I. M. D.

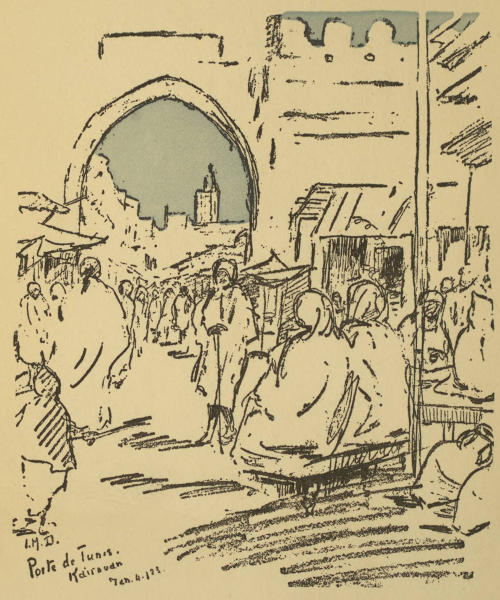

Porte de Tunis.

Kairouan

Jan. 4. ’23.

I. M. D.

Porte de Tunis.

Kairouan

Jan. 4. ’23.

THE EDGE OF

THE DESERT

By

IANTHE DUNBAR

LONDON

PHILIP ALLAN & Co.

QUALITY COURT

First published in 1923.

Made and Printed in Great Britain by

Southampton Times Limited, Southampton.

To

J. W. H.

TO WHOSE SYMPATHY AND CRITICISM I OWE SO MUCH

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Kairouan | 9 |

| II. | Sects and Superstitions | 21 |

| III. | An Arab Wedding | 31 |

| IV. | Sousse | 48 |

| V. | Passing Through | 56 |

| VI. | Sfax | 72 |

| VII. | Oasis Towns | 82 |

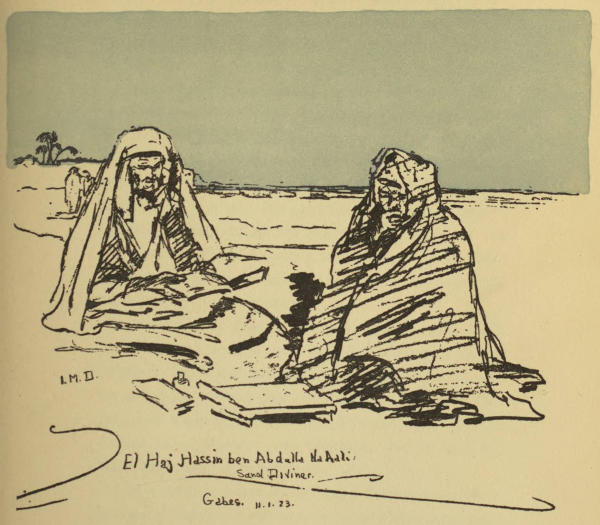

| VIII. | The Sand Diviner | 96 |

| IX. | The Circus | 106 |

| X. | Round About Gabès | 118 |

| XI. | Customs | 126 |

| XII. | Tunis | 137 |

It was cold, but a glorious morning when I left by motor for Kairouan. Soon the white houses of Tunis were left behind. The sun was rising as we flung its outskirts behind us, and the car headed for open country. Rocky hills showed themselves on the horizon, and there were abrupt peaks rising out of stretches of carefully cultivated vineyards, orchards of olive trees, and broad fields just tinged with the promise of early wheat. No walls, but occasional cactus hedges. The road climbed a saddle of hill from whence one could look back on the sea. A few houses here and there, flat-roofed and built in the Moorish style, were obviously the homes of the landowners. Not an inch of ground seemed wasted. Arabs were already at work behind their wooden ploughs, drawn either by horses, mules, bullocks, or camels. These last looked as if they were inwardly protesting against the indignity, and stalked along with their usual disdainful air. After a time the road led into wilder country, bare stretches covered only with a sort of rough heathery plant, with scattered encampments of Bedouins, their black tents surrounded by a[10] zareba of piled thorns. At last we caught the gleam of the white domes of Kairouan against the sky.

It lies in an open plain, and one’s first impression is of its whiteness. White-washed mosques and tombs, white flat-topped houses, enclosed in a high brown crenellated wall. Once inside the gates, all touch of European atmosphere is left behind. The city is Eastern to the core, “une vraie ville arabe,” as Hassan said. It is one of the sacred Moslem places and is a great centre for pilgrimages. The chief mosque is Sidi-Okba, with its large courtyard and numerous doorways leading into the interior, where in the gloom one sees the roof supported by row after row of Roman pillars. The effect in the vast emptiness is striking. The existing structure is said to date from the ninth century, and the builders must have ransacked ancient ruins for their materials. Some of the columns are of red porphyry, and the antique minbar or pulpit-chair is beautifully carved in wood, but beyond this the decorations are poor.

From the minaret in the courtyard there is a lovely view, the holy city crouched below with the frequent bubbles of its domed tombs and mosques, and beyond the wall, wide spaces stretching to distant hills.

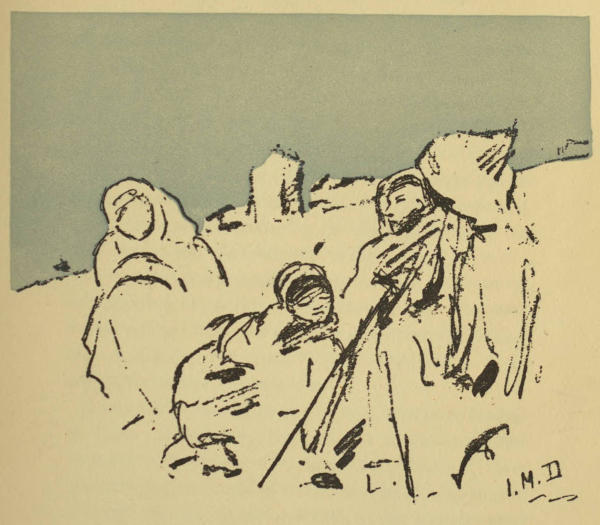

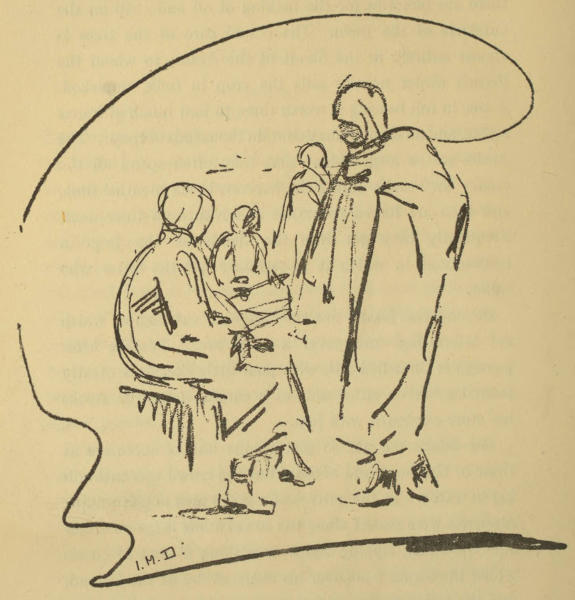

But the crowded streets and souks, or covered arcades, were the chief attraction of Kairouan. Nearly all the men wore a burnous with a hood that came over the head. The[11] women did not wear the ugly face covering seen in Tunis, but they were so closely wrapped in voluminous black or white draperies that they looked like walking bundles. Occasionally an eye peered out from amongst the folds, but one wondered how they could see to make their way. Bedouin women strode past, good-looking and haughty, their head-covering thrown back showing their tattooed faces, their necks covered with coins; whilst the blue of their robes made a pleasant note of colour. Their men were tall and sinewy with hawk features, and they wore their sand-coloured burnous like dispossessed princes. Here and there one saw the vivid green cloak or turban of some holy man who had done the journey to Mecca, or there was a splash of madder or burnt orange; but for the most part the crowd was neutral-tinted. Everything, buildings, streets, mosques, and crowds, was drenched in a glow of sunlight. Even the shadows seemed warm and throbbing. The market-place was the great centre, and here it was almost difficult to push through the throng. Men in grave and dignified draperies sat outside the cafés, drinking from tiny handleless cups and smoking meditatively.

I said the place was untouched by modernism, but I must confess that they were usually listening with grave pleasure to a gramophone reproduction of the voices of their own singers! It was fortunate when it kept to that.[12] I was sketching one morning near a café, and through my absorption I became aware of the gramophone giving piercing shrieks and discoursing in a high-pitched woman’s voice. It began to worry me. “What on earth is that record, Hassan?” I asked impatiently, and was appalled at the ready response that it was a Jewess adding to the numbers of Israel! Needless to say, Hassan did not use such a roundabout way of expressing himself. I cast a swift glance at the Arab audience. Impassively they sat, sipping their coffee, and it was impossible to tell what they were thinking of. But Hassan assured me it was a favourite record and most amusing; I hastily became very busy with my painting.

Ali Hassan was my guide in Kairouan and showed an intelligent interest in points of view to sketch. He was a portly Arab, disinclined to exert himself, so the job just suited him. And he spoke French well. He told me he had been born in Kairouan but that he was a travelled man. Had he not been to Tunis, to Algiers, and even to Marseilles? He claimed kinship with nearly every person in Kairouan and this proved a great asset. When I expressed a wish to see the women’s Turkish Baths, “That is easily done,” said he, “for is not the Keeper of the Baths my mother-in-law?” As we passed the outer door he thrust his head in and called to her to come forth. I pushed open a second door, and an old wrinkled crone appeared[13] in a cloud of steam and led me through the various rooms. None of the bathers seemed the least embarrassed at my sudden appearance, but greeted me with smiles as I picked my way through the puddles of water and the pale olive of nude limbs. There were family parties of mothers and daughters and even tiny babies of a few months old, all chattering happily together and plastering themselves with a kind of grey clay. The outer room, where all the clothes were left, was in charge of a girl of fifteen or so, and here were numerous clients in various stages of cooling-off. Arab women in the towns go to the baths two or three times a week, so it is pleasant to feel that the people under the black shrouds that one meets in the streets, are at least clean.

On cold days when Hassan sat huddled in his white burnous by my campstool, looking like an elderly and discontented Father Christmas, it was usually not long before one of his invaluable relatives appeared bringing him a cup of coffee. “The waiter at the Snake Charmer’s café is my sister’s son,” remarked Hassan, complacently sipping, whilst I mused on the vista of relationships opened up by a plurality of wives. I had already met two uncles, two mothers-in-law, five or six of his children, a wife and a nephew. How many more were there? Soon I wanted a small boy to pose in the foreground of my picture. “I will fetch one of my sons,” remarked the conjuror, and[14] walked across the street, returning with a most unwilling small child. “And it is not necessary to give him anything. The sight of money makes the eye greedy,” said his father, peacefully relapsing into the folds of his cloak whilst I settled to work.

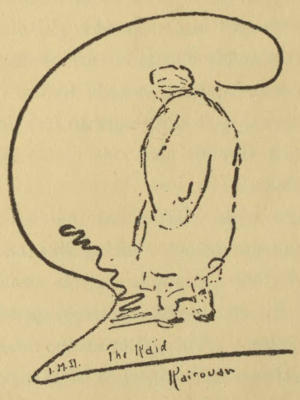

I. M. D.

The Kaïd

Kairouan

Were one to sit for long at the doorway of the Baths, facing the gate of the city, one would see the whole world of Kairouan pass through in the course of the day. It was New Year’s day, and every one was abroad. A deputation of notable townspeople came through the old gateway on their way to present a New Year’s Resolution to someone or something. Their full flowing robes made a[15] picture of the procession, and I sighed at the thought of the top hats and glittering watch chains of England.

Then came three old and venerable men clad in snowy white, two of them supporting the footsteps of the most aged. He was the Kaïd, the authority in Mussulman law, and was nearly ninety.

It was a fête day too at my tiny hotel, and the proprietor supplied ‘champagne’ with a generosity more apparent than real. There was much toasting and making of speeches amongst the small bourgeois who formed the clientèle; and a baby of two was given long sips of champagne by a humorous father, who then acted the part of a waiter with a napkin over his arm, to the intense amusement of his feminine belongings. The rôle suited him admirably. Doubtless Mrs. Noah and the young Shem, Ham and Japhet were also convulsed with mirth in their day at a similar buffoonery played by the head of the family. Jokes die hard.

The military quarters, the Government building, and the hotel were all outside the city gates and provided with small public gardens, full of the green of palms, of pepper trees, of oleanders. A few trees were planted down some of the streets of the tiny modern quarter; but it all ended as abruptly as if a line were ruled across it. Beyond were sand and cactus hedges and roads that led to the horizon. There is something attractive about French colonial quarters[16] however small. They are so trim and neat and provided with the shade of eucalyptus trees, mimosas and anything that will grow in a sandy soil.

Close to the Gate Djelladine was the Snake Charmer’s café and the sound of a native drum and the squeal of a pipe led my steps there one day. He and the two musicians were squatting on a small raised platform at the end of the low room and I as a European was given the doubtful privilege of a place in the front row where my knees were pressed against the platform. The charmer was a strange looking man with a thin wild face, dressed in a striped burnous and wearing nothing on his mop of long black hair. On the floor in front of him lay a bag of sacking that stirred and moved. After the room had filled up with a crowd of Arabs and the music had been going on for some time, he opened the mouth of the sack and from an inner jar pulled out a large cobra. This he began to tease, dancing in front of it, flapping his long hair at it and tapping its tail with a stick. Naturally annoyed, it reared up ready to strike, but the constant movement of the man seemed to daze it. It struck at him once or twice as he swayed and danced in front of it but he took care to keep just out of range. Then he brought a young snake out of the bag, and this sat up too and tried to look like its mother. Meanwhile there was dead silence in the room, except for the drone of the music and the thud of the[17] charmer’s bare feet as he danced. Every eye was fixed on him, the Arab waiter with a tray of coffee in his hands stood motionless, staring, and the dark faces of the audience watched with the intent unblinking gaze of an eastern race. Again the man dived into the bag and brought out a yellow snake which he lowered by the tail into his open mouth, then laughing wildly he took it out and wound it round his head where it looked like a horrible chaplet in the midst of his rough hair, its head pointing out over his brow. I asked if the poison fangs of the cobras had been extracted, and he brought the largest one for me to see, holding it just below the head. An obliging Arab provided a pin, and with this he prized open the jaws. I saw the tooth but I think the top of it had been broken off.

All this time the drone of the native music went on interminably. There is something curiously compelling about its minor key with the little quirks and quavers. It seems to get on the nerves and to hammer and hammer on them insistently. It fits well with the blazing sun and the intensity of the sky. I heard afterwards that the charmer was a Bedouin, but had been brought up in Kairouan from childhood. I wanted to paint him and the musicians, and the sitting was arranged one afternoon.

Hassan was always full of zeal and spurred me to great deeds.

“Mais oui, you must paint them in an open space outside the town, and then behind them you can paint in the whole of Kairouan and the desert beyond. It will be a magnificent picture.”

I bowed my head, and only hoped he would forget to look for the accessory town and landscape when the sketch was finished. The men grouped themselves very naturally, and even the cobras when the time came seemed to have an instinct for posing. The oldest musician had lost a finger of his right hand through the bite of one of the stock-in-trade. They took a deep interest in the sketch, and the usual small boy that springs out of the dust whenever one stops for a moment, obligingly kept them posted as to its progress. I worked for two hours and then shut up my paint box. Hassan, who had been smoking cigarettes in the background on a chair brought of course by a relation, seemed hurt at my want of enthusiasm when he suggested I should now go and paint a mosque. I had worked all morning as well, and it was now four o’clock, but he evidently thought me a poor thing.

The wide stretches of country beyond the walls were sandy and bare, with only a sparse growth of a heather-like plant on which the camels fed. There were herds of a hundred or more, brown or fawn-coloured or sometimes white. They are the Arabian species having but the one hump, over which is fastened a large mat that fits down[19] over it and looks like a hat, I suppose serving as a protection. The herds are taken out to graze during the day and brought back at night. These are the beasts that belong to town owners and that are hired out for caravans. The foals run by their mothers’ sides, as furry and long-legged as young donkeys. A good deal of trade is carried on with the Bedouins, who bring grain and wool, honey, eggs and butter into the town, and go out again laden with sugar, salt and other goods.

There was a fondouk close by the hotel, and from my window I could hear the roaring of reluctant camels being loaded in the early morning and the cries of their drivers. Looking out I could see them standing in the road, one knee bent, and fastened up by a rope by way of hobbling them. They are wonderful animals, for at a pinch they will eat anything from thorns to cactus leaves, and in times of scarcity they are even fed on date stones. I saw heaps of these being sold in small market-places for this purpose.

But though he does not disdain such accessory diet, the camel requires a large quantity of food, and possesses the useful gift of being able to store up any superfluity of nourishment in his hump, on which to live in hard times. The popular fallacy that he can go for days without food is erroneous, but he lays no stress on the punctuality of his meals as a horse does, and this is a valuable trait in a beast that is used for long journeys across the desert where fodder[20] is scarce. His strange figure with its thin, fragile-looking legs that fold up like a pocket ruler when he lies down, and the small cynical head set on the long swaying neck, suits the sandy wastes and the exotic charm of the East. He walks with slippered tread, wrapt in aloofness. One is baffled by his haughty indifference. He groans and protests as his load is being fastened on, but only as a matter of form, for his docility is remarkable. Overload him, or force him to journey when he is ill, still his protests are no louder. He just dies. Quite quietly and without warning, he lies down and refuses to live, baffling, in death as in life, the comprehension of the bewildered European.

Mohammedanism is the national religion of Tunisia, but it is not always realised that there are many sects, each basing its belief on the teaching of different religious leaders during the first centuries after the death of the Prophet. The divergences arose in the first instance from varying interpretations of the words of the Koran, and doubtless these divergences have crystallised since into very marked tenets. There are, I believe, more than eighty religious “orders” in the Moslem world, but the word does not bear the same signification as it does in European countries. The follower of an order belongs to an association which does not interfere with his family life or with his profession. At the head of each denomination is a “sheik” who takes up his dwelling, as a rule, near the tomb of its founder.

The sect of the Aïssaouia is remarkable for its extraordinary religious dances. It was founded by Si Mohamed ben Aïssa who died in 1524 at Meknès. Its disciples claim a complete immunity from the effect of poison. According to the legend, its founder was exiled by the Sultan of[22] Morocco on account of his popularity with the people. Crossing the desert his followers suffered greatly from hunger, whereupon their leader told them they might safely eat scorpions, snakes, stones and thorns. This the votaries of his religion still do during their celebrations, endeavouring to prove that the faithful can at will suspend his bodily sensations through fasting and prayer.

Their services are usually held once a week, and I went to one at Kairouan in the Mosque of the Three Doors. It began at 5 p.m. The worshippers squatted in two rows on a square of matting facing each other and reciting prayers. One man after another called out the phrase in a high nasal voice, and the rest made a response in chorus. They kept swaying backwards and forwards and getting more excited. Sometimes the recitation was followed by a low abrupt sound from the rest, that sounded like the growl of a tiger. Meanwhile a boy handed round a cup of water at intervals to the worshippers, and afterwards brought in a brazier of hot coals at which he busied himself warming the parchment of the native drums.

It was fast getting dusk. In a corner sat a group of European spectators, and behind them was a pierced door through which came the fanatical ull-ul-la of women devotees. It was a weird scene. The floor of the mosque was paved with narrow bricks set edgeways, with here and there a slab of mosaic. Stone pillars lost themselves in[23] the gloom of the roof, from which hung common kerosene lamps, strings of ostrich eggs and the coloured glass balls beloved of natives. Shadows gathered in the dim corners, and through the open doorway one could catch a glimpse of the evening sky; whilst interminably the rows of squatting figures swayed backwards and forwards and the chant grew more and more insistent. After what seemed hours, they rose to their feet, and the thudding of tom-toms began. The worshippers ranged themselves standing in a row, and a wretched unhealthy looking creature in a ragged brown burnous was brought forward. Louder and louder came the throb of the music, faster and faster the figures intoned and swayed. It seemed a whirlpool of sound, with that sinister group of devotees at the centre of it.

There was a sudden piercing wail from the women behind the door which seemed to cleave through the clotted sound of the drums and chant like the flash of a poignard. The grey light from the door fell on the ghastly face of the ragged youth. Twitches ran over his body and he staggered out from the rest. His head was thrust forward, and he held his arms stiffly behind him, jerking himself convulsively to the rhythm of the chants. He seemed to be half-hypnotised. His sickly face shone livid in the dim light, his eye-balls were turned up, and he moved in a series of jerks, staggering from side to side. And still the chanting and the music went on, barbaric and horrible, till[24] the tension of one’s nerves became almost unbearable. The chief priest shouted something in a strident voice, and seizing the wretched creature by the shoulder he guided him round the mosque holding an object that dangled between the fingers of the other hand. As the group neared us, I saw it was a live scorpion about two inches long.

Meanwhile the boy was staggering and nearly falling and seemed to have little or no power over his limbs. It was horrible to watch, but I could not turn my eyes away. Suddenly the priest pressed the victim’s head back and dropped the wriggling insect into his open mouth. As far as I could see, the wretched creature devoured it ecstatically; I marked the movements of his throat as he swallowed. This was repeated twice. After that he was given large pieces of jagged glass, and these too he seemed to swallow. I cannot describe how horrible the whole thing was: the gloomy interior, the fanatical howling of the worshippers, and the dazed half-mad youth in the midst. He had been clinging to his guide, staggering from side to side. Suddenly he fell unconscious on the ground, and lay there groaning.

Meanwhile the ceremony went on, paying no more attention to him. Now first one and then another of the worshippers began to jerk backwards and forwards and to pull off their outer garments. One kept flinging his head from side to side, whilst his long black hair flapped first[25] this way and then that. Long metal spikes about four feet in length were brought and the fanatics drove them into their throats or seemed to do so. In any case they drove them in so far that they held without support. They were led round, the ‘swords’ sticking out of their bare necks like pins in a pincushion. I felt quite sick, but worse was yet to come when they knelt down and the priest drove the flat-headed spikes still further in with a hammer. No blood flowed. All this time the drums and the chanting went on, till one’s brain reeled.

I think the men were in a state of hypnotic trance—their eyes were half-closed and they jerked backwards and forwards grunting at every stroke of the hammer. It was so horrible that I could not look at it for more than a few seconds. It was not only the dance itself but the whole feeling of barbarism and degradation. The atmosphere itself felt evil.

The doors were wide open and a few native children stood there staring at the scene within. One after another the row of worshippers began to jerk and step forward, already one burly man had fallen forward on his face and lay inert, the scorpion-eater was a mere twitching mass in a corner, and I had had enough and was thankful to push my way into the open air.

I stepped out into the courtyard of the mosque. Already the sky had paled to a clear amber, barred with the few[26] flaming clouds of sunset. At the fondouk near by, camels were being loaded up to leave the town. They padded silently past in the dusk, their nodding heads turned to the tawny plain that stretched away in the distance to the soft purple of distant hills. Far away, twinkling lights showed the Bedouin encampments for which they were bound. One by one the great creatures passed me, the dust like smoke about their feet, followed by silent hooded figures along the white streak of road that led into the golden haze where the sun went down. Slowly the procession melted away into the distance till it merged into the blue haze that hung about the plain, leaving but a little feather of ruffled sand to show which way it had gone.

Though the educated classes, at least the men, are probably not much influenced by superstitions, the lower classes, especially the women, are cumbered about with them from the day of their birth to that of their death. The Koran allows the existence of certain supernatural beings, midway between angels and men, called genii, and these consist of two kinds, peris and djinns: the former are friendly, but the djinn if not actually malevolent is full of mischief, and it is as well to placate him. Different varieties live in fire, air and water. When drawing water from a well, the prudent housewife does not let down the bucket too suddenly, lest she might disturb a sleeping water-djinn. Any sudden movement might hurt or[27] affront these invisible beings. Besides the constant anxiety to keep on the right side of them, there are a hundred and one things which are unlucky and must be avoided. Should you go to see an invalid on Friday, that person will die. Indeed, on any day of the week it is wiser not to call on him in the afternoon.

The black hand (erroneously called the hand of Fatma, Mohammed’s favourite daughter) painted on the walls of houses and on the prows of fishing boats is designed to avert the evil eye, and a tiny hand is often tattooed on the cheek or worn in the form of a brooch fastened in the folds of the turban. A piece of paper with a verse or two of the Koran written on it is put above the door to warn off scorpions, and many carry round their necks or in their turbans small amulets containing verses of the holy writings. These are also often hung round the necks of horses and camels. The burning of hyssop in the rooms of a house keeps evil spirits at bay, and seems a pleasantly easy method of disconcerting them.

Naturally enough in this atmosphere of superstition, the services of sorcerers and ‘wise women’ are much sought after, for the providing of talismans or for more nefarious designs. Nearly all are of Moroccan extraction, it being well known that those of that country are particularly powerful. The following legend explains how this came about.

One day Allah sent forth some angels on a special mission to the earth. But beguiled by the charms of earthly women, the spirits lingered so long over their task and performed it so badly that they incurred the wrath of the Most High. Fearing lest their conversation on their return might trouble the limpid peace of heaven or sow discontent in young seraph hearts, Allah condemned the culprits to be cast forth for several centuries to a region midway between heaven and the earth. There, suspended in the æther above Fez, the exiled angels busy themselves in making amulets which they throw upon the earth below, to the great aggrandisement of the sorcerers of Morocco.

When it is feared that someone has been ‘overlooked’ by the evil eye, a magician is hastily sent for, and verses of the Koran are usually administered either externally in the shape of an amulet applied to the afflicted part, or internally, chopped up in hot water. Should the patient show no immediate signs of relief, the prescription is repeated till he either dies or recovers. A good deal is also done by the muttering of incantations and the touching of the sufferer. These ‘wise people’ are also extremely useful should a person wish to do harm to an enemy. By the saying of certain incantations accompanied by the shutting of a knife, his life may be quietly cut off with no unpleasant fuss whatever. Or magic powders can be introduced into the water he drinks or the food he eats,[29] which will ensure the destruction of the peace of his household or serious illness to himself. This latter seems the more likely result of the two.

I. M. D.

They are also much sought after for love-philtres, or methods of reviving a waning love. There is a horrible story of a woman of good birth in Tunis many years ago, who consulted a magician as to the best way to regain her husband’s love. She was told she must give him couscous to eat, “made by a dead hand.” By dint of bribes, she made her way to a cemetery at midnight, had the newly buried body of a woman disinterred, set the corpse against a gravestone, and holding its rigid hand in hers used it to stir the contents of the cooking pot she had brought. The dead woman was then returned to the peace of her grave, and next day the unconscious husband ate the couscous. But alas! we do not know with what results. The facts leaked out and there was a great scandal over the desecration of a grave, but owing to the social position of the culprit the matter was hushed up.

I was told a strange story too by a European resident in Tunis. Some young man of Arab extraction became engaged, but wearying of his fiancée and wishing to marry someone else he consulted a native sorcerer. By degrees the girl became ill and seemed to be wasting away mysteriously. Doctors could do nothing and the mother was overcome with grief, as also appeared to be the young[30] man. At last an old negress servant declared to the parents that their daughter must have been bewitched. Distracted at the girl’s rapid decline, they finally let the negress take them to consult a famous Arab sorcerer, in fact the very man to whom the young man had applied. Yes, he said, she would die, but he could save her were they prepared to give a higher sum than the young man had paid him to have the curse laid upon her. To this they agreed. A black cock was brought, its heart was taken out and transfixed with a nail on which was skewered her name, and it was then roasted at a slow fire. “And for a further larger sum,” remarked the magician, “I will transfer the malady to the young man himself.” But the parents fled. The patient recovered, and the engagement was speedily broken off.

Within a mile or two of Kairouan were various small orchards and gardens, and Ali Hassan told me importantly that he was the owner of one of these, consisting of olive trees, fruit trees and vines, for which he had given 600 francs, and that with taxes and extra payments the whole had cost him no less than a thousand. I was suitably impressed. But during a drive in that direction some of his pride collapsed. He had shown me his property with its mud hut in one corner which he referred to magnificently as “ma maison.” He intended to have it moved down to the roadside end of the field, “for a highway brings much money.” There he will have a little shop and sell coffee and beans, grapes and fruit.

The garden itself looked like a child’s game in the road, just bare twigs sticking up in small heaps of dust; but that was December and Hassan saw it in his mind’s eye by March, pink with almond blossom and starred with the bloom of apricots. Further along the road a gloom fell upon him, and at last he turned from the box seat beside the driver.

“Do you see that truly magnificent garden on the other side, and the beautiful house with three rooms? That was once mine.”

There was a dramatic pause. I enquired delicately how he had been forced to part with it.

“Because the owner of it died, and it was sold for more francs than would stretch from here to the city.”

It was indeed a beautiful property. Many olives and apricot trees were in it and there was a good well, and at his house he had a little business where he sold cakes and coffee and such like. And as many travellers and Bedouins pass up and down the way to Kairouan, he had made money. “Mais oui, it is the road that brings money,” and he sank into a brooding silence.

However, he recovered his cheerfulness when he took me to see his town house. He was anxious I should make a picture of his wife and family, but when we arrived it was to find the former had gone to the baths, taking the smaller children with her. I had seen her before, but now I was introduced to the eldest daughter, a pretty girl of thirteen whom we found at her loom weaving carpets. Her father explained she was busy making money towards her wedding, which would probably take place in a year or two. He would select the bridegroom, and she would not even have seen him beforehand. The little bride-to-be smiled up shyly at me. Her hair was curling and very black, and[33] her complexion olive. Beautiful dark eyes, fringed with long lashes and underlined with kohl gave character to her face, with its straight nose inclined to the aquiline and the full well-drawn mouth. She gave promise of unusual beauty, and already looked three or four years older than she was, to my English eyes. She made a charming picture dressed in a dark short sleeved bodice over a pink cotton under-shift, full cotton pantaloons drawn in at the ankle, and her slim brown feet tucked under her. A faded red handkerchief was tied over her hair, and her bare slender arms moved backwards and forwards as she bent forward deftly knotting in the pieces of wool on the fabric. She worked with the swiftness of long practice, her pretty henna-stained fingers picking out the colours required from a pile of coloured wools in front of her. The little room she sat in was quite bare except for the loom and the matting spread on the beaten earth floor.

On coming in from the door in a quiet street, we had bent down to get through the opening into the room on the left. The walls were whitewashed, roughly decorated with crude coloured drawings of the lucky hand of Fatma. Through this living-room one stepped into a small courtyard, with a collection of green plants in pots in one corner, and a clothes line stretched across it on which flapped a few coloured garments. Two more rooms and a tiny cooking-place opened off it. I was shown the bedroom[34] with great pride. There were rugs on the floor, and two large beds built into recesses. Coloured illustrations from European magazines adorned the walls, and a very well drawn portrait of Hassan’s father done by some French artist to whom he had acted as guide. There was a portrait of a very wooden and staring-eyed Bey and another of his predecessor. Hassan stood in the room watching my face for an expression of surprise and delight which I managed to produce. To my remarks he waved his hand round his possessions. “It is nothing,” he said, “you should have seen my country house.”

There was another woman in the living room, Hassan’s sister, who with her husband occupied the other bedroom, a discontented-looking handsome girl, about twenty-two, more gaudily dressed than the little carpet-weaver. She squatted on the floor cracking almonds with her white teeth and putting the kernels into a small earthenware bowl. A smouldering good-looking piece, thoroughly bored with life and probably meditating a speedy change of husbands.

I met some English missionaries who had been in the country for thirty years, and they told me that divorce is very common amongst the inhabitants. It is even rather the rule than the exception, and it is almost as often resorted to on the part of the wife as on that of the husband. It can be procured for the most trifling causes, and the[35] divorcée does not lose social caste. She returns to her father’s house and usually remarries, though in that case the father cannot command as good a payment for her as he received from her first husband. Should there be children the question of their maintenance is settled by the Kaïd. The missionaries naturally were brought more in contact with the lower classes, amongst whom they thought divorce was commoner than in the wealthier circles. The poorer women go out closely veiled, but those of better birth live almost entirely in their houses and on the very rare occasions when they do go out, it is in a closed carriage with all the blinds down. However, they rarely resent their seclusion in the harem; they look on it as an enhancement of their value, and these missionaries had never heard any complaint of the system.

It is quite likely that whilst we are pitying the women of the harem for their secluded, miserable lives, they are also wasting compassion on us, as poor creatures whom their husbands value so little that they let them wander anywhere unveiled! But I think compassion is hardly the sentiment with which we inspire them. Horror and disgust are their more probable feelings. At every turn we run counter to their idea of what is seemly and in good taste; and this question alone, of the different conception of women’s standing in the East and in the West, makes mutual understanding difficult between the two races.

Though the Koran allows four wives, it is not often a man avails himself of the permission. It is too expensive, and he prefers to take his supply consecutively. He can get as much change as he likes, by the easy way of divorce. I went to an Arab wedding of the poorer classes at Kairouan, and found it deeply interesting. It was a cold clear night with a bright moon, the open space outside the walls of the city silvered in its light. It seemed strangely quiet and empty after the stir and bustle of the day; the little booths were shut, and a slinking white dog nosed amongst the shadows. From a distant café came the sound of a stringed instrument and the singing of a reedy voice. Otherwise silence. But when we had passed through the city gates, we heard a loud hum of voices. Muffled figures were hurrying along and soon we found ourselves in a crowd waiting for the marriage procession. Knots of musicians appeared and struck up their queer wavering tunes on pipes and drums and barbaric looking stringed instruments, whilst some hand held aloft a lamp which made a small radius of ruddy flame, lighting up the group below it and making the hooded figures look more mysterious than ever. From a side street came the shrill call of women shouting to keep evil spirits from the dwelling of the newly married pair, whilst nearer and nearer came the sound of the approaching procession.

In a few moments it moved past, the bridegroom in the[37] middle of it, his head and shoulders shrouded in a thick covering. The noise woke a bundle of inanimate rags against the wall at our feet; it stirred, groaned and sat up. To the sound of shouting and drums and the intoning of a nasal chant, the bridegroom disappeared down the echoing street on his way to the mosque. Already the bride had been fetched to his home, the civil service having taken place the day before. We made a short cut there, between blank walls where the path seemed a trickle of light through impenetrable shadows.

And so we came to the house itself. Mysterious veiled figures stood motionless on the roof, like sentinels of Fate. In the gloom my hand was seized by a native woman’s, small and dry, and I was led into the house followed by my English companion. We were taken across one room, and brought to the doorway of another from whence came a hum of voices and laughter. Peering into this smaller room we saw it packed with gaily-dressed women squatting on the ground, whilst in the corner sat the bride like a waxen image. She was swathed in a robe of heavily tinselled stuff and over her head was thrown a drapery that quite hid her face. Not a soul spoke French, but we were hospitably beckoned in. It proved a matter of some difficulty to avoid stepping on the human mosaic which covered the floor but we managed it somehow and sat down in very cramped positions in places of honour close[38] to the bride. She sat with her back against the bed, which in Arab fashion was in an alcove. So great was the throng, that our advent had pressed a small child under the bed itself, from whence first came a doleful snuffling, followed at last by a determined wail. It was as much a work of art to rescue the victim as to extract a winkle from its shell with a pin, but it was ultimately restored to the bosom of its family.

All this time the bride sat rigid and unbending as befits a modest Arab maiden. She made no sign of life, even when the woman next her raised the heavy veil for us to see her. She was a rather heavy-featured girl, her face artificially whitened, with a brilliant dab of rouge on either cheek, her forehead painted with an ornamental design in black and her eyebrows made to meet in a straight line. Her fingers had been dipped in some dark scented ointment, whilst the backs were decorated in an intricate pattern with henna and the palms dabbed here and there. Her hair was in two heavy plaits on either shoulder and she wore a coloured silk handkerchief bound over it and above that a tinselled head-dress with a long tail to it that hung down her back.

The heat in the small room was stifling. The women were all unveiled and many of them were heavily powdered and rouged, their fingers loaded with rings and wearing necklaces and earrings. Some were dressed in queer décolleté[39] dresses reminding one of fashions of twenty years ago, with tight pointed bodices, much be-sequined and trimmed and with a kind of gilt epaulettes on the shoulders. Everyone chattered hard, small babies cried, outside the shouting and noise of drums went on, and the atmosphere grew thicker and thicker with the odour of packed humanity, scent and powder, and the sweet musty smell of garments that had been laid away in aromatic herbs. Most of the women were of a warm olive colouring, with beautiful long dark eyes, and one or two were as fair as English brunettes with a natural carnation in their cheeks.

Amongst them I made out the mother of the bride, dressed in shabby black. She had a fine worn face, with features that showed more mind than the rest of the crowd, and dark eyes tear-stained in their hollowed sockets. The cheekbones were high, the nose short and straight, and the sad mouth drooped at the corners. It was the face of a woman who could think and suffer, and stood out amongst the comely crowd in the same way that her black draperies ‘told’ against their gay clothes. She reminded me of the Virgin in the Pietà of Francia in the National Gallery. At times she wept softly with eyes that seemed already burnt out with sorrow, drying her tears with a fold of her veil. I longed to know Arabic, that I might speak to her. Amongst foreigners whose language one does not know and having no mutual tongue for comprehension, one is as[40] deaf and dumb, all power of observation and understanding centred in sight. So, I suppose, must a deaf mute pass through the world, striving to participate in the brotherhood of humanity, watching for a gleam here, a glance there, to unlock the perpetual riddle.

At last the bridegroom was approaching.

The women began to leave for the larger room where we thankfully followed. But there we were not much better off, as in a moment a feminine crowd closed in upon us in a frenzy of friendly curiosity. It was like stepping into a cageful of monkeys. They seized our arms, ran their hands over us, exclaiming and gesticulating, fingered our blouses, our ornaments, and trying to pull off our hats. It was only the arrival of the bridegroom that averted their attention. He was brought by another way into the room, still veiled, and then the bride was brought to him and amidst much laughter and shouting his head covering was removed. After this they were conducted to the door of another bedroom, stepping over the sill of which each tried to step on the other’s foot, the one who succeeds being supposed to have the predominance in their future married life. The door was shut on them, “et voilà tout” as a small Arab boy remarked to me, glad to air his slender French.

I was told later that when the bridegroom finds himself alone with his bride he lifts her veil and sees her face for[41] the first time. He takes off her slippers and outer coat and then leaves her, and rejoins his men friends outside. If he has not been satisfied with his bride’s appearance it is still open to him to repudiate her, in which case she will return to her father’s house. Should he be pleased with her, however, the next day is given up to a banquet to all their friends, and he returns to his house where the married life of the young couple begins.

As soon as the bridal pair had disappeared the crowd turned its friendly attention to us, and I thought we should never fight our way through the mob of women. I caught a glimpse of the young Englishwoman in a perfect maelstrom of females, her hat off, her blouse almost torn from her shoulders. I waded to her with difficulty as one might through heavy surf, and laughing and breathless we at last got clear and out into the open air. The Englishmen and Hassan had had to stay outside, only women being allowed in. “And was the bride very beautiful?” Hassan asked with romantic interest. He told us the feast that would take place next day would be a great one: half a sheep roasted, cakes and sweetmeats of every kind.

“Indeed marriage is always a very expensive affair,” he sighed. “A man is lucky if he is not 500 francs the poorer by the time it is all over. For his bride he must give 300 to 400 francs, perhaps even more. Then he must provide the furniture for the house, and the bed, and one[42] set of silk garments for the bride. And also there is the wedding banquet and for that too he must pay.”

I asked what the bride’s contribution to the household was; she must bring the mattress and the bedding, also the cooking pots, and her own clothes.

“Yes, it is not many who can afford to have more than one wife,” he went on. “And if a man be wishful to have two, never do they get on together, and thereupon he must perhaps have two houses or be for ever deafened with their quarrels.”

He fell into a reverie, whilst we made our way through the outskirts of the town, past the deserted market-place that slept in the moonlight, under the shadowy pepper trees that made a grateful shade in the heat of the day for the vendors of oranges and sweetmeats, and so through the city gate back to the quiet little square and the open door of the hotel.

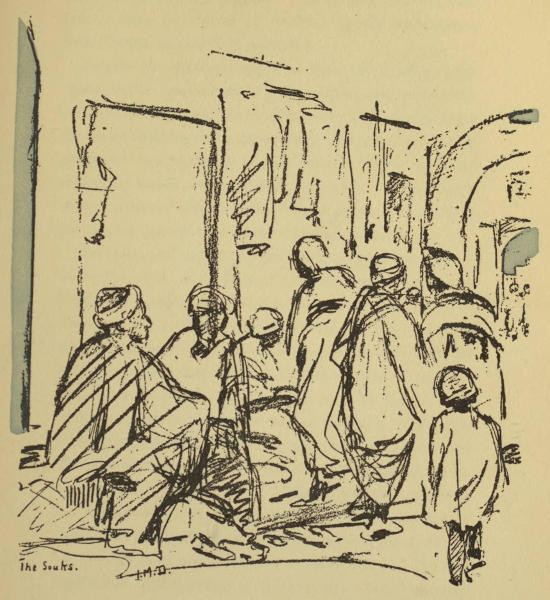

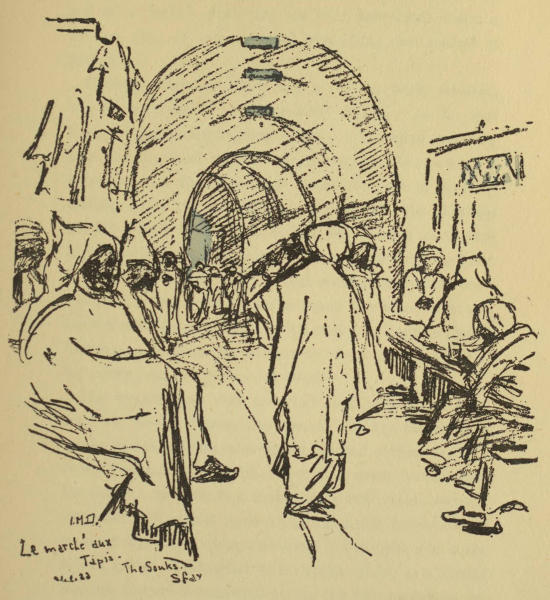

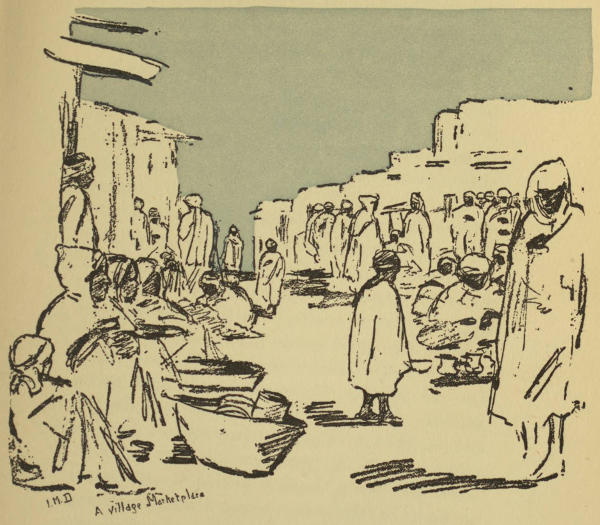

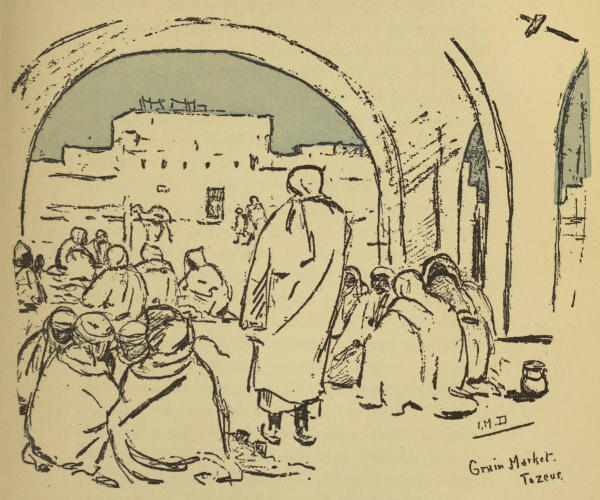

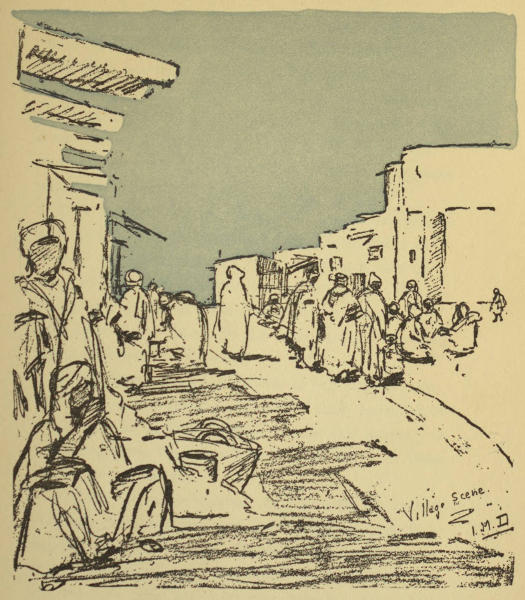

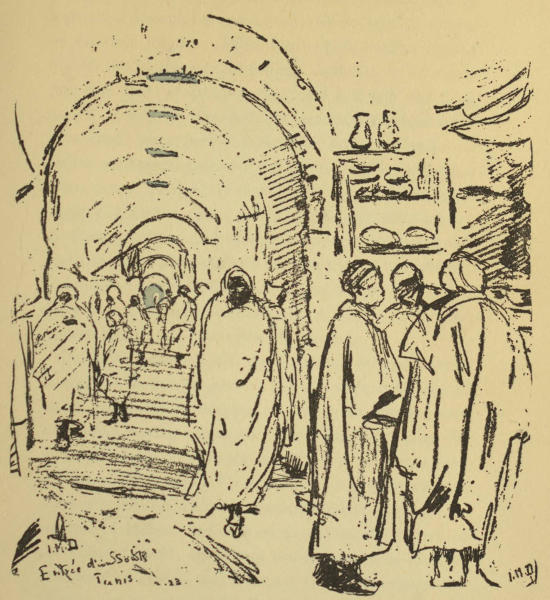

The scene in the Kairouan Souks was one of great animation in the afternoon, when auctions were held by the shopkeepers. The buildings consisted of long narrow passage-ways whose arched roofs were pierced here and there with openings to let in light. The shops were on a raised level on either side as in all Eastern bazaars, and were just recesses Where the seller squatted amongst his wares, whilst the customers and spectators sat along the broad stone edge covered with matting that ran along the front[43] of the booths, their discarded red and yellow slippers neatly ranged on the ground below.

I. M. D.

Business is conducted slowly and with dignity in the East, there is much talk and bargaining, coffee is brought and sipped during the process and then finally, perhaps, a purchase is made. The shopman in his flowing soft-coloured robes, probably wearing a flower over one ear, slowly measures the desired carpet or rug by hand, from the elbow to the tips of his fingers. There is more discussion, and at last the purchaser brings out a worked leather purse and counts out the requisite payment.

But during an auction, the scene was much more animated. Shop assistants rushed up and down carrying goods and bawling at the top of their voices “What offers? what offers?” Customers bid against each other and the noise and bustle were tremendous. Every other moment a panting native rushed back to the owner of the shop to ask if the latest offer were to be accepted. Up the side-passages opening into the central Souk, more auctions might be going on simultaneously, and the crowd was so great that sketching had to be of the snapshot variety.

I. M. D.

Nearly all the men were in white or sand-coloured burnous, with the hood partly pushed back, showing the small twisted turban and close red fez worn underneath. The Tunisian countrymen are in general fine looking men, tall and aquiline featured, with good foreheads and clearly[44] marked eyebrows. Nearly all have a moustache and a dark closely clipped beard, but one sees a few of fairer type amongst them. They are friendly and courteous. A gamin told one grave and dignified looking figure that I was sketching him, whereupon my model glanced at me, smiled and shrugged his shoulders. I showed him the sketch and he laughed, much amused. Very often the shopkeepers near whom I was sitting with my sketch-book offered me coffee and I always met with hospitality and goodwill. If one asks their permission before settling[45] down, it is always granted, and they usually take one more or less under their protection, and try to prevent a crowd from collecting.

I like the Arabs’ fine dignity. Probably their flowing style of dress helps to give this effect, and the hooded cloak makes a becoming setting to their dark faces. Even the tiny boys wear the burnous and go about looking like small elves in their pointed hoods.

Outside the western walls of the city, the graveyards stretched right away as far as the Mosque du Barbier, which lay about half a mile from the town. The tombs were not marked by any inscriptions, and often were only covered by a small rounded slab or just roughly enclosed by an edging of bricks. On these poorer graves a cluster of bricks set sideways in the earth told the sex of the dead: if set close together they mark the resting place of a man, if scattered, that of a woman. There is something inexpressibly forlorn about these Moslem cemeteries, the graves so huddled together, no green, no flowers. The tiny spectacled owl perches on the low headstones or makes his silent flight from one to the other, and beyond the graveyard itself the whole sky flames to brilliant red at the going down of the sun.

The sunsets in Kairouan were magnificent. The whole of the west seemed to burst into fire and the desert glowed with a deep reflected rose. I call it ‘desert’ but it was[46] not really this. ‘Le vrai desert’ is far off. But the wide stretches of sandy waste looked the name, and at sunset they turned a wonderful red, with washes of dusty purple, whilst the far hills were first violet and then almost black against the last splendour of the sky.

Coming home through the cemetery one evening, Ali Hassan was anxious to know if I had read the Koran, and begged me to carry one about with me; “it would protect you greatly.” I asked him if the Fast of Ramadan was kept very strictly in Kairouan. He said yes, “except that there are always some who do not follow their religion seriously. They do not pray regularly, neither do they fast carefully for a month at Ramadan. But they will find the difference when they reach the other world. For every Ramadan they have broken here, they will have to fast a year hereafter. Ils auront joliment faim,” he ended with satisfaction. I gather he himself is a scrupulous observer of his religion.

When I left Kairouan, Hassan came to see me off, wishing me happiness and prosperity, and hoping I should return some day. He presented me with one of his most treasured possessions, a picture postcard of himself and his family at the Marseilles Exhibition. There they all were posing under a tent, and labelled ‘Fabrication de Tapis de Kairouan (Tunisie) Maison Ali Hassan.’ Even under these trying conditions I was glad to see Hassan had still[47] continued to look dignified. There was his wife to the left of the picture wearing all the family jewels and watching a sleeping baby that even in slumber seemed to remember it was ‘en exposition.’ The little girls were working at their handloom, whilst Hassan himself sat with a son on either side, and a row of family slippers in varying sizes ranged along the edge of the mat in front of him. He was immensely proud of this work of art.

As my train steamed slowly away from Kairouan, I saw him still on the platform, his portly figure wrapped in the voluminous folds of a white burnous, watching till the distance had swallowed me up.

The country through which the train passed from Kairouan to Sousse was bare and desolate, with scarce scattered Bedouins’ tents now and again that seemed to blend with their surroundings like the nests of wild birds. A few grazing camels wandered near them, herded by ragged children who turned to stare at the train. The plains stretched as far as the eye could reach to the feet of distant hills. We passed one or two shallow lakes, obviously rainfall collected in depressions of the ground, that would dry up as some we had already seen which were now nothing but stretches of cracked and seamed mud, looking like jigsaw puzzles.

Sousse proved to be a picturesque little town on the sea, built about the base of the old Kasba or fort, whose walls stand on a hill above it, looking out over the flat-roofed white houses of the modern town to the waters of the Mediterranean. From the fort itself there was a magnificent view: on one side the curving coastline with its dotted white villages and the gentian sea fading to a pale mist in the distance, on the other, vistas of olive groves and orchards.

The great local industry is the cultivation of olives, and there are factories for the making of oil and soap on the outskirts of the town. The actual care of the trees is almost entirely in the hands of the Arabs, to whom the French owner usually sells the crop in bulk, unpicked. A tree in full bearing is worth three to four hundred francs a year, and an orchard may contain thousands of trees. The Arabs are so improvident that they often spend all the money they make during the harvest, in six months’ time, and then are forced to realise in advance on their next. Frequently they get into the hands of the Jews in transactions in which it is certainly not the latter who suffer.

Beyond the Kasba are the Christian catacombs, which are interesting, and cover a large area. Passage after passage is tunnelled out, with poor little skeletons neatly stowed away on either side as a careful housewife stocks her store cupboard with jam.

The Souks are not so picturesque nor as extensive as those of Kairouan and of Sfax, but the crowd was enthralling to watch. In the native cafés grave men in picturesque draperies were seated along the broad stone ledge on either side the room, sipping coffee or playing a kind of chess, whilst the owner bent over his charcoal fire at the far end, and the assistant sped about on bare feet carrying sheaves of the long-handled coffee holders, just big enough to fill each minute cup. To this is often added a drop of orange flower water or some sweet essence.

I. M. D.

In the brilliant sunshine outside the arcade a peasant squatted on the paved path whittling at flutes made from a cut piece of cane ornamented with red and green paint. He played a few sweet husky notes to show his skill. Opposite to him sat a vendor of oranges, and a seller of the brown flat loaves of native bread sprinkled on the top with seeds, and beyond them a man with a tray of sweetmeats, slabs of toffee, cakes of chopped nuts, brilliantly coloured strips of pink rock, and sugar birds striped red and green and set on wire stems to attract children. All these huddled on the ground, their wares spread round them, whilst at the end of the steep stony street one saw the frowning battlements of the Kasba rising sheer against the sky, and looking downhill caught a glimpse of the blue of the sea and the white sails of fishing boats like drowning butterflies in the harbour. Across the bay were the houses of the little fishing village of Monastir. The country just round Sousse is all olive groves, with huge hedges of spiked cactus, and when I was there in January, shrivelled prickly pears still hung along the edges of the leaves. There had been so many that year that they had not all been picked. The whole country teems with Roman remains, and one sees fragments sticking up out of the ground wherever foundations are being dug for a house.

I went from there to spend the day at El Djem to see the wonderful ruins of its amphitheatre. To reach it, one again travels through a great stretch of bare country. The engine of the train broke down and we were delayed for about two hours en route. We first ran over an Arab, and in his efforts to avoid this, the driver had put on his brakes so suddenly that he injured the mechanism of the engine. None of the passengers seemed to be much perturbed when they heard afterwards of the Arab having been killed. Indeed the man must have been a confirmed suicide, for the country is so bare that a train can be seen coming two miles off, and its progress is deliberate enough to give the most dreamy of pedestrians time to realise his danger. Perhaps it is like the Trans-Siberian railway, where compensation used to be given to the family of the deceased, till it was discovered that the peasants were driving a lucrative trade in aged relatives.

Before reaching El Djem, I saw the huge ruins of the amphitheatre against the sky. They looked immense, with a small Arab village about their feet. In colour they were a warm brown, built of enormous blocks of stone; and the size of the building took my breath away. I am told it is as fine as the Colosseum at Rome, and of course it gains in grandeur from its isolated position. Forlorn and ruined as the building is, with its arches like empty eye-sockets staring into space, there is still something[53] magnificent and defiant about it. Most of the tiers for spectators are still there, part of the Imperial entrance and ranges of arched openings. Below, in the centre, are the prisoners’ cells and the dens for wild beasts, with the openings by which the latter were released into the arena.

I sat on a large block of stone. Pigeons flew in and out of the galleries where Roman ladies used to sit and watch the gladiators and the fights with savage animals below. Grass grew along the edges of the walls, and a tuft of wild thyme waved in the breeze. It was a grey day, and against the sad sky the great edifice seemed to stand brooding over its past splendour.

I went with the Arab custodian across fields, by narrow footpaths edged with spiked battledores of prickly pears, and was shown vestiges of a paved Roman road and the remains of a villa. We passed an old well, used still by the villagers, at which a young girl was drawing water. These village people go unveiled and she stared at us, a slender brown slip of a child in a ragged blue robe caught across her smooth shoulder by silver brooch pins. Her face was pointed, a tiny trident was tattooed on her forehead, and another mark on her chin. She gazed at me with her bright dark eyes the underlids of which were darkened with kohl, and then turned again to the filling of the red amphora-shaped jar she carried. I watched her walk away, graceful and erect, bearing the earthenware vessel[54] of water on her head, her bare feet moving noiselessly along the dusty path.

Numberless children ran out to meet us in the village, laughing merry little things in tattered burnous and blue gown, incredibly dirty and cheerful, with a constant flash of white teeth. Even the tiniest girls wore thick metal anklets, and tots of five or six carried baby brothers astride their hips. The children’s playtime is a short one; at seven or eight years old they are already at work herding cattle or collecting fodder and fetching heavy jars of water from the wells. I have often seen a small girl almost weighed down with the weight of a jar of water. They crouch down whilst an older one lifts it on to their back and passes a cord round their forehead to hold the jar in place. Then, staggering, the poor little thing gets to her feet and starts off, almost bent double. The Arabs are very fond of their children and good to them, but they never seem to realise what heavy work they put on them.

Later, from the small station, I watched the day fade and dusk settling on the countryside. Slow-pacing camels were making their homeward way driven by young boys, whilst here and there a little group of workers was returning from the fields. The sky turned to a clear translucence in the West, the amphitheatre blurred to a formless mass of grey girdled about the knees with a blue haze of smoke from the Arab village. Dogs barked from behind its mud[55] walls, and the pale stars began to peer from between the clouds. First here, then there, the warm flicker of a fire showed through an open doorway; and all these homely signs of village life seemed to make ever more and more remote the great outline of the ruins. For a time I could still see the sky through the top arches of the building, but even that faded by degrees, till at last night folded her mantle about the vastness of its desolation.

The dark trees along the centre of the boulevard looked almost artificial against the greenish glare of the electric lights. From every café streamed bands of revellers, their brilliant costumes adding to the theatrical appearance of the streets. Dominoes of every colour flitted about; orange, purple, emerald and lemon yellow. Showers of confetti made a pink and blue snow upon the ground, and the moving crowd passed in and out from the dark shadows below the trees to the clear-cut brilliance of the light. Rattles and toy trumpets sounded shrill above the under-note made by the murmur of the populace. From some building came the noise of dancing and the crash of a band. Groups of absurdly dressed figures pushed their way through the restaurants, here a Teddy bear linking arms with a Red Indian or an English jockey escorting a ballet-dancer.

And up and down the roadway went little knots of the poorer people in family parties, father and mother in dominoes from under which appeared cheaply-shod feet, whilst rather shabby small Pierrots trotted by their side. The few fiacres could only move at a foot’s pace, the trams[57] had ceased running. Behind the noise of the carnival and the hum of voices the town itself was strangely hushed and the tideless sea down by the harbour made no sound. Through the foliage of the trees gazed the quiet stars.

There was a queer unreality about it all, thought the Englishman as he sat at a small table on the raised terrace of a café and looked down on the passers-by. Vaguely it struck him what a fine design it might make, the dark heavy mass of greenery carved against the glittering background of the lamps, and the coloured snake of people that wound amongst the stems, paused, coiled and uncoiled. They shared the unreality of the whole thing. He felt they could not be real, they were just a boxful of dolls taken out to be played with and to be swept back into oblivion when one was tired of them.

The air was soft and warm and it was pleasant to sit there and gaze dreamily at the shifting scene. A few Arabs passed, looking impassively at it all: and it was impossible to read the expression on their dark faces. A group of palms stood black against the star-freckled sky. The whole picture in its strangeness stirred his imagination. This was Africa, even though the country of Tunis were but the fringe of it. No sea stretched between him where he sat and the hot wide spaces of the Sahara. Were one to ride and ride into the far distance, at last one would escape civilisation altogether, would reach to the primitive[58] roots of humanity. And it was a mere chance that had brought him here.

He loved the sea and hated all liners, so was taking a trip in the Mediterranean on a small steamer. There had been a slight breakdown of the engines, and the ship had put into this little port for repairs. The first night he spent on board watching the twinkle of lights on the shore, but to-day he had landed and found himself in the midst of Carnival rejoicings. He was the only Englishman on board, and it seemed to him that he was the only Englishman in this town. At any rate he had seen no other. He heard French, Italian and Arabic spoken round him, but nothing else. During the afternoon he had wandered about the native town, and climbing up a steep and narrow street that seemed just a gash in the white walls, he had come out on a height near the fort, from whence he looked down on the harbour spread below, dotted with tiny craft, beyond it the restless rim of the sea. He did not know the East, and the picturesqueness of the Arab town delighted him; the hooded groups that sat about the doorways, the statuesque folds of their drapery, the clash of women’s anklets, the glowing sunlight that seemed to pour into every nook and cranny like some rich golden wine. It was all new and strange.

And now to-night there was the feeling of being an onlooker at some fantastic theatre-scene. As he sat[59] smoking and watching, a passing Columbine glanced at him and smiled; the Englishman in the grey tweed suit looked so alien in this stir and flutter. And he was young and good looking. Why should he be alone? But her glance was thrown away upon him. He sat watching the scene, absorbed.

He had been there, perhaps, an hour, and was about to pay for his drink and move on, when a child’s voice made itself heard at his elbow. He turned. By his side stood a small Arab boy, wrapped in a mud-coloured garment, and it was his voice that had aroused his attention. He gave the child a coin, paid his bill and stepped out into the street. And again he found the boy beside him. He was talking in a mixture of broken French and Arabic impossible to follow. What on earth did the child want? He turned on him impatiently and the small figure shrank away, but a few minutes later it was back again, still repeating some unintelligible phrase. Telling him angrily in French to go away, the traveller pushed his way into the crowd. Long festoons of coloured paper had been flung from hand to hand and fragments of them hung dangling in the branches, stirred now and then by a passing breath of wind too faint to set the foliage itself in motion.

It was close on midnight. He wandered down the central street on his way to the harbour. As he drew[60] near, the tang of seaweed and shipping reached him on the night air; and turning, he looked back at the coloured necklace of lights that ringed the shore. His steamer was due to leave early the next day, and this was the last glimpse he would have of the place. Queer, he thought, how he had dipped for a moment into its life. Like opening the pages of a book, reading a few lines, and then being forced to close it again.

As he stood there, he became aware of a movement in the shadows and instinctively drew himself together. The place was lonely, he was a stranger and might be thought worth robbing. Then his keen eyes made out the figure of the child who had already followed him. The boy came up to him, and this time silently held out a scrap of white paper on which something was written. The Englishman took it to the light of a lamp and read it with difficulty. The paper had evidently been torn from a pocket book, and across it was scrawled in pencil the words “Please come,” with an almost illegible signature underneath them. He stared at the writing, puzzled. He knew no one in the place, and his first idea was that the paper had been picked up somewhere. But the Arab boy was pulling his coat gently and pointing to the town. The man hesitated. Stories of decoyed travellers, of murder and robbery passed through his mind, and again he examined the piece of paper.

The writing was evidently English and it was an educated hand, though faltering and uncertain. The signature was unreadable but he guessed it to be a man’s. He questioned the messenger but could not understand what he said, and the boy kept on pointing to the town and tugging his coat softly. The traveller did not hesitate long. His curiosity was roused and there was something adventurous and romantic about the situation that appealed to his youth. He signified his decision by a nod, and prepared to follow his guide.

Swiftly and silently the latter sped in front, turning now and again to make sure he was followed. His bare feet made no sound and the cloak wrapped round him so merged into the surroundings that more than once he seemed to have disappeared altogether. A late moon had risen and the roadway gleamed in its light. As they neared the central thoroughfare with its glare and gay crowds, the boy struck off into a maze of small streets that led away from it towards the Arab quarter. The sound of revelry became fainter and as they climbed the narrow way they left it behind. Black and white in the moonlight stood the gate of the native town, and they passed through it.

The narrow dimly lit streets were almost deserted. In leaving the modern town they seemed to step suddenly into a different world, a world where men moved[62] mysteriously on secret errands. The stranger found himself trying to hush the frank sound of his own footsteps, to bring himself into line, as it were, with his surroundings. A solitary shrouded figure here and there approached on noiseless feet and passed, absorbed and enigmatic. The roadway became so narrow that there seemed but a knife-blade of light between the black shadows of the overhanging houses which drew together like conspirators. Turning and twisting through the tortuous streets the figure ran ahead, and the Englishman still followed, though inwardly somewhat dismayed at the distance he was being taken.

At last they stopped. A low entrance stood in a recess before them, and the boy softly pushed a door open and went in, leading the other a few steps through darkness to a second one which opened into a small courtyard.

The moon shone clearly upon it, showing the arcaded passage that ran round it on which several rooms opened. From one there came a thread of lamplight. There was a small stone well in the centre of the court and the moonlight lit the dim carving on it and on the slender pillars of the arcade. Evidently the house had once been a building of some importance, but it was now shabby and dilapidated. The paving was uneven with gaping cracks, and the pillars were broken and defaced.

At the sound of their approach the door with the light[63] was held ajar and a woman’s muffled figure appeared. The small Arab made a gesture to the Englishman to wait and went into the room closing the door behind him.

A creeper growing in a pot with its leaves trained against the wall gave out a faint scent. There was the squeak and scuffle of a bat in the eaves. From far away came the sounds of merrymakers, so attenuated by distance as to be little louder than the bat’s squeak. And in the silence round the listener pressed the sense of people at hand, of sleepers stirring to far-off sounds. Then the door on which his eyes were fixed opened slowly and a bar of ruddy light slid across the cold whiteness of the moonlight. He was beckoned in.

On entering he found himself in a small and lofty room with a marble floor on which a few poor rugs were spread. There seemed to be no windows and a lamp stood on the ground. The figure of a woman wrapped in a mantle squatted on the floor, and on a couch in an alcove the figure of an Arab raised itself with difficulty on one elbow to look at him.

“What is it? Why have you sent for me?” the Englishman asked impatiently, feeling there had been some hoax, if nothing worse.

At his voice the figure smiled. “It’s rough luck on you bringing you here at this time of night, you must forgive me.”

The traveller stood amazed. The other was no Arab, then! It was an English voice, drawling and weak, but unmistakably that of a gentleman.

“By Jove! you’re English!” said the bewildered newcomer, staring at the strange figure on the couch.

It was that of a tall man in native dress, the face yellowed and lined and so thin that every bone seemed to show. He was evidently very ill, his deep-set eyes burning with fever, his movements weak and uncertain. The Eastern robes hung loosely on his gaunt body and he was half sitting, half lying on the couch, propped up with pillows. Close by him the figure of a woman crouched over a bowl in which she stirred a dark liquid that gave out a pungent smell.

The invalid spoke in Arabic and she got up with a jingle of ornaments and left the room by another door, whilst the boy went back to the courtyard. The visitor watched her ungainly figure moving away, more and more bewildered. What on earth was an Englishman doing here, in these surroundings and with these people?

The other had been regarding him with a faint ironical smile about his lips.

“Yes,” he said, “it’s hard to understand. But there it is. It’s too long a story to tell. Anyway here I am. I’ve lived the life of an Arab for years. What’s the phrase for it?—‘gone under’—yes, that’s it. I’ve gone under. My[65] name is Dunsford, and there’s something I want you to do for me.” He paused.

“My name’s Forde,” the traveller answered. “What is it you want me to do? Why did you send for me? We have never met before.”

“I know, I know, but I had to get hold of some Englishman—you as well as another—I can’t live much longer, and there’s something I want done. I daresay there are one or two of our countrymen in the place, but I specially wanted a stranger. I don’t want people here poking into my affairs.”

“But,” expostulated Forde, “why not see a doctor? Or have you got one? I could look up someone in the town: I’m only passing through myself, but I could find someone.”

“It’s not a doctor I want. I went to see one some time ago and there’s nothing to be done. I’ve got medicine and things,” the other added impatiently seeing an interruption imminent, “I don’t mind the snuffing out for myself but I’m worried about one of my boys. I mean for after I’m gone. He’s taken after my side,” he went on with a crooked smile, “and he’ll never settle down out here, I want him got out of it.”

Good heavens! Was he going to ask him to take over the child? The newcomer was appalled. But the invalid seemed to read his thoughts.

“It’s all right,” he assured him, “it’s not such a big job I want you to do. I’ve a brother at home, a J.P. and landowner and all that sort of thing. He’s a hard man, but he’s just, and he won’t have a down on the little chap because his father’s been a rotter. He’ll get him to England and give him his chance. But I don’t want to write to him even if I could.” He looked down at his wasted hands. “No, I want you to look him up when I’m safely gone and to tell him about the boy, and he’ll do the rest.”

“But I’m only here to-night and I’m off again to-morrow,” broke in the other. “It’s just an accident I’m in the place at all. The ship put in for repairs, and I shall never be here again.”

“All the better,” was the answer, “if I had wanted someone on the spot I’d have got hold of a consul. But I’ve cut adrift from all my own lot and I don’t want to be mixed up with them again. That’s why I told Ibrahim to find a stranger. And I fancy, by the look of you, that you can keep your mouth shut.” He grinned. “He’s been out looking for weeks past and it’s just your rotten luck that he pitched on you. But you’ll do—you’ll do!”

“But how am I to know?” began Forde, and hesitated.

“Know when I’m downed? I’ve thought it out. The best plan is for you to leave a postcard with me addressed to yourself, and when the time comes the boy will post it. No need to write anything on it: you’ll understand.”

He stopped exhausted, whilst the young man stared at him. After a minute he went on again.

“I’ve got my brother’s address written out ready. His on one side, and mine on the other, and I’ll give it to you. You’ll do it for me?” he added.

Forde nodded.

“I’d like to show you my son,” the invalid said, “if you wouldn’t mind giving me an arm I think I can manage it.”

The younger man helped him to his feet and supported him to the inner room. Here there were two beds. On one lay two sleeping dark-skinned children, but the father passed them and drew back the coverlet to show the occupant of the further bed. Seldom had Forde seen a lovelier boy. Flushed with sleep, his fair hair touzled and rough, he lay fast asleep, his open shirt showing the dimpled milk-white neck. In his hand he clutched some cherished toy. He lay on his side, his rosy cheek burrowed into the pillow, little feathers of gold about his damp forehead. He seemed about seven.

Dunsford stood looking down at him, a look of mingled pride and pain on his face, and Forde was able to study him unobserved. It was a curious and interesting face, the brow well-shaped and the eyes dark blue and with something wistful about them. The watcher fancied that the sleeping child, when awake, might show much the same[68] wide and faintly-puzzled look. The father too must have been fair, but the hot suns of the East had burnt his skin to a deep tan. Below the close red fez and small twisted turban his fair hair seemed going grey. His extreme thinness made the sharp ridge of his nose stand out like a beak, and there was a deep groove on either side between the nostrils and the hollowed cheeks. He had been recently shaved and only a gleam of grey showed along the narrow jaw. The mouth was compressed, but it seemed more from habit than nature. And now that he was off his guard its natural mobility could be noted. It was a face that showed intelligence and sensitiveness, allied with self will and determination, even a touch of fanaticism. The face of a man who might be fired by an impracticable idea, and who would break himself to pieces in trying to drive it through. He seemed a personality driven in upon himself. His bearing showed distinction as did also his well-kept hands.

As he watched the boy his face broke up and softened. Whatever wall he had built up about his inner self his defences were down before his son. He re-arranged the sheet, it seemed more with the motive of touching the child than for any other reason, and his hand lingered by the pillow. In the silence could be heard the soft breathing of the sleeper, till it was broken by a rustle of draperies as the Arab woman rose from the floor where she had been[69] sitting beyond the bed. At sight of her the man’s face changed. He dropped the coverlet and made a sign to his companion to help him back to the other room.

“You can tell my brother the little beggar’s all right,” he said as he sank back again upon the couch. “Legal and all that, you know. I married his mother,” with a jerk of the head towards the inner room, “before a consul as well as by Mohammedan law. The boy hasn’t been christened but my brother will enjoy getting all that done. Tell him I called him Humphrey after our old grandfather.” He stopped.

Then following his instructions Forde brought him a box which he unlocked. Inside it were some documents tied together, and from the bundle he took a slip of paper with the addresses and gave it to his companion.

“Now there’s only the post card,” he said. “You’ll find one on that table. Address it to yourself: to your home address. Then it is sure to find you.”

The other obeyed and the invalid put the post card carefully away in the box.

“That’s all, my dear fellow, and a thousand thanks. It’s a weight off my mind and I hope it won’t be a great nuisance to you.” He was silent for a time, then “Are you fond of women?” he asked abruptly. “It was over one that I went to pieces long ago.” Forde thought of the huddled shapelessness in the next room.

“I was an Army man,” began the voice again, but checked. “Sorry there’s nothing I can offer you, you don’t take opium?... But I expect you’ll be glad to be off, and I can tell you I’ll sleep easier to-night. You’ll find Ibrahim in the courtyard and he’ll show you the way back.”