The Project Gutenberg EBook of Cassell's Natural History, Vol. 3 (of 6), by

P. Martin Duncan and A. H. Garrod and W. S. Dallas and R. Bowdler Sharpe

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States

and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no

restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it

under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this

eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not

located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the

country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Cassell's Natural History, Vol. 3 (of 6)

Author: P. Martin Duncan

A. H. Garrod

W. S. Dallas

R. Bowdler Sharpe

Release Date: November 1, 2020 [EBook #63592]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CASSELL'S NATURAL HISTORY ***

Produced by Jane Robins, Reiner Ruf, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Notes

This e-text is based on ‘Cassell’s Natural History, Vol. III,’ from

1893. Inconsistent and uncommon spelling and hyphenation have been

retained; punctuation and typographical errors have been corrected.

The spelling of toponyms might differ slightly from today’s

orthographical conventions.

The cover image was created by the transcriber and

is placed in the public domain.

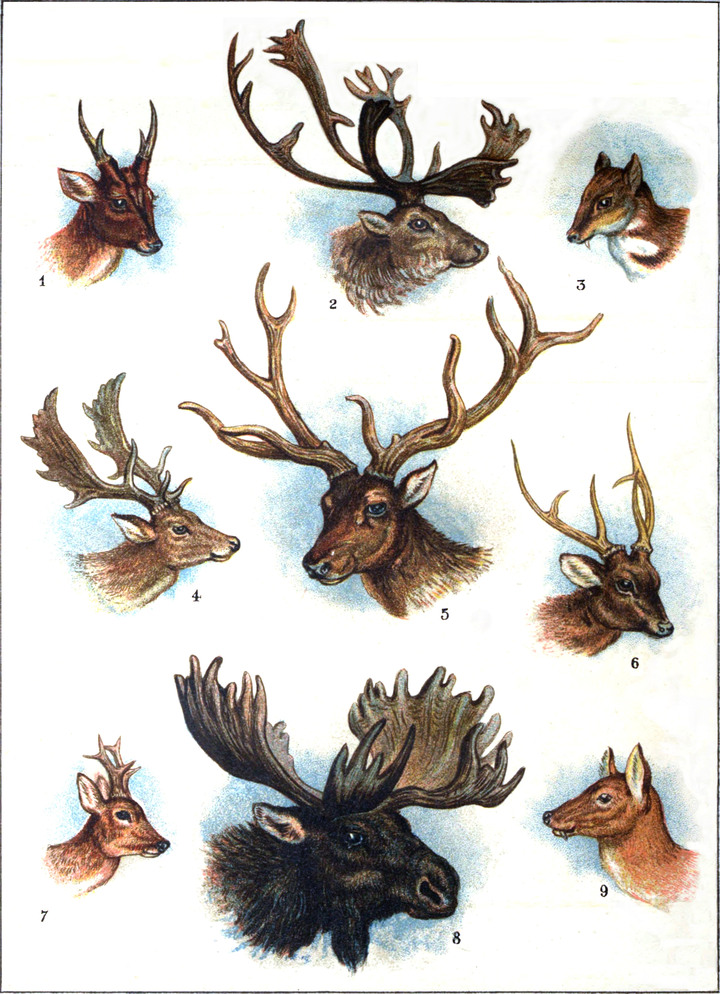

CASSELL & COMPANY, LIMITED, LITH. LONDON.

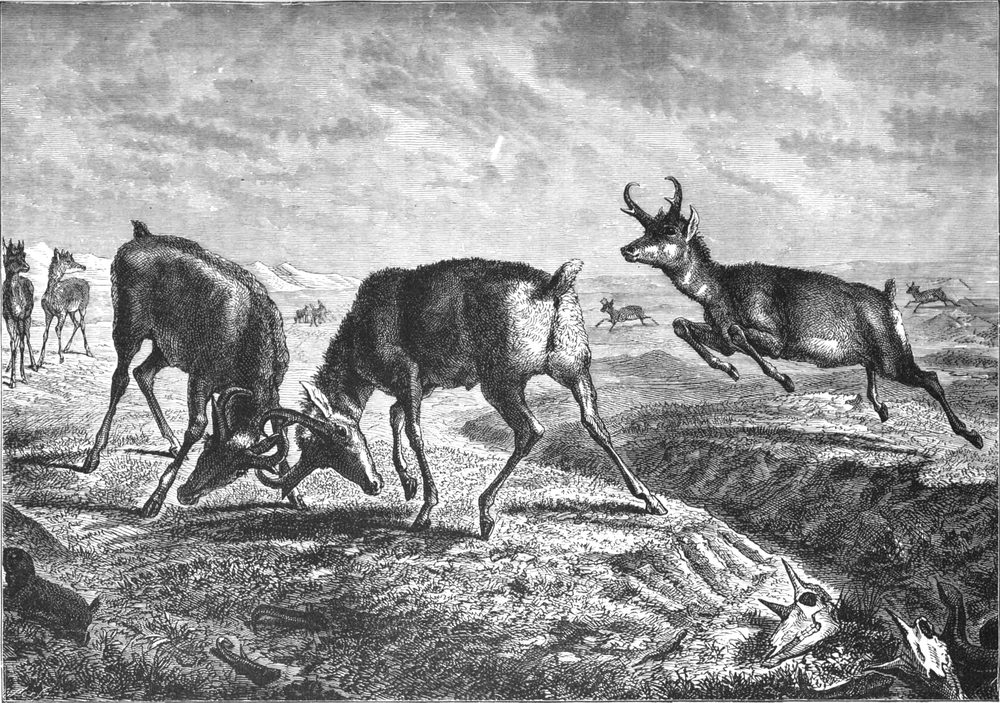

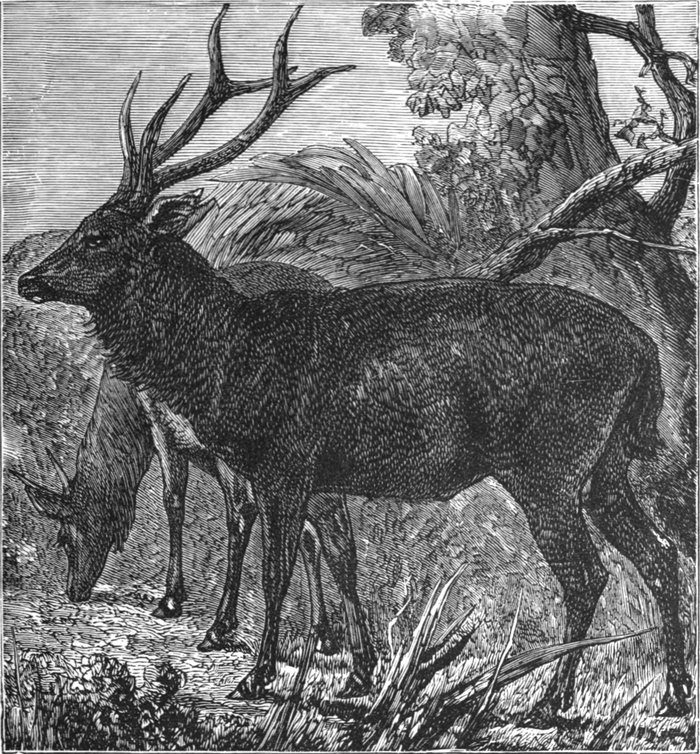

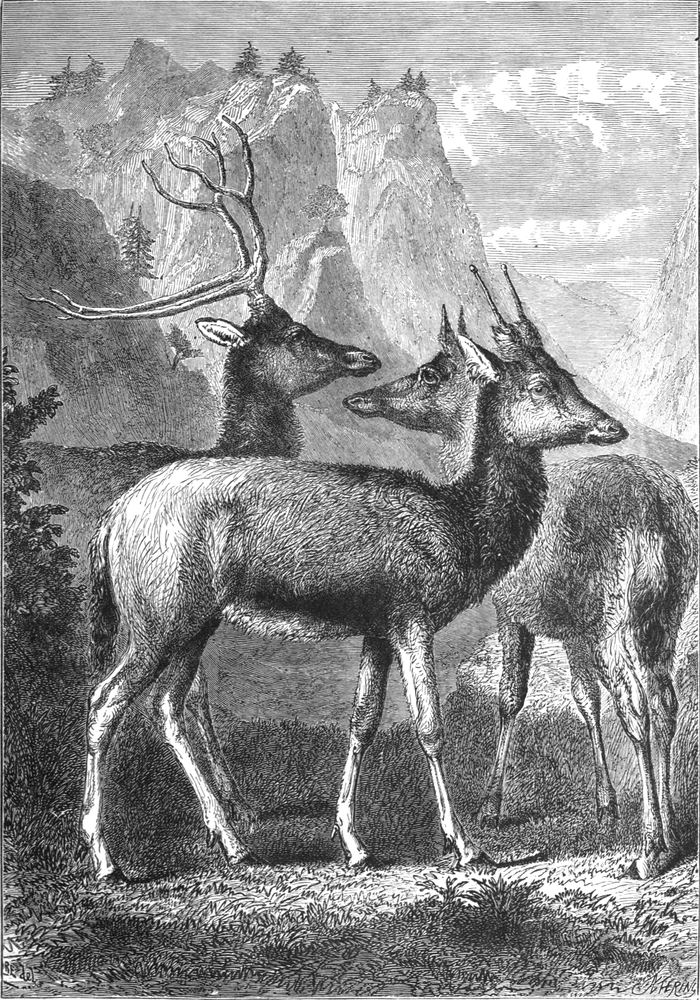

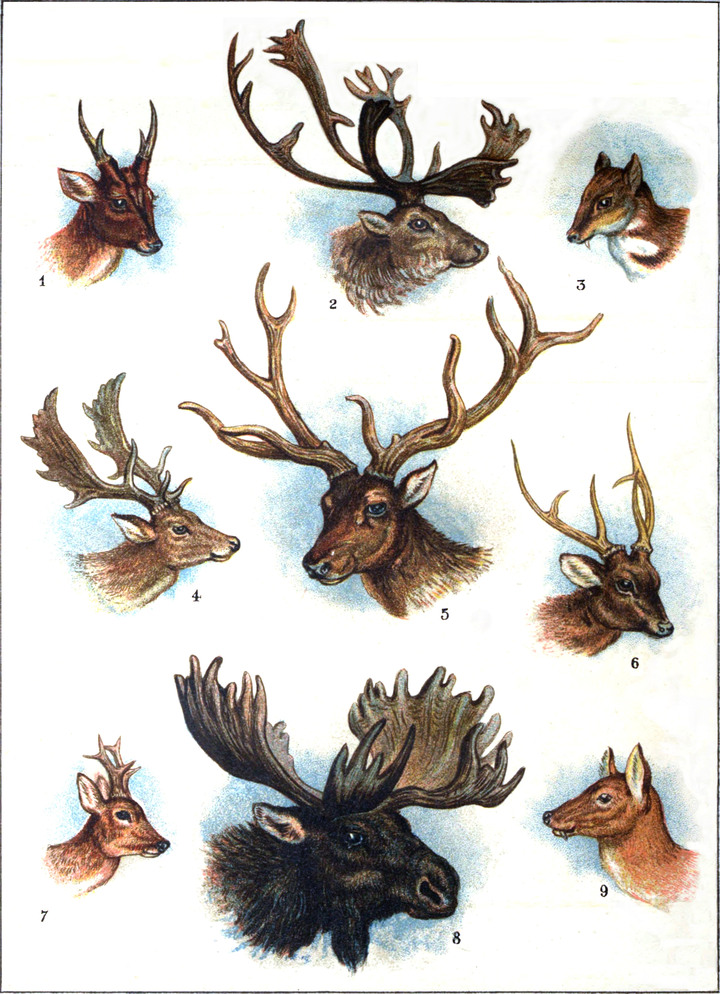

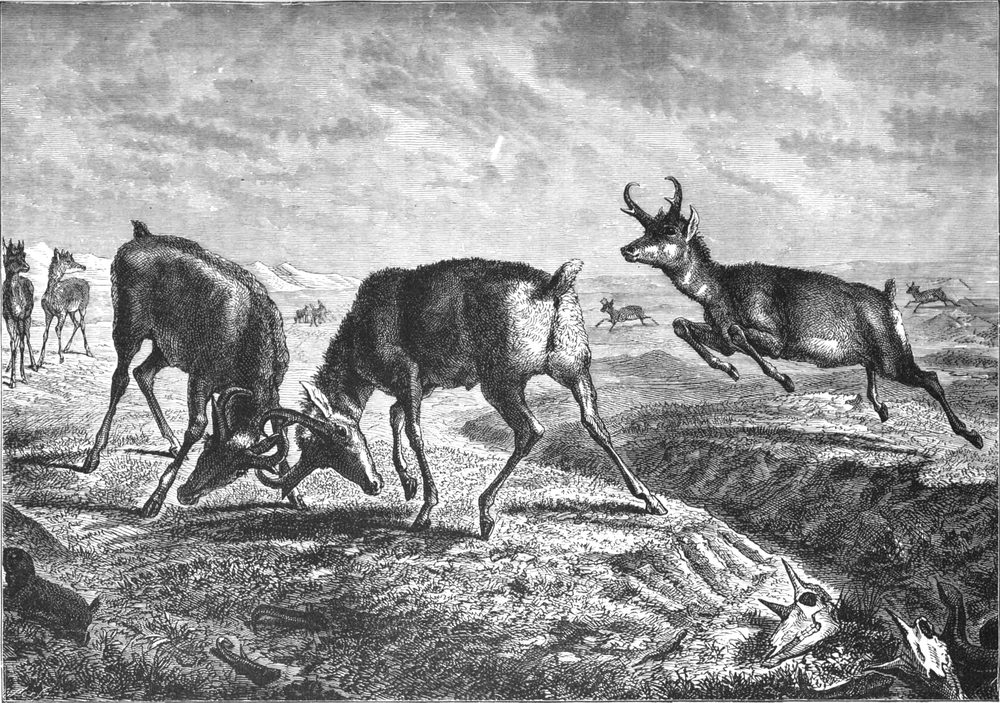

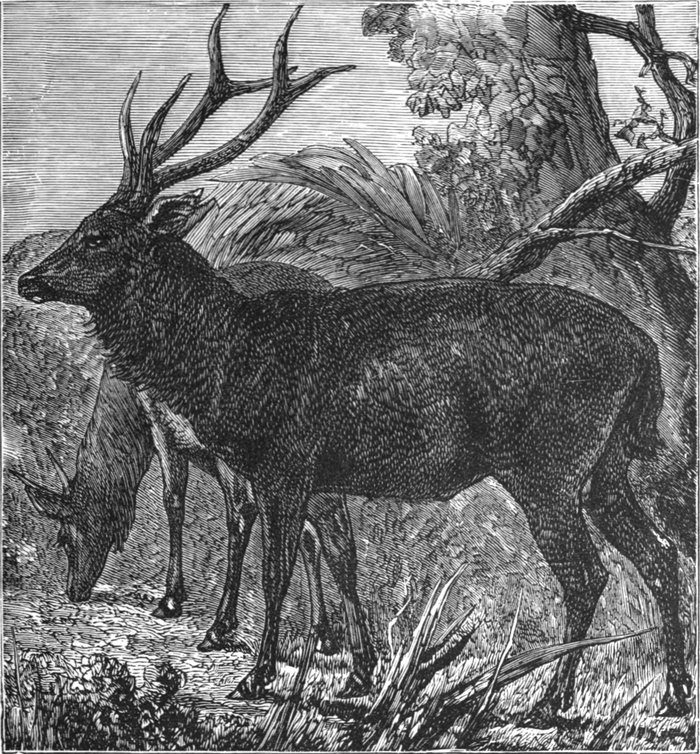

DEER FAMILY.

1. Indian Muntjac (

Cervulus muntjac).

2. Reindeer (

Rangifer tarandus).

3. Javan Deerlet (

Tragulus napu).

4. Fallow Deer (

Dama vulgaris).

5. Wapiti Deer (

Cervus strongyloceros).

6. Porcine Deer (

Hyelaphus porcinus).

7. Roebuck (

Capreolus caprea).

8. Elk (

Alces machlis).

9. Chinese Water Deer (

Hydropotes inermis).

CASSELL’S

NATURAL HISTORY

EDITED BY

P. MARTIN DUNCAN M.B. (LOND.) F.R.S.,

F.G.S.

PROFESSOR OF GEOLOGY IN AND HONORARY FELLOW OF KING’S

COLLEGE, LONDON

CORRESPONDENT OF THE ACADEMY OF NATURAL SCIENCES

PHILADELPHIA

VOL. III.

ILLUSTRATED

CASSELL AND COMPANY

LIMITED

LONDON PARIS & MELBOURNE

1893

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

UNGULATA:—

RUMINANTIA.

A. H. GARROD, M.A., F.R.S.

RODENTIA.

W. S. DALLAS, F.L.S.

EDENTATA.

P. MARTIN DUNCAN, M.B. (LOND.),

F.R.S., F.G.S.

MARSUPIALIA.

P. MARTIN DUNCAN, M.B. (LOND.),

F.R.S., F.G.S.

AVES.

R. BOWDLER SHARPE, F.L.S., F.Z.S.

|

|

PAGE

|

|

|

|

ARTIODACTYLA—RUMINANTIA:

|

|

BOVIDÆ—SHEEP, GOATS, AND GAZELLES.

|

|

Ruminantia—Chewing the Cud—Metaphorical Expression—The Complicated Stomach: Paunch, Honey-comb Bag, Manyplies,

Reed—Order of Events in Rumination—Feet and Dentition of Ruminants—Brain—Classification—HORNED

RUMINANTS—Divided into two Groups—Difference between them—BOVIDÆ—Horns—Aberrant Members—SHEEP

AND GOATS—General Characteristics—Sheep of South-Western Asia—Merino Sheep—Breeds of Great Britain—Dishley,

or Improved Leicesters—Mr. Bakewell’s Description—Southdowns, Cheviots, Welsh, and other British

Breeds—Table of the Importation of Colonial and Foreign Wool into the United Kingdom—MARCO POLO’S

SHEEP—OORIAL—SHAPOO—MOUFLON—AMMON—BURHEL—AMERICAN ARGALI—WILD SHEEP OF BARBARY—THE

GOAT—Compared with the Sheep—Descent—Cashmere Goat—IBEXES—PASENG—Their remarkable Horns—Old

Theories as to the Use of the Horns—MARKHOOR—TAHR—GAZELLES—General Characteristics—Sir Victor Brooke’s

Classification—THE GAZELLE—Appearance—Habits—ARABIAN GAZELLE—PERSIAN GAZELLE—SOEMMERRING’S

GAZELLE—GRANT’S GAZELLE—SPRINGBOK—SAÏGA—CHIRU—THE PALLAH, OR IMPALLA—THE INDIAN ANTELOPE,

OR BLACK BUCK

|

|

|

CHAPTER II.

|

|

ARTIODACTYLA—RUMINANTIA:

|

|

BOVIDÆ: (continued)—ANTELOPES.

|

|

THE STEINBOKS: KLIPSPRINGER, OUREBI, STEINBOK, GRYSBOK, MADOQUA—THE BUSH-BUCKS—Appearance—Distinctive

Marks—THE FOUR-HORNED ANTELOPES—Peculiarity in the Chikarah—THE WATER ANTELOPES: NAGOR, REITBOK,

LECHÈ, AEQUITOON, SING-SING, WATER-BUCK, POKU, REH-BOK—THE ELAND—Beef—Appearance—Captain

Cornwallis Harris’ Description—Hunting—Scarcity—THE KOODOO—Appearance—King of Antelopes—ANGAS’

HARNESSED ANTELOPE—THE HARNESSED ANTELOPES: GUIB—BUSH BUCK, OR UKOUKA—Appearance—Pluck—THE

BOVINE ANTELOPES—THE BUBALINE—HARTEBEEST—BLESBOK—BONTEBOK—SASSABY—THE GNU—Grotesque

Appearance—Habits—BRINDLED GNU—THE CAPRINE ANTELOPES—SEROW—Ungainly Habits—GORAL—CAMBING-OUTAN—TAKIN—MAZAMA—THE

CHAMOIS—Distribution—Appearance—Voice—Hunted—THE

ORYXES—BLAUBOK—SABLE ANTELOPE—BAKER’S ANTELOPE—ORYX—BEISA—BEATRIX—GEMSBOK—ADDAX

|

17

|

|

CHAPTER III.

|

|

ARTIODACTYLA—RUMINANTIA:

|

|

BOVIDÆ (concluded)—OXEN, PRONGHORN ANTELOPE, MUSK [DEER], AND GIRAFFE.

|

|

THE NYL-GHAU—Description—Habits—THE MUSK OX—Difficulties in associating it—Distribution—Habits—THE

OX—Chillingham Wild Cattle—Their Habits—Domestic Cattle—The Collings, Booth, and Bates Strains—American

Breeding—Shorthorns, and other Breeds—Hungarian Oxen—Zebu—Gour—Gayal—Curious mode

of Capturing Gayals—Banting—THE BISONS—Description—European Bison, or Aurochs—Almost extinct—Cæsar’s

Description of it—American Bison—Distribution—Mythical Notions regarding it—Their Ferocity and Stupidity—“Buffalo”

Flesh—THE YAK—Habits—THE BUFFALOES—Varieties—Description—Fight between two Bulls—THE

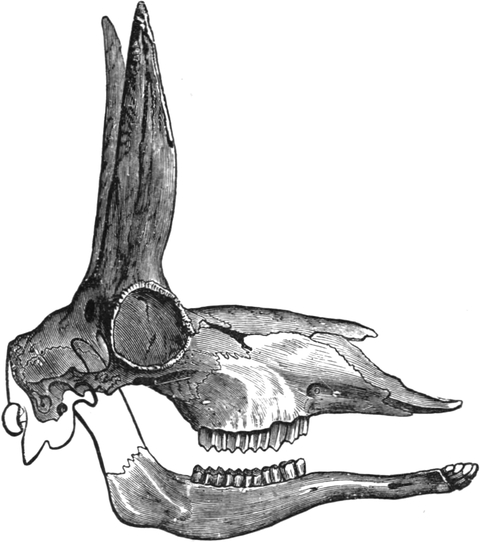

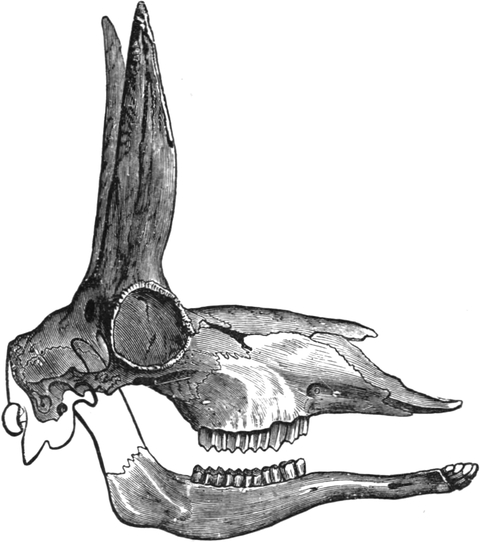

ANOA—THE PRONGHORN ANTELOPE—Peculiarity as to its Horns and Skull—Professor Baird’s and Mr.

Bartlett’s Independent Discovery of the Annual Shedding of the Horns—Habits—Peculiarity about its Feet—Colour—Difficulties

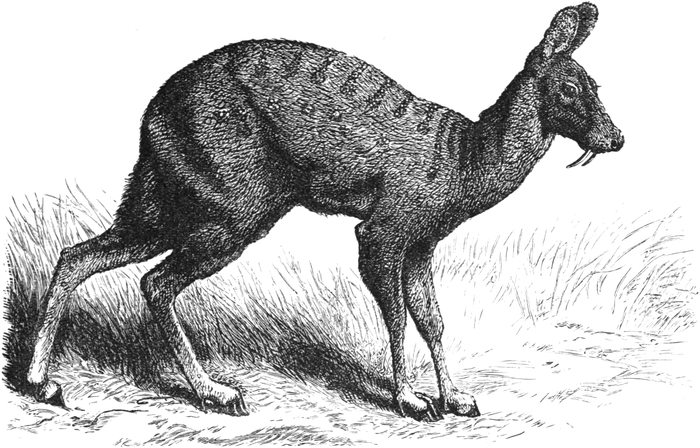

as to its Position—THE MUSK [DEER]—Its Perfume—Where is it to be placed?—Description—Habits—Hunters

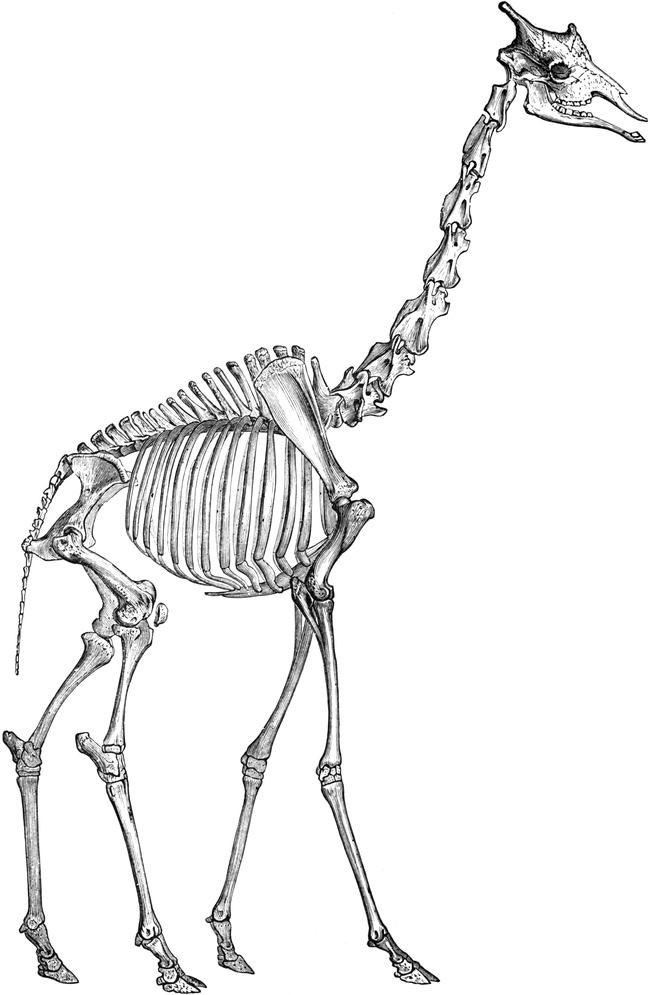

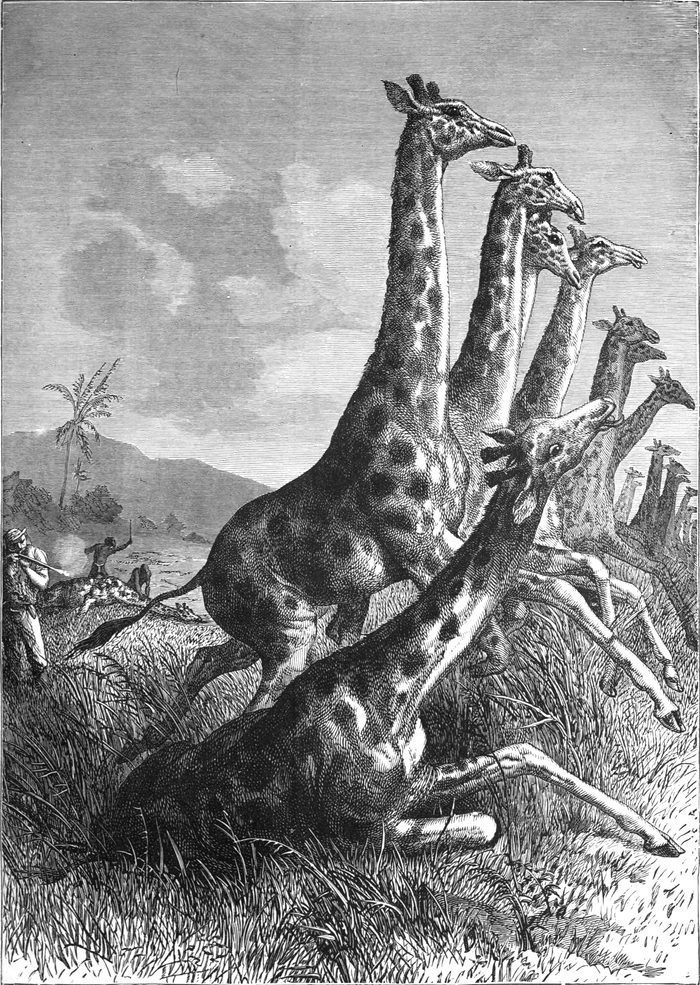

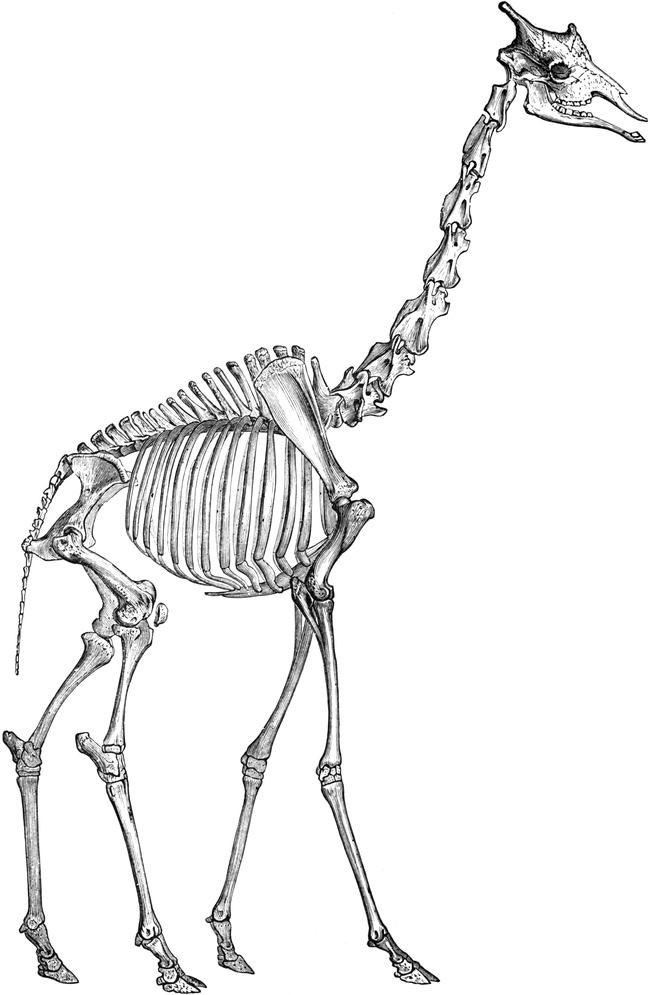

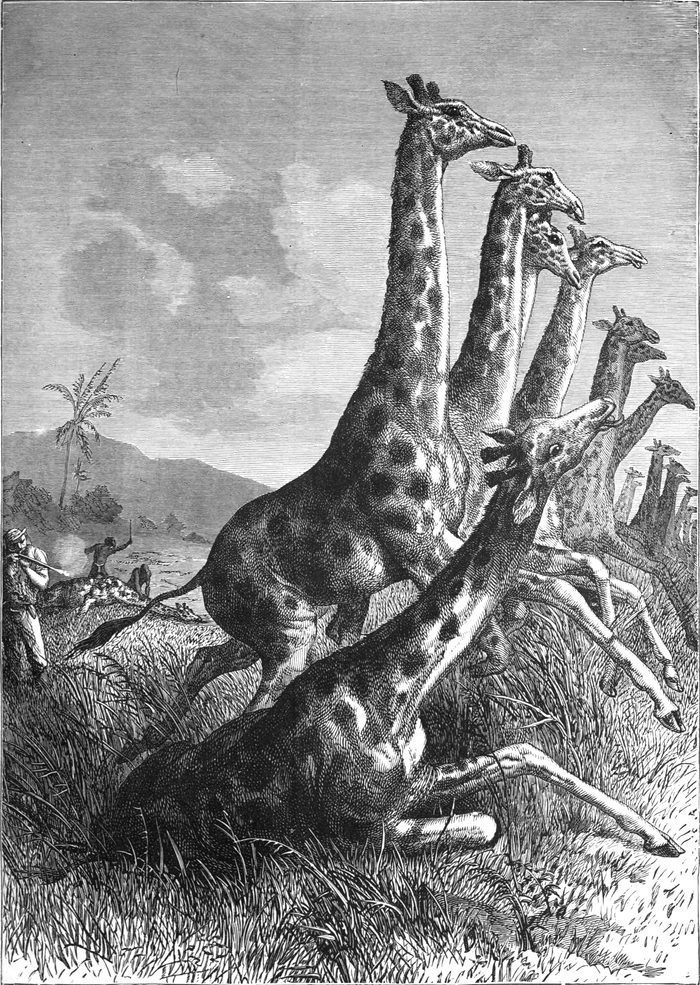

for the Perfume—Their Sufferings—THE GIRAFFE—Peculiarities—Skull processes—Its Neck—Habitat—Running

power—Habits—Hunting

|

29

|

|

CHAPTER IV.

|

|

THE CERVIDÆ, OR ANTLERED RUMINANTS:

|

|

THE ELK, ELAPHINE, SUB-ELAPHINE, AND RUSINE DEER.

|

|

The Deer Tribe—Distinguishing Characters—Exceptions to the rule—The Musk (Deer) and Chinese Water Deer—Other

Characters of the Cervidæ—Antlers, their Nature, Growth, and Shedding—The Knob—“Velvet”—Getting

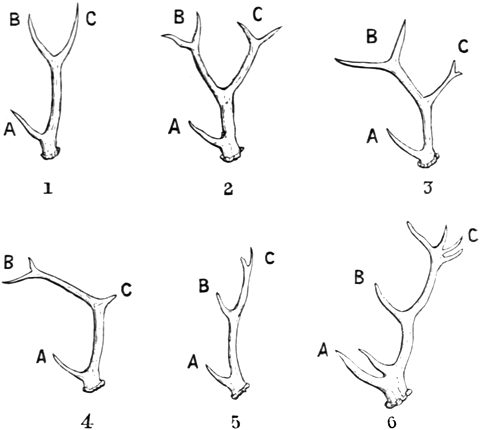

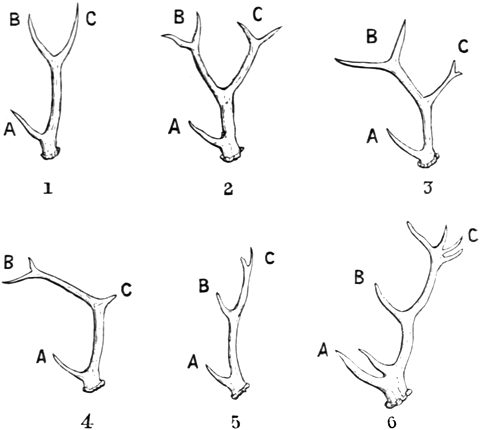

rid of the “Velvet”—Full equipment—Contests—Interlocking Antlers—Distribution—Classification—Development

of Antlers in the Common RED DEER—Explanation of the various stages—Splendid “Heads”—Simple

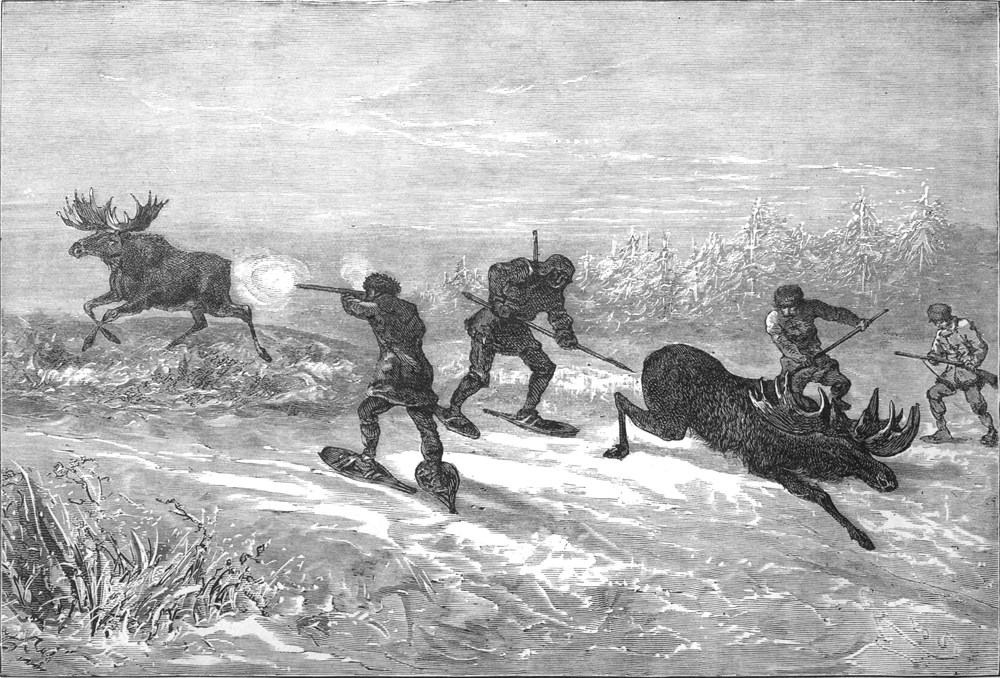

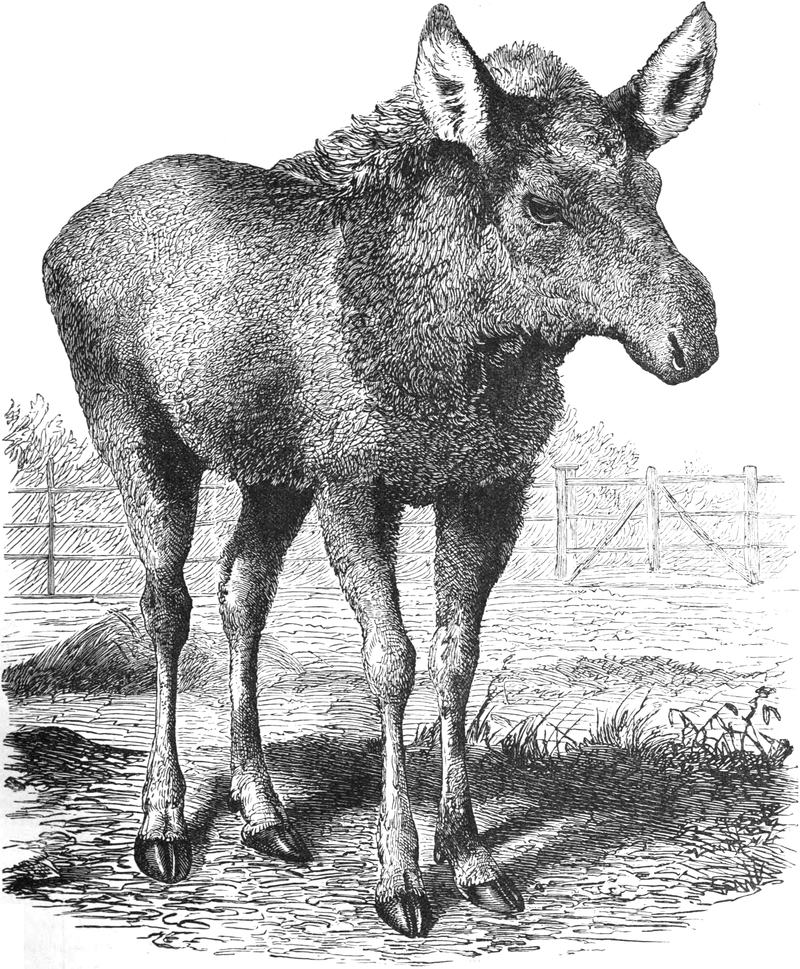

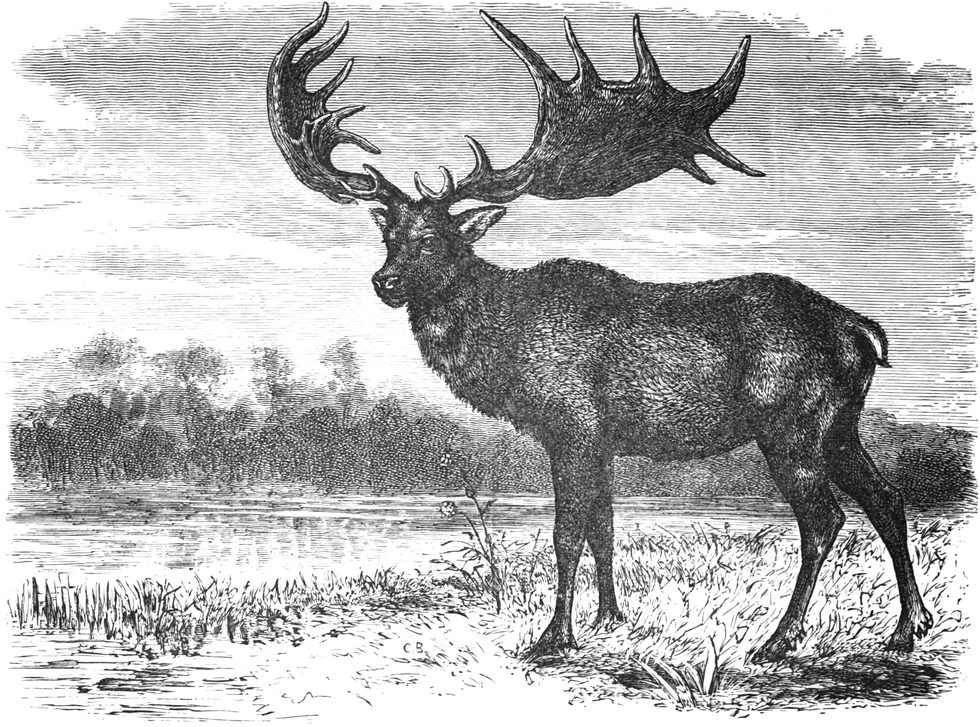

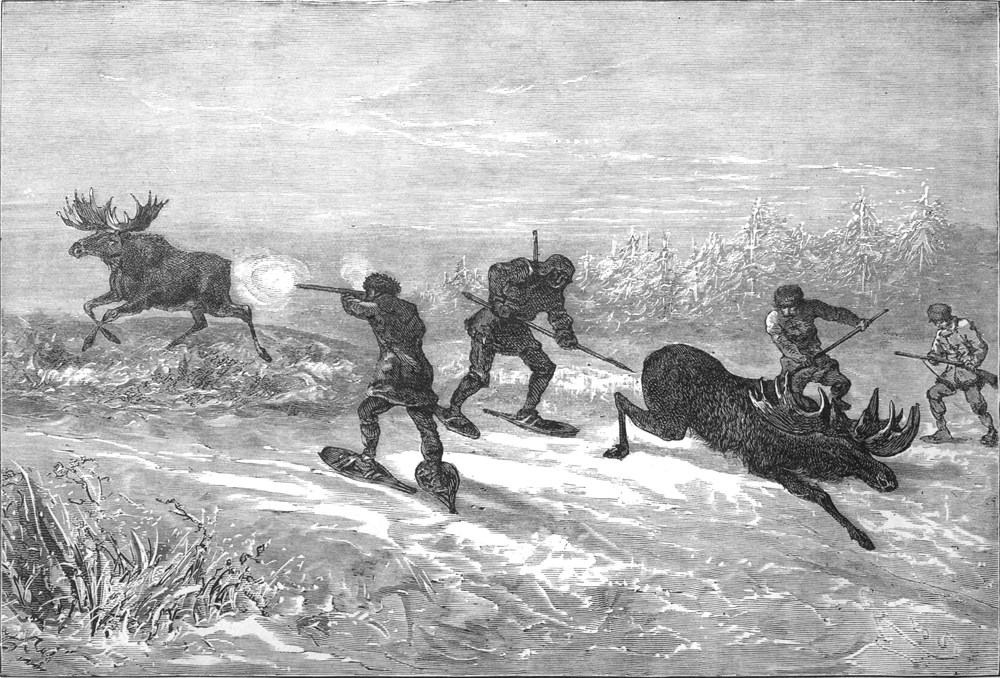

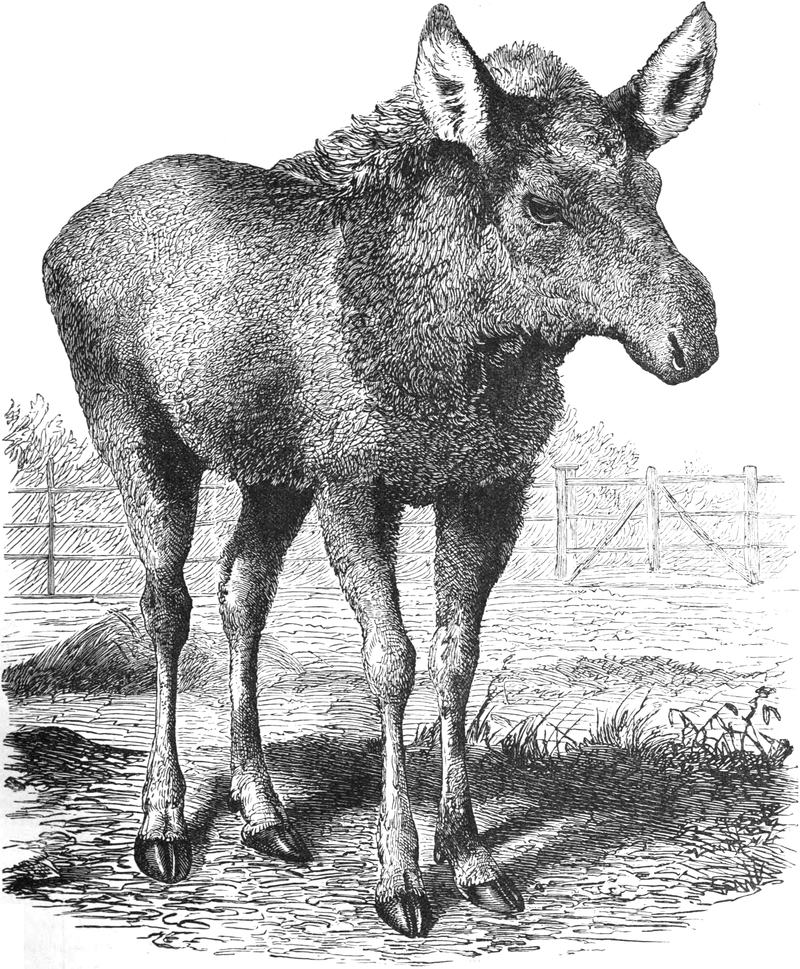

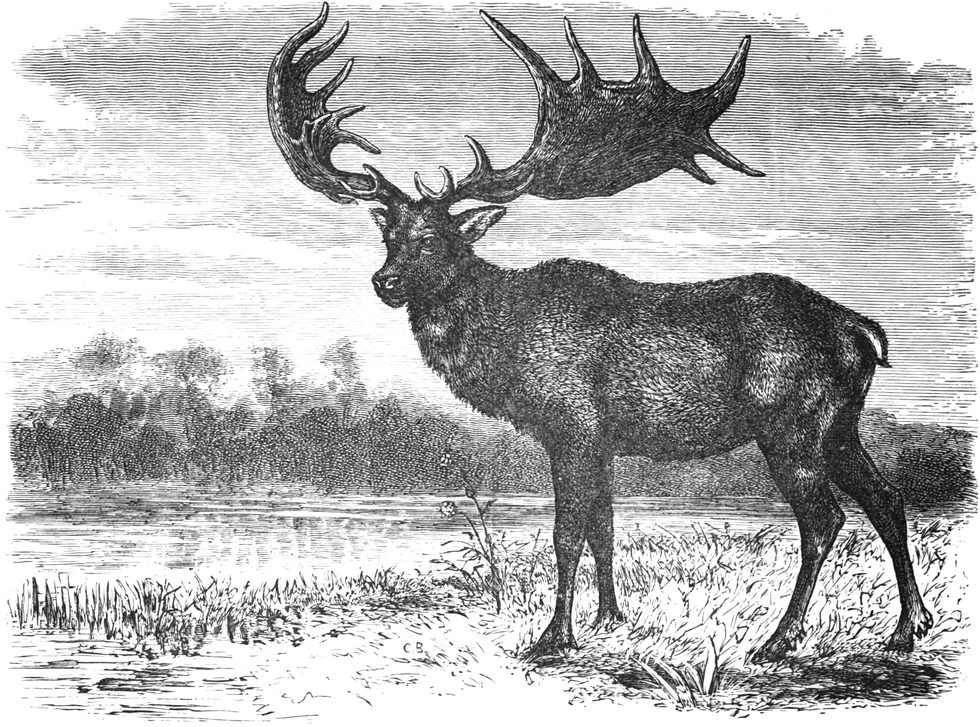

and Complex Antlers—Types of Antlers—THE ELK, OR MOOSE DEER—Appearance—Antlers—Habits—Hunting—THE

ELAPHINE DEER—THE RED DEER—Distribution—Appearance—Hunting—THE WAPITI—Acting of the

Fawns—THE PERSIAN DEER, OR MARAL—THE CASHMERIAN DEER, OR BARASINGHA—Habits and General

[Pg vi]

Appearance—BARBARY DEER—SUB-ELAPHINE DEER—THE JAPANESE, FORMOSAN, AND MANTCHURIAN DEER—THE

FALLOW DEER—Peculiarity of its Antlers—THE PERSIAN FALLOW DEER—THE RUSINE DEER—THE SAMBUR, OR

GEROW—Habits—Species of Java, Formosa, Sumatra, Borneo, Timor, Ternate, and The Philippines—THE HOG

DEER—THE AXIS DEER—PRINCE ALFRED’S DEER—THE SWAMP DEER—SCHOMBURGK’S DEER—ELD’S DEER, OR THE

THAMYN—Description—Habits—Hunting—Shameful havoc

|

46

|

|

CHAPTER V.

|

|

THE MUNTJACS—THE ROEBUCK—CHINESE

DEER—REINDEER—AMERICAN DEER—DEERLETS—CAMEL

TRIBE—LLAMAS.

|

|

THE MUNTJACS—Distribution—Characters—THE INDIAN MUNTJAC, OR KIDANG—Hunting—THE CHINESE

MUNTJAC—Habits—DAVID’S MUNTJAC—“Shanyang”—THE ROEBUCK—THE CHINESE WATER DEER—Peculiarity—Chinese

Superstition regarding it—THE CHINESE ELAPHURE—Peculiarity of its Antlers—THE REINDEER—Distribution—Character—Colouration—Antlers—Canadian

Breeds—Food—THE AMERICAN DEER—THE VIRGINIAN DEER—THE

MULE DEER—THE BLACK-TAILED DEER—THE GUAZUS—THE BROCKETS—THE VENADA, OR PUDU DEER—THE

CHEVROTAINS, OR DEERLETS—Antlerless—Their Position—Bones of their Feet—General Form and

Proportions—Species—THE MEMINNA, OR INDIAN DEERLET—THE JAVAN DEERLET—THE KANCHIL—THE

STANLEYAN DEERLET—THE WATER DEERLET—THE CAMEL TRIBE—Their Feet—Stomach—Its Peculiarity—The

Water Cells—THE (TRUE) CAMEL—Description—The Pads of Hardened Skin—Its Endurance—Its Disposition—Anecdote

of its Revengeful Nature—THE BACTRIAN CAMEL—THE LLAMAS—Description—Habits—Used as

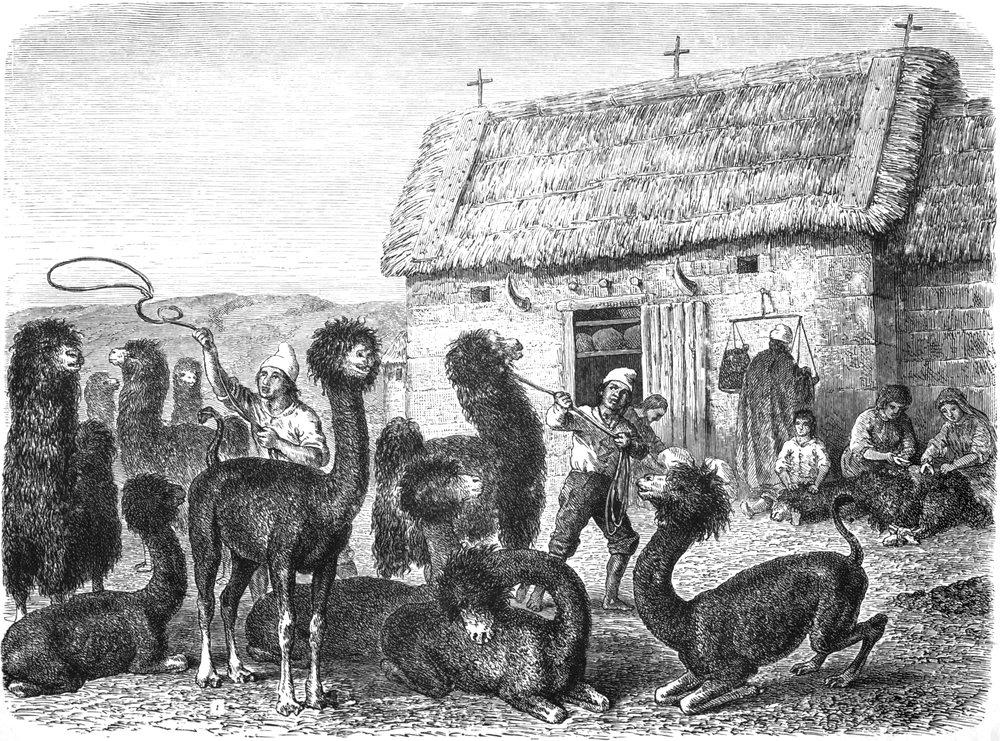

Beasts of Burden—Wild and Domesticated Species—THE HUANACO—THE LLAMA—THE VICUNA—THE ALPACA—The

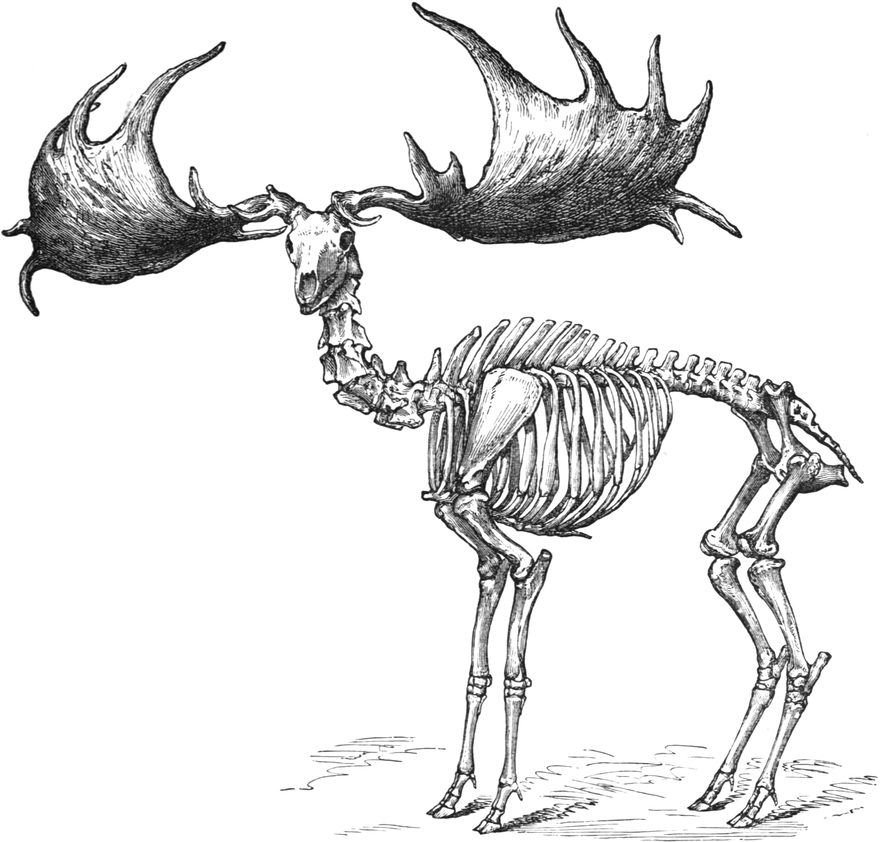

Alpaca Industry—FOSSIL RUMINANTIA—Strata in which they are found—Chœropotamus—Hyopotamus—Dichobune—Xiphodon—Cainotherium—Oreodon—Sivatherium—Fossil

Deer, Oxen, Goats, Sheep, Camels,

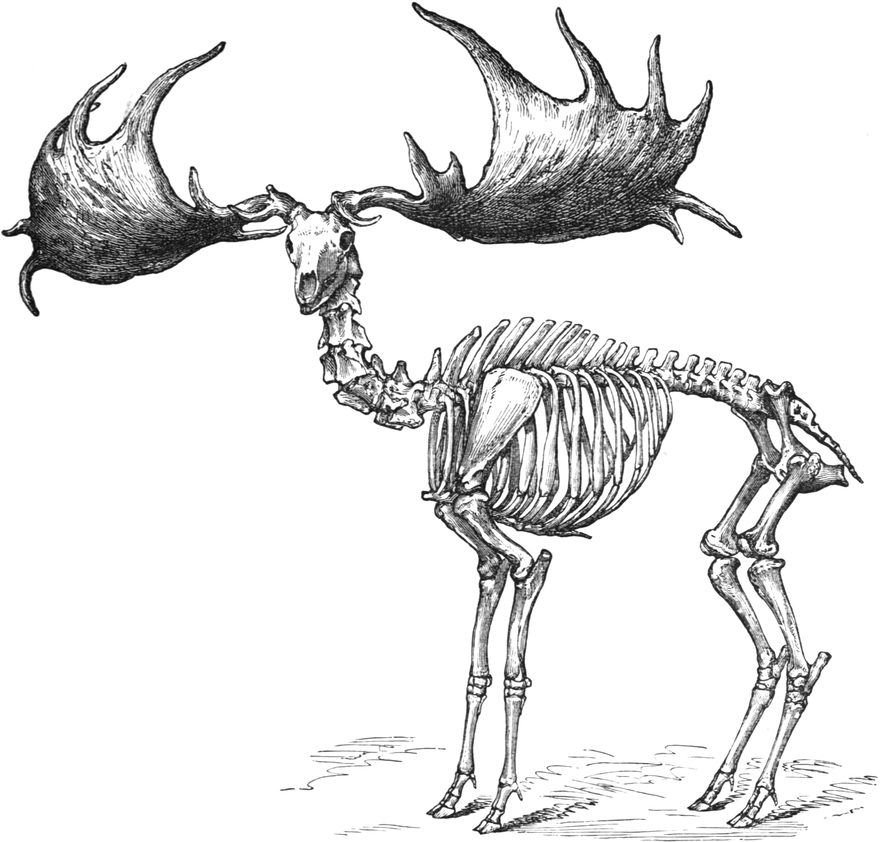

Llamas, Antelopes, Giraffes—The Irish Elk—Its huge Antlers—Its Skeleton—Ally—Distribution

|

61

|

|

ORDER RODENTIA.

|

|

CHAPTER I.

|

|

INTRODUCTION—THE SQUIRREL, MARMOT, ANOMALURE,

HAPLODONT, AND BEAVER FAMILIES.

|

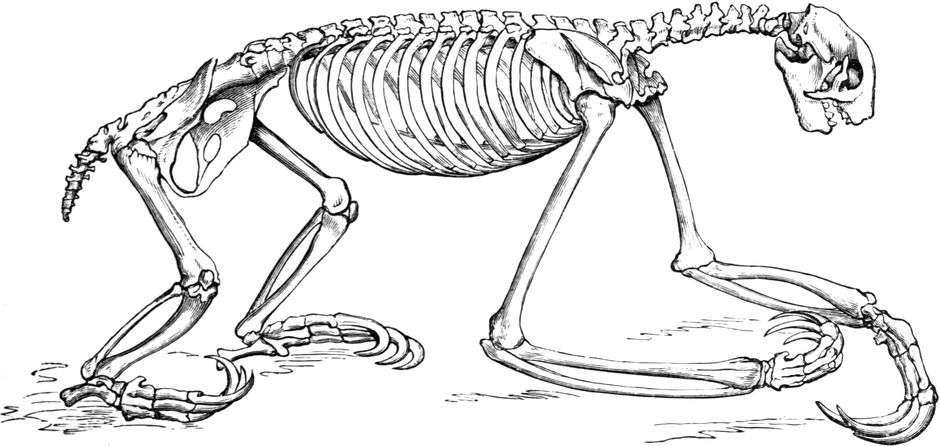

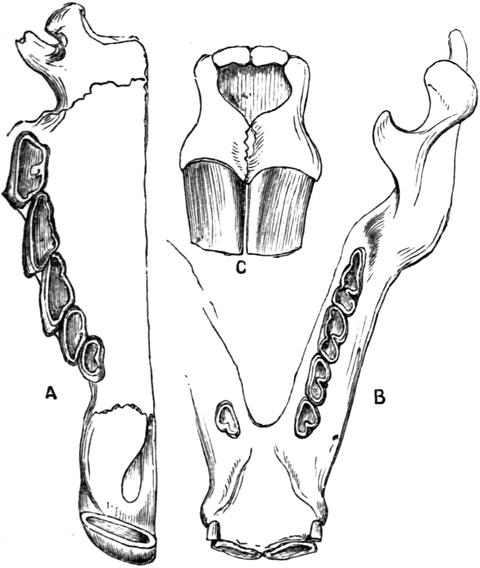

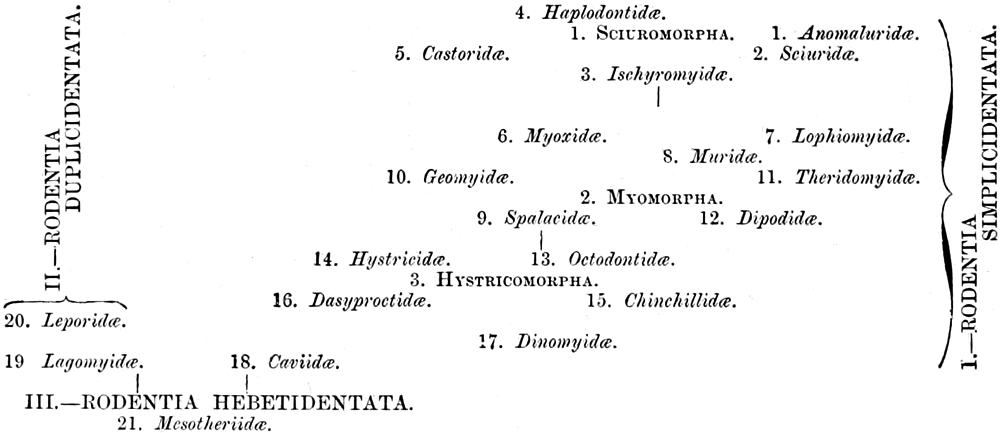

| Character of the Order—A well-defined Group—Teeth Evidence—Kinds and Number of Teeth—The Incisors: their

Growth, Renewal, and Composition—The Molars—The Gnawing Process—Skeleton—Brain—Senses—Body—Insectivora

and Rodentia—Food of Rodents—Classification—THE SIMPLE-TOOTHED RODENTS—Characteristics—THE

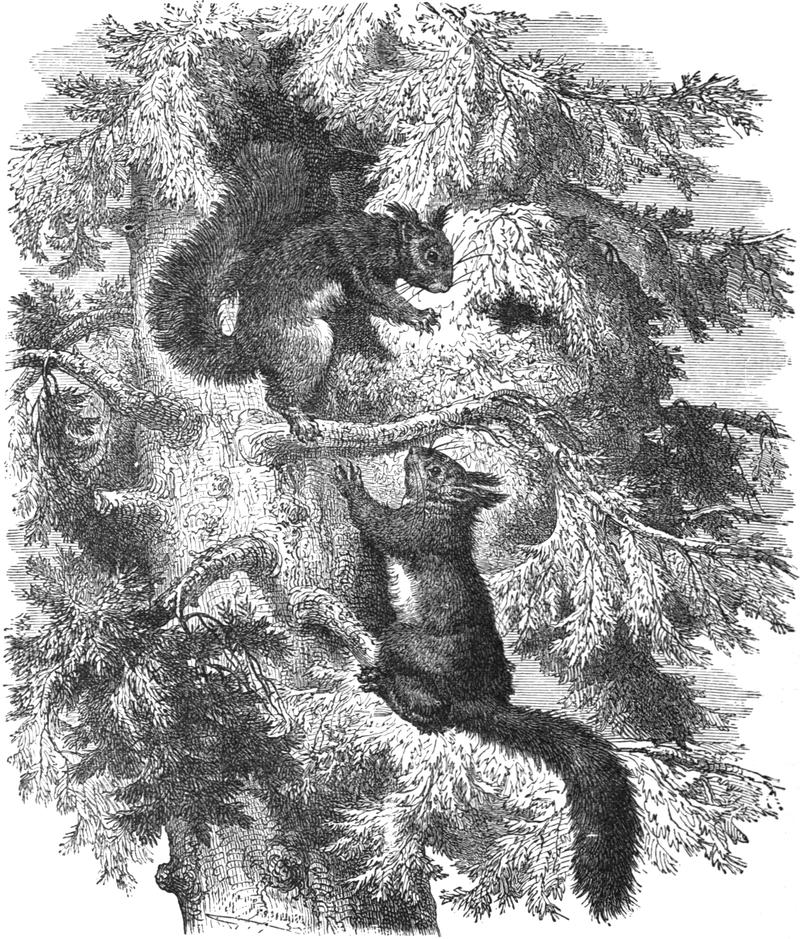

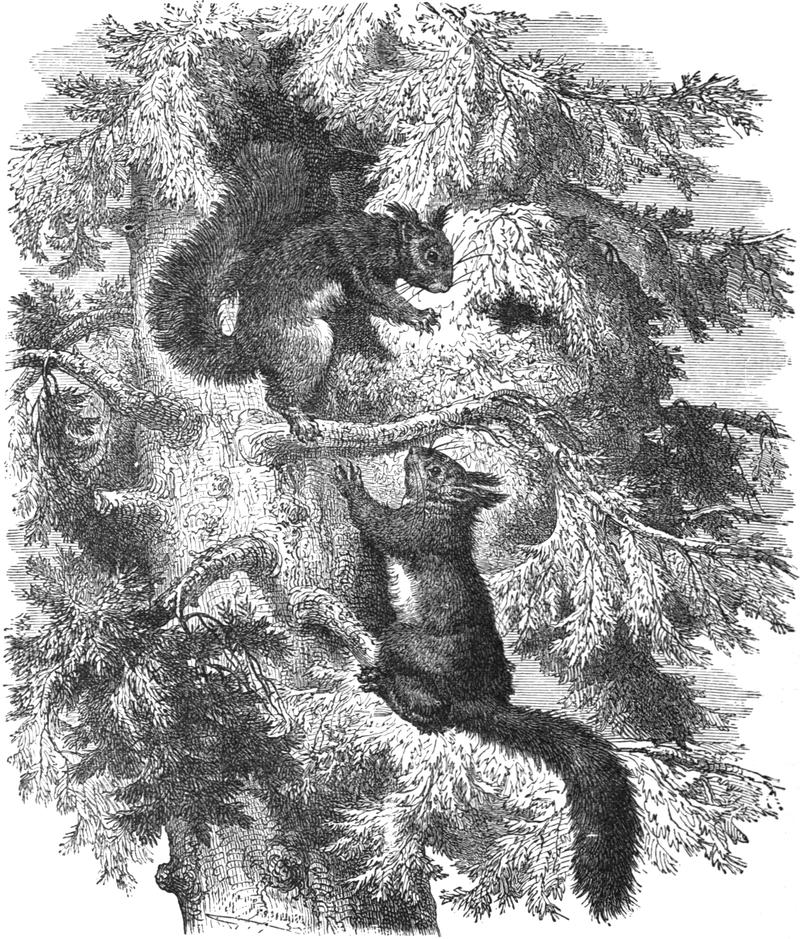

SQUIRREL-LIKE RODENTS—SCIURIDÆ—Distinctive Features—THE COMMON SQUIRREL—Form—Distribution—Food—Bad

Qualities—Habits—THE GREY SQUIRREL—THE FOX SQUIRREL—Flying Squirrels—Their

Parachute Membrane—THE TAGUAN—Appearance—Habits—Other Species—THE POLATOUCHE—THE

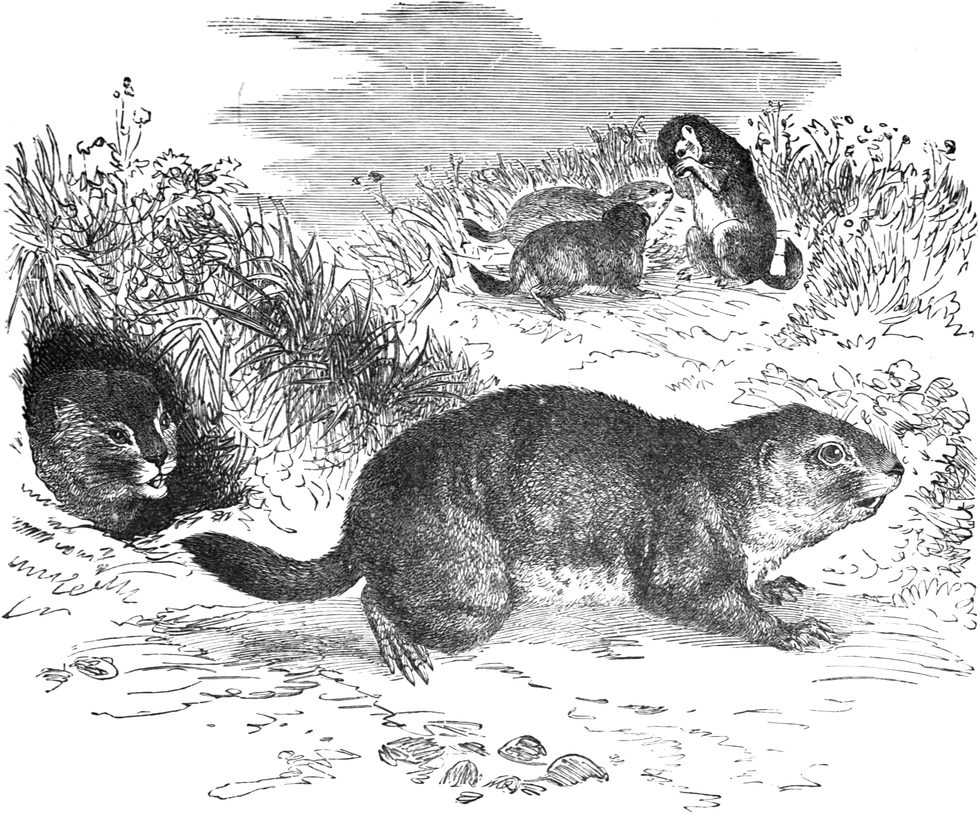

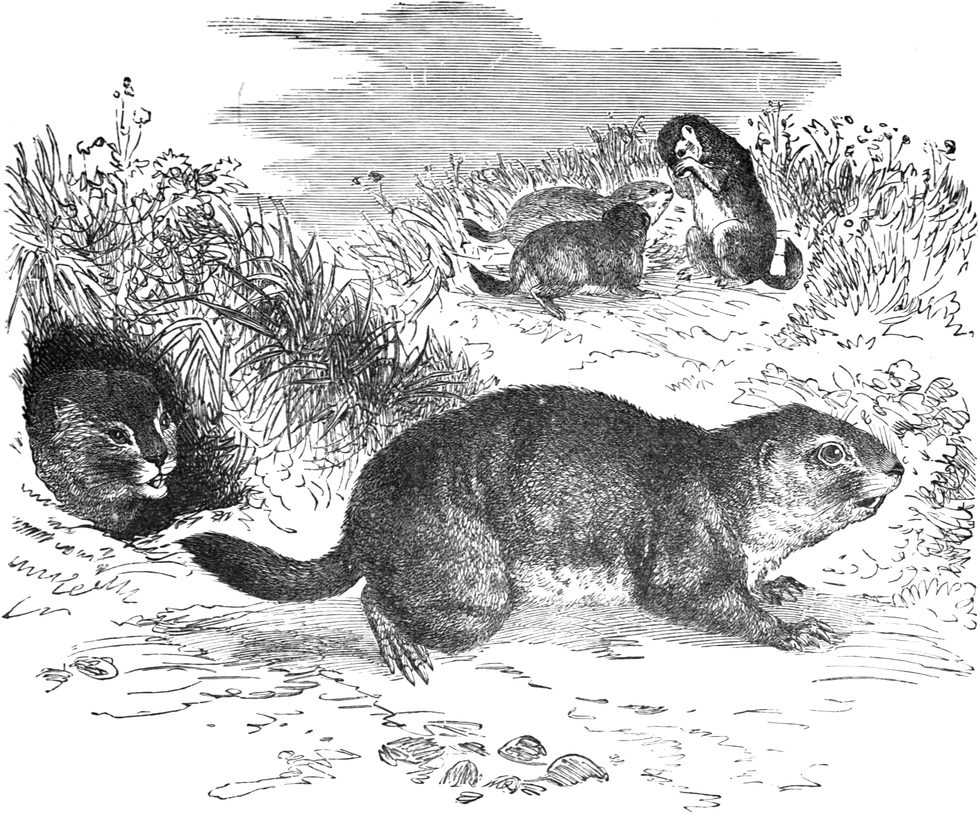

ASSAPAN—The Genus Xerus—THE GROUND SQUIRRELS—THE COMMON CHIPMUNK—THE MARMOTS—Distinguishing

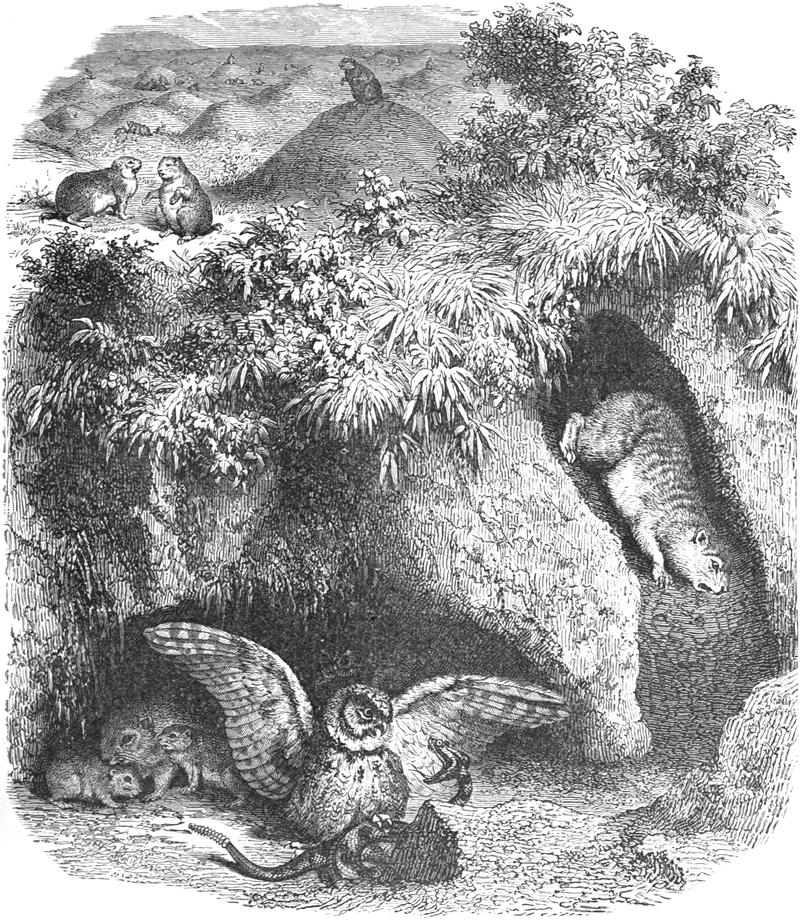

Features—THE SPERMOPHILES—THE GOPHER—THE SISEL, OR SUSLIK—THE BARKING SQUIRRELS—THE PRAIRIE

DOG—Description—Species—Habits—Burrows—Fellow-inmates in their “Villages”—THE TRUE MARMOTS—THE

BOBAC—THE ALPINE MARMOT—THE WOODCHUCK—THE HOARY MARMOT, OR WHISTLER—ANOMALURIDÆ—Tail

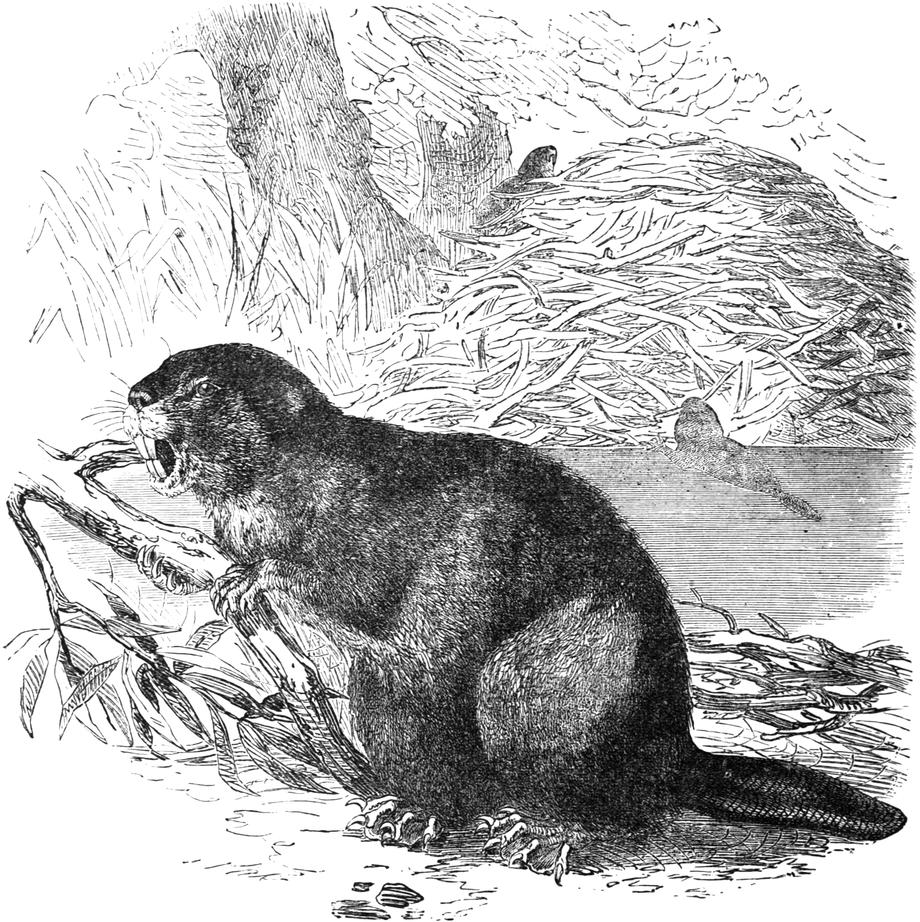

Peculiarity—Distinctive Features—HAPLODONTIDÆ—Description—THE SEWELLEL—CASTORIDÆ—THE

BEAVER—Skeletal Peculiarities—General Form—Appearance—Distribution—The Beavers of the Old and New

World—Habits—Wonderful Sagacity—The Building Instinct—Their Method of Working—The various Stages—Their

Lodges—Their Dams—Activity by Night—Flesh—Hunted—The Castoreum

|

81

|

|

CHAPTER II.

|

|

THE DORMOUSE, LOPHIOMYS, RAT, AND MOUSE FAMILIES.

|

|

THE MOUSE-LIKE RODENTS—MYOXIDÆ—Characteristics—THE DORMOUSE—Description—Habits—Activity—Food—Winter

Condition—THE LOIR—THE GARDEN DORMOUSE—LOPHIOMYIDÆ—How the Family came to be Founded—THE

LOPHIOMYS—Milne-Edwards’ Opinion—Skull—General Form—Habits—MURIDÆ—Number of Species—Characteristics—Variety

of Forms—Distribution—The Murine Sub-Family—THE BROWN RAT—History—Fecundity

and Ferocity—Diet—At the Horse Slaughter-houses of Montfaucon—Shipwrecked on Islands—Story

of their Killing a Man in a Coal-pit—In the Sewers of Paris and London—THE BLACK RAT—THE EGYPTIAN

RAT—THE COMMON MOUSE—Habits—Destructiveness—Colours—THE LONG-TAILED FIELD MOUSE—Description—Food—THE

HARVEST MOUSE—Description—Habits—In Winter—Agility—Their Nest—THE BANDICOOT RAT—THE

TREE RAT—THE STRIPED MOUSE—Allied Genera—THE WHITE-FOOTED HAPALOTE—The American Murines—THE

WHITE-FOOTED, OR DEER MOUSE—THE GOLDEN, OR RED MOUSE—THE RICE-FIELD MOUSE—THE AMERICAN

HARVEST MOUSE—THE FLORIDA RAT—Description—Their Nest—Food—Mother and Young—THE BUSHY-TAILED

WOOD RAT—THE COTTON RAT—THE RABBIT-LIKE REITHRODON—THE HAMSTERS—Characteristics—Appearance—Distribution—Burrows—Disposition—Food—Habits—THE

TREE MICE—THE BLACK-STREAKED TREE MICE—THE

GERBILLES—Characteristics—Habits—Other Genera—THE WATER MICE—Characteristics—Species—THE

SMINTHUS—THE VOLES—Characteristics—THE WATER VOLE—Appearance—Distribution—Food—THE FIELD

VOLE—THE BANK VOLE—THE SOUTHERN FIELD VOLE—THE SNOW MOUSE—THE ROOT VOLE—THE MEADOW

MOUSE—THE PINE MOUSE—THE MUSQUASH, MUSK RAT, OR ONDATRA—Distinguishing Features—Habits—His

House—THE LEMMING—Description—Food—Habits—Disposition—Their Extraordinary Migrations—Other

Lemmings—THE ZOKOR

|

101

|

|

[Pg vii]

CHAPTER III.

|

|

MOLE RATS, POUCHED RATS, POUCHED MICE, JERBOAS, AND OCTODONTIDÆ.

|

|

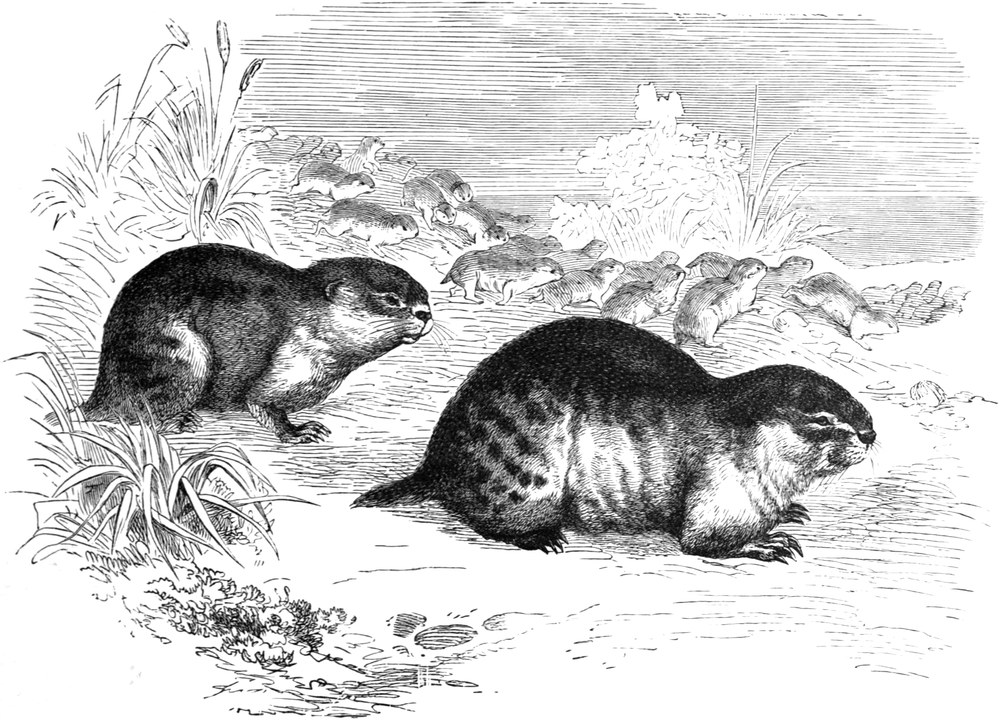

SPALACIDÆ, OR MOLE RATS—Characteristics of the Family—Habits—Food—THE MOLE RAT—Distribution—Description—THE

CHESTNUT MOLE RAT—THE NAKED MOLE RAT—THE STRAND MOLE RAT—Description—Habits—THE

CAPE MOLE RAT—GEOMYIDÆ, OR POUCHED RATS—Characteristics of the Family—The

Cheek-pouches—THE COMMON POCKET GOPHER—Distribution—Description—Burrowing—Runs—Subterranean

Dwelling—THE NORTHERN POCKET GOPHER—HETEROMYINÆ, OR POUCHED MICE—Difficulties as to Position—Characteristics—PHILLIPS’

POCKET MOUSE—Where Found—Description—THE YELLOW POCKET MOUSE—THE

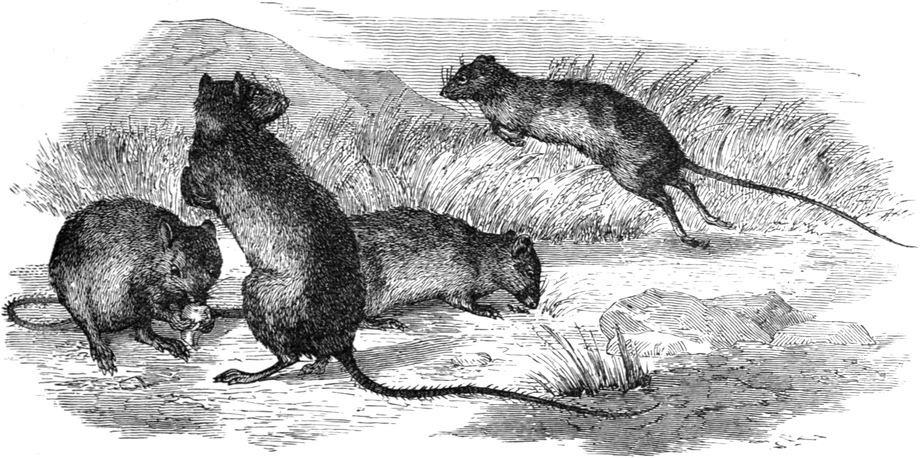

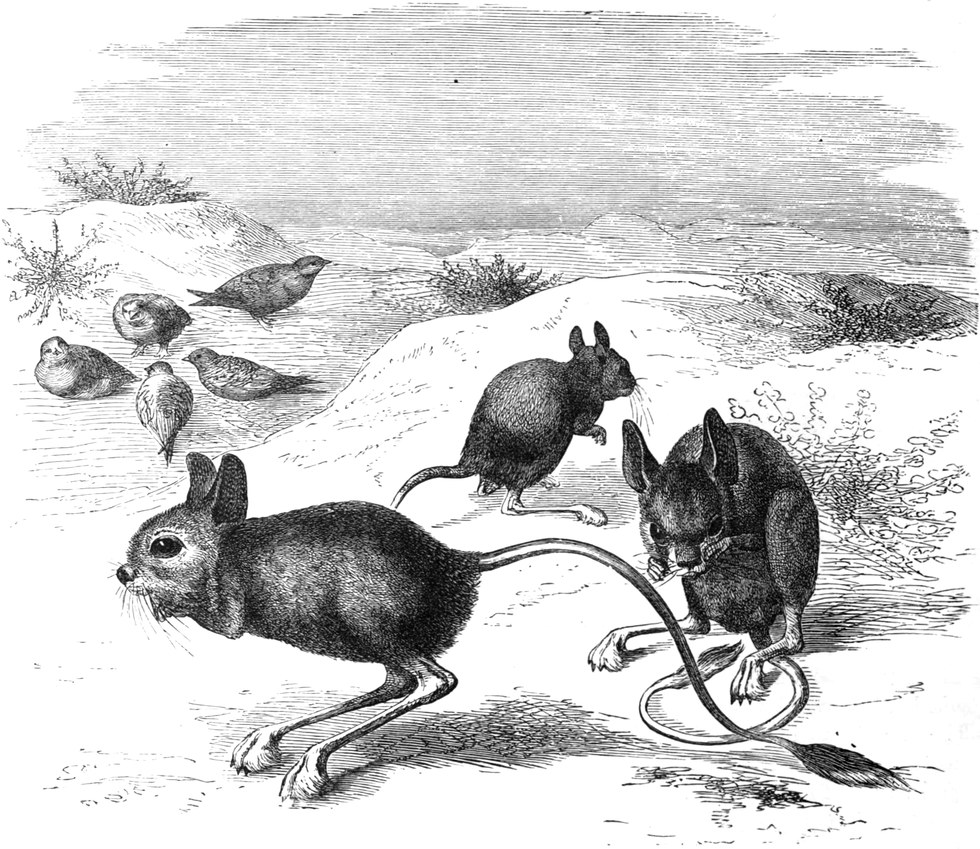

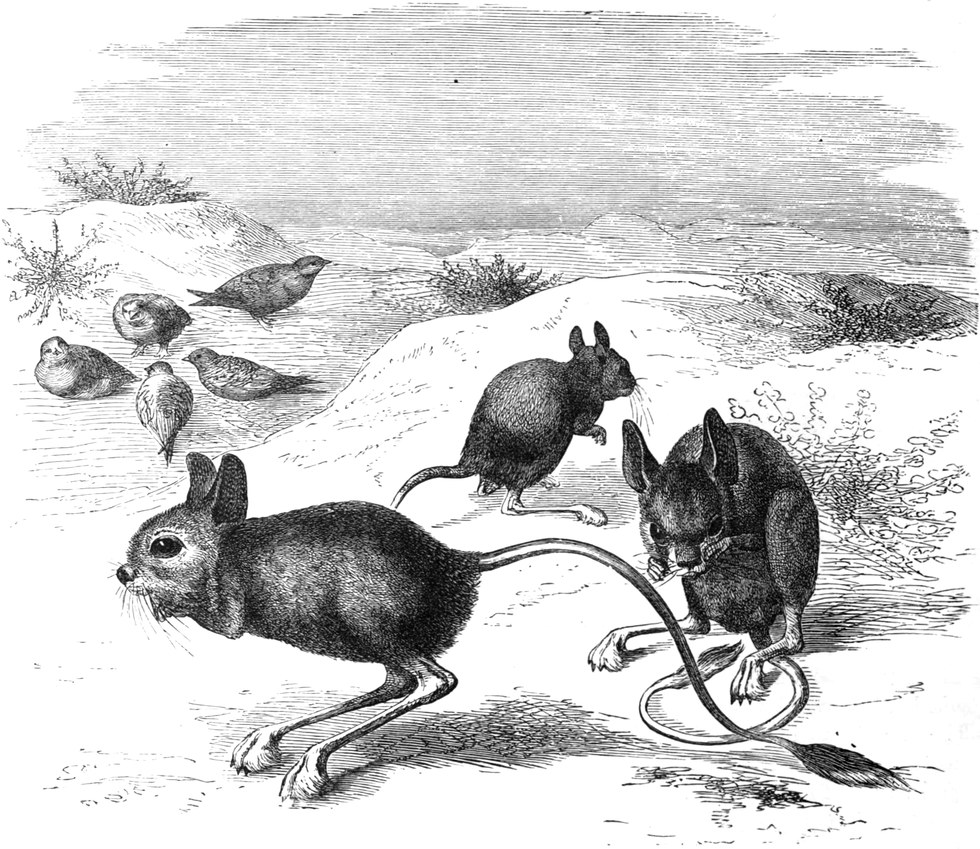

LEAST POCKET MOUSE—DIPODIDÆ, OR JERBOAS—Organisation for Jumping—Characteristics—Distribution—THE

AMERICAN JUMPING MOUSE—Description—Characters peculiar to itself—Habits—THE TRUE JERBOAS—Characters—THE

JERBOA—Distribution—Habits—Mode of Locomotion—THE ALACTAGA—THE CAPE JUMPING

HARE—THE PORCUPINE-LIKE RODENTS—OCTODONTIDÆ—Characteristics—Sub-Family CTENODACTYLINÆ—THE

GUNDI—THE DEGU—Description—Habits—THE BROWN SCHIZODON—THE TUKOTUKO—THE CURURO—THE

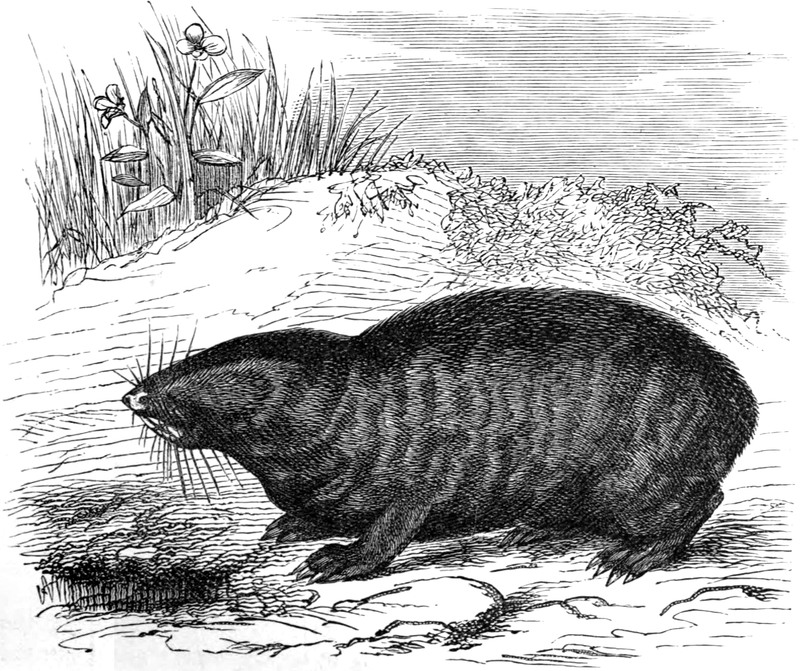

ROCK RAT—Sub-Family, ECHINOMYINÆ—THE COYPU—One of the Largest Rodents—Description—Burrows—Habits—Mother

and Young—THE HUTIA CONGA—THE HUTIA CARABALI—THE GROUND RAT

|

120

|

|

CHAPTER IV.

|

|

PORCUPINES—CHINCHILLAS—AGOUTIS—CAVIES—HARES

AND RABBITS—PIKAS.

|

|

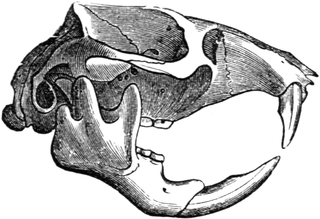

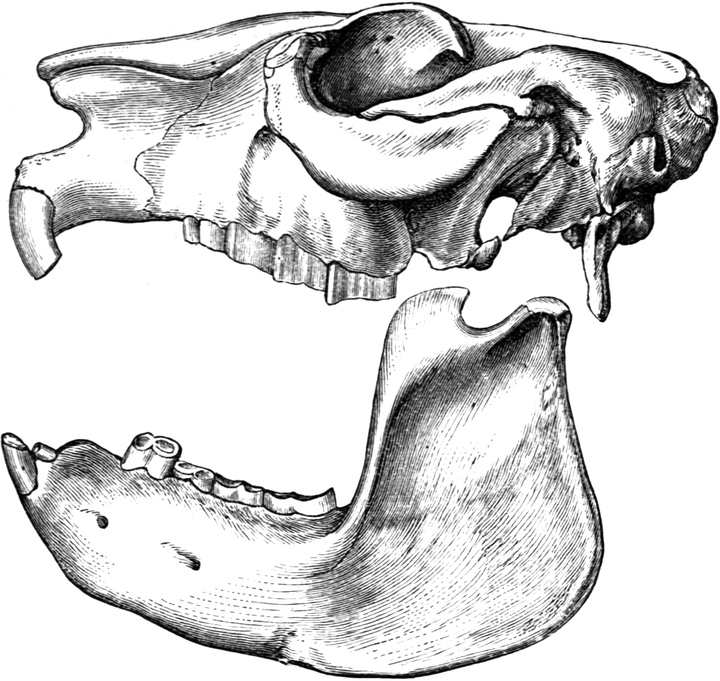

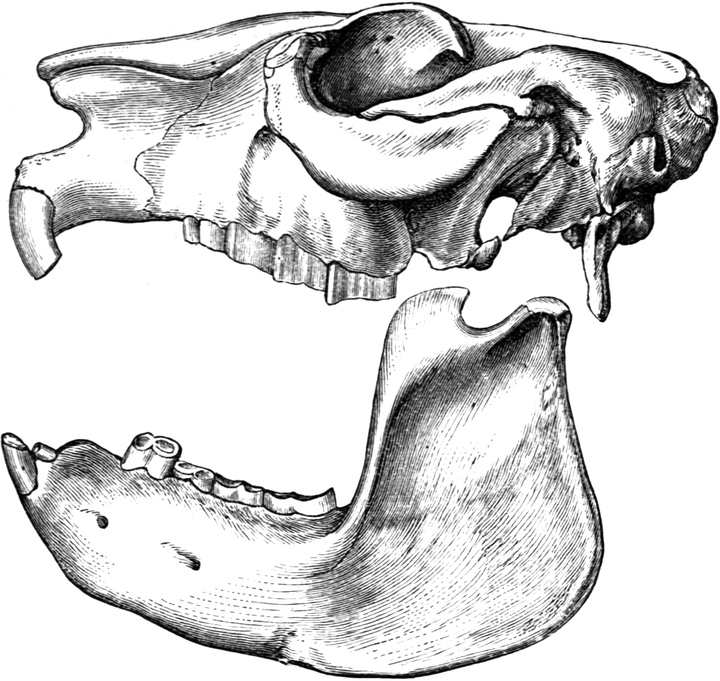

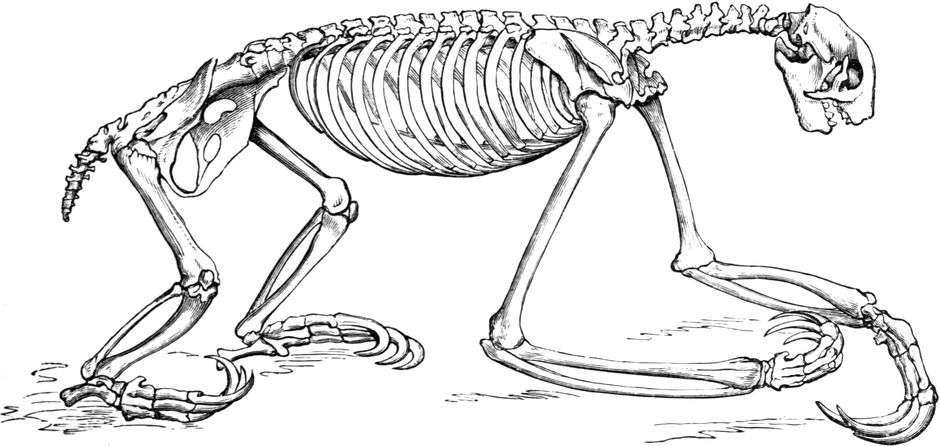

HYSTRICIDÆ, THE PORCUPINES—Conversion of Hairs into Spines—Skull—Dentition—Tail—Sub-families—The True

Porcupines—The Tree Porcupines—THE COMMON PORCUPINE—Distribution—Description—The Crest of Bristles—Nature

of the Spines—Habits—Young—Flesh—On the Defensive—Other Species—Species of Tree Porcupines—THE

COUENDOU—THE COUIY—Description—Habits—THE URSON, OR CANADA PORCUPINE—Description—Habits—Food—CHINCHILLIDÆ,

THE CHINCHILLAS—Characteristics—THE VISCACHA—Description—Life on the

Pampas—Their Burrows—Habits—The Chinchillas of the Andes—THE CHINCHILLA—THE SHORT-TAILED CHINCHILLA—CUVIER’S

CHINCHILLA—THE PALE-FOOTED CHINCHILLA—DASYPROCTIDÆ, THE AGOUTIS—Characters—THE

AGOUTI—Distribution—Appearance—Habits—AZARA’S AGOUTI—THE ACOUCHY—THE PACA—Appearance—Distribution—Habits—DINOMYIDÆ—Founded

for a Single Species—Description—Rarity—CAVIIDÆ, THE

CAVIES—Characteristics—THE RESTLESS CAVY—Appearance—Habits—The Guinea-Pig Controversy—THE

BOLIVIAN CAVY—THE ROCK CAVY—THE SOUTHERN CAVY—THE PATAGONIAN CAVY, OR MARA—Peculiar Features—Its

Burrows—Mode of Running—THE CAPYBARA—Its Teeth—Where Found—Habits—THE DOUBLE-TOOTHED

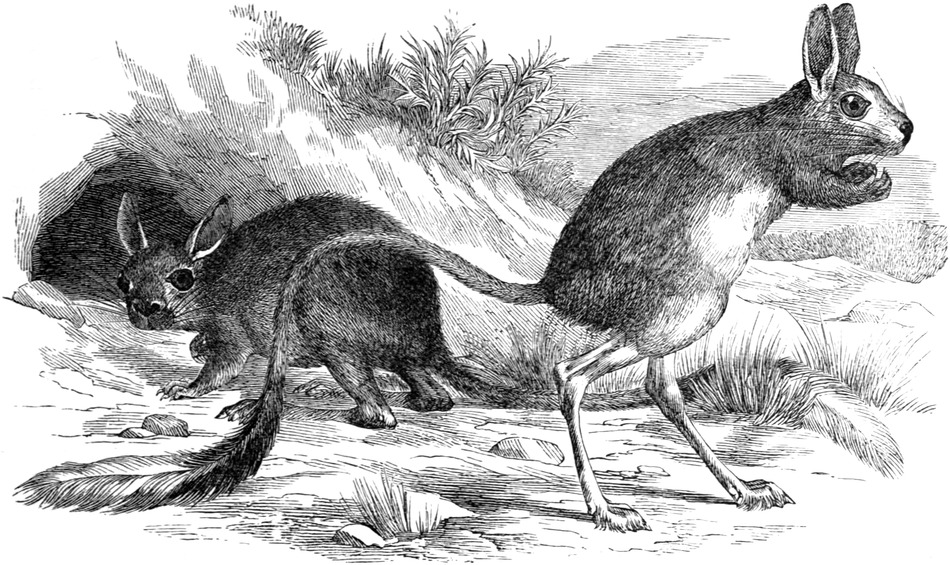

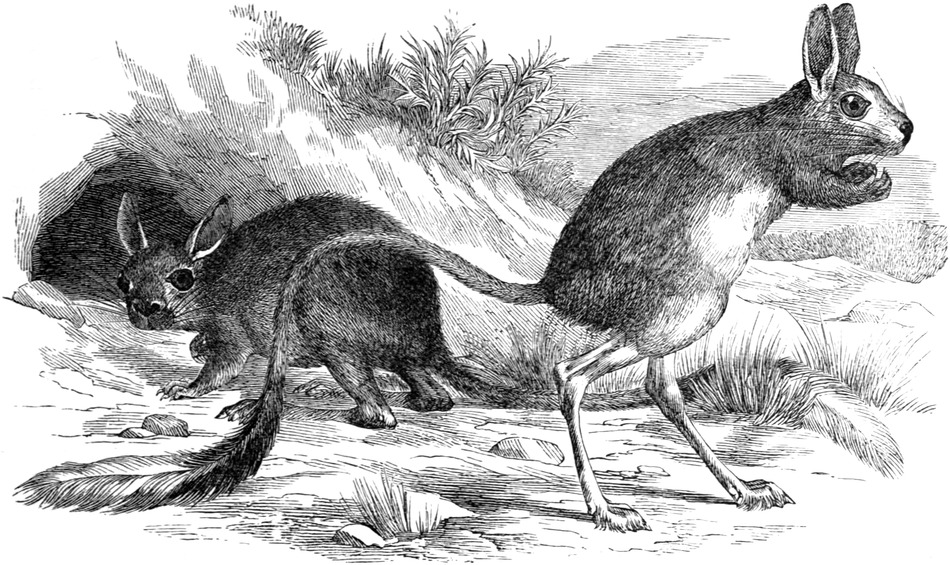

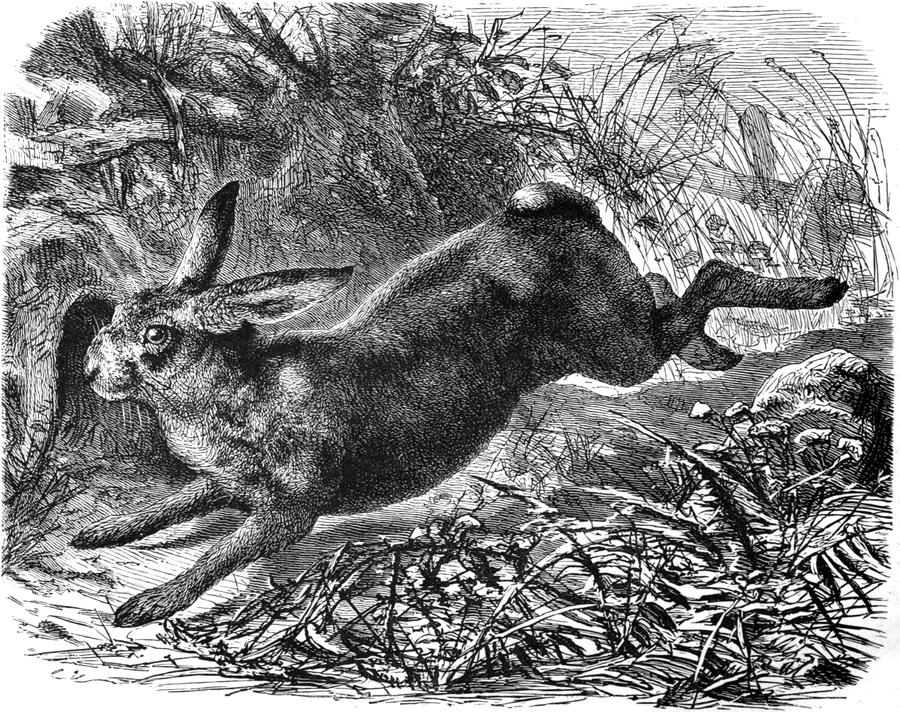

RODENTS—Characteristics—LEPORIDÆ, THE HARES AND RABBITS—Structural Peculiarities—Distribution—Disposition—THE

COMMON HARE—Hind Legs—Speed—Its “Doubles”—Other Artifices—Its

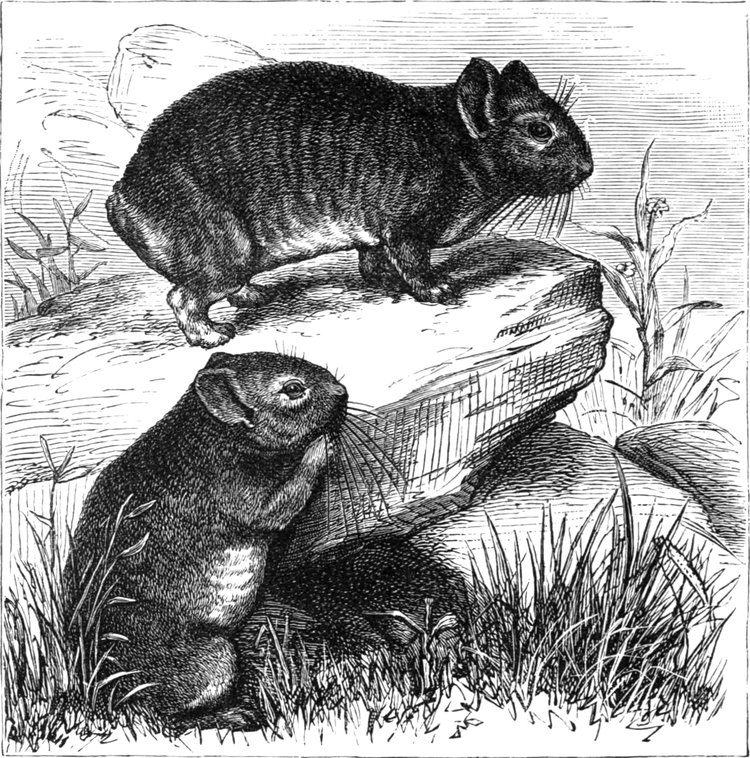

“Form”—Habits—Food—Pet Hares—THE RABBIT—Distribution—Habits—Domesticated—THE MOUNTAIN HARE—LAGOMYIDÆ,

THE PIKAS—Characteristics—Distribution—THE ALPINE PIKA—THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN PIKA

|

133

|

|

CHAPTER V.

|

|

FOSSIL RODENTIA.

|

|

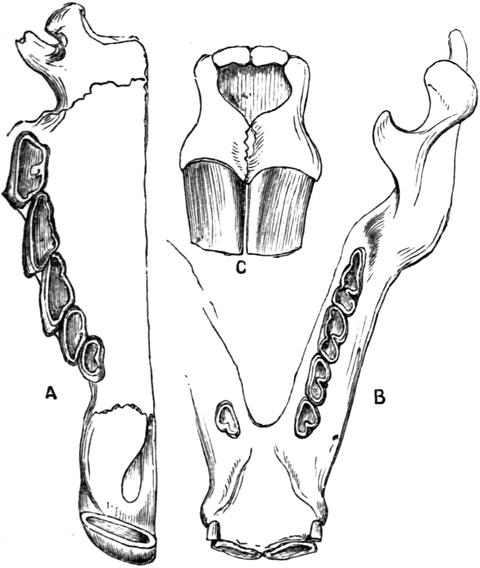

Families of Rodents represented by Fossil Remains—State of the “Record of the Rocks”—THE SCIURIDÆ—Sciurine

Genera now Extinct—No Fossil ANOMALURIDÆ and HAPLODONTIDÆ—ISCHYROMYIDÆ—Pseudotomus hians—Gymnoptychus—CASTORIDÆ—Mr.

Allen’s CASTOROIDIDÆ—THE MYOXIDÆ—No Fossil LOPHIOMYIDÆ—THE

MURIDÆ—THE SPALACIDÆ—THE GEOMYIDÆ—THE DIPODIDÆ—THE THERIDOMYIDÆ—THE OCTODONTIDÆ—THE

HYSTRICIDÆ—THE CHINCHILLIDÆ—THE DASYPROCTIDÆ—THE CAVIIDÆ—THE LEPORIDÆ—THE LAGOMYIDÆ—Mesotherium

cristatum—Difficulties concerning it—Mr. Alston’s Suggestion—THE HEBETIDENTATA—Teeth—Skull—Skeleton—Conclusions

regarding it—Table of Rodent Families—Concluding Remarks

|

151

|

|

ORDER EDENTATA, OR BRUTA (ANIMALS WITHOUT FRONT TEETH).

|

|

CHAPTER I.

|

|

SLOTHS.

|

|

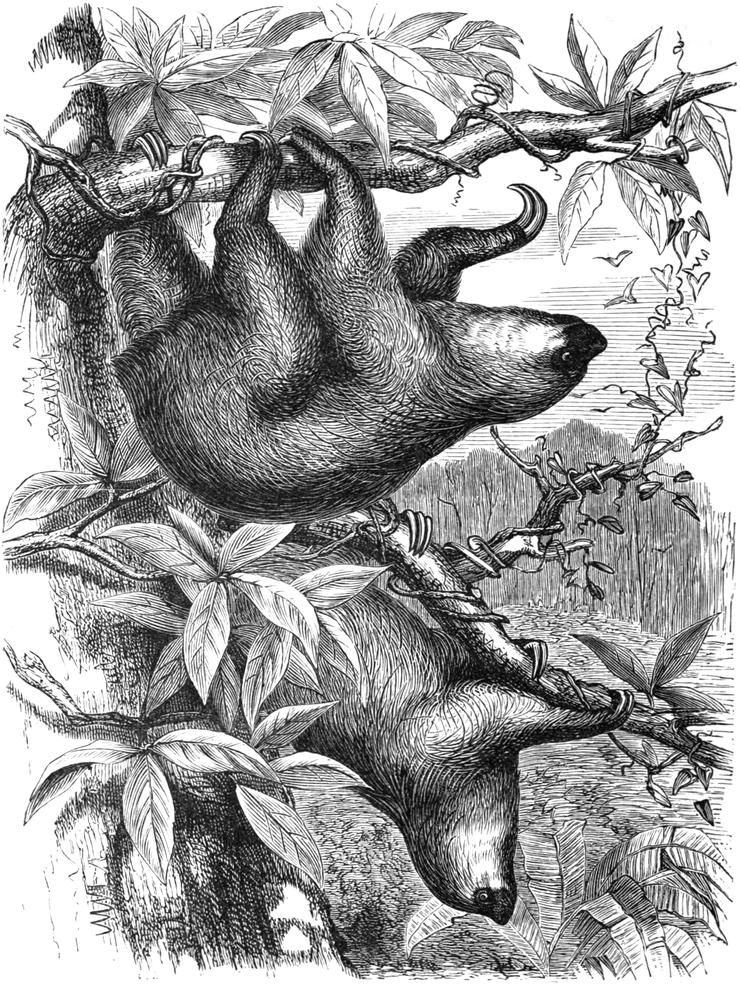

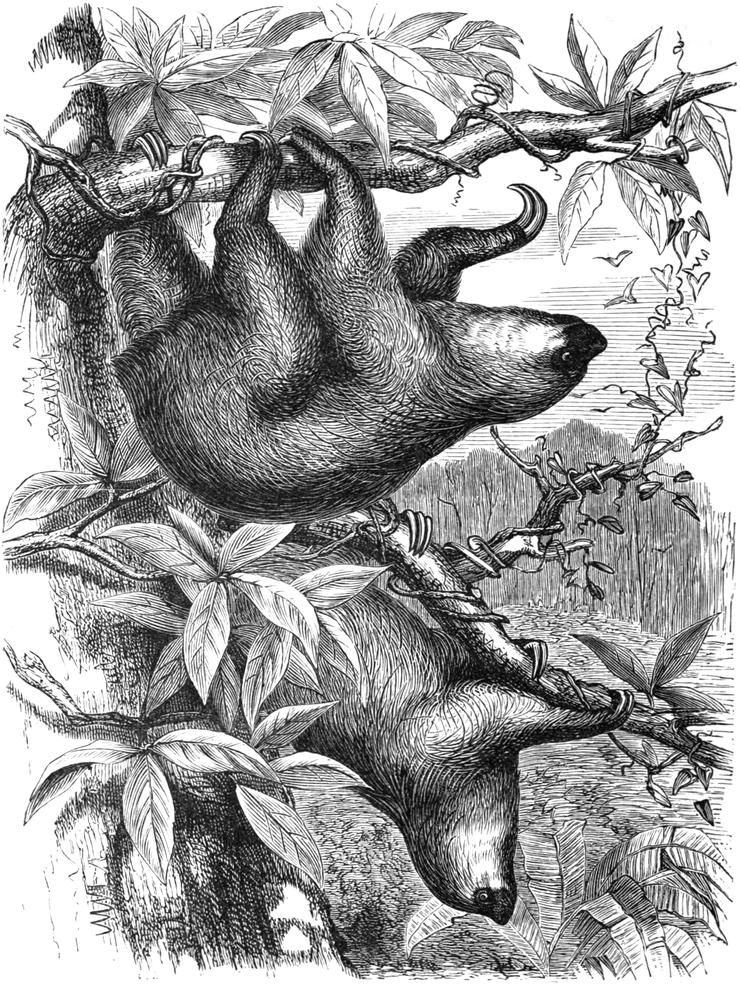

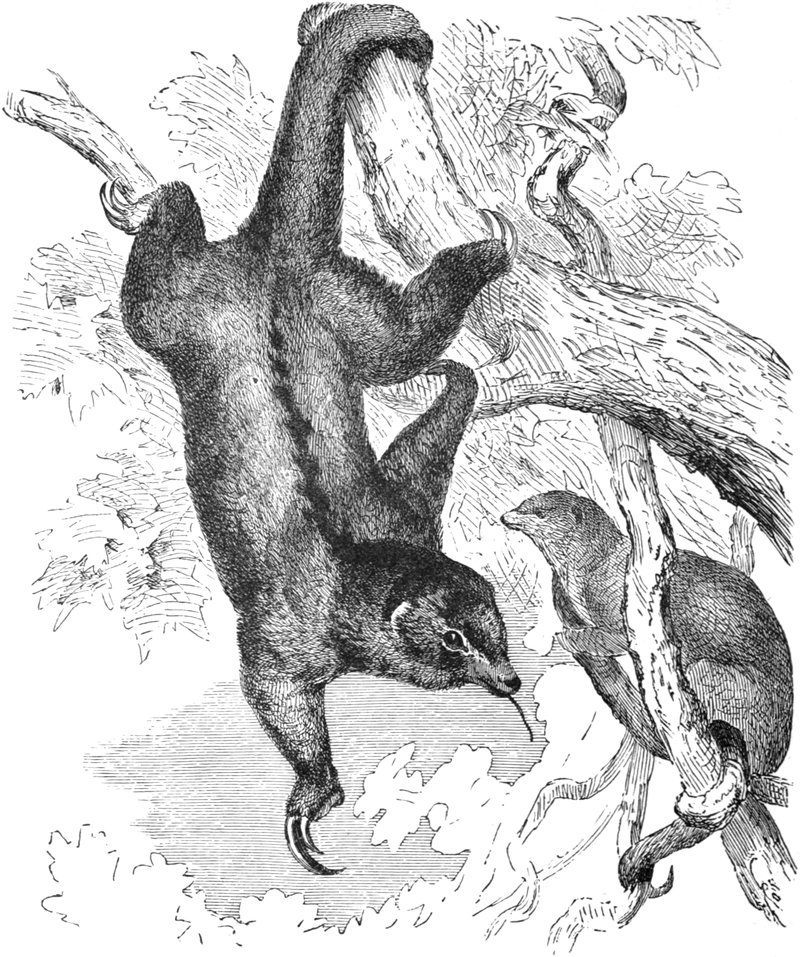

The South American Forests—Discovery of the Sloth—How it derived its Name—Peculiarities of Dentition—Food—Fore

Limbs and Fingers—Hind Limbs and Heel—Other Modifications of Structure—Kinds of Sloth—Waterton’s

Captive Sloth—Habits of the Animal—Burchell’s Tame Sloths—Manner of Climbing Trees—Disposition—Activity

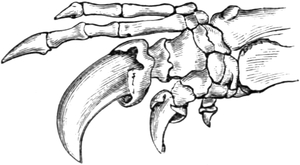

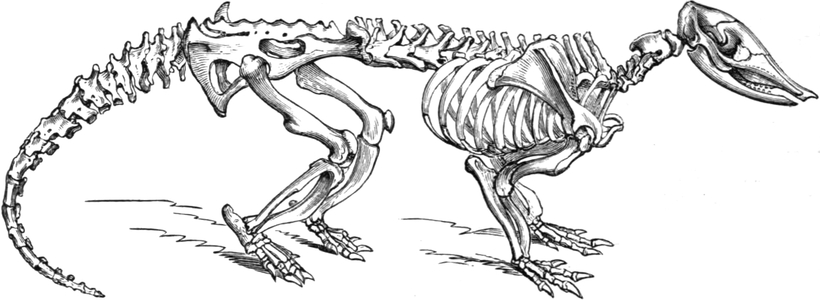

among Trees—Naturalists’ Debate about Anatomy—Probable Conclusion regarding it—Skeleton—Vertebræ—the

Rudimentary Tail—Most Distinctive Skeletal Characters—Arm, Wrist, Hand, Fingers, Claws—Mode of

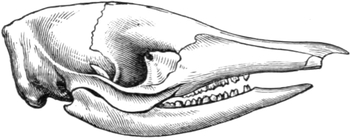

Walking—Great Utility of the Claws—Face of Sloth—Skull—Teeth—Classification—TARDIGRADA—BRADIPODIDÆ—Genus

BRADYPUS—Characteristics—Genus ARCTOPITHECUS—Characteristics—CHOLŒPODIDÆ—THE

COLLARED SLOTH—Description—Skull Bones—Habits—Circulation of the Blood—Rete Mirabile—THE AI—THE

UNAU—Appearance—Skull and Teeth—Skeleton—Interesting Anatomical Features—Stomach—HOFFMANN’S

SLOTH—Description—Habits

|

158

|

|

CHAPTER II.

|

|

THE ANT-EATERS.

|

|

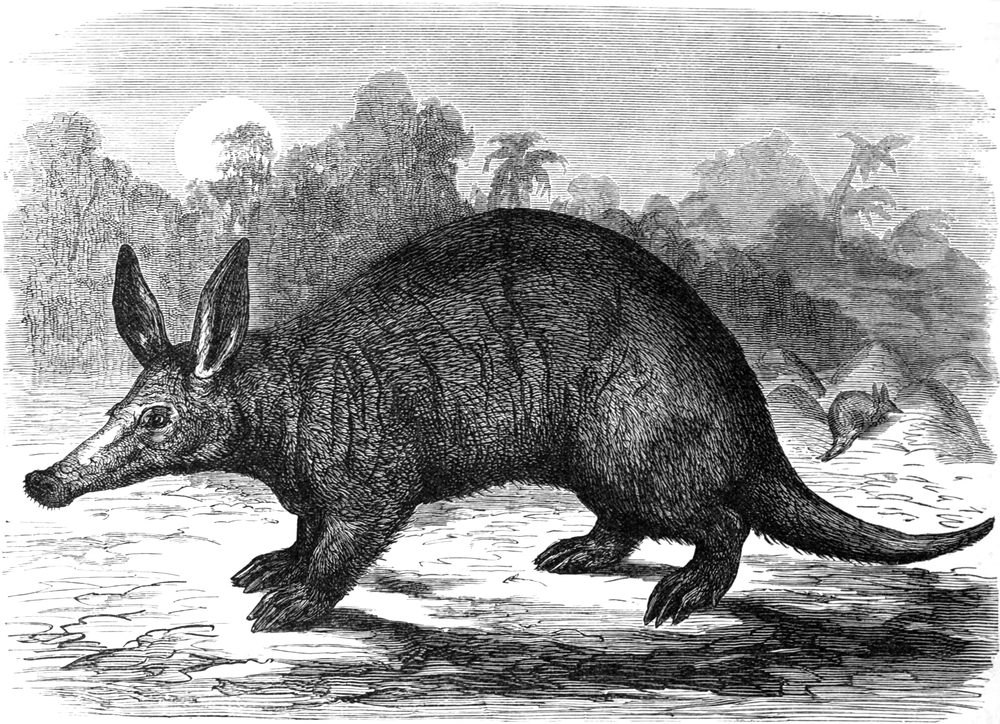

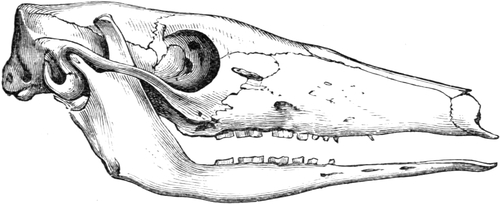

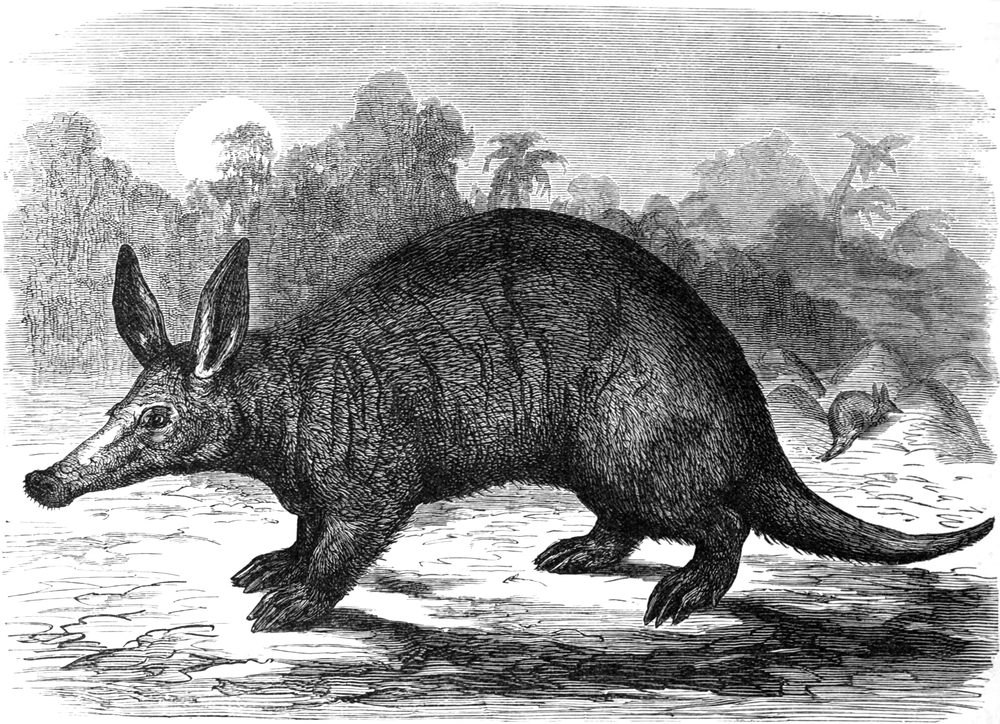

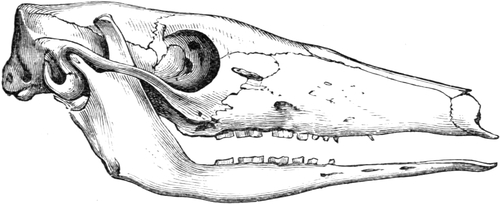

THE CAPE ANT-EATER—The Cage at “the Zoo”—Appearance of the Animal—Its Prey—The Ant-hills-How the

Orycteropus obtains its Food—Place in the Order—Teeth—Skull—Tongue—Interesting Questions concerning

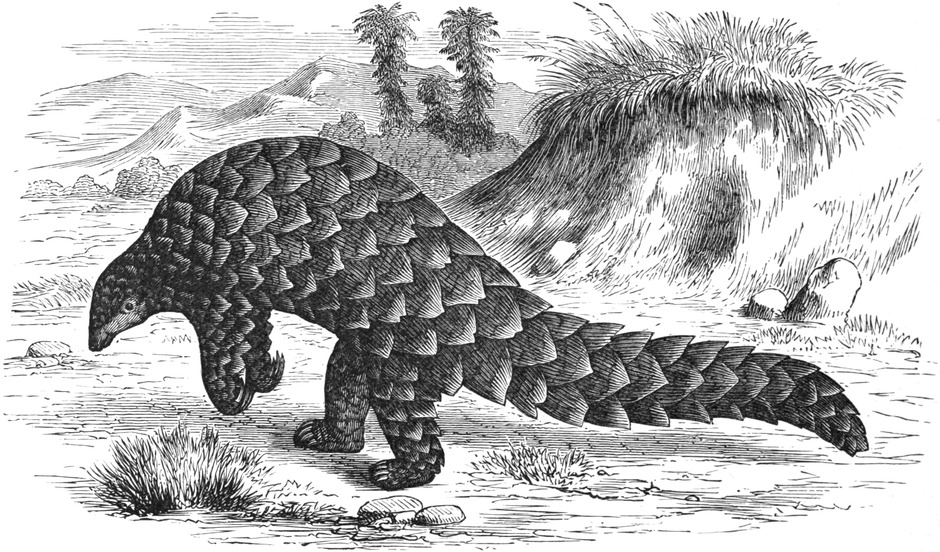

the Ant-eater—THE PANGOLINS, OR SCALY ANT-EATERS—THE AFRICAN SCALY ANT-EATERS—Differences between

[Pg viii]

the Pangolins and Cape Ant-eaters—Their Habitat—Description—TEMMINCK’S PANGOLIN—Habits—Food—How

it Feeds—Superstitious Regard for it shown by the Natives—Scarcity—Appearance—THE LONG-TAILED, OR FOUR-FINGERED

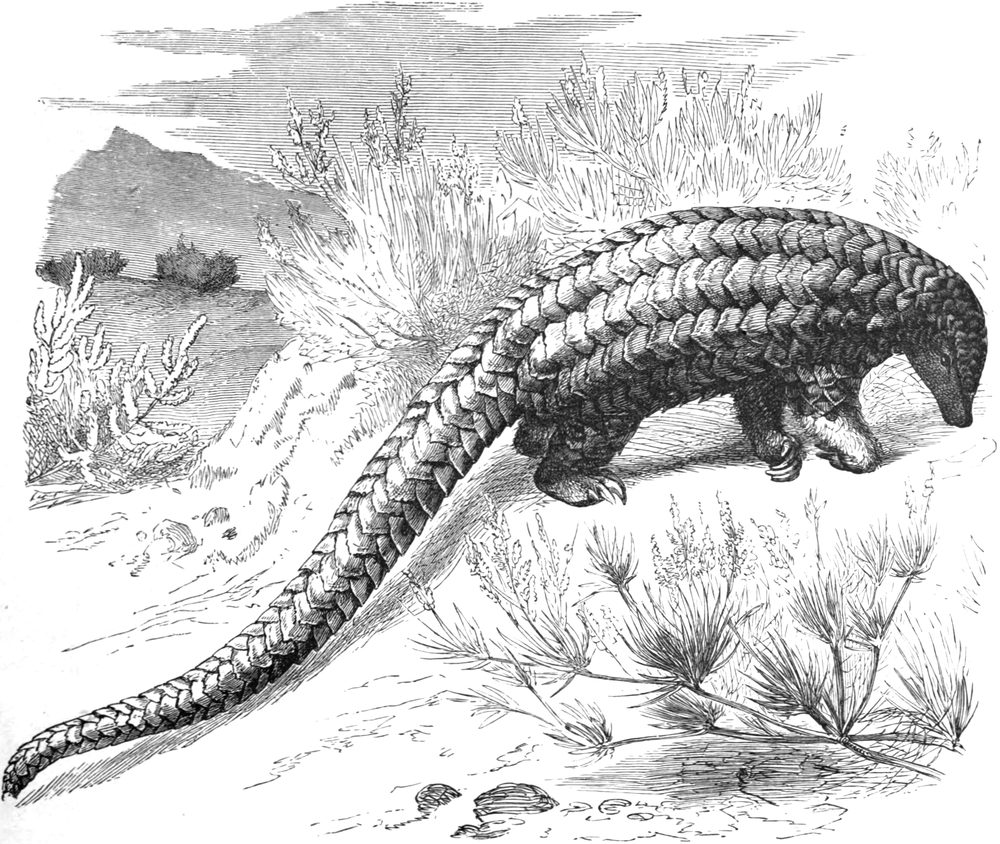

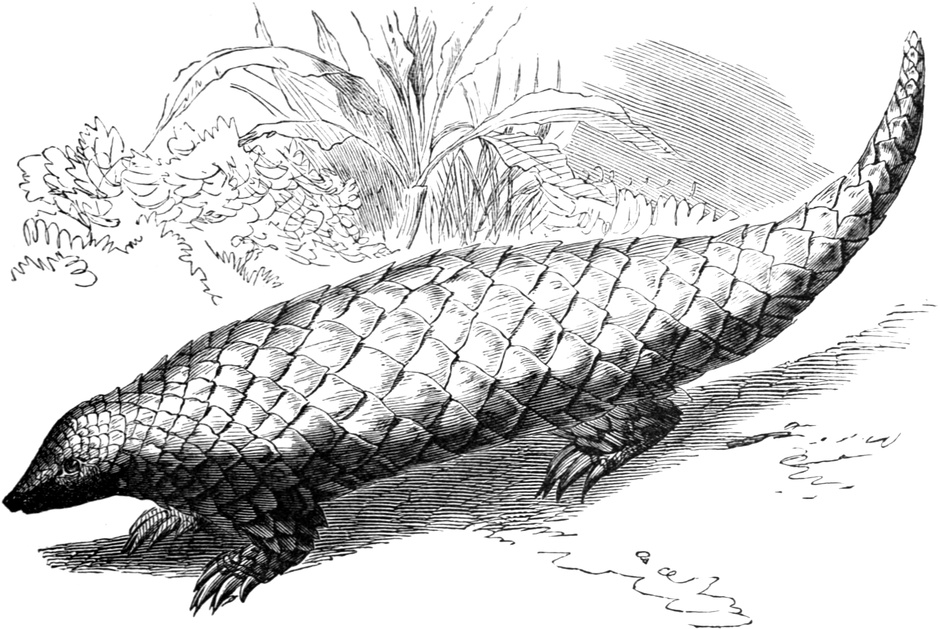

PANGOLIN—THE GREAT MANIS—THE ASIATIC SCALY ANT-EATERS—THE SHORT-TAILED, OR FIVE-FINGERED

PANGOLIN—The Species of Manis—Skull—Stomach—Claws fitted for Digging—Other Skeletal

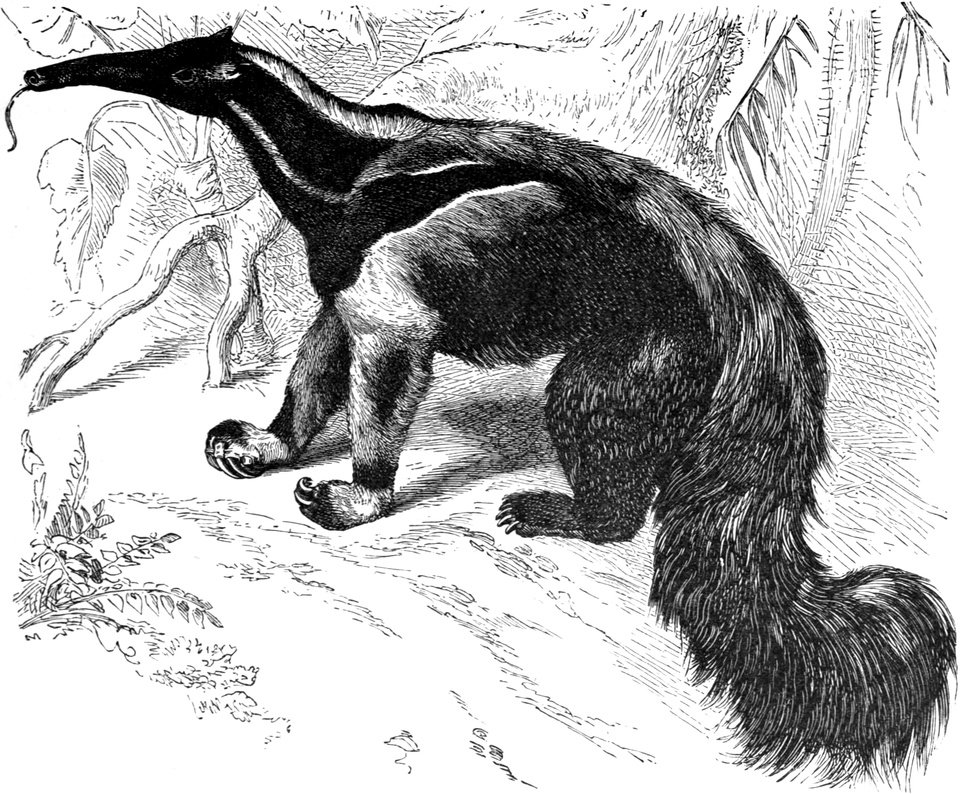

Peculiarities—THE AMERICAN ANT-EATERS—General Appearance—Genera—THE GREAT ANT-BEAR—Habits—Diet—How

it Procures its Food—Distribution—Mode and Rate of Locomotion—Stupidity—Manner of Assault and

Defence—Stories of its Contests with other Animals—Appearance—THE TAMANDUA—Description—Where Found—Habits—Odour—THE

TWO-TOED ANT-EATER—Appearance—Two-clawed Hand—Habits—Von Sach’s Account of

his Specimen

|

169

|

|

CHAPTER III.

|

|

THE ARMADILLO FAMILY.

|

|

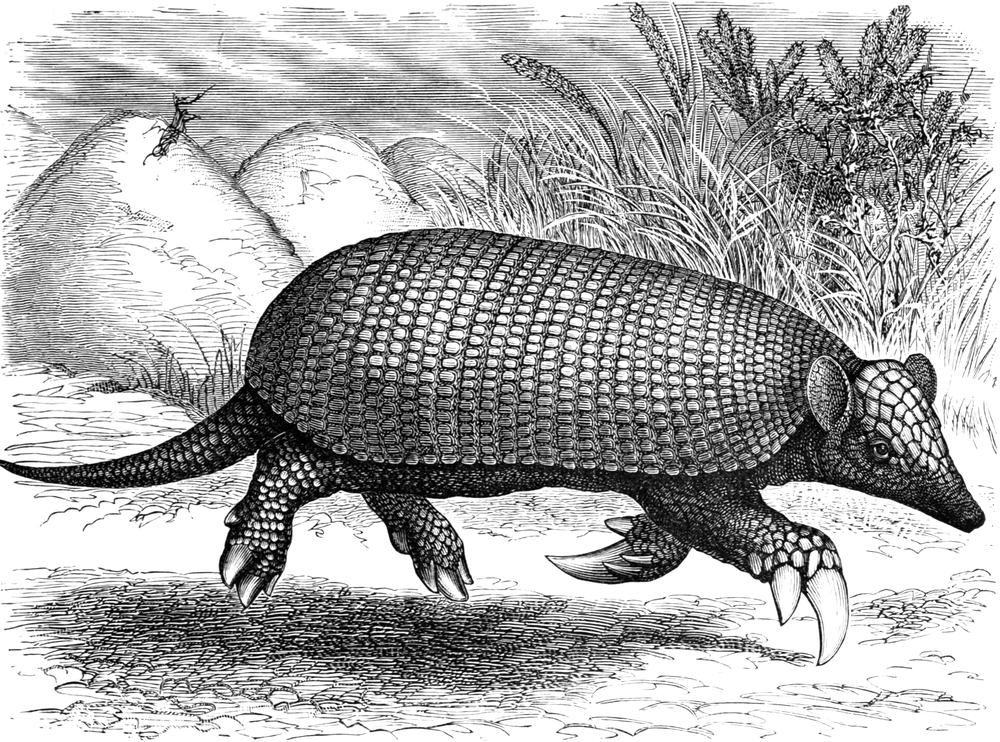

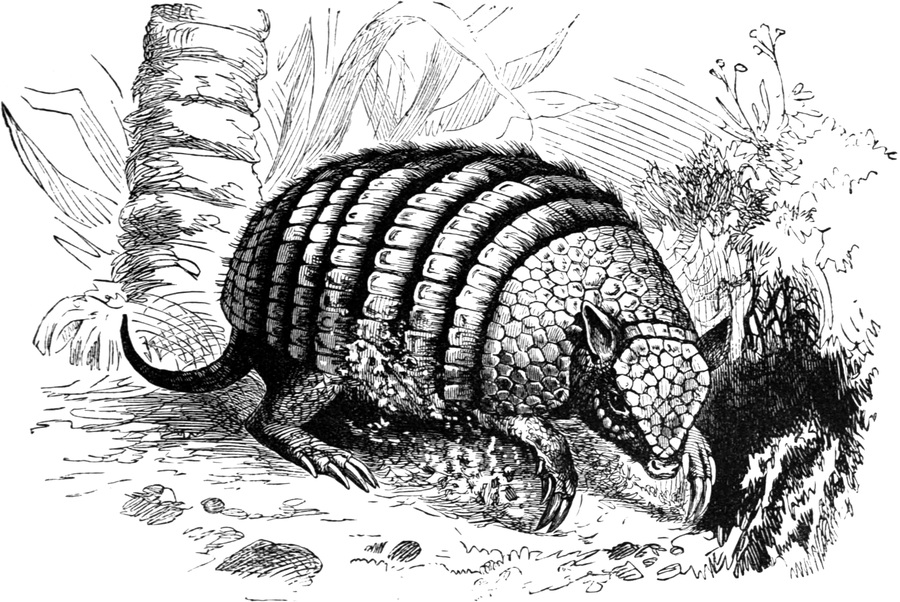

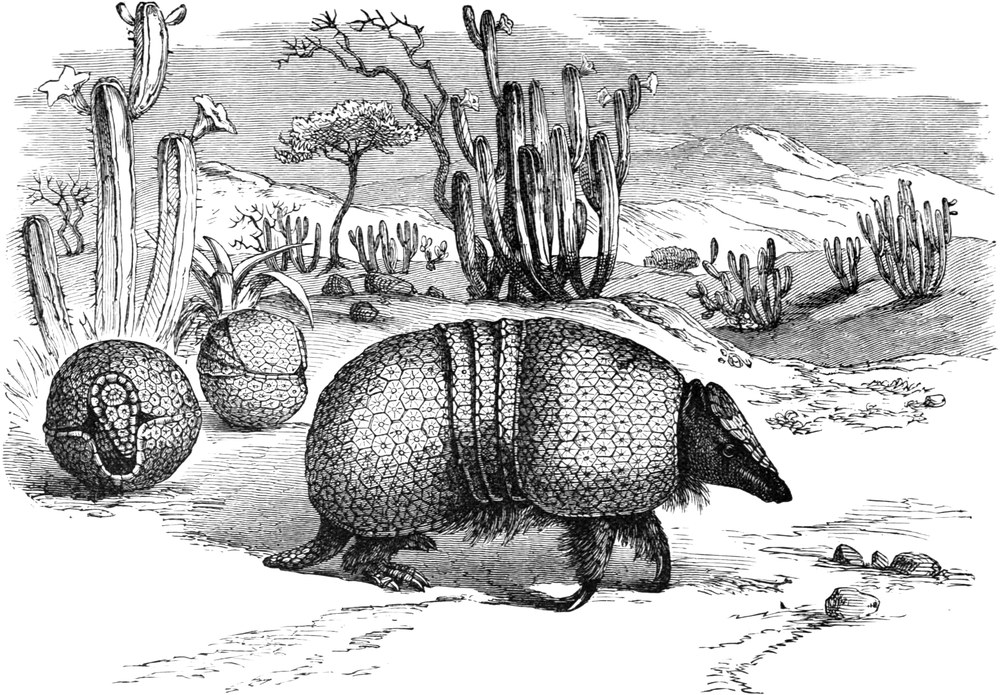

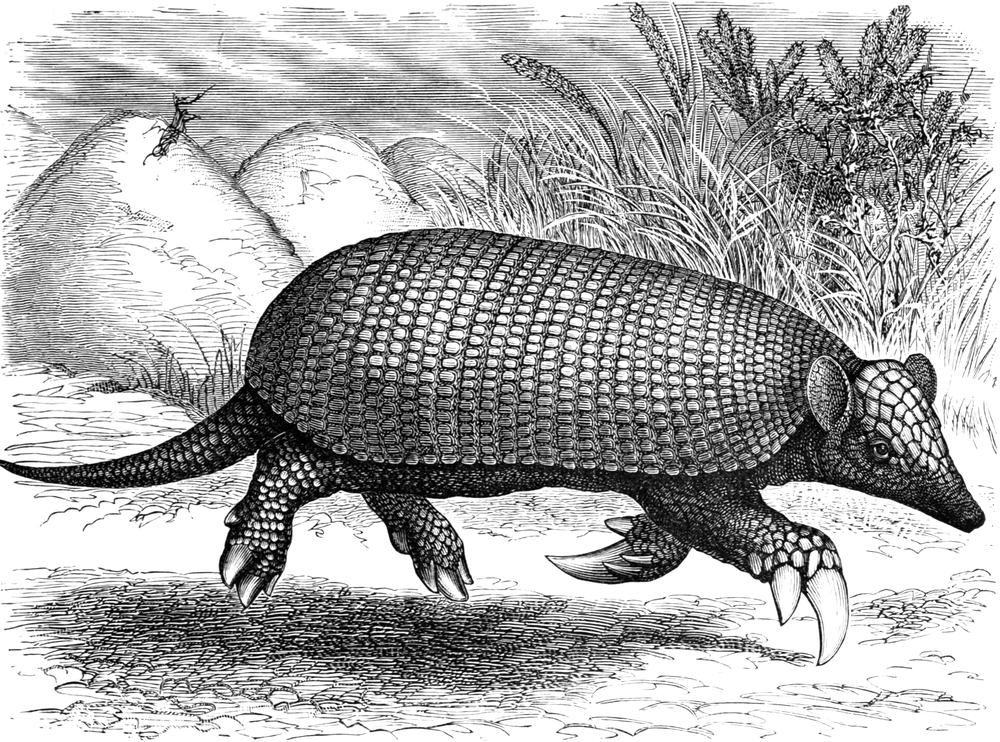

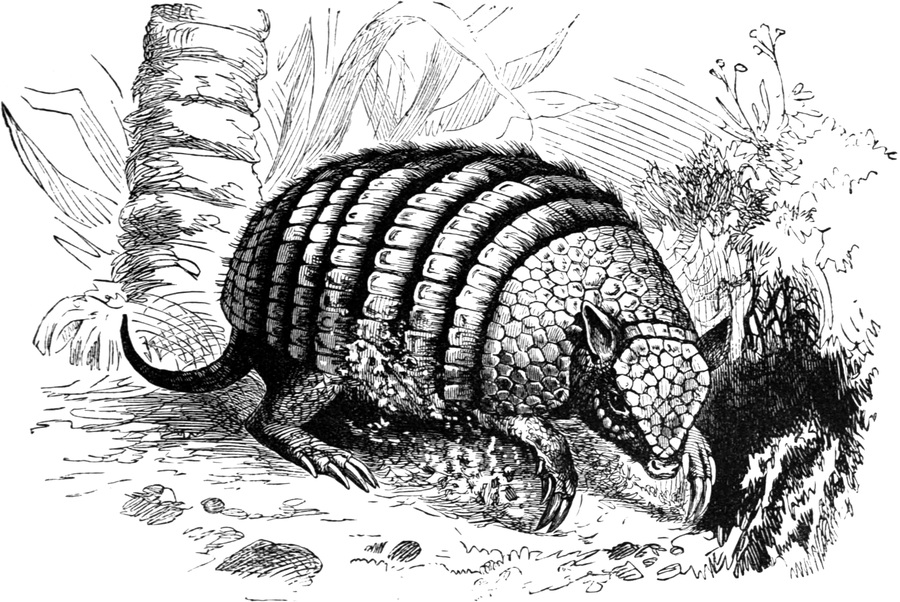

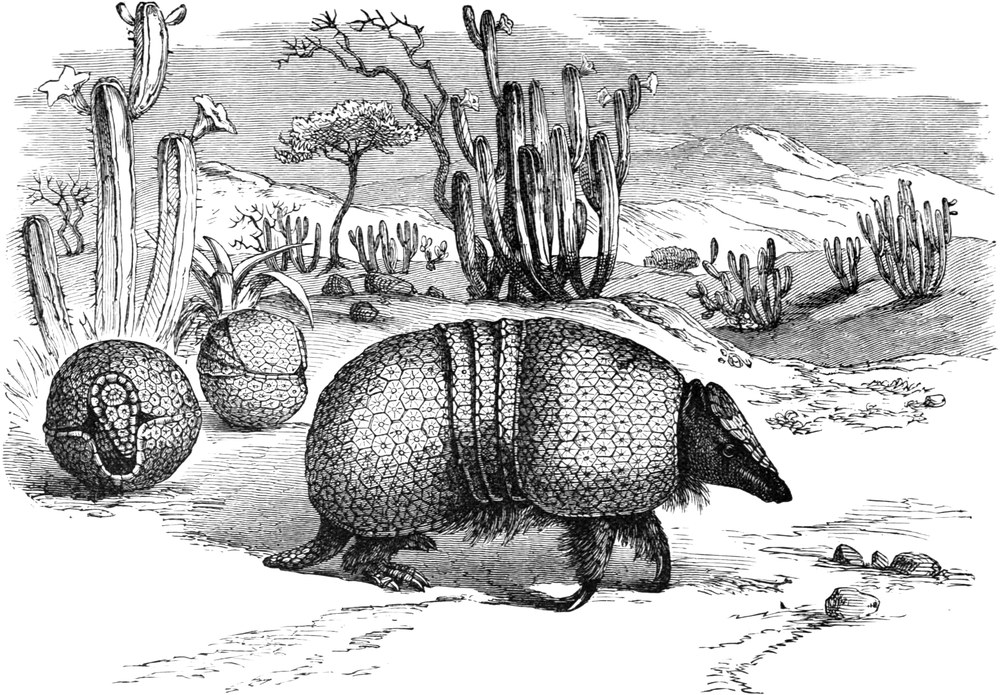

The Armour-plates—How the Shields are formed—Their connection with the Body—Description of the Animals—Mode

of Walking—Diet—Skeleton—Adaptation of their Limbs for Burrowing—Classification—THE GREAT ARMADILLO—Appearance—Great

Burrower—THE TATOUAY—THE POYOU, OR YELLOW-FOOTED ARMADILLO—THE PELUDO, OR

HAIRY ARMADILLO—THE PICHIY—THE PEBA, OR BLACK TATOU—THE MULE ARMADILLO—THE BALL ARMADILLO—Dr.

Murie’s Account of its Habits—Description—The Muscles by which it Rolls itself up and Unrolls itself—THE

PICHICIAGO—Concluding Remarks: Classification of the Order, Fossil Edentates, the Allied Species of Manis in

South Africa and Hindostan

|

181

|

ORDER MARSUPIALIA, MARSUPIAL OR POUCHED ANIMALS.

SUB-ORDER MARSUPIATA.

|

|

CHAPTER I.

|

|

THE KANGAROO AND WOMBAT FAMILIES.

|

|

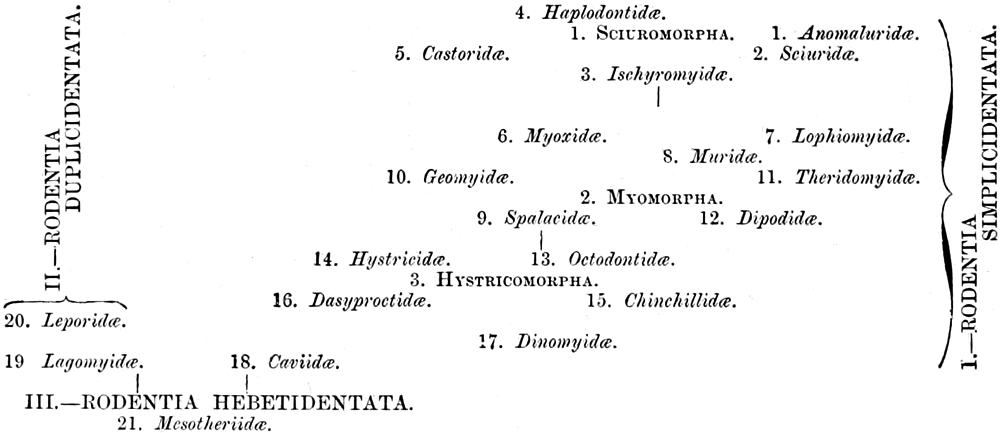

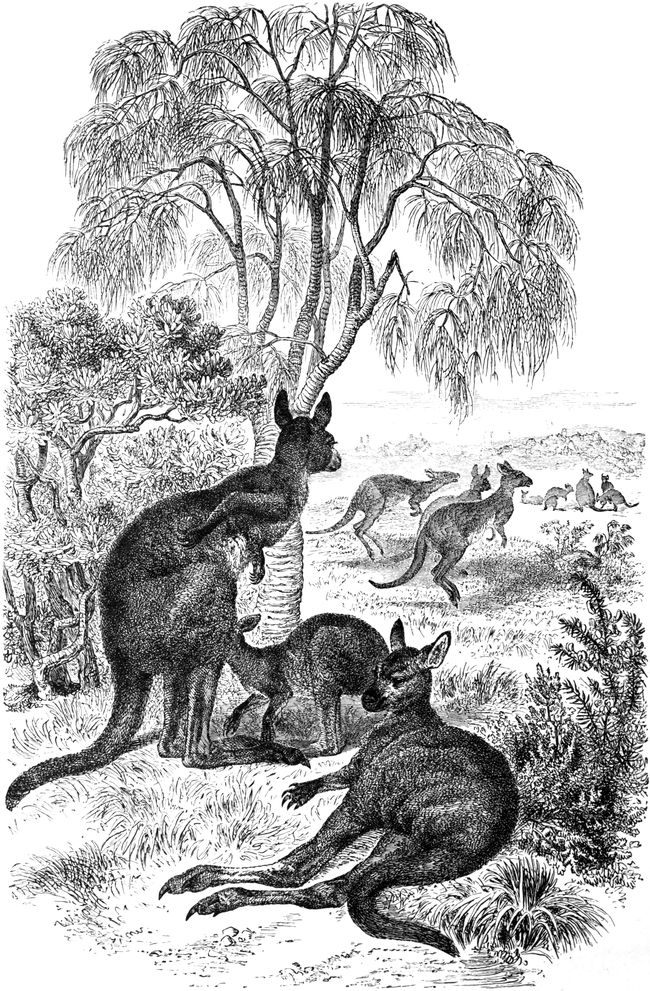

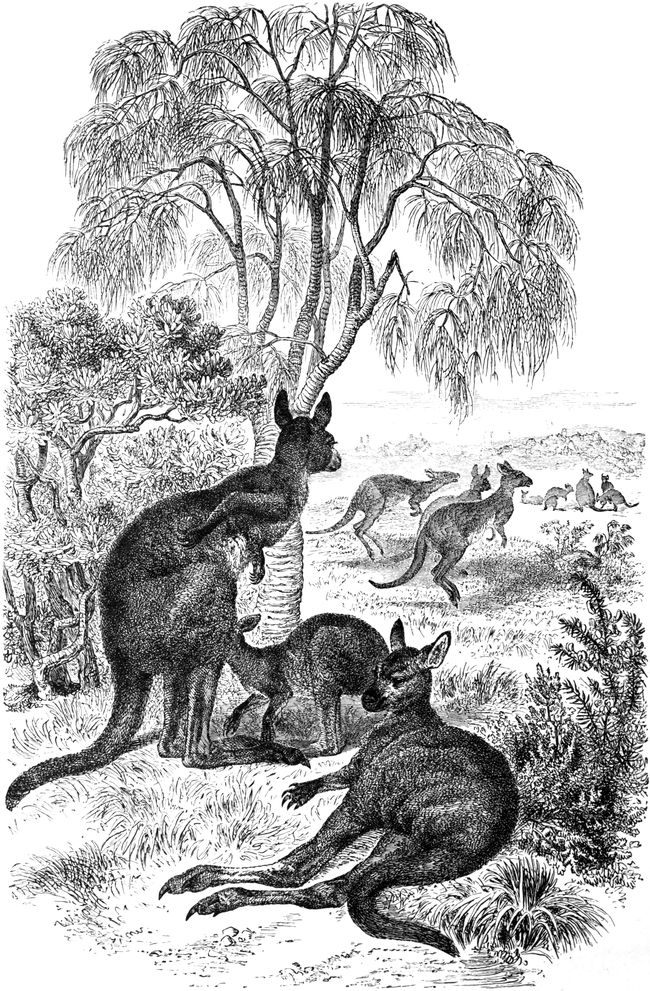

THE GREAT KANGAROO—Captain Cook and the Great Kangaroo—Habitat—Appearance of the Animal—Marsupials

separated from the other Mammalian Orders, and why (Footnote)—Gestation and Birth of Young (Footnote)—Mode

of Running—The Short Fore Limbs—The Marsupium, or Pouch—Head—Dentition—Peculiarities in the

Teeth—Hind Extremities—Foot—Great Claw—How the Erect Position is maintained—Whence their Jumping

Power is derived—Other Skeletal Peculiarities—Kangaroo Hunts—Becoming Rarer—Mode of Attack and

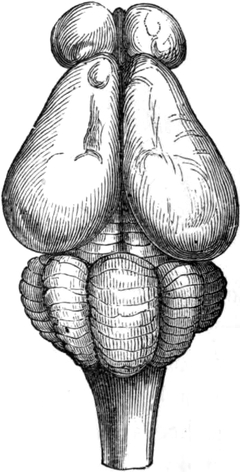

Defence—Hands—Bones of the Fore Limbs—Skull—Stomach—Circulation of Blood—Peculiarity in Young—Nervous

System not fully developed—Brain—The Baby Kangaroo in the Pouch—THE HARE KANGAROO—THE

GREAT ROCK KANGAROO—THE RED KANGAROO—THE BRUSH KANGAROO—THE BRUSH-TAILED ROCK KANGAROO—THE

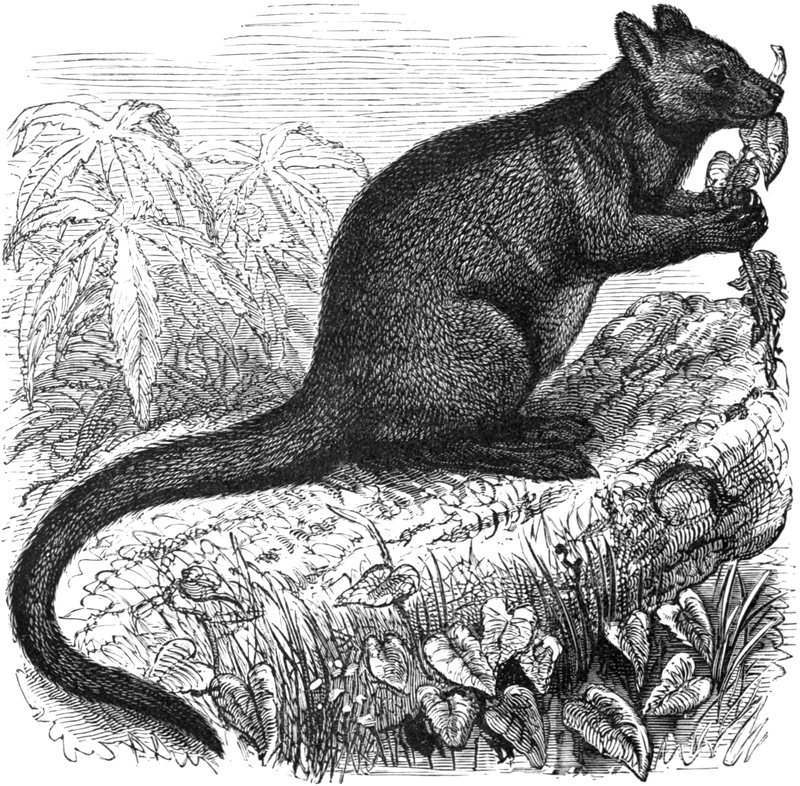

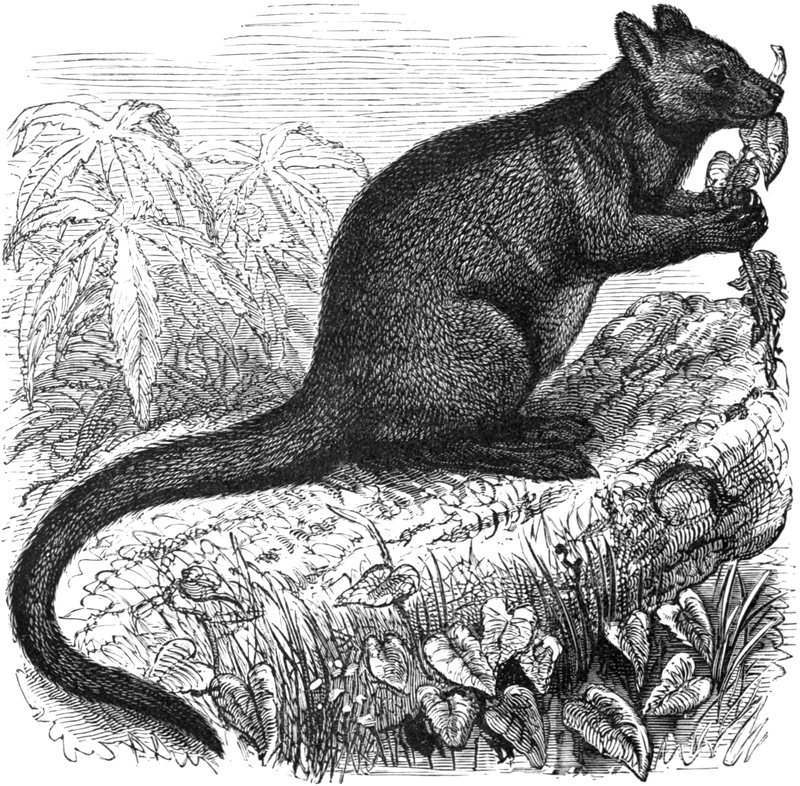

COMMON TREE KANGAROO—THE KANGAROO-RATS—Characteristics—THE RAT-TAILED HYPSIPRYMNUS—Description—THE

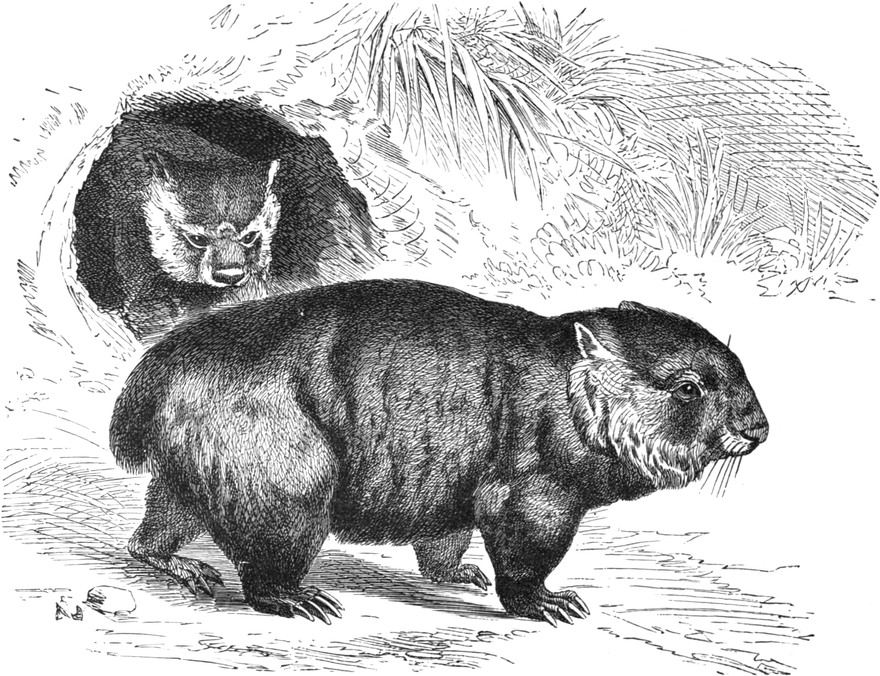

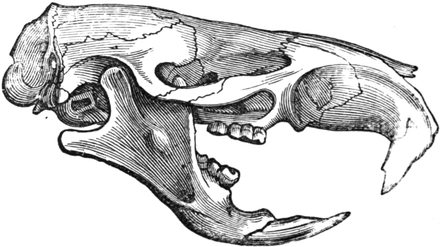

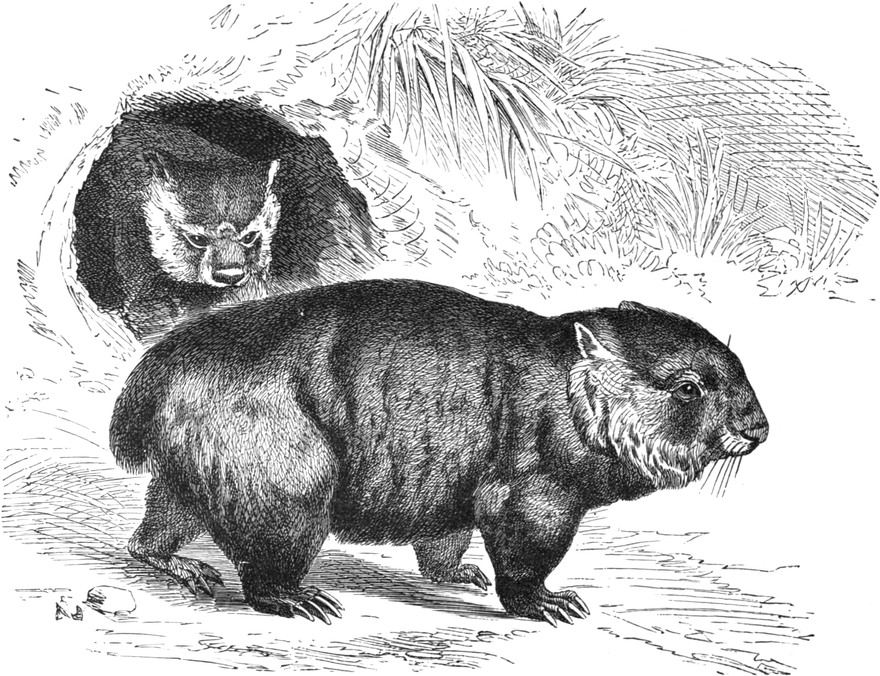

WOMBAT FAMILY—THE WOMBAT—Peculiarities—Description—Habits—Teeth—Skeleton

|

191

|

|

CHAPTER II.

|

|

THE PHALANGER, POUCHED BADGER, AND DASYURE FAMILIES.

|

|

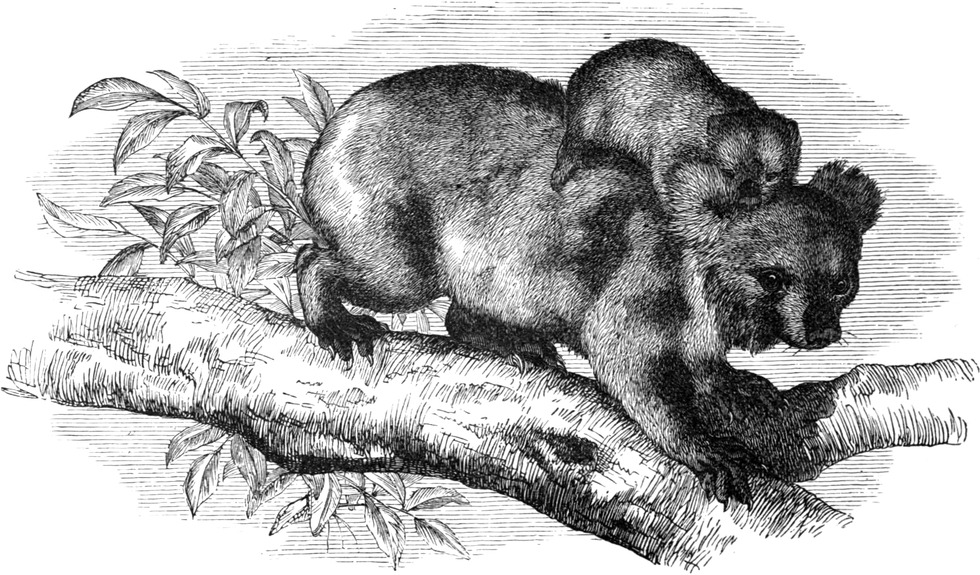

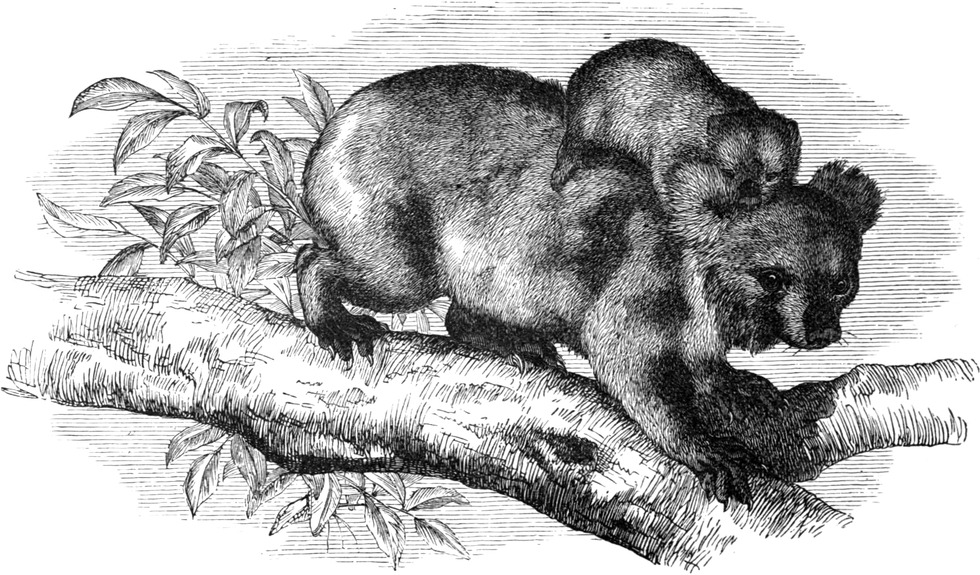

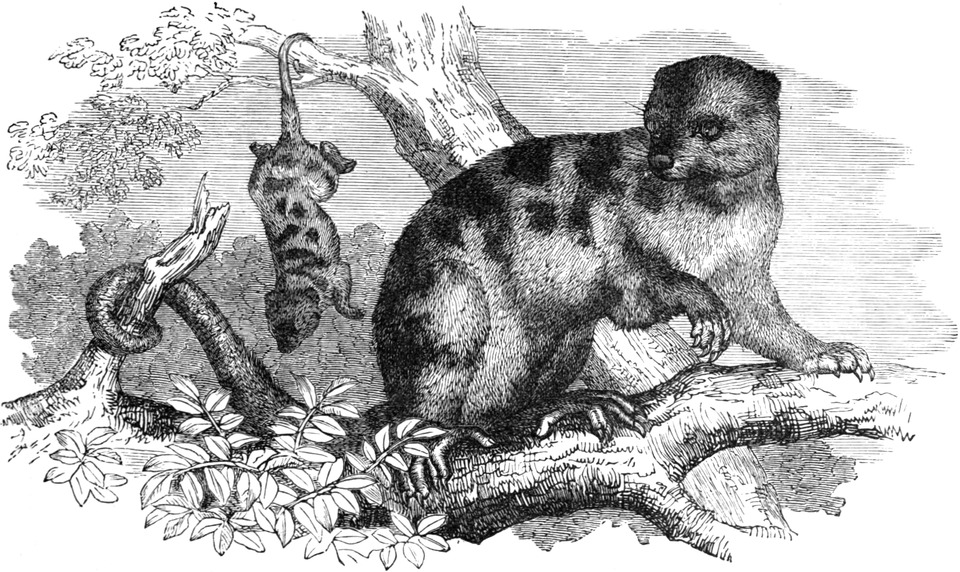

THE PHALANGER FAMILY—THE KOALA—Habits—Characteristics—THE CUSCUS—THE VULPINE PHALANGER—THE

DORMOUSE PHALANGER—Habits—Remarkable Characters—THE FLYING PHALANGERS—Its Flying Machine—Habits—THE

SQUIRREL FLYING PHALANGERS—Habits—The Parachute-like Membrane—Exciting Scene on board

a Vessel—Characteristics—THE OPOSSUM MOUSE—THE NOOLBENGER, OR TAIT—A Curiosity among Marsupials—Distinctive

Features—THE POUCHED BADGER FAMILY—Characteristics—THE RABBIT-EARED PERAMELES—THE

BANDICOOT—THE BANDED PERAMELES—THE PIG-FOOTED PERAMELES—Discussion regarding it—Characteristics—THE

DASYURUS FAMILY—Characteristics—THE POUCHED ANT-EATERS—THE BANDED

MYRMECOBIUS—Description—Great number of Teeth—History—Food—Habits—Range—THE URSINE DASYURE—Appearance—“Native

Devil”—Ferocity—Havoc among the Sheep of the Settlers—Trap to Catch them—Its

Teeth—A True Marsupial, though strikingly like the Carnivora—Skeletal Characters peculiar to itself—MAUGE’S

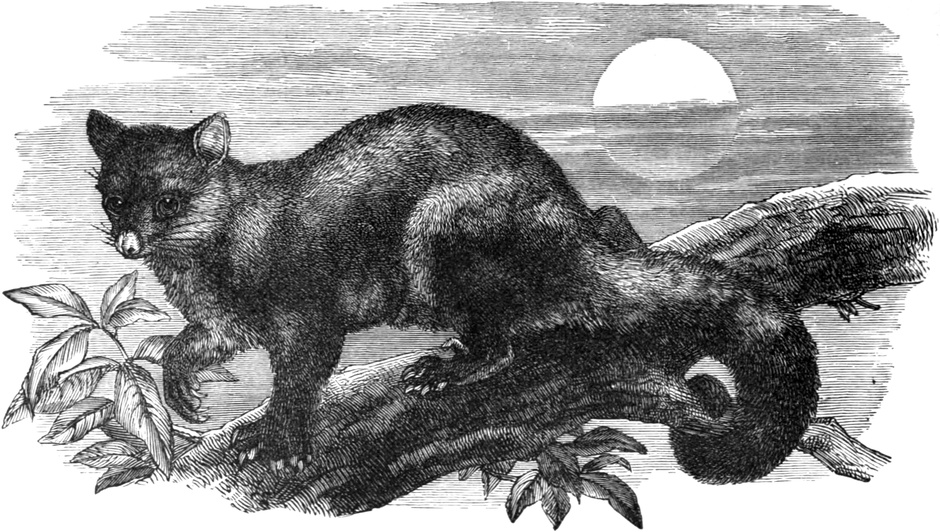

DASYURE—THE DOG-HEADED THYLACINUS—Description—Resemblance to the Dog—Habits—Peculiarities—THE

BRUSH-TAILED PHASCOGALE—Description—Other Varieties

|

203

|

|

CHAPTER III.

|

|

THE OPOSSUMS.

|

|

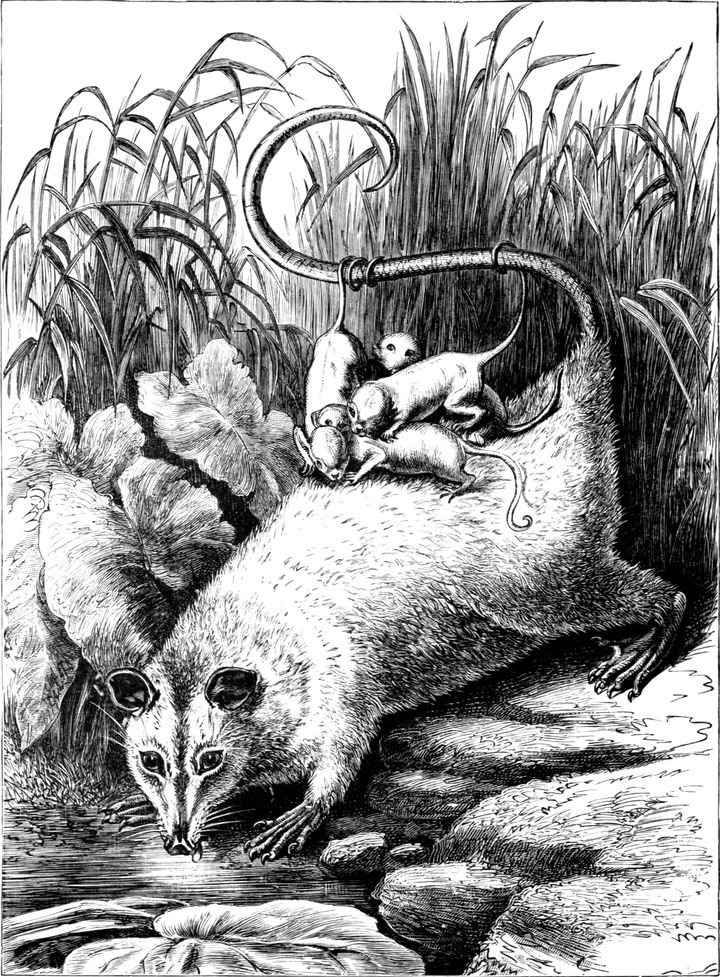

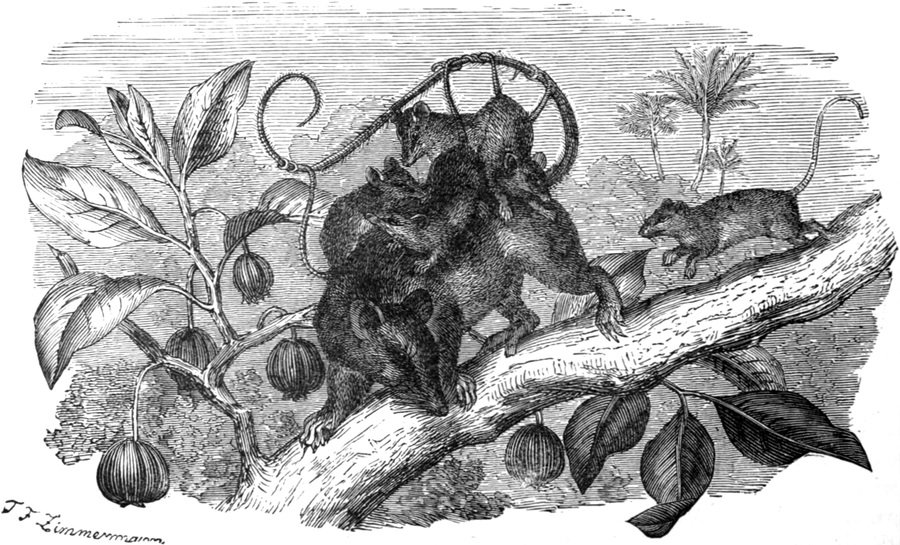

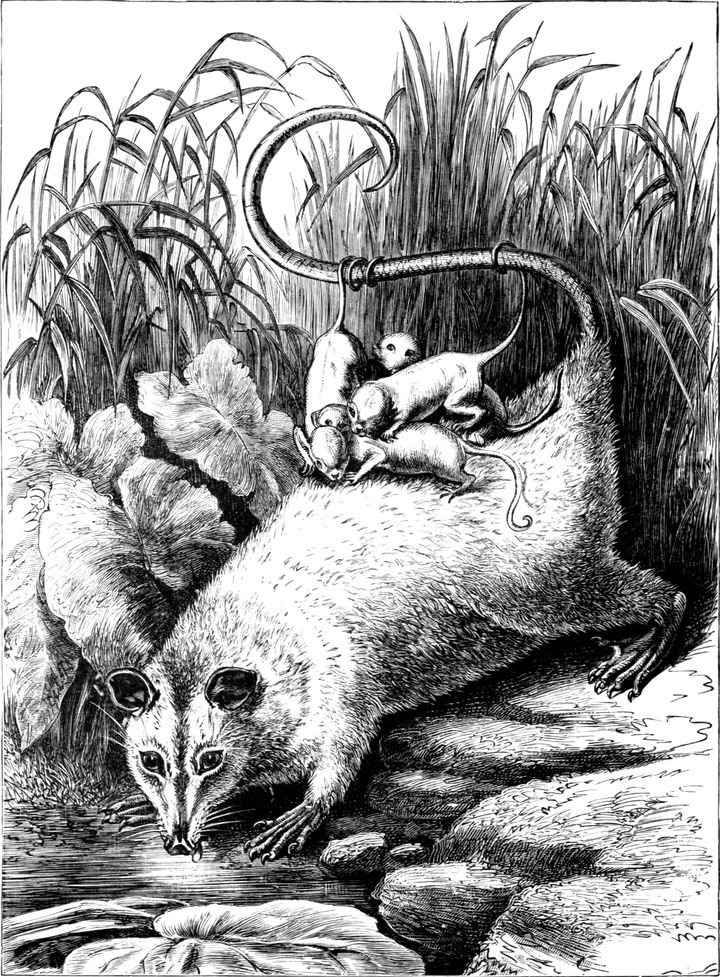

Prehistoric Opossums—Description of the Animal—Their Teeth—Habits—THE COMMON OPOSSUM—Appearance—Use of

its Tail—Food—The Young—How they are Reared—D’AZARA’S OPOSSUM—THE CRAB-EATING OPOSSUM—THE

THICK-TAILED OPOSSUM—MERIAN’S OPOSSUM—Pouchless Opossums—Their Young—THE MURINA OPOSSUM—THE

ELEGANT OPOSSUM—THE YAPOCK—Classification of Marsupial Animals—Geographical Distribution of the Sub-Order—Ancestry

of the Marsupials—Fossil Remains

|

219

|

|

SUB-ORDER—MONOTREMATA.

|

|

CHAPTER IV.

|

|

THE PORCUPINE OR LONG-SPINED ECHIDNA AND DUCK-BILLED PLATYPUS.

|

|

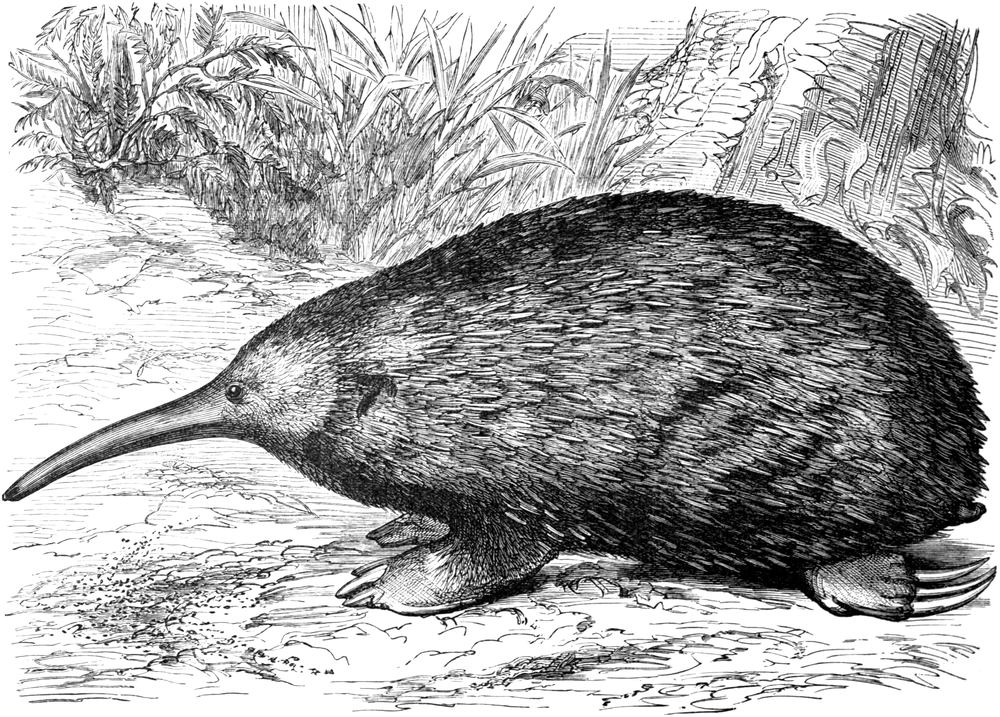

Why the Monotremata are formed into a Sub-order—The lowest of the Mammalian Class—THE PORCUPINE OR LONG-SPINED

ECHIDNA—An Ant-eater, but not an Edentate—Its Correct Name—Description of the Animal—Habits and

Disposition—Manner of Using the Tongue—Where it is Found—Anatomical Features: Skull, Brain, Marsupial

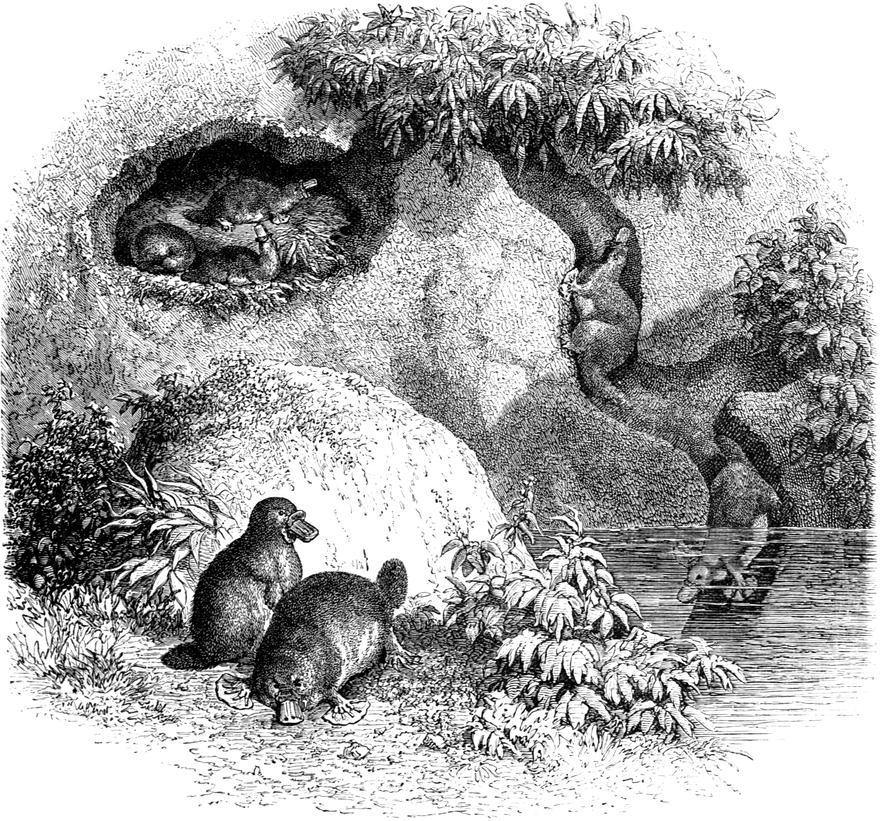

Bones—The Young—Species of Van Diemen’s Land and New Guinea—THE WATER-MOLE, OR DUCK-BILLED

PLATYPUS[Pg ix]—The most Bird-like Mammal—Various Names—Description—Their Appearance and Movements in

Water—Their Burrows—Habits of an Individual kept in Confinement—Used by Natives as Food—How they

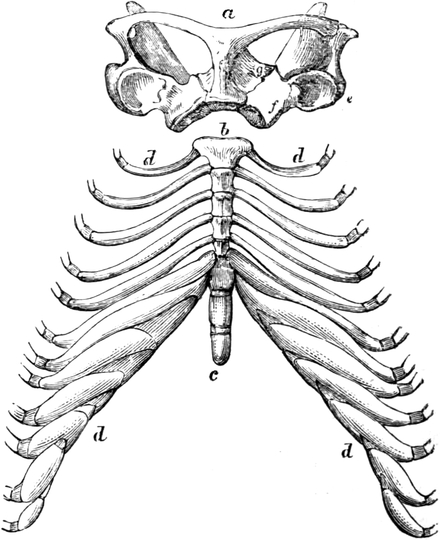

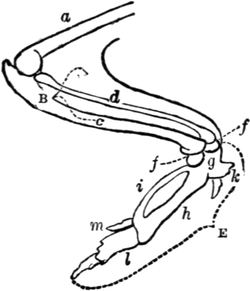

are Captured—The Young—A Family in Captivity—The Snout—Jaws—Teeth—Tongue—Fore and Hind Feet—Heel—Spur—The

Shoulder Girdle—Breastbone—Concluding Remarks on the Sub-orders—Postscript

|

227

|

|

THE CLASS AVES.—THE BIRDS.

|

|

CHAPTER I.

|

|

INTRODUCTION—WING STRUCTURE AND

FEATHERS—DISTRIBUTION.

|

|

Introduction—Distinctive Characters of the Class Aves—Power of Flight—The Wing—Its Structure—The Six Zoo-geographical

Regions of the Earth—Birds peculiar to these Regions

|

235

|

|

CHAPTER II.

|

|

THE ANATOMY OF A BIRD.

|

|

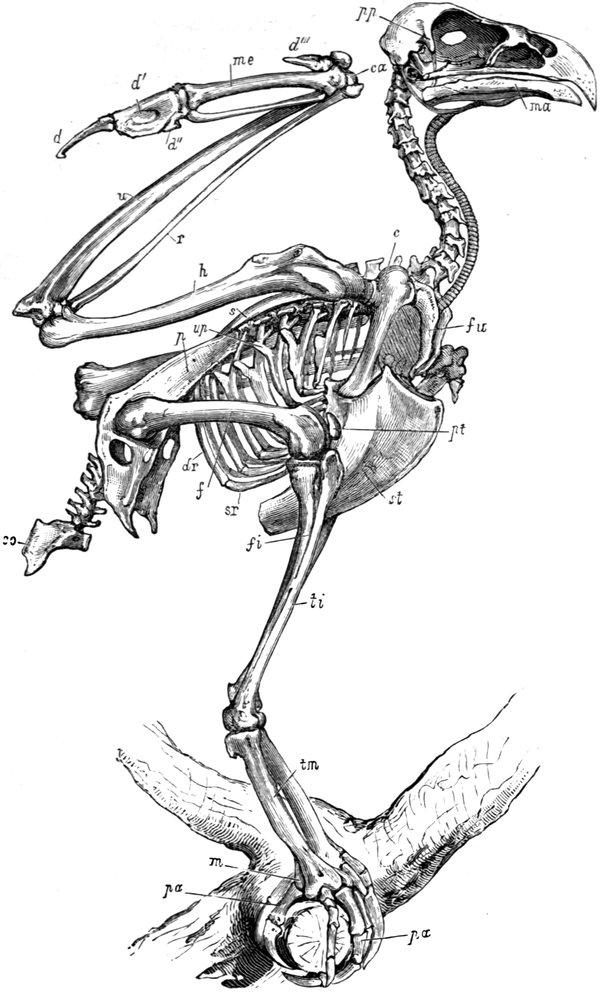

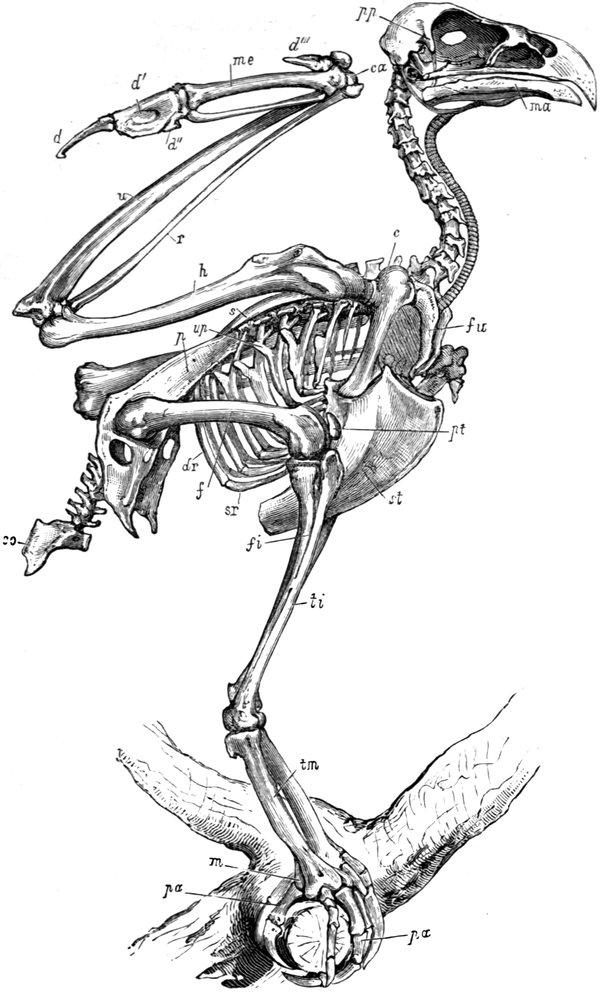

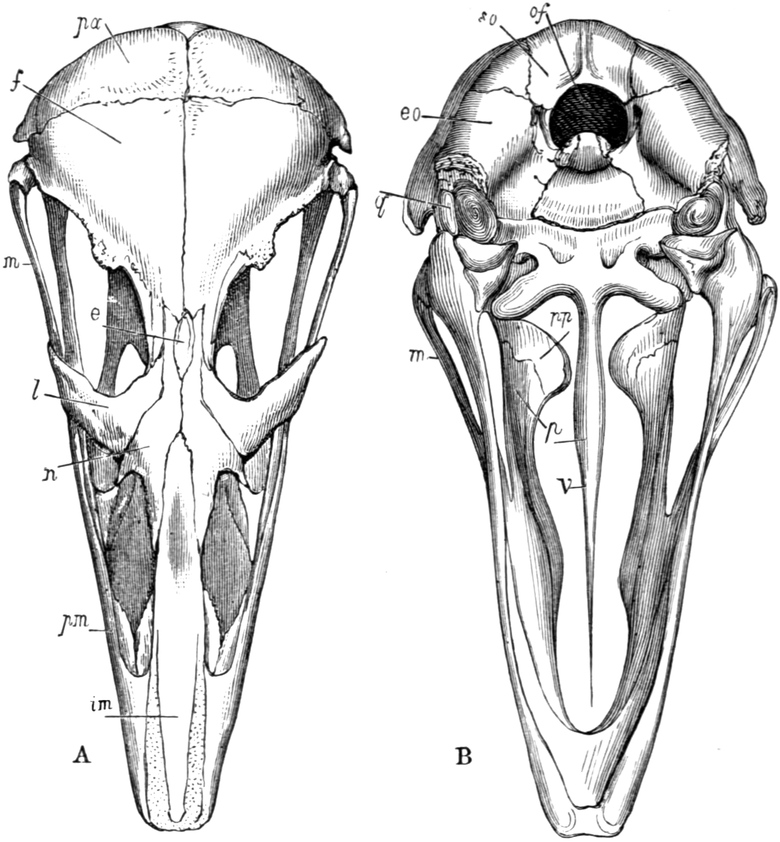

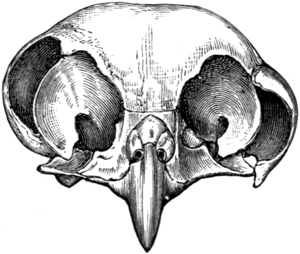

The Three Divisions of the Class Aves—ANATOMY OF A BIRD—The Skeleton—Distinctive Features—Peculiar Bone

Character—The Skull—Difference between the Skull of Birds and that of Mammals—The Jawbones—Vertebral

Column—Sternum—Fore-limbs—Hind-limbs—Toes—The Muscular System—How a Bird remains Fixed when

Asleep—The Oil-gland—The Nervous System—The Brain—The Eye—The Ear—The Digestive System—The

Dental papillæ—The Beak—Tongue—Gullet—Crop—Stomach—Uses of the Gizzard—Intestine—The Liver,

Pancreas, and Spleen—The Blood and Circulatory System—Temperature of Blood of a Bird—Blood Corpuscles—The

Heart—The Respiratory System—Lungs—Air-sacs—The Organs of Voice—The Egg—Classification of the

Class Aves

|

239

|

CHAPTER III.

DIVISION I.—THE CARINATE BIRDS (CARINATÆ).

THE ACCIPITRINE ORDER—BIRDS OF PREY.

|

|

VULTURES AND CARACARAS.

|

|

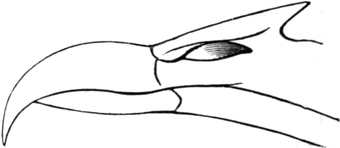

The Birds of Prey—Distinctive Characters—The Cere—How the Birds of Prey are Divided—Difference between a Hawk,

an Owl, and an Osprey—The Three Sub-orders of the Accipitres—Sub-order FALCONES—Difference between the

Vultures of the Old World and the Vultures of the New World—THE OLD WORLD VULTURES—Controversy as to

how the Vultures reach their Prey—Waterton on the Faculty of Scent—Mr. Andersson’s, Dr. Kirk’s, and Canon

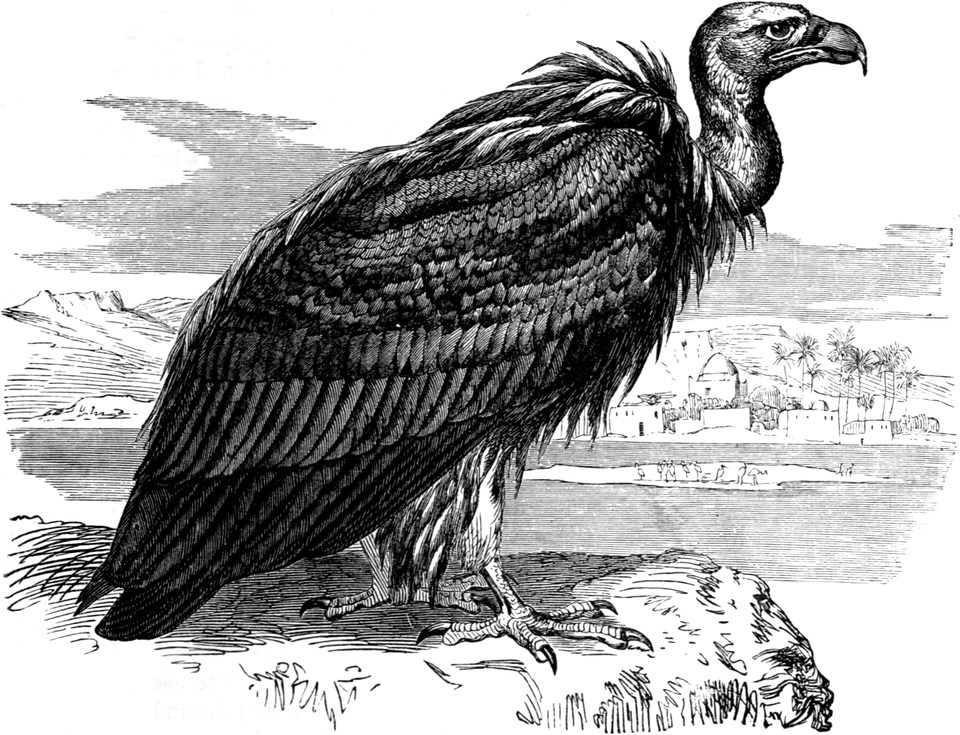

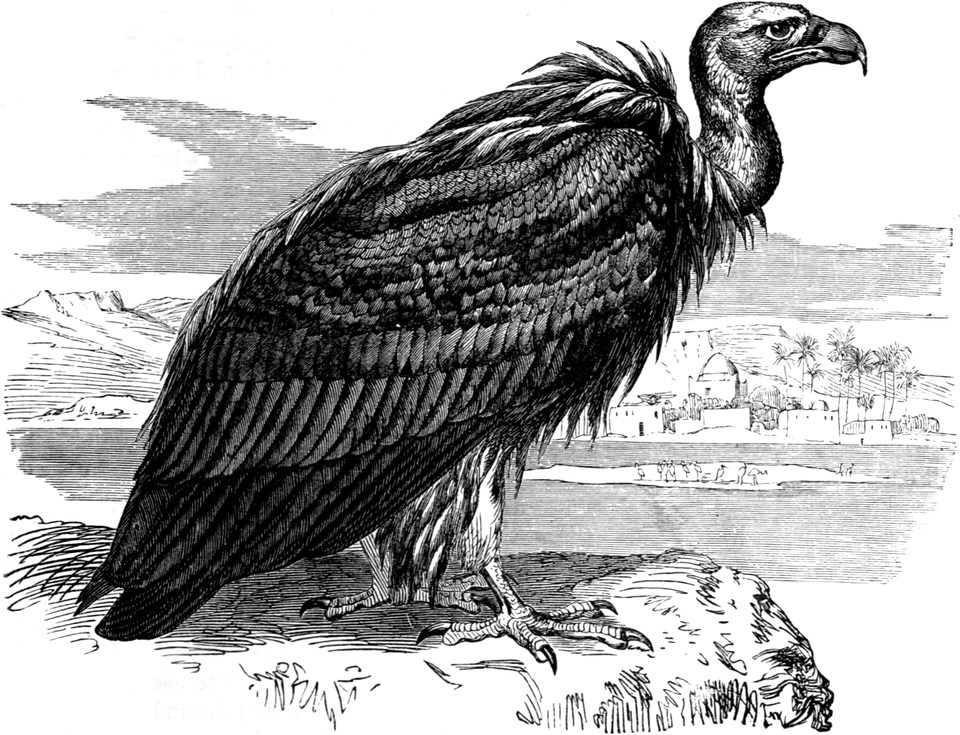

Tristram’s Views in Favour of Sight—THE BLACK VULTURE—THE GRIFFON VULTURE—Its Capacity for Feeding

while on the Wing—THE EARED VULTURE—One of the Largest of the Birds of Prey—Whence it gets its Name—THE

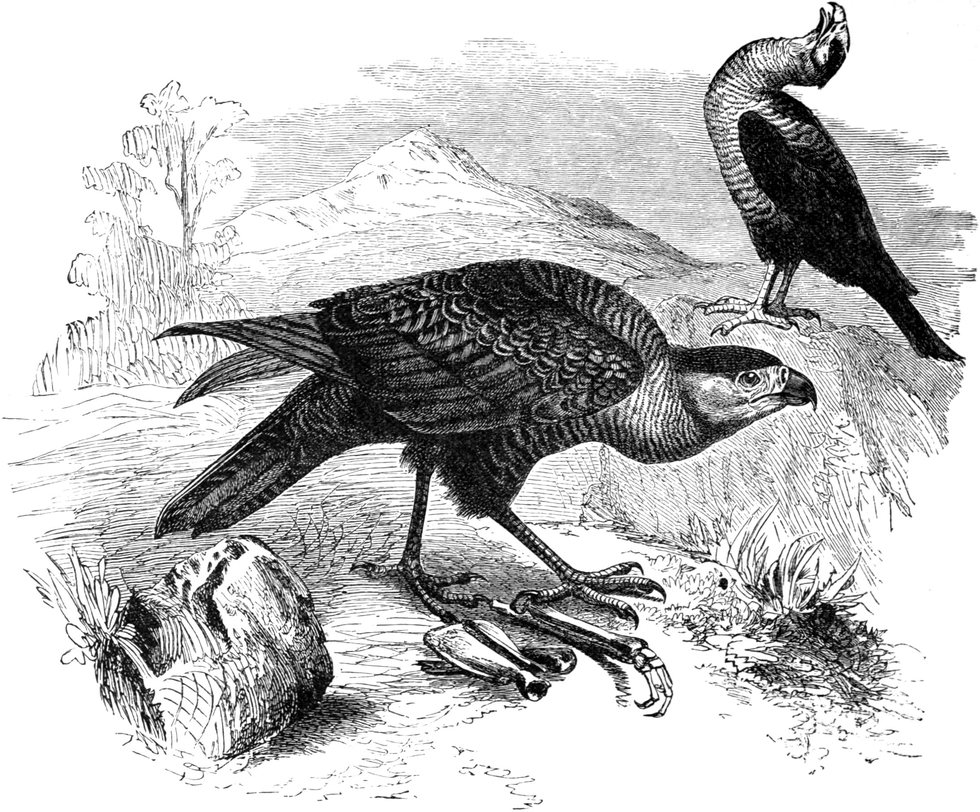

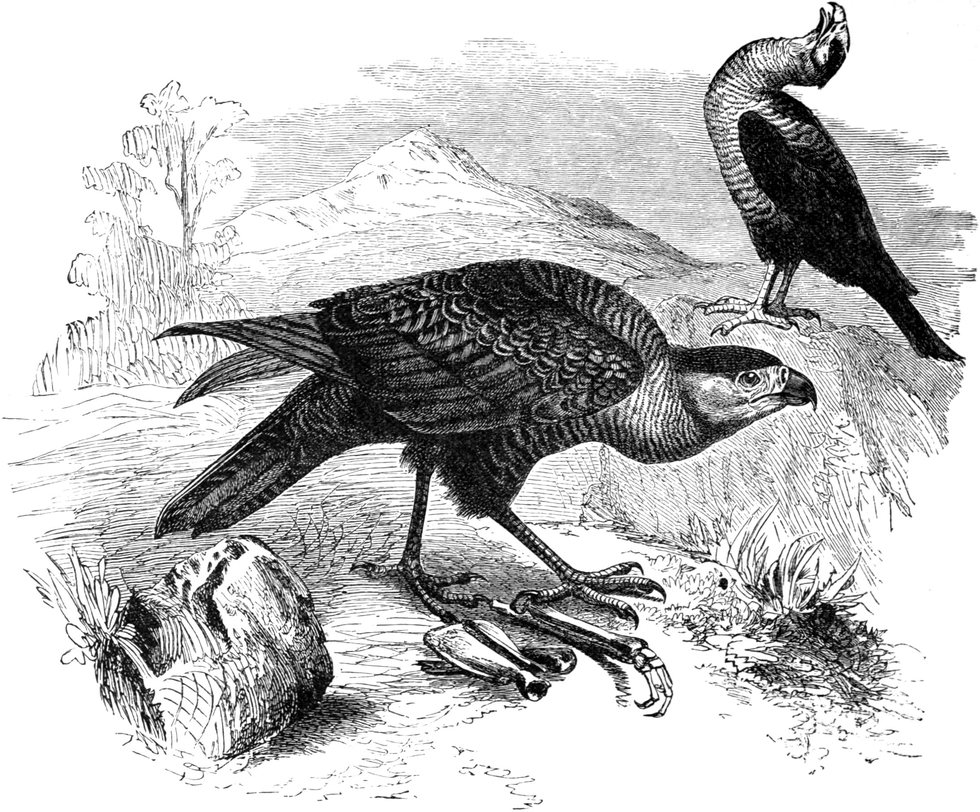

EGYPTIAN VULTURE—A Foul Feeder—THE NEW WORLD VULTURES—THE CONDOR—Its Appearance—Power

of Flight—Habits—THE KING VULTURE—THE TURKEY VULTURE—THE CARACARAS—Distinctive

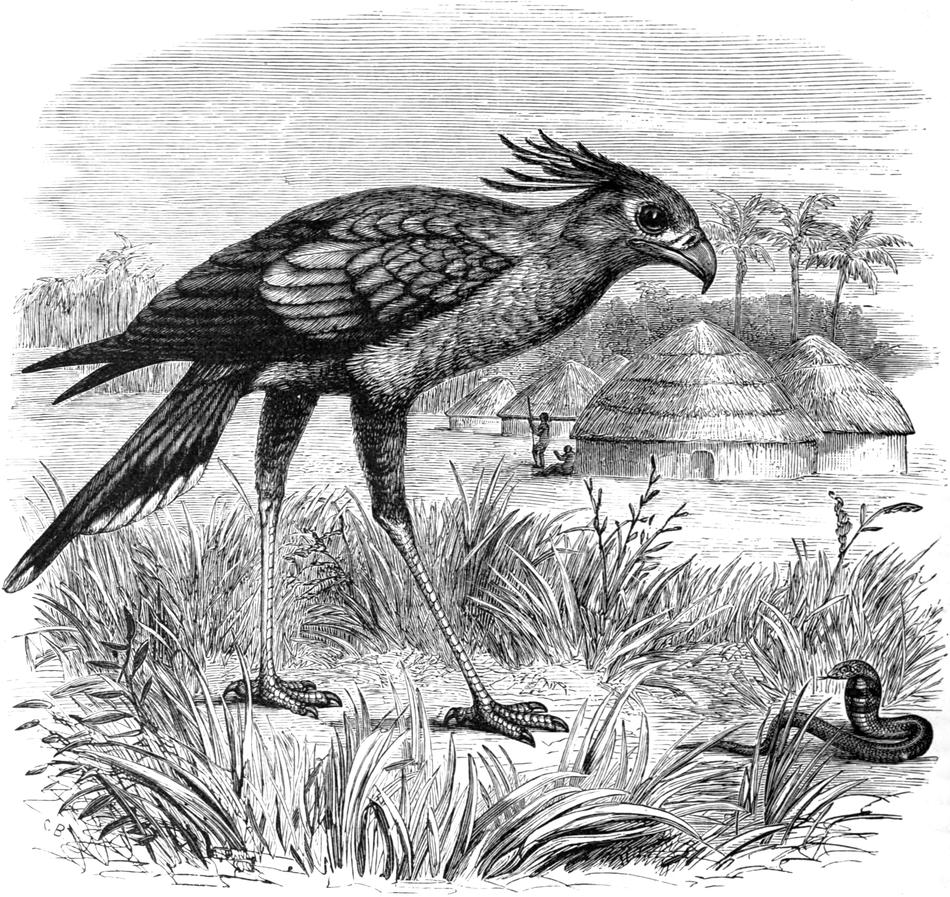

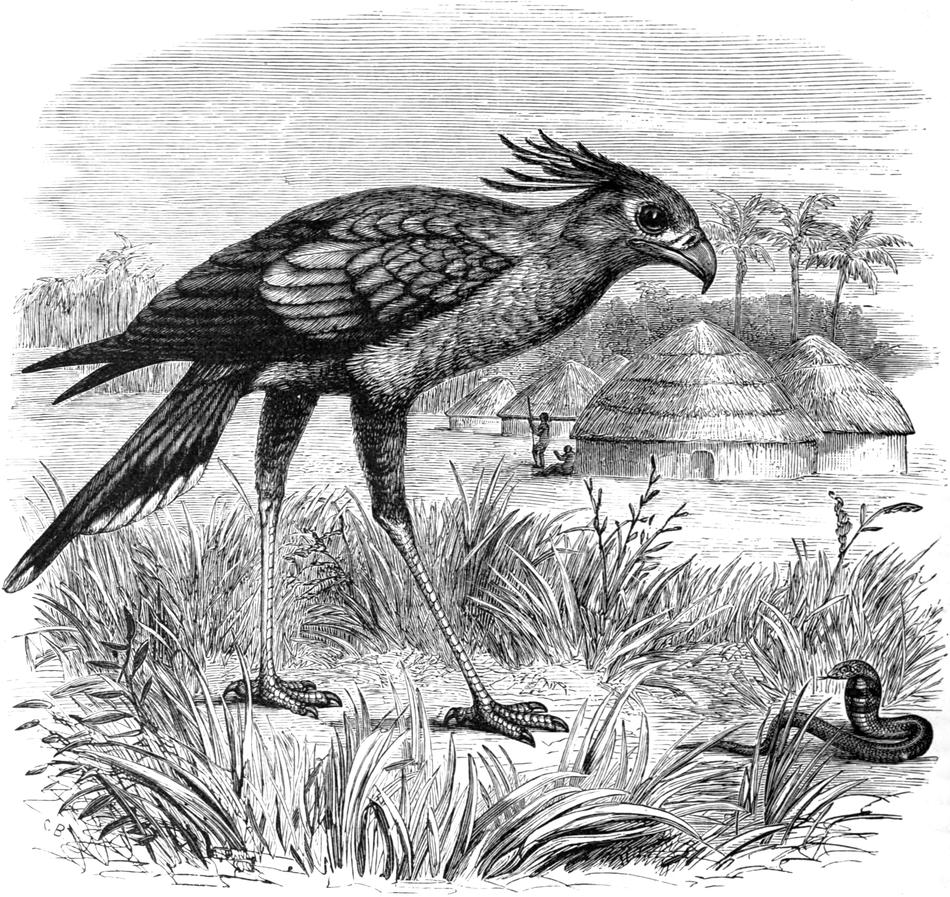

Characters—Habits—THE SECRETARY BIRD—How it attacks Snakes—Habits—Appearance—THE ÇARIAMA.

|

254

|

|

CHAPTER IV.

|

|

THE LONG-LEGGED HAWKS AND BUZZARDS.

|

|

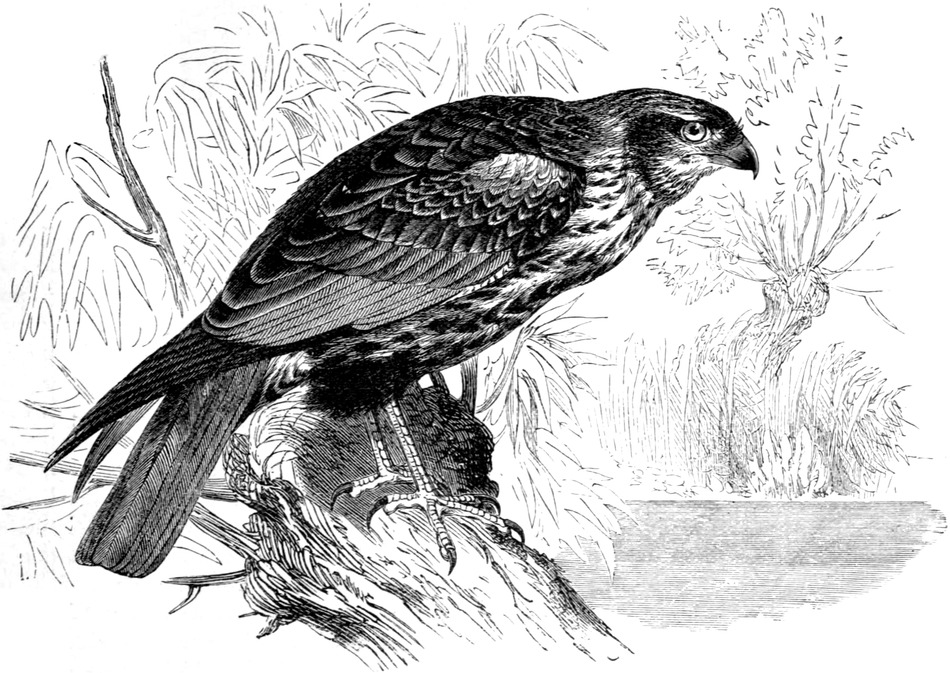

THE BANDED GYMNOGENE—Habits—Its Movable Tarsi—THE HARRIERS—Distinctive Features—THE MARSH HARRIER—Habits—Its

Thievish Propensities—THE HARRIER-HAWKS—Colonel Greyson’s Account of their Habits—THE

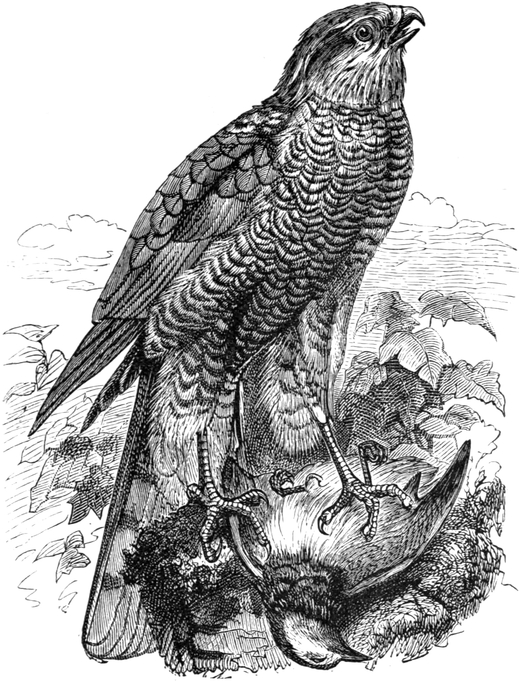

CHANTING GOSHAWKS—Why so Called—Habits—THE TRUE GOSHAWKS—Distinctive Characters—THE GOSHAWK—Distribution—In

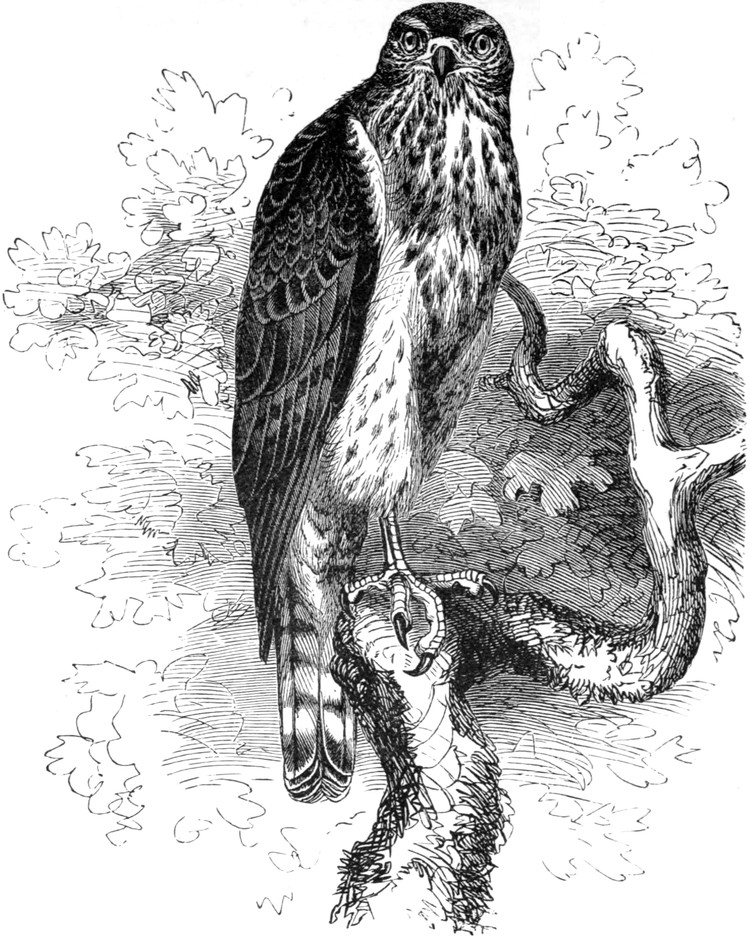

Pursuit of its Prey—Appearance—THE SPARROW-HAWKS—Distinctive Characters—THE

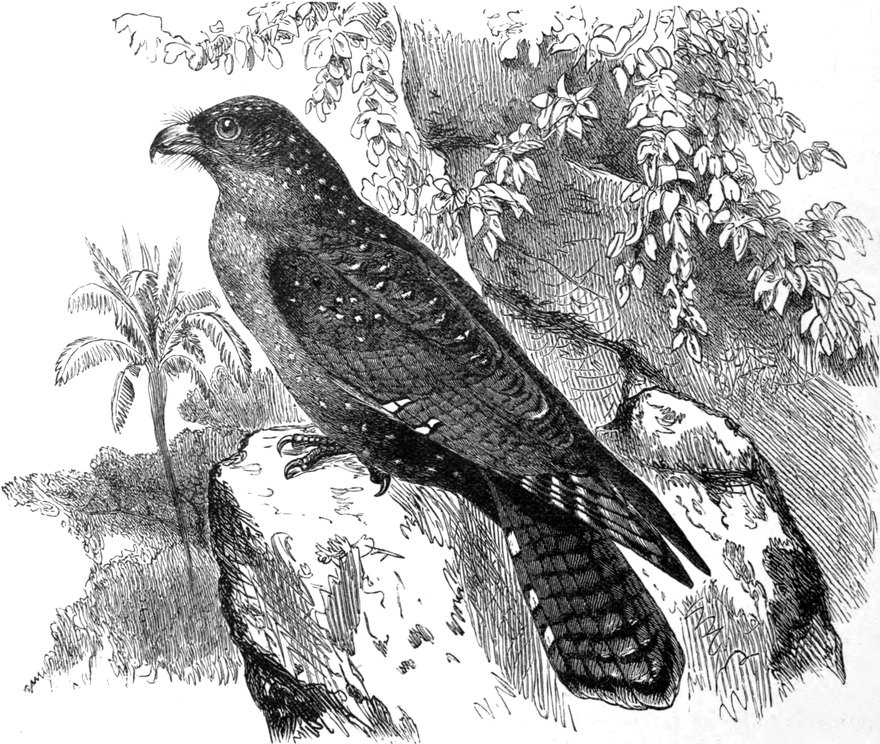

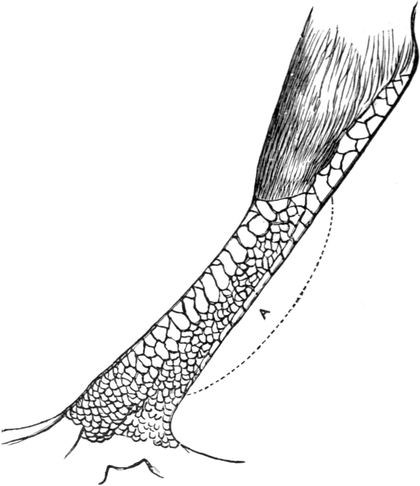

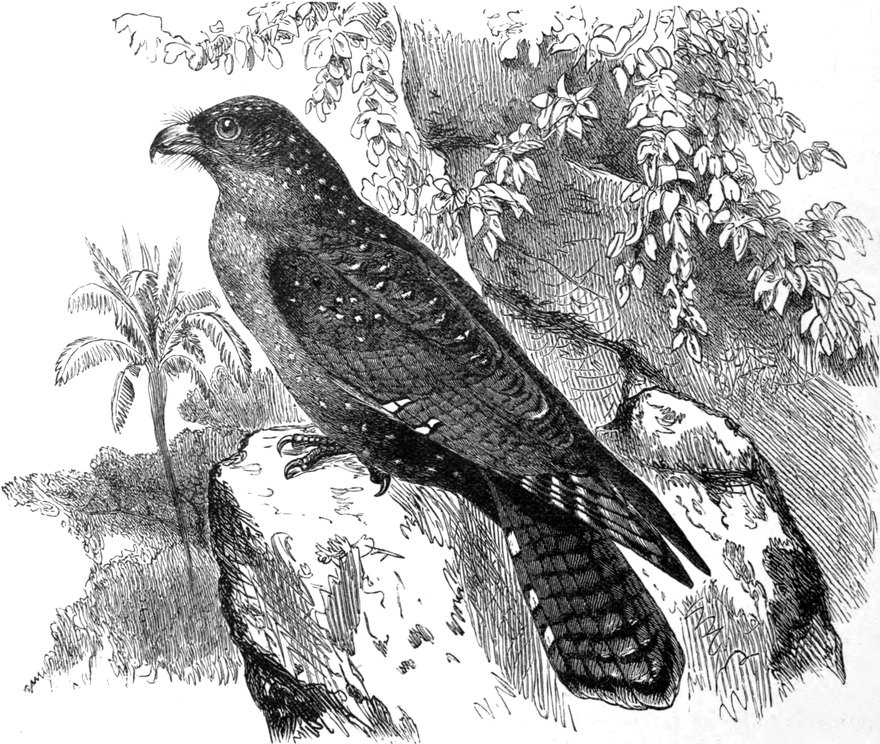

COMMON SPARROW-HAWK—Habits—Appearance—THE BUZZARDS—Their Tarsus—THE COMMON BUZZARD—Where

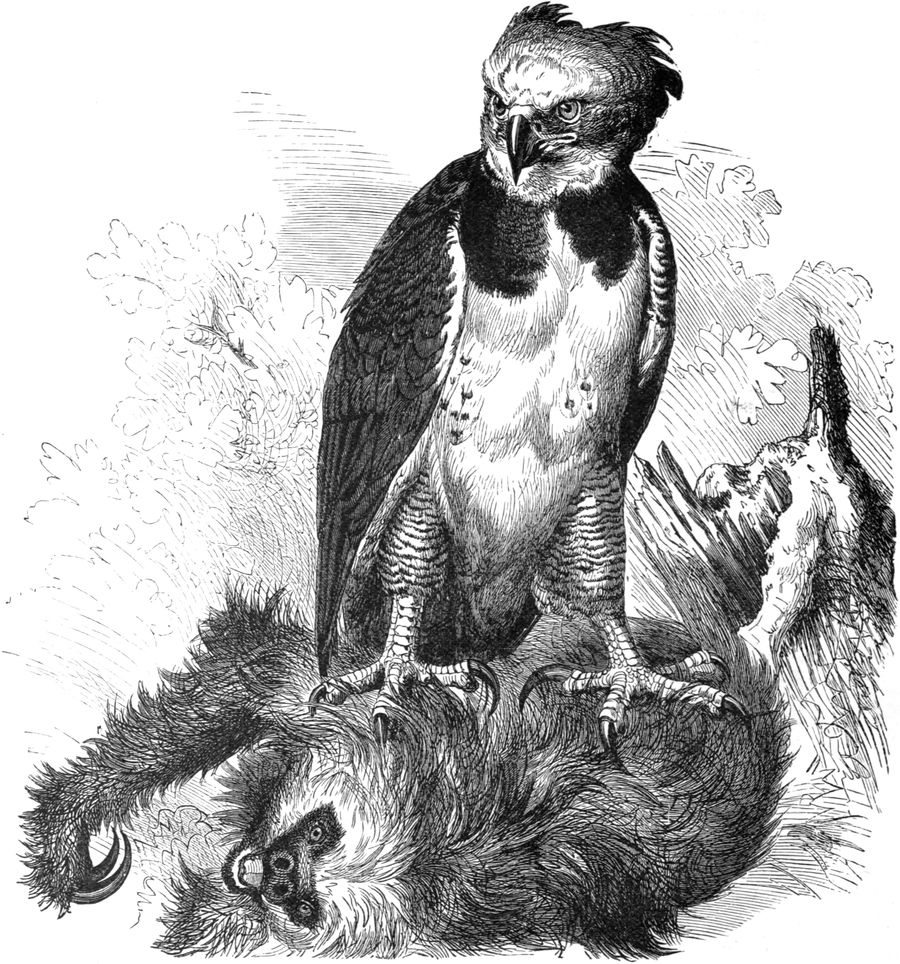

Found—How it might be turned to Account—Food—Its Migrations—Habits—Appearance—THE HARPY

|

267

|

|

CHAPTER V.

|

|

EAGLES AND FALCONS.

|

|

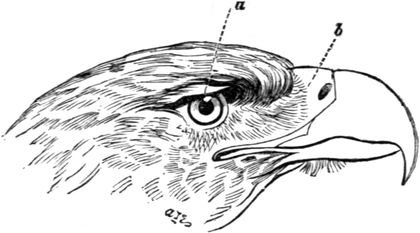

THE EAGLES—THE BEARDED EAGLE, OR LÄMMERGEIER—A Visit to their Nest—Habits—A Little Girl carried off

Alive—Habits in Greece—Appearance—Von Tschudi’s and Captain Hutton’s Descriptions of its Attacks—THE

TRUE EAGLES—THE WEDGE-TAILED EAGLE—Eye—Crystalline Lens—How Eagles may be Divided—THE

IMPERIAL EAGLE—THE GOLDEN EAGLE—In Great Britain—Macgillivray’s Description of its Habits—Appearance—THE

KITE EAGLE—Its Peculiar Feet—Its Bird’s-nesting Habits—THE COMMON HARRIER EAGLE—THE INDIAN

SERPENT EAGLE—THE BATELEUR EAGLE—THE WHITE-TAILED EAGLE—A Sea Eagle—Story of Capture of some

Young—THE SWALLOW-TAILED KITE—On the Wing—THE COMMON KITE—THE EUROPEAN HONEY KITE—Habits—ANDERSSON’S

PERN—THE FALCONS—The Bill—THE CUCKOO FALCONS—THE FALCONETS—THE

PEREGRINE FALCON—Its Wonderful Distribution—Falconry—Names for Male, Female, and Young—Hawks and

Herons—THE GREENLAND JER-FALCON—THE KESTRELS—THE COMMON KESTREL—Its Habits and Disposition

|

277

|

|

CHAPTER VI.

|

|

THE OSPREYS AND OWLS.

|

|

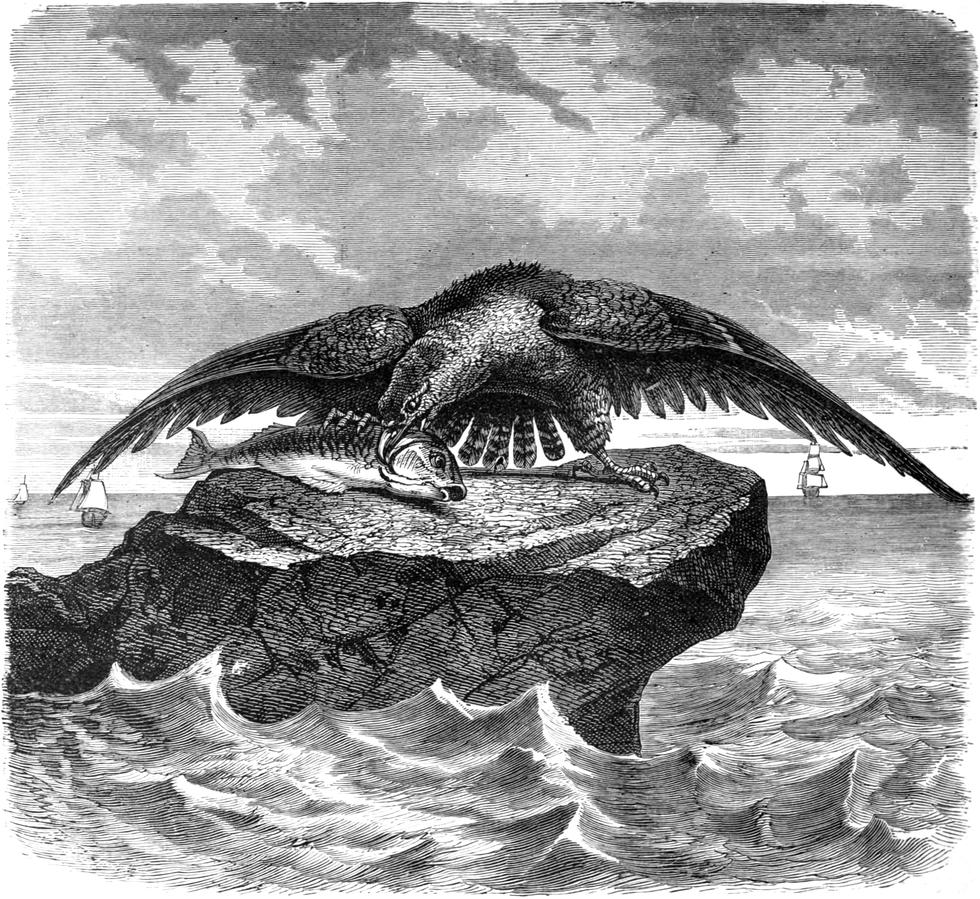

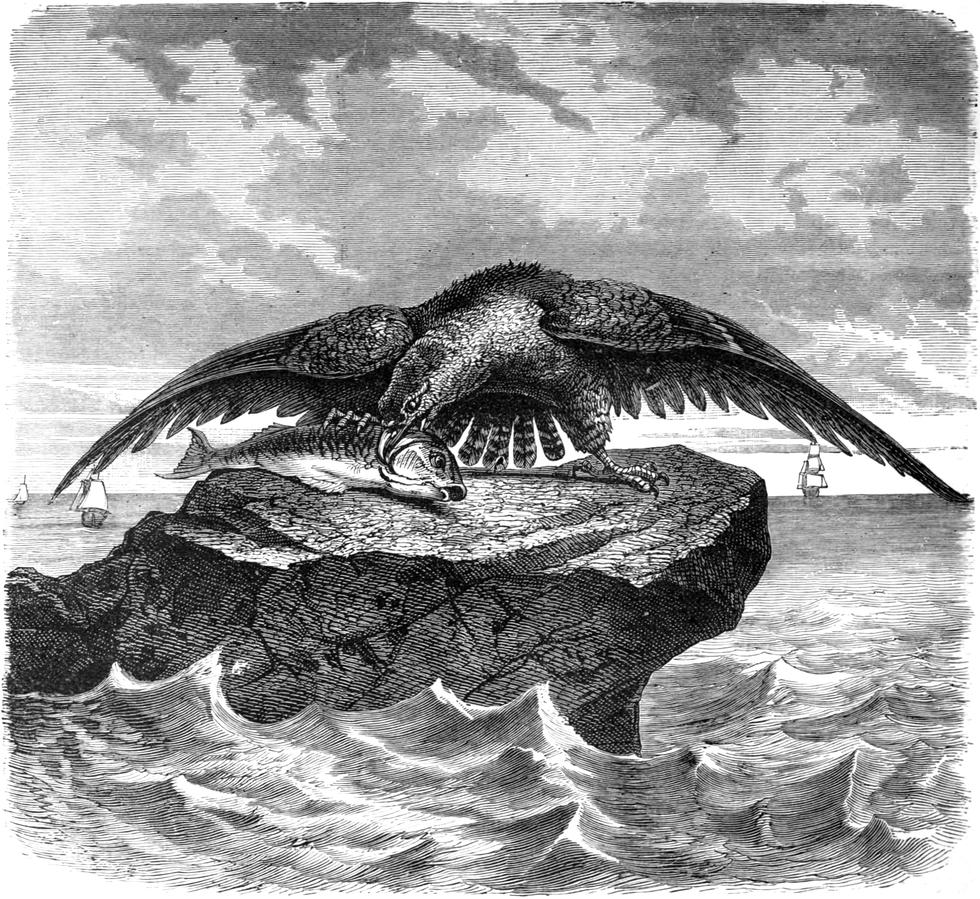

THE OSPREY—Distribution—Food—How it Seizes its Prey—Nesting Communities—STRIGES, or OWLS—Distinctions

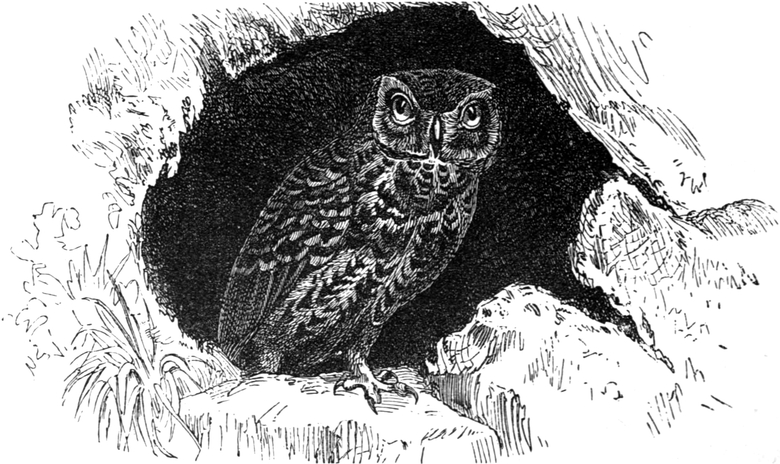

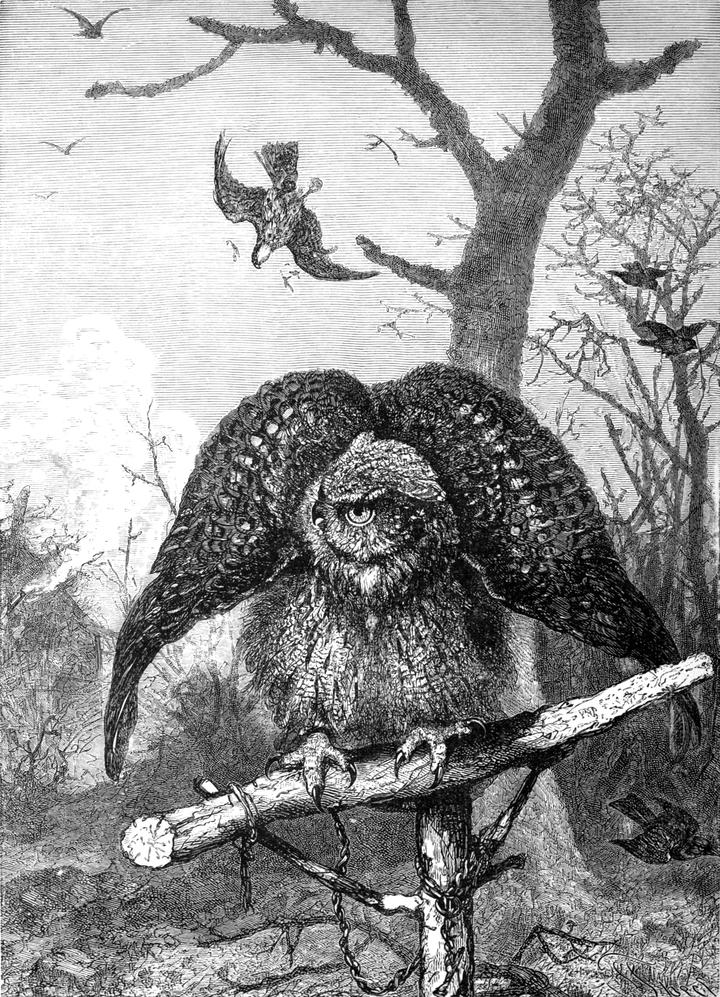

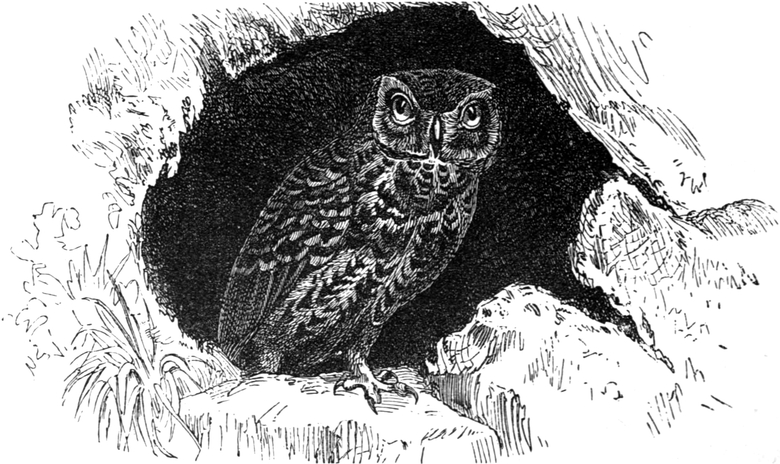

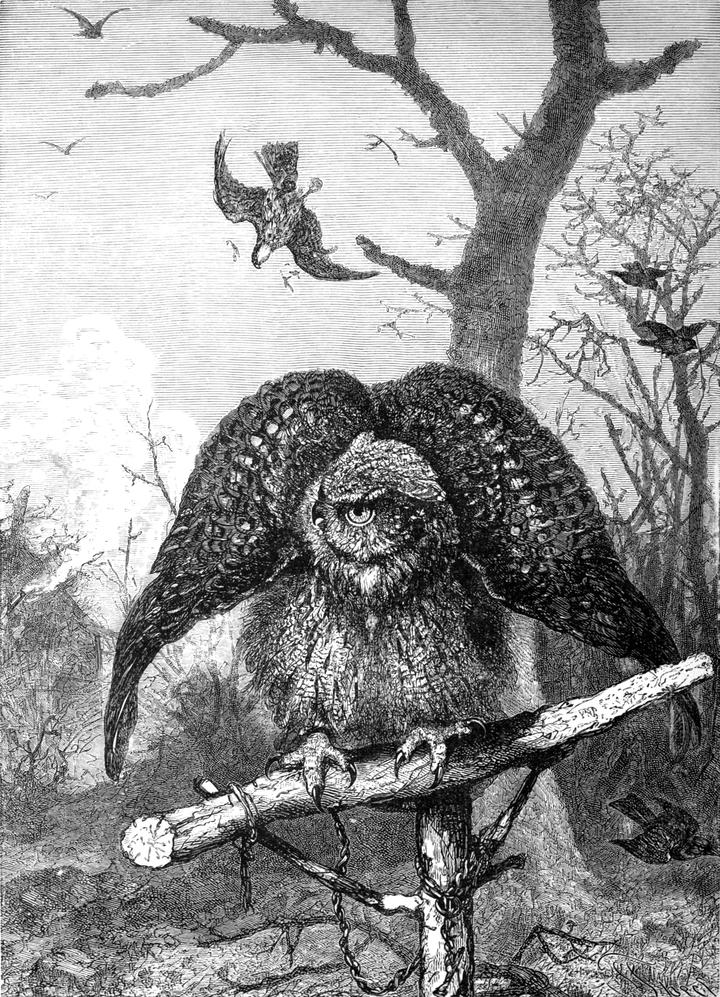

between Hawks and Owls—Owls in Bird-lore and Superstition—Families of the Sub-order—THE FISH OWL—PEL’S

FISH OWL[Pg x]—THE EAGLE OWL—Dr. Brehm’s Description of its Appearance and Habits—THE SNOWY

OWL—HAWK OWLS—PIGMY OWLETS—THE SHORT-EARED OWL—THE LONG-EARED OWL—THE BARN OWL—The

Farmer’s Friend—Peculiar Characters—Distribution

|

296

|

|

THE SECOND

ORDER.—PICARIAN BIRDS.

|

|

CHAPTER VII.

|

|

THE PARROTS.

|

|

Characteristics of the Order—The Sub-orders—ZYGODACTYLÆ—THE PARROTS—Their Talking Powers—Sections of

the Family—THE GREAT PALM COCKATOO—THE PYGMY PARROTS—THE AMAZON PARROTS—THE AMAZONS—THE

GREY PARROT—Court Favourites—Historical Specimens—In a State of Nature—Mr. Keulemans’ Observations—THE

CONURES—THE ROSE-RINGED PARRAKEET—Known to the Ancients—Habitat—Habits—THE

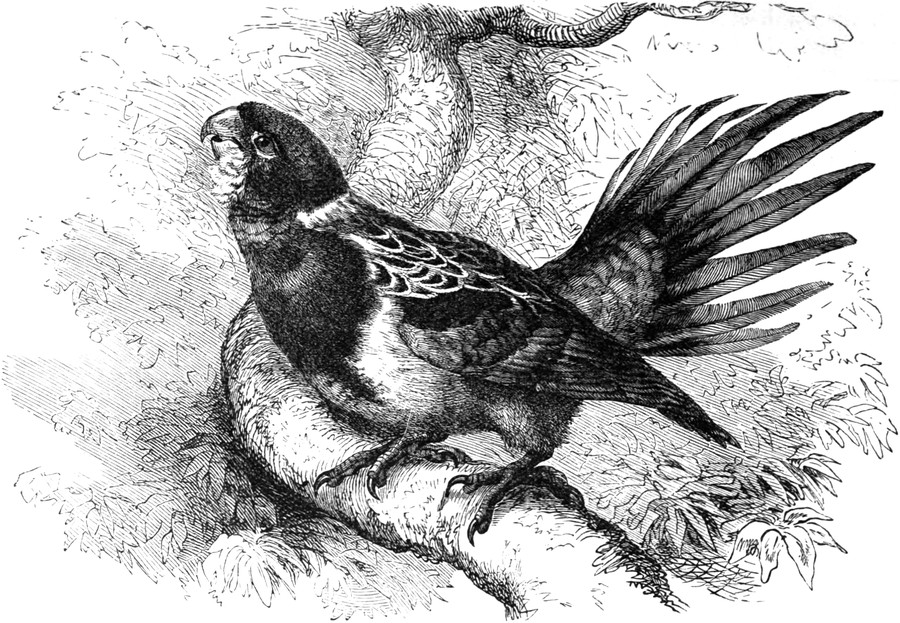

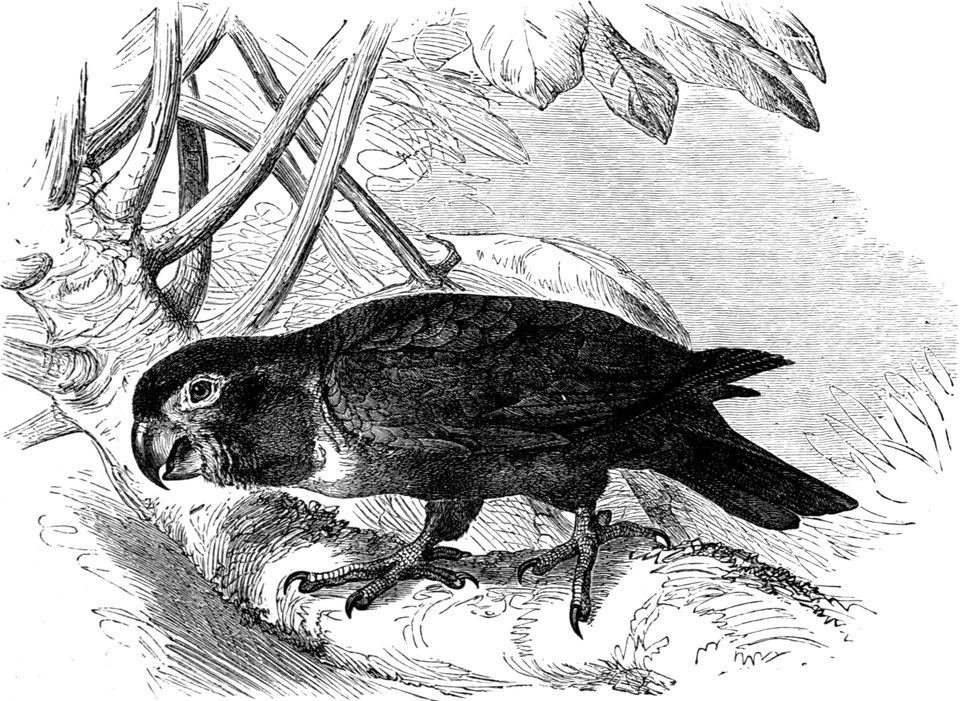

CAROLINA CONURE—Destructive Propensities—THE PARRAKEETS—THE OWL PARROT—Chiefly Nocturnal—Incapable

of Flight—How this Fact may be accounted for—Dr. Haast’s Account of its Habits—THE STRAIGHT-BILLED

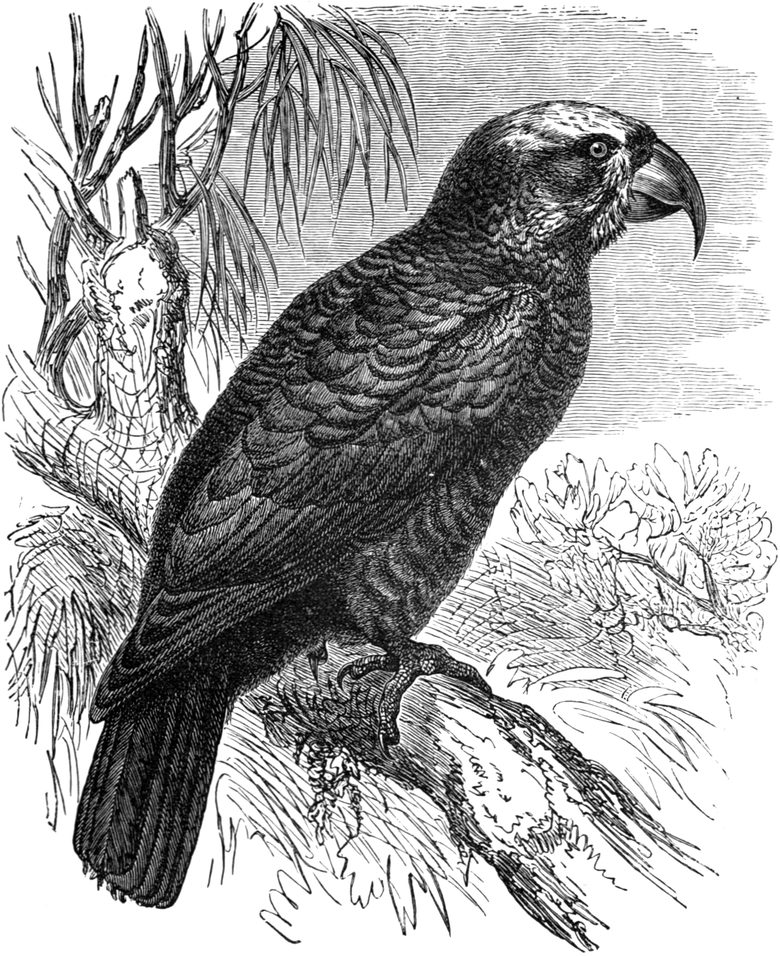

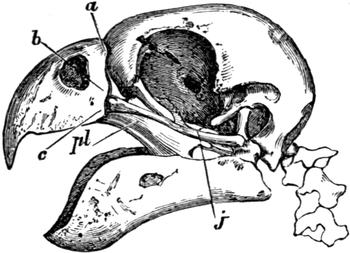

PARROTS—THE BRUSH-TONGUED PARROTS—THE NESTORS—THE KAKA PARROT—Skull of a Parrot—The

Bill

|

308

|

THE SECOND ORDER.—PICARIAN

BIRDS.

SUB-ORDER I.—ZYGODACTYLÆ.

|

|

CHAPTER VIII.

|

|

CUCKOOS—HONEY

GUIDES—PLANTAIN-EATERS—WOODPECKERS—TOUCANS—BARBETS.

|

|

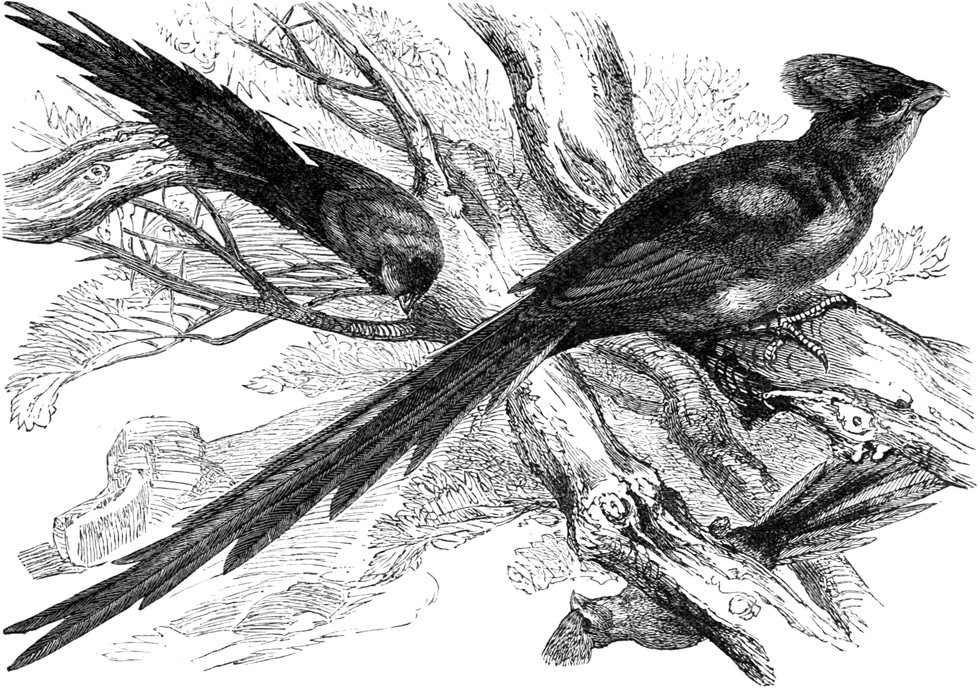

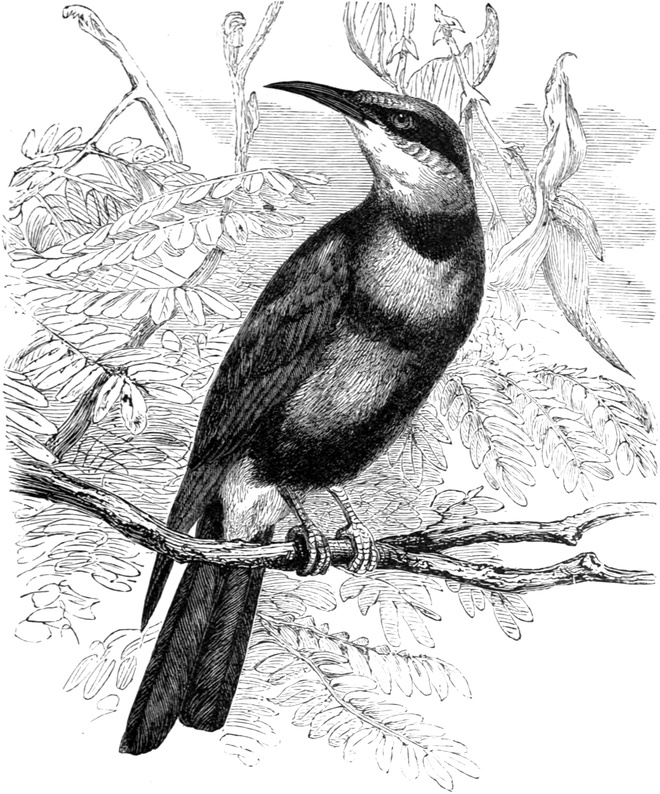

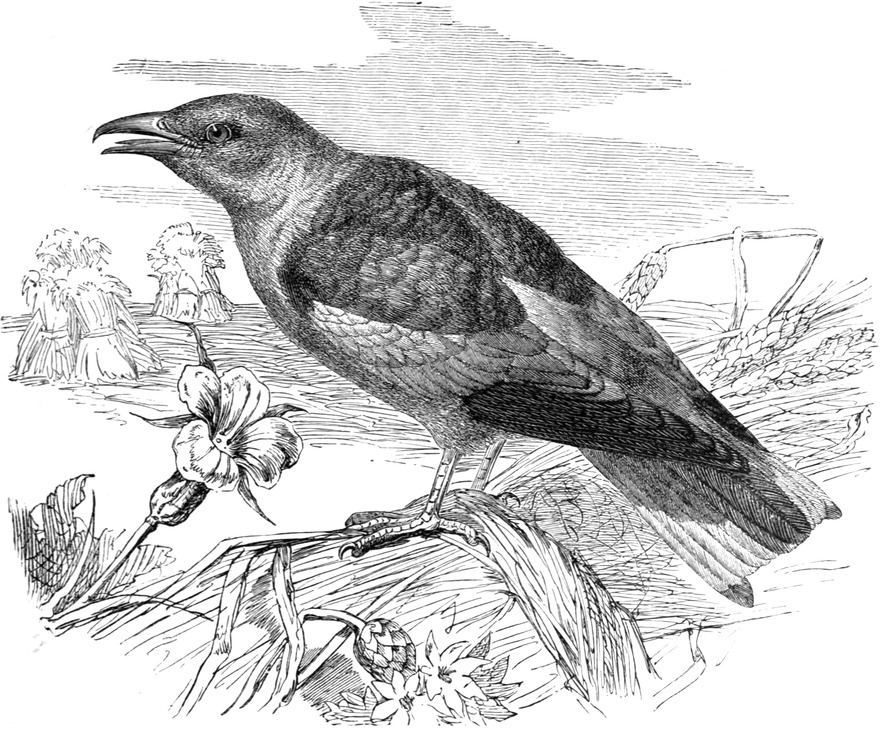

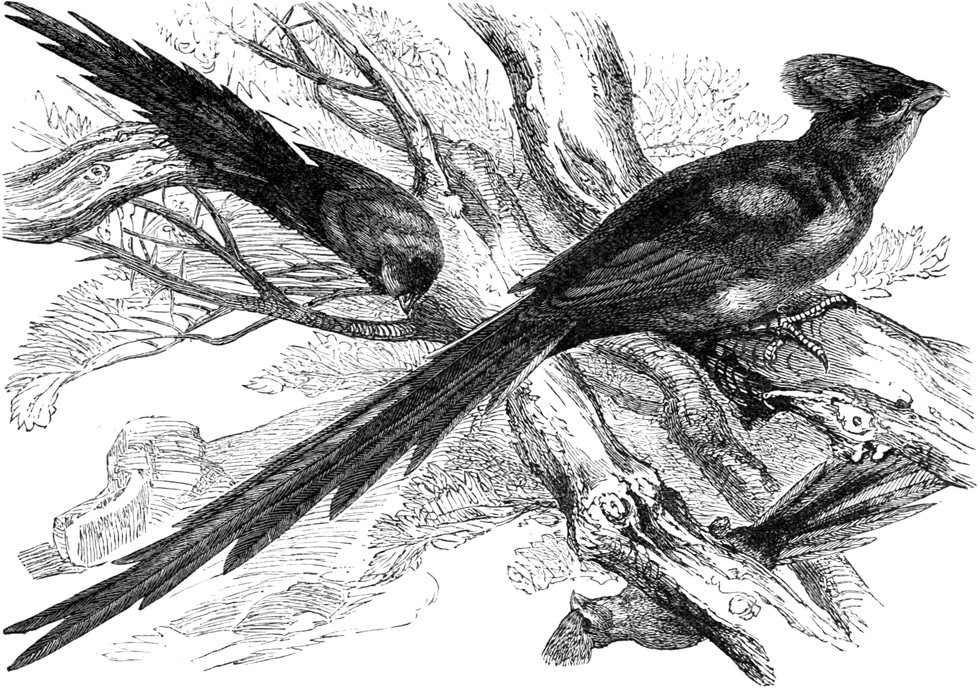

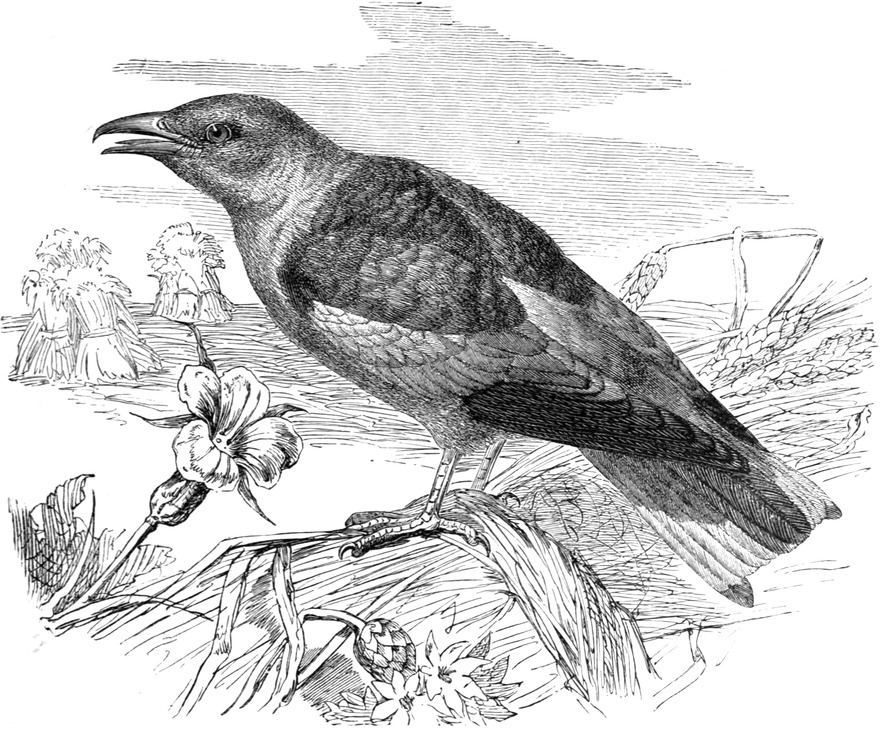

THE CUCKOOS—THE BUSH CUCKOOS—THE LARK-HEELED CUCKOOS, OR COUCALS—THE COMMON CUCKOO—Its

Characteristics—Mrs. Blackburn’s Account of a Young Cuckoo Ejecting a Tenant—Breeding Habits—The Eggs—The

Call-notes of Male and Female—Food—Its Winter Home—Its Appearance and Plumage—THE HONEY

GUIDES—Kirk’s Account of their Habits—Mrs. Barber’s Refutation of a Calumny against the Bird—THE

PLANTAIN-EATERS—THE WHITE-CRESTED PLANTAIN-EATER—THE GREY PLANTAIN-EATER—THE COLIES—THE

WHITE-BACKED COLY—THE WOODPECKERS—How they Climb and Descend Trees—Their Bill—Do they

Damage Sound Trees?—THE WRYNECKS—THE YAFFLE—THE RED-HEADED WOODPECKER—THE SPOTTED

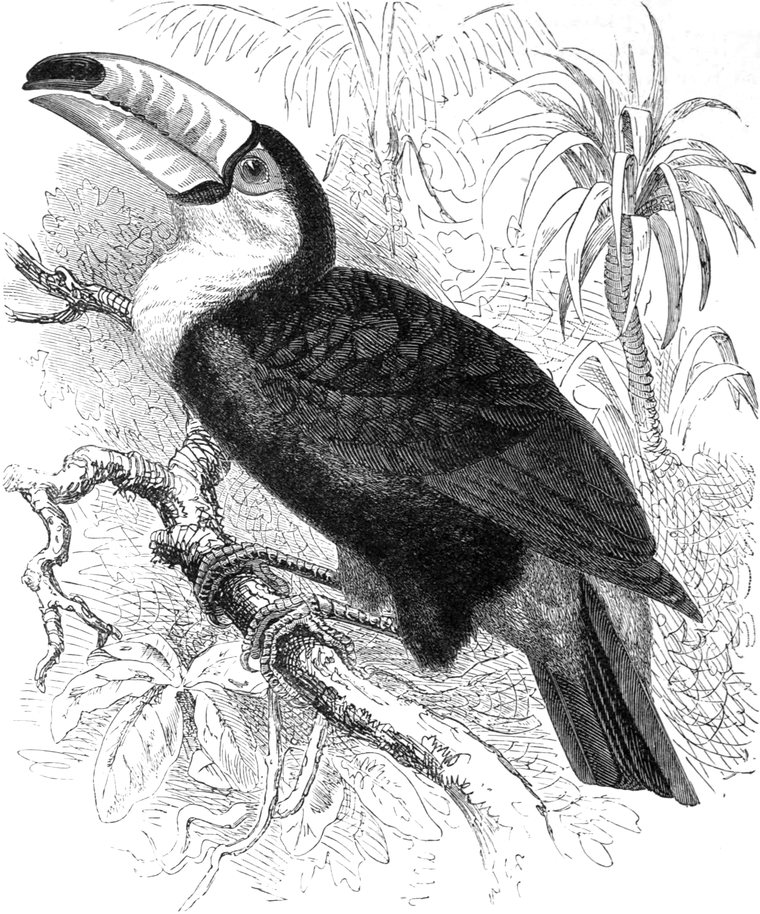

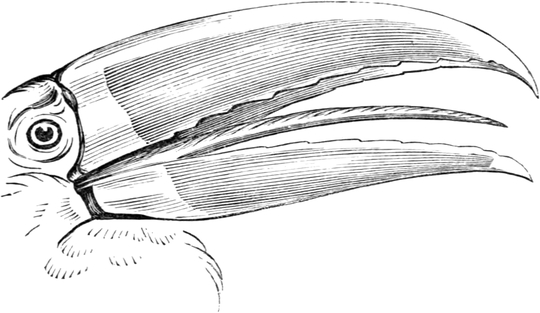

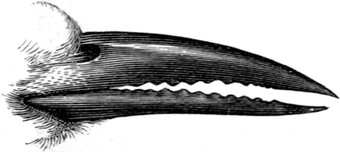

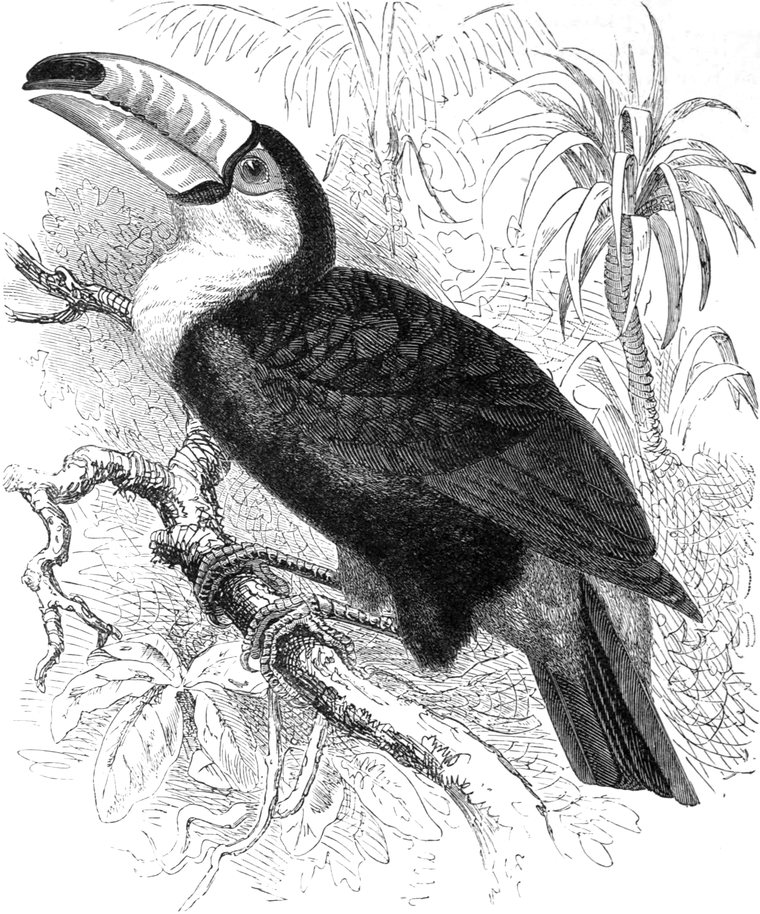

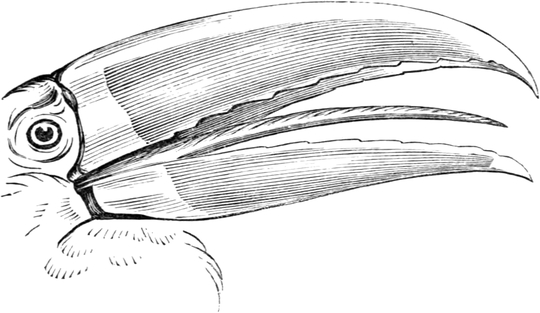

WOODPECKER—THE TOUCANS—Mr. Gould’s Account of their Habits—Mr. Waterton’s Account—The

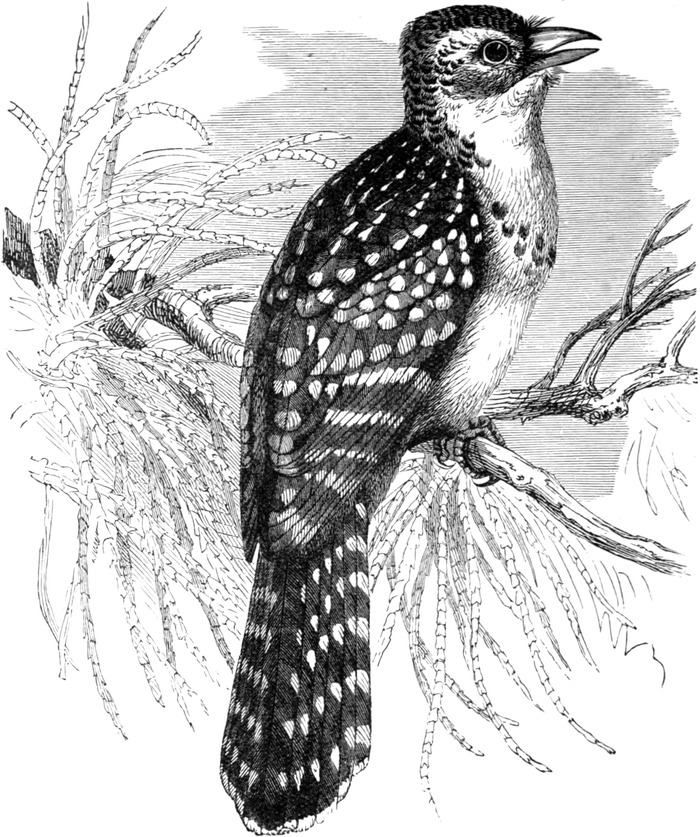

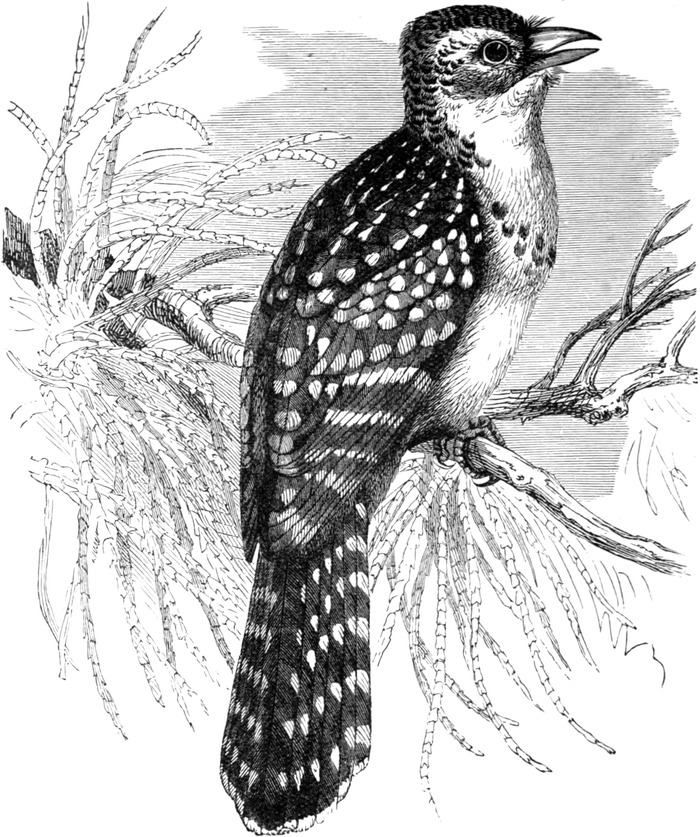

Enormous Bill—Azara’s Description of the Bird—Mr. Bates’ History of a Tame Toucan—THE BARBETS—Messrs.

Marshall’s Account of the Family—Mr. Layard on their Habits

|

323

|

THE SECOND ORDER.—PICARIAN

BIRDS.

SUB-ORDER II.—FISSIROSTRES.

|

|

CHAPTER IX.

|

|

THE JACAMARS, PUFF BIRDS, KINGFISHERS, HORNBILLS,

AND HOOPOES.

|

|

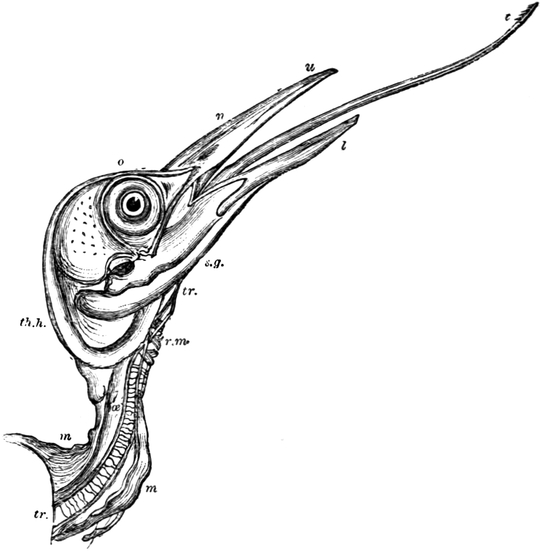

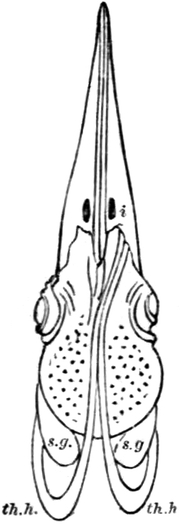

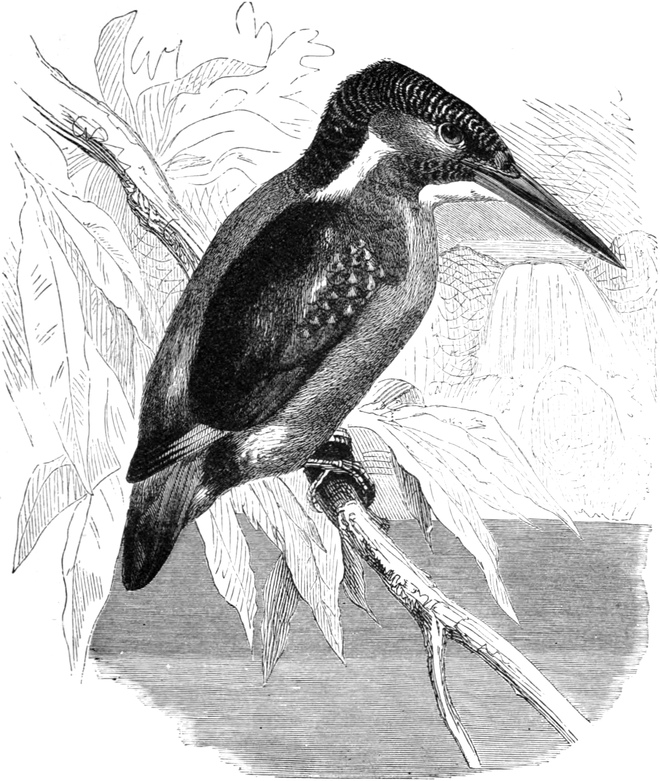

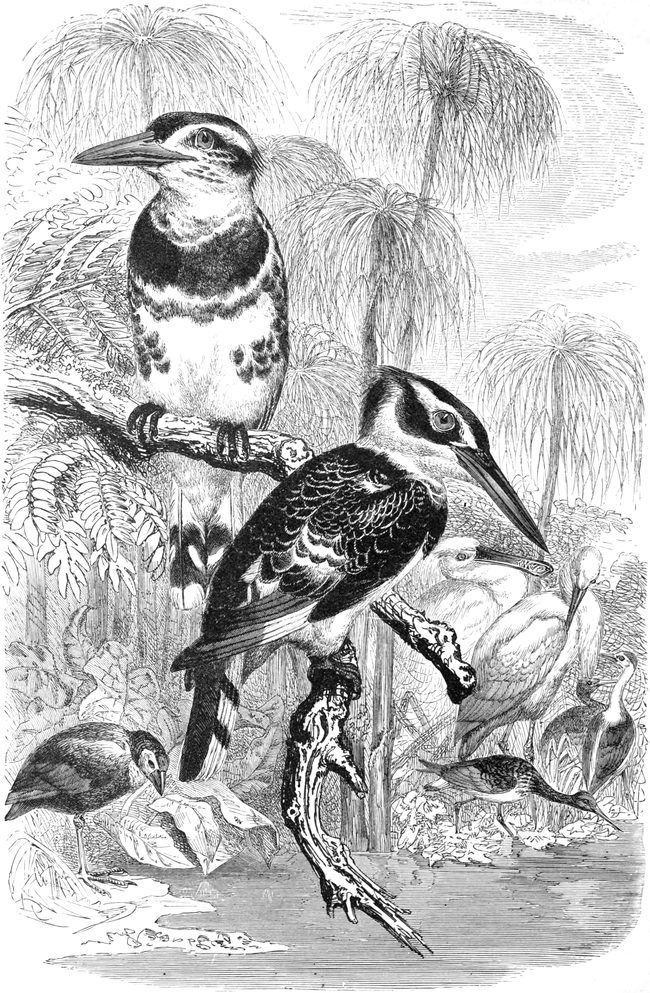

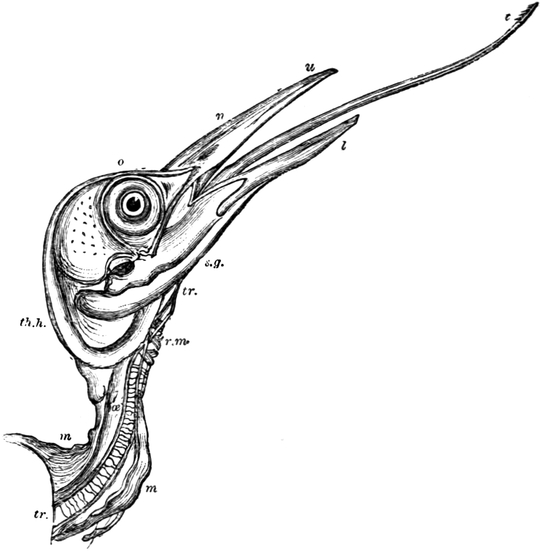

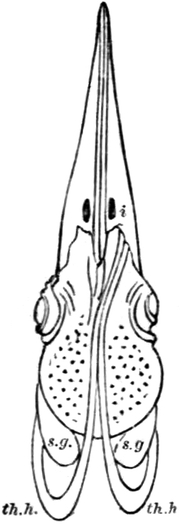

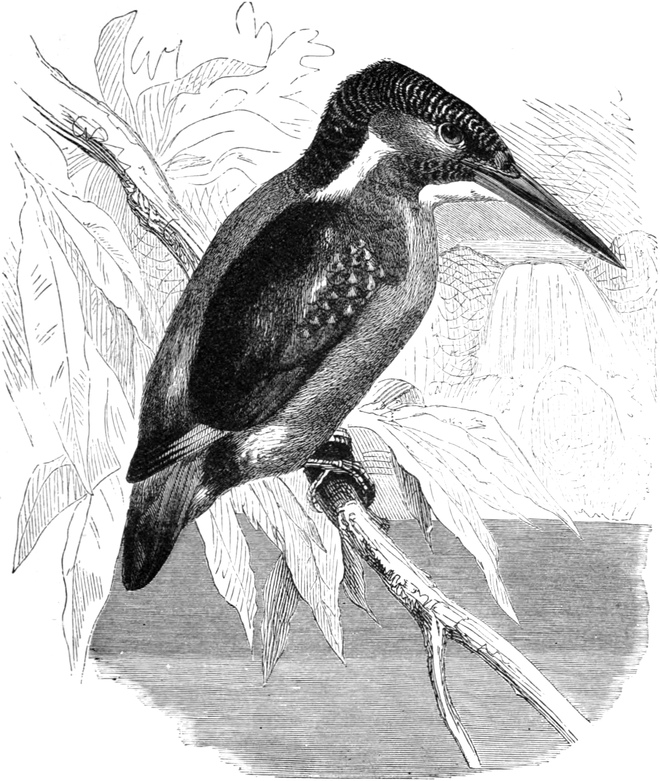

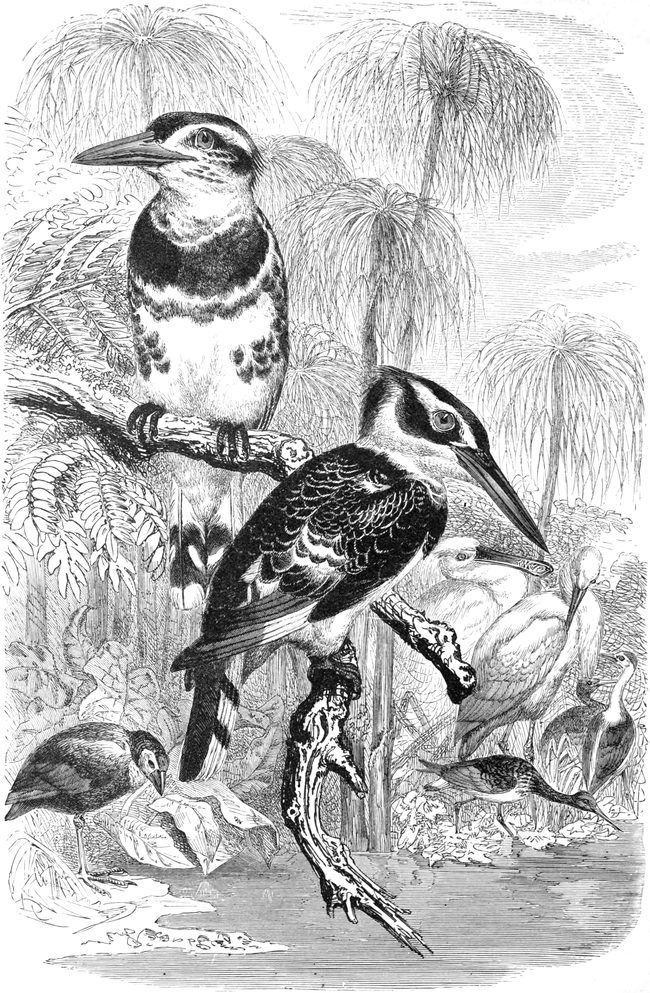

THE JACAMARS—THE PUFF BIRDS—THE KINGFISHERS—Characters—THE COMMON KINGFISHER—Distribution—Its

Cry—Habits—After its Prey—Its own Nest-builder—Mr. Rowley’s Note on the Subject—Nest in the

British Museum—Superstitions concerning the Kingfisher—Colour—Various Species—CRESTED KINGFISHER—PIED

KINGFISHER—Dr. Von Heuglin’s Account of its Habits—New World Representatives—OMNIVOROUS KINGFISHERS—THE

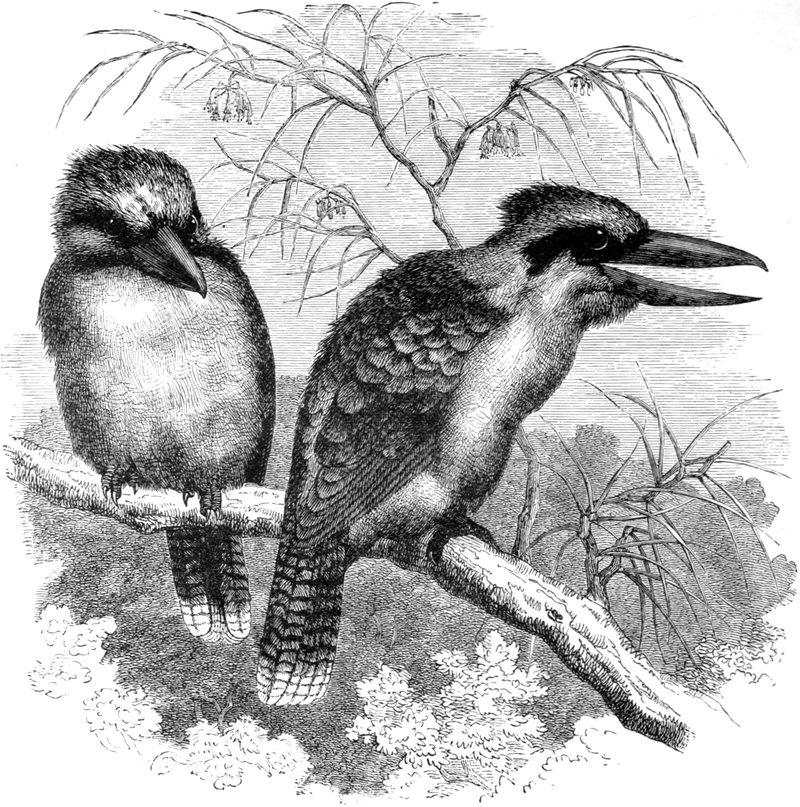

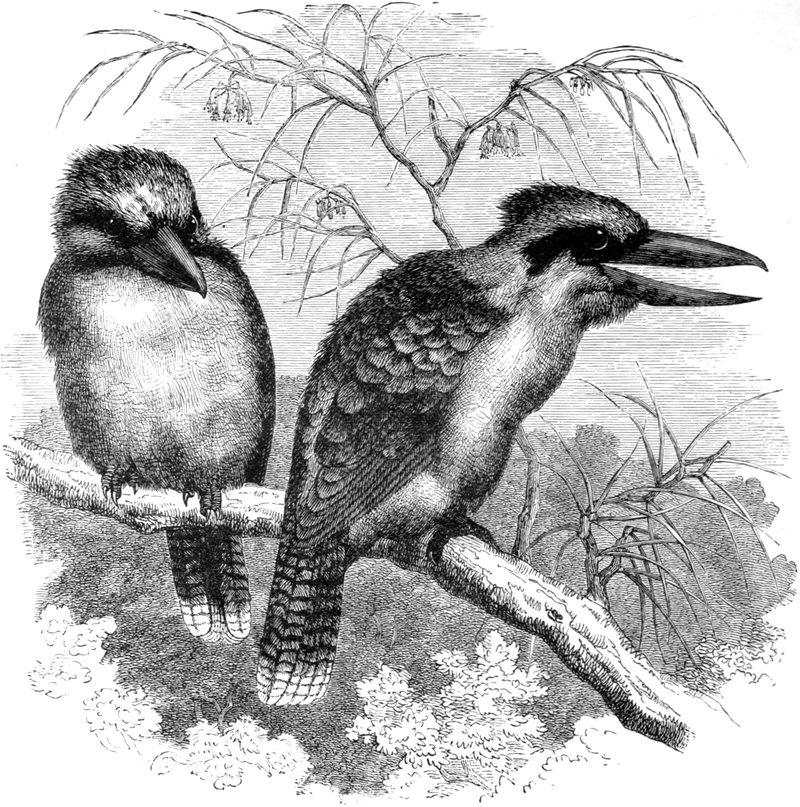

AUSTRALIAN CINNAMON-BREASTED KINGFISHER—Macgillivray’s Account of its Habits—THE LAUGHING

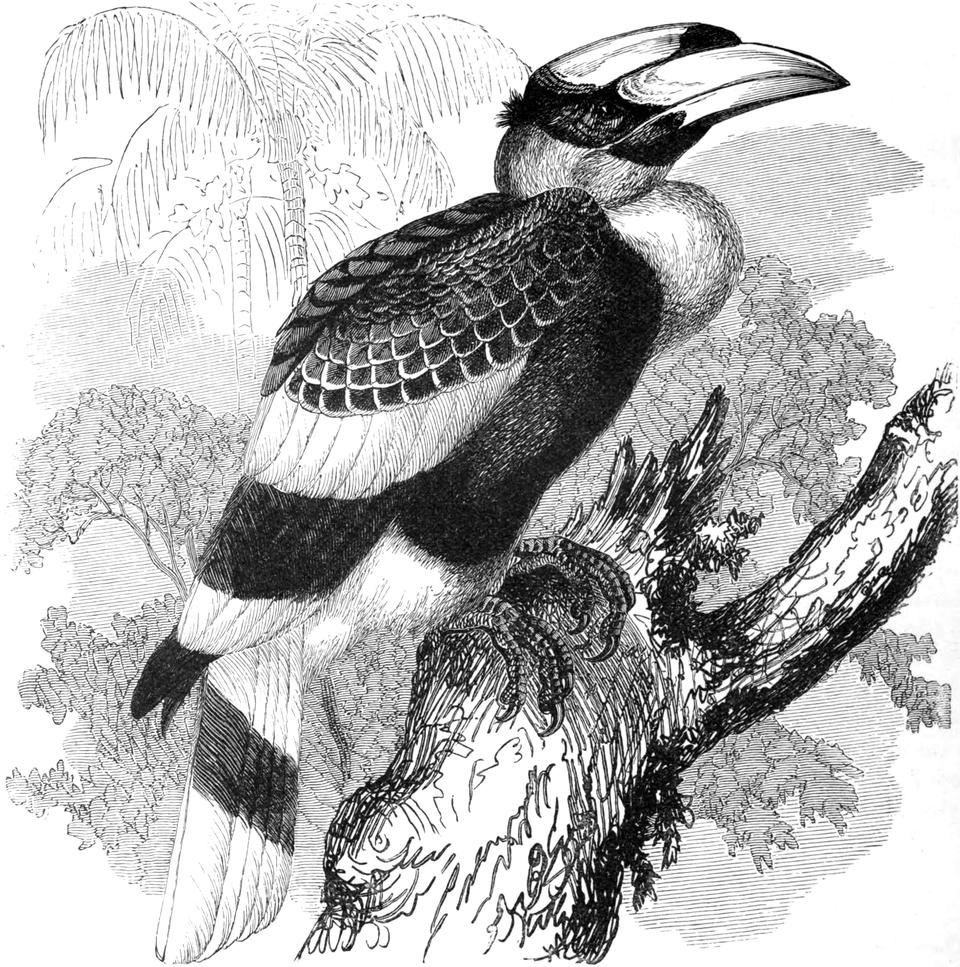

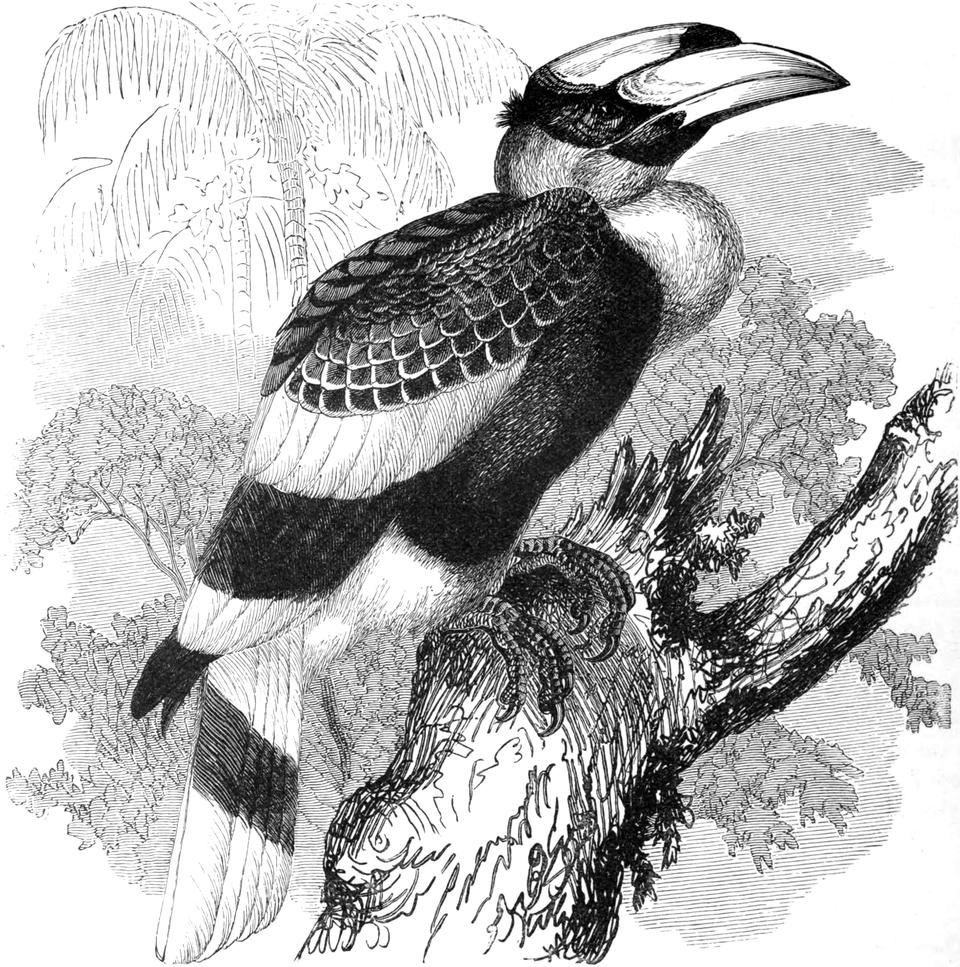

JACKASS of Australia—Its Discordant Laugh—The “Bushman’s Clock”—Colour—Habits—THE HORNBILLS—Character—Their

Heavy Flight—Noise produced when on the Wing—Food—Extraordinary Habit of

Imprisoning the Female—Native Testimony—Exception—Fed by the Male Bird—Dr. Livingstone’s Observations

on the point, and Mr. Bartlett’s Remarks—Strange Gizzard Sacs—Dr. Murie’s Remarks—Mr. Wallace’s Description

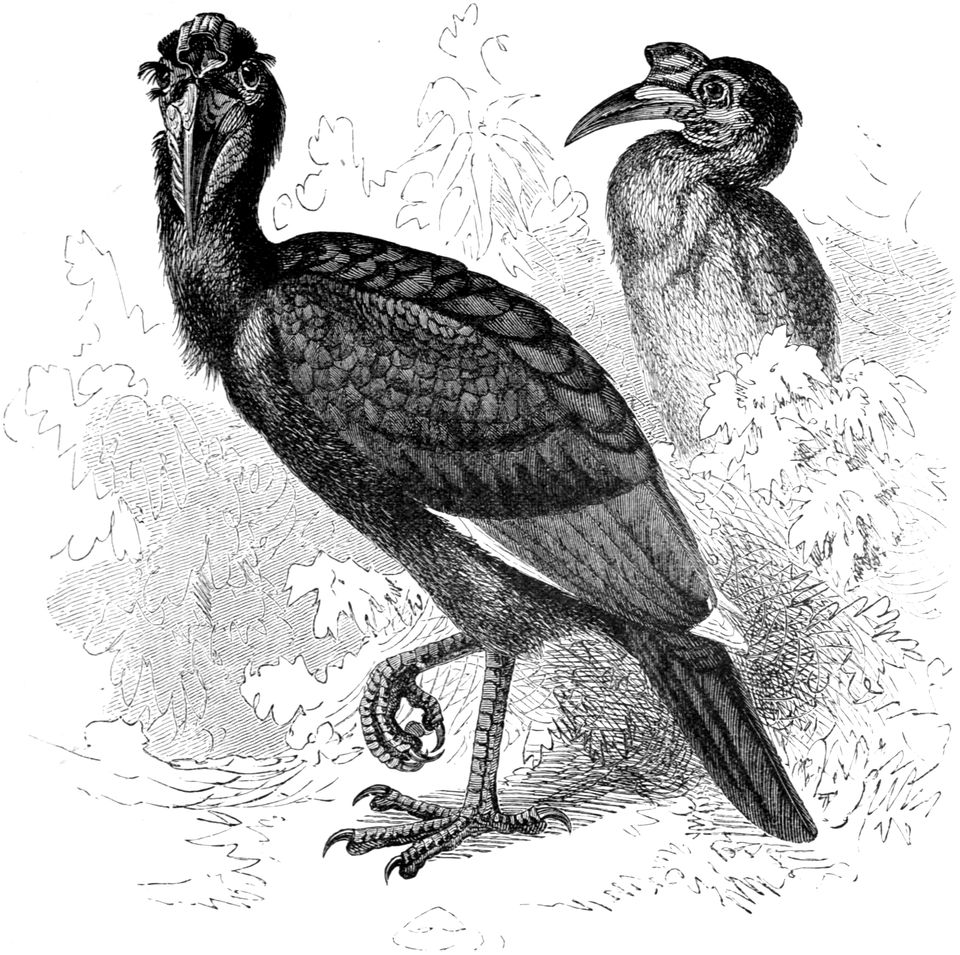

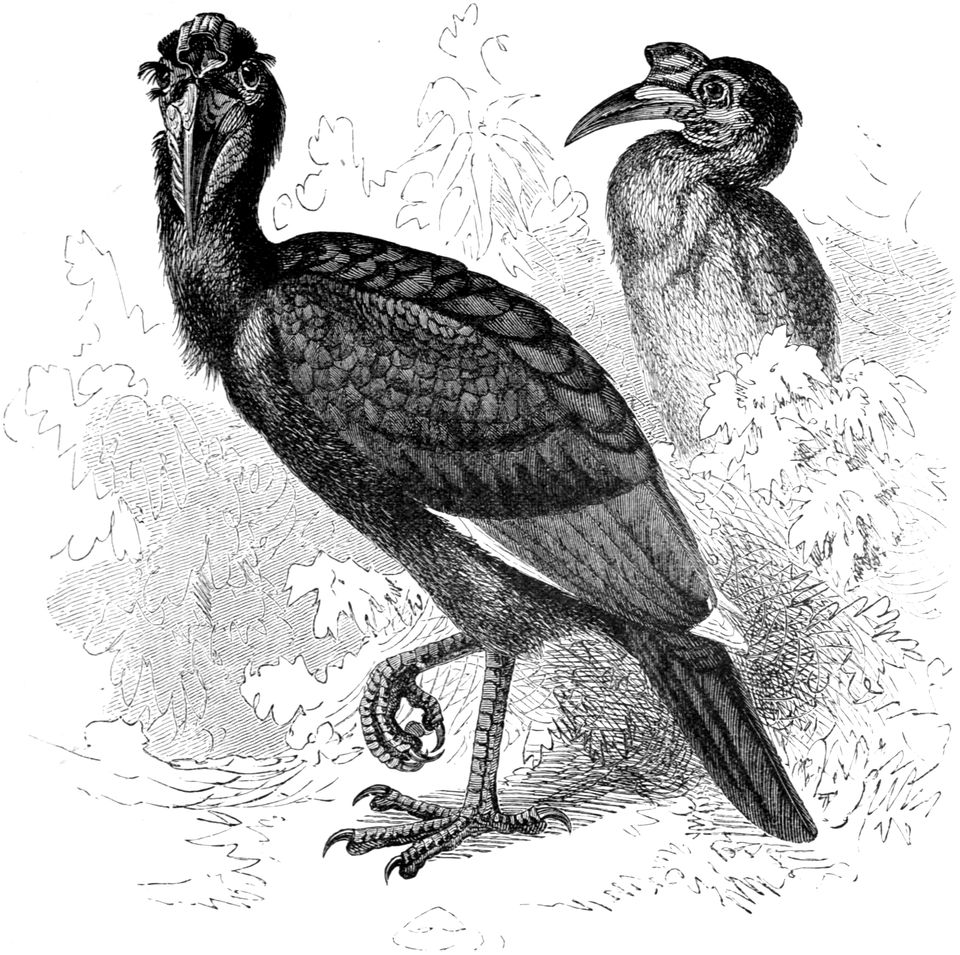

of the Habits of the Hornbills—Capture of a Young One in Sumatra—THE GROUND HORNBILLS—South

African Species—Kaffir Superstition regarding it—Habits—Mr. Ayres’ Account of the Natal Species—How it Kills

Snakes—The Call—Habits—Mr. Monteiro’s Description of the Angola Form—Turkey-like Manner—Wariness—Food—THE

HOOPOES—Appearance—Distribution—THE COMMON HOOPOE—Habits—The Name—How does it

produce its Note?—THE WOOD HOOPOES—Habits

|

343

|

|

CHAPTER X.

|

|

THE BEE-EATERS—MOTMOTS—ROLLERS—TROGONS—NIGHTJARS,

OR GOATSUCKERS—SWIFTS—HUMMING-BIRDS.

|

|

THE BEE-EATERS—Their Brilliant Plumage—Colonel Irby’s Account of the Bird in Spain—Shot for Fashion’s sake—THE

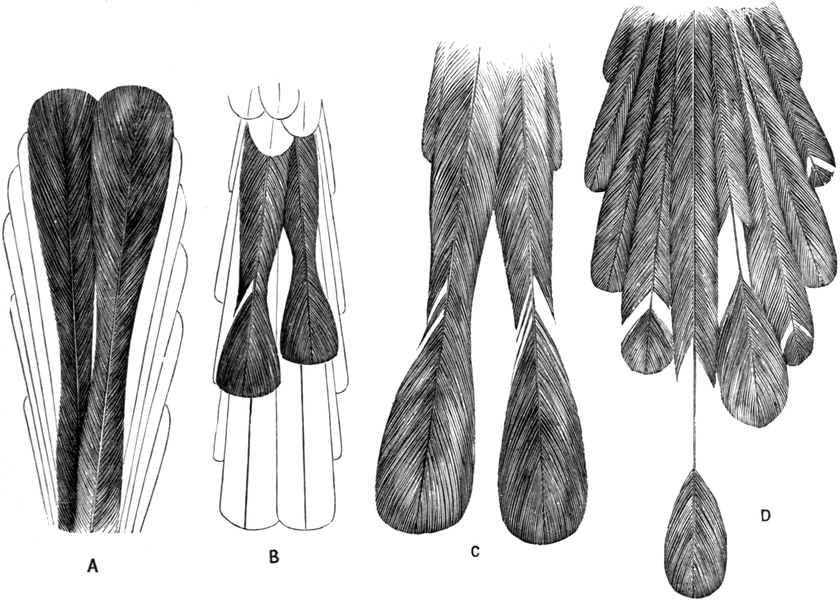

MOTMOTS—Appearance—Mr. Waterton on the Houtou—Curious Habit of Trimming its Tail—Mr. O.

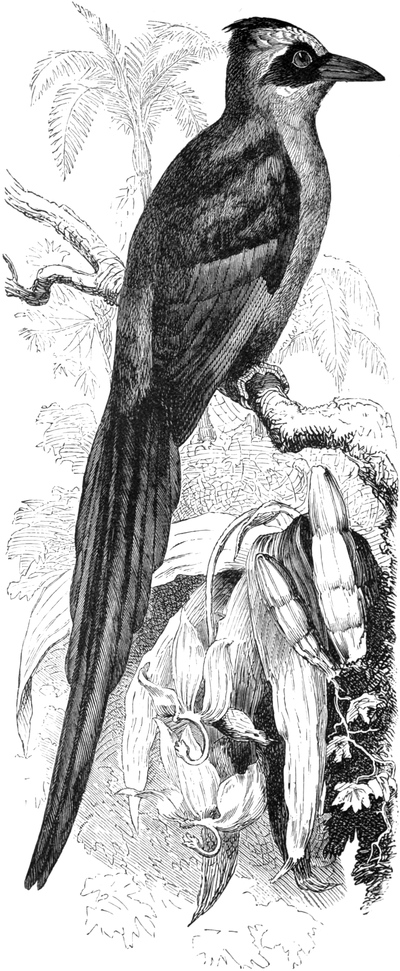

Salvin’s Observations on this point—Mr. Bartlett’s Evidence—THE ROLLERS—Why so called—Canon Tristram’s

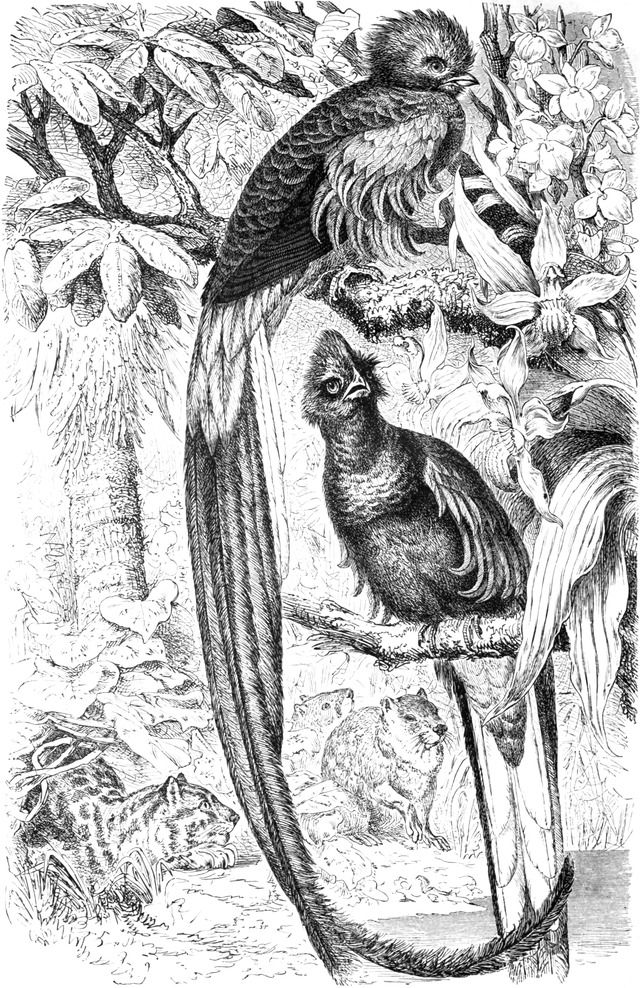

Account of their Habits—Colour—Other Species—THE TROGONS—Where found—Peculiar Foot—Tender Skin—Inability

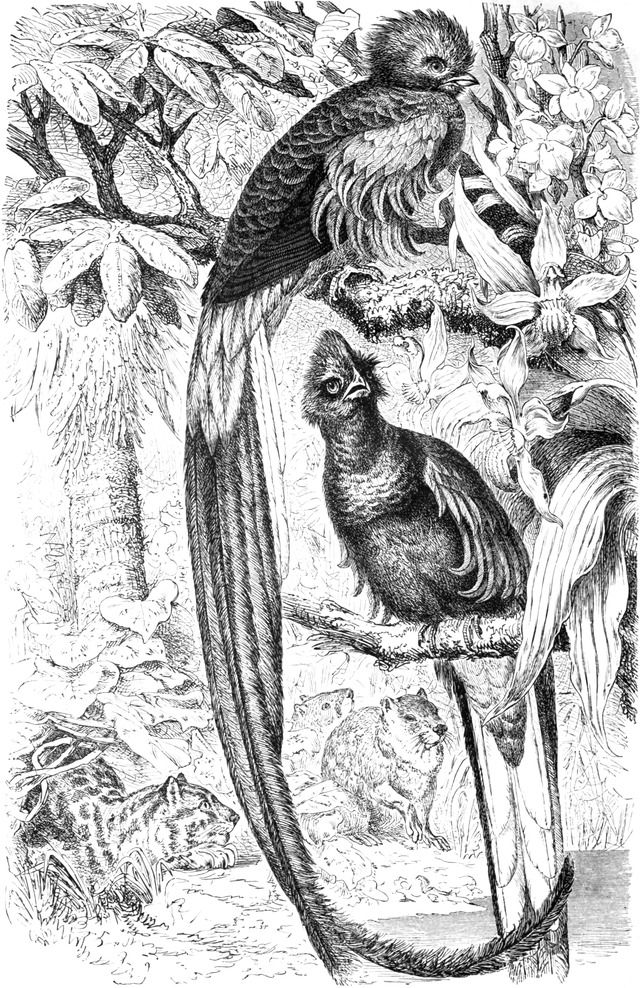

to Climb—Their Food—THE LONG-TAILED TROGON, OR QUESAL—Mr. Salvin’s Account of its Habits—Its

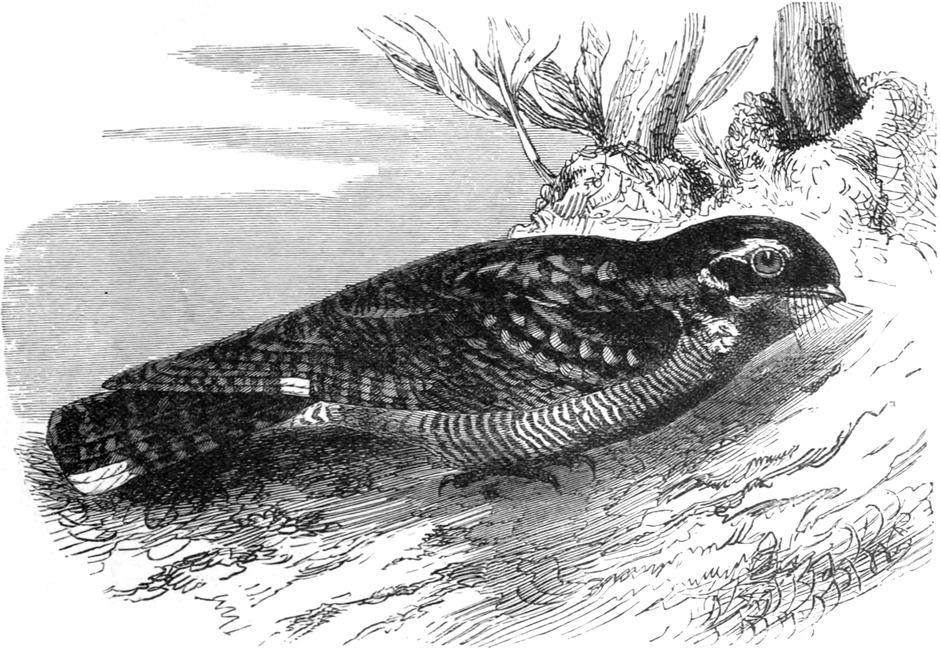

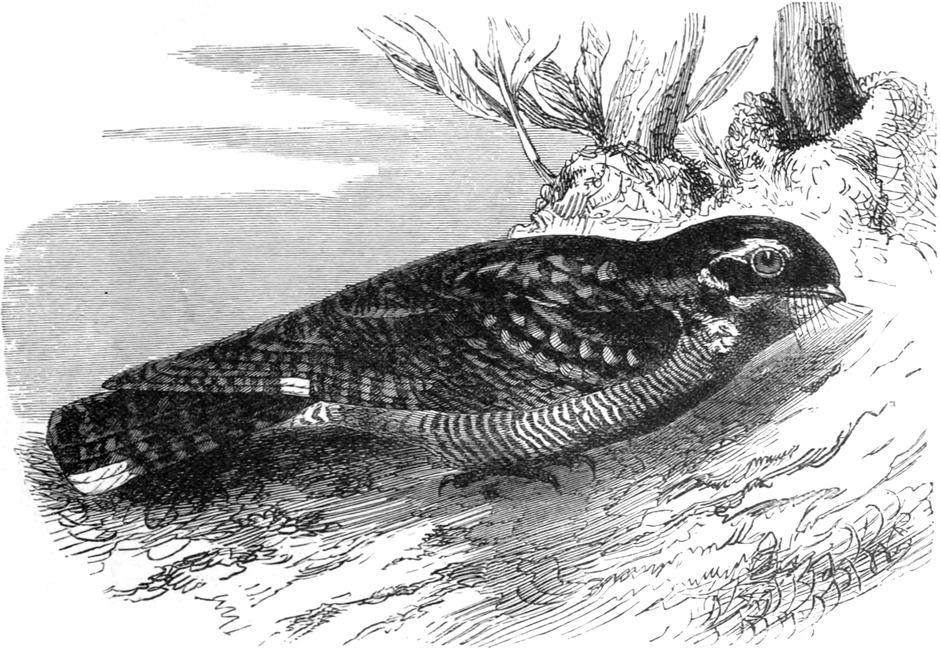

Magnificent Colour—How they are Hunted—THE NIGHTJARS, OR GOATSUCKERS—Appearance—Distribution—The

Guacharo, or Oil Bird—“Frog-mouths”—Mr. Gould’s Account of the Habits of the Tawny-shouldered

Podargus—How it Builds its Nest—Mr. Waterton’s Vindication of the Goatsucker—What Services the Bird does

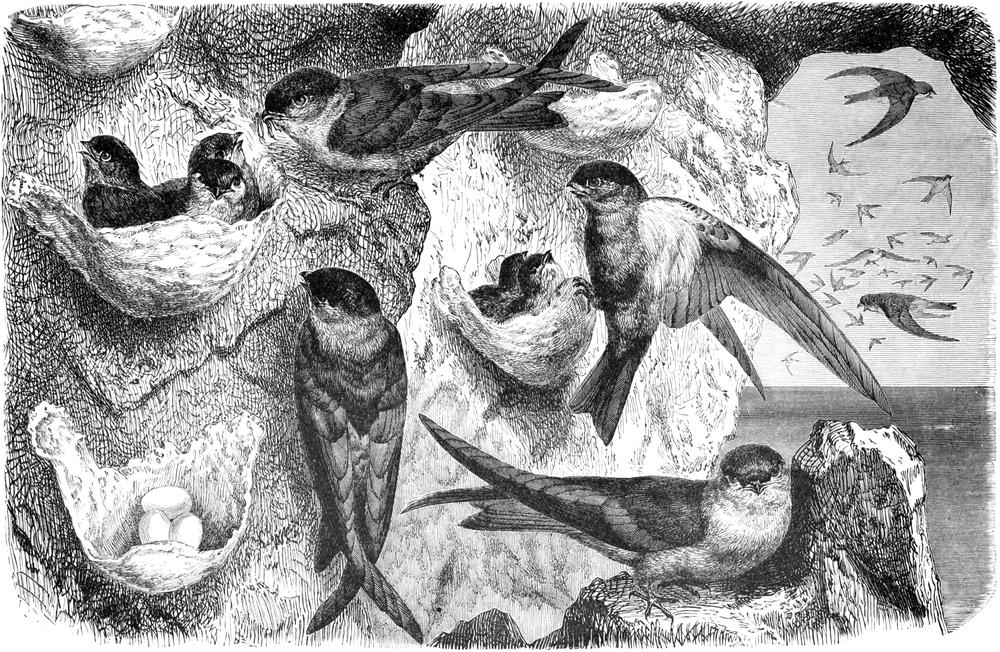

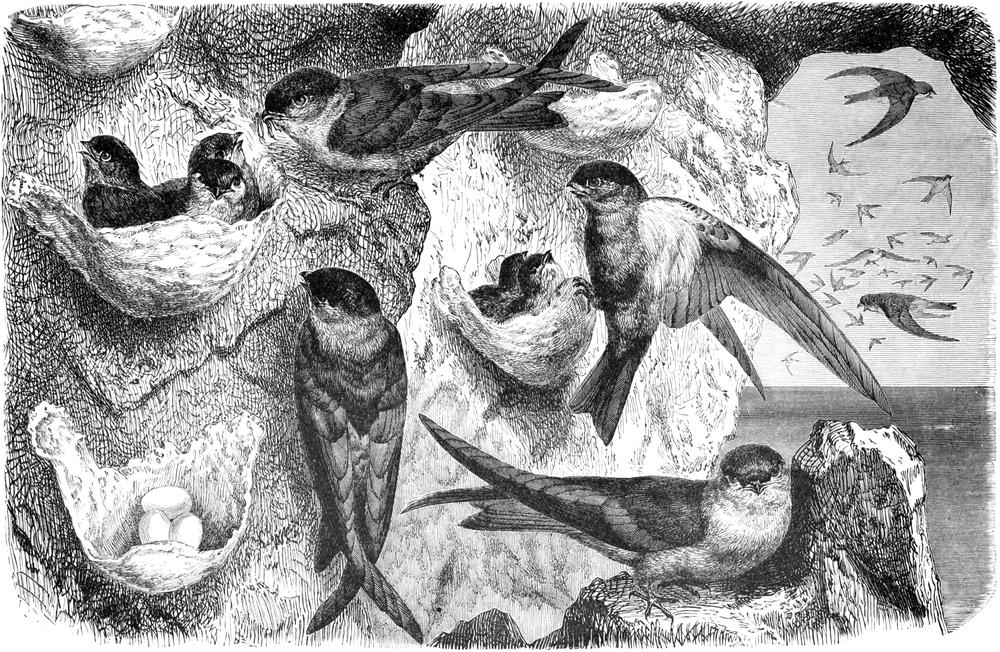

really render Cattle, Goats, and Sheep—Its Cry—THE COMMON GOATSUCKER—THE SWIFTS—THE COMMON

SWIFT—Migration—Their Home in the Air—When they Breed—Nest—TREE SWIFTS—The Edible-Nest Swiftlets—Mr.

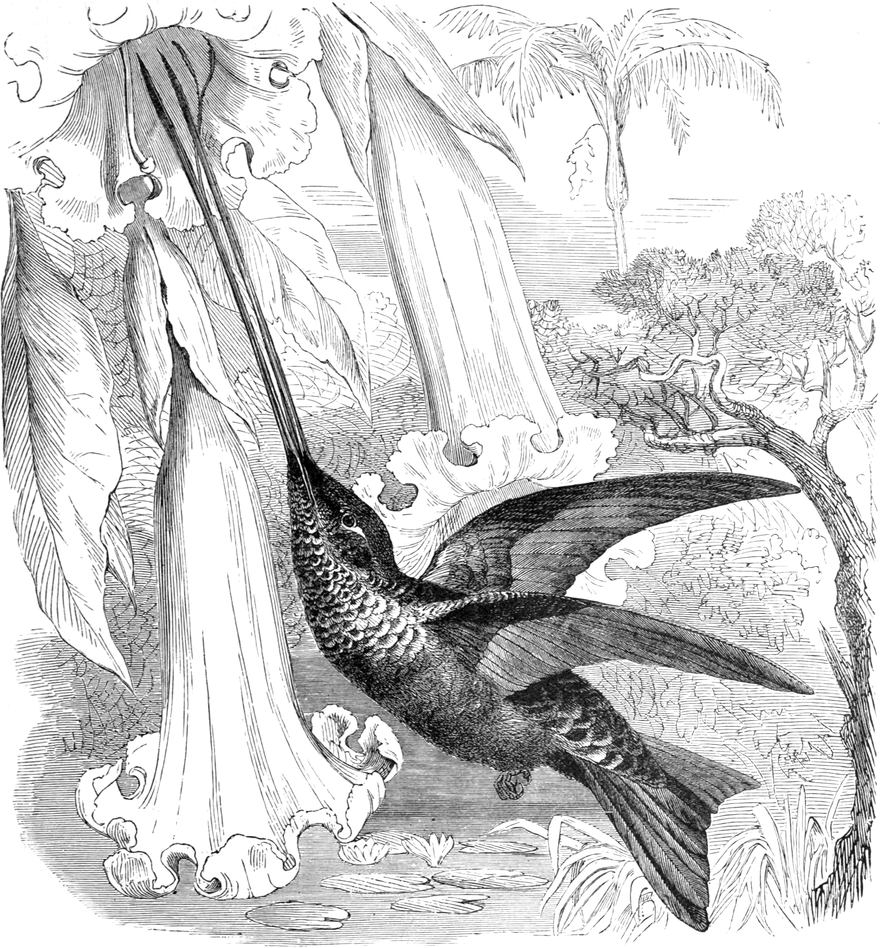

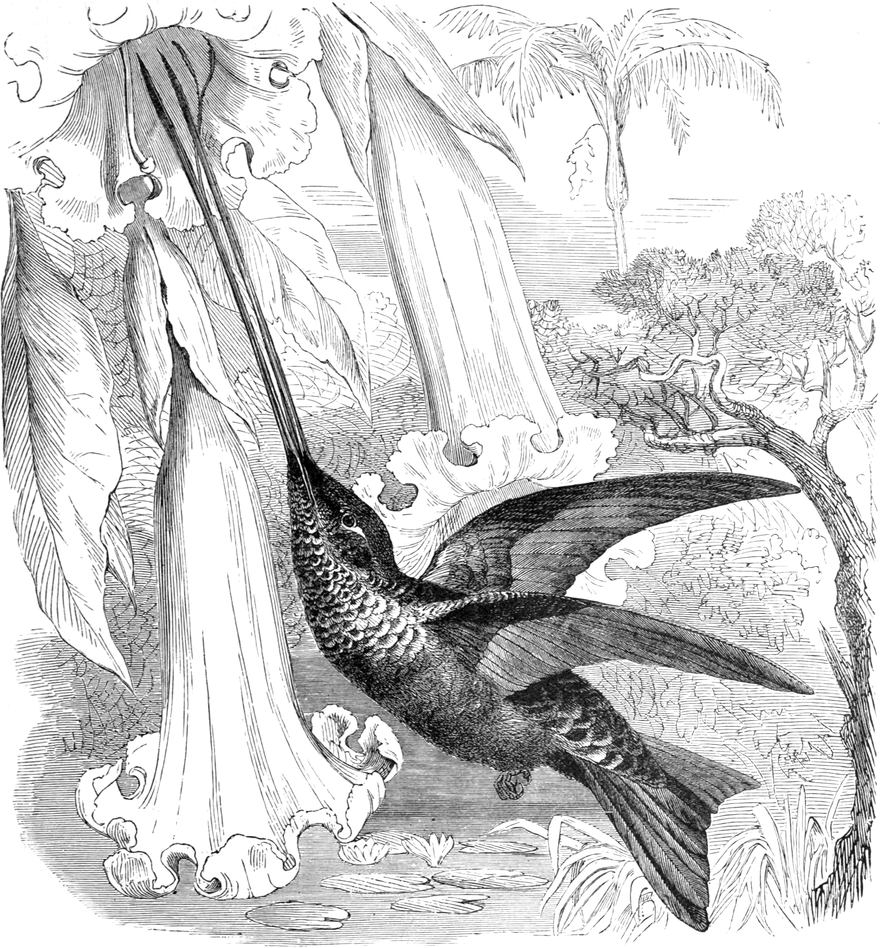

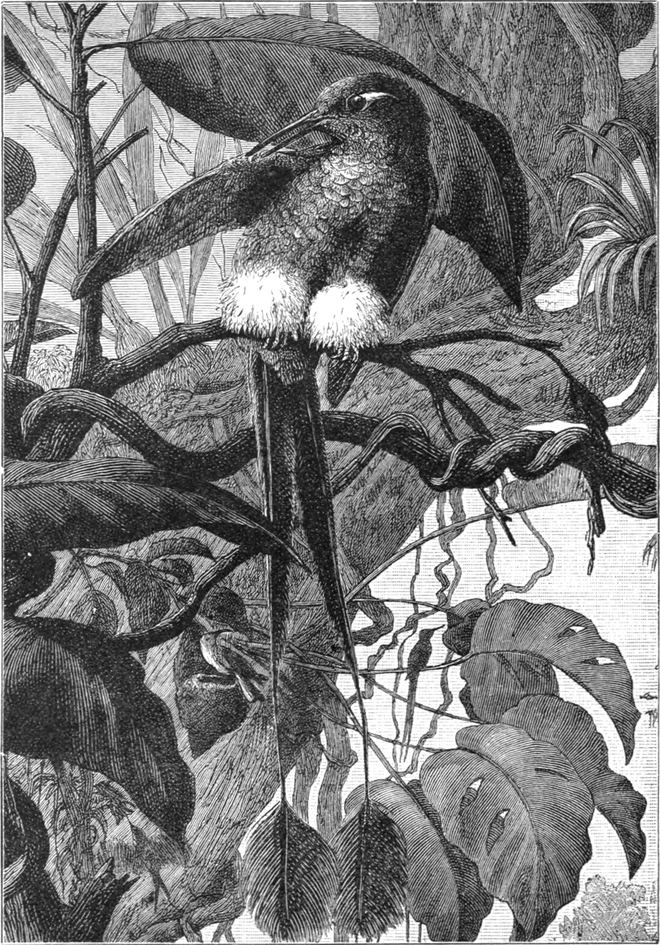

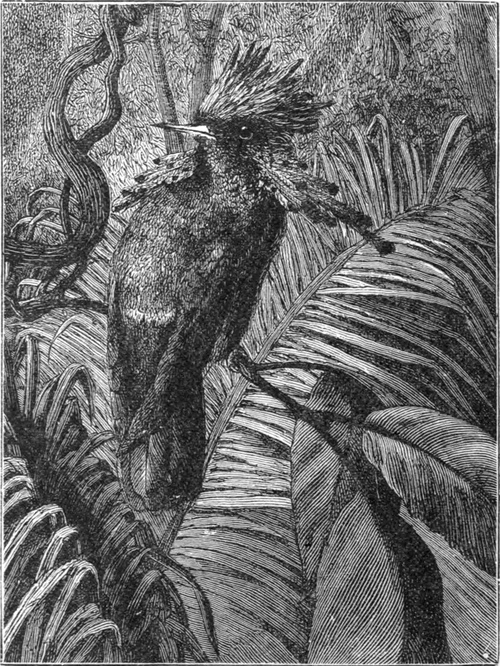

E. L. Layard’s Visit to the Cave of the Indian Swiftlet—THE HUMMING BIRDS—Number of Species—Distribution—Professor

Newton’s Description of the Bird—Mr. Wallace on their Habits—Wilson on the North

American Species

|

360

|

[Pg xi]

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

|

|

|

PAGE

|

|

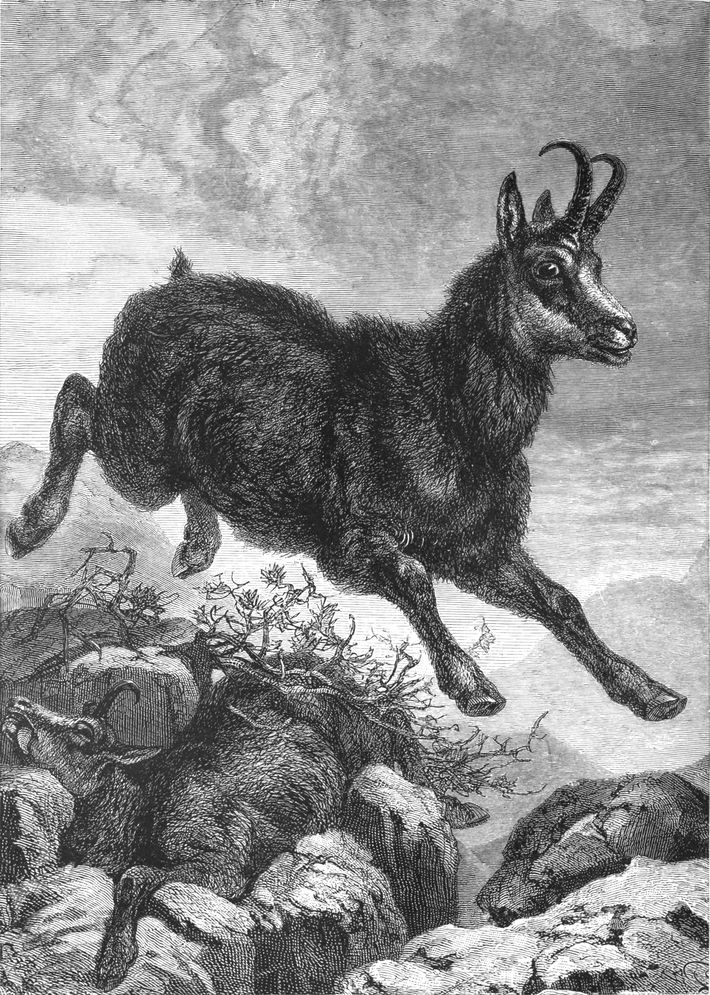

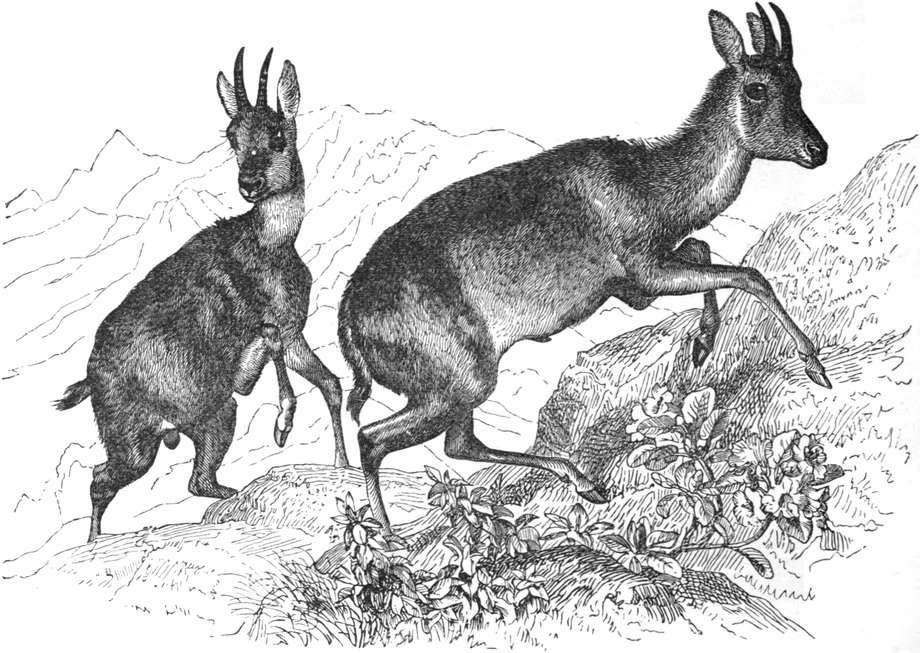

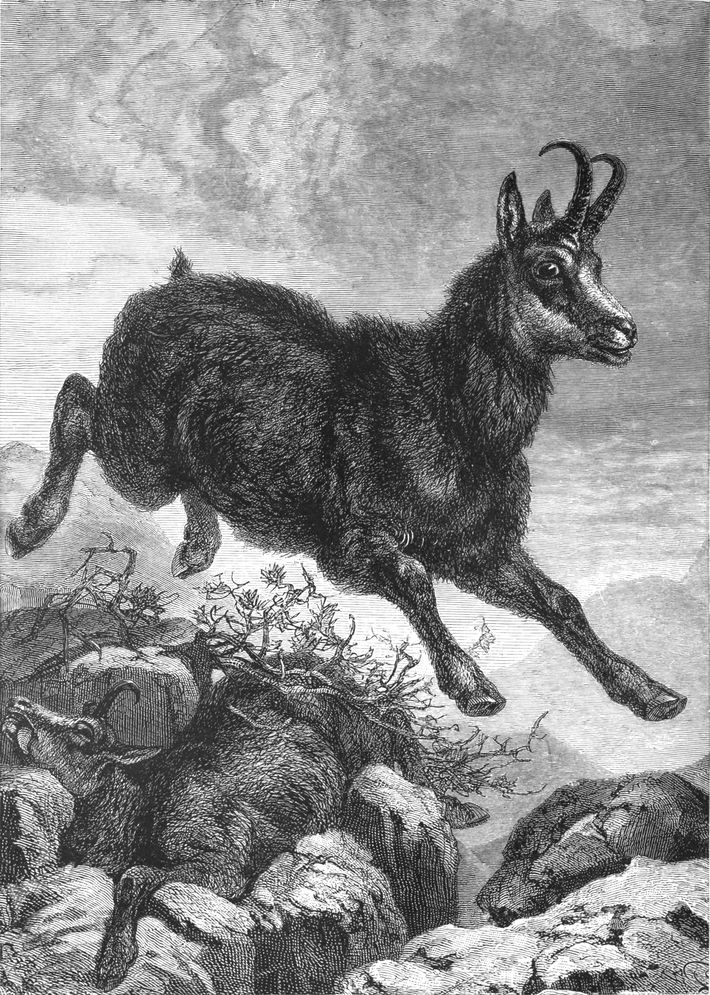

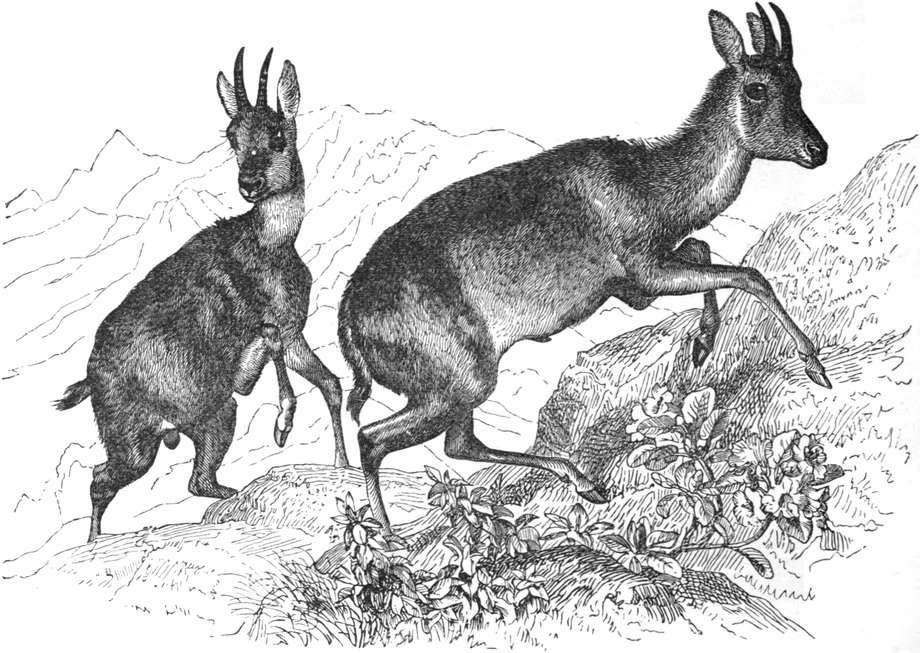

The Chamois

|

|

|

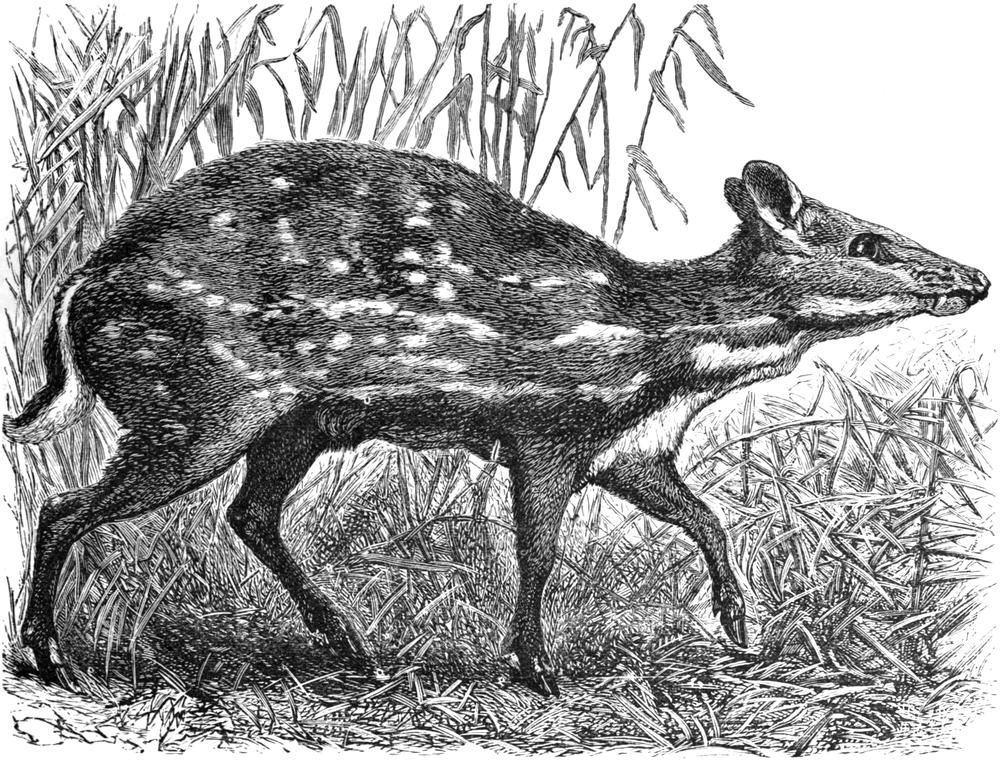

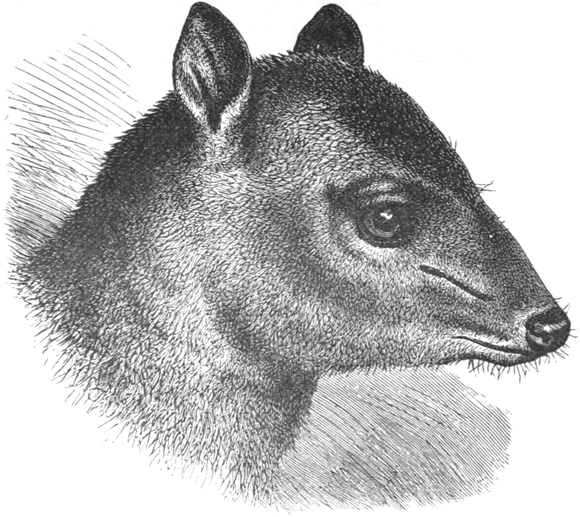

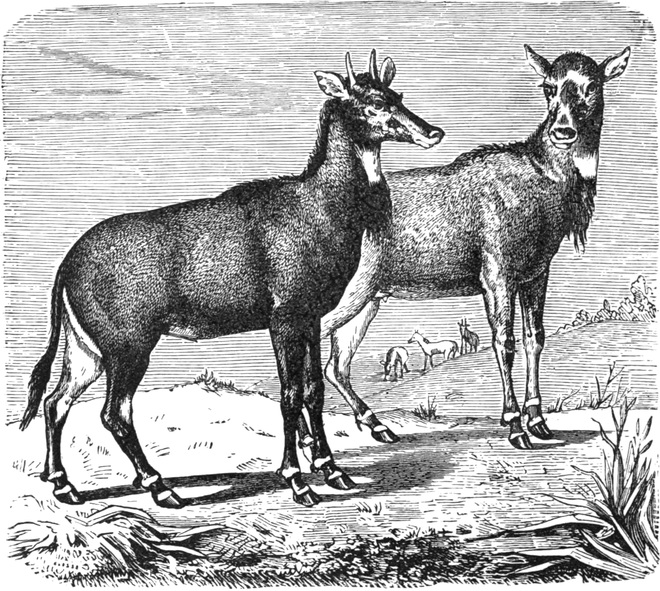

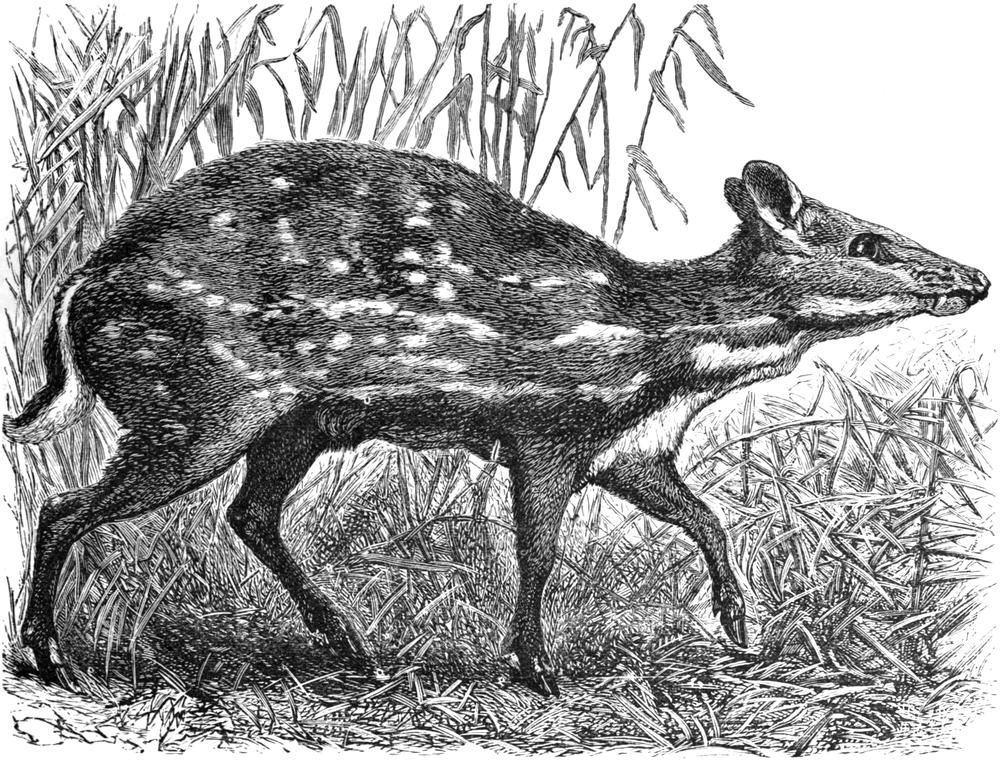

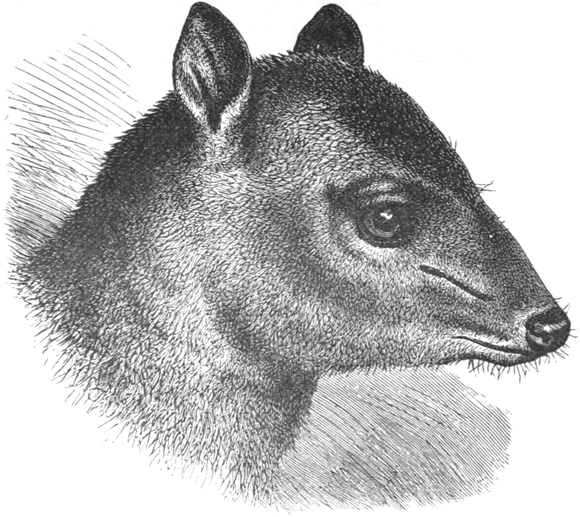

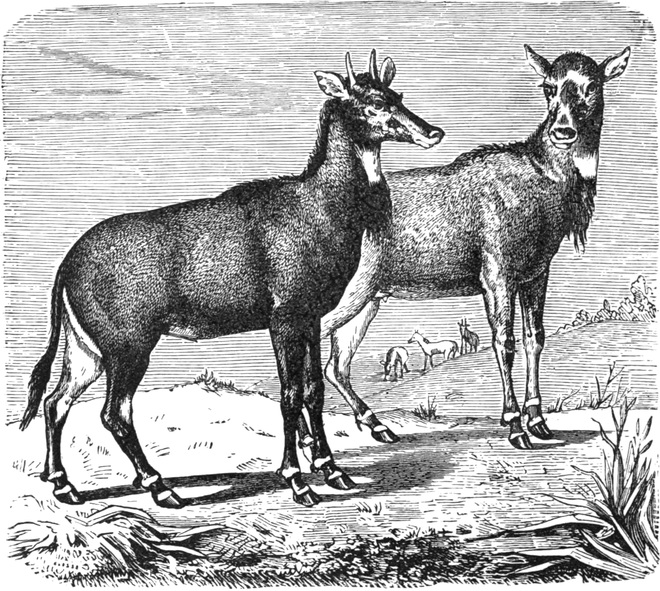

The Water Deerlet, or Chevrotain

|

|

|

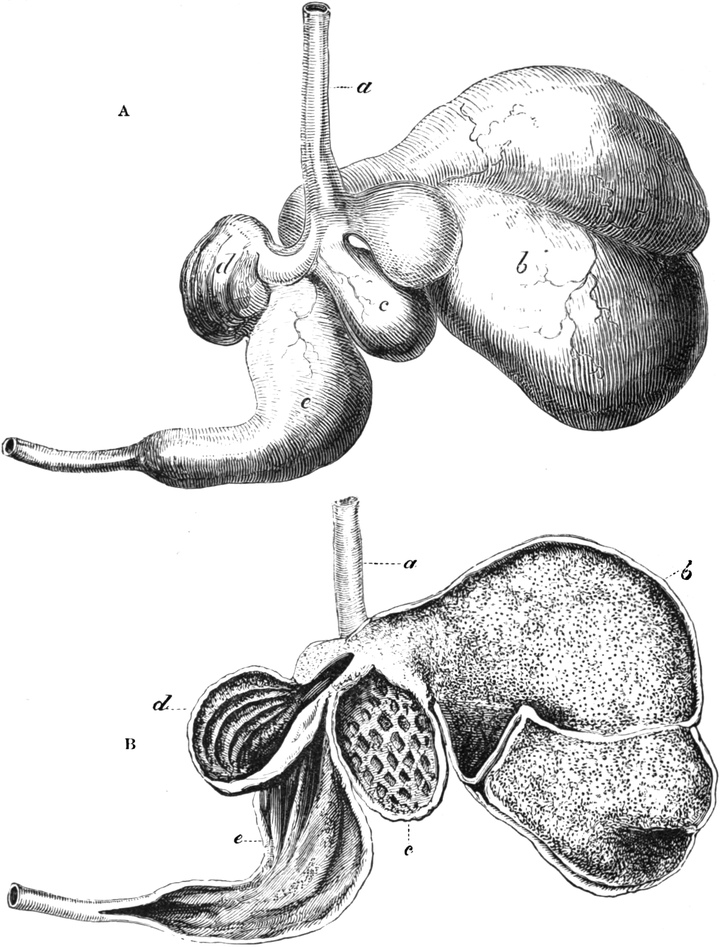

Stomach of a Ruminating Animal: exterior and interior

|

|

|

Brain of a Sheep

|

|

|

Merino Sheep

|

|

|

The Ammon

|

|

|

The Ammon

|

|

|

The Barbary Wild Sheep

|

|

|

The Ibex

|

|

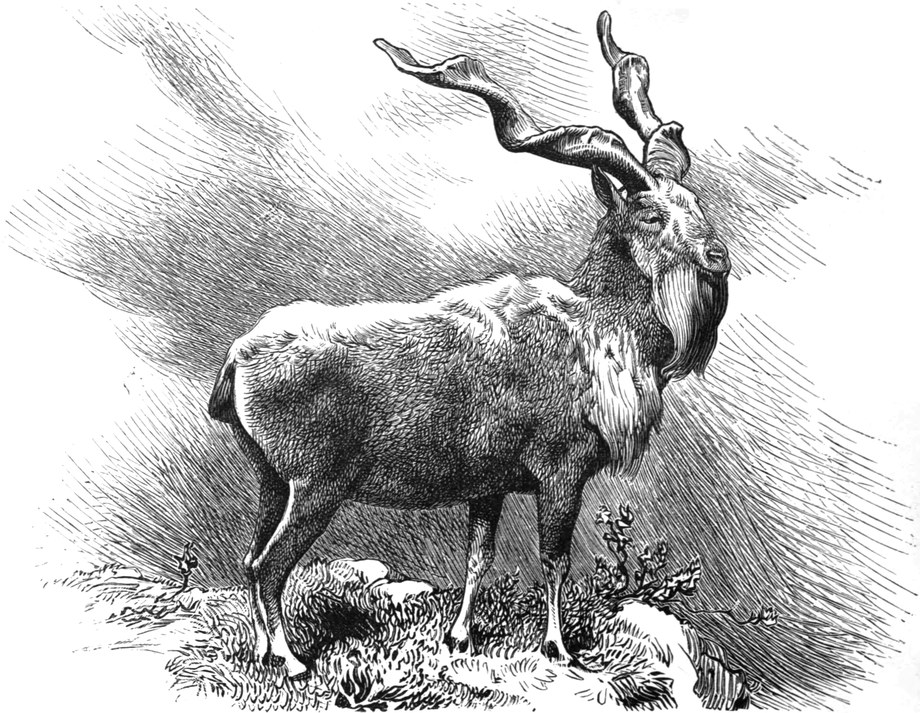

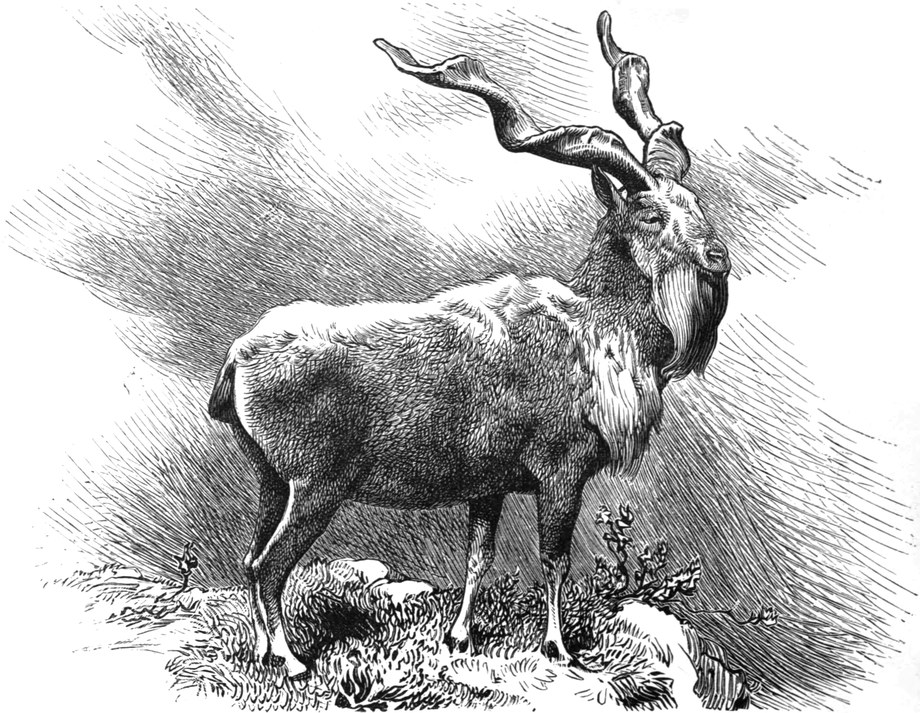

|

The Markhoor

|

|

|

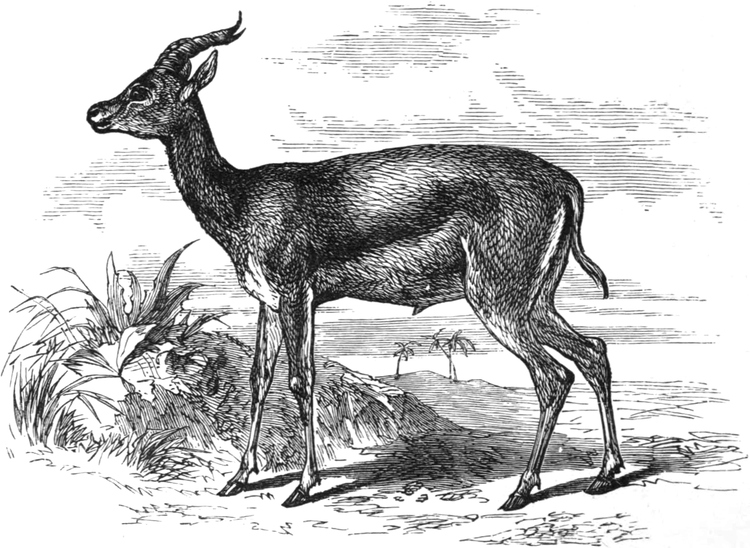

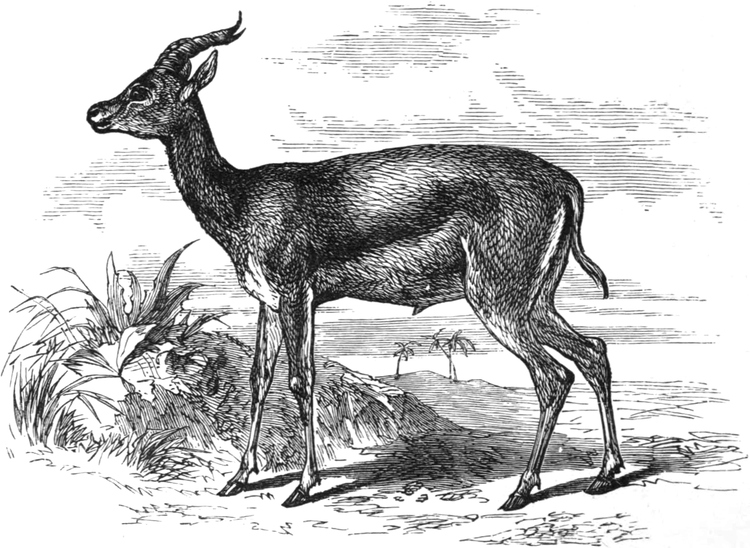

The Dorcas Gazelle

|

|

|

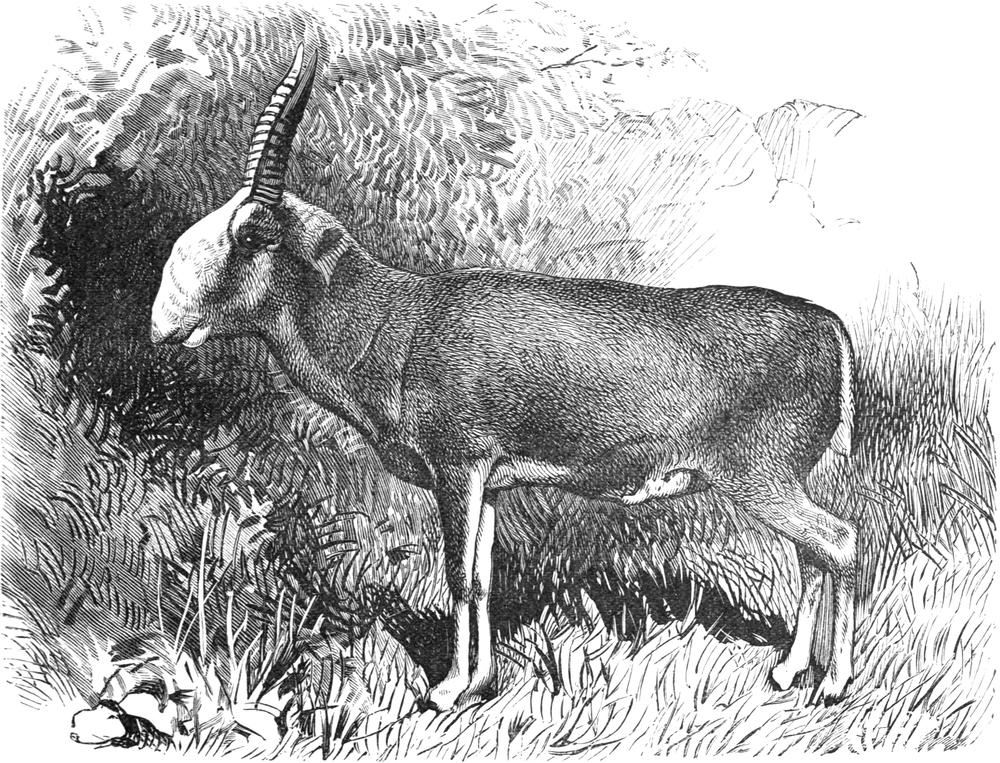

The Saïga

|

|

|

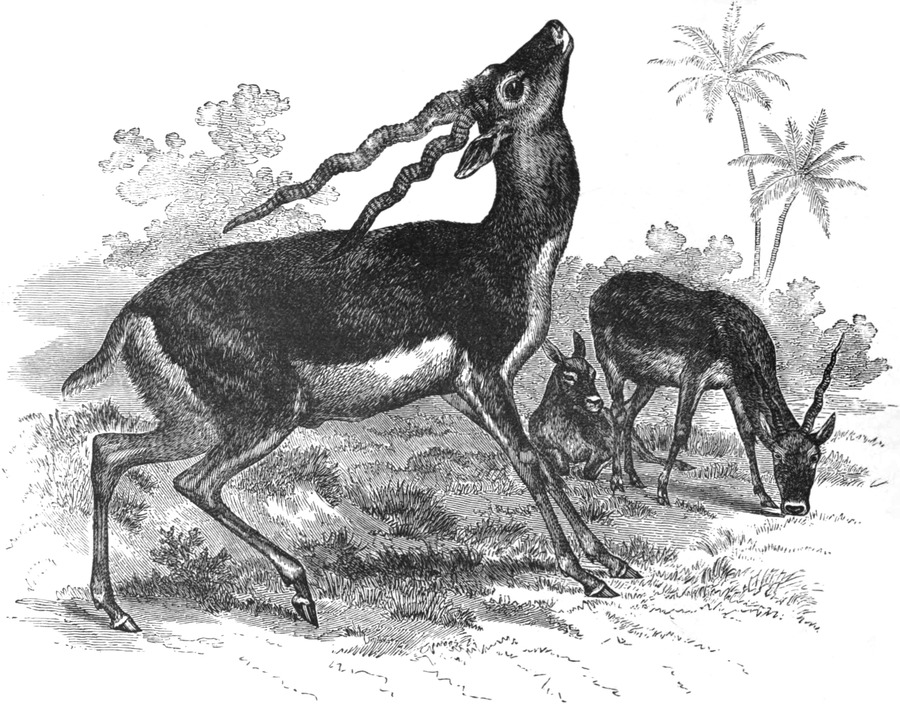

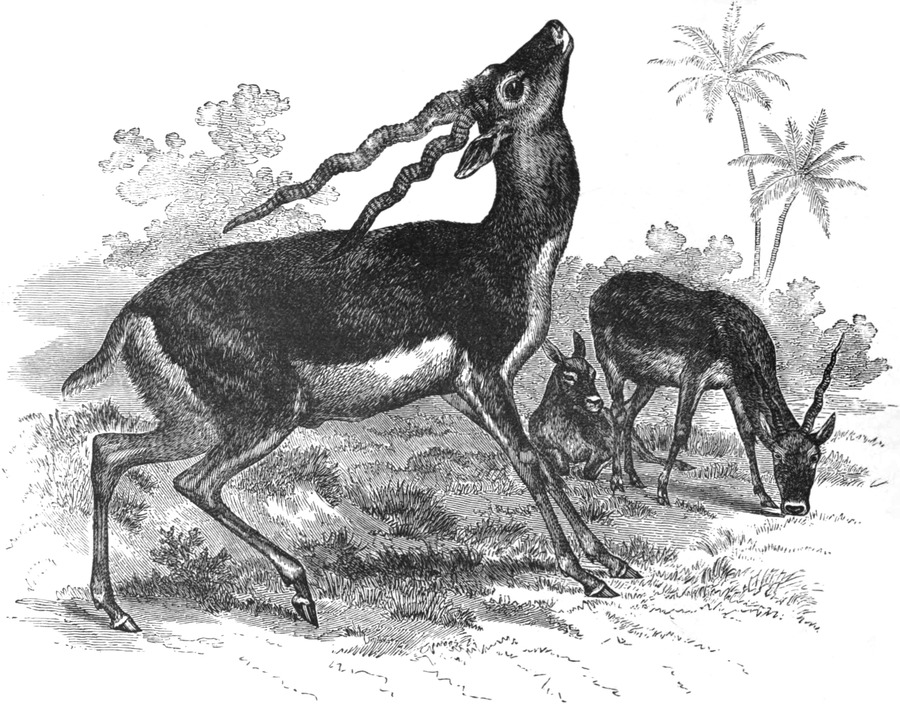

The Indian Antelope

|

|

|

Head of Female Bush-buck

|

|

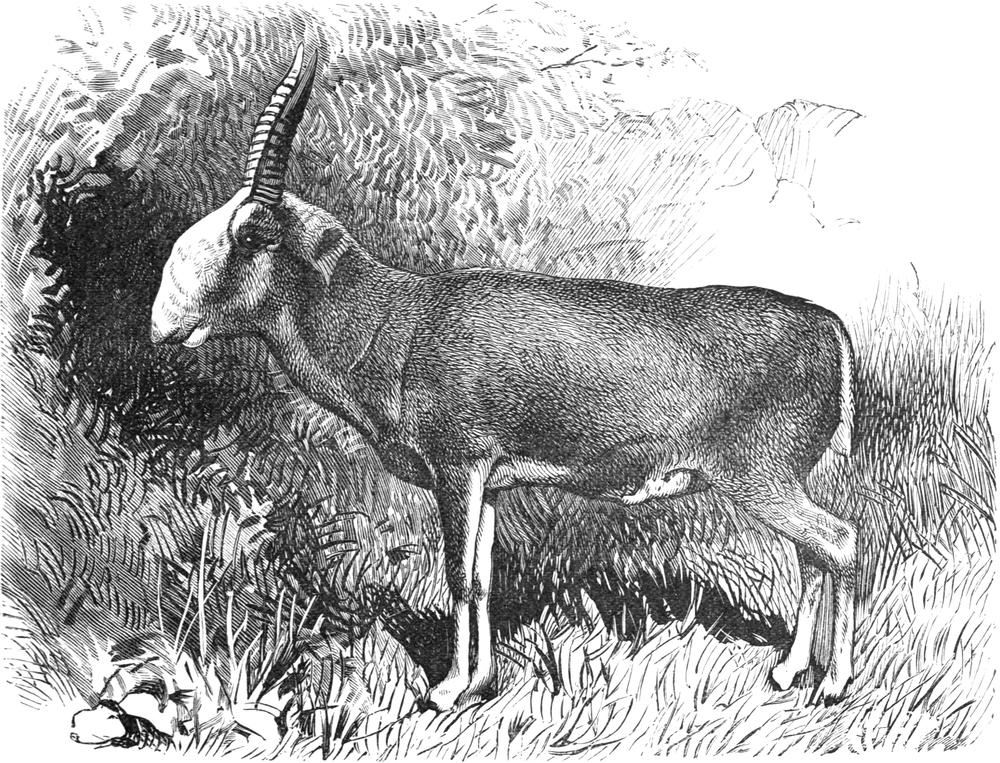

|

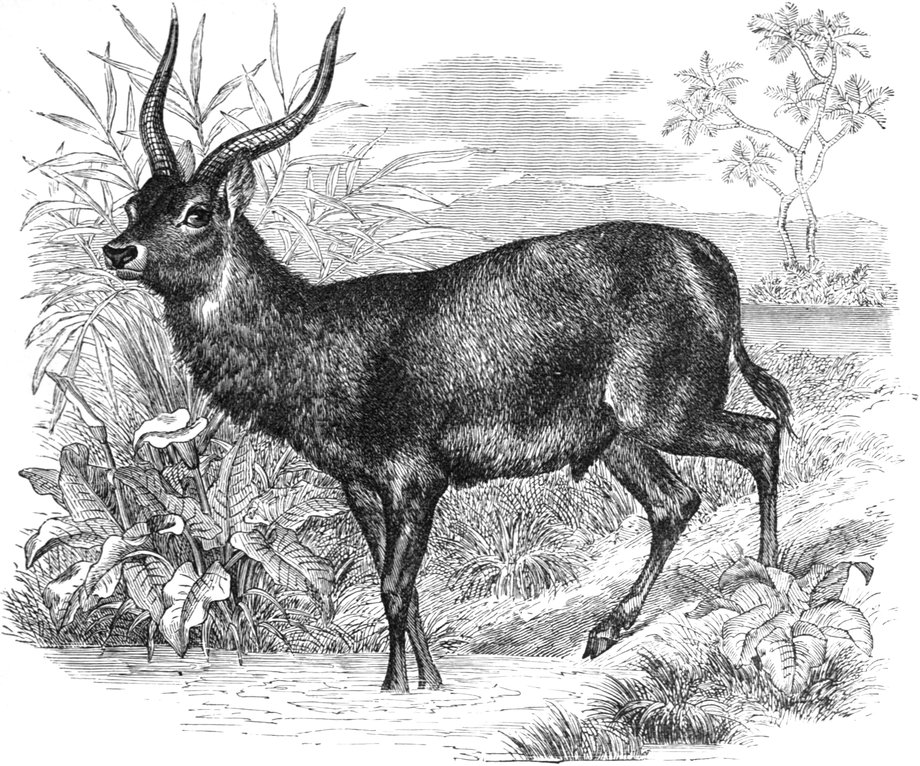

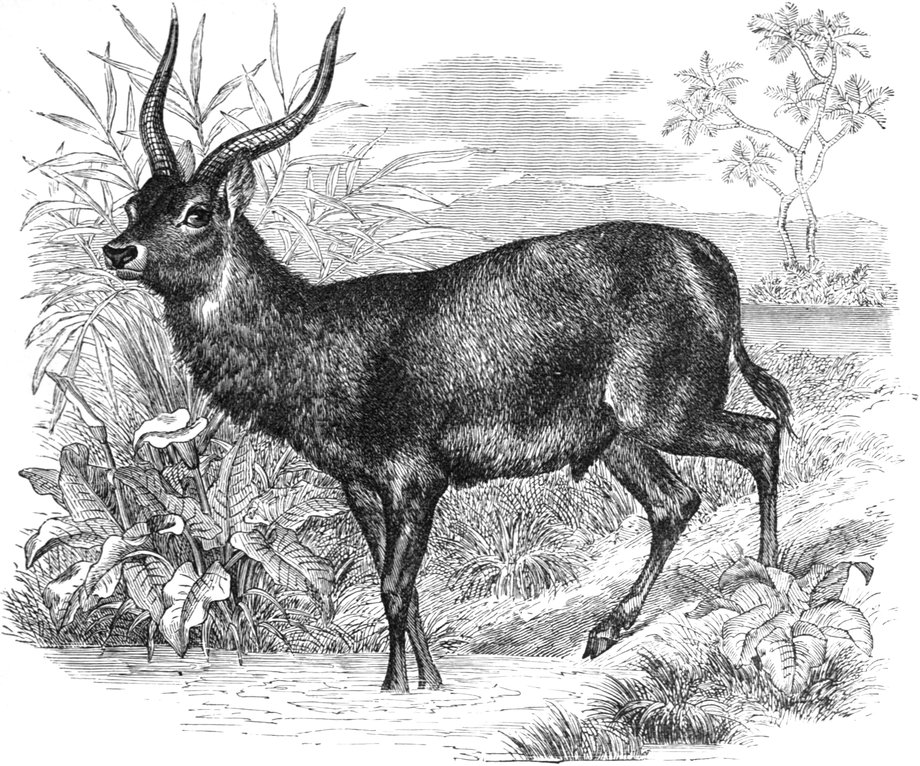

The Water-buck

|

|

|

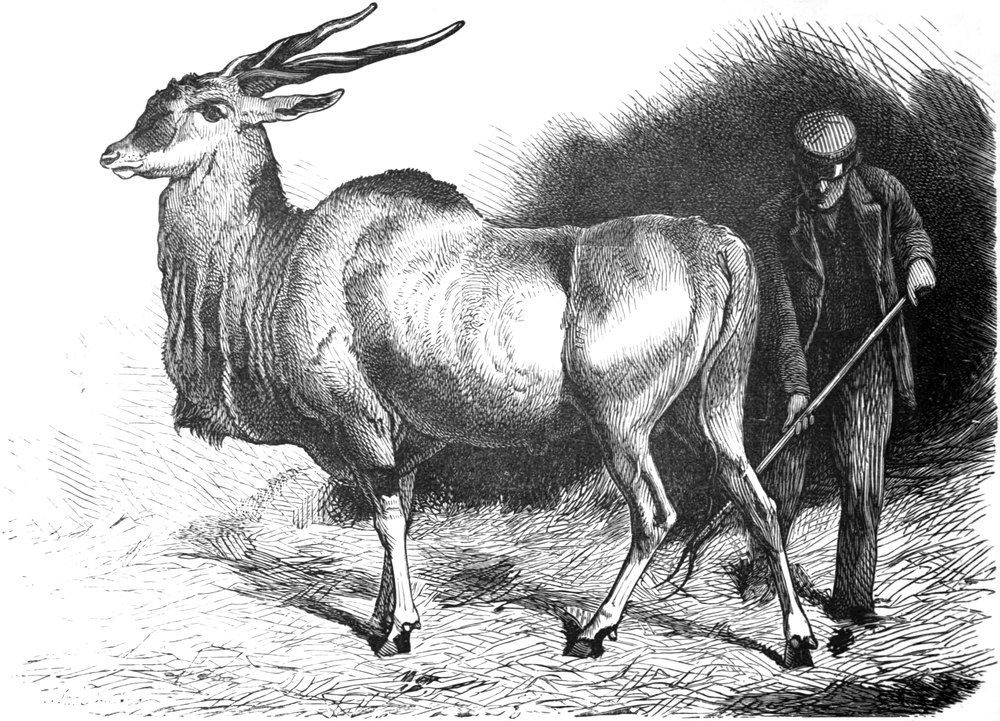

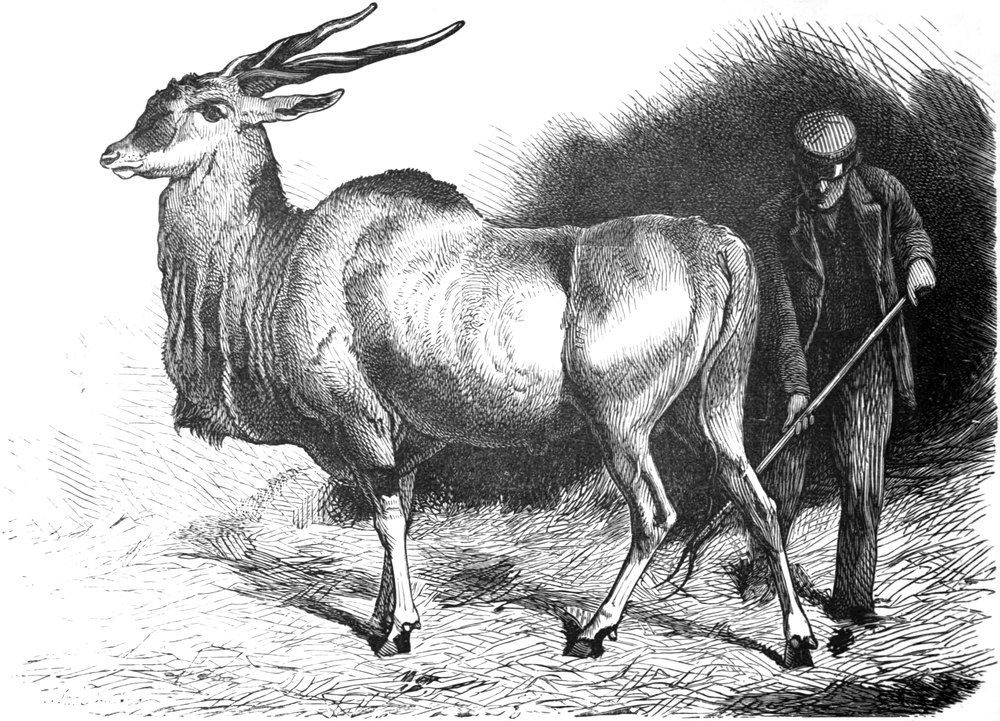

The Eland

|

|

|

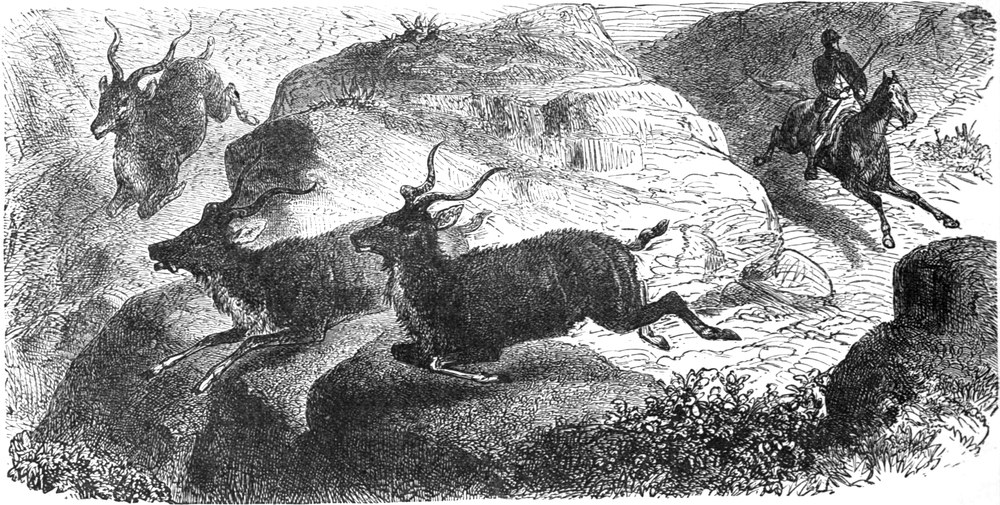

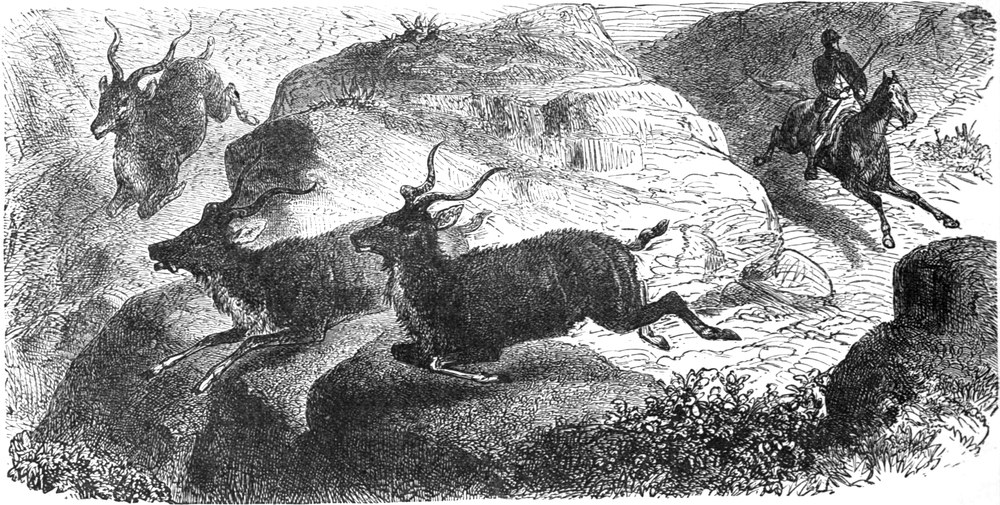

The Koodoo

|

|

|

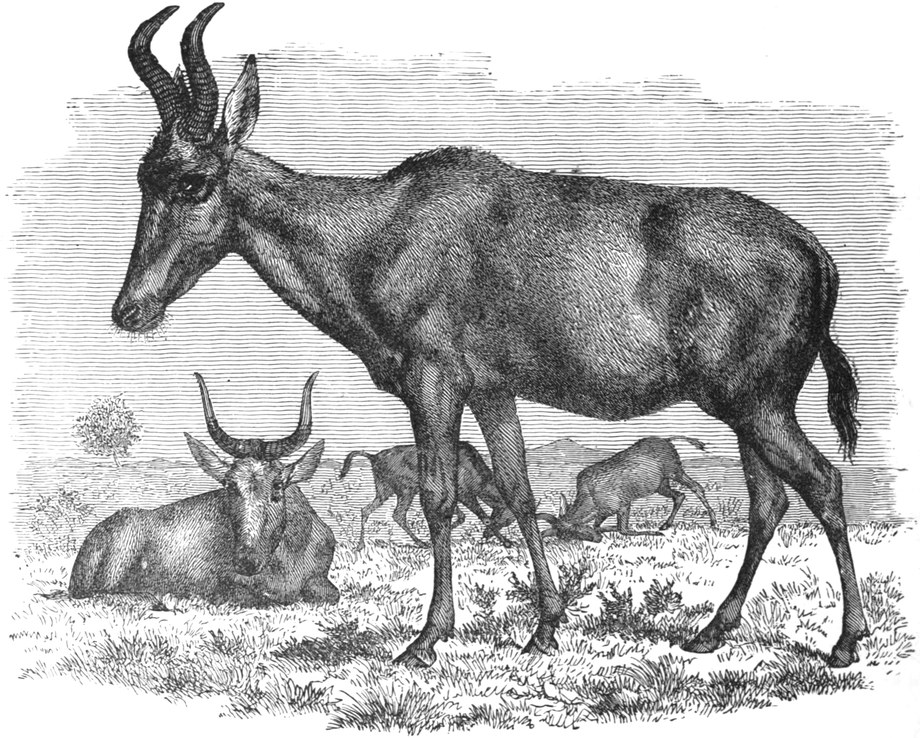

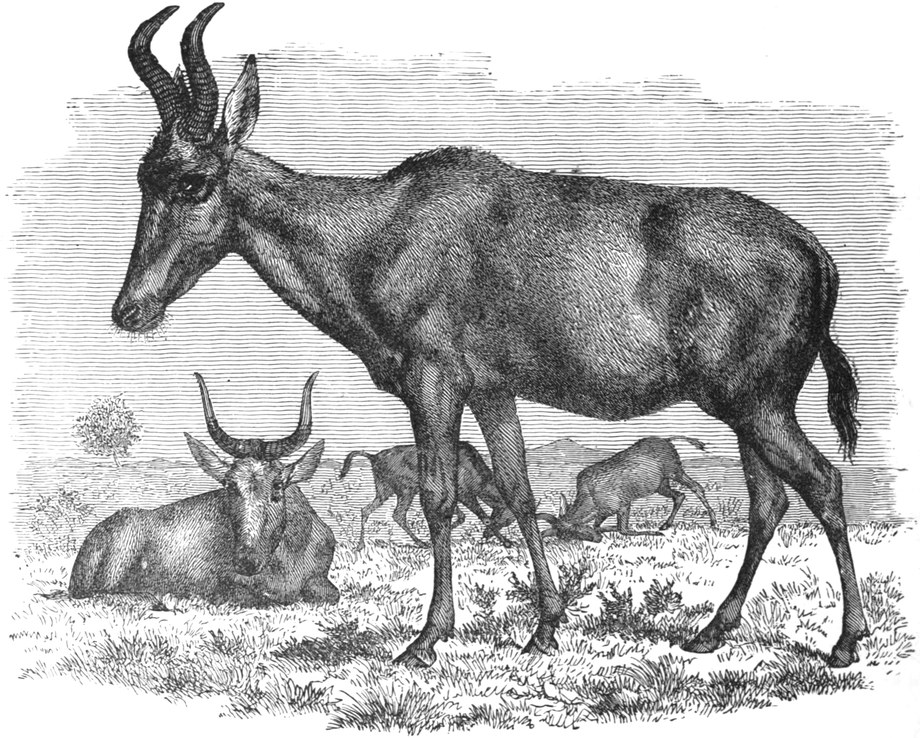

The Bubaline Antelope

|

|

|

The Gnu

|

|

|

The Goral

|

|

|

Head of the Chamois

|

|

|

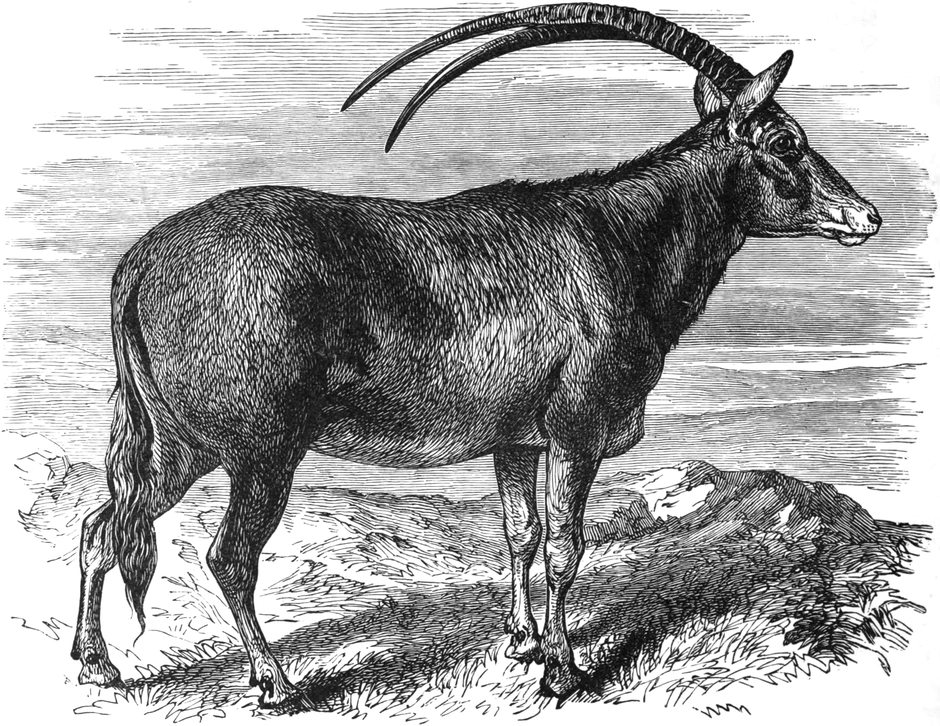

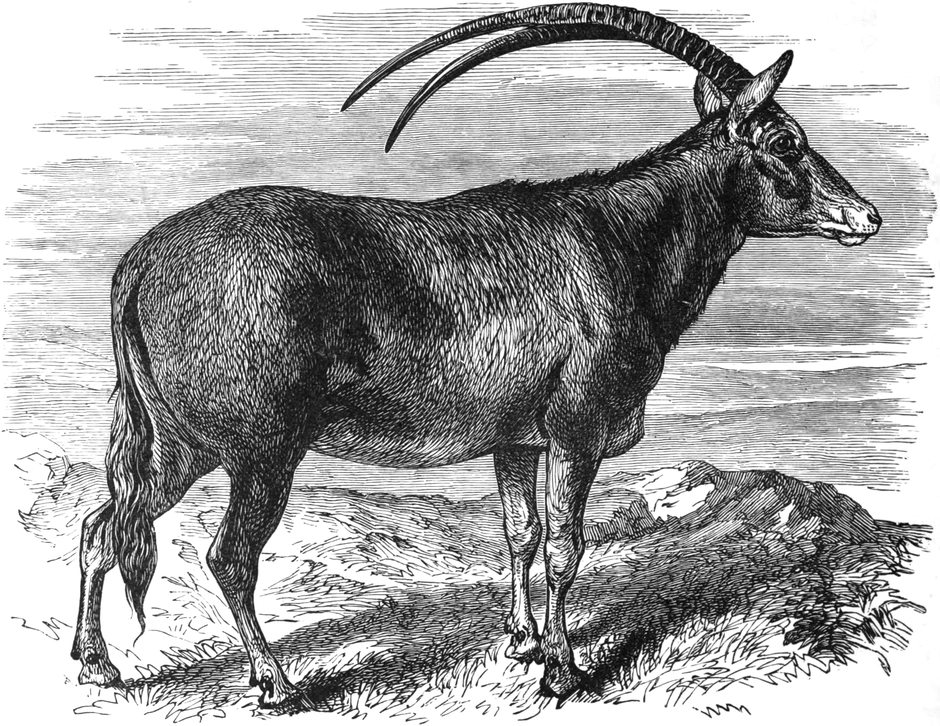

The Oryx

|

|

|

The Nyl-ghau

|

|

|

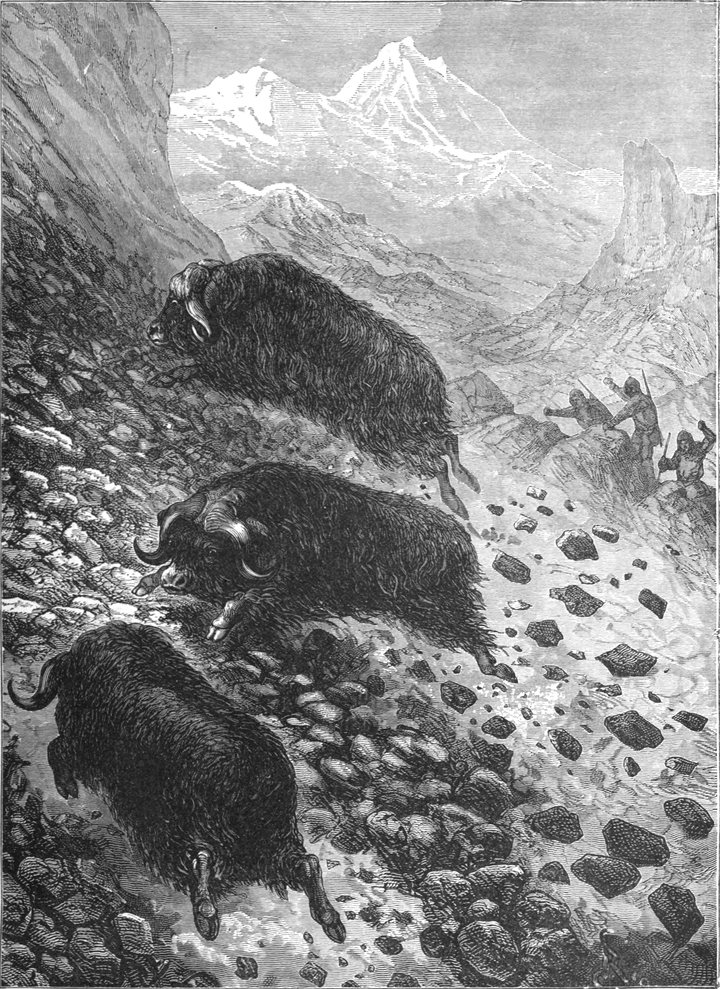

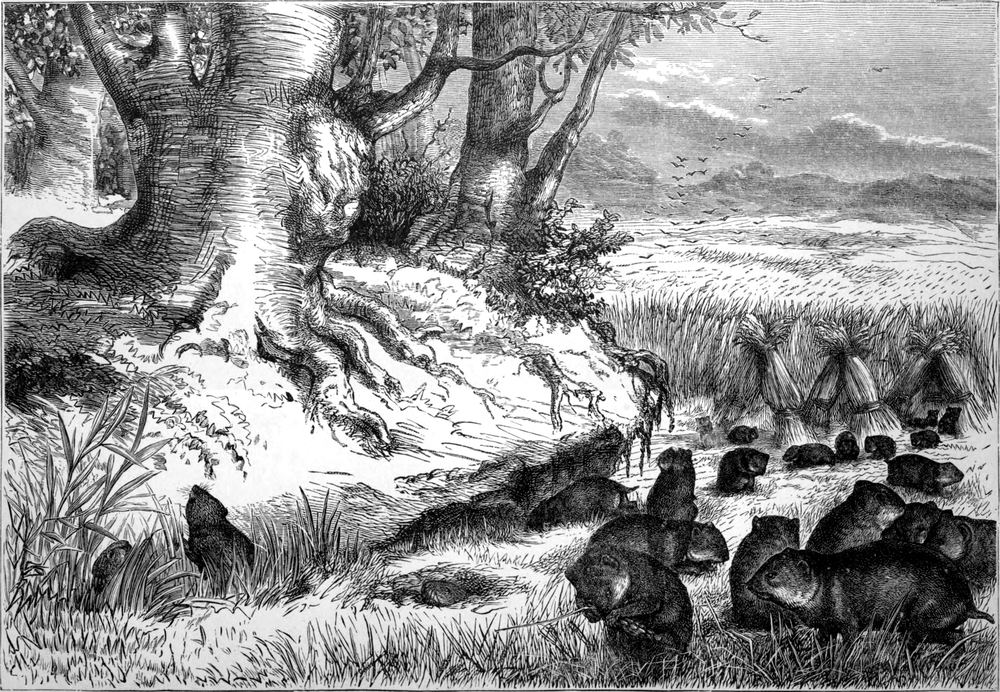

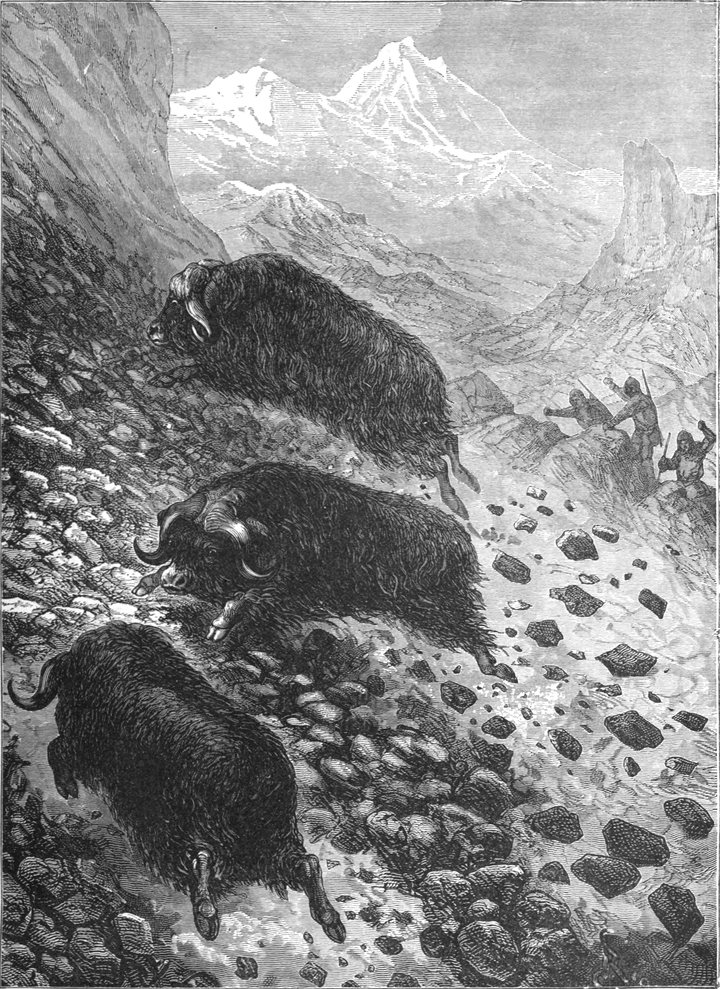

Musk Oxen

|

|

|

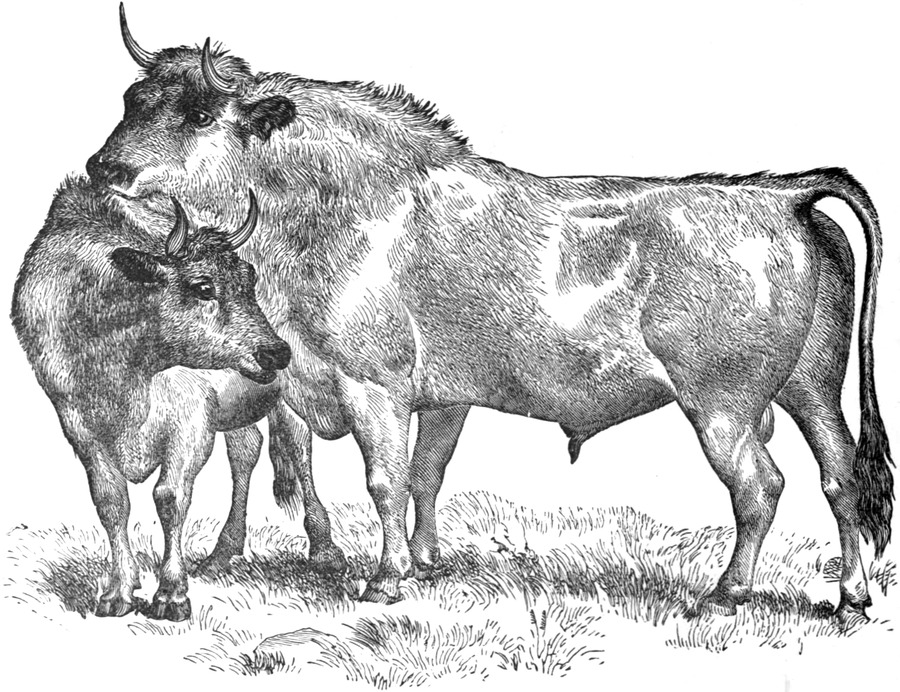

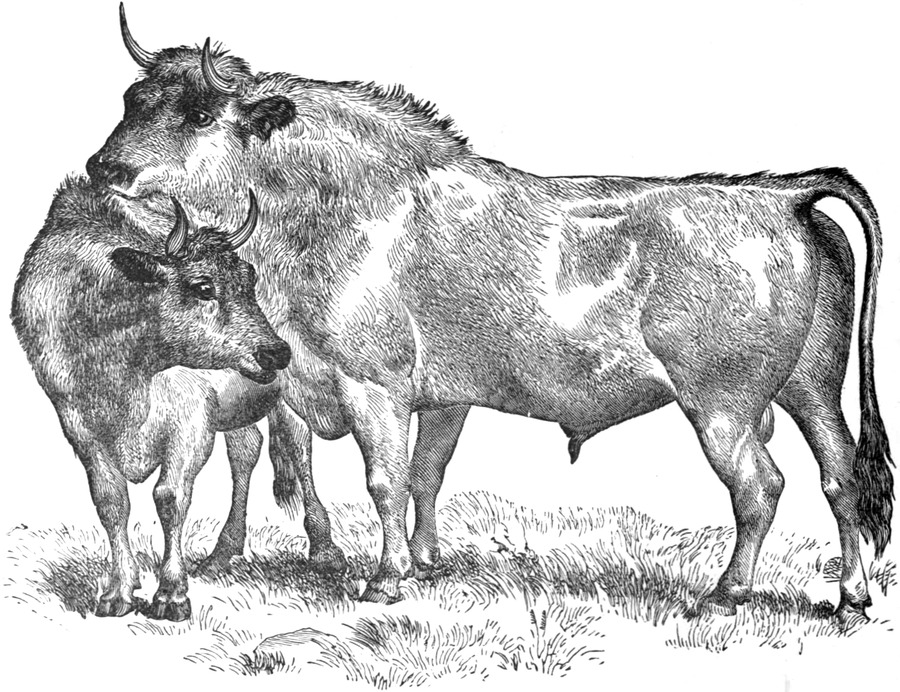

Chillingham Cattle

|

|

|

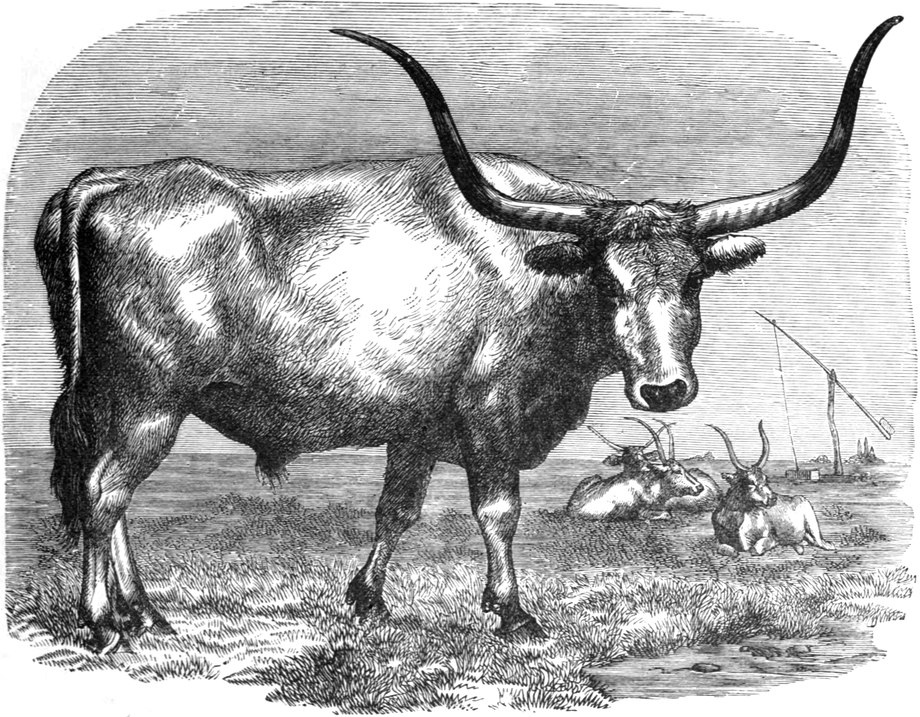

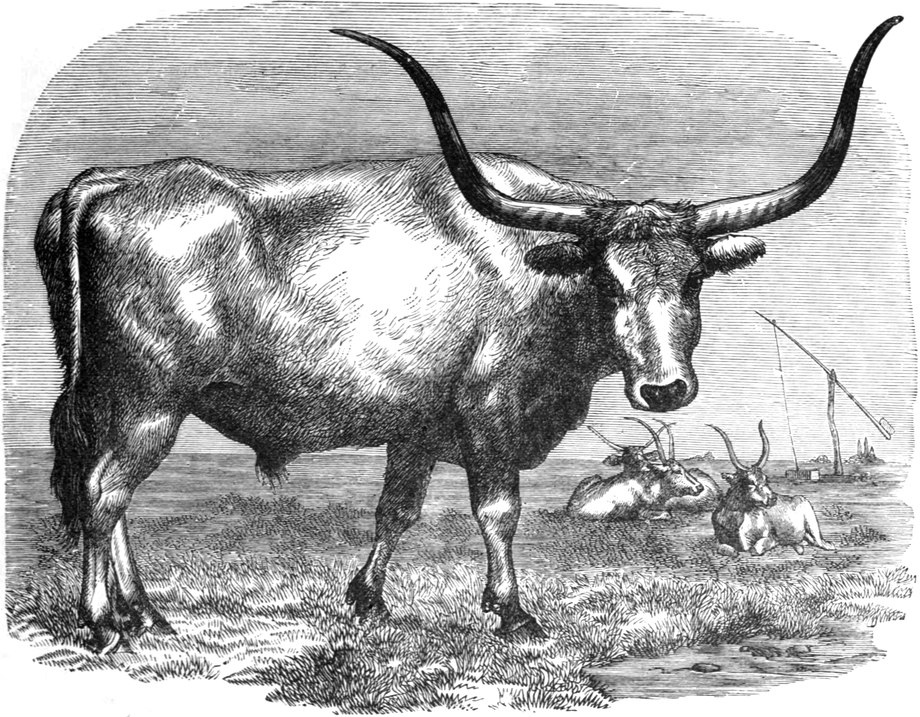

The Hungarian Bull

|

|

|

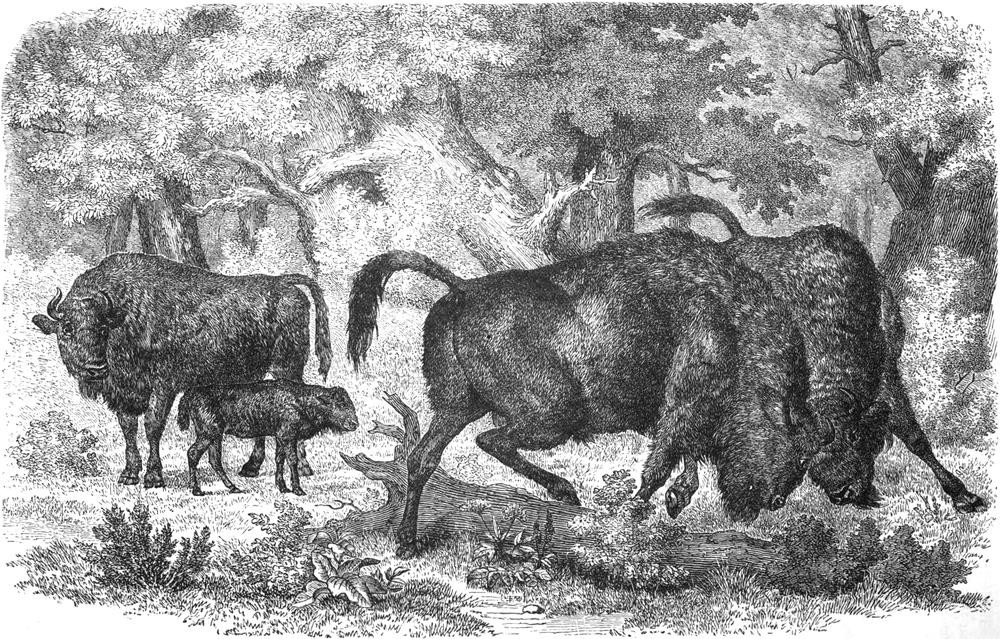

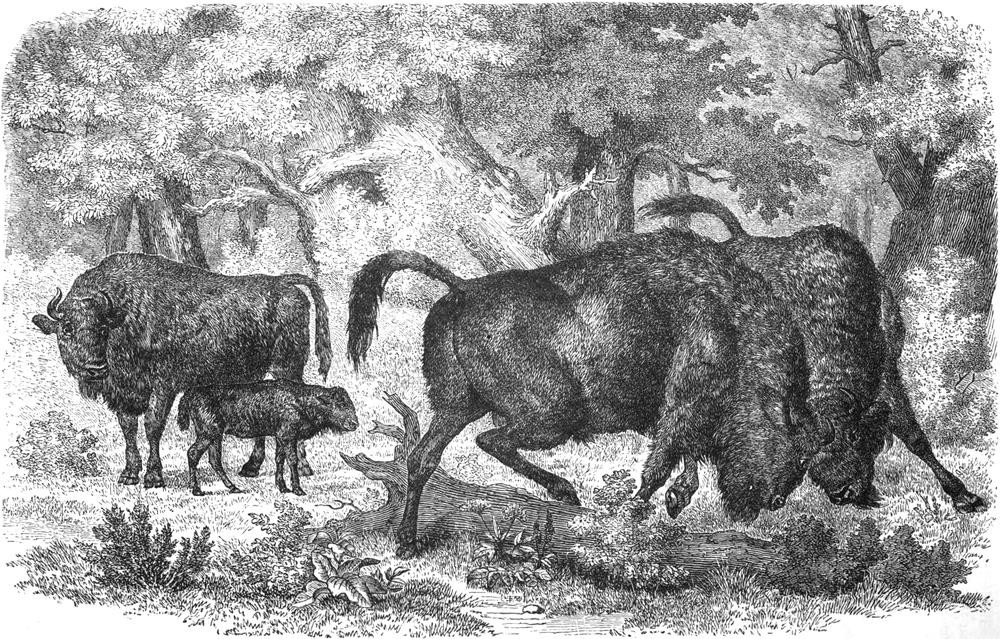

The European Bison

|

|

|

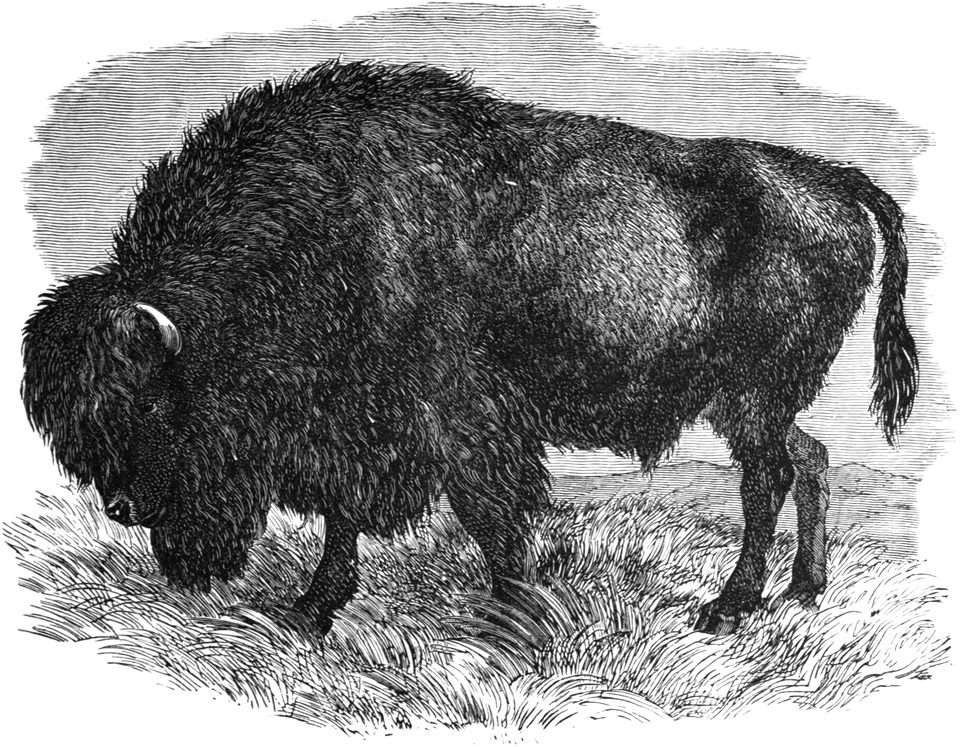

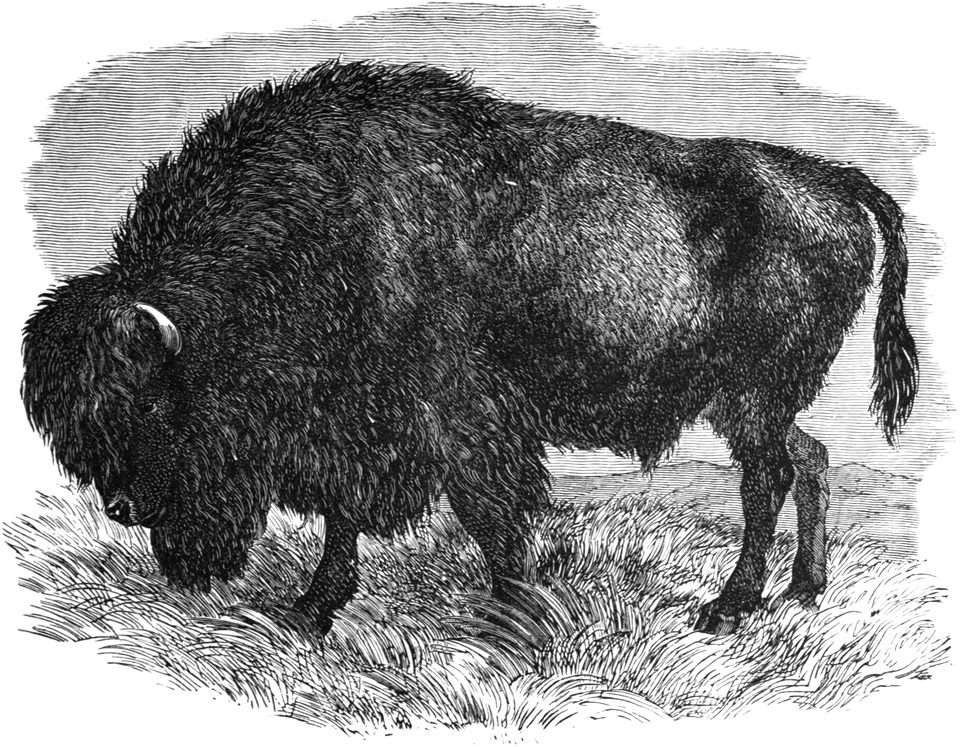

The American Bison

|

|

|

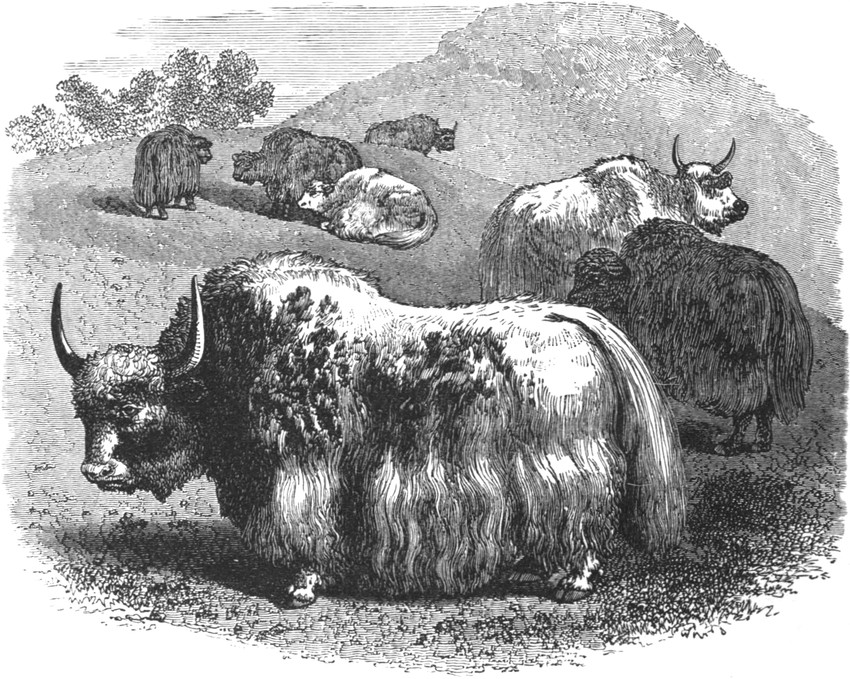

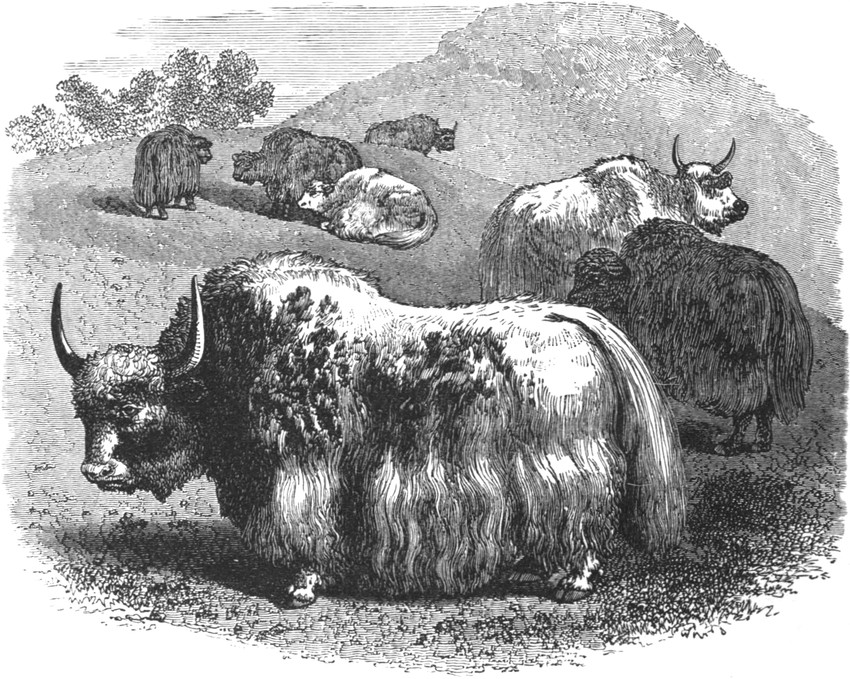

The Yak

|

|

|

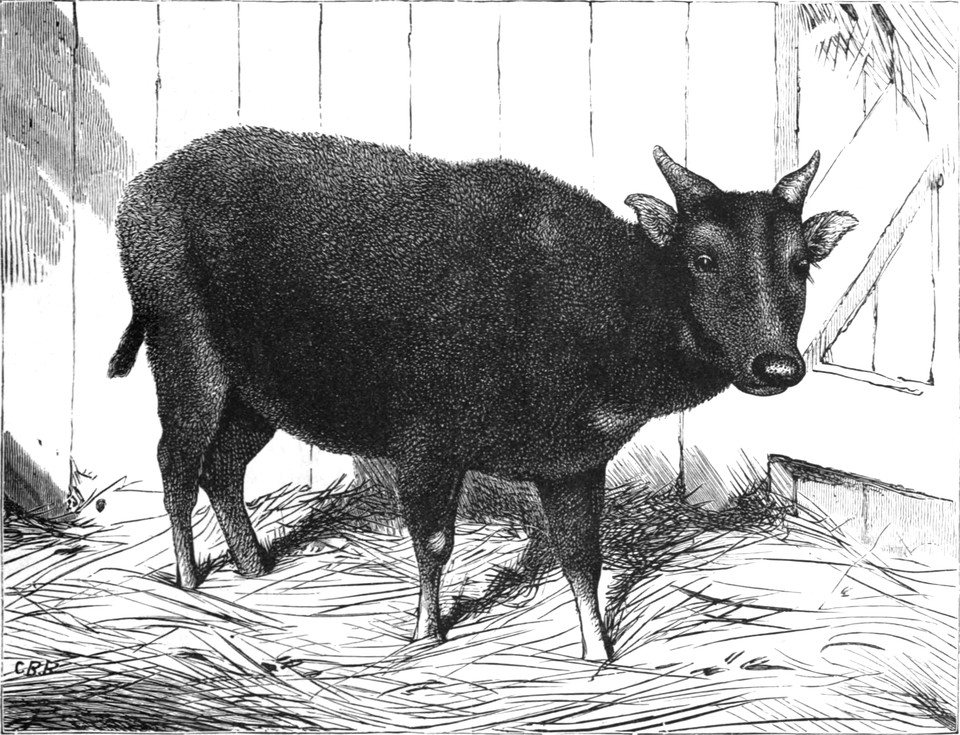

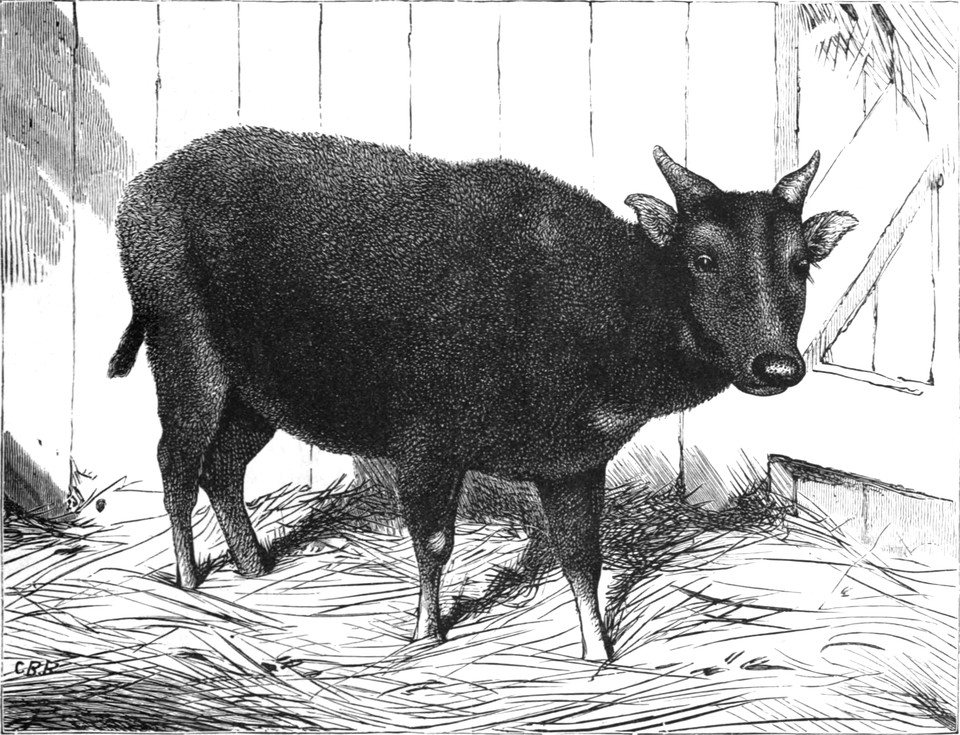

The Anoa

|

|

|

Skull of the Pronghorn Antelope

|

|

|

The Pronghorn Antelope

|

|

|

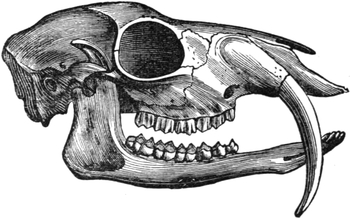

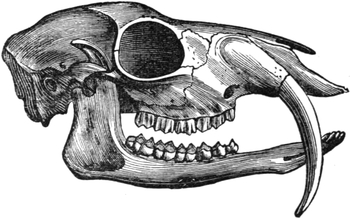

Skull of the Musk [Deer]

|

|

|

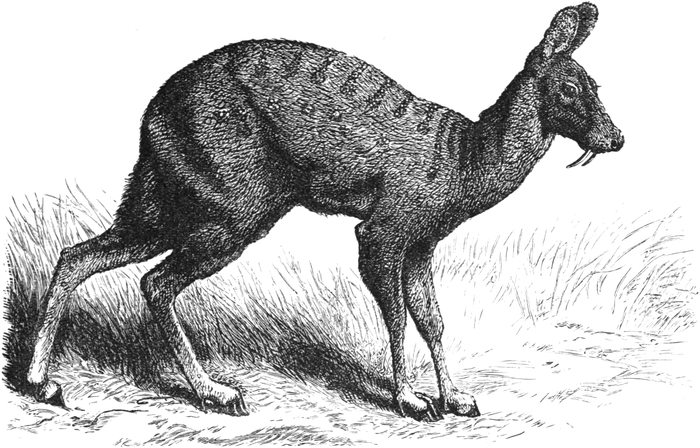

The Musk [Deer]

|

|

|

Skeleton of the Giraffe

|

|

|

Giraffes

|

|

|

Head of Red Deer, in which the growing Antlers are seen covered with

“velvet”

|

|

|

Head of Red Deer, in which the Antler is fully developed and the “velvet”

has disappeared

|

|

|

Various Types of Antlers

|

|

|

Elk Hunt

|

|

|

Young Elk

|

|

|

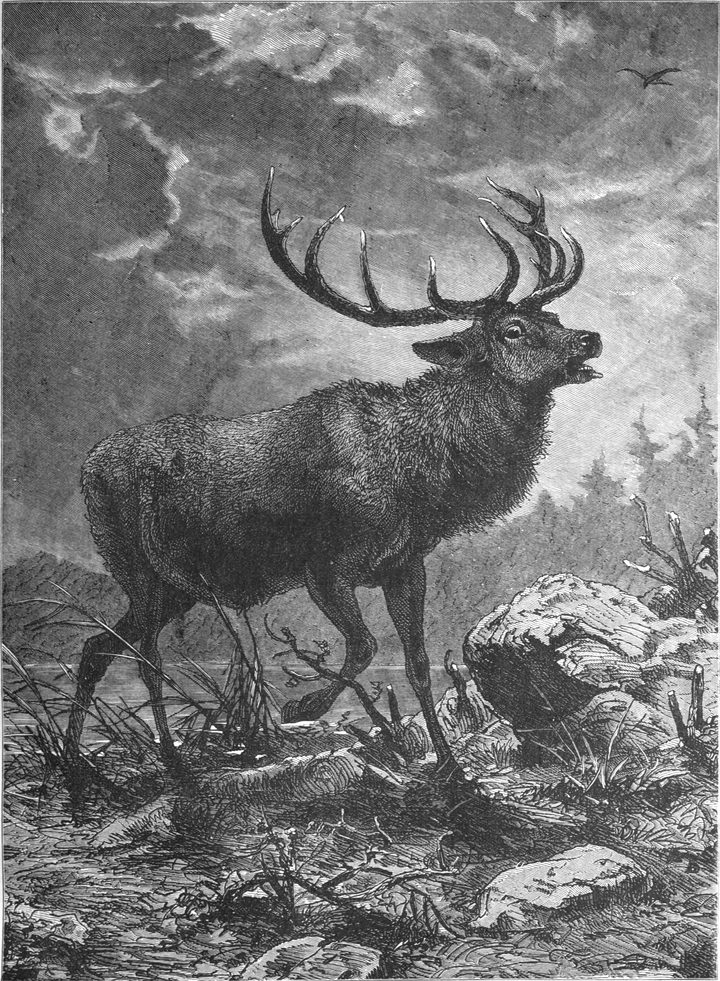

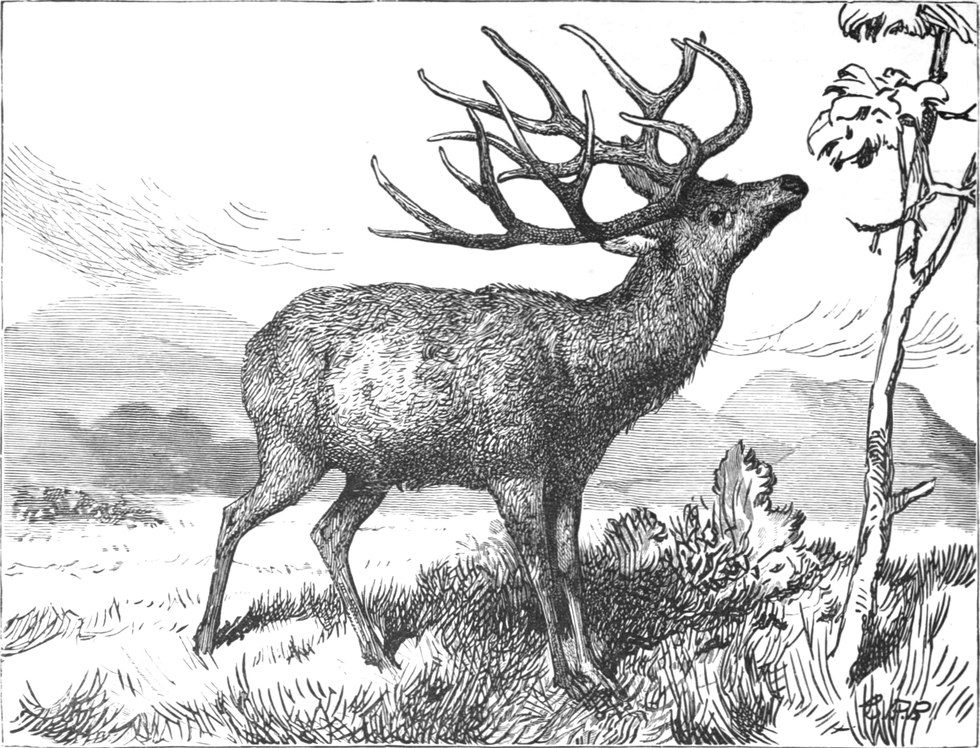

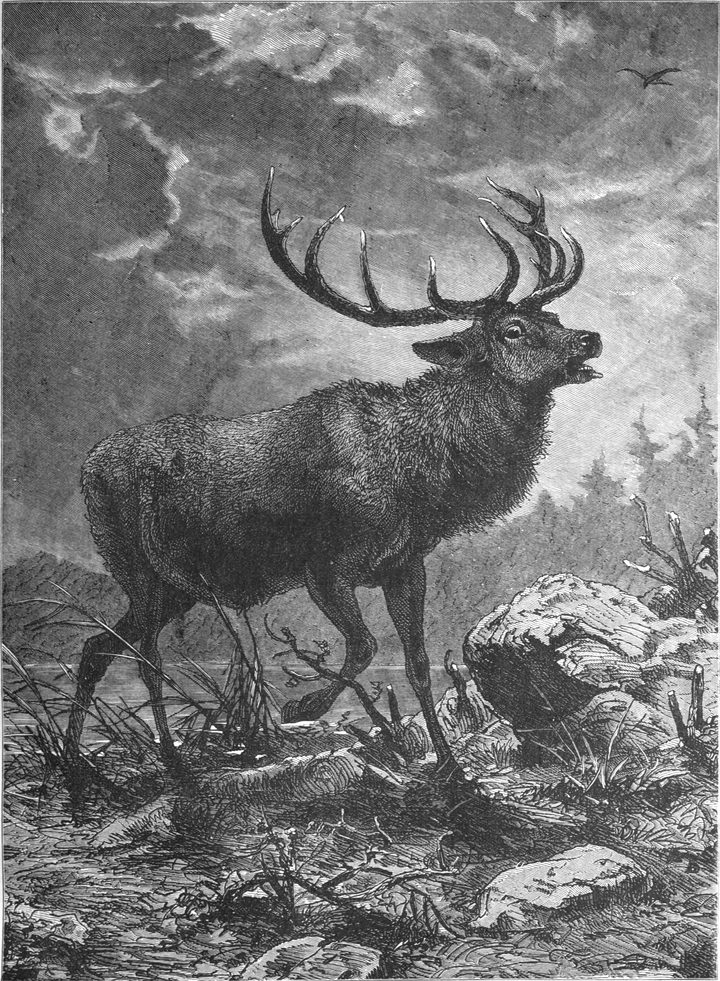

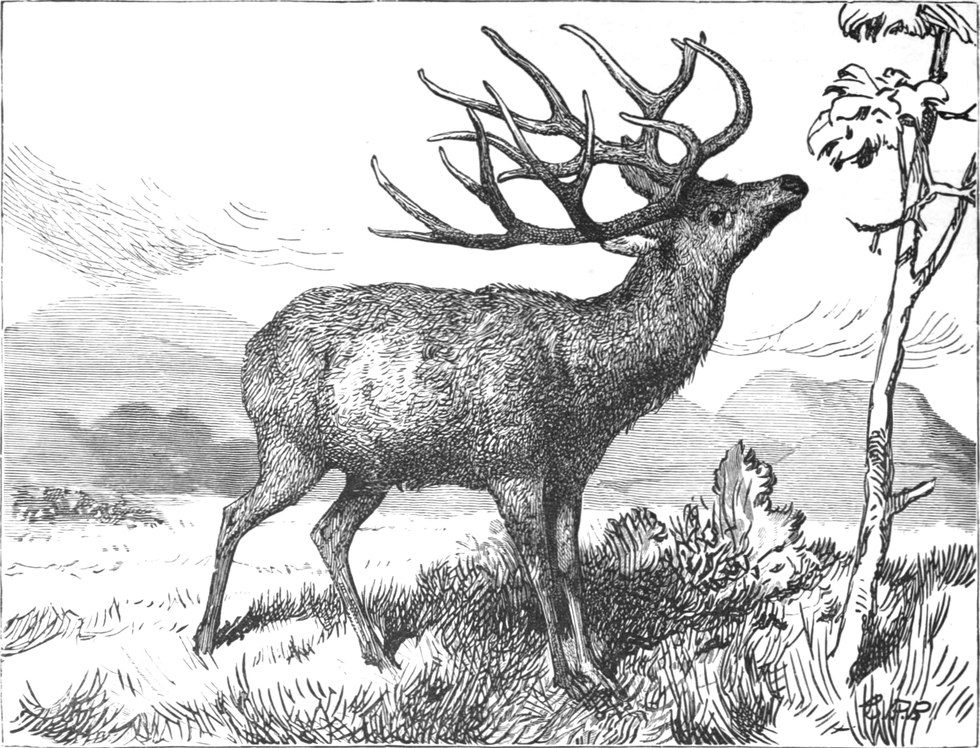

The Red Deer

|

|

|

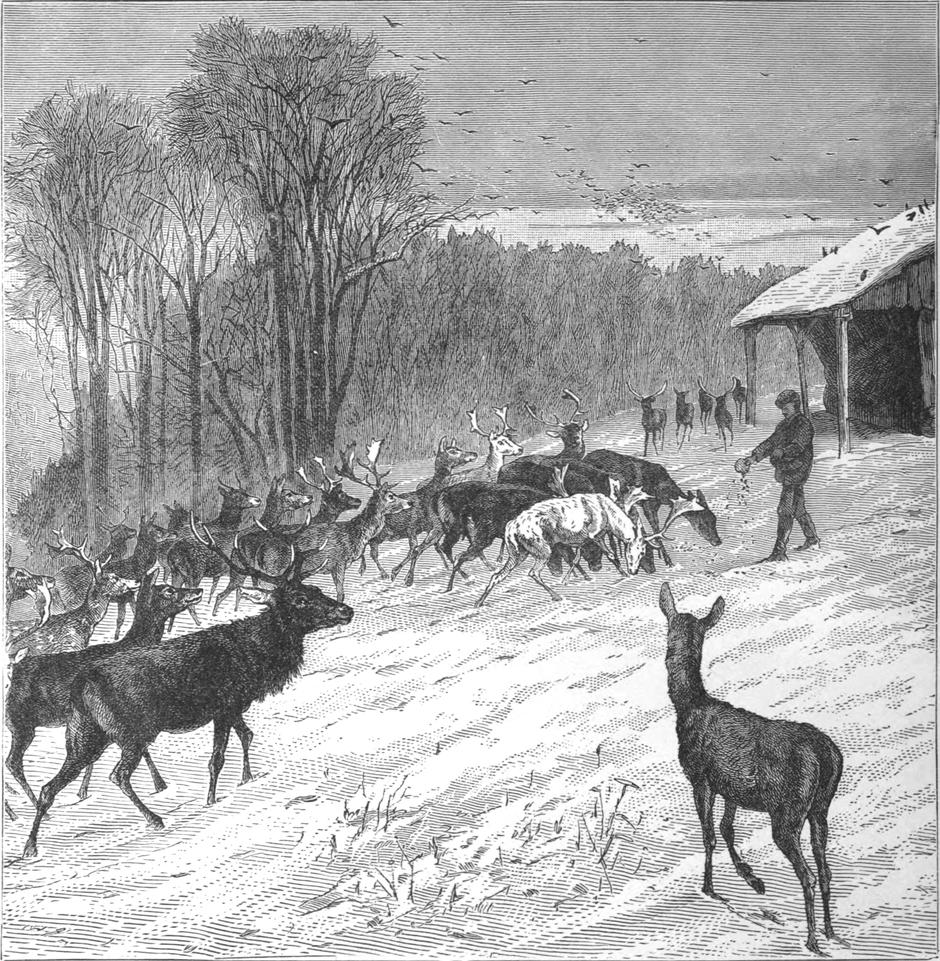

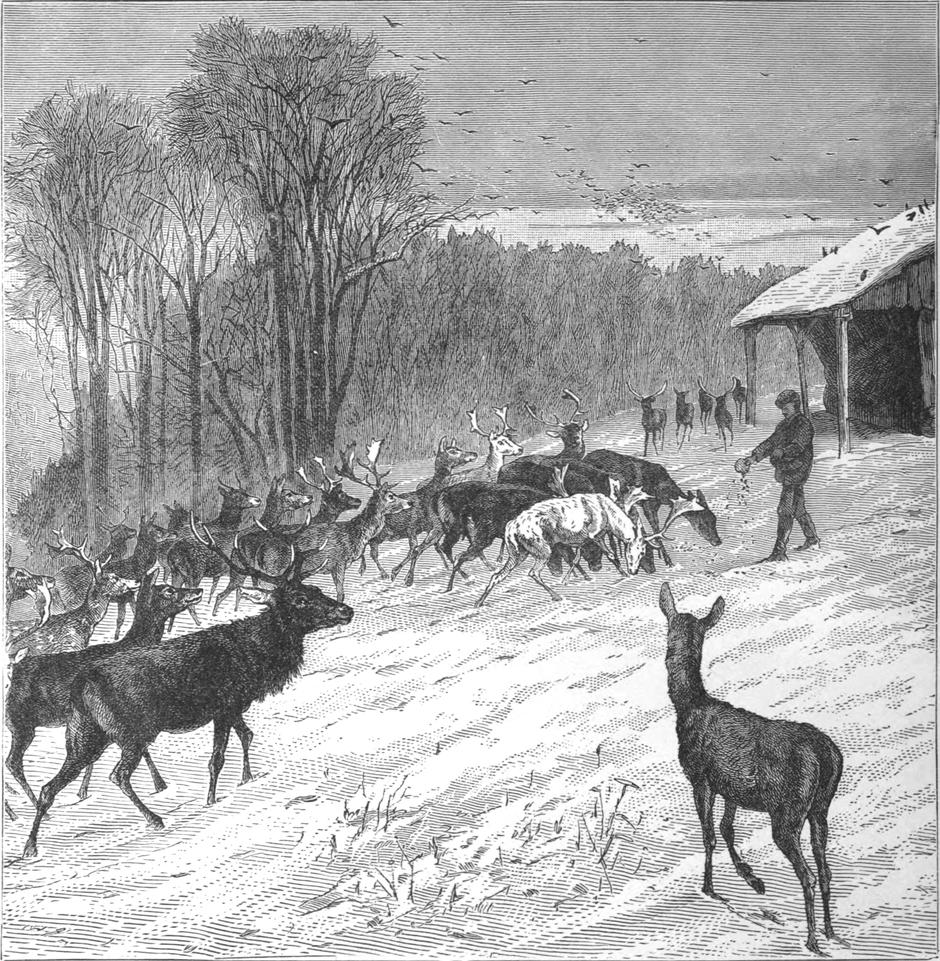

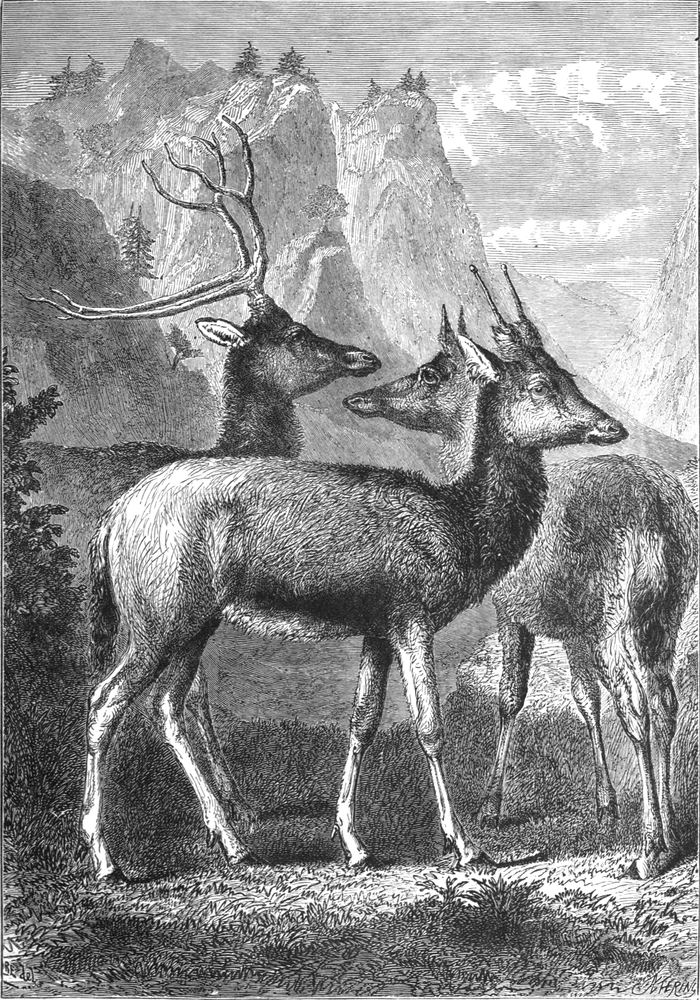

Red Deer and Fallow Deer in Winter

|

|

|

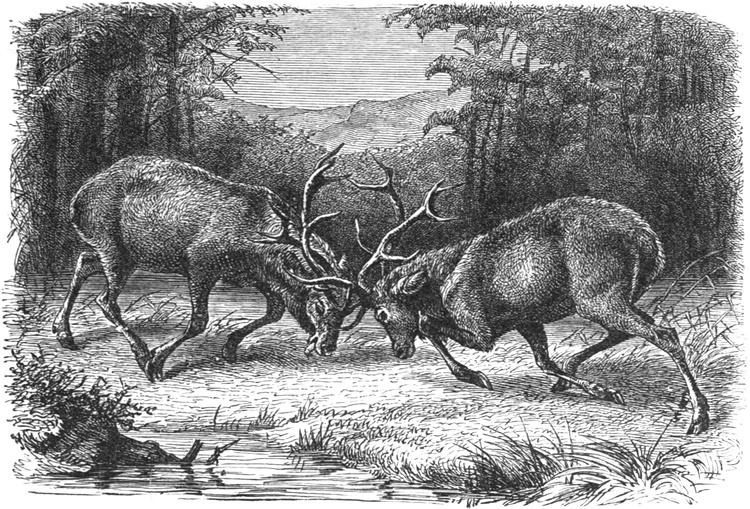

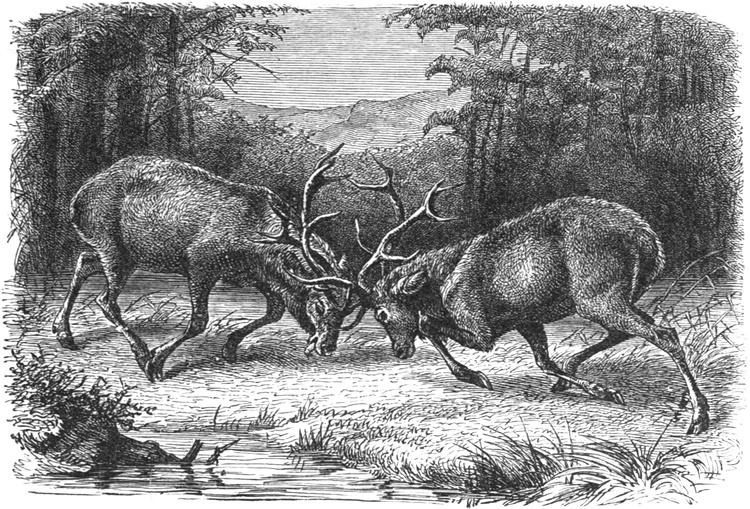

Red Deer Fighting

|

|

|

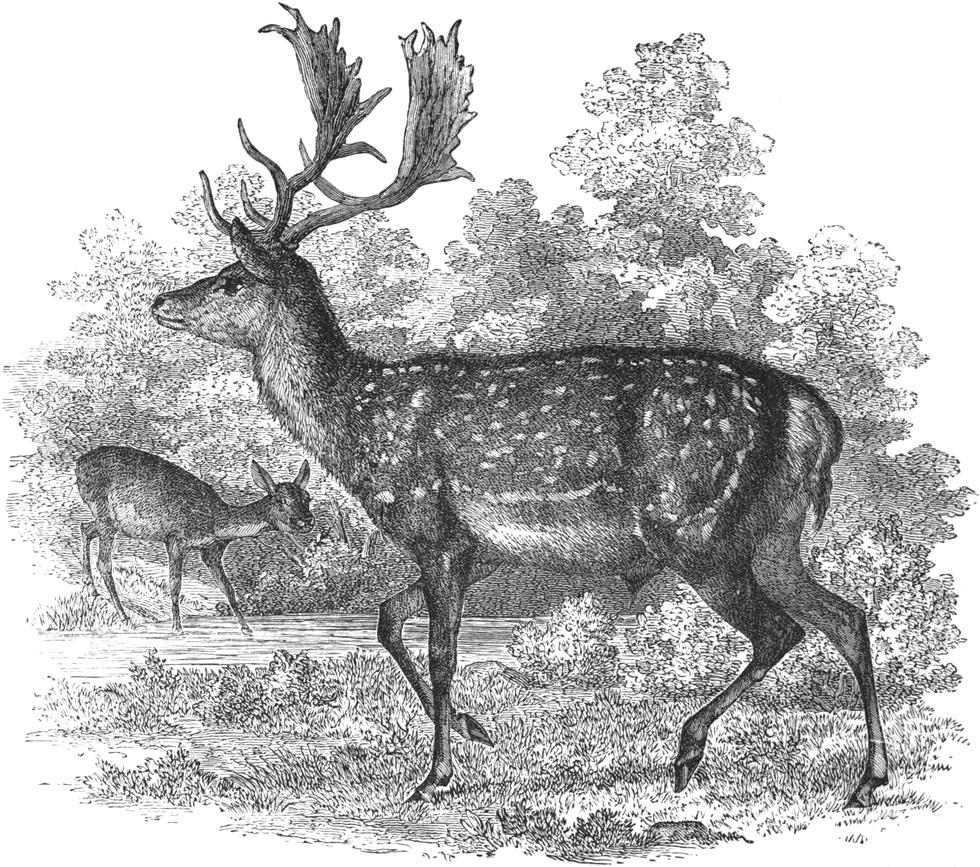

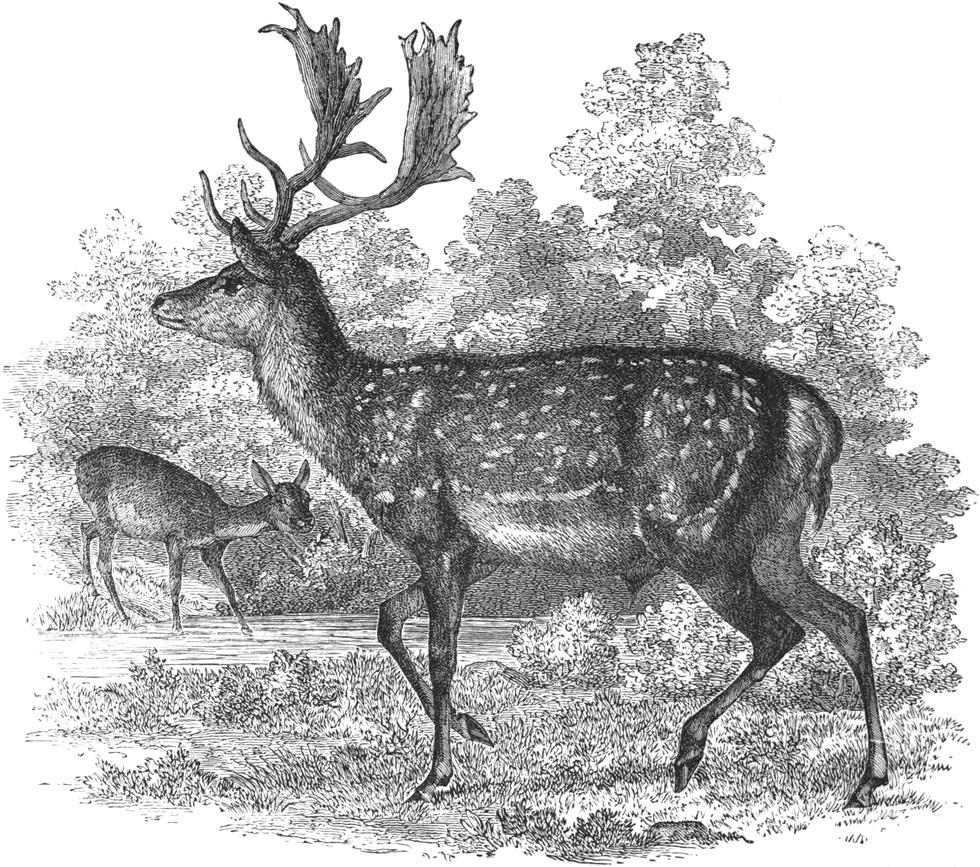

The Fallow Deer

|

|

|

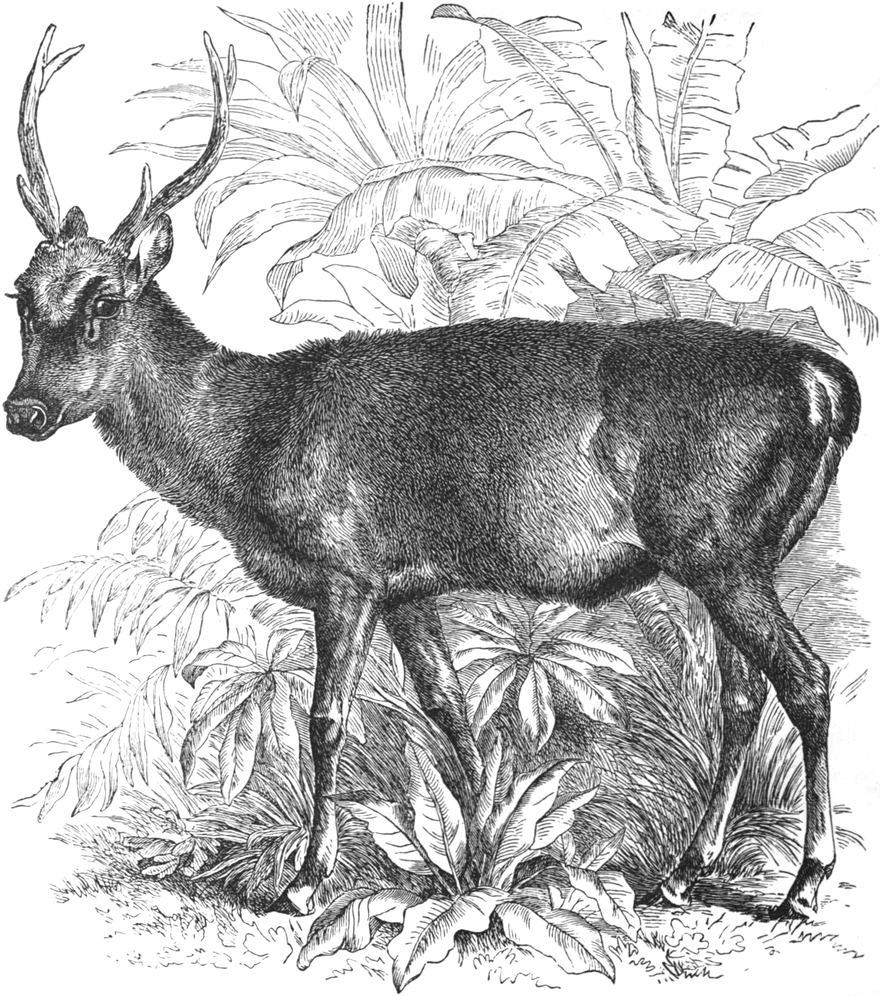

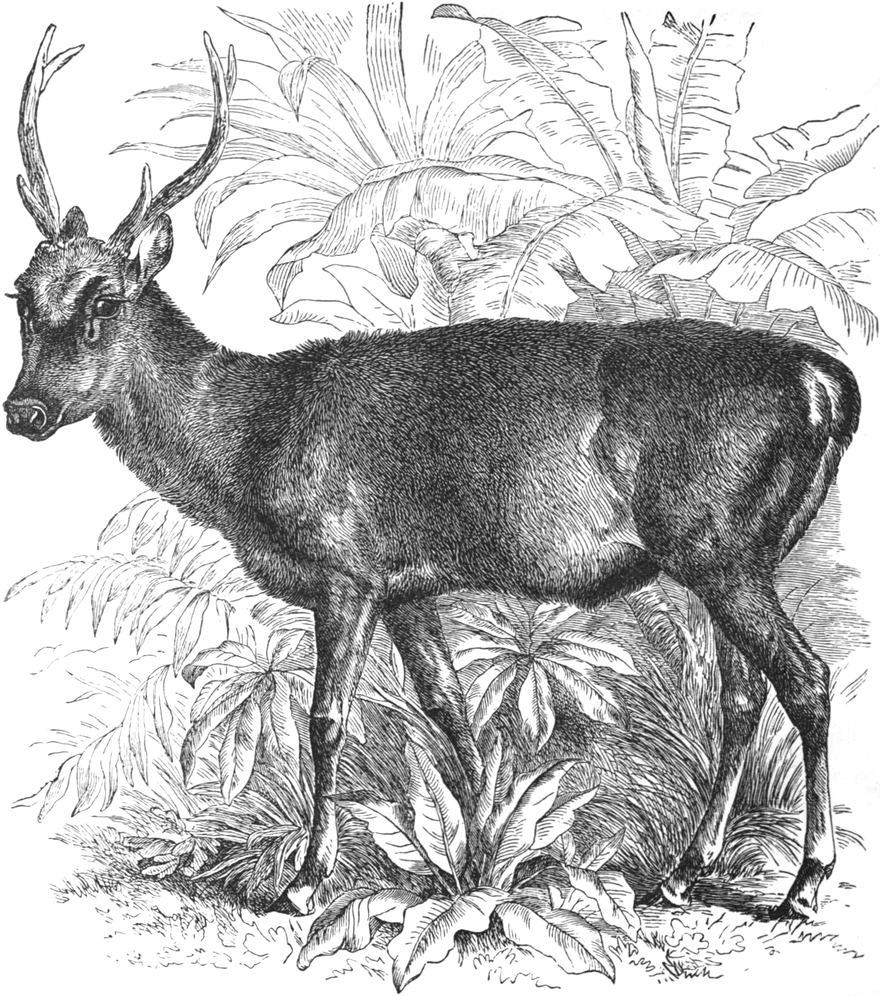

The Sambur Deer

|

|

|

The Borneo Rusine Deer

|

|

|

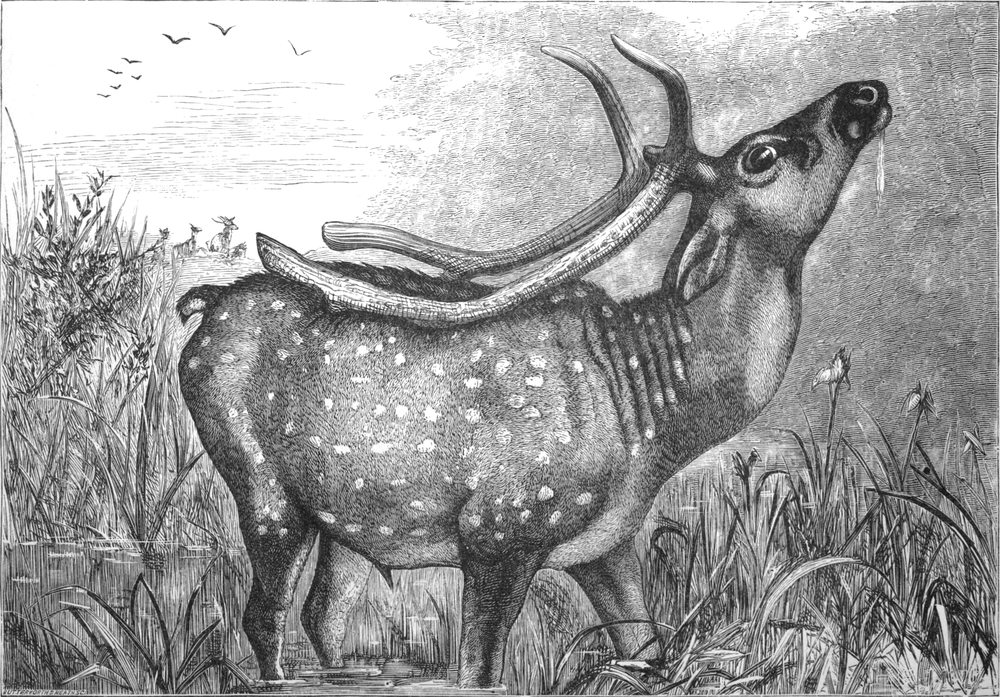

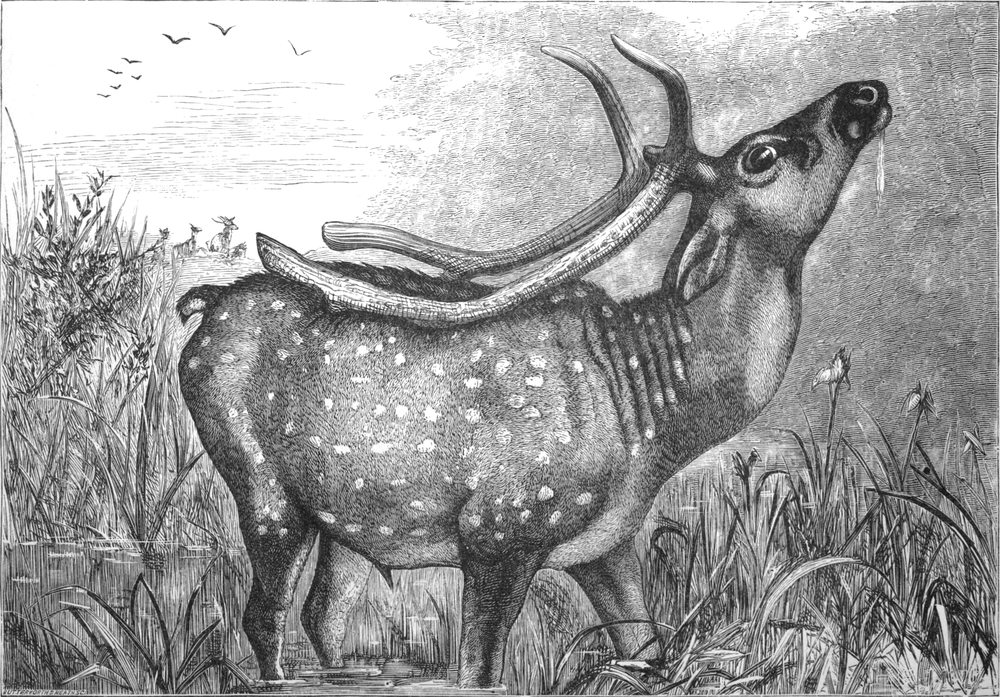

The Axis Deer

|

To face page

|

|

|

Schomburgk’s Deer

|

|

|

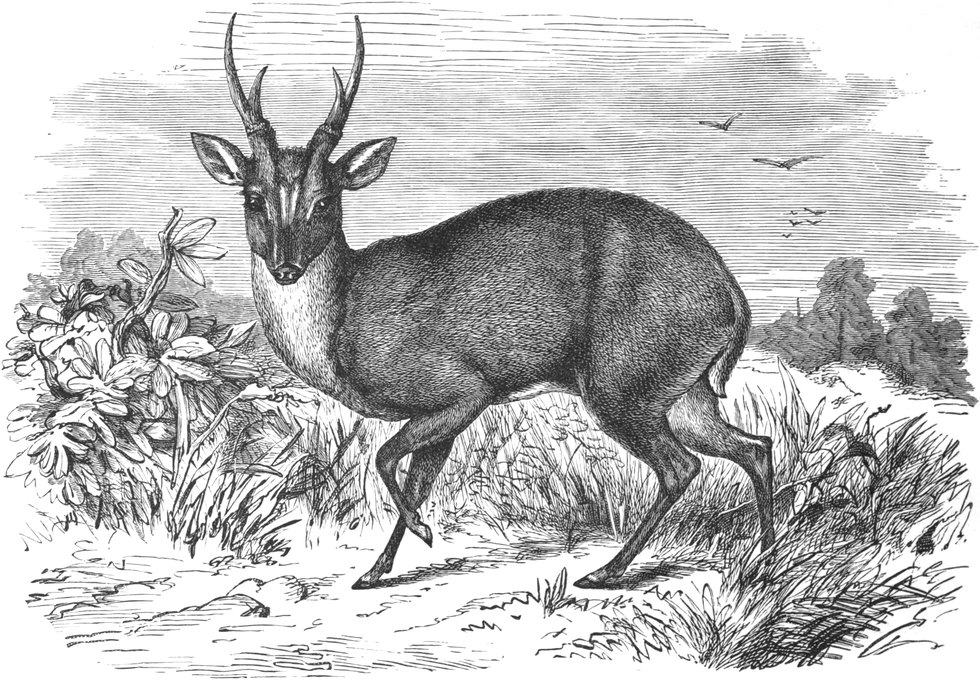

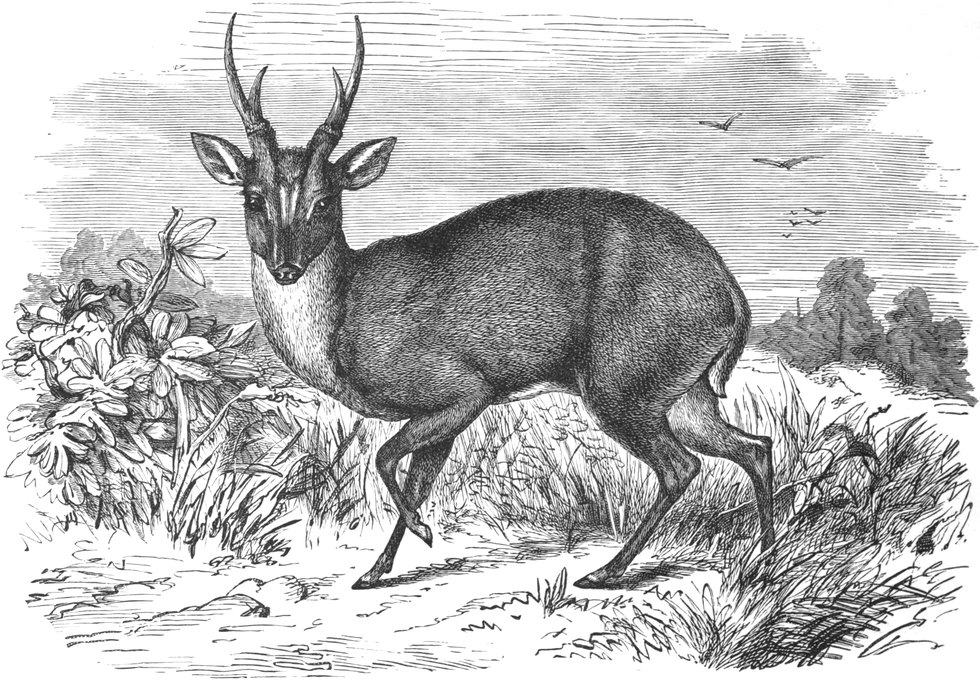

The Indian Muntjac

|

|

|

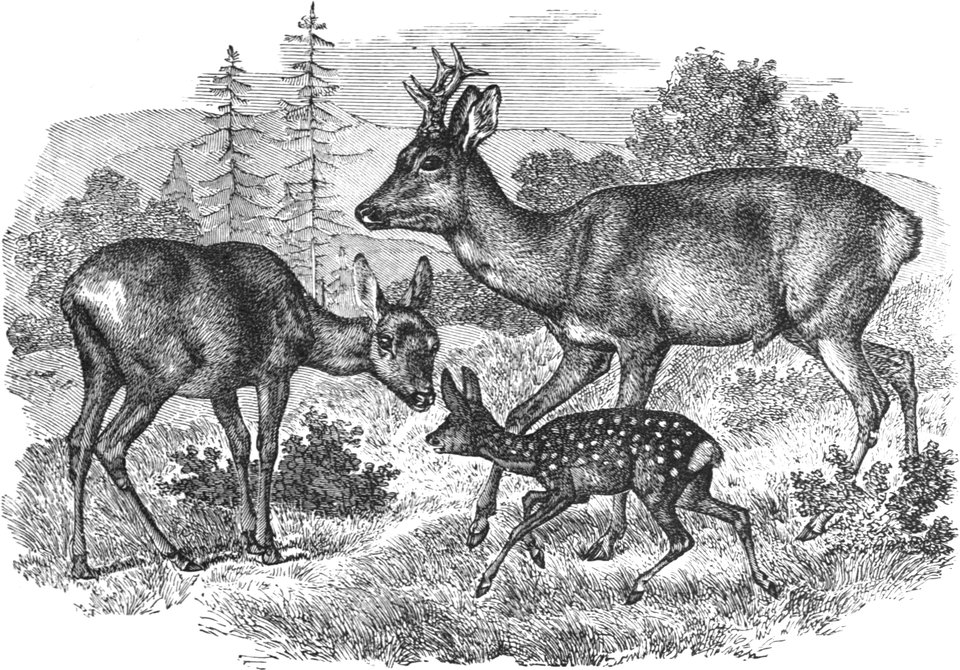

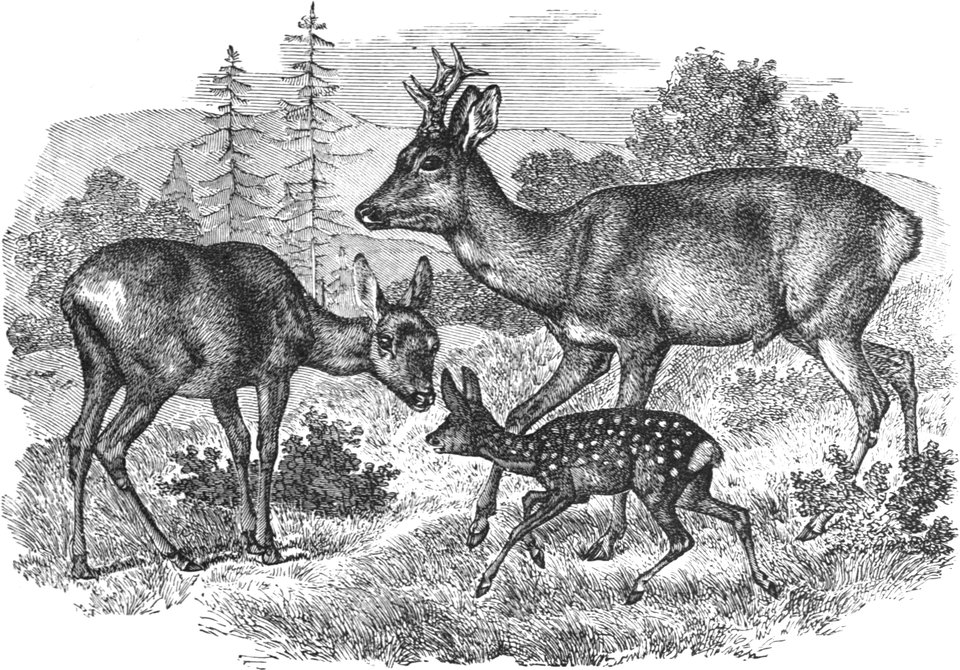

The Roebuck: Male, Female, and Young

|

|

|

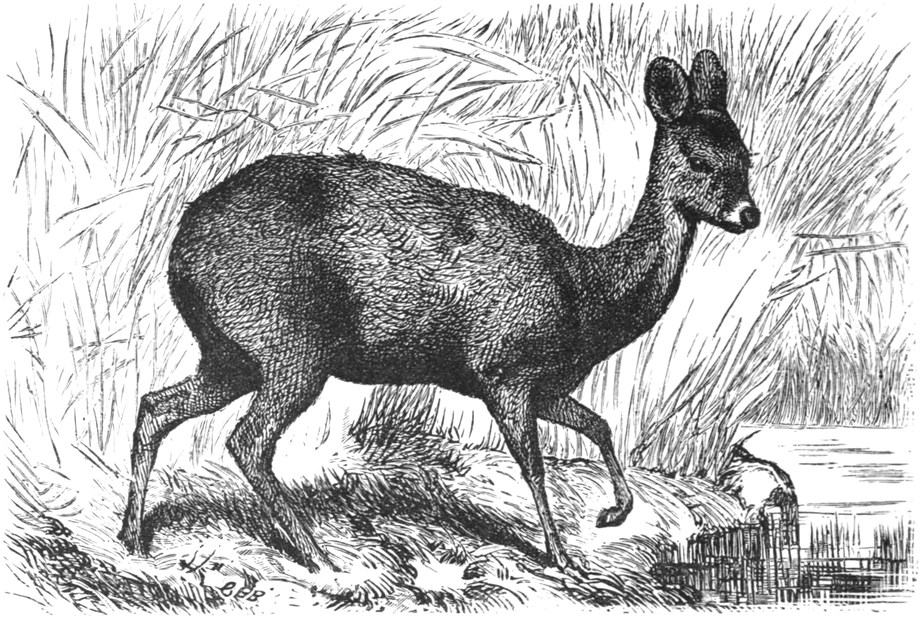

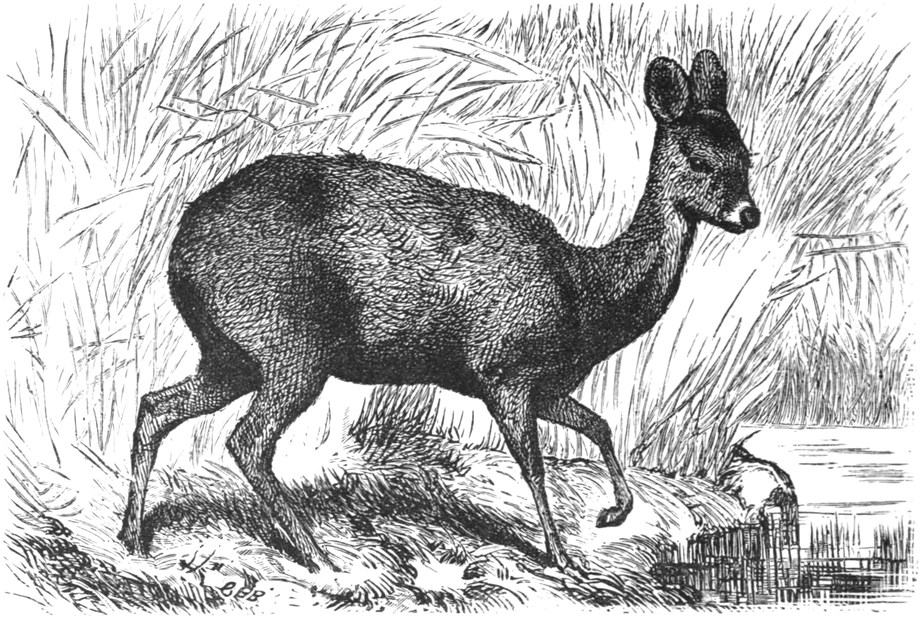

The Chinese Water Deer

|

|

|

The Chinese Elaphure

|

|

|

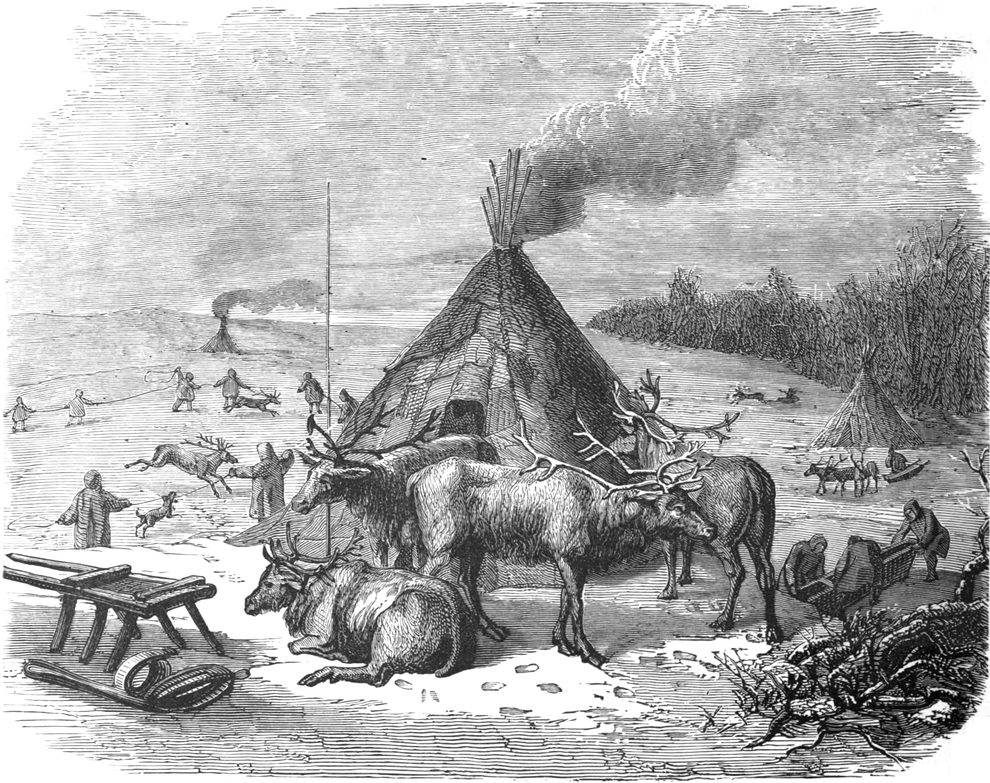

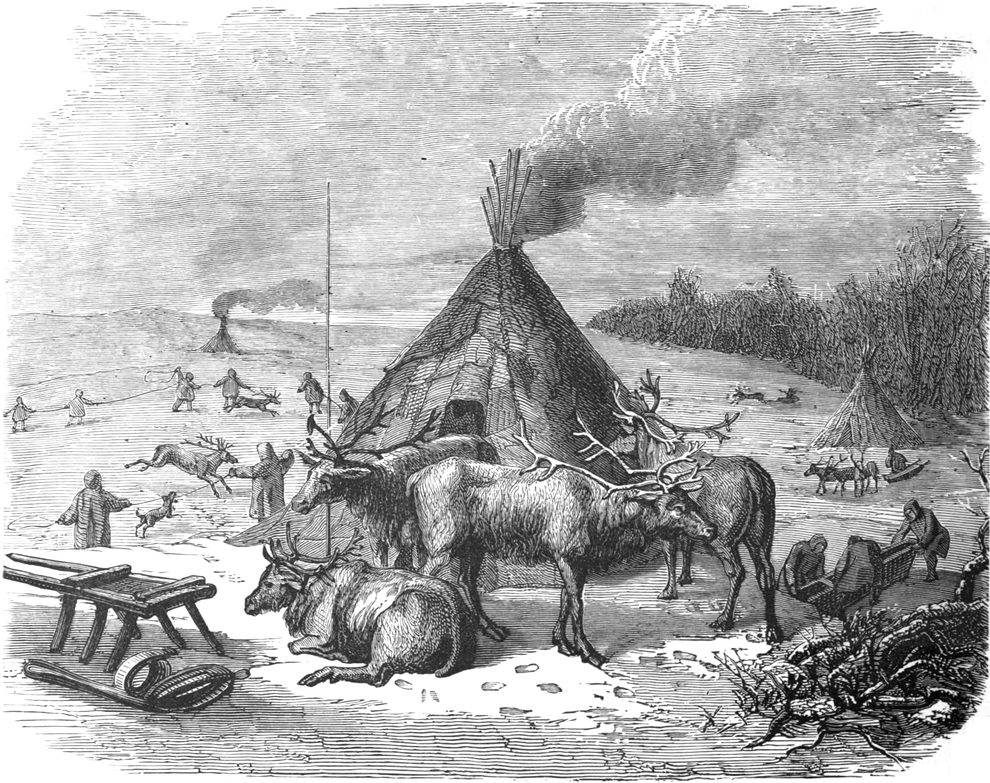

Reindeer at a Lapp Encampment

|

|

|

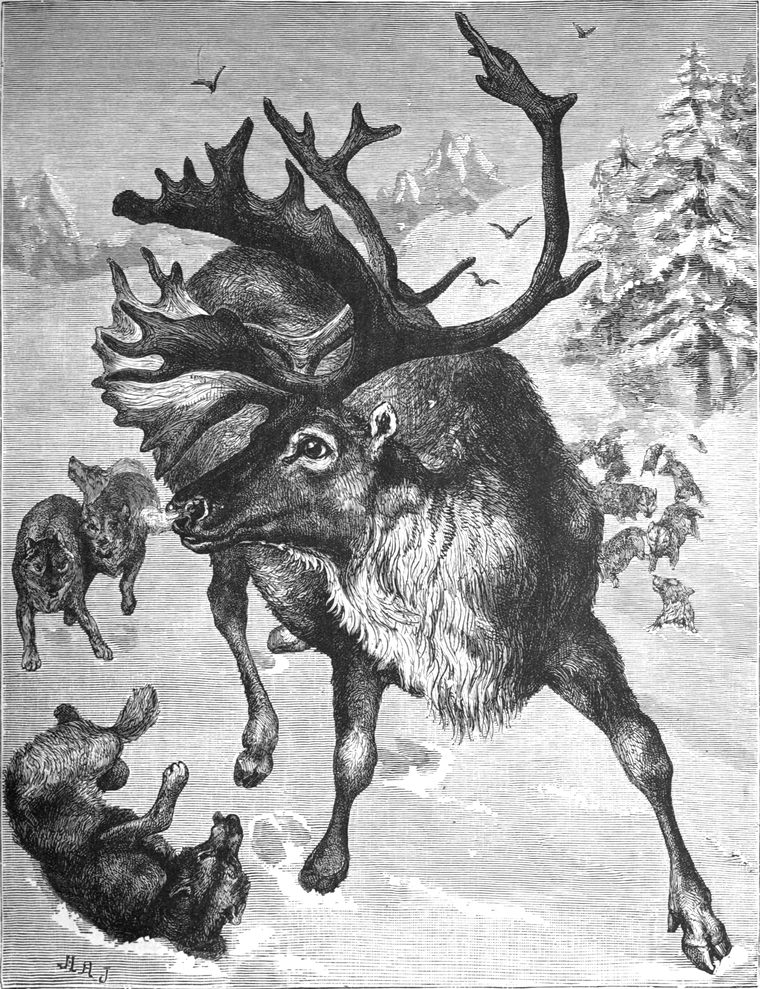

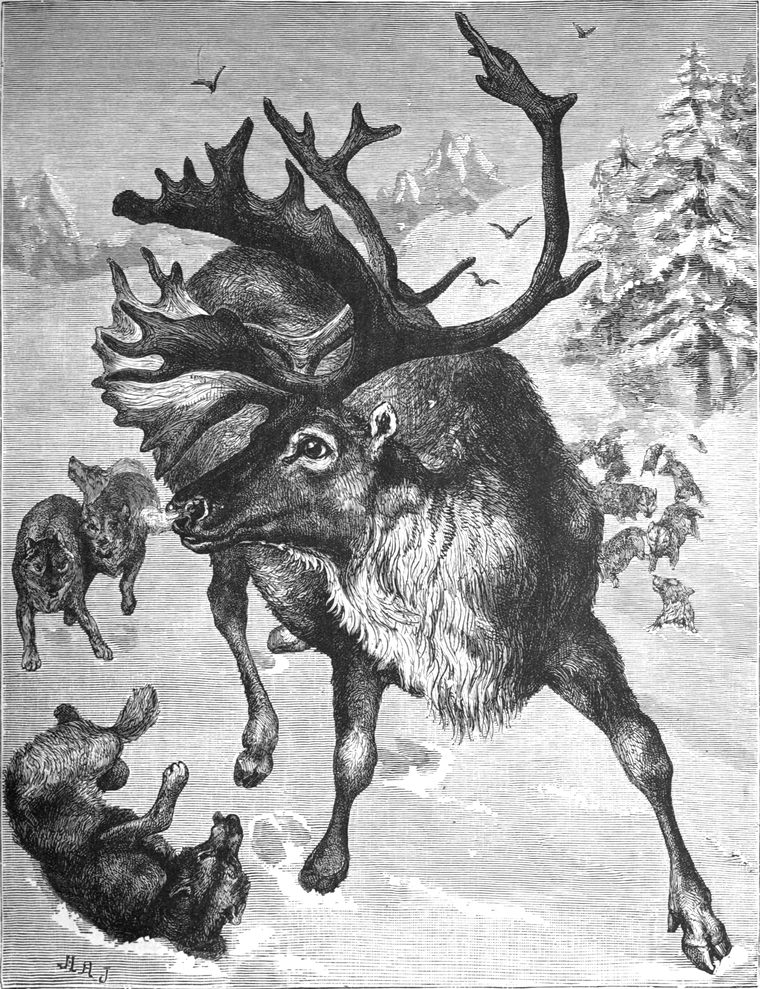

The Reindeer

|

|

|

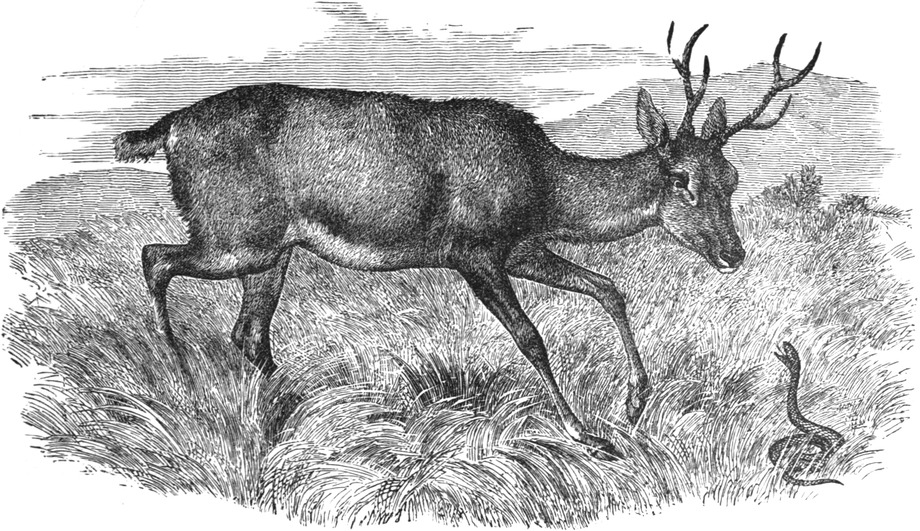

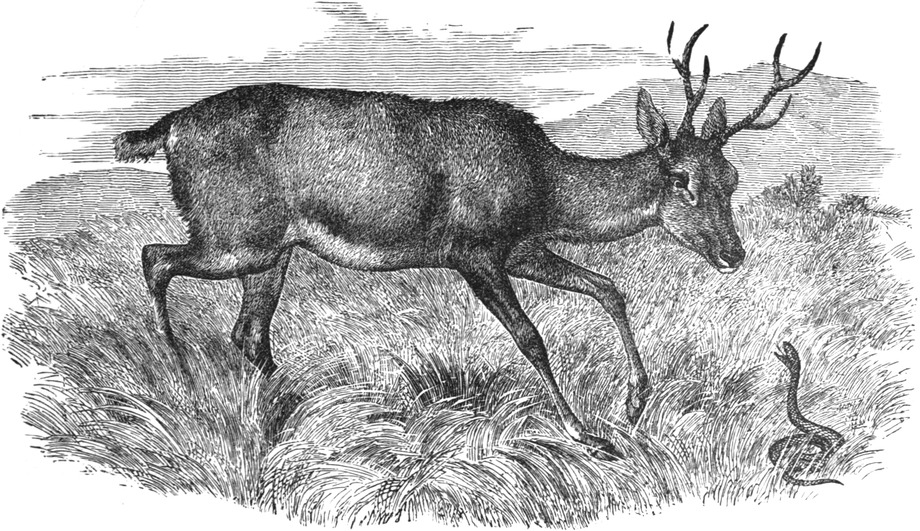

The Guazuti Deer

|

|

|

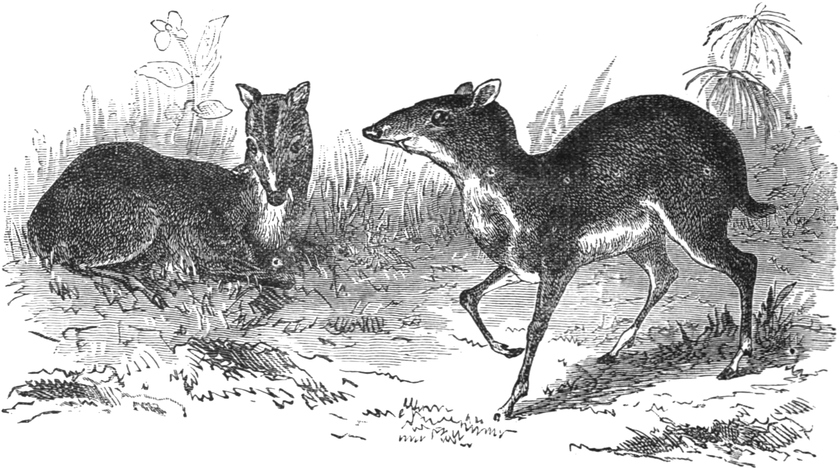

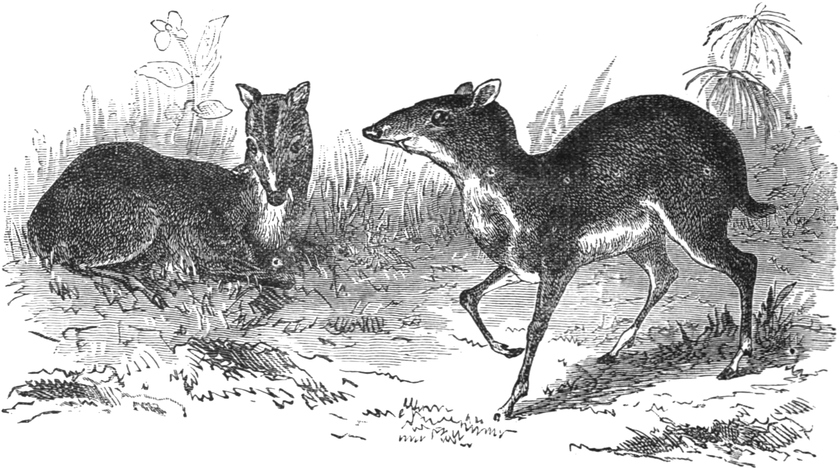

The Javan Deerlet

|

|

|

The Stanleyan Deerlet—Foot of Camel

|

|

|

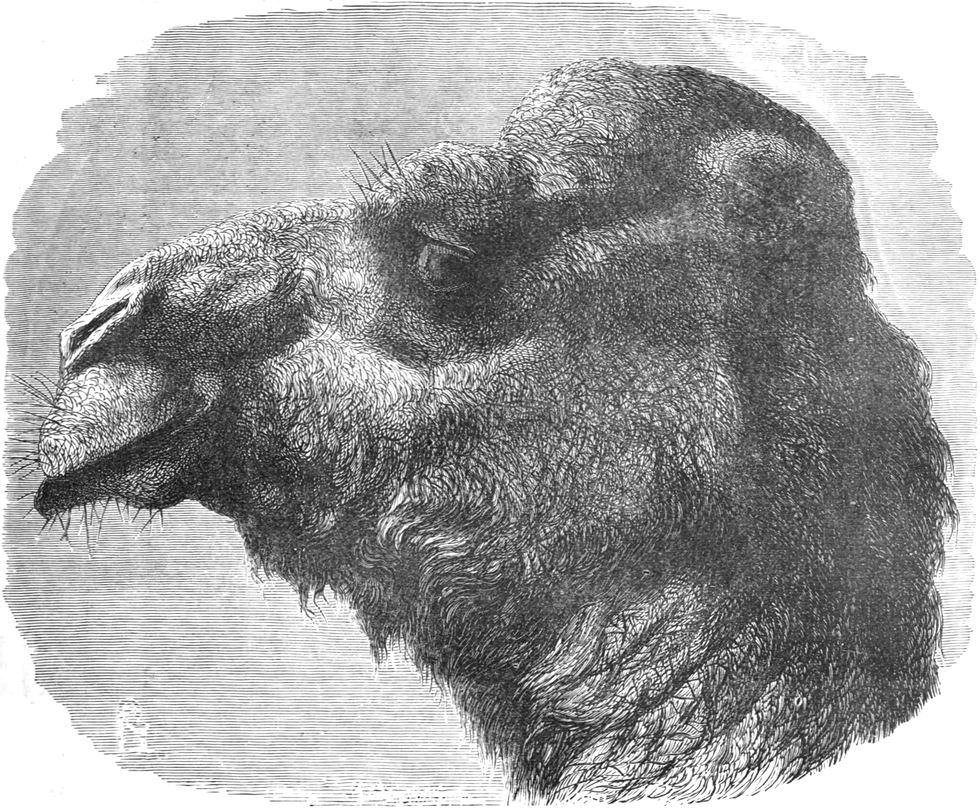

Stomach of the Llama—Water Cells of the Camel

|

|

|

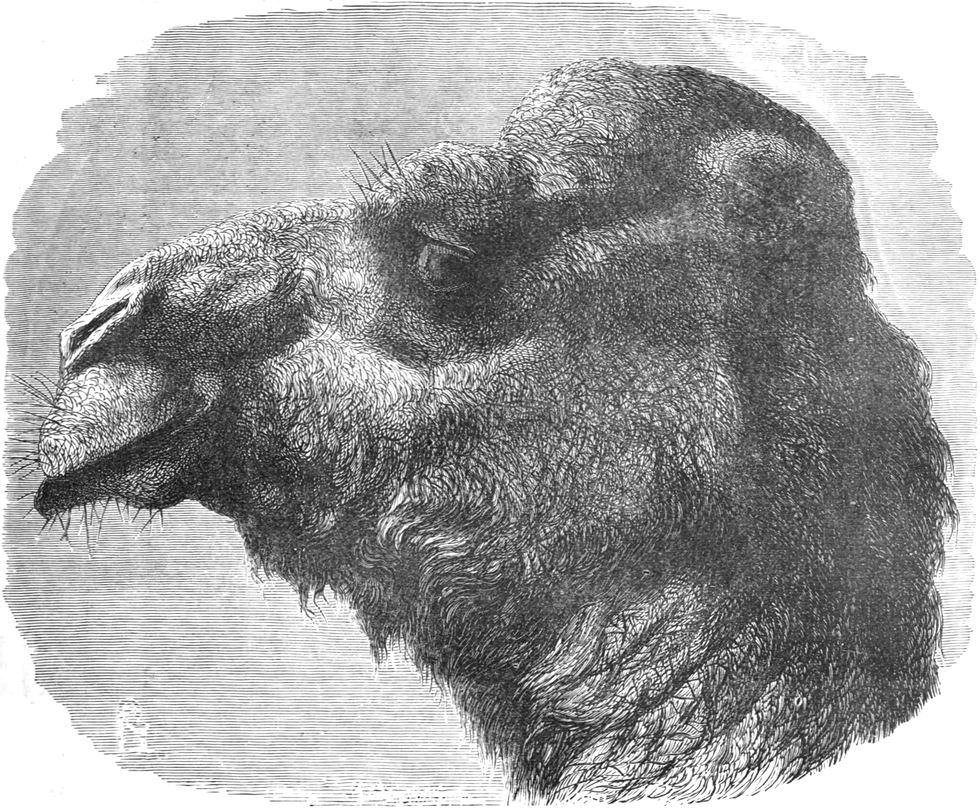

Head of the (true) Camel

|

|

|

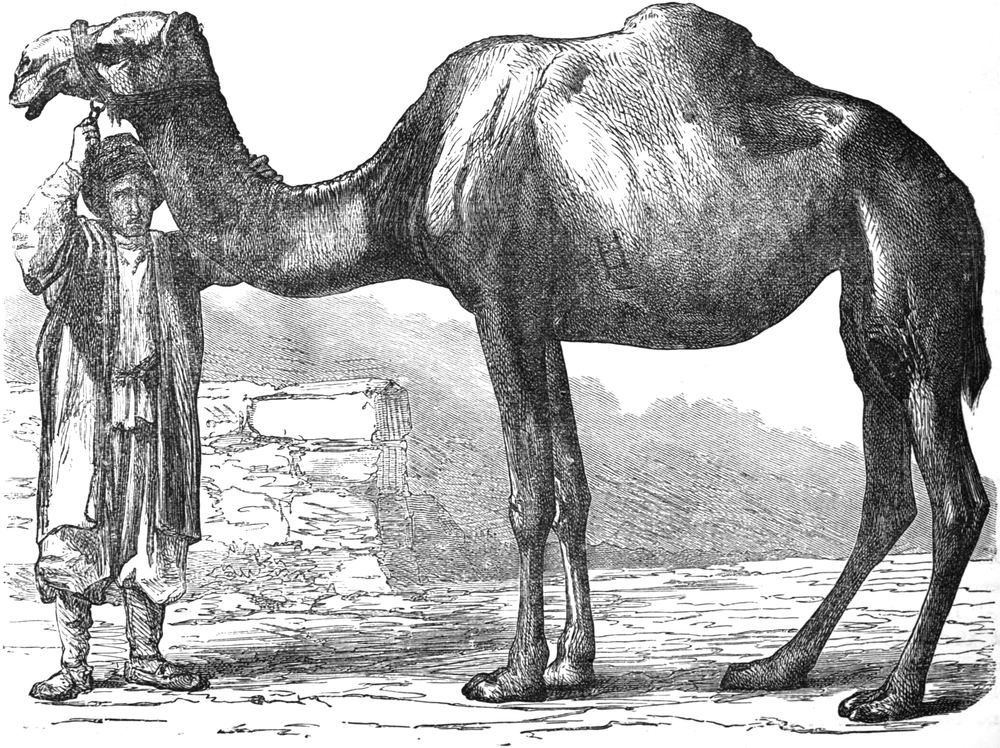

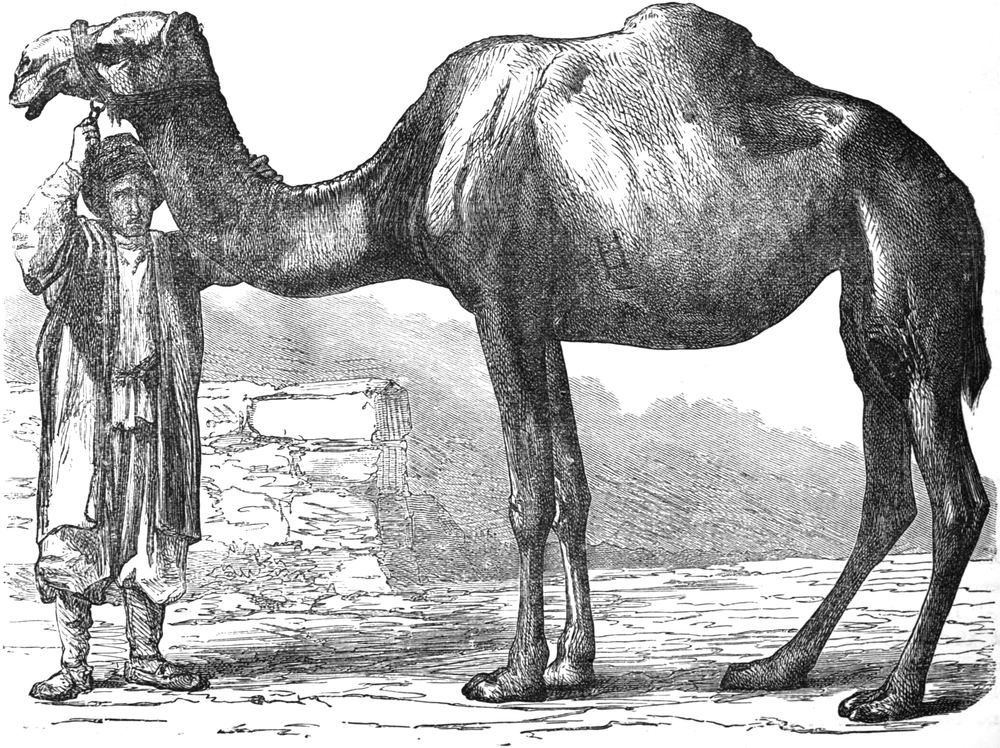

The (true) Camel

|

|

|

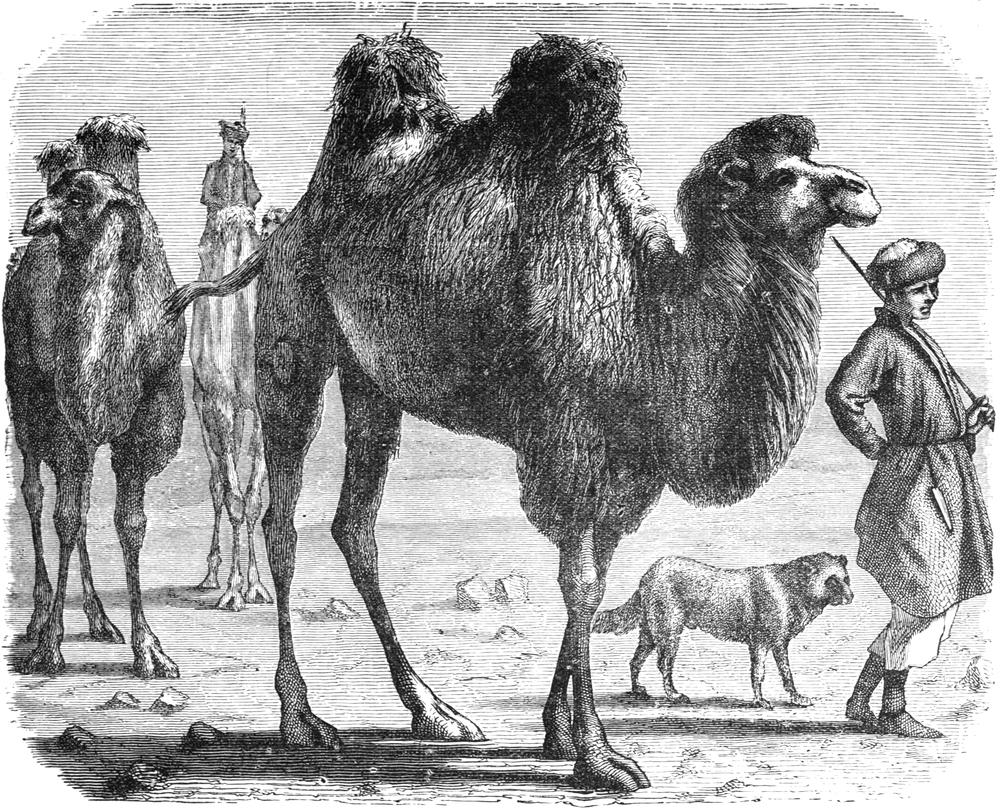

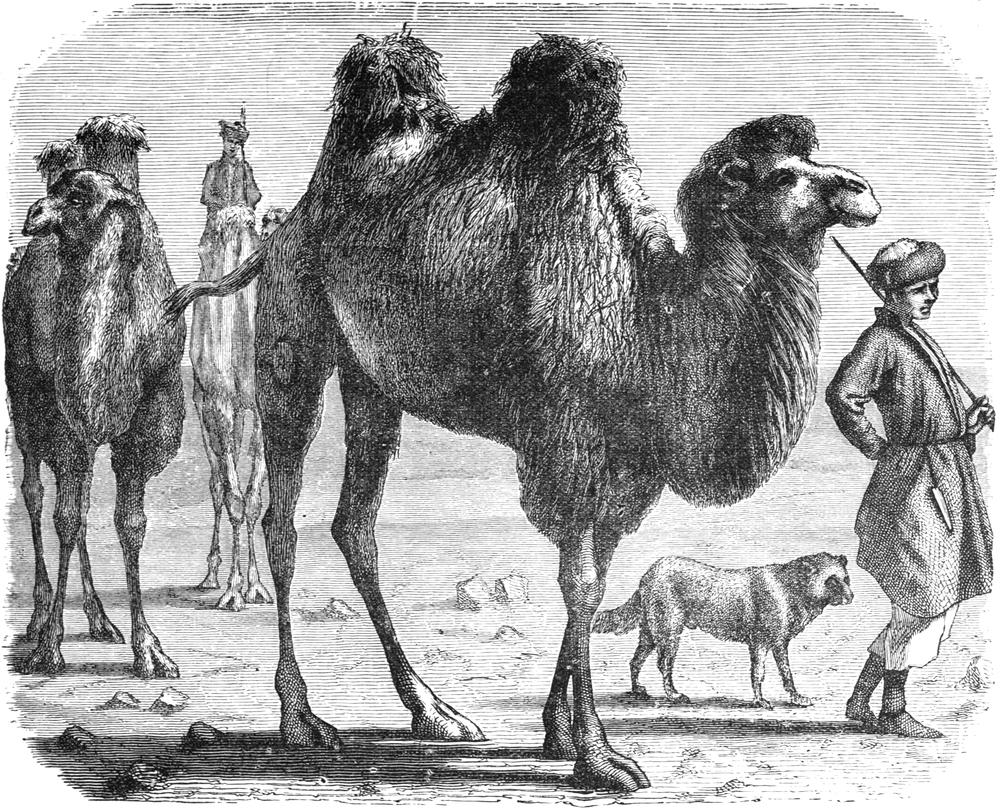

The Bactrian Camel

|

|

|

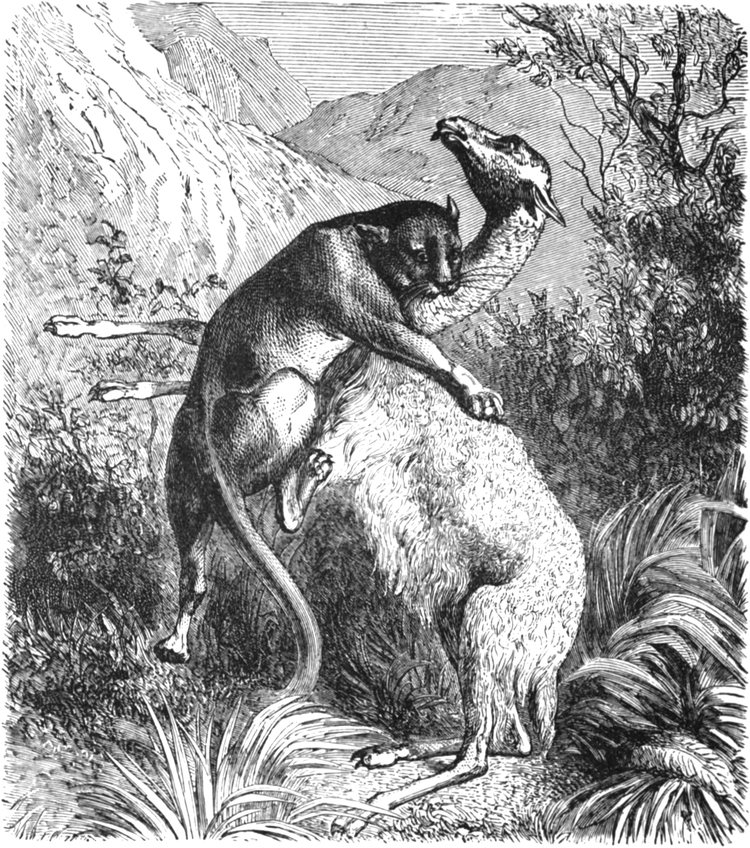

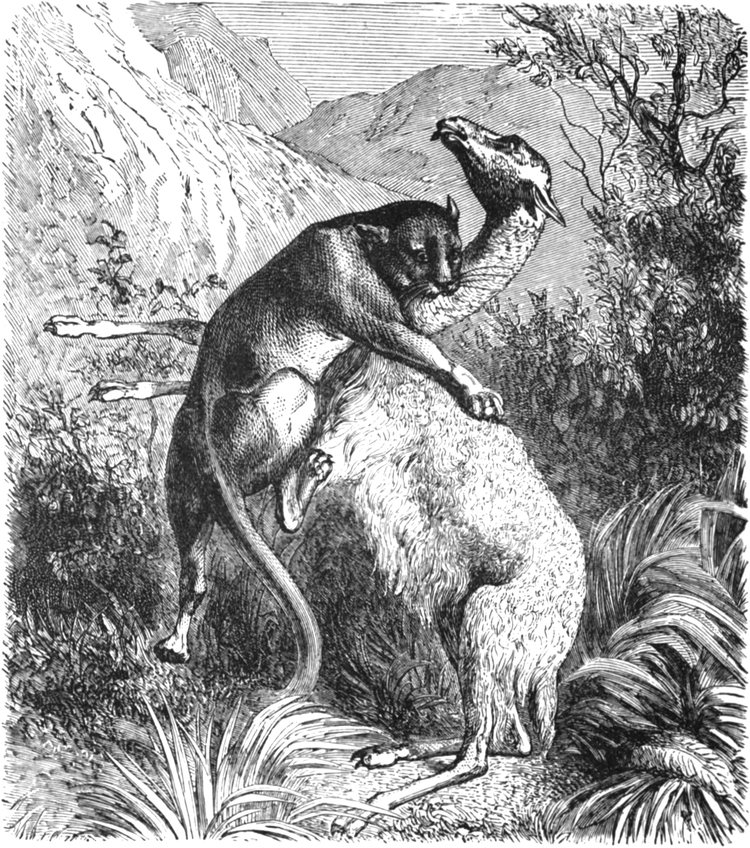

Huanaco attacked by a Puma

|

|

|

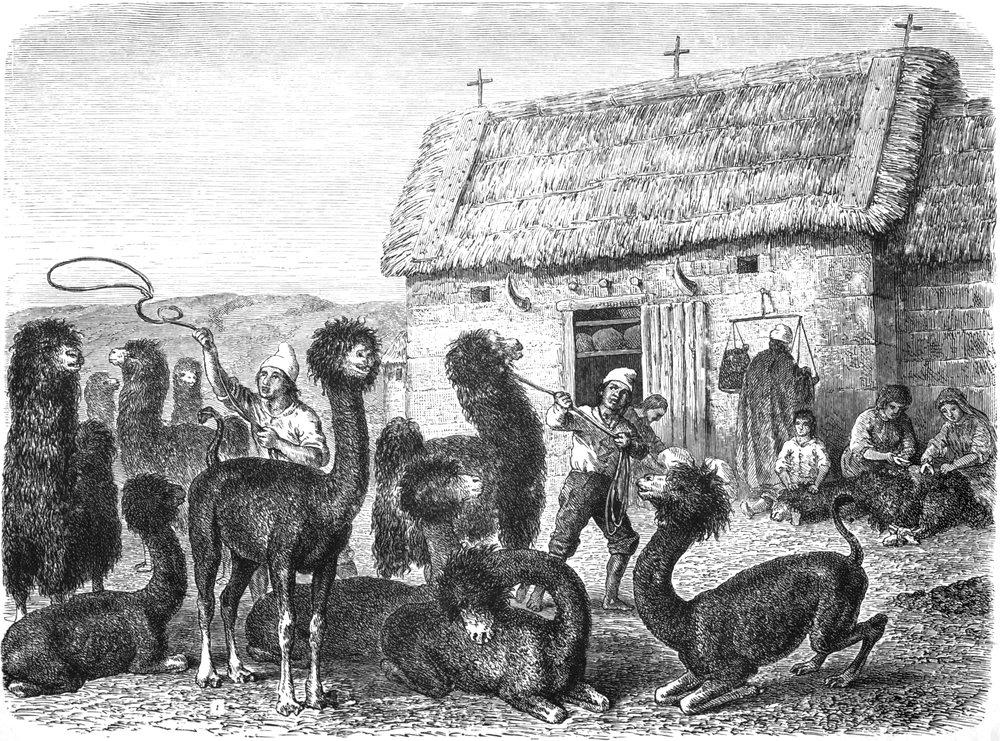

The Alpaca

|

To face page

|

|

|

The Llama

|

|

|

Skeleton of the Irish Elk

|

|

|

The Irish Elk (Restored)

|

|

|

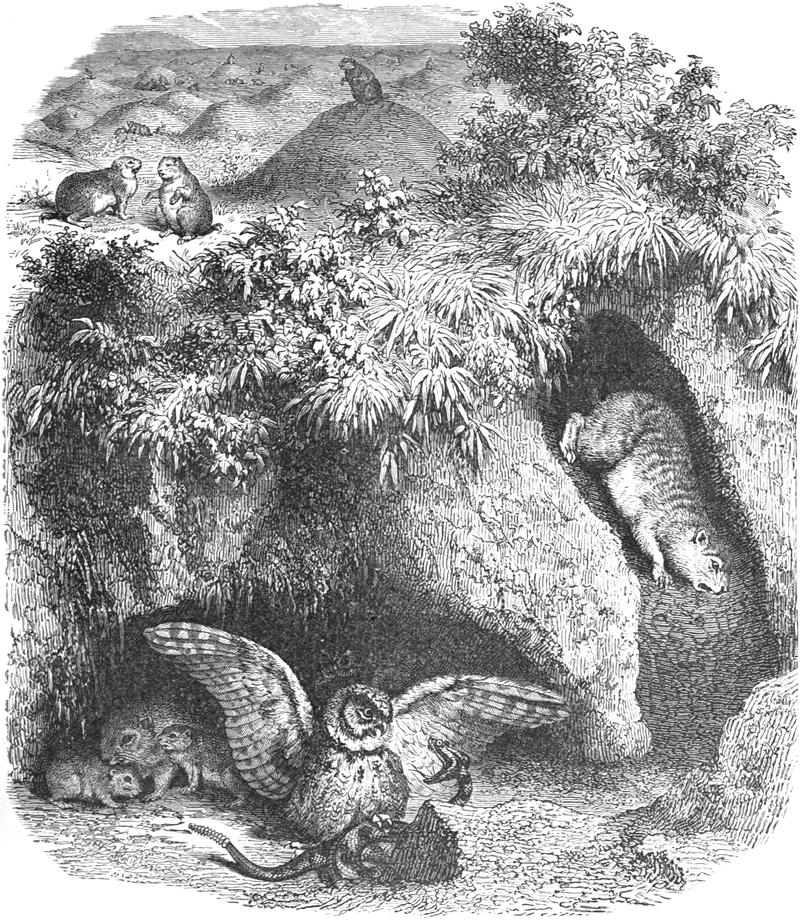

The Prairie Dog

|

|

|

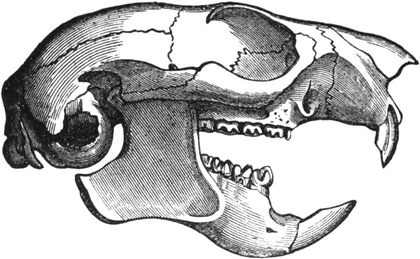

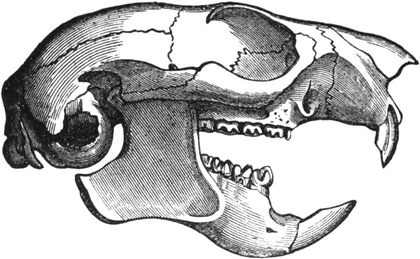

Skull of the Taguan, a Flying Squirrel—Dentition of the Hare

|

|

|

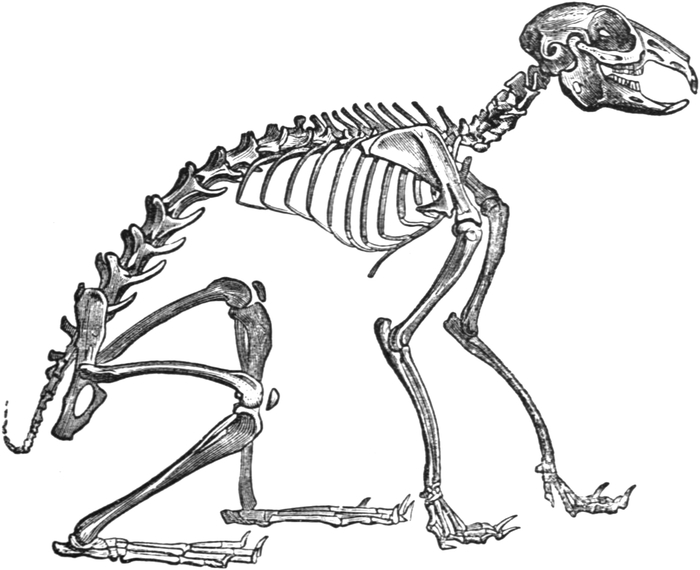

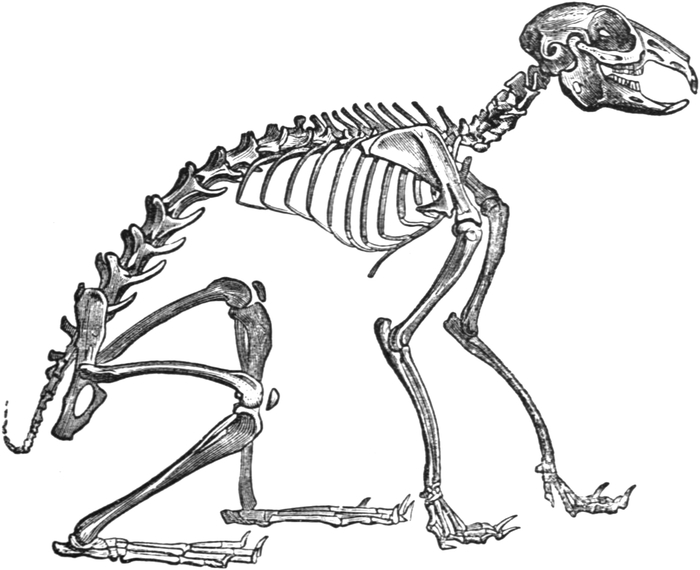

Skeleton of the Rabbit

|

|

|

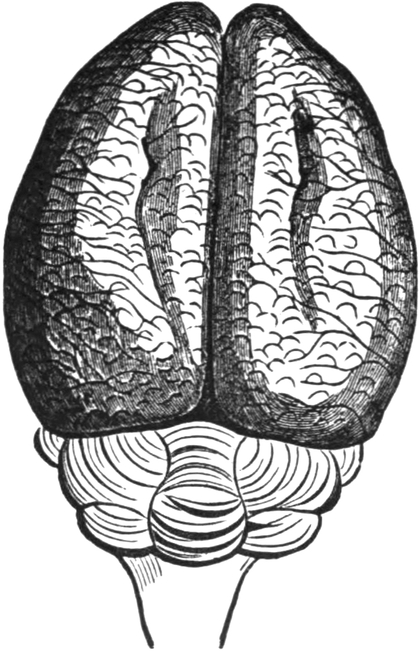

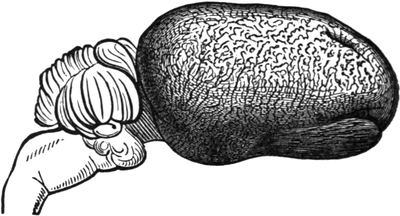

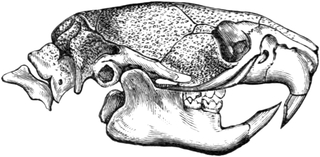

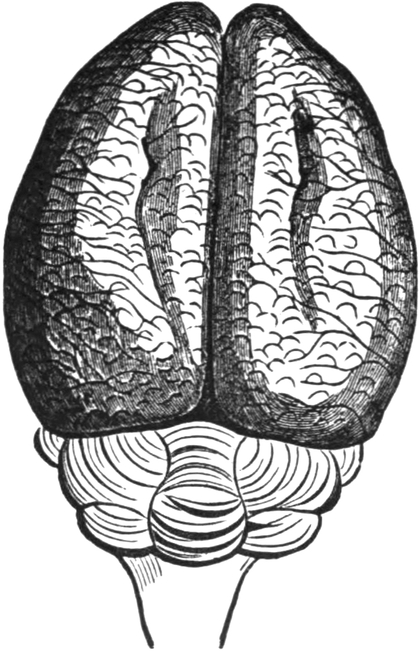

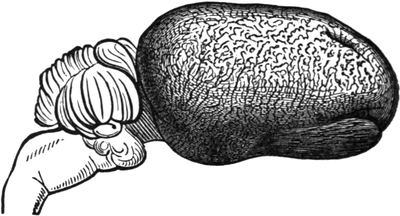

Brain of Beaver, from above and in profile

|

|

|

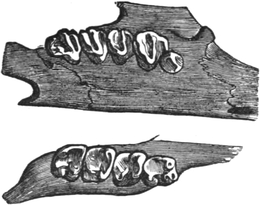

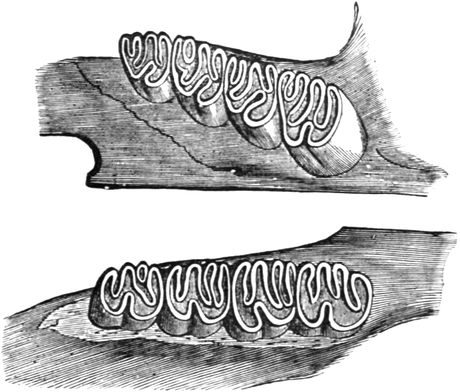

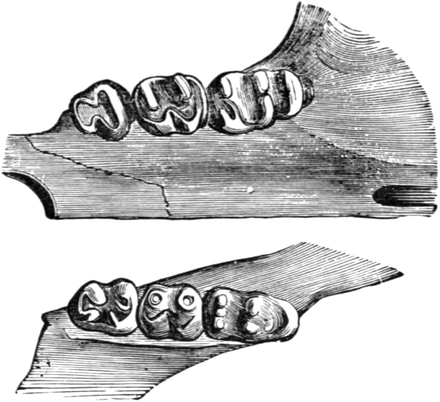

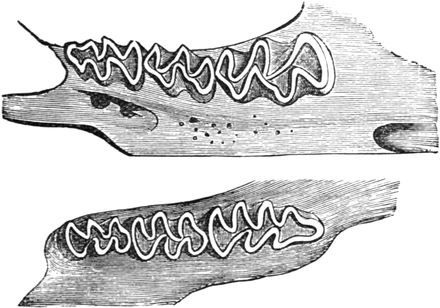

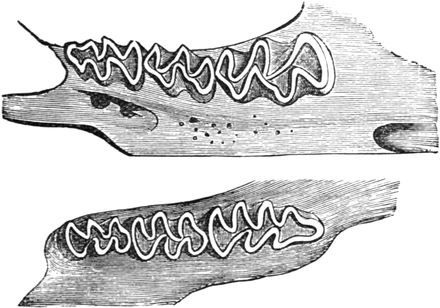

Teeth of the Taguan

|

|

|

The Common Squirrel

|

|

|

The Black Fox Squirrel

|

|

|

The Taguan

|

|

|

The Polatouche

|

|

|

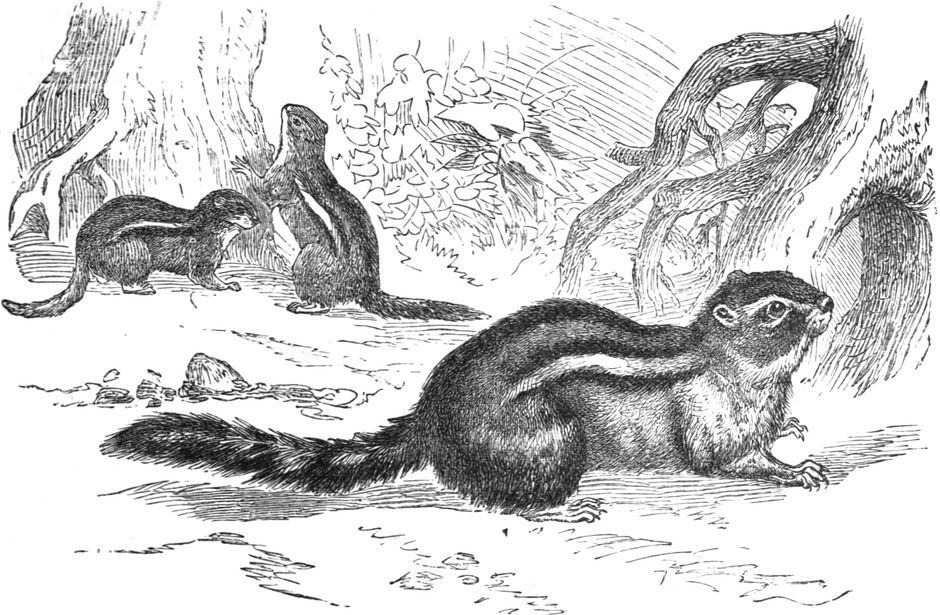

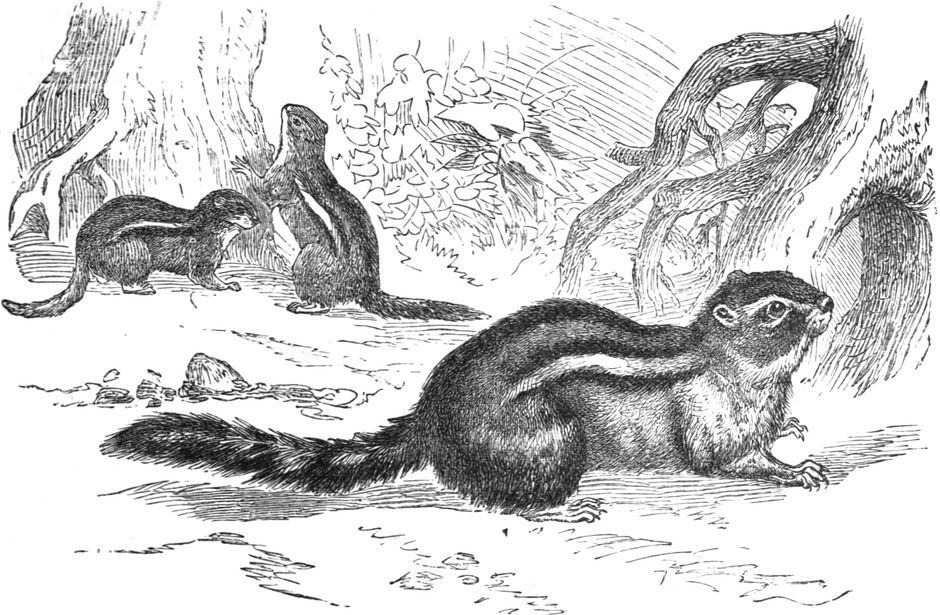

The Common Chipmunk

|

|

|

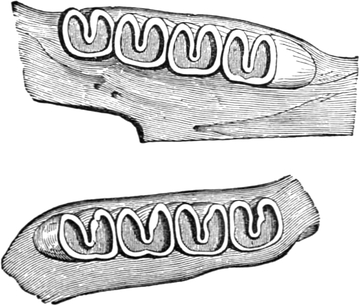

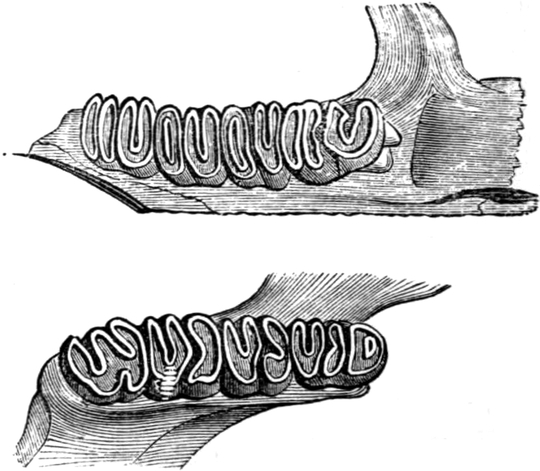

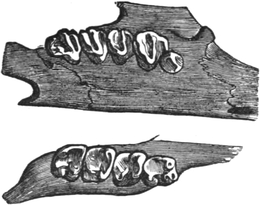

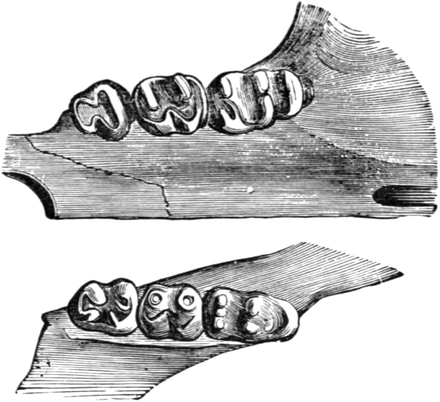

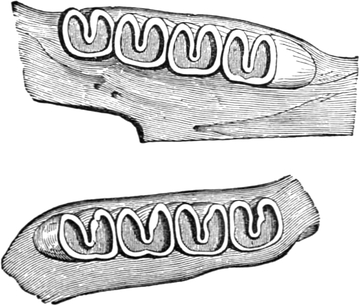

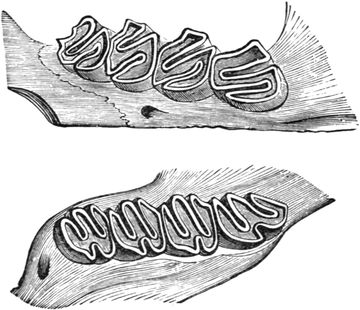

Molar Teeth of the Marmot—The Striped Spermophile, or Gopher

|

|

|

Burrows of the Prairie Dog

|

|

|

The Alpine Marmot

|

|

|

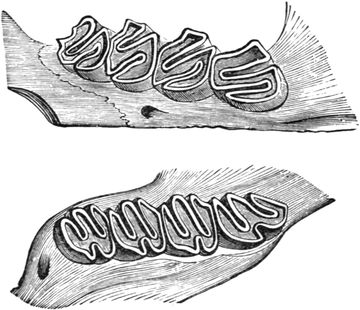

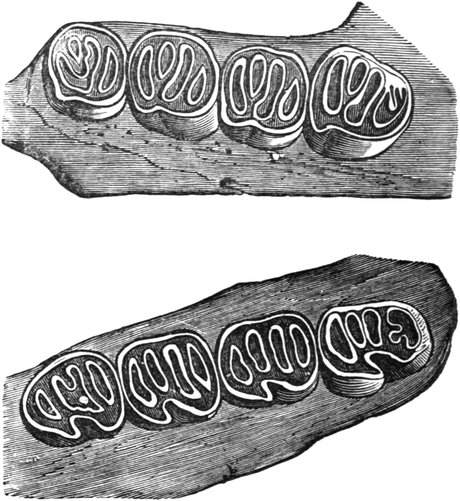

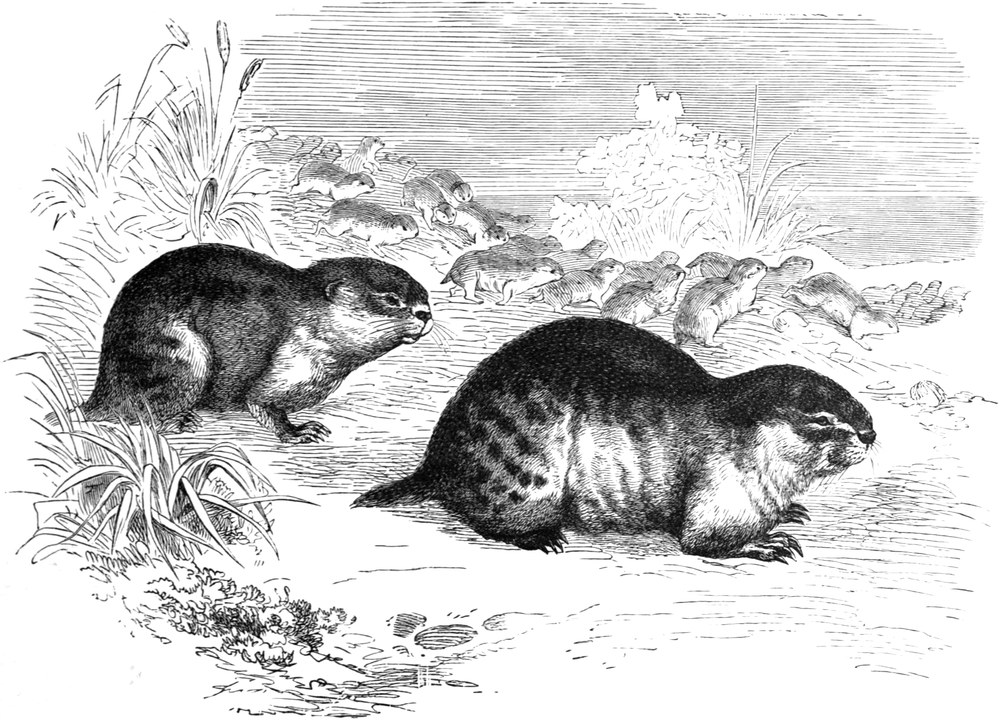

The Fulgent Anomalure—Molar Teeth of the Anomalure

|

|

|

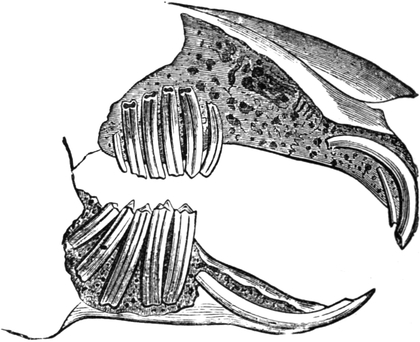

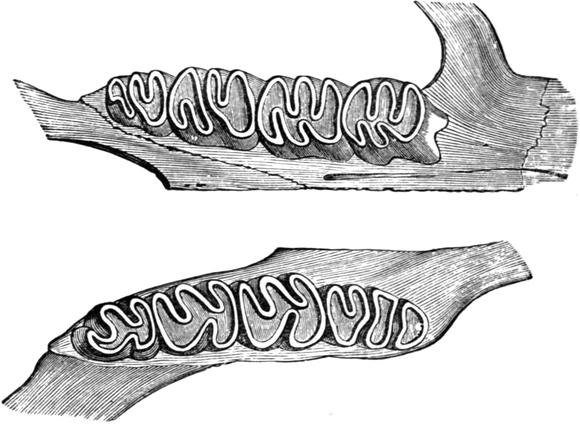

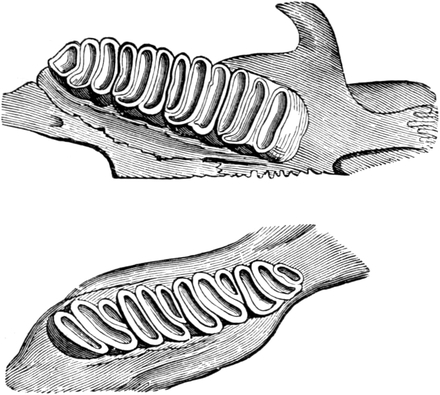

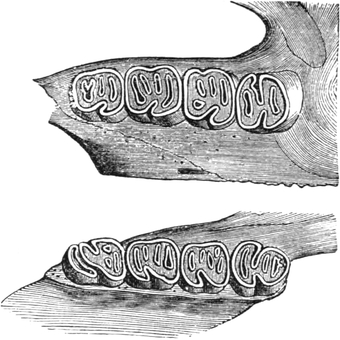

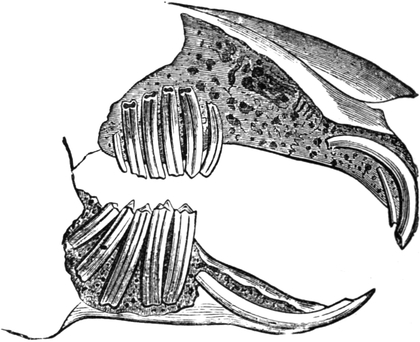

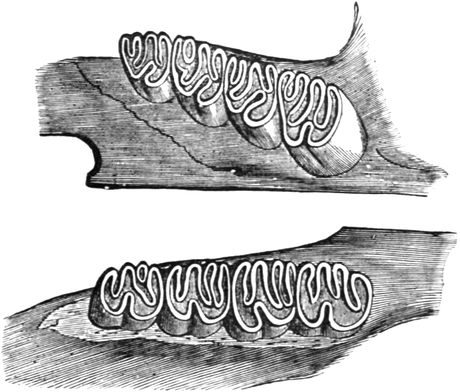

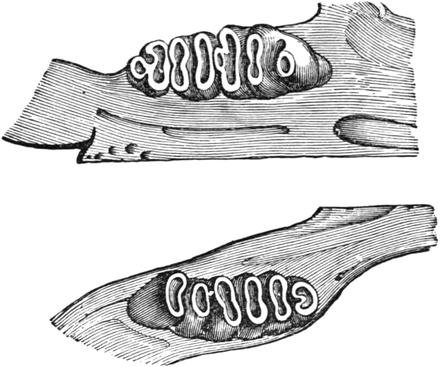

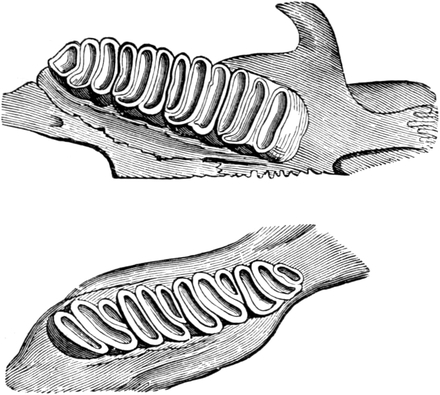

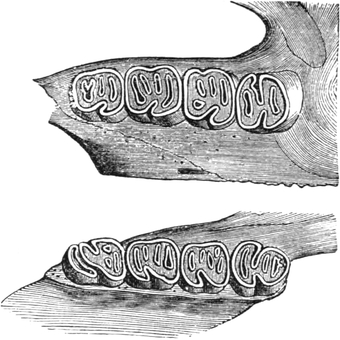

Molar Teeth of the Beaver

|

|

|

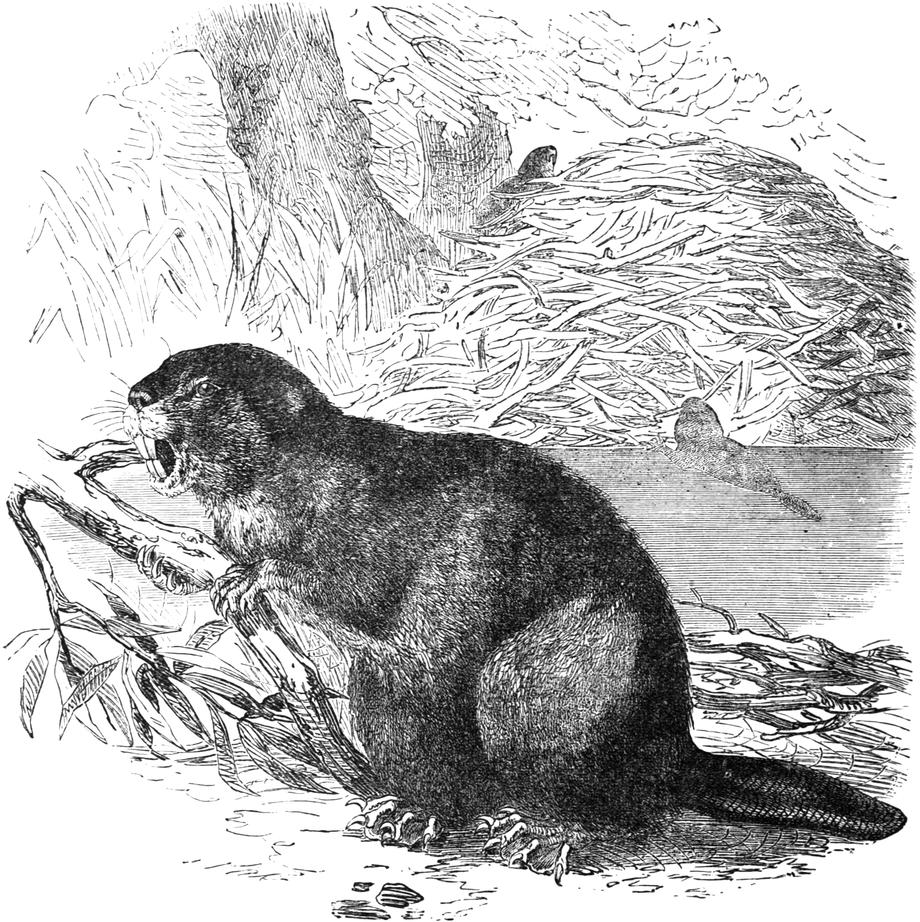

The Beaver

|

|

|

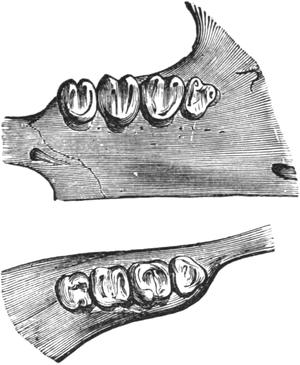

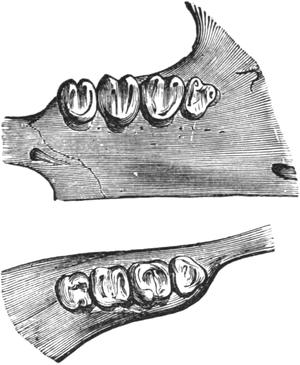

Molar Teeth of the Dormouse—The Dormouse

|

|

|

The Garden Dormouse

|

|

|

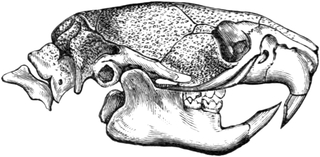

Skull of Lophiomys—The Lophiomys

|

|

|

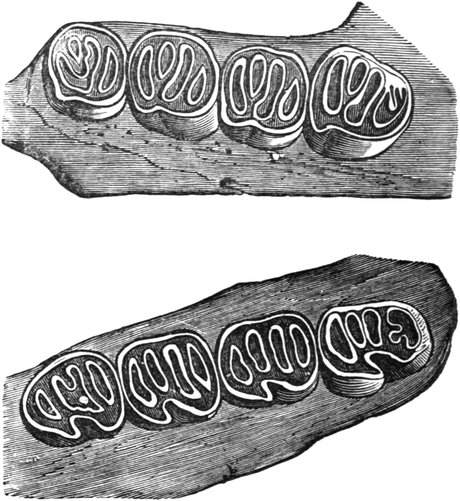

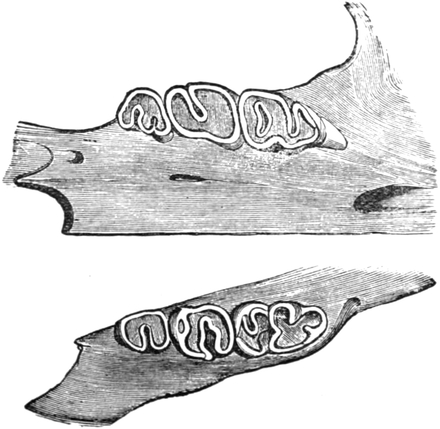

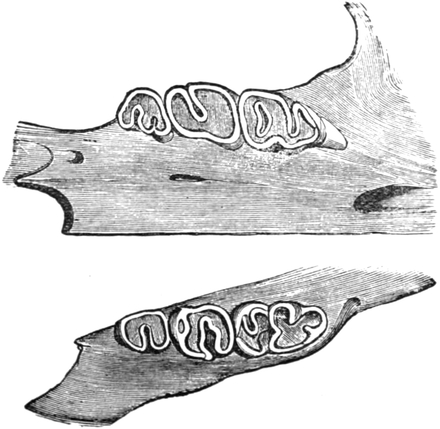

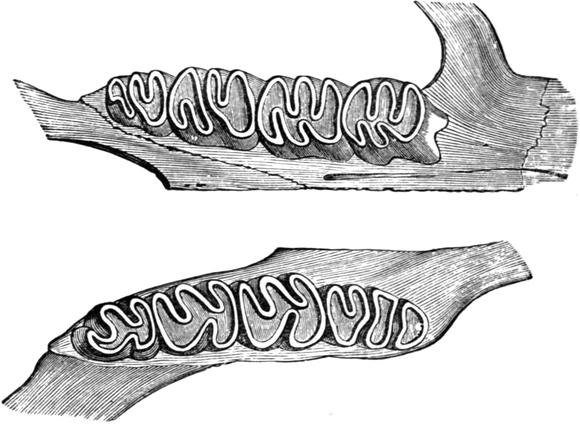

Molar Teeth of the Black Rat

|

|

|

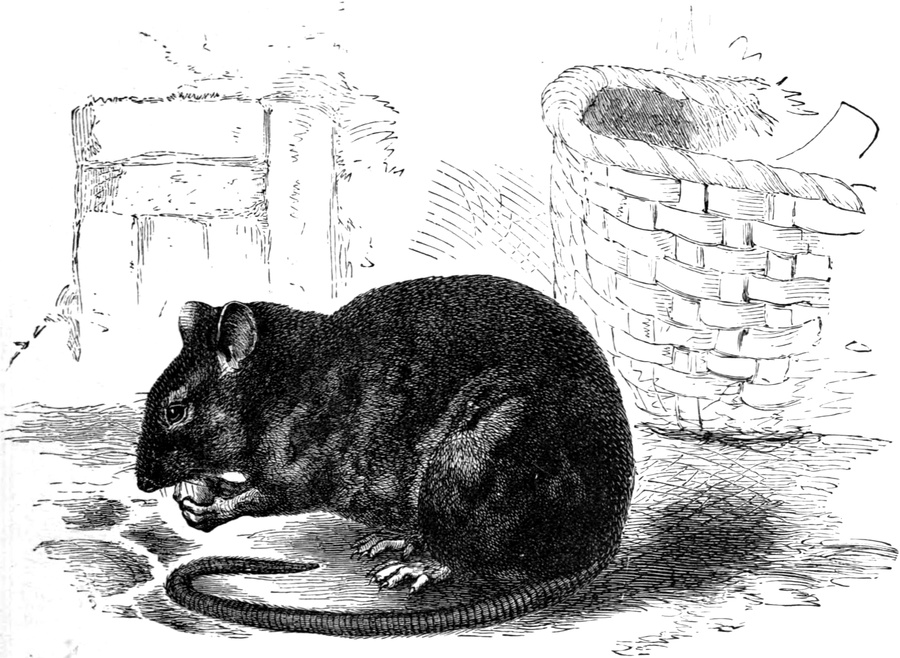

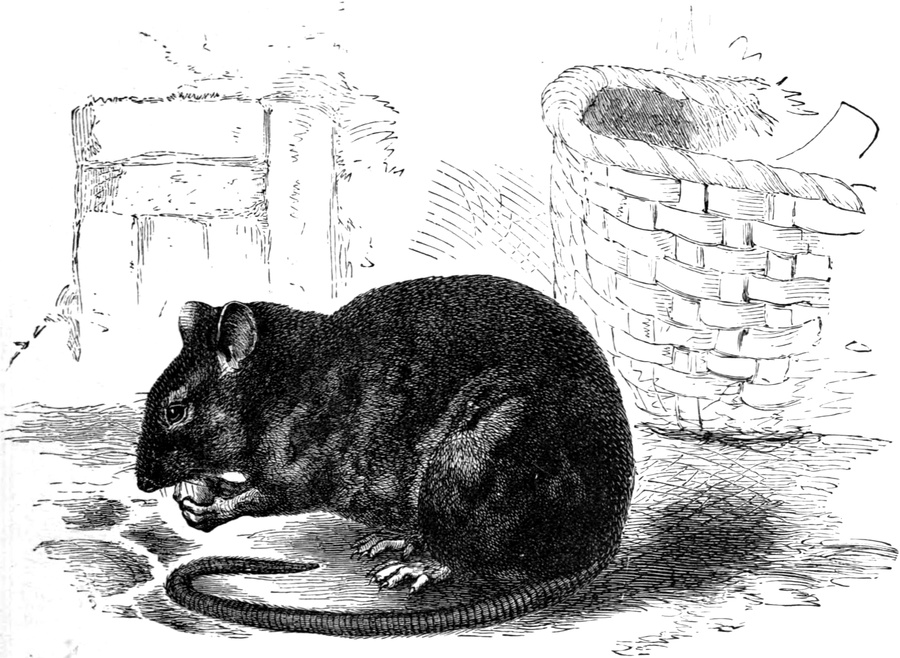

The Brown Rat

|

|

|

The Black Rat

|

|

|

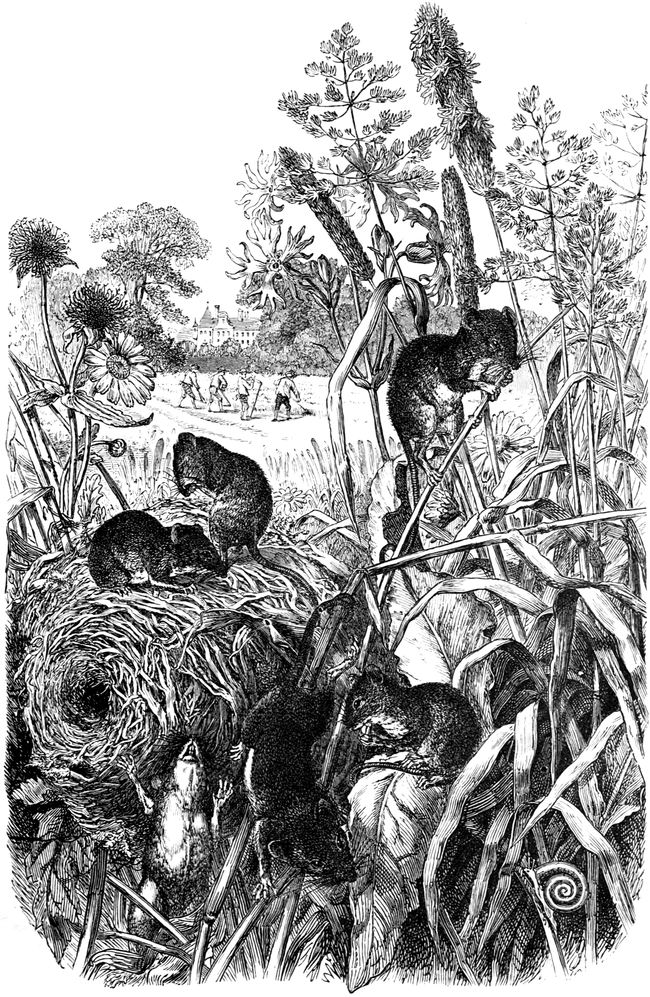

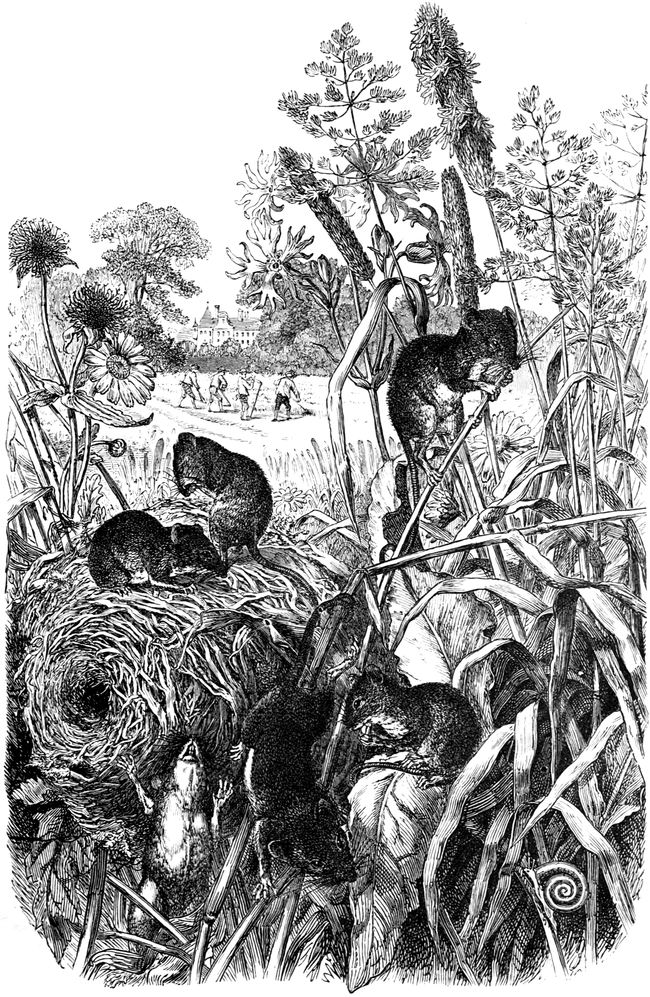

Harvest Mice

|

|

|

Molar Teeth of the Hapalote

|

|

|

Head of the Rabbit-like Reithrodon

|

|

|

Hamster

|

To face page

|

|

|

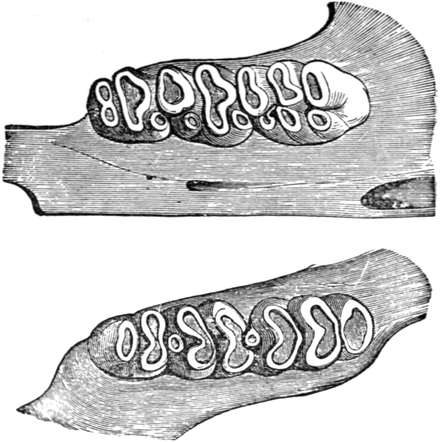

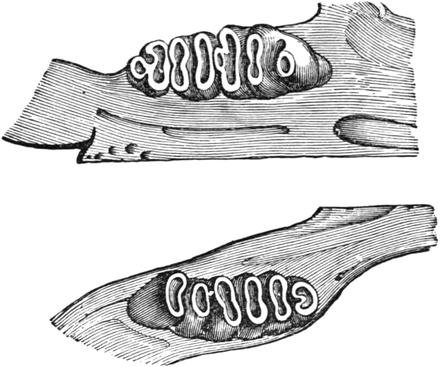

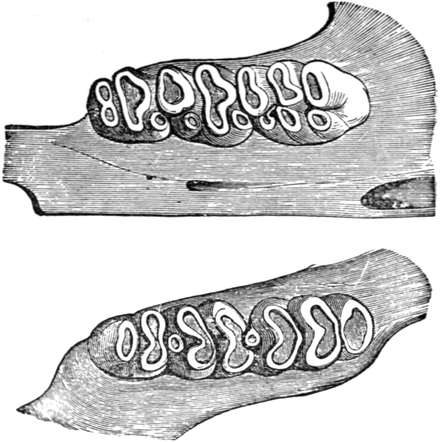

Molar Teeth of the Hamster

|

|

|

Molar Teeth of the Gerbille—Skull of the Water Mouse—Teeth

of Sminthus

|

|

|

Molar Teeth of the Water Rat

|

|

|

The Southern Field Vole

|

|

|

The Musquash

|

|

|

The Lemming

|

|

|

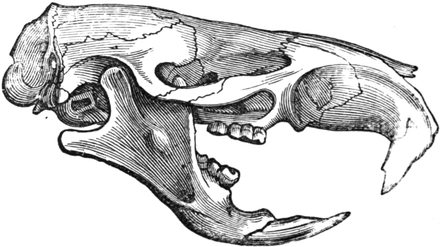

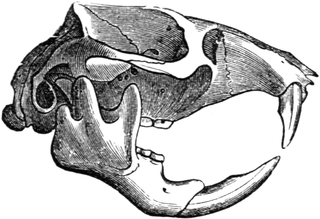

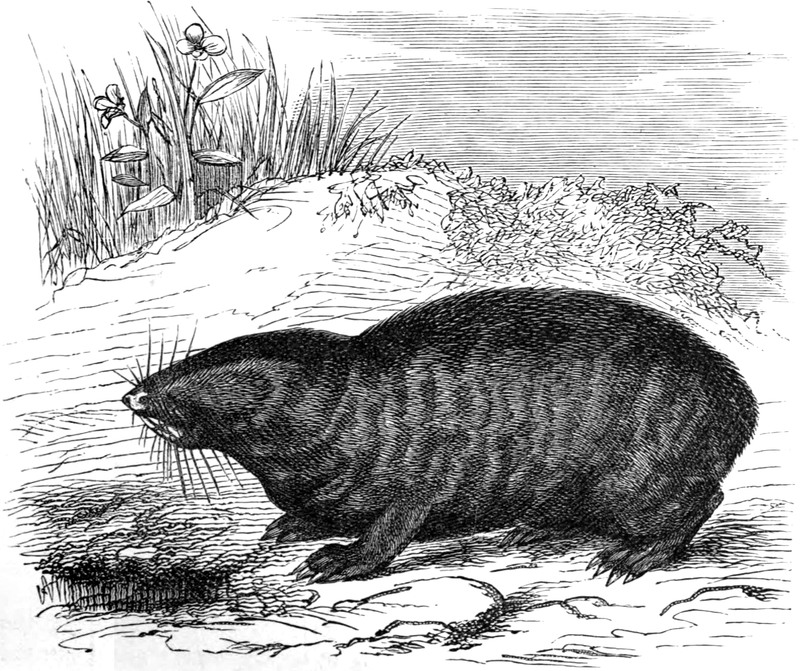

Skull of Mole-Rat—The Mole-Rat

|

|

|

Molar Teeth of the Mexican Pouched Rat—Under Surface of the Head

of Heteromys

|

|

|

Skull of the Mexican Pouched Rat

|

|

|

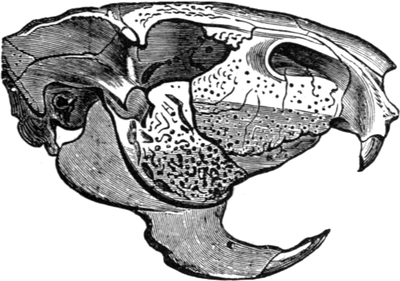

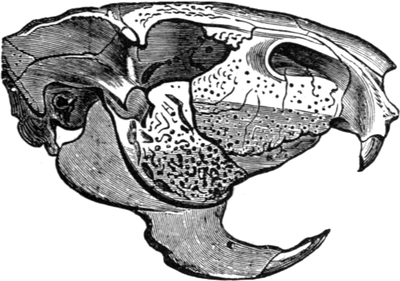

Skull of the Cape Jumping Hare

|

|

|

The American Jumping Mouse—Molar Teeth of the Jerboa

|

|

|

The Jerboa

|

|

|

The Alactaga—Molar Teeth of the Jumping Hare

|

|

|

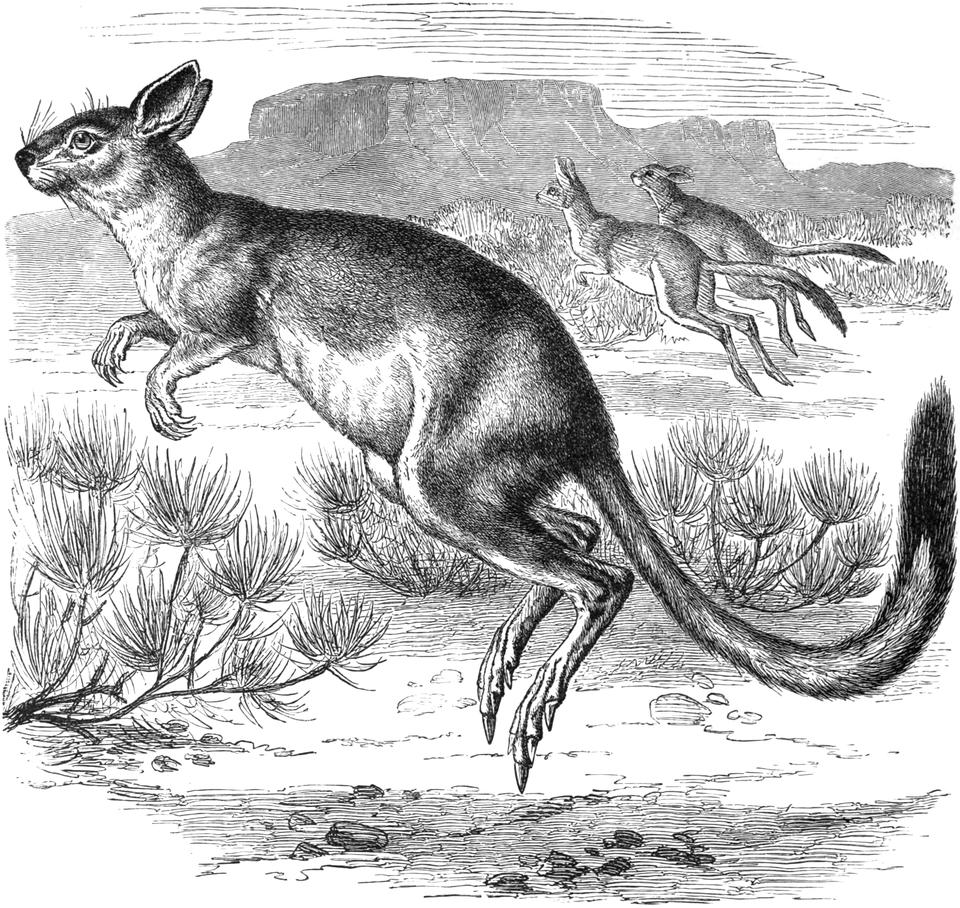

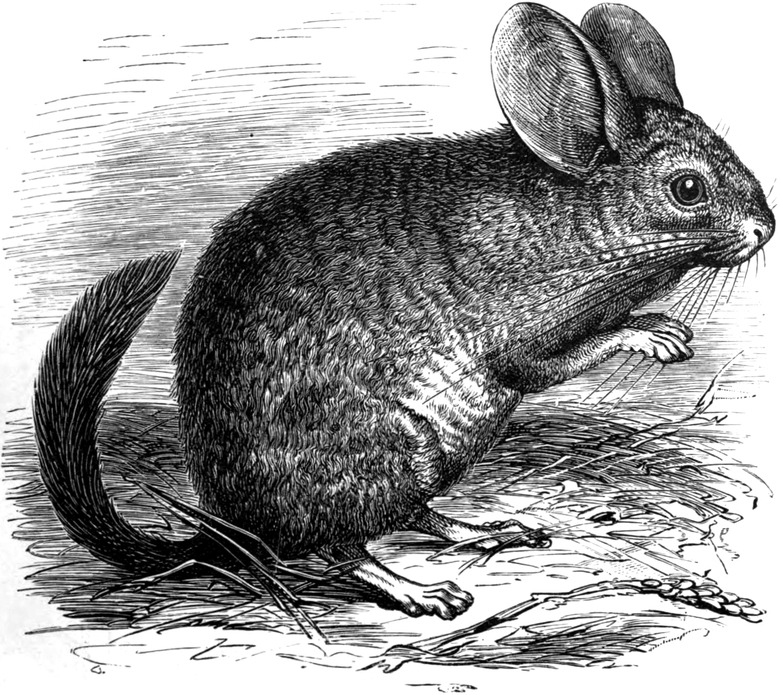

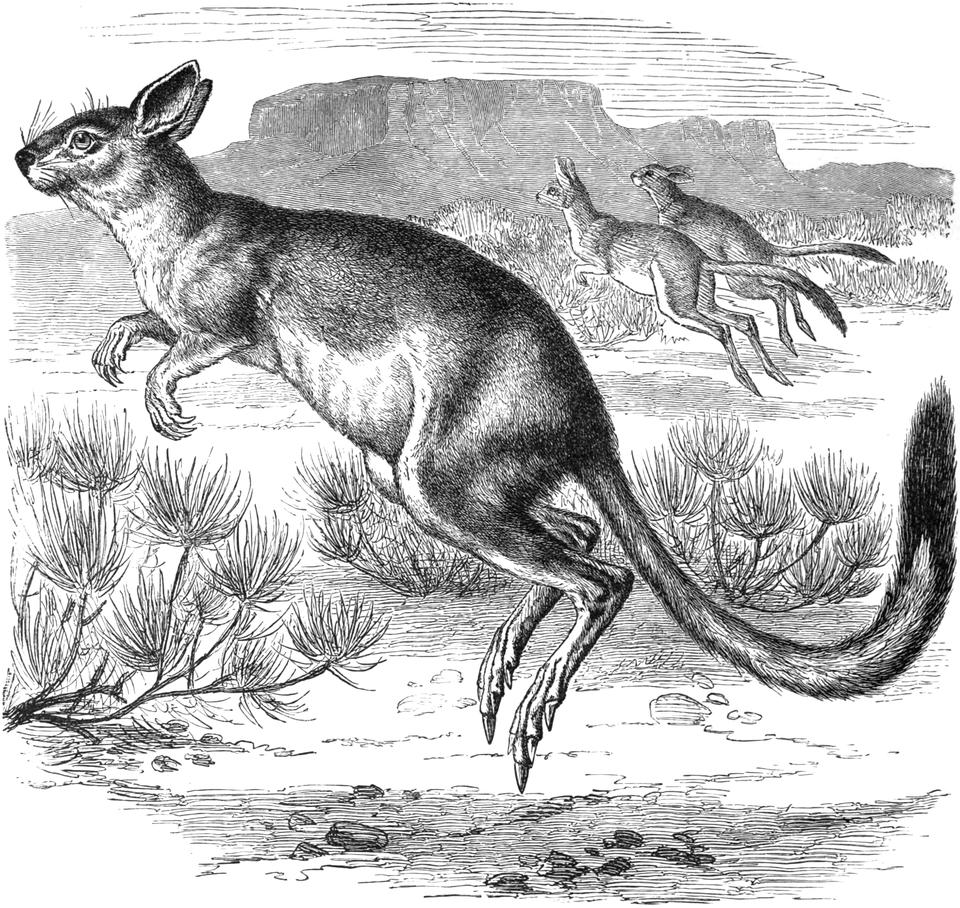

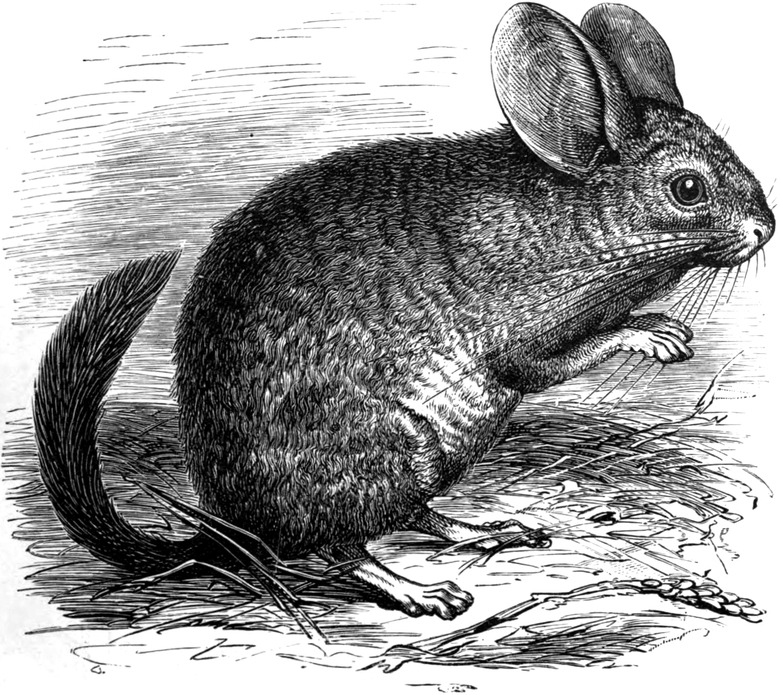

The Cape Jumping Hare

|

|

|

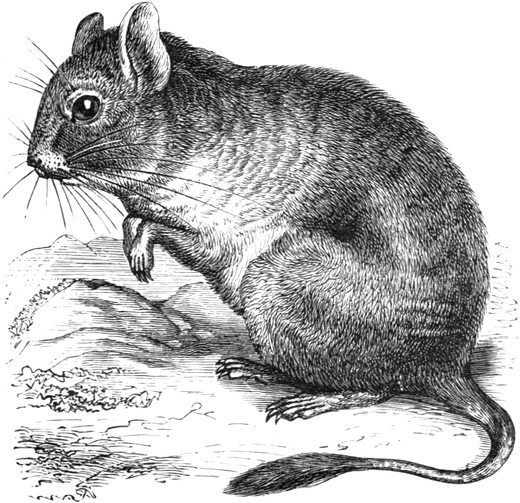

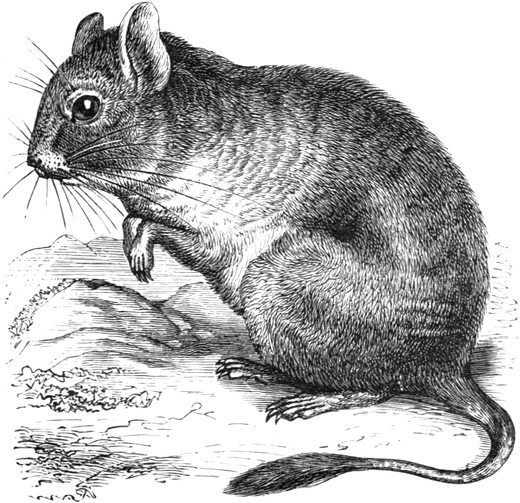

The Degu

|

|

|

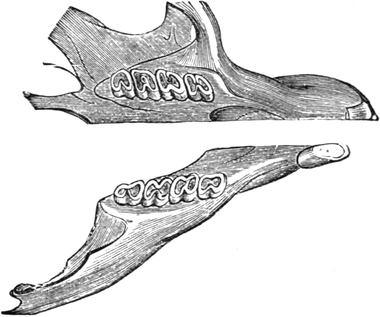

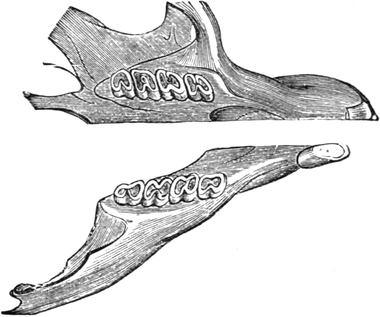

Dentition of the Rock Rat—Teeth of the Spiny Rat

|

|

|

The Coypu

|

|

|

The Hutia Conga—Teeth of Plagiodon—Molar Teeth of Loncheres

|

|

|

Skull of Loncheres

|

|

|

Skull of the Porcupine—The Common Porcupine

|

|

|

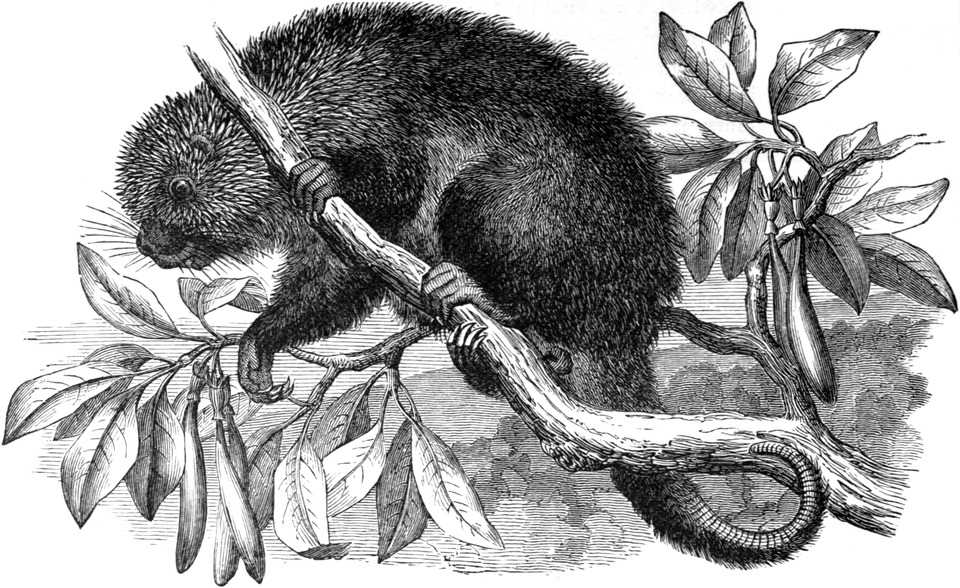

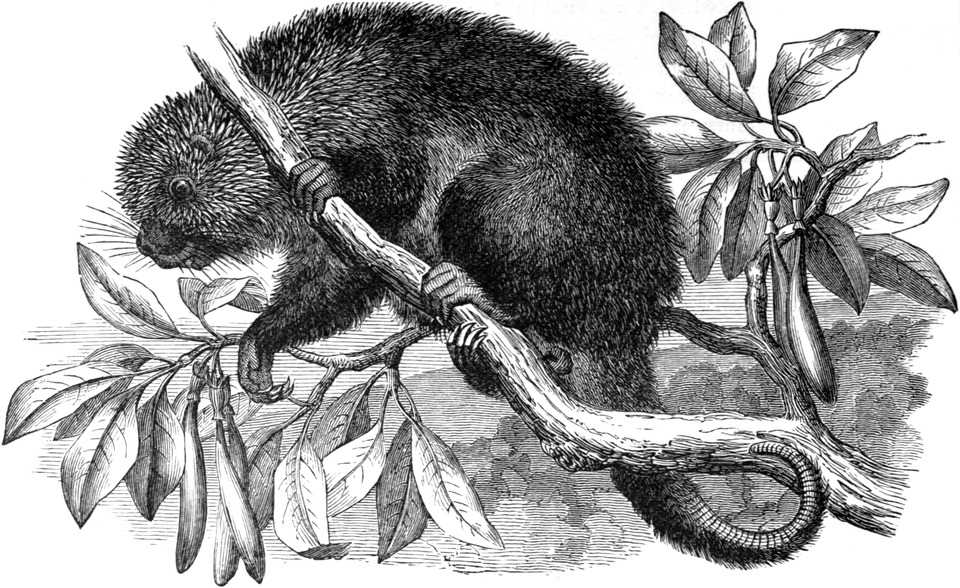

The Tree Porcupine

|

|

|

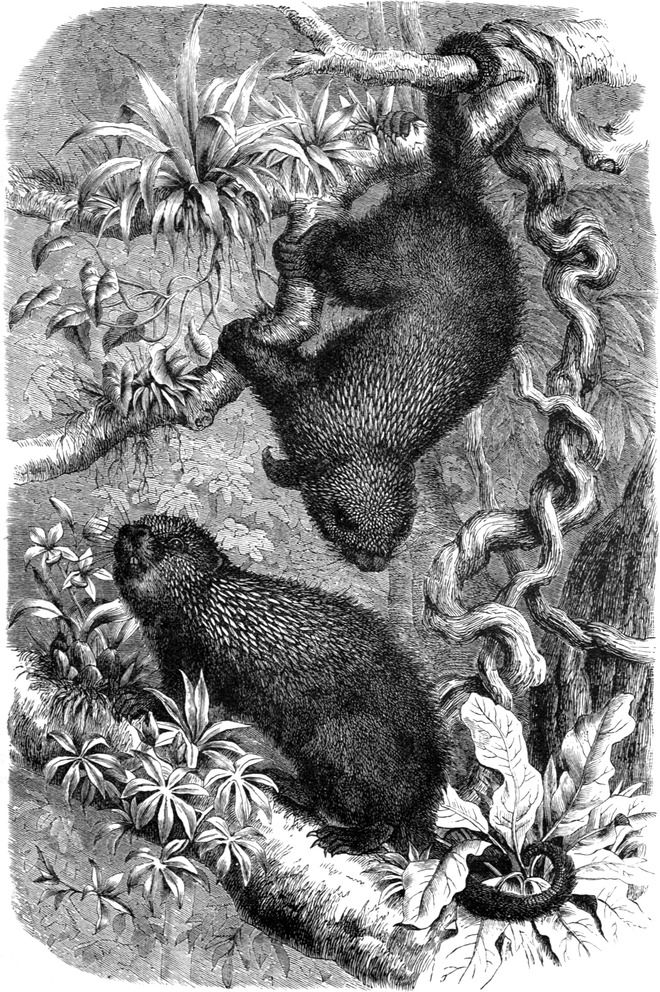

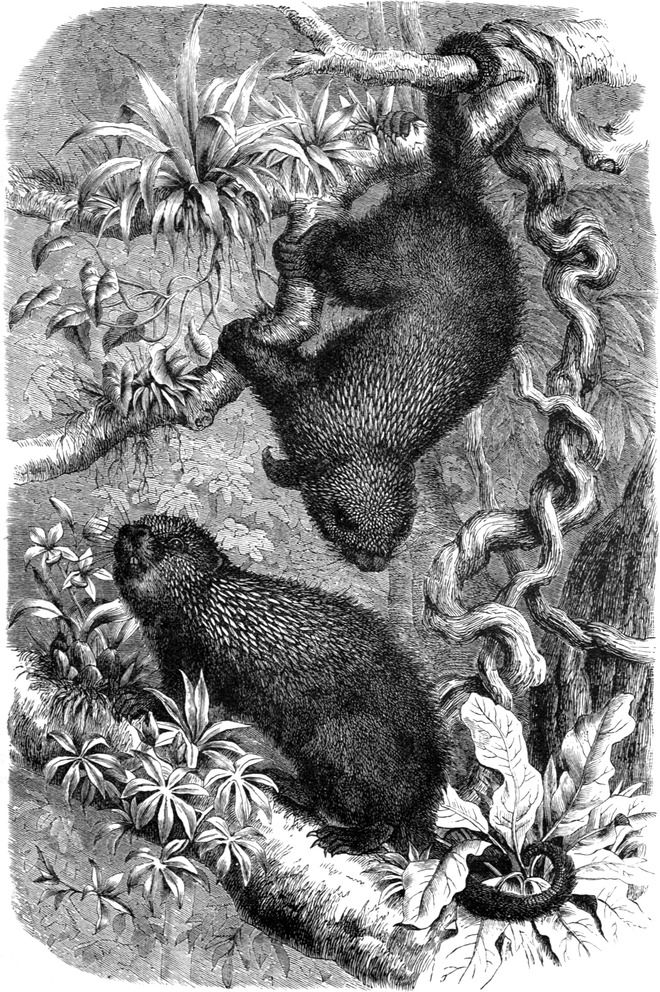

Mexican Tree Porcupines

|

|

|

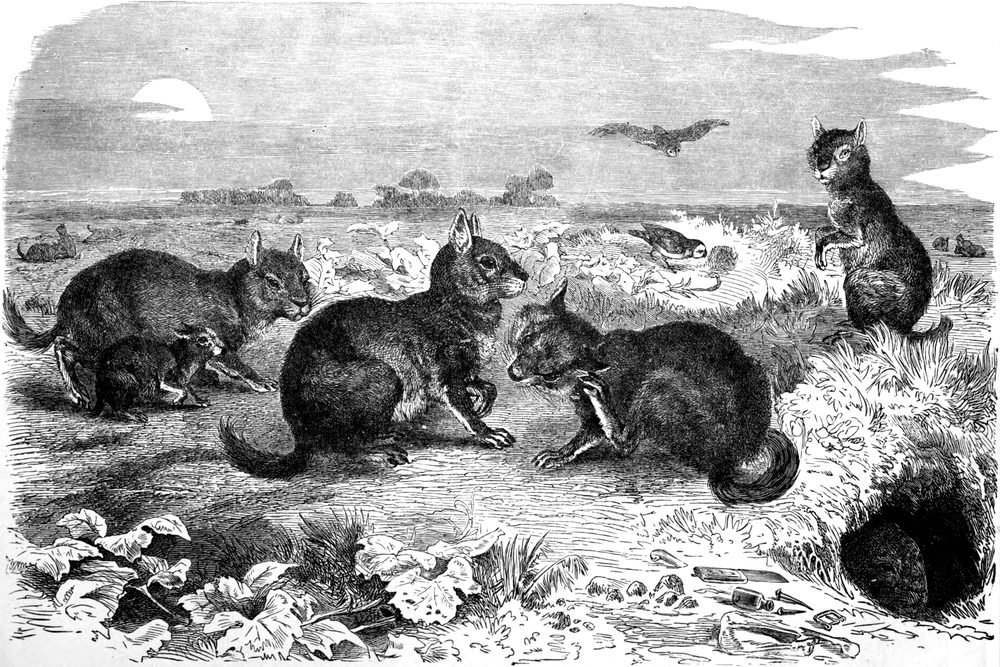

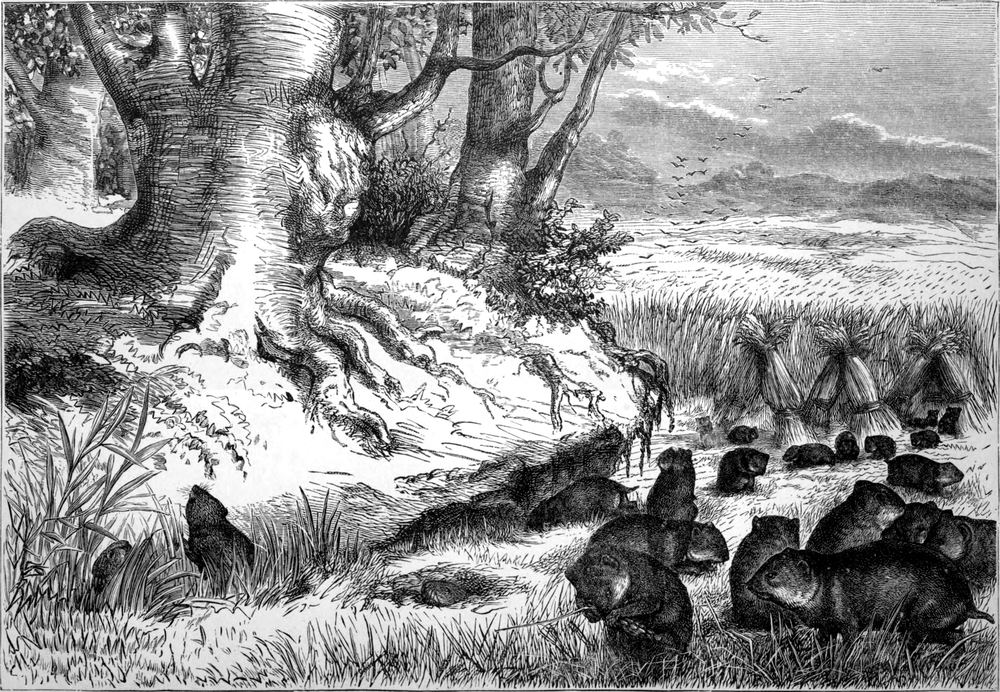

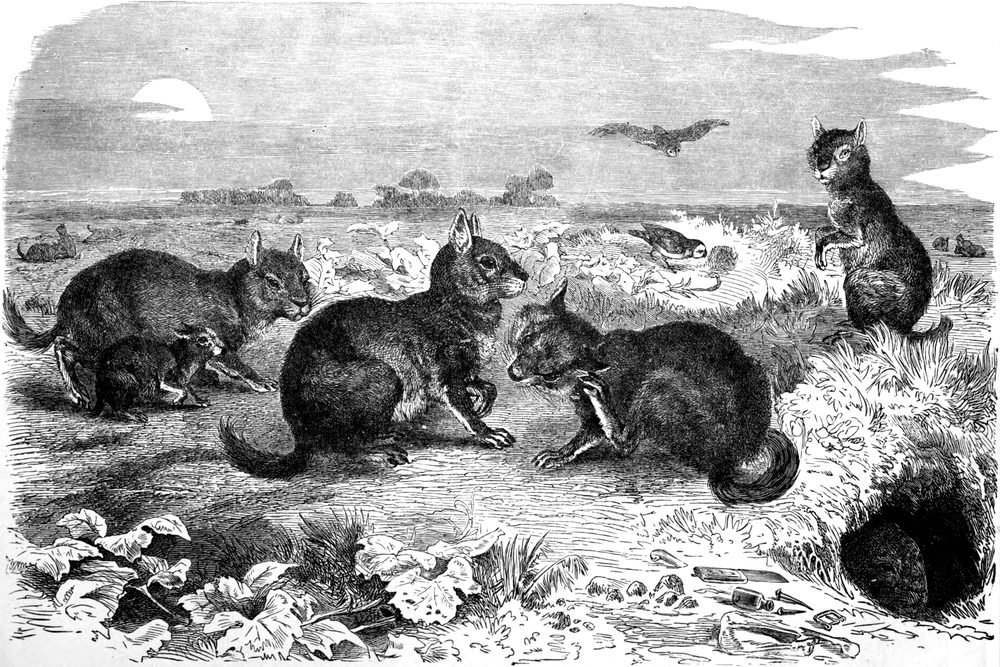

Viscachas

|

To face page

|

|

|

Molar Teeth of the Chinchilla—The Chinchilla

|

|

|

Molar Teeth of the Agouti—Azara’s Agouti

|

|

|

Skull of the Paca—The Paca

|

|

|

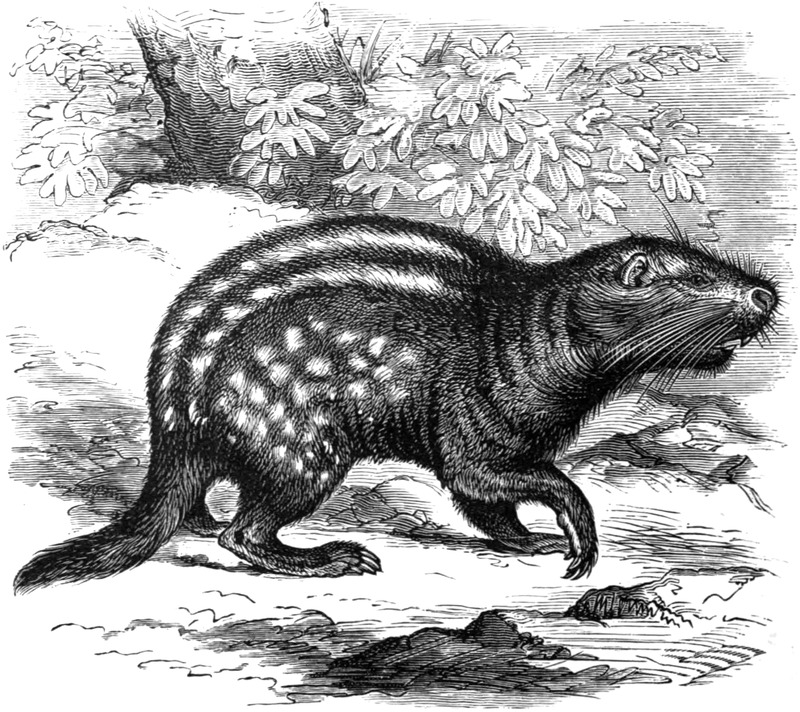

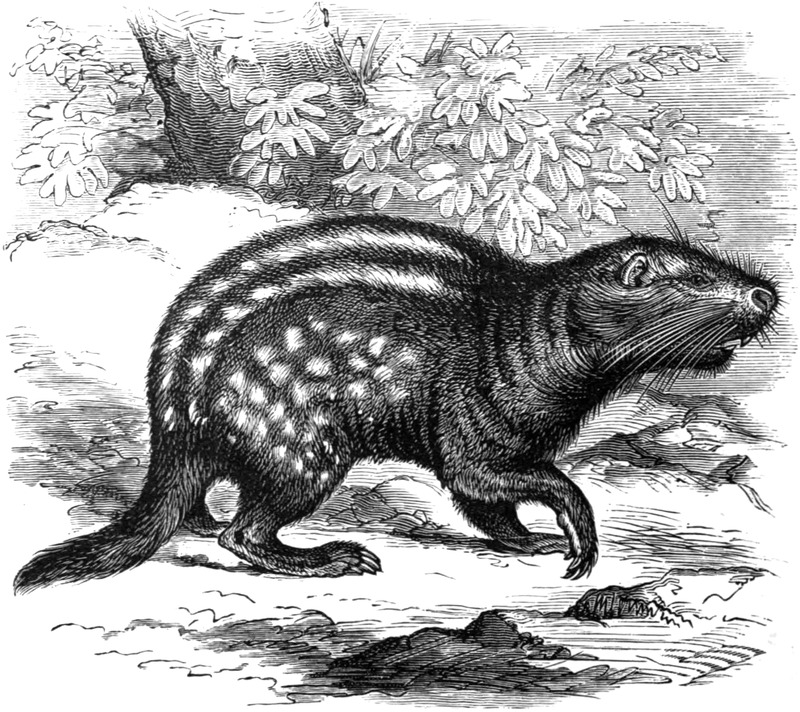

The Dinomys

|

|

|

The Patagonian Cavy

|

|

|

Molars of the Capybara

|

|

|

The Capybara

|

|

|

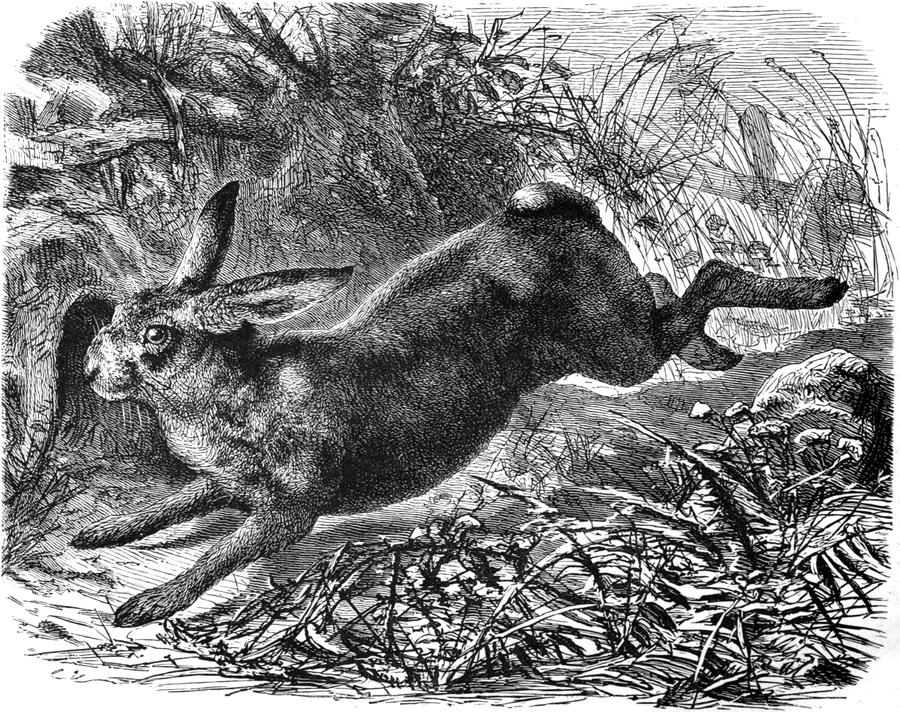

The Common Hare

|

|

|

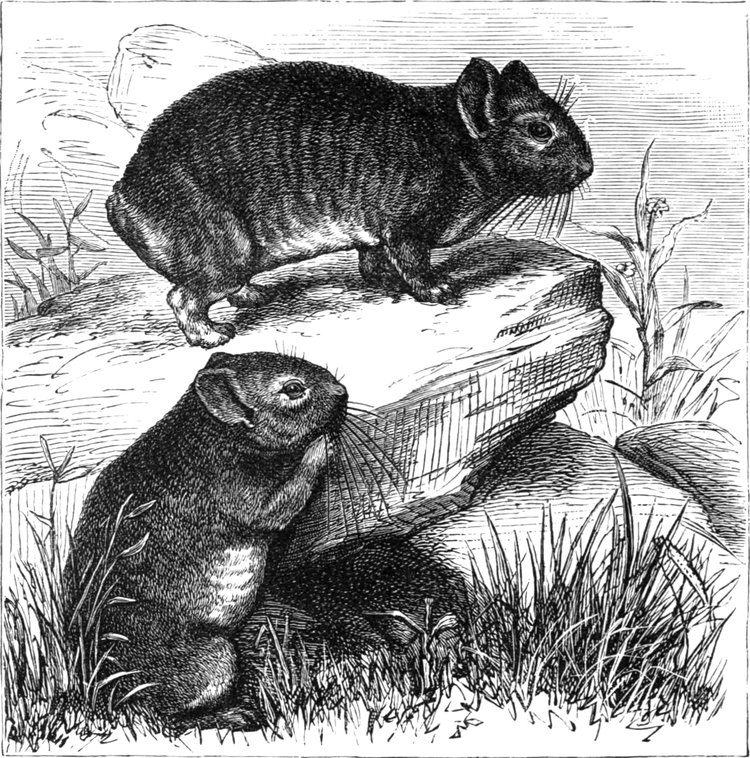

The Alpine Pika

|

|

|

Side View of Skull and Lower Jaw of Mesotherium Cristatum—Dentition

of Mesotherium Cristatum

|

|

|

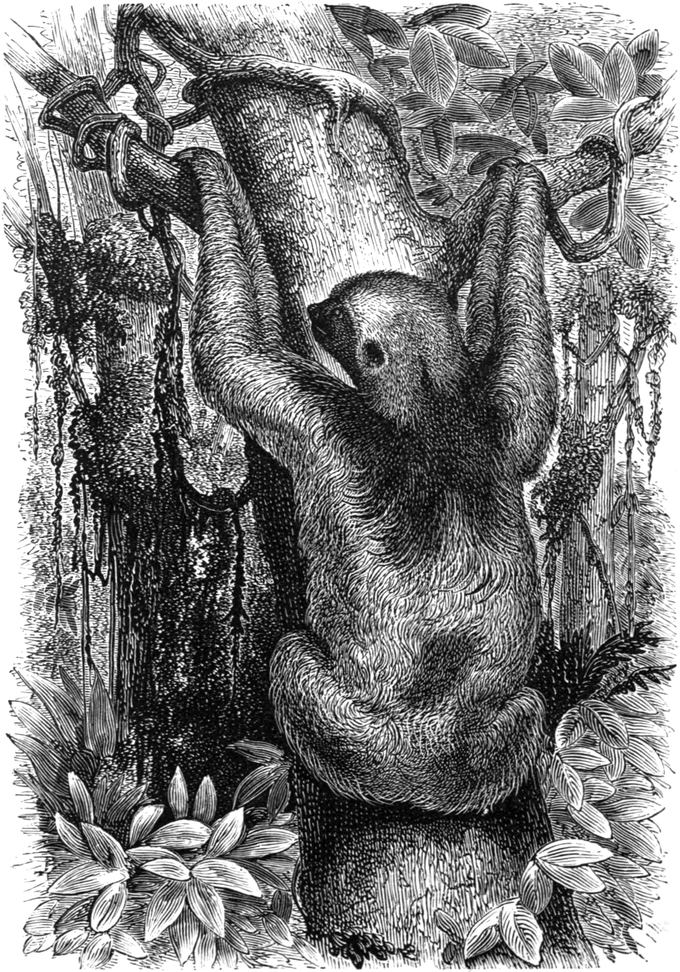

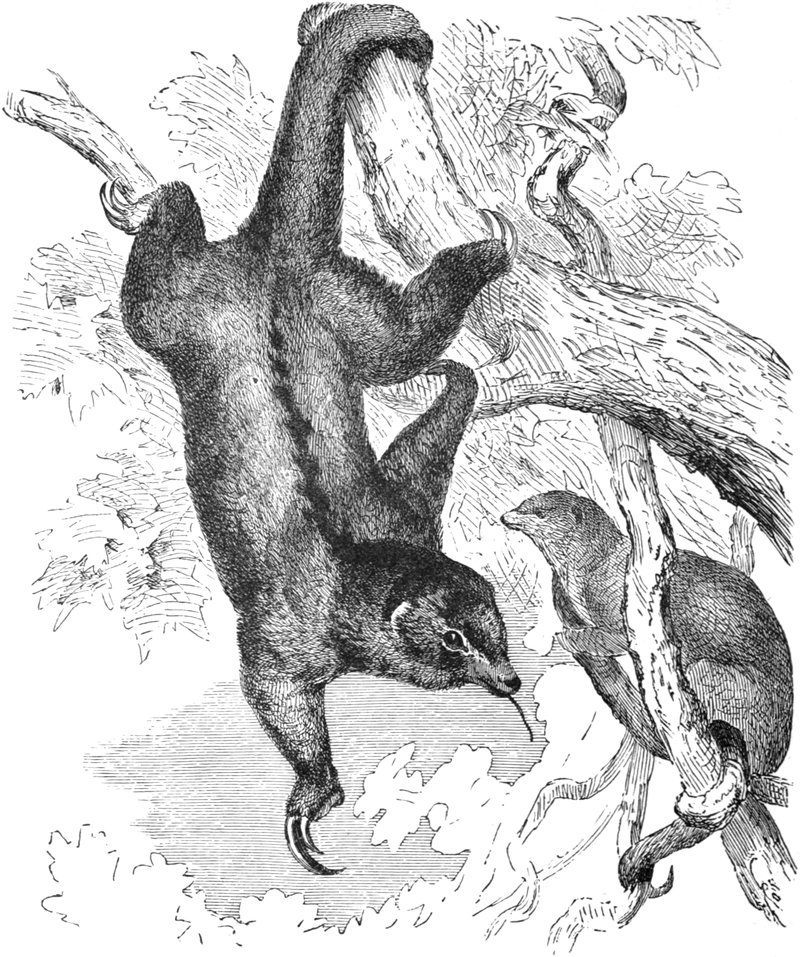

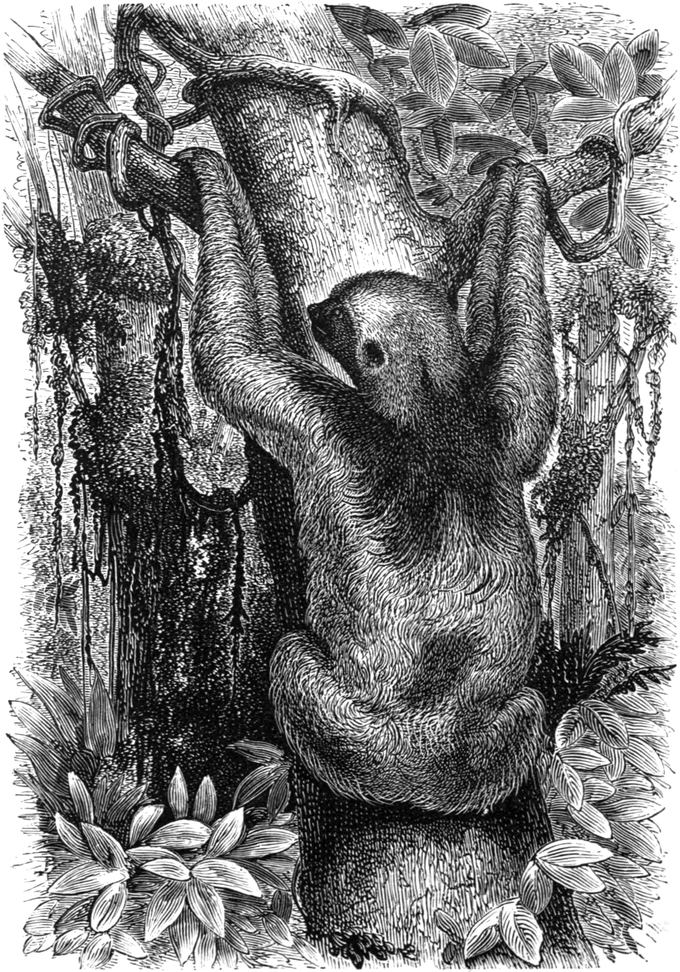

Group of Sloths

|

|

|

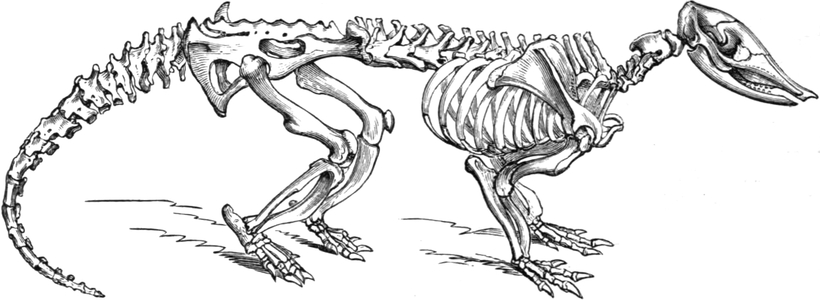

Skeleton of the Sloth

|

|

|

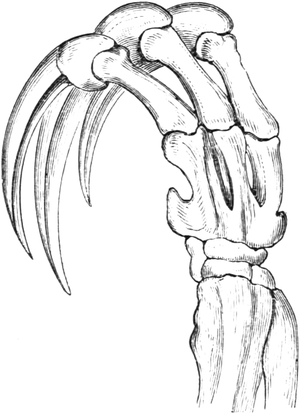

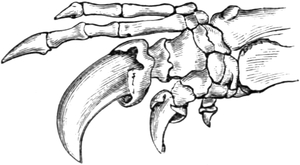

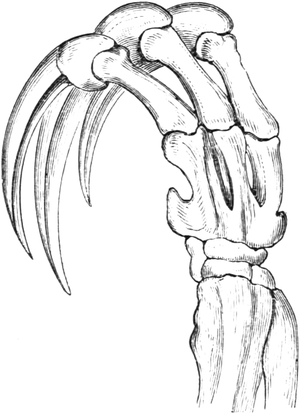

Bones of Hand of Three-toed Sloth

|

|

|

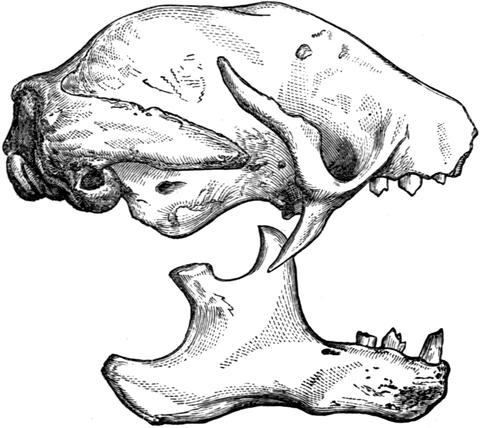

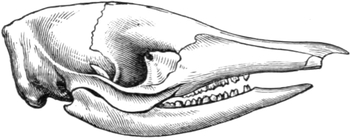

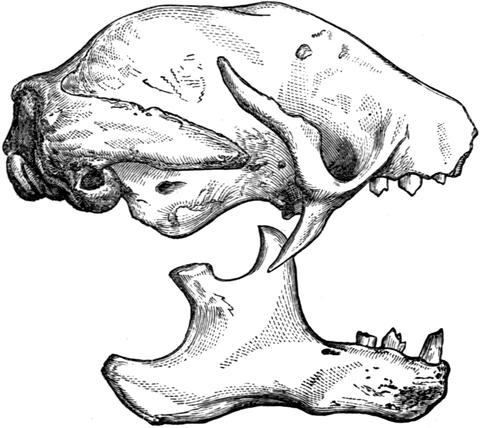

Skull of Sloth

|

|

|

The Collared Sloth

|

|

|

The Ai

|

|

|

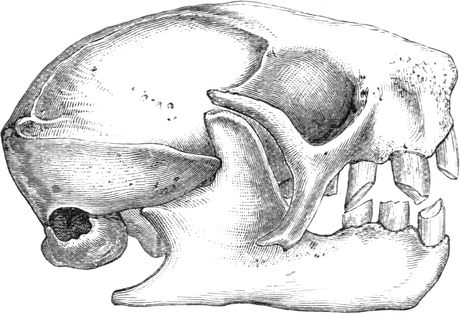

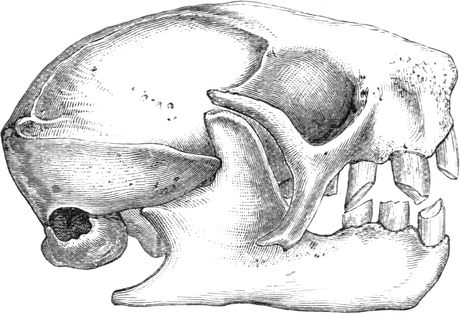

Skull of Ai

|

|

|

[Pg xii]

Stomach of Sloth

|

|

|

Hoffmann’s Sloth

|

|

|

The Cape Ant-eater

|

|

|

Skull of the Cape Ant-eater

|

|

|

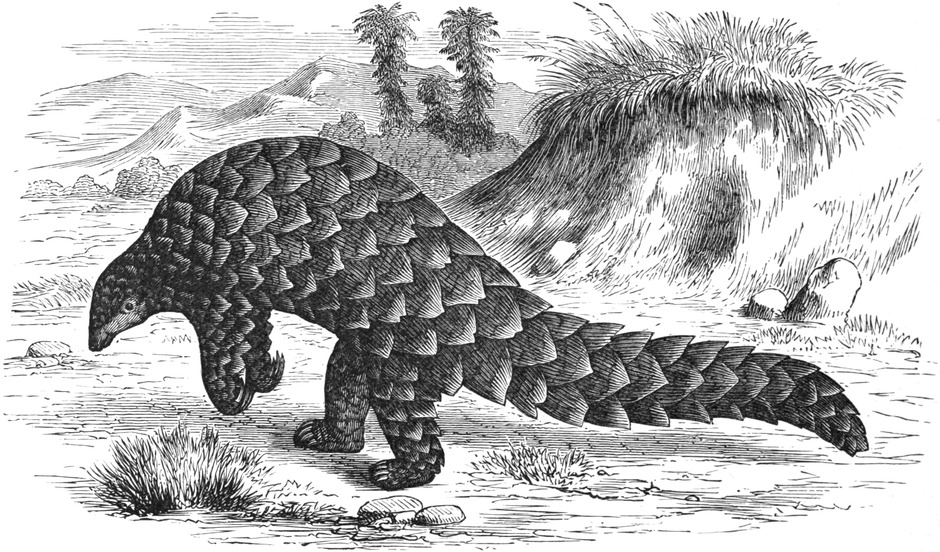

Temminck’s Pangolin

|

|

|

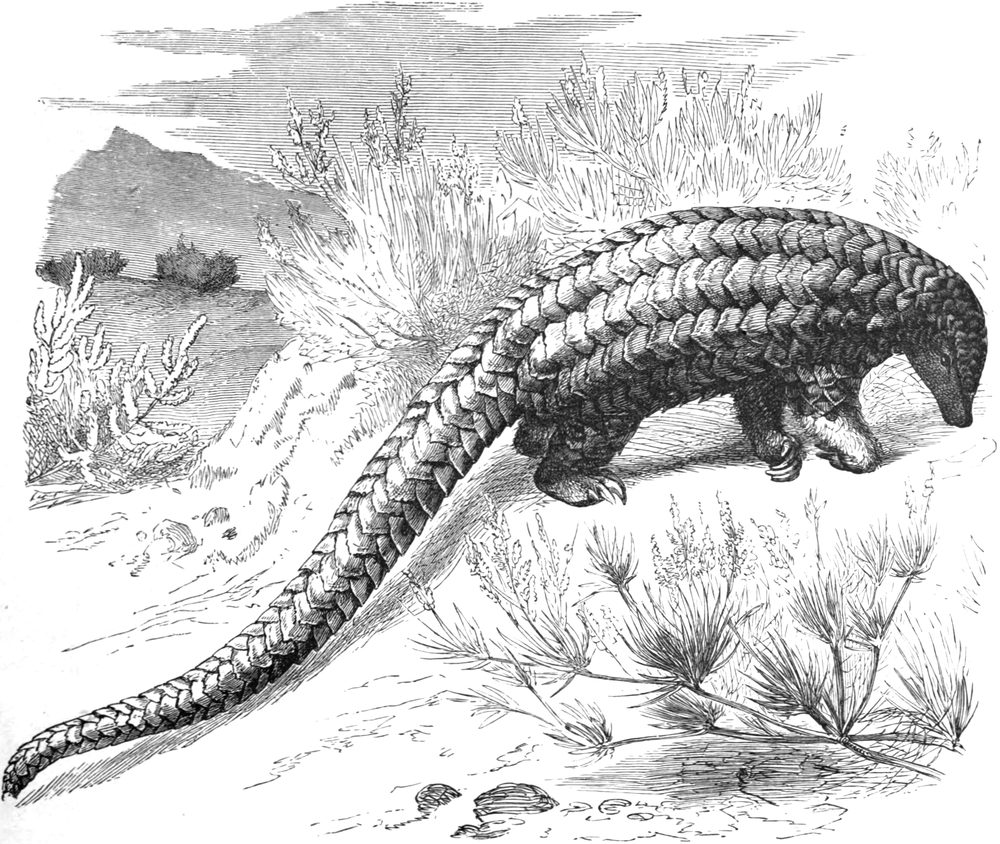

The Four-fingered Pangolin

|

|

|

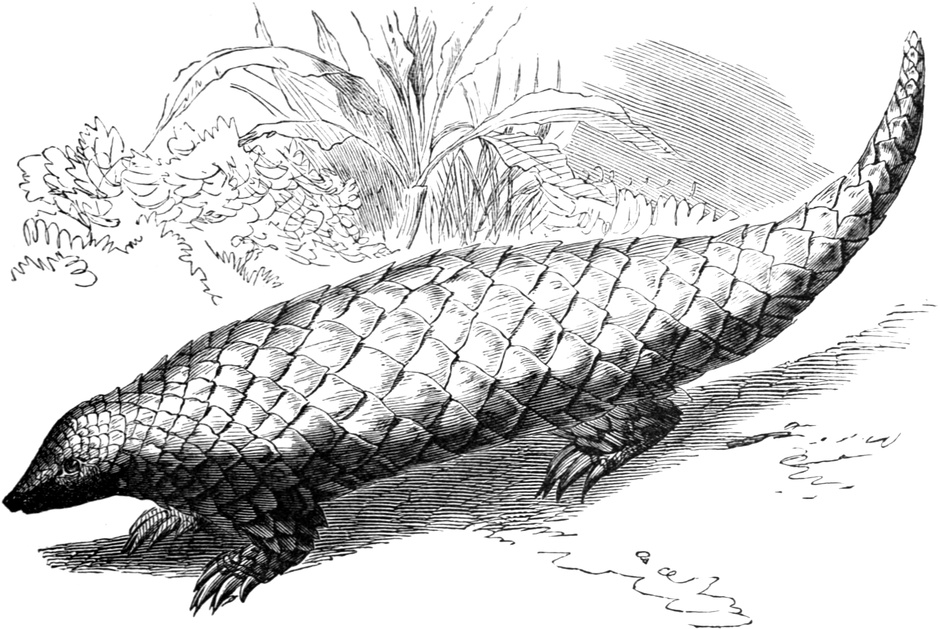

The Five-fingered Pangolin

|

|

|

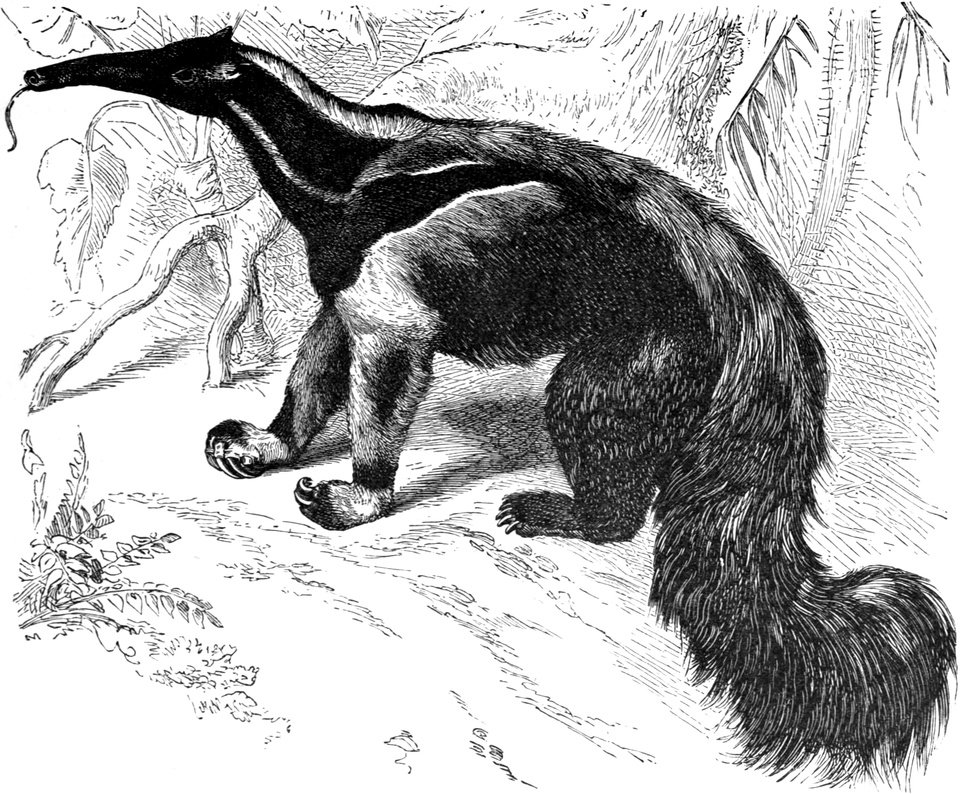

The Great Ant-Bear

|

|

|

The Two-toed Ant-eater

|

|

|

Bones of Claw of Great Armadillo

|

|

|

Skeleton of the Armadillo—Skull of the Armadillo

|

|

|

The Great Armadillo—Brain of the Armadillo

|

|

|

The Poyou

|

|

|

The Ball Armadillo

|

|

|

The Pichiciago

|

|

|

The Great Kangaroo

|

To face page

|

|

|

Skeleton of the Great Kangaroo

|

|

|

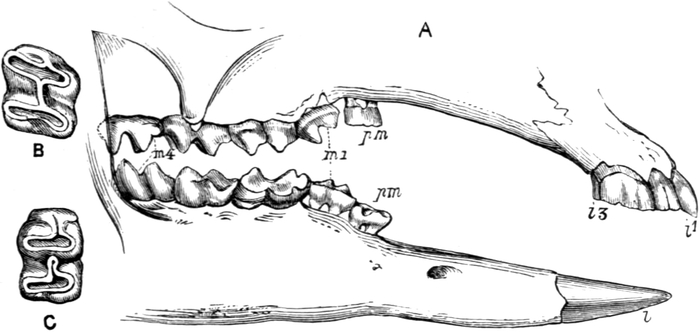

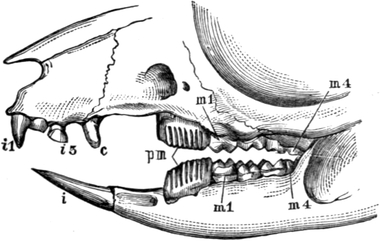

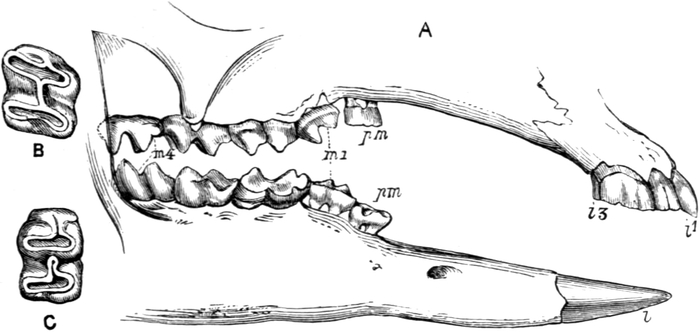

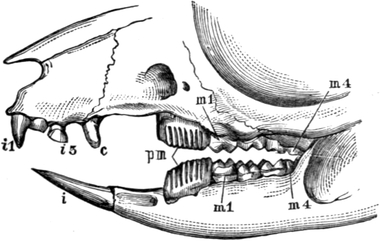

Teeth of the Great Kangaroo

|

|

|

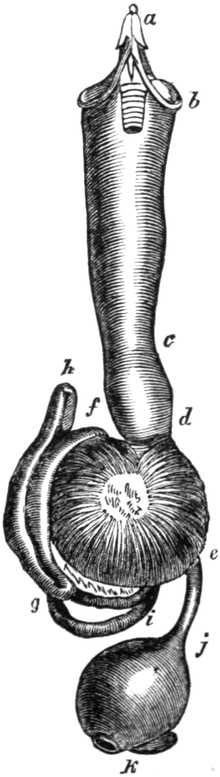

Stomach of the Great Kangaroo

|

|

|

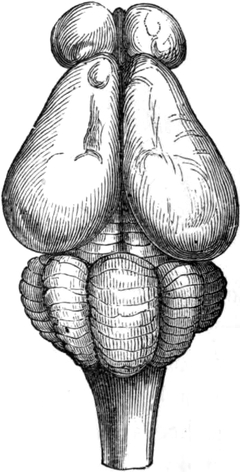

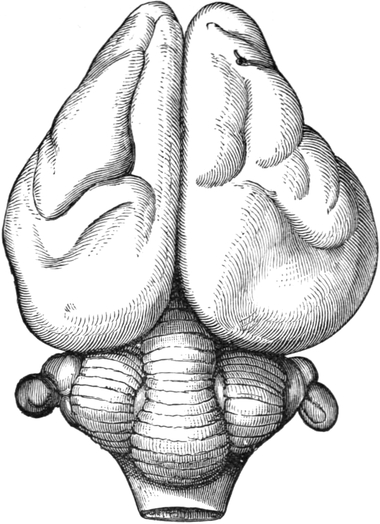

Brain of the Great Kangaroo

|

|

|

The Brush-tailed Rock Kangaroo

|

|

|

The Common Tree Kangaroo

|

|

|

The Kangaroo Rat—Teeth of the Kangaroo Rat

|

|

|

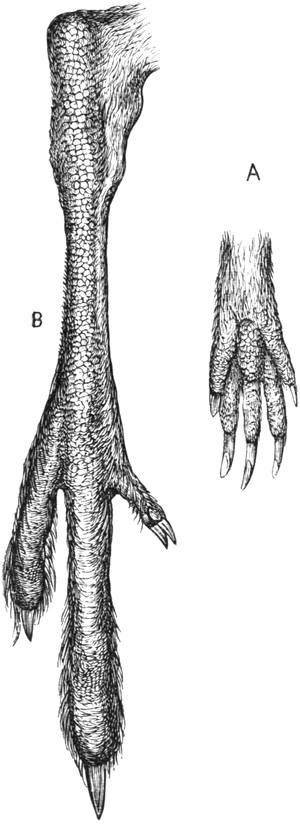

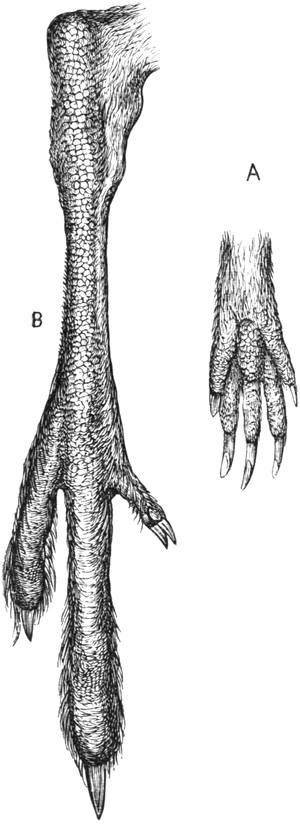

Fore and Hind Foot of Hypsiprymnus

|

|

|

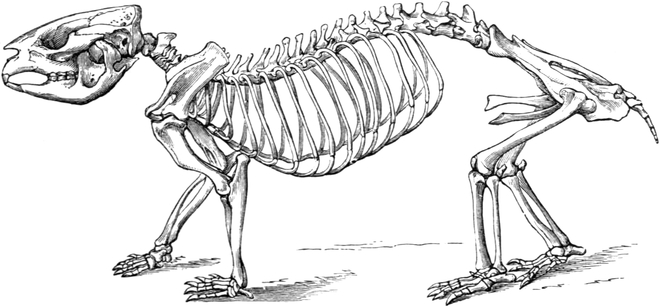

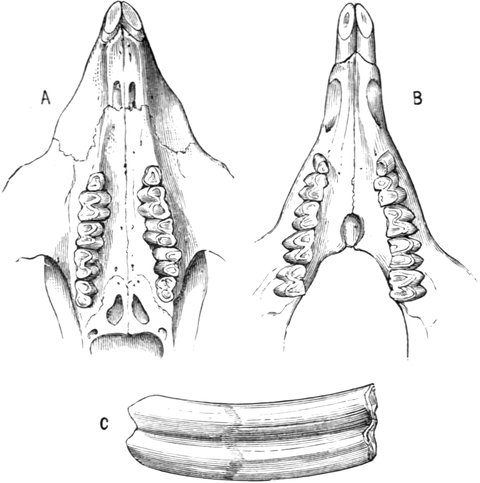

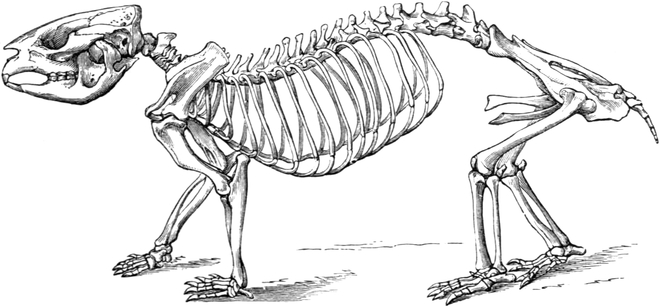

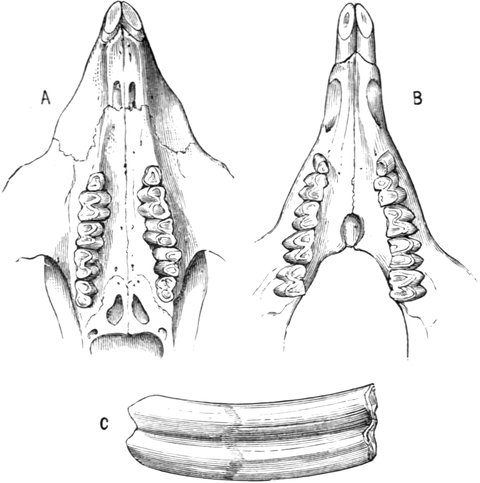

Skeleton of the Wombat

|

|

|

The Wombat—Lower Jaw of the Wombat

|

|

|

Teeth of the Wombat

|

|

|

The Koala

|

|

|

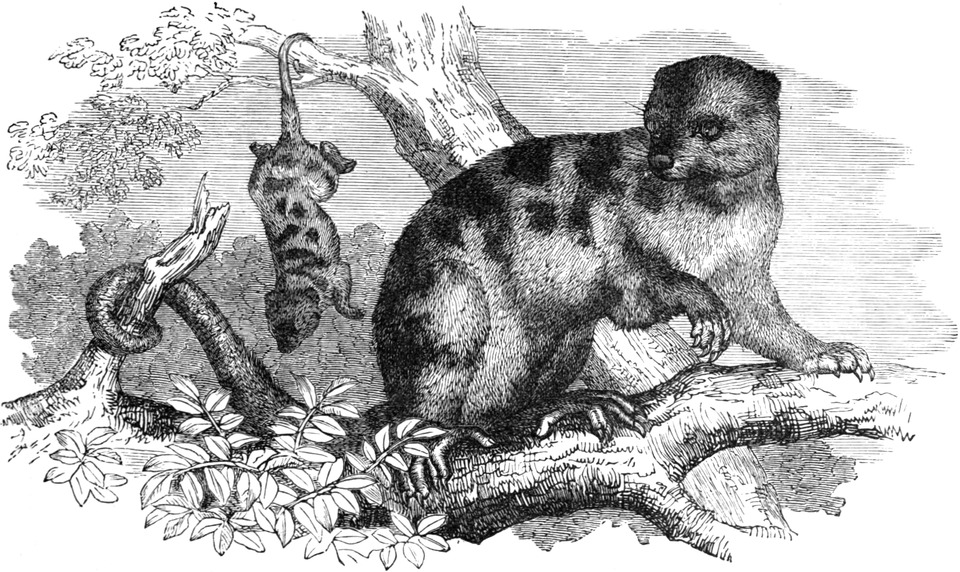

The Cuscus

|

|

|

The Vulpine Phalanger

|

|

|

The Squirrel Flying Phalanger

|

|

|

The Banded Perameles

|

|

|

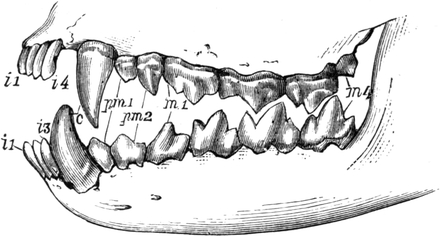

The Dasyure

|

|

|

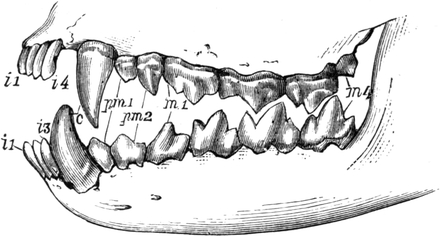

Teeth of the Dasyure—Brain of the Dasyure

|

|

|

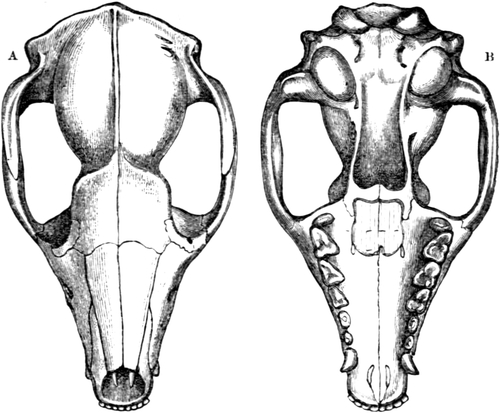

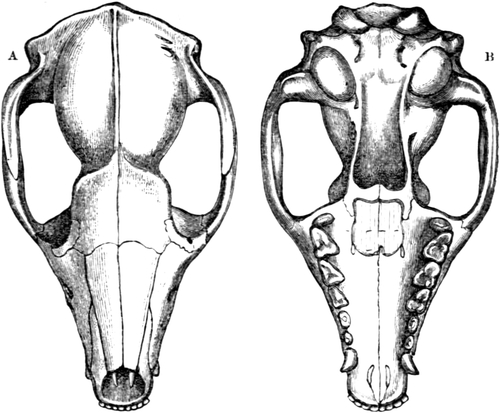

Upper and Under View of Skull of Dasyure

|

|

|

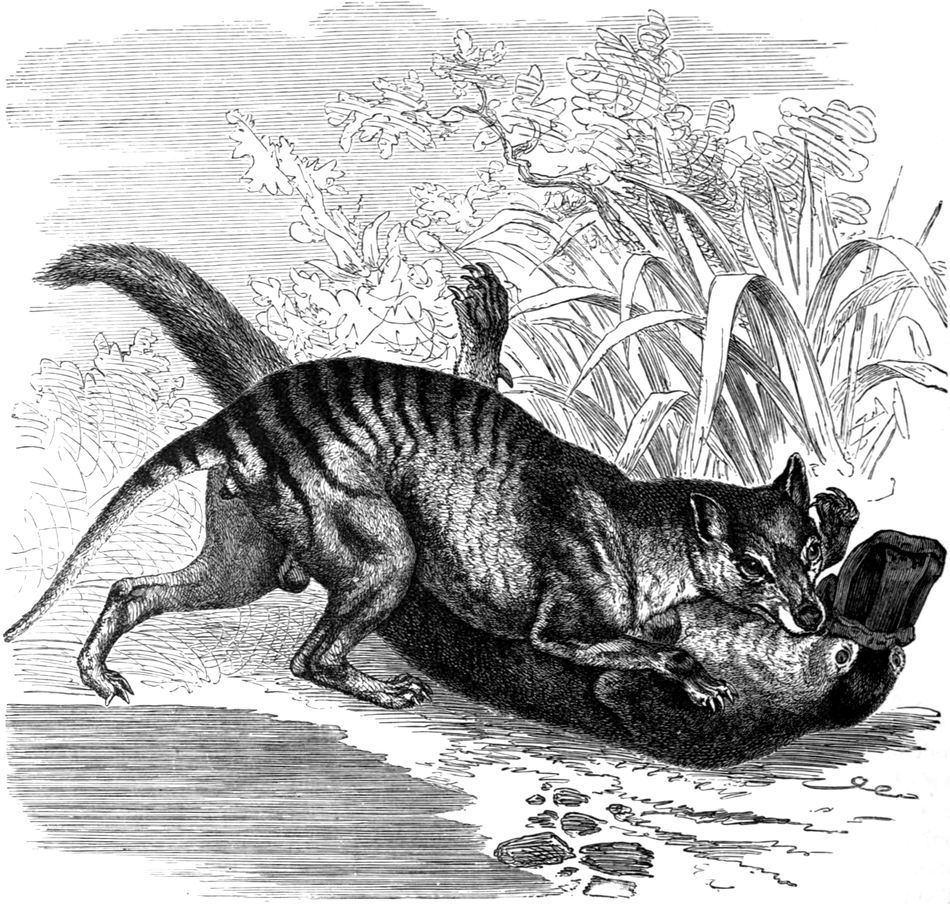

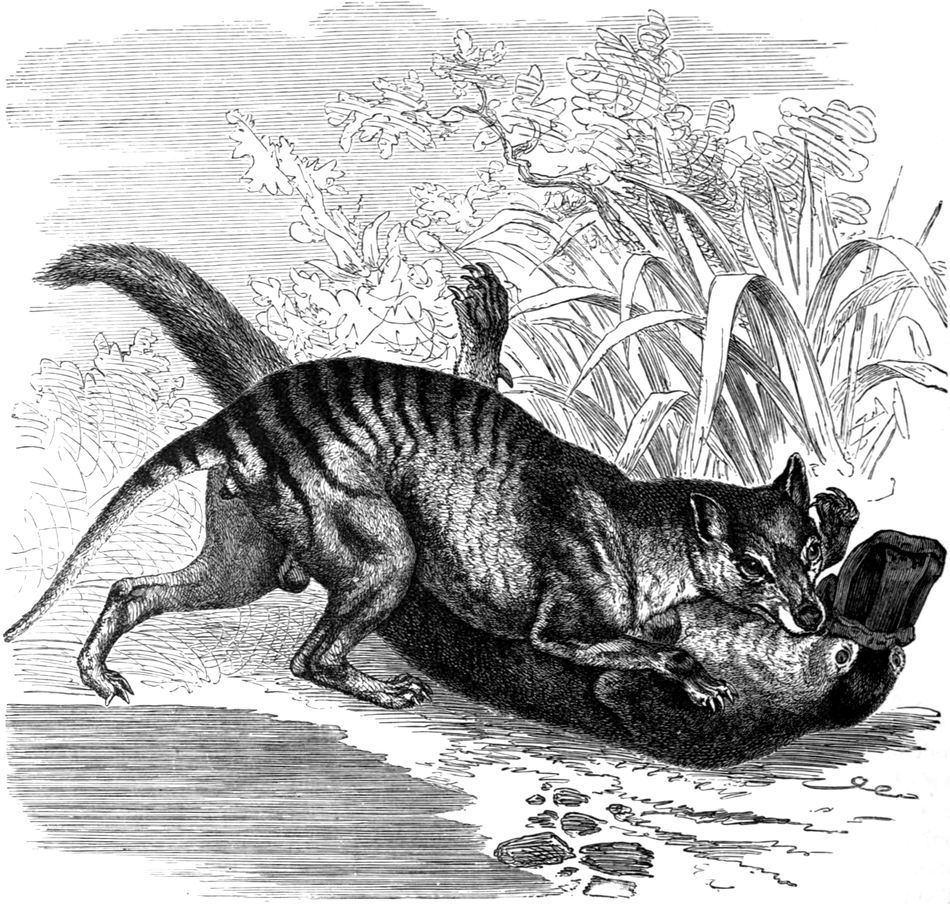

The Dog-headed Thylacinus

|

|

|

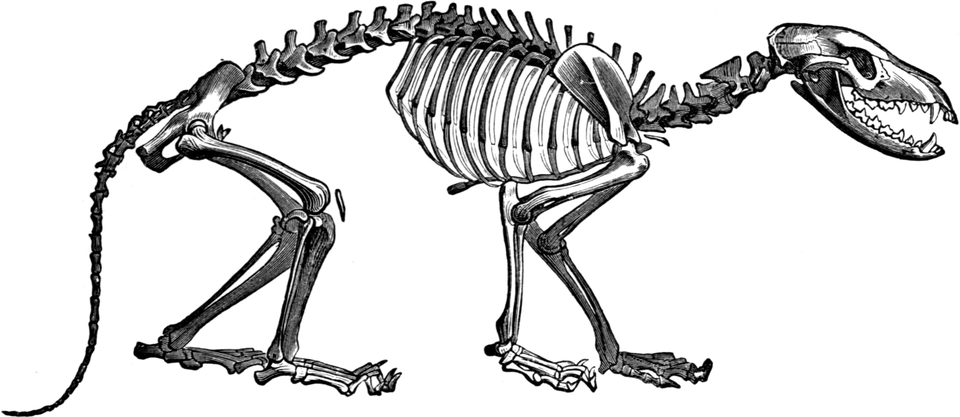

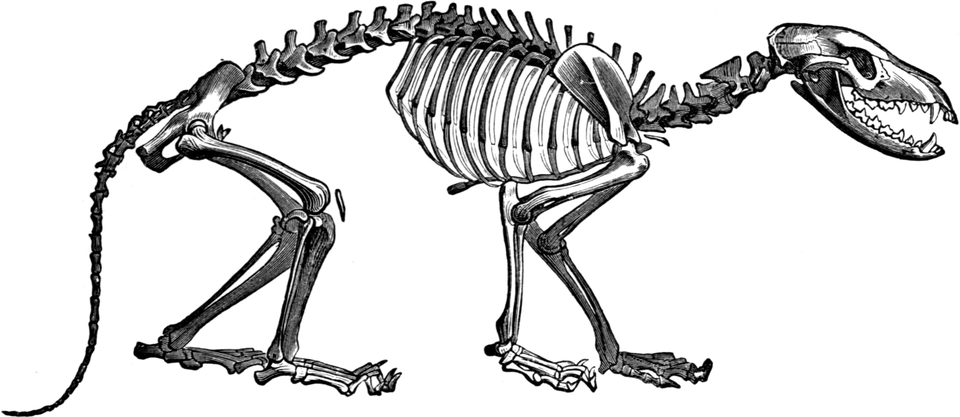

Skeleton of the Dog-headed Thylacinus

|

|

|

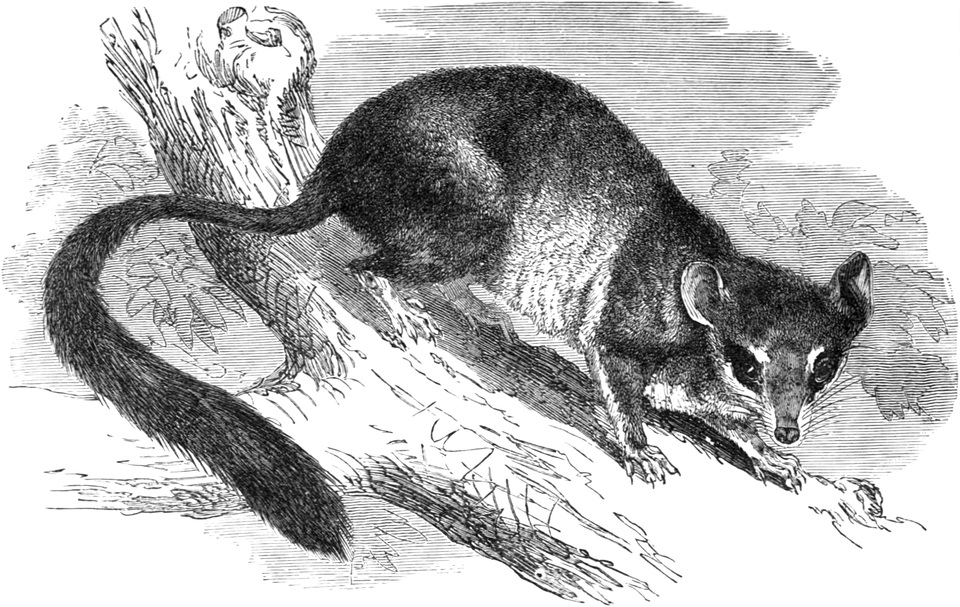

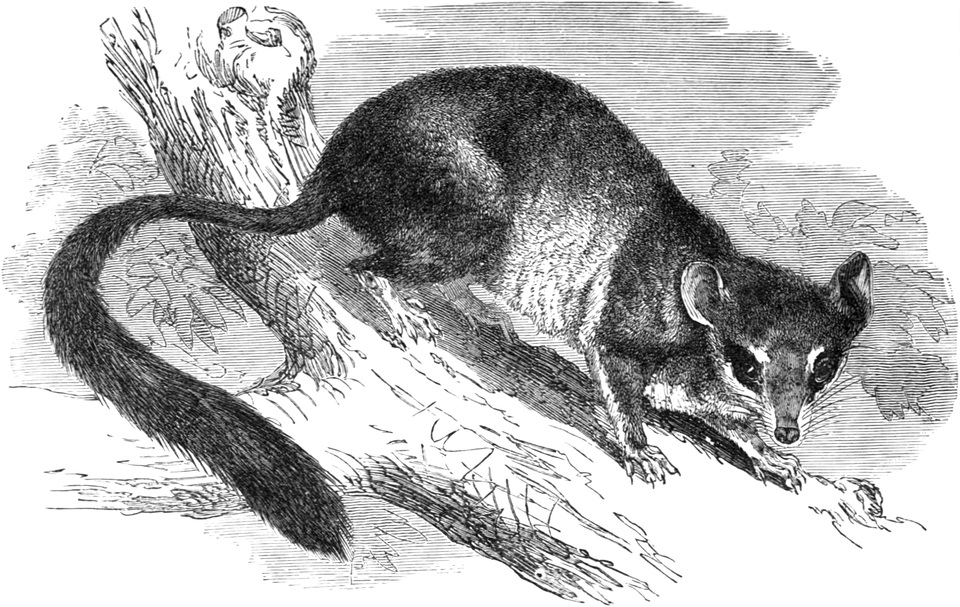

The Brush-tailed Phascogale—The Antechinus

|

|

|

Opossum and Young

|

To face page

|

|

|

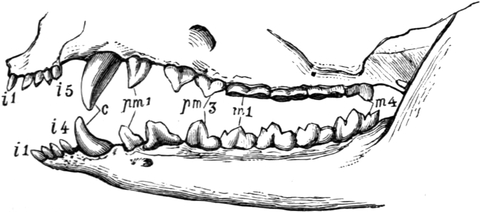

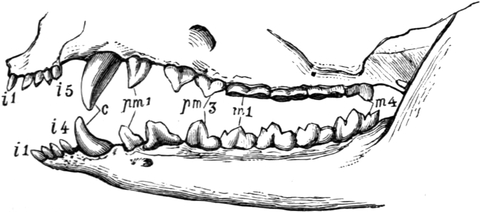

Teeth of the Opossum

|

|

|

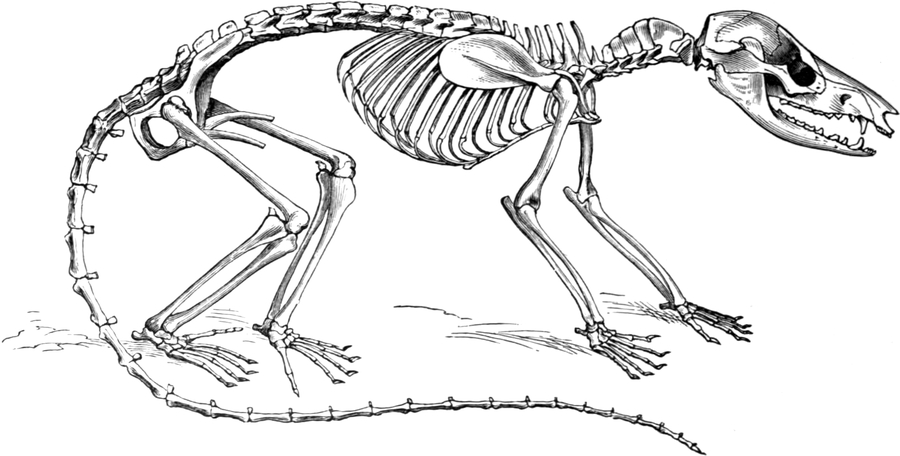

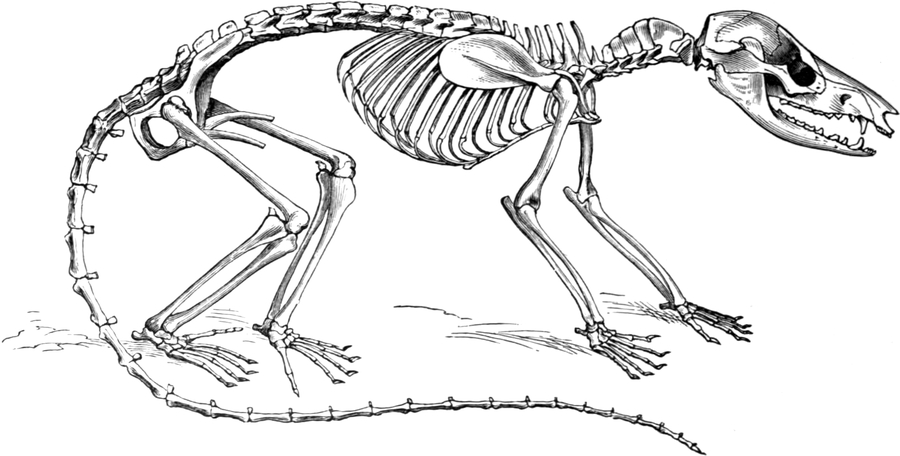

Skeleton of the Crab-eating Opossum

|

|

|

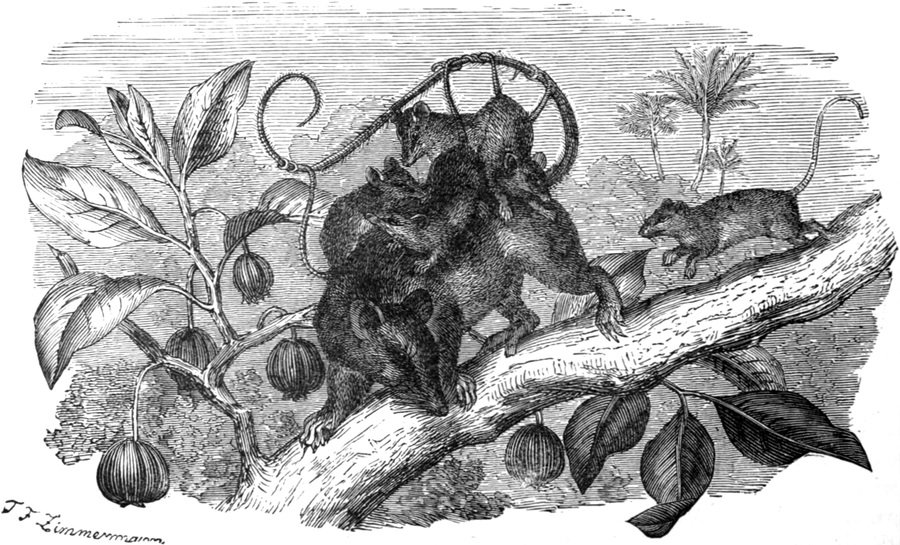

The Crab-eating Opossum

|

|

|

Merian’s Opossum

|

|

|

The Yapock

|

|

|

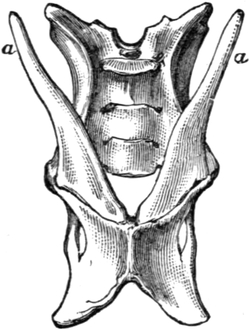

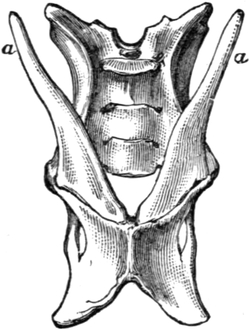

Pelvic Arch of the Echidna

|

|

|

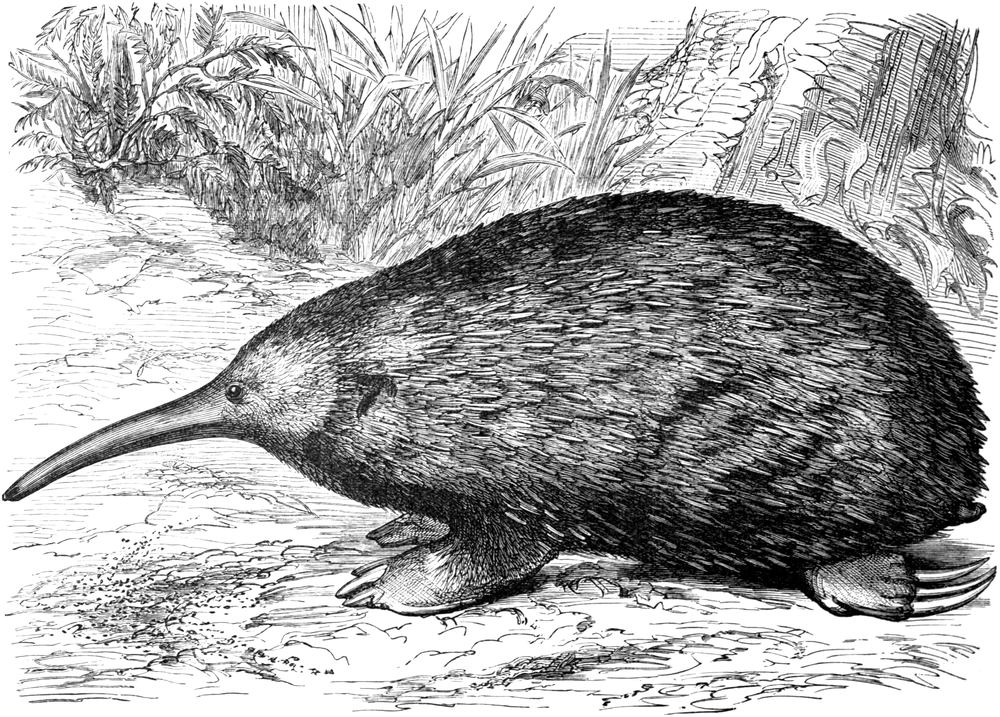

The Porcupine Echidna

|

|

|

Mouth and Nose-snout of Echidna

|

|

|

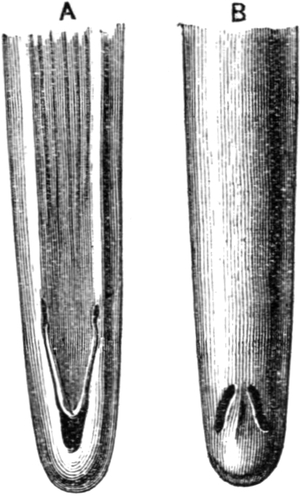

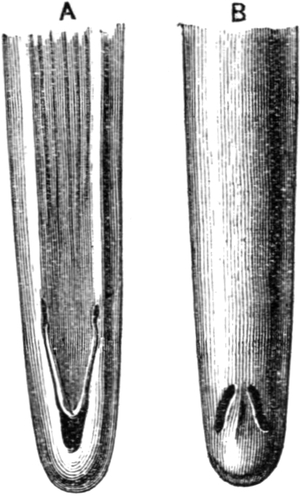

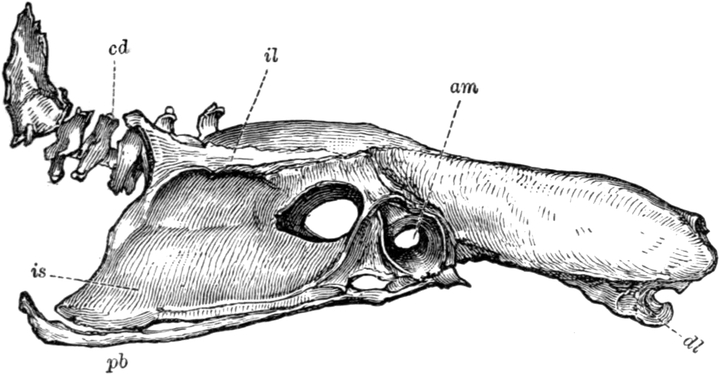

Jaws of the Duck-billed Platypus

|

|

|

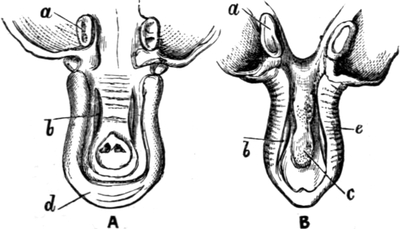

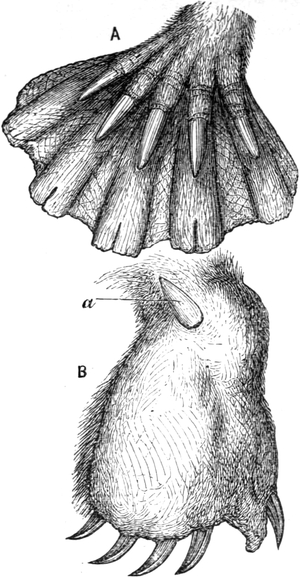

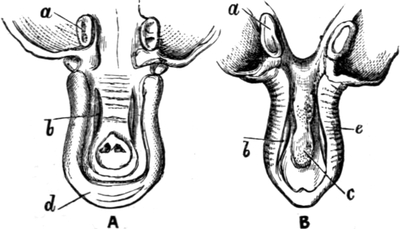

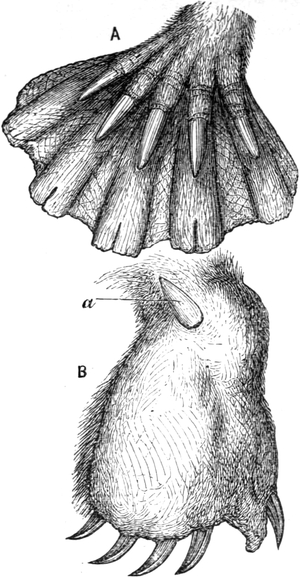

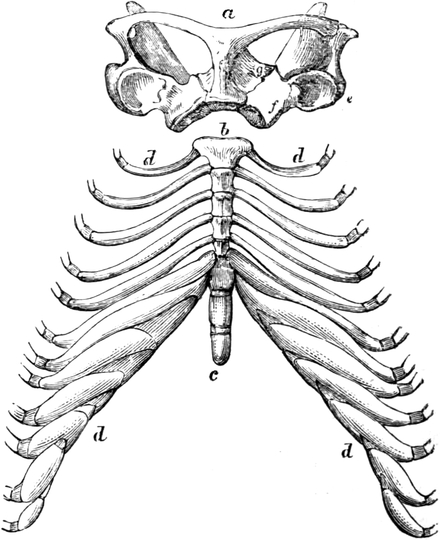

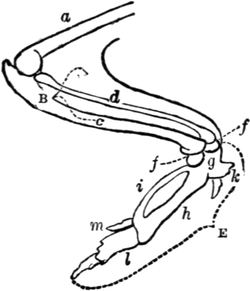

Fore and Hind Foot of the Duck-billed Platypus—Shoulder-girdle

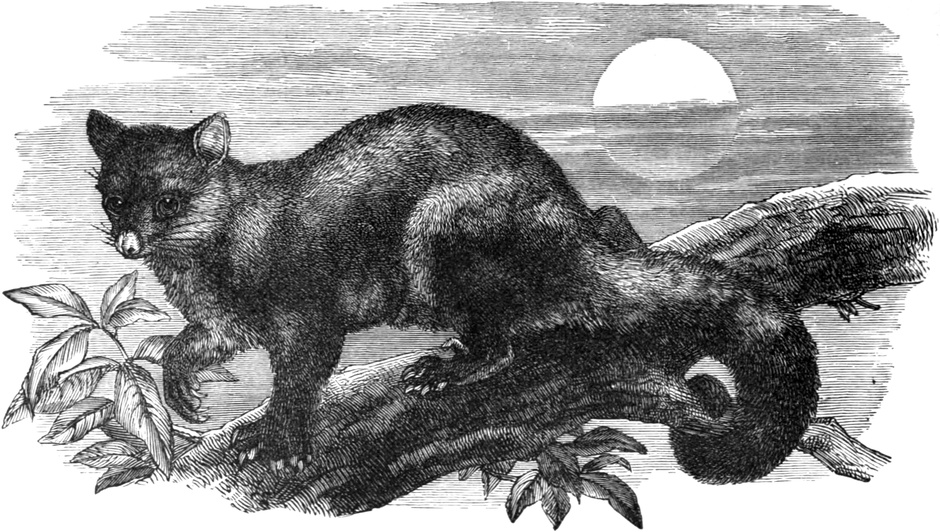

and Sternum of the Echidna

|

|

|

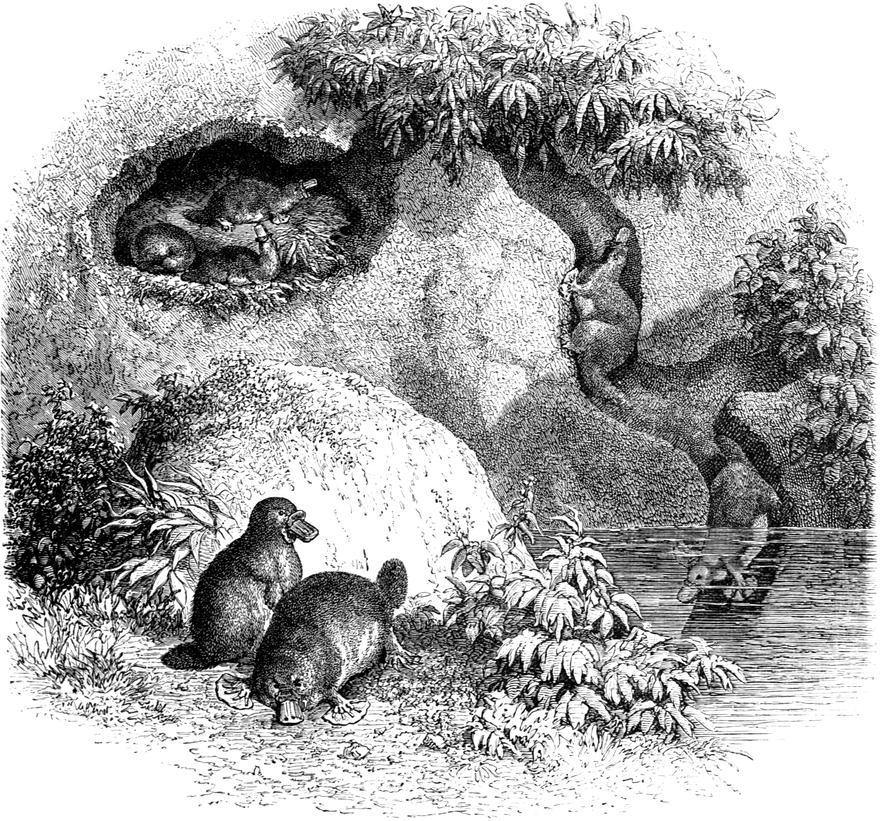

The Duck-billed Platypus

|

|

|

The Imperial Eagle

|

|

|

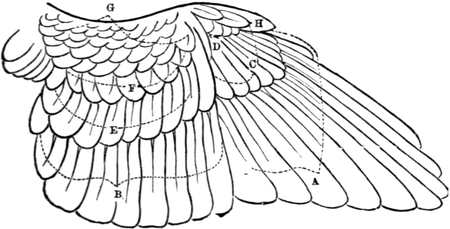

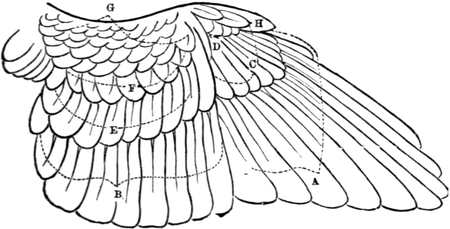

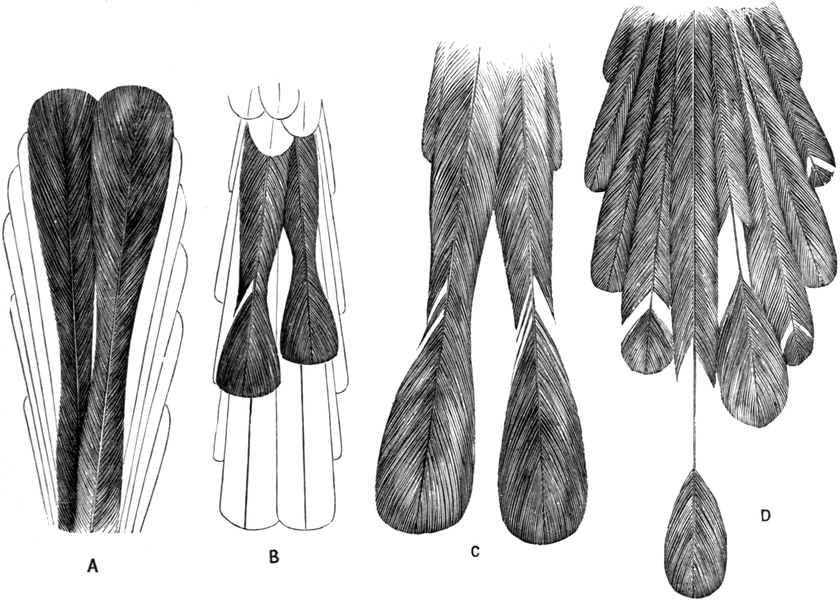

Bones of Wing of Bird—Feathers of Wing of Bird

|

|

|

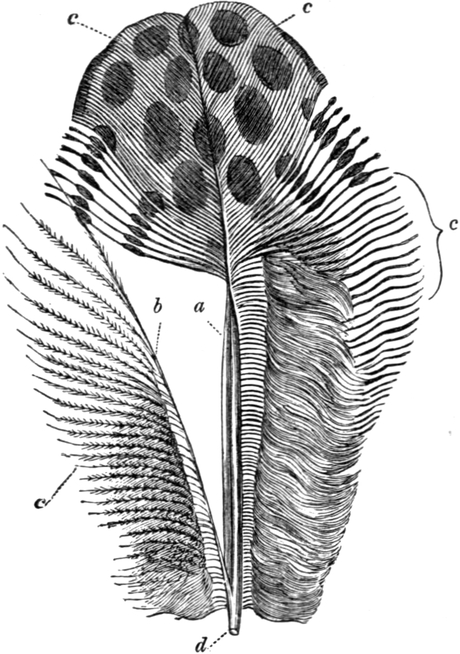

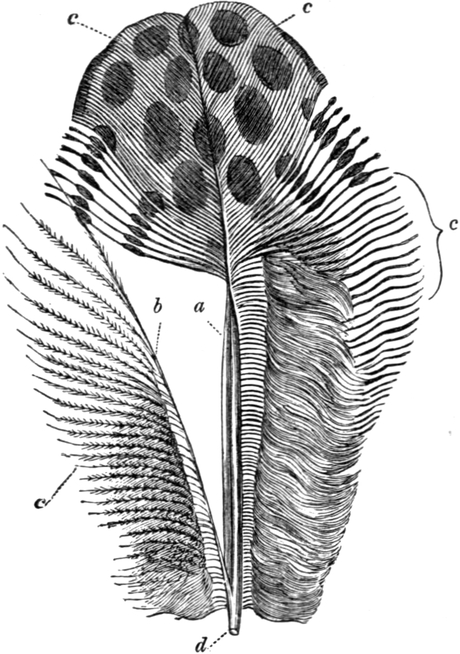

Parts of a Feather

|

|

|

Skeleton of Eagle

|

|

|

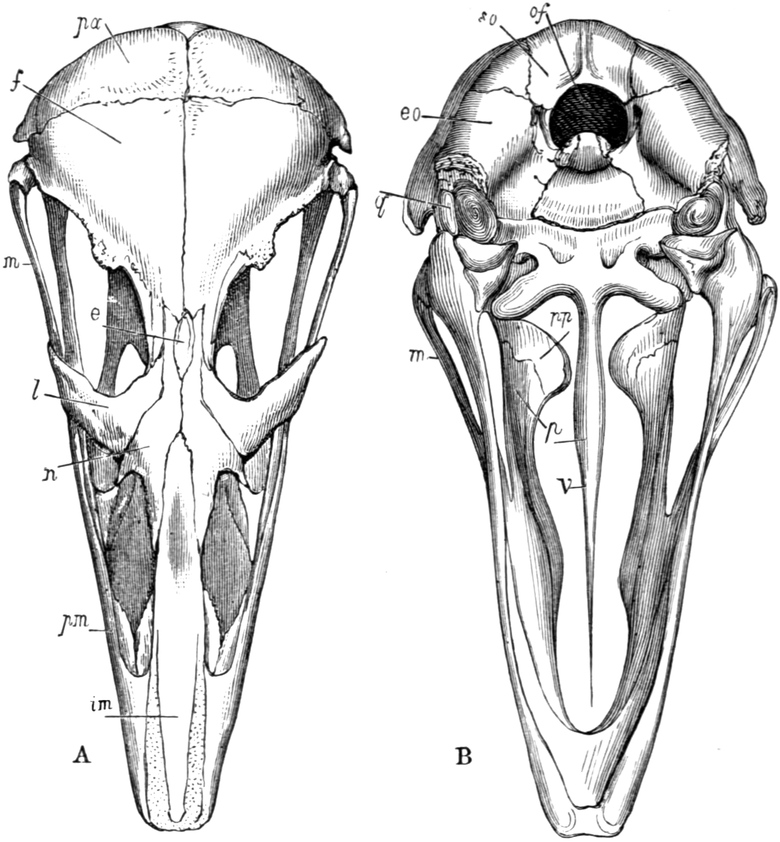

Skull of Young Ostrich from above and from below

|

|

|

Sternum of Fregilupus varius—Pelvis of an Adult Fowl, side view

|

|

|

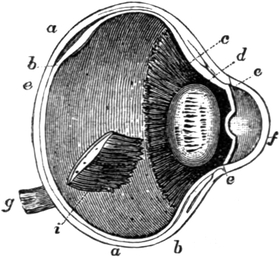

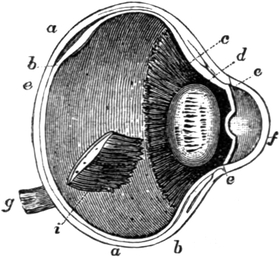

Section of the Eye of the Common Buzzard

|

|

|

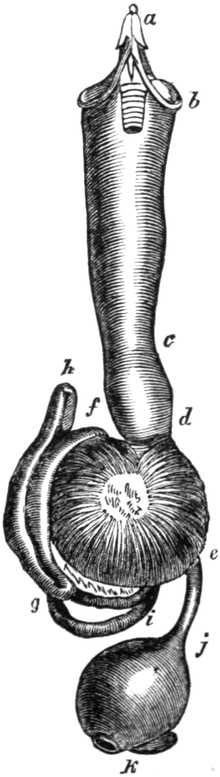

Digestive Organs of the Kingfisher

|

|

|

Front View and Section of Inferior Larynx of Peregrine Falcon

|

|

|

Diagrammatic Section of a Fowl’s Egg

|

|

|

Head and Bill of Sea Eagle

|

|

|

Bill of Egyptian Vulture, to show form of Nostril—Bill of Turkey

Vulture, to show the perforated Nostril

|

|

|

The Griffon Vulture

|

|

|

The Egyptian Vulture

|

|

|

The Condor

|

|

|

The Brazilian Caracara

|

|

|

The Secretary Bird

|

|

|

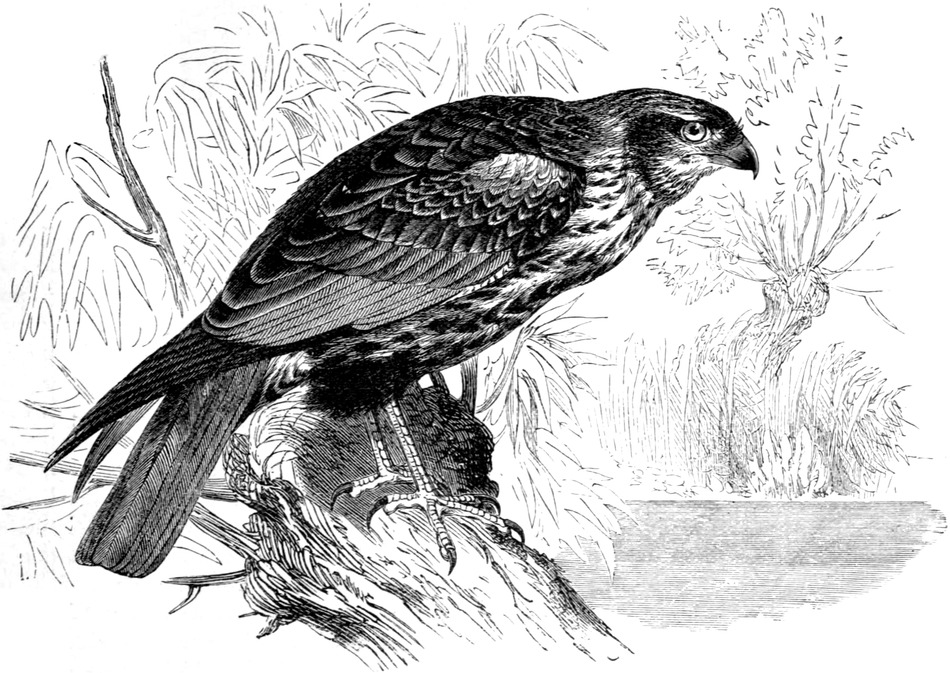

The Marsh Harrier

|

|

|

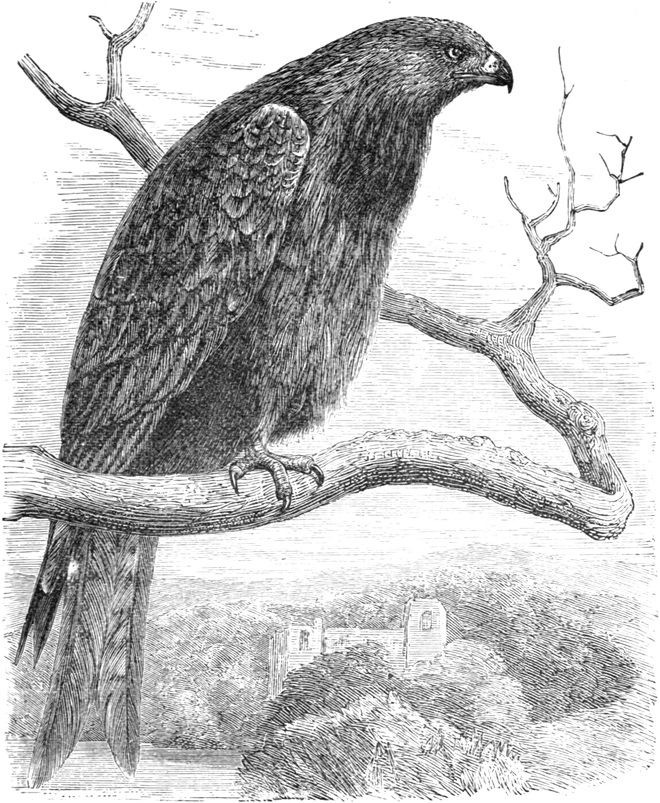

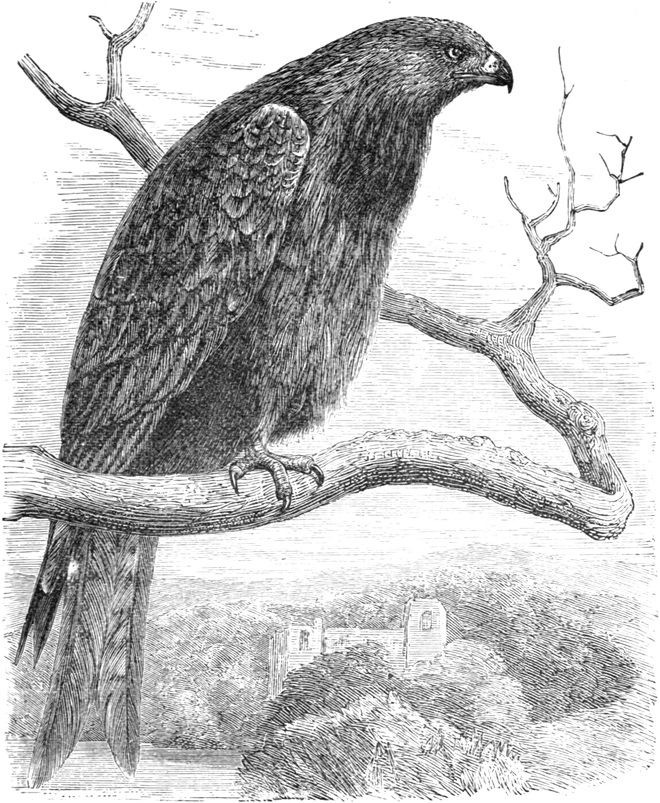

The Goshawk

|

|

|

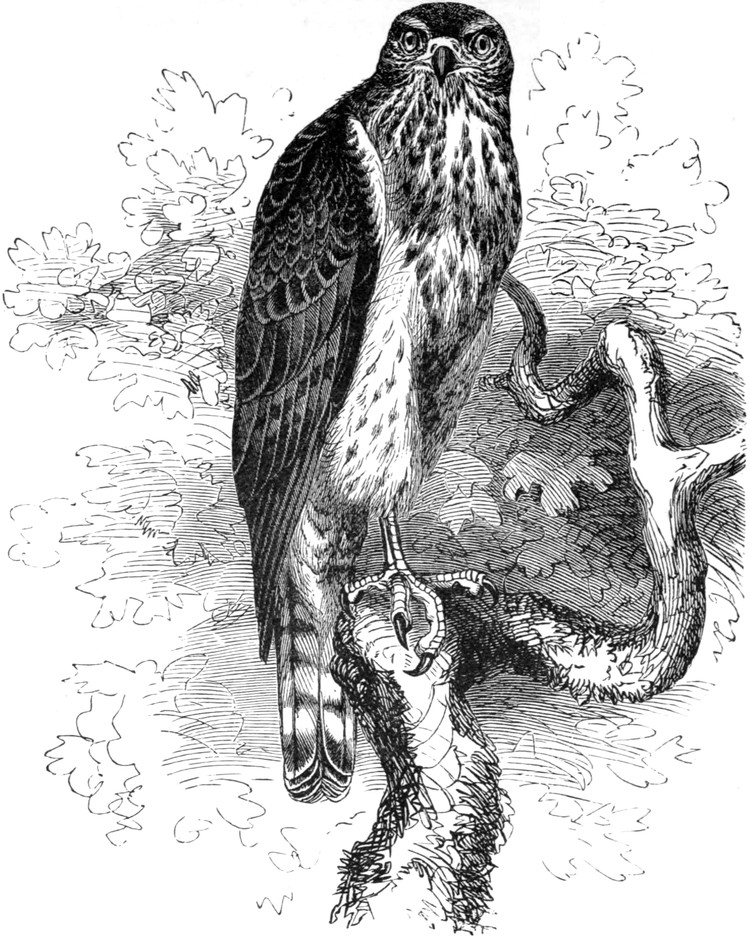

The Sparrow-Hawk

|

|

|

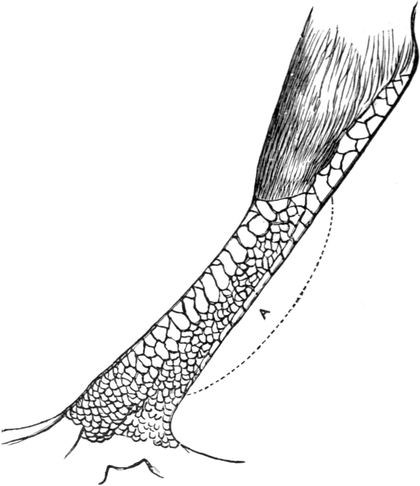

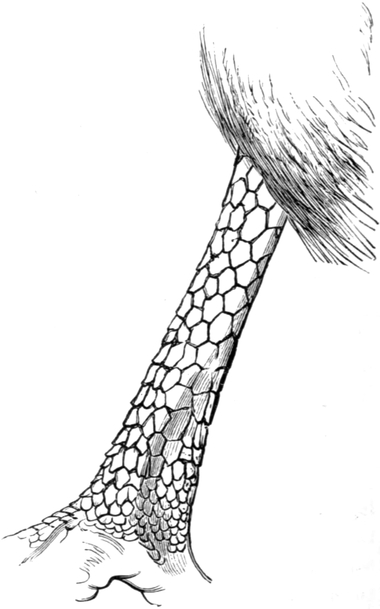

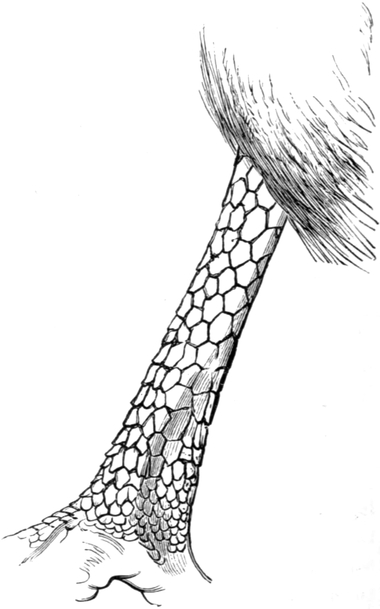

Hind View of Tarsus of Buzzard, showing the plated arrangement of

Scales—Hind View of Tarsus of Serpent Eagle, showing the reticulated

arrangement of Scales

|

|

|

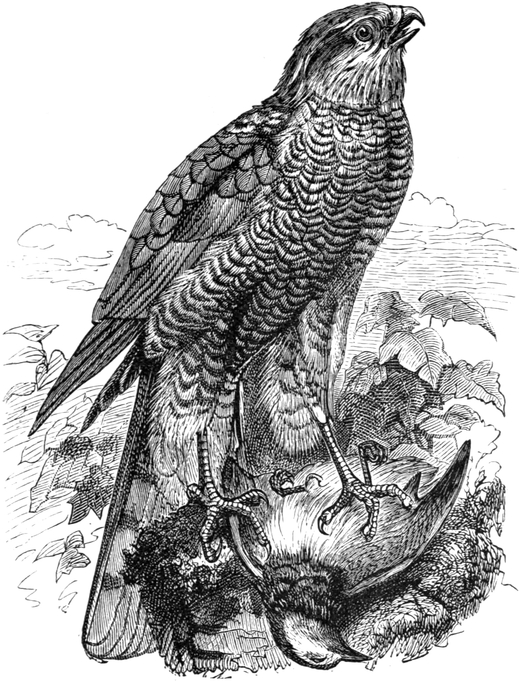

The Common Buzzard

|

|

|

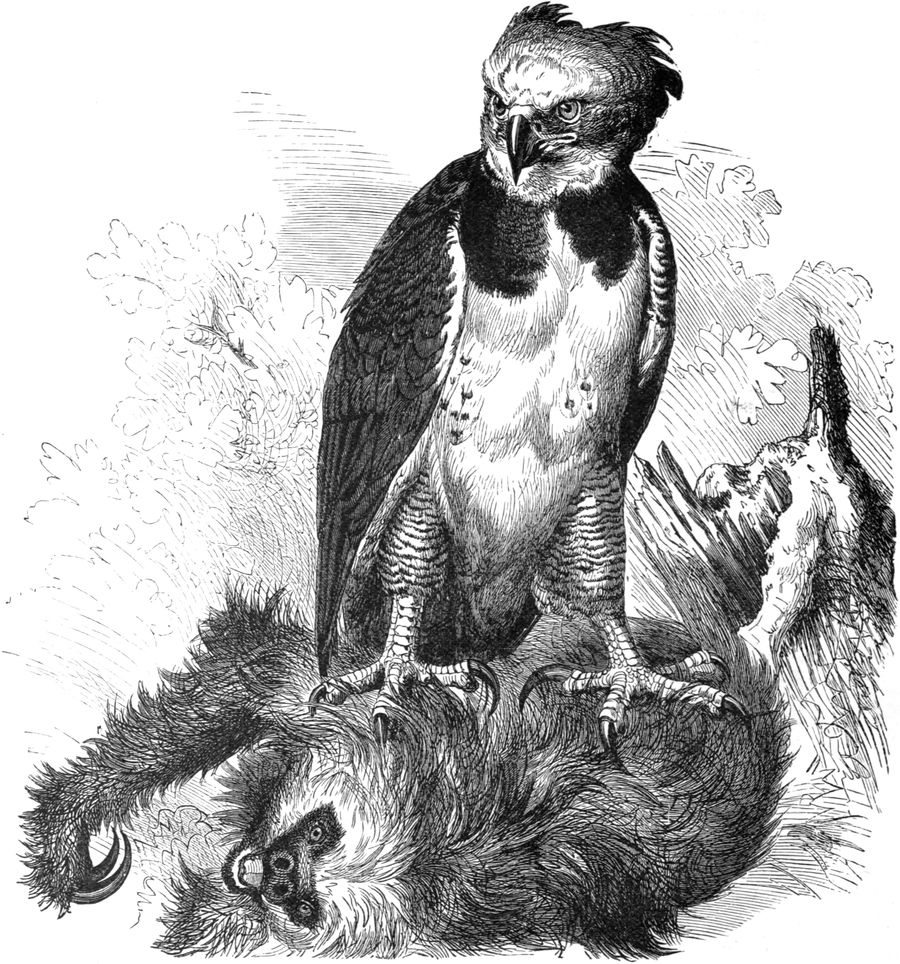

The Harpy

|

|

|

The Bearded Eagle, or Lämmergeier

|

|

|

Eye of Eagle, showing Crystalline Lens

|

|

|

The Golden Eagle

|

|

|

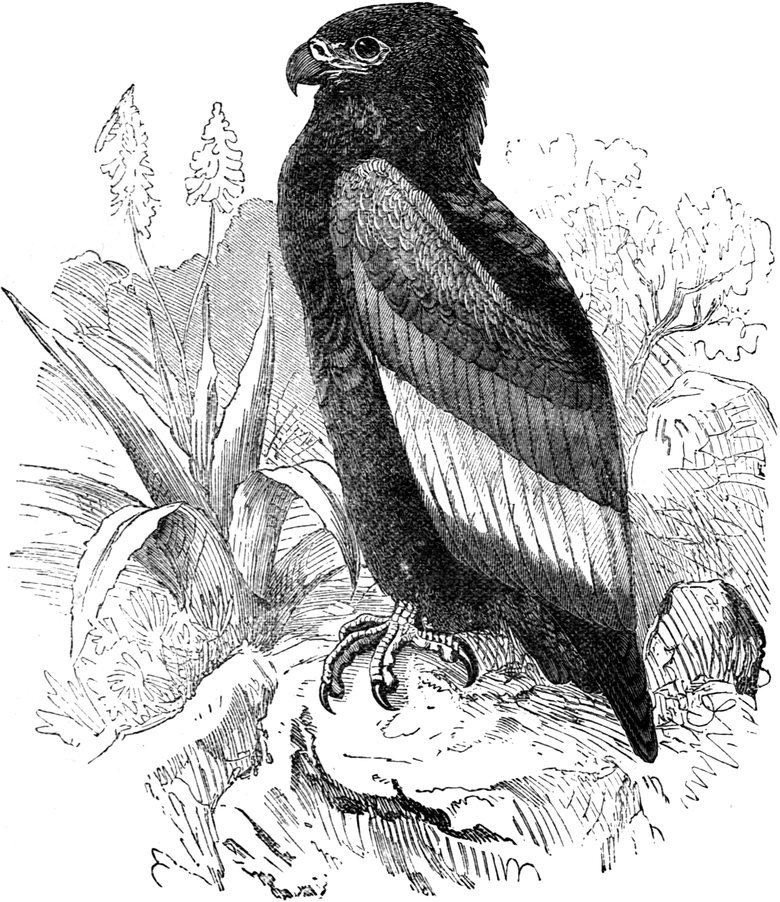

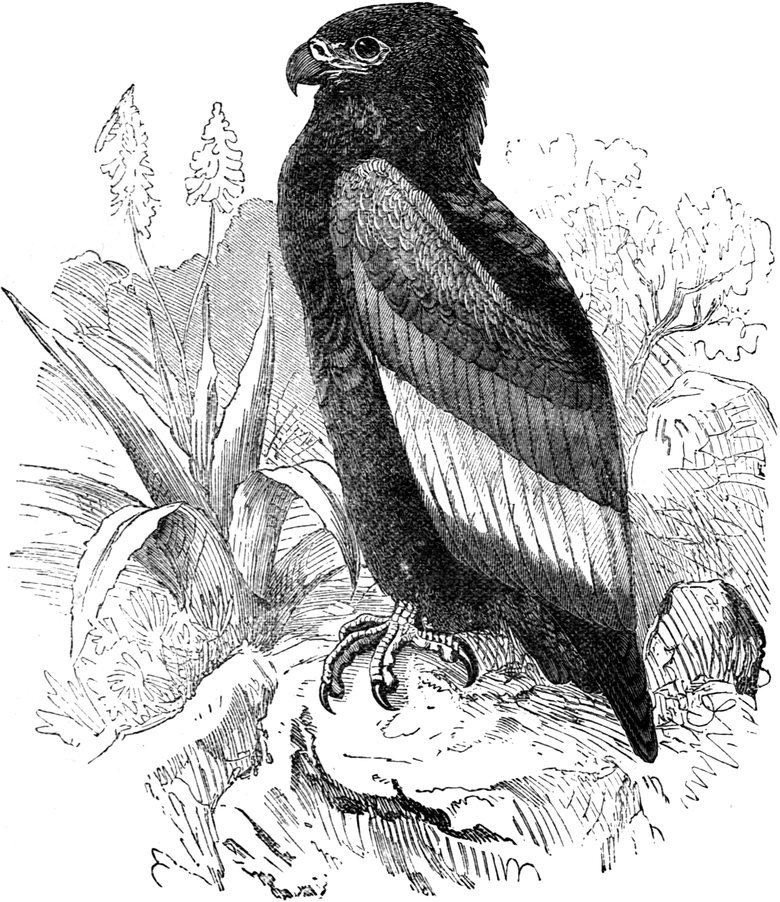

The Bateleur Eagle

|

|

|

The White-tailed Eagle

|

|

|

The Common Kite

|

|

|

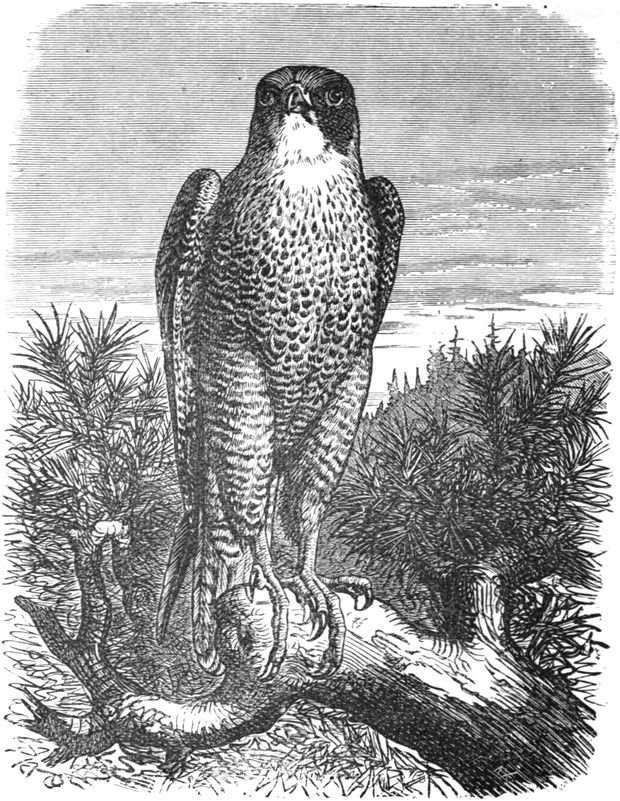

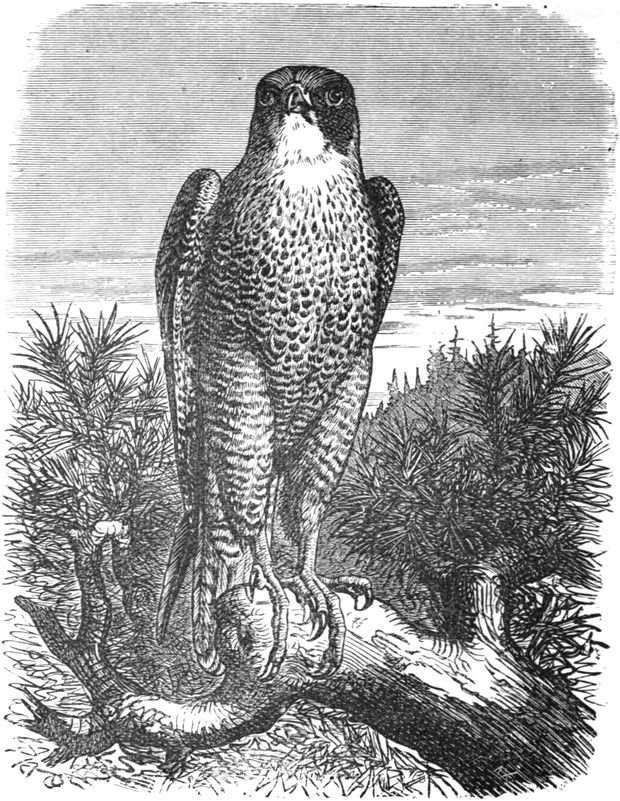

The Peregrine Falcon

|

|

|

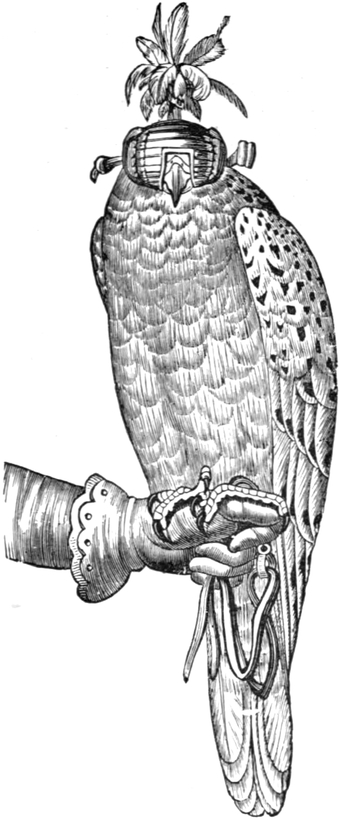

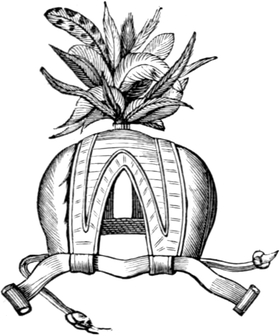

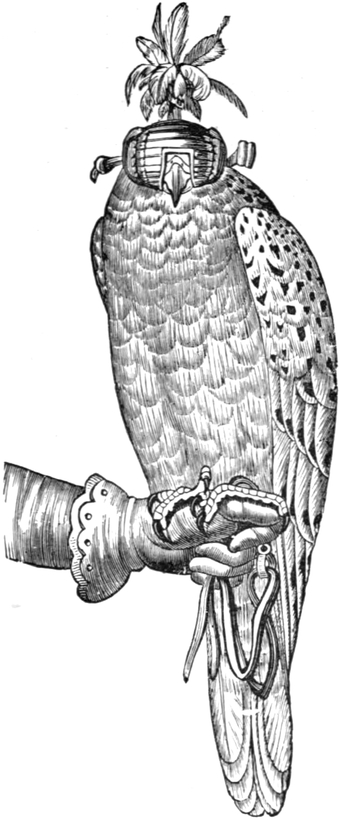

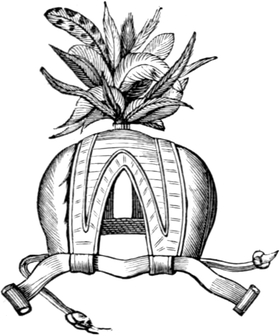

A Hooded Falcon—Falcon’s Hood

|

|

|

The Common Kestrel

|

|

|

The Osprey

|

|

|

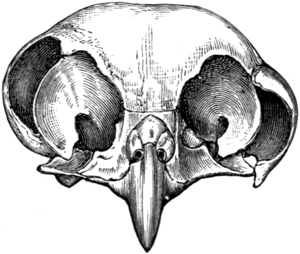

Skull of Tengmalm’s Owl

|

|

|

The Little Owl

|

|

|

The Eagle Owl

|

To face page

|

|

|

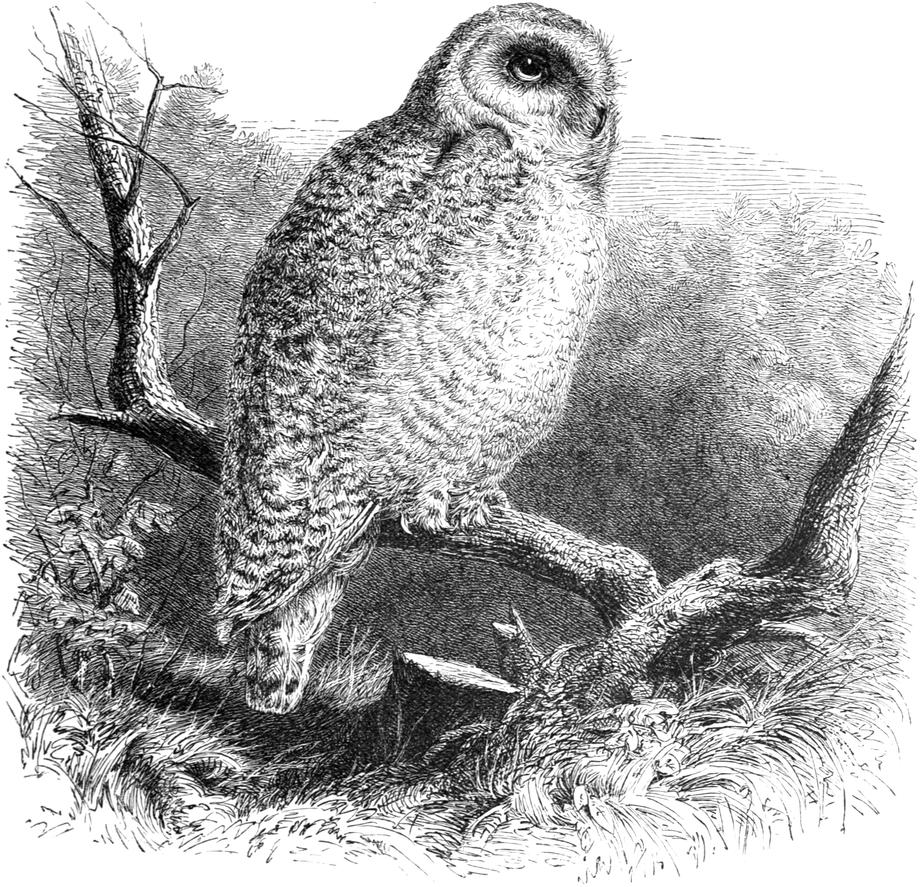

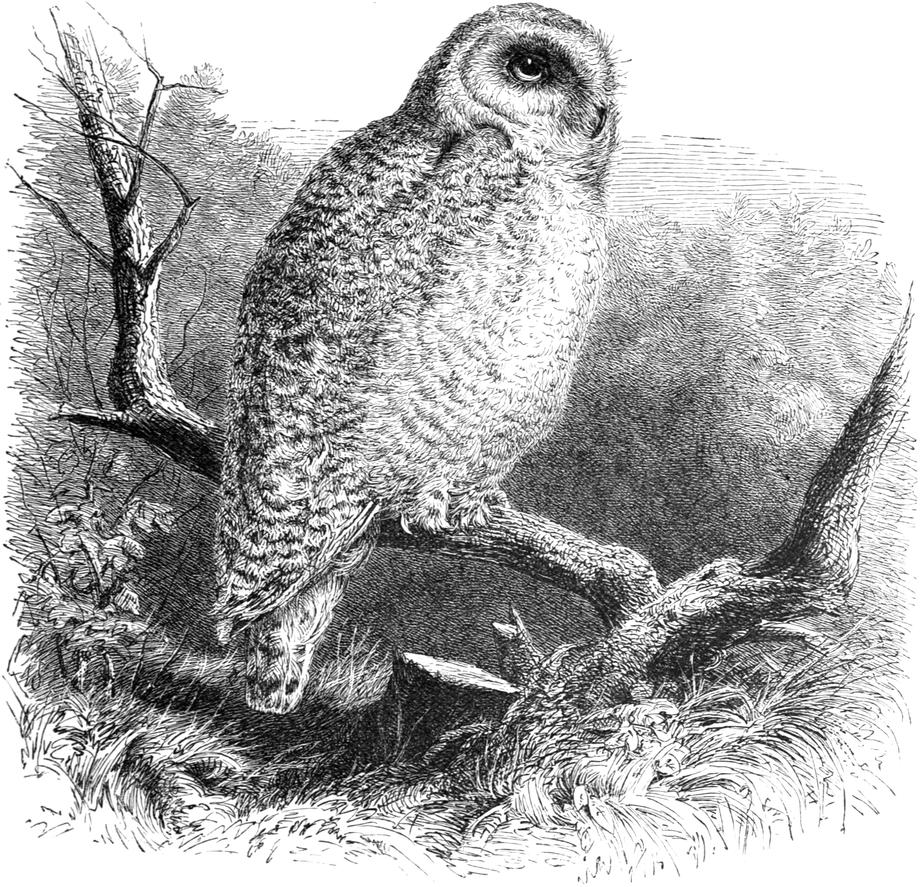

The Snowy Owl

|

|

|

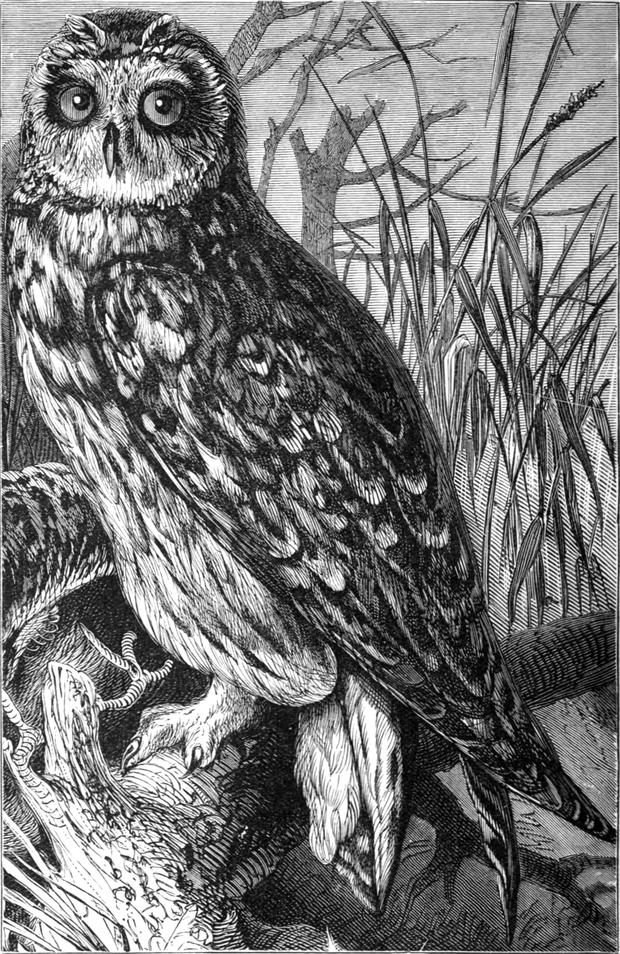

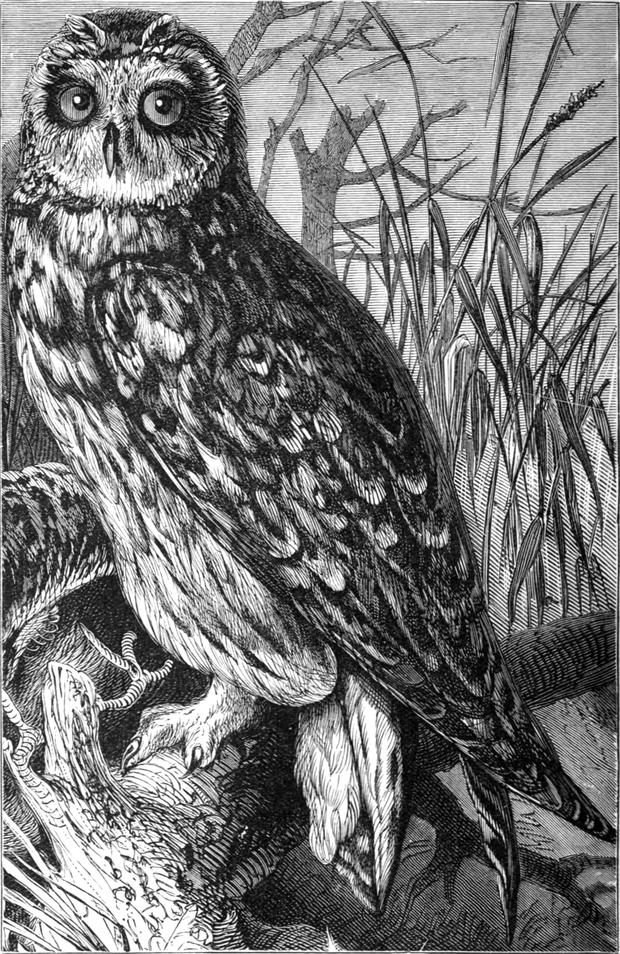

The Short-eared Owl

|

|

|

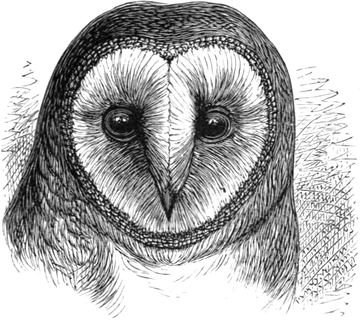

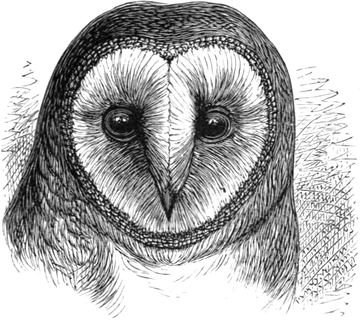

Face of the Barn Owl

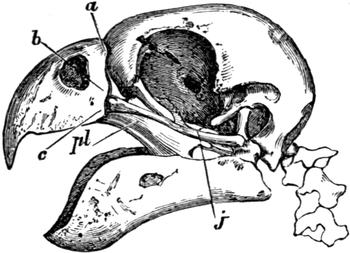

|

|

|

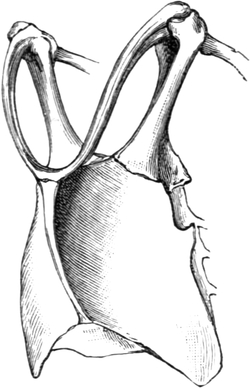

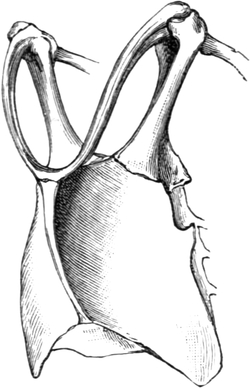

Breast-bone of the Barn Owl

|

|

|

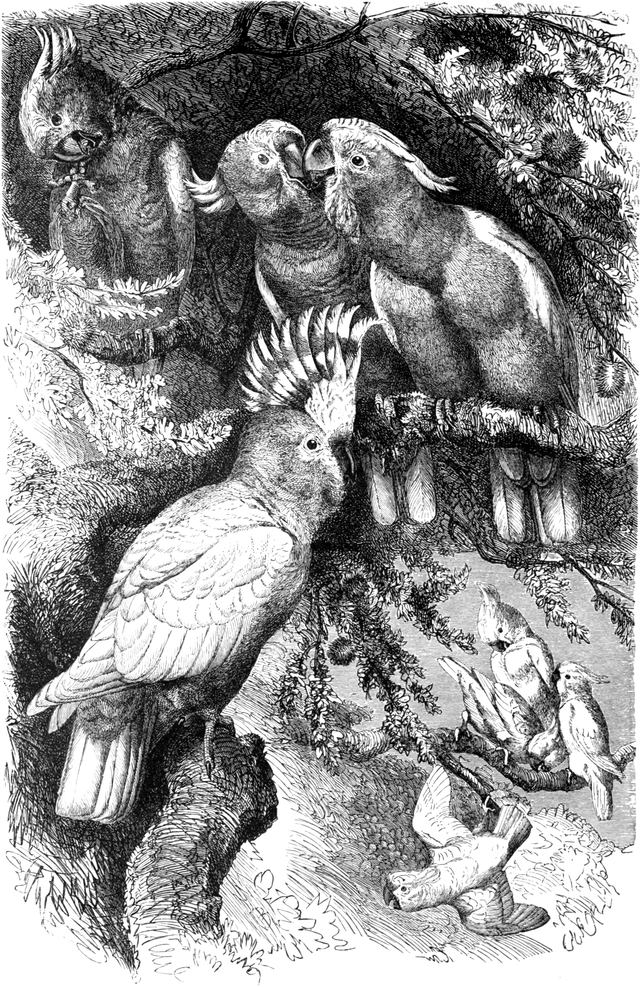

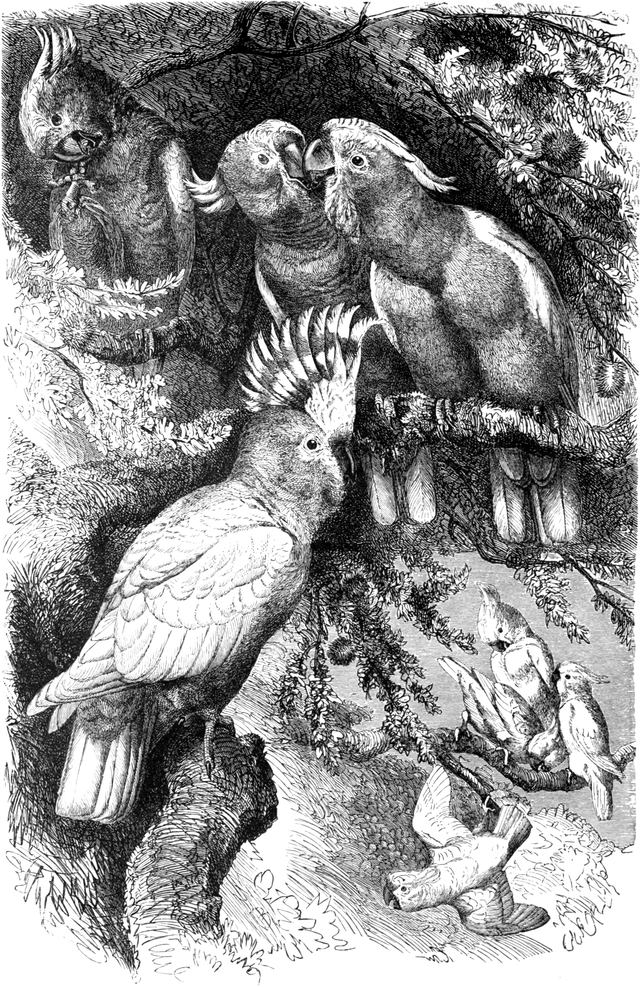

Cockatoos

|

To face page

|

|

|

The Amazon Parrot

|

|

|

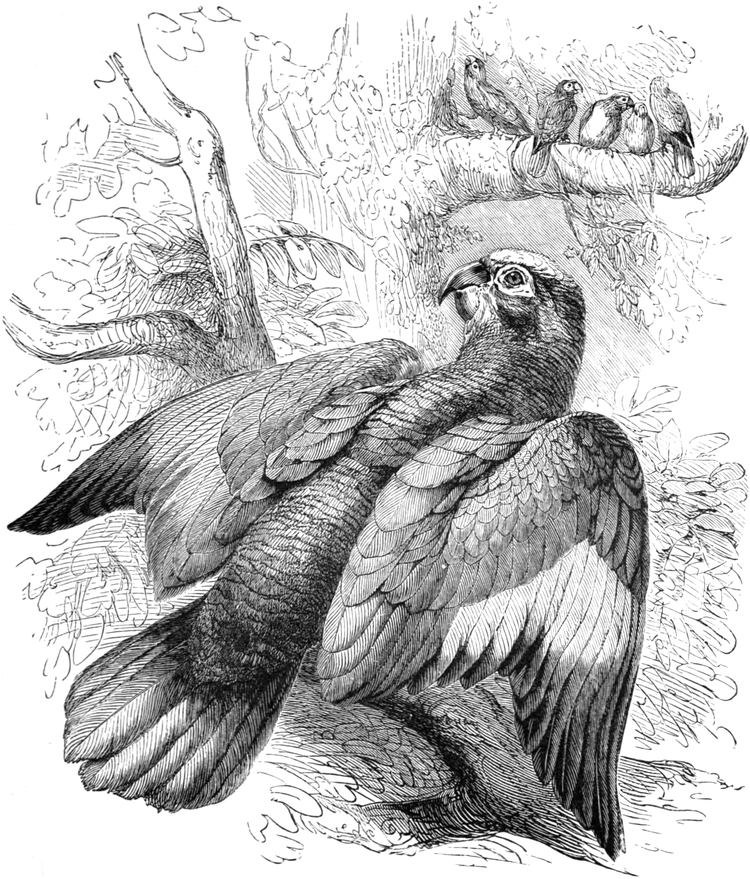

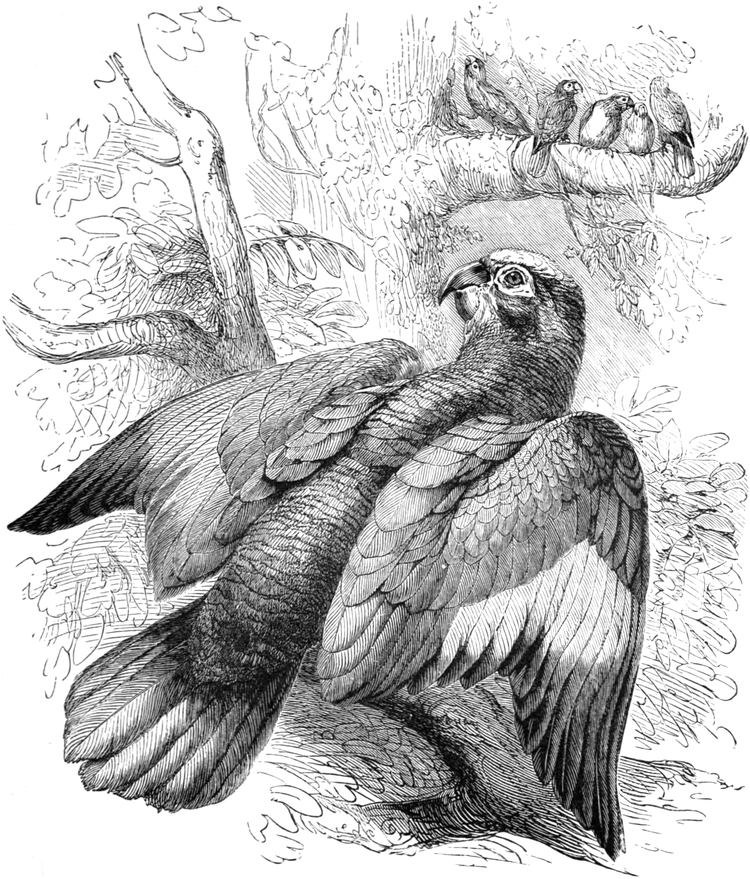

Great Macaws

|

To face page

|

|

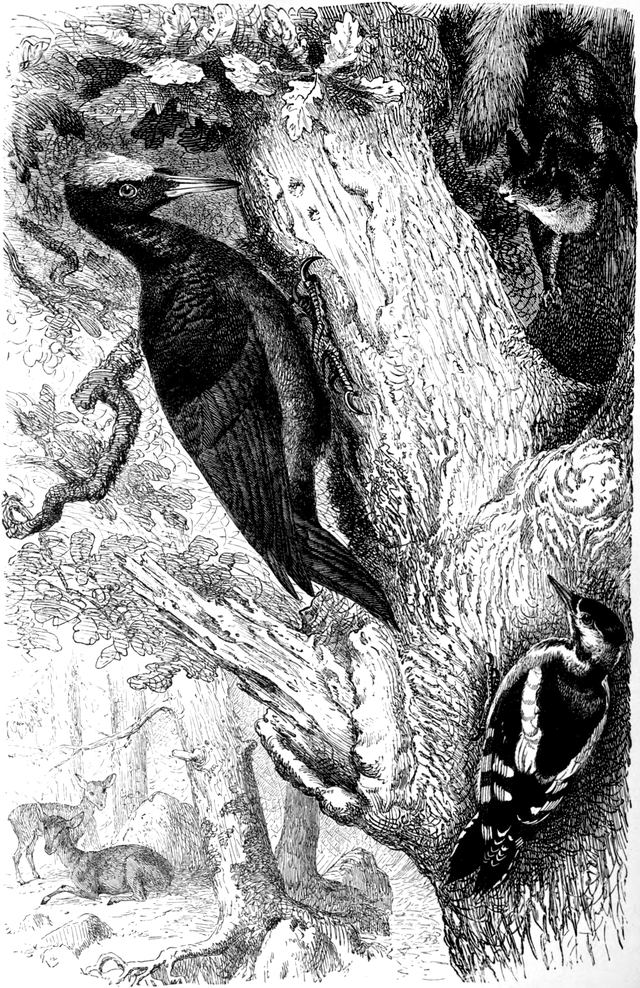

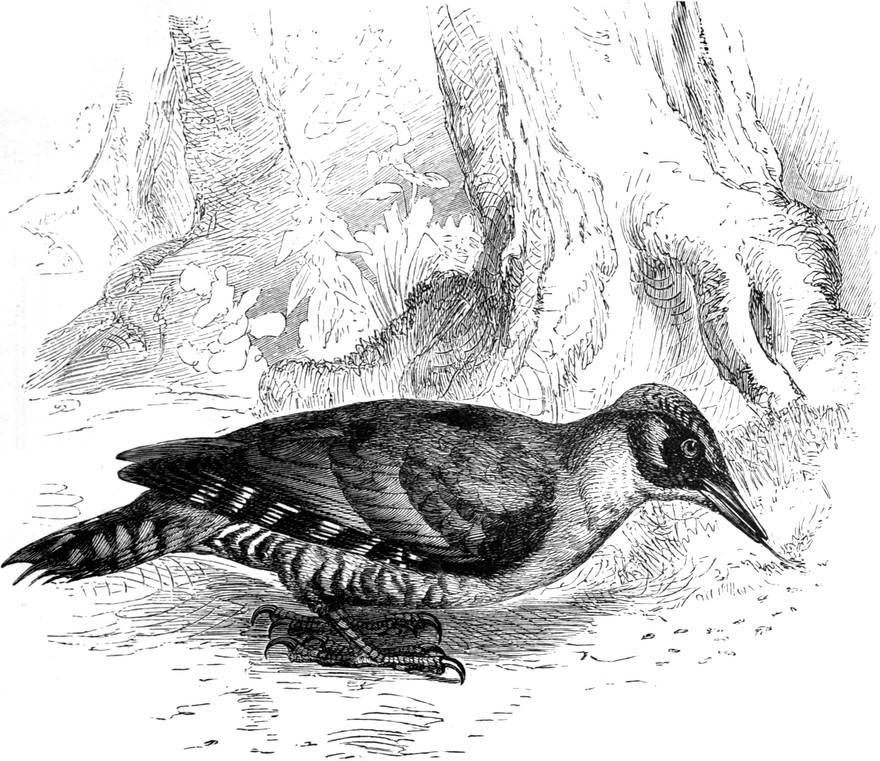

|

The Grey Parrot

|

|

|

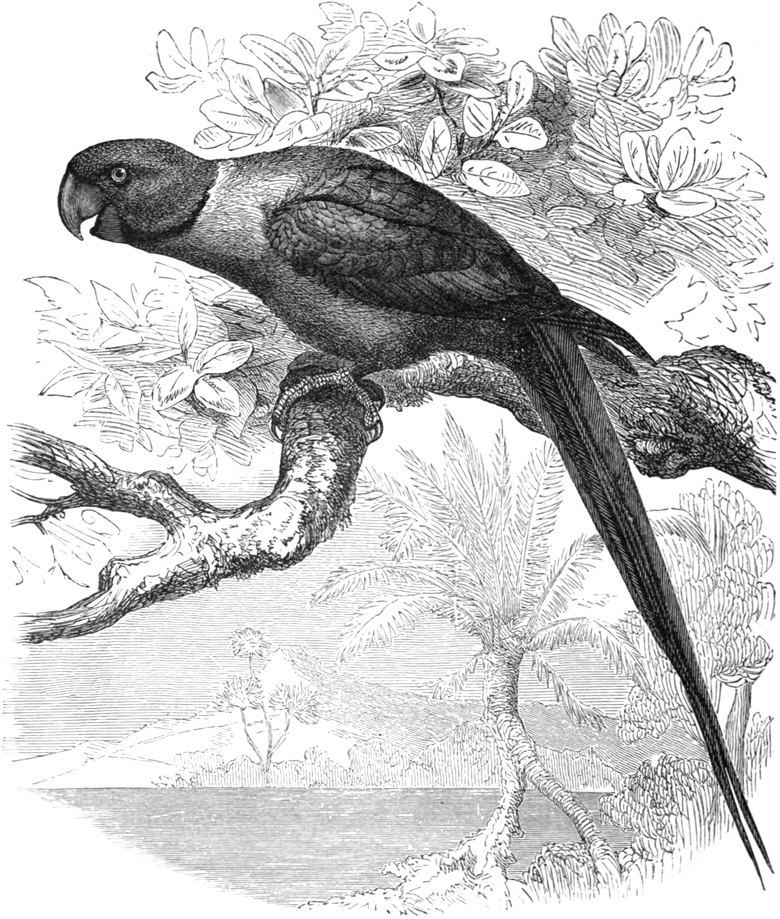

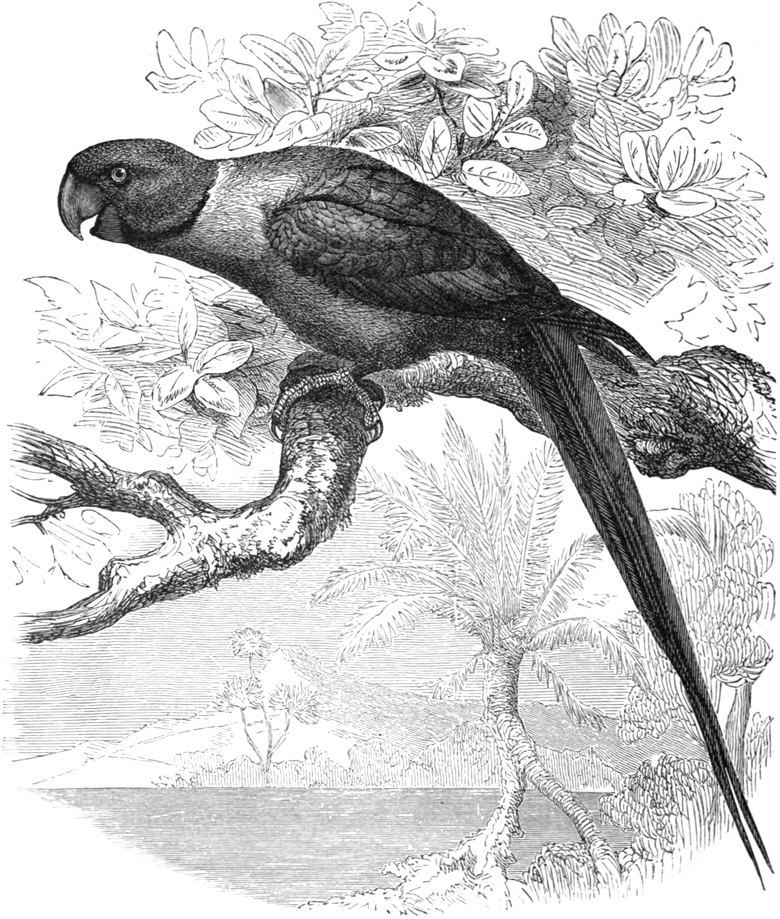

The Rose-ringed Parrakeet

|

|

|

The Rosella

|

|

|

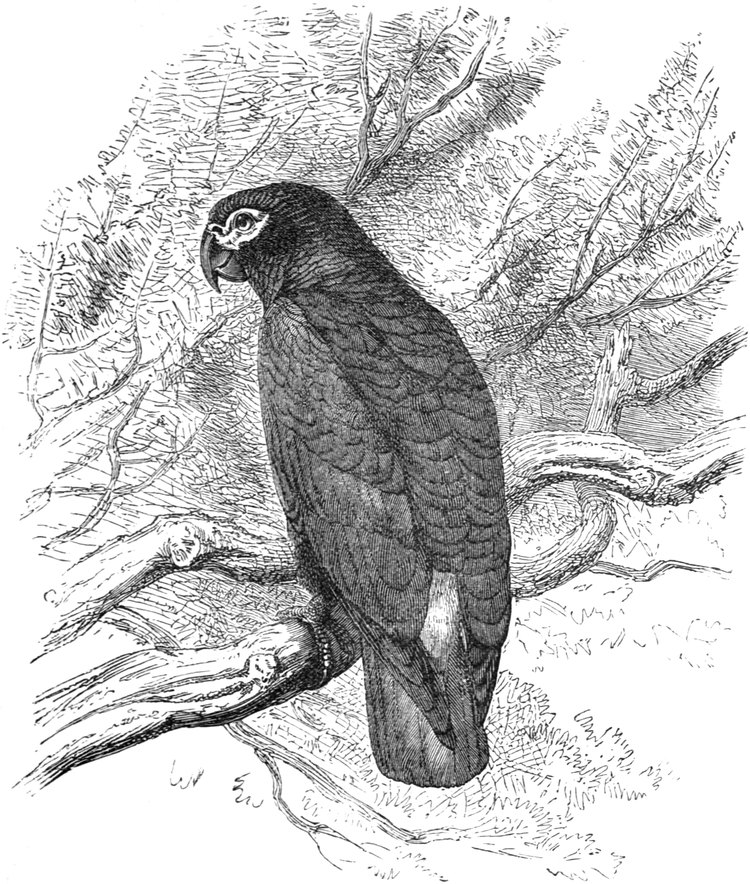

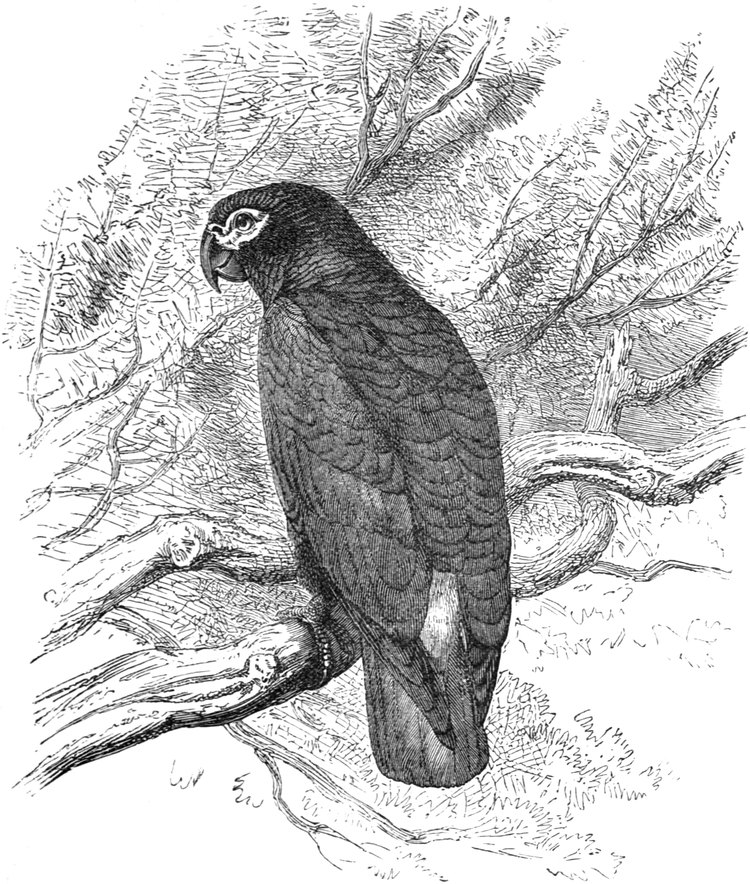

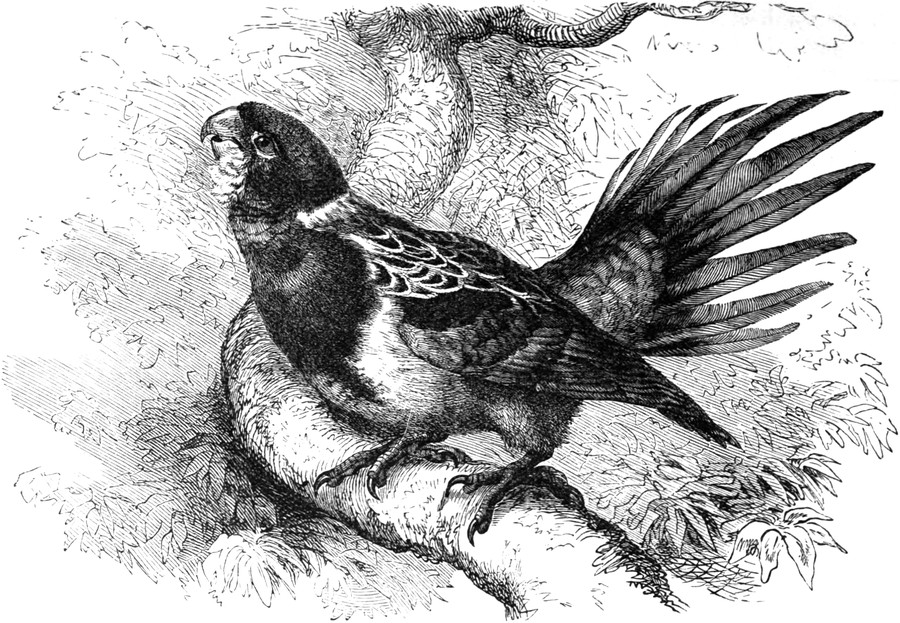

The Owl Parrot

|

|

|

The Lorikeet

|

|

|

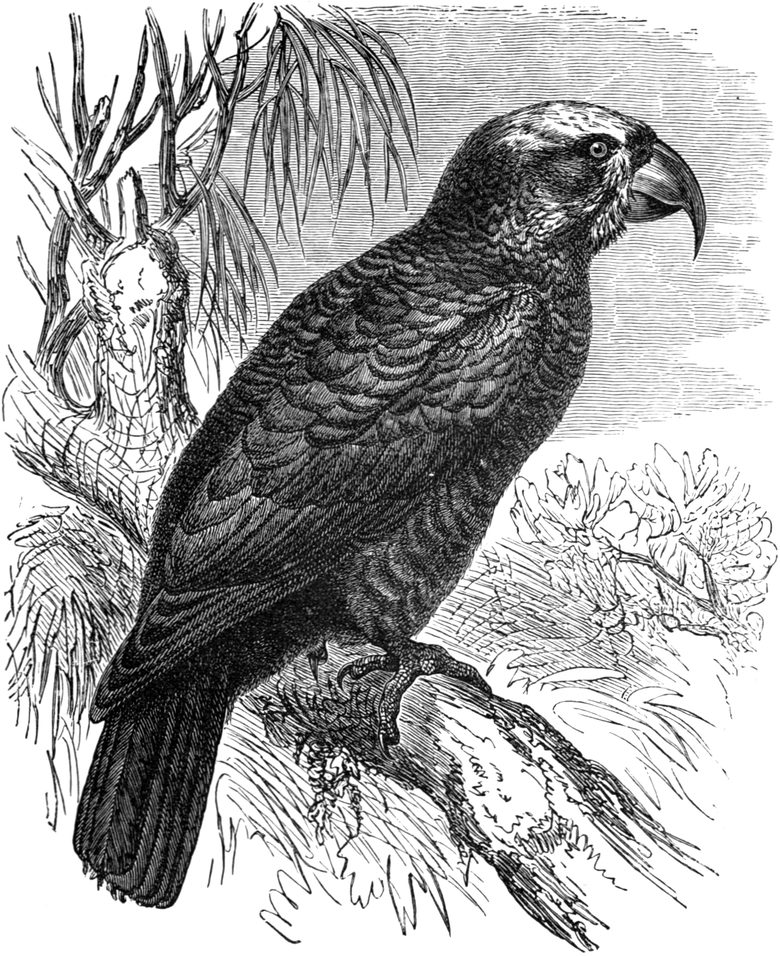

Tongue of Nestor

|

|

|

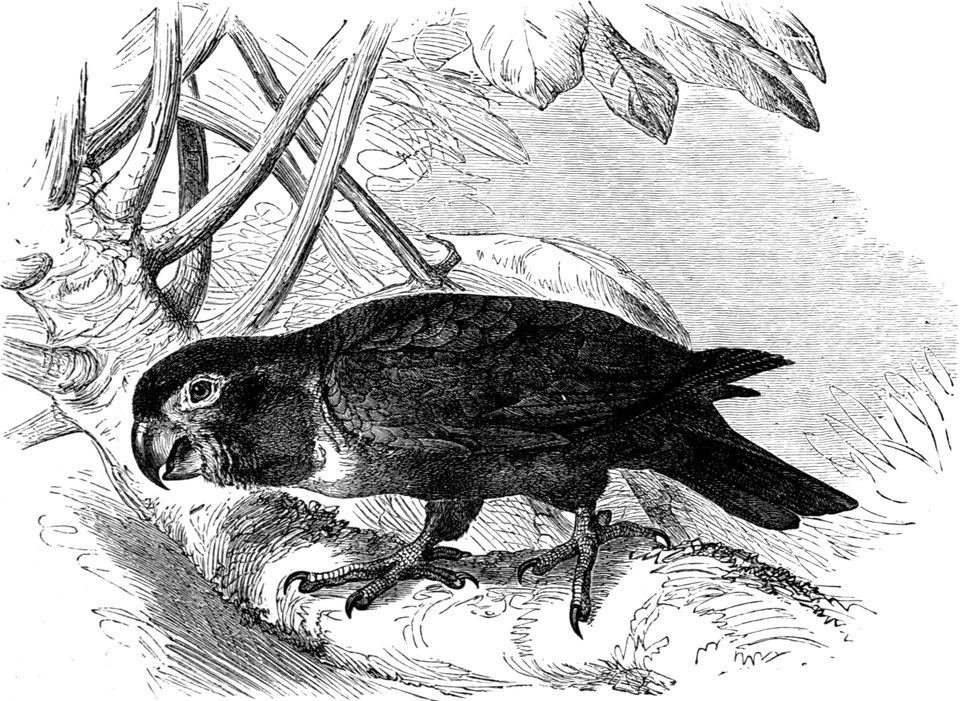

The Kaka Parrot

|

|

|

Skull of the Grey Parrot

|

|

|

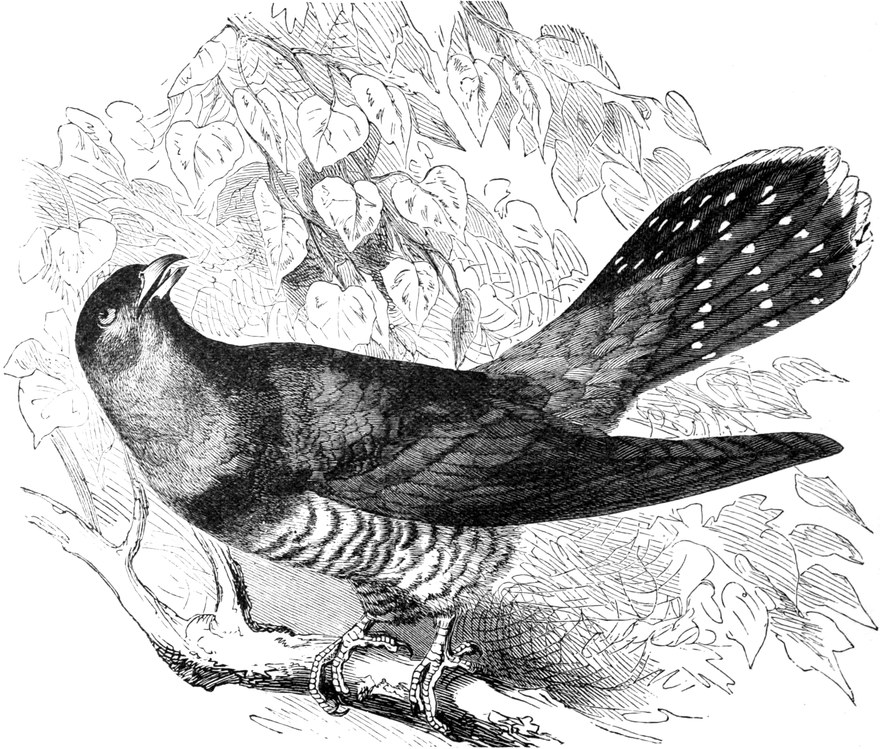

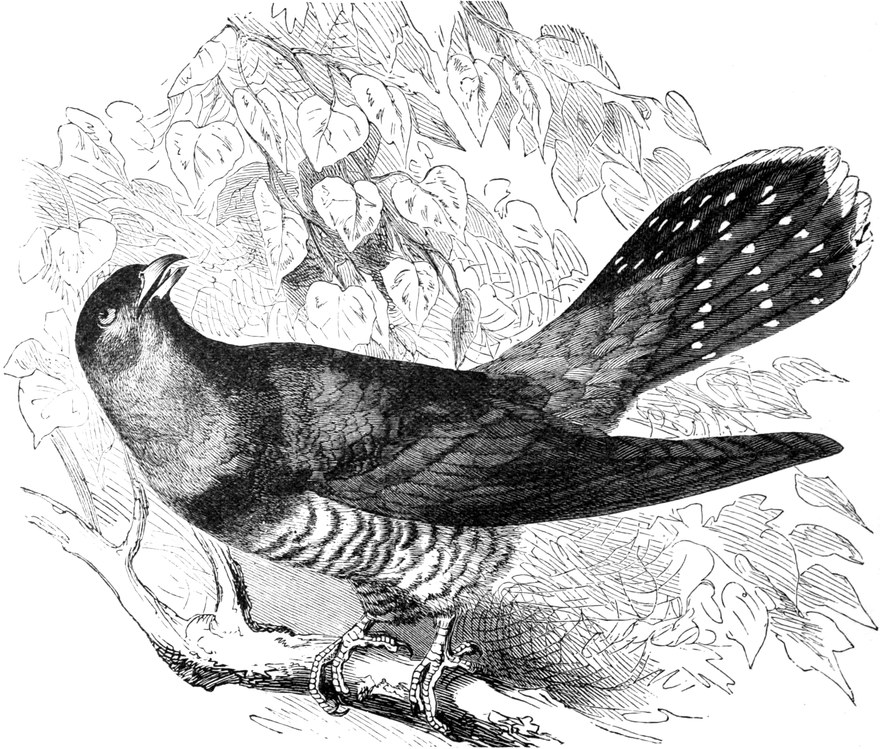

The Common Cuckoo

|

|

|

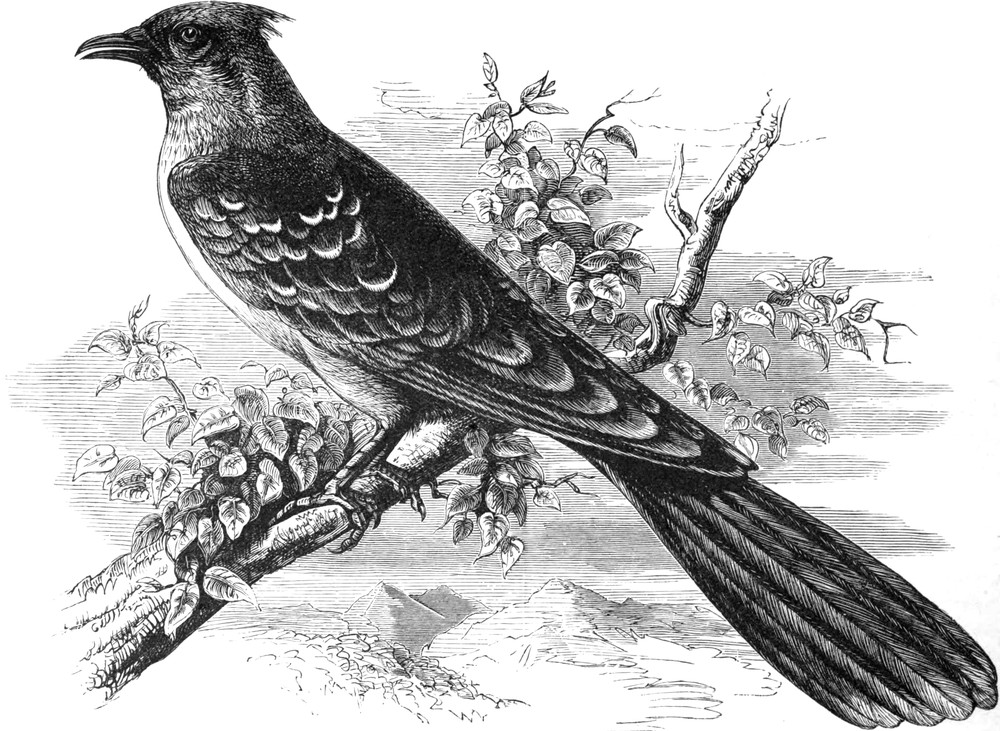

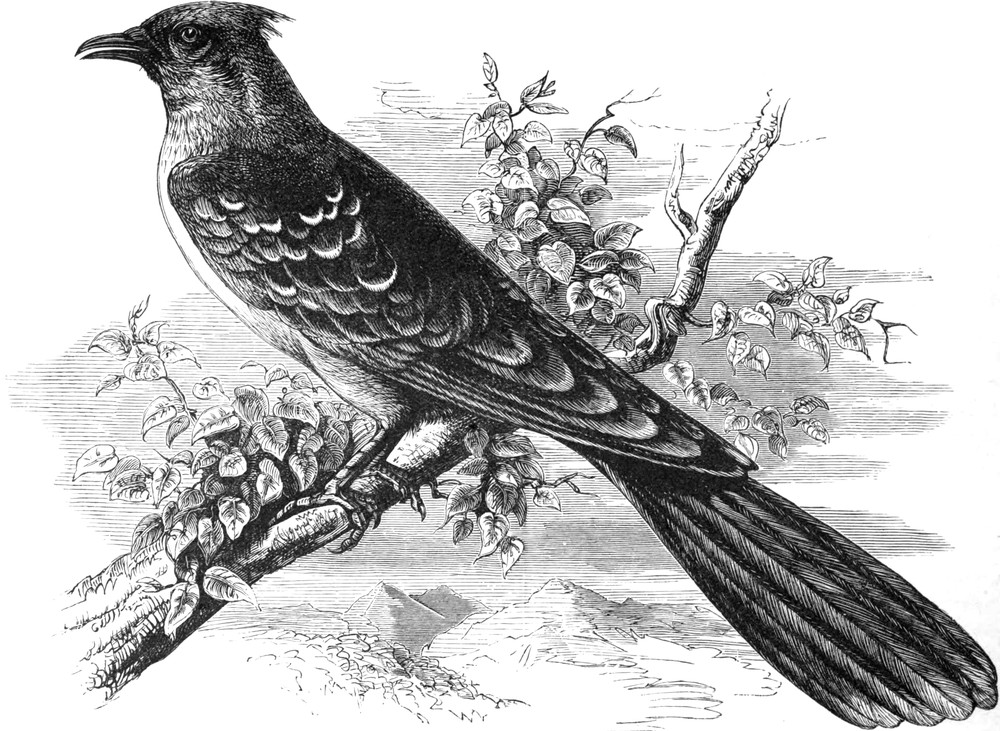

The Great Spotted Cuckoo

|

|

|

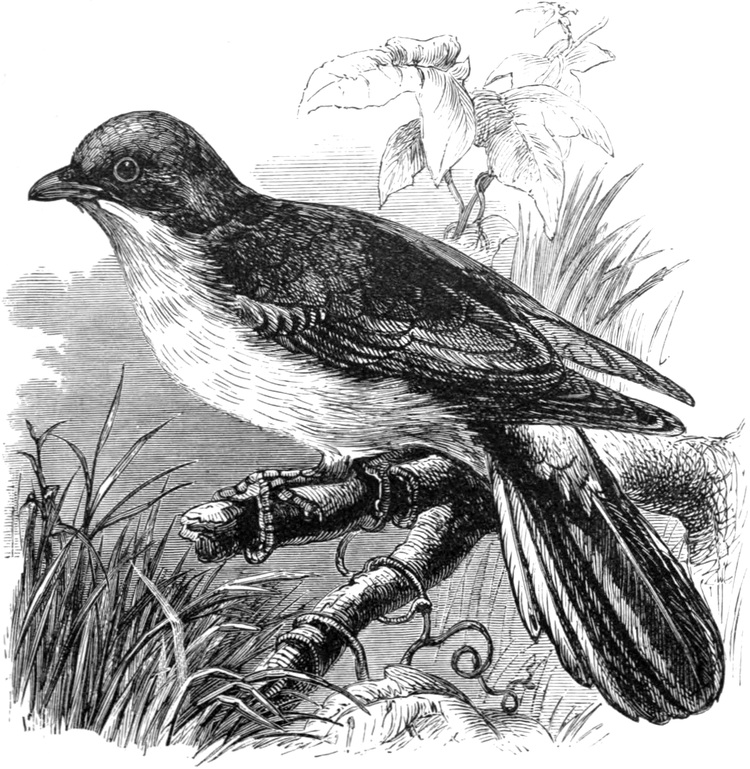

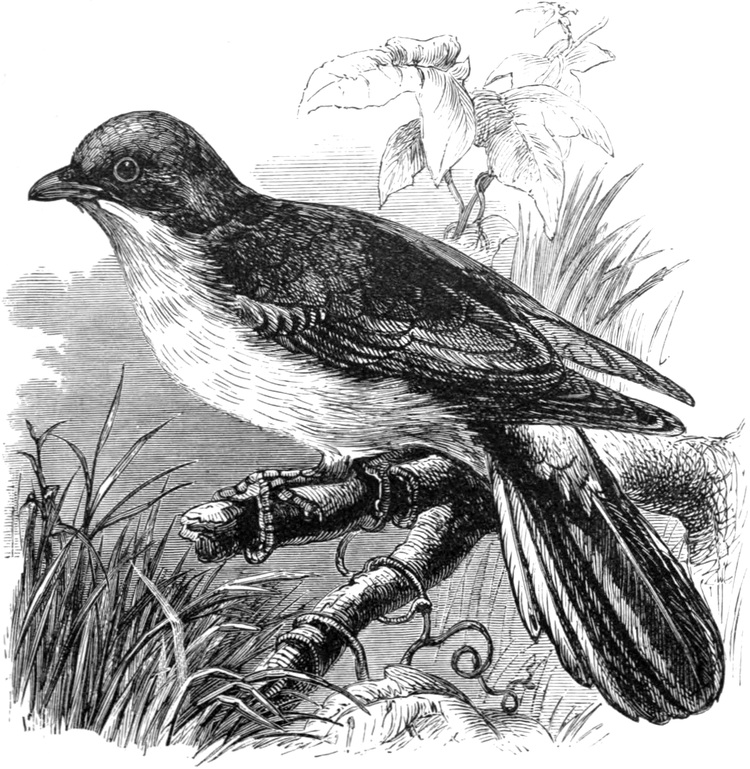

The Honey Guide

|

|

|

The White-crested Plantain-eater

|

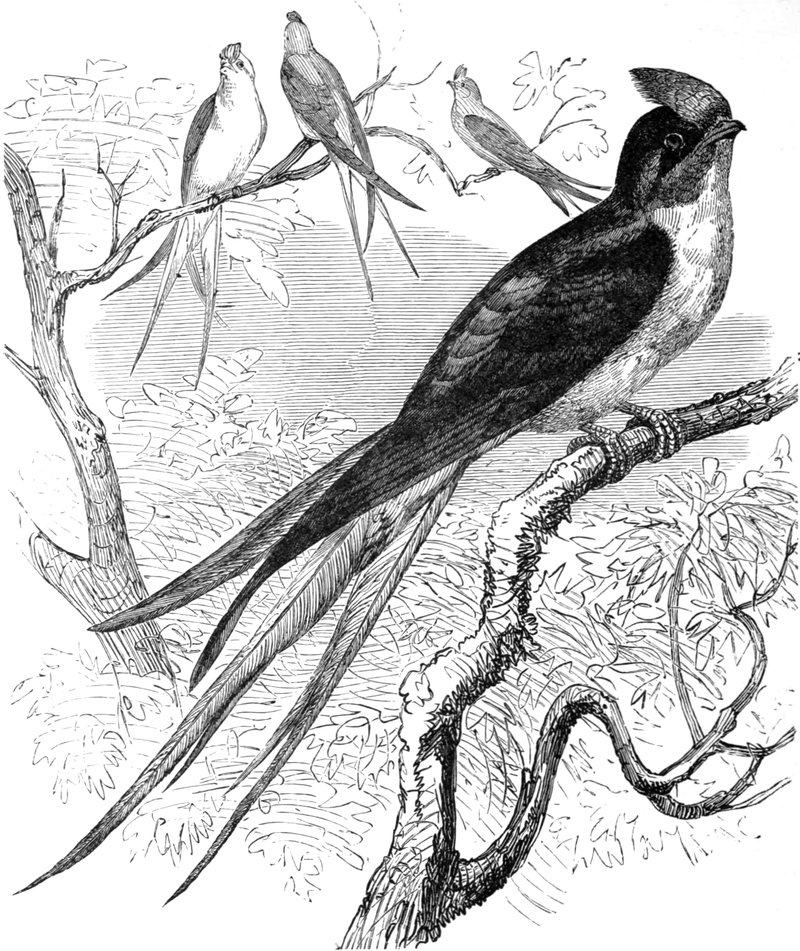

|

|

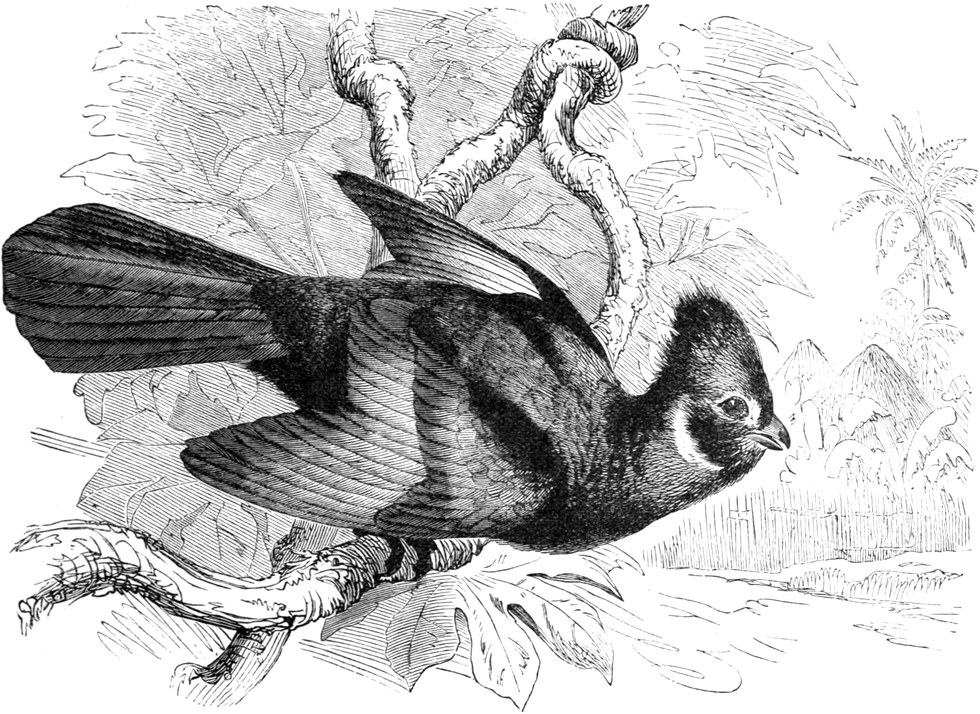

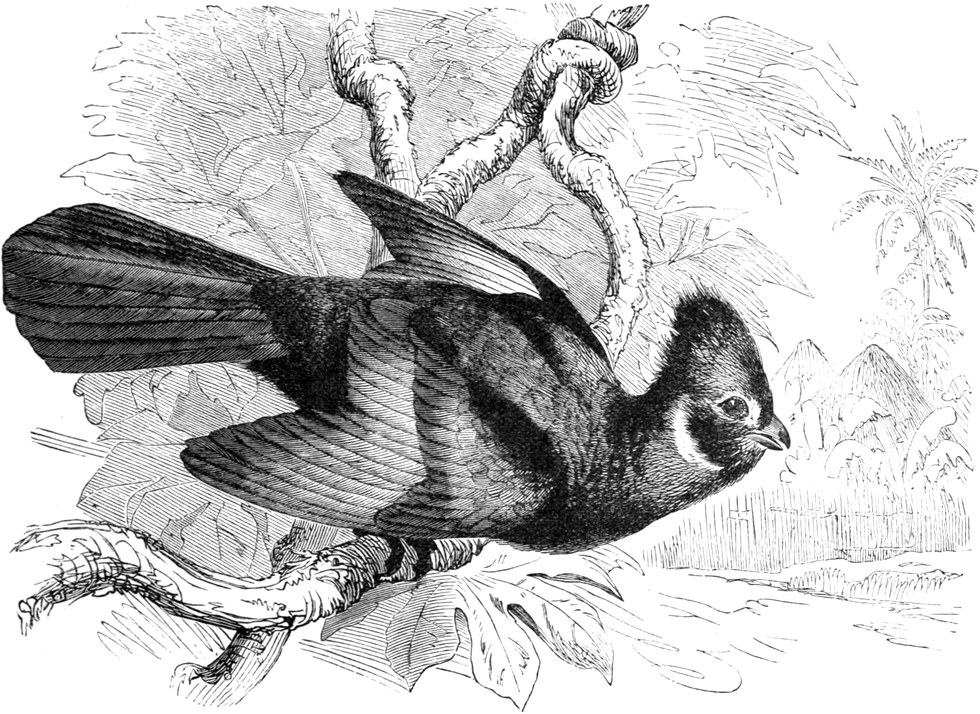

Colies

|

|

|

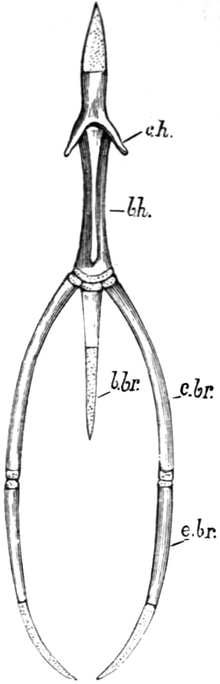

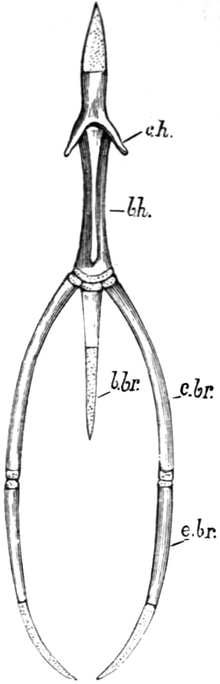

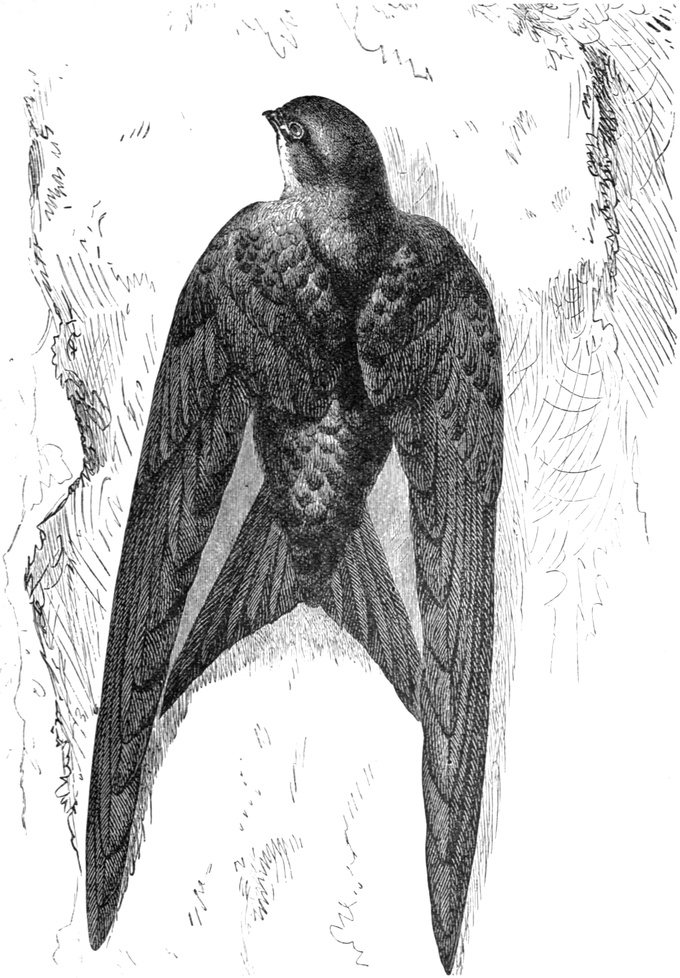

“Hyoid” Bone of Adult Fowl—Side View of Dissection of Head of

Common Green Woodpecker

|

|

|

Upper View of Skull of Green Woodpecker—Dissection of Head of Green

Woodpecker, viewed from below

|

|

|

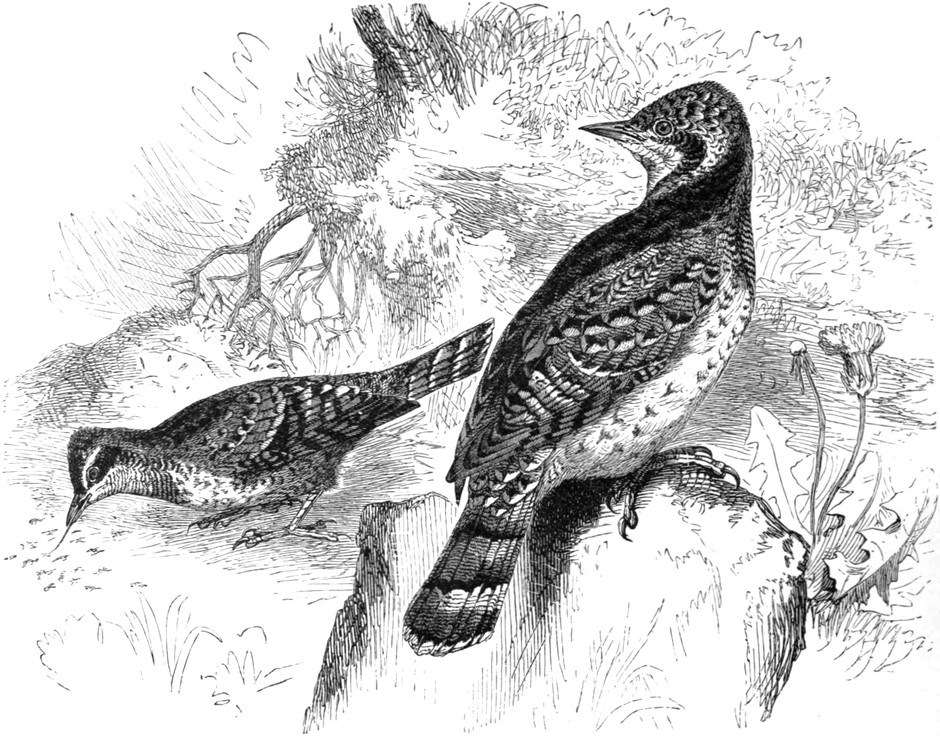

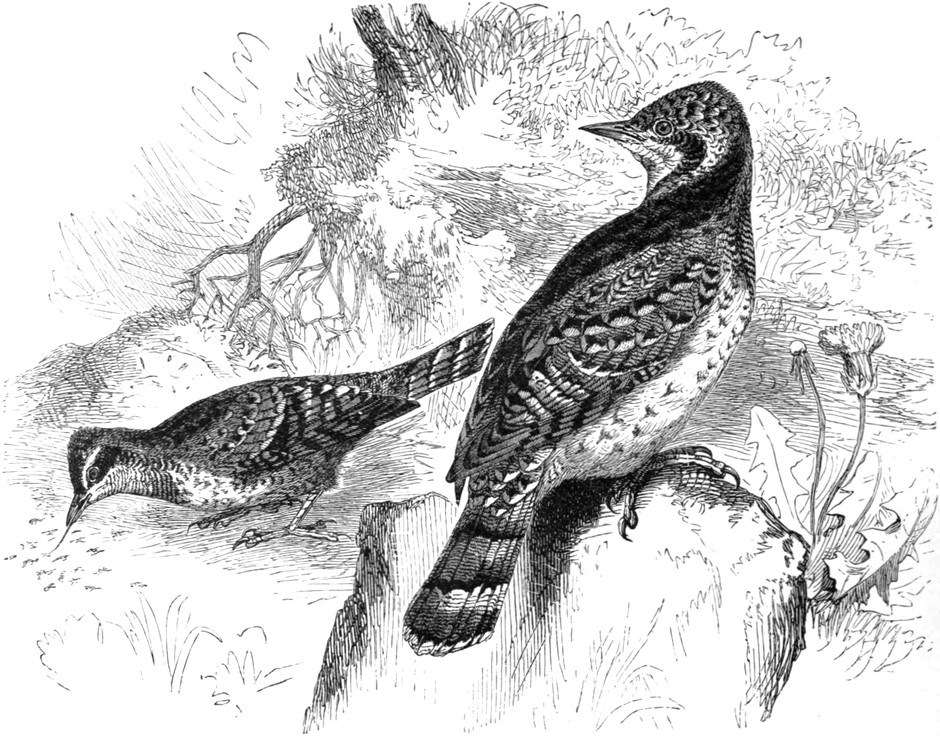

The Wryneck

|

|

|

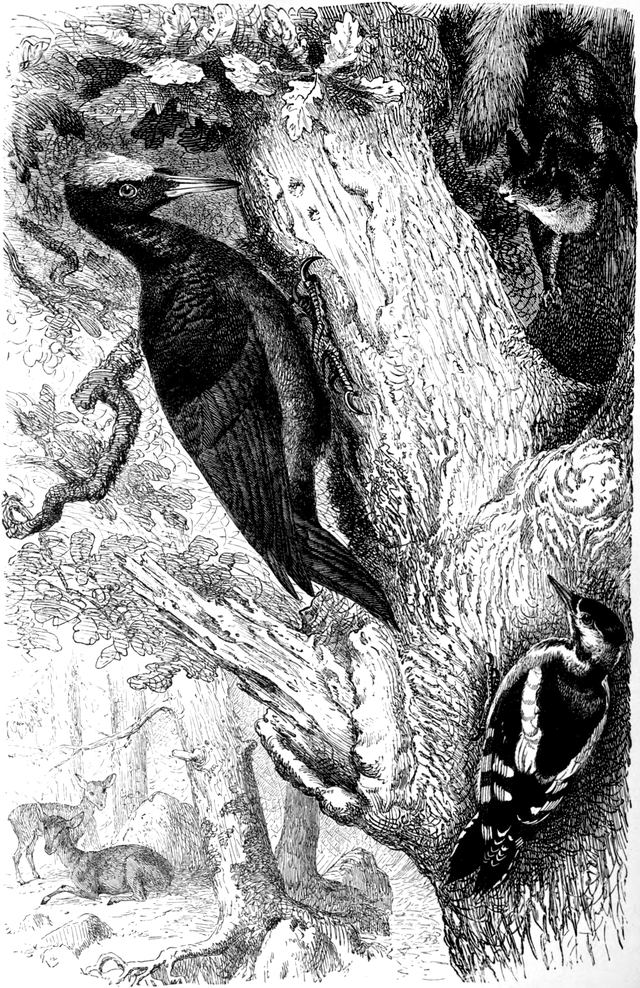

The Great Black Woodpecker and Great Spotted Woodpecker

|

To face page

|

|

|

The Green Woodpecker

|

|

|

The Toucan

|

|

|

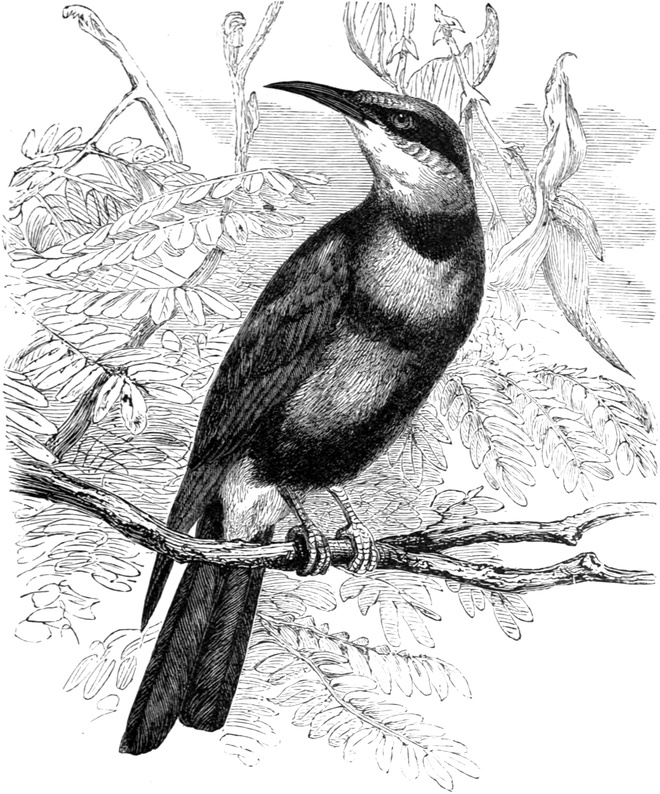

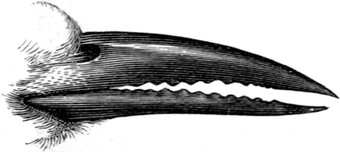

Bill of Toucan

|

|

|

The Pearl-spotted Barbet

|

|

|

The Common Kingfisher

|

|

|

The Pied Kingfisher

|

|

|

The Laughing Jackass

|

|

|

The Great Hornbill

|

|

|

The Ground Hornbills of Abyssinia

|

|

|

The Common Hoopoe

|

|

|

The Australian Bee-eater—Bill of Motmot

|

|

|

The Motmot

|

|

|

Tail-feathers of Motmot

|

|

|

The Blue Roller

|

|

|

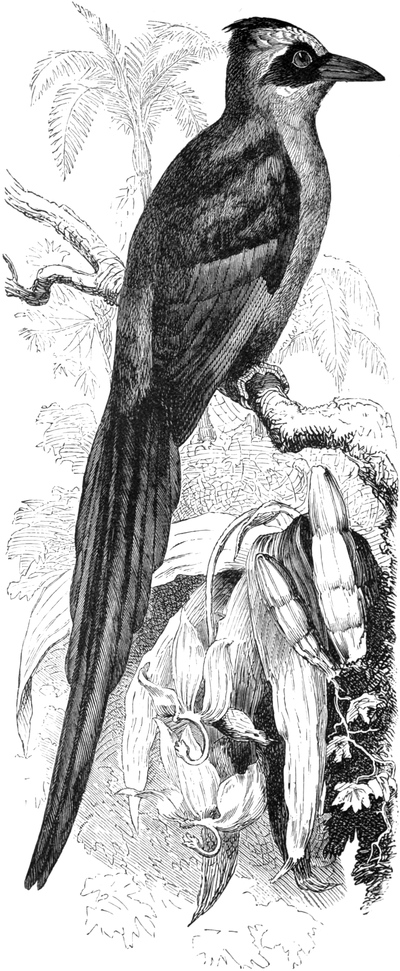

The Long-tailed Trogon, or Quesal

|

To face page

|

|

|

Mouth of Goatsucker—The Oil-bird

|

|

|

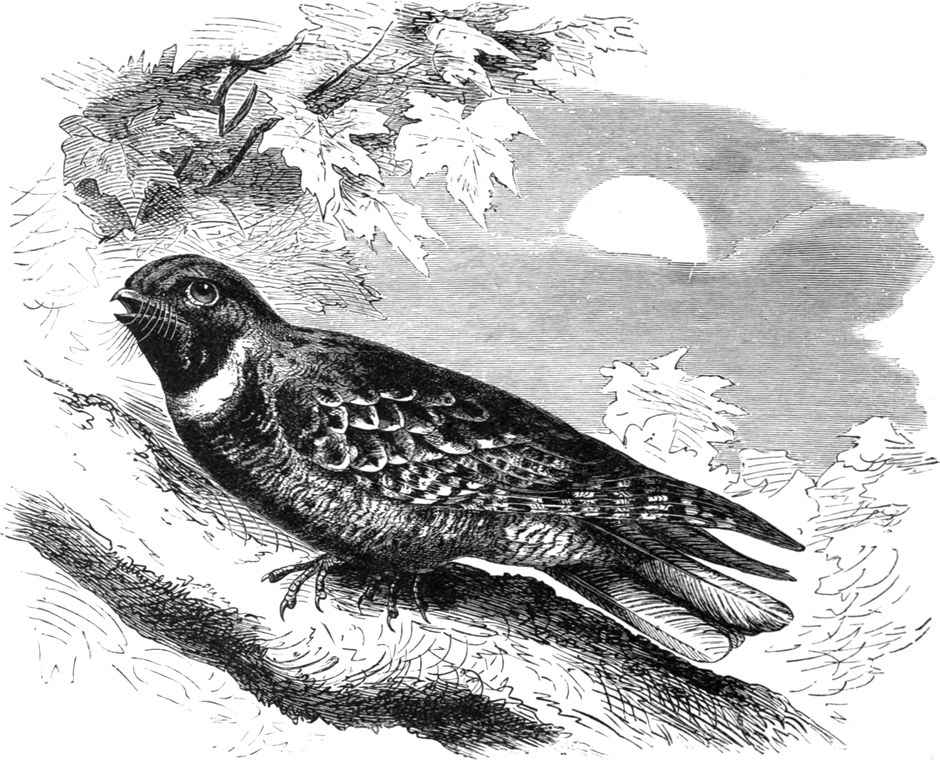

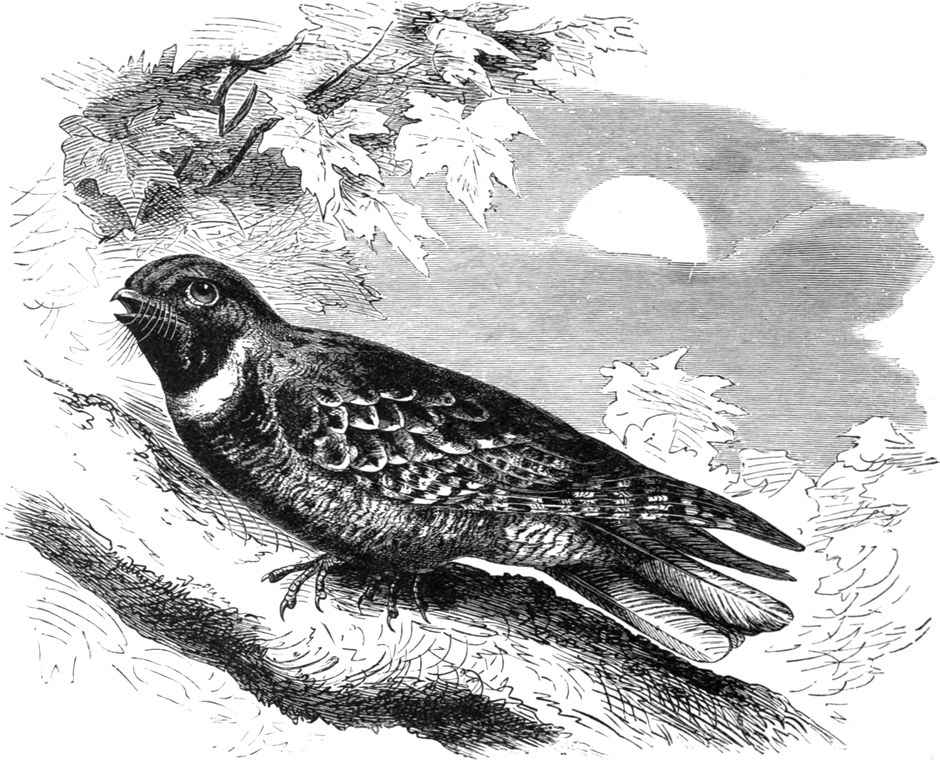

The Common Goatsucker

|

|

|

The Whip-poor-will

|

|

|

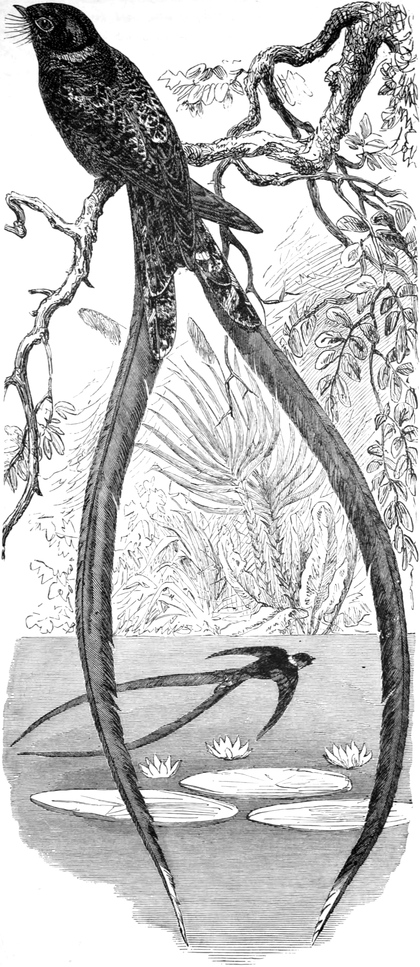

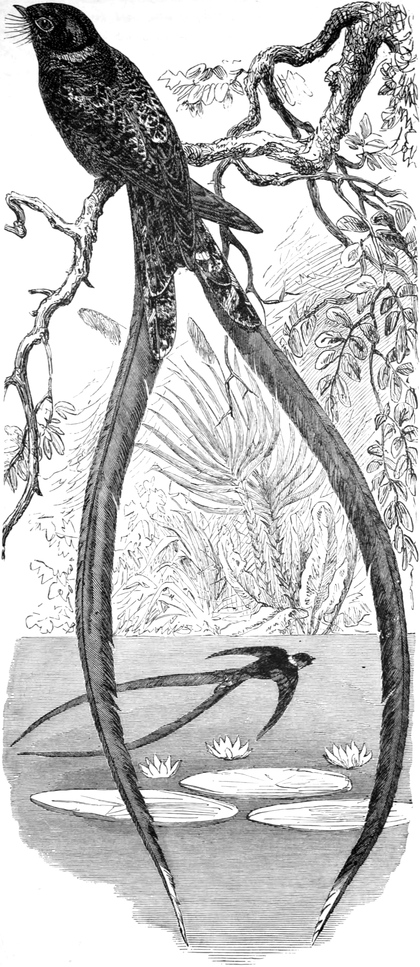

The Lyre-tailed Nightjar

|

|

|

Foot of the Common Goatsucker

|

|

|

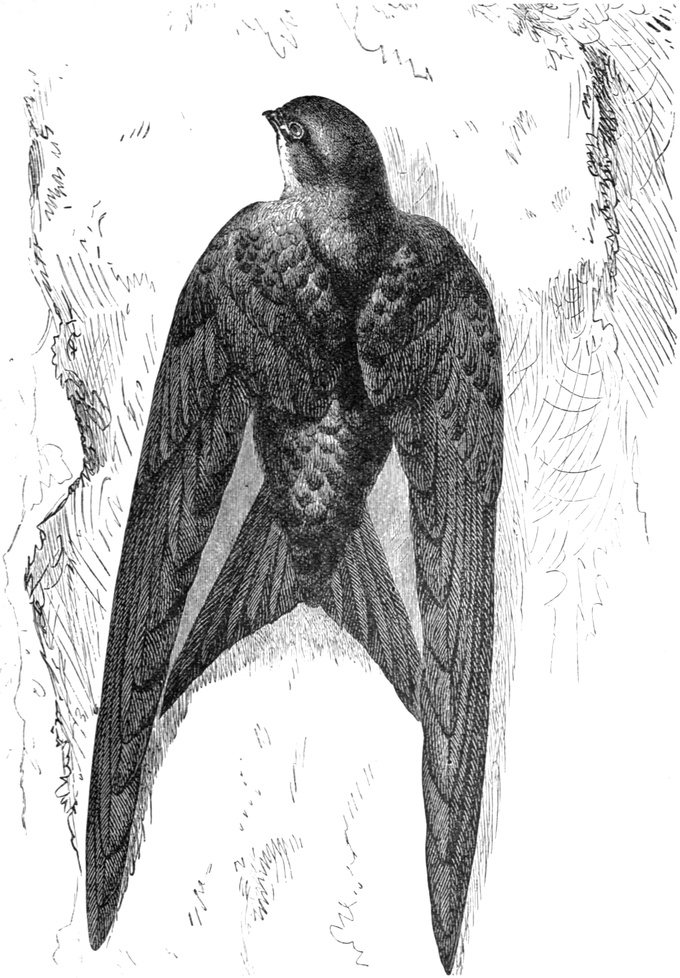

The Common Swift

|

|

|

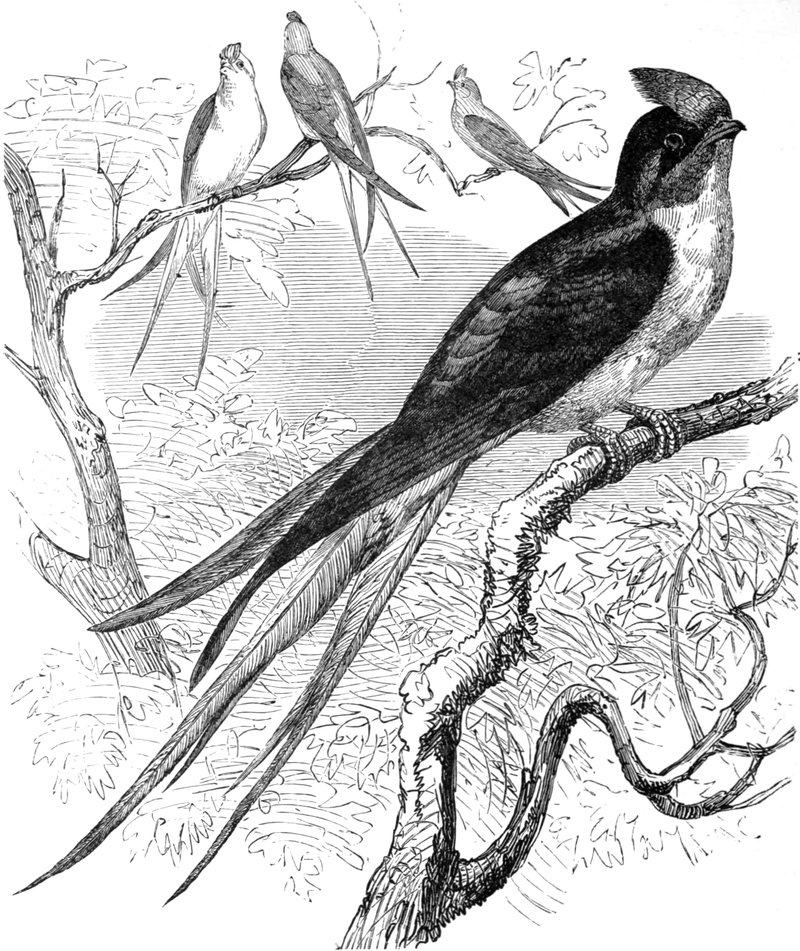

The Tree Swift

|

|

|

The Edible-nest Swiftlets

|

|

|

The White-throated Spine-tailed Swift

|

|

|

The Sword-bill Humming Bird

|

|

|

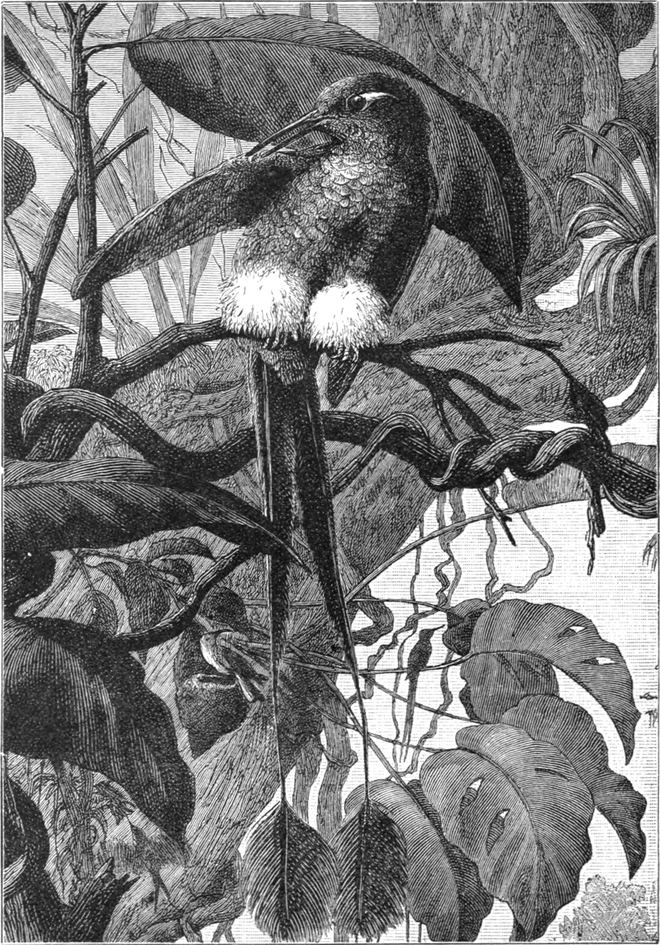

The White-booted Racket Tail

|

|

|

The Common Topaz Humming Bird

|

|

|

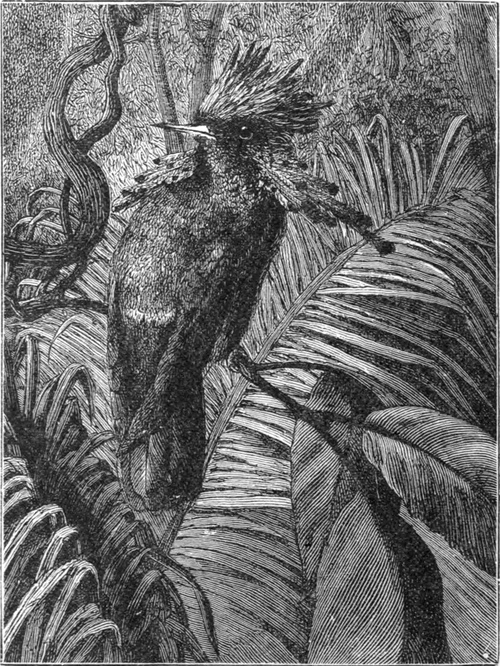

The Crested Humming Bird

|

|

CHAMOIS.

[Pg 1]

CASSELL’S NATURAL HISTORY.

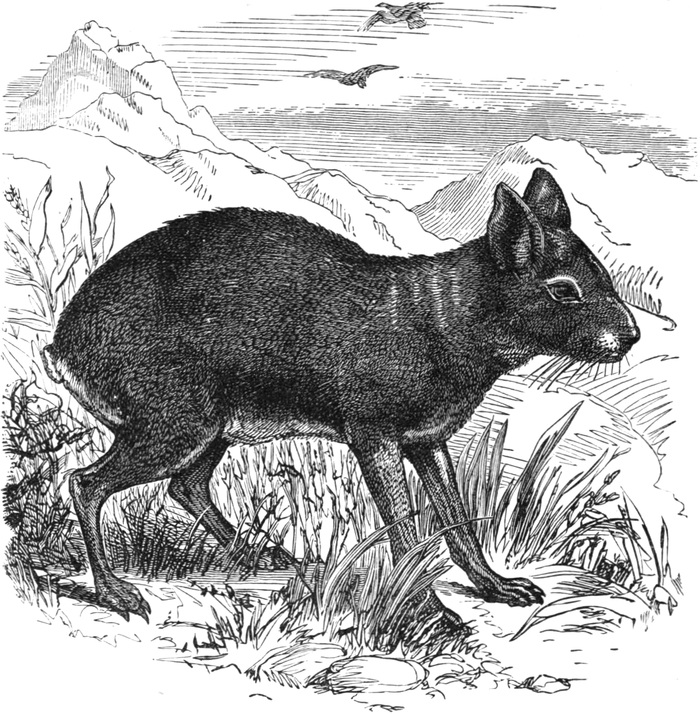

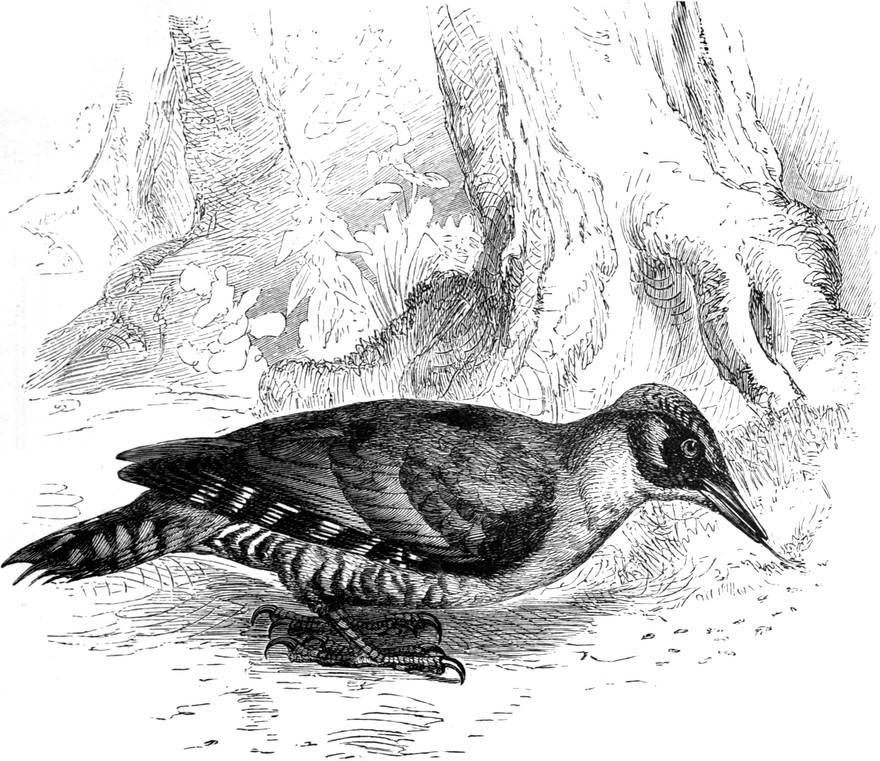

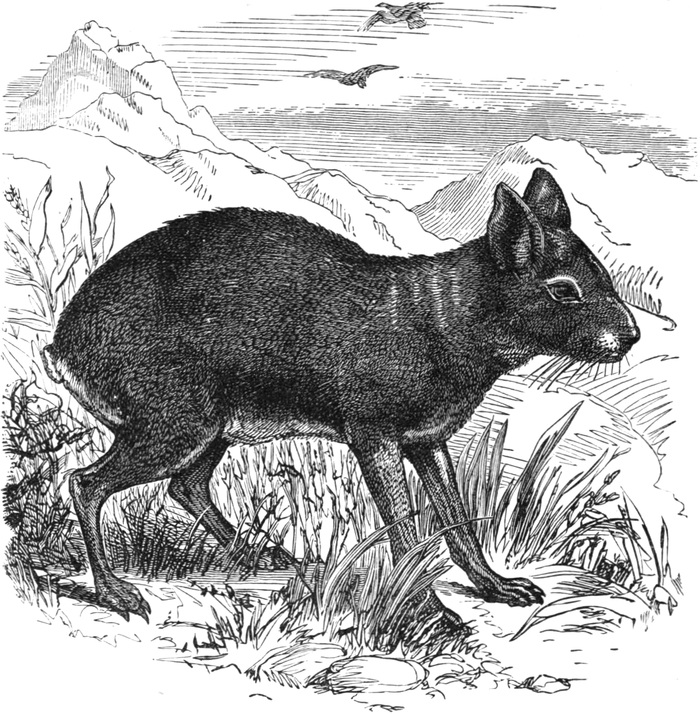

WATER DEERLET, OR CHEVROTAIN.

CHAPTER I.

ARTIODACTYLA—RUMINANTIA: BOVIDÆ—SHEEP, GOATS, AND GAZELLES.

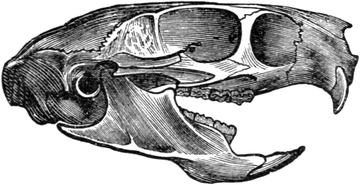

THE Swine, together with those animals which most nearly approach them,

namely, the Peccaries and Hippopotami, form but a small division of the

cloven-hoofed order of the Mammalian animals; by far the greater number

of the species of the Artiodactyla being included in a group known

familiarly as that of the Ruminantia, because, as part of the digestive

process, they chew the cud.

This chewing the cud is a phenomenon restricted to the group of animals

now under consideration, although it may be mentioned that some

naturalists have thought that the Kangaroos among the Marsupials do the

same to a certain extent.

[Pg 2]

As to the details of the process, the individual, a Cow, for instance,

whilst grazing, nips off the grass between the large cutting teeth

in the front of the lower jaw, and the tough pad which replaces in

these creatures the similarly situated teeth of the upper jaw. After

each mouthful it does not proceed to masticate the food, but swallows

it forthwith, and continues thus to graze until it has satisfied its

appetite. Seeking a quiet and shaded spot, it then seats itself that

it may ruminate, or chew the cud, at leisure. If watched it will be

seen that it commences shortly to perform a slight hiccough action, in

which some contraction of the flanks is to be noticed. Its mouth, which

was previously empty, is found to be full of what it is not difficult

to recognise to be coarsely-masticated grass, which has been forced up

into it; and this it immediately proceeds to chew between its back or

grinding teeth, in a slow and continuous manner, moving its lower jaw

uniformly from one side to the other—from right to left. When this

chewing process has lasted for a time sufficient to convert the food

into a pulpy state, it is again swallowed, after which another bolus

is brought up to undergo a similar operation. And this is repeated at

frequent intervals until most of the food swallowed has been masticated.

A complicated stomach is necessary for the operation of this elaborate

chewing process, the undisturbed duration of which has led to the word

by which it is designated being applied metaphorically to a brooding

condition of mind. Thus the poet of the “Night Thoughts” says:—

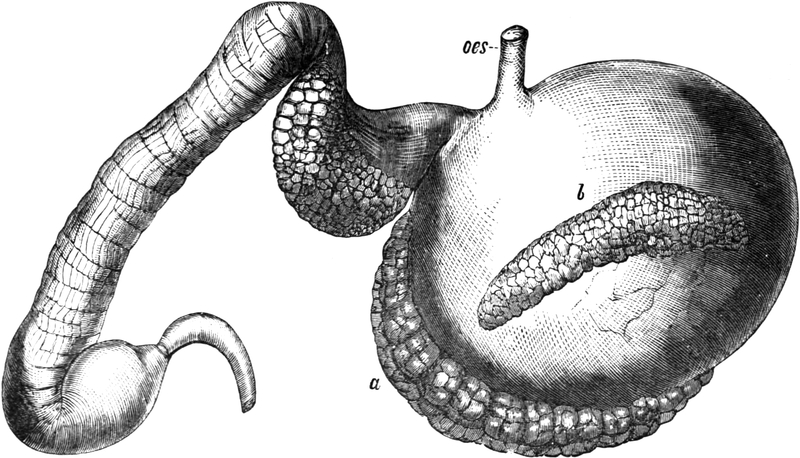

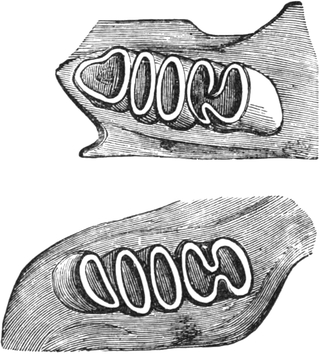

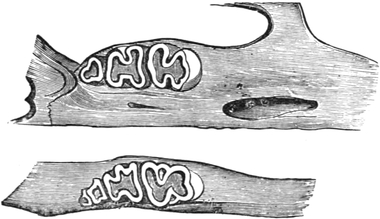

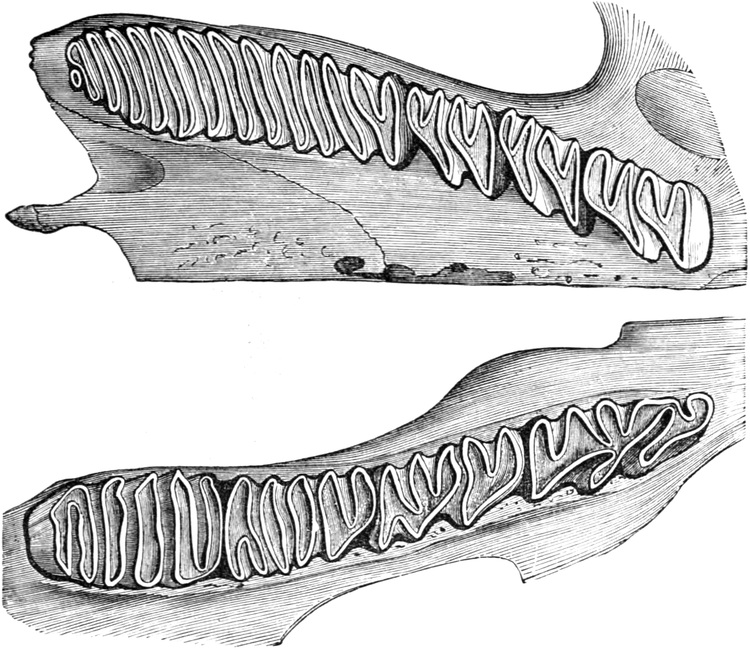

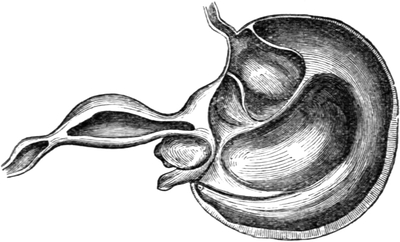

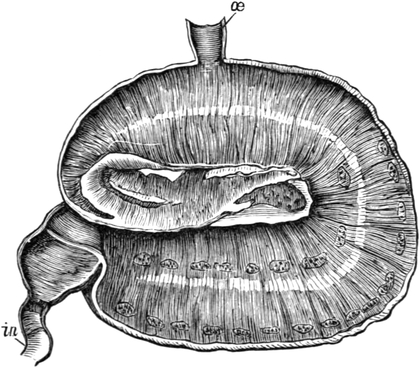

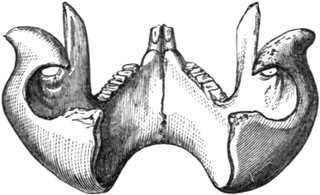

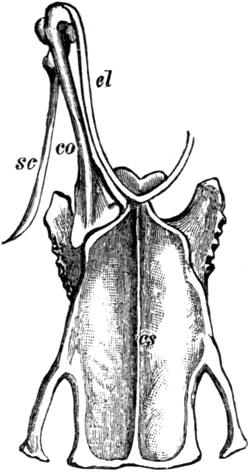

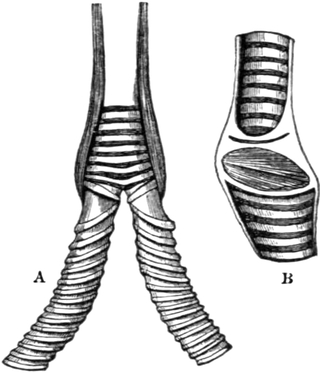

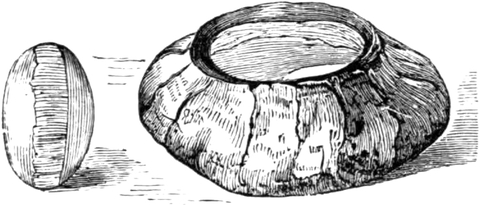

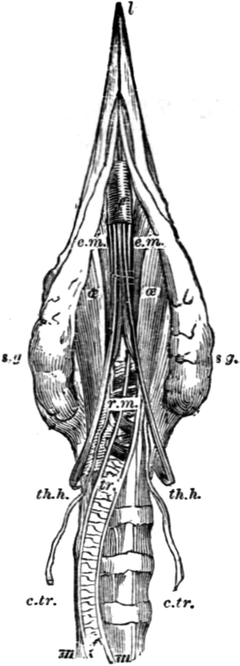

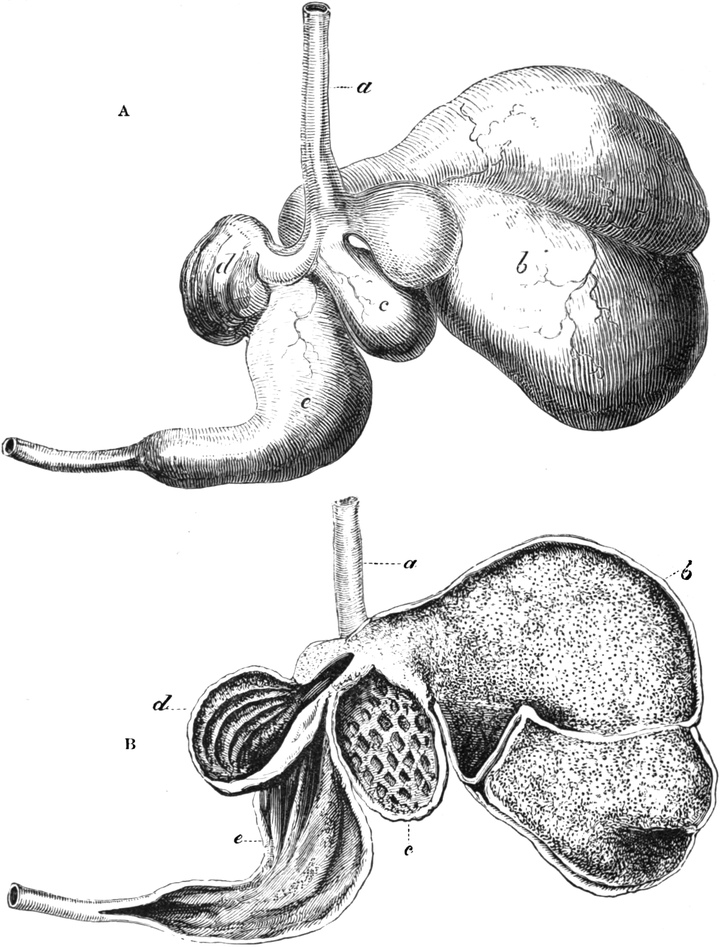

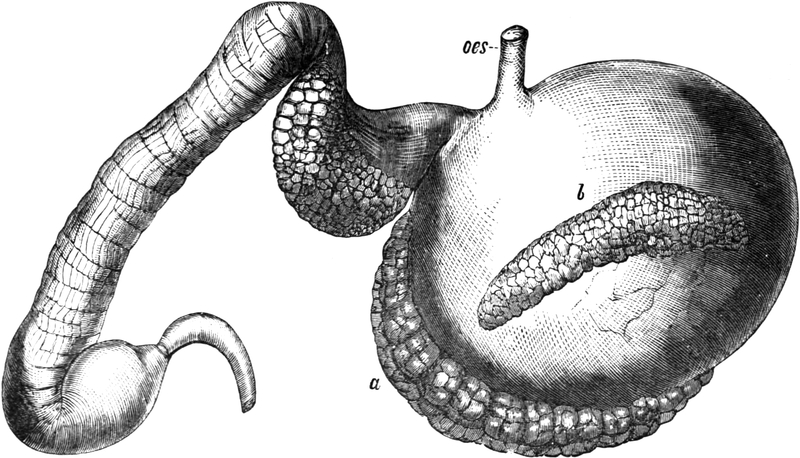

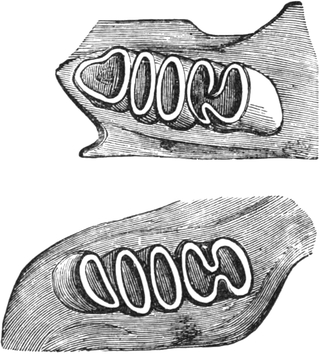

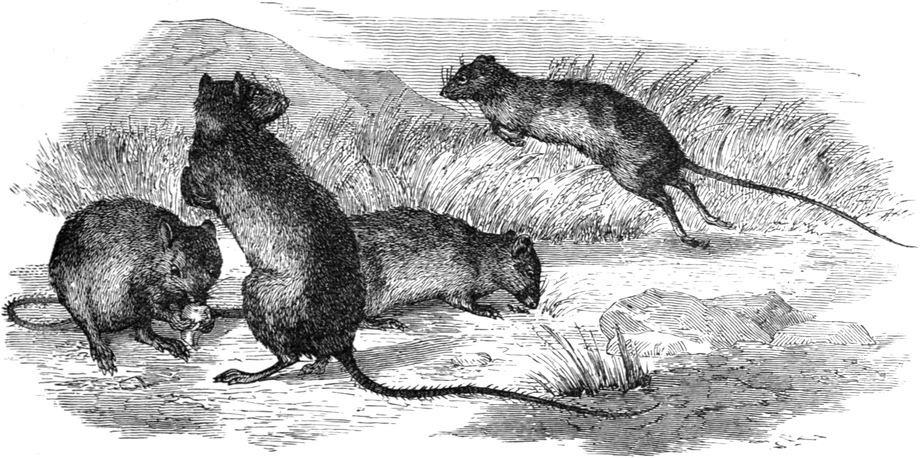

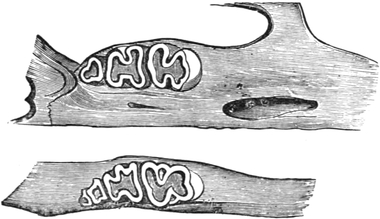

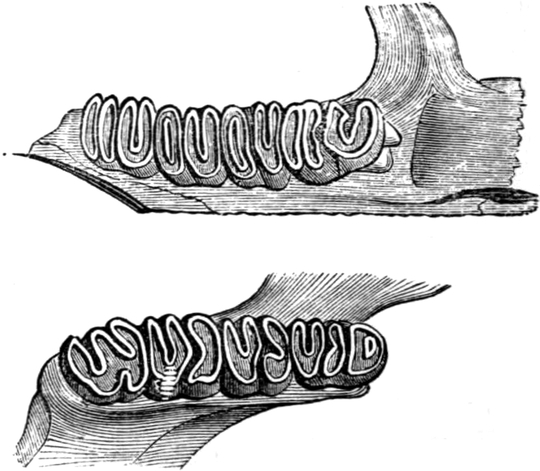

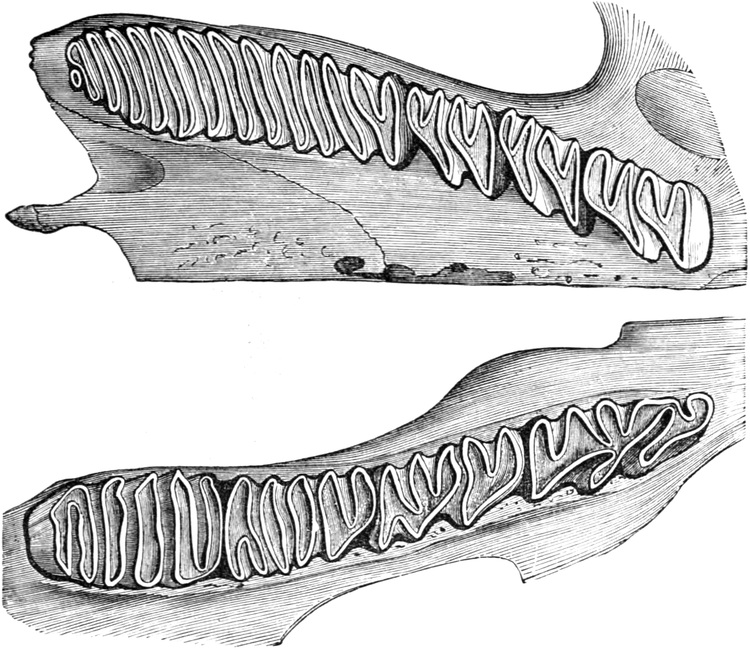

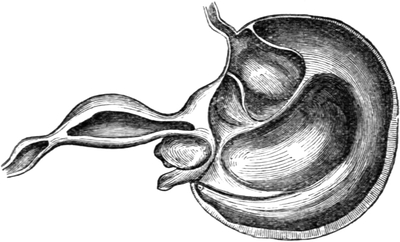

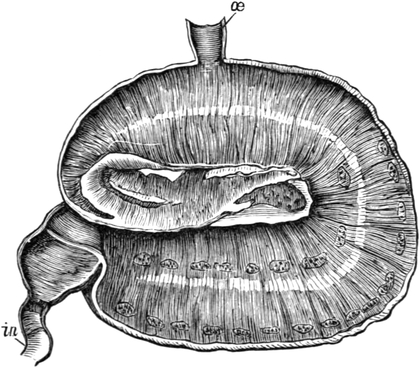

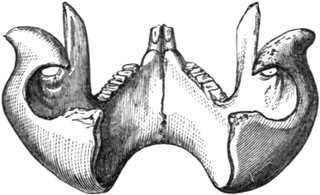

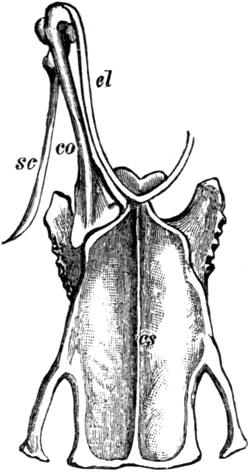

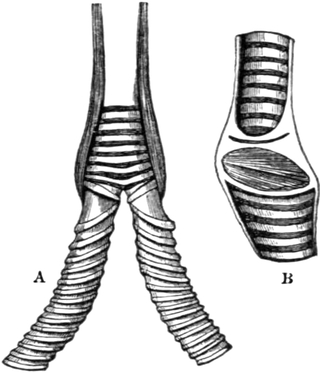

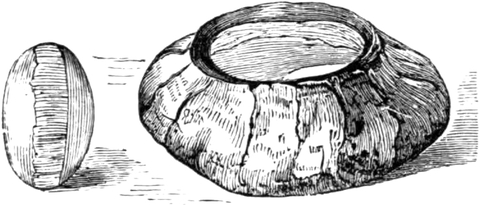

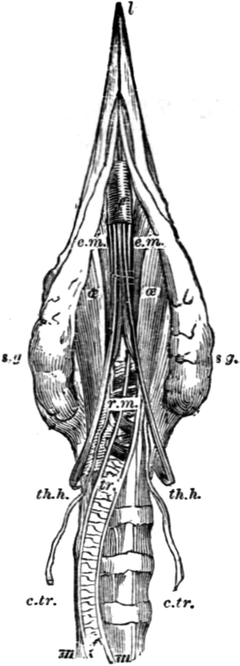

STOMACH OF A RUMINATING ANIMAL: (A) EXTERIOR, (B)

INTERIOR.

“As when the traveller, a long day past

In painful search of what he cannot find,

At night’s approach, content with the next cot,

There ruminates awhile his labour lost.”

This complicated stomach is not identical in all the Ruminantia. In the

Camels and the Llamas it presents many points of difference from that

of all the other members of the group, and in the Chevrotains it has

slight peculiarities of its own.

This organ, as found in the Ox—and it is almost identically the same

in the Giraffes, the Antelopes, the Sheep, and Deer—is seen to be

divided into four well-defined compartments, as represented in the

accompanying figures. These are known as—

- The Rumen, or Paunch (b).

- The Reticulum, or Honey-comb Bag (c).

- The Psalterium, or Manyplies (d).

- The Abomasum, or Reed (e).

The paunch (b) is a very capacious receptacle, shaped like a

blunted cone bent partly upon itself. Into its broader base opens the

œsophagus, or gullet (a), at a spot not far removed from its[Pg 3] wide

orifice of communication with the second stomach, or honey-comb bag

(c). Its inner walls are nearly uniformly covered with a pale skin

(known as mucous membrane), which is beset with innumerable close-set,

short, and slender processes (known as villi), resembling very much

the “pile” on velvet. It is this organ, together with its villi, which

constitutes the well-known article of food termed “tripe.”

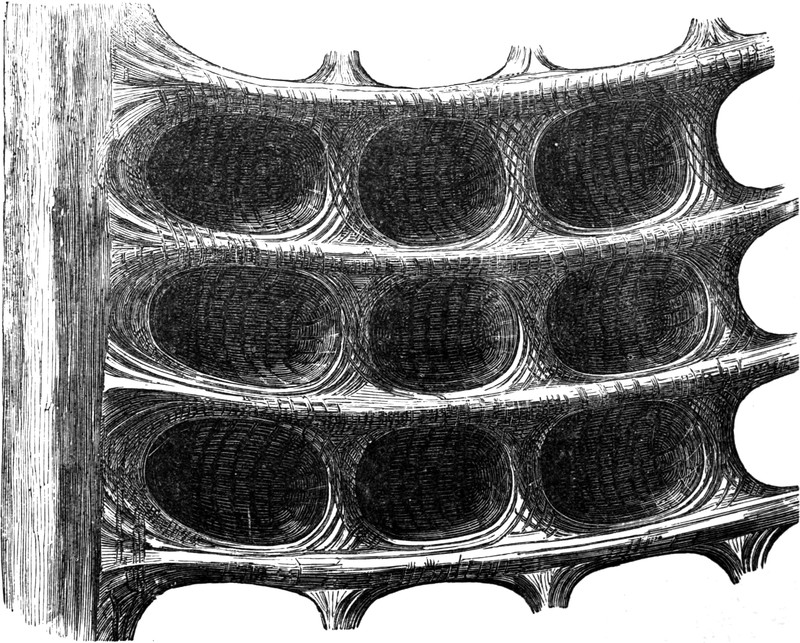

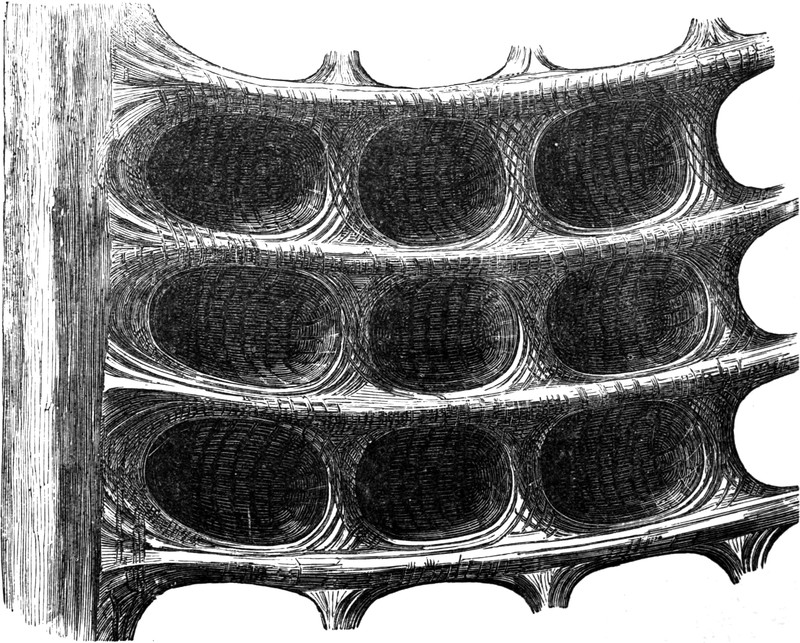

The honey-comb bag (c) is very much smaller than the paunch. It

is nearly globose in shape, and receives its name on account of the

peculiar arrangement of the ridges on the mucous membrane which lines

it, these being distributed so as to form shallow hexagonal cells all

over its inner surface, as seen in the figure on the previous page.

It is situated to the right of the paunch, with which, as well as with

the manyplies (d), it communicates. Running along its upper wall

there is a deep groove coursing from the first to the third stomach.

This groove plays an important part in the mechanism of rumination; its

nature must therefore be fully understood.

Its walls are muscular, like those of the viscus with which it is

associated, which allows its calibre to be altered. Sometimes it

completely closes round so as to become converted into a tube by the

apposition of its edges. At others it forms an open canal.

The manyplies (d) is a very peculiar organ. It is globular, but most

of its interior is filled up with folds, or laminæ, running between its

orifices of communication with the second and fourth stomachs. These

folds are arranged very much like the leaves of a book, and very close

together. They are, however, not of equal depth, but form series of

greater or less breadth. Their surfaces are roughened by the presence

of small projections or papillæ.

The reed (e) is the stomach proper, corresponding with the same

organ in man. Its shape is somewhat conical. The valve which partially

obstructs its communication with the intestine is at the left of the

foregoing figure. Its walls are formed of a smooth mucous membrane,

which secretes gastric juice, and it is this stomach that, in the

manufacture of cheese, is employed to curdle the milk.

Whilst grazing, the possessor of this complicated stomach fills its

paunch with the imperfectly masticated food, and it is not until it

commences to chew the cud that any of the other parts are brought into

play.

In the act of rumination, the following is the probable order of

events:—The paunch contracts, and in so doing forces some of the

food into the honey-comb bag, where it is formed into a bolus by the

movement of its walls, and then forced into the gullet, from which,

by a reverse action, it reaches the mouth, where it is chewed and

mixed with the saliva until it becomes quite pulpy, whereupon it

is again swallowed. But now, because it is soft and semi-fluid, it

does not divaricate the walls of the groove communicating with the

manyplies, and so, continuing on along its tubular interior, it finds

its way direct into the third stomach, most of it filtering between

the numerous laminæ on its way to the fourth stomach, where it becomes

acted on by the gastric juice. After the remasticated food has reached

the manyplies, the groove in the reticulum is pushed open by a fresh

bolus; and so the process is repeated until the food consumed has all

passed on towards the abomasum, or true digestive stomach.

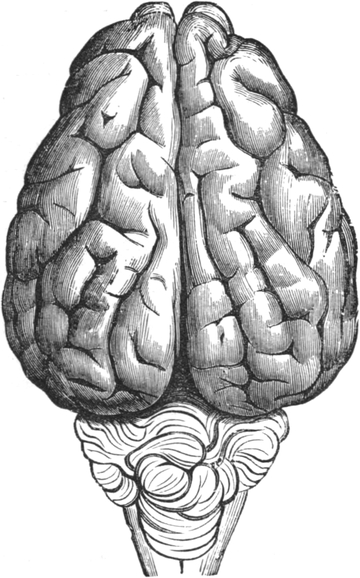

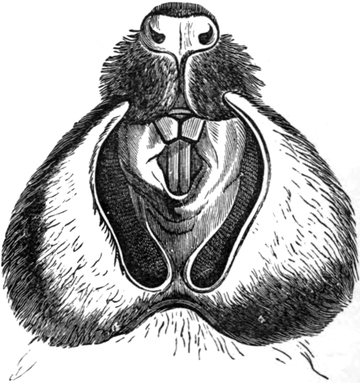

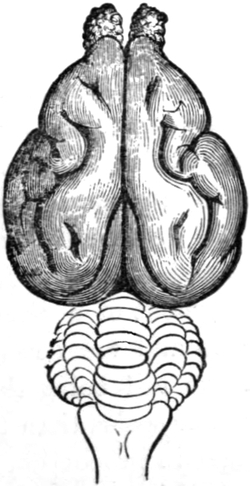

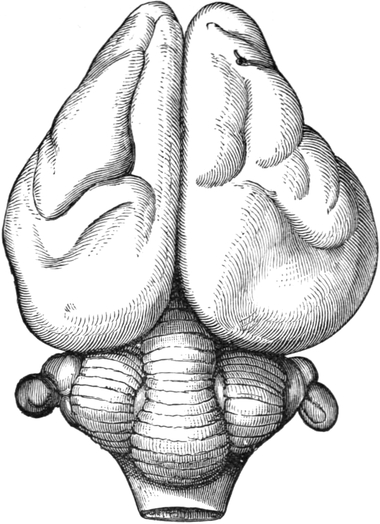

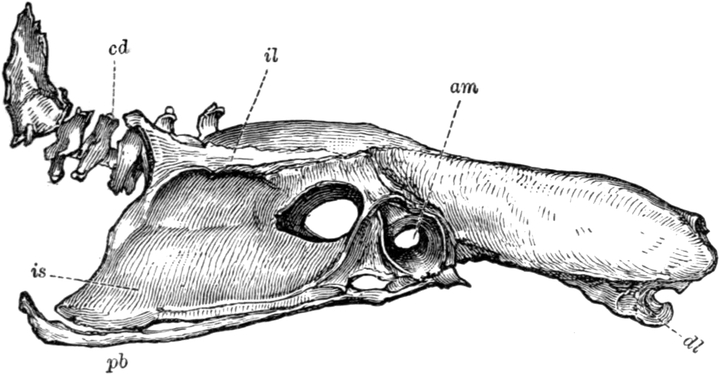

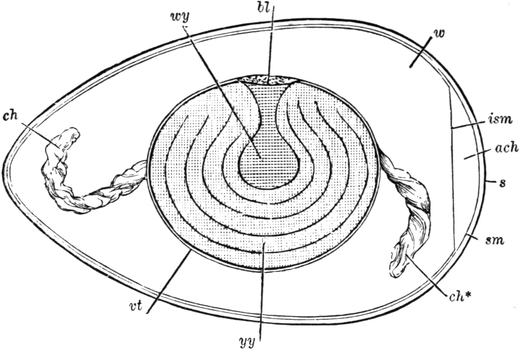

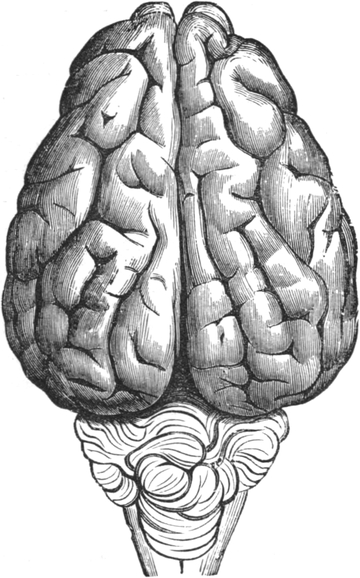

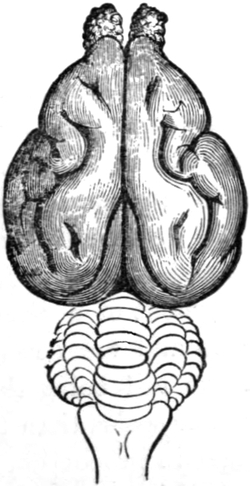

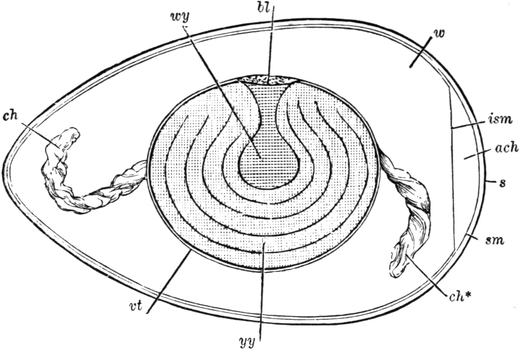

BRAIN OF A SHEEP.

There are other features also which are characteristic of the

ruminating animals. Their symmetrical four-toed feet (in which the

thumb on the fore and the great toe on the hind are entirely absent)

have the toes so proportioned that the axis of the limb runs down

between the two middle toes at the same time that both the inside and

outside toes are much reduced in size, and lost entirely in the Camel

tribe, the Giraffe, and the Cabrit.

[Pg 4]

Another peculiarity which exists in all ruminating animals is the

absence of cutting-teeth in the middle of the upper jaw; and it is only

in the Camels and their intimate allies, the Llamas, that there are any

upper cutting-teeth at all, they being replaced in all the others by a

callous pad, on which the lower cutting-teeth impinge in mastication.

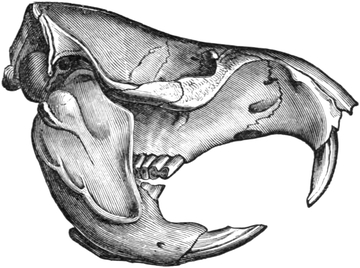

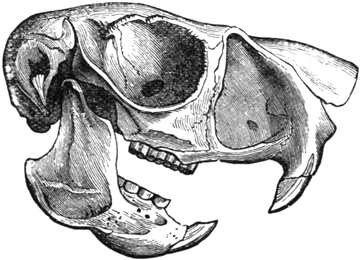

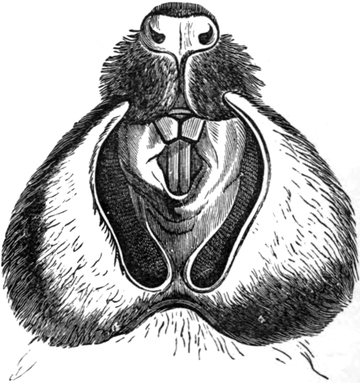

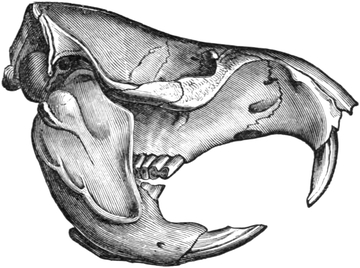

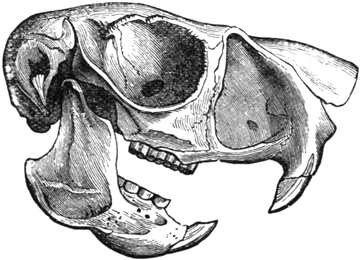

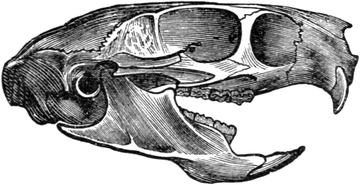

The canine teeth, which correspond to the tusks of the Lion and Dog,

also deserve attention. Those of the lower jaw are always present, and

are modified so as to appear like lateral cutting-teeth. In the upper

jaw they are most often absent, but are enormous, projecting far down

outside the lip, in the Musk, the Chinese Water Deer, and the Muntjacs.

In some other Deer they are present, but small, and generally they are

wanting.

The grinders are six on each side of each jaw, and are so formed that

their surfaces wear down unevenly by the lateral movement to which

they are subject during mastication. As in the Elephant, this depends

upon each tooth being made up of alternate layers of enamel, dentine,

and cementum, which, being of different degrees of hardness, are

differently affected by the grinding action.

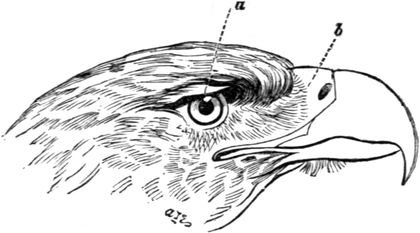

The ruminating animals exhibit a fair amount of intelligence, never,

however, attaining that power of perception and memory exhibited by

the Carnivora and other higher forms. The figure of the surface of the

brain of the Sheep indicates that the convolutions of the brain are far

from inconsiderable in number, and its allies of the same size agree

with it in this respect, whilst larger species have more, and smaller

less elaborate brain-markings, as is nearly always found to be the case

in every group.

The accompanying table gives an outline sketch of the classification of

the ruminating animals which has been adopted by zoologists:—

|

Sub-order.

|

|

Section.

|

|

Division.

|

|

Group.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ox-tribe

(Bovidæ)

|

|

|

|

|

|

HORNED

RUMINANTS.

|

|

|

|

|

TRUE

RUMINANTS.

|

|

Deer-tribe

(Cervidæ)

|

|

RUMINANTIA.

|

|

CHEVROTAINS OR

DEERLETS

(Tragulidæ).

|

|

|

|

CAMEL

TRIBE

(Tylopoda).

|

|

|

The large sub-order of the Ruminantia is seen to be primarily divided

into two sections, namely, the typical Ruminants and the aberrant

Ruminants (the Tylopoda). The typical Ruminants, in which the stomach

is formed upon the plan of that described above in the Oxen, fall

into two divisions, the smaller of which—that of the Chevrotains

or Deerlets—possesses no psalterium, or third stomach, except in

a rudimentary condition. The Horned Ruminants, including the Deer,

Muntjacs, Elk, Oxen, and Antelopes, compose by far the largest number

of the whole sub-order, and will be first described.

HORNED RUMINANTS.

The Horned Ruminants—with which, anomalous as it may at first

seem, have to be included one or two hornless species, on account

of their so closely resembling them in other respects—have their

cranial appendages developed after one or other of two principles.

In one group, which, from the fact that the Oxen are included with

them, are named the Bovidæ, the horns are hollow, straight, or

variously-twisted cones, supported upon bony prolongations from the

forehead, resembling them in shape upon a smaller scale. These horns

are permanent, except in the American Antelope, increasing in size each

year, at the same time that they often exhibit transverse markings,

which indicate the annual increase. In the other group—the Cervidæ,

or Deer Tribe—the horns or antlers are deciduous, being cast off each

year, to be shortly replaced by others, which share the fate of their

predecessors. These antlers are entirely made of bone, and when fully

grown are not covered with any less dense investment.

To commence, then, with the Bovidæ, or Oxen, and their allies.

[Pg 5]

THE BOVIDÆ, OR HOLLOW-HORNED RUMINANTS.

In these ruminating animals the permanent bone-cones on the forehead

are covered with a black horny coating, which is not shed during the

whole life of their owners, and in which, as they continue to grow

until adult life at least, the tips are the oldest parts. The females

in some species have horns like their mates, but smaller, as in the

Ox and Eland; while in others—the Koodoo and the Sing-Sing Antelope,

for example—the males alone are horned. The most aberrant members of

this group are the Giraffe, the Cabrit, and the Musk, which will be

considered after the less peculiar genera have been discussed. These

include the Oxen, Bush-Bucks, Antelopes, Koodoos, Goats, Sheep, &c.,

which will be referred to more in detail.

MERINO SHEEP.

THE SHEEP AND GOATS.[1]

Between the bearded Goat and the beardless Sheep there exist

intermediate species, which so completely fill up the gaps that it

is almost impossible to separate the two into different genera. With

triangular, curved, and transversely-ridged horns in both sexes,

a characteristic general appearance, and feet formed for mountain

climbing, the species present differences which are recognised with

facility.

With reference to the domestic Sheep, it is the opinion of most

naturalists that it has descended from several distinct species. “Abel

was a keeper of Sheep,” is a Biblical statement from which the immense

antiquity of a domestic breed may be inferred, whose origin cannot

be better studied than by a comparison of the different forms found

wild in Asia, the head-quarters of the genus. That no Sheep existed

in Australia when that continent was first discovered is a well-known

fact.

[Pg 6]

“Endowed by nature,” as Mr. Spooner, in his work on the Sheep aptly

puts it, “with a peaceable and patient disposition, and a constitution

capable of enduring the extremes of temperature, adapting itself

readily to different climates, thriving on a variety of pastures,

economising nutriment where pasturage is scarce, and advantageously

availing itself of opportunities where food is abundant,” it is not to

be wondered at that the animal has become the companion of man from the

earliest times.

The fleece of the wild species of Sheep is composed of hair with wool

at its roots, in the same way that in the Duck there is a covering of

feathers and down. In the domesticated species the hair, by selection,

has been reduced to a minimum, so that the wool forms the only coat.

In the southern parts of Western Asia many of the Sheep have a curious

tendency to the deposition of fat on the tail rather than under the

skin of the body generally, and this may occur to such an extent that

the thus loaded caudal appendage may contain a large part of the entire

weight of the body.

The Astracan breed, of small size, has a fine spiral black and white

wool, sometimes entirely black, which is obtained from the lamb when

the finest furs are required.

Of all the breeds of Sheep the Merino of Spain is one of the most

important, on account of the excellence of its wool. In England the

breed can hardly be said to exist, because the dampness of the climate

does not suit its constitution. It is extensively found in Germany,

and is the Sheep of Australia. The animal is small, flat-sided, and

long-legged. The males have long horns, these appendages being absent

in the females. The face, ears, and legs are dark, and the forehead is

woolly, at the same time that the skin about the throat is lax. The

body-wool is close-set, soft, twisted in a spiral, and short.

In Great Britain the breeds of Sheep are very numerous, some of the

best being of quite recent origin. First among the heavy breeds are

the Dishley, or Improved Leicesters, which, from their early maturity,

aptness to fatten, smallness of bone, and gentle disposition, well

deserve the high repute in which they stand. It is to the persevering

energy and acuteness of Mr. Bakewell that we are indebted for the

present animal, which in origin is far from pure bred. His aim was

entirely in the direction of the carcass, and in his object he and

his followers have quite succeeded, notwithstanding an inherent

delicacy in constitution and an inferiority of the wool. “The head of

this breed,” we are told, “should be hornless, long, small, tapering

towards the muzzle, and projecting horizontally forwards; the eyes

prominent, and with a quiet expression; the ears thin, rather long,

and directed backwards; the neck full and broad at its base, where it

proceeds from the chest, but gradually tapering towards the head, and

being particularly fine at the junction of the head and neck; the neck

seeming to project straight from the chest, so that there is, with the

slightest possible deviation, one continuous horizontal line from the

rump to the poll; the breast broad and full; the shoulders also broad

and round, and no uneven or angular formation where the shoulders join

either the neck or the back, particularly no rising of the withers or

hollow behind the situation of these bones; the arm fleshy through its

whole extent, and even down to the knee; the bones of the leg small,

standing wide apart, no looseness of skin about them, and comparatively

bare of wool; the chest and barrel at once deep and round; the ribs

forming a considerable arch from the spine, so as in some cases—and

especially when the animal is in good condition—to make the apparent

width of the chest even greater than the depth; the barrel ribbed

well home; no irregularity of line on the back or the belly, but on

the sides, the carcass very gradually diminishing in width towards

the rump; the quarters long and full, and, as with the fore-legs, the

muscles extending down to the hock; the thighs also wide and full;

the legs of a moderate length; the pelt moderately thin, but soft and

elastic, and covered with a good quantity of white wool, not so long as

in some breeds, but considerably finer.”

The large-sized Lincoln Sheep, with lengthy fleece, those of the

Cotswold Hills, the Teeswater, and Romney Marsh, are also heavy breeds,

not equal in the totality of their points to the Improved Leicesters,

although excelling them either in quantity of wool or hardiness of

constitution.

The Short-woolled Southdowns, with close-set fleece of fine wool, face

and legs dusky brown, curved neck, short limbs, and broad body, is one

of the oldest and most valuable unmixed breeds that we possess. Their

mutton greatly excels that of the Improved Leicesters, which, taken

in[Pg 7] association with their other good qualities, has caused them to

extend to nearly every county. In parts of Hampshire, Shropshire, and

Dorsetshire there are local breeds of Short-woolled Sheep which replace

the Southdowns.

The Cheviot and the Black-faced, or Heath breed of our northern

counties are mountain Sheep, of small size and hardy constitution, the

former horned, the latter hornless and with a white face.

Welsh mutton is obtained from the small, soft-woolled Sheep with a

white nose and face. The rams alone have horns, wherein the breed

differs from that of the higher mountains, in which the ewes also are

horned, at the same time that a ridge of hair is present along the top

of the neck.

As wool forms so important an element of the mercantile transactions

of Great Britain, and as Sheep-farming has so rapidly increased in

Australia and New Zealand, a few words with reference to the statistics

of the subject will not be out of place.

In 1788, when Governor Phillip landed at Port Jackson, there was not a

Sheep in all Australia, and it was not until 1793 that about thirty of

the Indian breed reached Sydney, their number being shortly augmented

by the importation of breeding-stock from England and the Cape of

Good Hope, principally Merinos. The progeny soon spread towards the

interior, where the growing of wool became a lucrative pursuit. Sheep

were first imported into New Zealand in 1840. It is estimated there are

now one hundred million sheep in Australia, and nearly thirty million

in New Zealand.

The following table of the number of bales of wool imported into Great

Britain at twenty-year intervals, that is, in 1836, 1856, and 1876,

gives a better idea than can be otherwise obtained as to the changes

in the sources of wool as well as to the richness of each colonial

district:—

IMPORTATION OF COLONIAL

AND FOREIGN WOOL INTO

THE UNITED KINGDOM

(IN BALES).

|

|

|

1836.

|

|

1856.

|

|

1876.

|

|

New South Wales and Queensland

|

19,066

|

|

59,342

|

|

169,874

|

|

Victoria

|

None

|

|

64,843

|

|

306,803

|

|

Tasmania

|

15,449

|

|

17,951

|

|

20,480

|

|

South Australia

|

None

|

|

16,618

|

|

102,067

|

|

West Australia

|

None

|

|

1,267

|

|

7,510

|

|

New Zealand

|

None

|

|

6,840

|

|

162,154

|

|

Total Australasian

|

34,515

|

|

166,861

|

|

768,888

|

|

Cape of Good Hope

|

1,740

|

|

50,607

|

|

169,908

|

|

Total Colonial

|

36,255

|

|

217,468

|

|

938,796

|

|

German

|

90,426

|

|

22,272

|

|

29,580

|

|

Spanish and Portuguese

|

20,451

|

|

8,106

|

|

7,906

|

|

East Indian and Persian

|

1,981

|

|

45,236

|

|

86,678

|

|

Russian

|

15,072

|

|

4,181

|

|

34,511

|

|

River Plate

|

|

|

|

5,151

|

|

118,593

|

|

Peru, Lima, and Chili

|

16,653

|

|

52,477

|

|

Alpaca

|

|

|

Mediterranean and Africa

|

|

14,714

|

|

13,665

|

|

Mohair

|

|

No returns

|

13,515

|

|

Sundry

|

|

12,784

|

|

10,735

|

|

Total Foreign

|

172,081

|

|

175,338

|

|

277,268

|

|

TOTAL

IMPORTATION

|

208,336

|

|

392,806

|

|

1,216,064

|

So much for the domestic Sheep; of other species of the genus Ovis

we have Marco Polo’s Sheep.[2] This splendid Sheep, one of the finest

species of the genus, has horns, describing a spiral of about a circle

and a quarter when viewed from the side, pointing directly outwards,

and sometimes measuring as many as sixty-three inches from base to tip

along their curve, and as much as four and a half feet from tip to tip.

At the shoulder the animal measures just under four feet. It inhabits

the high lands in the neighbourhood of the lofty Thian Shan mountains,

north of Kashgar and Yarkand, not descending below an elevation of

9,000 feet above the sea level, often ascending much higher. It is[Pg 8] on

account of the rarefaction of the air in these regions that there is

considerable difficulty in obtaining specimens which have been wounded,

because Horses at these heights are much distressed in their breathing,

whilst the Sheep are not so. Mr. N. A. Severtzoff, an eminent Russian

naturalist, has described three or four other species closely allied to

Marco Polo’s Sheep, which are smaller than it, from Turkestan and the

district east of it. In this Sheep, during the winter, the sides of the

body are of a light greyish-brown, changing to white below. There is a

white mane all round the neck and a white disc round the tail. A dark

line runs the whole length of the middle of the back. In summer the

grey changes to dark brown.

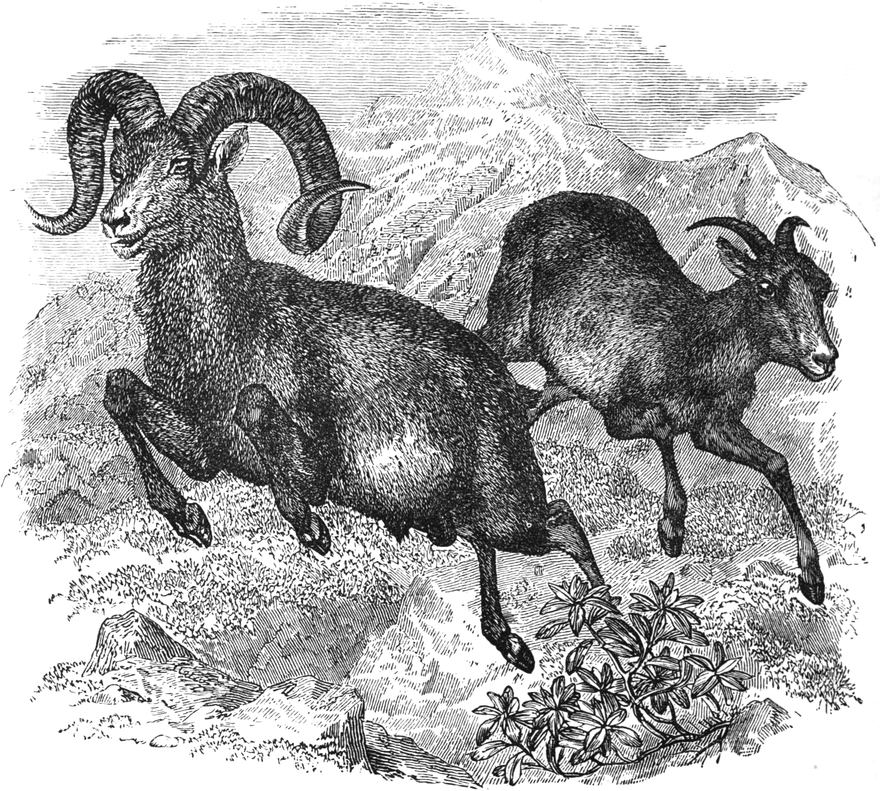

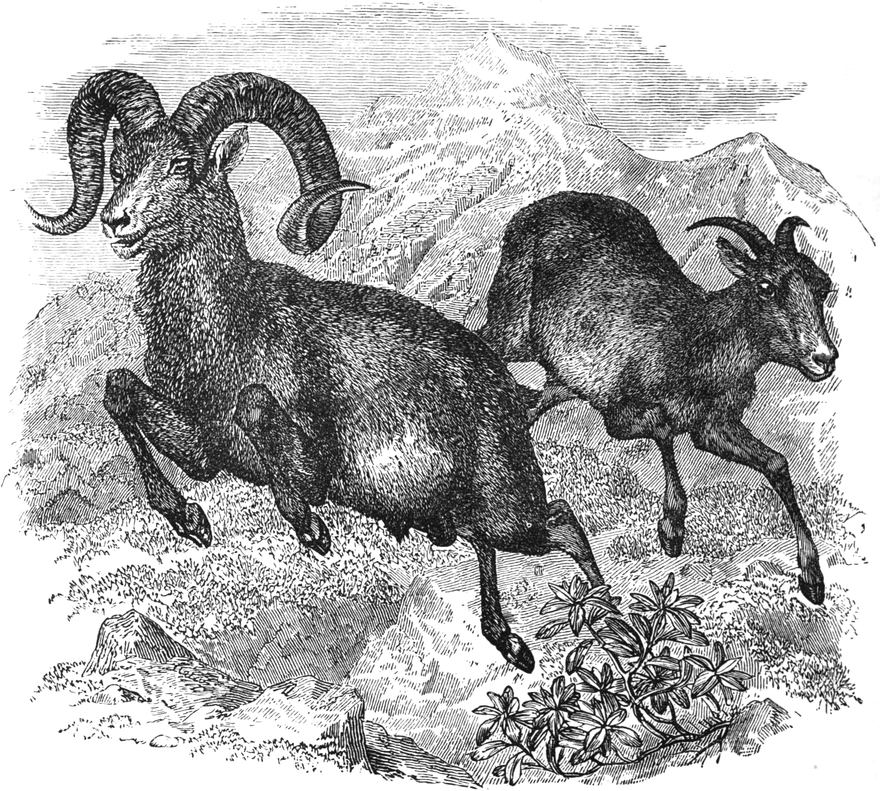

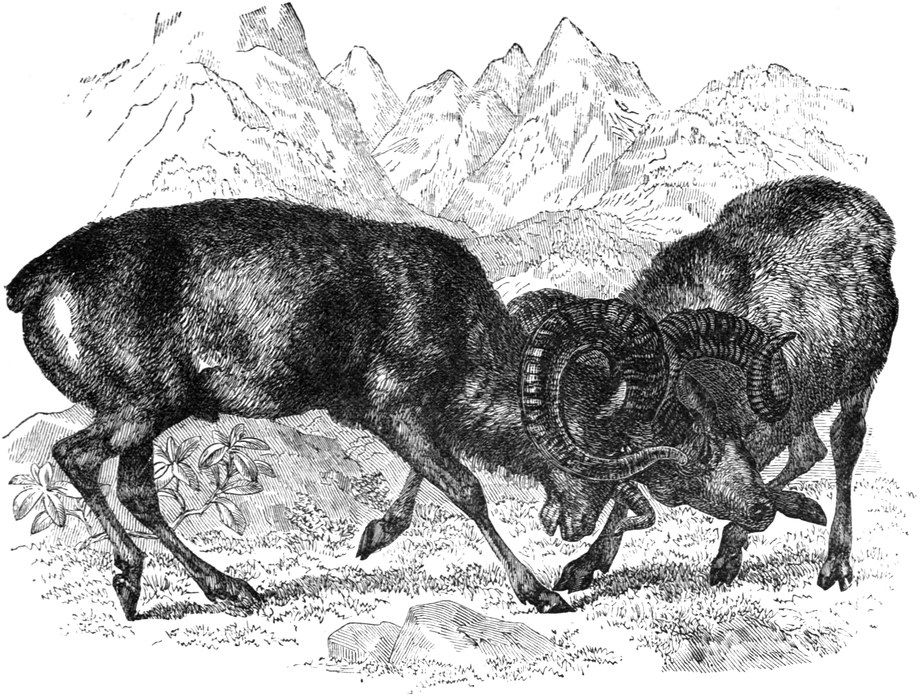

AMMON.

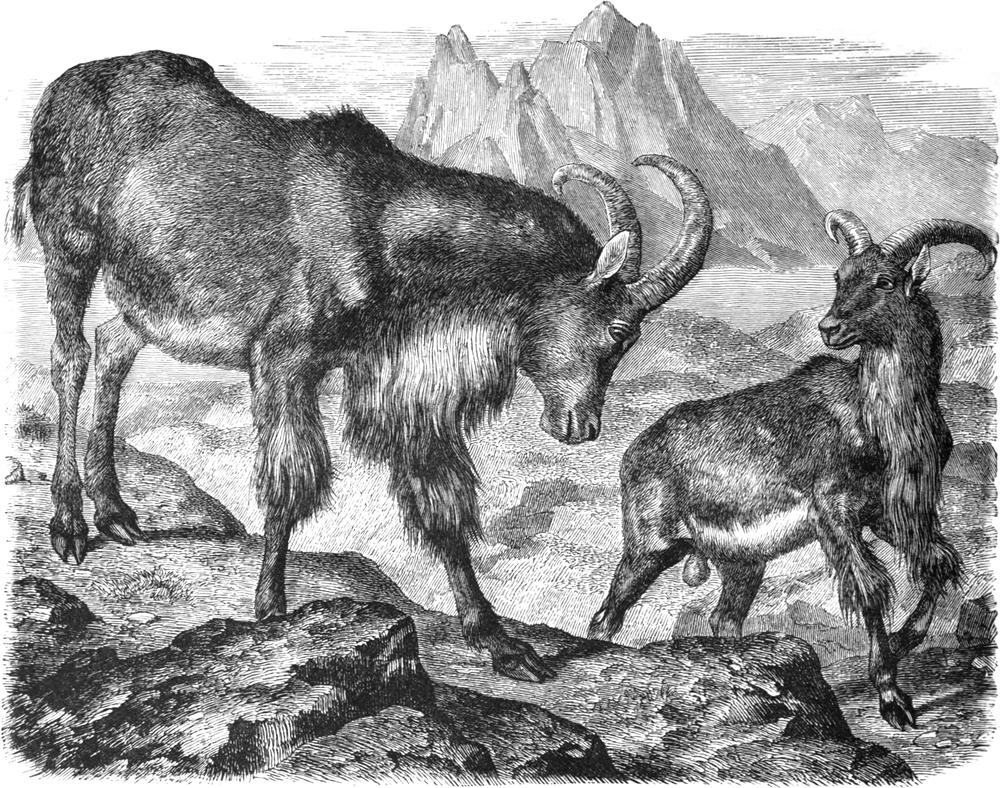

The OORIAL and the SHAPOO are bearded Sheep, from

Ladakh and the Suliman range of the Punjab respectively, with large

horns, which form not more than half a circle in the Shapoo and

nearly a complete one in the Oorial. The colour of the Oorial is

a reddish-brown above, paler beneath, the abdomen being white. A

lengthy dark beard, reaching to the knees, fringes the whole length

of the neck from the chin to the chest. The points of the horns are

directed inwards. It is found at altitudes of 2,000 feet. The Shapoo is

brownish-grey, white below, with a short brown beard. Its horns turn

outwards at the tips. It is never found at altitudes lower than 12,000

feet.

The MOUFLON at one time abounded in Spain, but is now

restricted to the islands of Corsica and Sardinia. The species is a

small one, of a brownish-grey colour, with a dark streak along the

middle of the back, at the same time that there is a varying amount of

white about the face and legs. The horns, present in the males only,

are proportionately not large, curve backwards and then inwards at the

tips. The tail is very short, in which respect they differ strikingly

from the domestic Sheep, to which otherwise they are intimately

related. The Mouflon frequents the summits of its native hills[Pg 9] in

small herds, headed by an old ram. Its skin is used by the mountaineers

for making jackets. It breeds freely with the domestic species.

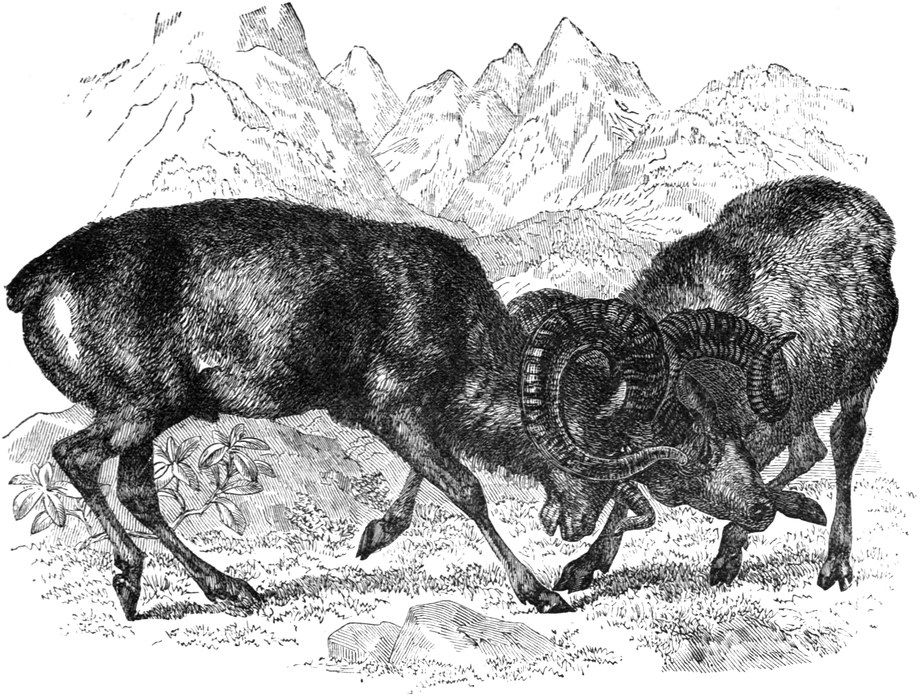

AMMON.

The AMMON of Tibet has been known to measure as much as four

feet and an inch at the shoulder, and has a most imposing appearance

on account of the erect attitude in which it holds its head. Its horns

attain a great size, being sometimes as much as four feet long and

twenty-two inches in circumference at their bases, forming a single

sweep of about four-fifths of a circle, their points being turned

slightly outwards and ending bluntly. Its body colour is dark brown

above, paler posteriorly and below. A mane surrounds its neck, white

in the male, dark brown in the female. The tail measures only an inch

in length. In the female the horns do not exceed twenty-two inches in

length.

The BURHEL, or Himalayan “blue wild Sheep,” stands three feet

at the shoulder, and has horns which, commencing very close together

on the forehead, describe a half circle of two feet or so, and are

directed very much outwards and backwards. In the female the horns

do not exceed eight inches in length, and stand backward instead of

diverging. The coarse fleece of winter is of an ashy-blue colour,

which, in summer, is replaced by one that is much darker. The abdomen

is white, and a black stripe runs along each side of the body, the

front of the legs and the chest being also black. It has no beard.

The AMERICAN ARGALI, or BIG-HORN, inhabits the range

of the Rocky Mountains. Its height is three and a half feet at the

shoulder. The horns form a complete circle, and are nearly three feet

long in the male. They are said to come so far forward and downward

that old rams find it impossible to feed on level ground. Its flesh is

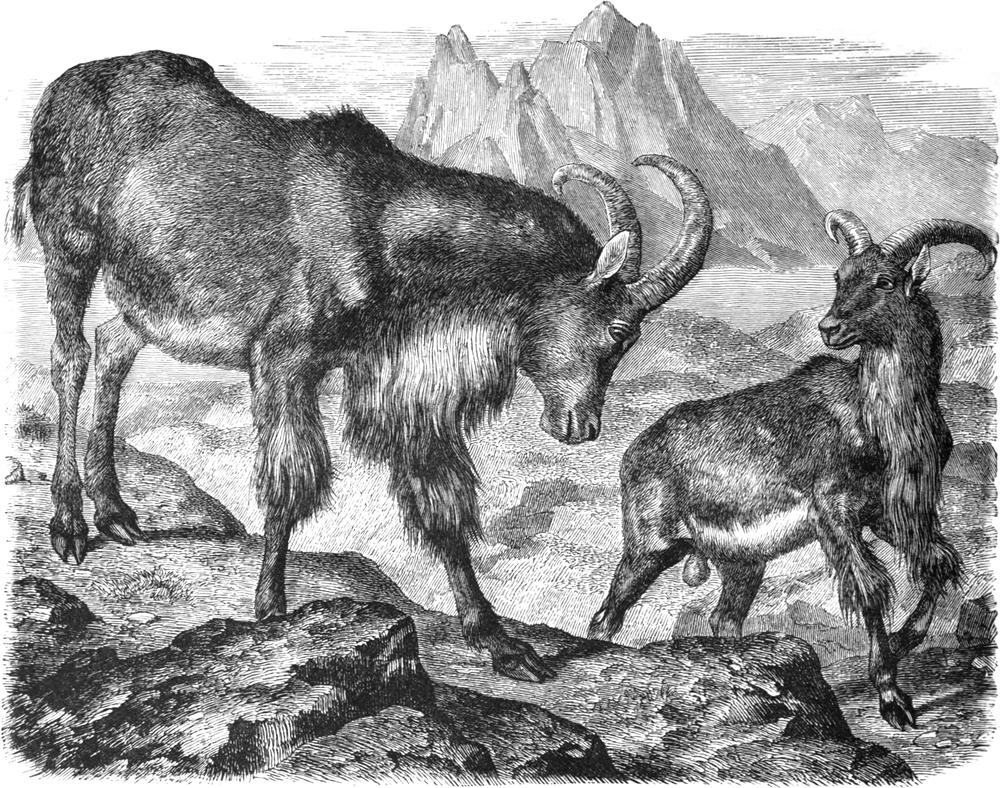

peculiarly well flavoured.