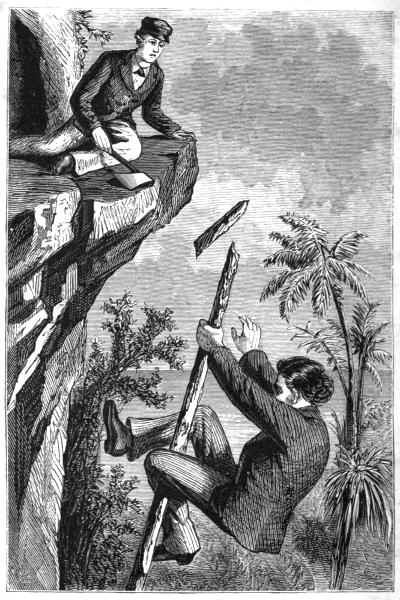

Pierre Foiled.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Sportman's Club Afloat, by Harry Castlemon This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: The Sportman's Club Afloat Author: Harry Castlemon Release Date: December 20, 2019 [EBook #60984] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SPORTMAN'S CLUB AFLOAT *** Produced by David Edwards and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Pierre Foiled.

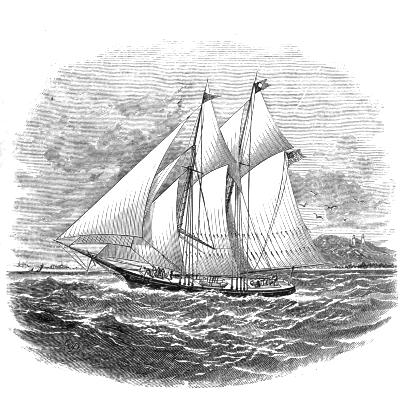

THE

SPORTSMAN’S CLUB

AFLOAT.

BY HARRY CASTLEMON,

AUTHOR OF “THE GUNBOAT SERIES,” “GO AHEAD SERIES,”

“ROCKY MOUNTAIN SERIES,” ETC.

PHILADELPHIA:

PORTER & COATES,

CINCINNATI:

R. W. CARROLL & CO.

FAMOUS CASTLEMON BOOKS.

GUNBOAT SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. Illustrated. 6 vols. 16mo. Cloth, extra, black and gold.

ROCKY MOUNTAIN SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. Illustrated. 3 vols. 16mo. Cloth, extra, black and gold.

SPORTSMAN’S CLUB SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. Illustrated. 3 vols. 16mo. Cloth, extra, black and gold.

GO-AHEAD SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. Illustrated. 3 vols. 16mo. Cloth, extra, black and gold.

FRANK NELSON SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. Illustrated. 3 vols. 16mo. Cloth, extra, black and gold.

BOY TRAPPER SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. Illustrated. 3 vols. 16mo. Cloth, extra, black and gold.

ROUGHING IT SERIES. By Harry Castlemon. Illustrated. 16mo. Cloth, extra, black and gold.

Other Volumes in Preparation.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1874, by

R. W. CARROLL & CO.,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| On the Gulf again | Page 5 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| A Surprise | 25 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Outwitted | 45 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Fairly afloat | 66 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| The Deserters | 88 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| A Chapter of Incidents | 111 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Don Casper | 129 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Chase rises to explain | 148 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Wilson runs a race | 164 |

| [iv]CHAPTER X. | |

| A Lucky Fall | 181 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| “Sheep Ahoy!” | 198 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| The Banner under fire | 214 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| The Spanish Frigate | 231 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| The Yacht Lookout | 254 |

“I assure you, gentlemen, that you do not regret this mistake more than I do. I would not have had it happen for anything.”

It was the captain of the revenue cutter who spoke. He, with Walter Gaylord, Mr. Craven, Mr. Chase and the collector of the port, was standing on the wharf, having just returned with his late prisoners from the custom-house, whither the young captain of the Banner had been to provide himself with clearance papers. The latter had narrated as much of the history of Fred Craven’s adventures, which we have attempted to describe in the first[6] volume of this series, as he was acquainted with, and the recital had thrown the revenue captain into a state of great excitement. The yacht was anchored in the harbor, a short distance astern of the cutter, and alongside the wharf lay the only tug of which the village could boast, the John Basset, which Mr. Chase and Mr. Craven had hired to carry them to Lost Island in pursuit of the smugglers.

“There must be some mistake about it,” continued the captain of the cutter. “A boy captured by a gang of smugglers and carried to sea in a dugout! I never heard of such a thing before. I know you gentlemen will pardon me for what I have done, even though you may think me to have been over-zealous in the discharge of my duty. Your yacht corresponds exactly with the description given me of the smuggler.”

“You certainly made a great blunder,” said Mr. Craven, who was in very bad humor; “and there is no knowing what it may cost us.”

“But you can make some amends for it by starting for Lost Island at once,” said Mr. Chase. “You will find two of the smugglers there, and perhaps you can compel them to tell you something of the vessel of which you are in search. More than[7] that, they have made a prisoner of my son, and he knows what has become of Fred Craven.”

“I am at your service. I will sail again immediately, and I shall reach the island about daylight. If you gentlemen with your tug arrive there before I do and need assistance, wait until I come. Captain Gaylord, if you will step into my gig I shall be happy to take you on board your vessel. You may go home now, and these gentlemen and myself will attend to those fellows out there on Lost Island. If we find them we shall certainly capture them.”

“And when you do that, I shall not be far away,” replied Walter.

“Why, you are not going to venture out in this wind again with that cockle-shell, are you?” asked the captain, in surprise.

“I am, sir. I built the Banner, and I know what she can do. She has weathered the Gulf breeze once to-night, and she can do it again. I am not going home until I see Fred Craven safe out of his trouble. In order to find out where he is, I must have an interview with Henry Chase.”

Mr. Craven and Mr. Chase, who were impatient to start for Lost Island again, walked off toward the tug, and Walter stepped down into the captain’s[8] gig and was carried on board the Banner. His feelings as he sprang on the deck of his vessel were very different from those he had experienced when he left her. The last time he clambered over her rail he was a prisoner, guarded by armed men and charged with one of the highest crimes known to the law. Now he was free again, the Banner was all his own, and he was at liberty to go where he pleased.

“Mr. Butler, send all the cutter’s hands into the gig,” said the revenue captain, as he sprang on board the yacht.

“Very good, sir,” replied the lieutenant. “Pass the word for all the prize crew to muster on the quarter-deck.”

“Banner’s men, ahoy!” shouted Walter, thrusting his head down the companion-way. “Up you come with a jump. Perk, get under way immediately.”

For a few seconds confusion reigned supreme on board the yacht. The revenue men who had been lying about the deck came aft in a body; those who had been guarding the prisoners in the cabin tumbled up the ladder, closely followed by the boy crew, who, delighted to find themselves once more[9] at liberty, shouted and hurrahed until they were hoarse.

“All hands stand by the capstan!” yelled Perk.

“Never mind the anchor,” said Walter. “Get to sea at once.”

“Eugene, slip the chain,” shouted Perk. “Stand by the halliards fore and aft.”

“Hold on a minute, captain,” exclaimed the master of the cutter, who had been extremely polite and even cringing ever since he learned that the boys who had been his prisoners were the sons of the wealthiest and most influential men about Bellville. “I should like an opportunity to muster my crew, if you please.”

“Can you not do that on board your own vessel?” asked Walter.

“I might under ordinary circumstances, but of late my men have been seizing every opportunity to leave me, and I am obliged to watch them very closely. They have somehow learned that a Cuban privateer, which has escaped from New York, is lying off Havana waiting for a crew, and they are deserting me by dozens. There may be some deserters stowed away about this yacht, for all I know.”

“Never mind,” replied Walter, who was so impatient to get under way that he could think of nothing else. “If there are, I will return them to you when I meet you at Lost Island. Good-bye, captain, and if you see me on the Gulf again don’t forget that I have papers now.”

By this time the Banner was fairly under sail. Perk saw that the revenue men were still on board, and knew that they would have some difficulty in getting into their boat when the yacht was scudding down the harbor at the rate of eight knots an hour, but that made no difference to him. His commander had ordered him to get under way, and he did it without the loss of a moment. He slipped the anchor, hoisted the same sails the Banner had carried when battling with the Gulf breeze three hours before, and in a few seconds more was dragging the revenue gig through the water at a faster rate than she had ever travelled before. Her crew tumbled over the rail one after another, and when they were all in the boat Bab cast off the painter, and the Banner sped on her way, leaving the gig behind.

“What was the matter, Walter? did they really take us for smugglers?” asked the Club in concert,[11] as they gathered about the young captain. “What did you tell them; and has anything new happened that you are going to sea again in such a hurry?”

“Ask your questions one at a time and they will last longer,” replied Walter; who then proceeded in a very few words to explain matters. The captain of the cutter had really been stupid enough to believe that the Banner was a smuggler, he said, and so certain was he of the fact that he would listen to no explanation. Mr. Craven had told him the story of the two smugglers who had taken a prisoner to Lost Island, but the revenue commander would not believe a word of it, and persisted in his determination to take his captives to the village. When they arrived there and the collector of the port had been called up, of course the matter was quickly settled, and then the captain appeared to be very sorry for what he had done, and was as plausible and fawning as he had before been insolent and overbearing. Pierre and his father would certainly be captured now, for Mr. Chase and Mr. Craven had chartered the John Bassett to carry them to Lost Island, and the revenue captain would also sail at once and render all the assistance in his power.

“Humph!” exclaimed Eugene, when Walter[12] finished his story, “We don’t want any of his help, or the tug’s either. Crack on, Walter, and let’s reach the island and have the work over before they get there.”

“That would be useless,” answered the cautious young captain. “The Banner’s got as much as she can carry already; and besides we can’t expect to compete with a tug or a vessel of the size of the cutter. If we reach the island in time to see Chase rescued, I shall be satisfied. If any of you are in want of sleep you may go below, and Bab and I will manage the yacht.”

But none of the Club felt the need of rest just then. Things were getting too exciting. With a couple of smugglers before them to be captured, two swift rival pursuers behind, to say nothing of the gale and the waves which tossed the staunch little Banner about like a nut-shell, and the intense impatience and anxiety they felt to learn something of the situation of the missing secretary—under circumstances like these sleep was not to be thought of. They spent the next half hour in discussing the exciting adventures that had befallen them since their encounter with Bayard Bell and his crowd, and then Eugene, after sundry emphatic injunctions from his[13] brother to keep his weather eye open and mind what he was about, took Perk’s place at the wheel, while the latter, who always acted as ship’s cook in the absence of Sam the negro, went below to prepare the eatables which Walter had provided before leaving home. The baskets containing the provisions had been taken into the galley. In the floor of this galley was a small hatchway leading into the hold where the water-butts, fuel for the stove, tool-chests, ballast, and extra rigging were stowed away; and when Perk approached the galley from the cabin he was surprised to see that the hatchway was open, and that a faint light, like that emitted by a match, was shining through it from below.

The sight was a most unexpected one, and for an instant Perk stood paralyzed with alarm. His face grew as pale as death, and his heart seemed to stop beating. Who had been careless enough to open that hatch and go into the hold with an uncovered light? Eugene of course—he was always doing something he had no business to do—and he had set fire to some of the combustible matter there. Perk had often heard Uncle Dick tell how it felt to have one’s vessel burned under him, and shuddering at the recital, had hoped most fervently that[14] he might never know the feeling by experience. But now he was in a fair way to learn all about it. Already he imagined the Banner a charred and smoking wreck, and he and his companions tossing about on the waves clinging to spars and life-buoys. These thoughts passed through Perk’s mind in one second of time; then recovering the use of his legs and his tongue, he sprang forward and shouted out one word which rang through the cabin, and fell with startling distinctness upon the ears of the watchful crew on deck.

“Fire!” yelled Perk, with all the power of his lungs.

That was all he said, but it was enough to strike terror to the heart of every one of the boy sailors who heard it. Somebody else heard it too—some persons who did not belong to the Banner, and who had no business on board of her. Perk did not know it then, but he found it out a moment afterwards when he entered the galley, for, just as he seized the hatch, intending to close the opening that led into the hold and thus shut out the draft, a grizzly head suddenly appeared from below, one brawny hand holding a hatchet, was placed upon[15] the combings, and the other was raised to prevent the descent of the hatch.

If it is possible for a boy to see four things at once, to come to a conclusion on four different points, to act, and to do it all in less than half a second of time, Perk certainly performed the feat. He saw that the man who so suddenly made his appearance in the hatchway was dressed in the uniform of the revenue service; that he had a companion in the hold; that the latter was in the act of taking an adze from the tool-chest; and that he held in his hand a smoky lantern which gave out the faint, flickering light that shone through the hatchway.

When the boy had noted these things, some scraps of the conversation he had overheard between Walter and the revenue captain came into his mind. These men were deserters from the cutter, and he had discovered them just in time to prevent mischief. They were preparing to make an immediate attack upon the Banner’s crew, and had provided themselves with weapons to overcome any opposition they might meet. If they were allowed to come on deck they would take the vessel out of the hands of her crew, and shape her course toward[16] Havana, where the Cuban privateer was supposed to be lying. Perk did not object to the men joining the privateer if they felt so inclined—that was the revenue captain’s business, and not his—but he was determined that they should not assume control of the Banner, and take her so far into the Gulf in such a gale if he could prevent it.

“Avast, there!” exclaimed the sailor, in a savage tone of voice, placing his hand against the hatch to keep Perk from slamming it down on his head. “We want to come up.”

“But I want you to stay down,” replied the boy; “and we’ll see who will have his way.”

The sailor made an upward spring, and Perk flung down the hatchway at the same moment, throwing all his weight upon it as he did so. The result was a collision between the man’s head and the planks of which the hatchway was composed, the head getting the worst of it. The deserter was knocked over on the opposite side of the opening and caught and held as if he had been in a vise, his breast being pressed against the combings, and the sharp corner of the hatch, with Perk’s one hundred and forty pounds on top of it, falling across his shoulders.

“Now just listen to me a minute, and I’ll tell you what’s a fact,” said the boy, who, finding that the enemy was secured beyond all possibility of escape, began to recover his usual coolness and courage; “I’ve got you.”

“But you had better let me go mighty sudden,” replied the sailor, struggling desperately to seize Perk over his shoulder. “Push up the hatch, Tom,” he added, addressing his confederate below.

All these events, which we have been so long in narrating, occupied scarcely a minute in taking place. Walter sprang toward the companion-way the instant Perk’s wild cry fell upon his ears, and pale and breathless burst into the cabin, followed by Bab and Wilson. When he opened the door he discovered Perk in the position we have described. A single glance at the uniform worn by the man whose head and shoulders were protruding from the hatchway, was enough to explain everything.

“Now, here’s a go!” exclaimed Bab, in great amazement.

“Yes; and there’ll be a worse go than this if you don’t let me out,” replied the prisoner, savagely. “Push up the hatch, Tom.”

“The revenue captain was right in his suspicions[18] after all, wasn’t he?” said Walter, as he and Wilson advanced and wrested the hatchet from the sailor’s hand. “I don’t think that your attempt to reach Cuba will be very successful, my friend.”

“That remains to be seen. Push up the hatch, Tom. If I once get on deck I’ll make a scattering among these young sea monkeys. Push up the hatch, I tell you.”

This was the very thing the man below had been trying to do from the first, but without success. The hatchway was small, and was so nearly filled by the body of the prisoner, who was a burly fellow, that his companion in the hold had no chance to exert his strength. He could not place his shoulders against the hatch, and there was no handspike in the hold, or even a billet of wood strong enough to lift with. He breathed hard and uttered a good many threats, but accomplished nothing.

“I wish now I had given that captain time to muster his men,” said Walter. “This fellow is a deserter from the cutter, of course; but he shall never go to Havana in our yacht. Bab, go on deck and bring down three handspikes.”

Bab disappeared, and when he returned with the[19] implements, Walter took one and handed Wilson another.

“Now, Perk,” continued the young captain, “take a little of your weight off the hatch and let that man go back into the hold. We’d rather have him down there than up here.”

“I know it,” said Perk. “But just listen to me, and I’ll tell you what’s a fact: Perhaps he won’t go back.”

“I think he will,” answered Walter, in a very significant tone of voice. “He’d rather go back of his own free will than be knocked back. Try him and see.”

Perk got off the hatch, and the sailor, after taking a look at the handspikes that were flourished over his head, slid back into the hold without uttering a word; while Bab, hardly waiting until his head was below the combings, slammed down the hatch, threw the bar over it and confined it with a padlock. This done, the four boys stood looking at one another with blanched cheeks.

“Where’s the fire, Perk?” asked Walter.

“There is none, I am glad to say. The light I saw shining from the hold came from a lantern that[20] those fellows have somehow got into their possession.”

“Well, I’d rather fight the deserters than take my chances with a fire if it was once fairly started,” replied Walter, much relieved. “How many of them are there?”

“Only two that I saw. But they can do a great deal of mischief if they feel in the humor for it.”

“That is just what I was thinking of,” chimed in Bab. “You take it very coolly, Walter. Don’t you know that if they get desperate they can set fire to the yacht, or bore through the bottom and sink her?”

“I thought of all that before we drove that man back there; but what else could we have done? If we had brought him up here to tie him, he would have attacked us as soon as he touched the deck, and engaged our attention until his companion could come to his assistance. Perk, you and Wilson stay down here and guard that hatch. Call me if you hear anything.”

“I hear something now,” said Wilson.

“So do I,” exclaimed Perk. “I hear those fellows swearing and storming about in the hold; but they won’t get out that way, I guess.”

Walter and Bab returned to the deck and found Eugene in a high state of excitement, and impatient to hear all about the fire. He was much relieved, although his excitement did not in the least abate, to learn that the danger that had threatened the yacht was of an entirely different character, and that by Perk’s prompt action it had been averted, at least for the present. Of course he could not stay on deck after so thrilling a scene had been enacted below. He gave the wheel into his brother’s hands, and went down into the galley to see how things looked there. He listened in great amazement to Perk’s account of the affair, and placed his ear at the hatch in the hope of hearing something that would tell him what the prisoners were about. But all was silent below. The deserters had ceased their swearing and threatening, and were no doubt trying to decide what they should do next.

The crew of the yacht were not nearly so confidant and jubilant as they had been before this incident happened, and nothing more was said about the lunch. The presence of two desperate characters on board their vessel was enough to awaken the most serious apprehensions in their minds. During the rest of the voyage they were on the[22] alert to check any attempt at escape on the part of the prisoners, and those on deck caught up handspikes and rushed down into the cabin at every unusual sound. But the journey was accomplished without any mishap, and finally the bluffs on Lost Island began to loom up through the darkness. After sailing around the island without discovering any signs of the smugglers, the Banner came about, and running before the wind like a frightened deer, held for the cove into which Chase and his captors had gone with the pirogue a few hours before. The young captain, with his speaking-trumpet in his hand, stood upon the rail, the halliards were manned fore and aft, and the careful Bab sent to the wheel. These precautions were taken because the Banner was now about to perform the most dangerous part of her voyage to the island. The entrance to the cove was narrow, and the cove itself extended but a short distance inland, so that if the yacht’s speed were not checked at the proper moment, the force with which she was driven by the gale, would send her high and dry upon the beach.

The little vessel flew along with the speed of an arrow, seemingly on the point of dashing herself in pieces on the rocks, against which the surf beat with[23] a roar like that of a dozen cannon; but, under the skilful management of her young captain, doubled the projecting point in safety, and was earned on the top of a huge wave into the still waters of the cove. Now was the critical moment, and had Walter been up and doing he might have saved the Banner from the catastrophe which followed. But he did not give an order, and it is more than likely that he would not have been obeyed if he had. He and his crew stood rooted to the deck, bewildered by the scene that burst upon their view. A bright fire was roaring and crackling on the beach, and by the aid of the light it threw out, every object in the cove could be distinguished. The first thing the crew of the Banner noticed was a small schooner moored directly in their path—the identical one they had seen loading at Bellville; the second, a group of men, one of whom they recognised, standing on the beach; and the third, a cave high up the bluff, in the mouth of which stood one of the boys of whom they were in search, Henry Chase, whose face was white with excitement and terror. He was throwing his arms wildly about his head, and shouting at the top of his voice.

“Banner ahoy!” he yelled.

“Hallo!” replied Walter, as soon as he found his tongue.

“Get away from here!” shouted Chase. “Get away while you can. That vessel is the smuggler, and Fred Craven is a prisoner on board of her.”

But it was too late for the yacht to retreat. Before Walter could open his mouth she struck the smuggling vessel with a force sufficient to knock all the boy crew off their feet, breaking the latter’s bowsprit short off, and then swung around with her stern in the bushes, where she remained wedged fast, with her sails shaking in the wind.

The last time we saw Henry Chase he was sitting in the mouth of “The Kitchen”—that was the name given to the cave in which he had taken refuge after destroying the pirogue—with his axe in his hand, waiting to see what Coulte and Pierre, who had just disappeared down the gully, were going to do next. He had been holding a parley with his captors, and they, finding that he had fairly turned the tables on them, and that he was not to be frightened into surrendering himself into their hands again, had gone off to talk the matter over and decide upon some plan to capture the boy in his stronghold. Now that their vessel was cut to pieces, they had no means of leaving the island, and consequently they were prisoners there as well as Chase. He had this slight advantage of them, however: when the yacht arrived he would be set at liberty,[26] while they would in all probability be secured and sent off to jail, where they belonged.

“I’ll pay them for interfering with me when I wasn’t troubling them,” chuckled Chase, highly elated over the clever manner in which he had outwitted his captors. “I think I have managed affairs pretty well. Now, if the yacht would only come, I should be all right. It is to Walter’s interest to assist me, if he only knew it; for I can tell him where Fred Craven is. But I can safely leave all that to Wilson. He is a friend worth having, and he will do all he can for me. What’s going on out there, I wonder?”

The sound that had attracted the boy’s attention was a scrambling among the bushes, accompanied by exclamations of anger and long-drawn whistles. The noise came down to him from the narrow crevice which extended to the top of the bluff, and from this Chase knew that Coulte and Pierre were ascending the rocks on the outside, and that they were having rather a difficult time of it. He wondered what they were going to do up there. They could not come down into the cave through the crevice, for it was so narrow that Fred Craven himself would have stuck fast in it. The boy took his[27] stand under the opening and listened. He heard the two men toiling up the almost perpendicular sides, and knew when they reached the summit. Then there was a sound of piling wood, followed by the concussion of flint and steel; and presently a feeble flame, which gradually increased in volume, shot up from the top of the bluff.

“That’s a signal,” thought Chase, with some uneasiness. “Who in the world is abroad on the Gulf, on a night like this, that is likely to be attracted by it? It must be the smuggling vessel, for I remember hearing Mr. Bell say that he should start for Cuba this very night. I pity Fred Craven, shut up in that dark hold, with his hands and feet tied. I’ve had a little experience in that line to-night, and I know how it feels.”

Chase seated himself on the floor of the cave, under the crevice, rested his head against the rocks, and set himself to watch the two men, whose movements he could distinctly see as they passed back and forth before the fire. In this position he went off into the land of dreams and slept for an hour, at the end of which time he awoke with a start, and a presentiment that some danger threatened him. He sprang to his feet, catching up his axe and looking[28] all around the cave; and as he did so, a dark form, which had been stealthily creeping toward him, stopped and stretched itself out flat on the rocks, just in time to escape his notice.

“Was it a dream?” muttered Chase, rubbing his eyes. “I thought some one had placed a pole against the bluff and climbed into the cave; but of course that couldn’t be, for Coulte and his son have no axe with which to cut a pole.”

The boy once more glanced suspiciously about his hiding-place, which, from some cause, seemed to be a great deal lighter now than it was when he went to sleep, and hurrying to the mouth looked down into the gully below. To his consternation, he found that the danger he had apprehended in his dream was threatening him in reality. A pole had been placed against the ledge at the entrance to the cave, and clinging to it was the figure of a man, who had ascended almost to the top. It was Pierre. How he had managed to possess himself of the pole was a question Chase asked himself, but which he could not stop to answer. His enemy was too near and time too precious for that.

“Hold on!” shouted Pierre, when he saw the boy swing his axe aloft.

“You had better hold on to something solid yourself,” replied Chase, “or you will go to the bottom of the ravine. You are as near to me as I care to have you come.”

The axe descended, true to its aim, and cutting into the pole at the point where it touched the ledge severed it in twain, and sent Pierre heels-over-head to the ground. When this had been done, and Chase’s excitement had abated so that he could look about him, he found that he had more than one enemy to contend with. He was astonished beyond measure at what he saw, and he knew now why “The Kitchen” was not as dark as it had been an hour before. The whole cove below him was brilliantly lighted up by a fire which had been kindled on the beach, and the most prominent object revealed to his gaze was a little schooner which was moored to the trees. The sight of her recalled most vividly to his mind the adventure of which he and Fred Craven had been the heroes. It was the Stella—the smuggling vessel. Her crew were gathered in a group at the bottom of the gully, and Chase’s attention had been so fully occupied with Pierre that he had not seen them. As he ran his eye over the group he saw that there was one man in it besides[30] Pierre who was anything but a stranger to him, and that was Mr. Bell, who stood a little apart from the others, with his tarpaulin drawn down over his forehead, and his arms buried to the elbows in the pockets of his pea-jacket. Remembering the uniform kindness and courtesy with which he and Wilson had been treated by that gentleman, while they were Bayard’s guests and sojourners under his roof Chase was almost on the point of appealing to him for protection; but checked himself when he recalled the scene that had transpired on board the Stella, when he and Fred Craven were discovered in the hold.

“I’ll not ask favors of a smuggler—an outlaw,” thought Chase, tightening his grasp on his trusty axe. “It would be of no use, for it was through him that I was brought to this island.”

“Look here, young gentleman,” said a short, red-whiskered man, stepping out from among his companions, after holding a short consultation with Mr. Bell, “we want you.”

“I can easily believe that,” answered Chase. “I know too much to be allowed to remain at large, don’t I? I don’t want you, however.”

“We’ve got business with you,” continued the[31] red-whiskered man, who was the commander of the Stella, “and you had better listen to reason before we use force. Drop that axe and come down here.”

“I think I see myself doing it. I’d look nice, surrendering myself into your hands, to be shut up in that dark hole with poor Fred Craven, carried to Cuba and shipped off to Mexico, under a Spanish sea-captain, wouldn’t I? There’s a good deal of reason in that, isn’t there now? I’ll fight as long as I can swing this axe.”

“But that will do you no good,” replied the captain, “for you are surrounded and can’t escape. Where is Coulte?” he added, in an impatient undertone, to the men who stood about him.

“Surrounded!” thought Chase. He glanced quickly behind him, but could see nothing except the darkness that filled the cave, and that was something of which he was not afraid. “I’ll have friends here before long,” he added, aloud, “and until they arrive, I can hold you all at bay. I will knock down the poles as fast as you put them up.”

“Where is Coulte, I wonder?” said the master of the smuggling vessel, again. “Why isn’t he[32] doing something? I could have captured him a dozen times.”

These words reached the boy’s ear, and the significant, earnest tone in which they were uttered, aroused his suspicions, and made him believe that perhaps the old Frenchman was up to something that might interest him. It might be that his enemies had discovered some secret passage-way leading into his stronghold, and had sent Coulte around to attack him in the rear. Alarmed at the thought, Chase no longer kept his back turned toward the cave, but stood in such a position that he could watch the farther end of “The Kitchen” and the men below at the same time.

A long silence followed the boy’s bold avowal of his determination to stand his ground, during which time a whispered consultation was carried on by Mr. Bell, Pierre, and the captain of the schooner. When it was ended, the former led the way toward the beach, followed by all the vessel’s company. Chase watched them until they disappeared among the bushes that lined the banks of the gully, and when they came out again and took their stand about the fire, he seated himself on the ledge at the[33] entrance of the cave, and waited with no little uneasiness to see what they would do next.

“I know now what that fire on the bluff was for,” thought he. “It was a signal to the smugglers, and they saw it and ran in here while I was asleep. They came very near capturing me, too—in a minute more Pierre would have been in the cave. I can’t expect to fight a whole ship’s company, and of course I must give in, sooner or later; but I will hold out as long as I can.”

Chase finished his soliloquy with an exclamation, and jumped to his feet in great excitement. A thrill of hope shot through his breast when he saw the Banner come suddenly into view from behind the point, and dart into the cove; but it quickly gave away to a feeling of intense alarm. His long-expected reinforcements had arrived at last, but would they be able to render him the assistance he had hoped and longed for? Would they not rather bring themselves into serious trouble by running directly into the power of the smugglers? Forgetful of himself, and thinking only of the welfare of Walter and his companions, Chase dropped his axe and began shouting and waving his arms about his head to attract their attention.

“Get away from here!” he cried. “That vessel is the smuggler, and Fred Craven is a prisoner on board of her.”

Walter heard the words of warning and so did all of his crew; but they came too late. The yacht was already beyond control. When her captain picked himself up from the deck where the shock of the collision had thrown him, and looked around to see where he was, he found the Banner’s fore-rigging foul of the wreck of the schooner’s bowsprit, and her stern almost high and dry, and jammed in among the bushes and trees on the bank. Escape from such a situation was simply impossible. He glanced at the cave where he had seen Chase but he had disappeared; then he looked at his crew, whose faces were white with alarm; and finally he turned his attention to the smugglers who were gathered about the fire. He could not discover anything in their personal appearance, or the expression of their faces, calculated to allay the fears which Chase’s words had aroused in his mind. They were a hard-looking lot—just such men as one would expect to see engaged in such business.

“Now I’ll tell you what’s a fact,” whispered Perk, as the crew of the Banner gathered about the[35] captain on the quarter-deck; “did you hear what Chase said? We know where Featherweight is now, don’t we?”

“Yes, and we shall probably see the inside of his prison in less than five minutes,” observed Eugene. “Or else the smugglers will put us ashore and destroy our yacht, so that we can’t leave the island until we are taken off.”

“I don’t see what in the world keeps the tug and the revenue-cutter,” said Walter, anxiously. “They ought to have beaten us here, and unless they arrive very soon we shall be in serious trouble. What brought that schooner to the island, any how?”

“That is easily accounted for,” returned Wilson, “Pierre is a member of the gang, as you are aware, and his friends probably knew that he was here, and stopped to take him off. Having brought their vessel into the cove, of course they must stay here until the wind goes down.”

“Well, if they are going to do anything with us I wish they would be in a hurry about it,” said Bab. “I don’t like to be kept in suspense.”

The young sailors once more directed their attention to the smugglers, and told one another that they did not act much like men who made it a point to[36] secure everybody who knew anything of their secret. They did not seem to be surprised at the yacht’s sudden appearance, but it was easy enough to see that they were angry at the rough manner in which she had treated their vessel. Her commander had shouted out several orders to Walter as the Banner came dashing into the cove, but as the young captain could not pay attention to both him and Chase at the same moment, the orders had not been heard. When the little vessel swung around into the bushes, the master of the schooner sprang upon the deck of his own craft, followed by his crew.

“That beats all the lubberly handling of a yacht I ever saw in my life, and I’ve seen a good deal of it,” said the red-whiskered captain, angrily. “Do you want the whole Gulf to turn your vessel in?”

“You’re a lubber yourself,” retorted Walter, who, although he considered himself a prisoner in hands of the smugglers, was not the one to listen tamely to any imputation cast upon his seamanship. “I can handle a craft of this size as well as anybody.”

“I don’t see it,” answered the master of the schooner. “My vessel is larger than yours, and I[37] brought her in here without smashing everything in pieces.”

“That may be. But the way was clear, and you came in under entirely different circumstances.”

“Well, if you will bear a hand over there we will clear away this wreck. I want to go out again as soon as this wind goes down.”

Wondering why the captain of the smugglers did not tell them that they were his prisoners, Walter and his crew went to work with the schooner’s company, and by the aid of hatchets, handspikes, and a line made fast to a tree on the bank, succeeded in getting the little vessels apart; after which the Banner was hauled out into deep water and turned about in readiness to sail out of the cove. Walter took care, however, to work his vessel close in to the bank, in order to leave plenty of room for the tug and the revenue cutter when they came in. How closely he watched the entrance to the cove, and how impatiently he awaited their arrival!

While the crew of the schooner was engaged in repairing the wreck of the bowsprit, Walter and his men were setting things to rights on board the yacht, wondering exceedingly all the while. They did not understand the matter at all. Pierre and[38] Coulte had brought Chase to the island, intending to leave him to starve, freeze, or be taken off as fate or luck might decree, and all because he had learned something they did not want him to know. Fred Craven was a prisoner on board the very vessel that now lay alongside them, and that proved that he knew something about the smugglers also. Now, if the band had taken two boys captive because they had discovered their secret, and they did not think it safe to allow them to be at liberty, what was the reason they did not make an effort to secure the crew of the Banner? These were the points that Walter and his men were turning over in their minds, and the questions they propounded to one another, but not one of them could find an answer to them.

“Perhaps they think we might resist, and that we are too strong to be successfully attacked,” said Eugene, at length.

“Hardly that, I imagine,” laughed Walter. “Five boys would not be a mouthful for ten grown men.”

“I say, fellows,” exclaimed Bab, “what has become of Chase all of a sudden?”

“That’s so!” cried all the crew in a breath, stopping[39] their work and looking up at the bluffs above them. “Where is he?”

“The first and last I saw of him he was standing in the mouth of ‘The Kitchen,’” continued Bab. “Where could he have gone, and why doesn’t he come back and talk to us? Was he still a prisoner, or had he succeeded in escaping?”

“Well—I—declare, fellows,” whispered Eugene, in great excitement, pointing to a gentleman dressed in broadcloth, who was lying beside the fire with his hat over his eyes, as if fast asleep, “if that isn’t Mr. Bell I never saw him before.”

The Banner’s crew gazed long and earnestly at the prostrate man (if they had been a little nearer to him they would have seen that his eyes were wide open, and that he was closely watching every move they made from under the brim of his hat), and the whispered decision of each was that it was Mr. Bell. They knew him, in spite of his pea-jacket and tarpaulin. Was he a smuggler? He must be or else he would not have been there. He must be their leader, too, for a man like Mr. Bell would never occupy a subordinate position among those rough fellows. The young captain and his crew were utterly confounded by this new discovery. The[40] mysteries surrounding them seemed to deepen every moment.

“What did I say, yesterday, when Walter finished reading that article in the paper?” asked Perk, after a long pause. “Didn’t I tell you that if we had got into a fight with Bayard and his crowd, we would have whipped three of the relatives of the ringleader of the band?”

“Well, what’s to be done?” asked Eugene. “We don’t want to sit here inactive, while Chase is up in that cave, and Fred Craven a prisoner on board the schooner. One may be in need of help, the other certainly is, and we ought to bestir ourselves. Suggest something, somebody.”

“Let us act as though we suspected nothing wrong, and go ashore and make some inquiries of Mr. Bell concerning Chase and the pirogue,” said Walter. “We’re here, we can’t get away as long as this gale continues, and we might as well put a bold face on the matter.”

“That’s the idea. Shall somebody stay on board to keep an eye on the deserters?”

“I hardly think it will be necessary. They’ll not be able to work their way out of the hold before we return.”

“But the smugglers might take possession of the vessel.”

“If that is their intention, our presence or absence will make no difference to them. They can take the yacht now as easily as they could if we were ashore.”

Walter’s suggestion being approved by the crew, they sprang over the rail, and walking around the cove—the Banner was moored at the bank opposite the fire—came up to the place where Mr. Bell was lying. He started up at the sound of their footsteps, and rubbing his eyes as if just aroused from a sound sleep, said pleasantly:

“You young gentlemen must be very fond of yachting, to venture out on a night like this. Did you come in here to get out of reach of the wind?”

“No, sir,” replied Walter. “We expected to find Henry Chase on the island.”

“And he is somewhere about here, too,” exclaimed Wilson. “We saw him standing in the mouth of ‘The Kitchen,’ not fifteen minutes ago.”

“The Kitchen!” echoed Mr. Bell, raising himself on his elbow and looking up at the cave in question. “Why, how could he get up there, and[42] we know nothing about it? We’ve been here more than an hour.”

“Haven’t you seen him?” asked Walter.

“No.”

“But you must have heard him shouting to us when we came into the cove.”

“Why no, I did not,” replied Mr. Bell, with an air of surprise. “In the first place, what object could he have in visiting the island, alone, on a night like this? And in the next, how could he come here without a boat?”

“There ought to be a boat somewhere about here,” said Walter, while his companions looked wonderingly at one another, “because Pierre and Coulte brought him over here in a pirogue.”

It now seemed Mr. Bell’s turn to be astonished. He looked hard at Walter, as if trying to make up his mind whether or not he was really in earnest, and then a sneering smile settled on his face; and stretching himself out on his blanket again he pulled his hat over his eyes, remarking as he did so:

“All I have to say is, that Chase was a blockhead to let them do it.”

“Now just listen to me a minute, Mr. Bell, and[43] I’ll tell you what’s a fact,” said Perk, earnestly. “He couldn’t help it, for he was tied hard and fast.”

The gentleman lifted his hat from his eyes, gazed at Perk a moment, smiled again, and said: “Humph!”

“I know it is so,” insisted Perk, “because I saw him and had hold of him. I had hold of Coulte too; and if I get my hands on him again to-night, he won’t escape so easily.”

“What object could the old Frenchman and his son have had in tying Chase hand and foot, and taking him to sea in a dugout?”

“Their object was to get him out of the way,” said Walter. “Chase knows that Coulte’s two sons belong to a gang of smugglers, and they wanted to put him where he would have no opportunity to communicate his discovery to anybody.”

“Smugglers!” repeated the gentleman, in a tone of voice that was exceedingly aggravating. “Smugglers about Bellville? Humph.”

“Yes sir, smugglers,” answered Wilson, with a good deal of spirit. “And we have evidence that you will perhaps put some faith in—the word of your own son.”

“O, I am not disputing you, young gentlemen,” said Mr. Bell, settling his hands under his head, and crossing his feet as if he were preparing to go to sleep. “I simply say that your story looks to me rather unreasonable; and I would not advise you to repeat it in the village for fear of getting yourselves into trouble. I have not seen Pierre, or Coulte, or Chase to-night. Perhaps the captain has, or some of his men, although it is hardly probable. As I am somewhat wearied with my day’s work, I hope you will allow me to go to sleep.”

“Certainly, sir,” said Walter. “Pardon us for disturbing you.”

So saying, the young commander of the Banner turned on his heel and walked off, followed by his crew.

“Well,” continued Walter, after he and his companions had walked out of earshot of Mr. Bell; “what do you think of that.”

“Let somebody else tell,” said Bab. “It bangs me completely.”

“Now I’ll tell you something,” observed Perk: “He is trying to humbug us—I could see it in his eye. If there is a fellow among us who didn’t see Henry Chase standing in the mouth of the cave, when we rounded the point, and hear him shout to us that that schooner there is a smuggler, and that Fred Craven is a prisoner on board of her, let him say so.”

Perk paused, and the Banner’s crew looked at one another, but no one spoke. They had all seen Chase, and had heard and understood his words.

“That is proof enough that Chase is on the[46] island,” said Walter, “for it is impossible that five of us should have been so deceived. Now, if we heard and saw him, what’s the reason Mr. Bell didn’t? That pirogue must be hidden about here somewhere. If you fellows will look around for it, I will go back to the yacht, see how our deserters are getting on, and bring a lantern and an axe. Then we’ll go up and give ‘The Kitchen’ a thorough overhauling.”

Walter hurried off, and his crew began beating about through the bushes, looking for the pirogue. They searched every inch of the ground they passed over, peeping into hollow logs, and up into the branches of the trees, and examining places in which one of the paddles of the canoe could scarcely have been stowed away, but without success. There was one place however, where they did not look, and that was in the fire, beside which Mr. Bell lay. Had they thought of that, they might have found something.

When Walter returned with the axe and the lighted lantern, the crew reported the result of their search, and the young captain, disappointed and more perplexed than ever, led the way toward “The Kitchen.” While they were going up the gully, they[47] stopped to cut a pole, with which to ascend to the cave, and looked everywhere for signs of anybody having passed along the path that night; but it was dark among the bushes, and the light of the lantern revealed not a single foot-print. Arriving at the bluff, they placed the pole against the ledge, and climbing up one after the other, entered the cave, leaving Eugene at the mouth to keep an eye on the yacht, and on the movements of the smugglers below. But their search here was also fruitless. There was the wood which the last visitors from the village had provided to cook their meals, the dried leaves that had served them for a bed, and the remains of their camp-fire; but that was all. The axe that had done Chase such good service, his blankets, bacon, and everything else he had brought there, as well as the boy himself, had disappeared.

Eugene, who was deeply interested in the movements of his companions, did not perform the part of watchman very well. On two or three occasions he left his post and entered the cave to assist in the search; and once when he did this, Mr. Bell, who still kept his recumbent position by the fire, made a sign with his hand, whereupon two men glided from the bushes that lined the beach, and clambering[48] quickly over the side of the smuggling vessel, crept across the deck and dived into the hold. Eugene returned to the mouth of the cave just as they went down the ladder, but did not see them.

“Now then,” said Walter, when the cave had been thoroughly searched, “some of you fellows who are good at unravelling mysteries, explain this. What has become of Chase? Did he leave the cave of his own free will, and if so, how did he get out? We found no pole by which he could have descended, and consequently he must have hung by his hands from the ledge and dropped to the ground. But he would not have done that for fear of a sprained ankle. He surely did not allow any one to come up here and take him out, for with a handful of these rocks he could have held the cave against a dozen men. Besides, he would have shouted for help, and we should have heard him.”

None of the crew had a word to say in regard to Chase’s mysterious disappearance. They sighed deeply, shook their heads, and looked down at the ground, thus indicating quite as plainly as they could have done by words, that the matter was altogether too deep for their comprehension. More bewildered than ever, they followed one another[49] down the pole, and retraced their steps toward the beach.

“What shall we do to pass away the time until the tug and cutter arrive?” asked Perk. “I wish that schooner could find a tongue long enough to tell us what she’s got stowed away in her hold.”

“If she could, and told you the truth, she would assure you that Fred Craven is there,” said Wilson, confidently. “Of that I am satisfied. He’s on some vessel, for Chase told me so while we were at Coulte’s cabin. If this schooner is an honest merchantman, why did she come in here? There’s nothing the matter with her that I can see. She didn’t come in to get out of the wind, for she can certainly stand any sea that the Banner can outride. Coulte and his sons belong to the smugglers, because I heard Bayard say so. Chase told me that he was to be carried to the island in a pirogue, and we met her as she came down the bayou. Now, put these few things together, and to my mind they explain the character of this vessel and the reason why she is here.”

“Go on,” said Eugene. “Put a few other things together, and see if you can explain where Chase went in such a hurry.”

“That is beyond me quite. But the matter will be cleared up in a very few minutes,” added Wilson, gleefully, “for here comes the cutter.”

As he spoke, the revenue vessel came swiftly around the point; and so overjoyed were the boys to see her, that they swung their hats around their heads and greeted her with cheers that awoke a thousand echoes among the bluffs. Being better handled than the Banner was when she came in, she glided between the two vessels lying in the cove, and running her bowsprit among the bushes on the bank, came to a stand still without even a jar. Her captain had evidently made preparations to perform any work he might find to do without the loss of a moment; for no sooner had the cutter swung round broadside to the bank, than a company of men with small-arms tumbled over the side, followed by the second lieutenant, and finally by the commander himself.

“Here we are again, captain,” said the latter, as Walter came up, “and all ready for business. Bring on your smugglers.”

“There they are, sir,” answered Walter, pointing to the crew of the schooner, who had once more[51] congregated about the fire, “and there’s their vessel.”

“That!” exclaimed the second lieutenant, opening his eyes in surprise. “You’re mistaken, captain. That is the Stella—a trader from Bellville, bound for Havana, with an assorted cargo—hams, bacon, flour, and the like. I boarded her to-night and examined her papers myself. She no doubt put in here on account of stress of weather.”

“Stress of weather!” repeated Walter, contemptuously. “That little yacht has come from Bellville since midnight, and never shipped a bucket of water; and the schooner is four times as large as she is. Stress of weather, indeed!”

“Well, she is all right, any how.”

“I am sure, captain, that if you will take the trouble to look into things a little, you will find that she is not all right—begging the lieutenant’s pardon for differing with him so decidedly,” said Walter. “Some strange things have happened since we came here.”

“Well, captain, I will satisfy you on that point, seeing that you are so positive,” replied the commander of the revenue vessel. “Mr. Harper,”[52] he added, turning to the lieutenant, “send your men on board the cutter and come with me.”

A landsman would have seen no significance in this order, but Walter and his crew did, and they were not at all pleased to hear it. The sending of the men back on board the vessel was good evidence that the revenue captain did not believe a word they said, and that he was going to “look into things,” merely to satisfy what he thought to be a boyish curiosity. It is not likely that he would have done even this much, had he not been aware that the young sailors had influential friends on shore who might have him called to account for any neglect of duty. Walter’s disgust and indignation increased as they approached the fire. The men composing the crew of the smuggling vessel stepped aside to allow them to pass, and Mr. Bell advanced with outstretched hand, to greet the revenue captain.

“Why, how is this?” exclaimed the latter, accepting the proffered hand and shaking it heartily. “I did not expect to find you here, Mr. Bell. Ah! Captain Conway, good morning to you,” he added, addressing the red-whiskered master of the schooner. “Captain Gaylord, there is no necessity of carrying this thing any farther. The presence of these[53] two gentlemen, with both of whom I am well acquainted, is as good evidence as I want that the schooner is not a smuggler.”

“A smuggler!” repeated the master of the Stella.

“Why, what is the matter?” asked Mr. Bell, opening his eyes in surprise, and looking first at Walter, and then at the revenue captain, while the crew of the schooner crowded up to hear what was going on.

“Why the truth is, that this young gentleman has got some queer ideas into his head concerning your vessel. He thinks she is the smuggler of which I have been so long in search.”

“And I have the best of reasons for thinking so,” said Walter; not in the least terrified or abashed by the angry glances that were directed toward him from all sides. “In the first place, does she not correspond with the description you have in your possession?”

“I confess that she does,” replied the revenue captain, running his eye over the schooner from cross-trees to water-line.

“She answers the description much better than the yacht, does she not?”

“Yes. But then she has papers, which my lieutenant[54] has examined, and I know these two gentlemen. You had no papers, and I was not acquainted with a single man on board your vessel.”

“A smuggler!” repeated the red-whiskered captain, angrily; “I don’t believe there’s such a thing in the Gulf.”

“I am inclined to agree with you,” answered the revenue commander. “I have looked everywhere, without finding one.”

“I own the cargo with which this vessel is loaded,” said Mr. Bell, producing his pocket-book, and handing some papers to the revenue captain, who returned them without looking at them, “and there are the receipts of the merchants from whom I purchased it. I am a passenger on her because I believe that, by going to Cuba, I can dispose of the cargo to much better advantage than I could sell it through agents. That is why I am here.”

“And the schooner is heavily loaded, and I couldn’t make the run without straining her,” said the master of the Stella. “Having got into the cove I must wait until the wind dies away before I can go out. That’s why I am here.”

The commander of the cutter listened with an air which said very plainly, that this was all unnecessary—that[55] he had made up his mind and it could not be changed—and then turned to Walter as if to ask what he had to say in reply.

“What these men have said may be true and it may not,” declared the young captain, boldly. “The way to ascertain is to search the schooner. There are some articles on board of her that are not down in her bills of lading.”

“And if there are it is no business of mine,” returned the commander of the cutter.

“It isn’t!” exclaimed Walter in great amazement. “Then I’d like to know just how far a revenue officer’s business extends. Haven’t you authority to search any vessel you suspect?”

“Certainly I have; but I don’t suspect this schooner. And, even if I did, I would not search her now, because she is outward bound. If she has contraband articles on board, the Cuban revenue officers may look to it, for I will not. All I have to do is to prevent, as far as lies in my power, articles from being smuggled into the United States; I don’t care a snap what goes out.”

“But you ought to care. There is a boy on board that schooner, held as a prisoner.”

“Why is he held as a prisoner?”

“Because he knows something about the smugglers, and they are afraid to allow him his liberty.”

“Humph!” exclaimed Mr. Bell.

“Every word of that is false,” cried the master of the Stella, who seemed to be almost beside himself with fury. “It is a villainous attempt to injure me and my vessel.”

“Keep your temper, captain,” said the commander of the cutter. “I want to see if this young man knows what he is talking about. Where are those two smugglers who brought that boy over here in a canoe?”

“I don’t know, sir. We have searched the island and can find no trace of them.”

“That is a pretty good sign that they are not here. Where is the boat they came in?”

“I don’t know that either. It is also missing.”

“Where is the boy they brought with them?”

“When the Banner rounded the point he was standing in the mouth of that cave,” replied Walter, pointing to the Kitchen, “and shouted to us to get away from here while we could—that this schooner is a smuggler and that Fred Craven is a prisoner on board of her.”

“Well, where is the boy now?”

“I can’t tell you, sir.”

“Isn’t he on the island?”

“We can find no signs of him.”

“Then he hasn’t been here to-night.”

“He certainly has,” replied Walter, “for we saw him and heard him too.”

“Who did?”

“Every one of the crew of the Banner.”

“Did anybody else? Did you, Mr. Bell? Or you, Captain Conway? Or any of your men?”

The persons appealed to answered with a most decided negative. They had seen no boy in the cave, heard no voice, and knew nothing about a prisoner or a pirogue. There was one thing they did know, however, and that was that no dugout that was ever built could traverse forty miles of the Gulf in such a sea as that which was running last night.

“Well, young man,” said the revenue officer, addressing the captain of the yacht somewhat sternly, “I am sure I don’t know what to think of you.”

“You are at liberty to think what you please, sir,” replied Walter, with spirit. “I have told you the truth, if you don’t believe it search that schooner.”

“You have failed to give me any reason why I should do so. Your story is perfectly ridiculous. You say that a couple of desperate smugglers captured an acquaintance of yours and put him in a canoe; that you met them in a bayou on the main shore and had a fight with them; that they eluded you and came out into the Gulf in a gale that no small boat in the world could stand, and brought their prisoner to this island. When I expressed a reasonable doubt of the story, you offered, if I would come here with you, to substantiate every word of it. Now I am here, and you can not produce a scrap of evidence to prove that you are not trying to make game of me. The men, the boy, and the boat they came in, are not to be found. I wouldn’t advise you to repeat a trick of this kind or you may learn to your cost that it is a serious matter to trifle with a United States officer when in the discharge of his duty. Mr. Bell, as the wind has now subsided so that I can go out, I wish you good-by and a pleasant voyage.”

“One moment, captain,” said Walter, as the revenue commander was about to move off; “perhaps you will think I am trifling with you, if I tell[59] you that I have some deserters from your vessel on board my yacht.”

“Have you? I am glad to hear it. I have missed them, and I know who they are. I thought they had gone ashore at Bellville, and it was by stopping to look for them that I lost so much time. Haul your yacht alongside the cutter and put them aboard.”

“I am going to set them at liberty right where the yacht lies,” replied Walter, indignant at the manner in which the revenue captain had treated him, and at the insolent tone of voice in which the order was issued; “and you can stand by to take charge of them or not, just as you please.”

“How many of them are there?”

“Two.”

“Only two? Then the others must have gone ashore at Bellville, after all,” added the captain, turning to his second lieutenant. “I wish they had taken your vessel out of your hands and run away with it. You need bringing down a peg or two, worse than any boy I ever saw.”

Walter, without stopping to reply, turned on his heel, and walked around the cove to the place where the Banner lay, followed by his crew, who[60] gave vent to their astonishment and indignation in no measured terms. The deserters were released at once. When informed that their vessel was close at hand, and that their captain was expecting them, they ascended to the deck, looking very much disappointed and crestfallen, and stood in the waist until the cutter came alongside and took them off. They were both powerful men, and the boy-tars were glad indeed that they had been discovered before they gained a footing on deck. If Walter had been in his right mind he would have examined the hold after those two men left it; but he was so bewildered by the strange events that had transpired since he came into the cove, that he could think of nothing else.

While the crew of the yacht were liberating the deserters, the smuggling vessel filled away for the Gulf—her captain springing upon the rail long enough to shake his fist at Walter—and as soon as she was fairly out of the cove, the cutter followed, and shaped her course toward Bellville.

The boys watched the movements of the two vessels in silence, and when they had passed behind the point out of sight, turned with one accord to[61] Walter, who was thoughtfully pacing his quarter-deck, with his hands behind his back.

“Eugene,” said the young captain, at length, “did you keep an eye on the smuggler all the time that we were in The Kitchen?”

“O, yes,” replied Eugene, confidently. “I saw everything that happened on her deck.” And he thought he did, but he forgot that he had two or three times left his post.

“You didn’t see Chase taken on board the schooner, did you?”

“I certainly did not. If I had, I should have said something about it.”

“Then there is only one explanation to this mystery: Chase was somehow spirited out of the cave and hidden on the island. We will make one more attempt to find him. Three of us will go ashore and thoroughly search these woods and cliffs, and the others stay and watch the yacht.”

Walter, Perk, and Bab, after arming themselves with handspikes, sprang ashore and bent their steps toward The Kitchen to begin their search for the missing Chase. As before, no signs of him were found in the cave, although every nook and crevice large enough to conceal a squirrel, was peeped into.[62] Next the gully received a thorough examination, and finally they came to the bushes on the side of the bluff. A suspicious-looking pile of leaves under a rock attracted Bab’s attention, and he thrust his handspike into it. The weapon came in contact with something which struggled feebly, and uttered a smothered, groaning sound, which made Bab start back in astonishment.

“What have you there?” asked Walter, from the foot of the bluff.

“I don’t know, unless it is a varmint of some kind that has taken up his winter quarters here. Come up, and let’s punch him out.”

Perk and Walter clambered up the bluff to the ledge, and while one raised his handspike in readiness to deal the “varmint” a death-blow the instant he showed himself, the others cautiously pushed aside the leaves, and presently disclosed to view—not a wild animal, but a pair of heavy boots, the heels of which were armed with small silver spurs. One look at them was enough. With a common impulse the three boys dropped their handspikes, and pulling away the leaves with frantic haste, soon dragged into sight the missing boy, securely bound and gagged, and nearly suffocated. To give him[63] the free use of his hands and feet, and remove the stick that was tied between his teeth, was but the work of a moment. When this had been done, Chase slowly raised himself to a sitting posture, gasping for breath, and looking altogether pretty well used up.

“You don’t know how grateful I am to you, fellows,” said he, at last, speaking in a hoarse whisper. “I’ve had a hard time of it during the half hour I have been stowed away in that hole, and I never expected to see daylight again.”

“Now I’ll tell you what’s a fact,” said Perk. “You never would have got out of there alive if Walter hadn’t been thoughtful enough to search the island before going home. Now let me ask you something: Where did you go in such a hurry, after shouting to us from the mouth of The Kitchen?”

“I can’t talk much, fellows, till I get something to moisten my tongue,” was the almost indistinct reply. “If you will help me to the spring, I will tell you all about it. Where are the smugglers?”

“Don’t know. We haven’t seen any,” said Walter.

“You haven’t?” whispered Chase, in great[64] amazement. “Didn’t you see those men who were standing on the beach when you came in?”

“Yes; but they are not smugglers. They’ve got clearance papers, and the captain of the cutter says he knows they are all right. Besides, one of them was Mr. Bell.”

“No difference; I know they are smugglers by their own confession, and that Mr. Bell is the leader of them. O, it’s a fact, fellows; I know what I am talking about. Where are they now?”

“Gone.”

“Gone! Where?”

“To Havana, most likely. That’s the port their vessel cleared for.”

“And did you rescue Fred Craven? I know you didn’t by your looks. Well, you’ll have to find that schooner again if you want to see him, for he’s on board of her, and—wait till I rest awhile, fellows, and get a drink of water.”

Seeing that it was with the greatest difficulty that Chase could speak, Perk and Walter lifted him to his feet, and assisted him to walk down the gully, while Bab followed after, carrying the handspikes on his shoulder. Arriving at the spring, Chase lay down beside it and took a large and hearty drink,[65] now and then pausing to testify to the satisfaction he felt by shaking his head, and uttering long-drawn sighs. After quenching his thirst, and taking a few turns up and down the path to stretch his arms and legs, he felt better.

“The first thing, fellows,” said Chase, “is to tell you that I am heartily sorry I have treated you so shabbily.”

“Now, please don’t say a word about that,” interrupted Walter, kindly. “We don’t think hard of you for anything you have done, and besides we have more important matters to talk about.”

“I know how ready you are, Walter Gaylord, to overlook an injury that is done you—you and the rest of the Club—and that is just what makes me feel so mean,” continued Chase, earnestly. “I was not ashamed to wrong you, and I ought not to be ashamed to ask your forgiveness. I made up my mind yesterday, while we were disputing about those panther scalps (to which we had not the smallest shadow of a right, as we knew very well), to give Fred Craven a good thumping, if I was man enough to do it, for beating me in the race for Vice-Commodore;[67] and the next time I met him he paid me for it in a way I did not expect. He tried to assist me, and got himself into a terrible scrape by it.”

“That is just what we want to hear about,” said Bab, “and you are the only one who can enlighten us. But Eugene and Wilson would like to listen to the story also; and if you can walk so far, I suggest that we go on board the yacht.”

“What do you suppose has become of Coulte and Pierre?” asked Walter. “Are they still on the island?”

“No, indeed,” replied Chase. “If the rest of the smugglers are gone, of course they went with them.”

After Chase had taken another drink from the spring, he accompanied his deliverers down the gully. The watch on board the yacht discovered them as they came upon the beach, and pulling off their hats, greeted them with three hearty cheers. When they reached the vessel, Wilson testified to the joy he felt at meeting his long-lost friend once more, by seizing him by the arms and dragging him bodily over the rail.

“One moment, fellows!” exclaimed Walter, and[68] his voice arrested the talking and confusion at once. “Chase, are you positive that Featherweight is a prisoner on board that schooner?”

“I am; and I know he will stay there until he reaches Havana, unless something turns up in his favor.”

“Then we’ve not an instant to waste in talking,” said the young captain. “We must keep that schooner in sight, if it is within the bounds of possibility. Get under way, Perk.”

“Hurrah!” shouted Eugene, forgetting in the excitement of the moment the object for which their cruise was about to be undertaken. “Here’s for a sail clear to Cuba.”

“Now, just listen to me a minute and I’ll tell you what’s a fact,” said Perk. “One reason why I fought so hard against those deserters was, because I was afraid that if they got control of the vessel they would take us out to sea; and now we are going out of our own free will.”

“And with not a man on board;” chimed in Bab, “nobody to depend upon but ourselves. This will be something to talk about when we get back to Bellville, won’t it?”

The crew worked with a will, and in a very few[69] minutes the Banner was once more breasting the waves of the Gulf, her prow being turned toward the West Indies. As soon as she was fairly out of the cove, a half a dozen pairs of eyes were anxiously directed toward the southern horizon, and there, about three miles distant, was the Stella, scudding along under all the canvas she could carry. The gaze of the young sailors was then directed toward the Louisiana shore; but in that direction not a craft of any kind was in sight, except the revenue cutter, and she was leaving them behind every moment. Exclamations of wonder arose on all sides, and every boy turned to Walter, as if he could tell them all about it, and wanted to know what was the reason the tug had not arrived.

“I don’t understood it any better than you do, fellows,” was the reply. “She ought to have reached the island in advance of us. And I don’t see why the Lookout hasn’t put in an appearance. If father and Uncle Dick reached home last night, they’ve had plenty of time to come to our assistance. It would do me good to see her come up and overhaul that schooner.”

“Isn’t that a cutter, off there?” asked Chase, who had been attentively regarding the revenue[70] vessel through Walter’s glass. “Let’s signal to her. She’ll help us.”

“Humph! She wouldn’t pay the least attention to us; we’ve tried her. The captain wouldn’t believe a word we said to him.”

It was now about nine o’clock in the morning, and a cold, dismal morning it was, too. The gale of the night before had subsided into a capital sailing wind, but there was considerable sea running, and a suspicious-looking bank of clouds off to windward, which attracted the attention of the yacht’s company the moment they rounded the point. The crew looked at Walter, and he looked first at the sky and clouds and then at the schooner. He had been on the Gulf often enough to know that it would not be many hours before the sea-going qualities of his little vessel, the nerve of her crew, and the skill on which he prided himself, would be put to a severer test than they had yet experienced, and for a moment he hesitated. But it was only for a moment. The remembrance of the events that had just transpired in the cove, the dangers with which Fred Craven was surrounded, and the determination he had more than once expressed to stand by him until he was rescued—all these things came[71] into his mind, and his course was quickly decided upon. Although he said nothing, his crew knew what he was thinking about, and they saw by the expression which settled on his face that there was to be no backing out, no matter what happened.

“I was dreadfully afraid you were going to turn back, Walter,” said Eugene, drawing a long breath of relief.

“I would have opposed such a proceeding as long as I had breath to speak or could think of a word to utter,” said Perk. “Featherweight’s salvation depends upon us entirely, now that the tug has failed to arrive and the cutter has gone back on us.”

“But, fellows, we are about to undertake a bigger job than some of you have bargained for, perhaps,” said Bab. “Leaving the storm out of the question, there is the matter of provisions. We have eaten nothing since yesterday at breakfast, and the lunch we brought on board last night will not make more than one hearty meal for six of us. We shall all have good appetites by the time we reach Havana, I tell you.”

“I can see a way out of that difficulty,” replied Walter. “We will soon be in the track of vessels bound to and from the Balize, and if we fall in with[72] one of those little New Orleans traders, we will speak her and purchase what we want. I don’t suppose any of us are overburdened with cash—I am not—but if we can raise ten or fifteen dollars, a trader will stop for that.”

“I will pass around the hat and see how much we can scrape together,” said Eugene, “and while I am doing that, suppose we listen to what Chase has to say for himself.”

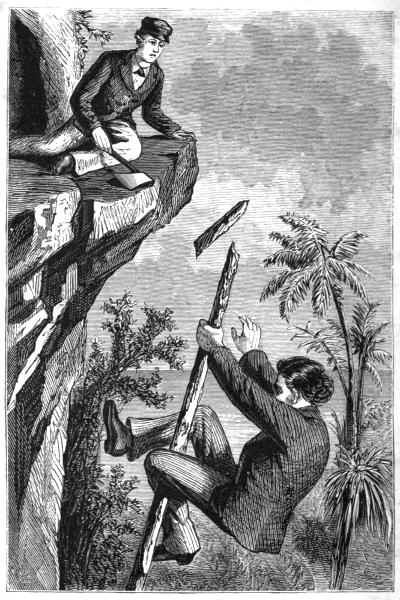

The Club Afloat.

The young sailors moved nearer to the boy at the wheel so that he might have the benefit of the story, and while they were counting out their small stock of change and placing it in Eugene’s hands, Chase began the account of his adventures. He went back to the time of the quarrel which Bayard Bell and his cousins had raised with himself and Wilson, told of the plan he and his companion had decided upon to warn Walter of his danger, and described how it was defeated by the smugglers. This much the Club had already heard from Wilson; but now Chase came to something of which they had not heard, and that was the incidents that transpired on the smuggling vessel. Walter and his companions listened in genuine amazement as Chase went on to describe the interview he had held with Bayard and[73] his cousins (he laughed heartily at the surprise and indignation they had exhibited when they found him in the locker instead of Walter, although he had thought it anything but a laughing matter at the time), and to relate what happened after Fred Craven arrived. At this stage of his story Chase was often interrupted by exclamations of anger; and especially were the crew vehement in their expressions of wrath, when they learned that Featherweight’s trials would by no means be ended when he reached Havana—that he was to be shipped as a foremast hand on board a Spanish vessel and sent off to Mexico. This was all that was needed to arouse the fiercest indignation against Mr. Bell. The thought that a boy like Fred Craven was to be forced into a forecastle, to be tyrannized over by some brute of a mate, ordered about in language that he could not understand, and perhaps knocked down with a belaying-pin or beaten with a rope’s end, because he did not know what was required of him—this was too much; and Eugene in his excitement declared that if Walter would crack on and lay the yacht alongside the schooner, they would board her, engage in a hand-to-hand fight with the smugglers, and rescue the secretary at all hazards.[74] Had the young captain put this reckless proposition to a vote it would have been carried without a dissenting voice.

When the confusion had somewhat abated Chase went on with his story, and finally came to another event of which the Club had heard the particulars—the siege in Coulte’s house. He described the sail down the bayou, the attempted rescue by the Club, the voyage to the island during the gale, the destruction of the pirogue, and his escape and retreat to The Kitchen. His listeners became more attentive than ever when he reached this point, and his mysterious manner increased their impatience to hear how he could have been spirited out of the cave without being seen by any one.