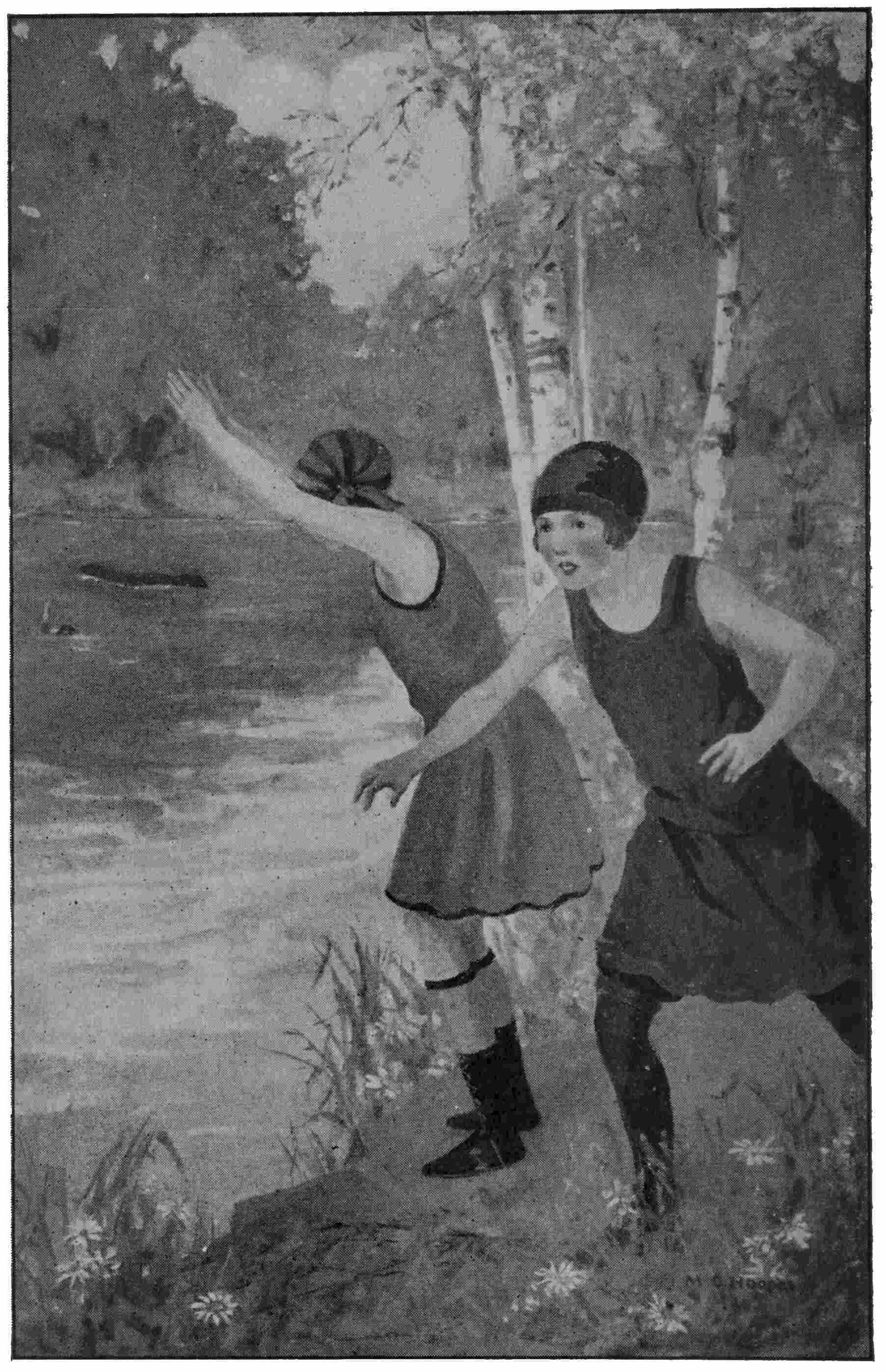

“Get a canoe, Hilary!” called Cathalina as she dived from the point in hope of catching Isabel in time.

“Get a canoe, Hilary!” called Cathalina as she dived from the point in hope of catching Isabel in time.

A blue-eyed, sunburned, slight young man leaped from a boat to the floating dock at Bath, Maine, and reached back for baggage handed him by two red-faced boys who were evidently most uncomfortable at being once more dressed in the garb of civilization. One of them pulled at his collar, and moved his head uneasily, as he balanced on the edge of the little launch, and then sprang out with a whoop which was the vent for his suppressed spirits.

“So long, boys,” said the two, in farewell to two others who remained in the boat.

“So long.”

“Goodbye, Mr. Stuart.”

“Goodbye, boys.”

The launch chugged away up the river toward Boothbay Camp, and the tall young camp councillor, with the two boys and their luggage, as well as his own, started up the slight rise toward the main street of the quaint New England town.

At the same time, an attractive, well-dressed lady, apparently under middle age, was walking briskly in the direction of this little street which led to the dock, and just before starting to cross it she saw the party of three coming toward her. Whereupon she waited, smiling a little.

“Well met, Campbell Stuart,” said she.

In pleased surprise, the young councillor stopped and held out his hand. “So here you are, Auntie! I was wondering when you would get here! All alone? Too early for the girls, I guess. I didn’t see anything of the boats from Merrymeeting Camp as we came down the river. However, that is no sign that they aren’t coming in shortly. I have to take these kids to the station up here and see that they make their train. Where shall I meet you and the girls?”

“I just came in on the train from Portland, and we forgot to arrange by letter just where to meet. So I think I’d better go down to the dock, don’t you?”

“It isn’t much of a place for you to stay, Aunt Sylvia, but I’ll be back soon, and you will be sure to catch the girls there. Where’s the car?—and Phil?”

“In Boston,” replied Mrs. Van Buskirk with a comical look. “I’ll tell you all about it later. Are these some of the young gentlemen from the boys’ camp?”

The boys, who had been standing aside, though listening with interest to the conversation, were introduced and soon hurried off, while Mrs. Van Buskirk went down to the dock, to which she had been directed, and sat down on a long bench there, with people who were waiting for some boat. Presently she saw the boats from Merrymeeting Girls’ Camp, which she recognized because of their load of happy girls, and walked across the muddy driveway toward the floating dock, where she saw that they were about to land. Her first glimpse of her daughter Cathalina came when the girls began to disentangle themselves from mass formation, and Cathalina jumped out, shaking out the wrinkles in her dress and tucking back wisps of hair which had been blown about by the Kennebec breezes.

“I don’t know where we shall find Mother,” Cathalina was saying, as Hilary and June Lancaster, Betty Barnes and Lilian North joined her, “but we can walk on up and look for the car. We forgot to appoint the spot.” Just then she saw her mother. “Why, Mothery! How nice of you to come down to meet us! Where’s Phil? Here are the rest of us.”

Mrs. Van Buskirk warmly greeted each girl and they turned away from the river to join the scattering girls, who made quite a procession up the short street.

“We have to see June off, you know, Mother,” explained Cathalina. “She goes straight through with the girls and councillors of that crowd. A good many of our friends are leaving. Do you care if we go?”

“Not at all. Where shall we meet?”

“You couldn’t take us to the station?”

“The car isn’t here, dear; it is in Boston.”

“Mercy! What shall we do!” exclaimed Cathalina.

“I have a good plan.” Cathalina and her mother were walking together and the rest of their group followed. “Do you think that they would enjoy going by boat to Boston?—at my expense, of course.”

Cathalina hesitated a moment. “Why, I imagine they’d like it. But why the change?”

“Your father could get away, he found, and we have been up in the White Mountains for a week and more. Then he went back and I came on to Portland for a few days. Philip was delayed until your father returned to New York. The chauffeur was to have the car and Philip in Boston either today or tomorrow, and I arrived at Bath about an hour ago—at your service, my daughter!”

Cathalina laughed. “I see. Our house party is to begin on a boat. You are a dear and a darling. Do you mind coming with us to the station? I’d like to have you meet some of the girls. Frances Anderson and Marion Thurman we may not see for a long time. They do not go to Greycliff, you know.”

“Very well. Campbell just went to the station with two sunburned boys from camp. I met him as I was coming to the dock. By the way, your own complexions are of the stylish summer type.”

“Oh, yes! We’re always in the state of being either red, blistered or brown. The girls with black hair are the only ones that show any contrast.”

At the station Mrs. Van Buskirk was highly entertained. It had been a long time since she had seen so many girls abroad together. There were eager last messages, goodbyes, clusters of happy, laughing girls, and finally the moving train, bright faces in windows and waving hands. Campbell had joined the party, and after the train left they returned to seats in the station while the matter of getting to Boston was under consideration. Mrs. Van Buskirk explained the change of plan as she had to Cathalina, to find the young people quite pleased with the idea of the boat trip to Boston.

“The boat does not leave till somewhere around seven o’clock,” said Campbell. “I’ll find out the exact time. We can have lunch at the Colonial on the way down. I don’t know what sort of accommodations we shall be able to get.”

“That’s so,” said Cathalina. “There are two parties from our camp taking the trip to Boston, New York and Washington.”

“I took it for granted,” said Mrs. Van Buskirk, “that we’d go by boat, and telegraphed from Portland for reservations.”

“I might have known,” said Cathalina, with relief, knowing, too, that the reservations would include the best staterooms on the steamer.

They left the station, Campbell, with courtesy, accompanying his aunt; but Mrs. Van Buskirk said that she must talk to Cathalina about several matters and thus changed the order of march. Betty and Lilian purposely fell in together, leaving Hilary free for Campbell.

“This house party,” said Campbell, “is one fine plan of Aunt Sylvia’s.”

“I guess Cathalina thought it up, didn’t she?” replied Hilary.

“Yes, but it takes Aunt Sylvia to give people the time of their lives!”

“She is too lovely for words,” assented Hilary. “I’ll never forget my other visit in New York. And she doesn’t seem to be making any effort, either.”

“She makes kind plans and is fortunate in having the means to carry them out. But I believe that her house is really the center of operations for our whole clan, the ‘sisters and cousins and aunts,’ as you said.”

“Shall we see the relatives this time?”

“Ann Maria’s home, I believe, and the Van Nesses. But you are not to spend too much time with any of them. I’m going to show you New York!”

“O, indeed!” laughed Hilary. “That sounds interesting. It will seem different from the wintry days I spent there and will be another new experience.”

At the Colonial they decided to make their meal a dinner at Cathalina’s suggestion, “so we won’t have to bother with it on the boat. I want some beefsteak with French fried potatoes—let’s see!”

“O, Cathalina,” said Hilary, “just ordinary beefsteak with all these seafood things? I want some sort of a clam broth and some shrimp salad, and I must have a last New England doughnut—”

There was plenty of quiet fun at that last meal in little Bath. Mrs. Van Buskirk enjoyed it as much as any of them. Then they strolled down to the dock to which the City of Rockland would come. “How many times at camp, girls,” said Lilian, “have we heard that old boat salute us—three long ‘toots’!”

“I’ve never been on the real ocean before,” said Hilary.

“Neither have I,” said Betty.

“We have good weather,” said Mrs. Van Buskirk, “and it will be moonlight.”

Moonlight it was, as they all sat well forward on the deck to watch the moon, the clouds, and the shores of the Kennebec. Then at last they reached the ocean. Hilary caught her breath a little as they first felt the ocean swell, but it was calm “on the deep,” and the ship fairly steady.

“Are you all right?” Campbell inquired with concern, as he drew up his chair next to Hilary.

“O, yes. I felt a little funny at first, but I love it!”

There was much to tell Mrs. Van Buskirk. Campbell told the most amusing tales of doings at the boys’ camp and the girls described the grand finale of the last week in Merrymeeting Camp, the banquet, the prizes, the last trips and fun, which had not been included in any of Cathalina’s letters home.

“Probably your last letter is waiting for me at home, Cathalina,” said Mrs. Van Buskirk. “When I left Boston for this little trip with your father I left word for the mail to be forwarded to New York. Our visit to the White Mountains was unexpected, you know, but Mr. Van Buskirk needed a cooler place to rest than Boston. Your Aunt Ann, Cathalina, was so disappointed, but it couldn’t be helped, and I had been there long enough anyway. By the way, what do you girls want to see in Boston?”

“Speak up, Hilary,” said Cathalina, smiling, as there was a slight hesitation on the part of the girls addressed.

“Oh, your mother will know where we ought to go. Of course I’d like to see the Bunker Hill Monument, and the place where the Boston Tea Party was, and if it isn’t too much trouble to drive there, Lexington and Concord—and the Harvard buildings are in Cambridge, aren’t they? And, Oh, I do want to see the place where Miss Alcott wrote ‘Little Women’!”

“You have chosen well, Hilary. Of course we shall drive out through Cambridge, Lexington and Concord. I think that I shall rest in the hotel in the morning and let the boys take you girls around the city. But after lunch we shall start early, and I believe I can tell you many interesting things about the different places. Nearly everything is historic or has literary associations. I love Concord myself, Hilary, and the Alcott home will delight you girls.”

It was late, indeed, when the party sought their staterooms. Mrs. Van Buskirk had one to herself, and had arranged for Cathalina and Betty to be together, Hilary and Lilian next door.

“My, this is different from the lake trip, isn’t it?” Betty commented, as the boat rolled about a little and she occasionally took hold of something to steady herself.

“Does it make you feel sick?”

“Not a bit, just funny.”

But both the girls, their chaperone, and the contented Campbell were soon in deepest slumber till time to rise and watch the boat come in to Boston Harbor.

“I do hope that Phil will be there!” said Cathalina.

“If he is not,” said Mrs. Van Buskirk, “we shall not waste any time. He knows the hotel at which I shall stop, and if our own car has not arrived we can take a taxi around the city, and, indeed, one of the motor trips out to Lexington and Concord.”

“But you wouldn’t get your rest, Mrs. Van Buskirk,” said Lilian.

“I was tired yesterday, but I believe that I shall go with you this morning anyway. It is going to be a fine day to drive. We shall see. I must get in a little time to take you all around to Aunt Ann’s, for she would be heart-broken if Cathalina and Phil were here and she did not see them.”

Mrs. Van Buskirk believed in having plans ready for any emergency, but Philip, to whom one of his mother’s telegrams had gone, was not only in the city, but at the dock with the car. This he left with the chauffeur, while he chose a place of vantage to see the people come off the boat, for Philip Van Buskirk was not going to miss any of this visit with Lilian North.

“Oh, there’s Philip now, Mothery,” exclaimed Cathalina, as Mrs. Van Buskirk and the girls, following the crowd which was crossing the gangplank, reached the outer air and made ready to cross. Lilian had seen him, but made no comment as she caught a welcoming glance from Philip’s dark eyes.

It was no time at all before they were leaning back on comfortable cushions in a luxurious car, while Philip and Mrs. Van Buskirk conferred a little with the chauffeur, who touched his cap and departed.

“Boston is the home of our chauffeur,” explained Mrs. Van Buskirk to the girls as Philip helped her into the machine. “He is to have a short vacation while Philip and Campbell drive us home.”

Philip Van Buskirk and Campbell Stuart were of about the same height, tall, slight and active, but of contrasting complexions, though Philip’s skin was clear and smooth.

“Phil is the handsomest,” thought Lilian, as she looked at the two boys in front, and she regretted her own present complexion, rather sunburned from the camp experience, though not as bad as Cathalina had extravagantly indicated. For Lilian was recalling a remark of Philip’s, in the pine grove at camp, when he looked at her admiringly while he said something about liking “golden-haired, blue-eyed, lovely-faced girls.”

At the same time, Hilary of the dark brown locks was admiring Campbell’s fairness and contrasting him favorably with the graceful, stylish Philip. Both youths had the square shoulders and fine carriage which their early years at the military school in the South had given them.

Cathalina, whose spiritual face and dreamy, sky-blue eyes had not changed much in spite of the practical experiences of the last two years, was thinking, “I’ll soon be in New York,” and visualized a call from a strong, well-built young officer with sunny brown hair about the shade of her own, a wave in one front lock, deep-set brown eyes, and a serious, kind face.

Betty, whose coloring was like Cathalina’s, but on whose rounder face two dimples chased in and out, was not thinking at all of any young man, but of Boston and the sights she was to see immediately, for her knight of the Hallowe’en mirror was far away, and she would not see Donald Hilton till school began.

So far, the weather had been ideal for the drive to New York. It was warm but not too warm. The roads were well dried off from recent showers, but not dusty, and the country looked fresh and green. They had stopped in some of the most delightful places their guests had ever seen, and the young people had made one long picnic of the whole trip, after their exciting day in Boston. Philip joked Campbell in private about the “Hilaryous” time he was having and Campbell retorted with a conundrum, “Why are you like a sailor?”

“The answer has something to do with ‘North,’ I suppose?”

Campbell nodded.

“Because my compass always points to the ‘North’?”

“That would be very good,” assented Campbell, “but I was thinking—because you always know where the North is.”

“What a pity that Aunt Sylvia and the girls have to miss our brilliant punning!”

But in spite of the special attraction which Hilary had for Campbell, and Lilian had for Philip, the gentlemen of the party were attentive to all the ladies, as they should be, and cheerfully performed the duties which naturally fell to them in the absence of the chauffeur.

On this occasion they were picnicking. They had stopped at a farmhouse to buy corn and melons, and had also found fresh cookies and a big, warm apple pie. Philip, Campbell and the girls came back to the car with hands full.

“I got some of the thickest cream, Mother,” called Cathalina, “and the farmer’s wife made fresh coffee for us.” Cathalina held up two thermos bottles with triumph, and began to sing, “The farmer in the dell, the farmer in the dell! High, ho, the Derry, O, the farmer in the dell!” She had never been real sure of the words, but that made no difference!

“Hush, Kittens,” said Philip, who was always evolving some new nickname for his sister. He was beginning to hand his bundles to Lilian, who had climbed into the car. “The man directed us, Mother, to a place where there is spring water that he says is all right. Say! Campbell, why didn’t I think to buy a chicken?”

“Oh, we don’t want one,” said Mrs. Van Buskirk. “It would take too long to cook it. You can roast or boil the corn in a jiffy. By the way, did they have fresh butter?”

“Oodles,” said Philip. “I saw them doing up a little pat for Cathalina in a clean cloth and some oiled paper!”

“If I hadn’t seen those chickens in time up the road—” began Campbell, and the rest started to laugh.

“That fat old hen that decided to cross the road just before we got to her would have been about the right size.”

“Too tough, Campbell,” said Betty, laughing.

“I saw a man just out of Boston,” remarked Philip, “that had chicken sense.”

“What sort of sense is that?” inquired his mother.

“Same kind that Campbell tells about. Concluded he wanted to cross just before we got there, couldn’t have waited till we passed, and I honked and put on the brakes just in time! It’s a sort of disturbance of the mental gearing, I guess. Seeing the machine makes them think of trouble.”

“I remember the incident,” said Mrs. Van Buskirk. “But we have to be ready for things like that. It’s the easiest thing in the world to blame the pedestrian. But I was brought up in the good old days of the carriages that we had up to about ten years ago, and we were trained to protect the people on foot.”

“Hear, hear!” said Philip as he started the car. “Everybody hold on to the lunch. It’s just around the curve in the road, I believe.”

In a few minutes, Philip turned the machine into the shade of some trees and bushes by the roadside, while they looked up a gently rising little hill to a tangled wood and a succession of ravines and hills.

“This looks good, plenty of wood for a fire, a cleared space in front, and stony. I suppose the spring is back farther. Think you can get up there, Mother?”

“It will certainly be a pity if I can’t,” replied his mother. “You just watch me! Come on, Campbell, give me a hand and we will hunt for the spring. I can carry that little hamper, too.”

“Indeed not, Mother,” replied Philip. “I’m convinced. You need not prove your prowess further! We’ll bring all the stuff up while you hunt for water. This is the Swiss Family Robinson! Can you tell, Hilary, by the bark, whether a banana tree is bearing cocoanuts this year or not?”

“One thing we can do, Philip,” said Betty—“make clothing for the family out of the skins of all the wild animals you and Campbell catch!”

“Look out, there!” cried Philip suddenly, and he reached out a hand to pull Lilian toward the car. She had gotten out on the side next the road and was gathering together some of their wraps and packages. With one wild honk, a car whizzed around the corner, balanced on its outer wheels, continued a little further and stopped. It was a large car like their own, with only one occupant, a man who was having trouble with his engine. It puffed and snorted for a while, but the girls and Philip did not wait to see the outcome when they saw that the car had not turned over. With their lunch, and various comforts in the way of robes and wraps to sit on, they pursued their way toward the woods, after Philip had closed and locked the car.

“Did you find the spring, Mother?” asked Philip. “I must needs bathe my fevered brow.”

“It is only a few steps down the side of the ravine,” replied Mrs. Van Buskirk, pointing. “All of you will want a cool drink, as Campbell and I did. This is a beautiful place for a picnic. I’m glad we came around this way. How did you happen to know about this road? It isn’t on the map.”

“Pat pointed it out as we came from home and said that there was a way to get through here, but not many tourists used the road because it was not good in some places, and especially bad in wet weather. If it had rained, I would not have brought you here. But I thought we could just about do it and make our next stopping place by night.”

While this conversation was going on the girls were preparing the eatables and the boys gathering sticks for the fire. All the accompaniments for a picnic lunch were contained in the Van Buskirk car. It was an easy matter to serve it. But to save time, most of their meals on the way were taken in hotels or tea rooms along the roads.

As the picnickers were enjoying their lunch, the man of the car below came up the hill with a cup, and inquired of Philip where the spring was located. Philip rose and showed him the place, asking if he needed any help on his car.

“I was going to ask you if you can loan me a few tools,” replied the man, “but I did not like to call you away till you had finished your lunch.”

“Oh, that is no matter,” and Philip went down hill to find one or two small implements that the man told him he lacked. “Just leave them on the step,” said Philip, “when you are through.”

“Funny looking customer,” remarked Campbell, when Philip came back.

“He was real polite, though,” said Betty.

“Do you suppose he will put the tools back?” asked Mrs. Van Buskirk.

“I guess so. He had almost everything he needed himself. His tire seems to be punctured and he is fixing it up.”

“Why doesn’t he put on a new one?” inquired Cathalina.

“Possibly he hasn’t any, or wants to be economical. Shall I go down and ask him?”

“You seem to be getting sarcastic, Philly,” was Cathalina’s comment. “I don’t blame you, though. Who can eat this last ear of corn? Going, going—gone!” and Cathalina put it on Philip’s picnic plate. “We ate more while you were gone. Now it’s time for pie. Mother, there’s more coffee for you, and, Lilian, you positively must finish up this marmalade you like. Campbell, can’t you eat another cookie? A New England cookie? a spice cookie? a crisp brown cookie?”

“Sounds like lines from the ‘Old Oaken Bucket,’” said Campbell, “but if I am to eat a piece of apple pie, I must positively refuse to take anything else. The ‘little birdies’ will eat it, Cousin. Lilian, can’t you compose an ode to ‘The Last Cookie’?”

“’Twas the last cookie in the hamper,” began Lilian in song, “left cru-hum-bling a-a-a-a-lone! All its—I fear me that the tune of the ‘Last Rose of Summer’ is a little intricate at this stage! May I have my piece of pie?”

“Pie it is,” answered Philip, as he took Lilian’s plate.

The party took its time over the dessert, much spring water, and the gathering up of impedimenta. While they were thus engaged, they heard the engine of their neighbor below start, a honk from his horn, and looked up to see him wave and call, “Thank you.” He looked back once with a broad grin upon his face, then disappeared in a cloud of gasoline smoke.

“That was a funny performance,” said Mrs. Van Buskirk. “I thought his face ugly enough before, but that grin was positively malicious. I suppose he has gone off with your tools, Philip.”

Philip was really annoyed at this implication of his carelessness, but was too courteous always to his mother to show it much.

“I guess we’ll find ’em all right, Mother,” he replied.

As they went down the hill to the car, they noticed a decided cooling of the atmosphere with the passing of the afternoon.

“Do you think that we will get in early enough, Philip?”

“Yes, Mother, and the night will be beautiful, moonlight still. We ought to make a hundred miles easily after we get out on the main road, and that will take us into a good town, though there are some fair little villages along. No, thanks, Campbell, I’ll drive till we get out of this hilly place. I know the car a little better.”

Everybody climbed in but Philip, who had picked up the borrowed tools from the step with an air of triumph, and paraded them before his mother and Cathalina. He took a last look at the tires and stepped around behind the car—when they heard him exclaim in surprise. “The scoundrel!” he said.

“Why, what’s the matter, Philip?”

“That thief has helped himself to our extra tire! That is why he gave us that farewell grin! Wait till I catch up with him!” Philip hurried into the car and made ready to start.

“Wait, Philip,” said Campbell. “Are you sure that our tires are all right? He would know, of course, that the first thing you would want to do would be to catch him or get to a telephone.”

“Telephoning would not do any good. He’ll keep to out of the way places and go around the towns. I bet that his car is a stolen one!”

Both Campbell and Philip got out, and went around to look closely at tires and wheels. “I can’t find a thing out of the way,” said Campbell.

“I thought they were all right when I looked before,” said Philip.

“Do be sure about it,” said Mrs. Van Buskirk anxiously, and the girls leaned out with faces showing concern.

“Maybe he has put a few tacks around,” suggested Campbell, beginning to look along the ground. “Perhaps he thought we would start, though, without finding out about the theft. The back of the car was so concealed by those bushes.”

“I wish I had thought to have the whole car where we could see it from where we were! Chicken sense! Chicken sense!”

At this the girls exploded into laughter, while Mrs. Van Buskirk reached out to pat Philip’s sleeve and say “Never mind, son, we can’t think of everything.”

“Oh, yes, Mother, you are very fine about it, but I know you are thinking how I just shook those tools in your face!” Philip was rather enjoying the joke on himself now. “That chap thought that we’d never notice if he left the tools all right.”

“Drive carefully, Philip, for fear the man did do something to the car.”

“I will, Mother.”

They started down the hill, around curves, across little bridges, where the narrow road like a ribbon wound in and out.

“Suppose the man had trouble again and we should catch up with him,” suggested Betty. “What would we do?”

“Not a thing, Betty,” replied Philip. “He would have a gun. The only way we could really catch him and get our tire would be to get the police after him at some place on the route. You girls need not worry. We are not anxious to take you into trouble. I only want to get on the main road before we have anything happen to a tire.”

“And we are one hundred miles from a town!” said Mrs. Van Buskirk.

“Oh, no, Mother. You are thinking of what I said; but, remember, I mentioned villages. It isn’t that far from a place where we could stay, and I think that it is only a few miles from a village where I could get a tire, or have something fixed if necessary. See, we are in sight of the main road now.”

Philip had scarcely spoken when there was a loud report—then a second.

“There are the tacks, Philip,” said Campbell. “The villain’s plot is bared!”

“Melodrama!” said Lilian.

The girls as well as the boys left the car to examine the road where the two tires had been punctured. “Glass and all sorts of sharp things,” said Philip. “He must go prepared for occasions like this. See? All this never came here by chance.”

Campbell walked over to the other side of the road. “Nothing here,” he reported. “But it was made sure that on the other side we couldn’t miss it.”

“Perhaps since we had been kind,” suggested Mrs. Van Buskirk, “he wouldn’t leave us stranded up in the hills, and let us come nearer civilization before our tires were punctured.”

“You would be bound to find some good in him, Mother,” said Philip. “Do we go forward on rims, or do we patch up? Two tires!”

Campbell was already getting out the “first aid” equipment. “He knew we’d need the things he borrowed, all right!” said he. “Come on, Phil, we may as well get to work. You ladies can enjoy the beauties of nature for the next hour or so. Get out your field glasses, Hilary. I heard a grasshopper sparrow over in that field.”

The girls scattered, Hilary and Lilian with the field glasses, Cathalina and Betty to look for wild flowers, while Mrs. Van Buskirk hunted out a book from the luggage. The two young mechanics worked busily, having taken the machine on beyond the possibility of another puncture. The “villain” had contented himself with preparing the one place for trouble.

“Say, Phil,” said Campbell, suddenly, “have you looked to see whether we have enough gas?”

“You haven’t forgotten, have you, that we just got a supply at the little town before we struck this road?”

“No, I haven’t, but you forget our friend who needed the tire. Perhaps he needed some gas, too.”

Philip finished the particular detail he was on with only the laconic remark, “Chicken sense,” and then started an investigation of the tank, with Campbell as an interested spectator and assistant. “You’re right. He needed almost all of it. But I think that there is enough, with that little can that Mother always insists we take along, to get us where we can fill up again. Mother, here is where your forethought gets the applause.”

Mrs. Van Buskirk smiled and placidly read on.

Finally the work was done. Philip and Campbell gave the whistles of their college fraternity, to call the wandering girls, and the party once more were off. The car ran easily, and the gasoline lasted until they reached the first town, which, fortunately, happened to be of a fair size, and Philip thought that he could find another tire there to replace the stolen one. But just as they turned into the street where they had been told the shop they were seeking was located, they saw a small crowd gathered about a machine a short distance ahead.

“It’s our man!” exclaimed Philip, and he brought up his car to the curb not far from the source of excitement. He and Campbell lost no time in arriving on the scene, while the girls and Mrs. Van Buskirk watched with interest.

“They’re taking him out of the car!” said Betty.

“Yes; see those two policemen?”

“I suppose that is the sheriff.”

“Philip’s talking to him. I wonder if we’ll have to wait for a trial or anything.”

“Mercy, no. At least, I hope not.”

“Look, there is a nice looking gentleman there—I wonder who he is.”

Thus ran the comments on the moving picture before them, which lacked the usual printed information. “I suppose it wouldn’t be proper for us to go any nearer,” said Cathalina, whose interest had reached the point of curiosity.

“Certainly not,” replied her mother. “Always keep away from anything like that. I think that the car probably was stolen and that the owner is identifying it.”

In a few minutes Philip came back to the car, while Campbell was helping the other gentleman unfasten the Van Buskirk’s tire from the back of the stolen machine. Philip brought his car up close, the tire was transferred to the place where it belonged, and the journey was resumed.

“Yes,” said Philip, in answer to the questions. “They caught the fellow outside of town and brought him in. This gentleman had telephoned to the police and by good luck had just arrived on the trolley car. He had had other business there and just happened to stop, had telephoned several towns. The man confessed to having stolen our tire, and the other man knew it was not his, so it was quickly attended to. It seems that this fellow is wanted on several charges. The police seemed to know him. He had a gun, as we thought he would, and tried to use it when they caught him.”

“He was an ugly customer,” remarked Campbell.

“We are very fortunate to have escaped so well,” said Mrs. Van Buskirk. “If you had not closed the windows and locked the car, Philip, I suppose he might have stolen more.”

The rest of the journey was pursued without any hindrance or unpleasant experiences. It seemed to the girls who were the guests that it was a beautiful dream of passing trees, hills, water and sky, seen from the midst of comfort and good companionship. Then came New York and the handsome home of the Van Buskirks.

Lilian and Betty were as much impressed as Hilary had been, upon her first visit, with the beauty and quiet elegance of Cathalina’s home. Betty shared Cathalina’s room with its blue, silver and white fittings, while Hilary and Lilian occupied the rose room, which had been Hilary’s upon that memorable Christmas time. “I thought it would be more fun for us to be close together,” Cathalina said, “but if any of you would like to be alone, it can just as well be arranged.”

“Who would want to be alone?” replied Lilian. “This is delightful.”

The baggage had come through safely, and the girls found their prettiest frocks all pressed and hanging in the closets. Cathalina’s maid was a different one from the girl Hilary remembered, and Cathalina laughed as she explained what Phil called her “alliterative succession” of maids, Etta, Edna, Ethel and now Edith, “my ‘French’ maids,” said Cathalina. “The last ones did not stay long. Mother did not think they were good, but Edith is fine. She is English.”

Hilary and Lilian found another maid appointed to answer their bell, and confided to each other that they hoped not to make any mistakes in their own deportment regarding her. “Oh, it does not make any real difference,” said Hilary. “If we are simple and nice, as we ought to be, I guess we shall not make any very bad mistakes. I think, Lil, that you might as well get used to one!”

Lilian blushed, for Hilary’s meaning was not hard to understand, and the state of Philip’s feeling toward Lilian had been quite apparent on their automobile trip. However, within the next twenty-four hours Lilian’s ideas were to change somewhat.

Cathalina and Philip were as busy as could be in those first hours after their arrival, making arrangements for different sorts of good times.

“You will excuse me, won’t you, girls, while I call up the family and get things started. I want some of them to come over tonight and I must find out who of the friends are in town.” Cathalina, fresh from her bath, her soft brown hair prettily arranged by her maid, a cool, light summer dress floating about her, was an attractive picture as she sat by the little table to telephone.

“Is that you, Ann Maria? Good! I thought you girls would be back in time for us to see you. Did you have a great time? Yes, we had a wonderful summer at camp—more fun! Yes, we just came in an hour or so ago. How are Uncle and Aunt Knickerbocker? Oh, is that so? Well, why can’t you stay all night here, then—you and Louise? We want you all to come after dinner tonight, to meet the girls. I’m going to call up Louise and Nan and Emily. Robert Paget will get in before dinner, Phil thinks. I’m calling Rosalie and Lawrence Haverhill, too. Anybody else that you can think of? Somebody we could ask on short notice. Oh, yes. I’ll get Phil to call him. We’ll have light refreshments. Come early.”

Cathalina danced away and over to Philip’s room, where she knocked.

“That you, Kitsie? All right, come in. That’s all, Louis. There are the letters to be mailed.”

Philip was as freshly attired as Cathalina and making great plans for happy hours with Lilian. “Be seated, Miss Van Buskirk!”

“No, thanks, Phil—I just had a little matter to speak to you about. If Mother thinks it’s all right, would you mind calling up a young man I met at school last year—if he’s in town—and can come—”

“Lots of ‘ifs’ in the way, it seems,” said Philip, his eyes sparkling. Why should Philip worry about anything? Was not the sweetest girl in the world in the same house with him?

“Yes, Philly, that’s so. I’m not sure it’s proper to be so informal with him, but Mother will know about that. It’s the Captain Van Horne that was nice to me at school last year, you know. We exchanged addresses and he asked me if he could call, or I invited him to call, I don’t remember which. He is an instructor in the military school.”

“I remember about him. Of course it’s proper for me to ask him to come around, and if he can’t come tonight, shall I ask him for the other party, or to call to see us?”

“Yes, please. You’re a good brother.”

“By the way, Cathalina, after the telephoning could you manage to let me have Lilian to myself a while—out on the veranda or somewhere? I’ll find the place, if I can get the girl!”

“Yes, Philly, indeed I will. You’ve hardly had a good visit with Lilian since we started from Boston.” Cathalina gave Philip a roguish glance as she whirled out of the room. Phil mischievously winked, put his hand over his heart and said, “I now call up the Van Horne at his ancestral abode, but I was saving you for Bob Paget.”

“Oh, let Betty have him,” Cathalina called as she disappeared down the hall in the direction of the girls’ room. “Boys always like Betty.”

“What is that, Cathalina?” asked Betty. “Seems to me I heard my name.”

“You did. I was just making the wise remark to Philip that boys always like you.”

“How horrid! That doesn’t sound like you, Cathalina.”

“You don’t know the circumstances. We were planning who was for whom at our party and I mentioned you for a certain young man and made that remark. You are always lovely and pretty and the boys do like you.”

The girls had been having a confab in the rose room in Cathalina’s absence. Lilian was looking in the mirror to see if the maid’s hair dressing had been effective. “Oh, Cathalina,” said she, “please tell me about some of your relatives that will be here. Remember that we haven’t been here before, like Hilary.”

“You’ll not have such a time as poor Hilary had,” said Cathalina with a laugh. “She had to meet the whole clan, aunts, uncles and cousins, at our regular Christmas gathering, and had a great time to straighten us all out. Campbell insisted on giving her the whole family history.”

“Probably that was just as well,” said Betty, with meaning.

“Tonight,” continued Cathalina, “there’ll just be the young folks. Campbell will bring his sisters over, or at least Emily. Sara is younger. Emily is about a year older than Campbell. Then Louise Van Ness, who is about Phil’s age, and Nan Van Ness, who is my age, will be here. Rosalie Haverhill is an old friend of mine, and her brother Lawrence, who has been attending the same school as Phil, has been one of his best friends. Oh, yes, Ann Maria Van Ness is the niece of Uncle and Aunt Knickerbocker, who lives with them. She and Louise have been great chums, and in the same set of young folks with Phil and Lawrence. Robert Paget is Phil’s friend, you know, who is coming today. Phil had a telegram from him not long ago. He’s going to the station in the car pretty soon to meet him. He and Phil and Campbell and Lawrence are all in the same fraternity. Ann Maria suggested another friend of hers and Philip’s, but he had another engagement. This will be a very informal affair indeed, gotten up on the spur of the moment, as it were. There’ll not be enough boys to go around, of course, but we can all have a jolly talk, and I’m going to have a real party before you leave.”

By this time the girls were on their way downstairs. Philip was in the hall with some fresh roses just picked, which he proceeded to give to the girls, saving Lilian’s till the last. He was so evidently waiting for her that the other girls kept on, out upon the wide porch with its fine columns, while Philip drew Lilian into the library, and put the rose in her hair. “I want to show you the gem of our whole place,” said he; “Dad’s library.” Many, many times in days to come was Lilian to remember that cool, beautiful room, the quiet talk with Philip, the rose in her hair and the look in Philip’s eyes.

They walked around looking at the books, then sat down on the window-seat to talk, more about the music, of which they were both so fond, than of the books.

“Your voice, Lilian, is wonderful. It has a quality in it that holds your audience. You’ve felt it yourself, I suppose.”

“I love it when I can hold them,” replied Lilian, “but I’m usually not thinking about them, only of what I’m singing.”

“You ought to be studying with some big New York teacher. We have better teaching right here in America than they have in Europe, and have had for years, so my professor at school said.”

“Oh, wouldn’t I love to study here!”

“Are you going back to Greycliff after this year?”

“I can’t tell. We all love Greycliff so, but Hilary thinks that her people may plan for her to go somewhere else, and if our ‘quartette’ is broken up we may not be so crazy about staying. We are going to have this year together, anyhow.”

“Campbell and I get through college this year. You remember what I said about the war—when we were in the pine grove at camp?”

“Yes, indeed,” said Lilian soberly.

“Well, we have promised the folks to finish this year at college, if possible, or at least not to go without their consent if we do get into the war. And you will write all year to me, won’t you, as you promised?”

“Oh, yes.”

“There is such a lot of us that I thought I’d better make sure to remind you. And, Lilian, did you mind what I said about——”

But Lilian did not hear the rest of this remark, for at this point Mrs. Van Buskirk entered the library and smilingly informed Philip that he would scarcely have time to reach the station before Robert Paget’s train arrived. Philip looked at his watch.

“You’re right, Mother! Excuse me, Lilian. I’m trying to persuade Lilian that she ought to have her voice cultivated right here in New York,” and Philip dashed off.

While Lilian and Mrs. Van Buskirk were chatting, Cathalina came in.

“I’ve been seeing to the refreshments for tonight, Mother. I believe you will have to plan for the real party with the housekeeper.”

“Very well. You want something more elaborate, I suppose.”

“Oh, yes; just as elaborate as I can have it.”

“Will it be very formal?” asked Lilian, who was thinking of her somewhat limited wardrobe. The girls had not taken much to camp except the regular camp attire.

“Oh, no. The boys would hate it. It is too hot for dress suits. They can wear their white flannels or palm beach suits or anything they like. I’ll have Phil call up all the boys and tell them ‘informal.’ There isn’t time to send written invitations ‘with propriety,’ as Aunt Katherine says, and it will not be such a big party. But I want to have everybody that we are indebted to, if they are in town.”

“What will the girls wear?”

“Their thin silks or lace and net, or sheer cotton stuffs. Your pink organdy will be just the thing, or that little silk that you sing in.”

“I guess I’d better wear the organdy tonight and the silk frock at the party. How would that do, Mrs. Van Buskirk?”

“Nicely, my dear. Anything that you have at school is quite suitable for all our occasions.”

“How comfortable and dear your mother is, Cathalina,” said Lilian after Mrs. Van Buskirk had left the room.

“Yes, isn’t she? And you ought to hear the things she says about you. I believe she likes you even better than Betty and Hilary, but I oughtn’t to say that. Her heart is big enough for our whole quartette. Come on, let’s get the other girls and see what flowers we can find for the rooms.”

“Imagine your having such lovely roses at this time in the year. How do you manage it?”

“They have special care, and some of them are from our little hothouse.”

The four girls were still outdoors when Philip returned with Robert Paget, and turned to look, as “Pat,” back from Boston, took out two bags and a suitcase, and three young men stepped out of the car.

“Three,” said Cathalina in surprise. “I wonder who the other one is. That is Robert in the light grey suit.”

“Why, that looks like Dick!” exclaimed Lilian. “It is Dick! How in the world did Dick——” Lilian started toward the house; then, recollecting that Dick was not the only young man there, drew back. The three young men did not see the girls and went up the steps and into the house.

“Let’s go in and fix the flowers,” said Cathalina, “and by that time the boys will be downstairs, I think, and Mother will know about it at least.”

Mrs. Van Buskirk met the girls in the hall. “Why, Lilian,” said she, “we have a great surprise for you.”

“I saw him,” replied Lilian. “How did it happen?”

“He came to New York on business again, Phil said; did not know that you were here, and he and Robert Paget were on the same train. Phil saw him get off just in front of Robert and, as he said, ‘nabbed him.’”

“He and your father were here while we were in camp, weren’t they?” said Betty, recalling some news of Lilian’s.

“Yes; for years one of Father’s old friends has been wanting to get him into a law firm here in New York, and now that Dick is starting Father is more interested, though he can’t bring himself to leave the old town.” So Lilian explained to Mrs. Van Buskirk and the girls. “He always laughs and says ‘Better be a big toad in a small puddle than a little toad in a big puddle.’”

“I believe your father would be a ‘big toad’ anywhere,” said Mrs. Van Buskirk. “We enjoyed him so much that time he and Richard were out for dinner with us.”

“Oh, wouldn’t it be lovely if your people would move to New York!” exclaimed Cathalina. “Why haven’t you said something about it before?”

“I never thought of it, because Father never gave us any reason to think he would do it. And it didn’t occur to me till now that it might be the reason for this summer’s visits. But I feel sure—almost—that it must be now that Dick is here again. Perhaps he will come if Father does not.”

“That makes another young man for tonight!” and Cathalina waved a hand full of flowers. “Is Dick engaged? Will he be bored at company?”

“No, to both your questions. Dick likes a good time as well as anybody. Oh, there he is!”

“Go on down and meet your sister,” said Philip from the landing, and Robert Paget, who was in the lead, stopped to let Richard North pass. Dick embraced his sister, and turned to greet Mrs. Van Buskirk. As by this time the others had reached the foot of the stairs, general introductions followed.

Dinner had been concluded some time ago. The girls were settling themselves in the swing, or wicker chairs, near one corner of the veranda.

“Lilian, you look like a rose in that pink organdy,” said Betty.

“That’s sweet of you to say, Pansy Girl.” Betty had sometimes been called that since she had worn the pansy dress in the masquerade. “But you look more like forget-me-nots tonight in blue. And Cathalina is like a lily—lilies of the valley and English violets.”

“My white and coral are not much like violets,” said Cathalina.

“Sweet peas, then. They have every color.”

“What’s Hilary, if we must all be flowers?”

“Oh, Hilary’s all the fresh spring flowers that we are glad to see in the spring, hyacinths and lilacs and syringas——”

“Fresh! I like that.”

“Don’t try to put a wrong construction on what I say. Heliotrope and mignonette, that is it.”

“Nonsense,” said Hilary. “I’ll be a sturdy old red geranium that lasts all the year around, and even if you hang it up by the roots in the cellar it grows leaves and flowers the next year.”

“All right, Hilary—our little red geranium!” The girls laughed at this nonsense and looked up in surprise to hear another laugh near by. Mr. Van Buskirk had come out on the porch and stood leaning against a pillar behind them.

“If you want my opinion,” said he, “I should say that this is as pretty a cluster of roses as we ever had at this house, Hilary quite as blooming as the rest.”

“We thank you,” said Betty, rising and curtseying deeply, while the rest followed her example.

“Are you expecting company soon?” inquired Mr. Van Buskirk.

“We told them to come early,” said Cathalina. “I think I see Campbell and Emily now. Do we stay out here or go inside?”

“Out here—why not?” said Philip appearing in the doorway and sauntering out toward them. “There come the Van Nesses. Come on out, Bob. Where’s Dick? Oh, here he comes,” added Philip as the rapid toe-tapping of some one running down stairs was heard, and Richard North followed Robert and Philip. Mrs. Van Buskirk made her appearance before Campbell and Emily had reached the top of the steps. The guests arrived at very nearly the same time and were cordially greeted. Robert Paget had been there before and knew Philip’s relatives, but everybody had to be introduced to Richard North, as well as to his sister and Betty. Mr. and Mrs. Van Buskirk were particularly interested in meeting Captain Van Horne, of whom Cathalina had written. Who was this young man who had succeeded in making an impression on their little girl? He disclaimed the title of captain as he was introduced, saying that it was only appropriate when he was a part of the military school organization, but the Greycliff girls continued to address him as Captain Van Horne.

Campbell’s sister Emily was glad to see Hilary again, and after a little chat with her, passed her over to Campbell, who, she guessed, was hoping to have a good visit with her. And as Cathalina was busy welcoming the different ones, Emily tried to make Captain Van Horne feel at home by chatting with him. It was like Emily, fine girl that she was, unconscious of herself and interested in every church and public or private enterprise to help others. Both were more mature than the rest of the young people.

“And here’s my dear cousin Philip!” exclaimed Ann Maria, handing her wrap and scarf to one of the maids who had come out to assist at this informal affair, and then holding out both hands to Philip. “Come and give an account of yourself. I’ve scarcely seen you all summer.”

“Naturally not, my dear young lady, when you have not been within calling distance. Come and meet our guests.”

Ann Maria Van Ness was as straight as Aunt Katherine, who had brought her up—graceful, with an assured manner and a handsome, striking face. Her voice had a pleasant quality and her dress a style which made Hilary and Lilian feel countrified at once. She fairly took possession of Philip, and claimed considerable attention from the other young gentlemen, all without a single unladylike act.

Philip, upon request, brought out his guitar, and the young company sang the well known songs of the year. When they started the pretty and sentimental song so familiar, then, among college students, “Why I Love You,” Lilian’s voice was so beautiful that all with one accord stopped singing and let Lilian’s soprano and Philip’s tenor finish the last two stanzas. But Ann Maria was fidgety and complained of mosquitoes.

“All right; let’s go in, folks,” invited Philip. “Ann Maria, I want to hear your latest recital number.”

Accordingly, all trooped into the large front room, where Ann Maria sat down at the piano, dashed off the latest popular tunes and finally entered the classical realm, playing a difficult composition exceedingly well.

“She can play well!” exclaimed Hilary, in surprise, to Campbell and Lilian, with whom she happened to be grouped. Robert Paget was near, also, and replied, “Yes, but she can not equal Phil. Wait till I get the old boy started.”

But it was not necessary for Robert to ask Philip. Ann Maria herself made the request, as she rose from the piano. “I have to get in my playing before Philly begins,” said his cousin. “Come and give us your latest composition.”

Philip rather protested, saying, “It is not for the host to play; it is for the guests.” But, seeing they all wanted to hear him, he took his place at the baby grand, played the different compositions they asked for, then placed some music before him and beckoned to Cathalina. After a few words with Philip, she went over to escort Lilian to the piano, Philip rose and said, “We promised several of the family that they shall hear you sing, Lilian. Will you please come now?”

“Yes, indeed,” replied Lilian, “but when I think of the music you people can hear in this city, I do hesitate to sing for you.”

“Oh, but we love your voice,” said Cathalina.

Lilian had scarcely ever found it so hard to sing. She knew that there was at least one listener who was critical, and she felt her own youth and lack of training. But Lilian was always ready to help make the social machine run smoothly, and now moved to the piano with much grace and sweetness. In a few minutes she had forgotten herself in singing to Philip’s sympathetic and beautiful accompaniment, and felt that exaltation which often held her and her hearers as well. A murmur of appreciation greeted her at the end of the first song and they kept her singing for a while, Philip so happy and proud, and Mrs. Van Buskirk leaning forward to listen and watch the flushed face and rapt eyes of the young singer.

Captain Van Horne managed to sit by Cathalina during the music, and in the intervals between numbers she entertained him by telling about the people present or their fun at camp, and asked him about his busy summer.

“My ‘attic’ has been quite warm,” said he, “but I have studied and read in different cool spots, attended my law classes and have filled up my time in other ways.”

Cathalina knew that he was doing something to help make his way, but she did not refer to that. She thought that he looked worn and wished that she might put a little cheer into his dull days. Cathalina was learning much sympathy, as she began to realize the responsibilities that some of her friends had to carry. The old self-centered little girl that knew nothing of life’s serious interests had long since disappeared.

Richard North was becoming acquainted with pretty, plump, fair Louise Van Ness, with Emily, and, of course, with the vivacious Ann Maria.

Nan Van Ness was the cousin of Cathalina’s age who used to copy Ann Maria, whom she greatly admired, as younger girls do admire the older ones sometimes. But Nan, now, had been away to school herself, and like Cathalina, had become interested in many things on her own account. She and Betty were having great fun with Lawrence Haverhill and Robert Paget. Rosalie Haverhill had not come.

It was “a nice party,” as Lilian said to herself, and she wondered why she could not seem to enjoy it more, for Lilian was a gay-hearted girl, at the head of most of the fun among her chums at school. In her heart she knew that it was the relation of Ann Maria to Phil that troubled her. But she went right on, taking part in all the visiting and fun. By chance she was with Louise and Ann Maria when the cooling ices and pretty cakes and fresh fruit were served and Philip himself waited on both her and Ann Maria, with the same courtesy to both!

“He is that way with all the girls,” she thought. “His attention to me hasn’t meant a thing. His ‘musical wife,’ indeed! Ann Maria plays, and I sing.” Lilian was thinking of Philip’s conversation in the pine grove at camp, when he “seemed so serious,” spoke of planning for a musical wife, and first asked her to write to him. And now jealousy whispered that it had not been earnest. All this ran through her mind while she talked to the girls, told of their most thrilling experiences in camp, and laughed with the rest. Ann Maria did not stay all night, as Cathalina had urged her to do. No, indeed. She handed her wraps to Philip to put on for her, and Philip took her home. To be sure, there were others in the car, Campbell, Emily, Louise and Nan, but Ann Maria sat in front with Phil, who drove. And Lilian did not know that Philip had asked his mother if he might not take Lilian, too. “You may, but it isn’t best,” Mrs. Van Buskirk had answered. “Since all the girls can’t go, you’d better not ask any of them.”

The days were few for all the good times. There was so much of the city to be seen, lunches to be taken in odd places, drives here and there, an entertainment or two on Broadway, a dinner at the Stuarts’, and as a climax the “real party.” For this, each lass had a lad, each lad a lass to escort to the tables for the elaborate meal served by Watta and a capable group of waiters. As Mrs. Van Buskirk had decided that there would be time to issue invitations, they had been sent out to all the more intimate circle of Cathalina’s and Philip’s friends.

Philip insisted that he was to have Lilian. Hilary, of course, was assigned to Campbell. Their friendship proceeded on its calm and apparently unsentimental way, but Campbell was there and with Hilary as much of the time as possible. There was quite a discussion between Cathalina and her mother about Captain Van Horne.

“Now, Mother dear,” said Cathalina, “if Captain Van Horne is invited for Emily or Louise, he’ll have to go for her, send her flowers, I suppose, and he hasn’t any car, and I would be right here, and it would be all right if he did not think of flowers.”

Her mother laughed. “You are greatly concerned, Cathalina.”

“Indeed I am. I like him, though I like Robert Paget, too. But Captain Van Horne is older and I think it would be all right for him to take me out to supper, don’t you? He’s a teacher, too.”

“How would you arrange it, then?”

“Let Bob take Betty, or would it be better to have him take Ann Maria?”

“Ann Maria would rather have one of our house guests, I think——”

“Since she can’t have Phil,” finished Cathalina.

“Don’t say that, Cathalina.”

“All right, then; Bob for Ann Maria, and Dick for Louise. They can go for the girls together in our car. Lawrence Haverhill can have Betty. Oh, yes, I had forgotten; he asked Phil if he might not.”

The girlish guests were quite excited when the fateful night arrived. Lovely bouquets had arrived for them. “Look at Cathalina!” said Betty. “With all the flowers she has, she is as excited as any of us over her roses.”

“Well, who sent them?” asked Cathalina. “Wouldn’t you be excited if a distinguished officer in a military school sent you flowers?”

“I am excited,” said Lilian, holding to view the most beautiful roses of all. “And I’m sure nobody could be more gifted than the young gentleman who sent these.”

“Listen to ’em rave,” said Betty to Hilary in pitying tones. “I fancy I hear Lilian sing ‘I Dreamt That I Dwelt in Marble Halls.’”

At this Lilian pretended to advance threateningly upon Betty, who fled behind Hilary. Hilary warded both off, and laughingly warned them that with their nonsense they might easily spoil all the bouquets.

“Don’t worry, Hilary, none of us ever really do anything. We just threaten. I can’t bear any physical nonsense or tricks.”

“Nor I, Lilian,” said Betty.

This social occasion was a much happier one to Lilian than the first, for while Philip was the attentive and gallant host, each lady was provided with an especial escort, and he had at last an opportunity to devote himself to Lilian. But Lilian was an uncertain quantity since she had observed Ann Maria with Philip. Her gay, though friendly, manner rather put a damper on any approach to the sentimental or serious, and she kept to the groups of young friends with whom they were surrounded. Mrs. Van Buskirk had engaged several professional musicians, in whose performance Lilian was especially interested. “You have everything, Philip,” she said once, “and you ought to be thankful!”

“I am,” said Philip, “but I haven’t everything I want. And sometimes I think I shall have to do without what I want most.”

That speech troubled Lilian for a moment, but just at that point Ann Maria and Robert Paget came up, with Nan Van Ness and her escort, and Philip turned a smiling face upon Ann Maria, as he replied to one of her sallies. “I need not worry about him,” thought Lilian.

As she and Hilary crept into bed late that night, too tired to sleep, she asked Hilary if Ann Maria were Cathalina’s first cousin.

“Oh, no,” replied Hilary. “I believe her father was a first cousin of Mrs. Van Buskirk’s. Oh, Lilian, wasn’t it fine to have a maid pick up after you? I’m getting spoiled in the lap of luxury. It’s a good thing I’m leaving. How convenient for you, too, that your brother could stay. I believe he had a good time, and now he can take you home.”

“Yes, we’ll have a good chat tomorrow on the train and I’ll have a better chance to find out what he and Father are going to do. Good night, Hilary.”

“Not so very closely related. Then Phil could marry Ann Maria if he—they—wanted to.”

A third year at Greycliff begun! Could it be possible? Where had the time gone? When the girls thought of their studies, they realized that there had been hard work enough to account for time, but when they thought of their frolics! And now they were in the collegiate classes. After all it was jolly to be a junior collegiate at Greycliff instead of a college freshman somewhere else. The senior collegiates were paying them a great deal of attention because of the society “rushing” which began at once. Most of these girls in the upper class they knew very well, because they had been senior academy students when some of our Lakeview corridor girls first entered as juniors in the academy.

Greycliff was as beautiful as ever, with its ivied buildings, velvet front campus, its “high hill” back of Greycliff Hall, its beaches, cliffs, windswept lake and tiny river. A new “Greycliff,” a larger launch than the one which had been wrecked the previous year, rocked on the water at the dock, to be raved over by the enthusiastic girls.

“I’m glad they didn’t change the name, aren’t you?” observed Hilary. “It’s so appropriate.”

“I don’t know but I’d rather have a new name. It’s hard for me to forget that time when we were all in the water, and afterward when we didn’t know whether Dorothy and Eloise would ever come to or not.”

“Oh, that’s just nerves, Betty. You’ll be all right after your first ride in this one. Think of bobbing up and down on the lake once more! I made myself get over it. It’s never going to happen again. I love the water and I’m going to be in it and on it as much as possible. Besides I’ve learned to swim so much better at camp this summer.”

“Yes,” acknowledged Betty, “we feel perfectly at home in water now, and that would make a difference even in a storm, I suppose.”

“I don’t intend to lose what I’ve gained, either,” added Cathalina. “I don’t suppose I’ll ever have the endurance that some folks have, but I can keep active, and, as you say, Betty, be at home in the water. No matter how heavy my school work is, I’m going to keep in the swimming classes, either in the lake, river or pool, as they have them.”

“Now, then,” said Lilian, “doesn’t Betty make a nice mummy? I’ve even put a pillow for her head.”

“Look out, and don’t get any sand in my eyes,” said Betty, winking, as Lilian patted the sand around her slender figure. “Now you’ve gotten my sandal loose,” and the “mummy” wiggled her sandaled feet free from the sand coverlet and sprang up. “Come on; one more dive and then we’ll go up and get ready for the Psyche Club meeting.”

The September day had been warm and ideal for beach parties and swimming. The sandy beach was well occupied by water sprites in bathing suits of different colors. Classes had closed earlier than usual that Friday afternoon, to let the girls take advantage of the unusually warm day so late in September. Miss Randolph herself, and most of the women teachers, were down, and were having a teachers’ beach party. But it was now almost time for dinner and some of the parties were beginning to break up.

“If the teachers are having such a big beach party, the dinner will be light, I’m afraid,” said Lilian, as the girls went up to the hall.

“You forget the men,” said Isabel Hunt, who had joined them. “They didn’t have any beach parties, and will be as hungry as we are. Trust the matron to remember that.”

“Anyhow we are going to have eats at the Psyche Club. We have a birthday cake for Virgie, you know. You didn’t hint a word to her, did you, Isabel?”

“Not I, and she has forgotten that we said our first feast would be in her honor.”

“Don’t be too sure of that. Remember, she said she never had a birthday celebrated in her life.”

“Well, she thinks we have forgotten, then; nobody has said a word about her birthday.”

“Yes, there has,” said Betty. “You know she came right on to Greycliff from camp, and I asked her if they celebrated her birthday, on the first, you know, and she said that she hadn’t told anybody about it, so of course nobody did.”

“Oh, they don’t celebrate birthdays at Greycliff!”

“No, but there were several girls here the latter part of the summer, and I thought perhaps they had had some fun.”

“Anyway, no one has called this a ‘feast,’ and I’m sure she can’t suspect about the cake.”

“Let’s hope so.”

“What else are you going to have?” asked Isabel.

“Sandwiches and lemonade,” replied Hilary. “They are going to let us have some ice. And we are going to have ice-cream delivered from Greycliff Village at exactly eight-thirty, and we have a box of candy for Virgie. Cathalina had Philip send it. That’s all beside the cake. We have permission to stay up till ten o’clock if we are quiet.”

“I think it would be fun if we all gave Virgie something.”

“It might make her feel uncomfortable,” said sensible Hilary. “We did think of getting some ten-cent store things, just for fun, but decided not to. Remember how dignified we are getting to be—collegiates!”

“And we have a lot of business to transact, too. Aren’t we going to elect officers, and maybe a new member or two?”

“I don’t know, Isabel. For my part I’d rather just have a social meeting. We might talk things over, of course.”

“Oh, yes, Hilary,” said Betty; “let’s not have any business this time.”

“Why bother to make any plans at all?” remarked Lilian; “no hurry about anything.”

“True,” said Hilary; “but we’ve got to straighten up our little suite before dinner. It’s a sight. We’ve been letting things go all week in the excitement of getting started in classes and everything else. Besides we have forgotten how to live at Greycliff. First we had simple living and taking turns at the little bit we had to do at camp. Then we had luxury at Cathalina’s with nothing to do, and if the rest of you were like me at home you did little but scramble around for some school clothes to wear, and visit with your folks. I followed Mother around and helped a little, while we talked all the time—so much to tell about the whole summer, and so little time to tell it in. One morning it was too funny. We had a regular procession. The maid was away, and I wiped the dishes for Mother and talked, while Gordon, Tommy, June and Mary were all in the kitchen, listening and putting in a little occasionally, especially June about camp. Then, when we went in another room, they all followed, and when Mother and I went out into the yard to hang up a few towels to dry, Father saw us, coming out in line, and nearly perished with mirth.”

“Imagine the dignified Dr. Lancaster’s ‘perishing with mirth’!” said Isabel.

“That was poetic exaggeration,” admitted Hilary.

After dinner and the usual stroll outdoors till darkness fell and the bell for study hours rang, the Psyche Club began to gather in the suite occupied by Cathalina and Betty, Hilary and Lilian, for there was the same arrangement which had been made the year before. Juliet Howe, Pauline Tracy, Eloise Winthrop and Helen Paget, also, were together. Isabel Hunt and Avalon Moore had moved into a suite with Virginia Hope and Olivia Holmes, but Isabel and Virginia roomed together, and Avalon was with Olivia. Whether Virginia and Olivia should now be taken into the Psyche Club was a question to be settled. Evelyn Calvert, who had been with the girls at camp, was invited to this gathering, but Helen Paget was to go after her, and Isabel was to bring the other girls at the proper time.

“Are we all here?” asked Hilary at last. “Let’s have a brief business meeting and get the elections over. What do you say, girls?”

“All right,” came from various quarters, and the president tapped for order.

“Has the nominating committee a report?”

“Yes, Madam President,” replied Isabel, its chairman. “We offer the names of Cathalina Van Buskirk for president and Lilian North for secretary and treasurer.”

“How shall we elect the officers? Are there any other names suggested? Sit down, Cathalina and Lilian. Nobody can refuse an office in the Psyche Club except when in—incapacitated!”

“I move that we elect by acclamation.”

“Is this motion seconded?”

“I second the motion.”

“It has been moved and seconded that Cathalina and Lilian be president and secretary, respectively. Any remarks? If any one has anything to say let him say it now or else forever after hold his peace!—except Cathalina or Lilian; they can’t say anything till afterward.”

The girls were all laughing at this high-handed proceeding.

“All in favor say ‘Aye!’” A chorus of “Ayes” responded.

“All opposed, ‘No.’” Silence.

“Cathalina and Lilian are unanimously elected.”

“We will now regard the place where Cathalina is as the ‘chair.’ My place is too comfortable to give to anybody.”

Cathalina gave smiling thanks to the girl for her “high honor,” and suggested that remarks about election of members were in order if some one would make a motion.

“I move, Madam President, that, considering our experience last year, we do not elect any members until their sentiments toward the Psyche Club be sounded out.”

“Hear, hear!” said Eloise. “I think that Isabel’s idea is good. Do you remember how we felt when Dorothy and Jane refused?”

“There were special influences there, and we might have known!”

“That’s so, Lilian. Did we ever tell you how we appreciated your being the victim?”

“Oh, I didn’t mind asking them, and I tried to take it gracefully. Shall we try to get them this year?”

“I was sure they hated to refuse, so let’s wait and see if they are as intimate with that other crowd as they were last year. And when the invitations are out for the collegiate literary societies it may make a difference, too.”

“How about Virginia and Olivia and Evelyn? I think it would be lovely to invite them tonight if we are going to do it.”

“Does anybody know how they feel about it?”

“I should say we do!” said Isabel and Avalon in one breath. “Of course they haven’t said a thing about it, but we can tell by looks and little remarks about the pins or compliments to you girls that they would be tickled to death if we asked ’em.” This was Isabel who spoke. “I’m sure that we’ll be proud to have Virginia wear our pin, and while Olivia isn’t quite so good a student, she is a sweet, generous girl. Is there anybody that doesn’t like her?” Isabel looked around the circle, while the girls shook their heads.

“This is all out of order, girls,” said the new president. “There is no motion before the house! And Isabel’s motion, which was not seconded, was negative so I can’t put it.”

“I move, Madam President,” said Isabel, very formally, “that we elect the guests who are coming tonight.”

“I second the motion.”

Cathalina put the motion and it was carried, the girls mentioning the names of Olivia, Virginia, and Evelyn Calvert. “Go for them, girls,” said Cathalina, “and spread the feast. Won’t it be fun?”

“Hurry up, Hilary, and get the cake out in the middle of the table. Where are the candles?”

“In it, Betty. Isn’t it a beauty? Virginia’s name in red cinnamon drops just like the kiddies at camp!” The sandwiches were set out, the ice fixed in the lemonade, and by that time the guests were heard coming down the hall and excited voices drew nearer.

“Who do you suppose is here?” cried Isabel, leading the way, and ushering in Diane Percy, while the other guests, all smiles, waited in the doorway.

“Diane!”

“Diane!”

“The other sweet P!”

“Why, Diane! You never told me you were coming!” cried Helen Paget. “My darling ‘Imp’!”

Virginia and Olivia were the only ones who would not have understood who Diane was, and it had been explained to them on the way, as with Isabel they had met Evelyn, Diane and Pauline. They were much amused to hear that Diane and Helen had been dubbed the “Imps” by some offended collegiates in their first year at Greycliff and had also been known as the sweet P’s—Percy and Paget.

After Diane had been duly embraced and welcomed, Cathalina called the girls to order for a moment and they dropped where they were, either into chairs or on the floor. Cathalina had had a brilliant thought, and explaining that she had a Psyche Club message to deliver which would not be a secret but for a few moments, she called Betty to her, whispered a moment, something which made Betty laugh and wave her hand in approval. Betty then made the rounds of the members, whispered a question, which was answered in every case with a fervent “Yes, indeed!” and returned to Cathalina with the report, announced publicly: “Your question, O most worthy President, is answered in the affirmative by every member of the club.”

“So be it,” said Cathalina. “Dear guests of the Psyche Club, a short time before you were summoned a motion was presented and passed electing our guests to membership in the Psyche Club. I have the honor, then, to ask Miss Olivia Holmes, Miss Virginia Hope, Miss Evelyn Calvert and Miss Diane Percy if they will join us.”

The girls enjoyed the surprised and happy expressions of Virgie and Olivia. Diane had not heard of the Psyche Club, but rose and said, “Whatever that club may be, beloved sisters, I am yours. Oh, isn’t this fun? Girls, I don’t see how I stood it not to come back last year!”

Evelyn told the girls that she had been aching for one of the butterfly pins, to say nothing of the honor of belonging to the club. Virgie and Olivia expressed their pleasure in a modest way, and Cathalina rapped for order again.

“There is one more happy event which I have the pleasure to announce. Part, indeed a great part, of this celebration is in honor of the birthday of one of our number.” Here the guests were wondering whose it was. “The day itself is past, but we were not here to celebrate it, so we are having a little spread in honor of Miss Virginia Hope. Minions, bring forward the banquet table!” Hilary and Betty were the minions who carried the table from behind a screen to the middle of the floor.

Virginia blushed deeply and stood dumbly while this was done, then lit the tapers as she was told. The girls joined hands and sang the camp birthday song as they circled around Virgie and the birthday cake. “Oh, it’s perfectly lovely of you! I’ll never get over it!” Isabel pretended to support her when the box of candy was presented by Lilian, and then the girls settled down to the joys of eating and talking, both of which they seemed to be able to do at the same time.

Eloise looked a bit sober. Lilian said afterward that she thought she saw tears in her eyes, and wondered why. But she soon brightened up and took her plate over close to Diane, where she sat down. As soon as she had opportunity, she said to Diane, “You used to room with Helen, you know, and I have been waiting to get a chance to tell you that I’ll not stand in your way. I’m sure that Miss Randolph can arrange something for me, and you can have your place with Helen back. I suppose we can’t do it tonight, but just as soon as it can be arranged.”

“Aren’t you a dear!” exclaimed Diane. “It is just like you, Eloise, but I wouldn’t think of letting you do it. It is all arranged, my dear girl. My trunk was just brought up to Evelyn’s room tonight. She and I, with Dorothy Appleton and Jane Mills, have a suite together.”

“Dorothy Appleton and Jane Mills!” exclaimed Eloise.

“Why do you exclaim over that?”

“Nothing, only—I’ll tell you some time. They are fine girls—and, Diane, it is lovely of you to let me stay with Helen.”

“I wanted to surprise Helen, so I did not write to anybody except to Evelyn after Miss Randolph suggested this arrangement. I’ve known Evelyn for a long time, though we were not very chummy that first year, and we shall be as happy as can be. You see I did not know whether I could come this year or not, and did not dare make arrangements till I was sure.”

Diane told Helen and some of the other girls about Eloise’s intended sacrifice, and Cathalina happened to repeat the story to Miss Randolph in one of her talks with her; for Miss Randolph never forgot to have an occasional visit with the niece of her firm friend, Katherine Knickerbocker. Not long afterward, Miss Randolph gave her first monthly address to the girls in the chapel. She had chosen as her subject “Heroines,” and in the course of her remarks referred to a girl who was willing to give up her cherished place in one of the best suites in school for the happiness, as she thought, of two friends. “A girl who does any act, great or simple, which requires courage and unselfishness, physical or spiritual, is a heroine. We want our girls to get so into the habit of doing the brave, noble thing, and of making the higher choice, that nothing else will ever occur to them. We want to train heroines in Greycliff!”

“Mercy sakes!” exclaimed Lilian, putting her books upon the table and inviting Isabel and Pauline to take seats by a wave of her hand. Cathalina, Betty, Hilary, Olivia and Eloise entered at the same time.

“Here’s Cathalina wanting me to take a duty in the Latin Club,” continued Lilian, “Hilary rooting for the French Club, Isabel for the Dramatic Club, everybody for the Collegiate Glee Club, to say nothing of the collegiate orchestra and the literary societies, if we get invited. I see what is ahead of me. When I am going to get time for mere studies is a question!”

“Nonsense, Lilian,” said Pauline, “you don’t have to prepare much for these clubs. The glee club practice and the different meetings only come at times when we’d be visiting or fooling around outdoors. The glee club will be adorable, and the girls always give one concert at Greycliff Village, and perhaps we are going to the military school this year, and to Highlands, too.”

“Listen!” said Lilian. “I have two hours of practice every day, two lessons in voice a week, and one in violin.”

“So have I,” said Eloise, “only it is piano instead of violin.”