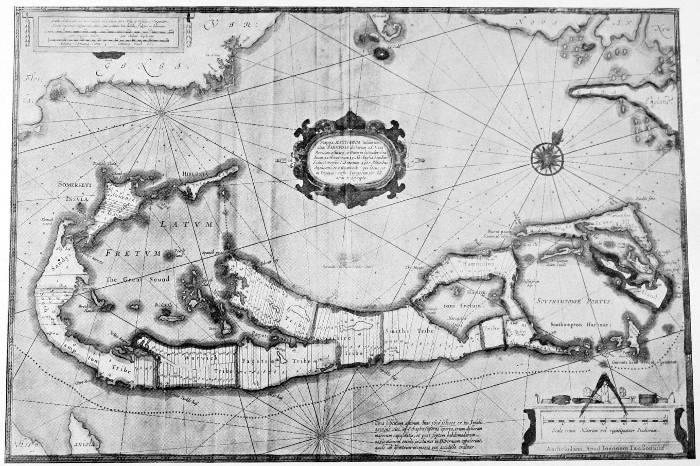

Plate 1. Norwood's Map of Bermuda.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Bermuda Houses, by John Sanford Humphreys This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Bermuda Houses Author: John Sanford Humphreys Release Date: May 30, 2020 [EBook #61736] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BERMUDA HOUSES *** Produced by ellinora, Karin Spence and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

This book has been prepared and published at the request of a number of prominent architects in New York and Boston. As an expression of endorsement, the following have voluntarily subscribed for copies:

| Chester H. Aldrich | New York |

| William T. Aldrich | Boston |

| Francis R. Appleton | New York |

| Donn Barber | New York |

| Robert P. Bellows | Boston |

| Theodore E. Blacke | New York |

| Boston Architectural Club Library | |

| Welles Bosworth | New York |

| Archibald M. Brown | New York |

| Charles A. Coolidge | Boston |

| Harvey W. Corbett | New York |

| Ralph Adams Cram | Boston |

| John W. Cross | New York |

| George H. Edgell | Cambridge |

| William Emerson | Boston |

| Ralph W. Gray | Boston |

| Harvard University, Library of the School of Architecture | |

| Thomas Hastings | New York |

| F. Burrall Hoffman, Jr. | New York |

| Little and Russell | Boston |

| Guy Lowell | Boston |

| H. Van Buren Magnonigle | New York |

| Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Library of the Department of Architecture | |

| Benjamin W. Morris | New York |

| Kenneth M. Murchison | New York |

| A. Kingsley Porter | Cambridge |

| Roger G. Rand | Boston |

| Rhode Island School of Design, Library | |

| Richmond H. Shreve | New York |

| Philip Wadsworth | Boston |

Plate 1. Norwood's Map of Bermuda.

Plate 2. Norwood's Inscription for His Survey of Bermuda.

BERMUDA HOUSES

BY

JOHN S. HUMPHREYS, A. I. A.

ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF ARCHITECTURE

SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

HARVARD UNIVERSITY

MARSHALL JONES COMPANY

BOSTON Ě MASSACHUSETTS

COPYRIGHT 1923

MARSHALL JONES COMPANY

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

The architect of today, in designing small houses, is beset with many exactions and complications. The high standard of living with its embarrassing variety of materials and appliances at the architect's disposal, the certainly high cost of labor and the desire for mechanical perfection and convenience, the client who knows too much and too little, and the passing fashions of revived styles and periods, all increase the difficulty of producing houses that fulfill requirements, satisfy clients, and at the same time have order, simplicity and appropriateness to surroundings.

The designers and builders of the old Bermuda houses had relatively few of these complications to contend with. Their pursuits were for the most part agricultural and seafaring, and their manner of life and their luxuries were simple. A generally mild climate, a fertile soil, and easily worked building stone always at hand, lime readily obtained, a plentiful supply of beautiful and durable wood, and cheap labor simplified their building problem. Traditions, if any, were those of English rural architecture, and these, interpreted by shipwrights rather than housebuilders, applied to island materials and island life, have helped to give to the older buildings of Bermuda a particular interest and charm, and have developed an architecture worthy of perpetuation.

The photographs presented in this book have been taken with the idea of collecting and preserving for architects and others interested in small buildings some of the characteristic features and picturesque aspects of the older architecture of the island that are tending to disappear. Many of the older houses are being altered and modernized ruthlessly, or without thought of preserving the old Bermudian character of architecture; others are falling into decay through neglect.

Bermuda is now prosperous, not only through its resources of agriculture in supplying northern markets with winter produce, but also from the great number of tourists and the number of permanent winter residents and house owners that bids fair to increase. Many of the newer houses built in different parts of the island are of the "suburban villa" type, commonplace and smug, devoid of interest, and[x] though not large houses, are so large in scale as to dominate and destroy the small scale of the natural surroundings or of nearby Bermudian architecture. Self conscious "Italian Renaissance," "Spanish Mission" and even "Tudor Gothic" and "Moorish" have put in appearance in some of the more pretentious, newer places.

If Bermuda's prosperity continues to increase, it is to be hoped that the designers of new houses that appear will seek their inspiration in Bermuda's own older architecture. It is eminently appropriate to the climate and other local conditions, harmonious and in scale with the surroundings. It has the unity, charm and simplicity of an architecture that is the unaffected expression and natural outcome of environment, and, from its simplicity, is entirely adaptable to the modern requirements of Bermuda. Architecture such as Italian Renaissance, Gothic and Moorish, referred to above, has no artistic excuse for existing in Bermuda.

To those who are familiar with Bermuda and the houses there, these colorless photographs may be but sorry representations of the actuality, and can only serve to stimulate memory. White, or softly tinted houses with weathered green blinds and doors, frequently buried in luxuriant foliage and blossoms of vivid hues, with glistening white roofs silhouetted against intensely blue sky, or backed against the dull green of red trunked cedars, through which may be glimpses of a turquoise sea, make a strong impression on the senses, but fail to register with the camera—even when held by a more experienced hand than that of the author.

What is now known as Bermuda, sometimes called the Bermudas and at one time known as Somers Islands, is a group of islands said to be over three hundred in actual number, lying in the Atlantic some seven hundred miles southeast from New York, the nearest point on the mainland being Cape Hatteras, in North Carolina, five hundred and seventy miles west. Of these three hundred odd islands, the eight principal ones, totalling in area less than twenty square miles, lie close together and are now connected by bridges, causeways and ferries. A glance at the map of Bermuda shows its general form, with its three almost enclosed bodies of water, the Great Sound, Harrington Sound and Castle Harbor, and nautical charts with soundings marked would show its form extending as reefs under water into a great oval connecting the two ends. These reefs made actual landing difficult, giving the island an evil reputation before its settlement, and no doubt were the cause of many shipwrecks.

The islands were known to exist as early as 1511, as they were noted on a map of that date. They received their name, however, from Juan de Bermudez, who came to Spain with an account of them a few years later, although there is apparently no evidence to show that the Spaniards or Portuguese ever occupied the islands or even landed there.

In 1593, Henry May, an Englishman, was cast away there with others and, eventually making his way back to England, he published an account of his adventures and a description of the group of Islands. Bermuda thus became known to the English. In 1609, the "Sea Venture" which was one of nine ships bound for the infant plantation of Virginia, with a party of "adventurers" ran ashore on Bermuda in a hurricane. The admiral of this fleet, Sir George Somers, with Sir Thomas Gates sent out to govern Virginia, and the entire company and crew of the "Sea Venture," said to number 149 men and women, were landed. With the ship stores saved from the wreck and what the island gave them, this company subsisted there for some ten months. During this time and in spite of mutiny among[xii] his charges, two ships were built under Somers' direction, and in May, 1610, the Company proceeded to the original destination, the colony of Virginia.

The Virginia colonists were in straits through lack of food, and Somers returned to Bermuda for provisions for the colony, having found hogs and fish plentiful on the islands. He died there in 1611, and his followers returned to England soon after.

The glowing and exaggerated accounts of the richness of the islands brought back by these colonists excited the cupidity of the organizers of the Virginia Company, who enlarged their original charter to include Bermuda and established a Colony there under Governor Moore in 1612. The shipment home of ambergris by Moore seemed to confirm the reported wealth of the islands, so that, following a method not unknown to more modern exploiters, members of the Virginia Company soon formed a new sub-company which took over the title to Bermuda as a separate proprietary colony, under the name of "The Governor and Company of the City of London, for the Plantation of the Somers Islands."

In 1616, Daniel Tucker was sent out by this company as the first Governor under the new charter. He caused the islands to be surveyed, dividing them into eight tribes, and public lands. These tribes, or proportional parts, assigned to each charter member, were for the most part what are the present-day parishes, being Sandys, to Sir Edwin Sandys; Southampton, to the Earl of Southampton; Paget, to William, Lord Paget; Smith's, to Sir Thomas Smith; Pembroke, to the Earl of Pembroke; Bedford, now Hamilton Parish, to the Countess of Bedford; Cavendish, now Devonshire, to Lord William Cavendish; Mansils', now Warwick, to Sir Robert Mansil. St. George's, St. David's and adjacent small islands were public lands. The tribes were subdivided into fifty shares of twenty-five acres each. Norwood's second map showing these tribes and shares is the basis of land titles in Bermuda today.

Governor Tucker's rule was harsh. The colonists included many criminals and convicts from English jails, so a merciless discipline seemed to him necessary. The severest penalties were enforced, executions, brandings and whippings were frequent. Negro slaves were introduced from Virginia in the endeavor to make money for the proprietors, with the resultant vices leaving their trail to this day. Progress was made in building the town of St. George. Roads and fortifications were constructed and the land planted with tobacco and semi-tropical fruits.

Tucker was replaced by Nathaniel Butler in 1619, but after securing his title to property rather doubtfully acquired, returned to Bermuda where he died in 1632. It was probably during Butler's term that the first stone dwellings began to appear, replacing the earlier thatched roofed cedar houses.

"The history of the colony from 1620, when the first Assembly met, until 1684, or 1685, when the Company was ousted of its charter by quo warranto in the King's Bench in England, is made up of the struggles of the Company in London to make as much out of the colonists as possible; of the struggles of the colonists to remove restrictions on trade with others than the Company, imposed upon them by the proprietaries; and of the efforts of the Governors sent out to the islands to maintain order, enforce the rules of the Company and defend their authority and exercise too often arbitrary power."—(William Howard Taft.)

From 1685 on, the island became self-governing and was largely left to its own devices by England. Agriculture was neglected or left in the hands of ignorant slaves, while the white islanders were occupied in such maritime pursuits as whaling, fishing and shipbuilding, and were dependent to a great extent on the mainland of America, with which they were in constant contact.

The outbreak of the American Revolution brought divided opinion on the islands as on the mainland. There is, however, little doubt but that there was great sympathy for the cause of freedom in the American colonies. Secret aid was given and commercial relations were resumed with America before the close of the war. If the Continental Congress had possessed a considerable navy, or if the islands had lain closer to the mainland, they might this day have been part of the United States. As it was, they remained ostensibly loyal to the mother country.

The War of 1812 brought changes to Bermuda. She became a port for prizes taken by the British navy and later was intermediary port for trade between America and the West Indies with the result that Bermudians prospered in the shipping trade. To the English, this war called attention to Bermuda's strategic position, and a naval station was established there. Convict labor from England was used to build dock yards, fortifications and roads, to the general benefit of the whole island. Slavery was abolished in 1834, an act which, though a general advantage, hurt Bermudian shipping, compelling, as it did, the employment at pay of sailors. With this decline of shipping attention was again turned to agriculture.

The Civil War brought a great period of activity and prosperity to Bermuda.[xiv] Through ties of blood and trade, sympathy was entirely with the South and the ports were full of blockade runners bringing cotton from the South for trans-shipment to England. The crews spent much of their high wages on the islands and the Bermudians also engaged in the gamble of blockade running. The end of the war brought losses to many, and Bermuda again settled down to its normal activities, agriculture and fishing.

In later years a new source of revenue to Bermuda has arisen, known there as the "tourist trade," and consisting in providing for the needs and desires of visitors to the island. This has grown to important size and promises a still further increase. The mild climate and charm of beautiful surroundings, excellent steamship service and luxurious modern hotels, attract thousands each year. Building is being revived and Bermuda's commercial future seems assured.

| PAGE | ||

|---|---|---|

| Plate 1. | Norwood's Map of Bermuda | Frontispiece |

| Plate 2. | Norwood's Inscription for His Survey of Bermuda | v |

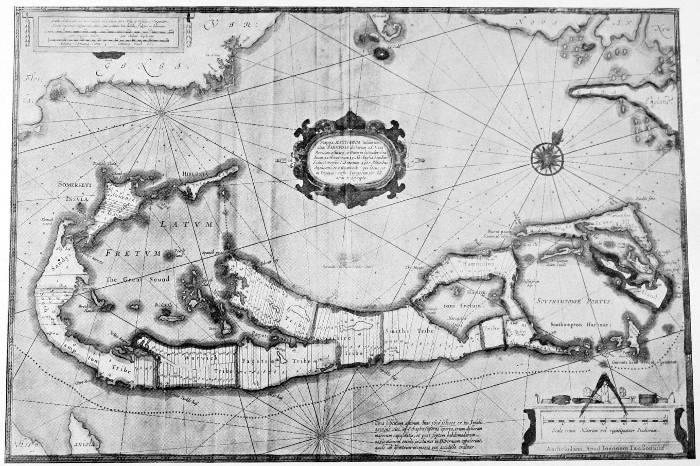

| Plate 3. | Diagrams of Typical Houses | 8 |

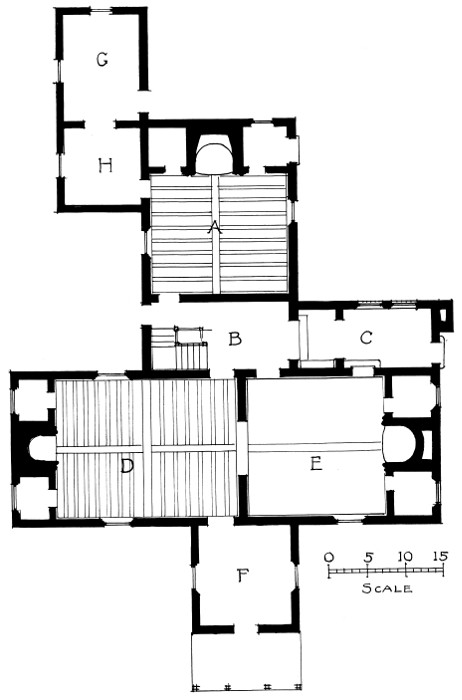

| Plate 4. | "Inwood," Paget. Plan of Ground Floor | 15 |

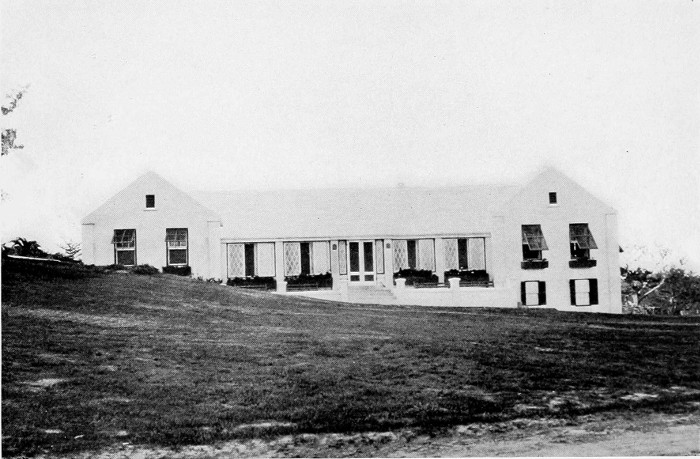

| Plate 5. | "Inwood," Paget | 17 |

| Plate 6. | "Inwood," Paget. Garden Gate | 19 |

| Plate 7. | "Inwood," Paget. Dining Room | 21 |

| Plate 8. | "Inwood," Paget. Vestibule | 21 |

| Plate 9. | "Inwood," Paget, Drawing-room | 23 |

| Plate 10. | "Cluster Cottage," Warwick. Plan of Ground Floor | 27 |

| Plate 11. | "Cluster Cottage," Warwick | 29 |

| Plate 12. | "Cluster Cottage," Warwick. Chimney and Rain Water Leaders | 31 |

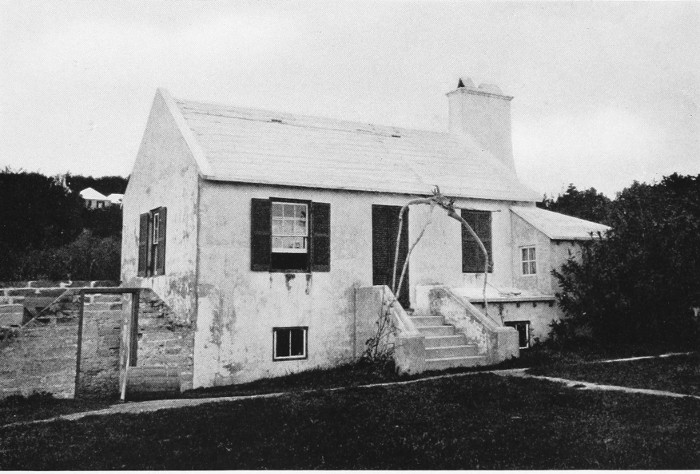

| Plate 13. | "The Cocoon," Warwick. Plan of Ground Floor | 35 |

| Plate 14. | "The Cocoon," Warwick. South Front | 37 |

| Plate 15. | "The Cocoon," Warwick. From the Garden | 39 |

| Plate 16. | "The Cocoon," Warwick. Approach to "Welcoming Arms" | 41 |

| Plate 17. | "The Cocoon," Warwick. Detail of Veranda | 43 |

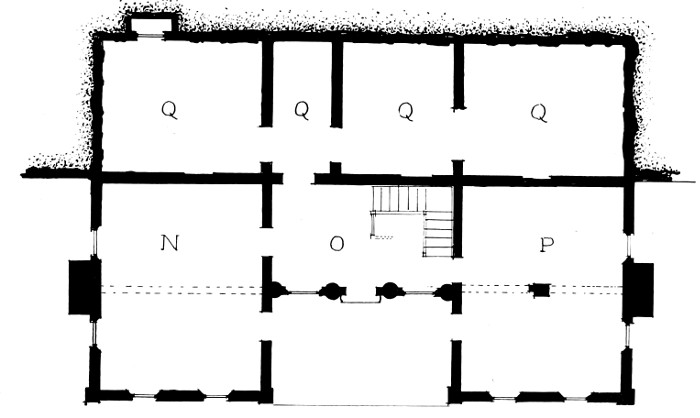

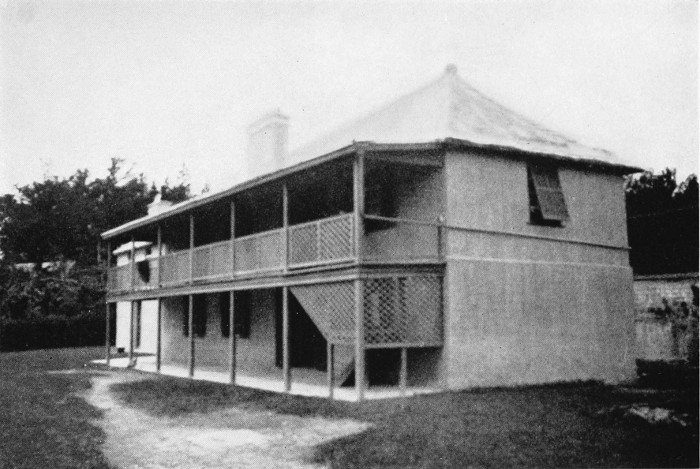

| Plate 18. | "Harmony Hall," Warwick. Plan of First Floor | 47 |

| Plate 19. | "Harmony Hall," Warwick. Plan of Basement | 47 |

| Plate 20. | "Harmony Hall," Warwick. Northern Front | 49 |

| Plate 21. | "Harmony Hall," Warwick. The Garden | 51 |

| Plate 22. | "Harmony Hall," Warwick. Southern Front | 53 |

| Plate 23. | "Harmony Hall," Warwick. Living Room, Showing "Tray" Ceiling | 55 |

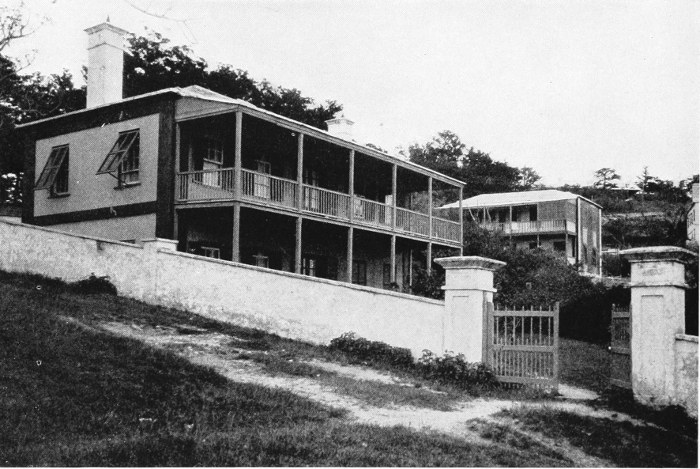

| Plate 24. | "Bloomfield," Paget. Plan of Ground Floor and Gardens | 59 |

| Plate 25. | "Bloomfield," Paget. South Front | 61 |

| Plate 26. | "Bloomfield," Paget. Looking West | 63 |

| Plate 27. | "Bloomfield," Paget. Looking East | 65 |

| Plate 28. | Small House in City of Hamilton | 67 |

| Plate 29. | Small House in City of Hamilton | 67 |

| Plate 30. | Shop in City of Hamilton | 69 |

| Plate 31. | Building in Public Library Garden, "Par la Ville," in City of Hamilton | 71 |

| Plate 32. | "Norwood," Pembroke. Veranda a Modern Addition | 73 |

| Plate 33. | "Norwood," Pembroke. Gate to Private Burying Ground | 75 |

| Plate 34. | Small House in Pembroke | 77 |

| Plate 35. | Detail of House in Pembroke | 79 |

| Plate 36. | Chimney on House in Paget | 81 |

| Plate 37. | "Beau Sejour," House in Paget | 83 |

| Plate 38. | Cottage in Paget | 85 |

| Plate 39. | Cottage in Paget | 87 |

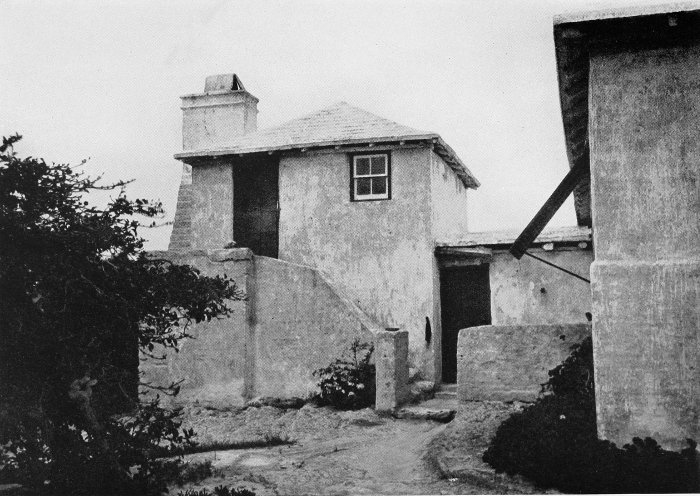

| Plate 40. | Old Tucker House, Paget | 89 |

| Plate 41. | Detail of Tucker House, Paget | 91 |

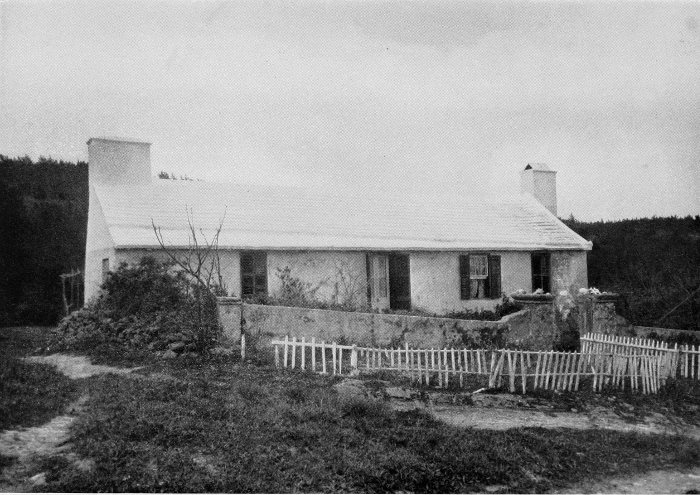

| Plate 42. | Old Farmhouse in Paget, built before 1687 | 93 |

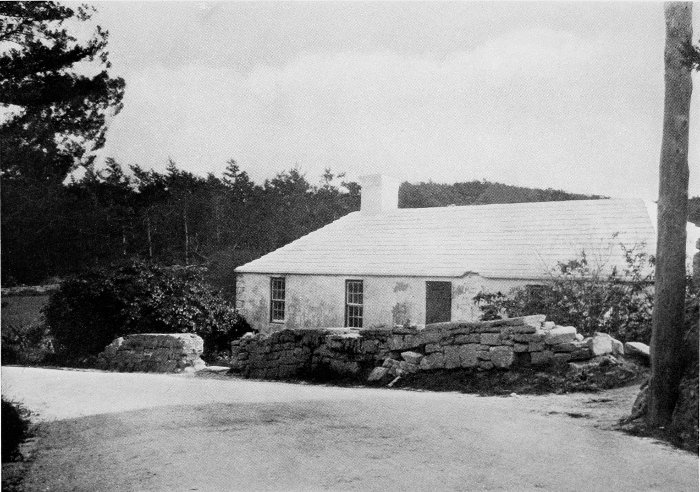

| Plate 43. | Old House in Paget | 95 |

| Plate 44. | Detail of House on Harbor Road, Paget | 97 |

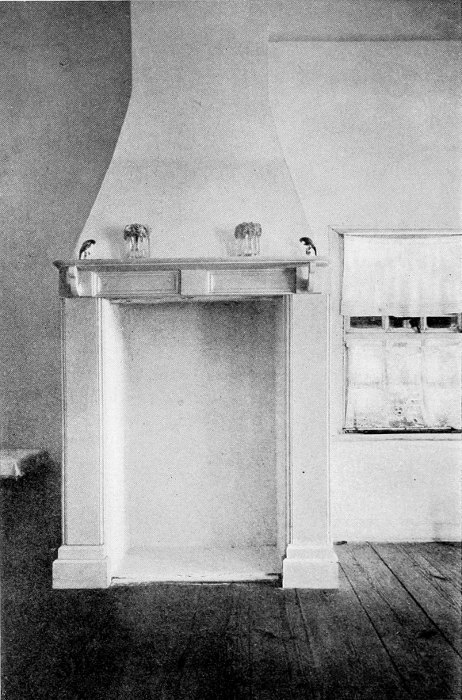

| Plate 45. | House in Paget. Interior (Recently Restored) | 99 |

| Plate 46. | House in Paget. Interior (Recently Restored) | 99 |

| Plate 47. | House in Paget | 101 |

| Plate 48. | House in Paget. Side View | 103 |

| Plate 49. | House in Paget. Front View | 103 |

| Plate 50. | House in Paget. Front View | 105 |

| Plate 51. | House in Paget. Side View | 105 |

| Plate 52. | Shop and Tenement in Warwick | 107 |

| Plate 53. | Poorhouse, Paget | 107 |

| Plate 54. | House on Harbor Road, Paget | 109 |

| Plate 55. | "The Chimneys," Paget. Road Front | 111 |

| Plate 56. | "The Chimneys," Paget. Garden Front | 111 |

| Plate 57. | "Southcote," Paget. Front View | 113 |

| Plate 58. | "Southcote," Paget. Rear View | 113 |

| Plate 59. | "Pomander Walk," Paget | 115 |

| Plate 60. | "Clermont," Paget. Garden Wall and Entrance | 117 |

| Plate 61. | Cottage in Paget | 119 |

| Plate 62. | House in Paget | 121 |

| Plate 63. | House and Garden, Paget | 123 |

| Plate 64. | Shop and Tenement, Warwick | 125 |

| Plate 65. | Old House, Harbor Road, Warwick | 127 |

| Plate 66. | Steps and Chimney, House on Harbor Road, Warwick | 129 |

| Plate 67. | House in Warwick | 131 |

| Plate 68. | Small House in Warwick | 133 |

| Plate 69. | Buttery To House Preceding | 135 |

| Plate 70. | Old Cottage in Warwick | 137 |

| Plate 71. | Old Cottage in Warwick | 139 |

| Plate 72. | Old Gateway in Warwick | 141 |

| Plate 73. | Old House in Warwick | 143 |

| Plate 74. | House on Harbor Road, Warwick | 145 |

| Plate 75. | House in Warwick | 147 |

| Plate 76. | Entrance Steps and Vestibule, House in Warwick | 149 |

| Plate 77. | "Periwinkle Cottage," Warwick | 151 |

| Plate 78. | Outhouses, Farm, in Warwick | 153 |

| Plate 79. | House near Riddle's Bay, Warwick | 155 |

| Plate 80. | Old House in Warwick | 157 |

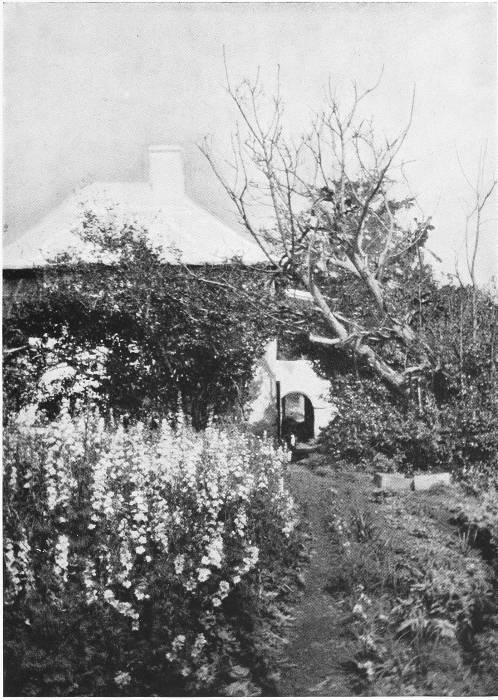

| Plate 81. | Dooryard Garden, Old House in Warwick | 159 |

| Plate 82. | Detail of House on Harbor Road, Warwick | 161 |

| Plate 83. | Detail of Garden on Harbor Road, Warwick | 161 |

| Plate 84. | Front of "Cameron House," Warwick. Built about 1820 | 163 |

| Plate 85. | "Cameron House," Warwick. Front Entrance | 165 |

| Plate 86. | "Cameron House," Warwick. Side Entrance | 165 |

| Plate 87. | Garden Gate in Paget | 167 |

| Plate 88. | Garden Gate in Hamilton | 167 |

| Plate 89. | Buttery of Farmhouse in Paget | 169 |

| Plate 90. | Buttery of Farmhouse on Somerset Island | 171 |

| Plate 91. | Old House in Southampton | 173 |

| Plate 92. | House in Southampton | 175 |

| Plate 93. | Old Cottage in Southampton | 177 |

| Plate 94. | Old Cottage in Southampton | 179 |

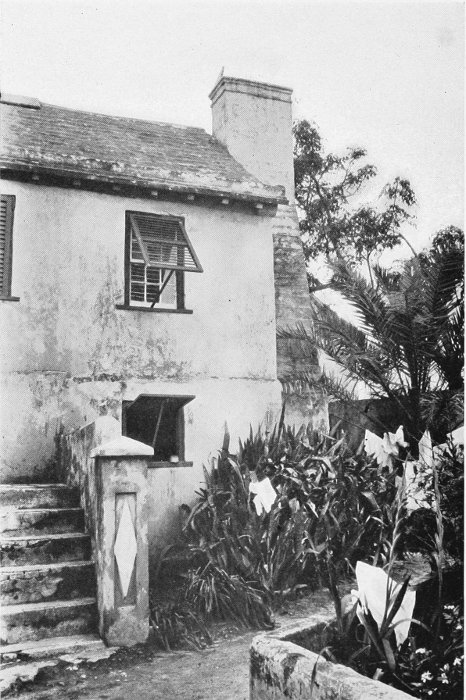

| Plate 95. | Detail of Old Cottage in Southampton | 181 |

| Plate 96. | Cottage in Southampton (Restored) | 183 |

| Plate 97. | Detail of Cottage in Southampton | 185 |

| Plate 98. | Small Cottage in Southampton | 187 |

| Plate 99. | "Glasgow Lodge," Southampton | 189 |

| Plate 100. | "Glasgow Lodge," Southampton. Detail | 191 |

| Plate 101. | "Glasgow Lodge," Southampton. Interior of Hall | 191 |

| Plate 102. | Schoolhouse in Southampton | 193 |

| Plate 103. | Farmhouse in Southampton | 195 |

| Plate 104. | "Midhurst," Sandys Parish | 197 |

| Plate 105. | "Midhurst," Sandys Parish. Kitchen Fireplace | 199 |

| Plate 106. | "Midhurst," Sandys Parish. Drawing-room Fireplace | 199 |

| Plate 107. | Cottage in Sandys Parish (Restored) | 201 |

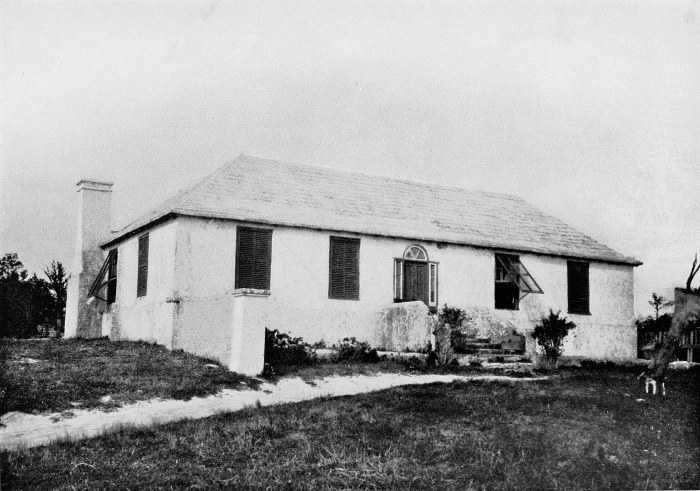

| Plate 108. | Old House on Somerset Island, Sandys Parish | 203 |

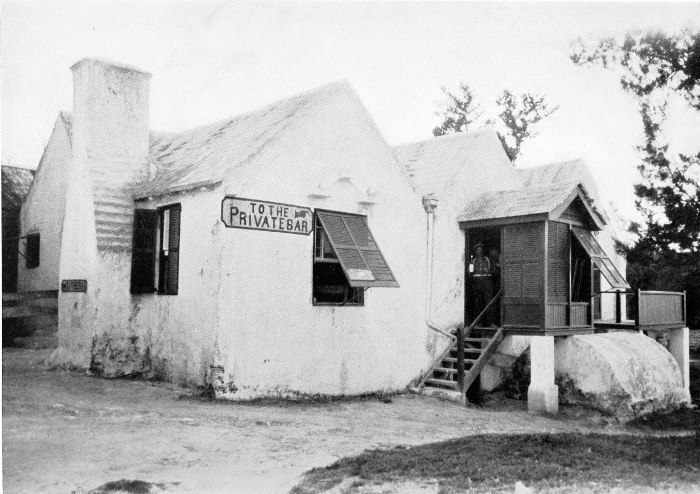

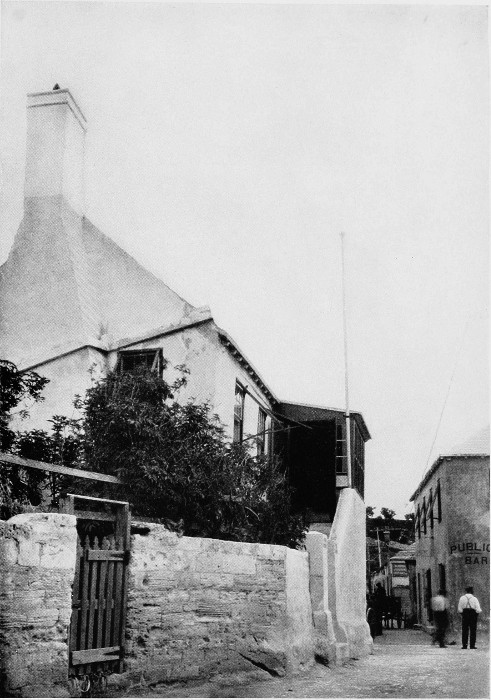

| Plate 109. | Old Tavern on Somerset Island, Sandys Parish | 205 |

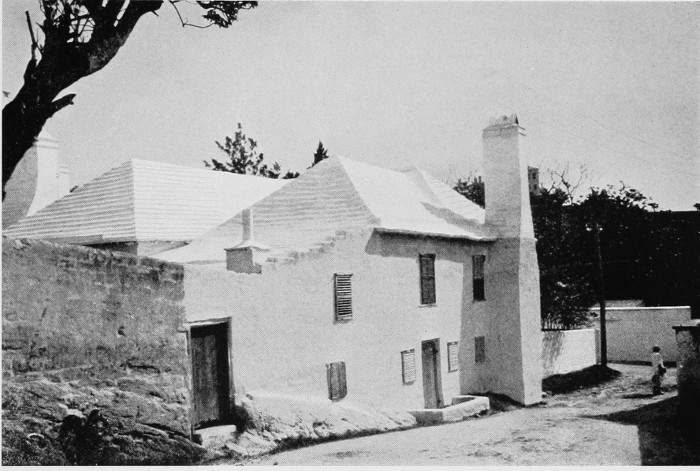

| Plate 110. | House on Somerset Island, Sandys Parish | 207 |

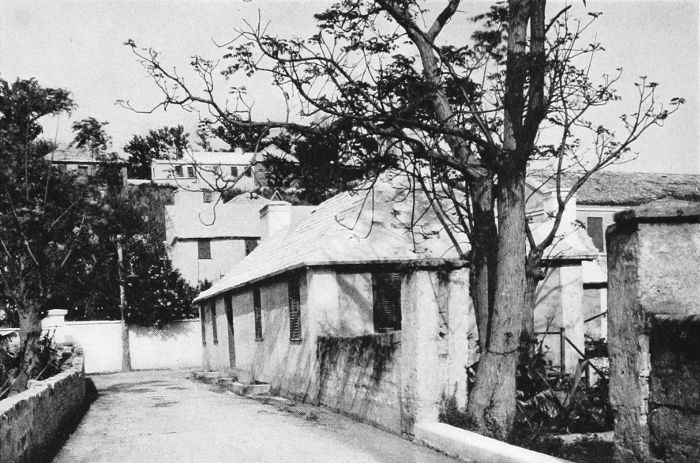

| Plate 111. | Old Cottage on Somerset Island, Sandys Parish | 209 |

| Plate 112. | House on Somerset Island, Sandys Parish | 211 |

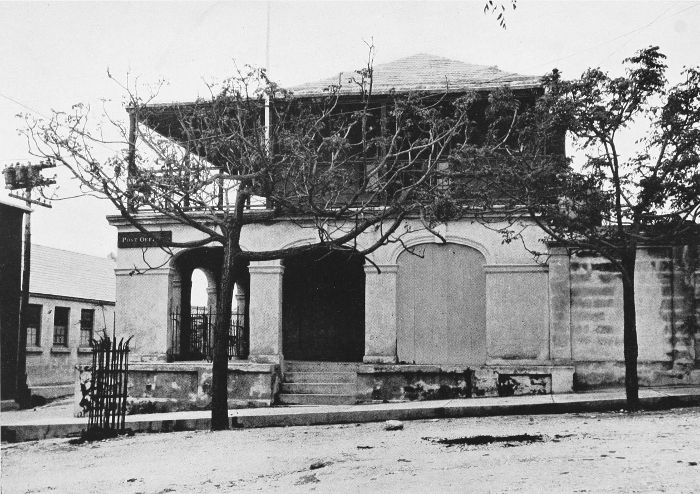

| Plate 113. | Old Post Office, Courthouse and Jail, Somerset Island, Sandys Parish | 213 |

| Plate 114. | Detail of House on Somerset Island, Sandys Parish | 215 |

| Plate 115. | Old House on Somerset Island, Sandys Parish | 217 |

| Plate 116. | Old House on Somerset Island, Sandys Parish | 217 |

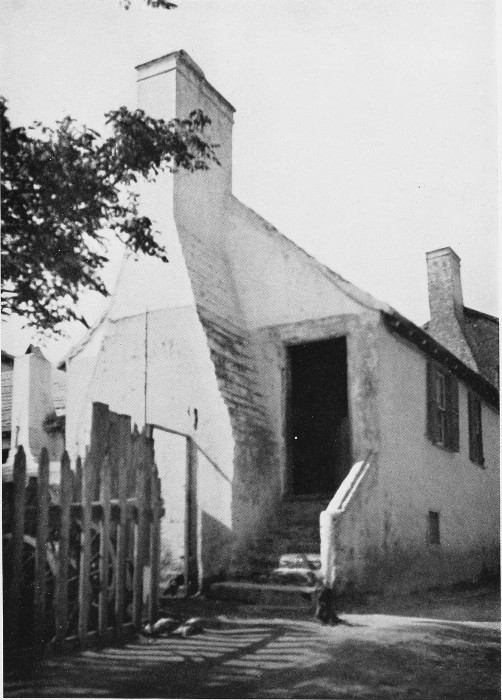

| Plate 117. | Deserted House in Sandys Parish | 219 |

| Plate 118. | Cottage on North Shore, Devonshire | 221 |

| Plate 119. | Cottage on South Shore, Devonshire | 223 |

| Plate 120. | House on North Shore, Devonshire | 225 |

| Plate 121. | "Welcoming Arms," North Shore, Devonshire | 227 |

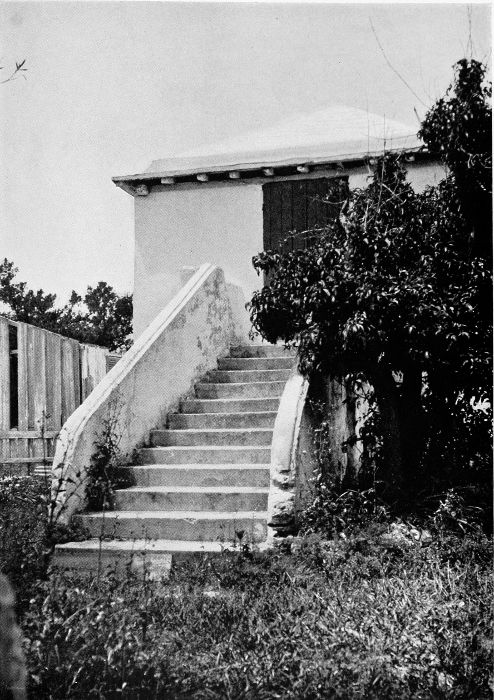

| Plate 122. | Farmhouse Steps, "Welcoming Arms," Devonshire | 229 |

| Plate 123. | Old House in Devonshire | 231 |

| Plate 124. | Old Devonshire Church | 233 |

| Plate 125. | Deserted Cottage on North Shore, Devonshire | 235 |

| Plate 126. | Cottage in Pembroke | 235 |

| Plate 127. | Old Cottage on North Shore, Devonshire | 237 |

| Plate 128. | Old Cottage on North Shore, Devonshire | 237 |

| Plate 129. | Cottage in Warwick | 239 |

| Plate 130. | Cottages on South Shore, Devonshire | 239 |

| Plate 131. | "Wistowe," Hamilton Parish | 241 |

| Plate 132. | "Wistowe," from the Garden | 243 |

| Plate 133. | Old House on Harrington Sound, Hamilton Parish. Side View | 245 |

| Plate 134. | Old House on Harrington Sound, Hamilton Parish. Entrance | 245 |

| Plate 135. | House on Harrington Sound, Smith's Parish | 247 |

| Plate 136. | Chimney on House, Harrington Sound, Smith's Parish | 249 |

| Plate 137. | Shop and Dwelling on Harrington Sound, Smith's Parish | 251 |

| Plate 138. | Cottage in Smith's Parish | 253 |

| Plate 139. | House in Smith's Parish | 255 |

| Plate 140. | Cottage in Smith's Parish | 257 |

| Plate 141. | Golf Club House, an Old Building Altered, Tuckerstown | 257 |

| Plate 142. | Farmhouse on St David's Island | 259 |

| Plate 143. | Farmhouse on St David's Island | 261 |

| Plate 144. | Farmhouse in Warwick | 261 |

| Plate 145. | House in Smith's Parish | 263 |

| Plate 146. | House in St. George. Two-storey Veranda | 263 |

| Plate 147. | House Near St. George | 265 |

| Plate 148. | Inn Near St. George | 267 |

| Plate 149. | Post Office in St. George | 269 |

| Plate 150. | Street and Shops in St. George | 271 |

| Plate 151. | Tavern in St. George | 273 |

| Plate 152. | Cottage in St. George | 275 |

| Plate 153. | House in St. George | 277 |

| Plate 154. | Cottage in St. George | 279 |

| Plate 155. | Cottage on North Shore, Hamilton Parish | 279 |

| Plate 156. | Cottage in St. George | 281 |

| Plate 157. | Cottage in St. George | 281 |

| Plate 158. | Cottage in St. George | 283 |

| Plate 159. | Cottage in St. George | 283 |

| Plate 160. | Cottages in St. George (Photo by Weiss) | 285 |

| Plate 161. | Cottage in St. George | 287 |

| Plate 162. | Small House in St. George | 289 |

| Plate 163. | Alley in St. George (Photo by Weiss) | 291 |

| Plate 164. | Dooryard in St. George | 293 |

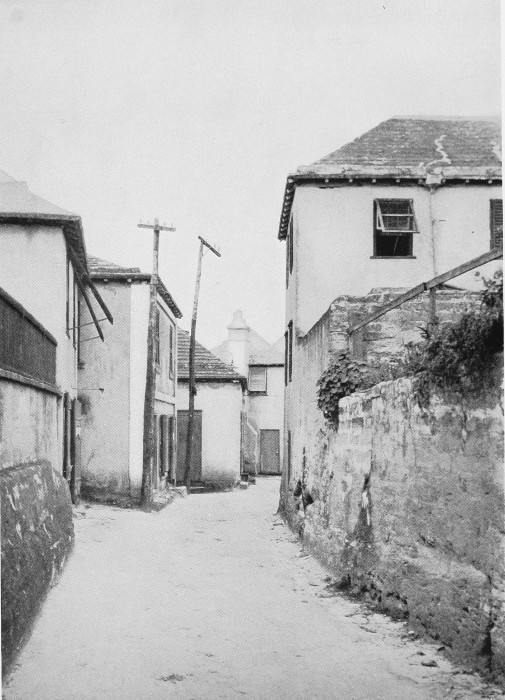

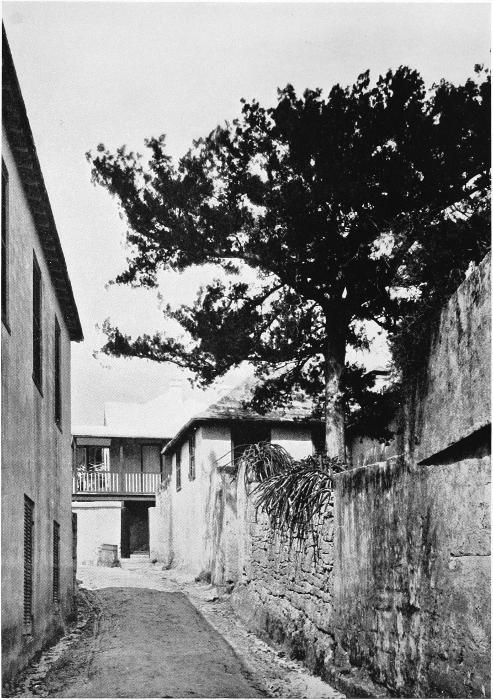

| Plate 165. | Alley in St. George | 295 |

| Plate 166. | Tavern in St. George | 297 |

| Plate 167. | Alley in St. George | 299 |

| Plate 168. | Alley in St. George | 301 |

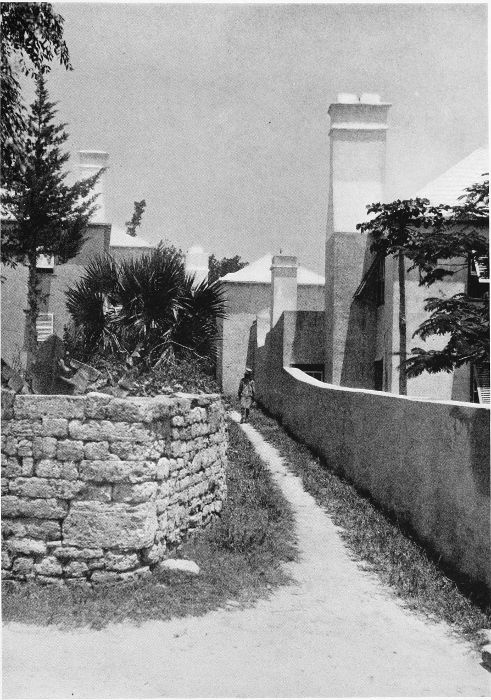

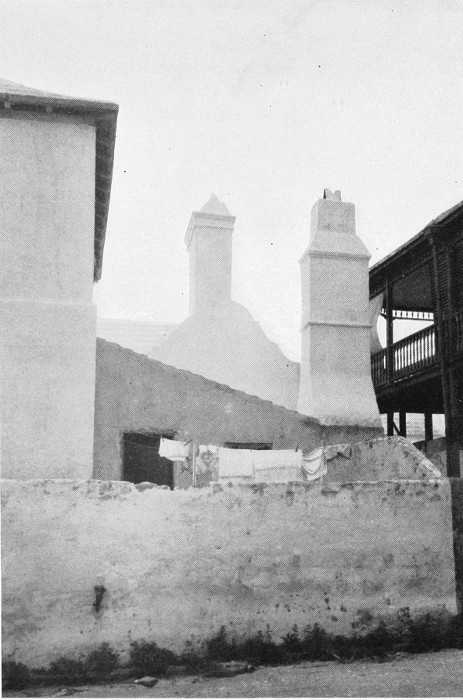

| Plate 169. | Chimneys in St. George | 303 |

| Plate 170. | Dooryard in St. George | 303 |

| Plate 171. | Cottage in St. George | 305 |

| Plate 172. | Street in St. George | 307 |

| Plate 173. | Street in St. George | 307 |

| Plate 174. | Street in St. George | 309 |

| Plate 175. | Gate in St. George | 311 |

| Plate 176. | Gate in St. George | 311 |

| Plate 177. | Gate in St. George | 313 |

| Plate 178. | Gate in St. George | 313 |

| Plate 179. | Gateway in St. George | 315 |

| Plate 180. | Gateway in St. George | 317 |

| Plate 181. | Gateway in St. George | 317 |

Bermuda has been written about from many points of view. Its interesting discovery and history have been written and rewritten; its volcanic origin investigated, discussed, tested and settled by able minds. The plant life existing there, the remarkably varied and beautiful aquatic life, has had its share of attention from scientists, and as an attraction is exploited for the amusement of visitors. The mild climate and hospitality to travellers has not lacked acclaimers and advertisement, and entirely adequate guide-books giving miscellaneous information of interest can be obtained without difficulty.

Bermuda's houses, however, seem to have had little attention called to them. A number of picture post-cards, it is true, exist, but these are misleading in that the views are chosen to show the islands as tropical, and the cards are colored by commercial "artists" who presumably have never seen the place. Some recent magazine articles have also slightly touched this interesting and characteristic part of old Bermuda.

The casual visitor and "tripper" cannot help being struck by the charm of the older buildings of the island, and the picturesque element that they add to many views through the entire fitness in scale and design to their surroundings. To students in architecture they present many points of singular interest and beauty. The architecture is in no sense grand, nor is it even important compared to that of other lands. Its interest lies chiefly in the fact that it is a very simple, straight-forward and complete expression and outcome of a number of unusual conditions and factors that were a marked and characteristic part of the earlier life of the colony. These factors were the climate, the unusual geological formation and structure of the island, and to a lesser degree the economic and social conditions under which the island had its early development.

The climate is a mild and humid one, with abundant rainfall, with a fairly even temperature throughout the year, varying not more than 35 degrees or so, subject,[4] however, to high winds and occasional hurricanes. With a fertile though rather scanty soil, agriculture has been carried on with varying degrees of success since the first settling of the island, though it appears the island was never wholly self-supporting in this respect. Fishing, whaling and shipbuilding were other pursuits carried on until recent times.

The local indigenous cedar, that still predominates and originally covered the island, afforded a lumber that could be used for housebuilding purposes, as well as giving an excellent wood for shipbuilding and for furniture. Many interesting pieces of furniture, in native cedar, made by island cabinetmakers, still exist.

The islands are formed of soft stone and sand with a thin surface of soil, the whole resting on a volcanic substructure of extreme age. The so-called "coral" of which the islands are formed is in reality a true Ăolian limestone, formed of wind-drifted shell sand with a small percentage of coral material. This stone occurs throughout the islands, varying in compactness and suitability for building purposes, but the hardest of it is easily quarried, cut into blocks for walls and slabs for roofing tiles, by handsaws, and may be trimmed with hatchet and adze. It is too soft and brittle to lend itself readily to fine ornament. For this reason Bermuda's houses show few purely ornamental motives in stone. In some of them there are semicircular arched projections over windows, called "eyebrow" windows, and a few crude pediment forms used as decorations. Finials on gable ends are not uncommon, but in any case all forms of carving are reduced to the lowest terms of simplicity. Mouldings on the exterior or moulded cornices on buildings seem to have come only with the advent of Portland cement. Some of the gateposts have coarse mouldings cut in stone.

Though the stone, when exposed to air, hardens somewhat, it remains too soft and porous to stand well without protection. When burned it gives an excellent lime, which is used with sand as a mortar in which to set the stone, and as a stucco inside and out to protect from moisture and disintegration, and finally as a whitewash for finish and cleanliness.

Besides the influence on building forms that this stone had, as a universally available and easily worked material, its presence throughout the island had another effect. In spite of abundant rainfall, the stone structure of the island is so porous that there is no natural accumulation of fresh water resulting in an entire absence of springs and streams, so that the inhabitants have been at all times dependent on[5] catching and storing rain water. Thus each roof serves not only its usual protective purpose, but must also serve to catch fresh water. The result is a feature, a marked Bermudian characteristic of roofs immaculate with whitewash and a system of gutters leading to that necessary adjunct of every Bermuda dwelling, "the tank."

The form of roofs employed varies considerably. Roofs with gable end and hipped roofs are both used, sometimes in the same building. There seems to be no generally adopted angle of pitch. One finds roofs almost flat and in different degrees of steepness to the sixty degree pitch of some of the outhouses and butteries. The roof surfaces are never interrupted by dormer windows.

The roof spans are in no cases large, rarely exceeding eighteen feet, probably governed by the limited sizes of the cedar lumber available for floor beams, but in any case apparently quite sufficient for the needs of the inhabitants. This smallness of span forced a smallness of division in plan, and contributed to the general small scale, a characteristic of island architecture referred to elsewhere.

The roof construction consisted of rather light sawn or hewn rafters, either butted at the summit or framed into a ridgepole, and securely fastened to a heavy plate placed on the inside line of the masonry wall. These rafters were tied over interior walls or partitions by long ties at the plate level, but elsewhere by ties placed too high up for structurally efficient service, with consequent thrust at the ends and irregular sagging of rafters. This was done for the purpose of allowing the ceilings of the rooms enclosed to run well up into what otherwise would have been dead roofspace, giving the rooms a surprising height and airiness in spite of low eaves. This form of ceiling, finished either in plaster or wood, gives rise to the not ungraceful, so-called "tray" ceilings, from a fancied resemblance to a serving tray. These, I think, are peculiar to old Bermuda, and Bermudians point them out with pride to visitors.

In the carpentry of many of the roofs, construction details of the shipwright rather than the carpenter prevail. Bermudians of the older days were well known for the excellence of their sloops and smaller sailing vessels, and one sees constantly the introduction of shipbuilding ideas in their houses—cedar knees locking at the angles, the timbers serving as roof plates, and tie-beams with the gentle curve or camber of a deck beam, are not infrequent.

The surface of the roof is constructed of sawn slabs or tiles of Bermuda stone about one and a half inches thick, by some ten inches to a foot in width with a[6] length slightly greater, known locally as "slates." These are fastened to strips of cedar set transversely to the rafters at proper intervals. An occasional slate is slightly raised, to secure necessary ventilation of enclosed roof space. These roof tiles usually overlap in the fashion of slates or shingles in horizontally parallel rows, but sometimes are laid flat with butting edges. The eaves have but a small projection of six to ten inches, and are supported on stubby square sectioned jack-rafters projecting from above the plate line to the edge of the tiling above. With the plate on the inside of the wall, this arrangement gives a shadow at the eave line that is decorative in its varying intensity, without the use of any mouldings whatever. In all likelihood, however, this type of eave, so different from the greatly projecting eaves of other sunny climates, was adopted to prevent the occasional hurricanes from unroofing the houses.[1]

[1] In spite of this a hurricane of unusual violence destroyed many roofs in September, 1922, uprooted hundreds of fine cedars and other trees and did thousands of pounds damage generally.

The whole roof surface is heavily coated with semi-liquid cement, which when it hardens serves to make the roof water-tight and softens the edges and angles to the eye. This, when freshly whitewashed, gives to the roofs the resemblance to "icing on a cake" spoken of by Mark Twain.

From the engineering point of view, the construction of the roofs may not be mechanically scientific, but whatever the deficiencies, the lack of precision and exactness has given to them that delightful quality of accidental irregularity and unevenness that is the despair of architects for new work, and can hardly be obtained by even obvious affectation.

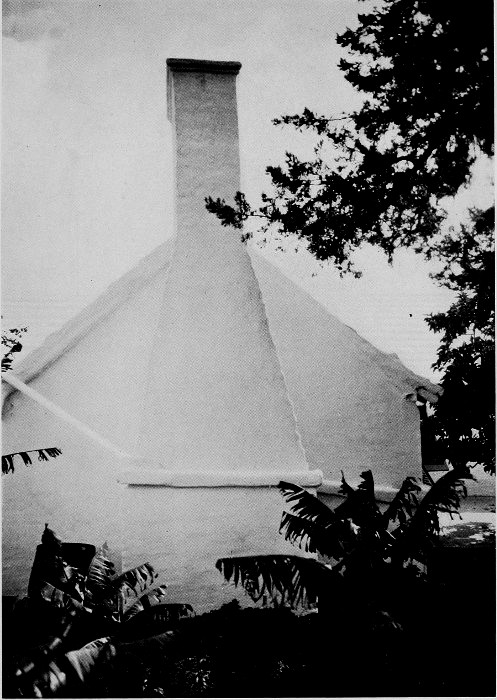

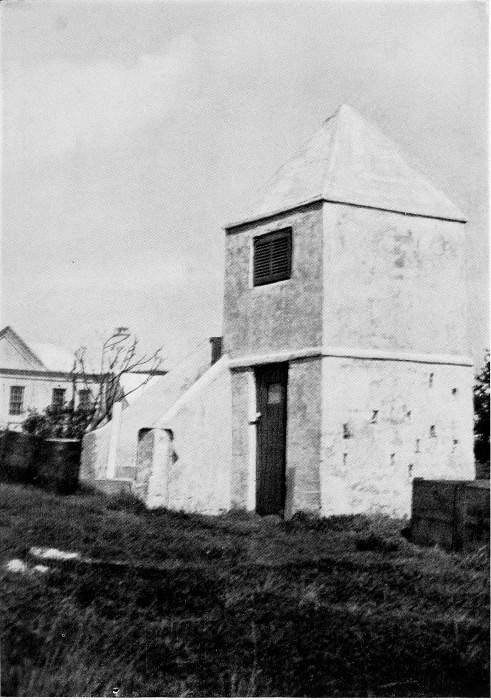

One of the characteristic and frequent adjuncts to Bermuda dwellings are the butteries. These are sometimes joined to the main building, but are often detached elements, and are, I believe, in the form that they appear on the islands, peculiar to Bermuda though Sicily is said to have somewhat similar out buildings. They are small two-story buildings with thick walls and small openings, with high pyramidal roofs, built by a series of inwardly encorbled courses of heavy masonry and present a decidedly monumental appearance. They were built before the days of ice, as a place to keep perishable food cool. Elevated and pierced with small shuttered openings to catch the breezes, they had thick walls and roofs as defense against the sun's rays.

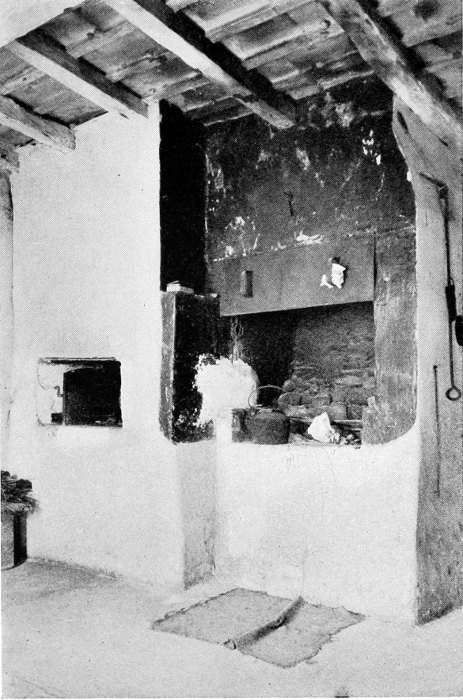

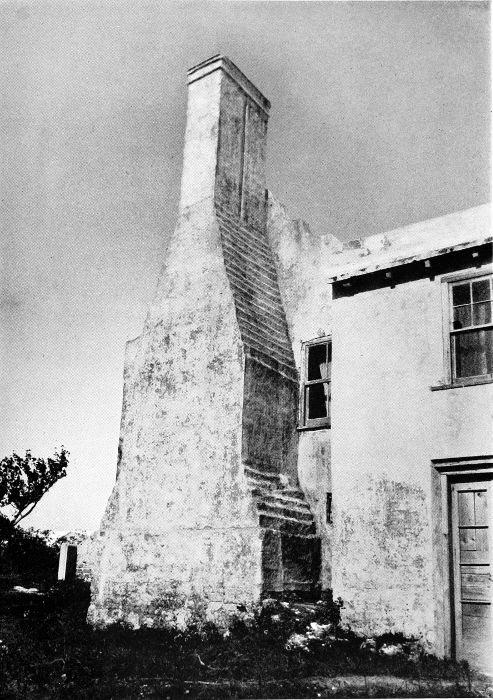

The chimneys area prominent feature, particularly in the smaller houses. Open fireplaces with hearths waist high were used for cooking, and are still in use for this purpose in some places, although oil stoves are generally replacing them.

The kitchen fireplace was accompanied by a built-in stone oven with its own flue, sometimes beside the kitchen fireplace, with independent chimney, and sometimes opening into it. The sides of these fireplaces sloped gently to a flue, so large and deep, that it carried off heat as well as the acrid smoke of burning cedar. Where the slave quarters were in the basement or cellar, there was a separate cooking fireplace for their use, so that even many of the small houses had two chimneys. In the larger houses of the more well-to-do, where slaves were owned in greater numbers, they were lodged in a separate building, and the owner's house usually had fireplaces to warm and dry the house during the colder weeks of winter. These fireplaces were of large size, with a raised hearth and no outer hearth. With the soft stone, the walls of the chimneys were necessarily thick, which gives them a prominence at first somewhat surprising for a sub-tropical climate. Chimneys projecting from the roof seemingly became a necessity to satisfy appearances, even when no real chimney existed. In many of the smallest houses, little false chimneys placed at the point of the hip are used as ornament to the roof.

Buttresses occur not infrequently and add to the character of the houses as well as having the structural function of overcoming the outward thrust of the rafters, that might otherwise be too great for the stability of the walls. These buttresses are sometimes reduced to salient pilasters on the thinner walls of the second story or pilasters of decided projection the full height of the house.

The ground plan of the smaller house presents little of great interest; in most cases a simple succession of intercommunicating rectangular rooms on the living floor; the kitchen dining room at one end distinguished by a large open cooking fireplace and built-in oven.

A greater number of rooms was obtained by adding projecting wings to the original plan. This was usually done in a rather haphazard fashion, but frequently with a distinct feeling of symmetry and order. The following diagrams show a number of such results that recur time and again with variations of gable and hip. The irregular additions were of great variety, sometimes producing by chance masses that composed in picturesque fashion. At other times the final outcome of successive additions was less fortunate with its complication of roofs and gutters. But the usual luxuriance of surrounding planting, the patina of age, and the very na´vetÚ of arrangement makes even these acceptable.

Where the house was located on sloping ground, which was a frequent and de[8]liberate choice of site as protection from the force of hurricanes the living floor was approximately at the higher level of the slope, necessitating a high basement wall on the lower side. This basement space, partially cut out from the natural rock, damp and almost totally dark, and with no direct connection to the floor above, was originally used for slave quarters with its own cooking fireplace, or for storage purposes. In the present day this lower part is little used. In some cases it makes shift for a stable, and more rarely, where conditions have permitted, is made into habitable rooms and connected by a stairway with the main floor.

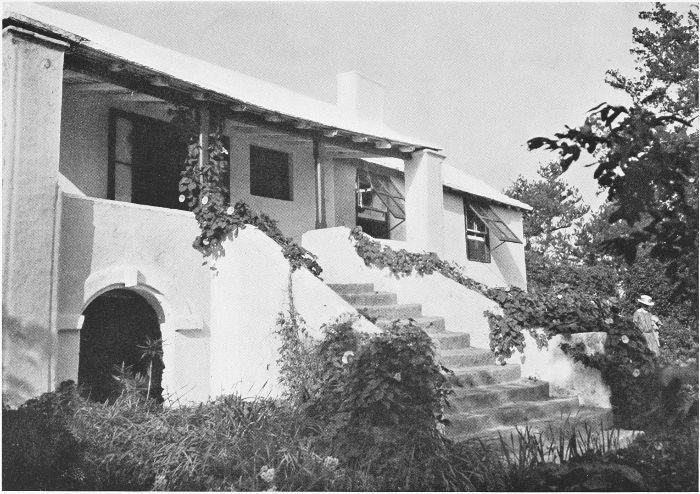

Plate 3. Diagrams of Typical Houses.

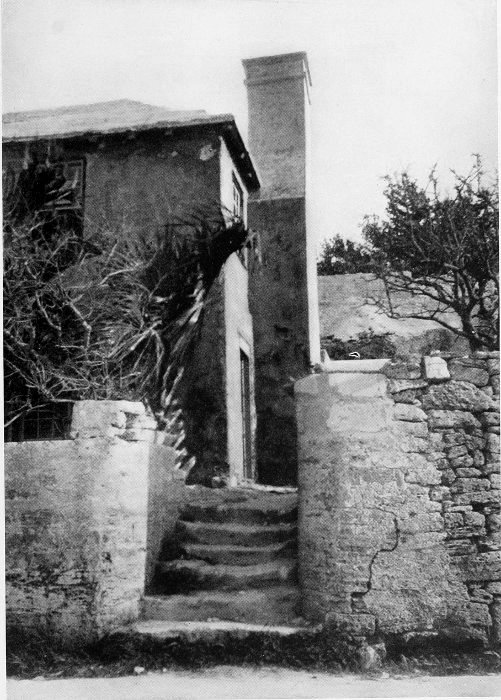

This form of building on a slope gives rise to another feature of many of the older houses, namely, the long flight of exterior steps, connecting the living floor with the lower ground level. These have brick risers and treads and substantial stone parapets with the landing at the top sometimes expanded to form a small terrace, or more rarely a covered veranda. These steps are as a rule much wider at the bottom than the top, with consequent diverging railing or parapet wall. On the landing itself, the walls have frequently an outward slant, giving a peculiar, tub-like effect. This stairway, or "stoop," as it would be called in some parts of America, with the outstretching sidewalls is known in Bermuda as "Welcoming Arms," significant of Bermudian hospitality.

Another frequent feature was the projecting vestibule or waiting room in many of the houses of early date. This was a small room, square or half octagon in plan,[9] that stood open to the visitor at all times, for shelter from sun and rain. The door from this to the rest of the house was the occupant's protection from intrusion. This room is said to have been furnished with chairs and table, and a hand bell, with which the caller announced his presence.

The infrequency of verandas or other roofed-over outdoor space is noticeable to the visitor from America, to whom this seems a very modest luxury, if not a necessity for ordinary comfort. In many cases where verandas now exist, they are additions to the house as first built. The original occupant and builder of these houses found indoors cooler and more comfortable in hot weather than any veranda, as screening against insects was then unknown. If he preferred outdoors, the shade of a tree or the north side of the house was sufficient. The sunshine was welcome in the winter to warm and dry the house, and in summer the prevailing wind was from the south and equally desirable. Many of the houses of the nineteenth century have verandas screened by shutters or lattice, some two-story ones. These are more common perhaps in the towns, where the houses were more crowded and the shade trees fewer. They seem more tropical or West Indian in character than the earlier houses, peculiarly Bermudian, and have a quite different interest. A few are shown in the photographs.

Bermuda from its earliest history as a proprietary settlement by the Virginia Company, throughout its development to its present condition as a self-governing Colony, has been uninterruptedly English. What tradition there is that has been an influence in its buildings is English. Some of the waved and stepped gable ends suggest at first sight a contact with Spanish America, but similar forms of gables in the domestic architecture of England, adapted to Bermudian materials, might well have produced the same result.

Though known to exist by the Spaniards before the English settled there, it was never occupied by them, and there seems no warrant for assuming there was Spanish influence at any time in the Islands.

Slave labor, cheap and plentiful, but unskilled, seems also to have been a contributory influence in the older houses, both in their planning and building and still more markedly in road building. Deep cuts through rock, and extensive building of substantial walls, that in the present day would be out of proportion in cost for the advantage gained, are frequent. Even the more modest smaller houses, with their dependent outhouses, butteries and garden walls, all in massive masonry, create[10] an appearance of permanence and solidity, that is striking to one accustomed to the flimsier frame construction so common in modern America.

Through the general mechanical progress of the world and particularly through modern means of transportation and consequent contact with the outside world, Bermuda has no longer its isolation, and has lost perhaps much that was picturesque and interesting in the life that formerly existed there, and which naturally and without conscious effort had its expression and reflection in the architecture of its dwellings.

Other activities have replaced the largely seafaring life that many of the old Bermudians followed and the agriculture though important has changed its character. Small farms have replaced the larger plantations, and Bermuda exports to northern markets, vegetables, potatoes and onions chiefly, and imports for its own use fruit and other foods formerly produced on the Island.

A new and important source of revenue, the tourist trade, has sprung up, has made great strides in the last years and is still increasing. Great and ugly hotels have been built to accommodate the thousands of visitors and more hotels are in prospect. The climate and the sea are inherent assets and attractions of Bermuda, which may not be changed, but there are other things perhaps less obvious that help to draw people there, which Bermuda alone possesses. Among these and not the least, is Bermuda's own architecture; the little white houses that fit so well in the landscape, and which appeal to the imagination with suggestions of a life apart from the rest of the world, one in which peace and ease replace the confusion and strenuousness of the more energetic North.

The number of regular winter residents is increasing, both those who have acquired property and those who annually rent houses. Some of these have adapted and altered older houses to modern needs, and in the changes made have kept to the spirit of Bermuda with no loss of material comfort. In other houses one sees changes made with little thought or care for appearances; iron tanks perched on roofs in conspicuous places, very much exposed plumbing, and corrugated iron roofs, are hard to ignore, Some of the newer houses are commonplace and vulgar, and impair the island's richness in beauty in direct proportion to their frequency; still others, large, pretentious, exotic in style, and out of keeping with all that makes for charm in Bermuda, are a positive detriment not only to their Vicinity but to Bermuda as a whole.

Bermuda's present and future needs in building can be satisfied, by thoughtful planning, in constructions adapted in form and spirit from the architecture that has evolved in the Islands. May those who control future building there either for personal use or in business ventures be persuaded that this is true—and that this will make not only for the enjoyment of future visitors but in the long run for the material prosperity of the Island and its inhabitants.

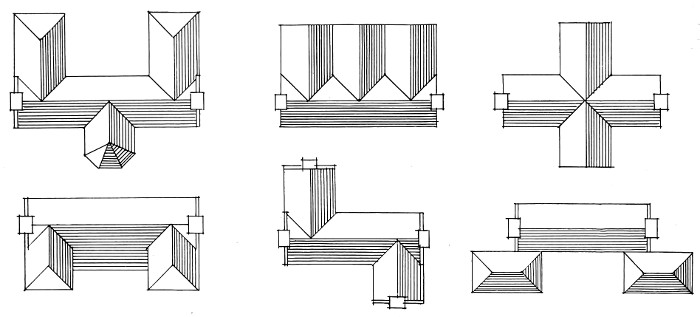

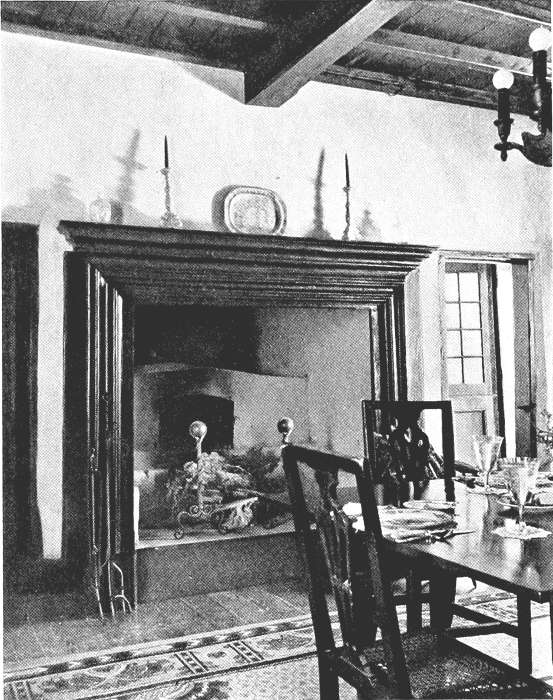

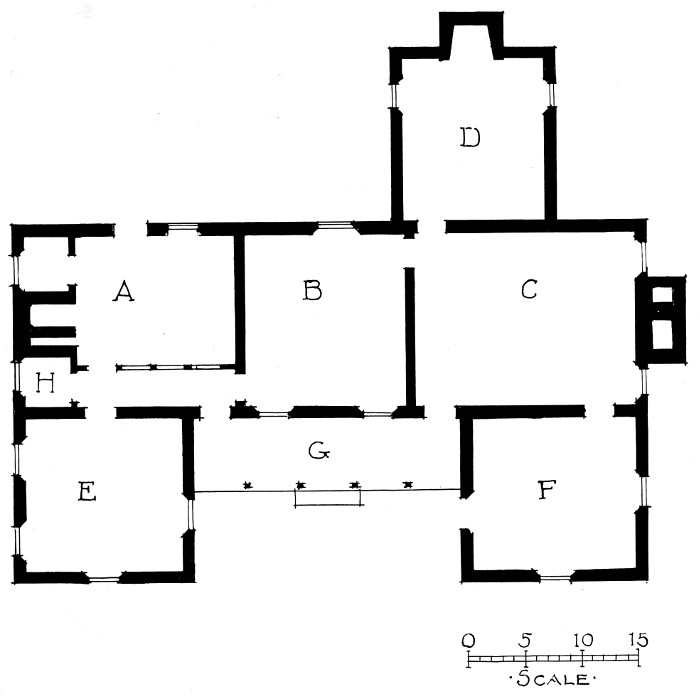

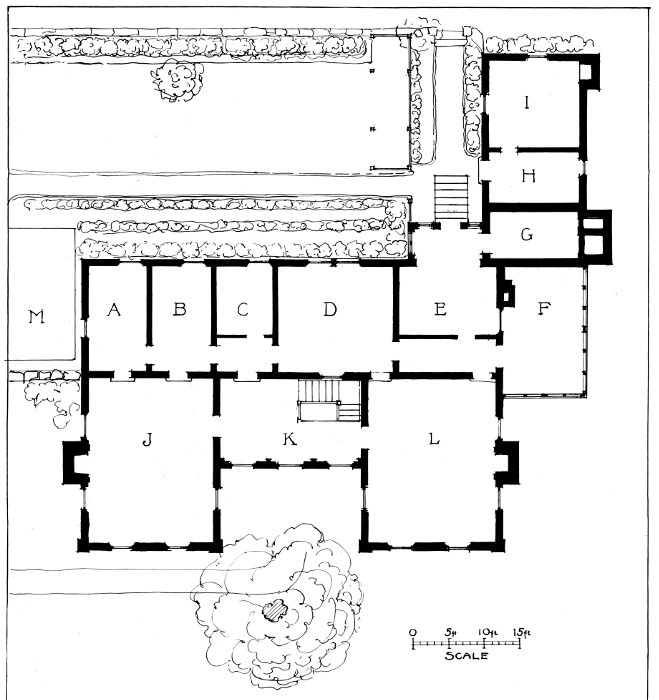

PLAN OF GROUND FLOOR

A—Dining Room, originally the Kitchen

B—Stairhall

C—Side Entrance, possibly originally a buttery or some other service

D—Living Room, with "Powdering Rooms," alcoves each side of fireplace

E—Present Library

F—Entrance Vestibule

G and H—Modern Kitchen and Pantry

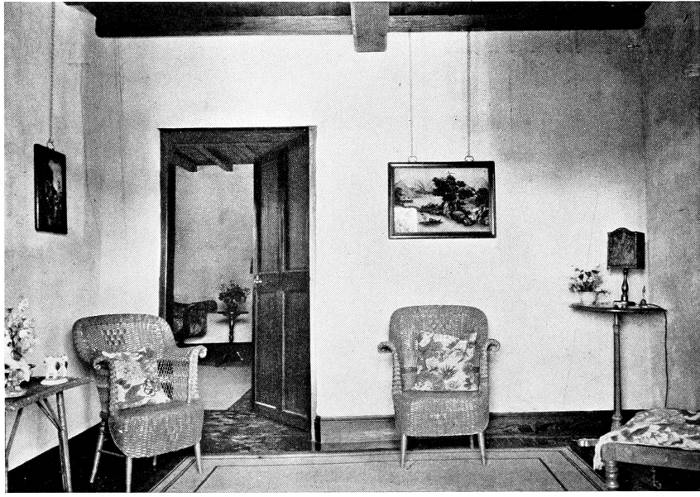

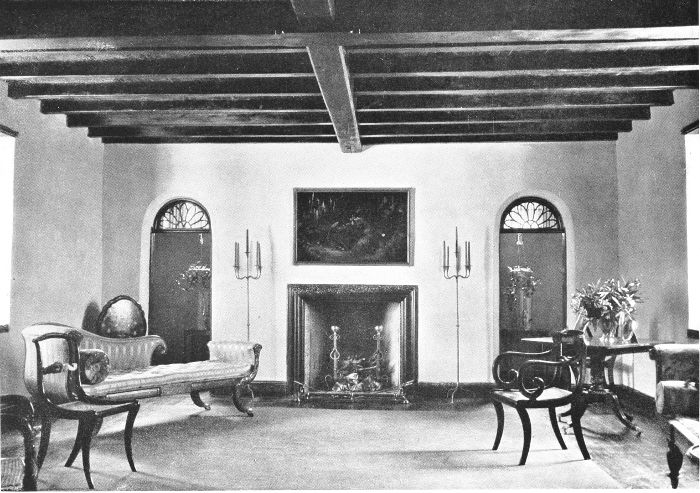

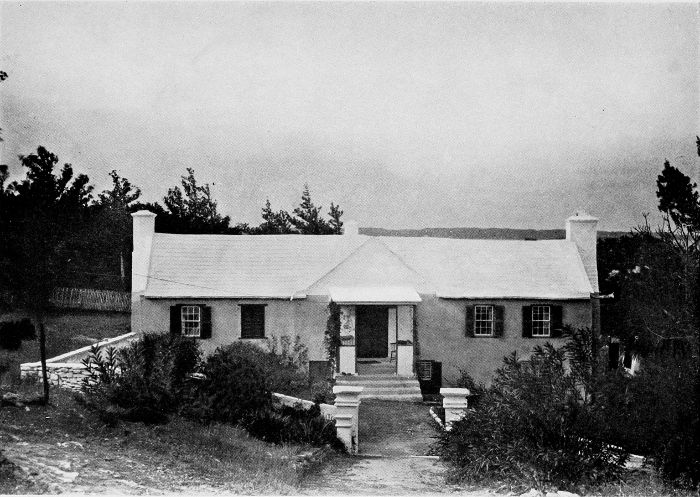

Inwood is a very well-preserved example of one of the earlier two-story dwellings in Bermuda. It has always been the house of the owner of a plantation large for Bermuda. It represents a certain degree of wealth and luxury. Its second story has now four good-sized bedrooms and two bathrooms. Three of the bedrooms have fireplaces with Dutch or English picture tiles and cedar mantles. This house was built about 1650 and was occupied by one of the early Governors when Bermuda was still a proprietary colony. Here he entertained and transacted business. It has a walled garden for fruits and flowers and another large piece now used as a vegetable garden surrounded by a high stonewall, said to have been built to prevent the depredations of wild hogs. The slave quarters are a separate building back of the house; other individual cottages were built for favorite slaves. Many interesting stories are told in connection with this place.

Plate 4. "Inwood," Paget. Plan of Ground Floor.

Plate 5. "Inwood," Paget.

Plate 6. "Inwood," Paget. Garden Gate.

Plate 7. "Inwood," Paget. Dining Room.

Plate 8. "Inwood," Paget. Vestibule.

Plate 9. "Inwood," Paget. Drawing-room.

PLAN

A—Kitchen

B—Dining Room

C—Living Room

D—Bedroom

E—Bedroom

F—Bedroom

G—Veranda

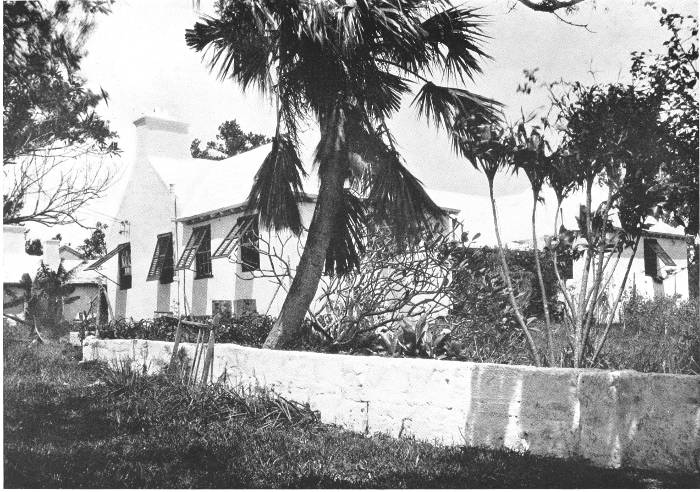

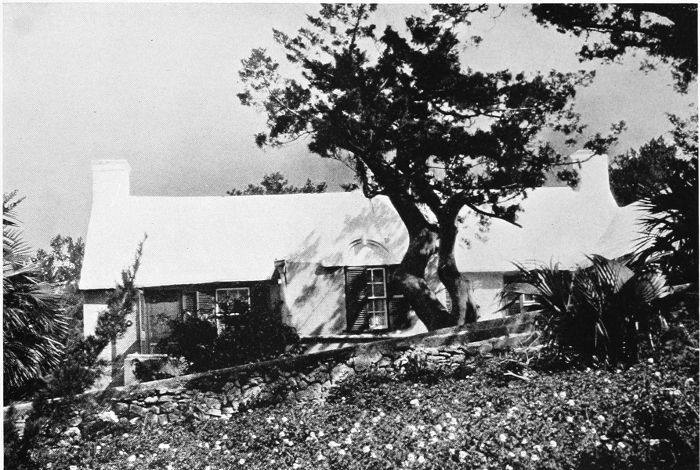

A one-story house built on flat ground previous to 1700. It remains today almost as at first built and is still in the possession Of the descendants of the original owners. The cellar space beneath this cottage, cut from the living rock, damp and almost unlighted, was used for slaves' eating and sleeping quarters. The chimney at the east end served a primitive open fireplace and oven. A detached summer kitchen is in the rear of the building. All the rooms have the so-called tray ceilings. The plate is joined at each corner with a natural bend cedar knee. The veranda is an addition to the original house.

Plate 10. "Cluster Cottage," Warwick. Plan of Ground Floor.

Plate 11. "Cluster Cottage," Warwick.

Plate 12. "Cluster Cottage," Warwick. Chimney and Rain Water Leaders.

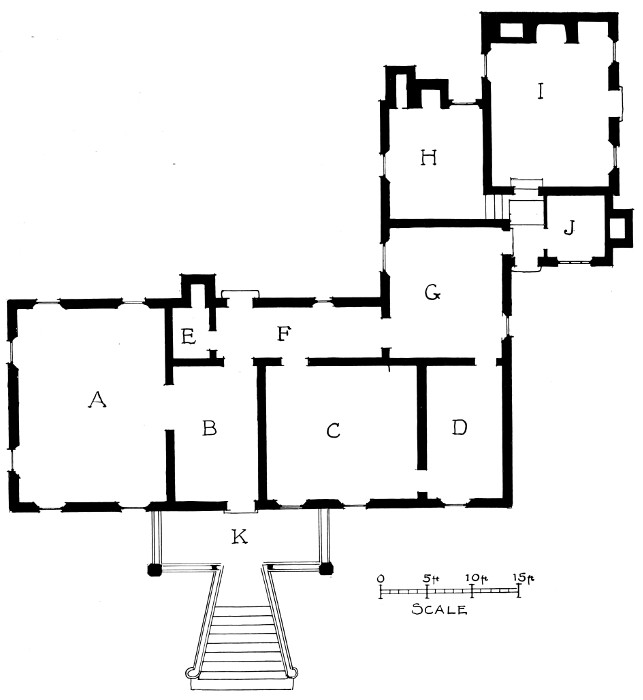

PLAN

A—Living Room

B—Entrance Hall

C—Bedroom

D—Bedroom

E—Closet

F—Hallway

G—Dining Room

H—Kitchen

I—Bedroom

This house dates from about 1700 and is little changed. It is a type of the house of medium size of that time. The bedroom—I—has been added since the original house was built. The front shows chimneys at the point of each hip. The right hand or east chimney probably connected with a cooking fireplace in the cellar, remains of which are still discernible. The flue has been cut away on this floor—leaving the chimney supported on the roof, as is the balancing false chimney on the west side.

Plate 13. "The Cocoon," Warwick. Plan of Ground Floor.

Plate 14. "The Cocoon," Warwick. South Front.

Plate 15. "The Cocoon," Warwick. From the Garden.

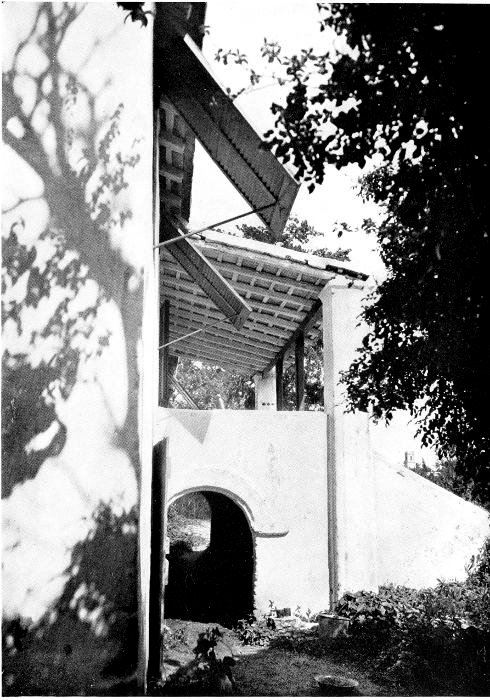

Plate 16. "The Cocoon," Warwick. Approach to "Welcoming Arms."

Plate 17. "The Cocoon," Warwick. Detail of Veranda.

A and B—Bedrooms

D—Bedroom Nursery

E—Kitchen

F—Covered Porch

G—Kitchen Pantry

H and I—Servants' Quarters

J—Living Room

K—Stair Hall

L—Dining Room

M—Tank

N—Billiard Room

O—Entrance Hall

P—Guest Room

Q—Cellar Space

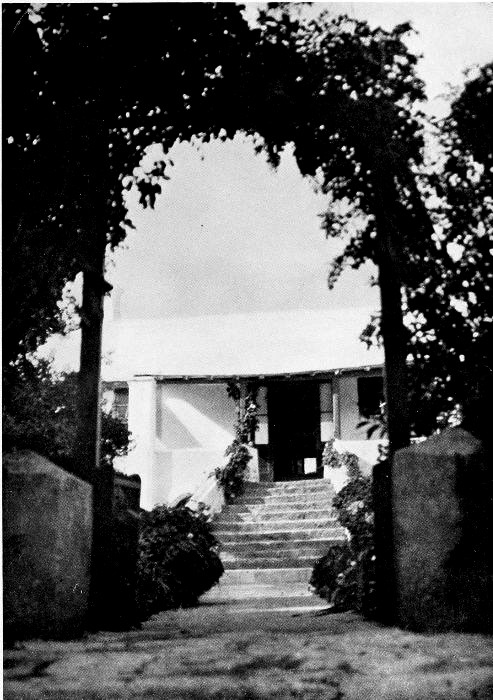

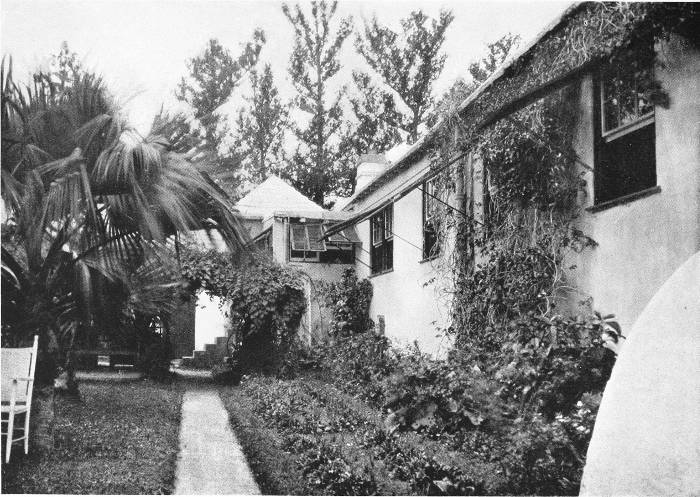

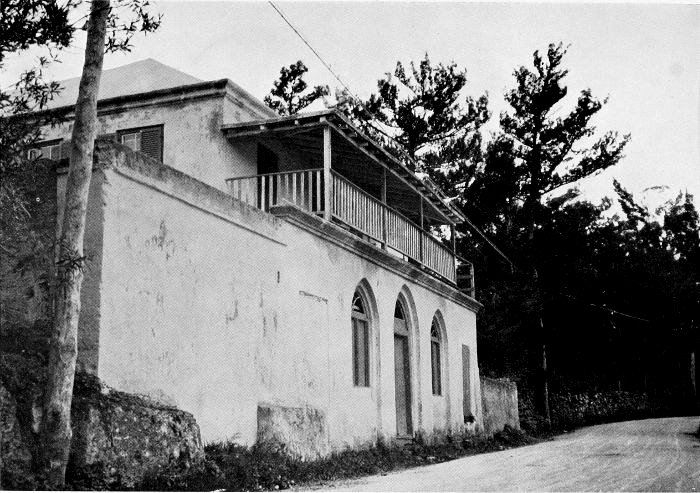

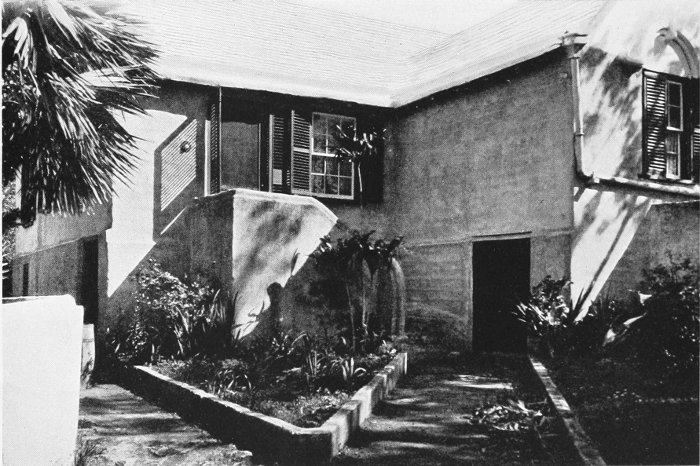

Harmony Hall is an example of a Bermudian house that has evolved by addition and alterations from a very simple original state to its present condition, but has remained Bermudian. The original part was probably built about 1700 or earlier. The first house consisted of the block A, B, C, D, E, and the buttery G, and the present servants' quarters. H and I were Kitchen Service. The house being on a slope, the front door was reached by a straight flight of steps opposite C. The basement was a storage space or cellar cut out from the hillside. At a somewhat later period wings J and L were added, the original steps removed, and an open portico and veranda, O and K, joined them. The house at this time was occupied by a shipowner and the large basement used for storing cargoes, etc., brought from nearby wharves. Early in the nineteenth century the portico was enclosed by filling in the arches and building a wall up to the veranda roof, and interior stairs were built.

Plate 18. "Harmony Hall," Warwick. Plan of First Floor.

Plate 19. "Harmony Hall," Warwick. Plan of Basement.

Plate 20. "Harmony Hall," Warwick. Northern Front.

Plate 21. "Harmony Hall," Warwick. The Garden.

Plate 22. "Harmony Hall," Warwick. Southern Front.

Plate 23. "Harmony Hall," Warwick. Living Room, showing "Tray" Ceiling.

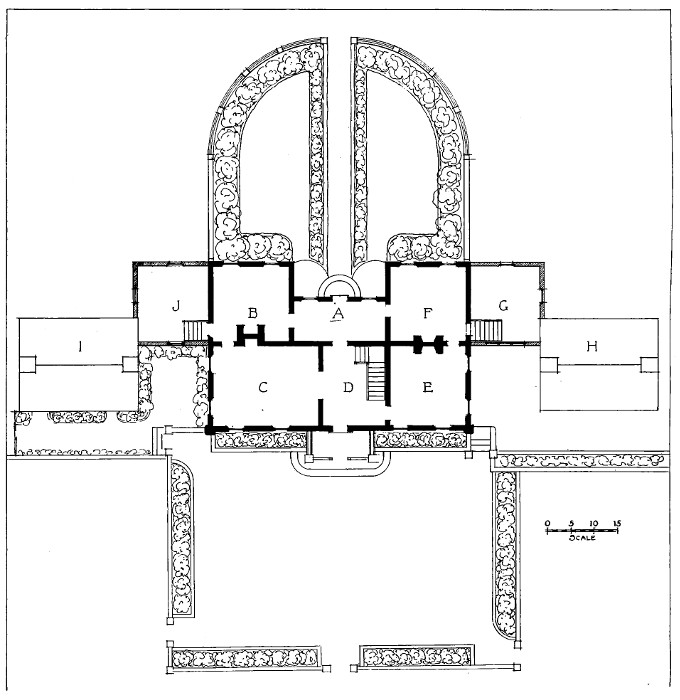

PLAN OF FIRST FLOOR

A—Entrance Hall

B—Study

C—Drawing-room

D—Stair Hall

E—Dining Room

F, G and H—Kitchen Service

I and J—Servants' Quarters

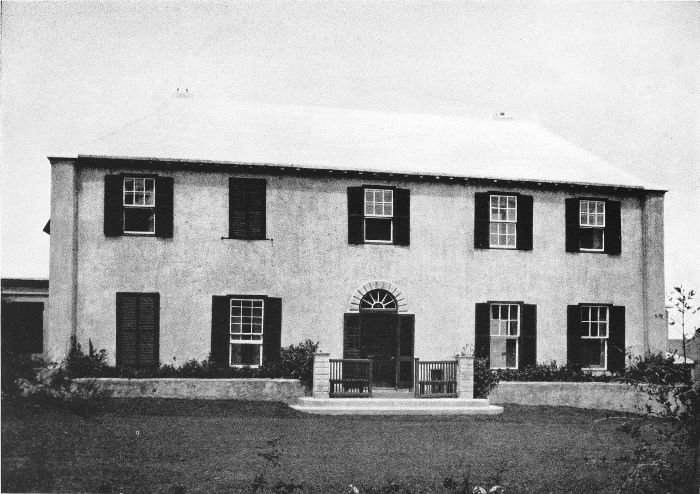

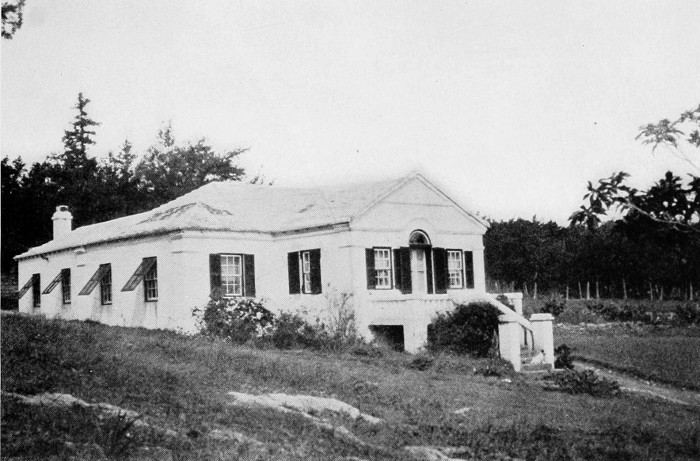

Bloomfield is a later type of house designed for a Bermudian gentleman. Built early in the nineteenth century, the symmetrical disposition of house and garden, and the detail of its interior show a distinctly Georgian inspiration. It is, nevertheless, completely Bermudian in expression, due to the smallness of its scale, the materials used and the exterior details.

Plate 24. "Bloomfield," Paget. Plan of Ground Floor and Gardens.

Plate 25. "Bloomfield," Paget. South Front.

Plate 26. "Bloomfield," Paget. Looking West.

Plate 27. "Bloomfield," Paget. Looking East.

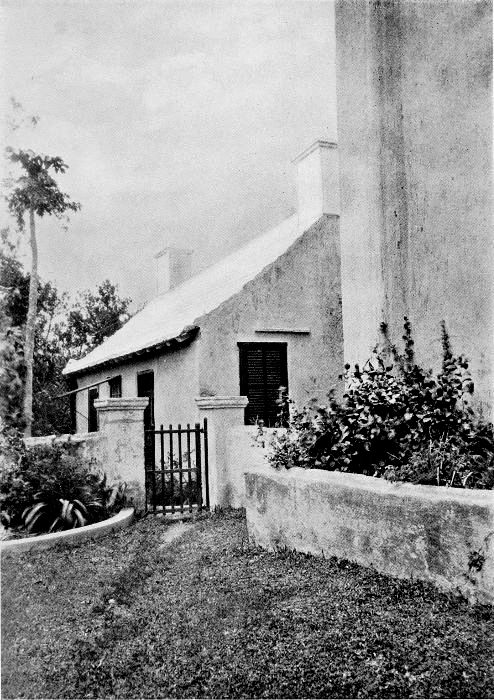

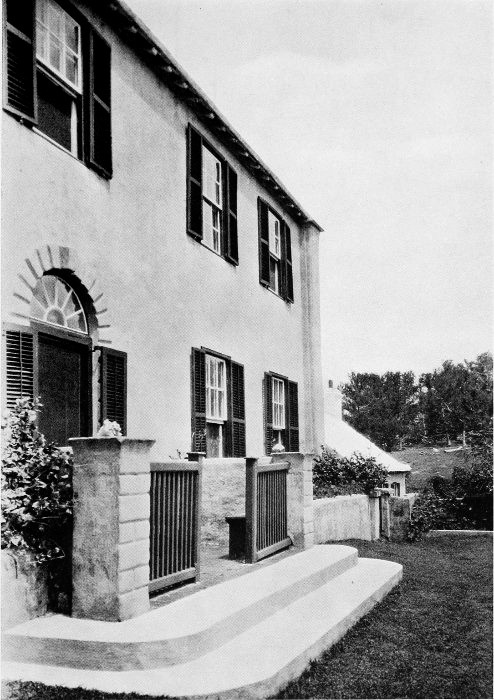

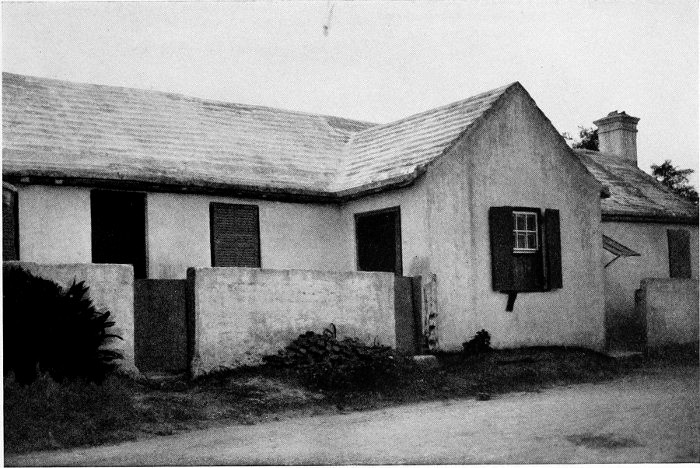

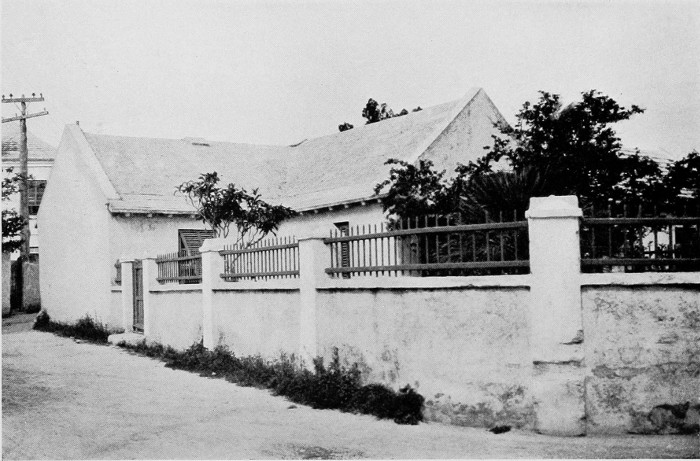

Plate 28. Small House in City of Hamilton.

Plate 29. Small House in City of Hamilton.

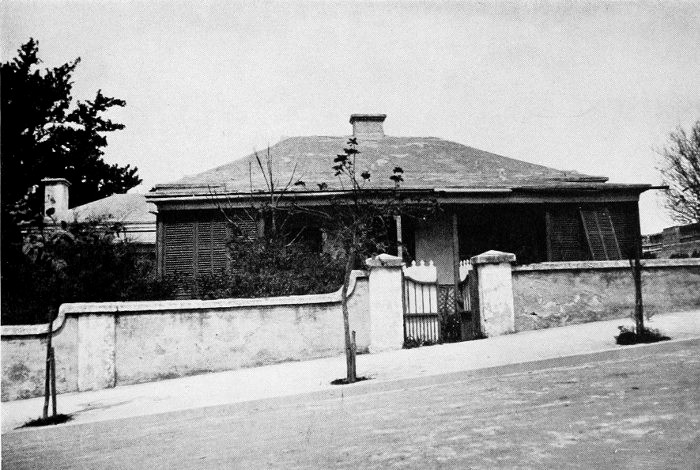

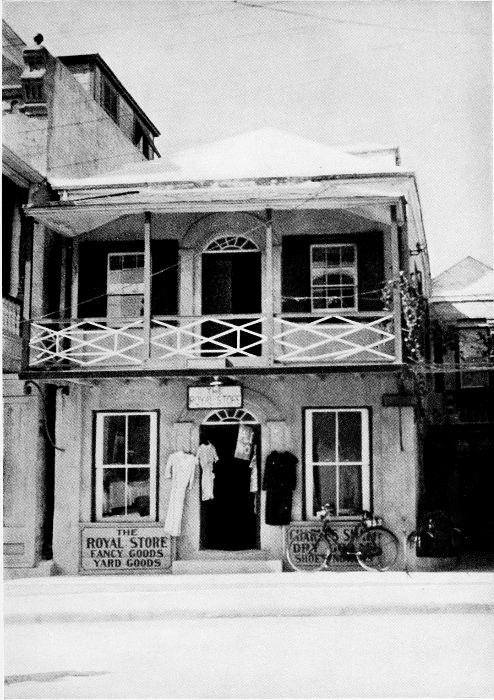

Plate 30. Shop in City of Hamilton.

Plate 31. Building in Public Library Garden, "Par la Ville," in City of Hamilton.

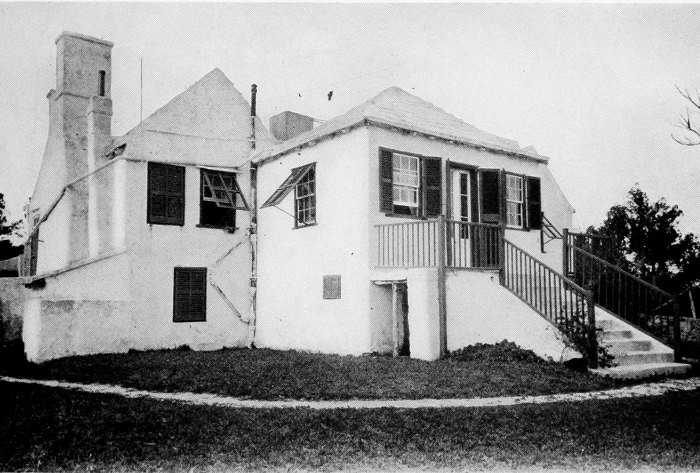

Plate 32. "Norwood," Pembroke. The Veranda is a Modern Addition.

Plate 33. "Norwood," Pembroke. Gate to Private Burying Ground.

Plate 34. Small House in Pembroke.

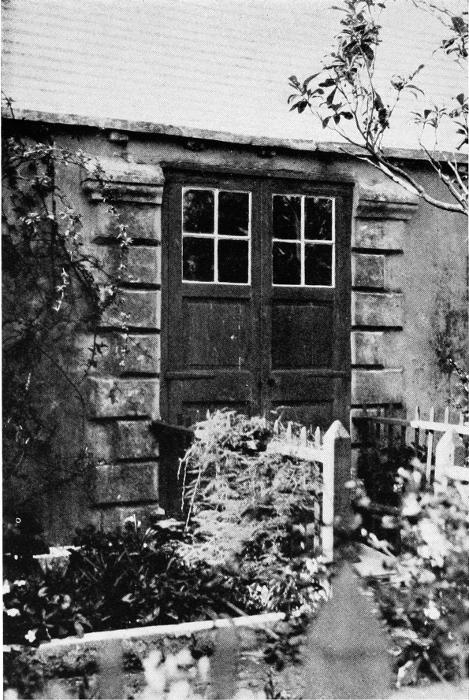

Plate 35. Detail of House in Pembroke.

Plate 36. Chimney on House in Pembroke.

Plate 37. "Beau Sejour," House in Paget.

Plate 38. Cottage in Paget.

Plate 39. Cottage in Paget.

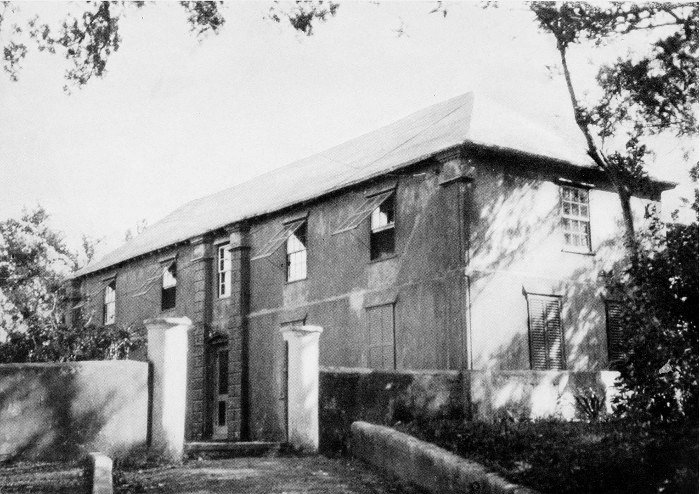

Plate 40. Old Tucker House, Paget.

Plate 41. Detail of Tucker House, Paget.

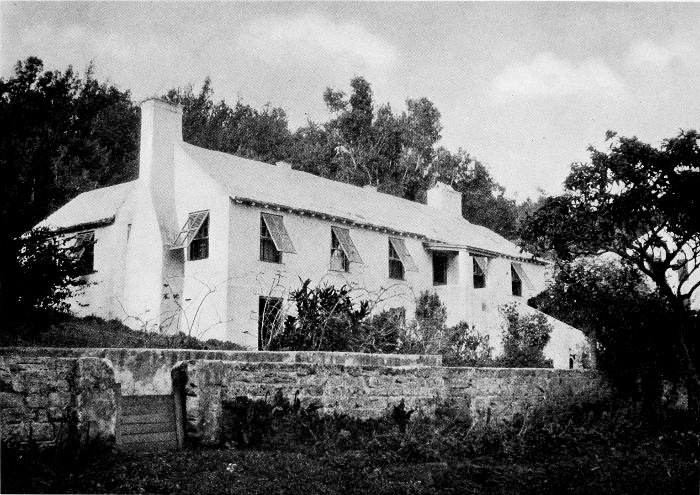

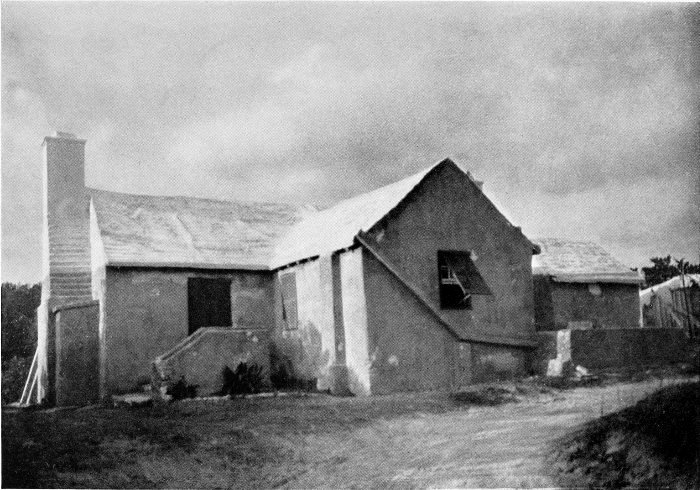

Plate 42. Old Farmhouse in Paget, built before 1687.

Plate 43. Old House in Paget.

Plate 44. Detail of House on Harbor Road, Paget.

Plate 45. House in Paget. Interior (Recently Restored).

Plate 46. House in Paget. Interior (Recently Restored).

Plate 47. House in Paget.

Plate 48. House in Paget. Side View.

Plate 49. House in Paget. Front View.

Plate 50. House in Paget. Front View.

Plate 51. House in Paget. Side View.

Plate 52. Shop and Tenement in Warwick.

Plate 53. Poorhouse, Paget.

Plate 54. House on Harbor Road, Paget.

Plate 55. "The Chimneys," Paget. Road Front.

Plate 56. "The Chimneys," Paget. Garden Front.

Plate 57. "Southcote," Paget. Front View.

Plate 58. "Southcote," Paget. Rear View.

Plate 59. "Pomander Walk," Paget.

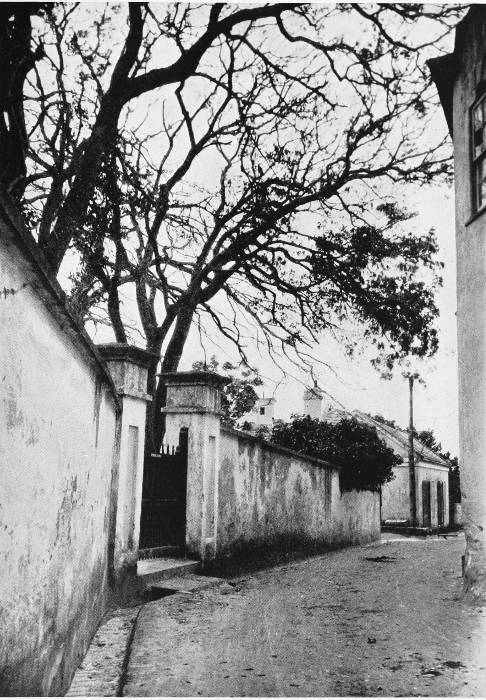

Plate 60. "Clermont," Paget. Garden Wall and Entrance.

Plate 61. Cottage in Paget.

Plate 62. House in Paget.

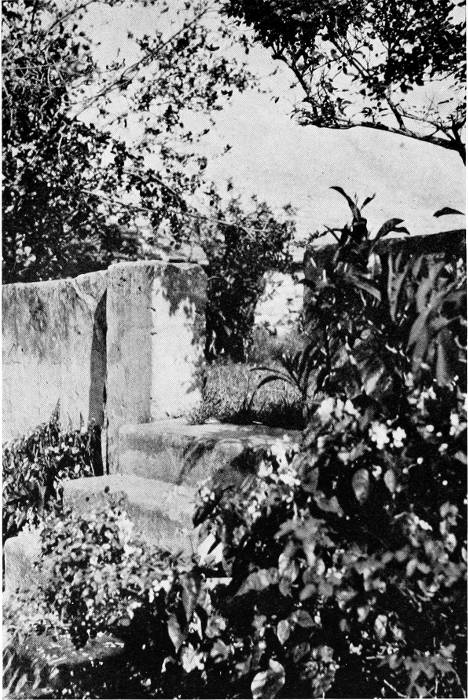

Plate 63. House and Garden, Paget.

Plate 64. Shop and Tenement, Warwick.

Plate 65. Old House, Harbor Road, Warwick.

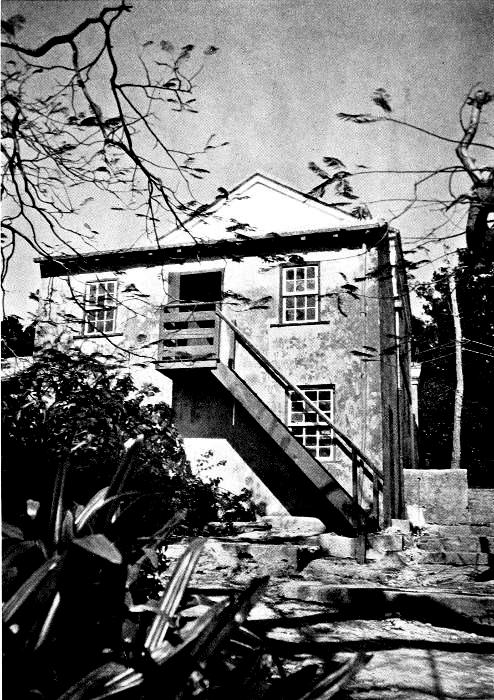

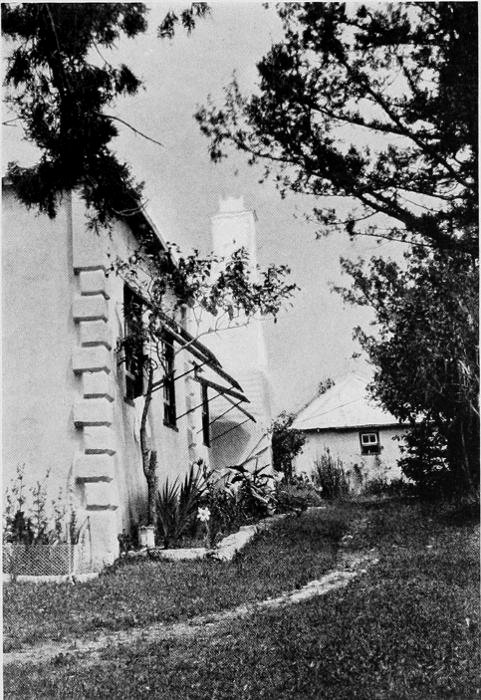

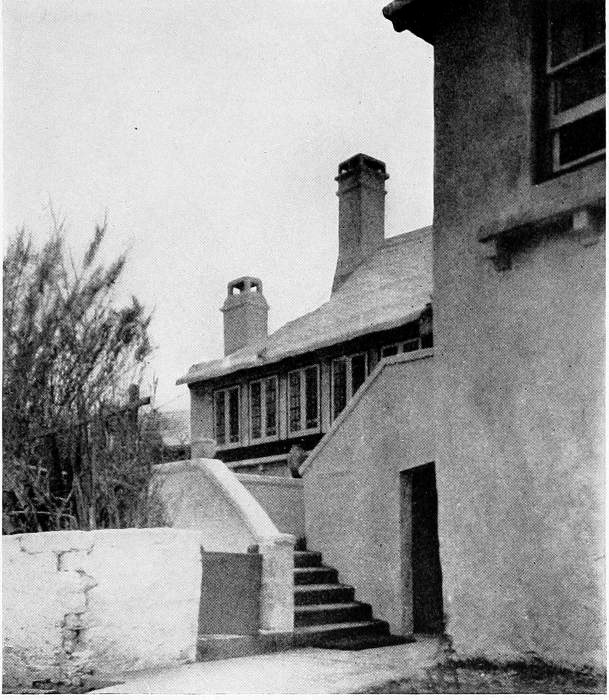

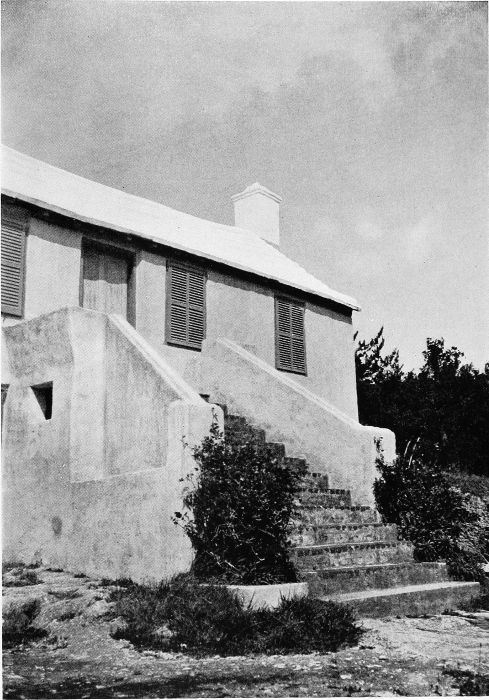

Plate 66. Steps and Chimney, House on Harbor Road, Warwick.

Plate 67. House in Warwick.

Plate 68. Small House in Warwick.

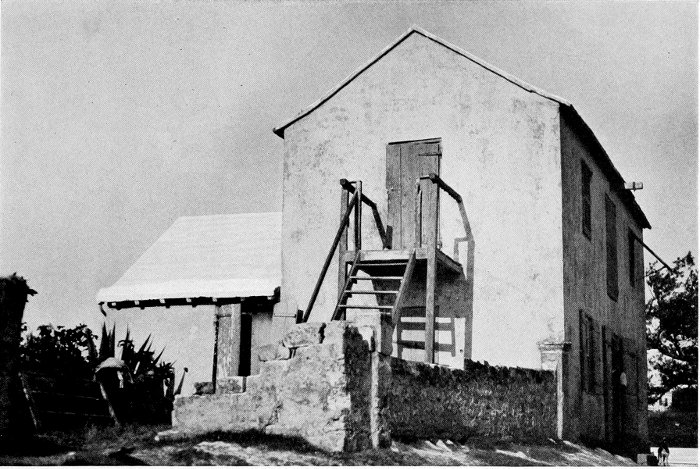

Plate 69. Buttery to House Preceding.

Plate 70. Old Cottage in Warwick.

Plate 71. Old Cottage in Warwick.

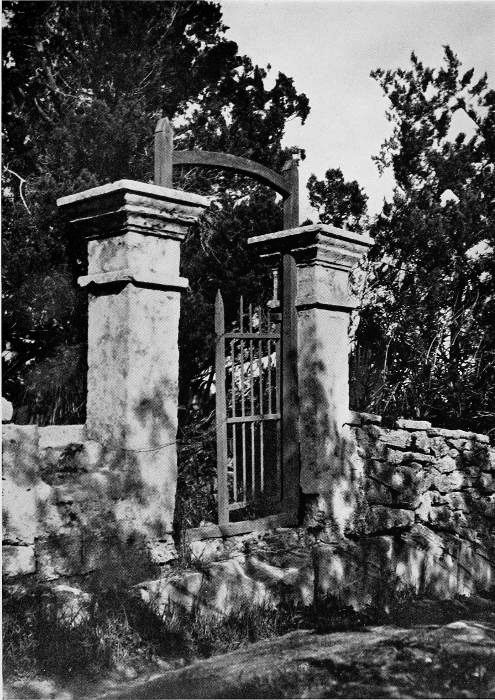

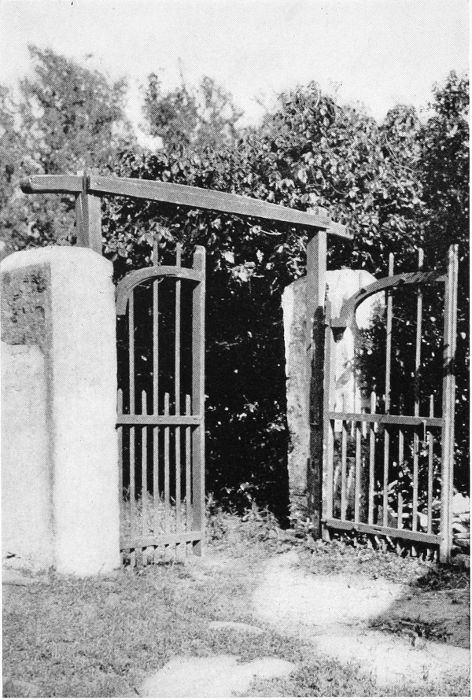

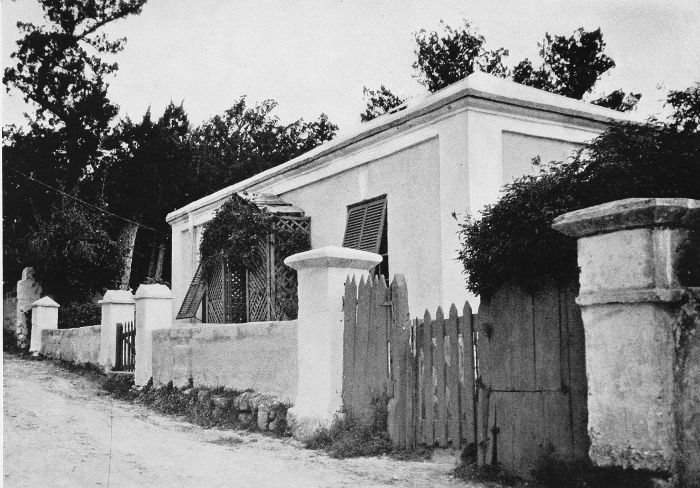

Plate 72. Old Gateway in Warwick.

Plate 73. Old House in Warwick.

Plate 74. House on Harbor Road, Warwick.

Plate 75. House in Warwick.

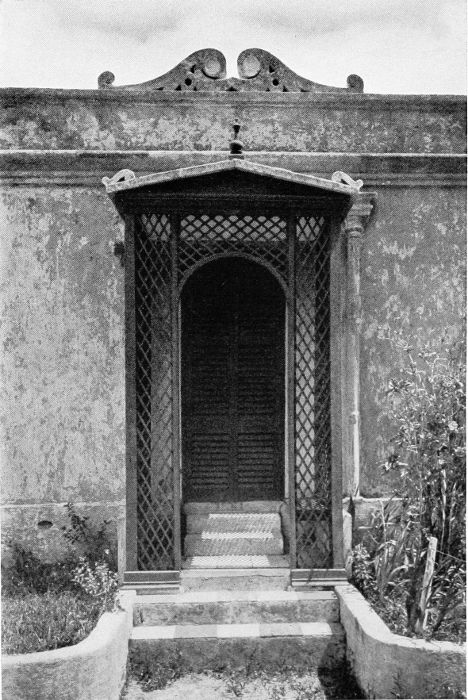

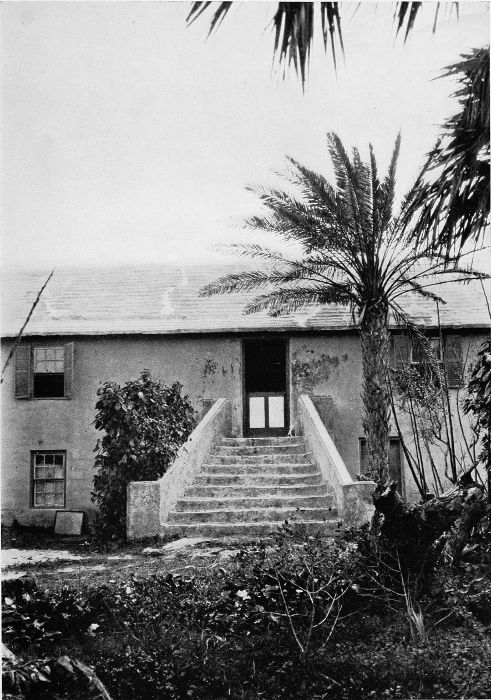

Plate 76. Entrance Steps and Vestibule, House in Warwick.

Plate 77. "Periwinkle Cottage," Warwick.

Plate 78. Outhouses, Farm in Warwick.

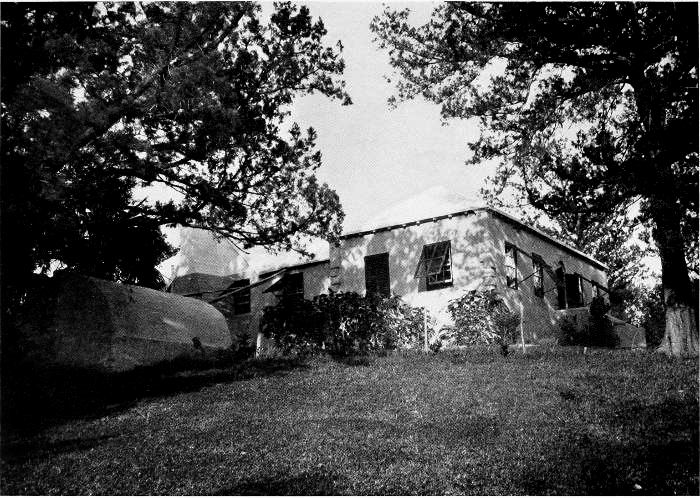

Plate 79. House near Riddle's Bay, Warwick.

Plate 80. Old House in Warwick.

Plate 81. Dooryard Garden, Old House in Warwick.

Plate 82. Detail of House on Harbor Road, Warwick.

Plate 83. Detail of Garden on Harbor Road, Warwick.

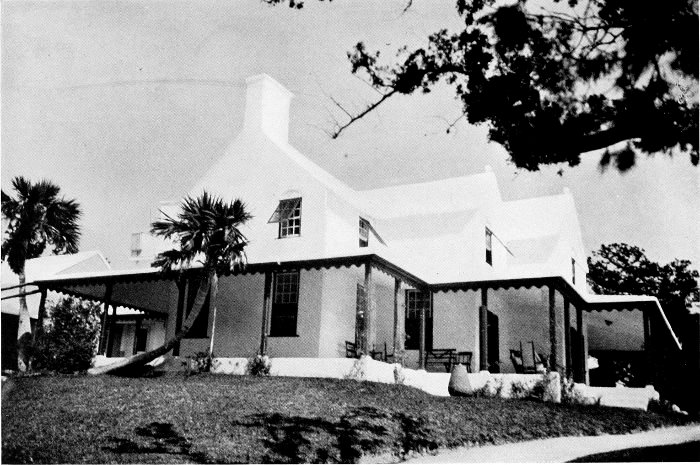

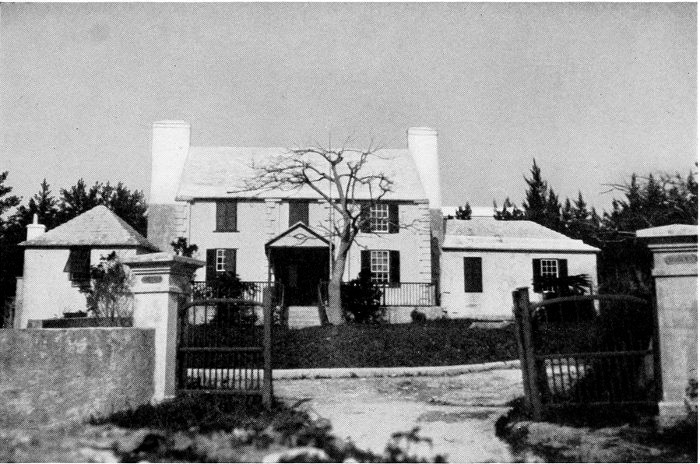

Plate 84. Front of "Cameron House," Warwick. Built about 1820.

Plate 85. "Cameron House," Warwick. Front Entrance.

Plate 86. "Cameron House," Warwick. Side Entrance.

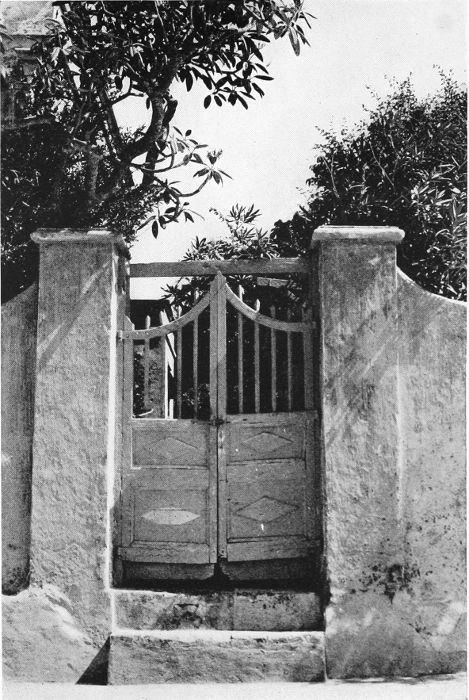

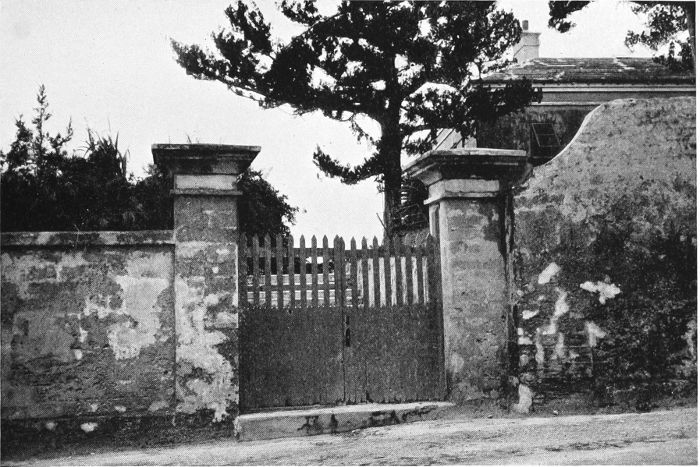

Plate 87. Garden Gate in Paget.

Plate 88. Garden Gate in Hamilton.

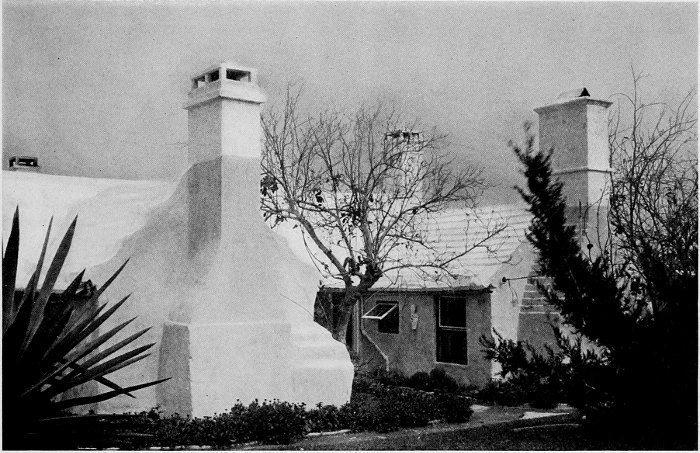

Plate 89. Buttery of Farmhouse in Paget.

Plate 90. Buttery of Farmhouse on Somerset Island.

Plate 91. Old House in Southampton.

Plate 92. House in Southampton.

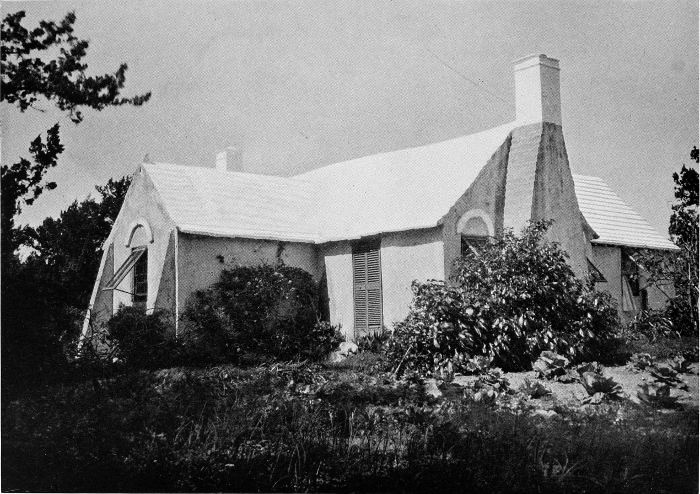

Plate 93. Old Cottage in Southampton.

Plate 94. Old Cottage in Southampton.

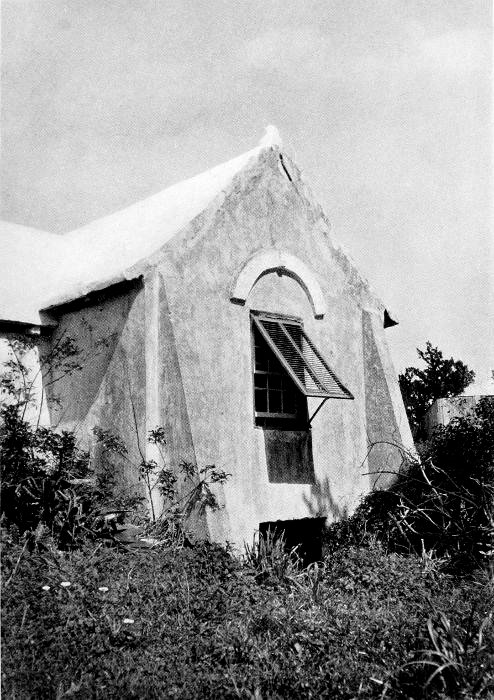

Plate 95. Detail of Old Cottage in Southampton.

Plate 96. Cottage in Southampton (Restored).

Plate 97. Detail of Cottage in Southampton.

Plate 98. Small Cottage in Southampton.

Plate 99. "Glasgow Lodge," Southampton.

Plate 100. "Glasgow Lodge," Southampton. Detail.

Plate 101. "Glasgow Lodge," Southampton. Interior of Hall.

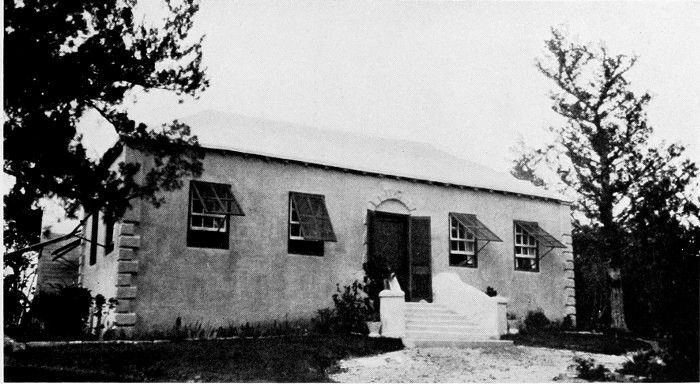

Plate 102. Schoolhouse in Southampton.

Plate 103. Farmhouse in Southampton.

Plate 104. "Midhurst," Sandys Parish.

Plate 105. "Midhurst," Sandys Parish, Kitchen Fireplace.

Plate 106. "Midhurst," Sandys Parish, Drawing-Room Fireplace.

Plate 107. Cottage in Sandys Parish (Restored).

Plate 108. Old House on Somerset Island, Sandys Parish.

Plate 109. Old Tavern on Somerset Island, Sandys Parish.

Plate 110. House on Somerset Island, Sandys Parish.

Plate 111. Old Cottage on Somerset Island, Sandys Parish.

Plate 112. House on Somerset Island, Sandys Parish.

Plate 113. Old Post Office, Courthouse and Jail, Somerset Island, Sandys Parish

Plate 114. Detail of House on Somerset Island, Sandys Parish.

Plate 115. Old House on Somerset Island, Sandys Parish.

Plate 116. Old House on Somerset Island, Sandys Parish.

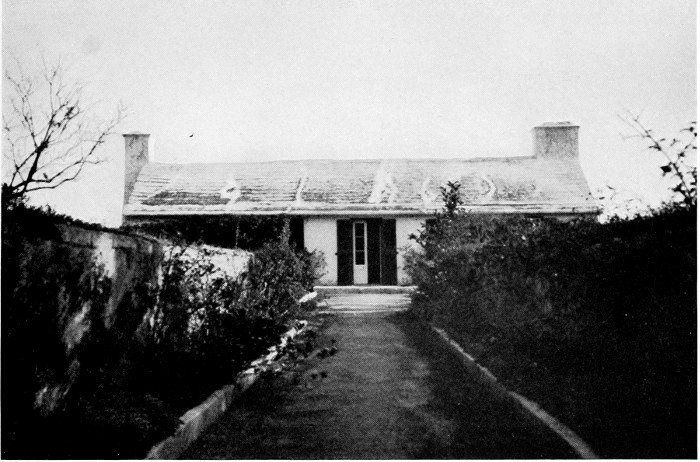

Plate 117. Deserted House in Sandys Parish.

Plate 118. Cottage on North Shore, Devonshire.

Plate 119. Cottage on South Shore, Devonshire.

Plate 120. House on North Shore, Devonshire.

Plate 121. "Welcoming Arms," North Shore, Devonshire.

Plate 122. Farmhouse Steps, "Welcoming Arms," Devonshire.

Plate 123. Old House in Devonshire.

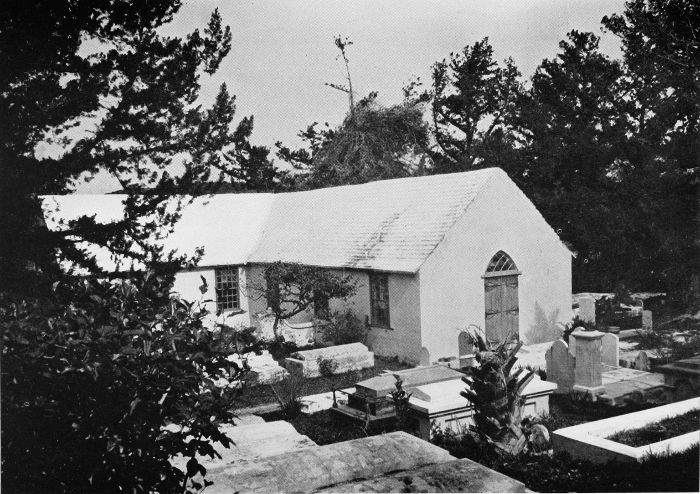

Plate 124. Old Devonshire Church.

Plate 125. Deserted Cottage on North Shore, Devonshire.

Plate 126. Cottage in Pembroke.

Plate 127. Old Cottage on North Shore, Devonshire.

Plate 128. Old Cottage on North Shore, Devonshire.

Plate 129. Cottage in Warwick.

Plate 130. Cottages on South Shore, Devonshire.

Plate 131. "Wistowe," Hamilton Parish.

Plate 132. "Wistowe," from the Garden.

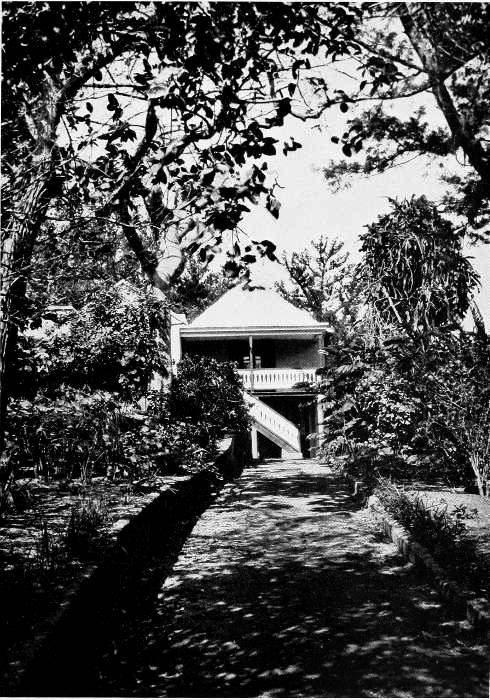

Plate 133. Old House on Harrington Sound, Hamilton Parish. Side View.

Plate 134. Old House on Harrington Sound, Hamilton Parish. Entrance.

Plate 135. House on Harrington Sound, Smith's Parish.

Plate 136. Chimney on House, Harrington Sound, Smith's Parish.

Plate 137. Shop and Dwelling on Harrington Sound, Smith's Parish.

Plate 138. Cottage in Smith's Parish.

Plate 139. House in Smith's Parish.

Plate 140. Cottage in Smith's Parish.

Plate 141. Golf Club House, an Old Building Altered, Tuckerstown.

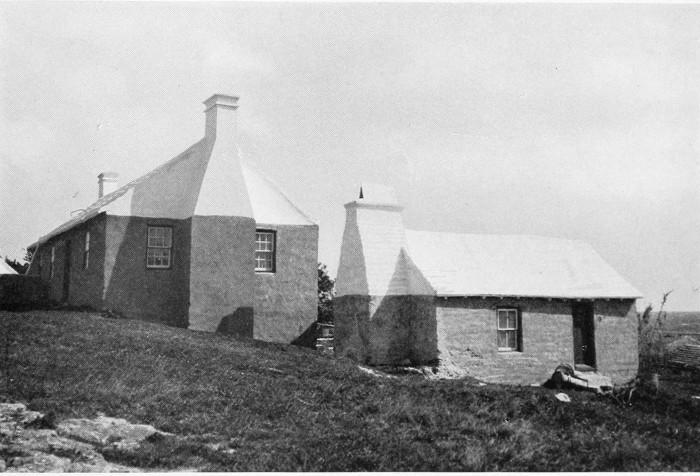

Plate 142. Farmhouse on St. David's Island.

Plate 143. Farmhouse on St. David's Island.

Plate 144. Farmhouse in Warwick.

Plate 145. House in Smith's Parish.

Plate 146. House in St. George. Two-Story Verandas.

Plate 147. House near St. George.

Plate 148. Inn near St. George.

Plate 149. Post Office in St. George.

Plate 150. Street and Shops in St. George.

Plate 151. Tavern in St. George.

Plate 152. Cottage in St. George.

Plate 153. House in St. George.

Plate 154. Cottage in St. George.

Plate 155. Cottage on North Shore, Hamilton Parish.

Plate 156. Cottage in St. George.

Plate 157. Cottage in St. George.

Plate 158. Cottage in St. George.

Plate 159. Cottage in St. George.

(Photograph by Weiss.)

Plate 160. Cottages in St. George.

Plate 161. Cottage in St. George.

Plate 162. Small House in St. George.

(Photograph by Weiss.)

Plate 163. Dooryard in St. George.

Plate 164. Dooryard in St. George.

Plate 165. Alley in St. George.

Plate 166. Tavern in St. George.

Plate 167. Alley in St. George.

Plate 168. Alley in St. George.

Plate 169. Chimneys in St. George.

Plate 170. Dooryard in St. George.

Plate 171. Cottage in St. George.

Plate 172. Street in St. George.

Plate 173. Street in St. George.

Plate 174. Street in St. George.

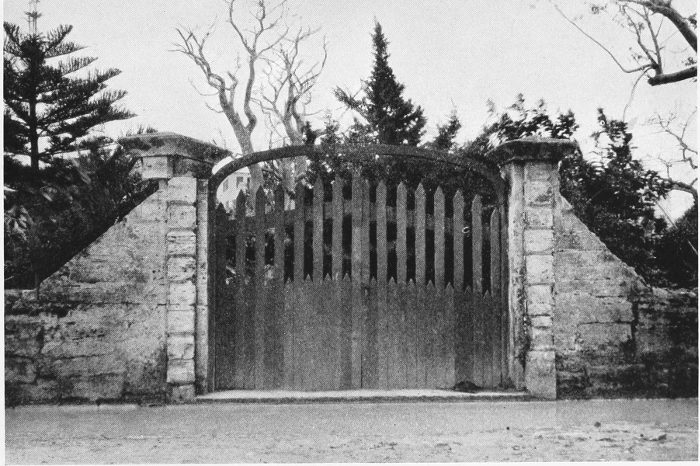

Plate 175. Gate in St. George.

Plate 176. Gate in St. George.

Plate 177. Gate in St. George.

Plate 178. Gate in St. George.

Plate 179. Gateway in St. George.

Plate 180. Gateway in St. George.

Plate 181. Gateway in St. George.

McGRATH-SHERRILL PRESS

Graphic Arts Building

BOSTON

End of Project Gutenberg's Bermuda Houses, by John Sanford Humphreys

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BERMUDA HOUSES ***

***** This file should be named 61736-h.htm or 61736-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/6/1/7/3/61736/

Produced by ellinora, Karin Spence and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions will

be renamed.

Creating the works from print editions not protected by U.S. copyright

law means that no one owns a United States copyright in these works,

so the Foundation (and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United

States without permission and without paying copyright

royalties. Special rules, set forth in the General Terms of Use part

of this license, apply to copying and distributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works to protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm

concept and trademark. Project Gutenberg is a registered trademark,

and may not be used if you charge for the eBooks, unless you receive

specific permission. If you do not charge anything for copies of this

eBook, complying with the rules is very easy. You may use this eBook

for nearly any purpose such as creation of derivative works, reports,

performances and research. They may be modified and printed and given

away--you may do practically ANYTHING in the United States with eBooks

not protected by U.S. copyright law. Redistribution is subject to the

trademark license, especially commercial redistribution.

START: FULL LICENSE

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full

Project Gutenberg-tm License available with this file or online at

www.gutenberg.org/license.

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or

destroy all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your

possession. If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a

Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound

by the terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the

person or entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph

1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this

agreement and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the

Foundation" or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection

of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual

works in the collection are in the public domain in the United

States. If an individual work is unprotected by copyright law in the

United States and you are located in the United States, we do not

claim a right to prevent you from copying, distributing, performing,

displaying or creating derivative works based on the work as long as

all references to Project Gutenberg are removed. Of course, we hope

that you will support the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting

free access to electronic works by freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm

works in compliance with the terms of this agreement for keeping the

Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with the work. You can easily

comply with the terms of this agreement by keeping this work in the

same format with its attached full Project Gutenberg-tm License when

you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are

in a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States,

check the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this

agreement before downloading, copying, displaying, performing,

distributing or creating derivative works based on this work or any

other Project Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no

representations concerning the copyright status of any work in any

country outside the United States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other

immediate access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear

prominently whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work

on which the phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed,

performed, viewed, copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no

restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it

under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this

eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the

United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you

are located before using this ebook.

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is

derived from texts not protected by U.S. copyright law (does not

contain a notice indicating that it is posted with permission of the

copyright holder), the work can be copied and distributed to anyone in

the United States without paying any fees or charges. If you are

redistributing or providing access to a work with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the work, you must comply

either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 or

obtain permission for the use of the work and the Project Gutenberg-tm

trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any

additional terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms

will be linked to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works

posted with the permission of the copyright holder found at the

beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including

any word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access

to or distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format

other than "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official

version posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site

(www.gutenberg.org), you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense

to the user, provide a copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means

of obtaining a copy upon request, of the work in its original "Plain

Vanilla ASCII" or other form. Any alternate format must include the

full Project Gutenberg-tm License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

provided that

* You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is owed

to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he has

agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments must be paid

within 60 days following each date on which you prepare (or are

legally required to prepare) your periodic tax returns. Royalty

payments should be clearly marked as such and sent to the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the address specified in

Section 4, "Information about donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation."

* You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or destroy all

copies of the works possessed in a physical medium and discontinue

all use of and all access to other copies of Project Gutenberg-tm

works.

* You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of

any money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days of

receipt of the work.

* You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work or group of works on different terms than

are set forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing

from both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and The

Project Gutenberg Trademark LLC, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm

trademark. Contact the Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

works not protected by U.S. copyright law in creating the Project

Gutenberg-tm collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may

contain "Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate

or corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other

intellectual property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or

other medium, a computer virus, or computer codes that damage or

cannot be read by your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium

with your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you

with the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in

lieu of a refund. If you received the work electronically, the person

or entity providing it to you may choose to give you a second

opportunity to receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If

the second copy is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing

without further opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS', WITH NO

OTHER WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT

LIMITED TO WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of

damages. If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement

violates the law of the state applicable to this agreement, the

agreement shall be interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or

limitation permitted by the applicable state law. The invalidity or

unenforceability of any provision of this agreement shall not void the

remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in

accordance with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the

production, promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works, harmless from all liability, costs and expenses,

including legal fees, that arise directly or indirectly from any of

the following which you do or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this

or any Project Gutenberg-tm work, (b) alteration, modification, or

additions or deletions to any Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any

Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of

computers including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It

exists because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations

from people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future

generations. To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation and how your efforts and donations can help, see

Sections 3 and 4 and the Foundation information page at

www.gutenberg.org Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent permitted by

U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is in Fairbanks, Alaska, with the

mailing address: PO Box 750175, Fairbanks, AK 99775, but its

volunteers and employees are scattered throughout numerous

locations. Its business office is located at 809 North 1500 West, Salt

Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887. Email contact links and up to

date contact information can be found at the Foundation's web site and

official page at www.gutenberg.org/contact

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

[email protected]

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To SEND

DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any particular

state visit www.gutenberg.org/donate

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations. To

donate, please visit: www.gutenberg.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project

Gutenberg-tm concept of a library of electronic works that could be

freely shared with anyone. For forty years, he produced and

distributed Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of

volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as not protected by copyright in

the U.S. unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not

necessarily keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper

edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search

facility: www.gutenberg.org