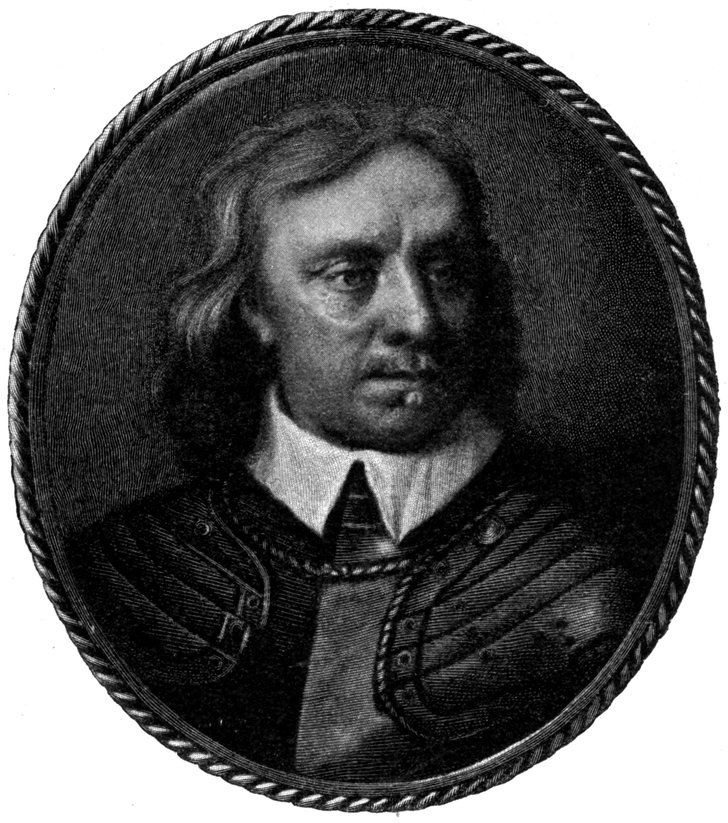

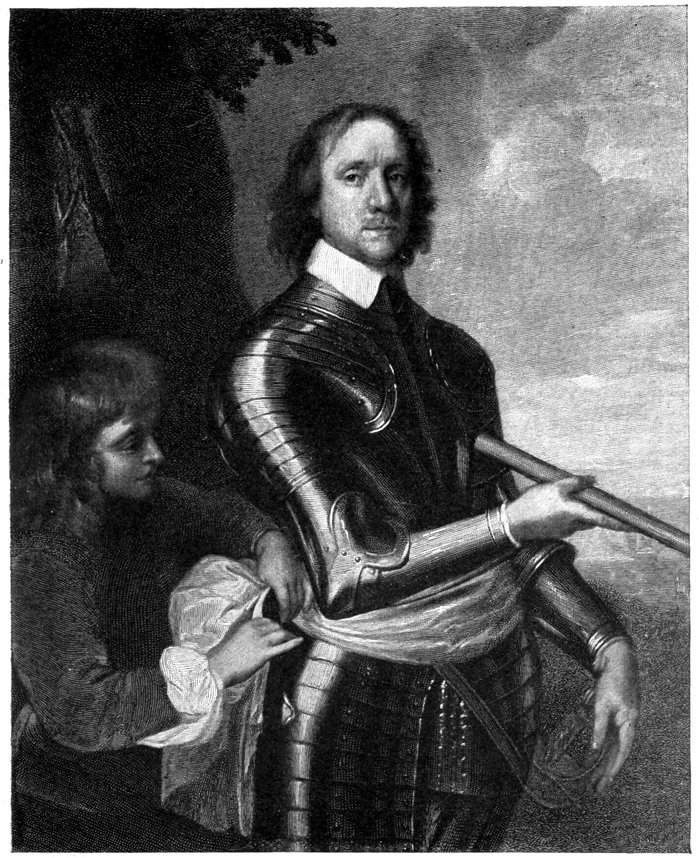

OLIVER CROMWELL.

From the portrait by Robert Walker at Hinchingbrooke.

By permission of the Earl of Sandwich.

(Probably painted soon after the beginning of the Civil War, when Cromwell was forty-three or -four years old.)

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

OLIVER CROMWELL.

From the portrait by Robert Walker at Hinchingbrooke.

By permission of the Earl of Sandwich.

(Probably painted soon after the beginning of the Civil War, when Cromwell was forty-three or -four years old.)

| PAGE | ||

|---|---|---|

| I. | THE TIMES AND THE MAN | 1 |

| II. | THE LONG PARLIAMENT AND THE CIVIL WAR | 51 |

| III. | THE SECOND CIVIL WAR AND THE DEATH OF THE KING | 99 |

| IV. | THE IRISH AND SCOTCH WARS | 141 |

| V. | THE COMMONWEALTH AND PROTECTORATE | 177 |

| VI. | PERSONAL RULE | 210 |

| Oliver Cromwell | Frontispiece |

| (From the portrait by Robert Walker at Hinchingbrooke.) | |

| FACING PAGE | |

|---|---|

| Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford | 8 |

| (From the miniature at Devonshire House.) | |

| Oliver Cromwell | 12 |

| (From a miniature by Cooper.) | |

| Sir John Eliot | 16 |

| (From the portrait by Van Somer at Port Eliot.) | |

| All Saints’ Church, Huntingdon | 24 |

| Cromwell’s House at Ely | 28 |

| Archbishop Laud | 34 |

| (From the portrait at Lambeth Palace, painted by Vandyke.) | |

| West Tower, Ely Cathedral, from Monastery Close | 40 |

| John Pym | 52 |

| (From the portrait by Cornelius Janssen.) | |

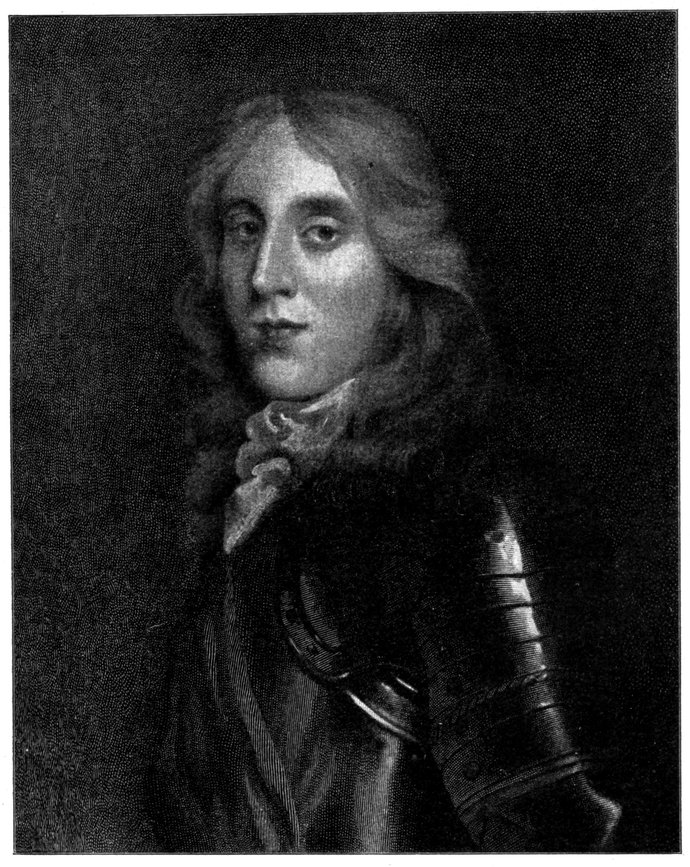

| Prince Rupert | 68 |

| (From the portrait by Vandyke at Hinchingbrooke.) | |

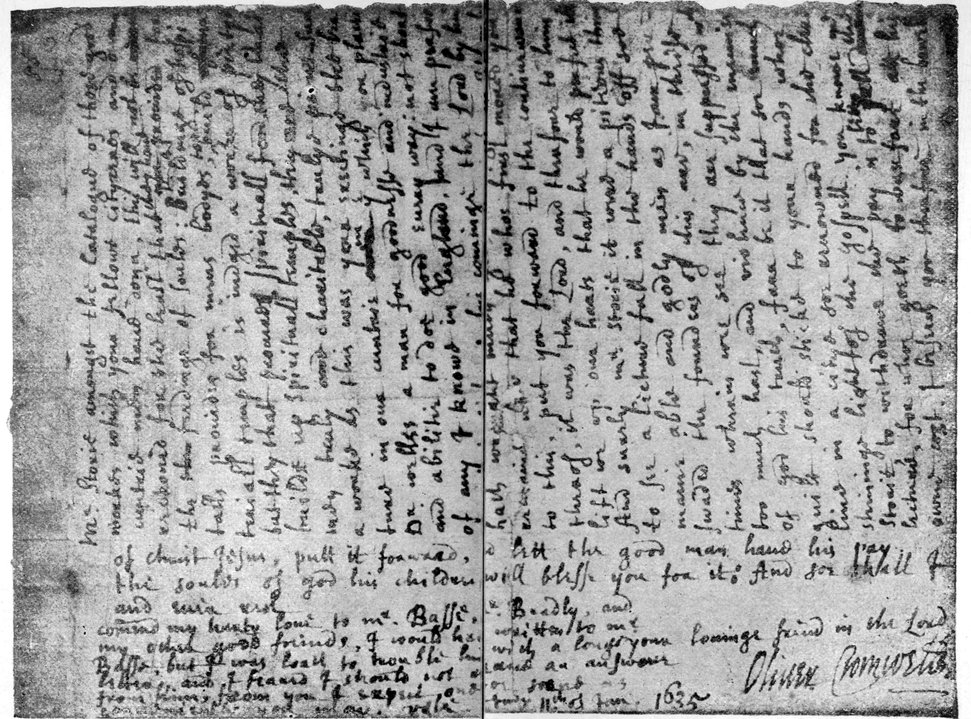

| Fac-simile of Letter from Oliver Cromwell to Mr. Storie, written January 11, 1635, said to be the earliest extant letter in Cromwell’s Handwriting | 74 |

| (From the original in the British Museum.) | |

| xJohn Hampden | 80 |

| (From the portrait by Robert Walker at Port Eliot.) | |

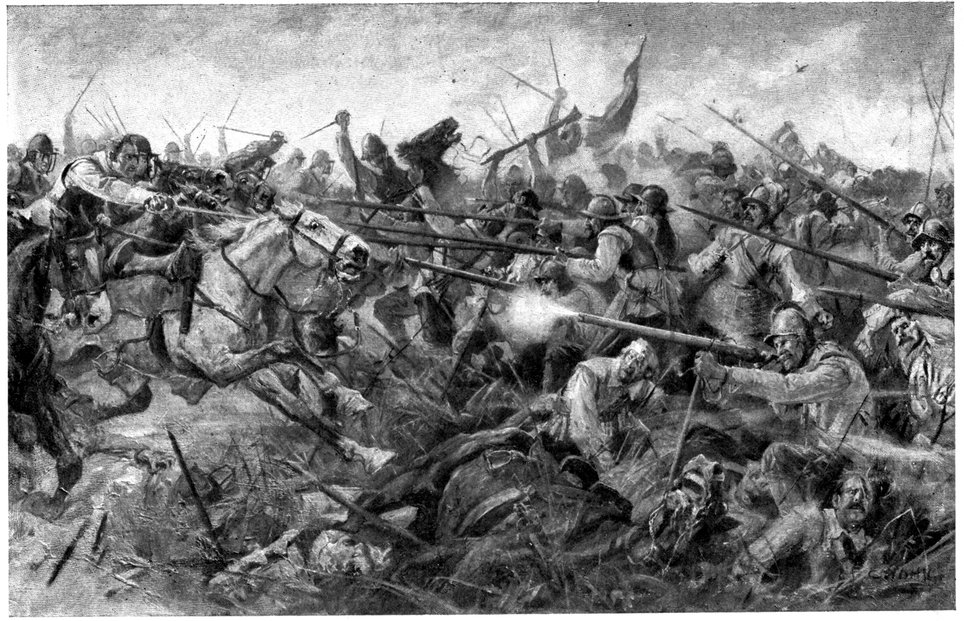

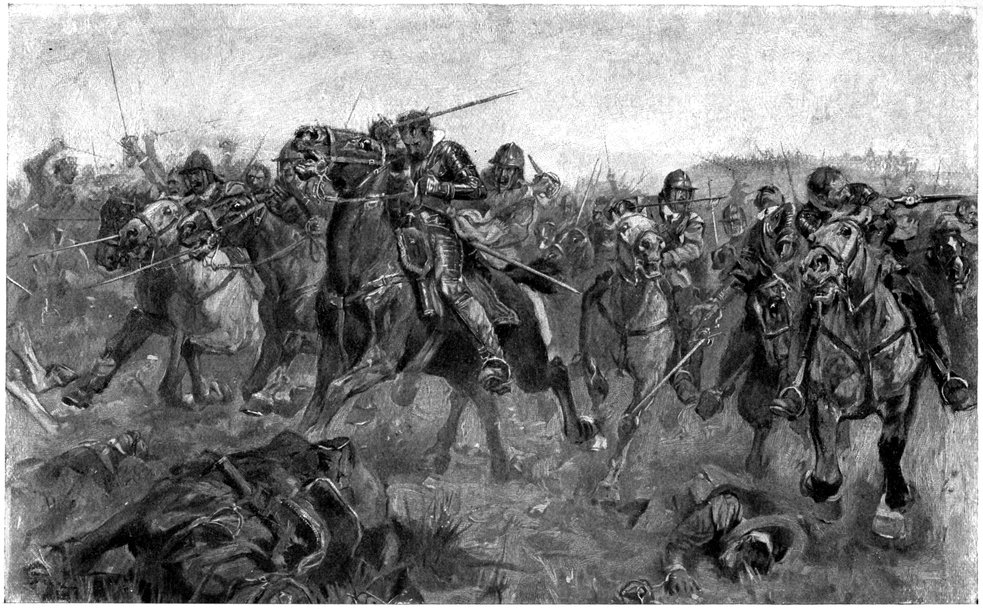

| Cromwell’s Engagement with the Marquis of Newcastle’s Regiment of “Whitecoats” in the Battle of Marston Moor | 88 |

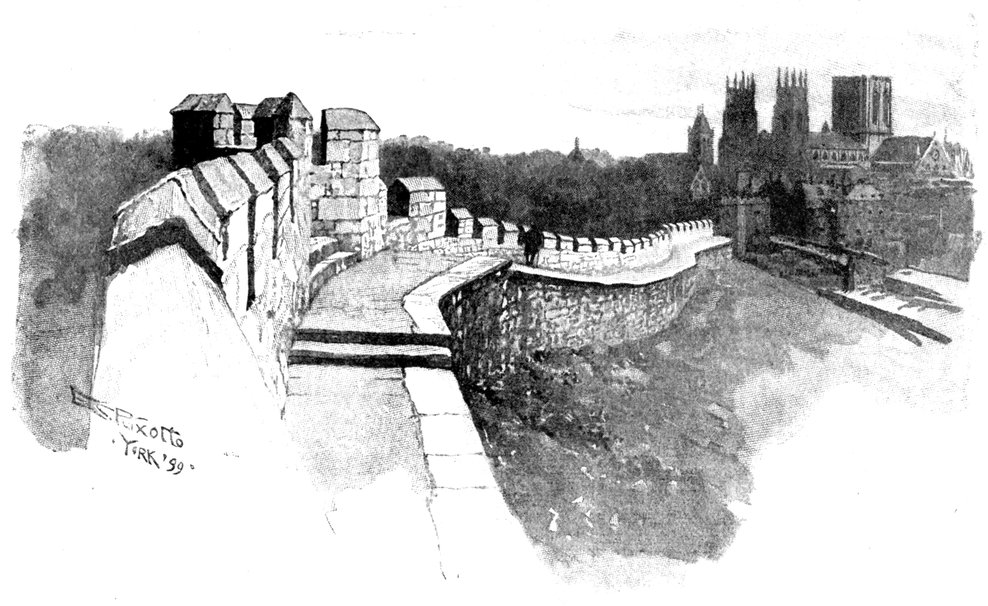

| The City Walls of York, with the Cathedral in the Distance | 96 |

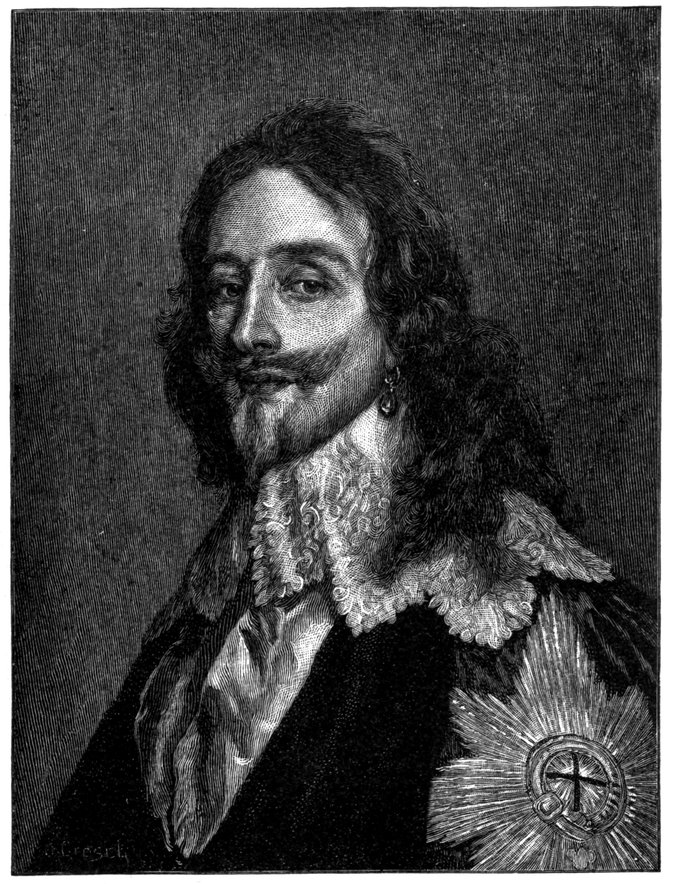

| King Charles I. | 108 |

| (From the replica at the Dresden Gallery, by Sir Peter Lely.) | |

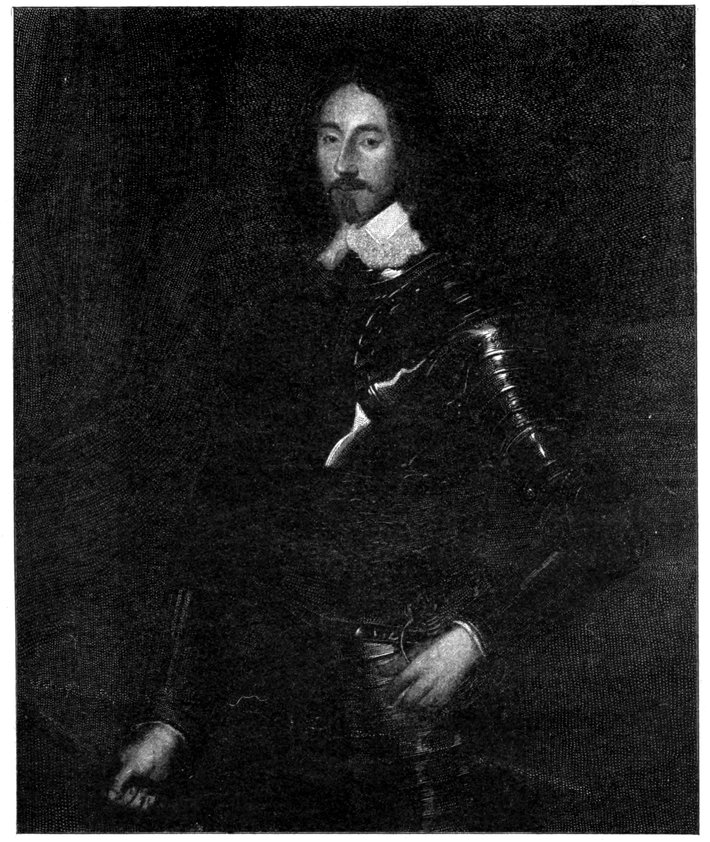

| General Sir Thomas Fairfax | 116 |

| (From the portrait by Robert Walker at Althorp.) | |

| John Milton | 120 |

| (From the drawing in crayon by Faithorne at Bayfordbury.) | |

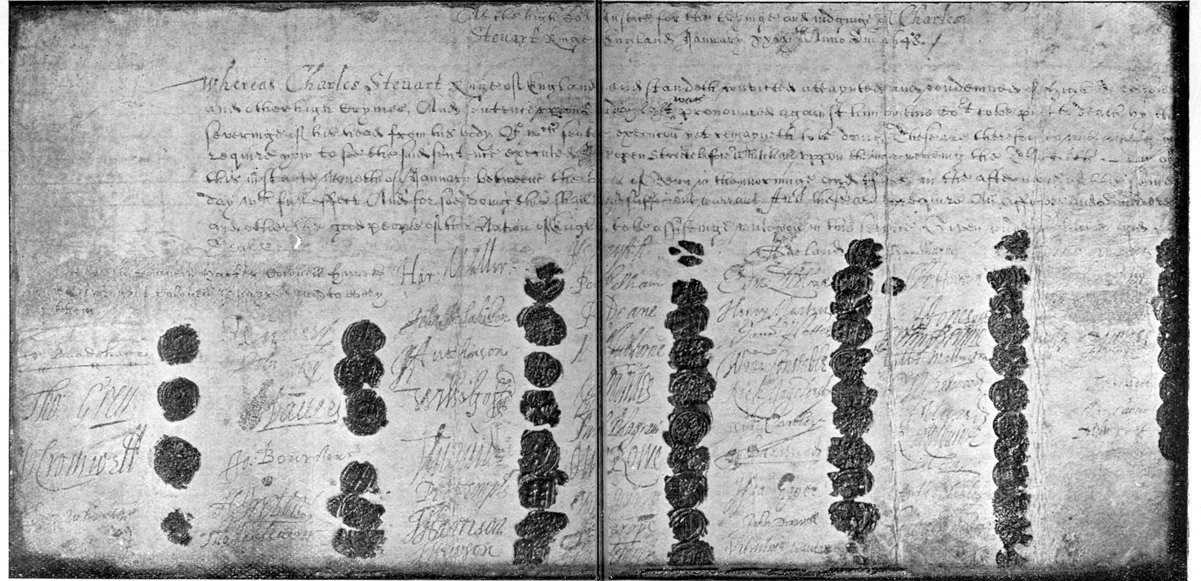

| The Death Warrant of King Charles I.—Signed by Oliver Cromwell and other members of the court | 128 |

| (From the original in the library in the House of Lords.) | |

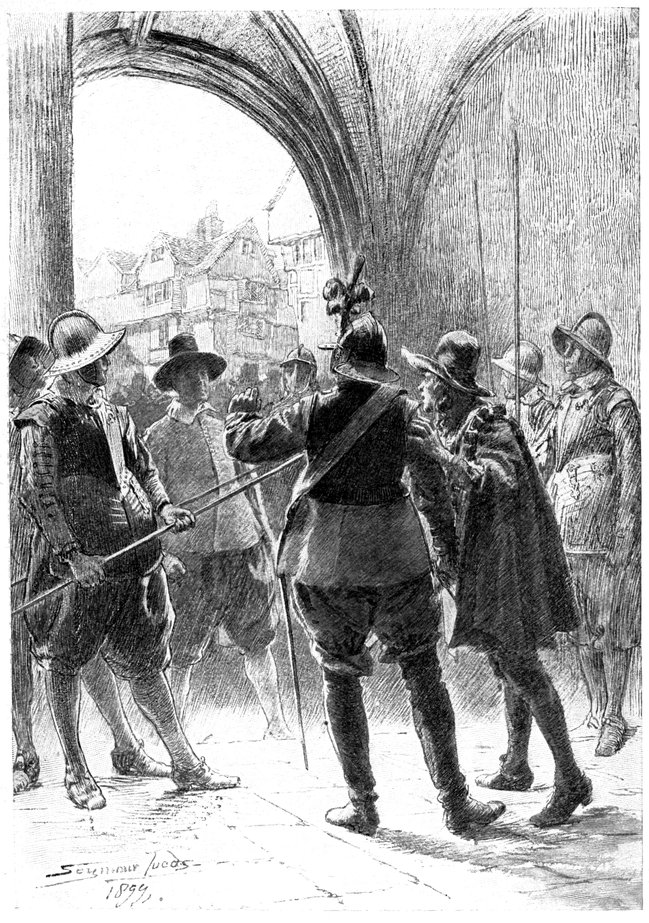

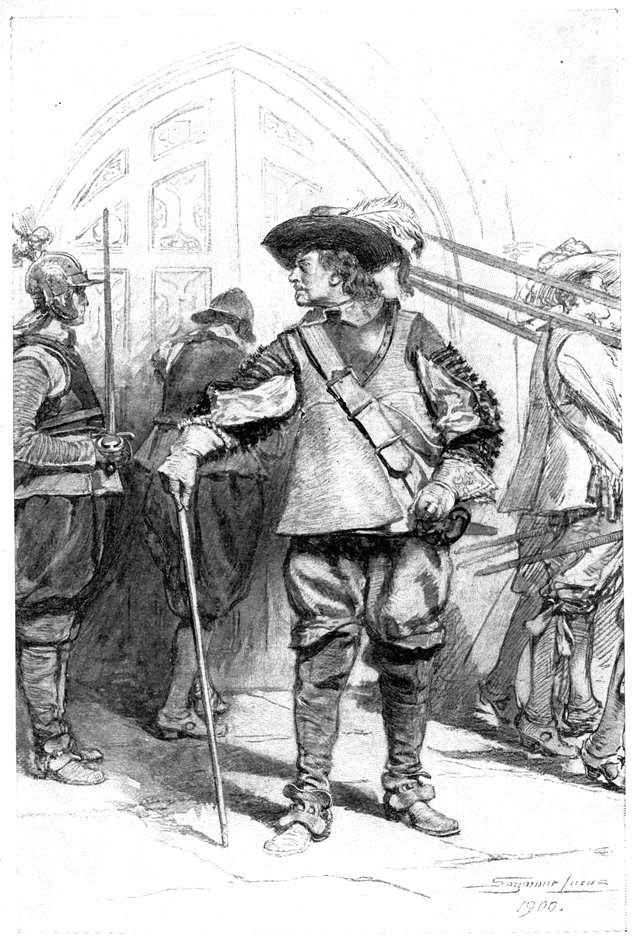

| Pride’s Purge | 136 |

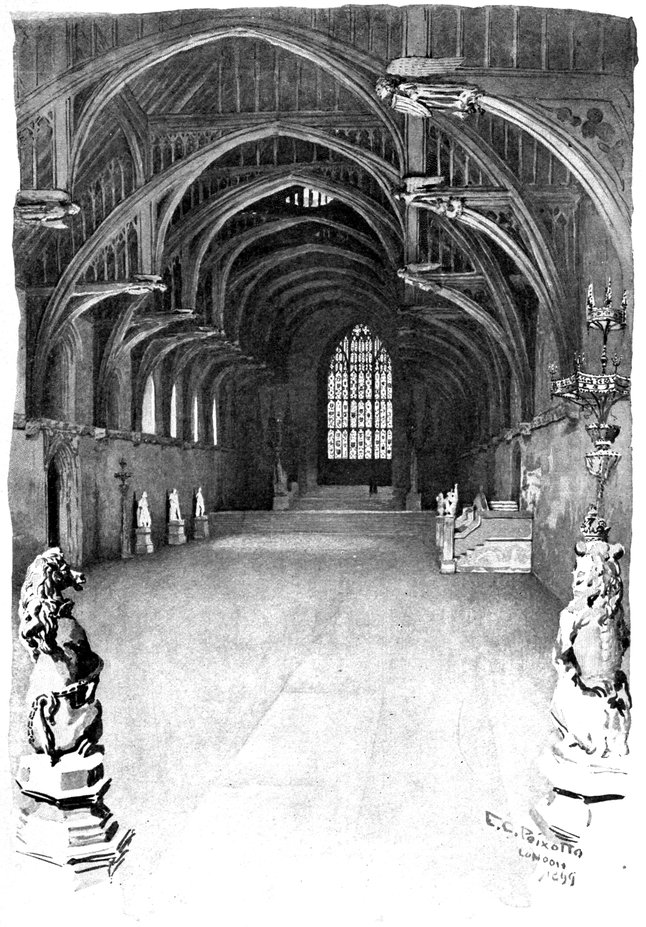

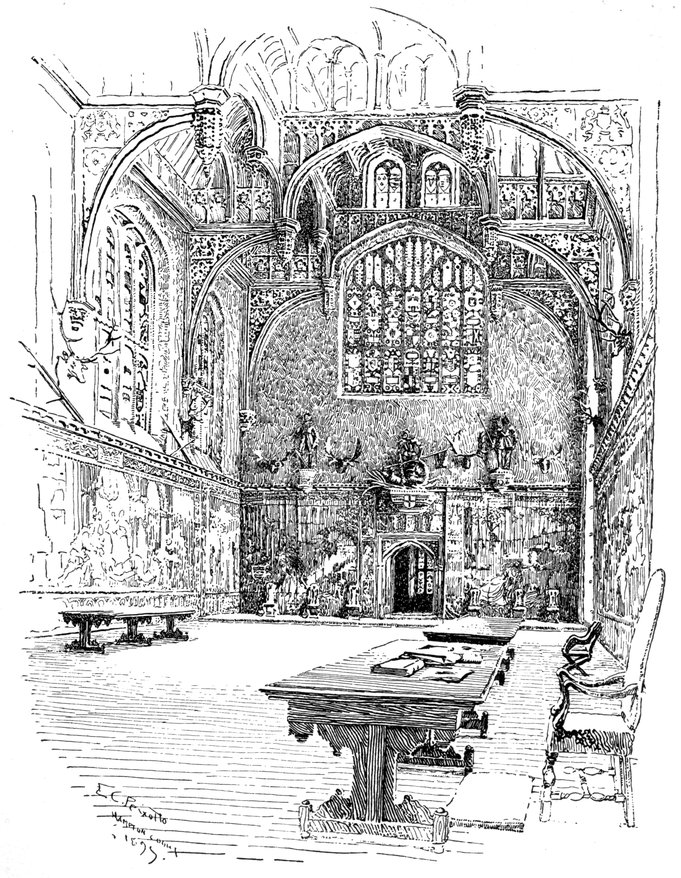

| Interior of Westminster Hall. Where Parliament sat and where King Charles I. was tried and sentenced | 140 |

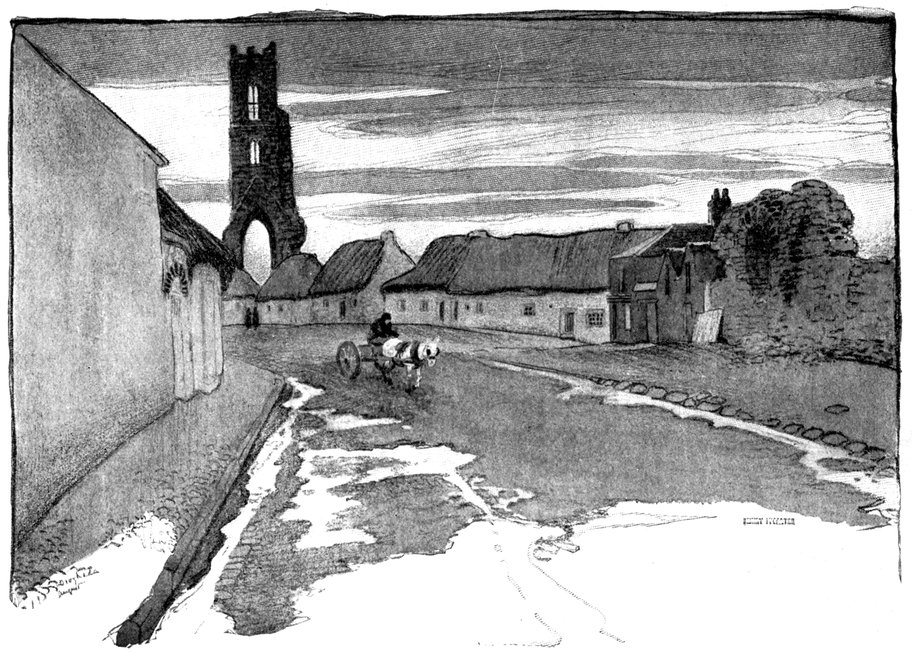

| Magdalen Tower, Drogheda | 154 |

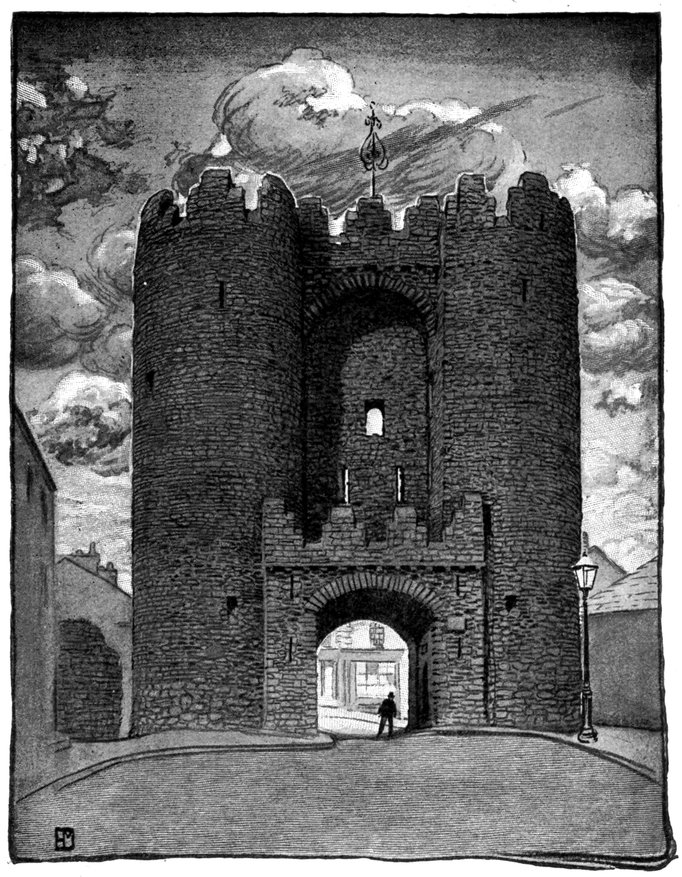

| St. Lawrence’s Gate, Drogheda | 158 |

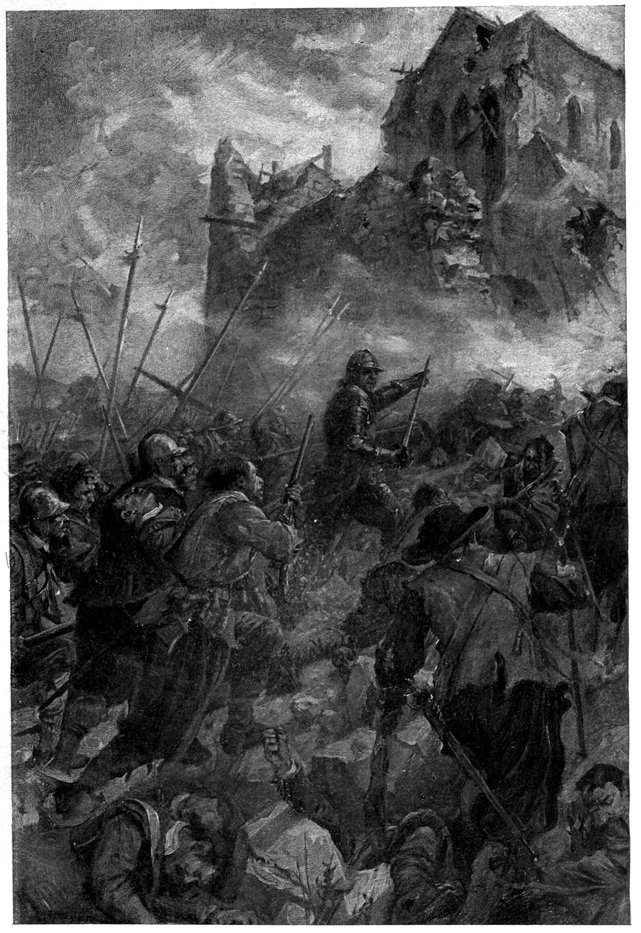

| Cromwell Leading the Assault on Drogheda | 164 |

| The Battle-field of Dunbar | 172 |

| Seal of the Protectorate | 178 |

| (From an impression in wax in the British Museum.) | |

| xiAdmiral Robert Blake | 184 |

| (From the portrait at Wadham College, Oxford.) | |

| Cromwell Dissolving the Long Parliament | 186 |

| Oliver Cromwell | 190 |

| (From the painting at Althorp by Robert Walker.) | |

| The Clock Tower, Hampton Court | 200 |

| The Great Hall, Hampton Court—In this room the state dinners were given under the Protectorate | 206 |

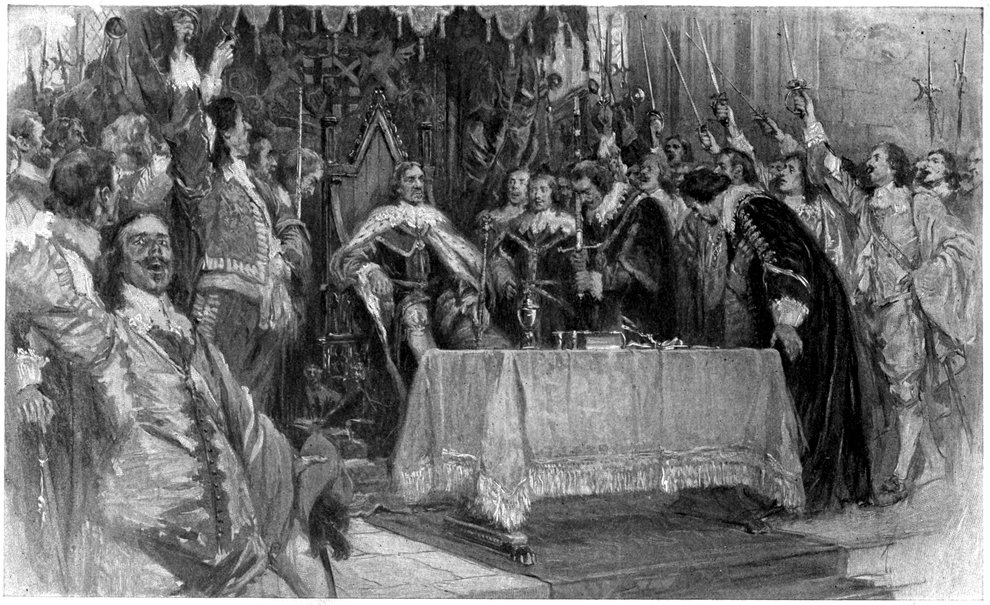

| The Second Installation of Cromwell as Protector, in Westminster Hall, June 26, 1657 | 210 |

| Sir William Waller | 216 |

| (From the portrait by Sir Peter Lely at Goodwood.) | |

| Henry Cromwell—Son of the Protector, and Governor of Ireland | 220 |

| The Last Charge of the Ironsides | 226 |

| Richard Cromwell | 232 |

| Exterior of Westminster Hall | 236 |

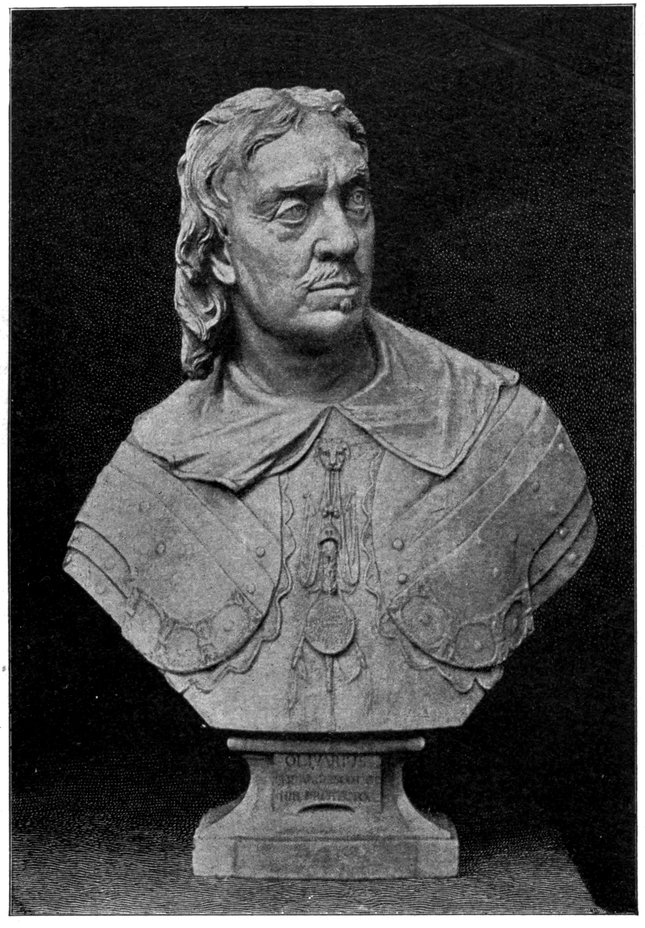

| Oliver Cromwell | 240 |

| (From the bust by Bernini.) | |

For over a century and a half after his death the memory of the greatest Englishman of the seventeenth century was looked upon with horror by the leaders of English thought, political and literary; the very men who were carrying to fruition Cromwell’s tremendous policies being often utterly ignorant that they were following in his footsteps. At last the scales began to drop from the most far-seeing eyes. Macaulay, with his eminently sane and wholesome spirit, held Cromwell and the social forces for which he stood—Puritanic and otherwise—at their real worth, and his judgment about them was, in all essentials, accurate. But the true appreciation of the place held by the greatest soldier-statesman of the seventeenth century began with the publication of his life and letters by Carlyle. The gnarled genius of the man who worshipped the heroes of 2the past as intensely as he feared and distrusted the heroes of the present, enabled him to write with a loftiness and intensity that befitted his subject. But Carlyle’s singular incapacity to “see veracity,” as he would himself have phrased it, made him at times not merely tell half-truths, but deliberately invert the truth. He was of that not uncommon cloistered type which shrinks shuddering from actual contact with whatever it, in theory, most admires, and which, therefore, is reduced in self-justification to misjudge and misrepresent those facts of past history which form precedents for what is going on before the author’s own eyes.

Cromwell lived in an age when it was not possible to realize a government based upon those large principles of social, political, and religious liberty in which—at any rate, during his earlier years—he sincerely believed; but the movement of which he was the head was the first of the great movements which, marching along essentially the same lines, have produced the English-speaking world as we at present know it. This primary fact Carlyle refused to see, or at least to admit. As the central idea of his work he states that the Puritanism of the Cromwellian epoch was the “last glimpse of the Godlike vanishing from this England; conviction and veracity giving place 3to hollow cant and formulism.... The last of all our Heroisms.... We have wandered far away from the ideas which guided us in that century, and indeed which had guided us in all preceding centuries, but of which that century was the ultimate manifestation; we have wandered very far; and must endeavor to return and connect ourselves therewith again.... I will advise my reader to forget the modern methods of reform; not to remember that he has ever heard of a modern individual called by the name of ‘Reformer,’ if he would understand what the old meaning of the word was. The Cromwells, Pyms, and Hampdens, who were understood on the Royalist side to be fire-brands of the devil, have had still worse measure from the Dry-as-Dust philosophies and sceptical histories of later times. They really did resemble fire-brands of the devil if you looked at them through spectacles of a certain color, for fire is always fire; but by no spectacles, only by mere blindness and wooden-eyed spectacles, can the flame-girt heaven’s messenger pass for a poor, mouldy Pedant and Constitution-monger such as these would make him out to be.”

This is good writing of its kind; but the thought is mere “hollow cant and unveracity;” not only far from the truth, but the direct reverse 4of the truth. It is itself the wail of the pedant who does not know that the flame-girt heaven’s messenger of truth is always a mere mortal to those who see him with the actual eyes of the flesh, although mayhap a great mortal; while to the closet philosopher his quality of flame-girtedness is rarely visible until a century or thereabouts has elapsed.

So far from this great movement, of which Puritanism was merely one manifestation, being the last of a succession of similar heroisms, it had practically very much less connection with what went before than with all that has guided us in our history since. Of course, it is impossible to draw a line with mathematical exactness between the different stages of history, but it is both possible and necessary to draw it with rough efficiency; and, speaking roughly, the epoch of the Puritans was the beginning of the great modern epoch of the English-speaking world—infinitely its greatest epoch. We have not “wandered far from the ideas that guided” the wisest and most earnest leaders in the century that saw Cromwell; on the contrary, these ideas were themselves very far indeed from those which had guided the English people in previous ages, and the ideas that now guide us represent on the whole what was best and truest in the thought of the Puritans. 5As for Pym and Hampden, their type had practically no representative in England prior to their time, while all the great legislative reformers since then have been their followers. The Hampden type—the purest and noblest of types—reached its highest expression in Washington. Pym, the man of great powers and great services, with a tendency to believe that Parliamentary government was the cure for all evils, followed to a line “the modern methods of reform,” and was exactly the man who, if he had lived in Carlyle’s day, Carlyle would have sneered at as a “constitution-monger.” It was men of the kind of Hampden and Pym who, before Carlyle’s own eyes, were striving in the British Parliament for the reforms which were to carry one stage farther the work of Hampden and Pym; who were endeavoring to secure for all creeds full tolerance; to give the people an ever-increasing share in ruling their own destinies; to better the conditions of social and political life. In the great American Civil War the master spirits in the contest for union and freedom were actuated by a fervor as intense as, and even finer than, that which actuated the men of the Long Parliament; while in rigid morality and grim devotion to what he conceived to be God’s bidding, the Southern soldier, Stonewall Jackson, was as true a type of the “General 6of the Lord, with his Bible and his Sword,” as Cromwell or Ireton.

The whole history of the movement which resulted in the establishment of the Commonwealth of England will be misread and misunderstood if we fail to appreciate that it was the first modern, and not the last mediæval, movement; if we fail to understand that the men who figured in it and the principles for which they contended, are strictly akin to the men and the principles that have appeared in all similar great movements since: in the English Revolution of 1688; in the American Revolution of 1776; and the American Civil War of 1861. We must keep ever in mind the essentially modern character of the movement if we are to appreciate its true inwardness, its true significance. Fundamentally, it was the first struggle for religious, political, and social freedom, as we now understand the terms. As was inevitable in such a first struggle, there remained even among the forces of reform much of what properly belonged to previous generations. In addition to the modern side there was a mediæval side, too. Just so far as this mediæval element obtained, the movement failed. All that there was of good and of permanence in it was due to the new elements.

To understand the play of the forces which 7produced Cromwell and gave him his chance, we must briefly look at the England into which he was born.

He saw the light at the close of the reign of Queen Elizabeth, in the last years of the Tudor dynasty, and he grew to manhood during the inglorious reign of the first English king of the inglorious House of Stuart. The struggle between the reformed churches and the ancient church, against which they were in revolt, was still the leading factor in shaping European politics, though other factors were fast assuming an equal weight. The course of the Reformation in England had been widely different from that which it had followed in other European countries. The followers of Luther and Calvin, whatever their shortcomings—and they were many and grievous—had been influenced by a fiery zeal for righteousness, a fierce detestation of spiritual corruption; but in England the Reformation had been undertaken for widely different reasons by Henry VIII. and his creatures, though the bulk of their followers were as sincere as their brethren on the Continent. Henry’s purpose had been simple, namely, to transfer to himself the power and revenues of the Papacy, so far as he could seize them, and thus to add to the spiritual supremacy against which the leaders of the 8Reformation had revolted: the absolute sovereignty which the Tudors were seeking to establish in England. Elizabeth stood infinitely above her father in most respects; but in religious views they were not far apart, and in theory they were both believers in absolutism. They had no standing army, and they were always in want of money, so that in practice they never ventured seriously to offend the influential and moneyed classes. But under Henry the misery and suffering of the lower classes became very great, and the yeomen were largely driven from their lands, while much of Elizabeth’s own administration consisted of efforts to grapple with the vagrancy and wretchedness which had been caused by the degradation of those who stood lowest in the social scale.

When the Stuarts took possession of the throne of England they found a people which, unlike the peoples of most of the neighboring States, had not fought out its religious convictions. The Reformation had deeply stirred men’s souls. Religion had become a matter of vital and terrible importance to Protestant and to Catholic. Among the extremists, the men who had given the tone to the Reformation in Germany, Switzerland, Holland, and Scotland, religion, as they understood it, entered into every act of their lives. In England there were men of this stamp; but in the English Reformation they had played a wholly subordinate part; and indeed had been in almost as great danger as the Catholics. Their force, therefore, had not spent itself. It had been conserved, in spite of their desires.

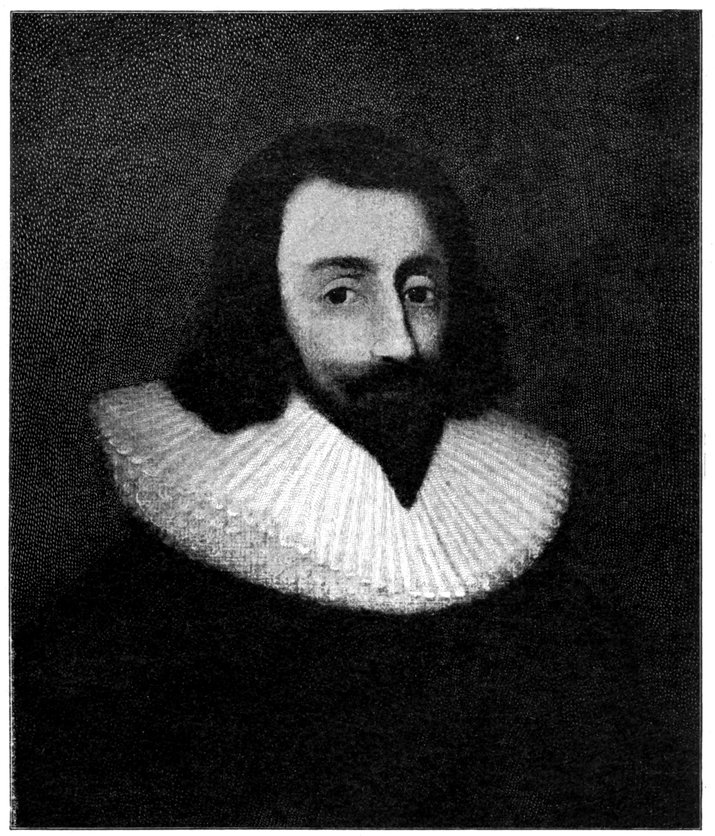

Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford.

From the miniature at Devonshire House.

By permission of the Duke of Devonshire, K.G.

9Thus it happened that the high tide of extreme Protestantism was reached in England, not as in other Protestant countries, in the sixteenth century, but in the seventeenth. The Stuarts were the only Protestant kings who were not in religious sympathy with their Protestant subjects. In theory the Anglican Church of Henry and Elizabeth stood for what we would now regard as tyranny. What Henry VIII. strove to do with the Anglican Church is what has actually been done by the Czars with the Orthodox Church in Russia; but that which was possible with the eastern Slavs was not possible with the westernmost and freest of the Teutonic peoples. Yet in the actual event it was probably fortunate that the English Reformation took the shape it did; for under such conditions it was not marked by the intense fanaticism of the reformers elsewhere.

The Stuarts not only found themselves masters of a kingdom where, supposedly, they were spiritually supreme, while actually their claim to supremacy was certain to be challenged; they also 10found themselves at the head of a form of government which was to all appearances despotic, while the people over whom they bore sway, though slow to object to the forms, were extremely intolerant of the practices of despotism. The Tudors were unarmed despots, who disliked the old feudal nobility, and who found it for their interest to cultivate the commercial classes, and to form a new nobility of their own, based upon wealth. The men at the lowest round of the social ladder—the workingmen and farm laborers—were yet, as they remained for a couple of centuries, so unfit for the work of political combination that they could be safely disregarded by the masters of England. At times their discontent was manifested, generally in the shape of abortive peasant insurrections; but there was never need to consider them as of serious and permanent importance. The middle classes, however, had become very powerful, and to their material interests the Tudors always took care to defer. At the very close of her reign, Elizabeth, who was at heart as thorough a tyrant as ever lived, but who possessed that shrewd good sense which, if not the noblest, is perhaps on the whole the most useful of qualities in the actual workaday world, found herself face to face with her people on the question of monopolies; and as soon as she understood that they 11were resolutely opposed to her policy, she instantly yielded. In other words, the Tudor despotism was conditioned upon the despot’s doing nothing of which the influential classes of the nation—the upper and middle classes—seriously disapproved; and this the Stuart kings could never understand.

Moreover, apart from the fact that the Stuarts were so much less shrewd and less able than the Tudors, there was the further fact that Englishmen as a whole were gradually growing more intolerant, not only of the practice but of the pretence of tyranny, whether in things material or in things spiritual. There was a moral awakening which rendered it impossible for Englishmen of the seventeenth century to submit to the brutal wrong-doing which marked the political and ecclesiastical tyranny of the previous century. The career of Henry VIII. could not have been paralleled in any shape when once England had begun to breed such men as went to the making of the Long Parliament.

Much of the aspiration after higher things took the form of spiritual unrest. It must always be remembered that the Protestant sects which established themselves in the northern half of Europe, although they warred in the name of religious liberty, had no more conception of it, as we of this day understand it, than their Catholic foes; and 12yet it must also be remembered that the bitter conflicts they waged prepared the way for the wide tolerance of individual difference in matters of religious belief which is among the greatest blessings of our modern life. An American Catholic and an American Protestant of to-day, whatever the difference between their theologies, yet in their ways of looking at real life, at its relation to religion, and the relations of religion and the State, are infinitely more akin to one another than either is to the men of his religious faith who lived three centuries ago. We now admit, as a matter of course, that any man may, in religious matters, profess to be guided by authority or by reason, as suits him best; but that he must not interfere with similar freedom of belief in others; and that all men, whatever their religious beliefs, have exactly the same political rights and are to be held to the same responsibility for the way they exercise these rights. Few indeed were the men who held such views at the time when Cromwell was growing to manhood. Holland was the State of all others in which there was the nearest approach to religious liberty; and even in Holland the bitterness of the Calvinists toward the Arminians was something which we can now scarcely understand. Arminius was no more at home in Geneva than in Rome; and his followers were prescribed by the most religious people of England, and so far as might be were driven from the realm. Calvinists and Lutherans felt as little inclination as Catholics to allow liberty of conscience to others; and as grotesque a compromise as ever was made in matters religious was that made in Germany, when it was decided that the peoples of the various German principalities should in mass accept the faiths of their respective princes.

Oliver Cromwell.

From a miniature by Cooper. Here reproduced for the first time.

By permission of Sir Charles Hartopp, Bart.

13Yet though the Reformers thus strove to establish for their own use the very religious intolerance against which they had revolted, the mere fact of their existence nullified their efforts. Sooner or later people who had exercised their own judgment, and had fought for the right to exercise it, were sure grudgingly to admit the same right in others. That time was as yet far distant. In Cromwell’s youth all the leading Christian churches were fiercely intolerant. Unless we keep in mind that this was the general attitude, an attitude which necessarily affected even the greatest men, we cannot do justice to the political and social leaders of that age when we find them, as we so often do, adopting toward their religious foes policies from which we, of a happier age, turn with horror.

In England hatred of Roman Catholicism had become almost interchangeable with hatred of 14Spain. Spain had been the one dangerous foe which England had encountered under the Tudor dynasty, and the only war she had ever waged into which the religious element entered was the war which put upon the English roll of honor the names of her great sixteenth-century seamen, Drake and Hawkins, Howard and Frobisher. Throughout the sixteenth century Spain had towered above every other power of Europe in warlike might; and though the Dutch and English sailors had broken the spell of her invincibility at sea, on shore her soldiers retained their reputation for superior prowess, in spite of the victories of Maurice of Orange, until Gustavus Adolphus marched his wonderful army down from the frozen North. During Cromwell’s youth and early manhood Spain was still the most powerful and most dreaded of European nations. Her government had become a mere tyranny; her religion fanatical bigotry of a type more extreme than any that existed elsewhere, even in an age when all creeds tended toward fanaticism and bigotry. It was in Spain that the Holy Inquisition chiefly flourished—one of the most fearful engines for the destruction of all that was highest in mankind that the world has ever seen. Catholics were oppressed in England and Protestants in France; but in each country the persecuted 15sect might almost be said to enjoy liberty, and certainly to enjoy peace, when their fate was compared with the dreadful horrors of torture and murder with which Spain crushed out every species of heresy within her borders. Jew, Infidel, and Protestant, shared the same awful doom, until she had purchased complete religious uniformity at the price of the loss of everything that makes national life great and noble. The dominion of Spain would have been the dominion of desolation; her supremacy as baneful as that of the Turk; and Holland and England, in withstanding her, rendered the same service to humanity that was rendered at that very time by those nations of southeastern Europe who formed out of the bodies of their citizens the bulwark which stayed the Turkish fury.

But if in her relations to one Catholic nation England appeared as the champion of religious liberty, of all that makes life worth having to the free men who live in free nations, yet in her relations to another Catholic people she herself played the rôle of merciless oppressor—religious, political, and social. Ireland, utterly foreign in speech and culture, had been ground into the dust by the crushing weight of England’s overlordship. During centuries chaos had reigned in the island; the English intruders possessing sufficient power to 16prevent the development of any Celtic national life, but not to change it into a Norman or English national life. The English who settled and warred in Ireland felt and acted as the most barbarous white frontiersmen of the nineteenth century have acted toward the alien races with whom they have been brought in contact. There is no language in which to paint the hideous atrocities committed in the Irish wars of Elizabeth; and the worst must be credited to the highest English officials. In Ireland the antagonism was fundamentally racial; whether the sovereign of England were Catholic or Protestant made little difference in the burden of wrong which the Celt was forced to bear. The first of the so-called plantations by which the Celts were ousted in mass from great tracts of country to make room for English settlers, was undertaken under the Catholic Queen Mary, and the two counties thus created by the wholesale expulsion of the wretched kerne were named in honor of the Queen and of her spouse, the Spanish Philip. Though Philip’s bigotry made him the persecutor of heretics, it taught him no mercy toward those of his own faith but of a different nationality, whether Irish or Portuguese. When England became Protestant, Ireland stood steadfastly for the old faith; and religious was added to race hatred. In Spain the Holy Inquisition was the handmaid of grinding tyranny. In Ireland the Catholic priesthood was the sole friend, standby, and comforter of a hunted and despairing people. In the Netherlands and on the high seas Protestantism was the creed of liberty. In Ireland it was one of the masks worn by the alien oppressor.

Sir John Eliot.

From the portrait by Van Somer at Port Eliot.

By permission of the Earl of St. Germans.

17France was Catholic, but her Catholicism differed essentially from that of Spain, and during the first part of the seventeenth century was quite as liberal as the Protestantism of England. When Cromwell was a child Henry of Navarre was on the French throne, and to him all creeds were alike. He was succeeded in the actual government of France by the great Cardinals Richelieu and Mazarin, who were Statesmen rather than Churchmen; and under them the French Protestants enjoyed rather more toleration than was allowed the Catholics of England. The natural foes of France were the two great Catholic powers of Spain and Austria, ruled by the twin branches of the House of Hapsburg; and her hostility to them determined her attitude throughout the Thirty Years’ War.

Meanwhile, Holland was at the height of her power. She had a far greater colonial empire than England, her commercial development was greater, and the renown of her war marine higher. Drake 18and Hawkins had but singed the beard of the Spanish king, had but plundered his vessels and harassed his great fleets. Van Heemskirk, Piet Hein, and the elder Tromp crushed the sea-power of Spain by downright hard fighting in great pitched battles, and captured her silver fleets entire.

In Great Britain itself—it must be kept in mind that Scotland was as yet an entirely distinct kingdom, united to England only by the fact that the same line of kings ruled over both—the difference between the Scotch and the English, though less in degree, was the same in kind as that between the English and the Dutch. In Scotland, outside of the Highlands, the mass of the people were devoted with all the strength of their intense and virile natures to the form of Calvinism introduced by Knox. Their Church government was Presbyterian. As both the Presbyterian ministers and their congregations demanded that the State should be managed in essentials according to the wishes of the Church, the general feeling was really in the direction of a theocratic republic, although the name would have frightened them. In Scotland, as in England, no considerable body of men had yet grasped the idea that there should be toleration of religious differences or a divorce between the functions of 19the State and the Church. In both countries, as elsewhere at the time through Christendom, religious liberty meant only religious liberty for the sect that raised the cry; but, as elsewhere, the mere use of the name as a banner under which to fight brought nearer the day when the thing itself would be possible.

In England there was practically peace during the first forty years of the century, but it was an ignoble and therefore an evil peace. Of course, peace should be the aim of all statesmen, and is the aim of the greatest statesman. Nevertheless, not only the greatest statesmen, but all men who are truly wise and patriotic, recognize that peace is good only when it comes honorably and is used for honorable purposes, and that the peace of mere sloth or incapacity is as great a curse as the most unrighteous war. Those who doubt this would do well to study the condition of England during the reign of James I., and during the first part of the reign of Charles I. England had then no standing army and no foreign policy worthy of the name. The chief of her colonies was growing up almost against her wishes, and wholly without any help or care from her. In short, she realized the conditions, as regards her relations with the outside world and “militarism,” which certain philosophers advocate at the present day 20for America. The result was a gradual rotting of the national fibre, which rendered it necessary for her to pass through the fiery ordeal of the Civil War in order that she might be saved.

In every nation there is, as there has been from time immemorial, a good deal of difficulty in combining the policies of upholding the national honor abroad, and of preserving a not too heavily taxed liberty at home. Many peoples and many rulers who have solved the problem with marked success as regards one of the two conditions, have failed as regards the other. It was the peculiar privilege of the Stuart kings to fail signally in both. They were dangerous to no one but their own subjects. Their government was an object of contempt to their neighbors and of contempt, mixed with anger and terror, to their own people. They made amends for utter weakness in the face of a foreign foe by showing against the free men of their own country that kind of tyranny which finds its favorite expression in oppressing those who resist not at all, or ineffectually. They were held on the throne only by a mistaken but honorable loyalty, and by an unworthy servility; by the strong habits formed by the customs of centuries; and, most of all, by the wise distrust of radical innovation and preference for reform to 21revolution which gives to the English race its greatest strength.

This last attitude, the dislike of revolution, was entirely wholesome and praiseworthy. On the other hand, the doctrine of the divine right of kings, which represented the extreme form of loyalty to the sovereign, was vicious, unworthy of the race, and to be ranked among degrading superstitions. It is now so dead that it is easy to laugh at it; but it was then a real power for evil. Moreover, the extreme zealots who represented the opposite pole of the political and religious world, were themselves, as is ordinarily the case with such extremists, the allies of the forces against which they pretended to fight. From these dreamers of dreams, of whose “cloistered virtue” Milton spoke with such fine contempt, the men who possessed the capacity to do things turned contemptuously away, seeking practical results rather than theoretical perfection, and being content to get the substance at some cost of form. As always, the men who counted were those who strove for actual achievement in the field of practical politics, and who were not misled merely by names. England, in the present century, has shown how complete may be the freedom of the individual under a nominal monarchy; and the Dreyfus incident in France would 22be proof enough, were any needed, that despotism of a peculiarly revolting type may grow rankly, even in a republic, if there is not in its citizens a firm and lofty purpose to do justice to all men and guard the rights of the weak as well as of the strong.

James came to the throne to rule over a people steadily growing to think more and more seriously of religion: to believe more and more in their rights and liberties. But the King himself was cursed with a fervent belief in despotism, and an utter inability to give his belief practical shape in deeds. For half a century the spirit of sturdy independence had been slowly growing among Englishmen. Elizabeth governed almost under the forms of despotism; but a despotism which does not carry the sword has to accommodate itself pretty thoroughly to the desires of the subjects, once these desires become clearly defined and formulated. Elizabeth never ventured to do what Henry had done. She left England, therefore, thoroughly Royalist, devoted to the Crown, and unable to conceive of any other form of government, but already desirous of seeing an increase in the power of the people as expressed through Parliament. James, from the very outset of his reign, pursued a course of conduct exactly fitted both to irritate the people, with the pretensions 23of the Crown, and to convince them that they could prevent these pretensions from being carried out.

Besides, he offended both their political and their religious feelings. England had been growing more and more fanatically Protestant; that is, more and more Puritan. Under Elizabeth there had been more religious persecution of Puritans, and of Dissenters generally, than of Catholics. But this could not prevent the growth of the spirit of Puritanism. During the reign of James there were marked Presbyterian tendencies visible within the Anglican Church itself, and plenty of Puritans among her divines. Unfortunately, both Presbyterian and Anglican were then at one in heartily condemning that spirit of true religious liberty, of true toleration, which we of to-day in the United States recognize as the most vital of religious rights. The so-called Independent movement, from which sprang the Congregational and indeed the Baptist Churches as we know them to-day, had begun under Elizabeth. Its votaries contended for what now seems the self-evident right of each congregation, if it so desires, to decide for itself important questions of doctrine and of church management. Yet Elizabeth’s ministers had actually stamped this sect out of existence, with the hearty approval of 24the wisest men in the realm and of the enormous majority of the people. Such an act, and, above all, such approval, shows how long and difficult was the road which still had to be traversed before the goal of religious liberty was reached.

The people were relatively less advanced toward religious than toward political liberty. Nevertheless, they were distinctly in advance of the King, even in matters religious. The resolute determination to fight for one’s own liberty of conscience, when it once becomes the characteristic of the majority, cannot but tend toward securing liberty of conscience for all; whereas, for one man, who claims supremacy in the Church as well as overlordship in the State, to seek to impose his will upon others in matters both spiritual and political, cannot but produce a very aggravated form of tyranny. The Stuarts represented an extreme, reactionary type of kingship; a type absolutely alien to all that was highest and most characteristic in the English character. They possessed the will to be despots, but neither their own powers nor the tendencies of the times were in their favor. The tendency was, however, very strongly in favor of hereditary kingship; so strongly, indeed, that nothing but the extreme folly as well as the extreme baseness of the Stuart kings could overcome it. Stability of government, and therefore order, depends in the last resort upon the ability of the people to come to a consensus as to where power belongs. This consensus is less a matter of volition than of long habit, of slow evolution; to Americans of to-day, the rule of the majority seems part of the natural order of things, whereas to Russians it seems utterly unnatural, and they could by no possibility be brought into sudden acquiescence in it. To Englishmen, in the early decades of the seventeenth century, hereditary kingship seemed the only natural government, and they could be severed from this belief only by a succession of violent wrenches.

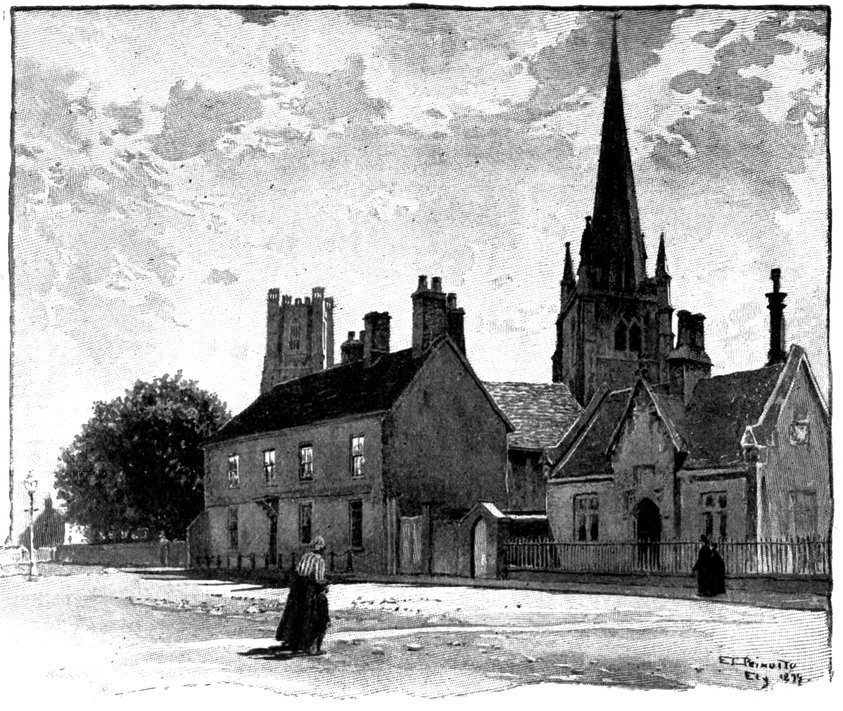

All Saints’ Church, Huntingdon.

Containing the registry of Oliver Cromwell’s birth and baptism—a fac-simile of which is here given. Above the record of his birth someone had written “England’s plague for five years;” but this is now partially obliterated.

25James I. stood for absolutism in Church and State, and quarrelled with and annoyed his subjects in the futile effort to realize his ideas. Charles I., whom James had vainly sought to marry to a Spanish princess, and succeeded in marrying to a French princess (Henrietta Maria), took up his father’s task. In private life he was the best of the Stuart kings, reaching about the average level of his subjects. In public life his treachery, mendacity, folly, and vindictiveness: his utter inability to learn by experience or to sympathize with any noble ambition of his country: his readiness to follow evil counsel, and his ingratitude toward any sincere friend, made him as unfit as either of 26his sons to sit on the English throne; and a greater condemnation than this it is not possible to award. Germany was convulsed by the Thirty Years’ War: but Charles cared nothing for the struggle, and to her humiliation England had to see Sweden step to the front as the champion of the Reformation. At one period Charles even started to help the French king against the Huguenots, but was brought to a halt by the outburst of wrath this called forth from his subjects. Once he made feeble war on Spain, and again he made feeble war on France; but the expedition he sent against Cadiz failed, and the expedition he sent to Rochelle was beaten; and he was, in each case, forced to make peace without gaining anything. The renown of the English arms never stood lower than during the reigns of the first two Stuarts.

At the outset of his reign Charles sought to govern through Buckingham, who was entirely fit to be his minister, and, therefore, unfit to be trusted with the slightest governmental task on behalf of a free and great people. Under Buckingham the grossest corruption obtained—not only in the public service, but in the creation of peerages. His whole administration represented nothing but violence and bribery; and when he took command of the forces to be employed 27against Rochelle, he showed that the list of his qualities included complete military incapacity.

It was after the failure at Rochelle that Charles summoned his third Parliament. With his first two he had failed to do more than quarrel, as they would not grant him supplies unless they were allowed the right to have something to say as to how they were to be used. He had, therefore, dissolved them, holding that their only function was to give him what may be needed.

With his third Parliament he got on no better. In it two great men sprang to the front—Sir Thomas Wentworth, afterward Lord Strafford, and Sir John Eliot, who had already shown himself a leader of the party that stood for free representative institutions as against the unbridled power of the King. Eliot was a man of pure and high character, and of dauntless resolution, though a good deal of a doctrinaire in his belief that Parliamentary government was the cure for all the evils of the body politic. Wentworth, dark, able, imperious, unscrupulous, was a born leader, but he had no root of true principle in him. At the moment, from jealousy of Buckingham, and from desire to show that he would have to be placated if the King were awake to self-interest, he threw all the weight of his great power on the popular side.

28Instead of giving the King the money he wanted, Parliament formulated a Petition of Right, demanding such elementary measures of justice as that the King should agree never again to raise a forced loan, or give his soldiers free quarters on householders, or execute martial law in time of peace, or send whom he wished to prison without showing the cause for which it was done. The last was the provision against which Charles struggled hardest. The Star Chamber—a court which sat without a jury, and which was absolutely under the King’s jurisdiction—had been one of his favorite instruments in working his arbitrary will. The powers of this court were left untouched by the Petition: yet even the service this court could render him was far less than what he could render himself if it lay in his power arbitrarily to imprison men without giving the cause. However, his need of money was so great, and the Commons stood so firm, that he had to yield, and on June 7th, in the year 1628, the Petition of Right became part of the law of the land. The first step had been taken toward cutting out of the English Constitution the despotic powers which the Tudor kings had bequeathed to their Stuart successors.

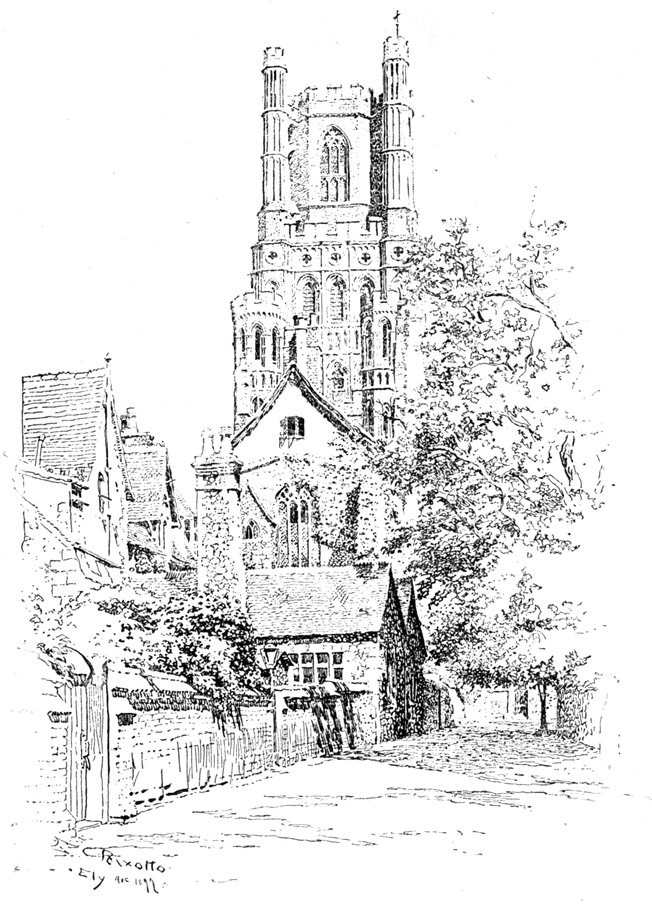

Cromwell’s House at Ely.

The tall spire is that of St. Mary’s Church, and the Cathedral tower is seen in the distance.

29Immediately afterward Buckingham was assassinated by a soldier who had taken a violent grudge against him, and the nation breathed freer with this particular stumbling-block removed, while it lessened the strain between the King and the Commons, who were bent on his impeachment.

There were far more serious troubles ahead. If the King could raise money without summoning Parliament, he could rule absolutely. If Parliament could control not only the raising, but the expenditure of money, it would be the supreme source of power, and the King but a figure-head; in other words, the government would be put upon the basis on which it has actually stood during the present century. For many reigns the Commons had been accustomed to vote to each king for life, at the outset of his reign, the duties on exports and imports, known as tonnage and poundage; but during the years immediately past men had been forced to think much on liberty and self-government. Parliament was in no mood to surrender absolute power to the King.

With the right to lay taxes and to supervise the expenditure of money—that is, to conduct the government—was intertwined the question of religion. The mass of Englishmen adhered rather loosely to the Anglican communion, and were not extreme Puritans; on certain points, however, they were tinged very deeply with Calvinism. 30They were greatly angered by the attitude of those bishops, who under the lead of Laud showed themselves more hostile to Protestant than to Catholic dogmas. These bishops preached not only that the views in Church matters held by the bulk of Englishmen were wrong, but furthermore that it was the duty of every subject to render entire obedience to the sovereign, no matter what the sovereign did, and they insisted that parliaments were of right mere ciphers in the State. Such doctrines were not only irritating from the theological stand-point; they also struck at the root of political freedom. The religious antagonism was accentuated by the fact that at this time the Protestant cause in Germany had touched the lowest point it ever reached during the Thirty Years’ War, and the anger and alarm of the English Protestants, as they saw the Calvinists and Lutherans of Denmark and North Germany overcome, were heightened by the indifference, if not satisfaction, with which the King and the bishops looked at the struggle.

In 1629 the Commons, under the lead of Eliot and Pym, took advanced ground alike on the questions of religion and of taxation. Pym was supplementing Eliot’s work, which was to make the House of Commons the supreme authority in England, by striving to associate together a majority 31of the members for the achievement of certain common objects; in other words, he was laying the foundation of party government. Under the lead of these two men, the first two Parliamentary and popular leaders in the modern sense, the House of Commons passed resolutions demanding uniformity in religious belief throughout the kingdom and condemning every innovation in religion, and declaring enemies to the kingdom and traitors to its liberties whoever advised the levying of tonnage and poundage without the authority of Parliament, or whoever voluntarily paid those duties. The first clause hit Catholics and Dissenters alike, but was especially aimed at the bishops and their followers, who stood closest to the King; and the second was, of course, intended to transfer the sovereignty from the King to Parliament—in other words, from the King to the people. Charles met the challenge by dissolving Parliament. Eleven years were to pass before another met. Meantime, the King governed as a despot; and it must be remembered that when he deliberately chose thus to govern as a despot, responsible to no legal tribunal, he at once threw his subjects back on the only remedies which it is possible to enforce against despotism—deposition or death.

Charles was bitterly angry at the sturdy independence 32shown by the Commons, and marked out for vengeance those who had been foremost in thwarting his wishes. His course was easy. The Petition of Right formulated a principle, but as yet it offered no safeguard against an unscrupulous king; while the Star Chamber court, and the other judges for that matter, held office at his pleasure, and acted as his subservient tools in fining and imprisoning merchants who refused payment of the duties, or men whose acts or words the king chose to consider seditious. Eliot and some of his fellow-members were thrown into prison because of the culminating proceedings in Parliament. Eliot’s comrades made submission and were released, but Eliot refused to acknowledge that the King, through his courts, had any right to meddle with what was done in Parliament. He took his stand firmly on the ground that the King was not the master of Parliament, and of course this could but mean ultimately that Parliament was master of the King. In other words, he was one of the earliest leaders of the movement which has produced English freedom and English government as we now know them. He was also its martyr. He was kept in the Tower without air or exercise for three years, the King vindictively refusing to allow the slightest relaxation in his confinement, 33even when it brought on consumption. In December, 1632, he died; and the King’s hatred found its last expression in denying to his kinsfolk the privilege of burying him in his Cornish home.

Charles set eagerly to work to rule the kingdom by himself. To the Puritan dogma of enforced unity of religious belief—utterly mischievous, and just as much fraught with slavery to the soul in one sect as another—he sought, through Laud, to oppose the only less mischievous, because silly, doctrine of enforced uniformity in the externals of public worship. Laud was a small and narrow man, hating Puritanism in every form, and persecuting bitterly every clergyman or layman who deviated in any way from what he regarded as proper ecclesiastical custom. His tyranny was of that fussy kind which, without striking terror, often irritates nearly to madness. He was Charles’s instrument in the effort to secure ecclesiastical absolutism.

The instrument through which the King sought to establish the royal prerogative in political affairs was of far more formidable temper. Immediately after the dissolution of Parliament Wentworth had obtained his price from the King, and was appointed to be his right-hand man in administering the kingdom. A man of great 34shrewdness and insight, he seems to have struggled to govern well, according to his lights; but he despised law and acted upon the belief that the people should be slaves, unpermitted, as they were unfit, to take any share in governing themselves. After a while Laud was made archbishop; and Wentworth was later made Lord Strafford.

Wentworth and Laud, with their associates, when they tried to govern on such terms, were continually clashing with the people. A government thus carried on naturally aroused resistance, which often itself took unjustifiable forms; and this resistance was, in its turn, punished with revolting brutality. Criticism of Laudian methods, or of existing social habits, might take scurrilous shape; and then the critic’s ears were hacked off as he stood in the pillory, or he was imprisoned for life.

Archbishop Laud.

From the portrait at Lambeth Palace, painted by Vandyke.

By permission of the Archbishop of Canterbury.

35The great fight was made, not on a religious, but on a purely political question—that of Ship Money. The king wished to go to war with the Dutch, and to raise his fleet he issued writs, first to the maritime counties, and then to every shire in England. He consulted his judges, who stated that his action was legal: as well they might, for when a judge disagreed with him on any important point, he was promptly dismissed from office. But there was one man in the kingdom who thought differently, John Hampden, a Buckinghamshire ’squire, who had already once sat as a silent member in Parliament, together with another equally silent member of the same social standing, his nephew, Oliver Cromwell. Hampden was assessed at twenty shillings. The amount was of no more importance than the value of the tea which a century and a half later was thrown into Boston Harbor; but in each case a vital principle—the same vital principle—was involved. If the King could take twenty shillings from Hampden without authority from the representatives of the people in Parliament assembled, then his rule was absolute: he could do what he pleased. On the other hand, if the House of Commons could do as it wished in granting money only for whatever need it chose to recognize in the kingdom, then the House of Commons was supreme. In Hampden’s view but one course was possible—he was for the Parliament and the nation against the King; and he refused to pay the sum, facing without a murmur the punishment for his contumacy.

The King and his ministers did not flinch from proceeding to any length against either political or religious opponents. Charles heartily upheld Laud and Wentworth in carrying out their policy of “thorough”; Laud in England; Wentworth, 36after 1633, in Ireland. “Thorough,” in their sense of the word, meant making the State, which was the King, paramount in every ecclesiastical and political matter, and putting his interests above the interests, the principles, and the prejudices of all classes and all parties; paying heed to nothing but to what seemed right in the eyes of the sovereign and the sovereign’s chosen advisers. Under Wentworth’s strong hand a certain amount of material prosperity followed in Ireland, although chiefly among the English settlers. There was no such material prosperity in England; 1630, for instance, was a famine year. The net effect of the policy would in the long run have been to bring down a freedom-loving people to a lower grade of political and social development. There was, of course, no oppression in England in any way resembling such oppression as that which flogged the Dutch to revolt against the Spaniards. But it was exactly the kind of oppression which led, in 1776, to the American Revolution. Eliot, Hampden, and Pym, stood for the principles that were championed by Washington, Patrick Henry, and the Adamses. The grievances which forced the Long Parliament to appeal to arms were like those which made the Continental Congress throw off the sovereignty of George III. In neither case was there the kind of grinding tyranny which 37has led to the assassination of tyrants and the frantic, bloodthirsty uprising of tortured slaves. In each case the tyranny was in its first stage, not its last; but the reason for this was simply that a nation of vigorous freemen will always revolt by the time the first stage has been reached. It was not possible, either for the Stuart kings or for George III., to go beyond a certain point, for as soon as that point was reached the freemen were called to arms by their leaders.

However, there was the greatest reluctance among Englishmen to countenance rebellion, even for the best of causes. This reluctance was eminently justifiable. Rebellion, revolution—the appeal to arms to redress grievances; these are measures that can only be justified in extreme cases. It is far better to suffer any moderate evil, or even a very serious evil, so long as there is a chance of its peaceable redress, than to plunge the country into civil war; and the men who head or instigate armed rebellions for which there is not the most ample justification must be held as one degree worse than any but the most evil tyrants. Between the Scylla of despotism and the Charybdis of anarchy there is but little to choose; and the pilot who throws the ship upon one is as blameworthy as he who throws it on the other. But a point may be reached where the people have to 38assert their rights, be the peril what it may; and in Great Britain this point was passed under Charles I.

The first break came, not in England, but in Scotland. The Scotch abhorred Episcopacy; whereas the English had no objection whatever to bishops, so long as the bishops did not outrage the popular religious convictions. In Scotland the spirit of Puritanism was uppermost, and was already exhibiting both its strength and its weakness; its sincerity and its lack of breadth; its stern morality and its failure to discriminate between essentials and non-essentials; its loftiness of aim and its tendency to condemn liberality of thought in religion, art, literature, and science, alike as irreligious; its insistence on purity of life, and yet its unconscious tendency to promote hypocrisy and to drive out one form of religious tyranny merely to erect another.

A man of any insight would not have striven to force an alien system of ecclesiastical government upon a people so stubborn and self-reliant, who were wedded to their own system of religious thought. But this was what Laud attempted, with the full approval of Charles. In 1637 he made a last effort to introduce the ceremonies of the English Church at Edinburgh. No sooner was the reading of the Prayer-Book begun than the congregation 39burst into wild uproar, execrating it as no better than celebrating mass. It was essentially a popular revolt. The incident of Jenny Geddes’s stool may be mythical, but it was among the women and men of the lower orders that the resistance was stoutest. The whole nation responded to the cry, and hurried to sign a national Covenant, engaging to defend the Reformed religion, and to do away with all “innovations”; that is, with everything in which Episcopacy differed from Puritanism and inclined toward the Church of Rome.

In England and Scotland alike the Church of Rome was still accepted by the people at large as the most dangerous of enemies. The wonderful career of Gustavus Adolphus had just closed. The Thirty Years’ War—the last great religious struggle—was still at its height. If, in France, the Massacre of St. Bartholomew stood far in the past, the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes yet lay in the future. The after-glow of the fires of Smithfield still gleamed with lurid light in each sombre Puritan heart. The men who, in England, were most earnest about their religion held to their Calvinistic creed with the utmost sincerity, high purpose, and self-devotion: but with no little harshness. Theirs was a lofty creed, but one which, in the revolt against levity and viciousness, 40set up a standard of gloom; and, though ready to fight to the death for liberty for themselves, they had as yet little idea of tolerating liberty in others. Naturally, such men sympathized with one another, and the action of the Scotch was heartily, though secretly, applauded by the stoutest Presbyterians of England. Moreover, while menaced by the common oppressor, the Puritan independents, who afterward split off from the Presbyterians, made common cause with them, the irreconcilable differences between the two bodies not yet being evident.

Soon the Scotch held a general assembly of the Church, composed of both clerical and lay members, and formally abolished Episcopacy, in spite of the angry protests of the King. Their action amounted in effect to establishing a theocracy. They repudiated the unlimited power of the King and the bishops, as men would do nowadays in like case; but they declared against liberty of thought and conduct in religious matters, basing their action on practically the same line of reasoning that influenced the very men they most denounced, hated, and feared.

West Tower, Ely Cathedral, from Monastery Close.

41The King took up the glove which the Scotch had thrown down. He raised an army and undertook the first of what were derisively known as the “Bishops’ Wars.” But his people sympathized with the Scotch rather than with him. He got an army together on the Border, but it would not fight, and he was forced reluctantly to treat for peace. Then Strafford came back from Ireland and requested Charles to summon a Parliament so that he could get funds. In April, 1640, the Short Parliament came together, but the English spirit was now almost as high as the Scotch in hostility to the King, and Parliament would not grant anything to the King until the grievances of the people were redressed. To this demand Charles would not listen, and the Parliament was promptly dissolved. Then, being heartened by Laud, and especially by Strafford, Charles renewed the war, only to see his army driven in headlong panic before the Scotch at Newburn. The result was that he had to try to patch up a peace under the direction of Strafford. But the Scotch would not leave the kingdom until they were paid the expenses of the war. There was no money to pay them, and Charles had to summon Parliament once more. On November 3, 1640, the Long Parliament met at Westminster.

When Oliver Cromwell took his seat in the Long Parliament he was forty-one years old. He had been born at Huntingdon on April 25, 1599, and by birth belonged to the lesser gentry, or upper 42middle-class. The original name of the family had been Williams; it was of Welsh origin. There were many Cromwells, and Oliver was a common name among them. One of the Protector’s uncles bore the name, and remained a stanch Loyalist throughout the Civil War. Oliver’s own father, Robert, was a man in very moderate circumstances, his estate in the town of Huntingdon bringing an income of some £300 a year. Oliver’s mother, Elizabeth Steward of Ely, seems to have been of much stronger character than his father. The Stewards, like the Cromwells, were “new people,” both families, like so many others of the day, owing their rise to the spoliation of the monasteries. Oliver’s father was a brewer, and his success in the management of the brewery was mainly due to Oliver’s mother. No other member of Oliver’s family—neither his wife nor his father—influenced him as did his mother. She was devoted to him, and he, in turn, loved her tenderly and respected her deeply. He followed her advice when young; he established her in the Royal Palace of Whitehall when he came to greatness; and when she died he buried her in Westminster Abbey. As a boy he received his education at Huntingdon, but when seventeen years old was sent to Cambridge University. A strong, hearty young fellow; fond of horse-play 43and rough pranks—as indeed he showed himself to be even when the weight of the whole kingdom rested on his shoulders. He nevertheless seems to have been a fair student, laying the foundation for that knowledge of Greek literature and the Latin language, and that fondness for books, which afterward struck the representatives of the foreign powers at London. In 1617 his father died, and he left Cambridge. When twenty-one years old he was married in London, to Elizabeth Bouchier (who was one year older than he was), the daughter of a rich London furrier. She was a woman of gentle and amiable character, and though she does not appear to have influenced Cromwell’s public career to any perceptible extent, he always regarded her with fond affection, and was always faithful to her.

For twenty years after his marriage he lived a quiet life, busying himself with the management of his farm. Nine children were born to him, of whom three sons and five daughters lived to maturity. About this time his soul was first deeply turned toward religious matters, and, like the great majority of serious thinkers of the time, he became devoted to the Puritan theology; indeed no other was possible to a representative of the prosperous, independent, and religious middle-class, from which all the greatest Puritan leaders sprang. 44While a boy Oliver had been sent to the free school at Huntingdon, and his first training had been received under its master, the Reverend Thomas Beard, a zealous Puritan and Reformer, as well as a man of wide reading and sound scholarship, and lastly, an inflamed hater of the Church of Rome. All his surroundings, all his memories, were such as to make the future Dictator of England sincerely feel that the Church of Rome was the arch-antagonist of all, temporal and spiritual, that he held most dear. In the first place his ancestors were among those who had profited by the spoliation of the monasteries; and the only way to avoid uncomfortable feelings on the part of the spoiler is for him to show—or if this is not possible, to convince himself that he has shown—the utmost iniquity on the part of the despoiled. When Oliver was a small boy the Gunpowder Plot shook all England. When he was a little older Henry of Navarre was stabbed in Paris; and though Henry was a cynical turncoat in matters of religion, and a man of the most revolting licentiousness in private life, he was yet a great ruler of men, and had been one of the props of the Protestant cause. Before Oliver came of age the Thirty Years’ War had begun its course. To Oliver Cromwell, warfare against the Church of Rome, broken by truces which, 45whether long or short, were intended only to be breathing-spells, must have seemed the normal state of things.

In 1631 Oliver sold his paternal estate in Huntingdon and managed a rented farm at St. Ives for five years; then he removed to Ely, in the fen country, and again took up farming, being joined by his mother and sisters. He served in the great Parliament which passed the Petition of Right, but played no part of prominence therein: standing stoutly, however, for Puritanism and Parliamentary freedom. During the ensuing eleven years of unrest, while all England was making ready for the impending conflict, Oliver busied himself with his farm and his family. He showed himself one of the strongest bulwarks of the Puritan preachers; zealous in the endeavor to further the cause of religion in every way, and always open to appeals from the poor and the oppressed, of whom he was the consistent champion. When certain rich men, headed by the Earl of Bedford, endeavored to oust from some of their rights the poor people of the fens, Oliver headed the latter in their resistance. He was keenly interested in the trial of his kinsman, John Hampden, for refusal to pay the Ship Money; a trial which was managed by the advocate Oliver St. John, his cousin by marriage.

46In short, Cromwell was far more concerned in righting specific cases of oppression than in advancing the great principles of constitutional government which alone make possible that orderly liberty which is the bar to such individual acts of wrong-doing. From the stand-point of the private man this is a distinctly better failing than is its opposite; but from the stand-point of the statesman the reverse is true. Cromwell, like many a so-called “practical” man, would have done better work had he followed a more clearly defined theory; for though the practical man is better than the mere theorist, he cannot do the highest work unless he is a theorist also. However, all Cromwell’s close associations were with Hampden, St. John, and the other leaders in the movement for political freedom, and he acted at first in entire accord with their ideas: while with the religious side of their agitation he was in most hearty sympathy.

It is difficult for us nowadays to realize how natural it seemed at that time for the Word of the Lord to be quoted and appealed to on every occasion, no matter how trivial, in the lives of sincerely religious men. It is very possible that quite as large a proportion of people nowadays strive to shape their internal lives in accordance with the Ten Commandments and the Golden 47Rule; indeed, it is probable that the proportion is far greater; but professors of religion then carried their religion into all the externals of their lives. Cromwell belonged among those earnest souls who indulged in the very honorable dream of a world where civil government and social life alike should be based upon the Commandments set forth in the Bible. To endeavor to shape the whole course of individual existence in accordance with the hidden or half-indulged law of perfect righteousness, has to it a very lofty side; but if the endeavor is extended to include mankind at large, it has also a very dangerous side: so dangerous indeed that in practice the effort is apt to result in harm, unless it is undertaken in a spirit of the broadest charity and toleration; for the more sincere the men who make it, the more certain they are to treat, not only their own principles, but their own passions, prejudices, vanities, and jealousies, as representing the will, not of themselves, but of Heaven. The constant appeal to the Word of God in all trivial matters is, moreover, apt to breed hypocrisy of that sanctimonious kind which is peculiarly repellent, and which invariably invites reaction against all religious feeling and expression.

At that day Cromwell’s position in this matter was, at its worst, merely that of the enormous 48majority of earnest men of all sects. Each sect believed that it was the special repository of the wisdom and virtue of the Most High: and the most zealous of its members believed it to be their duty to the Most High to make all other men worship Him according to what they conceived to be His wishes. This was the mediæval attitude, and represented the mediæval side in Puritanism; a side which was particularly prominent at the time, and which, so far as it existed, marred the splendor of Puritan achievement. The nobleness of the effort to bring about the reign of God on earth, the inspiration that such an effort was to those engaged in it, must be acknowledged by all; but, in practice, we must remember that, as religious obligation was then commonly construed, it inevitably led to the Inquisition in Spain; to the sack of Drogheda in Ireland; to the merciless persecution of heretics by each sect, according to its power, and the effort to stifle freedom of thought and stamp out freedom of action. It is right, and greatly to be desired, that men should come together to search after the truth: to try to find out the true will of God; but in Cromwell’s time they were only beginning to see that each body of seekers must be left to work out its own beliefs without molestation, so long as it does not strive to interfere with the beliefs of others.

49The great merit of Cromwell, and of the party of the Independents which he headed, and which represented what was best in Puritanism, consists in the fact that he and they did, dimly, but with ever-growing clearness, perceive this principle, and, with many haltings, strove to act up to it. The Independent or Congregational churches, which worked for political freedom, and held that each congregation of Protestants should decide for itself as to its religious doctrines, stood as the forerunners in the movement that has culminated in our modern political and religious liberty. How slow the acceptance of their ideas was, how the opposition to them battled on to the present century, will be appreciated by anyone who turns to the early writings of Gladstone when he was the “rising hope of those stern Tories,” whose special antipathy he afterward became. Even yet there are advocates of religious intolerance, but they are mostly of the academic kind, and there is no chance for any political party of the least importance to try to put their doctrines into effect. More and more, at least here in the United States, Catholics and Protestants, Jews and Gentiles, are learning the grandest of all lessons—that they can best serve their God by serving their fellow-men, and best serve their fellow-men, not by wrangling among themselves, but by a generous 50rivalry in working for righteousness and against evil.

This knowledge then lay in the future. When Cromwell grew to manhood he was a Puritan of the best type, of the type of Hampden and Milton; sincere, earnest, resolute to do good as he saw it, more liberal than most of his fellow-religionists, and saved from their worst eccentricities by his hard common-sense, but not untouched by their gloom, and sharing something of their narrowness. Entering Parliament thus equipped, he could not fail to be most drawn to the religious side of the struggle. He soon made himself prominent; a harsh-featured, red-faced, powerfully-built man, whose dress appeared slovenly in the eyes of the courtiers—who was no orator, but whose great power soon began to impress friends and enemies alike.

King Charles’s theory was that Parliament had met to grant him the money he needed. The Parliament’s conviction was that it had come together to hold the King and his servants to accountability for what they had done, and to provide safeguards against a repetition of the tyranny of the last eleven years. Parliament held the whip hand, for the King dared not dissolve it until the Scots were paid, lest their army should march at once upon London.

The King had many courtiers who hated popular government, but he had only one great and terrible man of the type that can upbuild tyrannies; and, with the sure instinct of mortal fear and mortal hate, the Commons struck at the minister whose towering genius and unscrupulous fearlessness might have made his master absolute on the throne. A week after the Long Parliament met, in November, 1640, Pym, who at once took the lead in the House, moved the impeachment of Strafford, in a splendid speech which set 52forth the principles for which the popular party was contending. It was an appeal from the rule of irresponsible will to the rule of law, for the violation of which every man could be held accountable before some tribunal. About the same time Laud was thrown into the Tower; but at the moment there was no thought of taking his life, for the ecclesiastic was not—like the statesman—a mighty and fearsome figure, and though he had done as much evil as his feeble nature permitted, he had unquestionably been far more conscientious than the great Earl. Strafford had sinned against the light, for he had championed liberty until the King paid him his price and made him the most dangerous foe of his former friends. He now defended himself with haughty firmness, and the King strove in every way to help him. But the Commons passed a Bill of Attainder against him: and then Charles committed an act of fatal meanness and treachery. There was not one thing that Strafford had done, save by his sovereign’s wish and in his sovereign’s interest. By every consideration of honor and expediency Charles was bound to stand by him. But the Stuart King flinched. Deeming it for his own interest to let Strafford be sacrificed, he signed the death-warrant. “Put not your trust in Princes,” said the fallen Earl when the news was brought to him, and he went to the scaffold undaunted.

John Pym.

From the portrait by Cornelius Janssen at the Victoria and Albert Museum, South Kensington.

53Cromwell showed himself to be a man of mark in this Parliament; but he was not among the very foremost leaders. He had no great understanding of constitutional government, no full appreciation of the vital importance of the reign of law to the proper development of orderly liberty. His fervent religious ardor made all questions affecting faith and doctrine close to him; and his hatred of corruption and oppression inclined him to take the lead whenever any question arose of dealing, either with the wrongs done by Laud in the course of his religious persecutions, or with the irresponsible tyranny of the Star Chamber, and the sufferings of its victims. The bent of Cromwell’s mind was thus shown right in the beginning of his parliamentary career. His desire was to remedy specific evils. He was too impatient to found the kind of legal and constitutional system which could alone prevent the recurrence of such evils. This tendency, thus early shown, explains, at least in part, why it was that later he deviated from the path trod by Hampden, and afterward by Washington and Washington’s colleagues: showing himself unable to build up free government or to establish the reign of law, until he was finally driven to substitute his 54own personal government for the personal government of the King whom he had helped to dethrone, and put to death. Cromwell’s extreme admirers treat his impatience of the delays and shortcomings of ordinary constitutional and legal proceedings as a sign of his greatness. It was just the reverse. In great crises it may be necessary to overturn constitutions and disregard statutes, just as it may be necessary to establish a vigilance committee, or take refuge in lynch law; but such a remedy is always dangerous, even when absolutely necessary; and the moment it becomes the habitual remedy, it is a proof that society is going backward. Of this retrogression the deeds of the strong man who sets himself above the law may be partly the cause and partly the consequence; but they are always the signs of decay.

The Commons had passed a law authorizing the election of a Parliament at least once in three years: which at once took away the King’s power to attempt to rule without a Parliament; and in May they extorted from the King an act that they should not be dissolved without their own consent. Ship Money was declared to be illegal; the Star Chamber was abolished; and Tonnage and Poundage were declared illegal, unless levied by Act of Parliament. Then the Scotch army was paid off and returned across the Border. The best 55work of the Commons had now been done, and if they could have trusted the King it would have been well for them to dissolve; but the King could not be trusted, and, moreover, the religious question was pushed to the front. Laud’s actions—actions taken with the full consent and by the advice of the King—had rendered the Episcopal form of Church government obnoxious. The House of Commons was Presbyterian, and it speedily became evident that it wished to establish the Presbyterian system of Church government in the place of Episcopacy; and, moreover, that it intended to be just as intolerant on behalf of Presbyterianism as the King and Laud had been on behalf of Episcopacy. There was a strong moderate party which the King might have rallied about him, but his incurable bad faith made it impossible to trust his protestations. He now made terms with the Scotch, in accordance with which they agreed not to interfere between himself and his English subjects in religious matters. He hoped thereby to deprive the Presbyterian English of their natural allies across the Border. This conduct, of itself, would have inflamed the increasing religious bitterness; but it was raised to madness by the news that came from Ireland at this time.

Inspired by the news of the revolt in Scotland 56and the troubles in England, the Irish had risen against their hereditary oppressors. It was the revolt of a race which rose to avenge wrongs as bitter as ever one people inflicted upon another; and it was inevitable that it should be accompanied by appalling outrages in certain places. It was on these outrages that the English fixed their eyes, naturally ignoring the generations of English evil-doing which had brought them about. A furious cry for revenge arose. Every Puritan, from Oliver Cromwell down, regarded the massacres as a fresh proof that Roman Catholics ought to be treated, not as professors of another Christian creed, but as cruel public enemies; and their burning desire for vengeance took the form, not merely of hostility to Roman Catholicism, but to the Episcopacy, which they regarded as in the last resort an ally of Catholicism.

In November, 1641, the Puritan majority in Parliament passed the Grand Remonstrance—which was a long indictment of Charles’s conduct. Cromwell had now taken his place as among the foremost of the Root and Branch Party, who demanded the abolition of Episcopacy, and whose action drove all those who believed in the Episcopal form of Church government into the party of the King. He threw himself with eager vehemence into the Party of the 57Remonstrance, and after its bill was passed told Falkland that if it had been rejected by Parliament he would have sold all he had, and never again seen England.

For a moment the Puritan violence, which culminated in the Grand Remonstrance, provoked a reaction in favor of the King; but the King, by another act of violence, brought about a counter-reaction. In January, 1642, he entered the House of Commons, and in person ordered the seizure and imprisonment in the Tower of the five foremost leaders of the Puritan party, including Pym and Hampden. Such a course on his part could be treated only as an invitation to civil war. London, which before had been wavering, now rallied to the side of the Commons; the King left Whitehall; and it was evident to all men that the struggle between him and the Parliament had reached a point where it would have to be settled by the appeal to arms.

In August, 1642, King Charles planted the royal standard on the Castle of Nottingham, and the Civil War began. The Parliamentary forces were led by the Earl of Essex. They included some 20 regiments of infantry and 75 troops of horse, each 60 strong, raised and equipped by its own captain. Oliver Cromwell was captain of 58the Sixty-seventh Troop, and his kinsfolk and close friends were scattered through the cavalry and infantry. His sons served with or under him. One brother-in-law was quartermaster of his own troop; a second was captain of another troop. His future son-in-law, Henry Ireton, was captain of yet another; a cousin and a nephew were cornets. Another cousin, John Hampden, was colonel of a regiment of foot; so was Cromwell’s close friend and neighbor, the after-time Earl of Manchester, who was much under his influence.