BOYS HUNTING

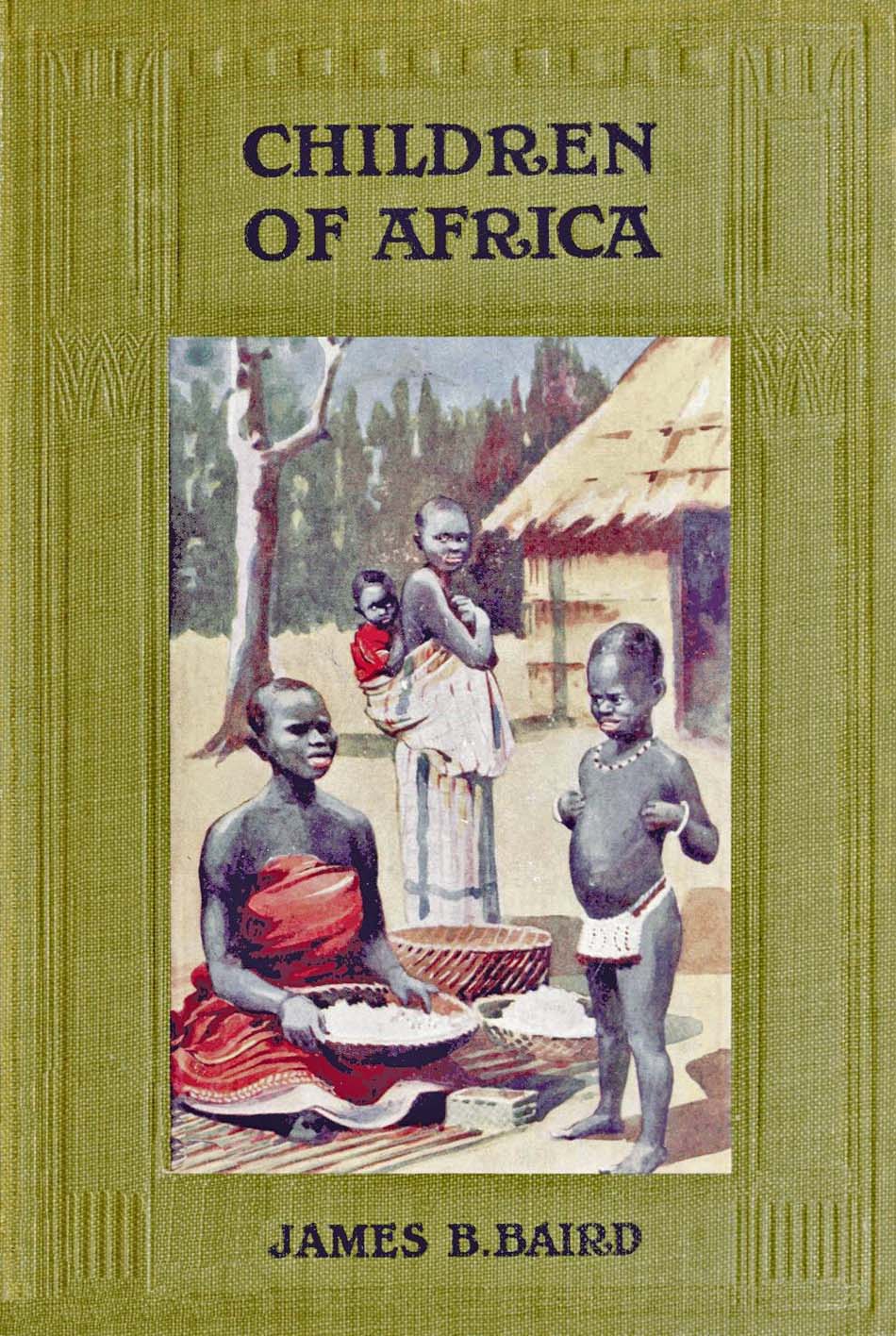

CHILDREN OF AFRICA

BY

JAMES B. BAIRD

AUTHOR OF

“NYONO AT SCHOOL AND AT HOME”

WITH EIGHT COLOURED ILLUSTRATIONS

FLEMING H. REVELL COMPANY

NEW YORK CHICAGO TORONTO

PRINTED BY

TURNBULL AND SPEARS

EDINBURGH

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | Introductory | 9 |

| II. | The Dark Continent | 10 |

| III. | The Great Races of Africa | 14 |

| IV. | An African House | 17 |

| V. | The African Child | 22 |

| VI. | An African Village | 25 |

| VII. | Games | 32 |

| VIII. | Fairy Tales | 40 |

| IX. | Animal Stories | 43 |

| X. | Finger Rhymes and Riddles | 49 |

| XI. | Food and Ornaments | 56 |

| XII. | The African’s Belief | 62 |

| XIII. | The African in Sickness | 66 |

| XIV. | Magic Medicine | 72 |

| XV. | The Dance and Musical Instruments | 76 |

| XVI. | Hindrances to the Gospel | 80 |

| XVII. | Methods of Mission Work | 84 |

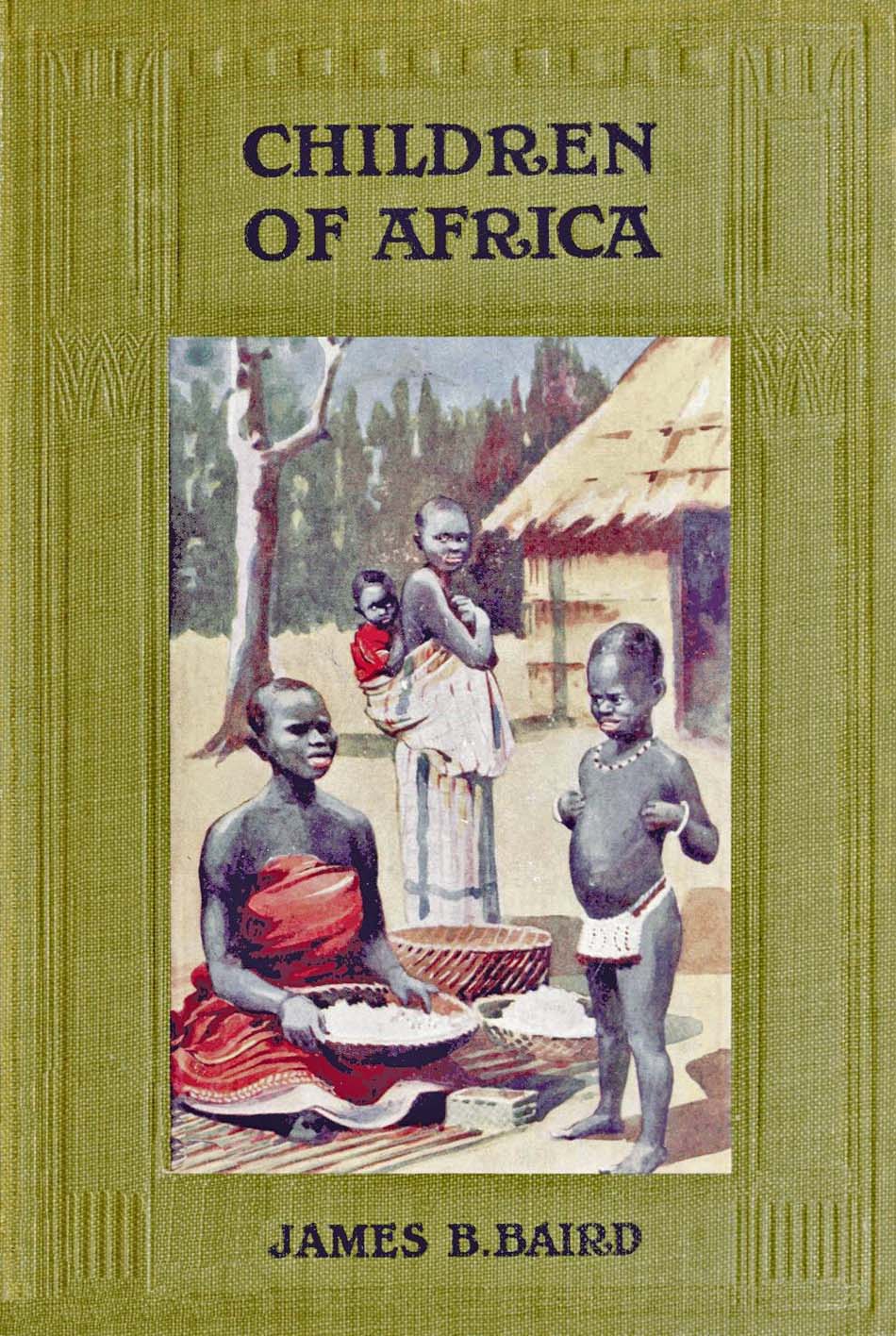

| 1. Boys Hunting | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

| 2. A Village Hut | 18 |

| 3. His First Suit | 22 |

| 4. An African Village | 30 |

| 5. A Bathing Pool | 60 |

| 6. Drill replaces the Dance | 78 |

| 7. A Mission School Class | 88 |

| 8. Attacked by a Leopard | 92 |

In preparing his coloured pictures, the artist has received much help from photographs kindly supplied by Mr J. W. Skinner and Mr A. J. Story.

There is not one of you, my dear boys and girls, who does not know this oft-sung missionary hymn. But if there is, then of this I am sure, there is not one who knows it who does not love it, for it is one of the most beautiful of all our hymns. Since it was written many years ago by Bishop Heber, hundreds and hundreds of young voices have sung it; hundreds and hundreds are singing it to-day; and hundreds and hundreds will yet sing it.

It is a great call to us who know Christ our Saviour to spread abroad into all heathen lands our knowledge of Him who came down from heaven and died to save mankind. And nobly has the call been responded to. The Christian Churches have sent forth messengers into all the ends of the earth to preach the “glad tidings of great joy which shall be to all people” in obedience to the command of their[10] risen Lord who said, “Go ye, therefore, and teach all nations.”

So in our own day we find that Christ’s ambassadors have gone into every continent and penetrated into the most distant lands; that the Bible, or some part of it at least, has been translated into many different languages; and that the lives of countless numbers of native peoples have been made purer and holier and happier by their knowledge of Him who loves them.

As you all know one of the continents of the earth is called Africa—the dark Continent; and it is about Africa and its children I want to write to you.

Africa has been called the Dark Continent, and the name is suitable in more ways than one. To the European people it was for ages a dark continent, because it was unknown, that is, unexplored by them. The name is also appropriate because Africa is the home of millions of dark-skinned people. But from a Christian point of view Africa is the dark continent, because over most of its inhabitants there still hangs a black cloud of heathen darkness that shuts out the glorious rays of the Gospel of Light and Love.

Of course you must know that Africa has not all been an unknown land. The northern part of it, which borders the Mediterranean Sea, has been known from ancient times. And is not Egypt the land of the Nile and the home of the Pharaohs in Africa,[11] although we sometimes do not realise it? But it is not so much of these northern lands that I want to tell you as about the far greater portion that stretches away south over the Equator right down to the Cape. This part was until not so long ago the dark unknown continent, the land of those teeming millions of dark-skinned people who lived out their lives without ever hearing the Gospel story and without knowing the love of God for the children of men.

For hundreds of years very, very little was known of this vast land lying away to the south. The ancient peoples must have been afraid to explore it, and it is no wonder, for Africa is a land full of dangers and difficulties that must have appeared overwhelming to the ancients. Here is a description of part of a voyage along the African Coast made in the old days. I read it the other day in a nice book about Central Africa. “Having taken in water we sailed thence straight forwards until we came to a great gulf which the interpreter said was called the Horn of the West. In it was a large island, and in the island a lake like a sea, and in this another island on which we landed; and by day we saw nothing but woods, but by night we saw many fires burning, and heard the sounds of flutes and cymbals, and the beating of drums, and an immense shouting. Fear came upon us, and the soothsayers bade us quit the island. Having speedily set sail, we passed by a burning country full of incense, and from it huge streams of fire flowed into the sea; and the land could not be walked upon because of the heat. Being alarmed we speedily sailed away thence also, and going along four days we saw by night the land full of flame, and in the midst was a lofty fire, greater than the rest,[12] and seeming to touch the stars. This by day appeared as a vast mountain called the Chariot of the Gods. On the third day from this, sailing by fiery streams, we came to a gulf called the Horn of the South.”

After reading such a description do you wonder that the ancients left the land to the south severely alone? We to-day can give a very simple explanation for the above fiery exhibition. These ancient mariners had evidently visited that part of Africa at the time of the bush fires and were consequently appalled.

In the year 1486 a Portuguese navigator, called Diaz, sighted the Cape of Good Hope; and a fellow countryman, Vasco da Gama, a few years later, discovered Natal and the Cape route to India. But of inland exploration there was little or none till men like James Bruce and Mungo Park made their famous journeys in the interior, the one on the Blue Nile, and the other on the Niger. Then bit by bit our knowledge of the interior of Africa was added to by such brave men of whom Dr Livingstone is the most famous.

If you ever get the opportunity of looking at an old map of Africa you will find that most of the interior is blank. But now the map of Africa is filled with names and features that are known to us through exploration. Mighty rivers and great lakes have been discovered, and mountains of which the ancients only dreamed are familiar to us. All honour to the brave men who have laid us so heavily under their debt, and to no one more than to David Livingstone, whose noble example was as an inspiration, and who as missionary and explorer laid down his life for the Dark Continent.

But for many years the European nations only looked upon Africa as a land whence slaves were to[13] be taken for their plantations in the New World. And this part of the history of Africa is a dark blot upon their fair fame. What with the European slave-buying in the West, the Arab slave-hunting in the East, and the chiefs perpetually at war and enslaving one another’s people, the lives of countless numbers of these ignorant people were made miserable in the extreme.

The village lies slumbering peacefully in the hollow in the midst of its gardens of maize and sweet potatoes. It is silently surrounded before dawn by the cruel Arab and his men. Shots ring out. The startled inhabitants rush forth into the grey morning with shouts of “Nkondo!” (“War!”) “Nkondo!” (“War!”) The men who resist or try to flee are ruthlessly shot down. Houses and gardens are burned and destroyed, the dead and dying are left where they fall, round the necks of the living is riveted the hateful slave stick, and the gang is on its way to the coast leaving behind only the abomination of desolation. Too often, alas! have the children of Africa tasted of this bitter cup.

And now that the European people know the sin from which they were freed by the mercy of God, it behoves them to try their best to make up to the black people for the injury they formerly did them. That much is being done we know for the whole continent is marked out as belonging to the different European nations and is ruled by them. So the days of the old tribal wars are over and the slave-hunter has disappeared from the land.

The future of the Dark Continent you will then see lies now to a large extent in the hands of the people of Europe. The old rule of the native chiefs has in[14] most places passed away, and in others is rapidly passing. The power has gone into the hands of the white man. Pray God he may use it wisely and guide his black brother towards the green pastures as becomes a follower of our Lord and Saviour, Jesus Christ.

Before I begin to speak to you about the children of Africa, I would like you to understand how the people of Africa are separated into different families or divisions. There are in Africa nearly two hundred millions of people, but they do not all belong to the same race. The three big families are the Berbers in the north, the Negroes in the middle, and the Bantus in the south. Besides these there are some smaller divisions to which belong the Pigmies or Dwarfs, those strange little people whom Stanley encountered on his famous journey through the terrible forests of the Congo. Then there are the Hottentots and the Bushmen of the south-west corner of Africa, who have been driven into the desert and hilly places by the more powerful invading Bantu tribes.

Many long years ago the whole of the northern part of Africa was invaded by large numbers of fierce Arab tribes. They were very warlike and soon overran the whole country and settled down in it, and lived side by side with the original people of the country as their masters, but with whom they afterwards mingled. So the North Africans of to-day are, you see, a people of mixed race.

[15]These hordes of conquering Arabs who overran the country were Mohammedans, and they forced their religion upon the people among whom they settled. Mohammedanism is therefore the chief religion of the north of Africa. Now these Berber tribes are very dark-skinned when compared with Europeans, but they do not belong to the black people. They are, in fact, classed along with the white races.

The true black people are the Negroes, and their home is in the middle part of Africa which stretches eastwards right across from the West Coast. They are the people with the black skins, the woolly heads, the thick lips, the flat noses, and the beautiful white teeth. It is they whose forefathers were bought as slaves and taken to America where we find their descendants to-day. They were a heathen people, and had many cruel customs, and some of them were cannibals. Mohammedanism has come upon them from the north and the east, and a great many of them now belong to that religion.

The home of the Bantu people is the great southern portion of Africa. The Bantus are not so black as are the Negroes, nor are they quite so thick-lipped and flat-nosed. But in all other ways they are very similar to their Negro neighbours. They are a heathen people although Christianity has made good progress among them. They are brave and intelligent, and are showing themselves able to adopt a higher and better way of living.

The other smaller tribes, the Pigmies, the Hottentots, and the Bushmen are far below the Negroes and Bantus in intelligence. The first of these, the Pigmies or Dwarfs, inhabit the dense forest region of the Congo, and not very much is known about them even to-day.[16] The Hottentots and the Bushmen live away down in the extreme south-west of Africa and the Kalahari Desert. It is said that they are the descendants of the older inhabitants of Africa, who had to seek refuge in the hills and deserts from the powerful Bantu tribes who invaded and seized their country.

Now I think this will be quite enough information about the different races dwelling in Africa. What I want you to understand is that the whole of the northern portion of Africa is Mohammedan, that the Negro people are many already Mohammedan, and that others are rapidly being converted to that religion, and that the Bantu people are mostly yet heathen, while some have become Christian, especially those of the south.

In Africa there is a great war going on. Three mighty forces or powers are fighting against one another, and victory cannot go to them all. These great forces are Mohammedanism, heathenism, and Christianity. But to those of us who know the African, it is plain that the great fight will be between the first and the last, that the Africans will be ruled by the Cross or the Crescent, that the Bible or the Koran will be their Holy Book, that Mohammed or Christ will be their guide in this life.

Already we see that the whole of the north follows the Prophet of Mecca. The nature-worship of the Negro and Bantu, although yet strong, will pass away with the passing years. The south is largely Christian, and Christianity is pushing up northwards. Christian missions are attacking the strongholds of Mohammedanism and heathenism in the north, west, and east, in Egypt and the newly opened Soudan.

You must be wondering when you are going to hear about the children of Africa, for I am sure you want to know about them now, the little sons and daughters of the big black people I have so far written about.

Well, it so happens that I am sitting writing this story in a native hut in Africa, many thousands of miles away from you; and if any of you wanted to come and join me here and see for yourselves, you would have to travel a good many weeks to reach me. Will you let me first try to describe this house I am in, and the village of which it is part, as being what most African huts and villages are like, and in which black boys and girls are born and play.

This hut is a square one, and a good deal larger than you would imagine. It is the size of a small cottage at home. Long ago most of the huts were round, I believe, and indeed many of them are so yet. But square ones have come into fashion here, for even in far-off Africa there is such a thing as fashion, and it can change too. This hut is divided into three rooms. The middle one is provided with a door to the front and another to the back. The rooms on each side have very small windows like spy holes looking out to each end. All round the house runs a verandah which prevents the fierce rays of the sun from beating against the walls of the house and throws off the heavy showers of rain of the wet season clear of the house. The whole house is built of grass and bamboos,[18] and is smeared over with mud inside and out. The roof, supported by stout cross beams in the middle of the partition walls in which other forked beams stand, slopes not very steeply down to the verandah posts which hold up its lower edges. It is heavily thatched with fine long grass. The owner knows by experience what a tropical thunder-shower means, so he leaves nothing to chance in thatching his house.

In the middle of the floor in the room with the doors a small hole has been scooped. It is surrounded with stones and forms the cooking hearth, although there is also attached to this house a very small grass shed about a dozen yards away at the back of the house, which is used as a kitchen on most occasions. The doors are made of grass and bamboos, and at night are put in place and held firm by a wooden cross bar. Such is the house of a well-off native of Africa. It takes but a few weeks to build and lasts but a few years.

Of course in a house with such small windows it is always more or less dark. In the end rooms with the spy holes it is always dark to me. But black boys and girls do not seem to mind this. In fact I believe they are like owls and cats, and can see in the dark. I am certain though of this that they can see ever so much better than white children can.

A VILLAGE HUT

There is not much to look at in the way of furniture in a black man’s house. Here is a table made in imitation of a European one and some chairs too, whose backs look forbiddingly straight, a few cooking pots, some sleeping mats, a hoe or two, some baskets, and some odds and ends complete the list. What[19] surprises a white man is the number of things the black people can do without. For instance, if a white man wants to travel in this country, he must first of all gather together a crowd of natives to carry him and his belongings. He must have a tent and a bed, pots and pans, boxes of provisions, a cook, and servants, before he can travel in comfort. But if a black man goes on a journey he simply takes a pot and some food with him, and maybe a mat and blanket, takes his stick in his hand and his bundle on his shoulder and off he goes, it may be to walk hundreds of miles before he comes to his destination.

To-day there is no fire in the hearth. There is no chimney in this house so I could not have a fire and enjoy my stay. The owner, however, would not mind the smoke from the firewood. He is used to crouching over a fire and his eyes get hardened. I see in one corner there is a heap of grain called millet, and in another a white ant-heap. It has risen in the night for I did not notice it before, and I am glad that none of my belongings were in that corner of the room. Nothing but iron seems amiss to the white ant. His appetite is terrible and he can play sad havoc with one’s property in a single night. There is grain in one corner I have said, and consequently there are rats.

The Pied Piper of Hamlin of whom you have all heard would find plenty of rats to charm in any African village. Then in the houses there are many kinds of biting insects, and some that don’t bite, but look ugly. The mosquito is calling ping! ping! everywhere, and night is made endurable only by retiring under a mosquito net. The mosquito is the most dangerous insect in Africa, for it has been[20] found out by clever doctors that it is the mosquito bite that causes the dreaded malaria fever.

In tropical Africa nearly all the insects bite or sting, even innocent-looking caterpillars, if touched, give one itch. Nor may you pull every flower you see, for some of them are more stinging than nettles. To-day I came across two boys hoeing a road. One was a bright fellow who kept things lively by singing snatches of songs and whistling at his work. When I came near I spied a fine large glossy black beetle hurrying away after having been thrown up by the hoe. I asked the lively youth what kind of insect it was. In reply he dropped his hoe and pounced upon the unfortunate beetle and held it up to me for inspection. “Does it bite?” I asked, astonished. “Oh! yes,” he said, “look.” So saying he stuck the point of one of his fingers close to the head of the angry creature, which promptly seized it with its pincers.

But one gets used to these pests, and even the sight of a spider the size of a two-shilling piece running up the wall does not disturb one. There is one insect, however, you may not despise, and which you can never get accustomed to, the red ant. He comes in millions, and if he deigns to pay your house a visit while on his journey, you had better leave him in possession of the place. Unless you happen to head him off early with burning grass and red hot ashes you need not stay to argue with him. Everything living disappears before him, rats, mice, lizards, cats, dogs, boys and girls, men and women give way before his majesty, the red ant.

I remember watching for half an hour an army of red ants on the march. They were streaming out[21] from a small hole in the grass, crossing over a hoed road, and disappearing into another hole in the grass on the other side. Each was carrying a tiny load that looked like a small grain of rice, and was hurrying after his neighbour as if the whole world depended on his speed. Here and there on each side of the hurrying companies were scouts and officers without loads evidently engaged in keeping the others in order and in watching for enemies. What I thought were grains of rice, the boys told me were “ana a chiswe,” that is white ant’s children. Somewhere underground there must have been dreadful war and the red ants were carrying off the spoils of victory.

Next there came along a poor little lizard home by eager and willing—I had almost said hands—pincers. Here a pair were fixed in, there another pair. Everywhere that a pair of pincers could find a grip there was the pair. I pulled the lizard out but it was quite dead. So I pushed it back into the excited line and it was soon on the march again. After a little there came past a curious round little object into which dozens of ants were sticking and which with ants swarming atop was being carried along with the stream. I rescued this strange thing too, because I was anxious to find out what it was—the thing inside this living ball of ants. One of the boys got a basin of water and plumped the ball into it, and with a piece of wood scraped the angry insects and frothy-looking stuff off. Then there was revealed a tiny toad which the boys called “Nantuzi.” It was just like a little bag with four legs, one at each corner. When annoyed it swells itself up like a ball and refuses to budge. When seized by the ants it had promptly covered itself with a frothy, sticky spittle,[22] and so was little hurt. Had I not rescued it, however, it would have been eaten at last overcome by numbers. Then I got tired watching, and left the never-ending ant army still on the march.

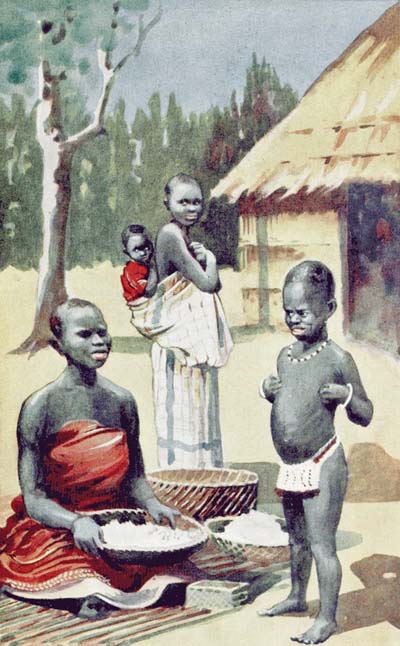

Inside such a house as has been described, and in many a smaller one, are born the children of Africa. At first and for a few days they are not black. I am told they are pink in colour and quite light, but that they soon darken. The mothers and grandmothers are very pleased to welcome new babies and bath and oil them carefully. Nearly all the women one meets about a village have children tied on their backs, or are followed by them toddling behind. These mites glisten in the sun as they are well oiled to keep their skins in good condition.

In some tribes very little children have no names. You ask the mother of an infant what she calls her baby, and she replies, “Alibe dzina”—It has no name. I once asked the father of a plump little infant what the name of his child was. He told me that it had not been named yet but that when the child would begin to smile and recognise people it would get a name. “Well,” I said, “when he smiles call him Tommy.” Months after I saw the child again, a fine boy he was too, and Tommy was his name. But alas! Tommy did not live more than two years. He took some child trouble and died.

HIS FIRST SUIT

Sometimes the father or the mother may give a child[23] its name, or sometimes a friend may name it. Many of the names have no special meaning, but some of them refer to things that happened or were seen at the time the child was born. Boys’ and girls’ names differ from one another although the difference is not clear to the white man. But if he stays long enough among the black children he will begin to know what are boys’ names and what are girls’. I know a bright boy who is called “Mang’anda.” In English you would have to call him Master Playful. Another child I can recall is called “Handifuna,” which means “Miss they don’t want me.” But wherever the white man is settling in Africa the people are picking up European names; and it is a pity, I think, that the old names will pass away.

Little black children are not nursed and tended so carefully as white children are. From a very early age they are tied on to their mother’s backs and are taken everywhere. It is seldom that an accident happens through a child falling out, for the black children seem to have an extraordinary power of holding on. If mother is too busy another back is soon found for baby to show his sticking-on ability. In any village you may see a group of women pounding corn in their mortars under a shady tree. It is hard work, this daily pounding of corn. Up and down go the heavy wooden pestles. Backwards and forwards go the heads of the babies tied on the mothers’ backs. At each downward thud baby’s neck gets a violent jerk, but he is all unconscious of it, and sleeps through an ordeal that would kill his white brother. Again a woman with an infant on her back may go a journey of many miles exposed to the full blaze of the African sun. Yet baby is quite comfortable[24] and never gives a single cry unless when he is hungry.

Then black children have no cribs and cradles as have white ones. When mother is tired of baby, and there is no other back at hand, she simply lays him down on a mat and leaves him to himself to do as he likes. If he makes a noise, well he can just make it. He will disturb nobody, and is allowed to cry until he is tired. Unless he is known to be ill, his squalling, be it never so loud, will attract no attention. Most of the mothers are very proud of their children, and oil them and shave their woolly heads with great care. But in spite of all this care on the mother’s part, great numbers of the babies die. Very often they are really killed through their mother’s ignorance of how they ought to be fed and nursed when sick. Then diseases like smallpox pass through the villages at intervals and carry off hundreds of children.

A black infant is not clothed like a white one. If his mother is very proud of him he will have a string of beads round his neck or waist. Round his fat little wrist or neck you will often see tied on by string a small medicine charm, put there by his fond mother to protect him against disease or evil influence. When the babies are big enough to toddle they begin to look out for themselves, and when they have fairly found their legs they go everywhere and do almost anything they like so long as they do not give trouble.

A little boy’s first article of clothing may be made of different coloured beads carefully woven into a square patch, which he wears hanging down before him from a string of beads encircling his waist. Or it may perhaps be only the skin of a small animal worn[25] in the same way as the square of beads. He may, however, begin with a cloth from the beginning. If so his mother provides him with a yard of calico, rolls it round him, and sends him out into the world as proud as a white boy with his first pair of trousers.

He gets no special food because he is a child. He eats whatever is going and whatever he can lay his hands upon. Thus he grows up not unlike a little animal. There is not much trouble taken with him. If he lives, he lives; and if he dies—well, he is buried. No fond lips have bent over him and kissed him asleep, for kissing is not known to his people. Nor has he learned to lisp the name of Jesus at his mother’s knee. It is not that his mother does not love him, for she does in her own peculiar way. But all are shrouded in ignorance, father, mother and children, all held in the grip of dark superstitions from which nothing but the light of the Gospel of Love can free them.

Shall we go round the village now? Well come away and we’ll have a walk through it. But as we are strangers and white, I must warn you that many pairs of curious eyes will be watching us when we know not, and all we do and say will be the talk of the village for a long time to come. It is not every day that the villagers get such a good look at a white person, and they will take advantage of their chance to-day. Babies on backs will cry if we come near[26] them, and little mites that can run will disappear behind their mothers and peep out at us, feeling safe but very much afraid. In fact, many of the women frighten their naughty children by telling them that if they do not behave better they will send them to the white people, who will eat them. Consequently when a white man comes along the children often scatter in terror as from a wild beast. And would not white children do just the same from a black man if they were told that he might eat them.

In a certain African Mission not long after school had been started for the first time, it was found necessary to build a kiln for the burning of bricks. But the eyes of the children had been watching the building, and whatever could it be but a large oven in which to cook them. So the whole school fled pell-mell to their homes. Of course you must remember that in several different parts of Africa some of the tribes were cannibals, and even in our day there are still tribes among which the eating of human flesh is not unknown.

Here we come to a house not unlike the one we have already described to you, but smaller and not so neatly finished. The owner will not be so well-off as the owner of that we occupied. Let us go near along this path. Here comes an old lady to receive us, and there go the children round the corner, and off goes baby yonder into tears, and even the dogs begin to bark. Banana trees grow all round the house, and yonder is a small grove of them on the other side of the courtyard. They are waving a welcome to us with their large ragged leaves. The fruit is hanging in bunches here and there on the old trees, and is evidently not yet ripe.

[27]But before we are introduced to the old lady, who is coming to meet us, let us take a hasty glance round about. First we see that the children are getting braver, and are, beginning to show themselves now. Ragged looking little things they are, who do not look overclean. The skin of their bodies is too white to have been washed recently. Isn’t it strange that a black boy when he is dirty looks white; just the opposite from a white boy, who, when he is dirty, looks black. The mother of the crying child has turned round so as to shut us off from baby’s frightened gaze. In one corner of the courtyard is a pot on a fire, the contents of which are boiling briskly. This we are informed is to be part of the evening meal which is in preparation. It seems to us but a mass of green vegetable. Really it consists of juicy green leaves of a certain kind plucked in the bush. Over there in the shade of the bananas stand one or two mortars in which the women pound their grain, and without which no village, however small, is complete. On the verandah of the house stands the mill—a very primitive one. A large flat stone slightly hollowed out holds the grain which is ground down by another stone, a round one, being rubbed backwards and forwards over the hollow one. Snuff too is ground from tobacco in this way, for many of the men enjoy a pinch of snuff and not a few of the women like to smoke a pipe. A fierce-looking little cat is blinking up at us, watching us narrowly through the dark slits in its large yellow-green eyes, seeming in doubt whether to run off or to put up its back at us. A sleeping mat, made of split reeds, and spread out on the ground near the mortars, is covered with maize ready to be pounded. Two or three baskets are[28] lying about, some shallow, some deep, some large, and some small. That stump of a tree there serves as a seat when the shade of the bananas is thrown on it. And down on the whole is pouring a flood of tropical sunshine, so hot that we are glad to retire into the shade of a friendly tree.

But the old lady is come and offers us her left hand. Her arms from the wrist almost to the elbow are covered with heavy bracelets, and her legs, from the ankles half way to her knees, are laden with great heavy anklets of the same metal. Clank! clank! clank! like a chained prisoner goes the poor old soul when she walks. Long ago she would carry these huge ornaments with no difficulty, and not a little joy. But now, although proud of them still, no doubt, they must be a trouble to her slipping up and down on her withered arms and legs, for she has tried to protect her old ankles by wrapping round them a rag of calico to keep the brass from hurting. She is dressed in a single calico, none too new, but, we are pleased to see, very clean. Other calicoes doubtless she will possess, carefully stored away and hidden in a basket in the darkest corner of her house.

Her old face is a mass of wrinkles and she has lost nearly all her teeth. But her upper lip! What a sight! Poor old creature, what a huge ring there is in it. Why, we can see right into her mouth when she speaks, and to us it is not a pleasant sight. This ring, seen in many old women, is called here a “pelele.” Men do not wear it. When a girl is young her upper lip is bored in the middle and a small piece of bone is put into the hole to keep it open. Gradually larger and larger pieces are put in until the full sized “pelele” is reached. Sometimes[29] these rings are as much as two inches in size, and the upper lip is fearfully stretched by wearing them. It hangs away down over the lower lip, and the tongue and inside of the mouth are seen when the old “pelele” wearer speaks.

The old dame is very polite but you can see that she is afraid of us and will be quite glad when we go elsewhere. She says her cat is not a bit fierce but is a first-rate ratter, so much so that there isn’t a single rat in her house.

Now to the next house through the bananas. It is like the last and very much the same kind of things are lying about. But instead of a cat we are met by the usual African yellow-haired dog. He, too, is suspicious of us, but retires growling. A hen is busy scraping among the rubbish at the side of the house to provide food for her numerous offspring that chirping follow her motherly cluck! cluck!

Between this house and the last stand the grain stores, round giant basket-like things with thatched roofs. The largest ones are for holding the maize, and the small ones for storing away the beans. That low building there built of very strong poles is the goat house. It needs to be strong as the hyæna and leopard, and even the lion sometimes pay the village a visit at night. And woe betide the poor goats if a fierce leopard should get in among them. Not satisfied with killing and eating one he will tear open as many as he can, simply for the pure love of killing.

The houses in the village are all much the same as that you have already read about and number about twenty. They are built here, there, and everywhere with no regard to plan or regularity. The corner[30] of the verandah of this one projects out over the footpath, and we have actually to cross the verandah to get down to the well. The owner only laughs when we ask him why he built his house so near to, and partly upon the path. Some day he says he will hoe a new path to go round about his house. That is African all over. He will do things some day. He thinks the European mad to be such a slave to time.

The owner of each house greets us with a smile, and we are well received by all except some of the old people who are really afraid of white people, and who, while glad to see them when they come to visit their village, are still more glad when they go away. We have gathered quite a crowd of little people about us, and they follow us round very respectfully, watching all we do, and looking at all we have on. Many of them you see suffer from ulcers.

Here and there are patches of tobacco and sweet potatoes, but most of the gardens are outside the village proper. Their chief crops are maize, millet, sweet potatoes and cassava root. Paths twist about and cross one another in a marvellous manner. This one leads down to the stream, that to the next village; this to the graveyard in yonder thicket, a place shunned by the children, that to the hill. A white stranger promptly gets lost in African paths and has to give himself up to the guidance of the native. The whole country is a vast net-work of such snake-like paths, and I verily believe you could pass from one coast to the other along them.

AN AFRICAN VILLAGE

But just as we get to the far end of the village there is something to interest us. It is a very small house well fenced in. On the roof and exposed to[31] the sun and rain are spread and tied down a blanket and various calicoes. This must be the grave of someone important. It is, and we ask to be allowed to see inside. Permission is given because it would not be polite to refuse it, not because it is given willingly. It proves to be the grave of the headman of the village who died about a year ago. His clothes and blanket, of no further use, have been spread over the roof covering the grave, and on the grave itself are lying his pots and baskets and drinking cups. In a small dish some snuff has been placed.

His house which was only a few yards away had been destroyed with much ceremony after the death of the owner, and the site is now heavily overgrown with castor oil plants and self-sown tomatoes. Not far from where his house had been is the tree at the foot of which he had offered up sacrifices to the spirits of his forefathers. Being the chief of the village he was buried beside his house and not away in the bush where the common people are laid to rest. I asked the children if they were not afraid of this grave in the middle of the village, and they said that during the day they were not afraid because the noises of the village kept the spirits away. All the time we were visiting this sacred place the old woman with the “pelele” was following us at a short distance, not at all too pleased to see us pry into such places, but too afraid to tell us so. She was much relieved when our steps were turned elsewhere.

Such is the home of the African children. Here they are born and grow up and play and laugh and cry to their heart’s content. It is a careless, easy life with nothing beyond food and clothing to be interested in, and not a thought for the morrow. But[32] we are here to give them a new interest in life. In this large courtyard we gather all the people of the village together, and with the western sun shining upon the little crowd we tell them of Jesus and give them something more to talk about than ourselves and our clothes. Here in the quiet of this African village, surrounded by the banana trees, is told once more the story of the love of Jesus. The old woman with the ring in her lip says our words are only white men’s tales, and will go on in her own way teaching the children the superstitions of her forefathers.

The seed we sow will not all fall on stony places. Some of it will fall on good ground and bear fruit in the lives of these simple village people.

When black children are small, the boys and girls play together; but when they grow up a bit the boys separate themselves from the girls and have their own games. They would never dream now of playing with the girls. The latter are not strong and brave like boys, and must play by themselves. In this respect they are just like white boys who feel ashamed to play with girls.

One of the boy’s greatest enjoyments is to go hunting in the woods with their bows and arrows. It is small birds they want, and their keen eyes scan the leafy boughs for victims of any kind. It does not matter how small or pretty a bird may be, down it[33] comes struck by a heavy-headed arrow. Victim and arrow fall back down at the feet of the cunning shooter. The reason why the boys kill even the smallest bird is that everything, no matter how small, will be eaten. They do not eat meat as white people do. All they want is just enough to make their porridge tasty and to let them have gravy. So any small animal, such as you would despise, is acceptable to them.

Pushing through the bush is difficult work, but the black boys do not seem to mind it although the grass towers far above their heads. All they fear is, that perhaps they may tread upon a snake or disturb a wild beast, but in the excitement of the chase they soon forget all about snakes and wild beasts. Should a boy be very good at imitating the call of birds he gets ready an arrow with many heads—six or seven. This he makes by splitting up one end of a thin bamboo and sharpening each piece. These ends he ties in such a way as to separate them from one another, leaving one in the middle. He then takes his bow and his newly made arrow and goes off to the bush. Having selected a likely spot he quickly pulls the grass together loosely over his head to hide him from above, crouches under it and begins to imitate the call of a certain bird of which kind he sees many about. In a short time the birds come hovering over the grass concealment, and the boy, watching his chance, sends his arrow into their midst. In this way several birds are obtained at a time.

Then the boys hunt small game, such as rabbits, with their dogs. The dogs chase the rabbits out of the long grass, and the boys stand ready to knock them over with their knobbed sticks. Another favourite occupation is to go down to the gardens[34] with hoes and dig out field-mice which are relished just as much as the birds are.

Traps of various kinds are set to catch game. Some are made with propped-up stones that fall down and crush the unwary victims. Some are made with a running noose that strangles the unfortunate beast. A very simple kind for catching birds is made out of a long bamboo. A spot is first chosen where birds are likely to gather together quickly. The bamboo is then split up the middle for about a third of its length. The ends, which if left to themselves would spring together with a snap, are held wide apart by a cross-pin of wood. To this pin is attached a long string which goes away over to the grass where the youthful trapper lies hidden. A handful of grain is then scattered over the space between the split ends of the bamboo. When everything is prepared the eager youth retires to hide in the grass and watch the birds. It is not long before several are enjoying the bait, and when a sufficient number have entered, the boy pulls the string which displaces the cross-pin and the two ends of the bamboo close together with a snap. The poor birds are not all quick enough to escape, and several lie dead to reward the cunning of the trapper. Such doings you would hardly call games, but so they are considered by the black boy, for whenever I ask them to tell me what games they play at, hunting and trapping are always among those given me.

Of games proper, hand-ball is a great favourite, and is played in the courtyard or any other cleared space. This is a kind of ball-play in which two sides contend against one another for possession of the ball, which is usually just a lump of raw rubber. When[35] the sides have been chosen, and it matters not how many a side so long as there are plenty, the game is started by a player throwing the ball to another boy on his side. Thus the ball passes through the air from player to player, it being the endeavour of the opposite side to intercept it and of the first lot to retain possession of it. Every time the ball is caught all the players with the exception of him who holds the ball, clap their hands together once and sometimes stamp with their feet.

The players may dodge about as they like and jump as high as they like in their endeavour to catch the ball. It is an excellent game and a hard one, and would be enjoyed, I am sure, by white boys, for no lazy bones need ever think he would get the ball. Only he who is quick of hand and eye would ever get a chance, and the more clever the players, the harder is the game. After the ball has gone round one side a certain number of times the players on that side shout out a little chorus and clap their hands to proclaim their victory. Then the game begins afresh and is carried on with such vigour that when finished each boy is sweating freely and glad to retire to a cool place to rest.

A quiet game in contrast to the hand-ball is the native game of draughts in which the opponents “eat” one another to use the native expression. Four rows of little holes are made in a shady place. The opponents sit on opposite sides and each has command of two rows. Sometimes there are six and at other times eight holes in each row. Each player has a number of seeds or little pieces of stone or other small things, about the size of marbles and he places one in each hole leaving a certain one empty. Then[36] begin mysterious movements of taking out and putting in. So it seems to the European at first. But there are rules, and the black boys know them well. The idea is to move one’s own “men” one hole along at a time, until those in any hole surpass in number those in the enemy’s hole opposite when they are taken and placed out of the game. The game is won when one is able to take the last remaining “man” on his opponent’s side. To the boys it is a very engrossing game, and they often forget all about time over it. Sometimes the holes are chiselled out on a board and the game played by the grown-up people on the verandah of their houses.

Quite a different game from any of those described is that played by both boys and girls among the cassava bushes in the gardens. When one finds a single leaf growing in a fork of a bush he calls out to his neighbour, “I have bound you.” The neighbour considers himself bound till he finds a leaf in a similar position, when he calls out, “I have freed myself.” He who first finds the leaf binds the other, and so the game goes on till the children are tired of it. The boys have another use for the cassava leaf. They pluck a nice big one. Then the left hand is closed fist-like, but leaving a hollow in the hand. The leaf is then laid across the hollow, resting on the thumb and the bent fore-finger. The open, right hand is now brought down whack upon the leaf, which is split in two with a loud report.

Hide-and-seek you all know. I think it must be played by children all over the world. It is played by the black children of Africa and enjoyed very much. There are splendid opportunities for hiding in the long grass. You have only to go into it a few feet,[37] and you are completely hidden. Sometimes the black children vary the game from the ordinary hide-and-seek. The seeker will be a wild beast—say a lion—and the hiders will be deer. They go off and hide in the grass and the lion has to find his prey. Sometimes the hider will represent a deer and go and conceal himself, and the seekers will be hunters on the chase. Then if there is water near one will hide in the water and pretend to be a crocodile, and when the others come down to the stream to bathe or draw water the crocodile rushes out on them and tries to seize them by the legs.

The boys also play at war with tiny bows and arrows made of grass stalks. They stand in rows facing one another and try to “kill” one another with their arrows.

There is another good game played by the boys called “nsikwa.” It has no English name or I would have written it instead of the native one. There are sides in this game, but two boys can play it. Of course the fun is better when there are perhaps four or five a side. The boys sit in the courtyard in lines facing one another and about ten feet apart. In front of each player is placed a small piece of maize cob about two or three inches high, from which the grain has been taken. It is then very light and easily overturned. In his right hand each player holds a native top. When all are ready, the players send their tops spinning across the clear space with great force and try to knock down the piece of maize cob belonging to the player opposite. To and fro in the battle are whirled the tops to the accompaniment of shouts and laughter of opponents and onlookers.

[38]Most of the games I have seen are boys’ games, but the girls of Africa can play too like the girls of other lands. But their play mostly consists of trying to do what they see their mothers do. Thus the girls will seize the pestles and try to pound at the mortars. Others will take the winnowing baskets and try if they can do as well as mother in sifting out the hard grains from the fine flour. They also play at keeping house and marriages. They borrow pots and cooking utensils from their mothers and go to the bush and build little houses and make believe to set up house on their own account. If they play this game in the village the girls mark out the walls of the supposed houses with sand, and say, “Here is my hearth, there is my sleeping place, and this is the doorway.” They also make food with mud and invite one another to afternoon mud cakes, and pretending to eat them throw the mud over their shoulders.

When the big people of the village go to work in the gardens the children often go to the bush and build little houses and bring flour and maize and other kinds of food and play at a new village. Then one will be chosen to be a hyena and another will be a cock. The hyena goes off to the grass and hides, and the cock struts about the village. Then someone will call out, “It is night, let us go to sleep.” So they all go to sleep, and in a short time the cock will crow, “Kokoliliko,” which is the black boys’ way of saying “Cock-a-doodle-do.” The hyena will also roar.

Those in the house will awake, and one will say, “It is daybreak,” but others will say, “It is only that foolish cock crowing in the middle of the night.” Then hearing the hyena one will get up, open the[39] door cautiously, and chase the beast away. When the big people go back to the village the children are not long in following them.

Boys and girls also play at funerals. One will pretend to be dead, and the others will gather round in sorrow and mourn over the dead one and lift him up with great ceremony and bear him off for burial. But if I make this chapter any longer I am afraid I may tire you. Let me finish with just one more pastime. Some of the black children play at making little animals out of mud, just as white boys and girls play at mud-pies. The African women do not bake pies, so the children know nothing of the pleasures of mud-pie making. Instead, they make little mud dogs and hens and lions and snakes. These they put out into the sun where they get baked hard. They can then be carried about and played with.

These games are some of the many played by African children, and I hope you will like reading about them. If you could only see the black children play them in this sunny land I am sure you would enjoy it and want to join them. I have watched them often, and as often wished I had a camera to take living pictures of African children at play so that you children at home might be able to see with your own eyes something of what I have but feebly tried to describe to you.

All Africans are great story-tellers. At night round the fire, when darkness covers the land and the boys appetites are appeased, many are the tales told. Let me translate one or two for you.

Long ago there lived a man named Naling’ang’a. He was a very foolish man, for he smoked bhang, and the fumes of this deadly weed had run off with all his wisdom. One day the chief of the village in which Naling’ang’a lived ordered all the people into his gardens to hoe for him, so that the maize might not “walk” with the grass—that it, might not be overgrown.

All the people obeyed the chief’s words and went early in the morning to the gardens, followed by the chief himself. But Naling’ang’a lingered on in the village to have a morning pipe of his favourite bhang. Afterwards, when all the people were already in the gardens hoeing away under the eye of the chief, Naling’ang’a came on alone. On his way he crossed over a stream and arrived at the plain near which were the chief’s gardens.

Lying on the side of the path was an old skull that had been there for many a day, and which Naling’ang’a had often passed. But to-day, because he had been smoking bhang, he was annoyed at it, and took the handle of his hoe and struck the skull,[41] saying, “Tell me, what killed you?” To his horror the skull moved, and said, “My tongue killed me.”

Poor Naling’ang’a was dreadfully afraid, and his knees shook under him hearing this dead thing speak so. But he plucked up courage and struck it again to see if it was really true, and again the skull spoke the same words. Being unable to stand it any longer, for his courage at this second exhibition had deserted him, he turned and fled as fast as his tottering legs could carry him to where the people were digging in the chief’s gardens, and lost no time in telling his story.

At first the people refused to believe him, but because of his earnestness and his frightened condition the chief ordered all the people to stop hoeing, and follow him back to the plain where he, the chief, would himself see this wonderful thing. Arrived at the spot the people stood round about in a frightened circle with Naling’ang’a and the chief in the centre. Naling’ang’a was brave now because of the crowd of people and, lifting his hoe, struck the poor skull a violent blow, saying, “Tell me, what killed you?” But the skull answered not a word. Again and again he struck it and demanded it to tell, but never a word spoke it.

The people saw now that they had been deceived, and the chief was mad with rage at having been made appear foolish before the eyes of the people and at the loss of time from the hoeing. So he ordered poor Naling’ang’a to be put to death there and then, and his head to be cut off and thrown beside the skull as a warning to all to speak the truth.

When the execution was over and the people had all departed the skull turned round to poor Naling’ang’a’s[42] head, and said, “My friend, Naling’ang’a, tell me, what killed you?” And Naling’ang’a replied, “My tongue.” “As with me,” said the skull, “my tongue caused a great quarrel and the people killed me.”

There was a freeman that had many slaves and he went with them on a journey. When they were on the journey the slaves sent the freeman, saying, “Go for water.” But he refused, and the slaves themselves went and drew water. When they returned with the water the freeman said, “Give me some water to drink.” But the slaves refused, saying, “We don’t want you to drink our water. Go to the well and draw water for yourself.” So the freeman had to go to the well himself. When he was about to drink, the slaves pushed him into the water and killed him. But a drop of blood leapt upwards and fell on a leaf of a tree, and thereupon became a bird and sang:—

“Ku! Ku! Ku!”

The slaves got ready for their journey, but the bird went before them and came to the village, and said, “They killed me. Make beer when the strangers come.” When the slaves entered the house to drink the beer the people set fire to the house and burned them.

There was a certain man that hoed his garden, and said, “Now that I have hoed my garden, what shall I do? These children finish the food in the garden.”[43] Then he went to look for bark and made a rope out of it and put it into the garden. When the children said, “Let us steal,” the rope became a serpent that drove off the children, who ran to the village, and said, “Father, in the garden yonder there is a snake.” And he said, “Let us go there and see.” When they came to the garden the father said, “Look now, that is a rope. You thought it was a snake. Is it that you were stealing the maize? You must never do so again.”

Such are African fairy tales, but there is a very great difference between a written story and one told by word of mouth. The teller stands up and, with hands going and eyes rolling and body bending backwards and forwards, imitates whatever birds or beasts, their calls and their cries, there are in his tale. At intervals he sings out a line or two of chorus, which is taken up by the audience and sung with great delight. Many additions are made in the spoken tale, and the written one is but the shadow of the other.

Now let me get you a few animal stories of which I am sure there must be hundreds stored up in the hearts of the black boys and girls. Where they learn them I know not, but they all seem to be able to tell stories. I really do believe they are born with them in their hearts all ready for the telling.

Among the animals, strange to say, the rabbit is[44] considered the cunning one. White children are accustomed to hear of the sly fox who said the grapes were sour; his place in Africa is taken by Mr Rabbit. Many are the tricks he plays on animals big and small, and even on people. The foolish animal is the hyena, and on him very often falls the punishment that ought to be borne by the cunning rabbit.

A rabbit made friends with an elephant, and they agreed together to hoe a large garden. While they were busy hoeing, the head of the rabbit’s hoe fell out, and as he could not see a stone on which to knock his hoe, he was at a loss to know what to do. Suddenly a good plan entered his head, and, turning to the elephant, he said, “Friend Elephant, let me knock in my hoe on your head.” The elephant agreed, and the hoe was knocked in by the rabbit. Then they went on hoeing again. Not long after the head of the elephant’s hoe fell off. So, turning to the rabbit, he said, “Friend Rabbit, let me knock in my hoe on your head.” But the rabbit, being afraid that the elephant would kill him, refused and ran off. On his way he met a hyena, who asked him why he was running at such a break-neck speed. “Ah!” replied the rabbit, “the elephant has much meat in the garden yonder. Go to him and you will be sure to get a bit. I am running to get a knife to cut it up.” When the elephant saw the hyena coming, he thought it was still the rabbit who had “bewitched” himself to be like another beast. So he caught him and killed him.

A rabbit, going down to the river to drink, met a hippopotamus and began to speak to him. Not far away was an elephant feeding on the trees near the bank of the river. “Come, let us try our strength,” said the rabbit to the hippopotamus, “you try to pull me into the water and I shall try to pull you to the bank, and whoever is pulled over must pay the other.” But the hippopotamus would not listen to such a proposal and laughed, saying, “Why should I waste time pulling with a creature so small as you?” But the rabbit urged him very much to have a try, so at last he consented. Then the rabbit went off to find a rope, but in passing the elephant, who was feeding quietly, he challenged him to a similar trial of strength, but this time the rabbit was to try to pull the elephant into the water. Like the hippopotamus, the elephant at first refused. But in the end he consented. So the rabbit gave him one end of the rope, saying that he would go down into the water and begin to pull. When he reached the river, however, he gave the other end of the rope to the hippopotamus, saying he would now run back and begin to pull. Then the rabbit, pretending to go to pull his end of the rope, slyly lay down in the grass and watched. Then the two great animals began to pull and tug against one another but neither could pull the other over, and all the time the rabbit lay laughing in the grass. All day the great beasts heaved and tugged at the rope. About sunset, quite worn out, they gave up the tug-of-war. The rabbit ran to the river bank where the hippopotamus was standing exhausted[46] half out of the water with the sand all trampled round about. “Well,” said the rabbit, “how did I pull?” The poor hippopotamus had to own up that he was beaten and agreed to pay. Thereupon the rabbit ran to where the elephant still panted amidst trampled grass and brushwood, and said, “Well, how did I pull?” The elephant also had to own defeat and agreed to pay. Thus was the rabbit made rich in a single day.

A rabbit once wanted to wear a lion’s skin, so he said, “Where shall I find one?” But his friends said, “You don’t mean it. The lion is a fearful animal.” But the rabbit said, “I shall deceive it.” So he went to a lion’s den where there were cubs, stood in the courtyard, and clapped his hands. The lioness came out and received his salutation and said, “Well, what?” And the rabbit replied, “I have come to stay.” So the lioness said, “Pass into the house there and take care of the children. Remain with them, and I myself shall go to kill game.” Then she went away to kill game. Not long afterwards the lioness came back and stood in the path and called out, saying, “Rabbit.” And the rabbit said, “Here I am.” And she said, “Take this meat. Are all the children well?” And the rabbit replied, “Yes, they are all well.” “All right,” said the lioness, “bring them that I may see them.” So the rabbit brought them, and said, “This is one, this is another, and this another.” In all there were three. Quite pleased, the lioness said, “Take the meat and give it them.” The rabbit went and received[47] the meat, but ate it all himself and the children got none. Then the lioness went off to kill more meat. When she had gone the rabbit took one child, killed it, took off its skin, and went away to hide it. The lioness soon returned, bringing more game, and said, “Are the children well? Bring them that I may see them.” So the rabbit brought them, saying, “This is one, this is another, and this another,” but one he brought twice. Again, well pleased, the lioness went away for more game, and the rabbit killed another cub, took off its skin, and went away and hid it. In the evening the lioness again returned, bringing meat, and said, “Are the children all well?” As usual the rabbit replied, “Yes, they are all well.” So he showed the lioness the same cub three times, and said, “This is one, this is another, and this another.” Again, well pleased, the lioness said, “Take this meat and give it them.” But the rabbit ate it all, and afterwards killed the cub that was left, skinned it, and went off to hide the skin. Then, afraid of the return of the lioness, he went to get string. Next he cut a small slave stick and tied himself by the neck. Then he twisted cords and tied his legs and bound himself to the stick again, and with another cord tied his arms. Then he made a great noise, and called out, “War! War! War against the lion. War!” The lioness came bounding back, and said, “What is the matter?” So the rabbit said, “The children are all taken, the soldiers carried them off.” And the lioness demanded, “Soldiers from where?” And the rabbit said, “I don’t know. Untie me.” The lioness set about untying, and the rabbit said, “Wait for me, I shall go in search of them.” So the rabbit went away and found monkeys spinning[48] their tops, saying, “Go! Go!” But the rabbit said, “Yes, nonsense, but you should say, ‘I have killed a lion and taken off his skin.’” The monkeys said, “Yes, very good,” and the rabbit left the monkeys repeating these words. He himself went back and met the lioness, and said, “The children were killed by these monkeys.” So the lioness said, “Deceive them, saying that we will do trade in tops.” So the rabbit went back to the monkeys, and said, “Let us deal in these tops.” So they said, “With what goods?” And the rabbit said, “With beans.” Then the monkeys said, “Well, bring them that we may buy.” So the rabbit went back and told all to the lioness, who said, “Weave a basket and tie me into it.” And the rabbit wove a basket, tied in the lioness, and put a few beans on top, lifted the basket, and departed. When he arrived at their courtyard he found the monkeys spinning their tops. So he called out, “I have brought that merchandise.” And they replied, “We shall buy it.” Just then a monkey sent his top spinning, saying, “I have killed a lion’s cub and have taken off its skin.” So the rabbit whispered to the lioness, “Listen, those fellows killed the children;” then to the monkeys, “Let us go and sell in this house.” Then the rabbit took a knife and cut the ropes that held the lioness, who sprang out upon the poor monkeys and killed them all. But the rabbit went for his skins and took them home and wore them.

Once a tortoise and a monkey made friends, and the monkey said to the tortoise, “Friend Tortoise,[49] come to my home and visit.” So the tortoise went and the monkey cooked food for him, but, wishing to play a trick on him, placed it on a high platform which the tortoise could not possibly reach up to. Then he called the tortoise, saying, “Friend Tortoise, go into the house and eat.” When the tortoise went in expecting a feast he found the food so high up that he could not reach it. So he came out very angry, and said, “Friend Monkey, you have been insolent to me.” So he went home, and brooded over the insult for three days. Then he sent a messenger to invite the monkey to his home, saying to himself, “Yon monkey was cheeky to me, I also will be cheeky to him.” So when the monkey came he found food already cooked and eyed it greedily. But the tortoise said, “Friend Monkey, there is no water in the house, go down to the stream and wash your hands.” So the monkey went down through the burned grass and washed his hands in anticipation of the feast. But in coming back from the stream he had to pass again through the burned grass and his hands were as black as ever. So seeing through the tortoise’s cunning he got angry, and said, “My friend has played a trick on me,” and departed to his own home.

Now I have told you four African tales of animals, and perhaps you are tired of such stories. If, however, I can remember a very good one before I am finished writing to you I shall put it into this chapter.

[50]Let me now tell you about the black boys and girls’ riddles, and there are one or two nursery rhymes that I know of. I am sure you would like to hear them, so I shall write them down for you as they are spoken here, and then translate them for you. Here is one of them:—

Can you guess what this is all about? You have a rhyme that means just the same. Well this is what these funny words mean:—

It is you see an African finger rhyme. You have all one of your own, but I am sure in it you never call your fore-finger a plate-scraper, nor your thumb an old fool. But if you had to eat without spoons and knives and forks, and wanted to make your plate very clean you would have to use your fore-finger a good deal, and you would then understand why the black children call it a plate-scraper.

This is another finger rhyme for counting up all the fingers:—

This is the English for it:

Then about guesses. I have tried to pick out one or two just to let you hear what like they are. Many of the answers to riddles I have heard seemed to me to have little or no point in them. So it is with the stories. But when I have failed to see the joke and have not laughed the black boys have not failed. They have their own funny stories and laugh at them heartily. But our jokes they do not understand, nor do they play pranks on one another as white boys do. Let me try to tell you how you can make black boys and girls roar with laughter, and yet to a white man there is nothing to laugh about. If you are telling them about people scattering helter-skelter[52] and say that the people, “nalimenya,” which means go off helter-skelter, the boys will go into fits of laughter. Now I can see nothing to laugh at in this, and I am sure you can’t either, and, if another word had been used, neither would the black boy. But here is the peculiar thing. It is the “li” in the middle of the word that makes it funny to African children here.

“Menya” means “beat,” but “limenya” means “run off helter-skelter.” Again “Sesa” means “sweep,” but “lisesa” means “run off helter-skelter;” and so on with a lot of other words, the addition of the syllable “li” makes them change their meanings entirely, and become “run off helter-skelter,” and so very funny that black boys and girls cannot keep from laughing. Now for the guesses:—

I think you will understand these answers to the above guesses, but what do you think of this one?

[53]I am certain you and I would never have thought of such an answer.

Here are one or two of their proverbs:—

which latter means—

“Help your neighbour now, for some day you may need help.”

By means of these guesses the African children while away the time and amuse themselves on wet days or on cold nights round the fire by asking them from one another. Now let me close this chapter by telling you the story of

There was once a lion that knew all about medicine. He did a good trade with people who came to buy it. One day some people from a far country came and begged him to come with them to heal their sick. So the lion agreed, and set about to get a servant to carry his bundle on the journey. Finding a wild pig near, he called him, saying, “Come, friend Pig, will you go on that journey?” and the pig agreed. So the lion gave him the load to carry.

When they were on the way the lion said to the pig, “Look there, Master Pig, that is the medicine for porridge. If they make porridge for us at the end of our journey you must run and get some of these leaves.” The pig said, “All right,” and they went on their journey.

While they were passing another bush the lion said again, “Look there, Master Pig, that is the medicine[54] for rice. If they make rice you must run and get some of these leaves.” The pig again said, “All right,” and they continued their journey.

When they reached the village of the sick people the lion and pig were well received. In the evening porridge was cooked for them, and the lion said to the pig, “Master Pig, go and get yon leaves.” So Master Pig ran off to get the leaves. When he came back with them he found that the lion had finished all the porridge. So that night Master Pig went to bed hungry. Next evening the people cooked rice, and the lion said to the pig, “Master Pig, go and get yon leaves;” and Master Pig set off in a hurry to bring the leaves. But when he got back, all puffing and blowing, he found that the lion had just finished the rice, and he had to go hungry to bed.

Next day they returned home, and the poor pig arrived at his village in a famished condition, to the great sorrow of his wife and children.

Not long afterwards other people came requesting the services of Dr Lion to heal their sick, and he agreed to go.

Looking around for a carrier he spied the rabbit, and said, “Come, friend Rabbit, will you go on that journey?” and the rabbit agreed. So the lion gave him his load to carry.

When they were on the way the lion said to the rabbit, “Master Rabbit, do you see that bush? That is the medicine for porridge. If they make porridge for us at the village you must run and get these leaves.” “All right,” said the rabbit, and they continued their journey. But they had not gone far when the rabbit stopped, and said, “Where is my knife; I must have left it where we rested. Let me[55] run back to get it.” “All right,” said the lion, “don’t be long.” So the rabbit ran back, pulled some leaves from the medicine bush, and hid them in the load. When he reached the lion they resumed their journey. Soon the lion stopped again at another bush, and said, “Master Rabbit, do you see that bush? That is medicine for rice. If they cook rice for us at the village you must run and get these leaves.” The rabbit said, “All right,” and they went on their way.

But in a short time the rabbit stopped, and said, “Where is my knife? I must have left it where we rested. Let me run back for it.” The lion was very angry this time, and said, “What kind of a servant are you, always losing your knife? Don’t be long.” So the rabbit ran back not to find his knife but to pull the medicine leaves for rice, which he hid in his bundle. When he made up on the lion again they continued their journey and soon arrived at the village.

In the evening porridge was cooked for the visitors, and the lion said to the rabbit, “Master Rabbit, go and get yon leaves.” So the rabbit untied his bundle and produced the leaves. The lion was so angry at seeing the leaves thus produced that he could not eat a bite, and the rabbit had all the porridge to himself. Next evening rice was cooked for them, and the lion said to the rabbit, “Master Rabbit, go for yon leaves.” But the rabbit again just opened his load and produced the leaves, and the lion was so sick and angry that he could not touch the rice, which the rabbit ate all to himself.

Next day they started on their homeward journey, and the first night slept in the same house, the lion[56] in a bed, the rabbit on a piece of bark. During the night the rabbit said out aloud, “He who sleeps on bark will be fresh for his journey in the morning, but he who sleeps in a bed will walk heavily and with pain.” The lion on hearing this got out of bed, saying, “You little one, get off that bark, I myself will sleep there.” So they changed sleeping places. In the middle of the night the rabbit got up and lit a fire while the lion slept. The heat of the fire soon caused the bark to shrivel up and tightly enclose the sleeping giant. Then the rabbit ran off home and left him.

In the morning great roars were heard coming from the house and the people, wondering what had befallen Dr Lion, rushed in and found him struggling to free himself. With their axes they soon had him out, and he went home a hungry and sorrowful beast. When his wife and children saw him looking so thin, they set up a great crying.

And so people who believe that they are very clever, will soon find others more clever than they. The lion thought himself very cunning when he deceived the poor pig, but he found the rabbit too much for him.

The principal dish of the African is a kind of maize porridge made rather thick, so as to hold together in lumps. It is for flour to make this porridge that the women are continually pounding at the mortars.[57] The porridge is always eaten with something tasty to send it down, and is never eaten without this relish. Now this relish may be simply juicy leaves got in the bush and boiled as we boil cabbage, or it may be meat of some kind no matter what, or it may be fish no matter how high, but it is oftenest beans—porridge and beans being the everyday food. African children have but two regular meals in the day and the porridge one is the afternoon meal. The forenoon one may be made of sweet potatoes, or green maize or pumpkins, or cucumbers—anything that does not require much cooking on the part of the mothers. But from early morning onwards the children always have an eye for anything that will help to appease their hunger.

Thus the boys go off early with their bows and arrows to shoot birds, or they may go digging for field mice, or setting traps for any small kind of animal that may be foolish enough to enter them. These little creatures are skinned and roasted, spitted on bamboos, and kept ready for porridge time. At certain seasons of the year a kind of caterpillar is gathered to be roasted to make relish. I have seen children with their hands full of yellow-green crawling things as proud as if they had been a handful of sweets. Then when the sky is dark with locusts the children are glad. Knowing the locusts cannot fly till the sun has warmed them, the boys and girls go out early in the morning and gather baskets full of them. The legs and wings are torn off and the bodies roasted. Then again at the time when the winged white ants are issuing forth from underground to fly off and make another home, the cunning children place a pot over the hole and catch hundreds. These[58] also they roast and consider delicious. Their sweets are very few—wild honey and sugar-cane. They do like sugar-cane, and tear it and munch it with their strong white teeth. It is very sweet and not unpleasant to chew. But a white man must get it cut into little bits for him before he can enjoy it. He cannot eat it as the black people do.

Some of the tribes eat frogs and snakes and land-crabs and snails, but many of them do not. Those who do not eat such things look down upon those who do, and consider them savages and altogether to be despised. Then again in every tribe there are certain superstitious customs as regards food. A mother will warn her child, saying, “My child, you must never eat rabbit. If you eat rabbit your body will be covered with sores.” So this child will refrain from rabbit, and so on with other kinds of meat, each child has something or other that is forbidden to him.

I remember once, when some boys of mine had gone rabbit-hunting, asking a very small boy who had been left behind if he was looking forward to the feast that was to come when the other boys returned, and how he would enjoy rabbit. “I don’t eat rabbit,” he replied, in a disconsolate voice. I asked him why. “Does not everyone, even the white man, eat rabbit!” “Yes,” he replied, “but my mother forbade me to eat rabbit, saying if I did, I would be covered with itch.” I advised him to try but he was afraid. Later on in the day, towards sunset, after the boys had returned from the woods. I saw the little disconsolate one all smiles. He was holding in his hand two miserable field mice, and was as happy as a king. The other boys had remembered[59] he did not eat rabbit, and had put off half an hour to capture some mice for him that he might be able to join in the feast.

Besides the food from the gardens there are many bush fruits that the African children eat. So, as far as food is concerned, the black boys and girls are very well off. They have none of the pleasant things you may buy with your pennies. But then they know nothing of your nice things, and so they do not feel the want of them. Give the African child bananas and sugar-cane and ground nuts, what you call monkey nuts, I think, and he is as happy as you with your toffy and chocolate and other sweets.

When a black boy or girl gets up in the morning, he or she has just a small wash. The real wash comes later on in the day when it is warmer. But they are very particular over their teeth and take very good care of them. In keeping them clean they use toothbrushes which they make out of little pieces of the wood of a certain tree about the length of a lead pencil but rather shorter and stouter. One end is cut and cut into again and again and teased out till it makes a very good toothbrush, and with it the black boy keeps his teeth in good condition. Of course it must be easy for him, because he can open his mouth so very wide.