The Table Of Contents has been harvested from the January edition of Godey's Magazine VOL. XLVIII.

A cover page has been created using images from this Month's Godey's Magazine; and '"Olde English", sans-serif;' font has been used for this periodical.

VOL. XLVIII.

| A Bloomer among us, by Pauline Forsyth, | 396 |

| Advice to a Bride, | 405 |

| A Few Words about Delicate Women, | 446 |

| A Great Duty which is Imposed upon Mothers, | 464 |

| A Lesson worth Remembering, | 478 |

| Annoyance, by Beata, | 452 |

| Blessington's Choice, by Fitz Morner, | 424 |

| Bright Flowers for her I Love, by Wm. Roderick Lawrence, | 450 |

| Celestial Phenomena, by D. W. Belisle, | 403 |

| Centre-Table Gossip, | 477 |

| Charity Envieth Not, by Alice B. Neal, | 417 |

| Cottage Furniture, | 454 |

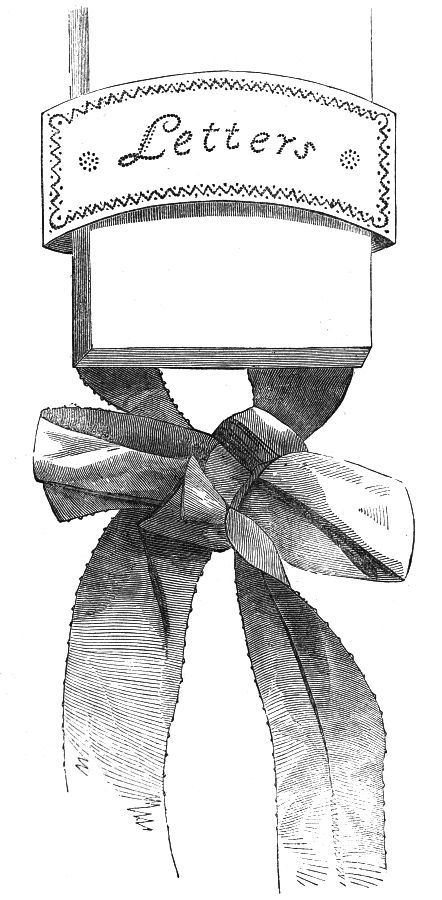

| Directions for a Letter-Band, | 458 |

| Directions for Knitting a Work-Basket, | 458 |

| Directions for taking Leaf Impressions, | 443 |

| Disappointed Love, by W. S. Gaffney, | 449 |

| Dress—as a Fine Art, by Mrs. Merrifield, | 412 |

| Editors' Table, | 462 |

| Embroidery with Cord, | 458 |

| Enigmas, | 474 |

| Evangeline and Antoinette.—Mantillas, | 457 |

| Everyday Actualities.—No. XIX | 393 |

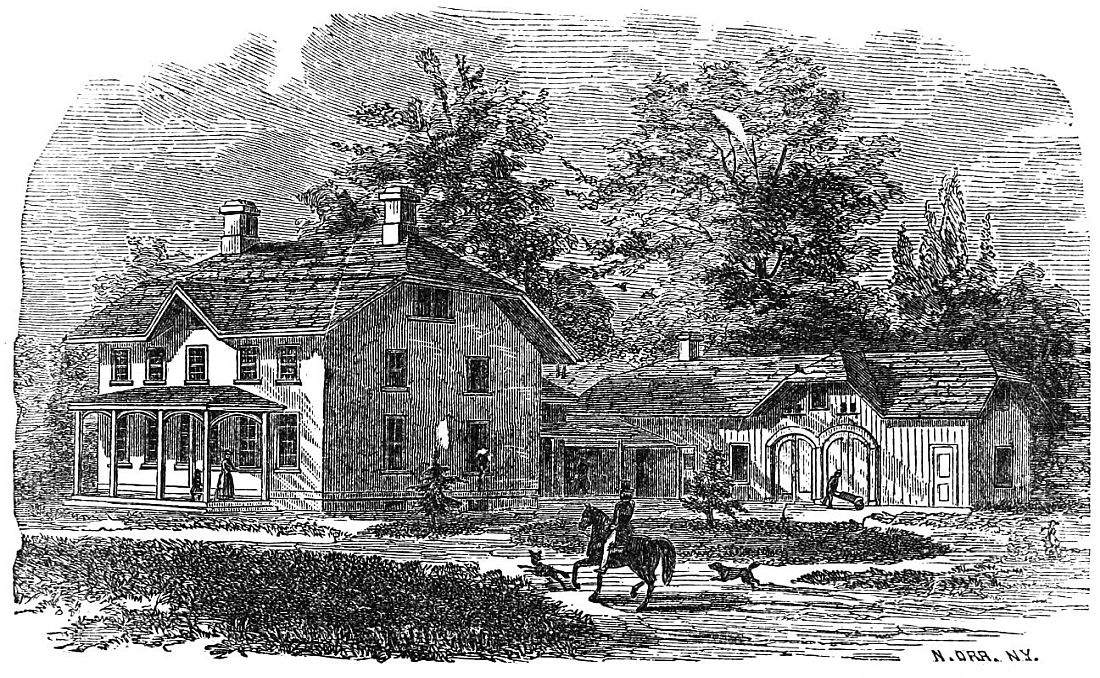

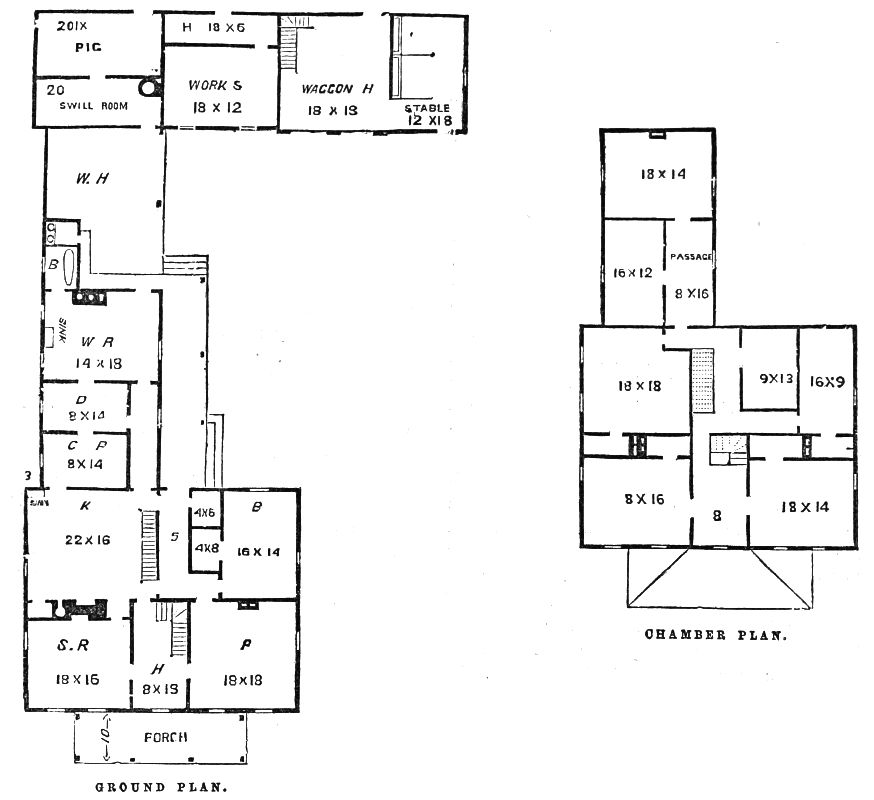

| Farm House, | 444 |

| Fashions, | 479 |

| Female Medical Education, | 462 |

| For the Lovers of Jewelry, | 478 |

| Godey's Arm-Chair, | 467 |

| Godey's Course of Lessons in Drawing, | 410 |

| House Plants, from Mrs. Hale's New Household Receipt-Book, | 472 |

| Instructions in Knitting, | 472 |

| Intellectual Endowments of Children, | 409 |

| Interesting Discovery at Jerusalem, | 395 |

| Lace Mantilla and Tablet Mantilla, | 457 |

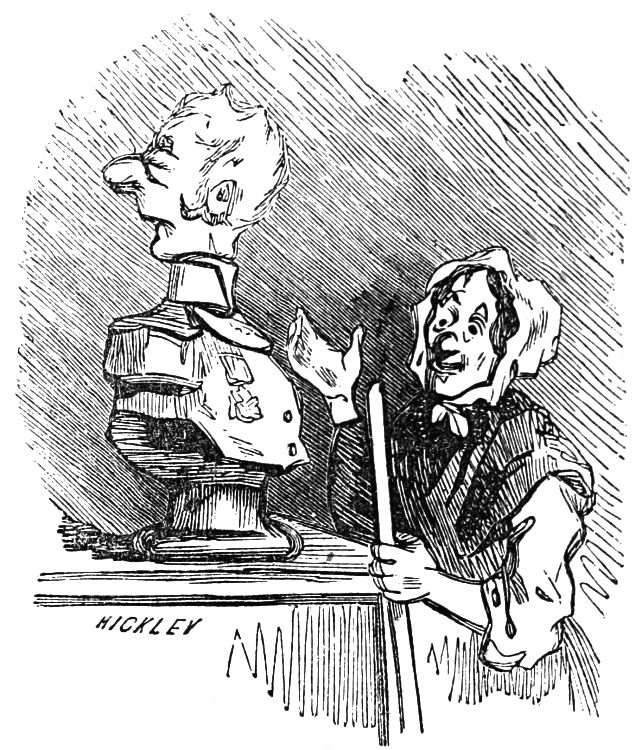

| Letters Left at the Pastry Cook's, Edited by Horace Mayhew, | 414 |

| Literary Notices, | 465 |

| Mantillas, from the celebrated Establishment of G. Brodie, New York, | 458 |

| Manufacture of Pins, | 404 |

| Marquise and Navailles.—Mantillas, | 389, 457 |

| May-Day, | 423 |

| May First, | 477 |

| New Revelations of an Old Country, | 427 |

| Ode to the Air in May, by Nicholas Nettleby, | 452 |

| Our Fashion Department, | 478 |

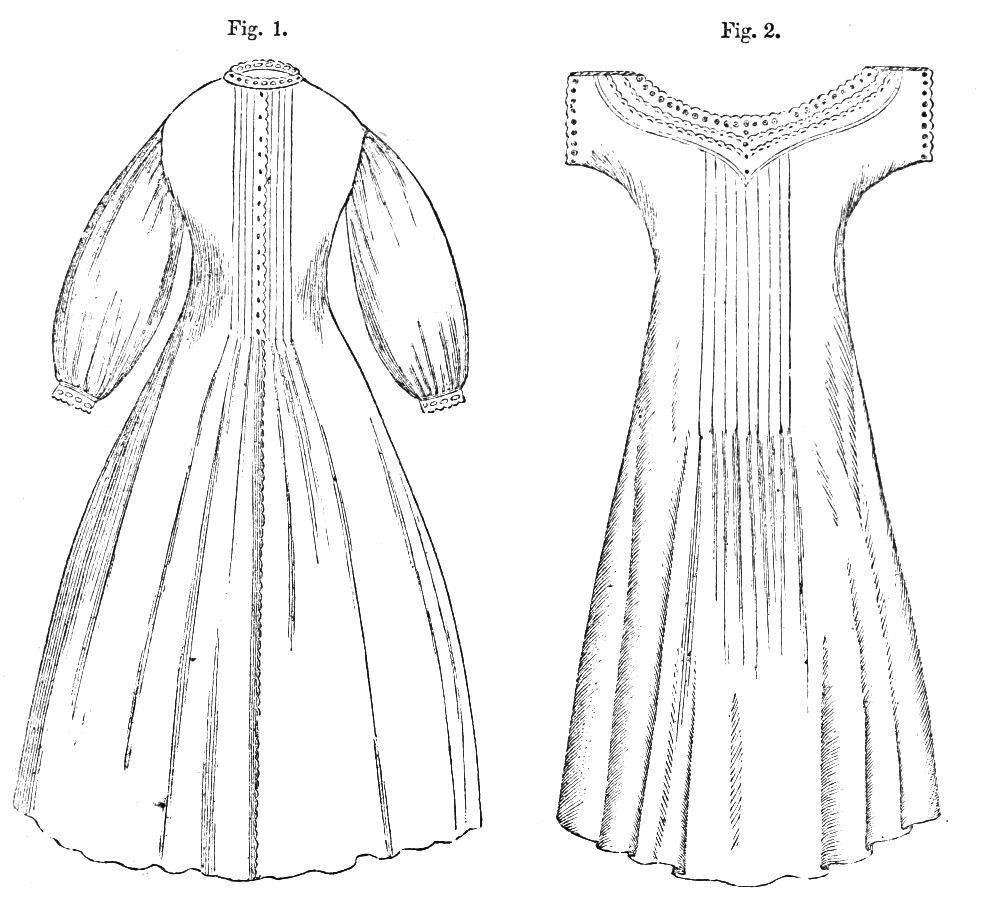

| Our Practical Dress Instructor, | 453 |

| Painting on Velvet, | 393 |

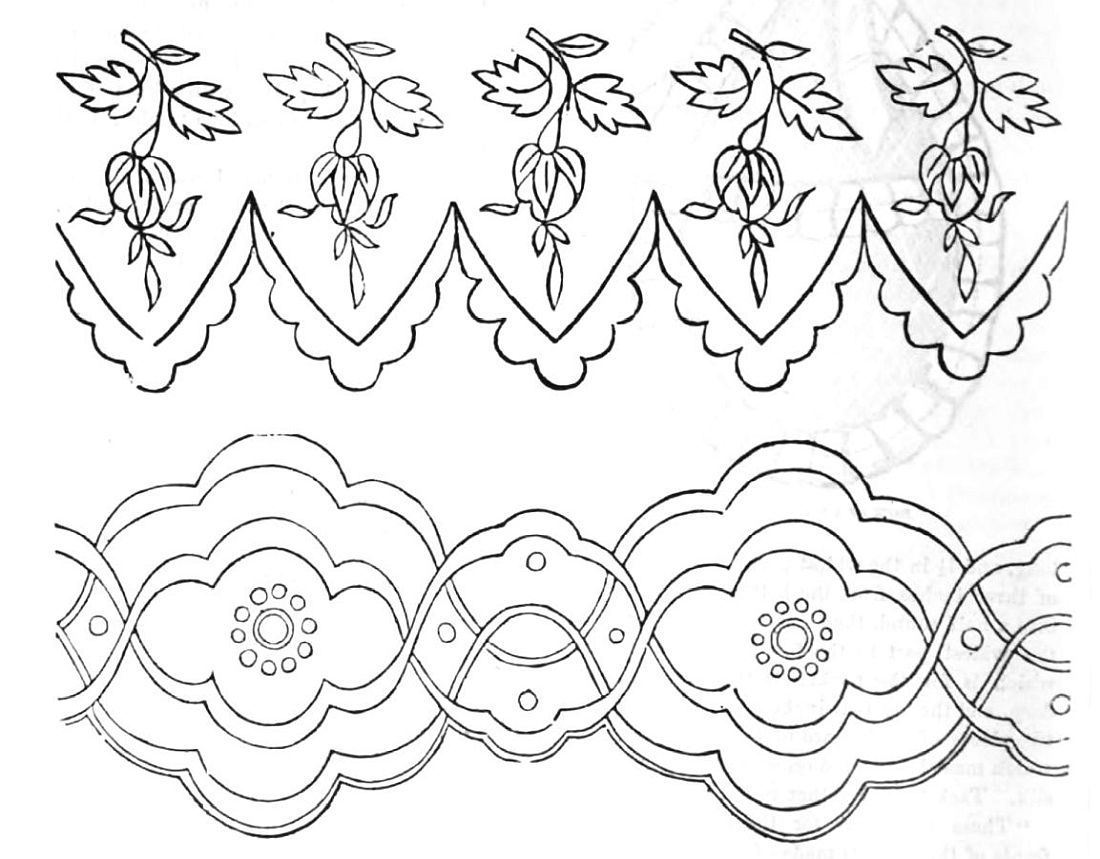

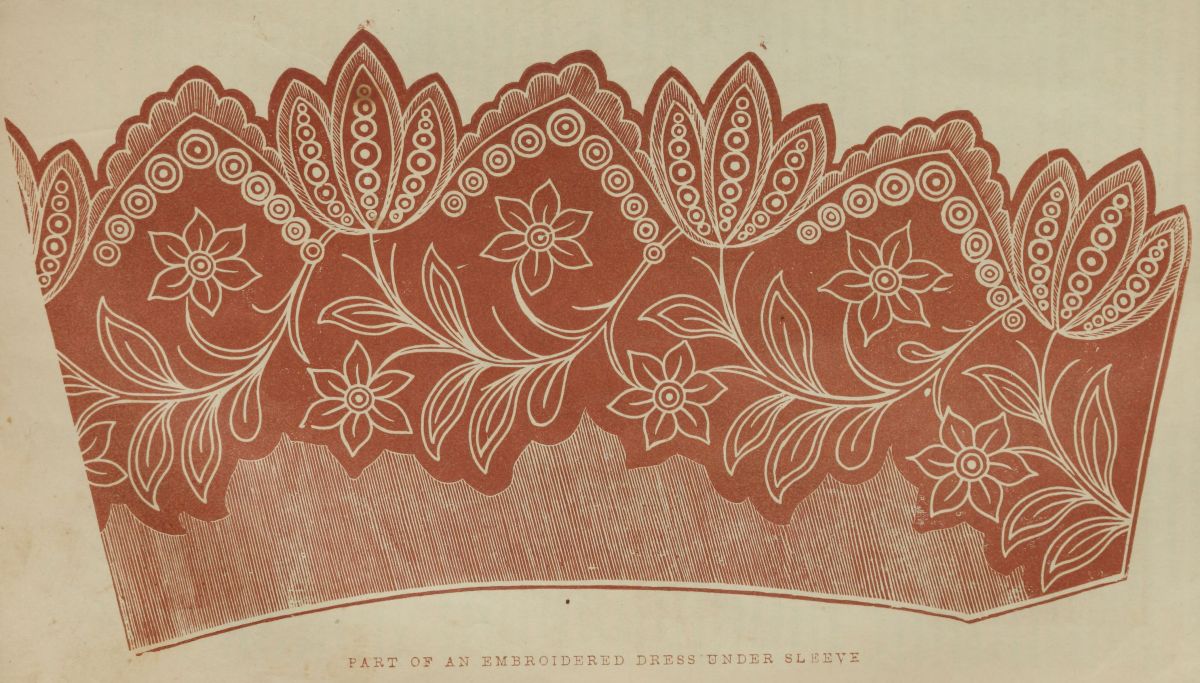

| Patterns for Embroidery, | 456 |

| Plain Work, | 460 |

| Poetry. | 449 |

| Receipts, &c., | 475 |

| Remembered Happiness, | 433 |

| Silent Thought, by Willie Edgar Tabor, | 440 |

| Sonnets, by Wm. Alexander, | 450 |

| Spring, | 464 |

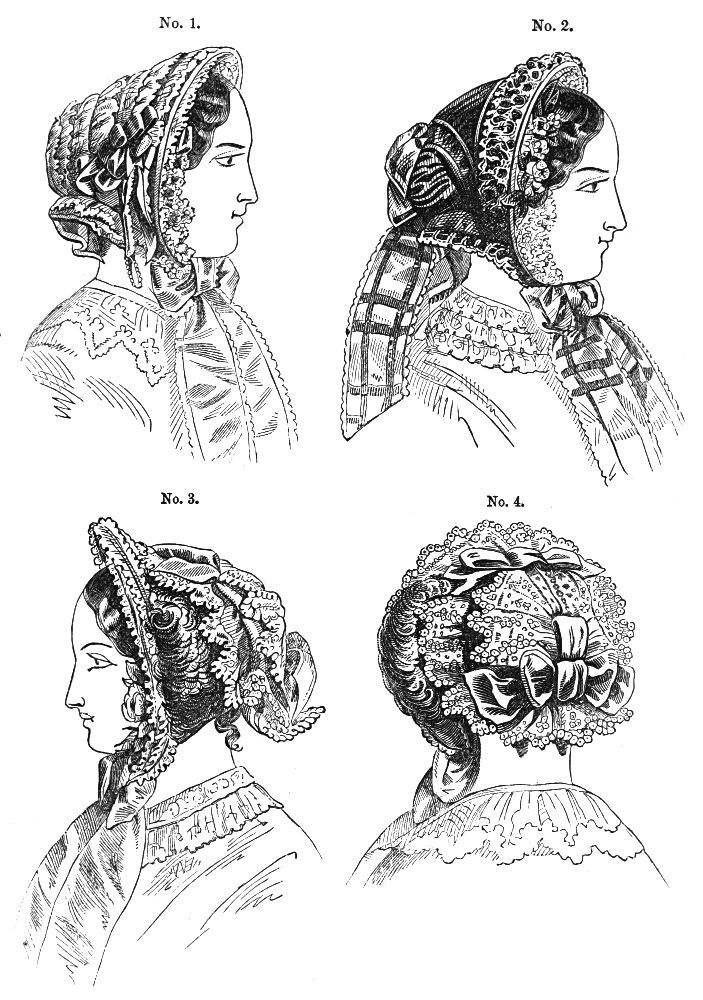

| Spring Bonnets, | 459 |

| Spring Fashions, | 390, 457 |

| Stanzas, by H. B. Wildman, | 450 |

| Stanzas, by Helen Hamilton, | 450 |

| Teaching at Home.—Language, | 442 |

| The Borrower's Department, | 475 |

| The Economics of Clothing and Dress, | 421 |

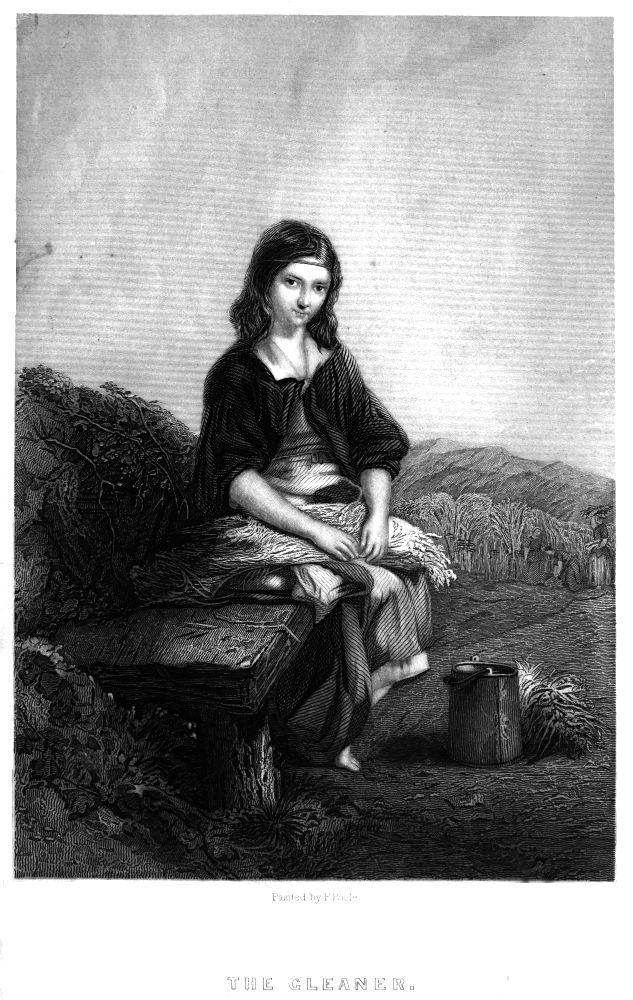

| The Gleaner, by Richard Coe, | 449 |

| The Mother's Lesson, by Elma South, | 441 |

| The Practical, | 463 |

| The Spring-time Cometh, | 463 |

| The Toilet, | 477 |

| The Trials of a Needle-Woman, by T. S. Arthur, | 434 |

| They say that she is Beautiful, by Mary Grace Halping, | 451 |

| 'Tis O'er, by I. J. Stine, | 452 |

| To Miss Laura, | 416 |

| To one who Rests, by Winnie Woodfern, | 451 |

| To our Friend Godey, by Mrs. A. J. Williams, | 468 |

| Treasures, | 420 |

| Truth Stranger than Fiction, | 406 |

| Work-Table for Juveniles, | 455 |

| Yankee Doodle with Variations, | 473 |

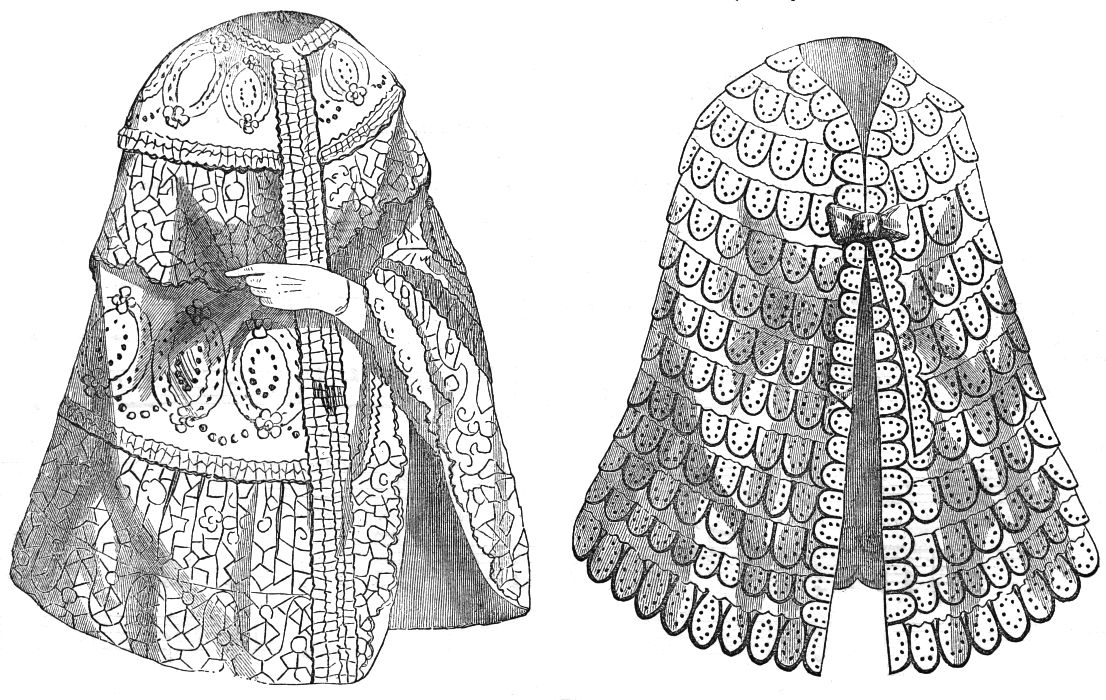

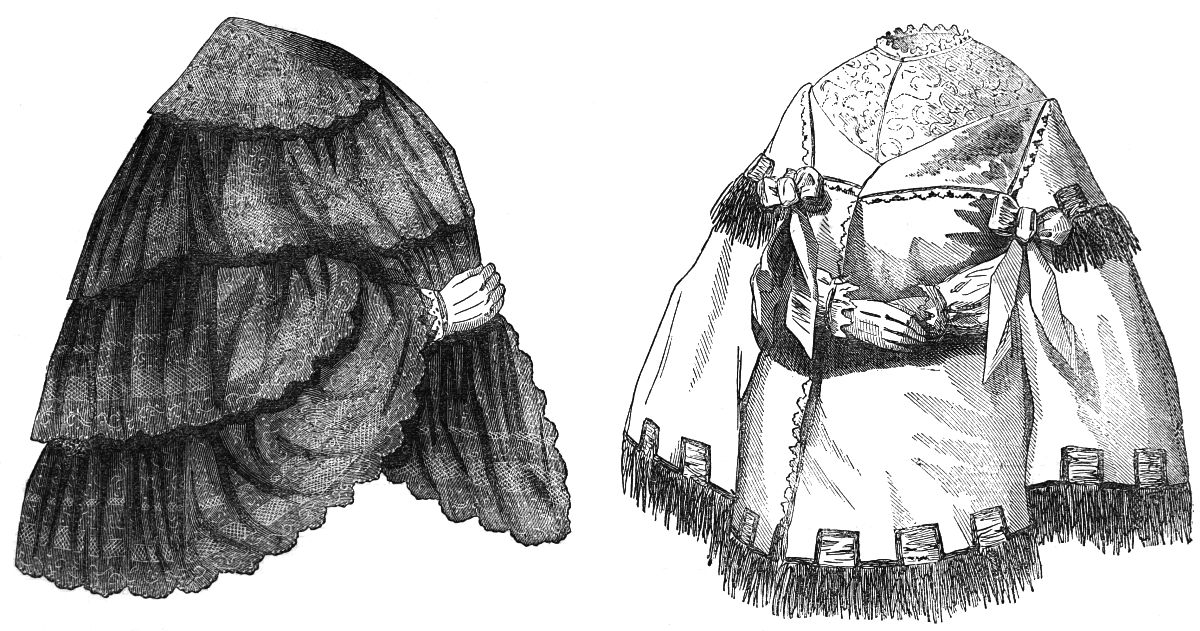

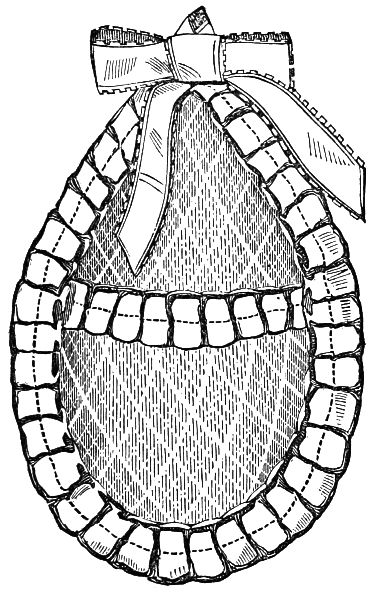

EVANGELINE. ANTOINETTE.

The latest French fashions. From the establishment of Messrs. T. W. Evans & Co., Philadelphia.

A pattern of either of the above will be sent on receipt of 62½ cents. Post-office stamps received in payment. These patterns are exact counterparts of the original, with trimmings, etc. (Description on page 457.)

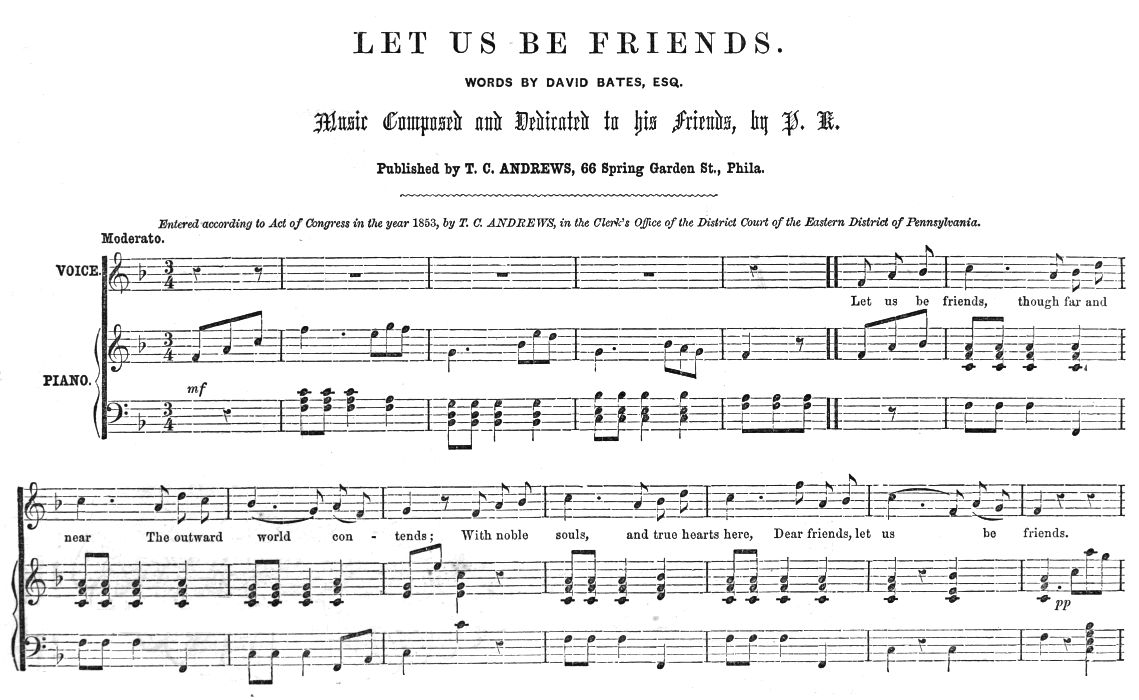

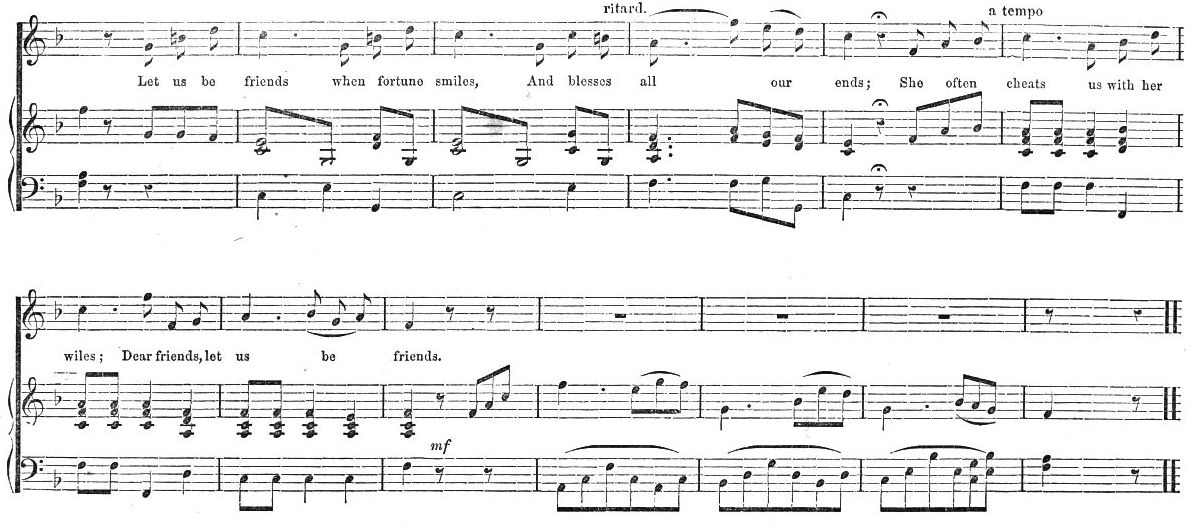

WORDS BY DAVID BATES, ESQ.

Music Composed and Dedicated to his Friends, by P. R.

Published by T. C. ANDREWS, 66 Spring Garden St., Phila.

Entered according to Act of Congress in the year 1853, by T. C. ANDREWS, in the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the Eastern District of Pennsylvania.

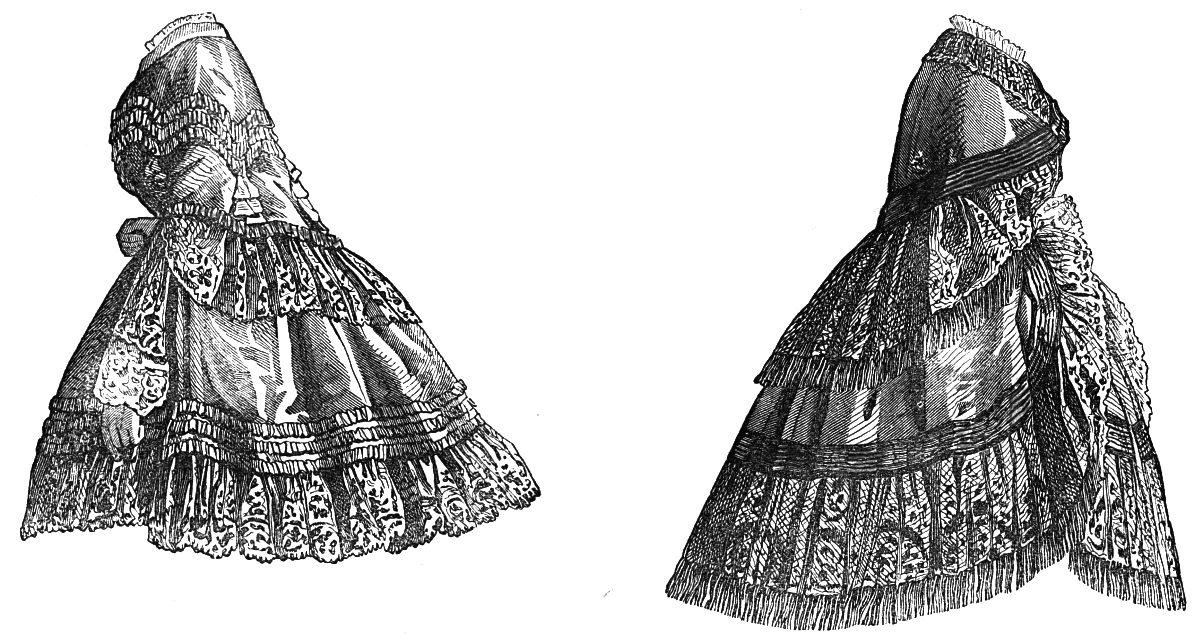

LACE MANTILLA. TABLET MANTILLA.

SPRING FASHIONS.—Designed, by Mrs. Suplee, expressly for Godey's Lady's Book.

A pattern of either of the above will be sent on receipt of 62½ cents. Post-office stamps received in payment. These patterns are exact counterparts of the original, with trimmings, etc. (Description on page 457.)

MARQUISE. NAVAILLES SHAWL-MANTELET.

PARISIAN FASHIONS RECEIVED BY THE LATEST ARRIVALS.

A pattern of either of the above will be sent on receipt of 62½ cents. Post-office stamps received in payment. These patterns are exact counterparts of the original, with trimmings, etc. (Description on page 457.)

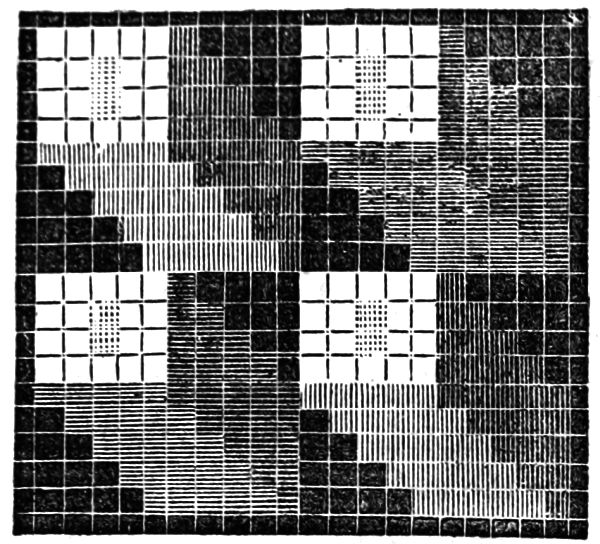

(Description on page 458.)

[From the establishment of G. BRODIE, No. 51 Canal Street, New York.]

(For description, see page 458.)]

PHILADELPHIA, MAY, 1854.

ILLUSTRATED WITH PEN AND GRAVER.

NUMEROUS inquiries have been addressed to us for some instructions in the elegant art of painting on velvet, and we have at length prepared an article on the subject, which, we think, will satisfy our readers. Papers on ornamental work are exceedingly useful, when, by the aid of practical experience, they convey simple and precise directions which can easily be learned.

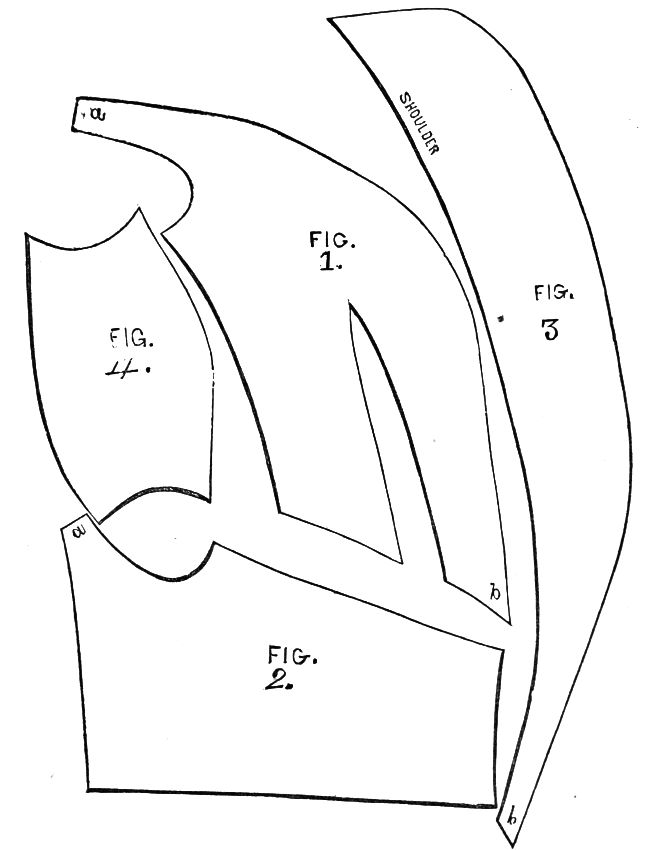

Formula 1.

Among the various accomplishments of the present day, no fancy work is perhaps more elegant, produces a better effect, and is, at the same time, more easily and quickly performed, than painting on velvet. Possessing all the beauty of color of a piece of wool-work, it is in every way superior, as the tints used in this style of painting do not fade; and an article, which it would take a month, at least, to manufacture with the needle, may be completed, in four or six hours, on white velvet, with the softest and most finished effect imaginable. Another recommendation greatly in favor of this sort of work is, that it does not require the knowledge of drawing on the part of the pupil, being done with formulas, somewhat in the manner of the old Poonah paintings, except that in this case the colors are moist. If these formulas be kept steady, a failure is next to impossible.

Formula 2.

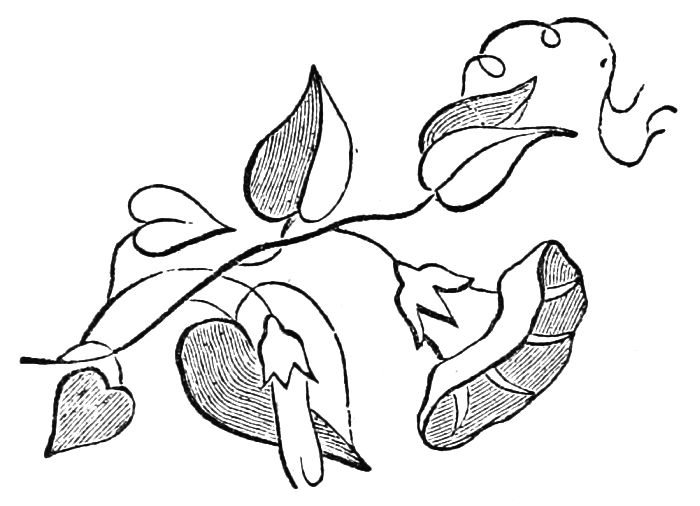

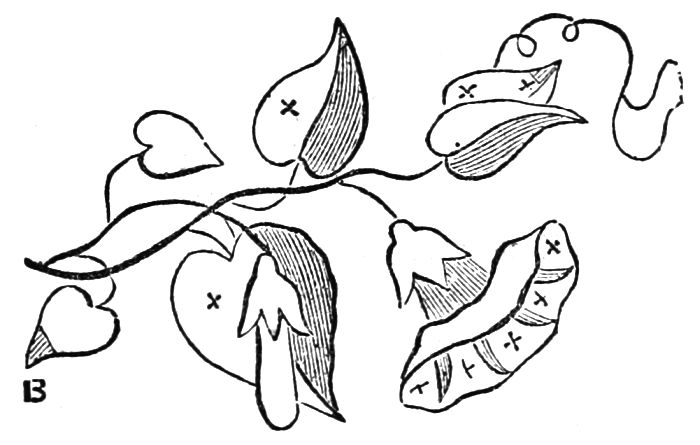

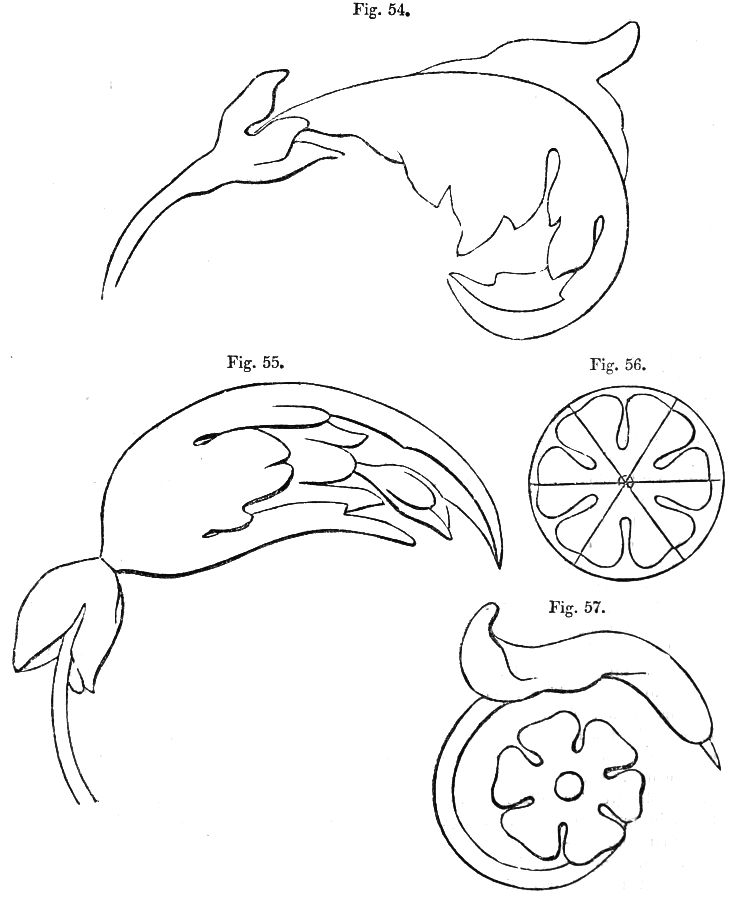

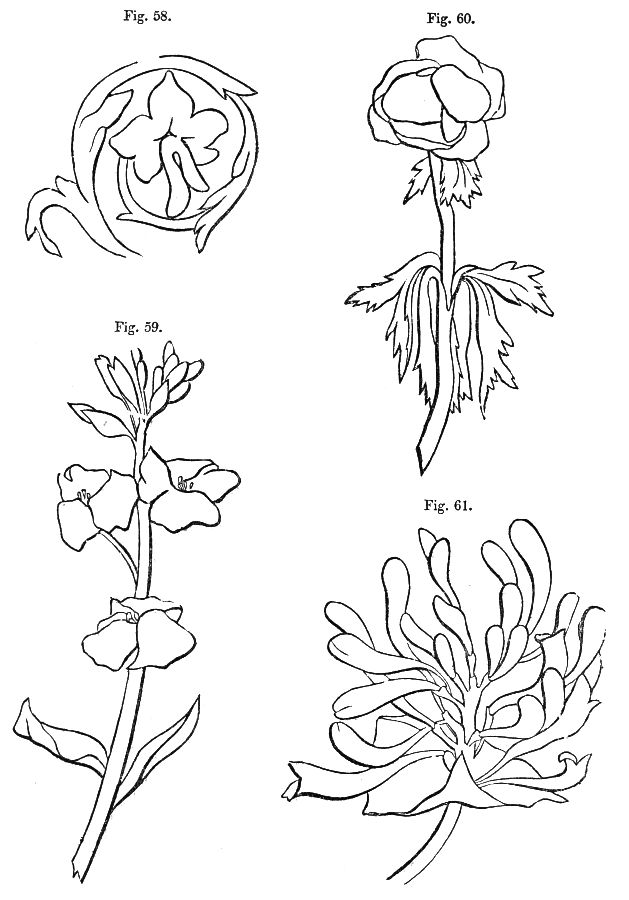

The first thing necessary to be done, after obtaining the colors and the velvet (which should be cotton, or more properly velveteen, as most common cotton velvets are not sufficiently thick, and silk velvet, besides the expense, is not found to answer), is to prepare the formula for the group intended to be painted. Get a piece of tracing or silver paper the size of the cushion, mat, or screen you wish to paint, then lay it carefully upon the group you wish to copy, and trace through. Should the paper slip, the formula will be incorrect; it will therefore be well to use weights to keep all flat. Having traced your flowers, remove the thin paper, and laying it on a piece of cartridge paper the same size, go over the pencil marks by pricking them out with a fine needle, inserted in a cedar stick. Now that you have your whole pattern pricked out clearly upon a stiff paper, take eight or nine more pieces of cartridge paper, of the same size as the first, and laying them one by one, in turn, under the pricked pattern, shake a little powdered indigo over, and then rub with a roll of list or any soft material. The indigo, falling through[Pg 394] the punctures, will leave the pattern in blue spots on the sheets of paper beneath; then proceed in like manner with the remaining formulas until you have the selfsame pattern, neatly traced, in blue dots on them all. Next, with a sharp pen-knife, you must cut out the leaves, petals, and calices of the group, taking care to cut only a few on each formula, and those not too near together, lest there should not be sufficient room to rub between the spaces, and that, for instance, the green tint intended for the leaf should intrude on the azure or crimson of the nearest convolvulus; for it must be kept in mind that in this sort of work erasure is impossible.

The foregoing diagrams will show how the formulas should be cut, so as to leave proper spaces, as above mentioned. The shading denotes the parts cut out.

Some leaves may be cut out in two halves, as the large ones in the pattern; others all in one, as the small leaf: but it is chiefly a matter of taste. The large leaves should, however, generally be divided. In each formula there should be two guides—one on the top of the left-hand side, the other at the bottom of the right-hand corner—to enable the formulas always to be placed on the same spot in the velvet. For instance, as in Formula 2, A and B are the two guides, and are parts cut out, in Formula 2, of leaves, the whole of which were cut out in No. 1; and therefore, after No. 1 is painted, and No. 2 applied, the ends of the painted leaves will show through, if No. 2 be put on straight; if, when once right, the formula is kept down with weights at the corners, it cannot fail to match at all points. Care should, however, be taken never to put paint on the guides, as it would necessarily leave an abrupt line in the centre of the leaf. While cutting out the formulas, it is a good plan to mark with a cross or dot those leaves which you have already cut out on the formulas preceding, so that there will be no confusion. When your formulas are all cut, wash them over with a preparation made in this manner: Put into a wide-mouthed bottle some resin and shellac—about two ounces of each are sufficient; on this pour enough spirits of wine or naphtha to cover it, and let it stand to dissolve, shaking it every now and then. If it is not quite dissolved as you wish it, add rather more spirits of wine; then wash the formulas all over on both sides with the preparation, and let them dry. Now taking Formula No. 1, lay it on the white velvet, and place weights on each corner to keep it steady; now pour into a little saucer a small quantity of the color called Saxon green, shaking the bottle first, as there is apt to be a sediment; then take the smallest quantity possible on your brush (for, if too much be taken, it runs, and flattens the pile of the velvet; the brush should have thick, short bristles, not camel-hair, and there ought to be a separate brush for each tint: they are sold with the colors). Now begin on the darkest part of the leaf, and work lightly round and round in a circular motion, taking care to hold the brush upright, and to work more, as it were, on the formula than on the velvet; should you find the velvet getting crushed down and rough, from having the brush too damp, continue to work lightly till it is drier, then brush the pile the right way of it, and it will be as smooth as before. Do all the green in each formula in the same manner, unless there be any blue-greens, when they should be grounded instead, with the tint called grass-green.

Next, if any of the leaves are to be tinted red, brown, or yellow, as Autumn leaves, add the color over the Saxon green, before you shade with full green, which will be the next thing to be done; blue-green leaves to be shaded also with full green. Now, while the green is yet damp, with a small camel-hair pencil vein the leaves with ultramarine. The tendrils and stalks are also to be done with the small brush. You can now begin the flowers: take, for instance, the convolvulus in the pattern. It should be grounded with azure, and shaded with ultramarine (which color, wherever used, should always be mixed with water, and rubbed on a palette with a knife); the stripes in it are rose-color, and should be tinted from the rose saucer. White roses and camellias, lilies, &c., are only lightly shaded with white shading; and if surrounded by dark flowers and leaves so as to stand out well, will have a very good effect.

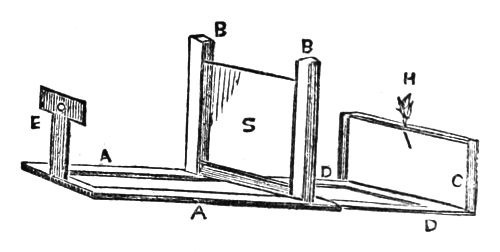

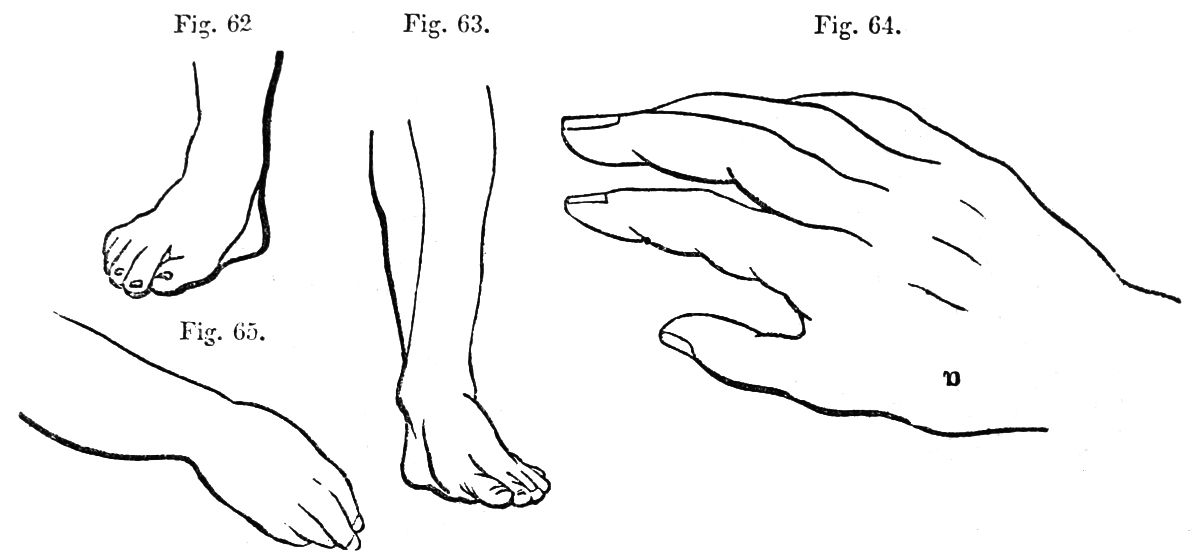

Flowers can easily be taken from nature in the following manner: A A, D D, is a frame of deal, made light, and about two feet long, and eight or ten inches in width. The part D D is made to slide in a groove in A A, so that the frame may be lengthened or shortened at pleasure. A vertical frame, C, is fixed to the part D, and two grooved upright pieces, B B, fixed to the other part. These uprights should be about nine inches high, and C half that height. There[Pg 395] is also a piece of wood at the end A of the frame, marked D, with a small hole for the eye, and there is a hole in the top C opposite to it. S is a piece of glass, sliding in the grooves in B B. In the hole H is placed the flower or flowers to be copied. If a group is wished, more holes should be made, and the flowers carefully arranged. The eye being directed to this through the hole in E, it can be sketched on the glass by means of a pencil of lithographic chalk. It is afterwards copied through by slipping the glass out, laying it on a table, and placing over it a piece of tracing-paper. When traced on the paper, proceed as before to make the formulas.

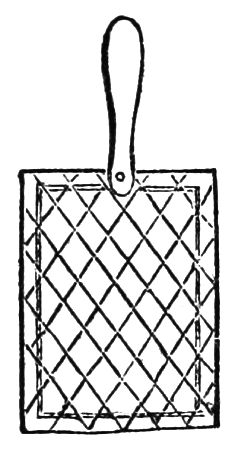

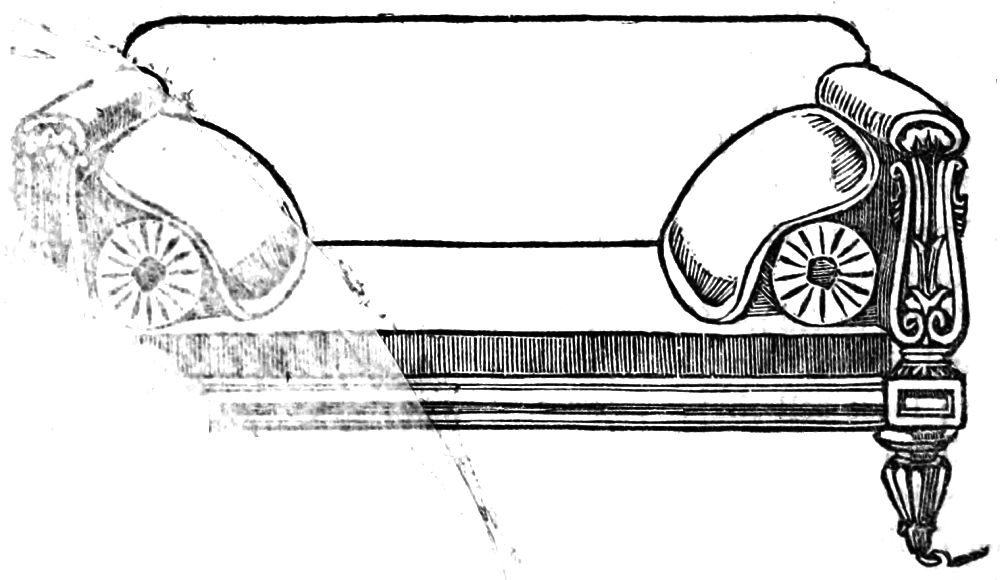

Of course, so delicate a thing as white velvet will be found at length to soil. When this is the case, it can be dyed without in any way injuring the painting. Dye in this manner: Get an old slate-frame, or make a wire frame; add to it a handle, thus; then tie over it a network of pack-thread; next, cut a piece of cardboard the exact size of your group, so as completely to cover it, the edges of the cardboard being cut into all the ins and outs of the outer line of the group; then placing it carefully over the painting, so as to fit exactly, lay a weight on it to keep it in place. Then dip a large brush into the dye, hold the frame over the velvet (which should be stretched out flat—to nail the corners to a drawing-board is best), and by brushing across the network, a rain of dye will fall on the velvet beneath. Do not let the frame touch the velvet; it should be held some little way up. Then just brush the velvet itself with the brush of dye, to make all smooth, and leave the velvet nailed to the board till it is dry. Groups, whether freshly done, or dyed, are greatly improved, when perfectly dry, by being brushed all over with a clean and rather soft hat-brush, as it renders any little roughness, caused by putting on the paint too wet, completely smooth and even as before. Music-stools, the front of pianos, ottomans, banner-screens, pole-screens, and borders for table-cloths, look very handsome when done in this manner.

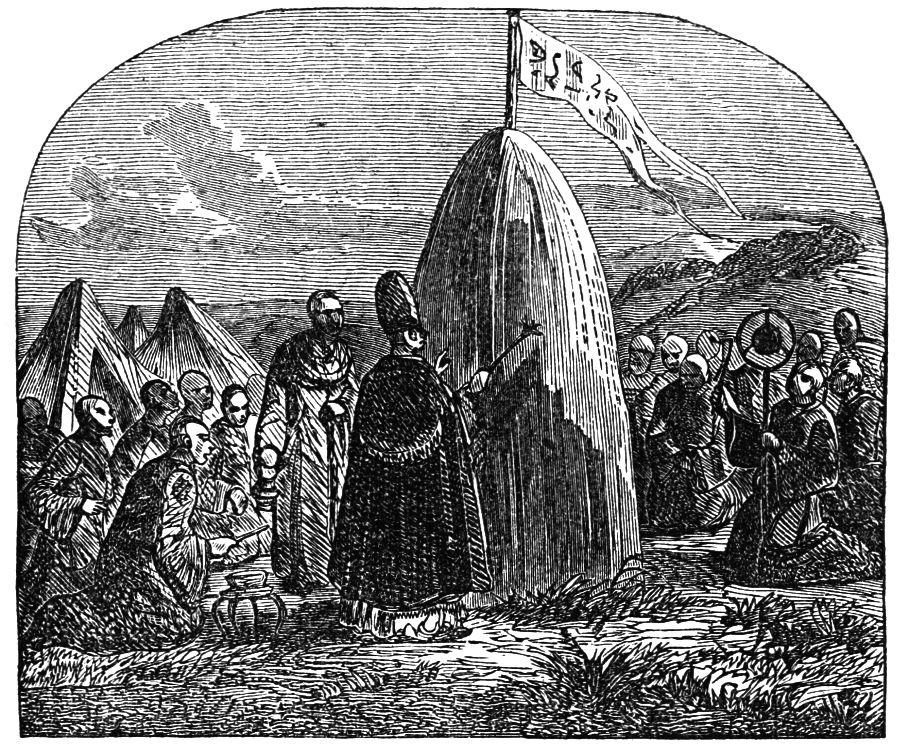

THE following, from a letter dated Jerusalem, May 16, 1853, has been sent by Mr. James Cook Richmond, for publication. "I was spending a couple of days in Artas, the hortus clusus of the monks, and probably the 'garden inclosed' of the Canticles, when I was told there was a kind of tunnel under the Pool of Solomon. I went and found one of the most interesting things that I have seen in my travels, and of which no one in Jerusalem appears to have heard. I mentioned it to the British Consul, and to the Rev. Mr. Nicolayson, who has been here more than twenty years, and they have never heard of it. At the centre of the eastern side of the lowest of the three pools, there is an entrance nearly closed up; then follows a vaulted passage some 50 feet long, leading to a chamber about 15 feet square and 8 feet high, also vaulted; and from this there is a passage, also arched, under the pool, and intended to convey the water of a spring, or of the pool itself, into the aqueduct which leads to Jerusalem, and is now commonly attributed to Pontius Pilate. This arched passage is six feet high, and three or four feet wide. Each of the two other pools has a similar arched way, which has not been blocked up, and one of which I saw by descending first into the rectangular well. The great point of interest in this discovery is this: It has now been thought for some years that the opinion of the invention of the arch by the Romans has been too hastily adopted. The usual period assigned to the arch is about B. C. 600. We thought we discovered a contradiction of this idea in Egypt, but the present case is far more satisfactory. The whole of the long passage of 50 feet, the chamber 15 feet square, the two doors, and the passage under the pools in each case, are true 'Roman' arches, with a perfect keystone. Now, as it has never been seriously doubted that Solomon built the pools ascribed to him, and to which he probably refers in Ecclesiastes ii. 6, the arch must of course have been well known about or before the time of the building of the first temple, B. C. 1012. The 'sealed fountain,' which is near, has the same arch in several places; but this might have been Roman. But here the arched ways pass probably the whole distance under the pools, and are therefore at least coeval with them, or were rather built before them, in order to convey the water down the valley. What I saw convinced me that the perfect keystone Roman arch was in familiar use in the time of Solomon, or 1,000 years before the Christian era."

BY PAULINE FORSYTH.

THROUGHOUT all the Union, there is no region more full of an abounding life and activity than western New York. Its people, inheriting from their New England ancestors their unresting energy in all practical affairs, and their habits of keen and close investigation in everything connected with their social or moral development, seem, in a great measure, to have laid aside the conservatism, the wary circumspection that the descendant of the Puritans has still retained. Enjoying the gifts of nature bestowed with a more bounteous hand and a freer mode of life, they have thrown off many of the shackles or restraints with which the worldly prudence of the New Englander hampers him in action, however loose he may suffer the reins to lie on his mind or fancy; but, whatever result his reason or benevolence works out, a genuine New Yorker would exemplify in his conduct, with a high disdain for all who suffered the baser motives of prudence or fear of censure to withhold them from the same course.

The people of that section of the country are so accustomed to see the singular theories, that are only talked about in other places, carried out into action by their zealous promulgators or defenders, that the eccentricities that, in most country villages, would throw all the people into a high state of astonishment, and supply them with a topic of conversation for months, there only causes a gentle ripple over the surface of society; or, to give a truer illustration, the waves there are always rolling so fast and high, that one wave more or less makes but little impression.

But when, from this unquiet ocean, a Bloomer was left stranded on the still shores of our quiet little town of Westbridge, our dismay and agitation can be but faintly described. Socially speaking, propriety is our divinity; Mrs. Grundy, our avenging deity. We frown on short sleeves; but when those short skirts were seen waving in our streets, when they even floated up the broad aisle on the Sabbath, it would be hard to say whether indignation or horror were the predominant feeling.

But, to begin at the beginning, as is in all cases most proper and satisfactory, Jane Atwood announced at our Sewing Society, and Mrs. Atwood mentioned, in the course of a round of calls, that they were expecting Miss Janet McLeod, a niece of the late Mr. Atwood, to pass the winter with them. We all knew Mr. McLeod by reputation, for Mrs. Atwood was very proud of her relationship to him, and references to her brother-in-law were frequently and complacently made. We had seen him, too, when now and then he had passed a day with the Atwoods—he never found time to stay in Westbridge more than a day—and were astonished to find that the rich Mr. McLeod, who had been for some time a sort of a myth among us, a Westbridge Mrs. Harris, was a plain, homespun-looking man, with a comely sun-browned face, white hair, and the kindest and most trusting brown eyes in the world. His manners were hearty and genial, but their simplicity prevented him from making a great impression on us; we like more courtliness and a little more formality. His benevolence and uprightness, together with his immense wealth, procured for him among us that degree of consideration which such things always do procure among the numerous class who take the world as they find it, and we dismissed him with the remark that, though plain and unpolished in his manners, he possessed sterling goodness and sound sense.

This last quality might not have been allowed him, if Mrs. Atwood had not been careful in concealing, as far as possible, the peculiar revelations he made in each visit of his reigning enthusiasm.

"That Mr. McLeod is a very strange man," said Mrs. Atwood's nurse to a former employer of hers. "Do you know, ma'am, he spent all yesterday pulverizing Miss Jane! Miss Jane went sound asleep, and I thought in my heart she would never wake up no more."

It was found out afterwards that Jane Atwood had been undergoing some experiments in mesmerism, which, although Mr. McLeod declared them triumphantly successful, Mrs. Atwood was[Pg 397] rather inclined to conceal than converse about. This was on Mr. McLeod's first visit. On his second, he found Mrs. Atwood suffering from an attack of rheumatism. He pulled out of a capacious pocket-book two galvanic rings, which he insisted on her wearing; and, for fear that they might not effect so speedy a cure as he wished, he hastened to the city and returned with a galvanic battery, by means of which he gave his sister-in-law such severe shocks that she assured us often "that her nervous system was entirely shattered by them." But, as I have known many ladies live and get a fair proportion of enjoyment out of this life with their nervous systems in the same dilapidated state, I have come to consider it a very harmless complaint.

At another time, Mr. McLeod had wonderful stories to tell of spiritual manifestations, and on his last visit he had been overflowing with indignation against society on the score of woman's rights and wrongs.

Yet, notwithstanding these peculiarities, Mrs. Atwood loved and esteemed Mr. McLeod with a sincerity that redeemed her otherwise worldly and timid character. Her husband had been left dependent on his half brother, and owed to him his education and his establishment in the world; and, when a fortune was left by some relation of their mother to be equally divided between them, Mr. McLeod refused to take any portion of it, saying that he had more than enough. These, with many other instances of his generosity and affection which Mrs. Atwood had received since her widowhood, made her forget his eccentricities, and listen with forbearance to his impetuous outbursts of zeal or indignation.

There was another person in Westbridge who shared Mrs. Atwood's affectionate gratitude to Mr. McLeod, and from similar causes; and this was Professor Mainwaring. He was the professor of ancient languages in the college at Westbridge, and the society of the place, as well as the members of the college, thought it a high honor to be able to number such a man as one of themselves. He combined, in a manner that is seldom seen, the high-bred gentleman with the accomplished scholar and the strict and severe theologian, for he was a clergyman as well as a professor; and when to this it is added that he was still unmarried, it will hardly be wondered at if he were an object of general attention, carefully restrained though within its proper limits.

He also had been indebted in early life to Mr. McLeod; for, although brought up in the habits, and with the expectation of being a rich man, he found himself in the second year of his college life left, by the sudden death of his father, Judge Mainwaring, entirely destitute. With no friends who were able or willing to assist him, George Mainwaring was about to give up reluctantly all hopes of completing the studies in which he had so far been eminently successful, and had already begun to look about for some means of obtaining a present support, when Mr. McLeod heard of his position, and, with the prompt and delicate generosity peculiar to him, came forward with offers of assistance. He claimed a right, as an old friend of George Mainwaring's father, to interest himself in the young student's welfare; and, with some hesitation, such as every independent mind naturally feels, Mr. Mainwaring accepted the offered aid.

The pecuniary obligation had long since been repaid, but the feeling of gratitude to the one who had enabled him to pursue the career best fitted to the bent of his mind remained in full force; and, from the influence of this feeling, he had been induced to make an offer to Mr. McLeod, which was the immediate occasion of Miss McLeod's visit to Westbridge.

Mr. McLeod had been for some years devoting himself spasmodically to the study of Revelations. He fancied that he had discovered the clue to the meaning of many of the most mysterious parts of this book; but, unfortunately, there were many little discrepancies between his ideas and those apparently conveyed by the words of this part of Holy Writ. These he attributed to a faulty translation, and had himself begun one that was to be free from such blemishes; but, finding that his knowledge of the language was insufficient, or that his patience was soon exhausted, he determined that his daughter Janet should qualify herself to perform this office for him.

She would have undertaken to learn Chinese, if her father had expressed a wish to that effect, and therefore made no opposition to studying Greek, nor to passing the winter in Westbridge with her aunt, that she might avail herself of the proposal Mr. Mainwaring had made to her father, that he should be her instructor. Miss McLeod had never been in Westbridge, and Mr. Mainwaring had never happened to meet her. He knew that she was a young lady of eighteen, and that, since her mother's death, some three years before, she had devoted herself entirely to making her father's home as comfortable and happy as possible. Her filial affection had prepossessed him very much in her favor, and he looked forward to aiding her in her studies with[Pg 398] an unusual degree of pleasure. Jane Atwood, too, was delighted at the prospect of renewing an acquaintance that had languished since her childhood.

Mr. McLeod was prevented, by some of his numerous engagements, from accompanying his daughter to Westbridge, as he had intended; and, placing her under the care of an acquaintance who was on his way to the city of New York, he telegraphed to Professor Mainwaring a request that he would meet Miss McLeod at the Westbridge depot.

The cars arrived about twilight, and, punctually at the appointed time, Mr. Mainwaring and Miss Atwood stood on the platform waiting for the stopping of the train. The young lady looked in vain among the group that sprang hurriedly out of the cars to find one that she could recognize as her cousin. Mr. Mainwaring scrutinized the crowd with a like purpose, but as fruitlessly. Their attention was arrested at the same moment by the same object—the singular attire of a person leaning on the arm of an old gentleman, who was looking around him evidently greatly hurried and perplexed. Mr. Mainwaring gave but one glance, and then looked away, apparently considering the individual hardly a proper subject of curiosity; but Jane Atwood, less scrupulous, stood gazing so absorbed in what she saw that she entirely forgot her cousin.

The person who thus attracted her notice was a small and youthful woman, dressed in a sort of sack or paletot of black cloth, belted around her waist and falling a little below the knee, and loose trowsers of the same material gathered into a band around the ankle, leaving exposed a small foot encased in thick-soled, but neatly-fitting gaiter boots. A linen collar tied around the throat with a broad black ribbon, and a straw bonnet and veil, completed the attire.

"That must be a Bloomer, Mr. Mainwaring," said Jane Atwood; "do just look at her. I am very glad she happened to come in this train. I have always wanted to see one."

"Indeed!" said Mr. Mainwaring, in a tone that expressed more surprise than approval. "Do you see your cousin anywhere, Miss Atwood?" asked he, after a moment's pause.

She replied in the negative.

"Allow me to leave you a moment, and I will make some inquiries." And, after attending Miss Atwood to the ladies' saloon, the professor hurried off to inquire after his charge.

Hardly had he gone before the old gentleman and the Bloomer entered.

"Excuse me, ma'am," said the gentleman, addressing Miss Atwood; "but I am afraid to wait here any longer, for fear the cars will leave me, and I promised Mr. McLeod I would see his daughter safely to her friends. Do you know whether Professor Mainwaring is here to meet her?"

"Yes, he is," said Miss Atwood, with a sudden misgiving. "Is—is—is this—person—lady—Miss McLeod?" Miss Atwood could hardly finish the question.

The Bloomer threw back her veil, and said, somewhat timidly—

"Is this Miss Atwood—Cousin Jane?"

Miss Atwood bowed, and the old gentleman, saying, "I am glad you have found your friends," hurried off.

There were a few moments of embarrassed silence, when Professor Mainwaring reappeared.

"Miss McLeod cannot be in this train," said he. "Shall we wait here for the next? It will be down in an hour."

"This is Miss McLeod, Professor Mainwaring," said Miss Atwood, hardly conscious of the ungracious manner in which she effected the introduction.

Mr. Mainwaring bowed with his usual ceremonious politeness; but he said not a word, and his lips closed with a firmer compression than usual. He was too indignant and astonished to speak. He wondered if his old benefactor had quite lost his senses that he should permit his young daughter to go about dressed in that outrageous costume. And he did not see with what propriety he, the guide and controller of more than a hundred young men, who required all the power of his example and authority to keep them in proper order, could be asked to teach, or in any way have his name connected with that of a Bloomer. He was more than half inclined to walk away; but, restraining himself, he observed that the carriage was waiting, and had instinctively half turned to Miss McLeod to offer her his arm, but, catching another glimpse of the costume, in itself a sort of a declaration of independence, and remembering having seen a number of students lingering around the depot, he bowed hastily and led the way to the carriage.

Miss McLeod's manner had all the time been very composed and quiet. She could not help observing that her greeting was not a very warm one; but this was her first absence from home, and her thoughts were so full of those she had left behind that she was not fully conscious of all that was passing around her. She seated herself in the carriage, and, after answering the few formal questions addressed to her by her[Pg 399] companions, she sank with them into a silence that remained unbroken until they reached Mrs. Atwood's door.

Declining Miss Atwood's invitation to walk in, Professor Mainwaring bade them good-evening, murmuring something hastily about seeing Miss McLeod again soon, and walked off, glad to be released even for a moment from his distasteful duty of attendance.

Miss Atwood ushered her companion into the drawing-room, and then went to seek her mother. She found her in the kitchen giving directions to a new cook about the preparations for tea. She beckoned her into the dining-room.

"She's come, mother," said Jane, with wide-open eyes.

"Yes, dear, I know it. Go and stay with her; I will come in in a minute."

"She's a Bloomer!" continued Jane, unheeding the maternal bidding.

"You don't say so, Jane! What! little Janet a Bloomer! Oh, Jane!" And Mrs. Atwood sank down on the nearest seat. This was worse than the galvanic battery. Her nervous system gave way entirely, and she burst into a flood of tears. "I cannot go in to see her," said Mrs. Atwood. "I don't think I can have her here in my house with my children."

"Oh yes, mother, we must," said Jane; "remember how kind uncle McLeod has always been to us. Don't be so distressed about it. Perhaps we can induce her to change her style of dress."

While Jane was endeavoring to soothe her mother, Janet McLeod had been trying to overcome the shyness of two little children whom she had found in the drawing-room. She was telling them about a pony and a dog she had at home, when the boy raised his head and asked, with the straightforwardness of a child—

"Who are you?"

"I know," said the little girl, shaking her head with a very wise look.

"Do you? Who am I?" asked Janet, amused by her earnest manner.

"I don't like to tell oo; but I'll tell Tarley, if he'll bend down his head."

Charley bent his head, and the child said, in a loud whisper—

"That's the little ooman that went to market to sell her eggs; don't oo see?"

"Are you?" asked Charley.

"No; I am your cousin Janet."

"Oh, I always thought Janet was a girl's name. I am glad you are a boy. I like boys a great deal the best."

Here Charley was interrupted by his mother's entrance. Mrs. Atwood had composed herself, and had come to the conclusion that she might as well make the best of it. She greeted Janet in a manner rather constrained and embarrassed, and yet not cold enough to be wounding; and this she thought was doing wonders.

The next day was Sunday, and Mrs. Atwood saw, with dismay, Janet preparing to go to church in the same attire.

"Have you no long dresses that you could wear to-day, my dear?" she asked. "We are so unaccustomed here to see anything of that kind, that I am afraid it will attract more attention than you would like."

"No," replied Janet, with a composure that was not a little irritating to Mrs. Atwood, "I did not bring any with me. I promised father that I would wear this dress at least a year."

Jane Atwood had a convenient headache, which prevented her from accompanying the rest of the family to church, and Mrs. Atwood had to bear the whole brunt of the popular amazement and curiosity, as, followed by a Bloomer, she made her entrance among the assembled congregation. The walk up the aisle was accomplished with a flurried haste, very unlike the usual grave decorum on which Mrs. Atwood piqued herself, and, slipping into her pew, she sat for some minutes without venturing to raise her eyes.

Miss McLeod did not share her aunt's perturbation. She appeared, in fact, hardly conscious of being an object of general remark, but addressed herself to the duties of the sanctuary with a countenance as calm and tranquil as a summer's day. A very sweet and rural face she had, as unlike her startling style of dress as anything could well be. Having always lived in the country, surrounded by an unsophisticated kind of people who had known her from her infancy, and loved her for her father's sake as well as her own, and who, reverencing Mr. McLeod for his noble and kindly traits of character, looked upon his many crotchets as the outbursts of a generous, if an undisciplined nature, Janet had never learned to fear the criticism or the ridicule of the unsympathetic world.

Like most persons brought up in the sheltered seclusion of the country, far away from the bustle and turmoil of the city, where every faculty is kept in activity by the constant demand upon its attention, her mind was slow in its operations, and her perceptions were not very quick. At ease in herself, because convinced by her father's advice and persuasions that she was in the path of duty, she hardly observed the[Pg 400] astonishment and remark of which she was the object. What Bulwer Lytton calls "the broad glare of the American eye" fell upon her as ineffectually as sunshine on a rock.

With a disposition naturally dependent, and inclined to believe rather than to doubt and examine for herself, she had grown up with such a deep reverence for her father, and with such an entire belief in him, that the idea of questioning the propriety or soundness of his opinions never entered her mind. It was hard labor for one so practical and unimaginative as Janet to follow up the vagaries of a man like Mr. McLeod, and it was one of the strongest proofs of her great affection for him, that she had laid aside her own correct judgment and good sense to do so.

That same evening Mrs. Atwood had a long conversation with Miss McLeod about her dress. It was a disagreeable task to one of Mrs. Atwood's timid disposition to find fault with any person; but she thought it a duty she owed to her motherless niece, at least, to expostulate with her about so great a singularity.

"Will you tell me, my dear," she said, "how you came to adopt that costume?"

"It was my father's wish," Janet replied. "He was convinced that it was a much more sensible and useful mode of dress than the usual fashion of long trailing skirts, and he was very anxious that it should be generally adopted; but he said it never would be unless it were worn habitually by ladies occupying a certain station in society. He thought that, as we had so many advantages, we ought to be willing to make some sacrifices for the general good. I did not much like the idea at first, but I found that father was right when he said that I should soon become accustomed to the singularity of the thing; and indeed it is hardly considered singular in Danvers now. Several of the ladies there have adopted the same style of dress. We find it a great deal more convenient."

Mrs. Atwood could not assent; she could not see a single redeeming quality in the odious costume.

"Would you object, Janet, to laying it aside while you remain in Westbridge? I am sure that you will effect no good by wearing it, and I am afraid you will be rendered painfully conspicuous by it. Young ladies should never do anything to make themselves an object of remark."

This aphorism, which was the guiding principle of every lady trained in Westbridge, was a new idea to Janet. She pondered upon it for a while, and then replied—

"It seems to me, at least so my father always tells me, that the only thing necessary to be considered is, whether we are doing right or not; and if this dress is to do as much good as father thinks it will, it must be my duty to wear it. I promised father I would wear it for a year at least."

"If your father will consent, will you not be willing to dress like the rest of us while you remain here? It would be a great favor to me if you would."

"Certainly, dear aunt, I will. But it seems strange to me that you should be so annoyed by what father is so much delighted with."

Mrs. Atwood wrote what she considered quite a strong appeal to Mr. McLeod, entreating him to allow his daughter to resume her former attire. But in reply, Mr. McLeod wrote that Janet was now occupying the position in which he had always wished a child of his to be placed. She was in the front rank of reformers; giving an example to the people in Westbridge, whom he had always considered shamefully behind the age, which he hoped would awaken in them some desire for progress and improvement. He was proud of her and of her position. He would not for the world have her falter now, when, for the first time, she had had any conflict to endure.

Janet read the letter, and, with a blush for her weakness in yielding to her aunt's suggestions, she resolved to allow no pusillanimous fear of censure to degrade her father's daughter from the high station in which he had placed her. Mrs. Atwood was indignant at Mr. McLeod's answer.

"I never read anything with so little common sense or common feeling in it. I am sure he would not be willing to subject himself to all the annoyances to which he is exposing his poor young daughter, persuading her that she is in the path of duty, and that she ought to make a sacrifice of herself. I have no patience with him," and Mrs. Atwood, in her vexation, came very near giving Charley a superfluous whipping.

Meantime, the people in Westbridge were debating as to the expediency of calling on the new arrival. They were in great perplexity about it. As Mrs. Atwood's niece, Miss McLeod ought certainly to be visited; but as a Bloomer she ought to be frowned upon and discountenanced. The general opinion was decidedly against showing her any attention. One lady did call, but repented it afterwards, and atoned for her imprudent sociability by declining to recognize Miss McLeod when she met her in the street. There were very few invitations sent to Mrs. Atwood's during the winter, and those that[Pg 401] came were very pointedly addressed to Mrs. and Miss Atwood. These they at first declined, with much inward reluctance on Jane's part; but Janet perceiving this, and divining that politeness to her was the cause of the refusals, insisted on being no restraint on her cousin's pleasure. She was willing to endure mortifications herself for what she considered her duty, but it would be a needless addition to her trials, she said, if those who did not approve of her course had to suffer for it.

It seems a pity that there should be such a superfluity of the martyr spirit in womankind, or that there were not something of more vital importance to wreak it upon than the rights and wrongs that are just now causing such an effervescence among them.

Meantime, Mr. Mainwaring had decided that, come in what shape she might, Mr. McLeod's daughter ought to receive from him all the attention that gratitude for her father's services might demand. Every morning he devoted an hour to giving her a lesson in Greek, and though for some time he continued to look upon her with suspicion and distrust as a femme forte, yet his urbane and polished manners prevented Janet from perceiving anything that might wound or offend her. She felt that the gentle cordiality with which she was at first inclined to receive him, as one whom her father loved and esteemed, met with no response, but she attributed it to his natural reserve. The first thing that lessened the cold disapproval with which Mr. Mainwaring regarded Janet was the discovery that study was to her a painful labor, and that she was not very fond of reading. There is a popular fallacy that a high cultivation of the intellect implies a corresponding deficiency in the affections, and profoundly sensible as Mr. Mainwaring was, he was, like most men, a firm believer in this erroneous opinion; and therefore he welcomed all Janet's mistakes as pledges that, though her judgment might be wrong, her heart was right.

And there was a yielding docility about her that was exceedingly pleasing to one accustomed, as Mr. Mainwaring was, to have his opinion regarded as law by most of those with whom he was thrown. It was not a mere inert softness either, but the pliability of a substance so finely tempered and wrought that it could be moulded by a master hand into any form without losing its native and inherent firmness and goodness. He began at last to understand her, and to perceive that she had one of those delicate and conscientious natures that, when once convinced of a duty, seize upon it with a grasp of iron, and would suffer to the death for it. With his admiration for Janet, his interest in her increased, and he became truly distressed to see her throwing away, as it seemed, her usefulness and her happiness in endeavoring to uphold a fantastic fashion.

The life of seclusion and study to which the resolute neglect of the people of Westbridge had condemned Janet was so unlike anything to which she had been accustomed, that, strong in constitution as she was, with all the vigor that a free country life gives, her health began at last to fail. The spring breezes sought in vain for the loses that the autumn winds had left upon her cheeks.

"It seems to me that you are looking rather pale, Miss McLeod," said Mr. Mainwaring, one day.

It was the first time that he had ever spoken to her on any subject unconnected with the lessons, and Miss McLeod colored slightly as she answered—

"I am quite well, I believe."

"I am afraid you do not exercise enough. I see Miss Atwood walking every pleasant afternoon. If you would join her sometimes, you might find a benefit from it."

Again Janet blushed as she answered, with a frank smile—

"Cousin Jane is very kind; but I believe she would do anything for me sooner than walk with me. At any rate, I would not like to place her in a position that would be so painful to her. And I do not like to walk by myself here."

Miss McLeod did not acknowledge, what Mr. Mainwaring had perceived, that a growing shyness had been coming over her since her residence in Westbridge, leading her to keep out of sight as much as possible. A very faint-hearted reformer was poor little Janet, and I am afraid that her co-workers would have disdained to acknowledge her.

"You have not made many acquaintances in Westbridge, I think, Miss McLeod?"

"No, none besides aunt Atwood's family and yourself."

"I am sorry for that, for there are many very agreeable and intelligent people here. Few country villages can boast of as good society. I do not see you often at church lately, I think."

"No, I do not go so regularly as I ought," said Janet, sadly.

"How would you like a class in the Sunday School? It might be an object of interest, and visiting your scholars would be a motive to take you out occasionally. The clergyman mentioned[Pg 402] lately that they were very much in want of teachers."

The tears came in Janet's eyes. It seemed to her that Mr. Mainwaring must be trying to wound her, or that he was one of the most unobservant of men, that, with so little tact, he was reminding her of all the social duties and kindnesses from which she was debarred.

"I offered my services the other day, but they were declined," said she.

"On account of your mode of dress, I presume," said he.

Janet bowed.

"If my obligations to your father had not been so great that they can never be repaid, I might feel that I was taking too great a liberty, if I should venture to express any disapproval of anything that you might think proper to do. But I will run the risk of displeasing you, and ask you whether you think it worth while, even supposing one mode of dress to possess far more real superiority over the prevailing fashion than the one does which you have adopted, to sacrifice not only your social enjoyments, but your usefulness, for the purpose of making an ineffectual attempt to change a fashion under which so many people have lived in health and comfort, that it will be difficult to persuade them that it is injurious?"

"At home, my style of dress was not thought so wrong," said Janet. "There are not many places, I think, where I should not have met with more liberality and charity than in Westbridge."

"All over the world, Miss Janet"—and, for the first time, the professor called Miss McLeod by her Christian name—"dress is considered as an exponent of character. When a person is thrown among strangers, they are judged almost as much by that as by their countenance. And when they adopt a style of dress, the mark of a particular clique, they are considered as indorsing all the opinions belonging to it. Now, the ideas of the Bloomerites are many of them so flighty, and have so little reason or common sense in them, that I am sure you are not acquainted with them, or you would not so openly rank yourself with their party."

Poor Janet had heard her father talk for hours about the absurdity of the usual mode of dress, and the advantages of the Bloomer costume; but now, in her time of need, she could not recall a single one of his arguments. Not that she was entirely overpowered by the professor's reasons, but, partly from her own observation of his character, and partly from general report, she had imbibed so high an opinion of Mr. Mainwaring's judgment and understanding, that she felt unequal to opposing him. There was a soundness in his opinions, with a firmness and strength in his whole nature, to which she yielded an unconscious deference.

This was by no means the only conversation Mr. Mainwaring and Janet had on the subject of her unfortunate dress. Slowly and gradually the young girl began to realize that she might have been wasting the whole energies of her earnest nature in a Quixotic contest with what was in itself harmless. At any rate, she became convinced that "le jeu ne vaut pas le chandelle," and yet she was unwilling to take any decided step without consulting her father. She was afraid that he would be greatly disappointed in her, when he found her so weak that she shrank from the notice and comments her attire attracted.

Seeing that Miss McLeod was disinclined to make the effort, Mr. Mainwaring wrote himself to Mr. McLeod, who, although he was unable to appreciate the "delicate distresses" which Mrs. Atwood had hinted at, as the consequence of his daughter's singularity, was alarmed and distressed at the idea of her illness. He came immediately to Westbridge, and took Janet home to recruit. But, before he went, Mr. Mainwaring had a long conversation with him, and, either by his cogent arguments, or because some new crotchet had displaced the old one, he obtained his permission that Janet should resume the flowing robes against which he had once declared such unsparing antipathy.

During the next summer, Janet stopped for a few weeks at Mrs. Atwood's, on her way to Saratoga, and we took advantage of the opportunity to call upon her, acting towards her as though this were her first visit to Westbridge, and considering it an act of delicate politeness to ignore the fact that the young lady, whom we saw so simply and tastefully attired, had any connection with the Bloomer who had awakened our horror not long before.

The latest piece of news in Westbridge is the established fact that Mr. Mainwaring is engaged to Miss McLeod. He who has withstood all the charms of the well brought up ladies of our town has been captivated by a Bloomer, and that, too, after having declared, openly and repeatedly, his disapproval and utter distaste for all women who had in any way made themselves conspicuous. But there seems to be naturally a perversity in all matters of this kind. Love evidently delights in bending the inclinations in that very direction against which the professions have been the loudest and most decided.

BY D. W. BELISLE.

COMA BERENICES.—This is a beautiful cluster of small stars, situated about five degrees east of the equinoctial colure, and midway between Cor-Caroli on the north-east, and Denebola on the south-west. The stars that compose this group are small, but very bright, and are in close proximity to each other; therefore the cluster is readily distinguished from all others. There is a number of small nebulæ in this assemblage, which give it a faintly luminous appearance, somewhat resembling the milky-way. The whole number of stars in this cluster is forty-three. It comes to the meridian on the 13th of May.

This constellation is of Egyptian origin. Berenice was married to Evergetes, King of Egypt, and, on his going out to battle against the Assyrians, she vowed to dedicate her hair, which was of extraordinary beauty, to the goddess of beauty, if her lord returned in safety. Evergetes returned victorious, and, agreeably to her oath, her locks were shorn and deposited in the temple of Venus, whence they shortly disappeared, and the king and queen were assured by Conon, the astronomer, that they had been taken from the altar by Jupiter and placed among the stars; and, to convince them of the truth of his assertion, pointed out this cluster, and

This group being among the unformed stars until that time, and not known as a constellation, the king became satisfied with the declaration of Conon, who, pointing to the group, said, "There, behold the locks of our queen." Berenice was not only reconciled to this petty larceny of Jupiter, but was proud of the partiality of the god. Callimachus, who flourished before the Christian era, thus adverts to it—

CORVUS.—This small constellation is situated east of the Cup, and may be readily distinguished by four bright stars of the third magnitude, which form a trapezium; the two upper ones being three and a half degrees apart, and the two lower ones six degrees apart. Algorab, the most eastern star of these four, forms the east wing of the Crow, and comes to the meridian on the 13th of May. Beta, in the foot of the Crow, is seven degrees south of Algorab, and is the brighter of the two lower stars; and on the left, six degrees west of Beta, is Epsilon, which marks the neck, while two degrees below it is Al Chiba, a star of the fourth magnitude, which marks the head.

This constellation is of Greek origin, and it is gravely asserted by their ancient historians that this bird was originally of the purest white, but was changed, for tale-bearing, to its present color.

Apollo, becoming jealous of Coronis, sent a crow to watch her movements. The bird discovered her partiality for Ischys, and immediately acquainted the god with it, which so fired his indignation: that

To reward the crow, he placed it among the constellations. Other Greek mythologists assert that it takes its name from a princess of Phocis, who was transformed into a crow by Minerva to rescue the maid from the pursuit of Neptune. One of the Latin poets reverts to it thus—

VIRGO.—This constellation lies directly south of Coma Berenice, and east of Leo. It occupies considerable space in the heavens, and contains one hundred and ten stars. It comes to the meridian the 23d of this month. Spica Virginis, which marks the left hand of the Virgin, is a star of the first magnitude, and is of great brilliancy, and, with Denebola in Leo, and Arcturus in Boötes, forms a large equilateral triangle, which, joined with Cor-Caroli, a star of the same brilliancy, at an equal distance north, forms the Diamond of Virgo. The stars in this diamond are of equal brilliancy, rendering it one of the most clearly defined and most beautiful figures in this part of the heavens.

This constellation is probably of Egyptian origin. A zodiac discovered among the ruins of Estne, in Egypt, commences with Virgo, and, according to the regular progression of the equinoxes, this zodiac must be two thousand years older than that at Dendera. This relic of the earliest ages of the human species is conjectured to have been preserved during the deluge by Noah, to perpetuate the actual appearance of the heavens immediately subsequent to the creation.

The Athenians also claim the origin of this constellation, maintaining that Erigone was changed into Virgo. Erigone was the daughter of Icarius, an Athenian, who was slain by some peasants whom he had intoxicated with wine; and it caused such a feeling of despair in Erigone, that she repaired to the wood and hung herself on the bough of a tree.

ASTERION ET CHARA.—This is a modern constellation, and embraces two in one. It lies north of Coma Berenice, and west of Bootes, and comes to the meridian the 20th of May. Cor-Caroli is the brightest star in this group, and marks Chara, the southern hound. Asterion is north of this, and is marked by a small star about three degrees above Cor-Caroli. These two hounds are represented as chasing the Great Bear around the Pole, being held in a leash by Bootes, who is constantly urging them on in their endless track. The remaining stars in this group are too small and scattered to excite interest.

URSA MAJOR.—This constellation is situated between Ursa Minor on the north, and Leo Minor on the south, and is one of the most conspicuous in the northern hemisphere. It has been an object of observation in all ages of the world. The shepherds of Chaldea, Magi of Persia, priests of Belus, Phœnician navigators, Arabs of Asia, and American aborigines seem to have been equally struck with its peculiar outlines, and each gave to the group a name which signified, in their respective languages, the same thing—Great Bear. It is somewhat remarkable that nations which had no knowledge or communication with each other should have given the same name to this constellation. The name is perfectly arbitrary, there being no resemblance in it whatever to a bear or any other animal.

This cluster is remarkable for seven of its brightest stars forming a dipper, four stars forming the bowl, and three, curving slightly, shaping the handle. These seven stars are of uncommon brilliancy, and need no description to point out their locality. The whole number of stars in this group is eighty-seven, and it comes to the meridian the 10th of May.

WE often hear the expression used, when talking of anything comparatively useless, that "it's not worth a pin;" and from this we might be led to suppose, did we not know it to be otherwise, that a pin was a very worthless thing, instead of being what it is—one of the most useful that is manufactured in this or in any other country. As the use of pins is principally confined to the female portion of our community, perhaps the following short account of their manufacture, for which we are indebted to Knight's "Cyclopædia of Industry," a very useful book, may not be uninteresting to our readers:—

"Pins are made of brass wire. The first process which it undergoes, by which any dirt or crust that may be attached to the surface is got rid of, is by soaking it in a diluted solution of sulphuric acid and water, and then beating it on stones. It is then straightened; after which, it is cut into pieces, each about long enough for six pins. These latter pieces are then pointed at each end in the following manner: The person so employed sits in front of a[Pg 405] small machine, which has two steel wheels or mills turning rapidly, of which the rims are cut somewhat after the manner of a file: one coarse for the rough formation of the points, and the other fine for finishing them. Several of these pieces are taken in the hand, and, by a dexterous movement of the thumb and forefinger, are kept continually presenting a different face to the mill against which they are pressed. The points are then finished off by being applied in the same manner to the fine mill. After both ends of the pieces have been pointed, one pin's length is cut off from each end, when they are re-pointed, and so on until each length is converted into six pointed pieces. The stems of the pins are then complete. The next step is to form the head, which is effected by a piece of wire called the mould, the same size as that used for the stems, being attached to a small axis or lathe. At the end of the wire nearest the axis is a hole, in which is placed the end of a smaller wire, which is to form the heading. While the mould-wire is turned round by one hand, the head-wire is guided by the other, until it is wound in a spiral coil along the entire length of the former. It is then cut off close to the hole where it was commenced, and the coil taken off the mould. When a quantity of these coils are prepared, a workman takes a dozen or more of them at a time in his left hand, while, with a pair of shears in his right, he cuts them up into pieces of two coils each. The heads, when cut off, are annealed by being made hot and then thrown into water. When annealed, they are ready to be fixed on the stems. In order to do this, the operator is provided with a small stake, upon which is fixed a steel die, containing a hollow the exact shape of half the head. Above this die, and attached to a lever, is the corresponding die for the other half of the head, which, when at rest, remains suspended about two inches above the lower one. The workman takes one of these stems between his fingers, and, dipping the pointed end of a bowl containing a number of heads, catches one upon it and slides it to the other end; he then places it in the lower die, and, moving a treadle, brings down the upper one four or five times upon the head, which fastens it upon the stem, and also gives it the required figure. There is a small channel leading from the outside to the centre of the dies, to allow room for the stem. The pins are now finished as regards shape, and it only remains to tin or whiten them. A quantity of them are boiled in a pickle, either a solution of sulphuric acid or tartar, to remove any dirt or grease, and also to produce a slight roughness upon their surfaces which facilitates the adhesion of the tin. After being boiled for half an hour, they are washed, and then placed in a copper vessel with a quantity of grain tin and a solution of tartar; in about two hours and a half, they are taken out, and, after being separated from the undissolved tin by sifting, are again washed; they are then dried by being well shaken in a bag with a quantity of bran, which is afterwards separated by shaking them up and down in open wooden trays, when the bran flies off and leaves the pins perfectly dry and clean. The pins are then papered for sale."

Pins are also made solely by machinery. There is a manufactory for this sort (the Patent Solid Headed Pins, near Stroud) where nearly 3,250,000 are made daily.

A pin, then, is not such an insignificant article, after all. We see it has to go through a great many processes and hands before it is finished. If we take one, examine it closely, and mark how nicely it is made, how neatly the head is fixed on to the shank, how beautifully it is pointed, and how bright it shines, we shall see a very good specimen of what the ingenuity and labor of man can do upon a piece of metal. It is really surprising what a large number are made, and how many persons are employed in their manufacture. We read, some time ago, an amusing article from "Bentley's Miscellany," wherein the writer asks the question: "What becomes of the pins?" and puts forth the rather curious assertion that, if they continue to be lost and made away with as they are now, some day or other the whole globe will be found to be "one vast shapeless mass of pins."

In conclusion, we would recommend our readers always to bear in mind the excellent maxim which Franklin attached to a pin, namely, "A pin a day, a groat a year."

I BEG to remind my daughter that the husband has a thousand elements of disturbance in his daily avocations to which his wife is an utter stranger; and it will be her privilege, and her title to the respect of all whose respect is worth having, to make his own fireside the most attractive place in the universe for the calm repose of a weary body or excited mind. The minor comforts, which are the most valuable, because the most constantly in requisition, will depend more upon her look, her manner, and the evidence of her forethought, than upon all the other occurrences of life.—Parental Precepts.

MR. GODEY: Miss Snipe left my house in great haste on the second day of April, forgetting, in her precipitation, several articles of her wardrobe and her portfolio. While waiting an opportunity to forward them to Wimpleton, a natural impulse of curiosity induced me to examine the contents of the portfolio, when, lo and behold, a letter, directed to yourself, fell on the floor. Being loosely folded and unsealed, I ventured to open it, supposing it merely a business communication. Imagine my surprise on discovering the nature of its contents, for I had been unable to penetrate the reasons of her hurried departure; but do not, I pray you, accuse me of having read it through.

Finding, as far as I proceeded, nothing very heinous laid to myself, nor any insinuations against my table, I judge proper to forward it without delay, according to the address. However, I can with difficulty forgive her for calling my boy a "cub," and think, moreover, that her dislike towards my Irish inmate is unreasonable. As to Mr. Sparks—I do not blame her so much—he has not yet paid me those gloves. And as to the writer herself, I am really astonished—we all thought her such a quiet and unobservant little body—on becoming acquainted with this spirited volley from her pen. Will there not be both laughing and wry faces in my household, if you publish it? And, though April is gone (I am sorry the letter was not sooner found), do give the world the benefit of her experience, to oblige and amuse

Yours, faithfully,

HELEN MASHUM.

April 1, 1854.

MY DEAR MR. EDITOR: Such a tumult as we have all day been in, by reason of that abominable practice of "fooling," has been enough to destroy the patience of a saint. I am nearly out of my wits. Here have I come, at my niece's invitation, to spend a fortnight with her, in a boarding-house. "She was lonely," she said; "Mr. Sparks was so much at the office; and it would be such a favor if I could stay with her a few days."

So I have come from my quiet country home, fifteen miles off, to this noisy town that calls itself a city, to visit Ann Sophia; and, between you and me, I was an April fool from the beginning. There are several other young married women boarding in the same house, who, like my flighty niece, have apparently nothing under the sun to do but go shopping and pop in and out of each other's rooms. Some of them are in her parlor every evening when she is not out at parties or lectures, and, as she spins street yarn every morning, I cannot for the life of me see what opportunity she takes to be lonesome. But I do see that she gives herself no time to keep her husband's shirts made up and in order; and I find that I have no lack of employment, for she has kept me sewing ever since I came.

"Sophy, dear," says I, the morning after my arrival, "give me some sewing; I cannot be idle, and have nothing but this knitting to do for myself."

Whereupon she brought out a whole piece of fine bleached cloth, and proposed that we should amuse ourselves by making it into shirts for her husband.

"Holton needs them so much," said she, "and you are so kind as to offer your services, aunty; it would cost so much to hire them done, and his salary is so small now, you know, and boarding so expensive."

And to work we began; but the truth is that it is very little which Ann Sophia has done thus far. Well, what is a single woman good for unless to make herself generally useful? A precious sight of twaddle have I read first and last in the papers and magazines about the delights and privileges of old-maidery. Delights of a fiddlestick! Pulled hither and thither, perhaps—as I have been—at the beck of married brothers and sisters, and a score of idle nephews and nieces; if you have a home of your own, not allowed to stay at it in peace for more than one week together. Sister Julia's children have all got the measles, and Aunt Abigail must go and take care of them; or brother Peter's wife is dead, and Abigail must pack up and go to keep house for him till she becomes attached to the motherless tribe, and feels quite at home among them, when he gets a new wife, and Abigail departs just as she begins to be happy. To crown all, when she puts her own house in order, and has a nice lot of sweetmeats and pickles made up, along comes a troop of relations, male[Pg 407] and female, young and old, to visit dear Aunt Abigail and eat up all her stores, to say nothing of completely kicking out the stair carpet. But I am wandering from my subject—a thing which I am apt to do.

The house is quiet now, and, having finished one of Holton Sparks's shirts this evening, I embrace the respite to retire to my own room. After all, I do not feel like scolding about Ann Sophia. The pleasant-tempered girl looks so much like her mother, brother Peter's first wife; I brought her up, too, at least till she was ten years old, when her father married again. Her chief fault is her youth, and she will get over that, dear child.

However, to return, I cannot sleep till I have expressed my indignation at the follies that have been perpetrated in honor—rather should I say, in dishonor—of All Fools' Day, hoping that you, Mr. Editor, will lift your voice in favor of putting a stop to such absurdities. In the first place, I had scarcely risen, when I was myself made the victim of imposition; for, while I was dressing, there was a rap at the door, and I heard Sparks's voice—

"Aunt Abigail, are you up? Here is a letter postmarked Wimpleton. It came by the night train, probably."

"As sure as fate," thought I, "there has something dreadful happened at home." And, being much agitated, I tore open the envelop in great haste, without observing that the superscription was not in brother Sam's hand, and wondering why Sparks did not wait to learn the nature of its tidings. As truly as I am a living woman, there was nothing inside but a great foolscap sheet, and on it these words, in staring capitals—

"APRIL FOOL."

I could have cried, so vexed was I at first. Then I felt thankful that no bad news had actually reached me; for, during the brief moment occupied in opening the letter, you can scarcely imagine the many terrible things that passed through my head. Mother had had a fit, fallen down and broken her leg, though brother Sam had promised me faithfully not to leave her alone while I was gone; or that stupid Dutch boy, who takes care of the cow and the fires, had left live coals in the ash-box, and the house was burned to the ground. Or Sam himself had got one of those severe attacks of inflammatory rheumatism, and nobody there but mother to take care of him, and take his fretting into the bargain, and she almost eighty years old. When I recovered myself a little, I took that wretched sheet of paper, and was on the point of penning a dignified expression of my sentiments below the odious words, and handing it in silent scorn to my nephew-in-law at the breakfast-table. But better feelings prevailed; I smoothed it nicely in my portfolio, and am now scratching this hasty epistle upon its surface, intending in the morning to write it more legibly on some of my own fair sheets of Bath.

A few among the follies of this tiresome day have, I must acknowledge, given me a certain sort of satisfaction. Holton Sparks has been come up with himself; not by any means of mine, I earnestly assure you, for, besides heartily despising it, I cannot in any shape perpetrate "April fooling." Sam often says that this is because I am so matter-of-fact; but, matter-of-fact or not, I trust that there is not enough matter-of-folly in my composition to attempt such performances. I always did abominate practical jokes, and Sam knows that; yet the jokes which that boy still puts upon me, though I am three years older than himself, would be deemed improbable.

Well, when the breakfast-bell rang this morning, I went down stairs with an air as erect and dignified as a woman of fif——no matter—with such a demeanor as one who has outlived the fooleries of early youth should make habitual. Holton Sparks is very fond of eggs, and invariably takes the biggest on the dish. I observed that our landlady directed the servant to hand them first to Mr. Sparks, who was too intent on securing his egg to notice her action. Indeed, he never hesitates to help himself first, quite regardless of the ladies who sit near, and even of Ann Sophia. Holton is a tremendous eater, seeming to think of nothing at table but disposing of his food as rapidly and in as large quantities as possible. The manner of this gentleman is to place a large piece of nicely buttered toast on his plate, pour the egg over it, pepper the whole thoroughly, and swallow it as if the preparation were some unpleasant dose that it is his duty to dispatch. Mrs. Mashum, who is altogether too much given to laughing, and too volatile for her station, sat behind the coffee urn shaking violently with suppressed mirth. He broke the shell of his egg as usual, when, behold, his plate was flooded with a dingy-looking liquid, which proved to be warm dish-water. On comprehending the joke, he sent it away with an offended air, and made his breakfast on beefsteak, without deigning to join in the universal laugh. It seems that last evening he laid a wager with Mrs. Mashum that she could not succeed in playing him a trick, he[Pg 408] should be so constantly upon his guard during All Fools' Day. The affair of the egg has put him out of humor to such an extent that we have been saved the infliction of any more jokes at his hands. He has worn his dignity all day, not even Ann Sophia succeeding in laughing or coaxing him into laying it aside. I rather think that he grudges the dollar which he will have to lay out for the gloves, as Mrs. Mashum has won the bet, and Ann Sophia assures him that a pair of her own will not do by any means. He proposed that expedient to settle the matter. Holton is stingy. But his wife declared that such a good joke deserved a pair of Alexander's best. It is not because I approve of betting that I mention this, for I hold the practice in great abhorrence. It was only of a piece with the other follies of the day, and shows up Holton Sparks a little.

A small fire of fooling was kept up throughout the morning. If the door-bell has been rung once, it has forty times, by Mrs. Mashum's cub of a boy, who would jerk the handle or toss up his ball at the wire, and then run out of sight. In going from my own room to my niece's, I saw a sixpence on the floor, and, stooping down to pick it up, found it fast. Congratulating myself on not having been observed, I was passing on, when that disagreeable urchin shouted, from behind a door—

"April fool, old lady!"

He deserves to be sent to the House of Refuge.

Ann Sophia herself has put me out of all manner of patience by saying, as I sat sewing at the front window in her parlor, "Pray, Aunt Abigail, whose carriage do you suppose that is?" when no vehicle was in view but the milkman's. Or, suddenly, she would exclaim, "What ladies are those crossing the street?" when none were anywhere to be seen.

But the meanest of all was a very rude thing, which she repeated several times upon different persons, apparently delighted with its efficacy. This was to rush up suddenly, and screaming out, "See there!" throw her arm directly across one's nose with so much force as to oblige that organ to follow the direction of her outstretched finger, whether or no. Such a sort of fooling by compulsion struck me as particularly reprehensible.

"I'd try it on you, aunty," said the volatile child, "if I were not afraid of scoring my arm."

Such an insinuation against my nose! Had it been any one besides Sophy, I could not have forgiven the speech. She is such a highty-tighty.

But one trick which she played was really good, especially as its object was a man to whom I have taken a huge dislike. He is an Irish gentleman connected with some legal firm in town, most desperately polite, with a very long round nose and fiery red hair. He is continually poking dishes at me across the table, and is fairly oppressive with his attentions. Moreover, he calls me "Mrs." perpetually. "Mrs.," indeed! Intimating that I am old enough to be a "Mrs.," if not one in fact. As he rises very late, he never appears at breakfast with ourselves; but at dinner we have the misery of his presence. To-day, when we were almost through with the first course, he entered with an air much flushed and uncomfortable.

"Are you ill, Mr. O'Killigan?" asked Mrs. Mashum.

"No, thank you, madam," said he, with one of his customary efforts at politeness. "But I have been trying for a long while to shave, till forced in despair to give up the attempt. The deuce has got into my soap."

"You have forgotten that it is the first of April. The day may have had some influence upon your dressing-case," remarked one of the ladies present.

"I declare, I have not thought of that," said he, and, springing from the table, he ran to his room, returning with something which he begged the ladies to examine. It proved to be a thick, fair slice of a raw potato, in size and color so much like his own soap, which had been removed, that he had detected no difference, except that it refused to form a lather. This was the work of my mischievous niece, who looked at it very gravely, and remarked, with much demureness—

"I always knew that you Irish were fond of potatoes, but was not aware that you carried it to such an excess as to shave with that vegetable."

It would have better pleased me had O'Killigan been angry; but the Irishman took the joke, and all the speeches made at his expense, with entire good-humor, laughingly assuring the ladies that he would be revenged before night. And, as he knew not whom to suspect, he adopted a course which involved most of us in its consequences. When we retire for the night, those who are not better provided equip themselves with a candle, of which a supply stands ready in the lower hall. Such a fuss as I had with my light this evening! It went out as soon as I reached my own door; and, after relighting it several times by means of matches, the tallow was exhausted, and I discovered that the blackened remnant of wick was stuck into a[Pg 409] carrot. That miserable Irishman had enlisted Biddy Flyn, the chambermaid, in his service, and this afternoon they spent two whole hours in the basement at their nefarious work, trimming off carrots and giving them a very thin coating of grease. Mrs. Mashum herself did not escape, for, just as she began taking her usual rounds to see that all was safe for the night, her treacherous light went out, leaving her in total darkness—in the lower regions, too, for she was on the point of inspecting a keg of mackerel in the cellar.

At this identical moment, having used up all my matches in vain endeavors to light a candle, which, like its manufacturer's locks, I had found to be carroty, I was on my way to the kitchen in pursuit of a more reliable means of illumination, when I heard Mrs. Mashum scream out—

"Bring a light, Biddy, for goodness sake! I shall step into this rat-trap that you've set, if I stir an inch in the dark."

And all the while the shameful Biddy stood holding her sides, and laughing in a most unreasonable way. Several persons were running along the upper hall calling for lights, the ladies in a sort of demi-toilet, and one of the young men, a dry-goods clerk, who dresses his hair with a curling-tongs, having on a black silk night-cap. But the real culprit did not suffer, after all, for Ann Sophia has her own solar lamp.

While these distressing events were transpiring, that mean Irishman, with his big nose and red head, sat in the parlor, as cool as possible, reading the "London News" by the light of a brilliant camphene lamp. I wonder his hair did not ignite and cause an explosion. It would have served him quite right.