The Project Gutenberg EBook of A System of Practical Medicine By American

Authors, Vol. IV, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: A System of Practical Medicine By American Authors, Vol. IV

Diseases of the Genito-Urinary and Cutaneous

Systems.--Medical Ophthalmology, and Otology

Author: Various

Editor: Pepper William

Starr Louis

Release Date: July 8, 2020 [EBook #62587]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PRACTICAL MEDICINE ***

Produced by Ron Swanson

|

DISEASES OF THE KIDNEYS, INCLUDING THE PELVIS OF THE KIDNEYS. By ROBERT T. EDES, M.D.

DISEASES OF THE PARENCHYMA OF THE KIDNEYS, AND PERINEPHRITIS. By FRANCIS DELAFIELD, M.D.

HÆMATURIA AND HÆMOGLOBINURIA OR HÆMATINURIA. By JAMES TYSON, A.M., M.D.

CHYLURIA. By JAMES TYSON, A.M., M.D.

DISEASES OF THE MALE BLADDER. By EDWARD L. KEYES, A.M., M.D.

SEMINAL INCONTINENCE. By SAMUEL W. GROSS, A.M., M.D.

DISPLACEMENTS OF THE UTERUS. By EDWARD C. DUDLEY, A.B., M.D.

DISORDERS OF THE UTERINE FUNCTIONS, INCLUDING AMENORRHOEA, DYSMENORRHOEA, AND MENORRHAGIA. By J. C. REEVE, M.D.

INFLAMMATION OF THE PELVIC CELLULAR TISSUE AND PELVIC PERITONEUM. By B. F. BAER, M.D.

PELVIC HÆMATOCELE. By T. GAILLARD THOMAS, M.D.

FIBROUS TUMORS OF THE UTERUS. By WILLIAM H. BYFORD, M.D.

SARCOMA OF THE UTERUS. By WILLIAM H. BYFORD, M.D.

CARCINOMA OR CANCER OF THE UTERUS. By WILLIAM H. BYFORD, M.D.

DISEASES OF THE OVARIES AND OVIDUCTS. By WILLIAM GOODELL, M.D.

DISEASES OF THE URINARY ORGANS IN WOMEN. By ALEXANDER J. C. SKENE, M.D.

DISEASES OF THE VAGINA AND VULVA. By EDWARD W. JENKS, M.D., LL.D.

DISORDERS OF PREGNANCY. By W. W. JAGGARD, A.M., M.D.

FUNCTIONAL DISORDERS IN CONNECTION WITH THE MENOPAUSE. By W. W. JAGGARD, A.M., M.D.

DISEASES OF THE PARENCHYMA OF THE UTERUS; METRITIS AND ENDOMETRITIS, INCLUDING LEUCORRHOEA. By W. W. JAGGARD, A.M., M.D.

ABORTION. By GEORGE J. ENGELMANN, M.D. (Berlin)

1 Though properly belonging in Vol. V., with Diseases of the Nervous System, this section has been placed here for convenience.

MYALGIA. By JAMES C. WILSON, A.M., M.D.

PROGRESSIVE MUSCULAR ATROPHY. By JAMES TYSON, A.M., M.D.

PSEUDO-HYPERTROPHIC PARALYSIS. By MARY PUTNAM JACOBI, M.D.

DISEASES OF THE SKIN. By LOUIS A. DUHRING, M.D., and HENRY W. STELWAGON, M.D.

MEDICAL OPHTHALMOLOGY. By WILLIAM F. NORRIS, A.M., M.D.

MEDICAL OTOLOGY. By GEORGE STRAWBRIDGE, M.D.

BAER, B. F., M.D.,

Professor of Obstetrics and Gynæcology in the Philadelphia Polyclinic and College for Graduates in Medicine, and Dean of the Faculty; Obstetrician to Maternity Hospital; President of the Obstetrical Society of Philadelphia, etc.

BYFORD, WILLIAM H., M.D.,

Professor of Gynæcology in the Rush Medical College, Chicago.

DELAFIELD, FRANCIS, M.D.,

Professor of Pathology and Practical Medicine in the College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York.

DUDLEY, EDWARD C., A.B., M.D.,

Professor of Gynæcology in the Chicago Medical College, Chicago.

DUHRING, LOUIS A., M.D.,

Professor of Skin Diseases in the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

EDES, ROBERT T., M.D.,

Jackson Professor of Clinical Medicine in Harvard University, Boston, Mass.

ENGELMANN, GEORGE J., M.D. (Berlin),

Professor of Obstetrics and Gynæcology in the St. Louis Polyclinic and Post-Graduate School of Medicine.

GOODELL, WILLIAM, M.D.,

Professor of Clinical Gynæcology in the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

GROSS, SAMUEL W., A.M., M.D.,

Professor of the Principles of Surgery and of Clinical Surgery in the Jefferson Medical College of Philadelphia.

JACOBI, MARY PUTNAM, M.D.,

Professor of Materia Medica and Therapeutics in the Women's Medical College, New York, and Professor of Diseases of Children at the New York Post-Graduate School.

JAGGARD, W. W., A.M., M.D.,

Professor of Obstetrics in the Chicago Medical College, Medical Department Northwestern University; Obstetrician to Mercy Hospital, Chicago.

JENKS, EDWARD W., M.D., LL.D., Detroit, Michigan,

Formerly Professor of Medical and Surgical Diseases of Women and Clinical Gynæcology in the Chicago Medical College, and in the Post-Graduate Medical School of New York.

KEYES, EDWARD L., A.M., M.D.,

Professor of Genito-Urinary Surgery and Syphilis in the Bellevue Hospital Medical College, New York; Surgeon to Bellevue Hospital; Consulting Surgeon to the Charity Hospital.

NORRIS, WILLIAM F., A.M., M.D.,

Clinical Professor of Ophthalmology in the University of Pennsylvania, Surgeon to Wills Ophthalmic Hospital, Philadelphia.

REEVE, J. C., M.D., Dayton, Ohio,

Formerly Professor of Materia Medica and Therapeutics in the Medical College of Ohio.

SKENE, ALEXANDER J. C., M.D.,

Professor of Gynæcology in the Long Island College Hospital, Brooklyn, and in the Post-Graduate Medical School of New York.

STELWAGON, HENRY W., M.D.,

Physician to the Philadelphia Dispensary for Skin Diseases; Chief of the Skin Dispensary of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

STRAWBRIDGE, GEORGE, M.D.,

Clinical Professor of Otology in the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

THOMAS, T. GAILLARD, M.D.,

Clinical Professor of Diseases of Women in the College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York; Surgeon to the New York State Woman's Hospital.

TYSON, JAMES, A.M., M.D.,

Professor of General Pathology and Morbid Anatomy in the University of Pennsylvania; Physician to the Philadelphia Hospital, Philadelphia.

WILSON, JAMES C., A.M., M.D.,

Physician to the Philadelphia Hospital, and to the Hospital of the Jefferson College; President of the Pathological Society of Philadelphia.

| FIGURE | |

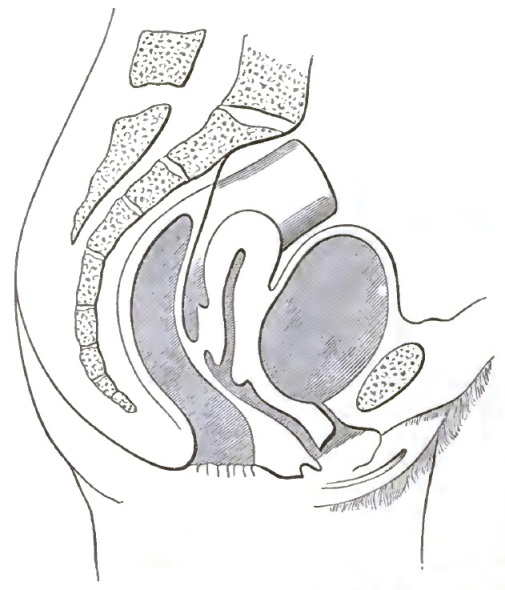

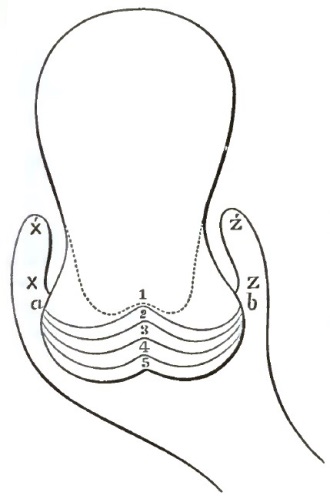

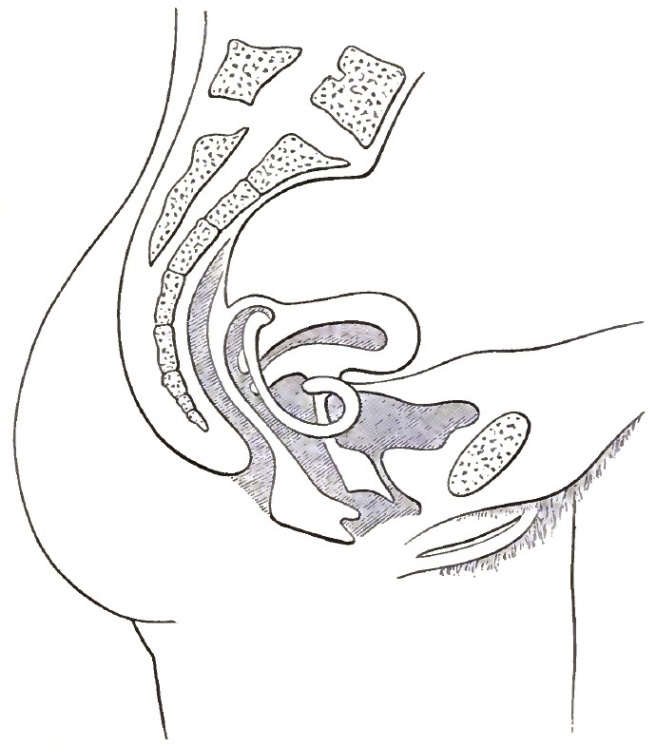

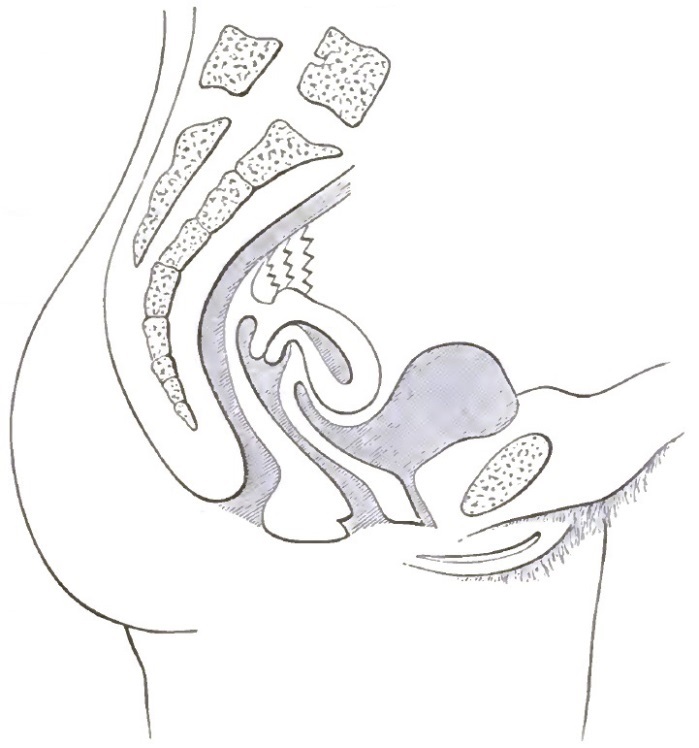

| 1. | THE CLASSICAL REPRESENTATION OF THE PELVIC ORGANS |

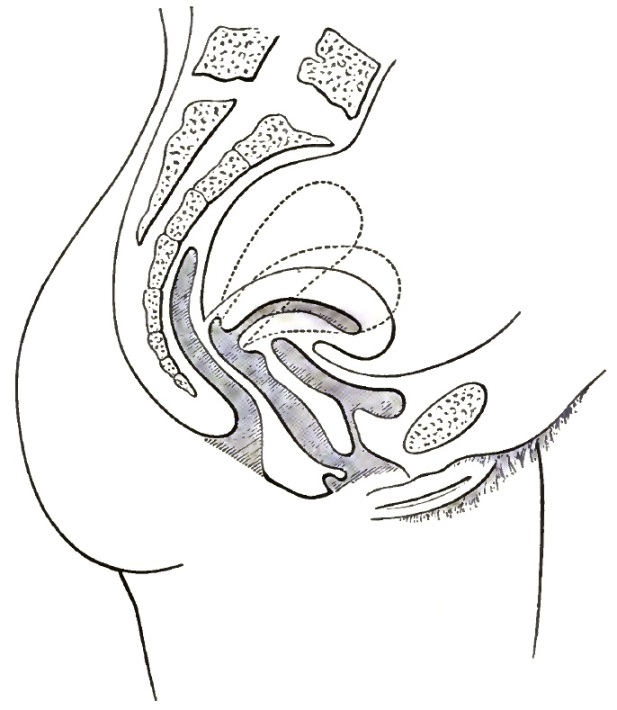

| 2. | THE CORRECT REPRESENTATION OF THE PELVIC ORGANS |

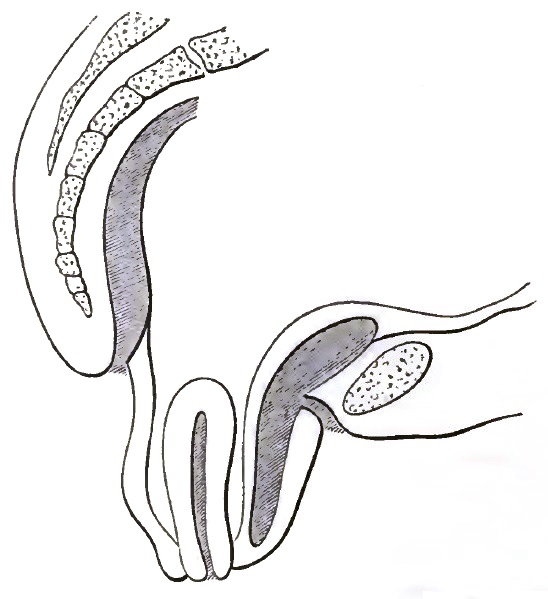

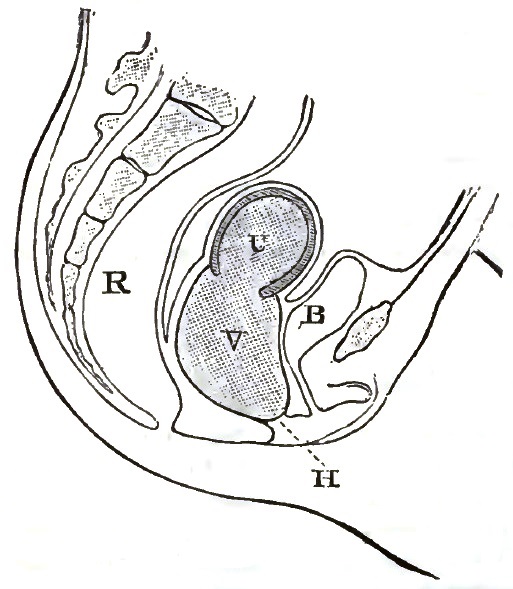

| 3. | FIRST DEGREE OF PROLAPSE OF THE POST-PARTUM UTERUS |

| 4. | SHOWING EXTREME DESCENT OF THE UTERUS AND OF THE PELVIC FLOOR, AND THE HERNIAL CHARACTER OF THE LESION |

| 5. | DESCENT OF THE VIRGIN UTERUS INTO THE VAGINAL CANAL, SHOWING THE REDUPLICATED VAGINAL WALLS |

| 6. | DESCENT OF THE UTERUS, SHOWING EXCESSIVE CIRCULAR ENLARGEMENT OF THE LACERATED CERVIX, CONSEQUENT UPON REDUPLICATION OF THE VAGINAL WALLS AND OUT-ROLLING OF INTRACERVICAL TISSUES |

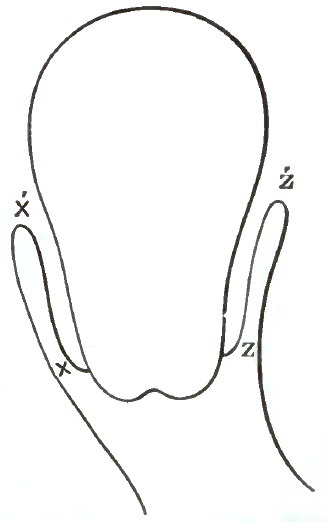

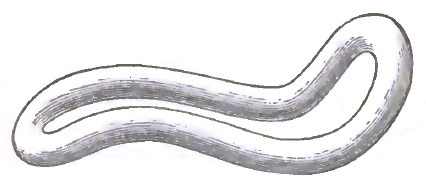

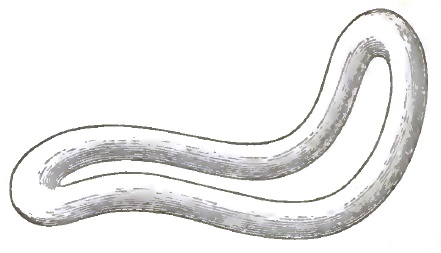

| 7. | THE EMMET CURVES (PESSARY) |

| 8. | THE ALBERT SMITH CURVES (PESSARY) |

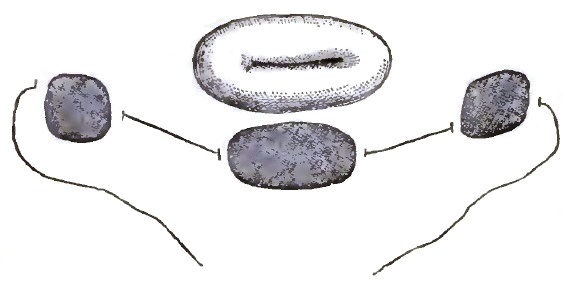

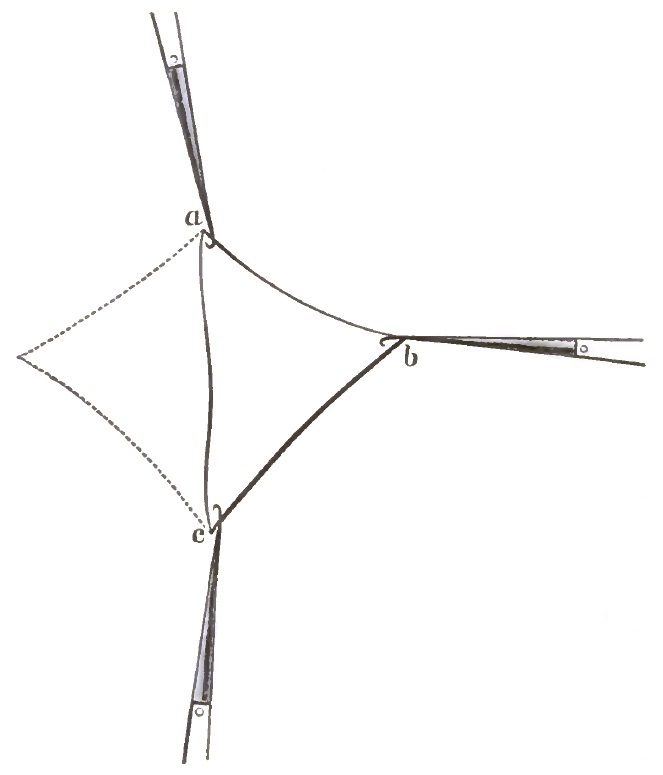

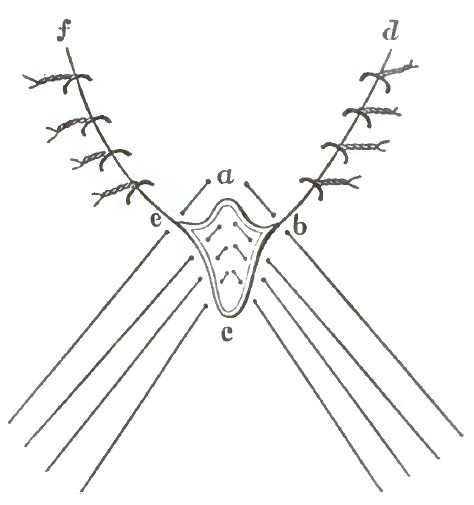

| 9. | THE FIRST SUTURE BEFORE TWISTING IN EMMET'S OPERATION IN PROCIDENTIA |

| 10. | FOLDS ON THE ANTERIOR VAGINAL WALL FORMED AFTER TWISTING THE FIRST SUTURE |

| 11. | EMMET'S OPERATION FOR PROCIDENTIA AND URETHROCELE COMPLETED |

| 12. | DIAGRAM OF EMMET'S OPERATION |

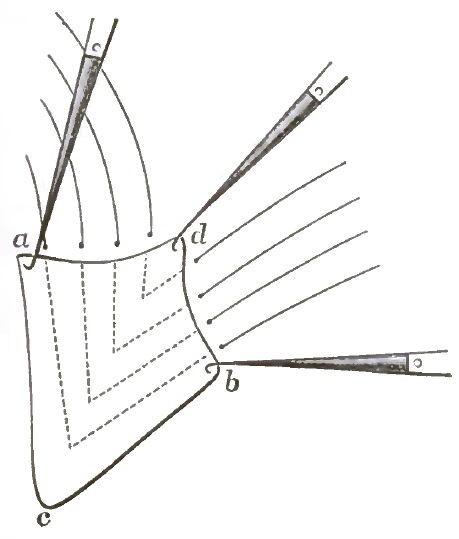

| 13. | THE SUTURES IN PLACE |

| 14. | THE VAGINAL SUTURES TWISTED |

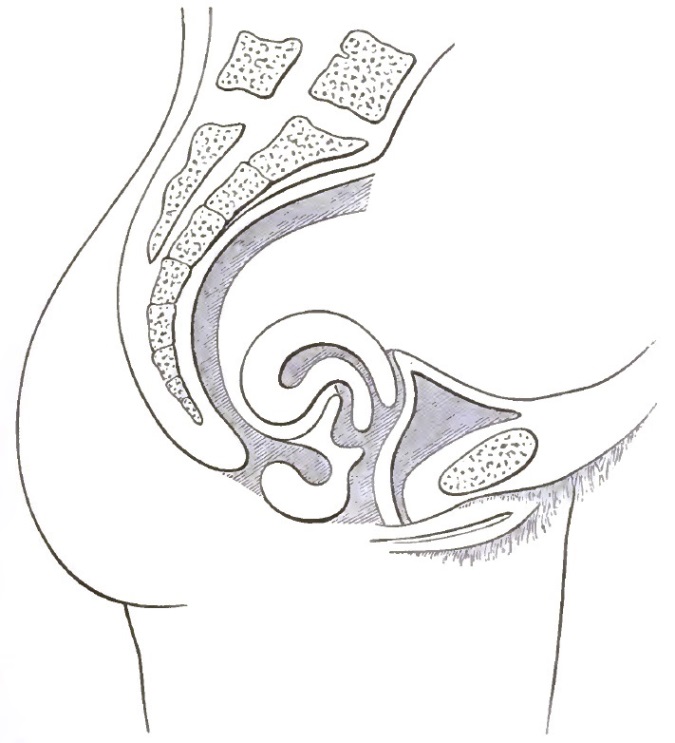

| 15. | EXTREME RETROFLEXION, WITH HYPERTROPHY OF THE CORPUS |

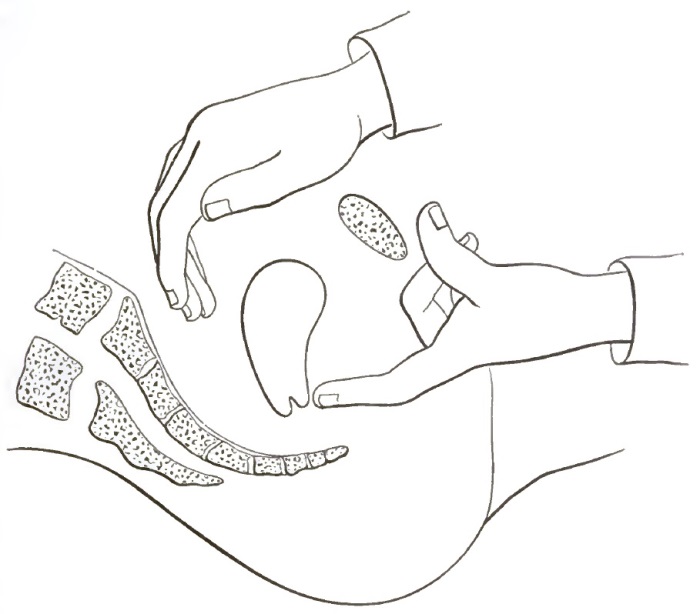

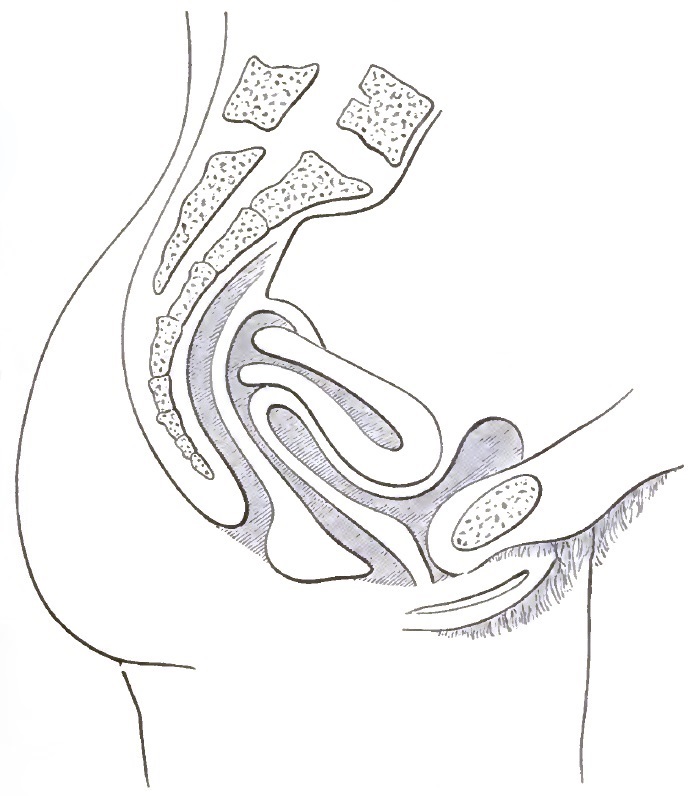

| 16. | COMMENCING REPOSITION OF THE RETROVERTED OR RETROFLEXED UTERUS BY CONJOINED MANIPULATION |

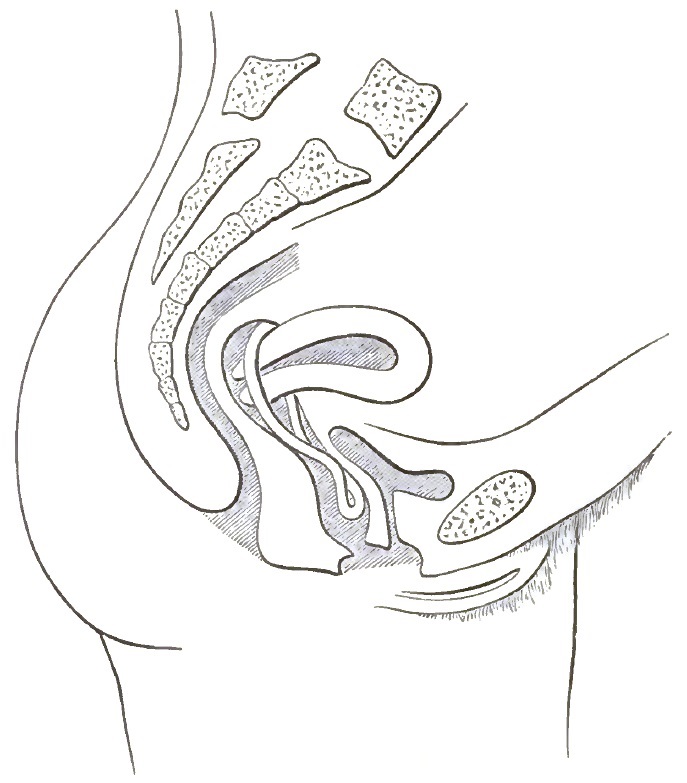

| 17. | COMPLETED REPOSITION OF THE RETROVERTED OR RETROFLEXED UTERUS BY CONJOINED MANIPULATION |

| 18. | SHOWING THE PELVIC ORGANS SUSTAINED BY THE EMMET PESSARY AFTER REPOSITION OF THE PROLAPSED, RETROVERTED, OR RETROFLEXED UTERUS |

| 19. | SCHULTZE'S SLEIGH PESSARY IN PLACE |

| 20. | FRONT VIEW OF SCHULTZE'S FIGURE-OF-EIGHT PESSARY |

| 21. | THOMAS'S RETROFLEXION PESSARY |

| 22. | PATHOLOGICAL ANTEVERSION |

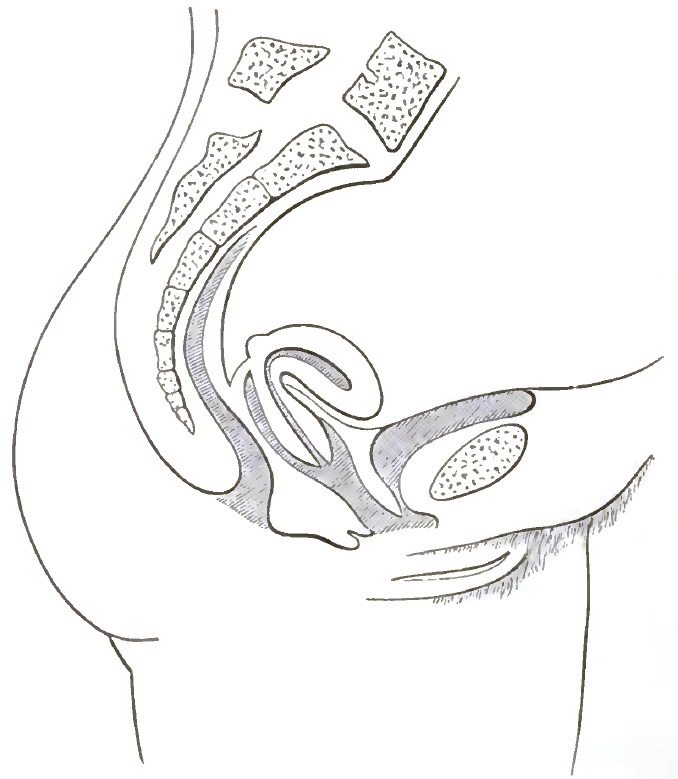

| 23. | CONGENITAL ANTEFLEXION |

| 24. | ANTEFLEXION WITH POST-UTERINE FIXATION |

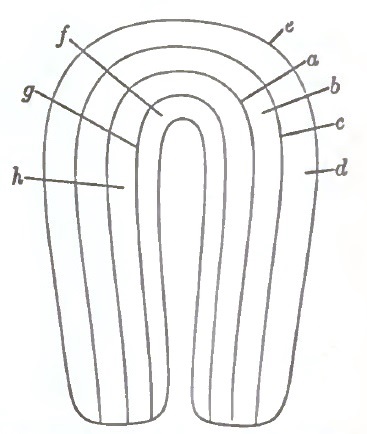

| 25. | DIAGRAM SHOWING MUSCULAR STRATA OF UTERUS, AS DIVIDED FOR CLINICAL PURPOSES |

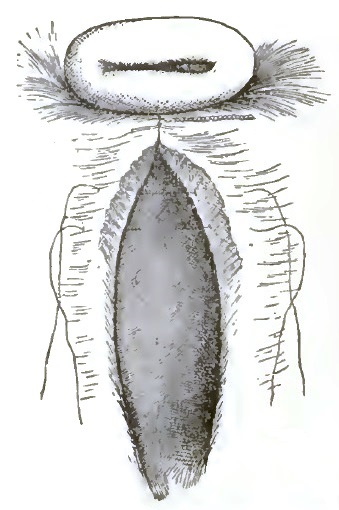

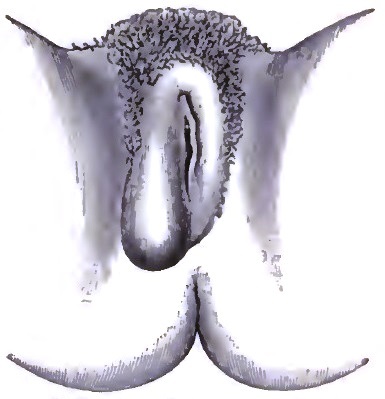

| 26. | IMPERFORATE HYMEN |

| 27. | SIMS'S VAGINAL DILATOR |

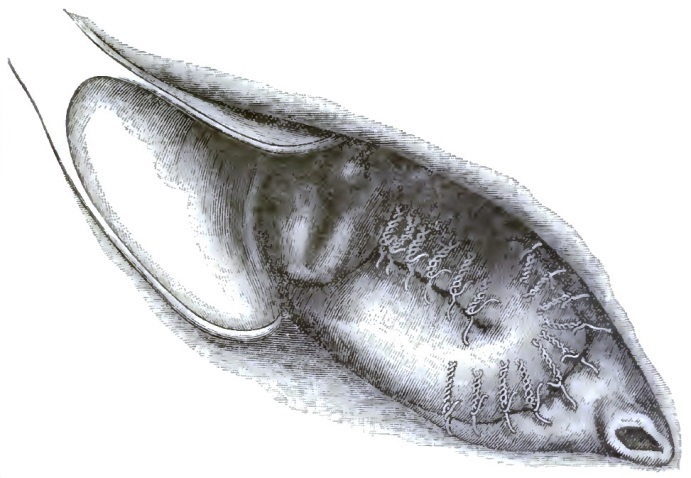

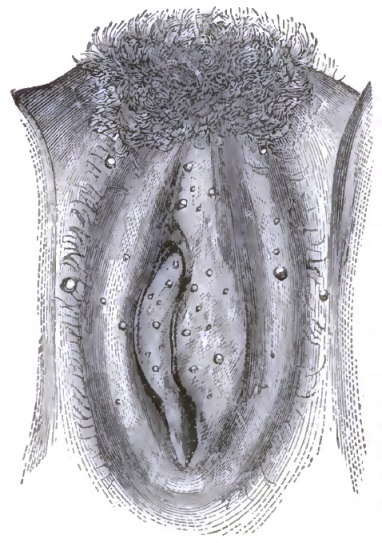

| 28. | FOLLICULAR VULVITIS (HUGINER) |

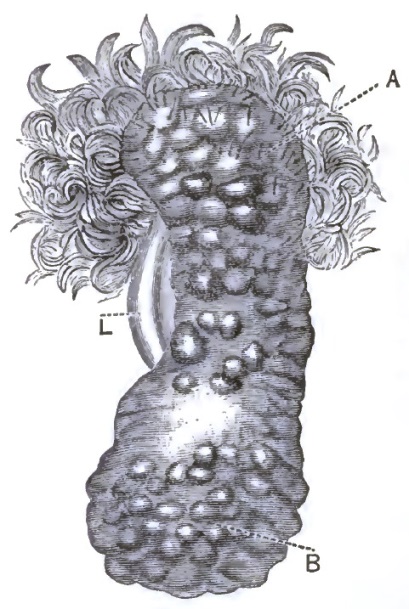

| 29. | ABSCESS OF GLANDS OF BARTHOLINI |

| 30. | ELEPHANTIASIS OF VULVA |

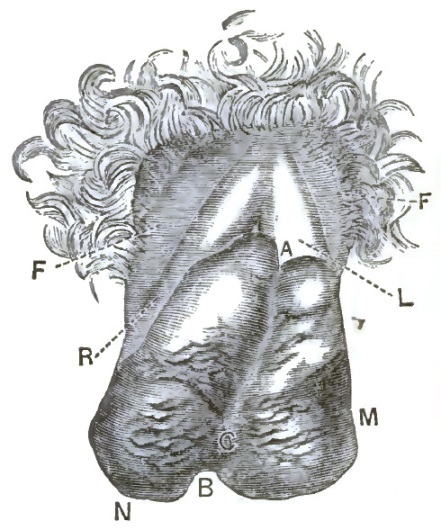

| 31. | ELEPHANTIASIS OF VULVA |

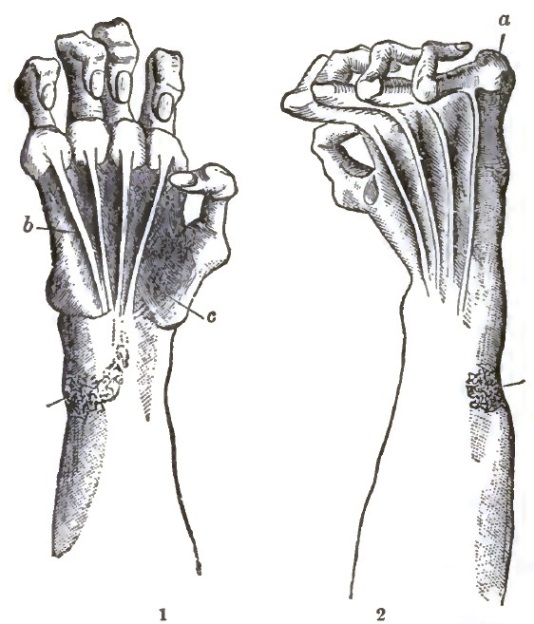

| 32. | DEFORMITY OF HAND IN PROGRESSIVE MUSCULAR ATROPHY |

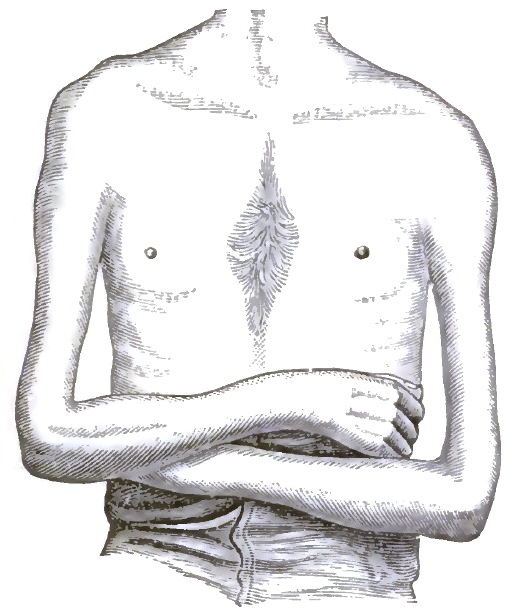

| 33. | SHOWING ATROPHY OF THE RIGHT DELTOID AND ARM, AND OF THE LEFT ARM |

| 34. | SHOWING ATROPHY OF THE DELTOID, POSTERIOR ASPECT, AND OF THE SCAPULAR MUSCLES |

The kidneys are two glandular organs, of a concavo-convex shape so characteristic as to be frequently used as a term of comparison, situated on each side of the vertebral column, with the longer diameters nearly parallel thereto, but slightly convergent toward the upper extremity, and extending from about the upper border of the eleventh rib on the left side and the middle of the corresponding rib on the right to the second or third lumbar vertebra. Hence they are somewhat less than half covered by the last two ribs.

The upper extremity is a little the wider and the thinner, and by this peculiarity and a recollection of the position of the vessels (from the front, vein, artery, ureter) the two kidneys may be assigned to their proper sides after removal from the body.

They are behind, and at their upper extremities nearly in contact with, the peritoneum, resting, with their more or less voluminous envelope of adipose tissue, upon the great muscles of the loins. The fat which in the normal condition surrounds the kidneys varies, as might be supposed, within wide limits, and is by no means devoid of importance, since its deficiency is undoubtedly a predisposing cause for some of the displacements hereafter to be described. In this fatty mass may also be situated perinephritic abscesses, and into it spread with considerable facility morbid growths originating in the kidney itself.

At the middle of the inner borders of the kidneys are situated the hiluses into which enter veins, arteries, ureters, nerves, and lymphatics, united by connective tissue and forming a sort of pedicle.

The normal weight of each kidney is to be expressed by a rough average as from four and a quarter avoirdupois ounces, or one hundred and twenty grammes, on the one hand, to seven ounces, or two hundred grammes, on the other; but since a deficiency in the size of one is not unfrequently compensated by an increase in the other, it would be safer to give the weight of the pair as from two hundred and forty to four hundred grammes, the lesser number representing those organs which are not only small but anæmic, and the larger those which are either distinctly hypertrophied or much congested: many diseased kidneys will also be found within these limits.

The size of the kidney is in a general way proportioned to the size of [p. 20] the body: the proportion is stated as 1 to about 240. A disproportionate change in the size of both kidneys without any change in structure is a true hypertrophy, and may be met with in persons whose habits as regards the ingestion of fluids (especially such as are freely secreted by the kidneys—for instance, beer or other forms of dilute alcohol) tend toward excess, or where a disease like diabetes throws a large amount of diuretic material into the circulation.

The deep position of the kidneys makes them usually inaccessible to physical exploration to any practical extent. In stout persons they are so entirely covered by their own immediate envelope of fat, by the adipose tissue of the mesentery, and by the thick abdominal walls as to be completely indistinguishable. In thinner persons deep palpation with both hands may enable us to say that there is a diminished resistance to pressure, as in the case of movable kidney, or that there is or is not any decided enlargement. Slighter changes in size cannot be accurately determined, although Bartels1 states that he was once enabled to detect a considerable enlargement in a case of parenchymatous nephritis by double palpation. In moderately thin persons the lower end of the kidney can be more or less distinctly felt.

1 Ziemssen, vol. xv.

A position upon the hands and knees (not the gynecological semi-prone position), allowing the whole abdomen to gravitate directly away from the backbone, is said to afford, by the varying concavity of the lumbar region on the two sides, information as to the absence of either kidney from its usual place. When the kidney, however, is displaced, and when it comes decidedly forward from increase in its own size or from the pressure of a tumor behind it, it may very often become extremely accessible.

Percussion gives even less information than palpation, since the dulness of the lumbar muscles extends laterally beyond that of the kidneys, and is of itself so complete as to offer no change from the addition or subtraction of the resistance of the underlying organ.2

2 It is probable that Simon's method of thrusting the hand into the rectum and large intestine might be made available by a person with a small hand and arm for diagnosis in doubtful cases where the value of the information to be obtained would be sufficient to compensate for the risk of serious injury.

The removal of the kidneys may be accomplished through the rectum—and has been effected many times by myself and assistants—in cases where a complete autopsy is refused. The manoeuvre is not very difficult through a large and especially a female pelvis, but under other circumstances may be somewhat fatiguing. Considerable post-mortem information in regard to other organs may be obtained in the same way.

The most marked anomaly in the shape of the kidneys when both are present, and the only one which possesses a clinical interest, is that known as the horseshoe kidney, being a more or less complete fusion of the organs of each side in front of the vertebral column and the great vessels. This fusion is usually at the lower end, but may be in the middle or at the upper end. Sometimes there is a portion lying directly in front of the vertebral column so large and thick as to appear almost like a middle lobe or a third kidney. In a few rare instances this portion has formed a pulsating enlargement mistaken for an aortic aneurism or other abdominal tumor. In others compression of the great vessels has given rise to phlebitis, or the abnormal position of the ureters has obstructed the passage of the urine, with the results, as regards the secondary affection of the kidneys, to be described below. [p. 21] These instances are, however, among the curiosities of medicine, and no rule for their diagnosis can be laid down. A horseshoe kidney is usually discovered only after death, and with no special frequency in cases of renal disease.

Variations in the number of the kidneys possess this point of practical interest, that diseases affecting a single organ are more dangerous than if another exists which can take upon itself extra duty. Apparent absence of one kidney may be due to atrophy, attended with very small size of the renal vessels; in which case a small mass of connective tissue is found at the upper end of the ureter, which is usually illy developed. The other kidney is usually hypertrophied.

The kidney may fail to be developed. In this case there are no vessels corresponding to the renal artery and vein, and the ureter is stated to be invariably absent, but the writer has seen a specimen where the left ureter terminated superiorly in a rounded cul-de-sac, no kidney or suprarenal capsule being present. The other kidney was of rather large size in proportion to the size of the patient, but of the usual form. This defect is apt to be associated with some anomaly of the genital organs.

Another condition, apparently similar, but really due to a fusion of the two embryonic kidneys, is sometimes found. In this the single organ, situated upon one side, is irregular in form and in the number and origin of its vessels. There are usually two ureters, arising one above or beside the other, and directed to their proper positions in the floor of the bladder. A single ureter arising from a single kidney has been seen to empty upon the opposite side of the bladder.

Supernumerary kidneys have been noted. In one case an extra pair, situated below the others, were intensely inflamed, while the normal organs were not so.

A position of one kidney has been noticed considerably higher than normal, so as to push the spleen from its place. A more common anomaly, however, is the situation of one kidney at a point much below the usual, most commonly at the brim of the pelvis. When this happens the kidney itself is usually more or less distorted in form, and receives its blood-supply from several small arteries which enter it at irregular points, forming as it were several small hiluses. They may originate from the aorta or from one or both iliacs. The ureter is correspondingly short. This position is of some importance, since a pelvic tumor is formed which has in one instance proved an obstacle in childbirth, while in another the misplaced kidney itself underwent an acute nephritis from the pressure of the foetal head. The kidney tumor has in a few instances been felt in this position during life, but its nature has not been diagnosticated.

The most clinically important change in the position of the kidney is not a permanent one, but varies from time to time with the posture of the patient and the altered conditions of pressure—externally by dress or apparatus, or internally by the other abdominal organs. It is known as floating or wandering kidney. In this affection the kidney ceases to [p. 22] be firmly imbedded in the fat usually found in the lumbar region, constituting a support and packing for these organs as well as for the suprarenal capsules, and is allowed more or less liberty of movement, which is restrained by a pedicle consisting of the ureter, vessels, and nerves, with more or less connective tissue. As it passes downward and forward it comes into more intimate relations with the peritoneum, which usually covers only the anterior surface, often with an intervening layer of fat, so that it may even gain a sort of special investment or meso-nephron.

The extent of the excursions of which the tumor thus formed is capable must naturally vary considerably. Sometimes the organ can be pushed or make its own way forward so as to come into contact with the anterior abdominal wall on the same side, and not much lower than the normal position, or it may pass considerably downward, and thus be confounded with tumors arising from the pelvis.

This affection is much more frequent among women than in men, and the right kidney is more frequently movable than the left: both, however, are sometimes dislocated. It is observed in a much larger proportion of cases in the laboring classes than in those whose work is less severe and carried on in less constrained attitudes. Judging from the relative amount of the literature of the subject, it would appear to be much less frequently observed in this country than among the lower classes of Germany, where so large a proportion of the severest outdoor labor is carried on by women.

Various causes are assigned for this displacement. It is stated to be usually congenital, but is not described as found post-mortem in children with at all the frequency that it occurs in adults; and it is certainly possible in adults to fix in many cases the beginning of the disease with a reasonable degree of certainty. That a certain amount of predisposition, or peculiarly favorable position of the kidney, or an unusual laxity of connective tissue, exists in a certain number of cases is undoubtedly true.

The next most important factor is undoubtedly a laxity of the abdominal walls, affording a less firm and unyielding support to the contained viscera, and a deficiency, usually an acquired one, of the fat surrounding the kidney, which enables it in the normal condition to be supported by the layer of peritoneum passing across its front from the spinal column to the flank. This is seen in a certain set of cases where the trouble dates from an acute disease or a rapid emaciation. The well-known influence of repeated pregnancies is undoubtedly exerted in this way.

Another set, especially those exceptional cases which occur in strongly-built and not thin persons, are referable to severe shocks received in gymnastic exercises, hard riding, or falls from a horse.

One of the most frequent causes, and one which accounts for the fact of the affection being most prevalent among the working classes, is the use of a tight strap or cord to support the garments. Corsets, which exercise a more even pressure over a larger surface, do not have this effect. The right kidney, from the position of its superior extremity in front of the liver and its slightly higher place in the abdomen, appears to be more influenced by this pressure than the left. The movements of respiration, especially when reinforced by the forced inspiration and [p. 23] compression of the abdominal viscera accompanying violent exertion, appear to assist in the dislodgment already favored by the pressure of the girdle.

According to Müller Warnek,3 who has laid especial stress on this method of causation, a slighter degree of displacement is possible in this way without or preceding the full development of wandering kidney. A pressure is exercised upon the descending duodenum with which the right kidney is brought into intimate relations behind, and bound down by, the peritoneum; which leads, as Bartels supposes, to a hindrance in the passage of food from the stomach, and consequent dyspeptic phenomena. In these cases, when the kidney has become a more freely movable one and has dropped farther down in the abdominal cavity, the pressure on the duodenum ceases, the consequent symptoms disappear, and give place to the dragging sensations and severe colicky attacks which are apt to characterize an older case.

3 Berl. klin. Woch., 1877, 38.

SYMPTOMATOLOGY.—There is great variety in the kind and amount of effect which the movable kidney exercises on the general organism and the local effects it produces. Neither the local nor the general symptoms are necessarily proportionate in severity to the amount of the displacement.

It may be said in advance that, contrary to what might be expected, the symptoms are not usually connected with any disturbance in the urinary function, and, although exceptions are not unknown, the rule is for a displaced kidney to be an otherwise healthy one. Cystitis and uterine affections have been observed in this connection, but it is doubtful if any relation other than coincidence or a mutual dependence upon impaired general nutrition and overwork exists between them. The partial stoppages which might be supposed to arise from the twisting of the ureters are not frequently observed.

Hysteria and hypochondriasis have been frequently attributed to this lesion, and might undoubtedly find their exciting cause in anxiety about a tumor of unknown character and origin; but there seems no good reason to connect them in any other relation of causation. It is undoubtedly true that many pains and discomforts exist in these cases which are neither satisfactorily explained nor gotten rid of by being called hysterical. These abdominal pains, especially of a dragging character, and also the sensation as of something falling or moving about in the abdomen, particularly when the patient assumes the upright posture or makes unusual exertions, are very naturally connected with the existence of the actual condition which is likely to give rise to them. Müller Warnek has recorded the frequent coincidence of flatulent dyspepsia and dilatation of the stomach depending on retention, and its consequent fermentation, in connection with the movable kidney and its supposed pressure on the duodenum. It is not probable, however, that all the symptoms are to be explained so simply, but it is quite as likely that the dragging and tension of the pedicle may have a remoter effect through the renal and sympathetic nerves.

Severer attacks occasionally occur with violent colic and inflammatory symptoms, the tumor formed by the misplaced organ becoming exceedingly sensitive to pressure. These have been attributed to some [p. 24] incarceration, but there is no evidence that this accident occurs, and it has not been found after death. They are probably due to a localized peritonitis of the investment of the kidney, or perhaps to simple neuralgia. Icterus and hepatitis, consequent upon a circumscribed peritonitis set up by the pressure of the movable kidney upon the liver, have been observed.

Death is not one of the usual results of this affection, but a recent surgical writer (Keppler4) has called attention to cases where long-continued dyspeptic symptoms, with constant pain and the chagrin and melancholy due to inability to work, have been followed by death from exhaustion, and nothing except a movable kidney has been found at the autopsy.

4 Arch. für Klin. Chirurg., 1879.

There can be no doubt that in many cases the symptoms are more severe than might be supposed from the ordinary descriptions, and are very unfairly characterized as hysterical. On the other hand, many cases are attended with but the mildest form of the symptoms just described, and the patients, ignorant of any tumor either from its discomfort or from having felt it, live in health and comfort for many years.

DIAGNOSIS.—The diagnosis of this condition, if the physician keeps in mind the possibility of its occurrence, is usually not difficult. In many cases a tumor has been felt by the patient which when called to the attention of the physician is recognized by its shape. In some cases in thin persons the form of the kidney, even to its hilus with the strongly-beating artery, can be made out. It glides easily from between the fingers, and can be moved more or less remotely from its normal position, to which, however, it returns without difficulty, especially when the patient assumes the recumbent position. The excursions are of course limited to a certain length of radius, of which the origin of the renal vessels is the centre, and seldom go much beyond the median line toward the side opposite to that on which the movable organ belongs.

The usual statement of text-books, that a depression or lessened resistance is to be felt in the loins of the side from which the kidney is absent, and a diminution of the normal dulness, which returns again when the organ is replaced, rests, as regards the majority of cases, rather upon theoretical considerations than on actual observation. The thickness of the lumbar muscles, upon which the kidney rests, is such that the dulness on percussion is not capable of much change. In most persons the outer limit of dulness in this region is not that of the outer edge of the kidney, but of the extensor dorsi communis. Palpation and percussion therefore in the renal region are not likely to be of much value in diagnosis, although an occasional case appears to justify the ordinary statement. The hand-and-knee position described above would be more likely than any other to show an existing depression.

Palpation for the purpose of finding the tumor, if it be not at once evident, or for examining it after it is found, should be bimanual, one hand being placed in the space between the ribs and the crest of the ilium of the supine patient and pressed strongly upward, while the surface rather than the points of the fingers of the other hand should be carried and pressed with some firmness into the relaxed abdominal parietes. In this way the kidney may be caught between the two hands and examined more or less completely according to the thickness of the abdominal walls. Sometimes the kidney can be partly grasped between the [p. 25] finger and thumb of one hand. In this way the size, shape, and sensitiveness of the tumor can be determined, as well as its position and movability.

A movable kidney may of course present some difficulties of diagnosis from other abdominal tumors. The liver is sometimes, though very rarely, movable, and never to the same extent as a wandering kidney, and as it is pushed downward discloses its much greater bulk. The base of the gall-bladder may occasionally be quite movable, but its excursions are of a more limited radius, being of course executed only by the base and not the whole organ.

The spleen, when it descends so as to be distinctly felt below the ribs, is much less movable, and if it descends deeply without great enlargement, its absence from its proper place is demonstrable by percussion. The splenic tumor is also larger, firmer, and more closely applied to the abdominal walls than the floating kidney. The left kidney, it should be remembered, is less frequently movable than the right.

A small ovarian tumor might be mistaken for a movable kidney low down in the abdomen, or vice versâ. The latter error has actually been committed, and has led to an attempted removal of the supposed cyst. The more easy movability of the kidney upward and of the ovary downward or laterally, as well as the shape, and in many cases the result of a vaginal examination, should be sufficient to make the distinction, which, if an exact diagnosis be absolutely necessary, may be confirmed by aspiratory puncture.

A malignant omental tumor might at the first examination present points of difficulty in diagnosis, but even if it were single and counterfeited with considerable accuracy the shape of the kidney, neither of these conditions would be likely to continue for any length of time.

TREATMENT.—The treatment usually suggested for this affection is based partly on the fact that many cases are hysterical, and also on that other more important one, that very little can be done to restrain the vagaries of the offending organ.

A correct diagnosis, it has been frequently remarked, is often sufficient to relieve the patient's mind, and secondarily her body, and may be all that is necessary in cases where the symptoms are all psychical and have arisen from the discovery of a tumor of unknown nature.

As a relief from the more serious annoyances the avoidance of certain disturbing causes may be of value, and such will consist in a proper regulation of the bowels and consequent avoidance of straining, and the choice of an occupation as little laborious and involving as little work in the upright posture as possible. No tight, narrow girdle should be worn about the upper part of the abdomen.

On the other hand, the use of a tight bandage over the whole abdomen is usually recommended, and seems to be useful in a small proportion of cases. It can of course act only by rendering the whole abdomen a little more tightly packed, and cannot exercise much restraint on any special portion of its contents. Pads of various shapes worn under the bandage may bring a little more local pressure to bear. One shaped like a carpenter's square, with an ascending branch to check the lateral movements, and a horizontal one to prevent the descent of the tumor, has been proposed. A truss with pads adapted to the loins and a front pad over the kidney has also been used.

[p. 26]It is impossible to read the history of many cases of this affection without becoming convinced that while the majority need but the mental assurance of the harmlessness of the tumor to restore their mental equilibrium, and others find their troubles bearable or capable of relief by mechanical appliances, no inconsiderable number are incapacitated from labor and the enjoyment of life by the necessity for great care in their movements, or suffer from severe symptoms, as pain and dyspepsia, which demand a more active treatment.

This has been afforded by operative surgery in two ways. Of these the most obvious is removal of the offending organ. It has now been clearly shown, by the number of nephrectomies that have been performed, that one healthy kidney is sufficient to support the function of urinary elimination; and if one kidney can be clearly shown to be healthy, the other can be safely removed. Such an operation undoubtedly adds to a patient's risks, since any subsequent renal affection is likely to prove fatal; but it has been now done a considerable number of times for the relief of the affection in question, and with good results. R. P. Harris5 has collected 16 cases with 10 recoveries, the organ removed in 3 out of the 6 fatal cases being diseased. Only 2 of these operations were by the lumbar incision, both being saved. They have since been reported.

5 Am. Journ. Med. Sci., July, 1882.

The operation has usually been done by the abdominal incision, which offers the advantages of greater accessibility of the pedicle for the purpose of ligating the arteries, and also greater ease in getting at the kidney itself, since it has often formed a partly separate pouch in the peritoneum, from which it would not be so easy to dislodge it by the lumbar incision. The latter operation is, as just stated, by no means impracticable nor specially dangerous. Of course it is desirable to avoid for some time after the operation anything which, like the use of diuretics or the excessive secretion of water, will throw any increased work upon the remaining kidney until it has had time to accommodate itself to them.

A singular case of attempted excision of a tumor supposed to be a wandering kidney, which could not be found after the incision was made, is recorded.6 In this case the symptoms, which, as well as the physical signs, had pointed distinctly to a movable kidney, disappeared after the operation. The author compares this case to another, in which great relief was experienced from a pretended operation for the removal of normal ovaries.

6 Hygeia, 11, 12, 1880, Svensson.

The other operation consists in the fixation of the movable organ. In one case a curved needle bearing a strong tape ligature was passed into the abdominal muscles, through the kidney, and out again. The ligature remained for some time, giving a certain amount of relief from the distressing symptoms, but maintaining a constant discharge until it came away without having accomplished any permanent benefit. The kidney was afterward removed by a lumbar incision, and a deep cicatrix found running longitudinally along the otherwise healthy organ.7

7 A. W. Smyth, New Orleans Med. and Surg. Journal, Aug., 1879.

In other cases8 a dissection has been made until the kidney was reached, which was then, with its adipose capsule, stitched firmly into [p. 27] the wound. In one of these cases the kidney became somewhat loosened again, but it is possible that the risk of this accident might be avoided by some modification in the operative procedure. If this operation can be made a successful one, and generally accepted, of which as yet the paucity of cases hardly permits us to judge, it is manifestly far preferable to removal, since it leaves in its place an organ usually perfectly capable of performing its functions.

8 Hahn, "Fixation of Movable Kidney," Am. Journ. of Med. Sci., April, 1882, from Cbl. für Chirurgie, 1881.

Polyuria is the name of a symptom the presence of which may be easily ascertained beyond a doubt, but which is notwithstanding occasionally overlooked. Its existence is to be determined by measuring the urine. In extreme cases this may be unnecessary, but slighter forms may easily escape notice if this is not done. The quantity of urine normally secreted varies considerably, owing to many causes, of which the principal are—the quantity of fluid ingested, not necessarily in the form of beverages, but of food more or less succulent; the activity of the other secretions, especially those of the skin and the intestines, and the presence of substances which increase the rapidity of its flow through the kidney or stimulate the glandular cells; and, to a certain extent also, individual peculiarities.

The quantity of water furnished by the kidneys depends largely upon the excess of pressure in the vessels, and especially in the Malpighian coils, over that in the interior of the tubes, and is consequently influenced by the general blood-tension.

The second factor of importance is the calibre of the renal vessels, especially the arterioles; and the third, the freedom of exit of the formed secretion from the uriniferous tubes. A certain amount of back pressure, so far from diminishing the amount of urine, seems to increase it, as shown in some of the cases of surgical polyuria, where the normal amount is considerably exceeded, while the renal parenchyma is being gradually destroyed.

The arterioles of the kidney being, like all other arterioles in the body, under the control of the nervous system through the vaso-motor nerves, it is easy to see how the various affections of this controlling element may act upon the secretion of urine; neither is it possible to deny (although by far the most important factor in the rapidity of the urinary secretion has been shown to be the blood-pressure) that the nervous system may have a direct effect upon the secreting renal parenchyma.

The normal quantity of urine for an adult of medium height and weight and ordinary habits as regards the ingestion of liquids may be stated as fifty fluidounces, or a liter and a half, which is of course to be considered as only a very rough approximation. One liter on the one hand, and two liters on the other, can hardly be considered pathological limits, unless the increase or decrease takes place under circumstances which ought to produce the opposite effect.

Frequency of micturition, especially if nocturnal, is often considered almost a proof of polyuria, but can at most only justify a presumption of it, which is to be confirmed or not by exact measurement. Any [p. 28] existing polyuria is likely to be greater during the night. Frequency of micturition may mean polyuria, or, on the contrary, may coexist with a considerably diminished total amount of urine; in which case it means only increased irritability of the bladder, and is then a purely nervous symptom; assuming, of course, the absence of inflammatory trouble. The rapidity with which the secretion accumulates in the bladder has a certain influence in determining the need for micturition; that is, a bladder containing five ounces of urine which has been gradually accumulating for some hours retains it with greater ease than if the same amount had been rapidly secreted, as, for instance, after a full meal with an abundant supply of fluids.

Polyuria is often, or always if persistent, an important symptom, and the suggestions made by it can easily be added to and confirmed by a more minute examination of the urine. Thus we may have the following combinations indicating important diseases:

Polyuria, moderate, with diminished specific gravity, albumen usually in small amount, and some casts; in chronic interstitial nephritis;

Polyuria, with pus and mucus and débris from the urinary passages, usually turbid and often alkaline and offensive; in irritation of the kidneys depending on lesions of the deeper urinary passages, prostate, or bladder (surgical polyuria);

Polyuria, with increase of urea (azoturia);

Polyuria, with increase of phosphates (phosphaturia);

Polyuria, with increased specific gravity and sugar; in diabetes mellitus;

Polyuria, with decreased specific gravity and diminished or normal solids; in diabetes insipidus.

These conditions have many points of mutual contact and resemblance, but the affection which is the subject of the present essay is diabetes insipidus—i.e. that form of polyuria which is accompanied by no abnormal constituents except occasionally inosite, a very little sugar, or a very small amount of albumen. In the cases where these constituents might lead to difficulties in the way of diagnosis the absence of other symptoms of the disease likely to be mistaken will suffice to mark off the affection as entirely distinct.

The normal elements may be decreased, normal, or increased. The disease thus defined includes not only diabetes insipidus, but many cases of so-called phosphaturia and azoturia, which, if not exactly coinciding, have many points in common.

In some cases which, from the character of the urine as well as from the other symptoms, should evidently be classed as diabetes insipidus, the quantity of urine, although somewhat increased, is not very excessive, reaching perhaps two liters, but in the great majority is discharged in much larger quantity. In a case which came under the observation of the writer by the kindness of H. E. Marion the amount of urine gradually rose from two or three gallons to five or six and seven, and on one occasion the patient, a girl of fifteen, after some unusual excitement is supposed to have passed eight gallons in the course of twenty-four hours. Of this eleven quarts was by actual measurement, and passed in the presence of her mother in the course of the afternoon.

The urine in these cases is, as would naturally be supposed, of a very [p. 29] pale color and of low specific gravity, which from 1005 to 1010, representing the usual range, may in extreme cases fall to or even below 1001 as measured by the ordinary urinometer. I have seen no case recorded where the specific gravity of such a urine has been determined by instruments of greater delicacy. Its odor is comparatively faint, but it is somewhat prone to decomposition. The solid constituents are often somewhat increased in the twenty-four hours, especially the urea, which may be present in double the usual amount. This is probably the result of an increased metamorphosis from the passage of so large an amount of water through the tissues.

It is not always true, however, that the solids are increased, and the difference in the amount of destructive metamorphosis taking place in different cases is probably closely connected with the clinical differences which may be observed in regard to the amount of wasting and affection of the general health. The phosphates are frequently increased, as found by Dickenson and Teissier; and such an increase has probably about the same meaning as the increase in urea. In other cases, however, they take part in the general diminution of solids, as in the case of Marion just alluded to, where they were reported as absent, which undoubtedly means simply present in so small amount as to escape the usual clinical tests.

Among the concomitant symptoms the most necessarily and closely connected with the increased discharge of fluid is its increased ingestion, so that the disease has been called polydipsia instead of polyuria, it being assumed that the thirst is the initial and important symptom upon which the diuresis naturally depends. It has been observed in many cases, however, that the quantity of water drunk is very much below that which is passed. In the case last spoken of the water ingested in the form of drink was but a small fraction of the quantity of the urine, so that the patient drank but two or three pints while passing many gallons. In cases where the beginning of the disease has been carefully observed patients have distinctly stated that the increased discharge began before they felt increased thirst. This of course takes no account of the quantity of water contained in solid or semi-solid food. Polyphagia is occasionally seen, as in the oft-quoted case of Trousseau, the terror of restaurant-keepers. So intense is the craving for water that in several instances where attempts have been made to limit its amount the unfortunate patient has drained the chamber-pot. Emaciation is probably connected with increased metamorphosis, as indicated by the increased secretion of urea and phosphates. Dryness of the skin has been frequently noted, and has been said to mark the distinction between polyuria and polydipsia, in the former the skin being dry, and in the latter moist. In one case, however, where copious perspirations were noted, the patient stated positively that the polyuria began a number of days before increased thirst was experienced. In another very extreme case, attended, however, with no wasting, night-sweats occurred. Pruritus has been mentioned as affording another point in the resemblance which undoubtedly exists between the severer cases of this disease and diabetes mellitus. Dyspeptic symptoms have been noted in some cases, and oedema may take place, as in many wasting diseases.

The nervous symptoms are perhaps the most important in the severer [p. 30] cases. In some which have been examined post-mortem distinct nervous lesions have been found, such as the remains of tubercular meningitis, tumors involving the cerebellum, and softening of the floor of the fourth ventricle; in others the patients are known to have been syphilitic.

Severe headache is a symptom of some importance, occurring in a considerable number, but not the majority, of cases. Atrophy of the optic nerve was present in two reported cases, to which the writer can add a third, where failing vision, headache, and emaciation were the principal and earliest phenomena, while at a later period the atrophy was demonstrable by the ophthalmoscope. The polyuria in this case, though marked, was not excessive, and the patient, a young man, after remaining for some years in a condition of chronic invalidism, died. Chronic interstitial nephritis had of course been suspected and sought for, but no evidence of it found beyond the symptoms already stated; neither were there any more definite cerebral symptoms.

Finally, it should be stated that a great many cases of this kind have no marked symptoms at all except the essential one, and so long as they are supplied with a sufficient amount of fluid live in comfort with their single inconvenience.

The diabète phosphatique of Teissier9 should be cited in this connection. In only a small proportion of his cases where an excess of phosphates was noted was the quantity of the urine also increased, and in these the symptoms seem as appropriate to the polyuria as to the phosphaturia. It is worthy of note, however, that one series of his cases is connected with disease of the nervous system; another alternates or coexists, as does also diabetes insipidus, with diabetes mellitus; and his fourth class closely resembles, with the exception of the increase of phosphates (if this can be looked upon, after what has been said above of the increase of solid urinary constituents, as an exception at all), the affection last named—i.e. diabetes mellitus. In fact, many of these cases of Teissier read like what would have evidently been called, without a quantitative analysis, simply polyuria or diabetes insipidus.

9 Du Diabète phosphatique, par L. S. Teissier, Paris, 1877.

According to Teissier, the presence of an excess of phosphates in the blood is sufficient to determine a polyuria. It is possible that in many cases where a polyuria accompanies phthisis, as noted in many of his cases, the symptom may be really due to actual organic (perhaps amyloid) disease of the kidney.

The COURSE AND TERMINATION naturally vary greatly with its etiology and the diseases with which it is associated. In some cases where nutrition is but little affected, and no attempt is made to check the natural appetite for water, the disease may go on for years with no essential change or impairment of the general health, as in the remarkable one quoted by Dickenson, where a French infant had at the age of three impoverished her family by her demand for water, which seems to have been an expensive luxury, and at a later period kept her husband—to whom, however, she bore eleven children—in a constant state of impecuniosity by the same depraved appetite. At the age of forty she drank in the presence of a scientific commission within ten hours fourteen quarts of water, of which she returned through her kidneys ten to their astonished gaze.

[p. 31]When polyuria is merely a symptom of cerebral inflammation, of central tumor, of syphilis, or of phthisis, the course and prognosis will of course be that of the primary disease. It occasionally comes on during pregnancy, and in one such case it is stated to have ceased two days after delivery, and in another the secretion, uninfluenced by parturition, resumed its normal quantity when lactation was fully established.

It is very rare, if indeed it ever happens, for life to be terminated by diabetes insipidus unaccompanied by any other disease, although from its association with many and severe affections, both of the nervous system and of the kidneys, it must of course not unfrequently happen that a patient dies in, though not on account of, the polyuric state. It is strange to observe, however, as has been often before remarked, how thin a shell of renal structure will suffice to carry on not only the usual, but an excessive, flow of water.

The ORIGIN of diabetes insipidus has been found in several conditions. Greater disposition toward it exists in early life, although it is by no means confined to youth. After middle life polyuria is likely to awaken the suspicion either of chronic interstitial nephritis or of prostatic disease, or other affection of the urinary passages setting up a sympathetic irritation of the kidney. It has been found to originate during convalescence from acute diseases, with perhaps preference for meningitis. Syphilis has its share of cases, as in most other organic nervous diseases. Shocks of various kinds, including fright, sudden or prolonged immersion in cold water, the rapid ingestion of large quantities either of water or of alcoholic fluids, are undoubted potent factors. In this respect, again, we may see the resemblance between diabetes without sugar and true or saccharine diabetes. It is favored by the hysterical diathesis. A very interesting case of severe hysteria with hemianæsthesia and hemiplegia and other marked symptoms varied for a time between almost complete anuria and the most profuse discharge of over two hundred ounces per diem.

A most interesting group of cases has been recorded by Weil,10 where out of a family of 91, 28 were polyuric. The head of the family, a polyuric, lived to the age of eighty-three, while his descendants were robust, many of them attaining a good old age. There were no anomalies of the circulation, and the persons affected were not alcoholics. Their only complaint was of a troublesome thirst, and they declined treatment.

10 Cbl. für die Med. Wiss., 1884, p. 263, from Virch. Arch., xcv.

The PATHOLOGY of diabetes insipidus, so far as is positively known, may be gathered from the previous account of its etiology and symptoms. It is evidently of nervous origin in the great majority if not all cases. It is often connected with distinct lesions of the nervous system, and attended with other nervous symptoms. In some cases it occurs in connection with a well-marked hysterical diathesis. The copious flow of pale urine as a sequel to the hysterical paroxysm is well known, and the same thing often attends a severe nervous headache in either sex. It is probable that the polyuria attending lesions of the urinary passages is a reflex nervous phenomenon, since it may be present when there is no suspicion of organic renal disease.

Guyon11 states that surgical polyuria occurs under three [p. 32] conditions—painful excitation of the sensibility of the deeper portion of the urethra or the vesical mucous membrane; repeated attempts to urinate during the night; retention of urine more or less complete, but especially when there is distension of the bladder. Of the first cause he gives an instance in the case of a young man who had a polyuria whenever a bougie was passed beyond a urethral stricture.

11 Leçons cliniques sur les Maladies des Voies urinaires, Paris, 1881.

Where, however, polyuria, especially chronic, is due to habitual over-distension, it is in the highest degree probable that it is at least partly due to structural alteration of the kidney. The well-known experiment of Bernard, by which an increased flow of urine was induced by a puncture of the floor of the fourth ventricle, and those of Eckhard on section of the splanchnic nerves, show how it is possible for nervous affections to influence the secretion of urine, though the path or paths of the influence are by no means completely made out.

One of the most noticeable points in the pathology of the more excessive cases of polyuria is the disproportion which often exists between the amount of fluid ingested and the amount discharged, the latter often exceeding the former several times. The source of the excess of water has not been satisfactorily determined, but it is evident from a careful experiment of Watson, repeated by Dickenson, that the body has under some circumstances the power of appropriating water from the atmosphere instead of discharging aqueous vapor through the lungs and skin as usual. In the experiments referred to persons affected with extreme polyuria were weighed immediately after passing water, and again after as long an interval as they were able to restrain their thirst, of course being also without food and under observation, when it was found that the weight had been increased by a number of ounces. In Dickenson's case, weighing thirty pounds more or less, where the amount of urine excreted daily was from seven to nine liters, the gain in weight at several observations was as follows: in three hours, 15½ oz.; in five hours twenty minutes, 19¾ oz.; in three and a half hours, 3¾ oz.

The DIAGNOSIS of this affection rests, in the first place, upon the determination of a permanent increase in the quantity of urine passed considerably above the normal, and, as has been already remarked, may require a measurement of the daily amount—a procedure which it is well to make a matter of routine in any cases where urinary trouble may be present. The increase being found, if it be very great it will only remain to determine whether sugar be present, which will be indicated by the specific gravity and the appropriate chemical tests. Traces of sugar are sometimes found in cases of polyuria which do not present the characteristics of saccharine diabetes, and can hardly be considered to materially affect the character of the disease.

A specific gravity decidedly above normal, with an excessive quantity of urine, is not likely to belong to anything but diabetes mellitus, though the chemical tests should never be neglected. If, however, the polyuria be only moderate, it becomes necessary to exclude surgical affections of the urinary passages, especially an enlarged prostate, often attended with retention and distended bladder. Pyelitis and hydro-nephrosis may also give rise to the same condition of over-activity of the kidneys. The appropriate surgical examinations with the sound may be necessary, but the presence of pus, bacteria, and the epithelium of the urinary passages [p. 33] in the surgical urine, as well as its frequent alkalinity, may direct a very strong suspicion before the sound is used. The age of the patient also will be of considerable weight in this connection.

A point of real difficulty of diagnosis, and great importance for treatment and prognosis, is the distinction between simple polyuria not excessive, but attended by constitutional symptoms, such as impaired nutrition, dyspepsia, and severe headache, from chronic interstitial nephritis, which often makes its appearance with similar symptoms. Mistakes between these two affections have undoubtedly occurred, and can in many cases hardly be avoided except by reserving the diagnosis for a time.

The similarity is rendered still more deceptive by the undoubted occurrence of a trace of albumen or a hyaline cast or two in cases of nervous disturbance, without justifying a diagnosis of progressive renal disease. High arterial tension also is likely to be found in both conditions. Nothing but repeated and careful examinations of the urine and of the circulation, especially at times when the nervous symptoms are less marked, and often a considerable amount of time, can fix the diagnosis.

Hypertrophy of the heart, and even slight dropsy, will undoubtedly be extremely decisive symptoms, but are not likely to occur until after a time when the doubt no longer exists. In other cases it may be highly important to carefully exclude organic cerebral disease before making a diagnosis of simple polyuria.

It is hardly appropriate to speak of a diagnosis from azoturia or phosphaturia, since these conditions are extremely likely to exist coincidently with typical polyuria and to make a part of the same disease. It is of much importance, however, to ascertain their presence with reference to the probable effect of the disease on the nutrition.

In regard to the TREATMENT, it may be remarked, to begin with, that restriction of water, although naturally diminishing somewhat the discharge of urine, does not cure the disease, but, on the contrary, in many cases augments not only the discomfort of the patient, but tends to the dryness of the skin, dyspeptic and nervous disturbances, and emaciation. Patients may recover flesh, strength, and spirits on being allowed to drink ad libitum, even although the inconvenience of excessive urination be thereby somewhat increased. Sufficient food and drink should therefore be allowed, although a patient may be ordered to observe such moderation as will not put his powers of endurance to too severe a test.

Of the drugs proposed, nearly all have offered some prospect of success, and have been accordingly reckoned almost specifics. Opium has in some cases been found as useful in these cases as in diabetes mellitus, and probably, as in that disease, by diminishing the sensitiveness of the nervous system. Valerian and valerianate of zinc, recommended by Trousseau and apparently successful in his hands, have reckoned both failures and successes in the hands of others. Nitric acid, in the dose of from 1 to 5 drachms per diem of the dilute in a large quantity of water, is said to have been highly efficacious in one series of cases.12 It is given until aching of the jaws and teeth, with some gingivitis, denoting its constitutional action, is produced. It was more successful than any other drug in Marion's case, although the specific symptoms were not produced, the patient being now in good health or free from [p. 34] her trouble. Atropia from its general action in diminishing secretion has been tried, and with occasional alleged success, but with many more failures. Pilocarpine from its action on the skin might be of value in those cases where the skin is very dry, but has no very general applicability.

12 Kennedy, Practitioner, vol. xx. p. 95.

The drug most frequently employed, and which can claim a larger proportion of successes than any other, is ergot in full doses, half a drachm or a drachm (2 to 4 cubic centimeters of the fluid extract) several times per diem. Its method of action is undoubtedly in the contracting effect which it exercises on the renal arterioles. In many cases it has decidedly diminished the amount of urine, and in some a permanent cure seems to have resulted.

In estimating the value of drugs in certain cases of this affection its not infrequent neurotic origin should be borne in mind, as well as the very capricious effect of supposed remedies in the hysterical diathesis. Unfortunately, many cases remain rebellious to all drugs, and can only be rendered as little uncomfortable as possible.

What has been said of treatment applies only to the well-marked cases of diabetes insipidus. Polyuria, as a symptom of other diseases or of surgical affections, is hardly likely to call for treatment other than that of the disease upon which it depends.

Albuminuria signifies a condition in which albumen appears in the urine, and has by some writers been made of equal significance with nephritis or Bright's disease. It is hardly necessary to say that this coincidence is far from being an exact one, and that the symptom may exist without Bright's disease, and also Bright's disease without the symptom. For our present purposes albuminuria will be taken to mean those conditions in which albumen may be found in the urine without the existence of decided diffuse nephritis. As a symptom, and a highly important one, of Bright's disease it will be considered elsewhere.

Albumen is secreted in the kidneys chiefly in the Malpighian capsules, where, if at all abundant, it may be easily demonstrated after death by hardening the kidneys by boiling. This coagulates the albumen in situ, where it may be shown by sections prepared in the usual method. It has been supposed that albumen is normally secreted in the capsules of the healthy kidney, and afterward absorbed by the epithelium lower down; but this view can easily be shown to be erroneous by subjecting a kidney which has not secreted albuminous urine to the process just described, which shows no coagulated albumen in the place where it ought to be most abundant.

The albumen found in the urine is chiefly that which forms the most important portion of the blood-serum, although other albuminoid bodies have from time to time made their appearance and have some diagnostic importance. Semmola13 states that the albumen appearing in the urine in true Bright's disease differs from that found with the cardiac or amyloid kidney. The distinction can, according to him, be shown in [p. 35] the appearance of the precipitate to a practised observer, and also by a more rapid diffusibility through animal membranes. He admits, however, that he has in vain sought for any distinct and clear chemical test by which the difference can be recognized.

13 Archives de Physiologie, 2d Serie, tome ix., and 3d Serie, tome iv.

Fibrin may occur in inflammatory conditions in the form of coagulated masses, and hence cannot affect the question of the presence of albumen. Casein has not been detected with certainty. Various albuminoid bodies, called albuminose, paralbumen, metalbumen, and serum-globulin, are occasionally met with in renal disease, and may give rise to some confusion during an analysis. They are at present, however, more suitable for chemical than for clinical study.

A variety of albumen is said to occur in osteomalacia which is not coagulated by heat alone nor by heat and nitric acid. This has been called Bence Jones's albumen, but has been seen by others. Peptone has been found in urine, but usually in such specimens as have been or which afterward become albuminous. Its exact signification when alone cannot be more exactly stated, as it has appeared in a variety of diseases, though not in perfect health.

Finally, a protein body, a ferment called nephrozymase, may be thrown down from every urine by an excess of alcohol.

Hæmoglobin gives a dark-red color to the urine, which on boiling forms a brown coagulum floating on the surface.

Hæmoglobinuria may be produced in animals by the intravenous injection of large quantities of water, causing a dissolution of the corpuscles, but the degree of hydræmia necessary to produce this condition is much in excess of any met with in diseases of the human being.

Human hæmoglobinuria may be the result of various pathological conditions, among which may be mentioned some infectious diseases, jaundice, burns, and the effects of many poisons, as well as the transfusion of sheep's blood.

Intermittent hæmoglobinuria, which is attended with fever, is usually the result of cold acting upon predisposed persons. The color of the urine and of the coagulum, together with the absence of red corpuscles under the microscope, will distinguish urine of this character from others which are also coagulable by heat.

Several methods are in use for the detection of albumen. Of these, boiling is perhaps the oldest and most generally employed, and if conducted with due care is a very delicate and useful test. The urine to be tested should be clear and slightly acid, when on boiling the albumen, if present, will be precipitated in whitish flocculi, more or less abundant according to the amount, or, if the quantity is very small, as a turbidity. The flocculi soon settle to the bottom of the tube when it cools, and the thickness of the deposit formed gives an approximation to a quantitative estimate. It is to the proportionate thickness of this deposit that the terms 30 or 50 per cent. of albumen are commonly but incorrectly applied. If the quantity is very small, it may not be distinctly perceptible until after cooling.

If alkaline or very slightly acid urine is boiled, a deposit of phosphates will be thrown down which closely resembles that from albumen, while, on the other hand, the albumen remains undissolved unless in large amount. These deposits of phosphates differ a little in appearance from [p. 36] an albuminous one, but in order to be accurate acetic or nitric acid should be added, drop by drop, to the hot urine, when the phosphates will be redissolved and the albumen, if present, precipitated. It is better, however, to add the acid cautiously to the point of slight acidity before boiling. A recent work14 gives the following directions for this reaction, which is then "absolutely conclusive and surpassed in delicacy by no other:" "The urine is first made distinctly acid with some drops of acetic acid, and then about one-sixth of its volume of a concentrated solution of chloride of sodium or sulphate of sodium or magnesium added. If the urine contains albumen, a precipitate of coarser or finer flakes appears on boiling." This reaction may be used as a quantitative test by diluting and acidifying, if necessary, a known quantity of urine, washing the precipitate on a weighed filter, drying, and weighing the whole.

14 Die Lehre vom Harn, Salkowski und Leube.

An exceedingly delicate and convenient test is that by nitric acid. The acid is placed in the bottom of a conical wine-glass, and the urine, filtered if necessary, allowed to flow on top of it from a pipette, so as to disturb the plane of junction of the two fluids as little as possible, and leave a distinct line of demarcation. At this plane of union, if albumen be present, will be formed an opaque white line varying in thickness according to the amount of albumen, so that after some practice and with care an approximate estimate of the percentage may be made. A deposit of urates may sometimes be formed a little above the plane of union, but it may be distinguished by its position, by its less distinct limitation on the upper surface, and also by its disappearance on warming. In a very concentrated urine and in cold weather this error may be conveniently avoided by previous warming of the urine and of the reagent. The same remark applies to the brine test.

A crystalline precipitate of nitrate of urea may give rise to error if the urine be very concentrated or the experiment conducted in the cold. This may be distinguished by its disappearance on warming or by the microscope. The action of the nitric acid on the coloring matter of the urine, forming a dark band at the point of junction, may obscure the reaction, but with care will not give rise to mistakes.

Another test recently introduced, which presents some advantages over the nitric acid, and is certainly quite as delicate, consists in a saturated solution of common salt in water acidulated with about 5 per cent. of the dilute hydrochloric acid of the Pharmacopoeia. This solution should be used exactly in the manner described for nitric acid. There is no change of color at the line of junction, and no precipitate takes place there except albumen or peptone, or resins when they have been administered. The opaque line of precipitate may, if the amount of albumen present be small, require a short time to form, so that in cases of doubt it is well to allow the test-glass to stand for a few minutes. It will, however, show very distinctly in any cases in which nitric acid shows any precipitate. The line does not, however, increase in thickness and density in proportion to the amount of albumen so exactly as that produced by nitric acid, so that the brine test is not so useful for approximately quantitative use as the nitric acid, although fully as delicate. If it be desired to distinguish peptone from albumen, it may be done by a comparison of this test [p. 37] with the nitric acid, which does not throw down peptone. If a deposit occur, which may consist of resin, the addition of more urine will dissolve it if resin, while albumen will not be affected.

Picric acid is a delicate and often a convenient test. The dry acid may be dissolved in the urine, or a saturated solution used into which the urine may be slowly dropped, each drop making a slight whitish cloud as it slowly falls through the yellow solution.

The iodo-hydrargyrate of potassium is perhaps the most delicate test of all: Potassii iodidi, 3.32 gm.; Hydrarg. bichlor., 1.35 gm.; Acidi acetici, 20 c.c.; Aq. destill. q. s. ut fiat 100 c.c.—Tauret's test. It may be used in the same way as the nitric acid or brine, or simply intermixed. Its only disadvantage is that it throws down alkaloids, but as this will not happen unless the alkaloid be taken in large quantity—as might happen, for instance, in the case of quinine—the chances of error from this source are not very great if this peculiarity be borne in mind.

Ferrocyanide of potassium in an acid solution has recently been proposed as a convenient test. It may be made up into pellets with citric acid or used in the same combination in the form of papers.

The phenic-acid test is prepared as follows:

| Ac. phenic. glacial. (95 per cent.), | drachm ij; |

| Ac. acet. puri., | drachm vij; |

| M. Add liq. potassæ, | ounce ij-drachm vj. |

| Millard. |

This is said to be very delicate, but the writer has no experience with it.

Tungstate of sodium is another recent addition to the list, which it is evident is already long enough for practical purposes.

Several of the tests mentioned have recently been prepared in the form of papers saturated with known quantities of the reagent and dried. They may be carried in the pocket-book and applied at the bedside, if desired, in a test-tube small enough to be very conveniently carried in the vest pocket. The iodo-hydrargyrate is perhaps the most useful. It is the most delicate, and a plan has been proposed for making with it a quantitative estimate of considerable accuracy by means of a standard solution or piece of gray glass adjusted by such a solution, with which the precipitate produced can be compared as to its opacity.

Exact quantitative examinations for albumen may be made by several processes, but that by boiling, if carried out with the precautions described in works on chemistry, is as accurate as any, and probably the best adapted to the needs of the practitioner if he should wish for such results.

For clinical purposes, however, it will rarely if ever be found useful to determine the amount of albumen more accurately than can be done by the various approximations mentioned above.

When even the smallest trace of albumen is discoverable by any of these methods, the question of the integrity of the kidneys at once arises—a question which a few years ago would have been considered as settled in the unfavorable sense by the same occurrence.

It is necessary to distinguish, first of all, between an essential and an accidental albuminuria, the first referring to that condition where the albumen is secreted with the urine and forms an essential part of it, and [p. 38] the other to the accidental admixture from the presence of pus or blood, which may have made its appearance at any point below the secreting tubes. When hemorrhage takes place from the kidney, albumen is of course present in the urine, but its signification under these circumstances is entirely different from that which it bears when unaccompanied by the corpuscular elements of the blood.

No means at present exist for determining whether a small amount of albumen present in the urine is more than enough to be accounted for by the pus or blood known to exist by the presence of its corpuscular elements or of its coloring matter. An approximate estimate may be made by one familiar with such examinations, but no rule can yet be laid down. Such a rule might be approximately established by a succession of counts with the hæmocytometer of the corpuscles found in albuminous urine of known percentage, or estimates of hæmoglobin by color tests.

The exact conditions of the kidney or of the blood which may cause the appearance in the urine of albumen without blood or pus—that is, of true albuminuria—have been the subject of much experiment and argument, which it would be impossible to reproduce, even in outline, within the limits of this article; and this is the less to be regretted since they have as yet led to no practical or generally accepted conclusion. A few of the more important facts bearing on the question may, however, be stated here.

Albumen other than serum-albumen, when introduced into the circulation either by injection into the veins subcutaneously, or if in very large quantity by the mouth, is rapidly excreted by the kidneys. This albumen also, if collected from the urine of the first animal and injected into the vein of a second, again comes through the kidneys. The albumen, however, which is obtained from the urine of an ordinary case of albuminuria—that is, serum-albumen—does not behave in this way, but is not excreted through healthy kidneys. These facts seem to show that the appearance of albumen in the urine in ordinary cases of renal disease is not to be attributed to any change in its quality approximating it to egg-albumen, for instance, but is due to the condition of the kidneys.

Disturbances of the renal circulation, especially those giving rise to venous stasis, are very likely to cause albuminuria; a temporary ligature of the renal vein causes albumen to appear in the urine after its removal, and ligature of the ureter has the same effect.

The albuminuria succeeding the collapse of Asiatic cholera or yellow fever seems to have a somewhat similar origin, being the result of re-establishment of the circulation after extreme anæmia of the kidney. Clinical facts in general seem to point to simple disturbance of the circulation and to alterations in the kidneys themselves as the usual causes of albuminuria, though in many cases the lesion seems to be a slight and temporary one.

Some other conditions under which such disturbances and alterations may arise, exclusive of Bright's disease, are the following:

Munn15 found albumen in small quantities in 11 per cent. of cases presenting themselves for life insurance, supposing themselves healthy and having no lesions of heart or lungs. It is not stated whether casts were found in these cases or not, and their value as representing healthy [p. 39] persons cannot, it is obvious, be correctly estimated until some time has elapsed. It is well known that renal lesions may be exceedingly slow in their progress, and it is by no means improbable that a part of these cases may have been really in the early stages of a chronic form of Bright's disease. Albumen has been found in the urine of boys and adolescents, as well as in that of healthy soldiers, tested immediately after rising: in most of these cases the amount was extremely small. Certain conditions, moreover, may greatly increase the proportion of cases in these same classes in which albumen is present. Thus, fatiguing exercise will bring it on in some persons, and the urine of a body of soldiers if examined late in the day after severe drill shows a much larger proportion of albuminurics than if examined after rising. The urine of the pedestrian Weston is said to have contained not only albumen, but casts. It is certainly not true that fatiguing exercise will cause albuminuria in everybody, and it is not claimed, even by those who report these and similar cases, that they prove albumen to be a normal constituent. Some of the cases are distinctly described as delicate without being actually ill. Cases have been reported where cold bathing has been followed by temporary albuminuria. Here it is in the highest degree probable that a disturbance in the circulation is produced by contraction of the cutaneous arterioles; and it is possible that we may find in this increased sensitiveness of certain persons an explanation of the occurrence of acute dropsy as a sequel to scarlatina or as the result of exposure in only a small proportion of the cases where the exposure takes place. It is hardly necessary to admit, on the basis of these observations, that albumen is a constituent of healthy urine, although this may be shown at some future day by still more delicate tests, but simply that the renal circulation may in certain sensitive persons be sufficiently influenced by slight and transient causes to permit albumen to pass into the urine. It is the almost unanimous conclusion of practical writers, taking fully into the account these recently-ascertained facts of albuminuria in alleged health, that the presence of albumen in the urine in sufficient quantity to be detected by any of the ordinary tests is a decidedly serious symptom.

15 New York Medical Record, xv. 297.

The influence of many well-recognized pathological states in bringing about venous stasis, and that delay of the blood in the renal—and more especially the Malpighian—vessels which seems the most essential factor in the secretion of albumen, is well known, and its recognition is of much importance in diagnosis and prognosis, since the unfavorable signification of albuminuria in certain cases is liable to be overrated, and a diagnosis of chronic renal disease made to depend upon symptoms which really belong to some other affection. How far alteration in the capillaries and epithelium is in each case concerned in the production of albuminuria it is often impossible to say, since any alteration in these elements which can be observed after death is almost certain to be complicated with lesions which can disturb the local circulation.