BUFFALO BILL AND THE

OVERLAND TRAIL

The American Trail Blazers

“THE STORY GRIPS AND THE HISTORY STICKS”

These books present in the form of vivid and fascinating fiction, the early and adventurous phases of American history. Each volume deals with the life and adventures of one of the great men who made that history, or with some one great event in which, perhaps, several heroic characters were involved. The stories, though based upon accurate historical fact, are rich in color, full of dramatic action, and appeal to the imagination of the red-blooded man or boy.

Each volume illustrated in color and black and white.

BEING THE STORY OF HOW BOY AND MAN WORKED HARD AND PLAYED HARD TO BLAZE THE WHITE TRAIL, BY WAGON TRAIN, STAGE COACH AND PONY EXPRESS, ACROSS THE GREAT PLAINS AND THE MOUNTAINS BEYOND, THAT THE AMERICAN REPUBLIC MIGHT EXPAND AND FLOURISH

BY

AUTHOR OF “WITH CARSON AND FRÉMONT,”

“ON THE PLAINS WITH CUSTER,” ETC.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY

AND A PORTRAIT

PHILADELPHIA & LONDON

COPYRIGHT, 1914, BY J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

SEVENTEENTH IMPRESSION

PRINTED IN UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

TO THE

OLD-TIME PLAINS FREIGHTERS

WHO UNDER THE ROUGH TITLE, “BULL WHACKERS,” PLODDING AT THREE MILES AN HOUR, BRIDGED WITH THEIR CANVAS-COVERED SUPPLY WAGONS THE THOUSAND HOSTILE MILES WHICH SEPARATED DESTITUTION FROM PLENTY

History is the record made by men and women; so the story of the western plains is the story of Buffalo Bill and of those other hard workers who with their deeds and even with their lives bought the great country for the use of us to-day.

The half of what Buffalo Bill did, in the days of the Overland Trail, has never been told, and of course cannot be told in one short book. He began very young, before the days of the Overland Stage; and he was needed long after the railroad had followed the stage. The days when the Great Plains were being opened to civilized people required brave men and boys—yes, and brave women and girls, too. There was glory enough for all. Everything related in this book happened to Buffalo Bill, or to those persons who shared in his dangers and his deeds. And while he may not remember the other boy, Dave Scott, whom he inspired to be brave also, he will be glad to know that he helped Davy to be a man.

That is one great reward in life: to inspire and encourage others.

Edwin L. Sabin

San Diego, California, June 1, 1914

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | Tall Bull Signals: “Enemies!” | 17 |

| II. | The Hero of the Mule Fort | 30 |

| III. | With the Wagon Train | 42 |

| IV. | Visiting Billy Cody | 58 |

| V. | Davy Goes on Herd | 71 |

| VI. | Davy Has an Adventure | 83 |

| VII. | Davy Changes Jobs | 100 |

| VIII. | The Gold Fever | 114 |

| IX. | The Hee-Haw Express | 127 |

| X. | “Pike’s Peak or Bust” | 140 |

| XI. | Some Halts by the Way | 157 |

| XII. | Perils for the Hee-Haws | 171 |

| XIII. | The Cherry Creek Diggin’s | 188 |

| XIV. | Davy Signs as “Extra” | 204 |

| XV. | Freighting Across the Plains | 218 |

| XVI. | Yank Raises Trouble | 231 |

| XVII. | Davy “The Bull Whacker” | 244 |

| XVIII. | Billy Cody Turns Up Again | 257 |

| XIX. | Davy Makes Another Change | 267 |

| XX. | Fast Time to California | 280 |

| XXI. | “Pony Express Bill” | 293 |

| XXII. | Carrying the Great News | 305 |

| XXIII. | A Brush on the Overland Stage | 318 |

| XXIV. | Buffalo Bill Is Champion | 336 |

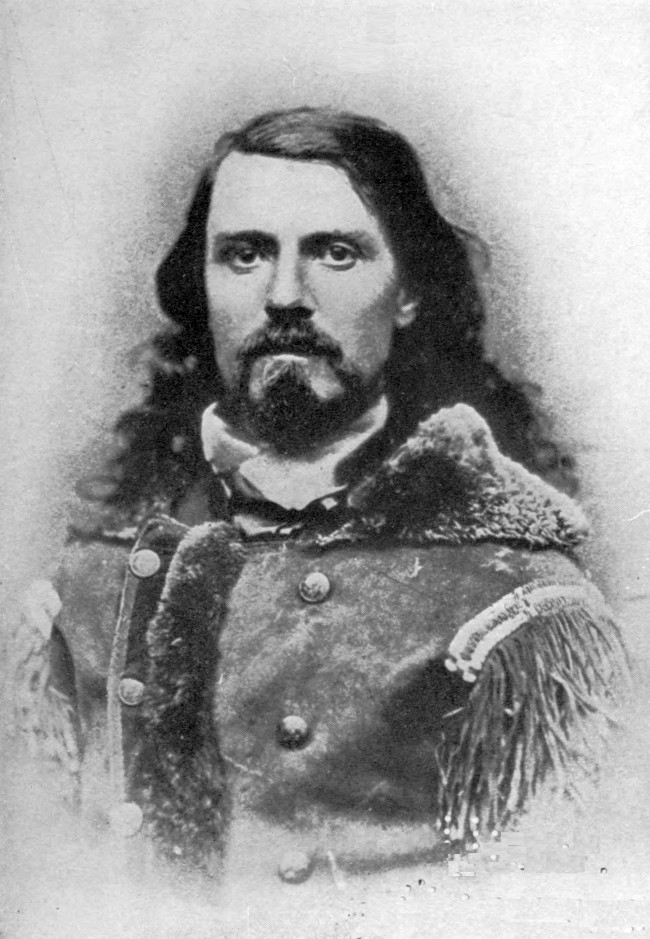

“BUFFALO BILL”

From a photograph taken in 1871, in the possession of Clarence S. Paine, Esq.

“BUFFALO BILL”

Celebrated American plains-day express rider, hunter, guide and army scout, who before he was fourteen years of age had won credit for man’s pluck and shrewdness. In his youth a dutiful and helpful son; in his later years an exhibitor of Wild West scenes, with which he has toured the world. Early known as “Will,” “Little Billy,” “Pony Express Bill,” “Scout Bill Cody”; by the Indians termed “Pa-he-haska” (“Long Hair”); but, the globe around, famed as “Buffalo Bill.”

Born on the family farm near LeClaire, Scott County, Eastern Iowa, February 26, 1845.

Father: Isaac Cody. Mother: Mary Ann Cody.

Childhood spent in Scott County, Iowa: at LeClaire and at Walnut Grove.

When eight years old, in 1853, is removed with the family overland to Kansas.

In the Salt Creek Valley, near the Kickapoo Indian reservation and Fort Leavenworth, Eastern Kansas, Mr. Cody takes up a claim and is Indian trader.

Young William is reared among the Free State troubles of 1853–1861, when the slave men and the anti-slave men strove against one another to obtain possession of Kansas. Mr. Cody, the father, was of the Free State party.

Aged 10, summer of 1855, Billy engages at $25 a month to herd cattle, just outside of Leavenworth, for the freighting firm of Russell & Majors. Gives the money, $50, to his mother.

Is instructed at home by Miss Jennie Lyons, the family teacher; attends district school.

Aged 11, summer of 1856, makes his first trip into the plains, as herder for a Russell, Majors & Waddell bull train.

Continues his cattle herding; and aged 12, in May, 1857, makes another trip across the plains, as herder for the cattle with a Russell, Majors & Waddell outfit bound for Salt Lake, Utah. Has his first Indian fight.

The same summer of 1857, is “extra man” with another Russell, Majors & Waddell wagon train for Utah. Returning, has his second Indian fight.

Arrives home again, summer of 1858. Becomes assistant wagon master with a fourth train, for Fort Laramie.

Fall of 1858, aged 13, joins a company of trappers out of Fort Laramie.

Winter and spring of 1859, attends school again, to please his mother.

To the Pike’s Peak country for gold, 1859.

Returns home to see his mother; and then spends winter of 1859–1860 trapping beaver in central Kansas.

Rides Pony Express, 1860–1861. The youngest rider on the line.

Ranger, dispatch bearer, and scout in the Union service, in Kansas, Missouri and the Southwest, 1861–1863.

Enlisted in Seventh Kansas Volunteer Infantry, 1864, and serves with it until close of the war.

Stage driver between Kearney, Nebraska, and Plum Creek, 35 miles west, 1865–1866.

Marries, March 6, 1866, Miss Louisa Frederici of St. Louis.

Proprietor of Golden Rule House hotel at his old home in Salt Creek Valley, Kansas, 1866.

Government scout at Fort Ellsworth, Fort Fletcher, and Fort Hays, Kansas, 1866–1867.

With William Rose, a construction contractor, promotes the town-site of Rome, near Fort Hays, 1867. Rome is eclipsed by Hayes City, its rival.

Earns title “Buffalo Bill” by supplying the work gang of the Kansas Pacific Railroad with buffalo, 1867–1868. In 18 months kills 4,280 buffalo.

Becomes Government scout with headquarters at Fort Larned, 1868. Performs some remarkable endurance rides between the posts on the Arkansas and those on the Kansas Pacific line. Once covers 355 miles, in 58 hours of riding by day and by night.

Appointed by General Sheridan guide and chief scout for the Fifth Cavalry, 1868.

Serves with the Fifth Cavalry on various expeditions, 1868–1872. Also acts as guide for numerous sportsmen parties.

Temporary justice of the peace at Fort McPherson, Nebraska, 1871.

Guide for the Grand Duke Alexis of Russia, on a celebrated hunting tour in the West, 1872.

Guide for the Third Cavalry, at Fort McPherson, 1872. Acts as guide for the Earl of Dunraven, and other distinguished sportsmen.

Elected on the Democratic ticket to the Nebraska Legislature, 1872.

Resigns from the Legislature and in the winter of 1872–1873 stars, with Texas Jack, as an actor in “The Scouts of the Plains,” a melodrama by Ned Buntline.

Organizes the “Buffalo Bill Combination,” with Texas Jack and Wild Bill, and plays melodrama in the Eastern cities, 1873–1874.

During 1874–1876 continues to be scout, guide and actor, according to the season.

Takes the field again in earnest as scout for the Fifth Cavalry, against the Sioux, spring of 1876. Fights his noted duel with Chief Yellow Hand.

In partnership with Major Frank North, of the Pawnee Government Scouts, establishes a cattle ranch near North Platte, Nebraska, 1877.

Seasons of 1876–1877–1878 resumes his theatrical tours in Western melodrama, portraying the late Sioux War and the incidents of the Mountain Meadow Massacre (1857).

Takes up residence at North Platte, Nebraska, spring of 1878. Continues to hunt, ranch, and act; writes his autobiography and his own plays.

In 1883 organizes his justly celebrated “Wild West” combination, with which for three years he tours the United States. In 1886 he takes it to England, and in 1889 to the Continent.

In 1888 appointed brigadier general of the National Guard of Nebraska.

In 1890 he again serves as chief scout, under General Nelson A. Miles, against the Sioux.

Since then, the “Wild West Show,” known also as the “Congress of Rough Riders of the World,” has continued its career as a spectacle and an education. Colonel Cody (still known as “Buffalo Bill”) is ranked as one of America’s leading characters in public life. He has shown what a boy can do to win honor and success, even if he starts in as only a cattle-herder, with little schooling and no money.

Since early dawn forty Indians and one little red-headed white boy had been riding amidst the yellow gullies and green table-lands of western Nebraska, about where the North Platte and the South Platte Rivers come together. The most of these Indians were Cheyennes; the others were a few Arapahoes and two or three Sioux. The name of the little red-headed boy was David Scott.

He was guarded by the two squaws who had been brought along to work for the thirty-eight men. They worked for the men, little Dave worked for them; and frequently they struck him, and told him that when the Cheyenne village was reached again he would be burnt.

In the bright sunshine, amidst the great expanse of open, uninhabited country, the Indian column, riding with its scouts out, made a gallant sight. The ponies, bay, dun, black, white, spotted, were adorned[18] with paint, gay streamers and jingly pendants. The men were bareheaded and bare bodied; on this warm day of June they had thrown off their robes and blankets. But what they lacked in clothing, they supplied in decoration.

Down the parting of the smoothly-combed black hair was run vermilion; vermilion and ochre and blue and white and black streaked coppery forehead, high cheek-bones and firm chin, and lay lavishly over brawny chest and sinewy arms. At the parting of the braids were stuck feathers—common feathers for the braves, tipped eagle feathers for the chiefs. The long braids themselves were wrapped in otter-skin and red flannel. From ears hung copper and brass and silver pendants. Upon wrists and upper arms were broad bracelets and armlets of copper. Upon feet were beaded moccasins worked in tribal designs. The fashion of the paint and the style of the moccasins it was which said that these riders were Cheyennes.

The column had no household baggage and no children (except little Dave) and no dogs; and it had no women other than just the two. The men were painted and although they rode bareheaded, from the saddle-horn of many tossed crested, feathered bonnets with long tails. These were war-bonnets. All the bows were short, thick bows. These were war-bows. All the arrows in the full quivers were barbed arrows. Hunting arrows were smooth. The lances were tufted and showy. The shields, slung to left[19] arm, were the thick, boastfully painted war shields. The ponies were picked ponies; war ponies. Yes, anybody with half an eye could have read that this was a war party, not a hunting party or a village on the move.

Davy could have proven it. Wasn’t he here, riding between two mean squaws? And look at the plunder, from white people—some of it from his own uncle and aunt, all of it from the “whoa-haw” trains, as the Indians had named the ox-wagon columns of the emigrants and freighters.

Ever since, two weeks back, these Cheyennes had so suddenly out-charged upon his uncle’s wagon and another, strayed from the main column, they had been looking for more “whoa-haws.” This year, 1858, and the preceding half dozen years had been fine ones for Indians in search of plunder. Thousands of white people were crossing the plains, between the Missouri River and the Rocky Mountains; their big canvas-covered wagons contained curious and valuable things, as well as women and children. They were drawn by cattle and horses or mules, and behind followed large bands of other cattle and horses and mules. Sometimes these “whoa-haw” people fought stoutly, sometimes they had no chance to fight—as had been the case with little Dave’s uncle.

Tall Bull was the young chief in charge of the squad that had attacked the two wagons. Now Tall Bull was one of the scouts riding on the flanks and[20] ahead of the war party, so as to spy out the country. In his two weeks with the Cheyennes Dave had learned them well. They were no fools. They rode cunningly. They were disciplined. While they kept to the low country their scouts skirted the edges of the higher country, in order to see far. By wave of blanket or movement of horse these keen-eyed scouts could signal back for more than a mile, and every Indian in the column could read the signs. Then the head chief, Cut Nose, would grunt an order, and his young men would obey.

The march was threading the bottom of a bushy ravine. Cut Nose, head chief, led; Bear-Who-Walks and Lame Buffalo, sub-chiefs, rode with him. Behind filed the long column. In the rear of all trailed the two squaws, guarding the miserable Davy.

Suddenly adown the column travelled, in one great writhe, a commotion. A scout, to the right, ahead, was signalling. He was Tall Bull. His figure, of painted self and mottled pony, was plainly outlined just at the juncture of brushy rim and sky. Now he had dismounted, and had crept forward, half stooped, as if the better to see, the less to be seen. But back he scurried, more under cover of the ravine edge; standing he snatched his buffalo robe from about his waist and swung it with the gesture that meant “Somebody in sight!”

He sprang to his spotted pony, and down he came, riding in a slow zigzag and making little circles, too.[21] The slow zigzag meant “No hurry” and the little circles meant “Not many strangers.” And he signed with his hand.

However, large party or small party, the news was very welcome. All the other scouts sped to see what Tall Bull had seen. From side ravines out rushed at gallop the little exploring detachments. ’Twas astonishing how fast the news spread. The two squaws jabbered eagerly; and the aides of Cut Nose went galloping to reconnoitre.

As for Cut Nose himself, he halted, and thereby halted the column, while he composedly sat to receive reports. The rear gradually pressed forward to hear, and the squaws strained their ears. Davy could not understand, but this is what was said, by sign and word, when Tall Bull had arrived:

“What is it?”

“White men, on horses.”

“How many?”

“Three.”

“How far?”

“A short pony ride.”

“What are they doing?”

“Travelling.”

“Any baggage?”

“No.”

“Are they armed?”

“Yes. Guns.”

Cut Nose grunted. Now Lame Buffalo, sub-chief,[22] came scouring back. He had seen the three men. It was as Tall Bull had said. Two of the men were large, one was small. They were riding mules, and were dressed in “whoa-haw” clothes, so they were not trappers or hunters, but probably belonged to that “whoa-haw” train of many men that the column had sighted travelling east. They were riding as if they wished to catch it. But they could be reached easily, said Lame Buffalo, his black eyes blazing. Blazed the black eyes of all; and fiercest were the snappy black eyes of the two squaws. The three “whoa-haws” could be reached easily by following up a side ravine that would lead out almost within bow-shot. Then the white men would be cut off in the midst of a flat open place where they could not hide.

“Good,” grunted Cut Nose; and he issued short, rapid orders. Little Dave had not understood the words but he could understand the gestures and signs that made up more than half the talk; and he could understand the bustle that followed. The Cheyennes, the few Arapahoes and Sioux, were preparing themselves for battle.

Blankets and robes were thrown looser. Leggings were kicked off, to leave the limbs still freer. The rawhide loops by which the riders might hang to the far side of their ponies were hastily tested. Quivers were jerked into more convenient position. Arrows were loosened in them. The unstrung bows were strung. The two warriors who had old guns freshened[23] the priming and readjusted the caps upon the nipples. Several of the younger warriors hurriedly slashed face and chest anew with paint. War bonnets were set upon heads; their feathered tails fell nearly to the ground.

With a single eagle glance adown his force Cut Nose, raising his hand as signal, dashed away up the ravine. After him dashed all his array, even to the two squaws and little Dave.

Braids tossed, hoofs thudded, war bonnets streamed, and every painted rider leaned forward, avid for the exit and the attack. Dave’s heart beat high. He was afraid for the white men. The Cheyennes were so many, so eager, and so fierce.

The scouts before kept signing that all was well. The white men evidently were riding unconscious of a foe close at hand. At the side ravine Cut Nose darted in. Its farther end was closed by brush and low plum trees, which rose to fringe the plateau above. A scout was here, peering, watching the field. He was Yellow Hand, son of Cut Nose. He signalled “Come! Quick! Enemy here!”

Thus urged, up the slope galloped Cut Nose, Lame Buffalo, Bear-Who-Walks; galloped all. At the top, emerging, Cut Nose flung high his hand, shaking his war bow. Over the top after him poured the racing mass, savage in paint and cloth and feather and decorated weapon. Swept onward with them rode little[24] Dave, jostled between the two squaws, who whipped his pony as often as they whipped their own.

The halloo of Cut Nose rose vibrant.

“Hi-yi-yi-yi-yi; yip yip yip!” he whooped, exultant and threatening.

“Hi-yi-yi-yi-yi; yip yip yip!” yelped every rider, the squaws chiming in more piercingly than any others.

Out from the plum tree grove and into the plateau they had burst, and went charging furiously.

The sun was shining bright, for the day was glorious June. The plateau lay bare, save for the grass dried by weather and the few clumps of sage and greasewood. And there they were, the three whites, stopped short, staring and for the moment uncertain what to do.

They were alone, between bending blue sky and wide plain; a little trio in the midst of a vast expanse. As the scouts had claimed, no shelter was near. At the other edge of the plateau flowed the North Platte River, but too distant to be reached now.

Louder pealed the whoops of the warriors, louder shrieked the shrill voices of the squaws, as onward charged, headlong, the wild company, to ride over the white dogs and snatch scalp and weapon.

Almost within gunshot swept forward the attack. Already had spoken, recklessly, with “Bang! Bang!” the guns in the hands of the two excited warriors. Were the white men going to run, or stand? They were going to stand, for they had vaulted to ground.[25] One of them was small enough to be a boy. Three puffs of blue smoke jetted from them. The leading Indians ducked low—but the shots had not been for them! Look! Down had dropped the three mules, to lie kicking and struggling.

The white men (yes, one was a boy!) bent over them, stoutly dragging and shoving; and next, in behind the bodies they had crouched. Only the tops of their broad hats and their shoulders could be described, and their gun muzzles projecting before. This, then, was their fort: the three dead mules arranged in triangle! Evidently the two men, and perhaps the boy, had fought Indians before. Davy felt like cheering; but from the forty throats rang a great shout of rage and menace. The squaws had halted, with Dave, to watch; unchecked and unafraid the warriors forged on, straight for the little barricade.

“Kill! Kill!” shrieked the squaws, glaring.

The warriors were shooting in earnest; arrows flew, the two guns again belched. The charge seemed almost upon the fort, when from it puffed the jets of smoke. “Bang! Bang! Bang!” drifted dully the reports; and with scarce an interval followed other jets, rapid and sharp: “Bang! Bang-bang! Bang! Bang!”

From the painted, parted lips of the two squaws issued a wilder, different note, and little Dave again felt like cheering; for from their saddles had lurched three of the Cheyennes, and a pony also had pitched in a heap.

Cut Nose swerved; he and every warrior flung themselves to the pony side opposite the fort, and parting, the column split as if the fort were a wedge. In two wings they went scouring right and left of it. Around and around the mule-body triangle they rode, at top speed, in a great double circle, plying their bows.

Their arrows streamed in a continuous shower, pelting the fort. They struck, quivering, in the mule bodies and in the ground. Now from every savage throat rang another shout—high, derisive. On their ponies the squaws capered, and shook their blanket ends. An arrow was quivering in a new spot—the shoulder of one of the whites. Now Davy felt like sobbing. But it was not in the shoulder of the boy; it was in the shoulder of the man beyond him, and facing the other way. However, that was bad enough.

Still, the man was not disabled; not he. His gun remain levelled, and neither the boy nor the other man paid any attention to him. The three occasionally shot, but lying low against their ponies’ sides the Indians, galloping fast, were hard to hit.

Cut Nose raised his hand again, and from the circle he veered outward. The circle instantly scattered, and after their chief galloped every warrior.

Forward hammered the two squaws, with vengeful look at little Dave which bade him not to lag. The warriors had gathered in a group, out of gunshot from the fort. Cut Nose was furious. Indians hate to lose[27] warriors; and there were three, and a pony, stretched upon the plain.

“Are you all old women?” scolded Chief Cut Nose, while Dave tried to guess at what was being shouted, and his two guardians pressed to the edge of the circle. “You let three whites, one of whom is very little, beat us? The dogs will bark at us when we go back and the squaws will whip us through the village. Everybody at home will laugh. They will say: ‘These are not Cheyennes. They are sick Osages! They are afraid to take a scalp, and when an enemy points a stick at them, they run!’ Bah! Am I a chief, and are you warriors, or are we all ghosts?”

Panting, the warriors listened. They murmured and shrugged, as the words stung.

“Those whites shoot very straight. The little one shoots the straightest of any. They must have many guns. They shoot once and without loading they shoot again,” argued Lame Buffalo.

“You talk foolish,” thundered Cut Nose. “These whites cannot keep shooting. All we need to do is to charge swift and not stop, and when we reach them their guns will be empty. Shall Cheyennes draw back and leave three brothers and a good pony lying on the prairie? These whites will go on and join their whoa-haw train, and tell how they three, from behind dead mules, fought off the whole Cheyenne nation! Or shall we send our squaws against them, to kill them! The little white boy will laugh,” and he pointed at Dave.[28] “He will not want to be a Cheyenne; he will stay white. Cheyennes are cowards.”

Through the jostling company ran a hot murmur; but Lame Buffalo, especially scolded, almost burst.

“No!” he yelled. “Cheyennes are not cowards! I am a Cheyenne. I can kill those three whites myself. I will go alone. I ask no help.”

He whirled his pony; he burst from the dense ring, and tossing high his plumed lance, with a tremendous shout he launched himself straight for the mule fort. He did not ride alone; no, indeed! Answering his shout, and imitating his gesture, every warrior followed, vying to outstrip him. Now woe for the whites. Dave’s heart beat so as well-nigh to choke him. His eyes leaped to the fort.

The two men and the boy in the little triangle had been busy. They had rearranged the carcasses to give more protection; the arrow had been pulled from the shoulder of the wounded man; he was as alert as if he had not been hurt at all; and over the mule bodies jutted the gun muzzles, trained upon the Indian charge.

Could that tiny low triangle formed by three dead mules outlast such a yelling, tearing mob, sweeping down upon it? Could it beat back Lame Buffalo alone—that splendid feather-crowned horseman, riding like a demon, shouting like a wolf? He still led, and with every few jumps of his pony he shook his lance and whooped.

Well might those three whites in the mule triangle[29] be afraid, at last; and who could blame the boy, there, if he, particularly, was afraid? It was a bad place for a boy. Dave watched him anxiously, and wondered.

The boy was facing toward the charge; the two men also were facing outward, to right and left of him, that they might cover the charge as it spread.

Up rose the boy’s gun; the two men seemed to be waiting upon him. He was aiming, but he would not shoot yet, would he, with the Indians so far off?

Yet, he shot! His gun muzzle puffed smoke. The squaws started, cried out, waved frantic hands—for three hundred yards from the muzzle had toppled, toppled from his pony, Lame Buffalo, smitten in mid-course! It seemed to Dave that he could hear the two white men cheering; but to the cries of the squaws were added the terrific yells of the warriors, drowning out every other sound.

Nevertheless, that was a long, long shot, for boy or man; and a good shot. The charge split again; and not daring even to pick up Lame Buffalo, who was crawling painfully and pressing a hand to his side, it circled around and around the mule fort, as before.

As Lame Buffalo had said, the “little one” shot the straightest of any.

Cut Nose signalled his band to council again. Four warriors had fallen, and two ponies. Now at a safe distance from that venomous, spit-fire little fort, they all dismounted, except for a few scouts, and squatted for a long confab.

“Kill! Kill!” implored the two squaws.

“Shut up!” rebuked Cut Nose; and they only wailed about the dead.

On the outskirts of the council, and annoyed by the wailing of the squaws, Dave could not hear all the discussion. Cut Nose asked the sub-chiefs for their opinion what to do; and one after another spoke.

“There is no use in charging white men behind a fort,” said Bear-Who-Walks. “We lose too many warriors, any one of whom is worth more than all the white men on the plains. It is not a good way to fight. I like to fight, man to man, in the open. If we wait long enough, we can kill those three whites when their hearts are weak with thirst and hunger.”

“They have medicine guns,” declared Yellow Hand. “They have guns that are never empty. No matter how much they shoot, they can always shoot[31] more. The great spirit of the white people is helping them. It is some kind of magic.”

At this, Dave wanted to laugh. The two white men and the white boy were shooting with revolvers that held six loads each, and the Cheyennes could not understand. The only guns that the Indians had were two old muskets which had to be reloaded after every shot.

“We will wait,” said Cut Nose. “We have plenty of time. The whoa-haws in front will travel on, leaving these three whites. We will wait, and watch, and when they have eaten their fort and their tongues are hanging out for water, we will ride to them and scalp them before they die. That is the easiest way.”

Some of the warriors did not favor waiting; the two squaws wept and moaned and claimed that the spirits of the slain braves were unhappy because those three whites still lived. But nobody made a decisive move; they all preferred to squat and talk and rest their ponies and themselves.

Meanwhile, in the mule body triangle the two men and the boy had been busy. They did not waste any time, talking and boasting. It was to be seen that they were digging hard with their knives, and heaping the dirt on top of the mule bodies, and between them. An old warrior noted this.

“See,” he bade. “The fort is stronger than ever. But by night the wind will change and we can make the whites eat fire. That is a good plan.”

“Yes,” they agreed. “Let us wait till dark. White men behind a fort in daytime are very hard to kill. There is no hurry.”

The afternoon passed. The Indians chewed dried buffalo meat, and squads of them rode to the river and watered the horses. While lounging about they amused themselves by yelling insults at the mule fort; and now and again little charges were made, by small parties, who swooped as close as they dared, and shot a few arrows.

The two men and the boy rarely replied. They, also, waited. Their barricade was so high, that in the trench behind it they were completely sheltered.

But over them and over the field of battle constantly circled two great black buzzards. Lame Buffalo had ceased to crawl, and lay still. The squaws begged the young warriors to go out and bring him in—him and the other stricken braves. The young men only laughed and shook their heads. One did dash forward; but a bullet from the gun of the boy grazed his scalp-lock, and ducking he scurried back faster than he had gone!

That boy certainly was cool and brave and sharp-sighted. Dave was proud of him; for Dave, also, was white, and a boy.

So the afternoon wore away. Evening neared. The sun, a large red ball, sank into the flat plains. A beautiful golden twilight spread abroad, tinging the sod and the sky. The world seemed all peaceful; but[33] here in the midst of the twilight were waiting and watching the painted Cheyennes, as eager as ever to get at those three persons in the mule fort. This twilight, Dave imagined, must be a very serious moment for the fort. The twilight warned that night was at hand.

Dusk settled, and deepened into darkness. The Sioux made no camp-fires. Davy wrapped himself in an old buffalo-robe, and guarded by the two squaws, one on either side of him, tried not to sleep. As he listened, while he gazed up at the million stars, and the plains breeze fanned across his face, he wondered what the boy in the mule fort was doing. No doubt he was listening, too, and wishing that the stars would come down and help, or else send a message to those freight wagons which were travelling on.

Davy must have dropped off to sleep, in spite of himself; because suddenly he was aroused by the squaws sitting up and jabbering. Had morning come? The plains yonder were light. No; that was fire! The Cheyennes, just as they had planned, had set the grass afire, to windward of the mule fort. While Davy, too, sat up, his heart beating wildly, the fire seemed to be sweeping right toward the fort. Behind the line of flames and smoke he could see the dark figures of the Indians fanning with blankets and robes, to make the line move faster and fiercer.

“Humph! A poor fire,” grunted one of the squaws. “Grass too short.”

“Yes. But it makes a smoke, so the men can charge up close,” answered the other.

That, then, was the scheme, if the fire itself did not amount to much. Some of the dark figures behind the line of fire fanned; others were stealing forward, into the smoke itself. The moment was exciting. The smoke was drifting across the fort; would the two men and the boy suspect that the Indians were following it in?

The line of fire seemed almost at the low mound which contained the three whites; the smoke drifted thick and fast; the figures of the Indians stole forward. Abruptly, from the dim mound spurted a jet of flame, and sounded a hollow “Bang!” Another jet spurted, with another “Bang!” And—“Bang! Bang! Bangity-bang-bang!” Hurrah! That fort was not being fooled; no, indeed. It was ready for anything. It knew what was behind the smoke, and had only been waiting.

“Kill! Kill!” shrieked the two squaws, enraged again. But the warriors gave up, as soon as they found that their smoke scheme had not worked. They shot their bullets and a few arrows, and lay low. Soon the fire and the smoke had passed beyond the mule fort. Some of the braves returned to the camp; the others continued to sneak about, on guard over the fort. Silence reigned.

“We might as well go to sleep,” said one squaw to the other. “Nothing will happen until morning.”

“Lie down, white red-head,” bade the second squaw, roughly, to Dave. “To-morrow we will have three more whites, and that will mean lots of fun.”

Davy obeyed. It was warmer lying down than sitting up. Thankful that the three whites were still unbeaten, and too smart for the Cheyennes, he fell asleep. When again he wakened, it really was morning. The sky was pink, and stars pale, the brush showed plainly. But he had no time to meditate, or invite another “forty winks.” The squaws had sprung to their feet; the air was full of clangor and shouting and shooting; the Indians were making a charge, the little fort was holding them off.

It was the angriest charge yet, all in the chill, pink dawn flooding high sky and broad plain. However, it didn’t work. The two men and the boy were just as ready as ever, and the charge split. Cut Nose waved his hand and motioned. The circle of galloping horsemen spread wider, and dismounting, the riders, holding to their ponies’ neck-ropes, sat down to wait like a circle of crows watching a corn-field.

The two squaws were disgusted. They grumbled, as they prepared breakfast; and under their scowls Davy felt afraid. He wondered what the Indians would do next.

Plainly enough, they did not intend to make any more charges. The sun rose high and higher. His beams were hot, so that the plain simmered. Without shade in that little open enclosure formed by the mule[36] carcasses, the three whites would soon be very uncomfortable. One was a boy and one was wounded. Circling and waiting, the two black buzzards had been joined by a third. Forming a wide ring of squatting warriors and dozing ponies, the Indians also waited. The air was still; scarcely a sound was to be heard, save as now and then the squaws with Davy murmured one to the other, or a warrior made a short remark.

What was to be the end? The grim siege was worse than the charges. The sun had climbed well toward the noon mark, and Davy felt heart-sick for those three prisoners in the mule fort, when, on a sudden, a new thing happened. First, a warrior, on his right, up-leaped, to stand gazing westward, listening. Another warrior stood—and another, and another. Cut Nose himself was on his feet; ponies were pricking their ears; the two squaws, bounding to their feet, likewise looked and listened.

Davy strained his ears. Hark! Distant shooting? Flat, faint reports of firearms seemed to drift through the stillness. No! Hurrah, hurrah! Those reports were the cracking of teamsters’ bull-whips. A wagon train was coming! Another wagon train, from the west! See—above that ridge there, only half a mile away, a wagon already had appeared: first the team of several span of oxen, then the white top of the big vehicle itself, and the driver trudging, and several outriding horsemen flanking on either side.

Team after team, wagon after wagon, mounted the[37] ridge, and flowed over and down. It was a large train, and a grand sight; only, it was not a grand sight for the Indians. But in the mule fort the two white men and the boy had jumped up and were waving their hats and cheering. Davy wanted to join, and wave and cheer.

To their ponies’ backs were vaulting all the Indians. The two squaws, panic-stricken, rushed to the safety of their saddles. They seemed to forget little Dave. Cut Nose had dashed to the front, his men were rallying around him. Evidently they were debating whether to fight or run. Louder sounded the smart cracks of the bull-whips; the wagon train was coming right ahead, lined out for the very spot. The Indians had short shift for planning. The two squaws, having hastily gathered their belongings, galloped for the council. Davy started to follow, but lagged, and paused. His own pony was making off, dragging his neck rope, to catch up with the other ponies. Davy wisely let him go.

Now Cut Nose raised his hand; and turning, quickened his pony to a furious gallop. Shrill pealed his war-whoop; whooping and lashing, after him pelted every warrior, with the two squaws racing behind. Straight for the little fort they charged. The three whites had dropped low, to receive them. And—look, listen—from the wagon train welled answering yell, and on, across the plain, for the fort, spurred a dozen and more riders shaking their guns and shouting.

Davy dived to cover of a greasewood bush, and lay low. But the Cheyennes did not stop to get him. They kept on; at the little fort they split, as before, and shooting and yelping they passed on either side of it. The three whites received them with a volley and sent a volley or two after them as they thudded away. And that was the end of the siege.

Davy did not dare to stand and show himself. To be sure, the Cheyennes, both men and squaws, were racing away, as hard as they could ride; but even yet they might send back after him. So he lay and peeped. However, in the mule fort the two men and the boy had risen upright, again to wave and cheer. Waving and cheering, the mounted men from the wagon train came galloping on, and presently the three in the fort stepped outside. Arrived, the foremost riders from the train hastily flung themselves from their saddles, and there was apparently a great shaking of hands and exchange of greetings. With volleys renewed, from their whip lashes, the teams also were hastening for the scene. The Cheyennes already were almost out of sight. So Davy stood, and trudged forward.

He had half a mile to walk, through the low brush. The first of the wagons beat him to the fort. When he drew near, the lead wagon had halted, and the others were trundling in one after the other. The men were crowding about their three comrades who had been rescued, and for a few moments nobody seemed to[39] notice ragged little red-headed Dave, toiling on as fast as he could.

It was a large train. There were twenty-five wagons, with their teamsters, and about two hundred extra men, some mounted on mules and horses. However, most of the men were afoot. The wagons were tremendous big things, with flaring canvas tops on, or else with the canvas stripped, leaving only the naked hoops of the frame-work. Each wagon was drawn by twelve panting bullocks, yoked in pairs, or spans.

The majority of the men were dressed alike, in flat, broad-brimmed plains hats, blue or red flannel shirts, and rough trousers belted at the waist and tucked into high, heavy boots. The teamsters were armed in hand with their whips, of short stock and long lash and snapper which cracked like a pistol shot. Those cracks could be heard half a mile. The extra men carried mainly large bore muskets, called (as Davy knew) Mississippi yagers; and all had knives and pistols, thrust into waist-band and belt. Whiskered and unshaven and tanned and dusty, it was a regular rough-and-ready crowd.

However, of course the three defenders of the mule fort took the chief attention. They were the two men (the shoulder of one was rudely bandaged with a blue bandanna handkerchief) and the boy. Even the boy wore freighter plains costume, of broad hat and flannel shirt and trousers tucked into boots; and he held a yager in his hand, and had a butcher knife and two big[40] Colt’s revolvers stuck in his belt. He and the two men looked pretty well tired out, but they stood fast and answered all kinds of questions.

The mule fort showed how hot had been the battle, for the mule bodies fairly bristled with arrows. Arrows were everywhere on the ground about.

The freighters had crowded close, and everybody was talking and laughing at once. Davy stood unnoted on the outskirts, gazing and listening—until on a sudden he was espied by a tall, lank teamster with long dusty whiskers.

“Hello, thar!” the man called, loudly. “Whar’d you come from, Red? Lookee, boys! Reckon we’ve picked up a trav’ler. Whoopee! Come hyar, son. Give us an account of yoreself.”

One after another, they all looked. Davy flushed and fidgeted and felt much embarrassed. The tall whiskered freighter strode forward and grasped him by the ragged shirt-sleeve.

“What’s yore name?”

“David Scott.”

“Whar’d you come from?”

“The Indians had me. They killed my uncle and aunt and made me go along.”

“Whar was that?”

“Back on the Overland Trail. We were with a wagon train and got separated.”

“How long ago?”

“Two weeks, I think.”

“What Injuns?”

“Those——” and Davy pointed in the direction taken by the Cut Nose band.

“I want to know!” The teamster gaped wide in astonishment, and from the crowd came a chorus of exclamations. “How’d you get away?”

“When you scared them off I hid behind a bush. Two squaws had me, and they didn’t wait.”

“You mean to say you war with those same pesky Injuns who war attackin’ this fort hyar?”

“Yes, sir. But I didn’t do any of the fighting.”

“No, o’ course you didn’t. Wall, I’m jiggered!” And the whiskered freighter seemed overwhelmed with amazement. But he rallied, as a thought struck him. “Come along hyar. I’ll interduce ye to another boy.” And by the sleeve he led Davy forward, through the staring crowd. “Hyar, now; I want to interduce ye to a reg’lar rip-snorter, not much older’n you are. Red, shake hands with little Billy Cody, the hero of the mule fort.”

“Little Billy Cody” was the boy who had been with the two men in the mule fort. Surrounded by the staring crowd Davy felt rather timid and did not know exactly what to do. But Billy Cody promptly put out his hand, Davy extended his, and Billy gripped it warmly.

“Hello,” he said, gruffly. “Where do you hail from?”

“I was out there, with the Indians, while you were fighting,” explained Davy.

“Didn’t we give it to ’em!” asserted Billy Cody. “They thought they had us; but they didn’t.”

“I saw you shoot Lame Buffalo,” said Davy, eagerly. “I guess you killed him.”

“He shore did,” declared the wounded man. “When little Billy draws bead on anything, it’s a goner.”

“Well, I had to do it,” said Billy Cody. “Lew told me to.”

“So I did,” uttered the second of the two men. “It was time those Injuns knew what they were up[43] against, when they tackled us and Billy. That one shot licked ’em.”

“Hurrah for little Billy!” cheered the crowd, good-natured; and Billy fidgeted, embarrassed, although anybody could see that he was rather proud.

He was a good-looking boy, although now his face was burned and grimy, and his clothing rough. He stood a little taller than Davy, but he was slender and wiry. He had brown hair and dark brown eyes and regular features; and under his grime and tan his skin was smooth. He was dressed just like the men, and carried himself like a man; but the muzzle of the long heavy yager extended above his hat-brim. Evidently his two companions thought highly of him, and so did the men of the wagon train.

“Some of you tend to Woods’ shoulder; then if you’ll hustle a little grub we’ll be ready for it,” quoth the man called Lew. “Those mule carcasses served a good purpose but they weren’t very appetizing.”

“First of all, I want a drink,” announced the man called Woods.

Prompt hands passed forward canteens, and Billy and the two men took long, hearty swigs of water.

“Arrow wasn’t pizened, was it?” queried several voices, of Mr. Woods.

“No. Lew looked at it, and said not. So he put a hunk o’ tobacco on it, and we haven’t paid much more attention to it,” answered Mr. Woods. “But it’s powerful sore.”

“Here; I’ll fix it up,” proffered a quiet man, who had not been saying much. Now noticing him, Davy thought that he was the finest figure in the whole party. This man was young (he could not have been more than twenty, but this pioneer life turned youths into men early) and was splendidly built. He stood a straight six feet, with slim waist and broad shoulders and flat back; his hair was long and light yellow, and his wavy moustache also was light yellow. His eyes were wide and steel gray, his nose hawk-like, his chin square and firm. His clothes fitted him well, and were worn with an easy grace. About his strong neck was loosely knotted a red silk handkerchief.

“All right, Bill,” responded Mr. Woods, sitting down. “’Twon’t need much, except a little washing.”

Bill calmly proceeded to inspect the arrow wound in the shoulder. Other men were hastily producing food from the wagons.

“Here, Red,” they bade, to Davy; and sitting in the half circle with Mr. Lew and Billy Cody, Davy gladly ate. It seemed good to be with white people again.

“How long did the Injuns have you?” asked Billy.

“About two weeks.”

“They were Cheyennes, weren’t they. Who was their chief?”

“Cut Nose. He was head chief. But Lame Buffalo and Bear-Who-Walks were chiefs, too.”

“That Cut Nose is a mean Injun,” pronounced[45] Billy, wagging his big hat. “But he didn’t catch us—not with Lew Simpson bossing our job. I thought we were wiped out, sure, till Lew told us to kill our mules quick and get behind ’em. That was a great scheme.”

“It shore was,” agreed all the men around, wagging their heads, too, while they listened. “Injuns hate to charge folks they can’t see well.”

“Weren’t you afraid?” asked Davy. He liked this Billy Cody, who acted so like a man and yet was only a boy.

“He afraid? Billy Cody afraid?” laughed the listeners. “You don’t know Billy yet.”

“Whether or not we were afraid, we were mighty glad to have those mules in front of us, weren’t we, Billy?” spoke up Lew Simpson. “They made a heap of difference.”

“That’s right,” answered Billy, frankly. And everybody laughed again.

The meal was quickly finished. It consisted of only cold beans and chunks of dried beef, but it tasted tremendously good to Davy; and he didn’t see that Billy or Mr. Simpson slighted their share, either. Mr. Woods had been eating while his wound was being dressed.

“George, you’d better ride in a wagon for a day or so,” called Mr. Simpson, rising, to Mr. Woods. “Well, Red,” and he addressed Davy, “I reckon you’ll travel along with us. We’re bound back to the States. Got any folks there?”

“No, sir,” said Davy, with a lump in his throat. “But I’d like to go on with you.”

“All right-o. Now, some of you fellows hustle us a mule apiece, while Billy and I plunder those Injuns out there. Then we’ll travel.”

Mr. Simpson spoke like one in authority. Billy Cody promptly sprang up, and he and Mr. Simpson strode out into the plain, where the dead Indians and the ponies were lying. Lame Buffalo was the farthest of all; but he was still, like the rest. Evidently he would ride and fight no more.

The wagon train men bustled about, reforming for the march. Three mules were saddled, as mounts for Davy and the two others. Having passed rapidly over the field, Mr. Simpson and Billy returned, laden with the weapons and ornaments of the warriors and the trappings of the ponies. They made two trips. Davy recognized the shield and head-dress of Lame Buffalo, who would need them not again. Billy proudly carried them and stowed them in a wagon.

“Those are yours, aren’t they?” asked Davy, following him, to watch.

“They’re mine if I want them,” said Billy. “Reckon I’ll take ’em home and give ’em to my sisters.”

“Where do you live?”

“In Salt Creek Valley, Eastern Kansas, near Leavenworth. Where do you?”

“Nowhere, I guess,” replied Davy, trying to smile.

“Pshaw!” sympathized Billy. “That’s sure hard luck. Ride along with me and I’ll tell you about things.”

“Here, boy—crawl into this,” called a teamster nearby; and he tossed at Davy a red flannel shirt. “It’ll match yore ha’r.” And he laughed good-naturedly.

“It’s my color all right,” responded Davy, without being teased, as he picked up the shirt. “Much obliged.” He slipped it over his head. It fitted more like a blouse than a shirt, but he needed something of the kind. After he had turned back the sleeves and tucked in the long tails, he was very comfortable.

“Climb on your mule, Red,” bade Billy Cody. “We’re going to start, and Lew Simpson won’t wait for anybody.”

Mr. Simpson was already on his mule. The other mounted men were in their saddles. Mr. Simpson cast a keen glance adown the line.

“All ready?” he shouted. “Go ahead.”

The long lash of the leading teamster shot out with a resounding crack.

“Gee-up!” he cried. “You Buck! Spot!” And again his whip cracked smartly. His six yoke of oxen leaned to their work; the wagon creaked as it moved. All down the line other whips were cracking, and other teamsters were shouting, and the wagons creaked and groaned. One after another they started, until the whole train was in motion.

Mr. Simpson and two or three companions led, keeping to the advance. The other riders were scattered in bunches back on either side of the train; the teamsters walked beside their wagons; and in the rear of the train ambled a large bunch of loose cattle and mules, driven by a herder.

Billy Cody and Dave rode together, well up toward the front.

“Did you ever freight any?” queried Billy. “What was that train you were with? Just emigrants?”

“Yes,” answered Davy. “We were going to Salt Lake.”

“Mormons?” demanded Billy, quickly.

“No. After we’d got to Salt Lake maybe we’d have gone on to California.”

“Expect I’ll go across to California sometime,” asserted Billy. “How old are you, Red?”

“Eleven.”

“I’m thirteen, but I’ve been drawing pay with a bull train three trips out and back. The first time I was herder from Fort Leavenworth out to Fort Kearney and back. Next time I was herder from Leavenworth for Salt Lake, but the Injuns turned us at Plum Creek just beyond Fort Kearney and we had to quit. I killed an Injun too dead to skin, but I was so scared I didn’t know what I was doing. Last summer I went out as extra hand with a big outfit for the soldiers at Salt Lake, but the Mormons held us up and took all our[49] stuff, so we couldn’t help the army, and we had to spend the winter at Fort Bridger, and all of us nearly starved.”

“What’s an extra hand?” asked Davy.

“He takes the place of any other man, who may be sick or hurt,” explained Billy, importantly. “I’m drawing man’s pay; forty a month. I’m saving it to give to my mother, as soon as I get back. Weren’t you ever with a bull train before?”

Davy shook his head.

“No.”

“This is a Russell, Majors & Waddell outfit,” proceeded Billy. “They’re the big freighters out of Leavenworth across the plains and down to Santa Fe. Gee, they haul a lot of stuff! We’re travelling empty, back from Fort Laramie to Leavenworth. This is only half the train; there’s another section on ahead of us. Lew and George and I were riding on to catch up with it, when those Injuns corralled us. If Lew hadn’t been so smart, they’d have had our hair, too. We wouldn’t have stood any show at all. But those mules did the business. And I had a dream that helped. Last night I dreamed my old dog Turk came and woke me; and when I did wake I saw the Injuns sneaking up on us. Then we all woke, and drove ’em back. I’m going to thank Turk for that. I don’t know how he found me. This isn’t the regular trail; but Lew thought he’d make a short cut.”

“Is he the captain?” asked Davy.

“He’s wagon boss; he’s boss of the whole train, and he’s a dandy. I reckon he’s the best wagon boss on the plains. George Woods—the man who was wounded—he’s assistant boss. He’s plucky, I tell you. That arrow didn’t phase him at all. Lew bound a big chunk of tobacco on it, and George went on fighting. Do you know what they call this outfit. It’s a bull outfit, and those drivers are bull-whackers. Jiminy, but they can throw those whips some!”

“When will we get to Leavenworth, do you think?”

“In about twenty-five days. We’re travelling light, and I guess we can make twenty miles a day. We’ve got a lot of government men with us, from Fort Laramie, and the Injuns will think twice before they interfere, you bet. We’re too many for ’em. I reckon those Cheyennes didn’t expect to see another bull train following that first one.”

“No. They thought you were left behind and were trying to catch up. So they waited to starve you out. That’s what fooled ’em.”

“It sure did,” nodded Billy, gravely. “Say, there’s another fine man with this outfit. He’s the one who dressed Woods’ shoulder. His name’s Jim Hickok, but everybody calls him ‘Wild Bill.’ Isn’t he a good-looker?”

“That’s right,” agreed Davy.

“Well, he isn’t just looks, either,” asserted Billy. “He’s all there. He’s been a mighty good friend of[51] mine. Because I was a boy some of the men thought they could impose on me. A big fellow slapped me off a bull-yoke, when I was sitting and didn’t jump the instant he bade me. I was so mad I threw a pot of hot coffee in his face; and I reckon he’d have killed me if Wild Bill hadn’t knocked him cold. When he came to he wanted to fight; but Wild Bill told him if he or anybody else ever bullied ‘little Billy’ (that’s what they call me) they’d get such a pounding that they wouldn’t be well for a month of Sundays. Nobody wants trouble with Wild Bill. He can handle any man in the outfit; but he doesn’t fight unless he has to. He’s quiet, and means to mind his own business.”

With the wagons creaking and groaning, and the oxen puffing and wheezing, and the teamsters cracking their long whips, the bull train slowly toiled on, across the rolling prairie. The trail taken occasionally approached the banks of the North Platte River, and soon there would be reached the place where the North Platte and the South Platte joined, to make the main Platte, flowing southeastward for the Missouri, 400 miles distant. Beyond the Missouri were the States, lined up against this “Indian country” where all the freighting and emigrating was going on.

The train made a halt at noon, and again at evening. Nothing especial had occurred since the rescue of the three in the mule fort. Davy was very glad, at night, to lie down with Billy Cody under a blanket, among friends, instead of shivering in an Indian camp.

Start was made again at sunrise. To-day the main travelled Platte Trail would be reached, and the going would be easier. Just as the trails joined in mid-morning, a sudden cry sped down the long line of wagons.

“Buffalo! Buffalo!”

All was excitement. Davy peered.

“See ’em?” said Billy, pointing. “That’s a big herd. Thousands of ’em. Hurray for fresh meat.”

Ahead, between the river at one side and some sand bluffs at the other, a black mass, of groups as thick as gooseberry bushes, had appeared. The mass was in slow motion, as the groups grazed hither and thither. On the edges, black dots told of buffaloes feeding out from the main body. There must have been thousands of the buffalo. Davy had seen other herds but none so large as this one. His blood tingled—especially when Lew Simpson, the wagon boss came galloping back.

“Ride on, some of you men,” he shouted. “There’s meat. You whackers follow along by the trail and be on hand when we’re butchering.”

“I can’t go, can I?” appealed Davy, eagerly, to Billy.

“No; you haven’t any gun,” answered Billy. “I’m going, though. I can kill as many buffalo as anybody. You watch us.”

Forward galloped Lew Simpson and Billy and twenty others. From a wagon George Woods, his[53] shoulder bandaged and painful, stuck out his head, and lamented the fact that he was too sore to ride. The buffalo hunt promised to be great sport; and, besides, the fresh meat would be a welcome change.

So away the hunters galloped, Lew Simpson and little Billy leading. The train, guarded by the other men, followed, closely watching. Even the very rear of it was excited.

Now arose another cry, passing from mouth to mouth.

“Lookee there! More hunters!”

That was so. Beyond the buffalo, up along the river were speeding another squad of horsemen, evidently intent upon the same prey. They were coursing rapidly, but already the buffalo had seen them, and with uplifted heads the farthest animals were gazing, alarmed.

“Our fellows will have to hurry,” remarked the teamster nearest to Davy. “Shucks! That’s no way to hunt buff’ler. Those fellers must be crazy. They’ll stampede the whole herd!”

“They’ll stampede the whole herd, sure,” agreed everybody.

It was a moment of great interest. Davy thumped his mule with his heels, and hastened ahead, the better to witness. The party led by Lew Simpson and Wild Bill and little Billy had been making a circuit, keeping to the cover of the low ground, until they were close enough to charge; but those other hunters were riding[54] boldly, as if to run the buffalo down. And as anybody should know, this really was not the right way to hunt buffalo.

“They’ll drive ’em into our fellows,” claimed several voices. “They’ll do the runnin’ an’ we’ll do the killin’!”

“Or else they’ll drive ’em into us!” cried others. “Watch out, boys! Watch yore teams! Steady with yore teams, or there’ll be the dickens to pay.”

That seemed likely. The stranger hunters were right upon the herd; the outside buffalo had wheeled; and tossing their heads and whirling, now with heads low and tails high the whole great herd was being set in motion, fleeing to escape. The thudding of their hoofs drifted like rolling thunder. After the herd pelted the stranger hunters.

Part of the herd plashed through the river; part made for the sand-hills—but smelling or sighting the Simpson party, they veered and came on, between the river and the sand-hills, straight for the trail and the wagon-train. In vain out dashed, to turn them, the Simpson party; from the train itself the horsemen spurred forward, as a bulwark of defense; the teamsters shouted and “Gee-hawed” and swung their bull-whips, and the oxen, surging and swerving, their nostrils wide and their eyes bulging, dragged the wagons in confusion. In his excitement Davy rode on, into the advance, to help it.

To shout and wave at those crazy hunters and order[55] them to quit their pursuit was useless. They didn’t see and they couldn’t hear; at least, they did not seem to understand. Panic-stricken, the buffaloes came straight on. Off to the side Lew Simpson and Wild Bill and little Billy and companions were shooting rapidly; the stranger hunters were shooting, behind; and now the reinforcements from the train were shooting and yelling, hoping to split the herd. Some of the buffaloes staggered and fell; others never hesitated or turned, but forged along as if blind and deaf. One enormous old bull seemed to bear a charmed life; he galloped right through the skirmish line; and the next thing that Davy, as excited as anybody, knew, the bull sighted him, and charged him.

Davy found himself apparently all alone with the big bull. He did not need to turn his mule; his mule turned of its own accord, and away they raced. Davy was vaguely conscious of shouts and shots and the frenzied leaps of his frightened mule, which was heading back to the wagon train. Davy did not know that he was doing right, to lead the angry bull into the train; he tugged in vain at his mule’s bit, and could not make the slightest impression. Then, down pitched the mule, as if he had thrust his foot into a hole; and the ground flew up and struck Davy on the ear. In a long slide he went scraping on ear and shoulder, before he could stagger to his feet.

The mule was galloping away; but Davy looked for[56] the buffalo. The big bull had stopped short and was staring and rumbling, as if astonished. The change in the shape of the thing that he had been chasing seemed to make him angrier. He stood, puzzled and staring and rumbling, only about twenty yards from Davy. Suddenly the red shirt must have got into his eyes, for his fore-hoofs began to throw the dirt higher, and Davy somehow knew that he was going to charge.

Not much time had passed; no, not a quarter of a minute, since the mule had fallen and had left Davy to the buffalo. The wagon train men were yelling and running, from the one direction; the hunters were yelling and riding, from the other; and whether they were yelling and hurrying on his account, Davy could not look, to see. Down had dropped the bull’s huge shaggy head, up had flirted his little knobbed tail; and on he came.

Davy never knew how he managed—he dimly heard another outburst of confused shouts, amidst which Billy Cody’s voice rang the clearest, with “Dodge him, Red! This way, this way!” He did not dare to glance aside, and he felt that it was not much use to run; but in a twinkling he peeled off the crimson shirt (which was so large for him) and throwing it, sprang aside.

Into the shirt plunged the big bull, and tossed it and rammed it and trampled it, while Davy watched amazed, ready to run off.

“Bully for you, Red!” sang out a familiar voice; riding hard to Davy’s side dashed Billy Cody, on lathered mule; he levelled his yager, it spoke, the big bull started and stiffened, as if stung. Slowly he swayed and yielded, with a series of grunts sinking down, and down; from his knees he rolled to his side; and there he lay, not breathing.

“All right, Red,” panted Billy Cody. “He’s spoiled your shirt, though. Lucky you weren’t inside it. Say, that was a smart trick you did. Get up behind me. The wagon train’s in a heap of trouble. Let’s go over there.”

Davy’s knees were shaking and he could not speak; he was ashamed to seem so frightened, but he clambered aboard the mule, behind the saddle. Away Billy spurred for the wagon train. Other hunters were spurring in the same direction.

The wagon train certainly was having a time of it. Those stranger hunters, from down the river, had driven the buffaloes straight into the teams. The cavvy of loose cattle and mules had scattered; ox-teams had broken their yokes or had stampeded with the wagons. Several wagons were over-turned; and a big buffalo was galloping away with an ox-yoke entangled in his horns. Wild Bill overhauled him in short order and returned with the yoke; but hither and thither across the field were racing and chasing other men, ahorse and afoot, trying to gather the train together again.

By the time that the buffalo charge had passed on[59] through and the animals were making off into the distance, most of the train’s hunters had arrived. The other hunters, from below, also arrived. They proved to be a party of emigrants, for California, who did not understand how to hunt buffalo. In fact, they had not killed a single one. However, Lew Simpson gave them a pretty dressing down for their carelessness.

“You’ve held us up for a day, at least,” he stormed; “and you’ve done us several hundred dollars’ worth of damage besides.”

“Well-nigh killed that boy, too,” spoke somebody. “Did you see him peel that shirt? Haw-haw! Slipped out of it quicker’n a snake goin’ through a holler log!”

“Little Billy came a-runnin’, though,” reminded somebody else.

“Yep; but didn’t save the shirt!”

That was true—everybody agreed that Davy would not have been saved had he not acted promptly. He was given another shirt (a blue one) to take the place of the one sacrificed to the big buffalo.

The California party rode away, taking a little meat that Lew Simpson offered them after they had properly apologized for their clumsiness. The rest of the day was spent in cutting up the buffaloes, and in repairing the wagons and harness. Not until the next noon was the train able to resume its creaking way, down the Platte River trail, for the Missouri River at Fort Leavenworth.

About twenty miles a day were covered now, regularly, and during the days Davy learned considerable about a “bull train” on the plains. He learned that he was lucky to ride instead of walk; nearly everybody with a bull train walked. However, this train was travelling almost empty, back from Fort Laramie, on the North Platte River in western Nebraska (for Nebraska Territory extended to the middle of present Wyoming), to Fort Leavenworth in eastern Kansas Territory. It was accompanied by a lot of government employes, who did not work for the train, and these rode if they could furnish their own mules. Lew Simpson, the wagon boss, and George Woods, the assistant wagon boss, Billy the extra hand, and the herder, rode, because that was the custom; all the other employes walked.

The oxen or “bulls” (as they were called) were guided by voice and whip. The whip, though, rarely touched them hard; just a flick of the lash at one side or the other of the leading span was enough. A sharp “Gee up!” or a “Whoa, haw, Buck!” and a motion of the lash, did the business. Some of the oxen seemed to be very wise.

“Do you know what those whips are, Red?” asked Billy.

“Raw hide.”

“Better than that. I’ll get one and show you when we camp.”

So he did that noon.

“Hickory stock, and lash of buffalo hide, tanned, with a buck-skin cracker,” informed Billy. “Eighteen inch stock, eighteen foot lash, and cost eighteen dollars. You ought to see some of these whackers sling a whip! They can stand at the fore wheel and pick a fly off the lead team! Yes, and they can take a chunk of hide out, too—but they don’t often do that.”

Davy curiously examined the bull whip. The stock was short and smooth, the lash was long and braided thickest in the middle, like the shape of a snake. The cracker was about six inches in length, and already had frayed at the tip; and no wonder, for it had often been made to snap like a pistol shot!

“I can swing the thing a little, but it’s sort of long for me,” announced Billy, proceeding to practise with it, until he had almost taken off his own ear, and made the whole mess uneasy. “I’m not going to quit, though,” he added, “until I can throw a bull whip as good as anybody;” and he took the whip back to its owner.

Billy was quite a privileged character, at camp and on the march. Everybody liked him, and considered him about as good as a man. To be an “extra hand” was no small job. It meant that whenever any of the teamsters was sick or hurt or otherwise laid off, “little Billy” took his place. The “extra hand” rode with the wagon boss (who was Lew Simpson), carried orders for him down the line, and was held ready to fill[62] a vacancy. So this duty required a boy of no ordinary pluck and sense.

Besides, it was generally known that Billy was drawing wages to give to his mother, who was a widow trying to raise a family. Billy was the “man” of the family, and they depended on him. The wagon train liked him all the more for this. Everybody spoke well of “little Billy,” for his good sense and his courage. Davy heard many stories of what he had done. The fight in the mule fort had showed his quality in danger; and he had proved himself in several other “scrimmages” with the Indians.

He and Davy and Lew Simpson and George Woods and Wild Bill and a squad of government men formed a mess, which ate together. The pleasantest part of the day was the noon halt, around the camp-fire; and the evening camp, at sunset. Billy put in part of his rests at practising writing with charcoal on any surface that he could find. Even when Davy had joined the train, the wagon boxes and tongues and wheels bore scrawls such as “Little Billy Cody,” “Billy Cody the Boy Scout,” “William Frederick Cody,” etc. However, as a writer Dave could beat Billy “a mile,” as the teamsters said. Billy was not much of a figurer, either. But he was bound to learn.

“Ma wants me to go to school some more,” he admitted. “So I suppose I’ll have to this winter. I went some last winter, and we had a teacher in the house, too. A little schooling won’t hurt a fellow.”

“No, I suppose it won’t,” answered Davy, gravely. “I’ve had to go to school. But I’d rather do this.”

“So would I,” confessed Billy. “I like it and I need the money—and I need the schooling, too. Reckon I can do both.”

As for Davy himself, the wagon train seemed to consider him, also, somewhat of a personage, because he had shown his “smartness” when the buffalo bull had attacked him. Of course, he had only slid out of his big flannel shirt, and fooled the buffalo with it; but that had been the right thing done in the right place at the right time, and this counted.

Nothing especial happened as the long train toiled on. The trail was fine, worn smooth by many years of travel over it. This was the old Oregon Trail, and California, from the Missouri River, over the plains and the mountains, clear to the Pacific coast of the West. Beaver trappers and Indian traders had opened it, thirty years ago, and it had been used ever since, by trappers and traders, and by soldiers and emigrants, and its name was known the world around.

The wagon train frequently met other outfits, freight and emigrants, bound west; and before the train turned off the main trail for the government road branching southeast for Leavenworth, the Hockaday & Liggett stage-coach from St. Joseph on the Missouri for Salt Lake City passed them. It wasn’t much of a stage, being only a small wagon covered with canvas and drawn by four mules, and running twice a month;[64] but it carried passengers clear through from the Missouri River to Utah. The wagon train gave it a cheer as it trundled by.

“What are you going to do when you reach Leavenworth, Red?” asked Billy one day, when they were riding along. Leavenworth was now only a few days ahead.

“I don’t know,” answered Davy. “I guess I can find a job somewhere. I’ll work for my board.”

“Oh, pshaw! I’ll get you a job with a bull train,” spoke Billy confidently. “I’ll ask Mr. Russell or Mr. Majors. They’ll take care of any friend of mine, and you’ve proved you’re the right stuff. But first you come home with me. I’ll give you a good time. Wild Bill’s coming, too, after a while.”

“Maybe your folks won’t want me.”

This made Billy almost mad.

“They will, too. What do you talk that way for? You ought to see my mother. I’ve got the best mother that ever lived. She’ll be glad to see anybody that I bring home, and so will my sisters, and Turk. You come along. The trail goes right past the place, and we’ll quit there, and not wait to reach Leavenworth. I’ll get paid off first.”

There was no resisting Billy, and Davy promised.

Yes, evidently Leavenworth and the end of that long Overland Trail were near. The talk in the train was largely of Fort Leavenworth and Leavenworth City, where the train would be broken and reorganized[65] for another trip, and the men would have a short rest and see the sights, if they chose. New farms were being passed, and the beginnings of new settlements; and the number of emigrant outfits was much increased. The greetings all referred to the farther West—Kansas, Utah, and California were on every tongue. Over the trail hung a constant dust of travel, and the air was vibrant with the spirit of pioneers pushing their way into a new country. These men, women and children, travelling with team and wagon, were brave people. Nothing, not even the Indians, was keeping them back. They intended to settle somewhere and establish homes again. The sight sometimes made Davy sick at heart, because he, too, had been travelling with one of these household wagons; but the Indians had “wiped it out.”

Well, he was in good hands now. Billy Cody would see him through.

“We’ll strike the Salt Creek Valley to-morrow morning,” announced Billy. “Hurrah! I’ll get my pay order to-night, so we can cut away to-morrow without any waiting.”

The morning was yet young when Billy pointed ahead.

“When we get over this hill we’ll see where I live, Red. It’s yonder, on the other side.”

The trail was ascending a long hill. From the top Billy waved his hat.

“There’s the Salt Creek Valley. I can see the[66] house, too. That’s it, down below. Goodby, everybody. Come on, Red.” And with a whoop away raced Billy down the hill.

As he rode he whistled shrill.

“Watch for Turk,” he cried to Red, galloping behind. And presently he cried again: “There he comes! I knew he would!”

Sure enough, from the house, before and below, near the trail, out had darted a dog, to stand a moment, listening and peering—then, head up and ears pricked, to line himself at full speed for Billy. On he scoured (what a big fellow he was when he drew near), while Billy whistled and shouted and laughed and praised.

When they met, Billy flung himself from his saddle for a moment, and he and the big dog wrestled in sheer delight.

“Isn’t he a dandy?” called Billy to Red. “Smartest old fellow in Kansas. He saved my sisters’ lives once from a panther. I’d rather have him than a man any time.”

They rode on, with Turk gambolling beside them. He was a brindled boar hound, looking like a Great Dane.

Now Turk raced ahead, as if to carry the news; and several people had emerged from the house and were gathered before the door gazing. Billy waved his big hat, and they waved back. They were a woman and four girls.

“That’s ma and my sisters,” said Billy. Down he rushed, at full gallop of his mule; Davy thudded in his wake.

“Hello, mother! Hello, sisses!”

“Oh, it’s Will! Will!”

Dismounting, Billy was passed from one to another and hugged and kissed. He was held the longest and closest in his mother’s arms. Turk barked and barked.

“Here, Red; come on,” ordered Billy, of Dave. “Mother, this is my friend Dave Scott. He’s going to visit us, and then I’ll get him a job on the trail. These girls are my sisters, Dave. Don’t be afraid of them. Take care of him, Turk. He’s all right, old fellow. He’s a partner.” And Turk, sniffing of Davy and wagging his great tail, seemed to understand.

“Any friend of Will’s is more than welcome,” said Billy’s mother, and she actually kissed Dave. The girls shyly shook hands, and he knew that they welcomed him, too.

Then they all went into the house, where Billy must sit down and tell about his experiences. That took some time, for he had been gone a year. But before he started to talk and answer questions, he said: “Here, ma; here’s my pay check. How do you want it cashed—gold or silver?”

“For goodness sake, Will!” gasped Mother Cody, while his sisters peeped. “Is this all yours?”

“No,” said Billy, solemnly shaking his head. “I can’t say it is, mother.”

“Then whose is it?” she asked anxiously.

“Yours,” laughed Billy.

The Cody house was a heavy log cabin of two rooms and a rough roof, in the Salt River Valley across which ran the Salt Lake overland trail. Fort Leavenworth and the Missouri River were only four miles eastward, and two miles below Fort Leavenworth was Leavenworth City. The Cody farm had been located by Billy’s father as soon as Kansas had been opened for settlement, in 1853, but Billy’s father had died two years ago. As Davy soon saw, Billy was the man of the family, and whatever he earned was badly needed.

It was good fun visiting at the Codys. There was Mrs. Cody and the four girls, Julia, Eliza, Helen and May, who seemed to think that Billy knew everything. Julia was older than he, but the others were younger. There was Turk the big dog; and not far from the Cody place lived other settlers who had children. But among all the boys Billy Cody was the only one who had been out across the plains drawing man’s pay with a wagon train.

The Codys lived right at the edge of the Kickapoo Indian reservation. Billy knew the Indians and they liked him; he could shoot with bow and arrow, and could talk Kickapoo, and had learned a lot of clever ways to camp and travel.

Best of all, past the Cody place, across Salt Creek Valley wended the Overland Trail—climbing the hill here, and disappearing into the west. Over it always[69] hung that veil of dust from the teams and wagons that had set out. All kinds of “outfits,” as Billy called them, travelled it: the straining, creaking “bull trains,” carrying freight for the big freighting firm of Russell, Majors & Waddell; the settlers, bound westward, with their canvas-topped wagons bursting with household goods, the women and children often walking alongside; soldiers, for the forts of the Indian country; gold-seekers with pack mules; “tame” Indians, from the reservations or from outside villages; parties returning for the “States,” from California and Utah and the mountains, some of them with droves of horses, some without anything at all.

It was a very important highway, this Salt Lake, California and Oregon “Overland” Trail, which had one beginning at Leavenworth on the Missouri, only six miles from the Cody place; and the Codys saw all the travel that started on it. So no wonder Billy had made up his mind to be a plainsman and work on the trail; and no wonder that Davy wanted to do likewise. It seemed a useful work, and much needed; but it called for stout mind and brave heart, as well as sturdy body. As for sturdy body the work itself made people strong. The proper mind and heart were the more necessary qualifications.

Billy soon took the two mules into Leavenworth, and returned them to the company. When he came home, he gave his mother a double handful of gold pieces.

“Will, it doesn’t seem possible that you’ve earned all this!”

“Well, I guess if you’d been along, ma, you’d have known that I earned them; wouldn’t she, Dave!” laughed Billy. “I earned enough just while I was in the mule fort to keep us the rest of our lives—only, I haven’t got it yet.”

“You’ll never go out again, will you, Will?” appealed his mother anxiously. “Promise me.”

Billy put his arms about her and hugged her tight. She was a frail little mother, not nearly as strong as Billy, and she never felt well, Billy had explained to Dave. Now he said, holding her: