The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Life of Abraham Lincoln, by Harriet Putnam

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

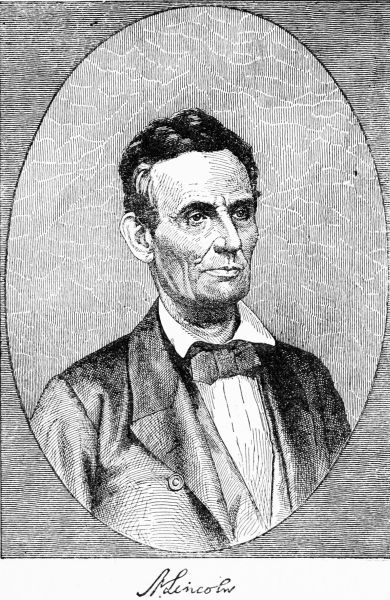

Title: The Life of Abraham Lincoln

For Young People Told in Words of One Syllable

Author: Harriet Putnam

Release Date: January 27, 2020 [EBook #61251]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE LIFE OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN ***

Produced by Donald Cummings and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

FOR YOUNG PEOPLE

TOLD IN WORDS OF ONE SYLLABLE

BY

New York

Copyright by

McLOUGHLIN BROTHERS

1905

Printed in the United States of America

| CHAPTER I. | |

| THE BABE OF THE LOG CABIN AND HIS KIN | 5 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| THE NEW HOME AND THE FIRST GRIEF | 13 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| READING BY THE FIRELIGHT; THE NEW MOTHER; THE FIRST DOLLAR | 20 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| THE SLAVE SALE. LINCOLN AS SOLDIER, POSTMASTER, SURVEYOR, AND LAWYER | 27 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| LEADER FOR FREEDOM; LAW MAKER | 39 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| LINCOLN AND DOUGLAS | 55 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| THE PEOPLE ASK LINCOLN TO BE THEIR PRESIDENT | 63 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| IN THE PRESIDENTIAL CHAIR; THE CIVIL WAR BEGINS | 75 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| EARLY BATTLES OF THE WAR | 85 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| GRANT WINS IN THE WEST, AND FARRAGUT AT NEW ORLEANS | 94 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| ANTIETAM, VICKSBURG, GETTYSBURG | 105 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| CHATTANOOGA, CHICKAMAUGA, LOOKOUT MOUNTAIN. LINCOLN’S GETTYSBURG SPEECH | 115 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| GRANT IN THE EAST. LINCOLN CHOSEN FOR SECOND TERM | 121 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| RETURN OF PEACE; LINCOLN SHOT; HIS BURIAL AT SPRINGFIELD | 133 |

Near five scores of years have gone by since a poor, plain babe was born in a log hut on the banks of a small stream known as the “Big South Fork” of No-lin’s Creek. This was in Ken-tuc-ky and in what is now La-rue Coun-ty.

It was Sun-day, Feb. 12, 1809, when this child came to bless the world.

The hut, not much more than a cow-shed, held the fa-ther and moth-er, whose names were Thom-as and Nan-cy, and their girl child, Sa-rah. These three were the first who saw the strange, sad face of the boy, who, when he grew to be a man, was so great and good and did such grand deeds that all the world gave most high praise to him.

The folks from whom the fa-ther came were first known in A-mer-i-ca in 1618. They came from Eng-land at that time, and made a home at Hing-ham, Mass. They bore a good name, went straight to work, had health, strength, thrift, and soon tracts of land for their own.

All the long line of men from whom this babe came bore Bi-ble names. The first in this land was Sam-u-el. Then came two Mor-de-cais. Next was John, then A-bra-ham, then Thom-as who was the fa-ther of that Ken-tuc-ky boy.

Though there was room for hosts of men in Mas-sa-chu-setts, yet scores left that state and took up land in New Jer-sey. Mor-de-cai Lin-coln, with his son John, went to Free-hold, New Jer-sey. They made strong friends there and had a good home. When more land was want-ed, Mor-de-cai left his son in New Jer-sey for a while, and went to the Val-ley of the Schuyl-kill in Penn-syl-va-ni-a, where he took up a large tract of land. John Lin-coln, the son, joined his fa-ther lat-er. Near their farm was that of George Boone who had come from Eng-land with e-lev-en chil-dren. One son of George had great love for the woods, the song of the[7] birds and camp life. He was Dan-iel Boone, the great hun-ter.

The men on Penn-syl-va-ni-a farms, thought it best to buy land on the oth-er side of the Po-to-mac, so the Lin-colns went in-to the val-ley of the Shen-an-do-ah and took up tracts on lands which had been sur-veyed by George Wash-ing-ton. The Boones went to North Car-o-li-na.

When John Lin-coln’s first born son, A-bra-ham, born in Penn-syl-va-ni-a, came of age, he left his Vir-gin-ia home and went to see the Boones in North Car-o-li-na. Here he met the sweet Ma-ry Ship-ley whom he wed.

Dan-iel Boone told them that there was a fine land be-yond the moun-tains. Boone and three more men had found a gate-way in the moun-tains in 1748. They named it Cum-ber-land Gap, in hon-or of the Duke of Cum-ber-land, Prime-min-is-ter to King George. They[8] found rich soil on that oth-er side of the moun-tains, and the haunts of the buf-fa-lo and deer. Boone got up a band of two score and ten men in 1775 and made a set-tle-ment at a spot to which he gave the name of Boons-bor-ough, in what is now Ken-tuc-ky.

When the war of the Rev-o-lu-tion came, the In-di-ans had arms and shot which had been giv-en to them by the Brit-ish. The red men fought hard for the lands where they were wont to hunt. The white men had to build forts and watch the foe at all points when they went forth to clear or till the ground.

Still, more and more folks went to Ken-tuc-ky. Of these, in 1778, were A-bra-ham Lin-coln and his wife, Ma-ry Ship-ley Lin-coln. With them were their three boys, Mor-de-cai, Jo-si-ah and Thom-as, the last a babe in the arms of his moth-er.

From their North Car-o-li-na home, on the banks of the Yad-kin, this group made a trip of 500 miles. The end of their route was near Bear-grass Fort, which was not far from what is now the cit-y of Lou-is-ville, Ken-tuc-ky.

A sad thing came to the Lin-colns in 1784. A-bra-ham with his three sons went out to clear the land on[9] their farm. A squad of In-di-ans was near. At the first shot from the brush the good fa-ther fell to the earth to breathe no more. The two old-er boys got a-way, but Thom-as, the third son, was caught up by a sav-age, and would have been tak-en off had not a quick flash come from the eld-est boy’s gun as he fired from the fort, tak-ing aim at a white or-na-ment on the Indian’s breast, and kill-ing him at once.

It was the way of those days that the first born son should have what his fa-ther left. So all went to Mor-de-cai. Jo-si-ah and Thom-as had to make their own way in the world.

Young Thom-as, at ten years of age was at work on land for small pay. As he grew in strength he took up tools, put by his coin, and, at last, could buy some land of his own. When he was a man grown he wed Nan-cy Hanks, who made a good and true wife for him. He built a hut for her near E-liz-a-beth-town. In a year’s time, the first child, Sa-rah, was born.

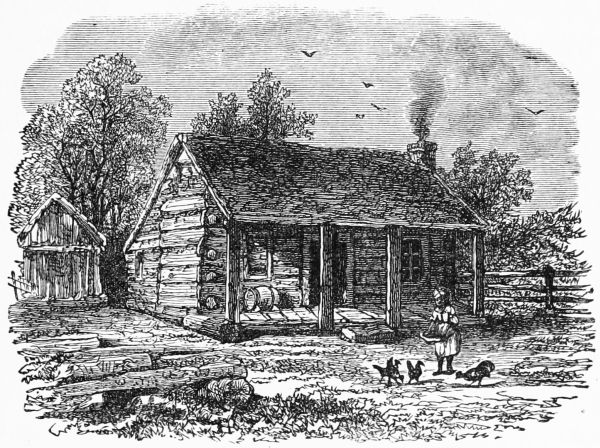

Two years went by, and as there was but small gain and scarce food for three there, the Lin-colns went to Big South Fork, put up a poor shack, a rude hut of one room. The floor was not laid, there was no glass for the win-dow and no boards for the door. In this poor place A-bra-ham Lin-coln, II, first saw the light.

The moth-er, Nan-cy Hanks, when she came to be the wife of Thom-as Lin-coln, was a score and three years old. She was tall, had dark hair, good looks, much grace, and a kind heart. It is said that at times she had a far off look in her eyes as if she could see what oth-ers did not see. She had been at school in her Vir-gin-ia home, could read and write, and had great love for books. She knew much of the Bi-ble by heart, and it made her glad to tell her dear ones of it. The brave young wife did all she could to help in that poor home.[11] The love she had for her babes kept joy in her heart. Her boy was ver-y close to her. As she looked in-to his deep eyes, she seemed to know that child was born for grand deeds. As he learned to talk, his moth-er hid his say-ings in her heart, tell-ing but few friends who were near her, how she felt a-bout that son. But she had too much to do to dream long. As Thom-as was much from home the young wife had to leave her babes on a bed of leaves, take the gun, go out and bring down a deer or a bear, dress the flesh, and cook it at the fire. She used skins for clothes, shoes, and caps. All the time it was toil, toil, but love kept the work less hard.

As the boy, A-bra-ham, grew in strength and health, his eyes turned to his moth-er for all that made life dear. In af-ter years he oft-en said, “All that I am I owe to my moth-er.”

There was no door to the Lin-coln hut, so the moth-er hung up a bear skin as a shield from the cold, and pressed her babe to her breast as the chill winds swept in be-tween the logs.

At the fire on the hearth the corn-cake was baked and the ba-con fried. Game was hung up in front of the[12] fire, and turned from time to time, that it might all be brown and crisp. When free from toil the moth-er taught her lad and lass, and the “gude-man,” too, that it might make him more than he was to her, to him-self, and to oth-ers. The truths the moth-er gave out sank deep in the heart of her boy, and in due time they put forth shoots which grew to a great size, and were of use to the world.

Four years went by, and then the Lin-colns took a bet-ter farm at Knob Creek, built a cab-in, dug a well, and cleared some land. The new home was but a short way from the patch on the side of that hill on No-lin’s Creek, but a good farm might have been made there if Thom-as Lin-coln had been a man who would stay in one place, and work the soil year in and year out. He had not the pluck to keep a farm up to the mark.

When A-bra-ham was five years old he oft-en went with his folks three miles from home to a place called “Lit-tle Mound.” A log-house had been built there, and a man found whose name was Rev. Da-vid El-kins, and who was glad to come a long way through the woods to preach from the Word of God.

The small boy soon had a great love for that good[13] man. The ways of the child drew the preach-er to him and they were soon fast friends.

Ere long one came by who said he could teach all the folks to spell and read. A class was made up, and, strange to say, the five-year-old A-bra-ham stood at the head of it! His moth-er had taught him. She, al-so, had told him to be kind and good to all. There were sol-diers on the road from time to time, go-ing home from the war of 1812. One day the young child saw one near him when he held in his hand a string of fish he had just caught. He gave all his fish to the sol-dier.

When A-bra-ham was sev-en years old, his fa-ther Thom-as Lin-coln, found his farm too much for him. What he liked best was change. He said it would suit him to move to the West, where rich soil and more game could be found.

He thought he would take what he could of their[14] poor goods, set off and hunt up a home. So he built a frail craft, put his wares on it, but soon got on the snags and lost most of what he had. He swam to the shore. In a few days the wa-ters, which had come up as high as the banks, went down, and folks a-long shore helped him get up a few of his goods from the bot-tom of the riv-er. These goods he put in-to a new boat, which he said he would pay for as soon as he could, and then float-ed down the O-hi-o to Thomp-son’s Land-ing. Here he put what he had brought with him in-to a store-house, and went off a score of miles through the woods to Pig-eon Creek. He found the soil all he thought it would be. He chose a tract of land, and then made a long trip to “en-ter his claim” at Vin-cennes. The next thing to do was to go back to Ken-tuc-ky.

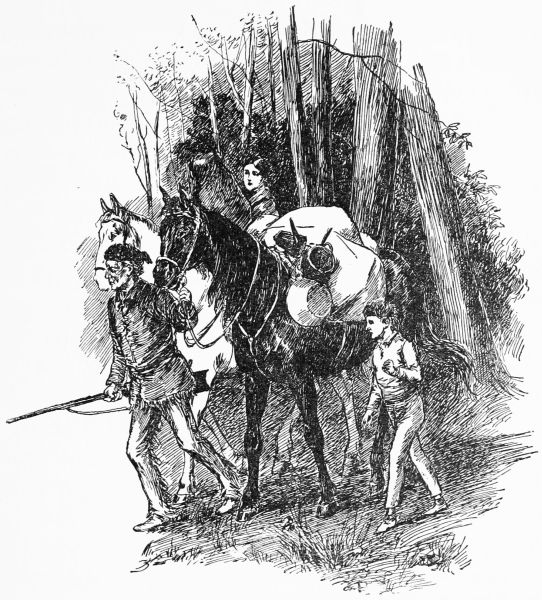

The cool days of No-vem-ber had come ere wife and chil-dren, with two hor-ses which a friend had loaned, and what goods were left, set out for the far off land of In-di-an-a. When night came they slept on the ground on beds made of leaves and pine twigs. They ate the game the ri-fles brought down, cooking it by the camp fire. From time to time they had to ford or swim streams. They were glad that no rain fell in all their long route.

Sa-rah and A-bra-ham thought it was nice to spend weeks in the free, wild life of the woods. A-corns and wal-nuts they found, and fish came up when they put[16] a fat worm on their hooks. They could wade and swim in the cool brooks and gather huge piles of dried leaves for their sound sleep at night.

But at last they came to the banks of one stream from which they could look far off to the land where they were to make their new home. All was still there save the sound of the birds and small game. Right in-to the heart of the dense woods they went on a piece of tim-ber-land a mile and a half east of what is now Gen-try-ville, Spen-cer Co. This was A-bra-ham Lin-coln’s third home. Here his fa-ther built a log “half-face,” half a score and four feet square. It had no win-dows and no chim-ney. For more than twelve months the Lin-colns staid in this camp. They got a bit of corn from a patch, and ground it in-to meal at a hand grist-mill, sev-en miles off, and this was their chief food. There was, of course, game, fish, and wild fruits.

Their beds were still heaps of dry leaves. The lad slept in a small loft at one end of the cab-in to which he went up by means of pegs in the wall. A-bra-ham was then in his eighth year, tall for his age, and clad in a home-spun garb or part skins of beasts. The cap was made of the skin of a coon with the tail on. The child[17] did much work. He knew the use of the axe, the wedge, and the maul, and with these he found out how to split rails from logs drawn out of the woods. To clear the land so that they could plant corn to feed the fam-i-ly, and hew tim-ber to build the new house was work that gave fa-ther and son much to do. At last Sa-rah and A-bra-ham felt that they had a house to be proud of, though it was not much bet-ter than the one they had left. Its floor had not been laid, and there were no boards of which to make the door when they moved in. Some friends had come to see them, and as there would be more room for them in the new house they went to live there. It was a glad day when Thom-as Spar-row, whose wife was Mr. Lin-coln’s sis-ter, and Den-nis Hanks, her nephew, came.

The brief joy of the Lin-colns was soon lost in a great grief. An ill-ness came to that place and man-y folks died. Mrs. Lin-coln fell sick. She knew that she must leave her dear ones. Her work was at an end. As her son stood at her bed-side she said, “A-bra-ham, I am go-ing a-way from you. I shall not come back. I know that you will be a good boy, that you will be kind to Sa-rah and to your fa-ther. I want you to live as I[18] have taught you, and to love your Heav-en-ly Fa-ther.”

The grief that came then to A-bra-ham Lin-coln made its mark on him, a stamp that went with him through life.

When that moth-er died, that dear moth-er, to whom he gave so much love, the boy felt that he did not want to live an-y long-er. He thought his heart would break. He staid days by his moth-er’s grave. He could not eat. He could not sleep. Soon Mr. and Mrs. Spar-row, the guests, died. The strange ill-ness came to them. It came, al-so, e-ven to the beasts of the fields in that land. Those were sad days.

Nan-cy Hanks Lin-coln was 33 years old when she died. Her hus-band, Thom-as, made a cof-fin for her of green lum-ber cut with a whip-saw, and she, with oth-ers, was bur-ied in a small “clear-ing” made in the woods.[19] There were no pray-ers or hymns. It was great grief to young A-bra-ham that the good man of God who spoke in the old home was not there to say some words at that time. It was then that the ten-year old child wrote his first let-ter. It was hard work, for he had had small chance to learn that art. But his love for his moth-er led his hand so that he put down the words on pa-per, and a friend took them five scores of miles off. Good Par-son El-kins took the poor note sent from the boy he loved, and, with his heart full of pit-y for the great grief which had come to his old friends, and be-cause of his deep re-gard for the no-ble wom-an who had gone to her rest, he made the long jour-ney, though weeks passed ere he could stand by that grave and say the words A-bra-ham longed to hear.

With moth-er gone, Sa-rah Lin-coln must keep the house, do the work, sew and cook for fa-ther and broth-er. She was 11 years old. The boy did his part but though he kept a bright fire on the hearth, it was still a sad home when moth-er was not there.

Books came to give a bit of cheer. An a-rith-me-tic was found in some way and al-so a co-py of Æ-sop’s Fa-bles. For a slate a shov-el was used. For a pen-cil a charred stick did the work.

A year went by, and one day Thom-as Lin-coln left home. He soon came back and brought a new wife with him. She was Sa-rah Bush John-ston, an old friend of E-liz-a-beth-town days. She had three chil-dren—John, Sa-rah and Ma-til-da. A kind man took them and their goods in a four-horse cart way to In-di-an-a.

A great change then came to the Lin-coln house. There were three bright girls and three boys who made a deal of noise. A door was hung, a floor laid, a win-dow[21] put in. There were new chairs, a bu-reau, feath-er-beds, new clothes, neat ways, good food, lov-ing care, and much to show A-bra-ham that there was still some hope in the world.

The new moth-er was a kind wom-an, and at once took the sad boy to her heart. All his life from that time, he gave praise to this friend in need.

A chance came then for a brief time at school, and this was “made the most of.” Folks said the boy “grew like a weed.” When he was twelve it was said one “could al-most see him grow.” At half a score and five years old he was six feet and four in-ches high. He was well, strong, and kind. He had to work hard. He did most of the work his fa-ther should have done. But in the midst of it all he found time to read. He kept a scrap-book, too, and put in it verse, prose, bits from his-to-ry, “sums,” and all print and writ-ing he wished to keep. At night he would lie flat on the floor and read and “fig-ure” by fire light.

One day some one told A-bra-ham that Mr. Craw-ford, a man whose home was miles off, had a book he ought to read. This was a great book in those days. It was Weems’ “Life of Wash-ing-ton.” The youth set[22] off through the woods to ask the loan of it. He got the book and read it with joy. At night he put it in what he thought was a safe place be-tween the logs, but rain came in and wet it, so he went straight to Craw-ford, told the tale, and worked three days at “pull-ing fod-der” to pay for the harm which had come to the book.

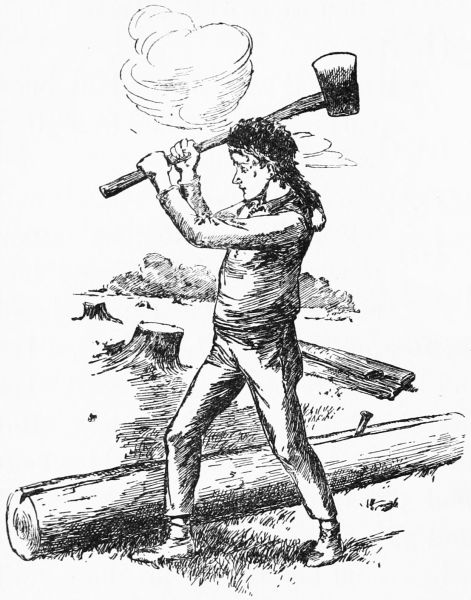

It was the way in those times in that place for a youth to work till he was a score and one years old for his fa-ther. This young Lin-coln did, work-ing out where he would build fires, chop wood, “tote” wa-ter, tend ba-bies, do all sorts of chores, mow, reap, sow, plough, split rails, and then give what he earned to his fa-ther.

Though work filled the days, much of the nights were giv-en to books. In rough garb, deer skin shoes, with a blaze of pine knots on the hearth, A-bra-ham read, read, fill-ing his mind with things that were a help to him all his life. He knew how to talk and tell tales, and folks liked to hear him. He led in all out of door sports. He was kind to those not so strong as he was. All were his friends.

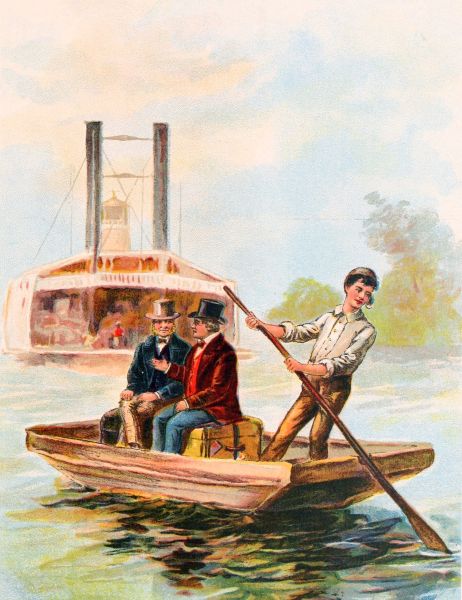

The first mon-ey that he thought he might call his own he earned with a boat he had made. It seems that one day as he stood look-ing at it and think-ing if he could do an-y thing to im-prove it, two men drove down to the shore with trunks. They took a glance at some boats they found there, chose Lin-coln’s boat, and asked him if he would take men and trunks out to the steam-er. He said he would. So he got the trunks on the flat-boat, the men sat down on them, and he sculled out to the steam-er.

The men got on board the steam-er, and their young boat-man lift-ed the hea-vy trunks to her deck. Steam was put on, and in an in-stant the craft would be gone. Then the youth sang out that his pas-sen-gers had not yet paid him.

Each man then took from his pock-et a sil-ver half-dol-lar and threw it on the floor of the flat-boat. Great was the sur-prise of young Lin-coln to think so much mon-ey was his for so lit-tle work. He had thought “two or three bits” would be a-bout right. The coin which came to him then, when off du-ty from his fa-ther’s toil, the youth thought might be his own. It made him feel like a man, and the world then was more bright for him.

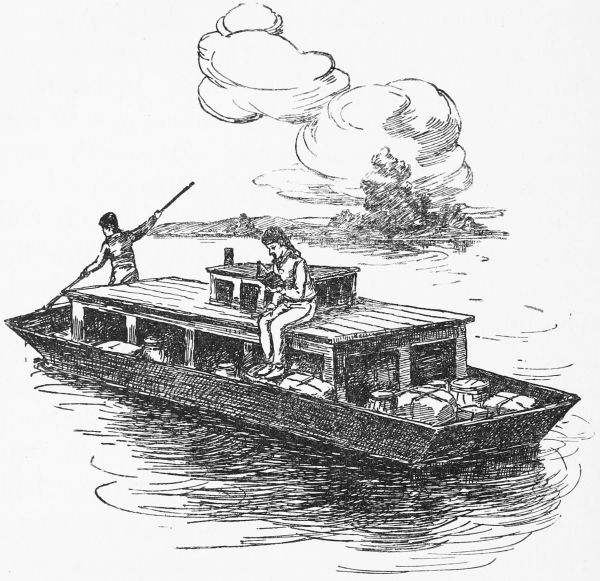

A man who kept a store thought he would send a “car-go load,” ba-con, corn meal, and oth-er goods, down to New Or-leans in a large flat-boat. As A-bra-ham was at all times safe and sure, the own-er, Mr. Gen-try, asked him to go with his son and help a-long. They had to trade on the “su-gar-coast,” and one night sev-en black men tried to kill and rob them. Though the young sail-ors got some blows, they at last drove off the ne-groes, “cut ca-ble,” “weighed an-chor,” and left. They went past Nat-chez, an old town set-tled by the French when they took the tract which is now Lou-is-i-an-a. The hou-ses were of a strange form to the boat-men. The words they heard were in a tongue they did not know. They passed large plan-ta-tions, and saw groups[25] of huts built for the slaves. At New Or-leans, in the old part of the town where they staid, all things were so odd that it seemed as if they were in a land be-yond the great sea. When they had left their car-go in its right place, they went back to In-di-an-a, and Mr. Gen-try thought they had done well.

A-bra-ham had more to think of when he came home. He had seen so much on his trip that the world was not quite the same to him. Scores of flat-boats were moored at lev-ees, steam-boats went and came, big ships[26] were at an-chor in the riv-er. Men were there who sailed far o-ver the seas in search of gold, rich goods, sights of pla-ces, tribes and climes to which Lin-coln had not giv-en much thought. If oth-er men went out in-to the world, why might he not go? Why stay in this dull place and toil for naught? He had come to an age in which there was un-rest. His fa-ther’s wish was that he should push a plane and use a saw all his days. This sort of work did not suit him. Why not strike out? Then the thought came to him that his time was not yet his own. His moth-er’s words spoke to him as they did when he was a small boy at her bed-side for the last time; “Be kind to your fa-ther.”

So A-bra-ham went back to Pig-eon Creek to work and bide his time.

One day a let-ter came to Thom-as Lin-coln. It bore the post-mark of De-ca-tur, Ill. It said that Il-li-nois was a grand state: “The soil is rich and there are trees of oak, gum, elm, and more sorts, while creeks and riv-ers are plen-ty.” It al-so told that “scores of men had come there from Ken-tuc-ky and oth-er states, and that they would all soon get rich there.”

To Thom-as Lin-coln this was good news. He was glad of a chance to make an-oth-er home. He knew, too, that the same sick-ness which took his first wife from him had come back, and that he must make a quick move if he would save those who were left. This was in March, 1830, when A-bra-ham was a score and one years old. He made up his mind to see his folks to their new home since go they would.

Then came an auc-tion, or, as they called it, a “van-doo.” The corn was sold; the farm, hogs, house goods, all went to those folks who would give the most for them.[28] Four ox-en drew a big cart which held half a score and three per-sons, the Hanks, the Halls, and Lin-colns. They had to push on through mud, and cross streams high from fresh-ets. A-bra-ham held the “gad” and kept the beasts at their task. With him the young man took a small stock of thread, pins, and small wares which he sold on the way. When half a score and five days had gone by the trip came to an end. The spot for a home was found when all were safe in Il-li-nois and it was on the north fork of the San-ga-mon Riv-er, ten miles west of the town of De-ca-tur.

The young men went to work and made clear half a score and five a-cres of land and split the rails with which to fence it. There was no one who could swing an axe like A-bra-ham, not one in the whole West. He could now “have his own time” for his 21 years of work for his fa-ther were at an end. The law said he was free. Though he need not now give all that he won by toil to his folks, still he did not let them want. To the end of his life he gave help to his kin, though he was far from rich.

When Spring had gone by, and the warm days of 1830 had come, A-bra-ham Lin-coln left home and set[29] off to get a job in that new land. He saw new farms with no fen-ces. He was sure that his axe could cut up logs and fell trees. He was in need of clothes. So he split 400 rails for each yard of “blue jeans” to make him a pair of trou-sers. The name of “rail-split-ter,” came to him. He knew that he could do this work well. All he met would at once like him. It was the same way in the new state as it had been in the last.

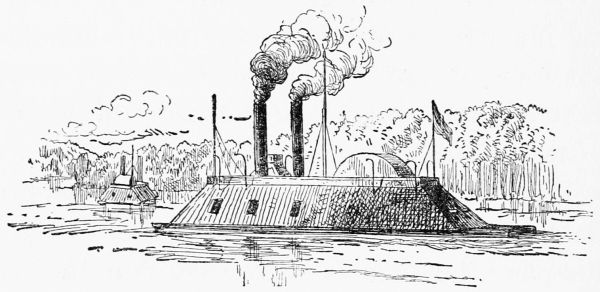

There was a man whose name was Of-futt. He saw what young Lin-coln was. He knew he could trust him to do all things. Mr. Of-futt said he must help sail a flat-boat down the Mis-sis-sip-pi riv-er to New Or-leans. He said he would give the new hand fif-ty cents a day. Poor A-bra-ham thought this a large sum. Of-futt said too, that he would give a third share in six-ty dol-lars to each of his three boat-men at the end of the trip. At a saw-mill near San-ga-mon-town the flat-boat was built. Young Lin-coln worked on the boat, and was cook too, for the men.

At last they were off with their load of pork, live hogs, and corn. When the flat-boat ran a-ground at New Sa-lem, and there was great risk that it would be a wreck, Lin-coln found a way to get it off. Folks[30] stood on the banks and cheered at the wise plan of the bright boat-man.

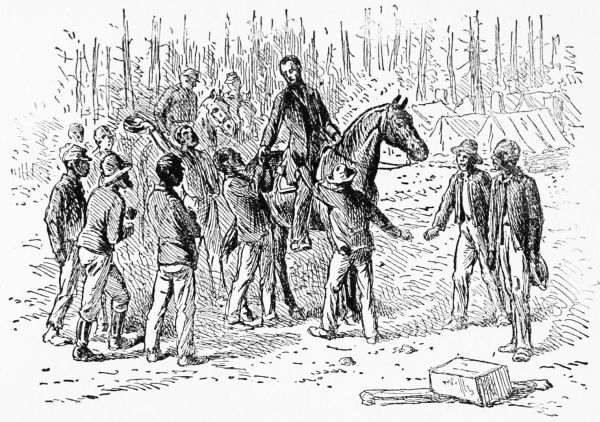

When first in New Or-leans, though Lin-coln had seen slaves, he had not known what a slave sale was like. This time he saw one and it made him sick.[31] Tears stood in his eyes. He turned from it and said to those with him, “Come a-way, boys! If I ev-er get a chance, some day, to hit that thing,” (here he flung his long arms to-ward that block), “I’ll hit it hard!”

The boat-men made their way home, while Of-futt staid in St. Lou-is to buy goods for a new store that he was to start in New Sa-lem. First A-bra-ham went to see his fa-ther and help him put up a house of hewn logs, the best he had ev-er had.

When Of-futt’s goods came A-bra-ham Lin-coln took his place as clerk. The folks who came to buy soon found out that there was one in that store who would not cheat. The coins at that time were Eng-lish or Span-ish. The clerk was ex-act in fig-ures, but if a chance frac-tion went wrong he would ride miles to make it right.

There were rough men and boys near that store. Lin-coln would not let them say or do things that were low and bad. The time came when he had to whip some of them. He taught them a les-son. His great strength was his own and his friends’ pride.

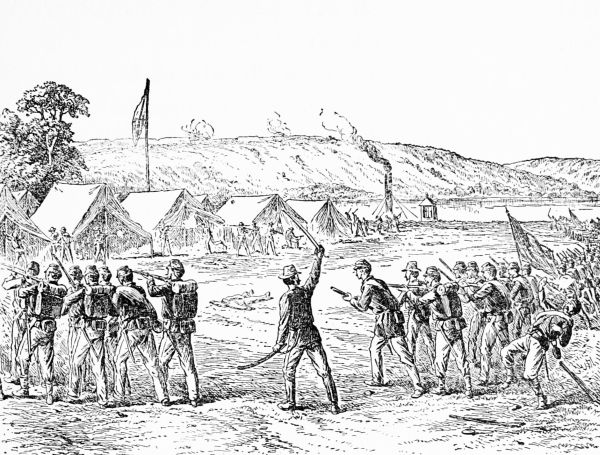

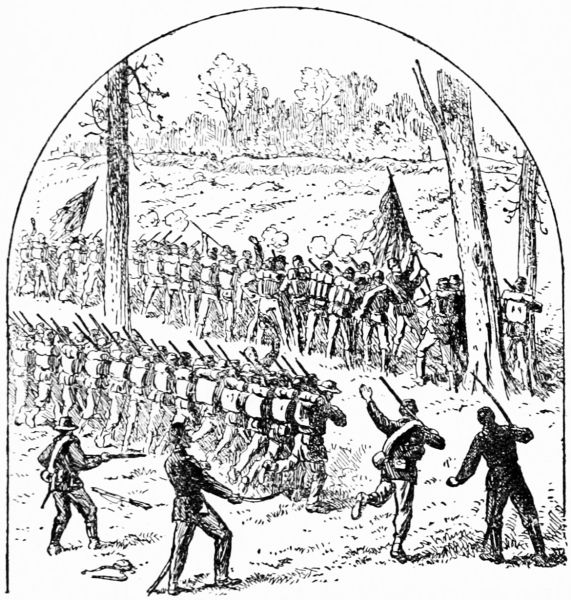

Days there were when small trade came to the store. Then the young clerk read. One thing he felt he[32] must have. That was a gram-mar. He had made up his mind that since he could talk he would learn to use the right words. He took a walk of some miles to get a loan of “Kirk-ham’s Gram-mar.” He had no one to[33] teach him, but he gave his mind to the work and did well. Each book of which he heard in New Sa-lem, he asked that he might have for a short time. He found out all that the books taught. Once, deep down in a box of trash, he found two old law books. He was glad then, and said he would not leave them till he got the “juice” from them. Folks in the store thought it strange that the young clerk could like those “dry lines.” They soon said that A-bra-ham Lin-coln had long legs, long arms, and a long head, too. They felt that he knew more than “an-y ten men in the set-tle-ment,” and that he had “ground it out a-lone.” He read the news-pa-pers a-loud to scores of folks who had a wish to know what went on in the land and could not read for them-selves. He read and spoke on the themes of the day, and at last, his friends said that he ought to help make the state laws, since he knew so much, and they felt that he would be sure to plan so that the poor as well as the rich should have a chance. So in March, 1832, it was known that A-bra-ham’s name was brought up as a “can-di-date” for a post in the Il-li-nois State Leg-is-la-ture. Ere the time for e-lec-tion came, that part of the land found men must be sent[34] to fight the In-di-ans who were on the war-path. The great chief, Black Hawk, sought to keep the red men’s lands from the white folks, but at last he had to give up, though he did all he could to help his own blood. He was brave and true to his own.

Young men of San-ga-mon went out to fight, with A-bra-ham Lin-coln as cap-tain. They were not much more than an armed mob, poor at drill, and with not much will to mind or-ders or live up to camp rules. Their cap-tain had hard work to gov-ern them, for when he gave a com-mand they were as apt to jeer at it as to mind it. But in time they learned that he meant what he said, and that while it was not his way to be too strict a-bout small things, he would not let them do a grave wrong.

One day a poor old In-di-an strayed in-to the camp. He had a pass from Gen-er-al Cass which said that he was a friend of the whites, but the men had come out to kill red-skins, and not hav-ing yet had a chance to do so, thought they must seize this one. They said the pass was forged, and that the old man was a spy, and should be put to death.

But Cap-tain Lin-coln heard the noise, and came to[35] the aid of the old man just in time. He put him-self be-tween his men and their vic-tim, and told them they must not do this thing. They were so full of wrath that Lin-coln’s own life was at risk for a while, but his brave look and firm words at length brought them to terms, and the old sav-age was let go with-out harm.

The time for which the men had en-list-ed was soon[36] at an end, and all but two of them went home. Lin-coln was one of those who took a place as a pri-vate in an-oth-er com-pa-ny, and he did not leave till the end of the war.

A-bra-ham Lin-coln, when he had got home from the war, sent out word that he would speak where there was need of him as “Whig,” for he was a “Clay man through and through.” He made his first “po-lit-i-cal” speech at a small place a few miles west of Spring-field. It was a short one. While what he said was to the point and no fault could be found with it, still, his strange looks and queer clothes made those who were not on his side laugh and make fun of his long legs and arms, and say he would not be the choice of the most for an-y post. Still, he made more friends than foes, and though he did not, at that time, get a chance to go to the Leg-is-la-ture, he had but to wait a while when bet-ter luck came to him.

In the mean time Mr. Lin-coln knew that he must find work of some kind, for he had no funds on which he could live. He then kept a store with a man, but the gain was small and at last they had to give up. There was a large debt and the part-ner would not help[37] pay it, so Lin-coln took it all on him-self, though long years went by ere it was all paid.

Law came to him as the next best move, and once more the young man gave his mind to it all his time, days as well as most of the nights. But coin could not come from that source for quite a while yet, and, in the mean-time, there must be food and clothes.

The new lands, just there, had not been sur-veyed. There was need of a man to do this. Lin-coln heard of a book which would tell him how to work with chain and rule. He spent six weeks with that book in his hand most of the time. Then he set off to start work, and as he was too poor to buy a chain, he found a strong grape vine to take its place. He was[38] right glad of the sums which came to him then for do-ing this work.

The pres-i-dent of the U. S. at that time was An-drew Jack-son. He was a strong friend of A-bra-ham Lin-coln and made him Post-mas-ter of New Sa-lem in 1833.

As folks did not write much in those days, the post of-fice took but a small part of Mr. Lin-coln’s time. The news-pa-pers which came by post were read, and passed from one to an-oth-er, and the post-mas-ter oft-en told the news as he went to the hou-ses where let-ters were to be left. The hat took the place of a mail bag. The grape vine chain and the tools with which the length and breadth of the land were found went a-long, too, as the good man took up his job at sur-vey-ing. Law books must have their share of time and that had to come then, most-ly from sleep hours. There were scores of folks who asked the post-mas-ter to help them. This he did with great good will. He now knew some law and could set them right. All had trust in him. It was not long, then, ere he was at the Bar.

When A-bra-ham Lin-coln was a score and five years old, a great chance to step up came to him. His friends sent him to the Il-li-nois Leg-is-la-ture. He had then not one dol-lar with which he could buy clothes to wear to that place. A friend let him have the funds of which he was in need, sure that they would come back to him.

At first, the young man in the new place did not talk or do much. He felt that it was best for him, then, to wait and learn. He made a stud-y of the new sort of men a-bout him at that time. When it came his turn to speak, he said just what he thought on the theme that came up. His mind told him that all who paid tax-es or bore arms ought to have the right to vote. He was not a-fraid to say that, though men of more years and more fame than he took the oth-er side. He was brave, but not rash. His speech was plain, but to the point. He did not boast. He did not try to hide the fact that he was poor. There were, some-times,[40] those who called them-selves “men,” who would point at his plain clothes of “blue jeans” and laugh at them, and try to get oth-ers to do the same. The great length of bod-y, the toil-worn hands, the back-woods ways made talk for foes, but Lin-coln bore these “flings” well, and oft-en used them for jokes.

Though this high post had come to A-bra-ham Lin-coln he did not feel too proud to do the “sim-ple deeds of kind-ness” which he had done all through his life. It seems that one day he went out with some law-mak-ers, for a ride on the prai-ries. He passed a place where a pig was stuck in the mud. The poor beast looked up at him as if beg-ging his help. The look plain-ly said that death must soon come un-less the horse-man gave his[41] aid. Lin-coln was wear-ing his best clothes at that time. They had been bought with the mon-ey his friend had loaned him. A new suit could not be his for a long time. And yet, e-ven though gone past, and at the risk of jeers from his com-rades, he went back, got off his horse, and pulled the pig out up-on firm land. To be sure there was mud on his clothes, but his heart was free from re-gret.

Though A-bra-ham Lin-coln had been ad-mit-ted to the Bar and had been made a mem-ber of the Leg-is-la-ture, still he went on with his stud-ies, nev-er let-ting a day go by on which he did not give some hours to books. These books told a-bout math-e-mat-ics, as-tron-o-my, rhet-o-ric, lit-er-a-ture, log-ic and oth-er things with hard names.

While at work with chain and tools, tak-ing the length and breadth of the land, Mr. Lin-coln earned from $12.00 to $15.00 each month. He used a part of this small sum to pay up an old debt and al-so had to help his kin from week to week. But he felt he must give up this small sure mon-ey for the sake of his new start in life, though the gains were by no means sure to be large. He said he would “take his chance” at the law.

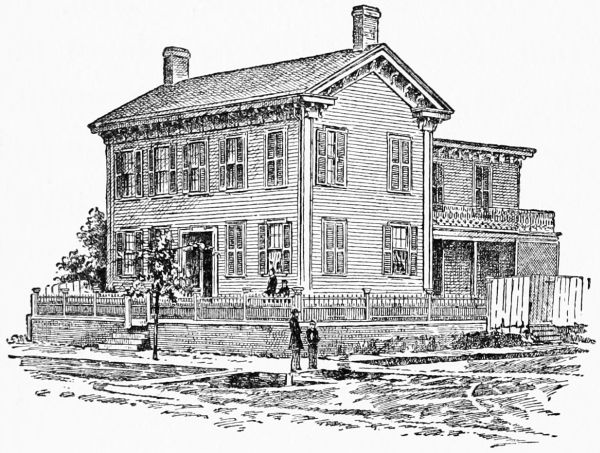

It was in A-pril, 1837, that Mr. Lin-coln rode in-to Spring-field, Ill., on a horse a friend had loaned him. A few clothes were all that he owned, and these he had in a pair of sad-dle bags, strapped on his horse. He drew up his steed in front of Josh-u-a Speed’s store and went in.

“I want a room, and must have a bed-stead and some bed-ding. How much shall I pay?” he asked.

His friend Speed took his slate and count-ed up the price of these things. They came to $17.00.

“Well,” said A-bra-ham Lin-coln, “I’ve no doubt but that is cheap but I’ve no mon-ey to pay for them. If you can trust me till Christ-mas, and I earn an-y-thing at law, I’ll pay you then. If I fail, I fear I shall nev-er be a-ble to pay you.”

Lin-coln’s face was sad. He had worked hard all his life, had helped scores of folks, and now, af-ter so man-y years, when he much need-ed mon-ey, he had none.

The friend-ly store-keep-er tried to cheer the good man. “I can fix things bet-ter than that,” he said. “I have a large room and a dou-ble bed up stairs. You are wel-come to share my room and bed with me.”

So A-bra-ham Lin-coln took his sad-dle-bags up[43] stairs, and then came down with a bright look on his face, and said, “There, I am moved!”

In Spring-field at that time was a man who had been with Lin-coln as a sol-dier in the In-di-an war. This was Ma-jor John T. Stu-art. He took Lin-coln in with him as a law-part-ner and their firm name was Stu-art & Lin-coln.

A-bra-ham Lin-coln’s first fee was three dol-lars made in Oc-to-ber, 1837. There was not much law work the first sum-mer. What there was had to be paid for, oft-en, in but-ter, milk, fruit, eggs, or dry goods.

In those days folks lived so far a-part, that courts were held first in one place and then in an-oth-er. So Lin-coln rode a-bout the land, to go with the courts and pick up a case here and there. In this way he saw lots of peo-ple, made warm friends, and told scores of bright tales.

At no time did he use a word which was not clear to the dull-est ju-ry-man. All things were made plain when Lin-coln tried a case. Not on-ly was he plain and straight in what he said and did, but his heart was ev-er ten-der and true.

A sto-ry is told of a thing that took place on one of[44] the “cir-cuit rid-ing” trips. Lin-coln saw two lit-tle birds that the wind had blown from their nest, but where that nest was one could not say. A close search at last brought the nest to light, and Lin-coln took the birds o-ver to it and placed them in it. His com-rades laughed at him as he jumped on his horse and was rid-ing a-way.

“That’s all right, boys,” said he. “But I couldn’t sleep to-night un-less I had found the moth-er’s nest for those birds.”

All ha-bits of stud-y were kept up, and in time fame as a speak-er came to A-bra-ham Lin-coln. As a wri-ter, too, he was prized. E-ven at the age of a score and nine years he wrote so well up-on themes of the day that the San-ga-mon Jour-nal and oth-er pa-pers would print his ar-ti-cles in full.

In the year 1840, Miss Ma-ry Todd of Ken-tuc-ky be-came Lin-coln’s wife, and helped him save his funds so well that, in a short time he was a-ble to buy a small house in Spring-field. Then, soon, he bought a horse and he was ver-y glad to do so.

By that year so well did Lin-coln speak that his name was put up-on the “Har-ri-son E-lec-to-ral Tick-et,” that[45] he should “can-vass the State.” As he went a-bout the land he oft-en met old friends, those who had known him as a poor boy. Some-times it chanced that he could be of use to them.

There was a Jack Arm-strong who once fought Lin-coln when he was a clerk at Of-futt’s. The son of this man was in trou-ble. The charge was mur-der. His fa-ther be-ing dead, the moth-er, Han-nah, who knew and had been kind to the boy Lin-coln, went, now, to the man Lin-coln to plead with him to save her son. The case was tak-en up, and much time and thought giv-en to it. Things which were false had been told but Lin-coln was a-ble to search out and find the truth, and when at last he saw it and made oth-ers see it, the lad went free.

Though, at first, A-bra-ham Lin-coln thought much of An-drew Jack-son, as time went on he found that Jack-son held views that he could not hold. So he came to be known as an an-ti-Jack-son man and made his first en-try in-to pub-lic life as such. At the age of 31 he was known as the a-blest Whig stump speak-er in Il-li-nois. Two great Whigs at that time were Dan-iel Web-ster and Hen-ry Clay. Lin-coln was[46] sent, as a Whig, in 1846, to the Con-gress of the U-ni-ted States, and he was the sole Whig mem-ber from Il-li-nois.

Of course, friends were proud to feel that the poor back-woods lad had come to so much fame. Some of the old folks said they “knew it was in him.” Oth-ers said “I told you so!”

Lin-coln had the same good sense that he had from the start.

He made up his mind to watch and wait. He knew that he could learn a deal from such great men as Web-ster and Clay. When he had to speak he said just what he thought in a plain strong way. He did not want war with Mex-i-co. He was not a-lone in this. But he thought that men who fought in that war, brave sol-diers, should have their re-ward.

A thing that was of great weight Lin-coln did at that time. He put in a bill which was to free the slaves in the Dis-trict of Co-lum-bia. By his vote more than once for the famed “Wil-mot Pro-vi-so” he hoped to keep sla-ver-y from the Ter-ri-to-ries gained through the war with Mex-i-co.

Though some fame came then to Lin-coln, funds did[47] not. Spring-field, home, and law work fol-lowed when the term in Con-gress was o-ver.

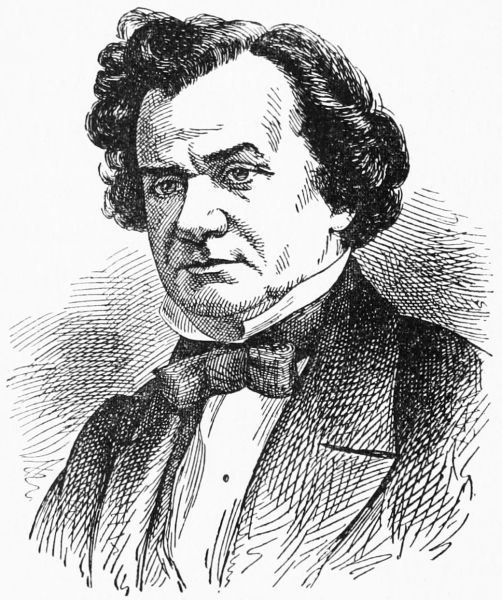

Those who took the oth-er side from Whigs were called Dem-o-crats. They made a strong par-ty in Il-li-nois, and were led by a bright man whose name was Ste-phen A. Doug-las. His friends called him “the Lit-tle Gi-ant.” This, they thought, would make known to all that though he was small in size he was great in mind. He was well thought of as a mem-ber of Con-gress, could make a good speech, was a fine law-yer, knew how to dress well, and had a way of mak-ing folks think as he did.

While hard at work in law ca-ses, all at once, the calm of Lin-coln’s life was bro-ken by a thing that took place in 1854. A plan or pro-mise had been made that[48] sla-ver-y should not spread north of the state of Mis-sou-ri. When the new states of Kan-sas and Ne-bra-ska were a-bout to be made, this good pro-mise was thrown a-side and a bill was passed by Con-gress which said that the folks who had their homes in those states might say that there should or should not be sla-ver-y there.

The man who put in that bill was Ste-phen A. Doug-las. The bill roused great rage in those who felt that sla-ver-y had gone quite far e-nough.

Most folks at the North felt that the time had come to cry “halt.” All through the states this theme was so much talked a-bout that two sides were made, one of which was formed of those who were will-ing that sla-ver-y should go on and spread, while the oth-er was[49] formed of those who did not wish to have black men held as slaves in the new lands.

Speech-es were made in great halls, and crowds came to hear what the speak-ers had to say. In Il-li-nois, Lin-coln, who all his life had been a-gainst sla-ver-y, spoke straight to the peo-ple, show-ing them the wrong or the “in-jus-tice” of that bill. His first speech on this theme, has been called “one of the great speech-es of the world.” He was brave and dared to say that “if A-mer-i-ca were to be a free land, the stain of sla-ver-y, must be wiped out.”

He said “A house di-vi-ded a-gainst it-self can-not stand. I be-lieve this gov-ern-ment can-not en-dure half slave and half free. I do not ex-pect the Un-ion to be dis-solved; I do not ex-pect the house to fall; but I ex-pect it will cease to be di-vi-ded. It will be-come all one thing or all the oth-er. Ei-ther the op-po-nents of sla-ver-y will ar-rest the fur-ther spread of it and place it where the pub-lic mind shall rest in the be-lief that it is in the course of ul-ti-mate ex-tinc-tion, or the ad-vo-cates will push it for-ward till it shall be-come a-like law-ful in all the states—old as well as new, North as well as South.”

This speech made a great stir in the land. Some men and wom-en had worked for years to do and say the best thing for the slave but not one had put things just right till Lin-coln said that “if A-mer-i-ca would live it must be free.”

Lin-coln’s friends told him that they felt that his speech would make foes for him and keep him from be-ing sen-a-tor. The good man then said:

“Friends, this thing has been re-tard-ed long e-nough. The time has come when those sen-ti-ments should be ut-tered; and if it is de-creed that I should go down be-cause of this speech, then let me go down linked to the truth—let me die in the ad-vo-ca-cy of what is just and right.”

From the first, Lin-coln felt as if he were in the hands of God and led by Him in what he was to say and do in the cause of Free-dom for all. He felt that he, him-self, was not much, but that “Jus-tice and Truth” would live though he might go down in their de-fence.

Though not quite half a cen-tu-ry had then gone by since his dear moth-er had held him in her arms in their poor Ken-tuc-ky home, and it was less, too, than a score and five years since he swung his axe in the[51] woods on the banks of the San-ga-mon to earn his bread and that of his kin from day to day, still, with the great prize be-fore him of that high post in the land, which he had long hoped to gain, he casts from him all chan-ces for his fur-ther rise, and in that hour stands forth one of the tru-est, no-blest men of all time.

Friends kept say-ing to Lin-coln “You’ve ruined your chan-ces. You’ve made a mis-take. Aren’t you sor-ry? Don’t you wish you hadn’t writ-ten that speech?”

Straight came the an-swer, and it was this:

“If I had to draw a pen a-cross my whole life and e-rase it from ex-ist-ence, and I had one poor lit-tle gift or choice left as to what I should save from the wreck, I should choose that speech and leave it to the world as it is.”

Men then be-gan to think as they had nev-er thought be-fore. It seemed as if a death-shot had been sent straight to the heart of sla-ver-y. That speech was, how-ev-er, but the first of a hard and fierce strug-gle be-tween two sides of one of the great-est ques-tions ev-er brought be-fore an-y na-tion.

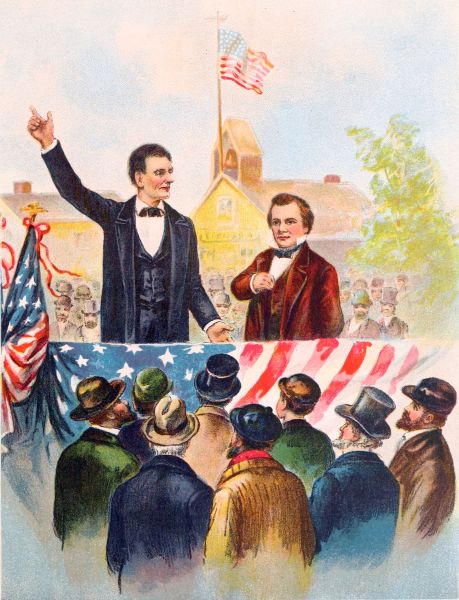

Lin-coln and Doug-las went up and down the state[52] of Il-li-nois talk-ing in halls and in “wig-wams” as the build-ings were called where they spoke. Some-times they made a speech on the same day, out of doors, where large crowds would come. Both oft-en held forth in the same hall, one mak-ing his views known be-fore din-ner and the oth-er talk-ing on the oth-er side af-ter din-ner. Lin-coln was not known to make fun of an-y one, but there were scores who made fun of him, and tried to make him an-gry. But he an-swered all their scoff with sound state-ments, and found friends where oth-ers would have made foes. Doug-las had a way of tell-ing folks that Lin-coln said some things which he did not say. This was hard to bear, but Lin-coln would tell the crowds just what he did say at such and such a meet-ing and peo-ple would be-lieve him.

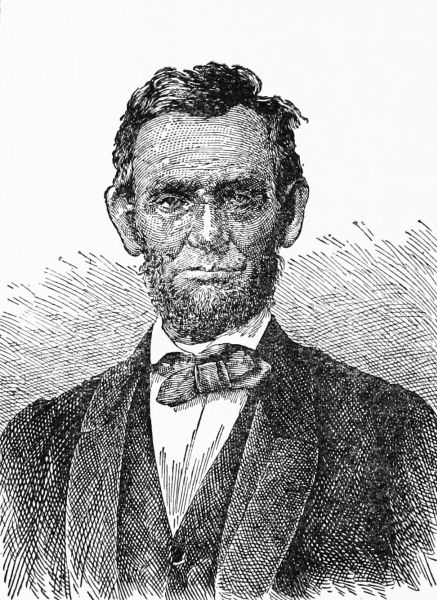

Lin-coln’s print-ed speech-es went through all the states, and soon folks out-side of his own state had a wish to hear him. They felt that he was at the head of the par-ty for real lib-er-ty. So the time came when A-bra-ham Lin-coln spoke East and West, in Il-li-nois, O-hi-o, Con-nect-i-cut, New Hamp-shire, Rhode Is-land, Kan-sas, and New York, and crowds would be still while he pled the cause of lib-er-ty and struck blows[53] at sla-ver-y. It is said that when he spoke in New York he ap-peared, in ev-er-y sense of the word, like one of the plain folks a-mong whom he loved to be count-ed. At first sight one could not see an-y-thing great in him save his great size, which would strike one e-ven in a crowd; his clothes hung in a loose way on his gi-ant frame, his face was dark and had no tinge of col-or. His face was full of seams and bore marks of his long days of hard toil; his eyes were deep-set and had a look of sad-ness in them. At first he did not seem at ease. The folks who were in that place to hear him were men and wom-en of note as well as those not so well known. There was a sea of ea-ger fa-ces to greet him and to find out what that rude child of the peo-ple was like. All soon formed great i-de-as of him, and these held to the end of his talk. He met with praise on all sides. He rose to his best when he saw what the folks thought of him. He spoke in his best vein. His eyes shone bright, his voice rang, his face seemed to light up the whole place. For an hour and a half he held sway in that hall and spoke straight to the point, clos-ing with these words,

“Let us have faith that right makes might, and in[54] that faith let us, to the end, dare to do our du-ty as we un-der-stand it.”

A tale is told of Lin-coln’s go-ing with a friend, while in New York, to vis-it a Sun-day School at Five Points, a place where waifs were brought each Sab-bath to meet kind men and wom-en whose wish was to help them.

As the good man saw the poor chil-dren from the slums of the cit-y, his ten-der heart was deep-ly touched. His own poor child-hood came up be-fore him, and when urged to speak he said words which brought tears to all eyes. He told them that he, too, had been poor; that his toes stuck out through worn shoes in win-ter, that his arms were out at the el-bows and he shiv-ered with the cold. He said he had found that there was on-ly one rule—“al-ways do the best you can.” He said he had al-ways tried to do the best he could, and that if they would fol-low that rule that they “would get on some-how.” When he felt that he had talked long e-nough and tried to bring his words to a close, there were cries of “Go on!” “Do go on!” and so he told his young hear-ers man-y things that they were glad to hear. Then they sang some of their songs for him, and one of[55] these moved him to tears. He asked for the book where those words were print-ed, and a cop-y hav-ing been giv-en to him he put the lit-tle hym-nal in-to his pock-et, and man-y a time in af-ter days drew it out to read.

At last, as he was leav-ing the school, one teach-er, who had not caught his name, when the head of the Mis-sion, Mr. Pease, gave it out, went up to him as he passed and asked what it was. The great man said, in low and qui-et tones, “A-bra-ham Lin-coln, from Il-li-nois.”

Though Lin-coln lost his e-lec-tion as Sen-a-tor he did not seem to care. Doug-las was the choice, and Lin-coln went back to Spring-field and took up his law work. This, too, all turned out well for Lin-coln and the cause he loved, for had he been e-lect-ed Sen-a-tor he might not have tak-en just the part he did in the work of help-ing[56] to form the Re-pub-li-can par-ty. While Lin-coln then gave much work to the Law, he felt the stress of the times so much, and knew the great need of help-ing the side of the right just then, that he did not go out of pol-i-tics. He took an ac-tive in-ter-est in ev-er-y cam-paign and wrote much to aid the cause.

It was in the cold months of 1855 that he went to a meet-ing of Free-soil ed-i-tors at De-ca-tur, Ill., and then and there a move was made to help on the new par-ty which was to do its best to stop sla-ver-y from spread-ing. He worked ear-ly and late for the good of this par-ty try-ing to make men of un-like views a-gree. He said his wish was “to hedge a-gainst di-vis-ions,” and keep all straight to the point of hold-ing back the spread of sla-ver-y.

Work as hard as he might for this great cause there were thou-sands who did not think as Lin-coln did. They said he was wrong and should they fol-low him the land would be in ru-ins and the Un-ion at an end. But all this could not stop this good man, for he knew that he spoke the truth, so threats, a-buse, and sneers could not stir him from his grand work.

Be-fore this, in Ju-ly 1854, moves be-gan in man-y[57] parts of the North to form a new par-ty which should be a-gainst the spread of sla-ver-y. So in June, 1856, most of the States sent del-e-gates to Phil-a-del-phi-a and then and there the Re-pub-li-can par-ty was formed. They chose John C. Fre-mont as their can-di-date for the Pres-i-den-cy. Fre-mont was known as a brave ex-plor-er in the plains of the West, and one who took part in the con-quest of Cal-i-for-ni-a.

There was, al-so, a par-ty called “The A-mer-i-can,” or “Know-noth-ing” and they named as their choice, ex-Pres-i-dent Mil-lard Fill-more. This par-ty grew fast two or three years and then came to an end. Its aim was to keep men from o’er the sea out of of-fice and make them wait more time ere they could vote. The theme of sla-ver-y then came to have a new form and there was no room for oth-er de-bate.

The Dem-o-crat-ic par-ty met in Cin-cin-na-ti and named James Bu-chan-an of Penn-syl-va-ni-a as their choice. Bu-chan-an was e-lec-ted.

Ste-phen A. Doug-las thought he was sure of a nom-i-na-tion for that same place. He had done much work for the men who held slaves but they did not mean to re-ward him for what he had done.

“Shall Kan-sas come in free or not?” was the ques-tion that, then, was up-on the minds of thou-sands up-on thou-sands of the peo-ple of the U-ni-ted States.

A-bra-ham Lin-coln, then, think-ing of the mil-lions of his fel-low-men in sla-ver-y and of that slave-mar-ket in New Or-leans, which had nev-er gone out of his mind, spoke, both in pub-lic and pri-vate, with the force that e-ven he had ne’er used be-fore. He felt God’s time was near at hand when those who had been bought and sold like beasts of the field, should be set free. He did not then see just how it would be done, but he said to a friend;

“Some-times when I am speak-ing I feel that the time is soon com-ing when the sun shall shine and the[59] rain fall on no man who shall go forth to un-re-quit-ed toil. How it will come, I can-not tell; but that time will sure-ly come!”

It was in March 1857, when Bu-chan-an had his in-au-gu-ral ad-dress all writ-ten out with care, and he was read-y to take his seat as Chief in the land, that he was told that a great step was a-bout to be tak-en by the “Su-preme Court,” the high-est court of law in the land. It seems that the jud-ges were then to de-cide in a case which dealt with the rights of men who held slaves un-der the Con-sti-tu-tion.

Mr. Bu-chan-an thought it would be well to put a few words more in-to his ad-dress, and these up-on the theme then brought up to him. So he wrote that he hoped the steps that were to be tak-en would “for-ev-er set-tle that vex-a-tious slave ques-tion.”

In a few days Rog-er B. Ta-ney of Ma-ry-land, Chief Jus-tice, gave the peo-ple of the U-ni-ted States a great sur-prise in what he had to say a-bout two slaves.

A sur-geon in the ar-my, Dr. Em-er-son, of St. Lou-is, owned Dred Scott and his wife Har-ri-et. He took them to Rock Is-land, in I-o-wa, to Fort Snell-ing, Min-ne-so-ta, and then back to St. Lou-is. As they had been[60] tak-en in-to a Free Ter-ri-to-ry the slaves made a claim that they were en-ti-tled to their lib-er-ty un-der the com-mon law of the coun-try. Five of the nine jud-ges of that court were from the Slave States. Sev-en of the jud-ges were of the same mind that the Con-sti-tu-tion “re-cog-nized slaves as prop-er-ty and noth-ing more.” The jud-ges held that as the blacks were not and nev-er could be cit-i-zens, they could not bring a suit in an-y court of the U-ni-ted States. The claim of Dred and Har-ri-et Scott would have to be set-tled by the Court of Mis-sou-ri. It was de-cid-ed that some laws made in 1820 and 1850 which could have helped the case of these two poor blacks, were “un-con-sti-tu-tion-al,” not le-gal or so as to a-gree with the law. They said all this showed, plain-ly, that a slave had no more rights than a cow or pig, and that be-ing the case sla-ver-y could not on-ly be in the Ter-ri-tor-ies, but just as well in the Free States. This sort of be-lief up-set the i-de-as that Mr. Doug-las taught, for he had told all to whom he made his great speech-es that on-ly those who lived in a Ter-ri-to-ry had a right to say wheth-er they would or would not have sla-ver-y.

Out of all these nine jud-ges there were but two who[61] were brave, wise, and just e-nough to hold to the point that it was up-on free-dom and not up-on sla-ver-y that the na-tion had been found-ed. The names of those two men were Mr. Cur-tis of Mas-sa-chu-setts, and Mr. Mc-Lean of O-hi-o.

The peo-ple rose in great wrath at what the sev-en jud-ges had said. With the blood of free-dom in their veins they plain-ly stat-ed that those un-just jud-ges had “de-cid-ed” what they did in the in-ter-ests of sla-ver-y.

The eyes of thou-sands of peo-ple o-pened. They saw now that there was much hard work to be done if there were to be a “Free Kan-sas,” and so they gave their votes and la-bor on the “free” side. Then when the slave-hold-ers felt there were more folks who want-ed Kan-sas free, they sent men from oth-er states in-to Kan-sas and this got in vast num-bers of votes that had no right to be put in-to the bal-lot-box-es.

The two sets had con-ven-tions, the Free States at To-pe-ka and the slave-hold-ers at Le-comp-ton. The pa-pers drawn up in these two pla-ces were sent to Wash-ing-ton. In the cit-y there were men who did their best to get Bu-chan-an to try to have Kan-sas made a state where there could be slaves.

Then it was that Ste-phen A. Doug-las went to see Pres-i-dent Bu-chan-an and have a talk with him. Doug-las was an-gry at what the un-just jud-ges said. The Pres-i-dent said that he, him-self, was in fa-vor of the Le-comp-ton pa-per, that for slaves in Kan-sas. Then Doug-las told him that he should work a-gainst the views there held, and Bu-chan-an told him that a Dem-o-crat could not have i-de-as that would dif-fer from those held by the pres-i-dent and lead-ers of his own par-ty, with-out be-ing crushed by them. So Doug-las went a-way. He knew the slave pow-er would not for-give him for the stand he took, but he al-so knew that if he did not work a-gainst hav-ing slaves in Kan-sas he would lose his own re-e-lec-tion to the Se-nate.

So a new al-ly a-gainst the spir-it of sla-ver-y was gained, though Doug-las did not work in the same har-ness as those who had formed the new par-ty of which we have spok-en—the Re-pub-li-can.

All this time A-bra-ham Lin-coln was go-ing on do-ing his work in law and help-ing as much as he could to fix in the minds of the peo-ple right i-de-as for the gui-dance of the na-tion.

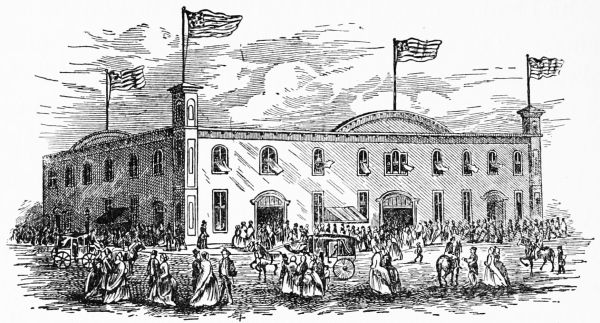

Those who could un-der-stand the true needs of the hour, and saw how strong they were, felt that if they could place this man, who had ris-en up in the land to lead the for-ces to lib-er-ty, in a post where he could have full sway and do his best, they must name him for just that work, so, when the “Na-tion-al Re-pub-li-can Con-ven-tion” met at Chi-ca-go, May 16th, 1860, to pro-pose some one for their Chief, they named A-bra-ham Lin-coln, and said he was the man whom they want-ed to be the next Pres-i-dent of the U-ni-ted States.

Not on-ly was this a great thing for Lin-coln, but it was, al-so, a bless-ed tri-umph for the A-mer-i-can peo-ple. There were three oth-er men whose names were[64] put up for the same post. These three men and their friends thought it a most un-wise act to name Lin-coln. But as time went on it was found that the e-lec-tion of A-bra-ham Lin-coln was the best thing that ev-er came to the coun-try.

At first, when Mr. Pick-ett, an ed-i-tor in Il-li-nois, wrote to Lin-coln, in A-pril, 1859, that he and his part-ner were off talk-ing to the Re-pub-li-can ed-i-tors of the state on the theme of hav-ing Lin-coln’s name come out at the same mo-ment from each pa-per, as a can-di-date for the Pres-i-den-cy, Lin-coln wrote to him in re-ply:

“I must, in truth, say that I do not think my-self fit for the Pres-i-den-cy.” Then he went on to say that he thanked his friends for their trust in him, but thought it would be best for the cause not to have such a step by all at the same time.

But some of Il-li-nois’ best men took the mat-ter se-ri-ous-ly in hand, and, at last, Lin-coln said they might “use his name.” Then his friends went to work, and in con-ven-tion it was found that A-bra-ham Lin-coln had not on-ly the whole vote of Il-li-nois to start with, but won votes on all sides, and did not make a foe of an-y ri-val.

The Dem-o-crat-ic par-ty had split in two on the slave theme. The ma-jor-i-ty of the Dem-o-crats who met at Bal-ti-more named Ste-phen A. Doug-las of Il-li-nois, the au-thor of the Kan-sas-Ne-bras-ka bill. Those Dem-o-crats who stuck close to the South put for-ward John C. Breck-in-ridge of Ken-tuc-ky. The “Con-sti-tu-tion-al Un-ion” par-ty, as it was called, which wished to make peace be-tween the an-gry sec-tions, named Bell of Ten-nes-see.

The Re-pub-li-cans were u-ni-ted and ea-ger. The e-lec-tion came on Nov. 6, 1860, and the re-sult was just what most thought it would be. The Re-pub-li-can e-lec-tors did not get a “ma-jor-i-ty,” of all the votes by near-ly a mil-lion, but the split of the Dem-o-crats left them a “plu-ral-i-ty.”

In the “E-lec-to-ral” col-le-ges A-bra-ham Lin-coln got a plu-ral-i-ty of 57 votes and so was the choice for Pres-i-dent of the U-ni-ted States.

A great crowd surged through the streets of Chi-ca-go at the time when the con-ven-tion nom-i-na-ted Lin-coln. Cheers rent the air, while can-non roared and bon-fires blazed. Then the men who had tak-en part in the work turned their steps home-ward.

The next morn-ing a pas-sen-ger car drawn by the fast-est en-gine of the “Il-li-nois Cen-tral Rail-road” rolled out from Chi-ca-go, and took some gen-tle-men straight to Spring-field to tell Mr. Lin-coln of his nom-i-na-tion, though, of course, the news had been sent there by wire the night be-fore.

It was eight o’clock in the morn-ing when the par-ty reached the Lin-coln home. The two sons, Wil-lie and Thom-as, or “Tad” as he was called, were sit-ting on the fence, laugh-ing with some boy friends. Tad stood up and shout-ed “Hoo-ray!” in wel-come to the com-mit-tee. A brief ad-dress was giv-en by the lead-er, and a[67] short re-ply came from Lin-coln. Then they all went in-to the li-bra-ry and met Mrs. Lin-coln, and a light lunch was served. It was thought, by some, that Lin-coln would set wines be-fore his guests at this time, but he thought this thing one that was not best for folks, and did not do it. He had learned a sad les-son from what he saw of this sort in his young days.

Folks far and near then came to tell Mr. Lin-coln that they were glad of the good news.

One good wom-an with but-ter and eggs to sell from her farm, said she thought she “would like to shake hands with Mr. Lin-coln once more.” Then she told him, as he did not seem to re-mem-ber her, that he had stopped at her house to get some-thing to eat when he was ‘rid-ing the cir-cuit,’ and that one day he came when she had noth-ing but bread and milk to give him, and he said that it was good e-nough for the Pres-i-dent of the U-ni-ted States, “and now,” she said, “I’m glad that you are go-ing to be Pres-i-dent!”

An-oth-er guest came one day when Lin-coln was talk-ing with the Gov-ern-or of his state and a few more. The door o-pened and an old la-dy in a big sun bon-net and farm clothes walked in and told Mr. Lin-coln[68] that she had a pres-ent for him. She said she had been want-ing to give him some-thing, and these were all she had. Then, with much pride, she put in-to his hands a pair of blue wool-len stock-ings, and said, “I spun the yarn and knit them socks my-self!”

The kind gift and thought pleased Mr. Lin-coln. He thanked her, asked for her folks at home, and walked with her to the door. When he came back he took up the socks and held them by their toes, one in each hand, while a queer smile came to his face and he said to his guest,—

“The old la-dy got my lat-i-tude and long-i-tude a-bout right, did-n’t she?”

The “plain peo-ple,” the sort from whom Lin-coln sprung, were ver-y proud of him, and day af-ter day some of them went to see him, bring-ing small gifts and kind words and wish-es.

One day, when Mr. Lin-coln, clad in a lin-en dus-ter, sat at the desk in his of-fice with a pile of let-ters and an ink-stand of wood be-fore him, he saw two shy young men peep in at the door. He spoke to them in a kind way and asked them to come in and make a call.

The farm hands thanked him and went in. Then they said that one of them, whose name was Jim, was quite tall. They had told him that he was as tall as the great A-bra-ham Lin-coln, and they had made up their minds to come to town and see if they could find out if that was the case.

So with a smile on his face Mr. Lin-coln left his desk, and the morn-ing’s mail, and asked the young man to stand up by the side of the wall. Then Mr. Lin-coln put a cane on the top of his head, and let the end of the stick touch the plas-ter-ing. Thus he found his height. Mr. Lin-coln told the man that it was now his turn to hold the cane and do the same for him. So Mr. Lin-coln stepped un-der the cane, and it was found that both were the same height. Jim’s friends had made a good guess.

Small deeds of kind-ness like these won hosts of friends for A-bra-ham.

As time went on the trains brought scores of folks to Spring-field. Some said they had just come to shake hands with Mr. Lin-coln, while more told a straight tale and said they came to ask for a post of some sort, and thought they would “take time by the fore-lock.” In[71] fact the crowds of men who came to ask for pri-zes were so large that Mr. Lin-coln had to leave his old desk and go to a room in the State-house which the Gov-ern-or of Il-li-nois had placed at his use. Here he met all in his kind way.

While Lin-coln wait-ed, af-ter his nom-i-na-tion, he kept track of all the moves that were made. Still, he had so much trust that he said, “The peo-ple of the South have too much sense to ru-in the gov-ern-ment,” and he told his friends that they must not say or feel an-y ill will to those who were not of the same mind, but “re-mem-ber that all A-mer-i-cans are broth-ers and should live like broth-ers.”

But, ere long, it was plain that the storm which had been mak-ing its way slow-ly but sure-ly, was a-bout to burst.

As soon as Lin-coln’s e-lec-tion was known the South be-gan to throw off the ties which bound it to the Un-ion.

The Sen-a-tors from South Car-o-li-na gave up their posts four days lat-er. Six weeks from that time that state went out from the Un-ion and set up a new gov-ern-ment.

One af-ter an-oth-er, oth-er states in the South went out, al-so, and joined South Car-o-li-na, un-til, by the first of Feb-ru-a-ry, 1861, all the sev-en cot-ton states had with-drawn from the Un-ion. Their claim was that the rights of a state were high-er than those of the Un-ion when it thought it ought to do so.

Mem-bers of Con-gress and oth-ers tried to set-tle the trou-ble but to no a-vail, and there seemed no way a-head but a tri-al of the is-sue on the bat-tle-field.

Lin-coln was in Spring-field and could do naught then, save with his pen and words of ad-vice to Bu-chan-an who was then Pres-i-dent. With great sad-ness he read what had been done at the South.

There was still much to do in Spring-field in his plans to leave his law work, and Mr. Lin-coln felt that a great load of care was up-on him, and the task, which[73] in a few brief months would be his, was sure to be more e-ven than that which fell to the first great Chief, George Wash-ing-ton. There were times when he spent whole days in deep thought, si-lent and sad.

Still, in the midst of all this work, there came times when in a light-er vein he would show mirth at in-ci-dents as they came up. A bus-i-ness trip had to be made. A group of small girls was met at the house of a friend. They gazed at the great man as if they would speak to him. He kind-ly asked them if he could help them in an-y way. One of them said that she would dear-ly like to have him write his name for her.

Lin-coln said he saw oth-er young girls there and thought that if he wrote his name for but one, the rest would “feel bad-ly.”

The child then told him there were “eight all told.” Then, with one of his bright smiles the kind man asked for eight slips of pa-per and pen and ink. He wrote his name so that each child might have it to take home with her.

There was a lit-tle girl, that same au-tumn, whose home was on the shores of Lake E-rie. She had a por-trait of Lin-coln and a pic-ture of the log-cab-in[74] which he helped build for his fa-ther in 1830. She had great pride in Mr. Lin-coln, and it was her wish that he should look as well as he could. So she asked her moth-er if she might write a note to Mr. Lin-coln and ask him if he would let his beard grow, for she thought this would make his face more pleas-ing.

The moth-er thought this plan of her child was strange, but know-ing that she was a strong Re-pub-li-can, said there could be no harm in writ-ing such a let-ter. So the let-ter was writ-ten and sent to “Hon. A-bra-ham Lin-coln, Esq., Spring-field, Il-li-nois.”

This young girl, whose name was Grace Be-dell, told Mr. Lin-coln how old she was, and that she thought he would look bet-ter, and so that scores more folks would like him, if he “would let his whis-kers grow.” She said, too, that she liked the “rail fence, in the pic-ture, a-round that cab-in that he helped his fa-ther make.” Then she asked that if he were too bus-y to an-swer her let-ter that he would let his own lit-tle girl re-ply for him.

Mr. Lin-coln was in his State-house room when that let-ter, with scores of oth-ers, came in. He could but smile at the child’s wish, but he took the time to an-swer[75] at once, in a brief note which be-gan, “Miss Grace Be-dell: My dear lit-tle Miss.” He told her of the re-ceipt of her “ver-y a-gree-a-ble let-ter.” He said he was “sor-ry to say that he had no lit-tle daugh-ter,” but that he “had three sons, one sev-en-teen, one nine, and one sev-en years of age.” He said he had nev-er worn whis-kers, and asked if folks would not think it sil-ly to be-gin, then, to wear them. The note closed with; “Your ver-y sin-cere well-wish-er, A. Lin-coln.”

One of the last things that A-bra-ham Lin-coln did ere he said good-bye to his Spring-field home was to go down to see the good old step-moth-er who did so much for him when he was a poor, sad boy. Proud in-deed, was she of the lad she had reared with so much care, but she felt that there were hard days to come to him. She told him that she feared she should not see him a-gain. She said “They will kill you; I know they will.”

Lin-coln tried to cheer her, and told her they would not do that. But she clung to him with tears, and a break-ing heart. “We must trust in the Lord, and all will be well,” said the good man as he bade his step-moth-er a ten-der fare-well and went a-way.

It was on Feb. 11, 1861, that Lin-coln left Spring-field for Wash-ing-ton. Snow was fall-ing fast as Lin-coln stood at the rear of his train to say his last words. A great crowd was at the rail-road sta-tion. Men stood si-lent with bare heads while he spoke.

Six firm friends of Mr. Lin-coln went with him to Wash-ing-ton. Mr. Lin-coln was ver-y much af-fect-ed when he went in-to the car af-ter say-ing good-bye to his old home folks. Tears were in his eyes.

Crowds were at each sta-tion a-long the route and Mr. Lin-coln oft-en spoke to those who had come there to see him. While talk-ing at West-field Mr. Lin-coln said that he had a young friend there who had sent a note to him, and that if Grace Be-dell were in the sta-tion he should like to meet the child. It seems she was there, and the word was passed on; “Grace, Grace, the Pres-i-dent is call-ing for you!” A friend led her through the crowd, and Mr. Lin-coln took her by the[77] hand and kissed her. Then he said, with a smile, “You see, Grace, that I have let my whis-kers grow!”

The train then rushed off, but a smile was on Mr. Lin-coln’s face, and for a brief time the weight of of-fice had left him.

Threats of a sad sort were then a-broad in the land. Foes said Lin-coln should nev-er be made Pres-i-dent. Their hearts were full of hate. They felt that this man would be sure to en-force the laws, e-ven a-gainst those who were joined to-geth-er to try to break them.

Lin-coln was brave. He did not fear. He felt that the Lord was on his side and that He would give him strength to do all the work that he had planned for him. Though he did not doubt this, yet, both he and his friends felt that it would not be right to risk his life at that time, so they did not take the route at first thought of, but went by a way, and at a time, which would make all safe.

Thus the train from Phil-a-del-phi-a rolled in-to Wash-ing-ton ear-ly one morn-ing and Lin-coln was safe, and must, in-deed, have felt the truth of those Bi-ble words, “He shall give His an-gels charge o-ver thee to keep thee in all thy ways.”

On the Fourth of March, 1861, A-bra-ham Lin-coln stood on a plat-form, built for that day, on the east front of the cap-i-tol, and took the oath of of-fice. He laid his right hand on the Bi-ble. A hush fell up-on the vast throng as he said, af-ter Chief Jus-tice Ta-ney, these words: “I, A-bra-ham Lin-coln, do sol-emn-ly swear that I will faith-ful-ly ex-e-cute the of-fice of Pres-i-dent of the U-ni-ted States, and will, to the best of my a-bil-i-ty, pre-serve, pro-tect, and de-fend the Con-sti-tu-tion of the U-ni-ted States.”

Then came the can-non sa-lute while cheer on cheer rent the air.

Lin-coln read his in-au-gu-ral ad-dress as Pres-i-dent of the U-ni-ted States. His old ri-val, Doug-las was near him, and to show his friend-ly and loy-al heart, held Lin-coln’s hat.

Lin-coln’s speech was a grand one. He did not boast nor tell what great things he would do. He spoke as would a fa-ther to way-ward chil-dren, and told those who were try-ing to break up the Un-ion that their move would bring ru-in to the Na-tion. He asked them to stop, and turn back while there was time.

In sad-ness he told them that it was not right for[79] an-y to try to des-troy the Un-ion; that it was his sworn du-ty to pre-serve it. This speech did much good, but most-ly where there were folks who had not known which side to take. These saw, then, that the Pres-i-dent was bound by his oath to do his dut-y.

No Chief of the U-ni-ted States, when he took his chair, had so hard a task be-fore him as Lin-coln had. Sev-en States had gone out of the Un-ion, made a start at a new gov-ern-ment, and found a pres-i-dent and a vice-pres-i-dent for them-selves. Some of the folks in oth-er states were mak-ing plans to leave the Un-ion. The peo-ple of the far South laid hold of Un-ion forts, ships, guns, and post-of-fi-ces. Some men who had held high posts in the ar-my and na-vy left the Un-ion and gave their help to the oth-er side. They had sent out the news to the world that they would have the name of the “Con-fed-er-ate States of A-mer-i-ca,” and that their pres-i-dent’s name was Jef-fer-son Dav-is.

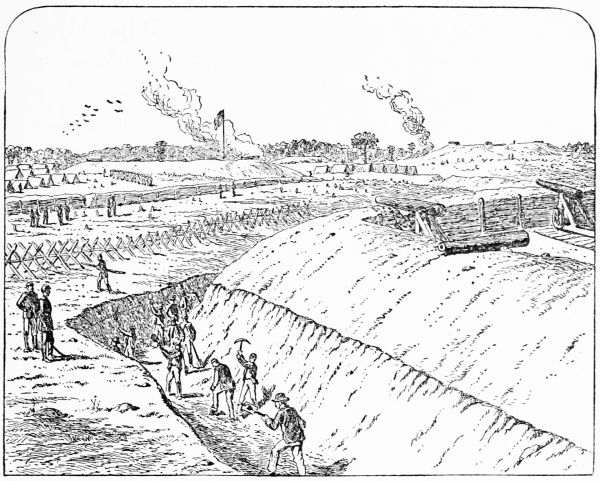

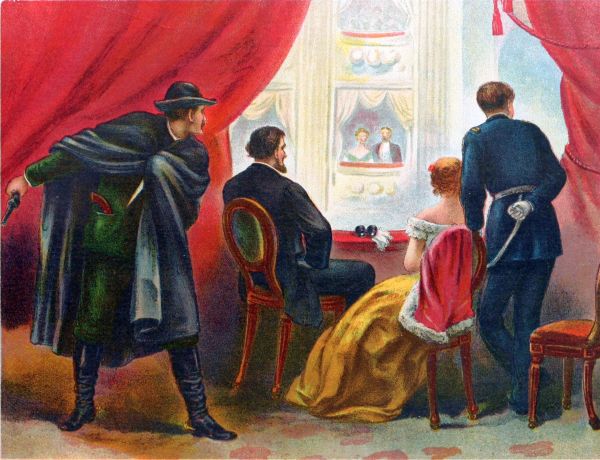

How to save the Un-ion, bring back all the states, make the North and South friends once more were themes of the day. These thoughts hung like a weight o-ver Lin-coln as he paced his room at night, and as he talked with the men he had with him. He did not wish[80] to de-clare war. He must, he thought, work for peace. This he did till he saw war must come, but he made up his mind that the first act that brought a-bout war should not come from him but from those whose wish was to break up the Un-ion. At last the foe struck the first blow.

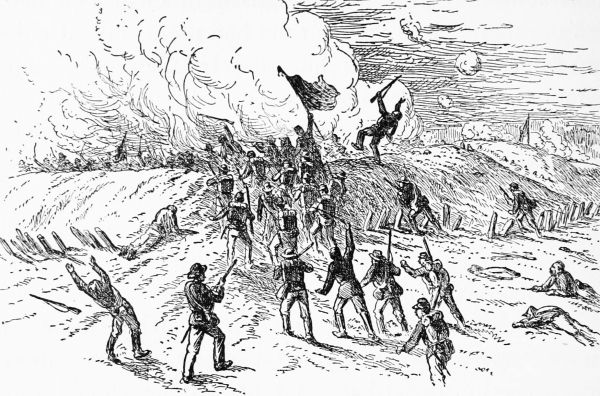

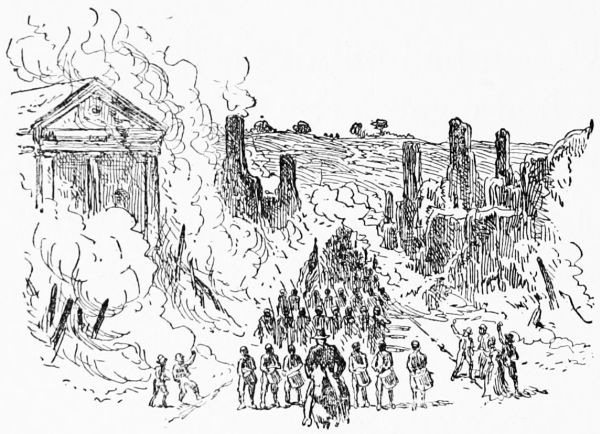

It was on a spring day, the twelfth of A-pril, 1861, that the first gun was fired in Charles-ton har-bor up-on the Un-ion flag on Fort Sum-ter. The call was sound-ed. The great heart of the North grew hot with shame and rage.

“What! De-grade our coun-try’s flag?” they cried. “’Tis the flag for which our fa-thers fought and died!” “We will give the last drop of our blood for it! We will leave our trades, our homes and dear ones, and fly[81] to put down the foe who has dared to strike a blow at it!”

But in Charles-ton, S. C. the folks were wild with joy. The Gov-ern-or of the state, Pick-ens, made a speech from the bal-co-ny of a ho-tel. He said, “Thank God, the day has come! The war is o-pen, and we will con-quer or pe-rish. We have de-feat-ed twen-ty mil-lions, and we have hum-bled their proud flag of stars and stripes.” There was much more talk in the same vein.

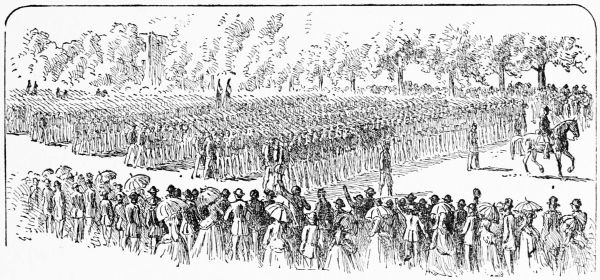

In the North men wept who ne’er had wept be-fore. It seemed as if the worst had come. “But Lin-coln, our brave Lin-coln, what will he do now?” they asked. A-bra-ham Lin-coln knew just what to do. He did not need to be told. He knew that the peo-ple would de-cide the mat-ter and to them he turned. He talked with his men near him, his “Cab-i-net,” and said that 75,000 of “the peo-ple” would come to his aid and quell this thing. Four times that num-ber came.

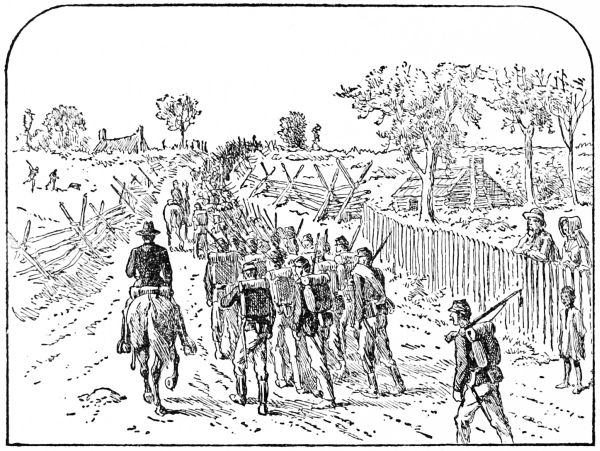

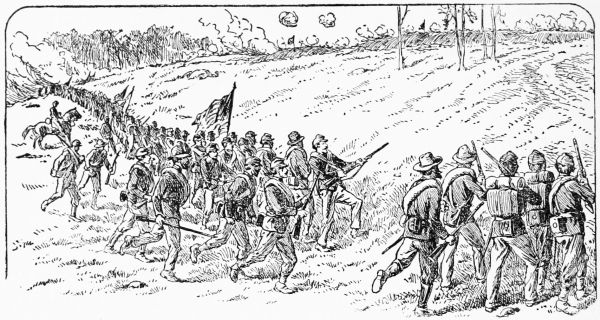

The par-ties, “Re-pub-li-can” and “Dem-o-crat,” for the time were both much of one mind, “For the Un-ion,” side by side to “fall in” and march south and save it.

One state had troops all read-y to start. It was[82] Mas-sa-chu-setts. Her Gov-ern-or, in 1860, N. P. Banks, had long seen the trend of things, the need of men that must come, so his sol-diers were a-ble to leave at the first call for help. On A-pril 19, the Sixth Reg-i-ment fought its way through the streets of Bal-ti-more, and reached Wash-ing-ton in time to aid Lin-coln in hold-ing the cap-i-tol.

In ev-er-y cit-y and town there were drum beats and the cry of “To arms! To arms!” Men were in haste to give their help to the great Chief, A-bra-ham Lin-coln, whose call they had heard.

Ste-phen A. Doug-las, now that the ver-y life of the Un-ion was at stake, left no doubt as to where he stood. He made it plain-ly known that he was “For the Un-ion,” and he led the loy-al Dem-o-crats of the North to up-hold the Un-ion, and they went glad-ly with him to the task.

Much as the men who led the South to try to go out of the Un-ion were to blame, it was well known that man-y in the South were loath to go and did so on-ly when their states said they must.

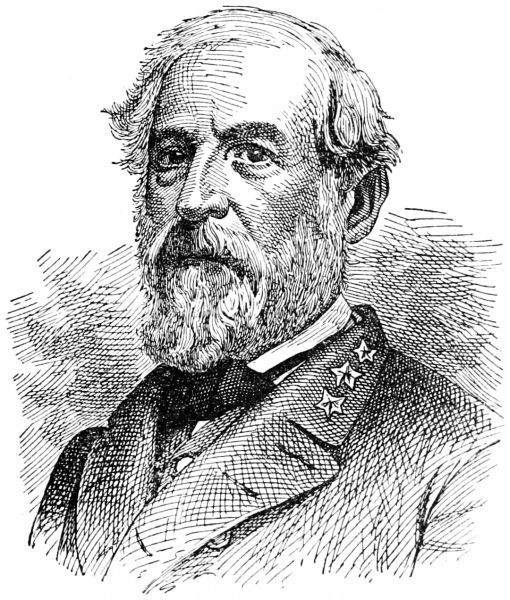

Some of the best gen-er-als on the side of the South, such as Lee, were of those un-will-ing men. Each of[83] them fought the North be-cause his own state told him to. The bad “doc-trine of State Rights,” brought this a-bout. Un-der it the state was held to have a claim up-on those who lived in it high-er than the claim which the na-tion had up-on them.