The X-87 was a red shambles. It roared the

starways, a renegade Venusian at the controls,

a swaggering Martian plotting the space-course.

And in an alumite cage, deep below-decks, lay

Penelle, crack Shadow Squadman—holding the

fate of three worlds in his manacled hands.

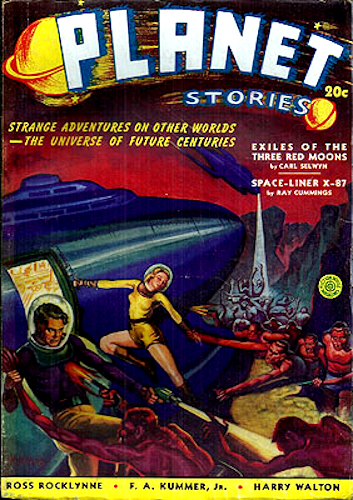

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Planet Stories Summer 1940.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

I am sure that none of you have had the real details of the tragic voyage of last year, which was officially designated as Earth-Moon Flight 9. The diplomacy of Interplanetary relations is ticklish at best. Earth diplomats especially seem afraid of their own shadows if there is any chance of annoying the governments of Venus or Mars, so that by Earth censorship most of the details of that ill-fated voyage of the X-87 were either distorted, or wholly suppressed. But the revolution at Grebhar is over now. If those Venus Revolutionists—helped perhaps by Martian money and supplies—had been successful, they would have been patriots. They lost, so they are traitors, and I can say what I like.

My name is Fred Penelle. I'm a Shadow Squadman, working in Great-New York and vicinity. Ordinarily I deal with the tracking of comparatively petty criminals. Being plunged into this affair of Interplanetary piracy which threatened to involve three worlds, Heaven knows was startling to me. I had never before even been on any flight into the starways. But I did my best.

My part in the thing began that August evening when an audiphoned call came to my home. It was my superior, Peter Jamison, summoning me to City Night-Desk 6.

"I've a job for you," he said. "Get here in a hurry, Fred." The audiphone grid showed his televised face; I had never seen it so grim.

I live at the outskirts of Great-New York, in northern Westchester. I caught an overhead monorail; then one of the high-speed, sixth level rolling sidewalks and in half an hour was at the S.S. Building, in mid-Manhattan. We S.S. men work in pairs. My partner, as it happened, was ill.

"You'll have to go in on this alone," Jamison told me. "And you haven't much time, Fred. The X-87 sails at Trinight."

"X-87?" I murmured. "What's that got to do with me?"

Jamison's fat little figure was slumped at his desk, almost hidden by the banks of instruments before him. Then he sat up abruptly, pushed a lever and the insulating screens slid along the doors and windows to protect us from any possible electric eavesdropping.

"I can't tell you much," he said with lowered voice. "This comes from the Department of Interplanetary Affairs. The X-87 launches at Trinight tonight, for the Moon. They want me to have a man on it. An observer." Jamison's face went even grimmer, and he lowered his voice still further. "Just what they know, or suspect, they didn't tell even me. But there's something queer going on—something we ought to know about. Quite evidently there's some plot brewing against the Blake Irite Corporation. They even hinted that it concerned perhaps both Venus and Mars—"

You all know the general history of the Moon, of course; but still it will do no harm to sketch it here. It was scarcely twenty years ago when Georg Blake established the first permanent Moon Colony, erecting the first practical glassite air-domes under which one might live and work on the airless, barren surface of our satellite. Two years later, it was the same Georg Blake who discovered the rich irite deposits on the towering slopes of Mt. Archimedes. The Blake Irite Corporation employs twenty thousand workers now.

"Mars and Venus have no irite," Jamison was saying. "They import it from us, for their inferior imitations of our gravity plates. And, combined with the T-catalyst, it runs our modern atomic engines and charges our newest long-range atomic guns. The Governments of Mars and Venus are building imitations of those engines. You know about that, Fred?"

I nodded. I had heard quite a bit, of course, about the mysterious T-catalyst. It is made only here on Earth—a guarded secret of the Anglo-American Federation, developed by our Government chemists in Great-London. Our War Department uses it for guns, of course. But its use is forbidden elsewhere, save for commercial purposes. Venus and Mars have been under strict guarantee, regarding its use. We have supplied them from time to time with limited quantities, for commercial purposes only.

"Do not misunderstand me. I have no possible desire to anger the present legal Governments of the Martian Union, nor the Venus Free State, and thus project myself—just one unimportant Earth-citizen—into a storm of Interplanetary complications. I am not even hinting that Mars or Venus have ever broken, or ever would break, their guarantees by using the T-catalyst for weapons of war. But in Grebhar, a very sizable revolution against the Venus Free State had broken out. That is something very different. A bandit Government. Bandit army—under guarantees to no one."

"What's all this got to do with me, and the X-87?" I suggested.

Jamison flung a swift look around his shadowed, dimly tube-lit office, as though he feared that someone might be lurking here. "The Blake Irite Corporation, on the Moon, needs the T-catalyst for a thousand things," he said slowly. "The engines of their air-renewers throughout that huge network of domes. The engines of their mining equipment—"

"You mean it's being stolen from them?"

Jamison shrugged. "Maybe." He paused, and then he drew me toward him. "Anyway, the X-87, on this Voyage 9 tonight, is taking the largest supply of T-catalyst to the Moon which has ever been transported." Jamison smiled wryly. "You and I, Fred, are among the very few people who know of it. The X-87 is not being unduly guarded. That in itself would look suspicious. Every possible precaution has been taken to keep the thing a secret. But there have been queer things happen. Perhaps only coincidences—"

"Such as what?"

"Well, Georg Blake died, quite mysteriously, a few days ago—"

"Murdered?"

Again Jamison shrugged. "The whole thing was censored. I don't know any more about it than you do. He has a son and daughter—young Blake, still under twenty—and Nina, his young daughter, who is only sixteen. The management of the entire Moon industry devolves now upon them."

I could envisage Interplanetary spies on the Moon—and with the forceful Georg Blake now out of the way, a raid upon that supply of the T-catalyst—

"Little Nina is going back to the Moon this voyage to take control of the company," Jamison was adding. "Her father died—was murdered if you like—here in Great-New York. And to make it still more mysterious, young Blake—the girl's brother—seems to have vanished. There is only Nina—"

Queer indeed. And even worse, Jamison now told me that several members of the X-87's crew were ill, and one or two had recently died, so that she was starting on her flight tonight with at least five new men....

The little space-ship was to sail at 3 a.m. I had my luggage aboard an hour ahead; and at quarter of three I was loitering on the tube-lit stage watching the passengers bidding good-bye to their friends and then going up the long incline to where the X-87 was cradled forty feet overhead. An S.S. Man, without too much equipment, can hide it all pretty comfortably. Most of my small apparatus was tucked into capacious pockets. And with my square-cut jacket buttoned over my weapon belt, I imagine I looked like any ordinary citizen. I was booked as a mathematics clerk, going to the Moon to take a position in the bookkeeping department of the Blake Company. I'm smallish, and dark—and not too handsome, my friends tell me. Just an unobtrusive fellow whom nobody would particularly notice. I certainly hoped now that that would prove to be so.

"How many passengers this voyage?" I asked young Len Smith, who was standing here on the landing shed beside me. He was a slim, handsome fellow, the X-87's radio-helio operator, ornate and exceedingly dapper in his stiff white-and-gold uniform.

"Damned if I know. Fifteen or twenty maybe. Usually are about that many."

A big seven-foot Martian stopped near us, directing the attendants who were carrying his luggage. "Who's that?" I murmured to Len Smith.

Dr. Frye, the X-87's surgeon—a weazened little fellow with a grim, saturnine face and scraggly iron-gray hair—had joined us. He answered me.

"Set Mokk, he calls himself."

"Going to the Moon, for what?" I persisted.

Dr. Frye shrugged. "Passengers aren't required to give their family history. Set Mokk is a wealthy man in Ferrok-Shahn, I understand. An enthusiastic Interplanetary traveler—"

Len, the young helio operator, diverted my attention. "Have a look," he murmured. "There comes Nina Blake. If she isn't a little beauty I'm a sub-cellar track-sweeper."

Now I'm not much for girls, but I don't mind stating thus publicly that Nina Blake struck me then as the most strikingly beautiful girl of any world whom I had ever seen.

As she came past, I saw that four stalwart attendants of the X-87 were carrying a long oblong box; one of her pieces of luggage. Quite obviously she was particularly concerned over it; she followed it closely, and signaled the men to precede her with it up the incline.

I got away from Len Smith and Dr. Frye and was up the incline close after Nina Blake. I saw the squat, square-rigged figure of Capt. Mackensie come forward to greet the girl, his most distinguished passenger. Instantly she spoke to the men carrying the oblong box, and they set it on end beside her on the desk; and at her gesture, they moved away.

Nobody noticed me as I got up to that box and stood in its shadow. I had no particular motive, save perhaps my instinct as an S.S. Man to probe anything that puzzles me. And suddenly I heard Nina say softly:

"No. I'm not—too frightened, Captain. I'll be quite all right."

That stiffened me. But a far greater shock came almost instantly afterward. The girl was whispering now to Mackensie, their voices too low for me to hear. She was leaning partly against the upright box, and I saw her slim white hand furtively roving it, one of her fingers pressing what might have been a hidden lever. The sleek, polished side of the box was close to my head—and abruptly, from within it, I seemed to hear a faint muffled, ticking sound! A mechanism in the huge box which the girl's furtive hand had started! It was a slow, rhythmic tick, and a faint swishing.

"Oh, you, Penelle. Come here—I want you to meet Miss Blake."

Captain Mackensie had noticed me, and his gesture brought me to join them. For a moment we stood in a group as I was introduced. Nina's hand had darted to the box again, perhaps to stop the ticking.

"Your first flight, Penelle?" Mackensie was saying. His voice was booming, hearty, loud enough to carry to any of the passengers and crew who were near us here on the dim side-deck. Jamison had told me that of everyone on the X-87, only Captain Mackensie would be aware of my true identity and purpose. I caught his significant glance now as he shot it at me from under his heavy gray-black brows. And then abruptly he stepped nearer to me.

"Never talk secretly to me," he murmured. "No insulation here. You take care of Miss Blake. Say nothing—keep your eyes wide. When we get to the Moon—"

I stiffened, went cold, with my heart suddenly pounding. My hand darted out, gripped the captain's arm. "Wait!" I murmured.

On my chest, underneath my shirt, a flat, round little detector-grid was abruptly glowing warm against my flesh. An interference current was overcharging its low-pressure wires so that they were heating and burning me. An eavesdropping current! No one save a Government criminal-tracker may legally use an eavesdropping ray. But there was one here, listening to us now!

I murmured it to Mackensie; turned and darted away. A dim door oval was nearby. I went through it, into a narrow, tube-lit corridor of the ship's superstructure. Momentarily no one was here; there was just the dim, vaulted little arcade, gleaming pallidly silver from its fittings and trim of alumite with rows of cabin doorways on each side. The name-plates glowed with the names of the occupants for this voyage. All the doors were closed; a few faint voices from passengers in the cabins were vaguely audible.

At a cross-corridor I stopped. Was someone here able to watch me? From my shirt I drew out the little detector-grid. It was cooling now, but still its direction needle was swaying. The source of the current seemed ahead of me in this cross corridor. How far, I could not say—the distance gauge-point was swiftly dropping to zero. The eavesdropping current had been snapped off. Wherever he was, this listener knew now that we were aware of him.

On my padded, felt-soled shoes I dashed ahead to where the corridor widened into a tiny smoking lounge.

"Oh, you Penelle? What's the matter? Can't you find your cubby?"

It was Dr. Frye, the ship's surgeon. Fortunately, he did not see the Banning heat-flash gun in my hand. He was sprawled here in a chair, smoking. His thin face grinned up at me. "Ask the purser your location," he added. His gesture waved me toward the purser's tiny office-cubby down the opposite corridor.

"Thanks," I agreed.

The purser's cubby was unoccupied. I passed it, came to the stern end where the superstructure stopped and the side decks converged into a triangle of open deck under the dome at the pointed stern. There were a few passengers lounging around and deckhands moving at their tasks of uncradling the vessel which now was ready to take off. Over at a glassite bull's-eye window in the side pressure-wall, the big Martian, Set Mokk, was standing, gazing at the people on the lower stage.

And suddenly, from the shadow of a cargo-shifter near at hand, a blob of figure detached itself and moved away. In a moment the deck-light gleamed on it; a member of the crew—squat, bent, misshapen gargoyle shape; a hideous Earth-man hunchback, with dangling gorilla-like arms that swayed as he walked. Then I saw his face; ghastly countenance, lumped with disease, a mouth that seemed to leer and eyes with puckered rims—eyes that seemed to glare at me with impish malevolence as he shambled past me and vanished around the other side deck.

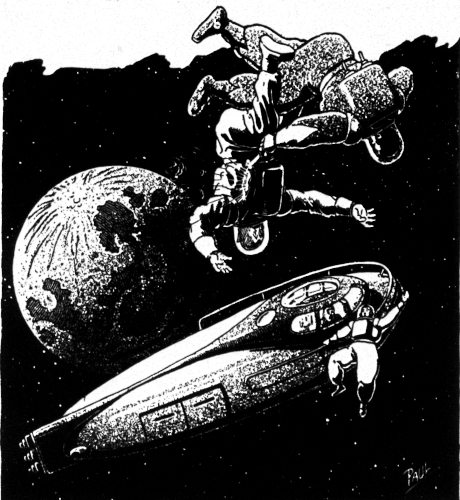

In a few minutes more, with a blast of sirens, the little X-87 trembled, lifted nose first from its cradle and was away, slanting up into the night. The lights of the giant city dropped beneath us. I stood at one of the side bull's-eyes watching them as they dwindled into a blob, merged with other lights of other cities along the coast.

I had been up into the stratosphere many times, of course, but this was to be my first flight into Interplanetary Space. I could envisage our gleaming silver vessel now, tiny little cylinder with pointed ends, alumite keel-bottom and the great rounded glassite dome on top, as we slid so swiftly up out of the atmosphere. A little world now to ourselves.

The little vessel pounded and quivered with the vibrations of its disintegrating atomic rocket-streams at the stern. Then as we slid into the upper reaches of the stratosphere, the rocket engines were silenced; the gravity-plates were de-insulated, set with Earth-repulsion as we swung toward the gleaming half-moon ahead and over our bow.

The ship was vibrationless now. All movement seemed detached from us. Alone in Space we seemed hovering, poised.

The voyage of doom had begun.

"Apparently you have not suffered from the miserable pressure sickness," Ollog Torio said. "Or have you, Set Mokk?"

"I have not. We Martians are made of sterner stuff. Is that not so, Dr. Frye?"

"Well," the saturnine little surgeon said, "well, for you, yes, Set Mokk. But Martians are humans, like anybody else. I have seen them in distress, upon occasion, when the pressure changes too fast, coming out of the atmosphere."

Four of us were sitting on the triangle of the X-87's bow deck—the towering, swaggering Martian Set Mokk, slumped in his chair, wrapped in his great cloak with his hairy brown legs like huge pillars of strength crossed beneath it, revealed by its flair; the weazened, morose-looking Dr. Frye, and Ollog Torio. I had just met this Venusian. Like most of them from our sister planet, Torio was slender, graceful, with the characteristic finely chiseled features, grayish skin and heavy black brows. He seemed a man of perhaps forty. Romantic in dress and bearing. His hair was sleek and black, with gray streaks in it. His pointed face, accentuated by a pointed, waxed beard, was pallid. His robe was white and purple, with a white ruff at his slender throat. He was, I understood, a wealthy man, a retired capitalist from Grebhar.

It was now, by the established ship-time, what might be termed mid-evening. The passengers had had two meals, and a normal time of sleep. They were dispersed about the little vessel, gathered in groups, gazing with a natural awe through the side bull's-eyes at the wonders of the great dome of the Heavens, spread now around us.

My first trip into Space. It would be out of place here for me to describe that queer, awed, detached feeling everyone gets, especially at his first view of the vast blackness of Interstellar Space with its blazing white stars. Behind us, the Earth hung, a great dull red ball, blurred and mottled with cloud-banks. The stern deck triangle gleamed dull-red. But up here in the bow the Moon hung round and white. We were still in the cone of the Earth's shadow. The moonlight here drenched the deck like liquid silver.

In romance, moonlight shimmers and sparkles to inspire a lover's smile. But the reality of the Moon is cold, bleak and desolate. Even without a telescope now, I could see the etched heights of the great lunar mountains. Archimedes, Copernicus and Kepler lay in full sunlight. The heights glared; the depths of the barren, empty seas were black pools of inky shadow. The great Mare Imbrium was solid, mysterious darkness.

I had been awed by the wonders of Space. But the feeling was past now, engulfed by the sense of disaster which more than ever was upon me. The Earth-light on our rear deck seemed to symbolize it. Red—as though already that deck were bathed in blood. I found myself shuddering. Somewhere on board—I had no idea where—a treasure of the precious T-catalyst was hidden. Had that fact leaked out? Why was the beautiful little Nina Blake so flooded with secret terror? What was the huge coffin-like trunk, which sounded like a time-bomb? The box, I knew, had been placed in her sleeping cubby.... And back in the S.S. Building my superior, Jamison, had said something which damnably now hung in my memory: "You keep your eyes and ears open, Fred. Things are not likely to be what they seem, on that voyage."

Accursed ineptitude of Earth's Interplanetary Relations Board, that would let a condition such as this come to pass! I felt wholly alone here, coping with God knows what. "Things are not likely to be what they seem." I found myself tensely suspicious of everything, of everybody. This swaggering Martian, Set Mokk—he was sitting now, gazing at me as though appraisingly, his lips twitching in a half-smile of sardonic humour. This Ollog Torio—was he what he seemed, just a wealthy traveler? Even little Dr. Frye, the Ship's Surgeon—I could not forget that when I had tried to nab that eavesdropper, it was Dr. Frye, gazing at me from his seat alone in the ship's smoking lounge, whom I had encountered.

"So you are going to the Moon to work for the Blake Company?" the Venus man was saying. He spoke English with only a trace of the prim, precise Venus accent.

"Yes," I agreed. "Mathematics clerk. It will be a novel experience for me, on the moon—"

"Quite," Set Mokk said out of his reverie. "Quite novel."

Did they really think I was a mathematics clerk? Someone here on board suspected me; that eavesdropper had turned his ray upon me quickly enough when I had stood talking to Captain Mackensie....

"You're having bad times in Grebhar," little Dr. Frye said presently to Torio. "How is the revolution going? We hear so little by helio—and most of it censored by your Venus Free State."

The slim Torio shrugged. "The fighting was in the mountains only, when I was there. I think those rebels will not make out too well."

"Rebels," I said. "If they lose, they will be traitors, worthy of death. But if they win, I expect you'll call them patriots?"

That made the hulking Martian laugh. "Human behavior is practical, never idealistic. The original right or wrong will be forgotten. It is only results that count."

"I pay little attention to it," Torio said blandly. "Venus should be for love, for romance. I have no stomach for killing."

"Speaking of romance," Dr. Frye interjected. "Here comes our Earth version of it."

We were all on our feet as the small, black and white clad, trousered figure of Nina Blake emerged from the end corridor of the superstructure. She hesitated; then took a seat among us. Her cloak was off; the moonlight and starlight bathed her with its silver. Was the terror still upon her? I could not at first tell. She was quiet, composed. We men were all smoking little white arrant cylinders. She told us smilingly to continue. But as she stretched herself in the cushioned chair, between me and Torio, it seemed that the flash of her gaze upon me carried relief—as though in me she had her only protector here on the ship.

"The little Earth-lady is very gracious," Torio commented with Venus smoothness as he lighted one of the cylinders. "I have always maintained that in the lush forests of Venus are the only really beautiful women in the Universe. I shall have to revise that now, Miss Blake."

She flushed a little under the boldness of his gaze. And he laughed. "That makes you even more beautiful. 'Flinging back a million starglints, the depths of Space remind me of Thine eyes,'" he quoted.

I am only an S.S. Man. Far be it from me now, so publicly to write what might cause Miss Nina Blake any offense. I try to state only what happened. There is no one, I feel sure, who could sit beside her and not be stirred by her beauty in that drenching moonlight. But to Torio, pretty speeches came with a laugh. Instinctive. It annoyed me. I might as well admit it.

For a time our little group chatted. Then, one by one, the men wandered away. Was it that one of them wanted to observe Nina and me alone? I could not help the thought as I leaned toward her.

"Easy now. Quiet!" And then I said aloud, "That Venus man makes very pretty speeches, Miss Blake. To us of Earth, they do not come so naturally."

Her startled gaze at my warning relaxed into a laugh—a laugh like silver glints of moonlight on a mountain stream.

"No woman can pretend that she dislikes them."

"No. I suppose not." I guess I was really pretty earnest; unsmiling; breathless. I was making conversation with the feeling that someone was watching us trying to lip-read perhaps, not daring to use a ray. But my talk was more than acting; I really meant it.

"A Venus man needn't think he has a monopoly on pretty speeches," I added.

"Inspired by the moonlight?"

"And you," I replied, smiling at her.

Adorable little dimples showed in her cheeks as she grinned at me. "Thank you, sir." Then she leaned closer. "You tell the Captain—Torio and Mokk—in the corridor a while ago—"

"Easy! Cover your mouth. You heard them?"

"Yes. Whispering. Eight men—five in the crew—"

"I'm only a mathematics clerk," I said. "But beauty like yours, Miss Blake—it makes me wish I were King. King of the Universe."

"That would be very nice," she laughed.

"Yes. Wouldn't it? 'If I were King, ah love, if I were King, the stars would be your pearls upon a string; the world a ruby for your finger ring; and you could have the sun and moon to wear—if I were King.'"

And I meant it. Surely no man ever made love under such a handicap as this! I bent closer over her, with the perfume of her intoxicating me; and she whispered,

"You tell him I'm afraid—tonight—at the next time of sleep—"

She suddenly checked herself, with a sharp sucking intake of her breath as she stared down the deck. My gaze followed hers. From the gloom beside the superstructure some twenty feet from us, a shadow had detached itself—misshapen shadow; that hunchback, malevolent looking member of the crew. He went shambling past us, with a coil of rope from a cargo shifter in his hand.

Did his sudden appearance strike terror into Nina? She was holding herself tense; not speaking, nor glancing at me, but staring seemingly fascinated by the man's gargoyle aspect. He perhaps did not notice us, and yet I had the feeling that his little eyes under the lumpy forehead had flung us a peering glance.

When he had gone past and vanished, back toward the stem on the other side deck, it seemed to me that the girl was shuddering.

"What is it?" I whispered.

"N-nothing."

"You're afraid of that fellow, Nina?"

"No! Oh no!" Her unnecessary vehemence seemed to belie her words.

The thing had so startled me that I had relaxed my caution. I realized it, as abruptly, from the ladder-steps which led up to the control turret on the roof of the superstructure almost over us, a long, lanky, white-uniformed figure was disclosed coming down. It was the ship's First Officer, young William Wilson. He was a handsome young giant. He smiled at us—mostly at Nina, and lounged into the chair beside her.

I had no further chance to be with the girl alone. A light meal was served us by one of the stewards, there on deck. The radio-helio operator, young Len Smith, had joined us. The squat, heavy-faced James Polter, ship's Purser, added himself to us; and then the fat, jolly, moon-faced little Peter Green, Second Officer, came puffing down from the chart room behind the control turret and drew up a chair. It was as though the girl were a magnet.

I left them presently. From back along the side-deck where I stood apparently gazing through a bull's-eye at the vast wonders of the glittering Heavens in which the little X-87 was hanging, I could see the group of men around Nina on the fore-deck, a gay little party in the moonlight. Why was Nina so terrified of that ugly hunchback? I had inquired about him casually from young Len Smith. His name was Durk; a new member of the crew, engaged to replace one of those so mysteriously sick. This was his first voyage.... Five of the crew, Nina had said. I was to tell the Captain about it. Vehemently now I wanted a talk with Mackensie. We'd have to chance an eavesdropper; if I was alert, my detector should warn me; and the promptness with which we had discovered the eavesdropping ray before, I figured would warn the fellow not to use it again.

It would have been, by Earth-routine, perhaps eleven p.m. The passengers were retiring to their sleeping cubbies. The decks now were almost deserted. I went up one of the side ladders to the superstructure roof. It glittered with starlight that came down through the glassite pressure dome which arched close overhead here. The superstructure roof was a rectangular deck space, a hundred feet long perhaps, by thirty wide. A low railing surrounded it at which one might look down upon the lower side decks. Chairs were scattered about up here, all of them unoccupied. Amidships was the little kiosk which housed the radio-helio equipment, with young Smith's sleeping cubby adjacent to it. The place was closed and locked now. Aft of it there was open deck space to where the roof-deck ended, with the stern deck-triangle a level below, where the earth-light still was red like blood.

I turned forward. The chart room backed against the control turret. The chart room was dark. In the control turret I could see Capt. Mackensie at the controls, his squat, square figure etched by moonlight. Would this be a good time to try and talk with him?

I started forward. The party down on the forward deck was just dispersing; I saw the boyish figure of Nina, starting for the superstructure corridor, with the giant handsome William Wilson escorting her. And then Dr. Frye came up the front ladder, went into the control turret and joined Mackensie. I turned aft; it was no time to see Mackensie now.

Suddenly I stopped, melted down into a black shadow near the helio kiosk and flattened myself on the deck. An S.S. Man, so they say, developes a sixth sense. Maybe so. Certainly I didn't see anything, nor hear anything. But I was aware that someone, or something, was up here on the silent deck with me. Perhaps it was a sense of smell; my nostrils dilated with the impression that the faint drift of artificial air up here had somehow changed its quality. Was there something artificially invisible stalking here? The Groff magnetic cloaks, so recently perfected, are closely held by Governmental orders. Even we S.S. Men seldom use them. But it is a queer thing—no matter what devices you use in crime-tracking, you may be pretty sure the criminal has them to use against you.

I tried my infra-red glasses. They disclosed nothing save the glowing heat of the ventilators where the warm air was coming up. The nearest I had to an eavesdropper was a pair of low-scale phones. In a second or two I adjusted them; tuned them. The myriad blended tiny sounds of the ship's interior gave me nothing that I could identify. And then it seemed that there was a very faint hissing—something, quite near me, which should not have been here.

Banning heat-gun in hand, I prowled around to the other side of the helio kiosk. How that lurking intruder got away, I don't know. To this day I have no idea. Doubtless he heard or saw me, and slid along the line of deck-shadows in a magnetic cloak, getting away so swiftly that my infra-red glasses could not pick up the heat of his body or his mechanism.

At all events he was gone. There was nothing but a faint chemical smell. And then, on the metal of the helio-room door, I saw a burned spot near the lock where his heat-torch just for a second had started its hissing; and then he had become aware of me and had taken flight. Someone trying to break into Smith's helio room!

That would have taken me to Captain Mackensie whether Dr. Frye was there or not. But abruptly, again I went tense, so suddenly startled that the blood seemed to chill in my veins. The low-scale magnifiers were still in my ears, murmuring with a chaos of tiny, meaningless sounds. My metal heel-tip by chance must have struck a metal cross-beam of the deck. Abruptly I heard a voice, which at that second must have been raised louder than it had been an instant before.

"Oh please! Oh my God, no!"

A girl's voice, gasping that fragment in an anguish of terror. Nina's voice!

I frantically tuned the magnifiers, to clarify it; but I lost it and could not get it back. Nina's voice, seemingly from her sleeping-cubby, which I knew was just about under me in the superstructure. I went down the side companion ladder with a rush; ducked into a nearby cross corridor. It was dim, silent and empty. The name-plates glowed on the doors. I came to hers, with its glowing greenish letters, Nina Blake.

Without the earphones there was only silence here now. For a second I stood, gun in hand, undecided. The door probably was locked; I did not dare try it to see. With my heat-torch, or even with a flash of the Banning gun, I could melt away the flimsy lock in a few seconds. But would that be quick enough? If one of the villains were in there with her now, and I blasted the door and startled him, his first move might be to kill her....

Tick-tick ... tick-tick....

With naked ears I suddenly realized that I was hearing the ticking from the big coffin-shaped box in her room.... Tick-tick ... tick-tick.... Rhythmic ... gruesome.... I own that my fingers were trembling as I crouched there by the door and adjusted my headphone.... The ticking rose to hammering thuds. Or was it my own pounding heart?... The hammering seemed to drown a tiny whisper of voices. Someone was in there with her, unquestionably.

I have no apologies for what an S.S. Man must do under stress. High over the top of the door there was a small transom-like opening, covered by a metal grillework. I could see faint tubelight glowing up there from within her room. I backed across the corridor, adjusting with hurried fingers my miniature projector of the Benson curve-ray. In another second its faint violet stream leaped from my hand in a crescent up to the grille. Curved light-rays, an arc through the grille and down into her room, bringing me along its curved path a faint distorted vista of the scene inside.

And then I heard her low voice quivering with terror:

"No! No, Jim—don't—"

James Polter, the Purser? In that confused second I stared along the Benson curve-light. Just an edge of the coffin-shaped box, which was lying flat on the floor against one wall, was visible to me. In the center of the dim room, Nina was standing—beautiful, slim little figure in a pale-rose, filmy negligee, with her dark hair streaming down over her pink-white shoulders. Her back was to me as she gazed at the deck window. It was a dark oval, with the shadows of the side-deck outside.

And in that second the blob of a man was visible in the window. I could only glimpse the hunched outline of him as he scrambled through, dropped to the deck and fled.

There was a cross corridor here which led directly to the forward end of that starboard side deck. I dashed its length; reached the deck. It was empty. That was my first confused impression; then as I whirled aft, I saw a blob on it, near the other end of the superstructure. A blob which rhythmically moved, sidewise and back again. And in the silence, there was the squish of water.

It was the hunchback deckhand. He was swabbing the deck, with a mop and a pail of water. I slowed my pace as I approached him, and dropped the Banning gun into my pocket. Could he by any wild chance, have been the figure I saw climb out of Nina's window? It seemed impossible.

"Evening, Durk," I said. I stopped beside him. His lumpy, disease-ridden face came up as he shot me a glance.

"Even-sir," he muttered.

His bulbous lips were parted, as though perhaps with a panting breath. The idea turned me cold. What ghastly hold could this fellow have upon Nina? I can't pretend to describe my emotions at that moment. Nina wasn't screaming now to tell that a man had forced himself into her room. She was willing to keep it secret. Or perhaps too terrorized to do anything else.

"What's your name?" I said pleasantly. I had stopped beside him; was lighting an arrant cylinder.

"You said my name, sir. It's Durk." His muttered voice was thick. The sort of voice one might use to disguise its natural tone? Was it that?

"Oh, yes. Durk," I agreed. "Jim Durk? You're a new man, aren't you?"

"First voyage, yes sir. But my name's Pete Durk."

Surely he was breathing too hard for a man scrubbing a deck—much more like a man who had been running.

"My first voyage too," I said. I started on; then turned back. "By the way, have you seen Mr. Polter? I was looking for him."

"The Purser, sir? I'm thinkin' he should be in his office."

I nodded; turned the superstructure corner; went into the main corridor. Polter's little office cubby had a light in it. He was sitting there casting up his accounts. Jim Polter. I had heard half a dozen people call him that. Nina's voice came echoing back into my mind.... "No—no Jim, don't—"

Was this the fellow who had climbed out of her window just a few moments ago? His desk light illumined his squat, thick-set figure. He was a man of perhaps forty. He glanced up at my step.

"Hello, Mr. Penelle. You're up late."

"Just going in," I said.

Polter was smoking. The fragile ash on the little white paper cylinder was nearly an inch long.

I passed on. At Nina's door I briefly paused. There was no sound. The ventilator grille overhead was dark now. Upon impulse I pressed her buzzer.

"Yes? Who is it?"

"It's I. Fred Penelle."

Her door opened an inch; the sheen of light in the corridor showed her white face framed by the flowing black hair. A wave of her perfume came out to me.

"What—what is it?" she murmured.

"Are you all right?" I whispered lamely.

"Yes. Yes—of course." And she added still more softly, "You're taking too much chance—here like this. The Captain—did you tell the Captain—what I told you—"

"I'm going there now."

She closed the door. I stood with the sudden realization that I might be going beyond my job as an S.S. Man; my personal interest in this girl leading me to pry into her private affairs. But the feeling was brief. The terror was still in her eyes; I could not miss it. I decided then to go to Mackensie in the control turret. Someone had tried to melt into the helio room. Mackensie must be told it. Heaven knows, there never had been an S.S. Man who felt as helpless as I did at that moment. I could not determine whether I should tell the Captain what I had seen and heard in Nina's room, or not. How much Mackensie himself knew of what might be going on, I could not guess. And there was not another person on the X-87 whom I could trust! It was as though I were wholly alone here, with lurking murderers in every shadow, watching their chance—waiting perhaps for a predetermined time when they would come into the open and strike.

I was part way along the corridor when without warning my body rose in the air. Like a balloon I went to the low vaulted ceiling, struck it gently, rebounded, and floated diagonally back to the floor, where I landed in a heap! Heaven knows, it was startling. For those seconds I had been weightless, the impulse of my last step wafting me up, and my thud against the ceiling knocking me back again. The weird loss of weight was gone at once; I was close to the floor when I felt myself drop down to it. And I scrambled to my feet. My heart was thumping; I knew what had happened. In the base of the ship, artificial gravity controls gave us Earth's normal gravity on board. Without them, the slight mass of the X-87 would give a gravity pull so negligible that everything in its interior would be almost without weight. Len Smith, the young helio operator, had taken me around the little vessel just before the voyage began, explaining me its mechanisms. I remembered the room of magnetic controls, where the X-87's artificial gravity was regulated. A young technician named Bentley had been there. I had spoken to him a moment. He and his partner alternated on duty there throughout all the voyage.

And the artificial gravity controls now were being tampered with! For just a second or two, this particular area of the corridor here had been cut off, so that as I came to the de-magnetized area my step had tossed me to the ceiling. The floor section was normal now; I stepped out on it gingerly to test it.

Why was Bentley experimenting with his controls? Surely that never went wrong by accident. If I could catch Bentley at it—force him to explain—Or was it someone else tampering with the complex gravitational mechanisms down there?...

I remembered the location of the little magnetic control room; rushed to the nearest descending ladder. The lower level, down in the hull, was a metal catwalk, with side aisles leading into suspended tiny rooms. Freight storage compartments bow and stern; air renewal systems; pressure mechanisms; heating and ventilating systems. Beneath me, at the bottom of the hull, were the rooms of gravity plate-shifting mechanisms—compressed air shifters of the huge hull gravity plates by which the course of the ship through Space was controlled. I was not concerned with them—merely with the magnetic artificial gravity of the vessel's interior. The little magnet room was near it hand; its door was open, with its blue tubelight streaming out.

No one was in sight to see me, apparently, as I padded swiftly along the catwalk. From the distant bow and stern mess-rooms I could hear the faint blended murmuring voices of some of the crew who were off duty. I came to the magnetic room doorway. The room seemingly was empty. The banks of dials, switches and levers which governed the different areas of the ship were ranged up one wall. They all seemed in normal operation; none of the tiny warning trouble-lights were illumined. Bentley's little table, with his pack of arrant cylinders and a scroll book he had evidently been reading, was here with its empty chair before it.

And then I saw him! He was lying sprawled, face down, over in a corner, with a monstrous shadow from the table upon him, and just the faint glow of the electronic flourescent tubes painting his dark worksuit so that I noticed him. He was dead; I turned him over, stooping beside him. His chest was drilled with a pencilray of heat, presumably from a low-caliber Banning gun....

"Don't move, Penelle! I've got you!"

I stiffened at the sound of the low, menacing voice in the dimness behind me.

"Leave that gun where it is. Put your hands up and turn around. By God if you try anything funny, I'll drill you through. I've got you covered."

I was kneeling by the body of Bentley, with my gun on the floor-grid beside me. With hands up, I slowly turned. The tall figure of William Wilson, the ship's First Officer loomed over me with the tubelight gleaming on his white and gold uniform. He was staring down grimly; he held a small heat-gun at his hip, leveled at me.

Out in the open at last. So this was one of the criminals; the fellow who had tried to melt into the helio room? The eavesdropper? The man who had been in Nina's room? Heaven knows, of all on board, I had least suspected him.

He thought, of course, he had me trapped. But you can't capture an S.S. Man just by holding a gun on him and telling him to put up his hands. Even with my hands up, and the Banning gun on the floor beside me,—I could have pointed my left shoulder at him, drilled him with a stab of heat from the heat-ray embedded in the padded shoulder of my jacket. My right elbow was pressing my side to fire it, with all my body tensed to try and drop under what might have been his answering shot. But I didn't fire. His next words checked me.

"So you're not just a mathematics clerk—a damned murderer here on board! Get up! We're going up to Mackensie."

I stared as his foot kicked at my gun, and he swiftly stooped and picked it up.

"Come on," he added with a rasp. "Climb to your feet, Penelle. We'll see what the Captain has to say about this—"

"That suits me," I murmured. I said nothing more. Docilly I let him shove me in advance of him, up the ladder, along the dim main corridor, up the companionway from the starlit bow deck triangle to the little catwalk bridge in front of the turret.

Fortunately we encountered no one. At his telescope in the peak of the bow, the forward lookout turned and gazed at us curiously. The dim control turret was empty, eerie with the spots of fluorescent light from its banks of instruments. The controls were locked for the vessel's present course. The door oval to the adjacent chart room was open. Mackensie was alone in there, plotting the X-87's future course on a chart. He stared blankly as the grim young Wilson shoved me in upon him.

"Caught this damned fellow in the magnet-room, Captain. He's killed Bentley. By God—something queer's in the air this voyage. Bentley murdered—"

Mackensie's first stare of startled amusement as I was shoved captive before him, faded into horror. His heavy, square jaw dropped.

"Bentley murdered? Good Lord—why—what ..."

"Somebody was tampering with the ship's gravity," I murmured swiftly. "I felt it go off in a section of the main corridor—went down to the magnet-room. Bentley's there dead—drilled through the chest—"

"Bentley killed? Murder, here on my ship! Why, by the Gods of the starways—" Big Mackensie was momentarily stupified, his eyes widened, his heavy face mottled an apoplectic red with his rush of anger.

"I caught this fellow Penelle—" young Wilson began.

"Don't be an ass," Mackensie roared. "He's a Government crime-tracker—stationed here on board this voyage—"

My gesture tried to stop him. "Easy Captain. Listeners might be on us—"

The chart room door, here beside us, which opened onto the superstructure roof, was closed. But the small oval window beside it, also facing sternward, was open. I dashed to it. The dim roof deck seemed empty. I noticed a light in Len Smith's helio cubby.

I drew down the metal shade of our window. Whirled back. The astonished young Wilson stared at me in numbed amazement. "They're coming into the open," I murmured. "Look here, Captain, we've got to plan—"

"Why—why, good Lord—I thought we were guarding against a plot on the Moon—"

"Well, we're not. It's here—now—" I told him what Nina had said; five of the crew. The new men, placed here on board. And how many of the officers might be in it—

"Why—why good Lord—" Mackensie was completely stricken. For an instant that floored me. I saw him now as a Captain of the old school—bluff, roaring; the sort of fellow who on a surface vessel would deal grimly and ruthlessly with mutineers. But he was frightened now; frightened and confused.

"Why—why Penelle—you mean to think that here on my ship—"

"Ready to strike—now," I murmured. I told him about the burned place on the helio room door. He could only stare, numbed. And now the murder of Bentley—the first tangible attack our adversaries had made. Who were they? Five of the crew—that would include the hunchback Durk ... Mokk, the Martian? Ollog Torio, the pallid Venus man? Some of the other passengers maybe? And of the ship's officers, whom could we trust?

"Why—why all of them, by God," Mackensie murmured, as I voiced it. "I wouldn't have traitors on my staff—"

But this treasure of the T-catalyst—it might be worth a million decimars to the Venus revolutionists. And money can buy men—even men who have long been in honest service. The Second Officer—fat, jolly little Peter Green—he perhaps could be trusted. James Polter, the Purser? Of him I could not guess. Dr. Fyre, the Surgeon? Even with a plugged, counterfeit thousandth part of a decimar, I wouldn't take my eyes off him.

The handsome young giant, Wilson, stood gazing at us now in blank horror. He was hardly more than a boy. Quite evidently he knew completely nothing of what was going on.

"But what are we going to do?" Mackensie was stammering. Then he spluttered, "By the God's I won't have this sort of thing on my ship. I'll muster them all up here—find out who this damned murderer is—"

I seized him. "Easy Captain." Then I bent closer to him. "Captain Mackensie—things I don't understand yet about this. That big box in Miss Blake's room—" And on impulse I whispered: "Someone was climbing out her window a while ago. She called him Jim. She's in terror of him. Captain, see here, you've got to tell me everything about this."

For an instant, his spluttering ineptitude left him. "I can't," he murmured. "That—that isn't mine to tell. Don't ask it, Penelle." Then he swung back to his own troubles. "What do you think we ought to do? By heaven—I'll turn back to Earth. Turn the whole damn ship's company over to the authorities."

We were now some forty thousand miles from Earth—just about a sixth of the way to the Moon.

"And have them see us swing?" I murmured. "Wouldn't that precipitate whatever it is they're planning to do?"

Three of us here, in the control turret and chart room—and except for Nina, down there alone in her cabin, so far as I really knew, everyone else on the ship might be against us. Swiftly I questioned Mackensie. The X-87 was not equipped with any long-range guns, and very few side arms. What there were, we had now with us here in the chart room. Mackensie gestured to the little arsenal-locker, here in one of the walls beside us.

"Are the crew members allowed to be armed?" I demanded.

"Good Heavens, no!"

"But they will be," young Wilson put in. "Mutineers will be armed—"

There was no argument on that. And each of the officers normally carried one small heat gun. Here in the chart room we had perhaps a half dozen of the heat ray projectors; a few old-fashioned weapons of explosion; powder rifles and automatic revolvers; a small collection of miscellaneous glass bombs—loaded with gas; darkness bombs; a few of the "fainting bombs," as they are popularly called—detonators, with tiny shrapnel impregnated with acetylcholine, which, when introduced into the blood stream by a fragment of shrapnel, instantly lowers the blood pressure so that the victim faints but is not otherwise damaged. And we had two or three small hand projectors of the Benson curve-light, with a device by which we could project the heat ray in a curve as well.

"Well, if I don't turn back, then I'll helio my owners for instructions," Mackensie was saying.

It sounded futile. What could financiers back at their desks in Great-New York have to do with us, embattled out here in Space, barricaded in our little chart room?

"Send a helio for the Interplanetary Patrol," I suggested. "A call for help. If we could contact one of the roving police vessels—"

"Not a one in telescopic sight," Mackensie murmured. "I had a routine report on that a few hours ago."

"Well, we might as well try anyway." Would the pirates be aware of our efforts? Would it bring an attack from them? My only idea was to stall the situation here, whatever it might be. That, and summon help. Then I had another thought: young Len Smith, the helio man—could he be trusted?

"Why—I suppose so," Mackensie stammered. And then he jerked himself out of his terror; his huge hamlike fist banged down on the chart room table, making his calipers and compasses jump. "Damnation, I'll find out quick enough which of my men are loyal. We'll fight this thing through. Penelle, you go tell Smith to get off a distress call. Blast the ether with it—call Interplanetary police. Tell Smith to keep at it till he raises one. You stay with him and see, by God, that he does it. You, Wilson, open up that cupboard—get out the weapons. I'll have my damned officers up here."

As I started for the door I gripped him, whispered: "Captain—where have you got the T-catalyst hidden?"

It startled him. For a second I saw that he was wondering if he could even trust me with the knowledge. Then he gestured. "Over there," he murmured with his lips against my ear. "Little safe hidden in that wall-panel. You press a spring at the left molding. The catalyst is in a small lead cylinder—Gamma-ray insulated."

I nodded.

"Only one other man on board knows that," he whispered. "If anything happens to me—or him—"

Him? Who? I had no time to ask. Mackensie had flung open the door; shoved me out onto the deck. It still seemed deserted; dim with starlight from the glassite dome overhead. Amidships, some forty feet from me, the light in Smith's little helio cubby showed faintly eerie in one of his windows.

I ran there. "Smith. Len Smith...." I called it softly. "Len Smith—"

There was only the faint echo of my voice, coming back at me from the steel cubby wall. The door was ajar. I shoved at it, burst in and stood stricken, transfixed, with so great a horror flooding me that the eerie scene in the helio cubby swam before my gaze. At his instrument table the white-uniformed figure of young Smith lay sprawled, a white figure crimsoned ghastly with blood. A knife handle protruded from his back. Horribly his head dangled sidewise, with grisly severed neck.

And as I rushed forward, my movement jostled the body. It slumped, fell from the stool, hitting the floor with a thud. The blow broke the neck vertebrae; the head—ghastly little ball—rolled across the room and stopped at the wall, gruesomely right side up, with Smith's dead eyes staring at me—eyes with the agony of death frozen in them.

Then I saw the wreckage of the instrument table. All our communications smashed, wrecked beyond repair! For another second I numbly stared. Then, from some distant point of the ship's interior, a strident little electric whistle sounded. A signal! From another section I heard it answered. And then a shot! The barking explosion of a powder-gun ... the hiss of a stabbing heat-ray ... a commotion in the lower corridors—shouts of startled passengers ... a turmoil everywhere....

The attack had begun!

The turmoil that all in those seconds was spreading about the ship like fire in prairie grass released me from my numbness. I whirled; dashed back through the helio cubby door to the roof deck. It was still unoccupied. Back on the stern deck triangle, where just the stern tip of it showed from here, with the dull-red Earth-light upon it, there was the sizzling flash of a heat-gun. I saw the stern lookout collapse back from his telescope; fall to the deck.

Toward the bow, through the chart-room window where the shade now was up, Wilson was staring out. "Penelle!"

His voice reached me. Beyond the kiosk of chart room and control turret, a figure appeared coming up the little catwalk ladder from the bow deck. It seemed to be the bow lookout, but whether friend or foe I had no way of guessing.

"Watch yourself, Wilson," I shouted. "Watch the turret—" I was dashing for the side companionway. Whatever transpired up here, there was only one thing in my mind in the chaos of that moment. Nina.... She was alone down in her cabin. I must get her up here....

I leaped down the last half of that little side ladder. On the dim side deck ten feet away, two men were fighting, one in white gold uniform, the other a deckhand. They rolled on the deck. A knife flashed.... Another man came suddenly from the smoking lounge doorway. He plunged at me, whirling an iron bar. My Banning flash met him head on; I jumped aside as his dead body catapulted to the deck. There was another flash. One of the rolling, fighting men on the deck went limp. The other rose. It was the fat little Peter Green, Second Officer. He was panting; his face streaked with blood.

"Get to your room," he gasped as he saw me. "All passengers stay in your cubbies. Piracy!"

The passengers were shouting now; from a nearby corridor entrance women were screaming. Then from up at the turret, Mackensie turned on the vessel's distress siren. Its shrill, dismal electrical whine sounded above the turmoil.

"Go up to the control turret," I shouted at Green. I dashed into the corridor. Passengers scattered to right and left before me.

"Get into your rooms," I shouted. "Everybody stay in. Barricade—"

An Earth-woman screamed; somebody shouted, "That big Martian—murderer—I saw him killing—" Two little Lunites, mine workers, a young man and a girl, stood with arms around each other in one of the doorways. Pallid little people, confused, helpless, cringing. I shoved them back into their room and banged their door.

Then I turned into the main corridor, ran aft along it, came to the next cross passage. Nina! I saw her, ahead of me in the corridor, close by her smashed door. She was struggling, fighting with the snaky Venus man Ollog Torio; his arms lifted her up as he tried to carry her. I shouted an oath; I did not dare fire. And at the sound of my voice he dropped her, made off through the end door so quickly that I had no time to drill him.

"Nina! Nina!"

I gathered her up, frail little thing in her negligee with her luxuriant black hair streaming down.

"Nina, did he hurt you?"

"No! No, I'm all right."

She was breathless; pallid; her dark eyes were pools of terror. "Oh, dear God!" she gasped. "It's come." She clutched at me. "That hunchback—that fellow Durk—have you seen him?"

"No, I haven't." Her question sent a shudder through me. I set her on her feet. "We've got to get up to the control turret. The captain—his loyal officers up there."

"Oh—Oh, Lord!" With a new anguish of terror upon her face she jerked away from me, ran for her doorway. I saw where Torio had melted through its lock with a heat blast. I dashed through it after her, and caught her in the center of her room.

"Nina, what's the matter?"

The oblong coffin box! It lay flat on the floor, over by the wall of the dim room. In a sudden lull of the ship's chaos the rhythmic ticking was audible. And now there were other sounds from within the box! A thumping! A low, mumbling man's voice!

A rasping voice in the cabin doorway sounded behind me. Gun in hand, I whirled. One of the huge deckhands stood there, murder on his face, a blood-stained knife between his teeth so that he looked like an ancient picture of a surface vessel pirate. He lunged in at us. My flash caught him full in the face; horribly his features blackened as he went down.

"Oh—Oh, I had no chance to let you out!" Nina was half sobbing it as she flung herself down over the box. The ship's alarm siren had suddenly died. Did that mean that the captain and the others in the control turret had been killed? The thought stabbed at me. Distant shots were still sounding. The oaths of fighting men were audible—the loyal members of the crew, fighting those traitors who had so suddenly set upon them. Footsteps were thudding on the roof-deck overhead.

"No chance to let you out!" The pallid girl with trembling fingers was fumbling at the box. Its lid rose up, with the head and shoulders of a man appearing beneath; a man entombed, hiding in there, breathing with the air-renewers of the ticking mechanism. A stalwart man of iron-gray hair. Georg Blake! Nina's father. I recognized him from the many pictures I had seen. He leaped out of the box, stared at me.

"A Government man," Nina gasped. "Here to help us."

The report of Blake's death—his possible murder—all that had been Blake's own doing. He gripped me now; murmured it swiftly. A giant, dominant fellow, he towered over me. Nina was unpacking his weapons from the box as he told me. He had believed there was a plot on the Moon against him; was smuggling himself to the Moon, where in secret, with the villains thinking him dead and only his young daughter to cope with, he expected to expose them. And most of the voyage he had been hidden in the box, afraid of eavesdroppers or some prying Benson curve-ray.

"Give me those guns, Nina. These damnable murderers—" Then he swung at me; lowered his voice: "Mackensie has the catalyst?"

"Yes," I murmured.

"Good! I know where. By Heaven, they can kill us both and still they won't find it." He was buckling his weapons to his huge belt.

"The captain's in the control turret," I said. "Making a stand up there. We should go to him."

"Yes. You're right. Come on."

We ran. I put my arm around the girl as she sagged like a terrified child against me. Bow and stern, the sounds of the fighting seemed somewhat to have slackened. The passengers still were screaming; I shoved them back in their doorways as we dashed past. And suddenly, reaching the side deck, I realized that the towering Blake was not with us. The deck here was wet with blood. Three or four bodies lay nearby. An Earth-woman lay writhing, her white throat slashed with crimson. There was nothing I could do to help her. My gun ranged the deck; there was nothing to shoot at. Off at the stern, I saw a running man leap high in the air and go down. Then the red Earth-light back there momentarily darkened. Someone had thrown a darkness bomb; its light-absorbing gas came spreading along the deck toward us.

"This way, Nina—climb. I'll follow."

We went up the little ladder. Near the top I held her back, poking my head cautiously up, in advance of her. The dimly starlit deck was blurred with gas and heat fumes. We were mid-forward, perhaps halfway between the helio cubby and the chart room. In a patch here on the deck, darkness gas hung in a layer, a black shroud nearly waist deep. Light still showed in the window of the helio room, where the grewsome body of Len Smith lay sprawled. The chart room was dark, its door closed; but the steel shutter of its window, facing this way, was up a few inches. I thought I saw the muzzle of a gun protruding.

Good enough. Mackensie, Wilson and perhaps others were in there—barricaded, still holding out. I shouted, "I'm Penelle. Don't fire!"

"Come ahead," Mackensie's great voice roared.

Life, or death, can hang upon such a little thing. Directly across the thirty-foot roof deck from me the top of the other side-ladder was visible above the layer of darkness. A man's head and shoulders suddenly appeared there. My weapon leveled; but then I saw that it was Nina's father. He saw me at the same instant, waved at me and jumped from the ladder, wading through the waist-high darkness toward the chart room.

I do feel that there was nothing I could have done. Heaven knows I would give anything now if only I had had some flash of intuition.

But I was thinking only of Nina. I turned to gaze down at her, where she stood a step or two below me on the ladder. "Come on, it's all safe."

Safe? I turned back just in time to see a hand and arm come up out of the layer of darkness. Weird, as though detached from its body, it swung; the fingers loosed a little globe. It was only a few feet behind Blake. The globe hurtled at his head, struck it—an explosive bomb. It burst with a sharp report and a little puff of yellow-red light. Perhaps I caught a glimpse of the ghastly scattered fragments of what had been a human head. There was only a grewsome gory neck-stump as the giant body of Blake toppled down into the layer of darkness.

I fired into the darkness gas. The stab of heat dispelled it a little. I hit nothing. Then, as I jumped from the ladder, forgetful of Nina, from the chart-room window Mackensie was wildly firing from two weapons. One of the sizzling heat-rays barely missed me. And then someone behind him, Wilson perhaps, tossed a light-bomb. Its blinding actinic glare momentarily dispelled the gloom. At the other side companion-ladder we caught a vague glimpse of the massive head and shoulders of Mokk as he leaped down to the lower deck. His triumphant laugh floated up after him.

"You, Penelle, bring the girl in here," Mackensie was roaring. "Hurry now."

I all but carried the half-fainting Nina. The darkness gas was floating away; but I thanked God that enough remained to shroud the fallen headless body of her father as we passed it. The door of the chart room opened; I dashed in with her; hands banged the steel door closed and bolted it.

"I guess we're all here," Mackensie said. The X-87 captain was grim, his thick face puffed with the choleric blood swelling it. His left arm hung almost limp at his side; I saw where his white uniform was burned with the scorching edge of a heat-stab. Young Wilson was here, disheveled, wild-eyed. The little oval to the control turret was open; I could see the fat little Peter Green and James Polter, the purser, in there, crouched at a slit of the forward visor window, weapons in hand. I went in to them.

"Just us," I murmured. "Where's Dr. Frye?"

Polter grimly gestured. "Down there—see him? Damned traitor. I drilled him. See him?"

The X-87 was still on her course. The forward deck triangle was still bathed in moonlight, save that gases blurred it. The forward lookout's telescope lay in a wreck, with his body upon it. Other motionless forms were strewn about; chairs were overturned—those same chairs where Nina and the rest of us had gathered in the moonlight so short a time ago. Dr. Frye's thin body lay huddled down there.

I was aware now that all the fighting had ceased; there was only the distant murmurs of the terrified passengers, in their cabins beneath us. The mutineers everywhere had won; I could not doubt it. The thing was a swift massacre. Those crew members who had tried to be loyal were all dead. I stared, from the tiny hatch-opening in the bow, which led down to the forward messroom, a hand cautiously appeared. There was a stab of flame; a report; an old-fashioned leaden slug thudded harmlessly against a corner of the catwalk bridge, only a few feet from the slit at which we were peering. And in the silence, the sniper's chuckle sounded.

At my elbow, suddenly there was a buzzing. Green turned his head slightly. "Call—coming from the main gravity plate room," he murmured. "Answer it, Penelle."

I moved toward the little mouthpiece. But Mackensie had heard it and came running in from the adjacent chart room. "I'll take it. Keep at your lookouts, everybody—this may be a ruse to catch us off guard."

I could hear the tiny voice coming from the receiver as Mackensie clapped it to his ear.

"This is Torio," the voice said suavely. "Have you had enough, Captain?"

"You go to hell," Mackensie roared.

"That would be very nice, Captain, but it's more likely to be your own destination." I could picture the sleek, ironically smiling Venus man down there at the speaking tube. "We demand your surrender now—if you do not wish to die."

"To hell with you—"

"All you have to do is come out of the turret, with your hands up. You'll be treated—like the passengers. Fair treatment, I do assure you."

"I'll have all you pirates in the detention pen before this is ended," Mackensie roared.

"All we want is your surrender. And to have you tell us where you've hidden that little leaden cylinder."

"By Heaven, you'll never find it. Dead or alive."

"Dead, if you say so," Torio's voice snapped. And then his irony returned. "We'll give you five minutes to decide."

"I want nothing from you. By the gods, I'm still Master here!"

"Empty title, Captain."

"I'm steering us back to Earth," the captain rasped. "The Interplanetary Patrol is coming for us."

That made the Venus man chuckle. "If only it were. But it isn't."

"We'll be back on Earth in eighteen hours," the choleric Mackensie asserted. "You can all go to hell—you murderers—bandits—"

"Back to Earth?" Torio sneered. "Watch us turn, Captain. Not back to Earth. It's Venus we're going to head for. Venus—where the new triumphant Government will be needing that treasure you've hidden. Up there with you in the turret, isn't it?"

"To hell with you—"

"Watch us turn, Captain."

I was aware of the glittering Heavens up through the glassite pressure dome as they made a dizzying swoop. The little X-87, with her gravity plates abruptly shifted by the manual controls in the hull room, was turning over.

"See it, Captain?"

"You damned fools," Mackensie roared. "Disconnect my controls if you like. What the hell of it? You can't chart a course down there. You haven't the instruments or the skill."

"Quite true, Captain. That's why we want you to surrender. We'd really rather not kill you. And if we go falling through Space this way, unguided, we might eventually hit something. Your five minutes are almost up. What do you say?"

My nostrils abruptly were dilating. What was this? Suddenly I was aware of a queer acrid smell here. And my head gave a swoop. Here in the turret Green and Polter were at the forward window. I saw them fling me a startled glance. Both of them staggered to their feet. And Mackensie, still gripping the receiver, was swaying.

"What's the matter, Captain?" Torio's suave ironic voice was demanding. "Do you smell it already? You're so silent."

William Wilson, with Nina, was alone on guard in the adjacent chart room. He gave a sudden startled cry. "Come quick! Something's the matter with me."

Poisonous gas here! We realized it abruptly; gas pouring in through the ventilators from below.

"Close those vents!" Mackensie gasped. "Poisoned air—" His hand was clutching at his throat. With his thick neck, full-blooded body, he felt it worse than any of us. His face was purpling; his eyes abruptly bulging. In that second he staggered and fell, ripping the receiver connection out as he went down, where still the ironic voice of Torio was jibing at us.

The rest of us sprang to the grid vents. There was no way of shutting the poisoned air off! The hinges of the multiple little visors were melted away!

"That—that damned Dr. Frye," Polter gasped. "He was up here a while ago. I wondered—"

A scream from Nina, mingled with a sizzling flash in the other room, transfixed us. With all the weird scene swaying before me, I dashed through the oval. Young Wilson was lying sprawling, dead from a bolt, with his head and shoulders on the window ledge. Nina was crouching in a corner, gasping, staring in terror. I started toward her. My ears were roaring as though with a thousand Niagaras. A titan hand seemed compressing my chest with a band of steel as I gasped for breath.

"Nina—Nina—" My own voice, so futile, sounded far away. Then I heard the steel shutter of the chart room window snap up to the top. Into the opening, a man came climbing. Mokk, with a patch of chemical fabric binding his nose and mouth like a mask. My gun sizzled at him, but the stab went wild as I staggered. Then he came leaping at me.

From the turret I was aware of other shots; a scream of agony from Polter as he was struck; thudding blows as the visor pane was crashed. And then a scream from little Green. The end! On the chart room floor grid I found myself wildly grappling the hulking Martian. My gun had clattered away as his three hundred-pound weight crashed me down. Dimly I realized that this sudden wild attack upon us was because the bandits, for their own sakes, had no desire to have any great amount of the poisoned air circulating about the little ship.

"You damned little Earth-fool," Mokk was growling. "Don't you see I'd rather not kill you?"

My puny little blows into his face only made him rasp with anger. I was trying to twist from under him. I almost made it. But abruptly he seized me around the middle, rose up and hurled me. Like a child I hurtled across the room, crashing against the alumite inner wall. The world went up into a blinding roar of light as my head struck. Dimly I was aware of dropping back to the floor. There was only blinding, roaring light, and Nina's choked scream of terror as my senses faded and I slid into the soundless abyss of unconsciousness.

I was at last aware that I was not dead, by the dim feeling that my head was throbbing. I was lying on something soft. Voices were here; the muffled, blended murmur of men's voices. At first they seemed very faint and far away. Then, as my returning senses clarified a little more, I knew that the voices were close to me.

I opened my eyes at last to find myself lying on a blanket on the chart room floor. In a chair Nina was huddled, mutely staring with wide, terrified eyes to where at his chart-table Captain Mackensie was slumped, sullenly staring at the celestial diagrams spread before him. The sleek, ironic figure of Torio was beside him, his slim gray hand gesturing at the charts.

"We are now just about here, Captain?"

"Yes," Mackensie growled.

"Then we want a computation of the swiftest course, from here to Venus. You will figure it out. Tell us the gravity plate combination."

I could feel that blood was stiffly matting the hair at the back of my head, a ragged scalp wound there. I was bathed in cold sweat; weak, so dizzy still that the eerie chart room swam before me. But my strength slowly was returning. How much time had passed? Considerable, I judged, from that blood so stiffly dry in my hair. With a fumbling hand I felt of my clothes. All my instruments and weapons had been taken.

Then I saw, in another chair, the huge slumped figure of Mokk, his massive legs crossed at ease. On his knees his hand held a gun alert. The room light fell on his heavy face. It bore an expression of grim irony, as his dark eyes, watchful, roved the room.

"The segment of a parabola, Captain," the soft voice of Torio was saying. "Would that be most swift? Remember, as we turn in past the Earth, we go no closer than forty thousand miles."

"You're fools," Mackensie muttered. "This voyage will take a month or more."

"Why not?"

"The alarm will be out for us. The Interplanetary Patrol will pick us up."

"Let us hope not, Captain. You and Miss Nina would be the first to die. But there is not too much danger, I think. The modern electro-telescopes are very wonderful, but there is none, at forty thousand miles, powerful enough to pick up so small a speck of floating dust as the X-87. Or at least, not to identify it."

"I wouldn't be too sure, Torio. And at best, your food will give out."

"We will hope not," Torio smiled. His voice turned brisk. "Chart your course, Captain. Remember, we kept you alive just for this duty."

Nina said suddenly, "This silence everywhere about the ship—where are the passengers?"

Torio turned smilingly to her. "Why, little lady, didn't you know? We gave them pressure suits and put them out the keel porte. Have no fear, they'll drift down safely. Some of the suits are powered. If they're clever they'll get back to Earth."

As though this were an old-fashioned surface vessel—giving the passengers life preservers and tossing them into the middle of an ocean.

"Penelle seems to have recovered his wits," Mokk said suddenly. "See what he knows, Torio."

It turned all their gazes upon me. I was up on one elbow. "What I know about what?" I said.

Torio leaped to his feet and stood bending over me. "Now then, you damned crime-tracker. Where is the T-catalyst? It's hidden around here somewhere. Where is it?"

"Catalyst," I mumbled. "I don't know what you mean."

Torio's foot kicked savagely at me. I tensed; the giant Mokk shifted his weapon to level down at me. I saw Mackensie flash me a glance.

"So you're going to try that too?" Torio rasped.

I stared. "He doesn't know any more about it than I do," Mackensie growled. "Nobody knew except Georg Blake, and you killed him. Find it for yourself. My guess it that Blake cast it adrift when the attack came."

"You talk without sense," Mokk put in. "Maybe the girl knows." He chuckled. "If you leave me alone with her, Torio, I can think of ways to make her tell."

"I know nothing about it," Nina gasped.

"Well, some one of you does," Torio said grimly. "We'll start with this damn crime-tracker." He leaped across the room, came back with a length of wire. My gaze strayed to the opposite wall; the treasure was there, back of a secret panel.

"Bare your chest, Penelle." Torio stooped to where I was backed against the wall, on the floor. He tore at my shirt, exposing the flesh of my chest. "Are you going to tell?"

"I can't. I don't know."

Beyond his slim shoulder I saw Nina's face, pallid, her dark eyes glistening with horror, her lips compressed as though to stifle a scream. Torio had a small cylinder in his hand, with the naked length of wire connected to it. The wire was glowing now—red, orange, white, then violet hot.

"A few lashes with this," Torio hissed at me. "Whatever you know will come out then." His pale face was blazing.

"He will talk even more quickly if you try that on the girl," Mokk growled.

"No!" I burst out. "No, damn you! We don't know where it is! I can't tell what I don't know."

"We'll see," Torio muttered. He dangled the wire at my face. The violet light of it was blinding; the heat scorched my skin.

"Stop! Oh, stop it! I'll tell you!" Nina's anguished cry rang out. The light and heat receded from my face.

"Oh, so you're the one who's willing to tell?" Torio swung on her; snapped off the current in his wire and flung it away. "All right, where is it? But remember, by the gods, if we don't find it where you say—"

"It's there." She gestured to the wall. "My father told me it's there."

"I hope so," the giant Mokk growled. "For your sake, I hope so, little lady."

I held my breath. If by some mischance it should not be there—

Then Torio found the pressure-clip and slid the panel. With a cry of triumph as he saw the hidden little safe; he did not wait to question us on how to open it, but seized a heat-torch; melted its lock in a moment. The foot-long leaden cylinder was disclosed. There could be no question of the authenticity of its contents—its contents-dial glowed with the Gamma rays bombarding it from within. The pointer trembled at the figures indicating the strength and character of the bombardment.

"All goes well," Mokk chuckled. "We have no problems now, friend Torio. You and I can trust each other, eh? Put it back in the safe. That is as good a place as any." The giant Martian stood up, yawning. "You work out our course with the captain. For me, I shall go down and take some rest." He grinned. "The little Earth-girl fascinates you, eh, Torio? I must leave her up here with you. Very well. I would not be one to quarrel over so small a thing. The girls of Mars please me better."

Torio, too, was smiling. They were highly pleased with themselves, these triumphant villains. "Take Penelle with you," Torio said contemptuously. "Lock him up in one of the cubbies. Have one of the men feed him."

I caught Torio's flashing, significant look, and one of grinning irony with which the Martian answered it. And Nina saw it also. A cry burst from her and she leaped up.

"You—you don't mean that! You're going to kill him, now that you haven't anything more to get out of him! Oh—Oh, please—"

Her slim little hands gripped Torio by the shoulders. I saw him tense; he stared; and then he laughed softly. "Well, my dear—when you ask me in such a way as this—"

"Oh, I do. I do."

"Then I will keep him alive."

"Don't—don't take him down there."

"You do not trust me?" His voice sounded hurt. He swung on Mokk. "Bind him and lock him up. Do not harm him. If you do, you will answer to me for it. I mean it now."

"Quite correct," Mokk agreed with a grin. "If that is your form of love-making, it is your own affair. Let us hope she will give you her favor, since you do this for her."

"Take him away," Torio commanded. "Come, Captain—let us get this course charted."