The choice was Miss Tweedham's. Either a thlat

and freedom—or Malovel and his esse. She chose

the latter. Dangerous, yes. But with them came

Sanderson, man among men on this desert star.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Planet Stories September 1953.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

L'Sor, the Martian, said, "Why don't you humans go back to Earth? You're too soft to stay alive on Mars." He spoke good English but his voice was edged with contempt.

"Maybe you've gone soft in Sandersonville but I haven't," Ed Early answered.

"Bah!" L'Sor said. "You talk big, but Malovel will hold you in the hollow of his hands just as he holds the rest of you humans here. You humans are all alike, big talk but no action."

Early looked startled. "I don't know this Malovel," he said.

"You will know him if you are going to stay here," L'Sor said. "You will know him, and the esse. But I do not think you will remain. I think you will tuck your tail between your legs and go sneaking away like a desert jackal."

Listening, John Sanderson, the boss of Sandersonville, made no effort to interfere. Now was a good time to learn what kind of metal was inside Early and L'Sor was a good instrument for the investigation. The Martian was completely outspoken. Sanderson waited quietly to see what Early would say and do. The woman, Miss Tweedham, was also silent. She watched this scene from startled eyes.

Early had come riding a thlat across the desert, a tough, grim, bitter little man with bluster a foot thick all over him. Sanderson had not asked him his business here. The woman, Miss Tweedham, had arrived in a rocket taxi from the space port. Both of them had been brought to him. At first meeting he had rather liked Miss Tweedham. She was a big woman tired of her work and had come to Mars to find something that had been missing in her life. At the thought, Sanderson shook his head. She would find plenty here!

She would also discover how glad she was that all of it had been missing from her life. Of course, they would have to send her back home, otherwise she would end up running screaming across the deserts toward the space port. In the meantime, she might as well see things as they really were. It would be something to whisper, in a shocked tone of voice, to her best friends when she got back to Earth. He watched her out of the corners of his eyes.

"Who's going to make me tuck my tail between my legs, Fiddlefoot?" Early said angrily.

"Fiddlefoot!" At the word, a violent tremor passed over the Martian. He reached for the knife bolstered at his belt. The anger of his race showed in his yellow eyes.

"The man is a fool," Sanderson spoke. "Overlook his words."

"Well, Great One—"

"Let him try to use the knife," Early said, his hand in the pocket of his ragged coat. "I'll make him eat it."

"I wouldn't advise—"

"No fiddlefooted Martian can run a bluff on me. And that goes for this Malovel too."

"Maybe he is not bluffing. He is one of Malovel's priests."

"I don't get this Malovel but what I said still goes, for Fiddlefoot here and his boss, too."

Sanderson gestured through a window to a terraced slope. Beyond it, mountains rose into the sky. Along the terraces, following the viaducts that brought water downward from the reservoirs above, Martian crops grew green and luxuriant. On the lowest level were the human fields, with the crops drying to stunted stems and twisted leaves. On top of this slope a square structure sprawled. Sanderson gestured toward it.

"Malovel is up there. He is the high priest, the ruler of the Martians here—and of the humans."

"I thought you bossed the humans," Early said.

"Malovel controls the water supply," Sanderson answered.

"Oh, I see!" Understanding gleamed in Early's eyes. "If you don't do what he says, he won't give you the water for irrigation. That's it, huh?"

Sanderson nodded.

"And you put up with this kind of treatment?" Surprise sounded in Early's voice. He studied Sanderson carefully as if he were re-evaluating him.

Again Sanderson nodded.

"Well, I'm damned!" Early said. "John Sanderson putting up with this! John Sanderson letting a local Martian big shot tell him what to do! Oh, I get it now." Again understanding gleamed in Early's eyes. "You've lost, your nerve! That's it. Johnny Sanderson has gone soft." Early seemed very pleased with himself for this computation.

The silence that followed was broken by a grunt of contempt from L'Sor. "Give the fool a thlat and send him on his way. We don't want him here."

Early seemed not to hear. "Hah! By heck! So you've lost your nerve! And Sandersonville is hanging here like a ripe peach ready to drop into the pocket of anybody who has the guts to shake the tree! I heard rumors that this had happened but I just didn't believe it."

He pulled an object from his pocket. It was a bum-bum gun. Sanderson seemed not to see it. L'Sor grunted contemptuously. Miss Tweedham caught her breath. Early moved toward the door.

"Where are you going?" Sanderson said.

"I'm going up and put the fix on this Malovel," Early said. "Then I'm coming back down here and I'm taking over Sandersonville. Johnny Sanderson has lost his nerve and he's through." He stalked through the door.

Through the window, Sanderson watched him go quickly up the slope. In this light gravity, the man walked rapidly. He was soon out of sight. L'Sor and Miss Tweedham moved to Sanderson's side at the window.

"You deliberately needled him into going up there," Miss Tweedham spoke.

"Why should I do that?"

"Maybe because you're scared to go yourself." Her voice had a cutting edge that grated along Sanderson's nerves. Beside him, he heard L'Sor's sharply indrawn breath, a sure sign of rising anger in the Martian.

"Why don't you go to this ruler and demand water?" The schoolteacher continued. "You're the leader here. Are you going to let your people starve?"

Sanderson wiped a thin film of sweat from his face. "Nobody has starved yet."

"How long before 'yet' becomes 'Died of Starvation A.D. 2179' on a tombstone? Or will Malovel let you erect tombstones?"

"He hasn't objected yet."

"Why don't you do something about this?"

"There are two reasons. One is our own bargain, our own agreement. The other is the esse. Malovel has the esse."

"What's the esse?"

"It's a weapon," Sanderson said, uncomfortably. "We don't talk much about it."

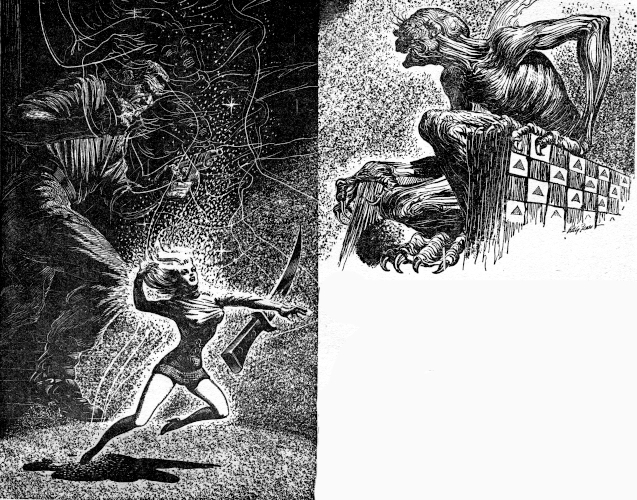

"Which means you're scared and don't knew what you're afraid of. I still think—EEK!" A gust of sharp, protesting sound exploded from her lips. A hand came up. With her index finger, she made little jabbing motions toward the chair where Early had been sitting.

"What—what is that?" Her voice was suddenly shrill.

A doll, or an old dwarf, or a worn-out elf was sitting in the chair. Miss Tweedham pointed at this. The doll was relaxed and at ease. Its head had fallen forward across its chest. The doll was remarkably life-like. Every hair was visible on the head, each skin wrinkle was clear on the back of the neck. The clothing was ragged, holes showed in the bottoms of the shoes.

"What—what is that?" the woman repeated.

"That's Ed Early," Sanderson said.

"Uh—uh—"

"The esse." L'Sor breathed. "Malovel used the esse."

"Early's dead," Sanderson said. "Quite dead." He stepped forward in time to catch Miss Tweedham before she fell.

In trying to be calm, Sanderson found he needed all of his years of training to grasp even a semblance of what he sought. Behind him, in the bedroom, he could hear Big Marie moving again. The moaning in there had stopped. He tried to distract himself by looking through the window but the sight of the withered crops trying to grow added nothing to the calm he was seeking. He thought how precarious was the hold of this little group of humans on Mars—and on life itself.

Two men carrying a small box came into view. The box was small but the men carried it as if it were heavy. The esse shrunk the size but did not reduce the mass. In the box, Early weighed just as much as he had ever weighed but he would not take up as much room in the graveyard.

Behind Sanderson the bedroom door opened. He turned quickly. Big Marie stood there. Her dark face was sullen.

"How is she?"

"She's all right. It was a strain on her, suddenly seeing him sitting there the size of a doll when the last time she had seen him he had been a full-sized man going up the slope."

"It always is a strain the first time you see it. Will she be all right?"

"Yes. Maybe her dreams won't be so good for a while. Why did she come here?"

"I didn't ask her."

Big Marie stared steadily at him. "What is she to you, John?"

"Nothing. She just arrived."

"If she becomes anything to you I will kill her," Big Marie said calmly.

"Damn it, Marie, I've got enough trouble on my hands without you trying to blow a fuse. If I want the woman, I'll take her. If I don't want her, I won't take her. Is that clear?"

"Ain't I enough for you?"

"You're enough for ten men. I'm thinking of establishing polyandry here, just for your sake. But—Well, hello." Miss Tweedham came through the door. "How are you feeling?"

"I'm alive, I guess." Her face was pale but composed, her walk was steady. "That awful thing." A shudder passed across her face. "How did it get back there in the chair without us seeing it coming?"

"Elogarsn, the Martians call such trips. Humans know it as telportation."

"But what is it?"

"You've got a word for it, what more do you want?"

"Nothing, I guess." She looked from Big Marie to Sanderson. "There was some talk about taking a woman. Were you talking about me?"

"What do you think?"

"I think I may have something to say about it."

"Then say it." Sanderson waited for the woman to speak. She looked confused, but did not answer.

"He is not really this hard," Big Marie said. "It is just that he is worried."

"Don't apologize for me."

The door opened and L'Sor entered without knocking. "They told me I would find you here," he said. "Malovel will see you at once."

"All right, I'm coming," Sanderson said. He turned to the door.

"Wait a minute," Miss Tweedham protested. "Do you mean you're going to—after what you just saw, you're going to—"

"What did I just see?" Sanderson said. He went out. L'Sor followed him without comment.

Miss Tweedham's lips formed unvoiced sounds. "But—that awful Martian may kill him."

"Do you think that would stop him?" Big Marie said. "What kind of a man do you think he is?"

"I don't care what kind of a man he is."

"He has kept us alive when nobody else could have done it," Big Marie said. "If he says he wants you, Baby, my advice is to play give-inee." Big Marie went into the bedroom and closed the door behind her. It opened again an instant later. "You'll be the luckiest woman this side of heaven." The door slammed shut this time.

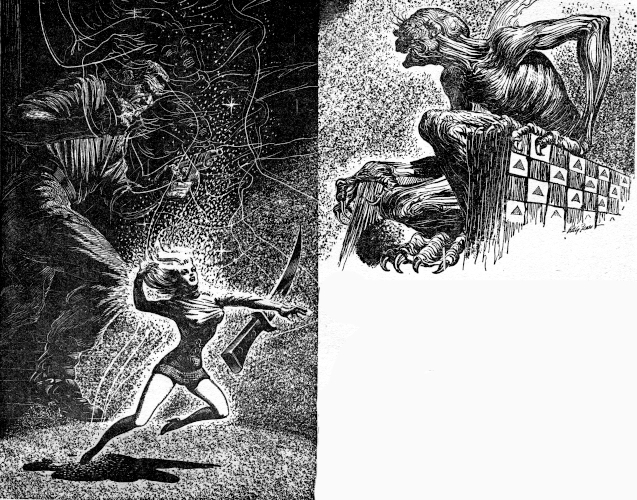

Malovel was old and wrinkled. His skin hung about his face in loose folds and his hands were the skinny claws of a bird. He slept, ate, and defecated in the big padded chair that was his throne. Under the bird-talon fingers a number of differently colored squares were set into the arms of the chair.

Officious priests in blue robes took Sanderson to him. L'Sor was not invited to accompany them and he did not request the privilege.

Malovel went straight to the heart of the matter. "There will be no more water for humans," he said. A slave standing beside his chair gave him a sip out of a small cup. His yellow eyes twinkled at the human.

"Eh? What?" Sanderson gasped. "Holy One! A bargain was made."

"What bargain?"

"That the humans would keep the peace and that the Holy One would see that we have adequate water for our fields. Other services of mutual advantage to both sides were included. Thus the humans taught the Martians how to raise grain from Earth, and supplied them—"

"Who made this bargain?" Malovel said.

"Does not the Holy One remember? He and I made it four years ago when the human settlement was started here."

A flicker of surprise passed through Malovel's eyes. The slave hastily placed the cup to his lips. He sipped the red liquid.

"Oh, yes, I remember now." The tone of his voice said that remembering was a matter of no importance. "I have changed my mind. There will be no more water for humans."

"But Holy One—"

"I have spoken. Does the human wish to dispute me?" Malovel's bird-talon fingers went eagerly to the squares on the arms of the chair. An eager look crept into his yellow eyes.

The slob is hoping I will defy him so he can have the pleasure of using the esse on me, Sanderson thought. Aloud he said: "Your will is our highest law, Holy One."

Regret showed on the Martian's face. "Then be gone, all of you, by the next rising of the sun." The fingers remained on the square as if Malovel was still treasuring a lingering hope that this human would defy him.

"Yes, Holy One," Sanderson said. Backing out of the audience hall, he wondered how even Malovel expected them to be gone by tomorrow even if they had a place to go! Inhospitable deserts surrounded them, making impossible a flight across Mars. Earth would welcome them back—if they could get there—but not a man or a woman here would welcome Earth.

Returning to the human settlement he saw that all work had stopped and that everyone was waiting for him. The news that he had been summoned to Malovel had gotten around. "Meeting right away," he said to each man he met. The drift to the assembly hall began immediately.

He stood in front of them, a tall man with bitterness on his face. Less than a hundred humans looked up at him, all who lived here. He did not have to ask for silence. The men and the women who entered here showed no inclination to talk.

"We have until tomorrow to leave," he said.

Silence continued in the big room. These people had already braced themselves against bad news.

"If you ask me why we have to leave, I can only tell you it is by order of Malovel. If you ask me why he gave this order, I can only say he is an old, tired, worn-out ruler, who is kept alive only by his greed for power. What better way to demonstrate his power than by ordering the humans to leave?"

He paused, took a deep breath. "We made a bargain with him. He has violated the agreement. This ties up the package. All rules are off."

At the words, a gust of something seemed to run through the room. It was partly sound, but more than anything else, it was pure emotion, a blast of it.

"What is happening?" Miss Tweedham whispered to Big Marie.

"He's turning loose his dogs," Big Marie answered. "Almost tamed, all of them were, until he turned them loose. Now they're pure wolf."

"I don't know what you're talking about."

"You'll find out, Baby," Big Marie said.

From the front of the room Sanderson's voice caught her ears, pulling her attention to him.

"All of you know that we have sincerely hoped that this would not happen. However, we have always considered the possibility that it might happen. Thus, we have made our plans down to the last detail."

Again the thin buzz and the blast of emotion went through the room.

"Miss Tweedham," Sanderson spoke. "Come forward, please."

His voice lifted her to her feet and took her to the front of the room. "Yes? What do you want?"

His face made a smile. "Since you are new here, and not one of us, you will want to leave."

She was confused. She felt it inside her and it showed on her face.

"It is impossible to call a taxi from the space port. We do not have radio facilities. However, we can provide a thlat for you to ride, and food and water for a week. In that time you can reach the space port. It will not be a comfortable trip but it will be more comfortable than staying here."

"I—is that—"

"I'm sorry but this is the best we can offer you. Our facilities here are primitive."

"What happens if I don't want to leave?" Miss Tweedham blurted out.

"Eh?" Sanderson was startled. He looked again at this rather big woman with the pleasant, tolerant face. "Do you mean that?"

"Would I say it if I didn't mean it?"

"Well—" Sanderson coughed. "In that case, you will be assigned duties."

"I'll take the duties."

"Without asking what they will be?" He seemed suddenly uneasy, and yet at the same time he seemed pleased.

"Yes."

He blinked at her, then nodded as if he was even better pleased. "Take your turn in line, please."

Men were already moving to the front of the hall. They lifted a large slab of stone from the floor there, revealing a box-filled cavity beneath. A man dropped down and began to hand up the boxes. A line was forming. Miss Tweedham moved into it. Sanderson was taking small objects from the boxes and was handing one to each person in line. Miss Tweedham did not see what the objects were until one was handed to her. Then she saw.

"But these are bum-bum guns!" she said. She did not take the weapon.

"Yes, they are," Sanderson said.

"That man, Early, had one of these."

"Yes, he did."

"It didn't do him any good."

"No, it didn't."

"Move on, Baby, you're holding up the line," Big Marie said.

Miss Tweedham took the bum-bum gun.

"Do you know how to operate it?" Sanderson said.

She turned the weapon in her fingers. "Yes, I know how to use it."

"Eh?" Sanderson seemed startled.

"Move on, Baby," Big Marie said again. Miss Tweedham moved on. Big Marie took a bum-bum gun. In addition, she requested a knife. From another box Sanderson supplied her with a blade ten inches long. She tested the edge on her thumb. "I'll have to hone it," she said.

"Be sure you remember whose throat you are to cut," Sanderson said.

"I won't forget that."

"It isn't my throat," Sanderson said.

"Isn't it?" Big Marie answered.

When the guns and knives had been distributed, Sanderson opened another box. Maps were in it. They were crudely but clearly drawn. He distributed them to a number of key men. "You will find detailed instructions here for you and your group. I don't suppose I need to remind you of the consequences of failure."

Again the buzz ran through the room.

"You seem to have everything well organized," Miss Tweedham said:

"Organization was my line before I came to Mars," Sanderson answered. He lifted his voice. "Deimos is the signal. When it rises above the horizon tonight, we go into action."

The buzz grew louder. To Miss Tweedham, it sounded like a swarm of angry hornets.

Seeming to be a part of the night, four figures crouched against the wall beside the closed door. Bright stars twinkled overhead. In this thin air there seemed to be millions of stars sprinkled like arc lights in the sky.

Miss Tweedham clutched the bum-bum gun and listened to the sound of her own heart. Beside her, Big Marie leaned against the wall in nonchalant ease. On the other side of her, Sanderson and the Martian L'Sor whispered quietly.

"Is that Martian all right?" Miss Tweedham said to Big Marie.

"If he ain't, we're in the soup."

"But how do we know?"

"We don't. John Sanderson trusts him. That's enough for me. And anyhow, if it hadn't been for L'Sor, we would never have learned enough about the esse to stand a chance against it."

Miss Tweedham made choking sounds as a vision of the doll came up before her eyes so real she could see it all over again.

On the horizon a light appeared. Deimos rising. It was not an impressive sight. Outlined against the arc lights of the stars, Deimos hung in the sky like a glow worm at the Feast of the Lanterns.

"The door, L'Sor," Sanderson said.

The Martian inserted a key in the slot. The door opened into a courtyard. The four passed through.

"Big Marie, you and Miss Tweedham are to stay here and guard this door. L'Sor and I will be returning this way."

"Yes, John."

The two women crouched against the wall. Sanderson and the Martian moved across the courtyard and vanished. Then Big Marie moved. "You stay here and guard this door. I'm going after them. Those two damned fools have assigned themselves the job of tackling Malovel and the esse all alone."

For a few minutes Miss Tweedham stayed beside the door. Then, clutching her bum-bum gun, she followed Big Marie.

At night, the big throne chair was moved into the sleeping quarters. Malovel dozed fitfully in it. A slave was constantly beside him, always ready to pass the precious liquid to lips as parched as the fields the humans were trying to cultivate. Through thin gauze curtains, female slaves could be seen sleeping in the adjoining room. They were at Malovel's beck and call but he had long since passed the stage where they were of any use to him.

He existed now as almost pure hate. All that kept him alive was his hatred of all creatures more nearly alive than he was. Martians, humans, the sand jackals howling in the deserts, he hated them all because they were what he was not—alive.

As he dozed, his fingers played over the squares in the arms of his chair. He dreamed of using the esse. Even in sleep his hate yearned to express itself.

A stir sounded at the door as his private guard challenged a wall watcher bringing information to him. The sound aroused him, irritated him. The wall watcher insisted on being brought before him.

"What is it?"

The tone sent shivers through the wall watcher. But he thought his news was important. "Holy One, I heard footsteps outside the walls."

Malovel considered this information. If it was true, he didn't like it. If it was untrue, he liked it even less. Most of all he disliked having his sleep interrupted.

"Fool! Some lover goes to his mistress and you interrupt my rest because of this!"

"But—Holy One—"

"Out of my sight."

The wall watcher hastily backed from the room. Malovel watched. Some residue of his dream remained in his mind. His fingers moved on the squares. A throb sounded in the room. The wall watcher screamed. Invisible fingers seemed to come out of nowhere and seize him. The fingers pressed against him with terrific force. He began to shrink in size. When he was the size of a doll, Malovel shifted his fingers on the squares. The doll was lifted upward and out of the room.

Malovel settled back in his chair. The slave hastily pressed the cup to his lips. He sucked greedily at the red liquid. Strength surged up in him. It came as much from the satisfaction of seeing the wall watcher die as from the red syrup. He had destroyed a wall watcher! He was a mighty killer! Who dared to oppose him?

His eyes circled the room, seeking any one who dared to oppose him. Beside his chair, the male slave froze. Beyond the thin curtains, the shivering females stopped moving.

Slowly, Malovel settled back into his chair. Again he dozed. This time there was satisfaction in him and he slept better than before. Beside him, the male slave dared to breathe again. His private guards went on tiptoe from the room. The females huddled down against the pillows and tried to sleep.

Sounds came from inside the building. A Martian shouted. The shout went into quick silence as soft phuts sounded.

A breathless palace guard again insisted on being admitted to Malovel's presence. The guards at the door told him what had happened to the wall watcher. The guard insisted his report was true and important. He was permitted to enter. Again Malovel awakened.

"The humans are in the palace, Holy One."

"What?"

"You can hear them."

Listening, Malovel caught an echo of a shout, then a burst of phuts. For a second he was startled. Then a gleam appeared in his eyes. As he had thought they would if he stopped the water for the fields, the humans had attacked the palace. Now he had a chance to use the esse again, to taste to the full the surge of power that came to him when he used that weapon.

At his word of command, the slave swung up in front of him what looked like a frosted mirror but which revealed what was happening where he sent the esse. The mirror showed a corridor, with Martians and humans fighting there.

A look of vast satisfaction appeared on Malovel's face. He caressed the squares on the arms of his throne chair.

"Once a bargain was made, Holy One," a voice said behind him.

Malovel spun in his chair. He stared in horror at what he saw there. The human, Sanderson, and the Martian, L'Sor. A Martian traitor! Behind them a secret door was open in the wall, a relic of the long-gone days when Malovel had used that exit. He had forgotten its existence. But L'Sor had smelled it out. Both the human and the Martian held the little weapons that the humans called bum-bum guns. L'Sor's weapon menaced the slave, who stood motionless.

"A bargain was made four years ago," Sanderson said.

"I changed my mind."

"Why?"

"Perhaps to start this fight, to give myself the pleasure of destroying you."

As he spoke, Malovel's fingers pressed a square. The human might be fast with the bum-bum gun but the esse was faster than any human action, as fast as light itself. As Malovel pressed the square, the esse formed.

A scream sounded in the room. Sanderson was shoved to one side. The esse caught something, Malovel did not quite see what it was. He poured power into it. Malovel caught a glimpse of the doll forming as the mighty fingers of the esse squeezed life from it.

A glimpse was all he caught. A bum-bum slug splashed his head over the room. The eager glow in his eyes seemed to turn into a yellow aura then lingered a second after he was gone. Then it went too.

Miss Tweedham went forward as quickly as she could. When the shouts and the phuts began, she was afraid, but she was even more afraid of losing sight of Big Marie. Then Big Marie did disappear. Miss Tweedham clutched her gun and waited, her heart up in her throat. A scream rang out ahead of her. The sound moved her forward and into the throne rooms of Malovel.

Malovel, headless, was lying stretched across his throne chair.

Staring down at something, Sanderson was kneeling on the floor. Miss Tweedham moved to his side, saw the object at which he stared.

He glanced up at her, nodded toward the object on the floor. "She shoved me out of the way and the esse got her. I had no idea it was that fast." His voice was tight with suppressed feelings.

"Back on Earth she killed two men. That was why she came to Mars. She died here, saving the life of a third man." Sanderson's face was wry and twisted.

The object on the floor was a doll with the features of Big Marie.

"Great One, work remains," L'Sor urged.

Sanderson rose. He lifted the body of Malovel from the throne chair, threw it across the room. Then he seated himself in the chair and began to study the controls. In the distance shouts sounded, Martians and humans locked in battle. The shouting of the Martians went into quick silence as Sanderson began to operate the controls on the arms of the chair.

A little later the humans were crowding into the room. They were a motley lot. Some were covered with blood, others carried arms in improvised slings, one supported himself between two companions. They looked at the occupant of the throne chair and began to grin.

"Well done, boys," John Sanderson said. "I never pulled a sweeter, cleaner, tougher job."

The room echoed with the fierce shouting of triumphant men.

Miss Tweedham went away.

When Sanderson found her, the stars were going down and the day was coming. Clutching her purse in one hand and the bum-bum gun in the other, she was seated on a bench outside the house where Big Marie had once lived. Sanderson came up. She moved and made room for him and he sat down beside her.

"Look," he said, pointing. "Water is coming down the ditches to our fields."

Miss Tweedham could see the water. Already the crops were responding to the magic touch of it. She could also see the glow on John Sanderson's face. The glow on his face was one of the nicest sights she had ever seen in her life. A man watching water come to parched fields....

"But I imagine you had a rather exciting night," he said, turning to her.

"Yes. Yes. It was that."

"Well, you will forget the horror of it. Maybe you can even learn to have fun telling your classes back on Earth about the wild night you spent on Mars." He grinned at her. "I don't know how you're fixed financially, but if you're broke, I imagine we can find passage money among us."

Miss Tweedham clutched her purse. "But what if I don't want to go back to Earth?"

His voice was gentle but with overtones of pain in it. "This is no place for a woman like you, a woman of refinement and culture."

"Why not?" she asked.

"Don't you know the truth about us yet?" he said, surprised. "Haven't you guessed it? None of us can go back to Earth. We're wanted men there."

"Criminals?" Miss Tweedham said, flinching.

"Yes." Sanderson choked over the word but he got it out.

"And what were you back on Earth?"

"I ran the Syndicate," Sanderson answered.

"Then that explains your genius for organization."

"I had had some experience in organization before I came here," Sanderson said, grimly. "That was why the boys made me boss. Now as to your return to Earth—"

"As I said before, maybe I don't want to go back."

Sanderson stared at her. "But you have to go back. You don't belong here."

"Maybe I came here for the same reason you and all the others came. Maybe I knew what I was coming to. Maybe I chose this place deliberately."

"What?" Sanderson gasped.

Miss Tweedham faced him without flinching. "You haven't asked me what I really was back on Earth."

"Eh? A school teacher—"

"You still haven't asked me."

"Eh? What were you?"

"A call girl," Miss Tweedham answered, without flinching.

"Uh—ah—"

"I'm not going back to that," Miss Tweedham said.

Sanderson sought for words. He stuttered them out. "Do—do you—do you think you will ever be a call girl again?"

"Only when you call," Miss Tweedham answered.

In the light of the coming dawn, John Sanderson's face showed beet red. Then, slowly, he began to grin. His eyes lifted from her, his gaze went to the fields where now the water was flowing in the irrigation ditches. "That's wonderful," he said.

Miss Tweedham did not know whether he was talking about what she had said, or the water bringing life to the parched fields. She decided that whatever he was talking about, the meaning was the same in the end.

"I'm going to see about the water," he said, rising.

She smiled. Deep in her heart she knew he was going there to feel the new growth beginning. When he was too far away to see what she was doing, she opened her purse. From it, she took a piece of stiff folded paper.

Lifetime Teaching Certificate, the paper said.

Slowly, Miss Tweedham tore the paper into tiny bits. She watched the dry, restless wind of Mars blow them away. Then she rose and followed John Sanderson toward the growing fields.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this eBook.