They had to kill it, finally.

Mad with despair, they fought back from the ruins.

Whoever these invaders were, they should not have

a world which its defenders themselves had destroyed!

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Planet Stories Winter 1948.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

The land was dark in the softly falling rain, and the smell of green things was in the air. The crew huddled in their cloaks and peered into the approaching dusk as they unloaded the great silver space ship. They were apprehensive of the stark ruins that began barely a mile from the ship, the ruins that seemed to sprawl interminably across the flat land beside the broad river.

In the metal headquarters hut, the commander glanced nervously at his chronometer. The astrogator looked up from his interminable reckonings and smiled.

"Don't worry, captain," he said. "They'll be all right. After all, we haven't seen any life but a few small animals. And they ran from us."

The commander nodded absently, but went to the open door and stared out into the rain. It made a musical tinkling on the thin metallic dome of the hut.

"I know," he said. "Perhaps that's why I'm worried. It's the feeling of death here, as though it might spring at us from some corner in those ruins.... I should have sent out a stronger scout party."

The astrogator shrugged and returned to his log. "If anything had gone wrong, they would have messaged us."

The commander smiled an unwilling agreement, but he stayed in the open door, searching the gathering darkness toward the city. He could not shake loose from the feeling of doom that had settled on him as soon as they had made their landfall and clambered from the airlocks of the spaceship. This was a strange world, the commander thought to himself. It seemed to have everything—everything but intelligent inhabitants. They had circled it for two days before they had chosen this wide green valley for their landfall. They had seen cities, many of them, great cities along seacoasts and in rich plains, cities in mountains and in valleys, but nowhere had they seen life.

The first cautious explorations after the landing that morning had shown that there was plenty of good water. The soil seemed rich, and vegetation grew in profusion, even among the ruins they had warily skirted. The atmosphere was perfect ... it was what they had searched for through the long bitter years ... this stable atmosphere with its abundance of life-giving oxygen. And minerals aplenty ... the burned and blasted metal skeletons of the ruined city showed that. The commander told himself that he was a fool for worrying, when he should be shouting with joy at his luck.

There was a shout from the outpost, a laugh, and then his second-in-command loped through the rain, smiling broadly. Behind him were the others, laughing and joking, shrugging their packs to the ground. Gladness and wonder were in their faces and their voices, and the commander knew that this was the world they had sought for so long.

The lieutenant ducked into the doorway and paused to warm himself at the little thermal unit. He wiped the rain from his face, reached for the wine bottle beside the astrogator's work board, and tilted it.

"This is it, sir," he said. He was young, and Fate had been good to him, and he was exulting in it. "It's everything we ever dared dream about. It will support the whole race, every one of us, I think, if the rest of this world is anything like what we've seen this day."

The commander grinned back at him, relief plain in his face. He was phrasing the message that he would send home across the void, the message they had waited for down through the weary years, the years that had rolled by while the land burned up under a blazing sun, while the water disappeared and the atmosphere became thin.... But there was still in him the doubt, the remnant of fear....

"Did you," he spaced the words carefully, "find any sign of—intelligent life?"

The lieutenant's smile faded. He glanced quickly out at the men, breaking out their rations, resting from the labor, and looked back at his captain. He nodded.

"Tracks," he said. "We came across them leading out of the deserted city."

"Many?"

"I don't think so. Five or six, perhaps. And we found where they had killed one of the small animals and eaten it."

"Did they seem—intelligent? Really, I mean?"

The lieutenant shrugged. "Who knows? They're bipeds, at any rate. We followed the tracks, but they had taken to a small stream bed, and we lost them."

The commander pondered. Then he made his decision.

"In a country as large as this," he said, "five or six can't make any difference to us, not even to a small party like our own. And certainly not when the ships begin arriving from home."

The lieutenant leaned back on his pack, his face content. The commander sat at a field desk and started writing, carefully, knowing that what he wrote would someday be in every textbook. The message was not difficult, really. Thousands of space captains had phrased the message in their minds down through, the years of The Search. So had he, time and again, as he lay in his bunk or watched the wheeling stars from the bridge. In the glow of the thermal unit his stern face glowed with pride and the certainty that it was his ship that had saved a world....

In another hut the scholar stared thoughtfully at the thing he had found in the old house where they had discovered the tracks. There had been a language on this dead world, and in his hand he held some of the brown mouldering pages upon which the language had been written. He applied his scholar's mind to the puzzle....

The city crouched grimly about them. Even though they had neither seen nor heard any life in these streets save a few small animals who had fled their coming, they gripped their projectors at the ready.

Almost every structure had been damaged. Many were mere twisted heaps of debris, timbers and girders thrusting insanely at a sky that today was blue and benign. The taller, sturdier buildings still stood, but their walls were cracked and their windows gaping hollow eyes in the blank faces. Rubble clogged the streets, and grass had split the pavements. Here and there among the ruins a sapling stood bravely, its roots grasping in the shattered masonry.

In the streets, rusting and ancient, were objects which they surmised must have been vehicles. In some of them they found fragments of bone and shreds of clothing. They had seen other bones; in doorways, on the ground floors of the few buildings they had penetrated.

"Whatever it was," the second-in-command said, "it struck them swiftly."

"Some sickness, a virus, perhaps?" the astrogator suggested.

The commander shook his head. "War," he said. "Only war could do this to a city."

The lieutenant said admiringly, "Whoever they were, they certainly developed some pretty terrific weapons."

The commander had smiled, and patted his projector. "No more terrific than these," he said. "Our own people developed weapons, too. Thank the stars that we have learned not to use them on each other."

The scholar looked up from the inscription he had found on the side of a building.

"And thank the stars," he said, "that we learned in time. The people of this world apparently did not."

It was then, while they spoke, that from somewhere in the ruins there was a sharp crack, and one of the crew spun around and fell in the street. In the shattered silence of the city the sound echoed crazily.

"Take cover!" the captain shouted, and he plunged into a huge doorway, peering around the protecting portal. There was another crack, and something whined by him.

"Projectile weapon!" whispered the lieutenant behind him. He was prone, sighting his projector at a half-ruined four-story house at the corner. He pressed the control switch, once, and a section of the second floor seemed to explode into hurtling gray dust and shrieking steel.

Other projectors were spitting from doorways and from behind piles of brick and debris in the streets. The captain, watching the building from which the answering fire seemed to come, thought he saw movement behind one of the blank windows. Before he could take aim, there was a ripping series of shots and the masonry of the portal flew into dust. He heard the low flat whine of ricochets, and he withdrew deeper into the dimness of the great entranceway. Up the street he heard a crew member cry out in pain.

"The second floor!" he cried, and a hurricane of electron bolts ripped into the building at the corner. The building seemed to rip apart under the impact and there was the roar of falling bricks and timber as a floor gave way with a crash. They dashed out of cover, crouching, firing as they went.

They found three bodies in the ruins. Bipeds. Pale pasty flesh, faces half-hidden by tangled hair. The bodies were only partially clad in faded tattered clothes, and the feet were encased in what appeared to be the tanned hide of an animal. The flesh and the clothing were filthy, and they stank. The bodies were huddled around their weapon, a metallic-looking projectile-thrower mounted on three legs. Its barrel was still hot.

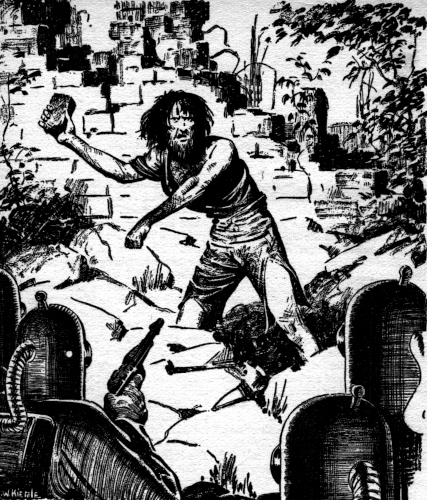

A little later they flushed another of the creatures in a narrow street. It howled gibberish at them and fled, but they cornered the thing against a heap of rubble. It mouthed things at them, and hurled bits of brick. Its eyes were wild and staring, and spittle trickled down the face into the sodden filthy rags it wore. They had to kill it, finally.

They had to kill it, finally.

The commander turned the dead thing over with his projector stock, and stared at it.

"Mad," he said. "There are only a few of them, and they are mad."

The scholar nodded. He had found many of the writings, and they were stuffed in his pack and in his pockets, and he held one while he talked.

"They are mad," he said, "and there cannot be many of them. Certainly not enough to halt the advance of civilization."

It was as if he saw, already, the soaring towers of the cities they would build here over the pitiful ruins, as though the busy highways already spanned this rich new world.

"We have won our bridgehead here," he said. "Soon we will have won the world. The world," he looked down at the carcass at his feet, "that these poor fools threw away."

The scholar made his greatest find late that afternoon, on the street-level floor of an almost-intact building. It must have been a place where writings had been stored, or perhaps sold. The brown rotting pages were everywhere, and the mouldering covers in which the writings had been bound. The scholar cried out with pleasure, and the commander was forced to delay their return to the ship so that the crew could carry part of the loot with them, for further study.

The scholar was squatting in a corner of the room, poring over one of the ancient records, when he looked up and shouted, "I think I've got it! I think I've got it! I think I've found the key to their language!"

The commander had smiled indulgently, for though he believed in action, he had respect for the scholar, and knew that the things the scholar might discover in the old writings might help him in his own task as leader of the expedition.

It was then that the creatures attacked for the last time. They must have crept into the building and gathered there in the dimness, waiting their opportunity. There were six of them. They poured through a rear door into the room of writings, howling, their projectile-throwers barking. Their wild ululations were the screams of the demented. The commander could see the madness in their eyes and he knew why he had been afraid.

The astrogator was down before they could return the fire, and then the projectors cracked out their blue-flamed doom.

The lieutenant cursed as he was hit; he dropped to one knee, firing swiftly, and then the creatures were down and it was over. The wild bearded faces were charred and blackened, and in the sudden silence was the crackle of the little blue flames as they danced over the filthy ragged clothing of the dead. The commander let his breath go, at last, in a long gasping sigh.

He started to walk toward the bodies, knowing that they were the last, knowing that if there had been any more they would have waited, gathering strength, and they would not have made the crazy suicidal attack. The fighting was over. The savage creatures, unbalanced by their miserable existence among the ruins of the glory that had been theirs, would never again threaten the bridgehead he had carved on this world. It was his world now.

There was a frantic tugging at his sleeve, and he shook the battle fog from his eyes and grinned at the scholar. The commander remembered that even while the fight had roared hot and sharp, the scholar had not moved from his corner, nor taken his eyes from the pages he was studying. And now the scholar was fairly dancing with excitement.

"I've got it!" he said, almost chortling. "It wasn't hard with the key—and I found the key!"

He gestured toward the little tangle of bodies, silent in the room of writings.

"They called themselves 'Men,'" he said.

The commander shrugged.