The Project Gutenberg EBook of Snythergen, by Hal Garrott This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Snythergen Author: Hal Garrott Illustrator: Dugald Walker Release Date: January 2, 2020 [EBook #61079] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SNYTHERGEN *** Produced by Tim Lindell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

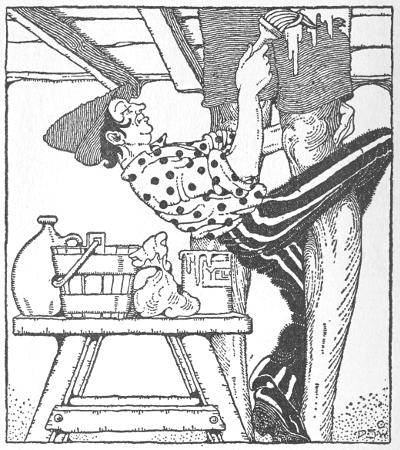

“I did not call you over to give me a bath,” cried Squeaky

BY

HAL GARROTT

ILLUSTRATIONS BY

DUGALD WALKER

NEW YORK

ROBERT M. McBRIDE & COMPANY

1923

Copyright, 1923, by

Robert M. McBride & Co.

First Published, 1923

Printed in the United States of America.

TO

Hal and Jean

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | Slender Foods and Round Foods | 1 |

| II | A Ticklish Tree | 11 |

| III | Played on a Musical Skirt | 21 |

| IV | A Bird and a Tree Play at Hide and Seek | 29 |

| V | How a Pig Learned to Talk | 37 |

| VI | The House at the End of a Rope | 45 |

| VII | Bear on Ice | 53 |

| VIII | A Runaway Tree | 65 |

| IX | The Doctor Discovers a Tree with St. Vitus’ Dance | 71 |

| X | The Bear Sees the “Grasshopper Pig,” Hears the “Huntsmen,” and is Present at the “Escape” | 87 |

| XI | The Journey to the Wreath—A Spin in a Humming-Top—An Unknown Friend | 99 |

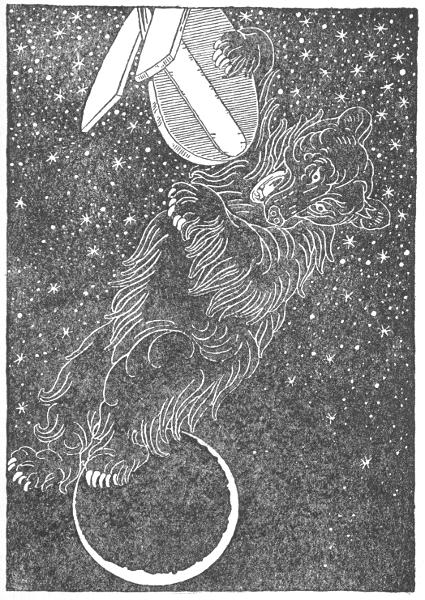

| XII | Aboard a Floating Beard | 113 |

| XIII | The Pie Room—Bear Again!—Sancho Wing Scolds | 123 |

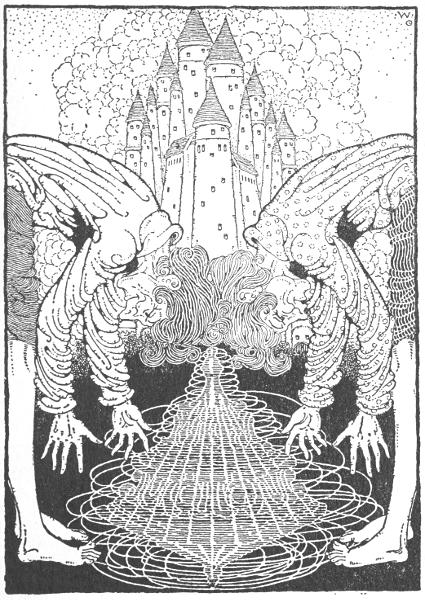

| XIV | Snythergen’s Troubles | 135 |

| XV | Toy Foods | 147 |

| XVI | Home | 155 |

| IN COLOR | |

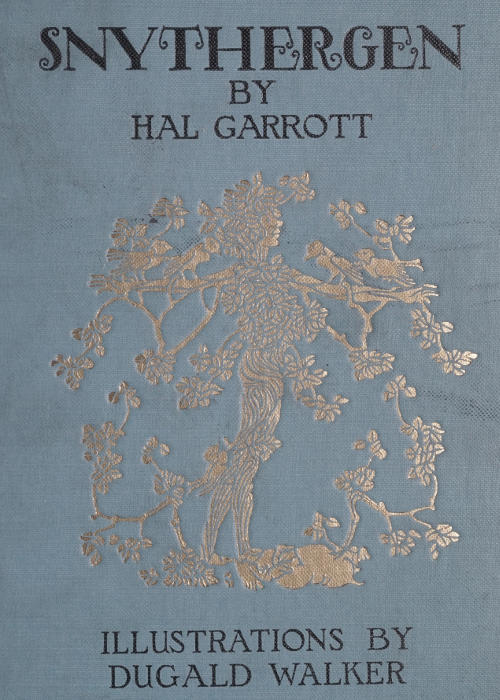

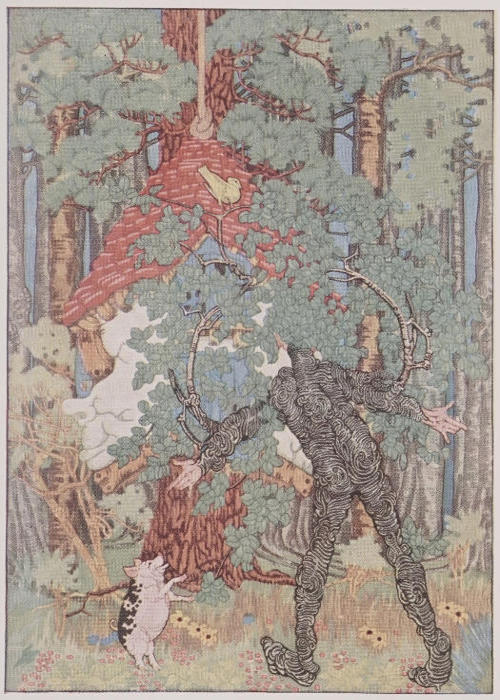

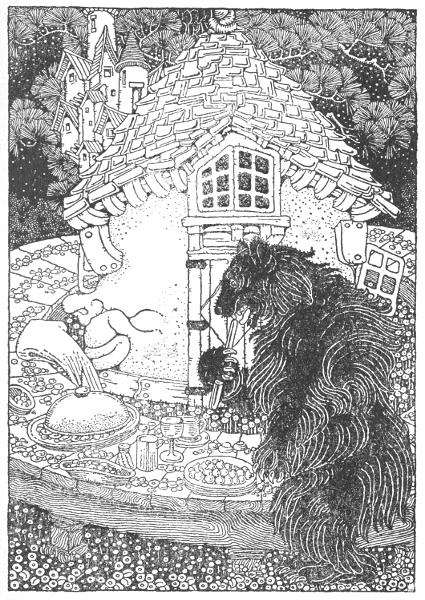

| “I did not call you over to give me a bath,” cried Squeaky | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| It was inspiring to hear this chorus accompanied by full orchestra | 24 |

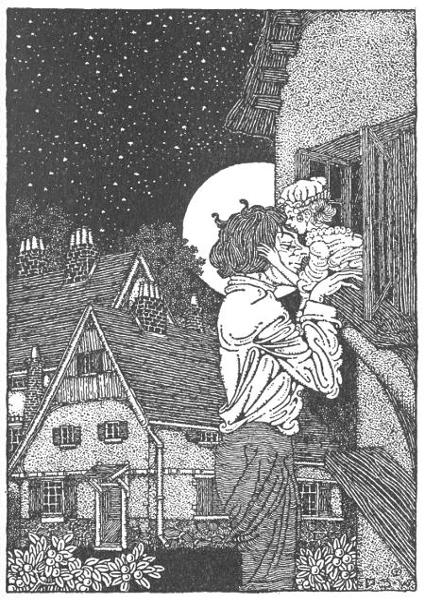

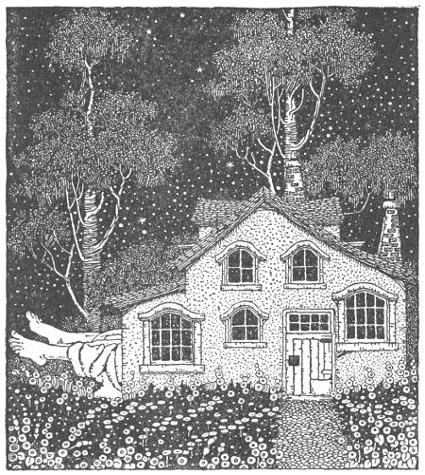

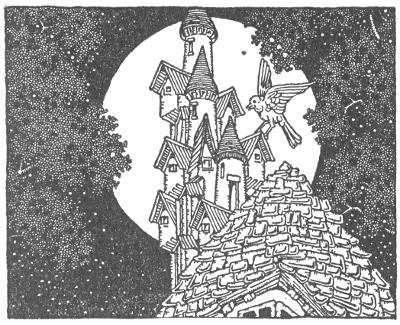

| The house was left dangling above ground to receive an airing out | 46 |

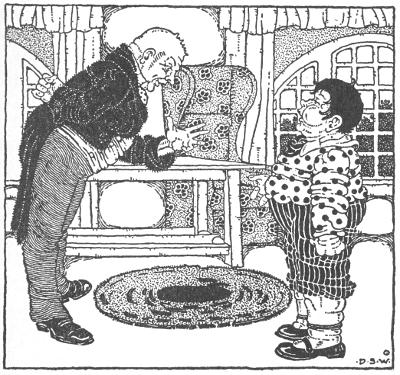

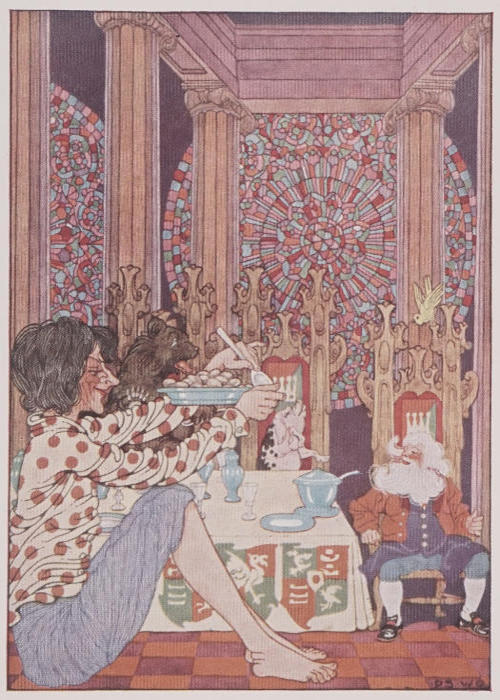

| “Bears should not talk when their mouths are full of food,” said Santa Claus kindly | 128 |

| IN BLACK AND WHITE | |

| PAGE | |

| His father would stand on one hand and his mother on the other | 5 |

| Like mothers the world over she knew how to sacrifice herself | 13 |

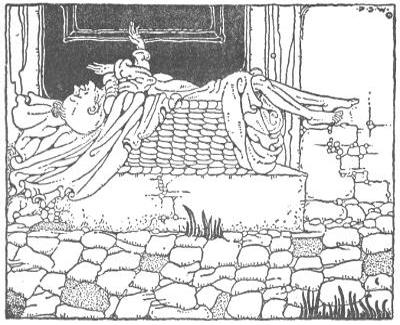

| His feet projected out of the window in the butler’s pantry | 19 |

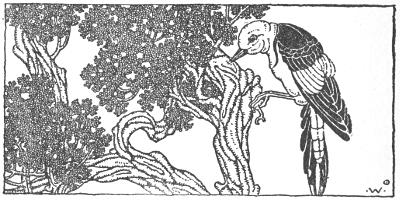

| Snythergen cried, “Don’t do that!” | 33 |

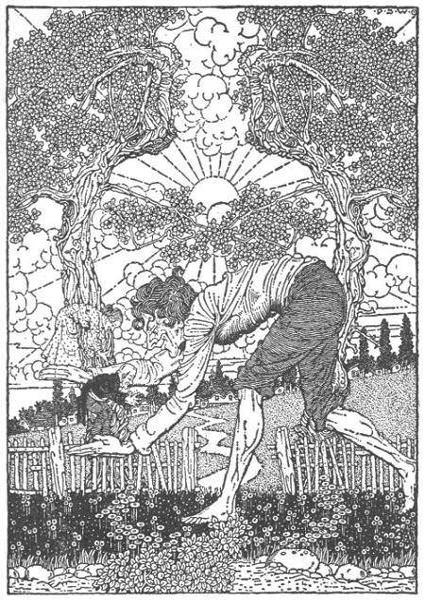

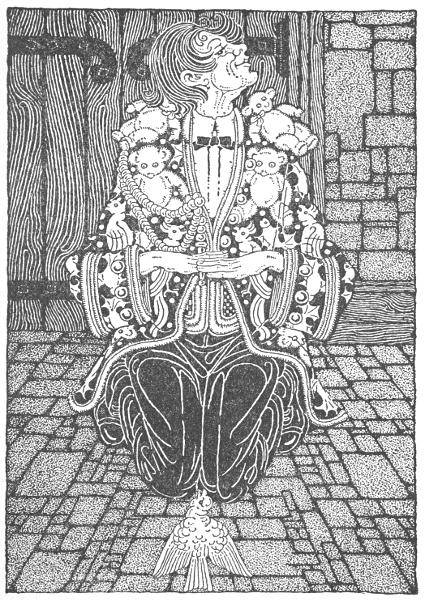

| To die in her arms would have been a happier lot than leaving her | 41 |

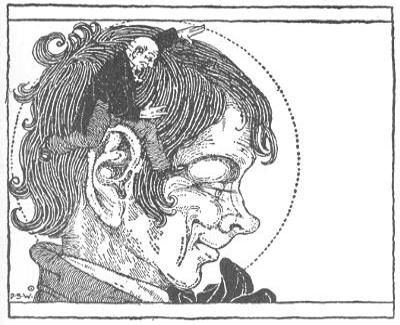

| “At least I can relieve his headache” | 59 |

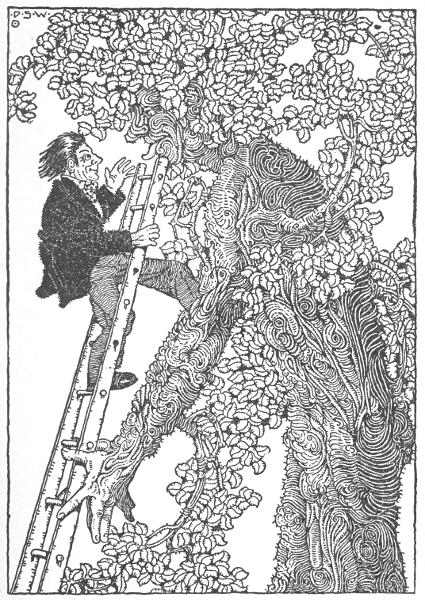

| “Stick out your tongue!” | 75 |

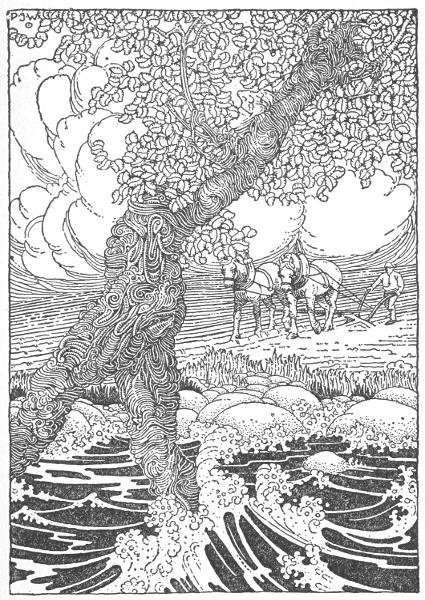

| He would strike a tree-like pose | 83 |

| Then went around again to see if he had overlooked any crumbs | 91 |

| “Some unusual weight behind” | 101 |

| “The only kind of humming-top to have” | 105 |

| “Stop the top, stop the top!” bellowed Squeaky | 109 |

| “Squeaky, who is a voice with a pig’s body” | 117 |

| The door-man, turning his head sideways, wiggled his left ear | 125 |

| A traffic butler stood at hall intersections | 141 |

| And squeezed him almost as tightly as the farmer’s wife had done | 151 |

Snythergen’s mother was poor—so poor that she did not feel able to support her baby boy. So she put him in a basket—it had to be a large one—and left it on the doorstep of a little old couple who had long wished for a child.

The pair were very much surprised, not only at finding Snythergen, but at his unusual appearance. He was thin as bones and very long—so long that he appeared to be wearing stilts. His body was very ungainly and the[2] couple’s first feeling was one of disappointment—until they looked into his eyes. These were bright and roguish and something else not easy to name—something that made them know he was their child, and they loved him.

The new papa and mamma were very proud. First of all they wanted their boy to fill out into a healthy well-fed child, so they stoked his neglected stomach with the richest of farm foods. The effect was prompt. It was amazing how Snythergen changed from day to day. His cheeks rounded, his shoulders broadened, and the layers of flesh spread over his lean trunk until he was as bulging as a rubber ball. He was getting enormous and his parents were beginning to sense a new danger.

“He will burst if he keeps on getting fatter,” said his mother anxiously.

“I must study the question,” said his father, who was a philosopher.

One day the father came in much excited. “I know what it is that makes baby so fat! He eats the wrong kind of food. His diet is too round. It is all pumpkins, potatoes, tomatoes, eggs, oranges. Now to get thin he should eat thin foods, like celery, asparagus, pie-plant, and macaroni.”

So they fed him long slender foods, and he[3] began changing at once. He shot up almost as fast as Jack’s beanstalk, until they were alarmed for fear he would never stop shooting up. He had grown until he could look into the second story windows standing on the ground, and could place his hand on the top of the chimney without getting on tiptoes. Again it was time something was done, and they sat down to think the matter over.

“I have it,” said the papa at last. “Son must[4] not eat all round nor all slender foods! The two must be mixed!”

So they mixed them just in time to save Snythergen from shooting up like a skyrocket. But by the time his growth was arrested he was altogether too big for a boy.

There was no room in the house large enough for him to sleep in and he could not go upstairs; the passage was too small and the ceiling too low. But they found a place by letting his legs and body curl around through the hallways and connecting rooms of the ground floor. His head rested on a pillow in the living room and his feet projected out of the window in the butler’s pantry. Every night before he went to bed his mother tucked him in carefully, unfurling a roll of sheets and quilts that had been sewed together and were long enough to stretch from his feet to his neck.

His father would stand on one hand and his mother on the other

Before he left for school in the morning his parents always kissed him good-by affectionately. The parting took place outdoors in front of the house. Snythergen would bend over and place his broad hands on the ground, palms up. His father would stand on one hand and his mother on the other, holding tightly to their son’s coat sleeves. Then Snythergen[7] would raise his arms, lifting his parents until they were on a level with his face.

“Now be a good boy, Snythergen,” said the little father, “or I shall spank you severely!”

“Of course he will be a good boy,” said the mother, as she leaned over and kissed him.

Then the papa would climb up his ear and place his hands on his son’s head and give him his blessing. Snythergen would then lower both parents gently to the ground and start for school.

Snythergen was nearly always late in starting for school. He seldom slept well, for his bed was uncomfortable and he could not turn over or even change his position, without injuring the house. Every night before going to sleep he would resolve to be up early on the morrow, but regularly failed. And one morning he arose so very late that it was necessary to find a short cut if he were to arrive at school in time.

What could he do? He tried to think of a scheme while collecting his books. Bending over to pick up his slate pencil, he placed his head between his heels, just for the fun of it. And this gave him an idea! With his head still in this position, he bent his body into a circle making a hoop of himself. Then he began to[8] roll down hill across the fields, slowly at first, then faster and faster, then so fast he could not stop. He bounded over fences and ditches, until, all out of breath and very much flushed, he found himself at the school house door! This short cut saved him at least a mile, and it was such fun rolling down hill, he went that way every morning thereafter, rolling up to the door just as the school-bell was ringing—to crawl into the passage on his hands and knees.

There was not room enough for Snythergen to stand up in school, so the janitor cut a trap door beside his desk so that his feet extended into the basement. Even then he stood taller in the school room than the other pupils. But he would have managed very well had the janitor not been absent-minded and near-sighted. He seemed never able to remember that those long shanks were legs—not pillars. Again and again he would tie the clothes-line to them, and on wash days when Snythergen went out at recess, usually he trailed a piece of clothes-line behind each leg, with the washing hanging on. And the janitor got such a scolding from his wife for this that he grew to dislike Snythergen almost as much as Snythergen disliked him.

One morning the janitor painted the basement. And when Snythergen went out at recess his legs were a brilliant yellow and pinned to each was a sign: “Fresh Paint.” That day he had an easy time playing tag, for no one wanted to get smeared with paint badly enough to touch him.

One day the janitor was so forgetful as to start to drive a nail into one of Snythergen’s legs. This was too much! The poor boy jumped out of the cellar, and in rising thrust his head through the roof. So angry was he, he hardly knew what he was doing. He stepped over the walls carrying the roof with him, then tossed it on the ground and hurried away. “I won’t, won’t go back to school,” he kept saying to himself. Rather than go back and face the ridicule of his schoolmates he decided to run away.

For some time Snythergen had been thinking of running away and had planned to go to the forest and live with the trees, whose size was about like his own. While waiting for the time to arrive, he had made himself a disguise—and a very good one it was, too,—it was a suit of brown and green that made him look just like a tree. For a long time he had kept it hidden in some[12] bushes. Yes, he had quite made up his mind to run away.

He went home that night and looked into the upstairs windows for a last sight of his dear mother and father. His father was already asleep when he arrived, but his mother was sitting anxiously by the window waiting for her little boy to come home. He rubbed his nose on the glass until she noticed that he was there, then placed a finger to his lips cautioning her to be quiet. She raised the window softly and whispered:

“Snythergen, what is the matter?”

“Mother, dear, I am going away. I cannot stand going to school any longer. I am too big and they are beginning to laugh at me. I was never meant for a student anyway. I am going to live in the forest with the trees. They will not make fun of me. I have made myself a suit of bark and branches which makes me look just like one of them. Some day I will come back to you and take you to my new home. But now I must leave you and go and seek my fortune!”

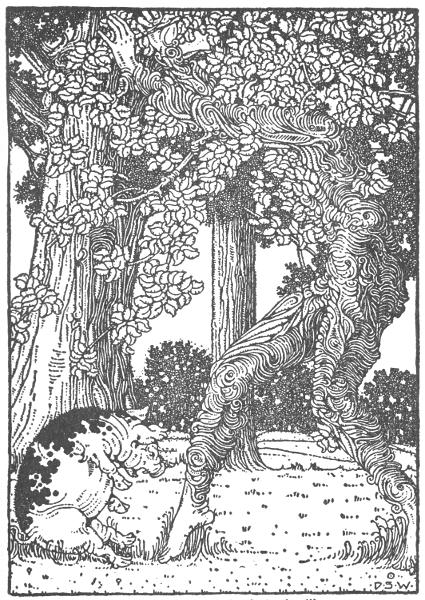

Like mothers the world over she knew how to sacrifice herself when it was for the good of her child

The poor mother’s heart was almost breaking. The tears streamed from her eyes, but deep in her heart she knew it was best for him to go. Like mothers the world over she knew[15] how to sacrifice herself when it was for the good of her child. She kissed him again and again. Just then the father turned uneasily in his sleep.

“Hurry, hurry, my darling boy! If your father hears you he will give you a terrible spanking.” As he rushed away, great tears were dashed from his eyes by the branches of tree-tops.

Snythergen went straight to the forest and very early the next morning dressed in his suit of green and took his place as a tree. For a long time he stood very still, holding his branches out and waving his leaves in the breeze. “I wish something would happen,” he said to himself. “It certainly bores one to be a tree.” He had been standing there since daybreak and the sun was now high in the sky. The birds as yet had not lighted on him. Some instinct made them hesitate. At last a daring woodpecker approached his trunk, and began a series of sharp pecks. Snythergen stifled an “ouch” and made a wry face. The first woodpecker was followed by others. They attacked his bark until it itched and smarted all over. In spite of his discomfort he tried to stand very still for he thought it beneath a tree’s dignity to show its feelings.

Unfortunately Snythergen was ticklish and whenever the birds touched a sensitive spot he could not help wiggling. This frightened the woodpeckers for a while and they flew to a neighboring limb to gaze at the strange tree. But as soon as they stopped tickling Snythergen always stopped shaking. This puzzled the birds. They could not understand why they felt the tree shake when they pecked, but could not see it move when they stopped to look at it. Finally they decided that they only imagined it moved, and after that they did not fly away unless the wiggling was very violent—which it was whenever a bird happened to blunder upon Snythergen’s “funny bone.” Snythergen was beginning to realize that the life of a tree is not all joy. Hardly could he wait for night to come when the birds would fly away. In the meantime he tried and tried to think of a plan to outwit them. “I have it!” he whispered to himself at last.

When it was quite dark he pulled off his tree suit, and went to a near-by town to purchase several xylophones. These are musical instruments with keys usually made of wood, and played on with a little mallet. Snythergen took the keys apart and strung them about his trunk so that they hung about him like a skirt of mail,[17] to protect his bark from woodpeckers. The next morning when the birds began to circle around him, he smiled to himself. When one of them lighted and began pecking away, a cheery sound came forth. And when the others followed his example the whole tree became a bedlam of musical jingles. “Peck away, peck away!” said Snythergen to himself, “you cannot hurt me now!”

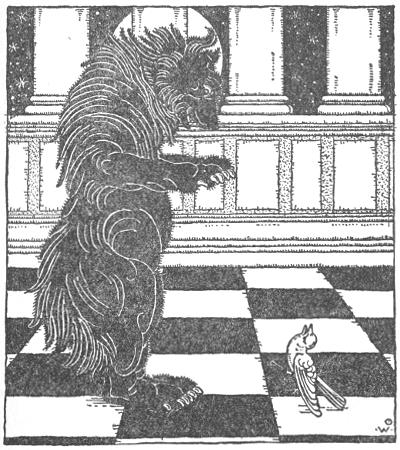

It was not long before the strange sounds issuing from the tree attracted all the wild life of the forest. The air became almost black with flying things, and the ground was swarming with animals little and big. Even a bear came along and Snythergen trembled from roots to peak leaf. How he wanted to run home to his mother! It would be easier to go back and face his schoolmates than to stay alone with a bear. But at heart Snythergen was really a brave little boy and his courage soon returned. He had set out to be a tree and he made up his mind he would be a worthy one. He did not want the forest to be ashamed of him. “I must not be the first tree that ever ran away. It would set all the others such a bad example!” he thought. So he held his teeth together very firmly, and stood up ever so straight and stiff. “I must appear calm and unconcerned,” he said[18] to himself, but his heart beat so rapidly and thumped so loudly he thought the bear must surely hear it. But the big brute was too much absorbed in the strange concert to think of anything else, and did not suspect that a spare-ribbed boy trembled behind a disguise of bark, boughs and leaves.

After a while the novelty wore off and the bear went about his business, much to Snythergen’s relief. The others, too, felt easier when the big brute was gone, and crowded more closely about the strange tree.

His feet projected out of the window in the butler’s pantry

A thoughtful appearing goldfinch hovered about the strange tree. He would sit long in one of Snythergen’s branches as if lost in a golden study. Occasionally he would peck at the various wooden keys and listen critically, but the sounds he produced were sickly compared to the woodpeckers’ ringing tremolo.

“I wonder what he’s up to,” thought Snythergen. “Some deviltry, I’ll wager! He[22] seems a wise little bird. Evidently he’s planning to do something to me. I suppose I’ll find out what it is when he gets ready to let me know, and not before!”

The goldfinch flew among the woodpeckers and assembled about two hundred of them in Snythergen’s branches. Then he made them a speech.

“He is explaining his project,” thought Snythergen. The finch would flit up to a key, peck it and return to his branch, chirping animatedly. When he had finished the woodpeckers tossed their heads and chorused something. Snythergen could not decide whether it was an oral vote or a cheer.

“The meeting must be over,” thought Snythergen, relieved. But his relief was short-lived. The entire flock flitted down, landing on his trunk, and covering it until there was a bird stationed beside each xylophone key.

“Whew,” gasped Snythergen. “It wouldn’t be so bad on a cold wintry day, but this is no time of year to be smothered in an overcoat of xylophones and birds!”

His sap coursed feverishly through his trunk and the veins of his leaves. He fanned his moist bark cautiously with his upper boughs. The birds were too absorbed in their scheme,[23] whatever it was, to pay any attention to the tree’s unusual motions.

Snythergen was almost suffocated with heat. “Why don’t they tar and feather me and be done with it!” he groaned. “It amounts to that anyhow, for my sap is as hot as tar—and as for feathers!”

Here he paused, struck by the sweet sounds issuing from his trunk. The goldfinch was apparently leading an orchestra of woodpeckers and they were playing bird calls!

“So this is your scheme,” thought Snythergen. “Not a bad idea at all!” A cool breeze had just sprung up from the north, enabling Snythergen to cool off and enjoy the performance. The finch was perched on a central limb and was pointing his bill at the different players when he desired them to respond. He was standing on one leg. With the other he beat time, using a tiny twig as baton. The music attracted many birds and animals and the goldfinch made them a speech. As nearly as Snythergen could guess from his gestures the little bird said something like this:

“We’re going to give a symphony concert to-night shortly after bug time! Everybody is invited to come and bring his family and friends.”

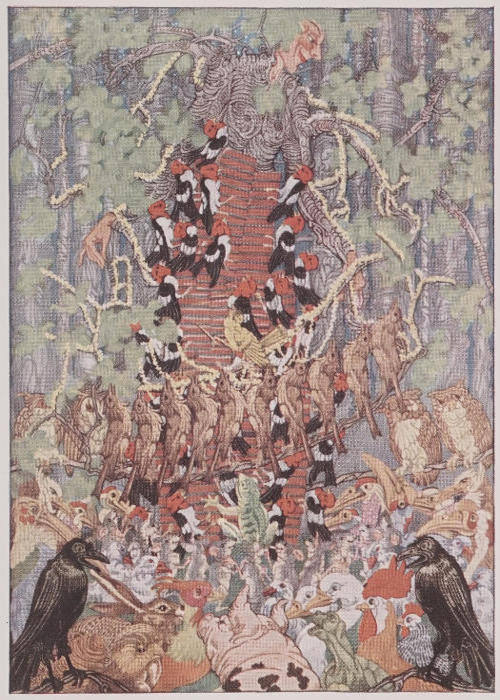

Preparations for the concert were in progress[24] all day. An hour before the audience was admitted the western sky was ablaze and the animals thought the forest was on fire. But it was only a cloud of fireflies coming to light the concert. When they arrived the business manager (an intelligent crow) directed them to stand just touching each other along all the branches, twigs and leaves of the tree, until Snythergen sparkled from roots to peak with thousands of points of light. The branch on which the goldfinch perched was lighted more brilliantly than the others. Festoons of acrobatic fireflies holding together hung down from it like ropes of light.

It was inspiring to hear this chorus accompanied by full orchestra

At the appointed time animals and birds were admitted to the reserved space about the tree. Crow ushers kept order and showed each one where to sit. Birds were admitted to all but the stage branches of the tree, and they covered every part of Snythergen unoccupied by fireflies. At first the fireflies were afraid of the great birds that stood close enough to touch them, and they would have flown off in terror if the crows had not watched over and protected them. By this time the ground was black with animals. Not only every seat, but every inch of standing room was taken. By eight o’clock every member of the orchestra[25] was perched at attention. Beside every xylophone key a woodpecker awaited the signal to begin.

When all were seated the goldfinch walked proudly forth from his dressing room of leaves and took his position in the center of the stage-limb. He was indeed a handsome fellow. His gay head-dress was gracefully arranged. His feathers were as smooth as satin, and his manicured claws shone in the light of the fireflies. His entrance was greeted with tremendous applause and he had to bow again and again. When it was quiet, he raised his baton and bill together and gave the signal. The concert began. All listened breathlessly to the wonderful strains. Aside from the music there was not the faintest sound of animal, bird or insect in the forest. Even the trees kept tight hold of their leaves, to keep them from rustling in the breeze.

Before the concert was over the call of nearly every being present had been given by the orchestra. The meadow lark’s song was encored again and again. It was so short it was over in a jiffy and the audience could not get enough of it.

Once during the evening the leader was worried for a moment. In a front seat he had[26] spied an old frog and he knew his bass woods did not go low enough to imitate the frog song. So when an usher came up and whispered in his ear that the frog was stone deaf and would not know it if his call were omitted, he was very much relieved. Happily the old fellow was the only frog present.

The favorite number proved to be the brown thrasher’s song. It was long enough to make a piece, and seemed just suited to xylophones. Since Snythergen wore at least twelve of these instruments in his skirt of mail, there were enough different keys to provide soprano, alto, tenor and bass. The audience was much stirred by the wonderful performance, and the leader as a compliment to the brown thrashers directed the ushers to conduct all of them present to a stage limb just beneath him. They were lined up in a row and firefly foot-lights shone upon a long line of feathery breasts in front and straight slender tails behind.

It was inspiring to hear this mighty chorus accompanied by full orchestra, in one of the most beautiful of bird songs. No wonder birds and animals clapped until their claws and paws ached, and when the concert was over, refused to go home until the leader announced another performance next week.

“Well, at last,” said Snythergen, when all had left, “I can have a moment’s rest. There won’t be another concert if I can help it—and I think I can!”

Snythergen took off his suit and lay upon the ground. In a minute he was fast asleep. Early the next morning he arose and put on his tree suit but not the xylophone skirt. It was a hot day and it would be cooler without that. And he believed that after their hard day the woodpeckers would sleep till noon. He was right. Not one came to disturb him in the morning. But without[30] them there were plenty of curious eyes staring. For the birds and animals could not understand the change that had come over the strange tree.

The goldfinch did not sleep as late as the woodpeckers, for he did not believe in lying abed in the morning even if he had been up late the night before. When he saw that the tree no longer wore its skirt of xylophone keys he studied Snythergen curiously, hopping from twig to twig and pondering. He discovered that this tree was much warmer than the others—for the heavy tree suit made Snythergen very hot. The little bird wondered if the strange tree would not be a good place in which to build a winter home. This would save him going south every year. In place of a one-room nest, why not build a mansion? He flew away excitedly to draw up the plans.

“At last I can enjoy a little peace,” murmured Snythergen and dozed off for a standing nap. When he awoke, it was with a start. “Stop biting my toes,” he cried. Glancing down he saw—a pig! “He must be hungry,” thought he. “Well, I’ve eaten enough pig in my day. It would only be fair to let one of his kind have a bite of me. But I am thankful his teeth are not sharp. The bites feel like little pinches.[31] I hope he is enjoying himself, but now he is beginning to damage my costume!” He gave a kick and the pig jumped back, so frightened that his hair and his tail stood pompadour. He was pale and trembling and his little eyes grew big and round.

“What in the world is the matter with that tree?” he exclaimed. “I thought it moved!”

It was now Snythergen’s turn to be surprised. “Can he talk, the little rascal? Now how did a pig ever learn to talk? I must investigate.”

Evidently the pig liked the taste of bark; and as Snythergen stood very still the pig’s courage returned. He approached the tree once more, and was just about to take a really good bite when Snythergen cried, “Don’t do that!”

“Who said that?” cried the pig, startled.

“Why, I did, of course.”

“Who are you and where are you?”

“Can’t you see, you simpleton!” said Snythergen. “I am the tree and I want you to stop biting my roots.”

The pig did not wait to hear more. So frightened was he that he ran away as fast as he could.

“Come back,” shouted Snythergen, “come back after dark and we can visit without being seen.”

Soon the little finch returned with plans all drawn, and set to work to build in one of the strange tree’s branches. This made Snythergen anxious for he did not fancy having his limbs tangled up in nests. And when the finch flew farther than usual in search of thistle down, Snythergen strolled softly to an open space several hundred feet away behind a hillock.

When the finch returned he could not find the tree. Nearly frantic he flew wildly about in circles; then darted across in diameters. Was he dreaming? He all but lost his reason and contracted a painfully stiff neck. “That tree must be somewhere!” he exclaimed, and turning suddenly he would charge the spot where it had been, as if to take it by surprise. Then he described larger and larger circles until at length he came upon Snythergen’s hiding place.

Joyfully he returned to his work careful this time not to let the tree out of his sight. It was now Snythergen’s turn to be perplexed. How was he to dodge that energetic nest builder! For every time he attempted to take to his roots there were those sharp little eyes regarding him.

“No chance! That is the most suspicious goldfinch I ever saw!” he sighed.

Snythergen cried, “Don’t do that!”

The nest was progressing alarmingly. The fuzzy material tickled Snythergen’s limb, and every time he tried to rub it, the goldfinch was watching.

“Is there no way to get rid of the little pest?” he groaned. “Can’t I ever get him to turn his back long enough for me to rub my itching limb? My, but he must love me, the way he keeps staring all the while! If this keeps up much longer I’ll get the St. Vitus’ dance.”

He remembered that the finch had gone a long way off for milkweed silk and thistle down with which to line his nest, and it was while he was searching for these that Snythergen had had his chance to hide.

“I’ll just pull out some of that fuzzy stuff and put it in my pocket the next time birdie turns his back,” he chuckled. “When he sees it is gone he will go for some more, and when he comes back—well, there won’t be any tree or any nest to welcome him!”

This thought amused Snythergen so much that he almost gave himself away by laughing out loud. Luckily the finch thought it was a child in the woods and turned his back to see. And the moment he did so Snythergen jerked out most of the fuzzy stuff and put it into his pocket. When the finch saw the damage he was very much puzzled.

“Bless my feathers! Now how in the world[36] did that happen?” he said. “This place must be bewitched!”

He looked around, painfully twisting his neck, then sat still on a branch for a long time, watching and thinking, but he failed to find a single clue leading to the cause of the damage. At length he gave it up and went to work to repair it. First he looked all around carefully, then dashed away to the place where the thistles grew, planning to grab a billful of down and fly back in the briefest possible time. But the moment he was out of sight Snythergen took to his roots and ran toward the place where he had told the pig to meet him, tearing off his tree suit as he ran, and he had barely gotten out of it when the finch flew screeching by.

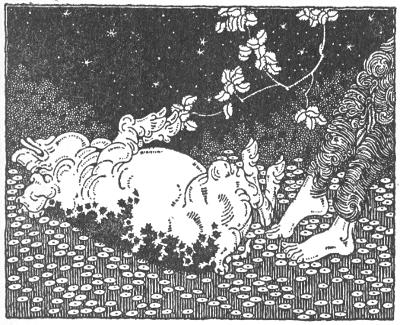

“This time I fooled you,” thought Snythergen, as he stretched out on the ground for a nap.

Snythergen dreamed that he was sitting on a pier, dangling his feet in the water. Little fishes were nibbling his toes, when suddenly a large one darted up and took a bite that hurt. Raising both feet quickly, he woke up.

“You don’t need to be so rough,” said the pig, who had been bowled over by the raising of Snythergen’s feet and lay on his back, waving his legs in the air.

“It’s you, is it! Up to your favorite trick of biting my toes! Well, it serves you right. Of course I am glad you like me, but I wish you would show your affection in some other way!”

“Oh,” cried the pig. “So you were the strange tree that kicked me and spoke to me! I recognize you by the taste of your toes. But how was I to know that the last time I nibbled you, you were a tree,—unless I nibbled you again to find out?”

“In that case, I’ll forgive you,” said Snythergen, “and I hope you’ll overlook the fright I gave you.”

They lay on the ground side by side and gazed up at the stars.

“Tell me, how did you learn to talk?” asked Snythergen.

“The farmer’s wife taught me,” said the pig.

“Why did she do that?”

“Because I was hungry.”

“That’s no reason. They give people food when they are hungry—they don’t teach them to talk.”

“This woman did. She would not give me anything to eat until I learned to ask for it. And as I was nearly starving I learned rapidly,” said the pig. “As soon as I could ask for things I gained in weight, and when the farmer saw I[39] was getting fat he asked his wife to keep right on feeding me so that—”

“Yes,” said Snythergen.

“So that they could eat me for dinner!” faltered the pig, dashing a tear from his eye.

“Then what did you do?” asked Snythergen.

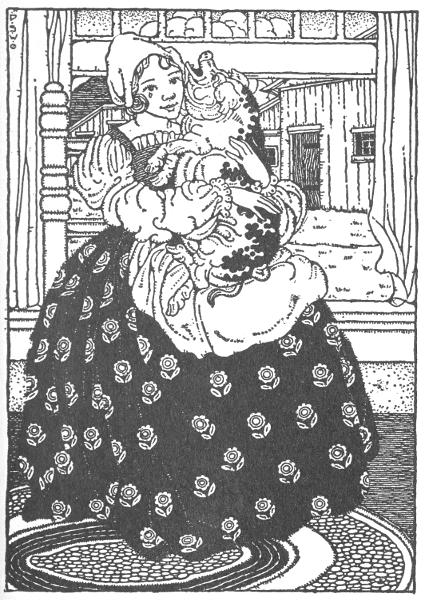

“I ate as little as possible until the farmer’s wife saw I was getting thin again. Then she told me to eat all I wanted and not to worry. She said she would manage somehow so—they would not have to—eat—me for dinner! I trusted her and after that enjoyed three good meals a day. You see she had taken a fancy to me because I kept myself looking neat, and tried to be gentlemanly. She called me ‘Squeaky’ and treated me like a child of her own. Little by little I began to understand what she said, and learned to talk.

“One day the farmer’s wife was sitting by the window sewing. The farmer had gone to town. I trotted up as usual for a chat, but instead of chatting—

“‘You must go away,’ she said, with a catch in her voice, ‘for my husband says we must have you—for—dinner—to-morrow!’

“She could hardly say the words. We looked at each other sadly. Then she took me in her arms and squeezed me so tightly I thought she[40] would break my bones; and I would not have cared much if she had. To die in her arms would have been a happier lot than leaving her.

“‘But surely I may come back some day,’ I managed to say, ‘or send for you when my fortune is made.’

“‘I’m afraid not,’ she faltered.

“I cannot tell you any more about our parting. It was too sad. Somehow I survived it—I suppose because I was young and the world lay before me.

“A farmer’s buckboard approached in the rough lane, thumping over the frozen ruts, announcing its coming long in advance. I hid in the cabbage-patch. The farmer’s wife stopped the vehicle and gossiped with the driver, to give me a chance to climb into the back and hide.

To die in her arms would have been a happier lot than leaving her

“It was not easy to scramble up into the vehicle, for I was fat, and could not get a foothold. I tried using the spokes of the wheel as a ladder, but kept slipping and falling back. I knew one side of the wheel would go up and the other down when the wagon started, but could not figure out which side did which. However, I decided to take a chance. Taking a firm grip on one of the lower spokes I braced my feet on the one below it. It happened to be the right side of the wheel. So when the[43] vehicle started the spoke I was holding to began to rise, carrying me up nearly to the top of the wagon. Bracing my legs, I gave a leap that landed me in the buckboard upon some empty potato sacks. Hurriedly selecting one I crawled into it.

“The farmer thought he had heard something fall into the wagon, and stopping his horses, he glanced back. I was hidden by this time but he saw a bulging under the pile of sacks and was about to poke into them when I said, ‘Please, Mr. Smythers, let me stay here until we get by those boys in the road. I am hiding from them.’

“When he heard my voice Mr. Smythers, of course, took me for a boy and he answered: ‘No, you cannot stay there. You will smother. Come out and I will protect you from the boys.’

“Receiving no reply he poked about among the sacks until he found the one I was in.

“‘Why, it’s a pig in the bag instead of a boy!’ he cried in great surprise. ‘Well, I’ll soon fix him so he can’t get away!’ and he tied up the opening with a string. ‘But where is that boy that spoke to me just now?’

“Mr. Smythers looked under the wagon, searched both sides of the road, and even the trees, but of course found no one. Greatly perplexed[44] he got into his buckboard and drove on, glancing back every few minutes to see if there wasn’t a boy around somewhere. After he had driven about a mile he ceased looking around, and as we were going through a dense forest, I decided to try to escape. The bag I was in had a hole in it (that is why I had chosen it), and it was not difficult to make the opening larger by tearing the rotten threads. Little by little I squeezed myself out, and dropping off the back of the buckboard, fell in a heap in the road.

“‘Now I am free,’ I thought, and I wandered deeper and deeper into the woods until I found you.”

“Hm,” said Snythergen when Squeaky had finished his tale, and for some time he remained silent. At last he spoke.

“I think we had better build a house!”

“Good,” said Squeaky, “but is this a safe place? Didn’t I see a bear in the crowd you attracted?”

“Yes, but I don’t think he’ll come back. If he does my tree suit will save us. I can bend over until my limbs touch the ground. Then[46] you can climb into my top branches and I’ll lift you out of danger. The bear will take me for a tree and leave us alone.”

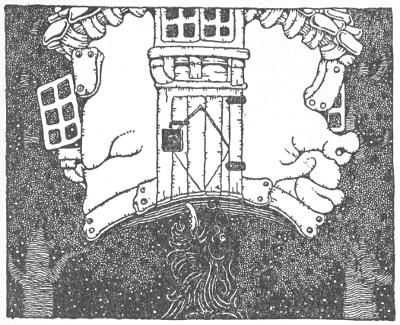

So they set to work very promptly. The plans they drew called for a round house. And to make sure it would be big enough for Snythergen, he lay on the ground curling up in the smallest space he could, and Squeaky traced a line around him in the dirt to mark the position of the outside wall. They planned to make the roof high enough for Snythergen when he was lying down, but of course he would be unable to stand up or even to sit up without bumping his head on the ceiling. The outer circle just inside the wall was to be Snythergen’s bedroom, and Squeaky was to occupy the space in the middle. It took several weeks to build the house and before the paint was quite dry Snythergen spread pine boughs over the ground floor to make a soft place for them to lie.

The house was left dangling above ground to receive an airing out

In the center of the roof was a hook to which was fastened a rope running up over a pulley attached to the top of a pine tree. From the other end of the rope hung a huge boulder, just as heavy as the house. The stone and the building balanced each other so nicely that a little pull would send the house up or down. In the daytime the house was pulled up and left[47] dangling above the ground to air out. At night when they went to bed Snythergen would lie down, bending himself into the exact shape of his bedroom by following a line marked out on the ground; and when he lay in just the right position so that the house when lowered would clear him, Squeaky would crawl over him into his little nest. Then Snythergen, reaching up, would pull the house down over their ears, making them snug and cozy for the night.

While they had been at work on their new house a most persistent little bird had followed them around, perching on a near-by tree or bush. He appeared to listen to their words and moved his bill as if practicing the sounds; and sometimes he would make the strangest noises! Squeaky, always glad of a chance to visit, fell into the habit of talking to the bird. It did not occur to him that a goldfinch would not be able to understand; besides the little fellow stood so still when Squeaky spoke to him he seemed to be taking it in.

“Do you understand me?” Squeaky would ask impatiently.

A strange sound not unlike “no” was the response.

“Then you do understand!” said Squeaky.

“No,” it came unmistakably now.

“Evidently the finch wants to learn to talk,” thought Squeaky, so he began to instruct him. He knew well how to set about it, for he had learned himself only with the greatest difficulty. He used the silent speech method—that is, he had the finch go through the motions of saying the words with his bill and throat, without actually making a sound. It was a good way to learn, but amusing to watch. The first day the goldfinch learned to make the motions for several words. When he did “cat” how he shuddered and flapped his wings as if to fly away in a hurry. How his bill did water and what a hungry gleam came into his eyes when he did “worm”!

Because his teacher would not permit sounds at first, the finch learned to put great feeling into his gestures and the expression of his face. And in time when he had learned to talk this assisted him greatly with animals and birds ignorant of the language. For those who did not understand what he said, knew what he meant by his gestures. After he had been instructing the finch for a fortnight and had come to like him, Squeaky decided to ask Snythergen to invite the little bird to share their quarters. “He is such a sensible little bird,”[49] thought Squeaky, “if he behaves well to-morrow, I’ll ask Snythergen’s permission then.”

That was the day the house was completed and that night the owners were very tired. They slept soundly until three o’clock in the morning when something woke them.

“What was that?” asked Squeaky in a shaky voice.

“It sounded like a growl,” said Snythergen, and his trembling was so violent it shook the house. Thereafter no more sleep was possible for either, but the sound did not return. When morning came they investigated and found bear tracks leading to the door.

“What shall we do?” asked Snythergen.

As usual the finch was perched on a branch listening, standing so close to Snythergen’s ear that his wing rubbed against it.

“Who’s tickling my ear?” said Snythergen, looking around. But the finch had hidden behind a leaf.

“What do bears want?” asked Squeaky.

“To make trouble, I guess,” said Snythergen.

During the building of the house Snythergen had been so busy he had not even noticed Squeaky’s little friend. Now the finch wished to join in the conversation, for his teacher had just given him permission to speak out loud.[50] He wanted to celebrate his first spoken words by saying them at the top of his voice, so pushing his little bill into Snythergen’s ear, he screamed:

“Bears don’t want to make trouble, they want food!”

Snythergen jumped as if a bee had stung him.

“What was that!” cried he, looking around and seeing nothing. For again the finch had hopped behind a leaf.

“It’s my good friend, the goldfinch,” said Squeaky. “I want you to meet him. I have been teaching him to talk, and you heard the first words he has spoken out loud. Don’t you think he did them rather well?” he asked, proud of his pupil.

“If loudness is an indication I should say he did, most decidedly,” said Snythergen, whose ears were still ringing. “If he keeps on improving they can hear him in the next county!”

“Come,” said Squeaky, looking around for the finch, “I want you to meet him.” At Squeaky’s request, the finch came out of his hiding place and was presented.

“If it isn’t the little goldfinch!” exclaimed Snythergen in surprise, and he burst out laughing.

“What are you laughing at?” asked the finch suspiciously.

“I was just thinking how difficult it seems to be for some birds to find their way back to their nests,” said Snythergen.

At this the sensitive bird flushed a brighter gold and hung his bill dejectedly.

“I suppose trees look a good deal alike,” continued Snythergen mockingly, “and that is why it is so hard to find the one your nest is in!”

Too confused to answer, the finch made up his mind to question Squeaky when they were alone, and at the first opportunity told the pig of his adventure with the strange tree. When Squeaky explained that Snythergen had a costume of bark, branches and leaves, the little bird understood how the “tree” had been able to hide from him, and why he had been unable to get any trace of his nest. Though he felt indignant about the way he had been treated, he decided for the present to say nothing and bide his time.

The goldfinch stayed close to his new friends and in the end they accepted him as one of them. They named him “Sancho Wing” and built him a little house on the roof of their new home. In many respects it was not unlike the permanent nest the bird had planned to build in one of the strange tree’s branches, but it was made of regular building materials—not woven of twigs and weeds—though Snythergen remembered Sancho Wing’s weakness for soft things, and caught and[54] saved all the thistle down and milkweed silk that blew against his leaves to use for lining the walls and floors. The living rooms were down stairs, but in the garret above there was ample space in which the finch might store stray bits of string, odd twigs, and curious little things he found in the woods—for Sancho Wing was an eager collector of curiosities. But the most interesting thing about the house was its watch tower, which rose to a dizzy height—even for a bird. For it was intended as a look-out from which Sancho might keep a sharp watch for the bear.

Sancho Wing was far too curious a little bird to sit quietly at home and wait for things to take their course. So, in addition to scanning the horizon daily for signs of the bear, he searched the forest over until he located the cave in which the beast lived, and actually flew into it. As it was getting dark and the beast was half asleep, he mistook the bird for a bat and paid no attention to him. Although very much frightened, Sancho hovered around until the brute’s heavy snoring indicated that he was fast asleep. Then hastening back he assured Snythergen and Squeaky they might now rest in peace, and retired to his own snug feather bed.

The three friends had been living together[55] happily and unmolested by the bear for about a month, when one Sunday at daybreak Sancho Wing opened his eyes and wondered what had awakened him. He listened. There was a faint sound like the crackling of twigs. He winged a few hundred yards into the woods in the direction of the cave and saw the bear approaching. Hastening back he pecked Snythergen until he opened his eyes.

“The bear is coming! Get into your tree suit at once, it’s your only chance!” said Sancho.

Snythergen pushed the house up out of the way and jumped out of bed, calling to the pig. But Squeaky would not wake up. He was too fond of sleep ever to allow himself to be disturbed before breakfast was on the table, and always he slept rolled into a ball, his head tucked under his body; and so tightly did he curl himself up that he kept this position no matter what any one did to him. Snythergen might have rolled him on the ground or tossed him into the air, without waking him. And had he done so Squeaky would have recounted these adventures afterwards as part of his dream.

Therefore Snythergen did not waste time trying to wake Squeaky, but hastened to arrange himself in his tree suit. This done, he bent[56] over and with his top branches picked Squeaky up and lifted him out of danger. Next he lowered the house to the ground to make the bear think it was occupied, and took his position as a tree. Hardly had he shaken out his leaves and arranged his branches when the beast arrived.

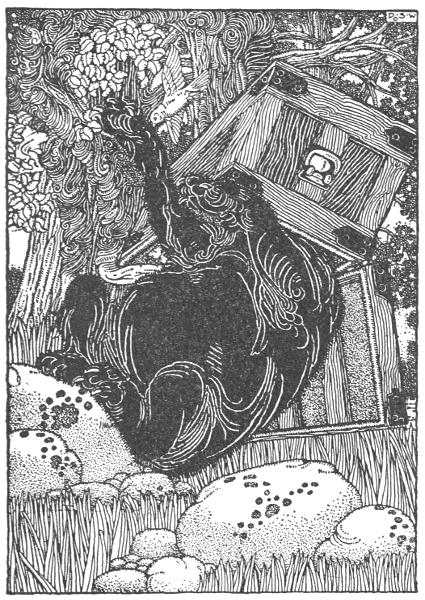

Casting an inquiring glance at the tree, the bear entered the house in search of food. He proceeded at once to the ice-box. Luckily (as it turned out) the door was open. Before leaving Snythergen had had the quick forethought to put a piece of cheese in his pocket and had neglected to close the ice-box door. When the bear had eaten up everything that was handy, he pushed his head far into one of the smaller compartments of the box to reach a last morsel of jam he had been unable to get before. This time he succeeded and, licking his lips, attempted to pull his head out.

He pulled and he pulled but he could not pull his head out. It was caught in the opening, and the harder he strained, the more firmly the ice-box became attached to him. He growled and he gnashed his teeth. He stood on his hind legs and pounded the ice-box against the walls, until Snythergen and Sancho Wing feared he would knock the house down.[57] Through a window Sancho saw the bear bracing himself for a mighty blow which, if allowed to land, would surely break through the wall.

“Quick, quick, pull the house up!” he called.

Grasping the rope with the twigs of a lower limb, Snythergen gave it a jerk. And just as the brute was delivering a terrific blow the house shot up and the bear’s effort spent itself in the air harmlessly, except that the big fellow was thrown sprawling to the ground, with a force that twisted his neck painfully.

For the moment Snythergen and Sancho Wing forgot their own fears to laugh at the beast’s comical state. Undoubtedly he was the most surprised bear in the whole world. Thinking himself still inside of the house (for whoever heard of a house running away!), he felt about for the walls, but there were no walls there! The ice-box fastened to his head, blinded him. Back and forth he stumbled, groping in every direction. And the pounding of the heavy box on the ground was giving him a splitting headache.

After he had pulled the house up Snythergen was not at all pleased to find the bear had eaten up all of their food. And now he beheld the intruder in a rage, bent on breaking their new[58] ice-box! He was so indignant, his branches fairly itched to punish the clumsy brute. And the moment the bear was in a favorable position Snythergen crept softly behind him, stripped the leaves and twigs from one of his stoutest limbs and gave the beast a sound thrashing. As the blows fell fast and heavy the bear yelled like a sick puppy. But Snythergen closed his ears to the sound, and not until he was out of breath and perspiring did he conclude the brute had had enough. Then his kind heart was touched, for with the headache and the spanking, the bear was aching and smarting at both ends.

“At least I can relieve his headache”

“At least I can relieve his headache,” thought Snythergen, bending over to examine the ice-box. There was still ice in one of the compartments. Removing a piece Snythergen was able to crowd it in against the bear’s head, and in spite of the brute’s wiggling, placed it so it rested against his forehead. Very gently the beast settled down on his aching haunches, to let the ice cool his throbbing brow. The ice-box was still attached to him as securely as ever. Apparently he had given up trying to free himself. But the bear was not to rest in peace for long. His head recently so hot now became freezing cold. And the pain of it drove him into a frenzy. Snythergen and Sancho were[61] about to come to his assistance when he charged blindly forward and a lucky jump was all that saved Snythergen from a fatal collision. The bear rushed back and forth beating the ice-box against the rocks and trees, not minding how it hurt his neck and shoulders. His one desire was to relieve the terrible freezing in his brain.

Snythergen quite understood all the bear’s thoughts and now decided that the big fellow had been punished enough. Grasping the rope from which the boulder dangled, and swinging it around his head, he brought it down squarely upon the ice-box. This well-aimed blow split open the box, freeing the bear’s head, but the door frame still clung about his neck—an absurd collar.

Stunned, lame, and aching, the poor bear crawled into the sunlight to thaw out his brain and to melt his frost-bitten thoughts. But the sun did not melt his hard heart or calm his rising indignation. He looked about angrily for his persecutors. He strode threateningly up to one tree after another, but they all stood very still and wore the innocent look that comes natural to trees. Snythergen, however, had not been a tree long enough to look as unconcerned as the others; besides he had a guilty conscience.

The bear may have smelled the cheese in[62] Snythergen’s pocket, or maybe something unusual in his appearance made the beast suspect him, for he came up and walked around and around the tree until poor Snythergen was dizzy, following with his eyes, and so frightened he could hardly stand. Uneasily he swayed from side to side, catching his balance just in time to avoid a fall. The bear stopped, rubbed his nose on Snythergen’s bark, dug a claw into it. And Snythergen could not avoid a cry of pain. Sancho Wing saw the danger his pals were in, and realized that something must be done quickly if they were to be saved.

“Throw the cheese to him!” cried the little bird. Snythergen tossed it on the ground a few yards away and the bear followed it eagerly, gulping it down in one mouthful. Sancho Wing thought he heard woodchoppers in the distance and flew away to summon help. Soon he found two men with axes and a rifle, and hiding in some leaves, he called to them:

“Hello, hunters! there is a bear over there near that shaking tree. Follow the sound of my voice and you will easily find the place.”

The men were simple fellows, only too eager to follow Sancho as he darted through the leaves calling: “This way, this way!” They could not see who was calling but supposed it was a[63] little boy who was keeping out of sight for fear of the bear. Now that help was near, in the midst of his anxiety Sancho could not avoid chuckling. For he had thought of a way to get even with Snythergen for the tricks he had played on him about the nest. As he hurried along he told the woodsmen, after driving away the bear to cut down a certain tree. “You will know it by the sleeping pig in its top branches,” he said. Just then the bear saw the huntsmen approaching and he did not wait for them to come up, but made tracks before they could get a shot at him.

Snythergen gave a sigh of relief when the bear went away and was just about to step out and un-bark, when he heard voices.

“This is the tree we are to chop down!” Snythergen heard one of them say, and already the woodchopper was swinging his axe. Snythergen did not wait for the blow to land, but leaped into the air and was off as fast as his roots would carry him. To be sure, he was hampered by his leaves and his branches and his[66] sheath bark skirt. Brushing none too gently against bushes and trees he trod on the toes of innumerable growing things. Apologizing with his bows to right and left, he did not pause even to see what damage he had done, nor did he know he had stepped heavily on the roots of an oak, or rubbed the shins of a birch. He knew only that two woodsmen were after him, threatening to chop him into kindling wood.

“Did you ever see such a rude tree?” cried a graceful elm suffering from a broken limb. “And it’s so untreelike to run away like that! Suppose the rest of us did likewise—what would become of the forest!”

“If he is restless, I don’t object to his walking about in a gentlemanly manner,” said the birch whose shins had been rubbed, “as long as he picks his steps carefully; but to go slamming through regardless of the rest of us is most inconsiderate!”

There was much bobbing of tree-tops and angry shaking of limbs in the direction the runaway tree had taken. But Snythergen might have saved himself running so far and so fast, had he taken the trouble to look around. For the hunters were not following but standing still, astonished at the spectacle of a tree racing through the forest at break-limb speed. In all[67] the years they had lived in the woods never had they seen a runaway tree before.

“Is the forest going crazy?” cried one. “What if all the trees were to run after us like a herd of buffalo! What chance would we have of escape?”

The mere thought of it was so terrifying they turned and ran, leaving coats, rifle, and axes where they lay, and they did not stop until they were well out of the woods and safe in their own home, behind locked doors and windows. And they did not stir abroad for two days.

When Sancho Wing saw the hunters and Snythergen running away from each other in opposite directions, it was too much for him. He laughed and laughed, and shook so that he fell from the limb he was perched on, and only saved himself from a bad fall by using his wings.

“Surely I have paid Snythergen now for all of his tricks,” he cried merrily.

During all this time Squeaky actually had remained asleep in Snythergen’s top branches, though his rest had been somewhat uneven.

“Where am I?” he cried, rubbing his eyes and waking up to find himself violently tossed about, and bumped against the branches of trees as Snythergen crashed through the forest.

With a breathless word here and there as he[68] ran, Snythergen gave the pig an idea of what had happened, and when Squeaky realized all the dangers he had slept through, he lost his grip and would have fallen had Snythergen not tightened his hold. On and on ran the tree, stumbling and reeling, and with every lurch Squeaky’s little heart quivered; for tree-riding was as terrifying as hanging to the top of a mast in a storm at sea. What a relief when Snythergen slowed up and stopped at the shore of a lake, panting like a porpoise!

“I think you had better get down now,” said Snythergen, “for I am going to wade across that lake and plant myself in the farmer’s yard on the other side. I shall remain there until the woodchoppers get tired of looking for me. I believe my leg is cut. Will you look on the ground and see if I am bleeding?”

“I guess your leg isn’t bleeding,” said Squeaky after looking around, “for I don’t see any sawdust.”

“Would you mind running home now, Squeaky, just to see that Sancho Wing is all right? I am a little worried about him. But if you will come back to this spot twice a day I will signal across the lake to let you know how I am getting on.”

Very much shaken Squeaky limped home[69] following the broad trail Snythergen had made through the woods, and found Sancho Wing still chuckling. After talking over their adventure for a little while they settled themselves for a nap.

As soon as Squeaky left him, Snythergen waded into the lake. He found the cool water refreshing to his overheated roots and tattered branches, but when he bent over to drink he came near losing his balance and floating away.

Only while he stood erect and kept in shallow water did his roots find a firm footing on the bottom of the lake. With much splashing of water and stirring of mud, and by wading around the deep places he managed to cross. When no one was looking, he crept into the farmer’s yard, where he hoped to find an end to his troubles. After looking the place over, he decided to plant himself where he would shade the dining-room window and could see what the family had for dinner. It occurred to him that if he became very hungry, he might reach through the window and help himself to a morsel of food. “Turn about is fair play,” he reasoned. “If I provide shade for them, they should not begrudge me a bite to eat now and then!”

Luckily the farmer and his wife were away[70] at camp meeting when Snythergen arrived, and when they returned, it was dark. A crescent moon and the stars revealed but a dusky outline of the place.

“Somehow things don’t look natural around here,” said the farmer when he reached home. “The place seems changed, swelled out! Why, I believe the house has got the mumps!”

“Silas, you don’t think baby has the mumps, do you?” cried his wife, thinking he must be referring to their child.

“No, no, it’s the house that’s got the mumps,” said the farmer.

“Nonsense, Silas, you must be out of your mind!” she said. She saw nothing out of the way, for her eyes sought only the windows of a room on the other side of the house where her small son had been left, and nothing more was said about the matter that night.

The next morning the discovery of a new tree in the farmer’s yard caused great surprise. At first the people were awed and afraid, and some were a little suspicious. Indeed, Snythergen had to stand very stiff and still and put on his very best tree manners to make them believe he was a real tree. He was watched so closely that he scarcely dared to breathe, and he feared the cool breeze from the lake might make him cough, for already he had[72] a slight cold from wading in the chilly water the day before. Once or twice he nearly exploded trying to hold in a sneeze. But the people on the ground saw only his top branches tossing and thought it due to an upper current of air.

Then an adventurous boy began climbing his trunk, and Snythergen thought surely the little fellow would feel his heart beat. But the child only climbed higher and higher, venturing out on a high limb which Snythergen held insecurely with the thumb and forefinger of his left hand. It had been difficult to support the branch alone and keep it from swaying, but with the heavy boy on it Snythergen found it almost impossible. The perspiration stood out on every bough. His left arm became so tired it pained him dreadfully, and it took all his strength to keep from dropping it to his side. He knew that he could not hold it out much longer, and yet if he let the branch drop the boy would be dashed to the ground and perhaps cruelly hurt. In spite of all he could do he was horrified to see the limb settling slowly downward and he closed his eyes to shut out the catastrophe that seemed sure to follow. Suddenly there was a cry from below.

“Get right down out of that tree,” called the[73] mother of the boy. Snythergen braced himself to hold on a moment longer, and just as the boy reached his trunk, the branch fell to his side. Snythergen breathed a prayer of thanksgiving. The child soon was safe on the ground.

Snythergen thought the people in the farmer’s yard curious and watchful, but he was mistaken. He was soon to learn what real curiosity and watchfulness are like. Some one had sent for a famous tree doctor, and he came promptly to look Snythergen over. When he appeared Snythergen put on his most correct forest behavior and really was a model tree, for the doctor’s benefit.

“I can’t see anything unusual about that tree,” said the physician, unpacking his instrument case. Snythergen was holding out his branches gracefully and letting his leaves flutter naturally in the breeze. The doctor spread his shining wood-carving tools out on a cloth on the ground. Much as the little man knew about trees, he had never learned to climb one, and the farmer had to fetch him a long ladder before he could make his examination.

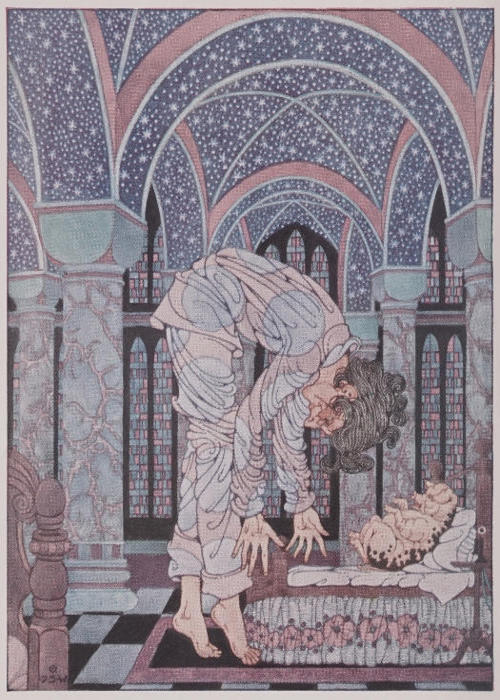

When the little man had mounted well up toward the top of Snythergen he placed a fever thermometer in a knothole, which happened to lead into Snythergen’s mouth. Leaving it there[74] he descended to the ground, and wrapped a rubber bandage about his trunk, winding it so tightly that Snythergen barely avoided a cry of pain. One look at the indicator gave the tree doctor a shock.

“Sap pressure 110!” he cried. “There must be some mistake!”

Again and again he tried it and each time it registered 110.

“Surely there is something very strange here!” said the doctor. “Never have I heard of a tree with a sap pressure over 30. Why, it’s as high as the blood pressure of a boy!”

But the tree doctor was to receive another shock when he tapped Snythergen’s bark and listened with a tree stethoscope.

“Why, I didn’t think there was a tree in the world with such a violent throb. It’s as fast and strong as the heart beat of a child!”

But the greatest shock of all was to come when he climbed up to read the fever thermometer. He could hardly believe his own eyes when he saw what it registered.

“I never heard of a tree having such a temperature!” he cried. “It is as high as a boy’s.” Indeed the temperature was so much like a boy’s, the little doctor so far forgot himself as to shout:

“Stick out your tongue!”

“Stick out your tongue!”

This command took Snythergen by surprise,[77] and without thinking, he stuck his tongue out through the knothole, and when the little man saw it, he was so frightened he nearly fell from the ladder. Snythergen drew back his tongue in a hurry. The doctor puzzled and puzzled over the matter. Finally he concluded that he must have seen a squirrel’s red head.

There were so many strange things about the tree that the physician made up his mind in the interest of science to watch it day and night. He camped in a tent beside Snythergen, and only when he retired for a cat nap did he take his owl-like eyes from the tree. Even then Snythergen could not attempt to escape, or even stretch his limbs and relax, for the little man was a light sleeper and would rush out at the faintest unusual rustle of a twig.

Snythergen realized more than ever that the life of a tree is not all joy. His roots were sore and calloused from standing in one position. A leg or an arm would go to sleep because he dared not move it. He was numb all over, besides being cold, tired and hungry. He gazed longingly into the dining room. His mouth watered and he swallowed hard at the sight of the rich home cooking. How eagerly would he[78] have eaten the crusts the farmer’s little boy tried to hide under the edge of his plate! How he would have enjoyed taking the heaping plate of his tormentor, the little doctor, when the latter’s back was turned! But usually the window was closed, or some one was looking.

All the next morning Snythergen watched impatiently for Squeaky to appear on the opposite shore of the lake. He wondered why Sancho Wing did not come, but he could not know that Sancho was spending all of his time keeping track of the bear, who was in a revengeful mood and very restless. The ice had given him mental chilblains and the pain served as a reminder, making him more determined than ever to find and punish his persecutors.

About eleven o’clock Snythergen thought he saw a little movement in the bushes along the opposite shore of the lake. Then he recognized Squeaky’s peculiar wobbling walk. So delighted was he that he forgot the little doctor, and waved his branches excitedly. Squeaky answered. Snythergen signaled back that he was hungry and wanted some bread and butter with sugar on it—not an easy message for a tree to wave to a pig all the way across a lake. It took ingenuity to figure it out, and this is how he did it.

First Snythergen held out two limbs and pretended he was carrying a slice of bread in each hand. Next he rubbed an upper branch over these in such a way that Squeaky would know he wanted them spread with butter—and not to save on the butter. Then he bent his top boughs down, shaking them vigorously to make the pig understand that he wanted all the powdered sugar the bread would hold.

The little tree doctor was watching this performance with the utmost amazement.

“Why, I believe that tree has the St. Vitus’ Dance!” said the physician. “I never heard of a tree having it before. The discovery will make me famous. But I must prove it beyond a doubt or the scientists will never give me credit for it. In order to be sure I must give it the brass band test for that is the only reliable one. If our leafy friend here dances when the band plays I will know then that he has the St. Vitus’ Dance. If he does not, I may have to ‘tree-pan’ him to find out.”

Snythergen shuddered at the horrible thought of being trepanned—or in other words of having his skull operated on so his brain could be examined. As he talked to himself the little man danced excitedly about.

“The fit seems to be over,” he said breathlessly,[80] when Snythergen had waved his last signal to Squeaky.

“Dinner is ready,” called the farmer’s wife from the house.

“I will be right in,” answered the doctor, for he had decided to wait until he had eaten before going for the musicians.

The chance of running away to meet Squeaky and bread and butter had become more and more doubtful now the little doctor had seen him waving, and Snythergen was so hungry! He looked in through the dining-room window to see what the family was having to eat. It was a very hot day and the window was wide open. The farmer was placing a steaming plate of meat and potatoes before the doctor, who sat facing the window where he could watch the tree while he ate. The rich odor of food arose to Snythergen’s nostrils and it was more than he could resist.

“I must have something soon, or I’ll fall over,” he said to himself. “I wonder how I can manage it?” For a moment he thought, then an idea came to him. Leaning over, with his top branches he beat violently upon the roof of the house.

“What’s happening upstairs!” cried the farmer’s wife in alarm.

“It sounds as if the roof was falling in!” said the farmer leaping from his chair, and they rushed out of the room. In his excitement the doctor followed part way upstairs. The instant he was gone Snythergen reached a forked limb into the dining room and helped himself to the doctor’s dinner.

“He will never miss it,” he thought. “He’s too excited to eat, anyway.”

When the physician returned and found his dinner had disappeared, he was dumbfounded.

“What has become of it?” he cried, jumping up and looking under the table. He searched behind the chairs, in the closets, and even in the hall. In each new place he cried out over and over again, “Who took my dinner? Who took my dinner?”

While he was thus occupied Snythergen had an opportunity to eat, but he was in such haste to be done before his tormentor looked out of the window again, that he entirely forgot his table manners and crammed and stuffed his mouth with his twigs. The farmer and his wife had found nothing out of the way upstairs to explain the noise on the roof, and when they returned the little man was still fussing about, looking in the china closet, the napkin and silver drawers, and other absurd places.

“What’s up now?” demanded the farmer, who was getting a bit tired of the tree doctor’s queer ways. The farmer’s wife too was looking on suspiciously. She did not fancy having a stranger poking into her drawers and closets.

The physician tried to explain but they only laughed at him.

“The very idea!” cried the farmer’s wife. “Nobody could come into the room and take your dinner away without your knowing it!”

“Besides, who would want something to eat that bad around here,” said the farmer. “Everybody knows we feed every tramp that comes along!”

The little doctor felt uncomfortable and embarrassed because they laughed at him, and he barely touched the second plate of food the farmer served him. Snythergen was right, he was too excited to eat. Scarcely could he wait until the dinner was over for the farmer to drive him to town to get the band.

Thereafter he would strike a tree-like pose not so difficult to hold

The doctor’s departure was Snythergen’s cue to escape. Cautiously he stole away from the house and waited for an opportunity to cross the lake. The man next door was plowing, and Snythergen had to be very careful. While the man’s back was turned he ran as fast as possible, but when he plowed toward him, Snythergen[85] had to stand motionless and trust that his altered position would not be seen; and whatever position Snythergen’s limbs were in when the farmer turned toward him, had to be held while the plow traveled the whole length of the field. Once when the man approached, Snythergen was in the lake with one root raised ready to step, and he dared not lower his root or make any other movement until the farmer had walked the whole distance and had turned his back again. Thus he stood balancing himself for fifteen minutes, and to make matters worse he had been caught with his branches pointing to the sky. The painful experience of holding this position taught him a lesson, and thereafter when the plow neared the end of the row, he would strike a tree-like pose not so difficult to hold. Luckily the farmer was near-sighted, and failed to remark the strange apparition of a tree wading across the lake up to its branch pits in water.

In spite of various discomforts Snythergen made the crossing successfully and had no difficulty in following the trail home. On reaching the house he found Sancho Wing and Squeaky feverishly preparing the bread and butter and sugar to take to him. They were overjoyed to see him, but Snythergen was too tired[86] to sit up and visit. He had been standing on his roots so long he was only too glad to lie down and sleep. But before he would close his eyes, they had to assure him that the woodchoppers had left the forest.

When Snythergen woke up, Sancho Wing was sorry to have to tell him that the bear had resumed his midnight prowlings and might call upon them at any time.

“We must prepare to defend ourselves,” said Sancho wisely, as he perched on Snythergen’s ear.

“How can a pig defend himself from a bear?”[88] asked Squeaky, absent-mindedly biting one of Snythergen’s toes.

“Simple,” said Sancho. “Give him what he wants. You flatter yourself if you think he wants you. He is after food, that is all.”

“Well, let us give it to him,” said Snythergen, “as long as he doesn’t share Squeaky’s weakness for toes.”

“Just what I was thinking,” said Sancho. “Let us set a bear lunch every night, and to make sure he will find it we must spread it in a circle around the house. Then, no matter from what direction the bear approaches, he will find something to eat across his path.”

“I’ve heard that round foods make people fat,” said Snythergen. “Maybe food served on a round table will make the bear fat.”

“That wouldn’t help us any,” said Sancho Wing, “for fat bears are as dangerous as lean ones.”

“Won’t it be pretty expensive boarding a bear?” asked Squeaky.

“Of course,” said Sancho Wing, “but if we find we can’t afford to feed him we can build an airplane and journey to a land where there are no bears. We may have to travel to the end of the sky to find such a place, but who cares?”

At Sancho Wing’s suggestion Snythergen set to work at once to build a supper table. When completed it encircled the house and resembled a well planed sidewalk. That night Squeaky set the table, being careful to spread the food so thin that it went all the way around.

There were so many hungry beings in the forest besides the bear that Sancho Wing had to keep a keen look-out for thieves, and his duties kept him very busy. One minute he would be scanning the woods from the top of his tower, the next he would dive down to the round table to scream at the small animals that were forever nibbling. Often he was obliged to call Squeaky and even Snythergen, to chase away the larger birds, the rabbits, and the squirrels. Each night they set the table as late as they dared to prevent so much of the food being stolen.

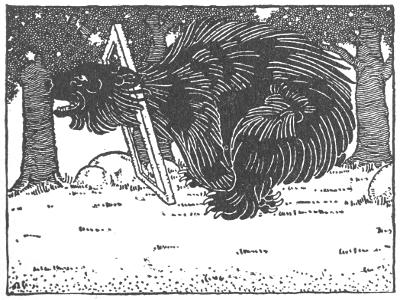

On the evening of the fourth day the bear paid them a call, but he did not attempt to enter the house. The lunch on the round table stopped him. Walking all the way around he ate everything, then went around again to see if he had overlooked any crumbs. Squeaky happened to be very fussy about table manners, and he had scattered salad forks, finger bowls and napkins here and there hoping the bear would take the hint; but the big beast paid no attention[90] to them, and ate only with his knife and his paws in the most vulgar manner.

The bear was a hearty eater and what made matters even more serious, his appetite was growing. Soon it was evident that the food supply would not last much longer. The three friends realized that the “outer works” as they called the lunch table, was all that stood between them and disaster. And now in spite of their efforts they were unable to keep abreast of the beast’s increasing desire for food. There was nothing to do but to adopt Snythergen’s plan of building an airplane and fleeing to a land where there were no bears. They began work immediately and hurried all they could, but even so they ran out of food when there was still another day’s work to be done on the plane.

“If we can only keep him away to-night we are saved,” said Squeaky.

Then went around again to see if he had overlooked any crumbs

Snythergen dressed in his tree suit to be ready in case of trouble. Carefully Squeaky set the round table with what few morsels he could scrape up, arranging them to appear like a bountiful meal. The bear came a little earlier than usual that night, and made short work of the slim repast. Indeed Snythergen had just time to tiptoe out and take his place as a tree when the beast devoured the last bite of food[93] and looked hungrily about for more. In a stage whisper Snythergen called to Squeaky who was still in the house, to warn him of his danger. Fortunately the pig was awake and whispered back that he was coming. A moment later Snythergen heard the most awful squealing and Squeaky came running out, the bear after him. Sancho Wing was flying above the pig to encourage him.

“Don’t squeal so! Save your breath for running!” he cried. The bear was gaining. Bending over Snythergen touched his roots with his top limbs, to be ready. But Squeaky was slow on his feet, even when running for his life, and already the bear was upon him. Sure of his prey the great beast slowed up to brace himself for a lunge. Quick as lightning Snythergen shot out his branches and grabbed the pig, lifting him to safety.

The bear did not suspect that a tree could come to the rescue of a pig, and so sure was he that his victim could not escape, he closed his eyes as he struck at him. But he opened them quickly enough when his paw struck nothing solider than air. The pig had vanished! But where, and how? His disappearance had been as sudden as it was complete, and the bear had not an idea where to look for him. Too surprised[94] for growls, the big brute rushed distractedly about looking here and there. Naturally it did not occur to him to look up into the tree tops, for whoever heard of a pig climbing a tree!

“Did I really see a pig at all?” thought the bear, “or am I losing my mind! It wouldn’t be surprising with that neuralgia from the ice!”

He paused as the thought struck him: “I wonder if by any possibility it could have been the Grasshopper Pig?”

The day before the bear had been reading the story of the Grasshopper Pig to a neighbor’s cubs out of a book of nursery rhymes called “Mother Moose.” This pig seemed to disappear in much the same way as the one in the story. For the Grasshopper Pig is said to make long leaps so suddenly that he cannot be seen making them. One moment he is standing beside you and the next, bingo! he is a hundred feet away!

“Well, if it’s the Grasshopper Pig, I might as well save myself the bother of looking,” thought the bear; “no one has ever been able to catch him!”

As he came to the place where Snythergen was standing he sniffed curiously, and although[95] Snythergen did his best to stand still, it is not surprising that he failed. For it takes something stronger than flesh and blood to stand still while a bear walks around you and stops to paw your bark, to rub his hungry head against your trunk, or to try his vicious teeth on your roots.

No wonder the trunk of the tree trembled and its branches twitched nervously. The big animal was puzzled by the shaking as he nosed about Snythergen’s extremities and clawed at them. It was more than wood and sap could stand and the badly frightened boy was weakening rapidly. Again Snythergen felt the sinking feeling that had come over him the day the small boy had crawled out on an upper branch. Tottering from side to side, he caught himself with an effort.

For a while Squeaky managed somehow to hold on with his teeth and legs, but his teeth were chattering and he was shivering all over with terror. And a sudden twist of the tree shook him so violently that he lost his footing. Desperately he reached for a limb. He missed it, and fell crashing through the branches!

With remarkable quickness of thought Snythergen brought his lower limbs together to form a basket in which to catch the falling pig.[96] Plunging through the branches Squeaky landed upon Snythergen’s leafy chest, safe for the time being, but stunned and out of breath.

“It is the Grasshopper Pig,” cried the bear, seeing him, “and I’ve got him up a tree!”

Eager to get at Squeaky, he pawed Snythergen’s tender bark and pushed against him roughly.

All this time Sancho Wing’s little brain had been puzzling to find some way to save his pals. Flying a little distance and hiding among the leaves he hallooed at the top of his piping voice, hoping the woodchoppers might be in the forest, and hear him. Anxiously the bear glanced around. The hallooing reminded him of the sound the hunters made, and thinking best not to take any chances he strolled away cautiously.

The three friends breathed a sigh of relief and Squeaky began to dance for joy.

“We haven’t escaped yet,” Sancho Wing reminded him. “The bear will return when he discovers the hunters are not after him. We must finish the airplane immediately.”

At once they resumed work and kept at it until the plane was completed. And now it needed only to be tested. It was new and stiff and repeatedly the engine refused to start, though Snythergen cranked it again and again.[97] It was nearing the bear’s lunch time and Sancho Wing flew away to the cave to see what the big brute was up to. Soon he came back out of breath, panting so hard he could scarcely speak, for he had raced all the way.

“Quick, quick!” he gasped.

Snythergen and Squeaky understood and Snythergen cranked so furiously he was wet through with perspiration.