First in my song shalt thou be, O Phœbus, the song that I sing

Of the heroes of old, who sped, at the hest of Pelias the king,

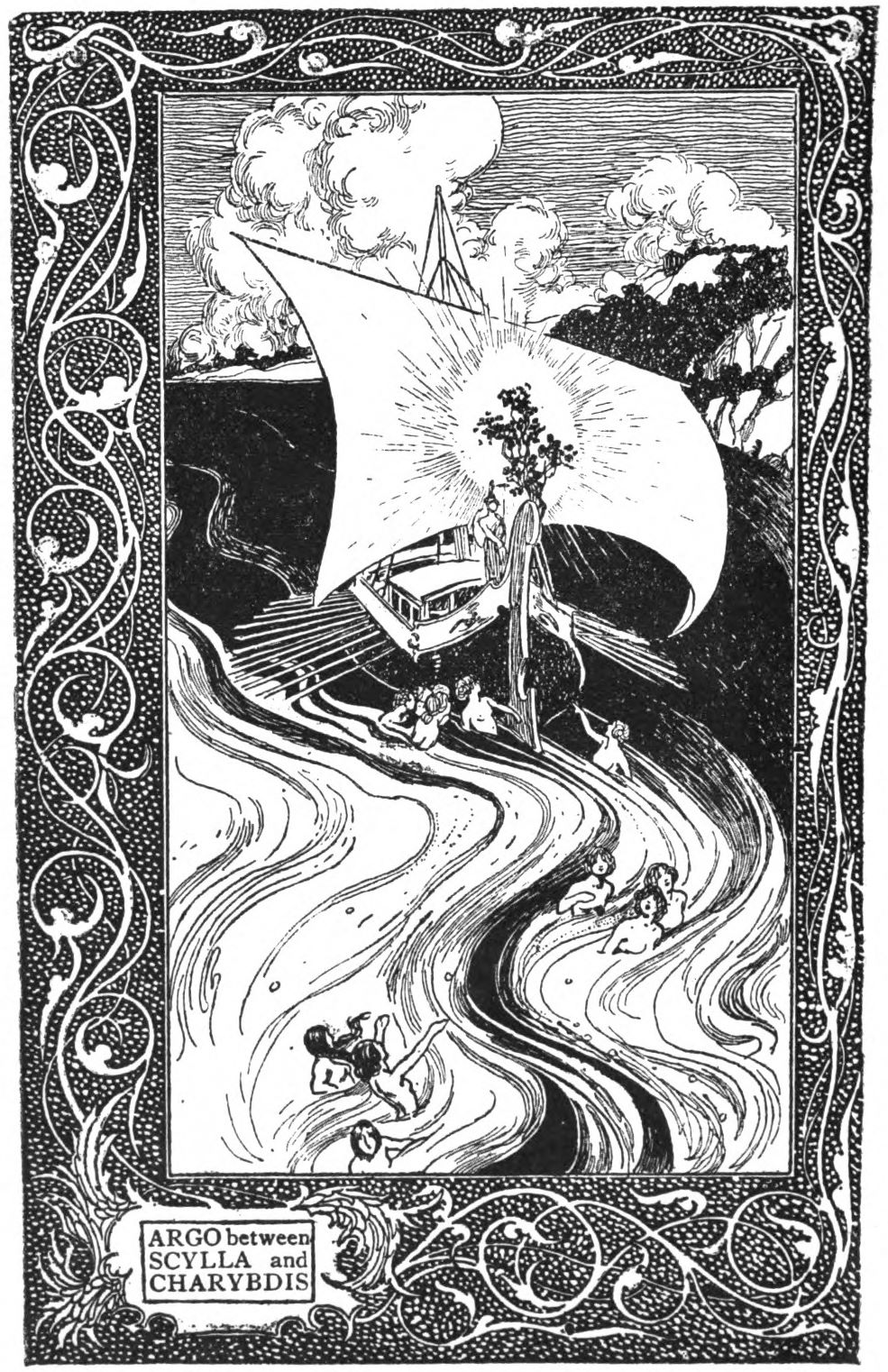

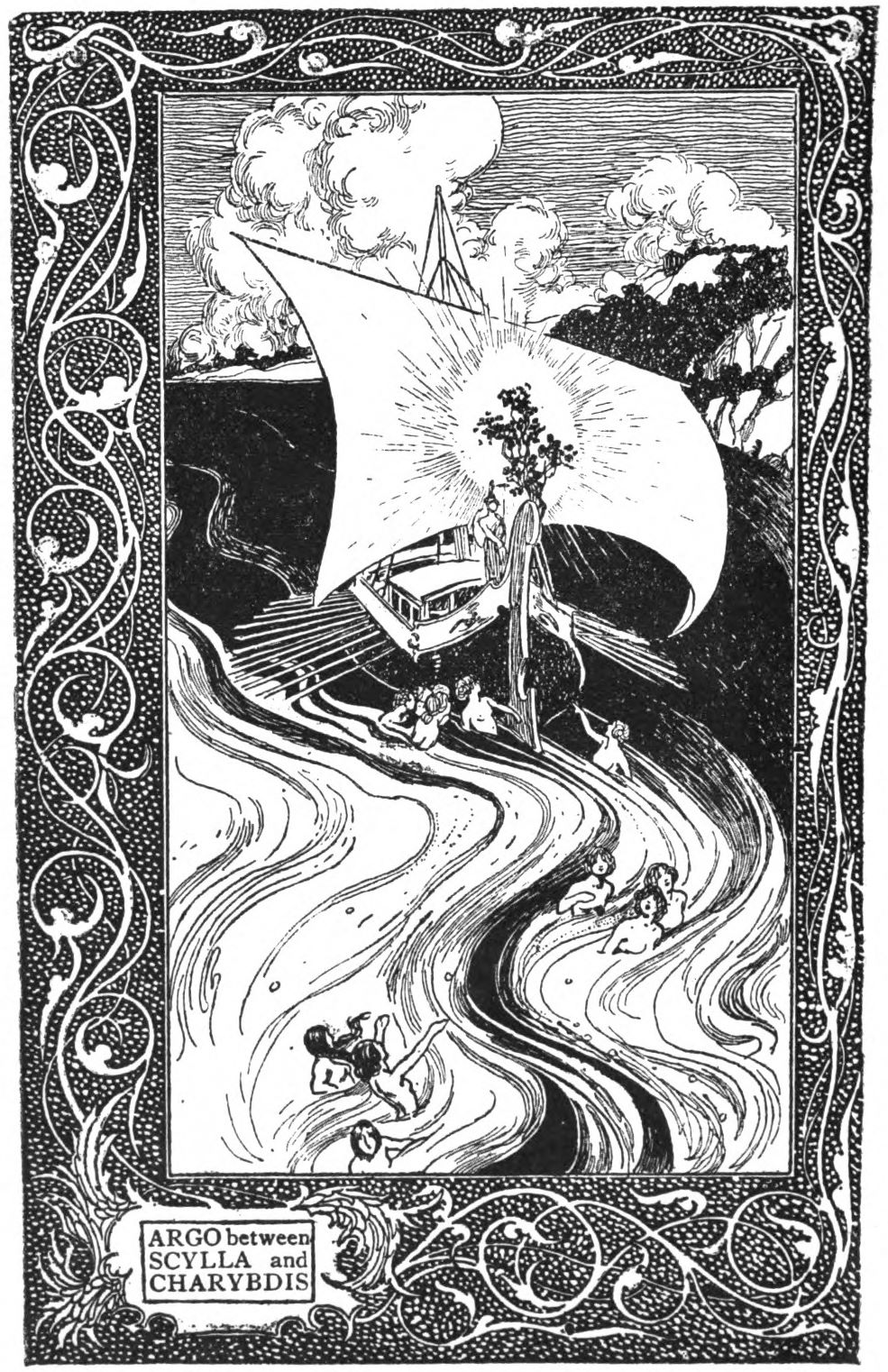

When down through the gorge of the Pontus-sea, through the Crags Dark-blue,

On the Quest of the Fleece of Gold the strong-ribbed Argo flew.

For an oracle came unto Pelias, how that in days to be

A terrible doom should be dealt him of him whom his eyes should see

From the field coming in, with the one foot only sandal-shod.

Nor long thereafter did Jason fulfil the word of the God:

For in wading the rush of Amaurus swollen with winter-tide rain

One sandal plucked he forth of the mire, but the one was he fain {10}

To leave in the depths, for the swirl of the waters to sweep to the main.

Straightway to the presence of Pelias he came, and his hap was to light

On a banquet, the which unto Father Poseidon the king had dight,

And the rest of the Gods, but Pelasgian Hêrê he heeded not.

And the king beheld him, and straightway laid for his life the plot,

And devised for him toil of a troublous voyage, that lost in the sea,

Or lost amid alien men his home-return might be.

Of the ship and her fashioning, bards of the olden time have told

How Argus wrought, how Athênê made him cunning-souled.

But now be it mine the lineage and names of her heroes to say, {20}

And to tell of the long sea-paths whereover they needs must stray,

And the deeds that they wrought:—may the Muses vouchsafe to inspire the lay.

Of Orpheus first will I sing, of the child that Calliopê bare,

As telleth the tale, for she loved Oeagrus, Thracia’s heir.

By the peak Pimplean was born the Song-queen’s wondrous child;

For they tell how he charmed by the voice of his song on the mountains wild

The stubborn rocks into life, made rivers their flowing refrain,

And the wildwood oaks this day be memorials of that weird strain;

For they burgeon and bloom by Zonê yet on the Thracian shore,

Ranked orderly line upon line, the selfsame trees which of yore, {30}

Spell-drawn by his lyre, from Pieria followed the minstrel on.

Such an one was the Orpheus that Aison’s son for a helper won

For his high emprise, when he followed the pointing of Cheiron’s hand,—

Orpheus, who ruled o’er the Bistonid folk in Pieria-land.

And swiftly Asterion came, whom Komêtês begat by the side

Of Apidanus, there where his seaward-swirling waters glide;

In Peiresiae he dwelt, anigh to Phyllêion’s leafy crest.

Mighty Apidanus, sacred Enipeus, have thitherward pressed

To mingle the waters, far-severed that rise from the earth’s deep breast.

Polyphemus forsook Larissa, and unto Jason he sought; {40}

Eilatus’ son: in his youth mid the Lapithan heroes he fought.

When the Lapithans armed them for fight, when the Centaur host they quelled,

Their youngest he was; but now were his limbs sore burdened with eld.

Yet even as of old his heart with the spirit of battle swelled.

Nor in Phylakê Iphiklus tarried to waste an inglorious life,

Uncle of Aison’s child, for that Aison had taken to wife

His sister the Phylakid maiden Alkimêdê: wherefore strong

Was the love of his kin to constrain him to join that hero-throng.

Neither Admêtus in Pherae, the goodly land of sheep,

In his palace would tarry beneath Chalkodon’s mountain-steep. {50}

Neither in Alopê tarried Echion and Erytus, sons

Of Hermes, wealthy in corn-land, crafty-hearted ones.

And their kinsman, the third with these, came forth, on the Quest as they hied,

Aithalides: where the streams of Amphrysus softly slide,

Him Eupolemeia the Phthian, Myrmidon’s daughter, bare,

But offspring of Antianeira the Menetid those twain were.

Came thither Korônus, forsaking Gyrton the wealthy town:

Right valiant was Kaineus’ son, yet he passed not his father’s renown.

For of Kaineus the poets have sung, how smitten of Centaurs he died,

Who could not be slain, when alone in his prowess, with none beside, {60}

He drave them before him in rout, but they rallied, and charged afresh,

Yet availed not their fury to thrust him aback, nor to pierce his flesh;

But unconquered, unflinching, down to the underworld he passed,

Battered from life by the storm of the massy pines that they cast.

And came Titaresian Mopsus withal, unto whom was given

Of Lêto’s son above all men the lore of the birds of the heaven.

And there was Eurydamas, Ktimenus’ son, which dwelt in the land

Of Dolopian folk: by the Xynian mere did his palace stand.

And from Opus Menoitius fared at Aktor his father’s behest

To the end he might go with the chieftains of men on the glorious Quest. {70}

And Eurytion hath followed with these; Eribôtes the mighty is gone,

This, Teleon’s scion, and that, of Irus, Aktor’s son;

For in sooth it was Teleon begat Eribôtes the glory-crowned,

And Irus, Eurytion. With these was a third, Oïleus, found,

Peerless in manhood, exceeding cunning to follow the flight

Of the foe, when the reeling battalions were shattered before his might.

Came the son of Kanêthus the scion of Abas; with eager speed

Came Kanthus forth of Eubœa: it was not fate-decreed

That again he should turn and behold Kerinthus, for doomed was he,

Even he and Mopsus withal, the wise in augury, {80}

To perish in Libya, lost in the waste of a wide sand-sea.

Sooth, never was mischief removed too far to be found of the doomed;

Forasmuch as in Libya’s desert were even these entombed,

As far from the Kolchian land as the space outstretched between

The sun’s uprising, and where the setting thereof is seen.

And Klytius and Iphitus gathered to that great mustering,

Oichalia’s warders, children of Eurytus, ruthless king,

Who received of Far-smiter a bow; but he had no profit thereof,

For in archery-skill with the giver’s self he wantonly strove.

And with these fared Aiakus’ sons, yet not from the selfsame place, {90}

Nor together, for far had they wandered away from the home of their race,

Aegina, what time in their folly the blood of their brother they spilt,

Even Phokus: to Salamis Telamon bare his burden of guilt:

But Peleus roved till in Phthia the halls of the outcast he built.

And with these from Kekropia Boutes, a lord of battle-fame,

Stout Teleon’s son, and Phalêrus the mighty spearman came.

It was Alkon his father that sent him forth: no sons save him

Had the ancient to cherish his age and his light of life grown dim:

Yet, albeit his only-begotten he was, and the last of his line,

He sent him, that so amidst valour of heroes his prowess should shine. {100}

But Theseus, of all the sons of Erechtheus most renowned,

At Tainarum under the earth by an unseen fetter was bound.

For he trod the Path of Fear with Peirithoüs; else that Quest

By the might of these had been lightlier compassed of all the rest.

And Tiphys, Hagnias’ son, hath forsaken the Thespians that dwell

In the city of Siphas: of all men keenest was he to foretell

The wrath of the waves on the broad sea, keen to foreknow from afar

The blasts of the storm, and to guide the galley by sun and by star.

’Twas Athênê Tritonis herself that made him eager-souled

To join that muster of heroes that longed his face to behold; {110}

For she fashioned the sea-swift ship, and Argus but wrought as she planned,

Arestor’s son, for the Goddess’s counsels guided his hand:

Therefore amongst all ships unmatched was the ship that he made,

Even all that with swinging oars the paths of the sea have essayed.

Came Phlias withal from Araithyriae to essay the Quest,

From a wealthy home, for the toil of his hands had the Wine-god blessed,

His father, where welleth Asôpus up from the green hill’s breast.

From Argos did sons of Bias, Arêius and Talaus, come,

And mighty Laodokus, fruit of Nêleus’ daughter’s womb,

Even Pero, for whose sake Aiolus’ scion Melampus bore {120}

In Iphiklus’ steading affliction of bonds exceeding sore.

Nor yet did the prowess of mighty-hearted Herakles fail

The longing of Aison’s son for his helping, as telleth the tale.

But as soon as the flying rumour of gathering heroes he heard,

He turned from the track that he trod from Arcadia Argos-ward,

On the path that he paced as he bare that boar alive from the glen

Of Lampeia, wherein he had battened, the vast Erymanthian fen.

At the entering-in of Mycenae’s market-stead he cast

From his mighty shoulders the beast, as he writhed in his bonds knit fast:

But himself of his own will, thrusting Eurystheus’ purpose aside, {130}

Hasted away; and Hylas, his henchman true and tried,

Which bare his arrows and warded his bow, with the hero hath hied.

Therewithal hath the scion of god-descended Danaus gone,

Nauplius, born unto King Klytonêus, Naubolus’ son;

And of Lernus Naubolus sprang; and Lernus, as bards have told,

Of Proitus, Nauplius’ son; and unto Poseidon of old

Amymônê, Danaus’ daughter, who couched in the God’s embrace,

Bare Nauplius, chief in the seafarer’s craft of the Earth-born race.

Last cometh Idmon the seer, of all that in Argos dwell,

Cometh knowing the doom he hath heard the birds of heaven foretell, {140}

Lest the people should haply begrudge him a hero’s glorious fame:

Yet not of the very loins of Abas the doomed seer came;

But the son of Lêto begat him to share the noble name

Of Aetolia’s sons, and in prophecy-lore he made him wise,

And in signs of the fowl of the heaven and tokens ’mid flame that rise.

Polydeukes the strong did Aetolia’s Princess Leda speed

From Sparta, and Kastor cunning to rein the fleetfoot steed.

These twain in Tyndareus’ palace, her dearly-beloved, her pride,

That lady at one birth bare; howbeit she nowise denied

Their prayer to depart, for her spirit was worthy of Zeus’ bride. {150}

Apharetus’ children, Lynkeus and Idas the arrogant-souled,

From Arênê went forth: in their prowess exceeding were these overbold,

Even both; but Lynkeus for eyes of keenest ken was renowned,

If in sooth that story be true, that, though one lay underground,

Yet lightly of Lynkeus’ eyes should the gloom-swathed corpse be found.

And with these Periklymenus Neleus’ son was enkindled to fare,

Eldest of all the sons that the Lady of Pylos bare

Unto Neleus the godlike; and might unmeasured Poseidon gave

To the prince, and a boon moreover, that whatso shape he should crave,

That, as he fought in the shock of the meeting ranks, he should have. {160}

From Arcadia Amphidamas and Kepheus came for the Quest,

Who were dwellers in Tegea-town, and the land that Apheidas possessed,

Two scions of Aleus; yea and a third followed even as they went,

Ankaius: Lykurgus his father was minded the lad to have sent,

Being elder brother to these, but himself was constrained to stay

In the city with Aleus, tending the dear head silver-grey.

Howbeit in charge to his brethren twain he gave the lad.

So he went, and the fell of a bear Maenalian for buckler he had,

And a battle-axe huge his right hand swung; for his armour of fight

Had his old grandsire in a secret chamber hidden from sight, {170}

If haply so he might cripple the wings of the eagle’s flight.

Fared thither Augeias; they named him in songs of the olden day

The Sun-god’s child, and the hero in Elis-land bare sway

In pride of his wealth: but he longed to behold the Kolchian coast,

And to look upon mighty Aiêtes the lord of the Kolchian host.

Asterius came, and Amphion, the sons that a fair queen bore,

When Pellênê’s king Hyperasius dwelt in the city of yore

By Pelles their grandsire built ’neath the cliffs of Achaia’s shore.

Euphêmus from Tainarus came to be joined to their company,

Europê’s child; and the swiftest of all men on Earth was he: {180}

For the daughter of Tityos the giant couched in Poseidon’s embrace;

And this their son would run o’er the grey sea’s weltering face,

Neither sank in the surge his fast-flying steps, but, with footsole alone

Bedewed with the spray, on his watery path was he wafted on.

Sons of Poseidon beside him withal two other came,

One leaving Miletus afar, the city of haughty fame,

Even Erginus, and one from Imbrasian Hêrê’s fane

Parthenia, Ankaius the mighty; and men of renown were the twain

In the craft of the sea, and withal in the toil of the battle-strain.

Hasting from Kalydon Oineus’ son to their muster hath hied, {190}

Meleager the stalwart; and there was Laocoön still at his side,

Brother to Oineus; but not of the selfsame womb were they,

For a handmaid bare him; and him, though flecked was his hair with grey,

For guide and for guard to his son hath Oineus the old king sent.

So it fell that a beardless lad to the valorous gathering went

Of heroes; yet no man of all that came had the deeds outdone

Of the lad, save Herakles, if that he might but have tarried on

One year mid Aetolia’s sons, till he grew to his strength, I ween.

Yea, and his mother’s brother, a javelin-hurler keen,

And a warrior tried, when foot is set against foot in the fray, {200}

Iphiklus, Thestius’ scion, trod the selfsame way.

Came Palaimonius, whose grandsire was Olenius, and his sire

Lernus in name; but in birth was he child of the Lord of Fire:

Wherefore he halted in either foot; but his bodily frame

And his prowess might no man contemn, for which cause also his name

Was found with the mighty who won for Jason deathless fame.

Came Iphitus, Ornytus’ son, from Phokis withal for the Quest,

Of Naubolus’ line: in the days overpast was Jason his guest,

What time unto Pytho he fared to inquire of the high Gods’ doom

Touching the Quest; for he welcomed him then in his mountain home. {210}

And Zetes and Kalais withal, the North-wind’s children, were there,

Whom Oreithyia, Erechtheus’ daughter, to Boreas bare

In the uttermost part of wintry Thrace; for the God swooped down,

And the Thracian North-wind snatched her away from Kekrops’ town,

Even as she whirled in the dance on the lawn by Ilissus’ flow.

And he brought her afar to the place where standeth the crag men know

For the Rock of Sarpedon, whereby doth Erginus the river glide:

And he shrouded her round with viewless clouds, and he made her his bride.

And lo, on the ankles of these did quivering pinions unfold,

Strong wings, as in air they upleapt, a marvel great to behold, {220}

Gleaming with golden scales; and about their shoulders strayed,

Down-streaming from neck and from head in the glory of youth arrayed,

Dark tresses that tossed in the rushing breezes amidst them that played.

Yea, and Akastus, his own son, had no will to abide

That day with his mighty sire in the halls of Pelias’ pride.

Nor would Argus be left, who had wrought as Athênê guided his hand;

But these twain needs must be numbered too with the glorious band.

This is the tale of the helpers with Aison’s son that were found:

These be the men whom the folk, even all which dwelt around,

Called ever the Minyan Chiefs: for of those that went on the Quest {230}

Born of the daughters of Minyas’ blood were the most and the best.

Yea, she which had borne this Jason to emprise perilous-wild,

Alkimedê, also was daughter of Klymenê, Minyas’ child.

Now when all things ready were made by the hands of many a thrall,

Even whatso the galley for sea ready-dight should be furnished withal,

When traffic lureth the shipmen afar to an alien land,

Then through the city they passed to their ship, where she lay on the strand

Which is called Magnesian Pagasae. Ever, as onward they strode,

To right and to left a mingled multitude ran: but they showed

Radiant amidst them as stars amid clouds; and some ’gan cry, {240}

As they gazed on the glorious forms that in harness of war swept by:

‘What is in Pelias’ thoughts, King Zeus, that so goodly a band

Of heroes is hurled by him forth of the Panachaian land?

In the day of their coming with ravening fire the halls shall they fill

Of Aiêtes, except he shall yield them the Fleece of his own good will.

But a long way lieth between, unaccomplished yet is the toil.’

So spake they on this side and that through the city: the women the while,

Heavenward uplifting their hands, to the Gods that abide for aye

Made vehement prayer for the heart’s delight of the homecoming day.

And one to another made answer, and moaned, as her tears fell fast: {250}

‘Hapless Alkimedê, thee too evil hath found at the last;

Nor to thee was vouchsafed amid bliss to the end of thy days to attain!

Woe’s me for Aison the ill-starred!—verily this had been gain

For him, if rolled in his shroud before this woeful day,

Deep under Earth, with the cup of affliction untasted, he lay:

And O that the darkling surge, when Hellê the maiden died,

Had whelmed down Phrixus too with the ram!—but a man’s voice cried

From the throat of the monster, the portent accurst, that so it might doom

For Alkimedê sorrow and griefs untold in the days to come.’

So ’mid the moan of the women marched the heroes along. {260}

And by this were the thralls and the handmaids gathered in one great throng.

Then fell on his neck his mother, and sharply the anguish-thorn

Pierced each soft breast, the while his father, the eld-forlorn,

Close-swathed as a corpse on his bed, lay groaning and groaning again.

But the hero essayed to hush their laments and assuage their pain

With words of cheer, and he spake, ‘Take up my war-array,’

To the thralls, and with downcast eyes did these in silence obey.

But his mother, as round her child her arms at the first she had flung,

So clave she, and wept without stint: as the motherless maiden she clung,

Whose forlorn little arms clasp fondly her grey old nurse, when the tide {270}

Cometh up of her woe:—she hath no one to love her nor comfort beside;

And a weary lot is hers ’neath a stepdame’s tyrannous sway,

Who with bitter revilings evil-entreateth her youth alway:

And her heart as she waileth is cramped as by chains in her frenzied despair,

That she cannot sob forth the anguish that struggleth for utterance there:

So stintlessly wept Alkimedê, so in her arms did she strain

Her son; and she cried from the depths of her love and her yearning pain:

‘Oh, that on that same day when I, the affliction-oppressed,

Hearkened the voice of Pelias the king, and his evil behest,

I had yielded up the ghost, and forgotten to mourn and to weep, {280}

That thyself, that thine own dear hands, in the grave might have laid me to sleep,

O my beloved!—for this was the one wish unfulfilled:

But with other thy nursing-dues long had mine heart in contentment been stilled.

And I, of Achaia’s daughters the envied in days that are gone,

Like a bondwoman now in tenantless halls shall be left alone,

Pining, a hapless mother, in yearning for thee, my pride

And exceeding delight in the days overpast, for whom I untied

For the first time and last my zone; for to me beyond others the doom

Of the stern Birth-goddess begrudged abundant fruit of the womb.

Ah me for my blindness of heart!—not once, not in dreams, might I see {290}

The vision of Phrixus’ deliverance turned to a curse for me!’

So mourned she, and ever she moaned amidst of her speech, and thereby

Stood her handmaids, and echoed her wail, an exceeding bitter cry.

But the hero with gentle words for her comfort made answer, and spake:

‘Fill me not thus overmeasure with anguish of soul for thy sake,

Mother mine, forasmuch as from evil thou shalt not redeem me so

By thy tears, but shalt add the rather woe unto weight of woe.

For the Gods mete out unto mortals afflictions unforeseen:

Wherefore be strong to endure their doom, though thine anguish be keen.

Take comfort to think that Athênê hereunto our courage hath stirred: {300}

Remember the oracles: call to remembrance how good was the word

Of Phœbus: be glad for this hero-array for mine help that is come.

Now, mother, do thou with thine handmaids in quiet abide in thine home,

Neither be as a bird ill-omened to bode my ship ill-speed;

And escort of clansmen and thralls thy son to the galley shall lead.’

So spake he, and turned him, and forth of his halls his way hath he ta’en.

And as goeth Apollo forth of his incense-bearing fane,

Through Delos the hallowed, or Klaros, or Pytho the place of his shrine,

Or Lycia the wide, where the waters of Xanthus ripple and shine,

So seemed he, as onward he pressed through the throng, and a loud acclaim {310}

Of their mingled cheering arose. And there met him an ancient dame,

Iphias, priestess of Artemis warder of tower and wall.

At his right hand caught she, and kissed it, but spake no word at all,

For she could not, how fain soe’er, so pressed the multitude on;

And she drifted away to the fringe of the crowd, and was left alone,

As the old be left by the young: and he passed on afar, and was gone.

So when he had left the streets of the city builded fair,

To the beach Pagasaean he came, and his comrades hailed him there

In a throng abiding beside the Argo ship as she lay

By the river’s mouth, and overagainst her gathered they. {320}

And they looked, and behold, Adrastus and Argus hasting amain

Thitherward from the city, and sorely they marvelled, beholding the twain

Despite the purpose of Pelias thitherward hurrying fast.

On his shoulders a bull’s hide Argus the son of Arestor had cast,

Great, dark with the fell; but the prince in a mantle fair was arrayed,

Twofold: Pelopeia his sister the gift in his hand had laid.

Howbeit Jason forbare to ask them of this or of that;

But he bade them for council sit them down where the others sat.

So there upon folded sails, and the mast as it lay along,

Row upon row were the heroes sitting all in a throng; {330}

And to these of his heart’s good will the son of Aison spake:

‘What things soever it needeth that sea-bound galleys should take,

All this ready dight for our going lieth in seemly array.

Wherefore for these things’ sake will we make no longer delay

From our sailing, so soon as the breezes but blow for the voyage begun.

But, friends—since in hope for the home-return to our land we be one,

And one in the way we must take to Aiêtes, the path of the Quest,

Therefore do ye now choose with hearts ungrudging our best

To be chief and captain, to order all our goings aright,

To take on him our quarrels with aliens, and pledge our covenant-plight.’ {340}

He spake, and the youths upon valiant Herakles turned their eyes,

As he sat in their midst, and from all the heroes did one shout rise,

Crying ‘Our captain be thou!’—but not from his place he stirred;

But he stretched his right hand forth, and he answered and spake the word:

‘Let no man offer this honour to me: I will nowise consent;

And if any man else would arise, I will also withstand his intent.

The selfsame man who assembled our band, let him too lead.’

He spake in his greatness of soul, and they shouted, praising the rede

Of Herakles: then did Jason the warrior wight rejoice;

And he sprang to his feet, and he spake in their midst with eager voice: {350}

‘If indeed ye be minded on me this glorious charge to cast,

Let our voyaging tarry no more; suffice the delays overpast.

But now, even now, let us offer to Phœbus the sacrifice meet,

And prepare us a feast even here; and, while yet tarry the feet

Of my thralls, overseers of my steading, which bear in charge my command

Fitly to choose for us beasts from the herd, and to drive to the strand,

We will launch on the sea our ship, we will set up her tackling therein,

And thwart by thwart cast lots for the place each oarsman shall win.

To Apollo, the Seafarers’ Saviour, uppile we then on the beach

An altar; for whatso I needs must do hath he promised to teach, {360}

And to show us the paths of the sea, if first with sacrifice

I seek unto him, or ever I strive with the king for the prize.’

So spake he, and turned him first to the work; and, his call to obey,

The heroes arose, and their garments row upon row heaped they

On a smooth rock-shelf: the waves of the sea beat not thereon;

But the dash of the stormy brine had cleansed it long agone.

Then, giving heed to the counsels of Argus, stoutly they braced

The ship with a hawser deftly twisted that girded her waist;

For they strained it from side to side, that the beams to the bolts might hold

Fast, and withstand the might of the meeting surge on-rolled. {370}

And a trench, in compass as great as the width of the galley, they delved;

And overagainst her prow to the sea so far it shelved

As the space that the hull should run, by the might of their hands on-sped:

And deepening ever afront of her stern they scooped that bed.

And smoothly-shaven rollers they laid in the furrow arow.

Then down on the foremost rollers slowly they tilted her prow,

That adown them one after other with one smooth rush she might slide.

Thereafter above did they pass the oars from side to side;

To the tholes did they lash them, outstanding a cubit on either hand;

And to right of the ship and to left at these did they take their stand; {380}

And with chest and with hands against them they bare, and to and fro

Went Tiphys the while, to shout in the season the yo-heave-ho.

Then gave he the word with a mighty shout, and the youths forthright

Drave her with one rush down, as they thrust with their uttermost might,

From her berth in the sand, as with feet hard-straining strongly they stept

Forcing her forward, and Pelian Argo seaward swept

Full swiftly, and shouted they all, as to right and to left they leapt.

And under the massy keel’s heavy grinding groaned aloud

The rollers, and spirted about them the smoke in a dusky cloud

’Neath the crushing weight: and into the sea she slid, and her crew {390}

Back with the hawsers warped her, and stayed her as onward she flew.

Then the oars to the tholes they fitted on either side, and the mast

And the well-fashioned sails, and the tackling withal, therein they cast.

But soon as with diligent heed they had ordered all things so,

First cast they the lots for the thwarts whereat each man should row,

Allotting one unto two men still; but the midmost thwart

For Herakles chose they first, from the rest of the heroes apart;

And Ankaius the dweller in Tegea-town for his fellow they chose.

So the midmost place of the benches they left unchallenged to those,

Neither cast for them lots; and with one consent of the voices of them {400}

Unto Tiphys was given the helm of the galley of goodly stem.

Then did they heap of the stones of the shingle, and, nigh at hand

To the sea, an altar they reared to Apollo the Lord of the Strand,

Who is called the Lord of the farers a-shipboard withal, and in haste

Billets of olive-wood sapless and dry thereon they placed.

And by this were the herdmen of Aison’s son drawn nigh thereto

Bringing oxen twain from the herd; and these the young men drew

And set them beside the altar; and others stood thereby

With the water of sacrifice and the meal. And now drew nigh

Jason, and unto Apollo his fathers’ god did he cry: {410}

‘Hearken, O King, who in Pagasae dwellest, whose fair halls be

In the city Aisonian, named of my sire, who didst promise to me,

When I sought unto thee at Pytho, to point me my journey’s goal

And fulfilment; for thou, even thou, to the emprise didst kindle my soul.

Now therefore my ship with my comrades safe and sound bring thou

Thither, and back unto Hellas again: and to thee do we vow,

For as many of us as shall win safe home, on thine altar to lay

Burnt offerings so many of goodly bulls: therewithal will I pay

At Pytho thy shrine, and Ortygia, other gifts beyond price.

Come then, Far-smiter, accept at our hands this sacrifice, {420}

Which now, at our going abroad, for the sake of this our ship

We offer, our first of all: and with prosperous weird may I slip

The hawsers, by thy devising: and soft bid blow the breeze

Whereby we may fare on ever through calm of summer seas.’

With the prayer then cast he the meal: and now for the slaughtering these

Girded themselves, Ankaius the mighty, and Herakles.

And this with his club on the forehead smote the steer mid-head;

And heavily all in a heap to the earth it dropped down dead.

And Ankaius hewed with his brazen axe at the second steer

On the broad neck: clean through the sinews strong thereof did it shear; {430}

And there on the earth, with horns doubled under its chest, it lay.

And swiftly their comrades severed the throats, and the skins did they flay,

And they sundered the joints, and they carved, and the sacred thighs they cut out,

And they laid them together, and closely with fat they wrapped them about,

And burnt on the cloven wood: drink-offerings unmingled of wine

Poured Aison’s son; and Idmon rejoiced, beholding shine

The splendour that gleamed all round from the sacrifice and the smoke,

As forth for an omen of good in wavering wreaths it broke.

And the purpose of Leto’s son, nothing doubting, straightway he spoke:

‘For you ’tis ordained of the doom of the Gods and of each man’s fate {440}

Hither to win with the Fleece; but meanwhile lie in wait

Toils without number, as thither ye fare, and as backward ye hie.

But for me by the hateful doom of a God is it fated to die

Far hence, I know not where, on the Asian mainland shore.

Yea, this is my doom: by birds evil-boding I knew it before;

Yet from my fatherland went I: to sail in your galley I came,

That so to mine house might be left the renown of a hero’s name.’

He spake, and the young men, hearing the words of the prophet, were glad

For their home-return, but for Idmon’s doom were their hearts made sad.

And so, at the hour when the sun from his noon-halt sinketh adown, {450}

And over the harvest-lands the long rock-shadows are thrown,

As the sun to the eventide dusk slow-slideth aslant from the sky,

Even then did the heroes all on the sands of the beach pile high

A couch of the wildwood leaves, and in front of the surf-line hoar

Row upon row lay down, and beside them was measureless store

Of meats, and of sweet strong wine which the cupbearers poured for them out

From the pitchers: thereafter they told, as each man’s turn came about,

Story and legend, as young men oft at the feast and the bowl

Will take their delight, when insatiate violence is far from their soul.

But there was Aison’s son, as a man in a nightmare dream, {460}

Struggling with deep dark thoughts, and as one distraught did he seem;

And Idas marked him askance, and he shouted in scoffing tone:

‘What thoughts to and fro in thine heart art thou turning, thou Aison’s son?

Speak out in our midst thy mind! Hath fear in thy spirit awoke

Overmastering thee—that thing which dazeth dastard folk?

Be witness my furious spear, wherewithal beyond others I win

Renown in the wars—nor is Zeus so present a helper therein,

Nor so mighty to save as my spear—that on thee no deadly bane

Shall light, nor shall any strife of thine hands be striven in vain,

While Idas attendeth thee, not though against thee a God should arise. {470}

Such a helper is this thou hast won from Arênê for thine emprise.’

He spake, and the brimming beaker with both hands lifted he up,

And the strong wine drank unmingled, and dashed with the dew of the cup

Were his lips and his swarthy cheeks: but a startled clamour broke

From all together; and openly Idmon rebuked him, and spoke:

‘Beshrew thee!—thy thoughts thus soon to thyself are deadly and fell!

Hath the strong wine caused thy reckless heart for thy ruin to swell

In thy breast, and eggeth thee on to set the Gods at nought?

Other words of comfort there be wherewithal a man might have sought

To hearten his friend; but thy words were wholly presumptuous-bold! {480}

So blustered, as telleth the tale, against the Blessèd of old

The sons of Alôeus: and thou—thou art nothing so mighty as they

In manhood: yet both did the swift shafts overmaster and slay

Of the Son of Latona, though giants they were and passing strong.’

Then Aphareus’ son brake forth into laughter loud and long,

And blinking upon him in drunken wise flung back the jeer:

‘Come now, by thy deep divination reveal unto me, thou seer,

If the Gods for me also be bringing to pass such doom as that

Which was dealt of that father of thine to the sons that Alôeus begat.

And bethink thee how thou shalt escape from mine hands alive, if we find {490}

Thee guilty of boding a prophecy vain as the idle wind!’

Wrathfuller waxed he in railing: and now had the strife run high,

But amidst of their wrangling their comrades with loud indignant cry,

With Aison’s son, restrained them:—and lo, with his lyre upheld

In his left hand, Orpheus arose, and the fountain of song upwelled.

And he sang how in the beginning the earth and the heaven and the sea

In the selfsame form were blended together in unity,

And how baleful contention each from other asunder tore;

And he sang of the goal of the course in the firmament fixed evermore

For the stars and the moon, and the printless paths of the journeying sun, {500}

And how the mountains arose, how rivers that babbling run,

They and their Nymphs, were born, and whatso moveth on Earth;

And he sang how Ophion at first, and Eurynomê, Ocean’s birth,

In lordship of all things sat on Olympus’ snow-crowned height;

And how Ophion must yield unto Kronos’ hands and his might,

And she unto Rhea, and into the Ocean’s waves plunged they.

O’er the blessed Titan-gods these twain for a space held sway,

While Zeus as yet was a child, while yet as a child he thought,

And dwelt in the cave Dictaean, while yet the time was not

When the Earth-born Cyclops the thunderbolt’s strength to his hands should give, {510}

Even thunder and lightning: by these doth Zeus his glory receive.

Low murmured the lyre, and slept, and the voice divine was still:

But moveless the heads of them all are bending forward, and thrill

Their eager-listening ears, through the hush as they strain, in thrall

To the spell; such wondrous glamour the song hath cast over all.

And a little thereafter they mingled, even as is meet and right,

The wine, and poured on the tongues where the altar-fires blazed bright.

Then turned they to sleep, and around them were folded the wings of the night.

But when radiant Dawn with her flashing eyes on the steeps looked down

Of Pelion’s crests, and, washed by the wind, the forelands that frown {520}

Over the tossing sea rose sharp and clear to view,

Then Tiphys awoke, and he hasted the Argo’s hero-crew

To hie them aboard, and to range the oars in order due.

And a weird dread cry from the haven of Pagasae rang to them; yea,

From Pelian Argo herself came a voice, bidding hasten away:

For within her a beam divine had been laid, which Athênê brought

From the oak Dodonaean, and into the midst of her stem was it wrought.

So the heroes went up to the thwarts, and twain after twain arow,

Even as fell the places by lot but a little ago,

Orderly ranged sat down, and by each was his harness of fight. {530}

On the midmost Ankaius, and next him Herakles’ giant might

Sat, and beside him he laid his club; and the keel of the ship

Under his massy tread plunged deep. And now did they slip

The hawsers, and poured on the sea the wine. Tear-dimmed that day

Were Jason’s eyes, from the fatherland-home as he turned them away.

And these—as the youths that in Pytho begin unto Phœbus the dance,

In Ortygia, or there where Ismenus’ ripples in sunlight glance,

Hand in hand to the notes of the lyre his altar around

With rhythmical fall of the feet swift-circling beat the ground,—

So smote with the oars, by the lyre of Orpheus timing the stroke, {540}

The sea’s wild water, and over the blades the surges broke.

And on this side and that with the foam the dark brine seething flashed;

Like muttered thunder it sounded by strokes of the mighty updashed.

And glanced in the sun like flame, as the ship winged onward her flight,

Their armour: the wake far-weltering ever behind gleamed white,

As an oft-trodden path through a grassy plain lieth clear in sight.

And all the Gods that day from the height of the heaven looked down

On the ship, and the might of the demigod heroes, the men of renown,

Sailing the sea; and afar on the crests of the hill-tops lone

The Maids of the Mountain, the Pelian Nymphs, in amaze looked on {550}

At the work of Athênê Itônis, the heroes’ goodly array,

As the ashen blades in their hands kept time with measured sway.

Yea, and there came one down from the mountain’s height to the shore,

Even Cheiron, Philyra’s son, and plashed the surf-wash hoar

On his feet, as his broad hand waving many a farewell sent,

And he shouted, ‘Good speed, and a sorrowless home-return!’ as they went.

And there was his wife, with Peleus’ babe in her arms held high,

Achilles, waving a greeting as sped his sire thereby.

So when they had rounded the headland, and left the haven behind

By the cunning and wisdom of Hagnias’ son the prudent of mind,— {560}

Even of Tiphys, who swayed in the master-craftsman’s grip

The helm smooth-shaven, to guide unswerving the course of the ship,—

Then set they up in the centre-block the towering mast,

And on either hand strained taut the stays, and they lashed them fast;

And the sail they unfurled therefrom, from the yard-arm spreading it wide.

And a breeze shrill-piping upsprang, and the sheets upon either side

O’er the polished pins on the deck then cast they in order meet;

And past the long Tisaian ness did they restfully fleet.

And Orpheus, in song whose rhythmical cadence kept time to the lyre,

Sang of the Saviour of Ships, the Child of the Glorious Sire, {570}

Artemis, she that hath those crags of the sea in her keeping,

The Lady that wardeth Iolkos-land. And the fishes leaping

Up from the deep sea came, and, drawn by the spell of the lay,

Both small and great followed gambolling over the watery way.

And as when in the track of a shepherd, the warder of flocks on the wold,

Follow sheep that have fed to the full of the grass, a throng untold,

And he goeth before with his shrill reed piping them home to the fold,

As sweetly he fluteth a shepherd’s strain,—so over the seas

Followed the fishes: on wafted her ever the chasing breeze.

And ere long melting in haze the Pelasgians’ land of corn {580}

Sank out of sight; and past Mount Pelion’s cliffs were they borne

Aye running onward; and sank in the offing the Sepian strand,

And sea-girt Skiathos rose, and a far-away gleam of sand,

The Peiresian beach and Magnesian, clear in the summer air

On the mainland; and lo, the barrow of Dolops: at eventide there

Beached they the ship, for against them the veering breeze had turned.

And they honoured the dead, and victims of sheep in the gloaming they burned,

While the sea-surge stormily tossed. Two days to and fro on the shore

They loitered, but ran on the third their galley asea once more;

And the broad sail spread they on high, and the keel from the strand shot away: {590}

Men call it ‘The Launching of Argo’—Aphetai—unto this day.

Onward they ran, ever onward: they left Meliboia behind;

They caught but a glimpse of the foam-flecked beach of the stormy wind:

And with dawning on Homolê looked they, and lo, it was looming anigh;

Broad-couched on the breast of the waters it lay as they passed it by.

Thereafter full soon by the outfall of Amyrus’ flood must they fly.

Eurymenê then, and the surf-tormented gorges they spied

Of Olympus’ and Ossa’s seaward face: wind-wafted they ride

By the slopes of Pallênê; beyond Kanastra’s foreland-height

They passed, running lightly before the breath of the breeze in the night. {600}

And before them at dawn on-speeding the pillar of Athos rose,

The Thracian mountain: its topmost peak’s dark shadow it throws

Far as a merchantman goodly-rigged in a day might win,

Even to Lemnos’ isle, and the city Myrinê therein.

And the wind blew all that day till the folds of the darkness fell,

Blew ever fresh, and the sail strained over the broad sea-swell.

Howbeit the wind’s breath failed them at going down of the sun:

So to Lemnos the craggy, the Sintian isle, by rowing they won.

There all the men of the nation together pitilessly

By the violent hands of the women were slain in the year gone by; {610}

Forasmuch as the hearts of the men from their lawful wives had turned,

And in love for their captive handmaids with baleful passion they burned,

Maids that themselves from the Thracian land in foray had brought

Oversea:—’twas the wrath of the Cyprian Queen that curse had wrought,

Because that for long they had left her unhonoured by sacrifice:—

Ah hapless, whose hungering jealousy craved that woeful price!

For not with the captives their husbands alone for the sin did they slay,

But every male therewithal, lest perchance in the coming day

Out of these might arise an avenger for that grim murder’s sake.

In one alone for an aged sire did compassion awake, {620}

Hypsipylê, daughter of Thoas, the king of the folk of the land.

In an ark did she send him to drift o’er the sea from the murder-strand,

If he haply might ’scape. And fisher-folk saved him and brought to the isle

Which men call Sikinus now, but Oinoë named it erewhile;

For from Sikinus folk renamed it, the child whom the Maid of the Spring,

Oinoë, bare, when she couched in love with Thoas the king.

So it came to pass that for these to tend the kine, and to wear

War-harness of brass, and to furrow the wheat-bearing land with the share,

In the eyes of them all seemed task more light than Athênê’s toil

Wherewithal were their hands aforetime busy: yet all the while {630}

Across the broad sea ever they cast and anon their eyes

With a haunting fear lest the Thracian sails in the offing should rise.

So when they beheld the Argo’s oars flashing down to their coast,

Forth from the gates of Myrinê straightway in one great host

Clad in their harness of battle down to the beach they poured

Like unto ravening Thyiads: they weened that the Thracian horde

Were come: and there was Hypsipylê clad in the war-array

Of Thoas her father: and all these speechless with wildered dismay

Streamed down,—such panic was wafted about them all that day.

But forth of the galley the while had the chieftains sent to the shore {640}

Aithalides, their herald swift, the man who bore

Charge of their messages, yea, and the wand they committed to him

Of Hermes his sire, who had given him memory never made dim

Of all things:—yea, nor forgetfulness swept even now o’er his soul

Of long-left Acheron’s flow, where the torrents unspeakable roll.

For the doom of his spirit is fixed, to and fro evermore is it swept,

Now numbered with ghosts underground, now back to the light hath it leapt,

To the beams of the sun among living men:—but why should I tell

The story of Aithalides that all men know full well?

Of him was Hypsipylê won to receive that sea-borne array {650}

As waned the day to the gloaming: yet not with the new-born day

Unmoored they the ship for the North-wind’s breathing to waft away.

Through the city the daughters of Lemnos into the folkmote pressed,

And there sat down, as Hypsipylê’s self sent forth her behest.

So when they were gathered in one great throng to the market-stead,

For their counselling straightway she rose in the midst of them all, and she said:

‘Friends, now, an ye will, good store of gifts to the men give we,

Even such as is meet that the farers a-shipboard should bear oversea,

Even meats and the sweet strong wine, that without our towers so

They may bide, nor for need’s sake passing amidst of us to and fro {660}

May know of us all too well, and our evil report shall go

Afar, for a terrible deed have we wrought, and in no wise, I trow,

Good in their sight shall it seem, if they haply shall hear the tale.

Lo, this is our counsel, and this, meseemeth, best shall avail.

But if any amidst you hath counsel that better shall serve our need

Let her rise; for to this have I summoned you, even the giving of rede.’

So spake she, and sat her down on the ancient chair of stone

That of old was her sire’s, and Polyxo her nurse uprose thereupon.

On her wrinkle-shrivelled feet she halted for very eld

Bowed over a staff; but with longing for speech the heart in her swelled. {670}

And hard by her side were there sitting ancient maidens four,

Virgins, whose heads with the thin white hair were silvered o’er.

And amidst of the folkmote stood she, and up from her crook-bowed back

Feebly a little she lifted her neck, and in this wise spake:

‘Gifts, even as unto the lady Hypsipylê seemeth meet,

Send we to the strangers, for thus were it better their coming to greet.

But you—by what art or device shall ye save your souls alive

If a Thracian host burst on you, or cometh in battle to strive

Some other foe?—there be many such chances to men that befall,

Even as now yon array cometh unforeseen of us all. {680}

But if one of the Blessèd should turn this affliction away, there remain

Countless afflictions beside, far worse than the battle’s strain.

For when through the gates of the grave the older women have passed,

And childless the younger have won to a joyless eld at the last,

How then will ye live, O hapless?—what, will the beasts freewilled

On their own necks cast the yoke, to the end that your lands may be tilled?

And the furrow-sundering share will they drag through the heavy loam?

And, as rolleth the year round, straight will they bring you the harvest home?

Now, albeit from me the Fates still shrink as in loathing and fear,

Yet surely on me, when the feet draw nigh of another year, {690}

The earth shall lie, when the burial rites have been rendered to me,

Even as is due, and the evil days I shall not see.

But for you which be younger, I counsel you, give good heed unto this,

For that now at your feet an open way of deliverance there is,

If ye will but commit your dwellings and all your spoil to the guard

Of the strangers, yea, and your goodly city for these to ward.’

She spake, and with clamour the folkmote was filled, for good in their eyes

Was the word, and straightway thereafter again did Hypsipylê rise,

And her voice pealed over the multitude, stilling the mingled cries:

‘If in sooth in the sight of you all well-pleasing is this same rede, {700}

Unto the ship straightway a messenger hence will I speed.’

To Iphinoê which waited beside her spake she her hest:

‘Up, Iphinoê, and to yonder man bear this my request,

That he come to our town, even he who is chief of the strangers’ array,

For the word that pleaseth the heart of my people to him would I say.

Yea, and his fellows bid thou to light in friendship down

On our shore, if they will, and to enter undismayed our town.’

She spake, and dismissed the assembly, and homeward she wended her way;

But Iphinoê to the Minyans went; and they bade her say

What was the mind wherewithal she was come, and what her need. {710}

And straightway she told them the words of her message with eager speed:

‘The daughter of Thoas, Hypsipylê, sent me hither away

To summon the lord of your ship, and the captain of your array,

That the will of her folk she may tell him, their heart’s desire this day.

Yea, and his fellows she biddeth to light in friendship down

On our shore, if they will, and to enter undismayed our town.’

So spake she, and fair in the sight of them all was the word that she said;

For they deemed that Hypsipylê reigned in the room of Thoas dead,

His daughter, his well-beloved; and they hasted Jason to meet

The island-queen, and they dight them to follow their captain’s feet. {720}

Then he flung o’er his shoulders the web by the Goddess Itonian wrought;

In the clasp of a brooch were the folds of the purple of Pallas caught,

Which she gave, when for Argo’s building the keel-props first she dight,

And taught him with rule of the shipwright to measure her timbers aright.

More easy it were in sooth on the sun at his rising to gaze

Than to fasten thine eyes on the flush of its glory, its splendour-blaze.

For the fashion thereof in the midst was fiery crimson glow,

And the top was of purple throughout; and above on the marge and below

Picture by picture did many a broidered marvel show.

For therein were the Cyclopes bowed o’er their work that perisheth not, {730}

Forging the levin of Zeus the King, and so far was it wrought

In its fiery splendour, that yet of its flashes there lacked but one:

And the giant smiths with their sledges of iron were smiting thereon;

While forth of it spurts as of flaming breath ever leapt and anon.

And there were the sons of Asôpus’ daughter Antiopê set,

Amphion and Zethus: and Thêbê, with towers ungirded as yet,

Stood nigh them; and lo, the foundations thereof were they laying but now

In fierce haste. Zethus had heaved a craggy mountain’s brow

On his shoulders: as one hard straining in toil did the image appear.

And Amphion the while to his golden lyre sang loud and clear, {740}

On-pacing; and twice so great was the rock that followed anear.

And next Kythereia with tresses heavily drooping was shown;

And the buckler of onset of Arês she bare: from her shoulder the zone

Of her tunic over her left arm fell with a careless grace

Low over her breast; and ever she seemed on the shield to gaze,

On the face that out of its brazen mirror smiled to her face.

And therein was a herd of shaggy kine; for the winning thereof

Elektryon’s sons and Teleboan raiders in battle strove:

For these were defending their own; but the Taphian rovers were fain

To rob them; and drenched was the dewy meadow with that red rain. {750}

But with that overmastering host were the herdmen striving in vain.

And therein had been fashioned chariots twain in the race that sped.

And Pelops was guiding the car that afront in the contest fled;

And Hippodameia beside him rode that fateful race.

And rushing behind him Myrtilus scourging his steeds gave chase;

And Oinomaus with him had couched his lance with a murderous face.

But, as snapt at the nave the axle, aslant was he falling in dust,

Even as at Pelops’ back he was aiming the treacherous thrust.

And therein was Phœbus Apollo, a slender stripling yet,

Shooting at him who the ravisher’s hand to the veil had set {760}

Of his mother, at Tityos the giant, whom Elarê bare; but the Earth

Nursed him, and hid in her womb, and gave to him second birth.

And Phrixus the Minyan was there; and it seemed that unto the ram

He verily hearkened; it seemed that a voice from the gold-fleeced came.

Thou wert hushed to behold them—wouldst cheat thy soul with the hope that perchance

Forth of the lifeless lips would break the utterance

Of speech—ay, long wouldst thou gaze in expectation’s trance.

Such was the gift of Athênê, the Goddess Itonian’s toil.

And a lance far-leaping he grasped in his right hand, given erewhile

Of the maid Atalanta on Mainalus’ height for the pledge of a friend. {770}

Gladly she met him, for sorely her soul desired to wend

On the Quest: howbeit the hero himself withheld the maid,

For the peril of bitter strife for her love’s sake made him afraid.

So he hied him to go to the town, as the radiant star to behold

Which a maid, as she draweth her newly-woven curtain’s fold,

Beholdeth, as over her dwelling upward it floateth fair;

And it charmeth her eyes, flashing out of the depths of the darkling air

Flushed with a crimson glory: the maid’s heart leapeth then

Lovesick for the youth who is far away amid alien men,

Her betrothed, unto whom her parents shall wed her on some glad day: {780}

So as a star was the hero treading the cityward way.

So when he had passed through the gates, and within the city he came,

The women thereof thronged after, and wafted him blithe acclaim,

Having joy of the stranger: but earthward ever his eyes he cast,

Pacing unfaltering on till he came to the palace at last

Of Hypsipylê: then at the hero’s appearing the maids flung wide

The gates and the fair-fashioned boards of the leaves on either side.

Then through the beautiful hall did Iphinoê lead on

Swiftly, and caused him to sit on a tinsel-glittering throne

Facing the Queen; and Hypsipylê turned her eyes away, {790}

For the maiden blood flushed hot in her cheek. But her shame that day

Tied not her tongue, and with crafty-winsome words did she say:

‘Stranger, wherefore so long have ye tarried without our towers?

Forasmuch as no man dwelleth within this city of ours;

But these have betaken them hence to dwell on the Thracian shore,

And there are they ploughing the wheat-bearing lands. I will tell thee o’er

The evil tale, to the end ye also may understand.

In the days when Thoas my father was king o’er the folk of the land,

My people in ships from Lemnos over the sea-ridges rode,

And harried the homes of the Thracians that overagainst us abode; {800}

And with booty untold they returned, and with many a captive maid.

But the curse of a baneful Goddess upon them now was laid;

For the Cyprian caused on their souls heart-ruining blindness to fall,

That they hated their lawful wives, and forth from bower and hall

At the beck of their folly they drove the Lemnian matrons away,

And beside those spear-won thralls in the bed of love they lay—

Cruel ones! Sooth, long time we endured it, if haply again,

Though late, their hearts might be turned; but our wrong and our bitter pain

Waxed evermore twofold; and the children of true-born blood

In our halls were dishonoured, and grew up amidst us a bastard brood. {810}

Yea, and our maids unwedded, and widowed wives thereto,

Uncared for about our city wandered to and fro.

No father had heeded, no, never so little, his daughter’s plight,

Not though before his eyes he beheld her slain outright

By a tyrannous stepdame’s hands: and sons would defend no more

A mother from outrage and shame, as they wont in the days of yore.

No love for a sister then the heart of the brother bore.

But only the handmaid-thralls in the home found grace in their sight,

In the dance, in the market-place, and whenso the banquet was dight.

Till at last some God in our hearts this desperate courage awoke, {820}

No more to receive them, when back they returned from the Thracian folk,

Our towers within, that so they might heed the right, or begone

Hence to another land, even they and their thralls war-won.

Then required they of us their sons, even what manchild soe’er

Had been left in the town, and returned unto Thrace; and to this day there

The Lemnian men on the snowy Thracian corn-lands dwell.

Then tarry ye sojourning here: and if haply it please thee well

To abide in the land, and it seem to thee good, of a surety thine

Shall be Thoas my father’s honour. I ween this land of mine

Thou shalt scorn not, for passing fruitful it is above all the rest {830}

Of the myriad isles that lie on the broad Aegean’s breast.

But come now, go to thy galley, and tell these words of ours

Unto thy comrades, nor longer tarry without our towers.’

She ended, with fair words veiling the deed of murder dread

Done on the men; and the hero answered the queen, and he said:

‘Hypsipylê, passing welcome this thy request shall be

Which thou tenderest us, whose desire withal is now unto thee.

Back through thy town will I come, when an end I have made to say

All this to my fellows in order: howbeit let all the sway

And the lordship be thine in the island. I make not in scorn my request, {840}

But a sore task thrusteth me onward still, and I may not rest.’

He spake, and the queen’s right hand hath he touched, and aback to the strand

He hath turned him to go; and around him the maidens on either hand

Danced blithely, a throng unnumbered, till forth of the gates he had strode.

Thereafter the women loaded them wains smooth-running, and rode

Down to the beach, and gifts of greeting they bare good store,

When now to his fellows the hero had told the message o’er,

Which Hypsipylê spake unto him when she sent and bade him come.

And with little ado the maidens drew the heroes home

To their halls; for sweet desire did the Lady of Cyprus awake, {850}

For a grace to Hephaistus the Lord of Craft, that Lemnos might take

New life, and unruined be peopled of men once more for his sake.

Now into Hypsipylê’s royal palace Aison’s son

Hath passed, and the rest, as it happed unto each man, so are they gone,

Save Herakles only; for still with the ship would the hero abide,

For he willed it so, and a few his chosen comrades beside.

And straightway rejoiced the city with dance and with festival,

And was filled with sacrifice-steam to the Deathless: but most of all

Honoured they Hêrê’s glorious son, and atonement’s price

To the Cyprian Queen they paid with song and with sacrifice. {860}

And ever from day unto day did the heroes their sailing forbear,

Loth to depart; and long had they tarried loitering there,

But Herakles gathered his comrades, and drew from the women apart,

And with words of upbraiding he spake, and rebuked them indignant of heart:

‘What, sirs, is it blood of kindred spilt that maketh us roam

From our land?—or came ye, because that ye found no brides at home,

Hitherward, scorning the maidens of Greece? Doth it please you to toil

Here dwelling, and driving the plough through the soft smooth Lemnian soil?

Good sooth, but little renown shall we win of our tarrying

Here long time with the stranger women! No God will bring {870}

That Fleece unto us, nor wrest from its warder, for our request!

Forth let us go each man to his place—him leave ye to rest

All day on Hypsipylê’s couch, till he people from shore to shore

Lemnos with menfolk: great his renown shall be therefor!’

So did he chide with the band; was none dared meet his eye,

Neither look in his face, nor was any man found that essayed reply.

But straight from his presence, to make their departing ready, they went

In haste; and the women came running, so soon as they knew their intent.

And as when round beautiful lilies the wild bees hum at their toil,

From their hive in the rock forth pouring; the dew-sprent meadow the while {880}

Around them rejoiceth, and hovering, stooping, now and again

They sip of the sweet flower-fountains—in such wise round the men

Forth streamed the women with yearning faces, making their moan;

And with hands caressing and soft sad words did they greet each one,

Beseeching the Blessed to grant them a home-coming void of bane.

Yea, so doth Hypsipylê pray, as her clinging fingers strain

The hand of Jason, and stream her tears with the parting-pain:

‘Go thou, and thee may the Gods with thy comrades scathless bring

Back to the home-land, bearing the Fleece of Gold to the king,

Even as thou wilt, and thine heart desireth: and this mine isle, {890}

And my father’s sceptre withal, shall wait for thee the while,

If haply, thine home-coming won, thou wouldst choose to come hither again.

Thou couldst gather from other cities a host unnumbered of men

Lightly—ah, but the longing shall never awaken in thee;

Yea, and mine own heart bodeth that this shall never be!

Yet O remember Hypsipylê whilst thou art far away,

And when home thou hast won; and leave me a word that thy love shall obey

With joy, if the Gods shall vouchsafe me to bear a son to my lord.’

Lovingly looked on her Aison’s son, and he spake the word:

‘Hypsipylê, so may the Gods bring all these blessings to be! {900}

Howbeit a better wish than this frame thou for me;

Forasmuch as by Pelias’ grace it sufficeth me still to live

In the home-land—only the Gods from my toils deliverance give!

But and if to return to the land of Hellas be not my doom,

Afar as I sail, and a fair manchild be the fruit of thy womb,

To Pelasgian Iolkos send him, when boyhood and manhood be met,

To my father and mother, to solace their grief,—if living yet

Haply he find them,—that so, in the stead of the prince their son,

They may win in their halls a dear one, to brighten the hearth left lone.’

He spake, and was gone; and afront of his fellows he strode to the ship, {910}

And the rest of the chiefs followed on, and the oars in their hands did they grip,

Row upon row as they sat; and the hawsers did Argus cast

Loose from the rock brine-lashed; and mightily then and fast

Fell they to smiting with oars long-bladed the seething wave.

And at even by Orpheus’ counsel the keel ashore they drave

On the isle of Elektra the daughter of Atlas, that there they might learn

The mystic rites whose unveiling is not soul-daunting nor stern,

And safelier so might voyage over the chill grey sea:—

No more will I speak of the Hidden Things—but a blessing be

Upon that same isle, and the Gods there dwelling, to whom belong {920}

Those rites whereof it is not vouchsafed that we tell in song.

And from thence o’er the Black Sea’s depths unfathomed they sped with the oar,

To leftward keeping the land of Thrace, and to rightward the shore

Of Imbros overagainst it; and, even as sank the sun,

Unto the long sea-foreland of Chersonese they won.

There did the strong swift south-wind blow, and the sail they spread

To the breeze, and into the outward-rushing waters they sped

Of Athamas’ daughter: and lo, astern with the morning light

The outsea lay, and along Rhœteion’s beach in the night

They coasted, and still on their right the land Idaean lay. {930}

And they left Dardania behind, and Abydos-ward steered they.

By Perkotê in that same night, and Abarnis’ stretches of sand

Onward they glided, and past Pityeia the hallowed land.

And the selfsame night, as with sails and with oars sped Argo on,

Through the sea-gorge darkly-swirling of Hellespont they won.

Now within the Propontis an island there is, both high and steep;

Short space from the corn-blest Phrygian land doth it rise from the deep

Seaward-sloped: to the mainland stretched a neck of land

Low as the wash of the sea; so the place hath a twofold strand.

And beyond the waterfloods of Aisêpus the river they lie. {940}

The Hill of the Bears it is called of them that dwell thereby.

And cruel oppressors and fierce have there their robber-hold,

Earth-born, a marvel great for the dwellers around to behold.

Six mighty arms each monster uplifteth against a foe,

Even two from his brawny shoulders that spring, and therebelow

Four other, that out of his sides exceeding terrible grow.

Now Dolian men on the isthmus abode, and about the plain;

And amidst them did Kyzikus, hero-son of Aineus, reign,

The son whom Ainêtê, the daughter of godlike Eusôrus, bare.

But these men the Earth-born giants, how mighty and dreadful soe’er, {950}

In no wise harried: their shield and defender Poseidon became,

For himself had begotten of old the first of the Dolian name.

Thitherward Argo, as chased by the Thracian breezes she fled,

Pressed, and the goodly haven received her as onward she sped.

And their light-weight anchor-stone did they cast away thereby

By Tiphys’ behest, and they left it beside the fountain to lie,

By Artakia’s spring; and another they chose, huge, meet for their need.

Howbeit their first, by Archer Apollo’s oracle-rede,

The Ionian Neleïds laid thereafter, a hallowed stone,

In the shrine of Athênê, Jason’s friend, as was meet to be done. {960}

And in all lovingkindness the Dolians came, and to meet them pressed

Kyzikus’ self, when their lineage he heard, and was ware of the Quest,

And knew what heroes were these; and with glad guest-welcome they met,

And besought them to speed in their rowing a short space onward yet,

And to fasten the hawser within the city’s haven fair.

To Apollo the Lord of Landing they builded an altar there:

By the strand they upreared it, and there did the smoke of the sacrifice rise;

And sweet strong wine did the king’s self give them, their need to suffice,

And sheep therewithal: for an oracle rang in his ears—‘In the day

When a godlike band of heroes shall come, meet thou their array {970}

With welcome of love, and thou shalt not bethink thee at all of the fray.’

And, like unto Jason, the soft down bloomed on the young king’s chin;

Neither yet was he gladdened with laughter of children his halls within;

For the pangs of the travailing hour not yet to his bride had been known,

Even to the lady born of Merops, Perkosius’ son,

Fair-tressed Kleitê. But now had she passed from her sire’s halls forth

On the mainland-shore, when he won her with gifts of priceless worth.

But for all this left he his bridal bower and the bed of his bride,

And arrayed them a banquet, and cast from his heart all fear aside.

And they questioned each other, the king and the heroes. Of them would he learn {980}

The end whereunto they voyaged, and Pelias’ bidding stern.

Of the dwellers around, and their cities, they asked and were fain to be taught

Touching all the gulf of Propontis the wide: but the king knew nought

Beyond to tell them, albeit with eager desire they sought.

So at dawn did they climb huge Dindymus’ sides, with purpose to gaze

With their own eyes over the unknown sea and her trackless ways;—

But forth of the outer haven first their galley they rowed;—

Still Jason’s Path is it named, that mountain-track they trode.

But the earth-born giants the while rushed down from the mountain-side,

And the seaward mouth they blocked of the haven of Chytos the wide {990}

With crags, like men that lie in wait for a wolf in his lair.

Howbeit with them that were younger had Herakles tarried there;

And he leapt to his feet, and against them his back-springing bow did he strain.

One after other he stretched them on earth; and the giants amain

Heaved up huge jagged rocks, and hurled them against their foe.

Yea, for that terrible monster-brood was nurtured, I trow,

Of Hêrê, the bride of Zeus, for a trial of Herakles.

Therewithal came the rest of their fellows, returning to battle with these

Or ever they won the mountain-crest. To the slaughter they fell

Of the Earth-born brood, those heroes: with arrows some did they quell, {1000}

And some on the points of their spears they received, until they had slain

All that to grapple of fight had rushed so furious-fain.

And even as when the woodmen with axes have smitten, and throw

The long beams down on the strand of the sea ranged row upon row,—

For the brine-sodden wood shall grip the strong bolts faster so,—

Even so at the entering-in of the foam-fringed haven they lay

One after other; some in a huddled heap where the spray

Dashed over their heads and their breasts, the while, stretched high on the land,

Stiffened their limbs: there were some yet again, whose heads on the sand

Rested, the while in the heaving waters swayed their feet;— {1010}

But doomed were they all alike for the birds’ and the fishes’ meat.

And the heroes, so soon as the peril afar from their emprise was driven,

Cast loose the hawsers of Argo before the breezes of heaven.

Forth shot she, and onward they drave, fast cleaving the broad sea-swell.

All day under canvas she ran: howbeit, as twilight fell

No longer the wind-rush steadily held, but the veering blast

Caught them, and swept them aback, till it brought them again at the last

To the guest-fain Dolian men. Then stepped they ashore in the gloom

Of the night; and unto this day is it called the Rock of Doom

Round which the hawsers of Argo in blind haste now did they pass; {1020}

Neither did any man deem that the selfsame island it was;

Nor yet were the Dolians ware that again in the night to their coast

The heroes were come, but haply they weened that a Makrian host

Of Pelasgian men for war had sailed to their land overseas:

Wherefore their armour they donned, and uplifted their hands against these.

And with onset of spears and with clashing of shields met they in the strife,

Like to the vehement blast of flame which hath leapt into life

Mid the copses dry, and the red tongues climb: and the battle-din then

Fearful and furious fell in the midst of the Dolian men.

Nor may Kyzikus now overleap his weird, and aback from the war {1030}

Win home to the bower of love and the arms of his bride any more.

But, even as he turned on him, full on the king leapt Aison’s son,

And stabbed in the midst of his breast, and shattered was all the bone

Around the spear, and falling in death-throes down on the sands

He filled up the measure of Fate. To escape her resistless hands

Is vouchsafed unto none: as a wide snare compassed we are with her bands.

Even so, as he weened that the bitterness now of death was past

At the hands of the heroes, lo, in her gin were his feet caught fast

In the night, as he battled with them, and many a champion withal

Was slain with the king; by Herakles’ hands did Telekles fall, {1040}

And fell Megabrontes; and Sphodris Akastus overthrew;

And Zelys, Gephyrus withal, the battle-swift Peleus slew.

Telamon’s ashen spear through Basileus’ heart is thrust;

Died Promeus by Idas, and Klytius laid Hyakinthus in dust;

And the Tyndarids twain slew Phlogius, slew Megalossakes;

And valiant Itymoneus fell before Oineus’ son amid these,

And Artakes with him, a chieftain of men: and unto this day

Unto all these slain do the people the worship of heroes pay.

Then wavered the ranks and broke; then fled they in panic affright,

As before the swift-winged hawks doth a cloud of doves take flight. {1050}

Through the gates in a huddled rout they poured, and the town straightway

With the war-yell was filled, and backward rolled was the woeful fray.

But at dawn were they ware, both these and those, of the cureless ill,

Of the ruinous error; and now did bitter anguish fill

The Minyan heroes, beholding before them Aineus’ child

Stretched in the dust, and Kyzikus lying blood-defiled.

For three whole days with rending of hair did they mourn his doom,

Even they with the Dolian folk. Thereafter about his tomb

Three times in their brazen armour the round of lament did they pace,

And buried him: funeral games held they in the selfsame place, {1060}

As was meet, in the meadow-plain where yet before the eyes

Of the folk of the latter day doth the heap of his grave-mound rise.

Yea, neither would Kleitê his wife any more mid the living abide,

Forlorn of her lord; but a woefuller evil she added beside

To the evil done, when clasping her neck with the noose she died.

Ah, but the Wildwood Maids made moan for the beautiful dead;

And of all the tears that to earth from their eyes for her sake they shed

A fountain the Goddesses made, and the name of it far and wide

Hath been heard, even Kleitê, the name of a most unhappy bride.

Ah, that was the darkest day that from Zeus did ever befall {1070}

The daughters and sons of the Dolian race, and in none of them all

Was there spirit to taste of food, and their hands for a weary while

By reason of grief hung down, and forgat the millstone’s toil:

But their lives dragged on, while untouched of the fire was the food that they ate.

Yea, the Ionian folk that in Kyzikus dwell even yet,

When they pour drink-offerings year by year, at the city’s mill

Grind ever their corn, for the querns in the houses of mourning are still.

And the wild winds woke at the sound of their mourning to shriek and to rave

Twelve days, twelve nights; and prisoned by wrath of wind and wave

Tarried the heroes from sailing, until, on the thirteenth night, {1080}

When the rest of the wanderers lay for the last time bowed by the might

Of slumber on that drear shore, while watch and ward was kept

Of Akastus and Mopsus Ampykus’ son over them that slept,—

Then over the golden head of Aison’s son did there fly

A kingfisher: clear through the hush his happy-boding cry

Rang for the lulling of winds; and Mopsus hearkening caught

The shore-bird’s note, and he knew it with happy omen fraught.

And a God’s hand guided its wing, that it wheeled and shot to the height

Of the Argo’s stern, and thereon hath it stayed its arrowy flight.

And the seer touched Jason, there on the fleeces soft as he lay {1090}

Of the sheep, and from slumber he roused him with haste, and thus did he say:

‘Aison’s son, thou must climb to the temple that standeth there

On Dindymus’ rugged height, and make to the Mother thy prayer,

The fair-throned Mother of all the Blest: and the stormy blast

Shall be stilled. For but now hath a cry by mine ears on the night-wind passed,

The weird sea-kingfisher’s cry; and around thy slumbering head

Wheeling its flight, it uttered the thing that my lips have said.

For swayed by her power be the winds, and the sea, and the earth below,

Yea also Olympus crowned with the everlasting snow.

And to her, when to heaven from her hills she ascendeth, doth Zeus give place, {1100}

Even Kronos’ son himself, and all the Deathless Race

Of the Blessèd in reverence bow before her awful face.’

So spake he: to hear that word the heart of Jason leapt.

Gladsome he sprang from his couch, and his comrades, there as they slept,

Did he waken in haste; and he told, as they gathered around him to hear,

The prophecy spoken of Mopsus Ampykus’ son, the seer.

Then steers from the byre the young men drave, and with speed they pressed

Up the steep hill-path with the beasts, till they won to the mountain’s crest.

From the Rock of Doom did others the hawsers of Argo slip:

To the Thracian haven they rowed, and leapt to the strand; and the ship {1110}

There guarded they left, for there tarried behind of their fellows a few.

And from Dindymus saw they the Makrian cliffs, and full in view

The stretch of the Thracian Coast oversea on this side lay,

And the Bosporus misty-dim, and the blue hills far away

Of Mysia-land, and the river Aisêpus on that side flowed,

And the town and the plain Nepeian of Adresteia showed.

Then found they the sturdy stock of a vine in the forest that grew,

A tree exceeding old: with the axes the same did they hew

For the Mountain-goddess’s sacred image: with cunning skill

Of the craftsman did Argus carve it; and so on the rugged hill {1120}

Did they set it up: for the shrine thereof stood tall oaks round,

Which of all trees root them the deepest beneath the face of the ground.

Then of loose stones built they an altar: with leaves from the oaken spray

They wreathed it around, and the sacrifice thereupon did they lay.