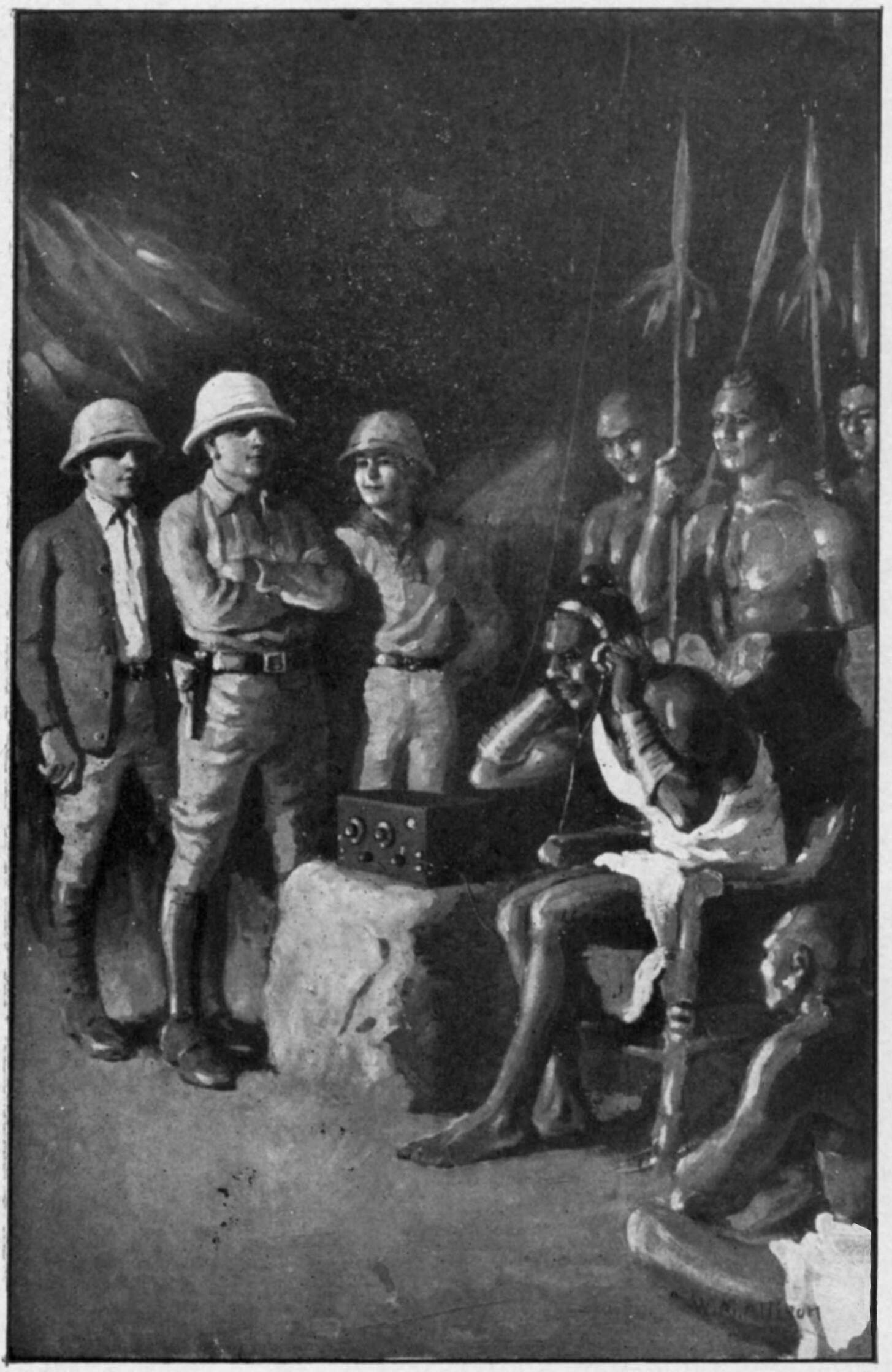

“You certainly won his heart that time, Bob. Look at his face if you want to see real amazement.”

Project Gutenberg's The Radio Boys in Darkest Africa, by Gerald Breckenridge This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: The Radio Boys in Darkest Africa Author: Gerald Breckenridge Release Date: September 2, 2020 [EBook #63099] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE RADIO BOYS IN DARKEST AFRICA *** Produced by Roger Frank

“You certainly won his heart that time, Bob. Look at his face if you want to see real amazement.”

“Look here, Jack, we ought to do something to help Wimba. I don’t believe he’s getting a square deal.”

“Nor I, Frank. But what can we do? Chief Ruku-Ru is supreme here. And if he decides against Wimba—”

Jack Hampton’s tone was as near hopeless as one could ever expect to hear from the lips of that optimistic young adventurer.

Nor is that to be wondered at. The predicament of their head man, Wimba, a Kikuyu of superior parts whose services they had been fortunate enough to obtain at Nairobi, administrative capital of British East Africa or Kenya Colony, was serious.

Here on the far fringe of the Kikuyu country, several hundred miles from Nairobi, the nearest outpost of white civilization in Central Africa, Wimba was being tried on a charge of murder. Chief Ruku-Ru, head of the local tribesmen, presiding as judge, gave every indication of being about to sentence Wimba to death.

And the two boys knew Wimba was innocent. They believed the latter’s story. Wimba said he had come upon two local tribesmen stealing from the effects of his employers and that, when discovered, they had attacked him. Fighting in self-defense he had been unfortunate enough to kill one, whereupon the other had run to Chief Ruku-Ru with the tale that Wimba had murdered his comrade.

During the course of the trial, which was being held beneath a great thorn tree, Jack Hampton and Frank Merrick had been breathless spectators. Their companion. Bob Temple, lay weak from fever in his tent, and could not be present.

In an old armchair which had been brought by a trader years before to this remote village, sat Chief Ruku-Ru, as if in a throne. His hair was drawn to a knob on the very top of his round head. His black face was preternaturally grave as became an administrator of justice. Around his neck were a half dozen strands of copper wire. His arms were covered from wrist to elbow with bracelets of similar material. Thrown across his right shoulder and drawn together beneath his left armpit was the single cotton garment which constituted his only clothing. And in his right hand he held a number of small sticks. These were important. If the prosecution scored a point in the testimony, he planted a stick in the ground on the right. If Wimba’s defense scored a point, he planted a stick on his left. At the end of the trial, he would count the number of sticks in each row and that side having the greater number would win.

This much had been explained to the boys by Wimba’s assistant, an intelligent young Kikuyu named Matse. But the latter’s command of English was not much to lean upon, and he could not inform the boys of every point in the case. From him, however, they had learned enough to realize that Wimba was drawing near the end of his defense, and that the prosecution had the better of it. The pile of sticks on the right was larger.

“If only Dad was here,” groaned Jack, in a whisper.

But Mr. Hampton, together with Oscar Niellsen, their cameraman, was off on an expedition to photograph wild animals at a water hole many miles away.

Frank squirmed at his companion’s side. “Jack, I’ve got an idea. It’s a long chance, but it may work.”

“What is it?”

For a minute or two Frank whispered in Jack’s ear, and the latter’s face lighted up.

“What do you think of it?” asked Frank, in conclusion, drawing back. “Will it work?”

“We’ll chance it,” whispered Jack, in reply, nodding. “But you’ll have to be quick. Now scud away with Matse and leave me to do my part.” Without further waste of words or time, Frank drawing the young Kikuyu interpreter after him drew back amongst the grass-thatched huts of the Kikuyu village fringing the council square.

His departure was unnoticed by the big crowd of tribesfolk gathered in a circle, and hanging upon the progress of the trial.

The minutes passed and with the passage of each one Jack grew more anxious. But presently Frank again slipped into position beside him.

“Thank goodness,” he whispered, breathlessly, “that we rigged up that loudspeaker in the council tree last night.”

“Yes,” replied Jack, “and that we haven’t had a chance to try it out yet. Nobody knows it’s there, But was Bob all right?”

“A little weak yet,” replied Frank. “But he took charge of operations, all right. Was tickled to death.”

“Well, we meant to give them a concert out of the council tree,” said Jack. “But this will be better. Wonder we didn’t think of it before.”

“Oh, well,” replied Frank, “so long as the idea came to us in time, what does it matter?”

“But Matse?” asked Jack, anxiously. “Does he understand the part he’ll have to play? Will he handle it all right?”

Frank smiled confidently. “When I give him the signal,” he said, “Matse will do his part, never fear. He’d undertake anything in order to save Wimba. But we’re not out of the woods yet, Jack. We don’t know what’s going on. Oh, if we only had another boy who could speak English and could translate this for us.”

Jack gripped his companion’s arm. “Look, Frank, the trial is over. Now Chief Ruku-Ru is about to pronounce sentence. See. Wimba is staring hard at us. Poor fellow, he believes his end has come and what a look of dumb appeal. Up, Frank, it’s time to act I’m sure.”

From their place on the outskirts and a little to one side of the semi-circle of savages, Frank and Jack rose with white determined faces and advanced the few steps necessary to bring them face to face with Chief Ruku-Ru seated opposite across the open space surrounding him.

The tall warriors forming the chief’s guard, coal-black, six foot tall, magnificent specimens of manhood, stood aghast. What did the white strangers contemplate?

Chief Ruku-Ru half rose from his chair in anger at this interruption. But before he could give a command to have the boys seized, if such discourtesy to his guests was contemplated, Jack holding himself proudly erect addressed the throne.

“Oh, great chief,” he cried in English, “we be strangers in your land, it is true. Yet have we watched with interest the progress of this trial, and your impartial conduct. But we believe you have been deceived by liars amongst those who seek Wimba’s life. Therefore we appeal to our gods to speak from the sky and tell you the truth. Wimba,” he commanded, “tell the chief what I have said. Forget nothing. There will be a voice from the sky and in the chief’s own language. Do not fear. But speak quickly.”

From his position between two tall Kikuyu warriors, Wimba who stood to the left of the chief, had been listening in blankest astonishment. His strong face with the thin lips and intelligent lines of many of the Kikuyu tribesmen had betrayed as much despair as his self-restraint under ordeal would permit him to betray, when Jack had begun to speak. But now not only the despair but the succeeding astonishment disappeared.

“Speak Wimba,” commanded Jack. “Remember what you placed in the council tree for us last night.”

He was safe, he knew, in thus reminding Wimba, as none in the audience had any knowledge of English. And he had explained enough of the mysteries of radio the previous night, when the entire village slept after heavy potations of native beer following a royal reception to the new guests, to give Wimba confidence now that Jack would be able as he promised to bring a voice seemingly out of the sky.

At any rate, Wimba was in a desperate situation. He was ready to grasp at any straw. Gazing about he saw the multitude of natives crowding close, awaiting the verdict. He saw Chief Ruku-Ru open-mouthed at the white boy’s interruption. He knew if he were going to act, he must act at once. Otherwise the chief would order the interrupters seized, perhaps; and most certainly would order him slain.

And he could not contemplate being staked out on an ant hill with equanimity.

Bowing low, Wimba addressed Chief Ruku-Ru in a loud voice. The boys could not understand his words, for he spoke in the Kikuyu tongue. But they could perceive that he was making their startling announcement, for over the chief’s face spread a look of startled bewilderment while through the swarm of natives sweeping around behind them in a semi-circle passed a murmur like a wind rippling the surface of a lake.

They watched Wimba closely, and saw the perspiration burst on his face. He was speaking in deadly earnestness, for it was a matter of life or death to him.

When Wimba ceased, Chief Ruku-Ru appeared to pull himself together and he addressed a few sharp words to Wimba in a contemptuous tone.

“He’s scared, but doesn’t want to show it,” was Jack’s whispered comment.

Frank nodded, but did not reply. His face was on that of Wimba. He knew the crisis had come. And the prisoner’s words confirmed his belief.

“Bring the voice from the sky, baas,” said Wimba. “The chief says he does not believe, but he is afraid.”

Frank was pale as death. Stepping a few paces in front of Jack, he paused in the middle of the open space before Chief Ruku-Ru’s armchair throne. Then lifting his eyes skyward, as if appealing to some Deity in the brazen vault overhead, he put his fingers between his lips and emitted a piercing whistle. Once, twice, thrice, it shrilled.

Silence.

Over all that assemblage of savage black men, over the group of bearers cowering to one side, awaiting the verdict upon their comrade, over the old gray-haired elders in a knot near the chief, over the tall warriors of the guard with their spears, over the ring of warriors with their shields of painted bullock and elephant hide on the ground before them, over the pushing mass of women and children behind, spread a deathlike silence.

Every eye was lifted in awe. Every face gazed skyward. The words of the white young men as interpreted by Wimba had spread unbelievable amazement. They waited, fascinated, half believing, half terrified, for the voice from the sky which the white men had promised.

Then it came.

From the top of the great council tree apparently boomed out a voice in the Kikuyu tongue. It was a voice unknown to them all. It was a voice the volume of which seemed supernatural. Yet every word was clear. And this great voice cried:

“Oh, Chief Ruku-Ru, great amongst the Kikuyus, I am the spirit invoked by the white men. Their fate is in my keeping. I watch over them and their servants. And I tell you that Wimba is guiltless. Let but a hair of his head be touched and thy village shall be levelled, thy people destroyed by plague, thy cattle die, thy springs dry up. I have spoken. Set Wimba free or these things shall come to pass. It is an order.”

Through the ranks of the Kikuyu tribesmen behind and encircling them, Jack and Frank could hear a murmur of fear that grew in volume until the air was filled with cries of fright. The warriors forming the inner ring of the circle shook with terror.

So, too, did those tallest of the Kikuyus forming the chief’s own bodyguard. As for Chief Ruku-Ru, over his face spread an ashen hue.

But Frank’s programme was not yet complete. In the few minutes with Bob and Matse in their tent beyond the grass-thatched village huts, he had concocted a second step which he assumed would clinch their hold over the chief and assure the complete terrorization of the Kikuyus. Now he proceeded to put this into execution.

Standing alone in the midst of the great circle Of savage blacks, facing the ashen chief, noting the spears of the bodyguard trembling like forest trees in a strong wind as the hands which held them shook with terror, he was filled with satisfaction. So far all had gone well. Now to strike the final blow.

“Quick, Wimba,” he cried to the prisoner, who alone of that alien multitude had any inkling as to the source of that mysterious voice from the sky, yet who was not sufficiently civilized to be free entirely from the terror which gripped the other blacks. “Quick, Wimba. Translate for me.” And facing the chief, Frank cried:

“Oh, Chief Ruku-Ru, thou hast heard the response of our gods. To show you there is none concealed within the council tree, who might have said these things, for it is thence came the voice, I ask that you order your warriors to discharge their arrows into the midst of the foliage.”

Well Frank knew that in the great hollow on the back side the main trunk, so opportunely found the previous night, the loudspeaker and its connections would be safe from stray arrows. Furthermore, the loop aerial employed was securely lashed amidst a thick bushy mass of leaves, and likewise would be safe from harm.

But Chief Ruku-Ru was past giving any orders. He attempted to speak, upon Wimba translating Frank’s words, but was unable to command his stricken tongue. Nor did the warriors of his bodyguard upon hearing Frank’s injunction show any inclination to shoot into the top of the sacred tree. That they were terror-stricken was plain to be seen. And equally plain was their reluctance to antagonize any supernatural agency which Frank had invoked.

This Frank had counted upon. Drawing his revolver, he levelled it at the treetops and himself announced that he would make the test. This Wimba translated. Again a murmur of awe swept through the encircling mass of natives.

Frank fired. Three shots he pumped into the treetop. Scarcely had the echo died away, and before Chief Ruku-Ru or anybody else, either, for that matter, could speak, than the voice from the air rang again in the Kikuyu tongue.

“I am a Spirit,” it cried. “Neither white man’s thunder nor Kikuyu arrows can avail against me. Obey, O Chief Ruku-Ru, or thy country shall be laid under my spell. Set Wimba free.”

Neither Frank nor Jack could understand what was said. But well they knew that Matse was merely uttering into the broadcasting phone in their tent, while Bob manipulated the motor, those statements which upon his signals Frank had arranged he should declaim. And that such was the case was apparent from the profound and devastating effect upon the chief and his followers.

It was unnecessary for Wimba to translate the messages from the air for the boys’ benefit.

Chief Ruku-Ru managed upon the dying away of the mysterious voice to gain some control over himself. Not for nothing was he chief. His self-command was remarkable. The more so in view of the fact that he was as profoundly impressed and terror-stricken by these manifestations which Frank had evoked as was the meanest of his followers.

He did not rise from his armchair throne, for the very good reason that he feared his treacherous knees would give way beneath him. But he did manage to speak.

Pointing to the two guards who clasped Wimba on either side, he ordered them to release their prisoner. To Frank and Jack, tense and anxious regarding the outcome of their experiment, his words were as so much Greek. But they were left in no doubt as to their meaning.

The guards at once untied the cords binding Wimba’s wrists together behind his back and unwound the heavier rope about his right ankle tying him to a stake in the ground. Likewise they released their grip on his arms. Then they bowed low to him.

A moment Wimba stood uncertain. He was dazed. He could hardly believe his good fortune. He gazed first at the chief, then at the encircling natives, half of whom were poised for flight, fearing a further demonstration by the white man’s god, and finally brought his eyes to bear upon Frank.

Then with an inarticulate cry of gratitude, he rushed across the intervening space, and threw himself on the ground. Tears streaming from his eyes, he clasped Frank’s feet and in broken sentences thanked him for his deliverance.

“Get up, Wimba,” commanded Frank. “Tell Chief Ruku-Ru that our Great Spirit is about to bless him for this deed.”

Once more Wimba faced the chief and in a voice trembling with feeling he repeated Frank’s words.

Then Frank inflated the final step in his hastily-thought-out plan. Setting his fingers to his lips he whistled. But this time only twice. It was the agreed signal.

From the air boomed forth again the mysterious voice:

“O, Chief Ruku-Ru, thy name shall be great as an administrator of justice. Thy tribe shall be fruitful, thy cattle fat, thy springs filled with sweet water. I have spoken.”

Silence.

“Let’s make our getaway now, Frank,” whispered Jack. “We’ve gotten out of this a whole lot better than we had any right to expect. Don’t tempt fate too much.”

But filled with the confidence of success, Frank only smiled. He whispered to Wimba, and the latter addressing Chief Ruku-Ru announced that in honor of the occasion his white masters would that night bring music from the air, and that they invited the whole tribe to assemble after dusk before the council tree.

With this, leaving the chief and all the assemblage stunned, the boys and Wimba departed. As they moved away, the Kikuyus opened a passage for them in grotesque haste. Now that the strain of the situation was over, both Frank and Jack were seized with an insane desire to laugh. But they managed to control their emotions, and to retain upon their faces a look of the most solemn gravity. Only when at length they had passed out of earshot of the multitude and had put the last of the grass-thatched huts behind them, did they give way to their feelings. Then they flung themselves prone into the long buffalo grass of the meadow separating the village from their encampment and rolling over and over they simply howled with laughter while Wimba watched them in the greatest astonishment.

“I’ll never forget that scene to my dying day,” laughed Jack, finally.

“Nor I,” said Frank, weak from hysterical laughter. “Come on. Let’s find Bob, and tell him how it worked out.”

Before he could strike away, however, Jack sobering turned to Wimba. Laying a hand on Frank’s shoulder, he said:

“Wimba, here is the fellow who saved your life. It was his idea. He’ll explain it all to you. It is to him you must give your thanks first, and then to your comrade Matse who helped.”

“Oh, come, Jack,” said Frank uncomfortably. But Wimba threw himself once more at Frank’s feet.

“My life belong you, baas,” he said in a choking voice.

In after days, Frank was to remember with thankfulness the gratitude of Wimba for his “baas” or master. But now he was embarrassed, and making light of the matter as possible without hurting the black’s feelings he hastened along by Jack’s side across the meadow toward the clump of tents which marked their encampment.

Leaving Jack and Frank to regale the convalescent Bob with the tale of what had occurred under the council tree, while Wimba and Matse put their heads together and discussed the same event surrounded by the awe-stricken native bearers from whom Wimba, at Frank’s warning, was careful to withhold the real explanation, let us consider briefly how the three white boys came to be here in Central Africa.

For those of our readers who have not followed their adventures in other parts of the world as set forth in previous volumes of The Radio Boys Series a brief word or two of introduction is necessary. Jack Hampton was the only son of an internationally famous engineer and explorer, whose wife had died when Jack was only a youngster. Frank Merrick, too, was orphaned and made his home with Bob Temple, whose father was his guardian. The Hampton and Temple country estates on the far end of Long Island, New York, adjoined each other. And the three boys, companions at preparatory school and now at Yale, were the closest of friends.

Supplied by wealthy parents with the means to gratify their scientific bent, all three boys from the beginning of the popularity of Radio had pushed their investigations in that field. And upon the numerous adventures into which they had been drawn in one way or another in South America, Alaska, their own land, and the Sahara Desert in Africa, they had found Radio time and again prove of the greatest service.

Now, as has been related in the previous chapters, it had again come to the fore to help them at a crisis in their affairs.

But how did they come to be again in Africa, where the previous year they had discovered in an unexplored mountain region in the southern Sahara a race of white men living in a high state of development and treasuring ancient papyrus records indicating continued existence of the race from the earliest period of the world’s history?

That is easily explained.

So widespread was the publicity showered upon the Radio Boys, as they had become known, following their repeated exploits in out-of-the-way corners of the world that one of the great motion picture concerns of America had come to them some months previously with a fine offer. Would they accompany a cameraman into Central Africa to explore little known or entirely unknown regions for the purpose of filming wild animals in their natural haunts and natives in the primitive state? That was the proposition, and, needless to state, the motion picture concern propounding it agreed to make acceptance worth the boys’ while.

Mr. Hampton was included in the offer. And upon his advice, coupled with that of Mr. Temple, the boys had yielded to their natural inclinations and had accepted.

“You boys have still some years of college ahead of you,” Mr. Temple had said. “It may be unwise to interrupt your college career, for such an expedition necessarily will be an interruption, as, undoubtedly, you will be a year or two in the wilds. Nevertheless, Central Africa cannot remain unexplored or unopened to civilization much longer. Here is a chance such as may never come your way again.

“Sometime, doubtless, Jack will want to become an engineer and follow in his father’s footsteps, and Frank and Bob will want to take charge of the export business, Frank’s father before he died and I, built up. But there is no hurry about those matters. In the meantime, here is a chance for the three of you to go on a big game hunting expedition with the strangest of weapons—a motion picture camera. And you will be well paid, to boot.

“Of course, the fame you fellows have piled up brought you this opportunity. Well, you deserve it. Three more rattle-brained rascals with the ability always to fall on their feet I never saw.” He smiled at them affectionately. “So,” he concluded, “I consent to Bob and Frank going. And as Jack’s father already has consented for him and is, besides, to head the expedition, I cannot see but what that settles the matter.”

Here, then, they were. From Mombasa on the east coast they had made their way on the railroad to Nairobi. This small but important settlement, which was the administrative center of Kenya Colony, marked their last touch with civilization.

Procuring bearers and guides, they had thence set out afoot into the Kikuyu country. Day had followed day without striking incident. The Kikuyus are a peaceful people, above the average of African intelligence, inhabiting a magnificent country abounding in streams, uplands and forest. It is one of the most healthful and fertile of regions.

Although, despite their proximity to the advance guards of white civilization, the boys had found the Kikuyus still living in primitive state, nevertheless they found them peaceful. Adventures had been few. Not only had they seldom been in any danger from the natives, but wild animals also had been scarce.

It was not until they came to Chief Ruku-Ru’s territory where Mr. Hampton had departed with Niellsen, the cameraman, for the dried-up bed of a river where baboons were said to be in the habit of coming to dig for water, that the first real adventure befell them. That was the arrest and trial of Wimba, and his consequent release as related.

It was only by accident that the boys were on hand. Ordinarily they would have been with Mr. Hampton and Niellsen. But Bob’s succumbing to fever had kept them behind to provide him with company and attendance. Bob’s fever was not sufficiently strong enough to cause Mr. Hampton any real anxiety, however, so, leaving the boys careful instructions regarding the medicines to be given their comrade, he had departed with Niellsen and a few bearers carrying camera, film box, etc.

With this digression, let us return to camp. The quick-falling African night was closing in and the boys were finishing preparations for the concert which they had promised to bring out of the air to the assembled villagers about the council tree.

Frank and Jack had just completed a complete overhauling of the talking machine which they planned to use and were dusting off the records of martial band music which they considered would provide the most acceptable concert for savage ears. Bob who was feeling considerably improved was lolling on a camp cot, watching them.

“Hey, fellows,” he said suddenly, “has it occurred to you that some warrior more curious and less fearful than the rest might climb up into the council tree? If one does, and if he finds the aerial or the loudspeaker which you concealed there, good night. Even if he ran away from it, he might damage it first so that your concert would be a fizzle.”

Jack stopped work, a record in one hand, dusting cloth in the other.

“That’s right, Bob. Hadn’t thought of that.”

But Frank looked unconcerned.

“From what Wimba and Matse tell me,” he said, “Most Kikuyus wouldn’t dare to climb into that sacred tree. I had a hard time getting even those two to ascend it with me last night and help locate our traps. And they’ve lived in Nairobi and come in contact with the whites and have lost some of their native superstitions. And now that we caused the voice of our mysterious spirit to emanate from the tree today, I feel pretty sure there isn’t a Kikuyu whom you could pay to climb it.”

Jack looked relieved, but Bob apparently was reluctant to relinquish his idea and needed further convincing.

“Just the same,” he said, “I believe we ought to send somebody over there to scout around for us and see that everything is all right before we pin our hopes on giving a concert. Why not send Matse?”

“All right, if you think it’s necessary,” replied Frank. “Let’s call him in.”

Putting aside the records he had been cleaning, he went to the door of the tent and, lifting the flap, poked his head out to utter the necessary call which would bring Matse from the bearer’s camp nearby.

But the call was not issued. Instead, Bob and Jack heard Frank utter a muffled exclamation and then step swiftly out of the tent, letting the flap fall behind him.

The two boys left behind in the tent stared perplexedly at each other in the light of the lantern hanging from the pole and casting a steady if not brilliant illumination over the canvas walls, bed rolls, packs and camp chairs. From his bed roll or flea bag, as the boys adopting the term of African explorers had come to call it, the outstretched Bob, propped on one elbow, looked toward the tent flap which had fallen behind his comrade and said:

“Gosh, Frank went out of there as if somebody had grabbed him by the hair. Wonder what he’s up to.”

“I’ll go see,” said Jack, getting up from his seat on a folding camp chair, and walking toward the exit.

But just as he was putting out his hand to draw the flap aside there came the sound of three revolver shots in rapid succession from nearby, followed by a hubbub of native cries. Jack leaped through the exit, drawing his automatic from its ever-ready position at his side, while Bob jumped to his feet with all thought of weakness forgotten.

Before he could follow Jack’s example, however, the tent flap was again thrust aside and Jack returned followed by Frank.

The latter’s face was white. In one hand he still gripped his automatic.

Bob stared at his comrades in astonishment too great for a moment for speech. And in the silence the yells of the natives could be heard withdrawing into the distance.

Frank flung himself into a camp chair. His revolver dropped from his relaxed fingers, and he put up his hands to his face. Bob saw he was trembling. Jack stooped and put an arm across his comrade’s shoulders.

“What in the world’s the matter?” cried Bob, finding his tongue at last. “What happened?”

“I haven’t got it straightened out,” said Jack, shaking his head. “It was all over when I got outside. Give Frank a minute’s time to collect himself. He had a bad experience, I guess.” He patted the smaller youth’s shoulder. “Take your time, old boy,” he said soothingly. “It’s all over now.”

Bob sank back onto his flea bag. This was too much for him, his expression of profound bewilderment seemed to say.

Frank looked up and essayed a smile. But it was ghastly in result.

“Guess you fellows think I’m crazy,” he said, in a shaking voice. “But it’s no joke to have to shoot at a man. I never get over the shakes when it’s necessary.”

“What?” cried Jack.

“A man?” exploded Bob. “You shot at a man?” Frank nodded. “It was that fellow who had it in for Wimba, I guess,” he said. “The one who charged him with murdering his pal. That Kikuyu thief, you know.”

With an effort, he pulled himself together, shook off Jack’s grip on his shoulder, and got up. “I poked my head out of the tent to call Matse,” he said, in a firmer voice. “The bearers have a big camp fire going. Between here and the camp fire I could see Wimba. He was approaching our tent. There was no mistaking his form, outlined against the glow of the fire. Then I saw a man spring up from the ground as Wimba passed and stalk after him.

“I was scared for Wimba, because the other obviously meant mischief. And it was plain Wimba was unaware of his presence. I didn’t want to yell a warning because his pursuer might leap on Wimba.

“So I started forward. But the fellow was creeping up on Wimba. I could see them both like silhouettes against the fire glow. There was no time to delay. I could see the rascal’s arm drawn back as if to bury a knife in poor old Wimba’s shoulders.”

“Then you shot?” asked Jack.

Frank nodded. “But I didn’t kill him,” he said. “I aimed to hit his upraised hand, and I guess I did.”

“But there were three shots,” objected Bob. “I counted them.”

“I shot over his head,” said Frank.

“What happened then?” asked Jack.

“He got away. And the bearers are chasing him.”

Bob’s face became grave. “That’s liable to get us into more trouble with Chief Ruku-Ru.”

“I sent Wimba to bring the boys back,” explained Frank. With a laugh, as his self-possession returned he added: “That was the quickest way to put an end to his expressions of gratitude.”

“Well,” said Jack, “you certainly have put that fellow in your debt. You’ve saved his life twice in one day.”

With his usual modesty, Frank’s thought dwelt not on himself and his own actions, but on the other fellow. “Poor Wimba,” he said. “He certainly had a hard time of it.”

The excited voices of the returning bearers could be heard without. Bob sank back on his flea bag as Frank went out to hear Wimba’s report. With an exclamation, Jack looked at his watch.

“So much excitement made me almost forget Dad,” he remarked, going to the corner where the radio sending apparatus was set up. Taking his seat and adjusting several loose wire connections, he began manipulating controls.

Then he pulled the transmitter toward him and began announcing on a 200-metre wave length a resume of the day’s activities, telling in detail of Wimba’s arrest and trial and of how he had been saved from execution by Frank’s ruse for playing upon Chief Ruku-Ru’s superstition through means of the loudspeaker installed in the council tree.

“Luckily we keyed it to 300-metres, Dad,” he explained. “So when we talk to you like this over your 200-metre length, the loudspeaker is inoperative.”

He than related the recent episode wherein Frank again had saved Wimba’s life, and concluded with the explanation that they were about to broadcast a concert of band music out of the council tree for the further mystification of the Kikuyus.

“Don’t worry about us, Dad,” he said, before hanging up. “We’re making out all right, I expect. I don’t look for any more trouble, after what happened today.”

Bob grinned as Jack, his task concluded, turned around to face him.

“Well, Mr. Reporter,” he said. “You’re becoming quite expert at making these daily reports.” Jack laughed. “Just the same,” he commented, “it’s not a bad idea, that of these individual portable sets. No matter where Dad is, it’s a pretty safe bet that he heard me.”

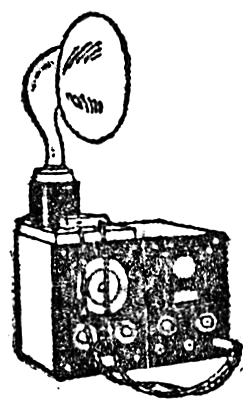

Each member of the expeditionary party was provided with a small but powerful portable radio set of wide range. Thus whenever, as in the present instance, anybody was absent on side expeditions by tuning in at a fixed hour each night and morning, he received a resume of the day’s activities and of any startling events occurring during the night, which those remaining at the headquarters encampment broadcasted.

These sets were the boys’ pride. All three had had a hand in their manufacture. Each set was mounted in a cabinet the size of a portable typewriter case. It contained a regenerative tuner, a detector and one stage of audio amplification, and was a powerful receiver with two tubes. The secret of its smallness was that it operated on ordinary little flashlight batteries. The head set clamped into the inside of the lid when not in use. Closed, the cabinet could be carried by means of a handle. The whole business weighed less than ten pounds. Throw an insulated wire over a tree, and one would be ready to listen-in.

Almost as compact, in its way, was the sending apparatus which now occupied a small collapsible table in one corner of the tent. Table and all, including the motor, fitted into the oblong box yawning emptily on the ground beneath at the present moment—a box two and a half feet by a foot in breadth and nine inches in height.

In its construction, the boys had labored to achieve an apparatus for both sending and receiving. When one spoke, the vocal impact against a sensitive diaphragm closed reception, but the minute the voice of the speaker ceased, the instrument again was ready to receive.

It was over this apparatus that the boys planned to broadcast a concert for the benefit and mystification of the Kikuyus, and now that his evening bulletins had been radioed to his father Jack got busy with final preparations. Moving their small talking machine into position and attaching the audion, he laid the records he and Frank had dusted within reach for quick adjustment. All was now ready, and the only thing he waited for was Matse’s report from a reconnaissance into the village that their loudspeaker and apparatus concealed in the council tree had neither been discovered nor tampered with.

The council tree arrangement which had been installed the previous night at a late hour, when all in the village were asleep, consisted of one of the portable receiving sets with loop aerial and loudspeaker attachment.

Really, the loop aerial had not been necessary. An insulated wire thrown over the topmost branches of the tree would have been sufficient. Installation of the small loop aerial had been considered by Bob as a “piece of dog.” But Frank and Jack had insisted upon it, in the desire to make their proposed concert a superlative success. And they considered the clearness of the voice from the air during Wimba’s trial ample justification of the extra trouble to which they had gone.

Frank returned as Jack finished his preparations, with the announcement that Matse reported the entire village assembled expectantly beneath the council tree about a great fire.

“So far as he could see or learn nobody has been into the council tree,” Frank added. “And I guess that’s correct. These Kikuyus wouldn’t go into that tree now, after what happened today, under any circumstances. So your fears are groundless, Bob. Well, let’s go, Jack.”

Jack arose and Bob with a humorous groan made his way to his comrade’s place at the radio apparatus.

Because it was bad for his health to be abroad in the night air, he had been elected to act as operative.

“You fellows have all the best of it,” he said.

Frank and Jack grinned sympathetically, then set out for the village center. They wanted to be on hand to see how Chief Ruku-Ru and his people took the concert.

Beside them trailed Wimba, who henceforth was to constitute himself Frank’s faithful shadow, while ahead went the chattering bearers with the exception of four left behind as guards over the encampment.

Frank looked back once over his shoulder. “I suppose Bob will be all right,” he said. “Only I don’t quite like the idea of leaving him alone.”

“Oh, come on,” said Jack. “To be sure he’ll be all right.”

So mystified were Chief Ruku-Ru and the Kikuyus by the concert that it was apparent the presence of the portable radio set with loudspeaker in the uppermost branches of the spreading council tree was totally unsuspected. And all lingering doubts as to whether any of the Kikuyus had ventured into the tree and discovered the apparatus were swept from the minds of Frank and Jack.

For both it was a weird experience. Under the silver radiance of the African moon, now at the full, the square was bright. Any lingering shadows not dispelled by that flood of moonlight, disappeared, vanquished before the dancing gleams of a great fire. For the night here on the uplands was cool and the savages had built a roaring fire which crackled and leaped in the center of the square. To one side sat Chief Ruku-Ru in his armchair throne, surrounded by his bodyguard of tall warriors with spears erect, while in a semi-circle about the fire and facing the council tree squatted row upon row of natives. And beyond them on every hand shown the conical roofs of the big huts.

At first alarmed at the music, the natives soon got over their fears and in no time at all, as Jack called to Frank’s attention, they were swaying to the strains. Jack decided to take advantage of this tendency on the part of the rhythm-loving blacks. On leaving their encampment, he and Frank had noted on a slip of paper the names of the records Bob intended to play and their order. Between each two records Bob was to permit the lapse of a couple of minutes, in order that his comrades might be able to announce to Chief Ruku-Ru and the Kikuyus what the next number would be. In this way, they could add to their reputation as wizards, for wizards the Kikuyus believed them to be.

“The next number is going to be one of those Hawaiian things,” he whispered to Frank, as the strains of a familiar Sousa march drew near their conclusion. “Let’s announce to Chief Ruku-Ru that we are about to summon out of the air a piece of music for the especial benefit of the wonderful Kikuyu dancers of whom we have heard so much.”

“Good idea,” Frank nodded. “That Hawaiian umty-tum will be just about their speed.”

Jack whispered to Wimba and, upon conclusion of the march, the latter arose in the scheduled interval before the next number was to be broadcasted, and made Jack’s announcement. That it met with friendly reception was apparent to the two boys by the stir of interest which went through the crowd.

“Who do you think will dance?” whispered Frank.

“I don’t know,” said Jack. “Perhaps everybody.”

The music began and at the first strains of the wailing syncopated air with its suggestion of beaten tom-toms, of jungles and of tropic nights, the Kikuyus uttered low cries of approval. From their place near Chief Ruku-Ru the boys looking out over that assemblage saw that now, indeed, they had won the hearts of the savages.

Suddenly, from amidst the ranks of the natives squatting on their heels, the lithe slim figure of a young Kikuyu warrior sprang into the wide space about the fire.

Firelight falling upon him illumined the gleaming muscles of his body, naked except for breech clout. He stood a moment, still, rigid as a statue, then began to turn slowly about as if on a pivot.

“A black Apollo,” whispered Jack.

The music swelled, the note of savagery became more insistent. It was as if the invisible orchestra were playing for this particular audience, as if into the players had crept the very spirit of this night in a remote corner of central Africa. Jack and Frank both felt a strange stirring within them as if a response to the music, to the occasion. But what they experienced in their cultivated minds was but a trifle, the merest breath, compared to the effect of the music upon the savage, uncivilized minds, of the blacks about them.

Wimba and Matse began to sway with the rest. A glassy look came into their eyes.

But they were strangers in this community. They did not dare to get to their feet.

Not so the young men of the Kikuyus. As the black Apollo ceased pivoting and began to circle the fire with arms rigid against his sides, body swaying, knees lifting high like those of a horse on parade, other young warriors leaped from the audience into the cleared space about the fire. Falling into line behind the leader, they circled in a dance at first rather stately but soon becoming madder and madder in movement until, upon the concluding strains of the record, they were flashing by the boys in a whirling, swirling mass of legs and gleaming ebon bodies.

“Wow,” said Frank, expelling a long breath as, following the subsidence of the music, the dancers ceased and melted back into the audience. “That was some sight. What a shame Niellsen wasn’t here to take a movie of that?”

“Certainly is a shame,” agreed Jack. “Can’t you just see the audience in some movie palace back home, sitting there in the dark, when suddenly this moonlit village square with its fire and its circle of blacks flashes on the screen? Then the dancers begin! Can’t you just see it? Oh, boy.”

The Hawaiian records had been the last number of the programme. At Jack’s prompting, Wimba bowing low to Chief Ruku-Ru made this announcement. In reply, the chief spoke at such length that the boys, unable to understand a word of what was said, became impatient. Then Wimba turned to them, his eyes big.

“Chief Ruku-Ru, him say tomolla him Kikuyus give warrior dance for um baas,” interpreted Wimba. “Him say white wizards give um good time tonight, him give white wizards good time tomolla. Warrior dance when sun come up.”

Jack let out a low whistle. “Tell Chief Ruku-Ru we are very much pleased,” said Jack, “and we’ll be there.”

Wimba started to speak, but Frank with an exclamation checked him.

“Ask him, too, Wimba, whether we can take pictures of the dance,” he commanded. “He may be scared of it, because we haven’t taken any movies here as yet, and he hasn’t become familiar with it.”

“He saw a music box once,” interpolated Jack. “And now he thinks every box with a handle to be turned ought to produce music.”

Frank grinned. Then, realizing that they had not yet thanked Chief Ruku-Ru for his invitation to witness the warrior dance and military tactics, he turned to the interpreter and ordered him to speak up. A man of superior parts, Wimba could be trusted to couch acceptance in the floweriest of diplomatic language.

The main body of Kikuyus were melting away into the moonlit darkness, doubtless discussing at a great rate the marvellous music played by the spirits of the air at the bidding of the young white wizards. The sound of laughter and high voices came muffled out of the darkness. As for Chief Ruku-Ru, he sat watching the boys, still surrounded by his bodyguard of tall black warriors, awaiting a reply.

Wimba spoke at length, the chief listening attentively. And when upon the interpreter’s conclusion, he replied, the boys saw by the relieved expression on Wimba’s features, even before he interpreted for their benefit, that the chief had given the required permission for the boys to photograph the warrior dance.

Such, indeed, proved to be the case. And, when diplomatic exchanges at last having been brought to a conclusion, the boys made their way back to their encampment followed by Wimba, Matse and the bearers, they were both jubilant and excited.

Contrary to Frank’s earlier formless fears regarding possible danger to Bob through his being left alone, nothing untoward had occurred during their absence. In fact, the big fellow was feeling better than for days, the medicine left for him by Mr. Hampton having routed the fever. By the morrow, he believed he would be back to normal. And this was a satisfaction, as it would enable him to witness the military tactics and warrior dance.

“Set that alarm clock for an hour before sun-up,” said Frank to Jack who, as the lightest sleeper, always took charge of waking everybody.

“All right,” said Jack. “But Wimba will see to getting us up, never fear. That fellow has the faculty of waking at any hour he decides upon. It’s a habit which all natives possess, he tells me.”

“It’s a good thing Niellsen gave us some lessons in the operation of a motion picture camera,” said Frank. “I wouldn’t have dared to try to take that picture stuff in front of the council tree by moonlight, because I don’t know enough about the game and would just have ruined a couple of hundred precious feet of film. But at this daylight stuff tomorrow, I expect we’ll be all right.”

With this the others agreed. The photographic equipment brought in by the expedition consisted of four film cameras, three Graflex hand cameras for obtaining “stills,” many film packs for the latter, and eighty thousand feet of film for the former.

At Nairobi was a motor truck outfitted as dark room and developing plant. Originally, it had been Mr. Hampton’s intention to take this motor truck with them on their wanderings, but so rough had proved to be some of the country negotiated on the first trip out from the settlement, that it had been decided to leave the plant thereafter at Nairobi so long as the party remained in the Kikuyu country.

Before the boys retired to sleep, there came a low call from outside and then Wimba parted the tent flap and looked in.

“Him funny bizness here, baas,” said he, as Jack advanced to meet him. “Wimba and Matse take um down.”

With that, he lifted the tent flap and thrust within the loudspeaker, loop aerial and portable radio set which several nights before, under the direction of Frank and Jack, he had installed in the council tree.

“By George, I forgot all about that,” said Jack, taking the articles one by one as Wimba passed them into the tent.

“You’re a good scout, Wimba,” said Frank approvingly. “I forgot, too.”

Wimba shrugged and ducked. “No good let um b’long council tree too long,” he said. “Mebbe Chief send um man up pretty soon to have look—see.”

“He’s right, fellows,” growled Bob from his cot. “These people are curious as monkeys, and after the novelty wore off they’d be sure to investigate.”

“Well,” said Jack, as Wimba dropped the flap behind him and departed, “thanks to Wimba, when Chief Ruku-Ru goes to investigate now he’ll not find anything. And certainly the old radio saved Wimba’s life and pulled us out of a bad hole.”

“Besides really being responsible for getting us a chance to see the Chief’s army at drill tomorrow,” said Frank sleepily. “Well, fade out, will you? I’m dog tired.”

Presently all three were sunk in slumber—a sleep tinged with pleasant thoughts of the novel sight in store for the morrow, but untouched by premonition of the perils to follow.

The night passed without disturbance, and dawn found the boys with the ubiquitous Wimba clinging like a shadow at Frank’s heels, stationed on a rise of ground west of the village.

The ground here rolled away in an open treeless plain filled with grass of vivid hue to where a half mile distant a line of trees marked the beginning of a forest. It was rolling country, rich green pasture uplands with clumps of forest here and there, and all rising in the background to a line of low hills that stretched away as far as the eye could see.

A never-ending source of surprise to the boys was the striking similarity of this country to the choicest New York State or New England landscapes. Evidences of civilized occupation such as farmhouses nestling amidst the greenery, the twin steel ribbons of railway, or stone fences or hedges, of course, were lacking. And the colors were more vivid, under the brilliant sunshine and seen through air untainted by the smoke of cities, than at home. The greens were greener, and the purples and greys of distance were deeper. Nevertheless, with cultivated fields and herds of cattle in the distant meadows, the similarity to scenes of home was so striking that on this particular morning Jack, at least, experienced a pang of homesickness.

This feeling was soon dispelled, however, for an exclamation from Frank, echoed by Bob who ventured forth for the first time in days, recalled Jack to the present. Following the indication of Frank’s pointing finger, he saw the distant forest suddenly spout warriors.

“By George, what a sight,” he cried as, the long slanting rays of the newly-risen sun full upon them, the warriors advanced, five hundred strong, spread out in open order, with the beautifully decorated hide shields carried by the front rank gleaming in the sunlight.

Frank already was turning the crank of the motion picture camera, while Chief Ruku-Ru, separated for once from his arm chair, stood to one side watching him with absorbed interest. The advance of his drilling warriors meant nothing to the dusky monarch, for it was something with which he was familiar. This strange machine, into which the young white wizard peered, while slowly turning a crank, was, on the other hand, a mystery.

So engaged in watching Frank was the chief that he did not at once note the panting messenger who came tearing up to the royal party from the direction of the village in the rear.

Then, as his eye fell on the boy, for such he was, the chief spoke a few words to him sharply. The youth replied between gasps, more at length.

Watching the advancing warriors, who now had come to a halt in the middle of the plain, where they knelt and took cover behind their shields, only their round black heads and long lances showing above, the boys paid no attention to this by-play.

Not so Wimba, however, for as the messenger poured out his tale, he clutched Jack by an arm and, having obtained his attention, repeated hastily what was being said.

“Him bad tribe raid village,” he said. “Carry off cattle and women. Boy escape and make tell Chief Ruku-Ru.”

“What! Great Scott!”

“What’s that? What’s that?” cried Bob, excitedly. “Say, Jack, if raiders cleaned out the village, maybe they went after our camp, too.”

Frank, unhearing, continued to crank his camera.

But Jack was dismayed. Bob’s words had aroused his own fears. Much of their paraphernalia was at the camp. Other cameras, thousands of feet of film, both taken and unused, clothing, gifts for various chiefs yet to be encountered, rifles and ammunition. These latter had been left behind, and the boys wore only their automatics. Above all, their radio apparatus had been left in camp. Clumsy handling might destroy it irreparably.

“Find out all you can, Wimba,” he commanded sharply. “Did the raiders go near our camp?”

“Maybe, they missed it,” he added hopefully to Bob. “You see we lie to one side and out of sight of the village.”

Wimba was rapidly interrogating the chief who, with a word or two, dismissed him, then turned to face the plain and using his arms as a semaphore went through a set of gestures which quite obviously were some kind of signal.

That they were so understood by the warriors was apparent, for the latter leaped forward in a tearing run that ate up the distance.

In the meantime, Frank, all unaware as yet of what was going forward, cranked away for dear life, delighted with the marvellous picture he was obtaining, while the others questioned Wimba as to the chief’s reply.

“Him say no know,” replied Wimba. “Raid come from other side. Mebbe your camp, baas, not found.”

“Anyhow, we left a half dozen bearers with guns on guard,” said Bob. “They’d be able to stand off these savages armed only with bows and arrows.”

“Yes, if they didn’t get scared and run,” said Jack. “Look at those fellows come. They’ll be here in a minute. What’s the chief going to do?” Frank for the first time withdrew his head from the camera hood.

“Say, you chaps,” he cried delightedly. “You ought to see this. It’ll make one great picture.” He was about to place his eyes again to the machine and resume grinding, but Bob gripped him by an arm, and in a few words apprised him of what was up.

To within twenty-feet of the chief, who had advanced several paces in front of the boys, charged his warriors at a furious rate. Then they suddenly halted, the whole mass, as if turned to stone. Execution of the maneuver in such dramatic fashion left the watching boys breathless. For a moment they forgot their own worries in admiration of the Kikuyus, and Frank mourned loudly because Bob had restrained him from resuming camera operations in time to get that last picture.

The black warriors gazed expectantly at their chief, and the latter addressed them in a loud voice. When he had ceased, angry cries went up, and then, like a wave splitting on a rock, the warriors without more ado, parted into two divisions and, flowing on either side of the chief and the dumbfounded boys, charged over the hill toward the village.

“Come on, fellows, here’s a chance to see some action. Maybe, to take a hand in it,” cried Bob, starting in pursuit.

Chief Ruku-Ru had placed himself at the head of his men and departed on the run before the boys could so much as ask his intentions. The blacks were still flowing along, on either side of the boys.

“But my camera,” wailed Frank, who was a great movie fan. “I can’t tote all this stuff myself. And I don’t want to leave it behind. Think of the chance to get a real battle picture.”

“I’ll take the dratted thing,” said Bob. And sweeping the legs of the tripod together, he gathered up tripod and camera, and started away, automatic already out and gripped in his free hand.

Jack picked up one reel case and Frank another, and, with Wimba and Matse clinging to their heels, away they went in pursuit of the running warriors.

Closer to civilization than most native tribes, by reason of the British development of Kenya Colony, yet the Kikuyus still cling to primitive customs. In nothing is this more apparent than in their methods of warfare and in the instruments employed.

Instead of paying many head of cattle to rascally traders for the trade guns smuggled to many tribes, they continue to use bows and arrows and spears, both for making war and for hunting.

So now as the boys galloped along at the tail end of the charging warriors of Chief Ruku-Ru, automatics in hand, they realized that if it came to close quarters with the enemy they would be of material assistance to their hosts by reason of the superiority of their weapons. For the enemy were Kikuyus, too, although of another clan, this big race being scattered in thirteen loosely-organized clans over a wide territory. And the raiders would be no differently armed than their hosts.

Down the hill, through a cover of woods, and into the village dashed Chief Ruku-Ru and his warriors, the boys at the rear but holding their own.

Loud cries from the foremost sounded warning that the enemy was still on the ground. At once the blacks ahead of them leaped to take cover behind the nearest huts, and began creeping forward from hut to hut, crouching and running close to the ground in covering open spaces.

The boys were not slow to follow this example, the wisdom of which became apparent when arrows began whizzing overhead, burying themselves in the thatched roofs of the huts or smacking with a dull thudding sound against the mud walls.

Sticking closely together, the three boys with Wimba, Matse and a number of bearers at their heels, took shelter behind one of the largest huts of the village as the rain of arrows increased.

So loud and close at hand now were the shouts that it was clear the enemy had been surprised by Chief Ruku-Ru before they could run away with their prisoners and loot. From the sounds, the hottest part of the fighting was not far away. In fact, Bob, who had leaned the tripod and film camera against the mud wall of the hut behind which they were momentarily sheltered, and had advanced to the nearest corner past which swept a perfect storm of arrows, returned with the report that in his opinion the main fight was being waged on the other side of the hut.

“And no wonder,” said Jack “Don’t you fellows recognize this hut? Well, I can’t blame you, for you’re seeing it for the first time from the rear. But this is Chief Ruku-Ru’s palace, I’m sure. Look. You can see the tip of a tree on the other side from here. There’s only one tree large enough to be seen like that, and that’s the council tree. Yes sir, fellows, this is the Chief’s palace.”

“Probably surprised the raiders looting it,” asserted Frank.

“May be so,” said Bob. “The chief has forty wives, you know. And these raiders undoubtedly came to carry the women away as captives. Women do the work amongst the Kikuyus, and they’re pretty valuable critters.”

“Listen to that,” interrupted Jack, as louder shouts gave warning of more intense fighting. “And, by George,” he added, in high excitement, clutching Bob by an arm, “look there. Those are some of Chief Ruku-Ru’s men, aren’t they?”

He pointed to several figures, crossing the open space by the side of the “palace,” speeding back toward the rear.

“Running away,” said Bob. “They’re getting the worst of it.”

He stepped back, gazing upward.

“I can do it,” he cried. “Give me a hand, Jack. Cup your hands for a leg up.”

“Do what?”

“Scale that wall,” cried Bob. “Mud wall’s about eight feet high. We can swarm over it, drop into the chief’s courtyard, and then from behind the wall on the other side we can attack the enemy in the rear. Come on.”

“Right,” said Jack, putting his back against the wall and cupping his hands.

Without more words. Bob set a foot therein and springing gripped the top of the wall and pulled himself up. Then, facing about, he lay down, with his arms hanging. And Jack, leaping upward, seized his wrists and was pulled to position beside him.

“All right, Frank,” cried Bob.

“Take this camera first,” Frank answered. “If you fellows are going to take potshots at the enemy from the chief’s domicile, I want some pictures of it.”

“Hurry, then,” cried Bob, impatiently. And Frank obediently hoisted aloft the camera on its long tripod, which was seized and whisked to position over the wall. Frank was boosted up by Wimba and hauled to position beside his comrades.

“Me come, too, baas,” pleaded the faithful fellow.

So Wimba, although without firearms to render him a useful ally, likewise was hoisted to the wall.

Then all four leaped down into the courtyard, where ordinarily Chief Ruku-Ru stabled his milch cows. But now the courtyard, deep in dung, was deserted. The raiders already had driven off the animals.

In one corner of the spacious yard lay two guards outstretched in the sun. The boys shivered.

“Killed,” said Bob, gritting his teeth. “Well, these rascals need a lesson. Come on.”

Yells from the other side of the opposite mud wall apprised them their surmise was correct. The fight was raging there, and with uncommon fierceness. But Chief Ruku-Ru’s forces were getting the worst of it. The raiders were too many for them.

Bob leaped to the low roof of a cow shed built against the wall, which overtopped it by two or three feet. Crouching behind this bulwark, he peered out. He found he faced the great village square. The two forces were fighting at close quarters. The air was filled with arrows. Here and there lay fallen warriors, never to move again, while others were dragging themselves away with ghastly wounds upon them.

It was easy to distinguish between the two forces. Easy for one thing, if for no other. Not because of the fact that one side had herded cattle and wailing women indiscriminately into one corner of the square at its back. That betokened the enemy host, right enough. But a clearer indication was afforded by the two leaders.

Chief Ruku-Ru, strongly built, a ferocious fighter, had thrown aside shield, spear, bow, and armed only with a wicked knife was engaged in hand to hand combat with a gigantic negro similarly accoutred who wore in addition a tuft of golden eagle feathers in his hair.

These were the respective chieftains, and their fighting men stood back to permit them free play. In fact, in the vicinity of the two warriors, all other fighting had died away.

The boys were unaware that Chief Ruku-Ru’s opponent was known as the Bone Crusher, and that his fame as a terrible fighter was widespread amongst all the Kikuyu clans. But that this individual combat had dwarfed all others for the moment was apparent. Not only those warriors in their vicinity had ceased fighting, as if by common consent, but over the whole square in a trice spread a truce that reached to the farthest combatants. The shouts of the fighters, the wails of the captive women, died away. Only the panting of the two gladiators could be heard.

Jack and Frank had clambered into position beside Bob, with Wimba close at Frank’s heels. Frank, moreover, as soon as he saw what was going on had set up the camera and already was busy grinding away as if with no thought except to obtain a motion picture of that contest.

“Like something out of the old tales of Homer,” whispered Jack.

Bob nodded, half absently. He was too busy watching that strange contest to waste time drawing comparisons with the past. Biggest of the boys, a youth of gigantic frame although still only in his teens. Bob was one of the cleverest amateur boxers and wrestlers in America. Moreover, although not exactly pugnacious of spirit, yet he did frankly and openly, as he was wont to express it, “love a good fight.”

And a good fight he was beholding now.

Crouching, wicked knives clasped in their right hands, left arms advanced with the long cotton garments betokening their chiefhood ripped from their shoulders and wrapped about the forearm as guard, the two warriors circled each other, looking for an opening. What Chief Ruku-Ru lacked in height and weight by comparison with his huger opponent, he made up in superior speed and litheness. The pliant muscles of his back and thighs could be seen writhing beneath the ebon skin of his naked body as he leaped this way and that.

That his blows did not all miss soon became apparent as first one and then another long rip gushing crimson appeared on the black skin of the Bone Crusher. The latter, on the other hand, try as he would, could not get past Chief Ruku-Ru’s guard. His knife struck and struck again, but always as if by a miracle Chief Ruku-Ru’s padded forearm fended off the blow at the last second of time.

Suddenly, the Bone Crusher, rendered desperate by his foe’s superiority with the knife, goaded into insensate fury by the repeated slashing to which he was subjected, tossed his knife high into the air and with a vast bellow leaped upon Chief Ruku-Ru. But he was canny, this Bone Crusher, and even as he sprang he flung the flowing cotton garment hanging from his left arm over the other’s head.

Thus confused and blinded, Chief Ruku-Ru lashed out wildly with his knife, but without being able to see to direct his blows.

Wrapping his long arms about the other’s waist, the Bone Crusher whirled him aloft and sent him spinning like a giant top into the midst of Chief Ruku-Ru palsied followers.

But he was not left long to enjoy his victory. Before his forces could renew the combat, before the stricken followers of Chief Ruku-Ru could turn and flee, a new assailant appeared.

He was none other than Bob. Leaping down from the mud wall before Jack and Frank could move to restrain him, big Bob launched himself like a thunderbolt at the Bone Crusher.

A shout of warning from his henchmen at his back caused the gigantic black to face about. But before he could put up any defense. Bob shot forward as if for a low football tackle. Many a time on the field he had swooped in just such irresistible fashion at the legs of an opposing player. But this time his intention was not merely to bring his man down.

His hands closed about the ankles of the Bone Crusher, and then he straightened up with startling swiftness. And for all his bulk, the Bone Crusher went hurtling through the air, over Bob’s shoulders, to fall, not amongst his own followers, but into the ranks of the enemy.

Had he fallen on his head, his neck might have snapped. For never had Bob put into that particular hold the viciousness he had employed now.

But in falling the Bone Crusher brushed against a warrior. His course was deflected. And instead of alighting on his head and shoulders, he fell on his side.

With a catlike agility not to be expected in a man so huge, he bounded up from the earth with an ear-splitting roar of rage, and ran foaming at the mouth toward Bob. Just what he intended will never be known.

Bob saw him coming and set himself. As the Bone Crusher lunged forward. Bob sidestepped and launched a triphammer blow with his right fist. It caught the Bone Crusher behind the point of the jaw with a thud that sounded like a dull explosion, and the huge Negro chieftain collapsed as if a mountain had fallen upon him. His great body jerked once or twice then lay still.

The tide was turned. The next moment, as Bob, flushed with victory, prepared to leap in amongst the wavering mass of the Bone Crusher’s followers, Jack and Frank appeared at his side. Too well they knew the big fellow’s rashness when his blood was up to hold back any longer. Not that they had been holding back, however. So quickly had Bob acted that the passage of time since he had leaped down from the top of the wall and made his sudden attack on the Bone Crusher could be measured in seconds.

Jack and Frank had followed at once, Wimba at Frank’s heels like a faithful dog. Now they ranged themselves beside their comrade.

“Steady, old thing,” warned Jack, as Bob with a wild gleam in his eyes appeared on the verge of tackling the enemy host single-handed. “Let’s stick together. You’ve thrown an awful scare into them.”

In fact, the Bone Crusher’s men showed little stomach for fighting, that is, for facing Bob. The mute evidence of the latter’s prowess was at his back, where the prone figure of the Bone Crusher lay without a quiver, since that blow on the point of the jaw.

But the lull in hostilities did not last. Chief Ruku-Ru’s men were heartened by the turn of events in their favor. They crowded forward with sharp yells. The flight of arrows into the mass of the enemy began anew.

“I haven’t the heart to shoot to kill,” muttered Frank. “But if they realize we have firearms, they may flee more quickly. I’m going to shoot over their heads.”

He suited action to word, and began pumping away with his automatic. It was the last thing needed to hasten the growing panic. In a trice, conditions were reversed. The Bone Crusher’s men broke into headlong flight, dashing away pell mell amongst the huts on the opposite side of the village square. And the villagers streamed past the boys in pursuit.

They found themselves practically alone in the square. Pursuit drew away into the distance. The victorious vengeful cries of the villagers mingling with the screams of the vanquished came back to them. Dazedly, they gazed about at the numerous evidences of the battle just ended, in the cowering women abandoned by their captors and not yet fully realizing their fortunate rescue, in the bodies of a score of men, including that of Chief Ruku-Ru and the Bone Crusher, and in arrows scattered here and there.

“By golly, Bob,” said Frank, whose face was pale, as he thought of the peril into which his big chum had launched himself, “I’ve seen you do a lot of foolish things, but that was the worst. To tackle that giant.”

“Huh,” was all the other deigned to reply.

Jack was bending above the form of Chief Ruku-Ru, and a moment later he straightened up and beckoned the others to join him.

“Unconscious but beginning to mutter,” he said. “He’ll recover soon. I think his right shoulder is dislocated, but I don’t believe he has any serious injury. Let’s carry him to his hut, and I’ll try to set his shoulder.”

With Wimba’s aid, the four boys bore the body of the chief to the door of his hut, from which one of the chief’s wives who hastened to join them brought out a pallet. On this they laid the unconscious form, while Jack worked at setting the dislocated shoulder. In this he was successful as, like all the boys, he was well drilled in administering first aid and performing rude surgery such as mishaps in the wilds necessitated.

Wimba and Matse rounded up the scattered bearers, and several were despatched to the boys’ camp to obtain the medical kit. They returned quickly, bringing the welcome intelligence that the camp had not been disturbed by the raiders who, approaching the village from an opposite direction, doubtless were unaware of its presence.

Thereupon, all three boys busied themselves administering to the wounded, a score of whom were collected. Women were pressed into service, as all the able-bodied men had joined in the pursuit of the routed enemy. Not until many hours of toil under the hot sun had been spent, however, was their self-imposed task of mercy completed. Then all the wounded had been attended to and made as comfortable as possible in the biggest hut of the chief’s enclosure, which had been commandeered as hospital.

It was nightfall, and most of the warriors had returned, under the leadership of Chief Ruku-Ru’s nephew, when the chief who had recovered consciousness and, in fact, was little the worse as a result of his encounter with the Bone Crusher, was informed that the boys had attended to all the injured.

He met them in the village square, where already a great fire was blazing and preparations for a big feast in celebration of the tribe’s victory were going forward. Wimba as usual acted as interpreter. And into his eyes came a gleam which warned the boys something unusual was afoot, before he ever interpreted the chief’s lengthy speech.

Lengthy though the chief’s speech had been, however, it was brief enough on Wimba’s lips. He was not so proficient in his command of English as to be able to render all the chief’s verbal flowers, and contented himself accordingly with reporting the gist of what the dusky monarch had said. Chief Ruku-Ru, one arm in a sling, in the meantime stood smiling at one side.

“Him much honor, baas,” said Wimba, addressing Frank whom, since the latter’s rescue of himself from death by means of the radio, he regarded as the leader of the boys. “Him chief say him take all three white young men into tribe and make Strong-Arm,”—indicating Bob, with a wave of the hand—“great chief.”

That this was an honor, the boys knew enough of local history to realize. Many African tribes degenerate when coming into contact with white men, and for them to make such an offer would be insolent and presumptuous. But the Kikuyus, far above the average of African intelligence, were a proud people. And the boys realized that, holding themselves in high esteem, the Kikuyus felt they were bestowing an honor.

In such a spirit, they accepted it.

“Tell Chief Ruku-Ru,” said Frank to Wimba, after consulting with his comrades, “that we shall make only one stipulation. We are very flattered. So much so that we want Mr. Hampton here to see when the ceremonies take place. Tell the chief that we shall summon Mr. Hampton through the air tonight to return, and that probably he can be back in two days. The ceremonies can be held then.”

Wimba translated this as best he could, and then interpreting the chief’s reply stated matters would be arranged as requested.

Before permitting the boys to depart, however. Chief Ruku-Ru pressed a bracelet of heavy silver, oddly worked by native silversmiths, and containing a turquoise matrix, upon Bob.

They examined it in turn as they made their way back to the camp, and many were their expressions of appreciation. The fact that it bore a family resemblance to the silver and turquoise bracelets of the Navajo Indians of the American Southwest was commented upon by Jack.

“Curious,” he said, “how the same sort of workmanship, as well as the combination of silver and turquoise, can bob up among two primitive peoples who never heard of each other.”

“Yes, it is,” said Frank. “But what I’m thinking of is this big bum with a bracelet. Lady stuff.” Bob made a grab for him, and the pair began rolling over and over in the long buffalo grass.

“Ouch. Leggo,” begged Frank, almost choked with laughter.

“Take it back.”

“Sure,” gasped Frank, and Bob arose. “Only thing that would be funnier,” cried Frank, sprinting for their tent, “would be for you to wear a lady’s wrist watch.”

Watching his comrades, the soberer Jack smiled sympathetically. They had all been through a trying experience, and it was natural that their spirits should find relief in play.

Then he, too, entered the tent, after giving Wimba orders regarding the preparation of dinner, and began tuning up to call his father and not only make report regarding the momentous adventures of the day, but also ask him to return so as to be present at the ceremonies of induction into the Kikuyus.

At the end of two days Mr. Hampton and Niellsen, the photographer, a tall rangy Scandinavian some ten years older than the boys, returned. And when this intelligence was communicated to Chief Ruku-Ru he made preparations for the carrying out of the ceremonies in honor of the boys that very night.

Prior to going to the village, the two parties exchanged experiences. And while Mr. Hampton and Niellsen had had no such exciting times as the boys, yet they, too, had not been without adventure.

In particular, the boys laughed heartily over Niellsen’s description of an incident attending the photographing of some baboons. It being the dry season, their guides had taken Mr. Hampton and Niellsen to a certain dry river bed in which water could be obtained by digging, a fact with which the baboons were well aware. Here, prophesied the guides, they would undoubtedly be able to obtain excellent pictures of baboons. And in this prophecy they had been correct.

“But,” laughed Mr. Hampton, “you should have seen what happened to Niellsen. Tell it, Oscar.”

Niellsen joined the older man in the laugh. He had an honest open face with a tip-tilted nose and sandy recalcitrant hair which gave him a humorous appearance calculated to induce smiles in his auditors before ever he spoke. And in keeping with his appearance he had a habit of dry speech which the boys found highly amusing.

“The joke was on me, all right,” he said.

“Or the baboon was,” said Mr. Hampton, laughing harder than ever, as if at some diverting recollection.

At this Jack could no longer conceal his impatience. “Come on, tell it,” he said. “Don’t keep this all to yourselves.”

“Well, it was this way,” said Niellsen. “You know if I’d have shown myself to the baboons with my camera, I’d never have gotten them to stand still long enough to have their pictures taken. Instead of watching the birdie, they’d have come up and tried to operate the machine. So I decided to hide myself. And for my place of concealment, I chose the branches of a small uprooted tree.

“There I was, had been waiting about half an’ hour, when the baboons arrived. They began digging in the sand like regular ditch diggers. How they did make the dirt fly. There were baboons everywhere, scores of them. The whole tribe must have eaten pretzels and then hustled off to this spot in the river with a whale of a thirst to be squenched.

“I was fooling around, trying to get a good focus, for the light was tricky. And at last I had just what I wanted, and set my hand to the crank, all ready to begin grinding.

“At that moment, something lighted on my head with such force that I fell clean out of my perch. But fortunately the ground wasn’t far away, a matter of three or four feet.

“I didn’t know what had struck me. But when I got to my feet and looked around, there sat a baboon in my old perch. And he was cranking away, just grinding for dear life, and chattering with delight.

“The beggar had jumped on my head, and then had taken my job away from me.”

The boys roared.

“What did you do?” asked Frank.

“Do? I bows to him and says, ‘Please, Mr. Baboon, won’t you go away?’ And after giving me a line of baboon talk that I couldn’t understand because I didn’t have my dictionary with me, he swung away to join his friends.”

“But the camera?” asked Jack. “Had the baboon damaged it?”

“Not a bit of it,” averred Niellsen. “I found the focus still good, and continued to grind out some more film. And I believe the beggar took some good stuff while he was at the crank. If it comes out all right in developing, I’m going to have stuff worth a fortune. ‘Baboons photographed by one of their number.’ Can’t you just see that caption on the screen?”