness of that tawny stream; the cattle receipts for the day may have broken all records, but there are schools that must be seen, a collection of pictures to visit, or lectures to attend. I unhesitatingly pronounce Omaha the lecture centre of the world—reception committees flutter at the arrival of all trains. Man does not live by bread alone—not even in the heart of the corn belt in a city that haughtily proclaims itself the largest primary butter-market in the world! It is the great concern of Kansas that it shall miss nothing; to cross that commonwealth is to gain the impression that politics and corn are hard pressed as its main industries by the cultural mechanisms that produce sweetness and light. Iowa goes to bed early but not before it has read an improving book!

Art exhibits ... now find a hearty welcome.

[21]In those Western States where women have assumed the burden of citizenship they seem to lose none of their zeal for art, literature, and music. Equal suffrage was established in Colorado in 1893, and the passing pilgrim cannot fail to be struck by the lack of self-consciousness with which the women of that State discuss social and political questions. The Western woman is animated by a divine energy and she is distinguished by her willingness to render public service. What man neglects or ignores she cheerfully undertakes, and she has so cultivated the gentle art of persuasion that the masculine check-book opens readily to her demand for assistance in her pet causes.

It must not be assumed that in this land of pancakes and panaceas interest in “culture” is new or that its manifestations are sporadic or ill-directed. The early comers brought with them sufficient cultivation to leaven the lump, and the educational forces and cultural movements now everywhere marked in Western communities are but the fruition of the labors of the pioneers who bore books of worth and a love of learning with them into the wilderness. Much sound reading was done in log cabins when the school-teacher was still a rarity, and amid the strenuous labors of the earliest days[22] many sought self-expression in various kinds of writing. Along the Ohio there were bards in abundance, and a decade before the Civil War Cincinnati had honest claims to being a literary centre. The numerous poets of those days—Coggeshall’s “Poets and Poetry of the West,” published in 1866, mentions one hundred and fifty-two!—were chiefly distinguished by their indifference to the life that lay nearest them. Sentiment and sentimentalism flourished at a time when life was a hard business, though Edward Eggleston is entitled to consideration as an early realist, by reason of “The Hoosier Schoolmaster,” which, in spite of Indiana’s repudiation of it as false and defamatory, really contains a true picture of conditions with which Eggleston was thoroughly familiar. There followed later E. W. Howe’s “The Story of a Country Town” and Hamlin Garland’s “Main Travelled Roads,” which are landmarks of realism firmly planted in territory invaded later by Romance, bearing the blithe flag of Zenda.

It is not surprising that the Mississippi valley should prove far more responsive to the chimes of romance than to the harsh clang of realism. The West in itself is a romance. Virginia’s claims to recognition as the chief field of tourney for romance in America totter before the history[23] of a vast area whose soberest chronicles are enlivened by the most inthralling adventures and a long succession of picturesque characters. The French voyageur, on his way from Canada by lake and river to clasp hands with his kinsmen of the lower Mississippi; the American pioneers, with their own heroes—George Rogers Clark, “Mad Anthony” Wayne, and “Tippecanoe” Harrison; the soldiers of Indian wars and their sons who fought in Mexico in the forties; the men who donned the blue in the sixties; the Knights of the Golden Circle, who kept the war governors anxious in the border States—these are all disclosed upon a tapestry crowded with romantic strife and stress.

The earliest pioneers, enjoying little intercourse with their fellows, had time to fashion many a tale of personal adventure against the coming of a visitor, or for recital on court days, at political meetings, or at the prolonged “camp meetings,” where questions of religion were debated. They cultivated unconsciously the art of telling their stories well. The habit of story-telling grew into a social accomplishment and it was by a natural transition that here and there some one began to set down his tales on paper. Thus General Lew Wallace, who lived in the day of great story-tellers, wrote[24] “The Fair God,” a romance of the coming of Cortez to Mexico, and followed it with “Ben Hur,” one of the most popular romances ever written. Crawfordsville, the Hoosier county-seat where General Wallace lived, was once visited and its romanticism menaced by Mr. Howells, who sought local color for the court scene in “A Modern Instance,” his novel of divorce. Indiana was then a place where legal separations were obtainable by convenient processes relinquished later to Nevada.

Maurice Thompson and his brother Will, who wrote “The High Tide at Gettysburg,” sent out from Crawfordsville the poems and sketches that made archery a popular amusement in the seventies. The Thompsons, both practising lawyers, employed their leisure in writing and in hunting with the bow and arrow. “The Witchery of Archery” and “Songs of Fair Weather” still retain their pristine charm. That two young men in an Indiana country town should deliberately elect to live in the days of the Plantagenets speaks for the romantic atmosphere of the Hoosier commonwealth. A few miles away James Whitcomb Riley had already begun to experiment with a lyre of a different sort, and quickly won for himself a place in popular affection shared only[25] among American poets by Longfellow. Almost coincident with his passing rose Edgar Lee Masters, with the “Spoon River Anthology,” and Vachel Lindsay, a poet hardly less distinguished for penetration and sincerity, to chant of Illinois in the key of realism. John G. Niehardt has answered their signals from Nebraska’s corn lands. Nor shall I omit from the briefest list the “Chicago Poems” of Carl Sandburg. The “wind stacker” and the tractor are dangerous engines for Romance to charge: I should want Mr. Booth Tarkington to umpire so momentous a contest. Mr. Tarkington flirts shamelessly with realism and has shown in “The Turmoil” that he can slip overalls and jumper over the sword and ruffles of Beaucaire and make himself a knight of industry. Likewise, in Chicago, Mr. Henry B. Fuller has posted the Chevalier Pensieri-Vani on the steps of the board of trade, merely, we may assume, to collect material for realistic fiction. The West has proved that it is not afraid of its own shadow in the adumbrations of Mrs. Mary A. Watts, Mr. Robert Herrick, Miss Willa Sibert Cather, Mr. William Allen White, and Mr. Brand Whitlock, all novelists of insight, force, and authority; nor may we forget that impressive tale of Chicago, Frank Norris’s “The Pit,” a work[26] that gains in dignity and significance with the years.

Education in all the Western States has not merely performed its traditional functions, but has become a distinct social and economic force. It is a far cry from the day of the three R’s and the dictum that the State’s duty to the young ends when it has eliminated them from the illiteracy columns of the census to the State universities and agricultural colleges, with their broad curricula and extension courses, and the free kindergartens, the manual-training high schools, and vocational institutions that are socializing and democratizing education.

In every town of the great Valley there are groups of people earnestly engaged in determined efforts to solve governmental problems. These efforts frequently broaden into “movements” that succeed. We witness here constant battles for reform that are often won only to be lost again. The bosses, driven out at one point, immediately rally and fortify another. Nothing, however, is pleasanter to record than the fact that the war upon vicious or stupid local government goes steadily on[27] and that throughout the field under scrutiny there have been within a decade marked and encouraging gains. The many experiments making with administrative devices are rapidly developing a mass of valuable data. The very lack of uniformity in these movements adds to their interest; in countless communities the attention is arrested by something well done that invites emulation. Constant scandals in municipal administration, due to incompetence, waste, and graft, are slowly penetrating to the consciousness of the apathetic citizen, and sentiment favorable to the abandonment of the old system of partisan local government has grown with remarkable rapidity. The absolute divorcement of municipalities from State and national politics is essential to the conduct of city government on business principles. This statement is made with the more confidence from the fact that it is reinforced by a creditable literature on the subject, illustrated by countless surveys of boss-ridden cities where there is determined protest against government by the unfit. That cities shall be conducted as stock companies with reference solely to the rights and needs of the citizen, without regard to party politics, is the demand in so many quarters that the next decade is bound to witness[28] striking transformations in this field. Last March Kansas City lost a splendidly conducted fight for a new charter that embraced the city-manager plan. Here, however, was a defeat with honor, for the results proved so conclusively the contention of the reformers, that the bosses rule, that the effort was not wasted. In Chicago, Cleveland, Cincinnati, and Minneapolis, the leaven is at work, and the bosses with gratifying density are aiding the cause by their hostility and their constant illustration of the evils of the antiquated system they foster.

The elimination of the saloon in States that have already adopted prohibition promises political changes of the utmost importance in municipal affairs. The saloon is the most familiar and the most mischievous of all the outposts and rallying centres of political venality. Here the political “organization” maintains its faithful sentinels throughout the year; the good citizen, intent upon his lawful business and interested in politics only when election day approaches, is usually unaware that hundreds of barroom loafers are constantly plotting against him. The mounting “dry wave” is attributable quite as much to revolt against the saloon as the most formidable of political units as to a moral detestation of alcohol. Economic considerations[29] also have entered very deeply into the movement, and prohibition advocated as a war measure developed still another phase. The liquor interests provoked and invited the drastic legislation that has overwhelmed their traffic and made dry territory of a large area of the West. By defying regulatory laws and maintaining lobbies in legislatures, by cracking the whip over candidates and office-holders, they made of themselves an intolerable nuisance. Indiana’s adoption of prohibition was very largely due to antagonism aroused by the liquor interests through their political activities covering half a century. The frantic efforts of breweries and distilleries there and in many other States to persuade saloon-keepers to obey the laws in the hope of spiking the guns of the opposition came too late. The liquor interests had counselled and encouraged lawlessness too long and found the retailer spoiled by the immunity their old political power had gained for him.

A sweeping Federal law abolishing the traffic may be enacted while these pages are on the press.[A] Without such a measure wet and dry forces will continue to battle; territory that is only partly dry will continue its struggle for bone-dry laws, and States that roped and tied[30] John Barleycorn must resist attempts to put him on his feet again. There is, however, nothing to encourage the idea that the strongly developed sentiment against the saloon will lose its potency; and it is hardly conceivable that any political party in a dry State will write a wet plank into its platform, though stranger things have happened. Men who, in Colorado for example, were bitterly hostile to prohibition confess that the results convince them of its efficacy. The Indiana law became effective last April, and in June the workhouse at Indianapolis was closed permanently, for the interesting reason that the number of police-court prisoners was so reduced as to make the institution unnecessary.

The economic shock caused by the prostration of this long-established business is absorbed much more readily than might be imagined. Compared with other forms of manufacturing, brewing and distilling have been enormously profitable, and the operators have usually taken care of themselves in advance of the destruction of their business. I passed a brewery near Denver that had turned its attention to the making of “near” beer and malted milk, and employed a part of its labor otherwise in the manufacture of pottery. The presence of a[31] herd of cows on the brewery property to supply milk, for combination with malt, marked, with what struck me as the pleasantest of ironies, a cheerful acquiescence in the new order. Denver property rented formerly to saloon-keepers I found pretty generally occupied by shops of other kinds. In one window was this alluring sign:

Buy Your Shoes

Where You Bought Your Booze

The West’s general interest in public affairs is not remarkable when we consider the history of the Valley. The pioneers who crossed the Alleghanies with rifle and axe were peculiarly jealous of their rights and liberties. They viewed every political measure in the light of its direct, concrete bearing upon themselves. They risked much to build homes and erect States in the wilderness and they insisted, not unreasonably, that the government should not forget them in their exile. Poverty enforced a strict watch upon public expenditures, and their personal security entered largely into their attitude toward the nation. Their own imperative needs, the thinly distributed population, apprehensions[32] created by the menace of Indians, stubbornly hostile to the white man’s encroachments—all contributed to a certain selfishness in the settlers’ point of view, and they welcomed political leaders who advocated measures that promised relief and protection. As they listened to the pleas of candidates from the stump (a rostrum fashioned by their own axes!) they were intensely critical. Moreover, the candidate himself was subjected to searching scrutiny. Government, to these men of faith and hardihood, was a very personal thing: the leaders they chose to represent them were in the strictest sense their representatives and agents, whom they retired on very slight provocation.

The sharp projection of the extension of slavery as an issue served to awaken and crystallize national feeling. Education, internal improvements to the accompaniment of wildcat finance, reforms in State and county governments, all yielded before the greater issue. The promise of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness had led the venturous husbandmen into woods and prairies, and they viewed with abhorrence the idea that one man might own another and enjoy the fruits of his labor. Lincoln was not more the protagonist of a great cause than the personal spokesman of a body of freemen[33] who were attracted to his standard by the facts of his history that so largely paralleled their own.

It is not too much to say that Lincoln and the struggle of which he was the leader roused the Middle West to its first experience of a national consciousness. The provincial spirit vanished in an hour before the beat of drums under the elms and maples of court-house yards. The successful termination of the war left the West the possessor of a new influence in national affairs. It had not only thrown into the conflict its full share of armed strength but had sent Grant, Sherman, and many military stars of lesser magnitude flashing into the firmament. The West was thenceforth to be reckoned with in all political speculations. Lincoln was the precursor of a line of Presidents all of whom were soldiers: Grant, Hayes, Garfield, Harrison, McKinley; and there was no marked disturbance in the old order until Mr. Cleveland’s advent in 1884, with a resulting flare of independence not wholly revealed in the elections following his three campaigns.

My concern here is not with partisan matters, nor even with those internal upheavals that in the past have caused so much heartache to the shepherds of both of the major political flocks.[34] With only the greatest delicacy may one refer to the Democratic schism of 1896 or to the break in the Republican ranks of 1912. But the purposes and aims of the Folks with respect to government are of national importance. The Folks are not at all disposed to relinquish the power in national affairs which they have wielded with growing effectiveness. No matter whether they are right or wrong in their judgments, they are far from being a negligible force, and forecasters of nominees and policies for the future do well to give heed to them.

The trend toward social democracy, with its accompanying eagerness to experiment with new devices for confiding to the people the power of initiating legislation and expelling unsatisfactory officials, paralleled by another tendency toward the short ballot and the concentration of power—these and kindred tendencies are viewed best in a non-partisan spirit in those free Western airs where the electorate is fickle, coy, and hard to please. A good deal of what was called populism twenty years ago, and associated in the minds of the contumelious with long hair and whiskers, was advocated in 1912 by gentlemen who called themselves Progressives and were on good terms with the barber. In the Progressive convention of 1916 I was[35] struck by the great number of Phi Beta Kappa keys worn by delegates and sympathetic spectators. If they were cranks they were educated cranks, who could not be accused of ignorance of the teachings of experience in their political cogitations. They were presumably acquainted with the history of republics from the beginning of time, and the philosophy to be deduced from their disasters. It was because the Progressive party enlisted so many very capable politicians familiar with organization methods that it became a formidable rival of the old parties in 1912. In 1916 it lost most of these supporters, who saw hope of Republican success and were anxious to ride on the band-wagon. Nothing, however, could be more reassuring than the confidence in the people, i. e., the Folks manifested by men and women who know their Plato and are familiar with Isaiah’s distrust of the crowd and his reliance upon the remnant.

The isolation of the independent who belongs to no organization and is unaware of the number of voters who share his sentiments, militates against his effectiveness as a protesting factor. He waits timidly in the dark for a flash that will guide him toward some more courageous brother. The American is the most self-conscious being on earth and he is loath[36] to set himself apart to be pointed out as a crank, for in partisan camps all recalcitrants are viewed contemptuously as erratic and dangerous persons. It has been demonstrated that a comparatively small number of voters in half a dozen Western States, acting together, can throw a weight into the scale that will defeat one or the other of the chief candidates for the presidency. If they should content themselves with an organization and, without nominating candidates, menace either side that aroused their hostility, their effectiveness would be increased. But here again we encounter that peculiarity of the American that he likes a crowd. He is so used to the spectacular demonstrations of great campaigns, and so enjoys the thunder of the captains and the shouting, that he is overcome by loneliness when he finds himself at small conferences that plot the overthrow of the party of his former allegiance.

The West may be likened to a naughty boy in a hickory shirt and overalls who enjoys pulling the chair from under his knickerbockered, Eton-collared Eastern cousins. The West creates a new issue whenever it pleases, and wearying of one plaything cheerfully seeks another. It accepts the defeat of free silver and turns joyfully to prohibition, flattering itself that its chief[37] concern is with moral issues. It wants to make the world a better place to live in and it believes in abundant legislation to that end. It experiments by States, points with pride to the results, and seeks to confer the priceless boon upon the nation. Much of its lawmaking is shocking to Eastern conservatism, but no inconsiderable number of Easterners hear the window-smashing and are eager to try it at home.

To spank the West and send it supperless to bed is a very large order, but I have conversed with gentlemen on the Eastern seaboard who feel that this should be done. They go the length of saying that if this chastisement is neglected the republic will perish. Of course, the West doesn’t want the republic to perish; it honestly believes itself preordained of all time to preserve the republic. It sits up o’ nights to consider ways and means of insuring its preservation. It is very serious and doesn’t at all like being chaffed about its hatred of Wall Street and its anxiety to pin annoying tick-tacks on the windows of ruthless corporations. It is going to get everything for the Folks that it can, and it sees nothing improper in the idea of State-owned elevators or of fixing by law the height of the heels on the slippers of its[38] emancipated women. It is in keeping with the cheery contentment of the West that it believes that it has “at home” or can summon to its R. F. D. box everything essential to human happiness.

Across this picture of ease, contentment, and complacency fell the cloud of war. What I am attempting is a record of transition, and I have set down the foregoing with a consciousness that our recent yesterdays already seem remote; that many things that were true only a few months ago are now less true, though it is none the less important that we remember them. It is my hope that what I shall say of that period to which we are even now referring as “before the war” may serve to emphasize the sharpness of America’s new confrontations and the yielding, for a time at least, of the pride of sectionalism to the higher demands of nationality.

AT the end of a week spent in a Middle Western city a visitor from the East inquired wearily: “Does no one work in this town?” The answer to such a question is that of course everybody works; the town boasts no man of leisure; but on occasions the citizens play, and the advent of any properly certified guest affords a capital excuse for a period of intensified sociability. “Welcome” is writ large over the gates of all Western cities—literally in letters of fire at railway-stations.[40] Approaching a town the motorist finds himself courteously welcomed and politely requested to respect the local speed law, and as he departs a sign at the postern thanks him and urges his return. The Western town is distinguished as much by its generous hospitality as by its enterprise, its firm purpose to develop new territory and widen its commercial influence. The visitor is bewildered by the warmth with which he is seized and scheduled for a round of exhausting festivities. He may enjoy all the delights that attend the triumphal tour of a débutante launched upon a round of visits to the girls she knew in school or college; and he will be conscious of a sincerity, a real pride and joy in his presence, that warms his heart to the community. Passing on from one town to another, say from Cincinnati to Cleveland, from Kansas City to Denver, from Omaha to Minneapolis, he finds that news of his approach has preceded him. The people he has met at his last stopping-place have wired everybody they know at the next point in his itinerary to be on the lookout for him, and he finds that instead of entering a strange port there are friends—veritable friends—awaiting him. If by chance he escapes the eye of the reception committee and enters himself on the books of an[41] inn, he is interrupted in his unpacking by offers of lodging in the homes of people he never saw before.

There is no other region in America where so much history has been crowded into so brief a period, where young commonwealths so quickly attained political power and influence as in the Middle West; but the founding of States and the establishment of law is hardly more interesting than the transfer to the wilderness of the dignities and amenities of life. From the verandas of country clubs or handsome villas scattered along the Great Lakes, one may almost witness the receding pageant of discovery and settlement. In Wisconsin and Michigan the golfer in search of an elusive ball has been known to stumble upon an arrow-head, a significant reminder of the newness of the land; and the motorist flying across Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois sees log cabins that survive from the earliest days, many of them still occupied.

Present comfort and luxury are best viewed against a background of pioneer life; at least the sense of things hoped for and realized in these plains is more impressive as one ponders the self-sacrifice and heroism by which the soil was conquered and peopled. The friendliness, the eagerness to serve that are so charming[42] and winning in the West date from those times when one who was not a good neighbor was a potential enemy. Social life was largely dependent upon exigencies that brought the busy pioneers together, to cut timber, build homes, add a barn to meet growing needs, or to assist in “breaking” new acres. The women, eagerly seizing every opportunity to vary the monotony of their lonely lives, gathered with the men, and while the axes swung in the woodland or the plough turned up the new soil, held a quilting, spun flax, made clothing, or otherwise assisted the hostess to get ahead with her never-ending labors. To-day, throughout the broad valley the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of the pioneers ply the tennis-racket and dance in country club-houses beside lakes and rivers where their forebears drove the plough or swung the axe all day, and rode miles to dance on a puncheon floor. There was marrying and giving in marriage; children were born and “raised” amid conditions that cause one to smile at the child-welfare and “better-baby” societies of these times. The affections were deepened by the close union of the family in the intimate association of common tasks. Here, indeed, was a practical application of the dictum of one for all and all for one.

[43]The lines of contact between isolated clearings and meagre settlements were never wholly broken. Months might pass without a household seeing a strange face, but always some one was on the way—an itinerant missionary, a lost hunter, a pioneer looking for a new field to conquer. Motoring at ease through the country, one marvels at the journeys accomplished when blazed trails were the only highways. A pioneer railroad-builder once told me of a pilgrimage he made on horseback from northern Indiana to the Hermitage in Tennessee to meet Old Hickory face to face. Jackson had captivated his boyish fancy and this arduous journey was a small price to pay for the honor of viewing the hero on his own acres. I may add that this gentleman achieved his centennial, remaining a steadfast adherent of Jacksonian democracy to the end of his life. Once I accompanied him to the polls and he donned a silk hat for the occasion, as appropriate to the dignified exercise of his franchise.

There was a distinct type of restless, adventurous pioneer who liked to keep a little ahead of civilization; who found that he could not breathe freely when his farm, acquainted for only a few years with the plough, became the centre of a neighborhood. Men of this sort[44] persuaded themselves that there was better land to be had farther on, though, more or less consciously, it was freedom they craved. The exodus of the Lincolns from Kentucky through Indiana, where they lingered fourteen years before seeking a new home in Illinois, is typical of the pioneer restlessness. In a day when the effects of a household could be moved in one wagon and convoyed by the family on horseback, these transitions were undertaken with the utmost light-heartedness. Only a little while ago I heard a woman of eighty describe her family’s removal from Kentucky to Illinois, a wide détour being made that they might visit a distant relative in central Indiana. This, from her recital, must have been the jolliest of excursions, for the children at least, with the daily experiences of fording streams, the constant uncertainties as to the trail, and the camping out in the woods when no cabin offered shelter.

It was a matter of pride with the housewife to make generous provision for “company,” and the pioneer annalists dwell much upon the good provender of those days, when venison and wild turkeys were to be had for the killing and corn pone or dodger was the only bread. The reputation of being a good cook was quite[45] as honorable as that of being a successful farmer or a lucky hunter. The Princeton University Press has lately resurrected and republished “The New Purchase,” by Baynard Rush Hall, a graduate of Union College and of Princeton Theological Seminary, one of the raciest and most amusing of mid-Western chronicles. Hall sought “a life of poetry and romance amid the rangers of the wood,” and in 1823 became principal of Indiana Seminary, the precursor of the State University. Having enjoyed an ampler experience of life than his neighbors, he was able to view the pioneers with a degree of detachment, though sympathetically.

No other contemporaneous account of the social life of the period approaches this for fulness; certainly none equals it in humor. The difficulties of transportation, the encompassing wilderness all but impenetrable, the oddities of frontier character, the simple menage of the pioneer, his food, and the manner of its preparation, and the general social spectacle, are described by a master reporter. One of his best chapters is devoted to a wedding and the subsequent feast, where a huge potpie was the pièce de résistance. He estimates that at least six hens, two chanticleers, and four pullets were lodged in this doughy sepulchre, which[46] was encircled by roast wild turkeys “stuffed” with Indian meal and sausages. Otherwise there were fried venison, fried turkey, fried chicken, fried duck, fried pork, and, he adds, “for anything I knew, even fried leather!”

The pioneer adventure in the trans-Mississippi States differed materially from that of the timbered areas of the old Northwest Territory. I incline to the belief that the forest primeval had a socializing effect upon those who first dared its fastnesses, binding the lonely pioneers together by mysterious ties which the open plain lacked. The Southern infusion in the States immediately north of the Ohio undoubtedly influenced the early social life greatly. The Kentuckian, for example, carried his passion for sociability into Indiana, and pages of pioneer history in the Hoosier State might have been lifted bodily from Kentucky chronicles, so similar is their flavor. The Kentuckian was always essentially social; he likes “the swarm,” remarks Mr. James Lane Allen. To seek a contrast, the early social picture in Kansas is obscured by the fury of the battle over slavery that dominates the foreground. Other States[47] fought Indians and combated hunger, survived malaria, brimstone and molasses and calomel, and kept in good humor, but the settlement of Kansas was attended with battle, murder, and sudden death. The pioneers of the Northwest Territory began life in amiable accord with their neighbors; Kansas gained Statehood after a bitter war with her sister Missouri, though the contest may not be viewed as a local disturbance, but as a “curtain raiser” for the drama of the Civil War. When in the strenuous fifties Missouri undertook to colonize the Kansas plains with pro-slavery sympathizers, New England rose in majesty to protest. She not only protested vociferously but sent colonies to hold the plain against the invaders. Life in the Kansas of those years of strife was unrelieved by any gayeties. One searches in vain for traces of the comfort and cheer that are a part of the tradition of the settlement of the Ohio valley States. Professor Spring, in his history of Kansas, writes: “For amusement the settlers were left entirely to their own resources. Lectures, concert troupes, and shows never ventured far into the wilderness. Yet there was much broad, rollicking, noisy merrymaking, but it must be confessed that rum and whiskey—lighter liquors like wine and beer could not be obtained—had[48] a good deal to do with it.... Schools, churches, and the various appliances of older civilization got under way and made some growth; but they were still in a primitive, inchoate condition when Kansas took her place in the Union.”

There is hardly another American State in which the social organization may be observed as readily as in Kansas. For the reason that its history and the later “social scene” constitute so compact a picture I find myself returning to it frequently for illustrations and comparisons. Born amid tribulation, having indeed been subjected to the ordeal of fire, Kansas marks Puritanism’s farthest west; her people are still proud to call their State “The Child of Plymouth Rock.” The New Englanders who settled the northeastern part of the Territory were augmented after the Civil War by men of New England stock who had established themselves in Ohio, Illinois, and Iowa when the war began, and having acquired soldiers’ homestead rights made use of them to pre-empt land in the younger commonwealth. The influx of veterans after Appomattox sealed the right of Kansas to be called a typical American State. “Kansas sent practically every able-bodied man of military age to the Civil War,”[49] says Mr. William Allen White, “and when they came back literally hundreds of thousands of other soldiers came with them and took homesteads.” For thirty years after Kansas attained Statehood her New Englanders were a dominating factor in her development, and their influence is still clearly perceptible. The State may be considered almost as one vast plantation, peopled by industrious, aspiring men and women. Class distinctions are little known; snobbery, where it exists, hides itself to avoid ridicule; the State abounds in the “comfortably well off” and the “well-to-do”; millionaires are few and well tamed; every other family boasts an automobile.

While the political and economic results of the Civil War have been much written of, its influence upon the common relationships of life in the border States that it so profoundly affected are hardly less interesting. The pioneer period was becoming a memory, the conditions of life had grown comfortable, and there was ease in Zion when the young generation met a new demand upon their courage. Many were permanently lifted out of the sphere to which they were born and thrust forth into new avenues of opportunity. This was not of course peculiar to the West, though in the Mississippi valley[50] the effects were so closely intermixed with those of the strenuous post-bellum political history that they are indelibly written into the record. Local hostilities aroused by the conflict were of long duration; the copperhead was never forgiven for his disloyalty; it is remembered to this day against his descendants. Men who, in all likelihood, would have died in obscurity but for the changes and chances of war rose to high position. The most conspicuous of such instances is afforded by Grant, whose circumstances and prospects were the poorest when Fame flung open her doors to him.

Nothing pertaining to the war of the sixties impresses the student more than the rapidity with which reputations were made or lost or the effect upon the participants of their military experiences. From farms, shops, and offices men were flung into the most stirring scenes the nation had known. They emerged with the glory of battle upon them to become men of mark in their communities, wearing a new civic and social dignity. It would be interesting to know how many of the survivors attained civil office as the reward of their valor; in the Western States I should say that few escaped some sort of recognition on the score of their military services. In the city that I[51] know best of all, where for three decades at least the most distinguished citizens—certainly the most respected and honored—were veterans of the Civil War, it has always seemed to me remarkable and altogether reassuring as proof that we need never fear the iron collar of militarism, that those men of the sixties so quickly readjusted themselves in peaceful occupations. There were those who capitalized their military achievements, but the vast number had gone to war from the highest patriotic motives and, having done their part, were glad to be quit of it. The shifting about and the new social experiences were responsible for many romances. Men met and married women of whose very existence they would have been ignorant but for the fortunes of war, and in these particulars history was repeating itself last year before our greatest military adventure had really begun!

The sudden appearance of thousands of khaki-clad young men in the summer and fall of 1917 marked a new point of orientation in American life. Romance mounted his charger again; everywhere one met the wistful war bride. The familiar academic ceremonials of college commencements in the West as in the East were transformed into tributes to the patriotism of[52] the graduates and undergraduates already under arms and present in their new uniforms. These young men, encountered in the street, in clubs, in hurried visits to their offices as they transferred their affairs to other hands, were impressively serious and businesslike. In the training-camps one heard familiar college songs rather than battle hymns. Even country-club dances and other functions given for the entertainment of the young soldiers were lacking in light-heartedness. In a Minneapolis country club much affected by candidates for commissions at Fort Snelling, the Saturday-night dances closed with the playing of “The Star-Spangled Banner”; every face turned instantly toward the flag; every hand came to salute; and the effect was to send the whole company, young and old, soberly into the night. In the three training and mobilizing camps that I visited through the first months of preparation—Forts Benjamin Harrison, Sheridan, and Snelling—there was no ignoring the quiet, dogged attitude of the sons of the West, who had no hatred for the people they were enlisted to fight (I heard many of them say this), but were animated by a feeling that something greater even than the dignity and security of this nation, something of deep import to the whole world had called them.

[53]

In “The American Scene” Mr. James ignored the West, perhaps as lacking in those backgrounds and perspectives that most strongly appealed to him. It is for the reason that “polite society,” as we find it in Western cities, has only the scant pioneer background that I have indicated that it is so surprising in the dignity and richness of its manifestations. If it is a meritorious thing for people in prosperous circumstances to spend their money generously and with good taste in the entertainment of their friends, to effect combinations of the congenial in balls, dinners, musicals, and the like, then the social spectacle in the Western provinces is not a negligible feature of their activities. If an aristocracy is a desirable thing in America, the West can, in its cities great and small, produce it, and its quality and tone will be found quite similar to the aristocracy of older communities. We of the West are not so callous as our critics would have us appear, and we are only politely tolerant of the persistence with which fiction and the drama are illuminated with characters whose chief purpose is to illustrate the raw vulgarity of Western civilization. Such persons are no more acceptable socially[54] in Chicago, Minneapolis, or Denver than they are in New York. The country is so closely knit together that a fashionable gathering in one place presents very much the appearance of a similar function in another. New York, socially speaking, is very hospitable to the Southerner; the South has a tradition of aristocracy that the West lacks. In both New York and Boston a very different tone characterizes the mention of a Southern girl and any reference to a daughter of the West. The Western girl may be every bit as “nice” and just as cultivated as the Southern girl: they would be indistinguishable one from the other save for the Southern girl’s speech, which we discover to be not provincial but “so charmingly Southern.”

Perhaps I may here safely record my impatience of the pretension that provincialism is anywhere admirable. A provincial character may be interesting and amusing as a type; he may be commendably curious about a great number of things and even possess considerable information, without being blessed with the vision to correlate himself with the world beyond the nearest haystack. I do not share the opinion of some of my compatriots of the Western provinces that our speech is really the standard[55] English, that the Western voice is impeccable, or that culture and manners have attained among us any noteworthy dignity that entitles us to strut before the rest of the world. Culture is not a term to be used lightly, and culture, as, say, Matthew Arnold understood it and labored to extend its sphere, is not more respected in these younger States than elsewhere in America. We are offering innumerable vehicles of popular education; we point with pride to public schools, State and privately endowed universities, and to smaller colleges of the noblest standards and aims; but, even with these so abundantly provided, it cannot be maintained that culture in its strict sense cries insistently to the Western imagination. There are people of culture, yes; there are social expressions both interesting and charming; but our preoccupations are mainly with the utilitarian, an attitude wholly defensible and explainable in the light of our newness, the urgent need of bread-winning in our recent yesterdays. However, with the easing in the past fifty years of the conditions of life there followed quite naturally a restlessness, an eagerness to fill and drain the cup of enjoyment, that was only interrupted by our entrance into the world war. There are people, rich and poor,[56] in these States who are devotedly attached to “whatsoever things are lovely,” but that they exert any wide influence or color deeply the social fabric is debatable. It is possible that “sweetness and light,” as we shall ultimately attain them, will not be an efflorescence of literature or the fine arts, but a realization of justice, highly conceived, and a perfected system of government that will assure the happiness, contentment, and peace of the great body of our citizenry.

In the smaller Western towns, especially where the American stock is dominant, lines of social demarcation are usually obscure to the vanishing-point. Schools and churches are here a democratizing factor, and a woman who “keeps help” is very likely to be apologetic about it; she is anxious to avoid the appearance of “uppishness”—an unpardonable sin. It is impossible for her to ignore the fact that the “girl” in her kitchen has, very likely, gone to school with her children or has been a member of her Sunday-school class. The reluctance of American girls to accept employment as house-servants is an aversion not to be overcome in the West. Thousands of women in comfortable conditions of life manage their homes without outside help other than that of[57] a neighborhood man or a versatile syndicate woman who “comes in” to assist in a weekly cleaning.

There is a type of small-town woman who makes something quite casual and incidental of the day’s tasks. Her social enjoyments are in no way hampered if, in entertaining company, she prepares with her own hands the viands for the feast. She takes the greatest pride in her household; she is usually a capital cook and is not troubled by any absurd feeling that she has “demeaned” herself by preparing and serving a meal. She does this exceedingly well, and rises without embarrassment to change the plates and bring in the salad. The salad is excellent and she knows it is excellent and submits with becoming modesty to praise of her handiwork. In homes which it is the highest privilege to visit a joke is made of the housekeeping. The lady of the house performs the various rites in keeping with maternal tradition and the latest approved text-books. You may, if you like, accompany her to the kitchen and watch the broiling of your chop, noting the perfection of the method before testing the result, and all to the accompaniment of charming talk about life and letters or what you will. Corporate feeding in public mess-halls will make[58] slow headway with these strongly individualistic women of the new generation who read prodigiously, manage a baby with their eyes on Pasteur, and are as proud of their biscuits as of their club papers, which we know to be admirable.

Are women less prone to snobbishness than men? Contrary to the general opinion, I think they are. Their gentler natures shrink from unkindness, from the petty cruelties of social differentiation which may be made very poignant in a town of five or ten thousand people, where one cannot pretend with any degree of plausibility that one does not know one’s neighbor, or that the daughter of a section foreman or the son of the second-best grocer did not sit beside one’s own Susan or Thomas in the public school. The banker’s offspring may find the children of the owner of the stave-factory or the planing-mill more congenial associates than the children on the back streets; but when the banker’s wife gives a birthday party for Susan the invitations are not limited to the children of the immediate neighbors but include every child in town who has the slightest claim upon her hospitality. The point seems to be established that one may be poor and yet be “nice”; and this is a very comforting philosophy and no[59] mean touchstone of social fitness. I may add that the mid-Western woman, in spite of her strong individualism in domestic matters, is, broadly speaking, fundamentally socialistic. She is the least bit uncomfortable at the thought of inequalities of privilege and opportunity. Not long ago I met in Chicago an old friend, a man who has added greatly to an inherited fortune. To my inquiry as to what he was doing in town he replied ruefully that he was going to buy his wife some clothes! He explained that in her preoccupation with philanthropy and social welfare she had grown not merely indifferent to the call of fashion, but that she seriously questioned her right to adorn herself while her less-favored sisters suffered for life’s necessities. This is an extreme case, though I can from my personal acquaintance duplicate it in half a dozen instances of women born to ease and able to command luxury who very sincerely share this feeling.

The social edifice is like a cabinet of file-boxes conveniently arranged so that they may be drawn out and pondered by the curious. The seeker of types is so prone to look for the eccentric,[60] the fantastic (and I am not without my interest in these varieties), which so astonishingly repeat themselves, that he is likely to ignore the claims of the normal, the real “folksy” bread-and-butter people who are, after all, the mainstay of our democracy. They are not to be scornfully waved aside as bourgeoisie, or prodded with such ironies as Arnold applied to the middle class in England. They constitute the most interesting and admirable of our social strata. There is nothing quite like them in any other country; nowhere else have comfort, opportunity, and aspiration produced the same combination.

The traveller’s curiosity is teased constantly, as he cruises through the towns and cities of the Middle West, by the numbers of homes that cannot imaginably be maintained on less than five thousand dollars a year. The economic basis of these establishments invites speculation; in my own city I am ignorant of the means by which hundreds of such homes are conducted—homes that testify to the West’s growing good taste in domestic architecture and shelter people whose ambitions are worthy of highest praise. There was a time not so remote when I could identify at sight every pleasure vehicle in town. A man who[61] kept a horse and buggy was thought to be “putting on” a little; if he set up a carriage and two horses he was, unless he enjoyed public confidence in the highest degree, viewed with distrust and suspicion. When in the eighties an Indianapolis bank failed, a cynical old citizen remarked of its president that “no wonder Blank busted, swelling ’round in a carriage with a nigger in uniform”! Nowadays thousands of citizens blithely disport themselves in automobiles that cost several times the value of that banker’s equipage. I have confided my bewilderment to friends in other cities and find the same ignorance of the economic foundation of this prosperity. The existence, in cities of one, two, and three hundred thousand people of so many whom we may call non-producers—professional men, managers, agents—offers a stimulating topic for a doctoral thesis. I am not complaining of this phenomenon—I merely wonder about it.