Project Gutenberg's Stories Pictures Tell Book 8, by Flora Carpenter This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Stories Pictures Tell Book 8 Author: Flora Carpenter Release Date: September 23, 2020 [EBook #63278] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK STORIES PICTURES TELL BOOK 8 *** Produced by David Garcia, Larry B. Harrison, Barry Abrahamsen, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

| PAGE | ||

| “The Death of General Wolfe” | West | 1 |

| “Portrait of the Artist’s Mother” | Whistler | 16 |

| Mural Decorations and Fresco | 27 | |

| “The Frieze of the Prophets” | Sargent | 29 |

| “The Holy Grail” | Abbey | 57 |

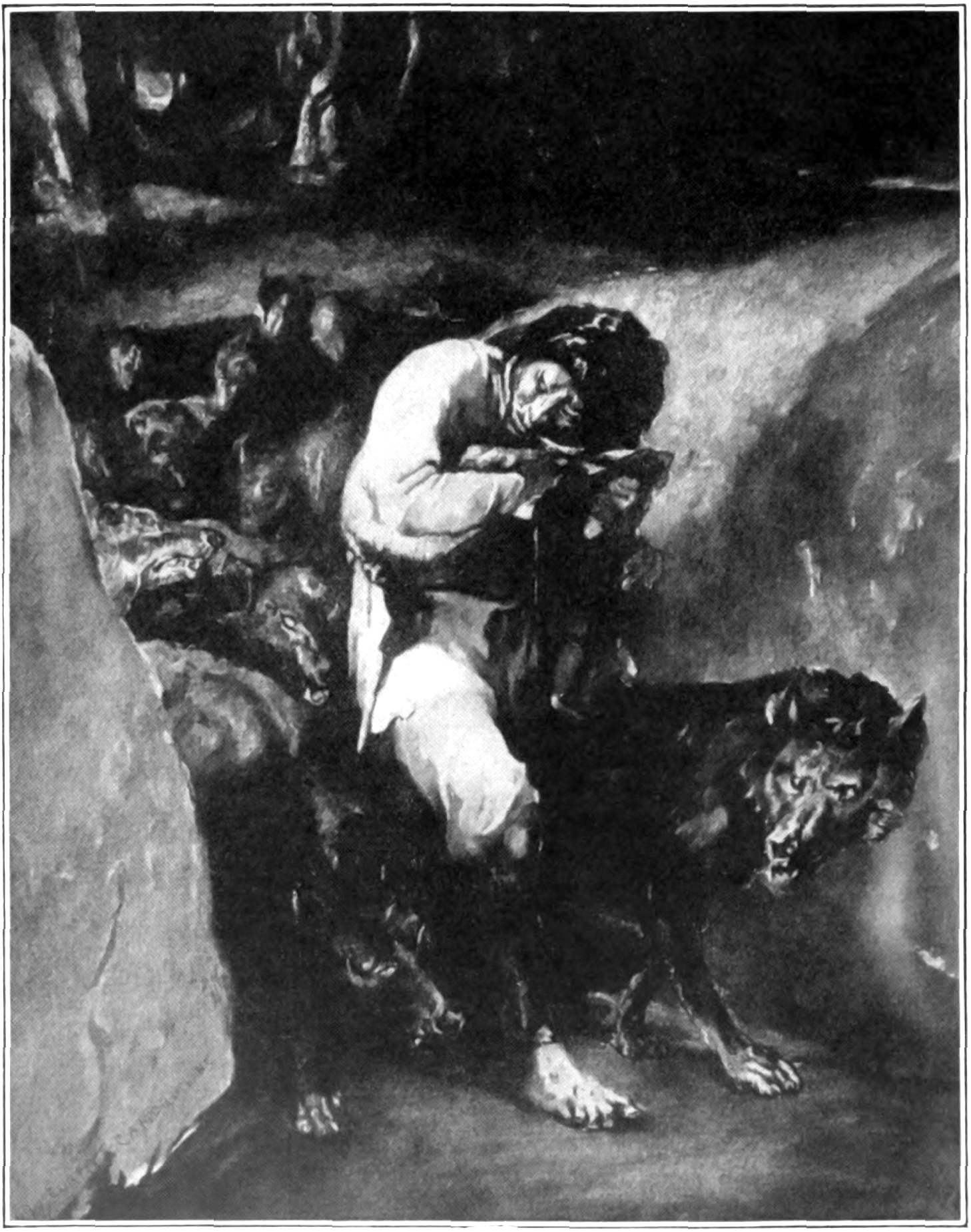

| “The Wolf Charmer” | La Farge | 79 |

| American Illustrators | 92 | |

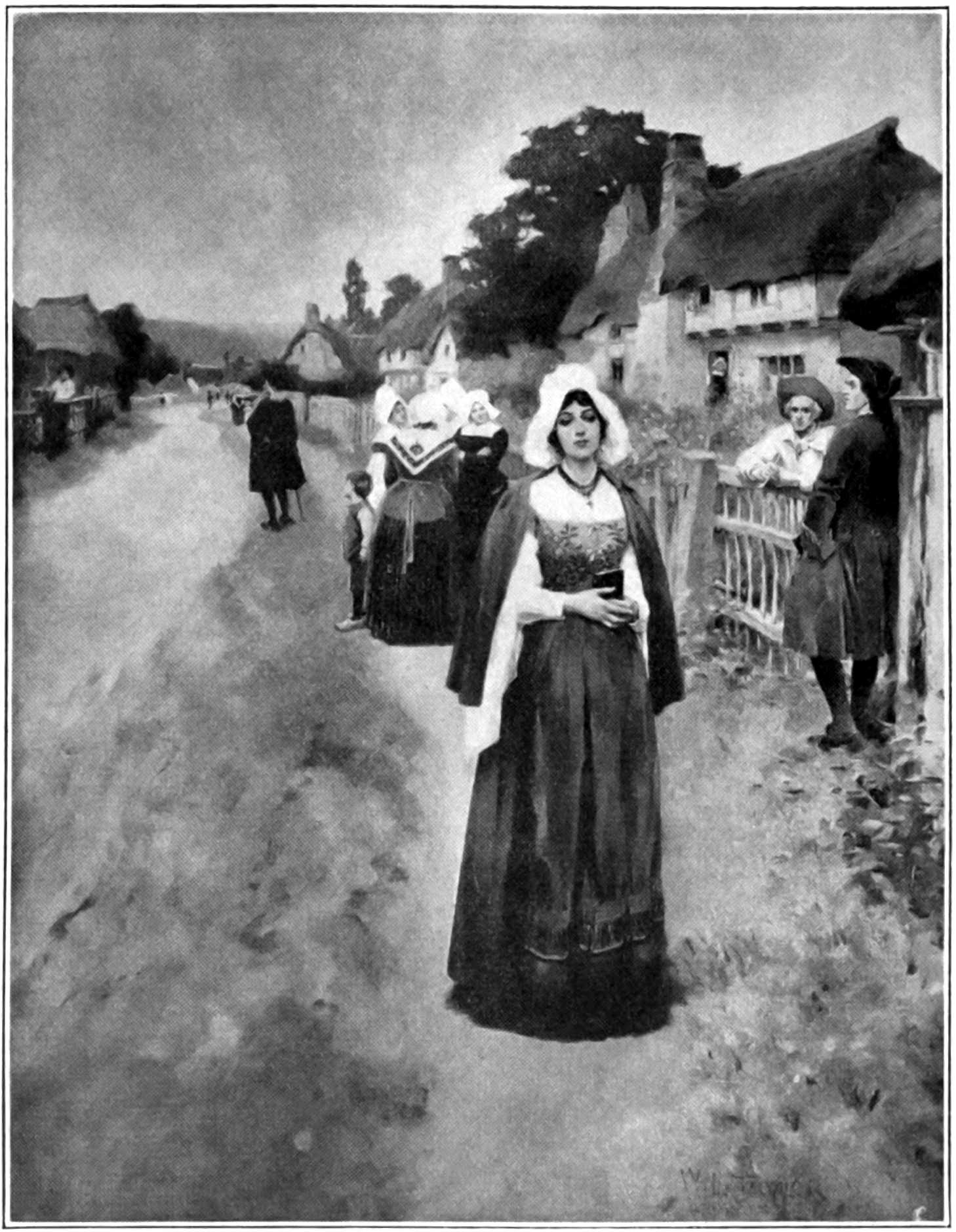

| “Evangeline” | Taylor | 97 |

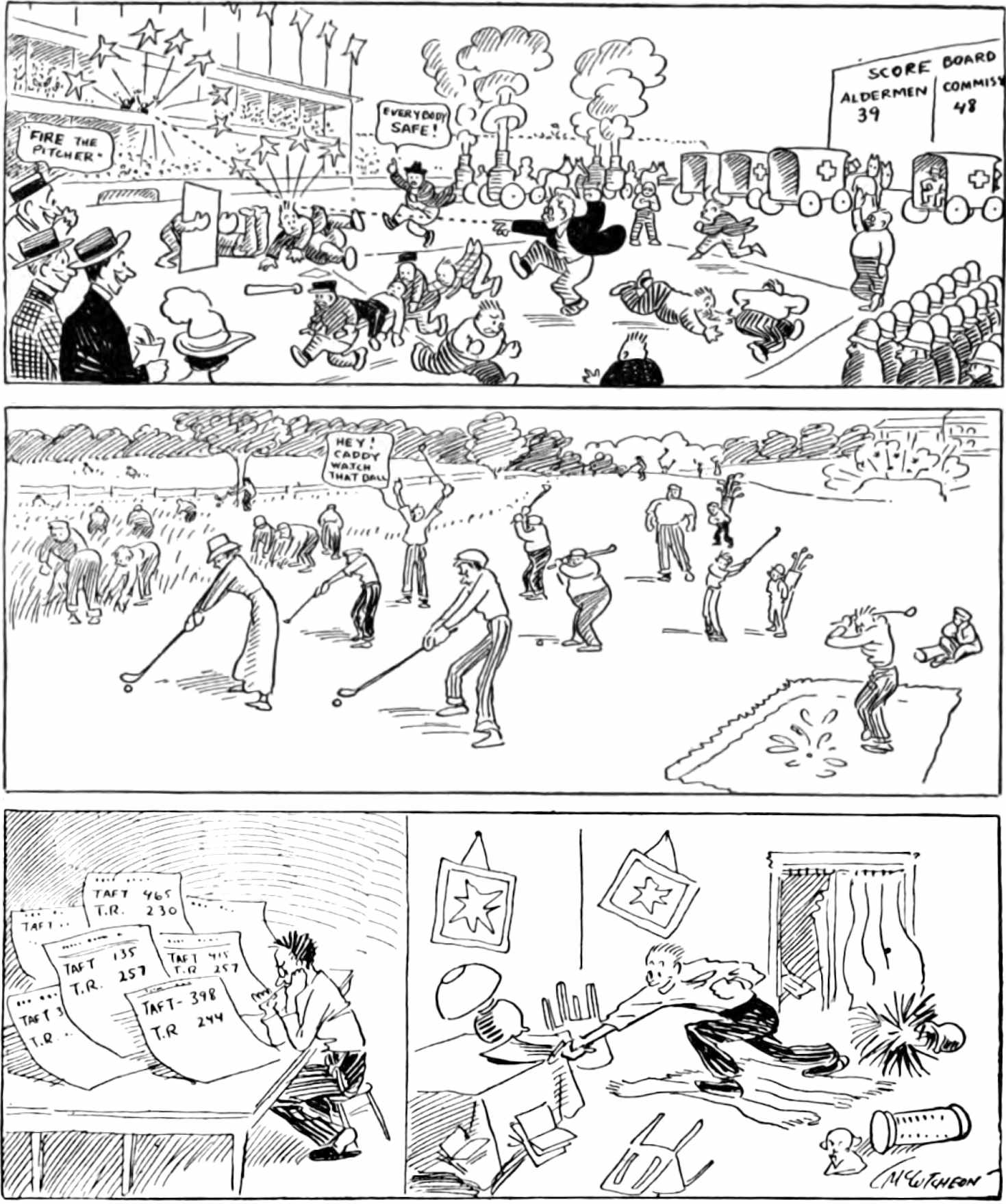

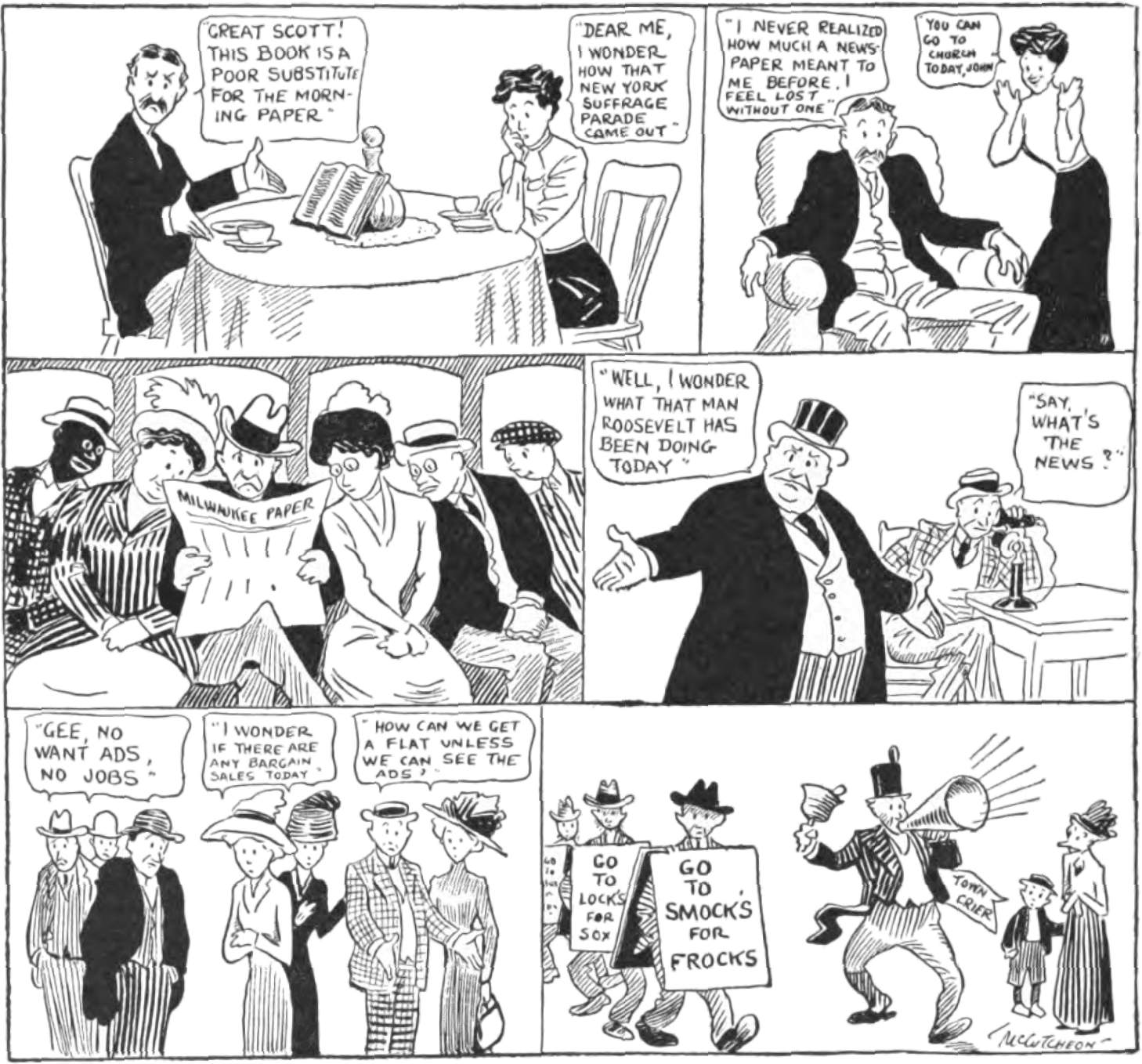

| Cartoons and Caricatures | 108 | |

| Engravings, Etchings, and Prints | 120 | |

| Lithography | 123 | |

| Review of Pictures and Artists Studied | ||

| The Suggestions to Teachers | 125 |

Art supervisors in the public schools assign picture-study work in each grade, recommending the study of certain pictures by well-known masters. As Supervisor of Drawing I found that the children enjoyed this work but that the teachers felt incompetent to conduct the lessons as they lacked time to look up the subject and to gather adequate material. Recourse to a great many books was necessary and often while much information could usually be found about the artist, very little was available about his pictures.

Hence I began collecting information about the pictures and preparing the lessons for the teachers just as I would give them myself to pupils of their grade.

My plan does not include many pictures during the year, as this is to be only a part of the art work and is not intended to take the place of drawing.

The lessons in this grade may be used for the usual drawing period of from twenty to thirty minutes, and have been successfully given in that time. However, the most satisfactory way of using the books is as supplementary readers, thus permitting each child to study the pictures and read the stories himself.

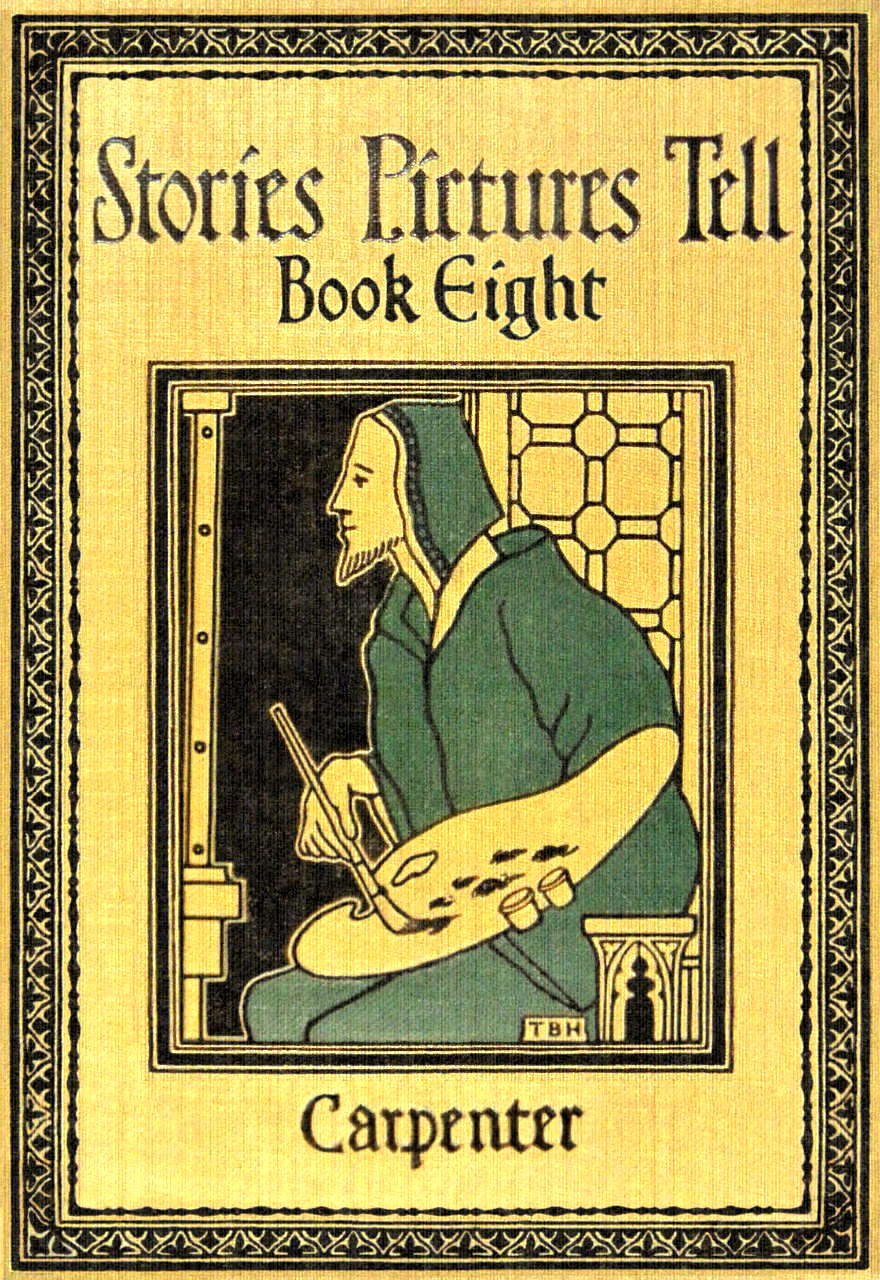

Questions to arouse interest. What is represented in this picture? What have these men been doing? What makes you think so? Why have they stopped? What can you see in the distance? Do you think the soldier running toward the group in the foreground is the bearer of good or bad news? What makes you think so? How many of you can tell what battle has just been fought, or something about General Wolfe?

The story of the picture. It is little wonder that the artist, Benjamin West, who overcame so many obstacles to follow his chosen calling, should admire a man like General Wolfe, who also had a great many difficulties to overcome. Each was born with an overwhelming desire,—the one to be a great artist; the other to be a great soldier. Both achieved their desire through their own earnest and praiseworthy effort. Perhaps the greatest difficulty James Wolfe had to contend with was his poor constitution and constant ill health. He could scarcely endure the long marches by land or voyages by sea—yet he would shirk neither. Duty to his country was always first.

He was only sixteen years old when he took part in his first campaign. Abbé H. R. Casgrain tells us: “He was then a tall but thin young man, apparently weak for the trials of war. Moreover, he was decidedly ugly, with red hair and a receding forehead and chin, which made his profile seem to be an obtuse angle, with the point at the end of his nose. His pale, transparent skin was easily flushed, and became fiery red when he was engaged in conversation or in action. Nothing about him bespoke the soldier save a firm-set mouth and eyes of azure blue, which flashed and gleamed. With it all, though, he had about his person and his manner a sympathetic quality which attracted people to him.” Although a severe illness compelled him to give up this first campaign and return home, Wolfe was by no means discouraged, and he later on managed to distinguish himself for his courage and military skill.

It was not long after this that the great William Pitt decided that Wolfe was a man to be trusted with great things. He appointed him commander of the English troops to be sent against Quebec.

American history had just reached the period when all the English colonies had been founded except Georgia, and the long struggle had come between France and England for the possession of Canada.

There were many older generals who thought they ought to have been appointed to the important command in place of Wolfe, and when the elated Wolfe made some wild boasts in their presence, they were quick to carry them to the king and to declare that James Wolfe was a mad fool, and not fit to command. But King George III liked Wolfe none the less for his enthusiasm, and declared that if “General Wolfe be mad, he hoped he would bite some of his generals.”

But even Wolfe’s enthusiasm could not break down the strong fortification at Quebec. The city was located on a high, rocky cliff in itself almost inaccessible, and the natural strength of the position was increased by the strong defense maintained by the French soldiers and the Indians. Wolfe spent the entire summer trying to find a way to take Quebec, and probably would not have succeeded but for a combination of circumstances which left one part of the cliff unprotected.

With the aid of a telescope, General Wolfe had discovered a hidden pathway up the side of the cliff behind the city at a point which was lightly guarded. Then came a deserter from the French army who informed him that the French were expecting some provision boats that night.

Without hesitation, General Wolfe ordered thirty-six hundred of his soldiers to prepare for the assault. Under cover of night, flying a French flag and with the aid of those of his generals who spoke French, Wolfe and his soldiers managed to sail past the sentry and enter the harbor in the guise of the French provision boats. In absolute silence they sailed up the river and landed at a spot since called “Wolfe’s Cove.” The ascent up the steep hill side was difficult but soon accomplished, and the few guards killed or taken prisoners. All the British soldiers successfully gained the heights and the next morning General Wolfe lined them up for battle on a field called the “Field of Abraham” after the name of its owner.

The French commander, Montcalm, surprised at the presence of the enemy on his own shore, went to meet them hurriedly and without proper support. A fierce battle ensued in which the English were victorious, and the French fled. General Wolfe was wounded three times in this battle, the last time fatally. Even then he called out to those nearest him, “Support me; let not my brave fellows see me fall. The day is ours; keep it.”

In our picture we see General Wolfe half supported on the ground, with his friends about him. At the left is the messenger who, history tells us, bore the news, “They run; see how they run!” The dying general heard the words and asked, “Who run?” Upon hearing the answer, “The enemy,” he exclaimed, “Now God be praised. I will die in peace.”

This victory not only gave Canada to England, but established the permanent supremacy of the English-speaking race in North America. Is it any wonder, then, that Benjamin West, a good American colonist, should be interested in this battle and wish to paint a picture of it?

He started it with great enthusiasm, and soon had the figures sketched in, ready to paint. West was then living in London, and Archbishop Drummond, happening in his studio at this time, was greatly shocked because West had dressed his men in costumes such as they actually wore. Strange as it seems to us now, it was the custom then to use classic models for everything, and to represent all figures as wearing Greek costumes, no matter in what period they lived. If we remember Benjamin West for no other reason, we shall remember him because he was the first in England and America to change this custom. He believed we should paint people just as they are. The archbishop tried to dissuade him from this, and failing, he asked Sir Joshua Reynolds to talk to West.

Finally King George III heard of the artist’s intention and sent for him. West listened to the king with great respect, and then replied: “May it please your Majesty, the subject I have to represent is a great battle fought and won, and the same truth which gives law to the historian should rule the painter. If instead of the facts of action I introduce fictions, how shall I be understood by posterity? The classic dress is certainly picturesque, but by using it I shall lose in sentiment what I gain in external grace. I want to mark the time, the place, and the people; to do this I must abide by the truth.”

The king could not fail to be convinced by so sensible an answer, yet he would not buy the picture. When Sir Joshua Reynolds came to look at the finished picture he praised it unreservedly, and not only told the artist it would be popular but predicted that it would lead to a revolution in art. His prediction was soon fulfilled.

King George III also greatly admired the painting, and said, “There! I am cheated out of a fine canvas by listening to other people. But you shall make a copy of it for me.”

And yet the critics tell us that West, with all his love for truth in dress, took even a greater artist’s license when he painted this picture. He represented men as standing near Wolfe (the two generals, Monckton and Barré) who were not there at all. These two men were fatally wounded in the same battle, but in another part of the field. Surgeon Adair, too, who is bending over the dying hero, was in another part of the country at the time. The Indian warrior, who intently watches the dying general to see if he is equal to the Indian in fortitude and bravery, was, it is claimed, an imaginary person.

But a far greater number of critics uphold West and consider his painting the more valuable because he has brought into prominence a number of the important men of that time, and linked their names in memory with that of General Wolfe and with the cause they represented.

It is interesting to note the manner in which the artist has grouped his figures in the foreground. We can separate them into at least three distinct groups, each complete in itself, yet held together by the direction of their gaze and the position of their bodies. For a moment these brave men have forgotten, in grief at the loss of a beloved companion and hero, even the joy of victory for a great cause.

The interest is centered about the dying general in many different ways—the light, the position of other figures, the direction of their gaze, and his position in the picture. Our attention and interest might remain with the group in the foreground of the picture but that it is drawn, for a moment, to the figure in the middle distance running toward us and from that figure to the mass in the background which, though vaguely outlined, is still distinct enough to give us the impression of troops in action.

Questions to help the pupil understand the picture. Why did the life of General Wolfe appeal so strongly to the artist Benjamin West? What great obstacles did General Wolfe have to overcome? Tell about his first campaign. Describe his personal appearance. Why did William Pitt choose Wolfe for an important office? What feeling did this cause among the other generals? What did George III say about General Wolfe? Explain the difficulties to be overcome in capturing Quebec. How did the English effect a landing? Where was the battle fought? Which army was victorious? What events aided the English in gaining this victory? What new idea did West introduce in this picture? Who opposed him at first? To what did this change lead? What can you say of the composition of this picture? What is its value as history?

The story of the artist. “What is thee doing, Benjamin?” A small boy, hearing this question, suddenly becomes quite confused and embarrassed as he tries to cover up a sheet of paper he has in his hand. His mother and sister, dressed in the severely plain clothing of the Quakers, are standing behind him, waiting for an answer. The boy looks up timidly, his face turning red as he answers hesitatingly, “N-nothing.”

Of course this does not satisfy his mother, and she speaks more sharply as she asks him again what he is doing and what he has in his hand. The boy, a little fellow of six, hands her a sheet of paper and nervously rocks the cradle in which his baby sister is sleeping. He expects to be punished, for he has done something that must be wrong, for he never heard of any one else doing it.

The mother and sister study the paper carefully, and find only a drawing done in red and black ink. They recognize it at once as a picture of the baby sister Sally, sound asleep, and they are pleased in spite of themselves. The mother asks him many questions, and he tells her that as he was taking care of his baby sister he had suddenly felt a great desire to copy the sleeping child’s face. He had found an old quill pen and some ink, and they could see what he had been doing. The mother looks pleased, but says, “I do not know what the Friends would say to such like.” However, Benjamin feels encouraged, and determines to try again soon.

This story is often told in giving the history of American art, because this same Benjamin West was our first native American artist. Other American men had copied European paintings, but his was the first original work in America.

Benjamin’s grandfather came to America with William Penn, the two being intimate friends. Later the West family moved to the small town of Springfield, Pennsylvania, where, in 1738, the grandson Benjamin was born, growing up under the stern observances of an early Quaker home. His father kept a small store, but the family was a large one and many hardships had to be endured in those early days.

At the age of seven Benjamin began to attend the village school. You will remember that the Indians remained very friendly after their treaty with William Penn, and that in those days they often came to visit and trade with the settlers. The boys in this little school always looked forward to these visits, as they liked to talk with the Indians in sign language and to trade with them for bows and arrows and other curious things the Indians made.

They came one day when Benjamin had been drawing some birds and flowers on his slate. When shown the sketches they grunted their approval and the next time they came the big chief brought Benjamin some red and yellow paint, the kind they used to decorate their bodies.

How delighted Benjamin was as he ran home with his colors; but what could he do without blue? Then his mother remembered the bluing she used for her clothes, and gave him a piece of indigo. Now he must have a brush. You have probably heard of how he cut the fur from the tip of the cat’s tail, and so made a very good brush, although it did not last long. This made it necessary for him to cut so much fur that the cat became a sorry sight indeed. Benjamin’s father thought it must have some disease and was about to chloroform it, when his son told him the true state of affairs.

Not long afterwards an uncle who was a merchant in Philadelphia sent Benjamin a complete painter’s outfit,—paints, brushes, canvas, and all. It is said that the day these came Benjamin suddenly disappeared from sight and could not be found either at school, where he should have been, or in any of his favorite haunts.

At last his mother thought of the attic, and there she found him so busily absorbed in painting his picture that at first he did not hear her. She had intended to punish him, but, seeing his pictures, she forgot all else as she said, “Oh, thou wonderful child!”

When the uncle came to visit them he was so delighted he took Benjamin back with him to Philadelphia, where he could have good instruction in drawing. At eighteen he began to paint portraits. Then, after living in New York several years, he traveled extensively in Europe, finally settling in London, where he remained the rest of his life.

He became court painter for King George III, and succeeded Sir Joshua Reynolds as president of the Royal Academy, holding this position until his death.

Benjamin West caused one complete change in the art of England. Until his time all art had followed the Greek ideas, the artists using the Greek costumes for figures of men of all periods. West believed we should paint people just as they are, so he dressed his people in the costumes of the day. At first, of course, he was criticized severely, but soon all the artists were following his example. Benjamin West became the founder of a school of his own, to which young artists from both America and England went for help and encouragement. Although he spent the last years of his life in England, Benjamin West always remained a patriotic American.

The first few painters of note who followed Benjamin West were greatly influenced by him. The list of prominent American artists is constantly increasing. J. Walker McSpadden, in his book called Famous Painters of America, has classified a few of the most prominent in a way that may help us remember them:

Benjamin West, the painter of destiny.

John Singleton Copley, the painter of early gentility.

Gilbert Stuart, the painter of presidents.

George Inness, the painter of nature’s moods.

Elihu Vedder, the painter of the mystic.

Winslow Homer, the painter of seclusion.

John La Farge, the painter of experiment.

James McNeill Whistler, the painter of protest.

John Singer Sargent, the painter of portraits.

Edwin Austin Abbey, the painter of the past.

William M. Chase, the painter of precept.

Questions about the artist. Who was the first American artist of note? Where was he born? Of what faith were his parents? Relate the circumstances which led to Benjamin West’s first drawing, and the result. How old was he at that time? How did he secure his first paints? his brushes? What gift did his uncle send him? What became of Benjamin the day this gift was received? What did his mother say? Where did he go to study art? In what way did he change art in England? What school did he establish? Name five other American artists, and tell why they are famous.

To the Teacher: Several pupils may prepare the subject-matter as suggested here, then tell it to the class. Later, topics may be written upon the blackboard and used as suggestive subjects for short compositions in English.

1. Relate an incident in the life of Benjamin West that persuaded his parents he would be an artist.

2. Explain some of the difficulties he had to overcome in order to paint.

3. What preparation did he make to become an artist?

4. In what ways was he of special benefit to the world of art?

5. Tell something of the progress of American painting from that time to this.

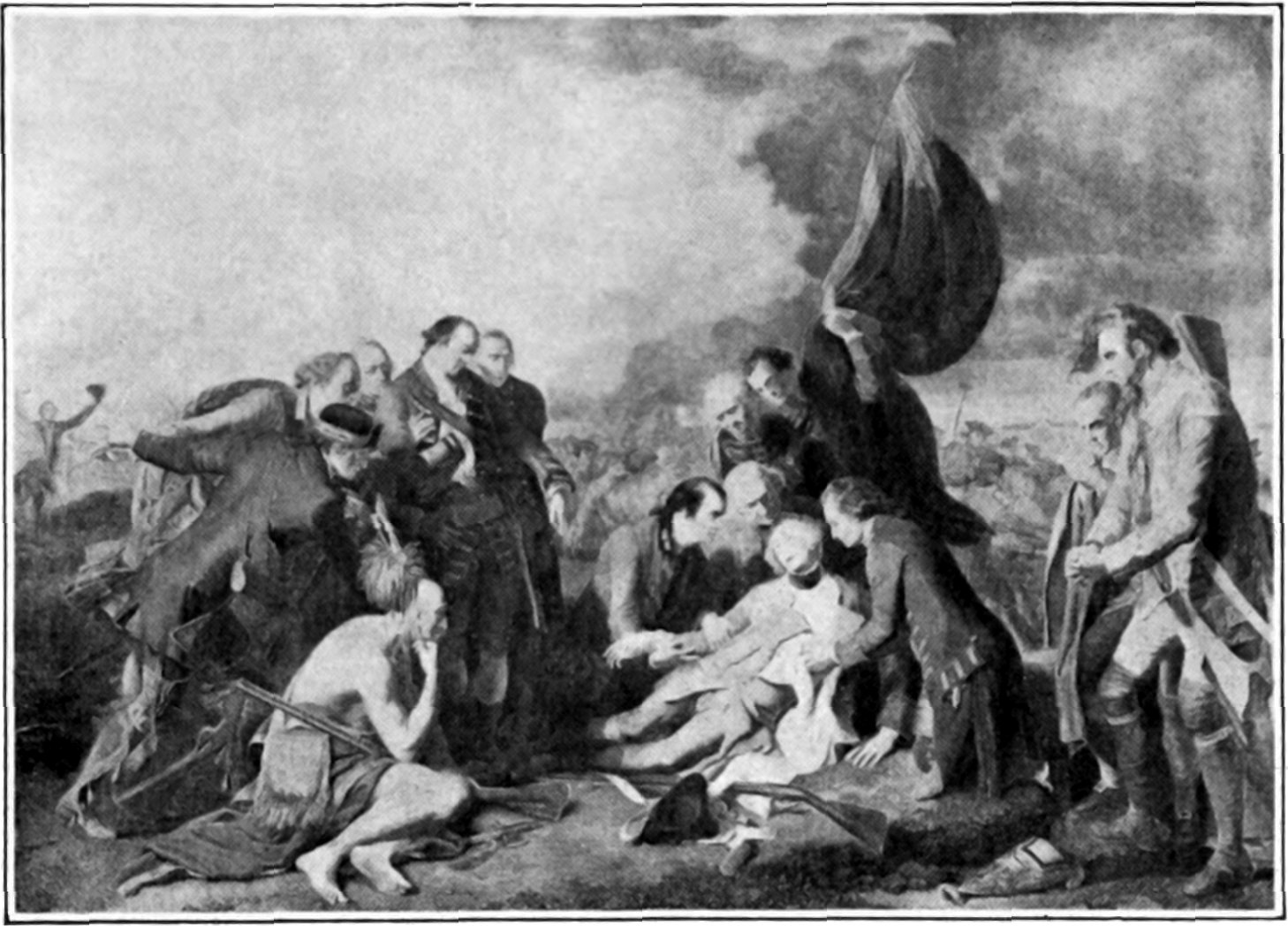

Questions to arouse interest. What is the name of this picture? Who painted it? Half close your eyes and tell what part of the picture stands out most distinctly. Which part should be most distinct? (The figure, especially the head, holds the center of interest.) From this glimpse of her, describe the character and disposition of Whistler’s mother as you would judge them to be. Give reasons. What would make you think she was neat and orderly? Where is she sitting? How is she dressed? What can you see in the background?

The story of the picture. Whistler called this picture “An Arrangement in Gray and Black,” for he felt that the public could not be interested in a portrait of his mother. He said, “To me, it is interesting as a picture of my mother; but what can or ought the public to care about the identity of the portrait?” However, this knowledge of relationship has appealed so strongly to the people that by common consent the picture has been renamed by them, “Whistler’s Mother,” or “Portrait of the Painter’s Mother,” or even “Portrait of My Mother.” Then again many critics declare the picture might well be called “A Mother,” for it represents a type rather than an individual. The face seems to speak to each and every one of us in a language all can understand.

This dear old lady in her plain black dress, seated so comfortably with her hands in her lap and her feet on a footstool, has an air of peace and restfulness about her that is good to look upon. A feeling of stillness and perfect quiet comes to us, and we do not at first realize the skill of the artist in producing such an effect.

Seated in this restful gray room, she seems to be in a happy reverie of the days gone by. The simple dignity of the thoughtful figure is increased by the refinement of her surroundings. A single picture and part of the frame of another hang on the gray wall behind her. At the left we see a very dark green curtain hanging in straight folds, with its weird Japanese pattern of white flowers.

All is gray and dull save the face. This contrast brings out its soft warmth. The dark mass of the curtain with its severely straight vertical lines, contrasted with the darker diagonal mass which represents the figure of the mother, gives us a feeling of solemnity and reverence. The severity of these dark masses is broken by the head and hands. The dainty white cap with its suggestion of lace on the cap strings softens the sweet face and relieves the glossy smoothness of her hair. In her hands she holds a lace handkerchief which we can barely distinguish from the lace on her cuffs. But the hands serve as an exquisite bit of light to lead the eye back to the face, where we study again the calm and tender dignity of the figure and the mysterious beauty of those far-seeing eyes.

By this very simplicity, quiet, and repose, Whistler has made us feel the love and reverence he has for his mother. He leaves us to guess what the mother herself may be thinking as she looks back over the life now past. With what reluctance she may have at first consented to pose for her portrait, believing that this great, wonderful son of hers had better choose some younger, fairer model, more responsive to his magic brush! But when she found his heart was set upon painting her portrait, she would hesitate no longer.

No doubt he knew just which dress he wished his mother to wear. We all know the dress we like to see our own mother wear. Very likely Whistler had planned the picture for days and knew exactly where he wished her to sit and just how the finished portrait was to look. And the mother, with her faith in her son’s talent, probably thought his wanting her picture was only a token of his love for her, little realizing that this portrait alone would make her son famous.

We are moved by the silence and reserve of this gentle lady to an appreciation of the love, reverence, and respect that are her due.

Held at a distance, our reproduction of this picture seems to consist merely of a black silhouette against a light gray wall. On closer examination we soon discover two other values—that of the floor, which is medium gray, and the darker mass of the curtain.

Whistler was so fond of gray that he always kept his studio dimly lighted in order to produce that effect. His pictures are full of suggestions rather than actual objects or details. In his landscapes all is seen through a misty haze of twilight, early morning, fog, or rain. They suggest rather than tell their story. He makes us think as well as feel.

Questions to help the pupil understand the picture. What did Mr. Whistler call this painting? Why was the name changed? What is it often called? why? Which name seems the most appropriate to you? What colors did the artist use? How many values are represented in this painting? What are they? What can you say about the division of space in the picture? of the light and shade? of the interior of the room?

To the Teacher: Tell about the picture and the artist, or have some one pupil prepare the story and tell it to the class. This may be followed by a written description of the picture and a short sketch of the artist’s life by the class, given in connection with the English composition work. These questions may be written upon the blackboard as a guide or suggestion.

The story of the artist. Perhaps there never was a boy more fond of playing practical jokes than James McNeill Whistler. For this reason he made many enemies as well as friends, for you know that, although very amusing in themselves, practical jokes are apt to offend.

But first we should know something about Whistler’s father and mother. Of a family of soldiers, the father was a graduate of West Point Military Academy, and became a major in the United States army. During those peaceful days there was very little to keep an army officer busy, so the government allowed its West Point graduates to aid in the building of the railroads throughout the country. Civil engineers were in great demand, and from a position as engineer on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, Major Whistler became engineer to the Proprietors of Locks and Canals at Lowell, Massachusetts. To Lowell, then a mere village, Major Whistler brought his family, and here James was born. Later the family moved to Stonington, Connecticut.

Whistler’s mother was a strict Puritan and brought up her son according to Puritan beliefs. Their Sundays were quite different from ours at the present day. They really began on Saturday night for little James, for it was then that his pockets were emptied, all toys put away, and everything made ready for the Sabbath. On that day the Bible was the only book they were allowed to read.

When they lived in Stonington, they were a long distance from the church and, as there were no trains on Sunday, the father placed the body of a carriage on car wheels and, running it on the rails as he would a hand car, he was able to take his family to church regularly. This ride to church was the great event of the day for James.

James’s first teacher at school, though a fine man, had unfortunately a very long neck. In his wish to hide this peculiarity he wore unusually high collars. One day little James came in tardy, wearing a collar so high it completely covered his ears. He had made it of paper in imitation of the teacher’s. As he walked solemnly to his seat, the whole school was in an uproar. James sat down and went about his work as if unconscious both of commotion and of the angry glare of his teacher. It was not many minutes before the indignant man rushed upon him and administered the punishment he so richly deserved.

When James was nine years old the family moved to Russia. The Emperor Nicholas I wished to build a railroad from the city of St. Petersburg (now called Petrograd) to Moscow, and had sent all over Europe and America in search of the best man to undertake this work, at last choosing Major Whistler. It was a great honor, of course, and the salary was twelve thousand dollars a year. Here the family lived in great luxury until the father died. Then Mrs. Whistler brought her children back to America to educate them.

When only four years old James had shown considerable talent for drawing, but although his mother admired his sketches she always hoped and planned that her son should become a soldier like his father. So at the age of seventeen she sent him to West Point, where he remained three years before he was discharged for failure in chemistry.

Although he had failed in most of his other studies, too, he stood at the head of his class in drawing. He received much praise for the maps he drew in his geography class, and some of them are still preserved. Whistler himself tells us: “Had silicon been a gas, I would have been a major general.” It was during an oral examination, after repeated failures, that his definition, “Silicon is a gas,” finally caused his dismissal.

Another story is told of his examination in history. His professor said, “What! do you not know the date of the Battle of Buena Vista? Suppose you were to go out to dinner and the company began to talk of the Mexican War, and you, a West Point man, were asked the date of the battle, what would you do?”

“Do?” said Whistler. “Why, I should refuse to associate with people who could talk of such things at dinner.”

Whistler’s real name was James Abbott Whistler, but when he entered West Point he added his mother’s name, McNeill. He did this because he knew the habit at West Point of nicknaming students, and he feared the combination of initial letters would suggest one for him, so he substituted McNeill for Abbott. He was called Jimmie, Jemmie, Jamie, James, and Jim.

The older he grew the more Whistler seemed to enjoy playing practical jokes. Soon after he left West Point he was given a position in a government office, but was so careless in his work he was discharged. As he was going past his employer’s desk he caught sight of an unusually large magnifying glass which that official used only on the most important occasions and which was held in great awe by the employes. Whistler quickly painted a little demon in the center of this glass. It is said that when the official had occasion to use the great magnifying glass again he hurriedly dropped it thinking he must be out of his head, for all he could see was a wicked-looking demon grinning up at him.

When Whistler began to paint in earnest he was very successful, and soon became the idol of his friends. In fact, the admiration of his friends proved quite a misfortune, for it sometimes made him satisfied with poor work. A friend coming in would find a half-completed picture on his easel and go into raptures over it, saying, “Don’t touch it again. Leave it just as it is!” Whistler, pleased and delighted, would say he guessed it was rather good, and so the picture remained unfinished.

Many stories are told of the models he chose from the streets. Often some dirty, ragged little child would find itself taken kindly by the hand and led home to ask its mother whether it might pose for the great artist. After some difficulty the mother would be persuaded to let the child go just as it was, dirt and all. As soon as Whistler began to paint, he usually forgot everything else and so at last the child would cry out from sheer weariness. Then with a start of surprise Whistler would say to his servant, “Pshaw! what’s it all about? Can’t you give it something? Can’t you buy it something?” Needless to say, the child always went home happy with toys and candy.

Whistler saw color everywhere, and he was especially quick to feel the beauty of color combinations. The names of his paintings suggest that this love of color was of first importance in his work, even before the object or person studied. So we have “A Symphony in White,” “Rose and Gold,” “Gray and Silver,” “A Note in Blue and Opal,” and “Green and Gold.”

Questions about the artist. Of what nationality was the artist? What was his father’s profession? What important positions did he hold? How did the family observe Sunday? What was the great event of the day for James McNeill Whistler? To what country did the family move? What happened after the father’s death? Where was James sent to school? Why did he fail? Why did he change his name? Tell about the position in the government office and what happened there. How did praise and admiration affect him? Name some of his best paintings.

The term “mural decoration” applies to the decoration of walls and ceilings. These decorations may be done in fresco, oils, sculpture in low relief, mosaics, carved and paneled woodwork, or tapestries. In fresco painting a damp plaster ground is prepared on the wall, upon which the moist colors are painted. These colors become fixed as they dry, and appear to be a part of the wall. The work must be done while the plaster is damp, so the painter prepares only that part of the wall which he expects to cover that day. As it cannot be used after it is dry, he must scrape away all that is left and prepare a new background the next day. If the artist wishes to change any part of his picture, he must scrape off the ground and repaint the entire picture. It is often easy to see where the new plaster has been added, and hence how much the artist did in one day.

The damp atmosphere in northern countries soon destroys fresco paints, while the warm, sunny climate of such countries as Italy and Spain preserves them. Most of the fresco paintings of such old masters as Fra Angelico, Raphael, Leonardo da Vinci, and Michelangelo are still to be seen in much of their original beauty.

In America, fresco is seldom used, as artists find that oil paints on canvas, which may be fastened to the wall with white lead, are much more lasting and satisfactory.

Some of the best-known mural paintings in the United States are found in the Boston Public Library, Boston, Massachusetts: “The Holy Grail,” by Edwin Abbey (American); “The Frieze of the Prophets,” by John Sargent (American); and “The Muses Welcoming the Genius of Enlightenment,” by Chavannes (French). In the Congressional Library, Washington, D.C., the artists represented are: Elihu Vedder (American), J. W. Alexander (American), H. O. Walker (American), Charles Sprague Pearce (American), Edward Simmons (American), G. W. Maynard (American), and Frederick Dielman (American by adoption). In the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, New York City, E. H. Blashfield (American) and Edward Simmons are represented. At the Carnegie Institute the work of John W. Alexander is represented, and at the Walker Art Building, Bowdoin College, Maine, we find works by Cox, Thayer, Vedder, and La Farge.

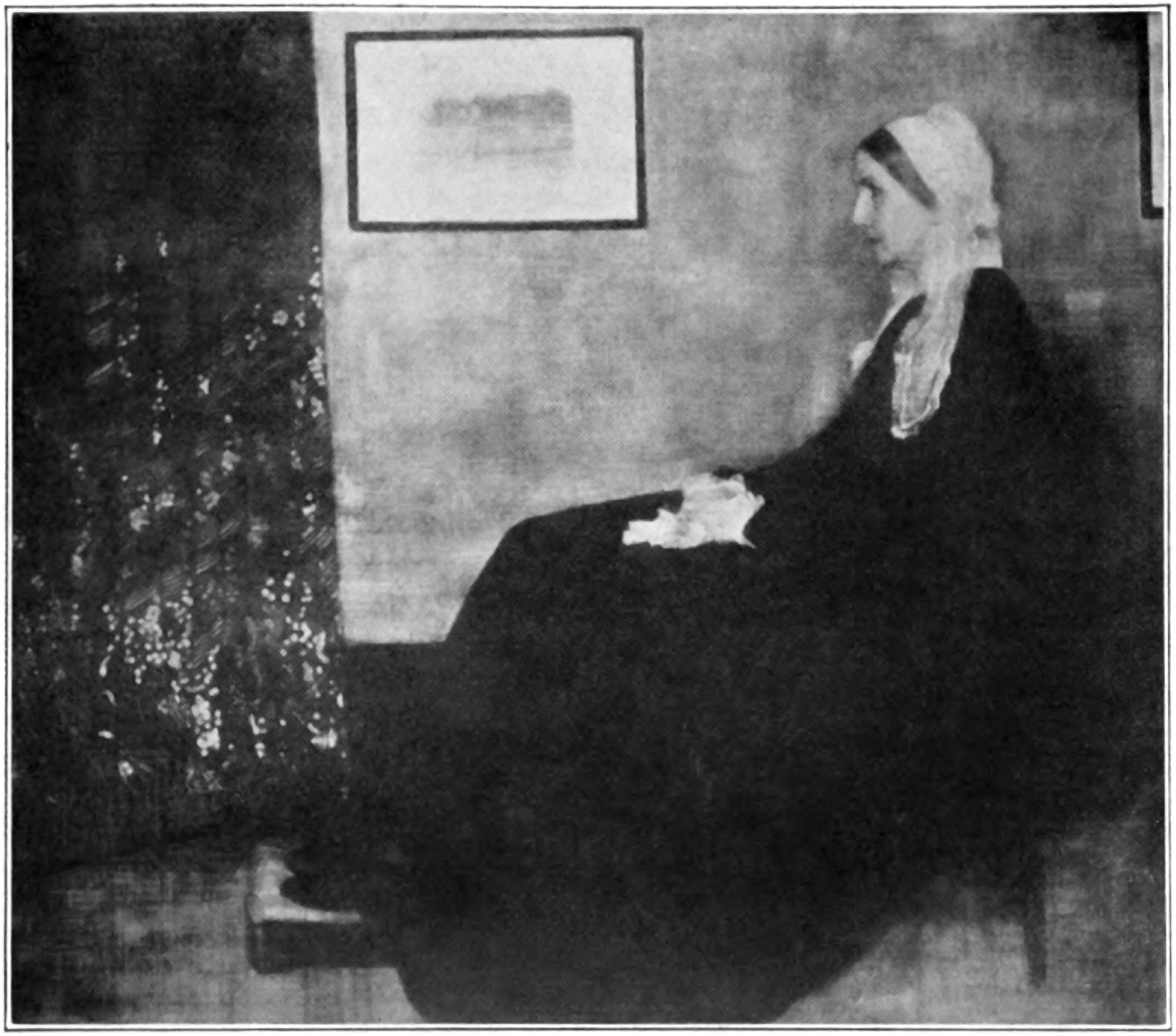

Questions to arouse interest. Who were the “prophets”? How many are represented in this picture? Relate some incident or event in the life of any one of them. What book tells about the lives of these men? Of what benefit were they to the world? How many groups are complete in themselves? How are the five groups held together to form a single composition?

The story of the frieze. This painting is placed on the third floor of the Boston Public Library, Boston, Massachusetts, in what is known as Sargent Hall. The third floor of the library contains valuable collections of books on special subjects, and to approach these rooms we must pass through a long, high gallery. This is Sargent Hall, named in honor of the artist who decorated its walls. At about the time that Mr. Abbey was asked to decorate the walls of the Delivery Room, Mr. Sargent, also an American, received a commission to decorate both ends of this hall or gallery. He was paid fifteen thousand dollars for the work. So successful was he in pleasing the people, and so much enthusiasm was aroused, that immediately an additional sum of fifteen thousand dollars was raised by popular subscription, and Mr. Sargent was urged to complete the decoration of the entire hall.

The “Frieze of the Prophets” is only a part of the decorations of Sargent Hall. Mr. Sargent has described the complete scheme of decoration as representing “the triumph of religion, showing the development of religion from early confusing beliefs to the worship of the one God upon the basis of the Law and the Prophets.”

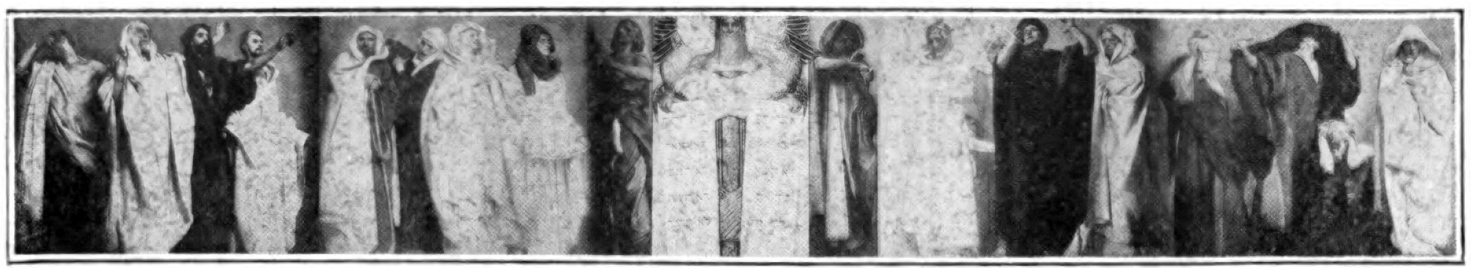

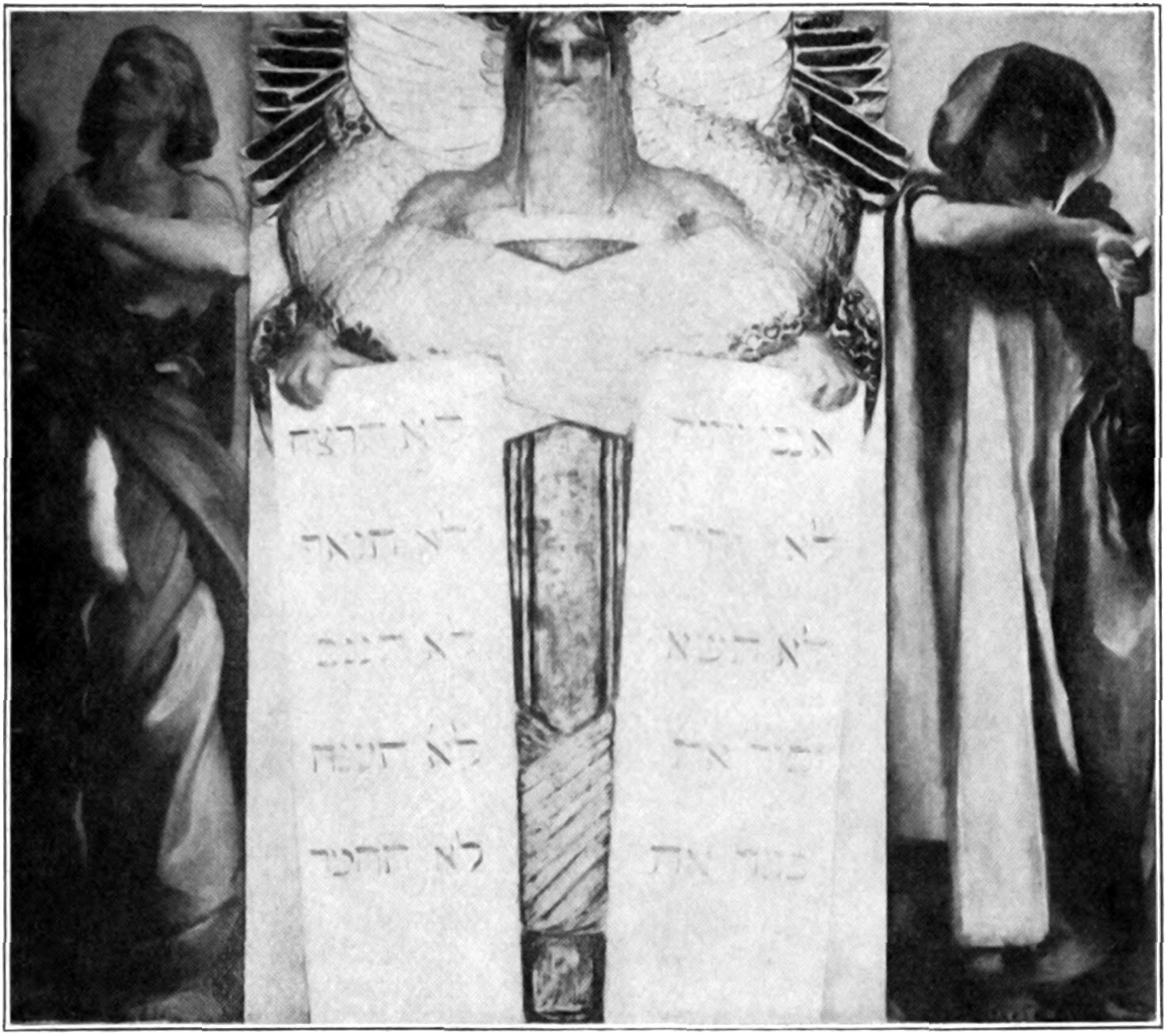

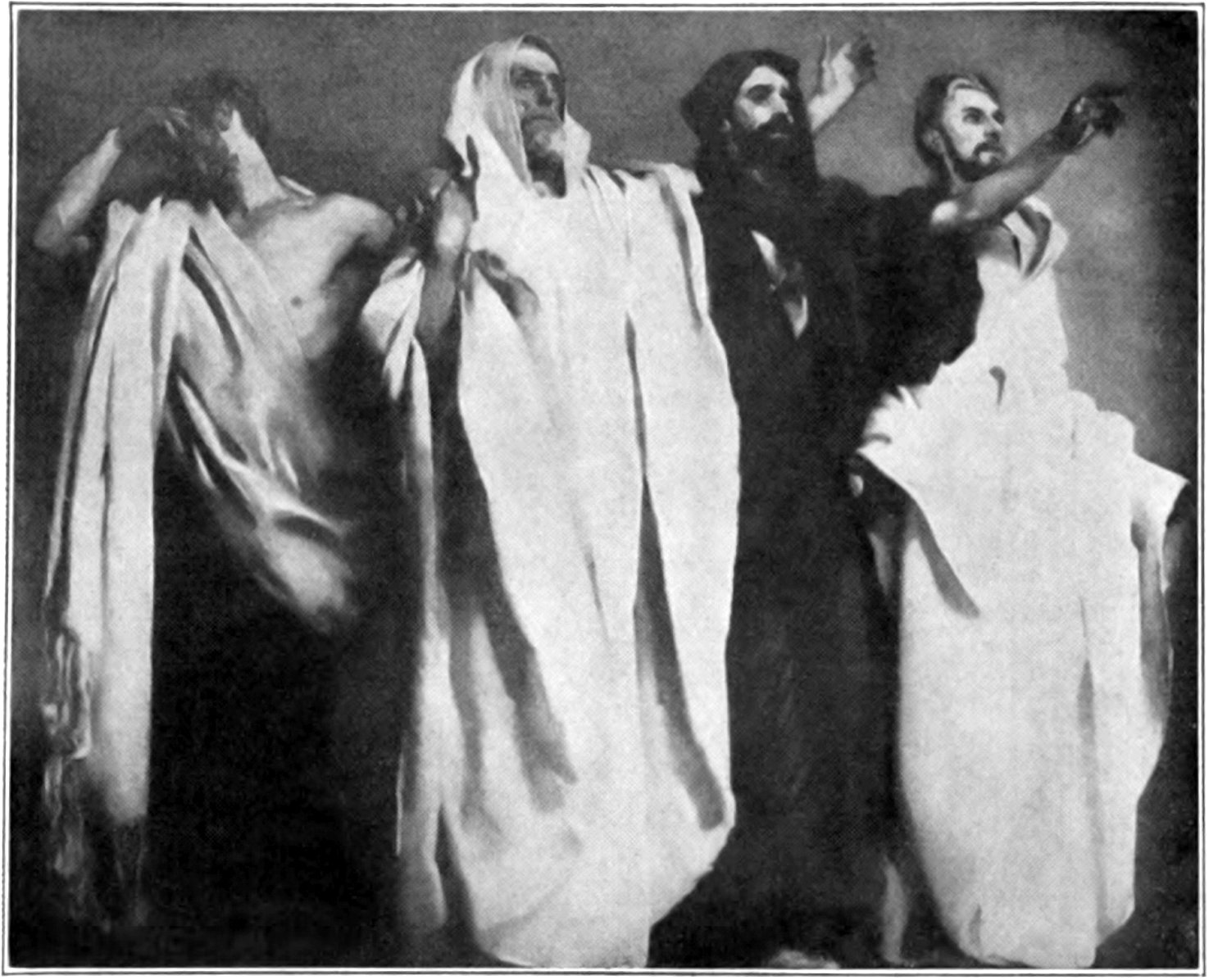

Elijah, Moses, Joshua. The Frieze of the Prophets

One glance at the picture tells us that the central figure, that of Moses, is the most important among the nineteen prophets represented. Of all the prophets Moses is considered the most ideal and superhuman, and thus Mr. Sargent has tried to represent him. By using more conventional lines, and by modeling the figure in low relief so that it stands out from the rest of the picture, he has produced this distinguishing effect. The face, beard, shoulders, arms, and Tables of the Law stand out in the painting as if they were carved from stone. In fact, as we look at him we think more of a monument than of a painting. The wings crossed so stiffly make the figure seem all the more erect, while the feathers seem to send out rays of light over the entire picture. The earnest face with its deep-set eyes suggests the strength and courage of that great leader who felt that upon him lay the responsibility for the restless, ignorant idolaters whom he was to lead.

When we read the story of the prophet’s life we are filled with wonder. From the very first it was unusual. Moses was born at the time when the wicked king of Egypt commanded that all boy babies of the Israelites should be drowned. But his mother kept him hidden until he was three months old. Then she placed him in a small boat or ark which she pushed out among the flags and grasses of the river.

We all know how the daughter of Pharaoh found the child and adopted him as her own son. She named him Moses, meaning “to draw out,” for, as she said, she had drawn him out of the water. Grown to manhood among the Egyptians, his open sympathy for his own people caused him to be banished. Then, in the vision of the burning bush, which burns yet never is consumed, the Lord appeared to him and told him that he was to deliver the people of Israel out of the hands of the Egyptians. But when he was told to go to speak to Pharaoh his courage deserted him, and it was not until after several miracles had been performed and divine help promised that he was willing to go.

Aaron, brother of Moses, went with him to ask Pharaoh to permit the Israelites to go on a three days’ journey into the wilderness to offer sacrifices to the Lord. But Pharaoh only laughed at them. A great many dreadful things had to happen to Pharaoh’s people before he would give his consent—the water was turned to blood; the land was covered with frogs, and lice, and flies; the cattle were afflicted with a dreadful disease; man and beast were covered with running sores; hail destroyed most of the crops; locusts came to devour the rest, and the whole country, except the land in which the Israelites dwelt, was cast into darkness. During each of these scourges Pharaoh would send for Moses and beg him to ask God to deliver the land, saying he would let the Israelites go. But as soon as the danger was removed he would refuse to keep his promise.

Then came the most dreadful scourge of all—the death of the first-born in every Egyptian home. Again Pharaoh had failed to heed the warning of Moses. There was weeping and wailing in Egypt that day, for every home lost a loved one. In great haste the king sent messengers to Moses, giving the Israelites his consent to go and even urging them on their way.

So with their families and their worldly goods the Israelites started out in search of the promised land under the leadership of Moses and Aaron. They had scarcely begun their weary journey before Pharaoh regretted having allowed them to go, and sent spies and an army after them. But a “pillar of cloud” came between the two camps and hid the Israelites that night. In the morning the Red Sea, over which they must cross, divided before them and they walked across on dry land between the walls of water. When they had passed, the waters closed in again and destroyed the pursuing Egyptians.

Then comes the wonderful history of those forty years’ wanderings in the wilderness, led by clouds by day and pillars of fire by night, until the Israelites reached the promised land. During all this time, under the guidance of the Lord, Moses taught his people and directed them in all their affairs. Yet they were not capable of understanding his great spiritual convictions, for at one time, when Moses remained on Mount Sinai forty days and forty nights communing with God, he found upon his return that his people had made themselves an idol and were worshiping it. Their faith seems never to have been very strong, and they were constantly in need of the help and encouragement of their great leader.

From Mount Sinai, Moses brought them the two stone tablets, with the Ten Commandments written upon them.

In his picture Mr. Sargent has represented Moses with two little horns on his forehead. After Moses came down from Mount Sinai, where God had spoken to him, his face shone, or, as the Bible says, “sent forth beams or horns of light.” These horns are also shown very distinctly in Michelangelo’s wonderful statue of Moses.

Here we see him represented as a sort of spiritual giant, holding toward us for our observance the two stone tablets containing the Ten Commandments upon which all Christian living should be based.

During the forty years’ wandering in the wilderness many hostile tribes were encountered and had to be subdued. Then a young man, strong, energetic, and skillful in arms, came forward to lead the army. This young leader was Joshua, represented at the right of Moses in the act of sheathing his sword.

Moses himself saw the promised land far off from the top of a mountain. The Lord had told him to go there to look upon it, as he could not live to reach it. Moses then spent his last days instructing his people and their new leader, Joshua the warrior, who was to guide them to the end of their journey.

Having received the promise of divine help, the Israelites under their new leader again took up the march. When they reached the River Jordan, it, like the Red Sea, divided and allowed them to walk over on dry land; the guarded massive walls of Jericho fell that they might enter and possess the land. But there were still other hostile tribes to be conquered before they could feel that the land was really theirs. They were successful in all their battles except one, in which defeat came to them because one man had stolen plunder and hidden it in his house contrary to his promise to God. The sin confessed, victory returned.

When all the land was conquered it became Joshua’s duty to divide it among the different tribes, a long and difficult task. This accomplished, he gathered his people together and told them that his time of leadership was about to end. Then he made them decide for themselves whether they would henceforth worship idols or the one God. They vowed they would worship the one God, and Joshua caused them to erect a monument as a reminder of their vow.

In our picture the simple, straight lines of the figure of Joshua are suggestive of the determined, forceful character of the man. They give an impression of great strength. Notice how the light falls upon his upraised arm and the straight folds of his garment. It seems to come directly from the wings of the figure of Moses, as if to acknowledge the wisdom and inspiration which Joshua received from the great leader. The face of Joshua, half hidden under his hood, is thoughtful yet determined. Here is a man of strong, steady purpose, pressing on persistently until he, with all his people, should reach the promised land.

Of a quite different type is the prophet Elijah, whom we see at the left of Moses. This enthusiastic leader, regardless of physical comforts or earthly pleasures, bends all his energies toward the one great cause. His complete forgetfulness of self is well represented here by the careless draperies, the intense feeling in the face, and the strained muscles of the neck and arms. We know little about his life until the time when he was sent as messenger to the palace of the wicked King Ahab. This king over the Israelites lived in a magnificent palace made of ivory and gold, with beautiful gardens about it. But his wife, Jezebel, was a wicked woman, and a worshiper of idols, and she persuaded Ahab to build a great temple to one of her gods, Baal, and to worship with her.

One day, without any warning, a strange-looking man wearing a cloak of camel’s hair and carrying a strong staff in his hand, appeared before Ahab in the throne room of his magnificent palace. It was Elijah, and without even bowing to the king or showing him any respect whatever, he delivered this dreadful message in a loud voice: “As the Lord God of Israel liveth, before whom I stand, there shall not be dew nor rain these years, but according to my word.” Before the astonished king could answer, Elijah had disappeared.

Then the Lord warned Elijah to hide by a certain brook called Cherith, for Ahab would pursue him. Here he lived three months, fed by the ravens and hiding in caves in the rocks, for this brook was hidden between two hills of rock covered with leaves. But soon the brook became dry, for there had been no rain. Then again came the message of the Lord, telling him to go to a certain widow’s home many miles away, where he would be taken care of. As Elijah neared the gates of the city where she lived, he met a woman gathering sticks. He asked her for some water and bread, but she told him she had just enough meal to make one little cake for herself and her small son. After that they must die, for she was very poor. She had been gathering the sticks to bake the cake. Then Elijah told her to make a cake for him first, and not to be afraid, for the Lord had told him her meal and oil should not give out before the rain came. She did as he said, and, sure enough, she had as much meal and oil as before. Then she knew this to be a man of God, and offered to let him stay in her home.

Elijah remained there two years, during which time the drought continued over Israel, and Ahab sought the prophet in vain.

Then came the voice of the Lord commanding him to go again to the king with a message. Ahab was very angry when Elijah again appeared; but Elijah was not afraid. He ordered Ahab to gather all the Israelites at Mount Carmel and to bring there also the prophets of Baal, the heathen god. But the wicked Jezebel had caused all the prophets of the Israelites to be put to death, so that Elijah was alone against the four hundred and fifty prophets of Baal. While he waited, Elijah spent the time in prayer.

When all were gathered at Mount Carmel, the king in his royal purple robes, the false prophets in their white robes and high pointed caps, and all the attendants, officers, and servants, the great figure of Elijah loomed up before them, demanding in a loud voice how long they were going to take to decide whether to serve God or Baal. None dared reply. He told them to bring two oxen; one, the prophets of Baal should prepare for sacrifice, the other he should prepare. Each should call upon his God, and the God that answered by fire should be supreme. The people thought this very fair, as Baal was supposed to be the god of fire.

The prophets of Baal were allowed to try first. In vain they called to the sun, and danced about the altar, waving their arms wildly, begging Baal to hear them and to send the fire—but there was no response. Is it any wonder Elijah said to them: “Cry aloud: for he is a god; either he is talking, or he is pursuing, or he is in a journey, or peradventure he sleepeth, and must be awaked.” They continued their supplication all day, but to no avail.

Then Elijah called the people close around him, prepared his offering, and commanded them to pour water over it several times and also to fill the ditch surrounding it with water, that they might be fully persuaded. Then Elijah’s prayer was immediately answered by a fire, which not only burned up the offering but licked up the water around it. Then the people were persuaded, the false prophets were slain, and rain descended upon the land.

But Jezebel was very angry when she heard these things, and sent word to Elijah that he, too, should share the fate of the prophets of Baal. Elijah fled. It was at this time he rested “under a juniper tree,” which has since been known as an expression of discouragement.

Again came the message of the Lord, sending him to the land of Israel, where he should proclaim his successor, Elisha. Elijah spent the rest of his life instructing young men, of whom Elisha was his most devoted follower. When his work was over he was taken up into heaven in a chariot of fire.

Next to Elijah in the frieze stands Daniel, that stanch leader whom nothing could dismay, not even the fear of being placed in the lions’ den. He does not look as if he could easily be persuaded to turn aside from what he believed was right. The fixed folds of his garment correspond with his features and his character as we know it. In his hands he carries a piece of parchment upon which is inscribed in Hebrew, “And they that be wise shall shine.”

His was an unusual life full of strange experiences. He was fourteen years old when the people of Judah were taken captives to Babylon by the victorious King Nebuchadnezzar. Daniel was chosen with several other boys to be trained as pages for the king; then many strange things happened to him. In the first place his name was changed from Daniel, which means “God is my judge,” to Belteshazzar, after one of the idols of the Babylonians. All the pages were given these strange heathen names. They were treated very kindly but were expected to eat the rich food from the king’s table, most of which had been offered to the idols.

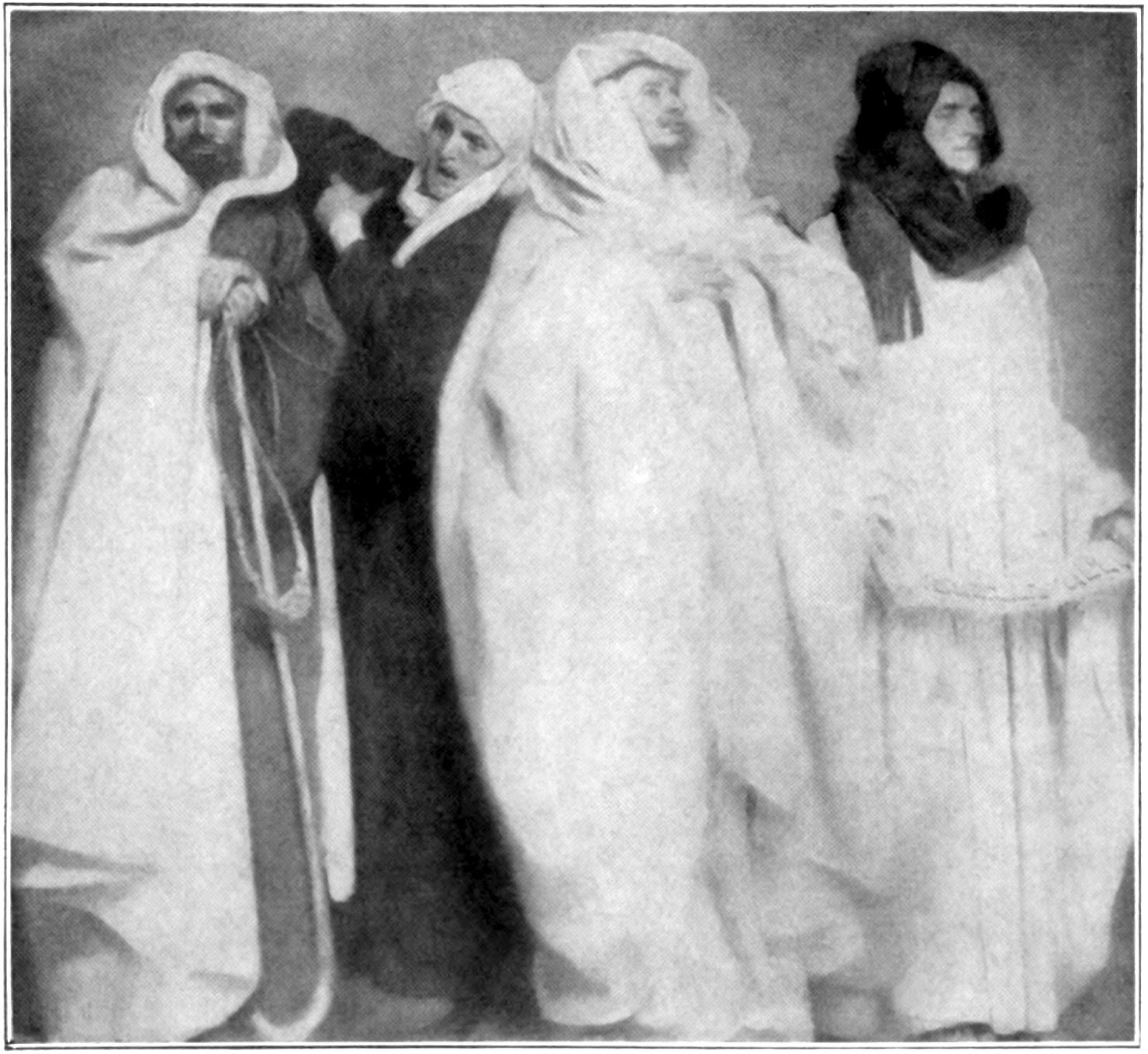

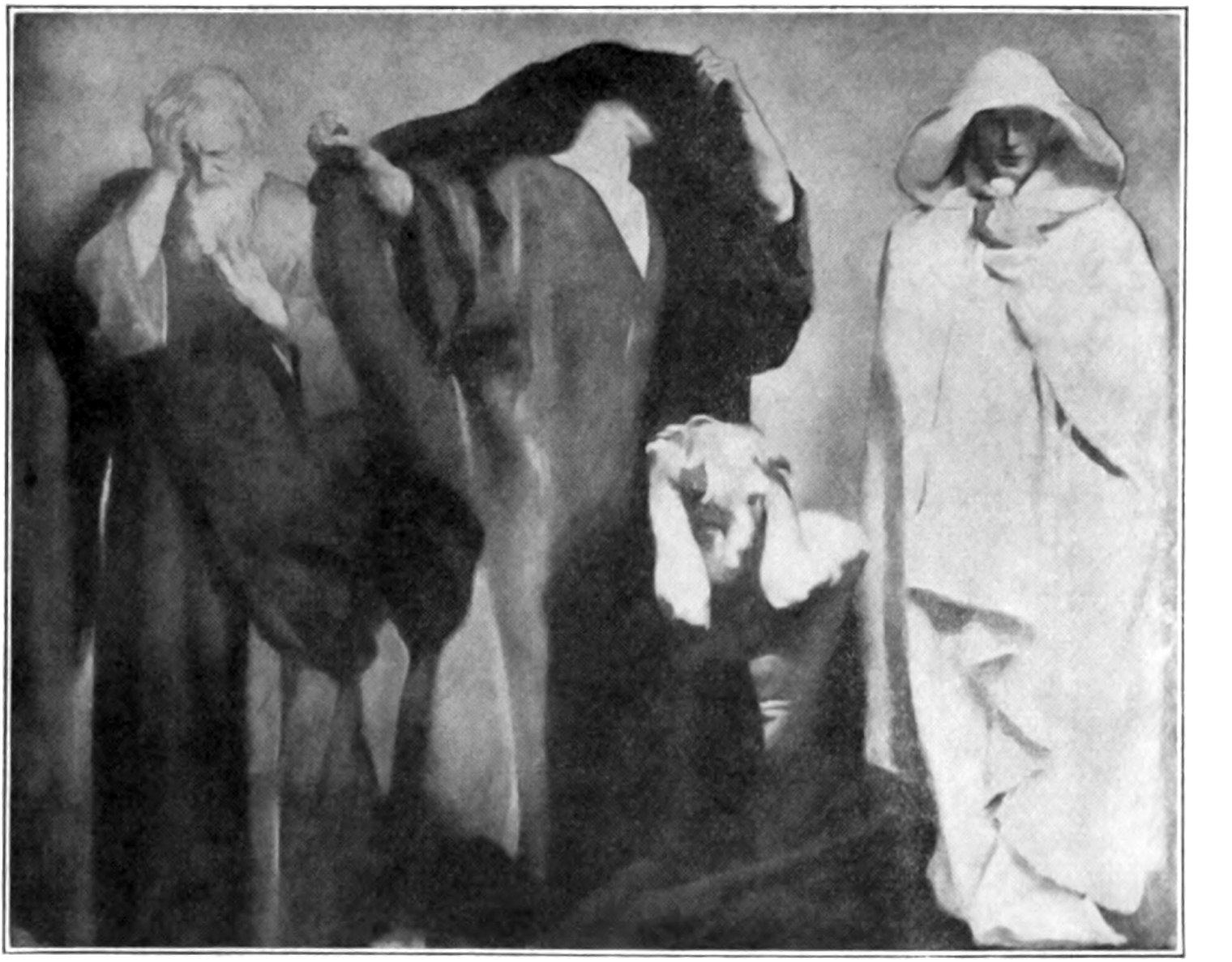

Amos, Nahum, Ezekiel, Daniel. The Frieze of the Prophets

When Daniel found this out he made his first stand for what he believed was right. Feeling that it was wrong to eat this food, he persuaded three of the other boys to go with him and ask the king’s officers to give them plainer food. The officers consented to test this diet with the four boys, and at the end of three months found they had gained in strength more than the other pages, who had continued to eat the rich food; and so Daniel’s request was granted. All the pages had to study very hard, for they had to learn the language of the Babylonians besides many other things. When they were brought before the king to be examined three years later, Daniel and his three friends were found to be the brightest scholars of all. People began to look up to them, and to call them very wise.

Not long after this King Nebuchadnezzar had a very strange dream, but when he woke up in the morning he could not remember what it was. He called his wise men together, but none could tell him what he had dreamed. He became very angry and ordered them all put to death, even Daniel and his friends, whom he thought ought to be wise enough to tell him.

All that night Daniel and his friends prayed for help, until, utterly weary, they fell asleep. In a dream the Lord told Daniel what to tell the king. King Nebuchadnezzar’s dream had been about his kingdom, and who should rule after him, and he was amazed that one so young as Daniel should tell him what he had dreamed and what the dream meant. He gave Daniel many presents and made him a great ruler.

Daniel continued in favor with Nebuchadnezzar’s successor, Darius. So much was he favored that the other officers of the king wished to destroy him. Appealing to his vanity, they persuaded Darius to set aside thirty days in which all his people should pray to him just as if he were a god. He made this dreadful law among his people, who were Medes and Persians. Of course we know how Daniel continued to pray to God, was watched, and reported to the king. Then King Darius saw the trap which his officers had set for Daniel. He was greatly distressed, but not even a king could change a law among the Medes and Persians. He had said that any one who disobeyed his law should perish in the den of lions.

But we know how Daniel was taken care of; how the king rejoiced to find him alive the next morning; and how all the people marveled and believed in the God who had saved him. At this time Daniel was eighty years old. God sent some wonderful dreams to him, and he was able to prophesy many things that should happen to the Jews. It was through him that they were delivered from their captivity.

At the right of Joshua we see Jeremiah, the prophet who so bitterly lamented the afflictions of his people. He is often called the “weeping prophet.” So Mr. Sargent has represented him in that attitude of grief and discouragement, standing there with his eyes cast down in sorrowful meditation. His whole life was spent in what seemed a fruitless strife against the evils of his time, for his warnings were disregarded, and his people were hurrying toward their destruction.

Jeremiah, Jonah, Isaiah, Habakkuk. The Frieze of the Prophets

Mr. Sargent has made us feel the hopeless despair of this strong man who tried so hard to save his people from all the misery they so willfully brought upon themselves. He even went about the streets wearing a yoke on his neck, to symbolize the coming servitude of the nation which refused to heed his warnings and repent. His life was in constant danger; he was imprisoned, thrown into a damp, unwholesome cistern, and was often obliged to hide for months in caves among the rocks to escape the king’s anger.

Other prophets could declare God’s protection and hold out some hope for the good to come, but Jeremiah’s message spoke only of evil and sorrow. It took great courage to go about on so unpopular and sad a mission, without even a miracle to prove his words true, and always alone among people who were unfriendly and did not believe in him.

The first one of Jeremiah’s predictions to come true was when Daniel and the Israelites were taken captives to Babylon by King Nebuchadnezzar. Again he warned them not to go into Egypt, but they not only went but compelled him to go with them.

The last we hear of Jeremiah is in Egypt, urging his people to give up their idols and worship God. He is indeed, as Mr. Sargent has represented him, “the prophet of sorrow”; and yet the figure is one of strength. Neither in his face nor in his bearing is there any sign of indecision or turning back.

Next, partly hidden from view, we see Jonah, the unwilling prophet, who tried to run away when the Lord told him to take his message of warning to Nineveh. The people in this city were known to be very wicked, and Jonah feared they might kill him, so he took a boat and started away in another direction. We all know of the fearful storm that arose and how the sailors prayed to their gods and urged Jonah to pray to his. But Jonah could not pray to God when he was disobeying Him. Then the sailors drew lots, as was the custom, to find out who had sinned and brought the fearful storm upon them. The lot fell to Jonah, who told them how he had run away from Nineveh. He urged the sailors to throw him overboard, saying the sea would then be still. The men did not want to do this, but, fearful lest all should be lost, they finally threw him overboard. At once the wind died down and the sea was still. We know how the whale was sent to swallow Jonah and to carry him safely to the shore, where he was left, now very willing to deliver his message to Nineveh.

He was to tell these wicked people that in forty days their city would be overthrown. He went about the streets dressed in a rough camel’s-hair cloak, very much like Elijah, and called out his prophecy in a loud voice. No wonder the people were frightened, and when he told them how he had not wanted to bring the message and had been forced to, they were more frightened than ever. All the people, and the king too, wept and prayed God for forgiveness, neither eating nor drinking. Then God heard their prayers and forgave them, and their city was not destroyed.

But Jonah felt very much hurt because his message had not proved true. He thought only of himself, and felt that he had been cheated. He went away by himself and built a small place of shelter just outside the walls of the city. Here he sat and waited, still hoping Nineveh would be destroyed. Suddenly a tree sprang up, its dense leaves protecting him from the hot sun. Jonah was greatly pleased and refreshed, but the tree as suddenly withered, and he was left grieving for it. God then spoke to him and asked him how he could grieve for the tree, yet harden his heart against the people of Nineveh, who had repented.

Jeremiah’s greatest grief was that the people would not heed his warnings, while Jonah felt aggrieved because his prophecy was not fulfilled.

In the picture we see Jonah reading a scroll bearing the one word “Jehovah.”

Next to Jonah we see Isaiah, the enthusiast, prophesying the coming of Christ’s kingdom. Note how the light falls on the head and shoulders, and on the upraised arms of the prophet, and is echoed, so to speak, by the light on the lower folds of his robe. All lines and lights lead the eye upward, even as Isaiah sought to lift his people up into a higher, better world. He is the hopeful figure in this group of four.

Habakkuk stands next with his far-seeing eyes missing the heavenly visions which surround Isaiah, but seeing the sorrows and evils of the world and trying in vain to remedy them.

The next group to the right represents the three prophets of hope, Haggai, Malacchi, and Zechariah, all pointing toward the section of the wall where Mr. Sargent’s new painting, “The Sermon on the Mount,” will be placed when finished. The one doubtful figure, Micah, who is looking back, serves to hold this section of the picture to the other figures in the frieze.

At the left-hand side of the frieze and next to Daniel, stands Ezekiel. Ezekiel lived at the same time as Daniel and, like him, began his prophetic career after he was exiled to Babylon. During the twenty-seven years of his exile he kept his fellow exiles informed as to all dangers which were besetting and threatening their people at home in Jerusalem and Judah. His book abounds in visions and poetical images. Mr. Sargent has given him the absorbed expression of one who sees beyond the present and whose vision includes both evil and good.

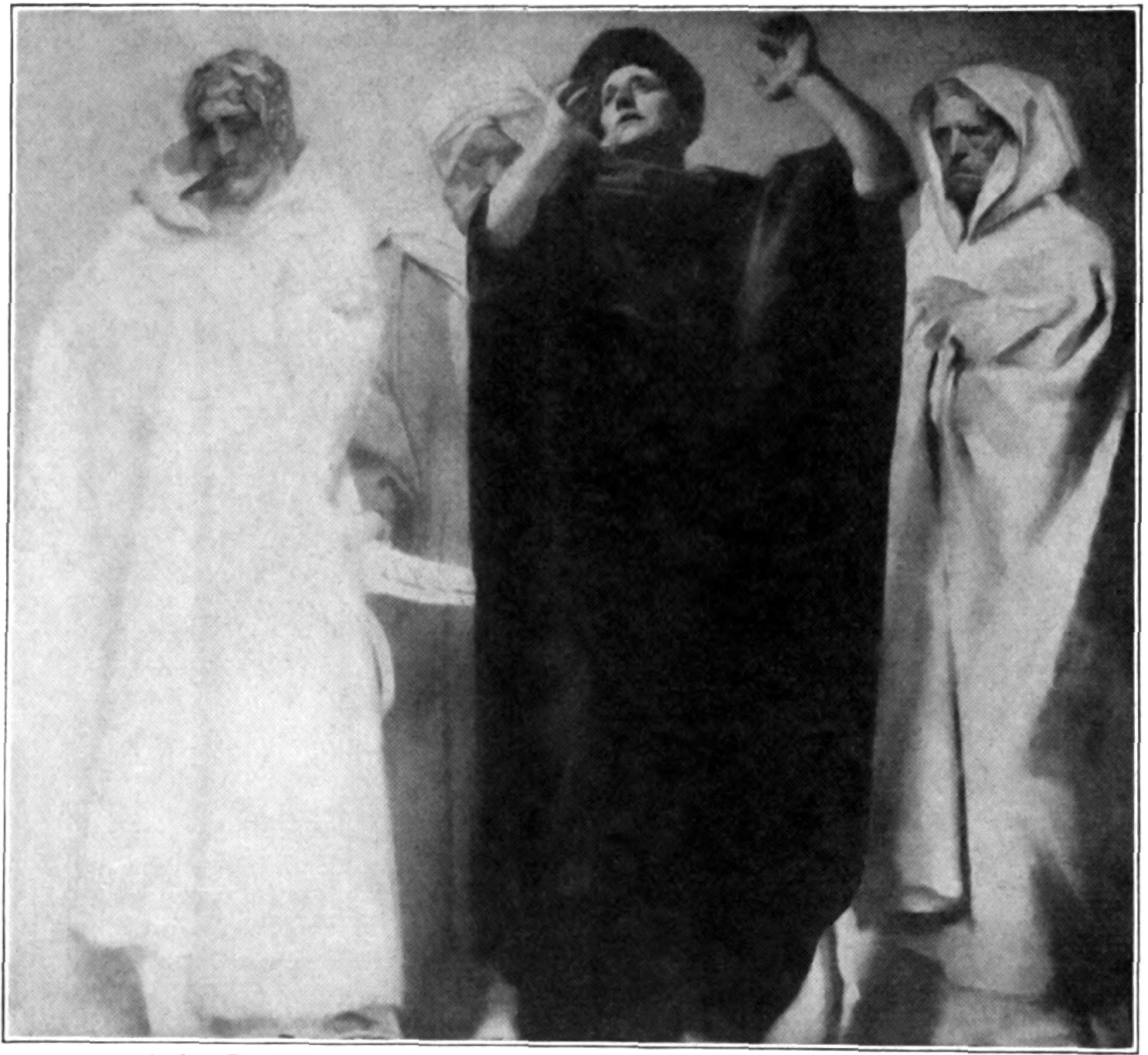

Micah, Haggai, Malacchi, Zechariah. The Frieze of the Prophets

Nahum, standing next to Ezekiel, seems to be predicting the wickedness and fall of Nineveh, of which he has given us such a powerful and vivid account; while Amos denounces idolatry and the sins of the nations, also predicting a brighter future for the people of Israel.

The four figures in the last panel to the left of Moses represent the prophets of despair. We cannot fail to notice that among the hopeful prophets there is one discouraged figure, while among the prophets of despair we find the hopeful figure of Hosea.

Obadiah, Joel, and Zephaniah urged their people to repentance of sin, and warned them of disaster to come, but their warnings were not heeded. In the picture Joel is attempting to shut out the sight of the fearful plague of locusts, of the famine, and of the drought which he knows must come to his people because they will not repent. The other two prophets seem crushed by a hopeless despair. But love is the keynote of Hosea’s pleadings. He speaks of the unquenchable love of Jehovah for his erring people.

It is interesting to know that Mr. Sargent’s favorite figure in the frieze is this young prophet in white, Hosea. Is it any wonder he should choose this one? The name Hosea means salvation. In him we see beauty, grace, and simplicity, and we feel the steady purpose, the earnest faith, of that calm, quiet face. There is no despair in that face or figure; the very folds of his robe give us a feeling of strength and stability; they suggest marble.

Obadiah, Joel, Zephaniah, Hosea. The Frieze of the Prophets

We are interested in this great mural painting, “The Frieze of the Prophets,” not only for its intellectual and religious suggestiveness, but for its composition, its masses of dark and light, and its beauty of form. Each of the groups of figures is complete in itself, yet by the position of the figures and by the light upon them, the frieze is held together as one composition.

Mr. Sargent spent many years, and studied his Bible very thoughtfully, before he attempted to draw this great picture.

Questions to help the pupil understand the picture. Who were the prophets? What had they to do with the development of religion? Who painted this picture? Where is the original? What can you say of the composition of this picture? of the light and shade? What do we call paintings on a wall? What is there unusual about this painting? For what do you admire it? Why was Moses given the most important place in this picture? Tell the story of his life. Why is he often represented with two little horns on his forehead? Tell something about each one of the prophets. Which one is Mr. Sargent’s favorite?

To the Teacher: Certain pupils may be selected to study and give orally a description of different portions of this picture.

The story of the artist. We are especially interested in Mr. Sargent because he is one of the living American artists who has won fame both in his own country and abroad. Although John Singer Sargent was born in Florence, Italy, we claim him as an American because his parents were Americans and because he has always considered himself an American. His boyhood was spent in Florence, where it was his delight to wander in the art galleries. He showed an early talent for drawing, and when he was nineteen years old he went to Paris to become the pupil of some of the best artists.

Mr. Sargent is famous for his many portraits as well as for his mural decorations. He has traveled extensively and has visited the United States many times, painting and exhibiting his paintings here, but most of his life has been spent in London, where he is now living. In 1908 he was elected to the Royal Academy. He has won many medals of honor for his paintings, and is a member of the leading art societies of America and Europe.

Among the noted pictures by Mr. Sargent are: “Carnation Lily, Lily Rose,” “Fishing for Oysters at Cancale,” “Neapolitan Children Bathing,” “El Jaleo” (Spanish Dance), “Fumes of Ambergris,” “Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth,” and “La Carmençita.” As a portrait painter Mr. Sargent has been commissioned by men and women of high distinction in literary, political, social, and artistic life in America and Europe. Among his eminent sitters have been: Joseph Chamberlain, Carolus Duran, Theodore Roosevelt, Secretary Hay, and Octavia Hill.

Questions about the artist. Why do we feel an especial interest in Mr. Sargent? Where was he born? Why do we claim him as an American? Where did he study drawing and painting? For what kind of paintings is he famous? Where does he live?

Copyright by Edwin A. Abbey; from a Copley Print

Copyright by Curtis & Cameron, Publishers, Boston

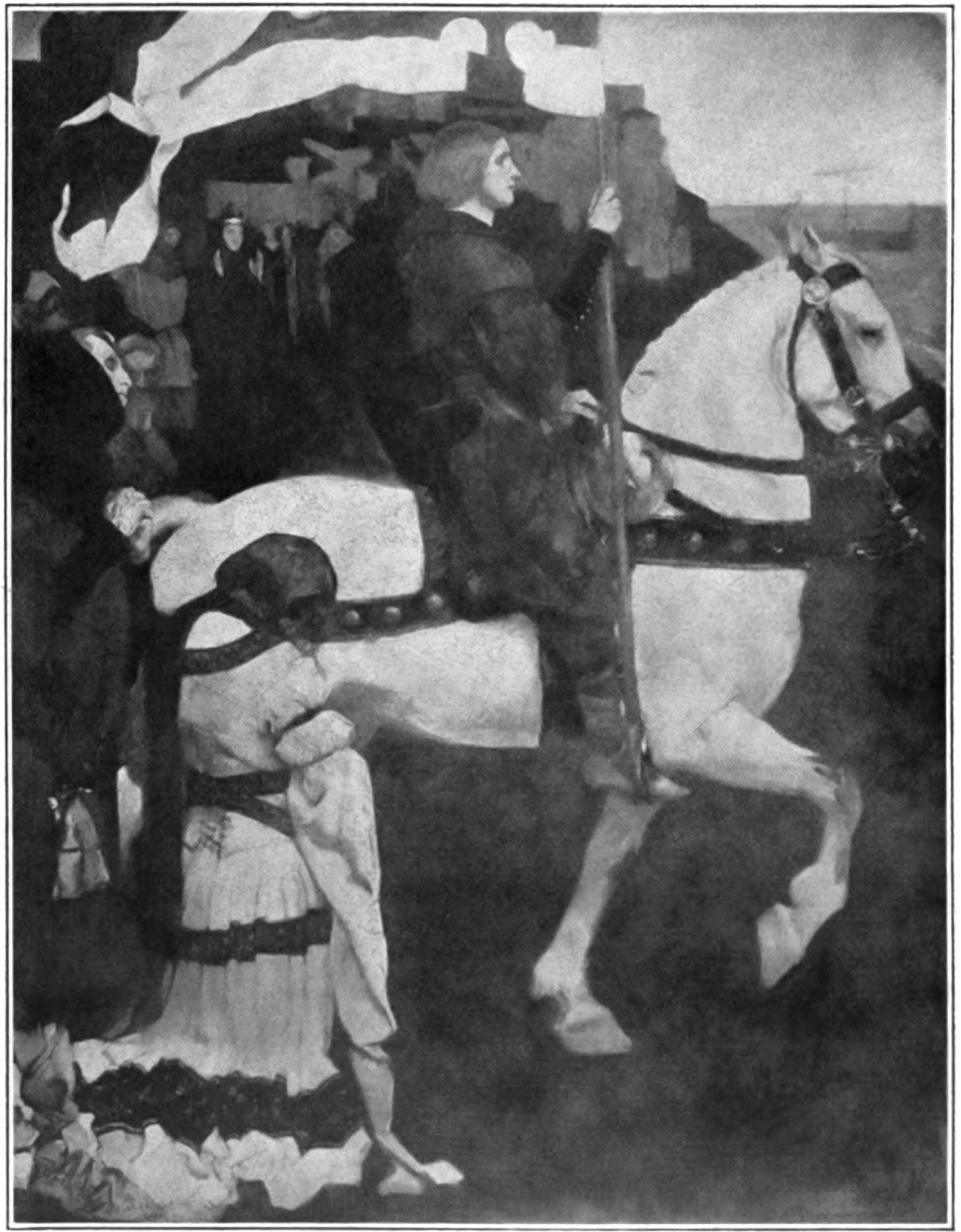

GALAHAD THE DELIVERER. THE HOLY GRAIL

Questions to arouse interest. How many of you have read Tennyson’s The Holy Grail? What was the Holy Grail? Why did men seek it? Tell what you can of Sir Galahad and his adventures.

The story of the picture. When asked to decorate the walls of the Delivery Room of the Boston Public Library Mr. Abbey planned to represent “The Sources of Modern Literature,” thinking this would be most appropriate, as Mr. Sargent had chosen “The Sources of the Christian Religion” for the subject of his pictures on the walls of a gallery on the third floor of the same building. But as Mr. Abbey read and studied the subject he became impressed with the story of the Holy Grail, which seemed to be woven in and out through all our literature. He realized also that he would be the first to represent this subject in a large decoration, and that it was altogether worthy of his best efforts.

The paintings occupy the wall space between the wainscot and the ceiling of this great room, where books of the library are given out and returned. The pictures are eight feet in height, but vary in length from the first, “The Vision,” which is six feet long, to the fifth, “The Castle of the Grail,” which is thirty-three feet long and extends the entire length of the north wall.

Mr. Abbey spent seven years in careful research work before he was able to complete these paintings. He received fifteen thousand dollars for his work.

According to an old legend, the Holy Grail was the cup from which Christ drank at the Last Supper. It was bought from Pilate by Joseph of Arimathæa, who caught in it the divine blood that fell from Christ’s wounds.

Joseph placed the cup in a castle, which he kept guarded night and day. It was passed on to his descendants, who received the charge in sacred trust and continued to guard it faithfully. The cup itself was most mysterious and wonderful. It could be seen only by those who were perfectly pure in word, thought, and deed. If an evil person came near, it was borne away as if by some invisible hand, completely disappearing from view.

The sight of it was as food to the one to whom it was revealed and enabled him “to live and to cause others to live indefinitely without food,” gave him “universal knowledge,” and made him invulnerable in battle. But there was one thing it did not do. No matter how perfect the knight, he could still be tempted. He must continue to resist temptation as long as he lived.

At length there came a king, keeper of the Grail, called Amfortas, the Fisher King, who was not strong enough to resist temptation. He yielded to an evil enchantment and was severely punished. Not only was the sight of the Grail denied him, but a spell was cast upon him and all his court so that they lived in a sort of trance, neither sleeping nor waking. Thus they must remain until a knight pure in body and soul should come to break the spell and set them free.

Little was known about the enchanted castle, where the king and his men were held in the power of the spell, but many a young man began to plan the quest of the Grail. He must so live that by his good thoughts and deeds he might reach the enchanted castle, see the Holy Grail, and so set free the unhappy knights. He must be perfect, indeed, if he would achieve this, and full of courage, perseverance, and patience.

In our picture we see Sir Galahad, the stainless knight, who succeeds in his quest of the Holy Grail.

Mr. Abbey has told the story in fifteen pictures, beginning with Sir Galahad as a child.

Galahad was the son of Launcelot and Elaine, for it was according to an old prophecy that these two should have a son who should become a great knight and find the Holy Grail.

They placed their small son in a convent to be brought up by the nuns. In the first picture we see the child attracted by a bright light visible to him alone. He laughs in great delight and reaches toward the Grail as he sees it gleaming fiery red through its veil-like covering. It is held in the hands of an angel radiant in white as the light from the Grail illumines her face and wings. She is supported by the wings of doves, upon which she seems to be borne along. These doves signify the Holy Spirit and are also represented as hovering near the Grail and acting as informants concerning good and evil. The odor of the incense from the Grail furnishes a mysterious sustenance to the child which causes him to grow in mind and body. He is held high in the arms of a sweet-faced young nun who does not see the vision but seems to feel vaguely that some unusual event is taking place. In the original painting the bluish black of her outer robe throws into greater prominence the creamy white of her draperies as they, too, are flooded with light from the Grail.

The background gives the effect of heavy tapestry and is made up of tones of blue and white embroidered in gold. The figures of lions and peacocks are used to signify the resurrection.

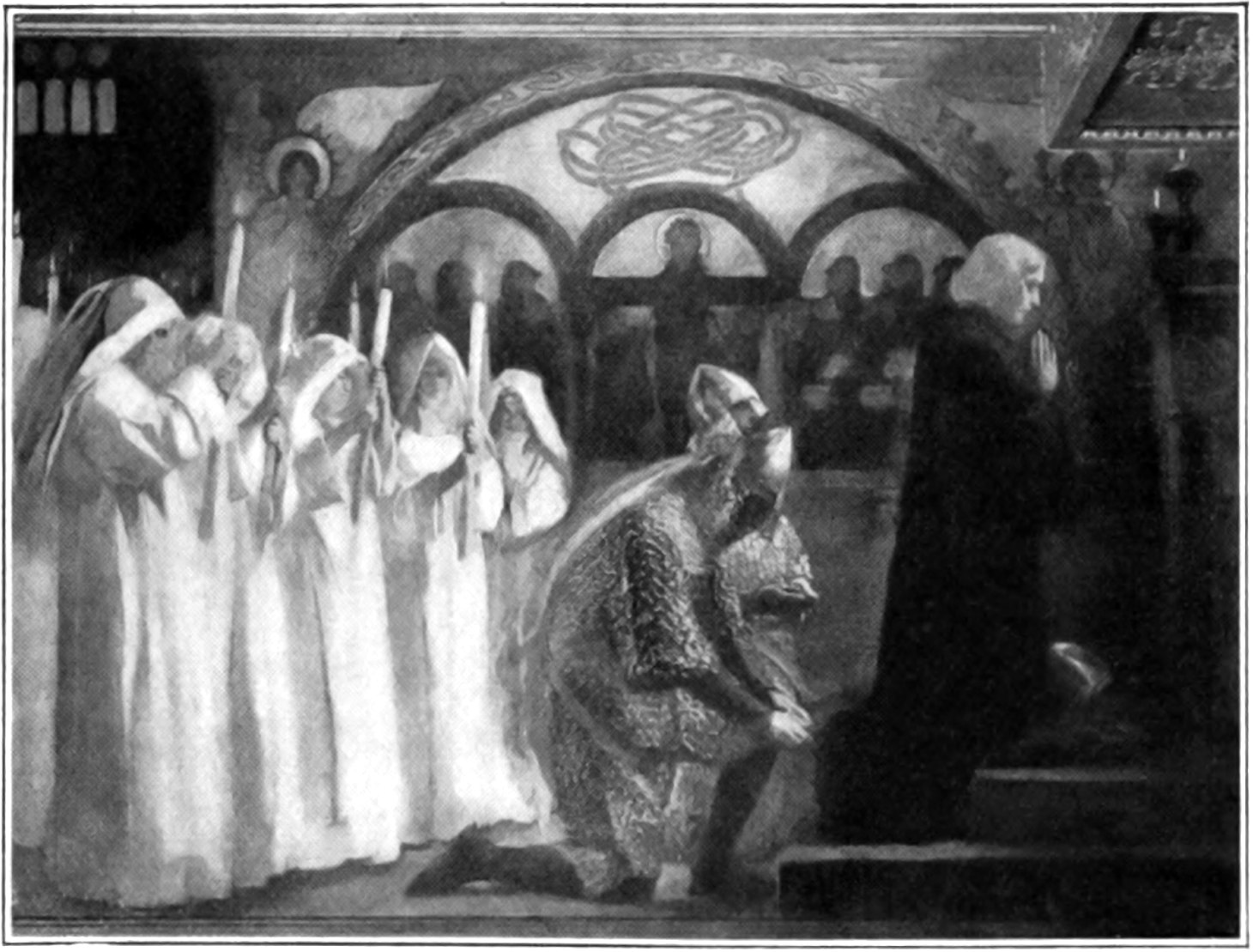

When the child had grown to manhood, Sir Launcelot was summoned to make him a knight. In this picture we see Galahad in the convent chapel, where he has just passed the night in prayer preparatory to his departure out into the world.

As he kneels at the altar, he is clad in the red robe which is worn by the hero throughout the series of pictures. Red is chosen as the color of spiritual purity and means the “spirit cleansed by fire.” “It stands for activity, conflict, human effort with the knowledge of good and evil that imparts the strength to achieve the good and resist the evil.”

The honor of knighthood is conferred upon Galahad by Sir Launcelot and Sir Bors, who can be seen in their heavy armor kneeling behind him. They fasten the spurs upon his feet as a signal that the moment of departure has arrived.

Copyright by Edwin A. Abbey; from a Copley Print

copyright by Curtis & Cameron, Publishers, Boston

The Oath of Knighthood. The Holy Grail

The time of day is shown by the two candles at the altar which have been burning all night and are now burned low in their sockets, and by the faint early light of dawn which comes stealing in through the small windows at the left of the picture. Just behind the knights stand a group of nuns, holding tall candles which light up the dark room and reflect on the white robes and shining armor. The interior decoration of the church is plainly shown. Our attention is drawn to the quaint crucifix just back of the kneeling knights, and the figures surrounding it.

The architecture is that of the Early Christian Romanesque. Sir Galahad’s face is partly in shadow, as if lost in deep thought. But the moment of departure has arrived. He will take up the helmet, which lies near him, and leave the convent for his first glimpse of the outside world. He must go to the wise teacher, Gurnemanz, to learn not only the rules of knighthood but the ways of the world, before he may start on his quest of the Holy Grail.

Having been fully instructed in all the ways of the world by the good Gurnemanz, Sir Galahad starts out on his quest. First he goes to the Round Table of King Arthur and his knights in Camelot. He finds them holding a solemn meeting, their leader having just declared that this is the day when, according to prophecy, the stainless knight should come who should occupy the Siege Perilous. The Siege Perilous was a chair over which the magician, Merlin, had cast a spell, so that no man could sit in it without peril of death. Even Merlin himself was lost while sitting in his own chair. Only a blameless knight could hope for safety in this perilous seat. While Arthur and the knights are discussing the prophecy, there suddenly appears a strange old man clothed in white, whom none has seen before.

He comes toward the throne of King Arthur, leading Sir Galahad by the hand. The door and windows quietly and mysteriously close of themselves; the room is filled with a strange light. The Angel of the Grail appears before them, and gently lifts the red drapery from the chair. The encircling choir of angels look on silently as all read above the chair, in letters of fire, the flaming words, “This is Galahad’s seat.”

This picture shows them at that breathless moment when the letters of golden light appeared over the chair. King Arthur has risen from his seat to greet Sir Galahad; a small page kneels beside the king, while the jester half rises at the wondrous sight. Sir Galahad wears the same red robe, fastened with a golden brown girdle—a gift from the nuns when he was leaving the convent.

A wonderful rock of red marble has been discovered, protruding from the surface of a river. From its side projects a shining sword which none has been able to draw out. The king and his knights hasten to see this sword, but none succeeds in moving it. Now Sir Galahad arrives and draws the sword without the slightest difficulty, placing it in his empty scabbard, where it fits exactly. He also secures a shield which had been left for him by his ancestor, and, thus armed, he is ready to start out in search of the Grail. Most of the knights, persuaded by this series of strange events that Sir Galahad is to be the true knight, decide to join him in his search.

Before they start on their long and perilous journey they gather in the church for a final benediction. So here again we see the interior of a church. The bishop’s hands are raised in a parting benediction over the group of kneeling knights clad in shining armor and holding their lances erect. Many strange banners float above them. Sir Galahad alone has bared his head. His helmet is on the floor beside him. Other kneeling priests may be seen just behind the bishop. The scene is one of solemnity and dignity.

King Amfortas, keeper of the Grail, who yielded to temptation and so was denied the sight of the Grail, and his knights, upon whom was cast a fearful spell which was neither sleeping nor waking, anxiously await the arrival of Galahad. But, it is not enough that he should come; he must ask a certain question which alone can free them from their living death.

Here we see Sir Galahad in the enchanted castle, a puzzled onlooker. He looks silently about him at the feeble old king and his wretched company. He sees, too, the procession of the Grail, which, although the king and his court cannot see it, is constantly passing before them. This procession includes the Angel, bearer of the Grail, a damsel carrying a golden dish, two knights who carry seven-branched candlesticks, and a knight holding a bleeding spear.

Sir Galahad must ask the meaning of what he sees and by his question remove the enchantment. But, over-confident in his own knowledge, he tries to solve the mystery by himself, and fails. The procession of the Grail is shown to the right of the throne upon which King Amfortas half sits, half reclines, while the rest of the weird company look solemnly on as Sir Galahad stands transfixed with amazement and perplexity because the spell is not removed as he expected. Because of his failure to ask the necessary question, these people must continue to suffer. Several years later he returns, a wiser man, and releases them. Personal purity alone was not enough; wisdom was necessary, and to secure this he must ask a certain question. He could not attain knowledge through himself alone, but must seek it from the experience and understanding of others.

The next morning after his failure the castle seems deserted, but when Galahad starts out he finds his horse saddled and waiting for him. The drawbridge is down, so thinking perhaps the king and knights are in the forest, he rides across the bridge in search of them. Instantly the drawbridge closes with a crash, and there is a great sound of groaning and of voices reproaching him for having failed in his quest. The castle disappears from sight, and Galahad roams disconsolately in the woods. Finally he sits down to rest and think. He is aroused by the passing of three enchanted maidens, the Loathly Damsel and her two followers.

In the picture we see her riding a white mule richly caparisoned. Her form suggests beauty, yet the face is ugly and distorted, her head bald so that she must wear a hood. In her hands she carries the ghastly head of a king wearing a crown, and she seems depressed by her burden. Forced by the spell to go about harming mankind against her will, she is angry with Sir Galahad for having failed to release her. In her anger she reproaches him for not having asked the question while within the castle, and so here for the first time Sir Galahad learns why he failed.

Once a beautiful woman, the Loathly Damsel must ride about thus unhappily. The head and shoulders are all that is visible of the second damsel, apparently riding. The third, dressed as a boy, carries a scourge with which she forces the two mules onward.

Sir Galahad bows his head in silence at their reproaches, humbly feeling that he deserves them.

Many years of sorrow and suffering must pass before he can again find the Castle of the Grail.

Continually seeking the Castle of the Grail, Sir Galahad wanders about in this enchanted land. At length, catching a glimpse of a strange castle, he makes haste to reach it, and finds it to be the Castle of Imprisoned Maidens. These maidens represent the Virtues; and their jailers, the Seven Deadly Sins. Arriving at the gate of the castle, he finds it guarded by these seven knights. A fierce conflict ensues in which Sir Galahad is victorious. This is the only picture in the series in which he is represented in violent physical conflict; the others represent more of the inner spiritual conflict. The seven knights, wearing heavy armor and carrying immense shields, are represented in dull gray colors, while our hero, wearing his chain armor over his red robe, is easily distinguished by the shining gold of his helmet and the red of his shield.

Sir Galahad defeats the seven knights but he does not slay them, and they turn and flee. This signifies that although the seven sins can no longer trouble the pure soul, yet they are still about in the world.

Passing the outer gate, Sir Galahad is greeted by the keeper of the inner gate, an aged man who blesses him and gives him the key to the castle. With helmet in hand, Sir Galahad kneels reverently before the saintly man who greets him kindly as he holds toward him the great key.

Sir Galahad enters the castle and is welcomed by the maidens, who have long been expecting him, for it was according to prophecy that a perfect knight should come to deliver them.

Mr. Abbey has represented these maidens as most beautiful in form and feature. They are dressed in pale colors such as blue, white, rose, and lilac, richly embroidered with gold. Our hero is turned away from us as he humbly receives the shyly offered gratitude of the fair maidens. His helmet and shield may be seen on the floor beside him. In size and importance this large picture is a sort of companion picture to the one on the opposite side of the room, “The Round Table of King Arthur.” Both are beautiful in color and symmetry.

Having released the imprisoned Virtues that they may go about in the world doing good, Sir Galahad returns to King Arthur’s court and marries the Lady Blanchefleur, to whom he had become betrothed while a pupil of Gurnemanz.

On his wedding morning the vision of the Grail appears to him many times, and the thought of poor old King Amfortas, awaiting the knight who is to release him, saddens Galahad. He is seized with a great desire to continue his quest, and finding his young bride in sympathy with his ambition, he decides to start out that day on his journey.