AND

ANCIENT PICTURESQUE EDIFICES OF ENGLAND.

FROM DRAWINGS BY

J. D. HARDING, G. CATTERMOLE, S. PROUT, W. MÜLLER, J. HOLLAND.

AND OTHER EMINENT ARTISTS.

EXECUTED IN COLOURED LITHOTINTS, BY DAY AND SON AND HANHART.

THE TEXT BY S. C. HALL, P.S.A.

EMBELLISHED WITH NUMEROUS ENGRAVINGS ON WOOD.

IN TWO VOLUMES.

VOL. I.

LONDON:

WILLIS AND SOTHERAN, 136, STRAND.

MDCCCLVIII.

| HOLLAND HOUSE | Middlesex | From a Drawing by | C. J. Richardson, F.S.A. |

| HOLLAND HOUSE, INTERIOR | —— | —— | C. J. Richardson, F.S.A. |

| BLICKLING HALL | Norfolk | —— | J. D. Harding. |

| BURGHLEY HOUSE | Northamptonshire | —— | T. Allom. |

| CASTLE ASHBY | —— | —— | F. W. Hulme. |

| KIRBY HALL | —— | —— | J. D. Harding. |

| WOLLATTON HALL | Nottinghamshire | —— | T. Allom. |

| BENTHALL HALL | Shropshire | —— | J. C. Bayliss. |

| PITCHFORD HALL | —— | —— | F. W. Hulme. |

| MONTACUTE, GREAT CHAMBER | Somersetshire | —— | C. J. Richardson, F.S.A. |

| CAVERSWALL CASTLE | Staffordshire | —— | H. L. Pratt. |

| INGESTRIE HALL | —— | —— | J. A. Hammersley. |

| THE OAK HOUSE | —— | —— | A. E. Everitt. |

| THROWLEY HALL | —— | —— | W. L. Walton. |

| TRENTHAM HALL | —— | —— | F. W. Hulme. |

| HELMINGHAM HALL | Suffolk | —— | J. D. Harding. |

| HENGRAVE HALL | —— | —— | C. J. Richardson, F.S.A. |

| WEST-STOW HALL | —— | —— | W. Muler. |

| HAM HOUSE | Surrey | —— | Henry Mogford. |

| LOSELEY HOUSE | —— | —— | Henry Mogford. |

| ARUNDEL CHURCH | Sussex | —— | Samuel Prout. |

| BOXGROVE CHURCH | —— | —— | S. Prout. |

| ASTON HALL | Warwickshire | —— | A. E. Everitt. |

| BEAUCHAMP CHAPEL, Warwick | —— | —— | George Cattermole. |

| CHARLECOTE | —— | —— | J. G. Jackson. |

| CHARLECOTE, INTERIOR | —— | —— | J. G. Jackson. |

| COMBE ABBEY | —— | —— | J. G. Jackson. |

| WARWICK CASTLE | —— | —— | J. D. Harding. |

| WROXHALL ABBEY | —— | —— | J. G. Jackson. |

| BROUGHAM HALL | Westmorland | —— | F. W. Hulme. |

| SIZERGH HALL | —— | —— | F. W. Hulme. |

| CHARLTON HOUSE | Wiltshire | —— | C. J. Richardson, F.S.A. |

| THE DUKE’S HOUSE | —— | —— | C. J. Richardson, F.S.A. |

| WESTWOOD HOUSE | Worcestershire | —— | F. W. Fairholt, F.S.A. |

| FOUNTAINS HALL | Yorkshire | —— | William Richardson. |

| HELMSLEY HALL | —— | —— | William Richardson. |

olland House stands upon rising ground, a little to the north of the

high-road which leads from Kensington to Hammersmith.[1] It is

interesting to all passers-by, as affording a correct idea of the

baronial mansions peculiar to the age of James I.; and, from its

vicinity to the metropolis, its examination is easy to thousands who

rarely obtain opportunities of viewing the “old houses,” with which are

associated the records and pictures of English hospitality as it existed

in the olden time. Although modern dwellings of all shapes and sizes

have grown up about it, the house retains so much of its primitive

character—its green meadows, sloping lanes, and umbrageous woods, in

which still sings the nightingale; with gables and chimneys bearing

tokens of a date two centuries back—that few traverse the highway

without a word of comment, and a sensation of pleasure, that neither

time nor caprice have yet operated{10} to remove it from its place, or even

to impair its imposing and impressive features. It is almost alone in

its “old grandeur,” in a vicinity at one period crowded with ancient

houses; the baronial halls have, with this exception, that of Campden

House,[2] adjacent, and Kensington Palace, a comparatively recent

structure, been removed, to make way for “detached villas” and streets

of narrow dwellings; and there are many sad surmises that, ere long, the

park, and gardens, and venerable mansion, will be also displaced, to

supply building-ground for speculators in brick and mortar. This will be

a grievous outrage on taste, and a sore mortification to the antiquary,

and be another terrible inroad on the picturesque in a district which,

within living memory, was as primitive in character as if London had

been distant a hundred miles.

olland House stands upon rising ground, a little to the north of the

high-road which leads from Kensington to Hammersmith.[1] It is

interesting to all passers-by, as affording a correct idea of the

baronial mansions peculiar to the age of James I.; and, from its

vicinity to the metropolis, its examination is easy to thousands who

rarely obtain opportunities of viewing the “old houses,” with which are

associated the records and pictures of English hospitality as it existed

in the olden time. Although modern dwellings of all shapes and sizes

have grown up about it, the house retains so much of its primitive

character—its green meadows, sloping lanes, and umbrageous woods, in

which still sings the nightingale; with gables and chimneys bearing

tokens of a date two centuries back—that few traverse the highway

without a word of comment, and a sensation of pleasure, that neither

time nor caprice have yet operated{10} to remove it from its place, or even

to impair its imposing and impressive features. It is almost alone in

its “old grandeur,” in a vicinity at one period crowded with ancient

houses; the baronial halls have, with this exception, that of Campden

House,[2] adjacent, and Kensington Palace, a comparatively recent

structure, been removed, to make way for “detached villas” and streets

of narrow dwellings; and there are many sad surmises that, ere long, the

park, and gardens, and venerable mansion, will be also displaced, to

supply building-ground for speculators in brick and mortar. This will be

a grievous outrage on taste, and a sore mortification to the antiquary,

and be another terrible inroad on the picturesque in a district which,

within living memory, was as primitive in character as if London had

been distant a hundred miles.

The approach to Holland House is by an avenue of venerable elms; the entrance-gates are examples of wrought iron, remarkably elegant in design and fine in execution. Within the demesne, small although it be, all sense is lost of proximity to a great city: the close foliage completely shuts out the view of surrounding houses, and the birds are singing among the branches, as if enjoying the freedom of the forest. Yet Holland House is now enclosed on all sides—north, south, east, and west—by brick houses of all sorts and sizes, upon which it seems to look down, from its elevated position, with supreme contempt for the convenient “whimsies” of modern architects.

Before we conduct the reader about the grounds and into the mansion, it will be well to give some history of the several personages through whose hands they have passed. As we have shewn in a note, the manor, during the reign of Elizabeth, became the property of Sir Walter Cope, a knight who became high in favour with her successor, James I., and who obtained, partly by grant and partly by purchase, considerable possessions in and around Kensington. By him the house, subsequently called “Holland House,” was built. His daughter, Isabella, having married Sir Henry Rich, the second son of Robert Rich, first Earl of Warwick, this Sir Robert inherited the estates in right of his wife; in 1622 he was created Baron Kensington; and in the 22d James I. was elevated to the dignity of Earl of Holland, and installed a Knight of the Garter. Having taken part with the king during the civil wars, he was tried by the Parliament, condemned to death, and beheaded on the 9th of March, 1649.[3] His lady was, however, permitted to return to Holland House, where{11} she brought up her family, and where she was succeeded by her son, Robert, the second earl, who, in 1673, became also Earl of Warwick, by the death of Charles, the fourth earl. He was succeeded by his son, the third earl, who married Charlotte, only daughter of Sir Thomas Middleton of Chirk Castle, Denbighshire, who survived, and subsequently took for her second husband, in 1716, the renowned Joseph Addison; “but,” writes Dr. Johnson, “Holland House, although a large house, could not contain Mr. Addison, the Countess of Warwick, and one guest—Peace:” they lived on ill terms, which probably hastened the death of Addison; an event which took place in the mansion on the 17th of June, 1719.[4] Edward Henry, the fourth Earl of Holland, dying unmarried, his cousin, Edward, succeeded as fifth earl; but he dying without issue, in 1759, his honours and titles became extinct; but the family estates were inherited by William Edwardes, Esq., son of the sister of Edward, the third earl, created Baron Kensington of the kingdom of Ireland in 1776. Holland House came into the possession of the family to whom it now belongs (the family of Fox), first about the year 1762, when the Right Hon. Henry Fox, Secretary of State (soon afterwards created Lord Holland), became a tenant of the mansion, which he subsequently purchased, together with the manor, from Mr. Edwardes. Here the first Lord Holland resided until his death in 1774, and was succeeded by his son, Stephen, the second peer,[5] who died the year following, and was succeeded by his son, Richard Vassal; during whose long minority the house was let to the Earl of Roseberry and Mr. Bearcroft. On his death in 1840, he was succeeded by the present peer, Henry Edward Fox, the fourth Lord Holland.

During the lifetime of the late peer, Holland House obtained a certain degree of fame as the occasional rendezvous of the wits of the age; and the fêtes at which they were assembled furnished brilliant themes for the exercise of poetical talent; but the records of genius{12} there fostered and encouraged are singularly few. The historian, the poet, the artist, and the man of science, became guests in the mansion when they had acquired fame, but those who were achieving greatness, and stood in need of “patronage,” were not permitted to share its enjoyments and advantages.

The grounds and gardens of Holland House have been skilfully and tastefully laid out; the trees are remarkably fine, and give a character of delicious solitude to the place, keeping away all thought of the vast city, the distant hum of which is at all times audible; and, although “prospects fresh and fair” are in a great degree shut out, imagination may easily follow the steps of Addison into this calm retreat, and quote the lines of Tickell on the poet’s death, as applicable to the present day as they were to a century back:—

The prospect, however, notwithstanding the multiplicity of houses by which the grounds are surrounded, is not all destroyed; vistas are here and there formed between the trees, which command extensive views; and garden-seats still exist, to wile the visitor into “shady places,” where the hill of Harrow and other striking objects are seen in the distance, while the surrounding shadow enhances the value of the bright scene beyond:—

But judgment, tastefully exercised, has made many openings among those thick woods; and those who wander among them enjoy the feelings of entire solitude—a feeling augmented if the time be evening; for, as we have intimated, although scarcely two miles distant from the heart of London, here the nightingale

The beautiful gates which open upon the avenue that leads to the principal entrance to the mansion are pictured in the appended woodcut; they were brought from Belgium by the late Lord Holland, and placed in their present position about twelve years ago; they are of wrought iron, and are considerably impaired by time. Recently they have been repainted, and picked out with gold; and they now make a gay appearance; they are, however, of a much later date than the venerable structure, with which they would be out of “keeping,” but that they are separated from it by considerable space—a long avenue of ancient and finely grown elm-trees, which shadow the broad path that conducts to the house. The immediate entrance is between two piers of Portland stone, designed by Inigo Jones, and “executed by Nicholas Stone in 1629, for which he was paid 100l.;” they have no peculiar merit, but serve the purpose of supporting “the arms of Rich quartering Bouldry, and impaling Cope.” The pleasure-grounds are behind the house, “falling abruptly to the north-east:” they were laid out by Mr. Hamilton in 1769. Scattered in various parts are memorials to some of the personal friends of the late Lord Holland: among others, the author of “The Pleasures of Memory” is honoured by this poor couplet:—

Some lines, scarcely better, have been appended by Henry Luttrell, Esq.; but the genius of the place has essayed a flight no higher than that which might grace a school-girl’s album. Nature has done more for the domain than art; from various points, fine views are obtained of the country that surrounds London; and although, of late years, they have been sadly narrowed by “endless piles of brick,” when Tickell wrote his lines on the death of Addison, no doubt they were “Fresh and Fair.{14}”

Considerable alterations internally were made to the building by Inigo Jones. The entrance-hall, the two staircases, and the parlour leading out of the principal staircase, are the only parts of the mansion on the ground-floor that still retain their original character. On the first floor, beside the Gilt Room, is a noble long gallery, now the library, and the late Lady Holland’s drawing-room or boudoir. All these rooms preserve their ancient decorations, and are in the purest taste and the most costly style of execution.

“The Gilt Room,” which forms the subject of the appended print, is approached from the entrance-hall by a richly ornamented oak staircase. From the style of the details it would appear that it was the work of John Thorpe, and that the painted decorations were the produce of Francis (or Francesco) Cleyn, a favourite artist of the time, who was employed largely by the kings James I. and Charles I., from whom he derived an annuity of 100l., settled on him during his natural life, and which he enjoyed till the Civil War. The ceiling of the room was originally painted by him in the same style as the other portions of the apartment; being out of repair during the minority of his late lordship, it was removed, and a plain one put up in its stead. In the view here given, Mr. Richardson has supplied it from such fragments and sketches as were obtainable several years ago.

Notwithstanding the loss of its painted ceiling, the room presents an appearance of elaborate magnificence, and of unique singularity—carrying us back at once to that luxurious period, the early part of the reign of Charles I. The paintings, the figures over the fireplaces, deserve great praise, although we cannot entirely coincide with Horace Walpole, who declares (in his life of Cleyn) that they are not unworthy of Parmigiano. The paintings—such as remain over the fireplaces and soffites of the arches—certainly are masterly, though the architect might discover a little of the “contract style” about them. Cleyn was employed by Charles I., whose good taste led him to patronise only the most eminent men in art. The painter was denominated “Il famosissimo pittore Francesco Cleyn, miracolo del secolo, e molto stimato del Re Carlo della Gran Britania.”[6]

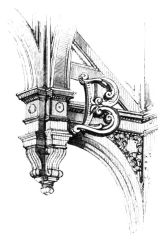

This cut represents some of Cleyn’s painting in the soffite of one of the arches in the gilt-room; it is roughly painted—although in a free and masterly style—in umber, on a white ground; the drapery, dress, and hair of the figures, are gilt.{16}{15}

![[Image unavailable.]](images/plt_003.jpg)

From a drawing by C. F. Richardson, F.S.A. Day & Son, Lithʳˢ to The Queen.

THE GILT ROOM, HOLLAND HOUSE.

The decorative panelling of the Gilt Room is continued round the four sides, and in the large recess in the centre (immediately above the entrance-porch); the interior of each panel has a small raised fillet, about an eighth of an inch in thickness, forming an ornamental border: this is gilt. In the centre of the panels are painted alternately cross-crosslets and fleur-de-lis, charges in the arms of Cope and Rich; they are surmounted by an earl’s coronet, with palm or oak branches, in gold, shaded with bistre. The figures over the fireplaces have the flesh painted, the rest is gold shaded; the lower columns of the fireplaces are painted black, the upper being of Sienna marble: both have gilt ornaments at the lower part of the shaft, and their caps and bases gilt: for the rest, all the prominent mouldings, the flutes, caps, and bases of the pilasters are gilt; the cima recta of the great entablature has a painted leaf enrichment, with acorns between, the latter of which are gilt. The groundwork of the whole is white. The busts in the room were placed there by his late lordship: over the fireplaces are those of King William the Fourth, and George the Fourth when Prince Regent. Arranged on pedestals round the room are busts of the late Lord Holland, Francis Duke of Bedford, Henry first Lord Holland, the late Duke of Sussex, John Hookham Frere, the Duke of Cumberland (of Culloden), Napoleon, Henry the Fourth of France, the Right Hon. Charles James Fox, by Nollekens, a duplicate made for the Empress Catharine of Russia. In the bow-recess are models of Henry Earl of Pembroke, and Thomas Winnington, Esq. The painted shields in the corner of the room bear the arms of Rich of Warwick, and Cope and Rich. Of the ancient furniture of the

Gilt Room two chairs alone remain; these are mentioned by Horace Walpole as being the work of Francesco Cleyn: they are painted white, and partly gilt. A large bench, formed by three of these chairs placed together, with one arm only at each end, was discovered by the artist some years ago, in a lumber-place over the stable, where, probably, it still remains. The Gilt Room, during the lifetime of his late lordship, was used as the state{20} dining-room: the state drawing-room, lined with silk, and hung with paintings, led out of it by the door on the right—seen in the print. Parallel to these rooms, at the back of the

building, is another line of drawing-rooms, modernised, but which contain a valuable collection of paintings. Among them is a celebrated one by Hogarth—the amateur performance, by children of the nobility, of “The Beggar’s Opera.” This painting is very large: the whole of the figures are portraits. Another painting by Hogarth is in the collection, which has never been engraved. It is a view of the entrance to Ranelagh Gardens, Chelsea. The collection contains a few very fine Sir Joshua’s. Among them is his portrait of Joseph Baretti, well known from the engraving. There are likewise a few first-rate pictures of the old masters. The library contains a series of portraits of political and literary friends of his late lordship; and, in the boudoir, are the series of the late J. Stothard’s most exquisite compositions to illustrate Moore’s poems. These drawings are very highly finished, and are twice the size of the engravings which were made from them.

In “Lady Holland’s Boudoir,” among other curiosities, are two candlesticks formerly belonging to Mary Queen of Scots; they are of brass, each of eleven and a half inches in height. They are of French manufacture; the sunk parts are filled up with an inlay of blue, green, and white enamel, very similar to that done at Limoge. These candlesticks are extremely elegant; one of them is represented in the above woodcut.

The accompanying woodcut represents the fireplace in “the ancient parlour;” leaving the principal staircase in the ground floor; the door on the left leads into this room. It is supposed to have been painted in a similar style to the great chamber above-stairs. The fireplace in this room is of the most excellent design and capital execution. A portion of the framing of the room is shewn by the side of the fireplace: this is likewise very elegant. One of the ancient windows of this apartment is blocked up, and an ornamental arch placed in front of it by Inigo Jones. It was in this room that{21} plays were performed by the direction of the first Lady Holland, when the theatres in London were shut up by the Puritans: it is commonly called “The Theatre Room.”[7]

The other rooms will require but a brief notice. “The Journal Room” is so named because a complete set of the journals of the Houses of Lords and Commons are there preserved: it contains several portraits, among which are three or four by Sir Joshua Reynolds. This is on the ground-floor. Underneath the hall is the ancient kitchen, not long ago fitted up as a servants’ hall. In the north-east wing is a large apartment, formerly the chapel of the mansion: it has been disused for half a century, having been converted into a bath-room.

The Libraries are spacious and “well stocked;” the principal, which forms the west wing of the house, is styled the Long Gallery; it is, in length, one hundred and two feet, and, in breadth, seventeen feet four inches. According to Mr. Faulkner (“History of Kensington”), whose account was written under the superintendence of the late Lord Holland, in the year 1746, this fine apartment was entirely out of repair, and even “unfloored:” it was, however, at that period completely restored, and converted from its ancient use, as the gallery for exercise, into a receptacle for books, of which it contains a rare selection. The first Lord Holland had fitted it up for pictures; blocking up many of the windows, and opening in lieu of them a large bow-window on the west side. The “West Library” and the “East Library”—two rooms of moderate extent—contain also several valuable folios—curious treasures of antiquity. Mr. Faulkner enumerates some of the more remarkable of the contents of the eastern library, which cannot fail to interest the reader:—

“A curious copy of Camoens, to which the praises of Mr. De Souza, the patriotic editor of the late splendid edition of that poet, have given extraordinary celebrity. It is a copy of one of the earliest editions, and Mr. De Souza alleges that it must have been in the hands of the poet himself. At the bottom of the title-page the following curious and melancholy testimony of his unfortunate death is written in an old Spanish hand, which states that the writer saw him die in an hospital at Lisbon, without even a blanket to cover him.

“‘Que coza mas lastimosa que ver un tan grande ingenio mal logrado! yo lo bi morir en un hospital en Lisboa, sin tener una sauana con que cubrirse, despues de aver triunfado en la India oriental, y de aver navigado 5500 leguas por mar: que auiso tan grande para los que de noche y de dia se cançan estudiando sin provecho, como la arana en urdir tellas para cazar moscas!’

“Specimens of all the types in the Vatican Library, printed in the Propaganda press, A.D. 1640, on silk.

“The music of the ‘Olimpiade,’ an opera of Metastasio, well authenticated to have been transcribed by J. J. Rousseau, when that extraordinary man procured his livelihood by copies of this kind. The hand-writing is so beautiful that it resembles copper-plate engraving.

“Four volumes of MS. Plays of Lope de Vega, the first containing three plays in his own hand-writing, with the original license of the censor.{22}

“The original copy, in MS., of the ‘Mogigata,’ a favourite play of the celebrated Moratin, the first writer of Spanish comedy now living, but who has been proscribed and exiled by Ferdinand the Seventh.

“There are several others of nearly equal interest, and among the MSS. there are many curious autographs of Philip the Second, Prince Eugene, Pontanus, Sannazarius, and others, and three original letters of Petrarch.

“Also a voluminous MS. collection of the proceedings in Cortes, from the earliest period, copied from the archives of the King of Spain. The original correspondence of Don Pedro Ronquillo, the Spanish ambassador, resident in London at the time of our Revolution; part in cypher, with the translation by the side, with several others of equal value and curiosity.”

The Long Gallery is ornamented with portraits of the Lenox, Digby, and Fox families; Dryden and Addison; Sir C. H. Williams; Admiral Lestock; Sir Robert Walpole; the Right Honourable Thomas Winnington; Cardinal Fleury, by Rigaud; and Van Lintz, by himself. Scattered throughout the apartments are King Charles II. and the Duchess of Portsmouth; Sir Stephen Fox, by Sir Peter Lely; Henry, Lord Holland; Stephen, Lord Holland, by Zoffany; the late Right Honourable C. J. Fox, when an infant;—when a boy, in a group with Lady Susan Strangeways and Lady Mary Lenox (by Sir Joshua Reynolds); and a fine picture of him in more advanced life by the same artist. There are two busts, also, of him, by Nollekens, one of which was taken not long before his death; and a statue, seated in the entrance-hall.

We may not take leave of this fine old mansion without expressing a fervent hope that the interesting work of two centuries may endure for many centuries to come; that modern improvements—although they may place the suburb of which it is the crowning gem in the centre of the Metropolis—will not displace it to make room for petty structures of a day, but that the tale of the Olden Time may be there told to our descendants as it has been there told to our ancestors.{24}{23}

![[Image unavailable.]](images/plt_004.jpg)

From a drawing by J. D. Harding Day & Son, Lithʳˢ. to The Queen.

BLICKLING HALL. NORFOLK.

From a drawing by J. D. Harding Day & Son, Lithʳˢ. to The Queen.

BLICKLING HALL. NORFOLK.

ourneying a dozen miles north of the city of Norwich, the Tourist

reaches the old town of Aylsham. A mile hence is the very ancient manor

of Blickling[8]—famous so far back as the time of the Confessor, when

it was in the possession of Harold, King of England; remarkable, in

after times, when occupied by the Bishops of the See, and celebrated, in

the history of various epochs, as a seat of the noble families of

Dagworth, Erpingham, Fastolff, Boleyne, Clere, and Hobart. From this

ancient house, Henry VIII. married the unfortunate mother of Queen

Elizabeth; here the virgin queen herself is said to have been a guest,

and here Charles II. and his consort were visitors—events referred to

by the court-poet, Stephenson:

ourneying a dozen miles north of the city of Norwich, the Tourist

reaches the old town of Aylsham. A mile hence is the very ancient manor

of Blickling[8]—famous so far back as the time of the Confessor, when

it was in the possession of Harold, King of England; remarkable, in

after times, when occupied by the Bishops of the See, and celebrated, in

the history of various epochs, as a seat of the noble families of

Dagworth, Erpingham, Fastolff, Boleyne, Clere, and Hobart. From this

ancient house, Henry VIII. married the unfortunate mother of Queen

Elizabeth; here the virgin queen herself is said to have been a guest,

and here Charles II. and his consort were visitors—events referred to

by the court-poet, Stephenson:

The mansion—Blickling Hall—is one of the most perfect examples remaining of the time of James I.; the exterior has undergone few changes; the bridge, the moat, the turrets, the curiously-formed gables, and the double row of spacious and convenient out-offices—connected with the mansion by an arcade—are characteristic of the period, while elaborate finish and costly ornament indicate the wealth and rank of its noble owners. The high-road passes the gates, and runs within a few yards of the house; a small green sward only separating it from the public pathway. The moat is crossed by a Bridge of remarkably light and graceful proportions; on either side of this bridge are Pedestals with bulls (the heraldic crest of the Hobarts) bearing blank shields. The entrance-porch is exceedingly beautiful; the design is simple and elegant; “it may be regarded,” according to Mr. Shaw, “as one of the earliest attempts at the restoration of classical architecture,{28} and appears to be formed upon the model of the Arch of Titus at Rome.” In the spandrels are sculptured figures of Victory. Over the entablature, supported by two Doric columns, is an enriched compartment, bearing the arms and quarterings of Sir Henry Hobart, Bart. (by whom the stately mansion was erected). A massive Oak Door contains the date 1620; the knocker of this door is peculiarly quaint; a copy of it acts as the initial letter commencing this description. Passing a small quadrangular court, we enter the Hall, from which opens the grand Staircase of Oak, the newels of which are crowned with figures. Unhappily, the oak has been covered with paint; and time having removed some of the figures, their places have been supplied by others out of harmony with the character of the venerable structure.[9] Of the several apartments, the only one that demands particular notice is the Library—a noble room, filled with the rarest and most valuable books. It measures one hundred and twenty-seven feet; the ceiling is a magnificent collection of works of art, unsurpassed by anything of the kind in Great Britain. It consists of a series of models, representing the Senses, the Passions and the Elements, in low relief—comprising a very large number of subjects, no two of which are alike. The library is—as a private collection—extensive; the books it contains are generally “large paper copies,” and in the finest possible state. Some of its treasures are unique—here are a volume of Saxon Homilies, and a Latin MS. of the Psalter, certainly as ancient as anything we possess in the Latin tongue, and several others, with and without illuminations, of very remote dates. Here also are two copies (imperfect) of the Coverdale Bible; an uncut copy of the diminutive Sedan New Testament, and a vast assemblage of the choicest productions of the early English press. It was formed by Maittaire for Sir Richard Ellys, Bart., of Norton, in Lincolnshire, to whom he dedicated his “Anacreon,” in 1725. The curiosities of the library were shown to us by the Rev. James Bulwer, whose own family seat of Heydon is in the neighbourhood of Blickling Hall.

Mr. Harding’s print of this fine old mansion affords an accurate idea of its elegance and grandeur. Its form is quadrangular—having a square turret at each angle. Viewed from any point it is highly picturesque. The Park, which surrounds it on three sides, contains above 1000 acres. Its trees are celebrated for their exceeding beauty and{29} prodigious growth. A remarkably fine piece of water, shaped like a crescent, adjoins the house, extending nearly a mile in length. Nature and Art have both contributed to adorn this artificial Lake; gentle acclivities rise from its sides, here and there fringed with evergreens infinitely varied, while gigantic oaks, and elms, and beeches, rising at intervals, seem the guardians of its banks.

We may sum up our account of Blickling Hall in the words of old Blomefield:—“The building is a curious brick fabric, four-square, with a turret at each corner; there are two good Courts, with a fine Library, elegant Wilderness, good Lake, Gardens, and Park; it is a pleasant, beautiful seat, worthy the observation of such as make the Norfolk Tour.”

The erection of the existing structure was commenced by Sir Henry Hobart, Bart., during the reign of James the First, but was not finished until the year 1628, when “the Domestic Chapel was consecrated.” The building, however, retained its original character, varying very little, in external appearance and internal arrangements, from the old Mansion in which Queen Anne Boleyne was born, and which had been famous for centuries.

When the Domesday Survey was made, one part of the Manor belonged to Beausoc, Bishop of Thetford (the seat of the See until 1088), the other part being in possession of the Crown. Both moieties were invested with the privileges of ancient demesne, were exempt from the hundred (of South Erpingham) and had the lete with all royalties. Having successively passed through the hands of many distinguished families, in 1431 it was the property of Sir Thomas De Erpingham, by whom it was sold to Sir John Fastolff, who, about the year 1452, sold it to Sir Geoffrey Boleyne, Knt., who was Lord Mayor of London in 1458, and who made Blickling his country-seat. From him inherited his second son, Sir William Boleyne, Knight,

who married Margaret, sister of James Butler, Earl of Ormond; dying in 1505, he was succeeded by his son, Sir Thomas Boleyne, who, the 18th of Henry VIII., was raised to the peerage by the title of Viscount Rochford, and three years afterwards was created Earl of Wiltshire. His daughter, Anne, was privately married to Henry VIII., on the 5th of January, 1533. On the 19th of May, 1536, she was beheaded; her dismal fate having been shared by her brother, Viscount Rochford; and the old Earl died in 1538—it is believed of a broken heart. Soon afterwards the estate of Blickling, having been for a short time in the family of the{30} Cleres, was purchased by Sir Harry Hobart, Bart., “a fortunate lawyer,” who became Lord Chief Justice of the Common Pleas. He was succeeded by his son and grandson, the second and third Baronets; the fourth Baronet was created, by George II., Lord Hobart of Blickling, in 1728; and in 1746, Earl of Buckinghamshire. His son, the second Earl, died without male issue, but left four daughters, one of whom married the late Marquis of Londonderry, another William Lord Suffield, the third Lord Mount Edgcombe, and a fourth the Marquis of Lothian, whose surviving son, the fifth Marquis, died at Blickling in 1841, leaving a son, an infant, who is heir-apparent to the estate, now in the possession of his great aunt, the Dowager Lady Suffield.

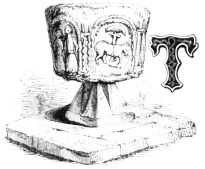

The venerable Church of Blickling adjoins the mansion. It is built—in the style of nearly all the Norfolk Churches—of flint, a material that essentially impairs the solemn dignity of the structure. Many of the Brasses and Tombs are of high interest; the one of which we append an engraving (on the preceding page) is to the memory of Edward Clere. It is described by Blomefield as “a most curious Altar Tomb, placed between the Chancel and Boleyne’s Chapel. The Effigy which laid upon it is now gone; but there remain the Arms and Matches of his family, from the Conquest to the time that his son and heir, Sir Edward Clere, erected this tomb.” As a work of art, the Tomb possesses considerable excellence. The carved Armorial Bearings retain much of the original brilliancy of their colouring. Among the Brasses is one for Anne Boleyne, aunt of the unfortunate Queen, and another of Isabella Cheyne, (date 1485) remarkable as exhibiting the earliest authentic example of the necklace. An elaborately-wrought Oak Chest, of great size, strongly banded with iron, and secured by five curiously formed locks and keys, is preserved in Blickling Church; but a relic still more curious and unique is a Poor-box, of very primitive character, heart-shaped, and painted blue, the letters, “Pray remember the Pore,” being gilt. We give engravings of both these peculiar and very interesting antiquities.{32}{31}

urleigh, or Burghley House, the princely seat of the Marquis of Exeter,

is one of the most magnificent mansions of its period; it has come down

to us intact, and is perhaps more interesting—from its associations

with the “glorious days”—than any other edifice now remaining in the

kingdom. The halls are still standing where the famous Lord Treasurer

entertained his Sovereign and her dazzling court; while Nonsuch,

Theobalds, and Cannons have vanished—their sites are ploughed over; and

Kenilworth has become a venerable antiquity, a moss-covered ruin.

urleigh, or Burghley House, the princely seat of the Marquis of Exeter,

is one of the most magnificent mansions of its period; it has come down

to us intact, and is perhaps more interesting—from its associations

with the “glorious days”—than any other edifice now remaining in the

kingdom. The halls are still standing where the famous Lord Treasurer

entertained his Sovereign and her dazzling court; while Nonsuch,

Theobalds, and Cannons have vanished—their sites are ploughed over; and

Kenilworth has become a venerable antiquity, a moss-covered ruin.

In the reign of the Confessor, Burghley was let to farm by the Church of Burgh, to Alfgar, the king’s chaplain, for his life. The crown having seized it at his death, Abbot Leofric redeemed it for eight marcs of gold. In Doomsday Book it is rated at 40s. As usual in the feudal ages, it often changed hands, when treasons and rebellions were every-day occurrences. In the 9th of Edward II. Nicholas de Segrave was possessed of Burleigh, which had descended to Alice de Lisle, as part of the inheritance of John de Armenters. The successor of Nicholas de Segrave was Warine de L’Isle. He was one of the great men who, in the 14th of Edward II., took up arms against the King, under the command of Thomas Earl of Lancaster; was made prisoner with him at the battle of Barrow Bridge, and the week following executed at Pontefract. In the 1st of Edward III., Gerard de Lisle, son of the above Warine, was restored to his father’s possessions, and accompanied several times the King in his wars with Scotland and France. After undergoing many of the usual changes to which property was subjected in such uncertain times, it finally passed into possession of a family named Cecil, as we now spell it, although it appears to have enjoyed many variations of orthography in its transition. The founder of the house and family was a gentleman named William Cecil, who accompanied the Duke of Somerset to Scotland. At the battle of Musselburgh field he{36} narrowly escaped being killed, a gentleman who out of kindness pushed him out of the level of a cannon, having his arm shattered as he withdrew it. On his return he was made Secretary of State, and in some political trouble was sent prisoner to the Tower: but no charge being brought against him he was released from his captivity, again made Secretary of State, became a Privy Councillor, and received the honour of knighthood. During the reign of Mary, he attached himself much to the fortunes of her younger sister, Elizabeth. When she ascended the throne, fresh honours were lavished on him: he became Chancellor of the University of Cambridge, Master of the Court of Wards, Baron Burleigh, Lord High Treasurer, and Knight of the Garter. He was much afflicted with gout in his latter years, and on one occasion when he was confined with an attack of it, at his house in the Strand (called Burleigh House, where a street of that name is now built), the Queen condescended to visit him. On one of these occasions, coming with a high head-dress, and the servant, as she entered the door, desiring her to stoop; she replied, “For your master’s sake I will stoop, but not for the King of Spain.” He died in 1598, having been Lord High Treasurer twenty-six years, and was buried in the parish-church of St. Martin, Stamford. A superb white alabaster monument, sixteen feet high, is raised over his tomb; his figure lies under a canopy supported by several black marble columns. It is in the style of the period, and stands under the arch of the north aisle and body of the church.

Thomas, Lord Burghley, the Lord Treasurer’s eldest son, was created Earl of Exeter in 1605; and Henry, tenth Earl of Exeter and eleventh Lord Burghley, his lineal descendant, was created Marquis of Exeter in 1801. His son, Brownlow Cecil, the second Marquis, who succeeded his father in 1804, is the present possessor of the princely mansion and estates.

The mansion we are about to notice is built on ground where there is but little undulation of surface, and stands about a mile and a half from the old town of Stamford, in Northamptonshire, separated from Lincolnshire by the river Welland, which runs through Stamford. At the northern extremity of the domain stand the park lodges: they are extremely handsome erections, and more than usually important buildings for such purposes. Although built so recently as the year 1801, by Henry the tenth Earl, they are in perfect harmony of design with the main edifice. The cost of their erection exceeded 5000l. The park is about two miles in length and a mile and a half in width. It was arranged and planted by the famous “Capability Brown,” and is well adorned with fine ash, elm, chestnut, and other trees, as well as plantations of shrubberies. A temple, grottos, and picturesque buildings for domestic or agricultural services, add to its beautiful character. It is well stocked with deer. On entering the park to proceed to the house, a noble piece of water, three quarters of a mile in length, is spanned by a handsome bridge of three arches, having the balustrades decorated with four{37} statues of lions couchant. In the park enclosure are the remains of the ancient Roman road, called Ermine Street, from Stilton through Castor to Stamford: it is easily traceable in many parts.

On arriving opposite the mansion, the eye is bewildered at its unusual extent: its numerous turrets, and the spire of the Chapel rising above the parapets, give it the aspect of a town comprised in comparatively diminished area, rather than a single abode. The appended engraving exhibits a portion of the west front. The mansion stands in an extensive lawn. Mr. Gilpin, in his “Tour to the Highlands,” thus describes it:—“Burghley House is one of the noblest monuments of British architecture of the time of Queen Elizabeth, when the great outlines of magnificence were rudely drawn, but unimproved by taste. It is an immense pile, forming the four sides of a large court, and although decorated with a variety of fantastic ornaments, according to the fashion of the time, before Grecian architecture had introduced symmetry, proportion, and elegance into the plans of private houses, it has still an august appearance. The interior court is particularly striking: the spire of the Chapel is neither, I think, in itself an ornament, nor has it any effect, except at a distance; when it contributes to give this immense pile the consequence of a town.” Horace Walpole says, John Thorpe was the architect; and that he superintended the erection of the greater part of this stupendous building. This assertion is corroborated by the plans, still extant, in this celebrated architect’s collection of designs, now in the Soane Museum. It is built of freestone and forms a massive parallelogram, enclosing a court 110 feet long and 70 feet wide. The principal entrance is on the north side,

and offers a frontage of nearly 200 feet, pierced with three ranges of large square-headed windows, divided by stone mullions and transoms. The outline is varied by towers at the angles surmounted by turrets with cupolas; the frontage is varied by advancing bays between the towers; a pierced parapet, occasionally embellished with ornaments that mark the Elizabethan era, crowns the walls. The chimneys are constructed in the hollows of Doric columns, which are in groups, connected by a frieze and cornice of the order; as they are very numerous, and of fine proportions—rising{38} loftily in the air—they combine with the turrets, &c. to give a great variety of forms to the superior portion of the main design. In the arched roof under the passage to the interior court, which was in the first instance intended to be the chief entrance, are escutcheons of the family arms, on one of which is inscribed “W. DOM de Burghley, 1577,” being the year when that part of the house was built. On the opposite side of the court, over the dial and under the spire, is carved the date 1585, which indicates when that part was erected; and on the present entrance, on the northern side, stands the date 1587 between the windows. The house has been much adorned by various successive possessors, and at the present time few seats, either in England or on the Continent, can vie with Burghley House.

Queen Elizabeth frequently visited her favourite minister, her Lord Treasurer, here; and on April 23, 1603, James I., on his journey from Scotland, came to Burghley: the next day, being Easter Sunday, he attended divine worship at the parish church, St. Martin’s, Stamford, when the Bishop of Lincoln preached before him.

Entering the court, the beauties of the architecture become apparent. The appended engraving represents the entrance from the courtyard. The eastern side is the most highly decorated, and its three stories adorned with the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian orders, in super-position. Above the last are two large stone lions, supporting the arms of the family. Over an arch before the chapel is a bust of King William III.; the balustrades are enriched with a variety of sculptured vases. Four large gates from the various sides open into the court, and give entrance to the several portions of the building, which contains nearly one hundred and fifty apartments, many of them of great dimensions, all furnished suitably for their purpose, and a considerable number in gorgeous profusion of decorative ornament and splendid furniture. It is one of the few palatial mansions of a refined, gay, and brilliant period, which remain carefully preserved, and undisturbed by modern upholsterers. It is impossible to speak too highly of the elegance and splendour of the interior. The first apartment on entering is the spacious Hall: from some of the remaining features of its construction, it has been imagined that the great Lord Treasurer did not build a new house from the foundation, but that{39} an edifice existed to which he imparted vastness by the additions he made. The dimensions of this Hall show at once that it includes a noble space, being sixty-eight feet long and thirty feet broad. It receives light from two large windows, and has a fine open-worked timber roof, springing from corbels, very similar in idea to the roofs of Westminster Hall, and the Parliament House at Edinburgh. The chimneypiece is in perfect keeping with the Baronial Hall, and is of stone, finely sculptured, bearing for its principal device in the centre the shield and supporters of the founder of the family; it is also ornamented by a number of pictures, some of which are portraits. There are statues in marble of life size, one of which, very much esteemed, represents Andromeda chained to the rock, and the Sea-monster. It was purchased in Rome, a century ago, by the fifth Earl of Exeter, for 300l. “Drakard’s Guide” attributes it to Peter Stephen Monnot; but Brydges, in his “History of Northamptonshire,” says it is by Domenico Guidi.

From the Hall, visitors pass through the Saloon, and up the ancient grand vaulted stone staircase in the north-west part of the house, to an apartment called the Chapel Room, which contains nearly fifty pictures, mostly of sacred subjects. A true description of the numerous pictures in the different rooms is sadly wanted, as we find one here called Titian’s Wife and Son, attributed to Teniers! in “Drakard’s Guide,” published at Stamford. Here also stands a model of the Holy Sepulchre at Jerusalem, curiously inlaid. The Chapel, to which the preceding serves as an ante-room, is spacious, being forty-two feet long, thirty-five feet wide, and eighteen feet high. The ceiling is panelled and studded with devices; the side-walls are wainscoted half-way up, and at intervals are placed, on pedestals, ten antique bronzed figures, of life size, each holding a lamp. Festoons of fruit and flowers, carved by Grinling Gibbons, are its principal ornaments. Many of the finest apartments in the house, such as chimneypieces, are profusely decorated with his valuable carving. A seat on the left-hand side, nearest to the altar, is pointed out as having been occupied by Queen Elizabeth when on a visit to Burghley. There are some large pictures placed on the walls of another space, which forms also a portion of the Chapel at the western end. This part, thirty-one feet long and twenty-four feet broad, is wainscoted to the ceiling, and is filled with open seats, for servants and others connected with the family to attend divine service.

The gorgeous Ball-room succeeds, fifty feet in length, twenty-eight in width, and twenty-six in height. The walls are painted with historical and other subjects by Laguerre. The candelabra, which are placed on pedestals of japan gilt about two feet high, are truly splendid. Two of them, placed by the sides of the lofty bow-window, are the figures of Negroes kneeling, and supporting the lights on their heads. The Brown Drawing-room, filled with pictures and a carved chimneypiece by Gibbons, leads to the Black Bedchamber, so called from the hangings of the bed, which are of black satin lined with yellow; the chimneypiece here is also by Gibbons. The west Dressing-room has in the window recess a toilette-table, set out with richly gilt dressing-plate. The north-west{40} Dressing-room is hung with pictures; indeed every one of the principal rooms boasts of pictorial decoration, and among the profusion are many fine examples of ancient art. In a small apartment called the China Closet is an extensive gathering of varied specimens of antique Chinese, and Indian porcelain. Queen Elizabeth’s Bed-room is hung with tapestry, and contains an ancient state bed with hangings of green embossed velvet, on a ground of gold tissue; with chairs to correspond. The toilette-table is set out with richly chased dressing-plate. A number of other apartments in this range follow, similarly furnished and adorned. On the south side of the house there is another suite of grand apartments called the George Rooms, which were decorated in 1789, under the express direction and control of Brownlow, earl of Exeter, who selected the whole of the ornaments from publications of ancient architecture in the library at Burghley. His lordship directed the whole, without the assistance of any professional person. The rooms are wainscoted with the finest Dutch oak, of a natural colour; the ceilings are mostly painted by Verrio, in mythological subjects; carving, gilding, and tapestry, are profusely employed; the furniture is of corresponding magnificence; and pictures, sculptures, and antiquities are dispersed, to add to the general embellishment. The Dining-room contains two superb sideboards laden with massive silver-gilt plate; a silver cistern weighs 3400 ounces, and a lesser one 656 ounces: there are also coronation dishes, ewers, &c. Two apartments are Libraries; they are filled with many MSS., fine and rare books, antiquities, and an extensive collection of ancient coins.

The new State Bed-room, in the suite of George Rooms, contains a state bed, which has the reputation of being the most splendid in Europe. It stands on a base or platform, ascended by a couple of steps. A canopy, richly carved and entirely gilt, is supported at the angles by clusters of columns rising from elaborate tripods, which support the canopy or dome. The height of this construction, which resembles a temple, is twenty feet from the ground; 250 yards of striped silk coral velvet and 900 yards of white satin are employed in the hangings. The bed is a couch, which stands under the temple. The fifth George Room is called “Heaven,” from the multitude of Pagan deities with which Verrio has covered it; and the grand staircase (not the vaulted one) is usually called “Hell,” in consequence of the painted ceiling representing the poetic Tartarus.

It would be vain to attempt a minute description of all that interests the learned or accomplished visitor; a volume has already been published, which in itself is but an abridged account. Every faculty of rational enjoyment is gratified to repletion in viewing the gorgeous halls of Burghley House.{42}{41}

astle Ashby, the venerable and deeply interesting seat of the Most

Noble the Marquess of Northampton, is situate about eight miles from the

town of Northampton.

astle Ashby, the venerable and deeply interesting seat of the Most

Noble the Marquess of Northampton, is situate about eight miles from the

town of Northampton.

Much curious information exists concerning the early history of the manor; to which, however, we shall not be able to enter at any length. No mention is made of the Saxon lord of “Asebi;” but in the time of the Confessor it was rated at twenty shillings yearly: this yearly value had quadrupled at the time of the Domesday Survey, when the estate “was held by Hugh, under the countess Judith.” In the reign of Henry III., the manor was seized under a forfeiture, incurred by David de Esseby, for aiding the confederate barons against the king. After the battle of Evesham, the estates of all these barons were confiscated; but by the subsequent conciliatory policy of the sovereign, the offenders were allowed to redeem their lands by payment of five years’ value within three years. This boon led to much disputation and some violence between the de jure and de facto holders; and in the case of Esseby (Ashby), Alan la Zouch, the then holder, died of fever induced by wounds inflicted on him before the king’s justices in Westminster Hall, by Earl Warren (guardian of Isabella, grandchild of David de Esseby), who sought to recover the estates for his ward. Immediately after this outrage Earl Warren fled, but was pursued by Prince Edward, son of the king, who captured him, and it was only by much crying for mercy, and many protestations of making such reparation as he could, that he saved himself from immediate punishment.

It is not necessary to trace the various hands through which Castle Ashby passed subsequently to this period, until we arrive at the fifteenth century, when the estates became the property of the Compton family, ancestors of the present noble possessor, who only succeeded in establishing a claim by a re-purchase in 1465, after fifty years’ possession, in consequence of “rival nuncupative wills” made by previous owners. Sir William Compton, the purchaser, was the head of a family long settled at Compton Winyate, in Warwickshire, from which place the family name was derived; at the death of his father, Sir William had not attained his majority, and being in ward to Henry VII., was chosen by the king to attend his son Prince Henry, who, on subsequently ascending the throne, gave him an{46} appointment as groom of the bed-chamber. Sir William, then Mr. Compton, soon became a favourite with the sovereign, one of whose freaks was to attend incog. a tournament got up by some of the courtiers, on which occasion he was attended by his favourite, Mr. Compton, who received a dangerous wound by an accidental collision with Sir Edward Nevill. In November 1510, the king proclaimed a tournament, “at which he with his two aids, Charles Brandon, afterwards Duke of Suffolk, and William Compton, gave an universal challenge with the spear at tilt one day, and at tourney with the sword the other.” Magnificently accoutred, the royal party entered the lists, gained great distinction, and received the prize. Afterwards, in 1511, the king granted to William Compton Esq., “his trusty serv’nte and true liegman, for the good and (acceptable) s’vyce whiche he hathe doone to his Hignesse, and durynge his lyfe entendithe to doo,” the manor of Tottenham, in Middlesex, and he was honoured, in the following year, with an armorial augmentation out of the royal arms. “Mayster Compton,” as he is called in an old MS., became Sir William in 1513, being knighted by the king after the battle of the Spurs (5 Hen. VIII.). He died in 1528, after retaining through life the confidence and regard of his wayward master, from whom he received many valuable marks of attachment. His son Peter, who was only six years of age, became the ward of Cardinal Wolsey, and afterwards of the Earl of Shrewsbury, to whose daughter he was married. He died in his minority, leaving one son, Henry Compton, who was knighted by the Earl of Leicester in 1566, and summoned to parliament by writ, as Baron Compton, in 1572 (14 Eliz.). About this time another attempt was made to wrest the estate of Ashby from the Compton family, which, however, ended in a compromise between the contending parties, each making some concessions, “for the finall endinge of all sutes and controversies.” Lord Compton was one of the Commissioners deputed to sit in judgment on Mary queen of Scots.

William, second Lord Compton, married the daughter and heiress of Sir John Spencer, alderman of London, and thus obtained a large addition to his possessions. This union would appear to have been made secretly, and without the consent of the lady’s father; it took place at the church of St. Catharine Colman, Fenchurch St., as the register shews: “18 Apr. 1599, William Lorde Compton, and Elizabeth Spencer, maryed, being thrice asked in the churche.” Lord Compton, by reason of zealous service, was regarded with great favour by James I., who made him President of the Council within the marches of Wales, to which he added the honour of Lord Lieutenant of the Principality, and the counties of Worcester, Hereford, and Salop. In 1617 he was created Earl of Northampton. He died in 1630, and was succeeded by his only son Spencer, who became one of the most distinguished men of the age. He was an accomplished linguist, and filled posts of much distinction about the person of the king; ultimately taking an active part in the great civil war, and after many brilliant feats of arms he was killed at Hopton Heth. He left six sons, all worthy of their heroic father, distinguished like him for their devotion to the royal cause.{47}

James, the eldest son of the loyal and gallant peer, became his successor—the third Earl of Northampton. At Hopton Heath he was carried wounded from the field, immediately before his father received his death-wound: afterwards, he greatly distinguished himself in the king’s service, particularly at Lichfield. On the Restoration he headed a troop of two hundred gentlemen, “clothed in grey and blue,” at the entry of Charles II. into London; and “his loyalty was subsequently rewarded with several honourable appointments, which he held till his death, at Castle Ashby, December 15, 1681.” George, fourth Earl, died in 1727, and was succeeded by his eldest son, James, fifth earl, who was summoned to the House of Peers, by writ, in 1711. He married Elizabeth Shirley, Baroness Ferrars, of Chartley, by whom he had issue, and left Charlotte, his only surviving child, who married the first Marquess Townshend. George, the sixth earl, after enjoying his title but four years, died without issue, and was succeeded by his nephew, Charles, seventh earl, a nobleman of considerable accomplishments, who was made ambassador extraordinary to Venice in 1763. He died at Lyons, on his way home, leaving an only daughter, Elizabeth, wife of the late, and grandmother of the present, Earl of Burlington. Spencer, eighth earl, brother of the preceding, was succeeded, in 1797, by his only son, Charles, ninth earl, who was created Baron Wilmington, Earl Compton, and Marquess of Northampton in 1812. On his death, in 1828, the titles and estates devolved on his only son, Spencer Joshua Alwyne Compton, born in 1790,—the present Marquess of Northampton.

The noble marquess is not alone distinguished by high descent and lofty position; few persons of the age have more assiduously cultivated science and letters. His lordship is president of the Royal Society, and member of various other learned Institutions; and his “annual gatherings” of distinguished or accomplished men at his mansion in London, have been among the most gratifying and beneficial events of a period which recognises genius as a distinction, and gives its proper status to mind.[10]

Castle Ashby is about two miles from the White-Mill Station, on the Northampton and Peterborough Railway, from which a convenient road offers facilities to vehicles, while pedestrian visitors may shorten the distance, and enjoy extensive prospects of scenery, by taking a footpath over the hills—thus at once saving time and augmenting enjoyment. On ascending the first of these hills, he sees before him an extensive valley; on the opposite hill is placed the castle, of which, however, as yet he can obtain no glimpse, being hidden{48} from his view by a dense mass of noble trees, which protect it from the northern winds.

From this point the church is an object of much beauty in the landscape, and being partially screened by fine trees, offers, as the visitor proceeds towards it, many pleasing and picturesque combinations. Emerging suddenly from under thick foliage, we tread upon an extended lawn, and the whole of the southern front of the mansion is at once in sight: its symmetrical regularity, its not unhappy marriage of English with Italian, its stately octangular towers, and the silvery grey of its time-bleached walls, all combine to produce a most agreeable impression. It is placed on the crest of the hill, the slope in its rear, a large tract of table land in front; at right angles with the front a most magnificent avenue of noble trees passes far into the distance, terminating on the northern side of Yardley Chase.

Mr. Robinson, in the “Vitruvius Britannicus,” relates all that is known regarding the erection of the house. “The castle, embattled by license to Bishop Langton, in the reign of Edward I., was the occasional residence of successive proprietors. Sir William de la Pole, and Margaret Peveril, his wife, in 1358, dated a feoffment of their manors of Ashley and Little Brington at “Castell Assheby;” but when acquired by the family of Grey de Ruthyn, in the fifteenth century, its proximity to their patrimonial seat at Yardley Hastings, would naturally lead to its partial and, ultimately, entire desertion. A century had scarcely elapsed before Leland thus recorded its desolate condition. “Almost in the middle way betwixt Welingborow and Northampton I passed Assheby, more than a mile off on the left hand, wher hathe bene a castle, that now is clene downe, and is made but a septum for bestes.” By a survey in 1565, it appears that George Carleton, Esq., under a lease granted by Sir William Compton for sixty-one years, held the site of the manor and farm of “Asheby David,” with all the demesne lands, “whereunto pertaineth the old ruined castle.” Camden, in his “Britannica,” says:—“From hence (Northampton) men maketh haste away by Castle Ashby, where Henry L. Compton began to build a faire sightly house.” The commencement of the present stately edifice may, therefore, be safely dated between the expiration of the lease in 1583 and the death of this nobleman in 1589. One of the requests of the rich heiress of Spencer to her lord was, to “build up Ashby House.” And the original pile may be presumed to have been completed when King James I. and his queen favoured its noble owner with a visit in 1605. The dates of{49} 1624 on the east front and on the two turrets, must have reference to the subsequent alterations and erections by Inigo Jones.

The castle buildings occupy a huge quadrangle, with a garden court in the centre. The most important apartments are on the northern and the southern sides. The north front is of pure Elizabethan architecture, plain, but of massive design, combined with a grandeur and impressiveness not often attained with such unadorned simplicity. The principal, or southern front, is remarkable for the curious anomaly it presents in the mixture of Elizabethan with Italian architecture. Pure taste, of course, rejects such experiments, but if they be at all allowed, perhaps it would hardly be possible to find an instance in which the incongruous association is less offensive than in this front; arising, no doubt, from no attempt having been made to engraft the one style upon the other, both being kept distinct. The Italian façade was added to enclose the court, and complete the quadrangle: it was designed by Inigo Jones, and may be considered a good example of its peculiar character. In contrast with the plain, massive, Elizabethan wings, the work of Jones may, perhaps, justly be charged with something of a petite character; but, nevertheless, taking the whole together, it forms a composition by no means unpleasing. On entering the castle the visitor is ushered into the Great Hall, a room of noble dimensions, and which formerly possessed many claims to admiration, but, unfortunately, it has been modernised, and, therefore, after noting the fine pictures it contains,—chiefly old family portraits,[11]—we pass on to the Dining-Room, which also contains some choice pictures; the most striking are portraits of the present noble marquess and his lady, apparently by Hoppner, and some choice gems of the Dutch school. Hence we pass into the Billiard-Room, where, after admiring the table and a few good pictures, there is nothing to detain us, and we enter the Drawing-Room, in which is an excellent large picture of landscape, with cattle and figures, the painter of which is not known. Presently we come to the Great Staircase, which may be admired for its rich old oak, carved, according to the{50} fashion of Elizabeth’s time, into a variety of geometrical forms, intermingled with wreaths of fruit and flowers, some parts of which argue no mean skill in the artisan. From hence we gain entrance to an ante-room, containing tapestry, said to have been presented by Queen Elizabeth; and on leaving this room we pass into the gallery of the Great Hall, whence we must pause awhile to examine a portrait of Mrs. Chute, by Reynolds, a most valuable picture of an excellent lady; the dress is white, the picture is in a light key, clear, broad, and harmonious, and of perfect execution. The next room is the Octagon, where are two life-size figures, in marble, of Mercury and the Venus de Medici, and also various other statues, of minor size and merit. King William’s Room next engages attention: it is of large dimensions, and is chiefly remarkable for its ceiling, of which we have given one of the enrichments as our initial. There are two magnificent bay-windows in this room. The Long Gallery is contained in the upper part of Inigo Jones’ façade, or screen, of which it runs the entire length—ninety-one feet. It is not remarkable for any peculiar attractions. It contains a few good pictures, one of which is of interest, “The Battle of Hopton Heath,” where, as we have seen, several members of the Compton family were distinguished. It will be at once understood that our remarks and enumeration of objects refer solely to matters of artistic or antiquarian interest; we therefore pass over much that might greatly interest general readers. On the whole, the interior does not sustain the rich promise of the exterior; the plan does not seem to have been carried out with the fulness and determination so marked in many of our Baronial Halls. The gardens do not present any remarkable features: the grounds are picturesque, and contain a large artificial lake, formed by the famous landscape gardener Brown, to whom so many of our nobility entrusted their estates for such aids as art can supply to nature. The grounds of Castle Ashby needed, however, but little of such help; they are naturally of a kind which art cannot create, nor do much to improve.{52}{51}

irby Hall.—Although now deserted, this very venerable and exceedingly

beautiful Mansion ranks among the finest of the kingdom.[12] For upwards

of two centuries, it was the seat of “the Hattons,”—the famous Sir

Christopher and his lineal descendants, the Earls of Winchelsea. It was

built by Humphrey Stafford, the Sixth Earl of Northampton; the Architect

was John Thorpe, and two plans of the building are preserved among his

collection of sketches in the Museum bequeathed to the nation by the

late Sir John Soane; one of them is thus distinguished:—“Kirby, whereof

I layd the first stone, 1570.” Not long afterwards, it came into the

possession of the Lord Chancellor Hatton, who obtained it from Queen

Elizabeth in exchange for that of Holdenby—a superb structure erected

by him, and which Camden describes as “a faire pattern of stately and

magnificent building which maketh a faire glorious show,” and as “not to

be matched in this land.”[13] It is more than probable that Kirby was

largely added to—perhaps finished—by Sir Christopher; but that it was

commenced by the unhappy family of Stafford, is evidenced by the “Boar’s

head out of a Ducal Coronet,” and the name “Humfree Stafford,” to be

found on several parts of the building. The front was decorated by Inigo

Jones about the year 1638. The mansion is the property of the present

Earl of Winchelsea, who was born there. It remains in a comparatively

good state{56} of preservation; but it is certain that in its now neglected

and deserted condition, the encroachments of Time will not be withstood

much longer. Its situation, like that of so many structures of the same

date in England, is unfortunately low, and the difficulty of drainage

(it is liable at times to be flooded) offers some excuse for removal to

a more eligible site. The approach is through an avenue of finely-grown

trees, extending above three quarters of a mile. The first Court-yard

resembled that of Holdenby—a balustraded inclosure, with two grand

archways. The external front is the work of Inigo Jones, by whom also

much of the interior was considerably altered. Passing through this, the

visitor enters the principal Quadrangle (which forms the subject of Mr.

Richardson’s drawing). “On each side of the arched entrance are fluted

Ionic pilasters, with an enriched frieze and entablature; the arched

window above, opening upon a Gallery supported by consoles, has a

semicircular pediment, broken in the centre, and inclosing a bracket for

a bust, with the date 1638.” The window is, however, an insertion by

Inigo Jones; and being of a much later date than the other parts of the

front, sadly mars the effect of the architecture of old Thorpe. The

third story contains the motto and date “Je. Seray 1572, Loyal.” The

Garden front has a raised Terrace—now a corn-field—in which the slopes

and a few ornamental seats yet remain. This front supplies one of the

grandest examples of Elizabethan architecture existing in England. It

was built by Thorpe, and essentially agrees with the German School of

Architecture of that day—which the British Architect had evidently

studied. The Garden seats, vases, &c., of which there endure only broken

fragments, are in the style, and believed to be the works, of Inigo

Jones. The Garden was terminated by a remarkably picturesque little

bridge, ornamented with a balustrade and scroll work, now, like all

other objects about the structure, or connected with it, submitted to

the wanton assaults of every heedless passer-by. Modern Vandalism has,

indeed, been very busy everywhere within and around this venerable

Mansion;—a farmer occupies a suite of rooms, the decorations of which

would excite astonishment and admiration in a London Club-house;

farm-servants sleep surrounded by exquisite carvings; one room in the

south side of the Quadrangle, decorated with a fine old fire-place, in

which are the arms of the Lord Chancellor, served, at the time of the

artist’s visit, the purpose of a dog-kennel; and an elegant Chapel,

constructed by Inigo Jones, is entered with difficulty through piles of

lumber and heaps of rubbish.

irby Hall.—Although now deserted, this very venerable and exceedingly

beautiful Mansion ranks among the finest of the kingdom.[12] For upwards

of two centuries, it was the seat of “the Hattons,”—the famous Sir

Christopher and his lineal descendants, the Earls of Winchelsea. It was

built by Humphrey Stafford, the Sixth Earl of Northampton; the Architect

was John Thorpe, and two plans of the building are preserved among his

collection of sketches in the Museum bequeathed to the nation by the

late Sir John Soane; one of them is thus distinguished:—“Kirby, whereof

I layd the first stone, 1570.” Not long afterwards, it came into the

possession of the Lord Chancellor Hatton, who obtained it from Queen

Elizabeth in exchange for that of Holdenby—a superb structure erected

by him, and which Camden describes as “a faire pattern of stately and

magnificent building which maketh a faire glorious show,” and as “not to

be matched in this land.”[13] It is more than probable that Kirby was

largely added to—perhaps finished—by Sir Christopher; but that it was

commenced by the unhappy family of Stafford, is evidenced by the “Boar’s

head out of a Ducal Coronet,” and the name “Humfree Stafford,” to be

found on several parts of the building. The front was decorated by Inigo

Jones about the year 1638. The mansion is the property of the present

Earl of Winchelsea, who was born there. It remains in a comparatively

good state{56} of preservation; but it is certain that in its now neglected

and deserted condition, the encroachments of Time will not be withstood

much longer. Its situation, like that of so many structures of the same

date in England, is unfortunately low, and the difficulty of drainage

(it is liable at times to be flooded) offers some excuse for removal to

a more eligible site. The approach is through an avenue of finely-grown

trees, extending above three quarters of a mile. The first Court-yard

resembled that of Holdenby—a balustraded inclosure, with two grand

archways. The external front is the work of Inigo Jones, by whom also

much of the interior was considerably altered. Passing through this, the

visitor enters the principal Quadrangle (which forms the subject of Mr.

Richardson’s drawing). “On each side of the arched entrance are fluted

Ionic pilasters, with an enriched frieze and entablature; the arched

window above, opening upon a Gallery supported by consoles, has a

semicircular pediment, broken in the centre, and inclosing a bracket for

a bust, with the date 1638.” The window is, however, an insertion by

Inigo Jones; and being of a much later date than the other parts of the

front, sadly mars the effect of the architecture of old Thorpe. The

third story contains the motto and date “Je. Seray 1572, Loyal.” The

Garden front has a raised Terrace—now a corn-field—in which the slopes

and a few ornamental seats yet remain. This front supplies one of the

grandest examples of Elizabethan architecture existing in England. It

was built by Thorpe, and essentially agrees with the German School of

Architecture of that day—which the British Architect had evidently

studied. The Garden seats, vases, &c., of which there endure only broken

fragments, are in the style, and believed to be the works, of Inigo

Jones. The Garden was terminated by a remarkably picturesque little

bridge, ornamented with a balustrade and scroll work, now, like all

other objects about the structure, or connected with it, submitted to

the wanton assaults of every heedless passer-by. Modern Vandalism has,

indeed, been very busy everywhere within and around this venerable

Mansion;—a farmer occupies a suite of rooms, the decorations of which

would excite astonishment and admiration in a London Club-house;

farm-servants sleep surrounded by exquisite carvings; one room in the

south side of the Quadrangle, decorated with a fine old fire-place, in

which are the arms of the Lord Chancellor, served, at the time of the

artist’s visit, the purpose of a dog-kennel; and an elegant Chapel,

constructed by Inigo Jones, is entered with difficulty through piles of

lumber and heaps of rubbish.

Our initial letter is copied from one of the Finials, which crown the pilasters and gables in the Quadrangle. They formerly held staves with moveable vanes (in metal), “turning with every winde.{58}{57}”

ollatton Hall, the seat of the Right Hon. Digby Willoughby, the seventh

Baron Middleton, is situate three miles west of Nottingham, in the

centre of a finely wooded park, remarkable for a judicious combination

of wood and water. It stands on a considerable elevation, and is seen

from all parts of the surrounding country; of which, consequently, it

commands extensive views—not only of rich and fertile valleys, but of

one of the busiest and most populous of manufacturing towns. We give on

this page an engraving of the north entrance to the mansion.

ollatton Hall, the seat of the Right Hon. Digby Willoughby, the seventh

Baron Middleton, is situate three miles west of Nottingham, in the

centre of a finely wooded park, remarkable for a judicious combination

of wood and water. It stands on a considerable elevation, and is seen

from all parts of the surrounding country; of which, consequently, it

commands extensive views—not only of rich and fertile valleys, but of

one of the busiest and most populous of manufacturing towns. We give on

this page an engraving of the north entrance to the mansion.

The mansion was erected by Sir Francis Willoughby, Knt., towards the close of the sixteenth century, as we learn from an inscription

over one of its entrances. In the old history of the county of Nottingham by Thoroton there is a descent of this family, down to the builder of the present Mansion, whose daughter Bridget married Sir Percival Willoughby, of another branch of the family. Sir Percival left five sons, the eldest of whom, Sir Francis, who died in 1665, was father of Francis Willoughby, Esq., one of the greatest virtuosi in Europe. His renowned history of birds was published in Latin after his death, in 1676. He died in 1672, leaving two sons and one daughter. The latter, Cassandra, was married to James Duke of Chandos. The eldest son died unmarried, in his twentieth year. The second son was created a peer in the tenth of Queen Anne, A.D. 1711. In 1781, on the death of Thomas Lord Middleton without issue,{62} the estate and its honours descended to Henry Willoughby, Esq., of Birdfall, county of York. It is a remarkable circumstance, that up to the present time the heir-at-law, in consequence of there being no proximate issue, has always been a remote member of the family.