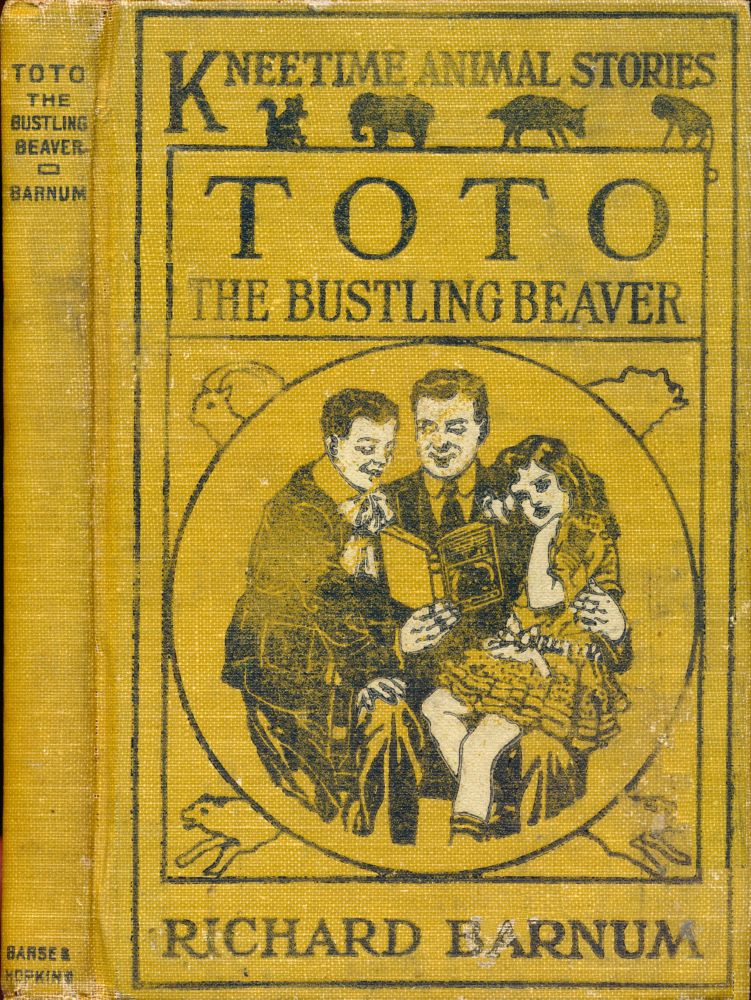

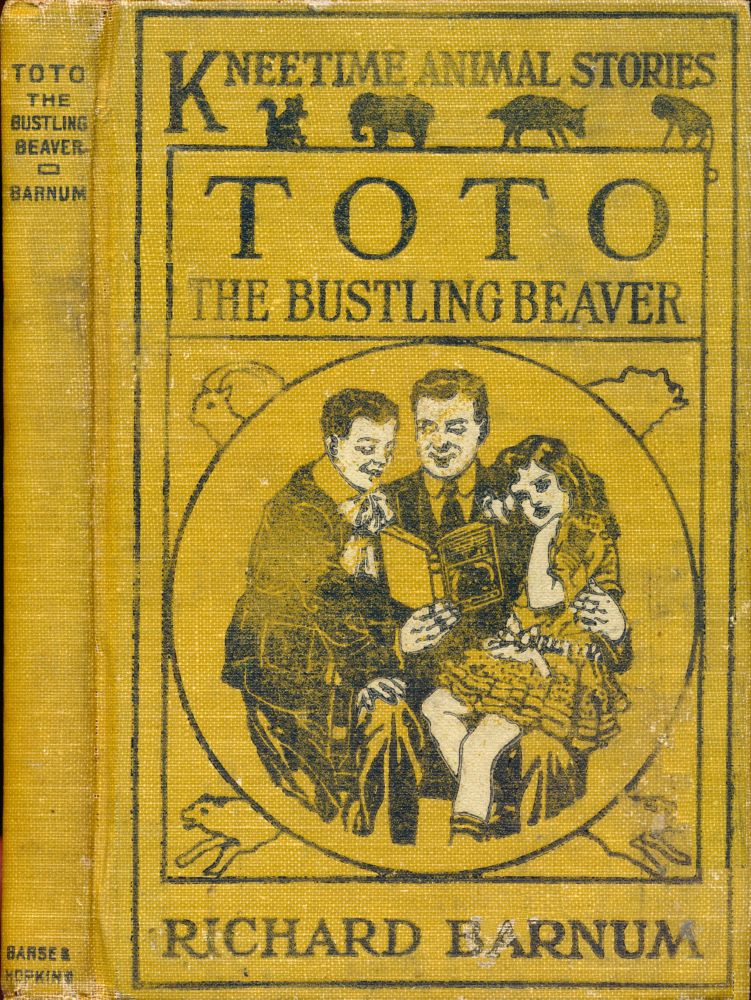

Kneetime Animal Stories

HIS MANY ADVENTURES

BY

Author of “Squinty, the Comical Pig,” “Tum Tum, the

Jolly Elephant,” “Sharp Eyes, the Silver Fox,”

“Tamba, the Tame Tiger,” “Nero,

the Circus Lion,” Etc.

ILLUSTRATED BY

WALTER S. ROGERS

NEW YORK

PUBLISHERS

By Richard Barnum

Large 12mo. Illustrated.

BARSE & HOPKINS

Publishers New York

Copyright, 1920

by

Barse & Hopkins

Toto, the Bustling Beaver

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I | Toto Helps Millie | 7 |

| II | Toto Learns to Gnaw | 17 |

| III | Toto Meets Don | 26 |

| IV | Toto and the Tramps | 35 |

| V | Toto Sees Something Queer | 46 |

| VI | Toto and the Burglars | 54 |

| VII | Toto and the Boy | 64 |

| VIII | Toto Meets Blackie | 71 |

| IX | Toto in a Trap | 81 |

| X | Toto on a Boat | 89 |

| XI | Toto Gets Home Again | 98 |

| XII | Toto in a Storm | 108 |

“Toto! Toto! Where are you?”

There was no answer to this call, which Mrs. Beaver, the mother of Toto, sounded as she climbed up on the ice and looked around for her little boy. Mrs. Beaver sat on her broad, flat tail, which really made quite a good seat, and with her sharp eyes she looked up and down Winding River for a sight of Toto. Then she called again, in beaver animal language of course:

“Toto! Toto! Come home this minute! You’ve been out on the ice long enough! And goodness knows we’ve had plenty of ice and snow this winter,” went on Mrs. Beaver, and she kept on looking up and down the frozen river. “I’ll be glad when spring comes so we beavers can gnaw down trees, eat the soft bark, and make dams for our houses,” she added.

But though she called as loudly as she could, and looked sharply up and down the river, which was covered with a sheet of smooth ice, Mrs. Beaver could see nothing of her little boy, Toto.

“What’s the matter?” asked an old gentleman beaver, who came along just then. “Has Toto run away?”

“I don’t know that I’d call it exactly running away, Mr. Cuppy,” answered Mrs. Beaver. “I said he could go out of the house and play on the ice a little while, but I told him to come back and get his willow bark lunch. But he hasn’t come, so I walked out to call him.”

“And he doesn’t answer,” said Mr. Cuppy, the old beaver gentleman, with a laugh—of course he laughed animal fashion, and not as you do. “I guess Toto is off playing tag, or something like that, on the ice with the other beaver boys,” added Mr. Cuppy. “I’m going down the river to call on some friends of mine. If I see Toto I’ll tell him you want him.”

“I wish you would,” said Mrs. Beaver. “Please tell him to come straight home.”

“I will,” answered Mr. Cuppy, and then he got up from the ice, where he had sat down on his broad, flat tail to talk to Toto’s mother, and walked slowly down the ice-covered river which ran into Clearwater Lake.

That is, the river ran in summer time. In[9] winter it was frozen over, though of course the water ran under the ice, where boys and girls could not see it. But Toto, Mr. Cuppy, and the other beavers could see it, for they could dive under the ice and swim in the water that flowed beneath it. In fact, they would rather swim in the water, cold as it was, than walk on the ice.

For a beaver can not very well walk on the ice—it is too slippery. Nor can a beaver walk very fast even on dry ground. But, my! how fast they can swim in water. So, though beavers very often come out on the land, or shore, they always run for the water, dive down, and swim away as soon as there is the least sign of danger.

Mrs. Beaver walked back toward the hole in the ice through which she intended getting into her house, where she lived with her husband, Mr. Beaver, Toto, and another little beaver boy named Sniffy.

Mrs. Beaver’s home looked just like a bundle of sticks from the woodpile, laid together criss-cross fashion. In fact, if you had seen it from the outside you would have said it was only a heap of rubbish.

This heap of sticks was built out near the middle of Winding River, which was not a very large stream. And now that the river was frozen, the pile of sticks, which made the beaver house, was heaped up above the frozen ice.

The front door to the beaver home was under water—so far under that it did not freeze—and when Toto or any of the family wanted to come out, they had to dive down, swim under water, and come out on top some distance away. When the river was not frozen they could come out of the water wherever they pleased. But when Jack Frost had made the river a solid, hard sheet of ice, the beavers had to come out of it just where a hole had been made for them. Sometimes they made the hole themselves by blowing their warm breath on the underside of the ice, and sometimes they used an airhole such as you often see when you are skating.

Mrs. Beaver found the hole through the ice, dived down into the water, swam along a short distance until she reached the front door of her house of sticks and frozen mud, and then she went up inside.

The house was nicely lined inside with soft grass, and there were a number of short pieces of sticks scattered about. It was the bark from these sticks that the beavers lived on in winter.

“Did you find Toto?” asked Mr. Beaver, who was taking a little nap in the house.

“No, I didn’t,” answered Mrs. Beaver. “But I met Mr. Cuppy, the old grandfather beaver, you know, and he said if he saw Toto he’d send our little boy home.”

“That is very kind of Mr. Cuppy.” Mr. Beaver stretched himself. “Well, I think I’ll gnaw a little more bark.”

“I want some, too!” called Sniffy, the other little beaver boy.

“Here you are!” said his mother, and she took some of the bark-covered sticks from a pile at one side of the house.

Of course it was dark inside the house, for mud was plastered thickly over the crossed sticks to keep out the cold and snow. But beavers can see well enough in the dark, just as owls can, or cats.

After Mr. Cuppy had watched Mrs. Beaver dive down through the ice and swim away, he walked on down the frozen river. He looked from side to side as he waddled slowly along, hoping to see Toto. But the beaver boy was not in sight.

And now, so that you may wonder no longer what had become of the little beaver boy, I’ll tell you where he was and some of the wonderful adventures that happened to him.

Toto had asked his mother if he might go out on the ice and play, and she had said he might. Toto was about a year old, having been born the previous spring, and he knew that in winter there was not much to eat outside the beaver house. But he had gnawed a number of sticks of poplar,[12] and of willow, with the sweet, juicy bark on, and now he was not hungry. He was tired of being cooped up in the dark house, frozen fast in the river. So Toto had gone out, and had walked along the ice until he was quite a long way from home.

“But I guess I can easily find my way back,” thought Toto to himself. “It’s pretty slippery walking, and I’d a good deal rather swim, but if I walk slowly I won’t slip.”

So he had walked along the ice until he was out of sight of his home, around one of the many curves in Winding River. That was the reason Mrs. Beaver could not see her little boy, and also why Toto could not hear his mother calling to him. He did not really mean to stay out when his mother did not want him to.

“Ah, that looks like something good to eat!” said Toto to himself, as he saw some straggly bushes growing on the bank of the river. The bushes had no leaves on, of course, for this was March, and winter was still king of the land. But Toto thought there might be bark on some of the twigs of the bushes, and bark was what the beavers mostly ate in winter. He was not hungry, but Toto, like other boys, was always ready to eat.

Toto walked slowly over the ice, and, standing up on his hind legs and partly sitting on his broad,[13] flat tail, which was almost like the mortar trowel a mason uses, the little beaver boy began to gnaw the bark.

But he had not taken more than a bite or two before he stopped suddenly.

“Ouch!” cried Toto. “Something bit me!”

He looked about—there were no bees or wasps flying, which might have stung him. Still something had pricked him on his tongue. Then he looked more closely at the twig he had been gnawing.

“Oh, ho!” exclaimed Toto. “No wonder! This is a blackberry bush, and the thorns pricked me. I won’t gnaw any more of this bark.”

Toto backed away and started over the ice again, but he had not moved more than a few feet from the thick clump of blackberry bushes, growing on the edge of the river, when, all of a sudden, the little beaver boy heard a queer noise—several noises, in fact.

One was a tinkly sound, a sound Toto remembered to have heard when in summer a farmer was hoeing corn in a field near the river, and his hoe struck on a stone in the dirt. Then came the noise of a thud, as if something heavy had fallen on the ice. And after that sounded the voice of a little girl saying:

“Oh dear! There goes my skate!”

Of course Toto did not understand man, girl,[14] or boy talk. But he knew what it was, for in the summer, as he played around his stick-home in the river, he had often heard the farmer and his hired men talking in the fields not far away. So, though Toto did not know what the little girl said, he knew it was the same sound the farmer and his men had made when they talked to one another. And Toto was afraid of men, and boys and girls, too, though I don’t believe any girl would have tried to hurt or catch the beaver, nice as is their fur.

But this particular little girl, whose name was Millie Watson, did not even know Toto was near her. She had been skating on the ice when one of her skates suddenly came off, and she fell down.

The tinkly sound the beaver heard was the loose steel skate sliding over the ice and striking a stone near the bush under which Toto was hidden. The thudding sound was that made by Millie when she fell. But she was not hurt.

“Oh, dear!” she said again. “I wonder where my skate slid to. I can’t get along on only one skate, and it’s slow walking on the ice. Where is it?”

She slowly arose to her feet. One skate was still on her foot, but on the other shoe was only a loose strap. Millie, who had skated from her home to take a little pail of soup to her grandmother,[15] who lived farther down the river, was on her way back when she lost her skate.

“I don’t see where it can be,” mused the little girl, looking here and there on the ice. The reason she could not see the skate was because it had slid under the edge of the overhanging berry bush.

“I hope she doesn’t see me!” thought Toto, as he crouched down under the twigs. “I wish it were summer, and there were leaves on this bush. I could hide better then, and the river wouldn’t be frozen, so I could swim away very fast if this girl comes after me. Dear me! I wonder what she is doing here, anyhow.”

Toto did not know much about skating. But as he peered out at the little girl he saw her pushing herself along on one foot, and on that foot was something long, thin and shiny. It sparkled in the sun, just as the blade of the farmer’s hoe sometimes sparkled.

Toto looked on either side of him, and there, close to him, was another shiny thing, just like the one the girl had on one foot. Toto could see the girl moving slowly along, and looking from side to side.

“She must be looking for me!” thought Toto, and his heart began to beat very fast, for his father and mother had told him always to keep[16] away from men and boys; and this girl was probably just like a boy, the little beaver thought. He had seen boys along the river bank in summer trying to catch muskrats, and sometimes trying to catch beavers, too. Toto did not want to be caught.

So he crouched lower and lower under the bush, and then, all of a sudden, his feet slipped on the ice and they struck the long, shiny thing that was like the object the girl had on one foot.

Instantly there was another tinkly sound, and the shiny thing slid across the ice, out from under the overhanging bush and straight toward the little girl.

“Oh! Oh!” cried Millie, clapping her mittened hands. “Here is my lost skate! It was under the bush, but I wonder what pushed it out! There must be something there! I’m going to look!”

Toto heard this talk, but did not know what it was. However, he could see the little girl stoop down and pick up the skate he had accidentally knocked over the ice to her. Then he saw Millie come straight toward the bush under which he was hiding!

Toto, the little beaver boy, was a bright, bustling chap. He was what is called a “hustler” or a “bustler”—that is, some one always ready for work or play. But just now, as Toto saw the little girl coming toward the bush where he was hidden, he did not know what to do.

“But I’m going to do something!” thought the beaver boy. “I’m not going to let her catch me! Maybe that’s a trap she tried to get me in—maybe that shiny thing is a trap!”

Toto knew what traps were, for his father and mother had told him about them, and how to keep away from their sharp teeth that caught beavers and muskrats by the legs.

Millie came closer and closer. With bright, eager eyes, almost as bright and eager as those of Toto himself, she looked at the bush.

Toto was all ready to run, and he wished, more than ever, that the river was not frozen, since he would not have been a bit afraid if he could have jumped in the flowing stream to swim away.[18] He was not afraid of any creature in the water, and the fishes were friends of his.

Then, all at once, just as Toto was going to start to run and do his best on the slippery ice, he felt himself falling. He had been standing on the edge of the frozen river, where the ice was very thin, and it had given away, letting him down through a hole into the water.

“Oh, now I’m all right!” said Toto to himself when he felt the water wetting his thick fur, though it could not wet his skin beneath.

And so he was. He was in water now, where he felt much more at home than on the ice. And as he slipped down, tail first through the hole that had broken, he had a glimpse of the little girl.

The little girl saw Toto, too, and as soon as she had seen him she clapped her red-mittened hands again and cried:

“Oh, it’s a little beaver! He knocked my skate out to me! Oh, don’t go away, little beaver!” cried Millie. “I won’t hurt you!”

But of course Toto did not know that, and he did not know what the little girl was saying. He just wanted to get away from her, and back to his own stick house. So he dived down under the water, his fur being so thick and warm that he was not a bit cold. And away he swam beneath the ice that covered Winding River.

“Oh, he’s gone!” cried Millie, when she saw[19] the beaver disappear. “I wish I could have him to take home! Maybe I’ll see him again! Anyhow, he was nice to shove my skate out to me!”

Millie sat down on the bank and began putting on the skate that had slipped off, causing her to fall. And, though she never guessed it, she was to see Toto again, and the beaver was to see how Millie and her grandmother were made happy.

“Well, Toto, where have you been?” asked his mother, when, some little time later, the beaver boy swam up to the front door of the stick house. “I’ve been looking all over for you!”

“I didn’t mean to stay away so long, Mother,” answered Toto, in beaver talk, of course. “But it was so slippery on the ice that, when I got to going, it was hard to stop. I tried to eat some bark, but it was full of stickers, and then I had an adventure.”

“What’s an adventure?” asked Sniffy, who was not quite so bold and daring as was Toto.

“It’s something that happens to you,” Toto answered.

“And what happened to you?” asked Mr. Beaver.

Toto told them about Millie’s skate coming off, though of course he did not call it a skate. He said it was a “trap.”

“You did well to hurry away,” said his father. “It’s lucky for you that you fell through the hole[20] in the ice and could swim. Always, when you are in danger, get in the water if you can. Very few animals can swim as fast as we beavers swim. The water is the place for us, even though we have to go on land to gnaw down the trees for the dams we make.”

“Why do we have to make dams?” asked Sniffy.

“To make the water deep enough for our houses in places where it is otherwise too shallow,” answered Mr. Beaver. “By putting a lot of trees, sticks, clumps of grass, and mud across a stream the water backs up, and gets deep behind the dam, over which it flows, making a waterfall. We need to build our houses behind the dam, so as to have our doors under water. If we didn’t, other animals from the land would come in and get us. But land animals can not get into our houses as long as the front doors are under water, though it is easy for us to dive down and come up inside where the water does not reach. Did anything else happen to you, Toto?” asked his father.

“Well, I swam home under the ice as fast as I could,” answered the little beaver boy.

“Did you see anything of Mr. Cuppy?” asked Mrs. Beaver.

“No, I didn’t,” Toto answered. “Did some one try to catch him in a trap, too?”

“No. But he said he’d send you home if he[21] met you,” replied Mrs. Beaver. “Of course he didn’t meet you. I’ll go out and tell him he needn’t look for you any more, as you are now at home.”

“Yes, and I’m hungry, too,” said Toto. “The bark on the bush under which I hid was full of thorns. I couldn’t eat it.”

“Here is some nice aspen bark,” said Mr. Beaver. “Let me see your teeth, Toto?”

“What for?” the little beaver boy wanted to know.

“To see if they are going to be strong enough to help us gnaw down trees this summer,” went on Mr. Beaver.

Toto opened his mouth. His teeth were strong and white, that is all except the four front, or gnawing teeth. Two of these in his upper jaw and two in his lower jaw were a sort of red, or orange, color. All beavers have orange-colored gnawing teeth, and the rest are white, like yours.

“Humph! Yes, I think you’ll be big enough to help us gnaw down trees this summer,” said Daddy Beaver, as he looked at Toto’s orange teeth, which were almost as sharp and strong as the chisels the carpenter uses to smooth wood with which to build a house.

“Is it very hard to gnaw trees down?” Toto wanted to know.

“It must be easy,” said Sniffy, who was eating some aspen bark in the stick house. “See how easy I can strip this bark off this piece of log.”

“Gnawing bark is much easier than gnawing through the wood of a big, hard tree,” said Mr. Beaver. “You boys will learn that soon enough. But here, Toto, try some of this bark.”

So Toto and Sniffy gnawed the bark, and Toto told his brother more about the little girl he had seen. He thought she had tried to trap him, but we know Millie had done nothing of the sort. Only her skate had come off.

“And what do you think!” the little girl said, after she had reached home and was telling her mother about it that night at supper. “My skate slid right over the ice, under a bush, and a little beaver that was there pushed it out to me.”

“So the beavers are around here, are they?” asked Millie’s father. “I wondered what made a part of Winding River flow so slowly this fall. The beavers must have dammed it up. Well, the beavers are hard-working animals and do little harm. We won’t disturb them.”

The rest of that winter Toto lived in the stick house with the other beavers. He did not go out very often, for there is not much beavers can do until the ice and snow are gone. Toto went out on the frozen river a few times, however, but he did not again see the little girl on skates. And though Millie went out skating, she did not see Toto until later in the season. I’ll tell you about that after a while.

Meanwhile the sun climbed higher and higher in the sky. It warmed the earth, the snow and ice melted, the banks of Winding River became green, as the leaves came out on the trees and bushes, and one day Mr. Beaver said:

“Come with me, Toto and Sniffy. You are going to learn how to gnaw down trees.”

“Are we going to help build the dam bigger?” asked Toto.

“Yes, that’s what you are,” his father said.

He dived down in the water, to slip out of the front door, and the two beaver boys followed him. Their noses closed, and they kept their mouths tightly shut while under water. But they had their eyes open to see where to swim. They came out on top of the water not far from their own house. But almost as soon as they had poked up their noses to take long breaths, Toto and Sniffy heard a booming, whacking noise, and their father cried:

“Back! Back, boys! Dive down! There’s danger!”

You may well believe that Toto and Sniffy did not lose any time diving down under water as soon as they heard their father tell them to do so. Many times before, when they were first learning to swim, they had dived down quickly like this just after they had poked up their noses to get a breath of air. And always their father or mother had swum with them out of danger.

“What was that whacking noise, Dad?” asked Sniffy, when they were once more safely back in their stick and mud house.

“That was Mr. Cuppy banging his flat tail on the water to let us know there was some danger,” answered Mr. Beaver. “Cuppy, or some of the older beavers, are always on guard at or near the dam. If they hear, see or smell danger they whack with their tails. And whenever you hear that whacking sound you little fellows must dive into the water and swim away just as fast as you can.”

“Oh, now I remember about Mr. Cuppy whacking[27] with his tail!” exclaimed Toto. “You told us that last summer, didn’t you, Dad?”

“Yes. But the winter has been long, and all that time you have had no chance to hear Mr. Cuppy bang his tail on the water, so I was afraid you had forgotten,” said Mr. Beaver.

“I did forget,” answered Sniffy.

“And I did, too,” said Toto. “But now I’m always going to listen for Mr. Cuppy’s tail.”

“And run and dive into the water as fast as you can when you hear him whacking and banging,” advised Mr. Beaver. “Now we’ll wait a little while and then we’ll swim up again. The danger may have passed.”

Toto and his brother waited with their father perhaps five minutes in the beaver house. Then, once more, they dived down, out of the front door, and up into the river, a little farther away. Mr. Beaver went ahead, and poked up his nose first to look about. He saw a number of beavers working on the dam, among them Mr. Cuppy.

“Is it all right?” called Mr. Beaver to the old gentleman.

“Yes, come along. We need lots of help to make the dam bigger and stronger,” answered Mr. Cuppy. “Where are your two boys?”

“Right here,” answered their father. “It’s all right! Bob up your heads!” he called to Toto and Sniffy.

Up they swam, and soon they were among their friends on the dam, which was made of a number of trees laid crosswise over the narrow part of the river. Sticks had been piled back of the trees, and mud, grass-hummocks, and leaves were piled back of the sticks, so that very little water could run through. Back of the dam the water was quite deep, but in front it was very shallow. The beavers all had their houses back of the dam.

“What was the danger?” asked Mr. Beaver of Mr. Cuppy, as the two animal gentlemen walked along on top of the dam. “Did you see a bear or some other big animal?”

“No,” answered Mr. Cuppy. “The reason I whacked my tail was because I saw five or six men over in the woods where the trees are that we are going to cut down for our dam.”

“Were they hunter men, with guns?” asked Mr. Beaver.

“No, they didn’t seem to be hunters,” answered Mr. Cuppy. “They were rough-looking men, and not dressed as nicely as most hunters are. These men had old rusty cans in their hands—cans like those we sometimes find in our river. I thought they were coming over to our dam to catch us, but they didn’t. However I gave the danger signal.”

“Yes, it’s best to be on the safe side,” returned[29] Mr. Beaver. “Well, now we are here—my two boys and myself—and we are ready to help gnaw down trees for you. My wife will be here in a little while. She has gone to see if she can find some aspen bark for our dinner.”

“My wife has gone to look for some, too,” said Mr. Cuppy. “Well, now, let’s see! Have Toto and Sniffy ever cut down any trees?”

“No, this will be the first time for them,” said their father.

“Well, take them over to the little grove and show them how to work,” advised Mr. Cuppy. “We shall need many trees this spring. How are you, boys? Ready to gnaw with your red teeth?”

“Yes, sir,” answered Toto and Sniffy.

“Come along!” called their father, and into the water they jumped from the top of the dam, to swim to where the trees grew beside the river.

Beavers always swim, if they can, to wherever they want to go. They would much rather swim than walk, as they can swim so much better and faster. So, in a little while, Toto and Sniffy stood with their father beside a tree which, near where the tree trunk went into the ground, was as large around as your head.

“We will cut down this tree,” said Mr. Beaver.

“What! That big tree?” cried Toto. “We can never gnaw that down, Dad! It will take a year!”

“Nonsense!” laughed Mr. Beaver. “We can gnaw down larger trees than this. Before you boys are much older you’ll do it yourselves. But now come on, let’s start. I’ll watch you and tell you when you do things the wrong way. That’s the way to learn.”

“I guess I know how to gnaw a tree down!” boasted Sniffy. “I’ve often watched Mr. Cuppy do it.” This little beaver boy stood up on his hind legs, using his tail as a sort of stool to sit on, and he began cutting through the bark of the tree, using his four, strong orange-colored front teeth to gnaw with.

“Here! Hold on! Wait a minute!” cried Mr. Beaver to his son, while Toto, who was just going to help his brother, wondered what was the matter.

“Isn’t this the tree you want gnawed down, Dad?” asked Sniffy.

“Yes, that’s the one,” his father answered. “But if you start to gnaw on that side first the tree will fall right on top of those others, instead of falling flat on the ground as we want it to. You must begin to gnaw on the other side, Sniffy. Then, as soon as you have nearly cut it through, the tree will fall in this open place.”

“Oh, I didn’t know that,” said Sniffy.

“Nor I,” added his brother.

“Always look to see which way a tree is going[31] to fall,” advised Daddy Beaver, “and be careful you are not under it when it falls. If you do as I tell you then you will always be able to tell just which way a tree will fall to make it easier to get it to the dam.”

Then Mr. Beaver told the boys how to do this—how to start gnawing on the side of the tree so that it would fall away from them. Lumbermen know which way to make a tree fall, by cutting or sawing it in a certain manner, and beavers are almost as smart as are lumbermen.

How they do it I can’t tell you, but it is true that beavers can make a tree fall almost in the exact spot they want it. Of course accidents will happen now and then, and some beavers have been caught under the trees they were gnawing down. But generally they make no mistakes.

“How are we going to get the tree to the dam after we gnaw through the trunk?” asked Toto, as he and Sniffy began cutting through the outer bark with their strong, red teeth. “We can’t carry it there.”

“We could if we could bite it into short pieces, as we bite and gnaw into short pieces the logs we gnaw bark from in our house all winter,” said Sniffy.

“We don’t want this tree cut up into little pieces,” said Daddy Beaver. “It must be in one, long length, to go on top of the dam.”

“We never can drag this tree to the dam after we have gnawed it down!” sighed Toto. “It will be too hard work!”

“You won’t have to do that,” said his father with a laugh. “We will make the water float the tree to the dam for us.”

“But there isn’t any water near here,” said Sniffy.

“No, but we can bring the water right here,” went on Mr. Beaver.

“How?” Toto wanted to know, for he and his brother were young beavers.

“We can dig a canal through the ground, and in that the water will come right up to where we want it,” said Mr. Beaver. “We’ll dig out the dirt right from under the tree, after we have cut it down, and bring the canal to it. The canal will fill with water. The tree, being wood, will float in the water, and a lot of us beavers, getting together, can swim along and push and pull the tree through the canal right to the place where we need it for the dam.”

“Are we going to learn how to dig canals, too?”

“Yes, building dams and canals and cutting down trees are the three main things for a beaver to know,” said his father. “But learn one thing at a time. Just now you are to learn how to cut down this tree. Now gnaw your best—each of you!”

So Toto and Sniffy gnawed, taking turns, and their father helped them when they were tired. Soon a deep, white ridge was cut in the side of the tree.

“The tree is almost ready to fall now,” said Mr. Beaver. “You boys may take a little rest, and I’ll finish the gnawing. But I want you to watch and see how I do it. Thus you will learn.”

“May I go over there by the spring of water and get some sweet bark?” asked Toto.

“Yes, I’ll wait for you,” answered his father. “I won’t finish cutting the tree down until you come back.”

“Bring me some bark,” begged Sniffy, as he sat down on his broad, flat tail.

“I will,” promised Toto.

The little beaver boy waddled away, and soon he was near an aspen tree. Beavers like the bark from this tree better than almost any other. Toto was gnawing away, stripping off some bark for his brother, when, all at once, he heard a rustling sound in the bushes, and a big animal sprang out and stood in front of Toto.

“Oh, dear me! It’s a bear!” cried Toto.

“No, I am not a bear,” answered the other animal. “Don’t be afraid of me, little muskrat boy. I won’t hurt you.”

“I’m not a muskrat! I’m a beaver!” said Toto. “But who are you?”

“I am Don,” was the answer. “And I am a dog. Once I was a runaway dog, but I am not a runaway any longer. But what are you doing here, beaver boy?”

“Helping my father cut down a tree for the dam,” Toto answered. “What are you doing, Don?”

“I am looking for a camp of tramps,” was the answer, the dog and beaver speaking animal talk, of course. “A dog friend of mine said there was a camp of tramps in these woods, and I want to see if I can find them,” went on Don.

“What are tramps?” asked Toto.

“Ragged men with tin cans that they cook soup in,” answered Don. “Have you seen any around here?”

“No, but Cuppy, the oldest beaver here, saw some ragged men over in the woods,” began Toto. “Maybe they are—”

But before he could say any more he heard a loud thumping sound, and Toto knew what that meant.

“Look out! There’s danger!” cried Toto.

Toto, the bustling beaver, ran as fast as he could and took shelter under a big rock that made a place like a little cave on the side of the hill.

“What’s the matter?” asked Don, the dog. “Are you afraid because I told you about the tramps?”

“Oh, no,” answered Toto. “But didn’t you hear that thumping sound just now?”

“Yes, I heard it,” answered Don. “What was it—somebody beating a carpet?”

“I don’t know what a carpet is,” replied Toto. “We don’t have any at our house. But, whatever it is, it wasn’t that. The noise you heard was one of my beaver friends thumping his tail on the ground.”

“Oh, you mean wagging his tail!” barked Don. “Well, I do that myself when I feel glad. I guess one of your beaver friends must feel glad.”

“No, it isn’t that,” went on Toto. “Whenever any of the beavers thumps his tail on the ground it means there’s danger around, and all of us who[36] hear it run and hide. You’d better come under this rock with me. Then you’ll be out of danger.”

Once more the thumping sound echoed through the woods.

“Better come under here with me,” advised Toto.

“Well, I guess I will,” barked Don.

No sooner was he under the big rock with Toto than, all of a sudden, there was a loud crash, and a great tree fell almost on the place in the woods where Toto and Don had been standing talking.

“My goodness!” barked Don, speaking as dogs do. “It’s a good thing we were under this rock, Toto, or else that tree would have fallen on us! Did you know it was going to fall?”

“Well, no, not exactly. My brother and I have been practicing on gnawing a tree this morning, but ours isn’t cut down yet. My father is going to finish cutting it, and show Sniffy and me how it is done. But he promised not to cut all the way through until I got back. So I don’t believe it was our tree that fell.”

“Is it all right for us to come out now?” asked Don. Though he was older than the beaver boy, he felt that perhaps Toto knew more about the woods—especially when tree-cutting was going on.

Toto sat up on his tail under the big rock and listened with his little ears. He heard the[37] beavers, which were all about, talking among themselves, and he and Don heard some of them say:

“It’s all right now. Cuppy and Slump have cut down the big tree for the dam. It has fallen, and now it is safe for us to come out.”

The dog and the little beaver came out from under the overhanging rock, and Don noticed the pieces of bark Toto had stripped off.

“What are you going to do with them?” asked Don. “Make a basket?”

“A basket? I should say not!” exclaimed Toto. “I’m going to eat some and take the rest to my father and brother. They are farther back in the woods, cutting down a tree. Don’t you like bark?”

“Bark? I should say not!” laughed Don in a barking manner. “I like bones to gnaw, but not bark, though I bark with my mouth. That is a different kind, though. But I suppose it wouldn’t do for all of us to eat the same things. There wouldn’t be enough to go around. But tell me: Do you always hear a thumping sound whenever there is danger in the woods?”

“Yes, that’s one of the ways we beavers have of talking to one another,” answered Toto. “Whenever one of us is cutting a tree down, and he sees that it is about to fall, he thumps on the ground as hard as he can with his tail. You see[38] our tails are broad and flat, and they make quite a thump.”

Don turned and looked at Toto’s tail.

“Yes, it’s quite different from mine,” said the dog. “I sometimes thump my tail on the floor, when my master gives me something good to eat or pats me on the head. But my tail doesn’t make much noise.”

“Well, a beaver’s tail does,” explained Toto. “So whenever any of us hear the thumping sound we know there is danger, and we run away or hide.”

“I’m glad to know this,” said Don. “When I’m in the woods, from now on, and hear that thumping sound, I’ll look around for danger, and I’ll hide if I can’t get out the way. Well, I’m glad to have met you,” went on Don. “I don’t suppose you have seen Blackie, have you?”

“Who is Blackie?” asked the beaver boy. “Is he another dog?”

“No, she’s a cat!” explained Don, with a laugh. “She’s quite a friend of mine. She has a story all to herself in a book, and I have one, too. I don’t suppose you were ever in a book, were you, Toto?”

“Did you say a brook?” asked the beaver boy. “Of course I’ve been in a brook many a time. I even built a little dam across a brook once—I and my brother Sniffy.”

“Ho, I didn’t say brook—I said book,” cried Don. “Of course I don’t know much about such things myself, not being able to read. But a book is something with funny marks in it, and boys and girls like them very much.”

“Are they good to eat?” asked Toto.

“Oh, no,” answered Don, laughing.

“Then I don’t believe they can be very good!” said Toto, “and I don’t care to be in a book.”

But you see he is in one, whether he likes it or not, and some day he may be glad of it.

“Well, I must be going,” barked Don. “I want to see if I can find that camp where the tramps live. Tramps are no good. They come around the house where I live, near Blackie, the cat, and take our master’s things. If I see the tramps I’m going to bark at them and try to drive them away.”

Then he trotted on through the woods, and Toto, after eating a little more bark, gathered some up in his paws, and, walking on his hind legs, brought it to where his father and Sniffy were waiting for him.

“Here’s Toto,” said Sniffy.

“Where have you been?” asked Mr. Beaver.

“Oh, getting some sweet bark,” answered Toto, and he laid down on some clean moss the strips he had pulled off. “I met a dog, too.”

“A dog!” cried Mr. Beaver. “My goodness,[40] I hope he isn’t chasing after you!” and he looked through the trees as if afraid.

“Oh, this was Don, a good dog,” explained Toto. “He’s only looking for some tramps. He won’t hurt any beavers.”

“Well, if he’s a good dog, all right,” said the beaver daddy. “But hunters’ dogs are bad—they’ll chase and bite you. I suppose they don’t know any better.”

“Where were you when Cuppy whacked with his tail just before the big tree fell?” asked Sniffy, as he nibbled at some of the tender bark his brother had brought.

“Oh, Don and I hid under a big rock,” answered Toto. “I told him the whacking sound meant danger. He didn’t know it. And it’s a good thing we hid when we did, for the tree would have crushed us if we hadn’t been under the rock. Is our tree ready to finish gnawing down, Daddy?”

“Yes,” answered Mr. Beaver. “You and Sniffy may start now, and cut a little more. I’ll tell you when to stop.”

“But I thought you were going to finish, Dad,” said Sniffy.

“He will, Sniffy, if he said so. But he’s letting us help a little more first so we can learn faster!”

So the beaver boys sat up on their tails again, and gnawed at the big tree—the largest one they had ever helped to cut down. They gnawed and gnawed and gnawed with their orange-colored front teeth, and then Mr. Beaver said:

“That’s enough, boys. I’ll do the rest. But you may whack on the ground with your tails to warn the others out of the way.”

So Toto and Sniffy, much delighted to do this, found a smooth place near a big rock, and then they went:

“Whack! Whack! Whack!”

“Danger! Danger!” cried a lot of other beavers who were working near by. “A tree is going to fall! Run, everybody! Danger!”

“See!” exclaimed Toto to his brother. “We can make the old beavers run out of the way just as Cuppy made Don and me run.”

“Yes, you beaver boys are growing up,” said Mr. Beaver, who had waited to see that his two sons gave the danger signal properly. “You are learning very well. Now here goes the tree.”

He gave a few more bites, or gnaws, at the place where the tree was almost cut through, and then Mr. Beaver himself ran out of the way.

“Crash! Bang!” went the big tree down in the forest. It broke down several other smaller trees, and finally was stretched out on the ground near the waters of Winding River.

“We helped do that!” said Toto to Sniffy, when the woods were again silent.

“Yes, you have learned how to cut down big[44] trees,” said their father. “You are no longer playing beavers—you are working beavers. Now we must dig the canal to float the tree nearer the dam, as it is too heavy for us to roll or pull along, and we do not want to cut it.”

I will tell you, a little farther on, how the beavers cut canals to float logs to the places where they want to use them. Just now all I’ll say about them is that it took some time to get the tree Toto and Sniffy had helped cut to the place where it was needed for the dam. The two beaver boys and many others of the wonderful animals were busy for a week or more.

Then, one day, when the tree was in place, Toto asked his mother if he might go off into the woods and look for some more aspen bark, as all that had been stored in the stick house had been eaten.

“Yes, you may go,” said Mrs. Beaver. “But don’t go too far, nor stay too long.”

“I won’t,” promised Toto. Then he waddled off through the woods, after having swum across the beaver pond, made by damming the river, and soon he found himself under the green trees.

“I wonder if I’ll meet Don, the nice dog, or Whitie, the cat?” thought Toto. “Let me see, was Whitie her name? No, it was Blackie. I wonder if I’ll meet her, or that little girl who scared me so that day on the ice?”

Toto looked off through the trees, but he saw neither Don nor Blackie.

Toto found a place where some aspen bark grew on trees, and he gnawed off and ate as much as he wanted. Then he walked on a little farther and, pretty soon, he saw something in the woods that looked like a big beaver house. It was a heap of branches and limbs of trees, and over the outside were big sheets and strips of rough bark.

“But that can’t be a beaver house,” thought Toto. “It isn’t near water, and no beavers would build a house unless it had water near it. I wonder what it is.”

Toto sat up on his tail and looked at the queer object. Then all at once he heard rough voices speaking, and he saw some ragged men come out of the pile of bark. One or two of them had tin cans in their hands, and another was holding a pan over a fire that blazed on a flat rock.

“Oh, I know who they are!” said Toto to himself. “These must be the tramps Don was looking for. This is the tramp camp! I’ve found the bad men. I wish I could find Don to tell him!”

Crouching down behind a green bush, Toto, the bustling beaver, kept very quiet and watched the tramps. He was not at all bustling now, however. He was not doing any work. Instead he was watching to see if the tramps were going to do any work.

But you know better what tramps are than did Toto. Tramps, as a rule, are men who don’t like to work. They are lazy, and wander about like gypsies, living as best they can, putting up an old shack or a bark cabin in the woods, as these tramps had done, boiling soup or stewing something in a tomato can over a fire in the woods. Those are tramps.

“I wish I could find Don to tell him,” thought Toto. “These must be the very tramps for whom he was looking.”

But though the beaver boy peered around among the trees he could not see Don. The dog was not in that part of the woods just then.

The tramps, however, were in plain sight. Some were stretched out on the soft moss beneath[47] the trees. Others sat in the doorway of the rough, bark house they had built, and still others were cooking something over a fire.

“What a lot of hard work they have to do to get something to eat,” thought Toto. “They have to make a fire, and fires are dangerous. I don’t like them!”

Well might Toto say that, for he had heard his father and Cuppy tell of fires in the forest that, in dry seasons, burned beaver dams and beaver houses.

“We never have to make a fire when we are hungry,” thought Toto. “And we don’t have to hunt for tin cans, to put in them our things to eat. When I’m hungry all I have to do is to gnaw a little bark from a tree, or eat some grass or some lily roots from the pond. I wouldn’t like to be a tramp. That would be dreadful. I’d rather be a beaver.”

So Toto watched the tramps. He saw them make the fire bigger, and noticed many of the ragged men holding over it tin cans which, later, they ate from.

Then, as the day was warm and sunny, all the tramps stretched out under the trees and went to sleep.

“Now would be a good time for Don to come along and scare them away,” thought Toto. “I wish he would. It isn’t good to have a camp of[48] tramps so near our beaver dam. They may come and try to catch some of us.”

But Don, the dog, did not come, and after watching the ragged men for a while Toto thought he had better start back home. He stripped off some bark to take to his mother, who liked it very much, and then the bustling beaver waddled along until he came to a stream of water. Into this he jumped and swam the rest of the way, as that was easier than walking, or “waddling” as I call it, for Toto was rather fat, and he sort of “wobbled” as he walked.

“Well, did anything happen to you this time?” asked Mrs. Beaver, when Toto reached home.

“It didn’t exactly happen to me,” he said. “But I saw the camp of tramps Don was looking for.”

“Tramps! In our woods!” exclaimed Mr. Beaver, who came along just then. He was coming home to supper, having been at work with Cuppy and the others on the big dam. “Where did you see the tramps, Toto?”

The little beaver boy told his father, and that evening after they had eaten all the beavers gathered out on the big dam which held back the waters of the pond. It was a sort of meeting, and though it took place nearly every night, it was not always as serious as was this one.

On other nights the beavers gathered to talk[49] to one another, the older ones looking to see that the dam was all right, and the younger ones, like Toto and Sniffy, playing about.

But this evening there was very little playing. After a few holes in the dam had been plastered shut with mud, which the beavers carried in their forepaws, and not on their tails, as many persons think, Cuppy whacked his tail on the ground. Every beaver grew silent on hearing that.

“There is no special danger just now,” said Cuppy, speaking to all the others. “I mean no tree is going to fall, or anything like that. But there is likely to be trouble. Toto, tell us about the tramp camp you saw in the woods.”

You may easily believe that Toto was quite surprised at being called on to sit up and speak before all the other beavers in the colony. But he was a smart little chap, and he knew that each one must help the others. So he told what he had seen.

“And now,” said Cuppy, “what is to be done? We do not want these tramps around here. Some of them may be hunters, and may try to catch us. Others may tear out our dam, and that would be very bad for us, as the water would all run out of our pond and our houses would be of no use. Now we must either drive these tramps away, or else make our dam so big and strong that they will not want to try to tear it apart.”

“How can we drive the tramps away?” asked Toto’s father.

“I don’t believe we can,” answered Cuppy. “If we were bears or wolves we might, but, being beavers, we can’t very well do it. The next best thing to do is to make our dam stronger. So to-morrow morning we must all—young and old who can gnaw trees—we must all cut down as many as we can and build the dam bigger. In that way we may be safe from the tramps. Now remember—everybody come out to cut down trees in the morning.”

“We can cut trees now, can’t we, Dad?” asked Toto of his father.

“Yes, you and Sniffy must do your share,” replied Mr. Beaver. “We must all help one another.”

The woods around the dam were a busy place next morning. All the beavers who were able began cutting down trees. Later the trees would be floated in canals to the big pond and made a part of the wall that held back the waters.

“Sniffy, do you want to come with me?” asked Toto of his brother, when the two boys had, together, cut down a pretty good-sized tree.

“Where are you going?” asked Sniffy.

“Farther off into the woods,” answered Toto. “I know where there is a nice, smooth, straight[51] tree that we can cut down. It stands all by itself, and when it falls it won’t lodge in among other trees, so it will be easy to get out for the dam. Come, and we’ll cut it down together.”

“All right, I will,” said Sniffy.

Now Toto did not tell his brother that the tree he intended gnawing down was close to the camp of the tramps. Toto thought if he told his brother that, Sniffy might be afraid to go.

“But we can keep hidden from the tramps,” thought Toto, “and our teeth do not make much noise when we gnaw. The tramps will not hear us. Besides, I want to see if they are still there. Maybe Don has barked at them and driven them away.”

But when Toto and Sniffy reached the place in the woods where the tall tree grew, there was the bark shack in the same place, and some of the ragged men were still in and about it.

“Oh, look!” exclaimed Sniffy, catching sight of the tramps. “Who are the ragged men, Toto? Are they hunters?”

“No,” answered Toto. And then he told his brother who the men were. “But don’t be afraid,” went on Toto. “We’ll gnaw very silently, and the tramps won’t know we are here. These are the ragged men I told about at the meeting. But don’t be afraid, Sniffy.”

“All right. I won’t be afraid if you’ll stay with me,” said Sniffy. “Now which tree are we going to cut, Toto?”

The other beaver showed his brother the tree he meant, and Sniffy said it was a fine one.

“If we cut that down all by ourselves, it will help make the dam much bigger,” he said. “But we can’t cut it in one day, Toto.”

“No, nor in two days,” answered the other. “It may take us a week. But we can do it.”

After that, each day, Toto and Sniffy slipped off by themselves and went to the place near the camp of the tramps. There the two beaver boys gnawed and gnawed and gnawed away at the tree they were cutting down. And they worked so quietly that none of the tramps heard them.

One day the big tall tree was almost cut through.

“We shall finish gnawing it down in about an hour,” said Sniffy.

“Yes,” agreed Toto, “it will soon fall.”

“And shall we whack on the ground with our tails to signal for danger?” Sniffy wanted to know.

“We had better; yes,” agreed Toto. “We can’t tell but what some of the other beavers may be around here, though I haven’t seen any.”

So the two boy animals gnawed and gnawed some more, and soon the tree began to topple slowly to one side.

“There it goes!” cried Sniffy.

“Yes, it’s going to fall,” agreed Toto. “Whack with your tail as hard as you can! Whack your tail!”

Toto and Sniffy banged their flat tails on the ground. It was the beavers’ signal for danger. Then Toto and Sniffy ran and hid in a hollow place under a big stump. But they could look out and see the tree leaning over farther and farther as it toppled to the earth.

Suddenly Toto cried:

“Look! The tree is going to fall right on the place where the tramps live! It is going to fall on their house and it will be smashed!”

And so it was. The beaver boys had forgotten about the shack of the tramps when they gnawed at the tree. Now it was toppling over directly on the bark cabin. Toto and his brother were going to see something very queer happen.

“Bang with your tail! Bang with your tail, and give the danger signal to the tramps!” cried Toto.

And he and Sniffy whacked away as hard as they could.

Now, the tramps who had built the shack of bark in the woods knew nothing about beavers and their ways. The tramps did not know that when a beaver whacks his tail on the ground it means danger from a falling tree, or from something else.

But the tramps in the shack, toward which was falling the tree Toto and Sniffy had gnawed down—these tramps heard the queer whacking sounds, and they knew they had never heard them before. So some of them, who were not as lazy as the others, ran out to see what it meant.

One tramp looked up and saw the tall tree swaying down toward the bark shelter. The tramp did not know that two little beaver boys had, all alone, gnawed down the big tree. But the tramp could see it falling.

“Come on! Get out! Everybody out of the shack!” cried the tramp who saw the falling tree. “Everybody out! The whole woods are falling down on us!”

Of course that wasn’t exactly so. It was only[55] one tree that was falling, and the same one which Toto and Sniffy had gnawed down. But the tramp who called out was so excited he hardly knew what he was saying.

And as soon as the other tramps, some of whom were sleeping in the bark shack, heard the calls, they came running out, some rubbing their eyes, for they were hardly awake. They had been asleep in the daytime, too—the daytime when all the beavers were busy.

“Come on! Come on! Get out! Everybody out!” yelled the tramp who had first caught sight of the falling tree.

As soon as the others knew what the danger was, out they rushed also, and then they all stood outside the shack and to one side and watched the tree crash down.

Right on top of the bark cabin crashed the tree. There was a splintering of wood, a breaking of branches, a big noise, and then it was all over.

For a few minutes the tramps said nothing. They all stood looking at the fallen tree that had crushed their home in the woods.

“Well!” exclaimed several of the men.

“It’s a good thing we got out in time,” growled one tramp.

“I should say so!” exclaimed another. “Lucky you saw it coming,” he added to the tramp who had called the warning.

“Did some one chop the tree down?” asked a third tramp.

“No, I guess the wind blew it,” said a fourth.

“There isn’t enough wind to blow a tree down,” decided the first tramp, who had red hair.

Of course we know it wasn’t the wind that blew the tree down. It was Toto and Sniffy who gnawed it and made it fall. But the tramps were too lazy to go and see what had caused the tree to topple over. They just stood there and looked at their crushed house.

“It will be a lot of work to build that up again,” said one tramp. “She’s smashed flat.”

“Build it up again! I’m not going to help build it up!” said another. “It’s too hard. I’m tired of this place, anyhow. Let’s move off to another woods. Maybe we can find a place near a chicken yard, and we can have all the chickens we want. Let’s move away, now that our house is smashed.”

“Yes, let’s do that!” cried some of the other tramps.

And those ragged men were so lazy that they did not want to go to the trouble of building a home for themselves! Perhaps they thought they could go off into the woods and find another already built. Anyhow, they stood around a little while longer. One or two of them picked up ragged coats and hats that were in the ruins of the hut, and some took old cans in which they[57] heated soup. That was all they had to move.

“Well, come on! Let’s hike along!” said the red-haired tramp.

With hardly a look back at what had been a home for some of them for a long time, the tramps walked away through the woods. Toto and Sniffy, hiding in the bushes, watched the ragged men go.

“Look what we did!” said Sniffy to his brother.

“Yes, we cut down a tree, but we didn’t mean to make it fall on the house where the tramps lived,” said Toto.

“Anyhow, they’re going away, and that’s a good thing for us,” went on Sniffy. “Now we won’t have to make the dam so strong, nor move away ourselves.”

“That’s so,” agreed Toto. “I didn’t think about that. Why, Sniffy, we really drove the tramps away, didn’t we?”

“Yes,” answered his brother, “we did.”

“Don, the dog, will be glad to know this,” went on Toto. “I guess he’ll wish he had helped drive the tramps away himself. Come on! let’s go back and tell Dad and Mr. Cuppy about cutting down the tree and smashing the tramps’ cabin.”

Mr. Beaver, Cuppy, and all the others in the colony were much surprised when Toto and Sniffy told what had happened. Almost all the grown animals, and certainly every one of the boys and[58] girls, went out to see the fallen tree and the smashed cabin.

“Well, you did a lot to help us,” said Cuppy to the two brothers; “but we can’t use that tree in the dam.”

“Why not?” asked Toto.

“Because it fell the wrong way. It would be too much work to dig a canal to it and float it to the dam. It will be easier to cut down another tree. But I don’t know that we shall need any more as long as the tramps have moved away. We need not make our dam any bigger now.”

“Are all the tramps gone?” asked Toto’s mother.

“Yes, every one,” answered Cuppy. He was a wise old beaver, and he knew none of the ragged men were left near what had once been their shack of bark.

So that was another adventure Toto had—driving away the tramps. And if I had told you, at first, that two little beavers, not much bigger than small puppy dogs, could make a number of big, lazy men move, you would hardly have believed me. But it only goes to show in what a strange way things happen in the woods.

Now that it was not needful to make the dam bigger, the beavers turned to other work. Some of the canals they had dug had become filled up at a time when there was too much rain and the banks had caved in. Some of the beavers began to clear out these canals. Others mended holes in the dam, and still others cut down, and brought to the pond, tender branches of trees on which grew soft bark for the small beaver children to eat.

Everybody in the beaver colony had work to do. There was not a lazy one among them, and Toto and Sniffy worked as hard as any. They had time to play, too, and I’ll tell you about that in another chapter or two. Just now I want to speak about another wonderful adventure that happened to Toto.

The little beaver boy was growing larger now. He was quite strong for his size, and he was growing wiser every day. Often he went off in the woods alone to hunt for tender bark, or perhaps for some berries he liked to eat.

One day Toto was walking along near a canal he had helped to dig. He was thinking of Don, and wishing he might meet the nice dog again, and tell him about the tramps being driven away. And Toto was also thinking of the little girl with the red mittens, whose skate had come off on the ice.

Then, as Toto stepped from the woods into a little clearing, or place where no trees grew, he saw something big—bigger than a thousand beaver houses made into one.

“I wonder what that is?” thought Toto. “It looks something like the shack the tramps had in the woods, but it is much nicer. I wonder if it is a house?”

And then as Toto, hidden behind a bush, watched, he saw a little girl and an old lady come out of the house (for such it was) and walk away through the woods on a path.

“Why! Why!” exclaimed Toto to himself. “That’s the same little girl I saw on the ice! Only she’s different now. She hasn’t any red things on her paws.”

Of course, Toto thought the little girl’s hands were her paws. And the “red things” were her mittens. But, as it was summer now, she did not wear mittens. It really was the little girl who had been skating that Toto now saw come out of the house in the woods. The little girl had come to get her grandmother and take her for a visit to the little girl’s house.

Toto stayed hiding under the bush until the little girl and her grandmother were out of sight. Then, just as he was about to travel on, he heard some voices coming from behind a big stump. And, somehow or other, Toto seemed to know those voices. Carefully he looked up over the top of the bush.

“Now’s our chance!” said one of the voices, though of course Toto did not know what the[63] words meant. “Now’s our chance! The old lady and the little girl have gone out! Now we can break into the house and take whatever we want!”

“Yes, we might as well be burglars while we’re at it,” said another voice. “We can’t get any work, so we’ll take things that other people work for!”

And then, to the surprise of Toto, he saw, bobbing up from behind the stump, some of the very same ragged tramps that had gone away when the tree smashed their shack. They were now near the home of Millie’s grandmother.

“I heard there was some jewelry in that house,” said the red-haired tramp. “We can take it and sell it and then we can buy good things to eat.”

“That’s right,” said a black-haired one. “We’ll break in and get the jewelry. Nobody is at home to stop us.”

And then and there, as Toto watched, the bad tramps went toward the house to take the little girl’s grandmother’s jewelry.

“Oh, if Don were only here now!”

Toto, being only a beaver, did not know very much about the different things that men do. Toto knew how to gnaw down trees, how to strip off bark when he was hungry, how to dig canals for the water to run in and float logs for the dam, and he knew how to help make dams. But he never thought of going into another beaver’s house and taking the bark which that beaver had stored away.

And now these men were going into the house of the little girl’s grandmother, and they were going after jewelry which had been hidden by the old lady when she went away on a little visit with her granddaughter. But Toto knew nothing of this. All he knew was that he was hiding behind a bush, watching the tramps steal softly toward the lonely house.

One of the tramps, the red-haired one, broke open the door of the grandmother’s house. It was just the same as if Sniffy and Toto should break into the house of Mr. Cuppy, when that kind old gentleman beaver was out working on[65] the dam. Into the house went the tramps—four of them, big, ragged men.

“I hope they don’t see me,” thought Toto, for he knew it was dangerous to be where he was. His father and mother had told him to keep away from men who had traps and guns. And though these tramps were too lazy to do any hunting or shooting, Toto did not know that.

Really he ought not to have been so far away from home, but you know how it is with boys—even animal boys. Beavers sometimes don’t do the right thing, any more than real boys do. So, though he felt that there was danger, Toto wanted to stay near and watch.

He saw the tramps break into the house, but of course he did not see what they did when they got inside, so I shall have to tell you that part of the story myself.

The tramps easily broke open the door and got inside. The first thing they did was to look for something to eat, for, being lazy men, they did not work, and all the food they had was what they stole or begged. And as Millie’s grandmother was a good cook, there was plenty in her house to eat. The tramps had a fine meal, and they then looked about for something to take away with them.

Millie’s grandmother was not rich, but she had some gold and silver jewelry put away in a box[66] in her home. Some of the rings and pins were those Millie’s grandmother had had since she was a little girl herself, and there was one pretty bracelet that Mrs. Norman (which was the grandmother’s name), had promised to give Millie.

Mrs. Norman had hidden her box of jewelry under the bed when she went out, thinking that would be a safe place. But, would you believe it? That was one of the first places the tramps looked when they finished their meal.

“Ho! Ho!” laughed the tramps. “Here it is!”

With their coarse, rough hands they broke open the box, for the lock was not strong. Inside glittered the gold and silver jewelry of Mrs. Norman, and the sun sparkled on the pretty bracelet that was to be Millie’s.

“Ho! Ho!” laughed the tramps. “This will bring us money when we sell it!”

The tramps were looking at the jewelry in the box when, all at once, the red-haired one cried:

“Hark! I hear some one coming! We’d better run!”

“Come on!” exclaimed another.

So the next thing Toto, the watching beaver, saw was tramps come rushing from the house. Toto did not know what the tramps had done in the house, but he saw them come rushing out, the red-haired one carrying a small box. Of course[67] Toto did not know what was in the box. Beavers have no use for jewelry.

“Come on!” cried the red-haired tramp. “Come on! Maybe the police are after us!”

And so the tramps ran across the fields towards the woods where they had built themselves another shack. And these woods were not far from those where Toto and the other beavers lived, near the dam.

Now the noise which had scared the tramps was made by a boy knocking at the side door of the house where Millie’s grandmother lived. This boy, whose name was Bobbie Thompson, had been sent by his mother to borrow a cup of sugar from Mrs. Norman. Bobbie’s mother lived almost half a mile from Millie’s grandmother, and as there were very few stores in that part of the country the neighbors used to borrow things from one another. So Bobbie’s mother had sent him to borrow some sugar.

Bobbie did not know that Millie and her grandmother had gone out, and he did not know that tramps were in the house, when he knocked at the side door. And it was his knocking that had scared the ragged men.

Out of the front door of the house they rushed, and, as they hurried away, Bobbie, who was a sturdy little chap, saw them go.

“Hello there! What’s this?” cried Bobbie,[68] who was very much surprised. “What’s this?”

Then, as he saw what kind of men they were and that one of them had the box of jewelry under his arm, Bobbie understood.

“Tramps! Tramps!” cried Bobbie. “I wish I had my dog with me now! Those tramps have been robbing Mrs. Norman!”

Bobbie stood on the side steps a few seconds, watching the tramps run across the field. Then, being a brave boy, he decided to run after them. I don’t believe Bobbie really thought he could catch the tramps, nor that he hoped he could get the box of jewelry away from them if he did catch them. He just wanted to see where they went, so he could tell the police.

“Hi there! Come back with that box!” called Bobbie, and then he began to run. Off the steps he jumped, dropping the cup which he had come to get filled with sugar. He had forgotten all about that now.

After the tramps he ran, shouting and calling to them, and the queer part of it was that the tramps did not look back to see who was after them. They were too frightened, as they knew they had done wrong and could be arrested for it.

“Are the police after us?” asked one tramp.

“Yes, I guess so,” answered the red-haired one who had the jewel box. “We’d better hide this stuff, too! If they catch us with it we’ll have to[69] go to jail. We’ll hide it as soon as we get to the woods!”

And so the tramps ran on, never once looking back. If they had looked back they would have seen it was only a small boy chasing them, and not two or three policemen. But that is often the way with persons who do wrong. Their own fears scare them.

“Hi there! Hold on! Stop!” cried Bobbie. But the tramps did not stop. They only ran the faster toward the woods. And, finally reaching the forest, the red-haired tramp looked around for a place to hide the box of jewelry.

“I’ll put it in this hollow tree!” he said to the other tramps, as, reaching a big chestnut tree, he saw a hole in the trunk. “I’ll hide the jewelry here and, when the police go, we can come back and get it out again.”

So he thrust the box of gold and silver jewelry, with Millie’s bracelet in it, into the hollow of the tree. Then the tramps ran on through the woods, and scattered, some going one way and some another, still thinking the police were after them.

But it was only Bobbie, and the little boy, seeing that the tramps were fast running away from him, soon gave up the chase.

“I guess I’ll go back to Millie’s grandmother’s house,” said Bobbie to himself. “Maybe she’s come back. If she has I’ll get the sugar and tell[70] her about the tramps. If she isn’t at home I’ll go and tell my mother.”

Now all this time Toto was wondering what it all meant. He had seen the bad, ragged tramps break into the house, and he had seen them rush out, and Bobbie chasing after them. But the beaver did not know what it was all about. However, being very curious, as are most wild animals, Toto wanted to find out. So when Bobbie began to run Toto slowly followed after, taking care, however, to keep in the shadow of the bushes and trees.

Thus it happened that when Bobbie turned back, after he had lost sight of the tramps in the woods, he saw Toto ambling along.

“Hello! A beaver!” cried Bobbie. “I haven’t seen one of them for a long while! I’m going to get him! I’ll take him home for a pet!”

And then, running as fast as he could, Bobbie chased after Toto, wishing to catch our little friend with the broad, flat tail.

“My goodness!” thought Toto as he saw Bobbie coming. “I’d better run!”

By this time Bobbie had forgotten all about the tramps who took the jewelry. He was thinking only of catching Toto.

“Oh ho! You’re a fine, fat one!” laughed Bobbie. “I’d like you for a pet!”

“I’ve got to get away as fast as I can!” thought Toto. “I wish I had not come so far from the dam and the water back of it. If I could find some deep water now I’d dive into it and this boy chap couldn’t find me. I’d stay under a long time.”

But, just then, Toto could see no water near him, though he remembered he had swum in a brook almost up to the house into which the tramps had broken to get food and the box of jewelry.

“If I could only find that brook now!” thought poor Toto.

“I’ll get you! I’ll get you!” cried the boy. Of course Toto did not know what these words meant any more than the boy could understand beaver talk. But Toto knew he was in danger,[72] and the boy knew the little animal, with the flat tail, was trying to get away.

Now Toto could smell water even when he could not see it. His nose was very good for smelling, and, as he ran along—or rather “waddled,” as I call it—he kept sniffing to see if he could not smell water somewhere. And at last he did. Off to his left he caught the smell he so much wanted, and he turned sharply to one side.

“I wonder where he’s going now,” said the boy, aloud. “Maybe he has a nest over there. No, beavers don’t live in nests, so Jake told me. They have their houses in the water near a dam. I wish I could find a beaver dam. Then I could get two beavers for pets.”

Bobbie did not know how hard it was to capture beavers once those busy animals are in the water.

“I’ll get him! I’ll get that beaver!” cried the boy.

“If I can only get to the water I’ll be all right!” thought poor Toto, whose heart was beating very fast, both in fear and because he had to hurry along so quickly.

Just as the beaver reached the edge of the little stream Bobbie got there too, and made a grab for Toto. So close was Bobbie to Toto that the boy could almost touch the flat tail of[73] our friend. But Toto gave a jump, and into the water he landed, making a great splash. Down, down toward the bottom dived Toto, and at once he began to swim under water, for beavers can do that, just as muskrats can. Of course they are not like a fish, who has to stay under water all the while, and can not breathe in the open air. Beavers, and animals like that, can hold their breath a long while under water, and so can stay hidden and out of sight.

“Oh, there he goes!” cried Bobbie, much disappointed as he saw Toto dive into the stream. “But maybe I can get him!”

The boy ran along the bank of the stream, but Toto knew better than even to stick out so much as the tip of his nose. The beaver did not need to do this. He could swim under water for quite a long time, and that’s what he was doing now. His hind feet were webbed, like those of a duck, and his broad, flat tail helped him, too. It was like the propeller of a boat. In a half minute he was far enough away from Bobbie to be safe, and, though the boy ran along the stream for several minutes, he did not again see Toto—that is not for some days. Toto had got safely away, and, half an hour later, he was back at the dam, where he found his father and his mother and Sniffy waiting for him.

“Where have you been?” asked Mr. Beaver.[74] “You were gone so long that I thought something had happened.”

“Something did happen,” answered Toto. “A boy chased me, and I saw the ragged men—the tramps as Don, the dog, called them!”

“My goodness!” exclaimed Mrs. Beaver. “Chased by a boy! Did he catch you?”

“No, I got away just in time,” answered Toto.

“I hope those tramps aren’t coming to our woods again,” said Mr. Beaver.

“Well, they ran in among the trees,” said Toto, “and they stopped at a hollow one, put something in there, and then they ran on.”

“Maybe they hid a lot of bark in the hollow tree,” said Sniffy. For a beaver, you know, bark is the best thing there is in the world. It is better to him than jewelry ever could be.

“I don’t know what it was they hid,” said Toto. “But the boy chased them and then he chased me.”

“You must always be careful,” warned his father. “These woods are too often visited by hunter men and boys these days. Watch out for traps.”

Toto and Sniffy said they would, and then the beaver boys went out on a little hill, near the pond back of the dam, to have some fun. And the fun they had was sliding downhill!

I suppose it may sound odd to you to be told[75] that beavers slide downhill, but they really do, and other wild animals in the woods do the same thing. They don’t wait for snow and ice to cover the hill, either, as you boys and girls do. In fact, most animals do not like snow and ice—unless perhaps it is polar bears—and when winter comes many animals take a long sleep until warm weather comes again.

Of course Toto and the other beavers have to stand the cold, and perhaps be out in the ice and snow, and that is why they have such a thick, warm coat of fur.

But the sliding downhill fun I am going to tell you about took place in the summer, and I suppose you are wondering how any one can slide downhill when there is no snow or ice.

Well, the beavers slide down on mud. You know how slippery mud is when it is wet. And there is a kind of mud, called “clay,” which is very slippery indeed. If you have ever been near a brickyard, and have seen the clay dug out and wet, you know how slippery it is. It is even more slippery than snow or ice.

Now near the beaver pond was a hill of clay, and some of it had been taken by Cuppy and the older animals to plaster up holes in the dam. This digging out of the clay, made a bare place on the hill, where the grass was torn away, leaving the soil exposed.

This clay slide was where Toto, Sniffy and the other beavers had their fun. And not only the young beavers, but the old ones as well, even Cuppy, took their turns going down the slide. Otters also make slippery slides to coast down, and I have even heard that big bears, when they can find a place, like to slide downhill.

The animals do this not only for fun, but to keep their muscles and legs limber and strong. It is their exercise, just as you raise your arms and bend your bodies in school when you take your exercise.

Now to be slippery, clay has to be wet. And, as it would not do to wait for a rain to come to wet the slide, the beavers, otters, and other animals wet the slides themselves. They go into the water at the foot of the slide, get themselves soaking wet, climb out and go to the top of the hill. There they sit down and the water, dripping from their bodies, makes the hill slippery. Down they go, splashing into the stream or the pond at the foot. Almost all the slides end in water.

“Come on out and slide down!” called Toto to Sniffy, and away they ran. They climbed up the hill at a place where it was not slippery and, taking turns, sat down at the top of the slide. Then, giving themselves a little push with their paws, as you give yourself a push with your feet when you sit on your sled, down they went.

Sometimes the beavers slid down on their tails, and sometimes on their backs. Some even slid down on their stomachs, or went down sideways. Down they went, any way to get a slide, and into the water they splashed.

“Hi there! Look out!” cried Toto to Dumple, a little fat beaver boy who lived in the stick house next to him. “Look out! I’m coming!”

But Dumple did not get out of the way quickly enough, and when Toto slid down he bumped right into him, and the beaver chaps went down the slide together and into the water with a splash.

“Ho! Ho! That was fun! Let’s do it again,” cried Dumple.

“All right!” agreed Toto. “But did I hurt you?”

“Not a bit!” laughed Dumple. “Come on, Sniffy! Let’s bump into one another on the slide!” he called.

So Toto’s brother joined the fun, and many other beavers played on the slide, climbing up and coasting down.

When supper time came Toto and the others had very good appetites for the bark which was waiting for them. Darkness came, and the beavers went to sleep. The night settled down on the beaver pond and dam. As Toto went to sleep perhaps he thought of the adventures of that day—how he had seen the boy chase the[78] tramps, and how the ragged men had hidden something in the hollow tree. But Toto did not think much about that. He was too tired and sleepy after playing on the mud slide.

It was two or three days after this that, as our beaver friend was walking through the woods, looking for some soft bark for his mother, he heard a funny little noise up in a tree. The noise went:

“Mew! Mew! Meaouw!”

“Hello! what’s that?” called Toto, looking here and there. “Is anything the matter?” he asked.

“I should say there was!” came the answer. “A bad dog chased me up this tree and now I’m afraid to come down.”

“Who are you?” asked Toto.

“I am Blackie, and once I was a lost cat,” was the answer. “I guess I’m pretty nearly lost now. Oh, dear! what shall I do?”

Toto looked up in the tree from which the mewing noise came. There he saw a black cat. The cat sat in a place where a branch joined the main trunk of the tree, and Toto wondered why, if she got up there, she could not get down.

“What happened to you?” asked the beaver boy.

“A dog chased me,” was the answer. “I was out walking in the fields, and a dog ran along after me. I was so frightened that I scampered as fast as I could. Then I ran up this tree. I hardly knew what I was doing, or how I got up so high. But here I am, and though it seemed easy to get up, I’m afraid to try to get down. I might slip and fall.”

“Did you walk up the tree?” asked Toto, wondering why she couldn’t walk down again.

“No, I stuck my claws into the bark and pulled myself up,” answered the black cat. “But it’s harder to go down. I don’t know what to do! I wish that dog had let me alone.”

“Was the dog who chased you named Don?” asked Toto. “I know him.”