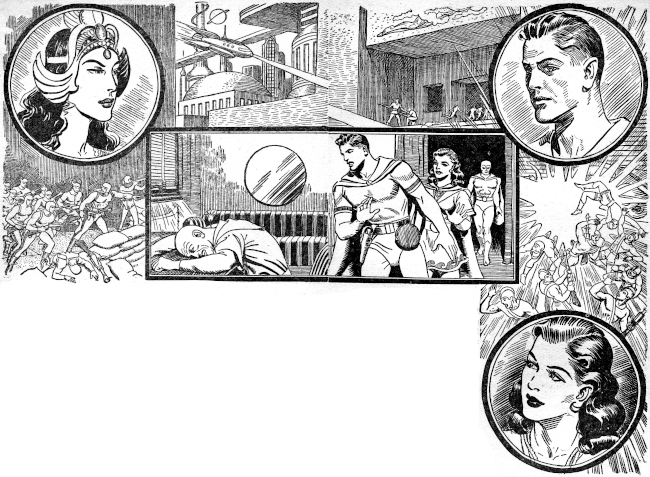

Death was Jaro Moynahan's stock in trade, and

every planet had known his touch. But now, on

Mercury, he was selling his guns into the

weirdest of all his exploits—gambling his life

against the soft touch of a woman's lips.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Planet Stories Summer 1945.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

On the stage of Mercury Sam's Garden, a tight-frocked, limber-hipped, red-head was singing "The Lady from Mars." The song was a rollicking, ribald ditty, a favorite of the planters and miners, the space pilots and army officers who frequented the garden. The girl rendered it with such gusto that the audience burst into a roar of applause.

She bent her head in acknowledgment so that her bronze red hair fell down about her face. There was perspiration on her upper lip and temples. Her crimson mouth wore a fixed smile. Her eyes were frightened.

The man, who had accompanied the singer on the piano, sat at the foot of the stage, his back to the crowded tables. He did not look up at the singer but kept his pale, immature face bent over the keys, while his fingers lightly, automatically picked out the tune. Sweat trickled down the back of his neck, plastered his white coat to his back. Without looking up, he said: "Have you spotted him?" His voice was pitched to reach the singer alone.

The girl, with an almost imperceptible gesture, shook her head.

The night was very hot; but then it is always hot on Mercury, the newest, the wildest, the hottest of Earth's frontiers. Fans spaced about the garden's walls sluggishly stirred the night air, while the men and women sitting at the tables drank heavily of Latonka, the pale green wine of Mercury. Only the native waiters, the enigmatic, yellow-eyed Mercurians, seemed unaffected by the heat. They didn't sweat at all.

Up on the stage the singer was about to begin another number when she stiffened.

"Here he is," she said to the pianist without moving her lips.

The pianist swung around on his stool, lifted his black eyes to the gate leading to the street.

Just within the entrance, a tall, thin man was standing. He looked like a gaunt gray wolf loitering in the doorway. His white duraloes suit hung faultlessly. His black hair was close-cropped, his nose thin and aquiline. For a moment he studied the crowded garden before making his way to a vacant table.

"Go on," said the pianist in a flat voice.

The red-head shivered. Stepping from the stage she picked her way through the tables until she came to the one occupied by the newcomer.

"May I join you?" she asked in a low voice.

The man arose. "Of course. I was expecting you. Here, sit down." He pulled out a chair, motioned for the waiter. The Mercurian, his yellow incurious eyes like two round topazes, sidled up. "Bring us a bottle of Latonka from the Veederman region, well iced." The waiter slipped away.

"So," said the red-head; "you have come. I did not think you would be in time." Her hands were clenched in her lap. The knuckles were white.

The man said nothing.

"I did not want to call you in, Jaro Moynahan." It was the first time she had used his name. "You have the reputation of being unpredictable. I don't trust you, but since...."

She stopped as the waiter placed glasses on the table and deftly poured the pale green wine. The man, Jaro Moynahan, raised his glass.

"Here's to the revolution," he said. His low voice carried an odd, compelling note. His eyes, light blue and amused, were pale against his brown face.

The girl drew in her breath.

"No! Mercury is not ready for freedom. Only a handful of fanatics are engineering the revolution. The real Mercurian patriots are against it, but they are afraid to protest. You've got to believe me. The revolution is scheduled to break during the Festival of the Rains. If it does, the Terrestrials here will be massacred. The Mercurians hate them. We haven't but a handful of troops."

Jaro Moynahan wiped the sweat from his forehead with a fine duraweb handkerchief. "I had forgotten how abominably hot it can be here."

The girl ignored the interruption. "There is one man; he is the leader, the very soul of the revolution. The Mercurians worship him. They will do whatever he says. Without him they would be lost. He is the rebel, Karfial Hodes. I am to offer you ten thousand Earth notes to kill Karfial Hodes."

Jaro Moynahan refilled their empty glasses. He was a big man, handsome in a gaunt fashion. Only his eyes were different. They were flat and a trifle oblique with straight brows. The pupils were a pale and penetrating blue that could probe like a surgeon's knife. Now he caught the girl's eyes and held them with his own as a man spears a fish.

"Why call me all the way from Mars for that? Why not have that gunman at the piano rub Hodes out?"

The girl started, glanced at the pianist, said with a shiver: "We can't locate Karfial Hodes. Don't look at me that way, Jaro. You frighten me. I'm telling the truth. We can't find him. That's why we called you. You've got to find him, Jaro. He's stirring up all Mercury."

"Who's putting up the money?"

"I can't tell you."

"Ah," said Jaro Moynahan; "so that's the way it is."

"That's the way it is."

"There isn't much time," he said after a moment. "The Rains are due any day now."

"No," the girl replied. "But we think he's here in the city."

"Why? What makes you think that?"

"He was seen," she began, then stopped with a gasp.

The lights had gone out.

It was as unexpected as a shot in the back. One moment the garden was glowing in light, the next the hot black night swooped down on the revelers, pressing against their eyes like dark wool. The fans about the walls slowed audibly and stopped. It grew hotter, closer.

Jaro Moynahan slipped sideways from the table. He felt something brush his sleeve. Somewhere a girl giggled.

"What's coming off here?" growled a petulant male voice. Other voices took up the plaint.

Across the table from Jaro there was the feel of movement; he could sense it. An exclamation was suddenly choked off as if a hand had been clamped over the girl's mouth.

"Red!" said Jaro in a low voice.

There was no answer.

"Red!" he repeated, louder.

Unexpectedly, the deep, ringing voice of Mercury Sam boomed out from the stage.

"It's all right. The master fuse blew out. The lights will be on in a moment."

On the heels of his speech the lights flashed on, driving the night upward. The fans recommenced their monotonous whirring.

Jaro Moynahan glanced at the table. The red-headed singer was gone. So was the pianist.

Jaro Moynahan sat quietly back down and poured himself another glass of Latonka. The pale green wine had a delicate yet exhilarating taste. It made him think of cool green grapes beaded with dew. On the hot, teeming planet of Mercury it was as refreshing as a cold plunge.

He wondered who was putting up the ten thousand Earth notes? Who stood to lose most in case of a revolution? The answer seemed obvious enough. Who, but Albert Peet. Peet controlled the Latonka trade for which there was a tremendous demand throughout the Universe.

And what had happened to the girl. Had the rebels abducted her. If so, he suspected that they had caught a tartar. The Red Witch had the reputation of being able to take care of herself.

He beckoned a waiter, paid his bill. As the Mercurian started to leave, a thought struck Jaro. These yellow-eyed Mercurians could see as well in the dark as any alley-prowling cat. For centuries they had lived most their lives beneath ground to escape the terrible rays of the sun. Only at night did they emerge to work their fields and ply their trades. He peeled off a bill, put it in the waiter's hands.

"What became of the red-headed singer?"

The Mercurian glanced at the bill, then back at the Earthman. There was no expression in his yellow eyes.

"She and the man, the queer white one who plays the piano, slipped out the gate to the street."

Jaro shrugged, dismissed the waiter. He had not expected to get much information from the waiter, but he was not a man to overlook any possibility. If the girl had been abducted, only Mercurians could have engineered it in the dark; and the Mercurians were a clannish lot.

Back on the narrow alley-like street Jaro Moynahan headed for his hostelry. By stretching out his arms he could touch the buildings on either side: buildings with walls four feet thick to keep out the heat of the sun. Beneath his feet, he knew, stretched a labyrinth of rooms and passages. Somewhere in those rat-runs was Karfial Hodes, the revolutionist, and the girl.

At infrequent intervals green globes cut a hole in the night, casting a faint illumination. He had just passed one of these futile street lamps when he thought he detected a footfall behind him. It was only the whisper of a sound, but as he passed beyond the circle of radiation, he flattened himself in a doorway. Nothing stirred. There was no further sound. Again he started forward, but now he was conscious of shadows following him. They were never visible, but to his trained ears there came stealthy, revealing noises: the brush of cloth against the baked earth walls, the sly shuffle of a step. He ducked down a bisecting alley, faded into a doorway. Immediately all sounds of pursuit stopped. But as soon as he emerged he was conscious again of the followers. In the dense, humid night, he was like a blind man trying to elude the cat-eyed Mercurians.

Jaro Moynahan

In the East a sullen red glow stained the heavens like the reflection of a fire. The Mercurian dawn was about to break. With an oath, he set out again for his hostelry. He made no further effort to elude the followers.

Once back in his room, Jaro Moynahan stripped off his clothes, unbuckled a shoulder holster containing a compressed air slug gun, stepped under the shower. His body was lean and brown as his face and marked with innumerable scars. There were small round puckered scars and long thin ones, and his left shoulder bore the unmistakable brownish patch of a ray burn. Stepping out of the shower, he dried, rebuckled on the shoulder holster, slipped into pajamas. The pajamas were blue with wide gaudy stripes. Next he lit a cigarette and stretching out on the bed began to contemplate his toes with singular interest.

He had, he supposed, killed rather a lot of men. He had fought in the deadly little wars of the Moons of Jupiter for years, then the Universal Debacle of 3368, after that the Martian Revolution as well as dozens of skirmishes between the Federated Venusian States. No, there was little doubt but that he had killed quite a number of men. But this business of hunting a man through the rat-runs beneath the city was out of his line.

Furthermore, there was something phony about the entire set up. The Mercurians, he knew, had been agitating for freedom for years. Why, at this time when the Earth Congress was about to grant them self-government, should they stage a revolution?

A loud, authoritative rapping at the door interrupted further speculation. He swung his bare feet over the edge of the bed, stood up and ground out his cigarette. Before he could reach the door the rapping came again.

Throwing off the latch, he stepped back, balancing on the balls of his feet.

"Come in," he called.

The door swung open. A heavy set man entered, shut and locked the door, then glanced around casually. His eyes fastened on Jaro. He licked his lips.

"Mr. Moynahan, the—ah—professional soldier, I believe." His voice was high, almost feminine. "I'm Albert Peet." He held out a fat pink hand.

Jaro said nothing. He ignored the hand, waited, poised like a cat.

Mr. Peet licked his lips again. "I have come, Mr. Moynahan, on a matter of business, urgent business. I had not intended to appear in this matter. I preferred to remain behind the scenes, but the disappearance of Miss Mikail has—ah—forced my hand." He paused.

Jaro still said nothing. Miss Mikail must be the red-headed singer, whom at different times he had known under a dozen different aliases. He doubted that even she remembered her right name.

"Miss Mikail made you a proposition?" Albert Peet's voice was tight.

"Yes," said Jaro.

"You accepted?"

"Why, no. As it happened she was abducted before I had the chance."

Mr. Peet licked his lips. "But you will, surely you will. Unless Karfial Hodes is stopped immediately there will be a bloody uprising all over the planet during the Festival of the Rains. Earth doesn't realize the seriousness of the situation."

"Then I was right; it is you who are putting up the ten thousand Earth notes."

"Not entirely," said Peet uncomfortably. "There are many of us here, Mercurians as well as Earthmen, who recognize the danger. We have—ah—pooled our resources."

"But you stand to lose most in case of a successful revolution?"

"Perhaps. I have a large interest in the Latonka trade. It is—ah—lucrative."

Jaro Moynahan lit a cigarette, sat down on the edge of the bed. "Why beat about the bush," he asked with a sudden grin. "Mr. Peet, you've gained control of the Latonka trade. Other Earthmen are in control of the mines and the northern plantations. Together you form perhaps the strongest combine the Universe has ever seen. You actually run Mercury, and you've squeezed out every possible penny. Every time self-government has come before the Earth Congress you've succeeded in blocking it. You are, perhaps, the most cordially-hated group anywhere. I don't wonder that you are afraid of a revolution."

Mr. Peet took out a handkerchief and mopped his forehead. "Fifteen thousand Earth notes I can offer you. But no more. That is as high as I can go."

Jaro laughed. "How did you know Red had been kidnapped?"

"We have a very efficient information system. I had the report of Miss Mikail's abduction fifteen minutes after the fact."

Jaro raised his eyebrows. "Perhaps then you know where she is?"

Mr. Peet shook his head. "No. Karfial Hodes' men abducted her."

A second rapping at the door caused them to exchange glances. Jaro went to the door, opened it. The pianist at the gardens was framed in the entrance. His black eyes burned holes in his pale boyish face. His white suit was blotched with sweat and dirt.

"They told me Mr. Peet was here," he said.

"It's for you," said Jaro over his shoulder.

Mr. Peet came to the door. "Hello, Stanley. I thought Hodes had you? Where's Miss Mikail?"

"I got away. Look, Mr. Peet, I got to see you alone."

Albert Peet said, "Would you excuse me, Mr. Moynahan?" He licked his lips. "I'll just step out into the hall a moment." He went out, drawing the door shut after him.

Jaro lit a cigarette. He padded nervously back and forth across the room, his bare feet making no noise. He sat down on the edge of the bed. He got up and ground out the cigarette. He went to the door, but did not open it. Instead, he took another turn about the room. Again he came to a halt before the door, pressed his ear against the panel. For a long time he listened but could distinguish no murmur of voices. With an oath he threw open the door. The hall was empty.

II

Jaro returned to his room, stripped off his pajamas, climbed back into his suit. He tested the slug gun. It was a flat, ugly weapon which hurled a slug the size of a quarter. He preferred it because, though he seldom shot to kill, it stopped a man like a well placed mule's hoof. He adjusted the gun lightly in its holster in order that it wouldn't stick if he were called upon to use it in a hurry. Then he went out into the hall.

At the desk he inquired if any messages had come for him. There were none, but the clerk had seen Mr. Peet with a young fellow take the incline to the underground. Above the clerk's head a newsograph was reeling off the current events almost as soon as they happened. Jaro read:

"Earth Congress suspends negotiations on Mercurian freedom pending investigation of rumored rebellion. Terrestrials advised to return to Earth. Karfial Hodes, Mercurian patriot, being sought."

Jaro descended the incline to the network of burrows which served as streets during the flaming days. Here in the basements and sub-basements were located the shops and dram houses where the Mercurians sat around little tables drinking silently of the pale green Latonka. The burrows were but poorly lit, the natives preferring the cool gloom, and Jaro had to feel his way, rubbing shoulders with the strange, silent populace. But when he reached the Terrestrial quarter of the city, bright radoxide lights took the place of the green globes, and there was a sprinkling of Colonial guards among the throng.

Jaro halted before a door bearing a placard which read:

"LATONKA TRUST"

He pushed through the door into a rich carpeted reception room. At the far end was a second door beside which sat a desk, door and desk being railed off from the rest of the office. The door into Albert Peet's inner sanctum was ajar. Jaro could distinguish voices; then quite clearly he heard Albert Peet say in a high girlish tone:

"Stanley, I thought I left you in the native quarter. Why did you follow me? How many times have I told you never to come here?"

The reply was unintelligible. Then the pale-faced young man came through the door shutting it after himself. At the sight of Jaro Moynahan he froze.

"What're you sneaking around here for?"

Jaro settled himself warily, his light blue eyes flicking over the youth.

"Let's get this straight," he said mildly. "I've known your kind before. Frankly, ever since I saw you I've had to repress a desire to step on you as I might a spider."

The youth's black eyes were hot as coals, his fingers twitching. His hands began to creep upward.

"You dirty ..." he began, but he got no further. Jaro Moynahan shot him in the shoulder.

The compressed air slug gun had seemed to leap into Jaro's hand. The big slug, smacked the gunman's shoulder with a resounding thwack, hurled him against the wall. Jaro vaulted the rail, deftly relieved him of two poisoned needle guns.

"I'll get you for this," said Stanley, his mouth twisted in pain. "You've broken my shoulder. I'll kill you."

The door to the inner sanctum swung open.

"What's happened?" cried Albert Peet in distress. "What's wrong with you, Stanley?"

"This dirty slob shot me in the shoulder."

"But how badly?" Peet was wringing his hands.

"Nothing serious," said Jaro. "He'll have his arm in a sling for a while. That's all."

"Stanley," said Mr. Peet. "You're bleeding all over my carpet. Why can't you go in the washroom. There's a tile floor in there. If you hadn't disobeyed this wouldn't have happened. You and your fights. Has anyone called a doctor? Where's Miss Webb? Miss Webb! Oh, Miss Webb! That girl. Miss Webb!"

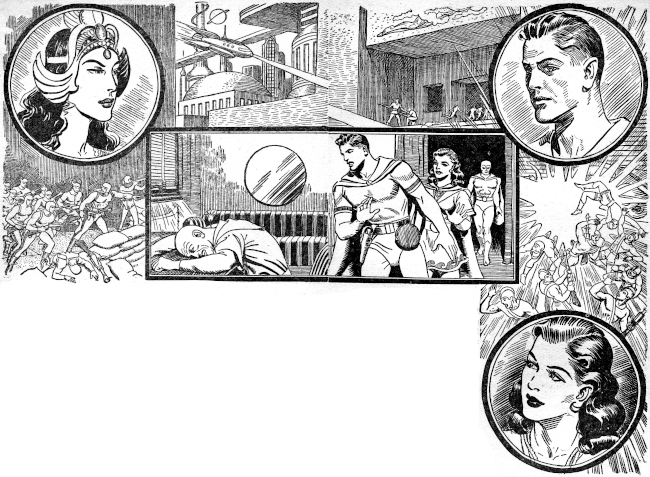

Stanley climbed to his feet, swayed a moment drunkenly, then wobbled out a door on the left just as a tall brunette hurried in from the right. She had straight black hair which hung not quite to her shoulders, and dark brown eyes, and enough of everything else to absorb Jaro's attention.

"Oh!" exclaimed Miss Webb as she caught sight of the blood staining the carpet.

Joan Webb

"There's been an—ah—accident," said Mr. Peet, and he licked his lips. "Call a doctor, Miss Webb."

Miss Webb raised an eyebrow, went to the visoscreen. In a moment she had tuned in the prim starched figure of a nurse seated at a desk.

"Could Dr. Baer rush right over here? There's been an accident."

"Rush over where?" said the girl in the visoscreen. "These gadgets aren't telepathic, honey."

"Oh," said Miss Webb, "the offices of the Latonka Trust."

The girl in the visoscreen thawed like ice cream in the sun. "I'm sure Dr. Baer can come. He'll be there in a moment."

"Thank you," said Miss Webb. She flicked the machine off, then added: "You trollop."

Mr. Peet regarded Jaro Moynahan with distress.

"Really, Mr. Moynahan, was it necessary to shoot Stanley? Isn't that—ah—a little extreme? I'm afraid it might incapacitate him, and I had a job for him."

"Oh," cried Miss Webb, her brown eyes crackling. "Did you shoot that poor boy? Aren't you the big brave man?"

"Poor boy?" said Jaro mildly. "Venomous little rattlesnake. I took these toys away from him." He held out the poisoned dart guns. "You take them, Mr. Peet. Frankly, they give me the creeps. They might go off. A scratch from one of those needles would be enough."

Mr. Peet accepted the guns gingerly. He held them as if they might explode any minute. He started to put them in his pocket, thought better of it, glanced around helplessly.

"Here, Miss Webb," he said, "do something with these. Put them in my desk."

Miss Webb's eyes grew round as marbles. "I wouldn't touch one of those nasty little contraptions for all the Latonka on Mercury."

"Here, I'll take them," said Stanley coming back into the room. He had staunched the flow of blood. His face was even whiter, if possible. Jaro eyed him coldly as with his good hand the youth dropped the dart guns back into their holsters.

"Act like you want to use those and I'll put a slug in your head next time."

"Now, Mr. Moynahan." Mr. Peet licked his lips nervously. "Stanley, go into my office. The doctor will be here in a moment. Miss Webb, you may go home. I'll have no more work for you today."

Albert Peet led Stanley through the door. Jaro and Miss Webb were alone. With his eye on the door, Jaro said:

"When you go out, turn left toward the native quarter. Wait for me in the first grog shop you come to."

Miss Webb raised her eyebrows. "What's this? A new technique?"

"Look," began Jaro annoyed.

"My eyes are practically popping out of my head now," she interrupted. "Another morning like this and I take the first space liner back to Earth." She jammed her hat on backward, snatched her bag from the desk drawer.

"I'm not trying to pick you up. This is...."

"How disappointing."

Jaro began again patiently. "Wait for me in the first grog shop. There's something I must know. It's important." He cleared his throat. "Don't you find the heat rather uncomfortable, Miss Webb. But perhaps you've become accustomed to it."

Mr. Peet came back into the room.

"Why, no, I mean yes," replied Miss Webb, a blank expression in her eyes.

"Goodbye, Miss Webb," said Mr. Peet firmly.

Jaro grinned and winked at her. Miss Webb tottered out of the room.

As the door closed behind the girl, Albert Peet licked his lips, said: "Mr. Moynahan, I suppose my disappearance back at your room requires some explanation. But the fact is that Stanley brought an important bit of news." He paused.

Jaro said nothing.

"You might be interested to know that Miss Mikail is quite safe. Karfial Hodes has her, but Stanley assures me she will be quite safe." Again he paused. As Jaro remained silent, his neck mottled up pinkly.

"The fact is, Mr. Moynahan, that we won't need you after all. I realize that we've put you to considerable trouble and we're prepared to pay you whatever you believe your time is worth. Say five hundred Earth notes?"

"That's fair enough," replied Jaro.

Albert Peet sighed. "I have the check made out."

"Only," continued Jaro coldly, "I'm not ready to be bought off. I think I'll deal myself a hand in this game."

Mr. Peet's face fell. "You won't reconsider?"

"Sorry," said Jaro; "but I've got a date. I'm late now." He started to leave.

"Stanley!" called Albert Peet.

The pale-faced young man appeared in the doorway, the dart gun in his good hand. Jaro Moynahan dropped on his face, jerking out his slug gun as he fell. There was a tiny plop like a cap exploding. He heard the whisper of the poisoned dart as it passed overhead. Then he fired from the floor. The pale-faced young man crumpled like an empty sack.

Jaro got up, keeping an eye on Albert Peet, brushed off his knees.

"You've killed him," said Peet. "If I were you, Mr. Moynahan, I would be on the next liner back to Earth."

Without answering, Jaro backed watchfully from the room.

Once Jaro Moynahan had regained the street, he mopped his forehead with his handkerchief. Whatever was going on, these boys played for keeps. Warily he started down the passage toward the native quarter. At the first basement grog shop he turned in. His eyes swept the chamber, then he grinned.

At a corner table, a tall glass of Latonka before her, sat Miss Webb. Her hat was still on backwards, and she was perched on the edge of her chair as if ready to spring up and away like a startled faun.

"Bang!" said Jaro coming up behind her and poking a long brown finger in the small of her back.

Miss Webb uttered a shriek, jerked so violently that her hat tilted over one eye. She regarded him balefully from beneath the brim.

"Never a dull moment," she gritted.

Still grinning, Jaro sat down. "I'm Jaro Moynahan, Miss Webb. I think Albert Peet forgot to introduce us. There's some skullduggery going on here that I'm particularly anxious to get to the bottom of. I thought you might be able to help me."

"Yes," replied Miss Webb sweetly.

A native waiter, attracted no doubt by her scream, came over and took Jaro's order.

"All right," Jaro smiled, but his pale blue eyes probed the girl thoughtfully. "I'll have to confide certain facts which might be dangerous for you to know. Are you game, Miss Webb?"

"Since we're going to be so chummy," she replied; "you might begin by calling me Joan. You make me feel downright ancient."

"Well then," he said. "In the first place, I just killed that baby-faced gunman your boss had in his office."

"Awk!" said Joan, choking on the Latonka.

"It was self-defense," he hastened to assure her. "He took a pot shot at me with that poisoned dart gun."

"But the police!" she cried, as she caught her breath.

"There'll never be an investigation. Albert Peet will see to that. I was called here on what I supposed was a legitimate revolution. Instead I was offered ten thousand Earth notes to assassinate the leader of the revolution."

"What revolution? I'm going around in circles."

"The Mercurians, of course."

"I don't believe it," said the girl. "The Mercurians are the most peaceable people in the Universe. They've been agitating for freedom, yes. But they believe in passive resistance. I don't believe you could induce a Mercurian to kill, even in self-protection. That's why Albert Peet and the rest of the combine had such an easy time gaining control of the Latonka trade."

"Score one," breathed Jaro, "I begin to see light. Miss Webb—ah, Joan—I've a notion that we're going to be a great team. How do you happen to be Albert Peet's private secretary?"

"A gal's gotta eat. But the truth is, I was quitting. The Latonka Trust is almost on the rocks. Their stock has been dropping like a meteor."

Jaro Moynahan raised his oblique brows but did not interrupt.

"Albert Peet," she continued, "has been trying to sell out but nobody will touch the stock, not since it looks as if the Earth Congress is going to grant the Mercurians their freedom. Everybody knows that the first thing the Mercurians will do, will be to boot out the Latonka Trust."

"What about this Karfial Hodes?" said Jaro. "I've heard that he's inciting the Mercurians to rebellion. The newscaster had a line about the revolution too. The government has advised all Terrestrials to return to Earth."

"It's not true," Joan flared. "It's all a pack of lies invented by the Latonka Trust. I know."

"But I should think rumors like that would run down the Latonka stock."

Joan shook her head. "It doesn't add up, I know. But Karfial Hodes is a real patriot. He wouldn't advocate a bloody revolution. That's not his way."

They both sipped their wine. Joan's eyes were narrowed thoughtfully but Jaro's features were impassive.

"Well," he said at last, "I wouldn't give a Venusian kapek for Karfial Hodes' life right now."

"Why?"

Jaro shrugged. "They wanted me to find him and kill him. Stanley, that little rattlesnake, is captured by Hodes' men and escapes, then Albert Peet doesn't need me anymore. What would you say?"

The girl's eyes widened. "They know where he is?"

"Exactly."

"But he's such a gentle old man. Surely they wouldn't murder him."

Jaro said nothing. He sat facing the entrance. From time to time he flicked his eyes to the girl's face but for the most part, he watched the doorway like a cat at a mouse hole. For some minutes past he had been unobtrusively studying a plump, bald-headed man who had entered and was loitering about the door. The plump man's hand disappeared inside the breast of his gray coat. When it reappeared there was the glint of metal in his fist.

Without a word of warning, Jaro seized the edge of the table, upended it with a crash of glass. In the same movement, he slipped to the floor, using the table as a shield. Joan was left sitting in her chair, a foolish expression on her face.

"For heaven's sake," she hissed, "get up! Everybody's staring at us."

Jaro shifted the slug gun to his left hand, grabbed the girl by one shapely ankle, yanked her to the floor.

"Oof!" she gulped as she lit with a solid smack. Her hat slid to the back of her head.

"Stay down!" said Jaro impassively.

The plump man in the gray suit was circling the table warily. Jaro took a pot shot at him over the top of the table. The plump man spun around as if jerked by an unseen hand. The occupants of the other tables simultaneously dived for the door which was at least ten feet too narrow to accommodate them all. The plump man was sitting on the floor, his back to the wall, a surprised expression on his face. His poisoned dart gun lay a dozen feet away.

"Come on," said Jaro yanking the girl to her feet as abruptly as he had tumbled her down. "This joint should have a back exit."

Joan clapped her hand to her hat as they dashed around the bar and through a door. They came out into a narrow, devious alley which paralleled the main passage.

"What happened?" Joan gasped when she caught her breath.

Jaro slipped the slug gun back in its holster. "Give me a slug gun any day. It's got a kick like a rocket tube. When you hit a man with it, he says down. Knocked that gunman right off his feet. Did you see him?"

"No," said Joan bitterly. "I'm not accustomed to being thumped around like a sack of flour. I didn't see anything, after bouncing off the floor, but stars."

"One of Peet's men tailed me into the grog shop," he explained, "and took a shot at us."

"Us?" she gulped. "But why?"

"We know too much."

They had emerged into a well-lit, well-traveled passage. Jaro looked at the girl seriously, his light blue eyes unreadable. "What can I do with you?"

"Must you do anything? I'm really a very frail girl. You play too rough."

He ignored the interruption. "You'd better come to my room." He took her arm, started off toward the native quarter.

"Please, Mr. Moynahan," she protested trotting along beside him.

"Now, listen," said Jaro patiently. "I didn't kill that gunman. When he lets Peet know that we were together your life won't be worth anymore than Karfial Hodes'."

"Oh," said Miss Webb. Then increasing her pace she repeated with rising inflection: "Oh! Well let's not loiter along like this. Let's get there!"

III

At his room, Jaro locked the door under the girl's suspicious eyes.

"If I were to listen to my better judgment," she remarked dryly, "I would leap out the window right now."

"And probably get sunstroke before you hit the street," he supplemented. "I'm hungry enough to eat a cow, hoofs, horns, and tail." He went to the telescreen and ordered dinners to be brought to the room.

"Am I going to spend the rest of my life here?" she asked.

"Heaven forbid."

Joan stood in the middle of the floor like a skater on thin ice. Jaro went over to the bed, sat down, lit a cigarette. He flipped the match out the window.

"Sit down," he said abruptly. "Unless, of course, you can rest on your feet like a horse."

Joan sank primly into a chair across from the bed. "What are we going to do?"

He shrugged. "We're in a spot. Albert Peet probably has another gunman after us by this time. We might have lost his men when we ducked out the back of that bar, but I doubt it. He has a very efficient spy system. Karfial Hodes' men have been tailing me since last night. Actually Miss Webb—uh—Joan—we're in a state of siege. There's something big afoot. So big they can't afford to let us escape."

Joan gulped, her eyes big as saucers. "But what do we know?"

"Well," he replied seriously; "we know first that Peet is hiring a bunch of gunmen to rub out Karfial Hodes—and incidentally, us."

"Us? What's incidental about that?" Joan interrupted vigorously. "Maybe you consider having gunmen take a pot shot at you incidental, but as far as I'm concerned it's the nub of the whole nasty business."

Jaro ignored the interruption. "Furthermore, we know that the Latonka Trust is almost on the rocks because the Earth Congress is about to grant the Mercurians their freedom. And this time Albert Peet and his combine haven't been able to block it. Not yet anyway."

"Don't forget the revolution," said Joan.

"I'm not. A revolution would burst open the Latonka Trust like a ripe watermelon. Peet would be lucky if he got away with his pants. But...."

A discreet knocking at the door interrupted him. Miss Webb clapped her hand to her mouth as if to stifle a scream.

"Don't open it," she hissed loud enough to be heard on the next floor.

Jaro drew his slug gun, threw off the latch, then with a swift cat-like movement yanked open the door.

Just outside stood a serving wagon loaded with food. The native waiter looked up, startled at the sudden opening of the door, and found himself staring down the barrel of Jaro's slug gun. His yellow eyes popped out like agates and he almost completed a back somersault.

"Bring it in," said Jaro sheathing the gun.

With a reproachful glance the waiter set the dishes on the table and retreated hastily. The serving wagon took the curve into the hall on two wheels.

Suppressed giggles rocked Joan's body. "Oh, if you could have seen yourself." She burst out laughing. "The mother bird defending its young." She rocked back and forth in the chair.

"You'd better come eat," said Jaro stiffly, "before the food gets cold."

Joan stifled her laughter, wiped the tears out of her eyes, pulled up a chair.

"I'm not a bit hungry," she protested; "but what a lovely steak." She attacked it with vigor. "Um, um," she said between mouthfuls. "Delicious." There were half a dozen other dishes. Her strong white teeth wrought havoc with their contents. Jaro, a light eater, picked at a salad, but for the most part he watched the girl with growing interest. From time to time she cast covetous glances at his steak which he had pushed aside.

"If you're not going to eat your steak," she ventured hesitantly.

Jaro pushed it across the table. "For a girl who wasn't a bit hungry," he said; "you've shown remarkable staying powers. What do you do? Store it up in case of famine?"

"Really," said Joan polishing off Jaro's steak; "you embarrass me."

Just then a loud knock at the door caused her to gulp the last of it unchewed.

"What is this?" she asked, "the crossroads of Mercury? You certainly entertain a lot."

Jaro drew his slug gun again, tiptoed to the door, pulled it open. A big blond young man was leaning against the door frame. He was a good six feet, three inches tall and his shoulders almost filled the entrance. He had light blue eyes, a short straight nose. The rest of his face wore a broad grin.

"Hello, Jaro, you old butcher," said the big young man. "Quit tickling my nose with that slug gun and invite me in."

Joan tittered as Jaro holstered the gun. The big young man caught sight of her for the first time. He looked quickly away.

"Sorry, old man," he said in a low voice, "didn't know you had company. No end sorry. Meet me tonight at Mercury Sam's Garden."

Jaro's face broke into a grin.

"Come in," he said. "It's much worse than it looks." He turned to Joan. "Miss Webb, this is Irving Landovitch. He's with the Terrestrial Intelligence Service; so naturally he has a suspicious mind."

Landovitch

Joan blushed hotly. "Oh," she said. "How do you do?"

The T.I.S. agent acknowledged the introduction, sat down on the bed.

"What are you doing here, Irving?" asked Jaro. "The last time I saw you, you were working on a smuggling case back on Earth."

"That's what I should ask you," replied the big young man, "but I don't mind telling you Jaro, I'm investigating a report that a revolution is about to break here on Mercury. Frankly, we didn't put much credence in it until we learned that you'd landed."

"How did you find me?"

"Oh that," chuckled the T.I.S. agent. "We've had a man shadowing you ever since you hit the space port."

For the first time Jaro exhibited annoyance. "First Hodes' men, then Albert Peet's men and now the T.I.S. I knew was being tailed, but I didn't realize I was leading a parade."

The T.I.S. agent glanced at Joan. "No offense, Miss Webb, but could I see Mr. Moynahan alone? It won't take but a moment."

She glanced helplessly at Jaro. "Where shall I go?"

Jaro grinned. "You might step in the shower, pull the curtain around you and turn on the water."

The big young man looked perplexed. "Couldn't we join her in the dining room in a few moments?"

"No," expostulated Jaro. "I should say not. She just ate enough to last a Mercurian family a week. If I turned her loose down with all that food she'd probably flounder herself. Besides Albert Peet's gunmen would like nothing better than to catch her alone. No, Irving, you'll have to talk in front of her."

"I don't like it," replied Landovitch. He shook his head full-like from side to side. "But, well Jaro, how are you mixed up in this?"

Jaro hitched his chair closer. "Listen, I was at Valego, organizing the Martian army. The prince had commissioned me."

"We know all about your disreputable past," Landovitch interrupted blandly.

"Quit heckling him," said Joan. "For all I've been able to gather he was born yesterday. He's the most uncommunicative man ever."

Irving Landovitch clucked sympathetically. "Jaro, how did you impose on this poor innocent child. If you'd let me know, maybe I could, too."

"I was on Mars," Jaro continued patiently, "when I got a flash from the Red Witch—she's using the name of Mikail—to grab the first spaceship for Mercury. She said she was singing at Mercury Sam's Garden." In as few words as possible he sketched his adventures since arriving. Landovitch whistled.

"The Rains are three days overdue," he said.

"What is the Festival like?" asked Jaro. "I've heard something about it, but I've never been here during the Rains."

The T.I.S. agent rolled his eyes. "It would make a Roman orgy look like a Sunday School picnic. Ordinarily the Mercurians are the meekest people in the Universe, but during the Rains, they go a little crazy."

"A little?" said Joan. "They're mad as hatters." She paused, her expression undergoing an abrupt change. "Listen!"

At first they could distinguish nothing, then from outside the window came a persistent sigh which gradually deepened into a full-throated roar.

"The Rains," breathed Joan with a catch in her throat. "In a moment we will hear the flutes."

Out in the hall someone knocked on the door.

"Third time's the charm," said Jaro, and drew the slug gun.

Landovitch said: "He won't be expecting me. When he shoots you I ought to be able to catch him by surprise."

"Maybe I should allow you to answer the door."

"Go on." Landovitch waved his gun. "I'm right behind you, but out of the line of fire, of course."

Jaro threw open the door. Both men thrust their guns in the face of the little Mercurian waiter who had served the food.

"I'm growing accustomed," the waiter said; "to your peculiar sense of humor." He marched between the two big men, closed and locked the heavy storm shutters, marched back out. Joan burst into peals of laughter. Jaro and Landovitch sheepishly returned their guns to their holsters.

"Will you quit laughing like a hyena," said Jaro, "I think I hear something."

Joan subsided into giggles. From beneath their feet came a thin minor melody. It possessed a maddening undercurrent indescribable in its effect. Other instruments joined the first until the sound was like a field of katydids.

"The flutes," said Joan. "It's the flutes."

Jaro, listening to their reedy melody, thought of the pipes of Pan. He allowed his pale blue eyes to examine Joan Webb. She had long legs, hips that were full, rounded, but not too broad, a slim waist, high breasts. He took a long drink of Latonka. He said, "I want to revel."

Landovitch said with admiration in his voice, "You sure can pick 'em, Jaro."

She glanced in alarm from Jaro to Landovitch. "Don't get any ideas, you two predatory wolves, you. I absolutely refuse to be a party to any orgies."

"Tell me," said Jaro, "what is this Festival of the Rains? What does it symbolize?"

Joan explained: "It celebrates the marriage of Nemi, the god of the rain, with the soil. Each year Nemi takes a new bride. She's chosen from the prettiest girls of Acecia. She symbolizes the earth. The last night of the festival, she is led into a beautiful chamber deep in the lower levels of the rain god's temple and placed in bed and left. Nemi, himself, is—ah—er, supposed to visit her during the night. For a whole year she must remain faithful to Nemi. The people actually believe her a goddess. But at the end of that time Nemi divorces her, and she is relegated to the Temple Priestesses. The Temple Priestesses," she added dryly, "aren't noted for their rigidity of morals."

They all took a drink of Latonka. The flutes were louder, more insistent in their suggestion. Landovitch twitched his blond scalp pensively. He did it like a horse twitches a patch of hide. Joan stared at him fascinated. She said, "How did you do that?" She wrinkled her nose, frowned, trying to imitate his feat.

"Gimme that jug," said Jaro. He turned to Joan. "We," he said impressively, "are the revolution." Joan realized that the two men had consumed considerable wine. Landovitch threw wide his arms. "Camarade!" he shouted. There were tears in his eyes.

Jaro put down the jug empty. "Camarade!" he cried. They embraced.

Joan watched them, her brown eyes round as saucers. Jaro turned to Joan. "Camarade!" he said. He embraced her. She said, "Camarade" in a weak voice. He continued to embrace her. Landovitch lost interest in the revolution. He was searching for another jug. With a chortle, he dragged one forth from beneath the bed.

He observed Jaro and Joan with a lifted eyebrow. "Such brazenness," he said in a reproving voice; "and right before my eyes, too."

"Oh!" exploded Joan angrily. She pushed Jaro away. "Of all the disgusting tricks!" she said. "This isn't any time for clowning."

"I think," said Jaro Moynahan, "our best plan is to locate Karfial Hodes. I have an idea that he is the key to this mess."

Landovitch said, "Lead on, Moynahan. Your faithful friend, Last Ditch Landovitch, is with you." He waved the jug. "Camarade," he said.

"Camarade," said Jaro. They opened their arms. They embraced like two football tackles. Jaro turned to Joan, "Camarade," he said.

"No you don't!" said Joan grimly. "I've been 'cameraded' the last time." Jaro's arms encircled her like bands of steel. She had never imagined such strength. "Oh well," she said, "camarade."

Landovitch opened the door. The music of the flutes swept into the room. Jaro and Landovitch linked their arms in Joan's. She was not a small girl, but she appeared fragile and doll-like between the two big men. The T.I.S. agent twirled the two gallon jug of Latonka on his finger. They paraded into the hall, down the stairs, three abreast.

Jaro saw with surprise that the lobby was deserted. The clerk seemed nervous, irritable, anxious to join the revelry which assailed their ears from the runs.

Joan suddenly went, "Awk."

Landovitch, under the impression that she was choking, thumped her on the back.

"For God's sake!" said Joan. "Stop it before you jar my teeth loose."

"Yeah! Stop it," Jaro said.

Landovitch desisted.

"I thought," said Joan; "that Albert Peet's men were trying to kill us?"

"They are," said Jaro.

Joan started back toward the steps. "Then I'm going to lock myself in your room," she said.

Jaro grabbed her arm.

Landovitch said, "Well take care of Peet's men."

"Give me a drink of that dutch courage," said Joan, taking the Latonka jug. She took a long drink. They all took a long drink. They descended into the runs.

IV

At once they were engulfed in a concourse of Mercurians. Jaro stared about him in amazement. The narrow dim-lit way was jammed with revelers. The women wore the historic costume, a short skirt low on bare hips and a diminutive jacket with squared sleeves. Their black hair was done up on top of their heads with blossoms of the red egalet that only blooms during the Rains. Wooden clogs were fastened to their feet. The men wore gaudy, loose trousers and cummerbunds of green. Their chests were bare, and many bands of hammered silver ornamented their arms.

The three revolutionists wriggled their way into a grog shop. They were served wine and thin strips of cheese with some strange, hexagonal crackers.

"Why can't I get assignments like this often?" bewailed Landovitch.

"Don't look now," said Joan, "but a man's following us."

Jaro lit a cigarette, allowed his eyes to scrutinize the room. A short, fat Earthman lounged at the door. The waiter offered him a glass of Latonka which he refused. He had a hat perched on the back of his head. He wore a white coat but no shirt. A second Earthman pushed through the door. The fat man raised an eyebrow, nodded imperceptibly toward Jaro. The second man took a seat at a table to their left. Jaro's eyes flitted about the room. On the other side two men sipped Latonka. They were Venusians. Tall, lean, yellow skinned men, they reminded him of Manchus. Each, he noticed with a start, had a pale blue star about the size of a dime tattooed on his forehead. Fazoqls! The caste of professional killers! His experience during the wars among the Federated Venusian States had given him a great respect for the Fazoql's cast. They were men without fear. He nudged Landovitch.

"We're in a trap," he smiled, sipped his wine. He looked as if he were passing the time of day. He said, "Joan get between us. Saunter toward the door."

Two more Earthmen squeezed inside. The fat man nodded his head. The two Venusian Fazoqls pushed back from the table.

The fat man intercepted them. "Where you going?" he asked with a smile.

Jaro hit him in the mouth. Landovitch kicked someone in the stomach; shot one of the Fazoqls, clouted a third ruffian over the head. Jaro was grateful that Landovitch was with him. The big T.I.S. agent in action combined the destructive ability of an octopus and a tornado. They dived for the door. Then Jaro saw Landovitch topple over.

The second Fazoql had walloped him over the head with the leg of a chair. The lights went out. Joan screamed. Jaro felt her hand torn from his arm. He thought, "Mercurians!"

Something hit him over the head.

After a while Jaro came to. He stood up, bumped his head against the ceiling. It was dark. He felt about with his hands. He seemed to be in a cubical cell about four feet square and not much higher. He could neither stand up nor lie down. It was so deep beneath the city, he couldn't hear the flutes. His head ached. The walls, floor, and ceiling of the cell, he discovered by the sense of touch, were stone. He sat down, his back to the wall. He wondered dully what had happened to Landovitch and Joan. Did Albert Peet or Karfial Hodes have the girl?

He thought ruefully that Peet probably had her. The presence of the Earthmen and the two Venusian Fazoqls convinced him that Peet was behind the attack. Then he too must be a prisoner of Peet. He was faintly surprised that he hadn't been killed.

He closed his eyes to shut out the absolute darkness which pressed in on him from all sides. With a touch of panic he considered the possibility that he might be blind. He shuddered, refusing to think about it, speculating on the fine collection of rogues which Albert Peet had gathered in support of his collapsing economic empire.

He was not surprised that the Latonka Czar had hired the Fazoqls. The caste of Venusian killers were active all over the Universe. Like the Greek mercenaries of ancient times, it was a respected profession on Venus. As long as Peet fulfilled his side of the contract, the Fazoqls would be loyal. But the Earthmen!

Earthmen gone bad were more feared than mad dogs and given a much wider berth. They were just as apt to destroy Albert Peet as his enemies. When he thought of Joan Webb being left to their tender care, he writhed mentally.

There was something fresh, likeable, wholesome about the girl. He made no melodramatic vows of revenge to himself should he discover that the girl had been harmed. Instead a coldness crept over his mind. He would, he knew, hunt them to the outermost ports of the Universe's far-flung frontiers.

His head was no better. He felt that a drink of Latonka would clear his mind. After a while he went back to sleep.

When he awoke he was very thirsty. He set about exploring his cell with his fingers, encountered a jug and a pan of food. They must have been placed there while he slept. He ate and drank. His head didn't ache so badly, his mind was clearer. He felt his chin. He thought he would like a bath and a shave.

He shifted position, leaned back against the wall, felt it give slightly beneath his weight. He scrambled around, feverishly ran his hand over the smooth blocks of stone. One of the blocks, he discovered, had been pushed back in the wall about an inch. He shoved outward against it. The stone receded further, leaving a hole scarcely large enough for his broad shoulders.

Jaro squeezed into the hole, wriggled forward, pushing the stone ahead of him. It ran in grooves. This was not the regular door he felt sure, but a secret entrance of whose existence he doubted that even his guards suspected. After about four feet, he felt himself clear of the wall. The stone came to a stop. He could push it no further. He had come through into a second chamber or passage, he didn't know which as still no glimmer of light relieved the intense darkness.

He stood, cracked his head against the ceiling. He recalled the small stature of the Mercurians, grinned ruefully.

He bethought himself of his captors' surprise when they discovered his escape, got back down on hands and knees, pushed the stone back into the exit. It came to a stop with a small click. The hole was plugged. He tried to move the stone. It was latched fast. He realized that the lock must not have been caught or else no amount of pressure would have moved that stone. Backing out into the passage behind the cells, he stood up again. He was free.

Stooping painfully he crept along the wall. He had taken five hundred and twenty-three steps when he stumbled up a stair. Recovering his balance, he climbed up sixteen steps which wound back on themselves, came out in another passage. This second corridor he judged ran directly above the one he had just left. There was still no light. With increasing confidence he began its exploration.

The first thing his groping fingers encountered was a narrow alcove inset in the wall. Like a blind man he passed his hand across the back wall of the alcove, felt a knob-like protuberance, pulled. A small stone plug came out, revealing a peep hole. A ray of light streamed through the aperture. He wasn't blind!

He put his eye to the peep hole, saw a large, delicately furnished room. In the center was a bed on a dais. Several luxurious chairs, fashioned like chaise lounges and upholstered in white fur, squatted invitingly about the floor. A deep-piled aquamarine carpet covered the cold stone blocks under foot. The walls were a solid mass of bas relief. The ancient sculptor had exhibited a robust sense of realism in his choice of subjects.

He felt about the walls, sure that there must be some means of ingress. His fingers discovered a second handle. He pulled. A section of the wall swung back.

For a moment he hesitated like a gray wolf coming into a clearing, then crossed the chamber to the door. Cautiously, he inched it open. A long corridor met his eyes. It was lighted like the chamber with the pale green globes of the Mercurians. Like the chamber too, it was deserted.

He stepped back in the room, drew the door shut, bolted it. With growing curiosity he set about examining his surroundings. If this belonged to Albert Peet's establishment, he surely did himself proud. He discovered a closet full of rich feminine apparel, then a second door leading through a mirror paneled dressing room into a bath with a sunken tub.

Jaro sighed. He stripped off his clothes, filled the tub, let himself into the warm water. Having bathed he searched a small built-in cabinet, found a hair remover used by the Mercurian women on their legs. It doubled for a razor quite successfully. He ran his hand over his chin, laughed, returned to the main chamber. Unlocking the door to the hall in order not to create suspicion, he retreated into the secret passage, shut the door, plugged the peep hole.

A dozen steps further along the corridor, he found a second alcove identical with the last. There was a corresponding peep hole. The room he looked into resembled the other except that its appointments differed. It too, was deserted. He thought everyone must be above celebrating the Festival. He wondered where he was. The last two chambers had held no clue.

A third alcove revealed a room similar to the others except that it was occupied. A pale Mercurian girl was asleep on the bed. Her black hair lay on her white shoulders like stains of ink. A broad band of green metal encircled one naked ankle.

Jaro drew in his breath sharply. A temple priestess, one of the ex-brides of Nemi. He was beneath the temple of the rain god. Albert Peet's men had not captured him after all. The thought induced a new chain of reasoning. He remembered the lights flashing out back in the grog shop. His thought at the time: "Mercurians." It dawned on him that Karfial Hodes' men must have rescued them from Peet's hired Mercenaries. But why? He put the plug back into place.

The following two chambers were empty. At first, he thought the next one was too. He was about to insert the plug when a girl entered from the dressing room. His lips formed an inaudible whistle. The girl was Joan Webb.

Jaro, observing Joan Webb through the peep hole, saw that her tawny brown eyes were strained, frightened, her shorts and blouse rumpled as if slept in. He wondered suddenly how much time had elapsed since the fight in the grog shop.

Joan turned and went back into the dressing room. Jaro, with a broad grin, found the handle, swung back the secret panel. He squeezed through the narrow aperture, drew shut the panel behind him.

Joan came back into the room.

He said: "Hail, fairest of all maidens. I am Nemi come for my bride."

Joan screamed, sprang back into the dressing room, peered at him wildly around the edge of the frame.

"You!" she said. She came out. "Where did you come from?"

Jaro bounced up and down on the edge of the bed. "How did you rate this?" he asked. "You should have seen my cell. You've been imprisoned in the lap of luxury."

Joan repeated, "Where did you come from?"

He waved his hand airily. "Out of the nowhere into the here."

She observed him dubiously, said, "Listen Nemi, if you can get in and out as you please, let's not loiter."

He grinned, led her to the secret entrance, pushed back the panel.

"Oh!" said Joan. "You almost had me believing that Nemi stuff."

"Come on." He squeezed through the exit, disappeared.

Joan hesitated, peering with alarm into the black hole. "The way I have to trust you!"

Jaro reached out a hand, pulled her through, pushed the panel in place. They were immediately in darkness so thick, so dense that they could feel it.

"Where are you?" said Joan, a panicky note in her voice.

"Here," Jaro laughed.

"Oh!" she ejaculated. "Really, Mr. Moynahan."

"What happened back in the grog shop?"

Joan hesitated, said, "It's all kind of foggy. I was simply petrified with fright. When the lights went out, someone grabbed me. I tried to cry out for you only someone had his hand over my mouth. I couldn't do anything but gurgle. They dragged me toward the back of the shop. I thought.... Well, never mind what I thought."

Jaro chuckled.

"It wasn't funny," said Joan, indignantly. "They hauled me down some stairs, into an alley. I saw then that they were Mercurians, and I wasn't so scared. They brought me here, and here I've been ever since. But I still don't understand how you found me."

He said, "There seems to be a regular network of these secret passages running through the walls. It was the merest accident that I stumbled into them. Where they lead, though, I don't know any more than you."

"What are we going to do?" she wanted to know.

"Find Karfial Hodes. I've a hunch that he's hidden here."

"I was afraid of that," she said in a plaintive tone.

Jaro found her hand, led her to the next alcove, applied his eye to the peep hole. The room, he saw, was identical with the one in which Joan had been imprisoned. On the bed lay the red-headed singer of Mercury Sam's Garden.

"The Red Witch," he whispered. "We're getting hot."

"Who's she?" said Joan. She pushed Jaro aside, put her eye to the peep hole. "Where do you meet these people?" she asked.

Jaro said, "I'm going in and talk to her. Wait here."

"What?" cried Joan, "Leave me out in this dark hole? I should say not."

"All right," he replied. He glanced again through the peep hole. The woman was asleep. She lay on her side, her red hair turning the pillow to blood. She still had on the abbreviated costume she had been wearing on Mercury Sam's stage.

Jaro opened the panel, crawled into the room, Joan on his heels.

He went up to the bed, looked down at the sleeping woman. He thought she looked hollow cheeked, unhappy in her sleep; nothing like the flaming wanton who was known throughout the Universe as the Red Witch. He touched her shoulder.

She opened her eyes. They were a vivid green. Recognition swept her features.

V

"Jaro!" she cried, a note of fright in her voice. She jerked up, swung her bare legs off the bed onto the floor. "What do you want? How did you get here?" Those amazing green eyes flicked past him, discovered Joan. She wasn't too frightened to raise her eyebrows.

"There are a few questions I'd like to ask," he replied coolly. "Just who is behind this revolution?"

There was the faintest hesitancy in her reply. "Hodes. Who did you think?"

He looked skeptical, waited.

She said, "You don't believe me? When I talked with you, I exaggerated perhaps. But there is very much money involved, very much indeed. Should the Mercurians be successful, they would take possession of the Latonka Trust, the plantations, and the mines. The Earthmen would be dispossessed. Naturally, they are very anxious to frustrate the revolution."

"But the Mercurians are in the right," Joan burst out. She had been swelling up like a toad in the effort to contain herself. "Albert Peet and his kind, stole everything in the first place. They deserve to be kicked out. Mercury has a right to self-government."

The Red Witch shrugged. "I'm not curious about the ethics. I'm paid by the Earthmen, not the Mercurians. Are you with us or against us, Jaro?"

He ignored her question, asked, "Are you being held by Karfial Hodes?"

She nodded.

"Why?"

She exhibited surprise. "Karfial Hodes knows that I am the principal agent of the counter revolutionaries. But if he thinks that by eliminating me he can block the forces opposing him, he's overestimating my importance."

"Eliminating?" said Jaro mildly. "Are you in any danger?"

She shrugged again. "The Mercurians aren't butchers. They merely hold me until the revolution begins."

Jaro said: "Where does Karfial Hodes keep himself?"

She shook her head.

"That little pianist, the gunman, how did he escape?"

"Stanley, you mean Stanley. Did he get away?" she asked him eagerly.

He nodded.

Her eyes narrowed; she bit her lip.

"That's all you want to tell me?" he said.

The look of fright reappeared in her green eyes. "What do you mean, Jaro?"

He said nothing.

"You know as much as I do," she assured him. "You believe me now, don't you, Jaro." Her voice was eager.

"No," he replied calmly.

"What are you going to do?" she whispered.

"Who are the others in this with you?"

"I can't tell you." She bit her lip, looked more frightened than ever.

"Who are the others?" he repeated mildly.

The red-headed singer leaped to her feet. Her figure was full, strikingly beautiful. She was well aware of her appeal. "Jaro," she cried, "I can't tell you. It would be as much as my life is worth. Not until I know what side you're on."

Jaro regarded her calmly. At length he said, "You'll excuse us if we lock you in the dressing room?"

"But Jaro," she said; "aren't you going to take me with you?"

He shook his head.

"You're going to leave me here?" she repeated. She couldn't keep the relief out of her voice.

He laughed, said, "I'm afraid so."

A great weight seemed lifted from the red-headed singer's mind. With a resumption of her old bravado, she shrugged, walked into the dressing room. Her hips moved from side to side. Jaro shut the door, pushed the bed in front of it.

"The hussy!" said Joan.

Jaro wasn't sure but he thought he detected a feline note in her tone. He led the way back into the passage, closed the exit.

Joan clutched his hand again. "That woman!"

"Attractive, isn't she?" he said with a chuckle. "Ouch!" he said. "That wasn't very lady-like."

"What wasn't?" asked Joan sweetly. "I didn't do anything."

"Well, someone kicked me," he replied.

"You don't think I'd do a thing like that? Do you?"

"Yes," he said. He inched ahead along the lightless passage.

"Jaro."

There was no reply.

"Jaro!" cried the girl in panic. "Where are you? Wait for me, Jaro. I'll never kick you again."

"Is that a promise?" he asked from the darkness right at her ear.

"Eeek!" she gasped. "Yes, it's a promise, though I regret it already."

He chuckled, said, "Give me your hand," led her forward.

They had gone only a few yards, when his foot struck an obstacle. "Careful," he warned. "Here's a stair." They crept up to the next level. The familiar alcoves began again along the right hand wall. He tried the first one. It revealed a rectangular tank of water some ten by twenty feet. The walls were a mosaic of hand painted tile depicting Nemi, the rain god, descending to Mercury in a shower, Nemi searching for his bride, Nemi at the nuptial feast. The fourth wall was the one through which they were looking; and they couldn't see its decoration. From the realism of the ancient artist and the sequence of events, Jaro decided it was just as well they couldn't.

"Whew," he said, "what a bathroom!"

Joan put her eye to the peep hole. Jaro gaped in amazement. From a circular hole in the ceiling poured a curtain of rain. The shaft, he realized, must lead straight up through the different levels and through the roof. A raised dais with a rim around it received the rain in the center of the room. The surface of the dais he saw, was composed of a springy wire mesh through which the water drained into some subterranean channel.

"The bed of Nemi," said Joan. "That's where the queen must sleep on her wedding night. Nemi is supposed to visit her in the rain."

"What a clammy way to spend your wedding night," Jaro said, putting his eye back to the aperture. The appointments of the chamber were magnificent. It glowed with a rosy, pulsating light. The floor was carpeted with a shaggy white rug; a divan large enough to hold at least six people rested against the left hand wall. Around the walls ran murals depicting the exploits of Nemi: Nemi touching the red egalet which burst into flower, Nemi squeezing the juice from a cluster of Latonka grapes.

The next room proved to be an ordinary sleeping chamber, obviously the bedroom of the queen for the remainder of the year. Jaro saw a beautiful Mercurian girl packing clothes and trinkets into a chest. The green band about her ankle marked her as a temple priestess. She was singing a lilting, happy refrain in the odd language of Mercury as she went about her work.

Joan put her eye to the hole.

"That's the ex-queen," she informed him. "She's getting ready to move to the apartments of the temple priestess."

"She doesn't seem unhappy at her approaching bereavement," said Jaro.

Joan sniffed. "Not likely."

"I'm going in to talk to her," said Jaro.

"Are you crazy?" cried Joan in alarm. She tugged at him arm, but he was already pulling back the secret entrance.

The queen had her back to them. Jaro closed the entrance, coughed discreetly. The girl spun around, her hand to her mouth.

"How should I address her?" He whispered over his shoulder.

"I don't think you need bother with formalities," observed Joan in a bitter voice, "not after your entrance."

The queen said, "You are an Earthman."

Jaro said, "Yes, your majesty."

"Majesty?" echoed the Mercurian girl. Her eyes were golden, oblique, curious, her hair a fine graven ebony. She had long, black lashes, bright red lips. Her skirt and jacket were green. "I don't quite understand. I am not very familiar with your language."

Jaro grinned. "I suppose our entrance was not exactly orthodox but the fact is that we are escaped prisoners." The queen raised her fine black brows.

"How did you get here?" Her voice had an odd foreign flavor. Jaro couldn't put his finger on it, but it was there. He said, "That is unimportant. We are searching for Karfial Hodes. I know of no one more apt to be informed of his whereabouts than you."

"And what is it that you want with Karfial Hodes?"

Jaro had the impression that she was stalling, listening expectantly. He said, "Where is Hodes?"

Before she could answer, the doors on either side burst open. A dozen priests of Nemi burst into the room. Jaro caught a triumphant smile on the queen's face, then he kicked the closest Mercurian on the knee. The priest screamed, doubled to the floor. He lifted a second bodily, hurled him into the press, bowling over several others. A priest lit on his back. He flipped him over his shoulder. He rammed an elbow into someone's eye, smashed his fist against a mouth. He kicked another priest on the knee. He got hold of one of the fellows by a leg, whirled him around like a club. He caught a glimpse of the queen, her expression registering frightened dismay. She was stabbing a button on the table, obviously the means by which she had summoned her defenders. A whole horde of priests crowded into the room.

Behind him Joan screamed. "Jaro," she cried. "Help!"

Jaro laid the poor fellow he had been using as a bludgeon on the floor.

"All right," he said. "I surrender." Everyone, especially the priests, appeared relieved.

"Take them before Karfial Hodes," directed the queen. Her yellow eyes regarded the gaunt Earthman with amazement, tinged with respect. The priests laid hold of him gingerly, urged him toward the door. He stood head and shoulders above the Mercurians.

He looked at Joan quizzically, said: "All roads lead to Rome."

"Oh dear," said Joan. "I'm not fitted for this kind of a life. I'm a secretary, a darned good secretary. I don't know how I ever got involved in this mess."

From the queen's apartment they emerged into a broad passage. A concourse of Mercurians moved in streams all about them. They flung eager questions at their guards, chattered, laughed. The flutes, too, were audible once more: thin treble pipings, like the pipes of Pan, Jaro thought.

"How long does the Festival last?" he asked Joan.

"What?" she said. "Oh. Roughly a week. It's half over now."

They came to the end of the corridor, mounted a broad staircase. Jaro sensed that they were still deep in the bowels of Mercury. At length, they were halted before a massive door. A priest stood at the entrance. There was an exchange of words between their captors and the solitary guard. Satisfied, the priest stood aside, flung open the door. Jaro and Joan were motioned inside. The portal clanged shut behind them.

"Caught again," said Joan. "I'll never feel at home now unless I'm behind bars."

Jaro chuckled. "This isn't a jail," he pointed out. "The cells are below us. I think we are about to see Karfial Hodes at last."

The room in which Jaro and Joan found themselves was a large, bare, vaulted hall. At the far end, Jaro saw an imposing door. He advanced curiously toward it.

"Are we just supposed to wait?" asked Joan. "How does Karfial Hodes know we're here?"

"He's probably been notified by visoscreen," he assured her. He pushed experimentally at the massive door. It moved easily beneath his touch. "Hey!" he said. "It's not locked." His voice echoed hollowly in the vaulted antichamber.

"Are we going in?" asked Joan weakly. "As if I didn't know already."

Jaro gave the door a push. It swung wide.

"Look!" cried Joan. "My god, look!"

He saw a magnificent room, the floor of polished marble. A row of fluted columns ran down each side. There was a desk, a modern desk, strangely out of place in the antique setting, opposite the door through which they had entered. Across its polished surface a man sprawled limply, just as if he had fallen forward from his chair in sleep.

With a bound Jaro sprang across the room, felt the man's withered wrist for any signs of pulse. He was a very old man, he saw, and he was quite dead.

"Karfial Hodes!" murmured Joan in a low frightened voice. "I saw him once in a street procession. Is he dead, Jaro?"

Jaro nodded. From the back of the old man's neck, he plucked a tiny metallic splinter. "They got him with a poisoned dart gun. He's still warm. It couldn't have happened but a minute before."

"Oh, Jaro, and he was such a nice old man. Who could have done it?"

Jaro straightened, said, "One of Albert Peet's renegade whites."

"Ugh! And to think I worked for that man."

But Jaro wasn't listening. He had gone behind the desk. "This is how they got him," he said, excitement in his voice. It was, Joan sensed, the excitement of the man hunter when he grows hot on the trail of his quarry. There was a cold and ruthless edge to his voice which she had not heard before, and for the first time she found herself a little afraid of this strange man about whom she really knew so little. Hesitantly she edged after him.

Behind the desk, she saw a panel gaping ajar in the stone wall. It was the same kind of panel which gave admittance to the secret passages on the lower levels. Jaro was nowhere in sight.

"In here," he called, and Joan thought of the baying of wolves running strong on a hot scent. She bit her lip, slipped into the blackness after him.

"Jaro, where are you?"

"This must be how they got him," he said from the darkness beside her. "When that gunman—the little one who was abducted along with the Red Witch, you remember—when he escaped he must have stumbled on these passages, I suppose that was the important information he had for Albert Peet."

"They couldn't have gone very far," suggested Joan.

"No," said Jaro. "Not very far, I hope." He closed the panel. At once the darkness gathered about them, pressed in on them from every side. It was so dark that the girl could bring her hand right up to her face without being able to distinguish a thing.

A ray of light jumped from the panel as Jaro extracted the plug, applied his eye to the aperture. He could see the back of the dead Mercurian leader crumpled across the desk and beyond him the open door into the vaulted antichamber.

As he looked, a Mercurian, the priest who had been on guard at the entrance, appeared in the doorway. Other Mercurians were staring over the priest's shoulder. Consternation was written large across their usually impassive features.

"Sehr Karfial Hodes!" the priest cried, and then uttered a string of Mercurian words quite unintelligible to the listening Jaro.

Suddenly, it seemed to dawn on the priest that there had been foul play. He ran across the floor, turned up his dead leader's face. The benign, peaceful, half smile on the old Mercurian's lips seemed to belie his tragic murder. Jaro put back the plug.

"We're in for it," he said grimly. "The Mercurians must believe that we murdered Karfial Hodes."

"What will they do?" the girl asked in a small voice.

"I don't imagine they'll pin any medals on us," he replied dryly.

"Why did they have to kill Karfial Hodes?" There was a puzzled, tragic note in the girl's voice. "He was such a harmless old man."

"Albert Peet can answer that question," Jaro said quietly. "In fact, he can answer a lot of questions that I intend to ask him. But where can I hide you?"

"Hide me!" ejaculated Joan. "If you get three feet away I'll scream. I don't know why I should feel safer when you're here—I've been shot at, abducted and jailed since I met you—but I do."

For a moment Jaro hesitated, then he fumbled for her wrist in the dark, found it. "Come on," he said. "We'll see where this passage leads."

They crept ahead, encountered a stair, descended thirty-two steps. Again they felt their way along a passage, went down a second flight of steps.

"If this keeps up we'll come out on the under side of Mercury," he said. "Ouch!" There was a dull thud.

"What was that?" cried Joan.

"Me. I cracked my skull on this confounded ceiling." He paused. "Joan, we must be on the same level as my cell." He got down on hands and knees, crawled along the passage, running his fingers across the stones.

"Ah!" he said. His questing fingers had discovered a hole close to the floor.

"Where are you?" Joan cried.

"Here."

She moved up cautiously until she bumped into him. "Whatever are you after, groveling on the floor?" she asked greatly relieved.

"I've a hunch," he replied. "Wait here!"

He wormed his way into the hole, found it blocked by the stone. Delicately, he ran his fingers over its surface seeking its mechanism. A catch? There it was. He released it, hauled. The stone slid towards him. Backing out of the hole, he drew the block after him. Joan stifled a scream as he bumped into her.

With the block clear of the wall, he wriggled back into the hole. If possible the Stygian blackness was thicker than ever. There should be a cell on the other side of the wall. He lay still, listened. The silence was as absolute as the dark. He wormed his way ahead. With a shock he felt his fingers come in contact with bare flesh. A hand flicked across his face, clutched his throat with a grip of iron.

Jaro wrenched backward, tried to call out, but that unrelenting grip on his throat held like a vise, choked off his words. His antagonist never uttered a sound. Silently, blindly they fought in the four foot square cell.

Jaro got his hands on his antagonist's wrists, wrenched. His lungs were on fire, he thought wildly that no sensation was as agonizing as not being able to draw a breath. The man had succeeded in getting both hands on his throat. Jaro drew up his legs, kicked. His feet struck flesh, the iron fingers were torn from his throat. Blessed air poured into his lungs.

Dimly, he realized that Joan was calling his name from the passage. Then she screamed.

A man's voice beside him said: "Jaro! My God! Is that you, Jaro?"

"Yes," panted Jaro, recognizing Landovitch, the T.I.S. agent. "I was looking for you. There's a hole here some place." His fingers were wildly running across the cold stones. "Joan's outside in the passage. Something's happened."

Again the girl screamed.

"Here it is," said Jaro with relief, dived through. Once clear of the walls, he stood up, cracked his head on the low ceiling.

"Joan!" he said. He could hear Landovitch grunting and puffing, trying to squeeze his big frame through the narrow aperture. The girl did not answer.

"Joan!" he called louder. His voice came back to him hollowly in the pitch black corridor. "Joan!"

There was no answer. The girl was gone.

VI

Jaro hesitated undecided which way to go.

"Pull me out of here," Landovitch pleaded. "I'm stuck."

He felt around, seized the big T.I.S. agent's wrist, tugged. Landovitch came free, stood up, cracked his head against the roof with a thud.

"It's a low ceiling," said Jaro.

"This is a fine time to be telling me."

"They've got Joan," said Jaro. "Which way could they have gone?"

"Joan?" echoed Landovitch dubiously. "Oh, you mean Miss Webb, that pretty girl who was with us when the fight started in the grog shop." He paused. "Who's got her? Where are we anyway?"

"Shut up!" said Jaro impolitely. "I'm trying to orientate myself. We're in the Temple of Nemi."

Landovitch whistled softly. "The rain god."