Transcriber’s Note

Transcriber added text to the existing Cover; the result has been placed in the Public Domain.

By Dr. G. HARTWIG,

AUTHOR OF

“THE SEA AND ITS LIVING WONDERS,” “THE HARMONIES OF NATURE,”

AND “THE TROPICAL WORLD.”

WITH ADDITIONAL CHAPTERS AND ONE HUNDRED AND SIXTY-THREE ILLUSTRATIONS.

NEW YORK:

HARPER & BROTHERS, PUBLISHERS,

FRANKLIN SQUARE.

1869.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1869, by

HARPER & BROTHERS,

In the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the United States for the Southern

District of New York.

v

The object of the following pages is to describe the Polar World in its principal natural features, to point out the influence of its long winter-night and fleeting summer on the development of vegetable and animal existence, and finally to picture man waging the battle of life against the dreadful climate of the high latitudes of our globe either as the inhabitant of their gloomy solitudes, or as the bold investigator of their mysteries.

The table of contents shows the great variety of interesting subjects embraced within a comparatively narrow compass; and as my constant aim has been to convey solid instruction under an entertaining form, I venture to hope that the public will grant this new work the favorable reception given to my previous writings.

G. Hartwig.

I have made no alterations in the text of Dr. Hartwig’s book beyond changing the orthography of a few geographical and ethnological terms so that they shall conform to the mode of representation usual in our maps and books of travel. For example, I substitute Nova Zembla for “Novaya Zemla”, and Samoïedes for “Samojedes.” Here and there throughout the work I have added a sentence or a paragraph. The two chapters on “Alaska” and “The Innuits” have been supplied by me; and for them Dr. Hartwig is in no way responsible.

The Illustrations have been wholly selected and arranged by me. I found at my disposal an immense number of illustrations which seemed to me better to elucidate the text than those introduced by Dr. Hartwig. In the List of Illustrations the names of the authors to whom I am indebted are supplied.vi The following gives the names of the authors, and the titles of the works from which the illustrations have been taken:

Atkinson, Thomas Witlam: “Travels in the Regions of the Upper Amoor;” and “Oriental and Western Siberia.”

Browne, J. Ross: “The Land of Thor.”

Dufferin, Lord: “Letters from High Latitudes.”

Hall, Charles Francis: “Arctic Researches, and Life among the Esquimaux.”

Harper’s Magazine: The Illustrations credited to this periodical have been furnished during many years by more than a score of travellers and voyagers. They are in every case authentic.

Lamont, James: “Seasons with the Sea-Horses; or, Sporting Adventures in the Northern Seas.”

Milton, Viscount: “North-west Passage by Land.”

Whymper, Frederick: “Alaska, and British America.”

Wood, Rev. J. G.: “Natural History;” and “Homes without Hands.”

I trust that I have throughout wrought in the spirit of the author; and that my labors will enhance the value of his admirable book.

A. H. G.

vii

| Page | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| THE ARCTIC LANDS. | |

| The barren Grounds or Tundri.—Abundance of animal Life on the Tundri in Summer.—Their Silence and Desolation in Winter.—Protection afforded to Vegetation by the Snow.—Flower-growth in the highest Latitudes.—Character of Tundra Vegetation.—Southern Boundary-line of the barren Grounds.—Their Extent.—The forest Zone.—Arctic Trees.—Slowness of their Growth.—Monotony of the Northern Forests.—Mosquitoes.—The various Causes which determine the Severity of an Arctic Climate.—Insular and Continental Position.—Currents.—Winds.—Extremes of Cold observed by Sir E. Belcher and Dr. Kane.—How is Man able to support the Rigors of an Arctic Winter?—Proofs of a milder Climate having once reigned in the Arctic Regions.—Its Cause according to Dr. Oswald Heer.—Peculiar Beauties of the Arctic Regions.—Sunset.—Long lunar Nights.—The Aurora. | 17 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| ARCTIC LAND QUADRUPEDS AND BIRDS. | |

| The Reindeer.—Structure of its Foot.—Clattering Noise when walking.—Antlers.—Extraordinary olfactory Powers.—The Icelandic Moss.—Present and Former Range of the Reindeer.—Its invaluable Qualities as an Arctic domestic Animal.—Revolts against Oppression.—Enemies of the Reindeer.—The Wolf.—The Glutton or Wolverine.—Gad-flies.—The Elk or Moose-deer.—The Musk-ox.—The Wild Sheep of the Rocky Mountains.—The Siberian Argali.—The Arctic Fox.—Its Burrows.—The Lemmings.—Their Migrations and Enemies.—Arctic Anatidæ.—The Snow-bunting.—The Lapland Bunting.—The Sea-eagle.—Drowned by a Dolphin. | 34 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| THE ARCTIC SEAS. | |

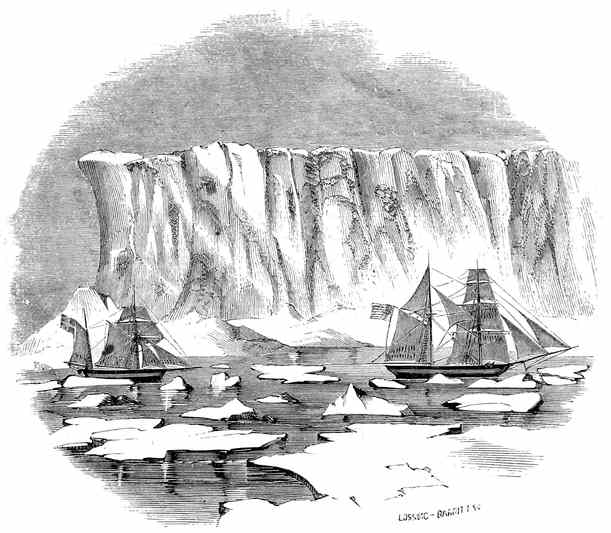

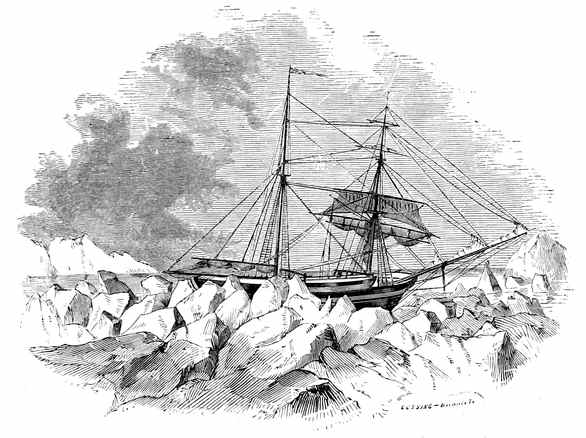

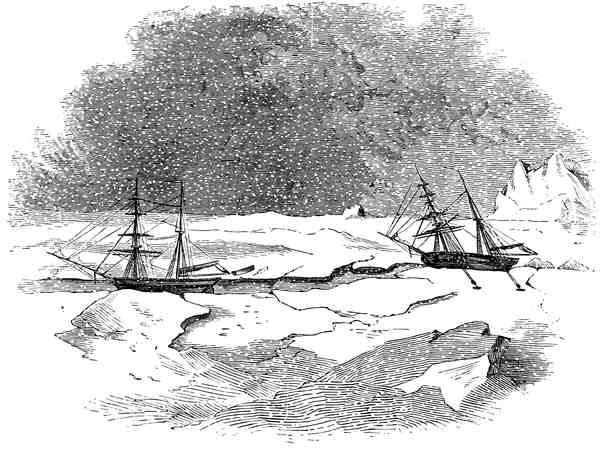

| Dangers peculiar to the Arctic Sea.—Ice-fields.—Hummocks.—Collision of Ice-fields.—Icebergs.—Their Origin.—Their Size.—The Glaciers which give them Birth.—Their Beauty.—Sometimes useful Auxiliaries to the Mariner.—Dangers of anchoring to a Berg.—A crumbling Berg.—The Ice-blink.—Fogs.—Transparency of the Atmosphere.—Phenomena of Reflection and Refraction.—Causes which prevent the Accumulation of Polar Ice.—Tides.—Currents.—Ice a bad Conductor of Heat.—Wise Provisions of Nature. | 45 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| ARCTIC MARINE ANIMALS. | |

| Populousness of the Arctic Seas.—The Greenland Whale.—The Fin Whales.—The Narwhal.—The Beluga, or White Dolphin.—The Black Dolphin.—His wholesale Massacre on the Faeroe Islands.—The Orc, or Grampus.—The Seals.—The Walrus.—Its acute Smell.—History of a young Walrus.—Parental Affection.—The Polar Bear.—His Sagacity.—Hibernation of the She-bear.—Sea-birds. | 59 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| ICELAND. | |

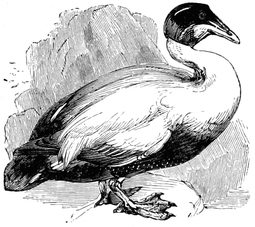

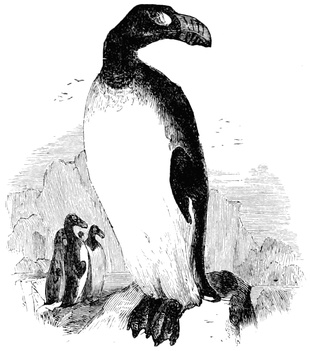

| Volcanic Origin of the Island.—The Klofa Jökul.—Lava-streams.—The Burning Mountains of Krisuvik.—The Mud-caldrons of Reykjahlid.—The Tungo-hver at Reykholt.—The Great Geysir.—The Strokkr.—Crystal Pools.—The Almanuagja.—The Surts-hellir.—Beautiful Ice-cave.—The Gotha Foss.—The Detti Foss.—Climate.—Vegetation.—Cattle.—Barbarous Mode of Sheep-sheering.—Reindeer.—Polar Bears.—Birds.—The Eider-duck.—Videy.—Vigr.—The Wild Swan.—The Raven.—The Jerfalcon.—The Giant auk, or Geirfugl.—Fish.—Fishing Season.—The White Shark.—Mineral Kingdom.—Sulphur.—Peat.—Drift-wood. | 68viii |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| HISTORY OF ICELAND. | |

| Discovery of the Island by Naddodr in 861.—Gardar.—Floki of the Ravens.—Ingolfr and Leif.—Ulfliot the Lawgiver.—The Althing.—Thingvalla.—Introduction of Christianity into the Island.—Frederick the Saxon and Thorwold the Traveller.—Thangbrand.—Golden Age of Icelandic Literature.—Snorri Sturleson.—The Island submits to Hakon, King of Norway, in 1254.—Long Series of Calamities.—Great Eruption of the Skapta Jökul in 1783.—Commercial Monopoly.—Better Times in Prospect. | 89 |

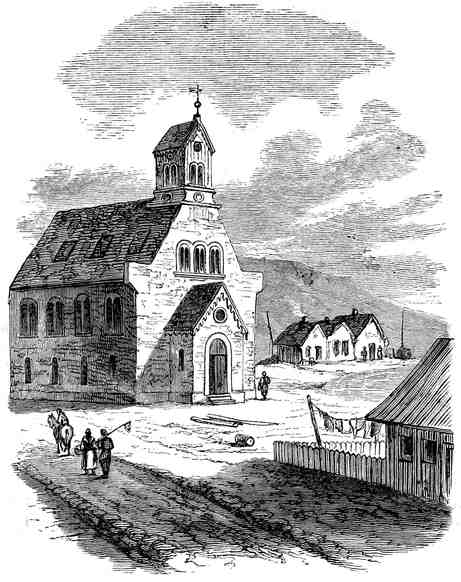

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| THE ICELANDERS. | |

| Skalholt.—Reykjavik.—The Fair.—The Peasant and the Merchant.—A Clergyman in his Cups.—Hay-making.—The Icelander’s Hut.—Churches.—Poverty of the Clergy.—Jon Thorlaksen.—The Seminary of Reykjavik.—Beneficial Influence of the Clergy.—Home Education.—The Icelander’s Winter’s Evening.—Taste for Literature.—The Language.—The Public Library at Reykjavik.—The Icelandic Literary Society.—Icelandic Newspapers.—Longevity.—Leprosy.—Travelling in Iceland.—Fording the Rivers.—Crossing of the Skeidara by Mr. Holland.—A Night’s Bivouac. | 98 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| THE WESTMAN ISLANDS. | |

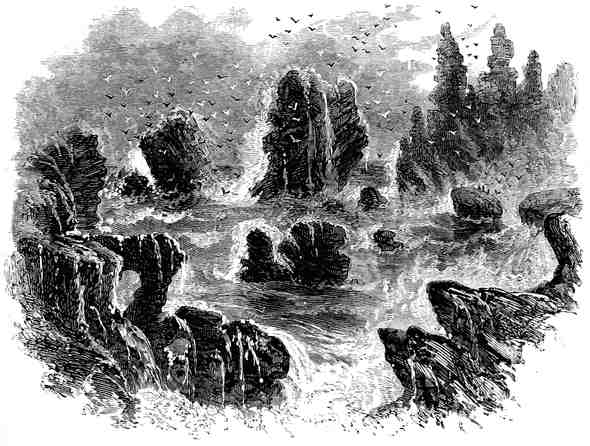

| The Westmans.—Their extreme Difficulty of Access.—How they became peopled.—Heimaey.—Kaufstathir and Ofanleyte.—Sheep-hoisting.—Egg-gathering.—Dreadful Mortality among the Children.—The Ginklofi.—Gentleman John.—The Algerine Pirates.—Dreadful Sufferings of the Islanders. | 114 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| FROM DRONTHEIM TO THE NORTH CAPE. | |

| Mild Climate of the Norwegian Coast.—Its Causes.—The Norwegian Peasant.—Norwegian Constitution.—Romantic coast Scenery.—Drontheim.—Greiffenfeld Holme and Väre.—The Sea-eagle.—The Herring-fisheries.—The Lofoten Islands.—The Cod-fisheries.—Wretched Condition of the Fishermen.—Tromsö.—Altenfiord.—The Copper Mines.—Hammerfest the most northern Town in the World.—The North Cape. | 120 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| SPITZBERGEN—BEAR ISLAND—JAN MEYEN. | |

| The west Coast of Spitzbergen.—Ascension of a Mountain by Dr. Scoresby.—His Excursion along the Coast.—A stranded Whale.—Magdalena Bay.—Multitudes of Sea-birds.—Animal Life.—Midnight Silence.—Glaciers.—A dangerous Neighborhood.—Interior Plateau.—Flora of Spitzbergen.—Its Similarity with that of the Alps above the Snow-line.—Reindeer.—The hyperborean Ptarmigan.—Fishes.—Coal.—Drift-wood.—Discovery of Spitzbergen by Barentz, Heemskerk, and Ryp.—Brilliant Period of the Whale-fishery.—Coffins.—Eight English Sailors winter in Spitzbergen, 1630.—Melancholy Death of some Dutch Volunteers.—Russian Hunters.—Their Mode of wintering in Spitzbergen.—Scharostin.—Walrus-ships from Hammerfest and Tromsö.—Bear or Cherie Island.—Bennet.—Enormous Slaughter of Walruses.—Mildness of its Climate.—Mount Misery.—Adventurous Boat-voyage of some Norwegian Sailors.—Jan Meyen.—Beerenberg. | 131 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| NOVA ZEMBLA. | |

| The Sea of Kara.—Loschkin.—Rosmysslow.—Lütke.—Krotow.—Pachtussow.—Sails along the eastern Coast of the Southern Island to Matoschkin Schar.—His second Voyage and Death.—Meteorological Observations of Ziwolka.—The cold Summer of Nova Zembla.—Von Baer’s scientific Voyage to Nova Zembla.—His Adventures in Matoschkin Schar.—Storm in Kostin Schar.—Sea Bath and votive Cross.—Botanical Observations.—A natural Garden.—Solitude and Silence.—A Bird Bazar.—Hunting Expeditions of the Russians to Nova Zembla. | 147ix |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| THE LAPPS. | |

| Their ancient History and Conversion to Christianity.—Self-denial and Poverty of the Lapland Clergy.—Their singular Mode of Preaching.—Gross Superstition of the Lapps.—The Evil Spirit of the Woods.—The Lapland Witches.—Physical Constitution of the Lapps.—Their Dress.—The Fjälllappars.—Their Dwellings.—Store-houses.—Reindeer Pens.—Milking the Reindeer.—Migration.—The Lapland Dog.—Skiders, or Skates.—The Sledge, or Pulka.—Natural Beauties of Lapland.—Attachment of the Lapps to their Country.—Bear-hunting.—Wolf-hunting.—Mode of Living of the wealthy Lapps.—How they kill the Reindeer.—Visiting the Fair.—Mammon Worship.—Treasure-hiding.—“Tabak, or Braende.”—Affectionate Disposition of the Lapps.—The Skogslapp.—The Fisherlapp. | 156 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| MATTHIAS ALEXANDER CASTRÉN. | |

| His Birthplace and first Studies.—Journey in Lapland, 1838.—The Iwalojoki.—The Lake of Enara.—The Pastor of Utzjoki.—From Rowaniémi to Kemi.—Second Voyage, 1841–44.—Storm on the White Sea.—Return to Archangel.—The Tundras of the European Samoïedes.—Mesen.—Universal Drunkenness.—Sledge Journey to Pustosersk.—A Samoïede Teacher.—Tundra Storms.—Abandoned and alone in the Wilderness.—Pustosersk.—Our Traveller’s Persecutions at Ustsylmsk and Ishemsk.—The Uusa.—Crossing the Ural.—Obdorsk.—Second Siberian Journey, 1845–48.—Overflowing of the Obi.—Surgut.—Krasnojarsk.—Agreeable Surprise.—Turuchansk.—Voyage down the Jenissei.—Castrén’s Study at Plachina.—From Dudinka to Tolstoi Noss.—Frozen Feet.—Return Voyage to the South.—Frozen fast on the Jenissei.—Wonderful Preservation.—Journey across the Chinese Frontiers, and to Transbaikalia.—Return to Finland.—Professorship at Helsingfors.—Death of Castrén, 1855. | 168 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| THE SAMOÏEDES. | |

| Their Barbarism.—Num, or Jilibeambaertje.—Shamanism.—Samoïede Idols.—Sjadæi.—Hahe.—The Tadebtsios, or Spirits.—The Tadibes, or Sorcerers.—Their Dress.—Their Invocations.—Their conjuring Tricks.—Reverence paid to the Dead.—A Samoïede Oath.—Appearance of the Samoïedes.—Their Dress.—A Samoïede Belle.—Character of the Samoïedes.—Their decreasing Numbers.—Traditions of ancient Heroes. | 179 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| THE OSTIAKS. | |

| What is the Obi?—Inundations.—An Ostiak summer Yourt.—Poverty of the Ostiak Fishermen.—A winter Yourt.—Attachment of the Ostiaks to their ancient Customs.—An Ostiak Prince.—Archery.—Appearance and Character of the Ostiaks.—The Fair of Obdorsk. | 185 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| CONQUEST OF SIBERIA BY THE RUSSIANS—THEIR VOYAGES OF DISCOVERY ALONG THE SHORES OF THE POLAR SEA. | |

| Ivan the Terrible.—Strogonoff.—Yermak, the Robber and Conqueror.—His Expeditions to Siberia.—Battle of Tobolsk.—Yermak’s Death.—Progress of the Russians to Ochotsk.—Semen Deshnew.—Condition of the Siberian Natives under the Russian Yoke.—Voyages of Discovery in the Reign of the Empress Anna.—Prontschischtschew.—Chariton and Demetrius Laptew.—An Arctic Heroine.—Schalaurow.—Discoveries in the Sea of Bering and in the Pacific Ocean.—The Lächow Islands.—Fossil Ivory.—New Siberia.—The wooden Mountains.—The past Ages of Siberia. | 191x |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| SIBERIA—FUR-TRADE AND GOLD-DIGGINGS. | |

| Siberia.—Its immense Extent and Capabilities.—The Exiles.—Mentschikoff.—Dolgorouky.—Münich.—The Criminals.—The free Siberian Peasant.—Extremes of Heat and Cold.—Fur-bearing Animals.—The Sable.—The Ermine.—The Siberian Weasel.—The Sea-otter.—The black Fox.—The Lynx.—The Squirrel.—The varying Hare.—The Suslik.—Importance of the Fur-trade for the Northern Provinces of the Russian Empire.—The Gold-diggings of Eastern Siberia.—The Taiga.—Expenses and Difficulties of searching Expeditions.—Costs of Produce, and enormous Profits of successful Speculators.—Their senseless Extravagance.—First Discovery of Gold in the Ural Mountains.—Jakowlew and Demidow.—Nishne-Tagilsk. | 204 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| MIDDENDORFF’S ADVENTURES IN TAIMURLAND. | |

| For what Purpose was Middendorff’s Voyage to Taimurland undertaken?—Difficulties and Obstacles.—Expedition down the Taimur River to the Polar Sea.—Storm on Taimur Lake.—Loss of the Boat.—Middendorff ill and alone in 75° N. Lat.—Saved by a grateful Samoïede.—Climate and Vegetation of Taimurland. | 220 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| THE JAKUTS. | |

| Their energetic Nationality.—Their Descent.—Their gloomy Character.—Summer and Winter Dwellings.—The Jakut Horse.—Incredible Powers of Endurance of the Jakuts.—Their Sharpness of Vision.—Surprising local Memory.—Their manual Dexterity.—Leather, Poniards, Carpets.—Jakut Gluttons.—Superstitious Fear of the Mountain-spirit Ljeschei.—Offerings of Horse-hair.—Improvised Songs.—The River Jakut. | 228 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| WRANGELL. | |

| His distinguished Services as an Arctic Explorer.—From Petersburg to Jakutsk in 1820.—Trade of Jakutsk.—From Jakutsk to Nishne-Kolymsk.—The Badarany.—Dreadful Climate of Nishne-Kolymsk.—Summer Plagues.—Vegetation.—Animal Life.—Reindeer-hunting.—Famine.—Inundations.—The Siberian Dog.—First Journeys over the Ice of the Polar Sea, and Exploration of the Coast beyond Cape Shelagskoi in 1821.—Dreadful Dangers and Hardships.—Matiuschkin’s Sledge-journey over the Polar Sea in 1822.—Last Adventures on the Polar Sea.—A Run for Life.—Return to St. Petersburg. | 233 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| THE TUNGUSI. | |

| Their Relationship to the Mantchou.—Dreadful Condition of the outcast Nomads.—Character of the Tungusi.—Their Outfit for the Chase.—Bear-hunting.—Dwellings.—Diet.—A Night’s Halt with Tungusi in the Forest.—Ochotsk. | 244 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| GEORGE WILLIAM STELLER. | |

| His Birth.—Enters the Russian Service.—Scientific Journey to Kamchatka.—Accompanies Bering on his second Voyage of Discovery.—Lands on the Island of Kaiak.—Shameful Conduct of Bering.—Shipwreck on Bering Island.—Bering’s Death.—Return to Kamchatka.—Loss of Property.—Persecutions of the Siberian Authorities.—Frozen to Death at Tjumen. | 248 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| KAMCHATKA. | |

| Climate.—Fertility.—Luxuriant Vegetation.—Fish.—Sea-birds.—Kamchatkan Bird-catchers.—The Bay of Avatscha.—Petropavlosk.—The Kamchatkans.—Their physical and moral Qualities.—The Fritillaria Sarrana.—The Muchamor.—Bears.—Dogs. | 254 |

| CHAPTER XXIV.xi | |

| THE TCHUKTCHI. | |

| The Land of the Tchuktchi.—Their independent Spirit and commercial Enterprise.—Perpetual Migrations.—The Fair of Ostrownoje.—Visit in a Tchuktch Polog.—Races.—Tchuktch Bayaderes.—The Tennygk, or Reindeer Tchuktchi.—The Onkilon, or Sedentary Tchuktchi.—Their Mode of Life. | 262 |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| BERING SEA—THE RUSSIAN FUR COMPANY—THE ALEUTS. | |

| Bering Sea.—Unalaska.—The Pribilow Islands.—St. Matthew.—St. Laurence.—Bering’s Straits.—The Russian Fur Company.—The Aleuts.—Their Character.—Their Skill and Intrepidity in hunting the Sea-otter.—The Sea-bear.—Whale-chasing.—Walrus-slaughter.—The Sea-lion. | 268 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| ALASKA. | |

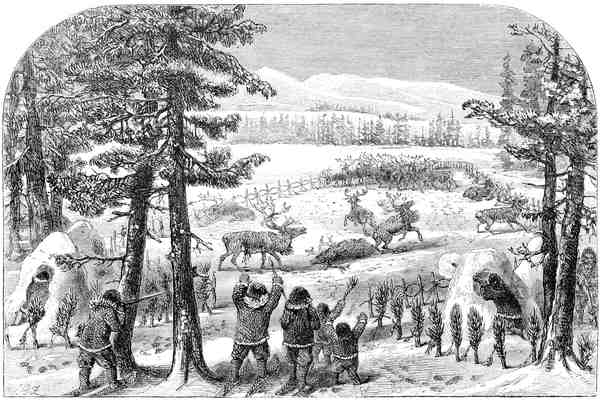

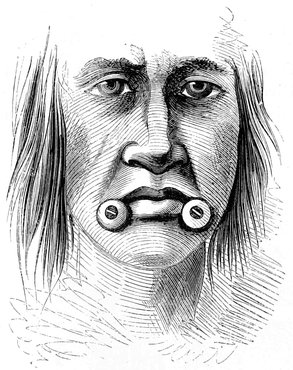

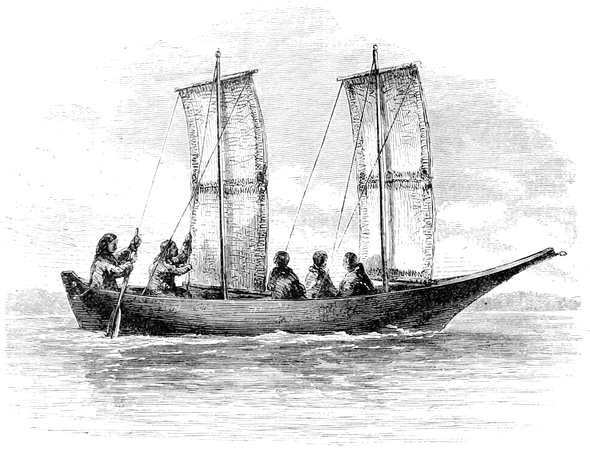

| Purchase of Alaska by the United States.—The Russian American Telegraph Scheme.—Whymper’s Trip up the Yukon.—Dogs.—The Start.—Extempore Water-filter.—Snow-shoes.—The Frozen Yukon.—Under-ground Houses.—Life at Nulato.—Cold Weather.—Auroras.—Approach of Summer.—Breaking-up of the Ice.—Fort Yukon.—Furs.—Descent of the Yukon.—Value of Goods.—Arctic and Tropical Life.—Moose-hunting.—Deer-corrals.—Lip Ornaments.—Canoes.—Four-post Coffin.—The Kenaian Indians.—The Aleuts.—Value of Alaska. | 277 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| THE ESQUIMAUX. | |

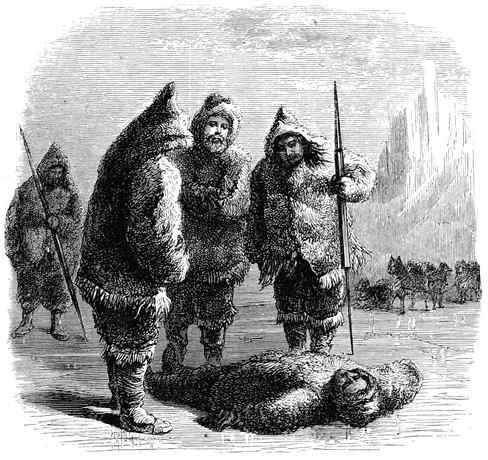

| Their wide Extension.—Climate of the Regions they inhabit.—Their physical Appearance.—Their Dress.—Snow Huts.—The Kayak, or the Baidar.—Hunting Apparatus and Weapons.—Enmity between the Esquimaux and the Red Indian.—The “Bloody Falls.”—Chase of the Reindeer.—Bird-catching.—Whale-hunting.—Various Stratagems employed to catch the Seal.—The “Keep-kuttuk.”—Bear-hunting.—Walrus-hunting.—Awaklok and Myouk.—The Esquimaux Dog.—Games and Sports.—Angekoks.—Moral Character.—Self-reliance.—Intelligence.—Iligliuk.—Commercial Eagerness of the Esquimaux.—Their Voracity.—Seasons of Distress. | 290 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

| THE FUR-TRADE OF THE HUDSON’S BAY TERRITORIES. | |

| The Coureur des Bois.—The Voyageur.—The Birch-bark Canoe.—The Canadian Fur-trade in the last Century.—The Hudson’s Bay Company.—Bloody Feuds between the North-west Company of Canada and the Hudson’s Bay Company.—Their Amalgamation into a new Company in 1821.—Reconstruction of the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1863.—Forts or Houses.—The Attihawmeg.—Influence of the Company on its savage Dependents.—The Black Bear, or Baribal.—The Brown Bear.—The Grizzly Bear.—The Raccoon.—The American Glutton.—The Pine Marten.—The Pekan, or Wood-shock.—The Chinga.—The Mink.—The Canadian Fish-otter.—The Crossed Fox.—The Black or Silvery Fox.—The Canadian Lynx, or Pishu.—The Ice-hare.—The Beaver.—The Musquash. | 304 |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | |

| THE CREE INDIANS, OR EYTHINYUWUK. | |

| The various Tribes of the Crees.—Their Conquests and subsequent Defeat.—Their Wars with the Blackfeet.—Their Character.—Tattooing.—Their Dress.—Fondness for their Children.—The Cree Cradle.—Vapor Baths.—Games.—Their religious Ideas.—The Cree Tartarus and Elysium. | 319 |

| CHAPTER XXX. | |

| THE TINNÉ INDIANS. | |

| The various Tribes of the Tinné Indians.—The Dog-ribs.—Clothing.—The Hare Indians.—Degraded State of the Women.—Practical Socialists.—Character.—Cruelty to the Aged and Infirm. | 327 |

| CHAPTER XXXI.xii | |

| THE LOUCHEUX, OR KUTCHIN INDIANS. | |

| The Countries they inhabit.—Their Appearance and Dress.—Their Love of Finery.—Condition of the Women.—Strange Customs.—Character.—Feuds with the Esquimaux.—Their suspicious and timorous Lives.—Pounds for catching Reindeer.—Their Lodges. | 331 |

| CHAPTER XXXII. | |

| ARCTIC VOYAGES OF DISCOVERY, FROM THE CABOTS TO BAFFIN. | |

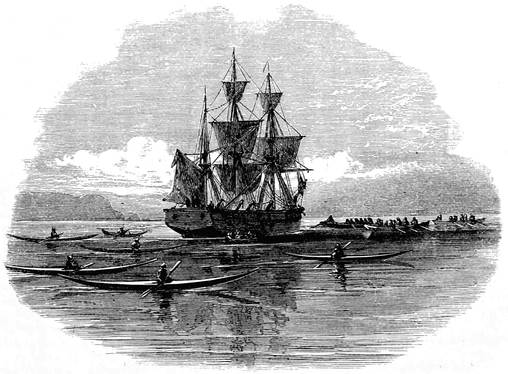

| First Scandinavian Discoverer of America.—The Cabots.—Willoughby and Chancellor (1553–1554).—Stephen Burrough (1556).—Frobisher (1576–1578).—Davis (1585–1587).—Barentz, Cornelis, and Brant (1594).—Wintering of the Dutch Navigators in Nova Zembla (1596–1597).—John Knight (1606).—Murdered by the Esquimaux.—Henry Hudson (1607–1609).—Baffin (1616). | 335 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. | |

| ARCTIC VOYAGES OF DISCOVERY, FROM BAFFIN TO M’CLINTOCK. | |

| Buchan and Franklin.—Ross and Parry (1818).—Discovery of Melville Island.—Winter Harbor (1819–1820).—Franklin’s first land Journey.—Dreadful Sufferings.—Parry’s second Voyage (1821–1823).—Iligliuk.—Lyon (1824).—Parry’s third Voyage (1824).—Franklin’s second land Journey to the Shores of the Polar Sea.—Beechey.—Parry’s sledge Journey towards the Pole.—Sir John Ross’s second Journey.—Five Years in the Arctic Ocean.—Back’s Discovery of Great Fish River.—Dease and Simpson (1837–1839).—Franklin and Crozier’s last Voyage (1845).—Searching Expeditions.—Richardson and Rae.—Sir James Ross.—Austin.—Penny.—De Haven.—Franklin’s first Winter-quarters discovered by Ommaney.—Kennedy and Bellot.—Inglefield.—Sir E. Belcher.—Kellett.—M’Clure’s Discovery of the North-west Passage.—Collinson.—Bellot’s Death.—Dr. Rae learns the Death of the Crews of the “Erebus” and “Terror.”—Sir Leopold M’Clintock. | 344 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV. | |

| KANE AND HAYES. | |

| Kane sails up Smith’s Sound in the “Advance” (1853).—Winters in Rensselaer Bay.—Sledge Journey along the Coast of Greenland.—The Three-brother Turrets.—Tennyson’s Monument.—The Great Humboldt Glacier.—Dr. Hayes crosses Kennedy Channel.—Morton’s Discovery of Washington Land.—Mount Parry.—Kane resolves upon a second Wintering in Rensselaer Bay.—Departure and Return of Part of the Crew.—Sufferings of the Winter.—The Ship abandoned.—Boat Journey to Upernavik.—Kane’s Death in the Havana (1857).—Dr. Hayes’s Voyage in 1860.—He winters at Port Foulke.—Crosses Kennedy Channel.—Reaches Cape Union, the most northern known Land upon the Globe.—Koldewey.—Plans for future Voyages to the North Pole. | 365 |

| CHAPTER XXXV. | |

| NEWFOUNDLAND. | |

| Its desolate Aspect.—Forests.—Marshes.—Barrens.—Ponds.—Fur-bearing Animals.—Severity of Climate.—St. John’s.—Discovery of Newfoundland by the Scandinavians.—Sir Humphrey Gilbert.—Rivalry of the English and French.—Importance of the Fisheries.—The Banks of Newfoundland.—Mode of Fishing.—Throaters, Headers, Splitters, Salters, and Packers.—Fogs and Storms.—Seal-catching. | 376 |

| CHAPTER XXXVI. | |

| GREENLAND. | |

| A mysterious Region.—Ancient Scandinavian Colonists.—Their Decline and Fall.—Hans Egede.—His Trials and Success.—Foundation of Godthaab.—Herrenhuth Missionaries.—Lindenow.—The Scoresbys.—Clavering.—The Danish Settlements in Greenland.—The Greenland Esquimaux.—Seal-catching.—The White Dolphin.—The Narwhal.—Shark-fishery.—Fiskernasset.—Birds.—Reindeer-hunting.—Indigenous Plants.—Drift-wood.—Mineral Kingdom.—Mode of Life of the Greenland Esquimaux.—The Danes in Greenland.—Beautiful Scenery.—Ice Caves. | 382 |

| CHAPTER XXXVII.xiii | |

| THE ANTARCTIC OCEAN. | |

| Comparative View of the Antarctic and Arctic Regions.—Inferiority of Climate of the former.—Its Causes.—The New Shetland Islands.—South Georgia.—The Peruvian Stream.—Sea-birds.—The Giant Petrel.—The Albatross.—The Penguin.—The Austral Whale.—The Hunchback.—The Fin-back.—The Grampus.—Battle with a Whale.—The Sea-elephant.—The Southern Sea-bear.—The Sea-leopard.—Antarctic Fishes. | 391 |

| CHAPTER XXXVIII. | |

| ANTARCTIC VOYAGES OF DISCOVERY. | |

| Cook’s Discoveries in the Antarctic Ocean.—Bellinghausen.—Weddell.—Biscoe.—Balleny.—Dumont d’Urville.—Wilkes.—Sir James Ross crosses the Antarctic Circle on New Year’s Day, 1841.—Discovers Victoria Land.—Dangerous Landing on Franklin Island.—An Eruption of Mount Erebus.—The Great Ice Barrier.—Providential Escape.—Dreadful Gale.—Collision.—Hazardous Passage between two Icebergs.—Termination of the Voyage. | 401 |

| CHAPTER XXXIX. | |

| THE STRAIT OF MAGELLAN. | |

| Description of the Strait.—Western Entrance.—Point Dungeness.—The Narrows.—Saint Philip’s Bay.—Cape Froward.—Grand Scenery.—Port Famine.—The Sedger River.—Darwin’s Ascent of Mount Tarn.—The Bachelor River.—English Reach.—Sea Reach.—South Desolation.—Harbor of Mercy.—Williwaws.—Discovery of the Strait by Magellan (October 20, 1521).—Drake.—Sarmiento.—Cavendish.—Schouten and Le Maire.—Byron.—Bougainville.—Wallis and Carteret.—King and Fitzroy.—Settlement at Punta Arenas.—Increasing Passage through the Strait.—A future Highway of Commerce. | 408 |

| CHAPTER XL. | |

| PATAGONIA AND THE PATAGONIANS. | |

| Difference of Climate between East and West Patagonia.—Extraordinary Aridity of East Patagonia.—Zoology.—The Guanaco.—The Tucutuco.—The Patagonian Agouti.—Vultures.—The Turkey-buzzard.—The Carrancha.—The Chimango.—Darwin’s Ostrich.—The Patagonians.—Exaggerated Accounts of their Stature.—Their Physiognomy and Dress.—Religious Ideas.—Superstitions.—Astronomical Knowledge.—Division into Tribes.—The Tent, or Toldo.—Trading Routes.—The great Cacique.—Introduction of the Horse.—Industry.—Amusements.—Character. | 417 |

| CHAPTER XLI. | |

| THE FUEGIANS. | |

| Their miserable Condition.—Degradation of Body and Mind.—Powers of Mimicry.—Notions of Barter.—Causes of their low State of Cultivation.—Their Food.—Limpets.—Cyttaria Darwini.—Constant Migrations.—The Fuegian Wigwam.—Weapons.—Their probable Origin.—Their Number, and various Tribes.—Constant Feuds.—Cannibalism.—Language.—Adventures of Fuegia Basket, Jemmy Button, and York Minster.—Missionary Labors.—Captain Gardiner.—His lamentable End. | 425 |

| CHAPTER XLII. | |

| CHARLES FRANCIS HALL AND THE INNUITS. | |

| Hall’s Expedition.—His early Life.—His reading of Arctic Adventure.—His Resolve.—His Arctic Outfit.—Sets sail on the “George Henry.”—The Voyage.—Kudlago.—Holsteinborg, Greenland.—Population of Greenland.—Sails for Davis’s Strait.—Character of the Innuits.—Wreck of the “Rescue.”—Ebierbing and Tookoolito.—Their Visit to England.—Hall’s first Exploration.—European and Innuit Life in the Arctic Regions.—Building an Igloo.—Almost Starved.—Fight for Food with Dogs.—Ebierbing arrives with a Seal.—How he caught it.—A Seal-feast.—The Innuits and Seals.—The Polar Bear.—How he teaches the Innuits to catch Seals.—At a Seal-hole.—Dogs as Seal-hunters.—Dogs and Bears.—Dogs and Reindeers.—Innuits and Walruses.—More about Igloos.—Innuit Implements.—Uses of the Reindeer.—Innuit Improvidence.—A Deer-feast.—A frozen Delicacy.—Whale-skin as Food.—Whale-gum.—How to eat Whale Ligament.—Raw Meat.—The Dress of the Innuits.—A pretty Style.—Religious Ideas of the Innuits.—Their kindly Character.—Treatment of the Aged and Infirm.—A Woman abandoned to die.—Hall’s Attempt to rescue her.—The Innuit Nomads, without any form of Government.—Their Numbers diminishing.—A Sailor wanders away.—Hall’s Search for him.—Finds him frozen to death.—The Ship free from Ice.—Preparations to return.—Reset in the Ice-pack.—Another Arctic Winter.—Breaking up of the Ice.—Departure for Home.—Tookoolito and her Child “Butterfly.”—Death of “Butterfly.”—Arrival at Home.—Results of Hall’s Expedition.—Innuit Traditions.—Discovery of Frobisher Relics.—Hall undertakes a second Expedition.—His Statement of its Object and Prospects.—Last Tidings of Hall. | 433xiv |

xv

| PAGE | |||

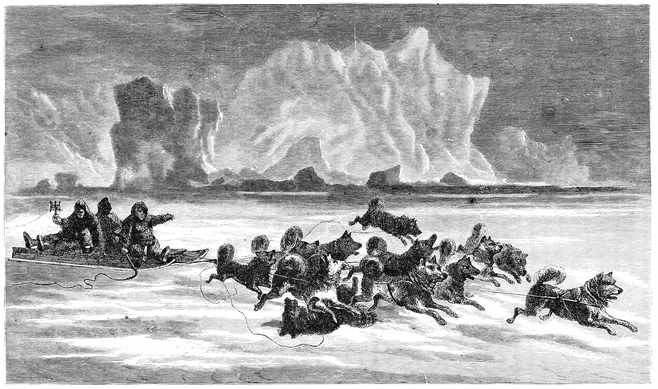

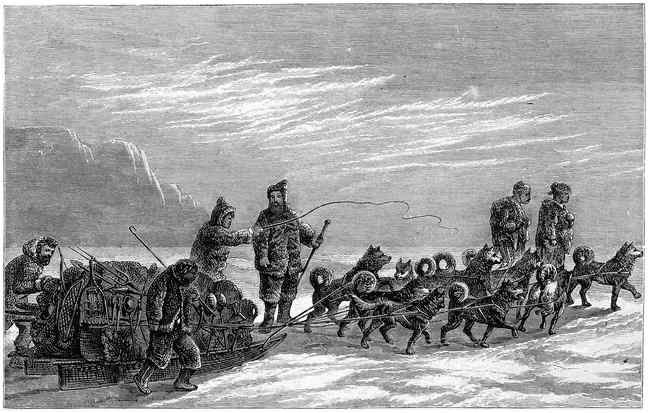

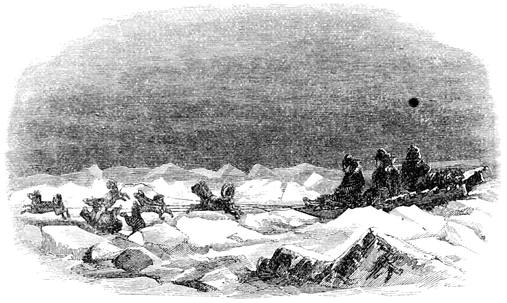

| 1. | Esquimaux Dog-team. | Hall. | 1 |

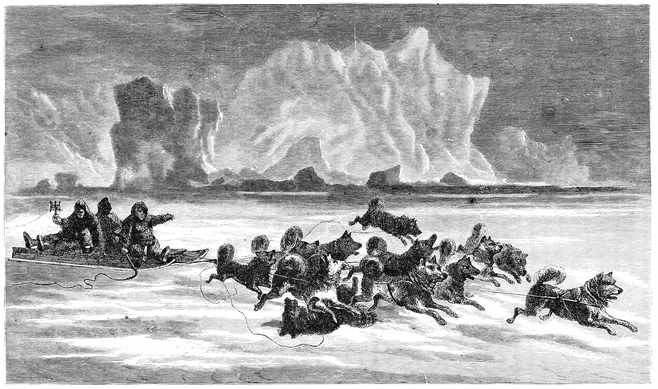

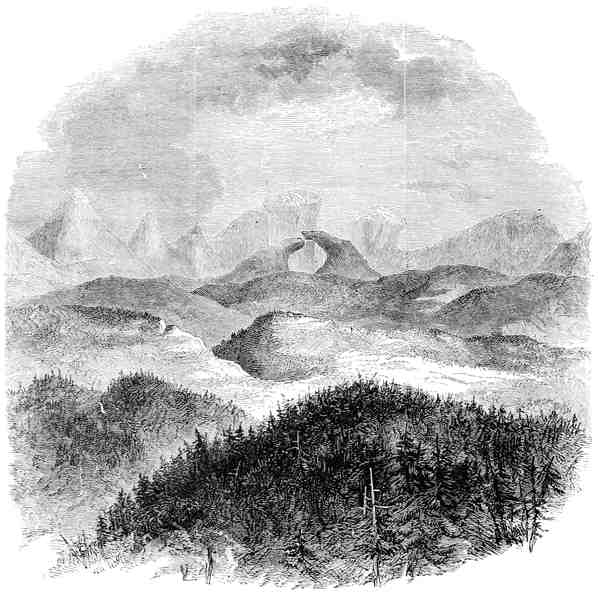

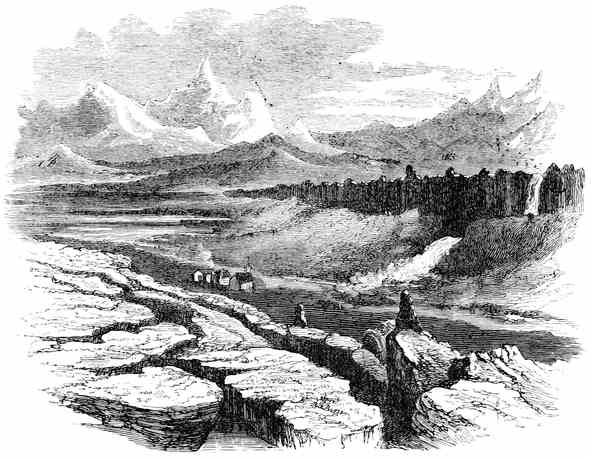

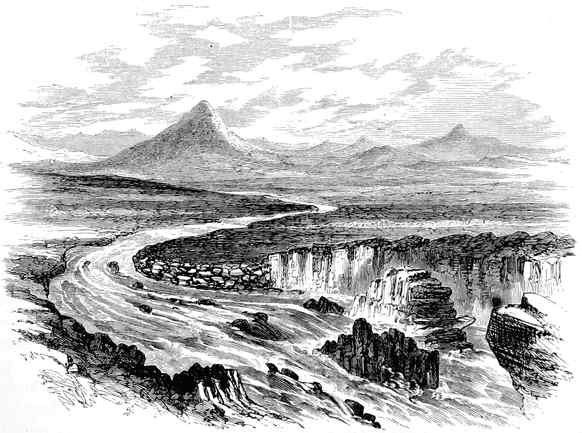

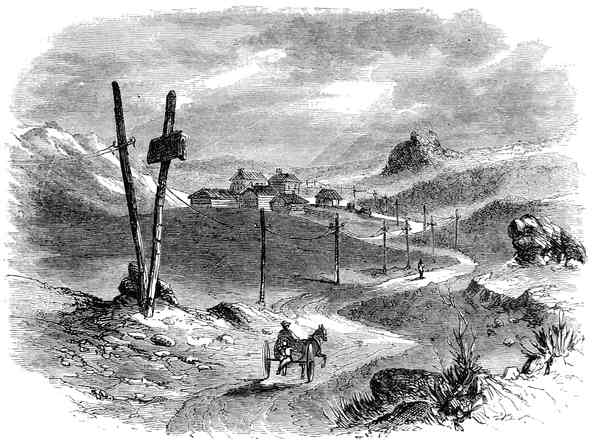

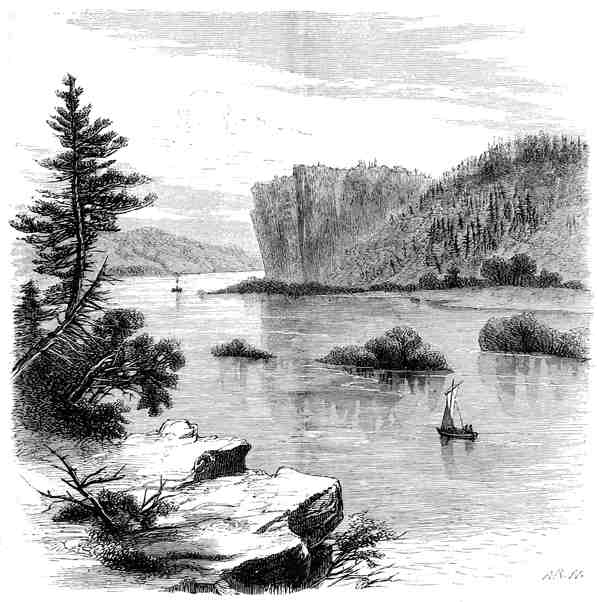

| 2. | The Tundra of Siberia. | Atkinson. | 17 |

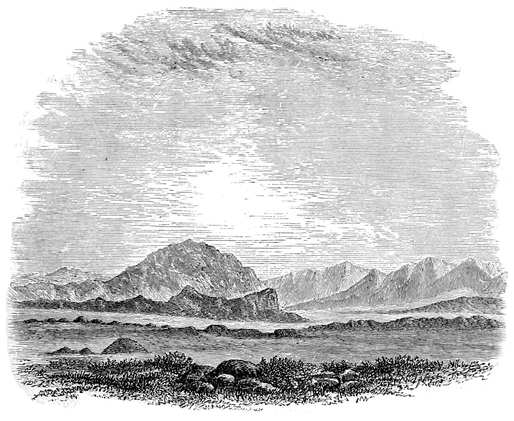

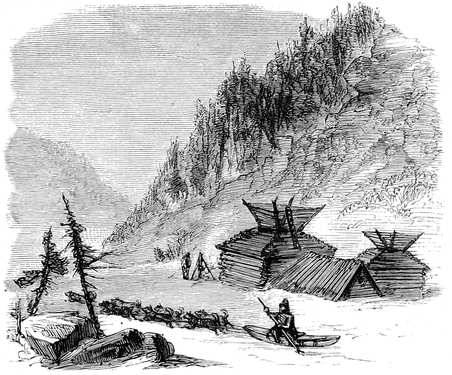

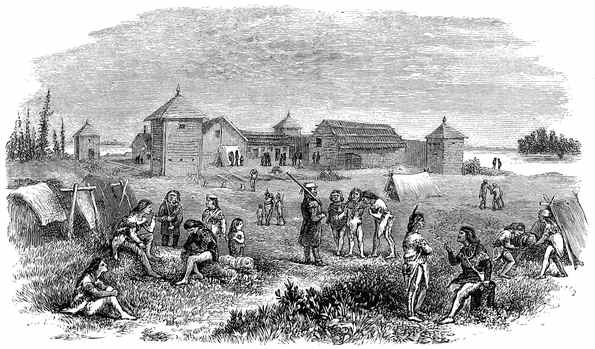

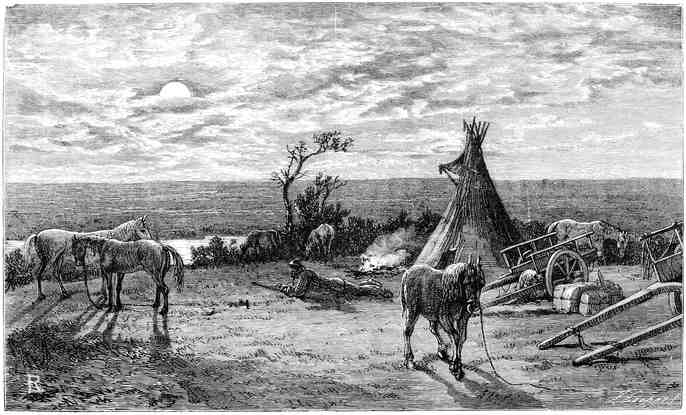

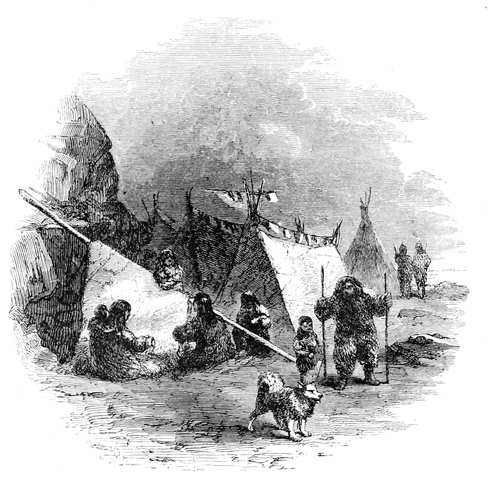

| 3. | Indian Summer Encampment, Alaska. | Whymper. | 18 |

| 4. | Rocks and Ice. | Hall. | 20 |

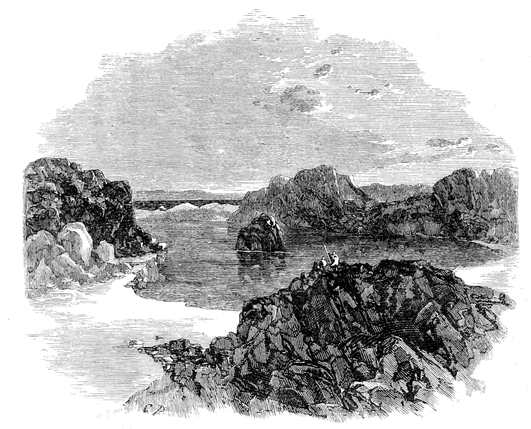

| 5. | Coast of Labrador. | Harper’s Mag. | 21 |

| 6. | Coast of Norway. | Browne. | 22 |

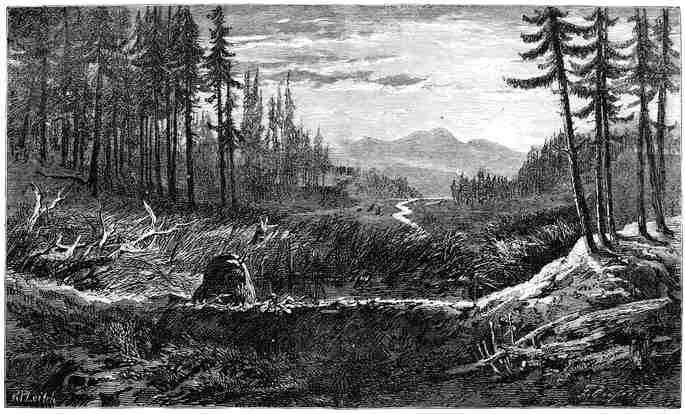

| 7. | Arctic Forest. | Lamont. | 23 |

| 8. | Verge of Forest Region. | Harper’s Mag. | 24 |

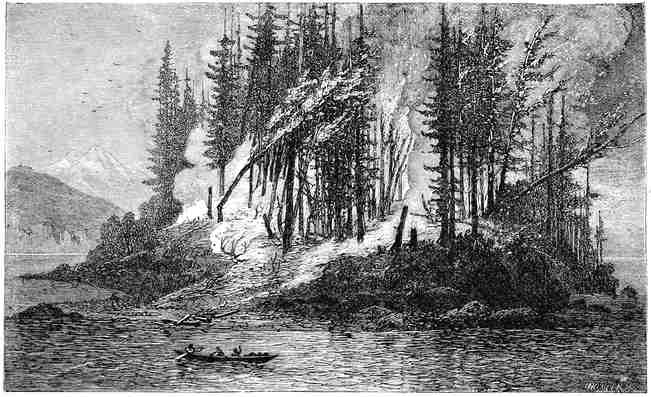

| 9. | Forest Conflagration. | Whymper. | 26 |

| 10. | Arctic Clothing. | Harper’s Mag. | 29 |

| 11. | Arctic Moonlight. | Hall. | 30 |

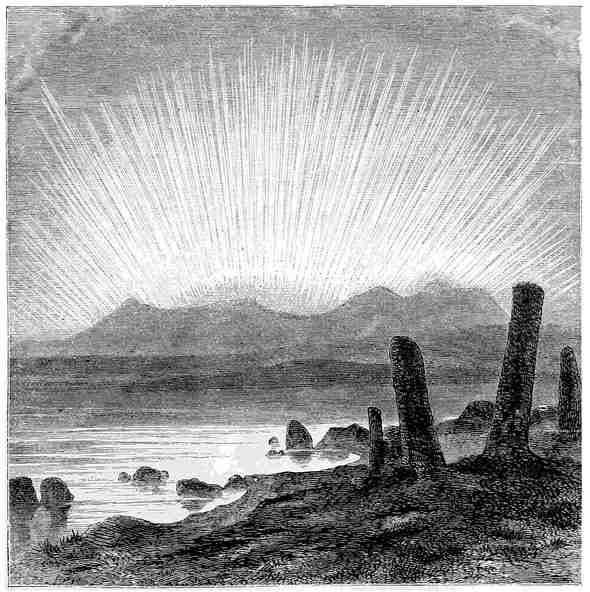

| 12. | Aurora seen in Norway. | Harper’s Mag. | 31 |

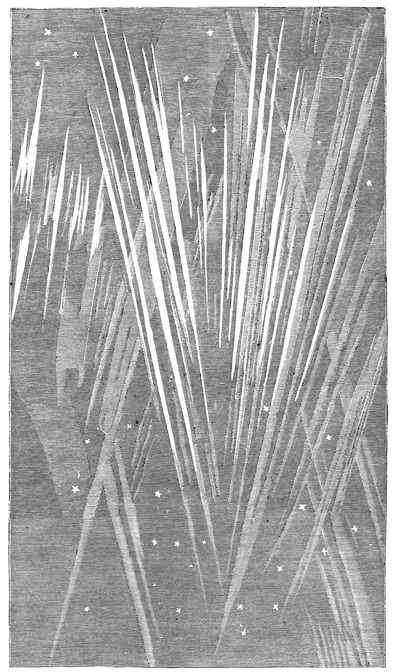

| 13. | Aurora seen in Greenland. | Hall. | 32 |

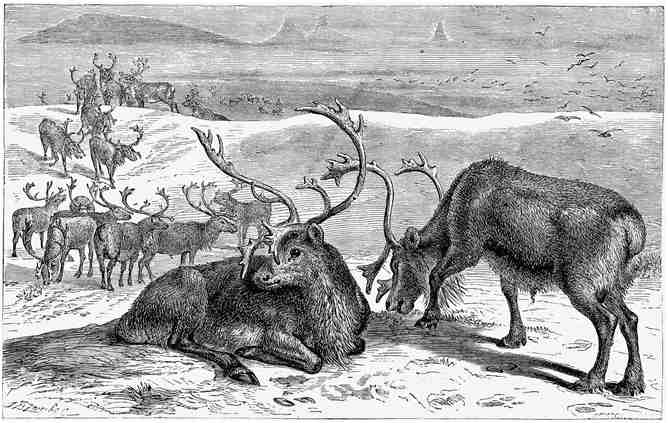

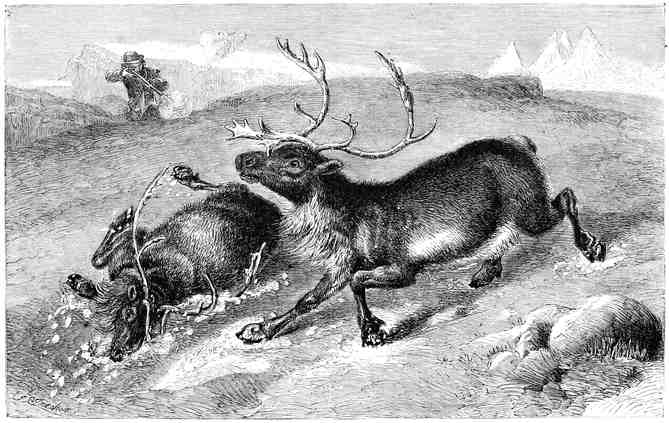

| 14. | Group of Reindeer. | Lamont. | 35 |

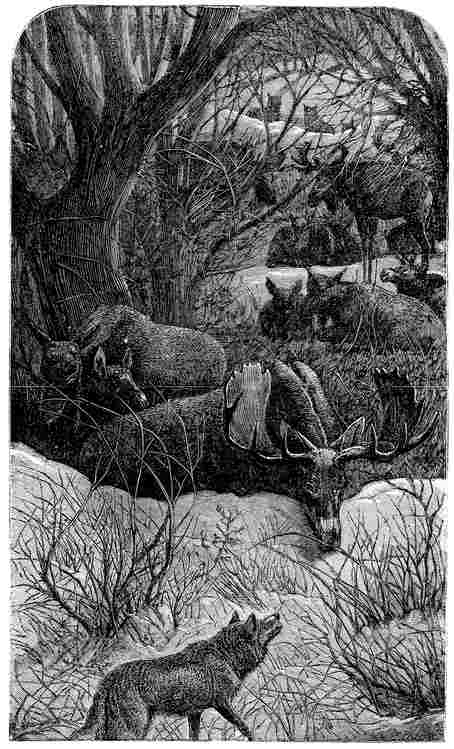

| 15. | Elks. | Wood. | 39 |

| 16. | The Musk-ox. | Wood. | 40 |

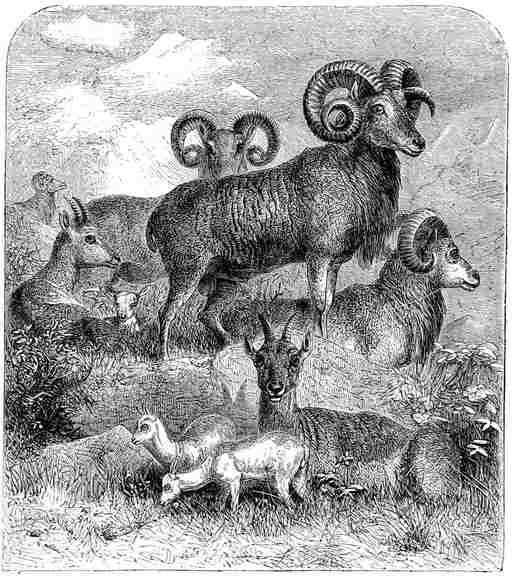

| 17. | Argali. | Atkinson. | 41 |

| 18. | The Snowy Owl. | Wood. | 43 |

| 19. | Bernide Goose. | Wood. | 44 |

| 20. | The Sea-eagle. | Wood. | 44 |

| 21. | Arctic Navigation. | Harper’s Mag. | 45 |

| 22. | Among Hummocks. | Harper’s Mag. | 46 |

| 23. | Drifting on the Ice. | Harper’s Mag. | 47 |

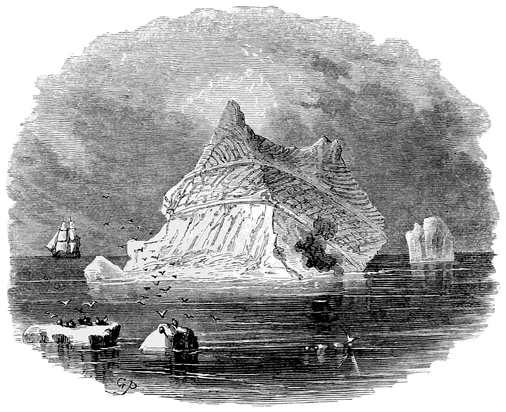

| 24. | Forms of Icebergs. | Hall. | 47 |

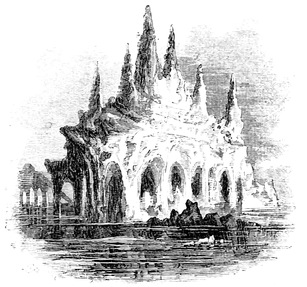

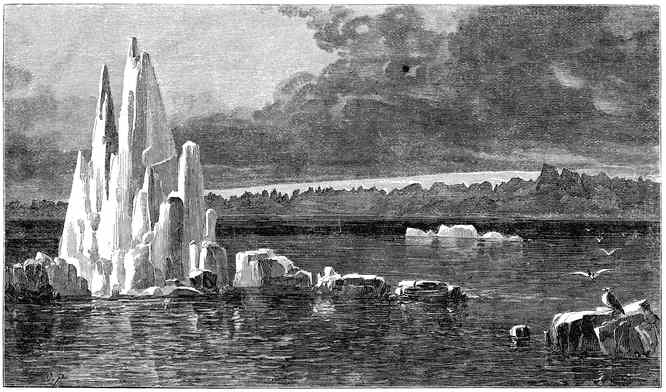

| 25. | Gothic Icebergs. | Hall. | 48 |

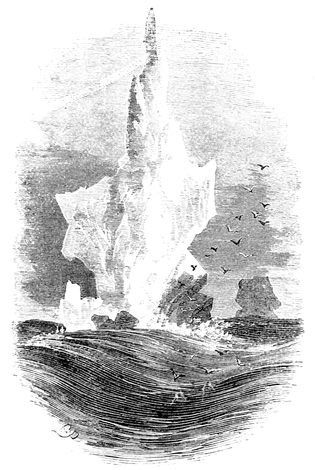

| 26. | Pinnacle Icebergs. | Hall. | 48 |

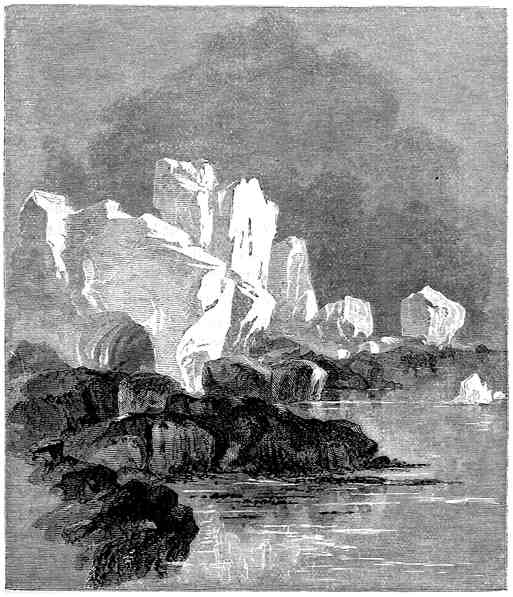

| 27. | Icebergs aground. | Hall. | 49 |

| 28. | Icebergs and Glacier, Frobisher Bay. | Hall. | 51 |

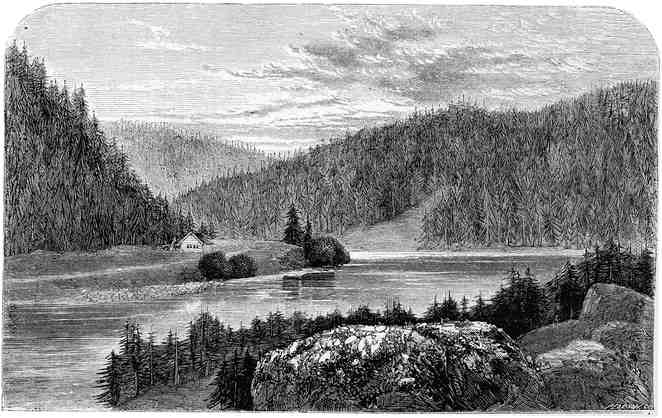

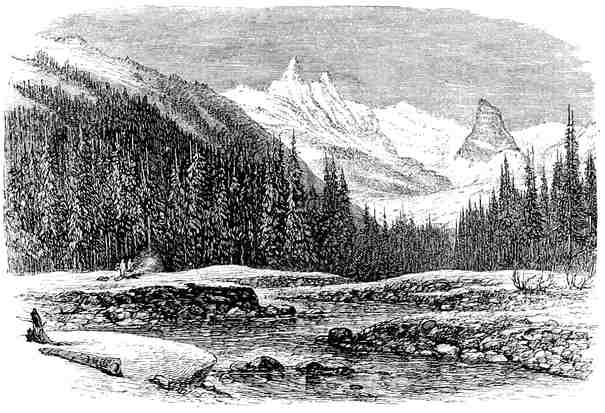

| 29. | Glacier, Bute Inlet. | Whymper. | 52 |

| 30. | Scaling an Iceberg. | Hall. | 53 |

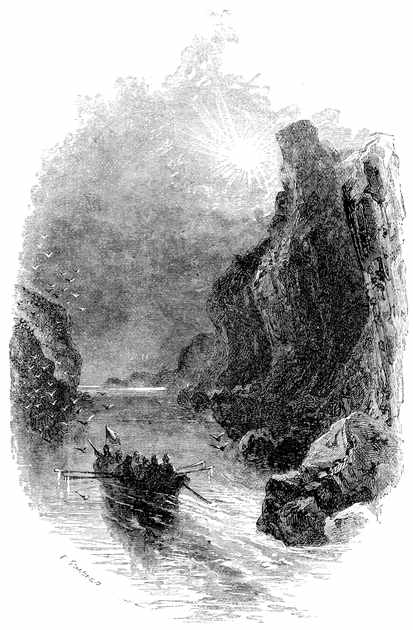

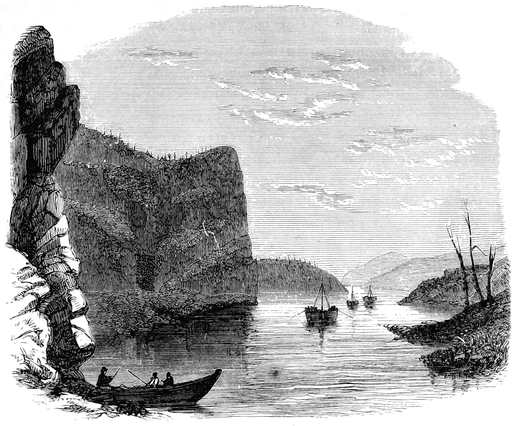

| 31. | An Arctic Channel. | Hall. | 56 |

| 32. | Open Water. | Hall. | 57 |

| 33. | Glacier Discharging. | Hall. | 58 |

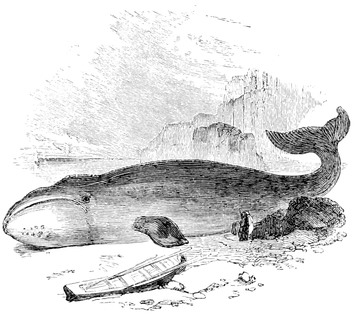

| 34. | The Whale. | Wood. | 60 |

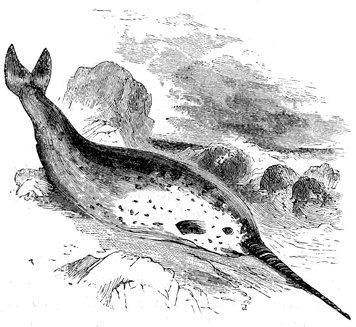

| 35. | The Narwhal. | Wood. | 61 |

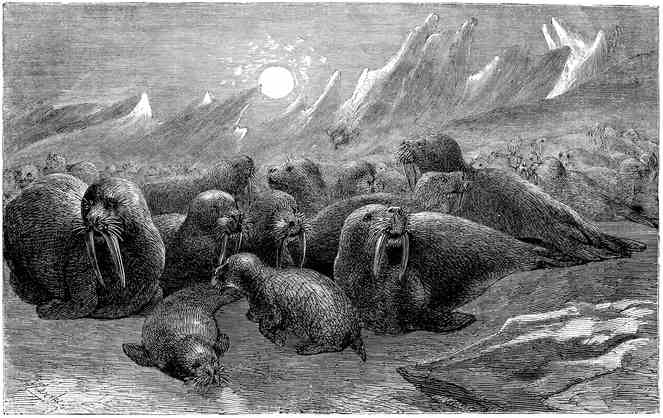

| 36. | Walruses on the Ice. | Lamont. | 63 |

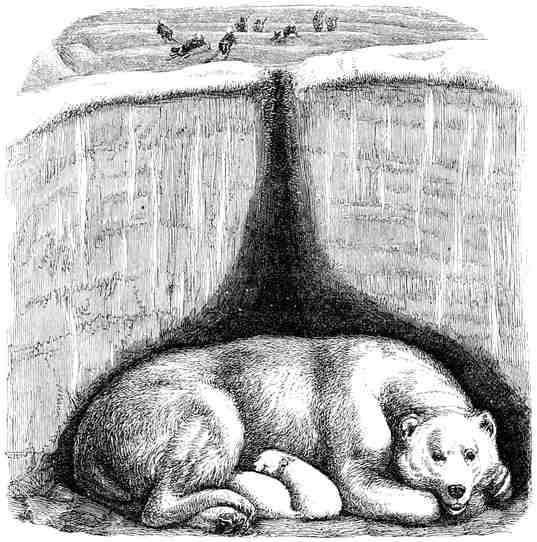

| 37. | Home of the Polar Bear. | Wood. | 66 |

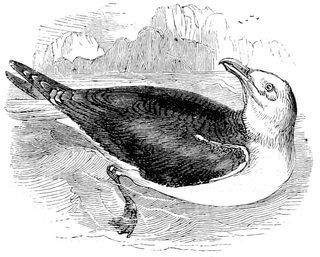

| 38. | The Gull. | Wood. | 67 |

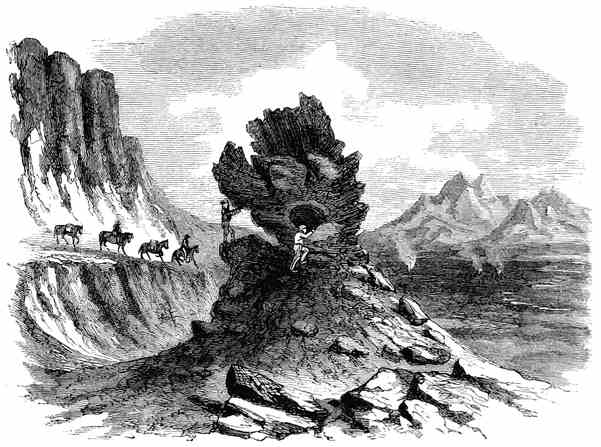

| 39. | Lava-fields. | Browne. | 68 |

| 40. | Effigy in Lava. | Browne. | 70 |

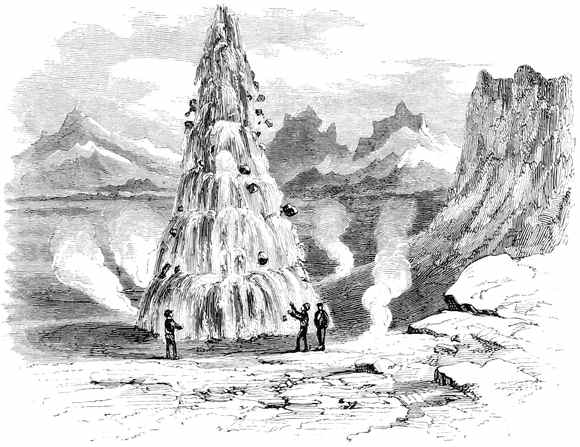

| 41. | The Strokkr. | Browne. | 72 |

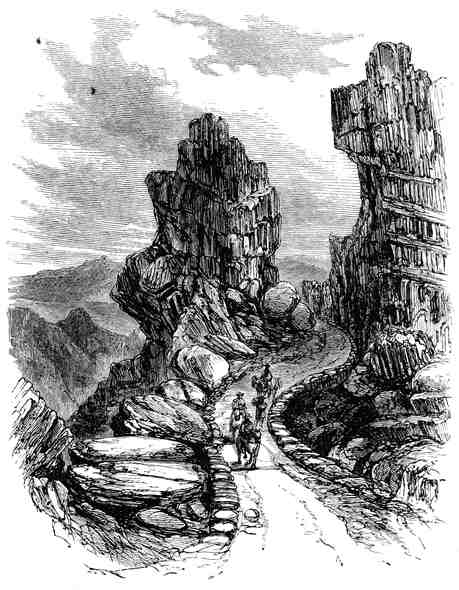

| 42. | Entrance to the Almannagja. | Browne. | 73 |

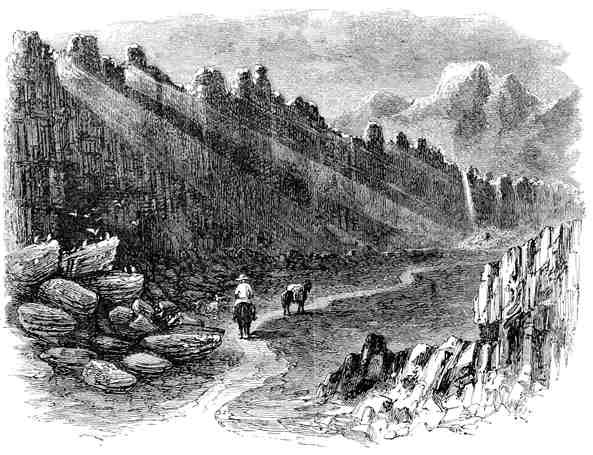

| 43. | The Almannagja. | Browne. | 74 |

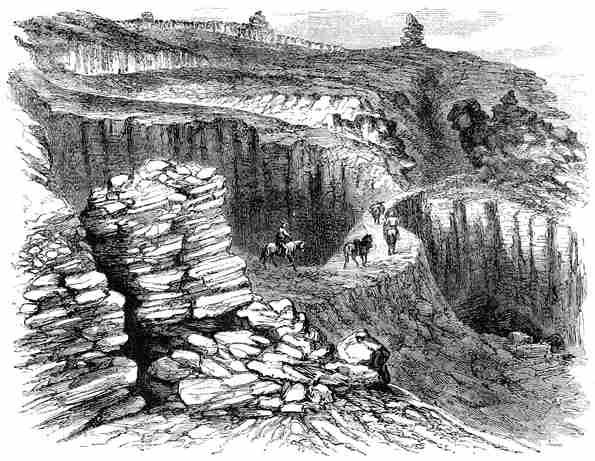

| 44. | The Hrafnagja. | Browne. | 75 |

| 45. | The Tintron Rock. | Browne. | 75 |

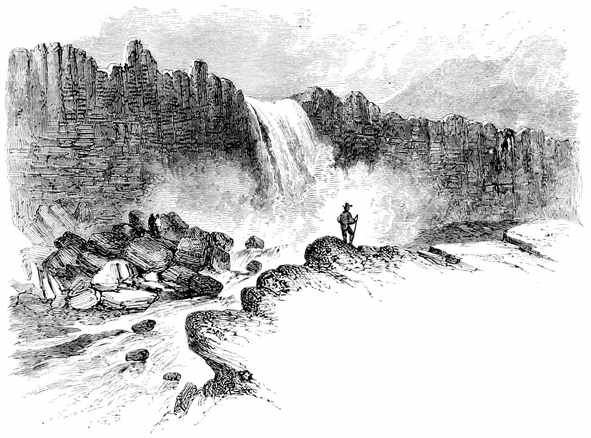

| 46. | Fall of the Oxeraa. | Browne. | 76 |

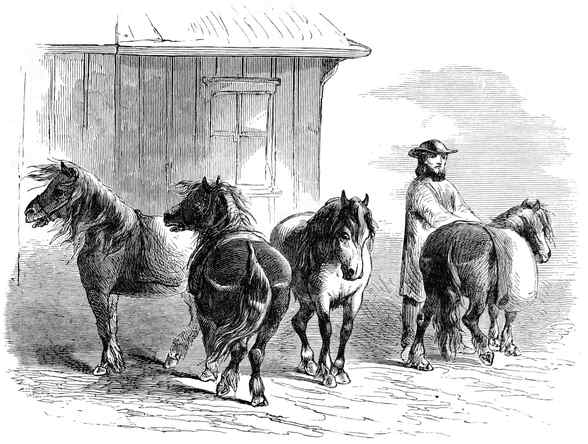

| 47. | Icelandic Horses. | Browne. | 81 |

| 48. | Shooting Reindeer. | Lamont. | 82 |

| 49. | The Eider-duck. | Wood. | 83 |

| 50. | The Jyrfalcon. | Wood. | 85 |

| 51. | The Giant Auk. | Wood. | 86 |

| 52. | Cathedral at Reykjavik. | Browne. | 89 |

| 53. | Thingvalla, Lögberg and Almannagja. | Browne. | 92 |

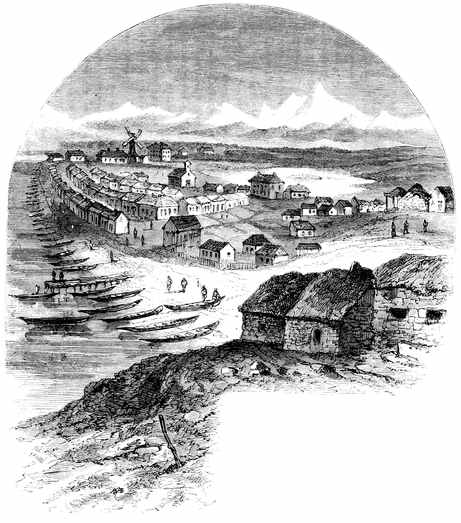

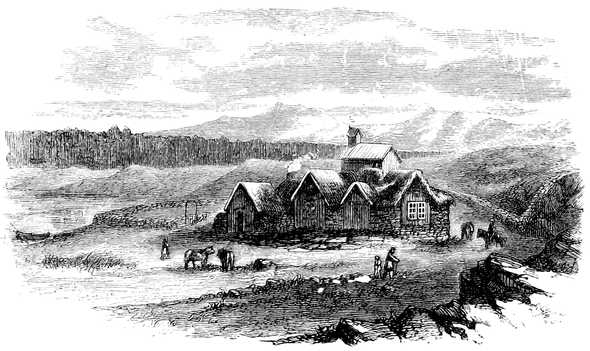

| 54. | Reykjavik, the Capital of Iceland. | Browne. | 98 |

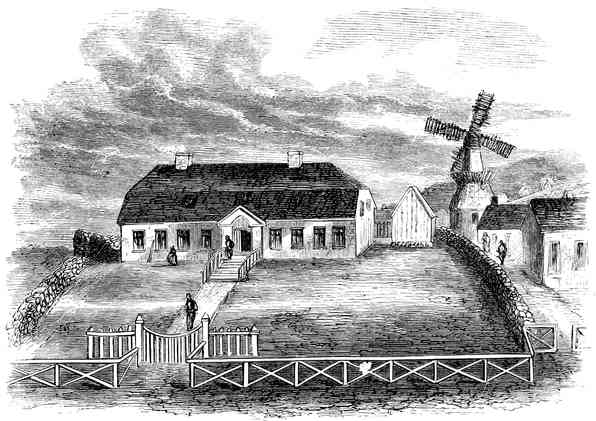

| 55. | Governor’s Residence, Reykjavik. | Browne. | 99 |

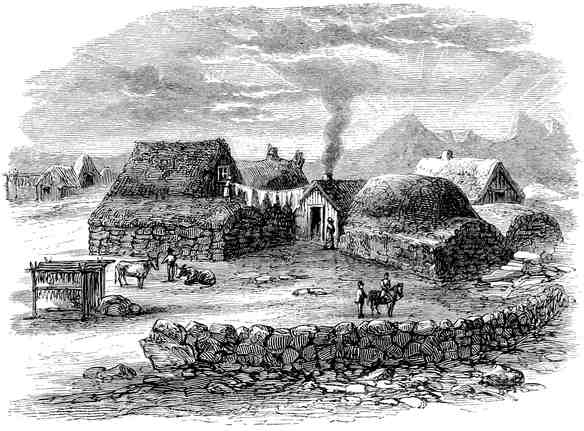

| 56. | Icelandic Houses. | Browne. | 103 |

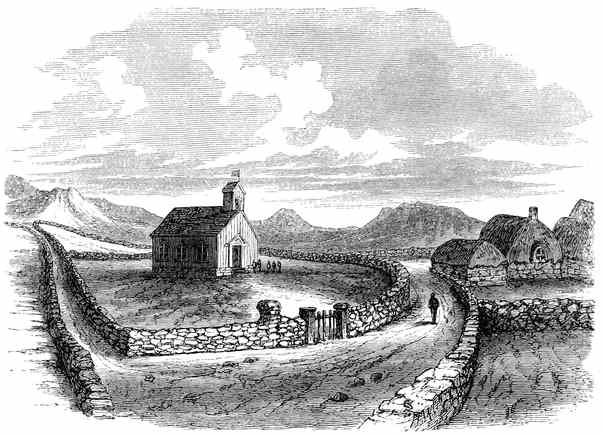

| 57. | Church at Thingvalla. | Browne. | 105 |

| 58. | The Pastor’s House, Thingvalla. | Browne. | 106 |

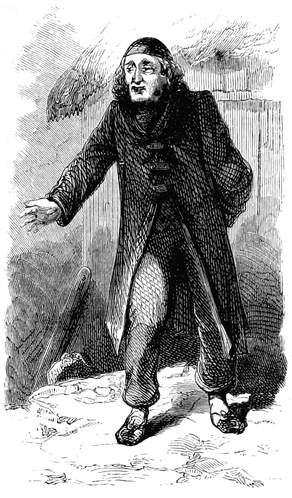

| 59. | The Pastor of Thingvalla. | Browne. | 107 |

| 60. | Bridge River, Iceland. | Browne. | 111 |

| 61. | Icelandic Bog. | Browne. | 113 |

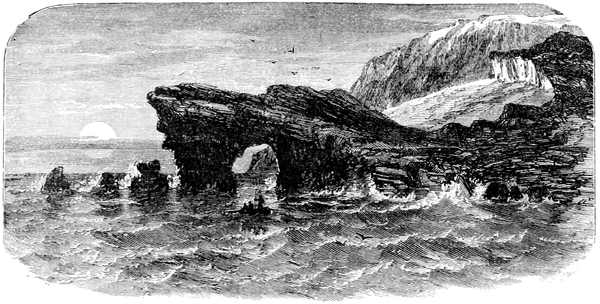

| 62. | Coast of Iceland. | Browne. | 114 |

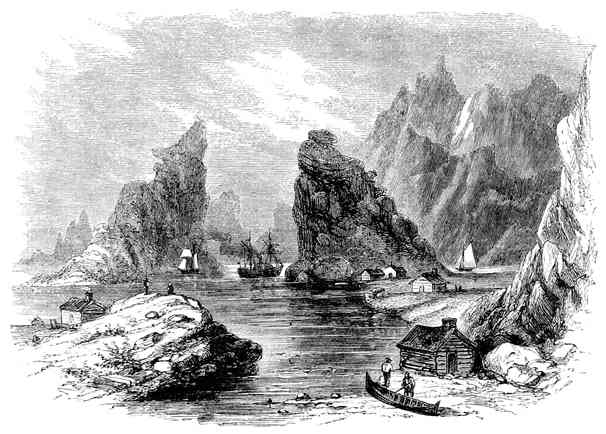

| 63. | Westman Isles. | Browne. | 115 |

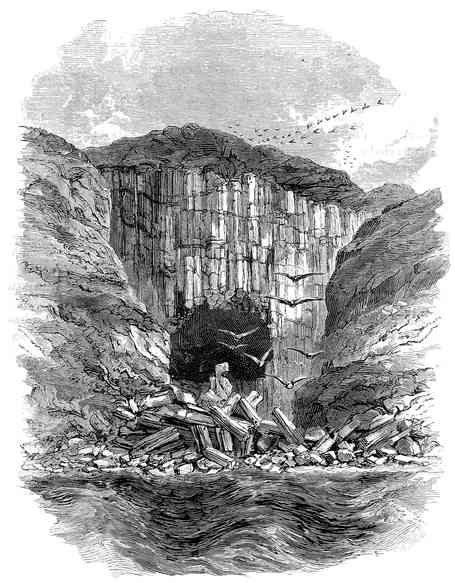

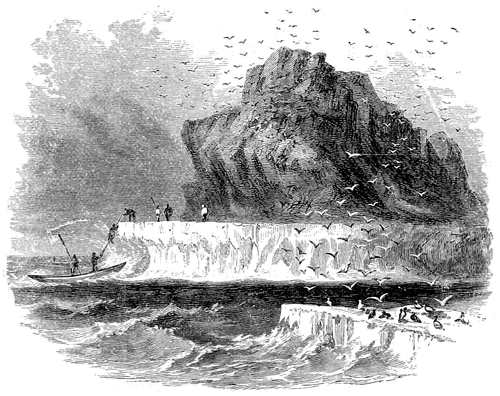

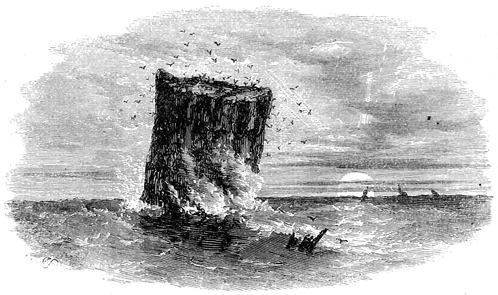

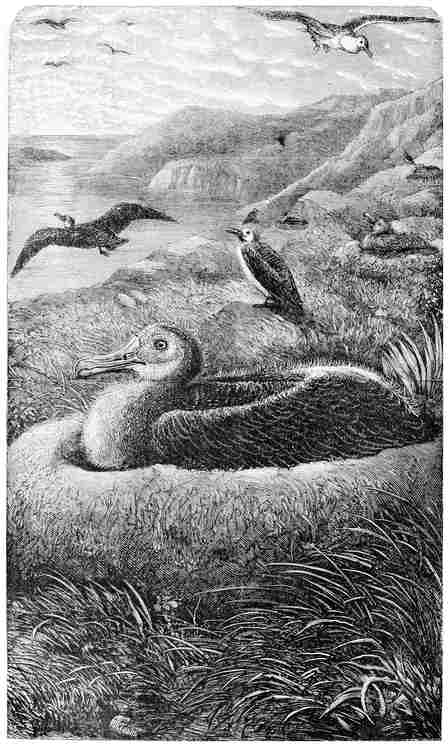

| 64. | Home of Sea-birds. | Browne. | 117 |

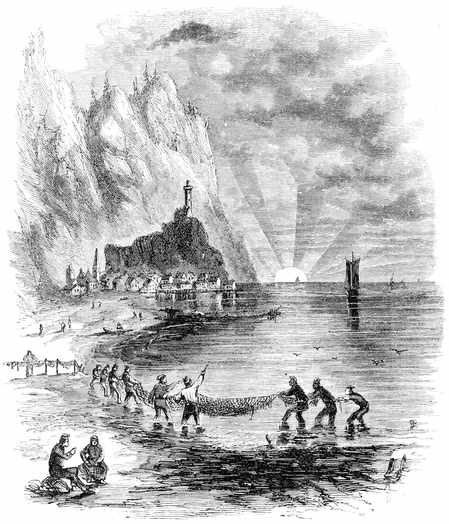

| 65. | Fishing in Norway. | Browne. | 120 |

| 66. | Norwegian Farm. | Browne. | 122 |

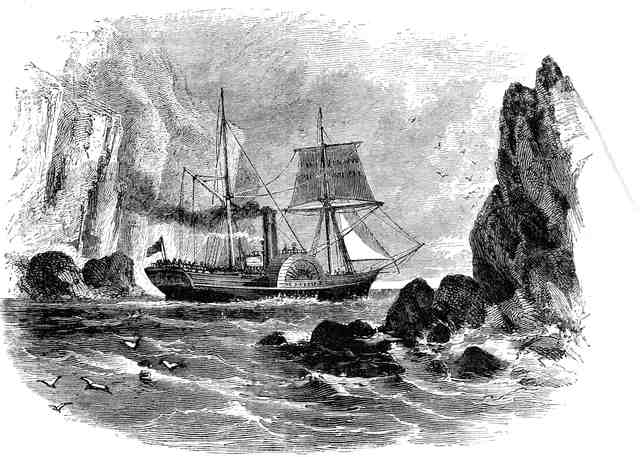

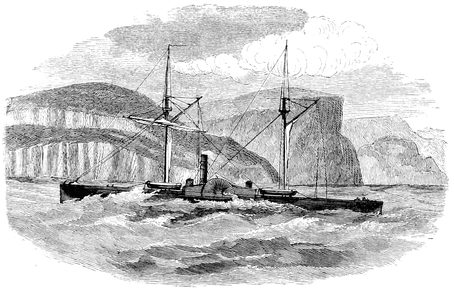

| 67. | Steaming along the Coast. | Browne. | 123 |

| 68. | The Puffin. | Wood. | 124 |

| 69. | The Dovrefjeld. | Browne. | 127 |

| 70. | Midnight Sun off Spitzbergen. | Dufferin. | 131 |

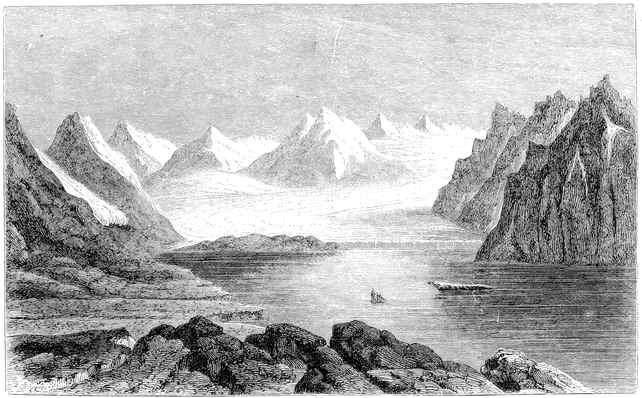

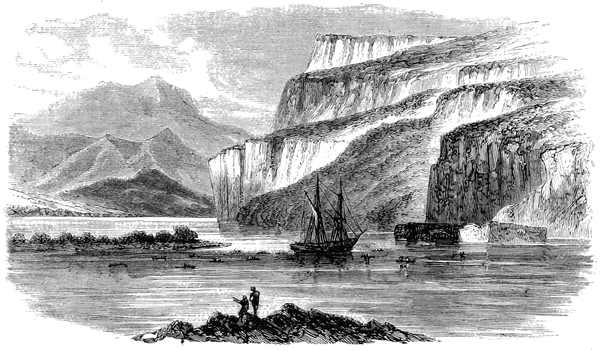

| 71. | Magdalena Bay, Spitzbergen. | Dufferin. | 134 |

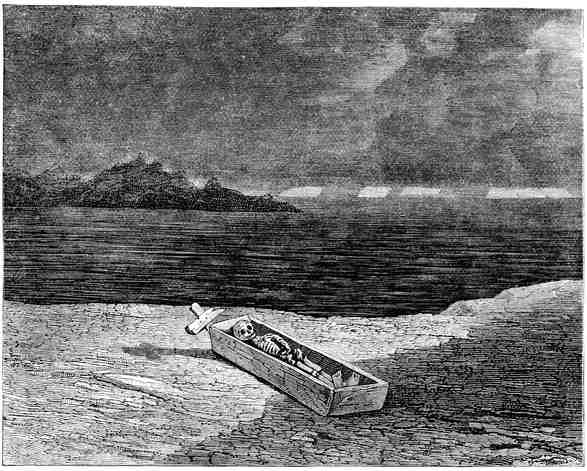

| 72. | Burial in Spitzbergen. | Dufferin. | 139 |

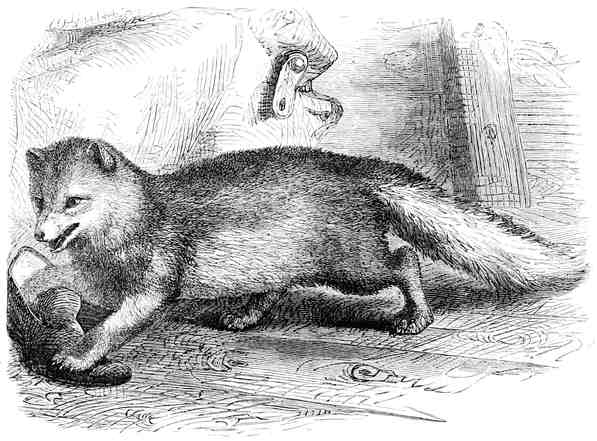

| 73. | Arctic Fox. | Dufferin. | 140 |

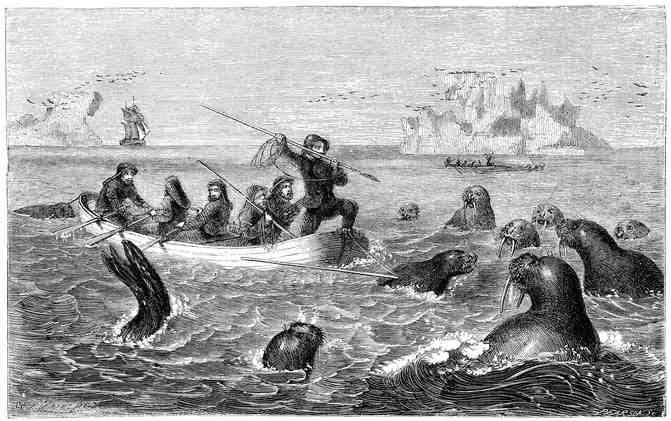

| 74. | Chase of the Walrus. | Lamont. | 143 |

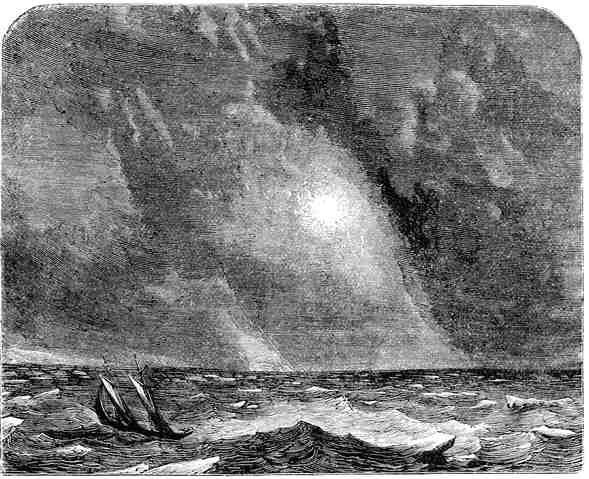

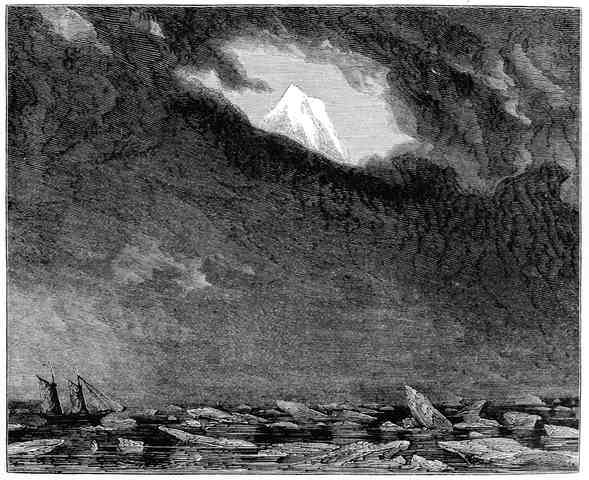

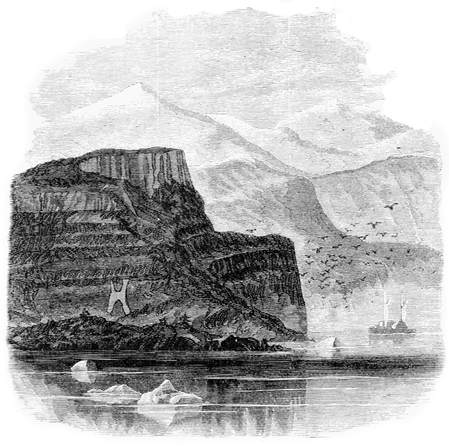

| 75. | A glimpse of Jan Meyen’s Island. | Dufferin. | 145 |

| 76. | A Samoïede Priest. | Atkinson. | 179xvi |

| 77. | Banks of the Irtysch. | Atkinson. | 185 |

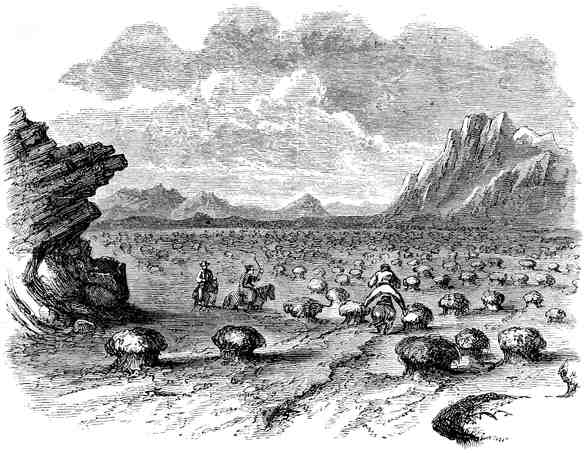

| 78. | Group of Kirghis. | Atkinson. | 188 |

| 79. | View of Tagilsk. | Atkinson. | 191 |

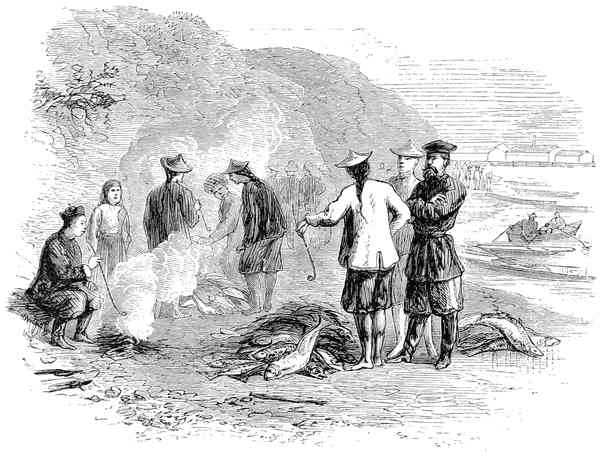

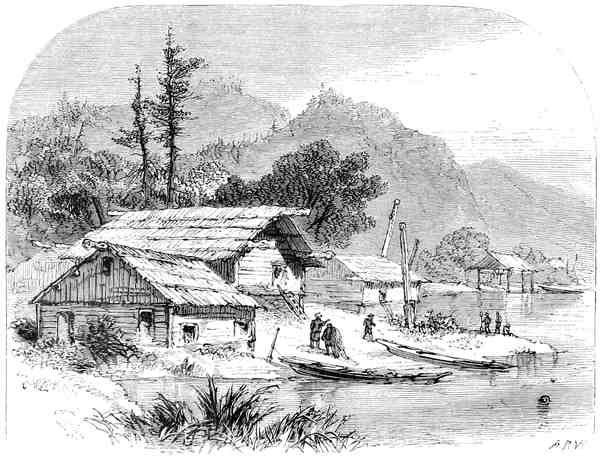

| 80. | The Beach at Nicolayevsk. | Harper’s Mag. | 196 |

| 81. | On the Amoor. | Harper’s Mag. | 197 |

| 82. | Village on the Amoor. | Harper’s Mag. | 198 |

| 83. | Koriak Yourt. | Harper’s Mag. | 199 |

| 84. | Kamchatka Sables. | Harper’s Mag. | 201 |

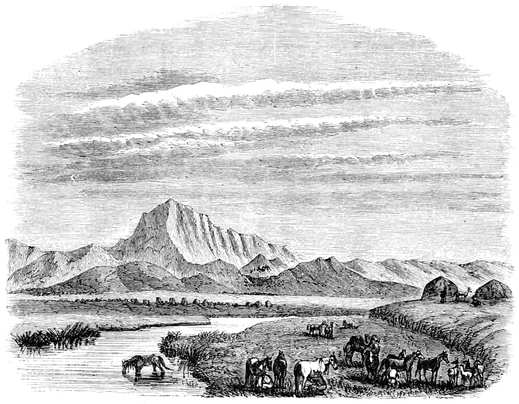

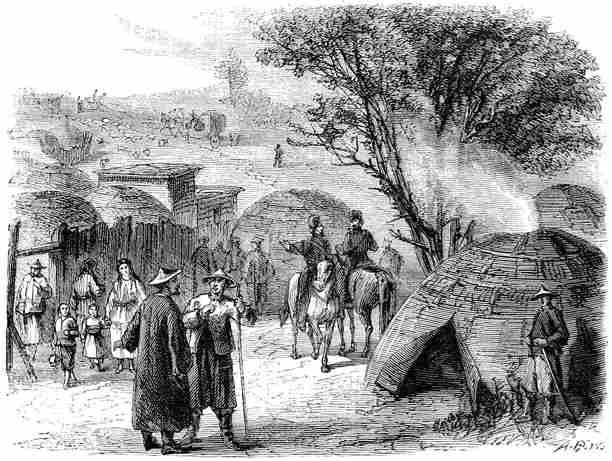

| 85. | Tartar Encampment. | Atkinson. | 204 |

| 86. | Siberian Peasant. | Atkinson. | 207 |

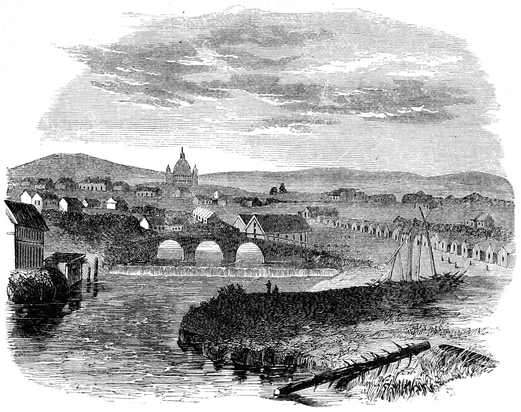

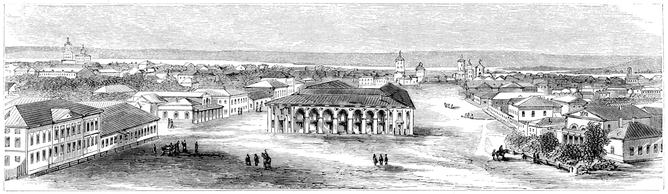

| 87. | View of Irkutsk. | Harper’s Mag. | 209 |

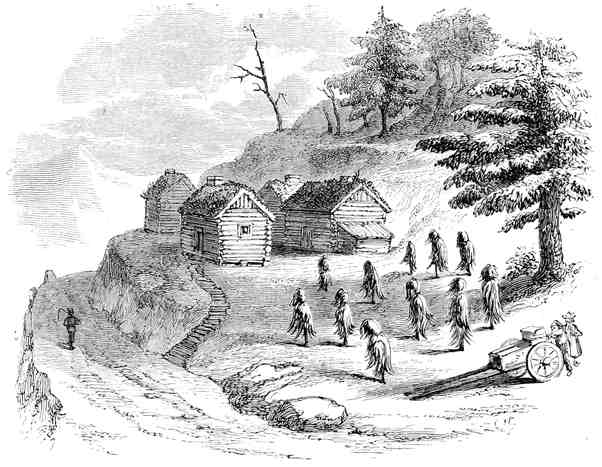

| 88. | A Jakut Village. | Harper’s Mag. | 229 |

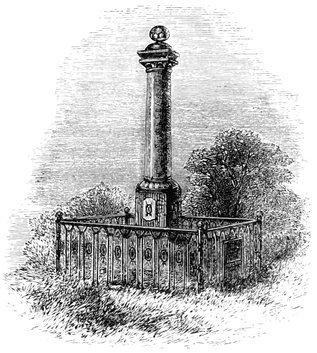

| 89. | Bering’s Monument at Petropavlosk. | Whymper. | 248 |

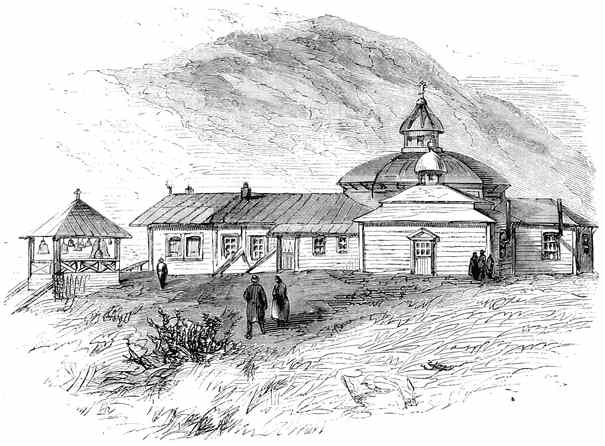

| 90. | Church at Petropavlosk. | Whymper. | 254 |

| 91. | View of Petropavlosk. | Harper’s Mag. | 257 |

| 92. | Dogs Fishing. | Harper’s Mag. | 259 |

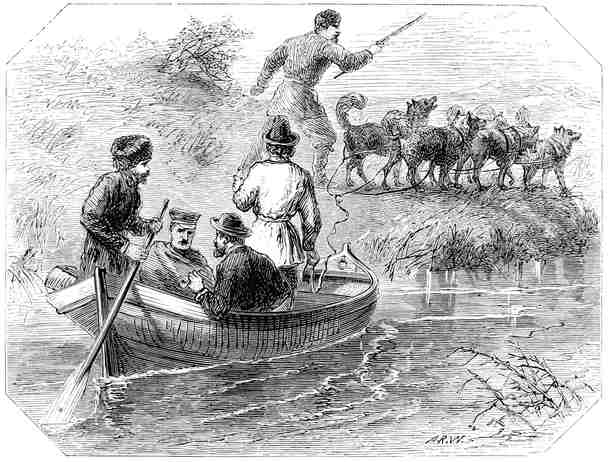

| 93. | Dog-team. | Whymper. | 259 |

| 94. | Dogs Towing Boat. | Harper’s Mag. | 260 |

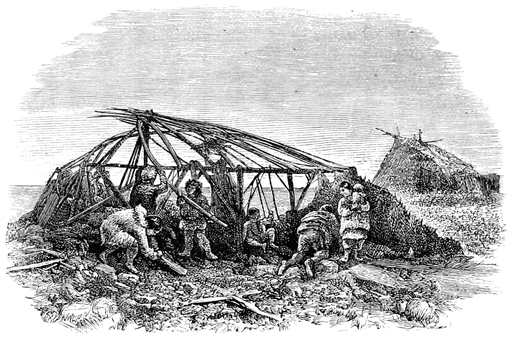

| 95. | Frame-work of Tchuktchi House. | Whymper. | 262 |

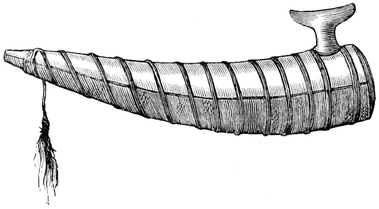

| 96. | Tchuktchi Canoe. | Harper’s Mag. | 263 |

| 97. | Tchuktchi Pipe. | Whymper. | 264 |

| 98. | An Aleut. | Whymper. | 268 |

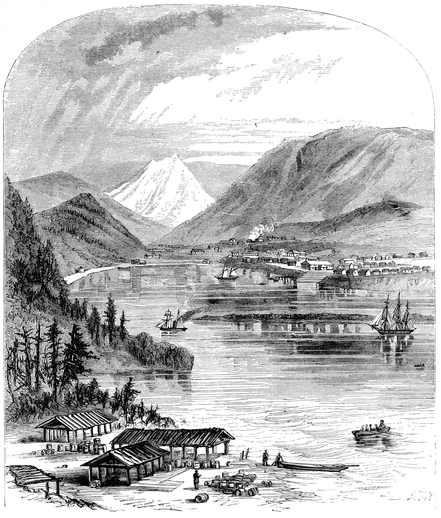

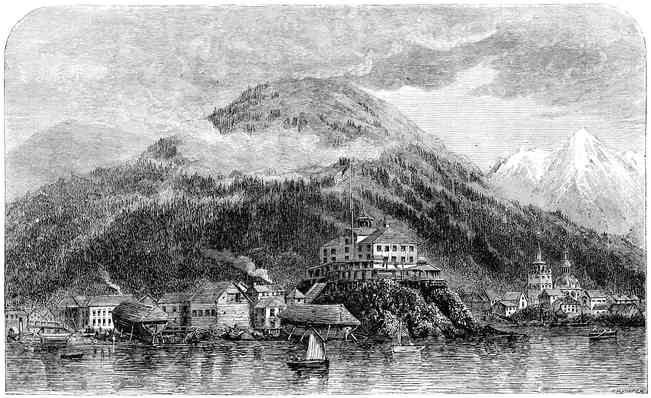

| 99. | View of Sitka. | Whymper. | 270 |

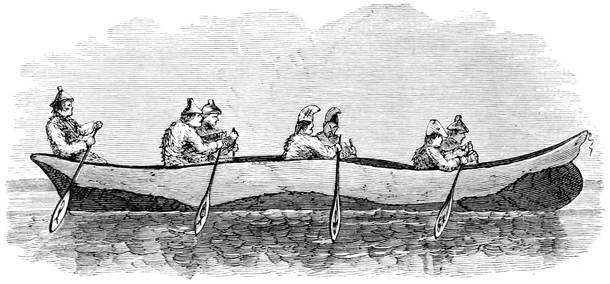

| 100. | A Baidar. | Harper’s Mag. | 272 |

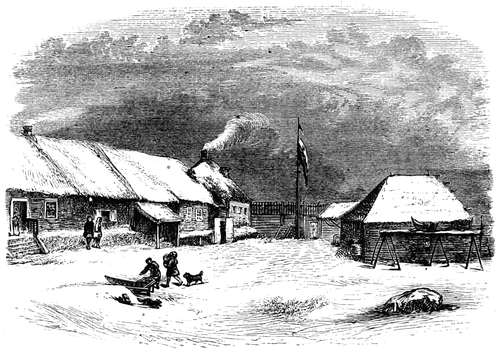

| 101. | Fort St. Michael. | Whymper. | 277 |

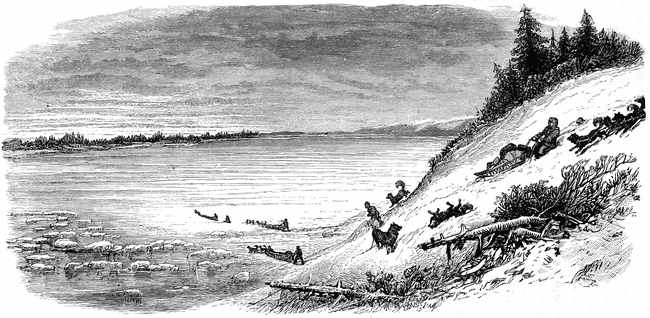

| 102. | The Frozen Yukon. | Whymper. | 279 |

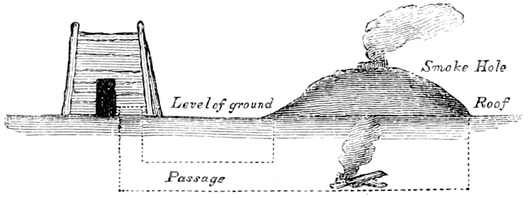

| 103. | Under-ground House. | Whymper. | 280 |

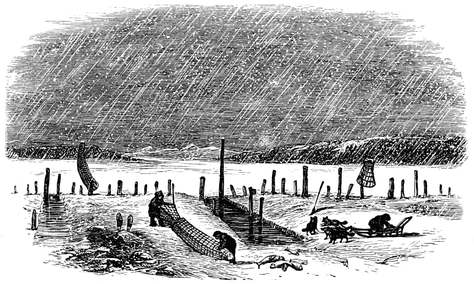

| 104. | Fish-traps on the Yukon. | Whymper. | 281 |

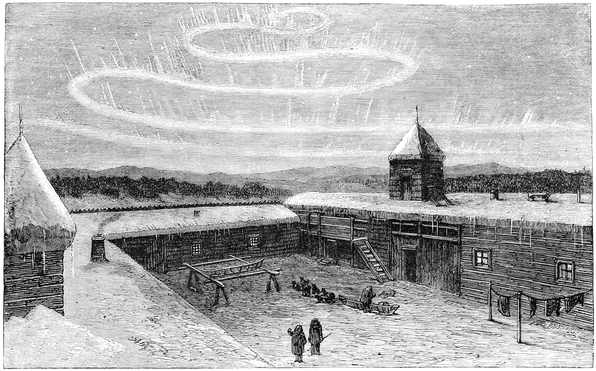

| 105. | Aurora at Nulato. | Whymper. | 282 |

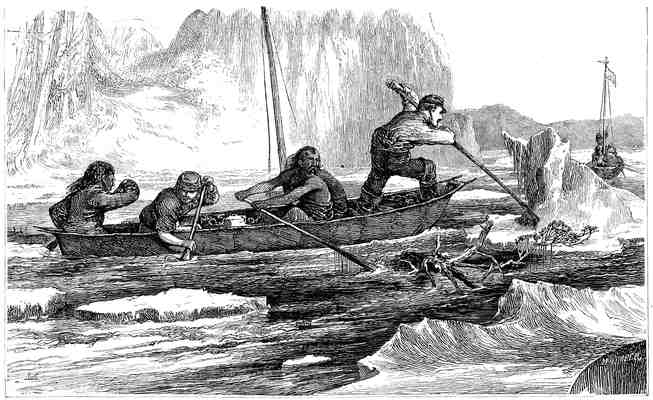

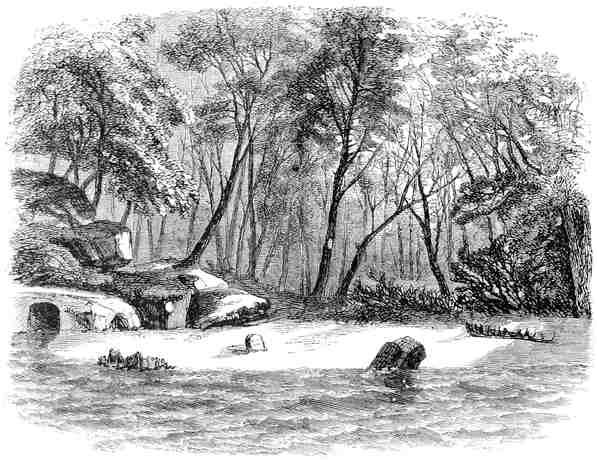

| 106. | Breaking up of the Ice. | Whymper. | 283 |

| 107. | Fort Yukon. | Whymper. | 285 |

| 108. | A Deer Corral. | Whymper. | 286 |

| 109. | Lip Ornaments. | Harper’s Mag. | 287 |

| 110. | A Baidar. | Harper’s Mag. | 288 |

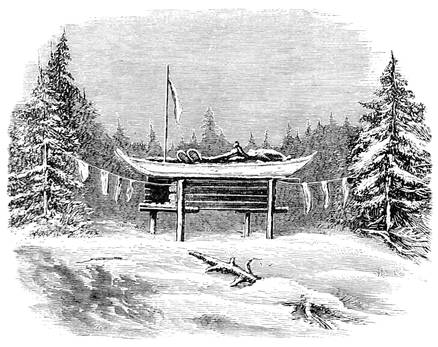

| 111. | Four-post Coffin. | Whymper. | 288 |

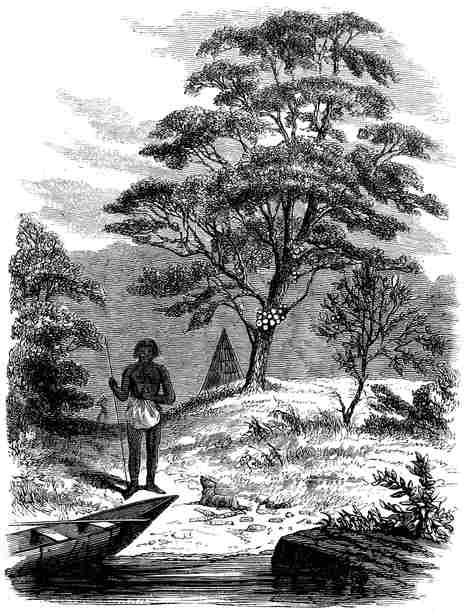

| 112. | Tauana Indian. | Whymper. | 289 |

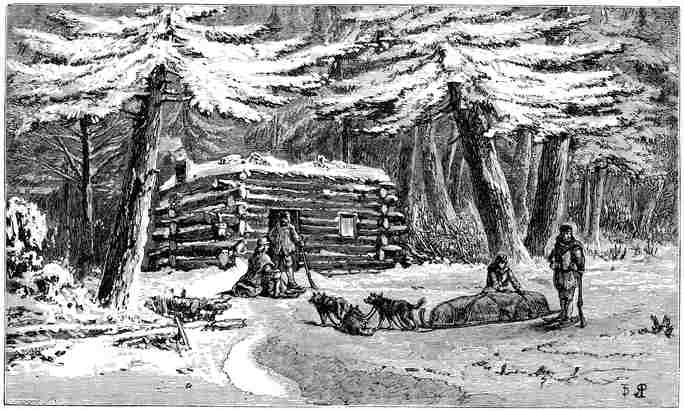

| 113. | Winter Hut of Hunters. | Milton. | 309 |

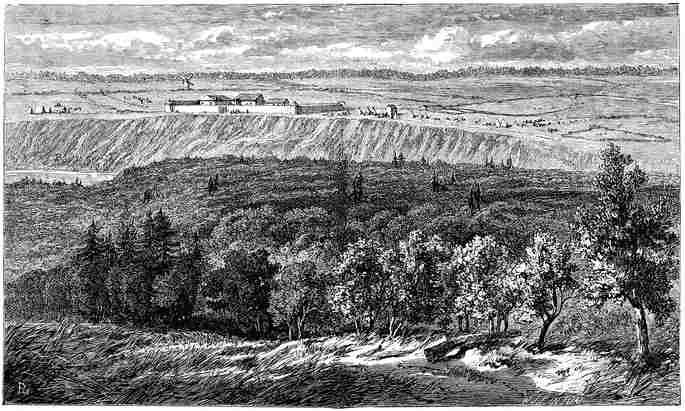

| 114. | Fort Edmonton, North Saskatchewan. | Milton. | 311 |

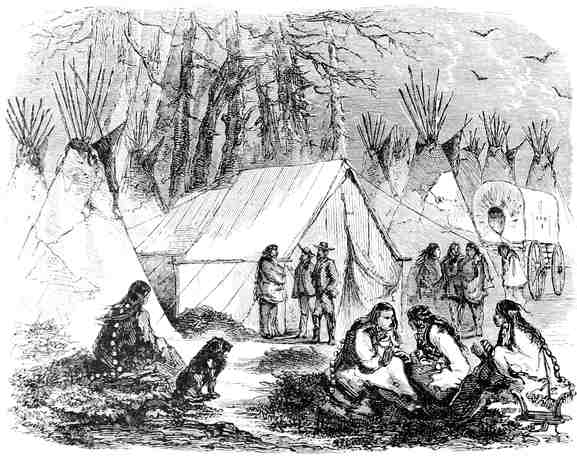

| 115. | Trader’s Camp. | Harper’s Mag. | 312 |

| 116. | Swamp formed by deserted Beaver Dam. | Milton. | 314 |

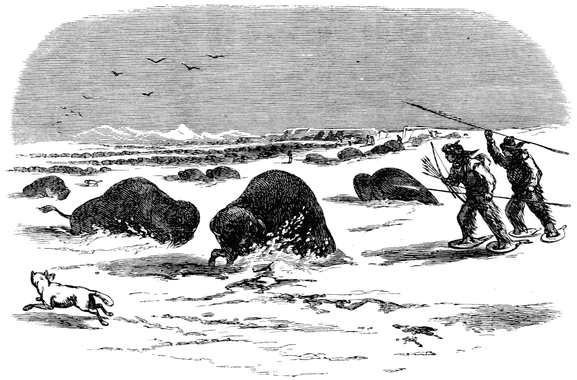

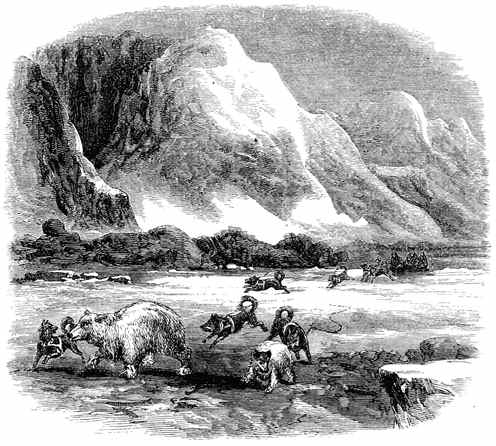

| 117. | Hunting Bison in the Snow. | Harper’s Mag. | 319 |

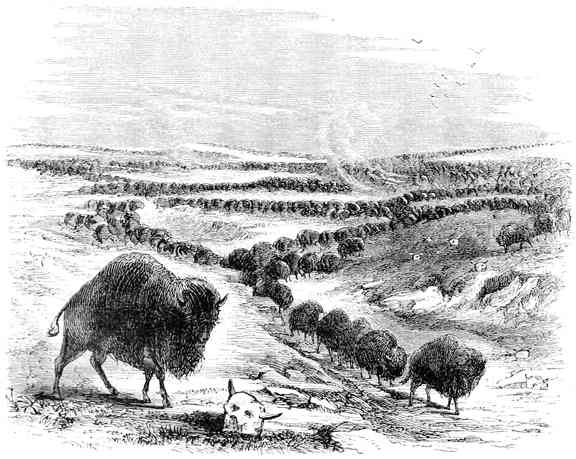

| 118. | Herd of Bison. | Harper’s Mag. | 320 |

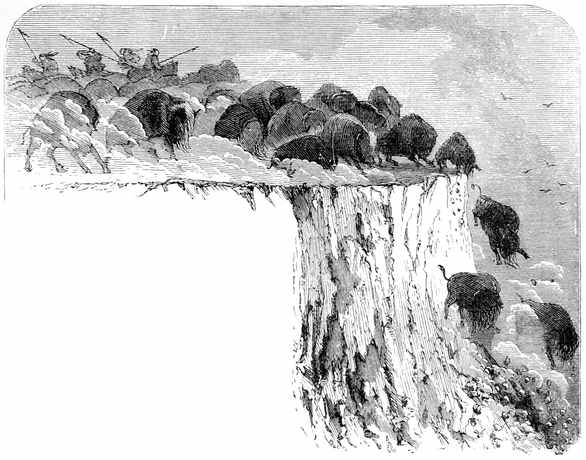

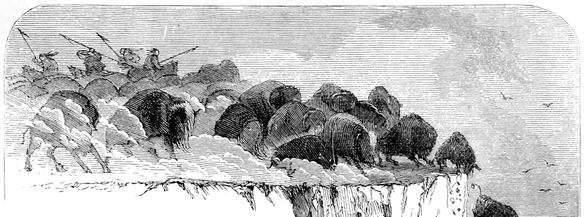

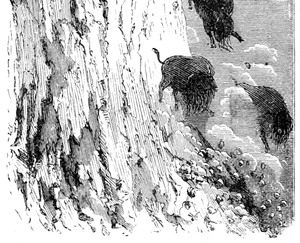

| 119. | Driving Bison over a Precipice. | Harper’s Mag. | 321 |

| 120. | Watching for Crees. | Milton. | 322 |

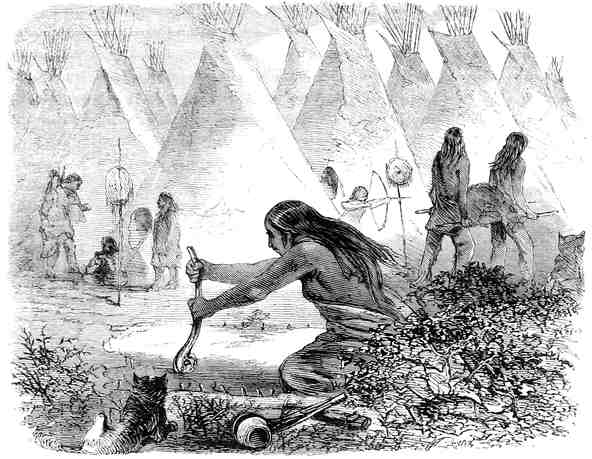

| 121. | A Cree Village. | Harper’s Mag. | 324 |

| 122. | The Albatross. | Wood. | 396 |

| 123. | Strait of Magellan. | Harper’s Mag. | 405 |

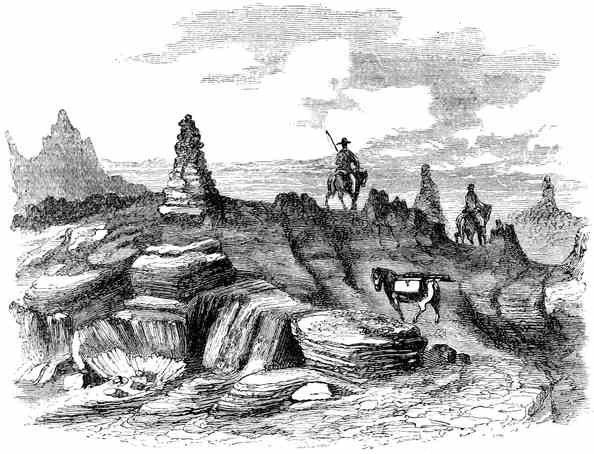

| 124. | A Highway of Commerce. | Harper’s Mag. | 416 |

| 125. | Patagonians. | Harper’s Mag. | 417 |

| 126. | Coast of Fuegia. | Harper’s Mag. | 425 |

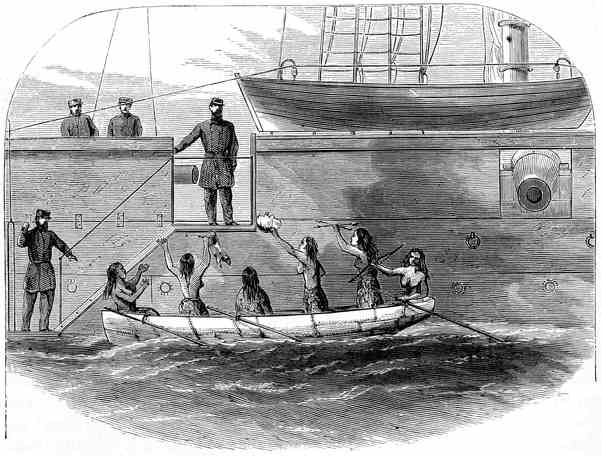

| 127. | Fuegian Traders. | Harper’s Mag. | 427 |

| 128. | A Fuegian and his Food. | Harper’s Mag. | 429 |

| 129. | Starvation Beach. | Harper’s Mag. | 432 |

| 130. | Surveying in Greenland. | Hall. | 433 |

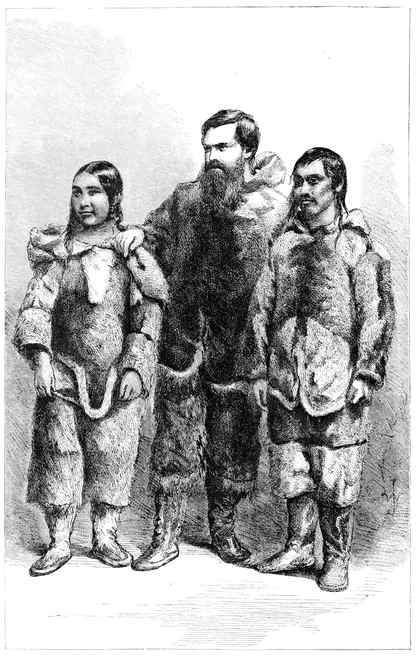

| 131. | Hall and Companions, in Innuit Costume. | Hall. | 434 |

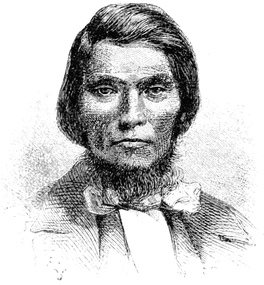

| 132. | Kudlago. | Hall. | 436 |

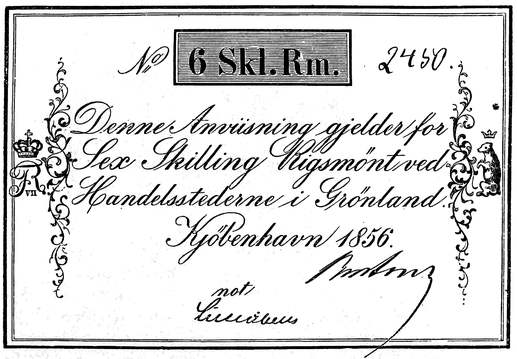

| 133. | Greenland Currency. | Hall. | 437 |

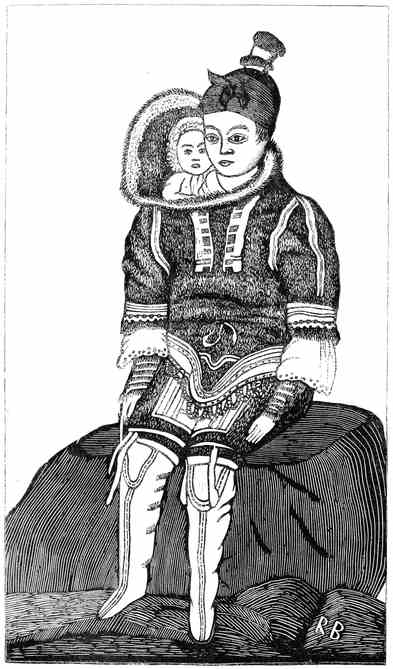

| 134. | Woman and Child. (Drawn and Engraved by an Innuit.) | Hall. | 438 |

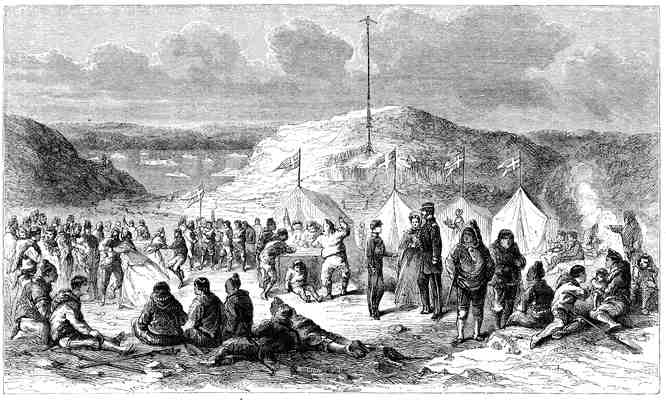

| 135. | Festival of the Birthday of the King of Denmark. | Hall. | 439 |

| 136. | Preparing Boot-soles. | Hall. | 440 |

| 137. | Wreck of the Rescue. | Hall. | 441 |

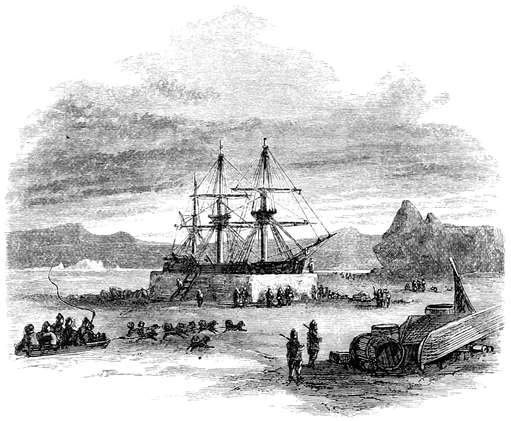

| 138. | The George Henry laid up for the Winter. | Hall. | 442 |

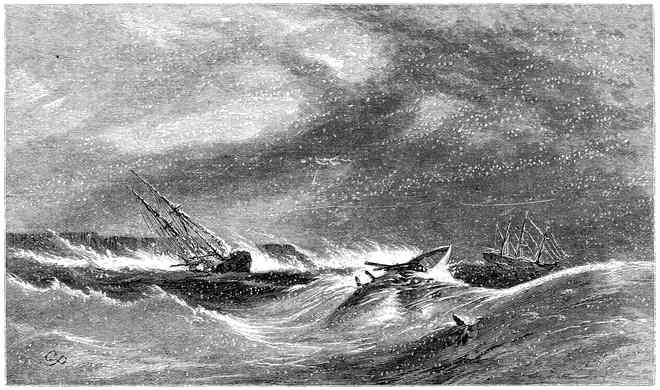

| 139. | Storm-bound. | Hall. | 443 |

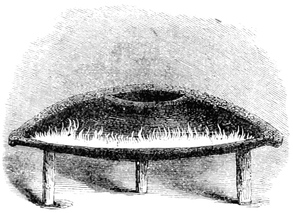

| 140. | Innuit Stone Lamp. | Hall. | 444 |

| 141. | Fighting for Food. | Hall. | 445 |

| 142. | Through the Snow. | Hall. | 446 |

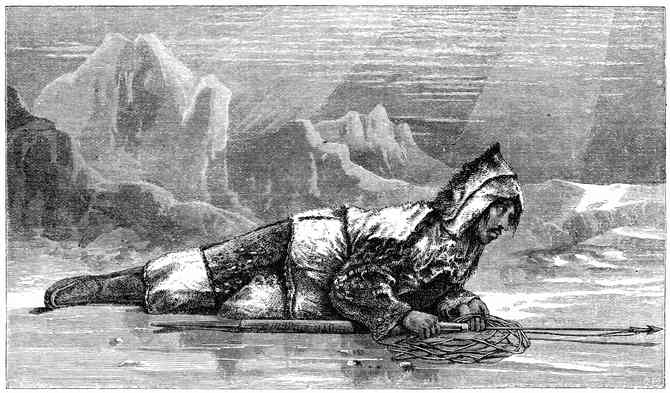

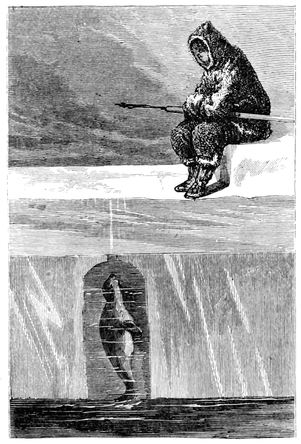

| 143. | Waiting by a Seal-hole. | Hall. | 447 |

| 144. | Looking for Seals. | Hall. | 448 |

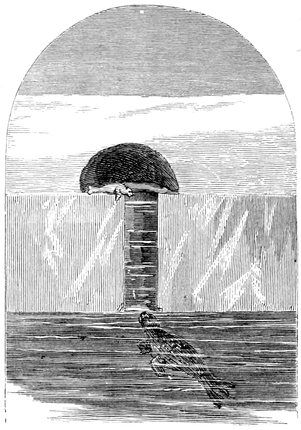

| 145. | Innuit Strategy to Capture a Seal. | Hall. | 449 |

| 146. | Seal-hole and Igloo. | Hall. | 450 |

| 147. | Waiting for a Blow. | Hall. | 450 |

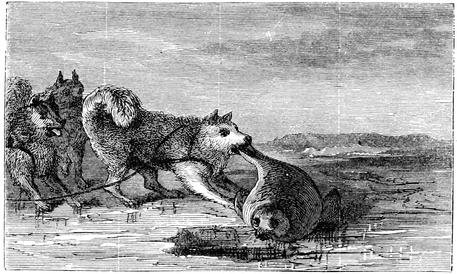

| 148. | Dog and Seal. | Hall. | 451 |

| 149. | Spearing through the Snow. | Hall. | 452 |

| 150. | Dogs and Bear. | Hall. | 453 |

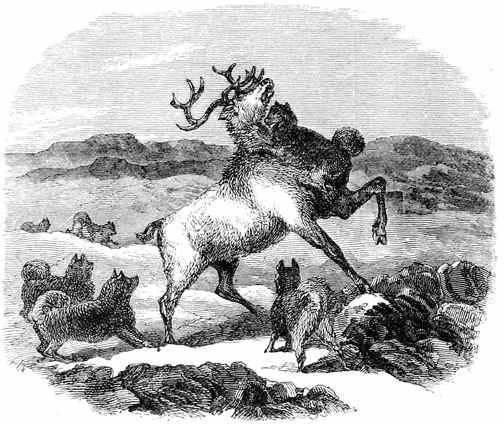

| 151. | Barbekark and the Reindeer. | Hall. | 454 |

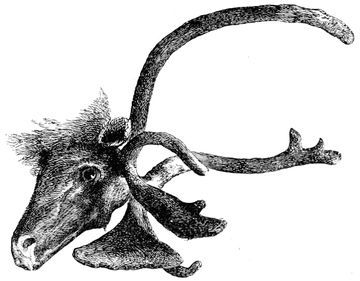

| 152. | Head of Reindeer. | Hall. | 454 |

| 153. | Spearing the Walrus. | Hall. | 455 |

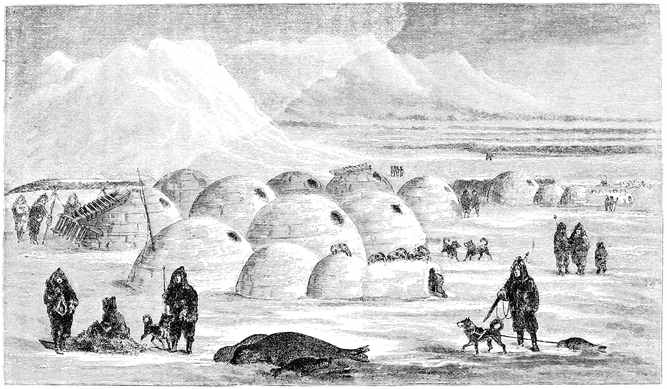

| 154. | Innuit Igloos. | Hall. | 456 |

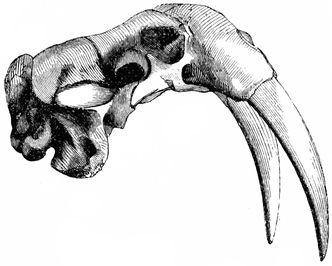

| 155. | Walrus Skull and Tusks. | Hall. | 457 |

| 156. | The Woman’s Knife. | Hall. | 457 |

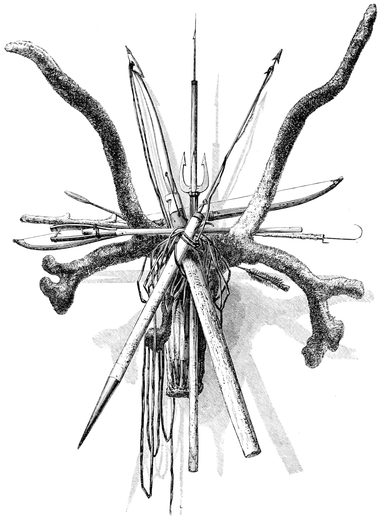

| 157. | Innuit Implements. | Hall. | 458 |

| 158. | Finding the Dead. | Hall. | 461 |

| 159. | Innuit Summer Village. | Hall. | 462 |

| 160. | Returning to the Ship. | Hall. | 463 |

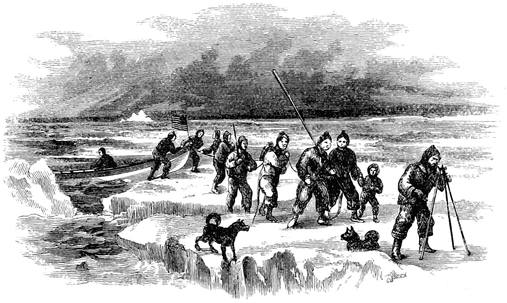

| 161. | Over the Ice. | Hall. | 464 |

| 162. | The Frozen Sailor. | Hall. | 465 |

| 163. | Farewell of the Innuits. | Hall. | 467 |

17

The barren Grounds or Tundri.—Abundance of animal Life on the Tundri in Summer.—Their Silence and Desolation in Winter.—Protection afforded to Vegetation by the Snow.—Flower-growth in the highest Latitudes.—Character of Tundra Vegetation.—Southern Boundary-line of the barren Grounds.—Their Extent.—The forest Zone.—Arctic Trees.—Slowness of their Growth.—Monotony of the Northern Forests.—Mosquitoes.—The various Causes which determine the Severity of an Arctic Climate.—Insular and Continental Position.—Currents.—Winds.—Extremes of Cold observed by Sir E. Belcher and Dr. Kane.—How is Man able to support the Rigors of an Arctic Winter?—Proofs of a milder Climate having once reigned in the Arctic Regions.—Its Cause according to Dr. Oswald Heer.—Peculiar Beauties of the Arctic Regions.—Sunset.—Long lunar Nights.—The Aurora.

A glance at a map of the Arctic regions shows us that many of the rivers belonging to the three continents—Europe, Asia, America—discharge their waters into the Polar Ocean or its tributary bays. The territories drained by these streams, some of which (such as the Mackenzie, the Yukon, the Lena, the Yenisei, and the Obi) rank among the giant rivers of the earth, form, along with the islands within or near the Arctic circle, the vast region over which the frost-king reigns supreme.

Man styles himself the lord of the earth, and may with some justice lay claim to the title in more genial lands where, armed with the plough, he compels the soil to yield him a variety of fruits; but in those desolate tracts18 which are winter-bound during the greater part of the year, he is generally a mere wanderer over its surface—a hunter, a fisherman, or a herdsman—and but few small settlements, separated from each other by immense deserts, give proof of his having made some weak attempts to establish a footing.

It is difficult to determine with precision the limits of the Arctic lands, since many countries situated as low as latitude 60° or even 50°, such as South Greenland, Labrador, Alaska, Kamchatka, or the country about Lake Baikal, have in their climate and productions a decidedly Arctic character, while others of a far more northern position, such as the coast of Norway, enjoy even in winter a remarkably mild temperature. But they are naturally divided into two principal and well-marked zones—that of the forests, and that of the treeless wastes.

The latter, comprising the islands within the Arctic Circle, form a belt, more or less broad, bounded by the continental shores of the North Polar seas, and gradually merging toward the south into the forest-region, which encircles them with a garland of evergreen coniferæ. This treeless zone bears the name of the “barren grounds,” or the “barrens,” in North America, and of “tundri” in Siberia and European Russia. Its want of trees is caused not so much by its high northern latitude as by the cold sea-winds which sweep unchecked over the islands or the flat coast-lands of the Polar Ocean, and for miles and miles compel even the hardiest plant to crouch before the blast and creep along the ground.

Nothing can be more melancholy than the aspect of the boundless morasses or arid wastes of the tundri. Dingy mosses and gray lichens form the chief19 vegetation, and a few scanty grasses or dwarfish flowers that may have found a refuge in some more sheltered spot are unable to relieve the dull monotony of the scene.

In winter, when animal life has mostly retreated to the south or sought a refuge in burrows or in caves, an awful silence, interrupted only by the hooting of a snow-owl or the yelping of a fox, reigns over their vast expanse; but in spring, when the brown earth reappears from under the melted snow and the swamps begin to thaw, enormous flights of wild birds appear upon the scene and enliven it for a few months. An admirable instinct leads their winged legions from distant climes to the Arctic wildernesses, where in the morasses or lakes, on the banks of the rivers, on the flat strands, or along the fish-teeming coasts, they find an abundance of food, and where at the same time they can with greater security build their nests and rear their young. Some remain on the skirts of the forest-region; others, flying farther northward, lay their eggs upon the naked tundra. Eagles and hawks follow the traces of the natatorial and strand birds; troops of ptarmigans roam among the stunted bushes; and when the sun shines, the finch or the snow-bunting warbles his merry note.

While thus the warmth of summer attracts hosts of migratory birds to the Arctic wildernesses, shoals of salmon and sturgeons enter the rivers in obedience to the instinct that forces them to quit the seas and to swim stream upward, for the purpose of depositing their spawn in the tranquil sweet waters of the stream or lake. About this time also the reindeer leaves the forests to feed on the herbs and lichens of the tundra, and to seek along the shores fanned by the cooled sea-breeze some protection against the attacks of the stinging flies that rise in myriads from the swamps. Thus during several months the tundra presents an animated scene, in which man also plays his part. The birds of the air, the fishes of the water, the beasts of the earth, are all obliged to pay their tribute to his various wants, to appease his hunger, to clothe his body, or to gratify his greed of gain.

But as soon as the first frosts of September announce the approach of winter, all animals, with but few exceptions, hasten to leave a region where the sources of life must soon fail. The geese, ducks, and swans return in dense flocks to the south; the strand-birds seek in some lower latitude a softer soil which allows their sharp beak to seize a burrowing prey; the water-fowl forsake the bays and channels that will soon be blocked up with ice; the reindeer once more return to the forest, and in a short time nothing is left that can induce man to prolong his stay in the treeless plain. Soon a thick mantle of snow covers the hardened earth, the frozen lake, the ice-bound river, and conceals them all—seven, eight, nine months long—under its monotonous pall, except where the furious north-east wind sweeps it away and lays bare the naked rock.

This snow, which after it has once fallen persists until the long summer’s day has effectually thawed it, protects in an admirable manner the vegetation of the higher latitudes against the cold of the long winter season. For snow is so bad a conductor of heat, that in mid-winter in the high latitude of 78°20 50° (Rensselaer Bay), while the surface temperature was as low as -30°, Kane found at two feet deep a temperature of -8°, at four feet +2°, and at eight feet +26°, or no more than six degrees below the freezing-point of water. Thus covered by a warm crystal snow-mantle, the northern plants pass the long winter in a comparatively mild temperature, high enough to maintain their life, while, without, icy blasts—capable of converting mercury into a solid body—howl over the naked wilderness; and as the first snow-falls are more cellular and less condensed than the nearly impalpable powder of winter, Kane justly observes that no “eider-down in the cradle of an infant is tucked in more kindly than the sleeping-dress of winter about the feeble plant-life of the Arctic zone.” Thanks to this protection, and to the influence of a sun which for months circles above the horizon, and in favorable localities calls forth the powers of vegetation in an incredibly short time, even Washington, Grinnell Land, and Spitzbergen are able to boast of flowers. Morton plucked a crucifer at Cape Constitution (80° 45’ N. lat.), and, on the banks of Mary Minturn River (78° 52’), Kane came across a flower-growth which, though drearily Arctic in its type, was rich in variety and coloring. Amid festuca and other tufted grasses twinkled the purple lychnis and the white star of the chickweed; and, not without its pleasing associations, he recognized a solitary hesperis—the Arctic representative of the wall-flowers of home.

Next to the lichens and mosses, which form the chief vegetation of the treeless zone, the cruciferæ, the grasses, the saxifragas, the caryophyllæ, and the compositæ are the families of plants most largely represented, in the barren grounds or tundri. Though vegetation becomes more and more uniform on advancing to the north, yet the number of individual plants does not decrease.21 When the soil is moderately dry, the surface is covered by a dense carpet of lichens (Corniculariæ), mixed in damper spots with Icelandic moss. In more tenacious soils, other plants flourish, not however to the exclusion of lichens, except in tracts of meadow ground, which occur in sheltered situations, or in the alluvial inundated flats where tall reed-grasses or dwarf willows frequently grow as closely as they can stand.

It may easily be supposed that the boundary-line which separates the tundri from the forest zone is both indistinct and irregular. In some parts where the cold sea-winds have a wider range, the barren grounds encroach considerably22 upon the limits of the forests; in others, where the configuration of the land prevents their action, the woods advance farther to the north.

Thus the barren grounds attain their most southerly limit in Labrador, where they descend to latitude 57°, and this is sufficiently explained by the position of that bleak peninsula, bounded on three sides by icy seas, and washed by cold currents from the north. On the opposite coasts of Hudson’s Bay they begin about 60°, and thence gradually rise toward the mouth of the Mackenzie, where the forests advance as high as 68°, or even still farther to the north along the low banks of that river. From the Mackenzie the barrens again descend until they reach Bering’s Sea in 65° N. On the opposite or Asiatic shore, in the land of the Tchuktchi, they begin again more to the south, in 63°, thence continually rise as far as the Lena, where Anjou found trees in 71° N., and then fall again toward the Obi, where the forests do not even reach the Arctic circle. From the Obi the tundri retreat farther and farther to the north, until finally, on the coasts of Norway, in latitude 70°, they terminate with the land itself.

Hence we see that the treeless zone of Europe, Asia, and America occupies a space larger than the whole of Europe. Even the African Sahara, or the Pampas of South America, are inferior in extent to the Siberian tundri. But the possession of a few hundred square miles of fruitful territory on the south-western frontiers of his vast empire would be of greater value to the Czar than that of those boundless wastes, which are tenanted only by a few wretched pastoral tribes, or some equally wretched fishermen.

The Arctic forest-regions are of a still greater extent than the vast treeless plains which they encircle. When we consider that they form an almost continuous23 belt, stretching through three parts of the world, in a breadth of from 15° to 20°, even the woods of the Amazon, which cover a surface fifteen times greater than that of the United Kingdom, shrink into comparative insignificance. Unlike the tropical forests, which are characterized by an immense variety of trees, these northern woods are almost entirely composed of coniferæ, and one single kind of fir or pine often covers an immense extent of24 ground. The European and Asiatic species differ, however, from those which grow in America.

Thus in the Russian empire and Scandinavia we find the Scotch fir (Pinus sylvestris), the Siberian fir and larch (Abies sibirica, Larix sibirica), the Picea obovata, and the Pinus cembra; while in the Hudson’s Bay territories the woods principally consist of the white and black spruce (Abies alba and nigra), the Canadian larch (Larix canadensis), and the gray pine (Pinus banksiana). In both continents birch-trees grow farther to the north than the coniferæ, and the dwarf willows form dense thickets on the shores of every river and lake. Various species of the service-tree, the ash, and the elder are also met with in the Arctic forests; and both under the shelter of the woods and beyond their limits, nature, as if to compensate for the want of fruit-trees, produces in favorable localities an abundance of bilberries, bogberries, cranberries, etc. (Empetrum, Vaccinium), whose fruit is a great boon to man and beast. When congealed by the autumnal frosts, the berries frequently remain hanging on the bushes until the snow melts in the following June, and are then a considerable resource to the flocks of water-fowl migrating to their northern breeding-places, or to the bear awakening from his winter sleep.

25 Another distinctive character of the forests of the high latitudes is their apparent youth, so that generally the traveller would hardly suppose them to be more than fifty years, or at most a century old. Their juvenile appearance increases on advancing northward, until suddenly their decrepit age is revealed by the thick bushes of lichens which clothe or hang down from their shrivelled boughs. Farther to the south, large trees are found scattered here and there, but not so numerous as to modify the general appearance of the forest, and even these are mere dwarfs when compared with the gigantic firs of more temperate climates. This phenomenon is sufficiently explained by the shortness of the summer, which, though able to bring forth new shoots, does not last long enough for the formation of wood. Hence the growth of trees becomes slower and slower on advancing to the north; so that on the banks of the Great Bear Lake, for instance, 400 years are necessary for the formation of a trunk not thicker than a man’s waist. Toward the confines of the tundra, the woods are reduced to stunted stems, covered with blighted buds that have been unable to develop themselves into branches, and which prove by their numbers how frequently and how vainly they have striven against the wind, until finally the last remnants of arboreal vegetation, vanquished by the blasts of winter, seek refuge under a carpet of lichens and mosses, from which their annual shoots hardly venture to peep forth.

A third peculiarity which distinguishes the forests of the north from those of the tropical world is what may be called their harmless character. There the traveller finds none of those noxious plants whose juices contain a deadly poison, and even thorns and prickles are of rare occurrence. No venomous snake glides through the thicket; no crocodile lurks in the swamp; and the northern beasts of prey—the bear, the lynx, the wolf—are far less dangerous and blood-thirsty than the large felidæ of the torrid zone.

The comparatively small number of animals living in the Arctic forests corresponds with the monotony of their vegetation. Here we should seek in vain for that immense variety of insects, or those troops of gaudy birds which in the Brazilian woods excite the admiration, and not unfrequently cause the despair of the wanderer; here we should in vain expect to hear the clamorous voices that resound in the tropical thickets. No noisy monkeys or quarrelsome parrots settle on the branches of the trees; no shrill cicadæ or melancholy goat-suckers interrupt the solemn stillness of the night; the howl of the hungry wolf, or the hoarse screech of some solitary bird of prey, are almost the only sounds that ever disturb the repose of these awful solitudes. When the tropical hurricane sweeps over the virgin forests, it awakens a thousand voices of alarm; but the Arctic storm, however furiously it may blow, scarcely calls forth an echo from the dismal shades of the pine-woods of the north.

In one respect only the forests and swamps of the northern regions vie in abundance of animal life with those of the equatorial zone, for the legions of gnats which the short polar summer calls forth from the Arctic morasses are a no less intolerable plague than the mosquitoes of the tropical marshes.

Though agriculture encroaches but little upon the Arctic woods, yet the agency of man is gradually working a change in their aspect. Large tracts of26 forest are continually wasted by extensive fires, kindled accidentally or intentionally, which spread with rapidity over a wide extent of country, and continue to burn until they are extinguished by a heavy rain. Sooner or later a new growth of timber springs up, but the soil, being generally enriched and saturated with alkali, now no longer brings forth its aboriginal firs, but gives birth to a thicket of beeches (Betula alba) in Asia, or of aspens in America.

27 The line of perpetual snow may naturally be expected to descend lower and lower on advancing to the pole, and hence many mountainous regions or elevated plateaux, such as the interior of Spitzbergen, of Greenland, of Nova Zembla, etc., which in a more temperate clime would be verdant with woods or meadows, are here covered with vast fields of ice, from which frequently glaciers descend down to the verge of the sea. But even in the highest northern latitudes, no land has yet been found covered as far as the water’s edge with eternal snow, or where winter has entirely subdued the powers of vegetation. The reindeer of Spitzbergen find near 80° N. lichens or grasses to feed upon; in favorable seasons the snow melts by the end of June on the plains of Melville Island, and numerous lemmings, requiring vegetable food for their subsistence, inhabit the deserts of New Siberia. As far as man has reached to the north, vegetation, when fostered by a sheltered situation and the refraction of solar heat from the rocks, has everywhere been found to rise to a considerable altitude above the level of the sea; and should there be land at the North Pole, there is every reason to believe that it is destitute neither of animal nor vegetable life. It would be equally erroneous to suppose that the cold of winter invariably increases as we near the pole, as the temperature of a land is influenced by many other causes besides its latitude. Even in the most northern regions hitherto visited by man, the influence of the sea, particularly when favored by warm currents, is found to mitigate the severity of the winter, while at the same time it diminishes the warmth of summer. On the other hand, the large continental tracts of Asia or America that shelve toward the pole have a more intense winter cold and a far greater summer’s heat than many coast-lands or islands situated far nearer to the pole. Thus, to cite but a few examples, the western shores of Nova Zembla, fronting a wide expanse of sea, have an average winter temperature of only -4°, and a mean summer temperature but little above the freezing-point of water (+36½°), while Jakutsk, situated in the heart of Siberia, and 20° nearer to the Equator, has a winter of -36° 6’, and a summer of +66° 6’.

The influence of the winds is likewise of considerable importance in determining the greater or lesser severity of an Arctic climate. Thus the northerly winds which prevail in Baffin’s Bay and Davis’s Straits during the summer months, and fill the straits of the American north-eastern Archipelago with ice, are probably the main cause of the abnormal depression of temperature in that quarter; while, on the contrary, the southerly winds that prevail during summer in the valley of the Mackenzie tend greatly to extend the forest of that favored region nearly down to the shores of the Arctic Sea. Even in the depth of a Siberian winter, a sudden change of wind is able to raise the thermometer from a mercury-congealing cold to a temperature above the freezing-point of water, and a warm wind has been known to cause rain to fall in Spitzbergen in the month of January.

The voyages of Kane and Belcher have made us acquainted with the lowest temperatures ever felt by man. On Feb. 5, 1854, while the former was wintering in Smith’s Sound (78° 37’ N. lat.), the mean of his best spirit-thermometer showed the unexampled temperature of -68° or 100° below the28 freezing-point of water. Then chloric ether became solid, and carefully prepared chloroform exhibited a granular pellicle on its surface. The exhalations from the skin invested the exposed or partially clad parts with a wreath of vapor. The air had a perceptible pungency upon inspiration, and every one, as it were involuntarily, breathed guardedly with compressed lips. About the same time (February 9 and 10, 1854), Sir E. Belcher experienced a cold of -55° in Wellington Channel (75° 31’ N.), and the still lower temperature of -62° on January 13, 1853, in Northumberland Sound (76° 52’ N.). Whymper, on December 6, 1866, experienced -58° at Nulatto, Alaska (64° 42’ N.).

Whether the temperature of the air descends still lower on advancing toward the pole, or whether these extreme degrees of cold are not sometimes surpassed in those mountainous regions of the north which, though seen, have never yet been explored, is of course an undecided question: so much is certain, that the observations hitherto made during the winter of the Arctic regions have been limited to too short a time, and are too few in number, to enable us to determine with any degree of certainty those points where the greatest cold prevails. All we know is, that beyond the Arctic Circle, and eight or ten degrees farther to the south in the interior of the continents of Asia and America, the average temperature of the winter generally ranges from -20° to -30°, or even lower, and for a great part of the year is able to convert mercury into a solid body.

It may well be asked how man is able to bear the excessively low temperature of an Arctic winter, which must appear truly appalling to an inhabitant of the temperate zone. A thick fur clothing; a hut small and low, where the warmth of a fire, or simply of a train-oil lamp, is husbanded in a narrow space, and, above all, the wonderful power of the human constitution to accommodate itself to every change of climate, go far to counteract the rigor of the cold.

After a very few days the body develops an increasing warmth as the thermometer descends; for the air being condensed by the cold, the lungs inhale at every breath a greater quantity of oxygen, which of course accelerates the internal process of combustion, while at the same time an increasing appetite, gratified with a copious supply of animal food, of flesh and fat, enriches the blood and enables it to circulate more vigorously. Thus not only the hardy native of the north, but even the healthy traveller soon gets accustomed to bear without injury the rigors of an Arctic winter.

“The mysterious compensations,” says Kane, “by which we adapt ourselves to climate are more striking here than in the tropics. In the Polar zone the assault is immediate and sudden, and, unlike the insidious fatality of hot countries, produces its results rapidly. It requires hardly a single winter to tell who are to be the heat-making and acclimatized men. Petersen, for instance, who has resided for two years at Upernavik, seldom enters a room with a fire. Another of our party, George Riley, with a vigorous constitution, established habits of free exposure, and active cheerful temperament, has so inured himself to the cold, that he sleeps on our sledge journeys without a blanket or any other covering than his walking suit, while the outside temperature is -30°.”

29

There are many proofs that a milder climate once reigned in the northern regions of the globe. Fossil pieces of wood, petrified acorns and fir-cones have been found in the interior of Banks’s Land by M’Clure’s sledging-parties. At Anakerdluk, in North Greenland (70° N.), a large forest lies buried on a mountain surrounded by glaciers, 1080 feet above the level of the sea. Not only the trunks and branches, but even the leaves, fruit-cones, and seeds have been preserved in the soil, and enable the botanist to determine the species of the plants to which they belong. They show that, besides firs and sequoias, oaks, plantains, elms, magnolias, and even laurels, indicating a climate such as that of Lausanne or Geneva, flourished during the miocene period in a country where now even the willow is compelled to creep along the ground. During the same epoch of the earth’s history Spitzbergen was likewise covered with stately forests. The same poplars and the same swamp-cypress (Taxodium dubium) which then flourished in North Greenland have been found in a fossilized state at Bell Sound (76° N.) by the Swedish naturalists, who also discovered a plantain and a linden as high as 78° and 79° in King’s Bay—a proof that in those times the climate of Spitzbergen can not have been colder30 than that which now reigns in Southern Sweden and Norway, eighteen degrees nearer to the line.

We know that at present the fir, the poplar, and the beech grow fifteen degrees farther to the north than the plantain—and the miocene period no doubt exhibited the same proportion. Thus the poplars and firs which then grew in Spitzbergen along with plantains and lindens must have ranged as far as the pole itself, supposing that point to be dry land.

In the miocene times the Arctic zone evidently presented a very different aspect from that which it wears at present. Now, during the greater part of the year, an immense glacial desert, which through its floating bergs and drift-ice depresses the temperature of countries situated far to the south, it then consisted of verdant lands covered with luxuriant forests and bathed by an open sea.

What may have been the cause of these amazing changes of climate? The readiest answer seems to be—a different distribution of sea and land; but there is no reason to believe that in the miocene times there was less land in the Arctic zone than at present, nor can any possible combination of water and dry land be imagined sufficient to account for the growth of laurels in Greenland or of plantains in Spitzbergen. Dr. Oswald Heer is inclined to seek for an explanation of the phenomenon, not in mere local terrestrial changes, but in a difference of the earth’s position in the heavens.

We now know that our sun, with his attendant planets and satellites, performs a vast circle, embracing perhaps hundreds of thousands of years, round another star, and that we are constantly entering new regions of space untravelled31 by our earth before. We come from the unknown, and plunge into the unknown; but so much is certain, that our solar system rolls at present through a space but thinly peopled with stars, and there is no reason to doubt that it may once have wandered through one of those celestial provinces where, as the telescope shows us, constellations are far more densely clustered. But, as every star is a blazing sun, the greater or lesser number of these heavenly bodies must evidently have a proportionate influence upon the temperature of space; and thus we may suppose that during the miocene period our earth, being at that time in a populous sidereal region, enjoyed the benefit of a higher temperature, which clothed even its poles with verdure. In the course of ages the sun conducted his herd of planets into more solitary and colder regions, which caused the warm miocene times to be followed by the glacial period, during which the Swiss flat lands bore an Arctic character, and finally the sun emerged into a space of an intermediate character, which determines the present condition of the climates of our globe.

Though Nature generally wears a more stern and forbidding aspect on advancing toward the pole, yet the high latitudes have many beauties of their32 own. Nothing can exceed the magnificence of an Arctic sunset, clothing the snow-clad mountains and the skies with all the glories of color, or be more serenely beautiful than the clear star-light night, illumined by the brilliant moon, which for days continually circles around the horizon, never setting until33 she has run her long course of brightness. The uniform whiteness of the landscape and the general transparency of the atmosphere add to the lustre of her beams, which serve the natives to guide their nomadic life, and to lead them to their hunting-grounds.

But of all the magnificent spectacles that relieve the monotonous gloom of the Arctic winter, there is none to equal the magical beauty of the Aurora. Night covers the snow-clad earth; the stars glimmer feebly through the haze which so frequently dims their brilliancy in the high latitudes, when suddenly a broad and clear bow of light spans the horizon in the direction where it is traversed by the magnetic meridian. This bow sometimes remains for several hours, heaving or waving to and fro, before it sends forth streams of light ascending to the zenith. Sometimes these flashes proceed from the bow of light alone; at others they simultaneously shoot forth from many opposite parts of the horizon, and form a vast sea of fire whose brilliant waves are continually changing their position. Finally they all unite in a magnificent crown or copula of light, with the appearance of which the phenomenon attains its highest degree of splendor. The brilliancy of the streams, which are commonly red at their base, green in the middle, and light yellow toward the zenith, increases, while at the same time they dart with greater vivacity through the skies. The colors are wonderfully transparent, the red approaching to a clear blood-red, the green to a pale emerald tint. On turning from the flaming firmament to the earth, this also is seen to glow with a magical light. The dark sea, black as jet, forms a striking contrast to the white snow-plain or the distant ice-mountain; all the outlines tremble as if they belonged to the unreal world of dreams. The imposing silence of the night heightens the charms of the magnificent spectacle.

But gradually the crown fades, the bow of light dissolves, the streams become shorter, less frequent, and less vivid; and finally the gloom of winter once more descends upon the northern desert.

34

The Reindeer.—Structure of its Foot.—Clattering Noise when walking.—Antlers.—Extraordinary olfactory Powers.—The Icelandic Moss.—Present and Former Range of the Reindeer.—Its invaluable Qualities as an Arctic domestic Animal.—Revolts against Oppression.—Enemies of the Reindeer.—The Wolf.—The Glutton or Wolverine.—Gad-flies.—The Elk or Moose-deer.—The Musk-ox.—The Wild Sheep of the Rocky Mountains.—The Siberian Argali.—The Arctic Fox.—Its Burrows.—The Lemmings.—Their Migrations and Enemies.—Arctic Anatidæ.—The Snow-bunting.—The Lapland Bunting.—The Sea-eagle.—Drowned by a Dolphin.

The reindeer may well be called the camel of the northern wastes, for it is a no less valuable companion to the Laplander or to the Samojede than the “ship of the desert” to the wandering Bedouin. It is the only member of the numerous deer family that has been domesticated by man; but though undoubtedly the most useful, it is by no means the most comely of its race. Its clear, dark eye has, indeed, a beautiful expression, but it has neither the noble proportions of the stag nor the grace of the roebuck, and its thick square-formed body is far from being a model of elegance. Its legs are short and thick, its feet broad, but extremely well adapted for walking over the snow or on a swampy ground. The front hoofs, which are capable of great lateral expansion, curve upward, while the two secondary ones behind (which are but slightly developed in the fallow deer and other members of the family) are considerably prolonged: a structure which, by giving the animal a broader base to stand upon, prevents it from sinking too deeply into the snow or the morass. Had the foot of the reindeer been formed like that of our stag, it would have been as unable to drag the Laplander’s sledge with such velocity over the yielding snow-fields as the camel would be to perform his long marches through the desert without the broad elastic sole-pad on which he firmly paces the unstable sands.

The short legs and broad feet of the reindeer likewise enable it to swim with greater ease—a power of no small importance in countries abounding in rivers and lakes, and where the scarcity of food renders perpetual migrations necessary. When the reindeer walks or merely moves, a remarkable clattering sound is heard to some distance, about the cause of which naturalists and travellers by no means agree. Most probably it results from the great length of the two digits of the cloven hoof, which when the animal sets its foot upon the ground separate widely, and when it again raises its hoof suddenly clap against each other.

A long mane of a dirty white color hangs from the neck of the reindeer. In summer the body is brown above and white beneath; in winter, long-haired and white. Its antlers are very different from those of the stag, having broad palmated summits, and branching back to the length of three or four feet.35 Their weight is frequently very considerable—twenty or twenty-five pounds; and it is remarkable that both sexes have horns, while in all other members of the deer race the males alone are in possession of this ornament or weapon.

The female brings forth in May a single calf, rarely two. This is small and weak, but after a few days it follows the mother, who suckles her young but a36 short time, as it is soon able to seek and to find its food. The reindeer gives very little milk—at the very utmost, after the young has been weaned, a bottleful daily; but the quality is excellent, for it is uncommonly thick and nutritious. It consists almost entirely of cream, so that a great deal of water can be added before it becomes inferior to the best cow-milk. Its taste is excellent, but the butter made from it is rancid, and hardly to be eaten, while the cheese is very good.

The only food of the reindeer during winter consists of moss, and the most surprising circumstance in his history is the instinct, or the extraordinary olfactory powers, whereby he is enabled to discover it when hidden beneath the snow. However deep the Lichen rangiferinus may be buried, the animal is aware of its presence the moment he comes to the spot, and this kind of food is never so agreeable to him as when he digs for it himself. In his manner of doing this he is remarkably adroit. Having first ascertained, by thrusting his muzzle into the snow, whether the moss lies below or not, he begins making a hole with his fore feet, and continues working until at length he uncovers the lichen. No instance has ever occurred of a reindeer making such a cavity without discovering the moss he seeks. In summer their food is of a different nature; they are then pastured upon green herbs or the leaves of trees. Judging from the lichen’s appearance in the hot months, when it is dry and brittle, one might easily wonder that so large a quadruped as the reindeer should make it his favorite food and fatten upon it; but toward the month of September the lichen becomes soft, tender, and damp, with a taste like wheat-bran. In this state its luxuriant and flowery ramifications somewhat resemble the leaves of endive, and are as white as snow.

Though domesticated since time immemorial, the reindeer has only partly been brought under the yoke of man, and wanders in large wild herds both in the North American wastes, where it has never yet been reduced to servitude, and in the forests and tundras of the Old World.

In America, where it is called “caribou,” it extends from Labrador to Melville Island and Washington Land; in Europe and Asia it is found from Lapland and Norway, and from the mountains of Mongolia and the banks of the Ufa, as far as Nova Zembla and Spitzbergen. Many centuries ago—probably during the glacial period—its range was still more extensive, as reindeer bones are frequently found in French and German caves, and bear testimony to the severity of the climate which at that time reigned in Central Europe; for the reindeer is a cold-loving animal, and will not thrive under a milder sky. All attempts to prolong its life in our zoological gardens have failed, and even in the royal park at Stockholm Hogguer saw some of these animals, which were quite languid and emaciated during the summer, although care had been taken to provide them with a cool grotto to which they could retire during the warmer hours of the day. In summer the reindeer can enjoy health only in the fresh mountain air or along the bracing sea-shore, and has as great a longing for a low temperature as man for the genial warmth of his fireside in winter.

The reindeer is easily tamed, and soon gets accustomed to its master, whose society it loves, attracted as it were by a kind of innate sympathy; for, unlike37 all other domestic animals, it is by no means dependent on man for its subsistence, but finds its nourishment alone, and wanders about freely in summer and in winter without ever being inclosed in a stable. These qualities are inestimable in countries where it would be utterly impossible to keep any domestic animal requiring shelter and stores of provisions during the long winter months, and make the reindeer the fit companion of the northern nomad, whose simple wants it almost wholly supplies. During his wanderings, it carries his tent and scanty household furniture, or drags his sledge over the snow. On account of the weakness of its back-bone, it is less fit for riding, and requires to be mounted with care, as a violent shock easily dislocates its vertebral column; the saddle is placed on the haunches. You would hardly suppose the reindeer to be the same animal when languidly creeping along under a rider’s weight, as when, unencumbered by a load, it vaults with the lightness of a bird over the obstacles in its way to obey the call of its master. The reindeer can be easily trained to drag a sledge, but great care must be taken not to beat or otherwise ill-treat it, as it then becomes obstinate, and quite unmanageable. When forced to drag too heavy a load, or taxed in any way above its strength, it not seldom turns round upon its tyrant, and attacks him with its horns and fore feet. To save himself from its fury, he is then obliged to overturn his sledge, and to seek a refuge under its bottom until the rage of the animal has abated.

After the death of the reindeer, it may truly be said that every part of its body is put to some use. The flesh is very good, and the tongue and marrow are considered a great delicacy. The blood, of which not a drop is allowed to be lost, is either drunk warm or made up into a kind of black pudding. The skin furnishes not only clothing impervious to the cold, but tents and bedding; and spoons, knife-handles, and other household utensils are made out of the bones and horns; the latter serve also, like the claws, for the preparation of an excellent glue, which the Chinese, who buy them for this purpose of the Russians, use as a nutritious jelly. In Tornea the skins of new-born reindeer are prepared and sent to St. Petersburg to be manufactured into gloves, which are extremely soft, but very dear.

Thus the cocoa-nut palm, the tree of a hundred uses, hardly renders a greater variety of services to the islanders of the Indian Ocean than the reindeer to the Laplander or the Samojede; and, to the honor of these barbarians be it mentioned, they treat their invaluable friend and companion with a grateful affection which might serve as an example to far more civilized nations.

The reindeer attains an age of from twenty to twenty-five years, but in its domesticated state it is generally killed when from six to ten years old. Its most dangerous enemies are the wolf, and the glutton or wolverine (Gulo borealis or arcticus), which belongs to the bloodthirsty marten and weasel family, and is said to be of uncommon fierceness and strength. It is about the size of a large badger, between which animal and the pole-cat it seems to be intermediate, nearly resembling the former in its general figure and aspect, and agreeing with the latter as to its dentition. No dog is capable of mastering a glutton, and even the wolf is hardly able to scare it from its prey. Its feet are very short, so that it can not run swiftly, but it climbs with great facility38 upon trees, or ascends even almost perpendicular rock-walls, where it also seeks a refuge when pursued.

When it perceives a herd of reindeer browsing near a wood or a precipice, it generally lies in wait upon a branch or some high cliff, and springs down upon the first animal that comes within its reach. Sometimes also it steals unawares upon its prey, and suddenly bounding upon its back, kills it by a single bite in the neck. Many fables worthy of Münchausen have been told about its voracity; for instance, that it is able to devour two reindeer at one meal, and that, when its stomach is exorbitantly distended with food, it will press itself between two trees or stones to make room for a new repast. It will, indeed, kill in one night six or eight reindeer, but it contents itself with sucking their blood, as the weasel does with fowls, and eats no more at one meal than any other carnivorous animal of its own size.

Besides the attacks of its mightier enemies, the reindeer is subject to the persecutions of two species of gad-fly, which torment it exceedingly. The one (Œstrus tarandi), called Hurbma by the Laplanders, deposits its glutinous eggs upon the animal’s back. The larvæ, on creeping out, immediately bore themselves into the skin, where by their motion and suction they cause so many small swellings or boils, which gradually grow to the size of an inch or more in diameter, with an opening at the top of each, through which the larvæ may be seen imbedded in a purulent fluid. Frequently the whole back of the animal is covered with these boils, which, by draining its fluids, produce emaciation and disease. As if aware of this danger, the reindeer runs wild and furious as soon as it hears the buzzing of the ’fly, and seeks a refuge in the nearest water. The other species of gad-fly (Œstrus nasalis) lays its eggs in the nostrils of the reindeer; and the larvæ, boring themselves into the fauces and beneath the tongue of the poor animal, are a great source of annoyance, as is shown by its frequent sniffling and shaking of the head.

A pestilential disorder like the rinderpest will sometimes sweep away whole herds. Thus in a few weeks a rich Laplander or Samojede may be reduced to poverty, and the proud possessor of several thousands of reindeer be compelled to seek the precarious livelihood of the northern fisherman.

The elk or moose-deer (Cervus alces) is another member of the cervine race peculiar to the forests of the north. In size it is far superior to the stag, but it can not boast of an elegant shape, the head being disproportionately large, the neck short and thick, and its immense horns, which sometimes weigh near fifty pounds, each dilating almost immediately from the base into a broad palmated form; while its long legs, high shoulders, and heavy upper lip hanging very much over the lower, give it an uncouth appearance. The color of the elk is a dark grayish-brown, but much paler on the legs and beneath the tail.