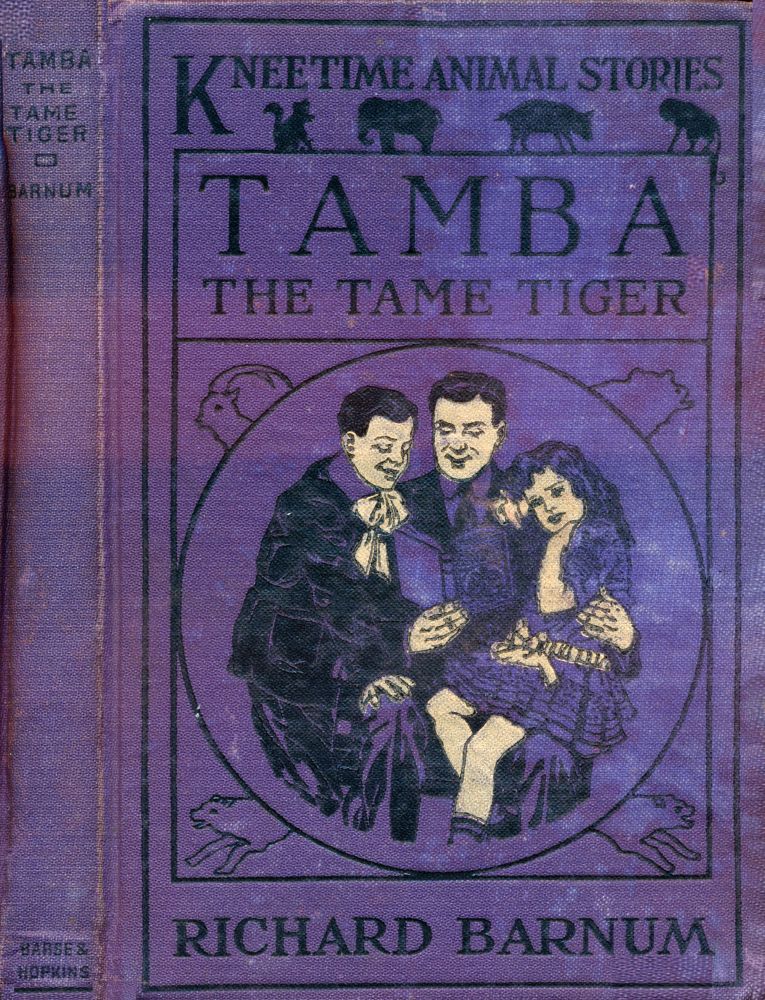

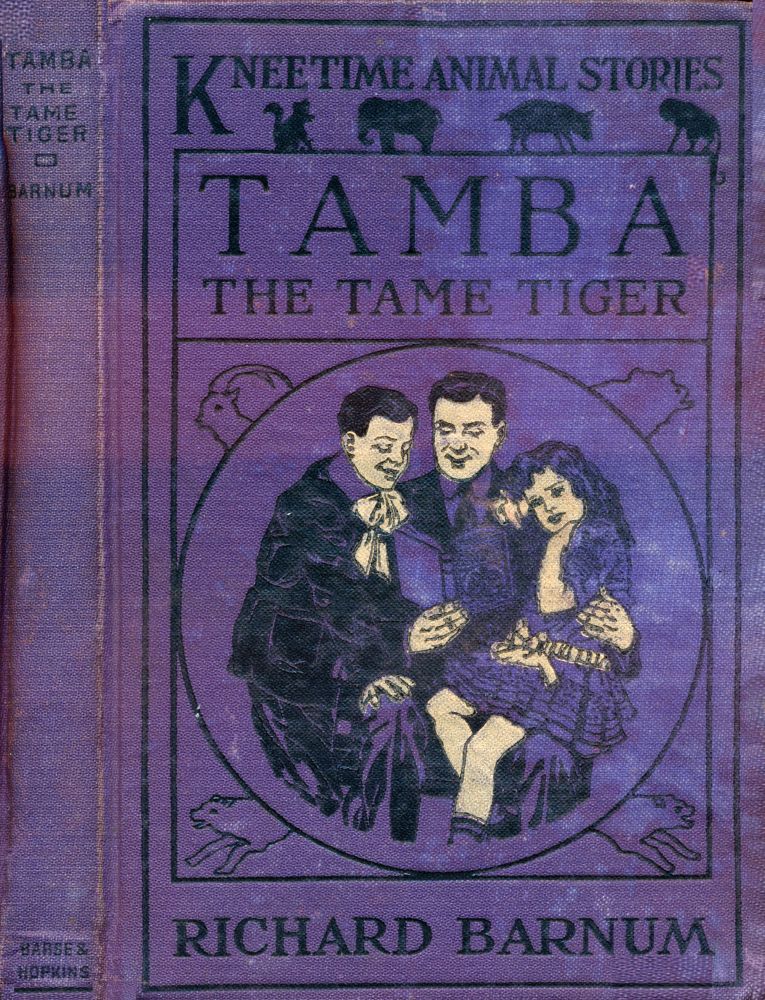

Kneetime Animal Stories

HIS MANY ADVENTURES

BY

Author of “Squinty, the Comical Pig,” “Tum Tum,

the Jolly Elephant,” “Chunky, the Happy Hippo,”

“Sharp Eyes, the Silver Fox,” “Nero, the

Circus Lion,” etc.

ILLUSTRATED BY

WALTER S. ROGERS

NEW YORK

PUBLISHERS

By Richard Barnum

Large 12mo. Illustrated.

BARSE & HOPKINS

Publishers New York

Copyright, 1919,

by

Barse & Hopkins

Tamba, the Tame Tiger

VAIL·BALLOU COMPANY

BINGHAMTON AND NEW YORK

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I | Tamba is Cross | 7 |

| II | Tamba’s Funny Trick | 17 |

| III | Tamba Plays a Joke | 26 |

| IV | Tamba in a Wreck | 34 |

| V | Tamba in a Barn | 45 |

| VI | Tamba Meets Tinkle | 53 |

| VII | Tamba and Squinty | 65 |

| VIII | Tamba in the City | 74 |

| IX | Tamba in the Subway | 84 |

| X | Tamba at the Dock | 95 |

| XI | Tamba on the Ship | 106 |

| XII | Tamba in the Jungle | 113 |

TAMBA,

THE TAME TIGER

“Here! Don’t you do that again, or I’ll scratch you!”

“I didn’t do anything, Tamba.”

“Yes, you did! You stuck your tail into my cage, and if you do it again I’ll step on it! Burr-r-r-r!”

Tamba, the tame tiger, looked out between the iron bars of the big circus-wagon cage where he lived and glared at Nero, the lion who was next door to him. Their cages were close together in the circus tent, and Nero, pacing up and down in his, had, accidentally, let his long, tufted tail slip between the bars of the cage where Tamba was.

“Take your tail out of my cage!” growled Tamba.

“Oh, certainly! Of course I will!” said Nero, and though he could roar very loudly at[8] times, he now spoke in a very gentle voice indeed; that is, for a lion. Of course both Tamba and Nero were talking in animal language, just as your dog and cat talk to one another, by mewing and barking.

“My goodness!” rumbled Tum Tum, the jolly elephant of the circus, as he turned to speak to Chunky, the happy hippo, who was taking a bath in his tank of water near the camels. “My goodness! Tamba is very cross to-day. I wonder what the matter is with our tame tiger.”

“He isn’t very tame just now,” said Dido, the dancing bear, who did funny tricks on top of a wooden platform strapped to Tum Tum’s back. “I call him rather wild!”

“So he is; but don’t let him hear you say it,” whispered Tum Tum through his trunk. “It might make him all the crosser.”

“Here! What’s that you’re saying about me?” suddenly asked Tamba. He came over to the side of his cage nearest Tum Tum. “I heard you talking about me,” went on the tame tiger, who was beautifully striped with yellow and black. “I heard you, and I don’t like it!”

“Well, then you shouldn’t be so cross,” said Tum Tum. He was not at all afraid of Tamba, as some of the smaller circus animals—such as the monkeys and little Shetland ponies—were. “You spoke very unkindly to Nero just now,”[9] went on Tum Tum. “And, really, if his tail did slip in between the bars of your cage, that didn’t hurt anything, did it?”

Tamba, the tame tiger, sort of hung his head. He was a bit ashamed of himself, as he had good reason to be.

“We ought to be kind to one another—we circus animals,” went on Tum Tum. “Here we are, a good way from our jungle homes, most of us. And though we like it here in the circus, still we can’t help but think, sometimes, of how we used to run about as we pleased in the woods and the fields. So we ought to be nice to each other here.”

“Yes, that’s right,” agreed Tamba. “I’m sorry I was cross to you, Nero. You can put your tail in my cage as much as you want.”

“I don’t want to!” growled the big lion. “My own cage is plenty good enough for me, thank you. I can switch my tail around in my own cage as much as I please.”

“Oh, don’t talk that way,” said Tum Tum. “Now that Tamba has said he is sorry, Nero, you ought to be nice, too.”

“Yes,” went on Tamba. “Come on, Nero. Put your tail in my cage. I won’t scratch it or step on it. I’m sorry I was cross. But really I am so homesick for my jungle, and my foot hurts me so, that I don’t know what I’m saying.”

“Your foot hurts you!” exclaimed the big lion in surprise. “Why, I didn’t know that. I’m sorry! Did some one shoot you in your paw as I was once shot in the jungle? I didn’t hear any gun go off, except the make-believe ones the funny clown shoots.”

“No, I am not shot in my foot,” answered Tamba. “But I ran a big sliver from the bottom of my cage in it, and it hurts like anything! I can hardly step on it.”

“Poor Tamba! No wonder you’re cross!” said the lion, in a purring sort of voice, for lions and tigers can purr just as your cat can, only much more loudly, of course. “How did you get the sliver in your paw?” Nero went on.

“Oh, I was jumping about in my cage, doing some of the new tricks my trainer is teaching me, and I jumped on the sharp piece of wood. I didn’t see the splinter sticking up, and now my paw is very sore,” replied Tamba.

“Well, lick it well with your red tongue,” advised Nero. “That’s what I did when the hunter man in my jungle shot the bullet into my paw. Perhaps your foot will get better soon.”

“Yes, I suppose it will,” admitted Tamba. “But then I want to go back to the jungle to live, and I can’t. I don’t like it in the circus any more. I want to go to the jungle.”

“Well, I don’t believe you’ll ever get there,”[11] said Nero. “Here you are in the circus, and here you must stay.”

It was just after the afternoon performance in the circus tent, and the animals were resting or eating until it should be time for the evening entertainment. It was while they were waiting that Nero’s tail had slipped into Tamba’s cage and Tamba had become cross.

But now the striped tiger was sorry he had acted so. He curled up in the corner of his cage and began to lick his sore paw, as Nero had told him to do. That is the only way animals have of doctoring themselves—that and letting water run on the sore place. And there was no running water in Tamba’s cage just then.

“So our tame tiger wants to go back to his jungle, does he?” asked Tum Tum of Nero, when they saw that the striped animal had quieted down.

“Yes, I guess he is getting homesick,” said Nero in a low voice, so Tamba would not hear him. “But his jungle is far, far away.”

“Did Tamba live in the same jungle with you, Nero?” asked one of the monkeys who were jumping about in their cage.

“Oh, no,” answered the big lion. “I came from Africa, and there are no tigers there. Tamba came from India. I’ve never been there, but I think the Indian jungle is almost as[12] far away as mine is in Africa. Tamba will never get there. He had much better stay in the circus and be as happy as he can.”

But Tamba did not think so, and, as he curled up in his cage, he looked at the iron bars and wondered if they would ever break so he could get out and run away.

“For that’s what I’m going to do if ever I get the chance!” thought Tamba. “I’m going to run back to my jungle!”

As he licked his sore paw, Tamba thought of his happy home in the Indian jungle. He had lived in a big stone cave, well hidden by trees, bushes and tangled vines. In the same cave were his father and mother and his brother and sister tigers. Tamba had been caught in a trap when a small tiger, and brought away from India in a ship. Then he had been put in a circus, where he had lived ever since.

Just before the time for the evening show some of the animal men, or trainers, came into the tent where the cages of Tamba, Nero and the other jungle beasts were standing.

“Something is the matter with Tamba,” said one of the keepers.

“What do you mean?” asked the man who took care of Nero. “Did Tamba try to bite you or scratch you?”

“No; but he isn’t acting right. He doesn’t do[13] his tricks as well as he used to. I think something is the matter with one of his paws. I’m going to have a look to-morrow.”

Of course Tamba did not understand what the circus men were saying. He knew a little man-talk, such as: “Get up on your stool!” “Stand on your hind legs!” “Jump through the hoop!”

These were the things Tamba’s trainer said to him when he wanted the tame tiger to do his tricks. But, though Tamba did not know what the men were saying, he guessed that they were talking about him, for they stood in front of his cage and looked at him. One of the men—the one who put Tamba through his circus tricks—put out his hand and touched, gently enough, the sore paw of Tamba. The tiger sprang up and growled fiercely, though he did not try to claw his kind trainer.

“There! See what I told you!” said the man. “That paw is sore, and that’s what makes Tamba so cross. I’ll have to get the doctor to look at him.”

Tamba did not do his tricks at all well that evening in the circus tent, and no wonder. Every time he jumped on his sore paw, the one with the splinter in it, he felt a great pain. And when the time came for him to leap through a paper hoop, as some of the clowns leap when they are riding around the circus rings on the[14] backs of horses, why, Tamba just wouldn’t do it! He turned away and curled up in the corner of his cage.

“Oh, how I wish I were back in my Indian jungle!” thought poor, sick, lonesome Tamba.

“Well, there’s no use trying to make that tiger do tricks to-night,” said the man who went in the cage with Tamba. “Something is wrong. I will look at his foot.”

And that night, after the show was over, the animal doctor came to the tiger’s cage. They tied Tamba with ropes, so he could not scratch or bite, and they pulled his paw—the sore one—outside the bars.

And then Tamba had an unhappy time. For suddenly he felt a very sharp pain in his paw. That was when the doctor cut out the splinter with a knife. Tamba howled and growled and whined. The pain was very bad, but pretty soon the men, who were as kind to him as they could be, put some salve on the sore place, took off the ropes and let Tamba curl up in the corner of his cage again.

“Oh, how my foot hurts!” thought Tamba. “It is worse than before! I don’t like this circus at all! I’m going to break out and run away the first chance I get! I’m going back to my jungle!”

Tamba did not know that now his paw would[15] get well, since the splinter had been taken out.

Night came. The circus began to move on toward the next town, and Tamba was tossed about in his cage. He could not sleep very much. But in a few days his paw was much better. During the time he was recovering he did not have to do any tricks. All he had to do was to stay in his cage and eat and sleep and let the boys and girls, and the grown folk, too, look at him when they came to the circus.

But, all the while, Tamba was trying to think of a way to get loose and run back to his Indian jungle. And one night he thought he had his chance.

The circus was going along a country road, from one town to another, and, as it was hot, the wooden sides of the animal cages had been left up, so Tamba, Nero and the other jungle beasts could look out at the stars. They were the same stars, some of them, that shone over the jungle.

Suddenly there was a bright flash of light and a loud noise.

“We are going to have a thunder storm,” said Nero, as he paced up and down in his moving cage.

“It will be cooler after it, anyhow,” said Dido, the dancing bear. “It is very hot, now.”

The lightning grew brighter and the thunder louder as the circus went up and down hill to the[16] next town. Then, suddenly, it began to rain very hard. The roads became muddy and slippery, and the horses, pulling the heavy circus wagons, had all they could do not to let them slip.

Suddenly there was a loud crash of thunder, right in the midst of the circus it seemed. The lions and the tigers roared and growled, and the elephants trumpeted, while men shouted and yelled. There was great excitement. What had happened was that a big tree, at the side of the road, had been struck by lightning. Some of the circus horses were so frightened that they started to run away, pulling the wild animal cages after them.

Tamba felt his cage rushing along very fast. His horses, too, were running away. Then, all at once, there was a great crash, and Tamba felt his cage turning over. Next it was upside down. The tiger was thrown on his back.

“Ha! Now is my chance to get away!” Tamba thought. “My cage will break open and I can get out! Now I can go back to my jungle!”

Bang! Crack! Crash! went the thunder, and the cage of Tamba, the tame tiger, as it slid along the slippery, muddy road, and struck a tree, made much the same noise, only not so loud.

Tamba himself, inside the iron-barred cage, was feeling much better than when he had had the sliver in his paw. His foot was almost well now, and he could step on it, though he limped a little.

“When my cage goes to smash I’ll slip out and run away,” thought Tamba. “I’m going to have lots of fun when I get back to my jungle.”

Over and over rolled the cage, for the horses had broken loose from it and were running away. Many other of the circus animal cages were being broken in the storm.

Tamba’s cage struck one tree, bounced away from that and hit another. Then it came to a stop, and Tamba, who had been rolling about inside, being sometimes on his head and sometimes on his feet, and again turning somersaults—Tamba, at last, found himself quiet.

“Now is my chance to get away!” thought the tame tiger, who wanted to be wild again and live in a jungle. “Now I’ll get out of my cage!”

He surely thought the big wagon with the iron bars on two sides—the cage in which he traveled—had been broken so he could get out. But when he tried, he found that this was not so. The tiger’s cage was broken a bit, here and there, but it was so strong that it had held together, and when Tamba tried to force his way out he could not. He was still a circus tiger, much as he wanted to go to the jungle.

“Oh, this is too bad!” growled Tamba to himself, as he tried to break out, first through one side of the cage and then the other. “This is too bad! I thought, when the storm wrecked the circus, that I could get loose. Now I’ll have to wait for another time.”

But if Tamba had not got out of his cage when the great storm came, some of the circus animals had. Nero, the circus lion, got loose, and he had many adventures before he was caught again, as I have told you in the book before this one. But Tamba had to stay in his cage.

After a while, when the worst of the storm had passed, the circus men began going about, getting back on the road some of the cages, like that of Tamba, that had rolled downhill.

“Tamba’s all right,” said a trainer, as he saw[19] the tame tiger. “He didn’t get loose, I’m glad to say. I want to teach him some new, funny tricks, now that his paw is well again.”

“No, Tamba didn’t get away,” remarked another man; “but Nero, the big lion, did. We’ll have to go out to hunt him.”

When morning came, and the circus was once more in order—except for the broken cages and the animals that had gotten away—Tamba felt, more than ever, that he would like to be back in his jungle.

“So Nero got away, did he?” thought the tame tiger, as he saw the lion’s broken cage, and noticed that Nero was no longer in it. “Well, I wish I were with him. Now he can go back to his jungle.”

But Nero did not do that, as those of you know who have read the book about him. I’ll just say, right here, that Nero had many adventures, but, as this book is about Tamba, I must tell about him, and the adventures the tame tiger had.

A few days after this, when the circus was traveling on again, though without Nero, who had not been caught, it came to a large city, where it was to stay nearly a week to give shows.

“And now will be a good chance for me to teach Tamba some new and funny tricks,” said the animal man who had charge of the tiger. “I[20] want him to make the people laugh when they come to the circus. The boys and girls will like to see Tamba do some funny tricks.”

And the next day, his paw being again well, Tamba began to learn something new. When his trainer entered the cage, Tamba, much as he wanted to run away to the jungle, was glad to see the man. For the man was kind to the tiger, and patted him on the head, and gave him nice bits of meat to eat.

“Now, Tamba,” said the trainer, speaking in a kind voice, “you are going to learn something new. Sit up!” he cried, and he held a little stick in front of Tamba.

The tiger knew what this meant, as he had learned the trick some time before. When the trainer spoke that way he meant that Tamba was to sit up, just as your dog may do when you tell him to “beg.”

“That’s very good,” said the man, when Tamba had done as he was told. “Now that is the first part of a new trick. Next I am going to put a little cracker on your nose. It isn’t really a cracker, it is a dog biscuit, and it has some meat in it. As you like meat I think you’ll like the dog biscuit.”

As the man spoke he took from his pocket one of the square cakes called dog biscuit. I dare say you have often given them to your dog.[21] The animal trainer broke off a bit of this biscuit and put it on Tamba’s nose. Tamba could smell that it was good to eat, and he quickly shook his head a little, jiggled the piece of biscuit to the floor of his cage, and the next minute the piece of biscuit was gone. Tamba had eaten it.

“Well, that’s what I want you to do,” said the man with a laugh, “but not just that way. This is to be one of your new, funny tricks, but you didn’t do it just right. I want you to hold the piece of biscuit on your nose until I call ‘Toss!’ Then I want you to flip it into the air and catch the piece of biscuit in your mouth. Now we’ll try it again.”

Tamba did the same thing he had done the first time, but the man was kind and patient, and, after many trials, Tamba at last understood what was wanted of him. He must hold the bit of dog biscuit on his nose until the man said he could eat it.

Then the tiger was to give his head a little jerk. This would snap the bit of biscuit into the air, and, if Tamba opened his mouth at the right time, the biscuit would fall into it. That would be the funny trick.

And, as I say, Tamba learned, after a while, how to do it just right. But it took nearly a week. At the end of that time his trainer could put a bit of dog biscuit on the tiger’s black nose.[22] Then Tamba would sit up on his hind legs, very still and straight, looking at his master.

“Now!” the man would suddenly call, and Tamba would jerk his head, up the piece of biscuit would fly, and into his mouth it would go.

“That’s fine!” cried the man, after the second week, during which time Tamba had practiced very hard. “Now we are ready to do the new trick in the tent for the boys and girls.”

And when the trick was done the boys and girls laughed very much and clapped their hands. They liked to see Tamba do his tricks. Nor was this the only new one he learned. His master taught him several others.

Tamba would lie down and roll over when he was told; he would walk around on his hind legs, wearing a funny pointed cap; and he would turn a somersault, just as he had done the night his cage rolled downhill in the storm. All these tricks were much enjoyed by the boys and girls and by the men and women who came to the circus. Tamba was a very smart tiger. But, for all that, he never gave up the idea of running away when he got the chance, and going back to his jungle.

All this while Nero, the circus lion, had not returned. He had been away since the night of the storm, and Tum Tum, and his other friends, missed Nero.

“But he is having a much better time than we are, just the same,” said Tamba, as he paced back and forth in his cage. “He is on the way back to the jungle!”

If he could have seen Nero just then he never would have said that. For the circus lion was in the kitchen of a country farmhouse watching a tramp eat ham, and—but there! This book is about Tamba, not about Nero, though I have to mention the lion once in a while.

About a week after Tamba had learned to do several new and funny tricks, there was a sudden noise at the entrance of the circus animal tent. It was after the afternoon show had ended, and not yet time for the evening performance.

“What’s the matter, Tum Tum?” asked Tamba, who could not see very well from his cage. “What has happened? Have some more of our animals gotten away?”

“I think not,” answered the big elephant, who could see the tent entrance. “I think they are bringing in a new lion. Maybe he is to take the place of Nero. We’ll soon know. Here they come with him.”

Just as Tum Tum had said, a lion’s cage was being wheeled into the circus animal tent, and in the cage was a big, tawny, yellow animal, which Tamba knew, at once, was a lion.

But, to the surprise of the tame tiger and his friends, it was not a new lion at all, but Nero himself. There he was, looking almost the same as when he had disappeared the night of the big storm, the night when Tamba thought he could get away.

“Why, Nero!” exclaimed the tiger, as his friend’s new cage was wheeled in, “where in the world have you been?”

“Oh, almost everywhere, I guess,” answered Nero. “I’ve had a lot of adventures!”

“Ha! Then you’ll be put in a book,” said Tum Tum quickly. And, as those of you who have read the volume which comes just before this one know, Nero was put in a book.

“Yes, I had adventures enough for a book,” went on the big lion, who had been caught by some circus men in a farmer’s woodshed and[27] brought back to the show. “I had a pretty good time, too, while I was away, though I didn’t get as much to eat as we do here in the circus. I guess I’m glad to be back, my friends!” and he curled up in his cage and got ready to go to sleep.

“Ho! Glad to get back, are you?” asked Tamba. “Well, I won’t say that if I get a chance to run away! I’ll stay, when I go!”

“That’s what you think now,” said Nero. “But really it isn’t as much fun as you’d think—running away isn’t.”

“Couldn’t you find your jungle?” asked Tamba.

“No,” answered Nero, “I couldn’t.”

“Well, I’ll find mine,” declared Tamba. “That’s why I want to run away—so I can get back to my jungle. And I’m going to do it, too!”

Of course all this talk went on in animal language, and none of the circus helpers or the trainers could understand it. If they could, they might have guarded Tamba more closely.

“Well, please don’t bother me now,” said Nero, as he curled his paws under his chin, just as your cat sometimes does when she goes to sleep. “I am going to have a nap after all my adventures and travels.”

“All right, go to sleep,” said Tum Tum. “We[28] won’t bother you, Nero. Only, some day, I hope you’ll tell us more of your adventures.”

“I will,” promised Nero.

Tamba, the tame tiger, paced up and down in his cage after Nero had gone to sleep.

“I wish I had had his chances!” thought Tamba, as he looked over toward the sleeping Nero. “I wouldn’t have let them catch me! I’d have run on and on until I found my jungle, no matter how far away it was.”

And then Tamba began to think of the life in India and of the days when he, a little tiger cub, was hiding in the deep, dark, green jungle. He thought of how he had tumbled about in the leaves, playing with his brother and sister, and of his mother sitting in the mouth, or front door, of the cave and watching her striped babies.

They had learned how to walk, and how to jump and stick out their claws whenever they wanted to catch anything. Their father and mother had taught the little tiger cubs how to hunt in the jungle for the meat they had to eat. They could not go to the store and buy something when they were hungry. Tigers, and other wild animals, must hunt for what they eat.

Of course, after he had been caught and sent to the circus, Tamba no longer had to hunt for his food. It was brought to him by the circus men, and thrust into his cage. Nor did he have[29] to hunt for water, the way the jungle animals have to go sniffing and snuffing about in the forest to find a pool or a spring. Tamba’s water was brought to his cage in a tin pail, and very glad he was to get it.

“But, for all that,” thought the tame tiger, as he paced up and down, “for all that I’d rather be loose and on my way back to the jungle instead of being cooped up here. Much as I like the things they give me to eat, I want to go home. And I’m going to get loose, too, and run away as Nero did. Only I won’t come back!”

The more Tamba thought of the green jungle, so far away in India, the more sad, unhappy and discontented the tame tiger became. He did not do his tricks as well as he used to do, and he was often cross in speaking to the other circus animals. Sometimes he wouldn’t speak at all, but only growl, or maybe grumble deep down in his throat, and that isn’t talking at all.

“I declare! I don’t know what’s the matter with Tamba,” said Tum Tum one day. “He doesn’t seem at all happy any more. Dido, do some of your funny dances and see if you can’t cheer up Tamba!”

So the dancing bear did some of his tricks, capering about in his cage, but Tamba would hardly look at him. Some boys, though, who had come to the circus, gathered in front of the[30] bear’s cage and laughed and laughed at his funny antics. They liked Dido. The boys liked to look at Tamba, also, but they were a little afraid of the big, striped tiger.

One day, when the afternoon performance was over, and Tamba, Nero and the other animals who had done their tricks in the big tent were brought back to the smaller one, where they were kept between the times of the shows, Nero said:

“Now I am going to lie down and sleep, and please don’t any one wake me up. I’m tired, for I did a new trick to-day, and it was very hard, and I want to rest so I can do better in the show to-night. So everybody let me alone.”

“We will,” said Tum Tum, the jolly elephant.

Now the lion is called the “King of Beasts,” and in the jungle he comes pretty near to being that, for all the other animals, except perhaps the elephant, are afraid of him.

So when a lion says he wants a thing done, it generally is done. Of course Nero could not have got out of his circus cage to make the other animals do what he wanted them to do, but most of them made up their minds that they wouldn’t bother him, even though they knew he couldn’t hurt them. Nero was still “King” in a way.

But that day Tamba was cross. Or perhaps I might say he felt as though he wanted to “cut up.” He wanted to play some tricks, make[31] some excitement. He wanted to do something!

I dare say you have seen your dog or cat act the same way. For days at a time they may be very quiet, eating and sleeping and doing only the things they do every day. And then, all at once, they will begin to race about and “cut up.” Your dog may run away with your cap, and, no matter how many times you call him, he’ll just caper about and bark, or perhaps pretend to come near you and then run off again. And your cat may dig her claws into the carpet, jump up on the window sill and knock down a plant or a flower vase, and do all sorts of things like that.

Well, this is just the way Tamba felt that day. He wanted to do something, and when he saw Nero sleeping so quietly in his cage the tame tiger made up his mind to play a trick on the lion.

“It isn’t fair that he should sleep so nicely when I have to stay awake!” grumbled Tamba. “He can dream of the good times he had when he ran away and had adventures, and all I can think of is how much I want to go back to my jungle! It isn’t fair! I’m going to make Nero wake up! I’ll play a trick on him!”

Of course this wasn’t right for Tamba to do, but circus tigers don’t always do right any more than boys, girls, or other animals.

Tamba’s cage was next to that of Nero, and close beside it, instead of being at one end. The cages were left that way when they were brought in from the larger performing tent, after the animals had done their tricks. So it happened that Tamba could look out through the bars of his cage in between the bars where Nero was kept. And Tamba could stick his paws out through the bars, but he could not quite reach over to the sleeping lion.

“If I could reach him,” said Tamba to himself, “I’d tickle him and wake him up. I wouldn’t let him sleep!”

But Tamba’s paws were not quite long enough to reach through the bars of the two cages. Again and again the tiger tried it, but he could not manage.

Then Tamba sat down on his haunches and looked at the sleeping Nero. At last a tricky idea came to Tamba.

“Ha!” exclaimed the tiger. “If I can’t reach him with my paws I can reach him with my tail! That’s what I’ll do! I’ll reach in between the bars with my long, slender tail, and I’ll tickle Nero on the nose!”

Tamba sort of laughed to himself as he thought of this trick. And he had no sooner thought of it than he began to try it. He turned about, so his back was toward Nero. Standing[33] thus, Tamba’s long, slender tail easily reached into Nero’s cage. Nearer and nearer the tip of Tamba’s tail came to the big black nose of the sleeping lion.

Tamba looked sideways over his back to see where to put his tail. At last the fuzzy tip-end of it touched Nero’s nose and tickled it. The big lion twitched in his sleep, just as your cat does, if you lightly touch one of her ears.

“Ha! I’ve found a good way to play a trick on Nero!” laughed Tamba. “I’ll keep on tickling him!”

He waved his tail to and fro, Tamba did, and once again he let the tip of it touch Nero’s nose. The sleeping lion raised his paw, and brushed it over his face. He must have thought some bug was crawling on his nose.

“Oh, this is lots of fun!” thought Tamba. So it was, for him. But was it fun for Nero?

“Now for a good tickle!” thought Tamba, as, once again, he put his tail over toward the sleeping lion’s nose. And this time something was going to happen.

Down on the black nose of the sleeping lion went the soft, fuzzy tip of Tamba’s tail. And Tamba tickled Nero so hard that the lion gave a big sneeze and awakened with a jump.

Then Nero threw himself against the bars of his cage until they shook where they were fastened into the wood, and the lion roared in his loudest voice:

“Where’s that fly? Where’s the tickling fly that wouldn’t let me sleep? If I catch that fly I’ll tickle him!” and Nero roared so loudly that the ground seemed to tremble, as it always does near a lion when he roars. I have often felt it in the zoölogical park where I sometimes go to look at the lions and the tigers.

“Where’s that fly? Where’s that fly?” roared Nero. For you see he thought the tickling tip of Tamba’s tail was a fly on his nose.

“What’s the matter here? What’s the trouble?” cried one of the circus men, as he ran into the animal tent, having heard Nero roar.

“Are some of the lions or tigers trying to get loose?” asked another man.

“No, it seems to be Nero,” replied the first. “What’s the matter, old boy?” he asked, as he saw how angry Nero was. For the lion was lashing his tail from side to side and roaring:

“Where’s that fly? Where’s that fly?”

Of course the circus men didn’t know exactly what Nero was saying, but they could tell he was angry, and they were afraid, if he bounded against the bars of his cage much more, he might break some.

“I don’t see what makes Nero act that way,” said the man who had charge of the lion, and who had taught him to do tricks. “Once before he acted like this, but it was when a bee stung him on the nose.”

“Maybe that is what happened this time,” said the second man.

“I don’t see any bees flying around,” went on the lion’s keeper. Just then Tamba, seeing that he had awakened Nero, and had played all the tricks he wanted to, pulled his tail out from between the bars of the lion’s cage. And, just as he did so, the keeper saw him.

“Oh, ho! I know what the matter was,” the man said. “The tiger tickled the lion. Tamba tickled Nero with his tail through the bars of the cage. That’s what made Nero angry. Tamba,[36] you’re a bad, mischievous tiger!” and he shook his finger at the striped animal. Tamba walked over to the corner of his cage and curled up.

“Well, I had some fun, anyhow!” he thought. “I waked Nero up all right!”

And so he had. And now Nero knew what had happened, for Tum Tum, the jolly elephant, had seen it all, and Tum Tum said:

“It wasn’t a fly on the end of your nose, Nero; it was the fuzzy tip of Tamba’s tail. I saw him tickle you!”

“Oh, you did, did you?” cried Nero, and this time he did not roar. “Why did you tickle me, Tamba?”

“Oh, I didn’t like to see you sleeping so nicely when I couldn’t sleep, because I’m thinking so much of the jungle,” answered the tiger. “Besides, it was only a joke. I wanted to see if I could make you think my tail was a fly on your nose. I did.”

“Yes, you surely did,” admitted Nero. “I felt the tickle, even in my sleep. But if it was only a joke, Tamba, I won’t be angry. I like a joke as well as any one,” and Nero laughed in his lionish way. “But, after this, I’m going to sleep in the far corner of my cage, where your tail won’t reach me. A joke is all right, but sleep is better. Now it will be my turn to play a joke on you, Tamba.”

“Yes,” said Dido, the dancing bear, “you want to look out for yourself, Tamba. A joke is a joke on both sides.”

“Oh, well, I don’t care,” said Tamba, but he was not as jolly about it as he might have been.

The circus men saw that something was wrong between Tamba and Nero, so they moved the cages farther apart, and then Nero and Tamba could not have reached each other if their tails had been twice as long. And then Nero went to sleep, and so did Tamba, waiting for the evening show to start. And as Tamba slept he dreamed of the Indian jungle, and wished he could go back there.

And soon something wonderful was going to happen to him.

That night in the big tent, which was bright with electric lights, Tamba did his tricks—catching a piece of dog biscuit off his nose, leaping through a paper hoop, and walking around on his hind legs. Nero also did his tricks, one of which was sitting up like a begging dog on a sort of stool like an overturned wash tub.

And Dido, the dancing bear, did his funny tricks on the wooden platform, which was strapped on the back of Tum Tum, the jolly elephant. So the boys and the girls, and the big folks, too, who went to the circus had lots of fun watching the animals.

But, all the while, Nero was watching for a chance to play a trick on Tamba. And at last he found a way. It was three or four days after Tamba had tickled Nero with the tail tip, and the circus had traveled on a railroad to a far-distant town.

In the animal tent the lions, tigers, elephants, monkeys and ponies had been given their dinners and were being watered. Tamba was taking a long drink from his tin of water, and wishing it could be turned into a jungle spring, when, all of a sudden:

Splash!

A lot of water spurted up into his face, and some, getting into his nose, made him sneeze. Then he looked and saw that a bone, off which all the meat had been gnawed, had come in through the bars of his cage and had fallen into his water-pan. It was the falling of the dry bone into the water that had made it splash up.

“Who did that? Who threw that bone at me?” growled Tamba. “Who made it splash water all over me?”

“Oh, I guess I did that,” said Nero with a loud, rumbling lionish laugh. “I wanted to see if I could toss it from my cage into yours, Tamba, and I did. So the water splashed on you, did it?”

“Yes, it did! You know it did!” growled Tamba. “It made me sneeze, too!”

“Oh, did it?” asked Nero. “Well, that was just a little joke of mine, my tiger friend. I wanted to see if I could tickle your nose the way you tickled mine with your tail. It was only a joke, splashing water on your nose. Only a joke! Ha! Ha! Ha!”

“Yes, it was only a joke!” said Tum Tum and all the other animals. “Only a joke, Tamba! Ha! Ha! Ha!”

Of course the striped tiger had to laugh, too, for really he had not been hurt, and he must expect to have a joke played on him after he had played one on Nero.

“Well, I’ll gnaw this bone after I take a drink,” said Tamba, as he dried his nose on his paw. “Much obliged to you for tossing it into my cage, Nero.”

“Oh, you’re very welcome, I’m sure!” laughed the lion. “Oh, you did jump and sneeze in such a funny way, Tamba, when the water went up your nose!” and Nero laughed again, as he thought of it.

And “Ha! Ha! Ha!” echoed Tum Tum.

And so life went on for the circus animals, something a little different happening every day. Now and then Tamba played other tricks, and so did Nero, and the first crossness of Tamba[40] seemed to wear off. He was still as anxious as ever to go to the jungle, but he did not see how he could get out of his cage. He watched carefully, every day, hoping that some time the man who came in to make him do his tricks would forget to fasten the door when he went out.

“If he only left it open once,” thought Tamba, “I could slip out and run away. Then I’d go back to the jungle.”

But the trainer never left the door open. Besides, it closed with a spring as soon as the man slipped out, and, quick as he was, Tamba could not have slipped out. However, he kept on the watch, always hoping that some day his chance would come.

And it did. I’ll tell you all about it pretty soon.

Sometimes, as I have told you, the circus went from town to town by the way of country roads, the horses pulling the big wagons with the tents on them and also the wagons in which the wild beasts were kept. It took eight or ten horses to pull some of the heavy wagons uphill.

At other times the wagons would all be put on big railroad cars, and an engine would haul them over the shiny rails. This was when it was too far, from one town to the next, for the horses to pull the wagons, or for the elephants and camels to walk. For when the circus traveled by[41] country road these big animals—the camels and elephants—always walked.

And one night after a stormy day the circus wagons were loaded on the railroad cars for a long journey to the next city in which the show was to be given.

“Well, you haven’t gone to your jungle yet, I see, Tamba,” said Tum Tum to the tiger. The big elephant was moving about, pushing the heavy wagons to and fro.

“No, I haven’t gone yet,” sadly said the beautifully striped beast. “And, oh, how I wish I could get loose!”

On through the night rumbled the long train of circus cars. There was no moon, and the stars did not shine. The night was very dark after the storm.

Suddenly there were some loud whistles from the train engine.

Toot! Toot! Toot! it went, and that meant there was danger. The engineer had seen danger ahead, but not in time to stop his train. One of the circus trains had run off the track and could not go on. It had come to a halt, and another train that was running not far behind the first one crashed into it.

There was a terrible noise, a clanging of iron and a breaking of wood. The cars were smashed, and so were some of the animal cages.

“What is it? What’s the matter? roared Nero.

“We’re in a wreck!” trumpeted Tum Tum, the elephant, who was not quite so jolly, now. “The circus train is wrecked! I was in a wreck once before. It’s very bad! I hope none of our animal friends are hurt!”

But some were, I am sorry to say, and so were some of the circus men.

Tamba, the tame tiger, felt his cage slide off the flat car on which it had been fastened. The car was smashed and tossed to one side. Off slid the tiger’s cage, and then it fell down the railroad bank and into a ditch. Tamba’s cage broke open, and the tiger was cut and bruised, but he knew that he was free. He was no longer in the cage.

“At last I am out!” he cried. “Now I can run away to my jungle! Now I am free!”

With the smashed circus cars, the broken animal cages, with some of the jungle beasts, including the elephants, cut and bruised, with shoutings, growlings, roarings and tootings going on, the scene at the circus train wreck was a terrible one. It was no wonder that Tamba, the tame tiger, wanted to run away from it all and get to a quiet place. And this he did.

He crawled out of his cage, that had been broken when it slipped off the smashed car, and gave one last look at it in the darkness.

“Good-by, old cage!” said Tamba, softly, as he turned to run away. “I’ve been in you for the last time. I’m never coming back to the circus!”

Leaving the noise and confusion of the circus wreck behind him, Tamba slunk off into the tall grass that grew in the fields beside the railroad track. The accident had happened at a lonely place, and there were no houses near at hand.

“Ha! This is a little like the jungle where I[46] used to live!” thought Tamba, as he slunk through the tall grass. “I can hide here until I see which way to go to get back home.”

And Tamba was right. The grass grew long, as it did in the jungle, but there were not so many trees and tangled vines as in India. Only at night it seemed a very quiet, restful place to the tiger who had been so shaken up in the wreck.

Tamba walked on and on through the darkness, not really knowing, and not much caring, which way he went. All he wanted to do was to get away and hide, and the tall grass was just the place for this.

In a little while Tamba came to a place where there was a small pool of water. It had leaked from a pipe that filled the tank where the railroad engines took their water. Tamba drank some, and then, finding a place where the grass was taller and thicker than any he had yet seen, he made himself a sort of nest and curled up in it.

“I can sleep here, and Nero, that big lion, can’t splash any water into my nose and make me sneeze,” thought Tamba, as he snuggled up.

At first he could not get to sleep. He had been too much frightened by the train wreck, though he was so far away now that he could not hear the din, which still kept up. But at last Tamba closed his eyes, and soon he was slumbering[47] as peacefully as your cat sleeps before the fire.

It was daylight when Tamba awakened, and, for a moment, he did not remember where he was. He stretched out first one big paw after another and then he called:

“Well, Tum Tum, what sort of day is it going to be?”

Tamba used to do this in the circus tent, for the jolly elephant was so big that he could look over the tops of the cages and tell whether or not the sun was going to shine. Most animals awaken before the sun comes up—just as it begins to get daylight, in fact.

But Tum Tum did not answer Tamba this time. The jolly elephant was badly hurt in the railroad accident, but of course the tiger did not know this just yet. Tamba did know, however, that he had made a mistake.

“Oh, I forgot!” he said to himself. “Tum Tum isn’t here! I’m not in the circus any more. I’m free, and I can go to my jungle. I must start at once!”

Then Tamba arose, and stretched himself some more. He liked to feel the damp earth under his paws, and he liked the feeling of the dry grasses as they rubbed against his sides.

“Why, I feel hungry!” suddenly said the tiger. “I wonder where I can get anything to eat in this,[48] the beginning of the jungle.” You see, Tamba still thought the jungle was close at hand, but, to tell you the truth, it was far away, over the sea, and Tamba could not get to it except in a ship.

The more Tamba thought about it the hungrier he became. He knew no men would come to him now with chunks of meat, as they had used to come in the circus.

“I must hunt meat for myself, the same as I did when I lived in the jungle with my father and mother,” thought the tiger. “Well, I did it once, and I can do it again. I wonder what kind of meat I can find?”

Tamba did not have to wonder very long, for he soon saw some big muskrats, and he made a meal off them.

Then Tamba looked about him, and began to think of what he would do to get to the deeper part of the jungle—the part where the trees grew. He wanted to be in the thick, dark woods. All wild animals love the quiet darkness when they are not after something to eat.

But it was now broad daylight, and Tamba knew he must be careful how he went about. Men could easily see him during the day. He remembered he had been told this in the jungle, years before, by his father. But in the jungle Tamba was not so easy to see as he was on this railroad meadow. The yellow and black stripes[49] of a tiger’s skin are so like the patches of light and shadow that fall through the tangle of vines in a jungle, that often the hunters may be very close to one of the wild beasts and yet not see it. The tiger looks very much like the leaves and sunshine, mingled.

“But I guess if I slink along and keep well down in the tall grass no one will see me,” thought Tamba. “That’s what I’ll do! I’ll keep hiding as long as I can until I get to my jungle. Then I’ll be all right. I’ll be very glad to see my father and mother again, and my sister and brother. The circus animals were all very nice, but still I like my own folks best.”

So Tamba slunk along, going very softly through the tall grass. If you had been near the place you would probably have thought that it was only the wind blowing the reeds, so little noise did Tamba make. Tigers and such cat-like animals know how to go very softly.

All at once, as Tamba was slinking along, he heard the sound of men’s voices talking. He knew them at once, though of course he could not tell what they were saying. Besides the voices of the men, he heard queer clinking-clanking sounds and the rattle of chains. Tamba knew what the rattle of chains meant—it meant that elephants were near at hand, for the circus elephants wear clanking chains on[50] their legs, being made fast by them to stakes driven into the ground.

“Ha! I had better look out,” thought Tamba. “Maybe those are the circus men after me.”

The tame tiger was partly right and partly wrong. The voices he heard were those of the circus men, and the chains clanking were those on the legs of elephants. The men were trying to clear away what was left of the circus wreck. Tamba had taken the wrong path, and had walked right back to where he had started from.

“This won’t do!” he said to himself. “I must get farther away and hide!”

He peered between the tall grasses and dimly saw where the circus men were working along the railroad tracks, lifting up some of the overturned cars and cages. The elephants were helping, for they were very strong.

“I’ll notice which way the sun is shining, and then I’ll know which way to go to keep away from the circus men,” thought Tamba. Then he turned straight about and ran off the other way.

On and on, over the big stretch of meadows and lonely land near the railroad went the tiger until he had placed many miles between himself and the scene of the wreck. In all this time Tamba did not see any men, or any living creatures except some muskrats, many of which lived in the swamp along the railroad. The muskrats[51] were not glad to see Tamba, for the tiger caught a number of them for food, but it could not be helped.

No one saw Tamba sneaking along through the grass. If any one had seen him they would have hurried to tell the circus men, for a general alarm had been sent out, telling that some of the wild animals, including a big, striped tiger, had got loose after the wreck.

But no one saw Tamba, and he saw no one, at least for a while. On and on he went until night came again. Then he found another snug place in among the dried grass where he curled up to sleep.

“My jungle is farther away than I thought it was,” said Tamba to himself, as he awoke on the second morning of his freedom. “I must run along faster to get there more quickly.”

After he had eaten and taken some water, he started off once again, and then began a series of very strange adventures for the tame tiger.

Toward the close of the afternoon of the second day of his freedom Tamba stepped out of a little patch of woods, into which he had gone from the meadow, and there, in the light of the setting sun, the tiger saw a red, wooden building which he seemed to know.

“Why, there’s a barn!” said Tamba to himself. “There’s a barn. I’ll go in there and stay for[52] the night. I wonder if there are any other animals in it.”

The reason Tamba knew this was a barn was because, when he had first joined the circus, he had been taken to a barn, and there was taught some tricks. The circus folk and the animals lived in a big barn instead of tents during the winter. So when Tamba saw this building he knew, at once, that it was a barn.

Now it happened that this was a barn belonging to a farmer, who also owned a house near by, but which Tamba could not see on account of the trees. So, making sure that no one was about, Tamba walked toward the barn, and, one of the doors being open, in walked the tiger.

He looked all around, as best he could, for it was not very light, and he sniffed and smelled the smell of animals.

“Maybe some of my friends are here,” thought Tamba. “I’ll slink around and see.”

So he walked softly and slinkingly to the middle of the barn floor, and peered about, and, right after that, a very strange thing happened.

At first when he went into the barn through the door which was open, Tamba, the tame tiger, could not see very much. It was the same as when you go into a dark moving-picture theater from the bright sunshine outside.

But, in a little while, Tamba’s eyes could see better, and he noticed some piles of hay and straw in the barn. That made him feel more at home.

“This is just like the circus barn where I used to be before we started out with the tents,” thought Tamba to himself. “That is hay, which Tum Tum and the other elephants used to eat. I don’t like it myself. I like meat and milk. But I don’t see any elephants here.”

And for a very good reason, as you know. Farmers don’t keep elephants and other circus animals in their barns.

So Tamba looked about in the barn, and he sniffed and smelled with his black nose, hoping to smell something good to eat. But though there was an animal smell about the place (because there were cows and horses in the lower[54] part of the barn) still Tamba did not want to eat any of them.

If he had been in the jungle he might have felt like eating a cow, or, what is very much the same thing, a water buffalo. But since he had been in the circus he had been used to eating the same kind of meat that you see in butcher shops. So, though the tiger was quite hungry, and though there were cows and hay in the farmer’s barn, Tamba did not see much chance of getting a meal.

“I’ll starve before I’ll eat hay,” he said. “It’s all right for elephants and horses and ponies, like the Shetland ponies we had in the circus, but hay is not good for tigers.”

So Tamba walked farther into the barn, looking about and sniffing about, and then, all at once, he heard some one whistle. Tamba knew what a whistle was, for often his own trainer or the trainer of Nero would go about the circus tent whistling. So, when Tamba, in the barn, heard some one coming along whistling a merry tune he at once thought to himself:

“Oh, perhaps that is one of the circus men coming to take me back to my cage in the tent! Well, I’m not going! I’m going to go back to my jungle, and not to the circus! I’ll just hide where they can’t find me!”

Now the big pile of hay in the barn seemed the[55] best place in the world for Tamba to hide in, and, as the whistling sounds came nearer and nearer, the tiger crept softly across the barn floor, and soon was snuggling down in the hay.

“I remember once, when I lived in the jungle, I hid in a pile of dry grass just like this hay,” thought Tamba. “It was when I wanted to play a trick on my brother Bitie. I jumped out at him and scared him so he ran off with his tail between his legs. Maybe I can jump out and scare this circus man so he won’t want to take me back.”

You see Tamba thought surely it was a circus man coming into the barn whistling. But it wasn’t at all. It was the boy who worked on the farm. His father had sent him to the barn to gather the eggs which the chickens had laid, and this boy, whose name was Tom, nearly always went about his chores whistling.

“I hope I get a lot of eggs to-day,” said Tom, speaking aloud to himself, as he stopped whistling. “Maybe I can get a whole basket full. I’ll look in the hay for them. Hens like to lay their eggs in the hay. It’s a good place for them to hide.”

Now, if that farmer boy had only known it, there was something else hidden in the hay besides hens’ eggs. There was Tamba, the tame tiger. Tamba had worked himself down into a[56] regular nest in the dried grass, and only his eyes peered out. They were very bright and shining eyes, and they watched every move of the farmer boy.

Tamba saw the basket which the boy carried in his hand so he might put the eggs in it, and, seeing this basket, the tame tiger thought to himself:

“Well, if he expects to take me back to the circus in that little basket he’s very much mistaken. Why, it wouldn’t hold two of my paws!”

And then Tamba took a second look, and he saw that the boy was not one of the circus keepers, as the tiger had at first supposed.

“But he whistles just like one,” thought Tamba. “I wonder what he wants.”

So the boy, not knowing anything about the tiger in the hay, walked right toward Tamba, hoping to gather eggs.

In another moment, just as the boy began poking his hand down in the loose hay, hoping to find a hen’s nest full of eggs there, Tamba made up his mind it was time for him to do something.

“I’ll give this fellow, whoever he is, a good scare!” said Tamba to himself. “I’ll teach him to come looking for me with a basket! Look out now, you whistling chap!” said Tamba to himself.

Then he gave a loud growl—one of his very loudest—and he raised himself from his nest in the hay, and stuck his head out.

Now if you had gone hunting hens’ eggs in your father’s barn, and had, all of a sudden, seen a great, big, striped tiger jump out at you from the hay, giving a loud growl, I believe you would have done just what this boy did. And what he did was this.

He dropped his basket, gave one look at Tamba in the hay, and then uttered such a yell that his father and mother in the farmhouse, quite a distance off, heard him. And then that boy ran out of the barn as fast as he could run. That’s what this boy did, and I think you would have done the same.

“Well, I guess he won’t come back right away,” thought Tamba. “But there may be others like him. If I stay here I may have to scare a whole lot of them. I guess I’ll find a new hiding place.”

So Tamba came out from his nest in the hay and began moving about in the barn, looking for a new place in which to snuggle, and perhaps find something to eat. And the first thing he knew he stepped right into a hen’s nest of eggs. Right down among the eggs Tamba put his paw.

Of course he broke some of the eggs, but he took up his paw so quickly again that not many[60] of the shells were cracked. And, as his paw was covered with the sticky whites and yellows of the eggs, Tamba began licking it with his tongue to make it clean.

“Hum! These eggs taste as good as the ones I used to get in the jungle,” said the tiger to himself. “Guess I’ll eat them. I’m hungry, and they’ll be almost as good as meat.”

So Tamba carefully cracked the egg shells and sucked out the whites and yellows. He ate a whole dozen of eggs before he finished, and then he felt better.

“Now I’ll go and find a new place to hide,” he said to himself.

He found a stairway leading from the upper part of the barn, where the hay was stored, to the lower part, where were the stables of the cows and horses. Down the stairs softly went Tamba, and no sooner was he down there than he felt right at home. For it smelled just like that part of the circus where the horses were kept. And, as a matter of fact, there were a number of horses in the barn, and quite a few cows.

At first the horses were afraid of the tiger, and pulled at the straps which held them fast in their stalls. But Tamba, speaking in animal talk, said:

“I am a tame tiger. I won’t hurt any of you. I only want to hide here so the circus men won’t[61] find me. I am on my way back to the jungle. I have run away from the circus.”

When Tamba spoke thus kindly the horses were no longer afraid. One of them said Tamba might hide in a pile of straw near his stall, and this the tiger was glad to do. He stretched out, and got ready to go to sleep.

Now I must tell you a little about the farmer boy. When he saw the tiger rear up at him out of the hay, and ran away, screaming with fear, he did not know what to do. All he could yell was:

“The tiger! The tiger! A big striped tiger is in our barn!”

The boy’s father and mother heard him shouting and yelling, and they ran out of the house to see what the matter was. They saw that Tom was very much frightened indeed.

“What is it?” they asked.

“Oh,” Tom answered, “I went to get some eggs out of the hay, and I found a tiger there! He had great big eyes, big teeth and a big mouth!”

“Oh, Tom! Really?” asked his mother.

“Really and truly!” he answered. “You can go and look for yourself!”

“No, I don’t believe I want to,” said Tom’s mother. “But do you really think he did see a tiger?” she asked her husband.

“Well, I don’t know,” he slowly answered. “I read in the paper something about a circus train having been wrecked, and maybe a tiger or an elephant got loose and is roaming about.”

“It’s a tiger—not an elephant—and he’s in our barn,” said Tom. “Come and see, Dad! But you’d better bring your gun!”

“Yes,” agreed the farmer, “I think I had. And I’ll call some of the men to help hunt the tiger, too!”

But, as it happened, by the time the farmer had called some neighbors in to help him and they had gotten their guns, Tamba had left the upper part of the barn, where the hay was, and had gone downstairs among the horses and cows. And as the farmer and his friends did not know this, and as none of the horses or cows called out to tell the men, they didn’t know where Tamba was.

They looked in the hay, where the boy had seen him, but Tamba was gone. The men even found the place where Tamba had eaten the eggs, but the jungle circus beast was not in sight. He was well hidden downstairs in the straw near the stall of the kind horse.

So the men hunted in vain, and some of them thought the tiger had gone back to the circus, while others thought he had run off to the woods, perhaps. At any rate, they did not find him in[63] the barn, though he was there all the while they were searching. A wild animal sometimes knows better how to hide than you boys and girls do when you are playing games.

And now I must tell you something that happened to Tamba, as he still hid in the lower part of the barn. He was snugly curled up in the straw when suddenly there was a patter of little hoofs on the floor, and a small pony trotted into his small stall, which was near that of the big horse, next to which Tamba was hiding.

“Well, friends, here I am back!” cried the little pony. “I have been giving the boys and girls a ride, and now I’ve come back to have something to eat. Has anything happened while I was out, hitched to the basket cart, giving rides to the boys and girls? Has anything happened?”

“Yes,” answered the old horse, near whose stall Tamba was hiding in the straw, “something strange has happened. A big striped animal, who calls himself a tiger, came into our barn.”

“A tiger!” cried the little pony. “Why, I’d like to see him. I know something about tigers.”

“Oh, do you?” asked Tamba himself, sticking his head out of the straw, as he had stuck it out of the hay at Tom. But the pony was not frightened. “So you know something about tigers, do[64] you?” went on Tamba. “Well, what is your name, if I may ask? Mine is Tamba.”

“Oh, ho! I know that very well!” neighed the pony. “You don’t know me, Tamba, but I have often seen you in the circus. I am Tinkle, the trick pony. I was in the circus a short time myself, but there were so many of us little Shetland ponies that I don’t suppose you remember me. But there were only a few tigers in the show, and I remember you very well. Didn’t you used to jump through a paper hoop as one of your tricks?”

“Yes,” answered Tamba, “I did. And, now that you speak of it, I believe I remember you. You used to pull, around the ring, a little cart with a funny clown in it, didn’t you?”

“Yes,” said Tinkle, “I did. Well, Tamba, I’m glad to see you again. But what brings you so far from the circus, and why are you hiding here?”

“That,” said Tamba, “is a long story. I’ll tell it to you!”

But, all of a sudden, one of the cows at the far end of the stable mooed out:

“Quick, Tamba! Here comes the man to milk us! Hide in the straw so he won’t see you!”

Tamba did not need to be told twice what to do. As soon as he heard the kind words of the cow the tame tiger ran softly on his padded feet and snuggled down again in the straw. And the man came in, milked the cows, and went out with the foaming pails without knowing anything about the circus tiger hiding in the lower part of the barn. He thought the tiger had gone away.

“Now it’s all right—he’s gone and you may come out,” said the cow to Tamba, and the tiger, shaking the straw from his striped black and yellow fur, walked out to talk some more to Tinkle, the trick pony.

“You were going to tell us how it was you left the circus, Tamba,” said Tinkle. “Make a good, long story of it. I like stories.”

“I haven’t time to make it too long,” said Tamba, “for I must be on my way. I want to get back to my jungle. At first I thought the long grass near the railroad was the place I wanted. But I see it is not the jungle where I used to live. So I must travel on a long way,[66] and the sooner I start the quicker I’ll be there. But I’ll tell you how I got loose from the circus.”

So Tamba told Tinkle the story I have told you—how the circus was wrecked in the railroad accident, and how the cage burst open, letting the tame tiger loose.

“And now I’m here,” finished Tamba. “But tell me, Tinkle, how did you come to leave the circus?”

“Well, I had many adventures,” said the trick pony. “I used to live on a stockfarm, something like this, only there were more horses on it. I was taken away to live with a nice boy, who taught me many tricks, and then a bad man, with a big moving wagon, came along one day and stole me away. He sold me to the circus, and it was there I saw you, Tamba. I know Tum Tum, too, and Dido, the dancing bear!”

“Yes, they are all friends of mine,” said Tamba. “At least they were before I left. Now, I suppose, I’ll never see them again, for I am going to the jungle. But you haven’t yet told me, Tinkle, how you came to leave the circus.”

“Oh, it’s all written down in a book,” answered the trick pony.

“Oh, a book!” exclaimed Tamba. “I’ve heard Tum Tum and Dido speak of being in[67] books, but I didn’t know what they meant. And I haven’t time to learn now, so suppose you tell me.”

“Well, there’s a book all about me and my adventures,” said Tinkle, the trick pony. “But, as long as you can’t read it, I’ll just tell you that, one day, when I was in the circus doing my tricks, George, the boy who used to own me before I was stolen away, came to the show. There he and his sister saw me and they knew me again, and I was taken out of the circus and given back to my little master. I’ve lived with him ever since. We often come to this farm in the summer, and I have just been giving him and his sister and some of the other children a ride in the pony cart. George is very nice to me, and gives me lumps of sugar.”

“I hope he isn’t the boy whom I scared in the hay,” said Tamba. “I would not want to scare any friend of yours, Tinkle.”

“Oh, well, if you only scared him, and didn’t scratch him, I guess it will be all right,” said the trick pony. “But I don’t believe it was George you frightened, as he was out driving me. It must have been Tom, or one of the other boys.” And so it was, as Tinkle learned later.

“And so you are going to the jungle, are you?” asked Tinkle of Tamba, when they had talked a while longer.

“Yes, I want to get back to my old home,” answered the tiger. “I don’t like it in the circus. But, still, there was one thing I liked in it, and that was the good meals I had. I’m very hungry right now.”

“Oh, excuse me!” exclaimed Tinkle. “I should have thought of that before. I’m so sorry! Won’t you have some of my hay or oats?”

“Yes, and give him some of our bran,” added the cow who had told about the man coming in to milk.

“Oh, thank you, very much, Tinkle. And you too, my cow friend,” replied the tiger gratefully. “But I can’t eat hay, bran, or oats. We tigers must have meat. I don’t suppose you eat any of that?”

“No,” said Tinkle, “we don’t. It’s too bad! I don’t know how we can give you anything to eat. It’s no fun to be hungry, either.”

“I know how we can feed your tiger friend,” said one of the big farm horses.

“How?” eagerly asked Tinkle. He felt just as you would feel if some friend came to visit you and you couldn’t give him anything to eat. “How can I feed Tamba on the meat that he likes?” asked Tinkle.

“I’ll tell you,” went on the horse. “You know[69] the big dog who drives the sheep to and from the meadow?”

“Oh, yes, I know our sheep-dog very well,” said Tinkle. “He is a friend of mine.”

“Well, he has company,” went on the horse. “A dog named Don has come to see him and spend the day. I came in just now from plowing one of the fields, and I saw the farmer’s wife put a big plate of meat and bones out near the dog kennel. She said it would do for our dog and his friend, Don.”

“Yes, but if the meat is for the dogs they’ll eat it all up, and there won’t be any for Tamba,” said Tinkle.

“Oh, but wait a minute!” neighed the horse. “I didn’t finish. Don and our dog went off to the woods. I heard them say they would be gone for a long time, and maybe they would find something to eat there. So if they don’t come back to eat the bones and meat Tamba can have it.”

“Yes,” said Tinkle, “I suppose he can. I hope Don doesn’t come back.”

“I hope so, too,” said Tamba. “I’m getting hungrier every minute.”

“I’ll go out and look,” said Tinkle. “It will soon be dark, and if the plate of meat is still by the dog kennel, you can sneak out and get it,[70] Tamba, and no one will see you. I’ll go and look.”

Tinkle, the trick pony, was not kept tied in a stall as were the other horses. He could roam about as he liked, and so he trotted out of the barn to where the farm dog had his house, or kennel. There, surely enough, was a big plate of meat and some large bones, large enough, even, for a lion or a tiger.

“It’s all right,” said Tinkle, when he came trotting back. “The meat is there, Tamba, and I didn’t see anything of Carlo, our dog, nor his friend, Don. Now if they don’t come back until dark, why, you can go out and have a good meal.”

“I will, thank you,” returned Tamba, and he wished, with all his heart, that Don and the other dog would not come back.

“Of course I don’t want to see them hungry,” thought Tamba, “but they may get something to eat in the woods, and perhaps I couldn’t do that. There may be no muskrats there.”

Everything came out all right. The twilight faded, and it became dark. Then Tamba, who remained hidden in the stable, crept softly out to the plate of meat and bones that had been left for the dogs. He ate up everything and gnawed the bones, and then he got a drink of water from the horse trough and felt much better.

“And now, Tinkle, I will bid you and your kind friends good-by and be on my way to get back to the jungle,” said Tamba, after he had eaten.

“Oh, are you going to run away?” asked the trick pony. “You’ll be just like Don, the dog, then. He ran away, too.”

“But he ran back again, as I have heard my friend, Nero, the circus lion, say,” replied Tamba. “I am not exactly running away from you. I ran away from the circus, but I am only leaving you after paying you a visit. And I liked my visit very much. That meat, too, was very good. Thank you, Tinkle.”

“I only wish there had been more of it,” said the trick pony. “But, if you have to go, I suppose you must leave. I hope you’ll get safely to your jungle.”

But Tamba had many adventures ahead of him before that time. He said good-by to Tinkle and the farm animals, and then, looking out of the barn and peering through the darkness, to see that none of the farmer’s men were on the watch with their guns, Tamba slunk out into the night.

Once more he was on his way, traveling to find his jungle. On through the dark woods and over the fields went Tamba, taking care to keep away from houses where people might live who[72] would see him and tell the circus men to come and get him. Tamba did not want to be caught.

So, for several days, Tamba traveled on. Often he was hungry and thirsty, but he managed to find things to eat once in a while, and now and again he came to springs of water or streams where he drank. So, though he did not have a very good time, he managed to live.

One evening, just as it was getting dark, Tamba sniffed the air and smelled a smell which told him he was near another stable and barn. It was not the one where Tinkle lived, though.

“I wonder if I can get anything to eat here,” thought Tamba.

Carefully and softly the tame tiger crept around the corner of the carriage house. Near by he saw what seemed to be a low building without any roof a little way ahead of him, and from this place came gruntings and squealings.

“Get over on your own side of the trough! You’re eating all my sour milk!” said one squealy voice.

“I am not, either, Squinty!” came the answer. “I want something to eat just as much as you do!”

“Ha! Something to eat!” thought Tamba who heard and understood this animal talk. “I wonder who those chaps are, and who Squinty is. And I wonder if they have enough for me to eat. I’m going to see!”

Up to the pen, which had no roof, went Tamba, and, rising on his two hind legs, he looked over the side and down in. There he saw a number of pigs who were drinking sour milk and bran from a trough.

One of the pigs, with a queer droop to one eye, looked up and saw Tamba peering in.

“Hello!” grunted this pig. “Who are you, and what’s the matter?”

“I’m Tamba, a tame tiger,” was the answer, “and the matter is that I’m hungry. Who are you?”

“Squinty, the comical pig!” was the grunting reply. “And you had better travel on! We have nothing here for tigers to eat!”

Tamba, the tame tiger, rearing up on his hind legs to look down into the pig pen, saw the funny look on the face of the animal who had spoken to him.

“What’s that you say?” asked Tamba in a growling voice.

“I said we didn’t have anything to give tigers,” went on the comical pig, and really he was comical, for his one eye had such a funny look as it drooped toward one ear. It seemed to be looking in two ways at once, and that is something you don’t often see in a pig.

“Well, it seems to me I smell something very good,” went on Tamba. “It smells like milk to me.” When he was a little tiger Tamba had liked milk very much, and now, even though he was older, he knew it would be good when he was hungry.

“Yes, you do smell milk,” went on Squinty. “But it is sour.”

“Sour or sweet, it makes no difference to me,” replied Tamba. “I am hungry enough to eat anything.”

“Well, I don’t want to be cross or impolite,” said Squinty, “but there is only enough sour milk for us pigs. We can’t give you any.”

“Ha! Well, I simply must have something to eat!” returned Tamba, and his voice was more growly now. “If I can’t get milk I must have meat. I remember once, in the jungle, eating a little pig who looked something like you. What’s to stop me taking a few bites off you, if you won’t give me any of your milk?”

“Oh, ho! So you think you can bite me, do you?” squealed Squinty. “Well, we’ll see about that!”

Now Squinty was a brave little animal, and he had seen more of the world than some of the other small pigs in the pen. In fact, Squinty had had a number of adventures, and those of you who have read my first book entitled, “Squinty, the Comical Pig,” know that Squinty was not much afraid of anything.

So no sooner did he hear Tamba talk that way, about taking bites, and so on, than Squinty ran to where there was a loose board in the pen, and out he popped.

“Ho! So you think because you’re a big, circus tiger that you can scare me, do you?”[76] squealed Squinty. “Well, I’ll show you that I’m not a bit afraid!”

Now, as it happened, near the pen, where the farmer intended to use it the next day, was a pail of whitewash. It was like thick, white water, and the pail was full of it. Squinty gave one look at the pail of whitewash, and a glance at Tamba, who had taken his forepaws down off the edge of the pen, and was standing on all four feet looking at Squinty.

“There! Take that and see how you like it!” squealed Squinty, and with his strong nose, made for digging down under the ground after roots and things, Squinty upset the pail of whitewash and gave it a push toward Tamba.

The whitewash splashed out, and lots of it splattered on the tame tiger, so that he was splashed and speckled with spots of white as well as being marked with black and yellow stripes.

“Now how do you like yourself?” asked Squinty of Tamba, as he looked at the tame tiger in the moonlight, for the moon was just coming up. “If you try to bite me or any of my friends I’ll splash some more whitewash on you!”

“You can’t,” said Tamba. “There isn’t any more left in the pail. It’s empty; I can see for myself. I guess I got most of it on me.”

“Well, if I can’t throw whitewash on you I’ll throw something else!” threatened Squinty. “You’ve got to leave us pigs alone!”

“Yes,” said Tamba, “I can see that I’d better. I didn’t know you were such a fierce chap, Squinty.”

“Well, I didn’t mean to be cross,” said the pig. “But when you talked of biting me, why, I just couldn’t help it. I’m sorry I spotted you with white like that.”

“It’s all my fault,” returned Tamba. “I shouldn’t have said anything about biting you. Being splashed with whitewash serves me right. But I am very hungry, and your sour milk smelled very good!”

“I’m afraid there isn’t much left now,” said Squinty. “The pigs were very hungry to-night. But if you’ll come over to the side of the pen, where I broke out to rush at you, I’ll see if there is anything else. Sometimes they throw kitchen table scraps into our trough, and there are bits of meat which we small pigs don’t eat. You may have that, if there is any. Tigers like meat, I’ve heard.”

“Yes,” said Tamba, “I like meat very much. It is about all I can eat, though I could manage to drink some milk—sour or sweet.”

“Come, we’ll go see what there is,” went on Squinty. “When I said we had nothing for tigers I didn’t think about the meat scraps.”

So Squinty led Tamba back to the side of the pen whence the little pig had pushed his way out. Then Squinty explained to the other pigs what had happened.

“Yes, here are some meat scraps,” said one of the pigs, when Squinty had told how hungry Tamba was. “It isn’t very much, though.”

“Even a little will keep me from starving,” said Tamba. “When I get to my jungle I’ll have all I want to eat, but just now it is pretty hard to find enough. In the circus I had plenty.”

“Oh, so you’re from the circus, are you?” asked Squinty. “I used to know some animals in a circus. There was Mappo, the merry monkey.”

“Yes, I have heard of him, too,” said Tamba. “But he isn’t with the show now. Ah, but this meat tastes good!”

The tame tiger was now chewing the scraps the pigs had brushed aside as they did not want them. Tamba did not feel so hungry now, but he did feel queer where the whitewash had splashed on him.

“I’m sorry about that,” said Squinty. “If you go down to the end of the meadow there is a pond, and you can wash off the white splashes. It’s warm enough to take a bath.”

“I’m not very fond of water,” said Tamba, “though I do take a bath now and then. I guess[81] I can wash off the white stuff by dipping my paws in the water and rubbing them over my striped coat. I’ll do it.”

And that is what Tamba did after he had eaten up all the meat scraps there were in the pigs’ pen. Then he said good-by to Squinty and the others and started off again.

“I must get to my jungle,” said the tiger. “I have been away from the circus quite a while now, and, as yet, I have not come to the jungle.”

“But you have had lots of adventures,” said Squinty, the comical pig, for Tamba had told of some of the things that had happened to him. “You have had almost as many adventures as I, Tamba. I suppose you can call that an adventure, when I splashed the whitewash on you.”

“Yes,” agreed Tamba, “I think that, most certainly, was an adventure. I don’t want another like it, though.”

So Tamba traveled on again. He thought, if he went far enough, he must, some day or other, come to the jungle where he used to live. But he did not know which way to go, and, often as not, he went wrong. However, as Squinty said, the tame tiger was having many adventures.

He had a queer one the second night after he had met Squinty, and this is the way it happened. Tamba had been roaming along in the night, after having caught something to eat in[82] the woods, and at last he came out on a road which stretched far and away in the moonlight.

“That is a long road to travel,” thought Tamba. “I think I will take a rest before I go down it any farther. I’ll hide somewhere and wait until morning.”

Tamba looked around for a place to hide, and saw a big pile of hay. He knew it was hay, since he had often seen it in the circus tent, and he remembered having hidden in the hay in the barn.