ECCLESIATICAL

HISTORY OF ENGLAND.

VOLUME I.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR.

In one volume, crown 8vo.

Church and State Two Hundred Years Ago:

Being a History of Ecclesiastical Affairs from 1660 to 1663.

"A volume that, regarded from every point of view, we can approve—contains proof of independent research and cautious industry. The temper of the book is generous and impartial throughout."—Athenæum.

"Mr. Stoughton's is the best history of the ejection of the Puritans that has yet been written."—North British Review.

"The thanks, not only of the Nonconforming community, but of all who are interested in the religious history of our country, are due to Mr. Stoughton for the ability, the impartiality, the fidelity, and the Christian spirit with which he has pictured Church and State two hundred years ago."—Patriot.

In crown 8vo., cloth.

Age of Christendom: Before the Reformation.

"We know not where to find, within so brief a space, so intelligent a clue to the labyrinth of Church History before the Reformation."—British Quarterly Review.

LONDON: JACKSON, WALFORD, & HODDER,

27, Paternoster Row.

FROM THE OPENING OF THE LONG PARLIAMENT TO THE DEATH OF OLIVER CROMWELL.

BY

JOHN STOUGHTON.

VOLUME I.

THE CHURCH OF THE CIVIL WARS.

London:

JACKSON, WALFORD, AND HODDER,

27, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C.

MDCCCLXVII.

UNWIN BROTHERS, GRESHAM STEAM PRESS, BUCKLERSBURY, LONDON, E.C.

English literature includes valuable histories of the Church, some of them prominently exhibiting whatever relates to Anglicanism, others almost exclusively describing the developments of Puritanism. In such works the ecclesiastical events of the Civil Wars and of the Commonwealth may be found described with considerable, but not with sufficient fullness. Many persons wish to know more respecting those times. The book now published is designed to meet this wish, by telling the ecclesiastical part of England's story at that eventful period with less of incompleteness. In doing so, the object is not to give prominence to any single ecclesiastical party to the disadvantage of others in that respect; but to point out the circumstances of all, and the spirit of each, to trace their mutual relations, and to indicate the influence which they exerted upon one another. The study of original authorities, researches amongst State Papers and other MS. collections, together with enquiries pursued by the aid[vi] of historical treasures of all kinds in the British Museum, have brought to light many fresh illustrations of the period under review; and the author, whilst endeavouring to make use of the results so obtained, has reached the conclusion, that the only method by which a satisfactory account of a single religious denomination can be given, is by the exhibition of it in connexion with all the rest.

His purpose has been carefully to ascertain, and honestly to state the truth, in reference both to the nature of the events, and the characters of the persons introduced in the following chapters. He is by no means indifferent to certain principles, political, ecclesiastical, and theological, which were involved in the great controversy of the seventeenth century. As will appear in this narrative, his faith in these is strong and unwavering: nor does he fail to recognize the bearing of certain things which he has recorded, upon certain other things occurring at this very moment; but he cannot see why private opinions and public events should stand in the way of an impartial statement of historical facts, or a righteous judgment of historical characters. For the principles which a man holds remain exactly the same, whatever may have been the past incidents or the departed individuals connected with their history. Happily, a change is coming over historical literature in this respect; persons and opinions are now being distinguished from each other, and it is seen, that advocates on the one side of a great question were not all perfectly good, and that those on the other side were[vii] not all thoroughly bad. The writer has sought to do honour to Christian faith, devotion, constancy, and love wherever he has found them, and never in any case to varnish over the hateful opposite of these noble qualities. And he will esteem it a great reward to be, by the blessing of God, in any measure the means of promoting what is most dear to his heart, the cause of truth and charity amongst Christian Englishmen.

The plan of the work, and the various aspects under which the public affairs, the principal actors, and the private religious life of England from the opening of the Long Parliament to the death of Oliver Cromwell are exhibited, may be discovered at a glance, by any one who will take the trouble to run over the table of contents.

Many defects which have escaped the Author will doubtless be noticed by his critics, and in this respect he ventures to throw himself upon their candour and generosity. One omission, however, may be explained. The theological literature of the period needs to be studied at large, for the purpose of making apparent the grounds upon which different bodies of Christians based their respective beliefs. Most ecclesiastical historians fail to exhibit those grounds. The Author is fully aware of this deficiency in his own case; but it is his hope, should Divine Providence spare his life, to be enabled, in some humble degree, to supply that deficiency at a future time.

He begs gratefully to acknowledge the valuable assistance rendered him by the Very Reverend the Dean of Westminster, in what relates to Westminster Abbey and the Universities—by Mr. John Bruce, F.S.A., for information and advice on several curious points—and by Mr. Clarence Hopper, who has collated with the originals, almost all the extracts from State Papers. Nor can he omit thankfully to notice the special facilities afforded him for consulting the large collection of Commonwealth pamphlets in the British Museum, and the polite attention and help which he has received from gentlemen connected with Sion College and with Dr. Williams' Library. He has also had other helpers in his own house—helpers very dear to him, whom he must not name.

| INTRODUCTION. | |

| PAGE. | |

|---|---|

| Opening of Long Parliament | 1 |

| ANGLICANS. | |

| Under Elizabeth | 4 |

| Under the Stuarts | 6 |

| Spirit of Anglicanism | 9 |

| Intolerance | 17 |

| Ecclesiastical Courts | 18 |

| High Commission Court | 20 |

| Star Chamber Court | 26 |

| Strafford | 29 |

| Laud | 31 |

| PURITANS. | |

| In the reign of Elizabeth | 40 |

| Change in the Controversy | 45 |

| Puritan dislike of Ceremonies | 48 |

| Sufferings | 49 |

| Emigration | 50 |

| Bolton and Sibbs | 53 |

| Puritanism a Reaction | 55 |

| Its defects | 56 |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| MEMBERS OF THE LONG PARLIAMENT. | |

| Lenthall | 59 |

| Holles—Glynne—Rudyard | 60 |

| Vane | 61 |

| Fiennes | 62 |

| Cromwell | 63 |

| St. John | 64 |

| Haselrig—Pym | 65 |

| Hampden | 66 |

| Marten | 68 |

| Selden | 69 |

| Falkland | 72 |

| Dering | 74 |

| Digby | 75 |

| Hyde | 77 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Grand Committee for Religion | 79 |

| Petitions from Prynne, Burton, and Bastwick | 79 |

| Debates on Religion | 83 |

| Pym's and Rudyard's Speeches | 83-85 |

| Committee appointed to prepare a Remonstrance | 86 |

| Debates respecting Strafford | 87 |

| Strafford impeached by Pym | 89 |

| Impeachment of Laud | 91 |

| Puritan Petitions | 93 |

| Debate on the Canons | 95 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Presbyterianism in England | 100 |

| Root and Branch Petition | 103 |

| Presbyterianism in Scotland | 104 |

| Scotch Commissioners in London | 107 |

| Petition and Remonstrance presented to the House | 109 |

| Other Petitions | 110 |

| Debate touching Root and Branch Petition | 112 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Lords' Committee on Innovations | 119 |

| Williams, Dean of Westminster | 119 |

| Meetings in Jerusalem Chamber | 121 |

| Ceremonial Innovations | 123 |

| The Prayer Book | 124 |

| Episcopacy | 124 |

| Resolutions for Reforming Pluralities and removing Bishops from the Peerage | 126 |

| Star Chamber and High Commission Courts | 127 |

| The Smectymnus Controversy | 128 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Marriage of the Princess Mary | 131 |

| The Solemn Vow and Protestation | 133 |

| Conference between the two Houses | 134 |

| No Popery Riots | 136 |

| Trial of Strafford | 137 |

| His Execution | 141 |

| Deans and Chapters | 142 |

| Bill for Restraining Bishops | 144 |

| Bill for Abolition of Episcopacy | 146 |

| Debated by the Commons | 148 |

| Conference between the two Houses | 150 |

| Further Debate | 152 |

| Discussion on Deans and Chapters | 154 |

| Discussions respecting Episcopacy | 157 |

| Complaints against the Clergy | 158 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Laud sent to the Tower | 160 |

| Bishop Wren arrested | 161 |

| Montague's Death | 162 |

| Davenant's Death | 163 |

| Impeachment of the Thirteen Prelates | 163 |

| Correspondence between English and Scotch Clergy | 163 |

| Visit of Charles to Scotland | 165 |

| Dislike of the Lower House to the Expedition | 166 |

| Charles departs for Edinburgh | 166 |

| Letters from Sidney Bere | 167 |

| Conduct of Charles in Scotland | 169 |

| Church Reforms | 170 |

| Innovations discussed | 171 |

| Parliament adjourns | 172 |

| Parliament less popular | 173 |

| Causes of the Reaction | 174 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Bill for excluding Bishops from Parliament | 176 |

| Dering's Speech | 176 |

| The Grand Remonstrance | 179 |

| Debated by the Commons | 182 |

| Discussion about the Printing of it | 183 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Return of the King | 186 |

| Vacant Bishoprics filled up | 186 |

| Reception of Charles in London | 187 |

| The Remonstrance presented | 191 |

| His Majesty's Answer | 192 |

| Arrest of the Five Members | 193 |

| Royalist Version of the Affair | 193 |

| Fatal Crisis in the History of Charles | 196 |

| Reaction in favour of the Puritans | 197 |

| Westminster Riots | 198 |

| Protest drawn up by Twelve Bishops | 203 |

| Presented to the King | 204 |

| Prelates sent to the Tower | 205 |

| Their Unpopularity | 205 |

| Dismissed on Bail | 206 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Bishops excluded from the Upper House | 207 |

| Those who died before 1650 | 209 |

| Wright—Frewen—Westfield Howell | 209 |

| Coke—Owen—Curle—Towers | 210 |

| Prideaux—Williams | 211 |

| Irish Rebellion | 212 |

| Protestant Churches in Ireland | 216 |

| Popish Massacre | 218 |

| Fears of the English | 220 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Episcopacy | 223 |

| Seceders from the Popular Party | 224 |

| Opponents of Episcopacy | 227 |

| Sectaries | 228 |

| Flight of the King | 229 |

| Charles at Windsor | 230 |

| Charles at York | 231 |

| Attempts at Mediation | 231 |

| Manifestoes | 233 |

| The Coming Conflict | 237 |

| Hostile Preparations | 239 |

| The Parliamentary Army | 240 |

| Royalist Army | 242 |

| Nature of the Struggle | 243 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Outbreak of the War | 246 |

| Puritan Troops on the March | 248 |

| Barbarity of the Cavaliers | 251 |

| Battle of Edge Hill | 253 |

| Church Politics in London | 255 |

| Popular Preachers | 259 |

| The Scotch advocate a thorough Reformation | 261 |

| The Fate of Prelacy | 262 |

| Negotiations at Oxford | 264 |

| Proposals from Parliament | 265 |

| Royal Answer | 266 |

| Scottish Petition | 267 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Westminster Assembly | 271 |

| Its Constitution | 273 |

| Meeting of the Members | 275 |

| Parliamentary Directions | 278 |

| Death of Brooke | 280 |

| Death of Hampden | 281 |

| Success of the Royalists | 283 |

| Bradford Besieged | 283 |

| Gloucester Besieged | 284 |

| Effect of the War upon the Assembly | 287 |

| Commissioners sent to Scotland | 289 |

| The Solemn League and Covenant | 292 |

| Taken by the Assembly | 294 |

| Battle of Newbury | 296 |

| Treaty with the Scotch | 297 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Death of Pym | 301 |

| Court Intrigues | 305 |

| Corporation Banquet | 307 |

| Marshall's Discourse | 308 |

| Iconoclastic Crusade | 312 |

| Cromwell at Ely | 319 |

| League and Covenant set up | 319 |

| Covenant imposed upon the Irish | 323 |

| Meetings of Westminster Assembly | 326 |

| Presbyterians | 329 |

| Erastians | 330 |

| Dissenting Brethren | 332 |

| Toleration—Chillingworth | 335 |

| Hales | 336 |

| Jeremy Taylor | 337 |

| Cudworth—More | 339 |

| John Goodwin | 343 |

| Busher—Locke | 346 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Early Congregational Churches | 348 |

| Browne | 349 |

| Barrowe—Greenwood | 353 |

| Penry | 356 |

| Jacob | 357 |

| Lathrop | 358 |

| Independents and Brownists | 365 |

| Spread of Congregationalism | 369 |

| Presbyterians and Independents | 371 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Charles at Oxford | 372 |

| Royalist Army | 373 |

| Reports Respecting the King and the Court | 374 |

| Conduct of his Majesty | 376 |

| Bishops at Oxford | 378 |

| Clergy at Oxford | 379 |

| Chillingworth and Cheynell | 381 |

| Barwick | 383 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Ecclesiastical Affairs | 385 |

| Committee for Plundered Ministers | 387 |

| Tithes | 389 |

| Local Committees | 390 |

| Church and Parliament | 391 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Laud's Trial | 395 |

| Accusations against him | 396 |

| His Defence | 397 |

| Bill of Attainder passed | 399 |

| His Execution | 401 |

| His Character | 402 |

| The Directory | 404 |

| Sanctioned by General Assembly and House of Lords | 406 |

| Ordinance enforcing the Directory | 407 |

| Dissatisfaction of the Scotch | 408 |

| Irish Loyal to Prayer Book | 409 |

| Forms of Devotion for the Navy | 409 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Treaty at Uxbridge | 412 |

| Debate between Royalists and Parliamentarians | 414 |

| Charles makes a shew of Concession | 415 |

| Debates at Westminster about Ordination | 417 |

| Debates on Presbyterian Discipline | 418 |

| Presbyterians and Independents | 419 |

| Committee of Accommodation | 421 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| Long Marston Moor | 425 |

| Naseby | 428 |

| Sufferings of the Clergy | 431 |

| Alphery—Alcock—Alvey | 433 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| Jealousy of Presbyterian Power | 436 |

| Unpopularity of Scotch Army | 437 |

| The Power of the Keys | 439 |

| Toleration | 443 |

| Divine Right of Presbyterianism | 446 |

| Assembly threatened with a Præmunire | 448 |

| Confession of Faith drawn up by Assembly | 450 |

| Revision of Psalmody | 451 |

| Character of Assembly | 452 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| New modelling of the Army | 455 |

| Richard Baxter | 456 |

| Religion in the Camp | 457 |

| Army Chaplains—Sprigg | 459 |

| Palmer | 461 |

| Saltmarsh | 462 |

| Preaching in the Army | 464 |

| Conference between Charles I. and Henderson | 469 |

| Newcastle Treaty | 471 |

| Letters to the Queen | 474 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| Ordinances for establishing Presbyteries | 477 |

| Final Measures with regard to Episcopacy | 479 |

| Ecclesiastical Courts | 481 |

| Registration of Wills | 483 |

| Tithes | 485 |

| Church Dues | 487 |

| University of Cambridge | 490 |

| Ordinance for its Regulation | 491 |

| Commissioners appointed to administer the Covenant | 491 |

| Sequestrations | 493 |

| Revival of Puritanism | 494 |

| Oxford | 496 |

| Military Occupation of the University | 497 |

| Parliamentary Commissioners | 497 |

| Dr. Laurence and Colonel Walton | 499 |

| Resistance to the New Authorities | 500 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| Presbyterians and Independents | 504 |

| Contentions at Norwich | 505 |

| Presbyterian Policy | 508 |

| Attack on the Sectaries | 509 |

| Supernatural Omens | 511 |

| Negotiations between the Parliament and the Scotch | 513 |

| The King at Holdenby | 514 |

| Presbyterians jealous of the Army | 515 |

| Earl of Essex | 517 |

| False Step of the Presbyterians | 518 |

| The King in the Hands of the Independents | 519 |

| Cromwell's attempt at reconciling Parties | 520 |

| Royalist Violence | 522 |

| Laws against Heresy | 523 |

| Newport Treaty | 526 |

| Concessions made by the King | 527 |

| Military Remonstrance | 528 |

| Presbyterian Efforts to save the King | 529 |

| Pride's Purge | 531 |

| Trial of Charles | 531 |

| Execution | 532 |

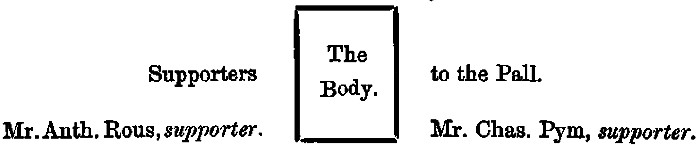

| Burial | 535 |

| VOL. I. | |||

| Page | Line | ||

| 114 | 29 | for Simon read Symonds. | |

| 192 | note | for Horton read Hopton. | |

| 207 | 1 | insert Bishops. | |

| 210 | 7 | for in 1646. He died read He died in 1646, | |

| 215 | 19 | for Rauthaus read Rathhaus. | |

| 453 | 22 | for condition read erudition. | |

| 521 | heading | for Denominations read Demonstrations. | |

| VOL. II. | |||

125 127 |

|

headings | read Sir Harry Vane. |

| 133 | 7 | for Naylor read Nayler. | |

| 146 | 3 | the word been is dropped into line 4. | |

| 151 | 31 | for Bordura read Bodurda. | |

| 262 | note | for according read accordingly. | |

| 361 | heading | for Fox and Cromwell read Fox's Disciples. | |

| 409 | 10 | for Isaac read Isaak. | |

| 427 | 1 & 13 | for Francis read Frances. |

On the third of November, 1640, at nine o'clock in the forenoon, the Earl Marshal of England came into the outer room of the Commons' House, accompanied by the Treasurer of the King's Household and other officers. When the Chancery crier had made proclamation, and the clerk of the Crown had called over the names of the returned knights, citizens, burgesses, and barons of the Cinque-ports; and after his Lordship had sworn some threescore members, and made arrangements for swearing the rest, he departed to wait upon his Majesty, who, about one o'clock, came in his barge from Whitehall to Westminster stairs. There the lords met him. Thence on foot marched a procession consisting of servants and officers of state.[1]

The King, so accompanied, passed through Westminster Hall and the Court of Requests to the Abbey, where a sermon was preached by the Bishop of Bristol. The King's Majesty, arrayed in his royal robes, ascended the throne. The Prince of Wales sat on his left hand: on the right stood the Lord High Chamberlain of England and the Earl of Essex, bearing the cap; and the Earl Marshal and the Earl of Bath bearing the sword of state occupied the left. Clarence, in the absence of Garter, and also the gentleman of the black rod, were near the Earl Marshal. The Earl of Cork, Viscount Willmott, the Lord Newburgh, and the Master of the Rolls, called by writ as assistants, "sat on the inside of the wool-sacks;" so did the Lord Chief Justices, Lord Chief Baron, and the rest of the judges under them. "On the outside of the woolsack" were four Masters of Chancery, the King's two ancient Serjeants, the Attorney-General, and three of the puisne Serjeants. To the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, apparelled in their robes, and seated in their places, and to the House of Commons, assembled below the bar, his Majesty delivered an address, declaring the cause of summoning this parliament. Then the Lord Keeper Finch made a speech; after which, the Commons having chosen William Lenthall, of Lincoln's Inn, as Speaker, that gentleman, being approved with the usual ceremonies, added another oration, in which he observed: "I see before my eyes the Majesty of Great Britain, the glory of times, the[3] history of honour, Charles I. in his forefront, placed by descent of ancient kings, settled by a long succession, and continued to us by a pious and peaceful government. On the one side, the monument of glory, the progeny of valiant and puissant princes, the Queen's most excellent Majesty. On the other side, the hopes of posterity, the joy of this nation, those olive-branches set around your tables, emblems of peace to posterity. Here shine those lights and lamps placed in a mount, which attend your Sacred Majesty as supreme head, and borrow from you the splendour of their government."

Thus opened the Long Parliament; knowing what followed, we feel a strange interest in these quaint items extracted from State Papers and Parliamentary Journals.[2] With such ceremonies Charles I. once more sat down on the throne of his fathers; and once more, too, clothed in lawn and rochet, the prelates occupied their old benches. Great was their power: Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury, might be said to discharge the functions of Prime Minister; Juxon, Bishop of London, clasped the Lord Treasurer's staff; and Williams, Bishop of Lincoln, had some years before held the great seal. They and their reverend brethren sat as co-equals with scarlet-robed and coroneted barons. They represented the stately and ancient Church of England, in closest union with the senate and the throne; suggesting, as to the relations of ecclesiastical and civil power, questions, which are as ancient as mediæval times, and as modern as our own. Thus too again the Commons' Speaker, in florid diction congratulated the monarch on the prosperity of his realms. That day can never be forgotten. Outwardly the Church, like the State, looked[4] strong; but an earthquake was at hand, destined to overturn the foundations of both. To understand the crisis in reference to the Church we must look a little further back.[3]

The Anglo-Catholic and Puritan parties stood face to face in the National Church, at the opening of the Long Parliament. They had existed from the time of the Reformation.

Anglo-Catholics, while upholding with reverence the three creeds of Christendom, did not maintain any particular doctrines as distinctive of their system. Neither did they, though their peculiarities were chiefly ecclesiastical, propound any special theory of Church and State. Under Queen Elizabeth they maintained theological opinions different from those which they upheld under Charles the First. At the former period they were Calvinists. Before the civil wars they became Arminians. Preaching upon the controversy was forbidden; and Bishop Morley, on being asked "what Arminians held," wittily replied, "the best bishoprics and deaneries in England!"[4]

Whereas in reference to doctrine there was change, in reference to ecclesiastical principles there was progress. The constitution of the Protestant Church of England being based on Acts of Parliament, and the supremacy of[5] the Crown in all matters "touching spiritual or ecclesiastical jurisdiction"[5] being recognized as a fundamental principle of the Reformation—the dependence of the Church upon the civil power appeared as soon as the great ecclesiastical change took place. The Act of Uniformity in the first year of Elizabeth was passed by the lay Lords alone—all the Bishops who were present dissented—and the validity of the consecration of the first Protestant Archbishop had to be ratified by a parliamentary statute.[6]

Of the successive High Commissions—which formed the great spiritual tribunals of the land—the majority of the Commissioners were laymen.[7] The Anglo-Catholics of Elizabeth's reign were obliged to accept this state of things, and sometimes to bow before their royal mistress, as if she had been possessed of an absolute super-episcopal[6] rule.[8] Yet gradually they shewed a jealousy of parliamentary interference, and rose in the assertion of their authority and the exercise of their power. Whitgift availed himself of the lofty spiritual prerogatives of the Crown to check the Commons in what he deemed their intrusive meddlings with spiritual affairs.[9] He strove to lift the Parliamentary yoke from the neck of the Church, and to place all ecclesiastical matters in the hands of Convocation. He preferred canons to statutes, and asked for the royal confirmation of the first rather than the second. But, after Whitgift and under the Stuarts, Church power made considerable advances. Anglo-Catholics, under the first James and the first Charles, took higher ground than did their fathers. Their dislike of Parliaments went beyond what Whitgift had dared to manifest. The doctrine of the divine origin of Episcopacy, which was propounded by Bancroft, when Whitgift's chaplain, probably at Whitgift's suggestion, certainly with his concurrence—though it startled some English Protestants as a novelty, and roused the anger of a Puritan privy councillor jealous of the Queen's supremacy,[10] became a current belief of the Stuart Anglicans. At the same time the power of Convocation was widely stretched, as will be seen in the business of the[7] famous canons of 1640. The encroachments of the High Commission upon the jurisdiction of the Civil Courts, and the liberties of the subject, produced complaints in everybody's mouth, and served, as much as anything, to bring on the great catastrophe. What is now indicated in a few words will receive proof and illustration hereafter.

Looking at changes in the doctrine and at progress in the policy of Anglo-Catholics, perhaps, on the whole, the persons intended by that denomination may be best described as distinguished by certain principles or sentiments, rather than by any organic scheme of dogma or polity. They formed a school of thought which bowed to the decisions of the past, craved Catholic unity, elevated the episcopal office, exalted Church authority, suspected individual opinion, gave prominence to social Christianity, delighted in ceremonial worship and symbolism, attached great importance to order and uniformity, and sought the mysterious operations of divine grace through material channels. The Anglo-Catholic spirit in most respects, as might be expected, appears more shadowy and in less power amongst the Bishops connected with the Reformation than amongst those who succeeded.[11] Parker, Whitgift, and Laud represent stages of advancement in this point of view. But from the very foundation of the Reformed Church of England this spirit, in a measure, manifested itself, and in no respect, perhaps, so much as in reverence for early patristic teaching. No one can be surprised that such tendencies remained with many who withdrew allegiance from the Pope, and [8]renounced the grosser corruptions of Rome. It is a notable fact that out of 9,400 ecclesiastics, at the accession of Elizabeth, less than 200 left their livings.[12] Many evaded the law under shelter of powerful patrons, or escaped through the remoteness and poverty of their cures. And it cannot be believed that, of those who positively conformed, all or nearly all became real Protestants.

The divines of this school, drawn towards the Fathers by their venerable antiquity, their sacramental tone and their reverence for the episcopate, did not miss in them doctrinal tendencies accordant with their own. Even the Calvinistic Anglican of an earlier period could turn to the pages of Augustine and of other Latin Fathers, and find there nourishment for belief in Predestination, and Salvation by faith. But the Arminian still more easily found his own ideas of Christianity in Chrysostom, Clement of Alexandria, and other Eastern oracles. The Greek Fathers were favourites with the Anglican party of the seventeenth century. Whether the study of that branch of literature was the cause or the effect of the Arminian tendencies of the day—whether a taste for the learning and rhetoric of the great writers of Byzantium and Alexandria paved the way for the adoption of their creed, or sympathies with that creed led to the opening of their long neglected folios, may admit of question. Certainly the formation of theological beliefs is always a subtle process, and is subject to so many[9] influences that, in the absence of conclusive evidence, it is hazardous confidently to pronounce a judgment.

The fairest side of Stuart-Anglicanism presents itself in the writings of Dr. Donne, and Bishop Andrewes. In the first of these great preachers there is a strong "patristic leaven,"—a lofty enforcement of church claims, a deep reverence for virginity, and an inculcation of the doctrine of the Real presence—such as we notice in the writings of the Fathers before the schoolmen had crystallized the feeling of an earlier age into the hard dogma of Transubstantiation. But there are also in some of his quaint and beautiful sermons statements of Christian truth, resembling the theology of Augustine; and at the same time, from the very bent of his genius, he was led to illustrate practical duty in many edifying ways. As to Bishop Andrewes, his "Greek Devotions" present him as a man of great spirituality; and we are not surprised to learn that he spent five hours every day in prayer and meditation. The formality of method in his celebrated manual, the quaintness of his diction, and his artificial but ingenious arrangement of petition and praise are offensive to modern taste; and, it must be allowed, his catholic animus is betrayed every now and then, so as to shock Protestant sensibilities; yet there are Protestants who still use these Devotions, and find in them helps to communion with God, aids to self-examination, and impulses to a holy life. On turning to his sermons, we discover expressed in his sententious eloquence (which has been rather too much condemned for pedantry and alliteration) doctrinal statements respecting the Atonement and Justification by Faith, quite in harmony with evangelical opinions. Though not a Calvinist, he was free from Pelagian tincture. Andrewes, Donne and others, however, are not—any more than the Fathers—to be judged by[10] extracts. A few passages do not accurately convey their pervading sentiments. Orthodox and evangelical in occasional statements of doctrine, still they are thoroughly sacramentarian and priestly in spirit. And, no doubt, their works, especially those of Andrewes, contributed in a great degree to foster that kind of religion which so much distressed, alarmed, and irritated the Puritans at the opening of the Civil War.

The admirable George Herbert, too, had strong Anglo-Catholic sympathies, on their poetical and devotional side. His hymns and prayers are in harmony with his holy quiet life, and may be compared to a strain of music such as he drew from his lute or viol, or to a deep-toned cathedral antiphony, in response to notes struck by an angel choir.

The type of character formed under such culture partook largely of a mediæval spirit. The saints of the Church were cherished models. The festivals of the Church were seasons for joy, its fasts for sorrow. The liturgy of the Church stereotyped the expressions of devotion, almost as much in its private as in its public exercise. The ministers of the Church were regarded more as priests than teachers, and their spiritual counsel and consolations were sought with a feeling, not foreign to that in which Romanists approach the confessional. The sacraments of the Church were received with awe, if not with trembling, as the mystic vehicles of salvation; and the whole History of the Church, its persecution and prosperity, its endurance and achievements, its conflicts and victories, were connected in the minds of such persons with the ancient edifices in which they worshipped. The cathedral and even many village choirs told them of "the glorious company of the Apostles," "the goodly fellowship of the[11] prophets," and "the noble army of martyrs," and "the Holy Church throughout all the world." They loved to see those holy ones carved in stone and emblazoned in coloured glass. A dim religious light was in harmony with their grave and subdued temper. The lofty Gothic roof, the long-drawn aisle, the fretted vault, and the pavement solemnly echoing every footfall, had in their eyes a mysterious charm. The external, the visible, and the symbolic, more exalted their souls than anything abstract, argumentative, and doctrinal: yet, though their understanding and reason had little exercise, it must not be forgotten, that, through imagination and sensibility awakened by material objects, these worshippers might rise into the regions of the sublime and infinite, the eternal and divine.

Such religion existed in the reign of Charles I. amongst the dignitaries of the Church. Occupying prebendal houses in a Cathedral close, they found nourishment for their devotion in "the service of song," as they occupied the dark oak stalls of the Minster choir. It was also cherished in the Universities. Heads of houses, professors, and fellows carried much of the Anglican feeling with them, as they crossed the green quadrangle, to morning and evening prayer. Town rectors and rural incumbents would participate in the same influence. Devout women, in oriel-windowed closets, also would kneel down, under its inspiration, to repeat passages in the Prayer book, or in Bishop Andrewes' devotions. And some English noblemen, free from courtly vice, would embody the nobler principles of the system. Yet, probably, the larger number of religious people in England were of a different class.

The following extract from a letter, belonging to the early part of the year 1641, giving an account of the[12] death of the Lady Barbara Viscountess Fielding, affords an idea of Anglican piety in the last hour of life, more vivid than any general description:—

"About twelve of the clock this Thursday, the day of her departure, Dr. More being gone, I went to her, and by degrees told her of the danger she was in, upon which she seemed as it were to recollect herself, and desired me to deal plainly with her, when I told her Dr. More's judgment of her, for which she gave me most hearty thanks, saying this was a favour above all I had ever done her, &c.; and when she had, in a most comfortable manner, given me hearty thanks, she desired me to spend the time she had to live here, with her in praises and prayers to Almighty God for her, desiring me not to leave her, but to pray for her, when she could not, and was not able to pray for herself, and not to forsake her until I had commended her soul to God her Creator. After which, some time being spent in praising God for her creation, redemption, preservation hitherto, &c., we went to prayers, using in the first place the form appointed by our Church (a form she most highly admired), and then we enlarged ourselves, when she added thirty or forty holy ejaculations;—then I read unto her divers of David's Psalms, after which we went to prayers again; then she desired the company to go out of the room, when she made a relation of some particulars of her life to me (being then of perfect judgment), desiring the absolution our Church had appointed, before which nurses and others were called in, and all kneeling by her, she asked pardon of all she had offended there, and desired me to do the like for her to those that were not there; and when I had pronounced the absolution, she gave an account of her faith, and then after some ejaculations she praised Almighty God[13] that He had given her a sight of her sins, giving Him most humble thanks that He had given her time to repent, and to receive the Church's absolution; and then she prayed in a very audible voice, that God would be pleased to be merciful to this our distressed Church of England for Jesus Christ his sake. After this she only spoke to my Lord, having spoken to her father, Sir J. Lambe, two or three hours before, and then at last of all, she only said, 'Lord Jesus, receive my soul;' but this was so weakly, that all heard it not, nor did I plainly, but in some sort guessed by what I heard of it."[13]

But the Anglo-Catholicism of the Stuart age presented other aspects. In a multitude of cases, ritual worship degenerated into mere ceremonialism. An ignorant peasantry, who could neither read nor write, and who were destitute of all that intellectual stimulus which, in a thousand ways, now touches the most illiterate, would derive little benefit from reading liturgical forms, unaccompanied by instructive preaching—against which, in the Puritan form, the abettors of the system were much prejudiced. Though the prayers and offices of the Church of England be incomparably beautiful, experience is sufficient to show that, familiar with their repetition, the thoughtless and demoralized, being quite out of sympathy with their spirit, fail to discern their excellence. And, when it is remembered, that the Book of Sports, instituted by King James, was the rule and the reward for Sabbath observance; that after service in the parish church (not otherwise), the rustics were encouraged to play old English games on the village green, to dance around the May-pole, or to shoot at butts;[14] we ask what could be the result, but religious formalism scarcely distinguishable from the lowest superstition? Should it be pleaded, that a pious and exemplary clergyman would impart life to what might otherwise have been dead forms, and restrain what otherwise would have been riotous excess; it may be replied, that a very considerable number of the holders of livings were not persons of that description; they sank to the level of their parishioners, and had no power to lift their parishioners to a level higher than their own.

The sympathies of the Church were with the people in their amusements; a circumstance which contributed to the strong popular reaction in favour of the Church, when Charles II. was restored. In the reign of Charles I. the wakes, or feasts, intended to celebrate the dedication of churches had degenerated into intemperate and noisy gatherings, and were, on that account, brought by the Magistrates under the notice of the Judges. But the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Bishop of Bath and Wells, backed by the King, came to the rescue. The complaints were attributed to Puritan "humourists." Alleged disorders were denied. The better sort of clergy in the diocese of Bath and Wells,—seventy-two in number, likened to the Septuagint interpreters, "who agreed so soon in the translation of the Old Testament,"—came together, and declared that these wakes were fit to be continued for a memorial of the dedication of churches, for the civilizing of the people, for lawful recreation, for composing differences, for increase of love and amity, for the relief of the poor, and for many other reasons.[14]

The charge has been brought against the high Church[15]men of that day, that they were papistically inclined. If by this term be meant any disposition to uphold the Papacy, and to acknowledge the authority of the Bishop of Rome over other Churches, even though modified by a charter of liberties like the Gallican, the charge is unfair. A distinct national establishment was always contended for by those who were suspected of the strongest papal leanings. They advocated an authority not derived from any foreign potentate, but, as they conceived, of immediate divine origin, and this authority they considered to be entitled to uncontrolled jurisdiction within the shores of the four seas. They wished for a Pope—to use the current language of the times—"not at Rome but at Lambeth." A reconciliation with the Church of Rome not involving submission, might have been agreeable to some of the party; yet, it must be acknowledged that, in solemn conclave, the Anglicans accused the Romanists of idolatry.[15] If, however, by papistic be meant a tendency to Catholic worship, and so ultimately to Romish conformity, then may the imputation be supported by facts. The history of Christendom shews that the Church gradually passed from its primitive simplicity to the corruptions of the papacy; that ante-Nicene innovations, with post-Nicene developments and traditionalism, were stepping-stones in the transition. The process, on a wide scale, requires many centuries for its accomplishment; but partially and in individual cases a few years may suffice for the experiment. Ecclesiastical annals, from Constantine to Hildebrand, may be epitomized in a brief chronology. Movements may rapidly pass through stages, like those of the Nicene and Mediæval. And sharp speaking, in order to maintain a certain eccle[16]siastical position against Rome, may immediately precede, and in fact, herald the approach of pilgrims to the very gate of the seven-hilled city.[16] What has occurred within our own time in individual instances, was likely to occur, to a large extent, in the first half of the seventeenth century.

Mediæval sympathies, at the period now under our review, are obvious not only in the rigorous enforcement of fasting and abstinence,[17] which had continued ever since the Reformation, but in certain monastic tendencies, and in slurs cast on the reformers. A document, prepared in 1633—no doubt under the influence of Laud—by Secretary Windebank, for the direction of Judges of assize, urged obedience to the proclamation for the better observance of Lent and fish-days, because their neglect had become very common, probably in many cases on Puritan grounds.[18] Monastic tendencies, about the same time, appeared in the famous Monastery at Gidding, in Huntingdonshire. While the devotions of the pious family there excited the admiration of Isaak Walton,—in whose account of it is reflected the more spiritual phase of the proceeding,—the superstitions, mingled with better things, provoked the severest animadversions of Puritan contemporaries,[19] who wondered at nothing more than, that in a settled Church government, Bishops could permit[17] "such a foundation so nearly complying with Popery." In connection with this may be mentioned the preface to the new statutes for the University of Oxford, published in Convocation, which "disparaged King Edward's times and government, declaring, that the discipline of the University was then discomposed and troubled by that King's injunctions, and the flattering novelty of the age, and that it did revive and flourish again in Queen Mary's days, under the government of Cardinal Pole, when by the much-to-be-desired felicity of those times, an inbred candour supplied the defect of statutes."[20]

In the sixteenth century, and far into the seventeenth, intolerance, inherited from former ages, infected more or less all religious parties. Few saw civil liberty to be a social right, which justice claimed for the whole community, whatever might be the ecclesiastical opinions of individuals. This position of affairs shewed how little dependent is spiritual despotism upon any particular theological system, and how it can graft itself upon one theory as well as upon another; for, while under Elizabeth persecution allied itself to Calvinism, in the first two of the Stuart reigns, Arminianism—at that time in Holland wedded to liberty of conscience—appeared in England embracing a form of merciless oppression. But, though without special theological affinities, intolerance certainly shewed kinship to certain forms of ecclesiastical rule. It fondly clung to prelacy before the Civil War. The relation in which subsequently it appeared to other Church organizations will be disclosed hereafter. Whitgift and Bancroft, inheriting intolerance from their predecessors,[18] persecuted Nonconformists. They silenced and deprived many; whilst others they excommunicated and cast into prison. The Anglican Canon Law—which must be distinguished from the Papal Canon Law[21]—remained a formidable engine of tyranny in the hands of those disposed to use it for that purpose. That law, of course, claimed to be not law for Episcopalians alone but for the people at large, who were treated altogether as subject to Episcopal rule; and neither creed nor worship inconsistent with canonical regulations could be tolerated for a moment. Only one Church was allowed in England; and for those who denied its apostolicity, objected to its government, disapproved of its rites and observances, or affirmed other congregations to be lawful churches, there remained the penalty of excommunication, with all its alarming consequences.[22]

Anglicanism allowed no exercise of private judgment, but required everybody to submit to the same standard of doctrine, worship, and discipline. Moderate Puritans were to be broken in, and Nonconformists "harried out of the land." It might seem a trifle that people should be fined for not attending parish churches; but imprisonment and exile for nonconformity struck most Englishmen as a stretch of injustice perfectly intolerable.[23]

Ecclesiastical Courts, not only consistory and commissary, but branching out into numerous forms, carried on actively and continuously the administration of canon[19] law after the Reformation. Discipline was, perhaps, not much less maintained after that event than before.[24] Such activity continued throughout the reigns of Elizabeth, James, and Charles; and so late as 1636 the Archdeacon of Colchester held forty-two sessions at four different towns during that single year. The object of the canon law and the ecclesiastical courts being pro morum correctione et salute animæ, immoralities such as the common law did not punish as crimes, came within the range of their authority, together with all sorts of offences against religion and the Church. The idea was to treat the inhabitants of a parish as members of the Anglican Church, and to exercise a vigilant and universal discipline by punishing them for vice, heresy, and schism. Intemperance and incontinence are offences very frequently noticed in the records of Archidiaconal proceedings in the latter part of the sixteenth and the early part of the seventeenth centuries, suggesting a very unfavourable idea of public morals at that time; and a long catalogue also appears of charges touching all kinds of misconduct. Some appear very strange,—such as hanging up linen in a church to dry; a woman coming to worship in man's apparel; a girl sitting in the same pew with her mother, and not at the pew door, to the great offence of many reverent women; and matrons being churched without wearing veils. Others relate to profaning Sundays and holidays, setting up maypoles in church time, and disturbing and even reviling the parish ministers. Certain of them point[20] distinctly to Puritan and Nonconformist behaviour, such as refusing to stand and bow when the creed was repeated, and to kneel at particular parts of divine service. Brownists are specifically mentioned, and extreme anti-sacramental opinions are described.

The method of proceeding ex officio was by the examination of the accused on his oath, that he might so convict himself if guilty, and if innocent, justify himself by compurgation[25]—a method, it may be observed, totally opposed to the criminal jurisprudence of our common law, and one which became increasingly offensive in proportion to the increase of national attachment to the English Constitution on the side of popular freedom. Though, as we look at the moral purpose of these institutions, and the cognizance they took of many vicious and criminal irregularities of conduct which did not come under the notice of civil magistrates, we are quite disposed to do justice to the motives in which the courts originated, and to admit that in the rude life of the middle ages they might possess some advantages—we must see, looking at them altogether, that they became the ready instruments of intolerance when great differences in religious opinion had appeared; that they were certain, in Puritan esteem, to attach odium to the old system of Church discipline; and that they were completely out of harmony with the modern spirit of Protestant civilization.

In the Tudor and Stuart days, there also existed two tribunals of a character which it is difficult in the nineteenth century to understand. The High Commission[21] Court was doubtless intended to promote and consolidate the Reformation on Anglo-Catholic principles, by exterminating Popery on the one hand, and checking Puritanism on the other. According to the terms of the Act of Uniformity, Elizabeth and her successors had power given them "to visit, reform, redress, order, correct and amend all such errors, heresies, schisms, abuses, contempts, offences and enormities whatsoever, which, by any manner of spiritual authority or jurisdiction, ought, or may be lawfully reformed, ordered, redressed, corrected, restrained or amended." Her Majesty became invested with authority to correct such heresies of the clergy as had been adjudged to be so by the authority of the canonical Scripture, or by the first four general councils, or any of them, or by any other general council, or by the High Court of Parliament, with the assent of the clergy in convocation.[26] Many Commissions were successively issued by the Queen.[27] Neal gives an abstract of that one which was issued in the month of December, 1583. After reciting the Act of Supremacy, the Act of Uniformity, the Act for the assurance of the Queen's powers over all states, and the Act for reforming certain disorders touching ministers of the Church, her[22] Majesty named forty-four commissioners, of whom twelve were bishops, some were privy councillors, lawyers, and officers of state, the rest deans, archdeacons, and civilians. They were authorized to enquire respecting heretical opinions, schisms, absence from church, seditious books, contempts, conspiracies, false rumours, and slanderous words, besides offences, such as adultery, punishable by ecclesiastical laws. In the first clause command is given to enquire, "as well by the oaths of twelve good and lawful men, as also by witnesses, and all other means and ways you can devise."[28] With this power of enormous latitude, instituting enquiry over vague offences, was connected a power of punishment, qualified by the word "lawful," and by reference "to the power and authority limited and appointed by the laws, ordinances, and statutes of the realm." Liberty was given to examine suspected persons "on their corporal oath"—in fact, the ex officio oath.[29][23] Any three of the members had authority to execute the commission.[30]

The Court so constituted extended its range, and increased its activity, and pressed beyond the boundaries of statute law, so as to become, in the reign of Charles the First, a means of arbitrary government intolerable to the country.

Records of the Court are still preserved in the State Paper Office,[31] shewing the modes of proceeding, the charges of which the Commissioners took cognizance, and the punishments they pronounced upon the convicted. Counsel for office—counsel for defendants—appearance and oath to answer articles—appearance, and delivering in of certificate—orders for defendants to give in answers—motion for permission to put in additional articles—commissions decreed for taking answers and examining witnesses—commissions brought in and depositions of witnesses published—and orders for taxation of costs—are forms of expression and notices of proceeding very frequent in these old Books. Some of them conveyed, no doubt, terrible meanings to the parties accused. We meet also with "suppressions of motion," "agreements[24] for subduction of articles," petitions to be admitted in "formâ pauperis," and reference of causes to the Dean of Arches. Collecting together heads of accusation, we find the following in the list—holding heretical opinions, contempt of ecclesiastical laws, seditious preaching, scandalous matter in sermons, using invective speeches unfit for the pulpit, nonconformity, publishing fanatical pamphlets, profane speeches, schism, blasphemy, raising new doctrines, preaching after deposition, and simoniacal contracts. Descending to minute particulars, we discover such items as these:—"locking the church door, and impounding the archdeacons, officials, and clergy," in the exercise of ecclesiastical jurisdiction; wearing hats in church; counting money on the communion-table; saying, "A ploughman was as good as a priest," and asking, "What good do bishops in Ireland?;" profane acts endangering parish edifices; praying that young Prince Charles might not be brought up in popery; and submission performed in a slight and contemptuous manner.[32] Entries of fines and imprisonment frequently occur.

It should be stated that occasionally other religious offences are noticed in these volumes, such as possessing a Romish breviary, and refusing the oath of allegiance. Enquiries also appear, as to persons who secreted young ladies "going to the nunneries beyond seas." There are, too, monitions "to bring to the office popish stuff and books."[33] But such instances are few compared with those relating to Puritans. Also now and then occur cases of flagrant clerical immorality, acts of violence, and of criminal behaviour.[34] But it was the persecution, the intolerance, the irritating control over so many persons and things, and the harsh treatment, and severe sentences of this absorbing jurisdiction, emulating as it did the worst ecclesiastical tribunals of the middle ages, and of Roman Catholic countries, that so roused the wrath of our forefathers against it.

It is very curious, after inspecting the records of the High Commission, to open Dr. Featley's Clavis, and there to find sermons, preached by him at Lambeth before the Commissioners, on such subjects as "The bruised reed and smoking flax," and "The still small voice,"—sermons filled with the mildest and gentlest sentiments. More curious, to light on other discourses in the same volume, bearing the very appropriate titles of "Pandora's box," and "The lamb turned into a lion." But for the knowledge we have of the preacher and of the contents of his discourses, we should suppose the former titles were ironical hits, and the latter outspoken truths. They are[26] neither; but are chosen, it is plain, with perfect simplicity.[35]

The Star Chamber is commonly associated in the minds of Englishmen with the High Commission Court. Unfettered by the verdict of juries, not guided by statute law, and irresponsible to other tribunals, it claimed an indefinable jurisdiction over all sorts of misdemeanours—"holding for honourable that which pleased, and for just that which profited." Though not a constituted ecclesiastical court, like the High Commission, bishops as privy councillors sat amongst its judges, and it took cognizance of religious publications. Whilst the High Commission confined its penalties to deprivation, imprisonment, and fines, the favourite punishments of the Star Chamber were whipping, branding, cutting ears, and slitting noses. The barbarous treatment of Leighton, Prynne, Burton, and Bastwick, will shortly be noticed.

These two arbitrary courts, which, in spite of their difference, were almost invariably linked together in the thoughts of our countrymen, concentrated on themselves an amount of public indignation equal to the fury of the French against the Bastile; and at last, like that prison, they fell amidst the execrations of a people whose[27] patience had been exhausted by such prolonged iniquities.[36]

Nor was it only the intolerance of the Church which exasperated the people, its secular intermeddling did so likewise. Before the Reformation Churchmen had held the highest offices in the State, indeed, had controlled all civil affairs; and Laud was now imitating the Cardinals of an earlier age. But the English Reformation had shaken off from itself the civil power of the Church; laymen, not the clergy, now claimed to guide the helm. The Puritanism of the seventeenth century, and the civil war which grew out of it, were practical protests against the attempts of Charles, Strafford, and Laud to revive what the Reformation in this country had destroyed. The modern spirit of civilization was seen rebelling against the intrusion of the spiritual on the secular power. It was a stage in the great European conflict which ended in the French Revolution; it was an assault upon a system which has now expired everywhere except in the city of Rome.

As was only consistent, the party supporting ecclesiastical intolerance also supported civil despotism. Never since the English Constitution had grown up were the liberties of the people so threatened as during the earlier part of the seventeenth century. The two checks on the tyranny of the Crown, the aristocracy and the Church, had long been enfeebled—the aris[28]tocracy by the wars of the Roses; the Church by the loss of independence at the Reformation. The nobles of England had wasted their strength in the fifteenth century; the Church of England had prostrated herself before the throne in the sixteenth. Neither of them had now the power, any more than they had now the will, to defend popular freedom against the invasions of regal prerogative. It is true, that the same causes, which weakened them as the possible friends of the people, weakened them also as actual friends of the Sovereign. What they did for the Crown in the Civil Wars, was far less than they might have done at an earlier period: even as what remained in their power to accomplish on behalf of popular rights was far less. But the malign aspect of the Church, then the chief power next the throne, towards the nation at large, and the Commons in particular, was most manifest and most alarming at the epoch under consideration. Old English liberties indeed had never been extinguished. The spirit of English self-government asserted under the house of Lancaster, though seemingly held in abeyance in the times of the Tudors, so far from expiring, had come out with renewed youth in the days of the Stuarts, through the parliamentary career of those eminent statesmen who formed the vanguard of the Commonwealth army. But against the illustrious Sir John Eliot, with his noble compeers, High Church contemporaries stood in defiant hostility. That kings are the fountains of all power; that they reign "by the grace of God," in the sense of divine right; that they are feudal lords—the soil their property, and the people their slaves—were doctrines upheld by sycophants of the Court, and endorsed and defended by doctors of the Church. Dr. Sibthorpe, a notorious zealot for passive obedience and non-resistance,[29] monstrously declared, "If princes command anything, which subjects may not perform, because it is against the laws of God, or of nature, or impossible; yet subjects are bound to undergo the punishment, without either resisting, or railing, or reviling; and so to yield a passive obedience where they cannot exhibit an active one. I know no other case, but one of those three wherein a subject may excuse himself with passive obedience, but in all other he is bound to active obedience."[37] Another preacher of the same class, Dr. Manwaring, was brought before Parliament for maintaining, "That his Majesty is not bound to keep and observe the good laws and customs of this realm; and that his royal will and command in imposing loans, taxes, and other aids upon his people, without common consent in Parliament, doth so far bind the consciences of the subjects of this kingdom, that they cannot refuse the same without peril of eternal damnation."[38]

The Church of the middle ages had commonly thrown its shield over subjects against the oppression of rulers: but in contrast with this, the Anglo-Catholic Church of the Stuart times stood in closest league with Government for purposes the most despotic. The tyranny of Buckingham in 1624, with his forced loans, became insupportable, and the obloquy of it all—alas for the Church of England!—fell largely upon its dignitaries, because favour had been strongly shown to the policy of that arrogant minister by such men as Sibthorpe and Manwaring. Strafford went beyond Charles[30] in imperious despotism; and Strafford found in Archbishop Laud not only a helper in his "thorough" policy, but an example of even more violent measures, and a counsellor instigating him to still greater lengths.[39]

Besides all this intolerance and oppression, it must be acknowledged that there was in the ministry of the Church of England a large amount of ungodliness and immorality. To believe that all the charges of clerical viciousness and criminality were true, would be to imbibe Puritan prejudice; whilst, on the other hand, to believe that all were false, would betray a strong tincture of High Church partiality; so much could not have been boldly affirmed, and generally believed, without a large substratum of fact. But more of this hereafter.

Rigid ceremonialism, desecration of the Sabbath, sympathy with Roman Catholicism, fondness for imitating popish practices, cruel intolerance, alliance with unconstitutional rule, and the immorality of clergymen, will serve to explain what gave such force to the antagonistic puritan feeling which surged up so fearfully in 1640. The Church had become thoroughly unpopular amongst the middle and lower classes in London and other large places; in short, with that portion of the people, which in the modern age of civilization, must and will carry the day. They did not then, with all their fondness for theological controversy, care so much for any abstract idea of Church polity as for the actual working of ecclesiastical machinery, and the character and conduct of ecclesiastical men before their eyes. It was not any Presbyterian or Independent theory, as opposed to the Episcopalian system of the[31] Church of England, that swept the nation along its fiery path in the dread assault which levelled the Episcopal establishment; but it was the indignation aroused by corruption, immorality, and intolerance, which kindled the blazing war-torch destined to burn to the ground both temple and throne. Had the Church of England been at that time a liberal and purely Protestant Church, and its rulers wise, moderate, and charitable men; whatever might have been the influence of ecclesiastical dogmas, its fate must have been far different from what it actually became.

The person who carried Anglo-Catholicism to its greatest excess, and who, by other unpopular proceedings, did more than anybody else, to alienate from the State religion a large proportion of his fellow-countrymen, was William Laud. Ritualism ran riot under the rule of this famous prelate. Alienated from the theology of Augustine, but relishing the sacerdotalism of Chrysostom, he delighted in a gorgeous worship such as accorded with the Byzantine liturgy, and was penetrated with that reverence for the priesthood and the Eucharist which the last of the Greek orators, in his flights of rhetoric, did so much to foster. Whatever might be the extravagances in Byzantium, they were nearly, if not quite, paralleled when Archbishop Laud held unchecked sway. A church was consecrated by throwing dust or ashes in the air.[40] The napkin covering the Eucharistic elements was carefully lifted up, reverently peeped under, and then[32] solemnly let fall again: all which performances were accompanied by repeated lowly obeisances before the altar. This ceremony was quite as childish and far less picturesque than the dramatic doings in the Greek Church, when choristers aped angels by fastening to their shoulders wings of gauze.[41] Into cathedrals, churches, and chapels, were also introduced pictures, images, crucifixes, and candles, which, with the aid of surplices and copes,[42] bowing, crossing, and genuflections, produced a spectacle which might be taken for a meagre imitation of the mass. Had not public opinion, which was beginning to be a mighty power, checked such proceedings, there can be no doubt they would speedily have reached such lengths, that an English parish church would have differed scarcely at all from a Roman Catholic chapel.[43]

Laud's size was in the inverse ratio of his activity—for he had the name of "the little Archbishop," though his capacities for work were of gigantic magnitude. His influence extended everywhere, over everybody, and everything, small as well as great—like the trunk of an elephant, as well suited to pick up a pin as to tear down a tree. His articles of visitation traversed the widest variety of particulars, descending through all conceivable ecclesiastical and moral contingencies, down to the humblest details of village life. Churchwardens were asked, "Doth your minister preach standing, and with his hat off? Do the people cover their heads in the Church, during the time of divine service, unless it be in case of necessity, in which case they may wear a nightcap or coif?" These functionaries were also required to state, how many physicians, chirurgeons, or midwives there might be in the neighbourhood; how long they had used the office, and by what authority; and how they demeaned themselves, and of what skill they were accounted in their profession.[44] A report of the state of his province he presented to the King year by year.[45] Every bishopric passed under his review, and[34] the substance of the information he obtained and digested, affords a bird's-eye view of the religious condition of each diocese, in the Archbishop's estimation. Oxford, Salisbury, Chichester, Hereford, Exeter, Ely, Peterborough, and Rochester, were in a tolerably fair condition, although furnishing matter here and there for some complaint. But in his own see of Canterbury there were many refractory persons, and divers Brownists and other separatists, especially about Ashford and Maidstone, who were doing harm, "not possible to be plucked up on the sudden."[46] London occasioned divers complaints of nonconformity. Factious and malicious pamphlets were circulated, Puritans were insolent, and curates and lecturers were "convented." From Lincoln came complaints, that parishioners wandered from church to church, and refused to come up to the altar rail at the holy communion; Buckingham and Bedfordshire also abounded in refractory people. Norwich had several factious men: Bridge and Ward are named, and it is said there was more of disorder in Ipswich and Yarmouth than in the cathedral city. Lecturers were abundant, and catechising neglected. In the diocese of Bath and Wells, lectures were put down in market towns, and afternoon sermons were changed into catechetical exercises. Popish recusants appeared fewer than before, and altogether the bishop had put things in marvellous order.

As Laud's eye—that ferret-like eye, which under its arched brow, looks with cunning vigilance from Vandyke's canvas—ran over his whole province, and his busy pen recorded what he learned, he sent to the Inns of Court—the benchers having betrayed Puritan[35] tendencies—and insisted upon surplice and hood, and the whole service prescribed for the occasion being used in chapel before sermon. He claimed rights of ecclesiastical visitation in the two universities, and inspected cathedrals and churches, as to their improvements and repairs; condescending even to order the removal of certain seats employed for the wives of deans and prebendaries, and directing them to sit upon movable benches, or chairs.[47]

English residents in Holland;[48] chaplains of regiments amongst the Presbyterian Dutch; Protestant refugees in this country; and the ecclesiastical affairs of Scotland, all came under his vigilant notice, and within his tenacious grasp.[49]

In his own diocese and province[50] Laud's hand fell heavily on those beneath his sway. "All men," it is remarked, "are overawed, so that they dare not say their soul is their own." The clergy of his cathedral muttered their dissatisfaction. Reports circulated that they were "a little too bold with him;" and his remedy was, "If upon inquiry I do find it true, I shall not forget that nine of the twelve prebends are in the king's gift, and[36] order the commission of my visitation; or alter it accordingly."[51] Dean and prebendaries were soon humbled under such discipline.

In court and country, in Church and State, Laud, next to the Earl of Strafford, must be considered to have been the most powerful minister in England.[52] Pledged to a thorough policy of arbitrary kingship, he helped in all things his royal master, and his able fellow-councillor. When Strafford was in Ireland as Lord Lieutenant, the Archbishop was the great power at home behind the throne. "He is the man," said courtiers, when they would point out the most favourable medium for approaching royalty.[53] His own power availed for the province of Canterbury; by the help of his archiepiscopal brother,[37] Neil of York, it sufficed for all England. Such a man, so bigoted, so imperious, and so marvellously active, was sure to make many more foes than friends. He had also ways, altogether his own, of making enemies. As he himself tells us, he kept a ledger, in which he preserved a strict account of the theological and ecclesiastical bias of clergymen, for the guidance of his royal master in the distribution of patronage. O and P were the letters at the heads of two lists. On the Orthodox all favours were showered. From those favours all Puritans were excluded.[54]

The Anglicanism of Laud was dear to Charles I. for two reasons. First, it harmonized with his own despotic principles. The King had been, ever since he assumed the crown, working out a problem in which the direst mischief was involved—whether it were not possible for an English sovereign, without casting away constitutional forms, to grasp at absolute dominion, to make the Commons a mere council for advice, or a Court to register decrees, rather than an integral branch of the Legislature; and, while conceding to them the office of filling the country's purse, to claim and exercise an independent power of managing the strings. He disliked parliaments, if they exercised their rights. "They are of the nature of cats," said he, "they ever grow curst with age, so that if you will have good of them, put them off handsomely when they come to any age, for young ones are ever most tractable."[55] His remedy for troublesome parliaments was dissolution. He preferred ship money to legal taxation: Anglicanism, from its maintenance of the Divine right of Kings, favoured his views in this respect, and[38] divines of that stamp were after his own heart. But there was a second reason why Charles was drawn towards Laud. It would be unjust to the King to represent him merely as a politician. Grave, cold, reserved and haughty—qualities indicated in the countenance which the pencil of Vandyke has made familiar to us all—he was also a man of sincere religious feeling; but that feeling appears in harmony with his natural character. Stately ceremonialism, court-like prelacy, priestly hauteur, and a frigid creed corresponded even more with the idiosyncracy of the man than with the prejudices of the monarch. From a youth he had shown a leaning towards the Roman Catholic form of worship, and this tendency had been nourished by the education received from his father. "I have fully instructed them," King James observed in a letter touching his sons, "so as their behaviour and service shall, I hope, prove decent, and agreeable to the purity of the primitive Church, and yet as near the Roman form as can lawfully be done, for it hath ever been my way to go with the Church of Rome usque ad aras."[56]

As we proceed in our review of parties, we feel the difficulty of defining the boundary between them. The majority of divines were thoroughly Anglican or thoroughly Puritan; yet a great many had only partial sympathies with the one or the other. Nor did they form a class of their own. In no sense were they party men, except so far as they were prepared to support episcopacy and defend the Common Prayer. Amongst these may be mentioned Dr. Jackson, sometime vicar of Newcastle, (afterwards Dean of Peterborough,) known in his own time as an exemplary parish priest, and very popular with the poor,[39] relieving their wants "with a free heart, a bountiful hand, a comfortable speech, and a cheerful eye;" better known in our day as the author of a goodly row of theological works, including discourses on the Apostles' Creed.[57] He was a decided Arminian, and a rather High Churchman. Bishop Horne acknowledged a large debt to Dean Jackson, and Southey ranks him in the first class of English divines.[58] But his writings present strong attractions for those who have no High Church sympathies, because the reasonings and contemplations of such a man rise far above sectarian levels, and are suited to enrich and edify the whole Church of God. Dr. Christopher Sutton, prebendary of Westminster, the learned author of two admirable practical treatises, "Learn to Live" and "Learn to Die,"—in which patristic taste and a special regard for the Greek Fathers appear in connection with a highly devout spirit—is another theologian of the same period and the same class, in whom, with some Anglican elements, others of a Puritan cast are combined. The well-known Bishop Hall is a still more striking example of the Puritan divine united with the Anglican ecclesiastic.

If Puritanism cared for antiquity it would be possible to make out for it a lineage extending back to the first ages of Christendom. As soon as the Church betrayed symptoms of backsliding, persons arose, jealous for her honour, who recalled her erring children to paths of pristine purity. When, boasting of numbers, the many who were predominant relaxed severity of discipline, and conformed to the world in various ways—a few zealous Novations and Donatists set up a standard of reform. In some cases they proceeded at the expense of charity, and[40] in a narrow spirit; but they aimed ultimately at restoring what they deemed primitive communion. At a later period the name, and some of the ecclesiastical sympathies of the Puritans, were anticipated by the Cathari: and in the Lollards and Wickliffites of England, we may trace the spiritual ancestors of the men who revolutionized the Church in the seventeenth century. Several of our Reformers went beyond their brethren in ideas of reform; and in the reign of Elizabeth—particularly amongst those who returned from the continent, where they had been brought into close fellowship with Zwinglians and other advanced Protestants—there were persons holding opinions substantially the same with those adopted by Puritans under Charles I.; and those who had no doctrinal tenets or ecclesiastical preferences to separate them from their contemporaries, but had become somewhat distinguished by objections to certain forms, and more so by superior religiousness and spirituality of life, were, on that account, reproached by laxer men as bigoted precisians. As was natural, this treatment drove such persons into the arms of others who had embraced distinctive views of polity, between which and the strict habits of these new allies there existed obvious harmony. The anti-hierarchical temper of Puritanism, and its presumed favourableness to the broad principles and popular spirit of the British constitution secured for it, on that side, countenance from such as were far from adopting its religious principles. Leicester and Walsingham looked on it with some favour as a counterpoise to prelatical arrogance, if not for other reasons. Burleigh shielded the persecuted from the violence of the High Commission. Raleigh defended the cause in Parliament. Connection with these politicians gave political significancy to a movement originating entirely in spiritual impulses.

Whenever any vigorous revival of religious life occurs, a tendency to "irregular proceedings" will be sure to appear in the movement party. Accordingly, one peculiarity of the early Protestants is seen in a love of meeting together for Christian culture and edification, apart from the formalities of established worship. The proceedings of these good people were such as would be now pronounced intensely Low Church. One neighbour conferred with another, and "did win and turn his mind with persuasive talk." "To see their travels," exclaimed our old martyrologist, "their earnest seeking, their burning zeal, their readings, their watchings, their sweet assemblies, their love and concord, their godly living, their faithful marrying with the faithful, may make us now, in these days of our free profession, to blush for shame."