BY

CHARLES G. HARPER,

AUTHOR OF “ENGLISH PEN ARTISTS OF TO-DAY.”

Illustrated with Drawings by several Hands, and with Sketches

by the Author showing Comparative Results obtained by the

several Methods of Reproduction now in Use.

LONDON: CHAPMAN & HALL, Ld.

1894.

TO CHARLES MORLEY, ESQ.

Dear Mr. Morley,

It is with a peculiar satisfaction that I inscribe this book to yourself, for to you more than to any other occupant of an editorial chair is due the position held by “process” in illustrating the hazards and happenings of each succeeding week.

Time was when the “Pall Mall Budget,” with a daring originality never to be forgotten, illustrated the news with diagrams fashioned heroically from the somewhat limited armoury of the compositor. Nor I nor my contemporaries, I think, have forgotten those weapons of offence—the brass rules, hyphens, asterisks, daggers, braces, and other common objects of the type-case—with which the Northumberland Street printers set forth the details of a procession, or the configuration of a country. There was in those days a world of meaning—apart from libellous innuendo—in a row of asterisks; for did [Pg iv] they not signify a chain of mountains? And what Old Man Eloquent was ever so vividly convincing as those serpentine brass rules that served as the accepted hieroglyphics for rivers on type-set maps?

These were the beginnings of illustration in the “Pall Mall Budget” when you first filled the editorial chair. The leaps and bounds by which you came abreast of (and, indeed, overlook) the other purveyors of illustrated news, hot and hot, I need not recount, nor is there occasion here to allude to the events which led to what some alliterative journalist has styled the Battle of the Budgets. Only this: that if others have reaped where you have sown, why! ’twas ever thus.

For the rest, I must needs apologize to you for a breach of an etiquette which demands that permission be first had and obtained before a Dedication may be printed. To print an unauthorized tribute to a private individual is wrong: when (as in the present case) an Editor is concerned I am not sure that the wrong-doing halts anything before lèse majesté.

London,

May, 1894.

Everywhere to-day is the Illustrator (artist he may not always be), for never was illustration so marketable as now; and the correspondence-editors of the Sunday papers have at length found a new outlet for the superfluous energies of their eager querists in advising them to “go in” for black and white: as one might advise an applicant to adventure upon a commercial enterprise of large issues and great risks before the amount of his capital (if any) had been ascertained.

It is so very easy to make black marks upon white cardboard, is it not? and not particularly difficult to seize upon the egregious mannerisms of the accepted purveyors of “the picturesque”—that cliché phrase, battered nowadays out of all real meaning.

But for really serious art—personal, aggressive, definite and [Pg vi] instructed—one requires something more than a penchant, or the stimulating impulsion of an empty pocket, or even the illusory magnetism of the vie bohême of the lady-novelist, whose artists still wear velvet coats and aureoles of auburn hair, and marry the inevitable heiress in the third volume. Not that one really wishes to be one of those creatures, for the lady-novelists’ love-lorn embryonic Michael Angelos are generally great cads; but this by the way!

What is wanted in the aspirant is the vocation: the feeling for beauty of line and for decoration, and the powers both of idealizing and of selection. Pen-drawing and allied methods are the chiefest means of illustration at this day, and these qualities are essential to their successful employ. Practitioners in pen-and-ink are already numerous enough to give any new-comer pause before he adds himself to their number, but certainly the greater number of them are merely journalists without sense of style; mannerists only of a peculiarly vicious parasitic type.

“But,” ask those correspondents, “does illustration pay?” “Yes,” says that omniscient person, the Correspondence-Editor. Then those pixie-led wayfarers through life, filled with an inordinate desire to draw, to [Pg vii] paint, to translate Nature on to canvas or cardboard (at a profit), set about the staining of fair paper, the wasting of good ink, brushes, pens, and all the materials with which the graphic arts are pursued, and lo! just because the greater number of them set out, not with the love of an art, but with the single idea of a paying investment of time and labour—it does not pay! Remuneration in their case is Latin for three farthings.

Publishers and editors, it is said, can now, with the cheapness of modern methods of reproduction as against the expense of wood-engraving, afford to pay artists better because they pay engravers less. Perhaps they can. But do they?

Pen-drawing in particular has, by reason of these things, almost come to stand for exaggeration and a shameless license—a convention that sees and renders everything in a manner flamboyantly quaint. But this vein is being worked down to the bed-rock: it has plumbed its deepest depth, and everything now points to a period of instructed sobriety where now the untaught abandon of these mannerists has rioted through the pages of illustrated magazines and newspapers to a final disrepute. [Pg viii]

Artists are now beginning to ask how they can dissociate themselves from that merely manufacturing army of frantic draughtsmen who never, or rarely, go beyond the exercise of pure line-work; and the widening power of process gives them answer. Results striking and unhackneyed are always to be obtained to-day by those who are not hag-ridden by that purely Philistine ideal of the clear sharp line.

These pages are written as a plea for something else than the eternal round of uninspired work. They contain suggestions and examples of results obtained in striving to be at one with modern methods of reproduction, and perhaps I may be permitted to hope that in this direction they may be of some service.

CONTENTS.

| PAGE | |

| INTRODUCTORY | 1 |

| THE RISE OF AN ART | 9 |

| COMPARATIVE PROCESSES | 22 |

| PAPER | 78 |

| PENS | 92 |

| INKS | 96 |

| THE MAKING OF A PEN-DRAWING | 102 |

| WASH DRAWINGS | 121 |

| STYLES AND MANNER | 135 |

| PAINTERS’ PEN-DRAWINGS | 154 |

WORKS BY THE SAME AUTHOR.

ENGLISH PEN ARTISTS OF TO-DAY: Examples of their work, with some Criticisms and Appreciations. Super royal 4to, £3 3s. net.

THE BRIGHTON ROAD: Old Times and New on a Classic Highway. With 95 Illustrations by the Author and from old prints. Demy 8vo, 16s.

FROM PADDINGTON TO PENZANCE: The Record of a Summer Tramp. With 105 Illustrations by the Author. Demy 8vo, 16s.

| PAGE | |

| Vignette on Title | |

| Kensington Palace. Photogravure | Frontispiece |

| The Hall, Barnard’s Inn | 25 |

| A Window, Chepstow Castle | 29 |

| On Whatman’s “Not” Paper | 31 |

| From a Drawing on Allongé Paper | 31,32 |

| Bolt Head: A Misty Day. Bitumen process | 38 |

| Bolt Head: A Misty Day. Swelled gelatine process | 39 |

| A Note at Gorran. Bitumen process | 43 |

| A Note at Gorran. Swelled gelatine process | 43 |

| Charlwood. Swelled gelatine process | 45 |

| Charlwood. Reproduced by Chefdeville | 45 |

| View from the Tower Bridge Works. Bitumen process | 48 |

| View from the Tower Bridge Works. Bitumen process. | |

| Sky revised by hand-work | 49 |

| Kensington Palace | 51 |

| Snodgrass Farm | 53 |

| Sunset, Black Rock | 55 |

| Drawing in Diluted Inks, reproduced by Gillot | 57 |

| Chepstow Castle | 61 |

| Clifford’s Inn: a Foggy Night | 65 |

| Pencil and Pen and Ink Drawing reproduced by Half-tone Process | 68[Pg xii] |

| The Village Street, Tintern. Night | 70 |

| Leebotwood | 71 |

| Examples of Day’s Shading Mediums | 75, 76 |

| Churchyard Cross, Raglan | 76 |

| Canvas-grain Clay-board | 84 |

| Plain Diagonal Grain | 85 |

| Plain Perpendicular Grain | 85 |

| Drawing in Pencil on White Aquatint Grain Clay-board | 86 |

| Black Aquatint Clay-board and Two Stages of Drawing | 87 |

| Black Diagonal-lined Clay-board and Two Stages of Drawing | 87 |

| Black Perpendicular-lined Clay-board and Two Stages of Drawing | 88 |

| Venetian Fête on the Seine, with the Trocadero illuminated | 89 |

| The Gatehouse, Moynes Court | 110 |

| Portrait Sketches | 118, 119 |

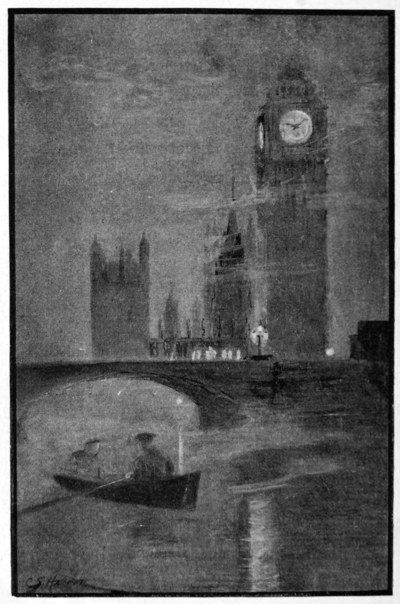

| The Houses of Parliament at Night, from the River | 122 |

| Victoria Embankment near Blackfriars Bridge: a Foggy Night | 123 |

| Corfe Railway Station | 125 |

| The Ambulatory, Dore Abbey | 127 |

| Moonlight: Confluence of the Severn and the Wye | 131 |

| Diagram showing Method of reducing Drawings for Reproduction | 133 |

| Painter’s Pen-drawing—Pasturage, by Mr. Alfred Hartley | 155 |

| "" Portrait, by Mr. Bonnat | 156 |

| Towing Path, Abingdon, by Mr. David Murray | 158 |

| A Portrait from a Drawing by Mr. T. Blake Wirgman | 159 |

| Finis | 161 |

A PRACTICAL HANDBOOK OF DRAWING

FOR REPRODUCTION.

Pen-drawing is the most spontaneous of the arts, and amongst the applied crafts the most modern. The professional pen-draughtsman was unknown but a few years since; fifteen years ago, or thereabouts, he was an obscure individual, working at a poorly considered craft, and handling was so seldom thought of that the illustrator who could draw passably well was rarely troubled by his publisher on the score of technique. For that which had deserved the name of technique was dead, so far as illustration was concerned, and “process,” which was presently to vivify it, was, although born already, but yet a sickly child. To-day the illustrators are numerous beyond computation, and the [Pg 2] name of those who are impelled to the spoiling of good paper and the wasting of much ink is indeed legion.

For uncounted years before the invention of photo-mechanical methods of engraving, there had been practised a method of drawing with the pen, which formed a pretty pastime wherewith to fleet the idle hours of the gentlemanly amateur, and this was, for no discoverable reason, called “etching.”

It is needless at this time to go into the derivatives of that word, with the object of proving that the verb “to etch” means something very different from drawing in ink with a pen; it should have, long since, been demonstrated to everybody’s satisfaction that etching is the art of drawing on metal with a point, and of biting in that drawing with acids. But the manufacturers of pens long fostered the fallacy by selling so-called etching-pens: probably they do so even now.

By whom pen-drawings were first called etchings none can say. Certainly the two arts have little or nothing in common: the terms are not interchangeable. Etching has its own especial characteristics, which may, to an extent, be imitated with the pen, but the quality and [Pg 3] direction of line produced by a rigid steel point on metal are entirely different from the lines drawn with a flexible nib upon paper. The line produced by an etching needle has a uniform thickness, but with the needle you can work in any imaginable direction upon the copper plate. With a nib upon paper, a line varying in thickness with the pressure of the hand results, but there is not that entirely free use of the hand as with the etching point: you cannot with entire freedom draw from and toward yourself.

The greatest exponents of pen-drawing have not entirely conquered the normal inability of the pen to express the infinite delightful waywardnesses of the etching-point. Again, the etched line is only less sharp than the line made by the graver upon wood; the line drawn with the pen upon the smoothest surface is ragged, viewed under a magnifying glass. This, of course, is not a plea for a clean line in pen-work—that is only the ideal of commercial draughtsmanship—but the man who can produce such a line with the pen at will, who can overcome the tendency to inflexible lines, has risen victorious over the stubbornness of a material.

The sketch-books, gilt-lettered and india-rubber banded, of the [Pg 4] bread-and-butter miss, and what one may be allowed, perhaps, to term the “pre-process” amateur generally, give no hint of handling, no foretaste of technique. They are barren of aught save ill-registered facts, and afford no pleasure to the eye, which is the end, the sensuous end, of all art. Rather did these artless folk almost invariably seek to adventure beyond the province of the pen by strokes infinitely little and microscopic, so that they might haply deceive the eye by similarity to wood engravings or steel prints. But in those days pen-drawing was only a pursuit; to-day it is a living art. Now, an art is not merely a storehouse of facts, nor a moral influence. If it was of these things, then the photographic camera would be all-powerful, and all that would be left to do with the hands would be the production of devotional pictures; and of those who produced them the best artist would infallibly be him with a character the most noted for piety. Art, to the contrary, is entirely independent of subject or morals. It is not sociology, nor ever shall be; and those who practise an art might be the veriest pariahs, and yet their works rank technically, artistically, among the best. Art is handling in excelsis, and its [Pg 5] results lie properly in the pride of the eye and the satisfaction of the æsthetic sense, though Mr. Ruskin would have it otherwise.

Is this the lashing of a dead horse, or thrice slaying the slain? No, I think not. The moral and literary fallacies remain. Open an art exhibition and give your exhibits technical, not subject titles, and you shall hear a mighty howl, I promise you. Mr. Hamerton, too, has recently found grudging occasion to say that, for artists, “it does not appear that a literary education would be necessary in all cases.” Whenever was it necessary? But then Mr. Hamerton is himself one of those philosophic writers of a winning literary turn who can practise an art in by no means a distinguished way, but who write dogma by the yard and fumble over every illustration of their precepts. His Drawing and Engraving—a reprint from his Encyclopædia Britannica article—is worse than useless to the student of illustration, and especially of pen-drawing, because Mr. Hamerton has long been left behind the times. He knows little of the admirable modern methods of reproducing line-work, but gives us etymologies of drawing and historical dissertations on engraving, which we do not want. Of such [Pg 6] antiquated matter are even the current editions of encyclopædias fashioned. The fact is, the bulk of art criticism is written by men who can only string platitudes and stale studio slang together, without beginning to understand principles. The appalling journalese of much “art criticism” is hopelessly out of date; the slang of a half-forgotten atélier is the lingo of would-be criticism to-day.

It seems strange that a man who can write pretty vers de société or another who writes essays (essays, truly, in the philological sense), should for such acquirements be amongst those to whom is delegated the criticism of art in painting, drawing, or engraving; but so it is. No one who has not surmounted the difficulties of a medium can truly appreciate technique in it, whether that medium be words, or paint, or ink. No one, for instance, would give a painter or a pen-artist the chance to review a poet’s new volume of poems. You would not send a plumber to pronounce upon a baker’s method of kneading his dough. No; but an ordinary reporter is judged capable of criticizing a gallery of pictures. You cannot get much artistic change out of his report, nor from the articles on art written by a man whose only claim to the [Pg 7] standing of “art critic” is the possession of a second-class certificate in drawing from the Science and Art Department. But of such stuff are the neurotic Neros of the literary “art critique” fashioned, and equally unauthorized by works are the lectures on illustration with which the ingenious Mr. Blackburn at decent intervals tickles suburban audiences or the amiable dilettante of the Society of Arts into the fallacious belief that they know all about it, “which,” to quote the Euclidian formula, “is absurd.” Indeed, not even the most industrious, the best-informed, nor the most catholic-minded man could ever lecture, or write articles, or publish an illustrated critical work upon illustration which should show an approximation to completeness in its examples of styles and methods. The thing has been attempted, but will never be done, because the quantity of work—even good work—that has been produced is so vast, the styles so varied. The great storehouses of the best pen-work are the magazines, and from them the eclectic will gather a rich harvest. The Century and Harper’s are now the chief of these. The Magazine of Art and the Portfolio, which were used to be filled with good original work, are now busied in providing such [Pg 8] réchauffés as photographic blocks from paintings old and new, but chiefly old, because they cost nothing for copyright. As for newspaper work, the Daily Graphic is creating a school of its own, which does far better work than ever its New York namesake (now defunct) ever printed.

Some beautiful and most suggestive pen-drawings are to be found in the earlier numbers of L’Art and many Parisian publications, such as the Courier Français, Vie Moderne, Paris Illustré, and La Petit Journal pour Rire. Many of the Salon catalogues, too, contain admirable examples.

Photo-mechanical processes of reproduction were invented by men who sought, not to create an art, not to help art in any way, but only to cheapen the cost of reproduction. “Line” processes—that is to say, processes for the reproduction of pure line—though not the first invented amongst modern methods, were the first to come into a state of practical utility; though even then their results were so crude that the artists whom necessity led to draw for them sank at once to a deeper depth than ever they had sounded when the fac-simile wood-cutter held them in bondage. They became the slaves of mechanical limitations and chemical formulæ, which was a worse condition than having been henchmen of a craftsman. So far as the æsthetic sense is concerned, the process illustration of previous date to (say) 1880 might all be destroyed and no harm done, save, perhaps, the loss of [Pg 10] much evidence of a documentary character toward the history of early days of processes.

There have been two great factors in their gradual perfection—competition with the wood-engravers and of rival process firms one with another, and, perhaps more important still, the independency of a few artists who have found methods of drawing with the pen, and have followed them despite the temporary limitations of the process-man. The workmen have “drawn for process” in the worst and most commercial sense of the term; they have set down their lines after the hard-and-fast rules which were formulated for their guidance. For years after the invention of zincography, artists who were induced to make drawings for the new methods of engraving worked in a dull round of routine; for in those days the process-man was not less, but more, tyrannical than his predecessor, the wood-engraver; his yoke was, for a time, harder to bear.

One was enjoined to make drawings with only the blackest of Indian ink, upon Bristol-board, the thickest and smoothest and whitest that could be obtained, and upon none other. It was impressed upon the draughtsman [Pg 11] that he should draw lines thick and wide apart and firm, and that his drawings should be made with a view to, preferably, a reduction in scale of one-third. Also that by no means should his lines run together by any chance, except in the matter of a coarse and obvious cross-hatch. And so, by reason of these things, the pen-work of that time is become dreadful to look upon at this day. The man who then drew with a view to reproduction squirmed on the very edge of his chair, and with compressed lips, and his heart in his mouth, drew upon his Bristol-board slowly and carefully, and with so heavy a hand, that presently his wrist ached consumedly, and his drawing became stilted in the extreme. Not yet was pen-drawing a profession, for few men had learned these formulæ; and the zincography of that time made miserable all them that were translated by it into something appreciably different from their original work. Illustration, although already sensibly increased in volume, was artistically at the lowest ebb. It was a manufacture, an industry; but scarcely a profession, and most certainly it had not yet become an art.

When technique in drawing for process began to appear as an individual [Pg 12] technique opposed to the old fac-simile wood-engraving needs, it was a handling entirely abominable and inartistic. If old-time drawing for the wood-engravers was pursued in grooves of convention, working for the zincographer proceeded in ruts. There have never been, before or since, such horribly uninspired things produced as in the first years of process-work in these islands. Such dull, scratchy, spotty, wiry-looking prints resulted: they were, as now, produced in zinc, and they proclaimed it unmistakably. Had not these new methods been about one-fifth the cost of wood-engraving, they would have had no chance whatever. But we are a commercial and an inartistic people, and publishers, careless of appearance, welcomed any results that gave them a typographic block at a fifth of its former cost.

Process, in its beginnings, was not a promising method of reproduction. Men saw scarcely anything in it save cheap (and nasty) ways of multiplying diagrams, and the bald and generally artless elevations of new buildings issued from architects’ offices. But in course of time, better blocks, with practice, became possible, and freer use of the pen was obtained; although at every unhackneyed stroke the process-man [Pg 13] shrieked disaster. It is incalculable how much time has been wasted, how many careers set back, by obedience to the hard-and-fast rules laid down for the guidance of artists by the process-people of years since. To those artists who, with an artistic recklessness of results entirely admirable and praiseworthy, set down their work as they pleased, we owe, more than to any others, the progress of process; by their immediate martyrdom was our eventual salvation earned. And in the sure and certain hope of a reproduction really and truly fac-simile, the draughtsman in the medium of pen-and-ink is to-day become a technician of a peculiar subtlety.

To-day, with the exercise of knowledge and discrimination, drawings the most difficult of reproduction may be rendered faithfully; it is a matter only of choice of processes. But in the mass of reproduction at this time, this knowledge, this discrimination, are often seen to be lacking. It is a matter of commerce, of course, for a publisher, an editor, to send off originals in bulk to one firm, and to await from one source the resulting blocks. But unknowing, or reckless of their individual merits and needs, our typical editor has thus consigned some [Pg 14] drawings to an unkind fate. There are many processes even for the reproduction of line, and drawings of varying characteristics are better reproduced by different methods; they should each be sent for reproduction on its own merits.

It was in 1884 that there began to arise quite a number of original styles in pen-work, and then this new profession was by way of becoming an art. You will not find any English-printed book or magazine before this date showing a sign of this new art, but now it arose suddenly, and at once became an irresponsible, unreasoning welter of ill-considered mannerisms. Ever since 1884, until within the last year or two, pen-draughtsmen have rioted through every conceivable and inconceivable vagary of manner. The artists who by force of artistry and character have helped to spur on the process-man against his will, and have worked with little or no heed to the shortcomings of his science, have freed the hands of a dreadful rabble that has revelled merely in eccentricity. Thus has liberty for a space meant a licence so wild that to-day it has become quite refreshing to turn back to the sobriety of the old illustrators of from thirty to forty years ago, who drew for the fac-simile wood-engraver. [Pg 15]

From 1857, through the ’60’s, and on to 1875, when it finally shredded out, there existed a fine convention in drawing for illustration and the wood-engraver. Among the foremost exponents of it were Millais, Sandys, Charles Green, Robert Barnes, Simeon Solomon, Mahony, J. D. Watson, and J. D. Linton. Pinwell and Fred Walker, too, produced excellent work in this manner, before they untimely died.

The Sunday Magazine, Once a Week, Good Words, Cornhill, the first two years of the Graphic, and, where the drawings have not been drawn down to their humourous legends, the volumes of Punch during this period, are a veritable storehouse of beautiful examples of this peculiarly English school. It was a convention that grew out of the wood-engraver’s imposed limits, and they became transcended by the art of the young artists of that day.

There is a certain sweetness and grace in those old illustrations that seems to increase with the widening of that gulf between our day and the day of their production. It is not for the sake of their draughtsmanship alone (though that is excellent), but chiefly for their [Pg 16] technical qualities, and their fine character-drawing, that those monumental achievements in illustration appeal so strongly to the artistic eye to-day. We have been accustomed during these last years to the stress of mannerism, the bravura treatment of imported art, bringing with it strange atmospheres which have nothing in common with our duller skies, and, truth to tell, we want a change. Now, we might do much worse than hark back to the ’60’s, and study the peculiar style brought about by the needs of the wood-engraver, but transformed into an admirable school by men who wrought their trammels into a convention so great that it cannot fail, some day, to be revived.

It is greatly to be deplored that we have not left to us the original drawings of that time and these men. In the majority of cases, and through a long series of years, the drawings from which these fac-simile wood-engravings were made were drawn by the artists on the wood block, and engraved, so that we have left to us only the more or less successful engraver’s imitation of the artists’ original line-work. But when these blocks were the work of the Dalziels, or of [Pg 17] Swain, we may generally take them as a close approximation to the original drawing. Pen and pencil both were used upon the wood blocks: some of these are to be seen at the South Kensington Museum, with the original drawings upon them still uncut, photography having in the mean while become applied to the use of transferring a drawing from paper to the wood surface.

Unless you have practised etching on copper, in which you have to draw upon the plate in reverse, you can have little idea of the relief experienced by the artists of thirty years ago, when the necessity for drawing in reverse upon the wood was obviated.

Now, I am not going to say that with pen and ink and process-reproduction you could obtain the sweetness of the wood-engraved line, but something of it should be possible, and the dignified, almost classic, reserve and repose of this style of draughtsmanship could be, in great measure, brought back to help assuage the worry of the ultra-clever pen-work of to-day, and to form a grateful relief from that peculiarly modern vice in illustration, of “making a hole in the page.”

The great difficulty that would lie in the way of such a revival would [Pg 18] be that those who would attempt it would need to be good draughtsmen; and of these there are not many. No tricks nor flashy treatment hid bad drawing in this technique, as in much of the slap-dashiness of to-day. And not only would sound draughtsmanship be essential, but also characterization of a peculiarly well-seen and graphic description. The illustrator of a generation ago worked under tremendous disadvantages. “Phiz” etched his inimitable illustrations of Dickens upon steel with all the attendant drawbacks of working in reverse, yet he would be a bold man or reckless who should decry him. He was, at his best, greater beyond comparison than the Cruickshank—George, in the forefront of that artistic trinity—and he reached his highest point in the delightful composition of “Captain Cuttle consoles his Friend,” in Dombey and Son. Composition and characterization are beyond anything done before or since. It is distinctly, obviously, great, and it fits the author and his story like—like a glove. One cannot find a newer and better simile than that for good fitting. And (not to criticize modern work severely because it is modern) the greater bulk of illustration to-day fits the stories it professes to elucidate like a Strand tailor. [Pg 19]

There are facilities now for buying electrotypes from magazines and illustrated periodicals, by which engravings that have already served one turn in illustrating a story can be purchased, to do duty again in illustrating another; and this is a practice very widely prevalent to-day. And why can this be so readily done? The answer is near to seek. It is because illustration is become so characterless that it is so readily interchangeable. Perhaps it may be sought to lay the blame upon the author; and certainly there is not at this time so ready a field for character-drawing as Dickens presented. But I have not seen any illustrations to Mr. Hardy’s tales, nor to Mr. Stevenson’s, that realize the excellently well-shown types in their works.

If you should chance to see any early volumes (say from 1859 to 1863) of Once a Week for sale, secure them: they should be the cherished possessions of every black and white artist. After this date their quality fell off. Charles Keene contributed to Once a Week some of his best work, and the Mr. Millais of that date in line is more interesting than the Sir John Millais of to-day in paint. There is, in [Pg 20] especial, a beautiful drawing by him, an illustration to the Grandmother’s Apology, in the volume for 1859, page 40. But, frankly, it is a mistake to instance one illustration where so very many are monumental productions. Fred Walker contributed many exquisite drawings; Mr. Whistler, few enough to make us ardently wish there were more; and the same may be said of Mr. Sandys’ decorative work—his Rosamond, Queen of the Lombards, his Yet once more let the Organ play, his King Warwulf, Harald Harfagr, or The Old Chartist. These things are a delight: the artist’s work so insistently good, the quality of the engraver’s lines so wonderfully fine.

For all the talk and pother about illustration, there is nothing to-day that comes within miles of the work done in, say, 1862-1863 for Once a Week. It would be difficult to over-praise or to over-estimate the value of this fine period. It was the period of the abominable crinoline; but even that hideous fashion was transfigured by the artistry of these men. That is evident in the beautiful drawing, If, contributed by Sandys to the Argosy for 1863, in which the grandly flowing lines of the dress show what may be done with the most unpromising material. [Pg 21]

The most interesting drawings in the Cornhill Magazine range from 1863 to 1867. Especially noteworthy are the illustrations by Fred Walker—Maladetta, May, 1863, page 621, and Out of the Valley of the Shadow, January, 1867, page 75. If you compare the first of these with the little pen-drawing by Charles Green, reproduced by process in Harper’s Magazine, May, 1891, page 894, entitled, “Give me those letters,” you will see how Mr. Green’s hand has retained the old technique he and his brother illustrators learnt in drawing for the wood-engraver, and you will observe how well that old handling looks, and how admirably it reproduces in the process-work of to-day. Two other most successful wood blocks from the Cornhill Magazine may be noted—Mother’s Guineas, by Charles Keene, July, 1864, and Molly’s New Bonnet, August, 1864, by Mr. Du Maurier.

Processes, at first chiefly of the heliogravure or photogravure variety—processes, that is to say, of the intaglio or plate-printing description, printed in the same way as etchings and mezzotints, from dots and lines sunken in a metal plate instead of standing out in relief—date back almost to the invention of photography in 1834; and all modern processes of reproducing drawings have a photographic basis. Even at that time it was demonstrated that a glass negative could be used to reproduce the photographic image as an etched plate that would print in the manner of a mezzotint. Mr. H. Fox-Talbot, to whom belongs, equally with Daguerre, the invention of photography, was the first to show this. He devised an etched silver plate that reproduced a photograph direct. [Pg 23]

Photo-relief, or type-printing, blocks date from such comparatively recent times as 1860, when the Photographic Journal showed an illustration printed from a block by the Pretsch process.

At this present time there are three methods of primary importance for the reproduction of line drawings—

The first of these three processes is the most expensive, and it has not so great a vogue as the less costly methods, which are employed for the illustration of journals or publications that do not rely chiefly upon the excellence of their work. It is employed almost exclusively by Messrs. A. and C. Dawson in this country, and it is in all essentials identical with the old Pretsch process that first saw the light thirty-three years ago.

Acids do not enter into the practice of it at all. The procedure is briefly thus: A good dense negative is taken of the drawing to be reproduced to the size required. The glass plate is then placed in [Pg 24] perfect contact with gelatine sensitized by an admixture of bichromate of potassium to the action of light. Placed in water, the gelatine thus printed upon from the negative, swells, excepting those portions that have received the image of the reduced drawing. These are now become sunken, and form a suitable matrix for electrotyping into. Copper is then deposited by electro-deposition. The copper skin receives a backing of type-metal, and is mounted on wood to the height of type, and the block, ready for printing, is completed.

This process gives peculiar advantages in the reproduction of pen-drawings made with greyed or diluted inks. The photographic negative reproduces, of course, the varying intensities of such work with the most absolute accuracy, and they are repeated, with scarcely less fidelity, by the gelatine matrix. Pencil marks and pen-drawings with a slight admixture of pencil come excellently well by this method.

Every pen-draughtsman who sketches from nature knows how, in re-drawing from his pencil sketches, the feeling and sympathy of his work are lost, wholly or in part; but if the finished pen-drawing is made over the original pencil sketch and the pencilling retained, the effect is generally a revelation. It is in these cases that the swelled gelatine process gives the best results. [Pg 25]

4¾ × 7½. THE HALL, BARNARD’S INN.

Drawing in pale Indian ink on HP Whatman paper.

Drawn without knowledge of process and reproduced

by the swelled gelatine method.

[Pg 27] This example (The Hall, Barnard’s Inn) of a pen-drawing not made for reproduction by process was made years ago. Now reproduced, it shows that almost everything is possible to mechanical reproduction to-day. This drawing, worked upon with never a thought or idea or knowledge of process, comes every whit as well as if it had been drawn scrupulously to that end. It is all pen-work, save the outline around it and the signature, and they are in black chalk. The reduction from the original is only three-quarters of an inch across, and the reproduction is in every respect exact. Of course it is only swelled gelatine that could perform this feat; but by that process it is clear that you get results at once sympathetic and faithful, without the necessity of caring overmuch about the purely mechanical drudgery of learning a convention in pen and ink that shall be suitable for the etched processes. That convention has been wrought—it may not be said by tears and blood, but certainly with prodigious labour—by the masters of the art of pen-drawing into something artistic and pleasing to the eye, while it [Pg 28] satisfies photographic and chemical needs. But here is a process that demands no previous training in drawing for reproduction, and leaves the artist unfettered. True, it opens a vista of easy reproduction to the amateur, which is a thing terrible to think upon; but, on the other hand, to it we owe some delightful reproductions of “painters’” pen-drawings that make the earlier numbers of the illustrated exhibition catalogues worth having. [Pg 29]

[Pg 30] The albumen process is perhaps the more widely used of the three. By it the vast majority of the blocks used in journalistic work are made. It is credibly reported that one firm alone delivers annually sixty-three thousand blocks made by this process, which (it will thus be seen) is particularly suited to reproduction of the most instant and straight-away nature. It is also the cheapest method of reproduction, which goes far toward explaining that gigantic output just quoted. But, on the other hand, the albumen process in the hands of an artist in reproduction (as, for instance, M. Chefdeville) is capable of the most sympathetic results. It gives a softer, more velvety line than one would think possible, a line of a different character entirely from the clear, cold, sharp, and formal line characteristic of processes in which bitumen is used. These two methods (albumen and bitumen) are incapable of reproducing scarcely anything in fac-simile but pure line-work; pencil marks or greyed ink are either omitted or exaggerated to extremity, and they can only be corrected by the subsequent use of the graver upon the block. But black chalk or Conté crayon used upon slightly granulated drawing-papers, either by themselves or mixed with pen-work, come readily enough and help greatly to reinforce a sketch. This sketch of A Window, Chepstow Castle, was made with a Conté crayon. Unfortunately, these materials smear very easily, and have to be fixed before they can be trusted to the photo-engraver with perfect safety. Drawings made in this way may be fixed with a solution composed of gum mastic and methylated spirits of wine: one part of the former to seven parts of the latter. This fixing solution is best applied with a spray apparatus, as sold by chemists. But better than crayons, chalks, or charcoals are the lithographic chalks now coming somewhat into vogue. They have the one inestimable advantage of fixity, and cannot be [Pg 31] readily smeared, even with intent. They are not fit for use upon smooth Bristol-board or glazed paper, but find their best mediums in HP and “not” makes of drawing-paper, and in the grained “scratch-out” cardboards, of which more hereafter. They give greater depth of colour than lead pencil, and reproduce more surely; and the drawings worked up [Pg 32] with them readily stand as much reduction as an ordinary pen-drawing. The No. 1 Lemercier is the best variety of lithographic chalks for this admixture; it is harder than others, and can be better sharpened to a fine point. For detail it is to be used very sparingly or not at all, because it is incapable of producing a delicate line; but for giving force, for instance, to a drawing of crumbling walls, or to an impressionist sketch of landscape, it is invaluable. The effects produced by working with a No. 1 Lemercier litho-chalk are shown here. The first example was drawn upon Whatman’s “not” paper, which gives a fine, bold granulation. The two remaining examples are from sketches on Allongé paper, a fine-grained charcoal paper of French make.

It is also worth knowing that a good grained drawing may be made with litho-chalk, by taking a piece of dull-surfaced paper, like the kind [Pg 33] generally used for type-writing purposes, pinning it tightly upon glass- or sand-paper and then working upon it, keeping it always in contact with the rough sand-paper underneath. A canvas-grain may be obtained by using the cover of a canvas-bound book in the same way.

Both the albumen and the bitumen processes are practised with the

aid of acids upon zinc. In the first named the zinc plate is coated

with a ground composed of a solution of white of egg and bichromate

of ammonia, soluble in cold water. A reversed photographic negative

is taken of the drawing and placed in contact with the prepared zinc

plate in a specially constructed printing-frame. When the drawing

is sufficiently printed upon this albumen surface, the plate is

rolled over with a roller charged with printing-ink thinned down with

turpentine, and then, when this inking has been completed, the plate

is carefully rubbed in cold water until the inked albumen has been

rubbed off it, excepting those parts where the drawing appears. The

lines composing the drawing remain fixed upon the plate, the peculiar

property of the sensitized albumen rendering the lines that have been

exposed to the action of light insoluble. The zinc plate is then dried

[Pg 34]

and sponged with gum; dried again, and then the coating of gum washed

off, and then inked again. The plate, now thoroughly prepared, is

placed in the first etching bath, a rocking vessel filled with

much-diluted nitric acid. There are generally three etchings performed

upon a zinc block, each successive bath being of progressively stronger

acid; and between these baths the plate is gummed, and powdered with

resin, and warmed over a gas flame until the printing-ink and the

half-melted resin run down the sides of the lines already partly

etched; the object of these careful stages being to prevent what is

technically termed “under-etching”—that is to say, the production of a

relief line, whose section would be thus:

![]() instead of

instead of

![]() .

The result in the printing of an under-etched block would be that the lines

would either break or wear down to nothingness, whereas a block showing

the second section would grow stronger and the old lines thicker with

prolonged use. The section of a wood engraving is according to this

second diagram.

.

The result in the printing of an under-etched block would be that the lines

would either break or wear down to nothingness, whereas a block showing

the second section would grow stronger and the old lines thicker with

prolonged use. The section of a wood engraving is according to this

second diagram.

In the case of the bitumen process, the photograph is taken as before, the negative placed upon the zinc plate in the same way, and the image [Pg 35] printed upon the bitumen. When this has been done, the plate is flooded with turpentine, and all the bitumen dissolved away, with the exception of that upon the image. The subsequent proceedings are as in the case of the albumen process, and need not be recounted.

It will be seen (if this outline can be followed) that the bitumen process differs from the albumen only in the composition of the ground (as an etcher would term it), but the quality of line is very different. The zinc plates used are cut from polished sheets of the metal, from one-sixteenth to one-eighth of an inch in thickness.

A well-etched block should feel sharp yet smooth to the thumb and fingers, as if it were cut. A badly etched or over-etched block has an altogether different feel: scratchy, and repulsive to the touch. Frequently it happens that by carelessness or mischance the process-man will over-etch a block; that is to say, he will allow it to remain in the acid-bath a minute or so too long, so that the upstanding lines become partly eaten away by the fluid. The result, when printed, is a wretched ghost of the original drawing. An over-etched block, or a good [Pg 36] block in which the lines appear too thin and the reproduction in consequence weak, can be remedied in degree by being rubbed down with oilstone. This, if the lines are not under-etched, thickens the upstanding metal and produces a heavier print. But some of the smaller process firms have an ingenious, if none too honest, practice of pulling a proof from the unetched plate, and sending it along with the defective block. This can readily be done by inking up the image with a roller before printing, and then passing the thin plate of metal through a lithographic press, or through a transfer press, such as is to be found in every process establishment. Of course the print thus secured is a perfect replica in little of the original drawing, and looks eminently satisfactory. One can generally identify these proofs before etching by their backs, which have, of course, not the slightest marks of the pressure usually to be discerned upon even the most carefully prepared proofs of finished blocks. The surface of a zinc block sometimes becomes oxidized by the acid used in etching not having been thoroughly washed off. This may occur at once if the acid is strong, and then it generally happens that the block is irretrievably ruined; but if oxidation occurs after some time, it is generally superficial, and can be rubbed down. The process of oxidation begins with an efflorescence, which may be best rubbed down with a thick stick of charcoal, broken across the grain. But zinc blocks are frequently ruined by carelessness in the printing-office after printing. When the printing has been done it is customary to clean type and blocks from the printing-ink by scrubbing them with a brush dipped in what printers call “lye”—that is, a solution of pearl-ash—which, although it does not injure the leaden types, is apt to corrode the zinc of which most process blocks are made, if they are not carefully and immediately washed in water and dried. A block with its surface destroyed in this manner prints miserably, with a fuzzy appearance. The easiest way of [Pg 37] protecting blocks from becoming oxidized is to allow the printing-ink to remain on them, or if you have none, rub them over with tallow. [Pg 38]

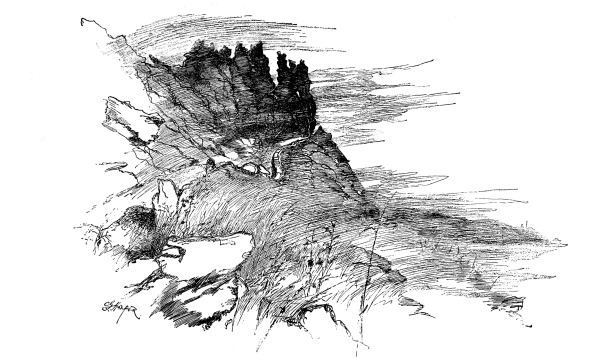

12½ × 9. BOLT HEAD: A MISTY DAY.

Pen and pencil drawing, reproduced by the swelled gelatine process.

Examples will now be shown of the varying results obtainable from the same drawings by different processes. [Pg 41]

The drawing representing a Misty Day at Bolt Head was made upon common rough paper, such as is usually found in sailors’ log-books; [Pg 42] in fact, it was a log-book the present writer used during the greater part of a tour in Devon, nothing else being obtainable in those parts save the cloth-bound, gold-lettered sketch-books whose porterage convicts one at once of amateurishness. And here let me say that a sailor’s log-book, though decidedly an unconventional medium for sketching in, seems to be entirely admirable. The paper takes pencil excellently well, and the faint blue parallel lines with which the pages are ruled need bother no one; they will not (being blue) reproduce. To save the freshness of the impression, the sketch was lightly finished in ink, and sent for reproduction uncleaned. The illustration shows the result. It is an example of the bitumen process, whose original sin of exaggerating all the pencil marks which it has been good enough to reproduce at all is partly cloaked by the intervention of hand-work all over the block. You can see how continually the graver has been put through the lines to produce a greyness, yet how unsatisfactory the result!

The drawing was now sent for reproduction by the swelled gelatine process. The result is a much more satisfactory block. Everything that the original contained has been reproduced. The sullen blacknesses of the pinnacled rocks are nothing extenuated, as they were in the first example, where they seem comparatively insignificant, and the technical qualities of pen and pencil are retained throughout, and can readily be identified. The same remarks apply even more strongly to the small blocks from the Note at Gorran. [Pg 43]

[Pg 44] But such a pure pen-drawing as that of Charlwood, shown here in blocks by (1) Messrs. Dawson’s swelled gelatine process, and (2) by Mr. Chefdeville’s sympathetic handling of the albumen process, would have come almost equally well by bitumen, or by an ordinary practitioner’s treatment of albumen. It offered no technical difficulties, and there is exceedingly little to choose between these two blocks. Careful examination would show that a very slight thickening of line had taken place throughout the block by the gelatine method, and this must ever be the distinguishing difference between that process and those in which acids are used to eat away the metal of the block—that the gelatine renders at its best every jot and tittle of a drawing, and would by the nature of the process rather exaggerate than diminish; and that in those processes in which acids play a part, the process-man must be ever watchful lest his zinc plate be “over-etched”—lest the upstanding metal lines be eaten away to a scratchy travesty of the original drawing. But you will see that although the lines in the swelled gelatine Charlwood are appreciably thicker than in its albumen fellow, yet the latter prints darker. The explanation is in the metals of which the two blocks are composed. Zinc prints more heavily than copper. [Pg 45]

[Pg 46] It should not be forgotten that, to-day, hand-work upon process-blocks is become very usual. To paraphrase a well-worn political catch-phrase, the old methods have been called in to redress the vagaries of the new: the graver has been retained to correct the crudities of the rocking-bath. To be less cryptic, the graver is used nowadays to tone down the harsh and ragged edges of the etched zinc. Here is an illustration that will convey the idea to perfection. Here is, in this View from the Tower Bridge Works, a zincographic block, grounded with bitumen and etched by the aid of acids. The original drawing was made upon Bristol-board, with Stephens’ ebony stain, and an F nib of Mitchell’s make. The size of that drawing was twelve and a half inches across; the sky drawn in with much elaboration. A first proof showed a [Pg 47] sky harsh and wanting in aërial perspective. A graver was put through it, cutting up the lines into dots, and thus putting the sky into proper relation with the rest of the picture.

Another interesting and suggestive comparison is between photogravure, or heliogravure, as it is sometimes called, and type-printing processes for the reproduction of line. The frontispiece to this volume is a heliogravure plate by Dujardin, of Paris, from a pen-drawing that offered no obstacles to adequate reproduction by the bitumen process. In fact, you see it here, reproduced in that way, and of the same size. The copper intaglio plate is in every way superior to the relief block, as might have been expected. The hardness of the latter method gives way, in the heliogravure plate, to a delightful softness, even when the plate is clean-wiped and printed in as bald and artless a fashion as a tradesman’s business card; but now it is printed with care and with the retroussage that is generally the meed of the etching, you could not have distinguished it from an etching had you not been told its history. [Pg 48]

[Pg 50] The procedure in making a heliogravure is in this wise:—A copper plate, similar to the kind used by etchers, receives a ground of bichromatized bitumen. A photograph is taken of the drawing to be reproduced, and from the negative thus obtained a positive is made. The positive, in reverse, is placed upon the grounded plate and printed upon it. The bitumen which has been printed upon by the action of light is thus rendered wholly insoluble, and the image of the drawing remains the only soluble portion of the ground. The plate is then treated with turpentine, and the soluble lines thus dissolved. Follows then the ordinary etching procedure. This is a more simple and ready process than the making of a relief block. It is, however, more expensive to commission, but then expense never is any criterion of original cost. The printing, though, is a heavy item, because, equally with etchings or mezzotints, it must be printed upon a copper-plate press, and this involves the cleaning and the re-inking of the plate with every impression.

The subject which the present plate bears does not show the utmost capabilities of the heliogravure. It was chosen as a fair example to show the difference between two methods without straining the limitations of the relief block. But if the drawing had been most carefully graduated in intensity from the deepest black to the palest brown, the copper plate would have shown everything with perfect ease. Large editions of these plates are not to be printed without injury, because the constant wiping of the soft copper wears down the surface. But to obviate this defect a process of acierage has been invented, by which a coating of iron is electrically deposited upon the surface of the plate, rendering it, practically, as durable as a steel engraving. [Pg 51]

[Pg 52] It is by experiments we learn to achieve distinction; by immediate failure that we rise to ultimate success; and ofttimes by pure chance that we discover in these days some new trick of method by which process shall do for the illustrator something it has not done before. There is still, no doubt, in the memory of many, that musty anecdote of the painter who, fumbling over the proper rendering of foam, applied by some accident a sponge to the wet paint, and lo! there, by happy chance, was the foam which had before been like nothing so much as wool. [Pg 53]

[Pg 54] In the same way, I suppose, some draughtsman discovered splatter-work. He may readily be imagined, prior to this lucky chance, painfully stippling little dots with his pen; pin-points of ink stilted and formal in effect when compared with the peculiarly informal concourse of spots produced by taking a small, stiff-bristled brush (say a toothbrush), inking it, and then, holding the bristles downwards and inclining toward the drawing, more or less vigorously stroking the inky bristles towards one with a match-stick. Holding the brush thus, and stroking it in this way, the bristles send a shower of ink spots upon the drawing. Of course this trick requires an extended practice before it can be performed in workmanlike fashion, and even then the parts not required to be splattered have to be carefully covered with cut-paper masks. [Mem.—To use a fixed ink for drawings on which you intend to splatter, because it is extremely probable that you will require to paint some portions out with Chinese white, and Chinese white upon any inks that are not fixed is the despair of the draughtsman.] Here is an excellent example of splatter. It is by that resourceful American draughtsman, Harry Fenn. Indeed, the greatest exponents of this method are Americans: few men in this country have rendered it with any frequency, or with much advantage. I have essayed its use to aid this sunset view of Black Rock, and to me it seems to come well. But the finer spots are very difficult of reproduction; some are lost here. There is a most ingenious contrivance, an American notion, I believe, for the better application of splatter. It is called the air-brush, and it consists of a tube filled with ink, and fitted with a description of nozzle through which the ink is projected on to paper by a pneumatic arrangement worked by the artist by means of a treadle. You aim the affair at your drawing, work your treadle, and the trick is done. The splatter is remarkably fine and equable, and its intensity can be regulated by the distance at which the nozzle is held from the drawing. The greater advantage, however, in the use of the air-brush would seem to lie with the lithographic draughtsmen, who have to cover immense areas of work. [Pg 55]

[Pg 56] Here follows an experiment with diluted inks: the drawing made upon HP Whatman with all manner of nibs. It is all pen-work, worked with black stain, and with writing ink watered down to different values. This is an attempt to render as truthfully as possible (and as unconventionally) the sunset shine and shadow of a lonely shore, blown upon with the wild winds of the Channel. A little stream, overgrown with bents and waving rushes, flows between a break in the low cliffs and loses itself in the sands. The sun sets behind the ruined house, and between it and the foreground is a clump of storm-bent trees, constrained to their uneasy inward pose not by present breezes, but to this shrinking habit of growth by long-continued stress of weather. The block is by Gillot, of Paris, who was asked to get the appearance of the original drawing in a line-block. This he has not altogether succeeded in doing: perhaps it was impossible; but the feeling is here. It is a line-block, rouletted all over in the attempt to get the effect produced by watered inks. The roulettes, by which these greynesses are produced, are peculiar instruments, consisting of infinitesimal wheels of hard steel whose edges are fashioned into microscopically small points or facets. Mounted at the end of a stick more nearly resembling a penholder than anything else, the wheel is driven along (and into) the surface of the metal by pressure, making small indentations in it. There are varieties of roulettes, the differences between them lying in the patterns of the projections from the wheel. The varieties in the texture of rouletting seen in this print are thus explained. [Pg 57]

10 × 6½. DRAWING IN DILUTED INKS, REPRODUCED BY GILLOT.

Block touched up by hand and freely rouletted.

[Pg 58] Now come some experiments in mixtures. The mixed drawing has many possibilities of artistic expression, and here are some essays in [Pg 59] mixtures, harnessed to tentative employments of process.

[Pg 60] First is this experiment in pen and pencil reproduced in half-tone. It is a view of Chepstow Castle—that really picturesque old border fortress—from across the river Wye, a river that comes rushing down from the uplands with an impetuous current full of swirls and eddies. The town of Chepstow lies at the back, represented in this drawing only by its lights. The huts and sheds that straggle down to the waterside, and the rotting pier, where small vessels load and unload insignificant cargoes, are commonplace enough, but they go to make a fine composition; and the last sunburst in the evening sky, the stars already brilliant, and the white gleams from the hurrying river, are immensely valuable, and things of joy to the practitioner in black and white. Rain had fallen during the day, and, when the present writer sat down to sketch, still lent a fine impending juicy air to the scene that seemed incapable of adequate translation into pure line; therefore, upon the pencil sketch was added pen-work, and to that more pencil, and, when finished, the drawing was sent to be processed, with special instructions that the white spaces in the sky should be preserved, together with those on the buildings, but that all else might acquire the light grey tint which the half-tone always gives, as of a drawing made upon paper of a silvery grey. In the result you can see this purely arbitrary, but delightful, ground tint everywhere; it gives absolutely the appearance of a drawing made upon tinted cardboard, but, truly, the only paper employed was a common, rough make, that would be despised of the lordly amateur. Here you see the half-tone process on its best behaviour, and I think it has secured a very notable result. [Pg 61]

11¾ × 8¾. CHEPSTOW CASTLE.

Drawing in pen and ink and pencil made on rough paper.

Reproduced by half-tone process.

[Pg 62] Here is another experiment, Clifford’s Inn: a Foggy Night—a mixture of pen and ink and crayon worked upon with a stump, and then lightly brushed over with a damp, not a full, brush; the lights in the windows [Pg 63] and the reflections taken out with the point of an eraser.

It should be said that in drawing thus for half-tone reproduction the drawing should be made much more emphatic than the print is intended to appear; that is to say, the deepest shadows should be given an additional depth, and the fainter shading should be a shade lighter than you would give to a drawing not made with a view to publication. If these points are not borne in mind, the result is apt to be flat and featureless. [Pg 64]

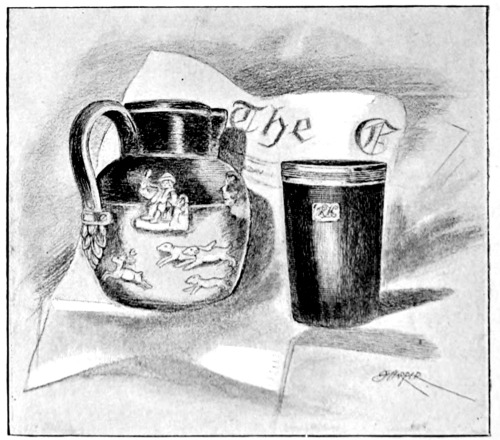

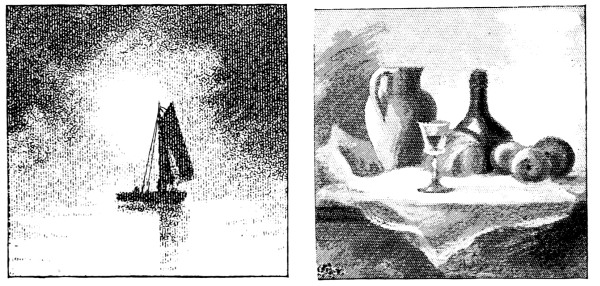

If a half-tone block exhibits these disagreeable peculiarities, high lights can always be created by the aid of a chisel used upon the metal surface of the block. The more important process firms generally employ a staff of competent engravers, who, now that wood engraving is less widely used, have turned their attention to just this kind of work—the correcting of process-blocks. The artist has but to mark his proof with the corrections and alterations he requires. The two illustrations shown on page 68, from different states of the same block, give a notion of correcting the flatness of half-tone. The second block shows a good deal of retouching in the lights taken out upon the paper and the jug, and in the hatching upon the drinking-horn. [Pg 65]

9½ × 6¾. CLIFFORD’S INN: A FOGGY NIGHT.

Drawn in pen and ink and crayon, and brushed over.

Reproduced by half-tone process, medium grain.

[Pg 66] Half-tone processes are practised in much the same way as the albumen and bitumen line methods already described, in so far as that they are [Pg 67] worked with acids and upon zinc or copper. At first these half-tone blocks were made in zinc, but recently some reproductive firms have preferred to use copper. Messrs. Waterlow and Sons, in this country, generally employ copper for half-tone blocks from drawings or photographs. Copper prints a softer and more sympathetic line, and does not accumulate dirt so readily as zinc. All the half-tone blocks in this volume are in copper. By these processes the photographs that one sees reproduced direct from nature appear in print without the aid of the artist. They are often referred to as the Meisenbach process, because the Meisenbach Company was amongst the first to use these methods in this country. The essential difference in their working is that there is a ruled screen of glass interposed between the drawing or object to be photographed and the negative. Generally a screen of glass is closely ruled with lines crossing at right angles, and etched with hydrofluoric acid. Into the grooves thus produced, printing-ink is rubbed. The result is a close network of black lines upon glass. This screen, interposed between the sensitized plate in the camera and the object to be photographed, produces upon the negative the criss-cross appearance we see in the ultimate picture. In the half-tone reproductions by Angerer and Göschl, of Vienna, this appearance is singularly varied. The screen used by them is said to be made from white silk of the gauziest description, hung before a wall covered with black velvet in such a manner that the blackness of the velvet can be seen and photographed through the silken film. A negative is made, and from it a positive is produced, which exhibits a curiously varied arrangement of dots and meshes. The positive is used in the same way as the ruled-glass screens.

6¾ × 6¼. PENCIL AND PEN AND INK DRAWING

REPRODUCED

BY HALF-TONE PROCESS.

[Pg 69] The network characteristic of half-tone relief blocks can be made fine, or medium, or coarse, as required. The fine-grained blocks are used for careful book and magazine printing, and the medium-grained for printing in the better illustrated weeklies; the coarse-grained are used for rougher printing, but still are nearly always too fine for newspaper work. The Daily Graphic, however, has solved the problem of printing them sufficiently well for the picture to be discerned. Beyond this the rotary steam-printing press has not yet advanced.

In appearance somewhat similar to a half-tone block, but with the tint differently applied, is the illustration of The Village Street, Tintern: Night. Here is a pure pen-drawing, scratched and scribbled to blackness without much care for finesse, the great reduction and the tint being reckoned upon to assuage all angularities. The original drawing was then lightly scribbled over with blue pencil to indicate to [Pg 70] the process-man that a mechanical tint was required to be applied upon the block, and word was specially sent that the tint was to be squarely cut, not vignetted. The result seems happy. This is a line block, not tone.

In such a case the procedure is normal until the image is printed upon the sensitized ground of the zinc plate. Then the prescribed tint is transferred by pressure of thumb and fingers, or by means of a burnisher, from an engraved sheet of gelatine previously inked with a printing roller. The zinc plate is then etched in the familiar way. [Pg 71]

[Pg 72] These tints are produced by Day’s shading mediums; thin sheets of gelatine engraved upon one side with lines or with a pattern of stipple. There are very many of these patterns. They can readily be [Pg 73] applied, and with the greatest accuracy, because the gelatine is semi-transparent, and admits of the operator seeing what he is about. These mechanical tints are capable of exquisite application, but they have been more frequently regarded as labour-saving appliances, and have rarely been used with skill, and so have come to bear an altogether unmerited stigma. They can be used by a clever process-man, under the directions of the draughtsman, with great effect, and in remarkably diverse ways. For it is not at all necessary that the tint should come all over the block. It can be worked in most intricately. The illustration, Leebotwood, shows an application of shading medium to the sky. The proprietors (for it is a patent) of these devices have endeavoured to introduce their use amongst artists, with a view to their working the mediums upon the drawings themselves. It has been shown that the varieties of shading to be obtained by shifting and transposing the gelatine plates is illimitable, but as their use involves establishing a printing roller and printer’s ink in one’s [Pg 74] studio, and as all artists are not printers born, it does not seem at all likely that Day’s shading mediums will be used outside lithographic offices or the offices of reproductive firms.

Here are appended some examples of the shading mediums commonly used.

The cost of reproduction by process varies very greatly. It is always calculated at so much the square inch, with a minimum charge ranging, for line-work, from two-and-sixpence to five shillings. For half-tone the minimum may be put at from ten shillings to sixteen shillings. Plain line blocks, by the bitumen or albumen processes, cost from twopence-halfpenny to sixpence per square inch, and handwork upon the block is charged extra. Some firms make a charge of one penny per square inch for the application of Day’s shading mediums. Line blocks by the swelled gelatine process are charged at one shilling per square inch, and reproductions of pencil or crayon work at one-and-threepence. Half-tone blocks from objects, photographs, or drawings range from eightpence to one-and-sixpence per square inch, and the cost of a photogravure plate may be put at two-and-sixpence for the same unit. The best work in any photographic process is infinitely less costly than wood engraving, which, although its cost is not generally calculated on the basis of the inch, as in all process work, may range approximately from three shillings to five shillings for engraving of average merit. [Pg 75]

EXAMPLES OF DAY’S SHADING MEDIUMS.

[Pg 77] Electrotype copies of line blocks cost from three-farthings to three-halfpence per square inch, and from half-tone blocks, twopence, although it is not advisable to have electrotypes taken of these fine and delicate blocks. If duplicates are wanted of half-tones, the usual practice is to have two original blocks made, the process-engraver charging for the second block half the price of the first.

The process engraver will tell you, if you seek counsel of him, that you should use Bristol-board, and of that only the smoothest and most highly finished varieties. But, however easy it may render his work of reproduction, there is no necessity for you to draw upon cardboard or smooth-surfaced paper at all. Paper of a reasonable whiteness is, of course, necessary to any process of line engraving which has photography as a basis, but to say that stiff cardboards or papers of a blue-white, as opposed to the cream-laid variety, are necessary is merely to obscure what is, after all, a simple matter.

Bristol-board is certainly a very favourite material, and the varieties of cardboards sold under that name are numerous enough to please anybody. Goodall’s sell as reliable a make as can be readily found. It [Pg 79] is white enough to please the photo-engraver, and of a smooth, hard surface; and a hard surface you must have for pen-work. But it is an unsympathetic material, and it is an appreciably more difficult matter to make a pencil sketch upon it than upon such papers as Whatman’s HP.

Mounting-boards are frequently used, chiefly for journalistic pen-work, when it may be supposed nobody cares anything about the finesse of the art, but only that the drawing shall be up to a certain standard of excellence, and, more particularly, up to time. Mounting-boards are appreciably cheaper than good Bristol-board, but if erasures are to be made they are troublesome, because under the surface they are composed of the shoddiest of matter. They are convenient, indeed admirable, for studies carried out in a masculine manner with a quill pen, or for simple drawings made with an ordinary writing nib, with not too sharp a point. For delicate technique they are not to be recommended.

Indeed, for anything but work done at home, cardboards of any sort are inexpedient; they are heavy, and take up too much space. If they were necessary, of course you would have to put up with the inconvenience of [Pg 80] carrying two or more pounds’ weight of them about with you, but they are not necessary.

Every one who makes drawings in pen and ink is continually looking out for an ideal paper; many have found their ideals in this respect; but that paper which one man swears by, another will, not inconceivably, swear at, so no recommendation can be trusted. Again, personal predilections change amazingly. One day you will be able to use Bristol-board with every satisfaction; another, you will find its smooth, dead white, immaculate surface perfectly dispiriting. No one’s advice can be implicitly followed in respect of papers, inks, or pens. Every one must find his own especial fancy, and when he has found it he will produce the better work.

The pen-draughtsman who is a paper-fancier does not leave untried even the fly-leaves of his correspondence. Papers have been found in this way which have proved satisfactory. All you have to do is to go to some large stationer or wholesale papermaker’s and get your fancy matched. It would be an easy matter to obtain sheets larger than note-paper. [Pg 81]

Whatman’s HP, or hot-pressed drawing-paper, is good for pen-drawing, but its proper use is not very readily learnt. To begin with, the surface is full of little granulations and occasional fibres which catch the pen and cause splutterings and blots. Sometimes, too, you happen upon insufficiently sized Whatman, and then lines thicken almost as if the drawing were being made upon blotting-paper.

A good plan is to select some good HP Whatman and have it calendered. Any good stationer could put you in the way of getting the calendering done, or possibly such a firm as Dickinsons’, manufacturers of paper, in Old Bailey, could be prevailed upon to do it. If you want a firm, hard, clear-cut line, you will of course use only Bristol-board or mounting-board, or papers with a highly finished surface. Drawings upon Whatman’s papers give in the reproductions broken and granulated lines which the process-man (but no one else) regards as defects. Should the block itself be defective, he will doubtless point to the paper as the cause, but there is no reason why the best results should not proceed from HP paper. Messrs. Reeves and Sons, of Cheapside, sell what they call London boards. These are sheets of Whatman mounted upon cardboard. [Pg 82] They offer the advantages of the HP surface with the rigidity of the Bristol-board. The Art Tablets sold by the same firm are cardboards with Whatman paper mounted on either side. A drawing can be made upon both sides and the tablet split up afterwards.

In connection with illustration, amongst the most remarkable inventions of late years are the prepared cardboards generally known amongst illustrators as “scratch-out cardboards,” introduced by Messrs. Angerer and Göschl of Vienna, and by M. Gillot of Paris. These cardboards are of several kinds, but are all prepared with a surface of kaolin, or china-clay. Reeves sell eight varieties of these clay-boards. They are somewhat expensive, costing two shillings a sheet of nineteen by thirteen inches, but when their use is well understood they justify their existence by the rich effects obtained, and by the saving of time effected in drawing upon them. Drawings made upon these preparations have all the fulness and richness of wash, pencil, or crayon, and may be reproduced by line processes at the same cost as a pen-drawing made upon plain paper. The simplest variety of clay-board is the one [Pg 83] prepared with a plain white surface, upon which a drawing may be made with pen and ink, or with a brush, the lights taken out with a scraper or a sharp-pointed knife. It is advisable to work upon all clay-surfaced papers or cardboards with pigmental inks, as, for instance, lampblack, ivory-black, or Indian ink. Ebony stain is not suitable. The more liquid inks and stains have a tendency to soak through the prepared surface of china-clay, rather than to rest only upon it, thereby rendering the cardboard useless for “scratch-out” purposes, and of no more value than ordinary drawing-paper. A drawing made upon plain clay-board with pen and brush, using lampblack as a medium, can be worked upon very effectively with a sharp point. White lines of a character not to be obtained in any other way can be thus produced with happy effect. Mr. Heywood Sumner has made some of his most striking decorative drawings in this manner. It is a manner of working remarkably akin to the wood-engraver’s art—that is to say, drawing or engraving in white lines upon a black field—only of course the cardboard is more readily worked upon than the wood block. Indeed, wood-engravers have frequently used this plain clay-board. They have [Pg 84] had the surface sensitized, the drawing photographed and printed upon it, and have then proceeded to take out lights, to cut out white lines, and to hatch and cross-hatch, until the result looks in every way similar to a wood engraving. This has then been photographed again, and a zinc block made that in the printing would defy even an expert to detect.

Other kinds of clay-boards are impressed with a grain or with plain indented lines, or printed upon with black lines or reticulations, which may be scratched through with a point, or worked upon with brush or pen. Examples are given here:

No. 1. White cardboard, impressed with a plain canvas grain.

[Pg 85] This gives a fine painty effect, as shown in the drawing of polled willows: a drawing made in pencil, with lights in foreground grass and on tree-trunks scratched out with a knife or with the curved-bladed eraser sold for use with these preparations.

2. Plain white diagonal lines. Pencil drawing. [Pg 86]

3. Plain white perpendicular lines. Pencil drawing.

4. Plain white aquatint grain. Pencil drawing.

These four varieties require greater care and a lighter hand in working than the others, because their patterns are not very deeply stamped, and consequently the furrows between the upstanding lines are apt to become filled with pencil, and to give a broken and spotty effect in the reproduction.

5. Black aquatint. This is not a variety in constant use. Three states are shown.

6. Black diagonal lines. This is the pattern in greater requisition. [Pg 87] The method of working is shown, but the possibilities of this pattern are seen admirably and to the best advantage in the illustration of Venetian Fête on the Seine.

BLACK AQUATINT CLAY-BOARD BLACK DIAGONAL-LINED CLAY-BOARD

AND TWO STAGES OF DRAWING.AND TWO STAGES OF DRAWING.

[Pg 88] 7. Black perpendicular lines. Same as No. 6, except in direction of line.

BLACK PERPENDICULAR-LINED CLAY-BOARD AND TWO STAGES OF DRAWING.

VENETIAN FÊTE ON THE SEINE, WITH THE TROCADERO ILLUMINATED.

Pen and ink on black diagonal-lined clay-board. Lights scratched out.

[Pg 90] Drawings made upon these grained and ridged papers must not be stumped down or treated in any way that would fill up the interstices, [Pg 91] which give the lined and granular effect capable of reproduction by line-process. Also, it is very important to note that drawings on these papers can only be subjected to a slight reduction of scale—say, a reduction at most by one quarter. The closeness of the printed grains and lines forbids a smaller scale that shall be perfect. Mr. C. H. Shannon has drawn upon lined “scratch-out” cardboard with the happiest effect.