This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

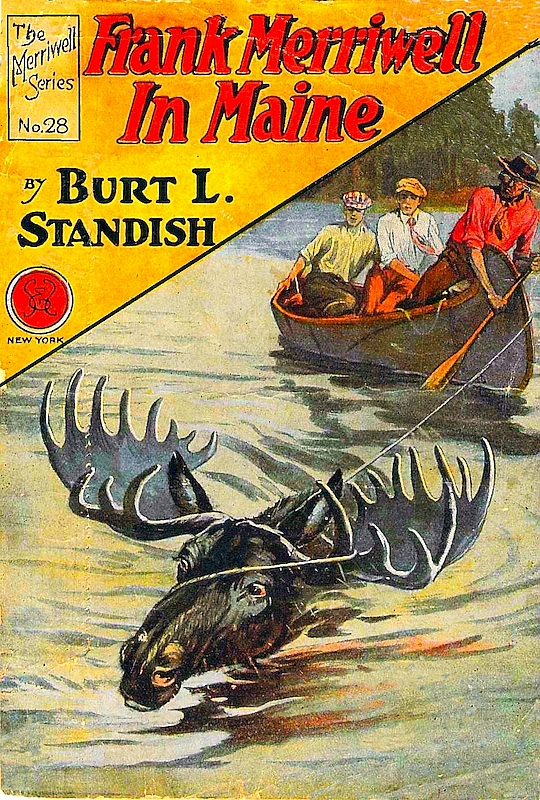

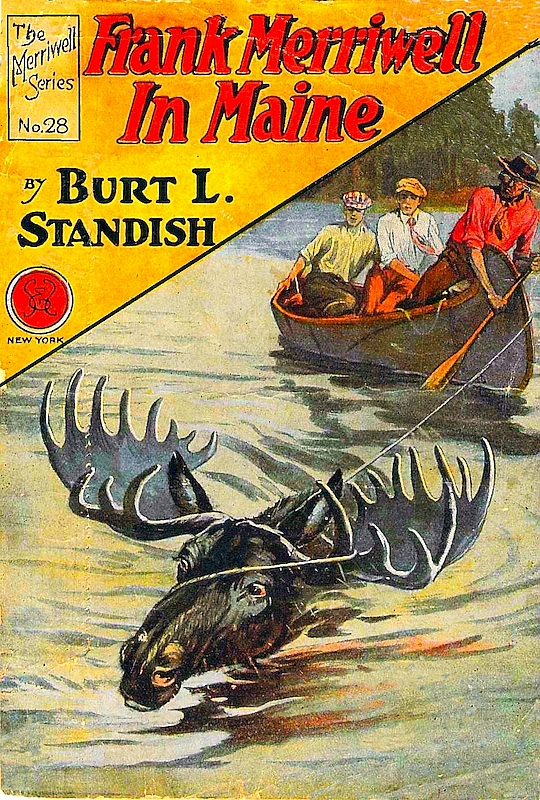

Title: Frank Merriwell in Maine

The Lure of 'Way Down East; The Merriwell Series No. 28

Author: Burt L. Standish

Release Date: February 29, 2020 [eBook #61535]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FRANK MERRIWELL IN MAINE***

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

The cover image was repaired by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Changes to the text are noted at the end of the book.

BOOKS FOR YOUNG MEN

MERRIWELL SERIES

Stories of Frank and Dick Merriwell

PRICE FIFTEEN CENTS

Fascinating Stories of Athletics

A half million enthusiastic followers of the Merriwell brothers will attest the unfailing interest and wholesomeness of these adventures of two lads of high ideals, who play fair with themselves, as well as with the rest of the world.

These stories are rich in fun and thrills in all branches of sports and athletics. They are extremely high in moral tone, and cannot fail to be of immense benefit to every boy who reads them.

They have the splendid quality of firing a boy’s ambition to become a good athlete, in order that he may develop into a strong, vigorous right-thinking man.

ALL TITLES ALWAYS IN PRINT

| 1—Frank Merriwell’s School Days | By Burt L. Standish |

| 2—Frank Merriwell’s Chums | By Burt L. Standish |

| 3—Frank Merriwell’s Foes | By Burt L. Standish |

| 4—Frank Merriwell’s Trip West | By Burt L. Standish |

| 5—Frank Merriwell Down South | By Burt L. Standish |

| 6—Frank Merriwell’s Bravery | By Burt L. Standish |

| 7—Frank Merriwell’s Hunting Tour | By Burt L. Standish |

| 8—Frank Merriwell in Europe | By Burt L. Standish |

| 9—Frank Merriwell at Yale | By Burt L. Standish |

| 10—Frank Merriwell’s Sports Afield | By Burt L. Standish |

| 11—Frank Merriwell’s Races | By Burt L. Standish |

| 12—Frank Merriwell’s Party | By Burt L. Standish |

| 13—Frank Merriwell’s Bicycle Tour | By Burt L. Standish |

| 14—Frank Merriwell’s Courage | By Burt L. Standish |

| 15—Frank Merriwell’s Daring | By Burt L. Standish |

| 16—Frank Merriwell’s Alarm | By Burt L. Standish |

| 17—Frank Merriwell’s Athletes | By Burt L. Standish |

| 18—Frank Merriwell’s Skill | By Burt L. Standish |

| 19—Frank Merriwell’s Champions | By Burt L. Standish |

| 20—Frank Merriwell’s Return to Yale | By Burt L. Standish |

| 21—Frank Merriwell’s Secret | By Burt L. Standish |

| 22—Frank Merriwell’s Danger | By Burt L. Standish |

| 23—Frank Merriwell’s Loyalty | By Burt L. Standish |

| 24—Frank Merriwell in Camp | By Burt L. Standish |

| 25—Frank Merriwell’s Vacation | By Burt L. Standish |

| 26—Frank Merriwell’s Cruise | By Burt L. Standish |

| 27—Frank Merriwell’s Chase | By Burt L. Standish |

| 28—Frank Merriwell in Maine | By Burt L. Standish |

| 29—Frank Merriwell’s Struggle | By Burt L. Standish |

| 30—Frank Merriwell’s First Job | By Burt L. Standish |

| 31—Frank Merriwell’s Opportunity | By Burt L. Standish |

| 32—Frank Merriwell’s Hard Luck | By Burt L. Standish |

| 33—Frank Merriwell’s Protégé | By Burt L. Standish |

| 34—Frank Merriwell on the Road | By Burt L. Standish |

| 35—Frank Merriwell’s Own Company | By Burt L. Standish |

| 36—Frank Merriwell’s Fame | By Burt L. Standish |

| 37—Frank Merriwell’s College Chums | By Burt L. Standish |

| 38—Frank Merriwell’s Problem | By Burt L. Standish |

| 39—Frank Merriwell’s Fortune | By Burt L. Standish |

In order that there may be no confusion, we desire to say that the books listed below will be issued during the respective months in New York City and vicinity. They may not reach the readers at a distance promptly, on account of delays in transportation.

| To Be Published in July 1922 | |

| 40—Frank Merriwell’s New Comedian | By Burt L. Standish |

| 41—Frank Merriwell’s Prosperity | By Burt L. Standish |

| To Be Published in August, 1922. | |

| 42—Frank Merriwell’s Stage Hit | By Burt L. Standish |

| 43—Frank Merriwell’s Great Scheme | By Burt L. Standish |

| To Be Published in September, 1922. | |

| 44—Frank Merriwell in England | By Burt L. Standish |

| 45—Frank Merriwell on the Boulevards | By Burt L. Standish |

| To Be Published in October, 1922. | |

| 46—Frank Merriwell’s Duel | By Burt L. Standish |

| 47—Frank Merriwell’s Double Shot | By Burt L. Standish |

| 48—Frank Merriwell’s Baseball Victories | By Burt L. Standish |

| To Be Published in November, 1922. | |

| 49—Frank Merriwell’s Confidence | By Burt L. Standish |

| 50—Frank Merriwell’s Auto | By Burt L. Standish |

| To Be Published in December, 1922. | |

| 51—Frank Merriwell’s Fun | By Burt L. Standish |

| 52—Frank Merriwell’s Generosity | By Burt L. Standish |

| To Be Published in January, 1923. | |

| 53—Frank Merriwell’s Tricks | By Burt L. Standish |

| 54—Frank Merriwell’s Temptation | By Burt L. Standish |

| To Be Published in February, 1923. | |

| 55—Frank Merriwell on Top | By Burt L. Standish |

| 56—Frank Merriwell’s Luck | By Burt L. Standish |

BY

BURT L. STANDISH

Author of the famous Merriwell Stories.

STREET & SMITH CORPORATION

PUBLISHERS

79-89 Seventh Avenue, New York

Copyright, 1898

By STREET & SMITH

Frank Merriwell in Maine

(Printed in the United States of America)

All rights reserved, including that of translation into foreign

languages, including the Scandinavian.

FRANK MERRIWELL IN MAINE.

Chu! chu! chu!

The sound came from the exhaust pipe of the little steamer.

“Chew! chew chew!” grunted Bruce Browning, lazily looking up at the escaping steam. “Do you know what that makes me think of?”

“Vot?” asked Hans Dunnerwust, who did not like the glance that Browning gave him, and who felt mentally sore because he had been laughed at for trying to get sauerkraut for breakfast. “Vat vos id you makes id t’ink uf?”

“Of the time you kicked that hornet’s nest, supposing it to be a football.”

“Py shimminy, uf dot feetpall did gick me und gid stung in more as lefendeen hundret blaces, id didn’t chewed me!”

“No, but you chewed the tobacco to put on the stings, and that old exhaust pipe sounds just like Merry, when he kept saying to you, ‘Chew! chew! chew!’—and you chewed like a goat!”

“Und peen so seasick vrom id! Ach! I vish dot dose hornets hat kilt me deat ven I stinged dhem.”

“Speaking of a goat,” remarked Hodge, “I saw one aboard a while ago. It belongs to the little boy that came on the boat with the lady as we were getting our things down to the landing.”

“Shouldn’t think they’d allow a goat on the steamer,” said Diamond, in disgust. “This isn’t a stock boat.”

“No, but it looks like a lumber van,” declared Browning, glancing about the deck, where some new furniture had been stowed, destined for Capen’s, or perhaps Kineo. “I guess it carries about everything that people are willing to pay for.”

“The man who can deliberately grumble on such a morning and amid such surroundings, ‘is fit for treasons, stratagems and spoils,’” declared Merriwell, looking admiringly across the water. “Tell me if any of you ever saw anything finer.”

Frank Merriwell and a party of friends were on the steamer Katahdin, out in the roomy sheet of water known as Moosehead Lake. The Katahdin had left the town of Greenville, near the southern extremity of the lake, some time before. Its ultimate destination was Kineo, the objective point of many tourists, but it was to stop at Capen’s, or Deer Isle, to put ashore some supplies there, together with Frank Merriwell’s party, consisting of Merriwell, Bart Hodge, Bruce Browning, Jack Diamond and Hans Dunnerwust, all friends of his at Yale.

They had left Greenville in a thick fog, which had at length rolled away, giving them a view of surpassing beauty. The water crinkled under the light breeze like a sea of silk. The sky was of so clear a blue that the black[7] smoke from the little funnel trailed across it like a blotch of ink.

All round were the lake’s grassy, timbered shores. In the northwest, the brown precipice of Mount Kineo lifted its hornstone face to a height of eight hundred feet. It was named for an old Indian chief, who lived on its crest for nearly fifty years. The volcanic cone known as Spencer Peaks rose in the east, while beyond them towered the granite top of Katahdin. In the southwest was the rugged head of “Old Squaw,” named for the mother of Chief Kineo, who dwelt on its top, as her son dwelt on the top of the mountain that bears his name.

Diamond glanced back toward Greenville, and sang, rather than said, “Farewell, Greenville!”

This started Frank Merriwell, who got out his guitar, put it in tune, then leaned back on the camp stool with which he had provided himself and sang:

“Farewell, lady!

Farewell, lady!

Farewell, lady!

We’re going to leave you now.”

Jack Diamond, who sang a fine tenor, joined him in the chorus, which in spite of its jolly words, floated over the water in a way that was almost melancholy:

“Merrily we roll along,

Roll along,

Roll along,

Merrily we roll along,

O’er the deep, blue sea!”

“That sentiment would be all right, now, if we were on one of those new-fangled roller boats,” observed[8] Browning, “but it hardly fits the present occasion. I’d suggest that you change that to ‘skim along,’ or ‘steam along’; we’re certainly not rolling. There isn’t enough sea going on this old lake to make a birch canoe roll!”

Diamond did not seem to hear this. There was a faraway look in his eyes that made Merriwell wonder if Jack were not thinking of a girl to whom he had said farewell at Bar Harbor earlier in the summer.

Merriwell started another old song, whose music and words were sad enough to bring tears, and Diamond’s rich tenor took it up with him. It was a song of the friends of long ago, and the last stanza ran:

“Some have gone to lands far distant,

And with strangers make their home;

Some upon the world of waters

All their lives are forced to roam;

Some have gone from earth forever,

Longer here they might not stay.

They have found a fairer region,

Far away, far away!

They have found a fairer region,

Far away, far away!”

“I vish you voult quit dot!” implored Hans, digging some very fat knuckles into some very red eyes. “Dot make me feel like my mutter-in-law lost me. I feel like somet’ing gid behint me und tickle dill I cry.”

He was interrupted by a warning scream, in a woman’s voice.

“Here, Billy! Look out! Look out!” was shouted.

At the same instant there was a blow, a sound of smashing glass, and with a squawk of astonishment and fright, Hans Dunnerwust shot forward and into the air, as if hit[9] by a pile driver. Something had “tickled” him from behind, in a most unexpected way. It was the goat, of which Hodge had spoken.

“Wow! Mutter! Fire! I vos shot! Hellup! Ye-e-e-ow!”

Hans clawed the air with feet and hands in a frenzy of alarm. Then he came down on the goat’s back and began to squawk again:

“Safe me! I vos kilt alretty! Somet’ings vos riting me avay! Hellup! Murter!” as the goat, frightened by Hans’ fall upon his back, made a forward dash.

Hans had been seated on a stool, which was a part of the new furniture stowed on the deck. A mirror leaned against this stool, the mirror being also a part of the furniture.

The goat was supposed to be kept somewhere below, but it had refused to remain there, and in its peregrinations over the vessel had finally wandered to the upper deck.

The boy had followed it, with the intention of taking it below again, but it had scampered by him.

Then it had suddenly become aware of the fact that there was another goat on the steamer. This new goat was in the mirror. The new goat looked pugnacious and put down its head in a belligerent way when the other goat put down its head. This was too much for any right-minded goat to endure, and so Billy made a rush with lowered head and smashed the mirror goat into a thousand pieces.

Fortunately it struck below Hans and merely hoisted him forward and upward. Its impact was like that of a[10] battering-ram, and if it had butted him fairly in the back it would have inflicted serious injuries. Still though not at all hurt, Hans thought himself as good as dead, and bellowed right lustily.

The other members of the party sprang to their feet, quite as startled, while the boy raced across the deck to stop the goat’s mad career, and the boy’s mother screamed in alarm.

Hans’ fat legs flailed the air, as the goat made its rush, then he tumbled off, with a resounding thump.

“Hellup!” he roared. “Something vos kilt py me! I vos smashed indo more as a hundret and sefendeen bieces!”

Seeing he was not injured, his friends began to laugh.

Hans rolled over, gave them a hurt and angry look, then glanced in the direction taken by the goat.

It had faced about and now stood with lowered head awaiting the turn of events. Plainly it was bewildered. The disappearance of the other goat was to it a puzzling mystery.

“Ba-a-aa!”

Its warning note sounded, as Hans lifted himself on his hands and knees. He was facing the goat, in what the goat thought a threatening attitude. Billy’s fighting instincts were aroused and he was ready for any and all comers, whether they were goats or men.

The comical pugilistic attitude of Hans and the goat was too much for Frank Merriwell’s risibilities. He shouted with laughter. And even Bart Hodge and Jack Diamond, who seldom laughed at anything, laughed at[11] this. Bruce Browning dropped limply back on his stool, haw-hawing.

“Yaw!” snorted Hans. “Dot vos very funny, ain’d it? Maype you seen a shoke somevere, don’d id? You peen retty to laugh a-dyin’, ven I vos kilt. Oh! you gone to plazes! I vos——”

The boy dashed by him toward the goat and Hans lifted himself still higher on his hands and knees.

This was too much for the goat.

“Ba-a-aa!”

Whish! Whack!

He made for Hans with lowered head, passing the boy at a bound, and struck a blow that tumbled Hans down on the deck. But the fire and force were taken out of the goat’s rush, for the boy caught him by his short tail as he passed, and gave the tail such a yank that the goat was skewed round and struck Hans’ shoulder only a glancing blow.

Hans went down in a bellowing heap, and the goat squared for another rush.

“Safe me!” Hans yelled. “You peen goin’ let me kill somet’ing, eh? Wow! Id’s coming do kill me again! Hellup! Fire! Murter! Bolice!”

Diamond picked up a rope’s end and gave the goat a whack across the back. It was like whacking a piece of wood. The goat did not budge.

The boy caught it by the tail. Hans lifted himself, and the goat, dragging the boy, made for him again.

This time Hans fell down without being touched.

Diamond leaped after the boy and sought to take the goat by the neck. It flung him off.

“Ba-a-aa!”

Whack!

That was the goat’s reply to Diamond for his attempted interference. The blow fell on Diamond’s legs, knocking them from under him, and the young Virginian promptly measured his length on the deck.

The goat wheeled again and struck at Bruce Browning, who was crawling off his easy stool. It missed Bruce.

The boy had lost his grip on the goat’s tail, after having been yanked about in a neck-breaking manner.

“Ye-e-ow!” screeched Hans, rolling over and over in a wild effort to gain a place of safety. “I pelief dot vos a sdeam inchine run py electricidy! Led id gid avay vrom me qvick! Somepoty blease holt me dill I gids avay vrom id! Hellup! Murter!”

Browning dashed to Diamond’s assistance, and was joined by Merriwell and Bart Hodge. But they could not hold the goat. It squirmed out of their hands like an eel and scampered to the other side of the deck.

Whish! Spat!

A stream of water from the steamer’s hose struck the goat amidships, at this juncture, and fairly bowled it over.

Some of the crew had decided to take a hand, and were now training the hose on the pugnacious creature.

The goat shook itself and lowered its head as if for the purpose of attacking this new foe. But it quickly changed its mind, and raced from the deck, followed by the stream,[13] sending back a defiant “Ba-a-aa!” however, as it disappeared.

Hans climbed slowly and hesitatingly to his feet, ready to drop down at the first warning. He steadied himself on his fat, shaky legs, and looked round the deck with owlish gravity, as if he doubted the goat’s disappearance.

“Are you hurt?” Merriwell sympathetically asked, advancing.

“Vos you hurt!” Hans indignantly squealed. “Dunder und blitzens! I vos kilt more as sefendeen hundret dimes, alretty yet! I vos plack und plue vrom your head to my heels.”

“Diamond caught it, too,” said Browning.

There was a faint smile on his face, which Hans did not let pass unnoticed.

“Dot vos de drouble mit me! You didn’t nopoby gatch id! Uf you hat gatched it, id vouldn’t haf putted me down so like a bile-drifer! Yaw! You vos a smart fellers, ain’d id! You vos a plooming idiot, und dot’s vot’s der madder mit me!”

“Better hunt up the goat and shake hands with it, and tell it you didn’t mean it!” suggested Browning, who couldn’t keep back a smile and some pleasantry when he saw that Hans was really not hurt in the least.

Hans turned away in disgust and sought his stool.

“You don’t know a shoke ven id seen you!” he declared. “Uf you vos murtered pefore my eyes, you voult laugh!”

He turned the stool over and jammed it down on the deck, causing a shower of glass to fall.

Although thoroughly disgusted and angry, Diamond decided not to make himself ridiculous by showing it.

An officer came forward to look at the broken mirror, and a man appeared with a broom to sweep up the glass and throw it overboard.

Merriwell picked up his guitar and began to strum the strings, and soon he and Diamond were again singing, and the laughable, almost disagreeable incident seemed on the way to speedy oblivion.

Hans maintained a glum silence, however, till the steamer reached Capen’s, now and then rubbing some portion of his anatomy as if to make certain it was all there and not violently swelling as a portent of his speedy death.

The lady apologized for the unruliness of the goat, and paid for the damage done to the mirror.

“Here we are,” announced Merriwell, as the steamer rounded to at the boat landing at Capen’s.

The boy came on deck with the goat, leading it by a rope, and Hans dodged behind the Virginian.

“Uf I see dot feller meppe he gid his mat oop again,” he muttered, “und uf I don’t see me he von’t knew me!”

But the goat seemed now to be very peaceably disposed. It obediently followed the boy and was led ashore by him.

The furniture was landed at Capen’s, too; and soon the steamer, with a much lighter burden, was standing off toward the northwest in the direction of Kineo.

One of the first things Merriwell did when they were comfortably located in the hotel was to inquire for a guide. He had written to Capen, explaining his needs, and he found Capen ready to supply them.

Merriwell’s party was in the Moosehead Lake region, in the tourist season for sport.

Not sport with the gun, however, in the ordinary sense, for it was the close season on all large game; but for a few days of the enjoyment of camping out.

Merriwell intended to do his hunting with a camera, he said; and had brought with him a fine, yet small and handy camera, well adapted to his purposes. He did not desire to shoot any large game, but he hoped to be able to snap the camera on something of the kind that would be worth while.

Above all, however, they intended to lounge and loaf and enjoy themselves without unnecessary exertion, for the time was right in the middle of August; and in August it often gets very hot, even along Moosehead Lake, as they well knew.

Capen, when spoken to by Frank about the promised guide, announced that he was ready to furnish the best and most reliable guide in all that country, and sent for the guide at once.

He came, an Old Town Indian, bearing the name of John Caribou.

Merriwell looked him over and nodded his approval.

“I think he’ll do!” he said.

“Do!” said Capen. “You couldn’t find a better, if you should hunt a year!”

The other members of the party were in the room, closely studying the face and figure of the guide. They saw an Indian of more than ordinary height and strength, dressed in very ordinary clothing, with long hair falling[16] to his shoulders. This hair was as black as a raven’s wing, but not blacker than the keen eyes set between the heavy brows and high cheek bones. The face was grave and unreadable, and the man’s attitude one of impassive silence. An observer might have fancied that the conference did not concern the Indian at all.

Capen offered to furnish the guide, two tents, two birch-bark canoes and supplies for the contemplated trip, for a certain sum, which was agreed to without haggling.

Then Frank Merriwell turned to the guide, who had, so far, not said a word.

“When can you go?” Merry asked.

“’Morrow,” said Caribou, with commendable promptness. “If want can go to-day.”

“He’ll be ready long before you are, gentlemen,” declared Capen. “I don’t doubt he could go in fifteen minutes should it be necessary. But I shall have to get an extra canoe which I can’t do before morning, as he knows, and with your permission I’ll send him for it.”

“Why didn’t he get us a white man?” grumbled Diamond when both Capen and John Caribou were gone. “Of course, it’s to his interest to brag about the fellow. I’m not stuck on Indians myself. It’s my opinion that you can’t rely on them; that they’re all right only so long as everything goes all right, and they’re treacherous, ungenerous and ungrateful. If our Indian guide doesn’t make us sorry we ever met him then I miss my guess.”

“I’m sure he’s all right!” asserted Merriwell. “I studied his face closely while we were talking. It’s Indian, to be sure, but there is no treachery in it. I’ll put[17] my opinion against yours that we’ll find John Caribou as faithful, honest and true as any white man.”

Statements are not always convincing, however, and the Virginian remained unchanged in his belief.

Who was right and who was wrong? We shall see.

“Caribou is starting out well, at all events,” said Merry, speaking to Bruce Browning.

The guide had built a rousing fire, which had now died down to a bed of coals, on which he was getting supper, handling coffeepot and frying pan with the skill that comes from long experience in the woods.

The light of the fire flung back the encroaching shadows of night and sent a red glare through the woods and across the surrounding stretches of water.

Frank Merriwell’s party was camped on one of the many small islands in Lily Bay, in the southeastern angle of Moosehead Lake, not a great distance from the mainland, which at this point was well wooded.

The tall pines were visible from the island in the daytime, but nothing could be seen now at any great distance beyond the ring of light made by the camp fire.

The wind was stirring in the tops of the low trees of the island and tossing the waves lappingly against the sterns of two birch-bark canoes that were drawn up on the shore and secured to stakes set in the earth.

John Caribou rose from his task, and stood erect in the light of the fire, a long bread knife in his hand. He presented a striking appearance as he stood thus, with the red fire light coloring face and clothing.

“That fellow is all right, even if Diamond thinks he isn’t!” declared Merriwell. “I’m willing to bank on him.”

The hoot of an owl came from across the water. Caribou started at the sound, stood for a moment in a listening attitude, then, observing that he was noticed, he resumed his work of getting supper.

They had reached the island, coming from Capen’s, late in the afternoon. But their two small A tents were already in position, and everything was in readiness for an enjoyable camping time.

Though there were so many tourists at Greenville and Capen’s that Frank and his friends had begun to doubt that they would see any game at all round Moosehead Lake, their present location seemed wild and remote enough to satisfy their most exacting demands.

They had already discovered there were trout in the lake, and big, hungry, gamey ones at that. The odor of some of these, which Caribou was cooking, came appetizingly on the breeze. It was the close season for trout as well as game, but fish wardens seldom trouble campers who catch no more than enough fish for their own use, and Caribou had declared that he would assume all responsibility.

Frank Merriwell got out his guitar again after supper. And what an enjoyable supper it was! Only those who have experienced the delights of camp life in the odorous woods, with the rippling music of water and the song of the wind in the trees, can have any true conception of its pleasures. Cares indeed “fold their tents like the Arabs and as silently steal away.”

The shadows advanced and retreated as the fire flared up or sank down, some wild beast screamed afar off on the mainland, a sleepy bird hidden somewhere in the bushes twittered a sleepy response to the music of the guitar and the words of the song, and the note of the owl heard earlier in the evening came again.

Merriwell played the guitar and he and Diamond sang until a late hour, when all retired, to speedily fall asleep. The night was well advanced, and there was a light mist on the face of the water, when Diamond roused up, pushed aside the canvas flap of the tent and looked out. The moonlight fell faintly.

The young Virginian had a feeling that something or somebody had disturbed him. Unable to shake this off, he crept softly into his clothing and slipped out of the tent. The fire had died down, but some coals still glowed in the bed of ashes.

He was about to put wood on these, when he heard a rustling.

“What was that?” he asked himself, turning quickly.

Then he saw the form of a man stealing away from the vicinity of the camp.

“That’s the guide,” he whispered, his suspicions instantly aroused. “Now, I wonder what he’s up to?”

He saw the form melting into the darkness, and wondered if he should call Merriwell or some member of the party.

“No, I’ll look into this thing myself!” he decided.

He had no weapon save a pocket knife; but, nevertheless,[21] he set out after the gliding form he supposed to be the guide.

“I must be careful, or I’ll miss him!” he thought, stopping when clear of the camp. “He walks like a shadow.”

He heard the bushes rustle, and, guided by the sound, hurried on, and soon came again in sight of the stealthy figure. He was still sure it was the guide, and was much exercised as to why the man should be astir at that hour of the night.

Straight across the island went the man, with Diamond hanging closely behind.

“He’s gone!” Diamond whispered, in astonishment, stopping again in the hope that other sounds would guide him.

When he had listened for full two minutes, he heard a splash like the dipping of a paddle blade in the water. It was at one side and some distance away.

He dashed through the bushes and stood on the shore of the lake. A canoe was vanishing in the mist.

“That rascally guide is up to some dirt, sure as I live!” he muttered. “I’ll just go back and rouse up the boys, and when he returns we’ll demand an explanation!”

With this resolution, he started back across the island, puzzling vainly over the guide’s queer actions.

Scarcely had he left the shore when he tripped and fell.

“Chug!”

“Spt! Spt! Gr-r-r!”

The first sound was made by Diamond dropping into a hole between some roots or rocks; the other sounds revealed[22] to him the unpleasant fact that he had tumbled into some den of wild animals.

“Goodness! what can they be?” he cried, scrambling out with undignified haste and retreating toward the high rock that he saw towering just at hand. “Wildcats, maybe! They sound like cats!”

There was a scratching and rattling of claws and an ugly-looking brute poked up a round, catlike head and stared at him with eyes that shone very unpleasantly in the moonlight.

Jack Diamond was not a person to scare easily, even though he was unarmed.

Another head appeared close by the first; then the two big cats crawled out on the ground, and sat erect like dogs, looking hard at him.

They were right in the path he desired to take.

“If I had a gun, I’d have the hide of one of you for your impudence!” he thought, returning their look with interest. “It would make a pretty rug, too.”

As he studied them, the knowledge came to him that they were the ferocious lynx called by the French Canadians loo-sevee—loup-cervier. There was a silky fringe on the tips of their ears, and they had heavy coats, sharp claws and cruel teeth.

Having decided that they were loup-cerviers, and believing that he had tumbled into their den, where were possibly some young, the Virginian, courageous as he was, lost much of his desire to fight.

He began to retreat, thinking to make a circuit and pass them.

“We’ll have fun with you in the morning!” he muttered. “There’s never any close season against loup-cerviers.”

But the lynxes seemed quite willing that the fun should begin then and there. As he retreated, they advanced, convinced, probably, that he was cowardly.

Thereupon, Diamond backed up against the rock, and picking up a stick, hurled it at them.

“Gr-r-r!”

Instead of frightening them, they came on faster than ever, uttering a sound that was nearer a growl than anything to which Diamond could liken it.

The young Virginian did not like the idea of turning about in an ignominious flight, so he climbed to the first shelf of the rocky ledge, feeling with his hands as he did so in hope of finding something that would be a valuable weapon.

“If I ever leave camp again without a rifle, I hope somebody will kick me!” he growled.

The loup-cerviers came up to the foot of the ledge and sat down like dogs, just as they had done before; and there remained, eying him hungrily, and evidently determined that he should not pass.

“This is decidedly unpleasant,” was his mental comment. “I guess I might as well call for help. If I’m kept here too long, that guide will have a chance to get back and declare that he hasn’t been away from camp a minute.”

Then he lifted his voice.

“Yee-ho-o!” he called, funneling his hands and sending the penetrating sound across the island like the blast[24] of a bugle. “Yee-ho-o! Come over here, you fellows, and bring your guns with you!”

That ringing call roused out the boys at the camp on the other side of the little island.

“What’s the matter?” demanded Browning.

Hans Dunnerwust drew back, shivering, and covered his head with the blanket.

“Oxcoose me!” he begged. “Shust tell dem dot you sawed me. I vos doo sick do gid up, anyhow. I don’d t’ink anypoty lost me, dot I shoult go hoonding vor mine-selluf. Oxcoose me!”

“That sounds like Diamond,” said Merriwell. “Is he gone? Hello! Jack old boy, are you in your tent?”

To this there was, of course, no reply.

“It’s Diamond all right, I guess,” said Hodge, tumbling out. “At any rate, he isn’t in his blanket.”

“Is anyone else missing?” asked Merriwell.

He looked around on the gathering company. John Caribou was there, and had been one of the first to appear.

Merriwell funneled his hands and sent back a resounding “Yee-ho-o!” Then he shouted:

“All right, old man; we’ll be with you in a minute!”

Hans Dunnerwust pulled the blanket down off his face and inquired timidly:

“Is I goin’ do leaf eferypoty? I dink somepoty petter sday py me till he come pack. I don’d pen britty veil!”

“Perhaps some one had better remain at the camp,” said Merriwell, with a wink. “Otherwise the wolves will come and eat up our provisions.”

Hans came out from under the blanket as if he had been suddenly stung by wasps.

“Vollufs!” he gasped. “Meppe dey voult ead der brovisions instit uf me, t’inkin’ I vos dhem! Shimminy Gristmas! Vollufs! Vy didn’t you tolt me dere vos vollufs on dis islant?”

Merriwell did not answer. Having sent back that call to Diamond, he hurried into his clothing. Then he ran from the tents in the direction of the calls, with John Caribou running at his side, and the other members of the party trailing behind.

“Vait!” Hans was bawling. “Vot made me in such a hurry do run avay from you?”

Then he heard the crashing of the bushes, and, thinking the wolves were coming, he picked up a gun and a heavy case of ammunition and hastened out of the tent.

“Vait!” he screeched. “Vait! Vait!”

He was in his white nightshirt, and his head and feet were bare. With the gun in his right hand and the heavy ammunition case tucked under his left arm, he was as comical a figure as moonlight ever revealed, as he wallowed and panted after his comrades.

“This way!” shouted Diamond, hearing their movements.

The big cats began to grow uneasy, for they, too, heard that rush of footsteps across the island, though the sound was still some distance away. One of them got up and walked to the foot of the ledge, as if it had half a notion to climb up and try conclusions with Diamond at close quarters. But it merely stretched up to its full height[26] against the rock and drew its claws rasping down the face of the rock as if to sharpen them.

“Not a pleasant sound,” was Diamond’s grim thought.

The loup-cervier retreated, after having gone through this suggestive performance, and again sat bolt upright beside its mate and stared at the prisoner with shiny bright eyes.

But they became more and more uneasy, as the sounds of hurrying feet came nearer and nearer, and at last rose from their sitting posture.

Once more Diamond funneled his hands.

“Don’t come too fast,” he cautioned. “There are some wildcats here that I want you to shoot. You’ll scare them away.”

“All that scare for that!” laughed Merriwell, dropping into a walk. “I thought he was in some deadly peril.”

“I’m just wanting a wildcat,” said Hodge, pushing forward his gun to hold it in readiness. “No close season on wildcats, is there, Merry?”

“Think not,” Merriwell answered. “You go on that side with Browning and Caribou, and I will go on this side. Look out how you shoot. Don’t bring down one of us, instead of a wildcat.”

“Vait! Vait!” came faintly to their ears from Hans, who was struggling through the bushes, having fallen far behind in spite of his frantic haste. “Vai-t-t!”

As a seeming answer came the report of Merriwell’s gun.

One of the cats, scared by the noise of the approaching force, sprang away from the foot of the rock and[27] scampered toward the cover of the trees. Merriwell saw it as it ran and fired.

Instantly there was an ear-splitting howl.

The other cat leaped in the other direction and was shot at by Bart Hodge.

The young Virginian descended from the ledge in anything but a pleasant mood.

“They’re loup-cerviers, and they had me treed nicely,” he said; “but you got one of them, for I heard it kicking in the bushes after it let out that squall. I tumbled into their nest a while ago and that seemed to make them more than ordinarily pugnacious. I came——”

He stopped and stared. At Merriwell’s side he saw John Caribou, and he had been about to announce that he had followed Caribou and seen him row out into the lake. Clearly he had been mistaken.

“What?” asked Merriwell.

“Better see if I’m right about that cat,” suggested Diamond, his brain given a sudden and unpleasant whirl.

He was not in error about the cat, whatever he had been about the guide. The biggest of the loup-cerviers was found dead in the leaves, where it had fallen at the crack of Merriwell’s rifle.

While they dragged it out and talked about it, the young Virginian gave himself up to some serious thinking. If that was not John Caribou he had followed—and he saw now that it could not have been—who was it?

The question was easier asked than answered.

However, he decided to speak only to Merriwell about it for the present, and began to frame some sort of a[28] story that should satisfactorily explain to the others why he had left the camp.

Hans Dunnerwust came flying into their midst, dropping his gun and the case of ammunition.

“Vollufs!” he gurgled. “One py my site peen shoost now! I snapped his teeth ad me. Didn’d you see him?”

Hans’ wolf was the loup-cervier, which had run close by him as it scampered away.

“Only a wildcat,” Merriwell explained, as he turned to Diamond.

“A viltgat!” screamed Hans. “Dot vos vorser yit. Say, I peen doo sick do sday on dis islant any lonker. Vollufs mid wiltgats! Dunder und blitzens! Dis vos an awvul blace!”

The next morning the ledge of rock was visited where Diamond had his adventure with the big cats, and he and Merriwell searched along the shore for some marks of the canoe in which the nocturnal visitor had made off. No young loup-cerviers were found, though a hole was discovered between some roots near the base of the rock, which the cats had no doubt used.

“I don’t understand it,” the young Virginian admitted, referring to the man he had seen sneak away from the camp. “The only thing I can imagine is that it must have been some one who hoped to steal something.”

“Yes,” said Merriwell, thinking of the suspicions Diamond had harbored against the guide. “Do you suppose Caribou could give us any ideas on the subject, if we should tell him about it?”

“Don’t tell him,” advised Diamond, who still clung to the opinion that John Caribou was not “square.”

The coming of daylight drove away the terrors that had haunted Hans Dunnerwust during the night. He became bold, boastful, almost loquacious.

When the sun was an hour high and its rays had searched out and sent every black shadow scurrying away, Hans took a pole and line and some angle worms and went out to a rocky point on the lake, declaring his intention of catching some trout for dinner. He might have had[30] better luck if he had pushed off the shore in one of the canoes and gone fly fishing: but no one wanted to go with him just then, and he was afraid to trust himself alone in a canoe, lest he might upset. This was a very wholesome fear, and saved Merriwell much anxiety concerning the safety of the Dutch lad.

“Yaw!” grunted Hans, after he had found a comfortable seat and had thrown his baited hook into the water. “Now ve vill haf some veeshes. I don’d peen vrightened py no veeshes. Uf I oben my moud and swaller do dot pait mit der hook on id, den der veeshes run mit der line and blay me!”

He had slipped a cork on the line. The cork gave a downward bob and disappeared for a moment in the water.

But before Hans could jerk, it came to the surface; where it lay, without further movement.

“Dose veeshes vos skeered py me, I subbose!” soliloquized Hans, eying the cork and ready to jerk the moment it appeared ready to dip under again.

Finally he pulled out the hook and, to his delight and surprise, found that the bait was gone.

“Hunkry like vollufs!” he said; then glanced nervously around, as if he feared the very thought of wolves might conjure up the dreaded creatures. “Vell, I vill feed mineselluf again mit anodder vorm.”

Baiting the hook he tossed it again.

Hardly was the cork on the wave when it went under. Instantly Hans gave so terrific a jerk that the hook went[31] flying over his head and lodged in the low boughs of a cedar.

“A troudt!” gurgled Hans, in a perfect spasm of delight. “Vot I tolt you, eh? A trout gid me der very virst jerk! Who vos id say dose veesh coultn’t gadch me?”

A little horned pout, or catfish, about three inches long, was dangling at the end of the line. It had swallowed the hook almost down to its tail.

Hans Dunnerwust’s fat hands fairly shook as he disengaged the line and tried to get the hook out of the pout’s mouth.

“Wow! Dunder und blitzens!” he screeched, dropping the pout with surprising suddenness and executing a war dance on the shore, while he caressed one of his fingers from which oozed a tiny drop of blood.

“Shimminy Gristmas! I ditn’d know dot dose troudt had a sdinger like a rattlesnake. I vost kilt!”

He hopped up and down like a toad on hot coals.

“Hello! What’s the matter?”

Frank Merriwell came round the angle of the rocky shore at that moment, seated in one of the canoes.

“Why are you dancing?” he asked.

Hans subdued the cry that welled to his lips, trying to straighten his face and conceal every evidence of pain.

“I shust caught a troudt,” he declared, with pride, “und scracht mineselluf der pushes on.”

He held up the little horned pout that was still on the hook.

Merriwell propelled the prow against the shore and leaped out, drawing the canoe after him.

“Yes; that’s a fine fish,” he admitted, trying to repress a smile of amusement.

Hans was so jubilant and triumphant that it seemed a pity to undeceive him.

“Und dot hunkry!” cried Hans, forgetting the pain. “He vos more hunkrier as a vollufs. See how dot pait ead him und den dry do svaller der line. I don’d know, py shimminy, how I dot hook gid oudt uf my stomach!”

“Cut it open,” Merriwell advised.

“My stomach? Und me alife und kickin’ like dot? Look oudt! Dot troudt haf got a sdinger apout him some blace.”

Merriwell gave the pout its quietus by rapping it with a stick on the head, and then watched Hans’ antics during the cutting out of the hook.

“Uf dey are hunkry like dot,” said Hans, tossing the line again into the water, “ve vill half more vor dinner as der troudt can ead.”

“Spit on the bait,” suggested Merriwell. “It makes the angle worm wiggle and that attracts the fish. If you had some tobacco to chew I expect you could catch twice as many.”

Hans made a wry face.

“Oxcoose me! I vos—— Look oudt!” he squawked, giving the line another terrific jerk. “Shimminy Gristmas! Did you seen dot? Dot cork vent oudt uf sight shust like a skyrocket.”

The bait was still intact and he tossed in the line again.

“Dere must be a poarting house down dere someveres dot don’t half much on der taple, py der vay dose troudt been so hunkry,” the Dutch boy humorously observed. “Look oudt! he vos piting again!”

He gave another jerk, and this time landed a pout double the size of the first.

His “luck” continued, to his unbounded delight; and in a little while he had a respectable string of fish.

“Who told me I couldn’t veesherman?” he exultantly demanded, struggling to his feet and waddling as fast as he could go to where the last pout was flopping on the grass. “He haf swallered dot hook again clean to his toes. Efery dime I haf do durn mineselluf inside oudt to gid der hook!”

The horns of the pout got in their work this time, and Hans stumbled about in a lively dance, holding his injured hand.

“Dose troudt sding like a rattlesnake,” he avowed. “Der peen leetle knifes py der side fins on, und ven he flipflop I sdick does knifes indo him. Mine gootness! Id veel vorser as a horned!”

“Shall I send for John Caribou?” asked Merriwell. “He has some tobacco.”

Hans glanced at him in a hurt way, then extracted the hook, put on another worm, and resumed his fishing.

A pout bit instantly, and Hans derricked it out as before; but the line flew so low this time that it caught Hans about the neck, and the pout dropped down in front, just under his chin, where it flopped and struggled in liveliest fashion.

“Dake id off!” Hans yelled. “Dake id off!”

Merriwell tried to go to his assistance, but only succeeded in drawing the line tighter about Hans’ neck.

“If you’ll stand still a minute, I can untangle the line, but I can’t do anything while you’re threshing about and screeching that way,” he declared.

The pout flopped up and struck Hans in the face, and thrust the point of one of its fins into his breast as it dropped back.

This was too much for the Dutch boy’s endurance, and the next moment he was rolling on the ground, meshing himself more and more in the snarl of the line, and getting a fresh jab from one of the pout’s stingers at each revolution.

“Hellup! Fire! Murter!” he yelled.

Finally the pout was broken loose, and Merriwell succeeded in making Hans understand that the dreaded stingers could no longer trouble him.

Hans sat up, a woe-begone figure. He was bound hand and foot by the line as completely as Gulliver was bound by the Lilliputians.

“Are you much hurt?” Merriwell asked.

“Much hurted?” Hans indignantly snorted. “I vos kilt alretty! Dose knifes peen sduck in me in more as sefendeen hundret blaces. Bevore dose troudt come a-veeshin’ vor me again I vill break my neck virst.”

It was impossible to untie the line, so Merriwell took out his knife and cut it.

“This was an accident,” he said. “I shan’t say anything[35] about it to the others. Take the fish to camp, and we’ll have them for dinner. They’re good to eat.”

As indeed they were.

Thereupon Hans’ courage came back. He washed his hands and face in the lake, carefully strung the pouts on a piece of the severed line, then waddled to camp with them, with all the proud bearing of a major-general.

Frank Merriwell sat for a time on the point of rock, looking out across Lily Bay. Then he started, as the sound of the deep baying of hounds came to him from the mainland.

“They’re after some poor deer, probably,” was his thought. “The only way to make a deerhound pay attention to the close season is to tie him to his kennel.”

Though the sounds drew nearer, the dogs were concealed from view in the woods of the mainland by a bend of the island.

At last there arose such a clamor that Merriwell entered the canoe and paddled quickly round the point in the direction of the sound.

He came on a sight that thrilled him. A large buck, with a finely-antlered head, had taken to the water to escape the hounds, and was swimming across an arm of the bay, with the dogs in close pursuit. Only the heads of the dogs were visible above the water, but he saw that they were large and powerful animals.

At almost the same moment Merriwell beheld John Caribou rush down the opposite shore and leap into a canoe—the other canoe belonging to the camping party.

“What can Caribou have been doing over on the mainland?”[36] thought Frank. “Oh, yes; probably looking for another camping place, for we were talking about changing last night.”

Caribou cried out to the hounds, trying to turn them from their prey; and, failing in this, he pushed out in the canoe and paddled with all speed toward the buck.

The hounds had overtaken it, and it had turned at bay, having found a shallow place where it could get a footing.

The largest hound swam round and round it, avoiding its lowered head; then tried to fasten on its flanks.

The buck shook it off, and waded to where the water was still shallower, in toward the shore.

The dogs followed, circling round and round.

Caribou shouted another command and paddled faster than ever.

The shout of the guide and the buck’s deadly peril now caused Frank Merriwell to push out also, and soon he was paddling as fast as he could toward the deer and the dogs. But the separating distance was considerable.

The shallower water aided the biggest hound, for it got a footing with its long legs and sprang at the buck’s throat. The buck shook the hound off and struck with its antlers.

“That’s it!” Merriwell whispered, excitedly. “Give it to them!”

The attacks of the three dogs kept the buck turning, but it met its assailants with great gallantry and spirit. When the big hound flew at its throat again, it got its antlers under him and flung him howling through the air,[37] to strike the water with a splashing blow and sink from sight.

“Good enough!” cried Merriwell. “Do it again!”

The other hounds seemed not in the least bit frightened by this mishap to their comrade, but crowded nearer, trying to get hold of the buck’s throat.

The big hound came to the surface almost immediately, none the worse for its involuntary flight and submergence, and swam back to the assault.

Merriwell looked at Caribou, who was now standing up in the canoe and sending it along with tremendous strokes.

“Hurrah!” Merry cried, not taking time to stop, however. “I’m coming, Caribou, to help you.”

The largest hound again flew at the buck’s throat, while one of the others, getting a foothold, climbed to the buck’s back.

But the advantage of the hounds was only temporary. The big hound was again caught on those terrible antlers, impaled this time, and when it was hurled through the air to sink again on the lake it did not rise.

The hound that still remained in the water in front of the buck, now caught the latter by the nose, and the buck fell with a threshing sound. It rose, though, shaking off both hounds.

“Hurrah!” screamed Merry, sending his canoe skimming over the water. “Hurrah! Hurrah!”

So admirable and plucky was the fight the buck was making that he was fairly wild with admiration and delight.

John Caribou was close to the buck, and still standing up in his canoe.

The hound that caught the buck by the nose now received a thrust that tore open its side and put him out of the fight; but the other one again leaped to the buck’s hip and hung there, refusing to be dislodged.

At this hound John Caribou struck with his heavy paddle.

The blow was a true one. It tumbled the hound into the water, where the guide came near following.

While Caribou sought to recover his balance, the buck, mistaking him for a new enemy, turned on him and made a savage dash that hurled him from the canoe.

Frank Merriwell was now so near that he could see the buck’s fiery eyes, note the ridging of hair along its spine, and could hear its labored and angry breathing. Its tongue protruded and was foam-flecked.

Caribou tried to seize the sides of the canoe as he went down, but the effort only served to hurl it from him, and send it spinning out into the lake.

The buck put down its head for a rush; while the hound that the guide had struck with the paddle blade did not try to renew the fight, but began to swim toward the shore, which was not distant.

“Look out!” cried Merriwell, warningly.

Caribou heard the cry, saw the antlers go down and tried to dive. But he was not quick enough. Before he was under water the buck struck him a vicious blow.

Though half stunned, he clutched it by the antlers, to[39] which he clung desperately, while the buck struck him again, this time with one of its sharp hoofs.

Caribou, realizing that his life was in peril, tried to get out his knife, but the enraged and crazed buck bore him backward with so irresistible a rush that Caribou was kept from doing this. Then he went under the water again.

This time the buck seemed determined to hold him down till he was drowned. Merry saw the guide’s hands and feet beating the water, and knew from their motions that he was rapidly weakening.

“I’m coming!” he shouted, though he must have known that the guide could hardly hear or comprehend.

With one deep pull on the paddle he put the canoe fairly against the buck; then rising to his feet, he brought the blade down with crushing force across the animal’s spine.

The buck half fell into the water and the antlered head was lifted.

When John Caribou came to the surface Merriwell clutched him by the hair and pulled him against the side of the canoe, regardless of the buck’s threatening attitude. Then, seeing that Caribou was drowning, he lifted him still higher, so that the water no longer touched Caribou’s face and head.

The buck put down its horns as if it meditated another rush. Merriwell remained quiet, holding the guide’s dripping head. He had a rifle in the bottom of the canoe, but he did not wish to use it unless driven to kill the buck[40] in self-defense. More than all else he did not want to let go of the guide.

The buck stood for a moment in this pugilistic attitude; then, understanding it was not to be attacked, it turned slowly and waded toward the land.

The hound that had preceded it had disappeared, and the other two were dead.

“How are you feeling, Caribou?” Merry anxiously asked, drawing the guide’s head still higher.

There was no answer, and Merriwell lifted the guide bodily into the canoe. Great caution was required to do this, together with the expenditure of every ounce of strength that Merriwell possessed.

A ringing and encouraging cheer came from the shore of the island, where the other members of the party had gathered, drawn by the baying of the hounds and the noise of the subsequent fight.

Merriwell had no power of lung to send back a reply. Instead he sank down by Caribou’s side and began an effort to restore him to consciousness.

This was successful in a little while. The guide opened his black eyes and stared about, then tried to get up. He comprehended at once what had occurred, and a look of gratitude came to his dark face.

“You’re worth a dozen drowned men,” announced Merry, in his cheeriest voice. “If you can lie in that water a little while without too much discomfort, I’ll try to catch your canoe with this one. The waves are carrying it down the bay.”

John Caribou did not seem to hear this. His eyes were fixed on Merry’s face.

“Caribou, him not forget soon! Not forget soon!”

Only a few words, but they were said so earnestly that Merriwell could not fail to understand the deep thankfulness that lay behind them.

Two days later Merriwell’s party moved from the island to a high, dry point on the mainland, where the tents were repitched and where they hoped to spend the remainder of their stay on Lily Bay. It was an ideal camping place, and freer from mosquitoes than the island had been.

Hans told Merriwell quite privately that the stings of those island mosquitoes were almost as bad as the stings of the “trout” he had caught.

Except that the sun was torridly hot during the midday hours, the weather was almost perfect. The skies were clear and blue, the bay placid. Trout, genuine trout, took the hook readily. The canoeing was all that could be desired. Merriwell, too, had secured some splendid views of wild life with his ever-ready camera. One of the finest of these was a trout leaping. When developed, the photograph showed the trout in the air above the surface of the lake, with the water falling from it in silvery drops, and its scales glinting in the sunlight.

Another fine view was a moonlight scene of a portion of Lily Bay, from the headland where Hans had done his fishing.

“I shall always regret that I didn’t snap the camera on that buck while he was making such a gallant fight against those dogs,” Merriwell often declared. “That would have been great. But really, I was so excited over[43] the buck’s peril that I entirely forgot that I had a camera.”

But he had caught other scenes and views, that were highly satisfactory, if they did not quite compensate for the fine scene of the combat between the hounds and the buck. Whose the hounds were they had no means of knowing, but Caribou suggested that they probably belonged to a gentleman who had a cottage not far from Capen’s.

Highly as Merriwell regarded John Caribou, there could be no doubt that there was something mysterious about his movements. Merriwell had once seen him steal out of camp in the dead of night, an act for which the guide had no adequate explanation when questioned. In fact, Merriwell’s questioning threw Caribou into singular confusion.

The day the camp was moved, Jack Diamond saw the guide meet a stranger in the woods, to whom he talked for a long time in the concealment of some bushes, in a manner that was undeniably surreptitious. Still, Merry clung to his belief in the guide’s honesty.

Hans Dunnerwust had become valiant and boastful since his great success at catching “trout.” He wanted to further distinguish himself.

“Uf I could shood somedings!” Merriwell once overheard him say in longing tones.

This remark, which Hans had only whispered to himself, as it were, came back to Merriwell with humorous force a couple of days after the setting up of the camp on the mainland.

“If only Hans could have come across this!” he exclaimed.

It was a dead doe lying in the woods not far from the camp. It had been shot, and after a long run had died where Merriwell had found it, nor had it been dead a great while.

“The work of poachers,” said Merriwell, with a feeling of ineffable contempt for men who could find it in their hearts to slaughter deer in this disgraceful and unlawful manner. “I wish the strong hand of the law could fall on some of those fellows.”

This was not the first evidence he had seen that poachers were carrying on their dastardly work around that portion of Moosehead Lake known as Lily Bay. A wounded deer had been noticed and distant shots had more than once been heard. He was beginning to believe that the dogs which had followed and attacked the buck belonged to these poachers.

After pushing the deer curiously about with his foot, Merriwell was about to turn away, when he chanced to see Hans Dunnerwust waddling down the dim path, gun in hand. It was plain that if Hans continued in his present course he could hardly fail to see the dead deer.

“Just the thing!” Merriwell whispered, while a broad smile came to his face. “If I don’t have some fun with Hans I’m a Dutchman myself!”

He put down his camera and rifle, and, lifting the body of the doe, stood it up against a small tree. By means of ingenious propping, he contrived to make it stand on its stiff legs and to give it somewhat of a natural appearance.

“It’s natural enough to fool Dunnerwust, anyway!” he muttered, picking up the camera and gun and sliding into the nearby bushes.

Hans came down the path, carrying his rifle like a veteran sportsman. He was looking for game, and he found it. His eyes widened like saucers when he saw the deer standing in the bushes by the tree.

“Shimminy Gristmas!” he gurgled. “Id don’d seen me, eidher! Uf dot deer don’d shood me, I like to know vot vos der madder mit me, anyhow! You pet me, I pud a palls righd t’rough ids head und ids liver. A veller can shood a teers dot don’d ged any horns, I subbose, mitoudt giddin’ arresded py dose game vardens! I vill shood him, anyhow, uf I can. Yaw! You pet me!”

He dropped to his knees, then began a stealthy approach, for the purpose of putting himself within what he considered good shooting distance. He was less than eighty yards from the game when he first saw it, but he knew so little about rifles that he doubted if his gun would carry so far. It is not easy for a fat boy to crawl stealthily sixty yards on his hands and knees, dragging a gun along the ground, but that was the task that Hans Dunnerwust now set for himself.

Merriwell, hidden in the bushes, shook with laughter, as Hans began this cautious advance. When half the distance was passed, Hans rose to a half upright posture and stared hard at the deer. This was an opportunity for which Merriwell had been waiting. He drew down on Hans the camera, but scarcely able to sight it accurately for laughing. The picture caught, showed Hans all[46] a-tremble with eagerness, his mouth wide open, his eyes distended and staring.

Assured that his game was still in position by the tree, Hans got down on his hands and knees again and made another slow advance.

When no more than twenty yards separated him from the deer, he lifted himself very cautiously and drew up the gun to take aim. He was shaking so badly he could hardly hold the weapon. Merriwell focused the camera on him at this instant and caught another view of this great hunter of the Moosehead country.

As he took the camera down, he saw Hans trying to shoot the gun without having cocked it. Again and again Hans pulled the trigger, without result.

“If only some of the other fellows were here!” Merriwell groaned, fairly holding his sides. “He’s shaking so I’m afraid he won’t hit the deer, after all.”

He had arranged the deer so that the slightest touch would cause it to fall.

Hans put down the gun and anxiously turned it over. Then Merriwell saw his puzzled face lighten. He had found out why the weapon would not go off.

This time when he lifted the rifle it was cocked. Then he pressed the trigger.

When the whiplike report sounded, the deer gave a staggering lurch and fell headlong.

Hans Dunnerwust could not repress a cheer. He sprang to his feet, swinging his cap, and ran toward the fallen doe as fast as his short, fat legs would carry him.

“Id’s kilt me! Id’s kilt me!” he was shouting.

Fearing it might not be quite dead, he stopped and drew his hunting knife. It did not rise, however, it did not even kick, and, made bold by these circumstances, Hans waddled up to it and began to slash it with the fury of a lunatic.

“Whoop!” he screeched. “I god id! I shooded id! I vos a teer gilt! Who said dot Hans Dunnerwust coult nod shood somedings, eh?”

Merriwell trained the camera on him once more, as he stood in this ferocious attitude, with the knife extended, from which no blood dripped, and looked triumphantly down at the deer at his feet. Then Merry rose and advanced.

Hans turned when he heard the snapping of the bushes, and was about to bolt from the place, but, seeing that it was Merriwell, he changed his mind and began to dance and caper like a crazy boy.

“You see dot?” he screeched, proudly pointing to the dead doe. “Dot vos a teer vot kilt me shust now. Tidn’t you heered id shood me?”

Merriwell’s face assumed a look of consternation.

“I’m very sorry you did that,” he declared.

“Vy? Vot you mean py dot?” Hans gasped.

“The game wardens are likely to hear of it.”

The face of the Dutch boy took on such a sickly look of fright that Merriwell relented.

“But you didn’t think, I suppose?”

“Yaw! Dot vos id.” Hans asserted. “Id shooded me pefore I know mineselluf.”

“Perhaps it will be all right for you to take the head[48] in to show the boys what you have done,” Merriwell suggested.

This was pleasing to Hans, and so in line with his heart’s desire, that he immediately decapitated the doe, and proudly bore the head into the camp, as proof of his skill as a deer-stalker.

“A moose!”

“Cricky! Isn’t he a fine one?”

“Him plenty big!”

The first exclamation was from Merriwell, the second from Bruce Browning, the third from John Caribou, the guide.

The three were in a canoe, which had been creeping along the wooded shore of a narrow arm of Lily Bay.

“Reach me the camera,” whispered Merriwell.

The camera was at Browning’s feet and was quickly handed up.

John Caribou was sitting in one end of the canoe as silently as an image of bronze.

The big moose that had not yet seen them, stepped from the trees into full view, outlining itself on a jutting headland, as it looked across the sheet of water.

Even the impassive guide was moved to admiration. A finer sight was never beheld. The moose was a very giant of its kind. With its huge bulk towering on the rocky point, its immense palmated antlers uplifted, its attitude that of expectant attention, it presented a picture that could never be forgotten.

Frank Merriwell lifted the camera, carefully focused it on the big beast and pressed the button.

He was about to repeat the performance when something[50] stirred in the trees a hundred yards or more to the left, and Hans Dunnerwust came into view.

He did not see the canoe and its occupants, but he saw the moose, and he stopped stock still, as if in doubt whether to retreat or proceed on his way.

The moose had turned and was looking straight at him, with staring, fear-filled eyes. Then it wheeled with surprising quickness for so large a beast and shambled off the headland toward the water’s edge.

This increased Hans’ courage. He was always very brave when anything showed fear of him. He had been on the point of turning in flight, but now he sprang clear of the trees, and ran toward the moose with a shout.

“A teer! A teer! Another teer!” he screeched, waving has hand and his gun.

Merriwell snapped the camera on the moose as it scrambled down the slope.

“Might have another negative of it standing, if Hans hadn’t put in an appearance,” he declared, feeling at the moment as if he wished he might give the Dutch boy a good shaking.

But he had reason in a little while to call down blessings on the head of Hans for this unintentional intervention.

Frightened by Hans’ squawking and the noise he made in running, the moose dashed up and down the shore for a few moments, then took to the lake.

“There he goes,” whispered Browning, roused to a state of excitement.

“Plenty skeer!” said Caribou. “Sometime moose him skeer ver’ easy.”

“He’s going to swim for the other shore,” declared Merriwell, putting down the camera and then picking it up again.

For a few yards the frightened moose made a tremendous splashing, but when it got down to business, it sank from sight, with the exception of its black neck and head and broad antlers, and forged through the water at a very respectable rate of speed.

Merriwell focused the camera on the swimming animal and was sure he got a good picture, then put down the camera and picked up his rifle. He wanted to get nearer the big beast, and he knew he would feel safer with a weapon in his hands in the event of its urgent need.

“Fun now, if want?” said the guide, suggestively, looking toward the moose with shining eyes. “Much fun with big bull moose in water some time.”

“A little fun won’t hurt us, if it doesn’t hurt the moose,” responded Merriwell, who as yet hardly knew just what was in the guide’s mind. “Eh, Browning?”

“Crowd along,” consented Browning. “I don’t mind getting close enough to that fellow to get a good look at him. If it wasn’t out of season I’d have that head of horns!”

“Aren’t they magnificent?” asked Merriwell, with enthusiasm.

The guide looked at Merriwell as if to receive his assent.

Hans Dunnerwust had rushed to the shore in a wild burst of speed, and was now hopping wildly.

Suddenly he caught sight of Merriwell and the others in the canoe.

“A teer! A teer!” he shrieked. “Didn’t you seen him? He roon vrum me like a bolicemans, t’inking dot he voult shood me. Put noddings vouldn’t shood me oudt uf seasons!”

“I don’t know about that,” grunted Browning. “Fools, as game, are never out of season, and the fool-killer is always gunning for them.”

“Yes; go on,” said Merriwell to the guide. “As I said, a little fun won’t hurt us if it isn’t of a kind to hurt the moose. See how he is swimming! That’s a sight to stir the most prosaic heart.”

John Caribou did not need urging. He dipped the paddle deeply into the water, and the canoe shot away in pursuit of the swimming animal.

The moose was already some distance from land, and forging ahead with powerful strokes; but under the skillful paddling of the guide the canoe quickly decreased the intervening distance.

It was worth something just to watch John Caribou handle the broad-bladed paddle. He dipped it with so light a touch that scarcely a ripple was produced; but when he pulled on it in a way that fairly bent the stout blade, the canoe seemed literally to leap over the waves. Every motion was that of unstudied grace.

Browning could not remain stolid and impassive under circumstances that would almost pump the blood through[53] the veins of a corpse. He grew as enthusiastic as Merriwell.

“See the old fellow go!” he whispered, referring to the speed of the moose. “He’s cutting through the water like a steamboat.”

The guide rose to his feet, still wielding the paddle.

“We’ll be right on top of him in a minute,” said Merriwell. “Look out there, Caribou! He may turn on us. We don’t want to have a fight with him, you know.”

Caribou did not answer. He only gave the canoe another strong drive forward, then dropped the paddle and caught up an end of the canoe’s tow line, in which he made a running noose.

He stood erect, awaiting a good opportunity to throw the line. The canoe swept on under the propulsion that had been given it. Then the noose left Caribou’s hand, hurled with remarkable precision, and fell gracefully over the broad antlers. Instantly Caribou grasped the paddle and whirled the canoe about so that the stern became the bow.

“Hurrah!” cried Merriwell, half expecting that the moose would now turn on them to give them battle. “That was a handsome throw. I didn’t know you were equal to the tricks of a cowboy, Caribou.”

The guide did not answer. Very likely he did not know the meaning of the word cowboy.

In another instant the line tightened, and they were yanked swiftly along.

“Towed by a moose!” exclaimed Browning. “That’s a new sensation, Merry!”

“Yes; this is great. This is what you might call moose-head express,” laughed Frank.

“It’s enough to make a fellow feel romantic, anyway,” grunted Browning. “Pulled by a moose on Moosehead Lake, with an Indian guide to do the steering.”

The moose was now badly frightened, and showed signs of wanting to turn around, whereupon the guide picked up the paddle and gave it a tap on the side of the head.

This brought a floundering objection from the scared animal, but it had, nevertheless, the desired effect, for the moose again started off smartly for the opposite shore, drawing the canoe after it.

The big beast did not seem to be tired, but it puffed and panted like a steam engine.

“That’s right, Caribou,” cried Merriwell, approvingly. “Just hang on and let him go. I don’t mind a ride of this kind. It’s a sort of sport we weren’t looking for, but it’s great, just the same.”

“Much fun with big bull moose in water some time,” Caribou repeated. “Drive big moose like horse.”

Then the guide gave them an exhibition of moose driving. By yanking this way and that on the line, he was able to alter the moose’s course, and that showed that he could turn it almost at his will.

Not once did the moose seek to turn and fight as Merriwell had thought he would do if lassoed. It seemed only intent on getting away from its tormentors, and appeared to think the way to do that was to swim straight ahead toward the land as fast as it could.

Hans was still hopping up and down on the shore, and now and then sending a screech of excitement and delight across the water.

After he had shown that the moose could be turned about if desired, Caribou let the scared animal take its own course. The distance across was considerable, and he knew the moose would be tired by the swim.

He held the line, while Frank and Bruce sat in their places enjoying the novel ride to the fullest extent.

Thus the canoe was towed across the arm of the bay, giving to our friends an experience that few sportsmen or tourists are able to enjoy.

As the moose neared the shore, Caribou severed the line close up to its antlers and let it go. It was pretty well blown, as the heaviness of its breathing showed.

Scrambling out of the water, it turned half at bay, as if feeling that, with its broad hoofs planted on solid ground it could make a stand for its life; but when the occupants of the canoe showed no intention of advancing to attack it, it gave its ungainly head a toss and shambled away, the severed end of the noose floating from its antlers.

Merriwell caught up his camera and snapped it on the moose before it entered the woods, so getting a picture of a moose fresh from a swim in the lake, with its shaggy sides wet and gleaming.

Then the moose broke into an awkward run, and was soon lost to view.

A half hour later, while they were still paddling along the shore, they heard a shot from the woods, in the direction taken by the moose.

“Poachers?” said Frank, questioningly. “Do you suppose somebody has fired at our moose?”

That afternoon an eccentric figure came capering through the woods, bearing a strange burden. Perhaps capering is not the exact word to use, for the figure was that of a rotund and fat-legged boy, and it is hard for such a person to caper. Ever and anon this figure sent up a pleased exclamation or a cry of delight.

“Anodder teer’s head!” he shouted, when he came in sight of the camp. “A moose’s teer head this dime, I pet you!”

It was Hans Dunnerwust, and the burden under which he waddled was the head of a moose. He tried to hold it triumphantly aloft as he shouted his announcement, and while making this attempt struck a foot against a protruding root, and went down in a heap, the antlered head falling on top of him.

“Mine gootness!” he gasped, sitting up and rubbing his stomach, while he looked excitedly around. “I t’ought, py shimminy, dot somepoty musd hid me, I go town so qvick!”

His eyes fell on the head, and the pleased look came again into his face.

“I pet you, I vill pe bleased mit Merriwell, ven he seen dhis. Dot odder teer got no hornses, und dis haf hornses like a dree sdick up. Id must pe vort more as lefendeen tollar, anyhow!”

After climbing to his feet and assuring himself that he had not sustained any serious injuries or broken bones, he picked up the heavy head and again hurried on, giving utterance to many exclamations of pleasure and delight.

Hans had found the head hanging in the branches of a tree, in a way to keep it out of the reach of carnivorous animals. Had he not been looking for a red squirrel, that had gone flickering through these very branches, he never would have discovered the head, so cleverly was it hidden.

“Dot is a petter head as dot odder vun I got,” he had whispered, wondering dully how it chanced to be there, but not for a moment thinking of poachers.

There were marks on the earth and grass showing where the moose had been skinned and cut up.

“Dose vellers don’d vand der head,” was his final conclusion, “und day chust hang id ub here. Vale, I vill dake id mineselluf, den!”

Then he had fastened his knife to a stick and, after many futile attempts, had succeeded in cutting the string by which the head was suspended from the bough.

“Whoop!” he screeched, when he drew near the tent. “Yaw. See vot got me, eh? A moose’s teer head got me de horns py!”

It was a hot afternoon, and the sweat was fairly streaming from his round, red face. He was panting, too, almost as loudly as the moose had panted while it drew the canoe across the water.

Merriwell and Diamond came to the door of one of the tents, and Browning, Bart Hodge and John Caribou looked from the other.

A more astounded party would have been hard to find.

“Where did you get that?” asked Merriwell, thinking at once of the shot they had heard in the direction taken by the moose.

“Id is a moose’s teer head,” announced Hans, holding it up. “See mine hornses?”

“I can see that it is a moose head; but where did you get it?”

The other members of the party were as surprised as Frank and equally as anxious for an answer to his questions. The guide looked as if he might have given an answer himself, but he only folded his arms and stared at the head with shining eyes and impassive features.

“Pushes vos hanging to him in a dree,” said Hans, and then, in his own peculiar way, he proceeded to make them acquainted with the manner in which he discovered it.

He put it down on the grass in front of the tent, where it was closely scrutinized.

“Same moose we saw this morning,” declared Bruce Browning, very emphatically. “Do you see that peculiar turn of the horn there? I noticed that on the fellow that towed us. Some scoundrel has shot him.”

“There can’t be any doubt of that, I guess,” admitted Merriwell, in a grieved tone. “What a magnificent beast he was, too! It is a shame. I hope the rascal will be caught and punished, but I don’t suppose he ever will be. This is a pretty wild country out here.”

“I tell you what,” said Hodge. “Whoever killed that moose will come back for the head. Those antlers are[60] worth something, and he won’t want to lose them. How would it do to hide out there and see if we can’t capture him?”

“The only trouble about that,” objected Diamond, “is that we’d have to take the scamp before some justice of the peace and waste a lot of time in trying to get him convicted. Nothing is slower than the law, you know.”

“See there!” exclaimed Merriwell, who had been closely examining the head. “He was shot in the head, just back of this ear.”

John Caribou pressed forward and looked at the bullet hole. He carried a rifle himself that threw a big ball like that.

Merriwell did not know whether to reprove Hans or not for bringing the head to camp, and let the question pass, while they talked of the dead moose and the poachers, and discussed the advisability of trying to capture those slippery gentlemen.

John Caribou disappeared within a tent and came out shortly with his long rifle.

“Where are you going?” Merriwell questioned. “Not after the poachers now?”

Caribou shook his head and held up his empty pipe.

“Tobac’ all gone,” he said. “No tobac’, Caribou him no good. Friend down here got tobac’. Come back soon.”