TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book.

BY

WILLIAM E. ROBINSON

Assistant to the late Herrmann

SIXTY-SIX ILLUSTRATIONS

MUNN & COMPANY

SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN OFFICE

New York City

1898

Copyrighted, 1898, by Munn & Company.

All rights reserved.

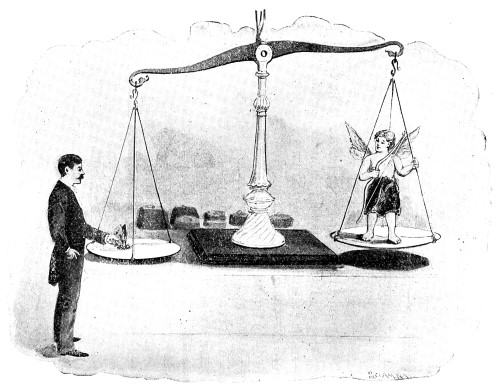

The author of the present volume is not an opponent of spiritualism—on the contrary, he was brought up from childhood in this belief; and though, at the present writing, he does not acknowledge the truth of its teachings, nevertheless he respects the feelings of those who are honest in their convictions. At the same time he confidently believes that all rational persons, spiritualists as well as others, will heartily indorse this endeavor to explain the methods of those who, under the mask of mediumship, and possessing all the artifices of the charlatan, victimize those seeking knowledge of their loved ones who have passed away. As a great New York lawyer once said, it was not spiritualism he was fighting, but fraud under the guise of spiritualism.

Owing to the fact that the author has for many years been engaged in the practice of the profession of magic, both as a prestidigitateur and designer of stage illusions for the late Alexander Herrmann, and has also been associated with Prof. Kellar, he feels[iv] that he is fitted to treat of clever tricks used by mediums. He has attended hundreds of séances both at home and abroad, and the present volume is the fruit of his studies.

Some of the means of working these slate tests may appear simple and impossible of deceiving, but in the hands of the medium they are entirely successful. It should be remembered it is not so much the apparatus employed as it is the shrewd, cunning, ever-observing sharper using it. The devices and methods employed by slate writing frauds seem innumerable. No sooner are they caught and exposed while employing one system than they immediately set their wits to work and evolve an entirely different idea. It is almost impossible at the first sitting with a slate writing medium to know what method he will employ, and should you, after the sitting, go away with the idea that you have discovered his method of operation and come a second time ready to expose him, you may be sadly disappointed, for the medium will undoubtedly lead you to believe he is going to use his former method, and so mislead you. He accomplishes his test by another method, while you are on the lookout for something entirely different. The great success of the medium is in disarming the suspicions of the skeptic, and at that very moment the trick is done. Slate writing is of course the great standby of[v] mediums, but there are many other tricks which they employ which are described in the present volume.

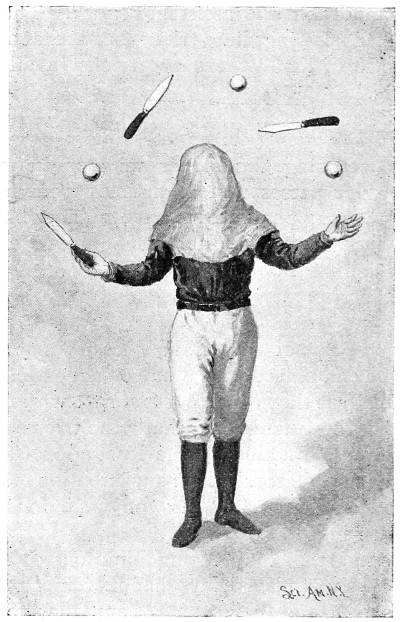

The publishers have added a chapter on “Miscellaneous Tricks” which may serve as a supplement to their “Magic: Stage Illusions and Scientific Diversions, Including Trick Photography,” which has already obtained an enviable position in the literature of magic, and has been even translated into Swedish. These tricks are by Mr. W. B. Caulk and the author.

New York, November, 1898.

| Chapter I. | |

| PAGE | |

| The Single Slate | 3 |

| Chapter II. | |

| The Double Slate | 32 |

| Chapter III. | |

| Miscellaneous Slate Tests | 41 |

| Chapter IV. | |

| Mind Reading and Kindred Phenomena | 51 |

| Chapter V. | |

| Table Lifting and Spirit Rapping | 71 |

| Chapter VI. | |

| Spiritualistic Ties | 82 |

| Chapter VII. | |

| Post Tests, Handcuffs, Spirit Collars, etc. | 93 |

| Chapter VIII. | |

| Séances and Miscellaneous Spirit Tricks | 101 |

| Chapter IX. | |

| Miscellaneous Tricks | 115 |

SPIRIT SLATE WRITING

AND

KINDRED PHENOMENA.

There has probably been nothing that has made more converts to spiritualism than the much talked of “Slate Writing Test,” and if we are to believe some of the stories told of the writings mysteriously obtained on slates, under what is known as “severe test conditions,” that preclude, beyond any possible doubt, any form of deception or trickery, one would think that the day of miracles had certainly returned; but we must not believe half we hear nor all that we see, for the chances are that just as you are about to attribute some unaccountable spirit phenomena to an unseen power, something turns up to show that you have been tricked by a clever device which is absurd in its simplicity.

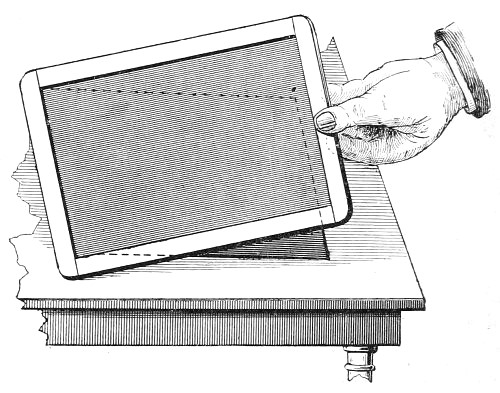

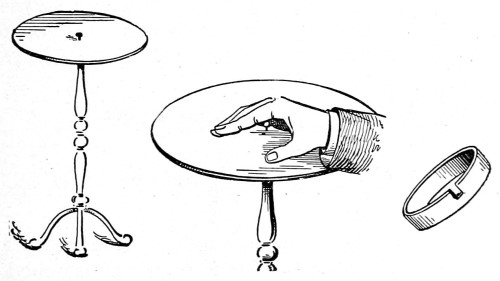

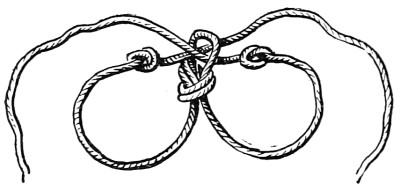

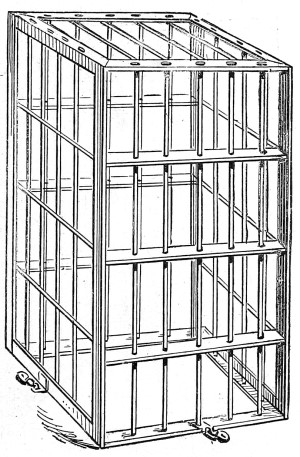

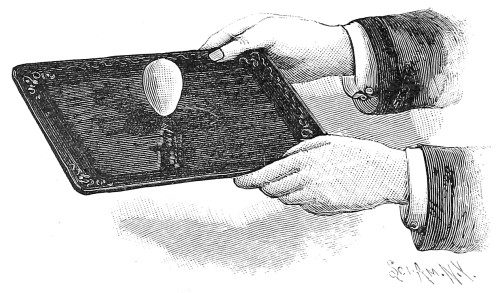

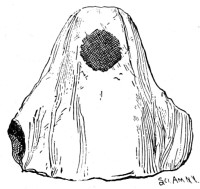

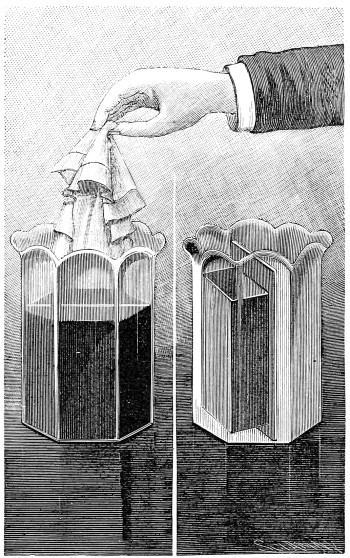

There are a large number of methods of producing slate writing, but the writer will describe a few which will be sufficient to give an idea of the working of slate tests in general. First we have the ordinary one in which the writing is placed on the slate beforehand, and then hidden from view by a[4] flap or loose piece of slate. (Fig. 1.) After both sides of the slate have been cleaned, the false flap is dropped on the table, the side which is then uppermost being covered with cloth similar to the table top, where it will remain unnoticed, or the flap is allowed to fall into a second slate with which the first is covered. In the latter case no cloth is pasted on the flap. Sometimes the flap is covered with a piece of newspaper and is allowed to drop into a newspaper lying on the table, then the newspaper containing the flap is carelessly removed, thus doing away with any trace of trickery.

Another way of utilizing the false flap is as follows: The writing is not placed beforehand on the slate, but on the flap, which, as before, is covered with the same material as the table top. This is[5] lying on the table writing downward. The slate is handed around for inspection, and, on being returned to the performer, he stands at the table and cleans the slate on one side, then turns it over and cleans the other. As he does so he lifts the flap into the slate. The flap is held in firmly by an edging of thin pure sheet rubber cemented on the flap between the slate and the cloth covering of the slate. This grips the wooden sides of the frame hard enough to prevent the false piece from tumbling out accidentally.

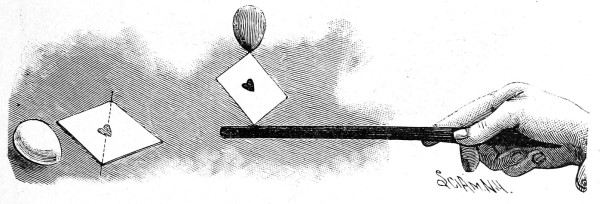

We now come to another style, wherein a slate is cleaned on both sides, and, while held in the hand facing the audience, becomes suddenly covered with writing, and the slate is immediately given for inspection. The writing is on the slate previous to the cleaning, and is hidden from view by a flap of slate colored silk, held firmly in place by a pellet of wax in each of the corners of the silk. Attached to this silk flap or covering (at the end that is nearest to the performer’s sleeve) is a stout cord or string, which is also made fast to a strap around the wrist of the hand opposite to that holding the slate. If the arms are now extended their full length, the piece of silk covering will leave the slate and pass rapidly up the sleeve out of the way, and thus leave the writing exposed to view. (Fig. 2.) The slate is found to be still a little damp from the cleaning with the sponge and water it had been given previously. This is easily accounted for. The water from the sponge penetrates just enough through the cloth to dampen the slate.

There is still another slate on which we can make[6] the writing appear suddenly. It is composed of a wooden frame, such as all wooden-edged slates have, but the slate itself is a sham. It is a piece of cloth painted with a kind of paint known as liquid, or silicate slating, which, when dry and hard, is similar to[7] the real article. This cloth is twice the length of the slate and just the exact width. The two ends of the cloth are united with cement, so as to make an endless piece or loop. There is a small rod or roller in both the top and bottom pieces of the frame, the ends being made hollow to receive them. Over these rollers runs the cloth, stretched firmly and tightly. Just where the cloth is joined or cemented is a little black button, or stud of hard rubber or leather. This allows the cloth to be pushed up and down, bringing the back to the front; and by doing so quickly, the writing which is written on the cloth at the rear of the frame is made to come to the front in plain view. (Fig. 3.)

Still another idea in a single slate is as follows: An ordinary looking slate is given out for examination, and, on its being returned to the medium, he takes his handkerchief and cleans or brushes both sides of the slate with it; and, upon again showing that side of the slate first cleaned, it is found covered with writing apparently done with chalk. The following is the simple explanation of it: Take a small camel’s hair brush and dip it in urine or onion juice, and with it write or trace on the slate whatever you desire, and when it becomes[8] dry, or nearly so, the slate can be given for examination without fear of detection. The handkerchief the performer uses to clean the slate with is lightly sprinkled with powdered chalk. He makes believe to clean the one side devoid of preparation, but the side containing the invisible writing is gently rubbed with the handkerchief, not too hard just enough to let the powdered chalk fall on the urine or onion juice, where it leaves a mark not unlike a chalk mark.

It will not be out of place to describe a trick by which writing is produced upon an ordinary china plate by a somewhat similar means. The plate is examined and cleaned with a borrowed handkerchief, and then the performer requests the loan of a pinch of snuff, or uses a little sand or dust, which he places on the plate. He now commences to move the plate around in circles, and while doing so the snuff or sand is seen to gradually form itself into writing. The explanation is simple—whatever writing you desire to appear on the plate is placed beforehand on it. It is done with a camel’s hair brush dipped in the white of an egg and allowed to become dry before being handed around for inspection. As the performer cleans the plate he breathes on both sides of it, as if to give it moisture enough to help take off any dirt that might be thereon when rubbed with the handkerchief. In breathing on the front of the plate containing the writing done with the white of the egg, he moistens the writing enough to make the snuff or sand, as the case may be, adhere to it. Of course, in cleaning the front of the plate, care must be taken not to brush or disturb the invisible writing.

It may not be amiss to also mention another method of producing writing, employed by mediums to obtain a message on a blank piece of paper which has been placed between two slates, which are held by the medium in his hand, high above his head, and, on afterwards taking the slate apart, the paper is covered with writing. This again calls into use the extra or false flap. (Fig. 1.) A piece of paper with writing on it is placed face downward on one of the slates and covered with the false flap. It then looks like an ordinary slate. On this is placed the plain piece of paper, and over this is laid the second slate. The slates are now held up in plain view of the audience, and on being lowered to the table they are turned over, thus bringing the blank piece of paper under the false flap and the one with the writing on it on the top of the flap, which has fallen from the slate, which is now the top, but originally the bottom one, on or into the under one, and, of course, on the removal of the present top slate, the writing is found on what is supposed to be the original blank paper.

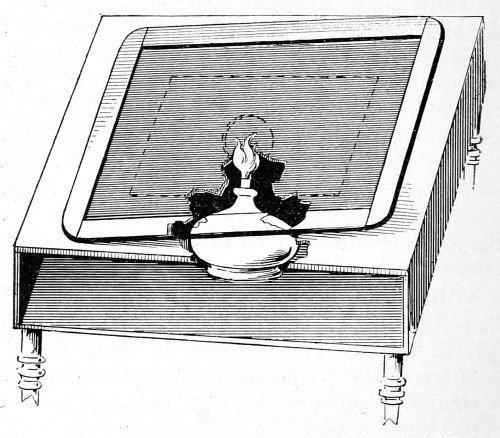

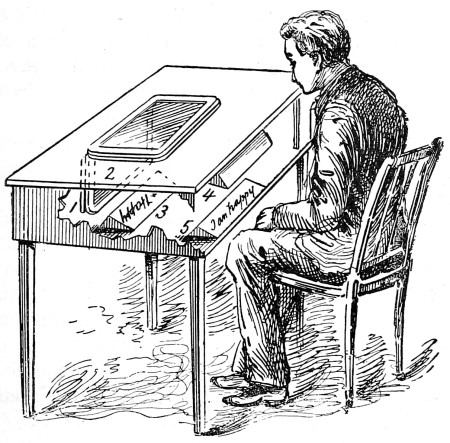

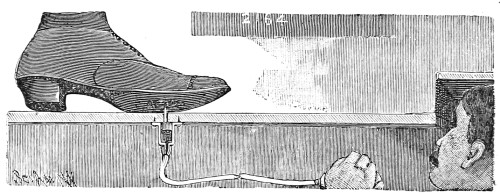

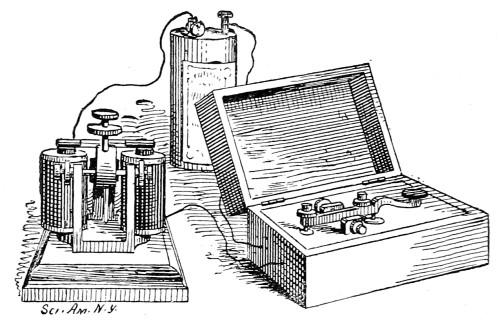

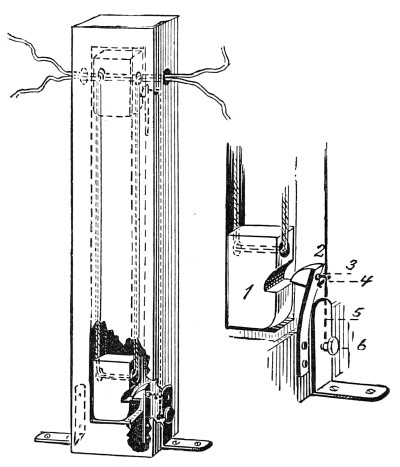

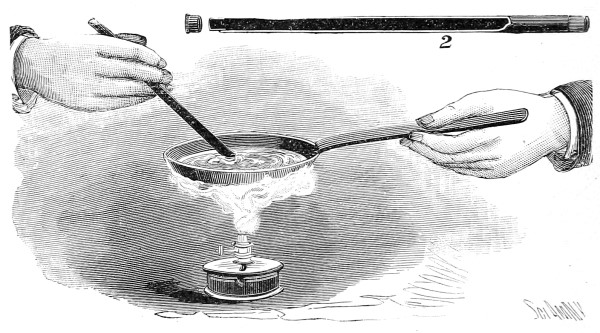

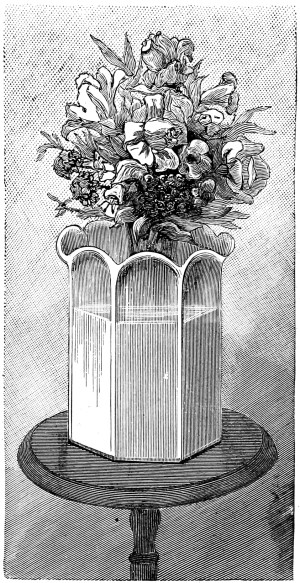

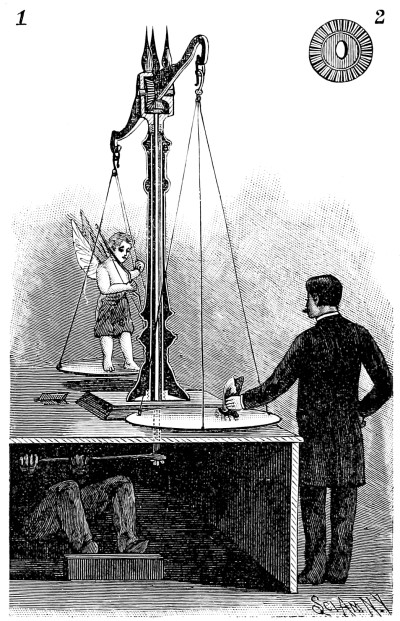

If the paper is to have a private mark put on it by an observer, so as to prove the writing really does appear on that identical piece of paper, the operation is varied as follows: The false flap is done away with, and the paper, which is furnished by the medium, has written on it the desired communication with ink, which is made visible and brought out black by means of heat. For the invisible ink you can use sulphuric acid, very much diluted, so as not to destroy the paper. The necessary heat is obtained in the following manner: The table (Fig. 4) on which[10] the slates are resting is hollow, and has concealed in it a spirit lamp filled with alcohol. This lamp sits directly under a trap in the table top, which is covered underneath for safety with sheet iron, so it will not catch fire. When the slates are placed on the table they are laid over the little trap door, which, in conjuring parlance, is known as a “trap.” This is now opened, and the slates allowed to become well heated and the trap then closed, and the prepared paper, upon coming in contact with the hot slate, is thus covered with writing.

Another medium employed a somewhat similar[11] method, only the paper in this case was placed in a glass vial (Fig. 5) which had been lying on the iron trap door. The medium’s hand covered the vial, which was corked and sealed, while the writing was making its appearance. You can also produce writing on the paper in the vial without resorting to the use of heat by using a vial that has been washed out with ammonia and kept well corked, and writing on the paper with a weak solution of copper sulphate, which is invisible until the paper is placed in the vial, when the two chemicals produce writing in blue. Still another message is produced as follows: The writing is done with iron sulphate on blank cards. Of course this is invisible. These cards are placed in envelopes and sealed up. Upon opening the envelopes shortly afterward the cards are covered with the writing which was before invisible, but is brought out by a solution of nut galls with which the inside of the envelopes had been slightly moistened.

The subject of sympathetic inks is such an interesting one that we give thirty-seven formulas, which include all those which are liable to be used by the medium.

The solutions used should be so nearly colorless that the writing cannot be seen till the agent is applied to render it visible. Sympathetic inks are of three general classes.

1. Write with a concentrated solution of caustic potash. The writing will appear when the paper is submitted to strong heat.

2. Write with a solution of ammonium hydrochlorate, in the proportion of 15 parts to 100. The writing will appear when the paper is heated by holding it over a stove or by passing a hot smoothing iron over it.

3. A weak solution of copper nitrate gives an invisible writing, which becomes red through heat.

4. A very dilute solution of copper perchloride gives invisible characters that become yellow through heat.

5. A slightly alcoholic solution of copper bromide gives perfectly invisible characters which are made apparent by a gentle heat, and which disappear again through cold.

6. Write upon rose colored paper with a solution of cobalt chloride. The invisible writing will become blue through heat, and will disappear on cooling.

7. Write with a solution of sulphuric acid. The characters will appear in black through heat. This ink has the disadvantage of destroying the paper. (See the caution given on page 9.)

8. Write with lemon, onion, leek, cabbage or artichoke juice. Characters written with these juices become very visible when the paper is heated.

9. Digest 1 oz. of zaffre, or cobalt oxide, at a gentle heat, with 4 oz. of nitro-muriatic acid till no more is dissolved, then add 1 oz. common salt and[13] 16 oz. of water. If this be written with and the paper held to the fire, the writing becomes green, unless the cobalt should be quite pure, in which case it will be blue. The addition of a little iron nitrate will then impart the property of becoming green. It is used in chemical landscapes for the foliage.

10. Put in a vial ½ oz. of distilled water, 1 drm. of potassium bromide and 1 drm. of pure copper sulphate. The solution is nearly colorless, but becomes brown when heated.

11. Nickel nitrate and nickel chloride in weak solution form an invisible ink, which becomes green by heating when the salt contains traces of cobalt, which usually is the case; when pure, it becomes yellow.

12. When the solution of acetate of protoxide of cobalt contains nickel or iron, the writing made by it will become green when heated; when it is pure and free from these metals, it becomes blue.

13. Milk makes a good invisible ink, and buttermilk answers the purpose better. It will not show if written with a clean new pen, and ironing with a hot flat iron is the best way of showing it up. All invisible inks will show on glazed paper; therefore unglazed paper should be used.

14. Burn flax so that it may be rather smoldered than burned to ashes, then grind it with a muller on a stone, putting a little alcohol to it, then mix it with a little gum water, and what you write, though it seem clear, may be rubbed or washed out.

15. Boil cobalt oxide in acetic acid. If a little common salt be added, the writing becomes green[14] when heated, but with potassium nitrate it becomes a pale rose color.

16. A weak solution of mercury nitrate becomes black by heat.

17. Gold chloride serves for forming characters that appear only as long as the paper is exposed to daylight, say for an hour at least.

18. Write with a solution made by dissolving one part of silver nitrate in 1,000 parts of distilled water. When submitted to daylight, the writing appears of a slate color or tawny brown.

19. If writing be done with a solution of lead acetate in distilled water, the characters will appear in black upon passing a solution of an alkaline sulphide over the paper.

20. Characters written with a very weak solution of gold chloride will become dark brown upon passing a solution of tin perchloride over them.

21. Characters written with a solution of gallic acid in water will become black through a solution of iron sulphate and brown through the alkalies.

22. Upon writing on paper that contains but little sizing with a very clear solution of starch, and submitting the dry characters to the vapor of iodine, or passing over them a weak solution of potassium iodide, the writing becomes blue, and disappears under the action of a solution of sodium hyposulphite in the proportions of 1 to 1,000.

23. Characters written with a 10 per cent. solution of nitrate of protoxide of mercury become black when the paper is moistened with liquid ammonia, and gray through heat.

24. Characters written with a weak solution of the soluble platinum or iridium chloride become black when the paper is submitted to mercurial vapor. This ink may be used for marking linen. It is indelible.

25. C. Widemann communicates a new method of making an invisible ink to Die Natur. To make the writing or the drawing appear which has been made upon paper with the ink, it is sufficient to dip it into water. On drying, the traces disappear again, and reappear by each succeeding immersion. The ink is made by intimately mixing linseed oil, 1 part; water of ammonia, 20 parts; water, 100 parts. The mixture must be agitated each time before the pen is dipped into it, as a little of the oil may separate and float on top, which would, of course, leave an oily stain upon the paper.

26. Write with a solution of potassium ferro-cyanide, develop by pressing over the dry, invisible characters a piece of blotting paper moistened with a solution of copper sulphate or of iron sulphate.

27. Write with pure dilute tincture of iron; develop with a blotter moistened with strong tea.

28. Writing with potassium iodide and starch becomes blue by the least trace of acid vapors in the atmosphere or by the presence of ozone. To make it, boil starch, and add a small quantity of potassium iodide in solution.

29. Copper sulphate in very dilute solution will produce an invisible writing, which will turn light blue by vapors of ammonia.

30. Soluble compounds of antimony will become red by hydrogen sulphide vapor.

31. Soluble compounds of arsenic and of tin peroxide will become yellow by the same vapor.

32. An acid solution of iron chloride is diluted till the writing is invisible when dry. This writing has the remarkable property of becoming red by sulphocyanide vapors (arising from the action of sulphuric acid on potassium sulphocyanide in a long necked flask), and it disappears by ammonia, and may alternately be made to appear and disappear by these two vapors.

33. Writing executed with rice water is visible when dry, but the characters become blue by the application of iodine. This ink was much employed during the Indian mutiny.

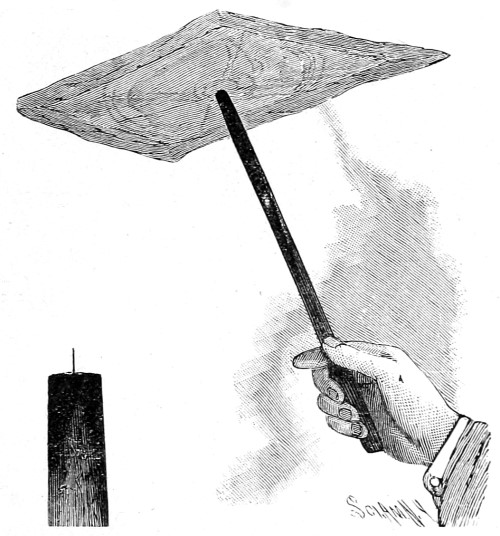

34. Write with a solution of paraffin in benzol. When the solvent has evaporated, the paraffin is invisible, but becomes visible on being dusted with lampblack or powdered graphite, or smoking over a candle flame.

35. To Write Black Characters with Water.—Mix 10 parts nutgalls, 2½ parts calcined iron sulphate. Dry thoroughly, and reduce to fine powder. Rub this powder over the surface of the paper, and force into the pores by powerful pressure, brush off the loose powder. A pen dipped in water will write black on paper thus treated.

36. To Write Blue Characters with Water.—Mix iron sesquisulphate and potassium ferrocyanide.[17] Prepare the paper in the same manner as for writing black characters with water. Write with water, and the characters will appear blue.

37. To Produce Brown Writing with Water.—Mix copper sulphate and potassium ferrocyanide. Prepare the paper in the same manner as before. The characters written with water will be reddish brown.

Here is another trick calling for the use of sympathetic ink. A medium suggests a number of questions to write on a paper, one of which you select and write on a slip of paper furnished by the medium. Writing is done with pen and ink. You are requested to dry it with a blotter, and not to remove the blotter for a time, the medium says, so as to keep the paper in the dark, thus giving the “spirits” better conditions under which to work. After a while the blotter is removed, and an answer to the question is found on the same paper. The questions suggested were all of such a character that one answer would nearly do for any one. The paper the question was written on had this answer written with invisible ink brought out by a reagent on the blotter, with which it was saturated, and thus another mystery is easily dispelled.

We will now take up a few slate tests, in which the slates are brought or furnished by the spectator or investigator. The tests in which the slates are brought by skeptics and tied and sealed by them, and still writing is obtained upon them, are the ones that are the most convincing and most talked about, and they are offered to the unbeliever as proof absolute of spirit power.

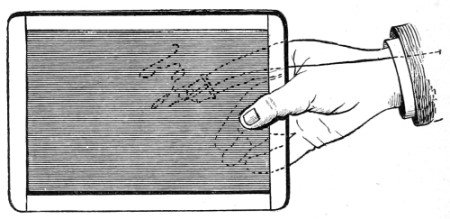

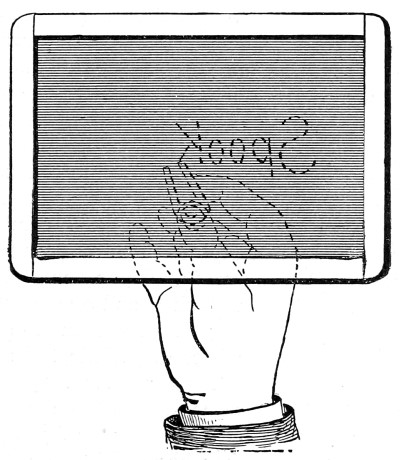

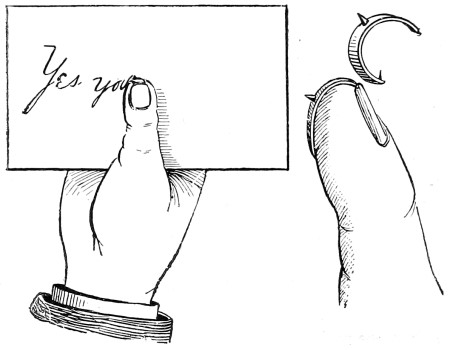

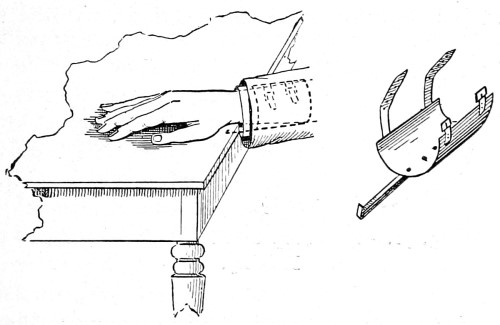

First we will begin with the single slate which has just been handed to the medium, after being thoroughly cleaned by the person bringing it. The skeptic holds one end of the slate in one hand and the medium the opposite end in one of his hands, and both persons clasp their disengaged hands. In a short time the slate is turned over and a few words written in a scrawling style are found. I must acknowledge that when I first witnessed this test it somewhat staggered me, but afterward, on seeing it the second time, I was enabled to fathom its mystery. It is patterned somewhat after the style claimed to have been used by Slade, wherein he used a piece of slate pencil fastened to a thimble, and with apparatus attached to his forefinger of the same hand holding the slate he did the writing. The thimble (Fig. 6) was fastened to an elastic which pulled the thimble out of sight up the sleeve or under the coat when it was done with. But it always required a little scheming and maneuvering both to use and conceal the device and get rid of it, and there was[19] always the fear of being detected with this bit of machinery about the person; so someone of an ingenious turn of mind hit upon another method. There are some slate pencils made the same as lead pencils, that is, a very small piece of slate pencil, about the size of a match, is enclosed in the wood after the manner of lead pencils. A tiny piece of this pencil is placed at the tip of the forefinger and over it is placed a piece of flesh-colored court plaster well fastened to the finger (Fig. 7) and well blended in with aniline dye with the finger, so both are exactly the same color. After everything becomes dry and hard a little hole is made in the court plaster, so as to allow the point of the piece of pencil to come through enough to mark on the slate. The finger thus prepared is what does the writing. The message or name must be written backward, so that when the slate is reversed it will appear in its correct position. To learn to do this quickly, stand in front of a looking-glass with the slate in your hand and watch your writing in the glass as you go along. You do not need to hold the slate underneath the table in this test; hold it in the air with a handkerchief over it, so as to disguise the movement of the[20] finger. The message must necessarily be short, on account of the radius through which the medium’s finger can travel.

We now come to another method of using the single slate. The medium takes the slate and places it on the table and requests the spectator to write a question on a piece of paper. He, the medium, gains knowledge of the contents of the paper in various ways; one is by using a pad of paper which contains underneath the second or third layer of paper a carbon sheet made of wax and lampblack. Whatever is written on the first sheet of paper will be transferred or copied by means of the carbon paper to the sheet underneath it. Another way is by requesting a person to fold the paper and hold it against his head, and, under the pretense of showing the person how to hold it, exchange it for a paper of his own folded in like manner. This exchanged paper is then opened and read by the medium while his hand is below the level of the table top, and while he is holding a conversation with the auditor. After it is read, the paper is again folded and kept in the performer’s lap until needed. As he now knows the contents of the paper, he can frame in his mind a suitable answer. He remarks: “I will ask the spirits first to give you a decided answer, through me as an independent trance slate writing medium, whether they will answer your question during this sitting.” So the medium takes a pencil in hand and writes on one side of the slate, apparently under spirit control, and then on the other side. The message is read, and it says the conditions are very favorable,[21] and no doubt, if the skeptic will place the utmost confidence in the medium, there will be satisfactory results. After the slate has been shown with both sides covered with writing, it is thoroughly cleaned and placed on the table. The medium now picks up the original paper from his lap and asks the person to give him the paper he is holding. This the medium apparently places under the slate; however, he really holds this one back and introduces the one he has had in his hand, which is the one originally written upon. He has now his own paper in his hand, and the one with the question is under the slate. On the slate being turned over in a short time, it is covered with writing, forming a sensible reply to the question on the paper, which is now opened and read to compare it with the answer. All that remains to be explained is how the writing on the slate appeared there. The false flap is again used, but in a directly opposite manner to which it has been employed heretofore. One side of this flap is covered with a portion of the writing that the medium first wrote under spirit control. Let us say the first half supposed to have been written on the one side of the slate, and which he afterward reads off in connection with that written on the last or second side of the slate. What he really wrote on the first half of the slate was a correct answer to the question, and after he turns the slate over to write on the opposite side he slips the false flap over the answer on the slate. Of course it is what is on this false flap and on the other side of the slate that the spectator really reads, and when the slate is cleaned it is this flap and the opposite side of the slate. The[22] writing, covered by the flap, which is the answer to the question, is never seen or touched until after the flap is allowed to drop into the medium’s lap. The slate can be examined; and, of course, no trickery can be found in connection with it. The method described above, in the hands of a calm and cool person, is a convincing one, and never fails to satisfy the most exacting of skeptics.

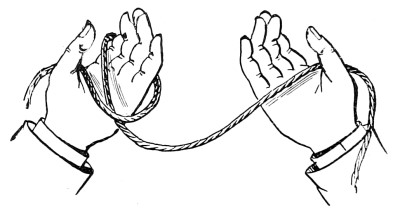

I wish to remark that, if any person tells you he took two slates of his own to a medium, thoroughly well tied or sealed, and that the slates never left his (the skeptic’s) hands, and that there was writing obtained upon the interior surface of the slates under those conditions, he was sadly mistaken, and has failed to keep track of everything that actually took place at the time of the sitting. Suppose two slates tied together are brought to the medium. Both he and the stranger sit at a table. The slates are held under the table, the medium grasping one corner and the skeptic the opposite corner, each with one hand, and the disengaged hands clasped together above the table. After a while the slates are laid upon the table, the string untied, the slates taken apart, but no writing is found. The medium states it must have been because there was no slate pencil between them. So a small piece of pencil is placed between the slates, and again they are tied with the cord by the medium, and he again passes them under the table, both persons holding the slates as before. Presently writing is heard, and, upon the skeptic bringing the slates from under the table and untying the cord himself, he finds one of the slates covered with writing, although but shortly[23] before they were devoid of even a scratch. Here is the explanation: The medium does not pass the slates under the table the first time, but drops them in his lap, with the side on which the string is tied or knotted downward, and really passes a set of his own for the skeptic to hold; he (the medium) supporting his end by pressing against the table with his knee, which leaves his hand disengaged. There is a slate pencil, called the soapstone pencil, which is softer than the ordinary. This is the one used by the medium. He now covers the face of the slate which is uppermost in his lap with writing, doing so very quietly and without any noise. Now, as he brings the slates above the table, he leaves his own in his lap and brings up the skeptic’s with the writing side down. The slates are untied and taken apart and shown, devoid of writing upon the inside, which he claims was caused by not having any slate pencil inside. The medium now places the pencil upon the slate which was originally the upper one, and covers this with what was the bottom slate, which is covered with the writing inside on the back or bottom of slate. This maneuver or action brings the slate on top with the writing upon its inside. Nothing could be more simple and natural. The slates are again tied together, and in doing so the slates are turned over, bringing the slate containing the writing, still upon the inside, at the bottom instead of the top, and the string tied or knotted above the top slate. Of course, when again separated, the writing is found upon the inside of the lower slate. When the slates are passed under the table the second time, the spectator himself is allowed to do this, and the medium, with one of his finger[24] nails, while holding his end of the slate, produces a scratching noise on the slate closely resembling the tracing of a pencil. It is not really necessary to pass the slates under the table the second time, but they can be held above it if preferred.

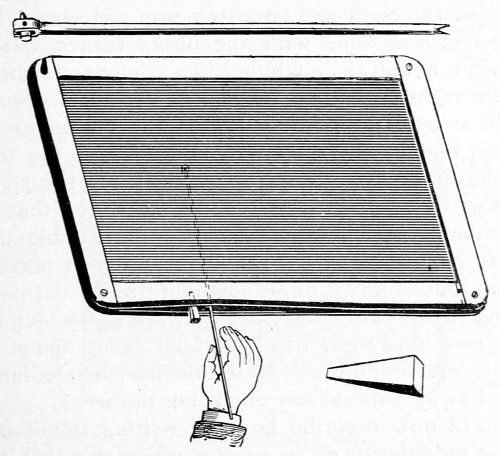

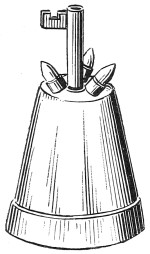

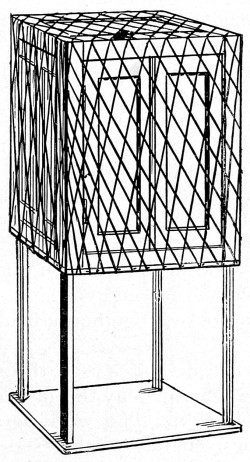

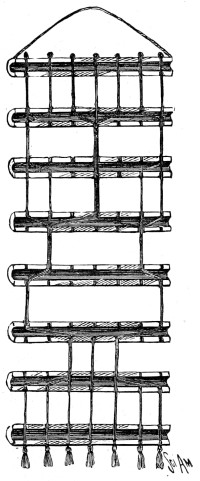

Now, suppose two slates are brought that are riveted or screwed or sealed at the four corners. How can writing be obtained upon them without disturbing any of the above arrangements? The slates are held under the table in the same manner as in previous tests. To produce the writing upon the slates the medium is provided with a few simple, though effective devices, one of which is a little hard wood tapering wedge, and a piece of thin steel wire, to one end of which is fastened a tiny piece of slate pencil. An old umbrella rib will be found to work admirably, because there is a small clasp at one end and at its other end a small eye. The pencil is made to fit into the end with the clasp. Now take the wooden wedge and push it between the wooden frames of the slates at the sides. The frames and slates will give enough to allow the wire and pencil to be inserted and the writing be accomplished with it, after which the wire is withdrawn, and then also the wooden wedge, and all is done without leaving any trace or mark behind as to how it is all performed. (Fig. 8.)

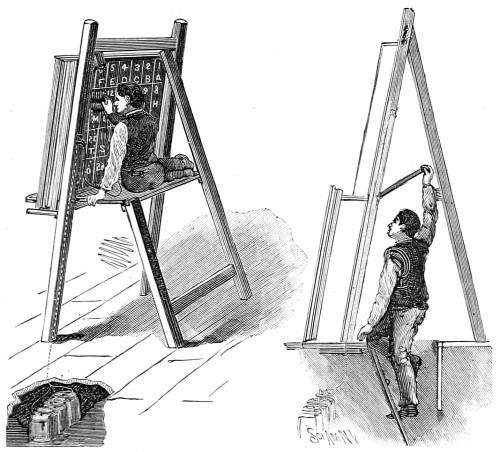

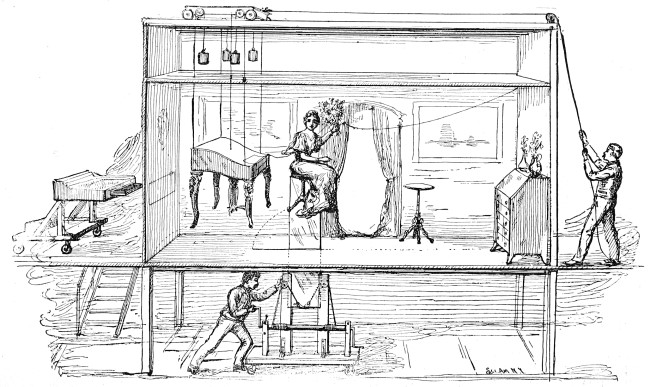

A well known conjuror at one time made a remark that he could duplicate any slate writing test he ever witnessed, he having publicly declared, time and time again, the slate writing test to be a fraud. He gave a test in private at his own home and hit upon a rather unique idea. A slate would be cleaned[25] on both sides and a private mark placed on it, and the slate allowed to lie flat on the table, and the magician and the committee sat around it and placed their hands upon the slate. Presently writing was heard, and upon lifting the slate the side underneath was found covered with writing. The table was a kitchen table with the ordinary hanging cloth cover, or table cloth. The table had a double top with room enough between the two to conceal a small boy. There was a neatly made trap in both the table cloth and the top of the table; the cloth being glued around the opening to keep it in place. The trap door opened downwards. The boy concealed[26] in the table opened the trap door and did the necessary writing on the slate, and closed the opening. The idea of having the committee hold their hands on the slate was to prevent the slate from being accidentally moved by the boy when writing. The above idea was improved upon by doing away with the use of the boy and the double top of the table. The trap in the cloth and table top was still used. But the test was done with the lights turned out or down low, and the medium had a confederate sitting at his right hand side. This allowed the medium to take away his right hand, introduce it under the table, open the trap, do the writing, shut the trap, replace his hand, and on the lights being turned up the writing is found. It should be stated that the medium and committee sat around the table with their hands resting on the slate, and each person’s hand touching that of his neighbor; so neither could move without the other being aware of the fact, but the medium’s right hand neighbor, being one of his confederates, allows him to take his (the medium’s) hand away without any one being the wiser.

I will now describe how the writing is obtained upon the interior of two slates sealed together, and all hands placed on them, and without the assistance of a confederate. The table is the same as previously described, that is, it contains the trap. The slates are two single ones hinged together and sealed around the edges in any manner the committee may see fit. One of the slates is a trick slate made in this fashion: The slate part itself is made to work on a pivot or hinge along one of its sides. (Fig. 9.) The side opposite to where both slates are hinged[27] together, by touching a portion of the hinges that hold the two slates together, a catch concealed in the wooden framework is released, which allows the slate part itself to drop down on its own hinge or pivot. So when the slates are placed on the table they are put directly over the trap in the table, and with the hinges of the two slates toward the medium. The medium, as he places the slates over the trap in the table, pushes the hinge releasing the catch, which allows the underneath slate to drop as far as the table. Now, when the trap in the table is opened, the slate opens or drops far enough for the medium to write on that part, also on the slate above it. He closes both the slate and the table, and the slates, upon being unsealed, are found covered with writing. The only thing that remains to be explained is how the medium gets his hand free to do the writing[28] without being detected. The lamp or gas jet is close to the medium’s right hand, where he can reach it. Now, all the persons are seated around the table with their hands on the slates, and each other’s hands or fingers touching one another. The medium takes his right hand away to turn down the light, and his next door neighbor, as soon as the light goes out, feels his (the medium’s) hand or finger replaced. At least, so he thinks. What really happens is this: The thumb of the medium’s left hand is stretched far enough over to touch the hand or finger of the person sitting on the performer’s right hand side. (Fig. 10.) The medium immediately goes to work and produces the writing, and when finished, just as he goes to relight the gas or lamp, he removes the left thumb to create the impression that he has just taken his right hand away again for the light.

Here is a trick I once saw a medium do. He[29] had a number of slates piled on top of the table; he would clean these, one at a time, showing each, and after they had been thoroughly examined, he placed them on the floor. He would then pick them all up together and replace them on the table, and select two of them, put them together, holding them in his hand above his head, would shortly separate them and show one covered with writing. The slates were devoid of all trickery, as was easily proved in allowing them to be thoroughly examined.

The explanation is as follows: The floor was covered with carpet. In this there was a slit or cut just large enough to pass or draw a slate through. A slate with writing on one side is previously placed under the carpet, with that side down. (Fig. 11.) The slates, as they are cleaned, are laid on the carpet[30] immediately over or near this concealed one, and, on lifting the slates from the floor, this one is also carried with them, and all placed on the table.

Of course, it is this slate and one of the prepared ones that are afterward used. There is little likelihood of any one taking notice of there being one more slate in the pile.

Some mediums use two single slates, and, after cleaning them on both sides, hold one in each hand. They sit a little way from the table and place the right hand, with the slate, under the chair, as if to draw the chair closer to the table. What the medium really accomplishes is an exchange of slates. There is a little shelf, or drawer, under the seat of the chair. On this lies a slate, one side of which is prepared with writing. The medium picks up the slate and leaves behind in its place the one held in his right hand as he moves the chair. This is a method used to a considerable extent and always successfully.

The following is a clever ruse, ofttimes used by mediums to destroy all traces of the use of the false flap when it is employed. It is the test where the flap is used to cover the writing on one slate, and then that slate is covered with another. Now, if the slates are turned over or reversed, the writing is uncovered and the flap remains in the opposite or underneath slate. Now, to get rid of that flap, the medium deliberately presses his knee against that slate, breaking not only the slate, but also the flap contained in it. The broken flap mingles in with the broken slate, and nobody is any the wiser. Nobody for a moment thinks of picking up the pieces[31] to see if there are one or more slates. Of course, when the slates are broken, it is done secretly under the table, and the medium remarks: “The spirit force is so strong it has smashed the slate.” A test with a single slate that I once saw done was rather neat in its way, and I think it worth describing. The slate was examined and cleaned on both sides, and placed on a small table covered with a little fancy cloth. On lifting the slate afterward, its underneath side was found with writing on it. The top of the table was no larger than the slate. When the slate was laid on the table, the medium remarked: “To convince you there is no trickery about the table, I will remove the cloth;” which he did, with the slate still on or in it, and then replaced the slate and cloth. Now, on this table top was resting another slate covered with writing on one side, and that side upward, and this covered with the table cloth. When the medium picked up the cloth and the slate, which had just been cleaned, he also carried along the second slate with it, which was under the cloth, and in replacing the cloth he simply reversed the sides, laying the first slate on the table, where it was covered by the cloth, and the second one was thus brought to view. It is astonishing how such barefaced and simple devices will deceive the spectator. It is the boldness and air of conviction of his assertions that carry a medium’s test successfully through.

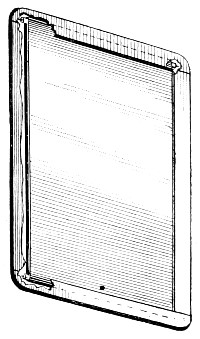

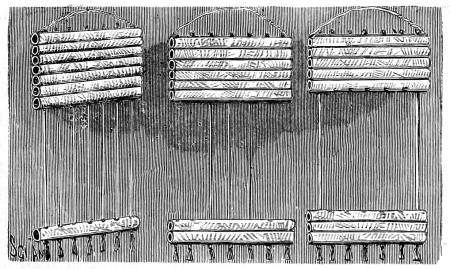

We now come to a slate called by the mediums “The double slate.” It is, to all appearances, two ordinary slates hinged together at one side and locked with a padlock, the shackle of which passes through a hole in the sides of the frame of each slate. This slate also contains the false flap or slate, but the slate or flap is held firmly in each frame as follows: The inside edges of both ends of each frame of the slates are beveled inward a trifle. One of these ends of each slate frame is also made to slide or pull out about one-quarter of an inch. These are prevented from sliding until wanted by the medium by a catch in the framework, which is connected with a screw in one of the hinges. This screw stands a little higher than the rest, so as to be easily found. The hinges are on the outside of the frame instead of inside. By pressing this screw it undoes the catch, which allows the ends to be moved a trifle. The false flap is just large enough to fill in the space under the bevels of the frame, and if, in the top frame, the catch is released and the end moved, the flap will drop into the bottom slate, where it is held tight and firm by releasing the catch in that frame, moving the end until the flap settles into its place and then sending the end back into its original place again. The writing is placed beforehand on one side of the flap and on one slate, both the written sides face to face, and after the flap has changed slates it presents two slates with written sides.

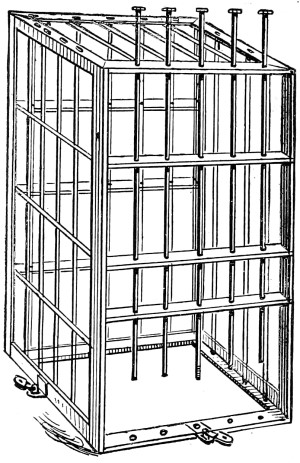

There is still another double slate used with hinges and padlock. (Fig. 12.)

One of the ends of the wooden frame of one slate is fastened securely to its slate, which is made to slide out completely from the groove in the frame. This allows the insides of both slates to be written upon. After that is done the slate is slid back into its frame. Care should be taken, in sliding the piece back, not to reverse it so as to bring the writing side out. The best way is not to pull the slate completely out, and write upon the inside of the stationary slate, and then reverse the slates, which will bring the inside of the movable slate into view. Write on that and then close the slate.

I have seen a medium use the double or folding slate and get rid of the false flap in this way: He used a pair of small slates. These he opened out with the flat side towards the audience, and while in his hand, cleaned those two sides away from the table. He now showed the reverse sides and cleaned them[34] likewise. He now closed the slates, but toward him, instead of away from him, holding them close to his body, and as he does so, the false flap, by this movement, slips easily and unperceived beneath his coat or vest.

I once witnessed a test which, for a time, completely nonplussed me, but, after considerable study and experimenting, I solved it.

This is the effect of the test: A person was allowed to bring two slates; he was to wash them himself and securely seal them in the presence of the medium, the medium placing, before the slates were sealed, a piece of chalk between them. The slates were sealed after this fashion: Around the whole length and width of the slates court plaster was stuck, and that was also sealed to the slates with sealing wax, making it an utter impossibility to insert a piece of wire, or like substance, between the slates. Nevertheless, the slates were held under the table and presently removed, unsealed, and writing in a very poor hand found upon the inner surface of one of the slates. It could hardly be called writing, being hardly more than a scrawl.

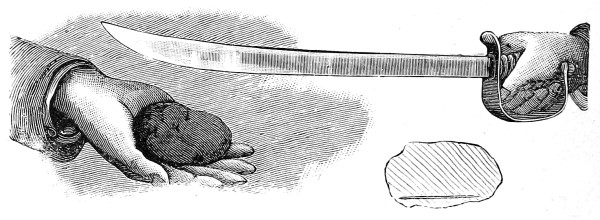

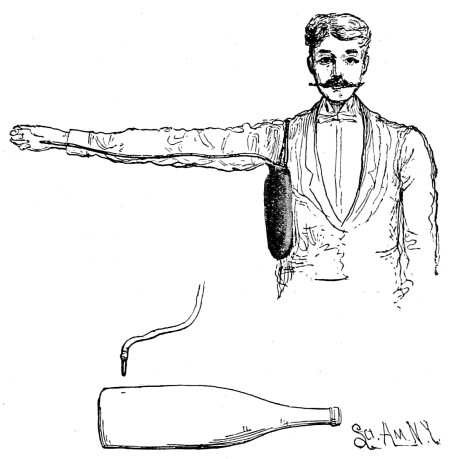

Now, how can this be accounted for? By one of the simplest devices imaginable. The medium placed the piece of chalk between the slates. This was composed of pulverized chalk, mixed with a little water, glue and iron filings, and allowed to become hard. The medium, while under cover of the table, traced with a magnet below the slate the words found upon the inside, but backward, the same as type is set for printing; if not, the writing on the slate will be in reverse. The chalk, on account of[35] the iron filings it contains, follows the direction of the magnet. (Fig. 13.)

We now come to another idea with two slates. Have two slates made with fairly deep wooden frames, deep enough to hold the slate proper and a false flap of slate. One made of silicate book-slate stuff is preferable. Your apparatus consists now of two slates and one false flap. The false flap is made to fit very tightly, so it will not fall out of its own weight. The slates in the frame also fit snugly. The frames are mortised out a little thicker than the slate, say twice as thick. This allows the slate to work backward and forward, from front to back, and[36] vice versa. If the slate is well pushed down and the flap placed on it, the flap will not fall out, but if you press the slate on the back forward, it shoves out the flap, and if it is covered with the other or second slate during this operation, it is forced into the second slate, which holds it firm and secure.

Another test, which was supposed to be convincing to skeptics, was one in which a double slate was used; it was hinged and provided with a lock in the wooden frame. The slates were examined, locked, and the key given to the skeptic. The skeptic was allowed to select from a number of pieces of colored chalk the color that he desired the message to be written in. Upon the slates being unlocked and opened, the writing is found in the color selected. While the slates are being examined, the medium seizes a duplicate key which fits the lock. (Fig. 14.) This key has a thimble attached to it which fits the performer’s right thumb; also attached lengthwise to the key are several small colored pencils or crayons of different lengths. When the slate has been examined, it is placed under the top of the table and held in position by the thumb of the right hand, which is underneath, and the fingers above the table. During this manipulation the thimble is placed on the thumb, and[37] the performer, with the key attached to it, opens the slate, using his knee to assist or support the slate. One part of the slate opens downward and rests on the knee, which holds it in position, i. e., at an incline, pressing it against the table top. On this part of the slate the writing is now done with the colored crayon selected, which are usually red, blue, green and white. When the color of the crayon is selected the performer turns the thimble around, bringing that color upward. Although not easy to execute, it is, nevertheless, a most surprising and effective test.

The above test was used by a medium very successfully for years in England and France, and was found out recently.

A test I once received was, I thought, quite clever. I was asked to write a question on a piece of paper furnished by myself and place it between two slates without the wooden frames. The medium said I would in a short time receive an answer. He then opened the slates, stating the answer must be there, but none was found. He remarked that perhaps we did not give the spirits time enough. So he replaced the slates together with the paper containing the question between. Again, on taking the slates apart, they were devoid of writing, but, strange to say, the answer in what looked like lead pencil was found on the paper containing the question. When the slates were removed the first time, the medium got a glimpse of the question on the piece of paper and then gave me one slate to examine, and apparently was looking at the other one himself. What he really was doing was this: On the side of the slate[38] toward him he was writing a brief answer to my question with a pencil composed of mutton tallow and lampblack pressed very hard. This pencil was attached to his thumb. He held the slate at the ends with both hands, thumbs behind and fingers in front, the writing being done backward. When the slates were replaced the writing, being black, was not seen against the black slate, and was placed immediately over the paper and the writing transferred to it. This is the reason the slates were used without the wooden frame, because with the frame the two slates would not come close together to press hard enough to transfer the answer.

A test, using a half dozen or so of slates, is as follows: Two slates are cleaned and examined and given to be held together by a skeptic, and the other slates cleaned on both sides and placed on the table. The medium now takes the two slates apart, but no writing is found; one slate is given to the skeptic and the other is placed on the table by the medium, who picks up another slate and places that with the one held by the unbeliever. After a short time the slates are again removed by the medium and no writing is found. As if in despair, the medium takes one slate away, placing it on the table, picks up another, showing both sides, places it with the one in the spectator’s hand, and in a little while the skeptic himself separates the slates and writing is found on one of them.

This method brings in use again the slate with a false flap. This slate is among the others on the table. The two slates first given to the individual to hold are all right when the medium takes one slate[39] away and places it on the table the first time and picks up another slate to place it with the one held by the skeptic. It is the flap slate, and this he places underneath the other slate and asks the skeptic to hold them. When the medium again separates the slates he turns them over, bringing the slate with the writing uppermost and also allowing the flap to fall into the lower slate, which is now taken away to be replaced by another taken from the table. Care is taken not to show the underneath side of the upper slate during this transaction. The slates the skeptic now holds are devoid of trickery, and when exposed with the writing on will cause wonderment.

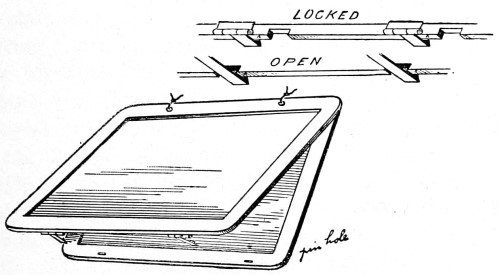

There is still another style of slate made, and used to good advantage. It is two slates hinged together, making a double slate. It has also two holes in the frame opposite to the hinges, through which tape or cord can be run and tied and sealed to the slates. (Fig. 15.) The secret of getting the writing upon the inside lies in the fact that at least one-half[40] of each hinge is screwed to the slate; the other half is made fast to a little projecting piece in which there is a slight notch. These projections enter corresponding holes in the other slate, in which is concealed a spring bolt which engages these catches of the hinge. This bolt is shoved back to release the catches by means of a pin pushed through a hole in the end of the frame.

At a public test or séance given by a medium I saw the following clever trick performed: A slate, clean on both sides, to all appearances, and, of course, devoid of writing, was given to a spectator to hold above his head. The medium then loaded a pistol, putting in, instead of a bullet, a piece of chalk, which he rammed well in. He then took careful aim at the slate, fired away, and the slate was covered with writing from the chalk that was placed in the pistol. The medium, beforehand, allows any one in the audience to choose from a plate containing different colored chalks the colors they desire. The chalk is all right, and is actually placed in the pistol and crushed to a powder by the ramrod. The slate has been written on one side with glycerine. This side of the slate is supposed to be cleaned, so as to keep clear of the glycerine, in order that the invisible writing may not be disturbed. It is this prepared side that faces the medium when he fires the pistol. The powdered chalk adheres to the glycerine, and thus we make clear another slate miracle.

A clever trick employed to deceive me on one occasion was as follows: I was handed a slate and a damp sponge, with a request to cleanse the slate. I did so, and handed it back to the medium, who held it in plain view in one hand. In a short time the slate was given back to me with writing on it that could not be produced by any of the methods I was already acquainted with. I witnessed this test a[42] second time, and it was only by accident that I discovered it, and all through the breaking of a string, to which the device employed was attached. The apparatus was a strip of narrow wood, nearly the length of the slate. Glued on it were raised letters of cork (felt would do also). These letters were in reverse, and were well rubbed with soft chalk. This strip of wood was attached to a cord running up the left sleeve, across the back, and down the right arm-hole, and thence under the vest and the end fastened to a button. The length of the string allowed the wood to hang behind the slate when held in the left hand. To keep the wood up in the sleeve until wanted, there was a loop on the string far enough up to suit the purpose. This loop was slipped over the button, where it could be easily detached with the right hand. The sponge was soaked in water containing alum, which makes the chalk adhere better to the slate. When the slate was handed to the medium, he held it downward in his left hand, and allowed the strip of wood to slip down behind it, when it was pressed firmly against the surface of the slate, and then pulled up into the sleeve again out of sight. This same idea has been utilized in using a blotter, the same as is used for ink, to dry the slate with. The blotter has the writing done on it with chalk, thus doing away with the strip of wood.

Take a slate and cover it with writing on one side. Cover this writing with a piece of slate-colored silk, held in the corners lightly with wax. At one end of this silk have a few minute hooks. The slate is now cleaned on both sides, and, placing the slate[43] on the floor, the piece of silk is allowed to attach itself by means of the hooks to the medium’s pants, or dress, as the case may be, thus leaving the slate devoid of trickery. It is hardly necessary to remark that the slate is placed on the floor written-side downward.

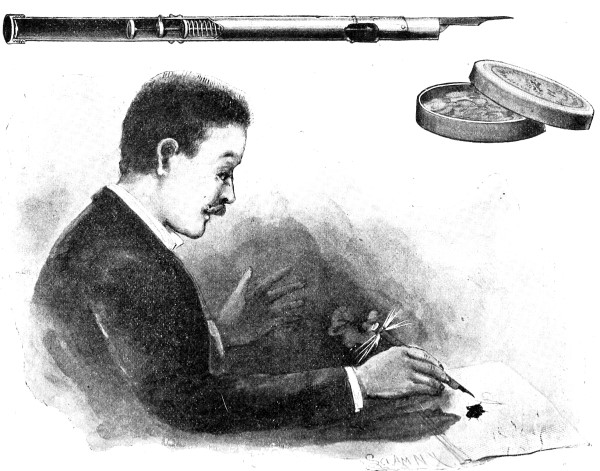

A friend of mine told me of a medium he once went to see, who gave him a most remarkable test. He brought his own slate, and, as he afterward said, there could have been no trick about it. The medium took the slate for a moment, and with a pencil covered the slate with writing on both sides, just to see, so he said, if it would be good enough for the test. He then cleaned off the slate on both sides and gave it back to my friend, requesting him to hold it close against his breast, and then in a short time remove it, and, when he did so, he was thunderstruck to find writing on it on the side nearest to him. This struck me as being a most astounding proof of spirit writing. I had a meeting with the medium, who gave me the same test. It seemed strange to me that he should want my slate to write on and wash it off again, for the same reason as he gave my friend, and that was to see “if it was good enough for the spirits to work with.” I received a message on the slate, after it was washed, and saw that there was none on there after it was cleaned and handed to me. I went home puzzled, and experimented to no avail. I had another sitting with the medium, but he did not give me the same test; so I returned home again and tried to fathom the mystery, and was eventually successful. The trick was mainly in the pencil. It was pointed at both[44] ends. (Fig. 16.) One end was a genuine slate pencil, the other end was a silver nitrate, or caustic pencil. In writing on the slate he wrote the lines quite a little distance apart with the slate pencil; in between these lines he wrote with the caustic pencil, the writing of which was invisible. The sponge the slate was cleaned with, was dipped in salt water. That part of the slate containing the writing done with the silver nitrate was just lightly tapped with the sponge, the rest of the slate was thoroughly cleaned. The salt water, when the slate becomes dry, brings out the silver nitrate white like a slate pencil mark. I consider this trick as ingenious and clever a one as it has been my good fortune to witness, and one that caused me much mental effort to solve.

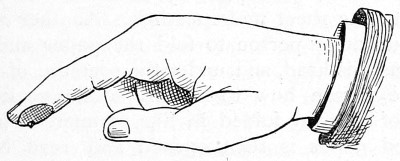

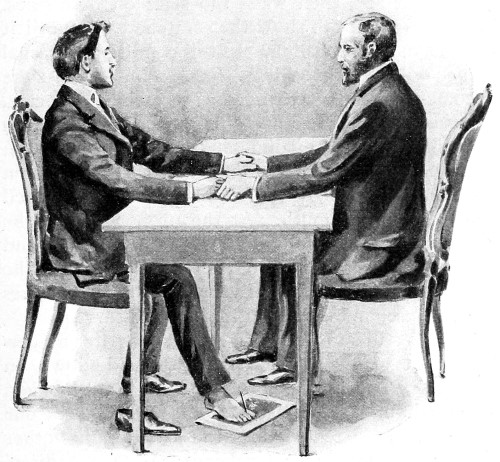

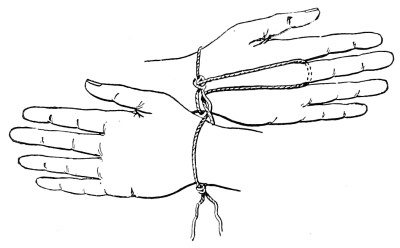

Here is another test. A slate just cleaned and marked is placed under the table on the floor. The medium and the skeptic grasp each other’s hands across the table. In a few seconds the slate is taken up from the floor and is found with writing on it. The solution of this, like all the rest of the slate phenomena, rests in simplicity and boldness. The medium wears slippers or low-cut shoes, that he can slip his foot out of easily. His stocking on his right foot is cut away so as to leave the toes bare. Now, attached to his great toe is a bit of pencil, and with[45] this the writing is done. (Fig. 17.) Sometimes the test is varied. Five or six pieces of chalk of different colors are on the table, and the investigator is allowed to select one, place it on the slate. In this case the chalk is held between the great and adjoining toe, and the writing is thus produced. It is surprising to see, with a little practice, what you can educate the foot to do. I myself can easily pick a pin off the floor and write quite well. Sometimes,[46] by way of variation, instead of the medium or investigator lifting the slate from the floor, it is seen to mysteriously make its appearance above the edge of the table, being lifted there by means of the toes of the medium’s foot. Another method used is that of scratching the writing on the slate with any metal instrument and then wash the slate on both sides, being careful not to show the scratched side until it is wet from the washing. In this condition a casual glance will reveal nothing, but as soon as the slate becomes dry the writing or scratching appears. Writing has also been made to appear on a slate on the table while the medium and investigator sit with both hands clasped across the table. The medium accomplished this by the simple means of a pencil concealed in his mouth. At the proper moment he holds it between his teeth, leans his head over and writes on the slate. Of course this is all done in the dark, and the writing is not very good, but it answers the purpose, and that is all that is necessary.

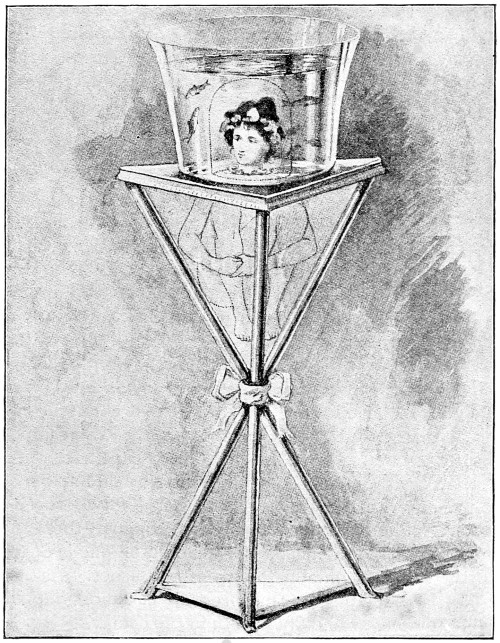

Here is still another test. A person writes a question on the slate and places it, written side down, on the table. All this when the medium is not looking. The medium takes his seat at the table, places one hand on the slate (so does the skeptic, the other hand on the medium’s forehead). With the disengaged hand the medium now proceeds to write on the upper surface of the slate. When he has finished, the communication is read, and it is found to be a correct answer to the question on the opposite side of the slate. To perform this seeming impossibility the medium has to employ a table containing a trap smaller than the frame of the slate. When the slate[47] is placed on the table, the medium shifts it over this trap. The trap is then opened, and by means of mirrors, 3, 4, 5, placed at angles of 45 degrees in the body of the table, the writing is reflected to the very place where the medium is sitting, and the image is reversed to normal by the third mirror, and it is easy then to give an answer to it. (Fig. 18.)

The following is how writing can be made to appear on a slate on which a person has placed his initials in one corner of it, which is then placed with that side downward on the table, and shortly afterward, on turning it over, it is found completely[48] covered with writing, and the signature of the visitor proves there has been no exchange of the slate. The secret of obtaining this effect is both a unique and quite original method.

The writing is already on the slate and is hidden from view by the false flap, which has a corner missing from it. This missing corner is where the clever idea comes in. After the medium cleans both sides of the slate, he says: “I will just draw a chalk mark down in this corner of the slate wherein the gentleman is to place his signature.” He really draws the chalk mark on the slate proper, but close to the edge of the missing corner of the flap, thus disguising the joint, and after the flap is dropped out of the slate of course this mark and signature still remains. (Fig. 19.)

Here is still another. The medium cleans a slate on both sides and hands it to a skeptic to place his mark on it. It is then placed on the table, face downward, and in a short time, on being turned over, it is found with a spirit message on it. This is performed as follows: Let the message be written on the slate and then sponged[49] out with alcohol, and when the slate dries, the writing will be as plain as ever.

Here is another slate writing secret. Dissolve in hydrochloric acid some small pieces of pure zinc, about one-half ounce to an ounce of acid. With this solution write upon the slate with a quill or a small camel’s hair brush the desired communication. When dry it closely resembles writing done with a slate pencil. When the time arrives for the test, wash the slate, and it appears to be perfectly clean; allow any one to examine it and hold it until it becomes dry, but with the prepared side down. On the slate being turned over it is found to be covered with writing while in the spectator’s hand.

Here is still another idea. The medium has a number of slates in his arms, say four. He hands the investigator the top one to clean. When he has done so, the medium receives it back and places it at the bottom of the pile of slates and hands him another again from the top to be cleaned, and repeats this operation until all four slates have been cleaned. He now takes two of the slates, places them together, and, on removing them again, writing is found on one of them. Here is the method of procedure: Prepare your communication on one of the slates, and let it be the bottom of the pile, with the writing side down. Have your visitor seated, stand by his side just a trifle behind him, hand him the top slate to clean; after he has done so, hand him the second one and receive the first one back, placing it at the bottom of all the slates, and repeat until the third slate. While this one is being cleaned, slip the fourth, now the top slate, to the bottom again. When the third[50] slate is received, place it on the bottom and hand the fourth, really the first one over again; it is, of course, the top one and dry by this time, and the investigator is none the wiser. Of course, the two slates placed together afterward are the one prepared with writing and one of the blank ones. Instead of slipping the top slate to the bottom, sometimes another dodge is used. The medium simply turns the three slates over by a twist of the hand. This brings the prepared slate at the bottom and the last slate cleaned at the top, and he says he will clean this one, thus saving time; really, however, to disguise the fact that it is still wet from the last cleaning. He says, however, to the visitor, “You can clean it also, if you desire.”

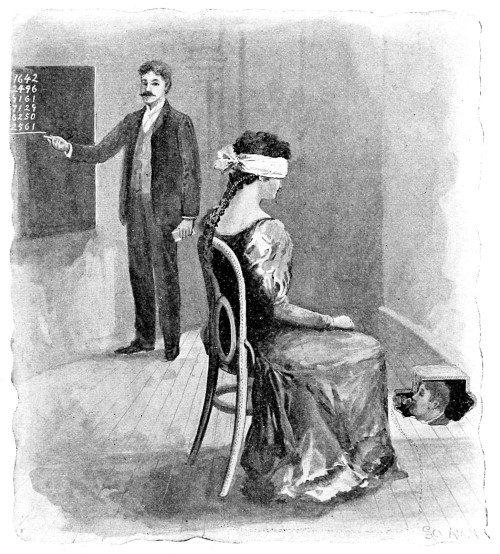

Having now described the principal slate tricks which mediums use to entangle the unwary for their own ends, we come to other tricks which are used from time to time to impress the credulous with the idea that the medium is imbued with supernatural power and can perform what are, in effect, miracles. These tricks are legion, and they vary from clumsy attempts at mystification to the use of elaborate pieces of magical apparatus which call for rare mechanical genius in their design and construction. The present chapter will deal more particularly with what might be termed mind reading tricks and the reading of concealed writing. Of these tricks one of the most perplexing is that of reading sealed communications, or answering questions placed in an envelope which is well sealed.

If I were to tell you that I could read whatever was written on a card inclosed in an envelope, and that envelope not only well sealed, but also stitched or sewn through with a thread and needle or machine, and the thread sealed to the envelope also, without removing the seal, stitches, etc., you would hardly credit the assertion. It is nevertheless true, and is easily and readily accomplished by very simple means.

Prepare a sponge with alcohol. With this you rub or brush the envelope, which immediately becomes transparent as glass, thus enabling you to see through it and read what is written on the card. It[52] takes but a few seconds for the alcohol to evaporate and leave the envelope in the same condition as before, without leaving a trace as to what or how it has done. This test was used most successfully for years by a celebrated Philadelphia medium.

We now come to a test often employed. A card is given by the medium to a skeptic with the request to write a question on it. The medium now holds the card in his hand against his forehead. Presently he hands the card back to the spectator, and on it, in writing, is found an answer to the question. The medium accomplishes the above feat by means of a little apparatus which is easily attached to the tip of the thumb. Part of it goes under the thumb nail and the lower part has a small needle point which embeds itself in the flesh. In the center of this little apparatus is a tiny piece of lead pencil. With[53] this clever bit of mechanism the medium does the writing with the thumb of the hand holding the card. (Fig. 20.)

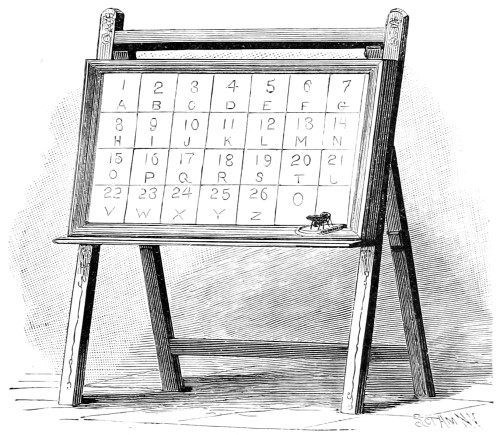

Four or five persons are seated around a table. They are given paper and pencil and requested to write questions, then fold their papers up and place them in their pockets. The medium will give them replies to their questions; in fact, can tell them the full text of the questions they asked, and, what is more mysterious, he has been out of the room all the time the writing has been going on. To produce this effect, you are provided with a table containing a hollow leg. Now, spread a piece of thin white silk on top of table, then on the top of that a piece of carbon, or duplicating paper, or cloth. Now, over all, a thin table cover, fastened around the edges, so it cannot be raised up and looked under by the inquisitive.

To the white piece of silk is fastened a string leading down the hollow leg, through a hole in the flooring, to the cellar or room below. Whatever writing is placed on the papers is transferred by the carbon paper to the silk below it. The medium pulls the string, down comes the silk. One corner of the silk has a mark corresponding with a certain corner of the table, and by this method not only does the medium know what is written, but who wrote it, as he has simply to see the position the writing occupies on the silk, and it will have been done by the party occupying the same position at the table. Another way is by using a pad of soft paper and hard pencils, and, after the writing, remove the pads. It will be found that the hard pencil has caused an imprint,[54] or indenture, of the writing on the page below, not readily seen by a casual glance, but easily seen by the skilled eye of the medium.

A test sometimes offered is as follows: A card is offered to a person to write a request. It is then placed in an envelope and sealed by the medium and placed on the table sealed side up. The medium now takes a pencil and slate and writes something on it. It is given to the skeptic who wrote the question, and it is found to be an answer to his query. The medium now opens the envelope by tearing it at one end, and takes out the card containing the question and hands it to the spectator. This is another humbug, and is accomplished by exceedingly simple but bold means. It will be observed that the medium places the card in the envelope, also takes it out. The skeptic never sees it. This is the secret: The envelope, on its face, has a slit cut in it a little lower down than the opening on the other side of the envelope. This side, the face of the envelope, is never shown. The card, in being placed in the envelope, is deliberately pushed through the slit in the envelope into the medium’s hand and palmed by him and read. Of course, it is an easy matter to write some kind of a sensible answer when the question is known. The card is inserted in the envelope in the same manner as it is taken out.

Another trick is to have an answer appear written upon the inside of the body of the envelope in which is enclosed the question. The envelope is closed and sealed with sealing wax. This is accomplished without disturbing the seal. In the ordinary manufacture of an envelope, three of the flaps are stuck[55] together with adhesive gum of far less strength than the fourth flap, which is to be moistened and closed by the user. It is generally an easy matter to insert the blade of a penknife behind the bottom flap, that is, between it and one of the end flaps, and separate them a trifle. Then, if you insert into this a wooden skewer, or hard, round-pointed stick, like a pencil, in fact, a lead pencil will do, but look out it does not leave marks behind; and by pushing this along, and giving it a rolling motion, you will separate the flaps up as far as the seal, and, if done carefully, without tearing or mutilating the envelope. Now, on a slip of paper write the answer or suitable message, but in reverse or backward writing, as the words would appear in a looking-glass, with a carbon or copying pencil. Pass this slip through the opening in the envelope, shake it into the desired position, now rub the envelope over this spot until you think the envelope has taken the impression. Then remove the slip of paper by the same way it came in, moisten and gum the opening, and the trick is done. In rubbing the envelope, it is a good plan to place a piece of paper over it to keep the envelope clean of marks, which would be liable to appear from damp or moist fingers during the rubbing.

The following is from the experiments of a German scientist. He discovered, by the use of an embryoscope, or egg-glass, that the shells of eggs were of very unequal thickness.

It occurred to him to make experiments in order to ascertain how many leaves of ordinary letter or official paper must be laid above and below a written leaf, in order to make it illegible to a highly sensitive[56] eye in the direct sunlight. He found that after he had rested his eye in a dark room for ten or fifteen minutes, he could read a piece of writing over the mirror of the embryoscope that had been covered with eight layers of paper. He called in other observers to confirm this. The letters, however, that could be thus deciphered were written in dark ink on one side of the paper only. If four written sides were folded together, and especially if there had been crossing, it was hard to make out the drift of the writing; and there are some kinds of writing which, when folded thrice or twice, admit too little light for the purpose of decipherment.

In this way, possibly, many of the performances of “clairvoyants” may be explained. By means of the egg-glass it is, as a rule, easier to make out the contents of a letter or telegram without the slightest tampering with the envelope than it is to detect the movements of the embryo in the egg.

Suppose the writer of a billet, the contents of which are known only to himself, lets it out of his hands and loses sight of it for five minutes, it may be carried either in the direct sunlight, or into electric or magnesium light, and be read by the aid of the egg-glass. The placing of a piece of cartridge paper in the envelope, or the coloring of it black, is a means of defense at hand. In their present form, telegrams cannot be protected from perusal, unless delivered at once into the hands of the addressees.

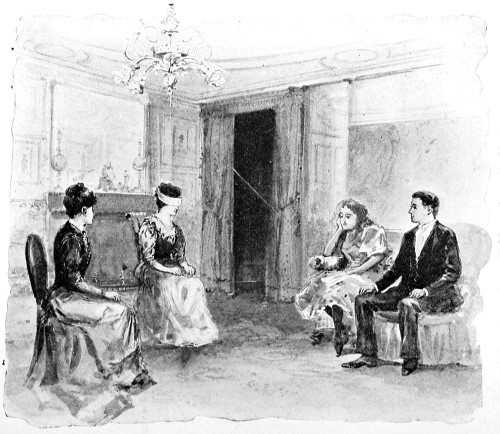

A few tests employed by mind readers and clairvoyants, so called from their presumed ability to read[57] other people’s minds, will, I think, prove interesting. Let us suppose the performer, as a means of proving his ability to cause his subject to read his mind from a distance, or by mental telegraphy, execute the following feat. His subject, let us say his wife, is at home. The professor is in a public place, a store, or banking house, etc. He requests some one to write a question; he hands this person a fountain pen and a pad of paper. After the person has done so, he is requested to fold the communication up, place it in an envelope and seal it, and then put it in his pocket. He is now asked to write a letter or note to the professor’s assistant, asking her to inform him what it was that he had asked on the paper inclosed in the envelope in his pocket. This note, and the pen also, for fear the lady has no writing utensils, is carried by the gentleman himself to the lady. She reads the request, and, turning the paper over, she writes the answer correctly on the other side. Sometimes, instead of the gentleman himself going with the note, a messenger boy is sent with it and the answer brought back by him. In either case the paper and pen are sent along. The pen is an ordinary fountain pen, and it is by means of it that the lady receives the desired information of what has been written. First the professor has to know what has been written. He simply says to the gentleman: “You must allow me to read the question; for, if I do not see it, how can my assistant see it, for it is through me she is enabled to know? What I see I convey to her by mental telegraphy, and thus convey the communication.” After the professor sees the communication he goes to a desk and gets an envelope, or takes one[58] out of his pocket, and gives it to the gentleman to place his question in and seal it. While this is being done he stealthily writes on a piece of fine, thin paper an exact copy of the question. This he makes into a little pellet and places it in the little cap or end that is made to cover the point of the pen for protection. Of course it is now easy to see the method by which the question is made known to the assistant. She has simply to remove the pellet of paper, unfold it and read it. Sometimes a pad of paper is used that has cunningly concealed between two of its leaves, near the top, a piece of carbon duplicating paper. These two sheets are pasted around the edges so as to appear as one, and when the person writes a question it is duplicated on the sheet of paper following the one wherein is concealed the carbon paper. The professor has simply to tear out this sheet and inclose it in the cap of the fountain pen. The name of Foster is almost invariably coupled with any test wherein there is reading of sealed letters, pellets, etc., just the same as Slade’s is connected with the slate writing tests.

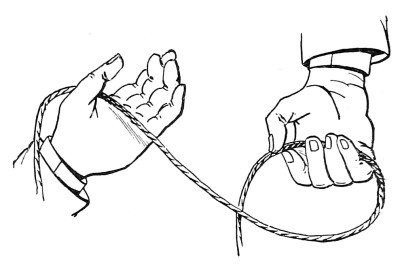

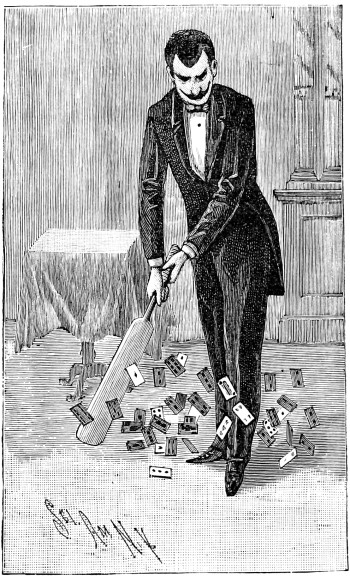

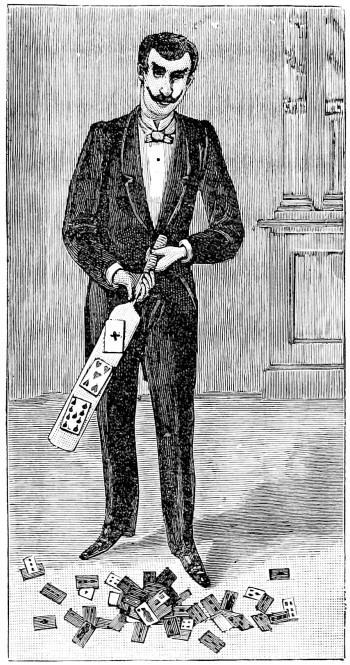

Foster was an inveterate smoker, anywhere and everywhere, especially at his séance, and it was all for a purpose. The visitor who desired a sitting with Foster was asked to write a few questions on small pieces of paper, fold them up separately, and press them into small balls or pellets. Foster would pick one of these up and hold it to his head, as if to try and penetrate it. Apparently failing to do so, he would place it back on the table. This he would repeat with others. Finally, he hands one of them to the visitor, after holding it against his forehead,[59] requesting him to hold it himself. Foster then took a pencil and paper, and scribbled something on it, and then bared one of his arms, and showed it devoid of any preparation. He then rubbed this arm with his hand, and, on removing it, a name was seen. On reading what Foster scribbled on the paper, the visitor finds an answer to one of his questions, and the name in blood red on Foster’s arm is found to be the name of a person addressed by the visitor in the note. Foster had a pellet of paper of his own concealed between his finger tips, and, at some convenient moment, instead of placing back on the table one of the pellets he has just taken up, he substitutes one of his own, keeping the bona fide one in his hand, which he lowers into his lap and unfolds. Holding it in the palm of his hand, he strikes a match and lights his cigar, and while doing so he is deliberately reading the note, which he afterward crumples into a ball and conceals in his hand. He now takes up another pellet and tries to see through it by holding it to his forehead. He, however, fails, and gives it to the visitor to hold, really exchanging it for the one he has just read. He now has his own and the visitor has his. He now allows his hands to lie carelessly in his lap, and, while conversing with the visitor, he pushes one of his coat sleeves up a short distance, and, with a sharp-pointed stick, writes the desired name on his arm, pressing down hard. In a second or two he writes the answer to the visitor’s question, minus the name he has just placed on his arm. He now shows his arm bare, and rubs the spot where he has written, with his fingers slightly moistened, whereupon the name appears[60] in bright pink writing. If it is desired to make it disappear, hold the hand above the head a few seconds. To make it appear again, rub once more with the fingers.