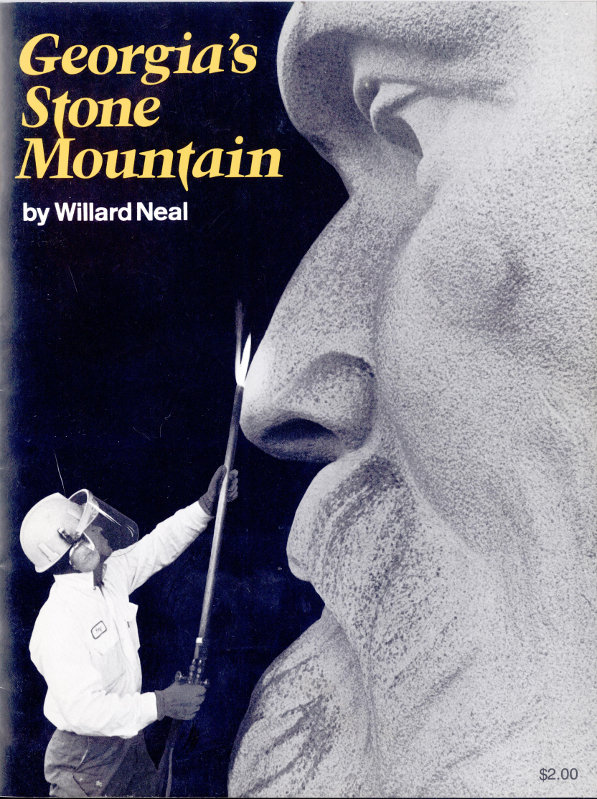

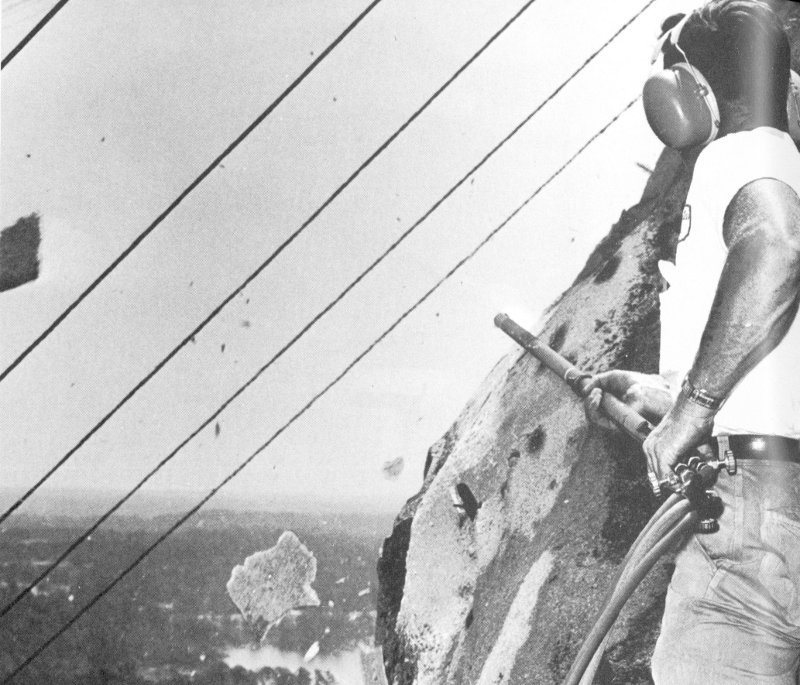

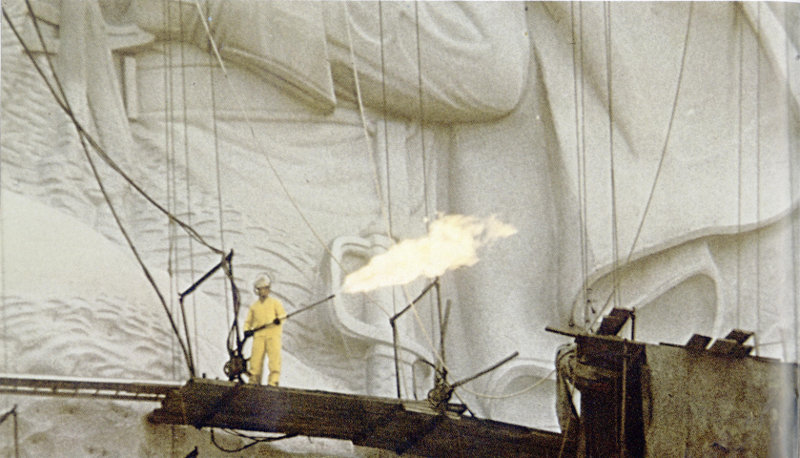

Chief carver Roy Faulkner at work on the Stone Mountain Memorial Carving, face of General Robert E. Lee.

by Willard Neal

$2.00

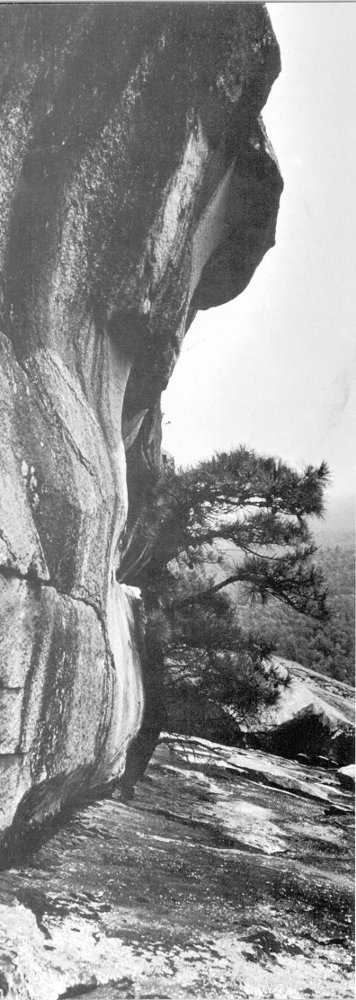

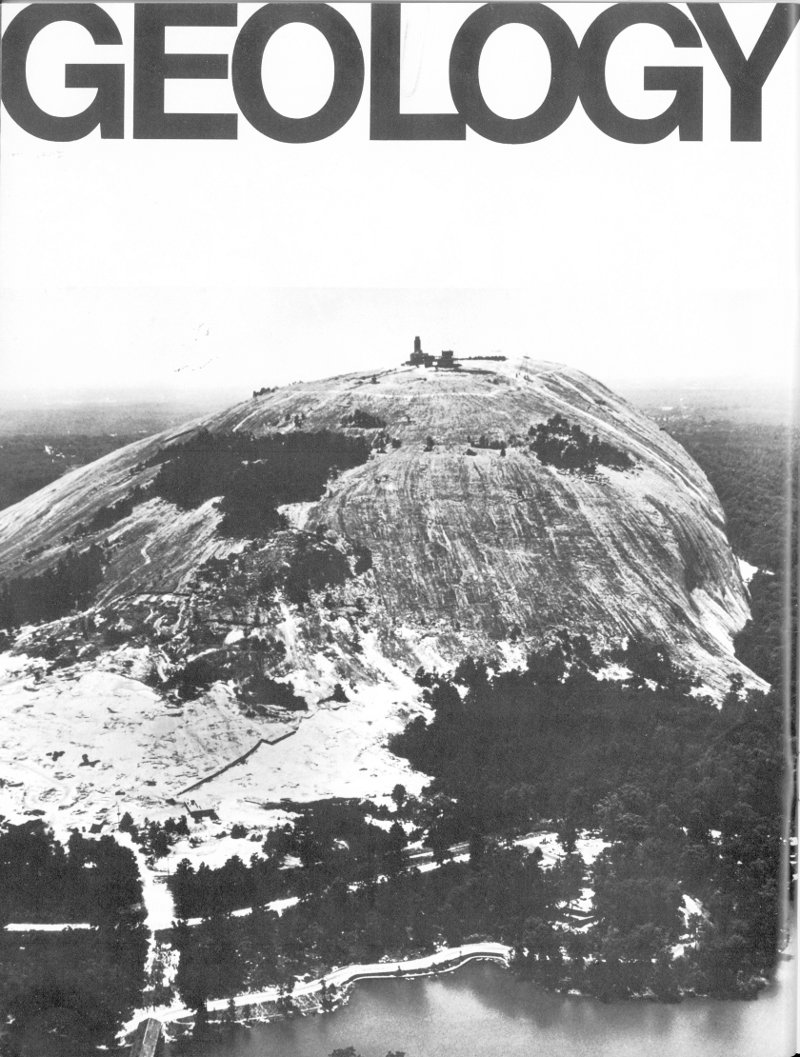

This is a view of Stone Mountain before the carving.

Every traveler, on first viewing Stone Mountain, has stood in awe at the foot of the looming monolith. Seasoned tourists and Georgia school children are affected just as pioneer explorers were. The towering rock is so impressive that each individual feels he is making the great discovery.

Questions arise. How did Stone Mountain come to be? How old is it, and how high? Exactly how large is this biggest carving in the world. How was it done? Who did it? Who first saw Stone Mountain? What effects has it had on the development of our country?

Thus, this book. It is dedicated to those who care enough to see and study the wonders of their country, and who, in their travels, have had the unexplainable and unexpected thrill of discovering Stone Mountain.

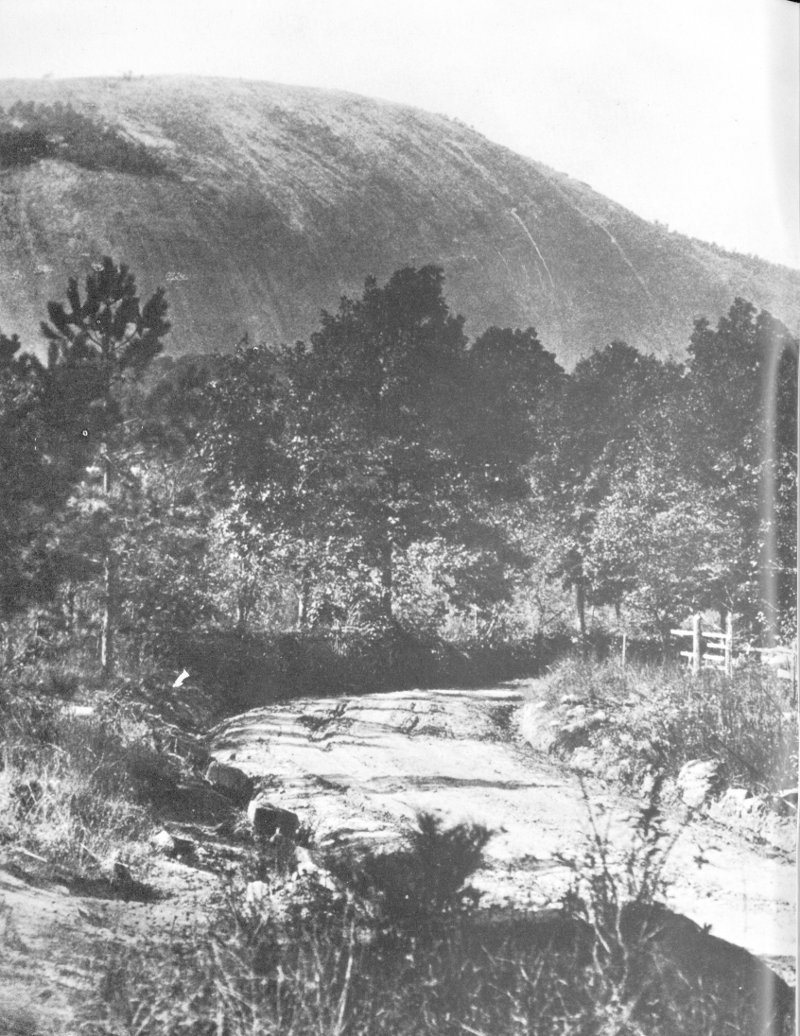

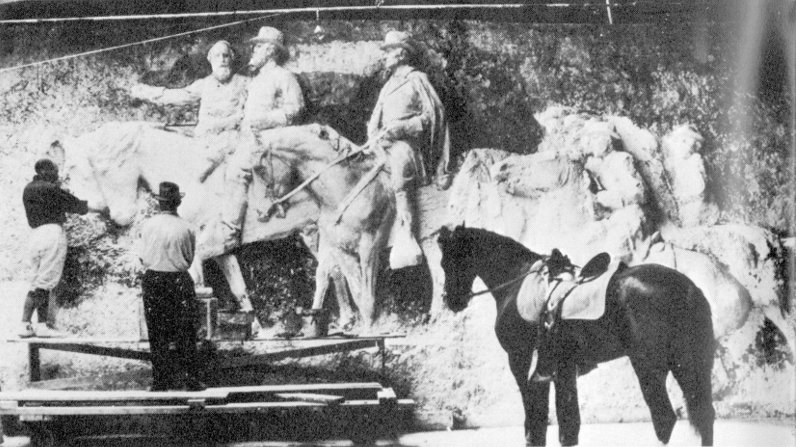

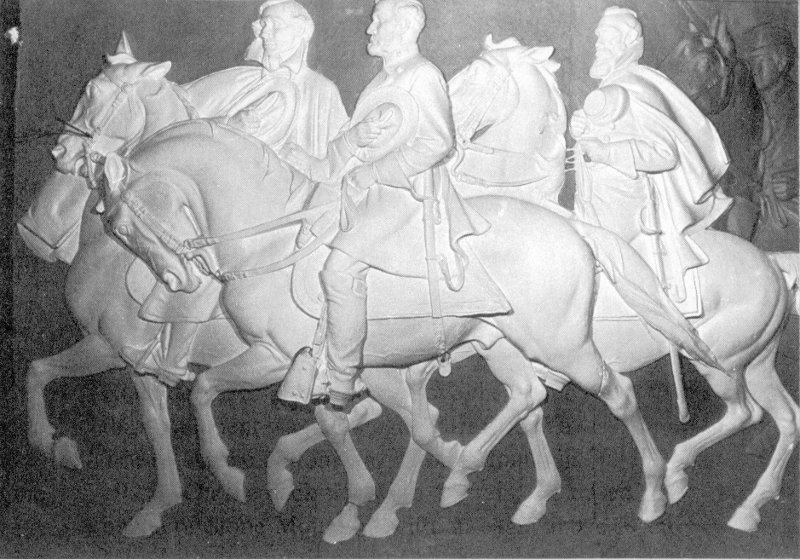

Confederate President Jefferson Davis and Generals Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson ride forever on Stone Mountain.

Stone Mountain’s Confederate Memorial is the world’s largest piece of sculpture, cut into the side of the world’s biggest exposed mass of granite. The carving is 90 feet tall and 190 feet wide, stands eleven and a half feet out from the side of the mountain, and towers 400 feet above the ground in a frame that is 360 feet square, or three acres. Fifty-five years elapsed from the time of the original concept in 1915 until completion of the three figures in 1970. Not a blow of the hammer was struck for 36 years, from 1928 to 1964.

At Stone Mountain things have a way of coming out quite differently than planned.

History is a little hazy on who first envisioned a Confederate Memorial on Stone Mountain. Mrs. Helen Plane, charter member of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, was quoted in 1909 as thinking it would be a fine place for a monument. In 1912 John Temple Graves, editor of the New York American, after a visit back home wrote a rousing editorial for the Atlanta Georgian urging that the world’s greatest monument be carved on the world’s finest piece of stone.

Actual movement began in 1915 when Mrs. Plane, then president of the Atlanta chapter of UDC, suggested having a 70-foot statue of General Robert E. Lee carved on the steep side of the mountain. The UDC consulted Gutzon Borglum, who just then was being acclaimed for his statue of Abraham Lincoln. The first look at Stone Mountain set Borglum’s imagination afire. Here was the biggest, finest solid block of granite any sculptor ever had an opportunity to carve. A small figure in its center, he pointed out, would be like a postage stamp stuck on a barn.

The sculptor stayed several weeks at the nearby home of Samuel H. Venable, head of the family that owned the mountain, while he studied the great stone. Then he drew up sketches of Confederate leaders riding around the mountain, which he submitted to a meeting of the UDC.

In 1915 women were not even permitted to vote. Their principal commercial experience was as salesladies, telephone girls and seamstresses. When Borglum said the monument would require ten years and cost three million dollars, the ladies were terrified. They wanted no part of such an undertaking.

On March 20, 1916, Sam Venable, Mrs. Coribel Venable Kellogg and Mrs. Robert Venable Roper deeded the face of Stone Mountain and ten adjoining acres to the UDC, with the proviso that the property would be turned back to the original owners if a suitable monument was not completed in twelve years. At their Chattanooga convention in 1917 the UDC ladies founded an independent chartered organization known as the Stone Mountain Confederate Monumental Association to manage the project.

World War I stopped non-essential activities. In 1923 Borglum announced that his designs were complete and he was ready to start carving.

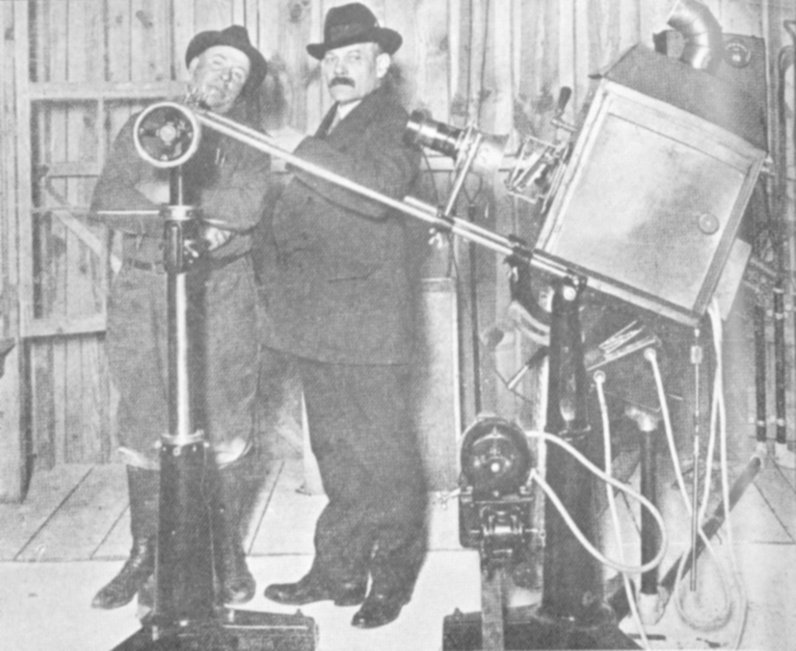

The world’s largest sculpture presented many unprecedented problems. A difficult one was how to get a sketch of the monument on the mountainside. Borglum announced that he would pour chemicals from above to coat the stone with photographic emulsion, flash an image of his 4 model through a giant enlarger, and develop the picture by pouring down more chemicals. By the time photographers explained to him that it could not be done, his plan had been described in magazines and newspapers around the world, and the Stone Mountain Memorial was news everywhere. Borglum devised a method for using the idea, anyway.

There was not even a precedent for determining the size of the carving. The nearest thing was the rule that decreed the diameter of court house clocks. By this scale the statues should be 35 feet high for viewing from the studio 1,300 feet away.

A crowd collected the evening the projector was set up. Borglum computed the lens setting to give a 35-foot-tall image, inserted the plate bearing a photograph of his model, and switched on the light. There was a gasp from the spectators. Horses and men looked like midgets.

Borglum enlarged the image until it assumed an impressive size, then called to two men, swinging down the mountain in bos’n’s chairs, to measure it. One dangled a tape from the top. The other, reading the figure at the bottom, called out, “One hundred and sixty-eight feet!”

Gutzon Borglum with his famous projector, and in the studio with his model.

Oxen hauled timbers up the mountain for the stairway.

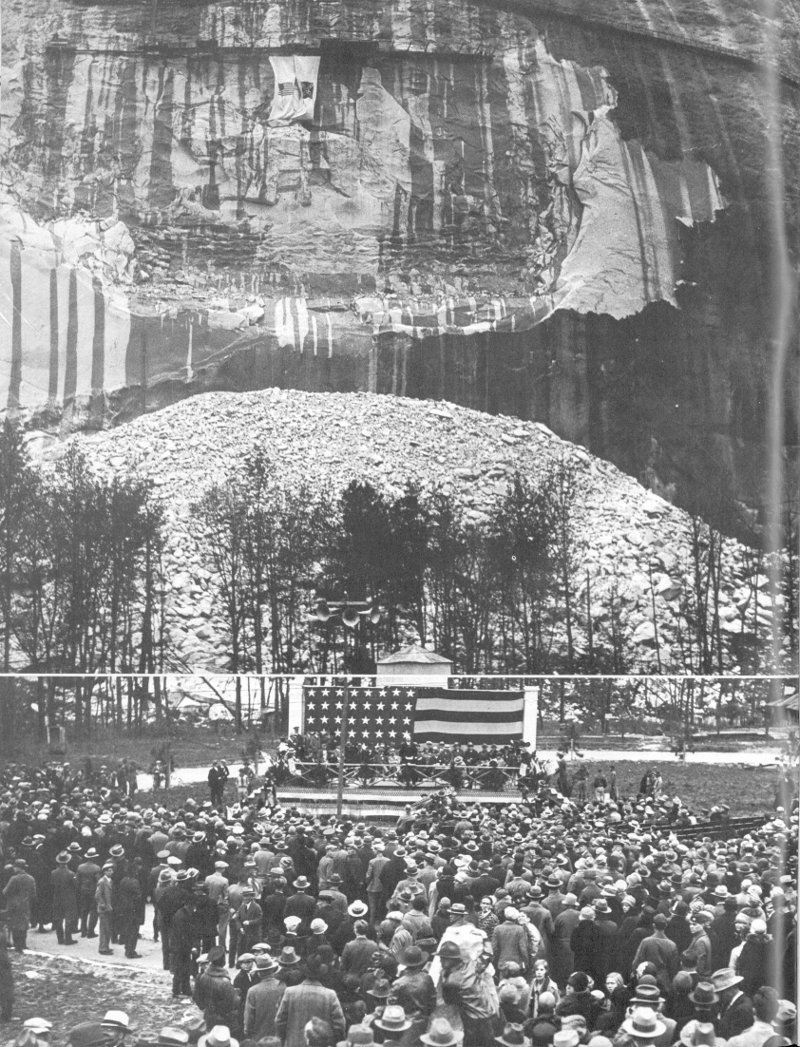

Visitors arriving the day carving was begun in June, 1923.

The men carried buckets of paint and brushes for outlining the picture; but when they started to work they could not tell men from horses nor heads from feet, or where one figure ended and another began. The next day Borglum traced the picture of his model as a 5 line drawing on another plate and that night his aides were able to outline the sketch.

Motor trucks of that period were not powerful enough to climb Stone Mountain. Materials needed to construct a stairway from the top down to the carving site were hauled up the foot trail by ox cart. After the stairs were finished, cable, pulley and winch were installed to bring up materials for stairs down to the ground, scaffolding and tools.

On June 23, 1923, Borglum led a group of dignitaries over the top of the mountain and down to the platform above the carving site. Gov. E. Lee Trinkle of Virginia made a dedicatory speech through a megaphone to throngs below. Then Borglum had himself lowered by bos’n’s chair and, with a pneumatic drill, punched several holes into the mountain as the official beginning of the carving.

Notables at lunch the day before Lee’s birthday in 1924.

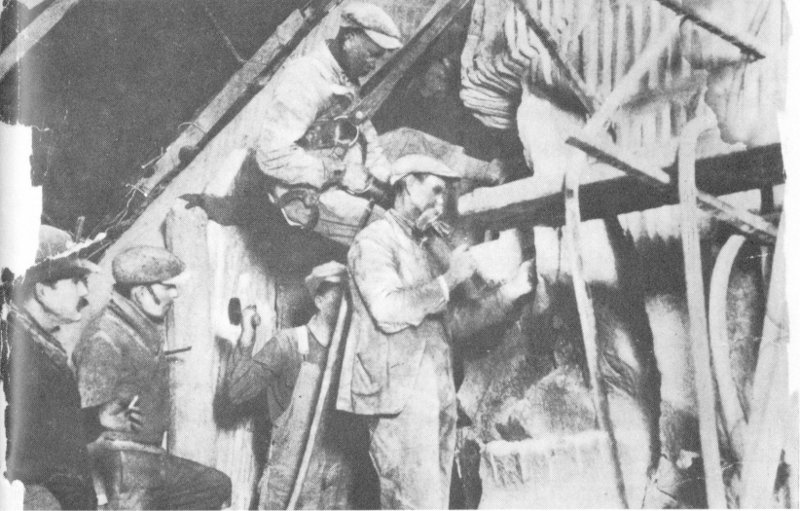

Borglum’s carvers at work.

Smoke descends with rock after a powder blast.

From the time he started, Borglum had five years to complete the monument before the end of the 12-year deadline. On January 19, 1924, anniversary of Lee’s birth, 20,000 gathered for the unveiling of General Lee’s head. On the previous day a select party, including the governors of Virginia, Texas and Alabama, had climbed over the mountain and descended the stairs for a dinner at a table set up on the granite shelf in front of the statue.

A few months later work on the carving began to slow down. Personality rifts between Borglum and members of the Association widened, 6 and in March, 1925, the sculptor destroyed his models and sketches, and left Georgia. Other artists said the real reason for his tantrums was distortion in the carving—he never could have finished it, and he was trying to hide the blame. Taking a short cut in projecting his sketch onto the mountain had been a fatal mistake. He went to South Dakota and gained lasting fame by carving the Mount Rushmore masterpiece.

No sign of Borglum’s work remains at Stone Mountain. However, he made a vital contribution. It is doubtful if any other artist would have had the imagination to visualize such a stupendous monument in such an inaccessible place, or have had the nerve to start carving it.

And he accomplished one thing that lasts. He designed the Confederate half-dollar. Congress agreed for the mint to produce five million of these coins, which, with the Association selling them for a dollar apiece, could have financed the carving of the memorial.

The next sculptor selected, Augustus Lukeman, was the exact antithesis of his predecessor—a man of few words and apparently no temperament whatever.

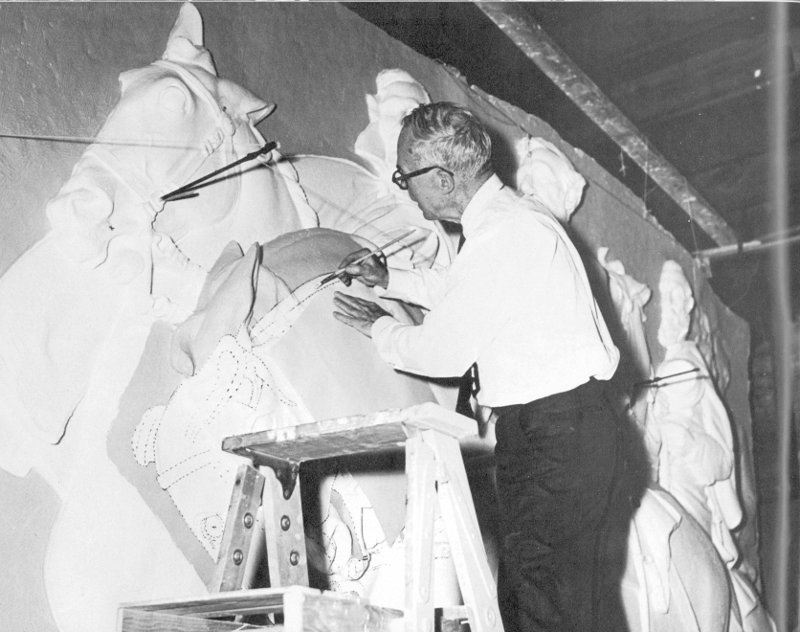

Augustus Lukeman inspecting work on Lee’s face. Note white model at left.

Starting April 1, 1925, Lukeman knew he could never complete the memorial before the 12-year contract would expire in 1928. His hope was to get enough done to show that he could and would finish it. So he worked at top speed. Lukeman made a new design in classic style showing President Jefferson Davis, General Robert E. Lee and Lieutenant General Stonewall Jackson on horseback as the central figures, followed by an army apparently marching out of the solid rock. His master model was on a scale of 12-to-1—one inch on the model corresponded to a foot on the mountain.

Lukeman had the curving face of the mountain blasted off to a vertical wall 305 feet wide by 190 feet high. Although the steep area looks almost straight up, the bottom of the cut made a shelf extending outward 42 feet.

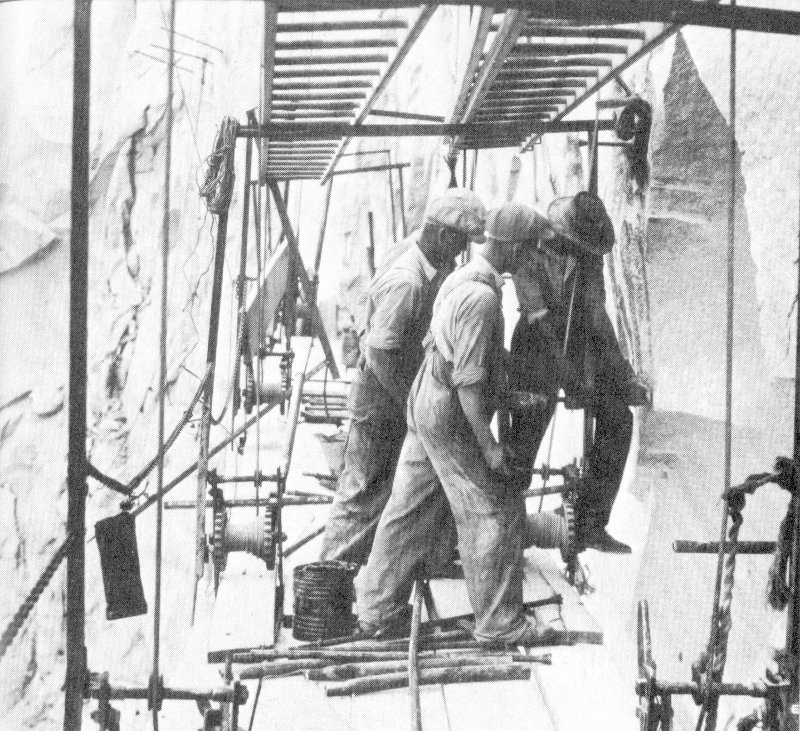

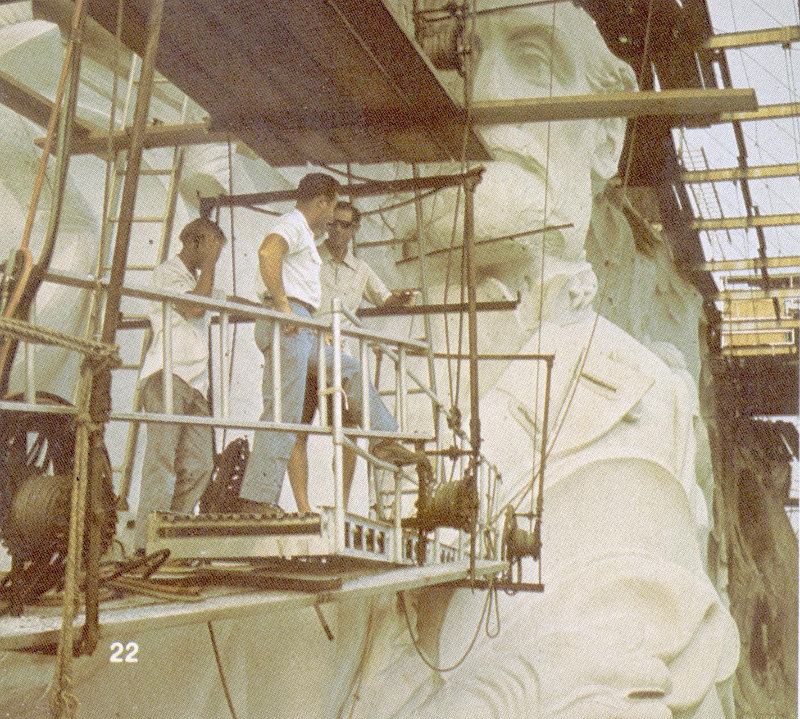

To get his men up against the wall where they could work, Lukeman had twenty-one 10-inch steel beams placed along the top of the cut, so they extended 30 feet out into space. Workmen’s scaffolds were suspended from these by steel cables, with winches to raise and lower them. A dozen men usually were on the job, although 42 crowded the scaffolds during one rush period. Only eight were carvers, the rest helpers.

The sketch of Lukeman’s model was painted onto the mountain by painstakingly measuring all the component points, so there could be no 7 distortions in the figures.

Four men directing a pneumatic drill.

Lukeman’s original master model.

Cutting into Stone Mountain had to be done mechanically since explosives can start a crack in granite that may run on for many feet. If an area four feet high by two feet wide needed to be gouged out two feet deep a jackhammer crew would drill a row of holes almost touching each other down the sides and across the bottom, then a row slanting downward across the top. Wedges were hammered into the slanting holes until the block broke loose and plummeted earthward.

A drill was good for only a few minutes in the hard granite before its point was dulled, and a fresh one had to be inserted. The dull drills were sent by cable and pulley down to the shop on the ground just out of range of falling rock, where two blacksmiths were kept busy sharpening and repairing tools.

Whereas one man can hold a pneumatic drill straight up and down to break up the paving in a street, it took four men per hammer to drill horizontal holes into the face of the mountain. One guided the drill and held it in place. Two helped lift the heavy hammer. The operator did his share of lifting and worked the trigger. All exerted what force they could to press the drill into the mountain.

After a figure was blocked out in this manner, skilled carvers with hand and air-powered tools completed the job.

Lukeman blocked out the figures of Lee and Davis and finished their faces and also roughly outlined Lee’s horse, Traveler, before the deadline of March 20, 1928. It was evident that he was capable of completing the monument. The Confederate Commemorative half-dollars were arriving from the mint, and the way they were being bought up by the public indicated that financing the carving would be no problem. Altogether, 2,314,000 of these coins were struck. A million were melted back into bullion, and the rest eventually were put into circulation.

Incidentally, the coins had about as much material as could be stamped into that small a piece of silver. On one side were Lee and Jackson on horseback. Thirteen stars for the thirteen Confederate States showed above them, and over this firmament was the slogan, “In God We Trust.” At the bottom was “Stone Mountain, 1925.” On the back side were 48 stars, the raised image of Stone Mountain with an eagle above it and Miss Liberty, and printed below, “United States of America Half Dollar. Memorial to the Valor of the Soldiers of the South.”

Mayor Jimmy Walker of New York was guest of honor when Lukeman’s Lee was unveiled.

The deadline date of March 20 came and went with no word from the Venables about extending the contract. On April 9, the 63rd anniversary of Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, Atlanta’s Gate City Guards militia unit hosted an unveiling of the Lee and Davis features. The extremely popular Mayor Jimmy Walker of New York was guest of honor.

On May 20, 1928, the Venables reclaimed their property, ending the UDC’s chance to complete the memorial.

In 1958 the Georgia Legislature finally got around to developing the state’s greatest tourist attraction. It named a Stone Mountain Memorial Association, with authority to purchase the mountain and surrounding land, 3,200 acres in all, for a state park, and to complete a satisfactory Confederate monument.

Nine of the nation’s leading sculptors were invited to visit Stone Mountain and submit plans for the memorial. The Association approved a suggestion by Walker Kirtland Hancook of Gloucester, Mass, for making Lukeman’s uncompleted design appear intentional by carrying the carving to a point that would be aesthetically satisfying, a device used effectively by Michelangelo.

Mr. Hancock was engaged in 1963 and charged with responsibility for finishing the design according to his plan, for serving as a direct consultant for the carving, and for developing the memorial area.

The Association employed George Weiblen, whose family had operated the quarry at Stone Mountain, to assemble a crew and get the mountain ready. In 37 years the steel supports for the stairway had rusted out and required replacing, as did the steel cables and scaffolding. Bids were asked for a 400-foot elevator up to the carving, and when the costs seemed entirely too high, a prefabricated elevator was ordered, and the work crew put it up in 28 days. It was the world’s highest outside elevator.

A skilled carver was hired to begin the carving. He rode up on the new elevator and studied from arm’s length the acre of granite which he was expected to fashion into three horsemen. He found that he simply could not visualize such gigantic figures at such close range.

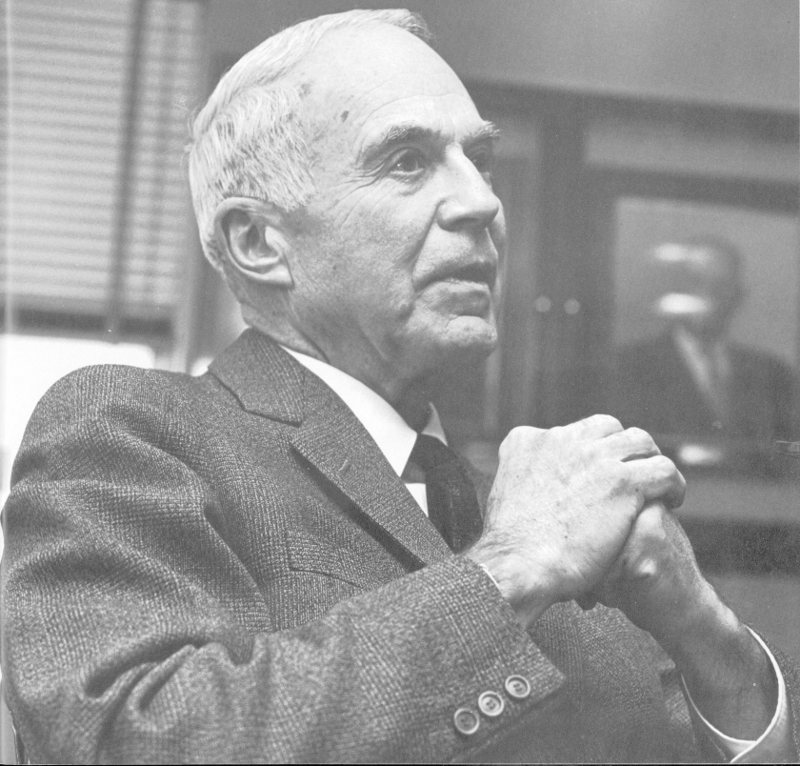

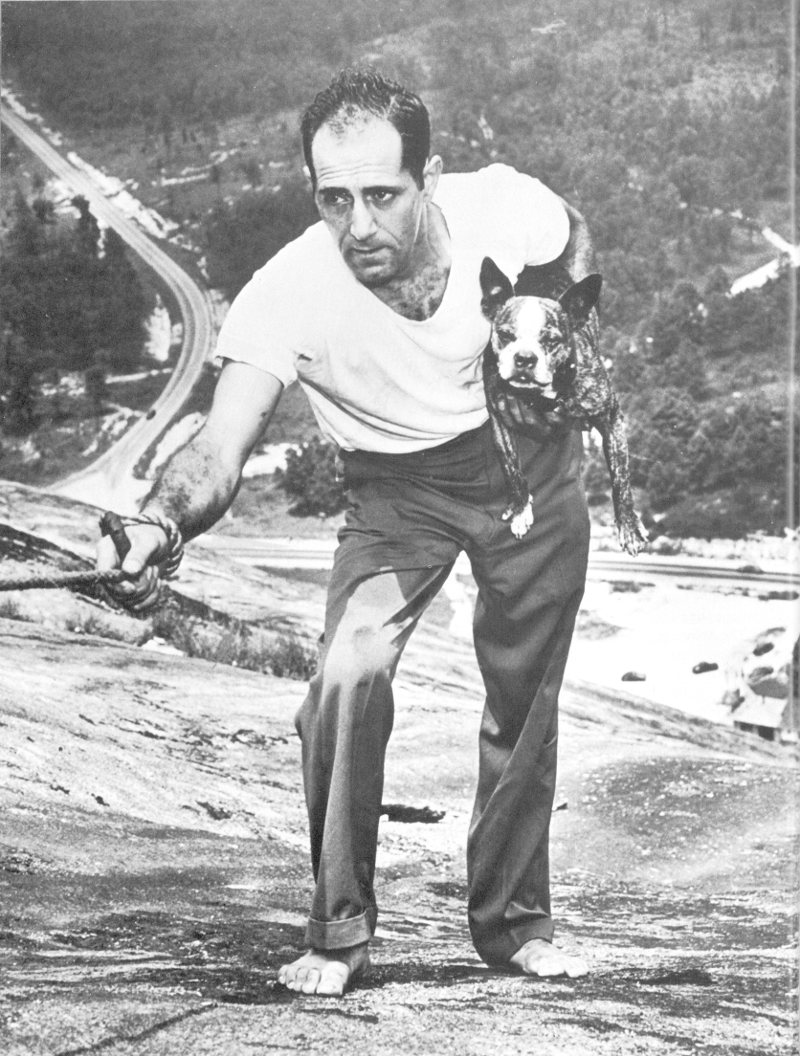

The foreman of the working crew, Roy Faulkner, a young Marine veteran from nearby Covington, experimented with the new carving tool to be used, and discovered he had a knack for it. Although the foreman had never had an art lesson, and his only previous experience with stones was throwing them, he was assigned some smoothing tasks by sculptor Hancock while the search continued for an experienced carver. Soon the search was forgotten. Roy Faulkner stayed on the face of the mountain for more than six years, to complete the world’s largest carving.

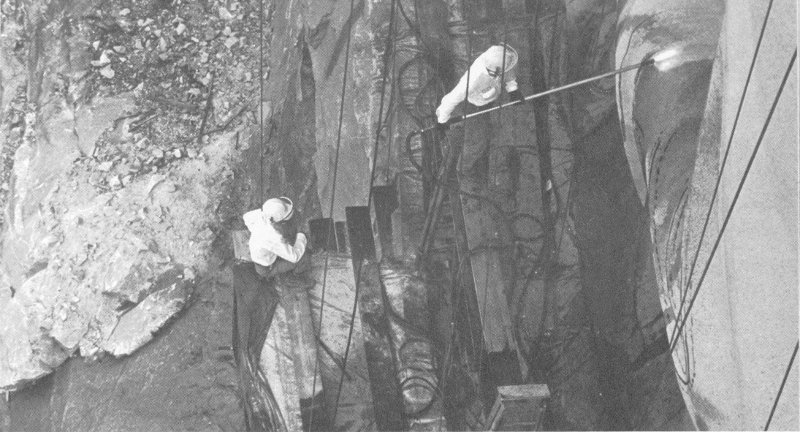

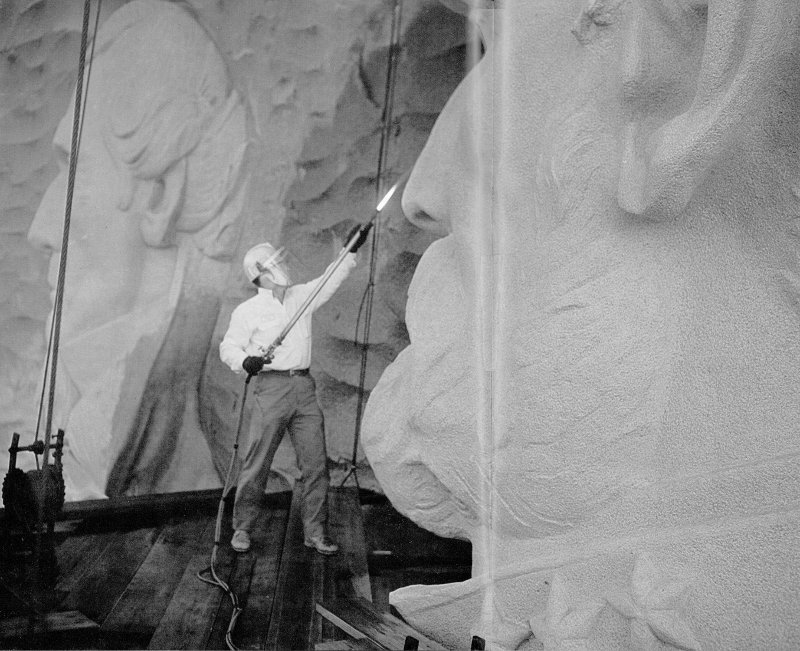

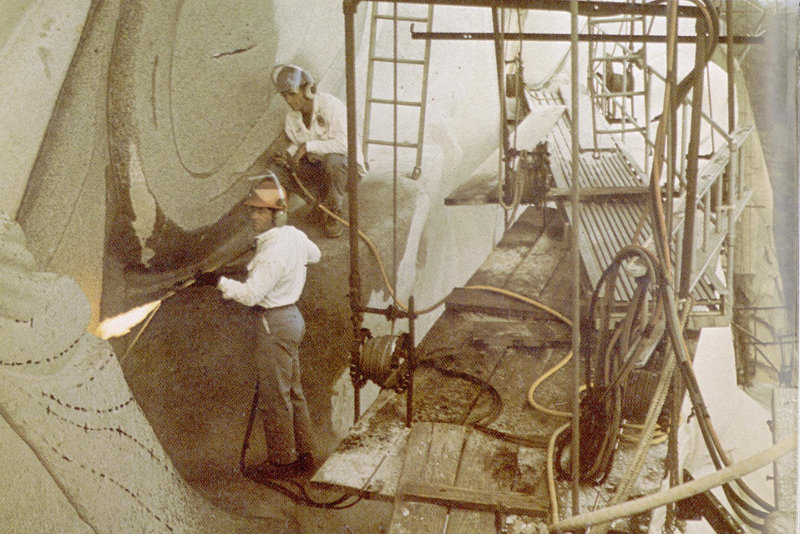

The new tool was the thermo-jet torch developed for use in granite quarries. It consisted of an eight-foot pipe fed by three hose lines. One hose carried kerosene, another oxygen, and the third water to be sprayed through the jet nozzle to keep it cool. The operator could adjust the flame to any temperature up to 4,000 degrees.

When such intense heat strikes granite the moisture between molecules is suddenly converted into steam, literally exploding the surface crystals, or flaking them off, as quarrymen say. Flakes fell away in a continuous stream. In 10 coarse, deep gouging, slivers as big as dinner plates and half an inch thick, sailed off the mountain like miniature red-hot flying saucers.

One thermo-jet torch could remove several tons of stone in a day; more than 48 men could do in a week with drills and wedges. Carving with it was a one-man job. Two men trying to work in the same area would have bombarded each other with hot rocks. Even one could expect some lumps. Exploding flakes popped out in many directions, sometimes straight back, or ricochetting off the mountain or steel cables. The operator wore a plastic shield over his face, as well as muffs to protect his ears from the roar of the torch, which was the dominant sound in the north end of the Park for six years.

The torch acted like a miniature jet engine, developing about as much backward thrust as an automatic shotgun. The carver had to keep his body braced against this force as long as the flame was lit.

Fine carving was done with a tool half as large. With the flame adjusted as thin as an acetylene torch’s, it could cut along a pencil mark.

The carving was continued from Lukeman’s master model, with several important changes made by Hancock. He stopped the monument below the riders’ knees, creating an illusion that the horsemen were just emerging from the rough stone. This saved months of carving that would have produced no more than a view of horses’ legs and hooves. The army that Lukeman planned to have following behind was left off entirely, making the three leaders the entire monument. The sculptor lowered the head and neck of General Lee’s horse so that more of President Davis and his horse could be seen, and he gave Davis a civilian hat instead of the campaign hat Lukeman modeled. And, Hancock modeled a new head of Stonewall Jackson to make him look more like the photographs taken just before the General’s death.

Looking at the finished work, it seems amazing that a man could get his first lesson in carving on the world’s biggest monument, and go on to complete it. In explaining how he carved, Faulkner said that mostly he measured. If he was to start a new feature, like the knuckle of General Lee’s first finger, he measured the distance to it from his center line on the master model. Then he checked to get the distance to the knuckle from Lee’s ear, his nose, Davis’ eye, the ear tips of the horses, and other spots. Interpolating inches on the model to feet for the mountainside, he measured from corresponding points on the carving. When all the measurements came out at the same place, he drilled a hole there to the exact depth corresponding to the distance from the knuckle to the plumb line at the front of the model. To insure against cutting away too much of the adjoining stone, he measured and drilled depth holes for all of the features nearby.

After making certain that all the measurements were correct, he fired up the large torch and cut down to within half an inch of the bottom of the holes, then switched to the smaller torch to carve the rest of the way.

He said he always tried to keep in mind the first fundamental of sculpture—never cut too deep nor in the wrong place. He thoroughly understood that carvers cannot erase mistakes nor paint over them nor sew them up. The only way is not to make them.

Stonewall Jackson’s cap.

Carving Jackson’s arm.

An interesting portrait of Sculptor Walker Kirtland Hancock.

Roy Faulkner’s torch sends out slabs of hot granite like flying saucers.

Sculptor Hancock lowering head of Lee’s horse on the master model.

The jet flames glazed the surface of the remaining stone, leaving a grayish glassy effect. This was removed and the whiteness of the live granite restored by going over it lightly with a surfacing machine, a vibrating tool driving a four-point tip.

Roy Faulkner figures that in six years he drilled thousands of holes in the acre of granite—more than ants ever dug in an acre of meadow. Experience did not speed up the work much. He was just as careful measuring the last points to be carved as the first.

There were special models of the heads of men and horses, on a scale of four-to-one. When working on a head Faulkner took the corresponding model up on the scaffold for ready and frequent references. Incidentally, errors in the harness showed that Mr. Lukeman’s experience with horses had been purely academic. He had all the harness buckles backward, so that a hard pull on the reins would have made the bridles come apart. The buckles are turned around right on the mountain.

The sheer side of Stone Mountain would seem a lonely place to spend six years, but the man who was up there never found it lonesome. He had a couple of aides to stretch the opposite end of the tape measure, help raise and lower scaffolding and do other jobs, but conversations could not be heard over the roar of the torch.

“The entire job was one of the most satisfying experiences anyone could have,” Faulkner declared. “In the first place, it was a privilege to be associated with such a great man as Mr. Hancock.

“Everything about the work was a challenge. The danger was very real. I was aware every minute I was up there that a misstep, or a little carelessness, could drop me to my death. The wind helped keep me on my toes. When you hardly noticed a breeze on the ground, it could be gusting at 50 miles an hour, first into your back, then bouncing off the mountain into your face.

“The work was hard enough to keep a man in trim. After leaning against the thrust of that jet for an hour or two or three, when I turned off the flame, I felt like taking a rest. There was enough climbing up and down ladders to keep legs and lungs in good order.

“For six years I worried that I might make a mistake. After coming down in the evenings I checked over the day’s figures in the studio to make sure they were right. Then I drove home with them in my head, ate with them, and often slept with them. The worst dream I ever had was the time I saw General Lee’s head lying in the ditch at the base of the mountain.

“Among my greatest experiences was, on several occasions, to look into the stone and visualize the full outline of the feature I was about to carve. Then I often got the opposite reaction just before I finished with a component such as a horse’s eye or nostril. From the close-up view it seemed to be the wrong shape or in the wrong place, and up there on the mountain you don’t step back for a better look. It was a relief, on coming down, to see that it fit.

“I realized at all times that I was carving the largest piece of sculpture that man ever attempted, one that would last through eternity.

“You could hardly do anything more satisfying than that.”

Magazine artist’s view of Stone Mountain in ante-bellum times.

The earliest history of the mountain was literally dug up by Lewis Larson, Jr., assistant professor of anthropology at Georgia State College in Atlanta. He explored the present bottom of the lake around the western side while the dam was being built. Along with more recent artifacts, Mr. Larson and his helpers collected shards of soapstone bowls and dishes, carved and used by Stone Age people possibly five thousand years ago, long before early Americans learned to shape and bake pottery.

Local historians have tried hard to find evidence that Hernando de Soto visited Stone Mountain. Actually, if that old conquistador had set out to touch all the points his name has been associated with, his iron-clad ghost would still be riding hard and only half way through its itinerary. De Soto certainly did not see this rock, or his chroniclers would have described it in detail as a large-scale replica of the Gibraltar they left behind.

The first white man to see Stone Mountain seems to have been Captain Juan Pardo, sent by the Spaniards in 1567 to encircle Georgia with forts. He followed somewhat the route taken by de Soto’s ill-fated expedition. Pardo fared some better. He got back to St. Augustine with his life, but he did little fortifying.

Pardo regarded as his most important achievement the discovery of what he called Crystal Mountain, a great mountain that glistened in the sun and was surrounded with diamonds and rubies and other precious stones lying on the ground for the picking up. Unfortunately, Indians kept him and his men too busy for gem collecting at that time.

The captain spent the rest of his life at St. Augustine trying to raise a force of 500 men for another trip to Crystal Mountain, promising to make every one of them rich, as well as any who would help finance the expedition. Since he had failed in his fort-building mission and had not been able to pick up a pocketful of gems, even when he was walking—or running—over them, he was unable to find 500 men willing to risk life and fortune on the venture. Pardo’s diamonds and rubies are still to be found on top of the ground at the base of the mountain. They are crystals of quartz, fully as beautiful as gem stones, but not so rare, and therefore not so valuable. Many of today’s visitors, less hurried than the captain and his men, pick up a few for souvenirs.

The first eye-witness description of Stone Mountain in English appears to have been an account written by a British officer and published in London in 1788. The Britisher almost certainly came into the area to incite Indians to fight against the colonists in the Revolutionary War. Unlettered traders probably viewed it earlier than that, but seeing no profit, dismissed it as being of no consequence to themselves.

The mountain enacted its first role in modern history on June 9, 1790. President George Washington had sent Colonel Marinus Willet to confer with chiefs of the Creek Nation and arrange for an emissary to visit him at the capitol in New York. In that era of few addresses in the wilderness the meeting was scheduled for Stone Mountain as a spot familiar to all the Indians.

The colonel reported in his Narration of the Military Acts of Col. Marinas Willet:

“Here we found the Cowetas and Curates to the number of eleven waiting for us. While I 16 was at Stony Mountain, I ascended the summit. It is one solid rock of a circular form about one mile across. Many strange tales are told by the Indians of the mountain. I have now passed all Indian settlements and shall only observe that the inhabitants of these countries appear very happy.”

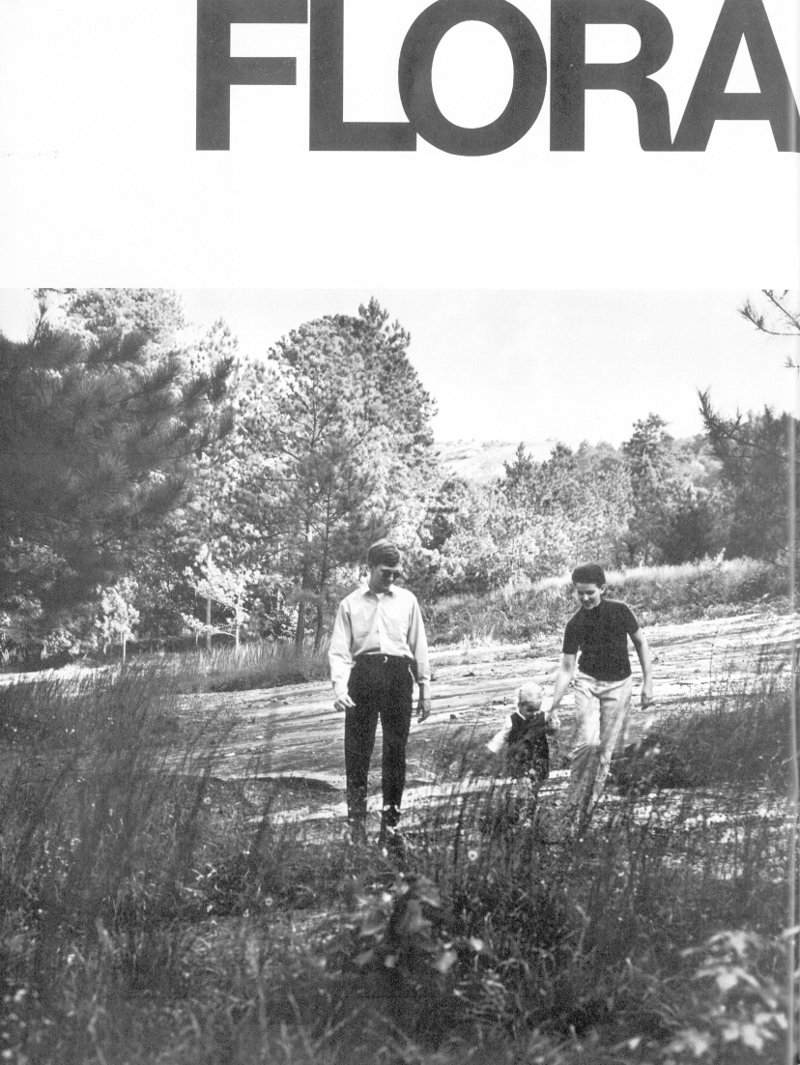

Elias Nour and Willard Neal near the top of Stone Mountain

The colonel could have made us all happier by setting down some of the stories he was told. By his failure to do so, those strange tales are lost forever. Incidentally, even in 1790 the southern Indians were no longer savage aborigines. They had been trading with the Spanish, British and French for more than two hundred years, had adopted many of the white men’s ways and utterly forgotten much of their tribal lore. Their extensive farms had grown up in trees and their elaborate system of trade had been abandoned, 17 while they depended largely for their living on hunting for furs or hiring out in the white men’s wars.

Head of the Indian delegation at Stone Mountain was Alexander McGillivray, son of a Scotch trader and a half-breed Indian princess. After completing his education in Baltimore, McGillivray worked in a counting house in Savannah until the start of the Revolution, then returned to his mother’s tribe in Alabama where he quickly rose to chief of the United Creeks, and the Seminoles and Chicamaugas as well. He also became a colonel in the British Army, in return for inciting his tribesmen to harass settlers in Georgia and Tennessee.

After the war ended and the British left, McGillivray accepted a similar role with the Spanish in Florida. President Washington sent 18 for him, hoping to placate him and stop the depredations along the frontier.

The assassination of Chief William McIntosh.

Twelve more chiefs arrived for the meeting at Stone Mountain, making twenty-three, with a lot of braves, most of whom were relatives of the chiefs, and Willet started with them on the long and colorful procession to New York.

McGillivray accepted payment for his property in Savannah that had been confiscated. The Georgia colony already had twice bought and paid for the land east of the Oconee River, but McGillivray sold the same land again, and signed a third treaty for $100,000. For assurance against further Indian troubles, Washington commissioned him brigadier general in the United States Army and awarded him a pension of $1,200 a year.

McGillivray went immediately to Pensacola, where the Spaniards proclaimed him emperor of the Creeks and Seminoles and paid him $3,500 a year to continue harassing Georgia settlers. He died in 1793 of “gout of the stomach,” which may have been an unidentified poison.

In 1802 the Creeks signed a treaty giving up their lands west of the Oconee River to the state line. Georgia then ceded the Alabama and Mississippi territories to the United States government in exchange for a promise to remove all the Indians from within the state’s borders, a pledge that was not carried out. The state began distributing the land by lottery in 1803.

Reports of the rock that was as big as a mountain continued to arouse wide interest, but they were descriptions given by Indians. Few white men still had seen it. M. F. Stephenson, the famous gold assayer of Dahlonega, wrote that in 1808 an Englishman returned to London with the story, but the location of the mountain was so far from the Blue Ridge peaks that he thought it was man-made. The president of the Academy of Arts and Sciences in Paris addressed a letter to the Hon. R. W. Habersham of Savannah asking for the dimensions and other data concerning this vast relic of architectural grandeur.

The frontier continued in turmoil, which reached a climax through incitement of the Indians by the British in the War of 1812. In 1814 Andrew Jackson, with 2,500 militiamen and a lot of Cherokees, cornered and practically annihilated the militant branch of the Creeks at Horseshoe Bend of the Coosa River in Alabama.

During the years several more treaties concerning the Stone Mountain area were signed and ignored. The Creeks enacted the death penalty for any chief who disposed of any more of the tribe’s properties. Then Chief William McIntosh again sold the land between the Oconee and Chattahoochee rivers for $400,000 in a treaty signed at Indian Springs in February, 1825. Two months later he was riddled with bullets from a hundred Creek rifles.

The next year, in 1826, President John Quincy Adams invited thirteen Creek chiefs to Washington and bought the land east of the Chattahoochee again.

One of the first literate descriptions of Stone Mountain was written by the Rev. Francis R. Goulding, noted novelist and inventor, who spent his later years at Roswell, forty miles away. Goulding visited the mountain on June 25, 1822, as a 12-year-old, with his father, a cousin, a Cherokee guide named Kanooka, and a slave boy named Scipio. The elder Goulding, a prosperous 19 merchant of Darien on the coast, had just recovered from a severe spell of fever and recuperated by taking his son to the mountains to visit with the Cherokees that summer. Young Francis wrote:

“Twenty miles away to the southeast a vast prominence of rock loomed in lonely grandeur above the horizon. It was the great natural curiosity of the neighborhood, of which we had often heard and which we had resolved to visit at our first opportunity. That time had now come. Indeed, the fame of the great rock had extended to the Old Country, and had there excited interest through the representation of a British officer who had visited and described it as early as the year 1788.

“At the time of our visit the country around had barely passed into the hands of the white man, and there were few roads and fewer houses of accommodation. Our tent was pitched beside a spring near the mountain’s base, around the north and west of which flows a pleasant stream. From this point the rock rose majestically, with an almost perpendicular face of a thousand feet. We enjoyed its rough grandeur almost as much by the soft light of the moon as we did by the red light of the setting sun.

“Taking an early breakfast the next morning, we made our way first to the eastern side of the mountain. Here the view was stupendous. A bare, hemispherical mass of solid granite rose before us to the height of two or three thousand feet, striped along its sides as if torn by lightning or ‘gullied’ by the action of water through countless ages.

“Our ascent was effected on the southwestern side, where the slope is comparatively easy and where the otherwise baldness of the rock is relieved by an occasional tuft of dwarfed cedars or stunted oaks, which find a root hold in the crevices. These trees, elevated a quarter of a mile above the surrounding level, seem to be a favorite resort for buzzards, many of which were wheeling in graceful flight in the air around, and a greater number which perched upon dead treetops, apparently resting from their labors and watching from the convenient height for objects on which they might feed in the level country below.

“We found the summit an irregularly flat oval about a furlong in length. The view from it was superb. Not another mountain could be seen in any direction within a distance of twenty-five or thirty miles. The country all around seemed to be an immense level, or rather a basin, the rim of which rose on all sides to meet the blue of the sky. To the east and south appeared a few clearings, but in every other direction the forest was unbroken.

“Encircling the summit, at a distance of nearly a quarter of a mile from its center, was a remarkable wall, about breast high, built of loose, fragmentary stone, and evidently meant for a military fortification; but when erected, and by whom, we could not learn. Kanooka said that it was there when his people first came, and that they knew no more of it than we did. In some places the stones were almost all dislodged by persons who had rolled them down the steep declivity but there were enough remaining to show that the wall had once been continuous all around the summit, and that the only place of entrance was by a natural doorway under a large rock, so narrow and so low that only one man could enter at a time, by crawling on his hands and knees.”

Carver Roy Faulkner working with the small finishing torch. Notice the fine detail in General Lee’s features and the sweep of his famous white beard.

The scaffolds swinging against the carving, hundreds of feet above the ground, were the working area for the carver and his aides for six years.

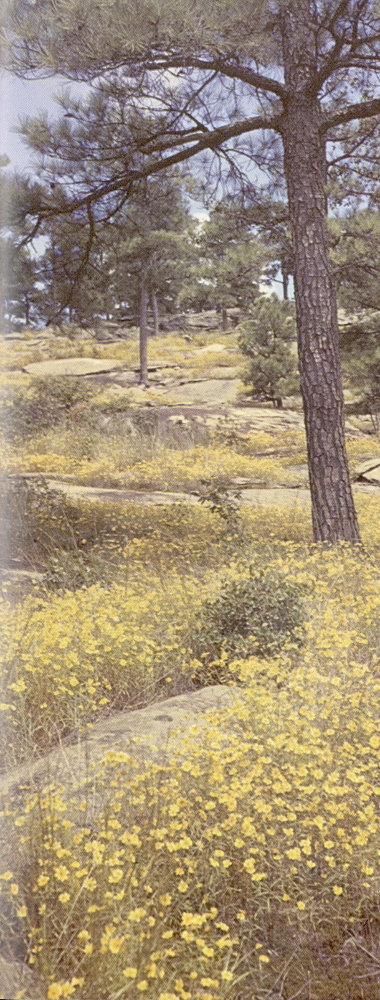

A field of Viguiera porteri, or Confederate daisies.

White milkweed, Asclepeas variegata.

Rare Hypericum splendens.

Evening primrose, Oenothera fruticosa.

Rosa Carolinia.

Practically every square foot of exposed granite is covered with lichens or mosses.

All the mountain’s early visitors were intrigued by the pre-historic wall. Some thought de Soto might have had it built, without considering that the aim of the conquistadores was to find treasure, grab it and run. They were not interested in defensive strongholds, and certainly not in building one that would entail carrying thousands of tons of rock up a steep mountain. All the early writers described the wall as a cleverly contrived fortress, since it blocked all trails leading to the summit. However, the most ignorant savage certainly would have realized that the top of Stone Mountain would be untenable in a siege, since there was no water and no access to food. It is the last place anyone would want to be caught when shooting started.

Most likely, the wall had some religious or ceremonial significance. Toting rocks and stacking them in a line is the kind of project ancient medicine men liked to think up to keep their tribesmen occupied, like building the great mounds throughout the South and down into Mexico and South America. Even today it is not hard to visualize weirdly painted warriors climbing the mountain in a torchlight procession and dancing all night around a roaring fire at the top. Consider, too, the old medicine men’s penchant for human sacrifice. At dawn the frenzied crowd probably hurled some luckless victim over the rim, while the women and children, who had waited below all night to see the poor devil fall, screamed and cheered, feeling sure that the gods would be so happy about the whole thing that they would assure bountiful crops and good hunting.

Another stone wall stands atop Fort Mountain overlooking Chatsworth, a hundred 27 miles to the northwest, and it, too, is built at the edge of a high precipice.

The Stone Mountain wall must have contained millions of rocks, for there were enough to let men and boys test their muscles by rolling stones off the mountain for more than a hundred years, until Gutzon Borglum, the sculptor, had the last ones thrown off in 1923 to make sure vandals did not start them rolling down among his workmen.

A feature on the mountain top surely as impressive as the great wall was the Devil’s Cross Roads. This was a tremendous flat boulder roughly two hundred feet across and five to ten feet thick, cleft by two smooth, straight breaks making avenues four feet wide, one running directly north and south, the other east and west. They joined at right angles at the center, and directly over this juncture was another flat rock twenty feet in diameter.

The Cross Roads became a favorite spot to have breakfast for parties who climbed the mountain to watch the sunrise. And everybody wondered that nature could make a compass as accurate and a great deal more spectacular than the ancient Egyptians could do. The entire formation disappeared in 1896 when quarrymen found that it was composed of superior building stone and broke it up and let it down the mountain by winches.

DeKalb County was founded Dec. 9, 1822.

The DeKalb County courthouse in Decatur burned in 1842, destroying most of the early deeds that were on record. There are some interesting legends concerning early ownership which, because of the destroyed documents, can neither be proved nor disproved.

Perhaps the first white settler to claim ownership of the mountain was John W. Beauchamp. His descendants still tell how their great-great-great-grandpa gave Indians forty dollars and a pony worth about fifty dollars for the big rock. They say he traded it to Andrew Johnson and Aaron Cloud for a muzzle-loading gun and twenty dollars. There are legends that a jug of whiskey figured in both deals.

If Beauchamp received or gave a bill of sale, it has not come to light in recent years. He never explained how the Indians got their claim to the property. It may have been a sudden inspiration, conjured up at sight of the jug. No formal deed could have been available, since the whole area was still in public domain.

In 1822, the year Francis Goulding explored the mountain, the State Legislature prepared the original land grants. The mountain lay in seven different land lots, which apparently were awarded to veterans of the Revolutionary War. One lot went to the orphans of a veteran.

It is said that a man in Athens was awarded one of the grants. He walked the sixty miles or so to the mountain to examine his property, and seeing that most of it was bare rock, he swapped it for a mule to ride home.

Andrew Johnson, who already had a shotgun claim to the mountain, was not one of those receiving grants, but he acquired bona fide title to considerable land at the base and also the main slice of the mountain in time to build an inn, about where the Administration Building is now, when the stage coach line came through in 1825. The stage ran from the capital at Milledgeville by Eatonton and Covington to Stone Mountain, then on by Winder to Athens 28 where the oldest chartered State University was already dispensing higher education.

Discovery of gold in the Dahlonega and Gainesville area in 1828, the first deposits found north of Mexico, brought a boom in traffic and another stage line from Stone Mountain to the gold fields. Fare was ten cents a mile, and since distances were great, the business must have been profitable.

Everybody bent on mining gold had to pass Stone Mountain, and any coming back, with or without new riches, stopped there again. Aaron Cloud, Johnson’s partner in the shotgun deal, built another inn to take care of the overflow. A town calling itself New Gibraltar grew up around the taverns, with general stores, a blacksmith shop and other services for the traveling public and the growing farm population.

In that era of typhoid, chronic malaria and yellow fever epidemics, prosperous planters and merchants in the lowlands sent their families to the mountains during the “summer miasmas”—the fly and mosquito seasons we realize now—and the most enjoyable part of the trip each way was the stopover of a day or two at Stone Mountain to climb the great rock and unlimber kinks caused by days of rough bouncing in stagecoach or carriage.

Aaron Cloud was the first to establish a tourist attraction. In 1838 he paid Andrew Johnson $100 for “150 feet square” at the highest point on the mountain, where he erected a tower 165 feet tall, appropriately called Cloud’s Tower. For fifty cents a visitor who already had winded himself reaching the summit could climb another 300 steps and get a still higher view.

William C. Richards, a correspondent for “Georgia Illustrated,” published in Macon, wrote in 1842:

“This singular edifice, resembling somewhat a lighthouse, is an octagonal pyramid built entirely of wood. It stands upon the rock with no fastening but its own gravity. It was built nearly three years ago at a cost of $5,000. The projector and proprietor is Mr. Aaron Cloud of McDonough, and the work is commonly called Cloud’s Tower.

“In the lower part is a hall one hundred feet square fitted up for the accommodation of parties.

“We ascended by nearly 300 steps. The eyes rest upon a continuity of forest. The plantations and settlements appear small amid the sea of foliage. By the aid of good telescopes we distinguished five county towns. Among the towns I located was Terminus, a few straggling huts beyond Decatur.”

While the 150-foot-square plat cost $100, another old deed shows that Cloud paid Johnson only $260 for 101½ acres of good forest land at the foot of the mountain.

Another enterprising showman operated sometime in the Roaring Forties. His name has been lost, but some of the work he did can still be seen. He cut a trail for 250 feet, high up along the steep face extending out from the Buzzard’s Roost, installed an iron railing, and charged anyone who had the courage for such an adventure twenty-five cents to walk gingerly out to the end and back.

These boulders guard the approach to Buzzard’s Roost, a grove of gnarled pines near the top. Stone Mountain’s only airplane crash occurred in this area.

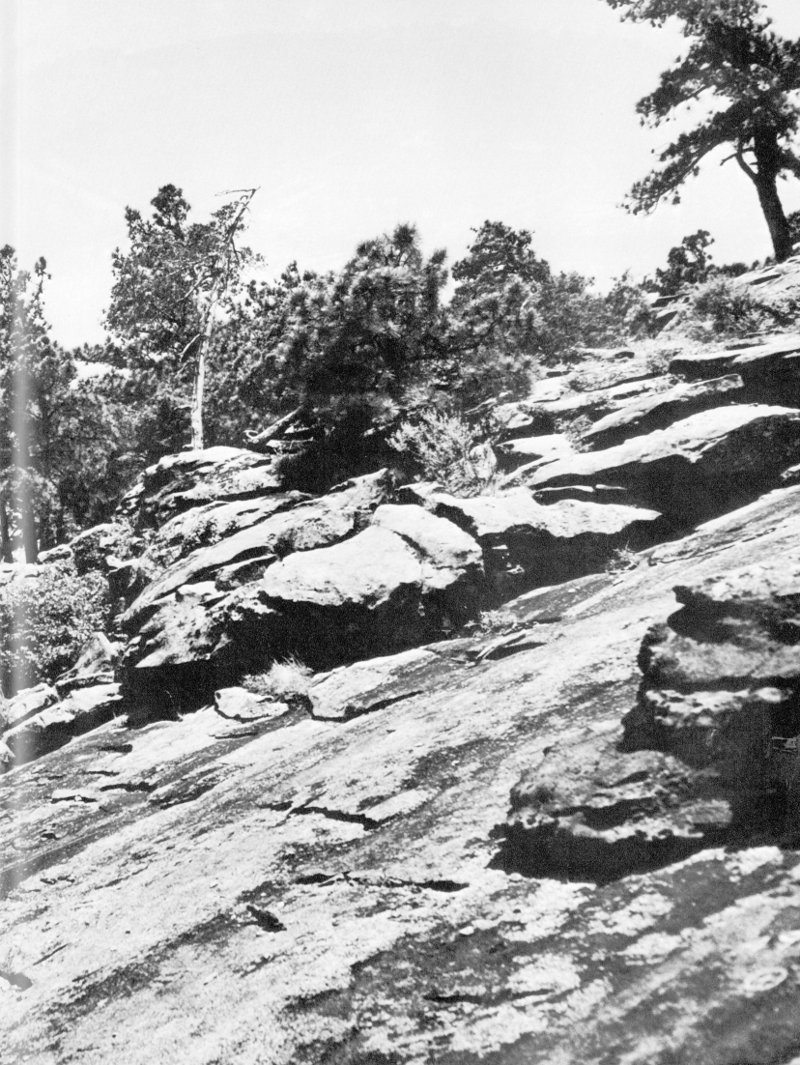

Broken ledges and scattered blocks of stone show where granite was quarried.

A coach was left when the Stone Mountain railway was abandoned.

In one respect the fellow was a hundred years ahead of his time. He solved the traffic problem completely. Since only one person could go out at a time, there was never a jam or collision. But ambition was his undoing. While extending his trail still farther he blew himself into oblivion with a premature explosion of blasting powder.

Correspondent Richards especially mentioned Terminus as one of the places he could see through Cloud’s telescope because the magic new town was very much in the news. In 1842 engineers had just completed a survey to establish the northernmost route a railroad could be built from Augusta, the head of navigation on the Savannah River, around the Blue Ridge Mountains and on to Chattanooga, a growing steamboat town on the Tennessee.

Terminus had been renamed Marthasville and then Atlanta by the time the first train came over the line in 1845. Most of the town’s leading citizens were waiting at Stone Mountain to board it for a triumphal ride into their new city.

The railroad had suddenly become so much more important than the stage line that New Gibraltar moved over beside the tracks. In 1847 the legislature granted the town a charter as Stone Mountain and also gave the granite knoll, which had been called Rock Mountain and Stony Mountain, the official name of Stone Mountain. That year a spur track was built from the depot out to a point between the two inns operated by Andrew Johnson and Aaron Cloud.

Another historic event took place on that first train ride from Stone Mountain to Atlanta, in 1845. The local leaders discussed organizing an agricultural society to promote better farming and merchandising methods. The first meeting of the South Central Agricultural Society was held at the mountain in 1846, with 61 charter members. The following year the Society held a fair at Stone Mountain. A Savannah reporter, covering the event for his paper, wrote: “Wagons, carriages, carts and pedestrians are arriving every minute. Ladies form a very large proportion.” The correspondent’s concluding notation, that he slept in a room with twenty-eight other people, explains why the fair was held at Stone Mountain only two seasons. It was moved to more populous Atlanta and grew into the great Southeastern Fair, while the society evolved into the Georgia Department of Agriculture.

The Civil War touched Stone Mountain to the extent that the flow of tourists stopped, and a detachment of Union cavalry swooped in and burned most of the town, sending up columns to join the smoke from Atlanta, Decatur and other unfortunate neighbors.

Stone Mountain’s granite, being too heavy for long hauls by wagon, had no commercial value whatever until the coming of the railroad. The spur line built in 1847 surely hauled rock as well as tourists. The first official mention of the granite industry appears on a deed filed in 1863, when W. B. Wood and John J. Meador sold a parcel of land, but reserved quarrying rights.

In the Reconstruction Period, when Southern industry was at its lowest ebb, the granite quarries flourished. Growing towns needed paving blocks and curb stones. Buildings destroyed in 32 the war had to be replaced. William H. and Samuel H. Venable, as the Venable Brothers, expanded until they had acquired the entire mountain in 1887, estimating that altogether it cost them $48,000. The firm operated for seventy more years, extending the railroad line around to the east side, where the finest stone was found.

Stone Mountain granite paved principal streets in most of the Southeastern towns. At the height of their operation, the quarries were turning out 200,000 paving blocks and 2,000 feet of curbing a day. In addition, building stones went into the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary, the famous Fulton Tower jail, many post offices, courthouses, warehouses, and commercial buildings, into the foundations of skyscrapers, to Panama for the canal locks; and tremendous blocks of granite were shipped to the seacoasts from Charleston to New Orleans for breakwaters.

Will T. Venable, who grew up in the house nearest the steep side of the mountain, told the writer of his boyhood there in the eighties for an article published sixty years later.

“The rarest sight is a rainbow on the mountain’s face,” Mr. Venable said. “I have seen but two or three in my lifetime. They can only appear very early in the morning, since the big rock faces to the north. The bow always starts on the ground, climbs the mountain and disappears on top. It almost makes you believe you might find a pot of gold up there.

“When it rains, the side of the mountain looks like a waterfall. The water turns into foam and literally bubbles down. When I was a youngster we used to hang our clothes on convenient limbs and stand under the falls for a foam bath. It was pleasant while you were taking it, but when you dried off, you found yourself covered with very fine, hard sand, which itched like the mischief. As you look at the side of the mountain, you see the courses taken by the water as it pours off. A close-up shows that the water has eroded little ditches two or three inches deep.

“The greatest show we ever had was the work on the carving,” Mr. Venable continued. “If you have ever stood fascinated while a steam shovel dug a hole in flat ground, maybe you can imagine how the work on the mountain kept us entertained.”

An incident odd enough to be typical of Stone Mountain’s history took place in 1928, just after air mail was inaugurated. Little single-seated biplanes gave overnight service between Atlanta and New York, at a period when night-flying instruments were few and crude, and Stone Mountain lay directly in the path of flight. At the pilots’ insistence, a contractor was commissioned to erect a safety light on top.

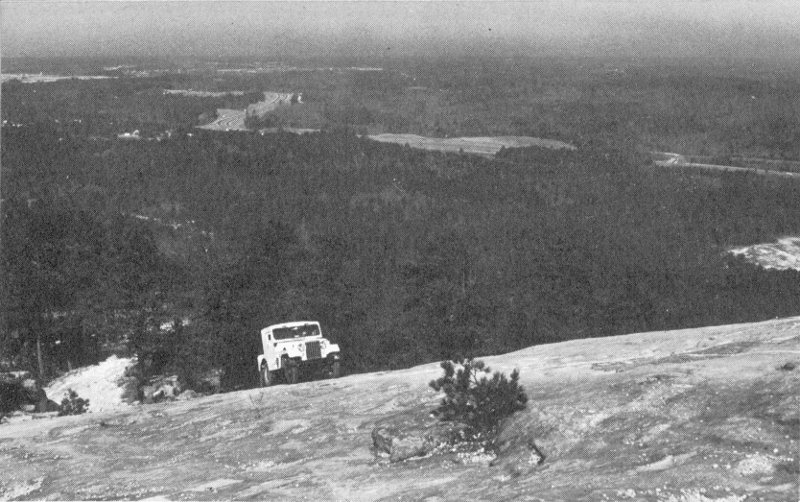

Lady fire watchers had an exciting Jeep ride and a long climb to the old tower.

Newspapers and visitors took note of the laborious work of carrying steel poles and wire up the steep trail, then nothing more was said or seen of the light until one dark night several weeks later Pilot Johnny Kytle’s plane smashed itself and nine bags of mail helter skelter up the steep slope, arousing neighbors for miles around. The Atlanta postmaster was among those who rushed to the mountain to help Johnny and his load of mail back to town.

Then an investigation was launched, to determine why there was no light on the mountain. The foreman on the job brought out his work sheet, showing how he had checked off each item—the poles, bolts and braces, the insulators, the wire, the socket, and the final item, he had turned on the electricity. But the list given him had contained no mention of a light bulb, so he had not screwed one in!

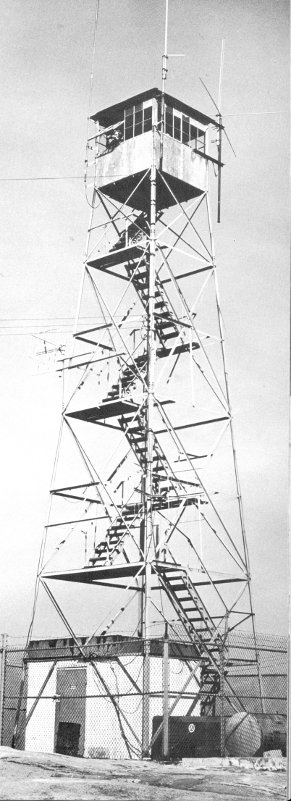

Until the new recreation hall and observation tower were erected the only construction on top of the mountain in recent years was a 60-foot-high forest fire-watcher’s tower, manned consecutively by two women. They drove up every morning and down in the evening along the foot trail by Jeep before any semblance of a road was made, and never had a mishap. If a thundercloud approached, they came down in a hurry, to reach the bottom before the storm bombarded the mountain with lightning.

This photo shows Elias Nour actually rescuing a dog that slid part way down the mountain.

Night watching was done by men of the county fire department, and they made it a point to go up before sundown and return after dawn. Trying to come down the mountain at night is a fearsome experience, say those who have done it. Every direction looks the same, and the horizon is just a few yards away, since the rock curves off into space.

The man most closely associated with Stone Mountain in recent years is Elias Nour, whose family operated a restaurant near the foot of the east trail. When Elias was thirteen he let himself be lowered at the end of a rope to rescue a boy who had slipped over the crest and was clinging for his life to a tiny depression in the rock. Since then he has rescued thirty-three more persons who ventured so far down the mountainside that they could not climb back.

A peculiar thing, he noted, is that hardly any of the people he saved ever bothered to thank him. Mostly they seemed embarrassed at having got themselves into such a predicament, and they also appeared to think that saving lives was part of his duties. An exception was a large dog, that clung whining to the rock until young Nour reached his side. The dog behaved perfectly while they were being hauled to safety. Once on top he jumped upon Mr. Nour so suddenly that he knocked him down, then licked his face and neck thoroughly before he was pulled away.

There is no record of the number who have fallen to their deaths at Stone Mountain, but it probably is far over a hundred. Some no doubt were suicides, but the great majority were innocent victims of the mountain’s treachery. The great dome rounds off so smoothly, and the curve downward increases so gradually that the too-venturesome explorer does not realize he is in trouble until he begins to slide, or attempts to climb back up. Then he is fortunate indeed if he can find a tiny crevice or slight depression that he can cling to until help comes down to him from above.

One of the first acts of the new Stone Mountain Memorial Association was to erect a steel storm fence around the rim of the mountain, probably about the same location as the ancient rock wall, as a grim warning that venturing farther would be courting disaster.

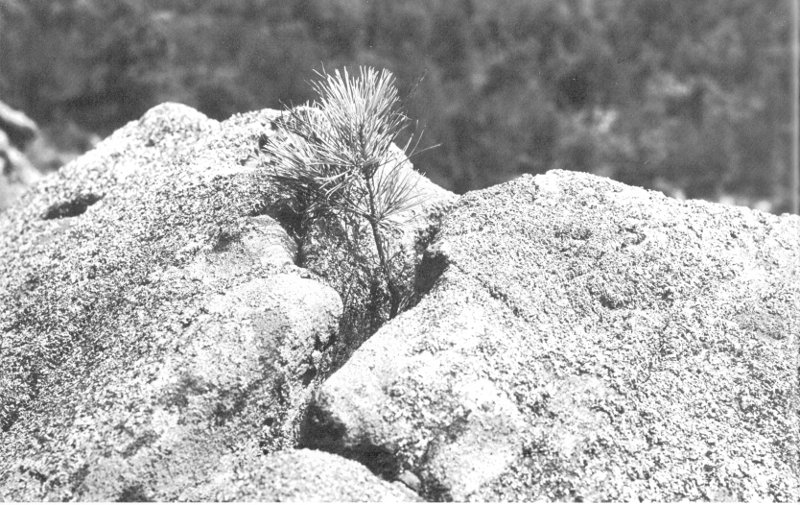

If you wish to see a Hypericum splendens, you will look for it on the steep slopes of Stone Mountain. This little hardwood shrub, about three feet tall with bright yellow blossoms, is found nowhere else on earth—not even on the similar, but lesser, granite outcrops of the area, in DeKalb and Rockdale Counties.

The Hypericums grow thickest in tiny crevices about halfway up the mountain and most are on the southwest side. None are found at the top nor the bottom. The saucy little golden blossoms with many stamens are about an inch across, and they appear in terminal clusters at the end of branches. Just a few open at a time, so blooming is continuous through most of June and July.

The hardy little plant seems immune to drought and even indifferent to weather. Rain or shine, hot or cold, has no effect on its growth or blossoms. But each plant has a life expectancy of only about three years, after which it dies down completely, to be replaced by descendants coming up from seed.

The great whale-shaped mountain of granite, far from being the bare rock that it appears, is literally covered with plant life. Thirty specimens of plants are listed as rare, and many more are so uncommon or so regional as to be total strangers to nearly all visitors.

Botanists from Emory and Georgia State Universities in nearby Atlanta, and the University of Georgia in Athens, have regarded Stone Mountain as their special laboratory since the schools were founded. In 1961 a full-time horticulturist was employed to live on the mountain. Harold Cox, from Stratford, England, studied at the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew. His assistant, Gerhard Oortman, grew up working in the magnificent gardens of Eastern Holland. They have become intimately acquainted with practically every weed, twig, bush and tree on Stone Mountain.

They have ascertained that the Hypericum is the only shrub that grows nowhere else. Hoping to have specimens where visitors could recognize them, without running the risk of having souvenir hunters exterminate the genus, Cox and Oortman rooted some cuttings in the greenhouse and set them out in a garden plot across from the carving—and saw them promptly wither and die. However, some seed planted in the same ground have sprouted and seem to be thriving.

Stone Mountain’s botanical treasures are governed partly by the seasons and partly by the amount of soil available. The most spectacular of the unusual plants is the Viguiera porteri. It is so rare that it had no common name until the Stone Mountain natives titled it Confederate Daisy. It has relatives in Mexico, but the American branch is confined entirely to Stone Mountain and other granite outcrops of Georgia’s Piedmont Plateau.

The Confederate Daisy grows in swales or crevices where sand or soil has collected to a depth of three or four inches to a foot. The plants would be regarded as skimpy little weeds throughout spring and summer. A dry summer stunts the year’s crop. But when frequent showers dampen the mountain’s surface, the scrawny plants put on a big spurt of growth in August. About the middle of September they burst into great beds of blooms, making the nearly bare rock look like a golden meadow. The profusion of color lasts until mid October.

In early spring the Diamorpha cymosa spread like a bright red carpet where soil is half to an inch deep. The color is in the plants, two or three inches tall, and in the succulent round leaves. Tiny white blossoms detract, rather than add, to the color.

The Amphianthus pusillus has no common name. It is a member of the snapdragon family, but is so small that it is rarely noticed except by naturalists who are looking for it. However, it leads a remarkable existence.

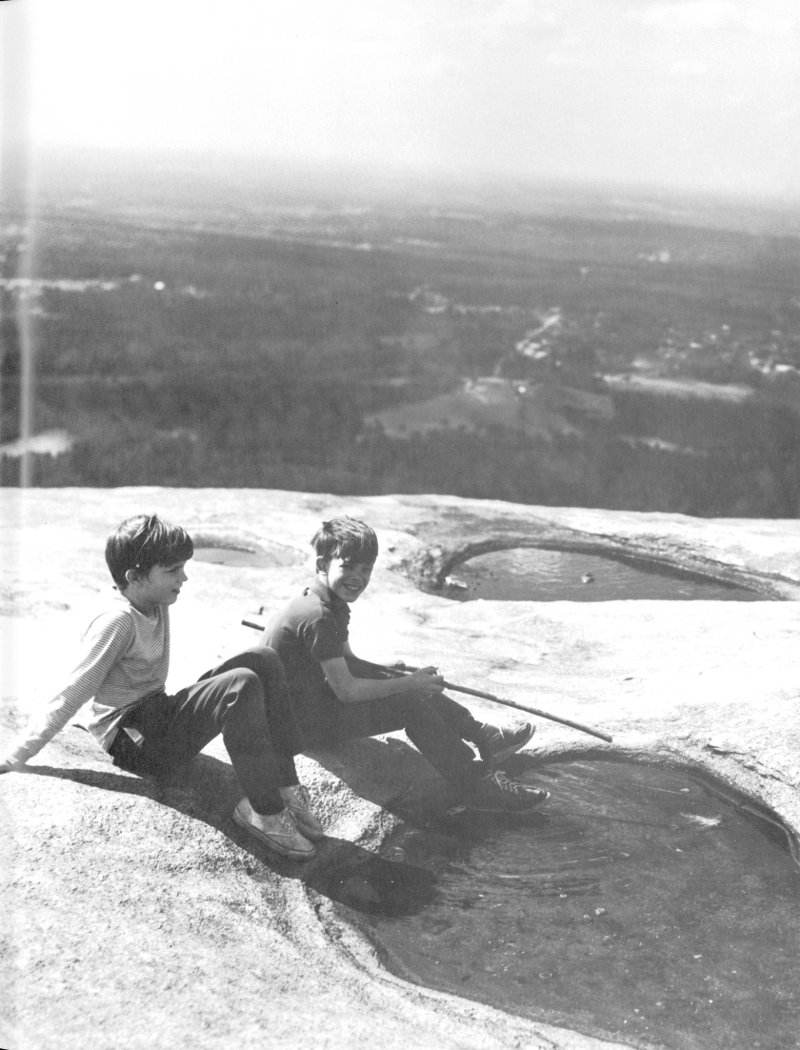

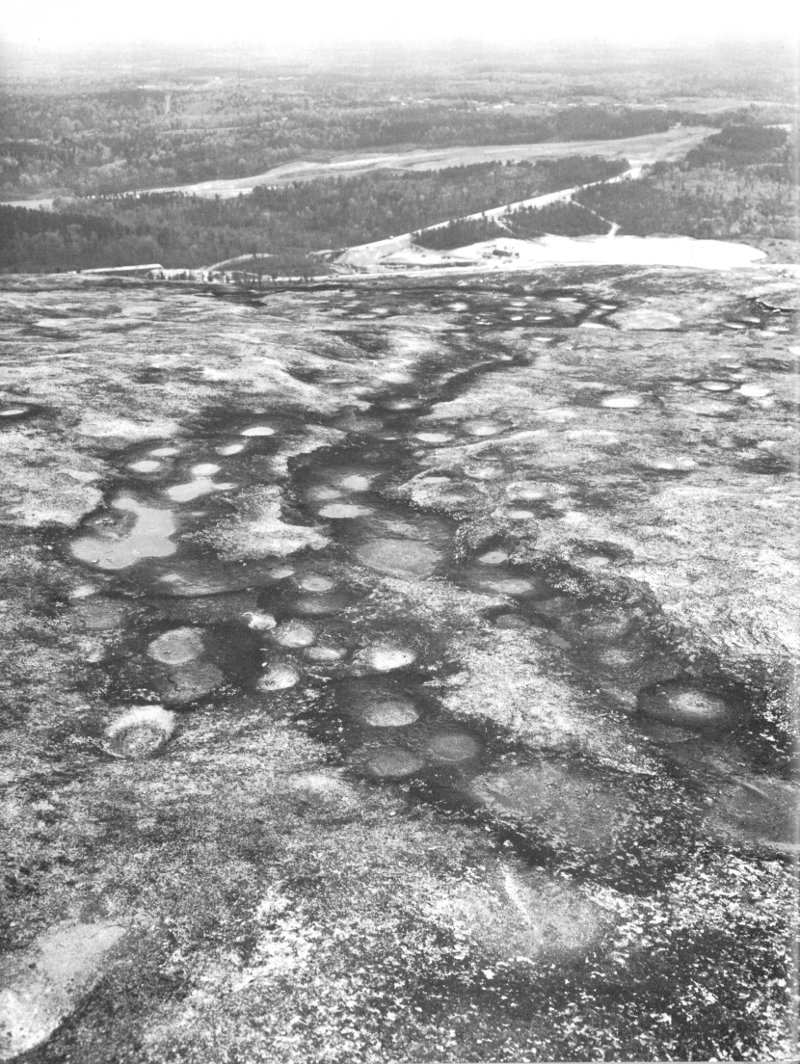

The Amphianthus lives in the rain pits on top of the mountain, small sunken areas where water collects after each shower. When the pit dries up, the only sign of the plant is a little cyst under the sand and gravel at the bottom. Immediately after a rain the cyst sends up a little rosette of reed-like leaves that stay submerged. From their midst a thread-like stem arises and sprouts two leaves half an inch across, that float on the surface. A tiny bud appears between the two leaves, and opens into a white flower no more than one-sixteenth of an inch across.

When the pool dries up, the plant disappears, quickly turning to dust, except for the cyst, which waits patiently for the next rain to bring it back to life.

The Amphianthus is not exclusive with Stone Mountain. It has been seen on Mount Rollaway in Rockdale County, but it is missing from some of the other granite outcrops. Cox called it a monotypic genus, which means it is represented by the one genus.

Sharing the larger rain pits are fairy shrimp, whose lives are frequently interrupted. These minute crustaceans, hardly more than an eighth of an inch long, look considerably like ocean-going shrimp when viewed through a magnifying glass, and they even swim backward. They disappear when the pits dry up, and come back soon after the next rain. It is presumed that all mature specimens die in the drought, leaving eggs which hatch when the water returns.

The dark gray color of Stone Mountain is not the granite, but the lichens which grow on practically all the weathered stone. Behaving like booby traps, these pioneer plants have tricked a number of venturesome climbers to their deaths. In a rain they absorb water and become quite slippery, almost as if the stone were coated with grease. In dry weather they crumble underfoot and the tiny particles roll like shot to start a hiker sliding. Walking on almost level ground can become an adventure.

The lichens are a pioneer plant form, a symbiotic relationship of fungi and algae. A fungus, unable to manufacture carbohydrates when alone, must live as a parasite on another plant. An alga can manufacture sugar or starch, provided it is kept moist and has the necessary ingredients. Working as partners, the fungi absorb and hold moisture and dissolve some essential chemicals from the rock; the algae mix these and cook with the sun’s energy to make food for the partnership. Their assault is the first step in reducing stone to soil. In this duty they are followed by grasses, weeds, shrubs and finally trees.

There are three growth types of fungi: crustose, which appears as thin crusts on the rocks, and is the most prevalent at Stone Mountain; foliose, which has leaflike body and draws almost recognizable pictures; and fruticose, which stands up in mossy little clumps.

Two young explorers beside a rain pit at the top, where fairy shrimp and the rare Amphianthus pusillus live.

Stone Mountain has a rare genus of the crustose, the Pyrenopsis phaecocca which is found only in Georgia, on the granite outcrops of the Piedmont section from Atlanta to Augusta. Another crustose variety is a dull, dark red and grows in splotches, so it looks as if a boy with a wide brush had been smearing the boulders with barn paint.

Some of Stone Mountain’s fruticose lichens stand up like little powder puffs an inch or two tall, and are comparative to the extensive reindeer moss of Alaska’s tundras. In a long drought many of the little clumps break off and go blowing about the mountainside like miniature tumbleweeds.

Veteran quarrymen have noted that it takes about 25 years for a freshly broken piece of granite to weather sufficiently for lichens to grow.

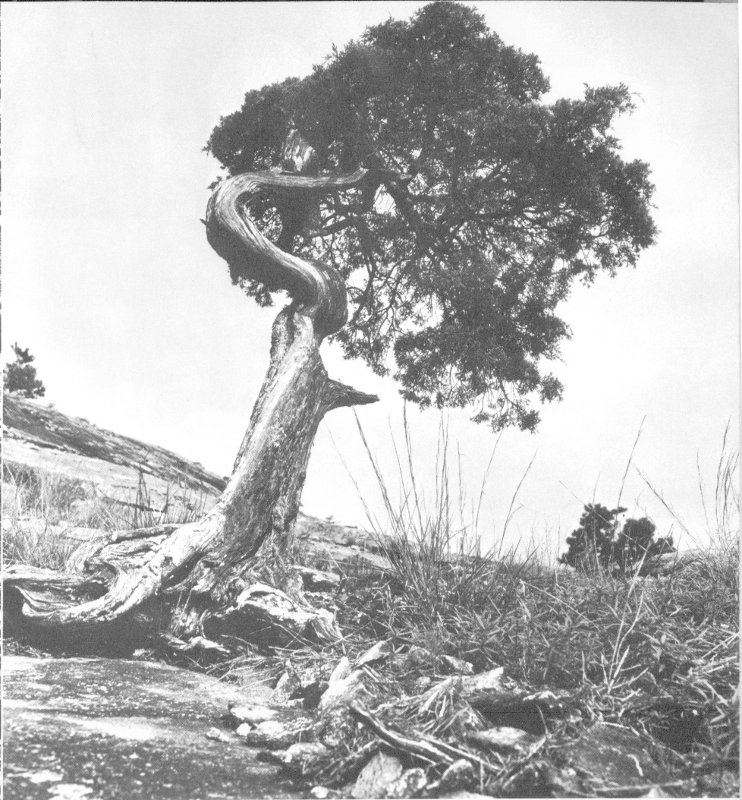

Most spectacular of all Stone Mountain’s plant life are the trees. Gnarled and twisted red cedars, almost a foot in diameter, cling desperately to narrow cracks in the deep slopes. Some are estimated at 500 to 800 years old, and they look every bit of their age.

Pines, stooped and bent by mountain winds and stunted by long summer droughts, poke their roots into rock crevices and strain mightily to widen the slits. Some of these may be 150 years old. On the other hand, a giant loblolly growing in the rich red loam at the foot of the mountain, near the grist mill, measured nine feet in circumference, and had only 90 growth rings.

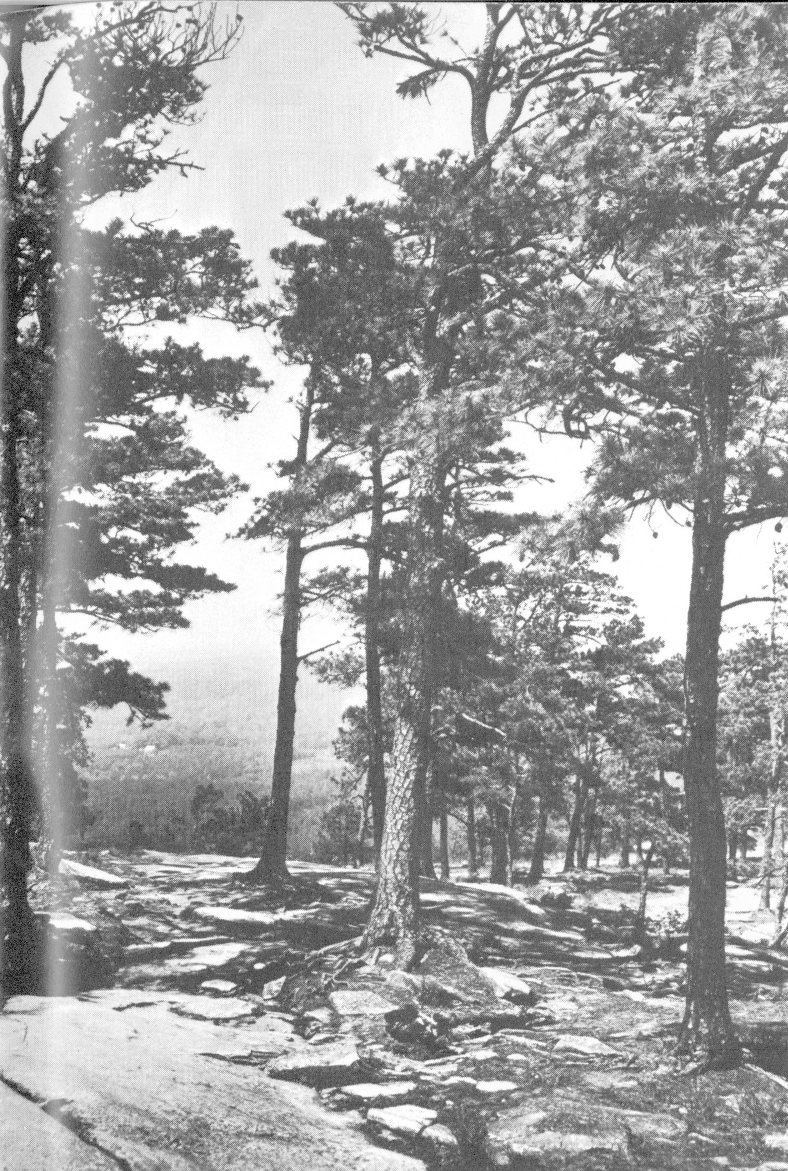

Along the foot trail up the west slope are tall slim pines growing almost normally in what appears to be little patches of dirt. There may be deep loam-filled crevices below, but the health of the trees in such sparse soil attests to the rich mineral content. High up on the eastern slope, where a little silt has accumulated, is a small pine forest called Buzzard’s Roost.

A rare tree is the Quercus Georgiana, or Georgia oak, which grows, but hardly flourishes, on Stone Mountain and neighboring outcrops. It has small glossy leaves two or three inches long, and tiny acorns. Few grow taller than about 25 feet.

Where enough dirt collects there may be blackberries, huckleberries, and muscadine vines.

Songbirds flock in great numbers to the gardens and groves around the foot of Stone Mountain, but there is little wild life up on the rock, itself. The soaring birds, such as vultures and hawks, are well acquainted with the updrafts which lift them skyward like elevators when the wind strikes the steep, smooth slopes, and they know where to find the best rides for each direction the wind blows.

While the memorial was being carved, workmen noticed a large hawk that soared by at eye level nearly every day, apparently quite interested in what they were doing. The men began leaving scraps of food at a certain place near the top of the carving. The bird flew in for lunch every afternoon, and he did not seem to mind if the men were working quite near. However, the loud roar of the jet torch disturbed him. When it was in operation he delayed his lunch until the flame was turned off.

The workmen placed their lunches in a locker in a shed at the foot of the mountain every morning. They began finding the latch unfastened and the tastiest sandwiches missing, and soon identified the thief by footprints in the dust—a raccoon. A more intricate latch kept the coon out of the locker. The men put out food for him, and he always picked it up after they were gone, but he did not fare as well on charity as he had done while stealing.

Stone Mountain has birds and bees and shrimp and lizards, but no snakes. Harold Cox reported that he had not seen a single one in all his years there.

Stone Mountain, sixteen miles east of Atlanta, is the world’s largest exposed granite monolith. It is as great a wonder to geologists today as it was to Indian medicine men of ancient times. While geologists know how it was formed and what it is made of, they still are amazed at its tremendous size, its wonderful symmetry and its location, high and alone on a gently rolling plateau over thirty miles from its nearest mountain neighbor.

This mountain is a perfect example of the unbelievably powerful forces and the eternal patience of nature, for it was a million years in the making and lay a hundred million years incubating before it arose like a great egg on a vast plain in another hundred million years.

Stone Mountain is 1,683 feet above sea level, and 825 feet above the surrounding land which is itself a dividing ridge. Rain water running off the eastern slope goes into the lake and out by the Yellow River. That on the west finds its way to South River. The streams join 50 miles away at Lake Jackson and flow on by the Ocmulgee and Altamaha to the Atlantic Ocean. Three or four miles to the north, headwaters of Peachtree Creek start their long trip to the Gulf of Mexico by way of the Chattahoochee and Apalachicola.

The exposed granite of Stone Mountain covers 25 million square feet, or 583 acres. A surveyor figured the mass at 7,532,750,950 cubic feet. Since that time several million cubic feet have been quarried and shipped away, but all of man’s endeavors show as insignificant peelings taken from the western and eastern slopes. Granite weighs 167.9 pounds per cubic foot, if you are interested in computing the weight of Stone Mountain.

Granite is the universal stone, containing practically all the natural elements from uranium and aluminum to iron and silica and the rarer minerals. It decomposes into fertile soil, as is readily seen by the growth that springs up where a little dirt and moisture collect on the gentler slopes of the mountain.

Stone Mountain is near the foot of the Appalachians, an extremely ancient mountain chain originally composed of granite gneiss. The peaks, in their youth, rose much higher than the brash young Rockies, or even taller than the Himalayas. Three hundred million years ago, when Stone Mountain was born, the land in the area stood perhaps 10,000 feet higher than it does now.

During a period that may have lasted a million years or more, molten stone under tremendous pressure was pushed upward from deep in the earth. If the force behind it had been sufficient to drive it out at the surface, the rock would have cooled rapidly and would have assumed a different form.

The weight of two miles or so of rocks and earth overhead was sufficient to contain the tremendous pressure of the molten flow, so the upper crust literally floated on a hot liquid base.

Something had to give as liquid rock thrust into an area where there was no space. Forty miles or so to the northwest is a chain of mountains, of which Kennesaw is the tallest, formed by pressure from the side which buckled underlying rocks up like a steep roof, or folded layers over each other. Some of that pressure may have been applied by Stone Mountain. This admittedly is theory—upper layers which held much of the factual story have long since washed away.

Since the intruding material was contained in its original prison cell and held under constant pressure, it cooled gradually, a process which took perhaps a hundred million years. By cooling slowly, the molecules formed compact, uniform crystals.

Meanwhile the older, softer granite overhead was weathering and turning to soil and eroding away. Some went to extend the coastal area of southeast Georgia and some to help build up the rich black belt of South Alabama.

In the two hundred million years since the intrusion, the two-mile-thick overlay has eroded down to its present level, leaving the hard core of Stone Mountain standing up like a great gray egg. The surface of the mountain wears very slowly—scuffing feet of millions of visitors have left barely discernible marks along the western trail. Meanwhile the original crust is still wearing away at a rapid rate, so Stone Mountain is continuing to grow taller in reference to its base.

Around the base have been noted fingers of Stone Mountain granite extending outward into the old rock, or sometimes soil, where the molten material was forced into crevices during the lateral movement of underground strata.

The mountain is a natural target for lightning. Thunderclouds bombard it with their heaviest artillery. A bolt of lightning behaves very much like the thermo-jet torch. Its extreme heat converts moisture in underlying molecules to steam and literally blasts off the surface crystals, making a slight saucer-shaped depression four to six inches across. Heat fuses the bottom of the depression, leaving a slick, glassy surface.

Every lightning bolt for many years has left its mark. It is noticeable that they are thickest not on the highest points, but in depressions. Meteorologists say that is where the first drops from a shower soak into the granite and therefore make the best ground to attract the lightning.

From the time Gutzon Borglum began carving in 1923, stone rubble piled up at the base of the mountain below the monument. Hardly a man alive could remember what lay under it. After nearly fifty years, when the rubble was removed, there was revealed a low hill of the original granite gneiss peeping out from under the mountain, or more accurately, pushing into its side. The old rock clearly shows how it was twisted, turned and tortured by the great pressures of two hundred million years ago. Unable to shove aside this lot of rock, the molten mass tried to engulf and digest it.

We see only the tip top of Stone Mountain. The shape around the base that will be revealed when more of the surrounding rock erodes away in the next million years is anybody’s guess. The depth surely is infinite, for it is still connected down through the channel by which it spewed upward.

Stone Mountain is unique. Chemical makeup of the granite, and its physical characteristics, are different enough from all other stone in the Southeast to indicate that this is the only portion of that ancient flow of molten rock that has yet reached the surface.

A Short History of Georgia, by E. Merton Coulter. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, N. C., 1933.

Georgia’s Landmarks, Memorials and Legends, Volume II, by Lucian Lamar Knight. Byrd Printing Co., Atlanta, 1913.

Georgia: Unfinished State, by Hal Steed. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1942.

Empire Builders of Georgia, by Ruth Elgin Suddeth, Isa Lloyd Osterhout and George Lewis Hutcheson. The Steck Company, Austin, Tex., 1962.

Georgia: A Guide to the Towns and Countryside. Federal Writing Project, University of Georgia Press, Athens, 1940.

Story of Georgia, Volume III, by Walter G. Cooper. The American Historical Society, Inc., New York, 1938.

Cyclopedia of Georgia, Volume III, by Ex-Governor Allen B. Candler and General Clement A. Evans. State Historical Association, Atlanta, 1906.

Sal-O-Quah or Boy Life Among the Cherokees, by Francis R. Goulding. Macon, Ga., 1870.

How Stone Mountain Was Created, by Poole Maynard, Ph.D. Waverly Press, Inc., Baltimore, U. S. A., 1929.

A Temple of Sacred Memories in the Breast of a Granite Mountain, by Augustus Lukeman. Lyon-Young, 1927.

History of Stone Mountain, by Leila Venable Mason Eldredge. 1950.

Miscellanies of Georgia, by Absalom H. Chappell. Gilbert Printing Co., Columbus, Ga., 1874.

The History of Stone Mountain Memorial, by Mildred Lewis Rutherford, State Historian of Georgia Division of United Daughters of the Confederacy.

Files of The Atlanta Journal, The Atlanta Constitution, The Atlanta Georgian, The Atlanta Journal Magazine, The Atlanta Journal and Constitution Magazine.

The Mary Carter Winter Stone Mountain Collection, donated to the Georgia Department of Archives and History.

Page 4: Borglum studio photo, courtesy Mary Carter Winters

Page 5: Blast photo, courtesy Arthur B. Kellogg

Page 6: Lukeman photo, courtesy Augustus Lukeman family

Page 7: Workmen photo, courtesy Mary Carter Winters; Lukeman model photo by Roy Faulkner

Page 8: Lukeman unveiling photo by Kenneth Rogers

Page 11: Upper left photo by Joe Tucker

Page 12: Torch photos by Frank Rippitoe; Hancock and model photo by Roy Faulkner

Page 16: Photo by Kenneth Rogers

Page 20-21: Carving color photo by Sara Stilwell

Page 23: Flower color photos by Kenneth Rogers

Page 26: Photo by Kenneth Rogers

Page 29: Photo by Kenneth Rogers

Page 32: Jeep photos by Sara Stilwell

Page 33: Tower photo by Kenneth Rogers

Page 39: Photo by Sara Stilwell

Page 40-41: Photos by Kenneth Rogers

Page 44: Photo by Kenneth Rogers

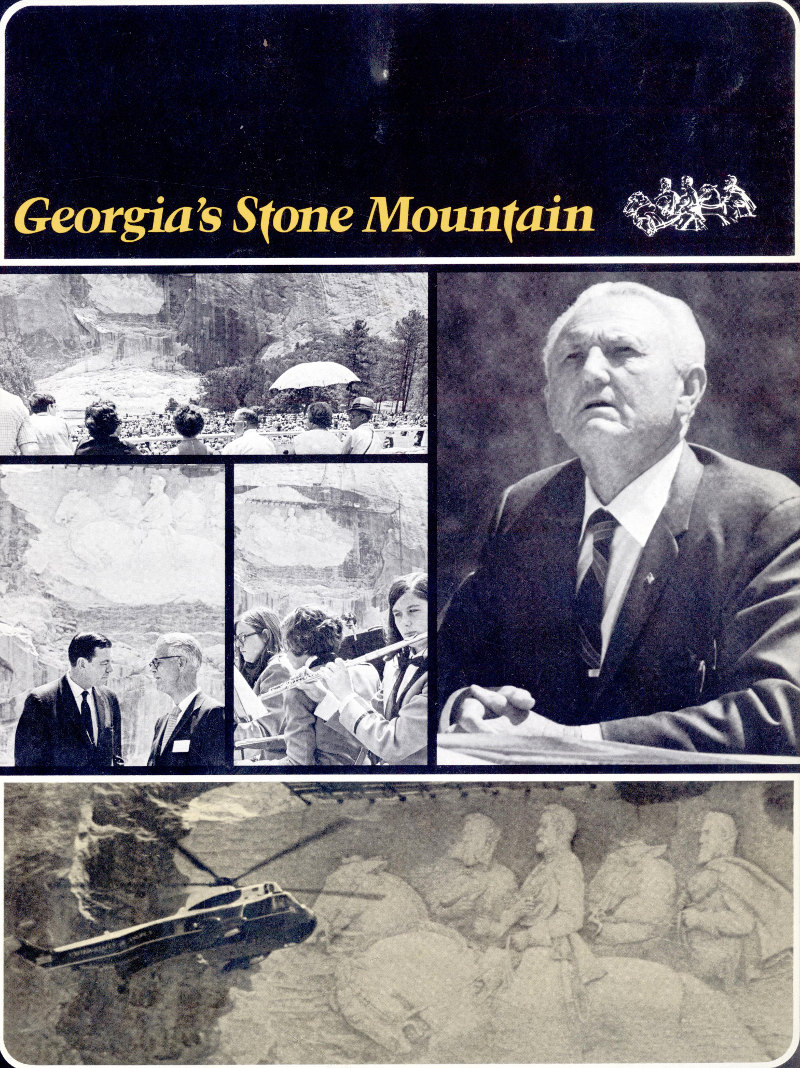

Scenes from the formal dedication of the Stone Mountain Memorial Carving, May, 1970.

Top left: 20,000 guests attended the ceremonies.

Center left: Georgia Senator Herman Talmadge (L)

and Stone Mountain Mayor Randolph Medlock.

Center: Young bandsmen from across the state

participated in day-long musical events.

Right: Georgia Secretary of State Ben W. Fortson,

Jr. was chairman of the Stone Mountain Memorial

Association during the dedication year.

Lower: The Vice President and his party arrived by

helicopter, flying directly by the carving.