Project Gutenberg's Peck's Bad Boy With the Cowboys, by George W. Peck This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Peck's Bad Boy With the Cowboys Author: George W. Peck Release Date: July, 2004 [EBook #6141] This file was first posted on November 19, 2002 Last Updated: October 5, 2016 Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PECK'S BAD BOY WITH THE COWBOYS *** Text file produced by Ralph Zimmerman, Charles Franks and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team Illustrated HTML file produced by David Widger

Author of Peck's Bad Boy Abroad, Peck's Bad Boy with the Circus, etc.

Relating the Amusing Experiences and Laughable Incidents of this Strenuous American Boy and his Pa while among the Cowboys and Indians in the Far West. Exciting Hunts and Adventures mingled with Humorous Situations and Laugh Provoking Events.

CONTENTS

The Bad Boy and His Pa Go West—Pa Plans to Be a Dead Ringer for Buffalo Bill—They Visit an Indian Reservation and Pa Has an Encounter with a Grizzly Bear.

Well, I never saw such a change in a man as there has been in pa, since the circus managers gave him a commission to go out west and hire an entire outfit for a wild west show, regardless of cost, to be a part of our show next year. He acts like he was a duke, searching for a rich wife. No country politician that never had been out of his own county, appointed minister to England, could put on more style than Pa does.

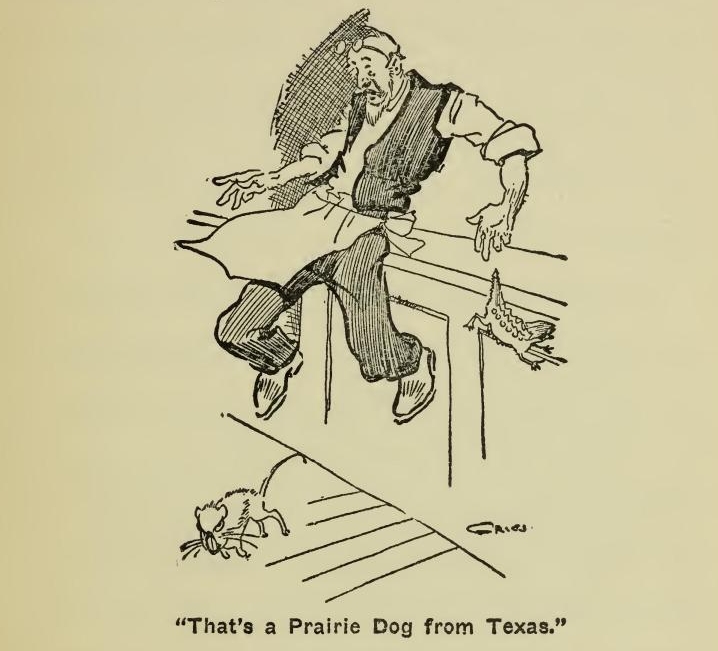

The first day after the show left us at St. Louis we felt pretty bum, 'cause we missed the smell of the canvas, and the sawdust, and the animals, and the indescribable odor that goes with a circus. We missed the performers, the band, the surging crowds around the ticket wagon, and the cheers from the seats. It almost seemed as though there had been a funeral in the family, and we were sitting around in the cold parlor waiting for the lawyers to read the will. But in a couple of days Pa got busy, and he hired a young Indian who was a graduate of Carlisle, as an interpreter, and a reformed cowboy, to go with us to the cattle ranges, and an old big game hunter who was to accompany us to the places where we could find buffalo and grizzly bears. Pa chartered a car to take us west, and after the Indian and the cowboy and the hunter got sobered up, on the train, and got the St. Louis ptomaine poison out of their systems, and we were going through Kansas, Pa got us all into the smoking compartment.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “I want you to know that this expedition is backed by the wealth of the circus world, and that there is nothing cheap about it. We are to hire, regardless of expense, the best riders, the best cattle ropers, and the best everything that goes with a wild west show. We all know that Buffalo Bill must soon, in the nature of things, pass away as a feature for shows, and I have been selected to take the place of Bill in the circus world, when he cashes in. You may have noticed that I have been letting my hair and mustache and chin whiskers grow the last few months, so that next year I will be a dead ringer for Bill. All I want is some experience as a hero of the plains, as a scout, a hunter, a scalper of Indians, a rider of wild horses, and a few things like that, and next year you will see me ride a white horse up in front of the press seats in our show, take off my broad-brimmed hat, and wave it at the crowned heads in the boxes, give the spurs to my horse, and ride away like a cavalier, and the show will go on, to the music of hand-clapping from the assembled thousands, see?”

The cowboy looked at pa's stomach, and said: “Well, Mr. Man, if you are going to blow yourself for a second Buffalo Bill, I am with you, at the salary agreed upon, till the cows come home, but you have got to show me that you have got no yellow streak, when it comes to cutting out steers that are wild and carry long horns, and you've got to rope 'em, and tie 'em all alone, and hold up your hands for judgment, in ten seconds.”

Pa said he could learn to do it in a week, but the cowman said: “Not on your life.” The hunter said he would be ready to call pa B. Bill when he could stand up straight, with the paws of a full-grown grizzly on each of his shoulders, and its face in front of pa's, if Pa had the nerve to pull a knife and disembowel the bear, and skin him without help. Pa said that would be right into his hand, 'cause he use to work in a slaughter house when he was a boy, and he had waded in gore.

The Indian said he would be ready to salute Pa as Buffalo Bill the Second, when Pa had an Indian's left hand tangled in his hair, and a knife in his right hand ready to scalp him, if Pa would look the Indian in the eye and hypnotize the red man so he would drop the hair and the knife, turn his back on pa, and invite him to his wigwam as a guest. Pa said all he asked was a chance to look into the very soul of the worst Indian that ever stole a horse, and he would make Mr. Indian penuk, and beg for mercy.

And we all agreed that Pa was a wonder, and then they got out a pack of cards and played draw poker awhile. Pa had bad luck, and when the Indian bet a lot of chips, Pa began to look the Indian in the eye, and the Indian began to quail, and Pa put up all the chips he had, to bluff the Indian, but Pa took his eye off the Indian a minute too quick, and the Indian quit quailing, and bet Pa $70, and Pa called him, and the Indian had four deuces and pa had a full hand, and the Indian took the money. Pa said that comes of educating these confounded red devils, at the expense of the government, and then we all went to bed.

The next morning we were at the station in the far west. We got off and started for the Indian reservation where the Carlisle Indian originally came from, and where we were to hire Indians for our show. We rode about 40 miles in hired buckboards, and just as the sun was Setting there appeared in the distance an Indian camp, where smoke ascended from tepees, tents and bark houses. When the civilized Carlisle Indian jumped up on the front seat of the buckboard and gave a series of yells that caused pa's bald head to look ashamed that it had no hair to stand on end, there came a war whoop from the camp, Indians, squaws, dogs, and everything that contained a noise letting out yells that made me sick. The Carlisle Indian began to pull off his citizen clothes of civilization, and when the horses ran down to the camp in front of the chief's tent the tribes welcomed the Carlisle prodigal son, who had removed every evidence of civilization, except a pair of football pants, and thus he reinstated himself with the affections of his race, who hugged him for joy.

Pa and the rest of us sat in the buckboard while the Indians began to feast on something cooking in a shack. We looked at each other for awhile, not daring to make a noise for fear it would offend the Indians. Pretty soon an old chief came and called Pa the Great Father, and called me a pup, and he invited us to come into camp and partake of the feast.

Well, we were hungry, and the meat certainly tasted good, and the Carlisle civilized Indian had no business to say it was dog, 'cause no man likes to smoke his pipe of peace with strong tobacco in a strange pipe, and feel that his stomach is full of dog meat. But we didn't die, and all the evening the Indians talked about the brave great father.

It seemed that they were not going to take much stock in pa's bravery until they had tried him out in Indian fashion. We were standing in the moonlight surrounded by Indians, and Pa had been questioned as to his bravery, and Pa said he was brave like Roosevelt, and he swelled out his chest and looked the part, when the chief said, pointing to a savage, snarling dog that was smelling of pa: “Brave man, kick a dog!”

We all told Pa that the Indian wanted Pa to give an exhibition of his bravery by kicking the dog, and while I could see that Pa had rather hire a man to kick the dog, he knew that it was up to him to show his mettle, so he hauled off and gave the dog a kick near the tail, which seemed to telescope the dog's spine together, and the dog landed far away. The chief patted Pa on the shoulder and said: “Great Father, bully good hero. Tomorrow he kill a grizzly,” and then they let us go to bed, after Pa had explained that if everything went well he would hire all the chiefs and young braves for his show.

{Illustration: Pa Kicked the Dog.}

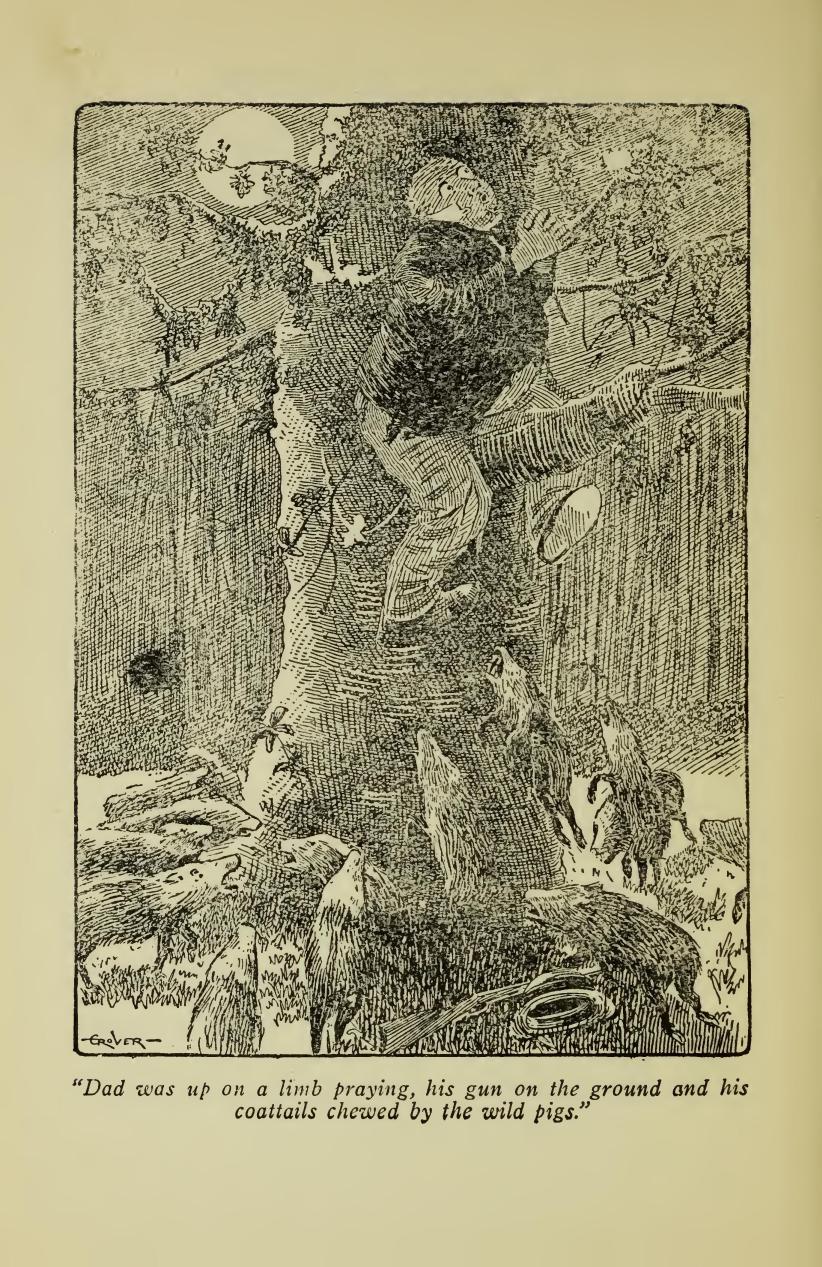

After we got to bed Pa said he was almost sorry he told the chief that he would take a grizzly bear by one ear, and cuff the other ear with the flat of his hand, as he didn't know but a wild grizzly would look upon such conduct differently from our old bear in the show used to. Any person around the show could slap his face, or cuff him, or kick him in the slats, and he would act as though they were doing him a favor. The big game hunter told pa that there was no danger in hunting a grizzly, as you could scare him away, if you didn't want to have any truck with him, by waving your hat and yelling: “Git, Ephraim.” He said no grizzly would stand around a minute if you yelled at him. Pa made up his mind he would yell all right enough, if we came up to a grizzly.

Well, we didn't sleep much that night, 'cause Pa kept practicing on his yell to scare a grizzly, for fear he would forget the words, and when they called us in the morning Pa was the poorest imitation of a man going out to test his bravery that I ever saw. While the Indians were getting ready to go out to a canyon and turn the dogs loose to round up a bear, Pa got a big knife and was sharpening it, so he could rip the bear from Genesis to Revelations. After breakfast the chief and the Carlisle Indian, and the big game hunter, and the cowman and I went out about two miles, to the mouth of the canyon, where it was very narrow, and they stationed Pa by a big rock, right where the bear would have to pass; the rest of us got up on a bench of the canyon, where we could see Pa be brave, and the young Indians went up about a mile, and started the dogs. Well, Pa was a sight, as he stood there waiting for the bear, so he could cuff its ears, and rip it open, right in sight of the chief, and skin it; but he was nervous, and we could see that his legs trembled when he heard the dogs bark up the canyon. I yelled to Pa to think of Teddy Roosevelt, and Daniel Boone, and Buffalo Bill, and set his teeth so they would not chatter and scare the bear, but Pa yelled back: “Never you mind, I will kill my bear in my own way, but you can make up your mind to have bear meat for supper.”

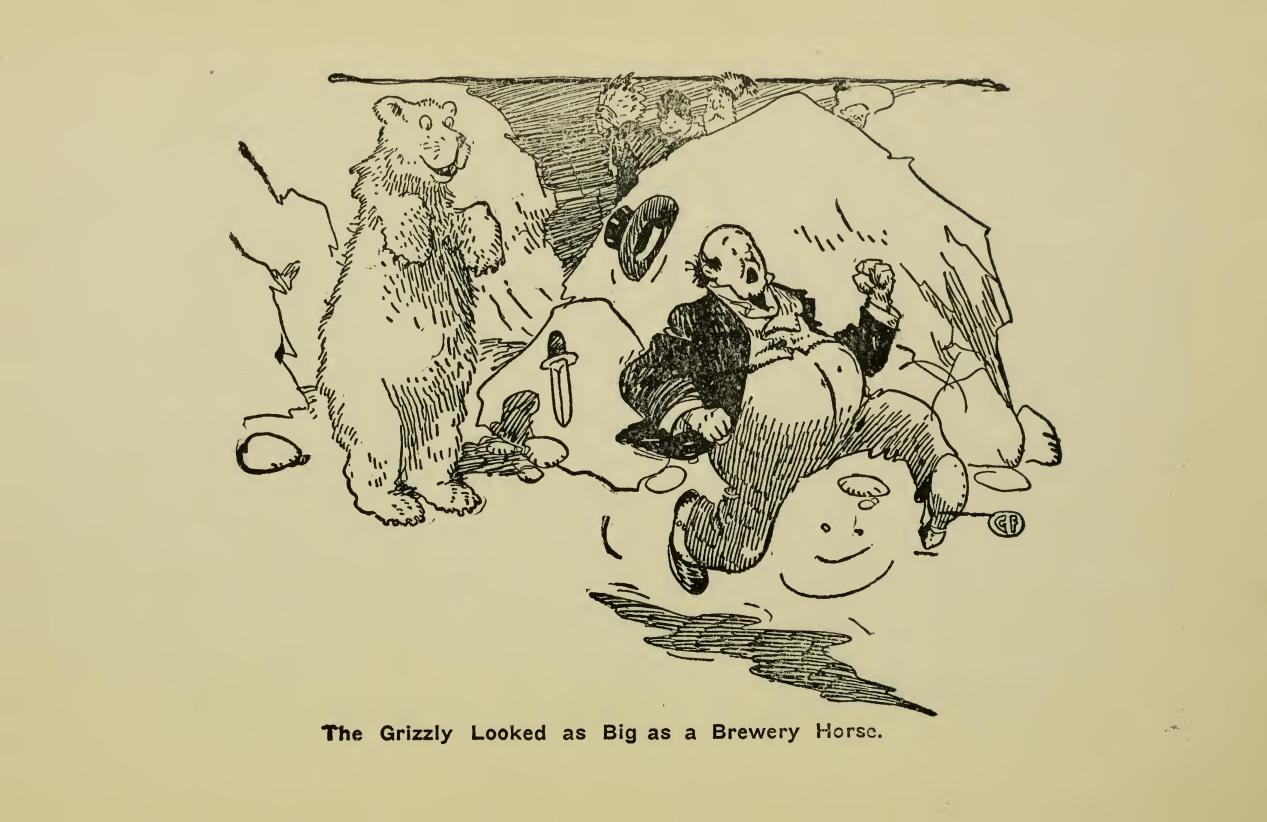

Pretty soon the big game hunter said: “There he comes, sure's you are born,” and we looked up the canyon, and there was something coming, as big as a load of hay, with bristles sticking up a foot high on its back, and its mouth was open, and it was loping right towards pa. Gee, but I was proud of pa, to see him sharpening his knife on his boot leg, but when the great animal got within about a block of pa, the great father seemed to have a streak of yellow, for he dropped his knife and yelled: “Git, Ephraim,” in a loud voice, but Ephraim came right along, and didn't git with any great suddenness. When the bear got within about four doors of Pa, he saw the great father, and stood up on his hind legs, and looked as big as a brewery horse, and he opened his mouth and said: “Woof,” just like that. That was too much for my Pa, who began to shuck his clothes, and then started on a run towards the mouth of the canyon. The bear looked around as much as to say: “Well, what do you think of that?” and we watched Pa sprinting toward the Indian camp like a scared wolf.

{Illustration: The Grilly Looked as Big as a Brewery Horse.}

The big game hunter put a few bullets in the bear where they would do the most good, and killed it, and we went down in the canyon and skinned it, and took the meat and hide to camp, where we found Pa under a bed in a squaw's tepee, making grand hailing signs of distress, and trying to tell them about his killing a bear by letting it run after him, so it would tire itself out and die of heart failure.

When we found Pa he had come out from under the bed, and was looking at the hide of the bear to find the place where he hit it with the knife, as he said he could see that the only chance for him to kill the bear was to throw the knife at it from a distance, 'cause the bear was four times as big as any bear he had ever killed. Pa took out a handful of gold pieces and distributed them among the Indians, and told the Carlisle Indian to explain to the tribe that the great father had killed the bear by hypnotism, and they all believed it except the chief, who seemed skeptical, for he said: “Great father heap brave man like a sheep. Go play seven-up with squaws.” Poor Pa wasn't allowed to talk with the men all day, 'cause the old chief said he was a squaw man. Pa says they don't seem to realize that a man can be brave unless he allows himself to be killed by a bear, but he says he will show them that a great mind and a great head is better in the end than foolishness. Now they want Pa to run a footrace with the young Indians, as the record he made getting to camp ahead of the bear is better than any time ever made on the reservation.

Indian Chief Compels Bad Boy's Pa to Herd with the Squaws—He Shows Them How to Make Buckwheat Cakes and Is Kept Making Them a Week—He Talks to the Squaws About Women's Rights and They Organize a Strike—Pa's Success in a Wolf Hunt—The Strike is Put Down and the Indians Prepare to Burn Pa at the Stake.

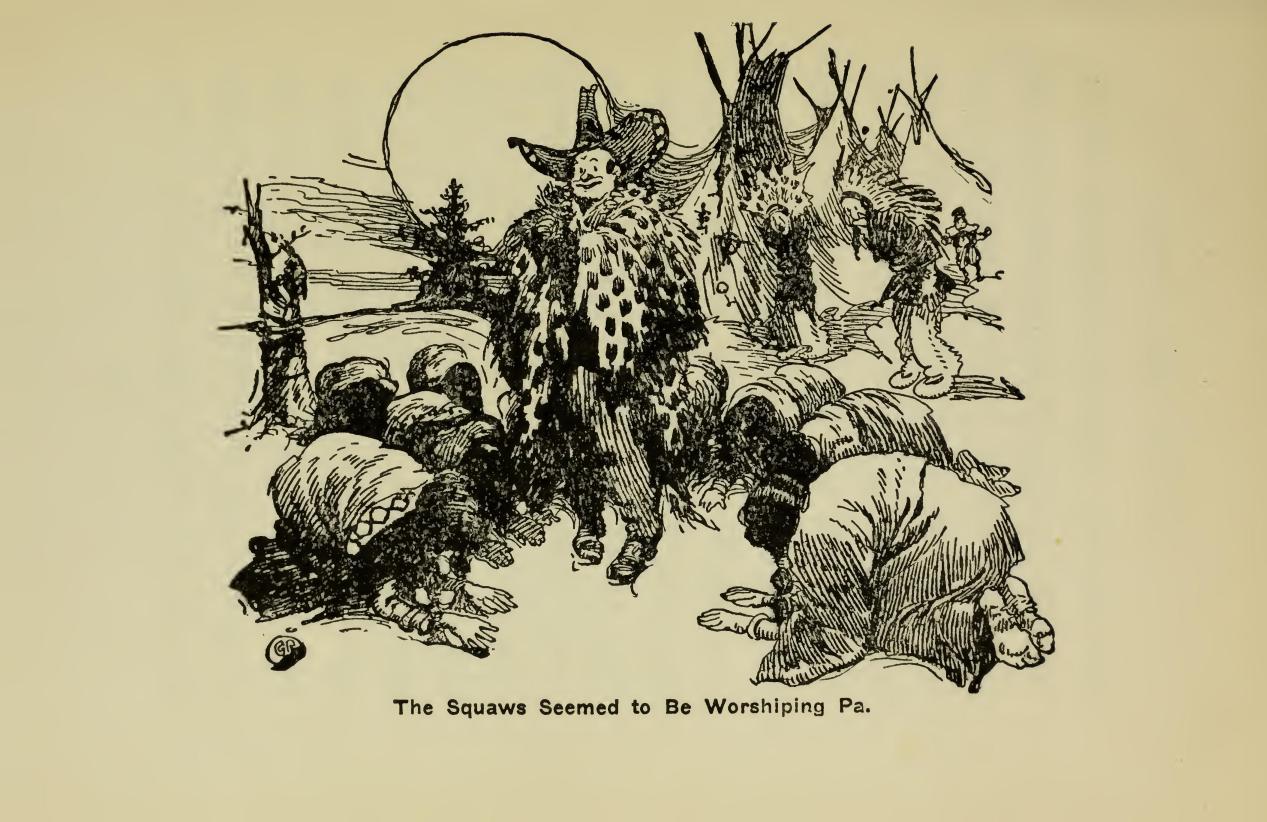

Since Pa's experience in trying to kill a grizzly by making the animal chase him and die of heart disease, the chief has made Pa herd with the squaws, until he can prove that he is a brave man by some daring deed. The Indians wouldn't speak to him for a long time, so he decided to teach the squaws how to keep house in a civilized manner, and he began by trying to show them how to make buckwheat pancakes, so they could furnish something for the Indians to eat that does not have to be dug out of a tin can, which they draw from the Indian agent. Pa found a sack of buckwheat flour and some baking powder, and mixed up some batter, and while he was fixing a piece of tin roof for a griddle, the squaws drank the pancake batter raw, and it made them all sick, and the chief was going to have Pa burned at the stake, when the Carlisle Indian who had eaten pancakes at college when he was training with the football team, told the chief to let up on Pa and he would give them something to eat that was good, so Pa mixed some more batter and when the buckwheat pancakes began to bake, and the odor spread around among the Indians, they all gathered around, and the way they ate pancakes would paralyze you. They got some axle grease to spread on the pancakes, and fought with each other to get the pancakes, and they kept Pa baking pancakes all day and nearly all night, and then the squaws began to feel better, and Pa had to bake pancakes for them, and when the flour gave out the chief sent to the agency for more, and for a week pa did nothing but make pancakes, but finally the whole tribe got sick, and Pa had to prescribe raw beef for them, and they began to get better, and then they wanted Pa to go on a coyote hunt, and kill a kiota, which is a wolf, by jumping off his horse and taking the wolf by the neck and choking it to death. Pa said he killed a tom cat that way once, and he could kill any wolf that ever walked, so they arranged the hunt Before we went on the hunt pa sent to Cheyenne for two dozen little folding baby trundlers for the squaws to wheel the papooses in, 'cause he didn't like to see them tie the children on their backs and carry them around. Where the trundlers came Pa showed the squaws how they worked, by putting a papoose in one of the baby wagons, and pushing it around the camp, and by gosh, if they didn't make Pa wheel all the babies in the tribe, for two days, and the Indians turned out and gave the great father three cheers, but when the squaws wanted to get in the wagons and be wheeled around, Pa kicked. After teaching the squaws how to put the children in the wagons and work them, we went off on the hunt, and when we came back every squaw had her papoose in a baby wagon, but instead of wheeling the wagon in civilised fashion, they slung the wagons, babies and all, on their backs, and carried the whole thing on their backs. Gee, but that made Pa hot. He says you can't do anything with a race of people that haven't got brain enough to imitate. He says monkeys would know better than to carry baby wagons on their backs. I never thought that Indians could be jealous, but they are terrors when the jealousy germ begins to work. There is no doubt but that the squaws got to thinking a great deal of pa, 'cause he talked with them, through the Carlisle Indian for an interpreter, and as he sat on a camp chair and looked like a great white god with a red nose, and they gathered around him, and he told them stories of women in the east, and how they dressed and went to parties, and how the men worked for them that they might live in luxury, and how they had servants to do their cooking, and maids to dress them, and carriages to ride in, and lovers to slave for them, it is not to be wondered at that those poor creatures, who never had a kind word from their masters, and who were looked upon as lower than the dogs, should look upon Pa as the grandest man that ever lived, and I noticed, myself, that they gave him glances of love and admiration, and when they would snuggle up closer to pa, he would put his hand on their heads and pat their hair, and look into their big black eyes sort of tender, and pinch their brown cheeks, and chuck them under the chin, and tell them that the great father loved them, and that he hoped the time would come when every good Indian would look upon his squaw, the mother of his children, as the greatest boon that could be given to man, and that the now despised squaw would be placed on a pedestal and honored by all, and worshiped as she ought to be.

{Illustration: The Squaws Seemed to Be Worshiping Pa.}

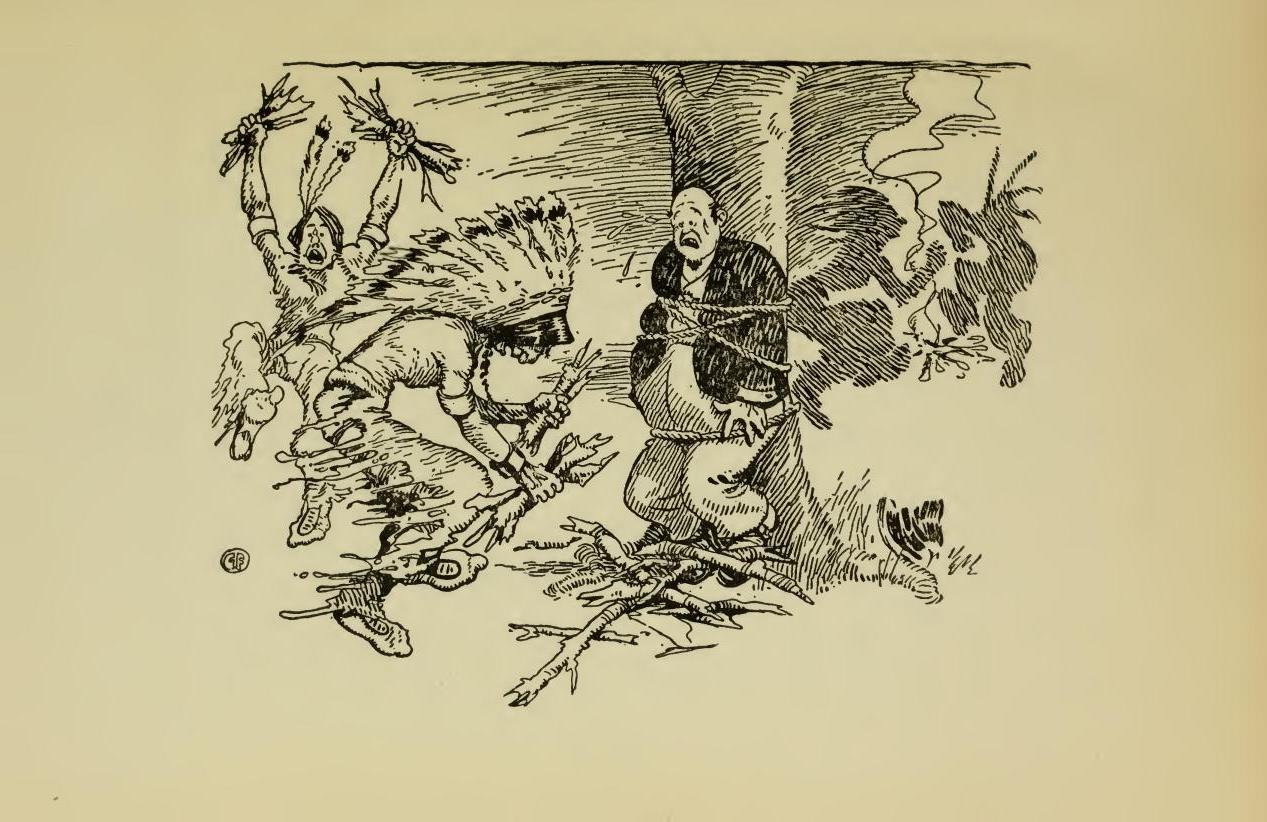

That was all right enough, but Pa never ought to have gone so far as to advise them to strike for their rights, and refuse to be longer looked upon as beasts of burden, but demand recognition as equals, and refuse longer to be drudges. I could see that trouble was brewing, for every squaw insisted on kissing the great father, and then there came a baneful light in their eyes, and they drew away together and began to talk excitedly, and Pa said he guessed they were organizing a woman's rights union. Pa and the Carlisle Indian and I went out for a stroll in the forest, and were gone an hour or so, and Pa got tired and he and I went back to camp before the Carlisle Indian did, and when we got in sight of camp we could see by the commotion that the squaw strike was on, 'cause the squaws were talking loud and the Indians were getting their guns and it looked like war. We crawled up close, and the squaws drew butcher knives and made a rush on the Indians, and the Indians weakened, and the squaws tied their hands and feet, and then the squaws had a war dance, and they told the Indians that they were now the bosses, and would hereafter run the affairs of the tribe, like white women did, and that the Indians must do the cooking, and do the work, while the squaws sat in the tents to be waited on, and that they would never do another stroke of hard work that an Indian could do. I never saw such a lot of scared Indians in my life, but when the squaws put the butcher knives to their necks, and looked fierce, and grabbed the Indians by the hair and looked as though they were going to scalp them, the Indians agreed to do all the work, and just then Pa and I came up, and the squaws hailed Pa as their deliverer, and they fell on his neck and hugged him, and they placed a camp chair for him, and put a tiger skin cloak around him, and a necklace of elk's teeth around his neck, and all kneeled down and seemed to be worshiping him, while the Indians looked on in the most hopeless manner, and then the Carlisle Indian came and said the squaws had made Pa the chief squaw of the tribe, and that the Indians had agreed to do the work hereafter. Pa counted the elk teeth on his necklace and figured that he could sell them for two dollars apiece, and pay the expenses of the trip. Then the squaws cut the strings that bound the Indians, and set them to work cooking dinner, and it was awful the way the spirit seemed to be knocked out of the Indians, just by a little rising on the part of the downtrodden squaws. The Indians cooked dinner, and waited on the squaws, and Pa and all of us whites, and after dinner the squaws ordered the horses and the squaws and us whites went off on a wolf hunt, with the dogs, where Pa was to show his bravery to the squaws instead of the Indians. The squaws gave Pa the old chief's horse, and the best one in the tribe, and leaving the chief to wash the dishes, and the Indians to clean up the camp, and clean some fish for supper, the victorious squaws with Pa at the head, and the rest of us whites on ponies, went out on the mesa and turned the dogs loose, and pretty soon they were after a wolf and Pa led out ahead on his racing pony, cheered by the yells of the squaws, and it was a fine race for about two miles. Pa and the cowboy and the big game hunter and I got ahead of the squaws, and after awhile we got up pretty near to the wolf, and the big game hunter said to pa: “Now, old man, is your chance to make yourself solid with the squaws. We will hold hack and when the dogs get the wolf surrounded you rush in and kill him or your name's Dennis.” Pa said: “You watch my smoke, and see me eat that wolf alive.” So we held up our horses, and let Pa go ahead. He rode up to the wolf, and I never saw a man with such luck as Pa had. Just as he got near the wolf and the animal showed his teeth, Pa tried to steer his horse away from the savage animal, but the horse stumbled in a prairie dog hole, and fell right on top of the wolf, crushing the life out of the animal, and throwing Pa over his head. Pa was stunned, but he soon came to, and when he realized that the wolf was dead, he grabbed the animal by the neck with one hand, and by the lower jaw with the other, and held on to it till the crowd came up, and when the squaws saw that Pa had killed the biggest wolf ever seen on the reservation, by rushing in single handed and choking the savage animal to death, they gave Pa an ovation that was enough to turn the head of any man. Us white fellows knew that Pa couldn't have been hired to go near that wolf until the horse fell on it and killed it, but we wanted to give Pa a reputation for bravery, and so we let the squaws compliment Pa and hug him, and make him think he was a holy terror. So they tied the wolf on the saddle in front of pa, and we all went back to camp, the squaws shouting for pa, and telling the Indians how the great white father had strangled the father of all wolves, and then the Indians served the fish supper, and all looked as though there had been a bloodless revolution, and that the squaws were in charge of the government, and Pa was “it,” but I could see the Carlisle Indian whispering to the Indians, and it seemed to me I could see signs of an uprising, and when the Indians had the supper dishes washed, and all seemed going right, and the squaws were rejoicing at being emancipated, just as the sun was setting, every Indian pulled out a bull whip and began to lash the squaws to their tents, and some young braves grabbed Pa and removed the leopard skin cloak, and the elk's teeth necklace, and tied his hands and feet, and carried him into a circle made by the Indians. I asked the Carlisle Indian what was the matter, and he said, pointing to some wood that had been piled at the roots of a tree: “The great white father is going to be tried for inciting a rebellion among the squaws, and the chances are that before the sun shall rise tomorrow your old dad will be broiled, fricasseed and baked to a turn.” I went up to Pa and said: “Gee, dad, but they are going to burn you at the stake,” and Pa called the cowboy, and told him to ride to the military post and ask for a detail of soldiers to hurry up and put a stop to it, and then Pa said to me: “Hennery, it may look as though I was in a tight place, but I place my trust in the squaws and soldiers,” and Pa rolled over to take a nap.

{Illustration: The Horse Stumbled, Throwing Pa Over His Head and Killing the Wolf}

How the Old Man Subdued the Indians with an Electric Battery and Phosphorus—He Tries His Hand at Roping a Steer—The Disastrous Result.

Gee, but I thought Pa was all in when I closed by last letter, when the Indians had him bound on a board, and had lighted a fire, and were just going to broil him. Jealousy is bad enough in a white man, but when an Indian gets jealous of his squaw there is going to be something doing, and when a whole tribe gets jealous of one old man, 'cause he has taught the squaws to be independent, and rise up as one man against the tyranny of their husbands, that white man is not safe, and as Pa lay there, waiting for the fire to get hot enough for them to lay him on the coals, I felt almost like crying, 'cause I didn't want to take pa's remains back home so scorched that they wouldn't be an ornament to society, so I went up to pa's couch to get his instructions as to our future course, when he should be all in.

I said, “Pa, this is the most serious case you have yet mixed up in. O, wimmen, how you do ruin men who put their trust in you.”

Pa winked at me, and said:

“Never you mind me, Hennery. I will come out of this scrape and have all the Indians on their kpeesan less than an hour, begging my pardon,” and then Pa whispered to me, and I went to pa's valise and got an electric battery and put it in pa's pocket and scattered copper wires all around pa's body, and fixed it so pa could touch a button and turn on a charge of electricity that would paralyze an elephant, and then I got some matches and took the phosphorus off and put it all over pa's face and hands and clothes and as it became dark and the phosphorus began to shine, Pa was a sight. He looked like moonlight on the lake, and I got the cowboy and the big game hunter and the educated Indian to get down on their knees around pa, and chant something that would sound terrible to the Indians. The only thing in the way of a chant that all of them could chant was the football tune, “There'll Be a Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight,” and we were whooping it up over pa's illuminated remains when the Indians came out to put Pa on the fire, and when they saw the phosphorescent glow all over him, and, his face looking as though he was at peace with all the world, and us whites on our knees, making motions and singing that hot dirge, they all turned pale, and were scared, and they fell back reverently, and gazed fixedly at poor pa, who was winking at us, and whispering to us to keep it up, and we did.

The old chief was the first to recover, and he saw that something had to be done pretty quick, so he talked Indian to some of the braves, and I slipped away and put some phosphorus all over a squaw, and she looked like a lightning bug, and told her to go and fall on pa's remains and yell murder. The Indians had started to grab Pa and put him on the fire when Pa turned on the battery and the big chief got a dose big enough for a whole flock of Indians, and all who touched Pa got a shock, and they all fell back and got on their knees, and just then the squaw with the phosphorus on her system came running out, and she fell across pa's remains, and she shone so you could read fine print by the light she gave, and that settled it with the tribe, 'cause they all laid down flat and were at pa's mercy. Pa pushed the illuminated squaw away, and went around and put his foot on the neck of each Indian, in token of his absolute mastery over them, and then he bade them arise, and he told them he had only done these things to show them the power of the great father over his children, and now he would reveal to them his object in coming amongst them, and that was to engage 20 of the best Indians, and 20 of the best squaws, to join our great show, at an enormous salary, and be ready in two weeks to take the road. The Indians were delighted, and began to quarrel about who should go with the show, and to quiet them Pa said he wanted to shake hands with all of them, and they lined up, and Pa took the strongest wire attached to the battery in his pistol pocket, and let it run up under his coat and down his sleeve, into his right hand, and that was the way he shook hands with them. I thought I would die laughing. Pa took a position like a president at a New Year's reception, and shook hands with the tribe one at a time. The old chief came first, and Pa grasped his hand tight, and the chief stood on his toes and his knees knocked together, his teeth chattered, and he danced a cancan while Pa held on to his hand and squeezed, but he finally let go and the chief wiped his hand on a dog, and the dog got some of the electricity and ki yield to beat the band. Then Pa shook hands with everybody, and they all went through the same kind of performance, and were scared silly at the supernatural power Pa seemed to have. The squaws seemed to get more electricity than the buck Indians, 'cause Pa squeezed harder, and the way they danced and cut up didoes would make you think they had been drinking. Finally Pa touched them all with his magic wand, and then they prepared a feast and celebrated their engagement to go with the circus, and we packed up and got ready to go to a cattle round up the next day at a ranch outside the Indian reservation, where Pa was to engage some cowboys for the show. As we left the headquarters on the reservation the next morning all the Indians went with us for a few miles, cheering us, and Pa waved his hands to them, and said, “bless you, me children,” and looked so wise, and so good, and great that I was proud of him. The squaws threw kisses at pa, and when we had left them, and had got out of sight, Pa said, “Those Indians will give the squaws a walloping when they get back to camp, but who can blame them for falling in love with the great father?” and then pa winked, and put spurs to his pony and we rode across the mesa, looking for other worlds to conquer.

{Illustration: “The Chief's Knees Knocked Together."}

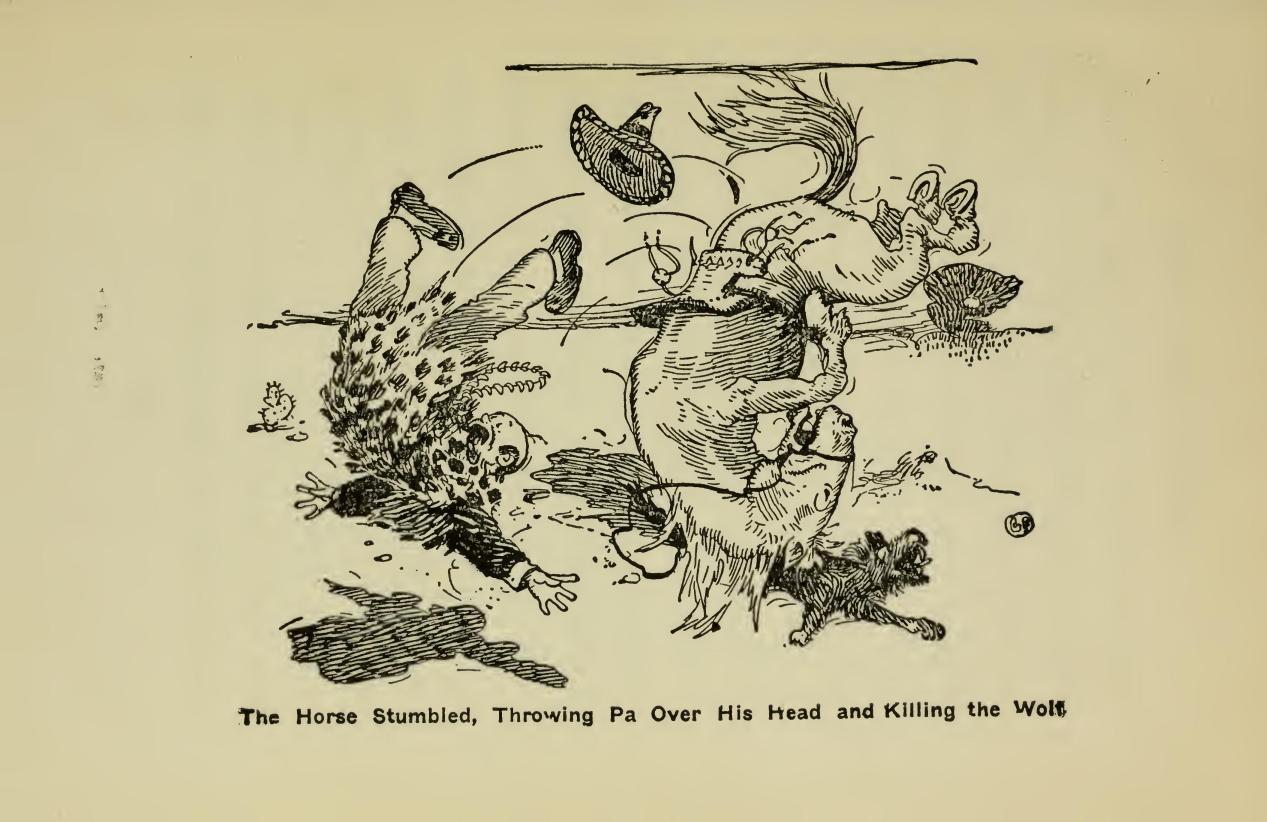

On the way to the ranch where we were to meet the cowboys and engage enough to make the show a success, the cowboy Pa had along told Pa that it might be easy enough to fool Indians with the great father dodge, and the electric battery, and all that, but when he struck a mess of cowboys he would find a different proposition, 'cause he couldn't fool cowboys a little bit. He said if Pa was going to hire cowboys, he had got to be a cowboy himself, and if he couldn't rope steers he would have to learn, 'cause cowboys, if they were to be led in the show by pa, would want him to be prepared to rope anything that had four feet. Pa said while he didn't claim to be an expert, he had done some roping, and could throw a lasso, and while he didn't always catch them by the feet, when he tried to, he got the rope over them somewhere, and if the horse he rode knew its business he ultimately got his steer, and he would be willing to show the boys what he could do.

We got to the cow camp in time for dinner, and our cowboy introduced Pa to the cowboys around the chuck wagon, and told them Pa was an old cowboy who had traveled the Texas trail years ago, and was one of the best horsemen in the business, a manager of a show that was adding a wild west department and wanted to hire 40 or more of the best ropers and riders, at large salaries, to join the show, and that Pa considered himself the legitimate successor of Buffalo Bill, and money was no object. Well, the boys were tickled to meet pa, and some said they had heard of him when he was roping cattle on the frontier, and that tickled pa, and they smoked cigarettes, and finally saddled up and began to brand calves and rope cattle to get them where they belonged, each different brand of cattle being driven off in a different direction, and we had the most interesting free show of bucking horses and roping cattle I ever saw. Pa watched the boys work for a long time, and complimented them, or criticised them for some error, until the crazy spirit seemed to get into him, and he thought he could do it as well as any of the boys, and he told our cowboy that whenever the boys got tired he would like to get on a buckskin pony that one of the men was riding, and show that while a little out of practice he could stand a steer on its head, and get off his horse and tie the animal in a few seconds beyond the record time.

I told Pa he better hire a man to do it for him, but he said, “Hennery, here is where your Pa has got to make good, or these cowboys won't affiliate. You take my watch and roll, 'cause no one can tell where a fellow will land when he gets his steer,” and I took pa's valuables and the boys brought up the buckskin horse, which smelled of Pa and snorted, and didn't seem to want Pa to get on, but they held the horse by the bridle, and Pa finally got himself on both sides of the horse, and took the lariat rope off the pommel of the saddle and began to handle it, kind of awkward, like a boy with a clothesline. I didn't like the way the cowboys winked around among themselves and guyed pa, and I told Pa about it, and tried to get him to give it up, but he said, “When I get my steer tied, and stand with my foot on his neck, these winking cowboys will take off their hats to me all right. I am Long Horn Ike, from the Brazos, and you watch my smoke.”

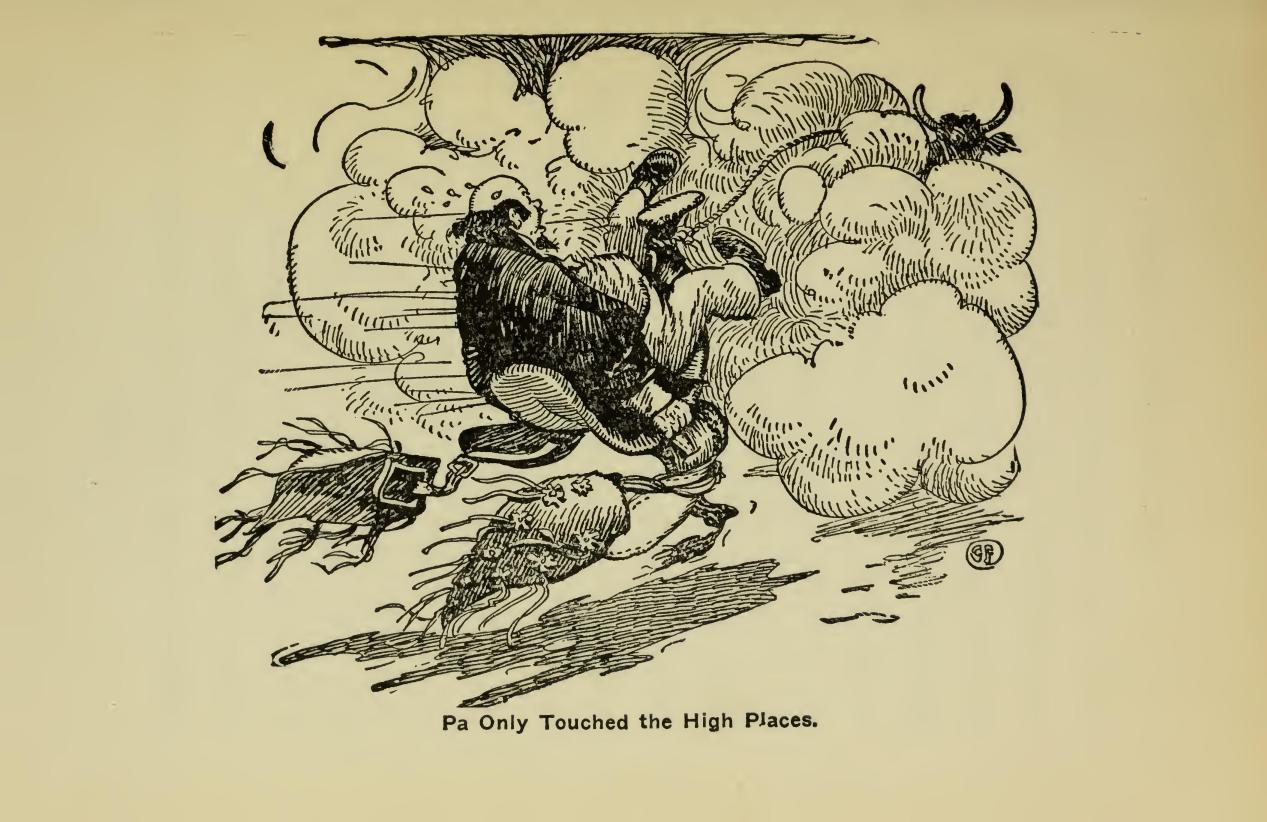

Well, the boys tightened up the cinch on pa's saddle, and pointed out a rangy black steer in a bunch down on the flat, and told pa the game was to cut that steer out of the bunch and rope it, and tie it, and hold up his right hand for the time keeper to record it. Gee, but Pa spurred the horse and rode into that bunch of cattle like a whirlwind, and I was proud of him, and he cut out the black steer all right, and rode up near it, and swung his lariat, and sent it whizzing through the air, and the noose went out over the head and neck and fore feet of the steer, and the horse stopped and set itself back on its haunches, and the rope got around the belly of the steer, and when the rope became taut, and the steer ought to have been turned bottom-side up, the cinch of pa's saddle broke, the saddle came off with pa hugging his legs around it, and the black steer started due west for Texas, galloping and bellowing, and you couldn't see Pa and the saddle for the dust they made following the steer. If Pa had let go of the saddle, he would have stopped, but he hung to it, and the rope was tied to the saddle. The buckskin horse, relieved of the saddle, looked around at the cowboys as much as to say, “wouldn't that skin you,” and went to grazing, the other cattle looked on as though they would say, “Another tenderfoot gone wrong,” and as the black steer and Pa and the saddle went over a hill, Pa only touching the high places, the boss cowboy said, “Come on and help head off the steer, and send a wagon to bring back the remains of Long Horn Ike from the Brazos,” and then I began to cry for pa.

{Illustration: “Pa Only Touched the High Places."}

Pa, the Bad Boy and a Band of Cowboys Go in Search of a Live Dinosaurus—The Expedition is Captured by a Gang of Train Robbers and Pa is Held for Ransom.

When I saw Pa clinging to the saddle, which had got loose from the horse that he was riding when he lassoed the black steer around the belly, and the steer was running away, dragging Pa and the saddle across the plains, I thought I never would see him alive again. But the cowboys said they would bring his remains back all right. When they rode away to capture the steer and release pa, I stopped crying and laid down under the chuck wagon with the dogs, to think over what I would do, alone in the world, and I must have fallen asleep, for the next thing I knew the dogs barked and woke me up, and I looked off to the south and the cowboys were coming back with pa's remains on a buckboard.

I went up to the wagon to see if Pa looked natural, and he raised up, like a corpse coming to, and said: “Hennery, did you notice how I roped the black steer?” and I said: “Yes, pa, I saw the whole business, and saw you start south, chasing the steer, armed only with a saddle, and what is the news from Texas?”

Pa said: “Look-a-here, I don't want to hear any funny business. I delivered the goods all right, and if the cinch of the saddle had held out faithful to the end, I would have tied the steer in record time, but man proposes and the rest you have to leave to luck. I was out of luck, that is all, but the ride I had across the prairie has given me some ideas about flying machines that will be worked into our show next year.”

Pa got up off the buckboard and shook himself, and he was just as well and hearty as ever, and the cowboys got around him, and told him he was a wonder, and that Buffalo Bill couldn't hold a candle to him as an all-around rough rider and cowboy combined. So pa hired about a dozen of the cowboys to go with our show, and then we went into camp for the night, and the cowboys told of a place about 20 miles away, where some scientists had a camp, where they were excavating to dig out petrified bone of animals supposed to be extinct, like the dinosaurus and the hoday, and Pa wanted to go there and see about it, and the next day we took half a dozen of the cowboys Pa had hired, and we rode to the camp.

Gee, but I never believed that such animals ever did exist in this country, but the scientists had one animal picture that showed the dinosaurus as he existed when alive, an animal over 70 feet long, that would weigh as much as a dozen of our largest elephants, with a neck as long as 15 giraffes, and then they showed us bones of these animals that they dug out and put together, and the completed mess of bones showed that the dinosaurus could eat out of a six-story window, and pa's circus instinct told him that if he could find such an animal alive, and capture it for the show, our fortunes would be made.

We stayed there all night, and Pa asked questions about the probability of there being such animals alive at this day, and the scientists promptly told Pa these animals only existed ages and ages ago, when the country was covered with water and was a part of the ocean, and that the animals lived on the high places, but when the water receded, and the ocean became a desert, the dinosaurus died of a broken heart, and all we had to show for it was these petrified bones.

Pa ought to have believed the scientists, 'cause they know all about their business, but after the scientists had gone to bed the cowboys began to string pa. They told him that about a hundred miles to the north, in a valley in the mountains, the dinosaurus still existed, alive, and that no man dare go there. One cowboy said he was herding a bunch of cattle in a valley up there once, and the bunch got into a drove of dinosauruses, and the first thing he knew a big dinosaurus reached out his neck and picked up a steer, raised it in the air about 80 feet, as easy as a derrick would pick up a dog house, and the dinosaurus swallowed the steer whole, and the other dinosauruses each swallowed a steer. The cowboy said before he knew it his whole bunch of steers was swallowed whole, and they would have swallowed him and his horse if he hadn't skinned out on a gallop. He said he could hear the dinosauruses for miles, making a noise like distant thunder, whether from eating the steers, giving them a pain, or whether bidding defiance to him and his horse, he never could make out but he said nothing but money could ever induce him to go into that valley again.

{Illustration: A Boy Dinosaurus Reached Out His Neck and Picked Up a Steer.}

Pa asked the other cowboys if they had ever been to that dinosaurus valley, and they winked at each other and said they had heard of it, but there was not money enough to hire them to go there, 'cause they had heard that a man's life was not safe a minute. Bill, who had told the story, was the only man who had ever been there, and the only man living that had seen a live dinosaurus.

Then we turned in, and Pa never slept a wink all night, thinking of the rare animals, or insects, or reptiles, or whatever they are, that he expected to land for the show. He whispered to me in the night and said: “Hennery, I am on the trail of the dinosaurus, and while I am not prepared to capture one alive, at this time, I am going to that valley and see the animals alive, and make plans for their capture, and report to the management of the show. What do you think about it?”

I told Pa that I thought that cowboy, Bill, was the worst liar that we had ever run up against, and I knew by studying geography in school that the dinosaurus was extinct, and had been for thousands of years. Pa said: “So they say the buffalo is extinct, but you can find 'em, if you have got the money. Lots of thing are extinct, till some brave explorer penetrates the fastnesses and finds them. The mastodon is extinct, according to the scientists, but they are alive in Alaska. The north pole is extinct, but some dub in a balloon will find it all right. I tell you, I am going to see a live dinosaurus, or bust. You hear me?” and Pa heard them cooking breakfast, and we got up.

Before noon Pa had organized a pack train and hired three cowboys, and got some diagrams and pictures of dinosauruses from the scientists, and we started north on the biggest fool expedition that ever was, but Pa was as earnest and excited as Peary planning a north pole expedition, and as busy as a boy killing snakes. After the cowboys and the scientists had tried to get Pa to make his will before he went, and got the addresses where Pa wanted our remains sent to in case of our being found dried up on the prairie, and our bones polished by wolves, we were on the move, and Pa was so happy you would think he had already found a live dinosaurus, and had him in a cage.

For four days we rode along up and down foothills, and divides, and small mountains, and all the time Pa was telling the boys how, after we had located our dinosauruses, we would go back east and organize an expedition with derricks and cages as big as a house, and come back and drive the animals in. And when we got them with the show people we would run trains hundreds of miles to see the rarest animals any show ever exhibited to a discriminating public, and we could charge five dollars for tickets, and people would mob each other to get up to the ticket wagon. Then the boys would wink at each other, and tap their foreheads with their fingers, and look at Pa as though they expected he would break out violently insane any minute.

Finally we got up on a high ridge, and a beautiful, fertile valley was unfolded to our view, and Bill, the cowboy who had had his herd of steers eaten by the dinosaurus, said that was the place, and he began to shiver like he had the ague. He said he wouldn't go any farther without another hundred dollars, and Pa asked the other cowboys if they were afraid, too, and they said they were a little scared, but for another hundred dollars they would forget it, forget their families, and go down into the death valley.

Pa paid them the money, and we went down into the valley, and rode along, expecting to jump a flock of dinosauruses any minute, but the valley was as still as death, and Pa said to Bill: “Why don't you bring on your dinosauruses,” and Bill said he guessed by the time we got up to the far end of the valley we would see something that would make us stand without hitching.

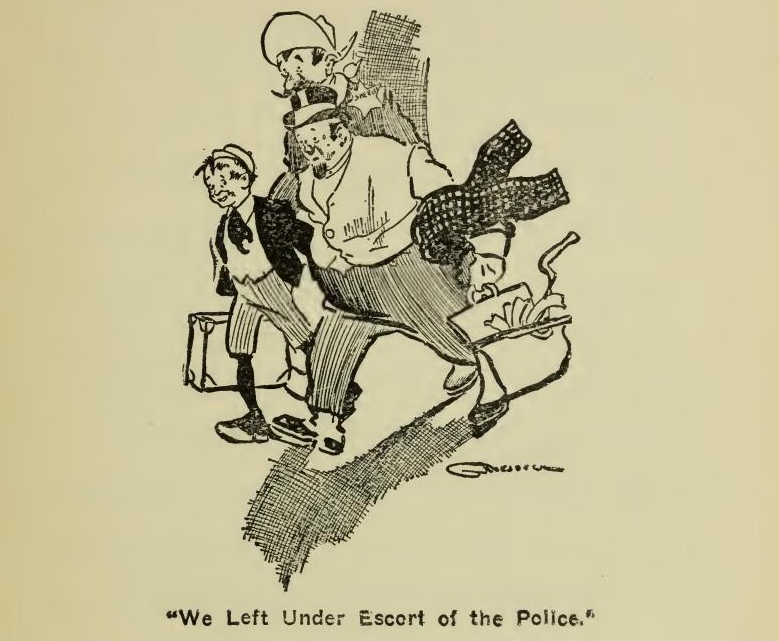

We went on towards where the valley came to a point where there seemed to be a hole in the side of the mountain, when all of a sudden four or five gun shots were heard, and four of our horses dropped dead in their tracks, and about a dozen men come out of the hole in the wall and told us to hold up our hands, and when we did so they took our guns away and told us to come in out of the wet.

{Illustration: We Were Captured by the Curry's Gang.}

We went into a cave and found that we had been captured by Curry's gang of train robbers, who made their headquarters in the hole in the wall. The leader searched Pa and took all his money, and told us to make ourselves at home. Pa protested, and said he was an old showman who had come to the valley looking for the supposed-to-be-extinct dinosaurus, to capture one for the show, and the leader of the gang said he was the only dinosaurus there was, but he hadn't been captured. Then the leader slapped our cowboys on the shoulders and told them they had done a good job to bring into camp such a rich old codger as Pa was, and then we found that the cowboys belonged to Curry's gang, and had roped Pa in in order to get a ransom.

The leader asked Pa about how much he thought his friends at the east could raise to get him out, and when Pa found he was in the hands of bandits, and that the dinosaurus mine was salted, and he had been made a fool of, he said to me: “Hennery, now, honest, between man and man, wouldn't this skin you?”

I began to cry and said: “Pa, both of us are skun. How are we going to get out of this?” and Pa said: “Watch me.”

Pa and the Bad Boy Among the Train Robbers—Pa Tries to Persuade the Head Bandit to Become a Financier—The Bandit Prefers Train Robbery and Puts Up a Good Argument.

I used to think I would like to be a train robber, and have a nice gang of boys to do my bidding. I have often pictured my gang putting a red light on the track and stopping a train laden with gold, holding a revolver to the head of the engineer, and compelling him to go and dynamite the express car. Then we would fill our pockets and haversacks with rolls of bills that would choke a hippopotamus, and ride away to our shack in the mountains, divide up the swag, go on a trip to New York, bathe in champagne, dress like millionaires, go to theaters morning, noon and night, eat lobster until our stomachs would form an anti-lobster union, and be so gay the people would think we were young Vandergoulds. Since Pa and I were captured by the Hole-in-the-Wall gang I have found that all is not glorious in the train-robbing and capturing-for-ransom business, and that robbers are never happy except when a robbery is safely over, and the gang gets good and drunk.

The first day or two after Pa and I and the traitorous cowboys were captured, we had a pretty nice time, eating canned stuff and elk meat, and Pa was kept busy telling the gang of what had happened in the outside world for several months, as the gang did not read the daily papers. When they robbed a train they let the newsboy alone for fear he would get the drop on them.

{Illustration: Pa Told Them About the Wave of Reform.}

Pa told them about the wave of reform that was going over the country, and how the politicians were taking the railroads and monopolists by the neck, and shaking them like a terrier would shake a rat; how the insurance companies that had been for years tying the policy holders hand and foot, and searching their pockets for illicit gains had been caught in the act, and how the presidents and directory were liable to have to serve time in the penitentiary. Pa told the Hole-in-the-Wall gang all the news until he got hoarse.

“And how is my old friend Teddy, the rough rider?” asked one of the gang, who claimed he had gone up to San Juan hill with the president.

“The president is in fine shape,” said pa, “and he is making friends every day, fighting the trusts, and trying to save the people from ruin.”

“Gee, but what a train robber Teddy would have made, if he had turned his talents in that direction, instead of wasting his strenuousness in politics,” said the leader of the gang. “I would give a thousand dollars to see him draw a bead on the engineer of a fast mail, and make him get down and do the dynamite act, and then load up the saddle bags and pull out for the Hole-in-the-Wall. That man has wasted his opportunities, and instead of being at the head of a gang of robbers, with all the world at his feet, ready to hold up their hands at the slightest hint, living a life of freedom in the mountains, there he is doing political stunts, and wearing boiled clothes, and eating with a fork.” And the bandit sighed for Teddy.

“Well, he will make himself just as famous,” said pa, “if he succeeds in landing the holdup men of Wall street, and compelling them to disgorge their stealings. But say,” said pa, looking the leader of the bandit gang square in the eyes, “why don't you give up this bad habit of robbing people with guns, and go back east and enter some respectable business and make your mark? You are a born financier, I can see by the way you divide up the increment when you rob a train. You would shine in the business world. Come on, go back east with me, and I will use my influence to get you in among the men who own automobiles and yachts, and drive four-in-hands. What do you say?”

“No, it is too late,” said the leader of the Hole-in-the-Wall gang of train robbers, with a sigh. “I should be out-classed if I went into Wall street now. I have got many of the elements in my make up of the successful financier, and the oil octopus, and if I had not become a train robber I might have been a successful insurance president, but I have always been handicapped by a conscience. I could not rob widows and orphans if I tried. It would give me a pain that medicine would not cure to know that women and children were crying for bread because I had robbed them and was living high on their money. If it wasn't for my conscience I could take the presidency of a life insurance company, and rob right and left, equal to any of the crowned heads who are now in the business. But if I was driving in my automobile and should run over a poor woman who might be a policy holder, I could not act as would be expected of me, and look around disdainfully at her mangled body in the road, and sneer at her rapidly-cooling remains, and put on steam and skip out with my mask on. I would want to choke off the snorting, bad-smelling juggernaut and get out and pick up the dear old soul and try to restore her to consciousness, which act would cause me to be boycotted by the automobile murderers' union and I would be a marked man.

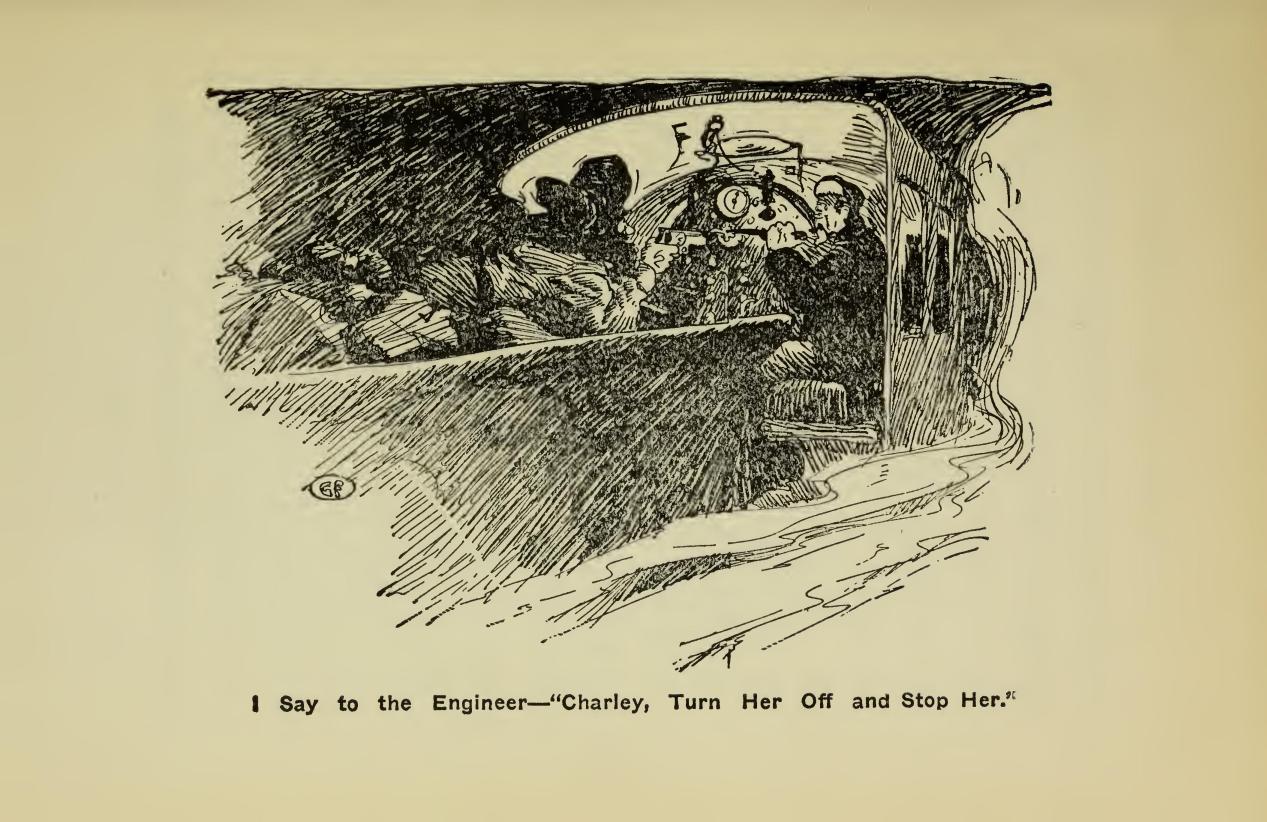

“As president of a life insurance company I could not vote myself a hundred and fifty thousand dollars a year salary, and take it from fatherless children and widows and retain my self respect. Out here in the mountains I can occasionally take my boys, when our funds get low, and ride away to a railroad, and hold up the choo-choo cars, and take toll, but not of the poor passengers. Who do we rob? Why the railroads are owned by Standard Oil, and if we take a few thousand dollars, all Mr. Rockefeller has to do is to raise the price of kerosene for a day or two and he comes out even. The express car stuff is all owned by Wall street, and when we take the contents of a safe, ten thousand or twenty thousand dollars, the directors of the express company sell stock short in Wall street and make a million or so to cover the loss by the bandits of the far west, and pocket the balance. So you see we are doing them a favor to rob a train, and my conscience is clear. I am always sorry when an engineer or expressman is killed, and when such a thing occurs I find out the family and send money to take care of them, but of late years we never kill anybody, because the train hands don't resist any more, for they do not care to die to save Wall street money. Now when I say to an engineer: 'Charley, turn her off and stop here in the gulch and take a dynamite stick and go wake up the express fellow by blowing off the door of his car,' the engineer wipes his hands on his overalls and says: 'All right, Bill, but don't point that gun at my head, 'cause it makes me nervous.' He blows up the express car as a matter of accommodation to me, and the expressman comes to the door, rubbing his sleepy eyes open and says: 'It's a wonder you wouldn't let a man get a little rest. That dinky little safe in the corner hasn't got anything in it to speak of.' And then we blow up the little safe first, and maybe find all we want, and we hurry up, so the boys can go on about their business as quietly as possible. It is all reduced to a system, now, like running a railroad or pipe lines, and I am contented with my lot, and there is no strain on my conscience, as there would be if I was robbing poor instead of the rich. Of course, there are some things that I would like to have the government do, like building us a house and furnishing us steam heat, because these caves are cold and in time will make us rheumatic, but I can wait another year, when we shall send a delegate to congress from this district who will look out for our interests. The Mormons are represented in congress, and I don't see why we shouldn't be.”

{Illustration: I Say to the Engineer—“Charley, Turn Her Off and Stop Her!”}

“Well, you have got gall, all right,” said Pa to the bandit. “You mean to tell me you had rather pursue your course as a train robber, away out here in the mountains with no doctor within a hundred miles of you, and no way to spend your money after you get it, sleeping nights on the rocks and eating canned stuff you pack in here after robbing a grocery, than to enter the realms of high finance and be respected by the people, and be one of the people, with no price on your head, one of the great body of eighty million men who rule a country that is the pride of the earth? You must be daffy,” said pa, just as disgusted as he could be.

“Sure, Mike,” said the robber. “Everybody here respects me, and who respects the Wall street high finance and life insurance robber? Not even their valets. Me one of the people? Ye gods, but you watch these same people for a few years. You say they run the government! They and their government are run by Wall street, which owns the United States senate, body and soul. The people are pawns on a chess board, moved by the players, and they only talk, while the Wall street owners act. Let me tell you a story. I once had a dog trained so that he would lay down and roll over for a cracker, and would hold a piece of meat on his nose until his mouth would water and his eyes sparkle, but he would wait for me to snap my fingers before he would toss the meat in the air with his nose and snatch it in his mouth, and swallow it whole for fear I would get it away from him. He would stand on his hind legs and speak and beg for a bone to be thrown to him so he could catch it. Do you know, the people of this country remind me of that dog. If they do not assert themselves and take monopoly, high finance, insurance robbery, grafting and millionaire and billionaire ownership of everything that pays by the throat and strangle them all, and do business themselves instead of having business done for them by the money power, they will never get noticed except when they do their tricks like my old dog. When the time comes that the people wear collars and are led by chains, and they have to stand on their hind legs and speak to their rich and arrogant masters for bones, and hold meat on their noses until Wall street snaps its fingers, you will want to come out here in the mountains and live the free life of a train robber with a conscience. What do you think about it, bub?” said the robber to me.

“Well,” says I to him, “you talk like a socialist, or a Democrat, but you talk all right. If I am one of the people I will do as the rest do, but I'll be darned if I will get down and roll over for anybody.”

Pa Plays Surgeon and Earns the Good Will of the Bandits—They Give Him a Course Dinner—Speeches Follow the Banquet—Pa is Made Honorary Member of the Band—Pa and the Bad Boy Allowed to Go Free Without Ransom.

We had the worst and the best two weeks of our lives while prisoners of the train robbers at the Hole-in-the-Wall, because we had plenty to eat, and good company, with hunting for game in the foothills by day, and cinch at night, but the sleeping on the rocks of the cave, with buffalo robes for beds, was the greatest of all. Pa got younger every day, but he yearned to be released and would look for hours down the dinosaurus valley, hoping to see soldiers or circus men who might hear of our capture, charging down the opposite hills and up the valley to our rescue, but nobody ever came, and Pa felt like Robinson Crusoe on the island.

Some times for a couple of days the robbers would go away to rob a train or a stage coach, and leave us with a few guards, who acted as though they wanted us to try to escape, so they could shoot us in the back, but we stayed, and fried bacon and elk meat and sighed for rescue.

One day the robbers came back from a raid with piles of greenbacks as big as a bale of hay, and it was evident they had robbed a train and been resisted, because one man had a bullet in his thigh, and Pa had to use his knowledge of surgery to dig out the shot, and he made a big bluff at being a surgeon, and succeeded in getting the balls out and healing up the sores, so the bandits thought Pa was great. When he insisted that the leader let him know how much it would be to ransom us, so we could send to the circus for money, the leader told Pa he had been such a decent prisoner, and had been such good company, and had been such a help in digging the bullets out of the wounded, that the gang was going to let us go free, without taking a cent from us, but was going to consider us honorary members of the gang and divide the money they had secured in the last hold-up with us.

{Illustration: One Day the Robbers Came Back from a Raid with Piles of Greenbacks.}

Pa said he wanted his liberty, thanked the leader for his kind words, but he said there was a strong feeling in the east against truly good people like himself taking tainted money, and while he would not want to make a comparison between the methods men adopt to secure tainted money, in business or highway robbery, he hoped the gang to which he had been elected an honorary member would not insist on his carrying away any of the tainted money.

“You are all right in theory, old man,” said the leader of the gang, “but this money which might have been tainted when it was chipped by express from Wall street to the far west, has been purified by passing through our hands, where it has been carried over mountain ranges on pack horses, in blizzards, till every tainted germ has been blown away. Now, we propose to give you a banquet to-morrow night, at which we shall all make speeches, and then you will be provided with horses, supplies and money, and guided away from here blindfolded, and within 48 hours you will be free as the birds, and all we ask is that you will never give us and our hiding place away to Billy Pinkerton. Is it a go?”

Pa said it was a go all right except taking the tainted money, but he would think it over, and dream over it, and maybe take his share of the swag, but he wanted to be allowed to return it if, after calling a meeting of his board of directors, they should refuse to receive the tainted money. Pa added that the board of directors of a circus might not be as particular as a church or college, and he thought he could assure the gang that the money would not come back to bother them.

The leader of the gang said that would be all right, and for pa and I and the boys to begin to pack up and get ready to return to civilization and all its wickedness. We worked all day and played cinch for hundred dollar bills all the evening, and the next day arranged for the banquet.

When night came, and the pine knots were lit in the cave, about 15 bandits and Pa and I sat down to a course banquet on the floor of the cave, and ate and drank for an hour. We had few dishes, except tin cups and tin plates, but it was a banquet all right. The first course was soup, served in cans, each man having a can of soup with a hole in the top, made by driving a nail through the tin, and we sucked the soup through the hole. The next course was fish, each man having a can of sardines, and we ate them with hard tack. Then we had a game course, consisting of fried elk, and then a salad of canned baked beans, and coffee with condensed milk, and a spoonful or two of condensed milk for ice cream. When the banquet was over the leader of the bandits rapped on the stone floor of the cave with the butt of his revolver for attention, and taking a canteen of whisky for a loving cup, he drank to the health of their distinguished guest, and passed it around, so all might drink, and then he spoke as follows:

“Fellow Highway Robbers: We have with us to-night one who comes from the outside world, with all its wickedness, this old man, simple as a child, and yet foxy as the world goes, this easy mark who is told that the dinosaurus still exists, and believes it, and comes to this valley to find it. If some one told him that Adam and Eve were still alive, and running a stock ranch up in the Big Horn basin, he would believe it, and if it came to him as a secret that Solomon in all his glory was placer mining in a distant valley over the mountains, he would rush off to engage Solomon to drive a chariot next year in his show. Such an ability to absorb things that are not so, in a world where all men are suspicious of each other, should be encouraged. This old man comes to our quiet valley, where all is peace, and where we are honest, fresh from the wicked world, where grafting is a science respected by many, and where the bank robber who gets above a million is seldom convicted and always respected, while we, who only occasionally meet a train with a red light and pass the plate, and take up a slight collection, are looked upon as men who would commit a crime. Why, gentlemen, our profession is more respectable than that of the man who is appointed administrator of the estate of his dead friend, and who blows in the money and lets the widow and orphan go to the poorhouse, or the officer of a savings bank who borrows the money of the poor and when they hear that he is flying high demand their money, and he closes the bank, and eventually pays seven cents on the dollar, and is looked upon as a great financier. It has been a pleasure to us to have this kindly old man visit us, and by his example of the Golden Rule, to do to others as you would be done by, make us contented with our lot. We are not the kind of business men who try to ruin the business of competitors by poisoning their wells, or freezing them out of business. If any other train robbers want to do business in our territory, they have the same rights that we have, and the world is big enough for all to ply their trade. Now I am going to call upon our friend, Buckskin Bill, my associate in crime, who was wounded by a misdirected load of buckshot in our latest raid, which buckshot were so ably removed from his person by our distinguished friend who is so soon to leave us, and the leader again passed the loving cup and gave way to Buckskin Bill, who said:

{Illustration: Dad among the cowboys.}

“Pals—I do not know if you have ever suspected that before I joined this bunch I was steeped in crime, but I must confess to you that I was a Chicago alderman for one term, during the passage of the gas franchise and the traction deal, but I trust I have reformed, because I have led a different life all these years, I like this free life of the mountains, where what you get in a hold-up is yours, and you do not have to divide with politicians, and if you refuse to divide they squeal on you, and you see the guide board pointing to Joliet. I would not go back to the wicked life of an alderman, to make a dishonest living by holding up bills until the agent came around and gave me an envelope, but I do want to hear from my old pals in the common council, and I would ask our corpulent friend, who so ably picked the buckshot out of my remains, when he passes through Chicago to go to the council chamber and give my benediction to my colleagues, and ask them to repent before it is too late, and come west and go into legitimate robbery, far away from the sleuths who are constantly on their trails. While the lamp continues to burn the vilest alderman may buy a ticket to the free and healthy west, and we will give him a welcome. Old man, shake,” and Buckskin Bill shook pa's hand and sat down on his knees, because his wounds were not healed.

The leader of the gang then called upon Pa for a few remarks, and Pa said: “Gentlemen, you have done me great honor to make me an honorary member of your organization, and I shall go away from here with a feeling that you are the highest type of robbers, men that it is a pleasure to know, and that you are not to be mentioned in the same category of the wicked men who rob the poor right and left, in what we consider civilization in the east. You only take toll from the great corporations who have plenty, and your robberies do not bring sorrow and sadness to the poor and hungry. No matter what inducements may be held out to me in the future, to join the life insurance robbers, the political robbers, the great corporations that wring the last dollar from their victims, I shall always remember, in declining such overtures, that I am an honorary member of this organization of honest, straightforward, conscientious hold-up men, who would rob only the rich and divide with the poor, and I hope some day, if our country goes to the dogs, so a respectable man cannot hold office, or do business on the square, to come back here and become one of you in fact, and work the game to the limit. If you find you cannot make it pay out here, come east and I will give you the three-card monte and the shell game concession with our show next summer, where you can make a good living out of the jays that patronize us, and always have a little money left when we get through with them, which it is a shame for them to be allowed to carry home after the evening performance. I thank you, gentlemen.”

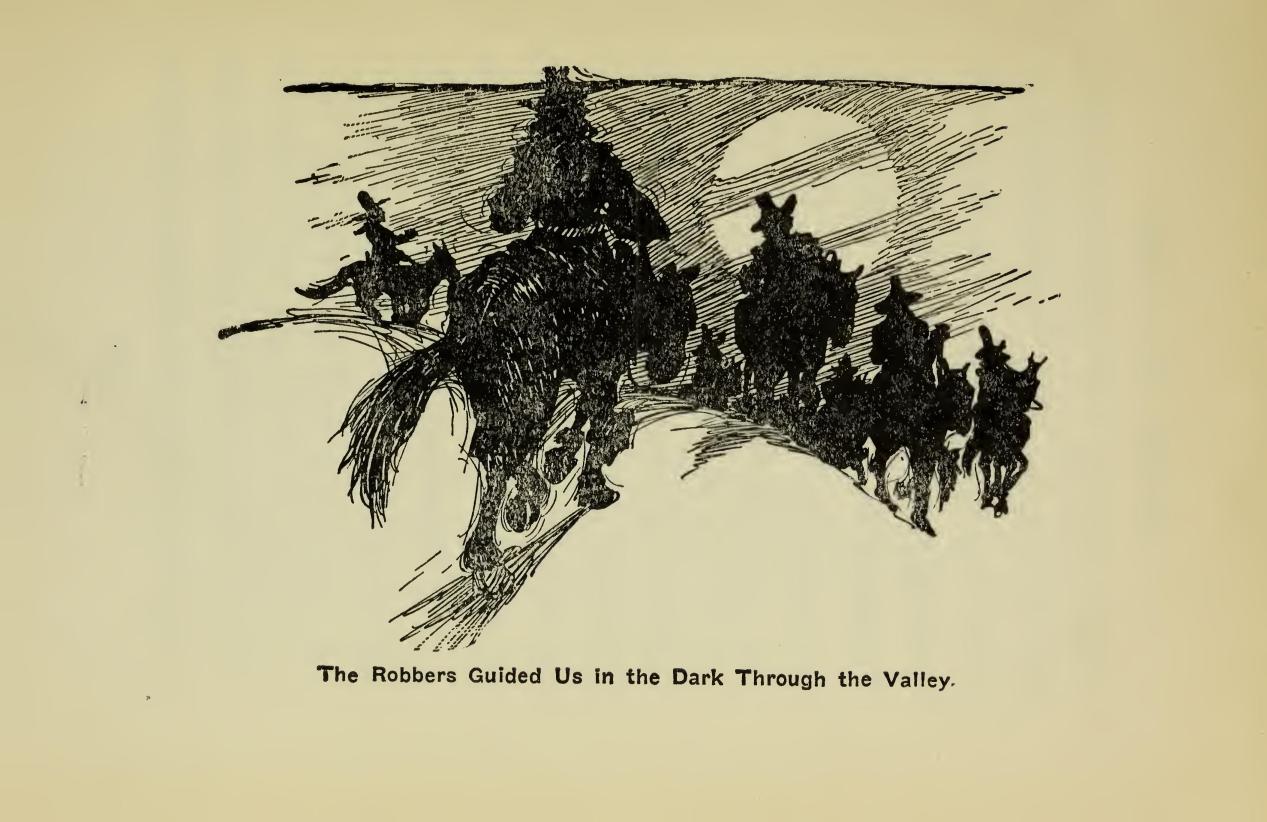

{Illustration: The Robbers Guided Us In the Dark Through the Valley.}

Then the loving cup was passed, we saddled our horses and the robbers guided us in the dark through the valley, and out towards the railroad, pa's saddlebags filled with the tainted money. At daylight the next morning, when the guides left us, Pa took a big roll of bills out of his saddlebags and opened it and, by gosh, if it wasn't a lot of old confederate money that wasn't worth a cent. Pa used some words that made me sick, and then I cried. So did pa.

Pa and the Bad Boy Stop Off at a Lively Western Town—Pa Buys Mining Stock and Takes Part in a Rabbit Drive.

Well, we are on the way back home, after having engaged Indians, cowboys, rough riders and highway robbers to join our show for next season. Pa felt real young and kitteny when we cam to the railroad, after leaving our robber friends at the Hole-in-the-Wall, far into the mountain country. We came to a lively town on the railroad, where every other house is a gambling house, and every other one a plain saloon, and there was great excitement in the town over our arrival, 'cause there don't very many rich and prosperous people stop there.

Pa had looked over the money the robbers had given him, to throw it away, because it was old-fashioned confederate money, when he found that there was only one bundle of confederate money, and the rest was all good greenbacks, the bundle of confederate money probably having been shipped west to some museum, and the robbers having got hold of it in the dark, brought it along. Pa burned up the bad money at the hotel, and then he got stuck on the town, and said he would stay there a few days and rest up, and incidentally break a few faro banks, by a system, the way the smart alecks break the bank at Monte Carlo.

I teased Pa to take the first train for home, so we could join the circus before it closed the season, and he could report to the managers the result of his business trip to the west, but Pa said he had heard of a man who had a herd of buffalo on a ranch not far from that town, and before he returned to the show he was going to buy a herd of buffalo for the cowboys and Indians to chase around the wild west show.

I couldn't do anything with pa, so we stayed at that town until pa got good and ready to go home. He bucked the faro bank some, but the gamblers soon found he had so much money that he could break any bank, so they closed up their lay-outs and began to sell pa mining stock in mines which were fabulously rich if they only had money to develop them. They salted some mines near town for Pa to examine, and when he found that they contained gold enough in every shovelful of dirt to make a man crazy, he bought a whole lot of stock, and then the gamblers entertained Pa for all that was out.

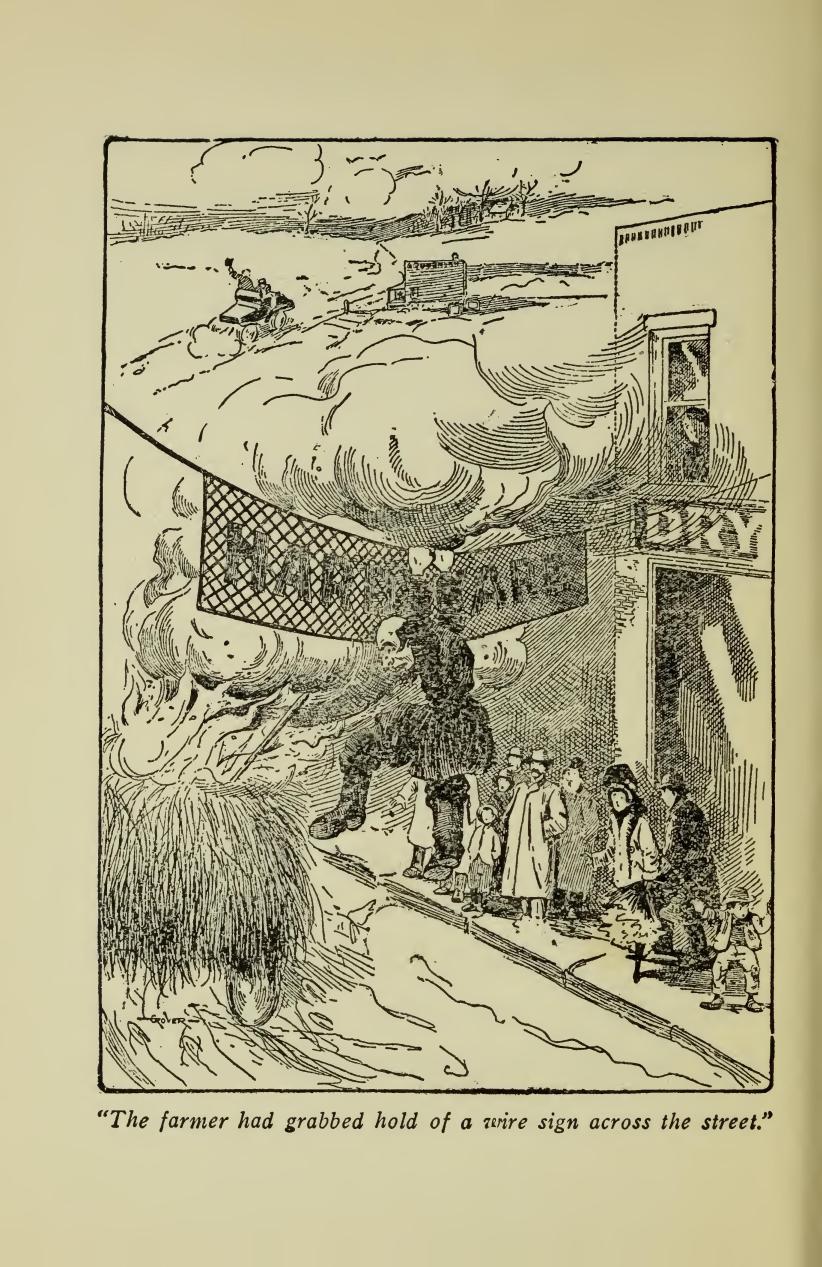

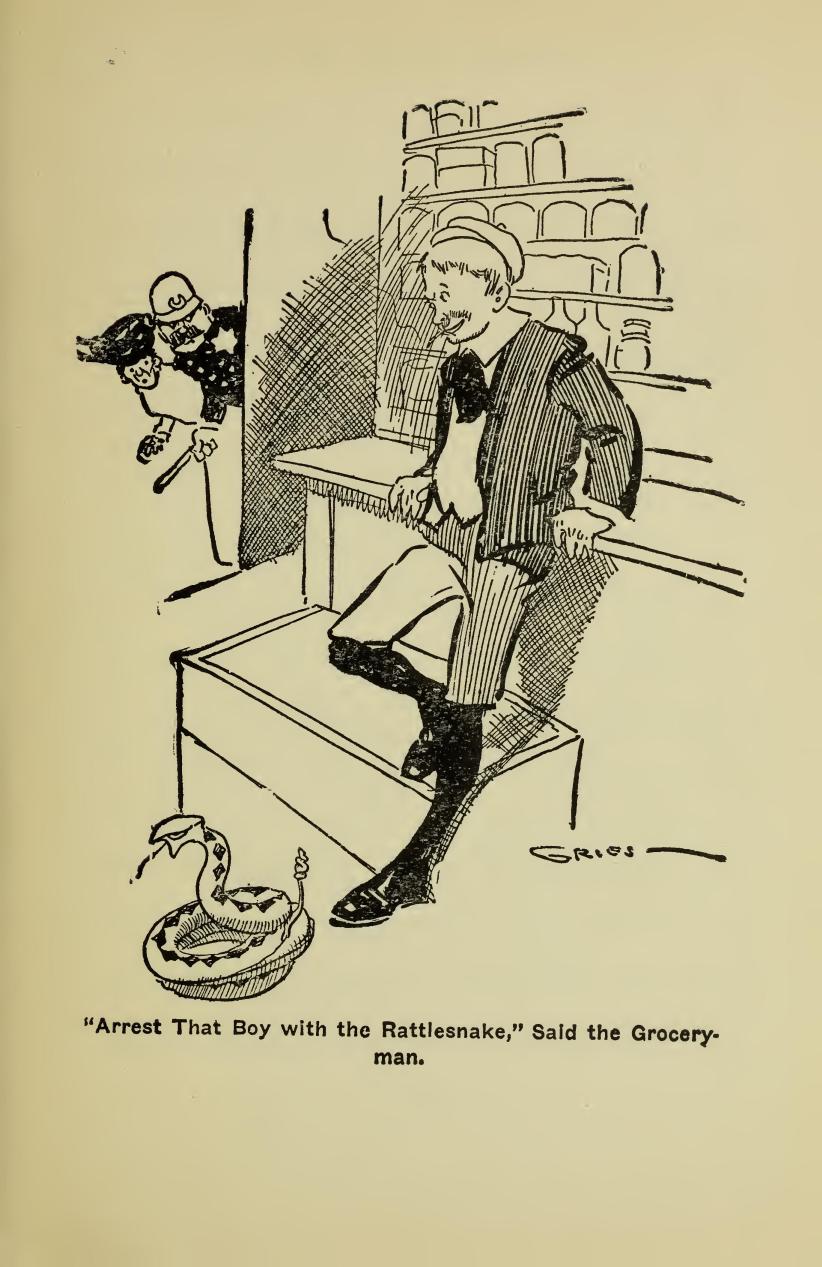

They got up dances and fandangos, and Pa was it, sure, and I was proud of him, cause he did not lose his head. He just acted dignified, and they thought they were entertaining a distinguished man. Everything would have gone all right, and we would have got out with honor, if it hadn't been for the annual rabbit drive that came off while we were there. Part of the country is irrigated, and good crops are grown, but the jackrabbits are so numerous that they come in off the plains adjoining the green spots, at night, and eat everything in sight, so once a year the people get up a rabbit drive and go out in the night by the hundred, on horseback, and surround the country for ten miles or so, and at daylight ride along towards a corral, where thousands of rabbits are driven in and slaughtered with clubs. The men ride close together, with dogs, and no guilty rabbit can escape.

Pa thought it would be a picnic, and so we went along, but pa wishes that he had let well enough alone and kept out of the rabbit game. Those natives are full of fun, and on these rabbit drives they always pick out some man to have fun with, and they picked out Pa as the victim. We rode along for a couple of hours, flushing rabbits by the dozen, and they would run along ahead of us, and multiply, so that when the corral was in sight ahead the prairie was alive with long eared animals, so the earth seemed to be moving, and it almost made a man dizzy to look at them.

The hundreds of men on horseback had come in close together from all sides, and when we were within half a mile of the corral the crowd stopped at a signal, and the leader told Pa that now was the time to make a cavalry charge on the rabbits, and he asked Pa if he was afraid and wanted to go back, and Pa said he had been a soldier and charged the enemy; had been a politician and had fought in hot campaigns; had hunted tigers and lions in the jungle, and rode barebacked in the circus, and gone into lions' dens, and been married, and he guessed he was not going to show the white feather chasing jackrabbits. They could sound the bugle charge as soon as they got ready, and they would find him in the game till the curtain was rung down.

That was what they wanted Pa to say, so, as pa's horse was tired, they suggested that he get on to a fresh horse, and Pa said all right, they couldn't get a horse too fresh for him, and he got on to a spunky pony, and I noticed that there was no bit in the pony's mouth, but only a rope around the pony's nose, and I was afraid something would happen to pa. I told him he and I better dismount, and climb a mesquite tree and watch the fun from a safe place.

Pa said: “Not on your life; your Pa is going right amongst the big game, and is going to make those rabbits think the day of judgment has arrived. Give me a club.”

The leader handed Pa an ax handle, and when we looked ahead towards the corral where the rabbits had been driven, it seemed as though there were a million of them, and they were jumping over each other so it looked as though there was a snow bank of rabbits four feet thick. When Pa said he was ready a fellow sounded a bugle, and pa's pony started off on the jump for the corral, and all the other horses started, and everybody yelled, but they held back their horses so Pa could have the whole field to himself.

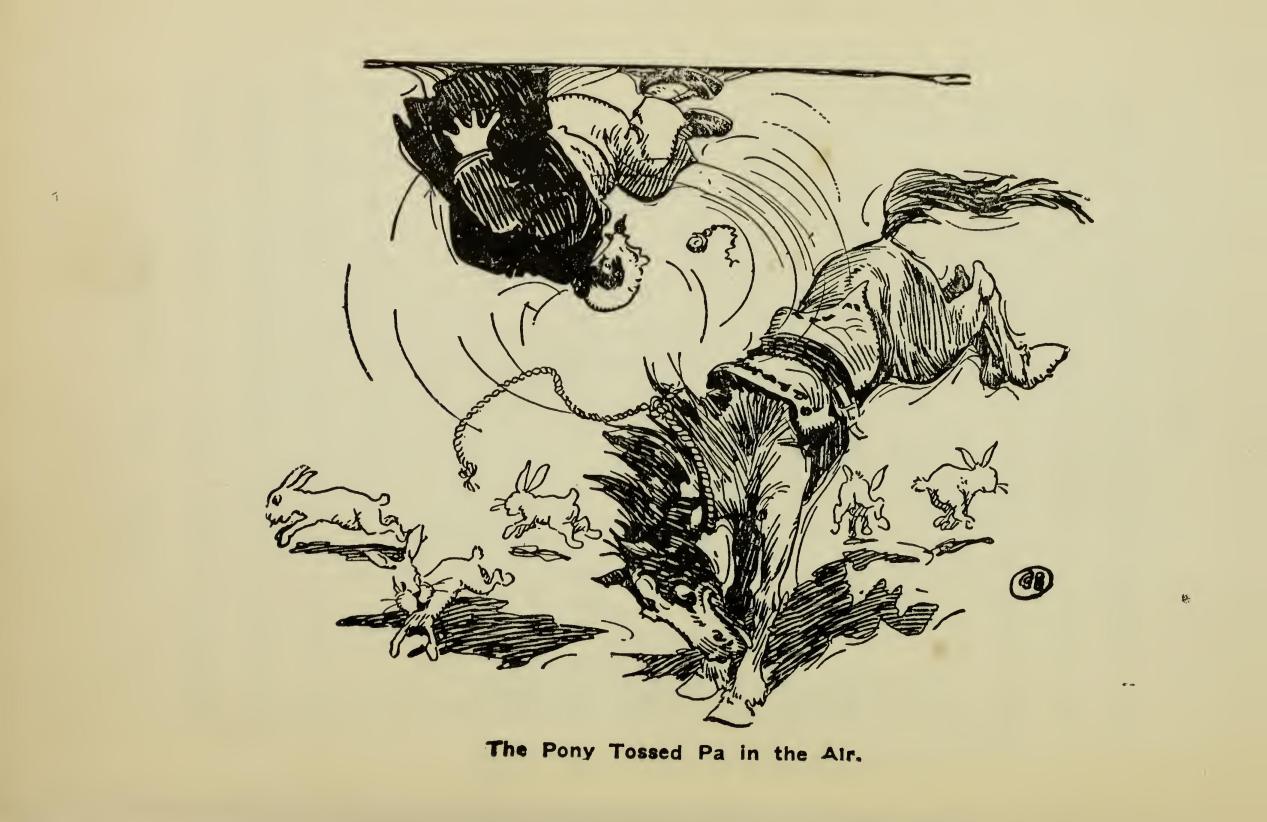

Gee, but I was sorry for pa. His horse rushed right into the corral amongst the rabbits, and when it got right where the rabbits were the thickest, the darn horse began to buck, and tossed Pa in the air just as though he had been thrown up in a blanket, and he came down on a soft bed of struggling and scared rabbits, and the other horsemen stopped at the edge of the corral and watched pa, and I got off my horse and climbed up on a post of the corral and tried to pick out pa. Then all the hundred or more dogs were let loose in amongst Pa and the rabbits, and it was a sight worth going miles to see if it had been somebody else than Pa that was holding the center of the stage, and all the crowd laughing at pa, and yelling to him to stand his ground.

{Illustration: The Pony Tossed Pa In the Air.}

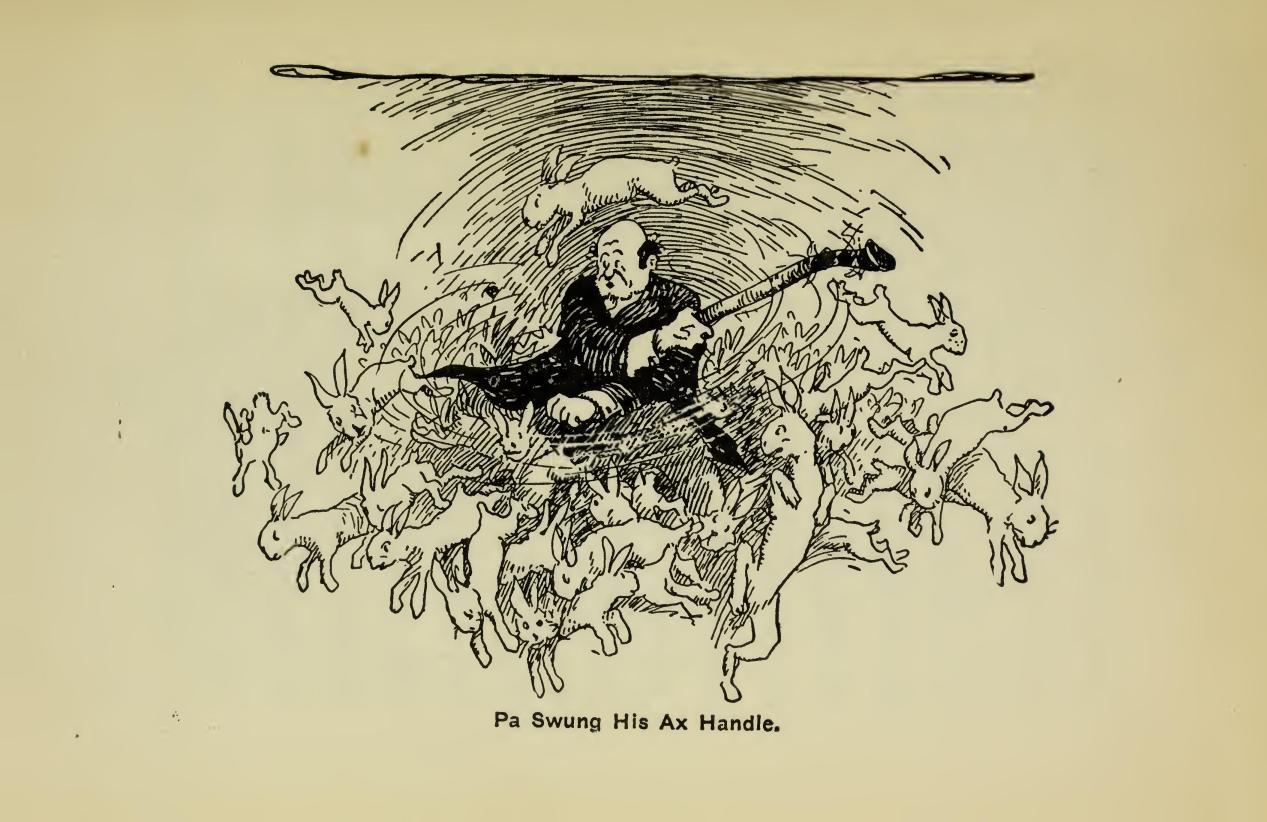

Well, Pa swung his ax handle and killed an occasional rabbit, but there were thousands all around, and Pa seemed to be wading up to his middle in rabbits, and they would jump all over him, and bunt him with their heads, and scratch him with their toe-nails, and the dogs would grab rabbits and shake them, and Pa would fall down and rabbits would run over him till you couldn't see Pa at all. Then he would raise up again and maul the animals with his club, and his clothes were so covered with rabbit hair that he looked like a big rabbit himself. He lost his hat and looked as though he was getting exhausted, and then he stopped and spit on his hands and yelled to the rest of the men, who had dismounted and were lined up at the edge of the corral, and said: “You condemned loafers, why don't you come in here and help us dogs kill off these vermin, cause I don't want to have all the fun. Come on in, the water is fine,” and Pa laughed as though he was in swimming and wanted the rest of the gang to come in.

{Illustration: Pa Swinging His Ax Handle.}

The crowd thought they had given the distinguished stranger his inning, and so they all rushed in with clubs and began to kill rabbits and drive them away from pa. In an hour or so the most of them were killed, and Pa was so tired he went and sat down on the ground to rest, and I got down off my perch and went to Pa and asked him what he thought of this latest experience, and I began to pick rabbit hairs off pa's clothes.

“I'll tell you what it is, Hennery,” said pa, as he breathed hard, as though he had been running a foot race, “this rabbit drive reminds me of the way the rich corporations look upon the poor people, just as we look upon the jackrabbits. We pity a single jackrabbit, and he runs when he sees us, and seems to say: 'Please, mister, let me alone, and let me nibble around and eat the stuff you do not want, and we drive them into a bunch, the way the rich and mean iron-handed trusts drive the people, and then we turn in and club them with the ax handle of graft and greed, and we keep our power over them, if enough are killed off so we are in the majority, but the jackrabbits that escape the drive keep on breeding, like the poor people that the trusts try to exterminate. Some day the jackrabbit and the poor people will get nerve enough to fight back, and then the jackrabbit and the poor people will outnumber the men who fight them and kill them, and they will turn on the cowboys with the clubs, and the trusts with the big head, and drive those who now pursue them into corrals on the prairies and into penitentiaries in the states, and those who are pig-headed and cruel will get theirs, see?”

I told Pa I thought I could see, though there were rabbit hairs in my eyes, and then I got Pa to get up and mount his horse, and we rode back to town with the gang, while the 5,000 rabbit carcasses were hauled to town in wagons and loaded on the cars.

“Where do you send those jackrabbits?” asked Pa of the leader of the slayers, as he watched them loading the rabbits.

“To the Chicago packing houses,” said the man. “They make the finest canned chicken you ever et.”

“The devil, you say,” said pa. “Then we have been working all day to make packing houses rich. Wouldn't that skin you?”

Then we went to the hotel and I put court-plaster on Pa where the rabbits had scratched the skin off, and Pa arranged to go out next day to the ranch where the herd of buffaloes live, to look for bigger game for the show, though he would like to have a rabbit drive in the circus ring next year if he could train the rabbits.

Pa and the Bad Boy Visit a Buffalo Ranch—Pa Pays for the Privilege of Killing a Buffalo, but Doesn't Accomplish His Purpose—He Hires a Herd for the Show Next Year.

This is the last week Pa and I will be in the far west looking for freaks for the wild west department of our show for next year. Next week, if Pa lives, we shall be back under the tent, to see the show close up the season, and shake hands all around with our old friends, the freaks, the performers, the managers and all of 'em.

It will be a glad day for us, for we have had an awful time out west. If Pa would only take advice, and travel like a plain, ordinary citizen, who is willing to learn things, it would be different, but he wants to show people that he knows it all, and he wants to pose as the one to give information, and so when he is taught anything new it jars him. Any man with horse sense would know that it takes years to learn how to rope steers, and keep from being tipped off the horse, and run over by a procession of cows, but because Pa had lassoed hitching posts in his youth, with a clothes line, with a slip noose in it, he posed among cowboys as being an expert roper, and where did he land? In the cactus.