CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS

London: FETTER LANE, E.C.

C. F. CLAY, Manager

Edinburgh: 100 PRINCES STREET

Bombay and Calcutta: MACMILLAN AND CO., Ltd.

Toronto: J. M. DENT & SONS, Ltd.

Tokyo: THE MARUZEN KABUSHIKI-KAISHA

All rights reserved

ENGLISH FOLK-SONG

AND DANCE

BY

FRANK KIDSON

AND

MARY NEAL

Cambridge:

at the University Press

1915

| ENGLISH FOLK-SONG | ||

| PAGE | ||

| Introduction | 3 | |

| i. | Definition | 9 |

| ii. | The Origin of Folk-Song | 11 |

| iii. | The Cante-Fable | 15 |

| iv. | The Construction of Folk-Music | 19 |

| v. | Changes that occur in Folk-Music | 25 |

| vi. | The Quality of Folk-Song, and its Diffusion | 36 |

| vii. | The Movement for collecting English Folk-Song | 40 |

| viii. | The Noting of Folk-Music | 47 |

| ix. | The Different Classes of Folk-Song | 52 |

| x. | The Narrative Ballad | 53 |

| xi. | Love Songs and Mystic Songs | 57 |

| xii. | The Pastoral | 60 |

| xiii. | Drinking Songs and Humorous Songs | 62 |

| xiv. | Highwayman and Poacher Songs | 64 |

| xv. | Soldier Songs | 66[Pg vi] |

| xvi. | Sea Songs | 67 |

| xvii. | Pressgang Songs | 69 |

| xviii. | Hunting and Sporting Songs | 70 |

| xix. | Songs of Labour | 71 |

| xx. | Traditional Carols | 74 |

| xxi. | Children’s Singing-Games | 77 |

| xxii. | The Ballad Sheet and Song Garland | 78 |

| Bibliography | 86 | |

| ENGLISH FOLK-DANCE | ||

| Introduction | 97 | |

| i. | The Morris Dance To-day | 125 |

| ii. | Tunes | 130 |

| iii. | Musical Instruments | 132 |

| iv. | The Dress | 136 |

| v. | Extra Characters | 141 |

| vi. | The Sword Dance | 145 |

| vii. | The Furry Dance | 150 |

| viii. | The Country Dance | 152 |

| ix. | The Present-Day Revival of the Folk-Dance | 158 |

| x. | Conclusions | 167 |

| Bibliography | 173 | |

| FACING PAGE | ||

| Morris Dancers at Bampton-in-the-Bush, Oxon. | 97 | |

| (By kind permission of The Daily Chronicle) | ||

| Abingdon Dances, whose tradition goes back to 1700 | 104 | |

| (From The Espérance Morris Book, Vol. I., | ||

| by kind permission of Messrs J. Curwen & Son) | ||

| Morris Dancers in the time of James I. | 120 | |

| Morris Dance and Music | 125 | |

| (From the Orchesographie of Thoinot-Arbeau, British Museum) | ||

| Whit-Monday at Bampton-in-the-Bush, Oxon. | 145 | |

| (By kind permission of The Daily Chronicle) | ||

| The Lock; Characteristic of Sword Dances | 148 | |

| (From The Espérance Morris Book, Vol. II., | ||

| by kind permission of Messrs J. Curwen & Son) | ||

BY FRANK KIDSON

NOTE

I am indebted to Miss Lucy E. Broadwood

for permission to use a folk-tune of her

collecting, and for many helpful suggestions.

Writing two centuries ago, Joseph Addison tells us in the character of Mr Spectator:—

“When I travelled I took a particular delight in hearing the songs and fables that are come down from father to son, and are most in vogue among the common people of the countries through which I passed; for it is impossible that anything should be universally tasted and approved of by a multitude, though they are only the rabble of the nation, which hath not in it some peculiar aptness to please and gratify the mind of man” (Spectator, No. 70). He further says:—

“An ordinary song or ballad, that is the delight of the common people, cannot fail to please all such readers as are not unqualified for the entertainment by their affectation or ignorance.”

It was not only the cultured Mr Addison who recognised the claims of the people’s songs as expressive of sentiments that were worthy the consideration of the more learned, for quotation upon quotation could [Pg 4] be given of examples where the refined and learned have found in the primitive song that which appealed in the highest degree.

The moderns need no excuse for the study of folk-song, and few will regard the consideration of people’s-lore as an idle amusement.

The present essay is put forth with all diffidence as a very slight dissertation upon a complex subject, and it does not pretend to do more than enter into the fringe of it.

The younger of the present generation have seen the gradual speeding up of technique in composition and performance, but with this increased standard there has been a tendency to let fall certain very sacred and essential things that belong to musical art. In too many cases the composer has not quite justified the complexity of his composition; while glorying in the skill of his craftsmanship he has too frequently forgotten the primitive demand for art and beauty, apart from technical elaboration.

That type of simple melody that formerly pleased what we might regard as a less cultured age, holds no place in present-day composition or in the esteem of a certain class.

It is probable that this melodic starvation turned so many, who had not lost the feeling for simple tune, towards folk-music when this was [Pg 5] dragged from obscurity and declared by competent musical judges to be worthy of consideration. Then people began to revel in its charm, and to feel that here was something that had been withheld from them, but which was good for their musical souls.

A simple air of eight or sixteen bars may not appear difficult to evolve, or even worth evolving at all, much less of record; but when the matter is further considered, we have to acknowledge that seemingly trivial melodies have wrought effects which have upset thrones and changed the fate of nations. Where they have not had this great political influence their histories show that they have rooted themselves deeply into the hearts of a people, and put into shade the finest compositions of great musicians. An undying vitality appears to be inherent in them, and this is shown by their general appeal throughout periods of thought and life totally unlike. Many examples prove this, and such an air as “Greensleeves” might be cited in this connexion.

One would suppose that nothing could be more apart in thought, action, and habit than the gallant of Elizabeth’s reign and an English farm labourer of the present day. And yet the tune “Greensleeves” that pleased the sixteenth century culture is found the cherished possession of countrymen in the Midlands, who execute a rustic dance to a [Pg 6] traditional survival of it. Further proof that it is one of those immortal tunes to which reference has been made is shown by the fact that it exists in various forms, and has had all kinds of songs fitted to it from its first recorded appearance in Shakespeare’s time (who mentions it) down to the present day.

“Greensleeves” is probably an “art” tune and not strictly folk-music. Hence in its passage downwards it has gradually got stripped of some of its subtilty, as it has been chiefly passed onward by tradition. This change will be noted further on.

Other tunes that, coming from remote antiquity, still find a welcome with the people are, “John Anderson my Jo,” and “Scots wha hae,” while “Lillibulero,” and “Boyne Water,” though of lesser age, fall into the same category.

We have even taken to our hearts tunes of other nationalities, and perhaps have more French airs among our popular music than of any other country. As every student of national song knows, “We won’t go home till morning” is but “Malbrook,” the favourite of Marie Antoinette, who learned it from the peasant woman called in to nurse her first child. “Ah vous dirai je” is known as “Baa baa black sheep” in every nursery, while “In my cottage near a wood” is a literal translation from an old French song to its proper tune. [Pg 7]

Such of these, or of this class, as are not folk-tunes have the same spirit, and it is this indefinable quality that causes folk-music to be so tenacious of existence. If it be good enough it is almost impossible for it to die and be totally forgotten. A tune may lie dormant for half a century, but it rises again and has its period of renewed popularity. One might name many a music-hall air, over which the people have for a period gone half wild, that is merely a resuscitation of a tune that has pleased a former generation. Thus such airs pass through strata of widely differing thought and mode of life.

It is folk-music that appeals to the bed-rock temperament of the people. Artificial music can only do so to a culture, which may change its standards with a change of thought, and that which is the applauded of one generation becomes the despised of a succeeding one; musical history can furnish many such examples. These facts justify our appreciation of folk-music and elevate its study.

The word “folk-song” is so elastic in definition that it has been freely used to indicate types of song and melody that greatly differ from each other. The word conveys a different signification to different people, and writers have got sadly confused from this circumstance. Even the word “song” has not a fixed meaning, for it can imply both a lyric with its music, and the words of the lyric only.

“Folk-song,” or “people’s song,” may be understood to imply, in its broadest sense, as Volkslied does to the German, a song and its music which is generally approved by the bulk of the people. Thus any current popular drawing-room song, or the latest music-hall production, would naturally hold this meaning, though it would not come into line with the other conceptions of folk-song, and probably not altogether satisfy the German ideal. Then, what may fitly be called “national” songs have a strong claim upon the word. “God save the King,” “Home sweet Home,” [Pg 10] “Tom Bowling,” “Heart of Oak,” and countless others that form our national store of song and melody could under this meaning be called folk-songs, and this might come closer to the German idea of a Volkslied.

The type, however, which lies nearest the definition of folk-song, as understood by the modern expert, is a song born of the people and used by the people—practically exclusively used by them before being noted down by collectors and placed before a different class of singers. To pursue the subject further one might split straws over the word “people,” but it may be generally accepted that “the people,” in this instance, stands for a stratum of society where education of a literary kind is, in a greater or lesser degree, absent.

This last definition of folk-song, as “song and melody born of the people and used by the people as an expression of their emotions, and (as in the case of historical ballads) for lyrical narrative,” is the one adopted in these pages and that generally recognised by the chief collectors and by the Folk-Song Society. In addition it may be mentioned that folk-song is practically almost always traditional, so far as its melody is concerned, and, like all traditional lore, subject to corruption and alteration. Also, that we have no definite knowledge of its original birth, and frequently but a very vague idea as to its period. [Pg 11]

It has been cleverly said that a proverb is the “wit of one and the wisdom of many.” In a folk-song or folk-ballad we may accept a similar definition, to the effect that it is in the power of one person to put into tangible form a history, a legend, or a sentiment which is generally known to, or felt by, the community at large, but which few are able to put into definite shape. We may suppose that such effort from one individual may be either crude or polished; that matters little if the sentiment is a commonly felt one, for common usage will give it some degree of polish, or at any rate round off some of its corners.

Every nation, both savage and civilized, has its folk-song, and this folk-song is a reflection of the current thought of the class among which it is popular. It is frequently a spontaneous production that invests in lyric form the commonly felt emotion or sentiment of the moment.

This type is more observable among savage tribes than among civilized nations. Folk-song is therefore not so permanent among the former as it [Pg 12] is among the latter. So far as we can gather, though it is difficult to get at the truth of this matter, among primitive people the savage does not appear to retain his song-traditions, but invents new lyrics as occasion calls. For example, one is continually reading in books of travel of negroes, or natives of wild countries, chanting extemporary songs descriptive of things which have been the happenings of the day, and telling of the white man who has come among them, of the feast he has provided, of the dangers they have encountered during the journey, and so forth. The tunes of these songs appear to be chiefly monotonous chants, and the accompanying music of the rudest character, produced on tom-toms, horns, reed-flutes, or similar kinds of instruments. A very typical description of this class of folk-song, the like of which may be found in most books of travel, occurs in Day’s Music and Musical Instruments of Southern India and the Deccan. The author says:—

“The ordinary folk-songs of the country are called “Lavanis,” and will be familiar to every one who has heard the coolies sing as they do their work, the women nursing their children, the bullock-drivers and dooley-bearers, or Sepoys on the march. The airs are usually very monotonous, the words, if not impromptu, are a sort of history, or ballad in praise of some warrior, or ‘burra-sahib.’ Some have a kind of chorus, each in turn singing an improvised verse.”

[Pg 13] This type appears to be the origin of a nation’s folk-song.

It is a sign of a country’s civilization when it begins to keep records, either by tradition or more fixed methods, and it is a theory (which may be probably accepted as correct) that chronicles were first chanted in ballad form and thus more easily passed downward in remembrance. This may be accepted as the origin of the folk-ballad. Its music has originated by the same natural instinct that produces language.

Much has been said of the communal origin of folk-song and folk-music, but it is somewhat difficult fully to realise what is meant by such a term in relation to these matters.

Those who hold this theory appear to assert that a folk-song with its music has had a primal formation at some early and indefinite time, and that this germ, thrown upon the world, has been fashioned and changed by numberless brains according to the popular demand, and has only met with general acceptance when it has fulfilled the requirements that the populace have demanded. This change is called its “evolution,” and it is sometimes claimed that this evolution still goes on where folk-songs [Pg 14] are yet sung; this means that the folk-song is virtually in a state of fluidity.

Such, briefly, appears to be the idea of those who hold the evolutionary, or communal, theory of folk-song origin. It cannot be denied that there is an obvious truth in such a contention, but before it can be generally accepted surely there must be much modification. It cannot be altogether decided that the original germ is absolutely different from the folk-song as found existing to-day, but that both folk-song and folk-music are subject to change also cannot be disputed. The parlour game “Gossip,” in which A whispers a short narrative to B, who in turn whispers it to C, the narrative passing finally to Z, has been used as an illustration of the variations that folk-song undergoes. In the game, the tale originally put forth by A is generally found to be much unlike that received by Z. Folk-song in some degree suffers such change by conscious or unconscious alteration. Unconscious alteration we can easily understand; that is merely the result of imperfect remembrance. Conscious alteration may be the effect, in vocal rendering, of a difficulty in individual singers of attaining certain intervals, or from choice. Alteration in instrumental rendering of folk-music is chiefly due to lack of skill in the performer on a [Pg 15] particular instrument. Thus, what may be difficult to render on a flute may be easy on a fiddle; hence we can conceive an alteration may be purposely made for facility of performance. This is decidedly not evolution, nor communal origin.

The existence of the “Cante-fable” has furnished another theory of folk-song origin. The Cante-fable is a traditional prose narrative having rhymed passages incorporated with the tale. These rhymes are generally short verses, or couplets, which recur at dramatic points of the story. They were probably sung to tunes, but present-day remembrance has failed to preserve more than a few specimens, and the verse, or couplet, is now generally recited.

It has been asserted that the Cante-fable is a sort of germ from which both ballad and prose narrative have evolved. Mr Jacobs, in English Fairy Tales, says—“The Cante-fable is probably the protoplasm out of which both ballad and folk-tale have been differentiated; the ballad by omitting the narrative prose, and the folk-tale by expanding it.” [Pg 16]

Mr Cecil J. Sharp, in English Folk-song: Some Conclusions, p. 6, tells of having noted a version of the ballad “Lord Thomas and Fair Eleanor”—“in which the whole of the story was sung, with the exception of three lines, which the singer assured me should be spoken. This was clearly a case of a Cante-fable that had very nearly, but not quite, passed into the form of a ballad, thus corroborating Mr Jacobs’ theory.”

The present writer is sorry to differ from Mr Jacobs as well as from Mr Sharp in this matter, but he does not think that facts quite justify the conclusion. He can but look upon the speaking of the three lines of the “Fair Eleanor” ballad, instead of singing them, as merely an individual eccentricity that has no value as pointing to a nearly completed evolution. Their theory indicates, to put it crudely, that the Cante-fable is in the condition of a tadpole which by and by will have its fins and tail turned into legs, will forsake its original element, and hop about a meadow, instead of being entirely confined to pond water.

An examination of existing Cante-fables will certainly reveal the fact that the fragments of verse are used either as a literary ornament, or to force some particular dramatic situation home to the hearer. Also, it must be noticed that the rhyme passages are not merely fragmentary [Pg 17] parts of a prose narrative which is gradually turning wholly into rhyme, but most frequently consist of a repeated verse, or couplet, that occurs at parts of the story, which could not be so effectively told in prose.

The commonly known story of “Orange,” versions of which, all having the same rhyme passages, are to be found in English, German, and other folk-tales is a good example. With little variation the story tells of a stepmother who kills her husband’s child, makes the body into a pie, to be eaten by the father, and buries the bones in the cellar. First one member of the family goes into this place and hears the voice of the murdered child sing,—

Then other members of the family go to the cellar and in turn hear the same voice repeating the rhyme (see Folk-Song Journal, vol. ii., p. 295, for a version of the tale and a tune sung to the above words learned from Liverpool children).

Another Cante-fable, surely a genuine one, is given by Charles Dickens in “Nurses’ Stories” in The Uncommercial Traveller. [Pg 18]

In this case the rhyme—

is brought out with vivid effect by the narrator at intervals and with terror-striking force due to its expected recurrence, just as in the case of the story of “Orange.” As Dickens puts it—“I don’t know why, but the fact of the Devil expressing himself in rhyme was peculiarly trying to me.” And again—“For this refrain I had waited since its last appearance with inexpressible horror, which now culminated.” And—“The invariable effect of this alarming tautology on the part of the Evil Spirit was to deprive me of my senses.”

There can be but little doubt that this Cante-fable is a real nurse’s story, remembered by the great author from his childhood, and Dickens so well describes the feeling of terror that the rhyme inspires in the childish listener, that we cannot but grant that the original makers of Cante-fable were quite alive to the dramatic force such recurring rhymes possess.

Other examples of the Cante-fable are to be found in Chambers’ Popular Rhymes of Scotland and elsewhere. All, however, point to the verse [Pg 19] being used as an ornamental and dramatic addition to the story, and certainly not as indicating a transitionary stage between a rhyming and a prose narrative.

The question of a Cante-fable origin of the folk-ballad is here somewhat fully dealt with, as it is a sufficiently romantic theory to lead people, who have not fully considered all the points involved, to accept it on trust.

It will be quite evident to the average hearer that much folk-music is built upon scales different from those that form the foundation of the ordinary modern tune. This fact is accounted for by the circumstance that a large percentage of folk-melodies are “modal”; i.e. constructed upon the so-called “ecclesiastical modes” which, whether adopted from the Greek musical system or not, had Greek nomenclature, and were employed in the early church services.

The ecclesiastical scales may be realised by playing an octave scale on the white keys of the piano only. Thus—C to C is Ionian, D to D [Pg 20] Dorian, E to E Phrygian, F to F Lydian (rarely used), G to G Mixolydian, A to A Æolian, and B to B Locrian (practically unused).

Progress in harmony and polyphony gradually revealed the cramping effect of many modal intervals, and already by the beginning of the seventeenth century our modern major and minor scales (the first, however, corresponding to the Ionian mode in structure) had supplanted the rest, so far as trained musicians were concerned. Not so with the folk-tune maker; he was conservative enough to preserve that which had become obsolete elsewhere. We find a large proportion of folk-airs are in the Dorian, Mixolydian, and Æolian modes, with much fewer in the Phrygian.

When folk-music began to be first studied scientifically a theory was held that because of its modal character it was necessarily a reflex of ecclesiastical music, and that secular melodies were either church chants set to songs, or in some other way derived from them. It is known that many of the early clerics established schools for the teaching of music, with intent to enrich the services. But while this theory is temptingly plausible, yet it is incapable of proof, and a reverse one might, with equal reason, be held to maintain that the church took its music directly from the people, or at any rate adapted its form from that mostly popular. [Pg 21]

It has also been asserted that the modal character of folk-music is a clear proof of great age. It is certainly more than likely that most of the modal tunes that are found are of considerable antiquity, but it is scarcely safe to conclude that all are so. How old any particular folk-tune may be is a problem incapable of solution, and all attempts to fix its age and period can be but, at best, mere guesswork.

We may grant that folk-music has been handed down traditionally by many generations of singers, but if it has pleased these different generations we must also admit that any new composition of folk-music, to please the people, must conform to their common demand.

Folk-music seems to have held its own traditional ideals longer and more closely than music composed for that class which has so persistently ignored it. The cultured musician is always, consciously or unconsciously, influenced by the music of his day, and as a consequence adheres to its idioms, or is genius enough to found a school of his own. His music too is far more elaborate than that produced by the rustic, or untaught musician. It has harmony, and many more points of evidence that enable us definitely to fix its period of composition. [Pg 22]

The composer of folk-music may be compared, in a sense, to the Indian, or Chinese art-worker who repeats the class of patterns that has come down to him from time immemorial. When European influence was brought to bear on his work his patterns became debased, lost their original beauty, and gained nothing from the new source of inspiration.

There is no space in this small manual to enter into a disquisition on the Modes. The reader is referred to such a work as the new edition of Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians (vol. iii., p. 222), to Carl Engel’s Study of National Music, and to a most valuable contribution to the subject by Miss A. G. Gilchrist, “Note on the Modal System of Gaelic Tunes,” in the Journal of the Folk-Song Society, vol. iv., No. 16.

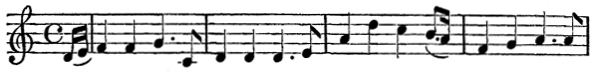

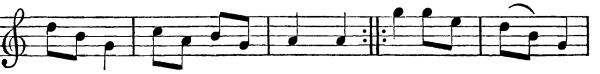

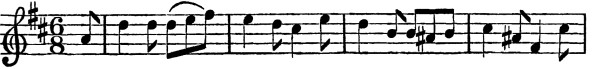

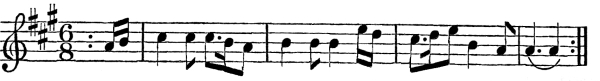

The following are given as examples of modal folk-tunes, in the modes most frequently found:—

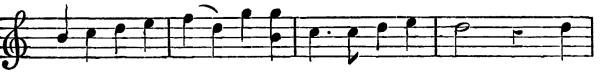

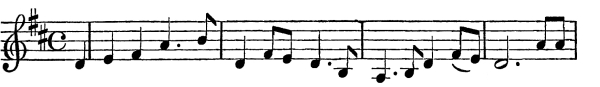

| ONE MOONLIGHT NIGHT | |

| Dorian | Sung in a “Cante-Fable” |

|

|

| One moonlight night, as I sat high, I looked for one, but two came by; The | |

|

|

| boughs did bend, the leaves did shake, To see the hole the fox did make. | |

[Listen] |

|

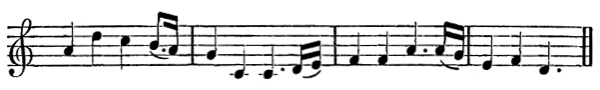

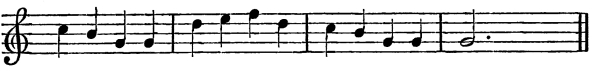

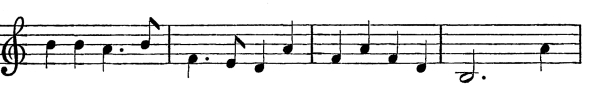

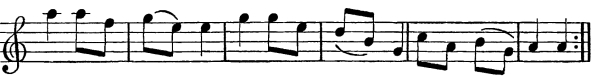

| THE BONNY LABOURING BOY | |

| Noted by Miss L. E. Broadwood | Sung by Mr Lough, Surrey |

| Mixolydian | |

|

|

| As I roved out one eve - ning, being in the blooming spring, | |

|

|

| I heard a love-ly dam-sel fair most grie-vously did sing,Say-ing | |

|

|

| “Cru-el were my pa - rents that did me so an - noy.They | |

|

|

| did not let me mar-ry with my bon-ny la-b’ring boy.” | |

[Listen] |

|

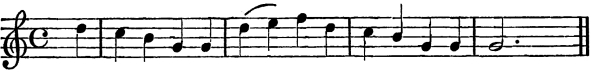

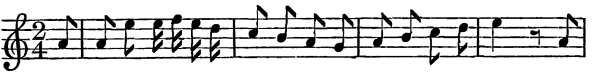

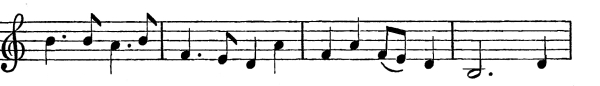

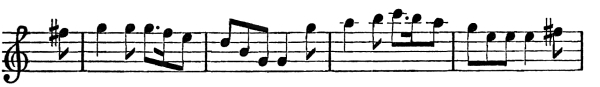

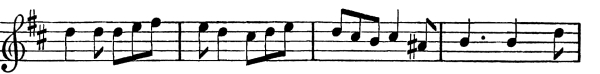

| CHRISTMAS CAROL AS SUNG IN NORTH YORKSHIRE |

|

| Æolian Mode | |

|

|

| God rest you merry, merry gentlemen, Let nothing you dismay,Re- | |

|

|

| member Christ our Saviour was born on Christmas day,To | |

|

|

| save our souls from Satan’s pow’r that long had gone astray,Oh, | |

|

|

| tidingsofcomfort andjoy, andjoy,and | |

|

|

| joy,Oh,tidingsof comfort and joy,andjoy. | |

[Listen] |

|

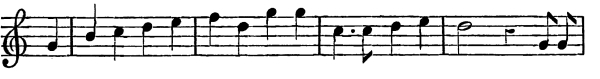

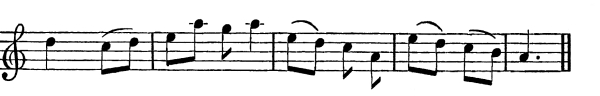

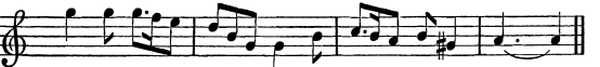

[Pg 24] In addition to modal tunes we have a certain number of folk-airs built upon a “gapped,” or limited, scale of five notes instead of the usual seven. This “pentatonic” scale, which appears to be very characteristic of the primitive music of all nations, was formerly held as an infallible sign of a Scottish origin, and the old recipe to produce a Scottish air was—“stick to the black keys of the piano.” It is quite true that a large number of Scottish melodies have the characteristics of the pentatonic scale, but so also have the Irish tunes, and there are a lesser number that may claim to be English.

Much nonsense has been written to account for the existence of the pentatonic scale, the general conclusion arrived at being that it arose from the use of an imperfect instrument that could only produce five tones. Whatever the instrument so limited may have been, it was neither the primitive flute (like the tin whistle) of six vents, which is sufficient to produce well over an octave, nor was it the human voice. [Pg 25] The universal use of the five note scale among many nations wide apart has never been satisfactorily explained. The following is an Irish pentatonic traditional air.

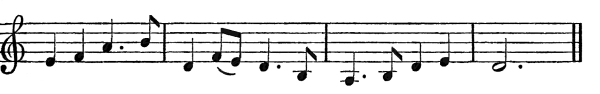

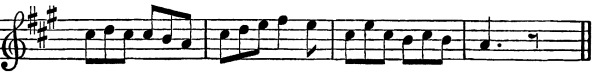

| THE SHAMROCK SHORE | |

| Pentatonic | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[Listen] |

|

That all traditional lore is subject to change is of course a well-recognised fact, and this change is so uncertain in its effects, and so erratic in its selection that no law appears to govern it. In ballads or prose narratives that exist only by verbal transmission we [Pg 26] may expect the dropping of obsolete words and phrases, and this usually occurs; though sometimes corruptions of such remain and are meaningless to those who repeat them.

For instance, in a certain singing-game, children of a particular district were accustomed to say—

“She knocked at the door and picked up a pin.” It is quite obvious that the original stood—

“She knocked at the door and tirled at the pin.” The “tirling pin” having completely gone out of usage, and even out of popular remembrance, in the limited area where it formerly served the purpose of attracting the attention of the householder, the phrase would have no meaning to the modern child; hence the change into something more comprehensible.

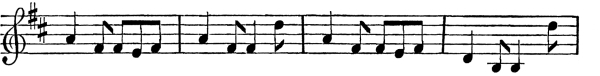

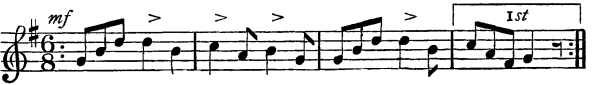

There is considerable analogy in the above to the change that takes place in folk-music. But as musical phrases do not, at any rate in folk-music, become so obsolete as words, the variation is less considerable and is probably due to different causes. These are chiefly wilful alteration for particular reasons, and unconscious change due to lapse of memory, or imperfect hearing. We may usefully consider two or three examples of these kinds of alterations. The tune “Greensleeves” is a very characteristic instance. The first record of the song is at the date 1580, when the ballad was entered at Stationers’ Hall. It is [Pg 27] evident that both words and tune became immediately popular, and from that time to our own day it has always retained considerable favour, for it was one of those stock tunes used for ephemeral political ditties, and for the scraps of verse that were employed in the early ballad operas. It is easy to trace, from the eighteenth century printed copies, how the tendency has been to eliminate complex passages, and generally to simplify, while retaining the essential features of the tune. Probably this is its pure sixteenth century form—

| GREENSLEEVES | |

| (Earliest form) 16th Century | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[Listen] |

|

[Pg 28] It is rather a shock to find that the beautiful air has by careless transmission or wilful change got so degraded as finally to appear in a manuscript book of fiddle airs dated 1838, thus,—

| GREENSLEEVES | |

| From a Manuscript Book, dated 1838 | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

[Listen] |

|

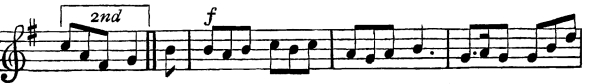

Other copies which have deplorably lost much of the purity of the original are to be seen in D’Urfey’s Wit and Mirth, The Beggar’s Opera and other early eighteenth century publications. This is from an edition of The Dancing Master, dated 1716:

| GREENSLEEVES AND YELLOW LACE | |

| Printed 1716 | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[Listen] |

|

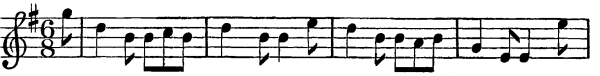

[Pg 29] We may trace a curious corruption in the tune as found in traditional usage in Ireland nearly eighty years ago. Thomas Moore employed this traditional version for his song, “Oh, could we do with this world of ours,” and published it united to his verses in his Irish Melodies, the tenth number dated 1834. He gives the tune the name of “The Basket of Oysters.” The real tune which went by this title, otherwise known as “Paddy the Weaver,” is to be seen in Aird’s Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs, vol. iii., Glasgow [1788], and elsewhere. It will be noticed that Moore’s tune is “Greensleeves,” to which is joined a part of “Paddy the Weaver.” It is a notable example of the manner in which traditional tunes suffer change from imperfect remembrances or other causes.

| THE BASKET OF OYSTERS | |

| Greensleeves, Irish Version, 1834 | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[Listen] |

|

| A BASKET OF OYSTERS, OR PADDY THE WEAVER |

|

| From Aird’s “Selection,” 1788 | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[Listen] |

|

Although “Greensleeves” is probably not a folk-tune, yet in some cases folk-tunes are apt to suffer a like degradation in character, although it must be clearly stated that tradition frequently holds them together in a wonderfully perfect manner. [Pg 31]

In this latter case we may rank “Joan’s placket is torn,” which survives in the modern “Cock o’ the North,” with “Greensleeves,” and their histories are well worth recalling.

We may pass over the tradition that “Joan’s placket” was played at the execution of Mary Queen of Scots. The structure of the tune shows it to have been originally a trumpet tune, and strangely enough throughout the whole course of its existence it seems to have been used in defiance or ridicule. Mr Pepys tells us that when the English sailors left the deserted “Royal Charles” in the Medway in 1667, a Dutch trumpeter sounded the tune from the deck of the captured ship. After this period political lampoons were adapted to the melody. It is difficult to find out when the tune was first named “The Cock o’ the North,” or when, under that title, it was adopted as a British army tune, but there is a striking instance of its use during the siege of Lucknow in the Mutiny of 1857. It was the practice to signal by flag and bugle call from the City to the Residency, both in a state of siege. On one occasion a drummer boy, named Ross, after the signalling was over again climbed to the high dome from which it was conducted, and in spite of the Sepoy rifles sounded “The Cock o’ the North” as a [Pg 32] defiance. We all know the story of the wounded piper, shot in the ankle during the rush at Dargai, crouching behind a rock and still sounding the pipe tune the “Cock o’ the North” that had inspired the onslaught. How little the traditional “Cock o’ the North” differs from “Joan’s Placket” the reader will be able to see from the following copies:—

| JOAN’S PLACKET IS TORN | |

| 17th Century | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

[Listen] |

|

| THE COCK O’ THE NORTH | |

| 20th Century | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[Listen] |

|

[Pg 33] Many other examples of traditional cohesion as regards folk-tunes might be cited did space permit.

The tune “A sailor loved a farmer’s daughter,” given in Edward Bunting’s Ancient Music of Ireland, 1840, has recently been noted from a farm labourer by Mrs Stanton of Armscott, Warwickshire, in a form practically identical with the printed version, though it is quite evident that the tune noted in Warwickshire has had a source independent of Bunting’s. Every collector could point to such instances from his own experience.

Another fact forces itself into notice. A tune may develop by traditional passage, or by wilful alteration, into several forms, and thus we get airs having points of similarity but also points of difference. In some cases the likeness may be so close that the different tunes are classed as “variants.”

It must be realised that a folk-song singer is under no bond to sing an air strictly as he has received it. Fortunately, in many cases, as shown above, he does, and religiously adheres to the melody as far as his memory, or skill, will permit. There are, however, difficult tunes to remember as well as easy ones, and this fact has considerable bearing on the question.

The reason why we find well-known folk-songs adapted to different airs [Pg 34] is somewhat obvious, and the following explanation may be I think accepted. Where a singer reads a folk-song from a ballad sheet and does not know its particular tune, it is easy to believe that he uses one with which he is already familiar, or adapts one, or even composes an air from the stock musical phrases that he knows in other melodies. Thus we find folk-songs sung to many different airs, and this is not evolution.

It may be noticed that in the lesser marked tunes, or rather less original airs, stock musical phrases are in use just as the stock phrases of the ballad-maker are employed by him over and over again. The folk-song singer looks for and welcomes these passages. They are conventional and are the most acceptable. Just as a child gives a better welcome to a story beginning “Once upon a time” than to a less hackneyed manner of opening, and as the folk-singer demands that every girl shall be “a fair damsel,” that the incident of the song shall happen “As I was a-walking one morning in May,” and that his mode of address shall be “I stepped up boldly to her,” or the like, so there are certain inevitable musical phrases in folk-music that one meets with in a particular type of melody.

Waggish musicians are sometimes guilty of inventing “a folk-melody” for [Pg 35] the purpose of deceiving and laughing at collectors. The collector, recognising the phrases he knows so well, may accept the tune as genuine. He is not wrong or ignorant in this; the musician has got possession of the material and spirit of folk-music, and then deception is easy. A man may have a Johnsonian method of diction without having the wit or learning of the great lexicographer, and might even pass off a short speech as a genuine one of the Doctor’s.

These stock phrases are of course freely used in folk-music, and it is quite easy for a singer of folk-song legitimately to make an air for a ballad whose proper tune he may not know. This is another way in which variation of tunes occurs, and such results are frequently very puzzling to the expert. The singer may have remembered a passage of a melody and to this he has fitted other phrases that he is also familiar with. He is probably not conscious of the composite tune he is making,—he may even think that he is singing the correct tune.

The strongest and most valuable feature of folk-song is its earnestness and good faith. Though the quality of earnestness is indefinable it is the soul of art work, and its presence is ever felt.

A folk-song may be very doggerel in verse, its subject trite and trivial, yet it possesses that subtle character that has the appeal and lasting power only belonging to sincerity. The maker of a folk-song did not produce his work for professional reasons; he sang because he must, and sometimes he was very ill-fitted for the task. Yet the work, being done in good faith, has not only the power of appeal to the class for which it was made, but also to a higher culture. Work of greater cleverness if it lack this great asset of earnestness cannot do more than please a particular cult for the moment.

As with folk-music and folk-song, so with the original folk-song singer. In general he does not sing anything that is not fully in accord with his own sentiments, and this is really why folk-song not only keeps in favour with him, but also why it maintains its integrity in tradition. It is seldom, except for the reasons I have before given, [Pg 37] that a folk-song singer wilfully alters his song. As I have said, he may, and indeed frequently does, make unconscious changes, but he has a respect for the songs handed down to him.

On the other hand a singer will without scruple rob another district of its right in a folk-song. What in one district is “Scarbro’ Fair” becomes “Whittingham Fair,” and “Birmingham Fair” becomes “Brocklesby Fair,” according to the places where the songs are current. Otherwise the song sustains no material change, and each set of singers will declare their own version is the true one.

The drawing-room vocalist has not the same constancy to his songs as the folk-song singer, nor have his songs the same stability. When the stout respectable father of a family proclaims his passion for a fascinating nymph, and entreats her to fly with him, his wife smiles approval and silently applauds his efforts. When a feeble-looking young man voices sentiments of a blood-thirsty or gruesome character nobody is expected to believe him. In fact he is not in earnest, and in neither of the two cases I have supposed do the singer’s voice their general sentiments. On the other hand, the folk-song singer really does feel the sentiments he sings. If he likes fox-hunting, he [Pg 38] sings a fox-hunting song, and is in perfect agreement with the ditty that proclaims fox-hunting a noble sport. And the song represents his feelings when he sings of the joys of farming, or of good liquor, or any other subject that appeals to him as a man, including love. When a young girl or even an old lady sings—

we may be quite sure that this puts into song some sentiments that either hold possession of the soul or recalls certain sacred memories.

Such songs as voice commonly felt sentiments are quickly diffused over the countryside, and they are to be found very widely spread. Where songs deal with the usages of a district, which, from some cause or another, do not obtain elsewhere, they are less likely to travel. For example, we find few harvest-home songs current in the north of England, and not so many that deal with the joys of farming. In the south-west, where there are large tracts of agricultural land, and more organised merry-makings at the close of the harvest, or at sheep-shearing, there are plenty of songs which proclaim that the life of a farmer, or a ploughman, is all that can be desired.

In the North, where there is more grazing land, and the harvest is [Pg 39] harder to wring from the soil, this type of song scarcely exists. The fact is therefore again forced upon us that the folk-song singer, or maker, deals with things with which he is most familiar. Except for these limitations it is unsafe to class a folk-song as “Yorkshire,” “Devonshire,” or otherwise fix it to a particular county.

There are, of course, a very small number of folk-songs that obviously belong to certain districts, but because a song is sung or noted in one county we cannot claim that such county is the place of its origin. Before folk-song collecting was so general as at present it was frequently customary to fall into this error, but as collectors and their published “finds” have increased in number, it has become apparent that folk-songs have been very widespread.

For some reason a song may linger longer in one place than another. Such a one may be compared to the snow which may have completely covered a hill-side, but ultimately melting leaves its remnants only in the sheltered nooks, to disappear last of all.

In a similar way we may find that a dialect word which might be hastily assumed to belong strictly to, say, Yorkshire, is used in another part of the country—quite remote, and is generally considered to be a local [Pg 40] word. Instances of such might be given, and we may speculate as to how the word, or the song has got there, whether by travel, or whether, like the snowdrift, by survival.

It remains now to consider what has been done towards the noting of traditionary songs and their airs. Little attention was paid to the songs sung by country singers prior to the first half of the nineteenth century. In England, the first step toward the recognition of country folk-song was made by the Rev. John Broadwood, squire of Lyne, on the Sussex and Surrey border. In 1843 he published (modestly keeping his name from the title page) a collection of sixteen songs which were harmonised by a country organist. The title of the Rev. John Broadwood’s book is lengthy, but so curious and explanatory that I reproduce it. The work itself is of extraordinary rarity.

“Old English Songs, as now sung by the peasantry of the weald of Surrey and Sussex, and collected by one who has learnt them by hearing them [Pg 41] sung every Christmas from early childhood by the country people who go about to the neighbouring houses, singing, or ‘wassailing,’ as it is called, at that season. The airs are set to music exactly as they are now sung, to rescue them from oblivion, and to afford a specimen of genuine old English Melody, and the words are given in their original rough state with an occasional slight alteration to render the sense intelligible. Harmonised for the collector, in 1843, by G. A. Dusart, organist to the Chapel of Ease at Worthing, London. Published for the Collector by Balls & Co., 408 Oxford St. for private circulation (folio, pp. 32).”

It was about this time that William Chappell was bringing into notice the fine store of English melodies, which were then quite unknown save to a few musical antiquaries. He had already published a couple of volumes of airs, but in 1856 he commenced the issue of his Popular Music of the Olden Time, and among the tunes there printed he included a small number of traditional melodies which he had taken down chiefly in the South of England. Many of these have won their way into the hearts of lovers of our national music, and it seems a pity that they are omitted from the new edition of Chappell’s work. For a long time after Chappell’s publication little attention was paid to the [Pg 42] folk-songs of our own country, though many German songs that claimed to be people’s song obtained considerable favour with us. About 1878 a revival of interest in the Northumbrian small pipes caused a search to be made for pipe tunes, and Mr John Stokoe, of South Shields, was an active worker in the field. Commencing in December 1878 he contributed to the Newcastle Courant a series of pipe and fiddle tunes once popular among Northumbrian pipers. They were chiefly taken from manuscript collections, but while the airs were, in many cases, merely transcripts from books of printed tunes for the violin or flute, published in England and Scotland during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, there remained a number of traditional melodies of purely Northumbrian usage.

In 1882, under the auspices of the Society of Antiquaries, Newcastle-on-Tyne, Mr Stokoe, in collaboration with Dr Collingwood Bruce, published a volume entitled Northumbrian Minstrelsy, and here the Courant tunes were republished with other material. The work has the fault of including as fresh material much of what had already been printed in early dance collections and elsewhere, but having small claim to be considered as of Northumbrian origin.

A book of traditional nursery rhymes, chiefly from a Northumbrian [Pg 43] source, had already been issued (in 1877) by Miss M. A. Mason. In 1888 a small illustrated booklet, The Besom Maker and other Country Folk-Songs, containing nine songs, was issued by Mr Heywood Sumner.

It was about this period that a wave of sympathy impelled several persons to turn their attention to the consideration of the songs sung by rustics and other persons who remembered the songs sung by their parents or elders. Most persons were under the impression that these country songs were merely remembrances from printed sources, and that practically little, or nothing, existed purely traditionary.

A little study of the question, however, soon convinced Miss Lucy E. Broadwood, Dr William Alexander Barrett, the Rev. Sabine Baring-Gould, and the present writer to the contrary.

Miss Broadwood, then living at Lyne in Sussex, found an unworked mine of great richness among the country people of her district. The late Dr Barrett had already gathered much, chiefly in the South of England, while a chance suggestion at a dinner-table caused Mr Baring-Gould to turn his attention to the collecting of the song current in Devonshire and Cornwall. Mr Baring-Gould absolutely revelled in this work, and his wild journeys over Dartmoor, with periods of settling down for a time [Pg 44] at village inns, brought him in a plentiful harvest of charming songs and delightful melody. In this task he was associated with the Rev. H. Fleetwood Sheppard and Mr F. W. Bussell. The work of these collectors saw publication in Songs of the West, the first part of which was issued about 1889, and the fourth and last part in 1891.

Another work of Mr Baring-Gould’s, in conjunction with the late Mr Sheppard, is a Garland of Country Songs, 1895. This is some portion of the material left over from Songs of the West; both were published by Methuen. A re-issue of Songs of the West with additions appeared in 1905.

A small part of Miss Broadwood’s work was incorporated in English County Songs, which she edited in collaboration with Mr J. A. Fuller Maitland in 1893. The great popularity of this work is justified by its excellence. A further selection appeared in English Traditional Songs and Carols (Boosey, 1908).

Dr Wm. Alex. Barrett, in February 1891, a few months prior to his death, issued, through Novello & Co., English Folk-Songs, a most interesting collection of fifty-four songs, some of which, however, are to be found in print in earlier publications. [Pg 45]

In the spring of 1891 the present writer issued the result of his collecting under the title Traditional Tunes, a collection of ballad airs chiefly obtained in Yorkshire and the South of Scotland, by Frank Kidson.

After these publications no further work on English folk-song appeared before the formation of the Folk-Song Society. This society, the most important factor in calling attention to the existence of unnoted folk-song, owed its existence to three or four enthusiasts in the cause who saw the utility of such a thing. At first it was projected as a branch of the Folk-Lore Society, but, finally, it was thought advisable that it should stand alone. The Folk-Song Society was duly formed on June 16th, 1898. The first president was the late Lord Herschell; the vice-presidents the late Sir John Stainer, Sir Alexander Mackenzie, Sir Hubert Parry, Professor (now Sir Charles) Stanford, and the committee as follows—Mrs Frederick Beer, Miss Lucy E. Broadwood, Sir Ernest Clarke, Mr W. H. Gill, Mrs (now Lady) Gomme, Messrs A. P. Graves, (the late) E. F. Jacques, Frank Kidson, J. A. Fuller Maitland, J. P. Rogers, W. Barclay Squire, and Dr Todhunter. The late Mrs Kate Lee acted as Hon. Secretary and Mr A. Kalisch as Hon. Treasurer, both being on the committee. [Pg 46]

In the first year 110 members joined; at the present time there are probably more than three times that number. In 1904 Miss Lucy E. Broadwood became Hon. Secretary, and the useful work of the society advanced by leaps and bounds. Mrs Walter Ford, and Mr Frederick Keel, the present secretary, followed Miss Broadwood.

The “Journals” of the Society, which by January 1914 had reached eighteen issues, are of the utmost importance in the study of folk-song. They contain material gathered by members of the Society in different parts of the United Kingdom. The original members of the Council of the Folk-Song Society who have died or retired have been replaced by musicians and collectors equally enthusiastic, and such additional names as Dr Vaughan Williams, Mr Percy Grainger, Mr Clive Carey, and Mr Cecil J. Sharp bear witness to the excellent hands in which the Society is held.

It would be invidious to name the individual members who have supplied matter to the Journals of the Folk-Song Society, but besides the above named, Miss A. G. Gilchrist, the late Dr Gardiner, the late H. E. D. Hammond, Mrs Leather, Miss Tolmie (with her Gaelic songs), and Mr W. P. Merrick have all contributed largely and well. Miss Gilchrist has written with great knowledge on the construction of folk-tunes, and has supplied other notes of much value. [Pg 47]

English folk-song and folk-music has been utilised in several compositions by Dr Vaughan Williams, Mr H. Balfour Gardiner, Mr Rutland Boughton, and Mr Percy Grainger.

The part that Mr Cecil Sharp has taken in the advancement of folk-song is well known. He has collected extensively, chiefly in Somerset, and his vigorous methods of bringing the subject before the public have caused “folk-song” to become a household word wherever the English language is spoken.

When the songs and the ballads of the people began to be recognised as belonging, more or less, to literature, the editors of collections deemed it was essential that their crudities of style, rhyme, and diction should be amended, and that the whole should undergo a polishing process before being launched to the public.

Bishop Percy, of course, naturally occurs to one’s mind in this connection, and we must grant that in the classic age when he issued his three volumes (1765) there was reason on his side, and he had some [Pg 48] justification for the trimming he did—the world was not yet ripe for the folk-ballad collector.

There is much reason to suspect the later editors of ballad lore did as much as Percy in the work of polishing, and even went beyond him by pure fabrication. No excuse for such work as this nowadays exists. People are quite prepared to accept fragments of traditional ballads or songs precisely in the state they are sung or recited.

In a much lesser degree the same kind of thing held as regards certain earlier collectors of folk-music. This attitude was not one of deceit, but rather of ignorance. The modal influence on folk-music was not understood. As a consequence intervals were altered to conform to the harmony of another scale. As folk-music began to be better realised more scientific knowledge was brought to bear on the subject, and every nerve strained to obtain accuracy of notation.

The phonograph at once suggested itself as a ready and accurate instrument for the work of noting traditional melody, and many collectors employ it for this purpose. There is, however, a section of workers in folk-song who rather mistrust its claim to give the best results. The motive that inspires the use of the phonograph is praiseworthy in the extreme, but those opposed to its use suggest that [Pg 49] these results are sometimes not very satisfactory where transcriptions taken directly from phonograph records have been published. They are generally complex and confusing, and for examples of the excessively elaborate rhythms and shifting tonality from phonographic records, the reader is invited to refer to some particular Journals of the Folk-Song Society. The transcriber should certainly bear in mind that mixed rhythms (2-4 time changing to 6-8, 7-8, 4-4, 5-8, and so forth in one short air) can hardly belong to the original structure of the tune, but rather to the method of singing it. If the performance of any great singer were phonographed, and its actual note-value faithfully transcribed, this would scarcely be considered a fair way of treating it. It would show a complexity of rhythms of which both the singer and the audience would be quite unaware. The composer would most certainly repudiate such a notation, though he might be quite satisfied with the singer’s treatment of the piece. He would claim that the most legitimate method would be to indicate time-deviations by the ordinary accepted marks of expression.

The difficulty of noting melodies from the ordinary possessor of folk-song is very great, and varies with every singer. Some are a [Pg 50] delight to listen to, others, though it is quite evident that they possess songs and melodies of the highest interest, produce an opposite effect on the listener. A phonographic record from one would be a joy, from the other a painful experience.

Practically every singer of original folk-song is an amateur, and this by no means lessens the beauty of his singing; in many cases, though, it offers much disadvantage to the one who notes his tunes. Unconsciously the vocalist sings the air frequently with more or less slight difference, and is sometimes not quite true to his note or key. Any mechanical contrivance for noting his song reproduces these inaccuracies, and, what is still more to the point, eight folk-singers out of ten asked to sing into that strange funnel above a moving cylinder will be nervous and not sing their best, either in time or tune. A sturdy young farmer, perhaps, who knows all about the gramophone, may come out of the ordeal with flying colours, and his strong masculine voice be reproduced with good effect, but not so a feeble old lady whose songs can only be obtained by careful tact and sympathetic manner, nor can such be noted otherwise than by getting constant repetitions and making selections from her differing renderings.

It is the business of the folk-song collector not to make a hard and fast record of one rendering of a folk-tune, with all its accidental [Pg 51] inaccuracies, but to obtain what the singer obviously means. Where possible, the best rendering should be given in its full integrity, and any emendation stated as such, with reasons given for the alteration. It is too much to expect that every folk-song singer should be a paragon of faithful accuracy. In many cases, as before observed, he sings his tune with some difference on occasions, and this is due to slips of memory, to wilful alteration, when he thinks such alterations an improvement, and to extraneous influences—nervousness and the like.

Therefore the collector to give a true rendering of the original folk-melody should get as many notations of it as possible, and make such selection as his judgment and knowledge dictate. The ordinary simple “composed” tune generally continues throughout its length in one character of rhythm or time. The folk-air as sung to-day frequently ignores this rule, and may have passages in the middle of it which differ from the general run of the tune. The earlier collectors ignored this fact, and practically always placed such airs under one time signature, considering that any alteration of time-rhythm made by the singer was a grammatical error on his part. In some cases they were probably right, but recent comparisons of certain tunes, noted by [Pg 52] different collectors in various parts of the country, go to prove that, to give particular effect to certain word passages, many folk-tunes have been composed with deliberate intention of breaking rhythm. The wary collector, therefore, while he is fully alive to the knowledge that folk-singers are not always to be relied upon for accurate transmission, is also aware of the fact I have above indicated.

The folk-song that does, or did within recent years, exist is manifold in its variety. It reflects very accurately the type of thought that is, or was, current among the class who sang it. Its limits are strictly within their understanding, though now and again its commonplaces are tinged with romance. Yet this romance is not above the comprehension of the most humble and constitutes a grown-up’s fairy tale.

It tells its story or voices its sentiment in the fewest possible words, and in tragedy is almost Biblical in narrative.

A consideration of a few of its types may be useful.

This in its earliest form is, without doubt, the oldest surviving kind of folk-song. In all cases it is a long rhyming story which tells of events more or less romantic, and more or less true. It is probable that such ballads have come down to us from the middle ages, when professional glee-men, or minstrels, went from one noble house to another and sang such lyrics to the harp or to other accompaniment.

The stories are dramatic and sufficiently well-marked in character to be easily remembered. Obsolete expressions may be changed or may even remain, but the essentials of the story will be retained.

We have sufficient remnants on ballad sheets as well as in popular remembrance to show that there must have been an enormous number of these lyrical narratives in common currency. How long these had remained in oral transmission before being printed on ballad sheets is a question not easily answered. The question whether, in some instances, they were printed before being handed to the people may be answered in the affirmative in respect to a certain number of obviously later ballads. [Pg 54]

The ballad-seller was bound to provide new wares for his patrons, and his trade could not go on without fresh material. Undoubtedly many of the ballads he printed were a re-dishing up of old stories, and many rhymesters, in default of newer ideas, fell back upon the Greek classic stories for subject. In fact, the common person of the sixteenth century might claim to be more familiar with the Homeric romance than the average “man in the street” of to-day. These can scarcely be called folk-ballads in the strictest sense, because they are evidently the work of people educated enough to put such matter from the classic, as well as from Italian authors, into doggerel verse.

The man of an earlier period was as anxious for novelty as he is to-day. The only difference is this—at the present time novelties so crowd upon him that they become stale very rapidly. In the “golden age” people gave leisurely consideration to and digested that which was put before them. Hence it was held tenaciously in memory, and ballads and tales lost none of their interest.

The invention of printing wrought a great change in every direction, and when the press gave forth the ballad sheet it produced a new era in folk-singing. The ballad sheet is so inextricably mixed up with the [Pg 55] folk-song that, for a clear understanding, it will be necessary to devote some pages to it later on.

It is a noteworthy fact that among our ballad literature we find numbers of stories that are practically the same in other languages and current in other countries. If we find, as we frequently do, a ballad common amongst Scandinavian folk that is also known in England, or perhaps Brittany, we cannot safely determine its original birthplace, for there can be no doubt that popular folk-tales and ballads travelled from one country to another in a very remarkable degree.

Scotland has always been famous for her wealth of dramatic ballads. No man can read unmoved the many fine ballad narratives that are published in her ballad books, and without wondering whence came the rich flow of fancy and poetic beauty that inspired them.

In spite of all that has been written, much regarding the Scottish ballads remains a mystery. The early collectors appear to have had little scruple in regard to the ballads being printed exactly as received.

One thing we have satisfaction in, namely, that ballads of this character did exist, and that emendation of phrase, or addition of verse, affects the matter, on the whole, very little. The consideration [Pg 56] of the Scottish ballad is, however, outside our inquiry, although some narrative lyrics that are commonly thought to have had origin in Scotland are found among English folk-singers. Of these, “Lammikin,” collected by Miss Broadwood in Surrey, is a notable example, as also the different versions of “The Gipsy Laddie,” and one or two others that may be found in the Folk-Song Society’s Journals. Certainly the best-known narrative ballad among English folk-singers is “Lord Bateman,” and versions of this exist in the Scottish ballad collections. “Barbara Allan” is another that has a Scottish variant, while the “Blind Beggar of Bethnal Green” seems to be entirely English. “Lord Thomas and Fair Eleanor,” “The Outlandish Knight,” “Geordie” are long ballads which, in a more or less fragmentary state, have been found in nearly every part of England.

One or two of the Robin Hood ballads have also been recovered from tradition, but such are, strangely enough, not common. All the tunes found united to the above-named narrative ballads appear to be ancient and contemporary with early versions of the words.

Love holds first place in all lyrics, and there is no exception to this rule in the folk-song. There is, however, this difference;—whilst the art-song is frequently couched in language abstract and sentimental, and enriched with metaphor and simile, the folk-song is almost always direct, and from its baldness of diction possessed of great force.

The declaration of love in a folk-song is simple, and there is no mincing of words. It is unmistakably fervent and in earnest. The tragedy of a girl’s forsakenness is Biblical in its plainness; sometimes it is a song rather of triumph than pity.

Few more beautiful and direct specimens of the former type exist than the one beginning—

and so forth.

Another very beautiful love song is “The bonnie bonnie boy” noted by Miss Broadwood, and published in English County Songs. It opens—

A great feature in the love song of the folk-singer is the use of allegory. The words “thyme,” “rue,” the “broom,” “barley,” “wearing the green gown,” and several other similes are freely used, and have an original meaning, for the most part, hidden from the modern singer. The ever popular “I sowed the seeds of love,” in which is inextricably entangled that other song, “The sprig of thyme,” is an inoffensive example of this type. The latter runs—

[Pg 59] As can be well realised, examples of love songs could be given to any extent.

The folk-singer delights in something that gives a thrill of mysticism, and there are many having this characteristic in traditional remembrance. “The unquiet grave” is an example in point. It begins—

“The Cruel Ship’s Carpenter,” and “The Nightingale” have each a ghost, as in a like manner has the one just quoted.

Of the mystic class is “The Prickly Bush.” It is undoubtedly very old and is found in different forms among country singers. A copy occurs in English County Songs—

Common all over the country, with place names that vary according to [Pg 60] the district, is “The Lover’s Test,” sometimes called “Scarborough Fair.” The lover in this demands a cambric shirt made without needle and thread, and other impossibilities, with the reward that the lady shall then be his true love. The lady, equally ready, demands an acre of land between the sea foam and the sea sand. This is to be ploughed with a ram’s horn, and to be sown all over with one peppercorn, and so on. When all this is done the lover can come for his cambric shirt. The story is a version of “The Elfin Knight,” and of the same type as “Captain Wedderburn’s Courtship.”

The pastoral song is fairly frequent, especially in the Southern counties of England. Its chief theme is the joys of country life. Such are the songs in which the ploughman is the chief personage, and one who glories in his calling. In Sussex Songs we find a very typical example—

[Pg 61] Then there are sheep-shearing songs, some of which may be seen in Dr Barrett’s English Folk-Songs and elsewhere. English County Songs provides this ordinary example—

Other verses would, of course, provide for consumption of more beer by drinking the health of all the members of the family, and of such neighbours as the contents of the barrel allowed.

Harvest-home songs too are not lacking, and a small number take the form of a dialogue between a gardener and a ploughman, or between a husbandman and a serving-man.

A famous song well known among farm-labourers is that known as “Poor Old Horse,” and of this there are several versions. This song probably suggested to Charles Dibdin his once popular song “The High-Mettled Racer,” and to Thomas Bewick, the wood-engraver, his fine print of a worn-out horse in the rain called “Waiting for Death.”

The ploughboy is sometimes in love and sings of his passion in the folk-song. Sometimes it is the lady who declares her love for the handsome ploughboy, and both varieties are quite popular specimens of rural simplicity.

The drinking song is not very common among folk-songs. “The good old leathern bottle,” and some other South country songs, chiefly dealing with harvest-home festivities, can scarcely be called such. They speak of the home-brewed farm ale in an honest fashion, and without the gloating over liquor which is so much a feature of the eighteenth century bacchanalian song. “When Joan’s ale was new” is popular over most parts of England, and “Drink old England dry” is another very harmless production.

The humorous song does not very frequently occur. Sometimes we may come across one that fulfils all the essentials of wit but will scarcely bear repetition. Others are humorous and in other respects quite satisfactory. “Richard of Taunton Dean” is too well known to quote, and “The Dumb Wife Cured” is another that has been frequently reprinted, and it is possibly, really, not a folk-song. “The Grey Mare” is an excellent example. It tells of a young miller who made overtures to a young lady’s father to obtain her hand. The dowry was agreed upon, save [Pg 63] that the young man had fixed his mind upon the farmer’s grey mare as part of it. The old man not being inclined to part with this the bargain was “off.” After the death of the farmer the miller again sought the lady, who declared she did not know him. Except that

“Eggs in the basket,” narrating the adventures of two sailors, of which there are several versions in the Folk-Song Journal, comes under the category of humorous songs, and the Devonshire song “Widdicombe Fair” has, since its publication in Songs of the West, met with wide appreciation. Songs in dispraise of a married life are not frequent in folk-song, but there is a well-known one in “Advice to Bachelors,” in Dr Barrett’s English Folk-Songs, that appears to be a genuine folk-song. Its end verse contains the gist of the story. A criminal under the gallows is offered free pardon if he will marry, but—

If the pressgang was an unpleasant factor in eighteenth century life, so also were the footpad and highwayman. The highwayman generally claimed the sympathy of the folk-song maker on the ground that—

“He never robbed a poor man upon the King’s highway,” and that his takings from the rich were distributed among the poor. This atoned for all crimes against person and property that were committed by such men as “Brennan on the Moor,” the hero of a very favourite ballad. Sometimes these highwayman songs take a more moral tone, and the criminal, in the condemned cell, offers his fate as a warning to others. Charles Reilly, for example, sings—

Poaching was a matter so near the class that sang folk-songs that as a subject it could not fail in interest. If the folk-singer was not himself a poacher he was sufficiently in touch to feel a brotherly sympathy with him in his misfortunes, and in his triumphs, over the gamekeeper. As a consequence there are many poaching songs well known in rural districts, as—“Young Henry the poacher,” “The Sledmere poachers,” “The death of Bill Brown,” “Hares in the old plantation,” etc.

Highway robbery and poaching led to execution and transportation, and both these are subjects for the folk-song maker. The execution songs appear, however, generally to be the work of professional ballad makers, and the “last dying speech and confession” of a criminal, with appended verses, was in print long before he had paid the penalty of his crime. The ballad was sung to one or other of those doleful tunes [Pg 66] especially appropriated to this kind of song by the ballad chanter, who hawked the broadsides through the towns on the night of the execution. Frequently the tag to such ditties was—

In a somewhat similar strain are the songs that tell of the miseries of transportation to Van Diemen’s Land, for poaching or other offences.

Of soldier songs the folk-singer has comparatively few. One of the prettiest is that indifferently called “The Summer Morning,” or “The White Cockade.” It commences—

[Pg 67] Another soldier’s song popular among folk-singers is “Pretty Polly Oliver,” or “Polly Oliver’s Ramble.”

Polly dresses herself in male attire, mounts her father’s black gelding, and joins the regiment, with the captain of which she is in love.

Then we have the pathetic “Deserter.”

Another favourite is “The Gentleman Soldier,” and yet another, “The bonny Scotch lad with his bonnet so blue.” The battle of Waterloo gave rise to several long ballads descriptive of the fight, and these in their full integrity of twenty or thirty verses used, not long ago, to be remembered by old soldiers.

These have always been welcome among English singers, and our nation [Pg 68] has a plenitude of fine ones. In folk-song they generally take a narrative form and treat of adventures with pirates, and the like. Examples of this type are “Paul Jones,” “Ward the pirate,” “Henry Martin,” “The bold Princess Royal,” and some others. The pressgang songs might, in a sense, go under the heading “sailor songs,” and, certainly, the Chanty, but these are dealt with separately. “The Golden Vanity” is popular, so is “The Mermaid,” and both are well known to modern singers. “The Greenland Whale Fishery” is a fine example of a genuine whaling ditty (see A Garland of Country Songs), and “All on Spurn Point” is a narrative of a wreck.

The charming song “Stowbrow,” or the “Drowned Sailor,” is chiefly known on the Yorkshire coast.

“The Cruel Ship’s Carpenter” is a story of a murder and a ghost, which follows the murderer to sea and denounces him. “William Taylor” (of which a parody exists) is fairly well known.

“The Coasts of Barbary” is a fine sea song, and “The Indian Lass,” “Just as the tide was flowing,” “On board a man-of-war,” “Outward bound,” and “The bold privateers” are sea songs that are commonly known but can boast no great degree of antiquity. “Fair Phœbe and her [Pg 69] dark-ey’d sailor,” and “The broken token”—the one being a variation of the other—are songs that fall under the heading “Love Songs.”

These have a greater dramatic effect than any other type before dealt with. In the eighteenth century, when the constant war with France demanded a supply of men to man the navy, the pressgang was a very vital thing in the lives of the humbler classes. The law empowered (under a press warrant) officers of the King’s Navy to seize any man, with few exceptions, and then and there remove him to a King’s ship to serve as a common sailor. Violence was freely used, and at dead of night whole villages were cleared of their male inhabitants, and husbands and bread-winners dragged away, never, in most cases, to return. Such occurrences were well within the memory of those only just passed away. With such happenings in their midst, the folk-song makers had no lack of thrilling and appealing material. The romantic element was not absent, for it was quite possible, as the folk-song generally makes it, for an irate father to bribe the pressgang for the removal of [Pg 70] an undesirable young ploughman, and so put an end to the love passages that existed between his daughter and him, thus leaving the ground clear for a wealthier or more favoured suitor. Poetic justice is almost always satisfied in the song by the lady seeking her true love on shipboard, and, by the production of “gold,” reclaiming him. “The Banks of Sweet Dundee,” which is widespread and a universal favourite, affords an excellent example of the pressgang song.

The beautiful song beginning—

and that one called “The Nightingale,” are earlier in date and quite charming specimens of the class.

The folk-singer does not lack songs dealing with the sports he loves. The fox-and hare-hunting songs are in a degree reflexes of the eighteenth century ones—of great compass, and of much allusion to the Greek gods. It is in these that Diana, Aurora and Phœbus figure so largely. [Pg 71]

The folk-song that deals with hunting, generally is local in its narrative, and tells of some particular famous fox hunt or hare hunt, naming every squire or yeoman farmer that joined in it. “The Fylingdale Foxhunt” in Traditional Tunes is a good and typical example. In the same work will be found “The White Hare” (a description of a hare hunt), and a song of a not very frequent type detailing a cock fight.

Primitive folk appear to have always had particular songs appropriate to specific kinds of labour. Such songs seem to have been traditionally associated with each class of work, and to have been used either to give a marked rhythm, by which the efforts of a number of people are united at a certain moment (as the pull upon a rope), or generally to lighten work, an effect which song certainly has. It is well known that girls in a weaving shop, or other factory, work twice as well and feel the strain lighter while they are singing in chorus some favourite song or hymn. Soldiers on the march are less tired if the men are allowed to sing, or while the band plays. The Irish regiments marched out of [Pg 72] Brussels before Waterloo to the strains of the then popular Moore’s “Melodies,” “The Young May Moon” being among the favourites. The men of the North during the American Civil War were cheered by the song “John Brown’s Body,” and our own soldiers in South Africa sung, with deep meaning (considering that the Boers always managed to have the advantage of the crest of the hill), “All that ever I want is a little bit off the top.” Every great river of the world has its boat songs; in most cases used by the rowers as an aid to their work. Specimens of these river boat songs have been noted in China, India, on the Nile, and elsewhere. The well-known “Canadian Boat Song,” of Thomas Moore, was adapted by him from a chant he himself heard on the St Lawrence river, the original of which chant, by the way, differs materially from the version he published.

The Sea Chanty is too wide a subject to be dealt with in this small volume. Its purpose is to give time to the pull of a rope, the thrust against a capstan bar, or on occasions when the pumps have to be used. The “Chanty” may be almost spoken of as obsolete. Its real home was the sailing vessel, but, at the present day, steam does so much of what formerly was man’s labour, that the chanty has almost died a natural death. [Pg 73]

There were capstan, pumping, and hauling chanties, and those used in furling sail, apart from the sailors’ songs pure and simple. The sea chanty was generally commenced by a leader—the chanty man, who would perhaps string a few extemporary rough rhymes together, fitted to a well-known tune, while the men joined in a recognised nonsense chorus as they did the pulling, thrusting, or other work required.

The Chanties mostly in evidence amongst the English, or English-speaking, sailors are “Whiskey for my Johnnie,” “Haul the bowline,” “We’re all bound to go,” “The Rio Grande,” “Reuben Ranzo,” “Tom’s gone to Ilo,” “Storm Along,” “Lowlands,” “Santa Anna,” “Sally Brown,” “Banks of Sacramento,” and many others, copies of which, with most of the above, are to be found in the Folk-Song Journals. The fact cannot be ignored that there is decided American influence in most of the sea chanties, and that points to them being interchangeable between the English and the American sailor. The ships trading to San Francisco and other sailing vessels that took long voyages round the “Horn” were fit resting-places for the chanty. In former times, on the old man-of-war ships, a fiddler was frequently requisitioned, or the anchor was raised to the music of a fife. [Pg 74]