It meant death if Vance McClean ever returned

to Ceres. Still, a cool million in palladium

was tempting bait to that exiled star-pirate.

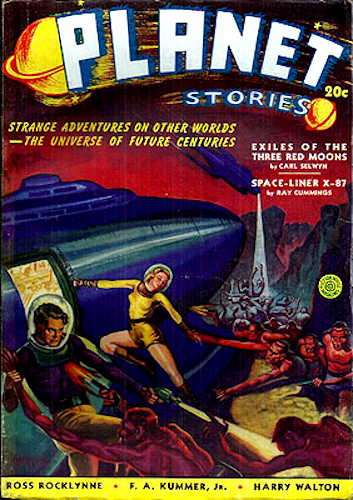

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Planet Stories Summer 1940.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

It was cold that night, I remember. Cold and clear as ice. And although Ceres has no moon ... it's hardly more than a satellite itself, ... the starlight penetrated its thin, dustless atmosphere with surprising brilliance, throwing weird shadows across the icy plain.

Gazing through the window of the little administration building, I could see the head of the mine shaft perhaps a mile away, and the huts of the miners, all dark, for now that the rich vein of palladium was exhausted, my uncle had dismissed our workmen. The scene was a familiar one to me. I had lived on the asteroid for fifteen years and my recollections of earth, which I had left at the age of five, were hazy, a series of dream-like impressions of big buildings, green grass, and warm yellow sunlight.

I felt very lonely that evening with the workmen gone and my Uncle John at Verlis arranging for our passage to earth. Cerean Mining, Inc., had paid well these fifteen years before the vein ran out; in the huge wall-safe behind me were stacks of the gray ingots, Uncle John's profits over that period of time. Nearly a million dollars' worth in earth currency. He planned to take the precious metal back to earth with him, where its sale would bring higher prices than on Ceres, then retire on his hard-earned proceeds. He was paying my fare back to earth, gratis, and had arranged to get me a job there, which was more than many uncles would have done for a needy and lonely nephew.

I was thinking about earth, as I sat there at the office desk, my back to the big wall safe, a heavy flame gun lying on the blotter before me. I was supposed to guard the palladium until Uncle John returned, though this was a mere formality. Ceres was too small for anyone to get very far, and all the passenger liners leaving Verlis were thoroughly checked. And even supposing some thief were to overcome me, force the huge, triply-reinforced safe, he would find it hard, even in Ceres' light gravity, to carry off a million dollars' worth of palladium. So I wasn't greatly worried about playing guard; my thoughts were busy trying to visualize earth, planning what I would do there when I arrived.

About eleven o'clock, earth-time, however, I awoke with a start from my day-dreaming. A light ... a lurid flickering light ... was dancing through the big glassex window. I leaped to my feet, gripping the flame gun, and peered out. A sleek, silvery little space-ship was settling down on the plain outside!

As I watched the ship ride in to land on its columns of fire, a vague uneasiness filled me. Vessels weren't accustomed to put in at the Cerean Mining field; especially swift little craft that were neither slovenly freighters nor stately liners. Gun in hand, I stepped to the door of the administration building.

The ship had landed as lightly as a snowflake on the barren plain, switched off her rockets. The air-lock clanged open and two bulky figures in asbestoid jumpers swung down; so hot was the rock from the rocket exhausts that their lead-soled gravity shoes left silvery patches as they strode toward the administration building. One of the men, to judge from his build, was a Jovian, huge, squat, mighty-thewed; the other, a slender earthman, his face hidden by the hood that protected him from the cold. I waited until they were within twenty feet of me, then raised the flame-gun.

"Stop where you are!" I said curtly. "This is private property ... the property of the Cerean Mining Company. What do you want?"

The earthman paused, studying me as I stood there in the light that streamed from the doorway.

"So big," I heard him mutter as though to himself. "Who'd have thought it! Eleven years! It's passed quickly ... for some."

This didn't make much sense, but it wasn't the meaning of his words that struck me. It was his voice. There was something about the voice that sounded a familiar chord in the back of my mind. For a moment I tried to puzzle out the disturbing memories but without much success. Then, shaking off the strange uneasiness, I raised the gun once more.

"Stay where you are! Another step and I'll shoot!"

The earthman continued to move toward me, the big Jovian in his wake.

"If you must shoot, Steve," he said quietly, "I suppose there's no help for it. You'd regret it, though, I think."

Again the puzzling familiarity of that voice! Where had I heard those calm, bitterly mocking tones before? And how did he know my name? Was this some trick to force an entrance into the administration building where Uncle John's fortune in palladium lay?

"You asked for it!" I cried, drawing a bead on him.

The stranger must have realized that I meant business. He was only ten feet from me, now, and could have guessed from my expression that I was about to shoot. With a swift movement he threw back the hood that concealed his face. My arm sagged down and I heard myself give a quick involuntary gasp. No mistaking those clean, sharp features, those frosty, sardonic eyes, that lined, thin mouth, lips twisted in an ironic smile! The man who stood there in the light that jetted from the doorway was my father!

It had been eleven years since I'd seen him, but he hadn't changed much, except that his black hair was gray at the temples. Apart from that, he didn't show his forty-five years in the least. Staring at him, my memory flashed back to that night eleven years before in this same administration building. There had been three owners of Cerean Mining in those days. My father; his brother-in-law, Uncle John; and big, red-haired Carl Conroy. They had formed the partnership on earth shortly after my mother's death, come here to Ceres looking for rare palladium. They'd just scraped along for five years, then struck the rich vein of ore. And about two months after the big strike, there came that terrible night.

I was only nine at the time, and had been sent off to bed. I was awakened by the hiss of a flame-gun, a short gasping cry. I remember lying there long minutes, terrorized, then creeping to the head of the stairs, peering down. On the floor of the big room, near the safe, was Carl Conroy, a terrible blackened form, with my father bending over him. I can remember Conroy's twisted figure, the stench of burned flesh, my father's hoarse breathing. Then suddenly the door opened and my Uncle John entered, his face gray, a gun in his hand. Uncle John spoke slowly. He said that he'd noticed some of the palladium was missing every morning, and he'd asked Conroy to watch the safe. Now he knew who the thief was. My father seemed sort of stunned, choked. And I'd clung there unnoticed, hoping to wake up and find it all a dream. But it hadn't been a dream. Keeping his prisoner covered, Uncle John had backed toward the micro-wave communications set to call the authorities at Verlis. For a long moment my father stared at him, then leaped for the door. I screamed.

Uncle John could have shot him in that instant, but he didn't. He just stood there, flame-gun in hand, as my father disappeared into the darkness; then he climbed the stairs to where I crouched, crying, and put an arm about my shoulders. "We'll try to forget this, Stephen," he said to me. "There's a space-ship leaving Verlis in the morning. Maybe he can make a fresh start somewhere else in the solar system. We'll bury Conroy out here, report that he died an accidental death. That's the least I can do to keep you from being known as the son of a murderer." And I cried myself to sleep on Uncle John's shoulder.

All that eleven years ago. We'd never mentioned my father again. When people asked me, I said that he was dead. I hoped he was. The thought of having a father who was a murderer, a thief, a fugitive in the solar system, wasn't pleasant. Better to think he'd died bravely, decently, on some far-flung world. And now, after eleven years...!

"You remember me, then ... son?" My father laughed ironically; he strode by me into the room, followed by the big Jovian. The latter, I noticed, carried several large cylinders on his back.

I stood there undecided, confused, fumbling with the flame-gun. My father perched himself on the edge of the table, lit a slender, aromatic Martian cigarette, an eyla, the same kind he'd smoked in the past. Its fragrant, sharp aroma awoke memories of my childhood. Suddenly he spoke.

"Where's John?"

"He's gone to Verlis, to arrange for our passage to earth. The vein's worked out."

"So that's why the miners' shacks are dark." He nodded. "I arrived just in time, then. And from the close watch you were keeping, I'd say the palladium was still here." For a long moment he eyed me, studying my face. "Healthy, and as sanctimonious as John, from the looks of you. Taon" ... he turned to the big silent Jovian ... "his gun!"

Before I realized what had happened, the Jovian had snatched the flame-gun from my grasp.

"I apologize, Steve," my father said blandly, "for using force. But in my past eleven years knocking about the solar system, I've noticed that people are unaccustomed to yield to reason. It's for your own good, as well. Some years ago on Jupiter I saved Taon's life. If you were to commit an indiscretion, such as killing me, he would tear you to bits. A faithful fellow, Taon. And since I am about to force this safe, I felt that you might do something rash with that gun...."

I stood there, speechless, as the huge Taon swung a double-cylindered oxy-hydrogen burner from his shoulders. He tinkered for a moment with first the hydrogen flash, then the oxygen one; a moment later a jet of cruel white flame bit into the big wall-safe.

"Good Lord!" I whispered. "I've known all along that you were a thief, a murderer, but with all the solar system to prey upon, why must you come back here! To rob your own brother-in-law, after he let you escape that night! And to make sure your son is known as the son of a common thief! I'd rather have the cheapest space-rat as a father than you!"

For just a moment there was a cloud in my father's eyes, but the ironic bitter smile clung to his lips.

"Very melodramatic," he applauded. "You inherit that, I think, from the other side of the family. John has the same flair for theatrics. I regret now that the business of obtaining a space-ship, of finding certain ... necessary persons ... took so long. Had I come sooner, I might have aided in your education." He turned to the big Jovian. "How goes it?"

"Safe good steel," Taon grunted. "One ... two ... hour job."

"No hurry." My father puffed lazily at his eyla, flicked a bit of ash from his coat sleeve. His gestures, his well chosen words, his carefully modulated voice, all indicated that he was playing the role of debonair, cosmopolitan man of the worlds. The perfect gentleman—even when engaged in cracking a safe! I hated him for it! This space-rover, thief, murderer ... my father! Better to see him imprisoned at Verlis, than to have him at large, adding to the shame of our name. With one leap, I crossed the room, snapped on the micro-wave communications set.

"Cerean Mining, calling Verlis!" I snapped. "Come...."

My father hardly seemed to move, but a pencil of blue flame from his gun leaped across the room, blasting the radio to bits.

"All right, Taon." He motioned back the Jovian, who, like a great faithful mastiff had sprung to his side. "No need to worry." Wiping off the gun, he turned to me. "As for you, Steve, you show more spirit than I had suspected. Although misdirected, since there was never a chance of contacting Verlis. However, I am going to pay you the compliment of putting you under lock and key while we complete our business here. In the next room, Taon, you will find, to the right of the heating unit, a closet, used, as I remember, for over-suits. Lock the boy in it."

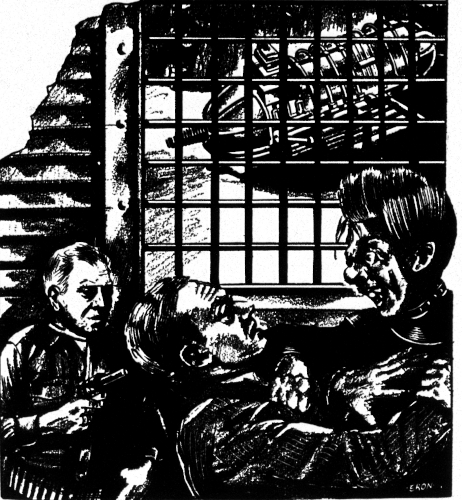

The big man nodded, his slitted, ice-green eyes expressionless. In his grip I was helpless; no earthman can match a Jovian in strength. I shot one furious glance at my father; who was perched upon the edge of the table, swinging one foot, humming placidly. For just an instant as he felt my gaze upon him, he paused in his humming, a peculiar expression upon his face. Then Taon carried me into the next room, pushed me into the closet, slid the loose, rattling bolt. I was a prisoner—a prisoner of my own father!

For my first few minutes in the closet, my mind was a skein of tangled thoughts. The past that I had believed securely buried, returned to haunt me! Another day and the palladium would have been aboard a space liner at Verlis, Uncle John and I would have left Ceres for earth. All my day-dreaming of a new life on Terra was ruined. If my father should get away with the fortune in palladium, it would be broadcast over the entire solar system. Uncle John had never reported the murder of Carl Conroy, in hopes of saving my name. But this would be bound to come out, and my chances of finding a job, a decent place in society, would be wrecked when the solar system learned that I was the son of the notorious Vance McClean. And Uncle John, who had been like a father to me since that night of Conroy's murder, would be rendered penniless after fifteen years' work! Unless I could escape, summon help....

The closet was roomy and had a light. Not one of the new astra-lux arcs, but an old-fashioned electric bulb hanging from the ceiling. We don't have all the modern gadgets on Ceres.

I snapped on the light, and glanced about seeking some means of escape. On a row of nails hung several over-suits; asbestoid garments, electrically heated, for use in the biting cold of the Cerean plains. Nothing there. I then turned my attention to the door. It was of very thin, very strong plastic. Taon had not locked it, only slid home the iron bolt that fitted loosely in the brass staples. No chance, however, of working it free from this side; and while I might conceivably force the door open by battering against it, the noise would be sure to bring Taon and my father from the next room to recapture me. If any escape were made, it must be done quietly. Outside I could hear the roar of the oxy-hydrogen torch, cutting into the big wall-safe where my uncle's fortune in palladium was stored.

Then suddenly the idea struck me. A wild idea, true, but one which, if it succeeded, would enable me to draw the bolt quietly. I turned to the rear of the closet, and began working back and forth one of the nails upon which over-suits were hung. After some difficulty, it came loose. My next task was more difficult ... stripping the wire from one of the electrically heated suits. The point of the nail aided me in ripping open the tough asbestoid. At length I obtained fully ten feet of wire and commenced wrapping it about the nail. This done, I tore loose the bulb and socket from the light, and, working in the dark, in danger of a severe shock, managed to connect the live wires to my wire-wrapped nail, forming a crude, but, I hoped, powerful magnet. But was it powerful enough to be effective through the thin, tough plastic door?

I paused, listening. The sound of the torch would cover the noise of drawing the bolt. And if I could escape unobserved, climb through one of the windows.... Holding my magnet against the door jamb, I moved it slowly to one side. A faint squeak seemed to indicate that the bolt had moved. I repeated the operation again, and again, drawing the bolt a fraction of an inch each time. The little magnet, separated from the piece of iron by a quarter inch of steel-tough plastic, still had sufficient force to grip the bolt, draw it slightly. At last, after a score or more attempts, the bolt slid clear of the brass staples. A touch of my shoulder sent the door ajar. I was free!

Very cautiously I peered through the crack. The room before me was dark, but beyond the doorway at its far end I could see Uncle John's office, brilliantly lighted by the whitish flame of the oxy-hydrogen torch. My father was still seated upon the edge of the table, swinging one foot; his face was intent, far-away. He seemed to be peering into the dim mists of the past as he sat there, and I noticed that his suave, bitter mask had vanished. Taon was working on the safe. His brutish, colossal shadow was visible on the wall like that of some great grim satyr.

With infinite care I pushed open the closet door, stepped out, then slid the bolt again to make it appear that I was still a prisoner. On tiptoe I approached a window, raised it. Still no sound other than the hiss of the torch. I swung down to the ground, closed the window behind me, and ran toward the sleek silvery little space-ship.

The ice-covered plain was bitter cold; I had neglected to put on one of the asbestoid over-suits. The deserted huts, the head of the mine shaft loomed like a row of dark specters in the wan starlight. And since the cold light of the stars was cast from different angles, double, triple and even quadruple shadows fell across the barren wastes. Bleak, desolate, to an earthman, but I was used to the cold Cerean scene. Great jagged pinnacles of rock stabbing like crooked daggers at the frosty sky; rounded meteor holes dug into the ground; occasional patches of pale ice-moss, dangling like white beards from the grotesque rocks; and beyond, the glistening plain, dropping away to a ridiculously close horizon. I gasped in the cold air as I ran, felt it bite my lungs. Without gravity shoes, I covered the distance to the ship in a dozen great bounding leaps. No signs of life were visible aboard her and I felt that from the size of the little vessel it was unlikely she carried more of a crew than my father and Taon. If there were others aboard, I would have to take my chances.

I glanced up at the ship. Her burnished hull shone in the thin light; the heavy outer door of the circular air-lock remained open as my father had left it. I reached up, grasped the metal stanchion, drew myself into the air-lock. A moment later I had pushed open the inner door, entered the vessel.

The little ship was dimly lit, shadowy, inside. Glancing about, I found myself in a narrow companionway, one end of which led to the living quarters of the craft, the other, stretching in the direction of the control room. I turned in this latter direction, running softly to prevent my shoes from clanging on the metal floor-plates; for while the ship was silent as a tomb, I could take no chances on anyone else being aboard, surprising me.

The door to the control room, at the end of the passage, was open. For a moment, as I raced along the corridor, I had entertained thoughts of making off with the ship, leaving my father and Taon marooned on Ceres, where they would soon be tracked down. Sight of the control panel, with its complicated array of dials, gauges, and switches, soon dispelled this illusion. I had never flown a space-ship before, and any attempt on my part to do so now must surely result in disaster. But with the big ultra-wave communications set that stood to one side of the control panel it would be a simple matter to call Verlis, as I had previously attempted, and notify Uncle John.

Hastily I spun the dial to the wave length of the station at Verlis, called their letters. The voice of the operator there answered me.

"CQR, Verlis, Ceres," he snapped. "Go ahead!"

"Stephen McClean, of Cerean Mining," I whispered, bending low over the mike. "My uncle, John Gibson, is in Verlis. He'll be either at the hotel or the space-port, making arrangements for the transport of his palladium to earth. Send someone to find him at once! It's vital! Tell him" ... I hesitated a moment, wondering whether to mention the robbery and bring in the I.P. patrolmen. But it might be possible to stop my father's evil work without disgracing our name ... "tell him," I went on, "that Vance McClean is here, that he'd better round up a few men and return as quickly as possible! Got it? As quickly as possible! It's urgent!"

"Right." The Verlis operator replied. "Checking back!" He repeated my message to me.

"Okay," I exclaimed. "Hurry!"

"Anything wrong?" the operator asked.

"Only a ... family affair," I said, and snapped off the set.

The message sent, my nerves lost some of their tension. Uncle John had gone to Verlis in his big rocket-sled. With its exhausts opened full, the sled could race over the icy plain well in excess of a hundred miles an hour. And since Verlis was only a short distance away he could reach the mine, with luck, in thirty minutes.

I glanced through the big observation port of the control room. The window of the administration building was still lit by the white-hot glare of the oxy-hydrogen torch. An hour was necessary to cut through the steel doors of the safe, Taon had said. But the hour must be nearly up. I had to make sure that they didn't get away before Uncle John arrived. But how? At that moment my glance fell on the intricate control panel. If that were smashed....

My eyes swept the crowded control room, fell upon a heavy metal stool, drawn up at the navigator's table. I seized it, swung it high above my head. Thrown into the panel, it was sure to wreck the array of delicate instruments. And with them smashed, the ship would be grounded here indefinitely. My muscles tensed as I prepared to heave the stool into the fragile mass of wire and glass tubing. Another moment and....

"Don't throw that chair!" A clear, firm feminine voice came from the doorway behind me. "Set it gently on the floor! Any tricks and I'll shoot!"

For just a moment I hesitated, the stool held high over my head. A woman ... here! Then I felt the muzzle of a gun dig into my back, and I knew that whoever the woman was, she meant business. I set the stool carefully on the floor, turned, hands raised, to face my captor.

The owner of the clear voice was young, slender, her well-modeled figure sheathed in a shining green cellatos dress. Her hair was the coppery red of a Martian desert, and her eyes were cloudy blue, the color of distant hills. The hand that held the gun was steady, her expression was determined.

"I thought I heard voices," the girl said. "Who were you talking to?"

"Only the radio." I nodded toward the set, grinning. "I called Verlis to tell them the Cerean Mining's safe is being cleaned out by my charming father."

"Your father!" The girl's figure stiffened. "Then you're Steve McClean! And you've notified your uncle to come here? Oh, you fool! You fool!" Tears of anger filled her eyes, adding rather than detracting from her beauty.

I stared at the girl, puzzled. What was she doing on this ship? And how did she know about me, about Uncle John? There was, of course, one simple explanation of her presence, but somehow I didn't like to think of it.

"Now that you've found out who I am," I said, "maybe you'll tell me your name? And your status aboard this ship?"

She didn't answer. Her lips moved, but she seemed to be talking to herself.

"Five minutes since he called Verlis; not over half an hour's run in a rocket sled." Then, squaring her shoulders. "Keep your arms raised! And head for the air-lock! We're going to the administration building to warn Captain McClean!"

I had no choice with the flame-gun tightly gripped in the girl's hand. Arms raised, I stumbled from the control room, along the companionway, through the air-lock. The girl walked behind me like a shadow, her face pale, deadly earnest.

Leaving the ship we set out across the bitter icy plain toward the administration building. The blue-white light no longer streamed from the window. Which meant only one thing. The great wall-safe had been forced! A million in palladium, Uncle John's life savings, were at my father's disposal! Unless that rocket-sled broke all records returning from Verlis....

"Hurry up!" the girl behind me said through chattering teeth. "I'm freezing!"

I quickened my pace, bounding across the all but gravity-less plain. Snow creaked under our feet, our breaths were white clouds, our shadows sprawled like grotesque monsters on the pale ice. At length we reached the low crystalloid building; the girl's gun digging into my back, I opened the door, entered.

The room was a scene of desolation. To one side of the safe stood the twin-cylindered blow torch, shut off, now that its work of destruction was done. The huge door of the safe, its lock melted away, the edges of the hole glowing cherry-red, gaped wide, revealing stacks of small, steel-white ingots. Palladium ... a million dollars' worth! Taon, the big silent Jovian, was busy taking the bars of precious metal from the safe, grunting with satisfaction as he stacked the ingots on the floor. My father, as we entered, had just taken a small, leather-bound book from the safe, was leafing through it with a queer expression on his face. On seeing us, he whirled about, gasping,

"Clare! And you, Stephen!" He turned, frowning, to the big Jovian. "This is your fault, Taon! You have done poorly! I ordered him locked up."

"Don't blame Taon," I grinned. "It wasn't his fault!"

Without a word my father strode into the next room, unbolted the closet. At sight of my home-made magnet, still dangling from its wires, he nodded blandly.

"Very good, Stephen," he said, re-entering the room. "You show signs of real ingenuity. I'm afraid I underestimated you." He glanced at me with an air of satisfaction.

"More than you think!" the girl Clare exclaimed. "We've got to hurry! He radioed John Gibson at Verlis to return at once! He put the call through before I knew he was on the ship!"

For a long minute my father remained silent, puffing at his eternal Martian eyla studying the greenish clouds of smoke as though the future lay revealed in their swirling tendrils. The girl bit her lip impatiently, glanced nervously toward the door. Taon stood motionless, his broad, ugly face stolid, awaiting orders.

"I must confess," my father said at length, "that matters haven't turned out just as I had expected. I had intended to take the palladium ... and my loving son, here ... aboard the ship, make a quick getaway. Now, thanks to that message to Verlis, I am known to be the person responsible for the ... ah ... robbery, and will be pursued by the I.P. men. Moreover, there is another matter" ... his glance fell upon the leather-bound book he had taken from the safe ... "that has caused me unexpectedly to change my plans. I think it is wiser all around for us to remain here."

"But you can't!" the girl cried. "It's madness! He can have you arrested for murder! My father's...."

I never heard the rest of what she was going to say. The staccato roar of rockets, the grinding of steel brakes biting into ice, drowned out her words. A rocket-sled was screaming to a stop before the building, the flare of its exhausts flickering through the window like terrestrial lightning.

Taon stiffened, his hairy hand seeking the butt of his flame-gun. The girl went whiter still. And I drew a quick sigh of relief for the first time in the past two hours. Only my father betrayed no emotion; he sat there like an image carved from ice, that bitter, mocking smile on his lips.

With a bang the door of the building slammed open. Uncle John, tall, gaunt, bushy-browed, strode into the room, frowning.

"Good evening, John," my father said pleasantly. "We've been missing you. You're all that's needed to complete this family reunion."

"Vance! Then it was true, Stephen's message! You've nerve, coming here!" Uncle John shook his head. "Thief! Murderer! Liar! I suppose I was a fool to let you escape that night. I only did so for the honor of the family and the name of Stephen, here. And so you return to commit another robbery, to make sure your son is known as the son of a space-rat!"

"You touch me deeply, John!" my father observed dryly. "As sanctimonious as ever! Pure, honest John Gibson! Ceres' outstanding citizen!" He surged to his feet, leaned across the desk; for the second time that night his cold, mocking mask dropped, revealing the man beneath. Eyes like glowing coals, face etched in savage lines, he stared at my uncle. "I've thought of you a great deal these eleven years! In the radium fields of that hell-planet Mercury, hunting gold in the stinking Venusian jungles, prospecting the dusty, choking deserts of Mars! And there was one thing that kept me going! The thought of this minute! A year ago I'd scraped together enough to buy the little space-yacht outside. Then I had to go to Terra, find Clare...." He motioned toward the girl.

Uncle John swung about, noticing the girl for the first time as she stepped from the shadows. His face took on a drawn, tight look.

"Who is this girl?" he croaked.

"Allow me." My father waved an airy hand. "Miss Clare Conroy, daughter of the late Carl Conroy."

"Daughter of...! But I didn't know he had a daughter! Why is she here?" Uncle John whirled about. "What deviltry is this? You, the murderer of her father, kidnaping the daughter...."

"Not kidnaping, Mr. Gibson," Clare said quietly. "I came of my own free will."

I gasped. This girl, Conroy's daughter! And she'd come with the man who had killed her father, to the scene of the crime, was aiding him in stealing the palladium. I felt as though I were living some mad nightmare.

My father, on the other hand, seemed to be enjoying himself hugely. He stumped out his eyla, smiled ironically across the desk.

"You see," he said, "Clare has faith in me. She believes that after her father's death, and my own foolish flight, the partnership agreements were destroyed, leaving you, John, sole possessor of Cerean Mining. You didn't know Conroy had a daughter on earth. I was a fugitive who'd never dare go to court over my share, and Stephen knew nothing of the arrangement, and wouldn't have contested if he had. Thus Cerean Mining was yours."

"You're accusing me of robbery?" Uncle John roared, the veins of his temple standing out. "You ... a murderer, a thief! Good Lord! You accuse me when I arrive to find you committing burglary!" He pointed to the blasted safe door.

"I'll admit," my father said, smiling, "that my original intention was to take two-thirds of the palladium, force Stephen aboard, and leave. With a murder charge hanging over me, I couldn't afford to take the matter of the metal to court. But now something has occurred that in my wildest dreams I hadn't hoped for. At no time did I take into account that vain, boastful streak in your character, John. You had committed an act which you thought supremely skilful, supremely clever, yet you had to play the pious, honest business man. You longed to boast of it, to tell someone, but to do so would have meant your neck. And so, bursting to recount your cleverness in gaining control of Cerean Mining, you yielded to sheer folly. You kept a diary!" My father waved toward the leather-bound book he had found in the safe.

For just an instant Uncle John remained motionless, shadows flickering over his gaunt face. Then he leaped, clutching for the book.

Quick as he had been, Taon was quicker. The big Jovian seemed to slide across the room as though on wires. His huge hand caught Uncle John, held him back as one would hold a child.

My father, who had not even blinked, flipped through the pages of the little black book.

"It was clever, John," he said serenely. "Very subtle. You heard me coming, that night, rayed Conroy, ran outside. I entered, knelt at his side. It was then, dying, that he told me of his daughter on earth. A moment later you entered, caught me supposedly red-handed. Stephen, on the stairs above, saw me kneeling beside Conroy, saw you enter. Even so, I might have had a chance in court if I hadn't lost my head, run away. Naturally you hushed the matter up, 'for the honor of the family.' You didn't want an I.P. patrol investigating the crime. The mine was in your control and you won Stephen over by not prosecuting me. It might have been wiser if you had. However, I also believe in the honor of the family. Clare and I have no wish to see you in the lethal-ray chamber. We'll take a third of the palladium apiece," he motioned toward the heap of gray ingots, "and leave you a third. Which you don't deserve."

Eyes hollow pits, my uncle stared at the precious metal. The million he had counted on, reduced by two thirds! His bony fingers clutched his belt tightly.

"And if I refuse?" he said slowly.

"You'll be turned over to the authorities at Verlis for the murder of my father!" Clare's voice was like a silken lash.

Then suddenly Uncle John threw back his head, laughing.

"You fools!" he said. "D'you think I'd come back here alone after my beloved nephew so kindly warned me? There's plenty of room in my sled!" He raised his voice, shouting, "Scott! Carr! Help! Quick!"

At once the front door of the administration building burst open and half a dozen space-rats, denizens of the slums of Verlis, swarmed into the room, flame guns in hand. Vaguely I heard Clare scream and I dove to snatch up the gun she let drop. As I whirled to face the intruders, a bolt of blue flame leaped out, knocking the gun from my hand. Taon crouched to spring, his huge muscles standing out in ridges, but my father's quiet voice halted him.

"No good, Taon," he said quietly. "They'd only blast you to bits. I must, I think, be getting old. I should have realized he'd have men with him. Well, John," he turned to my uncle, "you win this round. Just what do you propose to do?"

"Your ship is outside," Uncle John said with an unctuous smile. "And these men of mine can handle her. I'm taking this palladium back to earth with me!"

"And us?" my father asked quietly.

"So far as Ceres knows, you will have left aboard the yacht with me. So far as Terra will know, you four contracted space-fever and were buried in the void. All heirs, claimants, to the palladium gone, leaving me sole owner. As for this diary" ... he tossed the book onto the floor, blasted it to ashes with a beam from his flame-gun. "And now," he went on calmly, "my men will take the four of you outside, dispose of you. Buried under a few feet of ice, your bodies will certainly never be found."

Clare's hand fluttered to her throat. I stood there stupidly, gaping. My whole life seemed to be whirling like a pin-wheel. This cold killer, my Uncle John! My Uncle John whom I had trusted, who had been a father to me these eleven years! I felt that I should say something, do something heroic, but I could only stare. The six space-rats, their guns ready.... Clare's pallid face ... Taon, standing there like a colossal robot. All at once my father's voice broke the brittle silence.

"Come, come, John!" he said dryly. "You're being melodramatic now. Such slaughter is useless."

I watched him as he spoke. He was standing near the safe, hands behind his back, outwardly very calm, but I could see his eyes darting about the room in search of some means of escape. Uncle John must have noticed his eyes, too, for he waved the men forward.

"No chance for any of your tricks, Vance," he said harshly. "You four stand in my way and you're going to be removed! Take them out!"

Still stunned, I stumbled from the room between two of the space-rats. One of them, a half-breed with Venusian blood predominant, walked behind Clare, gun in hand. Despite her pallor she kept her chin high. Taon was stolid, emotionless as always, while my father was jaunty, careless, as though merely going for a stroll. As we passed through the door, I glanced back. Uncle John was busy picking up the ingots of palladium; he seemed to have forgotten us already. His eyes were bright with avarice, triumph, and he seemed to caress each bar of the precious stuff as he touched it. The sight filled me with sudden rage.

"You're mad!" I cried. "Mad! You can't hope to get away with this!"

He glanced up impatiently. "Hurry up with it!" he snapped, and slammed the door behind us.

Like four automatons, we crossed the icy plain. Near a jagged pinnacle of rock, on the edge of the landing field, the half-breed paused.

"As good a place as any," he grunted. "Line them up over there!"

They placed us with our backs to the rock, retreated several paces, flame-guns ready. I shot a furious look at my father. Was he going to see us all butchered by the energy blasts without so much as a struggle? Better to go down fighting than this. And Clare ... so young, lovely.... I was just flexing my muscles for a desperate leap when my father spoke.

"Gentlemen," he said, "it would be to your credit to permit at least one of us to die happy. Now it so happens that I am addicted to the use of the Martian eyla. It is, I find, far superior to terrestial tobacco, having a cheering effect not unlike benzedrine. If you would permit me to enjoy one last smoke of it, I would find my transition to another and, I hope, better world infinitely more pleasant."

The half-breed glanced questioningly at his companions, then at the little administration building across the plain.

"Come," my father said pleasantly. "Surely you won't refuse a man's last wish. It takes only eight minutes to smoke an eyla tube. And at the first sign of any trickery, you can shoot."

The half-breed shrugged. "Okay," he grunted.

With elaborate care my father drew one of the slim, greenish tubes from his pocket, lit it.

Quickly the minutes slipped by. The half-breed stamped his feet against the cold, glanced at the eyla. Only a tiny stump remained in my father's fingers.

"All right," the Venusian growled. "Let's get this over with!"

"As you wish," my father said cheerfully. He took a last puff of the tube, tossed it onto the ice, ground it out with his foot. One long glance he shot toward the lights of the administration building, shining through the gloom, then straightened up. "And now—" he murmured.

Six flame-guns swung up to face us. Taon, betraying his first signs of emotion, gazed anxiously at my father. The latter's face was tense, anxious. In another moment....

And then it happened. A blasting, thundering roar echoed across the plain! Dazed, I saw the windows of the administration building give forth a blinding flash, lighting up the ice like a magnesium flare! A sound of shattering glass, of splintering plastic reached us. The administration building was being wrecked systematically by a mystic, unknown force!

With the explosion, the space-rats whirled toward it, instinctively. At the same instant my father plunged forward, Taon at his heels. The huge Jovian seized two of the men, crashed their heads together with a sickening crack. Limp, they fell to the ground, and Taon passed on. While the giant was thus disposing of two of our adversaries, my father had leaped upon another, borne him to the ground in a wild tangle of arms and legs.

All this in a split second, before I could collect my wits. The three remaining space-rats leaped back, gripping their guns. A flash of blue flame leaped out, scorching Taon's shoulder, but before the man could fire again the Jovian's huge fist had stretched him upon the ice. Moving forward, I saw the Venusian half-breed aim at my father who was still struggling with his first opponent. With all the force at my command I hurtled forward, deflecting his arm so that the dazzling blue bolt of flame tore up the ice, harmlessly. As I struggled with the man I saw Taon pick up his third opponent, hurl the inert form at the remaining space-rat, sending him to the ground. Then my father arose from the unconscious figure of his antagonist, dug a flame-gun into the half-breed's ribs. At once his struggles ceased; he raised his hands submissively over his head.

"Thanks, Stephen," my father drawled. "I shouldn't be here if you hadn't deflected his aim. How badly are you hurt, Taon?"

"Little burn," the Jovian rumbled. "No hurt much." He grinned as Clare ran toward us. "No die now, missy."

"Chin up," my father said, patting her shoulder. "It's all right now, child. Let's go back to the house."

As soon as our prisoners were disarmed and bound, we returned to the administration building. It was wrecked by the explosion. Doors and windows blown out, walls blackened. Inside, it was even worse. Chairs, desks, splintered, the floor littered with débris—and Uncle John, a charred and terrible figure, sprawled before the safe, one hand still clutching an ingot of palladium.

"What ... what was it?" I whispered. "What caused the explosion?"

"Hydrogen," my father said gravely. "As I stood there with my hands behind my back, I opened the hydrogen valve of that oxy-hydrogen blow torch. We'd used a good bit of it to blast open the safe, but there was still plenty, under that pressure, to fill the room, unite with the oxygen already present. A gas explosion, and a powerful one."

"But," I demanded, "what caused the gases to unite? What ignited them?"

"And you've been working at these mines all these years?" he cried. "Don't you know that certain metals like platinum, or palladium, act as a catalyst? The gases are absorbed on their surface, unite. And when hydrogen and oxygen unite...." He stooped, picked up one of the gray ingots. "Here's what ignited that mixture! I knew I had only to stall until enough hydrogen had entered the room to create an explosion." He shrugged. "I suppose the play's ended. Now that John's gone, the metal will only be divided two ways. Half to Clare, as her father's only heir, and half to me. I'll turn my share over to you, Stephen, as recompense for any unpleasantness I may have caused you in the past. Your late uncle's rocket-sled is still outside. I'll have Taon load half the palladium aboard it and you can go to Verlis, set up as a wealthy young gentleman of leisure." He smiled, sardonically.

I stared at him. From that smiling mask his eyes were fastened upon me.

"And you, sir?" I asked.

"Me?" he seemed surprised. "I'll be taking Clare and her little fortune back to Terra. After that" ... he shrugged again. "It'd be of no interest to you, I'm sure. Taon, take half of these ingots and put them aboard the rocket-sled outside."

"No!" I heard myself saying in a queer choked voice. "No! I ... I'm coming with you and Clare. If you'll have me ... Dad."

For the third time that night my father's bitter mocking mask fell from him ... and this time for good.

"Steve!" he murmured, putting an arm about my shoulders. "Steve!"

Taon, busy picking up the gray ingots, paused, his gaze shifting from Clare to Dad to myself.

"Good!" he grinned. "Dam' good! All one family soon now! Very dam' good!"