*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 62958 ***

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

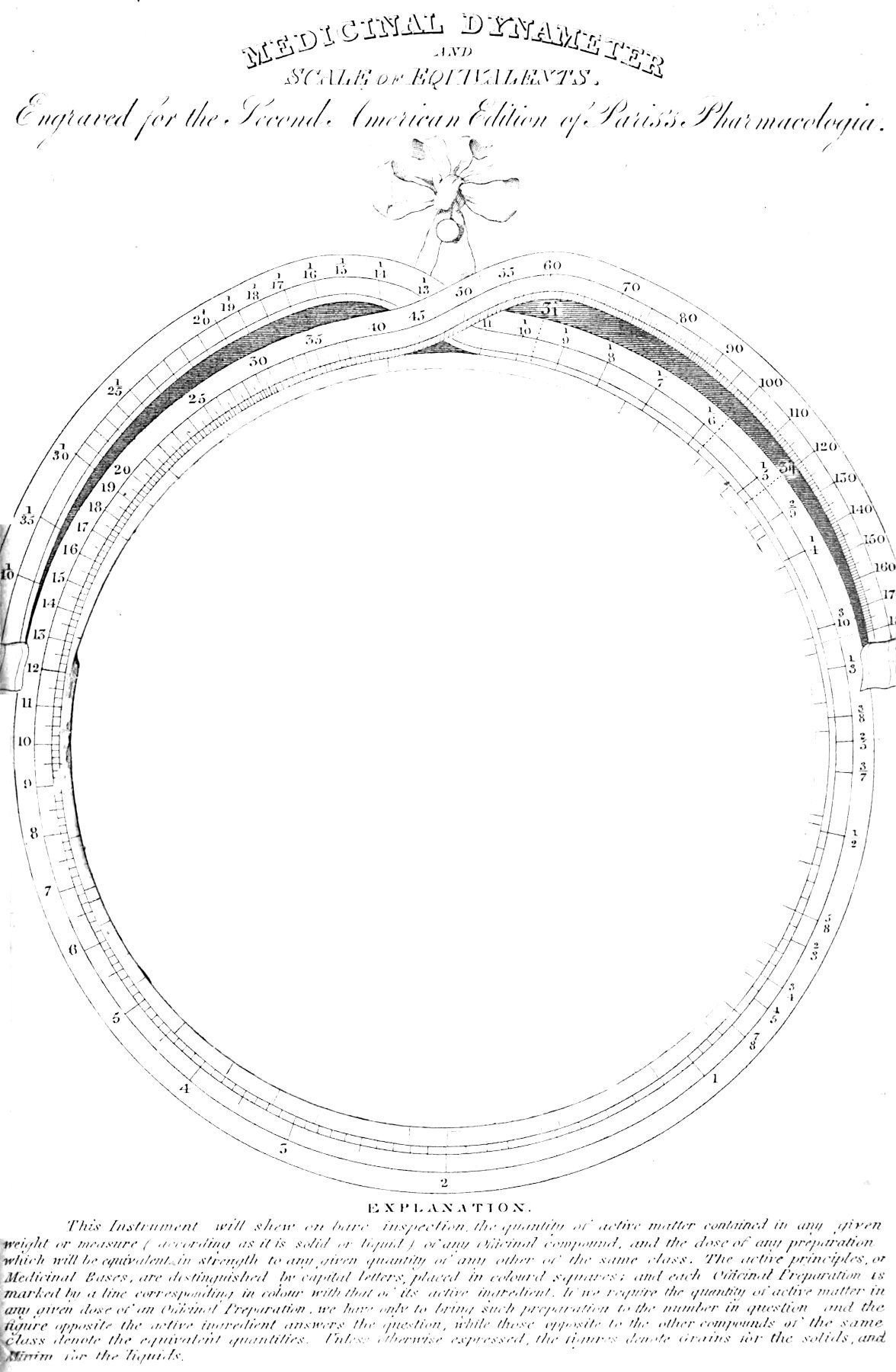

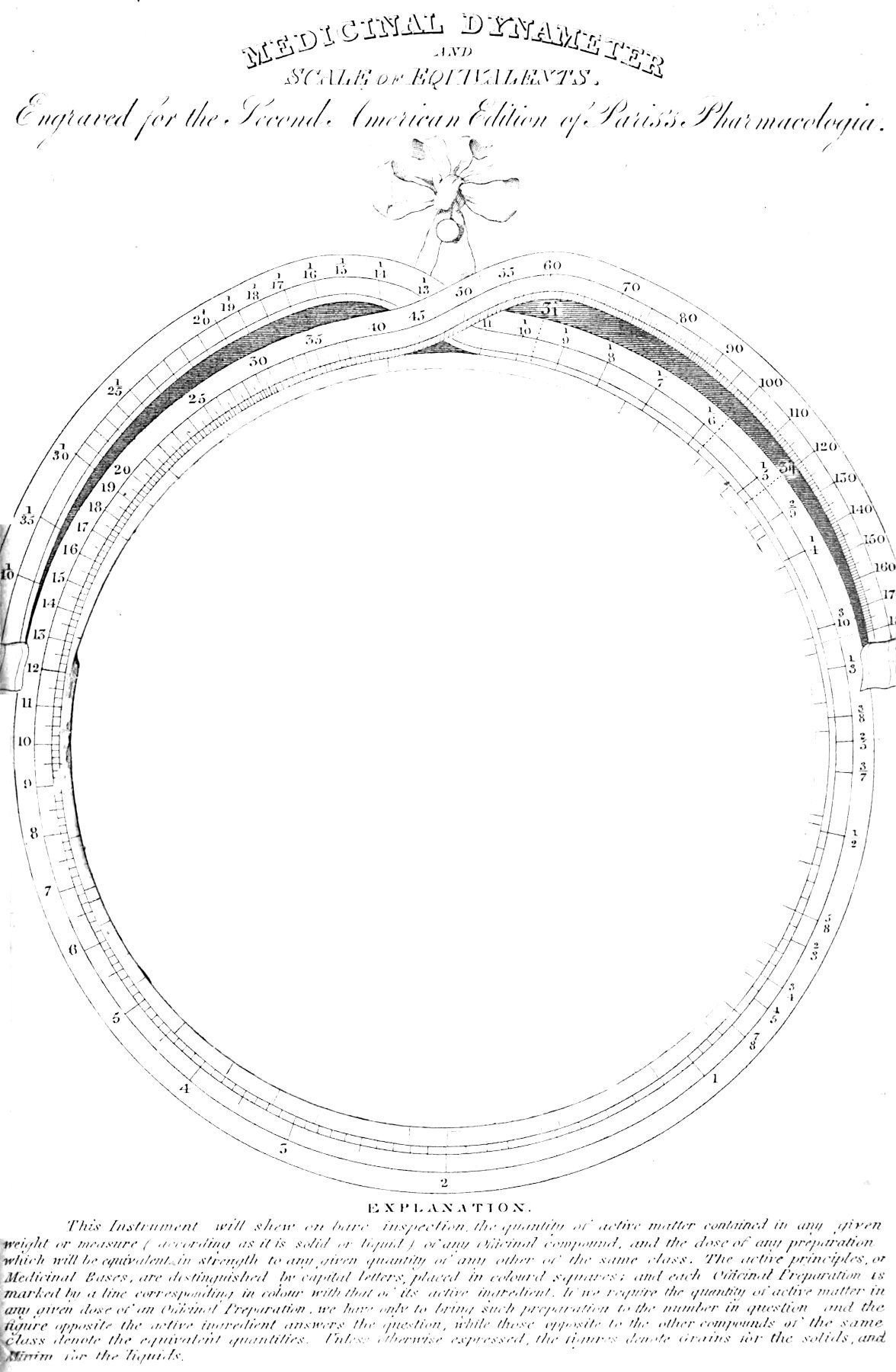

MEDICINAL DYNAMETER

AND

SCALE OF EQUIVALENTS.

Engraved for the Second American Edition of Paris’s Pharmacologia.

EXPLANATION.

This Instrument will shew on bare inspection, the quantity of active matter contained in any given weight or measure (according as it is solid or liquid) of any Officinal compound, and the dose of any preparation which will be equivalent in strength to any given quantity of any other of the same class. The active principles, or Medicinal Bases, are distinguished by capital letters, placed in coloured squares; and each Officinal Preparation is marked by a line corresponding in colour with that of its active ingredient. If we require the quantity of active matter in any given dose of an Officinal Preparation, we have only to bring such preparation to the number in question and the figure opposite the active ingredient answers the question, while those opposite to the other compounds of the same class denote the equivalent quantities. Unless otherwise expressed, the figures denote Grains for the solids, and Minim for the liquids.

PHARMACOLOGIA.

FOURTH AMERICAN,

FROM THE SEVENTH LONDON EDITION.

BY

J. A. PARIS, M.D. F.R.S. F.L.S.

FELLOW OF THE ROYAL COLLEGE OF PHYSICIANS OF LONDON, ETC., ETC., ETC.

Quis Pharmacopœo dabit leges, ignarus ipse agendorum?—Vis profecto dici potest, quantum hæc ignorantia rei medicæ inferat detrimentum.

GAUB: METHOD: CONCINN: FORMUL.

WITH NOTES AND ADDITIONS,

BY

JOHN B. BECK, M.D.

PROFESSOR OF MATERIA MEDICA AND MEDICAL JURISPRUDENCE IN THE UNIVERSITY OF THE STATE OF NEW-YORK, CORRESPONDING MEMBER OF THE MEDICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON, &C., &C.

NEW-YORK:

W. E. DEAN, PRINTER.

COLLINS AND HANNAY, COLLINS AND CO., AND WHITE, GALLAHER AND WHITE.

1831.

Entered according to the Act of Congress, in the year One

Thousand Eight Hundred and Thirty-one, by W. E. Dean,

in the Clerk’s Office of the Southern District of New-York.

TO

WILLIAM GEORGE MATON, M.D. F.R.S.

FELLOW OF THE ROYAL COLLEGE OF PHYSICIANS,

VICE-PRESIDENT OF THE LINNÆAN SOCIETY,

&c., &c., &c.

There is not an individual in the whole circle of the profession,

to whom I could with greater satisfaction, or with so much

propriety, dedicate this work, as to yourself.

Ardent and zealous in the advancement of our science, you must

deeply deplore the prejudices that retard its progress;—eminently

enlightened in Natural History, you can justly appreciate the importance

of its applications to Medicine; while your well known

earnestness in upholding the dignity, and in encouraging the legitimate

exercise of our profession, marks you as the most proper patron

of a work, the aim of which is to extinguish the false lights of

empiricism, and to substitute a steady beacon on the solid and permanent

basis of truth and science: at the same time, the extensive

practice which your talents and urbanity so justly command in this

metropolis, must long since have taught you the full extent of that

empiricism which it has been my endeavour to expose, and the

practical mischief of that ignorance which it has been my object to

enlighten.

Nor let me omit to mention the claims of that friendship which

has for many years subsisted between us; be assured that I am

gratefully sensible of those personal obligations which so fully justify

this public avowal of them; confidently trusting that you will not

measure the gratitude which your kindness has inspired, by the merits

of the offering by which it is acknowledged, but rather by the

truth and sincerity of the Dedication, by which I am enabled to express

My respect for your talents;

esteem for your virtues;

and wishes for your happiness;

JOHN AYRTON PARIS.

Dover-street, April, 1829.

STUDENTS OF THE COLLEGE

OF

PHYSICIANS AND SURGEONS

IN THE

CITY OF NEW-YORK,

THE PRESENT

EDITION OF THIS WORK IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED,

BY THEIR

FRIEND AND INSTRUCTOR,

CONTENTS

vii

PREFACE.

The Public are already in possession of many pharmaceutical compendiums

and epitomes of plausible pretensions, composed with the view of

directing the practice of the junior, and of relieving the occasional embarrassments

of the more experienced practitioner. Nothing is farther from

my intention than to disparage their several merits, or to question their

claims to professional utility; but in truth and justice it must be confessed

that, as far as these works relate to the art of composing scientific prescriptions,

their authors have not escaped the too common error of supposing

that the reader is already grounded in the first principles of the science;

or, to borrow the figurative illustration of a popular writer, that while they

are in the ship of science, they forget the disciple cannot arrive without a boat.

I am not acquainted with any book that is calculated to furnish such assistance,

or which professes to teach the Grammar, and ground-work of

this important branch of medical knowledge. Numerous are the works

which present us with the detail, but no one with the philosophy of the

subject. We have copious catalogues of formal recipes, and many of unexceptionable

propriety, but the compilers do not venture to discuss the

principles upon which they were constructed, nor do they explain the part

which each ingredient is supposed to perform in the general scheme of the

formula; they cannot therefore lead to any useful generalization, and the

young practitioner, without a beacon that can direct his course in safety, is

abandoned to the alternative of two great evils—a feeble and servile routine,

on one hand, or a wild and lawless empiricism, on the other. The

present volume is an attempt to supply this deficiency: and while I am

anxious to ‘catch the ideas which lead from ignorance to knowledge,’ it

is not without hope that I may also be able to suggest the means by

which our already acquired knowledge may be more widely and usefully

extended; and, by offering a collective and arranged view of the objects

and resources of medicinal combination, to establish its practice upon the

basis of science, and thereby to render its future career of improvement

progressive with that of the other branches of medicine; or, to follow up

the figurative illustration already introduced, to furnish a boat, which may

not only convey the disciple to the ship, but which may also assist in piloting the

ship herself from her shallow and treacherous moorings. That the design

however of the present work may not be mistaken, it is essential to remark

that it is elementary only in reference to the art of prescribing, for it is presumed

that the student is already acquainted with the common manipulations

of pharmacy, and with the first principles of chemistry. When any

allusions are made to the processes of the Pharmacopœia, they are to be

viiiunderstood as being only supplementary, or as explanatory of their nature,

in reference to the application or medicinal powers of the substance in question.

The term Pharmacologia, as applied to the present work, may

therefore be considered as contradistinctive to that of Pharmacopœia;

for while the latter denotes the processes for preparing, the former comprehends

the scientific methods of administering medicinal bodies, and explains

the objects and theory of their operation. The articles of the Materia

Medica have been arranged in alphabetical order, not only as being that

best calculated for reference, but one which, in an elementary work at

least, is less likely to mislead, than any arrangement founded on their

medicinal powers; for in consequence of the difficulty of discriminating in

every case between the primary and secondary effects of a medicine, substances

very dissimilar in their nature, have been enlisted into the same

artificial group, and when several of such bodies have, from a reliance upon

their unity of action, been associated together in a medicinal mixture, it

has often happened that, like the armed men of Cadmus, they have opposed

and destroyed each other. The object and application of the black

marginal letters, to which the name of Key Letters has been given, are

fully explained in the First Part of the work, and it is hoped, that the

scheme possesses a more substantial claim to notice than that of mere novelty:

it will be perceived that in the enumeration of the officinal formulæ

these letters are also occasionally introduced, to express the manner in

which the particular substance, under the head of which it stands, operates

in the combination. If any apology be necessary for the introduction of

the medicinal formulæ, it may be offered in the words of Quintillian, who

very justly observes, “In omnibus fere minus valent præcepta quam exempla;”

or in the language of Seneca; “Longum est iter per præcepta, breve et efficax

per exempla.” Under the history of each article, I have endeavoured to

concentrate all that is required to be known for its efficacious administration,

such as, 1. Its sensible qualities. 2. Its chemical composition, or the

constituents in which its medicinal activity resides. 3. Its relative solubility

in different menstrua, and the proportions in which it should be mixed, or combined

with different bodies, in order to produce suspension, or saturation. 4.

The Incompatible Substances; that is to say, those substances which are

capable of destroying its properties, or of rendering its flavour or aspect unpleasant

or disgusting. 5. The most eligible forms in which it can be exhibited.

6. Its specific doses. 7. Its Medicinal Uses, and Effects. 8. Its

Preparations, Officinal as well as Extemporaneous. 9. Its Adulterations.

That such information is indispensible for the elegant and successful exhibition

of a remedy, must be sufficiently apparent; the injurious changes

and modifications which substances undergo when they are improperly

combined by the ignorant practitioner, are not as some have supposed imaginary,

the mere deliramenta doctrinæ, or the whimsical suggestions of theoretical

refinement, but they are really such as to render their powers unavailing,

or to impart a dangerous violence to their operation. “Unda dabit

flammas et dabit ignis aquas.”

In the history of the different medicinal preparations, the pharmacopœia

of the London College is the standard to which I have always referred,

although it will be perceived that I have frequently availed myself of

the resources with which the pharmacopœias of Edinburgh and Dublin

abound. To a knowledge of the numerous adulterations to which

each article is so shamefully exposed, too much importance can be

ixscarcely attached; and under this palpable source of medicinal fallacy

and failure, may be fairly included those secret and illegitimate deviations

from the acknowledged modes of preparation, as laid down in the

pharmacopœia, whether practised as expedients to obtain a lucrative

notoriety, or from a conceit of their being improvements upon the ordinary

processes; for instance, we have lately heard of a wholesale chemist

who professes to supply a syrup of roses of very superior beauty, and

who, for this purpose, substitutes the petals of the red (rosa gallica) for

those of the damask rose (rosa centifolia); we need not be told, that a

preparation of a more exquisite colour may be thus afforded, but allow

me to ask if this underhanded substitution be not a manifest act of injustice

to the medical practitioner, who, instead of a laxative syrup, receives

one which is marked by the opposite character of astringency. These

observations will not apply, of course, to those articles which are avowedly

prepared by a new process; for in that case the practitioner is enabled

to make his election, and either to adopt or refuse them at his discretion.

Thus has Mr. Barry applied his ingenious patent apparatus for

boiling in vacuo, to the purpose of making Extracts; we might almost

say a priori, that the results must be more active than those obtained in

the ordinary way, but they must pass the ordeal of experience before

they can be admitted into practice. As a brief notice of the most notorious

Quack Medicines may be acceptable, the formulæ for their preparation

have been appended in notes, each being placed at the foot of the

particular article which constitutes its prominent ingredient; indeed it is

essential that the practitioner should be acquainted with their composition,

for although he would refuse to superintend the operation of a

boasted panacea, it is but too probable that he may be called upon to

counteract its baleful influence.

The Historical Introduction, comprehending the substance of the lectures

delivered before the Royal College of Physicians of London, from

the recently established chair of Materia Medica, has been prefixed to

the work, at the desire of several of the auditors; and I confess my

readiness to comply with this request, as it enabled me at once to obviate

any misconception or unjust representation of those remarks which I

felt it my bounden duty to offer to the College.

It will be observed that the work itself is divided into two separate

and very distinct parts, the First comprehending the principles of the

art of combination,—the Second, the medicinal history, and chemical habitudes

of the bodies which are the subjects of such combination. These

comprise every legitimate source of instruction, and to the young and

industrious student, they are at once the Loom and the Raw Material.

Let him therefore abandon those flimsy and ill-adapted textures, that are

kept ready fabricated for the service of ignorance and indolence, and by

actuating the machinery himself, weave the materials with which he is

here presented into the forms and objects that may best fulfil his intentions,

and meet the various exigencies of each particular occasion.

Dover-street, January, 1820.

1HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION.

COMPREHENDING

THE

SUBSTANCE OF SEVERAL LECTURES

DELIVERED BY THE AUTHOR

BEFORE THE

ROYAL COLLEGE OF PHYSICIANS,

FROM THE

CHAIR OF MATERIA MEDICA,

In the Years 1819–20 and 21.

“It has been very justly observed that there is a certain maturity of the human

mind acquired from generation to generation, in the MASS, as there is in the

different stages of life in the INDIVIDUAL man;—What is history when

thus philosophically studied, but the faithful record of this progress? pointing

out for our instruction the various causes which have retarded or accelerated

it in different ages and countries.”

Historical Introduction, p. 4.

3

HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION.

AN ANALYTICAL INQUIRY INTO THE MORE REMARKABLE CAUSES WHICH

HAVE, IN DIFFERENT AGES AND COUNTRIES, OPERATED IN PRODUCING

THE REVOLUTIONS THAT CHARACTERISE THE HISTORY OF MEDICINAL

SUBSTANCES.

“Historia quoquo modo scripta delectat.”

Before I proceed to discuss the particular views which I am prepared

to submit to the College, on the important but obscure subject of medicinal

combination, I propose to take a sweeping and rapid sketch of the different

moral and physical causes which have operated in producing the extraordinary

vicissitudes, so eminently characteristic of the history of Materia

Medica. Such an introduction is naturally suggested by the first

glance at the extensive and motly assemblage of substances with which

our cabinets[1] are overwhelmed. It is impossible to cast our eyes over

such multiplied groups, without being forcibly struck with the palpable

absurdity of some—the total want of activity in many—and the uncertain

and precarious reputation of all—or, without feeling an eager curiosity to

enquire, from the combination of what causes it can have happened, that

substances, at one period in the highest esteem, and of generally acknowledged

utility, have fallen into total neglect and disrepute;—why others,

of humble pretensions and little significance, have maintained their ground

for so many centuries; and on what account, materials of no energy

whatever, have received the indisputable sanction and unqualified support

of the best and wisest practitioners of the age. That such fluctuations

in opinion and versatility in practice should have produced, even in

the most candid and learned observers, an unfavourable impression with

regard to the general efficacy of medicines, can hardly excite our astonishment,

much less our indignation; nor can we be surprised to find, that

another portion of mankind has at once arraigned Physic as a fallacious

4art, or derided it as a composition of error and fraud.[2] They ask—and it

must be confessed that they ask with reason—what pledge can be afforded

them, that the boasted remedies of the present day will not, like their predecessors,

fall into disrepute, and in their turn serve only as humiliating

memorials of the credulity and infatuation of the physicians who commended

and prescribed them? There is surely no question connected

with our subject which can be more interesting and important, no one

which requires a more cool and dispassionate inquiry, and certainly not

any which can be more appropriate for a lecture, introductory to the history

of Materia Medica. I shall therefore proceed to examine with some

attention the revolutions which have thus taken place in the opinions and

belief of mankind, with regard to the efficacy and powers of different

medicinal agents; such an inquiry, by referring them to causes capable

of a philosophical investigation, is calculated to remove many of the unjust

prejudices which have been excited, to quiet the doubts and alarms

which have been so industriously propagated, and, at the same time, to

obviate the recurrence of several sources of error and disappointment.

This moral view of events, without any regard to chronological minutiæ,

may be denominated the Philosophy of History, and should be

carefully distinguished from that technical and barren erudition, which

consists in a mere knowledge of names and dates, and which is perused

by the medical student with as much apathy, and as little profit, as the

monk counts his bead-roll. It has been very justly observed, that there

is a certain maturity of the human mind, acquired from generation to generation,

in the mass, as there is in the different stages of life, in the individual

man; what is history, when thus philosophically studied, but the

faithful record of this progress? pointing out for our instruction the various

causes which have retarded or accelerated it in different ages and countries.

In tracing the history of the Materia Medica to its earliest periods, we

shall find that its progress towards its present advanced state, has been

very slow and unequal, very unlike the steady and successive improvement

which has attended other branches of natural knowledge; we shall

perceive even that its advancement has been continually arrested, and

often entirely subverted, by the caprices, prejudices, superstitions, and knavery

of mankind; unlike too the other branches of science, it is incapable

of successful generalization; in the progress of the history of remedies,

when are we able to produce a discovery or improvement, which has been

the result of that happy combination of Observation, Analogy, and Experiment,[3]

which has so eminently rewarded the labours of modern science?

Thus, Observation led Newton to discover that the refractive power of

transparent substances was, in general, in the ratio of their density, but

5that, of substances of equal density, those which possessed the refractive

power in a higher degree were inflammable.[4] Analogy induced him to

conclude that, on this account, water must contain an inflammable principle,

and Experiment enabled Cavendish and Lavoisier to demonstrate

the surprising truth of Newton’s induction, in their immortal discovery of

the chemical composition of that fluid.

The history of Astronomy furnishes another illustration equally beautiful

and instructive,—The Astronomer observed certain oscillations in the

motions of Saturn and Jupiter; by Analogy he conjectured that this phenomenon

was produced by the influence of a planet still more remote: a

supposition which was happily confirmed by a telescopic experiment, in

the discovery of Uranus, by Herschel.

But it is clear that such principles of research, and combination of methods,

can rarely be applied in the investigation of remedies, for every

problem which involves the phenomena of life is unavoidably embarrassed

by circumstances, so complicated in their nature, and fluctuating in their

operation, as to set at defiance every attempt to appreciate their influence;

thus an observation or experiment upon the effects of a medicine is liable

to a thousand fallacies, unless it be carefully repeated under the various

circumstances of health and disease, in different climates, and on different

constitutions. We all know how very differently opium, or mercury, will

act upon different individuals, or even upon the same individual, at different

times, or under different circumstances; the effect of a stimulant upon

the living body is not in the ratio of the intensity of its impulse, but in

proportion to the degree of excitement, or vital susceptibility of the individual,

to whom it is applied. This is illustrated in a clear and familiar

manner, by the very different sensations of heat which the same temperature

will produce under different circumstances. In the road over the

Andes, at about half way between the foot and the summit, there is a

cottage in which the ascending and descending travellers meet; the

former, who have just quitted the sultry vallies at the base, are so relaxed,

that the sudden diminution of temperature produces in them the feeling

of intense cold, whilst the latter, who have left the frozen summits of the

mountain, are overcome by the distressing sensation of extreme heat.

But we need not climb the Andes for an illustration; if we plunge one

hand into a basin of hot, and the other into one of cold water, and then

mix the contents of each vessel, and replace both hands in the mixture,

we shall experience the sensation of heat and cold, from one and the

same medium; the hand, that had been previously in the hot, will feel

cold, whilst that which had been immersed in the cold water, will experience

a sensation of heat. Upon the same principle, ardent spirits will

produce very opposite effects upon different constitutions and temperaments,

and we are thus enabled to reconcile the conflicting testimonies

respecting the powers of opium in the cure of fever: aliments, also, which

under ordinary circumstances would occasion but little effect, may in certain

conditions of the system, act as powerful stimulants; a fact which is

well exemplified by the history of persons who have been enclosed in coal

mines for several days without food, from the accidental falling in of the

6surrounding strata, when they have been as much intoxicated by a basin

of broth, as a person, in common circumstances, would have been by two

or more bottles of wine.[5] Many instances will suggest themselves to

the practitioner in farther illustration of these views, and I shall have occasion

to recur to the subject at a future period.

To such causes we must attribute the barren labours of the ancient

empirics, who saw without discerning, administered without discriminating,

and concluded without reasoning; nor should we be surprised at the

very imperfect state of the materia medica, as far as it depends upon what

is commonly called experience, complicated as this subject is by its numberless

relations with Physiology, Pathology, and Chemistry. John Ray

attempted to enumerate the virtues of plants from experience, and the system

serves only to commemorate his failure. Vogel likewise professed to

assign to substances, those powers which had been learnt from accumulated

experience; and he speaks of roasted toad[6] as a specific for the pains

of gout, and asserts that a person may secure himself for the whole year

from angina by eating a roasted swallow! Such must ever be the case,

when medicines derive their origin from false experience, and their reputation

from blind credulity.

Analogy has undoubtedly been a powerful instrument in the improvement,

extension, and correction of the materia medica, but it has been

chiefly confined to modern times; for in the earlier ages, Chemistry had

not so far unfolded the composition of bodies, as to furnish any just idea of

their relations to each other, nor had the science of Botany taught us the

value and importance of the natural affinities which exist in the vegetable

kingdom.

With respect to the fallacies to which such analogies are exposed, I

shall hereafter speak at some length, and examine the pretensions of those

ultra chemists of the present day who have upon every occasion arraigned,

at their self-constituted tribunal, the propriety of our medicinal combinations,

and the validity of our national pharmacopœias.

In addition to the obstacles already enumerated, the progress of our

knowledge respecting the virtues of medicines has met with others of a

moral character, which have deprived us in a great degree of another obvious

method of research, and rendered our dependance upon testimony

uncertain, and often entirely fallacious. The human understanding, as

Lord Bacon justly remarks, is not a mere faculty of apprehension, but is

affected, more or less, by the will and the passions; what man wishes to

be true, that he too easily believes to be so, and I conceive that physic

has, of all the sciences, the least pretensions to proclaim itself independent

of the empire of the passions.

In our researches to discover and fix the period when remedies were

7first applied for the alleviation of bodily suffering, we are soon lost in conjecture,

or involved in fable; we are unable to reach the period in any

country, when the inhabitants were destitute of medical resources, and

we find among the most uncultivated tribes, that medicine is cherished as

a blessing and practised as an art, as by the inhabitants of New Holland

and New Zealand, by those of Lapland and Greenland, of North America,

and of the interior of Africa. The personal feelings of the sufferer,

and the anxiety of those about him, must, in the rudest state of society,

have incited a spirit of industry and research to procure alleviation, the

modification of heat and cold, of moisture and dryness, and the regulation

and change of diet and habit, must have intuitively suggested themselves

for the relief of pain;[7] and when these resources failed, charms, amulets,

and incantations,[8] were the natural expedients of the barbarian, ever

more inclined to indulge the delusive hope of superstition, than to

listen to the voice of sober reason. Traces of amulets may be discovered

in very early history. The learned Dr. Warburton is evidently

mistaken, when he assigns the origin of these magical instruments to the

age of the Ptolemies, which was not more than 300 years before Christ;

this is at once refuted by the testimony of Galen, who tells us that the

Egyptian king, Nechepsus, who lived 630 years before the Christian era,

had written, that a green jasper cut into the form of a dragon surrounded

with rays, if applied externally, would strengthen the stomach and organs

of digestion.[9] We have moreover the authority of the Scriptures in

support of this opinion; for what were the ear-rings which Jacob buried

under the oak of Sechem, as related in Genesis, but amulets? and we

are informed by Josephus, in his Antiquities of the Jews,[10] that Solomon

discovered a plant efficacious in the cure of Epilepsy, and that he employed

the aid of a charm or spell for the purpose of assisting its virtues;

the root of the herb was concealed in a ring, which was applied to the

nostrils of the Demoniac, and Josephus remarks that he himself saw a

Jewish Priest practise the art of Solomon with complete success in the

presence of Vespasian, his sons, and the tribunes of the Roman army.[11]

Nor were such means confined to dark and barbarous ages; Theophrastus

pronounced Pericles to be insane, because he discovered that he wore an

amulet about his neck; and, in the declining æra of the Roman empire,

we find that this superstitious custom was so general, that the Emperor

8Caracalla was induced to make a public edict ordaining that no man

should wear any superstitious amulets about his person.

In the progress of civilization, various fortuitous incidents,[12] and even

errors in the choice and preparation of aliments, must have gradually unfolded

the remedial powers of many natural substances; these were recorded,

and the authentic history of medicine may date its commencement

from the period when such records began.

The Chaldeans and Babylonians, we are told by Herodotus, carried

their sick to the public roads and markets, that travellers might converse

with them, and communicate any remedies which had been successfully

used in similar cases; this custom continued during many ages in Assyria;

and Strabo states that it prevailed also amongst the ancient Lusitanians,

or Portuguese: in this manner, however, the results of experience

descended only by oral tradition; it was in the temple of Esculapius

in Greece that medical information was first recorded; diseases and cures

were there registered on durable tablets of marble; the priests[13] and

priestesses, who were the guardians of the temple, prepared the remedies

and directed their application, and thus commenced the profession of Physic.

With respect to the actual nature of these remedies, it is useless to

inquire; the lapse of ages, loss of records, change of language, and ambiguity

of description, have rendered every learned research unsatisfactory;

indeed we are in doubt with regard to many of the medicines which

even Hippocrates employed. It is however clearly shewn by the earliest

records, that the ancients were in the possession of many powerful remedies;

thus Melampus of Argos, the most ancient Greek physician

with whom we are acquainted, is said to have cured one of the Argonauts

of sterility, by administering the rust of iron in wine for ten days;

and the same physician used hellebore as a purge, on the daughters of

king Prætus, who were afflicted with melancholy. Venesection was

also a remedy of very early origin; for Podalirius, on his return from the

Trojan war, cured the daughter of Damethus, who had fallen from a

height, by bleeding her in both arms. Opium, or a preparation of the

poppy, was certainly known in the earliest ages; it was probably opium

that Helen mixed with wine, and gave to the guests of Menelaus, under

the expressive name of nepenthe,[14] to drive away their cares, and increase

their hilarity; and this conjecture receives much support from the fact,

that the nepenthe of Homer was obtained from the Egyptian Thebes;[15]

9and if we may credit the opinion of Dr. Darwin, the Cumæan Sibyll never

sat on the portending tripod without first swallowing a few drops of

the juice of the Cherry-laurel.[16]

“At Phœbi nondum patiens, immanis in antro

Bacchatur Vates, magnum si pectore possit

Excussisse deum: tanto magis ille fatigat

Os rabidum, fera corda domans, fingitque premendo.”

Æneid, l. vi. 78.

There is reason to believe that the Pagan priesthood were under the

influence of some powerful narcotic during the display of their oracular

powers, but the effects produced would seem to resemble rather those of

Opium, or perhaps of Stramonium, than of the Prussic acid. Monardes

tells us that the priests of the American Indians, whenever they were

consulted by the chief gentlemen, or casiques as they are called, took certain

leaves of the Tobacco, and cast them into the fire, and then received

the smoke, which they thus produced, in their mouths, in consequence of

which they fell down upon the ground; and that after having remained

for some time in a stupor, they recovered, and delivered the answers which

they pretended to have received, during their supposed intercourse with

the world of spirits.

The sedative powers of the Lactuca Sativa, or Lettuce,[17] were known

also in the earliest times; among the fables of antiquity, we read that

after the death of Adonis, Venus threw herself on a bed of lettuces, to

lull her grief, and repress her desires. The sea onion or Squill, was administered

in cases of dropsy by the Egyptians, under the mystic title of

the Eye of Typhon. The practices of incision and scarification were employed

in the camp of the Greeks before Troy, and the application of spirit

to wounds was also understood, for we find the experienced Nestor applying

a cataplasm, composed of cheese, onion, and meal, mixed up

with the wine of Pramnos, to the wounds of Machaon.[18]

The revolutions and vicissitudes which remedies have undergone, in

medical as well as popular opinion, from the ignorance of some ages, the

learning of others, the superstitions of the weak, and the designs of the

crafty, afford ample subject for philosophical reflection; some of these revolutions

I shall proceed to investigate, classing them under the prominent

causes which have produced them, viz. Superstition—Credulity—Scepticism—False

Theory—Devotion to Authority, and Established

Routine—The assigning to Art that which was the effect of unassisted

Nature—The assigning to peculiar substances Properties, deduced from

Experiments made on inferior Animals—Ambiguity of Nomenclature—The

progress of Botanical Science—The application, and misapplication

of Chemical Philosophy—The Influence of Climate and Season on Diseases,

as well as on the properties, and operations of their Remedies—The

ignorant Preparation, or fraudulent Adulteration of Medicines—The

10unseasonable collection of those remedies which are of vegetable origin,—and,

the obscurity which has attended the operation of compound medicines.

SUPERSTITION.

A belief in the interposition of supernatural powers in the direction of

earthly events, has prevailed in every age and country, in an inverse ratio

with its state of civilization, or in the exact proportion to its want of

knowledge. “In the opinion of the ignorant multitude,” says Lord Bacon,

“witches and impostors have always held a competition with physicians.”

Galen also complains of this circumstance, and observes that his

patients were more obedient to the oracle in the temple of Esculapius, or

to their own dreams, than they were to his prescriptions. The same popular

imbecility is evidently allegorized in the mythology of the ancient

poets, when they made both Esculapius and Circe the children of Apollo;

in truth, there is an unaccountable propensity in the human mind,

unless subjected to a very long course of discipline, to indulge in the belief

of what is improbable and supernatural; and this is perhaps more conspicuous

with respect to physic than to any other affair of common life, both

because the nature of diseases and the art of curing them are more obscure,

and because disease necessarily awakens fear, and fear and ignorance

are the natural parents of superstition; every disease therefore, the

origin and cause of which did not immediately strike the senses, has in

all ages been attributed by the ignorant to the wrath of heaven, to the

resentment of some invisible demon, or to some malignant aspect of the

stars;[19] and hence the introduction of a rabble of superstitious remedies,

not a few of which were rather intended as expiations at the shrines of

these offended spirits, than as natural agents possessing medicinal powers.

The introduction of precious stones into the materia medica, arose from

an Arabian superstition of this kind; indeed De Boot, who has written

extensively upon the subject, does not pretend to account for the virtues

of gems, upon any philosophical principle, but from their being the residence

of spirits, and he adds that such substances, from their beauty,

splendour and value, are well adapted as receptacles for good spirits![20]

11Every substance whose origin is involved in mystery,[21] has at different

times been eagerly applied to the purposes of medicine: not long since,

one of those showers which are now known to consist of the excrement

of insects, fell in the north of Italy; the inhabitants regarded it as Manna,

or some supernatural panacea, and they swallowed it with such avidity,

that it was only by extreme address, that a small quantity was obtained

for a chemical examination.

A propensity to attribute every ordinary and natural effect to some extraordinary

and unnatural cause, is one of the striking peculiarities of

medical superstition; it seeks also explanations from the most preposterous

agents, when obvious and natural ones are in readiness to solve the

problem. Soranus, for instance, who was cotemporary with Galen, and

wrote the life of Hippocrates![22] tells us that honey proved an easy remedy

for the aphthæ of children, but instead of at once referring the fact to

the medical qualities of the honey, he very gravely explains it, from its

having been taken from bees that hived near the tomb of Hippocrates!

And even those salutary virtues which many herbs possess, were, in these

times of superstitious delusion, attributed rather to the planet under whose

ascendancy they were collected or prepared, than to any natural and intrinsic

properties in the plants themselves; indeed such was the supposed

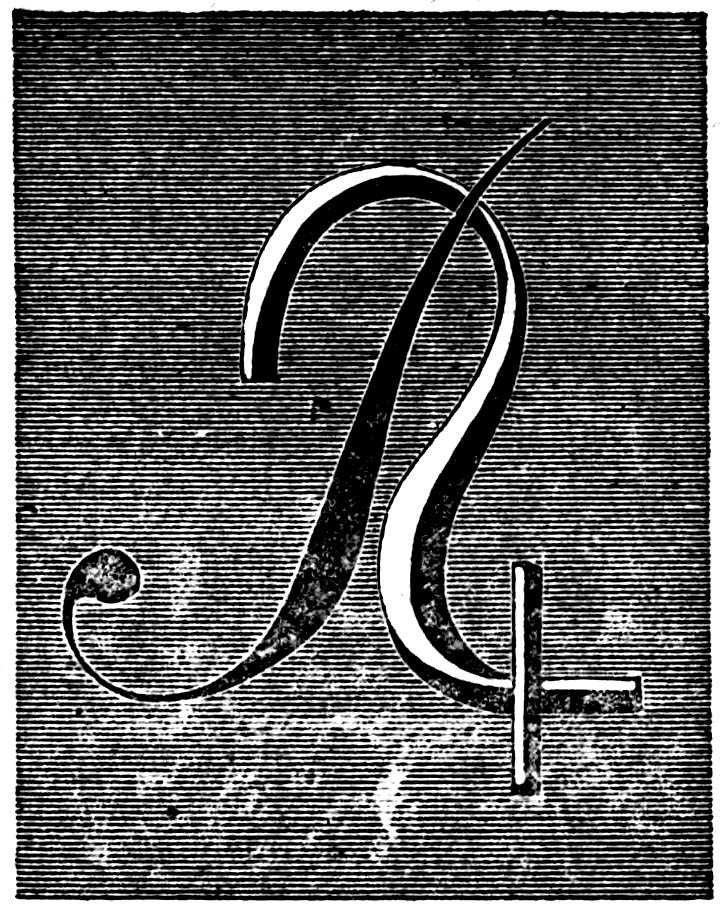

importance of planetary influence,[23] that it was usual to prefix to receipts

a symbol of the planet under whose reign the ingredients were to be collected,

and it is not perhaps generally known, that the character which

we at this day place at the head of our prescriptions, and which is understood,

and supposed to mean Recipe, is a relict of the astrological symbol

of Jupiter, as may be seen in many of the older works on pharmacy, although

it is at present so disguised by the addition of the down stroke,

which converts it into the letter ℞, that were it not for its cloven foot, we

might be led to question the fact of its superstitious origin.

12

A knowledge of this ancient and popular belief in Sideral influence,

will enable us to explain many superstitions in Physic; the custom, for

instance, of administering cathartic medicines at stated periods and seasons,

originated in an impression of their being more active at particular

stages of the moon, or at certain conjunctions of the planets: a remnant

of this superstition still exists to a considerable extent in Germany; and

the practice of bleeding at ‘spring and fall,’ so long observed in this country,

owed its existence to a similar belief. It was in consequence of the

same superstition, that the metals were first distinguished by the names

and signs of the planets; and as the latter were supposed to hold dominion

over time, so were astrologers led to believe that some, more than others,

had an influence on certain days of the week; and, moreover, that they

could impart to the corresponding metals considerable efficacy upon the

particular days which were devoted to them;[24] from the same belief,

some bodies were only prepared on certain days in the year; the celebrated

earth of Lemnos was, as Galen describes, periodically dug with great

ceremony, and it continued for many ages to be highly esteemed for its

virtues; even at this day, the pit in which the clay is found is annually

opened, with solemn rites by the priests, on the sixth day of August, six

hours after sun rising, when a quantity is taken out, washed, dried, and

then sealed with the Grand Signior’s seal, and sent to Constantinople.

Formerly it was death to open the pit, or to seal the earth, on any other

day in the year. In the botanical history of the middle ages, as more especially

developed in Macer’s Herbal, there was not a plant of medicinal

use, that was not placed under the dominion of some planet, and must

neither be gathered nor applied but with observances that savoured of the

13most absurd superstition, and which we find were preserved as late as the

seventeenth century, by the astrological herbalists, Turner, Culpepper,

and Lovel.

It is not the least extraordinary feature in the history of medical superstition,

that it should so frequently involve in its trammels persons who,

on every other occasion, would resent with indignation any attempt to

talk them out of their reason, and still more so, to persuade them out of

their senses; and yet we have continual proofs of its extensive influence

over powerful and cultivated minds; in ancient times we may adduce the

wise Cicero, and the no less philosophical Aurelius, while in modern days

we need only recall to our recollection the number of persons of superior

rank and intelligence, who were actually persuaded to submit to the magnetising

operations of Miss Prescott, and some of them were even induced

to believe that a beneficial influence had been produced by the spells of

this modern Circe.

Lord Bacon, with all his philosophy, betrayed a disposition to believe

in the virtue of charms and amulets; and Boyle[25] seriously recommends

the thigh bone of an executed criminal, as a powerful remedy in dysentery.

Amongst the remedies of Sir Theodore Mayerne, known to commentators

as the Doctor Caius of Shakspeare, who was physician to three English

Sovereigns, and who, by his personal authority, put an end to the distinctions

of chemical and galenical practitioners in England, we shall find

the secundines of a woman in her first labour with a male child; the

bowels of a mole, cut open alive; mummy made of the lungs of a man

who had died a violent death; with a variety of remedies, equally absurd,

and alike disgusting.

It merits notice, that the medicinal celebrity of a substance has not

unfrequently survived the tradition of its superstitious origin, in the same

manner that many of our popular customs and rites have continued,

through a series of years, to exact a respectful observance, although the

circumstances which gave origin to them have been obscured and lost in

the gloom of unrecorded ages. Does not the fond parent still suspend

the coral toy around the neck of her infant, without being in the least

aware of the superstitious belief[26] from which the custom originated?

while the chorus of derry down is re-echoed by those who never heard of

the Druids, much less of the choral hymns with which their groves resounded,

at the time of their gathering the misletoe; and how many a

medical practitioner continues to administer this sacred plant, (Viscus

14Quercinus) for the cure of his epileptic patients, without the least suspicion

that it owes its reputation to the same mysterious source of superstition

and imposture? Nor is this the only faint vestige of druidism which can

be adduced. Mr. Lightfoot states, with much plausibility, that in the

highlands of Scotland, evidence still exists in proof of the high esteem in

which those ancient Magi held the Quicken tree, or Mountain Ash, (Sorbus

Aucuparia) for it is more frequently than any other, found planted in the

neighbourhood of druidical circles of stones; and it is a curious fact, that

it should be still believed that a small part of this tree, carried about a person,

is a charm against all bodily evils,—the dairy-maid drives the cattle

with a switch of the Roan tree, for so it is called in the highlands; and in

one part of Scotland, the sheep and lambs are, on the first of May, ever

made to pass through a hoop of Roan wood.

It is also necessary to state, that many of the practices which superstition

has at different times suggested, have not been alike absurd; nay,

some of them have even possessed, by accident, natural powers of considerable

efficacy, whilst others, although, ridiculous in themselves, have actually

led to results and discoveries of great practical importance. The

most remarkable instance of this kind upon record is that of the Sympathetic

powder of Sir Kenelm Digby,[27] Knight of Montpellier. Whenever

any wound had been inflicted, this powder was applied to the weapon

that had inflicted it, which was, moreover, covered with ointment, and

dressed two or three times a-day.[28] The wound itself in the mean time

15was directed to be brought together, and carefully bound up with clean

linen rags, but, ABOVE ALL, TO BE LET ALONE for seven days; at the end

of which period the bandages were removed, when the wound was generally

found perfectly united. The triumph of the cure was decreed to the

mysterious agency of the sympathetic powder which had been so assiduously

applied to the weapon; whereas, it is hardly necessary to observe,

that the promptness of the cure depended upon the total exclusion of air

from the wound, and upon the sanative operations of nature not having

received any disturbance from the officious interference of art; the result,

beyond all doubt, furnished the first hint, which led surgeons to the improved

practice of healing wounds by what is technically called the first

intention.

The rust of the spear of Telephus, mentioned in Homer as a cure for

the wounds which that weapon inflicted, was probably Verdegris, and led

to the discovery of its use as a surgical application.

Soon after the introduction of Gunpowder, cold water was very generally

employed throughout Italy, as a dressing to gun-shot wounds; not

however from any theory connected with the influence of diminished temperature

or of moisture, but from a belief in a supernatural agency imparted

to it by certain mysterious and magical ceremonies, which were duly

performed immediately previous to its application: the continuance of the

practice, however, threw some light upon the surgical treatment of these

wounds, and led to a more rational management of them.

The inoculation of the small-pox in India, Turkey, and Wales, observes

Sir Gilbert Blane, was practised on a superstitious principle, long before it

was introduced as a rational practice into this country. The superstition

consisted in buying it—for the efficacy of the operation, in giving safety,

was supposed to depend upon a piece of money being left by the person

who took it for insertion. The members of the National Vaccine Establishment,

during the period I had a seat at the board, received from Mr.

Dubois, a Missionary in India, a very interesting account of the services,

derived from superstitious influence, in propagating the practice of vaccination

through that uncivilized part of the globe. It appears from this

document, that the greatest obstacle which vaccination encountered was a

belief that the natural small-pox was a dispensation of a mischievous

deity among them, whom they called Mah-ry Umma, or rather, that this

disease was an incarnation of the dire Goddess herself, into the person

who was infected with it; the fear of irritating her, and of exposing

themselves to her resentment, necessarily rendered the natives of the East

decidedly averse to vaccination, until a superstitious impression, equally

powerful with respect to the new practice, was happily effected; this was

no other than a belief, that the Goddess Mah-ry Umma had spontaneously

chosen this new and milder mode of manifesting herself to her votaries,

and that she might be worshipped with equal respect under this

new shape.

Hydromancy is another superstition which has incidentally led to the

discovery of the medicinal virtues of many mineral waters; a belief in

the divining nature of certain springs and fountains is, perhaps, the most

ancient and universal of all superstitions. The Castalian fountain, and

many others amongst the Grecians, were supposed to be of a prophetic

nature; by dipping a fair mirror into a well, the Patræans of Greece received,

as they imagined, some notice of ensuing sickness or health. At

16this very day, the sick and lame are attracted to various hallowed

springs; and to this practice, which has been observed for so many ages

and in such different countries, we are no doubt indebted for a knowledge

of the sanative powers of many mineral waters. There can be no doubt,

moreover, but that in many cases, by affording encouragement and confidence

to a dejected patient, and serenity to his mind, whether by the aid

of reason or the influence of superstition, much benefit may arise; for

the salutary and curative efforts of nature, in such a state of mind, must

be much more likely to succeed; equally evident is it, that the most

powerful effects may be induced by the administration of remedies

which, from their disgusting nature, are calculated to excite strong and

painful sensations of the mind.[29] Celsus mentions, with confidence, several

medicines of this kind for the cure of Epilepsy, as the warm blood of

a recently slain Gladiator, or a certain portion of human, or horse flesh! and

we find that remedies of this description were actually exhibited, and

with success, by Kaw Boerhaave, in the cure of Epileptics in the poor-house

at Haerlem. The powerful influence of confidence in the cure and

prevention of disease, was well understood by the sages of antiquity; the

Romans, in times of pestilence, elected a dictator with great solemnity,

for the sole purpose of driving a nail into the wall of the temple of Jupiter—the

effect was generally instantaneous—and while they thus imagined

that they propitiated an offended deity, they in truth did but diminish

the susceptibility to disease, by appeasing their own fears. Nor are

there wanting in modern times, striking examples of the progress of an

epidemic disease having been suddenly arrested by some exhilarating impression

made upon the mass of the population.

In the celebrated siege of Breda, in 1625, by Spinola, the garrison suffered

extreme distress from the ravages of Scurvy, and the Prince of

Orange being unable to relieve the place, sent in, by a confidential messenger,

a preparation which was directed to be added to a very large

quantity of water, and to be given as a specific for the epidemic; the remedy

was administered, and the garrison recovered its health, when it

was afterwards acknowledged, that the substance in question was no

other than a little colouring matter.

Amongst the numerous instances which have been cited to shew the

power of faith over disease, or of the mind over the body, the cures performed

by Royal Touch[30] have been generally selected; but it would appear,

17upon the authority of Wiseman, that the cures which were thus effected,

were in reality produced by a very different cause; for he states,

that part of the duty of the Royal Physicians and Serjeant Surgeons was

to select such patients, afflicted with scrofula, as evinced a tendency towards

recovery, and that they took especial care to choose those who approached

the age of puberty; in short, those only were produced whom

nature had shewn a disposition to cure; and as the touch of the king,

like the sympathetic powder of Digby, secured the patient from the mischievous

importunities of art, so were the efforts of nature left free and

uncontrolled, and the cure of the disease was not retarded or opposed by

the operation of adverse remedies. The wonderful cures of Valentine

Greatracks, performed in 1666, which were witnessed by cotemporary

prelates, members of parliament, and fellows of the royal society,

amongst whom was the celebrated Mr. Boyle, would probably upon investigation

admit of a similar explanation; it deserves, however, to be

noticed, that in all records of extraordinary cures performed by mysterious

agents, there is a great desire to conceal the remedies and other curative

means, which were simultaneously administered with them; thus Oribasius

commends in high terms a necklace of Pœony root, for the cure of

Epilepsy; but we learn that he always took care to accompany its use

with copious evacuations, although he assigns to them no share of credit

in the cure. In later times we have a good specimen of this deception presented

to us in a work on Scrofula, by Mr. Morley, written, as we are informed,

for the sole purpose of restoring the much injured character and

use of the Vervain; in which the author directs the root of this plant to

be tied with a yard of whited satin ribband, around the neck, where it is to

remain until the patient is cured; but mark,—during this interval he calls

to his aid the most active medicines in the materia medica!

The advantages which I have stated to have occasionally arisen from

superstitious influence, must be understood as being generally accidental;

indeed, in the history of superstitious practices, we do not find that their

application was exclusively commended in cases likely to be influenced

by the powers of faith or of the imagination, but, on the contrary, that

they were as frequently directed in affections that were entirely placed

beyond the control of the mind. Homer tells us, for instance, that the

bleeding of Ulysses was stopped by a charm:[31] and Cato the censor has

18favoured us with an incantation for the reduction of a dislocated limb. In

certain instances, however, we are certainly bound to admit that the

pagan priesthood, with their characteristic cunning, were careful to perform

their superstitious incantations, in such cases only as were likely to

receive the sanative assistance of Nature, so that they might attribute

the fortunate results of her efforts, to the potent influence of their own

arts. The extraordinary success which is related to have attended various

superstitious ceremonials will thus find a plausible explanation: the

miraculous gift, attributed by Herodotus to the Priestesses of Helen, is

one amongst many others of this kind that might be adduced; the Grecian

historian relates, that when the heads of ugly infants were adjusted on

the altar of this temple, the individuals so treated acquired comeliness, and

even beauty, as they advanced in growth: but is not such a change the

ordinary and unassisted result of natural developement? Those large and

prominent outlines which impart an unpleasing physiognomy to the infant,

when proportioned and matured by growth, will generally assume

features of intelligence in the adult face.

I shall conclude these observations, by remarking that, in the history of

religious ceremonials, we sometimes discover that they were intended to

preserve useful customs or to conceal important truths; which, had they

not been thus embalmed by superstition, could never have been perpetuated

for the use and advantage of posterity. I shall illustrate this assertion by

one or two examples. Whenever the ancients proposed to build a town,

or to pitch a camp, a sacrifice was offered to the gods, and the Soothsayer

declared, from the appearance of the entrails, whether they were propitious

or not to the design. What was this but a physiological inquiry into the

salubrity of the situation, and the purity of the waters that supplied it?

for we well know that in unwholesome districts, especially when swampy,

the cattle will uniformly present an appearance of disease in the viscera,

which an experienced eye can readily detect; and when we reflect upon

the age and climate in which these ceremonies were performed, we cannot

but believe that their introduction was suggested by principles of wise and

useful policy. In the same manner, Bathing, which at one period of the

world, was essentially necessary, to prevent the diffusion of Leprosy, and

other infectious diseases, was wisely converted into an act of religion, and

the priests persuaded the people that they could only obtain absolution

on washing away their sins by frequent ablutions; but since the use of

linen shirts has become general, and every one has provided for the cleanliness

of his own person, the frequent bath ceases to be so essential, and

therefore no evil has arisen from the change of religious belief respecting

its connection with the welfare and purity of the soul. Among the religious

impurities and rules of purification of the Hindoos, we shall be able

to discern the same principle although distorted by the grossest superstition.

The ancient custom of erecting “Acerræ” or Altars, near the bed

of the deceased, in order that his friends might daily burn Incense until his

burial, was long practised by the Romans. The Chinese observe a similar

custom; they place upon the altar thus erected an image of the dead

person, to which every one who approaches it bows four times, and offers

oblations and perfumes. Can there be any difficulty in recognising, in

this tribute to the dead, a wise provision for the preservation of the living?

The original intention was, beyond doubt, to overcome any offensive

smell, and to obviate the dangers that might arise from the emanations of

19the corpse. These instances are sufficient to shew the justness of my

position: if time and space would allow, many others of a striking and

interesting character might be adduced.[32]

CREDULITY.

Although it is nearly allied to Superstition, yet it differs very widely

from it. Credulity is an unbounded belief in what is possible, although

destitute of proof and perhaps of probability; but Superstition is a belief

in what is wholly repugnant to the laws of the physical and moral world.

Thus, if we believe that an inert plant possesses any remedial power, we

are credulous; but if we were to fancy that, by carrying it about with us,

we should become invulnerable, we should in that case be superstitious.

Credulity is a far greater source of error than Superstition; for the latter

must be always more limited in its influence, and can exist only, to any

considerable extent, in the most ignorant portion of society; whereas the

former diffuses itself through the minds of all classes, by which the rank

and dignity of science are degraded, its valuable labours confounded with

the vain pretensions of empiricism, and ignorance is enabled to claim for

itself the prescriptive right of delivering oracles, amidst all the triumphs

of truth, and the progress of philosophy. This is very lamentable; and

yet, if it were even possible to remove the film that thus obscures the

public discernment, I question whether the adoption of such a plan would

not be outvoted by the majority of our own profession. In Chili, says

Zimmerman, the physicians blow around the beds of their patients to drive

away diseases; and as the people in that country believe that physic consists

wholly in this wind, their doctors would take it very ill of any person

who should attempt to make the method of cure more difficult—they think

they know enough, when they know how to blow.

But this mental imbecility is not characteristic of any age or country.

England has, indeed, by a late continental writer,[33] been accused of possessing

a larger share of credulity than its neighbours, and it has been

emphatically called “The Paradise of Quacks,” but with as little truth as

candour. If we refer to the works of Ætius, written more than 1300

years ago, we shall discover the existence of a similar infirmity with regard

to physic. This author has collected a multitude of receipts, particularly

those that had been celebrated, or used as Nostrums,[34] many of

which he mentions with no other view than to expose their folly, and to

inform us at what an extravagant price they were purchased. We accordingly

learn from him that the collyrium of Danaus was sold at Constantinople

for 120 numismata, and the cholical antidote of Nicostratus for

two talents; in short, we shall find an unbounded credulity with respect

to the powers of inert medicines, from the elixir and alkahest of Paracelsus

and Van-Helmont, to the tar water of bishop Berkeley, the metallic tractors

of Perkins, the animal magnetism of Miss Prescott, and may I not add,

with equal justice, to the nitro-muriatic acid bath of Dr. Scott? The

20description of Thessalus, the Roman empiric in the reign of Nero, as

drawn by Galen, applies with equal fidelity and force to the medical

Charlatan of the present day; and, if we examine the writings of Scribonius

Largus, we shall obtain ample evidence that the same ungenerous

selfishness of keeping medicines secret, prevailed in ancient no less than

in modern times; while we have only to read the sacred orations of Aristides

to be satisfied, that the flagrant conduct of the Asclepiades, from

which he so severely suffered,[35] was the very prototype of the cruel and

remorseless frauds, so wickedly practised by the unprincipled Quack Doctors

and advertising “Medical Boards,” of our own times: and I challenge

the apologist of ancient purity to produce a more glaring instance of empirical

effrontery and success, in the annals of the nineteenth century,

than that of the sacred impostor described in the Alexander of Lucian,

who established himself in the deserted temple of Esculapius, and entrapped

in his snares some of the most eminent of the Roman senators.

SCEPTICISM.

Credulity has been justly defined, Belief without Reason. Scepticism

is its opposite, Reason without Belief and is the natural and invariable

consequence of credulity: for it may be generally observed, that men who

believe without reason, are succeeded by others whom no reasoning can

convince; a fact which has occasioned many extraordinary and violent

revolutions in the Materia Medica, and a knowledge of it will enable us

to explain the otherwise unaccountable rise and fall of many useless, as

well as important articles. It will also suggest to the reflecting practitioner,

a caution of great moment, to avoid the dangerous fault imputed

to Galen by Dioscorides, of ascribing too many and too great virtues to

one and the same medicine. By bestowing unworthy and extravagant praise

upon a remedy, we in reality do but detract from its reputation,[36] and run the

risk of banishing it from practice; for when the sober practitioner discovers

by experience that a medicine falls so far short of the efficacy ascribed to

it, he abandons its use in disgust, and is even unwilling to concede to it

that degree of merit to which in truth and justice it may be entitled; the

inflated eulogiums bestowed upon the operation of Digitalis in pulmonary

21diseases, excited, for a time, a very unfair impression against its use; and

the injudicious manner in which the antisyphilitic powers of Nitric Acid

have been aggrandised, had very nearly exploded a valuable auxiliary

from modern practice.

It is well known with what avidity the public embraced the expectations

given by Stöerk of Vienna in 1760, with respect to the efficacy of

Hemlock; every body, says Dr. Fothergill, made the extract, and every

body prescribed it, but finding that it would not perform the wonders ascribed

to it, and that a multitude of discordant diseases refused to yield,

as it was asserted they would, to its narcotic powers, practitioners fell

into the opposite extreme of absurdity, and declaring that it could do nothing

at all, dismissed it at once as inert and useless. Can we not then

predict the fate of the Cubebs, which has been lately restored to notice

with such extravagant praise and unqualified approbation? May the

sanguine advocates for the virtues of the Colchicum derive a useful lesson

of practical caution from these precepts: it would be a matter of regret

that a remedy which, under skilful management, certainly possesses considerable

virtue, should again fall into obscurity and neglect from the disgust

excited by the extravagant zeal of its supporters.

There are, moreover, those who cherish a spirit of scepticism, from an

idea that it denotes the exercise of a superior intellect; it must be admitted,

that at that period in the history of Europe, when reason first began

to throw off the yoke of authority, it required superiority of understanding

as well as intrepidity of conduct, to resist the powers of that superstition

which had so long held it in captivity; but in the present age,

observes Mr. Dugald Stewart, “unlimited scepticism is as much the child of

imbecility as implicit credulity.” “He who at the end of the eighteenth

century,” says Rousseau, “has brought himself to abandon all his early

principles, without discrimination, would probably have been a bigot in

the days of the league.”

FALSE THEORIES, AND ABSURD CONCEITS.

He who is governed by preconceived opinions, may be compared to a

spectator who views the surrounding objects through coloured glasses,

each assuming a tinge similar to that of the glass employed; thus have

crowds of inert and insignificant drugs been indebted to an ephemeral popularity,

from the prevalence of a false theory; the celebrated hypothesis

of Galen respecting the virtues and operation of medicines, may serve as

an example; it is a web of philosophical fiction, which was never surpassed

in absurdity. He conceives that the properties of all medicines

are derived from what he calls their elementary or cardinal qualities, Heat,

Cold, Moisture, and Dryness. Each of these qualities is again sub-divided

into four degrees, and a plant or medicine, according to his notion,

is cold or hot, in the first, second, third, or fourth gradation; if the disease

be hot, or cold in any of these four stages, a medicine possessed of a contrary

quality, and in the same proportionate degree of elementary heat or

cold, must be prescribed. Saltness, bitterness, and acridness depend, in

his idea, upon the relative degrees of heat and dryness in different bodies.

It will be easily seen how a belief in such an hypothesis must have multiplied

the list of inert articles in the materia medica, and have corrupted the

practice of physic. The variety of seeds derived its origin from this

22source, and until lately, medical writers, in the true jargon of Galen, spoke

of the four greater and lesser hot and cold seeds; and in the London Dispensatory

of 1721, we find the powders of hot and cold precious stones,

and those of the hot and cold compound powders of pearl. Several of the

ancient combinations of opium, with various aromatics, are also indebted

to Galen for their origin, and to the blind influence of his authority for

their existence and lasting reputation. Galen asserted that opium was

cold in the fourth degree, and must therefore require some corresponding hot

medicine to moderate its frigidity.[37]

The Methodic Sect, which was founded by the Roman physician

Themison,[38] a disciple of Asclepiades, as they conceived all diseases to

depend upon overbracing, or on relaxation, so did they class all medicines

under the head of relaxing and bracing remedies; and although this

theory has been long since banished from the schools, yet it continues at

this day to exert a secret influence on medical practice, and to preserve

from neglect some unimportant medicines. The general belief in the relaxing

effect of the warm, and the equally strengthening influence of the

cold bath, may be traced to conclusions deduced from the operations of hot

and cold water upon parchment and other inert bodies.[39]

The Stahlians, under the impression of their ideal system, introduced

Archœal remedies, and many of a superstitious and inert kind; whilst, as

they on all occasions trusted to the constant attention and wisdom of nature,

so did they zealously oppose the use of some of the most efficacious

instruments of art, as the Peruvian bark; and few physicians were so reserved

in the use of general remedies, as bleeding, vomiting, and the like;

their practice was therefore imbecile, and it has been aptly enough denominated,

“a meditation upon death.” They were however vigilant in observation

and acute in discernment, and we are indebted to them for some

faithful and minute descriptions.

The Mechanical Theory, which recognised “lentor and morbid viscidity

of the blood,” as the principal cause of all diseases, introduced attenuant

and diluent medicines, or substances endued with some mechanical

force; thus Fourcroy explained the operation of mercury by its specific

gravity,[40] and the advocates of this doctrine favoured the general introduction

of the preparations of iron, especially in schirrus of the spleen or

liver, upon the same hypothetical principle; for, say they, whatever is

23most forcible in removing the obstruction, must be the most proper instrument

of cure; such is Steel, which, besides the attenuating power with

which it is furnished, has still a greater force in this case from the gravity

of its particles, which, being seven times specifically heavier than any vegetable,

acts in proportion with a stronger impulse, and therefore is a more

powerful deobstruent. This may be taken as a specimen of the style in

which these mechanical physicians reasoned and practised.

The Chemists, as they acknowledged no source of disease but the

presence of some hostile acid or alkali, or some deranged condition in the

chemical composition of the fluid or solid parts, so they conceived all remedies

must act by producing chemical changes in the body. We find

Tournefort busily engaged in testing every vegetable juice, in order to

discover in it some traces of an acid or alkaline ingredient, which might

confer upon it medicinal activity. The fatal errors into which such an

hypothesis was liable to betray the practitioner, receive an awful illustration

in the history of the memorable fever that raged at Leyden in the

year 1699, and which consigned two thirds of the population of that city

to an untimely grave; an event which, in a great measure, depended upon

the Professor Sylvius de la Boe, who having just embraced the chemical

doctrines of Van Helmont, assigned the origin of the distemper to a prevailing

acid, and declared that its cure could alone be effected by the copious

administration of absorbent and testaceous medicines; an extravagance

into which Van Helmont, himself, would hardly have been betrayed:—but

thus it is in Philosophy, as in Politics, that the partisans of a

popular leader are always more sanguine, and less reasonable, than their

master; they are not only ready to delude the world, but most anxious to

deceive themselves, and while they warmly defend their favourite system

from the attacks of those that may assail it, they willingly close their own

eyes, and conceal from themselves the different points that are untenable;

or, to borrow the figurative language of a French writer, they are like the

pious children of Noah,[41] who went backwards, that they might not see

the nakedness which they approached for the purpose of covering.

Unlike the mechanical physicians, the chemists explain the beneficial

operation of iron by supposing that it increases the proportion of red globules

in the blood, on the erroneous[42] hypothesis that iron constitutes the

principal element of these bodies. Thus has iron, from its acknowledged

powers, been enlisted into the service of every prevailing hypothesis; and

it is not a little singular, as a late writer has justly observed, that theories

however different, and even adverse, do nevertheless often coincide in matters

of practice, as well with each other as with long established empirical

usages, each bending as it were, and conforming, in order to do homage to

truth and experience. And yet iron, whose medicinal virtues have been

so generally allowed, has not escaped those vicissitudes in reputation which

almost every valuable remedy has been doomed to suffer: at one period

the ancients imagined that wounds inflicted by iron instruments, were never

24disposed to heal, for which reason Porsenna, after the expulsion of the

Tarquins, actually stipulated with the Romans that they should not use

iron, except in agriculture; and Avicenna was so alarmed at the idea of

its internal use as a remedy, when given in substance, that he seriously

advised the exhibition of a magnet[43] after it to prevent any direful consequences.

The fame even of Peruvian bark has been occasionally obscured

by the clouds of false theory some condemned its use altogether,

“because it did not evacuate the morbific matter,” others, “because it

bred obstructions in the viscera,” others again, “because it only bound

up the spirits, and stopped the paroxysms for a time, and favoured the

translation of the peccant matter into the more noble parts.” Thus we

learn from Morton,[44] that Oliver Cromwell fell a victim to an intermittent

fever, because the Physicians were too timid to make a trial of the bark.

It was sold first by the Jesuits for its weight in silver;[45] and Condamine

relates that in 1690, about thirty years afterwards, several thousand pounds

of it lay at Piura and Payta for want of a purchaser.

Nor has Sugar escaped the venom of fanciful hypothesis. Dr. Willis

raised a popular outcry against its domestic use, declaring that “it contained

within its particles a secret acid—a dangerous sharpness,—which

caused scurvys, consumptions, and other dreadful diseases.”[46]

Although I profess to offer merely a few illustrations of those doctrines,

whose perverted applications have influenced the history of the Materia

Medica, I cannot pass over in silence that of John Brown, “the child of

genius and misfortune.” As he generalized diseases, and brought all

within the compass of two grand classes, those of increased and diminished

excitement, so did he abridge our remedies, maintaining, that every agent

which could operate on the human body was a Stimulant, having an identity

of action, and differing only in the degree of its force; so that, according

to his views, the lancet and the brandy bottle were but the opposite

extremes of one and the same class: the mischievous tendency of such a

doctrine is too obvious to require a comment.

But the most absurd and preposterous hypothesis that has disgraced