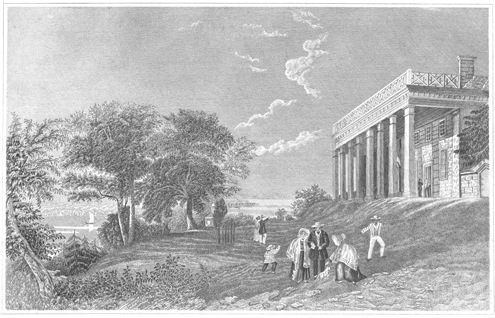

WASHINGTON’S HOUSE, MOUNT VERNON.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The American Encyclopedia of History,

Biography and Travel, by Thomas H. Prescott

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The American Encyclopedia of History, Biography and Travel

Comprising Ancient and Modern History: the Biography of

Eminent Men of Europe and America, and the Lives of

Distinguished Travelers.

Author: Thomas H. Prescott

Release Date: November 28, 2020 [EBook #63912]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK AMERICAN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF HISTORY ***

Produced by Carol Brown, Richard Hulse and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

THE

OF

HISTORY, BIOGRAPHY AND TRAVEL,

COMPRISING

ANCIENT AND MODERN HISTORY:

THE

BIOGRAPHY OF EMINENT MEN

OF EUROPE AND AMERICA,

AND THE

LIVES OF DISTINGUISHED TRAVELERS.

Illustrated with over 100 Engravings.

COLUMBUS:

PUBLISHED AND SOLD EXCLUSIVELY BY SUBSCRIPTION,

BY J. & H. MILLER.

1857.

Entered According to Act of Congress, in the Year 1855, by the

OHIO STATE JOURNAL COMPANY,

In the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the United States, for the Southern

District of Ohio.

Printed by Osgood and Pearce.

Bound by H. C Behmer.

COLUMBUS, OHIO.

One of the most useful directions for facilitating the study of history, is to begin with authors who present a compendium, or general view of the whole subject of history, and, afterwards, to apply to the study of any particular history with which a more thorough acquaintance is desired. The Historical Department of this work has been compiled with a view to furnishing such a compendium. It covers the whole ground of Ancient History, including China, India, Egypt, Arabia, Syria, the Phœnicians, Jews, Assyrians, Babylonians, Lydians, Modes and Persians, together with Greece and Rome, down through the dark ages to the dawn of modern civilization. It also embraces the history of the leading nations of modern Europe, and of the United States of America.

Wisdom is the great end of history. It is designed to supply the want of experience; and though it does not enforce its instructions with the same authority, yet it furnishes a greater variety of lessons than it is possible for experience to afford in the longest life. Its object is to enlarge our views of the human character, and to enable us to form a more correct judgment of human affairs. It must not, therefore, be a tale, calculated merely to please and addressed to the fancy. Gravity and dignity are essential characteristics of history. Robertson and Bancroft may be named as model historians in these particulars. No light ornaments should be employed—no flippancy of style, and no quaintness of wit; but the writer should sustain the character of a wise man, writing for the instruction of posterity; one who has studied to inform himself well, who has pondered his subject with care, and addresses himself to our judgment rather than to our imagination. At the same time, historical writing is by no means inconsistent with ornamented and spirited narration, as witness Macaulay’s popular History of England. On the contrary, it admits of much high ornament and elegance; but the ornaments must be consistent with dignity. Industry is, also, a very essential quality in an accurate historian.

As history is conversant with great and memorable actions, a historian should always keep posterity in view, and relate nothing but what may be of some account to future ages. Those who descend to trivial matters, beneath the dignity of history, should be deemed journalists rather than historians. As it is the province of a historian to acquaint us with facts, he should give a narration or description not only of the facts, or actions themselves, but likewise of such things as are necessarily connected with them; such as the characters of persons, the circumstances of time and place, the views and designs of the principal actors, and the issue and event of the actions which he describes. The drawing of characters is one of the most splendid, as it is one of the most difficult, ornaments of historical composition; for characters are generally considered as professed exhibitions of fine writing; and a historian who seeks to shine in them, is often in danger of carrying refinement to excess, from a desire of appearing very profound and penetrating. Among the improvements that have of late years been introduced into historical composition, is the attention that is now given to laws, customs, commerce, religion, literature, and every thing else that tends to exhibit the genius and spirit of nations. Historians are now expected to exhibit manners, as well as facts and events. Voltaire was the first to introduce this improvement, and Allison, Macaulay, and others, have adopted it.

The first and lowest use of history is, that it agreeably amuses the imagination, and interests the passions; and in this view of it, it far surpasses all works of fiction, which require a variety of embellishments to excite and interest the passions, while the mere thought that we are listening to the voice of truth, serves to keep the attention awake through many dry and ill-digested narrations of facts. The next and higher use of history is, to improve the understanding and strengthen the judgment, and thus to fit us for entering upon the duties of life with advantage. It presents us with the same objects which occur to us in the business of life, and affords similar exercise to our thoughts; so that it may be called anticipated experience. It is, therefore, of great importance, not only to the advancement of political knowledge, but to that of knowledge in general; because the most exalted understanding is merely a power of drawing conclusions and forming maxims of conduct from known facts and experiments, of which necessary materials of knowledge the mind itself is wholly barren, and with which it must be furnished by experience. By improving the understanding history frees the mind from many foolish prejudices that tend to mislead it. Such are those prejudices of a national kind, that have induced an unreasonable partiality for our own country, merely as our own country, and as unreasonable a repugnance to foreign nations and foreign religions, which nothing but enlarged views resulting from history can cure. It likewise tends to remove those prejudices that may have been entertained in favor of ancient or modern times, by giving a just view of the advantages and disadvantages of mankind in all ages. To a citizen of the United States, one of the great advantages resulting from the study of history is, that so far from producing an indifference to his own country, it disposes him to be satisfied with his own situation, and renders him, from rational conviction, and not from blind prejudice, a more zealous friend to the interests of his country, and to its free institutions. It is from history, chiefly, that improvements are made in the science of government; and this science is one of primary importance. Another advantage is, that it tends to strengthen sentiments of virtue, by displaying the motives and actions of truly great men, and those of a contrary character,—thus inspiring a taste for real greatness and solid glory.

The second department of our work has been devoted to Biography,—a species of history more entertaining, and in many respects equally useful, with general history. It represents great men more distinctly, unincumbered with a crowd of other actors, and, descending into the detail of their actions and character, their virtues and failings, gives more insight into human nature, and leads to a more intimate acquaintance with particular persons, than general history allows. A writer of biography may descend with propriety to minute circumstances and familiar incidents. He is expected to give the private as well as the public life of those whose actions he records; and it is from private life, from familiar, domestic and seemingly trivial occurrences, that we often derive the most accurate knowledge of the real character. To those who have exposed their lives, or employed their time and labor, for the service of their fellow men, it seems but a just debt, that their memories should be perpetuated after them, and that posterity should be made acquainted with their benefactors. To a volume of biography may be applied the language of a pagan poet:—

In the lives of public persons, their public characters are principally, but not solely, to be regarded. The world is inquisitive to know the conduct of its great men as well in private as in public; and both may be of service, considering the influence of their examples. In preparing this department of our work we have aimed to introduce variety,—selecting representative men from all the various pursuits of life.

The third department of our work has been designated as the Department of Travel. It embraces the principal voyages of discovery and the lives of great navigators and travelers, since the days of Columbus and Vasco de Gama. In the history of scientific expeditions, the five following divisions may be made: 1. The earliest age of the Phœnicians down to Herodotus, 500 years before Christ. The Phœnicians undertook the first voyages of discovery for commercial purposes, or to found colonies. 2. The travels of the Greeks and the military expeditions of the Romans, from 500 B. C. to 400 A. D. The Greeks made journeys to enlarge the territories of science. The armies of Rome, during this period, supplied an extensive knowledge of a part of Asia, Egypt, the northern part of Africa, and Europe to South Britain. 3. The expeditions of the Germans and Normans until 900 A. D. The Normans discovered the Faroes, Iceland and Greenland. 4. Besides the commercial and military voyages of the Arabs and Mongols, the travels of the Christian Missionaries, and other Europeans, down to 1400, furnished much valuable information. 5. The fifth period, from the year 1400 to the present time, is the period particularly embraced in this work. During this time, North and South America, a portion of Asia, and the interior of Africa, have been explored, and the adventurous voyagers in the Arctic and Antarctic seas, have pushed their researches to within twelve degrees of the poles. Sir J. Ross reached the south latitude of 78 deg. 4 min. in the year 1841. Such are the results of the labors of four centuries. The knowledge has been slowly gathered, but it will remain a lasting testimony to the triumphs of intellect. It is but recently that human enterprise has penetrated many of the secrets of the Antarctic regions,—that realm of mighty contrasts,—and it will doubtless pursue the investigation. ‘Meantime the wintry solitudes of the far south will be undisturbed by the presence of man; the penguin and the seal will still haunt the desolate shores; the shriek of the petrel and the scream of the albatross will mingle with the dash and roar of continual storms, and the crash of wave-beaten ice; the towering volcano will shoot aloft its columns of fire high into the gelid air; the hills of snow and ice will grow and spread; frost and flame will do their work; till, in the wondrous cycle of terrestrial change, the polar lands shall again share in the abundance and beauty which now overspread the sun-gladdened zones.’

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

| DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY. | ||

|---|---|---|

| ANCIENT HISTORY. | ||

| Ethiopian History | 18–20 | |

| Mongolian History.—The Chinese | 20–26 | |

| Caucasian History.—Ancient India—Eastern Nations—The Egyptians—Arabians—Syria—The Phœnicians—Palestine—The Jews—The Assyrians and Babylonians—The Medes and Persians—States of Asia Minor—The Lydians—The Persian Empire | 26–53 | |

| Grecian History.—Early History and Mythology—Religious Rites—Authentic History—Sparta—Lycurgus—Athens—Persian Invasion—Pericles—Alcibiades—Decline of Athenian Independence—Alexander the Great—Concluding Period | 53–78 | |

| Roman History.—The Latins—The Kings—The Commonwealth—Struggle between the Patricians and Plebeians—Invasion of the Gauls—The Samnite Wars—The Punic Wars—The Revolutions of the Gracchi—Social Wars—Marius and Sulla—Pompey, Cicero, Cataline, Cæsar—Gallic Wars—Extinction of the Commonwealth—Civil Wars—Augustus—Dissemination of Christianity—Division of the Empire—Downfall of the Western Empire | 78–112 | |

MIDDLE AGES. | ||

| —The Eastern Empire—Constantine—Julian the Apostate—Theodosius the Great—Justinian; his Code—Arabia—Mohammed—Empire of the Saracens—The Feudal System—Charlemagne—The New Western Empire—France—The German Empire—Italy—Spain—General state of Europe—The Crusades—Chivalry—Rise of new Powers—Wm. Tell—The Italian Republics—Commerce—The Turks—Fall of Constantinople—Rise of Civil Freedom | 112–145 | |

MODERN HISTORY. | ||

| Great Britain and Ireland.—Conquest by the Romans; by the Saxons; by the Normans—Early Norman Kings—William the Conqueror—Henry—Richard Cœur de Lion—John—Magna Charta—Origin of Parliament—Edwards—Conquest of Scotland—Richard II—House of Lancaster—House of York—House of Tudor—Henry VIII—The Reformation—Edward VI—Queen Mary; Elizabeth—Mary, Queen of Scots—The Stuarts—Gunpowder Plot—Revolution—Irish Rebellion—Oliver Cromwell—Trial and Execution of Charles I—The Commonwealth—Subjugation of Ireland and Scotland—The Protectorate—The Restoration—Charles II—Dutch War—Plague and Fire in London—The Rye House Plot—Death of Charles II—James II—Expedition of Monmouth—Arbitrary Measures of the King—The Revolution—William and Mary—Establishment of the Bank of England—Queen Anne—Union of England and Scotland—Marlborough’s Campaigns—House of Hanover—George I—Rebellion of 1715–16—George II—Rebellion of 1745–46—George III—American Stamp Act—American War of Independence—French Revolution—Rebellion in Ireland—Union with Great Britain—War with U. States—George IV—William IV—Queen Victoria—War with Russia—Alliance with France—Attack on Odessa—Operations in the Baltic—The Crimea—Battle of the Alma—Sebastopol described—Allies opening Trenches—Bombardment—Explosion of French Batteries and Russian Powder Magazine—The Allied Fleet—Cannonade—Battle of Balaklava—The Turks—The Highlanders—The Russian Cavalry—Capt. Nolan—Battle of Inkermann—Morning of the Battle—The Attack—The Zouaves—Chasseurs—Night after the Battle—Council of War—Determination to Winter—Reinforcements demanded | 145–256 | |

| History of France.—Clovis, A. D. 486; division of his Empire—The Merovingian Kings—The Carlovingians—Pepin—Charles Martel—Charlemagne; his Empire—Louis—Division of the Empire—Charles—Arnulf—Charles the Simple—Invasion of the Normans—Hugh Capet and his Successors—Philip VI of Valois—Wars with England, 1328–1415—Charles VI—Maid of Orleans—Louis XI—Francis II—France during the War of Religion—Persecution of the Huguenots—Coligni—The Massacre of St. Bartholomew, 1572—Henry III—Henry IV—Edict of Nantes—The Age of Louis XIV—Richelieu and Mazarin—Persecution of the Calvinists—Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, 1685—The Last Days of Absolute Monarchy—Louis XV—Louis XVI—The French Revolution—National Assembly—Mirabeau, Dante, Marat, Robespierre—The 10th of August—Dethronement of the King—National Convention—Trial and Execution of the King—Jacobins and Girondists—Exclusion of the Girondists from the Convention—Execution of the Queen, Madame Elizabeth, and the Duke of Orleans—La Vendee—Fall of Danton and Camille Desmoulins—Overthrow of Robespierre and the Jacobins—Reconstruction of the Government—Napoleon Bonaparte—Italian Campaign—Expedition to Egypt and Syria—Return to France—The First Consulate—Consul for Life—Duke d’Enghein—Napoleon Emperor—Austrian Campaign—Russians—Battle of Austerlitz—Confederation of the Rhine—War with Prussia—Alliance of Prussia and Russia—Victory at Friedland—Peace of Tilsit—Occupation of Portugal—Spain—Annexation of the Roman States and imprisonment of the Pope—New war with Austria—Peace of Vienna—Marriage with Maria Louisa—Russian Campaign—Conflagration of Moscow—Retreat of the French—Alliance of Russia, Prussia, etc.—Congress of Prague—Austria—Battle of Leipsic—Retreat of the French—Invasion of France by the Allies—Abdication of Napoleon—Louis XVIII—Escape of Napoleon from Elba—Defeat at Waterloo—Death at St. Helena—Louis XVIII—Charles X—Abdication—Louis Philippe—Revolution—Louis Napoleon—War with Russia and alliance with England and Turkey | 256–302 | |

| History of Spain.—Gothic Monarchy—The Moors—Castile—Henry IV—Ferdinand and Isabella—Conquest of Grenada—Christopher Columbus—Discovery of America—Charles V—Hernando Cortez—Conquest of Mexico—Francis Pizarro—Conquest of Peru—Ignatius Loyola—Philip II—War with England—Defeat of the Invincible Armada—Philip III—Banishment of the descendants of the Moors—Philip IV—Accession of the House of Bourbon—Charles III—The Seven Years’ War—Charles IV—Ferdinand—Joseph Bonaparte—Alliance of the Spaniards and English—Return of Ferdinand—Isabella II | 302–312 | |

| Germany and Austria.—Division of the Empire of Charlemagne, and formation of the German Empire—Succession of Henry the Fowler to the throne of Conrad of Franconia—The Germans build cities—Accession of Hildebrand—Pope Gregory III—His Excommunication of Henry IV—Strife of Guelphs and Ghibelines—Pope Adrian IV—Tancred—Richard III of England—The House of Hapsburg succeeds that of Swabia—Death of Albert—Charles IV issues the Golden Bull—Council of Constance—Martyrdom of John Huss and Jerome of Prague—Invention of Printing—Luther; the Reformation—Thirty Years’ War—Peace of Westphalia—Insurrection of Hungarians aided by Turks—The War of Succession—Prince Eugene—Maria Theresa—Pragmatic Sanction—Revolt of the Netherlands—Confederation of the Rhine—Congress of Vienna—Hungarian Revolution of 1848 | 312–326 | |

| History of Russia.—Russia rescued from the Tartars by John Basilowitz—Michael Theodorowitz, First of the House of Romanoff, Czar of Muscovy—Reorganization of Russia by Alexis—Reign of Peter the Great—Foundation and embellishment of St. Petersburg—Succession of the Czarina Catherine—Catherine II—Annexation of the Crimea—Dismemberment of Poland—Kosciusko—Suwarrow—Resignation of Stanislaus—Paul—War against the French Republic—Assassination of Paul—Alexander—Coalition against Napoleon, by Austria and England—Peace of Tilsit—Napoleon declares war against Russia—Smolensko—Burning of Moscow—Constantine—Nicholas—Extirpation of Poland—Siege of Sevastopol by France, England, and Turkey—Death of Nicholas—Succession of Alexander II | 326–334 | |

| HISTORY OF THE UNITED STATES. | ||

| I. | Colonial History.—Discoveries of Cabot—The Huguenots—Sir Walter Raleigh—Champlain—Henry Hudson—Virginia—Jamestown—John Smith—Pocahontas—Indian War—Gov. Berkeley—Nathaniel Bacon—New England Colonies—Puritans—Principles of their early Government—Quaker Persecution—Pequod Indian War—King Philip—Royal Governors—Salem Witchcraft—Connecticut—Rhode Island—Dutch Settlement of New Amsterdam—Indian War—Annexation of New Amsterdam to the English Colonies, and change of name to N. York—Lord Baltimore—Civil War—Carolina—Wm. Penn—Indian Treaty—Frame of Government—Oglethorpe—Wesley—Whitfield—Principles and characteristics of the Colonists | 334–363 |

| II. | Contest of France and England for America.—King William’s War—The French War—The Ohio Company—George Washington—Braddock—Gen. Wolfe—Rising Colonial prosperity | 363–368 |

| III. | The Revolution.—Stamp Act—N. Y. Congress—War of publications against Britain—Boston Massacre—Tea Party—Lexington—Declaration of Independence—Franklin, Lafayette, Kosciusko—Trenton—Brandywine—Burgoyne’s Defeat—Alliance of France and America—Baron Steuben—D’Estaing—Stony Point—Arnold—Col. Hayne—Capitulation of Cornwallis—Treaty at Paris—Washington—Paralyzed condition of the Government—Massachusetts Rebellion 1786—Formation of Government by the Constitutional Convention | 368–394 |

| IV. | Constitutional History.—Federalists and anti-Federalists—Defeat of Harmar and St. Clair—Prohibition of the Slave Trade—Death of Washington—Purchase of Louisiana—War with Tripoli—Embargo Acts—War with England—Campaign of 1812—American Naval Victories—Perry’s victory on Lake Erie—Gen. Harrison—Treaty at Ghent—Battle of New Orleans—Seminole War—Lafayette—Tariff—U. S. Bank—Nullification—Compromise of 1820—Commercial Bankruptcy—Annexation of Texas—Mexican War—Discovery of Gold in California—Gadsden Treaty | 394–413 |

| BIOGRAPHICAL DEPARTMENT. | ||

| Hernando Cortez | 415 | |

| William Penn | 441 | |

| Benjamin Franklin | 467 | |

| Peter the Great | 475 | |

| Count Rumford | 498 | |

| Nicholas Copernicus | 523 | |

| Tycho Brahe | 526 | |

| Galileo | 528 | |

| Kepler | 531 | |

| Sir Isaac Newton | 533 | |

| Huygens | 536 | |

| Halley | 537 | |

| Ferguson | 539 | |

| Sir William Herschel | 544 | |

| Simon Bolivar | 547 | |

| Francia, the Dictator | 554 | |

| Alexander Wilson | 562 | |

| James Watt | 569 | |

| John Howard | 572 | |

| Lord Byron | 598 | |

| Percy Bysshe Shelley | 612 | |

| Oliver Goldsmith | 615 | |

| Edward Gibbon | 619 | |

| David Hume | 623 | |

| Alexander Pope | 627 | |

| John Adams | 634 | |

| Thomas Jefferson | 644 | |

| Samuel Adams | 649 | |

| James Otis | 651 | |

| Fisher Ames | 653 | |

| Aaron Burr | 655 | |

| Alexander Hamilton | 657 | |

| Patrick Henry | 660 | |

| John Hancock | 664 | |

| Ethan Allen | 665 | |

| Benedict Arnold | 667 | |

| Horatio Gates | 680 | |

| Thaddeus Kosciusko | 681 | |

| Nathaniel Green | 685 | |

| Frederick William Augustus Steuben | 688 | |

| Baron de Kalb | 689 | |

| Richard Montgomery | 690 | |

| Gilbert Motier Lafayette | 691 | |

| Israel Putnam | 696 | |

| Stephen Decatur | 698 | |

| Isaac Hull | 700 | |

| Oliver Hazard Perry | 702 | |

| John Marshall | 704 | |

| John Paul Jones | 706 | |

| Andrew Jackson | 710 | |

| Winfield Scott | 713 | |

| Zachary Taylor | 714 | |

| John E. Wool | 724 | |

| Daniel Webster | 726 | |

| Henry Clay | 732 | |

| Levi Woodbury | 735 | |

| Robert Rantoul | 737 | |

| Franklin Pierce | 740 | |

| Samuel Finley Breese Morse | 741 | |

| M. Daguerre | 747 | |

| Victor Hugo | 749 | |

| Omar Pasha | 751 | |

| Edward Everett | 753 | |

| Washington Irving | 754 | |

| William Cullen Bryant | 756 | |

| George Bancroft | 756 | |

| William Hickling Prescott | 758 | |

| Hiram Powers | 759 | |

| DEPARTMENT OF TRAVEL. | ||

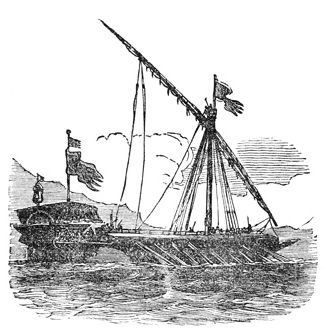

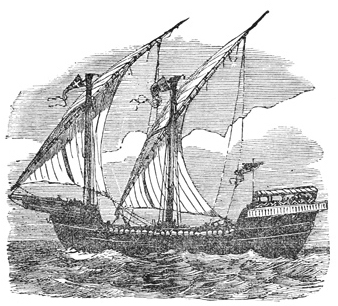

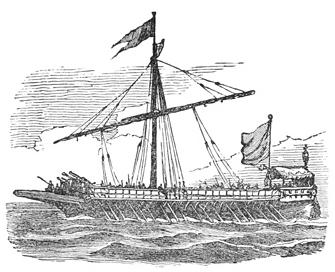

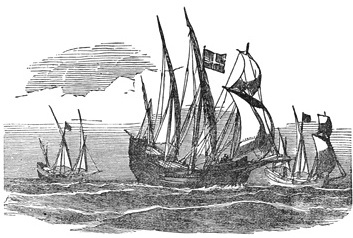

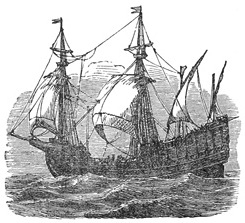

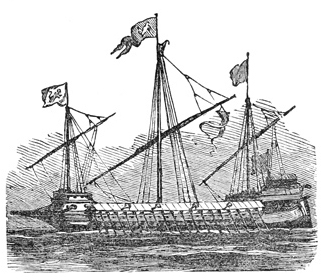

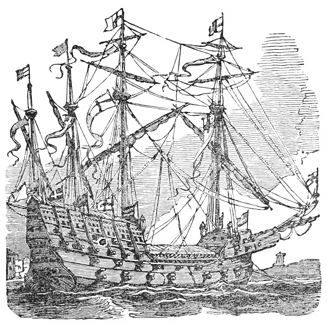

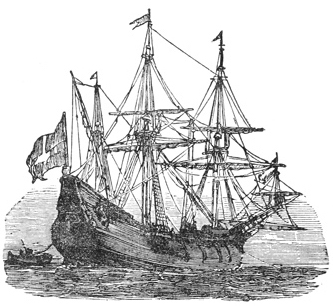

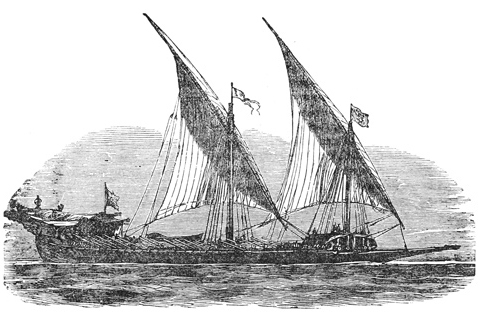

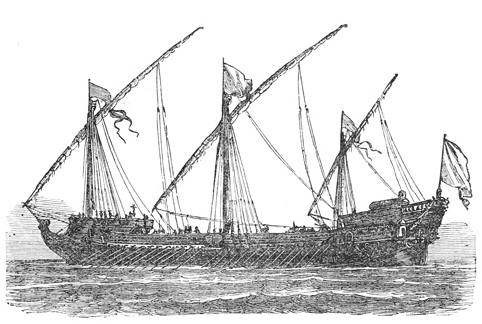

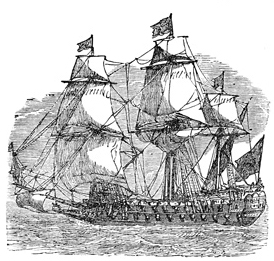

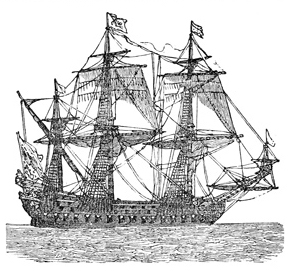

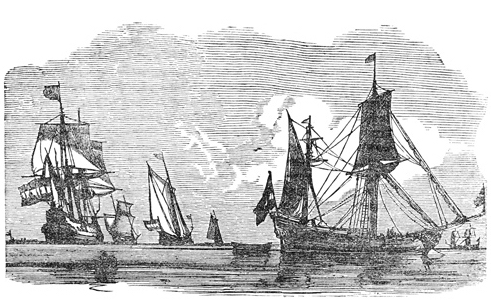

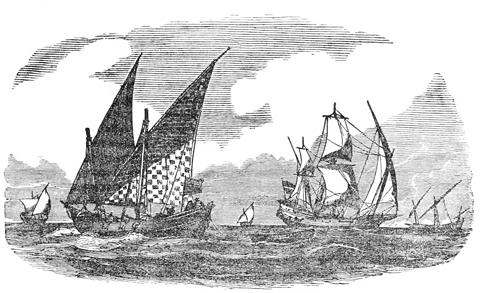

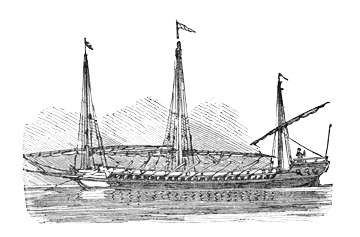

| Historical Sketch of Naval Architecture | 761 | |

| Early Maritime Discoveries | 774 | |

| Christopher Columbus | 775 | |

| Ferdinand Magellan | 800 | |

| Sir Francis Drake | 802 | |

| Henry Hudson | 804 | |

| Le Maire and Schouten | 805 | |

| Captain James | 806 | |

| William Dampier | 811 | |

| Captain Woodes Rogers | 814 | |

| John Clipperton | 815 | |

| Commodore Anson | 817 | |

| Captain Byron | 823 | |

| Captain Wallis | 829 | |

| De Bougainville | 832 | |

| Captain James Cook | 837 | |

| Captains Portlock and Dixon | 864 | |

| Monsieur De La Perouse | 870 | |

| George Vancouver | 891 | |

| Perry’s Voyages | 896 | |

| Sir John Franklin | 920 | |

| Travels in Africa—Parke, Denham, Clapperton, Lander and others | 927 | |

| Samuel Hearne | 953 | |

| John Lewis Burkhardt | 955 | |

| James Bruce | 958 | |

| John Ledyard | 966 | |

| John Baptist Belzoni | 967 | |

| George Forster | 974 | |

| Edward Daniel Clarke | 976 | |

| Richard Pococke | 979 | |

| Overland Journey to India | 981 | |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

| PAGE. | |

| Opium Smuggling | 22 |

| Japanese Funeral Procession | 23 |

| Aga | 30 |

| Japanese Agriculture | 31 |

| Terrace of St. Peter’s | 126 |

| Gibraltar | 127 |

| Marine Arsenal, Constantinople | 232 |

| Place of Kossuth’s Imprisonment | 233 |

| Castle of Eisenstadt | 322 |

| King of Denmark | 323 |

| Captain Smith and Pocahontas | 336 |

| Providence, R. I. | 338 |

| Newport, R. I. | 339 |

| New Haven, Conn. | 342 |

| Philadelphia, Pa. | 343 |

| Halifax, N. S. | 348 |

| Lake George | 349 |

| Castle William | 354 |

| Castle Garden | 355 |

| Wilmington, N. C. | 358 |

| Prison, Phila. | 359 |

| Fort Putnam | 364 |

| Pillar Rock | 365 |

| Place des Armes, New Orleans | 370 |

| Blackwell Penitentiary | 371 |

| Columbus, O. | 402 |

| Depot, Cleveland, O. | 403 |

| Cincinnati, O. | 406 |

| Sandusky City, O. | 407 |

| Battle Monument, Baltimore | 410 |

| Bombardment of Vera Cruz | 411 |

| State House, Wisconsin | 414 |

| View on Grand River, Ohio | 570 |

| Bridge, Conneaut River, O. | 571 |

| Kosciusko’s Monument | 683 |

| Paul Jonas | 707 |

| Gen. Scott | 712 |

| Fort Ancient | 716 |

| Milford, near Cincinnati, O. | 717 |

| Gen. Wool | 725 |

| Daniel Webster | 728 |

| Residence of Daniel Webster | 729 |

| Henry Clay | 733 |

| Hon. Levi Woodbury | 734 |

| Birth Place of John Q. Adams | 736 |

| Franklin Pierce | 738 |

| William R. King | 739 |

| Euclid Creek, O. | 742 |

| Red Bank | 743 |

| Prof. Morse | 744 |

| Daguerre | 746 |

| Victor Hugo | 748 |

| Omar Pasha | 752 |

| Disappointed Gold Seekers | 760 |

| Gold Seeker’s Grave | 760 |

| Naval Architecture, from the tenth to the seventeenth century (17 Engravings) | 762–770 |

| City of Panama | 812 |

| Panama Gate | 813 |

| City of Havana | 818 |

| Scene in Havana | 819 |

| Adelaide | 824 |

| Bathurst, N. S. W. | 825 |

| Valparaiso | 834 |

| Iron Bridge, Jamaica | 835 |

| Sidney, N. S. W. | 856 |

| Humboldt | 857 |

| California | 874 |

| Ranche | 875 |

| Post Office | 876 |

| River-bed Claim on the Turon | 877 |

| Removing Goods | 878 |

| Dry Diggings | 879 |

| Portraits of Sir John Franklin’s Expedition, (9 Engravings) | 922–926 |

| Calcutta | 973 |

| Rail Road Bridge | 964 |

| Elk Creek | 965 |

| East Branch Rocky River | 982 |

| West Branch Rocky River | 983 |

AMERICAN ENCYCLOPEDIA.

THE

OF

HISTORY, BIOGRAPHY AND TRAVEL.

ANCIENT HISTORY.

The general consent of mankind points to the region of Central Asia as having been the original seat from which the human race dispersed itself over the globe; and accordingly, it is this region, and especially the western portion of it, which we find to have been the theatre of the earliest recorded transactions. In short, it was in Central Asia that the first large mass of ripened humanity was accumulated—a great central nucleus of human life, so to speak, constantly enlarging, and from which emissaries incessantly streamed out over the globe in all directions. In process of time this great central mass having swollen out till it filled Asia and Africa, broke up into three fragments—thus giving parentage to the three leading varieties into which ethnographers divide the human species—the Caucasian, the Mongolian, and the Ethiopian or Negro—the Caucasians overspreading southern and western Asia; the Mongolians overspreading northern and eastern Asia; and the Ethiopians overspreading Africa. From these three sources streamed forth branches which, intermingling in various proportions, have constituted the various nations of the earth.

Differing from each other in physiological characteristics, the three great varieties of the human species have also differed widely in their historical career. The germs of a grand progressive development seem to have been implanted specially in the Caucasian variety, the parent stock of all the great civilized nations of ancient and modern times. History, therefore, concerns itself chiefly with this variety: in the evolution of whose destinies the true thread of human progress is to be found. Ere proceeding, however, to sketch the early development of this highly-endowed variety of our species in the nations of antiquity, a few observations may be offered regarding the other two the Ethiopian and Mongolian—which began the race of life along with the Caucasian, and whose destinies, doubtless, whatever may have been their historical functions hitherto, are involved in some profound and beautiful manner with the bearing of the race as a whole.

A German Historian thus sums up all that is known of Ethiopian history—that is, of the part which the great Negro race, inhabiting all Africa with the exception of the north-eastern coasts, performed in the general affairs of mankind in the early ages of the world:—‘On the history of this division of the species two remarks may be made: the one, that a now entirely extinct knowledge of the extension and power of this branch of the human family must have been forced upon even the Greeks by their early poets and historians; the other, that the Ethiopian history is interwoven throughout with that of Egypt. As regards the first remark, it is clear that in the earliest ages this branch of the race must have played an important part, since Meroe (in the present Nubia) is mentioned both by Herodotus (B. C. 408) and Strabo (A. D. 20); by the one as a still-existing, by the other as a formerly-existing seat of royalty, and centre of the Ethiopian religion and civilization.[1] To this Strabo adds, that the race spread from the boundaries of Egypt over the mountains of Atlas, as far as the Gaditanian Straits. Ephorus, too (B. C. 405), seems to have had a very great impression of the Ethiopians, since he names in the east the Indians, in the south the Ethiopians, in the west the Celts, in the north the Scythians, as the most mighty and numerous peoples of the known earth. Already in Strabo’s time, however, their ancient power had been gone for an indefinite period, and the Negro states found themselves, after Meroe had ceased to be a religious capital, almost in the same situation as that in which they still continue. The second remark on the Negro branch of the human race and its history, can only be fully elucidated when the interpretation of the inscriptions on Egyptian monuments shall have been farther advanced. The latest travels into Abyssinia show this much—that at one time the Egyptian religion and civilization extended over the principal seat of the northern Negroes. Single mummies and monumental figures corroborate what Herodotus expressly says, that a great portion of the Egyptians of his time had black skins and woolly hair; hence we infer that the Negro race had combined itself intimately with the Caucasian part of the population. Not these notices only, but the express testimonies also of the Hebrew annals, show Egypt to have contained an abundance of Negroes, and mention a conquering king invading it at the head of a Negro host, and governing it for a considerable time. The nature of the accounts on which we must found does not permit us to give an accurate statement; we remark, however, that the Indians, the Egyptians, and the Babylonians, are not the only peoples which aimed at becoming world-conquerors before the historic age, but that also to the Ethiopian stock warlike kings were not wanting in the early times. The Mongols alone seem to have enjoyed a happy repose within their own seats in the primitive historic times, and those antecedent to them; they appear first very late as conquerors and destroyers in the history of the west. If, indeed, the hero-king of the Ethiopians, Tearcho, were one and the same with the Tirhakah of the book of Kings (2 Kings, xix. 9), then the wonder of those stories would disappear which were handed down by tradition to the Greeks; but even Bochart has combatted this belief, and we cannot reconcile it with the circumstances which are related of both. It remains for us only to observe, by way of summary, that in an age antecedent to the historic, the Ethiopian peoples may have been associated together in a more regular manner than in our own or Grecian and Roman times; and that their distant expeditions may have been so formidable, both to the Europeans as far as the Ægean Sea in the east, and to the dwellers on the Gaditanian Straits (Gibraltar) on the west, that the dim knowledge of the fact was not lost even in late times. In more recent ages we observe here and there an Ethiopian influence, and especially in the Egyptian history; but as concerns the general progress of the human species, the Negro race never acquired any vital importance.

The foregoing observations may be summed up in this proposition:—That in the most remote antiquity, Africa was overspread by the Negro variety of the human species; that in those parts of the continent to which the knowledge of the ancient geographers did not extend—namely, all south of Egypt and the Great Desert—the Negro race degenerated, or at least dispersed into tribes, kingdoms, etc., constituting a great savage system within its own torrid abode, similar to that which even now, in the adult age of the world, we are vainly attempting to penetrate; but that on the coasts of the Mediterranean and the Red Sea, the race either preserved its original faculty and intelligence longer, or was so improved by contact and intermixture with its Caucasian neighbors, as to constitute, under the name of the Ethiopians, one of the great ante-historic dynasties of the world; and that this dynasty ebbed and flowed against the Caucasian populations of western Asia and eastern Europe, thus giving rise to mixture of races along the African coasts of the north and east, until at length, leaving these mixed races to act their part awhile, the pure Ethiopian himself retired from historic view into Central Africa, where he lay concealed, till again in modern times he was dragged forth to become the slave of the Caucasian. Thus Negro history hitherto has exhibited a retrogression from a point once occupied, rather than a progress in civilization. Even this fact, however, must somehow be subordinate to a great law of general progress; and it is gratifying to know that, on the coast of Africa, a settlement has recently been formed called Liberia, peopled by liberated negro slaves from North America; and who, bringing with them the Anglo-American civilization, give promise of founding a cultured and prosperous community.

MONGOLIAN HISTORY—THE CHINESE.

As from the great central mass of mankind, the first accumulation of life on our planet, there was parted off into Africa a fragment called the Negro variety, so into eastern Asia there was detached, by those causes which we seek in vain to discover, a second huge fragment, to which has been given the name of the Mongolian variety. Overspreading the great plains of Asia, from the Himalehs to the Sea of Okhotsk, this detachment of the human species may be supposed to have crossed into Japan; to have reached the other islands of the Pacific, and either through these, or by the access at Behring’s Straits, to have poured themselves through the great American continent; their peculiarities shading off in their long journey, till the Mongolian was converted into the American Indian. Blumenbach, however, erects the American Indian into a type by himself.

Had historians been able to pursue the Negro race into their central African jungles and deserts, they would no doubt have found the general Ethiopic mass breaking up there under the operation of causes connected with climate, soil, food, etc., into vast sections or subdivisions, presenting marked differences from each other; and precisely so was it with the Mongolians. In Central Asia, we find them as Thibetians, Tungusians, Mongols proper; on the eastern coasts, as Mantchous and Chinese; in the adjacent islands, as Japanese, etc.; and nearer the North Pole, as Laplanders, Esquimaux, etc.; all presenting peculiarities of their own. Of these great Mongolian branches circumstances have given a higher degree of development to the Chinese and the Japanese than to the others, which are chiefly nomadic hordes, some under Chinese rule, others independent, roaming over the great pasture lands of Asia, and employed in rearing cattle.

There is every reason to believe that the vast population inhabiting that portion of eastern Asia called China, can boast of a longer antiquity of civilization than almost any other nation of the world, a civilization, however, differing essentially in its character from those which have appeared and disappeared among the Caucasians. This, in fact, is to be observed as the grand difference between the history of the Mongolian and that of the Caucasian variety of the human species, that whereas the former presents us with the best product of Mongolian humanity, in the form of one great permanent civilization—the Chinese—extending from century to century, one, the same, and solitary, through a period of 3000 or 4000 years; the latter exhibits a succession of civilization—the Chaldean, the Persian, the Grecian, the Roman, the modern European (subdivided into French, English, German, Italian, etc.,) and the Anglo-American; these civilizations, from the remotest Oriental—that is, Chaldean—to the most recent Occidental—that is, the Anglo-American—being a series of waves falling into each other, and driven onward by the same general force. A brief sketch of Chinese history, with a glance at Japan, will therefore discharge all that we owe to the Mongolian race.

Authentic Chinese history does not extend father back than about 800 or 1000 years B. C.; but, as has been the case more or less with all nations, the Chinese imagination has provided itself with a mythological history extending many ages back into the unknown past. Unlike the mythology of the Greeks, but like that of the Indians, the Chinese legends deal in large chronological intervals. First of all, in the beginning of time, was the great Puan-Koo, founder of the Chinese nation, and whose dress was green leaves. After him came Ty-en-Hoang, Ti-Hoang, Gin-Hoang and several other euphonious potentates, each of whom did something towards the building up of the Chinese nation, and each of whom reigned, as was the custom in those grand old times, thousands of years. At length, at a time corresponding to that assigned in Scripture to the life of Noah, came the divine-born Fohi, a man of transcendent faculties, who reigned 115 years, teaching music and the system of symbols, instituting marriage, building walls round cities, creating mandarins, and, in short, establishing the Chinese nation on a basis that could never be shaken. After him came Shin-ning, Whang-ti, etc., until in due time came the good emperors Yao and Shun, in the reign of the latter of whom happened a great flood. By means of canals and drains the assiduous Yu saved the country, and became the successor of Shun. Yu was the first emperor of the Hia dynasty, which began about 2100 B. C. After this dynasty came that of Shang, the last of whose emperors, a great tyrant, was deposed (B. C. 1122) by Woo-wong, the founder of the Tchow dynasty.

In this Tchow dynasty, which lasted upwards of 800 years, authentic Chinese history commences. It was during it, and most probably about the year B. C. 484, that the great Con-fu-tse, or Confucius, the founder of the Chinese religion, philosophy, and literature, flourished. In the year B. C. 248, the Tchow dynasty was superseded by that of Tsin, the first of whose kings built the Great Wall of China, to defend the country against the Tartar Nomads. The Tsin dynasty was a short one: it was succeeded in B. C. 206 by the Han dynasty, which lasted till A. D. 238. Then followed a rapid series of dynastic revolutions, by which the nation was frequently broken into parts; and during which the population was considerably changed in character by the irruptions of the nomad hoards of Asia who intermingled with it. Early in the seventh century, a dynasty called that of Tang acceded to power, which ended in 897. After half a century of anarchy, order was restored under the Song dynasty, at the commencement of which, or about the year 950, the art of printing was discovered, five centuries before it was known in Europe. ‘The Song dynasty,’ says Schlosser, ‘maintained an intimate connection with Japan, as contrary to all Chinese maxims; the emperors of this dynasty imposed no limits to knowledge, the arts, life, luxury, and commerce with other nations. Their unhappy fate, therefore (on being extinguished with circumstances of special horror by the Mongol conqueror Kublai Khan, A. D. 1281), is held forth as a warning against departing a hairsbreadth from the old customs of the empire. From the time of the destruction of the Song dynasty by the Mongol monarchy, the intercourse between China and Japan was broken, until again the Ming, a native Chinese dynasty (A. D. 1366) restored it. The Mongol rulers made an expedition against Japan, but were unsuccessful. The unfortunate gift which the Japanese received from China was the doctrine of Foë. This doctrine, however, was not the first foreign doctrine or foreign worship that came into China. A religion, whose nature we cannot fix—probably Buddhism, ere it had assumed the form of Lamaism—was preached in it at an earlier date. About the time of the Tsin dynasty (B. C. 248–206), a warlike king had incorporated all China into one and subdued the princes of the various provinces. While he was at war with his subjects, many of the roving hordes to the north of China pressed into the land, and with them appeared missionaries of the religion above mentioned. When peace was restored, the kings of the fore-named dynasty, as also later those of Han and the two following dynasties, extended the kingdom prodigiously, and the western provinces became known to the Greeks and Romans as the land of the Seres. As on the one side Tartary was at that time Chinese, so on the other side the Chinese were connected with India; whence came the Indian religion. It procured many adherents, but yielded at length to the primitive habits of the nations. In consequence of the introduction of the religion of Foë, the immense country fell asunder into two kingdoms. The south and the north had each its sovereign; and the wars of the northern kingdom occasioned the wanderings of the Huns, by whose agency the Roman Empire was destroyed. These kingdoms of the north and south were often afterwards united and again dissevered; great savage hordes roamed around them as at present; but all that had settled, and that dwelt within the Great Wall, submitted to the ancient Chinese civilization. Ghenghis Khan, indeed, whose power was founded on the Turkish and Mongol races, annihilated both kingdoms, and the barbaric element seemed to triumph; but this was changed as soon as his kingdom was divided. Even Kublai, and yet more his immediate followers, much as the Chinese calumniate the Mongol dynasty of Yeven, maintained everything in its ancient condition, with the single exception that they did homage to Lamaism, the altered form of Buddhism. This religion yet prevails, accommodated skillfully, however, to the Chinese mode of existence—a mode which all subsequent conquerors have respected, as the example of the present dynasty proves.’ The dynasty alluded to is that of Tatsin Mantchou, a mixed Mongol and Tartar stock, which superseded the native Chinese dynasty of Ming in the year 1644. The present emperor of China is the sixth of the Tatsin dynasty.

From the series of dry facts just given, we arrive at the following definition of China and its civilization: As the Roman Empire was a great temporary aggregation of matured Caucasian humanity, surrounded by and shading off into Caucasian barbarism, so China, a country more extensive than all Europe, and inhabited by a population of more than 300,000,000, is an aggregation of matured Mongolian humanity surrounded by Mongolian barbarism. The difference is this, that while the Roman Empire was only one of several successive aggregations of the Caucasian race, each on an entirely different basis, the Chinese empire has been one permanent exhibition of the only form of civilization possible among the Mongolians. The Jew, the Greek, the Roman, the Frenchman, the German, the Englishman—these are all types of the matured Caucasian character; but a fully-developed Mongolian has but one type—the Chinese. Chinese history does not exhibit a progress of the Mongolian man through a series of stages; it exhibits only a uniform duration of one great civilized Mongolian empire, sometimes expanding so as to extend itself into the surrounding Mongolian barbarism, sometimes contracted by the pressure of that barbarism, sometimes disturbed by infusions of the barbaric element, sometimes shattered within itself by the operation of individual Chinese ambition, but always retaining its essential character. True, in such a vast empire, difference of climate, etc., must give rise to specific differences, so that a Chinese of the north-east is not the same as a Chinese of the south-west; true, also, the Japanese civilization seems to exist as an alternative between which and the Chinese, Providence might share the Mongolian part of our species, were it to remain unmixed; still the general remark remains undeniable, that from the extremest antiquity to the present day, Mongolian humanity has been able to cast itself but into one essential civilized type. It is an object of peculiar interest, therefore, to us who belong to the multiform and progressive Caucasian race, to obtain a distinct idea of the nature of that permanent form of civilization out of which our Mongolian brothers have never issued, and apparently never wish to issue. Each of our readers being a civilized Caucasian, may be supposed to ask, ‘What sort of a human being is a civilized Mongolian?’ A study of the Chinese civilization would answer this question. Not so easy would it be for a Chinese to return the compliment, confused as he would be by the multiplicity of the types which the Caucasian man has assumed—from the ancient Arab to the modern Anglo-American.

Hitherto little progress has been made in the investigation of the Chinese civilization. Several conclusions of a general character have, however, been established. ‘We recognise,’ says Schlosser, ‘in the institutions of the Chinese, so much praised by the Jesuits, the character of the institutions of all early states; with this difference, that the Chinese mode of life is not a product of hierarchical or theocratic maxims, but a work of the cold understanding. In China, all that subserves the wants of the senses was arranged and developed in the earliest ages; all that concerns the soul or the imagination is yet raw and ill-adjusted; and we behold in the high opinion which the Chinese entertain of themselves and their affairs, a terrible example of what must be the consequence when all behavior proceeds according to prescribed etiquette, when all knowledge and learning is a matter of rote directed to external applications, and the men of learning are so intimately connected with the government, and have their interest so much one with it, that a number of privileged doctors can regulate literature as a state magistrate does weights and measures.’ Of the Chinese government the same authority remarks—‘the patriarchal system still lies at the foundation of it. Round the “Son of Heaven,” as they name the highest ruler, the wise of the land assemble as round their counselor and organ. So in the provinces (of which there are eighteen or nineteen, each as large as a considerable kingdom), the men of greatest sagacity gather round the presidents; each takes the fashion from his superior, and the lowest give it to the people. Thus one man exercises the sovereignty; a number of learned men gave the law, and invented in very early times a symbolical system of syllabic writing, suitable for their mono syllabic speech, in lieu of their primitive system of hieroglyphics. All business is transacted in writing, with minuteness and pedantry. Their written language is very difficult; and as it is possible in Chinese writing for one to know all the characters of a certain period of time, or of a certain department, and yet be totally unacquainted with those of another department, there is no end to their mechanical acquisition.’ It has already been mentioned that Chinese thought has at various times received certain foreign tinctures, chiefly from India; essentially, however, the Chinese mind has remained as it was fixed by Confucius. ‘In China,’ says Schlosser, ‘a so-named philosophy has accomplished that which in other countries has been accomplished by priests and religions. In the genuine Chinese books of religion, in all their learning and wisdom, God is not thought of; religion, according to the Chinese and their oracle and lawgiver Con-fu-tse has nothing to do with the imagination, but consists alone in the performance of outward moral duties, and in zeal to further the ends of state. Whatever lies beyond the plain rule of life is either a sort of obscure natural philosophy, or a mere culture for the people, and for any who may feel the want of such a culture. The various forms of worship which have made their way into China are obliged to restrict themselves, to bow to the law, and to make their practices conform; they can arrogate no literature of their own; and, good or bad, must learn to agree with the prevailing atheistic Chinese manner of thought.’

Such are the Chinese, and such have they been for 2000 or 3000 years—a vast people undoubtedly civilized to the highest pitch of which Mongolian humanity is susceptible; of mild disposition; industrious to an extraordinary degree; well-skilled in all the mechanical arts, and possessing a mechanical ingenuity peculiar to themselves; boasting of a language quite singular in its character, and of a vast literature; respectful of usage to such a degree as to do everything by pattern; attentive to the duties and civilities of life, but totally devoid of fervor, originality, or spirituality; and living under a form of government which has been very happily designated a pedantocracy—that is, a hierarchy of erudite persons selected from the population, and appointed by the emperor, according to the proof they give of their capacity, to the various places of public trust. How far these characteristics, or any of them, are inseparable from a Mongolian civilization, would appear more clearly if we knew more of the Japanese. At present, however, there seems little prospect of any reörganization of the Chinese mind, except by means of a Caucasian stimulus applied to it. And what Caucasian stimulus will be sufficient to break up that vast Mongolian mass, and lay it open to the general world-influences? Will the stimulus come from Europe; or from America after its western shores are peopled, and the Anglo-Americans begin to think of crossing the Pacific?

While the Negro race seems to have retrograded from its original position on the earth, while the Mongolian has afforded the spectacle of a single permanent and pedantic civilization retaining millions within its grasp for ages in the extreme east of Asia, the Caucasian, as if the seeds of the world’s progress had been implanted in it, has worked out for itself a splendid career on an ever-shifting theatre. First attaining its maturity in Asia, the Caucasian civilization has shot itself westward, if we may so speak, in several successive throes; long confined to Asia; then entering northern Africa, where, commingling with the Ethiopian, it originated a new culture; again, about the year B. C. 1000, adding Europe to the stage of history; and lastly, 2500 years later, crossing the Atlantic, and meeting in America with a diffused and degenerate Mongolism. To understand this beautiful career thoroughly, it is necessary to observe the manner in which the Caucasians disseminated themselves from their central home—to count, as it were, and note separately, the various flights by which they emigrated from the central hive. So far as appears, then, from investigations into language, etc., the Caucasian stock sent forth at different times in the remote past five great branches from its original seat, somewhere to the south of that long chain of mountains which commences at the Black Sea, and, bordering the southern coast of the Caspian, terminates in the Himalehs. In what precise way, or at what precise time, these branches separated themselves from the parent stock and from each other, must remain a mystery; a sufficiently clear general notion of the fact is all that we can pretend to. 1st. The Armenian branch, remaining apparently nearest the original seat, filled the countries between the Caspian and Black Seas, extending also round the Caspian into the territories afterwards known as those of the Parthians. 2d, The Indo-Persian branch, which extended itself in a southern and eastern direction from the Caspian Sea, through Persia and Cabool, into Hindoostan, also penetrating Bokhara. From this great branch philologists and ethnographers derive those two races, the distinction between which, although subordinate to the grand fivefold division of the Caucasian stock, is of immense consequence in modern history—the Celtic and the Germanic. Pouring through Asia Minor, it is supposed that the Indo-Persian family entered Europe through Thrace, and ultimately, through the operation of those innumerable causes which reäct upon the human constitution from the circumstances in which it is placed, assumed the character of Celts and Germans—the Celts being the earlier product, and eventually occupying the western portion of Europe—namely, northern Italy, France, Spain and Great Britain—still undergoing subdivision, however, during their dispersion, into Iberians, Gaels, Cymri, &c.; the Germans being a later off-shoot, and settling rather in the centre and north of Europe in two great moieties—the Scandinavians and the Germans Proper. This seems the most plausible pedigree of the Celtic and Germanic races, although some object to it. 3d, The Semitic or Aramaic branch, which, diffusing itself southward and westward from the original Caucasian seat, filled Syria, Mesopotamia, Arabia, etc., and founded the early kingdoms of Assyria, Babylonia, Phœnicia, Palestine, etc. It was this branch of the Caucasian variety which, entering Africa by the Isthmus of Suez and the Straits of Babelmandel, constituted itself an element at least in the ancient population of Egypt, Nubia, and Abyssinia; and there are ethnographers who believe that the early civilization which lined the northern coasts of Africa arose from some extremely early blending of the Ethiopic with the Semitic, the latter acting as a dominant caste. Diffusing itself westward along the African coast as far as Mauritania, the Semitic race seems eventually, though at a comparatively late period, to have met the Celtic, which had crossed into Africa from Spain; and thus, by the infusion of Arameans and Celts, that white or tawny population which we find in northern Africa in ancient times, distinct from the Ethiopians of the interior, seems to have been formed. 4th, The Pelasgic branch, that noble family which, carrying the Greeks and Romans in its bosom, poured itself from western Asia into the south-east of Europe, mingling doubtless with Celts and Germans. 5th, The Scythian, or Slavonic branch, which diffused itself over Russia, Siberia, and the central plains of Asia, shading off in these last into the Mongolian Such is a convenient division of the Caucasian stock; a more profound investigation, however, might reduce the five races to these two—the Semitic and the Indo-Germanic; all civilized languages being capable, it is said, of being classified under these three families—the Chinese, which has monosyllabic roots; the Indo-Germanic (Sanscrit, Hindoostanee, Greek, Latin, German, and all modern European languages), which has dissyllabic roots; and the Semitic (Hebrew, Arabic, &c.), whose roots are trisyllabic. Retaining, however, the fivefold distribution which we have adopted, we shall find that the history of the world, from the earliest to the remotest times, has been nothing else than the common Caucasian vitality presenting itself in a succession of phases or civilizations, each differing from the last in the proportions in which it contains the various separate elements.

It is advisable to sketch first the most eastern Caucasian civilization—that is, that of India; and then to proceed to a consideration of the state of that medley of nations, some of them Semitic, some of them Indo-Persian, and some of them Armenian, out of which the great Persian empire arose, destined to continue the historic pedigree of the world into Europe, by transmitting its vitality to the Pelasgians.

Ancient India. One of the great branches, we have said, of the Caucasian family of mankind was the Indo-Persian, which, spreading out in the primeval times from the original seat of the Caucasian part of the human species, extended itself from the Caspian to the Bay of Bengal, where, coming into contact with the southern Mongolians, it gave rise, according to the most probable accounts, to those new mixed Caucasian-Mongolian races, the Malays of the Eastern Peninsula; and, by a still farther degeneracy, to the Papuas, or natives of the South Sea Islands. While thus shading off into the Mongolism of the Pacific, the Indo-Persian mass of our species was at the same time attaining maturity within itself; and as the first ripened fragment of the Mongolians had been the Chinese nation, so one of the first ripened fragments of the Indo-Persian branch of the Caucasians seems to have been the Indians. At what time the vast peninsula of Hindoostan could first boast a civilized population, it is impossible to say; all testimony, however, agrees in assigning to Indian civilization a most remote antiquity. Another fact seems also to be tolerably well authenticated regarding ancient India; namely, that the northern portions of it, and especially the north-western portions, which would be nearest the original Caucasian seat, were the first civilized; and that the civilizing influence spread thence southwards to Cape Comorin.

Notwithstanding this general conviction, that India was one of the first portions of the earth’s surface that contained a civilized population, few facts in the ancient history of India are certainly known. We are told, indeed (to omit the myths of the Indian Bacchus and Hercules), of two great kingdom—those of Ayodha (Oude) and Prathisthana (Vitera)—as having existed in northern India upwards of a thousand years before Christ; of conquests in southern India, effected by the monarchs of these kingdoms; and of wars carried on between these monarchs and their western neighbors the Persians, after the latter had begun to be powerful. All these accounts, however, merely resolve themselves into the general information, that India, many centuries before Christ, was an important member in the family of Asiatic nations; supplying articles to their commerce, and involved in their agitations. Accordingly, if we wish to form an idea of the condition of India prior to that great epoch in its history—its invasion by Alexander the Great, B. C. 326—we can only do so by reasoning back from that we know of its present condition, allowing for the modifying effects of the two thousand years which have intervened; and especially for the effects produced by the Mohammedan invasion, A. D. 1000. This, however, is the less difficult in the case of such a country as India, where the permanence of native institutions is so remarkable, and though we cannot hope to acquire a distinct notion of the territorial divisions, etc., of India in very ancient times, yet, by a study of the Hindoos as they are at present, we may furnish ourselves with a tolerably accurate idea of the nature of that ancient civilization which overspread Hindoostan many centuries before the birth of Christ, and this all the more probably that the notices which remain of the state of India at the time of the invasion of Alexander, correspond in many points with what is to be seen in India at the present day.

The population of Hindoostan, the area of which is estimated at about a million square miles, amounts to about 120,000,000; of whom about 100,000,000 are Hindoos or aborigines, the remainder being foreigners, either Asiatic or European. The most remarkable feature in Hindoo society is its division into castes. The Hindoos are divided into four great castes—the Brahmins, whose proper business is religion and philosophy; the Kshatriyas, who attend to war and government; the Vaisyas, whose duties are connected with commerce and agriculture; and the Sudras, or artisans and laborers. Of these four castes the Brahmins are the highest; but a broad line of distinction is drawn between the Sudras and the other three castes. The Brahmins may intermarry with the three inferior castes—the kshatriyas with the vaisyas and the Sudras; and the vaisyas with the Sudras; but no Sudra can choose a wife from either of the three superior castes. As a general rule, every person is required to follow the profession of the caste to which he belongs: thus the Brahmin is to lead a life of contemplation and study, subsisting on the contributions of the rich; the Kshatriya is to occupy himself in civil matters, or to pursue the profession of a soldier; and the Vaisya is to be a merchant or a farmer. In fact, however, the barriers of caste have in innumerable instances been broken down. The ramifications, too, of the caste system are infinite. Besides the four pure, there are numerous mixed castes, all with their prescribed ranks and occupations.

A class far below even the pure Sudras is the Pariahs or outcasts; consisting of the refuse of all the other castes, and which, in process of time, has grown so large as to include, it is said, one-fifth of the population of Hindoostan. The Pariahs perform the meanest kinds of manual labor. This system of castes—of which the Brahmins themselves, whom some suppose to have been originally a conquering race, are the architects, if not the founders—is bound up with the religion of the Hindoos. Indeed of the Hindoos, more truly than of any other people, it may be said that a knowledge of their religious system is a knowledge of the people themselves.

The Vedas, or ancient sacred books of the Hindoos, distinctly set forth the doctrine of the infinite and Eternal Supreme Being. According to the Vedas, there is ‘one unknown, true Being, all present, all powerful, the creator, preserver, and destroyer of the universe.’ This Supreme Being ‘is not comprehensible by vision, or by any other of the organs of sense, nor can he be conceived by means of devotion or virtuous practices.’ He is not space, nor air, nor light, nor atoms, nor soul, nor nature: he is above all these and the cause of them all. He ‘has no feet, but extends everywhere; has no hands, but holds everything; has no eyes, yet sees all that is; has no ears, yet hears all that passes. His existence had no cause. He is the smallest of the small and the greatest of the great; and yet is, in fact neither small nor great.’ Such is the doctrine of the Vedas in its purest and most abstract form; but the prevailing theology which runs through them is what is called Pantheism, or that system which speaks of God as the soul of the universe, or as the universe itself. Accordingly, the whole tone and language of the highest Hindoo philosophy is Pantheistic. As a rope, lying on the ground, and mistaken at first view for a snake, is the cause of the idea or conception of the snake which exists in the mind of the person looking at it, so, say the Vedas, is the Deity the cause of what we call the universe. ‘In him the whole world is absorbed; from him it issues; he is entwined and interwoven with all creation.’ ‘All that exists is God: whatever we smell, or taste, or see, or hear, or feel, is the Supreme Being.’

This one incomprehensible Being, whom the Hindoos designate by the mystical names Om, Tut, and Jut, and sometimes also by the word Brahm, is declared by the Vedas to be the only proper object of worship. Only a very few persons of extraordinary gifts and virtues, however, are able, it is said, to adore the Supreme Being—the great Om—directly. The great majority of mankind are neither so wise nor so holy as to be able to approach the Divine Being himself, and worship him. It being alleged that persons thus unfortunately disqualified for adoring the invisible Deity should employ their minds upon some visible thing, rather than to suffer them to remain idle, the Vedas direct them to worship a number of inferior deities, representing particular acts or qualities of the Supreme Being; as, for instances, Crishnu or Vishnu, the god of preservation; Muhadev, the god of destruction; or the sun, or the air, or the sea, or the human understanding; or, in fact any object or thing which they may choose to represent as God. Seeing, say the Hindoos, that God pervades and animates the whole universe, everything, living or dead, may be considered a portion of God, and as such, it may be selected as an object of worship, provided always it be worshiped only as constituting a portion of the Divine Substance. In this way, whatever the eye looks on, or the mind can conceive, whether it be the sun in the heavens or the great river Ganges, or the crocodile on its banks, or the cow, or the fire kindled to cook food, or the Vedas, or a Brahmin, or a tree, or a serpent—all may be legitimately worshiped as a fragment, so to speak, of the Divine Spirit. Thus there may be many millions of gods to which Hindoos think themselves entitled to pay divine honours. The number of Hindoo gods is calculated at 330,000,000, or about three times the number of their worshipers.

Of these, the three principal deities of the Hindoos are Brahma the creator, Vishnu the preserver, and Seeb or Siva the destroyer. These three of course, were originally intended to represent the three great attributes of the Om or Invisible Supreme Being—namely, his creating, his preserving, and his destroying attributes. Indeed the name Om itself is a compound word, expressing the three ideas of creation, preservation, and destruction, all combined. The three together are called Trimurti, and there are certain occasions when the three are worshiped conjointly. There are also sculptured representations of the Trimurti, in which the busts of Brahma, Vishnu, and Siva are cut out of the same mass of stone. One of these images of the Trimurti is found in the celebrated cavern temple of Elephanta, in the neighborhood of Bombay, perhaps the most wonderful remnant of ancient Indian architecture. Vishnu and Siva are more worshipped separately than Brahma—each having his body of devotees specially attached to him in particular.

Hindooism, like other Pantheistic systems, teaches the doctrine of the transmigration of souls: all creation, animate and inanimate, being, according to the Hindoo system, nothing else but the deity Brahm himself parceled out, as it were, into innumerable portions and forms (when these are reunited, the world will be at an end), just as a quantity of quicksilver may be broken up into innumerable little balls or globules, which all have a tendency to go together again. At long intervals of time, each extending over some thousand millions of years, Brahm does bring the world to an end, by reäbsorbing it into his spirit. When, therefore, a man dies, his soul, according to the Hindoos, must either be absorbed immediately into the soul of Brahm, or it must pass through a series of transmigrations, waiting for the final absorption, which happens at the end of every universe, or at least until such time as it shall be prepared for being reunited with the Infinite Spirit. The former of the two is, according to the Hindoos, the highest possible reward: to be absorbed into Brahm immediately upon death, and without having to undergo any farther purification, is the lot only of the greatest devotees. To attain this end, or at least to avoid degradation after death, the Hindoos, and especially the Brahmins, who are naturally the most intent upon their spiritual interests, practice a ritual of the most intricate and ascetic description, carrying religious ceremonies and antipathies with them into all the duties of life. So overburdened is the daily life of the Hindoos with superstitious observances with regard to food, sleep, etc., that, but for the speculative doctrines which the more elevated minds among the Brahmins may see recognised in their religion, the whole system of Hindooism might seem a wretched and grotesque polytheism.

A hundred millions of people professing this system, divided into castes as now, and carrying the Brahminical ritual into all the occupations of lazy life under the hot sun, and amid the exuberant vegetation of Hindoostan—such was the people into which Alexander the Great carried his conquering arms; such, doubtless, they had been for ages before that period; and such did they remain, shut out from the view of the rest of the civilized world, and only communicating with it by means of spices, ivory, etc., which found their way through Arabia or the Red Sea to the Mediterranean, till Vasco de Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope, and brought Europe and India into closer connection. Meanwhile a Mohammedan invasion had taken place (A. D. 1000); Mohammedans from Persia had mingled themselves with the Hindoos; and it was with this mixed population that British enterprise eventually came into collision.

Ere quitting the Indians, it is well to glance back at the Chinese, so as to see wherein these two primeval and contemporaneous consolidations of our species—the Mongolian consolidation of eastern Asia, and the Caucasian consolidation of the central peninsula of southern Asia—differ. ‘Whoever would perceive the full physical and moral difference,’ says Klaproth, ‘between the Chinese and Indian nations, must contrast the peculiar culture of the Chinese with that of the Hindoo, fashioned almost like a European, even to his complexion. He will study the boundless religious system of the Brahmins, and oppose it to the bald belief of the original Chinese, which can hardly be named religion. He will remark the rigorous division of the Hindoos into castes, sects, and denominations, for which the inhabitants of the central kingdom have even no expression. He will compare the dry prosaic spirit of the Chinese with the high poetic souls of the dwellers on the Ganges and the Dsumnah. He will hear the rich and blooming Sanscrit, and contrast it with the unharmonious speech of the Chinese. He will mark, finally, the literature of the latter, full of matters of fact and things worth knowing, as contrasted with the limitless philosophic-ascetic writing of the Indians, who have made even the highest poetry wearisome by perpetual length.’

History of the Eastern Nations till their Incorporation in the Persian Empire. Leaving India—that great fragment of the original Caucasian civilization—and proceeding westward, we find two large masses of the human species filling in the earliest times the countries lying between the Indus and the Mediterranean—namely, an Indo-Persian mass filling the whole tract of country between the Indus and the Tigris; and a Semitic-Aramaic mass filling the greater part of lesser Asia and the whole peninsula of Arabia, and extending itself into the parts of Africa adjoining the Red Sea. That in the most remote ages these lands were the theatres of a civilized activity is certain, although no records have been transmitted from them to us, except a few fragments relative to the Semitic nations. The general facts, however, with regard to these ante-historic times, seem to be: 1st, That the former of the two masses mentioned—namely, the population between the Indus and the Caspian—was essentially a prolongation of the great Indian nucleus, possessing a culture similar to the Indian in its main aspects, although varied, as was inevitable, by the operation of those physical causes which distinguish the climate of Persia and Cabool from that of Hindoostan; 2d, That the Semitic or Aramaic mass divided itself at a very early period into a number of separate peoples or nations, the Assyrians, the Babylonians, the Phœnicians, the Jews, the Arabians, etc., and that each of these acquired a separate development, and worked out for itself a separate career; 3d, That upwards of a thousand years before Christ the spirit of conquest appeared among the Semitic nations, dashing them violently against each other; and that at length one Semitic fragment—that is, the Assyrians—attained the supremacy over the rest, and founded a great dominion, called the Assyrian empire, which stretched from Egypt to the borders of India (B. C. 800); and 4th, That the pressure of this Semitic power against the Indo-Persic mass was followed by a reäction—one great section of the Indo-Persians rising into strength, supplanting the Assyrian empire, and founding one of their own, called the Persian empire (B. C. 536), which was destined in its turn to be supplanted by the confederacy of Grecian states in B. C. 326.

Beginning with Egypt, let us trace separately the career of each of the Eastern nations till that point of time at which we find them all embodied in the great Persian empire:—

The Egyptians. Egypt, whose position on the map of Africa is well known, is about 500 miles long from its most northern to its most southern point. Through its whole length flows the Nile, a fine large stream rising in the inland kingdom of Abyssinia, and, from certain periodic floods to which it is subject, of great use in irrigating and fertilizing the country. A large portion of Egypt consists of an alluvial plain, similar to our meadow grounds, formed by the deposits of the river, and bounded by ranges of mountains on either side. The greatest breadth of the valley is 150 miles, but generally it is much less, the mountain ranges on either side often being not more than a few miles from the river.

A country so favorably situated, and possessing so many advantages, could not but be among the earliest peopled; and accordingly, as far back as the human memory can reach, we find a dense population of a very peculiar character inhabiting the whole valley of the Nile. These ancient Egyptians seem, as we have already said, to have been a mixture of the Semitic with the Ethiopic element, speaking a peculiar language, still surviving in a modified form in the Coptic of modern Egypt. In the ancient authors, however, the Egyptians are always distinguished from the Ethiopians, with whom they kept up so close an intercourse, that it has been made a question whether the Egyptian institutions came from the Ethiopian Meroe, or whether, as is more probable, civilization was transmitted to Ethiopia from Egypt.

The whole country is naturally divided into three parts—Upper Egypt, bordering on what was anciently Ethiopia; Middle Egypt; and Lower Egypt, including the Delta of the Nile. In each there were numerous cities in which the population was amassed: originally Thebes, a city of Upper Egypt, of the size of which surprising accounts are transmitted to us, and whose ruins still astonish the traveler, was the capital of the country; but latterly, as commerce increased, Memphis in Middle Egypt became the seat of power. After Thebes and Memphis, Ombi, Edfou, Esneh, Elephantina, and Philoe seem to have been the most important of the Egyptian cities.