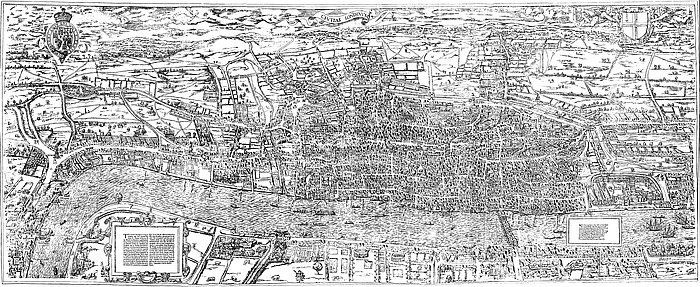

Project Gutenberg's London in the Time of the Tudors, by Sir Walter Besant This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: London in the Time of the Tudors Author: Sir Walter Besant Release Date: May 14, 2020 [EBook #62134] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LONDON IN THE TIME OF THE TUDORS *** Produced by Chris Curnow, Robert Tonsing, 'Junet' for finding, scanning and re-creating Agas' map, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

“It is a mine in which the student, alike of topography and of manners and customs, may dig and dig again with the certainty of finding something new and interesting.”—The Times.

“The pen of the ready writer here is fluent; the picture wants nothing in completeness. The records of the city and the kingdom have been ransacked for facts and documents, and they are marshalled with consummate skill.”—Pall Mall Gazette.

“The book is engrossing, and its manner delightful.”—The Times.

“Of facts and figures such as these this valuable book will be found full to overflowing, and it is calculated therefore to interest all kinds of readers, from the student to the dilettante, from the romancer in search of matter to the most voracious student of Tit-Bits.”—The Athenæum.

TUDOR SOVEREIGNS | ||

CHAP. |

PAGE |

|

|---|---|---|

1. |

Henry VII. | 3 |

2. |

Henry VIII. | 17 |

3. |

Edward VI. | 45 |

4. |

Mary | 52 |

5. |

Elizabeth | 65 |

6. |

The Queen in Splendour | 85 |

RELIGION | ||

1. |

The Dissolution and the Martyrs | 109 |

2. |

The Progress of the Reformation | 143 |

3. |

Superstition | 162 |

ELIZABETHAN LONDON | ||

1. |

With Stow | 171 |

2. |

Contemporary Evidence | 185 |

3. |

The Citizens | 196 |

GOVERNMENT AND TRADE OF THE CITY | ||

1. |

The Mayor | 209 |

2. |

Trade | 216 |

3. |

Literature and Art | 244 |

4. |

Gog and Magog | 209 |

SOCIAL LIFE | ||

1. |

Manners and Customs | 269 |

2. |

Food and Drink | 292 |

3. |

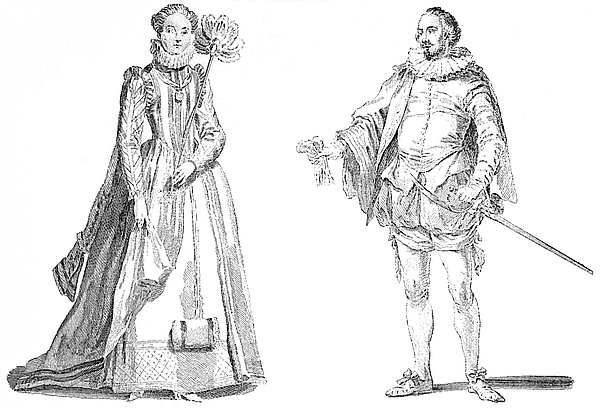

Dress—Weddings | 303 |

4. |

Soldiers | 316 |

5. |

The ’Prentice | 323 |

6. |

viThe London Inns | 333 |

7. |

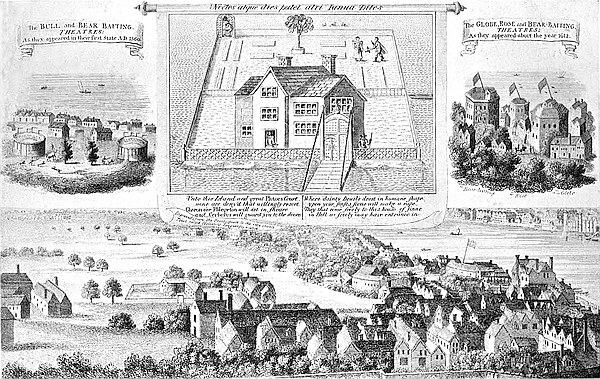

Theatres and Sports | 342 |

8. |

The Poor | 366 |

9. |

Crime and Punishment | 379 |

397 |

||

421 |

||

On stepping out of the fifteenth into the sixteenth century one becomes conscious of a change; no such change was felt in passing from the twelfth to the thirteenth century, or from the fourteenth to the fifteenth. The world of Henry the Sixth was the same world as that of Edward the First; it was also the same as that of Henry the Second. For four hundred years no sudden, perceptible, or radical change took place either in manners and customs, language, arts, or ideas. There had, of course, been outbreaks; there had been passionate longings for change; men before their4 time, like Wyclyf, had advanced new ideas which sprang up like grass and presently withered away; there had been changes in religious thought, but there was no change, so far, in religious institutions. At the beginning of the sixteenth century, however, we who know the coming events can see the change impending, change already begun. Whether the Bishops and Clergy, the Monks and Friars, were also conscious of impending change, I know not. It seems as if they must have been uneasy, as in France men were uneasy long before the Revolution. On the other hand, Rome still loomed large in the imagination of the world: the Rock on which the Church was established; the Throne from which there was no appeal; the hand that held the Keys. We have now, however, to chronicle the part, the large part, played by London in this great century of Revolution.

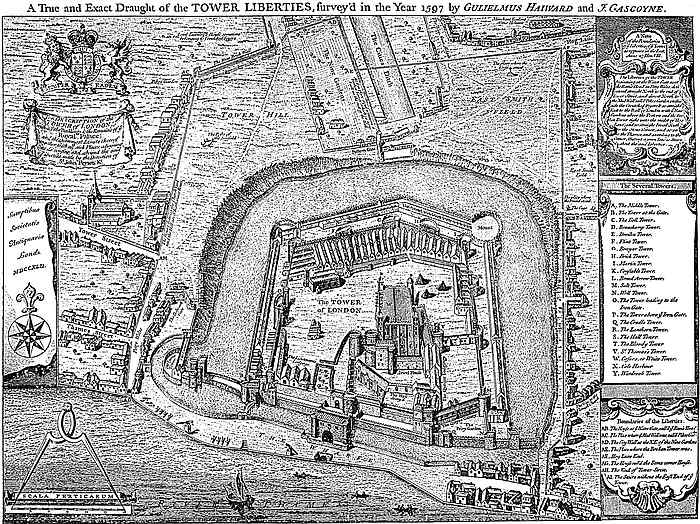

After forty years of Civil War,—with murders, exactions, executions, treacheries, and perjuries innumerable, with the ruin of trade, with the extinction of ancient families, with the loss of all the French conquests,—the City, no less than the country at large, welcomed the accession of a Prince who promised order and tranquillity at least. Of all the numerous descendants of Edward the Third who might once have called themselves heirs to the Crown before the Duke of Richmond, there remained but two or three. Of the Lancastrians Henry alone was left, and his title was derived from a branch legitimised. The two brothers of Henry V. had no children; the only son of Henry VI. was dead. On the Yorkist side Edward’s two sons were dead; Richard’s only son was dead; there remained the young Earl of Warwick, son of Clarence. He was the one dangerous person at the time of Henry’s accession. Edward Plantagenet, Earl of Warwick, was not the heir to the Yorkist claims—this was certainly the eldest daughter of Edward the Fourth; but he was the son of George, Duke of Clarence, and the last male descendant of the York line. He was now fifteen years of age, and had been kept in some kind of confinement at a place called Sheriff Hutton Castle, in the County of York. Considering the practice of the time, and the reputation of Richard III., one wonders at his forbearance in not murdering the boy. Henry sent him—it was his first act after his victory—to the Tower for better safety. Grafton[1] calls this unfortunate Prince “the yongling borne to perpetual captivitie.” He is said to have been a simple youth, wholly ignorant of the world. Though, as we shall see later on, Henry found it expedient to treat this young Prince after the manner of his time. A dead Prince can never become a Pretender.

And no other fate was possible in the long-run for one whom conspirators might put up at any moment as the rightful claimant of the Crown. The unfortunate youth was only one of a long chain of possible claimants, all of whom paid the penalty of their inheritance by death. Among them were Edward’s infant Princes; his own 5father; Henry’s son, Edward, Prince of Wales; and later on Lady Jane Grey, and Mary Queen of Scots.

In the same castle of Sheriff Hutton, in similar confinement, was the Lady Elizabeth, Edward the Fourth’s elder daughter, whom Richard proposed to marry with the sanction of the Pope, his own wife, Anne, having strangely and mysteriously come to her death. Bosworth Field put a stop to that monstrous design. According to Grafton, the purpose of Richard was well known to the world, and was everywhere detested and condemned.

Henry rode to London immediately after his victory. At Shoreditch he was received by the Mayor, Sheriffs, and Aldermen, clothed in violet and bearing a gift of a thousand marks. He then went on to St. Paul’s and there deposited three standards—on one was the image of St. George, on another a “red fierie dragon beaten upon white and greene sarcenet,” and on the third was painted “a dun cow upon yellow tarterne.” He also heard a Te Deum.

Four weeks after Henry’s entrance into the City there broke out, quite suddenly, with no previous warning, a most deadly pestilence known as the sweating sickness. This dreadful epidemic began with a “burning sweat that invaded the body and vexed the blood, and with a most ardent heat infested the stomach and the head grievously.” If any person could bear the heat and pain for twenty-four hours, he recovered, but might have a relapse; not one in a hundred, however, of those that took the infection survived. Within a few days it killed two Mayors, namely, Sir Thomas Hill and Sir William Stocker; and six Aldermen. The sickness seems to have been swifter, and more deadly while it lasted, than even the Plague or the Epidemic of 1349. But it went away after a time as quickly as it had appeared.

Henry’s coronation was celebrated on the 13th of October. His predecessor had disguised the weakness of his title by the splendour of his coronation. Henry, on the other hand, made but a mean display—perhaps to show that he was not dependent on show or magnificence. Stanley perceives in this absence of ostentation a kind of acknowledgment that his title to the Crown rested more upon his victory than his descent. This opinion seems to me wholly fanciful; Henry would never at any moment acknowledge that his title was weak. On the other hand, he stoutly claimed, through his mother, to be the nearest heir in the Lancastrian line. His known dislike to ostentation is quite a sufficient reason to account for the comparative poverty of the Coronation show—at which, however, one new feature was introduced, namely, the bodyguard of the King’s person, known as the Yeomen of the Guard. The King’s belief in the strength of his own title was shown in his treatment of the Lady Elizabeth. He had solemnly promised to marry her; he did so in January 1486, five months after his victory; but he was extremely loth to crown her, lest some should say that the Queen was Queen by right, and not merely the Queen consort. The coronation of the Queen was postponed for two6 years. The celebration, however, when it did take place, was accompanied by a great deal of splendour.

The business of Lambert Simnel shows the real peril of the King’s position. The experience of the last forty years had taught the people a most dangerous habit. They were ready to fly to arms on the smallest provocation. Who was Henry, “the unknown Welshman,” as Richard called him, that he should be allowed to sit in peace upon a throne from which three occupants had been dragged down, two by murder and one by battle? But the occasion of the rising was ridiculous. The young Earl of Warwick was in the Tower; it was possible to see him—Henry, in fact, made him ride through the City for all the world to see. Yet the followers of Lambert Simnel proclaimed that he was Edward Plantagenet, Earl of Warwick. Lambert’s father was a joiner of Oxford; Sir Richard Symon, a priest, was his tutor. The boy, who in 1486 was about eleven years of age, was of handsome appearance and of naturally good manners.

After the defeat of his cause, Lambert and the priest who had done the mischief were taken. The priest was consigned to an ecclesiastical prison for the rest of his natural life; the boy was pardoned—they could not execute a child—and contemptuously thrust into the King’s kitchen as a little scullion. He afterwards rose to be one of the King’s falconers—the only example in history of a Pretender turning out an honest man in the end. Can we not see the people about the Court gazing curiously upon the handsome scullion in his white jacket, white cap, and white shoes, going to and fro upon his duties, washing pans with zeal and scraping trenchers? The boy had a lovely face, and manners very far beyond his station. Can we not hear them whispering that this young man had once been as good as King, and knew what it was to exercise royal authority?

The Earl of Warwick was still, however, allowed to live.

The King, who was magnanimous when it was politic, could also exhibit the opposite quality on occasion. He had never found it easy to forgive Edward’s Queen for submitting herself and her daughters to Richard after she had consented to Henry’s attempt upon the Crown, on the condition of his marrying the eldest. He laid the matter before his Council, who determined that Elizabeth, late Queen, should forfeit all her lands and possessions, and should continue for the rest of her life in honourable confinement in the Abbey of Bermondsey. Here, in fact, she died, not long afterwards, the second Queen who breathed her last in that House.

One Pretender removed, another arose. Perkin Warbeck professed, as we know, to be the younger son of Edward IV., namely, Richard, Duke of York, who, it was pretended, had escaped from the Tower. The strange adventures of Perkin are told in every history of England. He is connected with that of London on three occasions. The first was after his abortive attempt to land in Kent. The Kentish men, refusing to join him, attacked his followers, drove some of them back to their ships, and took7 prisoners a hundred and sixty men with four Captains. These prisoners were all brought to London roped together, a curious sight to see. Those who lived on London Bridge saw many strange sights, but seldom anything more strange than these poor prisoners, who were not Englishmen but aliens, thus tied together. They were all hanged, every one: some on the seashore, where their bodies might warn other aliens not to come filibustering into England; and the rest at Tyburn.

The Cornish Rebellion was an episode in the history of the Perkin Warbeck business. The men of Cornwall refused to pay taxes and resolved to march upon London. Led by Lord Audley they advanced through Salisbury and Winchester into Kent: they were there opposed, and moved towards London, finally lying at Blackheath. The battle that followed was chiefly fought at the bridge at Deptford Strand. Two thousand of the rebels were killed; fifteen hundred were taken; Lord Audley was beheaded; two demagogues who had instigated the rising, namely, Flammock an attorney, and Joseph a farrier, were hanged; the rest were not pursued or punished.

The City, meantime, showed its loyalty by a loan of £4000 to the King and8 by putting London into a state of defence. Six Aldermen and a number of representatives from the Livery Companies were deputed to attend to the City ordnance; houses built close to the wall were taken down; the Mayor was allowed an additional twelve men, and the Sheriffs forty serjeants and forty valets to keep the peace.

Among those appointed to guard the City gates was Alderman Fabyan the Chronicler.

The next episode in Perkin’s career which touches London is that ride which he undertook, very much against his will, from Westminster to the Tower. Everybody knows how he gave himself up to the Prior of Shene. The King granted him his life, but he imposed certain conditions. He was placed in the stocks opposite the entrance to Westminster Hall, where he sat the whole day long, receiving “innumerable reproaches, mocks and scornings.” The day after he was carried through London on horseback, in sham triumph. They were ingenious in those days in their methods of putting offenders to open shame. At an earlier date the traitor Turberville had to ride in shameful guise; and when Lord Audley, Captain of the Cornish Rebels, was led out to execution, he was attired in a paper robe painted with his arms, the robe being slashed and torn. No doubt Perkin was handsomely attired in coloured paper, with a tinsel crown upon his head; no doubt, too, he bestrode a villainous hack, while all the ’prentices of London ran after him, laughing and mocking. They placed him on a scaffold by the Standard in Chepe and kept him there all day long. In the course of the day he read aloud his own confession, which is a very curious document.

“First it is to be knowne, that I was borne in the towne of Turneie in Flanders, and my father’s name is John Osbecke, which said John Osbecke was controller of the said towne of Turneie, and my moother’s name is Katherine de Faro ... againste my will they made me to learn Englishe and taught me what I shoulde do or say. And after this they called me Duke of Yorke.... And upon this the said Water, Stephen Poitron, John Tiler, Hubert Burgh, with manie others, as the aforesaid earles, entered into this false quarrell. And within short time after the French king sent an ambassador into Ireland, whose name was Loit Lucas, and maister Stephen Friham, to advertise me to come into France. And thense I went into France, and from thense into Flanders, and from Flanders into Ireland, and from Ireland into Scotland and so into England.” (Grafton.)

The last occasion of his public appearance was on the day when he was hanged. After his two days’ enjoyment of pillory he was taken to the Tower and was contemptuously told that he would have to end his days there in confinement. Here he soon brought an end upon himself. He found in the Tower the young Earl of Warwick, who, as we have seen, was a very simple young man. Perhaps Perkin understood very well that, even if his own pretensions were hopelessly discredited, with the real Earl of Warwick, Clarence’s undoubted son, grandson of the great Earl, the last male representative of the House of York, there would be the chance of a far greater rising than either Simnel’s or his own. He was already sick of9 prison; the chances of a rising seemed worth taking, with all its perils and dangers; he was probably desperate and reckless. He accordingly bribed his keepers with promises to connive at the escape of the Earl and himself. One has an instinctive feeling that they only pretended to connive; that the course of the plot was daily communicated to the Governor of the Tower, and by him to the King; that the wretched man was encouraged and urged on in order to give an opening for the greatly desired destruction of the Earl as well as his own. However that may be, in the end Perkin and a fellow-conspirator, one John Atwater, were placed on hurdles and drawn to Tyburn, where they received the attentions reserved for traitors. Perkin died, it is said, confessing his guilt. Guilty or not guilty, it was a convenient way of ridding the King not only of an impudent pretender, but also of a dangerous rival. Edward Plantagenet was beheaded on Tower Hill: his end is said to have been suggested by the King of Spain before the betrothal of Prince Arthur to Katherine of Aragon. It was sixteen years after his accession that Henry caused the unlucky youth to be beheaded; and now no rival was left to disturb the security of Henry’s crown.

There was, however, still a third personation, passed over by most historians, this time by a native of London. The new Pretender was named Ralph Wilford, the son of a shoemaker. He fell into the hands of a scoundrel named Patrick, an Augustine friar, who taught him what to say and how to say it. The two began to go about the country in Kent, and to whisper among the simple country folk the same story that Lambert Simnel had told. This lad was none other than the Earl of Warwick. When the friar found that the thing was receiving, here and there, a little credence, he began to back up the boy, and even went into the pulpit and preached on the subject. But this time the matter was not allowed to get to a head. There was no rebellion: both the rebels were arrested, the young man was hanged at St. Thomas Waterings, and the friar was put into prison for the rest of his natural life.

In the year 1500 was a “great death” in London and in other parts. The “great death” was due to an outbreak of plague; not the sweating sickness, which also returned later, but apparently some form of the old plague, the “Black Death.” It is one of the many visitations which fell upon the City, afflicted it for a time, filled the churchyards with dead bodies, then passed away and was forgotten. Twenty thousand persons, according to Fabyan, were carried off in London alone. The King retired to Calais till the worst was over.

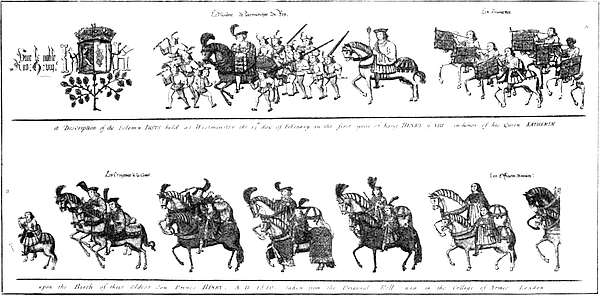

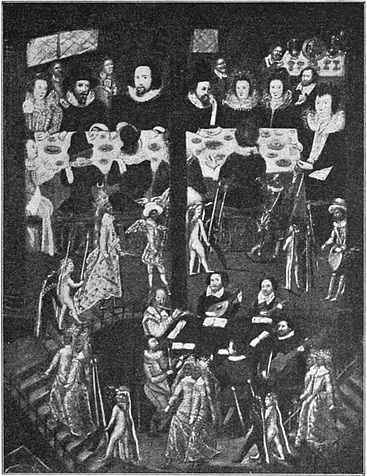

On the 14th November 1501, Prince Arthur, then a little over fifteen years of age, was married to Katherine of Aragon, who was then three years older. They were married in St. Paul’s Cathedral. Holinshed says that a long stage was erected, 6 feet high, leading from the west doors to the Choir; that at the end was raised a Mount on which there was room for eight persons, with steps to go up and down;10 and that on this platform stood the King and Queen and the bridegroom, and on it also the Mayor and Aldermen were allowed a place.

After the ceremony a splendid feast was held, with dancing and disguisings. Holinshed concludes his account of the wedding by an anecdote which, if true, proves that the Princess was truly the wife of Arthur. The day after, the Royal party went to Westminster, where there were tournaments and great rejoicings. The Prince died five months afterwards. Another royal wedding, held on the 25th January 1502, caused even greater rejoicing. It was that of the Princess Margaret with the King of Scotland; a marriage which promised peace and goodwill between the two nations; a promise which has been fulfilled in a manner unexpected, by the failure of the male line of Tudors. One observes how strong the desire of Henry VII. was to conciliate the goodwill of London. He borrowed money from the City over and over again, but he always repaid these loans. The exactions that we find recorded are chiefly those of his old age—when he was fifty-two years of age, which was old for that time, when he had grown covetous. He could be ostentatious when show was wanted, witness the marriage of Prince Arthur with Katherine. He could also entertain with regal splendour, witness the Christmas cheer he offered to the Mayor and Aldermen.

“Henry VII., in the ninth Year of his Reign, holding his Feast of Christmas at Westminster, on the twelfth Day, feasted Ralph Anstry, then Mayor of London, and his Brethren the Aldermen, with other11 Commoners in great number; and, after Dinner, dubbing the Mayor Knight, caused him with his Brethren to stay and behold the Disguisings and other Disports in the Night following, shewed in the great Hall, which was richly hanged with Arras, and staged about on both sides; which Disports being ended, in the Morning, the King, the Queen, the Embassadors, and other Estates, being set at a Table of Stone, sixty knights and esquires served sixty Dishes to the King’s Mess, and as many to the Queen’s (neither Flesh nor Fish), and served the Mayor with twenty-four Dishes to his Mess, of the same manner, with sundry Wines in most plenteous wise. And, finally, the King and Queen being conveyed, with great Lights, into the Palace, the Mayor, with his Company, in Barges, returned and came to London by Break of the next day.” (Maitland, vol. i. p. 218.)

Henry VII. was respected and feared, rather than loved. He kept his word; if he borrowed he paid back; he was not savage or murderous; and he was a great lover of the fine arts. But the chief glory of his reign is that he enforced order12 throughout the realm: it is his chief glory, because order is a most difficult thing to enforce at a time when the people have been flying to arms on every possible occasion for forty years. In the rising of Lambert Simnel; in that of Perkin Warbeck; in the strange determination of the Cornishmen to march upon London,—one can see the natural result of a long civil war. Men become, very easily, ready to refer everything to the arbitration of battle; in such arbitration anything may happen. It was such arbitration that set Edward up and pulled Henry down, and then reversed the arrangement. It was such arbitration that placed the crown on Henry Tudor’s head. Why should not young Perkin step into a throne as Richard, Duke of York? Henry accepted the arbitrament of battle, defeated his rival, and dispersed the rebel armies one after the other. One would think that the spirit of rebellion would be quickly daunted by so many reverses. It was not so; for nearly a hundred years later there were rebellions. They broke out again and again: the people could not lose that trick of flying to arms; the barons could not understand that their power was gone; the memory still survived of princes dragged down, and princes set up, as Fortune turned the way of Victory.

Henry, like all the Tudors, was arbitrary: he had no intention of being ruled by the City; by his agents Empson and Dudley he levied fines right and left upon the wealthier merchants; he put the Mayor and the Sheriffs in the Marshalsea on a trumped-up charge, and they had to pay a fine of £1400 before he would let them out. He seized Christopher Hawes, Alderman, and put him also in prison, but the poor man died of terror and grief. He imprisoned William Capel, Alderman, who refused to pay a fine of £2000 for his liberty, and remained in prison till the King died. Lawrence Aylmer, ex-Mayor, was also imprisoned in the Compter, where he remained till the King’s death. Henry understood very clearly that with a full Treasury many things are possible that are impossible with empty coffers. He accumulated, therefore, a tremendous hoard: it is said to have amounted to one million eight hundred thousand pounds in money, plate, and jewels.

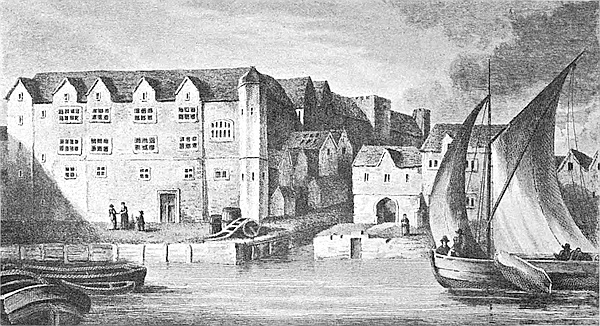

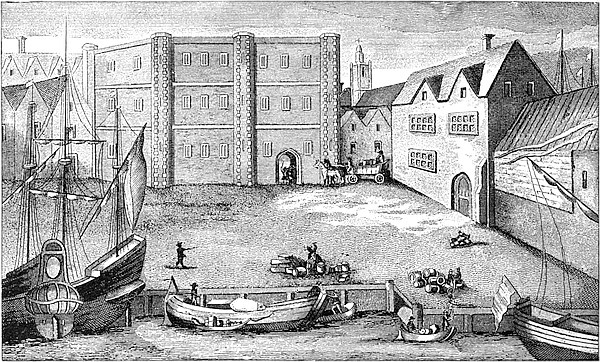

The events which belong especially to London in this reign, as we have seen, were not numerous, nor were they of enduring importance. As regards building, the King pulled down a chapel and a house—the house where Chaucer once lived—at the west end of Westminster Abbey, and built the Chapel called after his name; the Cross of Westchepe was finished and put up; Baynard’s Castle was rebuilt, “not after the former manner with embellishments and Towers,” but more convenient. It was the time when the castle was passing into the country house; it became now a large and handsome palace, built round two courts facing the river, much like those palaces built along the Strand, but without any garden except the courts.

The City showed more than its usual jealousy of strangers when in 1486 it passed an Ordinance that “no apprentice should be taken nor Freedom given, but to such as were gentlemen born, agreeable to the clause in the oath given to every 13Freeman at the time he was made Free.”... “You shall take no Apprentice but if he be free born.” These are Maitland’s words. The statement is surely absurd. For suppose such a regulation to hold good for the wholesale distributing Companies, how could it be sustained in the case of the Craft Companies? Did a gentleman’s son ever become a working blacksmith or a journeyman saddler? Another kind of jealousy was shown by the City when they passed an Act which prohibited any citizen under penalty of £100 (one-third to be given the Informer) for taking any goods or merchandise to any Fair or Market within the Kingdom, for the term of seven years. What did it mean? That the country merchants should come to London for their wares? Parliament set aside this Regulation the following year.

A sanitary edict was passed to the effect that no animals should be killed within the City. There is no information as to the length of time that this edict was obeyed, if it were ever obeyed at all.

In 1503 the King showed his opinion of the authority of the City when he granted a Charter to the Company of Merchant Taylors which practically placed them outside the jurisdiction of the Mayor. Some of the other Companies, perceiving that, if this new independence were granted everywhere, there would be an end of the City, joined in a petition to Parliament for placing them formally under the authority of the Mayor and Aldermen. The City got a Charter from the King in 1505. The Charter, which cost 5000 marks, was especially levelled against recent encroachments of foreigners in buying and selling, and was drawn up to the same effect, and partly in the same words, as the Fifth and last Charter of King Edward the Third. Thus the conclusion of Edward’s Charter was as follows:—

“We ... have granted to the said Mayor, etc., that no strangers shall from henceforth sell any Wares in the same City or Suburbs thereof by Retail, nor shall keep any House, nor be any Broker in the said City or Suburbs thereof, saving always the merchants of High Almaine, etc.”

Henry’s Charter was as follows:—

“That of all Time, of which the Memory of Man is not to the contrary, for the Commonweal of the Realm and City aforesaid, it hath been used, and by Authority of Parliament approved and confirmed, that no Stranger from the Liberty of the City may buy or sell, from any Stranger from the Liberties of the same City, any Merchandize or Wares within the Liberties of the same City, upon Forfeiture of the same.”

A curious story of this reign relates how the King, to use a homely proverb, cut off his nose to spite his face. For the conduct of Margaret, Duchess of Burgundy, in acknowledging the Pretender, so incensed him against the Flemings that he banished them all. No doubt he inflicted hardship upon the Flemings, but he also—which he had not intended—deprived the Merchant Adventurers of London of their principal trade. The Hanseatic Merchants, perceiving the possible advantage to themselves, imported vast quantities of Flemish produce. Then the ’prentices rose and broke into the Gildhalla Teutonicorum—the Steelyard—pillaging the rooms and warehouses. There was a free fight in Thames Street, and after a time the rioters were14 dispersed. Some were taken prisoners and a few hanged. As nothing more is said about the Flemings, one supposes that they all came back again.

There had been grave complaints about the perjuries of Juries in the City. The Jurymen took bribes to favour one cause or the other. It was therefore enacted:—

“That, for the future, no Person or Persons be impannelled or sworn into any jury or Inquest in any of the City Courts, unless he be worth forty Marks; and if the Cause to be tried amount to that Sum, then no Person shall be admitted as a Juror worth less than one hundred Marks; and every Person so qualified, refusing to serve as a Juryman, for the first Default to forfeit one Shilling, the second two, and every one after to double the Sum, for the Use of the City.”

“And when upon Trial it shall be found, that a Petty Jury have brought in an unjust Verdict, then every Member of the same to Forfeit twenty pounds, or more, according to the Discretion of the Court of Lord-Mayor and Aldermen; and also each Person so offending to suffer six Months’ imprisonment, or less, at the Discretion of the said Mayor and Aldermen, without Bail or Mainprize, and for ever after to be rendered incapable of serving in any jury.”

“And if upon Enquiry it be found, that any Juror has taken Money as a Bribe, or other Reward, or Promise of Reward, to favour either Plaintiff or Defendant in the Cause to be tried by him then, and in every such case, the Person so offending to forfeit and pay to the Party by him thus injured ten times the15 Value of such Sum or Reward by him taken, and also to suffer imprisonment as already mentioned, and besides, to be disabled from ever serving in that Capacity; and that every Person or Persons guilty of bribing any Juror, shall likewise forfeit ten times the value given, and suffer imprisonment as aforesaid.” (Maitland, vol. i. p. 219.)

Fortifications commanding roads and approaches to the City were erected in the year 1496, especially on the south side, in order to defend the City against the Cornish rebels. It is quite possible that some of them remained, and that some of the supposed works of 1642 were only a restoration or a rebuilding of forts and bastions on the same places.

16

In the year 1498 many gardens in Finsbury Fields were thrown into a spacious Field for the use of the London Archers or Trained bands. This field is now the Artillery Ground with Bunhill Fields Cemetery. In 1501 the Lord Mayor erected Kitchens and Offices in the Guildhall, by means of which he entertained the Aldermen and the principal citizens.

Towards the end of his reign, the King, finding himself afflicted with an incurable disease, took steps in the nature of atonement for his sins. He issued a general pardon to all men for offences committed against his laws—thieves, murderers, and certain others excepted. He paid the fees of prisoners who were kept in gaol for want of money to discharge their fees; he also paid the debts of all those who were confined in the “counters” of Ludgate, i.e. the free men of the City, for sums of forty shillings and under; and some he relieved that were confined for as much as ten pounds. “Hereupon,” says Holinshed, “there were processions daily in every City and parish to pray to Almighty God for his restoring to health and long continuance in the same.” But in vain; for the disease continued and the King died.

Here is a note on the first visit of Henry the Eighth to the City:—

“Prince Henry, who afterwards succeeded his father on the throne as King Henry VIII., but was at the time a child of seven years, paid a visit to the City (30 Oct. 1498), where he received a hearty welcome, and was presented by the Recorder, on behalf of the citizens, with a pair of gilt goblets. In reply to the Recorder, who in presenting this ‘litell and powre’ gift, promised to remember his grace with a better at some future time, the prince made the following short speech:—

‘Fader Maire, I thank you and your Brethren here present of this greate and kynd remembraunce which I trist in tyme comyng to deserve. And for asmoche as I can not give unto you according thankes, I shall pray the Kynges Grace to thank you, and for my partye I shall not forget yor kyndnesse.’” (Sharpe, London and the Kingdom, vol. i. p. 334.)

The funeral of the King was most sumptuous.

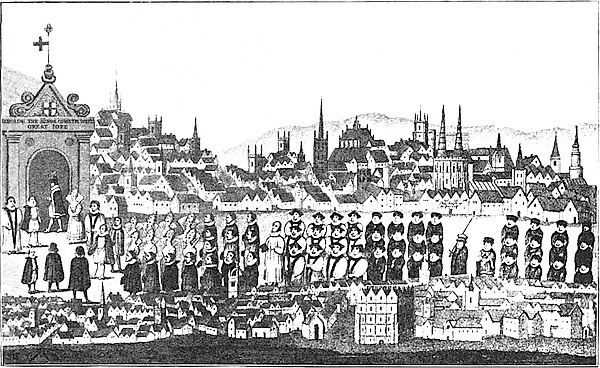

“His corpse was conveyed from Richmond to St. Paul’s on the 9th May, being met on its way at St. George’s Bar, in Southwark, by the mayor, aldermen, and a suite of 104 commoners, all in black clothing and all on horseback. The streets were lined with other members of the companies bearing torches, the lowest craft occupying the first place. Next after the freemen of the city came the ‘strangers’—Easterlings, Frenchmen, Spaniards, Venetians, Genoese, Florentines and ‘Lukeners’—on horseback and on foot, also bearing torches. These took up their position in Gracechurch Street. Cornhill was occupied by the lower crafts, ordered in such a way that ‘the most worshipful crafts’ stood next unto ‘Paules.’ A similar order was preserved the next day, when the corpse was removed from Saint Paul’s to Westminster. The lowest crafts were placed nearest to the Cathedral, and the most worshipful next to Temple Bar, where the civic escort terminated. The mayor and aldermen proceeded to Westminster by water, to attend the ‘masse and offering.’ The mayor, with his mace in his hand, made his offering next after the Lord Chamberlain; those aldermen who had passed the chair offered next after the Knights of the Garter, and before all ‘knights for the body’; whilst the aldermen who had not yet served as mayor made their offering after the knights.” (Ibid. p. 341.)

London has now changed its character: the old quarrels and rivalries of Baron, Alderman, or Lord of the Manor with merchant, of merchant with craftsman, of master with servant, have ceased. The Lord of the Manor has disappeared in the City; the craft companies have at last gained their share in the government of the City, but, so far to their own advantage, they are entirely ruled by the employers and18 masters who belong to them, so that the craftsmen themselves are no better off than before. The authority of the King over the City is greater now than at any preceding time, but it will be restrained in the future not so much by charters, by bribes and gifts, as by the power of the Commons. The trade of the City, which had so grievously suffered by the Civil wars, is reviving again under the peace and order of the Tudor Princes, though it will be once more injured by the religious dissensions. Lastly, the City, like the rest of the country, is already feeling the restlessness that belongs to a period of change. At Henry’s accession, men were beginning to be conscious of a larger world: wider thoughts possessed them; the old learning, the old Arts, were rising again from the grave; the crystallised institutions, hitherto fondly thought to be an essential part of religion, were ready to be broken up. Even the most narrow City merchant, whose heart was in his money-bags, whose soul was to be saved by a trental of masses, an anniversary, or a chantry, felt the uneasiness of the time, and yearned for a simpler Faith as well as for wider markets across the newly-traversed seas. I propose to consider the events of this reign, which were of such vast importance to London as well as the country at large, by subjects instead of in chronological order as hitherto.

19

And I will first take the relations of the City and the King.

They began with a manifest desire of the young King to conciliate the City. Evidently in answer to some petition or representation, he banished all “foreign” beggars, i.e. those who were not natives of London; and ordered them to return to their own parishes. It is easy to understand what happened: the “foreign” beggars, in obedience to the proclamation, retired to their holes and corners; the streets were free from them for some days; the Mayor and Sheriffs congratulated themselves; then after a decent interval, and gradually, the beggars ventured out again. The difficulty, in a word, of dealing with rogues and vagrants and masterless men was already overwhelming. In the time of Elizabeth it became a real, a threatening, danger to the town. We must remember that one effect of a long war, especially a civil war, which calls out a much larger proportion of the people than a foreign war, is to throw upon the roads, at the close of it, a vast number of those who have tasted the joys of idleness and henceforth will not work. They would rather be flogged and hanged than work. They cannot work. They have forgotten how to work. They rob on the high road; they murder in the remote farm-houses; in the winter,20 and when they grow old, they make for the towns, and they beg in the streets. However, Henry greatly pleased the City by his order, and for a time there was improvement. He then took a much more important step towards winning the affection of the City. He committed Empson and Dudley to the Tower. They were accused of a conspiracy against the Government—in reality they had been the approved agents of the late King; but this it would have been inconvenient to confess. They were therefore found guilty and executed—these unfortunately too willing tools of a rapacious sovereign. Henry offered restitution to all who had suffered at their hands. It was found on subsequent inquiry that six men, all of whom had been struck off the lists for perjury, had managed to get replaced, and had been busy at work for Empson and Dudley in raking up false charges against Aldermen or in taking bribes for concealing offences. These persons, as being servants and not principals, were treated leniently. They were set in pillory, and then driven out of the City.

The loyalty of the City showed itself on the day of the Coronation when the King, with his newly married Queen, rode in magnificent procession from the Tower to Westminster, where the Crowning was performed with a splendour which surpassed that of all previous occasions.

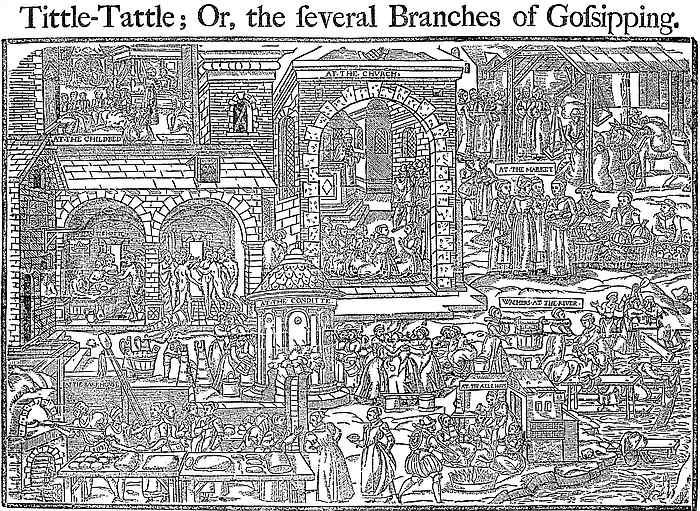

On St. John’s Eve 1510 the King, disguised as one of his own yeomen, went into the City in order to witness the finest show of the year, the procession of the City Watch. He was so well pleased with the sight that on St. Peter’s Eve following he brought his Queen and Court to Cheapside to see the procession again:—

“The March was begun by the City musick, followed by the Lord-Mayor’s officers in Party-coloured Liveries; then the Sword-Bearer on Horseback, in beautiful Armour, preceded the Lord-Mayor, mounted on a stately Horse richly trapped, attended by a Giant, and two Pages on Horseback, three Pageants, Morrice-dancers, and Footmen; next came the Sheriffs, preceded by their Officers, and attended by their Giants, Pages, Pageants, and Morrice-Dancers. Then marched a great body of Demi-Lancers, in bright Armour, on stately Horses; next followed a Body of Carabineers, in white Fustian Coats, with a symbol of the City Arms on their Backs and Breasts; then marched a Division of Archers, with their Bows bent, and Shafts of Arrows by their Side; next followed a Party of Pikemen in their Corslets and Helmets; after them a Body of Halberdeers in Corslets and Helmets; and the March was closed by a great Party of Billmen, with Helmets and Aprons of Mail; and the whole Body, consisting of about two thousand Men, had between every Division a certain Number of Musicians, who were answered in their proper Places by the like Number of Drums, with Standards and Ensigns as veteran troops. This nocturnal March was illuminated by Nine hundred and forty Cressets; two hundred whereof were defrayed at the City Expence, five hundred at that of the Companies, and two hundred and forty by the City Constables. The March began at the Conduit at the west end of Cheapside, and passed through Cheapside, Cornhill, and Leadenhall Street, to Aldgate; whence it returned by Fenchurch Street, Gracechurch Street, Cornhill, and so back to the Conduit. During this March, the Houses on each side the said streets were decorated with Greens and Flowers, wrought into Garlands, and intermixed with a great number of Lamps.” (Maitland, vol. i. p. 222.)

There is no more pleasant page in the whole of history than that which relates the first years of King Henry’s reign. He was young; he was strong; he was21 married to a woman whom he loved; he was tall, like his grandfather King Edward, and of goodly countenance, like his grandmother Elizabeth Woodville; he was a lover of arts, like his father; and of learning, like his grandmother Margaret, Countess of Richmond; he was brave, like all his race; he was masterful, as became a king as well as a Tudor; he was skilful in all manly exercises. Add to all this that at the time of his accession he was the richest man in Europe. This accomplished Prince, according to Holinshed, used, even in his progresses, to exercise himself every day in shooting, singing, dancing, wrestling, casting the bar, playing on the recorders, the flute, the virginals, or writing songs and ballads and setting them to music. His songs are principally amorous. He wrote anthems, one of which is extant. The words are taken from the Song of Solomon (Vulgate). His verse is melodious and pretty:—

Or a song of constancy:—

And the song which became so popular, “Pastyme with good Company.” This song was actually taken by Latimer as a text for a sermon before Edward the Sixth:—

At the outset there was nothing but feasting, jousts, feats of arms, masques, devices, pageants, and mummeries. At the feasts the King was lavish and free of hand; at the tilting the King challenged all and won the prize; at the masques and mummeries he was the best of all the actors; at the dance he was the most graceful and the most unwearied. There are long pages in contemporary history on this festive and splendid life at the Court, when as yet all the world was young to Henry, and no one had been executed except Empson and Dudley. The following extract from Holinshed shows the things in which he gloried, and the nature of a Court Pageant:—

“Then there was a device or a pageant upon wheels brought in, out of the which pageant issued out a gentleman richlie apparelled, that shewed how in a garden of pleasure there was an arbor of gold wherein were lords and ladies, much desirous to shew pastime to the queene and ladies, if they might be licenced so to doo; who was answered by the queene, how she and all other there were verie desirous to see them and their pastime. Then a great cloth of arras that did hang before the same pageant was taken away, and the pageant brought more neere. It was curiouslie made and pleasant to beholde, it was solemne and rich: for every post or piller thereof was covered with frised gold, therein were trees of hawthorne, eglantine, rosiers, vines, and other pleasant floures of diverse colours, with gillofers, and other hearbs, all made of sattin, damaske, silver and gold, accordinglie as the naturall trees, hearbs, or floures ought to be. In this arbor were six ladies, all apparelled in white satin and greene, set and embrodered full of H. & K. of Gold,23 knit together with laces of gold of damaske, and all their garments were replenished with glittering spangels gilt over, on their heads are bonets all opened at the foure quarters overfrised with flat gold of damaske, and orrellets were of rolles, wreathed on lampas doucke holow, so that the gold shewed through the lampas doucke: the fassis of their head set full of new devised fashions. In this garden also was the king and five with him apparelled in garments of purple sattin, all of cuts with H. & K. everie edge garnished with frised gold, and everie garment full of posies, made of letters of fine gold in bullion as thicke as they might be, and everie person had his name in like letters of massie gold. The first Cureloial, the second Bon Voloire, the third Bon Espoir, the fourth Valiant Desire, the fifth Bon Foy, the sixt Amour Loial, their hosen, cape, and coats were full of posies, with H. & K. of fine gold in bullion, so that the ground could scarse appeere, and yet was in everie void place spangles of gold. When time was come, the said pageant was brought foorth into presence, and then descended a lord and a ladie by couples, and then the minstrels which were disguised also dansed, and the lords and ladies dansed, that it was a pleasure to behold. In the meane season the pageant was conveyed to the end of the palace, there to tarie till the danses were finished, and so to have received the lords and ladies againe: but suddenlie the rude people ran to the pageant, and rent, tare, and spoiled the pageant so that the lord steward nor the head officers could not cause them to absteine, except that they should have foughten and drawen blood and so was this pageant broken. Then the king with the queene and the ladies returned to his chamber, where they had a great banket, and so this triumph ended with mirth and gladnes.” (Holinshed, vol. iii. p. 560.)

On the proclamation of war against France, the City was ordered to furnish a contingent of 300 men fully armed and equipped. There seems to have been no difficulty in getting the men. The money for their outfit was subscribed by the Companies, who raised £405, and so the men were despatched, clad in white with St. George’s Cross and Sword, and a rose in front and back.

In June 1516 Cardinal Wolsey addressed an admonition to the City: they must look to the maintenance of order; there was sedition among them; the statute of apparel was neglected; vagabonds and masterless men made the City their resort—an instructive commentary on the King’s ordinances of seven years before. The sedition of which Wolsey complained was due to the intense jealousy with which the people of London always regarded the immigration of aliens. They were always coming in, and the freemen—the old City families—were always dying out or going away. In 1500, and again in 1516, orders were issued for all freemen to return with their families to the City on pain of losing their freedom. Had they, then, already begun the custom of living in the suburbs and going into town every morning? The case against the foreigners is strongly put by Grafton:—

“In this season the Genowayes, Frenchmen and other straungers, sayd and boasted themselves to be in suche favor with the king and hys counsayle, that they set naught by the rulers of the city: and the multitude of straungers was so great about London, that the poore English artificers could scarce get any lyvyng: and most of al the straungers were so prowde, that they disdayned, mocked, and oppressed the Englishmen, which was the beginning of the grudge. For among all other thinges there was a carpenter in London called Wylliamson which boughte two stocke Doves in Chepe, and as he was about to pay for them, a Frenchman tooke them out of his hande, and sayde they were not meat for a Carpenter: well sayde the Englisheman I have bought them, and now payde for them, and therefore I will have them; nay sayde the Frenchman I will have them for my Lorde the Ambassador, and so for better or worse, the Frenchman called the Englishman knave and went away with the stock Doves. The straungers came to the French Ambassador, and surmised a complaint against the poore Carpenter, and the Ambassador came to my24 Lord Maior, and sayde so much, that the Carpenter was sent to prison: and yet not contented with this so complayned to the king’s counsayle, that the king’s commaundement was layde on him. And when syr John Baker and other worshipfull persons sued to the Ambassador for him, he aunswered by the body of God that the Englishe knave should loose his lyfe, for he sayde no Englisheman should denie what the Frenchmen requyred, and other aunswere had they none. Also a Frenchman that had slayne a man, should abjure the realme and had a crosse in his hande, and then sodainely came a great sort of Frenchman about him, and one of them sayde to the Constable that led him, syr is thys crosse the price to kill an Englisheman. The Constable was somewhat astonied and aunswered not. Then sayde another Frenchman, on that price we would be banished all by the masse, this saiying was noted to be spoken spitefully. Howbeit the Frenchmen were not alonly oppressors of the Englishemen, for a Lombard called Frances de Bard, entised a man’s wyfe in Lombarde Streete to come to his Chamber with her husband’s plate, which thing she did. After when her husband knew it, he demanded hys wife, but answere was made he should not have her; then he demanded his plate, and in like manner answere was made that he should neyther have plate nor wife. And when he had sued an action against the straunger in the Guyldehall, the stranger so faced the Englishman that he faynted in his sute. And then the Lombard arrested the poore man for his wyfes boord, while he kept her from her husband in his chamber. This mocke was much noted, and for these and many other oppressions done by them, there encreased such a malice in the Englishmen’s hartes: that at the last it brast out.” (Grafton’s Chronicles, vol. ii. p. 289.)

He goes on to relate that a certain John Lincoln, a broker, desired a priest named Dr. Standish to move the Mayor and Aldermen at his Spital sermon on Easter Monday to take part with the Commonalty against the aliens. Standish refused. John Lincoln then went to a certain Dr. Bele, Canon in St. Mary Spital, and represented the grievous case of the people.

... “lamentably declared to him, how miserably the common artificers lyved, and scarce could get any worke to find them, their wives and children, for there were such a number of artificers straungers, that toke away all their living in manner.”

Then followed the tumult known as Evil May Day. Dr. Bele preached the Spital Sermon of Easter Tuesday. He first read Lincoln’s letter representing the condition of the craftsmen thus oppressed by the aliens, and then taking for his text the words, “Caelum caeli Domino Terram autem dedit Filiis hominum”—the Heavens to the Lord of Heaven, but the Earth hath he given to the Sons of Men—he plainly told the people that England was their own, and that Englishmen ought to keep their country for themselves, as birds defend their nests. Thus encouraged, the people began to assault and molest the foreigners in the City. Some of them were sent to Newgate for the offence; but they continued. Then there ran about the City a rumour that on May Day all the foreigners would be murdered, and many of them, hearing this rumour, fled. The rumour reached the King, who ordered Cardinal Wolsey to inquire into it. Thereupon the Mayor called together the Council. Some were of opinion that a strong watch should be set and kept up all night; others thought that it would be better to order every one to be indoors from nine in the evening till nine in the morning. Both opinions were sent to the Cardinal, who chose the latter. Accordingly the order was proclaimed. But it was not obeyed. Some time after nine, Alderman Sir John Mundy found a company of25 young men in Cheapside playing at Bucklers. He ordered them to desist and to go home. One of them asked why? For answer the Alderman seized him and ordered him to be taken to the Compter. Then the tumult began. The ’prentices raised the cry of “Clubs! Clubs!” and flocked together; the man was rescued; the people crowded in from every quarter; they marched, a thousand strong, to Newgate, where they took out the Lord Mayor’s prisoners, and to the Compter, where they did the same; at St. Martin’s they broke open doors and windows and “spoiled everything.” And they spent the rest of the night in pulling down the houses of foreigners. When they grew tired of this sport, they gradually broke up and went home, but on the way the Mayor’s men arrested some three hundred of them and sent them to the Tower. Another hundred rioters were arrested next day. Dr. Bele was also sent to the Tower. Then began the trials. Lincoln and some twenty or thirty others were found guilty and sentenced to be hanged, drawn, and quartered. Ten pairs of26 gallows were set up in different parts of the City for their execution. Lincoln, however, was the only one who suffered. For the rest a reprieve was granted. Then the affair was concluded in a becoming and solemn manner:—

“Thursday the xxij day of May, the king came into Westminster Hall, for whome at the upper ende was set a cloth of estate, and the place hanged with arras. With him was the Cardinall, the Dukes of Norfolke and Suffolke, the Earles of Shrewsbury, of Essex, Wilshire and of Surrey, with manye Lordes and other of the kinges Counsale. The Maior and Aldermen, and all the chief of the City, were there in their best livery (according as the Cardinall had them appoynted) by ix of the clocke. Then the king commaunded that all the prisoners should be brought forth. Then came in the poore yonglings and olde false knaves bound in ropes all along, one after another in their shirtes, and every one a Halter about his necke, to the number of foure hundred men and xj women. And when all were come before the kinges presence, the Cardinall sore layd to the Maior and commonaltie their negligence, and to the prisoners he declared that they had deserved death for their offence: then all the prisoners together cryed mercy gracious Lorde, mercy. Then the Lordes altogether besought his grace of mercy, at whose request the king pardoned them all. And then the Cardinall gave unto them a good exhortation to the great gladnesse of the heerers. And when the generall pardon was pronounced, all the prisoners showted at once, and altogether cast up their Halters unto the Hall rooffe, so that the king might perceyve they were none of the discretest sort. Here is to be noted that dyvers offenders which were not taken, heeryng that the king was inclined to mercys, came well apparayled to Westminster, and sodainlye stryped them into their shirtes with halters, and came in among the prisoners willingly, to be partakers of the kinges pardon, by the which doyng, it was well knowen that one John Gelson yoman of the Crowne was the first that beganne to spoyle, and exhorted other to do the same, and because he fled and was not taken, he came in the rope with the other prisoners, and so had his pardon. This companie was after called the blacke Wagon. Then were all the Galowes within the Citie taken downe, and many a good prayer sayde for the king, and the Citizens tooke more heede to their servants.” (Grafton’s Chronicles, vol. ii. p. 294.)

A singular story belongs to the arrival of the French embassy charged with negotiating the marriage of the King’s infant daughter and the Dauphin. The ambassadors were escorted by a company of their own King’s bodyguard and another of the English King’s bodyguard. They were met at Blackheath by the Earl of Surrey, richly apparelled, and a hundred and sixty gentlemen; four hundred archers followed; they were lodged in the merchants’ houses and banqueted at Taylors’ Hall. And then, says the historian, “the French hardermen opened their wares and made Taylors’ Hall like to the paunde of a mart. At this doing many an Englishman grudged but it avayled not.” In other words, a lot of French hucksters, under cover of the embassy, brought over smuggled goods and sold them in the Taylors’ Hall at a lower price than the English makers could afford.

The reception of the Emperor Charles by Henry in this year was as royally magnificent as even Henry himself could desire. The procession was like others of the same period and may be omitted.

In 1524 a curious proclamation was made by the Mayor. Evidently papers or letters of importance had been lost.

“My lorde the maire streihtly chargith and commaundith on the king or soveraigne lordis behalf that if any maner of person or persons that have founde a hat with certeyn lettres and other billes and writinges therin enclosed, which lettres been directed to our said sovereign from the parties of beyond the27 see, let hym or theym bryng the said hat, lettres, and writinges unto my saide lorde the maire in all the hast possible and they shalbe well rewarded for their labour, and that no maner of person kepe the said hat, lettres, and writinges nor noon of them after this proclamacioun made, uppon payn of deth, and God save the king.” (Sharpe, London and the Kingdom, vol. i. p. 373.)

Two cases, that of Sir George Monoux and that of Paul Wythypol, prove that the City offices were not at this time always regarded as desirable. In the former case, Sir George Monoux, Alderman and Draper, was elected (1523) Mayor for the second time, and refused to serve. He was fined £1000, and it was ordained by the Court of Aldermen that any one in future who should refuse to serve as Mayor should be fined that amount. In this case Monoux was permitted to retire, probably on account of ill-health. The second case, which happened in 1537, was that of Paul Wythypol, merchant-taylor. He was a man of some position in the City: he had been one of the Commoners sent to confer with Wolsey on the “amicable” loan (Sharpe, London and the Kingdom, vol. i. p. 377); he attended the Coronation banquet of Anne Boleyn; he was afterwards M.P. for the City, 1529–1536. They elected him Alderman for Farringdon Within. For some reason he was anxious not to serve; rather than pay the fine he got the King to interfere on his behalf. Such interference was clearly an infringement of the City liberties; the Mayor and Aldermen consulted Wolsey, who advised them to seek an interview with the King, then at Greenwich. This they did, and went down to Greenwich. When they arrived they were taken into the King’s great chamber,28 where they waited till evening, when the King received them privately. What passed is not known, but in the end Wythypol remained out of office for a year afterwards. At the end of that time he was again elected Alderman, and was ordered to take office or to swear that his property did not amount to £1000. He refused and was committed to Newgate, the King no longer offering to help him. Three weeks later he appeared before the Court and offered to pay a fine of £40 for three years’ exemption from office. The Court refused this offer and sent him back to prison. Three months later—Wythypol must have been a very stubborn person—he again appeared before the Court, and was ordered to take up office at once or else swear that his property was not worth £1000. If he did not, he was to be fined in a sum to be assessed by the Mayor, Aldermen, and Common Council. He did not take office, and it is therefore tolerably certain that he paid a heavy fine.

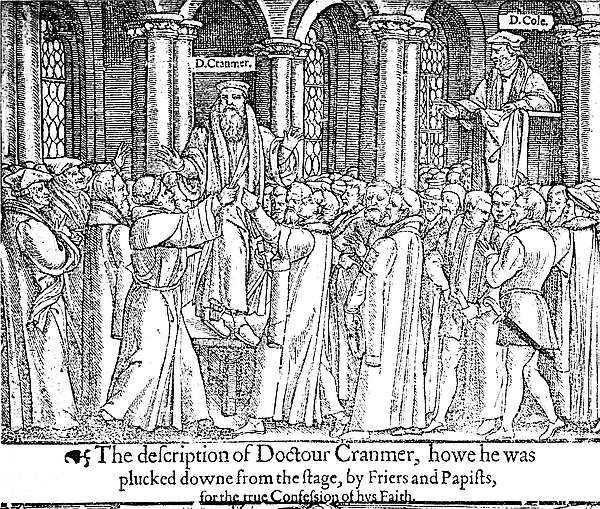

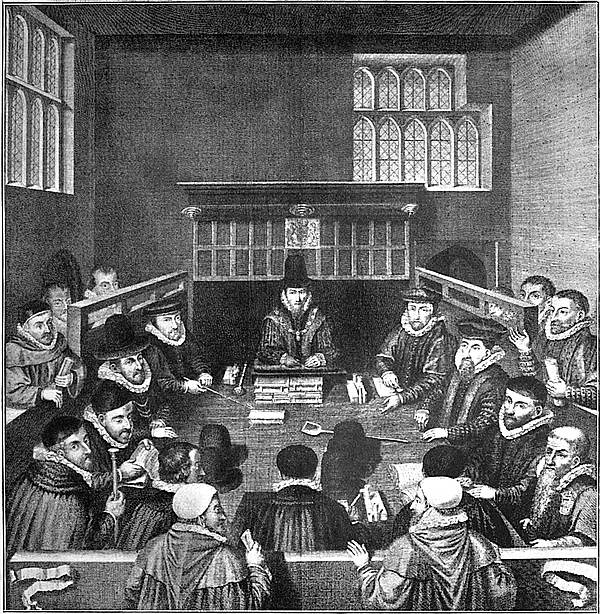

In the year 1529 sat the memorable Court presided over by Cardinals Campeggio and Wolsey, which was to try the validity of Henry’s marriage with his brother’s widow. It was held in the great hall of the Dominican Friars. No more important case was ever tried in an English Court of Law, nor one which had wider or deeper consequences. Upon this case depended the national Faith; the nation’s fidelity to the Pope; its continued adhesion to the ecclesiastical order as it had developed during fifteen hundred years. This trial belongs to the national history.

In October of that year (1529) the King, enraged by the Legate’s delay in the marriage business, deprived Wolsey of the Seals, seized his furniture and plate, and ordered him to leave London. In November of the same year, at a Parliament held in the Palace of Bridewell, a Bill was passed by the Lords disabling the Cardinal from being restored to his dignities. In February 1530 Wolsey was restored to his Archbishopric but without his palace, which the King kept for himself; he was summoned to London on a charge of treason, but he fell ill and died on the way.

No Englishman before or after Wolsey has ever maintained so much state and splendour; no Englishman has ever affected the popular imagination so much as Cardinal Wolsey. Contemporary writers exhaust themselves in dwelling upon the more than regal Court kept up by this priest. It is like reading of the Court of a great king. We must, however, remember, that all this state was not the ostentation of the man so much as, first, the glorification of the Church and of the ecclesiastical dignities, and next, a visible proof of the greatness of the King in having so rich a subject.

Between 1527 and 1534 there were disputes on the subject of tithes and offerings to the clergy. At this time began the dissolution of the Monasteries, to which we will return presently.

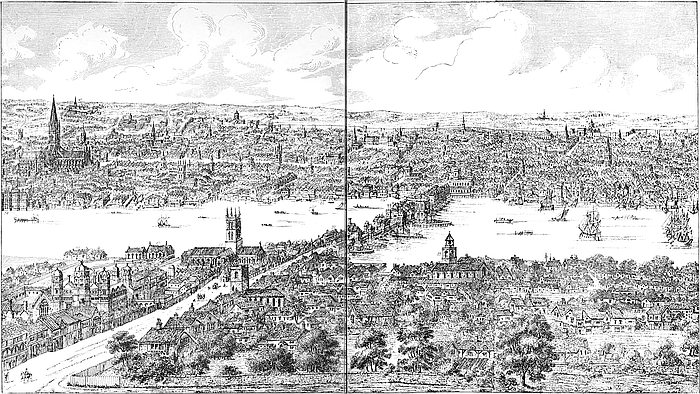

So far as regards the relations between the King and the City. Let us now return to the City itself. We have already seen that the intervals of freedom from plague were growing shorter. In this reign of thirty-eight years there was a return of the sweating sickness in 1518; a return of the plague, which lasted from 1519 to 1522; another appearance of the sweating sickness in 1528; and another attack of the plague in 1543. It seems strange that no physician should have connected the frequency and violence of the disease with the foulness and narrowness of the streets. From the beginning of the sixteenth century to the Great Fire of 1666, London, crowded and confined, abounded with courts and slums of the worst possible kind; it swarmed with rogues and tramps and masterless men who30 lived as they could, like swine. There were no great fires to cleanse the City. The condition of the ground, with its numberless cesspools, its narrow lanes into which, despite laws, everything was thrown; its frequent laystalls; the refuse and remains of all the workshops; the putrefying blood of the slaughtered beasts sinking into the earth,—must have been truly terrible had the people realised it; but they did not. Fluid matter sank into the earth and worked its wicked will unseen and unsuspected; the rains washed the surface; no man saw farther than the front of his own house; therefore when pestilence appeared among them it did not creep, according to its ancient wont, from house to house, but it flew swiftly with wings outspread over street and lane and court.

Steps were taken to protect and to improve the medical profession. It was ordained in 1512 that no one should practise medicine or surgery within the City or for seven miles outside the City walls without a license from the Bishop of London or the Dean of St. Paul’s; the said license only to be obtained by examination before the Bishop or the Dean by four of the Faculty. Two years later surgeons were exempted from serving on juries, bearing arms, or serving as constables. In 1519 the Physicians obtained a Charter of Incorporation, by which they were allowed a common seal; to elect a President annually; to purchase and hold land; and to govern all persons practising physic within seven miles of London. The College of Physicians, observe, was at first only considered as one of the City Companies: it had jurisdiction over London and over seven miles round London, but no more. The positions of both Physicians and Surgeons were enormously improved by these Acts of Parliament.

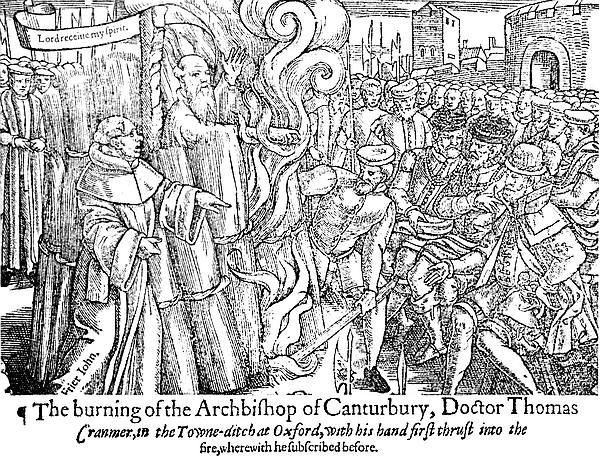

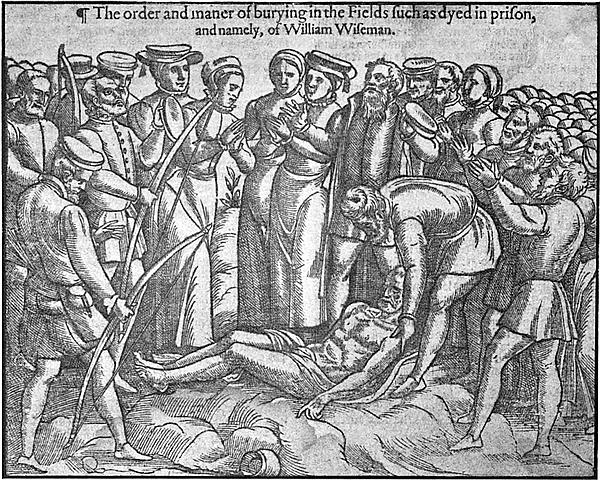

There were in this reign, for the admiration of the people, an extraordinary number of executions, both of noble lords and hapless ladies, as well as of divines, monks, friars, gentlemen, gentlewomen, and the common sort, for treason, heresy, and the crimes which are the most commonly brought before the attention of justice. What reign before this would exhibit such a list as the following? Two Queens, Anne Boleyn and Katherine Howard; of others, the Marquis of Exeter, the Earl of Surrey, the Earl of Kildare, the Duke of Buckingham, Lord Rochford, Lady Rochford, Lady Salisbury, Fisher, More, Empson, Dudley, Cromwell. Of abbots, priors, monks, friars, doctors, priests, for refusing the oath of the King’s supremacy a great number; of lesser persons for heresy or treason another goodly company. Some were beheaded—those were fortunate; others were burned, not being so fortunate; the rest were drawn on hurdles, and treated in the manner we have already seen.

The dissolution of the Religious Houses, the changes in the Articles of Religion, and their effect upon the City of London, will be found in another place (see p. 109). In this chapter a few cases are given to illustrate the changes of thought and the general excitement in the minds of men.

31

There is, first, the case of Lambert. He was a learned man and a schoolmaster who denied the Real Presence in the Sacrament. The case had been already brought before the Archbishop, who had given a sentence against Lambert. The King, who ardently believed in the Real Presence, announced his intention of arguing publicly with this heretic. The argument was actually held in Westminster Hall in the presence of a great number of people. In the end the King, apparently, got the worst of it, for we find him becoming judge as well as disputant, and ordering the unfortunate man to recant or burn. Lambert would not recant—the pride and stubbornness of these heretics were wonderful; in some cases, perhaps in this, the man stood for a party: he would not recant for the sake of his friends as well as himself. He was burned.

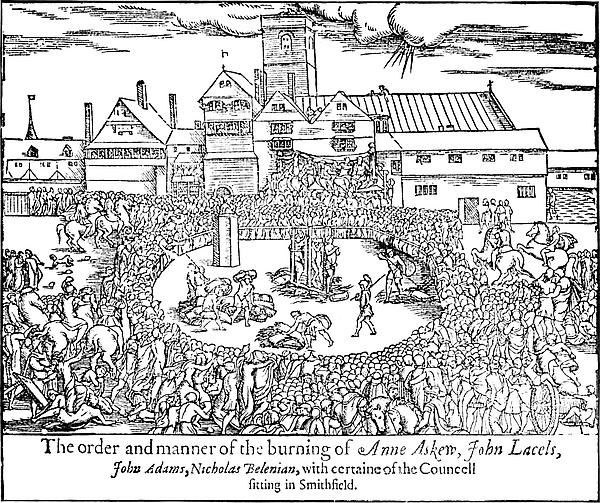

The case of Anne Askew is remarkable for the introduction of torture, which was then unusual either with criminals or heretics. She was so miserably tortured—yet perhaps the torture was intended as a merciful act, in the hope of rescuing her from worse than earthly flames—that she could not stand or walk. She, like Lambert, suffered for denying the Real Presence. She was a gentlewoman of very good understanding.

The Holy Maid of Kent, Elizabeth Barton, was a woman of a much lower order. She was hysterical and weak-minded. At the present day she would be32 looked after and gently cared for. She had fits and convulsions, during which her face and her body were drawn, and she talked rambling nonsense. That she was unintelligible was quite enough to make the ignorant country folk flock about her, listening for inspired words in her hysterical ejaculations. She passed among them for one to whom God had sent a new revelation of His Will and Intentions. She was taken to see Bishops Fisher and More, who do not seem to have regarded her as a person of the slightest importance. But certain priests—it is said so; one may believe it or not—obtained influence over her and persuaded her to prophesy—no doubt she believed what they told her—that if the King took another wife he would not remain King for another year. Henry was not the man to be turned aside from his fixed purpose by such a gross cheat. He arrested the Maid and her accomplices. They were all brought to the Star Chamber and examined; they all confessed. They were then exposed on a scaffold at St. Paul’s and publicly confirmed their confessions. Her confederates included six ecclesiastics, of whom two were monks of Canterbury and one a Friar Observaunt; two were private gentlemen; one was a serving-man. Confession made, they were taken back to the Tower and their case laid before Parliament, which met after Christmas. They were all sentenced to the same traitor’s death and, after being kept in prison for three months, were carried out to Tyburn. The last words of the girl if they are correctly reported are very pathetic and to the purpose. But they look as if they had been written for her.

“Hether am I come to die, and I have not beene the onele cause of mine owne death, which most justly I have deserved, but also I am the cause of the death of all these persons which at thys time here suffer: and yet to saye the truth I am not so much to be blamed, consydering it was well known unto these learned men that I was a poore wenche, without learnyng, and therefore they might have easily perceyved that the thinges that were done by me could not proceede in no suche sort, but their capacities and learning coulde right well judge from whence they were proceeded, and that they were altogether fayned: but because the things which I fayned was profitable unto them, and therefore they much praised mee and bare me in hande that it was the holy ghost, and not that I did them, and then being puffed up with their prayses, fell into a certaine pride and foolish phantasie with my self, and thought I might fayne what I would, which thing hath brought me to this case, and for the which now I crye God and the King’s highnesse most hartely mercie, and desire all you good people to pray to God to have mercie on me, and all them that here suffer with me.”

One cannot refrain in this place from remarking on the change which has come over the temper of the people as regards the sacred person of the priest. Henry the Seventh would not send to execution even those mischievous priests who invented and carried out the impudent personations. Yet his son, thirty years later, sends to block, stake or gallows, bishops, abbots, priors, priests, monks, and friars, by the dozen.

The story of Richard Hun illustrates the condition of popular feeling which made these executions of ecclesiastics possible. He was a citizen of good position and considerable wealth, a merchant-taylor by calling; he was greatly respected by33 the poorer sort on account of his charitable disposition. “He was a good almesman and relieved the needy.” It happened that one of his children, an infant, died and was buried. The curate asked for the “bearing sheet” as a “mortuary.”[2] Richard Hun replied that the child had no property in the sheet. The reply shows either bad feeling towards the curate or bad feeling towards the clergy generally. Most likely it was the latter, as the sequel shows.

The priest cited him before the spiritual court. He replied by counsel, suing the curate in a praemunire. In return Hun was arrested on a charge of Lollardry and put into Lambeth Palace. And here shortly afterwards he was found dead. He had hanged himself, said the Bishop and Chancellor. The people began to murmur. Hanged himself? Why should so good a man hang himself? A coroner’s inquest was held upon the body. The jury indicted the Chancellor and 34two men, the bell-ringer and the summoner, for murdering Richard Hun. The King’s attorney, however, would go no further in the matter. By the Bishop’s orders the body was burned at Smithfield. But the murder—if it was a murder—of Richard Hun was not forgotten. Nor was it forgotten that without a trial his body was burned as a heretic’s. These things lay in the minds of the people. And they rankled.

In the reign of Henry VI. (1447), four new grammar schools had been established in the City: viz. in the parishes of All Hallows the Great; St. Andrew’s Holborn; St. Peter’s Cornhill; and in St. Thomas Acons’ Hospital. Nine years later, five other parish schools had been founded or restored, namely, that of St. Paul’s; of St. Martin’s; of St. Mary le Bow; of St. Dunstan’s in the East; and of St. Anthony’s Hospital. All these schools seem to have fallen more or less into decay during the next hundred years. But very little indeed is known as to the condition of education during this period. There is, however, no doubt that in the year 1509 the Dean of St. Paul’s, John Colet, found the condition of St. Paul’s School very much decayed. He was himself a man of large means, being the son of a rich merchant who had been Sheriff in 1477, Mayor in 1486, and35 Alderman, first of Farringdon Ward Without, and afterwards of Castle Baynard and Cornhill successively. The Dean resolved upon building a new school and endowing it. He therefore bought a piece of land on the east side of the Cathedral; there placed a school and entrusted the revenues with which he endowed it to the Mercers’ Company, saying, that though there was nothing sacred in human affairs, he yet found the “least corruption” among them. Later on, the Merchant Taylors founded a school; the Mercers founded another school; and John Carpenter, Clerk, founded the City of London School. The educational endowments founded by London citizens amount to nearly a hundred.

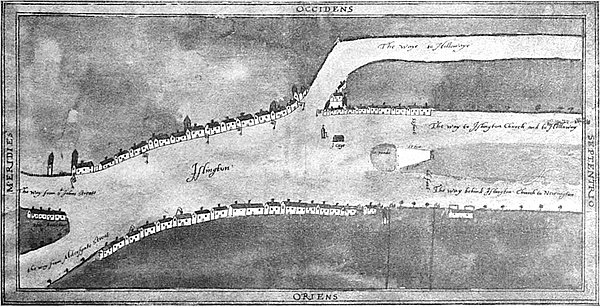

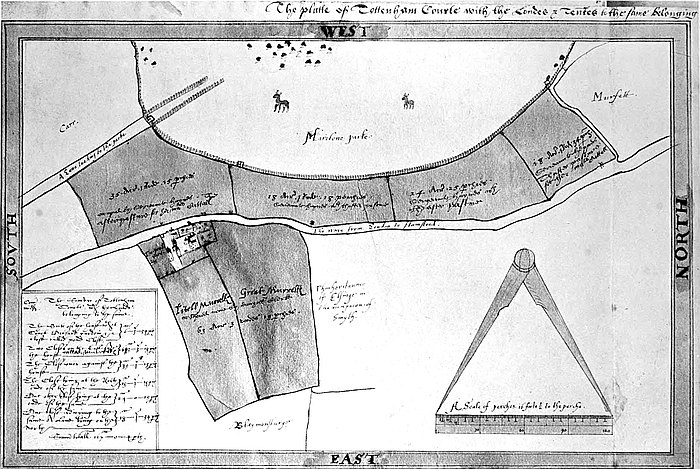

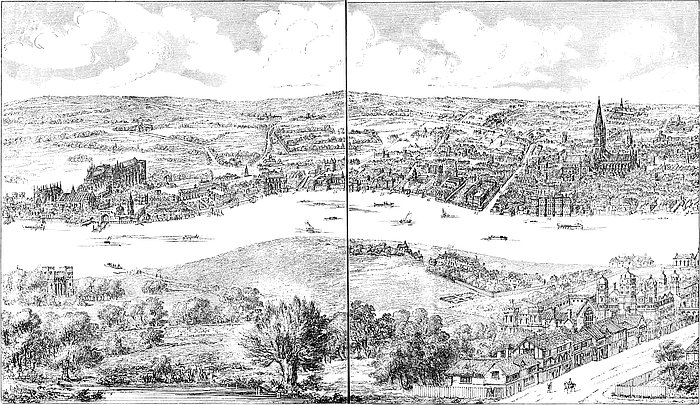

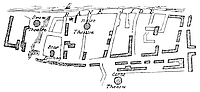

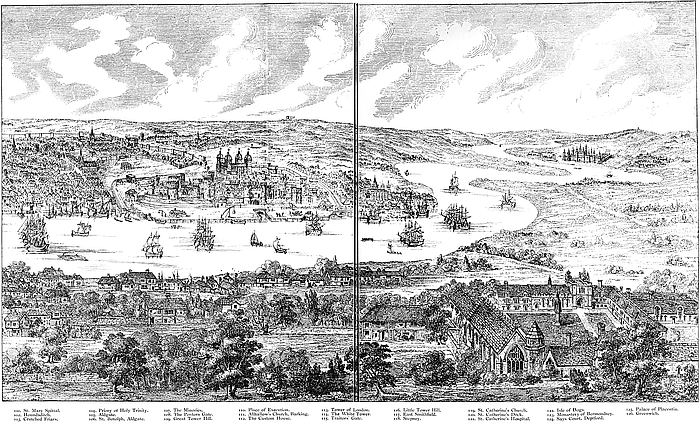

The enclosure of common lands has always been a temptation to those who live in the neighbourhood and a grievance to those who are thus robbed of their common property. Both in the north and south of London there stretched wide common lands in which the people possessed rights of pasture, cutting wood, and other things. Many of these common lands still remain, though greatly shorn of their former proportions. On the north Hampstead Heath is all that is left of land which began at36 Moorfields and stretched northwards as far as Muswell Hill and Highgate and eastward to include the Forests of Epping and Hainault. In a map of London of the sixteenth century these common lands must be laid down as a special and very fortunate possession of the City, where people could in a few minutes find themselves in pure country air. Early in the century, however, there were murmurings on account of the enclosure of the fields north of London. “Before this time,” says Grafton, “the townes about London, as Islington, Hoxton, Shordyche, and other, had enclosed the common fields with hedges and ditches that neyther the yonge men of the City might shoote, nor the auncient persons might walk for their pleasure in the fields, except eyther their bowes and arrows were broken or taken away, or the honest and substantiall persons arrested or indicted, saiving that no Londoner should goe oute of the City but in the high wayes.” It is not stated how long this grievance lasted; probably it grew gradually: field after field was cut off; one enclosure after another was made; until the Londoners rubbed their eyes and asked each other what had become of their ancient grounds—especially the delightful fields called the Moor, on whose shallow ponds they skated and slid in winter, and where they practised the long bow, while the elders looked on, in the summer. They were gone: in their place were fields hedged and ditched, with narrow lanes in which two people might walk abreast. How long they looked on considering this phenomenon we know not. At length, however, the pent-up waters overflowed. “Suddenly this yere” (1514) a great number of people assembled in the City, and a “Turner” attired in a fool’s coat ran about among them crying, “Shovels and Spades.” Everybody knew what was meant. In an incredibly short time the whole population of the City were outside the walls, armed with37 shovels and spades. Then the ditches were filled in, and hedges cut down, and the fields laid open again. The King’s Council, hearing of the tumult, came to the Grey Friars and sent for the Mayor to ascertain the meaning, for a tumult in the City might become a very serious thing indeed. When, however, they heard the cause and meaning of it they “dissimuled” the matter with a reasonable admonition to attempt no more violence, and went home again. But the fields were not hedged in or ditched round any more.

In 1532 there was held a general Muster of all the citizens aged from sixteen to sixty. The City, never slow to display its strength and wealth, turned out in great force. The men mustered at Mile End, probably because it was the nearest place which afforded a broad space for marshalling the troops. They were dressed in white uniforms with white caps and white feathers; the Mayor, Sheriffs, Aldermen, and Recorder wore white armour, having black velvet jackets with the City arms embroidered on them, and gold chains. Before each Alderman marched four halberdiers, each with a gilt halberd. Before the Lord Mayor marched sixteen men in white satin jackets, with chains of gold and long gilt halberds; four footmen in white satin; and two pages in crimson velvet, with gold brocade waistcoats; two stately horses carrying, the one the Mayor’s helmet, the other the Mayor’s pole-axe.

All citizens of distinction on such occasions wore white satin jackets and gold chains. The vast expenditure of money on a single day’s pageant such as this, was quite common at this time and in the preceding age. It may perhaps be explained by certain considerations. Thus: it was an age of great show and external38 splendour; the magnificence of dress, festivals, masques, ridings, and pageants, is difficult to realise in this sober time. Wealth, rank, position, privileges, were in fact marked by display. We have seen the splendour of the Baron who rode to his town house with an army of 500 followers all richly dressed. And it has been observed that it was not wholly the mere love of magnificence that caused a nobleman or an ecclesiastic to keep up this great state. So, in preparing this martial show, with 15,000 men of arms all fully and richly equipped, the Mayor and Aldermen intended to illustrate to the King and his Ministers the power of the City, the wealth of the City, and the resolution of the City to defend their liberties. And I have no doubt that this intention was thoroughly understood by Henry and taken to heart. The March began at nine in the morning. The troops marched through Aldgate, through the City, and so to Westminster by Fleet Street and the Strand—a little over four miles. At five in the evening the last company marched past the King. That part of the business therefore must have lasted about six hours.