A YEAR WITH A

WHALER

BY

Illustrated with Photographs

NEW YORK

OUTING PUBLISHING COMPANY

MCMXIII

Copyright, 1913, BY

OUTING PUBLISHING COMPANY

All rights reserved

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Lure of the Outfitter | 11 |

| II. | The Men of the "Alexander" | 21 |

| III. | Why We Don't Desert | 33 |

| IV. | Turtles and Porpoises | 46 |

| V. | The A, B, C of Whales | 59 |

| VI. | The Night King | 71 |

| VII. | Dreams of Liberty | 83 |

| VIII. | Gabriel's Little Drama | 95 |

| IX. | Through the Roaring Forties | 107 |

| X. | In the Ice | 118 |

| XI. | Cross Country Whaling | 128 |

| XII. | Cutting In and Trying Out | 137 |

| XIII. | Shaking Hands with Siberia | 149 |

| XIV. | Moonshine and Hygiene | 162 |

| XV. | News From Home | 171 |

| XVI. | Slim Goes on Strike | 182 |

| XVII. | Into the Arctic | 191 |

| XVIII. | Blubber and Song | 198 |

| XIX. | A Narrow Pinch [ 6 ] | 210 |

| XX. | A Race and a Race Horse | 219 |

| XXI. | Bears for a Change | 230 |

| XXII. | The Stranded Whale | 239 |

| XXIII. | And So—Home | 247 |

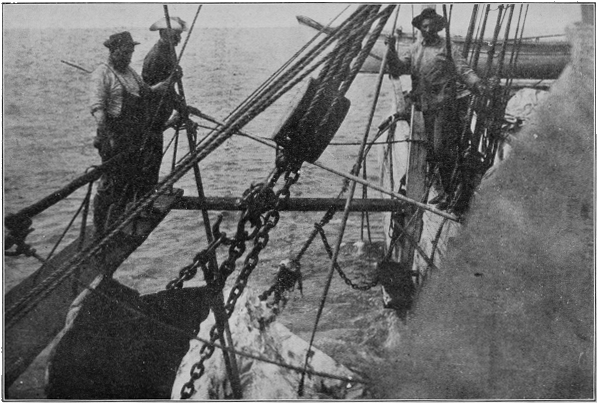

| "Cutting Out" a Whale | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

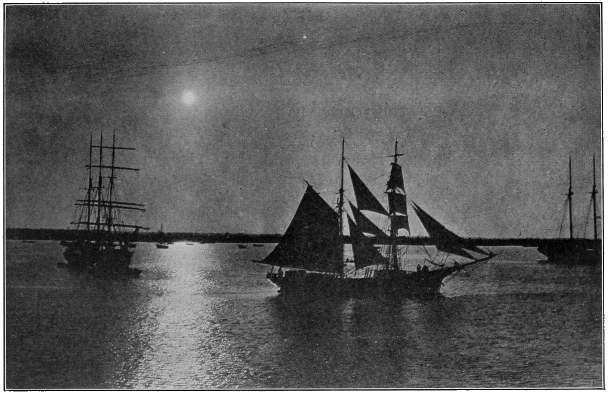

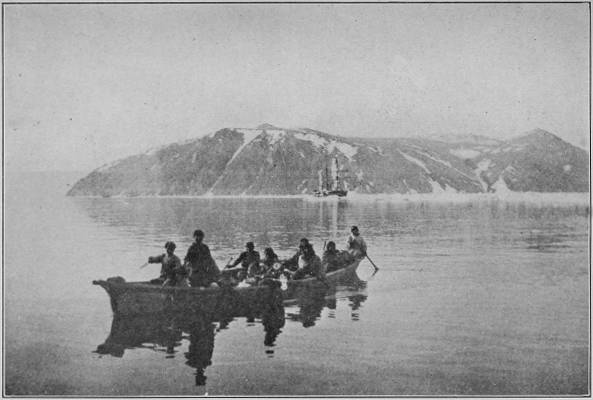

| In Bowhead Waters | 16 |

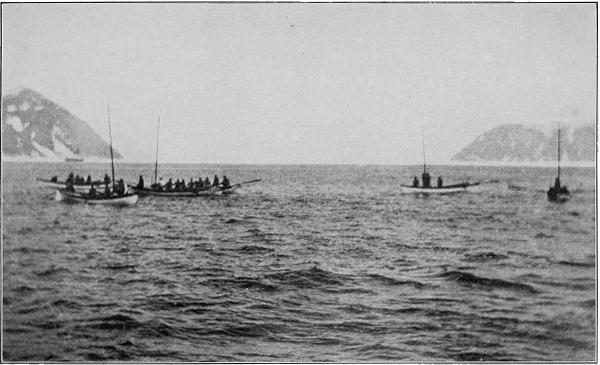

| When Whaling is an Easy Job | 40 |

| Waiting for the Whale to Breach | 72 |

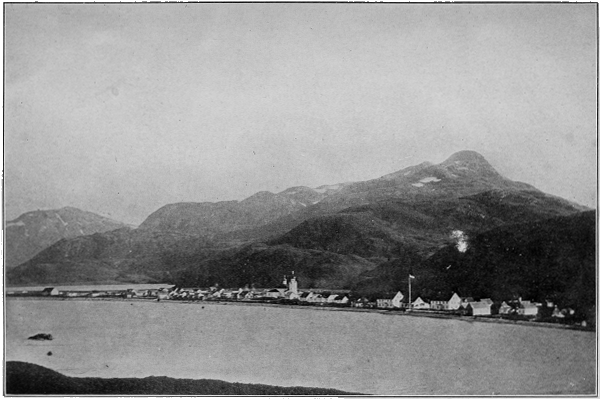

| Unalaska | 112 |

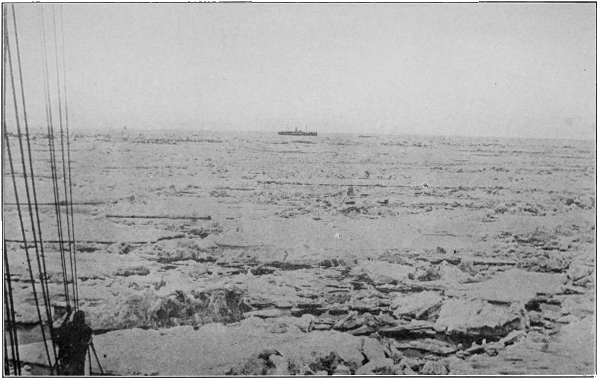

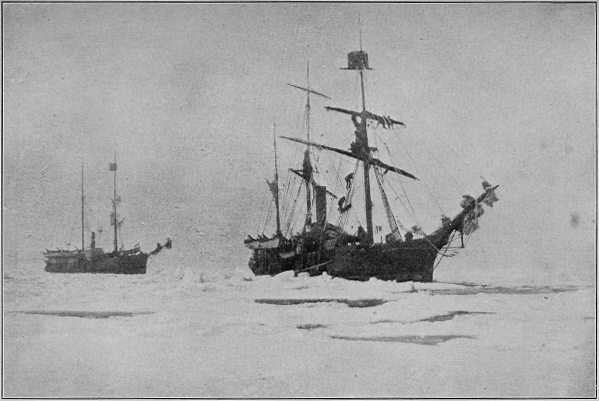

| Waiting for the Floes to Open | 120 |

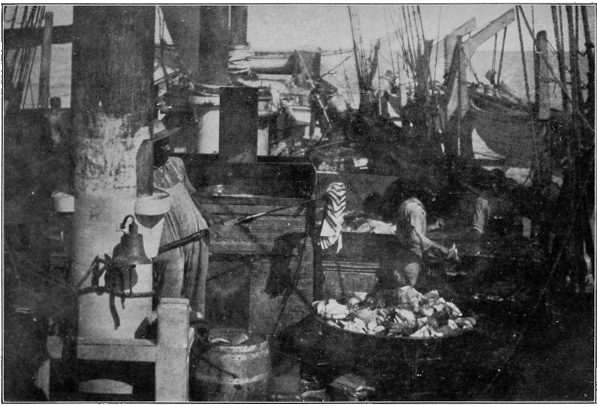

| "Trying Out" | 144 |

| Callers From Asia | 152 |

| Peter's Sweetheart | 160 |

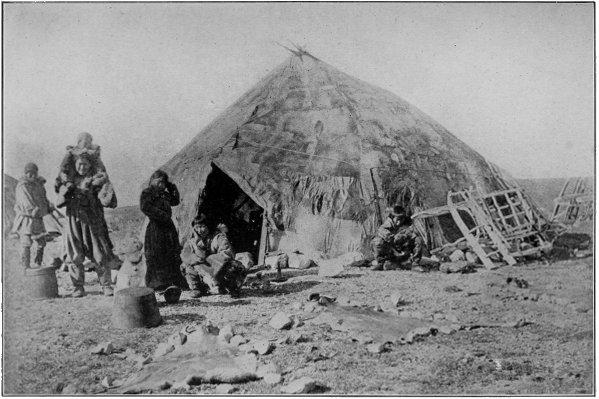

| Eskimos Summer Hut at St. Lawrence Bay | 168 |

| At the Gateway to the Arctic | 176 |

| Hoisting the Blubber Aboard | 184 |

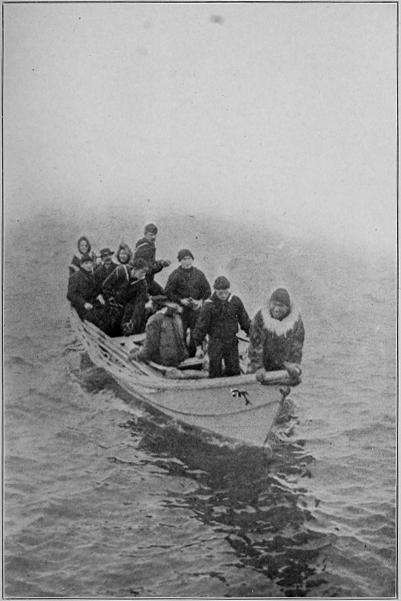

| Our Guests Coming Aboard in St. Lawrence Bay | 192 |

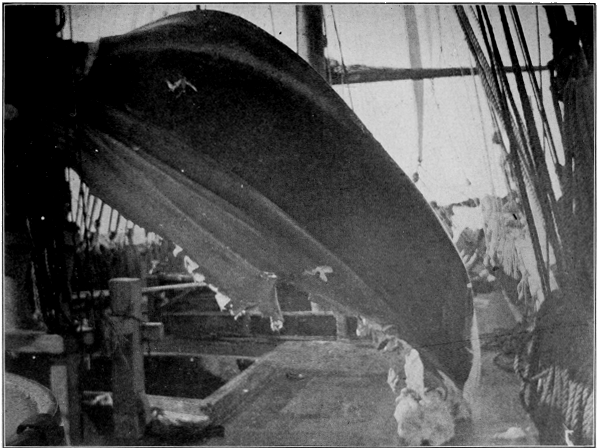

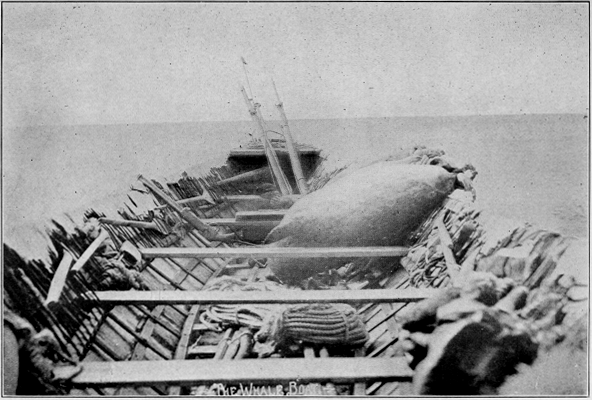

| The Lip of a Bowhead Whale | 208 |

| A Close Call Off Herald Island | 216 |

| Skin Boat of the Siberian Eskimos | 240 |

THE LURE OF THE OUTFITTER

When the brig Alexander sailed out of San Francisco on a whaling voyage a few years ago, I was a member of her forecastle crew. Once outside the Golden Gate, I felt the swing of blue water under me for the first time in my life. I was not shanghaied. Let's have that settled at the start. I had shipped as a green hand before the mast for the adventure of the thing, because I wanted to go, for the glamor of the sea was upon me.

I was taking breakfast in a San Francisco restaurant when, in glancing over the morning paper, I chanced across this advertisement:

Wanted—Men for a whaling voyage; able seamen, ordinary seamen, and green hands. No experience necessary. Big money for a lucky voyage. Apply at Levy's, No. 12 Washington Street.

Until that moment I had never dreamed of[ 12 ] going to sea, but that small "ad." laid its spell upon my imagination. It was big with the lure of strange lands and climes, romance and fresh experiences. What did it matter that I had passed all my humdrum days on dry land? "No experience necessary!" There were the magic words staring me in the face. I gulped down my eggs and coffee and was off for the street called Washington.

Levy's was a ship's outfitting store. A "runner" for the house—a hulking man with crafty eyes and a face almost as red as his hair and mustache—met me as I stepped in the door. He looked me over critically. His visual inventory must have been satisfactory. I was young.

"Ever been a sailor?" he asked.

"No."

"Makes no difference. Can you pull an oar?"

"Yes."

"You'll do. Hang around the store to-day and I'll see what vessels are shipping crews."

That was all. I was a potential whaler from that minute.

A young working man in overalls and flannel shirt came in later in the day and applied to go on the voyage. He qualified as a green hand. But no spirit of adventure had brought him to Levy's. A whaling voyage appealed to his canny mind as a business proposition.

"What can we make?" he asked the runner.

"If your ship is lucky," replied the runner, "you ought to clean up a pile of money. You'll ship on the 190th lay. Know what a lay is? It's your per cent. of the profits of the voyage. Say your ship catches four whales. She ought to catch a dozen if she has good luck. But say she catches four. Her cargo in oil and bone will be worth about $50,000. Your share will amount to something like $200, and you'll get it in a lump sum when you get back."

This was "bunk talk"—a "springe to catch woodcock"—but we did not know it. That fluent and plausible man took pencil and paper and showed us just how it would all work out. It was reserved for us poor greenhorns to learn later on that sailors of whaling ships usually are paid off at the end of a voyage with "one big [ 14 ] iron dollar." This fact being discreetly withheld from us, our illusions were not disturbed.

The fact is the "lay" means nothing to sailors on a whaler. It is merely a lure for the unsophisticated. It might as well be the 1000th lay as the 190th, for all the poor devil of a sailor gets. The explanation is simple. The men start the voyage with an insufficient supply of clothing. By the time the vessel strikes cold weather their clothes are worn out and it is a case of buy clothes from the ship's slop-chest at the captain's own prices or freeze. As a consequence, the men come back to port with expense accounts standing against them which wipe out all possible profits. This has become so definitely a part of whaling custom that no sailor ever thinks of fighting against it, and it probably would do him no good if he did. As a forecastle hand's pay the "big iron dollar" is a whaling tradition and as fixed and inevitable as fate.

The outfitter who owned the store did not conduct a sailor's boarding house, so we were put up at a cheap hotel on Pacific street. After [ 15 ] supper, my new friend took me for a visit to the home of his uncle in the Tar Flats region. A rough, kindly old laboring man was this uncle who sat in his snug parlor in his shirt sleeves during our stay, sent one of the children to the corner for a growler of beer, and told us bluntly we were idiots to think of shipping on a whaling voyage. We laughed at his warning—we were going and that's all there was to it. The old fellow's pretty daughters played the piano and sang for us, and my last evening on shore passed pleasantly enough. When it came time to say good-bye, the uncle prevailed on my friend to stay all night on the plea that he had some urgent matters to talk over, and I went back alone to my dingy hotel on the Barbary Coast.

I was awakened suddenly out of a sound sleep in the middle of the night. My friend stood beside my bed with a lighted candle in his hand.

"Get up and come with me," he said. "Don't go whaling. My uncle has told me all about it. He knows. You'll be treated like a dog aboard, fed on rotten grub, and if you don't die under [ 16 ] the hard knocks or freeze to death in the Arctic Ocean, you won't get a penny when you get back. Don't be a fool. Take my advice and give that runner the slip. If you go, you'll regret it to the last day of your life."

In the yellow glare of the candle, the young man seemed not unlike an apparition and he delivered his message of warning with prophetic solemnity and impressiveness. But my mind was made up.

"I guess I'll go," I said.

He argued and pleaded with me, all to no purpose. He set the candle on the table and blew it out.

"You won't come?" he said out of the darkness.

"No."

"You're a fool."

He slammed the door. I never saw him again. But many a time on the long voyage I recalled his wise counsel, prompted as it was by pure friendliness, and wished from my heart I had taken his advice.

Next day the runner for Levy's tried to ship me aboard the steam whaler William Lewis. When we arrived at the shipping office on the water front, it was crowded with sailors and rough fellows, many of them half drunk, and all eager for a chance to land a berth. A bronzed and bearded man stood beside a desk and surveyed them. He was the skipper of the steamer. The men were pushing and elbowing in an effort to get to the front and catch his eye.

"I've been north before, captain," "I'm an able seaman, sir," "I know the ropes," "Give me a chance, captain," "Take me, sir; I'll make a good hand,"—so they clamored their virtues noisily. The captain chose this man and that. In twenty minutes his crew was signed. It was not a question of getting enough men; it was a mere matter of selection. In such a crowd of sailormen, I stood no show. In looking back on it all, I wonder how such shipping office scenes are possible, how men of ordinary intelligence are herded aboard whale ships like sheep, how they even fight for a chance to go.

It was just as well I failed to ship aboard the William Lewis. The vessel went to pieces in [ 18 ] the ice on the north Alaskan coast the following spring. Four men lost their lives and only after a bitter experience as castaways on the floes were the others rescued.

That afternoon Captain Shorey of the brig Alexander visited Levy's. I was called to his attention as a likely young hand and he shipped me as a member of his crew. I signed articles for a year's voyage. It was provided that I was to receive a $50 advance with which to outfit myself for the voyage; of course, any money left over after all necessary articles had been purchased was to be mine—at least, in my innocence, I imagined it was.

The brig was lying in the stream off Goat Island and the runner set about the work of outfitting me at once. He and I and a clerk went about the store from shelf to shelf, selecting articles. The runner carried a pad of paper on which he marked down the cost. I was given a sailor's canvas bag, a mattress, a pair of blankets, woolen trousers, dungaree trousers, a coat, a pair of brogans, a pair of rubber sea boots, underwear, socks, two flannel shirts, a cap, a belt [ 19 ] and sheath knife, a suit of oil-skins and sou'wester, a tin cup, tin pan, knife, fork and spoon. That was all. It struck me as a rather slender equipment for a year's voyage. The runner footed up the cost.

"Why," he said with an air of great surprise, "this foots up to $53 and your advance is only $50."

He added up the column of figures again. But he had made no mistake. He seemed perplexed.

"I don't see how it is possible to scratch off anything," he said. "You'll need every one of these articles."

He puckered his brow, bit the end of his pencil, and studied the figures. It was evidently a puzzling problem.

"Well," he said at last, "I'll tell you what I'll do. Bring me down a few curios from the Arctic and I'll call it square."

I suppose my outfit was really worth about $6—not over $10. As soon as my bag had been packed, I was escorted to the wharf by the runner and rowed out to the brig. As I prepared [ 20 ] to climb over the ship's rail, the runner shook me by the hand and clapped me on the back with a great show of cordial goodfellowship.

"Don't forget my curios," he said.

THE MEN OF THE "ALEXANDER"

The brig Alexander was a staunch, sea-worthy little vessel. She had no fine lines; there was nothing about her to please a yachtsman's eye; but she was far from being a tub as whaling ships are often pictured. She was built at New Bedford especially for Arctic whaling. Her hull was of sturdy oak, reinforced at the bows to enable her to buck her way through ice.

Though she was called a brig, she was really a brigantine, rigged with square sails on her fore-mast and with fore-and-aft sails on her main. She was of only 128 tons but quite lofty, her royal yard being eighty feet above the deck. On her fore-mast she carried a fore-sail, a single topsail, a fore-top-gallant sail, and a royal; on [ 22 ] her main-mast, a big mainsail with a gaff-topsail above it. Three whale boats—starboard, larboard, and waist boats—hung at her davits. Amidships stood the brick try-works equipped with furnaces and cauldrons for rendering blubber into oil.

As soon as I arrived on board I was taken in charge by the ship keeper and conducted to the forecastle. It was a dark, malodorous, triangular hole below the deck in the bows. At the foot of the ladder-like stairs, leading down through the scuttle, I stepped on something soft and yielding. Was it possible, I wondered in an instant's flash of surprise, that the forecastle was laid with a velvet carpet? No, it was not. It was only a Kanaka sailor lying on the floor dead drunk. The bunks were ranged round the walls in a double tier. I selected one for myself, arranged my mattress and blankets, and threw my bag inside. I was glad to get back to fresh air on deck as quickly as possible.

Members of the crew kept coming aboard in charge of runners and boarding bosses. They were a hard looking lot; several were staggering [ 23 ] drunk, and most of them were tipsy. All had bottles and demijohns of whiskey. Everybody was full of bad liquor and high spirits that first night on the brig. A company of jolly sea rovers were we, and we joked and laughed and roared out songs like so many pirates about to cruise for treasure galleons on the Spanish Main. Somehow next morning the rose color had faded out of the prospect and there were many aching heads aboard.

On the morning of the second day, the officers came out to the vessel. A tug puffed alongside and made fast to us with a cable. The anchor was heaved up and, with the tug towing us, we headed for the Golden Gate. Outside the harbor heads, the tug cast loose and put back into the bay in a cloud of smoke. The brig was left swinging on the long swells of the Pacific.

The captain stopped pacing up and down the quarter-deck and said something to the mate. His words seemed like a match to powder. Immediately the mate began roaring out orders. Boat-steerers bounded forward, shouting out the orders in turn. The old sailors sang them out in [ 24 ] repetition. Men sprang aloft. Loosened sails were soon rolling down and fluttering from every spar. The sailors began pulling on halyards and yo-hoing on sheets. Throughout the work of setting sail, the green hands were "at sea" in a double sense. The bustle and apparent confusion of the scene seemed to savor of bedlam broke loose. The orders were Greek to them. They stood about, bewildered and helpless. Whenever they tried to help the sailors they invariably snarled things up and were roundly abused for their pains. One might fancy they could at least have helped pull on a rope. They couldn't even do that. Pulling on a rope, sailor-fashion, is in itself an art.

Finally all the sails were sheeted home. Ropes were coiled up and hung neatly on belaying pins. A fresh breeze set all the snowy canvas drawing and the brig, all snug and shipshape, went careering southward.

At the outset of the voyage, the crew consisted of twenty-four men. Fourteen men were in the forecastle. The after-crew comprised the captain, mate, second mate, third mate, two boat-steerers, [ 25 ] steward, cooper, cook, and cabin boy. Captain Shorey was not aboard. He was to join the vessel at Honolulu. Mr. Winchester, the mate, took the brig to the Hawaiian Islands as captain. This necessitated a graduated rise in authority all along the line. Mr. Landers, who had shipped as second mate, became mate; Gabriel, the regular third mate, became second mate; and Mendez, a boatsteerer, was advanced to the position of third mate.

Captain Winchester was a tall, spare, vigorous man with a nose like Julius Caesar's and a cavernous bass voice that boomed like a sunset gun. He was a man of some education, which is a rarity among officers of whale ships, and was a typical New England Yankee. He had run away to sea as a boy and had been engaged in the whaling trade for twenty years. For thirteen years, he had been sailing to the Arctic Ocean as master and mate of vessels, and was ingrained with the autocratic traditions of the quarter-deck. Though every inch a sea dog of the hard, old-fashioned school, he had his kindly human side, as I learned later. He was by far [ 26 ] the best whaleman aboard the brig; as skillful and daring as any that ever laid a boat on a whale's back; a fine, bold, hardy type of seaman and an honor to the best traditions of the sea. He lost his life—poor fellow—in a whaling adventure in the Arctic Ocean on his next voyage.

Mr. Landers, the mate, was verging on sixty; his beard was grizzled, but there wasn't a streak of gray in his coal-black hair. He was stout and heavy-limbed and must have been remarkably strong in his youth. He was a Cape Codder and talked with a quaint, nasal, Yankee drawl. He had been to sea all his life and was a whaleman of thirty years' experience. In all these years, he had been ashore very little—only a few weeks between his year-long voyages, during which time, it was said, he kept up his preference for liquids, exchanging blue water for red liquor. He was a picturesque old fellow, and was so accustomed to the swinging deck of a ship under him that standing or sitting, in perfectly still weather or with the vessel lying motionless at anchor, he swayed his body from side to side [ 27 ] heavily as if in answer to the rise and fall of waves. He was a silent, easy-going man, with a fund of dry humor and hard common sense. He never did any more work than he had to, and before the voyage ended, he was suspected by the officers of being a malingerer. All the sailors liked him.

Gabriel, the second mate, was a negro from the Cape Verde islands. His native language was Portuguese and he talked funny, broken English. He was about forty-five years old, and though he was almost as dark-skinned as any Ethiopian, he had hair and a full beard as finely spun and free from kinkiness as a Caucasian's. The sailors used to say that Gabriel was a white man born black by accident. He was a kindly, cheerful soul with shrewd native wit. He was a whaleman of life-long experience.

Mendez, the third mate, and Long John, one of the boatsteerers, were also Cape Verde islanders. Long John was a giant, standing six feet, four inches; an ungainly, powerful fellow, with a black face as big as a ham and not much more expressive. He had the reputation of being one [ 28 ] of the most expert harpooners of the Arctic Ocean whaling fleet.

Little Johnny, the other boatsteerer, was a mulatto from the Barbadoes, English islands of the West Indies. He was a strapping, intelligent young man, brimming over with vitality and high spirits and with all a plantation darky's love of fun. His eyes were bright and his cheeks ruddy with perfect health; he loved dress and gay colors and was quite the dandy of the crew.

Five of the men of the forecastle were deep-water sailors. Of these one was an American, one a German, one a Norwegian, and two Swedes. They followed the sea for a living and had been bunkoed by their boarding bosses into believing they would make large sums of money whaling. They had been taken in by a confidence game as artfully as the man who loses his money at the immemorial trick of three shells and a pea. When they learned they would get only a dollar at the end of the voyage and contemplated the loss of an entire working year, they were full of resentment and righteous, though futile, anger.

Taylor, the American, became the acknowledged leader of the forecastle. He quickly established himself in this position, not only by his skill and long experience as a seaman, but by his aggressiveness, his domineering character, and his physical ability to deal with men and situations. He was a bold, iron-fisted fellow to whom the green hands looked for instruction and advice, whom several secretly feared, and for whom all had a wholesome respect.

Nels Nelson, a red-haired, red-bearded old Swede, was the best sailor aboard. He had had a thousand adventures on all the seas of all the world. He had been around Cape Horn seven times—a sailor is not rated as a really-truly sailor until he has made a passage around that stormy promontory—and he had rounded the Cape of Good Hope so many times he had lost the count. He had ridden out a typhoon on the coast of Japan and had been driven ashore by a hurricane in the West Indies. He had sailed on an expedition to Cocos Island, that realm of mystery and romance, to try to lift pirate treasure in doubloons, plate, and pieces-of-eight, supposed [ 30 ] to have been buried there by "Bugs" Thompson and Benito Bonito, those one-time terrors of the Spanish Main. He had been cast away in the South Seas in an open boat with three companions, and had eaten the flesh of the man whose fate had been sealed by the casting of lots. He was some man, was Nelson. I sometimes vaguely suspected he was some liar, too, but I don't know. I think most of his stories were true.

He could do deftly everything intricate and subtle in sailorcraft from tying the most wonderful knots to splicing wire. None of the officers could teach old Nelson anything about fancy sailorizing and they knew it. Whenever they wanted an unusual or particularly difficult piece of work done they called on him, and he always did it in the best seamanly fashion.

Richard, the German, was a sturdy, manly young chap who had served in the German navy. He was well educated and a smart seaman. Ole Oleson, the Norwegian, was just out of his teens but a fine sailor. Peter Swenson, a Swede, was a chubby, rosy boy of sixteen, an ignorant, reckless, [ 31 ] devil-may-care lad, who was looked upon as the baby of the forecastle and humored and spoiled accordingly.

Among the six white green hands, there was a "mule skinner" from western railway construction camps; a cowboy who believed himself fitted for the sea after years of experience on the "hurricane deck" of a bucking broncho; a country boy straight from the plow and with "farmer" stamped all over him in letters of light; a man suspected of having had trouble with the police; another who, in lazy night watches, spun frank yarns of burglaries; and "Slim," an Irishman who said he had served with the Royal Life Guards in the English army. There was one old whaler. He was a shiftless, loquacious product of city slums. This was his seventh whaling voyage—which would seem sufficient comment on his character.

"It beats hoboing," he said. And as his life's ambition seemed centered on three meals a day and a bunk to sleep in, perhaps it did.

Two Kanakas completed the forecastle crew. These and the cabin boy, who was also a Kanaka, [ 32 ] talked fair English, but among themselves they always spoke their native language. I had heard much of the liquid beauty of the Kanaka tongue. It was a surprise to find it the most unmusical and harshly guttural language I ever heard. It comes from the mouth in a series of explosive grunts and gibberings. The listener is distinctly and painfully impressed with the idea that if the nitroglycerine words were retained in the system, they would prove dangerous to health and is fearful lest they choke the spluttering Kanaka to death before he succeeds in biting them off and flinging them into the atmosphere.

WHY WE DON'T DESERT

As soon as we were under sail, the crew was called aft and the watches selected. Gabriel was to head the starboard watch and Mendez the port. The men were ranged in line and the heads of the watches made their selections, turn and turn about. The deep-water sailors were the first to be chosen. The green hands were picked for their appearance of strength and activity. I fell into the port watch.

Sea watches were now set—four hours for sleep and four for work throughout the twenty-four. My watch was sent below. No one slept during this first watch below, but we made up for lost time during our second turn. Soon we became accustomed to the routine and found it as restful as the usual landsman's method of eight hours' sleep and sixteen of wakefulness.

It is difficult for a landlubber to understand how sailors on shipboard can be kept constantly busy. The brig was a veritable hive of industry. The watch on deck when morning broke pumped ship and swept and flushed down the decks. During the day watches, in addition to working the ship, we were continuously breaking out supplies, keeping the water barrel on deck filled from casks in the hold, laboring with the cargo, scrubbing paint work, polishing brass work, slushing masts and spars, repairing rigging, and attending to a hundred and one details that must be looked after every day. The captain of a ship is one of the most scrupulous housekeepers in the world, and only by keeping his crew busy from morning till night is he able to keep his ship spick and span and in proper repair. Whale ships are supposed to be dirty. On the contrary, they are kept as clean as water and brooms and hard work can keep them.

The food served aboard the brig was nothing to brag about. Breakfast consisted of corned-beef hash, hardtack, and coffee without milk or sugar. We sweetened our coffee with molasses, [ 35 ] a keg of which was kept in the forecastle. For dinner, we had soup, corned-beef stew, called "skouse," a loaf of soft bread, and coffee. For supper, we had slices of corned-beef which the sailors called "salt horse," hardtack, and tea. The principal variation in this diet was in the soups.

The days were a round of barley soup, bean soup, pea soup, and back to barley soup again, an alternation that led the men to speak of the days of the week not as Monday, Tuesday, and so on, but as "barley soup day," "bean soup day," and "pea soup day." Once or twice a week we had gingerbread for supper. On the other hand the cabin fared sumptuously on canned vegetables, meat, salmon, soft bread, tea, and coffee with sugar and condensed milk, fresh fish and meat whenever procurable, and a dessert every day at dinner, including plum duff, a famous sea delicacy which never in all the voyage found its way forward.

From the first day, the green hands were set learning the ropes, to stand lookout, to take their trick at the wheel, to reef and furl and work [ 36 ] among the sails. These things are the A B C of seamanship, but they are not to be learned in a day or a week. A ship is a complicated mechanism, and it takes a long time for a novice to acquire even the rudiments of sea education. Going aloft was a terrifying ordeal at first to several of the green hands, though it never bothered me. When the cowboy was first ordered to furl the fore-royal, he hung back and said, "I can't" and "I'll fall," and whimpered and begged to be let off. But he was forced to try. He climbed the ratlines slowly and painfully to the royal yard, and he finally furled the sail, though it took him a long time to do it. He felt so elated that after that he wanted to furl the royal every time it had to be done;—didn't want to give anyone else a chance.

Furling the royal was a one-man job. The foot-rope was only a few feet below the yard, and if a man stood straight on it, the yard would strike him a little above the knees. If the ship were pitching, a fellow had to look sharp or he would be thrown off;—if that had happened it was a nice, straight fall of eighty feet to the [ 37 ] deck. My own first experience on the royal yard gave me an exciting fifteen minutes. The ship seemed to be fighting me and devoting an unpleasant amount of time and effort to it; bucking and tossing as if with a sentient determination to shake me off into the atmosphere. I escaped becoming a grease spot on the deck of the brig only by hugging the yard as if it were a sweetheart and hanging on for dear life. I became in time quite an expert at furling the sail.

Standing lookout was the one thing aboard a green hand could do as well as an old sailor. The lookout was posted on the forecastle-head in fair weather and on the try-works in a storm. He stood two hours at a stretch. He had to scan the sea ahead closely and if a sail or anything unusual appeared, he reported to the officer of the watch.

Learning to steer by the compass was comparatively easy. With the ship heading on a course, it was not difficult by manipulating the wheel to keep the needle of the compass on a given point. But to steer by the wind was hard to learn and is sometimes a nice matter even for [ 38 ] skillful seamen. When a ship is close-hauled and sailing, as sailors say, right in the wind's eye, the wind is blowing into the braced sails at the weather edge of the canvas;—if the vessel were brought any higher up, the wind would pour around on the back of the sails. The helmsman's aim is to keep the luff of the royal sail or of the sails that happen to be set, wrinkling and loose—luffing, sailors call it. That shows that the wind is slanting into the sails at just the right angle and perhaps a little bit is spilling over. I gradually learned to do this in the daytime. But at night when it was almost impossible for me to see the luff of the sails clearly, it was extremely difficult and I got into trouble more than once by my clumsiness. The trick at the wheel was of two hours' duration.

The second day out from San Francisco was Christmas. I had often read that Christmas was a season of good cheer and happiness among sailors at sea, that it was commemorated with religious service, and that the skipper sent forward grog and plum duff to gladden the hearts of the sailormen. But Santa Claus forgot the [ 39 ] sailors on the brig. Bean soup only distinguished Christmas from the day that had gone before and the day that came after. No liquor or tempting dishes came to the forecastle. It was the usual day of hard work from dawn to dark.

After two weeks of variable weather during which we were often becalmed, we put into Turtle bay, midway down the coast of Lower California, and dropped anchor.

Turtle bay is a beautiful little land-locked harbor on an uninhabited coast. There was no village or any human habitation on its shores. A desolate, treeless country, seamed by gullies and scantily covered with sun-dried grass, rolled away to a chain of high mountains which forms the backbone of the peninsula of Lower California. These mountains were perhaps thirty miles from the coast; they were gray and apparently barren of trees or any sort of herbage, and looked to be ridges of naked granite. The desert character of the landscape was a surprise, as we were almost within the tropics.

We spent three weeks of hard work in Turtle [ 40 ] bay. Sea watches were abolished and all hands were called on deck at dawn and kept busy until sundown. The experienced sailors were employed as sail makers; squatting all day on the quarter-deck, sewing on canvas with a palm and needle. Old sails were sent down from the spars and patched and repaired. If they were too far gone, new sails were bent in their stead. The green hands had the hard work. They broke out the hold and restowed every piece of cargo, arranging it so that the vessel rode on a perfectly even keel. Yards and masts were slushed, the rigging was tarred, and the ship was painted inside and out.

The waters of the harbor were alive with Spanish mackerel, albacore, rock bass, bonitos, and other kinds of fish. The mackerel appeared in great schools that rippled the water as if a strong breeze were blowing. These fish attracted great numbers of gray pelicans, which had the most wonderful mode of flight I have ever seen in any bird. For hours at a time, with perfectly motionless pinions, they skimmed the surface of the bay like living aeroplanes; one wondered wherein lay their motor power and how they managed to keep going. When they spied a school of mackerel, they rose straight into the air with a great flapping of wings, then turned their heads downward, folded their wings close to their bodies, and dropped like a stone. Their great beaks cut the water, they went under with a terrific splash, and immediately emerged with a fish in the net-like membrane beneath their lower mandible.

Every Sunday, a boat's crew went fishing. We fished with hand lines weighted with lead and having three or four hooks, baited at first with bacon and later with pieces of fresh fish. I never had such fine fishing. The fish bit as fast as we could throw in our lines, and we were kept busy hauling them out of the water. We would fill a whale boat almost to the gunwales in a few hours. With the return of the first fishing expedition, the sailors had dreams of a feast, but they were disappointed. The fish went to the captain's table or were salted away in barrels for the cabin's future use. The sailors, however, enjoyed the fun. Many of them kept lines constantly [ 42 ] over the brig's sides, catching skates, soles, and little sharks.

By the time we reached Turtle bay, it was no longer a secret that we would get only a dollar for our year's voyage. As a result, a feverish spirit of discontent began to manifest itself among those forward and plans to run away became rife.

We were anchored about a half mile from shore, and after looking over the situation, I made up my mind to try to escape. Except for an officer and a boatsteerer who stood watch, all hands were asleep below at night. Being a good swimmer, I planned to slip over the bow in the darkness and swim ashore. Once on land, I figured it would be an easy matter to cross the Sierras and reach a Mexican settlement on the Gulf of California.

Possibly the officers got wind of the runaway plots brewing in the forecastle, for Captain Winchester came forward one evening, something he never had done before, and fell into gossipy talk with the men.

"Have you noticed that pile of stones with a [ 43 ] cross sticking in it on the harbor head?" he asked in a casual sort of way.

Yes, we had all noticed it from the moment we dropped anchor, and had wondered what it was.

"That," said the captain impressively, "is a grave. Whaling vessels have been coming to Turtle bay for years to paint ship and overhaul. Three sailors on a whaler several years ago thought this was a likely place in which to escape. They managed to swim ashore at night and struck into the hills. They expected to find farms and villages back inland. They didn't know that the whole peninsula of Lower California is a waterless desert from one end to the other. They had some food with them and they kept going for days. No one knows how far inland they traveled, but they found neither inhabitants nor water and their food was soon gone.

"When they couldn't stand it any longer and were half dying from thirst and hunger, they turned back for the coast. By the time they returned to Turtle bay their ship had sailed away [ 44 ] and there they were on a desert shore without food or water and no way to get either. I suppose they camped on the headland in the hope of hailing a passing ship. But the vessels that pass up and down this coast usually keep out of sight of land. Maybe the poor devils sighted a distant topsail—no one knows—but if they did the ship sank beyond the horizon without paying any attention to their frantic signals. So they died miserably there on the headland.

"Next year, a whale ship found their bodies and erected a cairn of stones marked by the cross you see over the spot where the three sailors were buried together. This is a bad country to run away in," the captain added. "No food, no water, no inhabitants. It's sure death for a runaway."

Having spun this tragic yarn, Captain Winchester went aft again, feeling, no doubt, that he had sowed seed on fertile soil. The fact is his story had an instant effect. Most of the men abandoned their plans to escape, at least for the time being, hoping a more favorable opportunity would present itself when we reached the Hawaiian [ 45 ] islands. But I had my doubts. I thought it possible the captain merely had "put over" a good bluff.

Next day I asked Little Johnny, the boatsteerer, if it were true as the captain had said, that Lower California was an uninhabited desert. He assured me it was and to prove it, he brought out a ship's chart from the cabin and spread it before me. I found that only two towns throughout the length and breadth of the peninsula were set down on the map. One of these was Tia Juana on the west coast just south of the United States boundary line and the other was La Paz on the east coast near Cape St. Lucas, the southern tip of the peninsula. Turtle bay was two or three hundred miles from either town.

That settled it with me. I didn't propose to take chances on dying in the desert. I preferred a whaler's forecastle to that.

TURTLES AND PORPOISES

We slipped out of Turtle bay one moonlight night and stood southward. We were now in sperm whale waters and the crews of the whale boats were selected. Captain Winchester was to head the starboard boat; Mr. Landers the larboard boat; and Gabriel the waist boat. Long John was to act as boatsteerer for Mr. Winchester, Little Johnny for Mr. Landers, and Mendez for Gabriel. The whale boats were about twenty-five feet long, rigged with leg-of-mutton sails and jibs. The crew of each consisted of an officer known as a boat-header, who sat in the stern and wielded the tiller; a boatsteerer or harpooner, whose position was in the bow; and four sailors who pulled the stroke, midship, tub, and bow oars. Each boat [ 47 ] had a tub in which four hundred fathoms of whale line were coiled and carried two harpoons and a shoulder bomb-gun. I was assigned to the midship oar of Gabriel's boat.

Let me take occasion just here to correct a false impression quite generally held regarding whaling. Many persons—I think, most persons—have an idea that in modern whaling, harpoons are fired at whales from the decks of ships. This is true only of 'long-shore whaling. In this trade, finbacks and the less valuable varieties of whales are chased by small steamers which fire harpoons from guns in the bows and tow the whales they kill to factories along shore, where blubber, flesh, and skeleton are turned into commercial products. Many published articles have familiarized the public with this method of whaling. But whaling on the sperm grounds of the tropics and on the right whale and bowhead grounds of the polar seas is much the same as it has always been. Boats still go on the backs of whales. Harpoons are thrown by hand into the great animals as of yore. Whales still run away with the boats, pulling them with amazing speed [ 48 ] through walls of split water. Whales still crush boats with blows of their mighty flukes and spill their crews into the sea.

There is just as much danger and just as much thrill and excitement in the whaling of to-day as there was in that of a century ago. Neither steamers nor sailing vessels that cruise for sperm and bowhead and right whales nowadays have deck guns of any sort, but depend entirely upon the bomb-guns attached to harpoons and upon shoulder bomb-guns wielded from the whale boats.

In the old days, after whales had been harpooned, they were stabbed to death with long, razor-sharp lances. The lance is a thing of the past. The tonite bomb has taken its place as an instrument of destruction. In the use of the tonite bomb lies the chief difference between modern whaling and the whaling of the old school.

The modern harpoon is the same as it has been since the palmy days of the old South Sea sperm fisheries. But fastened on its iron shaft between the wooden handle and the spear point is a brass cylinder an inch in diameter, perhaps, and about [ 49 ] a foot long. This cylinder is a tonite bomb-gun. A short piece of metal projects from the flat lower end. This is the trigger. When the harpoon is thrown into the buttery, blubber-wrapped body of the whale, it sinks in until the whale's skin presses the trigger up into the gun and fires it with a tiny sound like the explosion of an old-fashioned shotgun cap. An instant later a tonite bomb explodes with a muffled roar in the whale's vitals.

The Arctic Ocean whaling fleet which sails out of San Francisco and which in the year of my voyage numbered thirty vessels, makes its spring rendezvous in the Hawaiian Islands. Most of the ships leave San Francisco in December and reach Honolulu in March. The two or three months spent in this leisurely voyage are known in whaler parlance as "between seasons." On the way to the islands the ships cruise for sperm whales and sometimes lower for finbacks, sulphur-bottoms, California grays, and even black fish, to practice their green hand crews.

Captain Winchester did not care particularly whether he took any sperm whales or not, though [ 50 ] sperm oil is still valuable. The brig was not merely a blubber-hunter. Her hold was filled with oil tanks which it was hoped would be filled before we got back, but the chief purpose of the voyage was the capture of right and bowhead whales—the great baleen whales of the North.

As soon as we left Turtle Bay, a lookout for whales was posted. During the day watches, a boatsteerer and a sailor sat on the topsail yard for two hours at a stretch and scanned the sea for spouts. We stood down the coast of Lower California and in a few days, were in the tide-rip which is always running off Cape St. Lucas, where the waters of the Pacific meet a counter-current from the Gulf of California. We rounded Cape St. Lucas and sailed north into the gulf, having a distant view of La Paz, a little town backed by gray mountains. Soon we turned south again, keeping close to the Mexican coast for several days. I never learned how far south we went, but we must have worked pretty well toward the equator, for when we stood out across the Pacific for the Hawaiian Islands, our course was northwesterly.

I saw my first whales one morning while working in the bows with the watch under Mr. Lander's supervision. A school of finbacks was out ahead moving in leisurely fashion toward the brig. There were about twenty of them and the sea was dotted with their fountains. "Blow!" breathed old man Landers with mild interest as though to himself. "Blow!" boomed Captain Winchester in his big bass voice from the quarter-deck. "Nothin' but finbacks, sir," shouted the boatsteerer from the mast-head. "All right," sang back the captain. "Let 'em blow." It was easy for these old whalers even at this distance to tell they were not sperm whales. Their fountains rose straight into the air. A sperm whale's spout slants up from the water diagonally.

The whales were soon all about the ship, seemingly unafraid, still traveling leisurely, their heads rising and falling rhythmically, and at each rise blowing up a fountain of mist fifteen feet high. The fountains looked like water; some water surely was mixed with them; but I was told that the mist was the breath of the animals [ 52 ] made visible by the colder air. The breath came from the blow holes in a sibilant roar that resembled no sound I had ever heard. If one can imagine a giant of fable snoring in his sleep, one may have an idea of the sound of the mighty exhalation. The great lungs whose gentle breathing could shoot a jet of spray fifteen feet into the air must have had the power of enormous bellows.

Immense coal-black fellows these finbacks were—some at least sixty or seventy feet long. One swam so close to the brig that when he blew, the spray fell all about me, wetting my clothes like dew. The finback is a baleen whale and a cousin of the right whale and the bowhead. Their mouths are edged with close-set slabs of baleen, which, however, is so short that it is worthless for commercial purposes. They are of much slenderer build than the more valuable species of whale. Their quickness and activity make them dangerous when hunted in the boats, but their bodies are encased in blubber so thin that it is as worthless as their bone. Consequently they [ 53 ] are not hunted unless a whaling ship is hard up for oil.

We gradually worked into the trade winds that blew steadily from the southeast. These winds stayed with us for several weeks or rather we stayed with the winds; while in them it was rarely necessary to take in or set a sail or brace a yard. After we had passed through these aerial rivers, flowing through definite, if invisible, banks, we struck the doldrums—areas of calm between wind currents—they might be called whirlpools of stillness. Later in the day light, fitful breezes finally pushed us through them into the region of winds again.

The slow voyage to the Hawaiian islands—on the sperm whale grounds, we cruised under short sail—might have proved monotonous if we had not been kept constantly busy and if diverting incidents had not occurred almost every day. Once we sighted three immense turtles sunning themselves on the sea. To the captain they held out prospect of soups and delicate dishes for the cabin table, and with Long John as boatsteerer, [ 54 ] a boat was lowered for them. I expected it would be difficult to get within darting distance. What was my surprise to see the turtles, with heads in the air and perfectly aware of their danger, remain upon the surface until the boat was directly upon them. The fact was they could not go under quickly; the big shells kept them afloat. Long John dropped his harpoon crashing through the shell of one of the turtles, flopped it into the boat, and then went on without particular hurry, and captured the other two in the same way. The cabin feasted for several days on the delicate flesh of the turtles; the forecastle got only a savory smell from the galley, as was usual.

We ran into a school of porpoises on another occasion—hundreds of them rolling and tumbling about the ship, like fat porkers on a frolic. Little Johnny took a position on the forecastle head with a harpoon, the line from which had been made fast to the fore-bitt. As a porpoise rose beneath him, he darted his harpoon straight into its back. The sea pig went wriggling under, leaving the water dyed with its blood. It was hauled aboard, squirming and twisting. Little [ 55 ] Johnny harpooned two more before the school took fright and disappeared. The porpoises were cleaned and some of their meat, nicely roasted, was sent to the forecastle. It made fine eating, tasting something like beef.

The steward was an inveterate fisherman and constantly kept a baited hook trailing in the brig's wake, the line tied to the taff-rail. He caught a great many bonitos and one day landed a dolphin. We had seen many of these beautiful fish swimming about the ship—long, graceful and looking like an animate streak of blue sky. The steward's dolphin was about five feet long. I had often seen in print the statement that dolphins turned all colors of the rainbow in dying and I had as often seen the assertion branded as a mere figment of poetic imagination. Our dolphin proved the truth of the poetic tradition. As life departed, it changed from blue to green, bronze, salmon, gold, and gray, making death as beautiful as a gorgeous kaleidoscope.

We saw flying fish every day—great "coveys" of them, one may say. They frequently flew several hundred yards, fluttering their webbed [ 56 ] side fins like the wings of a bird, sometimes rising fifteen to twenty feet above the water, and curving and zigzagging in their flight. More than once they flew directly across the ship and several fell on deck. I was talking with Kaiuli, the Kanaka, one night when we heard a soft little thud on deck. I should have paid no attention but Kaiuli was alert on the instant. "Flying feesh," he cried zestfully and rushed off to search the deck. He found the fish and ate it raw, smacking his lips over it with great gusto. The Hawaiian islanders, he told me, esteem raw flying fish a great delicacy.

I never saw water so "darkly, deeply, beautifully blue" as in the middle of the Pacific where we had some four miles of water under us. It was as blue as indigo. At night, the sea seemed afire with riotous phosphorescence. White flames leaped about the bows where the brig cut the water before a fresh breeze; the wake was a broad, glowing path. When white caps were running every wave broke in sparks and tongues of flame, and the ocean presented the appearance of a prairie swept by fire. A big shark came [ 57 ] swimming about the ship one night and it shone like a living incandescence—a silent, ghost-like shape slowly gliding under the brig and out again.

The idle night watches in the tropics were great times for story telling. The deep-water sailors were especially fond of this way of passing the time. While the green hands were engaging in desultory talk and wishing for the bell to strike to go back to their bunks, these deep-water fellows would be pacing up and down or sitting on deck against the bulwarks, smoking their pipes and spinning yarns to each other. The stories as a rule were interminable and were full of "Then he says" and "Then the other fellow says." It was a poor story that did not last out a four-hour watch and many of them were regular "continued in our next" serials, being cut short at the end of one watch to be resumed in the next.

No matter how long-winded or prosy the narrative, the story teller was always sure of an audience whose attention never flagged for an instant. The boyish delight of these full-grown [ 58 ] men in stories amazed me. I had never seen anything like it. Once in a while a tale was told that was worth listening to, but most of them were monotonously uninteresting. They bored me.

THE A, B, C OF WHALES

One damp morning, with frequent showers falling here and there over the sea and not a drop wetting the brig, Captain Winchester suddenly stopped pacing up and down the weather side of the quarter-deck, threw his head up into the wind, and sniffed the air.

"There's sperm whale about as sure as I live," he said to Mr. Landers. "I smell 'em."

Mr. Landers inhaled the breeze through his nose in jerky little sniffs.

"No doubt about it," he replied. "You could cut the smell with a knife."

I was at the wheel and overheard this talk. I smiled. These old sea dogs, I supposed, were having a little joke. The skipper saw the grin on my face.

"Humph, you don't believe I smell whale, eh?" he said. "I can smell whale like a bird dog smells quail. Take a sniff at the wind. Can't you smell it yourself?"

I gave a few hopeful sniffs.

"No," I said, "I can't smell anything unless, perhaps, salt water."

"You've got a poor smeller," returned the captain. "The wind smells rank and oily. That means sperm whale. If I couldn't smell it, I could taste it. I'll give you a plug of tobacco, if we don't raise sperm before dark."

He didn't have to pay the tobacco. Within an hour, we raised a sperm whale spouting far to windward and traveling in the same direction as the brig. The captain hurried to the cabin for his binoculars. As he swung himself into the shrouds to climb to the mast-head, he shouted to me, "Didn't I tell you I could smell 'em?" The watch was called. The crew of the captain's boat was left to work the ship and Mr. Landers and Gabriel lowered in the larboard and waist boats. Sails were run up and we went skimming away on our first whale hunt. We had a long [ 61 ] beat to windward ahead of us and as the whale was moving along at fair speed, remaining below fifteen minutes or so between spouts, it was slow work cutting down the distance that separated us from it.

"See how dat spout slant up in de air?" remarked old Gabriel whom the sight of our first sperm had put in high good humor.

We looked to where the whale was blowing and saw its fountain shoot into the air diagonally, tufted with a cloudy spread of vapor at the top.

"You know why it don't shoot straight up?"

No one knew.

"Dat feller's blow hole in de corner ob his square head—dat's why," said Gabriel. "He blow his fountain out in front of him. Ain't no udder kind o' whale do dat. All de udder kind blow straight up. All de differ in de worl' between dat sperm whale out dere and de bowhead and right whale up nort'. Ain't shaped nothin' a-tall alike. Bowhead and right whale got big curved heads and big curved backs. Sperm whale's about one-third head and his back ain't got no bow to it—not much—jest lies straight [ 62 ] out behind his head. He look littler in de water dan de right and bowhead whale. But he ain't. He's as big as de biggest whale dat swims de sea. I've seen a 150 barrel sperm dat measure seventy feet.

"Blow!" added the old negro as he caught sight of the whale spouting again.

"Bowhead and right whale got no teeth," he continued. "Dey got only long slabs o' baleen hung wit' hair in de upper jaw. Sperm whale got teeth same as you and me—about twenty on a side and all in his lower jaw. Ain't got no teeth in his upper jaw a-tall. His mouth is white inside and his teeth stand up five or six inches out o' his gums and are wide apart and sharp and pointed and look jes' like de teeth of a saw. Wen he open his mouth, his lower jaw fall straight down and his mouth's big enough to take a whale boat inside.

"Sperm whale's fightin' whale. He fight wit' his tail and his teeth. He knock a boat out de water wit' his flukes and he scrunch it into kindlin' wood wit' his teeth. He's got fightin' sense too—he's sly as a fox. W'en I was young feller, [ 63 ] I was in de sperm trade mysel' and used to ship out o' New Bedford round Cape o' Good Hope for sperm whale ground in Indian Ocean and Sout' Pacific. Once I go on top a sperm whale in a boat an' he turn flukes and lash out wit' his tail but miss us. Den he bring up his old head and take a squint back at us out o' his foxy little eye and begin to slew his body roun' till he get his tail under de boat. But de boatheader too smart fer him and we stern oars and get out o' reach. But de whale didn't know we done backed out o' reach and w'en he bring up dat tail it shoot out o' de water like it was shot out o' a cannon. Mighty fine fer us he miss us dat time.

"But dat don't discourage dat whale a-tall. He swim round and slew round and sight at us out o' his eye and at las' he get under de boat. Den he lift it on de tip o' his tail sky-high and pitch us all in de water. Dat was jes' what he been working for. He swim away and turn round and come shootin' back straight fer dat boat and w'en he get to it, he crush it wit' his teeth and chew it up and shake his head like a mad bulldog [ 64 ] until dere warn't nothin' left of dat boat but a lot o' kindlin' wood. But dat warn't all. He swim to a man who wuz lying across an oar to keep afloat and he chew dat man up and spit him out in li'l pieces and we ain't never see nothin' o' dat feller again.

"Guess that whale was goin' to give us all de same medicine, but he ain't have time. De udder boats come up and fill him full o' harpoons and keep stickin' der lances into him and kill him right where he lays and he never had no chance to scoff the rest o' us. But if it ain't fer dem boats, I guess dat feller eat us all jes' like plum duff. Sperm whale, some fighter, believe me.

"Dere he white waters—blow!" added Gabriel as the whale came to the surface again.

"Sperm whale try out de bes' oil," the garrulous old whaleman went on. "Bowhead and right whale got thicker blubber and make more oil, but sperm whale oil de bes'. He got big cistern—what dey call a 'case'—in de top ob his head and it's full o' spermaceti, sloshing about in dere and jes' as clear as water. His old head [ 65 ] is always cut off and hoist on deck to bale out dat case. Many times dey find ambergrease (ambergis) floating beside a dead sperm whale. It's solid and yellowish and stuck full o' cuttle feesh beaks dat de whale's done swallowed but ain't digest. Dey makes perfume out o' dat ambergrease and it's worth its weight in gold. I've offen seen it in chunks dat weighed a hundred pounds.

"You see a sperm whale ain't eat nothin' but cuttle feesh—giant squid, dey calls 'em, or devil feesh. Dey certainly is terrible fellers—is dem devil feesh. Got arms twenty or thirty feet long wit' sucking discs all over 'em and a big fat body in de middle ob dese snaky arms, wit' big pop-eyes as big as water buckets and a big black beak like a parrot's to tear its food wit'. Dose devil feesh. Dey certainly is terrible fellers—is dem sperm whale nose 'em out and eat 'em. Some time dey comes to de top and de whale and de cuttle feesh fights it out. I've hearn old whalers say dey seen fights between sperm whale and cuttle feesh but I ain't never seen dat and I reckon mighty few fellers ever did. But when [ 66 ] a sperm whale is killed, he spews out chunks o' cuttle feesh and I've seen de water about a dead sperm thick wit' white chunks of cuttle feesh as big as a sea ches' and wit' de suckin' disc still on 'em.

"Blow!" said Gabriel again with his eyes on the whale. "Dat feesh certainly some traveler."

We were hauling closer to the whale. I could see it distinctly by this time and could note how square and black its head was. Its appearance might be compared not inaptly to a box-car glistening in the sun under a fresh coat of black paint. It did not cut the water but pushed it in white foam in front of it.

"Sperm pretty scarce nowadays," Gabriel resumed. "Nothing like as plentiful in Pacific waters as dey used to be in de ole days. Whalers done pretty well thinned 'em out. But long ago, it used to be nothin' to see schools of a hundred, mostly cows wit' three or four big bulls among 'em."

"Any difference between a bowhead and a right whale?" some one asked.

"O good Lord, yes," answered Gabriel. [ 67 ] "Big difference. Right whale thinner whale dan a bowhead, ain't got sech thick blubber neither. He's quicker in de water and got nothin' like such long baleen. You ketch right whale in Behring Sea. I ain't never see none in de Arctic Ocean. You ketch bowhead both places. Right whale fightin' feesh, too, but he ain't so dangerous as a sperm."

Let me add that I give this statement of the old whaleman for what it is worth. All books I have ever read on the subject go on the theory that the Greenland or right whale is the same animal as the bowhead. We lowered for a right whale later in the voyage in Behring Sea. To my untrained eyes, it looked like a bowhead which we encountered every few days while on the Arctic Ocean whaling grounds. But there was no doubt or argument about it among the old whalemen aboard. To them it was a "right whale" and nothing else. Old Gabriel may have known what he was talking about. Despite the naturalists, whalers certainly make a pronounced distinction.

By the time Gabriel had imparted all this information, [ 68 ] we had worked to within a half mile of our whale which was still steaming along at the rate of knots. They say a sperm whale has ears so small they are scarcely detected, but it has a wonderfully keen sense of hearing for all that. Our whale must have heard us or seen us. At any rate it bade us a sudden good-bye and scurried off unceremoniously over the rim of the world. The boats kept on along the course it was heading for over an hour, but the whale never again favored us with so much as a distant spout. Finally signals from the brig's mast-head summoned us aboard.

As the men had had no practice in the boats before, both boats lowered sail and we started to row back to the vessel. We had pulled about a mile when Mendez, who was acting as boatsteerer, said quietly, "Blow! Blackfish dead ahead."

"Aye, aye," replied Gabriel. "Now stand by, Tomas. I'll jes' lay you aboard one o' dem blackfeesh and we'll teach dese green fellers somethin' 'bout whalin'."

There were about fifty blackfish in the school. [ 69 ] They are a species of small toothed whale, from ten to twenty feet long, eight or ten feet in circumference and weighing two or three tons. They were gamboling and tumbling like porpoises. Their black bodies flashed above the surface in undulant curves and I wondered if, when seen at a distance, these little cousins of the sperm had not at some time played their part in establishing the myth of the sea serpent.

"Get ready, Tomas," said Gabriel as we drew near the school.

"Aye, aye, sir," responded Mendez.

Pulling away as hard as we could, we shot among the blackfish. Mendez selected a big one and drove his harpoon into its back. Almost at the same time Mr. Lander's boat became fast to another. Our fish plunged and reared half out of water, rolled and splashed about, finally shot around in a circle and died. Mr. Lander's fish was not fatally hit and when it became apparent it would run away with a tub of line, Little Johnny, the boatsteerer, cut adrift and let it go. Mendez cut our harpoon free and left our fish weltering on the water. Blackfish yield a fairly [ 70 ] good quality of oil, but one was too small a catch to potter with. Our adventure among the blackfish was merely practice for the boat crews to prepare them for future encounters with the monarchs of the deep.

THE NIGHT KING

The crew called Tomas Mendez, the acting third mate, the "Night King." I have forgotten what forecastle poet fastened the name upon him, but it fitted like a glove. In the day watches when the captain and mate were on deck, he was only a quite, unobtrusive little negro, insignificant in size and with a bad case of rheumatism. But at night when the other officers were snoring in their bunks below and the destinies of the brig were in his hands, he became an autocrat who ruled with a hand of iron.

He was as black as a bowhead's skin—a lean, scrawny, sinewy little man, stooped about the shoulders and walking with a slight limp. His countenance was imperious. His lips were thin [ 72 ] and cruel. His eyes were sharp and sinister. His ebony skin was drawn so tightly over the frame-work of his face that it almost seemed as if it would crack when he smiled. His nose had a domineering Roman curve. He carried his head high. In profile, this little blackamoor suggested the mummified head of some old Pharaoh.

He was a native of the Cape Verde islands. He spoke English with the liquid burr of a Latin. His native tongue was Portuguese. No glimmer of education relieved his mental darkness. It was as though his outside color went all the way through. He could neither read nor write, but he was a good sailor and no better whaleman ever handled a harpoon or laid a boat on a whale's back. For twenty years he had been sailing as boatsteerer on whale ships, and to give the devil his due, he had earned a name for skill and courage in a thousand adventures among sperm, bowhead, and right whales in tropical and frozen seas.

My first impression of the Night King stands out in my memory with cameo distinctness. In the bustle and confusion of setting sails, just after the tug had cut loose from us outside Golden Gate heads, I saw Mendez, like an ebony statue, standing in the waist of the ship, an arm resting easily on the bulwarks, singing out orders in a clear, incisive voice that had in it the ring of steel.

When I shipped, it had not entered my mind that any but white men would be of the ship's company. It was with a shock like a blow in the face that I saw this little colored man singing out orders. I wondered in a dazed sort of way if he was to be in authority over me. I was not long in doubt. When calm had succeeded the first confusion and the crew had been divided into watches, Captain Winchester announced from the break of the poop that "Mr." Mendez would head the port watch. That was my watch. While the captain was speaking, "Mr." Mendez stood like a black Napoleon and surveyed us long and silently. Then suddenly he snapped out a decisive order and the white men jumped to obey. The Night King had assumed his throne.

The Night King and I disliked each other from the start. It may seem petty now that it's all past, but I raged impotently in the bitterness of outraged pride at being ordered about by this black overlord of the quarter-deck. He was not slow to discover my smoldering resentment and came to hate me with a cordiality not far from classic. He kept me busy with some silly job when the other men were smoking their pipes and spinning yarns. If I showed the left-handedness of a landlubber in sailorizing he made me stay on deck my watch below to learn the ropes. If there was dirt or litter to be shoveled overboard, he sang out for me.

"Clean up dat muck dere, you," he would say with fine contempt.

The climax of his petty tyrannies came one night on the run to Honolulu when he charged me with some trifling infraction of ship's rules, of which I was not guilty, and ordered me aloft to sit out the watch on the fore yard. The yard was broad, the night was warm, the ship was traveling on a steady keel, and physically the punishment was no punishment at all. There was [ 75 ] no particular ignominy in the thing, either, for it was merely a joke to the sailors. The sting of it was in having to take such treatment from this small colored person without being able to resent it or help myself.

The very next morning I was awakened by the cry of the lookout on the topsail yard.

"Blow! Blow! There's his old head. Blo—o—o—w! There he ripples. There goes flukes." Full-lunged and clear, the musical cry came from aloft like a song with little yodling breaks in the measure. It was the view-halloo of the sea, and it quickened the blood and set the nerves tingling.

"Where away?" shouted the captain, rushing from the cabin with his binoculars.

"Two points on the weather bow, sir," returned the lookout.

For a moment nothing was to be seen but an expanse of yeasty sea. Suddenly into the air shot a fountain of white water—slender, graceful, spreading into a bush of spray at the top. A great sperm was disporting among the white caps.

"Call all hands and clear away the boats," yelled the captain.

Larboard and waist boats were lowered from the davits. Their crews scrambled over the ship's side, the leg-o'-mutton sails were hoisted, and the boats, bending over as the wind caught them, sped away on the chase. The Night King went as boatsteerer of the waist boat. I saw him smiling to himself as he shook the kinks out of his tub-line and laid his harpoons in position in the bows—harpoons with no bomb-guns attached to the spear-shanks.

In the distance, a slow succession of fountains gleamed in the brilliant tropical sunshine like crystal lamps held aloft on fairy pillars. Suddenly the tell-tale beacons of spray went out. The whale had sounded. Over the sea, the boats quartered like baffled foxhounds to pick up the lost trail.

Between the ship and the boats, the whale came quietly to the surface at last and lay perfectly still, taking its ease, sunning itself and spouting lazily. The captain, perched in the ship's cross-trees, signalled its position with flags, [ 77 ] using a code familiar to whalemen. The Night King caught the message first. He turned quickly to the boatheader at the tiller and pointed. Instantly the boat came about, the sailors shifted from one gunwale to the other, the big sail swung squarely out and filled. All hands settled themselves for the run to close quarters.

With thrilling interest, I watched the hunt from the ship's forward bulwarks, where I stood grasping a shroud to prevent pitching overboard. Down a long slant of wind, the boat ran free with the speed of a greyhound, a white plume of spray standing high on either bow. The Night King stood alert and cool, one foot on the bow seat, balancing a harpoon in his hands. The white background of the bellying sail threw his tense figure into relief. Swiftly, silently, the boat stole upon its quarry until but one long sea lay between. It rose upon the crest of the wave and poised there for an instant like some great white-winged bird of prey. Then sweeping down the green slope, it struck the whale bows-on and beached its keel out of the water on its glistening back. As it struck, the Night King let fly one [ 78 ] harpoon and another, driving them home up to the wooden hafts with all the strength of his lithe arms.

The sharp bite of the iron in its vitals stirred the titanic mass of flesh and blood from perfect stillness into a frenzy of sudden movement that churned the water of the sea into white froth. The great head went under, the giant back curved down like the whirling surface of some mighty fly-wheel, the vast flukes, like some black demon's arm, shot into the air. Left and right and left again, the great tail thrashed, smiting the sea with thwacks which could have been heard for miles. It struck the boat glancingly with its bare tip, yet the blow stove a great hole in the bottom timbers, lifted the wreck high in air, and sent the sailors sprawling into the sea. Then the whale sped away with the speed of a limited express. It had not been vitally wounded. Over the distant horizon, it passed out of sight, blowing up against the sky fountains of clear water unmixed with blood.

The other boat hurried to the rescue and the crew gathered up the half-drowned sailors [ 79 ] perched on the bottom of the upturned boat or clinging to floating sweeps. Fouled in the rigging of the sail, held suspended beneath the wreck in the green crystal of the sea water, they found the Night King, dead.

When the whale crushed the boat—at the very moment, it must have been—the Night King had snatched the knife kept fastened in a sheath on the bow thwart and with one stroke of the razor blade, severed the harpoon lines. He thus released the whale and prevented it from dragging the boat away in its mad race. The Night King's last act had saved the lives of his companions.

I helped lift the body over the rail. We laid it on the quarter deck near the skylight. It lurched and shifted in a ghastly sort of way as the ship rolled, the glazed eyes open to the blue sky. The captain's Newfoundland dog came and sniffed at the corpse. Sheltered from the captain's eye behind the galley, the Kanaka cabin boy shook a furtive fist at the dead man and ground out between clenched teeth, "You black devil, you'll never kick me again." Standing not [ 80 ] ten feet away, the mate cracked a joke to the second mate and the two laughed uproariously. The work of the ship went on all around.

Looking upon the dead thing lying there, I thought of the pride with which the living man had borne himself in the days of his power. I beheld in fancy the silent, lonely, imperious little figure, pacing to and fro on the weather side of the quarter-deck—to and fro under the stars. I saw him stop in the darkness by the wheel, as his custom was, to peer down into the lighted binnacle and say in vibrant tones, "Keep her steady," or "Let her luff." I saw him buttoned up in his overcoat to keep the dew of the tropical night from his rheumatic joints, slip down the poop ladder and stump forward past the try-works to see how things fared in the bow. Again I heard his nightly cry to the lookout on the forecastle-head, "Keep a bright lookout dere, you," and saw him limp back to continue his vigil, pacing up and down. The qualities that had made him hated when he was indeed the Night King flooded back upon me, but I did not forget the courage of my enemy that had redeemed [ 81 ] them all and made him a hero in the hour of death.

In the afternoon, old Nelson sat on the deck beside the corpse and with palm and needle fashioned a long canvas bag. Into this the dead man was sewed with a weight of brick and sand at his feet.

At sunset, when all hands were on deck for the dog watch, they carried the body down on the main deck and with feet to the sea, laid it on the gang-plank which had been removed from the rail. There in the waist the ship's company gathered with uncovered heads. Over all was the light of the sunset, flushing the solemn, rough faces and reddening the running white-caps of the sea. The captain called me to him and placed a Bible in my hands.

"Read a passage of scripture," he said.

Dumbfounded that I should be called upon to officiate at the burial service over the man I had hated, I took my stand on the main hatch at the head of the body and prepared to obey orders. No passage to fit my singular situation occurred to me and I opened the book at random. [ 82 ] The leaves fell apart at the seventh chapter of Matthew and I read aloud the section beginning:

"Judge not, that ye be not judged. For with what judgment ye judge, ye shall be judged; and with what measure ye mete, it shall be measured to you again."

At the close of the reading the captain called for "The Sweet Bye and Bye" and the crew sang the verses of the old hymn solemnly. When the full-toned music ceased, two sailors tilted the gang-plank upwards and the remains of the Night King slid off and plunged into the ocean.

As the body slipped toward the water, a Kanaka sailor caught up a bucket of slop which he had set aside for the purpose, and dashed its filth over the corpse from head to foot. Wide-eyed with astonishment, I looked to see instant punishment visited upon this South Sea heathen who so flagrantly violated the sanctities of the dead. But not a hand was raised, not a word of disapproval was uttered. The Kanaka had but followed a whaler's ancient custom. The parting insult to the dead was meant to discourage the ghost from ever coming back to haunt the brig.

DREAMS OF LIBERTY

At midnight after the burial, we raised the volcanic fire of Mauna Loa dead ahead. Sailors declare that a gale always follows a death at sea and the wind that night blew hard. But we cracked on sail and next morning we were gliding in smooth water along the shore of the island of Hawaii with the great burning mountain towering directly over us and the smoke from the crater swirling down through our rigging.

We loafed away three pleasant weeks among the islands, loitering along the beautiful sea channels, merely killing time until Captain Shorey should arrive from San Francisco by steamer. Once we sailed within distant view of Molokai. It was as beautiful in its tropical verdure as any of the other islands of the group, [ 84 ] but its very name was fraught with sinister and tragic suggestiveness;—it was the home of the lepers, the island of the Living Death.

We did not anchor at any time. None of the whaling fleet which meets here every spring ever anchors. The lure of the tropical shores is strong and there would be many desertions if the ships lay in port. We sailed close to shore in the day time, often entering Honolulu harbor, but at night we lay off and on, as the sailor term is—that is we tacked off shore and back again, rarely venturing closer than two or three miles, a distance the hardiest swimmer, bent upon desertion, would not be apt to attempt in those shark-haunted waters.

Many attempts to escape from vessels of the whaling fleet occur in the islands every year. We heard many yarns of these adventures. A week before we arrived, five sailors had overpowered the night watch aboard their ship and escaped to shore in a whale boat. They were captured in the hills back of Honolulu and returned to their vessel. This is usually the fate of runaways. A [ 85 ] standing reward of $25 a man is offered by whaling ships for the capture and return of deserters, consequently all the natives of the islands, especially the police, are constantly on the lookout for runaways from whaling crews.

When we drew near the islands the runaway fever became epidemic in the forecastle. Each sailor had his own little scheme for getting away. Big Taylor talked of knocking the officers of the night watch over the head with a belaying-pin and stealing ashore in a boat. Ole Oleson cut up his suit of oil-skins and sewed them into two air-tight bags with one of which under each arm, he proposed to float ashore. Bill White, an Englishman, got possession of a lot of canvas from the cabin and was clandestinely busy for days making it into a boat in which he fondly hoped to paddle ashore some fine night in the dark of the moon. "Slim," our Irish grenadier, stuffed half his belongings into his long sea-boots which he planned to press into service both as carry-alls and life-preservers. Peter Swenson, the forecastle's baby boy, plugged up some big [ 86 ] empty oil cans and made life buoys of them by fastening a number of them together.

Just at the time when the forecastle conspiracies were at their height we killed a thirteen-foot shark off Diamond Head. Our catch was one of a school of thirty or forty monsters that came swarming about the brig, gliding slowly like gray ghosts only a few feet below the surface, nosing close to the ship's side for garbage and turning slightly on their sides to look out of their evil eyes at the sailors peering down upon them over the rail. Long John, the boat-steerer, got out a harpoon, and standing on the bulwarks shot the iron up to the wooden haft into the back of one of the sharks, the spear-point of the weapon passing through the creature and sticking out on the under side. The stout manila hemp attached to the harpoon had been made fast to the fore bitt. It was well that this was so, for the shark plunged and fought with terrific fury, lashing the sea into white froth. But the harpoon had pierced a vital part and in a little while the great fish ceased its struggles and lay still, belly up on the surface.

It was hauled close alongside, and a boat having been lowered, a large patch of the shark's skin was cut off. Then the carcass was cut adrift. The skin was as rough as sandpaper. It was cut into small squares, which were used in scouring metal and for all the polishing purposes for which sandpaper serves ashore.

Life aboard the brig seemed less intolerable thereafter, and an essay at escape through waters infested by such great, silent, ravenous sea-wolves seemed a hazard less desirable than before. Taylor talked no more about slugging the night watch. Slim unpacked his sea-boots and put his effects back into his chest. Peter threw his plugged oil cans overboard. Bill White turned his canvas boat into curtains for his bunk, and Ole Oleson voiced in the lilting measure of Scandinavia his deep regret that he had cut up a valuable suit of oil-skins.

The captain of one of the whaling ships came one afternoon to visit our skipper and his small boat was left dragging in our wake as the brig skimmed along under short sail. It occurred to me, and at the same time to my two Kanaka [ 88 ] shipmates, that here was a fine opportunity to escape. It was coming on dusk, and if we could get into the boat and cut loose we might have a splendid chance to get away. The Kanakas and I climbed over the bow, intending to let ourselves into the sea and drift astern to the boat, but the breeze had freshened and the brig was traveling so fast we did not believe we could catch the boat; and if we failed to do so, we might confidently expect the sharks to finish us. We abandoned the plan after we had remained squatting on the stays over the bow for a half hour considering our chances and getting soaked to the skin from the dashing spray.