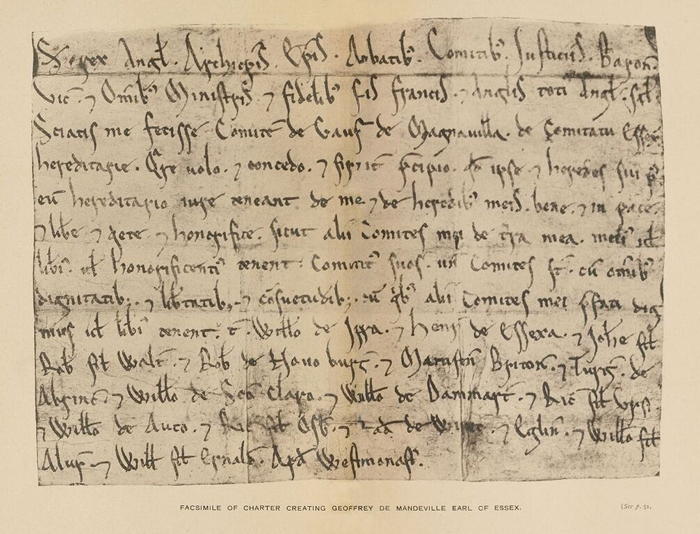

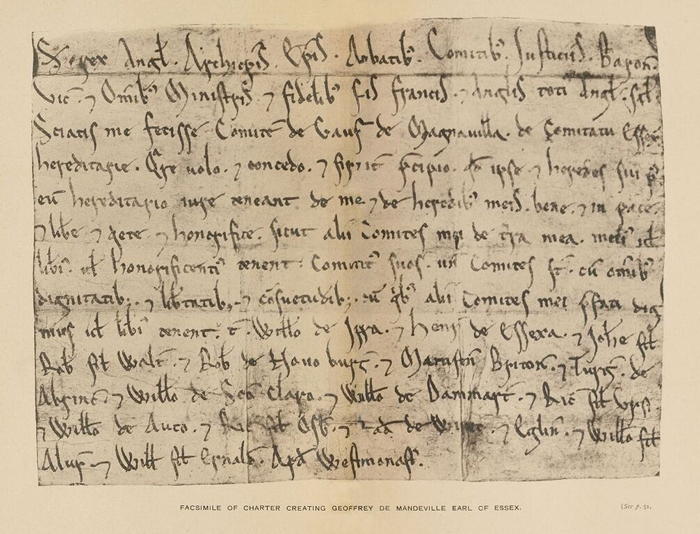

FACSIMILE OF CHARTER CREATING GEOFFREY DE MANDEVILLE EARL OF ESSEX (see p. 51).

Transcriber's Note:

Obvious printer errors have been corrected. Hyphenation has been rationalised. Inconsistent spelling (including accents and capitals) has been retained.

The sidenotes to the Empress' Charter in Chapter 4 have been transferred to "pop ups" that accompany underlined words. These may not display properly in all applications.Footnote references in the genealogical tables are not hyper-linked to the corresponding footnotes. Small capitals in the tables have been replaced by full capitals. Italics are indicated by _underscores_. The tables in Appendices K and U have been split into two in order to reduce their width.

Some references to years are encased in square brackets, as for example [1136]. To avoid confusion with the numbered footnotes, these references have instead been encased in rounded brackets.

FACSIMILE OF CHARTER CREATING GEOFFREY DE MANDEVILLE EARL OF ESSEX (see p. 51).

GEOFFREY DE MANDEVILLE

A STUDY OF THE ANARCHY

BY

J. H. ROUND, M.A.

AUTHOR OF "THE EARLY LIFE OF ANNE BOLEYN: A CRITICAL ESSAY"

"Anno incarnationis Dominicæ millesimo centesimo quadragesimo primo inextricabilem labyrinthum rerum et negotiorum quæ acciderunt in Anglia aggredior evolvere."—William of Malmesbury

LONDON

LONGMANS, GREEN, & CO.

AND NEW YORK: 15 EAST 16ᵗʰ STREET

1892

All rights reserved

"The reign of Stephen," in the words of our greatest living historian, "is one of the most important in our whole history, as exemplifying the working of causes and principles which had no other opportunity of exhibiting their real tendencies." To illustrate in detail the working of those principles to which the Bishop of Oxford thus refers, is the chief object I have set before myself in these pages. For this purpose I have chosen, to form the basis of my narrative, the career of Geoffrey de Mandeville, as the most perfect and typical presentment of the feudal and anarchic spirit that stamps the reign of Stephen. By fixing our glance upon one man, and by tracing his policy and its fruits, it is possible to gain a clearer perception of the true tendencies at work, and to obtain a firmer grasp of the essential principles involved. But, while availing myself of Geoffrey's career to give unity to my theme, I have not scrupled to introduce, from all available sources, any materials bearing on the period known as the Anarchy, or illustrating the points raised by the charters with which I deal.

The headings of my chapters express a fact upon which I cannot too strongly insist, namely, that the charters granted to Geoffrey are the very backbone of my work. By those charters it must stand or fall: for on their {vi} relation and their evidence the whole narrative is built. If the evidence of these documents is accepted, and the relation I have assigned to them established, it will, I trust, encourage the study of charters and their evidence, "as enabling the student both to amplify and to check such scanty knowledge as we now possess of the times to which they relate."[1] It will also result in the contribution of some new facts to English history, and break, as it were, by the wayside, a few stones towards the road on which future historians will travel.

Among the subjects on which I shall endeavour to throw some fresh light are problems of constitutional and institutional interest, such as the title to the English Crown, the origin and character of earldoms (especially the earldom of Arundel), the development of the fiscal system, and the early administration of London. I would also invite attention to such points as the appeal of the Empress to Rome in 1136, her intended coronation at Westminster in 1141, the unknown Oxford intrigue of 1142, the new theory on Norman castles suggested by Geoffrey's charters, and the genealogical discoveries in the Appendix on Gervase de Cornhill. The prominent part that the Earl of Gloucester played in the events of which I write may justify the inclusion of an essay on the creation of his historic earldom, which has, in the main, already appeared in another quarter.

In the words of Mr. Eyton, "the dispersion of error is the first step in the discovery of truth."[2] Cordially adopting this maxim, I have endeavoured throughout to correct {vii} errors and dispose of existing misconceptions. To "dare to be accurate" is, as Mr. Freeman so often reminds us, neither popular nor pleasant. It is easier to prophesy smooth things, and to accept without question the errors of others, in the spirit of mutual admiration. But I would repeat that "boast as we may of the achievements of our new scientific school, we are still, as I have urged, behind the Germans, so far, at least, as accuracy is concerned." If my criticism be deemed harsh, I may plead with Newman that, in controversy, "I have ever felt from experience that no one would believe me to be in earnest if I spoke calmly." The public is slow to believe that writers who have gained its ear are themselves often in error and, by the weight of their authority, lead others astray. At the same time, I would earnestly insist that if, in the light of new evidence, I have found myself compelled to differ from the conclusions even of Dr. Stubbs, it in no way impeaches the accuracy of that unrivalled scholar, the profundity of whose learning and the soundness of whose judgment can only be appreciated by those who have followed him in the same field.

The ill-health which has so long postponed the completion and appearance of this work is responsible for some shortcomings of which no one is more conscious than myself. It has been necessary to correct the proof-sheets at a distance from works of reference, and indeed from England, while the length of time that has elapsed since the bulk of the work was composed is such that two or three new books bearing upon the same period have appeared in the mean while. Of these I would specially mention Mr. Howlett's contributions to the Rolls Series, {viii} and Miss Norgate's well-known England under the Angevin Kings. Mr. Howlett's knowledge of the period, and especially of its MS. authorities, is of a quite exceptional character, while Miss Norgate's useful and painstaking work, which enjoys the advantage of a style that one cannot hope to rival, is a most welcome addition to our historical literature. To Dr. Stubbs, also, we are indebted for a new edition of William of Malmesbury. As I had employed for that chronicler and for the Gesta Stephani the English Historical Society's editions, my references are made to them, except where they are specially assigned to those editions by Dr. Stubbs and Mr. Howlett which have since appeared.

A few points of detail should, perhaps, be mentioned. The text of transcripts has been scrupulously preserved, even where it seemed corrupt; and all my extensions as to which any possible question could arise are enclosed in square brackets. The so-called "new style" has been adhered to throughout: that is to say, the dates given are those of the true historical year, irrespective of the wholly artificial reckoning from March 25. The form "fitz," denounced by purists, has been retained as a necessary convention, the admirable Calendar of Patent Rolls, now in course of publication, having demonstrated the impossibility of devising a satisfactory substitute. As to the spelling of Christian names, no attempt has been made to produce that pedantic uniformity which, in the twelfth century, was unknown. It is hoped that the index may be found serviceable and complete. The allusions to "the lost volume of the Great Coucher" (of the duchy of Lancaster) are based on references to that compilation {ix} by seventeenth-century transcribers, which cannot be identified in the volumes now preserved. It is to be feared that the volume most in request among antiquaries may, in those days, have been "lent out" (cf. p. 183), with the usual result. I am anxious to call attention to its existence in the hope of its ultimate recovery.

There remains the pleasant task of tendering my thanks to Mr. Hubert Hall, of H.M.'s Public Record Office, and Mr. F. Bickley, of the MS. Department, British Museum, for their invariable courtesy and assistance in the course of my researches. To Mr. Douglass Round I am indebted for several useful suggestions, and for much valuable help in passing these pages through the press.

| Page | ||

| CHAPTER I. | ||

| The Accession of Stephen | 1 | |

| CHAPTER II. | ||

| The First Charter of the King | 37 | |

| CHAPTER III. | ||

| Triumph of the Empress | 55 | |

| CHAPTER IV. | ||

| The First Charter of the Empress | 81 | |

| CHAPTER V. | ||

| The Lost Charter of the Queen | 114 | |

| CHAPTER VI. | ||

| The Rout of Winchester | 123 | |

| CHAPTER VII. | ||

| The Second Charter of the King | 136 | |

| CHAPTER VIII. | ||

| The Second Charter of the Empress | 163 | |

| CHAPTER IX. | ||

| Fall and Death of Geoffrey | 201 | |

| CHAPTER X. | ||

| The Earldom of Essex | 227 | |

| APPENDICES. | ||

| A. | Stephen's Treaty with the Londoners | 247 |

| B. | The Appeal to Rome in 1136 | 250 |

| C. | The Easter Court of 1136 | 262 |

| D. | The "Fiscal" Earls | 267 |

| E. | The Arrival of the Empress | 278 |

| F. | The Defection of Miles of Gloucester | 284 |

| G. | Charter of the Empress to Roger de Valoines | 286 |

| H. | The "Tertius Denarius" | 287 |

| I. | "Vicecomites" and "Custodes" | 297 |

| J. | The Great Seal of the Empress | 299 |

| K. | Gervase de Cornhill | 304 |

| L. | Charter of the Empress to William de Beauchamp | 313 |

| M. | The Earldom of Arundel | 316 |

| N. | Robert de Vere | 326 |

| O. | "Tower" and "Castle" | 328 |

| P. | The Early Administration of London | 347 |

| Q. | Osbertus Octodenarii | 374 |

| R. | The Forest of Essex | 376 |

| S. | The Treaty of Alliance between the Earls of Hereford and Gloucester |

379 |

| T. | "Affidatio in manu" | 384 |

| U. | The Families of Mandeville and De Vere | 388 |

| V. | William of Arques | 397 |

| X. | Roger "de Ramis" | 399 |

| Y. | The First and Second Visits of Henry II. to England | 405 |

| Z. | Bishop Nigel at Rome | 411 |

| AA. | "Tenserie" | 414 |

| BB. | The Empress's Charter to Geoffrey Ridel | 417 |

| EXCURSUS. | ||

| The Creation of the Earldom of Gloucester | 420 | |

| ADDENDA | 437 | |

| INDEX | 441 | |

Before approaching that struggle between King Stephen and his rival, the Empress Maud, with which this work is mainly concerned, it is desirable to examine the peculiar conditions of Stephen's accession to the crown, determining, as they did, his position as king, and supplying, we shall find, the master-key to the anomalous character of his reign.

The actual facts of the case are happily beyond question. From the moment of his uncle's death, as Dr. Stubbs truly observes, "the succession was treated as an open question."[3] Stephen, quick to see his chance, made a bold stroke for the crown. The wind was in his favour, and, with a handful of comrades, he landed on the shores of Kent.[4] His first reception was not encouraging: Dover refused him admission, and Canterbury closed her gates.[5] On this Dr. Stubbs thus comments:—

"At Dover and at Canterbury he was received with sullen silence. The men of Kent had no love for the stranger who came, as his predecessor Eustace had done, to trouble the land."[6]

{2} But "the men of Kent" were faithful to Stephen, when all others forsook him, and, remembering this, one would hardly expect to find in them his chief opponents. Nor, indeed, were they. Our great historian, when he wrote thus, must, I venture to think, have overlooked the passage in Ordericus (v. 110), from which we learn, incidentally, that Canterbury and Dover were among those fortresses which the Earl of Gloucester held by his father's gift.[7] It is, therefore, not surprising that Stephen should have met with this reception at the hands of the lieutenants of his arch-rival. It might, indeed, be thought that the prescient king had of set purpose placed these keys of the road to London in the hands of one whom he could trust to uphold his cherished scheme.[8]

Stephen, undiscouraged by these incidents, pushed on rapidly to London. The news of his approach had gone before him, and the citizens flocked to meet him. By them, as is well known, he was promptly chosen to be king, on the plea that a king was needed to fill the vacant throne, and that the right to elect one was specially vested in themselves.[9] The point, however, that I would here {3} insist on, for it seems to have been scarcely noticed, is that this election appears to have been essentially conditional, and to have been preceded by an agreement with the citizens.[10] The bearing of this will be shown below.

There is another noteworthy point which would seem to have escaped observation. It is distinctly implied by William of Malmesbury that the primate, seizing his opportunity, on Stephen's appearance in London, had extorted from him, as a preliminary to his recognition, as Maurice had done from Henry at his coronation, and as Henry of Winchester was, later, to do in the case of the Empress, an oath to restore the Church her "liberty," a phrase of which the meaning is well known. Stephen, he adds, on reaching Winchester, was released from this oath by his brother, who himself "went bail" (made himself responsible) for Stephen's satisfactory behaviour to the Church.[11] It is, surely, to this incident that Henry so pointedly alludes in his speech at the election of the Empress.[12] It can only, I think, be explained on the {4} hypothesis that Stephen chafed beneath the oath he had taken, and begged his brother to set him free. If so, the attempt was vain, for he had, we shall find, to bind himself anew on the occasion of his Oxford charter.[13]

At Winchester the citizens, headed by their bishop, came forth from the city to greet him, but this reception must not be confused (as it is by Mr. Freeman) with his election by the citizens of London.[14] His brother, needless to say, met him with an eager welcome, and the main object of his visit was attained when William de Pont de l'Arche, who had shrunk, till his arrival, from embracing his cause, now, in concert with the head of the administration, Roger, Bishop of Salisbury, placed at his disposal the royal castle, with the treasury and all that it contained.[15]

Thus strengthened, he returned to London for coronation at the hands of the primate. Dr. Stubbs observes that "he returned to London for formal election and coronation."[16] His authority for that statement is Gervase (i. 94), who certainly asserts it distinctly.[17] But it will be found that he, who was not a contemporary, is the only authority for this second election, and, moreover, that he ignores the first, as well as the visit to Winchester, thus mixing up the two episodes, between which that visit intervened. Of course this opens the wider question as to {5} whether the actual election, in such cases, took place at the coronation itself or on a previous occasion. This may, perhaps, be a matter of opinion; but in the preceding instance, that of Henry I., the election was admittedly that which took place at Winchester, and was previous to and unconnected with the actual coronation itself.[18] From this point of view, the presentation of the king to the people at his coronation would assume the aspect of a ratification of the election previously conducted. The point is here chiefly of importance as affecting the validity of Stephen's election. If his only election was that which the citizens of London conducted, it was, to say the least, "informally transacted."[19] Nor was the attendance of magnates at the ceremony such as to improve its character. It was, as Dr. Stubbs truly says, "but a poor substitute for the great councils which had attended the summons of William and Henry."[20] The chroniclers are here unsatisfactory. Henry of Huntingdon is rhetorical and vague; John of Hexham leaves us little wiser;[21] the Continuator of Florence indeed states that Stephen, when crowned, kept his Christmas court "cum totius Angliæ primoribus" (p. 95), but even the author of the Gesta implies that the primate's scruples were largely due to the paucity of magnates present.[22] William of Malmesbury alone is precise,[23] possibly because an adversary of Stephen could {6} alone afford to be so, and his testimony, we shall find, is singularly confirmed by independent charter evidence (p. 11).

It was at this stage that an attempt was made to dispel the scruples caused by Stephen's breach of his oath to the late king. The hint, in the Gesta, that Henry, on his deathbed, had repented of his act in extorting that oath,[24] is amplified by Gervase into a story that he had released his barons from its bond,[25] while Ralph "de Diceto" represents the assertion as nothing less than that the late king had actually disinherited the Empress, and made Stephen his heir in her stead.[26] It should be noticed that these last two writers, in their statement that this story was proved by Hugh Bigod on oath, are confirmed by the independent evidence of the Historia Pontificalis.[27]

The importance of securing, as quickly as possible, the performance of the ceremony of coronation is well brought out by the author of the Gesta in the arguments of Stephen's friends when combating the primate's scruples. They urged that it would ipso facto put an end to all question as to the validity of his election.[28] The advantage, in short, of "snatching" a coronation was that, in the language of modern diplomacy, of securing a fait accompli. Election was a matter of opinion; coronation a matter of fact. Or, to employ another expression, {7} it was the "outward and visible sign" that a king had begun his reign. Its important bearing is well seen in the case of the Conqueror himself. Dr. Stubbs observes, with his usual judgment, that "the ceremony was understood as bestowing the divine ratification on the election that had preceded it."[29] Now, the fact that the performance of this essential ceremony was, of course, wholly in the hands of the Church, in whose power, therefore, it always was to perform or to withhold it at its pleasure, appears to me to have naturally led to the growing assumption that we now meet with, the claim, based on a confusion of the ceremony with the actual election itself, that it was for the Church to elect the king. This claim, which in the case of Stephen (1136) seems to have been only inchoate,[30] appears at the time of his capture (1141) in a fully developed form,[31] the circumstances of the time having enabled the Church to increase its power in the State with perhaps unexampled rapidity.

May it not have been this development, together with his own experience, that led Stephen to press for the coronation of his son Eustace in his lifetime (1152)? In this attempted innovation he was, indeed, defeated by the Church, but the lesson was not lost. Henry I., unlike his contemporaries, had never taken this precaution, and Henry II., warned by his example, succeeded in obtaining the coronation of his heir (1170) in the teeth of Becket's endeavours to forbid the act, and so to uphold the veto of the Church.

Prevailed upon, at length, to perform the ceremony, the primate seized the opportunity of extorting from the {8} eager king (besides a charter of liberties) a renewal of his former oath to protect the rights of the Church. The oath which Henry had sworn at his coronation, and which Maud had to swear at her election, Stephen had to swear, it seems, at both, though not till the Oxford charter was it committed, in his case, to writing.[32]

We now approach an episode unknown to all our historians.[33]

The Empress, on her side, had not been idle; she had despatched an envoy to the papal court, in the person of the Bishop of Angers, to appeal her rival of (1) defrauding her of her right, and (2) breach of his solemn oath. Had this been known to Mr. Freeman, he would, it is safe to assert, have been fascinated by the really singular coincidence between the circumstances of 1136 and of 1066. In each case, of the rivals for the throne, the one based his pretensions on (1) kinship, fortified by (2) an oath to secure his succession, which had been taken by his opponent himself; while the other rested his claims on election duly followed by coronation. In each case the election was fairly open to question; in Harold's, because (pace Mr. Freeman) he was not a legitimate candidate; in Stephen's, because, though a qualified candidate, his election had been most informal. In each case the ousted claimant appealed to the papal court, and, in each case, on the same grounds, viz. (1) the kinship, (2) the broken oath. In each case the successful party was opposed by a particular cardinal, a fact which we learn, in each case, from later and incidental mention. And in each case that {9} cardinal became, afterwards, pope. But here the parallel ends. Stephen accepted, where Harold had (so far as we know) rejected, the jurisdiction of the Court of Rome. We may assign this difference to the closer connection between Rome and England in Stephen's day, or we may see in it proof that Stephen was the more politic of the two. For his action was justified by its success. There has been, on this point, no small misconception. Harold has been praised for possessing, and Stephen blamed for lacking, a sense of his kingly dignity. But læsio fidei was essentially a matter for courts Christian, and thus for the highest of them all, at Rome. Again, inheritance, so far as inheritance affected the question, was brought in many ways within the purview of the courts Christian, as, for instance, in the case of the alleged illegitimacy of Maud. Moreover, in 1136, the pope, though circumstances played into his hands, advanced no such pretension as his successor in the days of John. His attitude was not that of an overlord to a dependent fief: he made no claim to dispose of the realm of England. Sitting as judge in a spiritual court, he listened to the charges brought by Maud against Stephen in his personal capacity, and, without formally acquitting him, declined to pronounce him guilty.

Though the king was pleased to describe the papal letter which followed as a "confirmation" of his right to the throne, it was, strictly, nothing of the kind. It was simply, in the language of modern diplomacy, his "recognition" by the pope as king. If Ferdinand, elected Prince of Bulgaria, were to be recognized as such by a foreign power, that action would neither alter his status relatively to any other power, nor would it imply the least claim to dispose of the Bulgarian crown. Or, again, to take a mediæval illustration, the recognition as pope by an {10} English king of one of two rival claimants for the papacy would neither affect any other king, nor constitute a claim to dispose of the papal tiara. Stephen, however, was naturally eager to make the most of the papal action, especially when he found in his oath to the Empress the most formidable obstacle to his acceptance. The sanction of the Church would silence the reproach that he was occupying the throne as a perjured man. Hence the clause in his Oxford charter. To the advantage which this letter gave him Stephen shrewdly clung, and when Geoffrey summoned him, in later years, "to an investigation of his claims before the papal court," he promptly retorted that Rome had already heard the case.[34] He turned, in fact, the tables on his appellant by calling on Geoffrey to justify his occupation of the Duchy and of the Western counties in the teeth of the papal confirmation of his own right to the throne.

We now pass from Westminster to Reading, whither, after Christmas, Stephen proceeded, to attend his uncle's funeral.[35] The corpse, says the Continuator, was attended "non modica stipatus nobilium catervâ." The meeting of Stephen with these nobles is an episode of considerable importance. "It is probable," says Dr. Stubbs, "that it furnished an opportunity of obtaining some vague promises from Stephen."[36] But the learned writer here alludes to the subsequent promises at Oxford. What I am concerned with is the meeting at Reading. I proceed, therefore, to quote in extenso a charter which must have passed on this occasion, and which, this being so, is of great value and interest.[37]

Carta Stephani regis Angliæ facta Miloni Gloec' de honore Gloecestr' et Brekon'.

S. rex Angl. Archiepĩs Epĩs Abbatibus. Com̃. Baroñ. vic. præpositis, Ministris et omnibus fidelibus suis Francis et Anglicis totius Angliæ et Walliæ Saɫ. sciatis me reddidisse et concessisse Miloni Gloecestriæ et hæredibus suis post eum in feoᵭ et hæreditate totum honorem suum de Gloec', et de Brechenion, et omnes terras suas et tenaturas suas in vicecomitatibus et aliis rebus, sicut eas tenuit die quâ rex Henricus fuit vivus et mortuus. Quare volo et præcipio quod bene et honorifice et libere teneat in bosco et plano et pratis et pasturis et aquis et mariscis, in molendinis et piscariis, cum Thol et Theam et infangenetheof, et cum omnibus aliis libertatibus et consuetudinibus quibus unqũ melius et liberius tenuit tempore regis Henrici. Et sciatis q̃m ego ut dñs et Rex, convencionavi ei sicut Baroni et Justiciario meo quod eum in placitum non ponero quamdiu vixero de aliquâ tenatura ꝗ̃ tenuisset die quâ Rex Henricus fuit vivus et mortuus, neq' hæredem suum. T. Arch. Cantuar. et Epõ Wintoñ. et Epõ Sar'. et H. Big̃ et Roᵬ filio Ricardi et Ing̃ de Sai. et W. de Pont̃ et P. filio Joħ. Apud Rading̃.

The reflections suggested by this charter are many and most instructive. Firstly, we have here the most emphatic corroboration of the evidence of William of Malmesbury. The four first witnesses comprise the three bishops who, according to him, conducted Stephen's coronation, together with the notorious Hugh Bigod, to whose timely assurance that coronation was so largely due. The four others are Robert fitz Richard, whom we shall find present at the Easter court, attesting a charter as a royal chamberlain; {12} Enguerrand de Sai, the lord of Clun, who had probably come with Payne fitz John; William de Pont de l'Arche, whom we met at Winchester; and Payne fitz John. The impression conveyed by this charter is certainly that Stephen had as yet been joined by few of the magnates, and had still to be content with the handful by whom his coronation had been attended.

An important addition is, however, represented by the grantee, Miles of Gloucester, and the witness Payne fitz John. The former was a man of great power, both of himself and from his connection with the Earl of Gloucester, in the west of England and in Wales. The latter is represented by the author of the Gesta as acting with him at this juncture.[38] It should, however, be noted, as important in its bearing on the chronology of this able writer, that he places the adhesion of these two barons (p. 15) considerably after that of the Earl of Gloucester (p. 8), whereas the case was precisely the contrary, the earl not submitting to Stephen till some time later on. Both these magnates appear in attendance at Stephen's Easter court (vide infra), and again as witnesses to his Oxford charter. The part, however, in the coming struggle which Miles of Gloucester was destined to play, was such that it is most important to learn the circumstances and the date of his adhesion to the king. His companion, Payne fitz John, was slain, fighting the Welsh, in the spring of the following year.[39]

{13} It is a singular fact that, in addition to the charter I have here given, another charter was granted to Miles of Gloucester by the king, which, being similarly tested at Reading, probably passed on this occasion. The subject of the grant is the same, but the terms are more precise, the constableship of Gloucester Castle, with the hereditary estates of his house, being specially mentioned.[40] Though both these charters were entered in the Great Coucher (in the volume now missing), the latter alone is referred to by Dugdale, from whose transcript it has been printed by Madox.[41] Though the names of the witnesses are there omitted, those of the six leading witnesses are supplied by an abstract which is elsewhere found. Three of these are among those who attest the other charter—Robert fitz Richard, Hugh Bigod, and Enguerrand de Sai; but the other three names are new, being Robert de Ferrers, afterwards Earl of Derby, Baldwin de Clare, the spokesman of Stephen's host at Lincoln (see p. 148), and (Walter) fitz Richard, who afterwards appears in attendance at the Easter court.[42] These three barons should {14} therefore be added to the list of those who were at Reading with the king.[43]

Possibly, however, the most instructive feature to be found in each charter is the striking illustration it affords of the method by which Stephen procured the adhesion of the turbulent and ambitious magnates. It is not so much a grant from a king to a subject as a convencio between equal powers. But especially would I invite attention to the words "ut dominus et Rex."[44] I see in them at once the symbol and the outcome of "the Norman idea of royalty." In his learned and masterly analysis of this subject, a passage which cannot be too closely studied, Dr. Stubbs shows us, with felicitous clearness, the twin factors of Norman kinghood, its royal and its feudal aspects.[45] Surely in the expression "dominus et Rex" (alias "Rex et dominus") we have in actual words the exponent of this double character.[46] And, more than this, we have here the needful and striking parallel which will illustrate and illumine the action of the Empress, so strangely overlooked or misunderstood, when she ordered herself, at Winchester, to be proclaimed "Domina et Regina."

{15} Henry of Huntingdon asserts distinctly that from Reading Stephen passed to Oxford, and that he there renewed the pledges he had made on his coronation-day.[47] That, on leaving Reading, he moved to Oxford, though the fact is mentioned by no other chronicler, would seem to be placed beyond question by Henry's repeated assertion.[48] But the difficulty is that Henry specifies what these pledges were, and that the version he gives cannot be reconciled either with the king's "coronation charter" or with what is known as his "second charter," granted at Oxford later in the year. Dr. Stubbs, with the caution of a true scholar, though he thinks it "probable," in his great work, that Stephen, upon this occasion, made "some vague promises," yet adds, of those recorded by Henry—

"Whether these promises were embodied in a charter is uncertain: if they were, the charter is lost; it is, however, more probable that the story is a popular version of the document which was actually issued by the king, at Oxford, later in the year 1136."[49]

In his later work he seems inclined to place more credence in Henry's story.

"After the funeral, at Oxford or somewhere in the neighbourhood, he arranged terms with them; terms by which he endeavoured, amplifying the words of his charter, to catch the good will of each class of his subjects.... The promises were, perhaps, not insincere at the time; anyhow, they had the desired effect, and united the nation for the moment."[50]

It will be seen that the point is a most perplexing one, and can scarcely at present be settled with certainty. But there is one point beyond dispute, namely, that the so-called "second charter" was issued later in the year, {16} after the king's return from the north. Mr. Freeman, therefore, has not merely failed to grasp the question at issue, but has also strangely contradicted himself when he confidently assigns this "second charter" to the king's first visit to Oxford, and refers us, in doing so, to another page, in which it is as unhesitatingly assigned to his other and later visit after his return from the north.[51] If I call attention to this error, it is because I venture to think it one to which this writer is too often liable, and against which, therefore, his readers should be placed upon their guard.[52]

It was at Oxford, in January,[53] that Stephen heard of David's advance into England. With creditable rapidity he assembled an army and hastened to the north to meet him. He encountered him at Durham on the 5th of February (the day after Ash Wednesday), and effected a peaceable agreement. He then retraced his steps, after a stay of about a fortnight,[54] and returned to keep his Easter (March 22) at Westminster. I wish to invite special attention to this Easter court, because it was in many ways of great importance, although historians have almost ignored its existence. Combining the evidence of charters with that which the chroniclers afford, we can learn not a little about it, and see how notable an event it must have seemed at the time it was held. We should observe, in the first place, that this was no mere "curia de more": {17} it was emphatically a great or national council. The author of the Gesta describes it thus:—

"Omnibus igitur summatibus regni, fide et jurejurando cum rege constrictis, edicto per Angliam promulgato, summos ecclesiarum ductores cum primis populi ad concilium Londonias conscivit. Illis quoque quasi in unam sentinam illuc confluentibus ecclesiarumque columnis sedendi ordine dispositis, vulgo etiam confuse et permixtim,[55] ut solet, ubique se ingerente, plura regno et ecclesiæ profutura fuerunt et utiliter ostensa et salubriter pertractata."[56]

We have clearly in this great council, held on the first court day (Easter) after the king's coronation, a revival of the splendours of former reigns, so sorely dimmed beneath the rule of his bereaved and parsimonious uncle.[57]

Henry of Huntingdon has a glowing description of this Easter court,[58] which reminds one of William of Malmesbury's pictures of the Conqueror in his glory.[59] When, therefore, Dr. Stubbs tells us that this custom of the Conqueror "was restored by Henry II." (Const. Hist., i. 370), he ignores this brilliant revival at the outset of Stephen's reign. Stephen, coming into possession of his predecessor's hoarded treasure, was as eager to plunge into costly pomp as was Henry VIII. on the death of his mean {18} and grasping sire. There were also more solid reasons for this dazzling assembly. It was desirable for the king to show himself to his new subjects in his capital, surrounded not only by the evidence of wealth, but by that of his national acceptance. The presence at his court of the magnates from all parts of the realm was a fact which would speak for itself, and to secure which he had clearly resolved that no pains should be spared.[60]

If the small group who attended his coronation had indeed been "but a poor substitute for the great councils which had attended the summons of William and Henry," he was resolved that this should be forgotten in the splendour of his Easter court.

This view is strikingly confirmed by the lists of witnesses to two charters which must have passed on this occasion. The one is a grant to the see of Winchester of the manor of Sutton, in Hampshire, in exchange for Morden, in Surrey. The other is a grant of the bishopric of Bath to Robert of Lewes. The former is dated "Apud Westmonasterium in presentia et audientia subscriptorum anno incarnationis dominicæ, 1136," etc.; the latter, "Apud Westmonasterium in generalis concilii celebratione et Paschalis festi solemnitate." At first sight, I confess, both charters have a rather spurious appearance. Their stilted style awakes suspicion, which is not lessened by the dating clauses or the extraordinary number of witnesses. Coming, however, from independent sources, and dealing with two unconnected subjects, they mutually confirm one another. We have, moreover, still extant the charter by which Henry II. confirmed the former of the two, and as this is among the duchy of Lancaster records, we have every reason to believe that {19} the original charter itself was, as both its transcribers assert, among them also. Again, as to the lists of witnesses. Abnormally long though these may seem, we must remember that in the charters of Henry I., especially towards the close of his reign, there was a tendency to increase the number of witnesses. Moreover, in the Oxford charter, by which these were immediately followed, we have a long list of witnesses (thirty-seven), and, which is noteworthy, it is similarly arranged on a principle of classification, the court officers being grouped together. I have, therefore, given in an appendix, for the purpose of comparison, all three lists.[61] If we analyze those appended to the two London charters, we find their authenticity confirmed by the fact that, while the Earl of Gloucester, who was abroad at the time, is conspicuously absent from the list, Henry, son of the King of Scots, duly appears among the attesting earls, and we are specially told by John of Hexham that he was present at this Easter court.[62] Miles of Gloucester and Brian fitz Count also figure together among the witnesses—a fact, from their position, of some importance.[63] It is, too, of interest for our purpose, to note that among them is Geoffrey de Mandeville. The extraordinary number of witnesses to these charters (no less than fifty-five in one case, excluding the king and queen, and thirty-six in the other) is not only of great value as giving us the personnel of this brilliant court, but is also, when compared with the Oxford {20} charter, suggestive perhaps of a desire, by the king, to place on record the names of those whom he had induced to attend his courts and so to recognize his claims. Mr. Pym Yeatman more than once, in his strange History of the House of Arundel, quotes the charter to Winchester as from a transcript "among the valuable collection of MSS. belonging to the Earl of Egmont" (p. 49). It may, therefore, be of benefit to students to remind them that it is printed in Hearne's Liber Niger (ii. 808, 809). Mr. Yeatman, moreover, observes of this charter—

"It contains the names of no less than thirty-four noblemen of the highest rank (excluding only the Earl of Gloucester), but not a single ecclesiastical witness attests the grant, which is perhaps not remarkable, since it was a dangerous precedent to deal in such a matter with Church property, perhaps a new precedent created by Stephen" (p. 286).

To other students it will appear "perhaps not remarkable" that the charter is witnessed by the unusual number of no less than three archbishops and thirteen bishops.[64]

Now, although this was a national council, the state and position of the Church was the chief subject of discussion. The author of the Gesta, who appears to have been well informed on the subject, shows us the prelates appealing to Stephen to relieve the Church from the intolerable oppression which she had suffered, under the form of law, at the hands of Henry I. Stephen, bland, for the time, to all, and more especially to the powerful Church, listened graciously to their prayers, and promised all they asked.[65] In the grimly jocose language of the day, the keys of the Church, which had been held by Simon (Magus), were henceforth to be restored to Peter. To this {21} I trace a distinct allusion in the curious phrase which meets us in the Bath charter. Stephen grants the bishopric of Bath "canonica prius electione præcedente." This recognition of the Church's right, with the public record of the fact, confirms the account of his attitude on this occasion to the Church. The whole charter contrasts strangely with that by which, fifteen years before, his predecessor had granted the bishopric of Hereford, and its reference to the counsel and consent of the magnates betrays the weakness of his position.

This council took place, as I have said, at London and during Easter. But there is some confusion on the subject. Mr. Howlett, in his excellent edition of the Gesta, assigns it, in footnotes (pp. 17, 18), to "early in April." But his argument that, as that must have been (as it was) the date of the (Oxford) charter, it was consequently that of the (London) council, confuses two distinct events. In this he does but follow the Gesta, which similarly runs into one the two consecutive events. Richard of Hexham also, followed by John of Hexham,[66] combines in one the council at London with the charter issued at Oxford, besides placing them both, wrongly, far too late in the year.

Here are the passages in point taken from both writers:—

| Richard of Hexham. | John of Hexham. |

|---|---|

| Eodem quoque anno Innocentius Romanæ sedis Apostolicus, Stephano regi Angliæ litteras suas transmisit, quibus eum Apostolica auctoritate in regno Angliæ confirmavit.... Igitur Stephanus his et aliis modis in regno Angliæ confirmatus, episcopos et proceres sui regni regali edicto in unum convenire præcepit; cum quibus hoc generale concilium celebravit. | Eodem anno Innocentius papa litteris ab Apostolica sede directis eundem regem Stephanum in negotiis regni confirmavit. Harum tenore litterarum rex instructus, generali convocato concilio bonas et antiquas leges, et justos consuetudines præcepit conservari, injustitias vero cassari. |

{22} The point to keep clearly in mind is that the Earl of Gloucester was not present at the Easter court in London, and that, landing subsequently, he was present when the charter of liberties was granted at Oxford. So short an interval of time elapsed that there cannot have been two councils. There was, I believe, one council which adjourned from London to Oxford, and which did so on purpose to meet the virtual head of the opposition, the powerful Earl of Gloucester. It must have been the waiting for his arrival at court which postponed the issue of the charter, and it is not wonderful that, under these circumstances, the chroniclers should have made of the whole but one transaction.

The earl, on his arrival, did homage, with the very important and significant reservation that his loyalty would be strictly conditional on Stephen's behaviour to himself.[67]

His example in this respect was followed by the bishops, for we read in the chronicler, immediately afterwards:

"Eodem anno, non multo post adventum comitis, juraverunt episcopi fidelitatem regi quamdiu ille libertatem ecclesiæ et vigorem disciplinæ conservaret."[68]

By this writer the incident in question is recorded in connection with the Oxford charter. In this he must be correct, if it was subsequent to the earl's homage, for this latter itself, we see, must have been subsequent to Easter.

Probably the council at London was the preliminary to that treaty (convencio) between the king and the bishops, at which William of Malmesbury so plainly hints, {23} and of which the Oxford charter is virtually the exponent record. For this, I take it, is the point to be steadily kept in view, namely, that the terms of such a charter as this are the resultant of two opposing forces—the one, the desire to extort from the king the utmost possible concession; the other, his desire to extort homage at the lowest price he could. Taken in connection with the presence at Oxford of his arch-opponent, the Earl of Gloucester, this view, I would venture to urge, may lead us to the conclusion that this extended version of his meagre "coronation charter" represents his final and definite acceptance, by the magnates of England, as their king.

It may be noticed, incidentally, as illustrative of the chronicle-value of charters, that not a single chronicler records this eventful assembly at Oxford. Our knowledge of it is derived wholly and solely from the testing clause of the charter itself—"Apud Oxeneford, anno ab incarnatione Domini MCXXXVI." Attention should also, perhaps, be drawn to this repeated visit to Oxford, and to the selection of that spot for this assembly. For this its central position may, doubtless, partly account, especially if the Earl of Gloucester was loth to come further east. But it also, we must remember, represented for Stephen, as it were, a post of observation, commanding, in Bristol and Gloucester, the two strongholds of the opposition. So, conversely, it represented to the Empress an advanced post resting on their base.

Lastly, I think it perfectly possible to fix pretty closely the date of this assembly and charter. Easter falling on the 22nd of March, neither the king nor the Earl of Gloucester would have reached Oxford till the end of March or, perhaps, the beginning of April. But as early as Rogation-tide (April 26-29) it was rumoured that the king was dead, and Hugh Bigod, who, as a royal dapifer, had {24} been among the witnesses to this Oxford charter, burst into revolt at once.[69] Then followed the suppression of the rebellion, and the king's breach of the charter.[70] It would seem, therefore, to be beyond question that this assembly took place early in April (1136).

I have gone thus closely into these details in order to bring out as clearly as possible the process, culminating in the Oxford charter, by which the succession of Stephen was gradually and, above all, conditionally secured.

Stephen, as a king, was an admitted failure. I cannot, however, but view with suspicion the causes assigned to his failure by often unfriendly chroniclers. That their criticisms had some foundation it would not be possible to deny. But in the first place, had he enjoyed better fortune, we should have heard less of his incapacity, and in the second, these writers, not enjoying the same standpoint as ourselves, were, I think, somewhat inclined to mistake effects for causes. Stephen, for instance, has been severely blamed, mainly on the authority of Henry of Huntingdon,[71] for not punishing more severely the rebels who held Exeter against him in 1136. Surely, in doing so, his critics must forget the parallel cases of both his predecessors. William Rufus at the siege of Rochester (1088), Henry I. at the siege of Bridgnorth (1102), should both be remembered when dealing with Stephen at the siege of Exeter. In both these cases, the people had clamoured for condign punishment on the traitors; in both, the king, who had conquered by their help, was held back by the jealousy of his barons, from punishing their fellows as they deserved. We learn from the author of the Gesta that the same was the case at Exeter. The {25} king's barons again intervened to save those who had rebelled from ruin, and at the same time to prevent the king from securing too signal a triumph.

This brings us to the true source of his weakness throughout his reign. That weakness was due to two causes, each supplementing the other. These were—(1) the essentially unsatisfactory character of his position, as resting, virtually, on a compact that he should be king so long only as he gave satisfaction to those who had placed him on the throne; (2) the existence of a rival claim, hanging over him from the first, like the sword of Damocles, and affording a lever by which the malcontents could compel him to adhere to the original understanding, or even to submit to further demands.

Let us glance at them both in succession.

Stephen himself describes his title in the opening clause of his Oxford charter:—

"Ego Stephanus Dei gratia assensu cleri et populi in regem Anglorum electus, et a Willelmo Cantuariensi archiepiscopo et sanctæ Romanæ ecclesiæ legato consecra tus, et ab Innocentio sanctæ Romanæ sedis pontifice confirmatus."[72]

On this clause Dr. Stubbs observes:—

"His rehearsal of his title is curious and important; it is worth while to compare it with that of Henry I., but it need not necessarily be interpreted as showing a consciousness of weakness."[73]

Referring to the charter of Henry I., we find the clause phrased thus:—

"Henricus filius Willelmi Regis post obitum fratris sui Willelmi, Dei gratia rex Anglorum."[74]

Surely the point to strike us here is that the clause in Stephen's charter contains just that which is omitted in Henry's, and omits just that which is contained in Henry's. Henry puts forward his relationship to his father and his {26} brother as the sole explanation of his position as king. Stephen omits all mention of his relationship. Conversely, the election, etc., set forth by Stephen, finds no place in the charter of Henry. What can be more significant than this contrast? Again, the formula in Stephen's charter should be compared not only with that of Henry, but with that of his daughter the Empress. As the father had styled himself "Henricus filius Willelmi Regis," so his daughter invariably styled herself "Matildis ... Henrici regis [or regis Henrici] filia;" and so her son, in his time, is styled (1142), as we shall find in a charter quoted in this work, "Henricus filius filiæ regis Henrici." To the importance of this fact I shall recur below. Meanwhile, the point to bear in mind is, that Stephen's style contains no allusion to his parentage, though, strangely enough, in a charter which must have passed in the first year of his reign, he does adopt the curious style of "Ego Stephanus Willelmi Anglorum primi Regis nepos," etc.,[75] in which he hints, contrary to his practice, at a quasi-hereditary right.

Returning, however, to his Oxford charter, in which he did not venture to allude to such claim, we find him appealing (a) to his election, which, as we have seen, was informal enough; (b) to his anointing by the primate; (c) to his "confirmation" by the pope. It is impossible to read such a formula as this in any other light than that of an attempt to "make up a title" under difficulties. I do not know that it has ever been suggested, though the {27} hypothesis would seem highly probable, that the stress laid by Stephen upon the ecclesiastical sanction to his succession may have been largely due, as I have said (p. 10), to the obstacle presented by the oath that had been sworn to the Empress. Of breaking that oath the Church, he held, had pronounced him not guilty.

Yet it is not so much on this significant style, as on the drift of the charter itself, that I depend for support of my thesis that Stephen was virtually king on sufferance, or, to anticipate a phrase of later times, "Quamdiu se bene gesserit." We have seen how in the four typical cases, (1) of the Londoners, (2) of Miles of Gloucester, (3) of Earl Robert, (4) of the bishops, Stephen had only secured their allegiance by submitting to that "original contract" which the political philosophers of a later age evolved from their inner consciousness. It was because his Oxford charter set the seal to this "contract" that Stephen, even then, chafed beneath its yoke, as evidenced by the striking saving clause—

"Hæc omnia concedo et confirmo salva regia et justa dignitate meâ."[76]

And, as we know, at the first opportunity, he hastened to break its bonds.[77]

The position of his opponents throughout his reign would seem to have rested on two assumptions. The first, that a breach, on his part, of the "contract" justified ipso facto revolt on theirs;[78] the second, that their allegiance {28} to the king was a purely feudal relation, and, as such, could be thrown off at any moment by performing the famous diffidatio.[79]

This essential feature of continental feudalism had been rigidly excluded by the Conqueror. He had taken advantage, as is well known, of his position as an English king, to extort an allegiance from his Norman followers more absolute than he could have claimed as their feudal lord. It was to Stephen's peculiar position that was due the introduction for a time of this pernicious principle into England. We have seen it hinted at in that charter of Stephen in which he treats with Miles of Gloucester not merely as his king (rex), but also as his feudal lord (dominus). We shall find it acted on three years later (1139), when this same Miles, with his own dominus, the Earl of Gloucester, jointly "defy" Stephen before declaring for the Empress.[80]

Passing now to the other point, the existence of a rival claim, we approach a subject of great interest, the theory of the succession to the English Crown at what may be termed the crisis of transition from the principle of {29} election (within the royal house) to that of hereditary right according to feudal rules.

For the right view on this subject, we turn, as ever, to Dr. Stubbs, who, with his usual sound judgment, writes thus of the Norman period:—

"The crown then continued to be elective.... But whilst the elective principle was maintained in its fulness where it was necessary or possible to maintain it, it is quite certain that the right of inheritance, and inheritance as primogeniture, was recognized as co-ordinate.... The measures taken by Henry I. for securing the crown to his own children, whilst they prove the acceptance of the hereditary principle, prove also the importance of strengthening it by the recognition of the elective theory.[81]

Mr. Freeman, though writing with a strong bias in favour of the elective theory, is fully justified in his main argument, namely, that Stephen "was no usurper in the sense in which the word is vulgarly used."[82] He urges, apparently with perfect truth, that Stephen's offence, in the eyes of his contemporaries, lay in his breaking his solemn oath, and not in his supplanting a rightful heir. And he aptly suggests that the wretchedness of his reign may have hastened the growth of that new belief in the divine right of the heir to the throne, which first appears under Henry II., and in the pages of William of Newburgh.[83]

So far as Stephen is concerned the case is clear enough. But we have also to consider the Empress. On what did she base her claim? I think that, as implied in Dr. Stubbs' words, she based it on a double, not a single, {30} ground. She claimed the kingdom as King Henry's daughter ("regis Henrici filia"), but she claimed it further because the succession had been assured to her by oath ("sibi juratum") as such.[84] It is important to observe that the oath in question can in no way be regarded in the light of an election. To understand it aright, we must go back to the precisely similar oath which had been previously sworn to her brother. As early as 1116, the king, in evident anxiety to secure the succession to his heir, had called upon a gathering of the magnates "of all England," on the historic spot of Salisbury, to swear allegiance to his son (March 19).[85] It was with reference to this event that Eadmer described him at his death (November, 1120) as "Willelmum jam olim regni hæredem designatum" (p. 290). Before leaving Normandy in November, 1120, the king similarly secured the succession of the duchy to his son by compelling its barons to swear that they would be faithful to the youth.[86] On the destruction of his plans by his son's death, he hastened to marry again in the hope of securing, once more, a male heir. Despairing of this after some years, he took advantage of the Emperor's death to insist on his daughter's return, and brought her with him to England in the autumn of 1126. He was not long in taking steps to secure her recognition as his heir (subject however, as the Continuator and Symeon are both careful to point {31} out, to no son being born to him), by the same oath being sworn to her as, in 1116, had been sworn to his son. It was taken, not (as is always stated) in 1126, but on the 1st of January, 1127.[87] Of what took place upon that occasion, there is, happily, full evidence.[88]

We have independent reports of the transaction from William of Malmesbury, Symeon of Durham, the Continuator of Florence, and Gervase of Canterbury.[89] From this last we learn (the fact is, therefore, doubtful) that the oath secured the succession, not only to the Empress, but to her heirs.[90] The Continuator's version is chiefly important as bringing out the action of the king in assigning the succession to his daughter, the oath being merely an undertaking to secure the arrangement he had made.[91] Symeon introduces the striking expression that {32} the Empress was to succeed "hæreditario jure,"[92] but William of Malmesbury, in the speech which he places in the king's mouth, far outstrips this in his assertion of hereditary right:—

"præfatus quanto incommodo patriæ fortuna Willelmum filium suum sibi surripuisset, cui jure regnum competeret: nunc superesse filiam, cui soli legitima debeatur successio, ab avo, avunculo, et patre regibus; a materno genere multis retro seculis."[93]

Bearing in mind the time at which William wrote these words, it will be seen that the Empress and her partisans must have largely, to say the least, based their claim on her right to the throne as her father's heir, and that she and they appealed to the oath as the admission and recognition of that right, rather than as partaking in any way whatever of the character of a free election.[94] Thus her claim was neatly traversed by Stephen's advocates, at Rome, in 1136, when they urged that she was not her father's heir, and that, consequently, the oath which had been sworn to her as such ("sicut hæredi") was void.

It is, as I have said, in the above light that I view her {33} unvarying use of the style "regis Henrici filia," and that this was the true character of her claim will be seen from the terms of a charter I shall quote, which has hitherto, it would seem, remained unknown, and in which she recites that, on arriving in England, she was promptly welcomed by Miles of Gloucester "sicut illam quam justam hæredem regni Angliæ recognovit."

The sex of the Empress was the drawback to her claim. Had her brother lived, there can be little question that he would, as a matter of course, have succeeded his father at his death. Or again, had Henry II. been old enough to succeed his grandfather, he would, we may be sure, have done so. But as to the Empress, even admitting the justice of her claim, it was by no means clear in whom it was vested. It might either be vested (a) in herself, in accordance with our modern notions; or (b) in her husband, in accordance with feudal ones;[95] or (c) in her son, as, in the event, it was. It may be said that this point was still undecided as late as 1142, when Geoffrey was invited to come to England, and decided to send his son instead, to represent the hereditary claim. The force of circumstances, however, as we shall find, had compelled the Empress, in the hour of her triumph (1141), to take her {34} own course, and to claim the throne for herself as queen, though even this would not decide the point, as, had she succeeded, her husband, we may be sure, would have claimed the title of king.

Broadly speaking, to sum up the evidence here collected, it tends to the belief that the obsolescence of the right of election to the English crown presents considerable analogy to that of canonical election in the case of English bishoprics. In both cases a free election degenerated into a mere assent to a choice already made. We see the process of change already in full operation when Henry I. endeavours to extort beforehand from the magnates their assent to his daughter's succession, and when they subsequently complain of this attempt to dictate to them on the subject. We catch sight of it again when his daughter bases her claim to the crown, not on any free election, but on her rights as her father's heir, confirmed by the above assent. We see it, lastly, when Stephen, though owing his crown to election, claims to rule by Divine right ("Dei gratia"[96]), and attempts to reduce that election to nothing more than a national "assent" to his succession. Obviously, the whole question turned on whether the election was to be held first, or was to be a mere ratification of a choice already made. Thus, at the very time when Stephen was formulating his title, he was admitting, in the case of the bishopric of Bath, that the canonical election had preceded his own nomination of the bishop.[97] Yet it is easy to see how, as the Crown grew in strength, the elections, in both cases alike, would become, more and more, virtually matters of form, while a weak sovereign or a disputed succession {35} would afford an opportunity for this historical survival, in the case at least of the throne, to recover for a moment its pristine strength.

Before quitting the point, I would venture briefly to resume my grounds for urging that, in comparing Stephen with his successor, the difference between their circumstances has been insufficiently allowed for. At Stephen's accession, thirty years of legal and financial oppression had rendered unpopular the power of the Crown, and had led to an impatience of official restraint which opened the path to a feudal reaction: at the accession of Henry, on the contrary, the evils of an enfeebled administration and of feudalism run mad had made all men eager for the advent of a strong king, and had prepared them to welcome the introduction of his centralizing administrative reforms. He anticipated the position of the house of Tudor at the close of the Wars of the Roses, and combined with it the advantages which Charles II. derived from the Puritan tyranny. Again, Stephen was hampered from the first by his weak position as a king on sufferance, whereas Henry came to his work unhampered by compact or concession. Lastly, Stephen was confronted throughout by a rival claimant, who formed a splendid rallying-point for all the discontent in his realm: but Henry reigned for as long as Stephen without a rival to trouble him; and when he found at length a rival in his own son, a claim far weaker than that which had threatened his predecessor seemed likely for a time to break his power as effectually as the followers of the Empress had broken that of Stephen. He may only, indeed, have owed his escape to that efficient administration which years of strength and safety had given him the time to construct.

It in no way follows from these considerations that Henry was not superior to Stephen; but it does, surely, {36} suggest itself that Stephen's disadvantages were great, and that had he enjoyed better fortune, we might have heard less of his defects. It will be at least established by the evidence adduced in this work that some of the charges which are brought against him can no longer be maintained.

[3] Early Plantagenets, p. 13; Const Hist. (1874), i. 319.

[4] Gesta Stephani, p. 3.

[5] "A Dourensibus repulsus, et a Cantuarinis exclusus" (Gervase, i. 94). As illustrating the use of such adjectives for the garrison, rather than the townsfolk, compare Florence of Worcester's "Hrofenses Cantuariensibus ... cædes inferunt" (ii. 23), where the "Hrofenses" are Odo's garrison. So too "Bristoenses" in the Gesta (ed. Hewlett, pp. 38, 40, 41), though rendered by the editor "the people of Bristol," are clearly the troops of the Earl of Gloucester.

[6] Early Plantagenets, p. 14. Compare Const. Hist., i. 319: "The men of Kent, remembering the mischief that had constantly come to them from Boulogne, refused to receive him." Miss Norgate adopts the same explanation (England under the Angevin Kings, i. 277).

[7] There is a curious incidental allusion to the earl's Kentish possessions in William of Malmesbury, who states (p. 759) that he was allowed, while a prisoner at Rochester (October, 1141), to receive his rents from his Kentish tenants ("ab hominibus suis de Cantia"). Stephen, then, it would seem, did not forfeit them.

[8] In the rebellion of 1138 Walchelin Maminot, the earl's castellan, held Dover against Stephen, and was besieged by the Queen and by the men of Boulogne. Curiously enough, Mr. Freeman made a similar slip, now corrected, to that here discussed, when he wrote that "whatever might be the feelings of the rest of the shire, the men of Dover had no mind to see Count Eustace again within their walls" (Norm. Conq., iv. 116), though they were, on the contrary, quite as anxious as the rest of the shire to do so.

[9] "Id quoque sui esse juris, suique specialiter privilegii ut si rex ipsorum quoquo modo obiret, alius suo provisu in regno substituendus e vestigio succederet" (Gesta, p. 3). This audacious claim of the citizens to such right as vested in themselves is much stronger than Mr. Freeman's paraphrase when he speaks of "the citizens of London and Winchester [why Winchester?], who freely exercised their ancient right of sharing in the election of the king who should reign over them" (Norm. Conq., v. 251; cf. p. 856).

[10] "Firmatâ prius utrimque pactione, peractoque, ut vulgus asserebat, mutuo juramento, ut eum cives quoad viveret opibus sustentarent, viribus tutarentur; ipse autem, ad regnum pacificandum, ad omnium eorundem suffragium, toto sese conatu accingeret" (Gesta, p. 4). See Appendix A.

[11] "Spe scilicet captus amplissima quod Stephanus avi sui Willelmi in regni moderamine mores servaret, precipueque in ecclesiastici vigoris disciplinâ. Quapropter districto sacramento quod a Stephano Willelmus Cantuarensis archiepiscopus exegit de libertate reddenda ecclesiæ et conservanda, episcopus Wintoniensis se mediatorem et vadem apposuit. Cujus sacramenti tenorem, postea scripto inditum, loco suo non prætermittam" (p. 704). See Addenda.

[12] "Enimvero, quamvis ego vadem me apposuerim inter eum et Deum quod sanctam ecclesiam honoraret et exaltaret, et bonas leges manuteneret, malas vero abrogaret; piget meminisse, pudet narrare, qualem se in regno exhibuerit," etc. (ibid., p. 746).

[13] The phrase "districto Sacramento" is very difficult to construe. I have here taken it to imply a release of Stephen from his oath, but the meaning of the passage, which is obscure as it stands, may be merely that Henry became surety for Stephen's performance of the oath as in an agreement or treaty between two contracting parties (vide infra passim).

[14] Ante, p. 3.

[15] Gesta, 5, 6; Will. Malms., 703. Note that William Rufus, Henry I., and Stephen all of them visited and secured Winchester even before their coronation.

[16] Const. Hist., i. 319.

[17] "A cunctis fere in regem electus est, et sic a Willelmo Cantuarensi archiepiscopo coronatus."

[18] "The form of election was hastily gone through by the barons on the spot" (Const. Hist., i. 303).

[19] Select Charters, p. 108.

[20] Early Plantagenets, p. 14.

[21] "Consentientibus in ejus promotionem Willelmo Cantuarensi archiepiscopo et clericorum et laicorum universitate" (Sym. Dun., ii. 286, 287).

[22] "Sic profecto, sic congruit, ut ad eum in regno confirmandum omnes pariter convolent, parique consensu quid statuendum, quidve respuendum sit, ab omnibus provideatur" (pp. 6, 7). Eventually he represents the primate as acting "Cum episcopis frequentique, qui intererat, clericatu" (p. 8).

[23] "Tribus episcopis præsentibus, archiepiscopo, Wintoniensi, Salesbiriensi, nullis abbatibus, paucissimis optimatibus" (p. 704). See Addenda.

[24] "Supremo eum agitante mortis articulo, cum et plurimi astarent et veram suorum erratuum confessionem audirent, de jurejurando violenter baronibus suis injuncto apertissime pænituit."

[25] "Quidam ex potentissimis Angliæ, jurans et dicens se præsentem affuisse ubi rex Henricus idem juramentum in bona fide sponte relaxasset."

[26] "Hugo Bigod senescallus regis coram archiepiscopo Cantuariæ sacramento probavit quod, dum Rex Henricus ageret in extremis, ortis quibus inimicitiis inter ipsum et imperatricem, ipsam exhæredavit, et Stephanum Boloniæ comitem hæredem instituit."

[27] "Et hæc juramento comitis (sic) Hugonis et duorum militum probata esse dicebant in facie ecclesie Anglicane" (ed. Pertz, p. 543).

[28] "Cum regis (sic) fautores obnixe persuaderent quatinus eum ad regnandum inungeret, quodque imperfectum videbatur, administrationis suæ officio suppleret" (p. 6).

[29] Const. Hist., i. 146.

[30] See his Oxford Charter.

[31] See the legate's speech at Winchester: "Ventilata est hesterno die causa secreto coram majori parte cleri Angliæ, ad cujus jus potissimum spectat principem eligere, simulque ordinare" (Will. Malms., p. 746).

[32] Henry had sworn "in ipso suæ consecrationis die" (Eadmer), Stephen "in ipsa consecrationis tuæ die" (Innocent's letter). Henry of Huntingdon refers to the "pacta" which Stephen "Deo et populo et sanctæ ecclesiæ concesserat in die coronationis suæ." William of Malmesbury speaks of the oath as "postea [i.e. at Oxford] scripto inditum." See Addenda.

[33] See Appendix B: "The Appeal to Rome in 1136."

[34] See Appendix B.

[35] Hen. Hunt., 258; Cont. Flor. Wig., 95; Will. Malms., 705.

[36] Const. Hist., i. 321.

[37] Lansdowne MS. 229, fol. 109, and Lansdowne MS. 259, fol. 66, both being excerpts from the lost volume of the Great Coucher of the Duchy.

[38] Speaking of the late king's trusted friends, who hung back from coming to court, he writes: "Illi autem, intentâ sibi a rege comminatione, cum salvo eundi et redeundi conductu curiam petiere; omnibusque ad votum impetratis, peracto cum jurejurando liberali hominio, illius sese servitio ex toto mancipârunt. Affuit inter reliquos Paganus filius Johannis, sed et Milo, de quo superius fecimus mentionem, ille Herefordensis et Salopesbiriæ, iste Glocestrensis provinciæ dominatum gerens: qui in tempore regis Henrici potentiæ suæ culmen extenderant ut a Sabrinâ flumine usque ad mare per omnes fines Angliæ et Waloniæ omnes placitis involverent, angariis onerarent" (pp. 15, 16).

[39] Cont. Flor. Wig.

[40] "S. rex Angliæ Archiepĩs etc. Sciatis me reddidisse et concessisse Miloni Gloec̃ et heredibus suis post eum in feodo et hereditate totum honorem patris sui et custodiam turris et castelli Gloecestrie ad tenendum tali forma (sic) qualem reddebat tempore regis Henrici sicut patrimonium suum. Et totum honorem suum de Brechenion et omnia Ministeria sua et terras suas quas tenuit tempore regis Henrici sicut eas melius et honorificentius tenuit die qua rex Henricus fuit vivus et mortuus, et ego ei in convencionem habeo sicut Rex et dominus Baroni meo. Quare precipio quod bene et in honore et in pace et libere teneat cum omnibus libertatibus suis. Testes, W. filius Ricardi, Robertus de Ferrariis, Robertus filius Ricardi, Hugo Bigot, Ingelramus de Sai, Balduinus filius Gisleberti. Apud Radinges" (Lansdowne MS. 229, fols. 123, 124).

[41] History of the Exchequer, p. 135.

[42] I am inclined to believe that in Robert fitz Richard we have that Robert fitz Richard (de Clare) who died in 1137 (Robert de Torigny), being then described as paternal uncle to Richard fitz Gilbert (de Clare), usually but erroneously described as first Earl of Hertford. If so, he was also uncle to Baldwin (fitz Gilbert) de Clare of this charter, and brother to W(alter) fitz Richard (de Clare), another witness. We shall come across another of Stephen's charters to which the house of Clare contributes several witnesses. There is evidence to suggest that Robert fitz Richard (de Clare) was lord, in some way, of Maldon in Essex, and was succeeded there by (his nephew) Walter fitz Gilbert (de Clare), who went on crusade (probably in 1147).

[43] There is preserved among the royal charters belonging to the Duchy of Lancaster, the fragment of one grant of which the contents correspond exactly, it would seem, with those of the above charter, though the witnesses' names are different. This raises a problem which cannot at present be solved.

[44] In the fellow-charter the phrase runs: "sicut Rex et dominus Baroni meo."

[45] "The Norman idea of royalty was very comprehensive; it practically combined all the powers of the national sovereignty, as they had been exercised by Edgar and Canute, with those of the feudal theory of monarchy, which was exemplified at the time in France and the Empire.... The king is accordingly both the chosen head of the nation and the lord paramount of the whole of the land" (Const. Hist., i. 338).

[46] Compare the words of address in several of the Cartæ Baronum (1166): "servitium ut domino;" "vobis sicut domino meo;" "sicut domino carissimo;" "ut domino suo ligio."

[47] "Inde perrexit rex Stephanus apud Oxeneford ubi recordatus et confirmavit pacta quæ Deo et populo et sanctæ ecclesiæ concesserat in die coronationis suæ" (p. 258).

[48] "Cum venisset in fine Natalis ad Oxenefordiam" (ibid.).

[49] Const. Hist., i. 321.

[50] Early Plantagenets, pp. 15, 16.

[51] "The news of this [Scottish] inroad reached Stephen at Oxford, where he had just put forth his second charter" (Norm. Conq., v. 258).

"The second charter ... was put forth at Oxford before the first year of his reign was out. Stephen had just come back victorious from driving back a Scottish invasion (see p. 258)" (ibid., p. 246).

[52] See Mr. Vincent's learned criticism on Mr. Freeman's History of Wells Cathedral: "I detect throughout these pages an infirmity, a confirmed habit of inaccuracy. The author of this book, I should infer from numberless passages, cannot revise what he writes" (Genealogist, (N.S.) ii. 179).

[53] "In fine Natalis" (Hen. Hunt., 258).

[54] Sym. Dun., ii. 287.

[55] The curious words, "vulgo ... ingerente," may be commended to those who uphold the doctrine of democratic survivals in these assemblies. They would doubtless jump at them as proof that the "vulgus" took part in the proceedings. The evidence, however, is, in any case, of indisputable interest.

[56] Ed. Howlett, p. 17.

[57] "Quem morem convivandi primus successor obstinate tenuit, secundus omisit" (Will. Malms.).

[58] "Rediens autem inde rex in Quadragesimâ tenuit curiam suam apud Lundoniam in solemnitate Paschali, quâ nunquam fuerat splendidior in Angliâ multitudine, magnitudine, auro, argento, gemmis, vestibus, omnimodaque dapsilitate" (p. 259).

[59] "[Consuetudo] erat ut ter in anno cuncti optimates ad curiam convenirent de necessariis regni tractaturi, simulque visuri regis insigne quomodo iret gemmato fastigiatus diademate" (Vita S. Wulstani). "Convivia in præcipuis festivitatibus sumptuosa et magnifica inibat; ... omnes eo cujuscunque professionis magnates regium edictum accersiebat, ut exterarum gentium legati speciem multitudinis apparatumque deliciarum mirarentur" (Gesta regum).

[60] See in Gesta (ed. Howlett, pp. 15, 16) his persistent efforts to conciliate the ministers of Henry I., and especially the Marchers of the west.

[61] See Appendix C.

[62] "In Paschali vero festivitate rex Stephanus eundem Henricum in honorem in reverentia præferens, ad dexteram suam sedere fecit" (Sym. Dun., ii. 287).

[63] Dr. Stubbs appears, unless I am mistaken, to imply that they first appear at court as witnesses to the (later) Oxford charter. He writes, of that charter: "Her [the Empress's] most faithful adherents, Miles of Hereford" [recté Gloucester] "and Brian of Wallingford, were also among the witnesses; probably the retreat of the King of Scots had made her cause for the time hopeless" (Const. Hist., i. 321, note).

[64] See Appendix C.

[65] "His autem rex patienter auditis quæcumque postulârant gratuite eis indulgens ecclesiæ libertatem fixam et inviolabilem esse, illius statuta rata et inconcussa, ejus ministros cujuscunque professionis essent vel ordinis, omni reverentiâ honorandos esse præcepit" (Gesta).

[66] John's list of bishops attesting the (London) council is taken from Richard's list of bishops attesting the (Oxford) charter.

[67] "Eodem anno post Pascha Robertus comes Glocestræ, cujus prudentiam rex Stephanus maxime verebatur, venit in Angliam.... Itaque homagium regi fecit sub conditione quadam, scilicet quamdiu ille dignitatem suam integre custodiret et sibi pacta servaret" (Will. Malms., 705, 707).

[68] Ibid., 707.

[69] Hen. Hunt., p. 259.

[70] Ibid., p. 260.

[71] "Vindictam non exercuit in proditores suos, pessimo consilio usus; si enim eam tunc exercuisset, postea contra eum tot castella retenta non fuissent" (Hen. Hunt., p. 259).

[72] Select Charters, 114 (cf. Will. Malms.).

[73] Ibid.

[74] Ibid., 96.

[75] Confirmation Roll, 1 Hen. VIII., Part 5, No. 13 (quoted by Mr. J. A. C. Vincent in Genealogist (N. S.), ii. 271). This should be compared with the argument of his friends when urging the primate to crown him, that he had not only been elected to the throne (by the Londoners), but also "ad hoc justo germanæ propinquitatis jure idoneus accessit" (Gesta, p. 8), and with the admission, shortly after, in the pope's letter, that among his claims he "de præfati regis [Henrici] prosapia prope posito gradu originem traxisse."

[76] Select Charters, 115. But cf. Will. Malms.

[77] As further illustrating the compromise of which this charter was the resultant, note that Stephen retains and combines the formula "Dei gratiâ" with the recital of election, and that he further represents the election as merely a popular "assent" to his succession.

[78] Compare the clause in the Confirmatio Cartarum of 1265, establishing the right of insurrection: "Liceat omnibus de regno nostro contra nos insurgere."

[79] See inter alia, Hallam's Middle Ages, i. 168, 169.

[80] "Fama per Angliam volitabat, quod comes Gloecestræ Robertus, qui erat in Normannia, in proximo partes sororis foret adjuturus, rege tantummodo ante diffidato. Nec fides rerum famæ levitatem destituit: celeriter enim post Pentecosten missis a Normanniâ suis regi more majorum amicitiam et fidem interdixit, homagio etiam abdicato; rationem præferens quam id juste faceret, quia et rex illicite ad regnum aspiraverat, et omnem fidem sibi juratam neglexerat, ne dicam mentitus fuerat" (Will. Malms., 712). So, too, the Continuator of Florence: "Interim facta conjuratione adversus regem per prædictum Brycstowensem comitem et conestabularium Milonem, abnegata fidelitate quam illi juraverant, ... Milo constabularius, regiæ majestati redditis fidei sacramentis, ad dominum suum, comitem Gloucestrensem, cum grandi manu militum se contulit" (pp. 110, 117). Compare with these passages the extraordinary complaint made against Stephen's conduct in attacking Lincoln without sending a formal "defiance" to his opponents, and the singular treaty, in this reign, between the Earls of Chester and of Leicester, in which the latter was bound not to attack the former, as his lord, without sending him the formal "diffidatio" a clear fortnight beforehand.

[81] Const. Hist., i. 338, 340.

[82] Norm. Conq., v. 251.