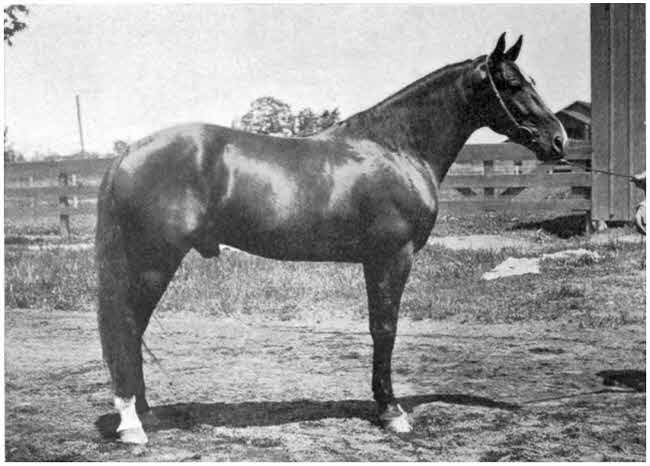

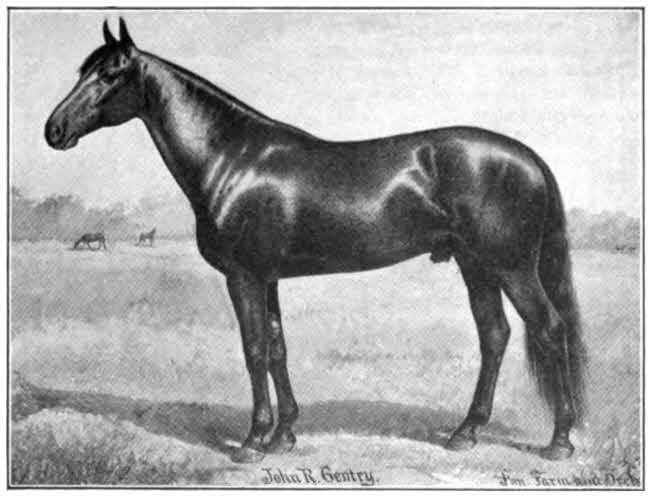

WALTER DIRECT, 2:05 3/4.

The Table of Contents was created by the transcriber and placed in the public domain.

Additional Transcriber’s Notes are at the end.

WALTER DIRECT, 2:05 3/4.

VOL. 1. NASHVILLE, TENN., OCTOBER, 1905. NO. 1

Luther Burbank

[4]

By Percy Brown, of Ewell Farm.

Note.—Mr. Brown is a practical forester, having been chief forester for the Houston Oil Co. and a graduate of Biltmore Forest School.—Ed.

The preservation of our forests is an imperative business necessity. We have come to see that whatever destroys the forest, except to make way for agriculture, threatens our well being.—President Roosevelt.

With abundant supplies of timber for farm consumption, farmers of the South have been inclined to regard the question of forest preservation merely as a matter of sentiment, and have come to look upon the forester as an impracticable sort of sentimentalist, whose main object in life is to keep some lumberman from cutting his timber.

This indifference has resulted in the loss of the support of the farming element to the cause of forestry, whereas the lumberman who at one time considered the forester his natural enemy and the forestry cause a clog in the wheels of progress, immediately began to investigate the question with a view of combatting forest legislation and the creation of a forestry sentiment throughout the country.

The result was that a thorough understanding of the objects of forestry and the aims of the forester has caused the lumbermen and lumber associations to give their unqualified support to all practical forestry legislation. And in the Southern States we find that the only journal of any importance that is persistently advocating forestry as a business is one of the foremost lumber journals south of the Ohio River.

The silence that the farm journals of the country have maintained on the question can be explained only by their ignorance of the question and its important bearing on the agricultural interests of the entire country. And as it is the purpose of this magazine to discuss all questions of vital importance as well as those that will be of passing interest to the farmers of the whole country it is well to begin with an understanding of what forestry is, and to advance a few reasons why the farmer should be the most ardent advocate of forestry.

Dr. W. H. Schlich, the noted English forester, says the task with which “forestry has to deal is to ascertain the principles according to which forests shall be managed and to apply these principles to the treatment of the forests.”

Dr. B. E. Fernow, formerly chief of the Division of Forestry, defines it as “The rational treatment of forests for forest purposes.”

Dr. C. A. Schenck, of the Biltmore Forest School, gives the following very broad and terse definition: “Forestry is the proper handling of forest investments.”

We see from these definitions that the forestry is purely a matter of business differing only from other investments in the time element. A forestry venture cannot be undertaken with a view of getting immediate returns, but contemplates the continuity of the investment which makes it the first duty of the forester to determine what is the best use the forest can be put to in order to obtain the greatest annual return upon the investment without drawing upon his capital invested. This does not necessarily mean that his forest must be devoted entirely to the production of timber, it may be maintained as a game preserve, or as a watershed, in which case the returns to be obtained from the sale of timber will be a secondary consideration.

Consequently we see that the forester is not merely a botanist or a tree planter, but in the fullest sense of the term is a technically educated man, with the knowledge of the forest trees and their history and of all that pertains to their production, combines further knowledge which enables him to manage forest property so as to produce certain conditions resulting in the highest attainable revenue from the soil by wood-crops.

The effect of forest cover and water-flow[5] has been so persistently and constantly proclaimed as the one great need for forest preservation that the more important one of supply has been neglected.

In a series of articles by Dr. Fernow, on “The Outlook of the Timber Supply in the United States” (Quarterly, 1903), after carefully considering the data compiled by the Chief Geographer, together with his personal investigations, he summarizes the situation, which justifies the urgent need of the forester’s art in the United States, from the point of view of supplies, as follows:

1. The consumption of forest supplies, larger than in any other country in the world, promises not only to increase with the natural increase of the population, but in excess of this increase per capita, similar to that of other civilized, industrial nations, annually by a rate of not less than three to five per cent.

2. The most sanguine estimate of timber standing predicates an exhaustion of supplies in less than thirty years if this rate of consumption continues, and of the most important timber supplies in a much shorter time.

3. The conditions for continued imports from our neighbor, Canada, practically the only country having accessible supplies such as we need, are not reassuring and may not be expected to lengthen natural supplies appreciably.

4. The reproduction of new supplies on the existing forest area could, under proper management, be made to supply the legitimate requirements for a long time; but fires destroy the young growth over large areas, and where production is allowed to develop in the mixed forest, at least, owing to the culling processes, which remove the valuable kinds and leave the weeds, these latter reproduce in preference.

5. The attempts at systematic silviculture, that is, the growing of new crops, are, so far, infinitesimal compared with the needs.

That this is a question of serious importance to the South, as well as to the whole country, is shown by the great increase in the South’s production of lumber, which, owing to the depletion in other sections of the country, has risen from eleven and nine-tenths per cent in 1880 to twenty-five and two-tenths per cent of the total output of the United States in 1900, and it is not hard to predict an even greater production for 1910, when one concern alone has increased the number of its mills in the long leaf pine belt from seven to fifteen, and its daily output from 500,000 to 1,000,000 feet during the period from 1900 to 1904.

Basing their estimates upon the present standards of grading, the hardwood lumber journals are predicting the total exhaustion of the available supplies of this timber in fifteen years, and the hardwood lumbermen are already looking to forestry as a means of relief.

In an address delivered before the third annual meeting of the Hardwood Manufacturers’ Association of the United States, as an introduction to the subject of “The Hardwood Producing Centers of the United States,” Mr. John W. Love, of Nashville, said:

“I hope to be able to briefly call the attention of this body of practical manufacturers to a few pertinent facts that may, in a measure, at least, open our eyes to a painful truth, viz., the rapidly decreasing area of hardwood timber in the United States, and when we consider how very little is being done to conserve our forest growth—how the forests are being cleaned from hoop-poles to giant oaks, and that to supply the one item of cross ties that are used in this country alone, about 4,000,000,000 feet of timber is required (clearing about 200,000 acres of wood lot annually), and a large proportion of these ties are cut from thrifty young trees, we must conclude that a matter so weighty as to give us pause. The one hopeful sign of the future is the hope that practical forestry methods may be enforced by the Government.”

This in an address from a lumberman to an association of lumber manufacturers is indeed an encouraging sign of the times, but I fear he has waked up “to the realization that our efforts to secure a more rational treatment of our forest resources and apply forestry in their management are not too early, but rather too late: that they are by no means sufficient; that serious trouble and inconvenience are in store for us in the not[6] too distant future; that the blind indifference and the dallying or amateurish playing with the problem of legislatures and officials is fatal.”

The railroads and the farmers of the Western plains were among the first to appreciate the importance of making provision for a future supply of construction timber and material for use on the farms.

With the far-sighted policy of manipulators of great corporations, the officials of the Santa Fe Railroad were among the pioneers in forest planting in America on railroads, as about twenty years ago they planted 1,280 acres in hardy catalpa at a total expense of $128,000, and they estimated that at the end of twenty-five years from date of planting this tract will have produced $2,500,000 of poles, ties and posts.

A few years ago the Illinois Central made a plantation of catalpa and black locust in Illinois and during the current year the Louisville & Nashville Railroad have arranged for a similar plantation in Alabama.

It has not been necessary for the farmers of the South to resort to plantations for their supplies of posts and fuel, and if we are not improvident of our supplies it will hardly become necessary, as we have left on nearly every farm enough timber of suitable varieties from which we can procure our future supplies by self-sown seed, provided the sections to be reserved for timber growth are protected from stock and fires. In some instances, however, it may prove cheaper and more expedient to plant as was the case with the now famous yaggy catalpa plantation near Hutchinson, Kan., in which a ten-year-old block showed a net value of $197, or a yearly net income of $19.75 per acre.

And a twenty-five-year-old plantation of red juniper, belonging to F. C. F. Schutz, Menlo, Iowa, showed a net value of $200.54 per acre, or a yearly net income of about $8—not a bad showing for forestry, when we bear in mind that the net income from other farm crops seldom exceeds that amount, but from the farm crops the returns are secured annually, while in the case of a forestry investment there is quite a period preceding the first harvest, during which we have to figure in an accumulative value.

All wood-lot planting should be governed by the local demand, for that reason it would be hard to suggest either methods or species for the South as a whole, but generally speaking, black locust (robinia pseudoacacia), hardy catalpa, mulberry and chestnut would be the most desirable, as the first three would be quickly available for fence posts, and the chestnut would always be in demand for telephone and telegraph poles as well as furnishing construction timber.

Wood-lot forestry has the advantage over similar work conducted on a large scale, as the farmer is at no expense for protection or supervision, the location of forest on the farm assures its safety from fire or trespass, and he gives it his personal attention.

However, to secure the most desirable management his supervision should be carried on under the direction of trained foresters.

To secure this without appreciable additional cost it is to his interest to ally himself with those who are striving for a State forestry system, under which a forester would be employed whose duty would be to look after the State reserves and give advice to farmers and timber land owners on the management of all forest tracts set aside for permanent forest investments.

The indirect utility of the forests is well known and appreciated by those who have given the matter any thought, but the average American farmer has little use for a thing which does not appeal to him in dollars and cents, however, the Bureau of Forestry realizing the great importance of this matter to the agricultural interests, sent Mr. J. W. Twomey to the San Bernardino Mountains of California to conduct investigations of the “Relation of Forests to Stream Flow,” and in the “Year-Book” of the Department of Agriculture for 1904 he reports these conclusions:

“In humid regions, where the precipitation is fairly evenly distributed over the year, and where the catchment area is sufficiently large to permit the greater part of the seepage to enter the stream above the point where it is gauged, the evidence accumulated to date indicates[7] that stream flow is materially increased by the presence of forests.

“In regions characterized by the short wet season and a long dry one, as in Southern California and many other portions of the West, present evidence indicates, at least on small mountainous catchment areas, that the forest very materially decreases the total amount of run-off.

“Although the forest may have, on the whole, but little appreciable effect in increasing the rainfall and the annual run-off, its economic importance in regulating streams is beyond computation. The great indirect value of the forest is the effect which it has in preventing wind and water erosion, thus allowing the soil on hills and mountains to remain where it is formed, and in other ways providing an adequate absorbing medium at the sources of the water courses of the country. It is the amount of water that passes into the soil, not the amount of rainfall, that makes a garden or a desert.”

With such evidence as this before them, what farmer in the South will dare question the importance of forestry to the agricultural interests of every section of the South, and especially those sections lying adjacent to streams having their sources in the territory of the proposed Appalachian Forest Reserve?

By protecting the forest growth on the watersheds of these streams the flow of the water is rendered more continuous, and the dangers from violent floods, which destroy fences and carry away the most fertile soil, are lessened.

The South to-day is pre-eminent in agriculture and timber production, but the wasteful destruction of our forest resources bids fair to transfer the laurels to the great undeveloped West, where we find over 60,000,000 acres of forest reserves, which will for all time to come offer a continuous supply of lumber for the manufacturer and an abundance of water for the farmers who have made a garden of the deserts.

It is the duty of the Southern farmer to join with the hardwood lumberman in his efforts to introduce forestry in the South, and by so doing give to succeeding generations the heritage that except for the destructive forces of man would have come to them in nature’s great scheme of things.

TO THE CAHABA RIVER

[8]

Little Sister was Col. Rutherford’s only grandchild. She was also Capt. John Rutherford’s only niece. I mention the last-named gentleman because he had a great deal to do with the making of this story. He was quite original himself, and a braver, bigger-hearted friend no man ever had.

The Rutherford home was in the Middle Basin of Tennessee. The house was built in 1812 by John Rutherford the first, who had eaten, slept, fought, and finally died, with his old friend, Andrew Jackson. No truer, better, braver people than the Rutherfords lived. No black sheep ever came out of the flock. I have always maintained that a family’s ability to refrain from throwing scrubs is the truest test of its purity. The prepotency that produced dead-game, honest and true men and women every time, is a long way ahead of “Norman blood.” “That’s the genuine stuff,” as little three-year-old Sister once naively remarked after looking over Uncle John’s pacing filly. However, that’s a story I will tell later.

When I first knew Little Sister she was only two years old, for just two years before a terrible gloom had settled over the Rutherford home when Little Sister’s mother, the Colonel’s daughter, had died. Death is a terrible, bitter, hollow mockery to those who live. Some day, in another world, we shall see things differently. In this, “cabined, cribbed, confined” in our puny environments, we see only “through a glass darkly,” and so God help us.

As I said, she was the old Colonel’s only daughter—the fairest, frailest, most lovely and most intellectual—a bride one year, and we buried her the next. That’s all, except Little Sister, a fair, frail, hot-tempered, sensitive—all brain and nerve—little tot who came to take her mother’s place. Her bright blue eyes, pale-pink face and red-flaxen hair kept one thinking of perpetual sunsets and twilights. She was a fac simile of her mother—intellect, impulsiveness, loveliness, all except one thing—temper. She was fire and powder there. A flash, an explosion—then she was sobbing for forgiveness in your arms. That was Little Sister.

“I can’t see where in the world she gets her temper from,” Grandmother Rutherford said when two-year-old Little Sister slapped her squarely in the face one day and then hung sobbing around the old lady’s neck as if the blow had broken her own heart.

“Col. Rutherford,” she would add impressively, “this child ought to be spanked till she is conquered.”

“Don’t do it, mother,” said Uncle John, while Little Sister gave him a grateful look through her tears; “don’t do it; that is not the way to train race colts. A conquering, your way, would spoil her. She will need all of that temper, if it is brought under control, to get through life with, and land[9] anywhere near the wire first. Besides, with her sensitiveness, don’t you see she is suffering now more than if we had punished her? If she were a plug, now, she would slap you and never be sorry till you made her sorry with a switch. But conscience beats hickory, and gentleness is away ahead of blows.”

And Uncle John would catch the two-year-old up and take her out to see the colts. At sight of these she would forget all other trouble. Her love for horses was as deep in her as the Rutherford blood. When she saw the colts it was comical to see the great burst of sunshiny laughter that spread all over her conscience-stricken face, while two big tears—such big ones as only little heart-broken two-year-olds can originate—were rolling slowly down her nose.

“Oh, Uncle John,” she would say gleefully, “now, ain’t they just too sweet for anything? Do let me get down and hug them, every one.” And Uncle John would let her if he had to catch every one himself.

The clear-cut way she talked English reminds me that there were two things about Little Sister that always astonished me—her intellect and her great sense of motherhood. I could readily see how she inherited the first, but could never understand how so tiny a thing had such a great big mother-heart. She loved everything little—everything born on the farm. The fact that anything in hair, hide or feathers had arrived was an occasion of jollification to her.

“Oh, do let me see the dear little thing,” would be the first thing from Little Sister that greeted the announcement. And she generally saw it; at least, if Uncle John was around. It is scarcely necessary to add that during the spring of the year, on a farm as large as the Rutherford place, she was kept in one continual state of happy excitement.

One day they missed her from the house, and Uncle John quickly “tracked” her to the cow barn, for it occurred to him he had only the day before shown her the Short-horn’s latest edition—a big, double-jointed, ugly, hungry male calf, who slept all day in the bedded stall like a young Hercules, and only waked up long enough to wrinkle his huge nose around and mentally make the remark the Governor of North Carolina is said to have made to the Governor of South Carolina. But Little Sister had declared he was “perfectly lovely.” That is where Uncle John found her. She had climbed over the high stall gate, unaided, and, after becoming acquainted, she had given young Hercules, as a propitiary offering, her own beautiful string of beads and placed them around his tawny neck.

“Come out of there, you little rascal,” laughed Uncle John. “What do you see pretty about that big, ugly calf?”

“Oh, Uncle John,” sighed Little Sister, “I’m so sorry for him—he isn’t pretty, to be sure—and so I have given him my beads. But he has a lovely curly head,” she added encouragingly, “and he seems to be such a healthy child.”

On another occasion they missed[10] Little Sister about night. Everybody started out in alarm. Grandma found her first, coming from the brood-sow’s lot.

“Where in the world have you been, darling?” asked Grandma, as she picked her up.

“Playing with the little yesterday pigs,” she said. “And, Grandma, I ought to have come home sooner, but I kissed one of the cunningest of the little pigs good-night, and all the others looked so hurt, and squealed so because I didn’t kiss them, too, I just had to catch every one of them and kiss them before they would go to sleep. Indeed, I did.”

Inheritance had played a Hamlet’s part in Little Sister’s make-up. Most children crow, and babble, and lisp, and talk in divers and different languages before they learn to talk English, while some never learn at all. But not so with Little Sister. The first word she ever attempted was perfectly pronounced. The first sentence she put together was grammatically correct. The correctness of her language, for one so small, made it sound so quaint that I often had to laugh at its quaintness, while her deep earnestness and intensity but added to its originality.

And she picked up so many things from Uncle John. Else where did she get this: Pete was a little darkey on the farm whose chief business was to entertain Little Sister when everything else failed. Pete’s repertoire consisted of all the funny things a monkey ever did, but his two star performances were “racking” like Deacon Jones’ old claybank pacer, and “playin’ possum.” Little Sister never tired of having Pete do these two. And it was comical. Everybody knew Deacon Jones, with his angular, sedate, solemn way of riding, and the unearthly, double-shuffling, twisting, cork-screw gait of his old pacer. The ludicrous gait of the old pacer struck Pete early in life, and he soon learned to get down on his all-fours and make Deacon Jones’ old horse ashamed of himself any day. The imitation was so perfect that Uncle John used to call in his friends to see the show, which consisted of Pete doing the racking act, while Little Sister, astraddle of his back, with one hand in his shirt collar and the other wielding a hickory switch, played the Deacon. One evening, as the company was taking in the performance, and Pete, now thoroughly leg-weary, had paced around for the twentieth time, Little Sister was seen to whack him in the flanks very vigorously and exclaim: “Come, pace along there, you son-of-a-gun, or I’ll put a head on you!”

Uncle John nearly fell out of his chair. Only a week before he had made that same remark to Pete for being a little slow about bringing in his shaving water. But he didn’t know that Little Sister had heard him.

The spring Little Sister was three years old the Colonel came in to breakfast one morning with a cloud on his brow. It was a great disappointment to him—old Betty, his saddle mare, the mare he had ridden for fifteen years, “the best bred mare in Tennessee,”[11] had brought into the world a most unpromising offspring. “It is weak, puny and no ’count, John,” he said to his son; “deformed, or something, in its front legs, knuckles over and can’t stand up, the most infernally curby-legged thing I ever saw.”

“That’s too bad,” remarked Uncle John, as he helped himself to another battercake. “I’ll go out after breakfast and look at the poor little thing.”

“No use,” remarked the Colonel gravely, “it’s deformed—can’t stand up; and out of compassion for it I’ve ordered Jim to knock it in the head. It’ll be better dead than alive.”

Little Sister, with her big, inquisitive eyes, had been taking it all in, as she gravely ate her oatmeal and cream. But the last remark of Grandpa stopped the spoon half way to her mouth. The next instant, unobserved, she had slipped out of her high-chair and flown to the barn.

“I tell you, John,” remarked the old Colonel, “I sometimes think this breeding horses is pure lottery. To think of old Betty, the gamest, speediest mare I ever rode, having such a colt as that; and by Brown Hal, too—the best young pacing horse I ever saw. It makes me feel bad to think of it. Now, take old Betty’s pedigree——”

But the old Colonel never got any further, for piercing screams from Little Sister came from the barn. Uncle John glanced at her empty chair, turned pale with fright, kicked over the two chairs which stood in his way, then his favorite setter dog that blockaded the door, and rushed hatless to the barn. There a pathetic sight met his eyes. A negro stood in old Betty’s stall door with an axe in his hand. In a far corner, on some straw, lay a sorry-looking, helpless colt. But it was not alone, for a three-year-old tot knelt beside it, and held the colt’s head in her lap while she shook her tiny fist at the black executioner, and screamed with grief and anger:

“You shan’t kill this baby colt—you shan’t—you shan’t! Don’t you come in here—don’t you come! How dare you?” And, child though she was, the flash of her keen, blue Rutherford eyes, like the bright sights of the muzzle of two derringers, had awed the negro in the doorway and stopped him in hesitancy and confusion.

“Go away, Jim,” said Uncle John, as he took in the situation. “Come, Little Sister,” he said, “let’s go back to Grandma.”

But for once in her life Uncle John had no influence over the little girl. She was indignant, shocked, grieved. She fairly blazed through her tears and sobs. She would never speak to Grandpa again as long as she lived. She intended her very self to kill Jim just as soon as she “got big enough,” and as for Uncle John, she would never even love him again if he did not promise her the baby colt should not be killed.

“Poor little thing,” she said, as she put her arm around its neck and her tears fell over its big, soft eyes; “God just sent you last night, and they want to kill you to-day.”

Uncle John brushed a tear away himself, and stooped over and critically[12] examined the little filly—for such it was. Little Sister watched him intently for, in her opinion Uncle John knew everything and could do anything. The tears were still rolling down her cheeks, as Uncle John looked up quickly and said in his boyish, jolly way: “Hello, Little Sister, this little filly is all right! Deformed be hanged! She’s as sound as a hound’s tooth—just weak in her front tendons. I’ll soon fix that. No sir, they don’t kill her, Mousey”—Uncle John called her Mousey when he wanted her to laugh.

The tears gave way to a crackling little laugh. “Well, ain’t that just too sweet for anything; and Oh, Uncle John, ain’t she just sweet enough to eat?” And Little Sister danced about, the happiest child in the world.

And what fun it was to help Uncle John “fix her up,” as he called it. She brought him the cotton-batting herself and watched him gravely as he made stays for the weak forelegs, and straightened out the crooked little ankles. Finally, when he called Jim, and made him take the little filly up in his arms and carry her into another stall where old Betty stood and held her up to get her first breakfast, the little girl could hardly contain herself. In a burst of generosity she begged Jim’s pardon, and told her Uncle John confidentially that she didn’t intend to kill Jim at all, now; but was going to give him a pair of her Grandpa’s old boots instead.

In return for this, Jim promptly named the filly “Little Sister,” a compliment which tickled the original Little Sister very much.

But having said the little filly was no-’count, the old Colonel stuck to it—refused to notice it or take any stock in it.

“Po’ little thing,” he would say a month after it was able to pace around without help from its stays—“po’ little thing; what a pity they didn’t kill it!”

But Uncle John and Little Sister nursed it, petted it, and helped old Betty raise it; and the next spring they were rewarded by seeing it develop into a delicate-looking, but exceedingly blood-like, nervous, highstrung little miss. Grandpa would surely relent now, but not so. Prejudice, next to ignorance, is our greatest enemy, and the old Colonel looked at the yearling and remarked:

“Po’ little thing—that old Betty should have played off on me like that!” And he turned indifferently on his heel and walked away, whereupon both the filly and the little girl turned up their noses behind the old man’s back.

In the fall that the little filly was three years old the county pacing stakes came off. A thousand dollars were hung up at the end of that race, but greater still, the county’s reputation was at the feet of the conqueror. The old Colonel had entered a big pacing fellow in the race, named Princewood, and it looked like nothing could beat him. The big fellow had been carefully trained for two seasons by a local driver, and had already cost his owner more than he was worth. “But it’s the reputation I am after, sir,” the Colonel would say to the driver—“the honor of the thing. My farm has already[13] taken it twice; I want to take it again.”

Now, Uncle John was quite a whip himself, and the old Colonel had failed to notice how all the fall he had been giving Betty’s filly extra attention, with a hot brush on the road now and then. The old man, wrapped up as he was in Princewood’s wonderful speed, had even failed to notice that Uncle John had frequently called for his light road wagon, and he and Little Sister, now six years old, had taken delightful spins down the shady places in the by-ways, where nobody could see them, behind the high-strung little filly, and that often, at supper, when Grandpa would begin to brag about Princewood’s wonderful speed, Uncle John would wink at Little Sister, and that little miss would have to cram her mouth full of peach preserves to keep from laughing out at the table and being sent supperless to bed.

There was a big crowd on the day of the race—it looked like all the county was there. The field was a large one, for the purse was rich and the honor richer—“and Princewood is a prime favorite,” chuckled the old Colonel, as he stood holding a little girl’s hand near the grandstand.

But the little girl was very quiet. For once in her life “the cat had her tongue.” Now, anybody half educated in child ways would have seen this tot clearly expected something to happen. If the old Colonel hadn’t been so busy talking about Princewood he might have seen it, too.

The bell had already rung twice, and all the drivers and horses were thought to be in, and were preparing to score down, when a newcomer arrived, who attracted a good deal of attention. Instead of a sulky, he sat in a spider-framed, four-wheeled gentleman’s road cart, at least four seconds slow for a race like that. Instead of a cap he wore a soft felt hat, and in lieu of a jacket, a cutaway business suit. He nodded familiarly to the starting judge and paced his nervous-looking little filly up the stretch.

“Who is that coming into this race in that kind of a thing?” asked the old Colonel of a farmer near by—for the old man’s eyesight was failing him.

“Why, Colonel, don’t you know your own son? That’s Cap’n John Rutherford,” said the farmer.

“The devil you say!” shouted the excitable old gentleman. “Why, damn it, has John gone crazy?” and he jumped over a bench and rushed excitedly up the stretch to head off the driver of the little filly.

“In the name of heaven, John,” he shouted, “are you really going to drive in this race?”

Captain John nodded and smiled.

“And what’s that po’ little thing you’ve got there?”

“It’s Little Sister, father,” said Captain John good naturedly. “I’m just driving her to please the little girl. I want to see how she’ll act in company, anyway.”

The old Colonel was thunderstruck. “Why, you’re a fool,” he blurted out. “They’ll lose you both in this race. For heaven’s sake, John, get off the track and don’t disgrace old Betty and the farm[14] this way. Po’ little no-’count thing,” he added, sympathetically, “it’ll kill ’er to go round there once!”

The Captain laughed. “It’s just for a little fun, father—all to please the baby. It’s her pet, you know. I’ll just trail them the first heat, and if she’s too soft I’ll pull out. But she’s better than you think,” he added indifferently. “I’ve been driving her a good bit of late.”

The old Colonel expostulated—he even threatened—but Captain John only laughed and drove off. Then the old Colonel repented, and it was comically pathetic to hear him call out in his earnest way: “John! Oh, John! Don’t tell anybody it’s old Betty’s colt, will you?”

Captain John laughed. “I’ll bet ten to one,” he chuckled to himself, “he’ll be telling it before I do.”

And the little filly—when she got into company she seemed to be positively gay. She forgot all about herself, threw off all her nervous ways, and went away with a rush that almost took Captain John’s breath. He pulled her quickly back. “Ho, ho! little miss,” he said, “if you do that again you’ll give us dead away,” and he looked slyly around to see if anybody had seen it. But they were all too busy chasing Princewood. That horse clearly had the speed of the crowd. And so Uncle John trailed behind, the very last of the long procession, with the little filly fighting for her head all the way. Nobody seemed to notice them at all—nobody but a little girl, who clung to her grandpa’s middle finger and wondered, in her childish faith, if the mighty Uncle John—the Uncle John who knew everything and could do everything, and who never missed his mark in all his life, was going, really going, to tumble now from his lofty throne in her childish mind? And with him Little Sister, too.

She got behind Grandpa. Princewood paced in way ahead. She stuck her fingers in her ears so she couldn’t hear the shouts, but took them out in time to hear Grandpa say, “Well, I thought John had more sense,” as that gentleman, after satisfying himself that he was not distanced, paced slowly in.

This made Little Sister think it was all up with Uncle John. She went after a glass of lemonade, but really to cry in the dark hall behind the grandstand and wipe her eyes on the frills of the pretty little petticoat Grandma had made her just to wear to the fair. It was too bad.

When she got back Grandpa was gone. He was over in the cooling stable, talking to Uncle John.

“John,” he said solemnly, “don’t disgrace old Betty any more. I’m downright sorry for the po’ little thing. I’m afraid she’ll fall dead in her tracks,” he added.

Captain John flushed, “Well, let her drop,” he said, “but if I’m not mistaken you’ll hear something drop yourself.”

The old Colonel turned on his heels in disgust.

But Uncle John meant business this time. He changed his cart for a sulky, and again they got the word. Gradually, carefully, he gave the little filly her head. Steadily,[15] gracefully, she went by them one by one, until at the half she was just behind Princewood, who seemed to be claiming all the grandstand’s attention. The field left behind! If Princewood wins this heat the race is over!

“Princewood’s got ’em, Colonel!” exclaimed a countryman to the old man. “They’s nothin’ that kin head ’im!” and “Princewood wins! Princewood wins!” as they headed into the stretch.

And then something dropped. Little Sister felt the reins relax, and a kindly chirrup came from Uncle John. In a twinkling she was up with the big fellow, half frightened at her own speed, half doubting, like a prima donna when her sweet voice first fills a great hall, that it was really she who had done it.

“Princewood! Princewood!” shouted the crowd around their idol, the Colonel. “Princewood will break the record!” from partisans who knew more about plow horses than race horses.

The old Colonel arose in happy anticipation—and then, as his trained eye really took in the situation, his jaw dropped. What was that little bay streak that had collared so gamely his big horse? Who was the quiet-looking gentleman in the soft felt hat, handling the reins like a veteran driver? His son John was in a cart—this driver was in a sulky. “Who the devil—” he started to say, when somebody clinging to his finger cried out: “Look! Look! Grandpa! It’s Little Sister. Ain’t she just too sweet for anything?”

And the next instant the little filly laughed in the big pacer’s face, as much as to say, “You big duffer, have you quit already?” And then, like a homing pigeon loosed for the first time, she sailed away from the field.

“Princewood! Princewood will break the record!” shouted a man who hadn’t caught on and was yelling for Princewood while looking at the champion pumpkin in the window of the agricultural hall.

And then the old Colonel lost his head and, I am sorry to say, the most of his religion, for he jumped up on a bench and shouted so loud the town crier heard him in the court-house window, a mile away: “Damn Princewood! Damn the record! It’s Little Sister! Little Sister! Old Betty’s filly—my old mare’s colt!”

And then Uncle John laughed till he nearly fell out of the sulky. “I said he’d be telling all about her first,” he said, while a little innocent-looking tot plucked the old man by the coat-tail long enough to get him to stop telling the crowd all about the marvelous breeding of the wonderful filly, as she naively remarked: “And the little thing did play off on you sure enough, didn’t she, Grandpa?”

The crowd laughed, and Grandma picked her up, kissed her, and shouted: “And here’s the girl that saved her, gentlemen—the smartest girl in Tennessee—and she’s got more horse sense than her old granddaddy!”

There was one more heat, of course; but it was only a procession, and those behind cannot swear to this day which way Little Sister went.

John Trotwood Moore.

[16]

By John Trotwood Moore.

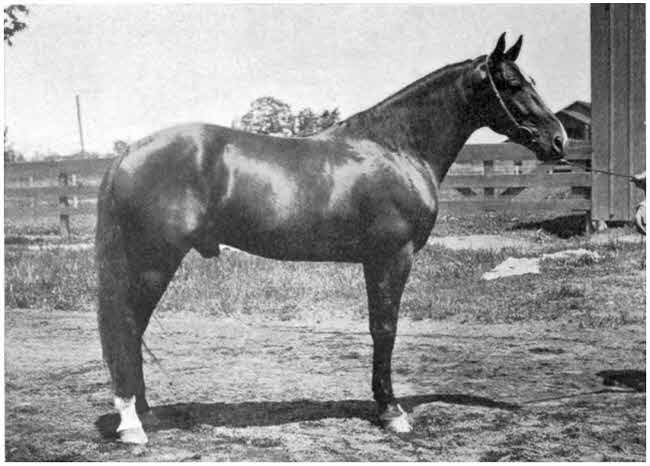

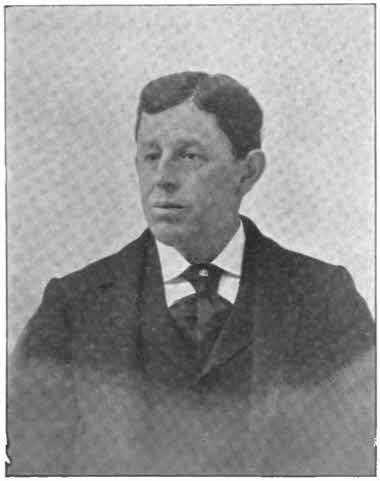

CAPT. THOMAS GIBSON.

Owner of Gibson’s Tom Hal and John

Dilliard.

The race horse has come, by common consent to represent all that is graceful and grand in the animal kingdom. The culmination of perfected strength and speed, courage and intelligence, he stands, nevertheless, the model of patience, gentleness and forbearance. How wonderful it seems that in this dumb creature, whose mental gifts, compared to man’s, are as a clay bed to a bank of violets, yet has he reached, through the misty channels of mere instinct, a physical perfection and often a moral excellence which his maker and molder may never attain! He is amiable in spite of force and desperate races, and often blows and cruelty; he is gentle, notwithstanding a training tending to make him a whirlwind of wrath and a tornado of tempests; he is honest in spite of the dishonesty of those around him and docile and contented despite the fact that there slumbers within him like sleeping bolts in a flying cloud the spirit of madness gathered from the nerve granaries of a long line of unnumbered ancestors.

A regiment with his courage would ride over the guns of a Balaklava; a state with his honesty would need no criminal laws; give scholars his patience, and the stars would be their playthings; imbued with his power of endurance, the weakest nation would tunnel mountains as a child a sand hill, build cities as a dreamer builds castles, and shoulder the world with a laugh. To one who sees him as he is, and loves him[17] for his intrinsic greatness, he is all this and more. Man’s honest servant, dumb exemplar, truest helper, best friend.

In his master’s hour of recreation, he is the joyful spirit that whirls him, at the swish of a whip, along the dizzy course where the whistling winds sing their warning. In his hours of stern reality, when fortunes hang on his hoof beats and fame stands balanced on the wire that ends the home-stretch, he is the embodiment of power and dignity, the champion of might and the god of victory. And finally, in his gentler moods, he is the faithful servant of the stubble and the plow, the gentle guardian of the family turn-out, who hauls the laughing children along the by-ways amid the sweet grasses, where the sunshine and the zephyrs play. Out from the past, the dim, bloody, shifting past, came this noble animal, the horse, side by side with man, fighting with him the battles of progress, bearing with him the burdens of the centuries. Down the long, hard road, through flint or mire, through swamp or sand, wherever there has been a footprint, there also will be seen a hoof-print. They have been one and inseparable, the aim and the object, the means and the end. And if the time shall ever come, as some boastingly declare, when the one shall breed away from the other, the puny relic of a once perfect manhood will not live long enough to trace the record of it on the tablet of time.

The greatest distinct family of horses that has ever lived is the Hal family of pacers, a distinctively Tennessee product, originating in that peculiar geological formation known as the Middle Basin—the bluegrass region of Tennessee. To understand the greatness of this family of horses—now known throughout the world, wherever speed and endurance has a name—it is only necessary to publish the following table of world-records held by them. These records have all been won in the last quarter of a century, the remarkable fact being that before that time these horses lived only for the plow, the saddle or the wheel, and that nearly all of them are sons and daughters or descendants of one horse—a roan, known locally as Gibson’s Tom Hal, from the fact that Capt. Thomas Gibson, a gentleman of the old school, then living on his estate in Maury County, Tenn., and now the efficient secretary of the Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis Railway Library, first reclaimed him from obscurity and brought him to the county where his greatness was recognized.

These world records, the choicest in the harness world, are held to-day, August, 1905, by the descendants of the old roan pacer:

1. First horse to go a mile in harness in 2 minutes, Star Pointer, 1:59 1/4.

2. Fastest 4-year-old mare, The Maid, 2:05 1/4.

3. Fastest green performer (1905), Walter Direct, 2:05 3/4.

4. Fastest heat in a race, stallion, Star Pointer, 2:00 1/2.

5. Fastest heat in a race, mare, Fanny Dillard, 2:03 3/4.

6. Fastest first heat in a race, Star Pointer, 2:02.

7. Fastest third heat in a race, Star Pointer, 2:00 1/2.

[18]

8. Fastest fifth heat in a race, The Maid, 2:05 3/4.

9. Fastest two heats in race (Dariel and) Fanny Dillard, 2:03 3/4, 2:05.

10. Fastest three consecutive heats in a race, Star Pointer, 2:02 1/2, 2:03 1/2, 2:03 3/4.

11. Fastest three heats in a race, Star Pointer, 2:02 1/2, 2:03 1/2, 2:03 3/4.

12. Fastest seven-heat race, The Maid, 2:07 1/4, 2:07 1/4, 2:05 1/4, 2:09, 2:05 3/4, 2:07, 2:08 3/4.

13. Fastest mile in a race to wagon, Angus Pointer, 2:04 1/2.

14. Fastest team, Direct Hal and Prince Direct, 2:05 1/2.

15. Fastest three-heat in race to wagon, Angus Pointer, 2:06 1/4, 2:04 1/2, 2:06 1/4.

16. Fastest green performer, stallion, Direct Hal, 2:04 1/2.

17. Fastest team in a race, Charley B and Bobby Hal, 2:13.

18. Fastest pacing team, amateur trials, Prince Direct and Morning Star, 2:06.

It will be observed that all of these records except a few were made in races and not against time.

Whence came this wonderful family of horses? What is this pacing gait? What mingling of blood lines have brought these horses of the plow, the saddle and the wheel to the grandstand and the pinacle of fame?

This is the story I shall tell as a serial during the first twelve issues of Trotwood’s Monthly.

The light-harness horse has come to be a type of its own. It is distinctly an American type, as distinguished from the English running, or thoroughbred horse, the German and French coach, the Russian Orloff and horses of other nationalities. There is a wide gap, however, between a race horse, whether runner or harness horse, and other breeds, however pure, their blood lines. It is the difference of intelligence, speed, endurance, of lung development, of steel bone. It is the difference between genius and mediocracy—for speed is to the horse what genius is to man.

Whence began this speed—in the English runner, in the American trotter and pacer? Traced back, the sheiks of the desert might tell; they who worshipped the midnight stars, or chased on steeds of fire the wild antelope of the plains, before Abraham came from “Ur of the Chaldees.” Knowing the past now from the present, seeing it so clearly through the glasses of twentieth century science, knowing the laws of the “survival of the fittest,” that land and air and sand and sun make both the physical man as well as the physical horse, we can easily guess what centuries of wild gallops across the desert will do for the horse, supplemented by that natural love of him in his master—that love which brings care and kindness and the exercise of common sense in mating and maternity.

As to the American horse, there are two distinct classes, based on their respective gaits—the trotter and the pacer. In another chapter these respective gaits are fully discussed, their difference shown, their origin and the speed attained by each. This brief history will deal only with the pacing gait, but so closely are these two great gaits related, and so often do the blood lines of trotter and pacer run in parallel columns that it is necessary for a clear explanation of the subject to say a foreword about the trotter, that grand type of beauty,[19] speed and utility, so purely American and so superbly great that the very mention of his name should excite a patriotic glow in the bosom of every American who loves his country and her just fame.

The history of the trotting horse began with Messenger, a gray thoroughbred foaled in 1780, and imported from England to America in May, 1788. He was royally bred for his time, being by Mambrino, son of Engineer, and through both sire and dam he traced to the famous Godolphin Arabian. An old description of him says he was 15 3/4 hands high, with “a large, long head, rather short, straight neck, with wind-pipe and nostrils nearly twice as large as ordinary; low withers, shoulders somewhat upright, but deep and strong; powerful loins and quarters; hocks and knees unusually large, and below them limbs of medium size, but flat and clean and, whether at rest or in motion, always in perfect position.” With this beginning, in 1822, a Norfolk trotter called Bellfounder, who had trotted two miles in six minutes, and had challenged all England to a trot, was imported. It was his daughter in which the strains of Messenger met that produced Hambletonian 10, the head of the trotting type in America, the first great trotting sire of the world, and through him perpetuated by his great sons, such as Geo. Wilkes, Electioneer, Dictator, and their descendants. Through all these years the trotting record has gradually been reduced, first by one great trotter and then another, beginning with the first queen of the trotting turf, Lady Suffolk, and ending with that superb little thing of fire and speed and sweetness, Lou Dillon. Literally, in that century of progress millions of dollars have been spent, not only by thousands of small breeders, but by such financial magnates and great breeders as Vanderbilt, Sanford, Bonner, Backman, Alexander, Forbes, Lawson and others, chiefly in New York, New England, Kentucky and California.

The effect of all this was to create that splendid race of trotters now known all over the world, and to produce a horse capable of trotting a mile in two minutes or better.

But even before the advent of Messenger there had developed in the eastern coast of the Colonies, chiefly in Delaware and Rhode Island, a family of extremely fast pacers known as the Narragansetts, an account of which will be seen a few chapters further on. These horses were small, but game, docile, excellent under the saddle, and used almost exclusively for travel in those early days of pioneer roads. Their speed was marvelous, if the testimony of Rev. Dr. McSparrow, 1721, an English minister who was stationed in the Colonies, may be accepted as proof. This reverend gentleman, writing to a friend in England says that he has seen them pace in races under saddle, going a mile in “a little less than two and a good deal better than three minutes.”

However, for nearly two centuries the pacer never was thought of as a factor in horse development, especially as a race horse until[20] the advent of the Hal family of Tennessee, in the early 70’s, with Little Brown Jug and Mattie Hunter, although the great bloodlines and speed of Pocahontas, James K. Polk and other noted pacers in the early ’40’s ought to have foretold what great possibilities lay in the despised pacing gait. As usual, the rejected stone found itself in the key of the arch, and out of Tennessee, by what some might term chance, but in fact the legitimate product of scientific breeding, of soil, of climate and grass, out of an obscure family of saddle horses, bred with no idea of racing and with never a thought of fame, but taken, like Coriolanus, literally from the plow, this horse is found—the first to go a mile in two minutes or better, and to do almost without price and without effort what the millionaires of horsedom had spent fortunes to do in vain.

This was first accomplished by Star Pointer, at Readville, Mass., September 2, 1897.

Such a family deserves to be perpetuated in history, however brief it may be and unpretentiously written. And I beg the future as well as the present historian not to criticise too closely its style, for in it, as I go along, a hundred fancies will twine themselves with my facts. There is so much about man and horse that is akin. There is so much of human nature in both—there is such a chance for moralizing on their life, their death, their fame, their fortune, their brief days’ strut on the stage of time, their passing out—“and the rest is silence.” And, speaking of fame in both man and horse, is it not all a lottery?

With men she is a sly and uncertain goddess, coming seldom to those who court her, and often to others who care nothing for her, so, in the rearing of race-horses the same uncertainty exists, and matron after matron bred in purple lines may go on throwing quitters and lunkheads year after year, while some obscure dam, whose breeding is barely tolerable, but stamped by nature with a spirit of fire and a soul of steel, sends out from some hithertofore obscure breeders’ farm a race horse that sets a new mark for speed and a new fashion for blood lines.

In a decision, Judge Gaynor, of the Supreme Court of King’s County, New York, in a case against the president of the Gravesend track, where runners are raced, held that horse racing was not a lottery. This may be true within the technical meaning of the term, lottery, but if the honorable court had held that breeding race horses was not a lottery, we have our doubt whether the decision would have met with the unanimous consent of the breeders themselves. And, as we remarked above, fame itself is not more uncertain.

There is so much similarity between man and horse that a student of either will constantly find himself comparing the two. Almost every quality possessed by man has its counterpart, though often in a less degree, in man’s favorite animal, while now and then the master fails to come up to the many excellencies of his beast.[21] A good judge of human nature is invariably a good judge of horses and horse nature. In fact, so well understood is this rule that “horse sense” in man has come to have a definite meaning of its own, and classes the human thus favored with a common sense stronger than usual.

It is almost certain failure for erring man to struggle only to be famous. She never yet came in all her splendor to the impetuous wooer. Like Cleopatra, who secretly tired of the infatuated Anthony, who could not fight at Actium for thoughts of her, and secretly died for love of the young Caesar who heartily despised the character of the ancient Langtry, so also with fame. “God tempers the wind to the shorn lamb,” and perhaps knows if he allowed the fools who burn up their lives and their midnight oil seeking to become famous, to become so, their heads would burst with conceit or their own vanity would wreck them. But on the other hand, He often showers on those who honestly fight for right, regardless of consequences, who care more for principle than for worldly honor, and more for truth than for glory, and who do their whole duty regardless of consequences, the greatest fame and honor. The strutting peacock has all he can carry in his gaudy plumage and resplendent feathers. It would have been as much a sacrilege to have added these decorations to either Ulysses S. Grant or Robert E. Lee, as it would have been cruel to deprive John Pope and Robert Tombs of them. And the gap between the pairs is the true distance between fame and feathers.

The wild, reckless and dissipated young rake, who left Rome more to be rid of his creditors than to fight the Gauls, never dreamed of the glory in store for him as he threw the fire of his soul in his work and blazed his way to fame both with a pen and sword—each so resplendently bright that the student of to-day is lost in wonder and admiration as he endeavors to decide on which Caesar’s greatest claim to renown rests. “Here lies one whose name is written on water,” is the epitaph which the poor, gentle, timid Keats begged to have carved on his tomb, begged it as he lay dying from shafts of cruelty and malice. And yet, his fame is as enduring as his art, and that is “a thing of beauty” and “a joy forever.” “What have I done to be worthy of this great honor?” asked Washington, when he heard he was elected the first president of the Republic. Shakespeare was silent, morose, dissatisfied, as all true artists are, with his own work, and judging from the epitaph, which it is said he himself wrote, it appears he was fearful he might not have even a place to rest his bones. And so, the world over. Simplicity is greatness. Truth is fame. Honesty is glory. If you doubt it compare Agricola and Cataline; Washington and Arnold; Paul and Iscariot; Shakespeare and Sheridan.

In the same line of reasoning it is an hundred to one when a breeder, pinning everything on a pedigree, an individuality, or some supposed[22] excellency, ever hits the mark. It is said that the same man once owned Kittrell’s Tom Hal and Copperbottom. The latter he thought was the better horse; the former was ignored. Time has shown, perhaps to his loss, the owner’s error. An exchange recently published a story of how a prospective buyer went to purchase one or two colts. The first was Hambletonian 10, then, I think, a yearling; the second was a horse called Abdallah. He regarded Abdallah the handsomest, the speediest, the best. He spent a good deal of time in his examination, and as they were priced the same, showing that even the owners had not discovered any difference, he finally purchased the Abdallah colt, and, the writer adds, “The first went to fame, the second to a double-tree.”

But some people think horse-breeding is not a lottery. Why, even man-breeding is.

And so the Hal family, thinking not of fame, find it thrust upon them.

(To be Continued.)

THE LAST HYMN OF THE BILOXI

(The Biloxi, a noble tribe of Indians who lived on the Gulf Coast many centuries ago, were defeated in battle and besieged in their last remaining fortress by an unrelenting enemy. Choosing rather to die in the sea than to be captured and enslaved, they marched out of their gate on a moonlit night, singing a death chant, a stately procession of men, women and children, and continued seaward until the waves swallowed them up. Their enemies stood on the shore and watched them, struck with surprise and admiration. The remains of their last fortress is said to be still standing at Biloxi, Miss., and to this day there is heard a weird music which comes in from the Gulf, oftenest on still, moonlit nights, which the natives call “The Last Hymn of the Biloxi.”)

By H. Alison Webster.

With the population of the world ever increasing, and the acreage of fertile lands ever decreasing, with the consequent increasing demand for, and decreasing supply of all products of the soil, is not the duty of redeeming worn-out lands, enriching naturally poor lands and preserving the fertility of fertile lands a duty that every land owner owes to posterity? If the results of robbing the soil of its plant foods has already been felt by the farmer, and if such a practice be continued, what will be the condition of the same soil by the time it descends to his great-grandchildren? If the vast majority of the inhabitants of the globe are poor, and scarcely able to provide food and raiment at the present prices, what will be the fate of such a people when prices rise higher and higher, as will be the inevitable result of an inadequate supply? Is confidence the cause of such shameful neglect, or does the farmer lack confidence in the practicability of the results of scientific research? It is true that the great variety of objects in nature are extremely bewildering, and if every farmer were forced to comprehend God’s creations in order to equip himself to cultivate his land intelligently, the soil would continue to get poorer and poorer, as the useful years of a long life would pass in study; but men of science, in the past and present generations, by faithful and noble work, have reduced all to simple facts to be made practicable by the farmer, and there is no longer any excuse for ignorance and neglect. Study the results of the work of these men of science. Put them into practice. Experiment and work with the soil. Study it and find out what it needs, and having found out, supply the right thing in the right way at the right time. It is work, hard work; but the reward is generous. In the words of Mr. Charles Barnard, “Try things and learn, and having learned, do what is right by your soil, and it will return all your labor in full measure, running over, and your children will inherit the land as a well-kept trust and blessing.”

As stated, things have been greatly simplified. Chemists, by thousands of experiments, have found in all sixty-five single separate things they call elements. Seventeen of these elements are in the soil. Out of these seventeen the farmer is obliged to provide only four, as the remaining thirteen, with favorable weather and proper tillage of the soil, will take care of themselves. The four to be provided are nitrogen, potassium, phosphorus and calcium. The first three elements are the most important, as they are plant foods or fertilizers. The last, calcium, or lime, is a stimulant, and serves in the capacity of neutralizing the acids of the soil. Lime is abundant in many soils and in such soils is not needed; but where it is needed it is needed badly and should be supplied. Nitrogen, potassium and phosphorus are the plant foods that are yearly consumed in various quantities by various crops, which are taken away and sold or otherwise disposed of. They are foods absolutely necessary to plant life, and if taken away and never returned, the soil is as certain to become poor and exhausted as the sun is to set in the west. This is the sum and substance of the whole matter. What you take from the soil, you have to replace or suffer loss. Your soil may need one, two, three or all four of the elements. What it requires can be found out by experiment, as will be shown further on. These elements as everyone must know, can be easily obtained at costs varying with, and depending upon, the form in which they are bought, or methods by which they are secured. The all-important thing is to study the soil and prepare it to accept and properly appropriate whatever foods are applied. No fertilizer is insurance against laziness and ignorance. It takes work and intelligence to accomplish any task. Study your soil, and you will appreciate the fact that it has a constitution like yourself, and will get worn out,[24] and sick, and need physic just as you do. After knowing its constitution, you can prescribe and administer the physic it requires. No doctor can prescribe medicine intelligently without knowing the constitution of his patient.

Naturally, though unfortunately, men of science, so far as the farmer is concerned, are quite as intricate in their explanations of the objects of nature, as are the objects themselves. Mr. Charles Bernard in his “Talks About Soils,” published by Funk & Wagnalls, New York, is the first to reduce matters to a practical plane. His explanations and experiments I therefore adopt to simplify and make clear many things which are of unquestionable importance.

The soil having been formed, in the main, by the weathering away of the rocks, its foundation is either sand or clay or both combined. On account of different quantities of sand and clay being found in different soils, and to distinguish one from another, soils have been divided into six classes. These are as follows:

A Light Sand.—This is a soil containing ninety per cent of sand. If it had more sand and less of clay and other matter it would hardly produce any useful plants, and could not fairly be called a soil.

2. A Pure Clay.—This would be a soil in which no sand could be found. A pure clay soil would be wet and cold, and would not be good for our common plants. Such soils are rare: and what is commonly called a pure clay soil is one containing a great excess of clay, and only a little sand or other matter.

3. A Loam.—This is one of the best of all soils. Such a soil contains both sand and clay as well as other matter.

4. A Sandy Loam.—This is a mixture of sand and clay, with more sand than clay.

5. A Clay Loam.—This is a mixture in which there is more clay than sand.

6. A Strong Clay.—This is a clay containing from five to twenty per cent of sand and other matter.

Experiments with Sand and Clay.—Procure a quart of pure sand and spread it out in the sun to dry, and when dry place a small quantity on a spoon, and hold over a hot fire. The heat has no effect upon it. Remove the spoonful of sand from the fire, and it will be found that the sand keeps its heat for a long time. Place a small quantity of sand in a small sieve and pour water over it. The water at first flows away more or less discolored, and presently runs quickly through the sand pure and clean. While wet the sand sticks together slightly. Place it in the air, and it soon dries, and the grains are as loose as before. Place a little of the washed sand in a bottle filled with water. Cork the bottle and shake it up. The sand will move about as long as the water is in motion, but the instant the bottle is at rest, it falls to the bottom, and forms a layer under the clear water. Place some of the sand in an oven or in the sun till perfectly dry. Place three tablespoonfuls of water in a saucer, and then pour carefully into the saucer a cupful of dry sand. It becomes wet around the little heap while still dry at the top; soon the water will begin to creep up the sand and in a short time it is all wet, and remains wet as long as there is water in the saucer.

These experiments show us that sand is not affected by heat, and that it keeps its heat for some time; that water passes through it readily and, if clean, the water passes through pure and clean. When wet it is very slightly sticky, when dry this stickiness disappears completely. In water it sinks the moment the water is at rest. Water rises through it easily by capillary attraction.

Another experiment, taking more time, is to place some clean sand in a flower pot, wet it, and sprinkle fine grass-seeds over it. Place in a warm room and the seeds will soon sprout and send small roots down into the sand.

These experiments show some of the characteristics of all soils composed largely of sand. We observed that sand when heated retains its heat for some time. Any soil having a large proportion of sand, when warmed by the sun will keep the heat after the sun has set or is hid by the clouds. We proved that water would flow quickly through it. A sandy soil is therefore a dry soil, and for this reason favorable to nearly all our[25] useful plants. We saw that water would rise through sand by capillary attraction, which makes sand useful in soil in dry weather to bring water up from a damp subsoil to feed the roots of plants growing in the soil.

However, there are objections to sand. As we saw, it is loose and easily moved about by water. A sandy soil is therefore easily washed away by rains, and, if too sandy, may suffer great injury by washing in heavy storms. Water flows through sand quickly, and if there is no damp subsoil immediately beneath, the soil may get so dry that plants will burn up. The water may also wash down all the light organic matter out of reach of the plants.

We observed that sand is easily moved about. This is important in that all soils where plants are growing must be frequently stirred, to let air come into the soil, and to kill the weeds. A sandy soil is easy to hoe or plow, because the sand is loose. This saves time and money, or work in caring for plants, and is a business advantage.

If you carry out the experiment with seeds planted on sand you will observe that the roots of the young plants easily find their way through the sand in search of food and water. This shows that a soil containing sand is favorable to the growth of plants, because in it their roots spread in every direction.

Procure a small quantity of clay from some clay bank. Place in a warm place to dry, and in a day or two you can crush it into a soft, impalpable powder. Pinch a little between the fingers and it appears to stick together slightly. Place some in a bottle of water, cork it tight and shake the bottle. The powder floats in the water in clouds, till the water appears completely filled with it. Let the bottle stand and it will be many hours before the clay settles and the water becomes clear. Wet some of the dry clay, and it forms a sticky, pasty mass, that has a soft, greasy feeling between the fingers. Spread some of the soft, pasty mass over a sieve, and pour water on it and the water will hardly pass through the sieve at all. Spread some wet clay over a rough board, and pour water over it, and the clay will cling to the board a long time before it is swept away. Place a lump of wet clay in the sun and it will be many hours before it is entirely dry. Spread some of the wet clay over a dish and place it in the sun, and when it slowly dries it will be found full of cracks. Place a lump of wet clay in an oven and it will dry hard like stone.

Place some of the wet clay in a pot and scatter fine seeds over it. The seeds may sprout and try to grow, but they will probably perish as tender roots are unable to push their way through the sticky clay.

After all these experiments have been performed with the clay and sand, another experiment can be made by drying both the clay and sand and then mixing them together in equal parts. When well mixed place in a pot and scatter fine seeds upon the mixture. Water well, and place in a sunny window; and the plants will sprout and grow longer and better than in either the pure sand or pure clay.

These experiments with the lump of clay show that if soil consists wholly of clay, it must be a poor place for plants. In every hard rain the water, instead of sinking into the soil to supply the plants, would run away over the surface and be wasted. After slow soaking rains the soil would remain wet and cold for a long time. When the sun dries the soil it splits and cracks and tears the roots of plants growing in it. This sticky, pasty soil sticks to spade and plows and we find it hard, slow work to cultivate it. A pure clay from these would appear to be a poor soil for plants. We must not, however, be led astray by our experiments, as it is not easy to find a soil composed wholly of clay. It is usually mixed with other things and then forms a valuable part of the best soils. Sand alone would be a poor soil. Clay alone would be a poorer soil. Mixed together and mixed with other things, they make a part of all good soils.

Organic and Inorganic Matter.—Organic matter is something that has life, or has had life at some time. The organic matter in the soil has been supplied by animals and plants, in one way or another. All else is inorganic. Both organic and inorganic matters are necessary[26] to the existence of plants. Peaty soils wholly organic will not grow plants, neither will sandy soils wholly sand. Inorganic matter forms the foundation of soils and generally forms from eighty to ninety per cent of the whole soil.

Testing Soils for Clay, Sand and Organic Matter.—Take from the ground you wish to test, a peck of soil and place on a board in a round heap, and with a trowel stir it until completely mixed. Then pile into a heap and divide into four equal parts. Next weigh out eight ounces, and spread it out to dry. When dry weigh it and note the loss by air-drying. Next put the soil in a pan and place it in an oven for three hours. Then take the soil out of the pan and weigh it, noting the loss by fire-drying. It is now dry soil and to estimate the organic and inorganic matter, place an iron shovel over the fire, and when red hot put the dry soil on it, let it burn, stirring it occasionally as it burns. It will smoke and smoulder away to ashes and dust. When it ceases to smoke, carefully weigh the ashes. This ash represents the inorganic sand and clay parts of the soil. All the organic matter disappeared in the smoke.

Now take this ash and pour it in a bottle of water. Shake the bottle well and then set on a table, and just so soon as the water becomes still the sand will immediately settle at the bottom, while the clay will remain for some time making the water muddy. As soon as the sand has settled, pour the muddy or clay water off, being careful not to pour any of the sand with it. Then pour some clear water in the bottle on the sand, shake it and pour sand water and all on a cloth fine enough to catch the sand. Dry the sand and weigh it. If it weighs two ounces, then out of the four ounces of dry soil you have tested you have two ounces of sand, one ounce of clay and one ounce of organic matter. Or your soil is twenty-five per cent organic matter and twenty-five per cent clay, and fifty per cent sand. You have a loam soil.

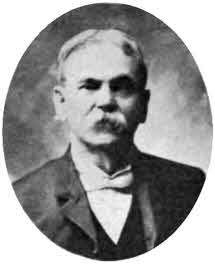

Testing Soils with Plant Foods and Lime.—In the field to be tested, select as level a place as possible and mark out ten squares, each measuring one rod on each side. Place these in two rows leaving spaces three feet wide between the squares. These empty spaces are to be kept clear of weeds and used as walks. Each square should be marked by stakes at the corners, and properly numbered as in the accompanying diagram.

The squares are to be planted with the same crop and well cultivated through the season. Two of these squares, Nos. 2 and 9, are to have no fertilizers, that they may serve as a check or guide in testing the other squares. Square No. 1 is to have a fertilizer containing nitrogen only. No. 4 potassium and phosphorous combined; No. 5 potassium alone; No. 6 nitrogen and phosphorus; No. 7 phosphorus alone; No. 8 all three plant foods combined, and No. 10 is to have calcium only.

Apply the fertilizers and work them in the soil about four inches deep before the crop is planted. Plant the same variety[27] of seed on all the squares at the same time, and carefully cultivate through the entire season, treating all exactly alike. Suppose that potatoes have been used. During the growing season, carefully watch the different plats and notice if any one or more seems more or less thrifty than others. Notice which plat appears to mature first, which blooms first and keep a record of all observations. At the end of the season, carefully dig the crop on each square, gathering all the tubers large and small, and weigh each lot. First weigh the crops on squares 2 and 9. This will serve as a standard of comparison, as it will show the natural condition of the soil. Record the weights in each lot and just for illustration we may say that they run something like this: Average of 2 and 9, 80 pounds; No. 1, 380 pounds; No. 3, 250 pounds; No. 4, 360 pounds; No. 5, 350 pounds; No. 6, 300 pounds; No. 7, 220 pounds; No. 8, 400 pounds; No. 10, 120 pounds.

On the particular soil we are supposed to be testing, we can clearly see that the land is benefited in some degree by every element used. Calcium helps, and that means that it should be used on that soil in addition to all of the others. This land plainly needs all four elements and needs potassium especially.

What to Do.—After having gone through with Mr. Barnard’s experiments, you will have a practical idea of what your soil is, and what it needs. The only remaining questions then are those of preparing the soil, and obtaining and applying the plant foods and the lime.

A cold, wet, clay soil needs to be made warmer and lighter, and a light, sandy soil, being too dry, needs some moisture-retaining substance. If conditions are favorable, it would be well at odd time to put sand on the clay soil and clay on the sandy soil; but in most cases this is too expensive, and therefore not practical. To redeem poor lands then, you will have to depend almost entirely upon green manure and lime. Barnyard manures are, of course, at all times, with all soils, the best of all fertilizers, as they return to the soil by the laws of nature, what has been taken from them, or what it should have. Besides the plant foods, it furnishes additional organic matter or humus, which makes the soil lighter and facilitates plant growth by furnishing food to bacteria essential to plant life. The trouble about barn-yard manure is its scarcity. Every farm needs more plant food and humus than can be supplied with common manure.

In the fall, apply 500 pounds of lime per acre to the poor land to be redeemed, break it and prepare it thoroughly, and seed it to rye. In the spring when the rye heads out, turn it under and sow cow peas. When the peas mature, scatter lime, 500 pounds to the acre, over them and turn them under. The lime will prevent the green stuff from souring the soil, will decompose it and fit it for plant food, and will prepare the soil to accept any other foods that may be applied. Follow the peas with wheat, or wheat and clover.

The land once redeemed, do not wear it out again, but preserve its fertility by the use of high-grade commercial fertilizers and barn-yard manure, always rotating the crops so as to get back to some leguminous crop and lime at least once every four years.

Do not retard agricultural education by making warfare on commercial fertilizers, for they are indispensable to every farmer in preserving the fertility of the soil. The world employs the use of just about one-tenth of the artificial fertilizers it should use, and about one-half of what is used is used intelligently. Make war on low grade fertilizers that have the attractive but deceiving feature of cheapness, and buy grade fertilizers by the unit under the guidance of the requirements of your soil.

The use of lime has been and is being sadly neglected, especially in the Southern States and, when it is absolutely necessary to all soils in which it does not exist or exists only in small or insufficient quantities, it does look like the move to provide it is one of imperative moment. Look at the Bluegrass Region of Tennessee and Kentucky, the fairest and most fertile of God’s country. What made it? The dissolution and weathering away of the original phosphatic limestone rock. It is strictly a limestone[28] country and teaches one of nature’s great lessons that the agricultural world should accept and be profited thereby.

All the limestone of this region contains more or less bone phosphate of lime, and in this fact lies the whole secret. In the past ages the foliage from the thick mass of trees and other vegetable growth fell to the ground, soured, and formed an acid which immediately attacked the bone phosphate of lime and converted it into phosphoric acid, while the calcium carbonate or lime decomposed all vegetable matter and conditioned it for plant food, neutralizing all acids and stood ready itself to enter into all future and standing vegetable growth. Now the forests have given place to the cleared fields and we no longer have the dropping from the trees to enrich our soils, neither have we in our fields in sections devoid of limestone any vegetation with roots that extend deep enough in the earth to bring up the carbonate of lime sufficient to support our crops. Therefore the vegetable matter the cheapest of all manures, we provide by turning under green leguminous or nitrogen-gathering plants. These plants sour and finally decompose, but without carbonate of lime to perform its important duties of creating plant food out of this decayed matter, all the fertilizer you get from your crop is the nitrogen it has gathered from the air. Then why not use powdered Tennessee phosphatic-limestone containing enough calcium carbonate (not quick lime) to furnish desired results and no more bone phosphate of lime than will be entirely and immediately converted into plant food. If this phosphatic-limestone product is used with leguminous crops, potash is the only plant food that you will have to provide during the two crop seasons following; however, every soil that has a clay subsoil is a safe bank that will retain all you place on deposit, and if you have the money to spare, deposit it in the soil by investing in high-grade fertilizers and draw a high rate of interest on it instead of letting it stand idle. The calcium in the phosphatic limestone will absolutely correct all free acids in the commercial fertilizers, the burning, deleterious effects of which you may have experienced, and it will rectify the sourness of any and all soils.