“’Sh!” was the first sound that came from her. “Don’t make a noise or you’ll frighten my friend. She’s nervous already.”

Books by

BASIL KING

HARPER & BROTHERS, NEW YORK

Established 1817

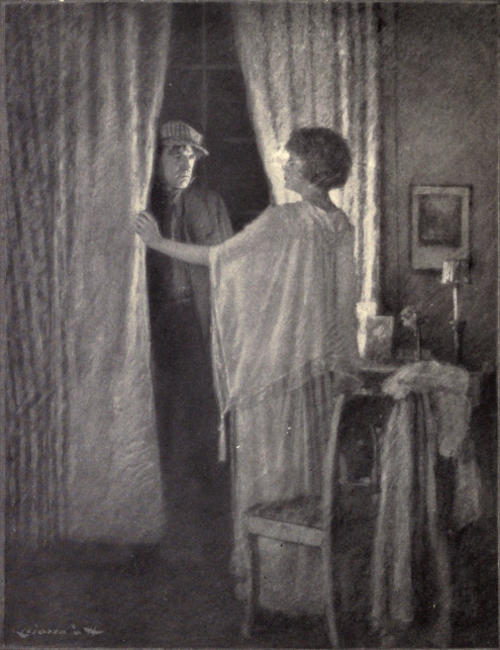

“’Sh!” was the first sound that came from her. “Don’t make a noise or you’ll frighten my friend. She’s nervous already.”

The

CITY OF COMRADES

BY

BASIL KING

Author of

“THE INNER SHRINE” “THE WILD OLIVE”

“THE WAY HOME” “THE HIGH HEART” ETC.

HARPER & BROTHERS PUBLISHERS

NEW YORK AND LONDON

Copyright, 1919, by Harper & Brothers

Printed in the United States of America

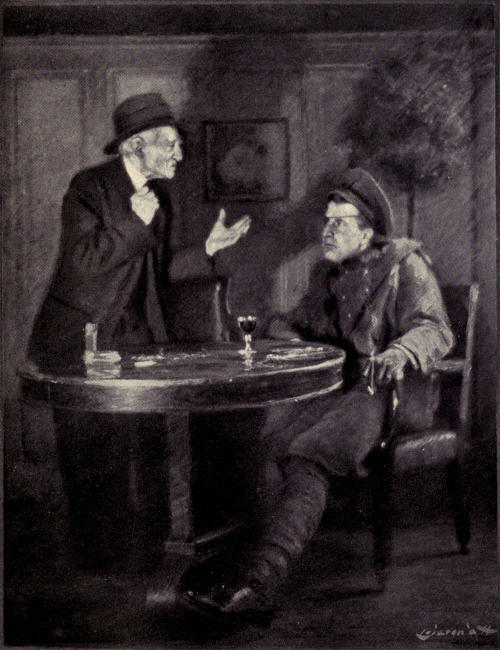

| “’Sh!” was the first sound that came from her. “Don’t make a noise or you’ll frighten my friend. She’s nervous already.” | Frontispiece | |

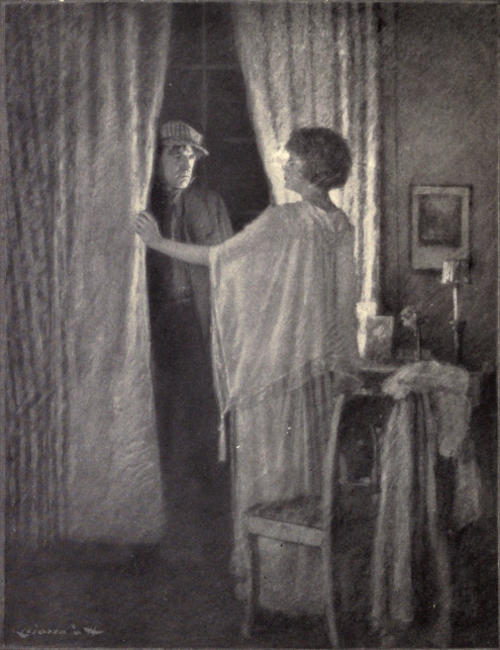

| “Didn’t you ever see any one put these pearls into his pocket before?” | Facing p. | 204 |

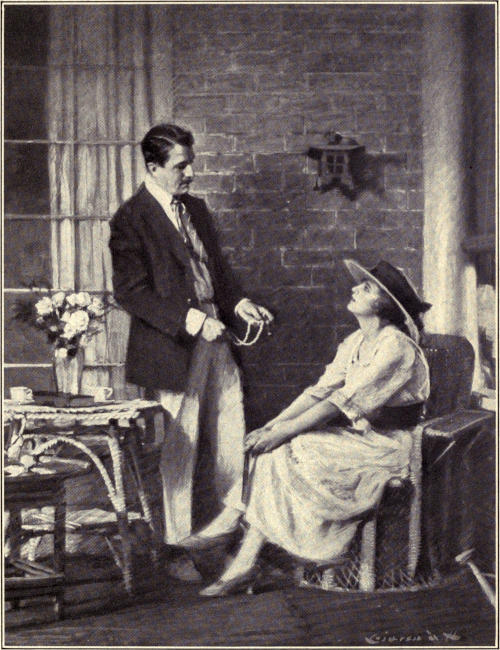

| “You’re going home to marry me.” “How can I be going home to marry you, when—when I never knew till within half an hour that you—that you cared anything about me?” | ” | 290 |

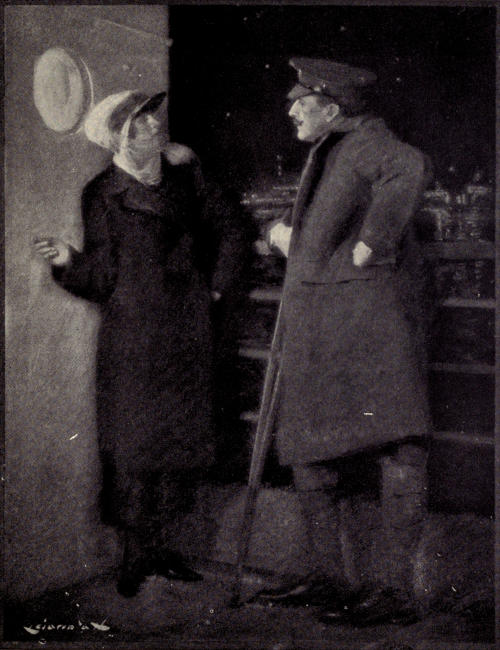

| “That you should ’ave come back to this—and me believin’ the war ’ad done ye good—lifted you up, like. Not but what you was the best man ever lived before the war—” | ” | 344 |

“No.”

“No?”

“No.”

In the slow swirl of Columbus Circle, at the southwest corner of Central Park, two seedy, sinister individuals could hold an exceedingly private conversation without drawing attention to themselves. There were others like us on the scene, in that month of June, 1913, cast up from the obscurest depths of New York. We could revolve there for five or ten minutes, in company with other elements of the city’s life, to be eliminated by degrees, sucked into other currents, forming new combinations or reacting to the old ones.

In silence we shuffled along a few paces, though not exactly side by side. Lovey was just sufficiently behind me to be able to talk confidentially into my ear. My own manner was probably that of a man anxious to throw off a dogging inferior. Even among us there are social degrees.

“Yer’ll be sorry,” Lovey warned me, reproachfully.

“Very well, then,” I jerked back at him over my shoulder; “I shall be sorry.”

“If I didn’t know it was a good thing I wouldn’t ’a’[2] wanted to take ye in on it—not you, I wouldn’t; and dead easy.”

“I don’t care for it.”

“Ye’re only a beginner—”

“I’m not even that.”

“No, ye’re not even that; and this’d larn ye. Just two old ladies—lots of money always in the ’ouse—no resistance—no weepons nor nothink o’ that kind; and me knowin’ every hinch of the ground through workin’ for ’em two years ago—”

“And suppose they recognized you?”

“That’s it. That’s why I must have a pal. If they’d git a look at any one it’d have to be at you. But you don’t need to be afraid, never pinched before nor nothink. Once yer picter’s in the rogues’ they’ll run ye in if ye so much as blow yer nose. You’d just get by as an unknown man.”

“And if I didn’t get by?”

“Oh, but you would, sonny. Ye’re the kind. Just look at ye! Slim and easy-movin’ as a snake, y’are. Ye’d go through a man’s clothes while he’s got ’em on, and he wouldn’t notice ye no more’n a puff of wind. Look at yer ’and.”

I held it up and looked at it. A year ago, a month ago, I should have studied it with remorse. Now I did it stupidly, without emotions or regrets.

It was a long, slim hand, resembling the rest of my person. It was strong, however, with big, loosely articulated knuckles and muscular thumbs—again resembling the rest of my person. At the Beaux Arts, and in an occasional architect’s office, it had been spoken of as a “drawing” hand; and Lovey was now pointing out its advantages for other purposes. I laughed to myself.

“Ye’re too tall,” Lovey went on, in his appraisement. “That’s ag’in’ ye. Ye must be a good six foot. But lots o’ men are too tall. They gits over it by stoopin’ a bit; and when ye stoops it frightens people, especially women. They ain’t near as scared of a man that stands straight up as they’ll be of one that crouches and wiggles away. Kind o’ suggests evil to ’em, like, it does. And these two old ladies—”

As we reached the corner of the Park I rounded slowly on my tempter. Not that he thought of his offer as temptation, any more than I did; it was rather on his part a touch of solicitude. He was doing his best for me, in return for what he was pleased to take as my kindness to him during the past ten days.

He was a small, wizened man, pathetically neat in spite of cruel shabbiness. It was the kind of neatness that in our world so often differentiates the man who has dropped from him who has always been down. The gray suit, which was little more than a warp with no woof on it at all, was brushed and smoothed and mended. The flannel shirt, with turned-down collar, must have been chosen for its resistance to the show of dirt. The sky-blue tie might have been a more useful selection, but even that had had freshness steamed and pressed into it whenever Lovey had got the opportunity. Over what didn’t so directly meet the eye the coat was tightly buttoned up.

The boots were the weakest point, as they are with all of us. They were not noticeably broken, but they were wrinkled and squashed and down at the heel. They looked as if they had been worn by other men before having come to the present possessor; and mine looked the same. When I went into offices to apply for work it was always my boots that I tried to keep out of sight; but it[4] was precisely what the eye of the fellow in command seemed determined to search out and judge me by.

You must not think of Lovey as a criminal. He had committed petty crimes and he had gone to jail for them; but it had only been from the instinct of self-preservation. He worked when he got a job; but he never kept a job, because his habits always fired him. Then he lived as he could, lifting whatever small object came his way—an apple from a fruit-stall, a purse a lady had inadvertently laid down, a bag in a station, an umbrella forgotten in a corner—anything! The pawnshops knew him so well that he was afraid to go into them any more—except when he was so tired that he wanted to be sent to the Island for a month’s rest. In general, he disposed of his booty for a few pennies to children, to poverty-stricken mothers of families, to pals in the saloons. As long as a few dollars lasted he lived, as he himself would have said, honestly. When he was driven to it he filched again; but only when he was driven to it.

It was ten days now since he had begun following me about, somewhat as a stray dog will follow you when you have given him a bone and a drink of water. For a year and more I had seen him in one or another of the dives I hung about. The same faces always turn up there, and we get to have the kind of acquaintance, silent, haunted, tolerant, that binds together souls in the Inferno. In general, it is a great fraternity; but now and then—often for reasons no one could fathom—some one is excluded. He comes and goes, and the others follow him with resentful looks and curses. Occasionally he is kicked out, which was what happened to Lovey whenever his weakness afforded the excuse.

It was when he was kicked out of Stinson’s that I had[5] picked him up. It was after midnight. It was cold. The sight of the abject face was too much for me.

“Come along home with me, Lovey,” I had said, casually; and he came.

Home was no more than a stifling garret, and Lovey slept on the floor like a dog. But in the morning I found my shoes cleaned as well as he could clean them without brush or blacking, my clothes folded, and the whole beastly place in such order as a friendly hand could bring to it. Lovey himself was gone.

Twice during the interval he had stolen in in the same way and stolen out. He asked no more than a refuge and the privilege of sidling timidly up to me with a beseeching look in his sodden eyes when we met in bars. Once, when by hook or by crook he had got possession of a dollar, he insisted on the honor of “buying me a drink.”

On this particular afternoon I had met him by chance in the region of Broadway between Forty-second Street and Columbus Circle. I can still recall the shy, half-frightened pleasure in his face as he saw me advancing toward him. He might have been a young girl.

“Got somethin’ awful good, sonny, to let ye in on,” were the words with which he stopped me.

I turned round and walked back with him to the Circle, and round it.

“No, Lovey,” I said decidedly, when we had got to the corner of the Park, “it’s not good enough. I’ve other fish to fry.”

A hectic flush stole into the cheeks, which kept a marvelous youth and freshness. The thin, delicate features, ascetic rather than degraded, sharpened with a frosty look of disappointment.

“Well, just as you think best, sonny,” he said, resignedly.[6] He asked, abruptly, however, “When did ye have yer last meal?”

“The day before yesterday.”

“And when d’ye expect to have yer next?”

“Oh, I don’t know. Sometime; possibly to-night.”

“Possibly to-night— ’Ow?”

“I tell you I don’t know. Something will happen. If it doesn’t—well, I’ll manage.”

He had found an opening.

“Don’t ye see ye carn’t go on like that? Ye’ve got to live.”

“Oh no, I haven’t.”

“Don’t say that, sonny,” he burst out, tenderly. “Ye’ve got to live! Ye must do it—for my sake—now. I suppose it’s because we’re—we’re Britishers together.” He looked round on the circling crowd of Slavs, Mongolians, Greeks, Italians, aliens of all sorts. “We’re different from these Yankees, ain’t we?”

Admitting our Anglo-Saxon superiority, I was about to say, “Well, so long, Lovey,” and shake him off, when he put in, piteously, “I suppose I can come up and lay down on yer floor again to-night?”

“I wish you could, Lovey,” I responded. “But—but the fact is I—I haven’t got that place any more.”

“Fired?”

I nodded.

“Where’ve ye gone?”

“Nowhere.”

“Where did ye sleep last night?”

I described the exact spot in the lumber-yard near Greeley’s Slip. He knew it. He had made use of its hospitality himself on warm summer nights such as we were having.

“Goin’ there again to-night?”

I said I didn’t know.

He gazed at me with a kind of timid daring. “You wouldn’t be—you wouldn’t be goin’ to the Down and Out Club?”

I smiled.

“Why should you ask me that?”

“Oh, I don’t know. See you talkin’ to one of those fellas oncet. Chap named Pyncheon. Worse than missions and ’vangelists, they are.”

“Did you ever think of going there yourself?”

“Oh, Lord love ye! I’ve thought of it, yes. But I’ve fought it off. Once ye do that ye’re done for.”

“Well, I don’t believe I’m done for—” I began; but he interrupted me coaxingly.

“I say, sonny. I’ll go to Greeley’s Slip. Then if you’ve nothin’ else on ’and, you come there, too—and we’ll be fellas together. But don’t—don’t—go to the Down and Out!”

As I walked away from him I had his “fellas together” amusingly, and also pathetically, in my heart. Lovey was little better than an outcast. I knew him by no name but that which some pothouse wag had fixed on him derisively. From hints he had dropped I gathered that he had had a wife and daughters somewhere in the world, and intuitively I got the impression that without being a criminal he had been connected with a crime. As to his personal history he had never confided to me any of the details beyond the fact that in his palmy days he had been in a ’at-shop in the Edgware Road. I fancied that at some time or another in his career his relatives in London—like my own in Canada—had made up a lump sum and bidden him begone to the land of reconstruction.[8] There he had become what he was—an outcast. There I was becoming an outcast likewise. We were “fellas together.” I was thirty-one and he was fifty-two. My comparative youth helped me, in that I didn’t look older than my age; but he might easily have been seventy.

Having got rid of him, I drifted diagonally across the Park, but with a certain method in the seeming lack of method in taking my direction. Though I had an objective point, I didn’t dare to approach it otherwise than by a roundabout route. It is probable that no gaze but that of the angels was upon me; but to me it seemed as if every glance that roved up and down the Park must spot my aim.

For this reason I assumed a manner meant to throw observation off the scent. I loitered to look at young people on horseback or to stare at some specially dashing motor-car. I strolled into by-paths and out of them. I passed under the noses of policemen in gray-blue uniforms and tried to infuse my carriage with the fact which Lovey had emphasized, that I had never yet been pinched. I had never yet, so far as I knew, done anything to warrant pinching; and that I had no intentions beyond those of the ordinary law-abiding citizen was what I hoped my swagger would convey.

Though I was shabby, I was not sufficiently so to be unworthy to take the air. The worst that could be said of me was that I was not shabby as the working-man is at liberty to be. Mine was the suspicious, telltale shabbiness of the gentleman—far more damning than the grime and sweat of a chimney-sweep.

Now that I was alone again, I had a return of the sensation that had been on me since waking in the morning—that I was walking in the air. I felt that I bounced like[9] a bubble every time I stepped. The day before I had been giddy; now I was only light. It was as if at any minute I might go up. Unconsciously I ground my footsteps into the gravel or the grass to keep myself on the solid earth.

It was not the first time I had gone without food for twenty-four hours, but it was the first time I had done it for forty-eight. Moreover, it was the first time I had ever been without some prospect of food ahead of me. With a meal surely in sight on the following day I could have waited for it. More easily I could have waited for a drink or two. Drink kept me going longer than food, for in spite of the reaction after it the need of it had grown more insistent. Had I been offered my choice between food and life, on the one hand, and drink and death, on the other, I think I should have chosen drink and death.

But now there was no likelihood of either. I had husbanded my last pennies after my last meal, to make them spin out to as many drinks as possible. I had begged a few more drinks, and cadged a few more. But I had come to my limit in all these directions. Before I sought the shelter of Greeley’s Slip a hint had been given me at Stinson’s that I might come in for the compliments showered on Lovey ten days previously. Now as I walked in the Park the craving inside me was not because I hadn’t eaten, but because I hadn’t drunk that day.

Two or three bitter temptations assailed me before I reached Fifth Avenue. One was in the form of a pretty girl of eight or ten, who came mincing down a flowery path, holding a quarter between the thumb and forefinger of her left hand. Satan must have sent her. I could have snatched the quarter and made my escape, only that I lacked the nerve. Then there was a newsboy counting[10] his gains on a bench. They were laid out in rows before him—pennies, nickels, and dimes. I stood for a minute and looked down at him, estimating the ease with which I could have stooped and swept them all into my palm. He looked up and smiled. The smile didn’t disarm me; I was beyond the reach of any such appeal. It was again that I didn’t have the nerve. Lastly an old woman, a nurse, was dealing out coins to three small children that they might make purchases of a blind man selling bootlaces and pencils. I could have swiped them all as neatly as a croupier pulls in louis d’or with his rake—but I was afraid.

These were real temptations, as fierce as any I ever faced. By the time I had reached the Avenue I was in a cold perspiration, as much from a sense of failure as from the effort at resistance. I wondered how I should ever carry out the plans I had in mind if I was to balk at such little things as this.

The plans I had in mind still kept me from making headway as the crow flies. I went far up the Avenue; I crossed into Madison Avenue; I went up that again; I crossed into Park Avenue. I crossed and recrossed and crisscrossed and descended, and at last found myself strolling by a house toward which I scarcely dared to turn my eyes, feeling that even for looking at it I might be arrested.

I slackened my pace so as to verify all the points which experts had underscored in my hearing. There was the vacant lot which the surrounding buildings rendered so dark at night. There was the low, red-brown fence inclosing the back premises, over which a limber, long-legged fellow like me could leap in a second. There were the usual numerous windows—to kitchen, scullery, pantry,[11] laundry—of any good-sized American house, some one of which was pretty sure to be left unguarded on a summer night. There were the neighboring yards, with more low fences, offering excellent cover in a get-away, with another vacant lot leading out on another street a little farther down.

I had so many times strolled by the house as I was doing now, and had so many times rehearsed its characteristics, that I made the final review with some exactitude before passing on my way.

My way was not far. There was nothing to do but to go back into the Park. As it was nearly six o’clock, it was too late to search for a job that day, and I should have had no heart for doing so in any case. I had found a job that morning—that of handling big packing-cases in a warehouse—but I was too exhausted for the work. When in the effort to lift one onto a truck I collapsed and nearly fainted, I was told in a choice selection of oaths to beat it as no good.

I sat on a bench, therefore, waiting for the dark and thinking of the house of which I had just inspected the outside. It was not a house picked at random. It was one that had possessed an interest for me during all the three years I had been in New York. I had, in fact, brought a letter of introduction to its owner from the man under whom I had worked in Montreal. Chiefly through my own carelessness, nothing came of that, but I never failed, when I passed this way, to stare at the dwelling as one in which I might have had a footing.

The occupant was also a well-known architect in New York. In the architects’ offices in which I found employment I heard him praised, criticized, condemned. His work was good or bad according to the speaker’s point of[12] view. I thought it tolerably good, with an over-emphasis on ornament.

It was an odd fact that, in starting out on what was clear in my mind as a new phase in my career, no other house suggested itself as a field of operations. As to this one I felt documented, and that was all. I had no sense of horror at what I was about to do; no remorse from the position from which I had fallen. I suppose my mind was too sick for that, and my body too imperatively clamorous. I had said to Lovey that I didn’t have to live—but I did. I had seen that very morning that I did. I had stood at the edge of Greeley’s Slip and watched the swirling of the brown-green water with a view to making an end of it. One step and I should be out of all this misery and disgrace! The world would be rid of me; my family would be rid of me; I should be rid of myself, which would be best of all. Had I been quite sure as to the last point, I think I could have done it. But I wasn’t quite sure. I was far from quite sure. I could imagine the step over the edge of Greeley’s Slip as a step into conditions worse than those I was enduring now; and so I had drawn back. I had drawn back and wandered up-town, in the hope of securing a job that would give me a breakfast.

I wonder if you have ever done that? I wonder if you have ever gone from dock to station and from station to shop and from shop to warehouse, wherever heavy, unskilled labor may be in demand, and extra hands are treated with a brutality that slaves would kick against, in the hope of earning fifty cents? I wonder if in your grown-up life you have ever known a minute when fifty cents stood for your salvation? I wonder if with fifty cents standing for your salvation you ever saw the day[13] when you couldn’t get it? No? Then you will hardly understand how natural, how much a matter of course, the thing had become which I was resolved to do.

It was no sudden idea. I had been living in the company of men who took such feats for granted. Their talk had amazed me at first, but I had grown used to it. I had grown used to the thing. I had come to find a piquancy in the thought of it.

Then Lovey’s suggestions had not been thrown away on me. True, he was out for small game, while I, if I went in for it, would want something bigger and more exciting; but the basic idea was the same. Lovey could make a haul and live for weeks on the fruit of it; I might do the same and live for months. And if I didn’t pull it off successfully, if I was nabbed and sent away—why, then there would be some let-up in the struggle which had become so infernal. Even if I got a shot through the heart—and the tales I heard were full of such accidents—the tragedy would not lack its element of relief. It might be out of one hell into another—but it would at least be out of one.

Not that I hadn’t found a bitter pleasure in the life! I had. I found it still. In one of Dostoyevsky’s novels an old rake talks of the joys of being in the gutter. Well, there are such joys. They are not joys that civilization knows or that aspiration would find legitimate; but one reaches a point at which it is a satisfaction to be oneself at one’s worst. Where all the pretenses with which poor human nature covers itself up are cast aside the soul can stalk forth nakedly, hideously, and be unashamed. In the presence of each other we were always unashamed. We could kick over all standards, we could drop all poses, we could flout all duties, we could own to all crimes, and[14] be “fellas together.” As I went lower and lower down it became to me a kind of acrid delight, of positively intellectual delight, to know that I was herding with the most degraded, and that there was no baseness or bestiality to which I was not at liberty to submit myself.

If there had never been any reactions from this state of mind!—but God!

It was a disadvantage to me that I was not like my cronies. I couldn’t open my lips without betraying the fact that I belonged to another sphere. Though the broken-down man of education is not unknown in the underworld, he is comparatively rare. He is comparatively rare and under suspicion, like a white swan in a flock of black ones. I might be open-handed, ingratiating, and absurdly fellow-well-met, but I was always an outsider. They would take my drinks, they would return me drinks, we would swap stories and experiences with all outward show of equality; but no one knew better than myself that I was not on a footing with the rest of them. Women took to me readily enough, but men were always on their guard. Try as I would I never found a mate among them, I never made a friend. Therefore, now that I was down and out, I had no one of whom to ask a good turn, no one who would have done me a good turn, but poor, useless old Lovey sneaking in the shade.

I was in a measure between two worlds. I had been ejected from one without having forced a way into the other. When I say ejected I mean the word. The bitterest moment in my life was on that night when my eldest brother came to his door in Montreal and gave me fifty dollars, with the words:

“And now get out! Don’t let any of us ever see your face or hear your name again.”

As I stumbled down the steps he gave me a kick that didn’t reach me and which I had lost the right to resent. He himself went back to the dinner-party his wife was entertaining inside, and of which the talk and laughter reached me as I stood humbly on the door-step. From the other side of the street I looked back at the lighted windows. It was the last touch of connection with my family.

But it had been a kindly, patient family. My father was one of the best known and most highly honored among Canadian public men. As he had married an American, I had a good many cousins in New York, though I had not made myself known to any of them since coming there to live. I didn’t want them. Had I met one of them in the street, I should have passed without speaking; but, as it happened, I never met one. I saw their names in the papers, and that was all.

My father and mother had had five children, of whom I was the fourth. My two brothers were married, prosperous and respected—one a lawyer in Montreal, the other a banker in Toronto. My elder sister was married to a colonel in the British army; the younger one—the only member of the family younger than myself—still lived at home.

We three sons were all graduates of McGill, in addition to which I had been sent to the Beaux Arts in Paris. Out of that I had come with some degree of credit; and there had been a year in which I was in sight—oh, very distant sight!—of the beginning of the fulfilment of my childhood’s ambition to revolutionize the art of architecture in Canada. But in the second year that vision went out; and in the third came the night on my brother Jerry’s door-step.

I had nothing to complain of. The family had borne with me—and borne with me. When we reached the time when I was supposed to be earning my own living and my father’s allowance came to an end, my mother, who had some money of her own, kept it up. She would be keeping it up still if she knew where I was—but she didn’t know. From the moment of leaving Montreal I decided to carry out Jerry’s injunction. They should neither see my face nor hear my name again. I didn’t stop to consider how cruel this would be to the best mother a man ever had—to say nothing of the best father—or rather, when I did stop to consider it it seemed to me that I was taking the kindest course. I had no confidence in myself or in the future. New surroundings and associations would not give me a new heart, whatever hopes those who wished me well might be building on the change. For a new heart I needed something which I hadn’t got and saw no means of getting.

Somewhere about dusk I fell asleep. It was dark when I woke up. It was dark and still and sultry, as it often is in New York in the middle of June.

The lamps were lit in the Park, and in their glow shadowy forms moved stealthily. When they went in twos I took them to be lovers; when they went alone I put them down as prowlers of the night. I didn’t know what they were after, but whatever it might be I was sure it was no good.

Not that that mattered to me! I had long been in a situation where I couldn’t be particular. When I had risen and stretched myself I, too, moved stealthily, dogged by a crime I hadn’t yet committed, but of which the guilt was already in the air.

As I had nothing by which to tell the time, I was obliged to wait till a clock struck. I hoped it was eleven at least, but when the sound came over the trees it was only nine. Only nine, and I could do nothing before one! Nothing before one, and nowhere to go! Nowhere to go, and no food to eat, and not a drop to drink! Doubtless I could have found water; but water made me sick. With four hours to wait, I thought again of the dark river with its velvety current, running below Greeley’s Slip.

Aimlessly I drifted toward it—that is, I drifted toward Columbus Circle, whence I could drift farther still through squalid, fetid, dimly lighted streets down to the water’s[18] edge. The night was so hot that the thought of the plunge began to appeal to me. After all, it would be an easy, pleasant way of stepping out.

But I didn’t do it. The unknown beyond the river once more drove me back. Besides, the adventure I had planned was not without its fascination. I wanted to see what it held in store. If it held nothing—well, then, Greeley’s Slip would still be accessible in the morning.

So I skulked back into the depths of the Park again. Those who went as twos began to disappear, and the lonely shadows to steal along more furtively. Now and then one of them approached me or hung in the distance suggestively. It was not like any of the encounters that take place in daylight. It was more as if these dark ghosts had floated up from some evil spirit land, into which before morning they would float down again.

But twelve o’clock struck at last, and I took midnight as a call. It was a call to leave the great human division in which I had hitherto been classed, and become a criminal. Once I had done this thing, I should never be able to go back. The angel with the flaming sword would guard that way, and I could never regain even such status as that which I was abandoning.

If my head had not been swimming I might at the last minute have felt a qualm at that, but my mind had lost the faculty of deconcentration. It was fixed on the thing before me in such a way that I couldn’t get it off. For this reason I went, on leaving the Park, directly to the street and number where my thoughts were.

I was surprised by the emptiness and silence of the thoroughfares. Not till then had I remembered that at this season of the year most of the houses would be closed. Closed they were, looking dark and blank and forbidding.[19] I happened to know that the house to which I was bound was not closed; and though the fact that there were so few to pass in the streets rendered me more conspicuous, it also made me the less subject to observation.

Indeed, there were no observers at all when I approached the black spot made by the vacant lot. There was nothing but myself and the blackness. Not a light in the house! Hardly a light in any of the houses roundabout! Not a footfall on the pavements! If ever there was a good opportunity to do what I had come for, it was mine.

But I passed. The black spot frightened me. It was like a black gulf into which I might sink down. I re-passed.

I went farther up the street and took myself to task. It was a repetition of my recoil from the children in the afternoon. I must have the nerve—or I must own to myself that I hadn’t. If I hadn’t it, then I had no alternative but Greeley’s Slip.

I turned in my steps and passed the house again. If from the blank windows any one had been looking out my actions would have been suspicious. I went far down the street, and came back again far up it. Then when I had no more power of arguing with myself I suddenly found my footsteps crushing the dusty, sun-dried shoots of nettle and blue succory. I was in the vacant lot.

All at once fear left me. As well as any old hand in the business I seemed to know what lay before me. At every second some low-down prompting, sprung from nameless depths in my nature, told me what to do.

I noted in the first place how accurate the experts had been as to light and shade. The house stood so far up on one of the long avenues that the buildings were thinning out. So, too, the street lamps. They were no more[20] than in the proportion of two to three as compared to their numbers half a mile lower down. Just here they were so placed that not a ray fell into the three or four thousand square feet which had probably never been built upon since Manhattan was inhabited. Even the wall of the house was windowless on this side, for the reason that within a few months some new building would probably block the outlook.

Once I had crept close to the wall, I knew I presented neither silhouette nor shade to any chance passer-by. I could feel my way at leisure, cautiously treading burdock and fireweed underfoot. I came to the low wooden fence, in which there was a gate for tradesmen, which was possibly unlocked; but I didn’t run the risk of a click. With my long legs a stride took me over into a small brick-paved court.

I paused to reconnoiter. The obscurity here was so dense that only my architect’s instincts told me where the doors and windows would probably be. I located them by degrees. The doors I let alone. The windows I tried, first one and then another, but with no success. There was probably some simple fastening that I could have dealt with had I had a pocket-knife, but the one I had carried for years had long since been lying in a pawnshop. To reflect I sat down on the cover of a bin that was doubtless used for refuse.

A footstep alarmed me. It was heavy, measured, slow. With the ease of a snake I was down on my belly, crawling toward cover. Cover offered itself in the form of the single shrub that the court contained—lilac or syringa—growing close against the kitchen wall. Lovey would have commended the silence and swiftness with which I slipped behind it.

The footstep receded, slow, measured, heavy. Coming to the conclusion that it was a policeman in the Avenue, I raised my head. I had no sense of queerness in my situation. It seemed as much a matter of course as if I had been doing the same sort of thing ever since I was born.

There was apparently a providence in all this, for, looking up, I spied a window I had not seen before, because it was hidden by the shrub. This, if any, would have been neglected by the servants when they went to bed.

With scarcely the stirring of a leaf I got on my feet again—and, lo! the miracle. The window was actually open. I had nothing to do but push it a few inches higher, drag myself up and wriggle in. I accomplished this without a sound that could be detected twenty feet away.

Coming down on my hands and knees, I found myself amid the odor of eatables, chiefly that of fruit. I rested a minute to get my bearings, which I did by the sense of smell. I knew I must be in a sort of pantry. By putting out my hands carefully, so as to knock nothing over, I perceived that it was little more than a closet with shelves. A thrill of excitement passed through me from head to foot when my hand rested on an apple.

I ate the apple there and then, kneeling upright, my toes bent under me. I ate another and another. Feeling cautiously, I discovered a tin box in which there were bread and cake. I ate of both. Getting softly on my feet, I groped for other things, which proved in the main to be no more than tea, coffee, spices, and starch. Then my fingers ran over a strawlike surface, and I knew I had hold of a demijohn.

Smell told me that it contained sherry, and such knowledge[22] of housekeeping as I possessed suggested that it was cooking-sherry. I took a long swig of it. Two long swigs were enough. It burnt me, and yet it braced me. With the food I had eaten I felt literally like a giant refreshed with wine.

It occurred to me that this was a point at which I might draw back. But the spell of the unknown was upon me, and I determined to go at least a little farther. Very, very stealthily I opened the door.

I was not in a kitchen, as I expected to find myself, but in a servants’ dining-room. I got the dim outlines of chairs and what I took to be a dresser or a bookcase. Another open door led into a hall.

My knowledge of the planning of houses aided me at each step I took. From the hallway I could place the kitchen, the laundry, and the back staircase. I knew the front hall lay beyond a door which was closed. At the foot of the back staircase I stood for some minutes and listened. Not a sound came from anywhere in the house. The kitchen clock ticked loudly, and presently startled me with a gurgle and a chuckle before it struck one. After this manifestation I had to wait till my heart stopped thumping and my nerves were quieted before venturing on the stairs. As the first step creaked, I kept close to the wall to get a firmer support for my tread. On reaching a landing I could see up into another hall. Here I perceived the glimmer or reflection of a light. It was a very dim or distant light—but it was a light.

I stood on the landing and waited. If there were people moving about I should hear them soon. But all I did hear was the heavy breathing of the servants, who were sleeping on the topmost floor.

Creeping a little farther up, I discovered that the light[23] was in a bedroom—the first to open from the front hall up-stairs. Between the front hall and the back hall the door was ajar. That would make things easier for me, and I dragged myself noiselessly to the top. I was now at the head of the first flight of back stairs, and looking into the master’s section of the house. Except for that one dim light the house was dark. It was not, however, so dark that my architect’s eye couldn’t make a mental map quite sufficient for my guidance.

It was clearly a dwelling that had been added to, with some rambling characteristics. The first few feet of the front hall were on a level with the back hall, after which came a flight of three or four steps to a higher plane, which ran the rest of the depth of the building to the window over the front door. In the faint radiance through this window I could discern a high-boy, a bureau, and some chairs against the wall. I could see, too, that from this higher level one staircase ran down to the front door and another up to a third story. What was chiefly of moment to me was the fact that the bedroom with the light was lower than the rest of this part of the house, and somewhat cut off from it.

With movements as quiet as a cat’s I got myself where I could peep into the bedroom where the lamp burned. It proved to be a small electric lamp with a rose-colored shade, standing beside a bed. It was a rose-colored room, evidently that of a young lady. But there was no young lady there. There was no one.

The fact that surprises me as I record all this is that I was so extraordinarily cool. I was cooler in the act than I am in the memory of it. I walked into that bedroom as calmly as if it had been my own.

It was a pretty room, with the usual notes of photographs,[24] bibelots, and flowered cretonne which young women like. The walls were in a light, cool green set off by a few colored reproductions of old Italian masters. Over the small white virginal bed was a copy of Fra Angelico’s “Annunciation.” Two windows, one of which was a bay, were shaded by loosely hanging rose-colored silk, and before the bay window the curtains were drawn. Diagonally across the corner of this window, but within the actual room, stood a simple white writing-desk, with a white dressing-table near it, but against the wall. On the table lay a gold-mesh purse, in which there was money. I slipped it into my pocket, with some satisfaction in securing the first fruits of my adventure.

With such booty as this it again occurred to me to be on the safe side and to go back by the way I came. I was, in fact, looking round me to see if there was any other small valuable object I could lift before departing when I heard a door open in some distant part of the house—and voices.

They were women’s voices, or, rather, as I speedily inferred, girls’ voices. By listening intently I drew the conclusion that two girls had come out of a room on the third floor and were coming down the stairs.

It was the minute to make off, and I tried to do so. I might have effected my escape had I not been checked by the figure of a man looming up suddenly before me. He sprang out of nowhere—a tall, slender man, in a dark-blue suit, with trousers baggy at the knees, and wearing an old golfing-cap. I jumped back from him in terror, only to find that it was my own reflection in the pier-glass. But the few seconds’ delay lost me my chance to get away.

By the time I had tiptoed to the door the voices were[25] on the same floor as myself. Two girls were advancing along the hall, evidently making their way to this chamber. My retreat being cut off, I looked wildly about for a place in which to hide myself. In the instants at my disposal I could discover nothing more remote than the bay window, screened by its loose rose-colored hangings. By the time the young ladies were on the threshold I was established there, with the silk sections pulled together and held tightly in my hand.

The first words I heard were: “But it will seem so like a habit. Men will be afraid of you.”

This voice was light, silvery, and staccato. That which replied had a deep mezzo quality, without being quite contralto.

“They won’t be nearly so much afraid of me,” it said, fretfully, “as I am of them. I wish—I wish they’d let me alone!”

“Oh, well, they won’t do that—not yet awhile; unless, as I say, they see you’re hopeless. Really, dear, when a girl breaks a third engagement—”

“They must see that she wouldn’t do it if she didn’t have to. Here—this is the hook that always bothers me.”

There were tears in the mezzo voice now, with a hint of exasperation that might have been due to the lover or the hook, I couldn’t be sure which.

“But that’s what I don’t see—”

“You don’t see it because you don’t know Stephen—that is, you don’t know him well.”

“But from what I do know of him—”

“He seems very nice. Yes, of course! But, good Heavens! Elsie, I want a husband who’s something more than very nice!”

“And yet that’s pretty good, as husbands go.”

“If I can’t reach a higher standard than as husbands go I sha’n’t marry any one.”

“Which seems to me what’s very likely to happen.”

“So it seems to me.”

The silence that followed was full of soft, swishing sounds, which I judged to come from the taking off of a dress and the putting on of some sort of negligée. From my experience of the habits of girls, as illustrated by my sisters and their friends, I supposed that they were lending each other services in the processes of undoing. The girl with the mezzo voice had gone up to Elsie’s room to undo her; Elsie had come down to render similar assistance. There is probably a psychological connection between this intimate act and confidence, since girls most truly bare their hearts to each other when they ought to be going to bed.

The mezzo young lady was moving about the room when the conversation was taken up again.

“I don’t understand,” Elsie complained, “why you should have got engaged to Stephen in the first place.”

“I don’t, either”—she was quite near me now, and threw something that might have been a brooch or a chain on the little white desk—“except on the ground that I wanted to try him.”

“Try him? What do you mean?”

“Well, what’s an engagement? Isn’t it a kind of experiment? You get as near to marriage as you can, while still keeping free to draw back. To me it’s been like going down to the edge of the water in which you can commit suicide, and finding it so cold that you go home again.”

“Don’t you ever mean to be married at all?” Elsie demanded, impatiently.

“I don’t mean to be married till I’m sure.”

Elsie burst out indignantly: “Regina Barry, that’s the most pusillanimous thing I ever heard. You might as well say you’d never cross the Atlantic unless you were sure the ship would reach the other side.”

“My trouble about crossing the Atlantic is in making up my mind whether or not I want to go on board. One might be willing to risk the second step, but one can’t risk the first. Even the hymn that says ‘One step enough for me’ implies that at least you know what that’s to be.”

“You mean that you balk at marriage in any case.”

“I mean that I balk at marriage with any of the men I’ve been engaged to. I must say that; and I can’t say more.”

During another brief silence I surmised that Regina Barry had seated herself before the dressing-table and was probably doing something to her hair. I wish I could say here that in my eavesdropping I experienced a sense of shame; but I can’t. Whatever creates a sense of shame had been warped in me. The moral transitions that had turned me into a burglar had been gradual but sure. With the gold-mesh purse in my pocket a burglar I had become, and I felt no more repugnance to the business than I did to that of the architect. Notwithstanding the natural masculine interest these young ladies stirred in me, I meant to wait till they had separated—gone to bed—and fallen asleep. Then I would slip out from my hiding-place, swipe the brooch or the chain that had been thrown on the desk, and go.

“What was the matter with the first man?” Elsie began again.

“I don’t know whether it was the matter with him or with me. I didn’t trust him.”

“I should say that was the matter with him. And the next man?”

“Nothing. I simply couldn’t have lived with him.”

“And what’s wrong with Stephen is that he’s no more than very nice. I see.”

“Oh no, you don’t see, dear! There’s a lot more to it than all that, only I can’t explain it.” I fancied that she wheeled round in her chair and faced her companion. “The long and short of it is that I’ve never met the man with whom I could keep house. I can fall in love with them for a while—I can have them going and coming—I can welcome them and say good-by to them—but when it’s a question of all welcome and no good-by—well, the man’s got to be different from any I’ve seen yet.”

“You’ll end by not getting any one at all.”

“Which, from my point of view, don’t you see, won’t be an unmixed evil. Having lived happily for twenty-three years without a husband, I don’t see why I should throw away a perfectly good bone for the most enticing shadow that ever was.”

“I don’t believe you’re human.” Before there could be a retort to this Elsie went on to ask, “How did poor Stephen take it?”

“Well, he didn’t go into fits of laughter. He took it more or less lying down. If he hadn’t—”

“If he hadn’t—what?”

“Oh, I don’t know. The least little bit of fight on his part—or even contempt—”

As this sentence remained unfinished I could hear Elsie rise.

“Well, I’m off to bed,” she yawned. “What time do you have breakfast?”

There was some little discussion of household arrangements, after which they said their good nights.

With Elsie’s departure I began for the first time to be uncomfortable. I can’t express myself otherwise than to say that as long as she was there I felt I had a chaperon. In spite of the fact that I had become a professional burglar the idea of being left alone with an innocent young lady in her bedroom filled me with dismay.

I was almost on the point of making a bolt for it when I heard Elsie call out from the hallway: “Ugh! How dark and poky! For mercy’s sake, come up with me!”

Miss Barry lingered at the dressing-table long enough to ask: “Wouldn’t you rather sleep in mother’s room? That communicates with this, with only a little passage in between. The bed is made up.”

“Oh no,” Elsie’s staccato came back. “I don’t mind being up there, and my things are spread out; only it seems so creepy to climb all those stairs.”

“Wait a minute.”

She sprang up. I breathed freely. My sense of propriety was saved. The voices were receding along the front hall. Once the young ladies had begun to mount the stairs I would slip out by the back hall and get off. Relaxing my hold on the silk hangings I stepped out cautiously.

My first thought was for the objects I had heard thrown down with a rattle on the writing-desk. They proved to be a string of small pearls, a diamond pin, and some rings of which I made no inspection before sweeping them all into my pocket.

I was ready now to steal away, but, to my vexation, the incorrigible maidens had begun to talk love-affairs again at the foot of the staircase leading up to the third[30] floor. They had also turned on the hall light, so that my chances were diminished for getting away unseen.

Knowing, however, that sooner or later they would have to go up the next flight, I stood by the writing-desk and waited. I was not nervous; I was not alarmed. As a matter of fact the success of my undertaking up to the present point, together with the action of food and wine, combined to make me excited and hilarious. I chuckled in advance over the mystification of Miss Regina Barry, who would find on returning to her room that her rings, her necklet, and her gold-mesh purse had melted into the atmosphere.

In sheer recklessness I was now guilty of a bit of deviltry before which I would have hesitated had I had time to give it a second thought. On the desk there was a scrap of blank paper and a pen. Stooping, I printed in the neat block letters I had once been accustomed to inscribe below a plan:

There are men different from those you have seen hitherto. Wait.

This I pinned to the pincushion on the dressing-table, beginning at once to creep toward the door, so as to seize the first opportunity of slipping down the back stairs.

But again I was frustrated.

“I’m all right now,” I heard Elsie say, reassuringly. “Don’t come up. Go back and go to bed.”

Miss Barry spoke as she returned along the hall toward her room: “The cook sleeps in the next room to you, so that if you’re afraid in the night you’ve only to hammer on the wall. But you needn’t be. This house is as safe as a prison.”

I had barely time to get into the bay window again and pull the curtains to.

Some five minutes followed, during which I heard the opening and shutting of drawers and closets and the swish and frou-frou of skirts. I began to curse my idiocy in fastening that silly bit of writing to the pincushion. My only hope lay in the possibility that she would go to bed and to sleep without seeing it.

With hearing grown extraordinarily acute I could trace every movement she made about the room. Presently I knew she had come back to the dressing-table again. Pulling up a chair, she sat down before it, to finish, I suppose, the arranging of her hair.

For a few seconds there was a silence, during which I could hear the thumping of my heart. Then came the faint rattling of paper. I knew when she read the thing by the slight catch in her breath. I expected more than that. I thought she would call out to her friend or otherwise give an alarm. If she went to a telephone to summon the police I decided to make a dash for it. Indeed, I meant to make a dash for it as it was, as soon as I knew her next move.

But of all the next moves, the one she made was the one I had least counted on. With a sudden tug at the hangings she pulled them apart—and I was before her.

I was before her and she was before me. It is this latter detail of which I have the most vivid recollection. In the matter of time all other recollections of the moment seem to come after that and to be subsidiary to it.

My immediate impression was of two enormous, wonderful, burning eyes, full of amazement. Apart from the eyes I hardly saw anything. It was as if the light of a dark lantern had been suddenly turned on me and I was blinded by the blaze. I was blinded by the blaze and[32] shriveled up in it. No words can do justice to my sudden sense of being a contemptible, loathsome reptile.

“’Sh!” was the first sound that came from her. She raised her hand. “Don’t make a noise or you’ll frighten my friend. She’s nervous already.”

Instinctively I pulled off my cap, stepping out of my hiding-place into the middle of the room. As I did so she recoiled, supporting herself by a hand on the writing-desk. Now that the discovery was made, I could see her grow pale, while the hand on the desk trembled.

“You mustn’t be afraid,” I began to whisper.

“I’m not afraid,” she whispered back; “but—but what are you doing here?”

“I’ll show you,” I returned, with shamefaced quietness. “I shall also show you that if you’ll let me go without giving an alarm you won’t be sorry.”

Pulling all the things I had stolen out of my pocket, I showered them on the dressing-table.

“Oh!”

The smothered exclamation made it plain to me that she hadn’t missed the articles.

“May I ask you to verify them?” I went on. “If you should find later that something had disappeared, I shouldn’t like you to think that I had carried it away.”

She made a feint at examining the jewelry, but I could see that she was incapable of making anything like a count. It was I who insisted on going over the objects one by one.

“There’s this,” I said, touching the gold-mesh purse, but not picking it up. “I see there’s money in it; but it has not been opened. Then there’s this,” I added, indicating the pearl necklet; “and this,” which was the[33] brooch. “The rings,” I continued, “I don’t know anything about. There are three here. That’s all I remember seeing; but I didn’t notice in particular.”

She said, in a breathless whisper, “That’s all there were.”

“Then may I ask if you mean to let me go?”

“How can I stop you?”

“Oh, in two or three ways. You could call your servants, or you could ring up the police—”

Her big, burning eyes were fixed on me hypnotically. The color began to come back to her cheeks, but she trembled still.

“How—how did you get in?”

I explained to her.

“And the only thing I’ve taken,” I went on, “is the food I ate and the wine I drank; but if you knew how much I needed them—”

“Were you hungry?”

“I hadn’t eaten anything for two days, and very little for two days before that.”

“Then you’re not—you’re not one of those gentleman burglars who do this sort of thing out of bravado?”

“As we see in novels or plays. I don’t think you’ll find many of them about. I’m a burglar,” I pursued, “or I—I meant to be one—but I’m not a gentleman.”

“You speak like a gentleman.”

“Unfortunately, a gentleman is not made by speech. A gentleman could never be in the predicament in which you’ve caught me.”

“Well, then, you were a gentleman once.”

“My father was a gentleman—and is.”

“English?”

“I’d rather not tell you. Now that I’ve restored the[34] things, if you’ll give me your word that I sha’n’t be molested I shall—”

“You sha’n’t be molested, only—”

As she hesitated I insisted, “Only what, may I ask?”

Her manner was a mixture of embarrassment and pity. She had not hitherto taken her eyes from me since we had begun to speak. Now she let them wander away; or, rather, she let them shift away, to return to me swiftly, as if she couldn’t trust me without watching me. By this time she was trembling so violently, too, that she was obliged to grasp the back of a chair to steady herself. She was too little to be tall, and yet too tall to be considered little. The filmy thing she wore, with its long, loose sleeves, gave her some of the appearance of an angel, only that no angel ever had this bright, almost hectic color in the cheeks, and these scarlet lips.

“Was it,” she asked, speaking, as we both did, in low tones, and rapidly—“was it because you—you had no money that you did this?”

I smiled faintly. “That was it exactly; but now—”

“Then won’t you let me give you some?”

I still had enough of the man about me to straighten myself up and say: “Thanks, no. It’s very kind of you; but—but the reasons which make it impossible for me to—to steal it make it equally impossible for me to take it as a gift.”

“But why—why was it impossible for you to steal it, when you had come here to do it?”

“I suppose it was seeing the owner of it face to face. I’d sunk low enough to steal from some one I couldn’t visualize—but what’s the use? It’s mere hair-splitting. Just let me say that this is my first attempt, and it hasn’t[35] succeeded. I may do better next time if I can get up the nerve.”

“Oh, but there won’t be a next time.”

“That we shall have to see.”

“Suppose”—the mixture of embarrassment and pity made it hard for her to speak—“suppose I said I was sorry for you.”

“You don’t have to say it. I see it. It’s something I shall never forget as long as I live.”

“Well, since I’m sorry for you, won’t you let me—?”

“No,” I interrupted, firmly. “I’m grateful for your pity; I’ll accept that; but I won’t take anything else.” I began moving toward the door. “Since you’re good enough to let me go, I had better be off; but I can’t do it without thanking you.”

For the first time she smiled a little. Even in that dim light I could see it was what in normal conditions would be commonly called a generous smile, full, frank, and kindly. Just now it was little more than a quivering of the long scarlet lips. She glanced toward the little heap of things on the desk.

“If it comes to that, I have to thank you.”

I raised my hand deprecatingly.

“Don’t.”

I had almost reached the threshold when her words made me turn.

“Do you know who I am?”

“I think I do,” was all I could reply.

“Well, then, why shouldn’t you come back later—in some more usual manner—and let me see if there isn’t something I could do for you?”

“Do for me in what way?”

“In the way of getting you work—or something.”

My heart had leaped up for a minute, but now it fell. Why it should have done either I cannot say, since I could be nothing to her but a fool who had tried to be a thief, and couldn’t, as we say in our common idiom, get away with it.

I thanked her again.

“But you’ve done a great deal for me as it is,” I added. “I couldn’t ask for more.” Somewhat disconnectedly I continued, “I think you’re the pluckiest girl I ever saw not to have been afraid of me.”

“Oh, it wasn’t pluck. I saw at once that you wouldn’t do me any harm.”

“How?”

“In general. I was surprised. I was excited. In a way I was overcome. But I wasn’t afraid of you. If you’d been a tramp or a colored man or anything like that it would have been different. But one isn’t afraid of a—of a gentleman.”

“But I’m not a—”

“Well then, a man who has a gentleman’s traditions. You’d better go now,” she whispered, suddenly. “If you want to come back as I’ve suggested—any time to-morrow forenoon—I’d speak to my father—”

“Not about this?” I whispered, hurriedly.

“No, not about this. This had better be just between ourselves. I shall never say anything to any one about it, and I advise you to do the same.” I had made a low bow, preparatory to getting out, when she held up the scrap of paper she had crumpled in her hand. “Why did you write this?”

But I got out of the room without giving a reply.

I was descending the back stairs when I heard a door[37] open on the third floor and Elsie’s voice call out, “Regina, are you talking to anybody down there?”

There was a tremor in the mezzo as it replied: “N-no. I’m just—I’m just moving about.”

“Well, for Heaven’s sake go to bed! It’s after two o’clock. I never was in a house like this in all my life before. It seems to be full of people crawling round everywhere. I think I’ll come down to your mother’s bed, after all.”

“Do,” was the only word I heard as I stole into the servants’ dining-room, then into the closet with shelves, where I shut the door softly. A few seconds later I was out on the cool ground, in the dark, behind the shrub.

I lay there almost breathlessly, not because I was unable to get up, but because I couldn’t drag myself away. I wanted to go over the happenings of the last hour and seal them in my memory. They were both terrible to me and beautiful.

I had been there some fifteen minutes when I heard the open window above me closed gently and the fastening snapped. I knew that again she was near me, though, as before, she didn’t suspect my presence. I wondered if the chances of life would ever bring us so close to each other again.

Above me, where the shrub detached itself a little from the wall of the house, I could see the stars. Lying on my back, with my head pillowed on the crook of my arm, I watched them till it seemed to me they began to pale. At the same time I caught a thinning in the texture of the darkness. I got up with the silence in which I had lain down. Crossing the brick-paved yard and striding over the low wall, I was again in the vacant lot.

It was not yet dawn, but it was the dark-gray hour[38] which tells that dawn is coming. I was obliged to take more accurate precautions than before, as, crushing the tangle of nettle, burdock, fireweed, and blue succory, I crept along in the shadow of the house wall to regain the empty street.

The city was beginning to wake. Mysterious carts and wagons rumbled along the neighboring avenues. From a parallel street came the buzz and clang of a lonely early-morning electric car. Running footsteps would have startled one if they had not been followed by the clinking of peaceful milk-bottles in back yards. Clanking off into the distance one heard the tread of solitary pedestrians bent on errands that stirred the curiosity. Here and there the lurid flames of torches lit up companies of gnomelike men digging in the roadways.

Going toward Greeley’s Slip, I skirted the Park, though it made the walk longer. Under the dark trees men were lying on benches and on the grass, but for reasons I couldn’t yet analyze I refused to thrust myself among them. A few hours earlier I would have done this without thinking, as without fear; but something had happened to me that now made any such course impossible.

My immediate need was to get back to poor old Lovey and lie down by his side. That again was beyond my power to analyze. I suppose it was something like a homing instinct, and Lovey was all there was to welcome me.

“Is that you, sonny?” he asked, sleepily, as I stooped to creep into the cubby-hole which a chance arrangement of planks made in a pile of lumber.

“Yes, Lovey.”

“Glad ye’ve come.”

When I had stretched myself out I felt him snuggle a little nearer me.

“You don’t mind, sonny, do you?”

“No, Lovey. It’s all right. Go to sleep again.”

For myself, I could do nothing but lie and watch the coming of the dawn. I could see it beating itself into the darkness long before there was anything to which one could give the name of light. It was like a succession of great cosmic throbs, after each of which the veil was a little more translucent.

In my nostrils was the sweet, penetrating smell of lumber, subtly laden with the memories of the days when I was a boy. The Canadian differs from the American largely, I think, in the closeness of his forest-and-farm associations. Not that the American hasn’t the farm and the forest, too, but he has moved farther away from them. The mill, the factory, and the office have supplanted them—in imagination when not in fact, and in fact when not in imagination. If the woods call him he has to go to them—for a week, or two, or three at a time; but he comes back inevitably to a life in which the woods play little part. The Canadian never leaves that life. The primeval still enters into his cities and his thoughts. Some day it may be different; but as yet he is the son of rivers, lakes, and forests. There is always in him a strain of the voyageur. The true Canadian never ceases to smell balsam or to hear the lapping of water on wild shores.

It was balsam that I smelled now. The lapping of water soothed me as the river, too, began to wake. It woke with a faint noise of paddle-wheels, followed by a bellow like the call of some sea monster to its mate.[41] Right below me and close to the slip I heard the measured dip of oars. Hoarse calls of men, from deck to deck or from deck to dock, had a weird, watchful sound, as though the darkness were peopled with Flying Dutchmen. Lights glided up and down the river—which itself remained unseen—mostly gold lights, but now and then a colored one. Chains of lights fringed the New Jersey shore, where, far away, sleepless factories threw up dim red flares. A rising southeast wind not only hid the stars under banks of clouds, but went whistling eerily round the corners of the lumber-piles. The scent of pine, and all the pungent, nameless odors of the riverside, began to be infused with the smell—if it is a smell—of coming rain.

I can best describe myself as in a kind of trance in which past and present were merged into one, and in which there seemed to be no period when two wonderful, burning eyes had not been watching me in pity and amazement. As long as I lived I knew they would watch me still. In their light I got my life’s significance. In their light I saw myself as a boy again, with a boy’s vision of the future. The smell of lumber carried me back to our old summer home on the banks of the Ottawa, where I had had my dreams of what I should do when I was big. All boys being patriotic, they were dreams not merely of myself, but of my country. It worried me that it was not sufficiently on the great world map, that apart from its lakes and prairies and cataracts it had no wonders to show mankind. As we were a traveling family, I was accustomed to wonders in other countries, and easily annoyed when one set of cousins in New York and another in England took it for granted that we lived in an Ultima Thule of snow. I meant to show them the contrary.

From the beginning my ardors and indignations translated themselves into stone. I had seen St. Peter’s in one country, St. Paul’s in another, and Chartres and châteaux in a third. I had seen New York transforming itself under my very eyes—the change began when I was in my teens—into a town of prodigious towers which in themselves were symbolical. Then I would go home to a red-gray city, marvelously placed between river and mountain, where any departure from its original French austerity was likely to be in the direction of the exuberant, the unchastened, the fantastic. All new buildings in Canada, as in most of the States, lacked “school.”

“School” was, more or less in secret, the preoccupation of my youth—“school” with some such variation from traditional classic lines as would create or stimulate the indigenous. I had not yet learned what New York was to teach me later—that necessity was the mother of art, and that pure new styles were formed not by any one’s ingenuity or by the caprice of changing taste, but because human needs demanded them. Rejecting the art nouveau, which later made its permanent home in Germany, I combined all the lines in which great buildings had ever been designed, from the Doric to the Georgian, in the hope of evolving a type which the world would recognize as distinctively Canadian, and to which I should give my name. In imagination I built castles, cathedrals and theaters, homes, hotels and offices. They were in the style to be known as Melburyesque, and would draw students from all parts of the architectural earth to Montreal.

It was not an unworthy dream, and even if I could never have worked it out I might have made of it something of which not wholly to be ashamed. But as early[43] as before I went to the Beaux Arts the curse of Canada—the curse, more or less, of all northern peoples—began to be laid upon me. In Paris I had some respite from it, but almost as soon as I had hung out my shingle at home I was suffering again from its cravings. I will not say that I put up no fight, but I put up no fight commensurate with the evil I had to face. The result was what I have told you, and for which I now had to suffer in my soul the most scorching form of recompense.

The point I found it difficult to decide was as to whether or not I ever wanted to see Regina Barry again—or whether I had it in me to go back and show myself to her in the state from which I had fallen more than three years before. In the end it was that possibility alone which enabled me to endure the real coming of the dawn.

For it came—this new day which out of darkness might be bringing me a new life.

As I lay with my face turned toward the west I got none of its first glories. Even on a cloudy morning, with a spattering of rain, I knew there must be splendors in the east, if no more than gray and lusterless splendors. Light to a gray world is as magical as hope to a gray heart; and as I watched the lamps on the New Jersey heights grow wan, while the river unbared its bosom to the day, that thing came to me which makes disgrace and shame and humiliation and every other ingredient of remorse a remedy rather than a poison.

I myself was hardly aware of the fact till Lovey and I had crept out of our cubby-hole, because all round us men were going to work. Sleepers in the open generally rise with daylight, but we had kept longer than usual to our refuge because we didn’t want to fare forth into the rain. As sooner or later it would come to a choice between[44] going out and being kicked out, we decided to move of our own accord.

I must leave to your imagination the curious sensation of the down and out in having nothing to do but to get up, shake themselves, and walk away. On waking after each of these homeless nights it had seemed to me that the necessity for undressing to go to bed and dressing when one got up in the morning was the primary distinction between being a man and being a mere animal. Not to have to undress just to dress again reduced one to the level of the horse. Stray dogs got up and went off to their vague leisure just as Lovey and I were doing. Not to wash, not to go to breakfast, not to have a duty when washing and breakfasting were done—knocked out from under one all the props that civilization had built up and deprived one of the right to call oneself a man.

I think it was this last consideration that had most weight with me as Lovey and I stood gazing at the multifarious activities of the scene. There were men in sight, busy with all kinds of occupations. They were like ants; they were like bees. They came and went and pulled and hauled and hammered and climbed and dug, and every man’s eyes seemed bent on his task as if it were the only one in the world.

“It means two or three dollars a day to ’em if they ain’t,” Lovey grunted, when I had pointed this fact out to him. “Don’t suppose they’d work if they didn’t ’ave to, do ye?”

“I dare say they wouldn’t. But my point is that they do work. It’s Emerson who says that every man is as lazy as he dares to be, isn’t it?”

“Oh, anybody could say that.”

“And in spite of the fact that they’d rather be lazy,[45] they’re all doing something. Look at them. Look at them in every direction to which your eyes can turn—droves of them, swarms of them, armies of them—every one bent on something into which he is putting a piece of himself!”

“Well, they’ve got ’omes or boardin’-’ouses. It’s easy enough to git a job when ye can give an address. But when ye carn’t—”

We were to test that within a minute or two. Fifteen or twenty brownies were digging in a ditch. Of all the forms of work in sight it seemed that which demanded the least in the way of special training.

Approaching a fiercely mustachioed man of clearly defined nationality, I said, “Say, boss, could you give my buddy and me a job?”

Rolling toward me a pair of eyes that would have done credit to a bandit in an opera, he emitted sounds which I can best transcribe as, “Where d’live?”

“That’s the trouble,” I answered, truthfully. “We don’t live anywhere and we should like to.”

He looked us over. “Beat it,” he commanded, nodding toward the central quarters of the city.

“But, boss,” I pleaded, “my buddy and I haven’t got a quarter between us.”

He pointed with his thumb over his left shoulder. “Getta out.”

“We haven’t got a nickel,” I insisted; “we haven’t got a cent.”

“Cristoforo, ca’ da cop.”

As Cristoforo sprang from the ditch to look for a policeman, Lovey and I shuffled off again into the rain.

We stood for a minute at the edge of one of the long, sordid avenues where a sordid life was surging up and[46] down. Men, women, and children of all races and nearly all ranks were hurrying to and fro, each bent on an errand. It was the fact that life provided an errand for each of them that suddenly struck me as the most wonderful thing in creation. There was no one so young or so old, no one so ignorant or so alien, that he was not going from point to point with a special purpose in view. Among the thousands and the tens of thousands who would in the course of the morning pass the spot on which we stood, there would probably not be one who hadn’t dressed, washed, and breakfasted as a return for his daily contribution to the common good. Never before and hardly ever since did I have such a sense of life’s infinite and useful complexity. There was no height to which it didn’t go up; there was no depth to which it didn’t go down. No one was left out but the absolute wastrel like myself, who couldn’t be taken in.

Though it was not a cold day, the steadiness of the drizzle chilled me. The dampness of the pavements got through the worn soles of my boots, and I suppose it did the same with Lovey’s. The lack of food made the old man white, and that of drink set him to trembling. The fact that he hadn’t shaved for the past day or two gave his sodden face a grisly look that was truly appalling. Though the pale-blue eyes were extinct, as if the spirit in them had been quenched, they were turned toward me with the piteous appeal I had sometimes seen in those of a blind dog.

It was for me to take the lead, and yet I couldn’t wholly see in what direction to take it. While I was pondering, Lovey made a variety of suggestions.

“There doesn’t seem to be nothink for it, sonny, but to go and repent for a day or two. I ’ate to do it; kind[47] o’ deceivin’ like, it is; but they’ll let us dry ourselves and give us a feed if we ’ave a sense of sin.”

I wondered if he had in mind anything better than what I had myself.

“Where?”

He took the negative side first.

“We couldn’t go to the Saviour, because I’ve put it over on ’em twice this year already. And the ’Omeless Men won’t do nothink for ye onless you make it up in menial work.”

“I won’t try either of them,” I said, briefly.

“Don’t blame you, sonny, not a bit. Kind o’ makes a hypercrite of a man, it does. I ’ate to be a hypercrite, only when I carn’t ’elp it.”

He went on to enumerate other agencies for the raising of the fallen, of most of which he had tested the hospitality during the past few years. I rejected them as he named them, one by one. To this rejection Lovey subscribed with the unreasoning dislike all outcast men feel for the hand stretched down to them from higher up. Nothing but starvation would have forced him to any of these thresholds; and for me even starvation would not work the miracle.

“What’s the matter with the Down and Out?” I sprang on him, suddenly.

He groaned. “Oh, sonny! It’s just—just what I was afeared of.”

I turned and looked down into his poor, bleared, suffering old face.

“Why?”

“Because—because—oncet ye try that they’ll—they’ll never let ye go.”

“But suppose you don’t want them to let you go?”

He backed away from me. If the dead eyes could waken to expression, they did it then.

“Oh, sonny!” He shook as if palsied. “Ye don’t know ’em, my boy. I’ve summered and wintered ’em—by lookin’ on. I’ve had pals of my own—”

“And what are they doing now, those pals of your own?”

“God knows; I don’t. Yes, I do; some of ’em. I see ’em round, goin’ to work as reg’lar as reg’lar, and no more spunk in ’em than in a goldfish when ye shakes yer finger at their bowl.”

Afraid of exciting suspicion by standing still, we began drifting with the crowd.

“Is there much that you can call spunk in you and me?”

Again he lifted those piteous, drunken eyes. “We’re fellas together, ain’t we? We’re buddies. I ’ear ye say so yerself when you was speakin’ to that Eyetalian.”

I have to confess that with his inflection something warm crept into my cold heart. You have to be as I was to know what the merest crumbs of trust and affection mean. A dog as stray and homeless as myself might have been more to me; but since I had no dog....

“Yes, Lovey,” I answered, “we’re buddies, all right. But for that very reason don’t you think we ought to try to help each other up?”

He stopped, to turn to me with hands crossed on his breast in a spirit of petition.

“But, sonny, you don’t mean—you carn’t mean—on—on the wagon?”

“I mean on anything that’ll get us out of this hell of a hole.”

“Oh, well, if it’s only that, I’ve—I’ve been in tighter places than this before—and—and look at me now.[49] There’s ways. Ye don’t have to jump at nothink onnat’rel. If ye’d only ’ave listened to me yesterday—but it ain’t too late even now. What about to-night? Just two old ladies—no violence—nothink that’d let you in for nothink dishonorable.”

“No, Lovey.”

We drifted on again. He spoke in a tone of bitter reproach.

“Ye’d rather go to the Down and Out! It’ll be the down, all right, sonny; but there’ll be no out to it. Ye’ll be a prisoner. They’ll keep at ye and at ye till yer soul won’t be yer own. Now all these other places ye can put it over on ’em. They’re mostly ladies and parsons and greenhorns that never ’ad no experience. A little repentance and they’ll fall for it every time. Besides”—he turned to me with another form of appeal—“ye’re a Christian, ain’t ye? A little repentance now and then’ll do ye good. It’s like something laid by for a rainy day. I’ve tried it, so I know. Ye’re young, sonny. Ye don’t understand. And when it’ll tide ye over a time like this—they’ll git ye a job, very likely—and ye can backslide by and by when it’s safe. Why, it’s all as easy as easy.”

“It isn’t as easy as easy, Lovey, because you say you don’t like it yourself.”

“I like it better than the Down and Out, where they won’t let ye backslide no more. Why, I was in at Stinson’s one day and there was a chap there—Rollins was his name, a plumber—just enj’yin’ of himself like—nothink wrong—and come to find out he’d been one of their men. Well, what do ye think, sonny? A fellow named Pyncheon blew in—awful ’ard drinker for a young ’and, he used to be—and he sat down beside Rollins and pled with ’im[50] and plod with ’im, and—well, ye don’t see Rollins round Stinson’s no more. I tell ye, sonny, ye carn’t put nothing over on ’em. They knows all the tricks and all the trade. Give me kind-’earted ladies; give me ministers of the gospel; give me the stool o’ repentance two or three times a month; but don’t give me fellas that because they’ve knocked off the booze theirselves wants every one else to knock it off, too, and don’t let it be a free country.”

We came to the corner to which I had been directing our seemingly aimless steps. It was a corner where the big red and green jars that had once been the symbols for medicines within now stood as a sign for soda-water and ice-cream.

“Let’s go in here.”

Lovey hung back. “What’s the use of that? That ain’t no saloon.”

“Come on and let us try.”