Project Gutenberg's Sappho and her influence, by David Moore Robinson

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Sappho and her influence

Author: David Moore Robinson

Release Date: February 24, 2020 [EBook #61505]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SAPPHO AND HER INFLUENCE ***

Produced by Turgut Dincer and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This book was

produced from images made available by the HathiTrust

Digital Library.)

[i]

Our Debt to Greece and Rome

EDITORS

George Depue Hadzsits, Ph.D.

University of Pennsylvania

David Moore Robinson, Ph.D., LL.D.

The Johns Hopkins University

[ii]

CONTRIBUTORS TO THE “OUR DEBT TO GREECE AND ROME FUND,” WHOSE

GENEROSITY HAS MADE POSSIBLE THE LIBRARY

Our Debt to Greece and Rome

Philadelphia

- Dr. Astley P. C. Ashhurst

- John C. Bell

- Henry H. Bonnell

- Jasper Yeates Brinton

- George Burnham, Jr.

- John Cadwalader

- Miss Clara Comegys

- Miss Mary E. Converse

- Arthur G. Dickson

- William M. Elkins

- H. H. Furness, Jr.

- William P. Gest

- John Gribbel

- Samuel F. Houston

- Charles Edward Ingersoll

- John Story Jenks

- Alba B. Johnson

- Miss Nina Lea

- George McFadden

- Mrs. John Markoe

- Jules E. Mastbaum

- J. Vaughan Merrick

- Effingham B. Morris

- William R. Murphy

- John S. Newbold

- S. Davis Page (memorial)

- Owen J. Roberts

- Joseph G. Rosengarten

- William C. Sproul

- John B. Stetson, Jr.

- Dr. J. William White (memorial)

- George D. Widener

- Mrs. James D. Winsor

- Owen Wister

- The Philadelphia Society for the Promotion of Liberal Studies.

Boston

- Oric Bates (memorial)

- Frederick P. Fish

- William Amory Gardner

- Joseph Clark Hoppin

Chicago

Cincinnati

Cleveland

Detroit

- John W. Anderson

- Dexter M. Ferry, Jr.

Doylestown, Pennsylvania

- “A Lover of Greece and Rome”

New York

- John Jay Chapman

- Willard V. King

- Thomas W. Lamont

- Dwight W. Morrow

- Mrs. D. W. Morrow

- Elihu Root

- Mortimer L. Schiff

- William Sloane

- George W. Wickersham

- And one contributor, who has asked to have his name withheld:

Maecenas atavis edite regibus,

O et praesidium et dulce decus meum.

Washington

- The Greek Embassy at Washington, for the Greek Government.

[iii]

The following lovers of Greek literature, and

of Sappho in particular, have kindly consented

to act as patrons and have made possible, by

generous contributions, the larger size of this

volume in the Series “Our Debt to Greece

and Rome”:

- Mr. Charles H. Carey

- Mr. James Carey

- Miss Lillie Detrick

- Professor Joseph Clark Hoppin

- Mrs. Harry C. Jones

- Mrs. Gardiner M. Lane

- Miss Emma Marburg

- Dr. John Rathbone Oliver

- Miss Julia R. Rogers

- Professor Herbert Weir Smyth

- Dr. Hugh H. Young

[iv]

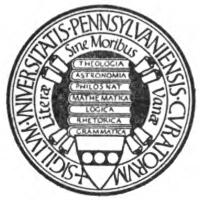

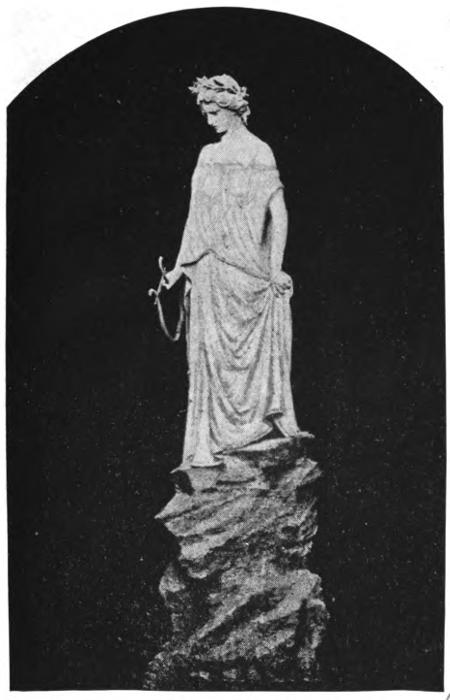

Plate 1. ALMA TADEMA’S SAPPHO

In the Walters’ Art Gallery, Baltimore

[v]

SAPPHO

AND HER INFLUENCE

BY

DAVID M. ROBINSON, Ph.D., LL.D.

W. H. Collins Vickers Professor of Archaeology and

Epigraphy and Lecturer on Greek Literature

The Johns Hopkins University

MARSHALL JONES COMPANY

BOSTON · MASSACHUSETTS

[vi]

COPYRIGHT · 1924 · BY MARSHALL JONES COMPANY

All rights reserved

Printed December, 1924

THE PLIMPTON PRESS · NORWOOD · MASSACHUSETTS

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

[vii]

To

THE MEMORY OF

BASIL LANNEAU GILDERSLEEVE

MASTER, COLLEAGUE, AND FRIEND

AND TO MY FORMER TEACHERS

EDWARD CAPPS

PAUL SHOREY

ULRICH von WILAMOWITZ-MOELLENDORFF

δῶρον ’αντὶ μαγάλου σμικρόν

A trifling gift in return for much.

Ἑτερος ἐξ ἑτέρου σοφὸς τό τε πάλαι τό τε νῦν.

οὐδὲ γὰρ ῥᾶστον ἀρρήτων ἐπέων πύλας

ἐξευρεῖν.

Poet is heir to poet, now as of yore; for in

sooth ’tis no light task to find the gates of

virgin song.

Jebb, Bacchylides, p. 413, frag. 4

[viii]

Immortal Sappho, maid divine,

Thou sharest with the heavenly nine

All honor. Shout through all the town

That on her head we place a crown.

Hasten with the chaplet green,

Greet her one and all as queen;

The Lesbian, a tenth muse we name,

And prophesy that her bright fame

Shall spread o’er all the world.

This title till the stars do fall,

Nations yet unborn shall call

And glorify her name.

(LUCY MILBURN)

[ix]

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER |

|

PAGE |

|

Contributors to the Fund |

ii |

| I. |

Some Appreciations, Ancient and Modern |

3 |

| II. |

Sappho’s Life, Lesbus, Her Love-Affairs, Her Personality and Pupils |

14 |

| III. |

The Legendary Fringe |

34 |

|

Sappho’s Physical Appearance, The Phaon Story, The Vice Idea |

|

| IV. |

The Writings of Sappho |

46 |

| V. |

Sappho in Art |

101 |

| VI. |

Sappho’s Influence on Greek and Roman Literature |

119 |

| VII. |

Sappho in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance |

134 |

| VIII. |

Sappho in Italy in the 18th and 19th Centuries |

139 |

| IX. |

Sappho in Latin Translations, in Spanish, and in German |

148 |

| [x]X. |

Sappho in French Literature |

160 |

| XI. |

Sappho in English and American Literature |

188 |

|

An Addendum on Sappho in Russian |

233 |

| XII. |

Sappho’s Influence on Music |

234 |

| XIII. |

Epilogue and Conclusion |

237 |

|

Notes |

251 |

|

Bibliography |

268 |

[xi]

ILLUSTRATIONS

| PLATE |

|

|

| 1. |

Alma Tadema’s Sappho |

Frontispiece |

| (At end of Volume) |

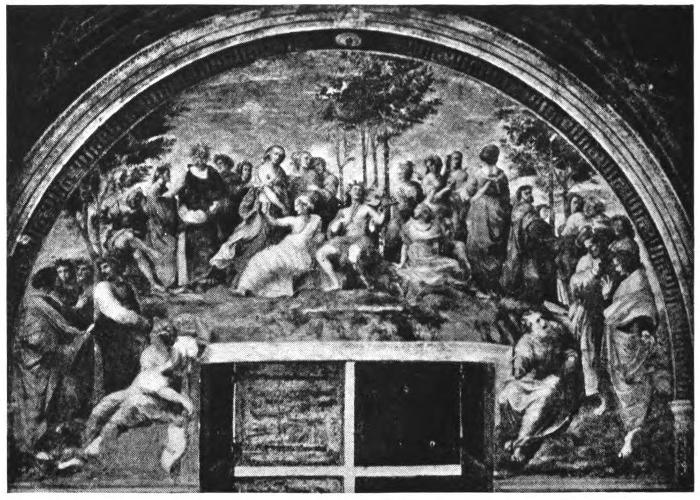

| 2. |

Bust of Pittacus |

| 3. |

Mytilene |

| 4. |

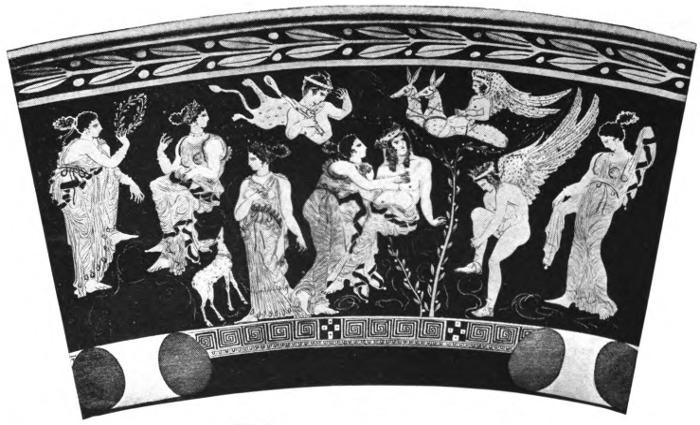

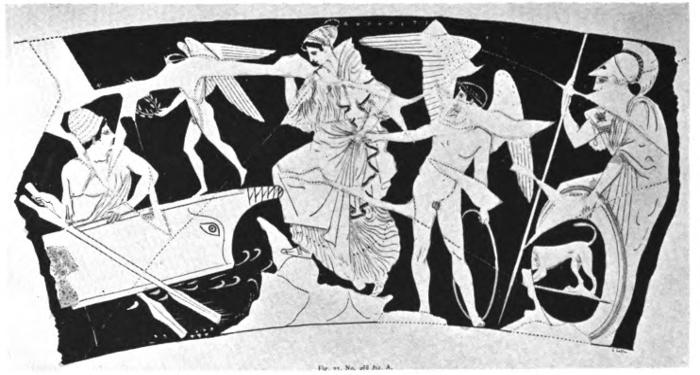

The Story of Phaon on a Vase in Florence |

| 5. |

Phaon on a Greek Vase in Palermo |

| 6. |

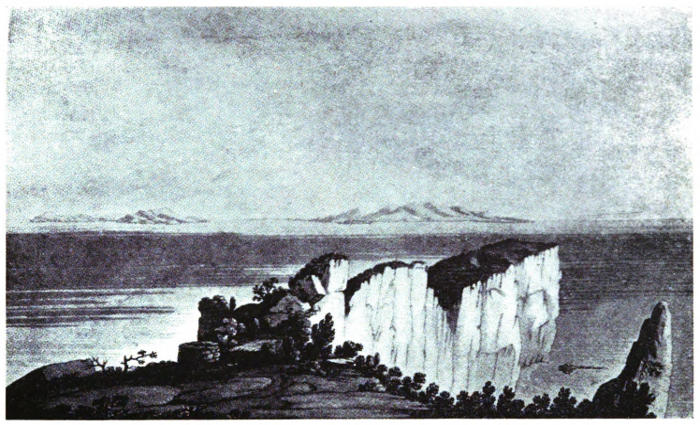

The Leucadian Promontory |

| 7. |

Roman Fresco in an Underground Building |

| 8. |

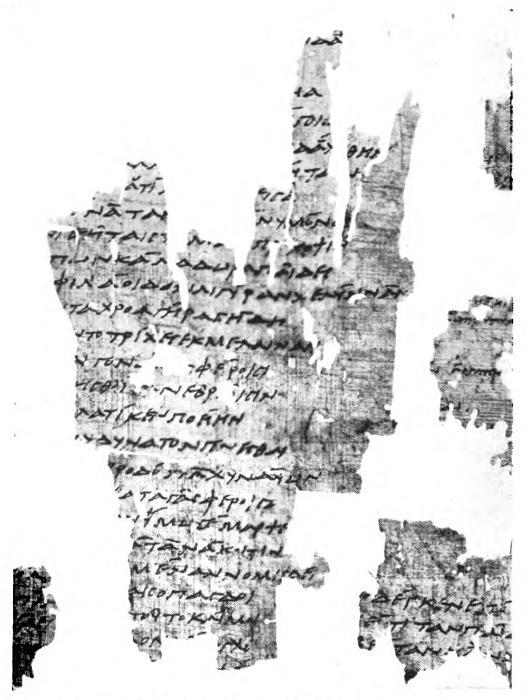

A Papyrus of the Third Century A.D. |

| 9. |

A Cylix by Sotades |

| 10. |

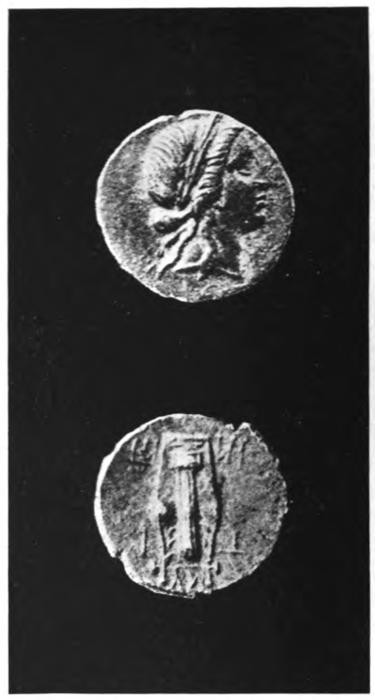

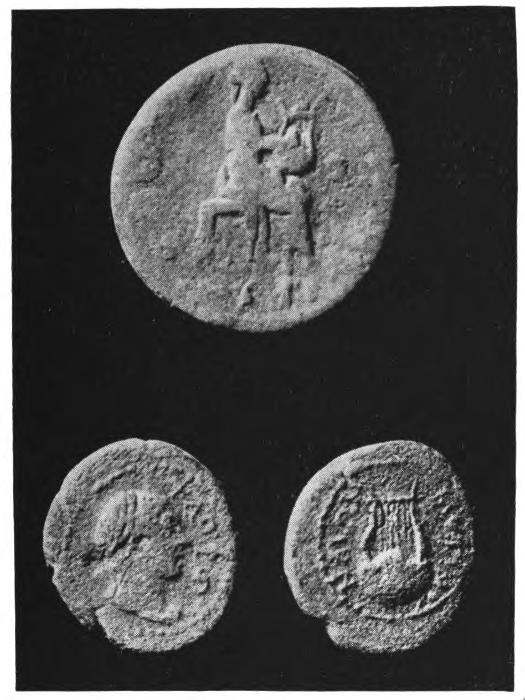

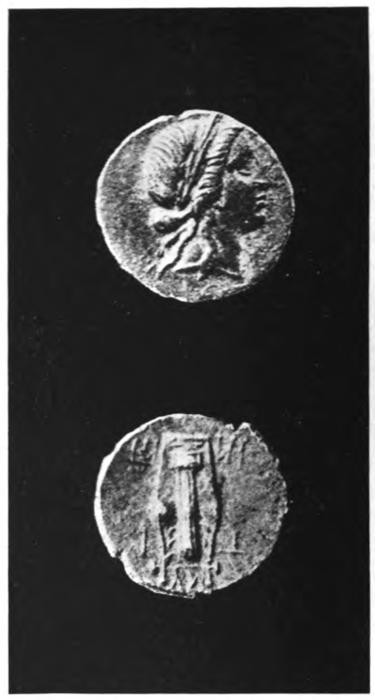

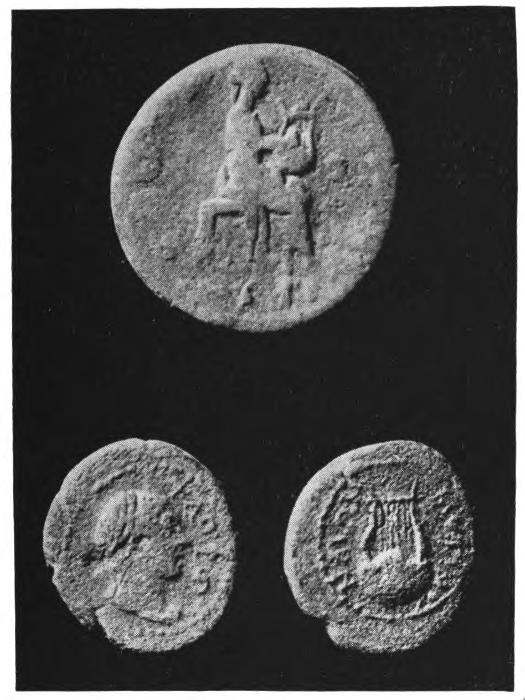

Greek Coin from Mytilene |

| 11. |

Imperial Coins |

| 12. |

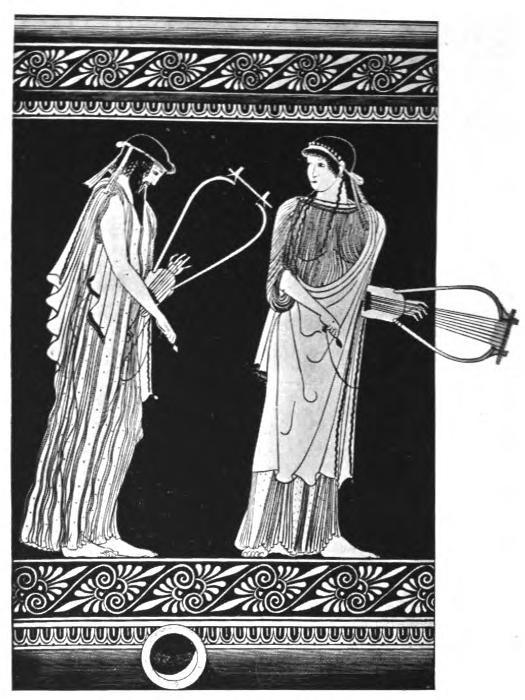

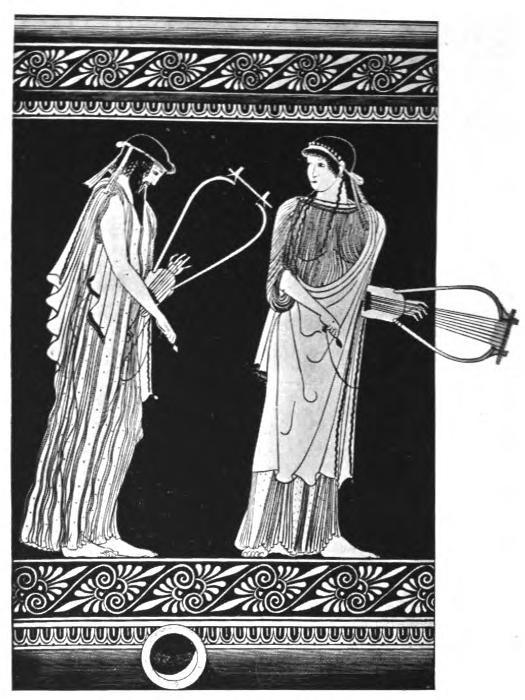

A Greek Vase in Munich |

| 13. |

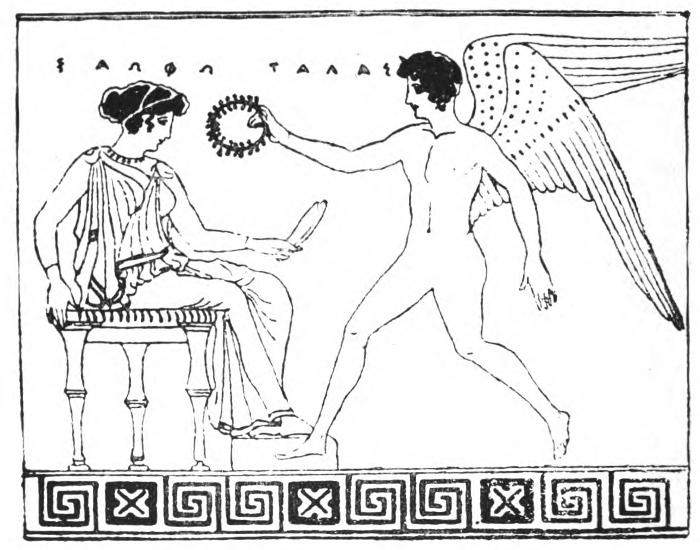

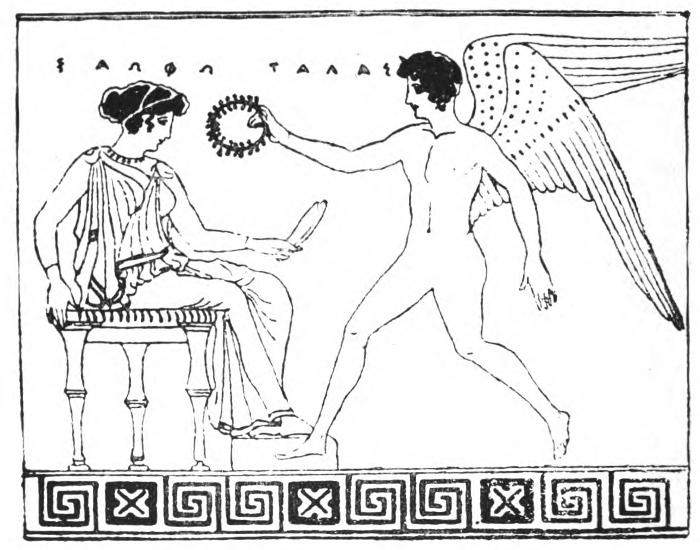

Sappho on a Vase in Cracow |

| 14. |

Sappho Seated before a Winged Eros |

| [xii]15. |

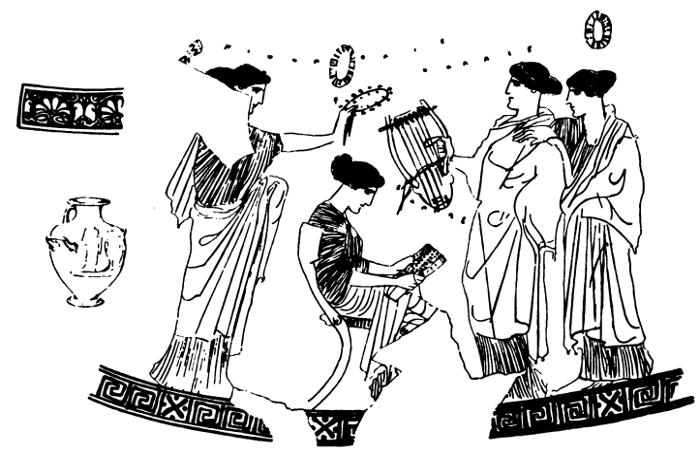

Greek Aryballus at Ruvo |

| 16. |

A Greek Hydria in Athens |

| 17. |

Phaon in His Boat |

| 18. |

A Pompeian Fresco |

| 19. |

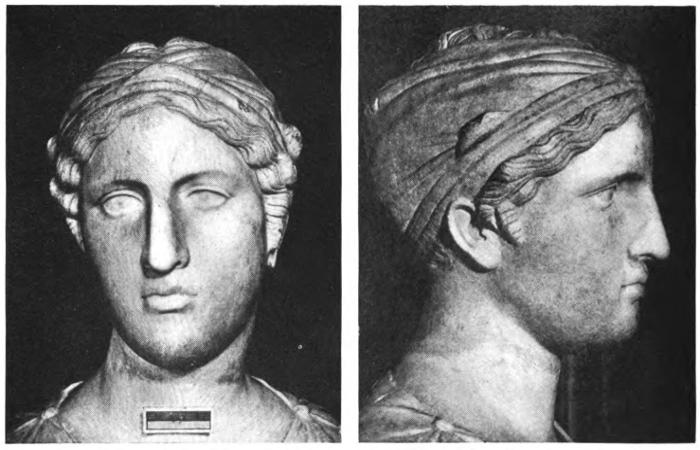

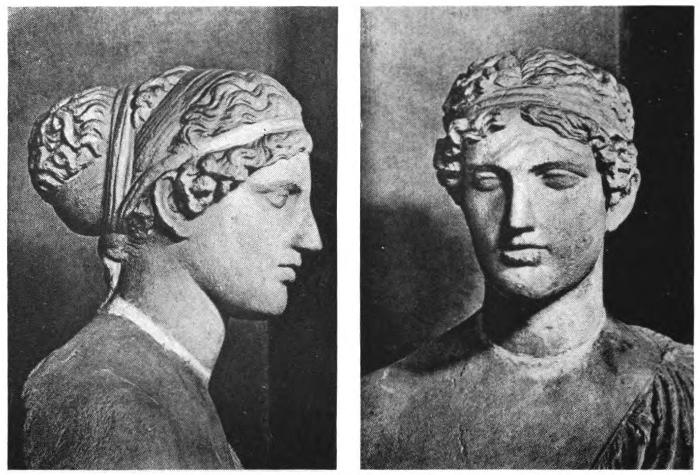

A Bust of Sappho in the Villa Albani |

| 20. |

The Oxford Bust |

| 21. |

A Bust in the Borghese Palace |

| 22. |

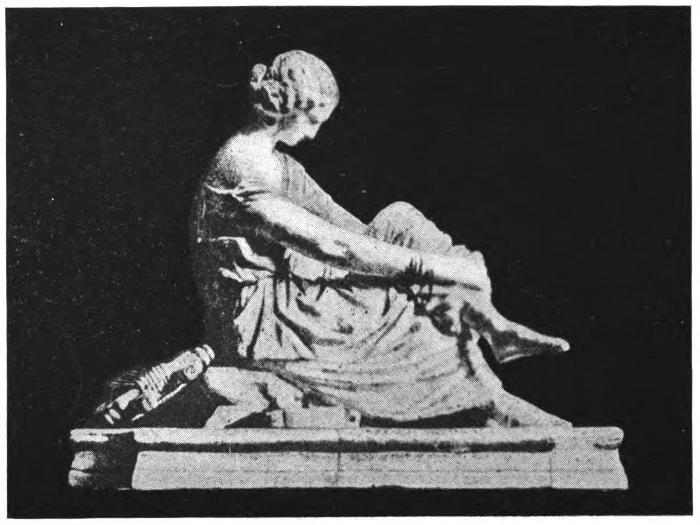

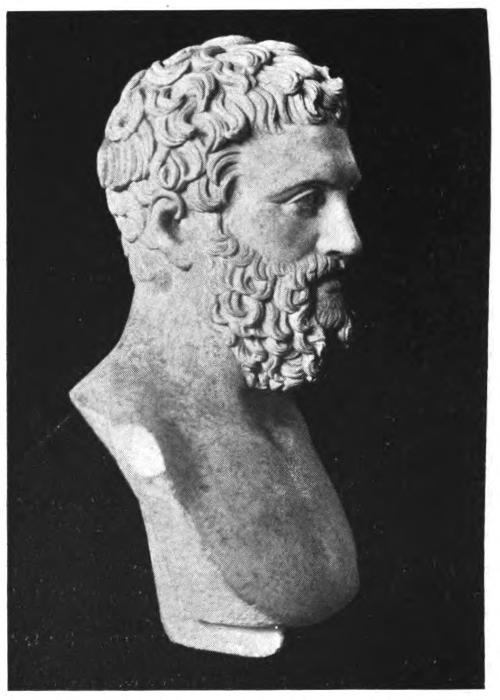

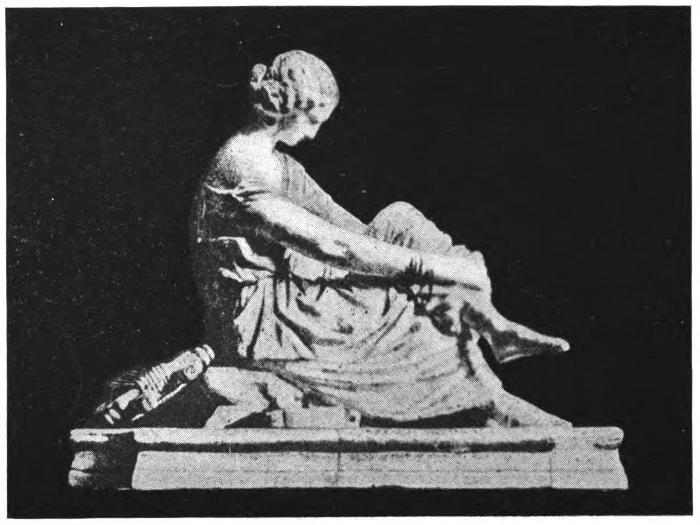

Statue of Sappho by Magni |

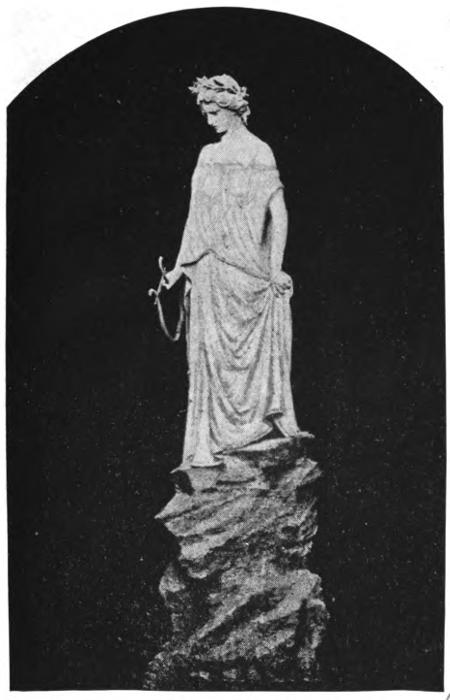

| 23. |

Statue of Sappho by Pradier |

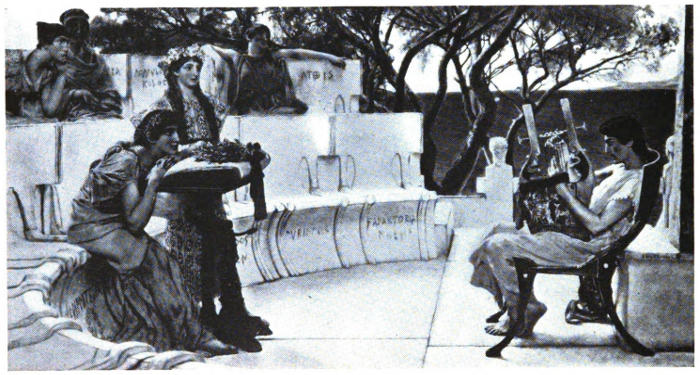

| 24. |

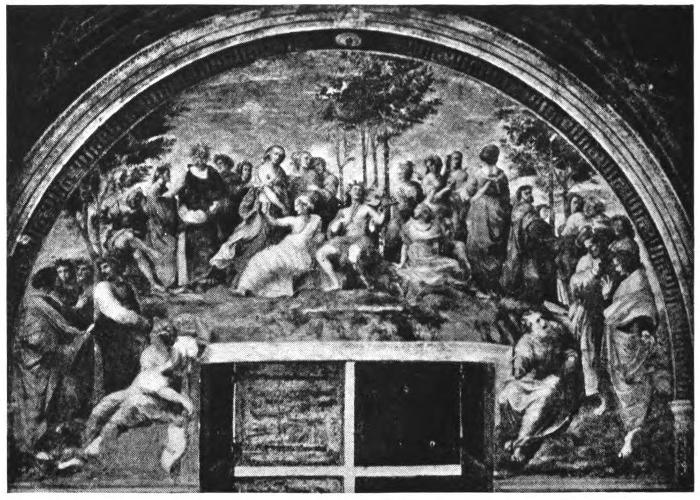

Raphael’s Parnassus |

[1]

SAPPHO AND HER INFLUENCE

[2]

[3]

I. SOME APPRECIATIONS, ANCIENT AND MODERN

The name of Sappho will never die.

But it lives in most of the minds that

know it at all to-day as hardly more

than the hazy nucleus of a ragged fringe suggestive

of erotic thoughts or of sexual perversion.

Very seldom does it evoke the vision of

a great and pure poetess with marvellous

expressions of beauty, grace, and power at her

command, who not only haunts the dawn of

Grecian Lyric poetry but lives in scattered and

broken lights that glint from vases and papyri

and from the pages of cold grammarians and

warm admirers, whose eulogies we would gladly

trade for the unrecorded poems which they

quote so meagerly. Sappho has furnished the

title of such a novel as Daudet’s Sapho. It

figures in suggestive moving pictures.1 The[4]

name will answer prettily as that of a bird or

even a boat such as the yacht with which Mr.

Douglas defended the American cup in 1871.

The modern idea of Sappho truly seems to be

based mainly on Daudet, who with Pierre

Louys in recent times has done most to degrade

her good character and who goes so far

as to say that “the word Sappho itself by the

force of rolling descent through ages is encrusted

with unclean legends and has degenerated

from the name of a goddess to that of a

malady.” But to the lover of lyrics, who is

also a student of Greek Literature in Greek,

this poetess of passion becomes a living and

illustrious personality, who of all the poets of

the world, as Symonds says, is the “one whose

every word has a peculiar and unmistakable

perfume, a seal of absolute perfection and

inimitable grace.” “Sappho,” says Tennyson in

The Princess, “in arts of grace vied with any

man.” She is one whose fervid fragments, as the

great Irish translator of the Odes of Anacreon

and the Anacreontics, Thomas Moore, says in

his Evenings in Greece,

Still, like sparkles of Greek Fire,

Undying, even beneath the wave,

Burn on thro’ time and ne’er expire,

[5]

a prophecy still true even in this materialistic

day. Sappho, herself, had intimations

of immortality, for she writes with perfect

beauty and modesty:

Μνάσεσθαί τινά φαμι καὶ ὔστερον ἀμμέων

I say some one will think of us hereafter.

This brief, pellucid verse Swinburne in his

Anactoria has distorted into the gorgeous emotional

rhetoric of fourteen verses. But its own

quiet prophecy stands good to-day. A fragment

first published in 19222 also seems to

make her say:

and yet great

glory will come to thee in all places

where Phaëthon [shines]

and even in Acheron’s halls

[thou shalt be honored.]

In general, antiquity thought of her as “the

poetess” κατ’ἐξοχήν, ἡ ποιήτρια,3 just as Professor

Harmon has recently shown4 that “the poet”

in ancient literature means Homer. Down to

the present day Sappho has kept the definite

article which antiquity gave her and has been

called the poetess, though we must be careful to

test a writer’s use of the term. Therefore, we[6]

must not understand by the absence of any

added epithet, as Wharton does, that Tennyson

rates her higher than all other poets, merely

because in Locksley Hall, Sixty Years After he

speaks of Sappho as “The Poet,” having called

her in his youth “The Ancient Poetess,”5—for

he also speaks of Dante as “The Poet,”

when in Locksley Hall he says, “this is truth

the poet sings,” and then cites verse 121 of the

Inferno. It is rare, however, even in modern

times to find Sappho classed with any other

poet as a peer, as in the beautiful tribute To

Christina Rossetti of William Watson, one of

the best modern writers of epigrams, where

Mrs. Browning and Sappho are the two other

women referred to:

Songstress, in all times ended and begun,

Thy billowy-bosom’d fellows are not three.

Of those sweet peers, the grass is green o’er one;

And blue above the other is the sea.

In ancient days Pinytus (1st cent. A.D.) composed

this epigram:6

This tomb reveals where Sappho’s ashes lie,

But her sweet words of wisdom ne’er will die.

(Lord Naeves)

[7]

Tullius Laureas, who wrote both in Greek and

Latin about 60 B.C., puts into her mouth the

following: “When you pass my Aeolian grave,

stranger, call not the songstress of Mytilene

dead. For ’tis true this tomb was built by the

hands of men, and such works of humankind

sink swiftly into oblivion; yet if you ask after

me for the sake of the holy Muses from each

of whom I have taken a flower for my posy of

nine, you shall know that I have escaped the

darkness of Death, and no sun shall ever rise

that keepeth not the name of the lyrist Sappho.”

(Edmonds, with variations.)

Posidippus7 (250 B.C.) says:

Sappho’s white, speaking pages of dear song

Yet linger with us and will linger long.

(T. Davidson)

Horace8 says:

vivuntque commissi calores

Aeoliae fidibus puellae.

That inadequate and misleading metaphor of

fire, as Mackail says, recurs in all her eulogists.

Μεμιγμένα πυρὶ φθέγγεται, “her words are

mingled with fire,” writes Plutarch,9 but the

“fire” of the burning Sappho is not raging hot,

it is an unscorching calm, brilliant lustre that[8]

makes other poetry seem cold by comparison.

No wonder that Hermesianax10 (about 290 B.C.)

called her “that nightingale of hymns” and

Lucian11 “the honeyed boast of the Lesbians.”

Strabo (1 A.D.) said: “Sappho is a marvellous

creature (θαυμαστόν τι χρῆμα), in all history you

will find no woman who can challenge comparison

with her even in the slightest degree.”

Antipater of Thessalonica (10 B.C.) named

Sappho as one of the nine poetesses who were

god-tongued and called her one of the nine

muses: “The female Homer: Sappho pride

and choice of Lesbian dames, whose locks have

earned a name.”12 In another epigram in the

Anthology,13 probably from the base of a lost

statue of Sappho in the famous library at Pergamum,14

and which Jucundus and Cyriac were

able to cite many hundreds of years later,

Antipater says,

Sappho my name, in song o’er women held

As far supreme as Homer men excelled.

(Neaves)

Some thoughtlessly proclaim the muses nine;

A tenth is Lesbian Sappho, maid divine,

are the words of Plato in Lord Neaves’ translation

of an epigram of which Wilamowitz15 now[9]

timidly defends the genuineness. Antipater of

Sidon (150 B.C.)16 in his encomium on Sappho

tells how

Amazement seized Mnemosyne

At Sappho’s honey’d song:

‘What, does a tenth muse,’ then, cried she,

‘To mortal men belong!’

(Wellesley)

He also speaks17 of Sappho as “one that is

sung for a mortal Muse among Muses immortal

... a delight unto Greece.” Dioscorides18

(180 B.C.) says: “Sappho, thou Muse of Aeolian

Eresus, sweetest of all love-pillows unto the

burning young, sure am I that Pieria or ivied

Helicon must honour thee, along with the

Muses, seeing that thy spirit is their spirit.”

Again, in an anonymous epigram19 it is said:

“her song will seem Calliope’s own voice.”

Another writer,20 also anonymous, discussing

the nine lyric poets, says:

Sappho would make a ninth; but fitter she

Among the Muses, a tenth Muse to be.

(Neaves)

Catullus21 speaks of the Sapphica Musa, and

Ausonius in Epigram XXXII calls her Lesbia

Pieriis Sappho soror addita Musis.22

If we turn now from the praise of the ancients[10]

to modern literary critics of classic lore

we shall not find any depredation but rather

an enhancing of that ancient praise. The classic

estimate of Sappho holds its own and more

than holds it to-day. J. A. K. Thomson in his

Greeks and Barbarians23 says: “Landor is not

Greek any more than Leconte de Lisle is Greek ...

they have not the banked and inward-burning

fire which makes Sappho so different.”

Mackail speaks of “the feeling expressed in

splendid but hardly exaggerated language by

Swinburne, in that early poem where, alone

among the moderns, he has mastered and all

but reproduced one of her favourite metres, the

Sapphic stanza which she invented and to which

she gave her name”—

Ah the singing, ah the delight, the passion!

All the Loves wept, listening; sick with anguish,

Stood the crowned nine Muses about Apollo;

Fear was upon them,

While the tenth sang wonderful things they knew not.

Ah, the tenth, the Lesbian! the nine were silent,

None endured the sound of her song for weeping;

Laurel by laurel,

Faded all their crowns; but about her forehead

...

Shone a light of fire as a crown for ever.

[11]

Swinburne himself was thoroughly steeped

in Sappho whom he considered “the supreme

success, the final achievement of the poetic art.”

He laid abounding tribute at her feet both in

verse and prose. In an appreciation first published

posthumously in 1914 in The Living Age,24

he says: “Judging even from the mutilated

fragments fallen within our reach from the

broken altar of her sacrifice of song, I for one

have always agreed with all Grecian tradition

in thinking Sappho to be beyond all question

and comparison the very greatest poet that ever

lived. Aeschylus is the greatest poet who ever

was also a prophet; Shakespeare is the greatest

dramatist who ever was also a poet, but Sappho

is simply nothing less—as she is certainly

nothing more—than the greatest poet who

ever was at all. Such at least is the simple and

sincere profession of my lifelong faith.” Alfred

Noyes recognizes in Swinburne’s praise of

Sappho a spirit which would make them congenial

companions in another world, when in

the poem In Memory of Swinburne he writes:

Thee, the storm-bird, nightingale-souled,

Brother of Sappho, the seas reclaim!

Age upon age have the great waves rolled

Mad with her music, exultant, aflame;

[12]

Thee, thee too, shall their glory enfold,

Lit with thy snow-winged fame.

Back, thro’ the years, fleets the sea-bird’s wing:

Sappho, of old time, once,—ah, hark!

So did he love her of old and sing!

Listen, he flies to her, back thro’ the dark!

Sappho, of old time, once.... Yea, Spring

Calls him home to her, hark!

Sappho, long since, in the years far sped,

Sappho, I loved thee! Did I not seem

Fosterling only of earth? I have fled,

Fled to thee, sister. Time is a dream!

Shelley is here with us! Death lies dead!

Ah, how the bright waves gleam.

Wide was the cage-door, idly swinging;

April touched me and whispered ‘Come.’

Out and away to the great deep winging,

Sister, I flashed to thee over the foam,

Out to the sea of Eternity, singing

‘Mother, thy child comes home.’

J. W. Mackail echoes Swinburne’s high

praise: “Many women have written poetry

and some have written poetry of high merit

and extreme beauty. But no other woman can

claim an assured place in the first rank of

poets” ... “The sole woman of any age or[13]

country who gained and still holds an unchallenged

place in the first rank of the world’s

poets, she is also one of the few poets of whom

it may be said with confidence that they hold

of none and borrow of none, and that their

poetry is, in some unique way, an immediate

inspiration.”

Many another modern critic ranks Sappho as

supreme. Typical are such eulogies as “Sappho,

the most famous of all women” (Aldington), or

“Sappho, incomparably the greatest poetess the

world has ever seen” (Watts-Dunton in ninth

ed. Encyclopædia Britannica).

[14]

II. SAPPHO’S LIFE, LESBUS, HER LOVE-AFFAIRS, HER PERSONALITY AND PUPILS

It is my purpose in the limited space at my

disposal to show in a general way, since it

will not be possible to go into details, the

truth of Sappho’s prophecy that men would

think of her25 in after-times: to show her importance

as a woman and poetess and our debt

to her, and also to give my readers some acquaintance

with the real and the unreal Sappho

so that they can judge how much is fact and

how much is fancy in what they hear and read

about Sappho, thus proving again that the warp

and woof of literature cannot be understood without

a knowledge of the original Greek threads.

This chapter will consider Sappho’s Life.

Unfortunately we know little of Sappho herself,

and about that little there is doubt. Even

the ancient lives of Sappho are lost. If we had

Chamaeleon’s work on Sappho,26 or the exegesis

of Sappho and Alcaeus27 by Callias of Mytilene,

or the book on Sappho’s metres by Dracon of

Stratonicea, we should not be left so in the dark;[15]

but all these have perished or, what comes to

the same thing, are undiscovered. Like Homer,

Sappho gives us almost no definite information

about herself, and we must depend on late lexicographers,

commentators, and imitators. Villainous

stories arose about her and gathered added

vileness till they reached a climax in the licentious

Latin of Ovid, especially as seen in Pope’s translation

of the epistle of Sappho to Phaon.

Sappho came of a noble family belonging to

an Aeolian colony in the Troad. Though Suidas

gives eight possibilities for the name of Sappho’s

father, the most probable is Scamandronymus,

a good Asia Minor name vouched for by Herodotus,

Aelian and other ancient writers and now

confirmed by a recently discovered papyrus.28

He was rich and noble and probably a wine-merchant.

He died, according to Ovid,29 when

Sappho’s eldest child was six years of age.

Her mother’s name, says Suidas, was Cleïs.30

Commentators assume that she was living when

Sappho began to write poetry because of the

reference to “mother” in the “Spinner in

Love”; but this may be an impersonal poem.

According to the Greek custom of naming the

child after a grandparent the poetess called her

only daughter Cleïs.

[16]

The poetess had three brothers, Charaxus,

Larichus, who held the aristocratic office of cup-bearer

in the Prytaneum to the highest officials

of Mytilene, and, according to Suidas, a third

brother, Eurygyius,31 of whom nothing is known.

Athenaeus tells us that the beautiful Sappho

often sang the praises of her brother Larichus;

and the name was handed down in families of

Mytilene, for it occurs in a Priene inscription32

as the name of the father of a friend of Alexander

who was named Eurygyius. This shows the

family tradition and how descendants of Sappho’s

family attained high ranks in Alexander’s army.

Charaxus, the eldest brother as we now know,

“sailed to Egypt and as an associate with a

certain Doricha spent very much money on

her,” according to the recently found late papyrus

biography. Charaxus had strayed from

home about 572 and sailed as a merchant to

Naucratis, the great Greek port colony established

in the delta of the Nile under conditions

similar to those of China’s treaty-ports. There

he was bartering Lesbian wine, Horace’s innocentis

pocula Lesbii, for loveliness and pleasures,

when he fell in love with and ransomed the

beautiful Thracian courtesan, the world-renowned

demi-mondaine. She was called Doricha[17]

by Sappho according to the Augustan geographer,

Strabo, but Herodotus names her Rhodopis,

rosy-cheeked,33 and evidently thought she

had contributed to Delphi34 the collection of

obeliskoi or iron spits, the small change of

ancient days before coin money was used to

any great extent. Herodotus, the only writer

preserved before 400 B.C. who gives us any

details about Sappho tells the story and how

the sister roundly rebuked her brother in a

poem. Some four hundred years later Strabo,

adding a legend which recalls that of Cinderella,

repeats the story and it is retold by Athenaeus

after another two hundred years. In our own

day it has slightly influenced William Morris

in the Earthly Paradise. Except for archaeology,

however, we should never have heard Sappho’s

own words. About 1898 the sands of Egypt

gave up five mutilated stanzas of this poem

which scholars had for many a year longed to

hear, but the beginnings of the lines are gone

and only a few letters of the last stanza remain.

My own interest in Sappho dates from that very

year when I wrote for Professor Edward Capps,

then of the University of Chicago, a detailed

seminary paper on The Nereid Ode, and for the

twenty-five years since I have been gathering[18]

material about Sappho. We must be careful

not to accept as certainly Sappho’s, especially

the un-Sapphic idea of the last stanza, the

restorations of Wilamowitz, Edmonds, and a

host of other scholars, who have changed their

own conjectures several times. Wilamowitz

goes so far as to think that the words apply to

Larichus, but most critics have restored them

with reference to Charaxus. I give a version

which I have based on Edmonds’ latest and

revised text,35 taking a model from the stanza

used by Tennyson in his Palace of Art.

In offering a new translation of such songs

as these it should be fully realized that no

translation of a really beautiful poem can possibly

represent the original in any fair or complete

fashion. Unfortunately languages differ;

and in translating a single word of Sappho into

a word of English which fairly represents its

meaning, one may easily have lost the musical

charm of the original, and still further he may

have broken up the general charm or spirit

which the word has because of its associations

with the spirit of the whole song. It ought to

be clear that in preserving the literal meanings

of the words in a song the translator may be

compelled to part in large measure with the[19]

musical note that comes from assonance, alliteration,

and association; or again that in rendering

the music as Swinburne could do, he may

have diluted or even lost the real meaning and

spirit of the poem; and finally that, though the

spirit of the poem may be seized ever so effectively,

the working out of the details of music

and meaning may fail to respond to those of

the original. Of course a slight measure of

successful representation may be attained. But

whatever poetical value anyone senses in these

translations must be almost indefinitely heightened

by imagination, if the beauty, grace, and

power of the original are to be realized. Why

then translate at all? Well, just because of a

desire to make an English reader share even in

a small measure the pleasure the translator feels

in the original and to furnish him with paths

along which his imagination may lawfully climb

toward the height reached by this strangely

gifted woman’s pen.

TO THE NEREIDS

O all ye Nereids crowned with golden hair

My brother bring, back home, I pray.

His heart’s true wish both good and fair

Accomplished, every way.

[20]

May he for former errors make amend—

If once to sin his feet did go—

Become a joy, again, to every friend,

A grief to every foe.

O may our house through no man come to shame,

O may he now be glad to bring

Some share of honor to his sister’s name.

Her heart with joy will sing.

Some bitter words there were that passed his lip,—

For me the wrath of love made fierce

And him resentful,—just as he took ship,

When to the quick did pierce

My song-shaft sharp. He sought to crush my heart,—

Not distant be the feasting day

When civic welcome on his fellows’ part,

Shall laugh all wrath away!

And may a wife, if he desires, be found

In wedlock due, with worthy rite—

But as for thee, thou black-skinned female hound,

Baleful and evil sprite,

Set to the ground thy low malodorous snout

And let my brother go his way

Whilst thou, along thy low-lived paths, track out

The trail of meaner prey.

(D. M. R.)

In this letter, handed perhaps to Charaxus

on his return from Egypt, the tone is that of[21]

reconciliation rather than that of rebuke, and

the rebuke itself may be found in a fragment

of another letter, if Edmonds’ restoration is

anywhere near the truth.35

You seek the false and shun the true,

And bid your friends go hang for you,

And grieve me in your pride and say

I bring you shame. Go, have your way,

And flaunt me till you’ve had your fill;

I have no fears and never will

For the anger of a child.

(Edmonds)

“Sappho,” or “Sapho,”36 as the name appears

on vases and papyri, or “Psappho,” as coins

and vases have it, or “Psappha,” as she herself

spelled it in her soft Aeolic dialect, is perhaps

a nom de plume,—the word meaning lapis lazuli.

According to Athenaeus37 (who wrote at

the beginning of the third century A.D.) she

lived in the time of the father of Croesus, Alyattes,

who reigned over Lydia from 628 to 560 B.C.

Jeremiah, Nebuchadnezzar, and at Rome Tarquinius

Priscus were her contemporaries. Suidas,

a Greek lexicographer of the tenth century

A.D., says that she flourished about the 42nd

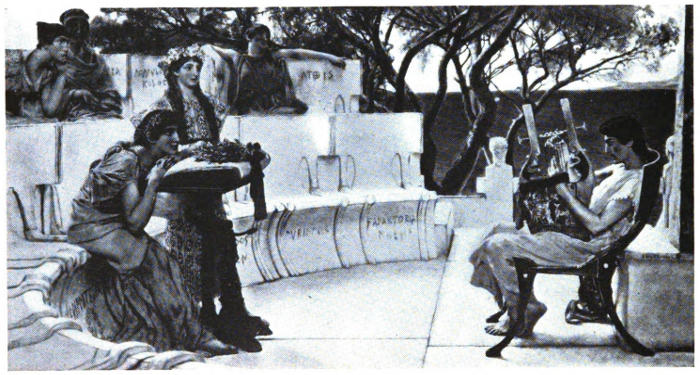

Olympiad (612-608 B.C.),38 along with Alcaeus and

Stesichorus and Pittacus,39 (Pl. 2) the latter, one[22]

of the seven wise men of Greece and lord of Lesbus.

This would indicate that she was then in

her poetic prime. If so, she must have been born

about 630 B.C. or earlier. Mackail dates her

birth as far back as the middle of the seventh

century. These early dates given above are

amply confirmed by her explicit reference to

Sardis and by her descriptions of the luxurious

life of the Lydians (E.40 20, 38, 86, 130, etc.)

which have lately been made so realistic by the

American excavations with their finds of gold

staters of Croesus, beautiful Lydian seals,

jewelry, pottery, and inscriptions.

In the seventh century after the founding of

Naucratis, about 650 B.C., many Mytilenaeans

migrated to Naucratis and engaged in trade in

wine and other products.41 Among these was

included, as Herodotus’ story shows, Sappho’s

brother Charaxus; the mention of his name

furnishes a further confirmation of the date we

have assumed, and proves that Sappho lived at

least after 572 B.C., the year of the accession to

the throne of Egypt of Amasis, in whose reign

Herodotus42 says that Rhodopis flourished.

This would make Sappho’s age at the time about

sixty and justify the epithet of “old” which

she applies to herself in the poem given in[23]

Edmonds 99. Fragment 42 in Edmonds seems to

say “age now causeth a thousand twisted wrinkles

to make their track along my face.”43 Stobaeus44

tells how one evening over the wine

Solon’s nephew, Execestides, sang to him a song

by Sappho, and Solon requested him to teach it

to him that he might learn it before he died.

Now Solon was one of the seven to whom

Pittacus also belonged. He died about 559 B.C.

at the age of eighty, and the incident serves to

indicate that Sappho’s poems were coming into

vogue among the young Athenians in Solon’s

old age.

Sappho’s birthplace was Eresus,45 the birthplace

also of Aristotle’s famous pupil Theophrastus.

She early moved to Mytilene (Pl. 3),

chief city of Lesbus. Lesbus had been renowned

for lovely ladies from Homer’s day, when beauty

contests were held there, as they have been

down to the present time. It had also been

famous from early days for its sweet wine.

Many an ancient author speaks of this wholesome

tipple, and to-day a thirsty traveller is

delighted to sit in a café on the quay and drink

a glass of the fine modern κρασὶ τῆς Μιτυλήνης.

Lesbus was so near to Lydia that it could not

help absorbing some of the Ionian and Lydian[24]

luxury. No one has better described the

position of Lesbus in Greek literature than

Symonds:46

“For a certain space of time the Aeolians occupied

the very foreground of Greek literature, and

blazed out with a brilliance of lyrical splendor that

has never been surpassed. There seems to have

been something passionate and intense in their

temperament, which made the emotions of the

Dorian and the Ionian feeble by comparison.

Lesbos, the centre of Aeolian culture, was the

island of overmastering passions: the personality

of the Greek race burned there with a fierce and

steady flame of concentrated feeling. The energies

which the Ionians divided between pleasure, politics,

trade, legislation, science, and the arts, and

which the Dorians turned to war and statecraft and

social economy, were restrained by the Aeolians

within the sphere of individual emotions, ready to

burst forth volcanically. Nowhere in any age of

Greek history, or in any part of Hellas, did the love

of physical beauty, the sensibility to radiant scenes

of nature, the consuming fervor of personal feeling,

assume such grand proportions and receive so illustrious

an expression as they did in Lesbos. At

first this passion blossomed into the most exquisite

lyrical poetry that the world has known; this was

the flower-time of the Aeolians, their brief and

brilliant spring. But the fruit it bore was bitter

and rotten. Lesbos became a byword for corruption.

The passions which for a moment had flamed

into the gorgeousness of art, burning their envelope

of words and images, remained a mere furnace of

sensuality, from which no expression of the divine[25]

in human life could be expected. In this the Lesbian

poets were not unlike the Provençal troubadours,

who made a literature of love, or the Venetian

painters, who based their art upon the beauty of

color, the voluptuous charms of the flesh. In each

case the motive of enthusiastic passion sufficed to

produce a dazzling result. But as soon as its freshness

was exhausted there was nothing left for art to

live on, and mere decadence to sensuality ensued.”

“Several circumstances contributed to aid the

development of lyric poetry in Lesbos. The customs

of the Aeolians permitted more social and

domestic freedom than was common in Greece.

Aeolian women were not confined to the harem

like Ionians, or subjected to the rigorous discipline

of the Spartans. While mixing freely with male

society, they were highly educated, and accustomed

to express their sentiments to an extent unknown

elsewhere in history—until, indeed, the present

time. The Lesbian ladies applied themselves successfully

to literature. They formed clubs for the

cultivation of poetry and music. They studied the

arts of beauty, and sought to refine metrical forms

and diction. Nor did they confine themselves to

the scientific side of art. Unrestrained by public

opinion, and passionate for the beautiful, they

cultivated their senses and emotions, and indulged

their wildest passions. All the luxuries and elegancies

of life which that climate and the rich

valleys of Lesbos could afford were at their disposal;

exquisite gardens, where the rose and hyacinth

spread perfume; river-beds ablaze with the

oleander and wild pomegranate; olive-groves and

fountains, where the cyclamen and violet flowered

with feathery maiden-hair; pinetree-shadowed coves,[26]

where they might bathe in the calm of a tideless

sea; fruits such as only the southern sun and sea-wind

can mature; marble cliffs, starred with jonquil

and anemone in spring, aromatic with myrtle and

lentisk and samphire and wild rosemary through

all the months; nightingales that sang in May;

temples dim with dusky gold and bright with

ivory; statues and frescoes of heroic forms. In

such scenes as these the Lesbian poets lived, and

thought of love. When we read their poems, we

seem to have the perfumes, colors, sounds, and

lights of that luxurious land distilled in verse.

Nor was a brief but biting winter wanting to give

tone to their nerves, and, by contrast with the

summer, to prevent the palling of so much luxury

on sated senses. The voluptuousness of Aeolian

poetry is not like that of Persian or Arabian art.

It is Greek in its self-restraint, proportion, tact.

We find nothing burdensome in its sweetness. All

is so rhythmically and sublimely ordered in the

poems of Sappho that supreme art lends solemnity

and grandeur to the expression of unmitigated

passion.”

A young woman of good birth in such surroundings

would be sure to have her love-affairs.

When Sappho was at the height of her fame in

young womanhood, the poet Alcaeus, her townsman,

was also in his glory. We are not told

whether he was older or younger than she, but

probably Sappho was the older and lived before

the political disorders which led to her exile from

Lesbus. Alcaeus was said, perhaps wrongly, to[27]

be her lover. The story is based on the verses

quoted by Aristotle in his Rhetoric,47 “pure

Sappho, violet-weaving and gently smiling, I

would fain tell you something did not shame

prevent me,” to which Sappho replied, “If your

desire were of things good or fair, and your

tongue were not mixing a draught of ill words,

then would not shame possess your eye, but

you would make your plea outright” (Edmonds).

Tradition even in classic times represented

her as beloved by Anacreon also,48 but

the bard of Teos flourished at least fifty years

after the Lesbian poetess. Archilochus and

Hipponax, the famous iambic satiric poets, the

former dead before Sappho was born, the latter

born after she was dead, were also represented

as her lovers by Diphilus,49 the Athenian comic

playwright in his play Sappho. But as Athenaeus

in the third century A.D. said, “I rather

fancy he was joking.”

Mackail says that “she was married and had

one or more children,” and many of the new

fragments, as well as Ovid, indicate this. A

fragment long known says:

I have a maid, a bonny maid,

As dainty as the golden flowers,

My darling Cleïs. Were I paid

[28]

All Lydia, and the lovely bowers

Of Cyprus, ’twould not buy my maid.

(Tucker)

Professor Prentice50 translates this fragment

(E. 130), “there is a pretty little girl named

Cleïs whom I love,” etc., and says that it does

not refer to her own daughter. But there is

no word for love in the Greek passage, and the

ancient interpretation of Maximus of Tyre51 is

preferable, especially as Cleïs is definitely mentioned

by Suidas and as the name reappears as

that of a young woman in another of the old

fragments and in one of the new pieces.52 The

matter seems now to be settled by the recent

discovery on a papyrus (about 200 A.D.) of a

new late prose biography of Sappho which is

so important a source for her life that a literal

translation of it is here given, especially as it

is not in Edmonds’ Lyra Graeca.53

“Sappho by birth was a Lesbian and of the

city of Mytilene and her father was Scamandrus

or according to some Scamandronymus. And

she had three brothers, Eurygyius, Larichus,

and the eldest, Charaxus, who sailed to Egypt

and as an associate with a certain Doricha spent

very much on her; but Sappho loved more[29]

Larichus, who was young. She had a daughter

Cleïs with the same name as her own mother.

She has been accused by some of being disorderly

in character and of being a woman-lover.

In shape she seems to have proved contemptible

and ugly, for in complexion she was dark, and

in stature she was very small; and the same

has happened in the case of ... who was

undersized.”

The man whom Sappho married, she herself

also being a person of some means, was said to

be Cercylas, a man of great wealth from the

island of Andrus. Cercylas sounds like concocted

comic chaff, but we can believe enough

of the tradition to say that she was married. A

Russian scholar54 made her a widow at thirty-five.55

Thereafter she sought for love and

companionship among the girls whom she made

members of her salon and instructed in the arts.

Sappho must have had a wonderful personality

or she could not have attracted so many pupils

and companions whom she trained to chant

or sing in the choruses for the marriage ceremony

and for other occasions. She was president of

the world’s first woman’s club. It was a thiasos

or a kind of sacred sorority to which the members

were bound by special ties and regulations.[30]

We have a long list of the members who were

her friends and pupils, not only from Lesbus

but from Miletus, Colophon, Pamphylia, and

even Salamis and Athens. For some of them

she had an ardent passion. When they left her,

she missed them terribly (E. 43, 44, 46). “Is

it possible for any maid on earth to be far apart

from the woman she loves?” She was so jealous

at times that she spited her wrath on her

rivals, especially Gorgo and Andromeda. She

“had enough of Gorgo,” and she scolds Atthis

for having come to hate the thought of her and

for flitting after Andromeda in her stead (E. 55,

81). Suidas tells us that she had three companions

or friends, Atthis, Telesippa, and Megara,

to whom she was slanderously declared to

be attached by an impure affection; and that

her pupils or disciples were Anagora (Anactoria)

of Miletus, Gongyla (the dumpling) of Colophon,

Euneica of Salamis. Ovid mentions

Atthis, Cydro, and Anactoria, the name which

Swinburne took for his poem in which he welded

together many of Sappho’s fragments with fine

expression and passionate thought. Maximus

of Tyre (xxiv, 9) says: “What Alcibiades,

Charmides, and Phaedrus were to Socrates,

Gyrinna, Atthis and Anactoria were to Sappho,[31]

and what his rival craftsmen, Prodicus, Gorgias,

Thrasymachus and Protagoras were to Socrates,

that Gorgo and Andromeda were to Sappho,

who sometimes takes them to task and at others

refutes them and dissembles with them exactly

like Socrates” (Edmonds). Philostratus in his

Life of Apollonius of Tyana56 tells of Sappho’s

brilliant pupil Damophyla of Pamphylia who is

said to have had girl-companions like Sappho

and to have composed love-poems and hymns

just as she did, with adaptations from the lectures

of her professor. Her own fragments

mention Anactoria, Atthis, Gongyla, Gyrinno

(which perhaps means Little Tadpole),

“Mnasidica, of fairer form than the dainty

Gyrinno” (E. 115), and possibly Eranna.57

One fragment says, “Well did I teach Hero of

Gyara, the fleetly-running maid” (E. 73). If

this is the famous Hero of the Hero and Leander

story so often pictured in Greek art and on coins

of Abydus, Sappho knew the story of two king’s

children who loved one another long before the

days of the painter Apelles.58 Sappho’s school

of poetry in modern times has been prettily

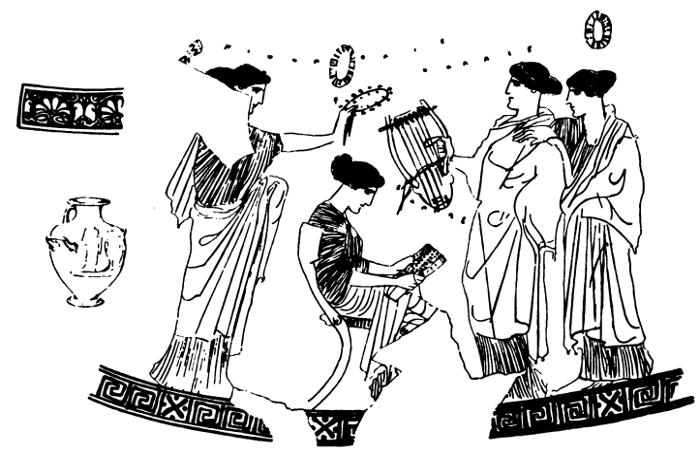

pictured in a painting by Hector Leroux (p. 118),

but the best representation of what her school

may have been is given by Alma Tadema (Pl. 1)[32]

in his academic and learned classical painting

“Sappho” in the Walters’ Art Gallery in Baltimore.

Archaic Greek inscriptions, of interest

to the specialist in epigraphy, can be read on

the marble seats of the theatre at Mytilene

represented in the picture,—the names of Erinna

of Telos, Gyrinno, Anactoria of Miletus, Atthis,

Gongyla of Colophon, Dika (short for Mnasidica),

and others. I quote the beautiful appreciation

which Professor Gildersleeve has

published:59

“A semi-circle of marble seats, veined and

stained, a screen of olive trees that fling their

branches against the sky, and against the sapphire

seas, a singing man, a listening woman, whose

listening is so intense that nothing else in the

picture seems to listen—not the wreathed girl in

flowered robe who stands by her and rests her hand

familiarly on her shoulder. Not she, for though

she holds a scroll in her other hand, the full face,

the round eyes, show a soul that matches wreathed

head and flowered robe. She is the pride of life.

Nor she on the upper seat, who props her chin with

her hand and partly hides her mouth with her fingers

and lets her vision reach into the distance of her

own musings. Nor her neighbor whose composed

attitude is that of a regular church-goer who has

learned the art of sitting still and thinking of

nothing. Nor yet the remotest figure—she who

has thrown her arms carelessly on the back of the

seat and is looking out on the waters as if they[33]

would bring her something. A critic tells us that

the object of the poet is to enlist Sappho’s support

in a political scheme of which he is the leader, if

not the chief prophet, and he has come to Sappho’s

school in Lesbos with the hope of securing another

voice and other songs to advocate the views of his

party. The critic seems to have been in the artist’s

secret, and yet Alma Tadema painted better than

he knew. Alkaios is not trying to win Sappho’s

help in campaign lyrics. The young poet is singing

to the priestess of the Muses a new song with a

new rhythm, and as she hears it, she feels that

there is a strain of balanced strength in it she has

not reached: it is the first revelation to her of the

rhythm that masters her own. True, when Alkaios

afterwards sought not her help in politics, but her

heart in love, and wooed her in that rhythm, she

too had caught the music and answered him in his

own music.”

[34]

III. THE LEGENDARY FRINGE

Sappho’s Physical Appearance, The Phaon

Story, The Vice Idea

So far we have been dealing with

ascertained facts, reasonable inferences as

to other facts, and strong probabilities:

in a word, with the real Sappho so far as her

history can be made out with at least some

measure of certainty. There is, however, a

legendary fringe attaching to every great outstanding

personality. It is one of the penalties

of personal or literary greatness to become the

centre of fanciful stories, personal detraction,

misrepresentation, and wild legends often conceived

in a most grotesque and improbable

fashion. To all this Sappho is no exception.

First the question will be discussed whether she

was a dwarf. The famous and far-flung story

of Phaon and the Leucadian Leap will then

claim our mention, and thirdly a word must be

said about her character.

According to Damocharis60 Sappho had a

beautiful face and bright eyes. The famous[35]

line of Alcaeus refers to her gentle smile. So

Burns in his Pastoral Poetry says, “In thy sweet

voice, Barbauld, survives even Sappho’s flame.”

Plato calls her beautiful as does many another

writer, though the epithet may refer, as Maximus

of Tyre says, to the beauty of her lyrics, one of

which practically says long before Goldsmith,

“handsome is that handsome does” (E. 58).

The word which Alcaeus employs does not necessarily

mean that she had violet tresses as

Edmonds translates it. It has generally been

rendered as violet-weaving, and it is to be regretted

that P. N. Ure without evidence, in his

excellent book entitled The Greek Renaissance

(London, 1921), tells us that Sappho had black

hair, even if Mrs. Browning does speak of

“Sappho, with that gloriole of ebon hair on

calmèd brows.” Tall blondes were popular in

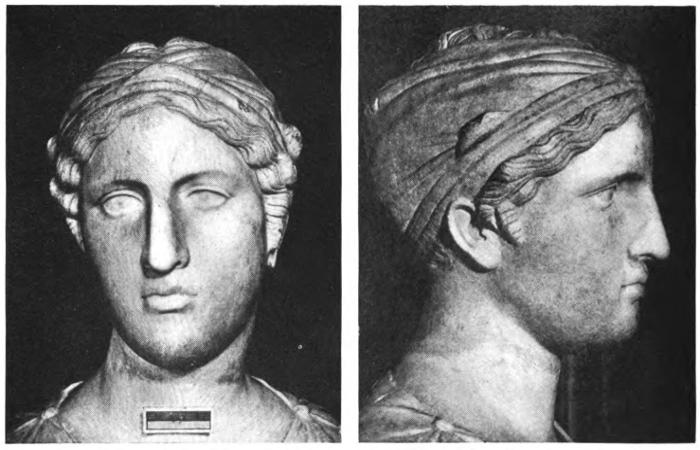

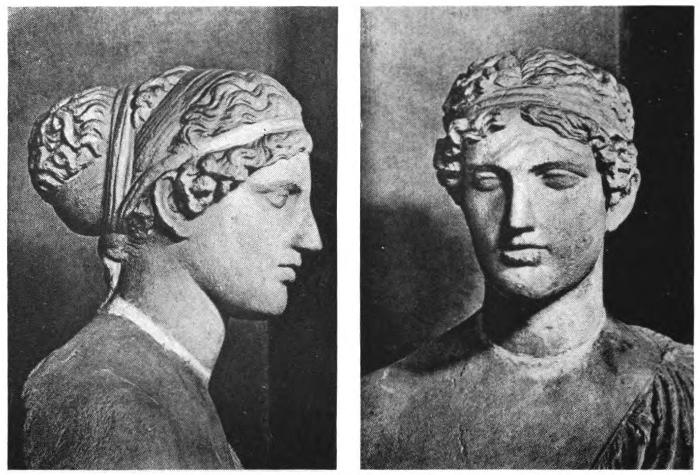

ancient days and Sappho was neither divinely

tall nor most divinely fair. But the ancient

busts, the representations of her as full-sized,

on coins of Lesbus and on many Greek vases,

belie the idea of the rhetorical Maximus of

Tyre who in the second century A.D. labelled

her “small and dark,” an idea that occurs also

in the new papyrus which we have already

quoted. Some have even interpreted her name[36]

as derived from Ψᾶφος, “Little Pebble,” i.e.,

short of stature. Undoubtedly the epithet of

Maximus reflects the Roman perverted idea

which finds expression in Ovid’s apology

for her appearance. The scholiast on Lucian’s

Portraits61 is repeating the same source when

he says “physically, Sappho was very ill-favored,

being small and dark, like a nightingale

with ill-shapen wings enfolding a tiny body.”

The famous fragment,

This little creature, four feet high,

Cannot hope to touch the sky,

(Edmonds)

may not refer to Sappho, and if it does, we must

remember, that Edmonds’ new reading is doubtful.

Perhaps Horace was thinking of this line

when he wrote62

sublimi feriam sidera vertice,

which recalls Tennyson’s

Old Horace! I will strike, said he,

The stars with head sublime.

(Epilogue)

Edmonds forces the meaning of the Greek to

get even four feet out of his new restoration.[37]

Sappho was surely taller than that and there is

no evidence earlier than Roman days to justify

even Swinburne’s

The small dark body’s Lesbian loveliness

That held the fire eternal.

In any case Sappho was no dwarf, otherwise

her deformity would not have escaped the

notice of the Athenian comic mud-slingers and

scandal-mongers who did so much to spoil her

good name. Such is the traditional, not the

real, human, historical Sappho of the sixth

century B.C.

The story of Sappho’s love for Phaon is

patently mythological, as indicated by the

legend of his transformation by Aphrodite from

an old man into a handsome youth. There can

be only slight historic foundation for connecting

Sappho with him and making Sicily the

scene of their first meeting. An inscription on

the Parian marble in Oxford says: “When Critius

the First was archon at Athens Sappho

fled from Mytilene and sailed to Sicily.” The

date is uncertain as there is a lacuna in the

inscription, but it is between 604 and 594 B.C.,

perhaps about 598. The recently discovered

hymn to Hera, Longing for Lesbus, lends support[38]

to this story of exile. She may have been

banished by Pittacus for engaging like Alcaeus

in political intrigues. She probably returned

to Lesbus under the amnesty of 581, as her grave

is often mentioned as in Lesbus. There is even

a tradition preserved by the English traveller

Pococke that her own sepulchral urn was once

in the Turkish mosque of the castle of Mytilene.

We have already cited one or two fragments

which seem to show that she had more than

reached middle age. She was old enough to feel

that she should not re-marry, especially if she

had to choose one younger than herself.63 Fragment

(E. 99) is in the style of Shakespeare’s

“Crabbed age and youth cannot live together.”

Nowhere in her poems is there any evidence

that she committed suicide for love of Phaon,

but as her name has started this legend we must

speak of it in some detail. The famous fragment

(E. 108), to judge from the context

where it is quoted in connection with Socrates’

death, seems to give her last words: “It is

not right that there be mourning in the house

of poetry; this befits us not.”

Now let us discuss the supposititious love

affair, to which we have referred, about which

I share the ancient and modern Lesbian doubt.[39]

The ancients tell of Sappho’s unrequited love

for the ferryman prototype of St. Christopher,

the beautiful Phaon. The story is well given

in Servius’ précis of Turpilius’ Latin paraphrase

of Menander,64 though he does not mention

Sappho by name: “Phaon, who was a ferryman

plying for hire between Lesbus (others

say he was from Chios65) and the mainland,

one day ferried over for nothing the Goddess

Venus in the guise of an old woman, and

received from her for the service an alabaster

box of unguent, the daily use of which made

women fall in love with him. Among those who

did so was one who in her disappointment is

said to have thrown herself from Mount Leucates,

and from this came the custom now in

vogue of hiring people once a year to throw themselves

from that place into the sea.” (Edmonds).

But neither Phaon nor anything connected with

Phaon is mentioned in any of Sappho’s fragments,

though Francis Fawkes and others have

connected Phaon’s name with the Hymn to

Aphrodite. A writer of the second century B.C.,

Palaephatus,66 makes the very inconsistent

statement that “this is the Phaon in whose

honor as a lover many a song has been written

by Sappho.” Nor is there any allusion to[40]

Sappho’s curing her passion by leaping from the

white Leucadian cliff. Athenaeus67 and Suidas

go so far as to say that the victim was another

Sappho, and even in the late lists of Leucadian

leapers, in Photius, Sappho is not included.

Who first conjured up a Phaon, we know not,

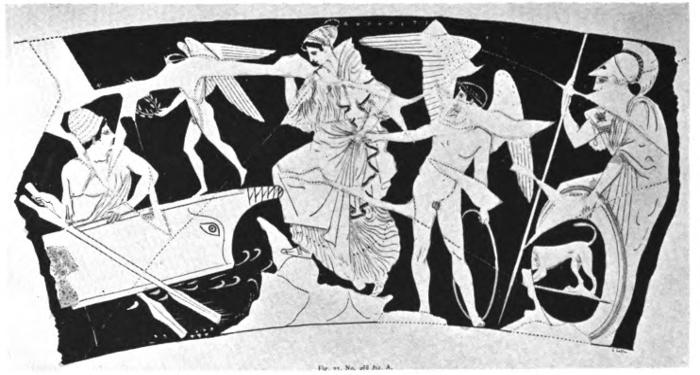

but the story belongs to folk-lore, and Phaon

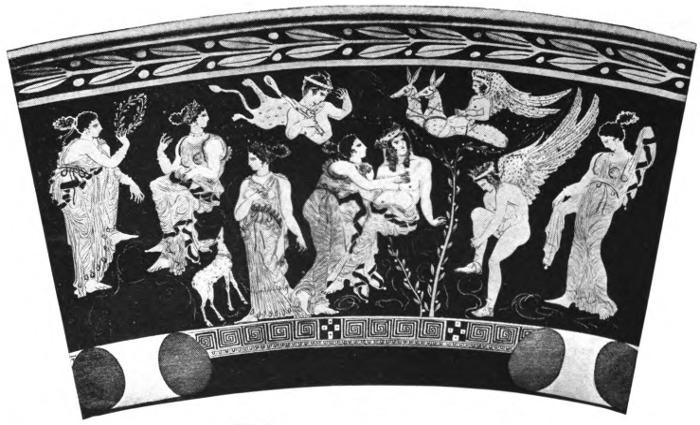

appears on Greek vases of the time and style

of Meidias, who is dated by most archaeologists

toward the end of the fifth century B.C.,

much earlier than Plato’s play (392 B.C.). His

indifference to the many ladies who are making

love to him is well portrayed, especially on

vases (Pl. 4, 5) in Florence and Palermo (p. 107)68.

The fair Phaon, Aphrodite’s shining star (φάων =

shining), is only another avatar of Adonis, who

appears in similar style on similar vases,

one even found in the same grave with

a Phaon vase. Phaon, I believe, is as

old as the fifth century; but the story of

Sappho’s leap transferred to the white cliffs in

the south of the white island of Leucas,

the modern Cape Ducato, is later. The Cape

is also called Santa Maura, some two hundred

feet high, and even to-day this rock of desperation

is haunted by Sappho’s ghost and known as

Sappho’s Leap (Pl. 6). The legend of the Lesbian’s[41]

leap first occurs in the poet of the Old

Comedy, Plato, who wrote the play called Phaon.

Later in the New Comedy, Menander was probably

adorning an old tale to point a contemporary

moral when he produced his Leucadia of which

Turpilius, a contemporary of Terence, wrote a

Latin paraphrase. A few anapaestic lines are

preserved by Strabo, who speaks of the Leucadian

Cliff:

Where Sappho ’tis said the first of the world

In her furious chase of Phaon so haughty

All maddened with longing plunged down from the height

Of the shimmering rock.

(D. M. R.)

Antiphanes probably told the story in both his

Leucadius and his Phaon; and Cratinus must

have mentioned Phaon, for Athenaeus69 tells us

that he told how Aphrodite, beloved by Phaon,

concealed him among the fair wild lettuce, just

as other writers say Adonis was hidden.

The practice of abandoned lovers taking the

leap may possibly have been known even in

Sappho’s day, for Stesichorus tells of a girl

throwing herself from a cliff near Leucas because

a youth had scorned her. By the time

of Anacreon (550 B.C.), the leap had become the[42]

symbol of a love passion that could no longer

be borne; “Lifted up from the Leucadian rock,

I dive into the hoary wave, drunk with Love.”

It is the same old story told at every summer

resort about some place called Lover’s Leap, but

in Anacreon nothing is said about drowning.

And legend70 says that sometimes wings or

feathers were attached to the person jumping

off the cliff to lighten the fall. In any case the

leap, legendary or not, was not suicide but a

desperate remedy, killing or curing, for hopeless

love. We hear of many who survived the

expiatory leap.

In a stucco fresco71 (Pl. 7) (not later than 40

A.D.) in the half dome of the apse at one end of the

underground building in Rome near the Porta

Maggiore, which served for the cult of some secret

neo-Pythagorean sect or possibly as a temple

of the Muses or possibly only as the underground

summer abode of an enthusiast over Greek

poets like the newly discovered underground

rooms of the Homeric enthusiast at Pompeii,

we have possibly an illustration of the Leucadian

leap, at least in symbolism, as personifying

the parting of the image of the soul. Sappho,

lyre in hand, is springing from the misty cliff,

which Ausonius mentions in his sixth idyl[43]

(cf. p. 131), and below in the sea is a Triton spreading

out a garment to break her fall. Opposite

on a height stands Apollo, who had a temple

on the spot and to whom according to Ovid’s

Fifteenth Heroic Epistle Sappho promised to

dedicate her lyre if he was propitious. Ovid is

the first writer from whom we have the story in

detail. It was often used in later literature,

as we shall see in a succeeding chapter.

Many know Pope’s translation of Ovid,72 but

if my readers desire to read an imaginative and

humorous circumstantial account of Sappho’s

leap, on which the modern popular idea is

mostly based, they may find it in Addison’s

Spectator, No. 233, November 27, 1711.

The moral purity of Sappho shines in its own

light. She expresses herself, no doubt, in very

passionate language, but passionate purity is a

finer article than the purity of prudery, and

Sappho’s passionate expressions are always

under the control of her art. A woman of bad

character and certainly a woman of such a

variety of bad character as scandal (cf. p. 128

and note 147) has attributed to Sappho might

express herself passionately and might run on

indefinitely with erotic imagery. But Sappho

is never erotic. There is no language to be[44]

found in her songs which a pure woman might

not use, and it would be practically impossible

for a bad woman to subject her expressions to

the marvellous niceties of rhythm, accent, and

meaning which Sappho everywhere exhibits.

Immorality and loss of self-control never subject

themselves to perfect literary and artistic taste.

It is against the nature of things that a woman

who has given herself up to unnatural and inordinate

practices which defy the moral instinct

and throw the soul into disorder, practices which

harden and petrify the soul, should be able to

write in perfect obedience to the laws of vocal

harmony, imaginative portrayal, and arrangement

of the details of thought. The nature of

things does not admit of such an inconsistency.

Sappho’s love for flowers, moreover, affords

another luminous testimony. A bad woman as

well as a pure woman might love roses, but a

bad woman does not love the small and hidden

wild flowers of the field, the dainty anthrysc

and the clover, as Sappho did. There is, moreover,

in a life of vice something narrowing as

well as coarsening. An imagination which like

Sappho’s sees in a single vision the moonlight

sweeping the sea, breaking across the shore and

illuminating wide stretches of landscape with[45]

life-giving light, and in the midst of all this far-spreading

glory sees and personifies the spirit

of the night, listening to the moanings of homesickness

and repeating them with far-flung voice

to those across the sea,—an imagination with

such a marvellous range as this is never given

to the child of sodden vice. Here once more is

a woman who made it her life business to adorn

and even to glorify lawful wedlock, and carried

on this occupation in a sympathetic and delightful

strain of dance and song which, however

passionate in their expression, contain no impure

words. It is simply unthinkable that such

a woman should be perpetually destroying the

very foundations of her own ideals.

[46]

IV. THE WRITINGS OF SAPPHO

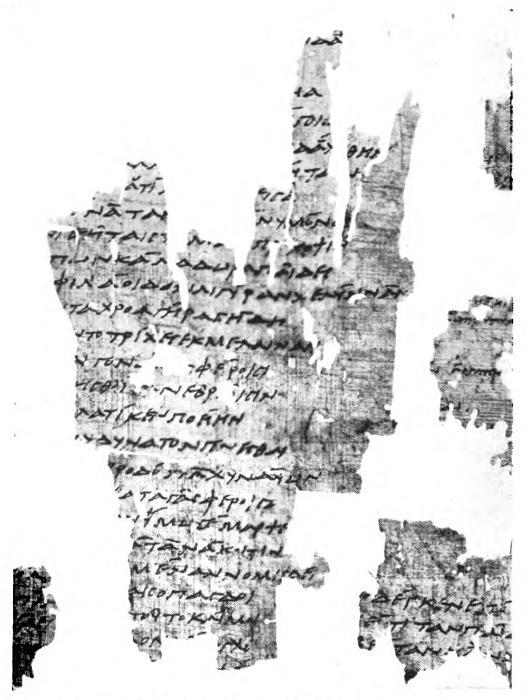

The number of poems or fragments

(Pl. 8) of Sappho has increased from a

hundred and twenty in Volger’s edition

(1810) to a hundred and ninety-one in Edmonds.

“Though few they are roses,” and a marvellous

vitality and mentality permeates their mangled

and marred members. Sappho probably had

her own collection of her poems, but they were

surely not published in a large edition as has

sometimes been said. An introductory poem is

possibly preserved on an Attic vase, but even

of that we cannot be sure. In Roman days

there were two editions, one arranged according

to subject and the other according to metre,

both based on some Alexandrian source much

earlier than the book On the Metres of Sappho,

published by Dracon of Stratonicea about

180 A.D. Sappho wrote many forms of literature

in many different metres, cult hymns or

odes, marriage songs, scolia or drinking songs,

songs of love and friendship, besides her nine

books of lyrics, epigrams, elegies, none of which

has survived or been described by any other[47]

author, iambics, monodies, and funeral songs

like that for Adonis. The Athenian dramatists

even pictured her as proposing puzzles and

riddles. Colombarius, as quoted by Meursius in

his notes on Hesychius, called Sappho the poetess

of the Trojans, the meaning of which has

recently been made clear by the discovery of the

Marriage of Hector and Andromache.

The first poem is the Ode to Aphrodite which

was cited by Dionysius of Halicarnassus for its

finished and brilliant style,—the style used by

Euripides among the tragedians and by Isocrates

among the orators. Though the rhythm, ardor,

terseness, and noble simplicity can be given in no

translation,73 nearly every lover of Greek lyrics

has tried his hand at it. Ambrose Philips made

thirty-four words out of the first stanza which

in the Greek has only sixteen; Merivale found

forty-three words necessary; but Tucker and

Leonard with strict compression and simplicity

manage to translate with twenty-three; Gildersleeve

in an unpublished version which I also

quote here, and Fairclough use twenty-four:

Broidered-throned goddess, O Aphrodite,

Child of Zeus, craft-weaving, I do beseech thee,

Do not crush my soul with distress and sorrow,

Wholly my mistress.

[48]

Rather come, if ever didst come aforetime,

Hearkening to my cry from afar in mercy;

And didst leave the palace of thine own father

Golden and gorgeous;

And didst yoke thy chariot, swift thy sparrows

Drew thee, beauteous sparrows, to earth’s dark surface,

Moving quick their wings from the height of heaven

Through the mid ether.

Soon their journey’s end was attained and smiling

Blessed goddess, smiling with heavenly visage,

Thou didst ask of me what it was I suffer’d,

Why I invoked thee,

What it was I wished to receive of all things,

Maddened in my soul, ‘Who is he thou seekest,

Whom shall I ensnare for my darling Sappho?

Who is it grieves thee?’

‘Nay, if thou but flee he will soon pursue thee,

If he get no presents, he’ll give thee presents,

If thou love him not, he will love thee quickly,

E’en if thou wilt not.’

Come then now again and relieve me, goddess,

From my carking cares and whate’er my spirit

Longeth for accomplish, and on my side do

Battle, my mistress;

(Gildersleeve)

or, with the translation of doves for sparrows:

[49]

Guile-weaving child of Zeus, who art

Immortal, throned in radiance, spare,

O Queen of Love, to break my heart

With grief and care.

But hither come, as thou of old,

When my voice reached thine ear afar,

Didst leave thy father’s hall of gold,

And yoke thy car,

And through mid air their whirring wing

Thy bonny doves did swiftly ply

O’er the dark earth, and thee did bring

Down from the sky.

Right soon they came, and thou, blest Queen,

A smile upon thy face divine,

Didst ask what ail’d me, what might mean

That call of mine.

‘What would’st thou have, with heart on fire,

Sappho?’ thou saidst. ‘Whom pray’st thou me

To win for thee to fond desire?

Who wrongeth thee?

Soon shall he seek, who now doth shun;

Who scorns thy gifts, shall gifts bestow;

Who loves thee not, shall love anon,

Wilt thou or no.’

So come thou now, and set me free

From carking cares; bring to full end

My heart’s desire; thyself O be

My stay and friend!

[50]

Here follow two translations where “he” is

changed to “she” in the sixth stanza. The

controversy as to the sex of the belovèd turns

on the admission or omission of a single letter

in the Greek.

Deathless Aphrodite, throned in flowers,

Daughter of Zeus, O terrible enchantress,

With this sorrow, with this anguish, break my spirit,

Lady, not longer!

Hear anew the voice! O hear and listen!

Come, as in that island dawn thou camest,

Billowing in thy yokèd car to Sappho

Forth from thy father’s

Golden house in pity!... I remember:

Fleet and fair thy sparrows drew thee, beating

Fast their wings above the dusky harvests,

Down the pale heavens,

Lighting anon! And thou, O blest and brightest,

Smiling with immortal eyelids, asked me:

‘Maiden, what betideth thee? Or wherefore

Callest upon me?

‘What is hers the longing more than others,

Here in this mad heart? And who the lovely

One belovèd thou wouldst lure to loving?

Sappho, who wrongs thee?’

[51]

‘See, if now she flies, she soon must follow;

Yes, if spurning gifts, she soon must offer;

Yes, if loving not, she soon must love thee,

Howso unwilling....’

Come again to me! O now! Release me!

End the great pang! And all my heart desireth

Now of fulfilment, fulfil! O Aphrodite,

Fight by my shoulder!

(W. E. Leonard, unpublished)

Richly throned, O deathless one, Aphrodite,

Child of Zeus, enchantress-queen, I beseech thee

Let not grief nor harrowing anguish master,

Lady, my spirit.

Ah! come hither. Erstwhile indeed thou heardest

When afar my sorrowful cry of mourning

Smote thine ears, and then from thy father’s mansions

Golden thou camest,

Driving forth thy chariot, and fair birds bore thee

Speeding onward over the earth’s dark shadows,

Waving oft their shimmering plumes thro’ heaven’s

Ether encircling.

Quickly drew they nigh me, and thou, blest presence,

Sweetest smile divine on thy face immortal,

Thou didst seek what sorrow was mine to suffer,

Wherefore I called thee.

[52]

What my soul, too, craved with intensest yearning,

Frenzy’s fire enkindling. ‘Now whom,’ thou criest,

‘Wouldst thou fain see led to thy love, or who, my

Sappho, would wrong thee?’

‘Though she flees thee now, yet she soon shall woo thee,

Though thy gifts she scorneth, she soon shall bring gifts;

Though she loves thee not, yet she soon shall love thee,

Yea, though unwilling.’

Come, ah! come again, and from bitter anguish

Free thy servant. All that my heart is craving,

That fulfil, O goddess. Thyself, my champion,

Aid in this conflict.

(H. Rushton Fairclough)

The second ode, quoted in a mutilated condition

by the treatise On the Sublime, is even

more difficult to translate. As Wordsworth

says, here

the Lesbian Maid

With finest touch of passion swayed

Her own Aeolian lute.

In its rich Aeolian dialect the ode glows with

true Greek fire. Sappho’s words are clear but

far from cold. They are a sea of glass, but a[53]

sea of glass mingled with fire such as the Patmos

seer saw from his island not far from Sappho’s

Lesbian home. They enable us to understand

why Byron in Don Juan speaks of “the isles of

Greece where burning Sappho loved and sung.”

This is what Swinburne means, when he speaks

of the fire eternal and in his Sapphics says that

about her “shone a light of fire as a crown for

ever.” We know from Plutarch75 that an

ancient physician, Erasistratus, included this

ode (which has influenced realistic descriptions

of passion from Euripides and Theocritus to

Swinburne and Sara Teasdale) in his book

of diagnoses as a compendium of all the symptoms

of corroding emotions. He applied this

psychological test whenever Antiochus looked on

Stratonice. “There appeared in the case of

Antiochus all those symptoms which Sappho

mentions: the choking of the voice, the feverish

blush, the obscuring of vision, profuse sweat,

disordered and tumultuous pulse and finally,

when he was completely overcome, bewilderment,

amazement and pallor.” Perhaps Sappho

was influenced by Homer’s76 description of fear

and she herself surely suggested such symptoms

to Lucretius.77 We must regard the ode primarily

as a literary product, but its pathological[54]

picture of passion is hardly secondary. Even

if the symptoms seem appalling to our cold and

unexpressive northern blood, we must remember

that this physical perturbation, as Tucker calls

it, was in no way strange to the ancients. Gildersleeve

put it well in his unpublished lecture

on Sappho, which he so kindly placed at my

disposal and to which I am greatly indebted:

“if a Greek melted, he melted with a fervent

heat, and if this is true of the average Greek

how much more was it true of an Aeolian and

an Aeolian woman, and of Sappho most Aeolian

of all.” Byron refers to this ode when he says

in Don Juan:

Catullus scarcely has a decent poem,

I don’t think Sappho’s Ode a good example,

Although Longinus tells us there is no hymn

Where the sublime soars forth on wings more ample.

With regard to Catullus’ rendering (LI), Swinburne

in his Notes on Poems and Reviews,

speaking of his poem Anactoria, says: “Catullus

translated or as his countrymen would now say

‘traduced’ the Ode to Anactoria; a more beautiful

translation there never was and will never

be; but compared with the Greek, it is colourless

and bloodless, puffed out by additions and[55]

enfeebled by alterations. Let anyone set against

each other the two first stanzas, Latin and Greek,

and pronounce.... Where Catullus failed I could

not hope to succeed; I tried instead to reproduce

in a diluted and dilated form the spirit

of a poem which could not be reproduced in

the body.”

Tennyson has given the best paraphrase in

Eleänore:

I watch thy grace; and in its place

My heart a charmed slumber keeps,

While I muse upon thy face;

And a languid fire creeps

Thro’ my veins to all my frame,

Dissolvingly and slowly: soon

From thy rose-red lips my name

Floweth; and then, as in a swoon,

With dinning sound my ears are rife,

My tremulous tongue faltereth,

I lose my color, I lose my breath,

I drink the cup of a costly death,

Brimm’d with delirious draughts of warmest life.

I die with my delight, before

I hear what I would hear from thee.

The following version I have based mainly on

Edmonds’ recent text,78 with a conjectural restoration

of the last stanza, of which only a few

words are preserved in the Greek:

[56]

O life divine! to sit before

Thee while thy liquid laughter flows

Melodious, and to listen close

To rippling notes from Love’s full score.

O music of thy lovely speech!

My rapid heart beats fast and high,

My tongue-tied soul can only sigh,

And strive for words it cannot reach.

O sudden subtly-running fire!

My ears with dinning ringing sing,

My sight is lost, a blinded thing,

Eyes, hearing, speech, in love expire,

My face pale-green, like wilted grass

Wet by the dew and evening breeze,

Yea, my whole body tremblings seize,

Sweat bathes me, Death nearby doth pass,

Such thrilling swoon, ecstatic death

Is for the gods, but not for me,

My beggar words are naught to thee,

Far-off thy laugh and perfumed breath.

(D. M. R.)

As J. A. K. Thomson says in his recent fascinating

book Greeks and Barbarians (London

and New York, 1921), “Sappho, in the most

famous of her odes, says that love makes her

‘sweat’ with agony and look ‘greener than[57]

grass.’ Perhaps she did not turn quite so green

as that, although (commentators nobly observe)

she would be of an olive complexion and had

never seen British grass. But even if it contain

a trace of artistic exaggeration, the ode as

a whole is perhaps the most convincing love-poem

ever written. It breathes veracity. It

has an intoxicating beauty of sound and suggestion,

and it is as exact as a physiological

treatise. The Greeks can do that kind of thing.

Somehow we either overdo the ‘beauty’ or we

overdo the physiology. The weakness of the

Barbarian, said they, is that he never hits the

mean. But the Greek poet seems to do it every

time. We may beat them at other things, but

not at that. And they do it with so little effort;

sometimes, it might happen, with none at all.”

The passion of love is the supreme subject of

Sappho’s songs, as shown by these first two and

many a short fragment, as for example (E. 81)

where Love is called for the first time in literature

“sweet-bitter.” Some scholars have

credited it to the much later Posidippus, but

he and Meleager took the word from Sappho,

though it may not have been original even with

her. Sappho’s order of the compound word is

generally reversed in translation, but Sir Edwin[58]

Arnold says “sweetly bitter, sadly dear,” and

Swinburne in Tristram of Lyonesse speaks of

“Sweet Love, that are so bitter.” Tennyson

also has the same order in Lancelot and Elaine

(pp. 205-206). To Sappho love is a second death,

and in the second ode death itself seems not

very far away. The Greek words for swooning

are mostly metaphors from death, and so we

are not surprised when we read that like death

love relaxes every limb and sweeps one away in

its giddy swirling, a sweet-bitter resistless wild

beast. Here is Sir Sidney Colvin’s translation

(John Keats, 1917, p. 332): “Love the

limb-loosener, the bitter-sweet torment, the

wild beast there is no withstanding, never

harried a more helpless victim.” Another

fragment (E. 54) also shows the power of love:

Love tossed my heart as the wind