THE GIRL’S OWN PAPER

Vol. XX.—No. 1009.]

[Price One Penny.

APRIL 29, 1899.

Vol. XX.—No. 1009.]

[Price One Penny.

APRIL 29, 1899.

[Transcriber’s Note: This Table of Contents was not present in the original.]

THE 1000TH NUMBER OF THE GIRL’S OWN PAPER.

SUCCESS AND LONG LIFE TO THE “G. O. P.”

SHEILA.

FROCKS FOR TO-MORROW.

IN THE TWILIGHT SIDE BY SIDE.

THE HOUSE WITH THE VERANDAH.

THE GIRL’S OWN QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS COMPETITION.

OUR SUPPLEMENT STORY COMPETITION.

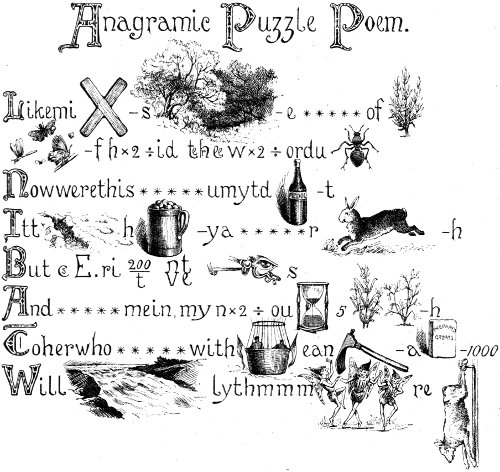

OUR NEW PUZZLE POEM.

ANSWERS TO CORRESPONDENTS.

[Photographic Union, Munich.

VIOLETTA.

All rights reserved.]

[Transcriber’s Note: The 1000th number is available from Project Gutenberg as etext number 60565, https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/60565.]

The Editor feels bound to record, for the pleasure of the general reader of this magazine, some of the charming expressions of goodwill called forth by the publication of the 1000th Number. He has been greatly cheered by them, and he knows so well that the readers will share the pleasure with him that he will unclose to them some of his recent correspondence, the actual letters themselves being sent to the printer as MS.

First, from readers old and young, and from every nation under the sun, he has received hearty congratulations.

One kind girl near London writes:

I must congratulate you on the charming 1000th Number of The Girl’s Own Paper. It is a very nice idea, giving the photographs of the contributors to the paper. I have taken The Girl’s Own Paper since it first came out, never missing one week, and I have also every one of the Summer and Christmas numbers. Although I was away one year on a sea-voyage, the paper was taken for me. When it first came out, I was quite a child; my mother took it for me, and I have always enjoyed reading it. I consider it the best paper published for either old or young, and would not give it up for anything. When I saw the 1000th number, I felt I must write and tell you what an old subscriber you had and one who appreciates The Girl’s Own Paper so much. It is not many, I think, could say they have every week of the paper. Wishing it every success for the future,

Believe me to be faithfully yours, N. H.

Another reader writes:

Dear Mr. Editor,—I have just been reading the 1000th Number of The Girl’s Own Paper, and I feel I must write to thank you (and congratulate you) for the pleasures and benefits which I have received from it during a very long acquaintance; in fact I knew it in its very first days, and distinctly remember being keenly interested in the tale “Zara, or, My Granddaughter’s Money.” I was really a girl then, and it seems, and is, a long, long while ago. I can but echo heartily Miss Burnside’s wish that it may live another 1000 weeks, and yet another; and—who knows?—another on to that. I should think one great reason for its popularity is that it suits so many different sorts of minds. There is no doubt that when catering for our mental food, you have remembered the old saying that “variety is charming.” More, it is also wholesome. With every good wish for a yet wider circulation of our dear paper, and the welfare of our Editor,

Believe me, truly yours, A. M.

Postscript.

Also one from the country:

Dear Editor,—I must write to thank you for presenting to us (to me) “Portrait Gallery of Contributors” to our dear Girl’s Own Paper. It is so nice to see their faces, to really know what those that give us pleasure, profit, etc., are like. Very nice to see our dear Editor’s face. We now know the one who for so many years has laboured much for us—your “girls.” No words will come to me to express all the gratitude I feel to you and all your helpers. God bless you, and all the others, and richly reward you, even here. You cannot see the great pleasure with which The Girl’s Own Paper is read as each month comes; and re-reading it and all those that have gone before is just as great; but let this letter just let you know how one heart is often cheered and encouraged to go on through its perusal. I did not mean when I began this letter to write about myself, only to try and express my loving thanks. Forgive all I have written, and let me sign myself

One of your grateful girls, Ellie.

Scores of girls in their teens, some of them only recent subscribers, write enthusiastically and in good taste; but as there is perforce much similarity in them, it is not desirable to print them.

However, the two following are original:

Dear and Honoured Sir,—I can hardly call myself one of the girl readers of The Girl’s Own Paper, seeing that I am on the shady side of seventy years old, and a wife of many years standing; but still I consider that I may take to myself the pleasant things you say in your article in the 1000th Number. You will think so too when I tell you that I have read almost every word in the nineteen volumes, and possess the said volumes all bound. I quite agree with the critics in what they say of the value of the publication, and also with them hope that you and your staff may long continue to instruct, amuse, and advise the “many millions” of the girls of the world. You see that if I were to subscribe myself “A Constant Reader,” I should not be telling an untruth; but I will only say

Yours gratefully, R. C. R.

Dear Mr. Editor,—Having been a constant reader of your Girl’s Own Paper for many years, I have long been very desirous of thanking you and those who contribute to it for many pleasant and enjoyable hours I have spent in reading its pages; it contains something to suit all.

I sometimes think I ought to discontinue magazines and books of the sort, but when I look on my dear old friend, The Girl’s Own Paper, I am constrained to say, How can I give thee up? So it comes on as usual, and is looked forward to and read as eagerly as ever.

May it go on and prosper in future as it has in the past.

Thank you also much for the nice Portrait Gallery; it gives me much pleasure to look at it and make comments on faces mentally, some brimming over with loving kindness, and others so thoughtful, and all good.

Dear Mr. Editor, please forgive me for intruding on your very valuable time.

Believe me,

Very faithfully and gratefully yours,

One who at eighty-three has never tired of

The Girl’s Own.

Another old reader who has every number mentions this with great pride, and adds, “I wonder how many could say the same.” This is also the wonder of the Editor, but he fears that it would be impossible to find out.

From our many and valued contributors, we have received hearty congratulations, but as their letters have a distinctly personal tendency, we can only quote from them.

A quite new writer on our staff says:

Until I received my monthly number of The Girl’s Own Paper this morning I did not realise what an important one it was. Allow me to add my congratulations to the many you have already doubtless received on the success attending your venture. I find The Girl’s Own Paper a household word wherever I go, and quite as much appreciated in Ireland and Scotland as in England. I think you have solved the problem how to instruct as well as amuse our daughters and young people most wonderfully, and feel proud{483} to be on your staff. I have been delayed in sending you the rest of my papers by fresh bereavement and continued illness. In a short time, however, I hope they will be in your hands. With repeated well wishes of a longer life and even more success to the magazine.

A quite old writer on our staff says:

My congratulations on the issue of No. 1000 of our dear Girl’s Own Paper in her pretty new dress. You must look back on the nearly twenty years of healthy, useful, and refining life that your and our paper has passed through with infinite pleasure and thankfulness, for it has been and it is a blessing both to the girls and their elders. It was with no little emotion that I looked at No. 1000, for to my connection with The Girl’s Own Paper I am indebted for one who has been from the beginning of our acquaintance the best and truest of friends to me that I am proud to call such. May God bless you, and give you in the future to see more and more abundant fruit for your labours. It seemed so wonderful for me to be able to say, “I had one complete short paper and two chapters of another in the second number of The Girl’s Own Paper, and the 1000th Number has in it a paper of mine also.” Didn’t I feel proud when I saw a paper of mine in the number? I have grown, I will not say gray, but very white in the service of The Girl’s Own Paper, and it will cost me a terrible pang when I am no longer able to write anything worthy of a place in the dear, familiar pages. I am trying to get new subscribers to our paper. I got two at the beginning of the volume. If only each reader could get one more! The paper ought to be a greater favourite than ever, for it is prettier, and has never been in every way so good as it is now.

One who has written but very seldom writes:

My Dear Old Friend,—Amid the many cries of congratulation from important people and numerous friends, let my small voice be heard. It seems to me a great triumph, in spite of opposition, to have sailed calmly on and made your thousandth port unattended by serious rivals.

My own idea of celebrating such an event is a dinner given by “the staff” to the Editor, and I for one would make a struggle to form one of such an interesting and pleasing company.

What happy memories for me are included in that span of 1000 Numbers, quorum pars parva fui.

Another very occasional contributor says:

This wonderful number of the Girl’s Own Paper will quite overwhelm you with congratulations, I am sure, for it is a record one! For myself, I am humbly delighted with it, and I never hope to have a greater honour than to be associated with so many infinitely more worthy names than my own.

This number will be treasured in the annals of the family, especially, too, as I see dear friends’ faces as well therein, and I am next but one to my father’s life-long friend.

You must have taken such an amount of pains to collect all the photographs, and our thanks are immensely due to you for all your kind trouble and taste in doing so. While most heartily echoing the first four lines of the last stanza of our valued mutual friend, Miss Helen Burnside,

Believe me, yours sincerely, ——.

An old favourite story writer—we wonder if our readers can guess the writer by the style!—sends the following:

Many thanks for the lovely number! I wish I could live in the Vicar of Wakefield’s room on the first page. How nice if we could all dine there on a summer evening!

Is it 1000 weeks ago since you started the Girl’s Own Paper? Old days come back—I go into Cassell’s and see you for the first time. And then I think of the old kindness and faithful friendship, and feel inclined to cry a little! You have done a wonderful work for girls; you have directed their feet to that narrow path in which alone they can find peace. It is a path that runs beside the Living Waters. Because it is so narrow the women of to-day are demanding a wider range, and so go a-wandering. Yesterday I received a copy of the —— from the editor, who asks for a portrait and sketch. In it there is rather a strong paper on the Religion of Women, or, rather, their irreligion. In my sketch, I ventured to touch on the true freedom that can only be obtained through restraint, and on the discipline of the interior life.

I think we can see very clearly that Almighty God has blessed you in your work, and I feel sure that you will be helped and strengthened to the end. This is my prayer for you.

One of our musical contributors sends a spirited setting (we have great pleasure in printing it in this Number) of Miss Burnside’s “Success and Long Life to the ‘G. O. P.,’” published in the 1000th Number, with the following kind words:

Best of Friends,—I enclose a little memento of the 1000th Number, over which and its editor we pray for the best of luck.

The enclosed “phrases” may seem rather trite, but equally trite is fast friendship, ripened affection and a grateful heart, of all of which accept this token from

Your Old Contributor.

A brother Editor, who has for many years afforded us friendly counsel and encouragement, but who is now, alas! no longer near at hand, sends the following:

I congratulate you on your thousand weeks, and on the promise which the energy and attractiveness of your thousandth issue give you of a thousand more. It is no small achievement to have held together so sympathetic a team of writers, and to have carried forward such a work so long with general approval.

I miss my chats with you and ——. By way of consolation, the last fortnight I have been clearing out arrears of MSS. and old letters. How they gather in the dust! They make me realise how much is past, and also how much wider and more various is an editor’s work than the part he gives to the public. This you know well, but for you is the future! May it be riper, richer, happier in all its years.

From the Editor of an important and long-established magazine, under whom we were trained, comes the following genial letter:

A thousand thanks for your 1000th Number, which is as bright and genial and clever as its Editor, and that’s saying a great deal for it. Your greeting does my heart good, but it brings me no sting of reproach. I often think of you, my dear old friend, and of the pleasant times we had together in the dear old days. Such is the force of habit that I still think of you as a youngster, and I thank your portrait for confirming that impression. Good luck to you, and to your thousand-week-old baby, and when she scores her second thousand, “may I be there to see” and to rejoice with you.

Your affectionate old chum, ——.

Last, but not least, we must mention, with sincere gratitude, a letter of congratulation from our painstaking printers. Also great indebtedness is due to the Officers of the Society for their expressions of congratulation, as also to the Committee of the Society who are the owners of the magazine.

WHAT THE PRESS SAYS:

“The Girl’s Own Paper—the most successful paper ever published for girls, alike from the pecuniary point of view, and from the point of view of supplying girls with literature equally wholesome and welcome—has just reached its thousandth number. Long may it live.”—The Queen.

“With the thousandth number of The Girl’s Own Paper, dated February 25th, is given a detached “Portrait Gallery,” containing the likeness of 105 contributors to that excellent periodical, among whom are the Queen of Roumania, Princess Beatrice, and (as it is fairly claimed) ‘many queens and princesses of prose, poesy, and music’—not to speak of princes.”—The Guardian.

“Without any trace of mawkish piety, it has always set before its readers the ideal of first things first, and has never descended to the depths of sensationalism to secure a wider circulation.”—Methodist Times.

“I congratulate The Girl’s Own Paper, which celebrates its thousandth birthday. It still leads.”—Sketch.

“The idea of its publication was a very happy one, and it has been thoroughly well carried out with sense, with catholicity, and with quickness of perception.”—British Weekly.

“The Editor says—‘Success shone upon us from the very first.’ That that success may never wane will be the hope of many thousands of present readers and of past readers who are no longer girls—women who realise that their lives were not only made brighter and happier by the Magazine, but better, fuller, and more useful.”—Brighton Herald.

“Let us congratulate the Editor and the Publishers of The Girl’s Own Paper upon the success which is indicated by the G. O. P. (as its readers affectionately call it) attaining its thousandth number. As the interests of girls have widened—and between the years 1880 and 1899 they have widened greatly—the scope of The Girl’s Own Paper has correspondingly enlarged, and there would appear to be no subject which young women can present to the consideration of the Editor of this favourite organ upon which they will not receive the most sympathetic and judicious advice.”—The Queen.

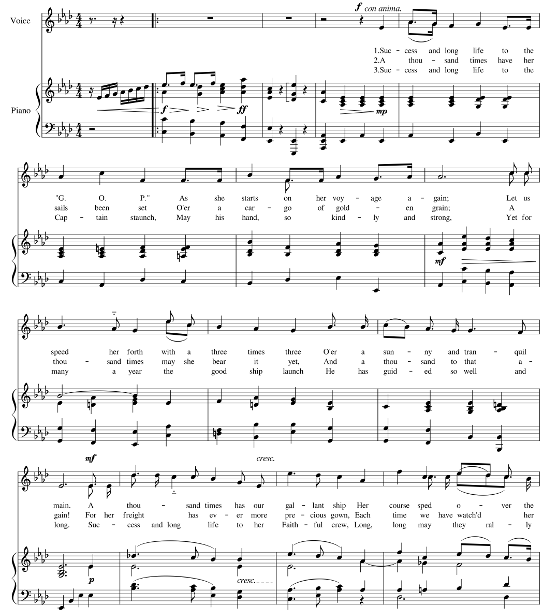

Words (in the 1000th Number) by Helen Marion Burnside.

Music by M. B. F.

If supported by your device, click to listen to a midi version of the above music.

[1] Signal for the waving of over 43 millions of girls’ pocket handkerchiefs.—M. B. F.

A STORY FOR GIRLS.

By EVELYN EVERETT-GREEN, Author of “Greyfriars,” “Half-a-dozen Sisters,” etc.

EFFIE.

he two girls remained quite still for a few minutes, looking curiously at one another. Mrs. Cossart, who had brought Sheila up to her daughter’s bright, pretty sitting-room, had been obliged to leave them after speaking a few phrases of introduction, as there were visitors awaiting her in the drawing-room.

Sheila saw, half reclined upon a couch beside the fire, a girl with a pinched face, dark hair and brown eyes, which looked out rather sharply through a pair of “nippers.” The girl was thin, but she did not look exactly ill. There was something a little defiant in her air as she raised herself and spoke to her visitor.

“So you are Sheila? Come here and sit down, and let us talk. I have heard a lot about you, and I suppose you’ve heard plenty about me. I wonder what kind of things the Tom Cossarts say about me in private. I always think they call me a humbug.”

“No, they don’t,” answered Sheila quickly, as she came forward, “I think they are kind people. They were all very kind to me.”

“I suppose you would have liked to stay there altogether. You don’t think it will be so amusing, shut up here with me.”

“I can’t tell till I try,” answered Sheila smiling, rather puzzled by Effie’s sharp speeches. “I liked being in River Street pretty well. But—well—it didn’t seem much like home. This house is much nicer. I think if you like having me, I shall like being here. I hope you will like me, Effie.”

Sheila spoke simply and impulsively, and Effie smiled, and her face looked pleasanter than it had done as yet.

“Oh, I daresay we shall get on. I’m not so cross as I expect you’ve been told. Once I was just cram full of fun, but being ill takes the life out of you. Sometimes I hate everything and everybody, but then I get better, and things seem different. Have you ever been ill? Do you know what it’s like?”

“Not much,” answered Sheila, “I’m very strong. Oscar has been ill oftener than I. Tell me about yourself, Effie? I want to know everything. Your mother wants me to be a sort of sister to you. Sisters ought to know everything about each other.”

Effie, nothing loath, began a long history of herself. In a few days’ time Sheila had discovered that the way to keep her most satisfied and entertained was to let her talk about herself. Poor child, it was scarcely her own fault. Her mother never tired of asking her about her every symptom, and listening to her accounts of how every hour had been passed. She talked almost ceaselessly of Effie to everybody who would listen. She had almost lost her identity in that of her last surviving child. It seemed to Sheila that poor Effie had had enough doctors and enough experiments in treatment tried upon her to kill anybody, and when she ventured to say as much to Effie herself, the girl at once and cordially agreed.

“I hate the very sight of them. I feel as though I’d never have another near me. I mean not to care now whether I get better or not. The harder I try, the worse I am. I’m just not going to care about anything again!”

That was decidedly one of Effie’s moods—a sort of defiance of everything and everybody. At other times she would be gentler, sometimes she was depressed. Then she would have a spell of high spirits, in which she often overdid herself, and brought on one of her attacks of breathlessness and oppression.

Sheila looked on and listened and wondered. Sometimes she was quite fond of Effie, sorry for her, and eager to do anything she could. At others, again, she felt a decided longing to shake her, and grew fairly out of patience at the way she had of bringing every subject started round to herself again. Others had noticed this defect in Effie. Her cousins had named it in Sheila’s hearing, but they had never spoken of it to the girl herself, and Sheila never meant to; but one day almost in spite of herself, the words sprang to her lips.

“Effie, do you ever think about anything or anybody but yourself? I do think you’d be so much better if you would. I don’t know if you know it or care; but you talk about yourself from morning to night. It does get so tiresome, and I’m sure it’s bad for you!”

Effie stopped short in what she was about to say, and stared at Sheila hard. The girl coloured under the sharp gaze. Sheila was very placable by nature, and hated anybody to be angry with her; but she had not learned the lesson yet of thinking before she spoke.

“I beg your pardon if I vexed you,” she said; “but——”

“That’ll do,” said Effie shortly; “I don’t want to hear any more! You can go now! You’d better take that ride you’ve been wanting to so long! I don’t want anybody with me who thinks it tiresome to talk to me!”

Sheila escaped from the room, half inclined to laugh, and half to cry. Shamrock had arrived at Cossart Place two days ago, and she was eager to have a gallop upon her; but Effie had not been well, and she had not liked to leave her. She fled away now to her own room, and put on her habit. Her cheeks were glowing with the excitement of her little quarrel with Effie, and with the prospect of her ride upon her favourite. She thought most likely she would get a scolding from her aunt on Effie’s account; but, after all, was it not a good thing for somebody to warn Effie of her besetting weakness? Sheila was sure she did not want to be selfish. She had many kind thoughts and plans for other people. Only she had got so into the way of being the first consideration with everybody about her. It was enough to spoil anybody.

When she was dressed, Sheila slipped down the almost unused staircase of the old part of the house; and made her way direct to the stable-yard. Sheila had obtained her wished-for quarters, and had two pleasant rooms of her own in the block of old building, which she liked so much better than the great modern addition, where the reception-rooms were, and where the family had their quarters. Her belongings, and a good many of Oscar’s, were stored here, and made her rooms home-like and bright. When Oscar came to see her, they felt almost in a separate house of their own. On the whole, Sheila was very pleased with her new life. She was kindly treated, and things were all smooth and easy. So long as she pleased Effie, that was all anybody expected of her; and so far Effie had seemed to like her companionship. But Sheila began to wonder how things would be if she got into Effie’s black books. She fancied that her Aunt Cossart could be pretty severe to anybody who offended or distressed her darling.

However, what was done could not be undone, and Sheila’s nature was hopeful and elastic. She ran to the coachman, and begged him to have Shamrock saddled for her, and laughed and shook her head when he suggested that a groom should attend her.

“Oh, no, I always rode alone at home,{487} if my father or Oscar could not come with me,” she answered; “Shamrock is perfectly safe. I want to explore the country. Some of the roads look quite pretty.”

She was soon mounted on her favourite, who expressed pleasure at having her pretty mistress on her back once more. Sheila was equally delighted, and rode gaily along the lanes, the sunshine throwing dancing lights and shadows across her path. She followed one winding lane after another, feeling joyfully the freedom of her independence, after being so many days shut up in the house, with only an occasional run into the garden; and she could hardly regret the little tiff with Effie which had brought it about.

“I’ll ride down to the works and see Oscar!” cried Sheila, as she paused upon the brow of a little hill, and saw the town and the chimneys lying like a map before her. “I should like to see him at his treadmill, poor boy; but he seems to like the work pretty well. He is a good boy, and never complains. I should, I know, if I were in his shoes.”

Sheila’s plan was put into speedy execution, and before long she had ridden into the enclosure surrounded by her uncle’s buildings, and had asked for her brother.

Oscar came out to her with a smile on his face but surprise in his eyes.

“Are you all alone, Sheila? How did you get leave to come?”

“I didn’t ask. Why should I? I just came. Effie was cross, and sent me away, and I got Shamrock saddled, and here I am!”

“Oh, but I think you should have asked Aunt Cossart first! They say she is very nervous about girls riding, and would never let them go alone. Besides, through the town it isn’t perhaps quite usual. It’s not like being at home, Sheila.”

“Oh, well, I hadn’t thought of going to the town when I started, Oscar, so you needn’t look so solemn! Nobody knows I’m out; so Aunt Cossart can’t be getting anxious. I want to see what you are doing, so that I may picture you better.”

North came up at this moment, and had a kindly welcome for his young cousin. He rather laughed at her independence, but was ready enough to have her horse taken care of whilst she went to see Oscar’s “treadmill,” and saw various interesting things at the works. Her pretty appealing little ways amused him, and he was quite ready to make something of a pet of her, as were most other people. She forgot all her troubles, laughed, chatted, and talked to the work-people, the clerks, and everybody she met, until finally a great bell booming out overhead proclaimed the hour of one; and Sheila realised that she should be late for luncheon.

Oscar put her up, and she started forth at a rapid pace, and covered the two miles between the works and Cossart Place in very good time; nevertheless she saw a visible commotion at the door as she cantered up the drive, and was aware that both her aunt and uncle were on the look-out, as well as several servants.

“Did they expect me to return on a shutter?” questioned the girl of herself, with a feeling of mischievous glee. She was in good spirits from her little jaunt, and was amazed by the agitated whiteness of her aunt’s face, as she dismounted and ran up the steps into the hall.

“I’m sorry to be late; but I overlooked the time. I was at the works, seeing Oscar and the people there. I hope you haven’t waited! Effie sent me off to have a ride, and it’s so delightful having Shamrock again! I did so enjoy it!”

Mrs. Cossart said not a word but turned again to the dining-room. The servants were about, and she had no intention of saying what was in her mind before them.

Mr. Cossart shook his head and said reprovingly—

“You have made us very seriously uneasy, Sheila. You ought not to have gone off like that without leave—and alone, too. We want you to be happy; but you must not be a modern unladylike girl, galloping alone over the country, and into the town too. I hope nobody saw you who would know you. What would they have thought of such proceedings?”

“I don’t know—probably nothing. I used to ride about everywhere at home,” answered Sheila, feeling rather aggrieved at the way her very small escapade was being treated. She took her seat at table; Effie’s was vacant.

Mr. Cossart asked if she were not coming down. “Was she not so well to-day?”

“Effie has been upset!” said Mrs. Cossart coldly. “She is not well enough to come down!” And she gave a look at Sheila which sent the blood into her cheeks. She knew very well that she was in disgrace; but her spirit rose against what seemed to her to be injustice; and she talked on gaily all through the meal, not apparently heeding the silence of her elders.

When she rose from table her aunt summoned her to the little boudoir sacred to her own use; and once within the door, the storm broke over her head.

Mrs. Cossart did not profess to know what had passed between the girls; but she knew that Sheila had said unkind things to Effie, and had reduced her to tears and made her very unhappy and agitated. That sort of thing could not and must not be. Effie was in no state to be upset. Probably she would have a return of the asthma and a succession of bad nights. Sheila must remember that ill-health was a terrible trial, and she must be kindly and gentle and unselfish. In vain Sheila strove to explain how very little it was she had said, and that she had apologised afterwards. Mrs. Cossart was rather like her daughter in one way; she liked to keep the ball of conversation in her own hands. She wanted to talk, not to listen. In the end Sheila grew angry. She was not used to being found fault with. She felt she was being unjustly treated, about Effie, about her ride, about her lateness for lunch. She had done nothing wrong. No harm had happened. It was horrid of her aunt to make such a to-do. The penitence she had felt at the outset was quickly gone, and when she finally flew up to her own room, it was to shed a tempest of angry tears and resolve that she would never, never care one bit for Effie, and that her aunt was a hard, unjust woman, whom she could never care to please.

“I shall never be happy here, and I’ll tell Uncle Tom so. I’ll tell Cyril how they treat me. I’ll get away and live somewhere with Oscar. I’ve never been scolded so before, and I won’t stand it. If I’d done wrong, I should be sorry, but to tell Effie she talked about herself too much, and to take a ride on Shamrock!—no, I won’t be sorry about that! I won’t, I won’t!”

She changed her dress, and began to wonder what she should do next. It was dull all alone up here, though the room was bright and pretty enough. She stood looking out of the window, and presently she saw Cyril’s figure approaching the house by the short cut through the garden. He had promised to come and see her soon, and surely this was his expected visit. Sheila dashed the last teardrops away from her eyes, caught up a bunch of violets and fastened them at her throat, and looked carefully to see if she “looked as though she had been crying.”

She spent a few minutes removing all traces of tears from her face, and by that time all anger had subsided, and she was ready to smile and be herself again, though a little load lay upon the background of her spirits. But no message came to her from Cyril, and she went restlessly out into the passage, and along to the corridor of the modern wing. Then she stood still and listened.

Effie’s door was close at hand, and it stood just ajar, though the heavy curtain veiled the room. Sheila heard a sound of voices, and went a step nearer. Yes, that was certainly Cyril’s voice, talking to Effie. She bit her lip and stood hesitating. Should she go in, or should she not? Had it not been for her aunt’s severe strictures she would never have thought of staying away. She was lonely by herself. And she wanted so much to see Cyril. Yes, she would go in. They could but send her away if they did not want her.

The next moment she was within the room, standing a moment hesitating on the threshold. Cyril was sitting beside Effie’s couch, talking kindly to her as it seemed. Effie’s face looked as though a storm had passed over it, but she was smiling at Cyril, and when both turned at the slight sound of Sheila’s entrance she exclaimed quickly—

“Oh, come in. Cyril came to ask whether you got forgiven for being late. Did you get a scolding? Mother was in a great state about your riding alone, but I see you’ve got in all safe.”

“Of course I have,” answered Sheila laughing, with a shy little look at Effie, as much as to ask if she had forgiven the plain speaking of the morning.

(To be continued.)

By “THE LADY DRESSMAKER.”

Those who are interested in the protection of birds, and object to their being killed to serve as mere ornaments for hats and bonnets, will be glad to read from the New York Times an account of the recent inventions and changes brought about by the great demand for feathers for the decoration of masculine headgear during the late war.

The trade in feathers amounts to many millions of pounds annually, and the supply of the birds furnishing them is decreasing so rapidly, that it was essential that substitutes should be found; and the American inventor has proved himself equal to the occasion. The supply of ostrich feathers from California is so ample that it has brought the price of feathers down to a reasonable figure, but still not low enough for the low prices that are asked for them. So there are plenty of good ostrich feathers manufactured of celluloid, of which the quills are made, while the barbs are of silk waste. These are so skilfully dyed and curled that only an expert could distinguish them. Other expensive feathers and plumes are made out of silk and cotton waste; and enormous quantities of poultry feathers are utilised, and are so exquisitely dyed and painted that these imitation plumes are more in demand than the real ones of the wild birds. A remarkable machine has been invented, and is in use for plucking the feathers from the dead poultry, which strips them of their feathers in just half a minute. Then the plucked feathers are passed rapidly along to another small room, where a current of air sorts the very fine from the heavy ones; and the very lightest and softest are used for pillows; but all the others find some use in the millinery trade. This state of things has made poultry quite wonderfully profitable.

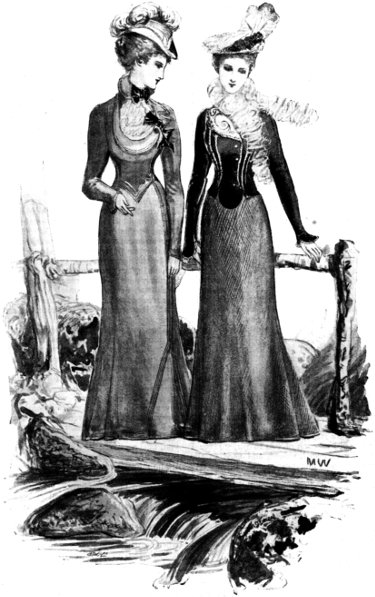

TWO SPRING GOWNS.

The first things I must mention are the white muslin, and white and cream washing silk blouses, which seem to be quite as fashionable this year as they were at any time during the last two years. They are made this year chiefly with a very small bishop’s sleeve and a tiny cuff. Tucks with lace insertion between them seem to be the style, when some form of yoke is not chosen. This last way of making both dress bodices and blouses is very evident in all the new models. The shape is narrow and long, extending over the shoulders, and tucks are the most popular decoration. Lace insertion is also seen on cambric and cotton shirts, and I notice that vertical stripes are much used for all the cambric ones. The muslin blouses have a fitted under-bodice of muslin, or batiste in colour, to wear underneath; and the skirt should be of cashmere, to match this in colour. The neck and waist-band may be of moire, or of satin, either to match the skirt, or in white. The latter, however, is said to make the waist look large. In a sense, blouses are not as fashionable as they were, for they are no longer seen in the evening as they were. A pretty evening gown, with the bodice and skirt alike, is more distinctly in the last mode.

In the way of dresses, everything just now seems to be of cloth, and very fine ones are made up for evening dress. Many rows of stitching seem to be the method of trimming most followed; and strappings of the same cloth for day dresses. Cashmeres and figured mohairs, gauzes, and plenty of new grenadines are in prominent view; the latter are beautiful in their designs, floral patterns as well as stripes being seen. Coloured silks will be more worn than black ones, as under-dresses for them; and I hear that deep flounces will be the new way of making up.

It has always been a funny thing to me to see the way in which men will bravely attack the corset, and issue orders against it. These attacks are made periodically, at intervals of about eight or ten years; and all kinds of accusations are hurled against the offending corsets during the assault. But, like Tennyson’s ever-quoted “Brook,” they go on for ever. Here and there one may find some woman who has dismissed them, but, as a general rule, women are not much affected by the clamour. Lately two fresh attacks have been made, one by the Russian Minister of Public Instruction, who, after paying many visits to schools and gymnasia for girls, has decided that the corset is not conducive to the health of its wearers. So he has issued an order to the pupils of the higher schools and gymnasia, as well as to the students at the Conservatories of music and art, prohibiting the wearing of them, and with the order goes a long paper, in which are the reasons for the prohibition. At the same time, on the other side of the Atlantic, a brave assemblyman in Wisconsin, has introduced a resolution into the State Legislature: “Resolved that three members be appointed to form a committee to draft a bill to protect the health of the misses, old maids, and married women of the State of Wisconsin, by making a law to prohibit tight lacing.” Now, who is to find out the tight lacers? One pities the police if they are to perform these duties! And while I am mentioning this, I must not forget to chronicle that the new spring makes of corsets are distinguished by straight fronts, the chief shaping being done at the sides and hips.

The reign of the toque seems to be more secure this spring than ever. Indeed, the bonnet, pure et simple, with strings, is nowhere, except for very elderly people. Plateaux of straw and crinoline are much used to pinch into any becoming style; and all kinds of fancy straws in every hue are prepared for toques. Many floral toques are seen, and only one kind of flower is used to make them. It has been quite remarkable this year how early the most summery-looking hats have been worn. Rose-covered ones were seen as early as the beginning of March, and plenty of white ones in the Park. All the new toques are full and high in the front, with some scraggy-looking tips straying upwards; and to many people they are not becoming, the essence of a toque being, I think, the snugness and closeness of its fitting to the head.

In the way of colours for cloth costumes, I see all shades of grey, stone and drab,{489} petunia, and blue of several shades, but I should say that greys are the most popular. Mauve toques and hats are really becoming a kind of uniform; they are so much worn; and every second woman wears violets.

It is said that all woollens will speedily become more expensive as wool itself has gone up; the reason of which lies in the prolonged drought of last year. Cotton is also said to be in the same case, and from the same reason. Let us hope that this will not last long enough to incommode us.

The two sitting figures in our illustration show the prevalent styles of the present spring. The one on the left wears a gown of electric blue, and a short jacket with rounded fronts. This and the narrow flounces on the skirt are braided with black braid. The revers on the jacket are of cream-coloured satin, covered with cream lace. On the right hand, the other sitting figure wears a purple cloth dress, which is scalloped with white; the front is of white cloth, with white lace at the neck. The hat on the left is one of the newest ones, with a square-topped crown, and the brims slightly turned up on both sides.

IN SHEPHERD’S PLAID.

“In Shepherd’s Plaid” shows us one of the prettiest of this season’s models, and so youthful-looking that it will be becoming and suitable for quite a young girl. It is made of silk; the yoke of the bodice is of deep rose-coloured silk, with écru lace edging. At the top of the sleeves are bands to match, and the rosy hue is repeated at the waist and at the top of the flounces on the skirt, which are also trimmed with two rows of black velvet. Black velvet rosette bows are on the bodice. A small white hat is worn with white tulle trimmings and white tips, and velvet bows under the brim. It will be seen that all the dresses worn are slightly trained, and that fashion has banished the comfortable short skirt which we have enjoyed for the past year. From what I notice, however, some women are not disposed to leave it off so easily, and I daresay we shall see it made for really useful gowns.

THE NEW BLACK VELVET JACKET.

The new black velvet jacket is shown in our next illustration; made in black velvet, very short—as all the new jackets are—and beautifully cut and fitted. These little jackets have been so much the fashion in Paris that we are sure to see many of them here, and very useful they promise to be. The revers are of white satin, and a ruffle of chiffon is worn round the neck. The toque is of white drawn tulle, with roses and white ostrich tips. The second figure wears a grey cloth gown, with a very short jacket, much pointed in the front, which is crossed over, and fastens at the side. The bodice is rounded out in front, the opening being filled in with lace and chiffon. The skirt and jacket are machine-stitched in many rows, and have bows of ribbon velvet. The hat is also a new shape, and is like the one in the first sketch, but is rather more sloping in the crown. The shapes of the sleeves at the wrist are fully shown. They are long and generally rounded, so as to fall over the hands. These tulle and chiffon ruffles are going, I think, to take the place of the feather ones which we have worn for some time. They are so pretty that the pity is that they are so perishable, especially in our grimy London. The tendency is so much towards wearing white this year that our purses will be quite depleted, if we are to follow the fashion, and keep ourselves daintily clean on all occasions.

By RUTH LAMB.

SABBATH AND REST.

See, for that the Lord hath given you the Sabbath.—Ex. xvi. 29.

At the close of our last open evening, I promised some of you, dear girl friends and correspondents, that I would take Sunday and Rest as the subject of one of our talks. I find that the minds of many amongst you are much exercised as to “the right way of keeping Sunday.”

“I shall be very glad if you will some time say a little about Sundays, and perhaps give us some little rule to help us to keep them holy,” wrote one. “People have such different ideas about what is right and wrong to do on Sunday.”

I do not wish to take that word “people” in too wide a sense.

Our twilight gathering is a large one, and now includes members of widely differing ages and positions in life. I hope we all rejoice in knowing that so many older friends have been drawn within our circle, and are in full sympathy with us.

Still, I love best of all to picture myself as “the old mother sitting surrounded by a countless family of girls, my adopted children of the twilight hours,” and between whom and myself links have been formed which will last through the life of this world and beyond it.

During our talk I should like to use the old sweet Bible word Sabbath, which can alone suggest its real subject. I want us all to feel its importance to ourselves as belonging to those who profess and call themselves Christians. We have not to consider how those spend the day of rest who are living without God in the world, and to whom the Sabbath and its ordinances are less than nothing; but how we can best use and enjoy the privileges it brings, and help others to do likewise.

What is the Sabbath?

If you were really within hearing, I could imagine most of you would reply, “Why do you ask such a question? Everybody knows the difference between it and other days.” And you would probably describe all its distinctive features. The open churches, the closed places of business, worshippers hurrying in one direction, holiday-makers in another. Or perhaps some would tell of joy experienced in meeting with fellow Christians in the House of God, or of happy family gatherings under the home roof, impossible on other days, but delightful on that precious day of rest.

After hearing all, and sympathising with your joys, I should ask you to turn your thoughts from the present, and go back with me to the first chapter of the world’s history for the answer to my question, “What is the Sabbath? What was its beginning?”

It is God’s first gift to mankind, bestowed when His work of Creation was completed by the instalment of the first human pair in the garden “eastward in Eden,” which He had planted as a fitting abode for them.

The Divine Creator of the universe consecrated the Sabbath by His example, and gave it to be a continuous blessing throughout endless ages.

It is beautiful to note the wisdom of God in dealing with the first human pair, and the lesson He taught them is for us to-day. Paradise or Eden was not to be the abode of idleness. By daily work rest was to be earned, and only by means of work could rest be enjoyed, and its preciousness realised in any great degree.

I may note, in passing, that the idle, self-indulgent time-killers are the persons who complain most of weariness. They are tired with doing nothing, yet not having earned the right to rest, they cannot enjoy it.

People often allude to the Sabbath as if it were a merely Jewish institution. Forgetting the earliest Bible record, they dwell on the time of Israel’s wanderings in the desert, on the double supply of manna bestowed on the sixth day to meet the wants of the seventh also; the disobedience of some, and the words which followed, addressed by the Lord to Moses:

“See, for that the Lord hath given you the Sabbath, therefore He giveth you on the sixth day the bread of two days.” The Fourth Commandment, given from Mount Sinai, and engraved on stone, was the renewal and confirmation of that first inestimable gift of a day of rest.

Now, dear ones, I want you to think how a gift can alone fulfil the giver’s object in bestowing it. It must be willingly and gratefully accepted, valued, and used in accordance with the intentions of the giver.

Even gifts are often received without being welcome, and for various reasons. We may fear to cause pain by refusing them, or we may be afraid of future loss if we do so. We may dislike the idea of being indebted to the person who offers the gift. The article itself may be one on which we set no value, and so on. Or, as often happens, gifts are prized at first for their novelty, then unused, hidden away and forgotten, together with the giver.

I have a very dear friend who is constantly receiving tokens of affectionate remembrance. He is one who never loses an opportunity of brightening a dark path or smoothing a rough one, of helping to relieve an overweighted back of some part of its burden, of saying a cheery or comforting word, or of doing a kindness at the right time and in the right way—always an unostentatious one.

This is a great deal to say of any man, but how delightful to be able to say it with absolute truth! Many of the little souvenirs that reach my friend are of small intrinsic value and seem almost out of place amongst the beautiful ornaments and works of art in his home. But whenever the donor of the humblest gift is a guest in that house, the little token of affection or gratitude is sure to be in evidence, and the sight of it adds to the pleasure of host and visitor. The former can only show a small number of these carefully-kept presents at one time, but they come out in turns, and prove that none have been thrown aside or forgotten.

Probably what I have said of my friend has put a new thought into the minds of many of you, and I hope it has suggested a way of giving pleasure to the humblest friend, which may not have struck you before. Above all, I trust it will lead each of you to ask, “Have I thankfully accepted, valued, and used in the right way God’s first precious gift of one day in seven for the rest and refreshment of mind and body, and the good of my soul?”

No mere rule will ever make any of us use this gift worthily. We must rejoice in it as a part of our divine inheritance. Surely, when we think that God has given us life and breath and all things, that from Him every good and perfect gift has come, a new glow of glad thankfulness should fill our hearts, as we remember that He did not omit to fix the periodical day of rest.

Well for us, dear ones, that we were not left to depend on any ordinance of man for the right to this blessing. Think what the world would be without it! The Sabbath is often abused, ignored, neglected, almost always undervalued. But would the most careless, or even the most irreligious, like it to be wholly abolished?

I daresay some, probably most, of you have read that amongst the horrors of the French Revolution the Sabbath was abolished together with all the services of religion.

I do not wish to enter into detail or to picture the horrible scenes which followed, but as there is a tendency amongst a large class of persons to undervalue the Sabbath in its hallowed character, it is well for us to glance at the state of France during its abolition. Listen to a few words only. “The services of religion were now universally abandoned. The pulpits were deserted through all the revolutionised districts; baptisms ceased; the burial service was no longer heard; the sick received no Communion; the dying no consolation. A heavier anathema than that of papal power pressed upon the peopled realm of France—the anathema of Heaven, inflicted by the madness of her own inhabitants. The village bells were silent; Sunday was obliterated; infancy entered the world without a blessing; age left it without a hope. On every tenth day a revolutionary leader ascended the pulpit and preached Atheism to the bewildered audience. On all the public cemeteries the inscription was placed, ‘Death is an eternal sleep.’”

I should not like to shock your ears or to leave with one of our twilight gatherings such memories as would haunt you, were I to continue my quotation; so I have only given a faint glimpse of a country without a Sabbath and its gracious Giver. May the little help us to realise more fully the preciousness of His first gift to mankind.

I wonder if you, my dear girl friends, have ever thought of a fact which establishes the Divine origin of the Sabbath. You know how we measure our years, calendar months and days, and how these periods are accounted for by the journeying of the earth round the sun, and other movements and positions which regularly recur. But there is nothing to divide week from week, or to mark a definite period of seven days, save the Divine example and the Divine command, as recorded in the Bible.

The story of God’s creative work during six days, and of His resting and sanctifying the seventh, the commandment, “Six days shalt thou labour and do all thy work, but the seventh day is the Sabbath of the Lord thy God,” are our only warrant for the division of time which we call a week. The lunar month divided by four will not give fully seven days. The calendar months are of unequal lengths, and even the year cannot be divided into so many exact weeks.

This fact may be already known to most of you, but you may have gone over the figures many a time without saying to yourselves, “The movements of the earth and her attendant moon mark various periods, but never an exact term of seven days. For this division we must refer to God’s word and His command to give six days to work and the seventh to rest.”

Are you saying to yourselves that I am dwelling too long on the institution itself, whereas you want to know how best to keep it in these days of varied opinions and many temptations? Forgive me if I have stepped aside a little from the path you asked me to tread. I longed—I cannot tell you how earnestly—to impress upon your minds, first of all, a sense of God’s love in bestowing the day{491} of rest and the infinite benevolence it manifests. We can neither value nor use such a gift as we ought to do, unless we feel that it was bestowed for our good and to make us both better and happier. Having once realised this, how can we help thanking God for it and feeling anxious to use it aright, so that we may derive from it all the benefit intended for us?

Most people, however irreligious and indifferent to the sanctified part of the Sabbath, practically acknowledge it as the best day of the seven. If they do not, why should it be the day for clean raiment, for the best clothes to be worn, the best food to be provided, and all done that can be done, according to the lights of different individuals, to make it stand out as being unlike the other six days?

It ought to be the brightest and happiest day of the week, and I, for one, have no sympathy with those who would make it a day of gloom and weariness to the young. On the other hand, I have as little sympathy with those who would leave God out of it, and dedicate it wholly to what they call pleasure, but which often results in over-wearied bodies, unrefreshed souls and unfitness to begin the work of the six days that follow.

To enjoy our Sabbath we must feel glad of and thankful for it, and we shall not be satisfied unless our immortal part is refreshed and strengthened, as well as our body, by the opportunities it gives.

We shall need no special command, no hard and fast rule to direct us. Our grateful hearts will incline us to turn our steps towards the house of God once during the day, if it be possible for us to do so. And, if not, we can mark the day in the quiet of home by devoting an hour to special study of God’s word, prayer, thanksgiving and self-examination.

There are many waking hours in our day. Let us ask ourselves whether, when prevented from joining in public worship, we habitually dedicate one in the way I have named.

I once heard a girl say, “I do like to take a bit of Sunday to talk myself over.”

It was her way of alluding to her weekly self-examination, and, whilst feeling conscious that I needed to “look within” much more frequently, I rejoiced to hear from young lips that the “talking herself over” was habitual.

Supposing that circumstances prevent one visit to the house of God, and there are only mother and daughter, mistress and maid, in the house, why should not these claim and enjoy the blessing promised in the words of Jesus, “For where two or three are gathered together in my name, there am I in the midst of them”?

I know by experience how very sweet and profitable such household services can be, even when there are literally only the two or three to share in them. And how very small is the fragment they take out of the day of rest, whilst sweetening and purifying the whole of it.

If our Sunday observances are not influenced by thankfulness for God’s gift, anxiety to use it rightly, and love for the Giver, they are generally fitful and, to a great extent, dependent on our immediate surroundings. For instance, when we are at home we may be regular in our attendance at church. We should feel ashamed were the friends who worship under the same roof with us to see our seats vacant week after week from any cause except illness or absence from home. Are we equally regular in our attendance when amongst strangers, or in a new neighbourhood? When taking holiday, do we not sometimes regard it as part of the holiday to excuse ourselves from going to church and say, “We want the fresh air and change of scene. We must make the most of our opportunities.” By so doing we show plainly that there is no heart in our ordinary worship, no realisation of the value of the Sabbath, or the needs of our spiritual nature.

I heard some young people talking together of a Continental tour they were about to take and the pleasure it would give them. They were unused to travel and were discussing the amount of luggage they must take: what articles must go, what could be done without.

An old friend listened to them with interest and amusement. He had travelled much and wished that he could renew past pleasure by witnessing the enjoyment of these bright girls amid new scenes and experiences. His opinion was often asked as to what might be called necessaries and what luxuries. At length he said—

“I have noticed that so many people forget one thing which they seem to value at home, but leave behind, though they could take it with them and have no extra cost for luggage.”

“What is that?” was the eager question.

“Sunday.”

No other word was needed. The girls understood their old friend’s meaning. They had heard their travelled acquaintances speak of Sundays spent in other lands, and knew how easily they had been induced to fall in with the ways of those amongst whom they found themselves.

One of yourselves told me that when abroad last summer the party of tourists found there was no English service in the town where they were, so it was settled they should travel on Sunday to their next stopping-place. “I,” wrote my girl friend, “had kept the last month’s Twilight Talk to read in the train at the time that, had I been in England, I should have been at church.” Then she related an incident that followed and brought with it a temptation to do something which would have put self before others; but, she added, “with the words I had been reading fresh in my mind, I had the strength to overcome my selfishness.”

It was very delightful to know that, even when so far from home, a dear member of our circle had been influenced for good by reading our last talk, and I am sure she will forgive my quoting this little incident, because it will give pleasure to us all and be helpful also.

You no doubt remember the Bible phrase, “a Sabbath day’s journey,” which surely suggests Sunday travelling, you will say.

It is wonderful how often we hear an expression without finding out its meaning, so there may be some of you who do not know that a Sabbath day’s journey meant seven and a half furlongs, rather less than a mile.

Now, in these days it would be impossible to confine travelling to such narrow limits, but I do venture to protest against the needless journeying on Sunday, which helps to keep many people at work who sorely need the day of rest that God ordained for them.

When, many years ago, the dear partner of my happiest days and I were travelling together, we always rested on the Sunday, if possible, in some place where we could attend church; if not, where we could spend the day peacefully, and claim the blessing promised to the “two or three.” We reaped the benefit, when we resumed our journey, in the sense of freshness and vigour, which gave keener enjoyment to every new scene and experience.

Apart from all religious sentiment, we were in these abundantly repaid for our observance of the Sabbath.

I have more to say on this subject, but it must wait until our next meeting, when we will take such glimpses of the Sabbaths of Jesus as the Bible gives us in the picture of His Manhood. We shall also have more to say about “Rest.”

(To be continued.)

By ISABELLA FYVIE MAYO, Author of “Other People’s Stairs,” “Her Object in Life,” etc.

ON A HEIGHT.

At last the “final word” before the silence came in form of a telegram—“Safe on board. This will be despatched by pilot on his return. All well.” The exhilaration of feeling that the great scheme was really put a-working carried Lucy over the first consciousness that the silence had begun. Besides, next day there came another alleviation in a kindly letter from Mrs. Grant, the captain’s wife, who wrote that she thought Lucy might like to hear the very latest news of her husband—as she always did, of the captain. She narrated that she and her husband had thought Mr. Challoner looking wonderfully well, considering the great illness he had had, that he would have been in the very best of spirits, if only he had not been leaving his wife and boy behind. She added that, for her own part, she was delighted that her husband should have the boon of Mr. Challoner’s company. The captain was always glad of a pleasant companion, but could seldom hope to secure the society of an old and valued friend such as Mr. Challoner was. She ended by saying that she would not fail to let Lucy have any item of news which might reach her concerning the ship, and could trust Lucy would do the same towards her, especially as Lucy would surely get long letters from Mr. Challoner at every opportunity; whereas “the captain” was often too busy to send anything but{492} the briefest line, and was but a poor correspondent at best.

All this, of course, cheered Lucy greatly, as does always the sympathy of those whose interests are bound up with our own, or at least allied to them. There was also plenty to do. Every housewife knows how her household runs down from the lofty paths of order and precision when there is illness in the home, and everything has to give way to the preservation of a beloved life. Then, too, while her memory of the golden days at Deal was still fresh, Lucy wanted to finish the sketches she had made there. She had always her great ambition, to wit, that by her own work, her teaching and her sketches, she might be able “to keep the house going” without trenching at all on the little store—their all—which Charlie had left with her. It would be so cheering to him to come home and begin life again not a bit poorer than when he went away. While she could do something for Charlie, he seemed not so far off!

Florence Brand appeared less helpful than she had promised to be in securing a servant. She sent Lucy two or three girls from sundry registry offices. Lucy was not much attracted to any of them. One wore long plumes; another had taken a seat in the parlour and did not even rise, as any guest would do, when Mrs. Challoner entered. Lucy was really relieved when she found that they all asked higher wages than she had given while Mr. Challoner was at home—a point which it was, of course, impossible to concede. When she mentioned this to her sister, Florence said—

“Oh, well, they were the nicest of the girls I saw, and I didn’t think a pound or two need make any difference. It is often economy in the end.”

“I know that perfectly,” Lucy answered. “But it would be preposterous for me, under my present circumstances, to pay more for service for two than I have ever paid for service for three. There will be so much less to do. We shall never have two sitting-rooms going at once as we often had when Charlie had evening work; nor late dinner, as we were obliged to have for him coming from his office; nor an occasional hot supper as we had when he could not get home in time for dinner. It will be a very easy place.”

“Used Pollie to do your washing?” asked Florence meditatively.

“Yes,” said Lucy. “She had a weekly small wash. Charlie always wore flannel shirts, so there were only collars and cuffs to starch. Then once a month we had a heavier wash, and a woman came to help. There is a nice little laundry at the back, so that the steam does not go through the house.”

“Servants don’t like doing washing nowadays,” observed Florence.

“Should I come across a nice girl who would agree to take lower wages if I put out most of the things, I would agree to the plan,” Lucy answered. “I will agree to any arrangement which will not cost me more money, for that I absolutely cannot afford.”

“‘Generals’ are so scarce nowadays,” said Mrs. Brand. “A good ‘general’ in a house is as hard to get as a good General in the field. That’s how the saying goes. To get cooks and housemaids is possible. It’s easier still if parlourmaid and nurse are kept. The more the merrier, I suppose.”

“But a general servant is what I want,” returned Lucy, rather stiffly. “Not necessarily a ‘thorough’ one—except in character. Apart from that, I will accept mere cleanliness and willingness.”

She could scarcely keep from adding that Florence’s own experience of a crowd of servants had not seemed so satisfactory as to tempt her into the same lines, even if that were possible. Yet Mrs. Brand’s remarks made her sister uneasy. She began to realise that she would have to place far more confidence in the stranger that should come within her gates than she had ever reposed in the long-familiar Pollie. She had trained Pollie. She had always supervised her. She had given considerable help. Much of this would be impossible now she herself was to be the bread-winner of the household.

She began to realise, too, that for the first time she confronted the difficulties of modern housekeeping. Hitherto, everything had been idyllic. Of course, Pollie had made mistakes sometimes, especially at first, but she had been always willing to learn, honest as sunlight, and clean with rural cleanliness. When Lucy had heard the perpetual grumble and bewailing of the mistresses among her acquaintance, she had, in her secret heart, been inclined to think there was a great deal in the adage “Good mistresses make good servants,” which was often openly and severely enunciated by dignified old dames supported by retainers of twenty or thirty years’ standing. Also she had recognised the defects of her sister Florence’s household management, at once so exacting and so careless. She had owned to herself that if she were a servant, she would not wish to remain in the Brand establishment.

Now she felt, however, that she was driven out upon slippery places, where Florence, however unsuccessful in keeping her feet, yet had some experience where she herself had none. Yet Lucy might have been wiser to have tried her experiments after her own fashion. But a woman happily married and then suddenly deprived of her husband’s counsel and decision, is only too ready to lean upon any reed which offers itself to her hand, especially when her mind is distracted by duties which seem to her of paramount importance.

No suitable maiden had presented herself when Pollie’s departing day arrived. But Mrs. Brand, far from being disconcerted by this, had been thinking it an advisable course of circumstances, and ignoring all Lucy’s wishes in the contrary direction.

“I should prefer to have the two girls here together for a day or two,” Lucy had pleaded; “then the newcomer would see just what was expected from her.”

“Nonsense,” said Mrs. Brand with decision. “Never allow your old servant and your new one to meet. Even in my house, it is always a comfort when there is a regular clearance. The old ones put the stranger up to all your weaker points, tell them just where they can deceive you, and the demands they would advise them to make, ‘if they would begin as they would like to go on.’ Consequently you never really have even the brief advantage of ‘the new broom that sweeps well.’”

“I cannot regard Pollie as a natural enemy,” Lucy answered. “I feel sure she would say the place is a good one, that we are not ill to live with, and that a girl who could not get on with us must be hard to please.”

Mrs. Brand laughed gaily.

“Will you ever learn wisdom, my dear?” she said. “You persist in judging Pollie by yourself. But would you have treated anybody as she has just treated you?—suddenly casting off an old tie precisely at a critical time?”

“Yet it is certainly for a great event in her life,” replied Lucy. “Of course, I feel that in her place I should have acted differently. For one thing, I hate secrecy, and if Pollie had told me of her future intentions the moment they were decided (as I told her of mine), and had not resolved to make the great jump at a moment’s notice, as it were, without any reference to us, then I think there might have been very little trouble in the adjusting of our interests. She might have seen me well over my sorrows and difficulties without much hindrance of her own happiness.”

Mrs. Brand broke into explosions of merriment.

“Pollie and her future intentions!” she echoed. “I daresay she met the man only the week before! With these people, we waste our judgments in quite wrong directions.”

“Pollie told me she had known the man for years,” said Lucy.

“Oh, they always say that,” returned Mrs. Brand. “Their ‘knowing’ means that they have seen the man in the street, or in some shop, or, at best, at their chapel. Pollie was a great hand at chapel-going. I always thought there was something at the bottom of it. Then as for her ‘happiness,’ if these girls knew what was good for them, they wouldn’t marry at all. In less than a year’s time, she will wish she hadn’t. Very likely she will come and tell you so. She will come with a black eye, and a baby in her arms, and she will own she would be glad to come back to you, if it wasn’t for that baby! That has happened to me more than once.”

“Flo, Flo,” cried Lucy, her own heart soft with tender remembrance of her absent husband, “do you think that nobody can be loving and happy save the wealthy and leisurely?”

“I’m not blaming the poor wretches, I’m sure,” Flo defended herself. “If Jem and I had to live in one room, I should not wonder much if he beat me sometimes. He’s cross enough often; but then I can leave him to himself. What would he get like, fancy, if he{493} saw me worn out with cleaning up and nursing, and dressed in rags? When all that comes in at the door, love goes out at the window. Pollie will soon find there is a great difference between workaday reality and the courting times of her evenings out and bank holidays.”

“Well, the love that cannot sustain any conditions that life imposes, has never been love at all. So it is not much loss when it goes!” said Lucy, with an indignant note in her voice. She felt keenly how her own position looked in such eyes as those of Florence and Jem Brand.

“Ah, you live in the grand style—in blank verse, I may say,” Flo went on carelessly. “But that was never my way. Perhaps, after all, each gets what each most cares for. I should not have married Jem, perhaps, if I had been of the blank verse style. But here we are, wandering off into the fields of romance. The business in hand is, let Pollie go. Engage your washerwoman—you say you have one once a month—to come to you every day till you are suited. Then you’ll get at the bottom of all Pollie’s little ways, and will find out what kitchen things you have really got, and what is gone past recovery, down the sink or up the chimney. You can make out new lists, and then the minute you see a suitable girl, there’s the place ready for her, and so she starts fair.”

Lucy resented all Mrs. Brand’s doubts of Pollie. She could not see why a single act of inconsideration and rashness should so condemn character, root and branch, in a servant, when the same would be easily condoned in a friend or relative, and possibly even regarded as rather pretty and romantic; simply another illustration of “all for love and the world well lost.” She knew young men and women, too, who had treated their own parents quite as thoughtlessly as Pollie had treated her master’s household. Lucy had always regarded such conduct with great severity, whereas Flo had only laughed over it, retailing “delicious” incidents of how the “old folks” had been “sold.” This was but another instance of higher standards of conduct being set for the kitchen than for the drawing-room. It had always seemed to Lucy’s chivalrous nature to be a gross injustice that, from those members of society who are presumed, conventionally, to have had the fewest “advantages,” more should be expected than from those who are said to have had “every advantage.” She could not understand it, not yet having learned that this injustice, like all injustice, is rooted in sheer selfishness. Many people care nothing at all for “rights and wrongs” save as these affect their own personal convenience. Many more are seldom brought even to consider “rights and wrongs” until these reach the same point.

Alas, our household state would be actually worse than it is, were not our servants in a general way, at least, more punctual and more “tidy” than many of ourselves!

Notwithstanding Lucy’s instinctive abhorrence of so many of her sister’s domestic standpoints, she yet accepted Mrs. Brand’s advice as to letting Pollie go and having a charwoman interregnum. Indeed, as no other alternative offered, she was forced to accept it.

Pollie went off, tearful and subdued, and full of humbly-expressed hopes “that the master would come back quite strong.”

“It would have troubled him terribly to know you were leaving me just now, Pollie,” said Lucy, sufficiently reconciled to be able to show the wound to the hand which had dealt it. “I believe he would have deferred going away. Yet this is the right season for him to go—to say nothing of the opportunity of going with a good friend. You have made me keep a secret from my husband, Pollie, for the very first time, and the bare thought of it makes me unhappy!”

“Why, it’s the sort o’ secret the angels in heaven must keep for us all!” cried Pollie, who had “Irish blood” on the mother’s side which moved when she was deeply stirred. “Sure, there’s many a thing they must see hanging over our heads that they just manage for us with never a word or a sign, and we never knowing what we should thank them for!”

“Well, Pollie,” said her mistress, “let me hear of you sometimes, I shall be always glad to get good news of you, and you may care to know how we get on.”

Pollie looked grave.

“There’s no fear but you’ll do well enough, ma’am,” she said, with an emphasis on the personal pronoun, which was not without significance in a prospective bride. “There’s many a girl would jump sky high to get into such a place. An’ I’d never have left you for any other missis.”

Lucy felt very lonely when she found herself left in the house with only little Hugh. The charwoman would come early in the morning, but would sleep in her own home as she had sons “to look after.” Lucy put Hugh to bed, heard him say his little prayer for dear papa, and talked about ships to him till he fell asleep, hugging a wooden rabbit which was Pollie’s parting gift. Then Lucy went wandering through the empty rooms. Pollie had left everything in “apple-pie” order. The pathetic traces of Charlie’s illness and convalescence were all cleared away. The kitchen, too, was neat and trim. Lucy mechanically pulled out the drawers, and set open the cupboard doors. All was as it should be, and Lucy was deeply thankful that Pollie had left behind no further disappointment in herself. For the hushed heart of yearning sorrow and anxiety shrinks from those squalid revelations of human nature, which torture it much as vermin might torment a helpless invalid.

Under the infliction of Pollie’s bustle and Mrs. Brand’s chatter, Lucy had actually longed for this quiet hour. She had craved for the silence and the solitude in which it had seemed to her that her spirit might get nearer to the absent Charlie. For a brief spell there was sweetness in it, but it was not long before she felt that it might become a perilous and painful luxury. When she had gone through the house, giving here and there the little touch which must be always left for the hand of the mistress, and when there was absolutely nothing more to do that night, then she found that she realised not so much any spiritual communion with Charlie, as the silence and separation which lay between them.

“I have been wrong,” she said to herself. “I have been fancying lately that the peculiar weight of my cross lay in the need for bearing it together with petty money cares, and with work for which one must brace oneself up, and shut away one’s mere personal feelings. Now I begin to see that these are less added weights than props on which from time to time the burden of a great trial may rest till it is almost lifted from one’s own strength.”

“We are taught, too,” she went on musingly, “that we can best approach God and serve Him by our service to others—the simple service which comes naturally out of our living and working among them. Does it not, therefore, seem reasonable that in the same fashion we may also best approach and serve those whom we love—the parted—or the dead?” and Lucy’s lips quivered. “It is the day’s hard work, too, which gives the sweet sleep and the good dreams! How absurd it sounds to put into words what is really the wonderful discovery that one makes, sooner or later (though one is always forgetting it!), to wit, that God knows what is best for His children, and that if they keep in His ways, they shall find the food and the tasks that are the most ‘convenient’ for them.”

“I thank Thee, my Father,” she said aloud, clasping her hands together as she stood in the shadowy little parlour, “I thank Thee that Thou hast filled my hands with duties so that I need have no empty hour. I thank Thee that my love for Charlie may run, woven into my love for Thee, through all my work and all my thoughts—the golden thread, which binds all together into a chaplet, not indeed meet to present to Thee, yet which Thou wilt accept, because it is Thy daughter’s offering. And I thank Thee—oh, how I thank Thee!—for the little child Thou hast given me, to whom I must be, for a while, both mother and father too. And, Father, be with Charlie in his ship tossing on Thy seas. Give him sweet sleep and happy dreams. Make him feel assured that all is well—with Hugh and me.” She paused; she could not bring herself to pray. “Bring him home safely, if it be Thy will.” She could only say, “Father, we are in Thy will, and there we are safe—and together—always!”

Nobody was there to see her then, or they would have marked the shining of her face—for she had been with God. But such mounts of transfiguration rise abruptly from the broil and bicker of life’s dusty plain, and often it is when we descend from them that we encounter the demons!

(To be continued.)

Who are the Prize-Winners and Certificate-Holders?

Examiners: JAMES MASON and the EDITOR.

There are no girls more engaging than those who are trying to do or to be something of value, and having said that, our opinion may be inferred of the numerous company who have worked so diligently during the three months of this interesting competition. It has been an affair of “long breath,” and has proved this, if it has proved anything, that our girls are of the right sort.

That it has been enjoyed is clear from many letters received from competitors. “It has taken up a good deal of time,” writes one girl, “but the time has been well spent, because the questions asked were of real value, and to be able to answer at least the greater number of them, might be regarded as a general test of our being well informed.”