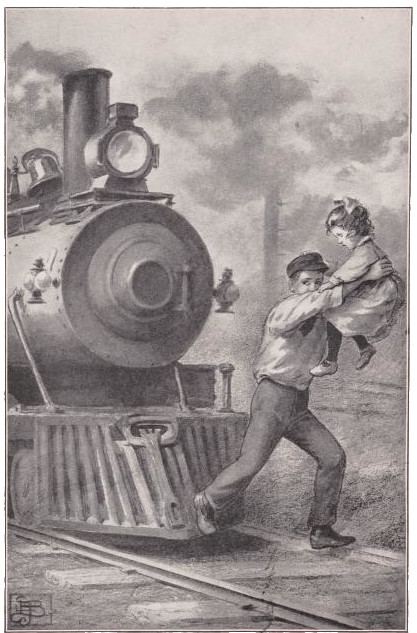

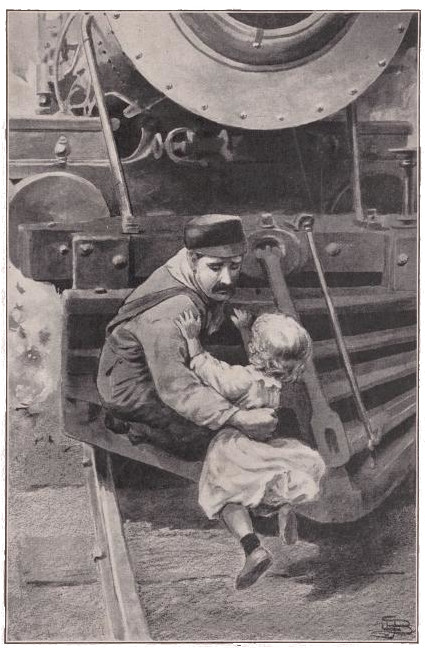

“CAUGHT THE CHILD FROM UNDER THE VERY WHEELS OF THE ENGINE”

“CAUGHT THE CHILD FROM UNDER THE VERY WHEELS OF THE ENGINE”

| CONTENTS | |

|---|---|

| I. | The Bottom Round |

| II. | A New Experience |

| III. | An Adventure and a Story |

| IV. | Allan Meets an Enemy |

| V. | Allan Proves His Metal |

| VI. | Reddy to the Rescue |

| VII. | The Irish Brigade |

| VIII. | Good News and Bad |

| IX. | Reddy’s Exploit |

| X. | A Summons in the Night |

| XI. | Clearing the Track |

| XII. | Unsung Heroes |

| XIII. | A New Danger |

| XIV. | Allan Makes a Discovery |

| XV. | A Shot from Behind |

| XVI. | A Call to Duty |

| XVII. | A Night of Danger |

| XVIII. | The Signal in the Night |

| XIX. | Reddy Redivivus |

| XX. | The Road’s Gratitude |

“Excuse me, sir, but do you need a man?”

Jack Welsh, foreman of Section Twenty-one, on the Ohio division of the P. & O., turned sharply around at sound of the voice and inspected the speaker for a moment.

“A man, yes,” he said, at last. “But not a boy. This ain’t boy’s work.”

And he bent over again to sight along the rail and make sure that the track was quite level.

“Up a little!” he shouted to the gang who had their crowbars under the ties some distance ahead.

They heaved at their bars painfully, growing red in the face under the strain.

“That’ll do! Now keep it there!”

Some of the men braced themselves and held on to their bars, while others hastened to tamp some gravel solidly under the ties to keep them in place. The foreman, at leisure for a moment, turned again to the boy, who had stood by with downcast face, plainly undecided what to do. Welsh had a kindly Irish heart, which not even the irksomeness of section work could sour, and he had noted the boy’s fresh face and honest eyes. It was not an especially handsome face, yet one worth looking twice at, if only for its frankness.

“What’s yer name, sonny?” he asked.

“Allan West.”

“An’ where’d y’ come from?”

“From Cincinnati.”

The foreman looked the boy over again. His clothes were good, but the worn, dusty shoes told that the journey of nearly a hundred miles had been made on foot. He glanced again at the face—no, the boy was not a tramp; it was easy to see he was ambitious and had ideals; he was no idler—he would work if he had the chance.

“What made y’ come all that way?” asked Welsh, at last.

“I couldn’t find any work at Cincinnati,” said the boy, and it was evident that he was speaking the truth. “There’s too many people there out of work now. So I came on to Loveland and Midland City and Greenfield, but it’s the same story everywhere. I got some little jobs here and there, but nothing permanent. I thought perhaps at Wadsworth—”

“No,” interrupted the foreman. “No, Wadsworth’s th’ same way—dead as a doornail. How old’re you?” he asked, suddenly.

“Seventeen. And indeed I’m very strong,” added the boy, eagerly, as he caught a gleam of relenting in the other’s eye. “I’m sure I could do the work.”

He wanted work desperately; he felt that he had to have it, and he straightened instinctively and drew a long breath of hope as he saw the foreman examining him more carefully. He had always been glad that he was muscular and well-built, but never quite so glad as at this moment.

“It’s mighty hard work,” added Jack, reflectively. “Mighty hard. Do y’ think y’ could stand it?”

“I’m sure I could, sir,” answered Allan, his face glowing. “Just let me try.”

“An’ th’ pay’s only a dollar an’ a quarter a day.”

The boy drew a quick breath.

“That’s more than I’ve ever made regularly, sir,” he said. “I’ve always thought myself lucky if I could earn a dollar a day.”

Jack smiled grimly.

“You’ll earn your dollar an’ a quarter all right at this work,” he said. “An’ you’ll find it’s mighty little when it comes t’ feedin’ an’ clothin’ an’ lodgin’ yerself. But you’d like t’ try, would y’?”

“Yes, indeed!” said Allan.

There could be no doubting his eagerness, and as he looked at him, Jack smiled again.

“I don’t know what th’ road-master’ll say; mebbe he won’t let me keep you—I know he won’t if he sees you can’t do th’ work.” He looked down the line toward the gang, who stood leaning on their tools, enjoying the unusual privilege of a moment’s rest. “But I’m a man short,” he added. “I had t’ fire one this mornin’. We’ll try you, anyway. Put your coat an’ vest on th’ hand-car over there, git a pick an’ shovel an’ go up there with th’ gang.”

The boy flushed with pleasure and hurried away toward the hand-car, taking off his coat and vest as he went. He was back again in a moment, armed with the tools.

“Reddy, you show him the ropes!” shouted the foreman to one of the men.

“All roight, sir!” answered Reddy, easily distinguishable by the colour of his hair. “Come over here, youngster,” he added, as Allan joined the group. “Now you watch me, an’ you’ll soon be as good a section-man as they is on th’ road.”

The others laughed good-naturedly, then bent to work again, straightening the track. For this thing of steel and oak which bound the East to the West, and which, at first glance, would seem to have been built, like the Roman roads of old, to last for ever, was in constant need of attention. The great rails were of the toughest steel that forge could make; the ties were of the best and soundest oak; the gravel which served as ballast lay under them a foot deep and extended a foot on either side; the road-bed was as solid as the art of man could make it, pounded, tamped, and rolled, until it seemed strong as the eternal hills.

Yet it did not endure. For every hour of the day there swept over it, pounding at it, the monstrous freight locomotives, weighing a hundred tons, marvels of strength and power, pulling long lines of heavy cars, laden with coal and iron and grain, hurrying to give the Old World of the abundance of the New. And every hour, too, there flashed over it, at a speed almost lightning-like, the through passenger trains—the engines slim, supple, panting, thoroughbred; the lumbering mail-cars and day coaches; the luxurious Pullmans far heavier than any freight-car.

Day and night these thousands of tons hurled themselves along the rails, tearing at them at every curve, pounding them at every joint. Small wonder that they sometimes gave and spread, or broke short off, especially in zero weather, under the great pressure. Then, too, the thaws of spring loosened the road-bed and softened it; freshets undermined it and sapped the foundations of bridge and culvert. A red-hot cinder from the firebox, dropped on a wooden trestle, might start a disastrous blaze. And the least defect meant, perhaps, the loss of a score of lives.

So every day, over the whole length of the line, gangs of section-men went up and down, putting in a new tie here, replacing a defective rail there, tightening bolts, straightening the track, clearing the ditches along the road of water lest it seep under the road-bed and soften it; doing a thousand and one things that only a section-foreman would think needful. And all this that passengers and freight alike might go in safety to their destinations; that the road, at the year’s end, might declare a dividend.

There was nothing spectacular about their work; there was no romance connected with it. The passengers who caught a glimpse of them, as the train flashed by, never gave them a second thought. Their clothes were always tom and soiled; their hands hard and rough; the tugging at the bars had pulled their shoulders over into an ungraceful stoop; almost always they had the haggard, patient look of men who labour beyond their strength. But they were cogs in the great machine, just as important, in their way, as the big fly-wheel of a superintendent in the general offices; more important, sometimes, for the superintendent took frequent vacations, but the section work could not be neglected for a single day.

Allan West soon discovered what soul-racking work it was. To raise the rigid track a fraction of an inch required that muscles be strained to bursting. To replace a tie was a task that tried every nerve and sinew. The sun beat down upon them mercilessly, bringing out the sweat in streams. But the boy kept at it bravely, determined to do his part and hold the place if he could. He was under a good teacher, for Reddy, otherwise Timothy Magraw, was a thorough-going section-hand. He knew his work inside and out, and it was only a characteristic Irish carelessness, a certain unreliability, that kept him in the ranks, where, indeed, he was quite content to stay.

“Oi d’ want nothin’ else,” he would say. “Oi does me wor-rk, an’ draws me pay, an’ goes home an’ goes t’ sleep, with niver a thing t’ worrit me; while Welsh there’s a tossin’ aroun’ thinkin’ o’ what’s before him. Reespons’bility—that’s th’ thing Oi can’t stand.”

On the wages he drew as section-hand—and with the assistance, in summer, of a little “truck-patch” back of his house—he managed to keep himself and his wife and numerous children clothed; they had enough to eat and a place to sleep, and they were all as happy as possible. So that, in this case, Reddy’s philosophy seemed not a half-bad one. Certainly this freedom from responsibility left him in perpetual good-humour that lightened the work for the whole gang and made the hours pass more swiftly. Under his direction, the boy soon learned just what was expected of him, and even drew a word of commendation from his teacher.

“But don’t try to do the work all by yourself, me b’y,” he cautioned, noting Allan’s eagerness. “We’re all willing t’ help a little. If y’ try t’ lift that track by yerself, ye’ll wrinch y’r back, an’ll be laid up fer a week.”

Allan laughed and coloured a little at this good-natured raillery.

“I’ll try not to do more than my share,” he said.

“That’s roight!” approved Reddy, with a nod. “Whin each man does his share, why, th’ wor-rk goes along stiddy an’ aisy. It’s whin we gits a shirker on th’ gang like that there Dan Nolan—”

A chorus of low growls from the other men interrupted him. Nolan, evidently, was not a popular person.

“Who was he?” asked Allan, at the next breathing-spell.

“He’s th’ lazy hound that Jack fired from th’ gang this mornin’,” answered Reddy, his blue eyes blazing with unaccustomed wrath. “He’s a reg’lar bad ’un, he is. We used t’ think he was workin’ like anything, he’d git so red in th’ face, but come t’ find out he had a trick o’ holdin’ his breath t’ make hisself look that way. He was allers shirkin’, an’ when he had it in fer a feller, no trick was too mean or dir-rty fer him t’ try. Y’ remimber, boys, whin he dropped that rail on poor Tom Collins’s foot?”

The gang murmured an angry assent, and bent to their work again. Rod by rod they worked their way down the track, lifting, straining, tamping down the gravel. Occasionally a train thundered past, and they stood aside, leaning on their tools, glad of the moment’s rest. At last, away in the distance, Allan caught the faint sound of blowing whistles and ringing bells. The foreman took out his watch, looked at it, and closed it with a snap.

“Come on, boys,” he said. “It’s dinner-time!”

They went back together to the hand-car at the side of the road, which was their base of supplies, and slowly got out their dinner-pails. Allan was sent with a bucket to a farmhouse a quarter of a mile away to get some fresh water, and, when he returned, he found the men already busy with their food. They drank the cool water eagerly, for the hot sun had given them a burning thirst.

“Set down here,” said the foreman, “an’ dip in with me. I’ve got enough fer three men.”

And Allan sat down right willingly, for his stomach was protesting loudly against its continued state of emptiness. Never did cheese, fried ham, boiled eggs, bread, butter, and apple pie taste better. The compartment in the top of the dinner-pail was filled with coffee, but a share of this the boy declined, for he had never acquired a taste for that beverage. At last he settled back with a long sigh of content.

“That went t’ th’ right place, didn’t it?” asked Jack, with twinkling eyes.

“That it did!” assented Allan, heartily. “I don’t know what I’d have done if you hadn’t taken pity on me,” he added. “I was simply starving.”

“You had your breakfast this mornin’, didn’t y’?” demanded Jack, sharply.

Allan coloured a little under his fierce gaze.

“No, sir, I didn’t,” he said, rather hoarsely. “I couldn’t find any work to do, and I—I couldn’t beg!”

Jack looked at him without speaking, but his eyes were suspiciously bright.

“So you see, I just had to have this job,” Allan went on. “And now that I’ve got it, I’m going to do my best to keep it!”

Jack turned away for a moment, before he could trust himself to speak.

“I like your grit,” he said, at last. “It’s th’ right kind. An’ you won’t have any trouble keepin’ your job. But, man alive, why didn’t y’ tell me y’ was hungry? Jest a hint would ’a’ been enough! Why, th’ wife’ll never fergive me when she hears about it!”

“Oh,” protested Allan, “I couldn’t—”

He stopped without finishing the sentence.

“Well, I’ll fergive y’ this time,” said Jack. “Are y’ sure y’ve ate all y’ kin hold?”

“Every mite,” Allan assured him, his heart warming toward the friendly, weather-beaten face that looked at him so kindly. “I couldn’t eat another morsel!”

“All right, then; we’ll see that it don’t occur ag’in,” said Jack, putting the cover on his pail, and then stretching out in an easier position. “Now, d’ y’ want a stiddy job here?” he asked.

“If I can get it.”

“I guess y’ kin git it, all right. But how about your home?”

“I haven’t any home,” and the boy gazed out across the fields, his lips quivering a little despite his efforts to keep them still.

The foreman looked at him for a moment. There was something in the face that moved him, and he held out his hand impulsively.

“Here, shake!” he said. “I’m your friend.”

The boy put his hand in the great, rough palm extended to him, but he did not speak—his throat was too full for that.

“Now, if you’re goin’ t’ stay,” went on the other, “you’ve got t’ have some place t’ board. I’ll board an’ room y’ fer three dollars a week. It won’t be like Delmonicer’s, but y’ won’t starve—y’ll git yer three square meals a day. That’ll leave y’ four-fifty a week fer clothes an’ things. How’ll that suit y’?”

The boy looked at him gratefully.

“You are very kind,” he said, huskily. “I’m sure it’s worth more than three dollars a week.”

“No, it ain’t—not a cent more. Well, that’s settled. Some day, maybe, you’ll feel like tellin’ me about yerself. I’d like to hear it. But not now—wait till y’ git used t’ me.”

A freight-train, flying two dirty white flags, to show that it was running extra and not on a definite schedule, rumbled by, and the train-crew waved their caps at the section-men, who responded in kind. The engineer leaned far out the cab window and shouted something, but his voice was lost in the roar of the train.

“That’s Bill Morrison,” observed Jack, when the train was past. “There ain’t a finer engineer on th’ road. Two year ago he run into a washout down here at Oak Furnace. He seen it in time t’ jump, but he told his fireman t’ jump instead, and he stuck to her an’ tried to stop her. They found him in th’ ditch under th’ engine, with his leg mashed an’ his arm broke an’ his head cut open. He opened his eyes fer a minute as they was draggin’ him out, an’ what d’ y’ think he says?”

Jack paused a moment, while Allan listened breathlessly, with fast-beating heart.

“He says, ‘Flag Number Three!’ says he, an’ then dropped off senseless ag’in. They’d forgot all about Number Three, th’ fastest passenger-train on th’ road, an’ she’d have run into them as sure as shootin’, if it hadn’t been fer Bill. Well, sir, they hurried out a flagman an’ stopped her jest in time, an’ you ort t’ seen them passengers when they heard about Bill! They all went up t’ him where he was layin’ pale-like an’ bleedin’ on th’ ground, an’ they was mighty few of th’ men but what was blowin’ their noses; an’ as fer the women, they jest naturally slopped over! Well, they thought Bill was goin’ t’ die, but he pulled through. Yes, he’s still runnin’ freight—he’s got t’ wait his turn fer promotion; that’s th’ rule o’ th’ road. But he’s got th’ finest gold watch y’ ever seen; them passengers sent it t’ him; an’ right in th’ middle of th’ case it says, ‘Flag Number Three.’”

Jack stopped and looked out over the landscape, more affected by his own story than he cared to show.

As for Allan, he gazed after the fast disappearing train as though it were an emperor’s triumphal car.

“When I was a kid,” continued Welsh, reminiscently, after a moment, “I was foolish, like all other kids. I thought they wasn’t nothin’ in th’ world so much fun as railroadin’. I made up my mind t’ be a brakeman, fer I thought all a brakeman had t’ do was t’ set out on top of a car, with his legs a-hangin’ over, an’ see th’ country, an’ wave his hat at th’ girls, an’ chase th’ boys off th’ platform, an’ order th’ engineer around by shakin’ his hand at him. Gee whiz!” and he laughed and slapped his leg. “It tickles me even yet t’ think what an ijit I was!”

“Did you try braking?” asked Allan.

“Yes—I tried it,” and Welsh’s eyes twinkled; “but I soon got enough. Them wasn’t th’ days of air-brakes, an’ I tell you they was mighty little fun in runnin’ along th’ top of a train in th’ dead o’ winter when th’ cars was covered with ice an’ th’ wind blowin’ fifty mile an hour. They wasn’t no automatic couplers, neither; a man had t’ go right in between th’ cars t’ drop in th’ pin, an’ th’ engineer never seemed t’ care how hard he backed down on a feller. After about six months of it, I come t’ th’ conclusion that section-work was nearer my size. It ain’t so excitin’, an’ a man don’t make quite so much money; but he’s sure o’ gettin’ home t’ his wife when th’ day’s work’s over, an’ of havin’ all his legs an’ arms with him. That counts fer a whole lot, I tell yer!”

He had got out a little black pipe as he talked, and filled it with tobacco from a paper sack. Then he applied a lighted match to the bowl and sent a long whiff of purple smoke circling upwards.

“There!” he said, leaning back with a sigh of ineffable content. “That’s better—that’s jest th’ dessert a man wants. You don’t smoke, I guess?”

“No,” and Allan shook his head.

“Well, I reckon you’re as well off—better off, maybe; but I begun smokin’ when I was knee high to a duck.”

“You were telling me about that engineer,” prompted Allan, hoping for another story. “Are there any more like him?”

“Plenty more!” answered Jack, vigorously. “Why, nine engineers out o’ ten would ’a’ done jest what he done. It comes nat’ral, after a feller’s worked on th’ road awhile. Th’ road comes t’ be more t’ him than wife ’r childer—it gits t’ be a kind o’ big idol thet he bows down an’ worships; an’ his engine’s a little idol thet he thinks more of than he does of his home. When he ain’t workin’, instead of stayin’ at home an’ weedin’ his garden, or playin’ with his childer, he’ll come down t’ th’ roundhouse an’ pet his engine, an’ polish her up, an’ walk around her an’ look at her, an’ try her valves an’ watch th’ stokers t’ see thet they clean her out proper. An’ when she wears out ’r breaks down, why, you’d think he’d lost his best friend. There was old Cliff Gudgeon. He had a swell passenger run on th’ east end; but when they got t’ puttin’ four ’r five sleepers on his train, his old engine was too light t’ git over th’ road on time, so they give him a new one—a great big one—a beauty. An’ what did Cliff do? Well, sir, he said he was too old t’ learn th’ tricks of another engine, an’ he’d stick to his old one, an’ he’s runnin’ a little accommodation train up here on th’ Hillsboro branch at seventy-five a month, when he might ’a’ been makin’ twict that a-handlin’ th’ Royal Blue. Then, there’s Reddy Magraw—now, t’ look at Reddy, y’ wouldn’t think he was anything but a chuckle-headed Irishman. Yet, six year ago—”

Reddy had caught the sound of his name, and looked up suddenly.

“Hey, Jack, cut it out!” he called.

Welsh laughed good-naturedly.

“All right!” he said. “He’s th’ most modest man in th’ world, is Reddy. But they ain’t all that way. There’s Dan Nolan,” and Jack’s face darkened. “I had him on th’ gang up till this mornin’, but I couldn’t stan’ him no longer, so I jest fired him. That’s th’ reason there was a place fer you, m’ boy.”

“Yes,” said Allan, “Reddy was telling me about him. What was it he did?”

“He didn’t do anything,” laughed Jack. “That was th’ trouble. He was jest naturally lazy—sneakin’ lazy an’ mean. There’s jest two things a railroad asks of its men—you might as well learn it now as any time—they must be on hand when they’re needed, an’ they must be willin’ t’ work. As long as y’re stiddy an’ willin’ t’ work, y’ won’t have no trouble holdin’ a job on a railroad.”

Allan looked out across the fields and determined that in these two respects, at least, he would not be found wanting. He glanced at the other group, gossiping together in the shade of a tree. They were not attractive-looking, certainly, but he was beginning to learn already that a man may be brave and honest, whatever his appearance. They were laughing at one of Reddy’s jokes, and Allan looked at him with a new respect, wondering what it was he had done. The foreman watched the boy’s face with a little smile, reading his thoughts.

“He ain’t much t’ look at, is he?” he said. “But you’ll soon learn—if you ain’t learnt already—that you can’t judge a man’s inside by his outside. There’s no place you’ll learn it quicker than on a railroad. Railroad men, barrin’ th’ passenger train crews, who have t’ keep themselves spruced up t’ hold their jobs, ain’t much t’ look at, as a rule, but down at th’ bottom of most of them there allers seems t’ be a man—a real man—a man who don’t lose his head when he sees death a-starin’ him in th’ face, but jest grits his teeth an’ sticks to his post an’ does his duty. Railroad men ain’t little tin gods nor plaster saints—fur from it!—but they’re worth a mighty sight more than either. There was Jim Blakeson, th’ skinniest, lankest, most woe-begone-lookin’ feller I ever see outside of a circus. He was brakin’ front-end one night on third ninety-eight, an’—”

From afar off came the faint blowing of whistles, telling that, in the town of Wadsworth, the wheels in the factories had started up again, that men and women were bending again to their tasks, after the brief noon hour. Welsh stopped abruptly, much to Allan’s disappointment, knocked out his pipe against his boot-heel, and rose quickly to his feet. If there was one article in Welsh’s code of honour which stood before all the rest, it was this: That the railroad which employed him should have the full use of the ten hours a day for which it paid. To waste any part of that time was to steal the railroad’s money. It is a good principle for any man—or for any boy—to cling to.

“One o’clock!” he cried. “Come on, boys! We’ve got a good stretch o’ track to finish up down there.”

The dinner-pails were replaced on the hand-car and it was run down the road about half a mile and then derailed again. The straining work began; tugging at the bars, tamping gravel under the ties, driving new spikes, replacing a fish-plate here and there. And the new hand learned many things.

He learned that with the advent of the great, modern, ten-wheeled freight locomotives, all the rails on the line had been replaced with heavier ones weighing eighty-five pounds to the yard,—850 pounds to their thirty feet of length,—the old ones being too light to carry such enormous weights with safety. They were called T-rails, because, in cross-section, they somewhat resembled that letter. The top of the rail is the “head”; the thinner stem, the “web”; and the wide, flat bottom, the “base.” Besides being spiked down to the ties, which are first firmly bedded in gravel or crushed stone, the rails are bolted together at the ends with iron bars called “fish-plates.” These are fitted to the web, one on each side of the junction of two rails, and bolts are then passed through them and nuts screwed on tightly.

This work of joining the rails is done with such nicety, and the road-bed built so solidly, that there is no longer such a great rattle and bang as the trains pass over them—a rattle and bang formerly as destructive to the track as to the nerves of the passenger. It is the duty of the section-foreman to see that the six or eight miles of track which is under his supervision is kept in the best possible shape, and to inspect it from end to end twice daily, to guard against any possibility of accident.

As the hours passed, Allan’s muscles began to ache sadly, but there were few chances to rest. At last the foreman perceived that he was overworking himself, and sent him and Reddy back to bring up the hand-car and prepare for the homeward trip. They walked back to where it stood, rolled it out upon the track, and pumped it down to the spot where the others were working, Reddy giving Allan his first lesson in how to work the levers, for there is a right and wrong way of managing a hand-car, just as there is a right and wrong way of doing everything else.

“That’s about all we kin do to-day,” and Jack took out his watch and looked at it reflectively, as the car came rolling up. “I guess we kin git in before Number Six comes along. What y’ think?” and he looked at Reddy.

“How much time we got?” asked the latter, for only the foreman of the gang could afford to carry a watch.

“Twelve minutes.”

“That’s aisy! We kin make it in eight without half-tryin’!”

“All right!” and Jack thrust the watch back into his pocket. “Pile on, boys!”

And pile on they did, bringing their tools with them. They seized the levers, and in a moment the car was spinning down the track. There was something fascinating and invigorating in the motion. As they pumped up and down, Allan could see the fields, fences, and telegraph-poles rushing past them. It seemed to him that they were going faster even than the “flier.” The wind whistled against him and the car jolted back and forth in an alarming way.

“Hold tight!” yelled Reddy, and they flashed around a curve, across a high trestle, through a deep cut, and down a long grade on the other side. Away ahead he could see the chimneys of the town nestling among the trees. They were down the grade in a moment, and whirling along an embankment that bordered a wide and placid river, when the car gave a sudden, violent jolt, ran for fifty feet on three wheels, and then settled down on the track again.

“Stop her!” yelled the foreman. “Stop her!”

They strained at the levers, but the car seemed alive and sprang away from them. Twice she almost shook them off, then sullenly succumbed, and finally stopped.

“Somethin’s th’ matter back there!” panted Jack. “Give her a shove, Reddy!”

Reddy jumped off and started her back up the track. In a moment the levers caught, and they were soon at the place where the jolt had occurred.

The foreman sprang off and for an instant bent over the track. Then he straightened up with stern face.

“Quick!” he cried. “Jerk that car off th’ track and bring two fish-plates an’ some spikes. West, take that flag, run up th’ track as far as y’ kin, an’ flag Number Six. Mind, don’t stop runnin’ till y’ see her. She’ll have her hands full stoppin’ on that grade.”

With beating heart Allan seized the flag and ran up the track as fast as his legs would carry him. The thought that the lives of perhaps a hundred human beings depended upon him set his hands to trembling and his heart to beating wildly. On and on he went, until his breath came in gasps and his head sang. It seemed that he must have covered a mile at least, yet it was only a few hundred feet. And then, away ahead, he saw the train flash into sight around the curve and come hurtling down the grade toward him.

He shook loose the flag and waved it wildly over his head, still running forward. He even shouted, not realizing how puny his voice was. The engine grew larger and larger with amazing swiftness. He could hear the roar of the wheels; a shaft of steam leaped into the air, and, an instant later, the wind brought him the sound of a shrill whistle. He saw the engineer leaning from his window, and, with a great sob of relief, knew that he had been seen. He had just presence of mind to spring from the track, and the train passed him, the wheels grinding and shrieking under the pressure of the air-brakes, the drivers of the engine whirling madly backwards. He caught a glimpse of startled passengers peering from the windows, and then the train was past. But it was going slower and slower, and stopped at last with a jerk.

When he reached the place, he found Jack explaining to the conductor about the broken fish-plates and the loose rail. What had caused it could not be told with certainty—the expansion from the heat, perhaps, or the vibration from a heavy freight that had passed half an hour before, or a defect in the plates, which inspection had not revealed. Allan sat weakly down upon the overturned hand-car. No one paid any heed to him, and he was astonished that they treated the occurrence so lightly. Jack and the engineer were joking together. Only the conductor seemed worried, and that was because the delay would throw his train a few minutes late.

Half a dozen of the passengers, who had been almost hurled from their seats by the suddenness of the stop, came hurrying up. All along the line of coaches windows had been raised, and white, anxious faces were peering out. Inside the coaches, brakemen and porters were busy picking up the packages that had been thrown from the racks, and reassuring the frightened people.

“What’s the matter?” gasped one of the passengers, a tall, thin, nervous-looking man, as soon as he reached the conductor’s side. “Nothing serious, I hope? There’s no danger, is there? My wife and children are back there—”

The conductor smiled at him indulgently.

“There’s no danger at all, my dear sir,” he interrupted. “The section-gang here flagged us until they could bolt this rail down. That is all.”

“But,” protested the man, looking around for sympathy, and obviously anxious not to appear unduly alarmed, “do you usually throw things about that way when you stop?”

“No,” said the conductor, smiling again; “but you see we were on a heavy down-grade, and going pretty fast. I’d advise you gentlemen to get back into the train at once,” he added, glancing at his watch again. “We’ll be starting in a minute or two.”

The little group of passengers walked slowly back and disappeared into the train. Allan, looking after them, caught his first glimpse of one side of railroad policy—a policy which minimizes every danger, which does its utmost to keep every peril from the knowledge of its patrons—a wise policy, since nervousness will never add to safety. Away up the track he saw the brakeman, who had been sent back as soon as the train stopped, to prevent the possibility of a rear-end collision, and he understood dimly something of the wonderful system which guards the safety of the trains.

Then, suddenly, he realized that he was not working, that his place was with that little group labouring to repair the track, and he sprang to his feet, but at that instant Jack stood back with a sigh of relief and turned to the conductor.

“All right,” he said.

The conductor raised his hand, a sharp whistle recalled the brakeman, who came down the track on a run; the engineer opened his throttle; there was a long hiss of escaping steam, and the train started slowly. As it passed him, Allan could see the passengers settling back contentedly in their seats, the episode already forgotten. In a moment the train was gone, growing rapidly smaller away down the track ahead of them. A few extra spikes were driven in to further strengthen the place, and the hand-car was run out on the track again.

“Y’ made pretty good time,” said Jack to the boy; and then, as he saw his white face, he added, “Kind o’ winded y’, didn’t it?”

Allan nodded, and climbed silently to his place on the car.

“Shook y’r nerve a little, too, I reckon,” added Jack, as the car started slowly. “But y’ mustn’t mind a little thing like that, m’ boy. It’s all in th’ day’s work.”

All in the day’s work! The flagging of a train was an ordinary incident in the lives of these men. There had, perhaps, been no great danger, yet the boy caught his breath as he recalled that fearful moment when the train rushed down upon him. All in the day’s work—for which the road paid a dollar and a quarter!

Jack Welsh, section-foreman, lived in a little frame house perched high on an embankment just back of the railroad yards. The bank had been left there when the yards had been levelled down, and the railroad company, always anxious to promote habits of sobriety and industry in its men, and knowing that no influence makes for such habits as does the possession of a home, had erected a row of cottages along the top of the embankment, and offered them on easy terms to its employés. They weren’t palatial—they weren’t even particularly attractive—but they were homes.

In front, the bank dropped steeply down to the level of the yards, but behind they sloped more gently, so that each of the cottages had a yard ample for a vegetable garden. To attend to this was the work of the wife and the children—a work which always yielded a bountiful reward.

There were six cottages in the row, but one was distinguished from the others in summer by a mass of vines which clambered over it, and a garden of sweet-scented flowers which occupied the little front yard. This was Welsh’s, and he never mounted toward it without a feeling of pride and a quick rush of affection for the little woman who found time, amid all her household duties, to add her mite to the world’s beauty. As he glanced at the other yards, with their litter of trash and broken playthings, he realized, more keenly perhaps than most of us do, what a splendid thing it is to render our little corner of the world more beautiful, instead of making it uglier, as human beings have a way of doing.

It was toward this little vine-embowered cottage that Jack and Allan turned their steps, as soon as the hand-car and tools had been deposited safely in the little section shanty. As they neared the house, a midget in blue calico came running down the path toward them.

“It’s Mamie,” said Welsh, his face alight with tenderness; and, as the child swept down upon him, he seized her, kissed her, and swung her to his shoulder, where she sat screaming in triumph.

They mounted the path so, and, at the door, Mrs. Welsh, a little, plump, black-eyed woman, met them.

“I’ve brought you a boarder, Mary,” said Welsh, setting Mamie down upon her sturdy little legs. “Allan West’s his name. I took him on th’ gang to-day, an’ told him he might come here till he found some place he liked better.”

“That’s right!” and Mrs. Welsh held out her hand in hearty welcome, pleased with the boy’s frank face. “We’ll try t’ make you comf’terble,” she added. “You’re a little late, Jack.”

“Yes, we had t’ stop t’ fix a break,” he answered; and he told her in a few words the story of the broken fish-plates. “It don’t happen often,” he added, “but y’ never know when t’ expect it.”

“No, y’ never do,” agreed Mary, her face clouding for an instant, then clearing with true Irish optimism. “You’ll find th’ wash-basin out there on th’ back porch, m’ boy,” she added to Allan, and he hastened away to cleanse himself, so far as soap and water could do it, of the marks of the day’s toil.

Mrs. Welsh turned again to her husband as soon as the boy was out of ear-shot.

“Where’d you pick him up, Jack?” she asked. “He ain’t no common tramp.”

“Not a bit of it,” agreed her husband. “He looks like a nice boy. He jest come along an’ wanted a job. He said he’d come from Cincinnati, an’ hadn’t any home; but he didn’t seem t’ want t’ talk about hisself.”

“No home!” repeated Mary, her heart warming with instant sympathy. “Poor boy! We’ll have t’ look out fer him, Jack.”

“I knew you’d say that, darlint!” cried her husband, and gave her a hearty hug.

“Go ’long with you!” cried Mary, trying in vain to speak sternly. “I smell th’ meat a-burnin’!” and she disappeared into the kitchen, while Jack joined Allan on the back porch.

How good the cool, clean water felt, splashed over hands and face; what a luxury it was to scrub with the thick lather of the soap, and then rinse off in a brimming basin of clear water; how delicious it was to be clean again! Jack dipped his whole head deep into the basin, and then, after a vigorous rubbing with the towel, took his station before a little glass and brushed his black hair until it presented a surface almost as polished as the mirror’s own.

Then Mamie came with the summons to supper, and they hurried in to it, for ten hours’ work on section will make even a confirmed dyspeptic hungry—yes, and give him power properly to digest his food.

How pretty the table looked, with its white cloth and shining dishes! For Mary was a true Irish housewife, with a passion for cleanliness and a pride in her home. It was growing dark, and a lamp had been lighted and placed in the middle of the board, making it look bright and cosy.

“You set over there, m’ boy,” said Mary, herself taking the housewife’s inevitable place behind the coffee-pot, with her husband opposite. “Now, Mamie, you behave yourself,” she added, for Mamie was peeping around the lamp at Allan with roguish eyes. “We’re all hungry, Jack, so don’t keep us waitin’.”

And Jack didn’t.

How good the food smelt, and how good it tasted! Allan relished it more than he would have done any dinner of “Delmonicer’s,” for Mary was one of the best of cooks, and only the jaded palate relishes the sauces and fripperies of French chefs.

“A girl as can’t cook ain’t fit t’ marry,” Mary often said; a maxim which she had inherited from her mother, and would doubtless hand down to Mamie. “There’s nothin’ that’ll break up a home quicker ’n a bad cook, an’ nothin’ that’ll make a man happier ’n a good one.”

Certainly, if cooking were a test, this supper was proof enough of her fitness for the state of matrimony. There was a great platter of ham and eggs, fluffy biscuits, and the sweetest of yellow butter. And, since he did not drink coffee, Allan was given a big glass of fragrant milk to match Mamie’s. They were tasting one of the best sweets of toil—to sit down with appetite to a table well-laden.

After supper, they gathered on the front porch, and sat looking down over the busy, noisy yards. The switch-lamps gleamed in long rows, red and green and white, telling which tracks were open and which closed. The yard-engines ran fussily up and down, shifting the freight-cars back and forth, and arranging them in trains to be sent east or west. Over by the roundhouse, engines were being run in on the big turntable and from there into the stalls, where they would be furbished up and overhauled for the next trip. Others were being brought out, tanks filled with water, and tenders heaped high with coal, ready for the run to Parkersburg or Cincinnati. They seemed almost human in their impatience to be off—breathing deeply in loud pants, the steam now and then throwing up the safety-valve and “popping off” with a great noise.

The clamour, the hurry, the rush of work, never ceasing from dawn to dawn, gave the boy a dim understanding of the importance of this great corporation which he had just begun to serve. He was only a very little cog in the vast machine, to be sure, but the smoothness of its running depended upon the little cogs no less than on the big ones.

A man’s figure, indistinct in the twilight, stopped at the gate below and whistled.

“There’s Reddy Magraw,” said Jack, with a laugh. “I’d forgot—it was so hot t’-day, we thought we’d go over t’ th’ river an’ take a dip t’-night. Do you know how t’ swim, Allan?”

“Just a little,” answered Allan; “all I know about it was picked up in the swimming-pool at the gymnasium at Cincinnati.”

“Well, it’s time y’ learned more,” said Jack. “Every boy ought t’ know how t’ swim—mebbe some day not only his own life but the lives o’ some o’ his women-folks’ll depend on him. Come along, an’ we’ll give y’ a lesson.”

“I’ll be glad to!” Allan cried, and ran indoors for his hat.

Reddy whistled again.

“We’re comin’,” called Jack. “We won’t be gone long,” he added to his wife, as they started down the path.

“All right, dear,” she answered. “An’ take good care o’ th’ boy.”

Reddy greeted Allan warmly, and thoroughly agreed with Jack that it was every boy’s duty to learn how to swim. Together they started off briskly toward the river—across the yards, picking their way carefully over the maze of tracks, then along the railroad embankment which skirted the stream, and finally through a corn-field to the water’s edge. The river looked very wide and still in the semidarkness, and Allan shivered a little as he looked at it; but the feeling passed in a moment. Reddy had his clothes off first, and dived in with a splash; Jack waded in to show Allan the depth. The boy followed, with sudden exhilaration, as he felt the cool water rise about him.

“This is different from a swimmin’-pool, ain’t it?” said Jack.

“Indeed it is!” agreed Allan; “and a thousand times nicer!”

“Now,” added Jack, “let me give you a lesson,” and he proceeded to instruct Allan in the intricacies of the broad and powerful breast stroke.

The boy was an apt pupil, and at the end of twenty minutes had mastered it sufficiently to be able to make fair progress through the water. He would have kept on practising, but Jack stopped him.

“We’ve been in long enough,” he said; “you mustn’t overdo it. Come along, Reddy,” he called to that worthy, who was disporting himself out in the middle of the current.

As they turned toward the shore the full moon peeped suddenly over a little hill on the eastern horizon, and cast a broad stream of silver light across the water, touching every ripple and little wave with magic beauty.

“Oh, look!” cried Allan. “Look!”

They stood and watched the moon until it sailed proudly above the hill, and then waded to the bank, rubbed themselves down briskly, and resumed their clothes, cleansed and purified in spirit as well as body. They made their way back through the corn-field, but just as they reached the embankment, Reddy stopped them with a quick, stifled cry.

“Whist!” he said, hoarsely. “Look there! What’s that?”

Straining his eyes through the darkness, Allan saw, far down the track ahead of them, a dim, white figure. It seemed to be going through some sort of pantomime, waving its arms wildly above its head.

“It’s a ghost!” whispered Reddy, breathing heavily. “It’s Tim Dorsey’s ghost! D’ y’ raymimber, Jack, it was jist there thet th’ poor feller was killed last month! That’s his ghost, sure as I’m standin’ here!”

“Oh, nonsense!” retorted Jack, with a little laugh, but his heart was beating faster than usual, as he peered through the darkness at the strange figure. What could it be that would stand there and wave its arms in that unearthly fashion?

“It’s his ghost!” repeated Reddy. “Come on, Jack; Oi’m a-goin’ back!”

“Well, I’m not!” said Jack. “I’m not afraid of a ghost, are you, Allan?”

“I don’t believe in ghosts,” said Allan, but it must be confessed that his nerves were not wholly steady as he kept his eyes on the strange figure dancing there in the moonlight.

“If it ain’t a ghost, what is it?” demanded Reddy, hoarsely.

“That’s just what we’re goin’ t’ find out,” answered Jack, and started forward, resolutely.

Allan went with him, but Reddy kept discreetly in the rear. He was no coward,—he was as brave as any man in facing a danger which he knew the nature of,—but all the superstition of his untutored Irish heart held him back from this unearthly apparition.

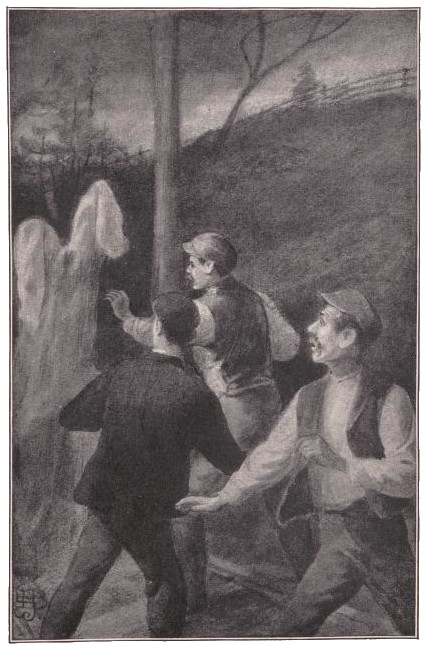

As they drew near, its lines became more clearly defined; it was undoubtedly of human shape, but apparently it had no head, only a pair of short, stubby arms, which waved wildly in the air, and a pair of legs that danced frantically. Near at hand it was even more terrifying than at a distance, and their pace grew slower and slower, while Reddy stopped short where he was, his teeth chattering, his eyes staring. They could hear what seemed to be a human voice proceeding from the figure, raised in a sort of weird incantation, now high, now low. Was it really a ghost? Allan asked himself; was it really the spirit of the poor fellow whose life had been crushed out a few weeks before? could it be....

“NEAR AT HAND IT WAS EVEN MORE TERRIFYING THAN AT A DISTANCE”

Suddenly Jack laughed aloud with relief, and hurried forward.

“Come on,” he called. “It’s no ghost!”

And in a moment Allan saw him reach the figure and pull the white garment down over its head, disclosing a flushed and wrathful, but very human, face.

“Thankee, sir,” said a hoarse voice to Jack. “A lady in th’ house back there give me a clean shirt, an’ I was jest puttin’ it on when I got stuck in th’ durn thing, an’ couldn’t git it either way. I reckon I’d ’a’ suffocated if you hadn’t come along!”

Jack laughed again.

“We thought you was a ghost!” he said. “You scared Reddy, there, out of a year’s growth, I reckon. Come here, Reddy,” he called, “an’ take a look at yer ghost!”

Reddy came cautiously forward and examined the released tramp.

“Well,” he said, at last, “if you ain’t a ghost, you ought t’ be! I never seed anything that looked more loike one!”

“No, an’ you never will!” retorted Jack. “Come along; it’s time we was home,” and leaving the tramp to complete his toilet, they hurried away.

They found Mary sitting on the front porch, crooning softly to herself as she rocked Mamie to sleep. They bade Reddy good night, and sat down beside her.

“Well, did y’ have a nice time?” she asked.

“Yes,” laughed Jack, and told her the story of the ghost.

They sat silent for a time after that, looking down over the busy yards, breathing in the cool night air, watching the moon as it sailed slowly up the heavens. Allan felt utterly at rest; for the first time in many days he felt that he had a home, that there were people in the world who loved him. The thought brought the quick tears to his eyes; an impulse to confide in these new friends surged up within him.

“I want to tell you something about myself,” he said, turning to them quickly. “It’s only right that you should know.”

Mrs. Welsh stopped the lullaby she had been humming, and sat quietly waiting.

“Just as y’ please,” said Jack, but the boy knew he would be glad to hear the story.

“It’s not a very long one,” said Allan, his lips trembling, “nor an unusual one, for that matter. Father was a carpenter, and we lived in a little home just out of Cincinnati—he and mother and I. We were very happy, and I went to school every day, while father went in to the city to his work. But one day I was called from school, and when I got home I found that father had fallen from a scaffolding he had been working on, and was so badly injured that he had been taken to a hospital. We thought for a long time that he would die, but he got better slowly, and at last we were able to take him home. But he was never able to work any more,—his spine had been injured so that he could scarcely move himself,—and our little savings grew smaller and smaller.”

Allan stopped, and looked off across the yards, gripping his hands together to preserve his self-control.

“Father worried about it,” he went on, at last; “worried so much that he grew worse and worse, until—until—he brought on a fever. He hadn’t any strength to fight with. He just sank under it, and died. I was fifteen years old then—but boys don’t understand at the time how hard things are. After he was gone—well, it seems now, looking back, that I could have done something more to help than I did.”

“There, now, don’t be a-blamin’ yerself,” said Jack, consolingly.

The little woman in the rocking-chair leaned over and touched his arm softly, caressingly.

“No; don’t be blamin’ yerself,” she said. “I know y’ did th’ best y’ could. They ain’t so very much a boy kin do, when it’s money that’s needed.”

“No,” and Allan drew a deep breath; “nor a woman, either. Though it wasn’t only that; I’d have worked on; I wouldn’t have given up—but—but—”

“Yes,” said Mary, understanding with quick, unfailing sympathy; “it was th’ mother.”

“She did the best she could,” went on Allan, falteringly. “She tried to bear up for my sake; but after father was gone she was never quite the same again; she never seemed to rally from the shock of it. She was never strong to start with, and I saw that she grew weaker and weaker every day.” He stopped and cleared his voice. “That’s about all there is to the story,” he added. “I got a little from the furniture and paid off some of the debts, but I couldn’t do much. I tried to get work there, but there didn’t seem to be anybody who wanted me. There were some distant relatives, but I had never known them—and besides, I didn’t want to seem a beggar. There wasn’t anything to keep me in Cincinnati, so I struck out.”

“And y’ did well,” said Welsh. “I’m mighty glad y’ come along jest when y’ did. Y’ll find enough to do here, if y’ will keep a willin’ hand. Section work ain’t much, but maybe y’ can git out of it after awhile. Y’ might git a place in th’ yard office if ye’re good at figgers. Ye’ve got more eddication than some. It’s them that git lifted.”

“You’d better talk!” said the wife. “’Tain’t every man with an eddication that gits t’ be foreman at your age.”

“No more it ain’t,” and Jack smiled. “Come on; it’s time t’ go t’ bed. Say good night t’ th’ boy, Mamie.”

“Night,” murmured Mamie, sleepily, and held out her moist, red lips.

With a quick warmth at his heart, Allan stooped and kissed them. It was the first kiss he had given or received since his mother’s death, and, after he had got to bed in the little hot attic room, with its single window looking out upon the yards, he lay for a long time thinking over the events of the day, and his great good fortune in falling in with these kindly people. Sometime, perhaps, he might be able to prove how much their kindness meant to him.

It was not until morning that Allan realized how unaccustomed he was to real labour. As he tried to spring from bed in answer to Jack’s call, he found every muscle in revolt. How they ached! It was all he could do to slip his arms into his shirt, and, when he bent over to put on his shoes, he almost cried out at the twinge it cost him. He hobbled painfully down-stairs, and Jack saw in a moment what was the matter.

“Yer muscles ain’t used t’ tuggin’ at crowbars an’ shovellin’ gravel,” he said, laughing. “It’ll wear off in a day or two, but till then ye’ll have t’ grin an’ bear it, fer they ain’t no cure fer it. But y’ ain’t goin’ t’ work in them clothes!”

“They’re all I have here,” answered Allan, reddening. “I have a trunk at Cincinnati with a lot more in, and I thought I’d write for it to-day.”

“But I reckon ye ain’t got any clothes tough enough fer this work. I’ll fix y’ out,” said Welsh, good-naturedly.

So, after breakfast, he led Allan over to a railroad outfitting shop and secured him a canvas jumper, a pair of heavy overalls, and a pair of rough, strong, cowhide shoes.

“There!” he said, viewing his purchases with satisfaction. “Y’ kin pay fer ’em when y’ git yer first month’s wages. Y’ kin put ’em on over in th’ section shanty. You go along over there; I’ve got t’ stop an’ see th’ roadmaster a minute.”

Allan walked on quickly, his bundle under his arm, past the long passenger station and across the maze of tracks in the lower yards. Here lines of freight-cars were side-tracked, waiting their turn to be taken east or west; and, as he hurried past, a man came suddenly out from behind one of them and laid a strong hand on his arm.

“Here, wait a minute!” he said, roughly. “I’ve got somethin’ t’ say t’ you. Come in here!” And before Allan could think of resistance, he was pulled behind the row of cars.

Allan found himself looking up into a pair of small, glittering black eyes, deeply set in a face of which the most prominent features were a large nose, covered with freckles, and a thick-lipped mouth, which concealed the jagged teeth beneath but imperfectly. He saw, too, that his captor was not much older than himself, but that he was considerably larger and no doubt stronger.

“Ye’re th’ new man on Twenty-one, ain’t you?” he asked, after a moment’s fierce examination of Allan’s face.

“Yes, I went to work yesterday,” said Allan.

“Well, y’ want t’ quit th’ job mighty quick, d’ y’ see? I’m Dan Nolan, an’ it’s my job y’ve got. I’d ’a’ got took back if ye hadn’t come along. So ye’re got t’ git out, d’ y’ hear?”

“Yes, I hear,” answered Allan, quietly, reddening a little; and his heart began to beat faster at the prospect of trouble ahead.

“If y’ know what’s good fer y’, y’ll git out!” said Nolan, savagely, clenching his fists. “When’ll y’ quit?”

“As soon as Mr. Welsh discharges me,” answered Allan, still more quietly.

Nolan glared at him for a moment, seemingly unable to speak.

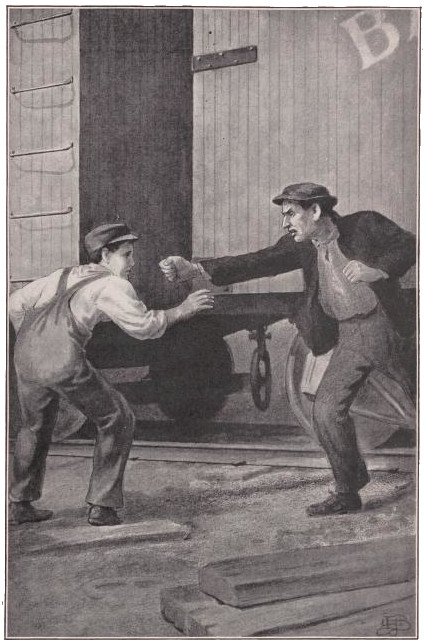

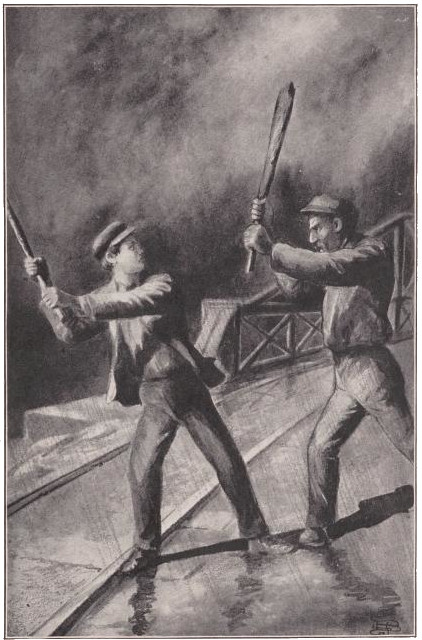

“D’ y’ mean t’ say y’ won’t git out when I tells you to? I’ll show y’!” And he struck suddenly and viciously at the boy’s face.

But Allan had been expecting the onslaught, and sprang quickly to one side. Before Nolan could recover himself, he had ducked under one of the freight-cars and come up on the other side. Nolan ran around the end of the car, but the boy was well out of reach.

“I’ll ketch y’!” he cried after him, shaking his fists. “An’ when I do ketch y’—”

He stopped abruptly and dived back among the cars, for he had caught sight of Jack Welsh coming across the yards. Allan saw him, too, and waited for him.

“Wasn’t that Dan Nolan?” he asked, as he came up.

“Yes, it was Nolan,” answered Allan.

“Was he threatenin’ you?”

“HE STRUCK SUDDENLY AND VICIOUSLY AT THE BOY’S FACE”

“Yes; he told me to get out or he’d lay for me.”

“He did, eh?” and Jack’s lips tightened ominously. “What did y’ tell him?”

“I told him I’d get out when you discharged me.”

“Y’ did?” and Jack clapped him on the shoulder. “Good fer you! Let me git my hands on him once, an’ he’ll lave ye alone! But y’ want t’ look out fer him, m’ boy. If he’d fight fair, y’ could lick him; but he’s a big, overgrown brute, an’ ’ll try t’ hit y’ from behind sometime, mebbe. That’s his style, fer he’s a coward.”

“I’ll look out for him,” said Allan; and walked on with beating heart to the section shanty. Here, while Jack told the story of the encounter with Nolan, Allan donned his new garments and laid his other ones aside. The new ones were not beautiful, but at least they were comfortable, and could defy even the wear and tear of work on section.

The spin on the hand-car out into the open country was full of exhilaration, and, after an hour’s work, Allan almost forgot his sore muscles. He found that to-day there was a different class of work to do. The fences along the right of way were to be repaired, and the right of way itself placed in order—the grass cut back from the road-bed, the gravel piled neatly along it, weeds trimmed out, rubbish gathered up, cattle-guards, posts, and fences at crossings whitewashed. All this, too, was a revelation to the new hand. He had never thought that a railroad required so much attention. Rod after rod was gone over in this way, until it seemed that not a stone was out of place. It was not until the noon-hour, when he was eating his portion of the lunch Mrs. Welsh had prepared for them, that he learned the reason for all this.

“Y’ see we’re puttin’ on a few extry touches,” remarked Jack. “Th’ Irish Brigade goes over th’ road next week.”

“The Irish Brigade?” questioned Allan; and he had a vision of some crack military organization.

“Yes, th’ Irish Brigade. Twict a year, all th’ section foremen on th’ road ’r’ taken over it t’ look at th’ other sections, an’ see which man keeps his in th’ best shape. Each man’s section’s graded, an’ th’ one that gits th’ highest grade gits a prize o’ fifty dollars. We’re goin’ t’ try fer that prize. So’s every other section-gang on th’ line.”

“But what is the Irish Brigade?” questioned the boy.

“The foremen of the section-men. There’s about a hundred, and the officers give us that name. There’s many a good Irishman like myself among the foremen;” and a gleam of humour was in Jack’s eyes. “They say I’m puttin’ my Irish back of me in my talk, but the others stick to it, more or less. It’s a great time when the Irish Brigade takes its inspection tour.”

Allan worked with a new interest after that, for he, too, was anxious that Jack’s section should win the fifty dollars. He could guess how much such a sum would mean to him. He confided his hopes to Reddy, while they were working together cutting out some weeds that had sprung up along the track, but the latter was not enthusiastic.

“Oi don’t know,” he said. “They’s some mighty good section-men on this road. Why, last year, when Flaherty, o’ Section Tin, got th’ prize, his grass looked like it ’ud been gone over with a lawnmower, an’ he’d aven scrubbed th’ black gr’ase from th’ ingines off th’ toies. Oh, it looked foine; but thin, so did all th’ rist.”

But Allan was full of hope. As he looked back over the mile they had covered since morning, he told himself that no stretch of track could possibly be in better order. But, to the foreman’s more critical and experienced eye, there were still many things wanting, and he promised himself to go over it again before inspection-day came around.

Every train that passed left some mark behind. From the freights came great pieces of greasy waste, which littered up the ties, or piles of ashes sifted down from the fire-box; while with the passengers it was even worse. The people threw from the coach windows papers, banana peelings, boxes and bags containing remnants of lunch, bottles, and every kind of trash. They did not realize that all this must be patiently gathered up again, in order that the road-bed might be quite free from litter. Not many of them would have greatly cared.

“It’s amazin’,” remarked Reddy, in the course of the afternoon, “how little people r’ally know about railroadin’, an’ thin think they know ’t all. They think that whin th’ road’s built, that’s all they is to it, an’ all th’ expinse th’ company’s got’s fer runnin’ th’ trains. Why, on this one division, from Cincinnati t’ Parkersburg, they’s more’n two hunderd men a-workin’ ivery day jest kapin’ up th’ track. Back there in th’ shops, they’s foive hundred more, repairin’ an’ rebuildin’ ingines an’ cars. At ivery little crossroads they’s an operator, an’ at ivery little station they’s six or eight people busy at work. Out east, they tell me, they’s a flagman at ivery crossin’. Think o’ what all that costs!”

“But what’s the use of keeping the road-bed so clean?” asked Allan. “Nobody ever sees it.”

“What’s th’ use o’ doin’ anything roight?” retorted Reddy. “I tell you ivery little thing counts in favour of a road, or agin it. This here road’s spendin’ thousands o’ dollars straightenin’ out curves over there in th’ mountings, so’s th’ passengers won’t git shook up so much, an’ th’ trains kin make a little better toime. Why, I’ve heerd thet some roads even sprinkle th’ road-bed with ile t’ lay th’ dust!

“Human natur’ ’s a funny thing,” he added, shaking his head philosophically, “’specially when it comes t’ railroads. Many’s th’ man Oi’ve seen nearly break his neck t’ git acrost th’ track in front of a train, an’ thin stop t’ watch th’ train go by; an’ many another loafer, who never does anything but kill toime, ’ll worrit hisself sick if th’ train he’s on happens t’ be tin minutes late. It’s th’ man who ain’t got no business that’s always lettin’ on t’ have th’ most. Here comes th’ flier,” he added, as a shrill whistle sounded from afar up the road.

They stood aside to watch the train shoot past with a rush and roar, to draw into the station at Wadsworth on time to the minute.

“That was Jem Spurling on th’ ingine,” observed Reddy, as they went back to work. “Th’ oldest ingineer on th’ road—an’ th’ nerviest. Thet’s th’ reason he’s got th’ flier. Most fellers loses their nerve after they’ve been runnin’ an ingine a long time, an’ a year ’r two back, Jem got sort o’ shaky fer awhile—slowed down when they wasn’t no need of it, y’ know; imagined he saw things on th’ track ahead, an’ lost time. Well, th’ company wouldn’t stand fer thet, ’specially with th’ flier, an’ finally th’ train-master told him thet if he couldn’t bring his train in on time, he’d have t’ go back t’ freight. Well, sir, it purty nigh broke Jem’s heart.

“‘Oi tell y’, Mister Schofield,’ he says t’ th’ train-master, ‘Oi’ll bring th’ train in on toime if they’s a brick house on th’ track.’

“‘All right,’ says Mr. Schofield; ‘thet’s all we ask,’ an’ Jem went down to his ingine.

“Th’ next day Jem come into th’ office t’ report, an’ looked aroun’ kind o’ inquirin’ like.

“‘Any of it got here yet?’ he asks.

“‘Any o’ what?’ asks Mr. Schofield.

“‘Any o’ thet coal,’ says Jem.

“‘What coal?’ asks Mr. Schofield.

“‘Somebody left a loaded coal-car on th’ track down here by th’ chute,’ says Jem.

“‘They did?’

“‘Yes,’ says Jem; ‘thought they’d throw me late, most likely; but they didn’t. Oi’m not loike a man what’s lost his nerve—not by a good deal.’

“‘But th’ car—how’d y’ git around it?’ asks Mr. Schofield.

“‘Oh, Oi didn’t try t’ git around it,’ says Jem. ‘Oi jest pulled her wide open an’ come through. They’s about a ton o’ coal on top o’ th’ rear coach, an’ Oi thought maybe I’d find th’ rest of it up here. I guess it ain’t come down yit.’

“‘But, great Scott, man!’ says Mr. Schofield, ‘that was an awful risk.’

“‘Oi guess Oi’d better run my ingine down t’ th’ repair shop,’ went on Jem, cool as a cucumber. ‘Her stack’s gone, an’ the pilot, an’ th’ winders o’ th’ cab are busted. But Oi got in on toime.’

“Well, they laid Jem off fer a month,” concluded Reddy, “but they’ve niver said anything since about his losin’ his nerve.”

So, through the afternoon, Reddy discoursed of the life of the rail, and told stories grave and gay, related tragedies and comedies, described hair-breadth escapes, and with it all managed to impart to his hearer many valuable hints concerning section work.

“Though,” he added, echoing Jack, “it’s not on section you’ll be workin’ all your life! You’ve got too good a head fer that.”

“I don’t know,” said Allan, modestly. “This takes a pretty good head, too, doesn’t it?”

“It takes a good head in a way; but it’s soon learnt, an’ after thet, all a man has t’ do is t’ keep sober. But this is a, b, c, compared t’ th’ work of runnin’ th’ road. Ever been up in th’ despatcher’s office?”

“No,” said Allan. “I never have.”

“Well, y’ want t’ git Jack t’ take y’ up there some day; then y’ll see where head-work comes in. I know thet all the trainmen swear at th’ despatchers; but jest th’ same, it takes a mighty good man t’ hold down th’ job.”

“I’ll ask Jack to take me,” said Allan; and he resolved to get all the insight possible into the workings of this great engine of industry, of which he had become a part.

Quitting-time came at last, and they loaded their tools wearily upon the car and started on the five-mile run home. This time there was no disturbing incident. The regular click, click of the wheels over the rails told of a track in perfect condition. At last they rattled over the switches in the yards and pushed the car into its place in the section-house.

“You run along,” said Jack to Allan. “I’ve got t’ make out a report to-night. It’ll take me maybe five minutes. Tell Mary I’ll be home by then.”

“All right!” and Allan picked up his bundle of clothes and started across the yards. He could see the little house that he called home perched high on its bank of clay. Apparently they were watching for him, for he saw a tiny figure running down the path, and knew that Mamie was coming to meet him. She did not stop at the gate, but ran across the narrow street and into the yards toward him. He quickened his steps at the thought that some harm might befall her among this maze of tracks. He could see her mother standing on the porch, looking down at them, shading her eyes with her hand.

And then, in an instant, a yard-engine whirled out from behind the roundhouse. Mamie looked around as she heard it coming, and stopped short in the middle of the track, confused and terrified in presence of this unexpected danger.

As Allan dashed forward toward the child, he saw the engineer, his face livid, reverse his engine and jerk open the sand-box; the sand spurted forth under the drivers, whirling madly backwards in the midst of a shower of sparks, but sliding relentlessly down upon the terror-stricken child. It was over in an instant—afterward, the boy could never tell how it happened—he knew only that he stooped and caught the child from under the very wheels of the engine, just as something struck him a terrific blow on the leg and hurled him to one side.

He was dimly conscious of holding the little one close in his arms that she might not be injured, then he struck the ground with a crash that left him dazed and shaken. When he struggled to his feet, the engineer had jumped down from his cab and Welsh was speeding toward them across the tracks.

“Hurt?” asked the engineer.

“I guess not—not much;” and Allan stooped to rub his leg. “Something hit me here.”

“Yes—the footboard. Knocked you off the track. I had her pretty near stopped, or they’d be another story.”

Allan turned to Welsh, who came panting up, and placed the child in his arms.

“I guess she’s not hurt,” he said, with a wan little smile.

But Jack’s emotion had quite mastered him for the moment.

“Mamie!” he cried, gathering her to him. “My little girl!” And the great tears shattered down over his cheeks upon the child’s dress.

The others stood looking on, understanding, sympathetic. The fireman even turned away to rub his sleeve furtively across his eyes, for he was a very young man and quite new to railroading.

The moment passed, and Welsh gripped back his self-control, as he turned to Allan and held out his great hand.

“You’ve got nerve,” he said. “We won’t fergit it—Mary an’ me. Come on home—it’s your home now, as well as ours.”

Half-way across the tracks they met Mary, who, after one shrill scream of anguish at sight of her darling’s peril, had started wildly down the path to the gate, though she knew she must arrive too late. She had seen the rescue, and now, with streaming eyes, she threw her arms around Allan and kissed him.

“My brave boy!” she cried. “He’s our boy, now, ain’t he, Jack, as long as he wants t’ stay?”

“That’s jest what I was tellin’ him, Mary dear,” said Jack.

“But he’s limpin’,” she cried. “What’s th’ matter? Y’re not hurted, Allan?”

“Not very badly,” answered the boy. “No bones broken—just a knock on the leg that took the skin off.”

“Come on home this instant,” commanded Mary, “an’ we’ll see.”

“Ain’t y’ goin’ t’ kiss Mamie?” questioned Jack.

“She don’t deserve t’ be kissed!” protested her mother. “She’s been a bad girl—how often have I told her never t’ lave th’ yard?”

Mamie was weeping bitter tears of repentance, and her mother suddenly softened and caught her to her breast.

“I—I won’t be bad no more!” sobbed Mamie.

“I should hope not! An’ what d’ y’ say t’ Allan? If it hadn’t ’a’ been fer him, you’d ’a’ been ground up under th’ wheels.”

“I—I lubs him!” cried Mamie, with a very tender look at our hero.

She held up her lips, and Allan bent and kissed them.

“Well, m’ boy,” laughed Jack, as the triumphal procession moved on again toward the house, “you seem t’ have taken this family by storm, fer sure!”

“Come along!” cried Mary. “Mebbe th’ poor lad’s hurted worse’n he thinks.”

She hurried him along before her up the path, sat him down in a chair, and rolled up his trousers leg.

“It’s nothing,” protested Allan. “It’s nothing—it’s not worth worrying about.”

“Ain’t it!” retorted Mary, with compressed lips, removing shoe and sock and deftly cutting away the blood-stained underwear. “Ain’t it? You poor boy, look at that!”

And, indeed, it was rather an ugly-looking wound that lay revealed. The flesh had been crushed and torn by the heavy blow, and was bleeding and turning black.

“It’s a mercy it didn’t break your leg!” she added. “Jack, you loon!” she went on, with a fierceness assumed to keep herself from bursting into tears, “don’t stand starin’ there, but bring me a basin o’ hot water, an’ be quick about it!”

Jack was quick about it, and in a few moments the wound was washed and nicely dressed with a cooling lotion which Mary produced from a cupboard.

“I keep it fer Jack,” Mary explained, as she spread it tenderly over the wound. “He’s allers gittin’ pieces knocked off o’ him. Now how does it feel, Allan darlint?” “It feels fine,” Allan declared. “It doesn’t hurt a bit. It’ll be all right by morning.”

“By mornin’!” echoed Mary, indignantly. “I reckon y’ think yer goin’ out on th’ section t’-morrer!”

“Why, of course. I’ve got to go. We’re getting it ready for the Irish Brigade. We’ve got to win that prize!”

“Prize!” cried Mary. “Much I care fer th’ prize! But there! I won’t quarrel with y’ now. Kin y’ walk?”

“Of course I can walk,” and Allan rose to his feet.

“Well, then, you men git ready fer supper. I declare it’s got cold—I’ll have t’ warm it up ag’in! An’ I reckon I’ll put on a little somethin’ extry jest t’ celebrate!”

She put on several things extra, and there was a regular thanksgiving feast in the little Welsh home that evening, with Allan in the place of honour, and Mamie looking at him adoringly from across the table. Probably not a single one of the employés of the road would have hesitated to do what he had done,—indeed, to risk his life for another’s is the ordinary duty of a railroad man,—but that did not lessen the merit of the deed in the eyes of Mamie’s parents. And for the first time in many days, Allan was quite happy, too. He felt that he was making himself a place in the world—and, sweeter than all, a place in the hearts of the people with whom his life was cast.

But the injury was a more serious one than he had been willing to admit. When he tried to get out of bed in the morning, he found his leg so stiff and sore that he could scarcely move it. He set his teeth and managed to dress himself and hobble down-stairs, but his white face showed the agony he was suffering.

“Oh, Allan!” cried Mary, flying to him and helping him to a chair. “What did y’ want t’ come down fer? Why didn’t y’ call me?”

“I don’t want to be such a nuisance as all that!” the boy protested. “But I’m afraid I can’t go to work to-day.”

Mary sniffed scornfully.

“No—nor to-morrer!” she said. “You’re goin’ t’ stay right in that chair!”

She flew around, making him more comfortable, and Allan was coddled that day as he had not been for a long time. Whether it was the nursing or the magic qualities of Mary’s lotion, his leg was very much better by night, and the next morning was scarcely sore at all. The quickness of the healing—for it was quite well again in three or four days—was due in no small part to Allan’s healthy young blood, but he persisted in giving all the credit to Mary.

After that, Allan noticed a shade of difference in the treatment accorded him by the other men. Heretofore he had been a stranger—an outsider. Now he was so no longer. He had proved his right to consideration and respect. He was “th’ boy that saved Jack Welsh’s kid.” Report of the deed penetrated even to the offices where dwelt the men who ruled the destinies of the division, and the superintendent made a mental note of the name for future reference. The train-master, too, got out from his desk a many-paged, much-thumbed book, indexed from first to last, and, under the letter “W,” wrote a few lines. The records of nearly a thousand men, for good and bad, were in that book, and many a one, hauled up “on the carpet” to be disciplined, had been astonished and dismayed by the train-master’s familiarity with his career.

Of all the men in the gang, after the foreman, Allan found Reddy Magraw the most lovable, and the merry, big-hearted Irishman took a great liking to the boy. He lived in a little house not far from the Welshes, and he took Allan home with him one evening to introduce him to Mrs. Magraw and the “childer.” The former was a somewhat faded little woman, worn down by hard work and ceaseless self-denial, but happy despite it all, and the children were as healthy and merry a set of young scalawags as ever rolled about upon a sanded floor. There were no carpets and only the most necessary furniture,—a stove, two beds, a table, and some chairs, for there was little money left after feeding and clothing that ever hungry swarm,—but everywhere there was a scrupulous, almost painful, cleanliness. And one thing the boy learned from this visit and succeeding ones—that what he had considered poverty was not poverty at all, and that brave and cheerful hearts can light up any home.

His trunk arrived from the storage house at Cincinnati in due time, affording him a welcome change of clothing, while Mrs. Welsh set herself to work at once sewing on missing buttons, darning socks, patching trousers—doing the hundred and one things which always need to be done to the clothing of a motherless boy. Indeed, it might be fairly said that he was motherless no longer, so closely had she taken him to her heart.

Sunday came at last, with its welcome relief from toil. They lay late in bed that morning, making up lost rest, revelling in the unaccustomed luxury of leisure, and in the afternoon Jack took the boy for a tour through the shops, swarming with busy life on week-days, but now deserted, save for an occasional watchman. And here Allan got, for the first time, a glimpse of one great department of a railroad’s management which most people know nothing of. In the first great room, the “long shop,” half a dozen disabled engines were hoisted on trucks and were being rebuilt. Back of this was the foundry, where all the needed castings were made, from the tiniest bolt to the massive frame upon which the engine-boiler rests. Then there was the blacksmith shop, with its score of forges and great steam-hammer, that could deliver a blow of many tons; and next to this the lathe-room, where the castings from the foundry were shaved and planed and polished to exactly the required size and shape; and still farther on was the carpenter shop, with its maze of woodworking machinery, most wonderful of all, in its nearly human intelligence.

Beyond the shop was the great coal chute, where the tender of an engine could be heaped high with coal in an instant by simply pulling a lever; then the big water-tanks, high in air, filled with water pumped from the river half a mile away; and last of all, the sand-house, where the sand-boxes of the engines were carefully replenished before each trip. How many lives had been saved by that simple device, which enabled the wheels to grip the track and stop the train! How many might be sacrificed if, at a critical moment, the sand-box of the engine happened to be empty! It was a startling reflection—that even upon this little cog in the great machine—this thoughtless boy, who poured the sand into the boxes—so much depended.

Bright and early Monday morning they were out again on Twenty-one. Wednesday was inspection, and they knew that up and down those two hundred miles of track hand-cars were flying back and forth, and every inch of the roadway was being examined by eyes severely critical. They found many things to do, things which Allan would never have thought of, but which appealed at once to the anxious eyes of the foreman.

About the middle of the afternoon, Welsh saw a figure emerge from a grove of trees beside the road and come slouching toward him. As it drew nearer, he recognized Dan Nolan.

“Mister Welsh,” began Nolan, quite humbly, “can’t y’ give me a place on th’ gang ag’in?”

“No,” said Jack, curtly, “I can’t. Th’ gang’s full.”

“That there kid’s no account,” protested Nolan, with a venomous glance at Allan. “I’ll take his place.”

“No, you won’t, Dan Nolan!” retorted Jack. “He’s a better man than you are, any day.”

“He is, is he?” sneered Nolan. “We’ll see about that!”

“An’ if you so much as harm a hair o’ him,” continued Jack, with clenched fists, “I’ll have it out o’ your hide, two fer one—jest keep that in mind.”

Nolan laughed mockingly, but he also took the precaution to retreat to a safe distance from Jack’s threatening fists.

“Y’ won’t give me a job, then?” he asked again.

“Not if you was th’ last man on earth!”

“All right!” cried Nolan, getting red in the face with anger, which he no longer made any effort to suppress. “All right! I’ll fix you an’ th’ kid, too! You think y’re smart; think y’ll win th’ section prize! Ho, ho! I guess not! Not this trip! Purty section-foreman you are! I’ll show you!”

Jack didn’t answer, but he stopped and picked up a stone; and Nolan dived hastily back into the grove again.

“He’s a big coward,” said Jack, throwing down the stone disgustedly, and turning back to his work. “Don’t let him scare y’, Allan.”

“He didn’t scare me,” answered Allan, quietly, and determined to give a good account of himself should Nolan ever attempt to molest him.

But Jack was not as easy in his mind as he pretended; he knew Nolan, and believed him quite capable of any treacherous meanness. So he kept Allan near him; and if Nolan was really lurking in the bushes anywhere along the road, he had no opportunity for mischief.