The Cambridge Handbooks of Liturgical Study

General Editors:

CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS

London: FETTER LANE, E.C.

C. F. CLAY, Manager

Edinburgh: 100, PRINCES STREET

Berlin: A. ASHER AND CO.

Leipzig: F. A. BROCKHAUS

New York: G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

Bombay and Calcutta: MACMILLAN AND CO., Ltd.

All rights reserved

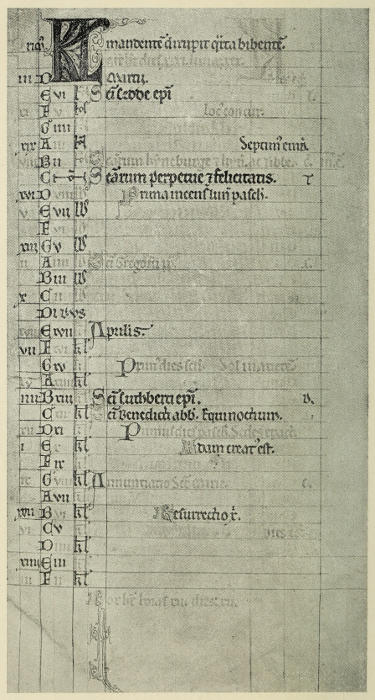

Kalendar of Peterborough Psalter (March)

Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (MS. 12). Cent. xiii.

THE CHURCH YEAR AND

KALENDAR

BY

JOHN DOWDEN, D.D.,

Hon. LL.D. (Edinburgh), late Bishop of Edinburgh

Cambridge:

at the University Press

1910

Cambridge:

PRINTED BY JOHN CLAY, M.A.

AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS

The purpose of The Cambridge Handbooks of Liturgical Study is to offer to students who are entering upon the study of Liturgies such help as may enable them to proceed with advantage to the use of the larger and more technical works upon the subject which are already at their service.

The series will treat of the history and rationale of the several rites and ceremonies which have found a place in Christian worship, with some account of the ancient liturgical books in which they are contained. Attention will also be called to the importance which liturgical forms possess as expressions of Christian conceptions and beliefs.

Each volume will provide a list or lists of the books in which the study of its subject may be pursued, and will contain a table of Contents and an Index.

The editors do not hold themselves responsible for the opinions expressed in the several volumes of the series. While offering suggestions on points of detail, they have left each writer to treat his subject in his own way, regard being had to the general plan and purpose of the series.

H. B. S.

J. H. S.

[The manuscript of the present volume was sent to the press only a few weeks before the lamented death of the author, and therefore the work did not receive final revision at his hands. In its original draft the manuscript contained a somewhat fuller discussion of some of the topics handled, e.g. the work of the mediaeval computists, and such technical terms as ‘Sunday Letters,’ ‘Epacts,’ etc., as well as a fuller treatment of the various Eastern Kalendars. Exigencies of space, however, and the scope of the present series, made it necessary for the author to curtail these portions of his work, while suggesting books in which the study of these topics may be pursued by the student. The Editors have endeavoured, as far as possible, to verify the references and to supplement them, where it seemed necessary to do so. In a few cases they have added short additional notes, enclosed in brackets, and bearing an indication that they are the work of the Editors.]

| PAGE | |

| Introduction | xi |

| A short Bibliography | xxi |

| I. The ‘Week’ adopted from the Jews. The Lord’s Day: early notices. The Sabbath (Saturday) perhaps not observed by Christians before the fourth century: varieties in the character of its observance. The word feria applied to ordinary week days: conjectures as to its origin. Wednesdays and Fridays observed as ‘stations,’ or days of fasting | 1 |

| II. Days of the Martyrs. Local observances at the burial places of Martyrs. Early Kalendars: the Bucherian; the Syrian (Arian) Kalendar; the Kalendar of Polemius Silvius; the Carthaginian. The Sacramentary of Leo; the Gregorian Sacramentary. All Saints’ Day; All Souls’ Day. The days of Martyrs the dominant feature in early Kalendars: the Maccabees | 12 |

| [viii]III. Origins of the feasts of the Lord’s Nativity and The Epiphany. Festivals associated with the Nativity in early Kalendars | 27 |

| IV. Other commemorations of the Lord. The Circumcision; Passiontide, Holy Week; mimetic character of observances. The Ascension. The Transfiguration. Pentecost | 37 |

| V. Festivals of the Virgin Mary. Hypapante (the Purification), originally a festival of the Lord. The same true of the Annunciation. The Nativity and the Sleep (Dormitio) of the Virgin. The Presentation. The Conception. The epithet ‘Immaculate’ prefixed to the title in 1854. Festivals of the Theotokos in the East | 47 |

| VI. Festivals of Apostles, Evangelists, and other persons named in the New Testament. St Peter and St Paul. St Peter’s Chair,—the Chair at Antioch. St Peter’s Chains. St Andrew. St James the Great. St John: St John before the Latin gate, a Western festival. St Matthew. St Luke. St Mark. St Philip and St James. St Simon and St Jude. St Thomas. St Bartholomew. St John the Baptist; his Nativity, his Decollation. The Conversion of St Paul. St Mary Magdalene. St Barnabas. Eastern commemorations of the Seventy disciples (apostles). Octaves. Vigils | 58 |

| [ix]VII. Seasons of preparation and penitence. Advent: varieties in its observance. Lent: its historical development; varieties as to its commencement and its length. Other special times of fasting: the three fasts known in the West as Quadragesima. Rogation days. The Four Seasons (Ember Days). Fasts of Eastern Churches | 76 |

| VIII. Western Kalendars and Martyrologies: Bede, Florus, Ado, Usuard. Old Irish Martyrologies. Value of Kalendars towards ascertaining the dates and origins of liturgical manuscripts. Claves Festorum. The modern Roman Martyrology | 93 |

| IX. Easter and the Moveable Commemorations. Early Paschal controversies. Rule as to the full moon after the vernal equinox. Hippolytus and his cycle: the so-called Cyprianic cycle; Dionysius of Alexandria. Anatolius. The Council of Nicaea and the Easter controversy. Later differences between the computations of Rome and Alexandria. Festal (or Paschal) Letters of the Bishops of Alexandria. Supputatio Romana. Victorius of Aquitaine. Dionysius Exiguus. The Nineteen-year Cycle. The Paschal Limits. The Gregorian Reform. The adoption of the New Style | 104 |

| [x]X. The Kalendar of the Orthodox Church of the East. The Menologies. I. Immoveable Commemorations. The twelve great primary festivals; the four great secondary festivals. The middle class, greater and lesser festivals. The minor festivals, and subdivisions. Explanation of terms used in the Greek Kalendar. II. The Cycle of Sundays, or Dominical Kalendar | 133 |

| Appendix I. The Paschal Question in the Celtic Churches | 146 |

| Appendix II. Note on the Kalendars of the separated Churches of the East | 147 |

| Appendix III. Note on the history of the Kalendar of the Church of England since the Reformation | 149 |

| 1. | Kalendar of the Peterborough Psalter | to face Title |

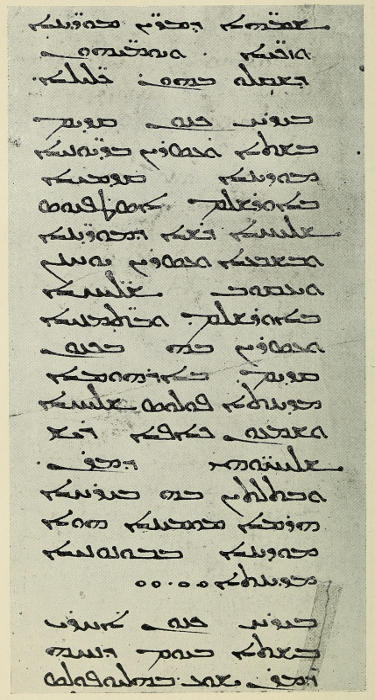

| 2. | The Syriac Martyrology | ” p. 15 |

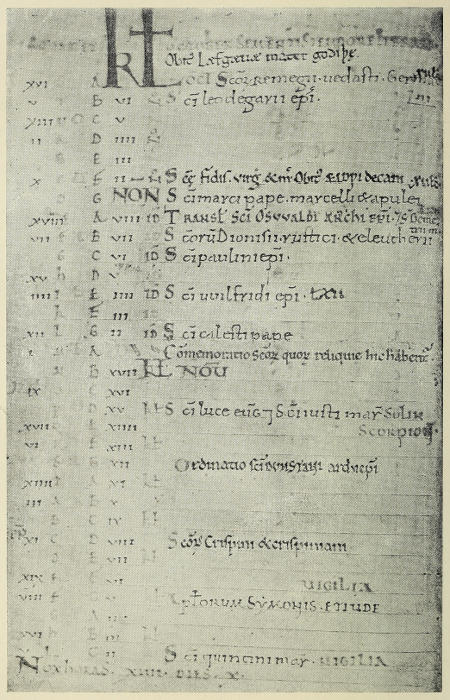

| 3. | Kalendar of the Worcester Book | ” p. 93 |

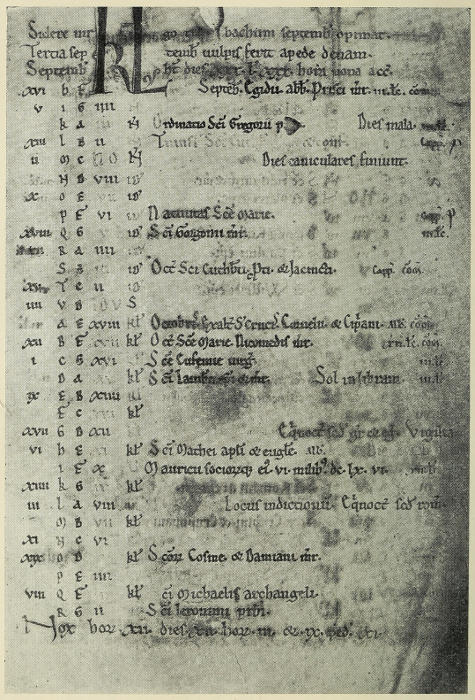

| 4. | Kalendar of the Durham Psalter | ” p. 99 |

The Church’s Year, as it has been known for many centuries throughout Christendom, is characterised, first, by the weekly festival of the Lord’s Day (a feature which dates from the dawn of the Church’s life and the age of the Apostles) and, secondly, by the annual recurrence of fasts and festivals, of certain days and certain seasons of religious observance. These latter emerged, and came to find places in the Kalendar at various periods.

In order of time the season of the Pascha, the commemoration of the death, and, subsequently, of the resurrection of the Saviour, is the first of the annual observances to appear in history. Again, at an early date local commemorations of the deaths of victims of the great persecutions under the pagan Emperors were observed yearly. And some of these (notably those who suffered at Rome) gradually gained positions in the Church’s Year in regions remote from the places of their origin. Speaking generally, little as it might be thought probable beforehand, it is a fact that martyrs of local celebrity emerge in the history of the Kalendar at an earlier date than any[xii] but the most eminent of the Apostles (who were also martyrs), and earlier than some of the festivals of the Lord Himself. The Kalendar had its origin in the historical events of the martyrdoms.

So far the growth of the Kalendar was the outcome of natural and spontaneous feeling. But at a later time we have manifest indications of artificial constructiveness, the laboured studies of the cloister, and the work of professional martyrologists and Kalendar-makers. To take, for the purpose of illustration, an extreme case, it is obvious that the assignment of days in the Kalendar of the Eastern Church to Trophimus, Sosipater and Erastus, Philemon and Archippus, Onesimus, Agabus, Rufus, Asyncretus, Phlegon, Hermas, the woman of Samaria (to whom the name Photina was given), and other persons whose names occur in the New Testament, is the outcome of deliberate and elaborate constructiveness. The same is true of the days of Old Testament Patriarchs and Prophets, once, in a measure, a feature of Western, as they are still of Eastern Kalendars. But even all the festivals of our Lord, save the Pascha, though doubtless suggested by a spontaneous feeling of reverence, could be assigned to particular days of the year only after some processes of investigation and inference, or of conjecture. Whether the birthday of the Founder of the Christian religion should be placed on January 6 or on December 25 was a matter of debate and argument. Commentators on the history of the Gospels, the conjectures of interpreters of Old Testament prophecy, and such information[xiii] as might be fancied to be derivable from ancient annals, had of necessity to be considered. The assignment of the feast of the Nativity to a particular day was a product of the reflective and constructive spirit.

It is not absolutely impossible that ancient tradition, if not actual record, may be the source of June 29 being assigned for the martyrdom of St Peter and St Paul; but a more probable origin of the date is that it marks the translation of relics. Certainly the days of most of the Apostles (considered as the days of their martyrdoms) have little or no support from sources that have any claim to be regarded as historical. They find their places but gradually, and, it would seem, as the result of a resolve that none of them should be forgotten.

Commemorations which mark the definition of a dogma, or which originated in the special emphasis given at some particular epoch to certain aspects of popular belief and sentiment, have all appeared at times well within the ken of the historical student. Thus, ‘Orthodoxy Sunday’ (the first Sunday in Lent) in the Kalendar of the Greek Church is but little concerned with the controversies on the right faith which occupied the great Councils of the fourth and fifth centuries. It commemorates the triumph of the party that secured the use of images over the iconoclasts; this was the ‘orthodoxy’ which was chiefly celebrated; and we can fix the date of the establishment of the festival as A.D. 842. Again, the commemoration of All Souls in the West was the[xiv] outcome of a growing sense of the need of prayers and masses on behalf of the faithful departed. The ninth century shows traces of the observance of some such day; but it was not till the close of the tenth century, under the special impetus supplied by the reported visions of a pilgrim from Jerusalem, who declared that he had seen the tortures of the souls suffering purgatorial fire, that the observance made headway. We then find Nov. 2 assigned for the festival, which came to be gradually and slowly adopted. The feast of Corpus Christi, which now figures so largely in the popular devotions of several countries of Europe, and is marked as a ‘double of the first class’ in the service-books of the Church of Rome, emerges for the first time in the thirteenth century, and was not formally enjoined till the fourteenth. The feast of the Conception of St Mary the Virgin seems to have originated in the East, and to have been simply a historical commemoration, even as the Greeks commemorate the conception of St John the Baptist. The Eastern tradition represents Anna as barren and well stricken in years, when, in answer to her prayers and those of Joachim her spouse, God revealed to them by an angel that they should have a child. This conception was according to the Greek Menology ‘contrary to the laws of nature,’ like that of the Baptist. In the West the festival of the Conception appears at the end of the eleventh or beginning of the twelfth century. The controversies as to its doctrinal significance form part of the history of dogma, and are full of instruction: but they cannot[xv] be considered here. Up to the year 1854 the name of the festival in the Kalendars of the authorised service-books of the Roman Church was simply Conceptio B. Mariae Virginis. It was as recently as Dec. 8, 1854, by an ordinance of Pope Pius IX, that the name was changed into Immaculata Conceptio B. Mariae Virginis. It will thus be seen how changes in the Kalendar illustrate the changes and accretions of dogma, facts which are further exhibited by the changes in the rank and dignity of festivals of this kind, at first only tolerated perhaps, and of local usage, but eventually enjoined as of universal obligation, and elevated in the order and grade of festal classification. Again, the considerable number of festivals of the Greek and Russian Churches connected with relics and wonder-working icons throws a light on the intellectual standpoint and the current beliefs in these ancient branches of the Catholic Church.

Not less instructive in exhibiting the extraordinary growth in the cultus of the Blessed Virgin in the West are the inferences which may be gathered from a knowledge of the fact that no festival of the Virgin was celebrated in the Church of Rome before the seventh century, when we compare the crowd of festivals, major and minor, devoted to the Virgin in the Roman Kalendar of to-day. But considerations of this kind are only incidentally touched on in the following pages; and they are referred to here simply with a view to show that the study of the Kalendar is not an enquiry interesting merely to dry-as-dust antiquaries,[xvi] but one which is intimately connected with the study of the history of belief, and is inwoven with far-reaching issues.

In the enquiry into the origins of ecclesiastical observances the discovery within recent years of early documents, hitherto unknown in modern days, enforces the obvious thought that our conceptions on such subjects must be liable to re-adjustment from time to time in the light of new evidence. Until the day comes, if it ever comes, when it can be said with truth that the materials supplied by the early manuscripts of the East and West have been exhausted, there can be no finality. The document discovered some ten or twelve years ago, in which a lady from Gaul or Spain, who had gone on pilgrimage to the East, records her impressions of religious observances which she had witnessed at Jerusalem towards the close of the fourth century, has furnished some important light on the subject before us, as well as on the history of ceremonial. In the following pages this document is referred to as the Pilgrimage of Silvia (‘Peregrinatio Silviae’), without prejudice to the question relating to the true name of the writer. The period when the work was written is the important question for our purposes; and those who are most competent to express an opinion consider that it belongs to the time of Theodosius the Great, and to a date between the years 383 and 394.

The influence of the early mediaeval martyrologists, Bede, Florus, Ado, and Usuard, upon the mediaeval Kalendars, is unquestionable; but the relations of[xvii] their works to one another, the variations of the different recensions and the sources from which they were drawn, are still subjects of investigation. In addition to the brief notices of the martyrologists which will be found in the following pages, the enquirer who desires further information should not fail to study with care the recent treatise of Dom Henri Quentin, of Solesmes, Les Martyrologes historiques.

Of necessity a general outline sketch of the formation of the Kalendar is all that can be attempted in the following pages. Local Kalendars, more especially, for most of our readers, those of the service-books of England, Scotland, and Ireland, present many interesting and attractive features; but it has been impossible to deal with them in an adequate manner. Some space has, however, been devoted to the consideration of the Kalendar and Ecclesiastical Year of the Orthodox Church of the East, including the peculiar arrangement of the grouping of Sundays; and brief notices are given of the fasts and festivals of some of the separated Churches of the East.

The questions concerning the determination of Easter will form the main trial of the patience of the student.

The early controversies on the Paschal question are not free from obscurity; and the interests attaching to the construction of the various systems of cycles, intended to form a perpetual table for the unerring determination of the date of Easter, are mainly the interests which are awakened by the history of human[xviii] ingenuity grappling more or less successfully with a problem which called for astronomical knowledge and mathematical skill. Religious interests are not touched even remotely. Profound as are the thoughts and emotions which cluster around the commemoration of the Lord’s Resurrection, they are quite independent of any considerations connected with the age of the moon and the date of the vernal equinox. The scheme for a time seriously entertained by Gregory XIII of making the celebration of Easter to fall on a fixed Sunday, the same in every year, has much to commend it. Had it been adopted we should, at all events, have been spared many practical inconveniences, and the ecclesiastical computists would have been saved a vast amount of labour. But we must take things as they are.

If anyone contends that the safest ‘Rule for finding Easter’ is ‘Buy a penny almanack,’ I give in a ready assent. It has in principle high ecclesiastical precedent; for it was exactly the same reasonable plan of accepting the determinations of those whom one has good reason to think competent authorities, which in ancient times made the Christian world await the pronouncements as to the date of Easter which came year by year from the Patriarchs of Alexandria in their Paschal Epistles: while for the date of Easter in any particular year in the distant past, or in the future, there are few who will not prefer the Tables supplied in such works as L’Art de vérifier les Dates, or Mas Latrie’s Trésor de Chronologie, to any calculations of their own, based on the Golden[xix] Numbers and Sunday Letters[1]. In the present volume the limits of space forbid any detailed discussion of the principles involved and the methods employed in the determination of Easter by the computists both ancient and modern. A brief historical sketch of the successive reforms of the Kalendar is all that has been found possible. Those who seek for fuller information can resort to the treatises mentioned above or in the course of the volume. The chapter on Easter has for convenience been placed near the conclusion of this volume.

In dealing with both Eastern and Western Kalendars the student will bear in mind that only comparatively few of the festivals affected the life of the great body of the faithful. A very large number of festivals were marked in the services of the Church by certain liturgical changes or additions. Many of them had their special propria; others were grouped in classes; and each class had its own special liturgical features. Only comparatively few made themselves felt outside the walls of the churches. Some of them carried a cessation from servile labour, or caused the closing of the law courts, or, as chiefly in the Greek Church, mitigated in various degrees (according to the dignity of the festival) the rigour of fasting. The distinction between festa chori and festa fori is always worthy of observation. A relic of the distinction is preserved[xx] in an expression of common currency in France, when one speaks of a person as of insignificant importance, C’est un saint qu’on ne chôme pas.

Although the general scope of the following pages is wide in intention, the origins of the Kalendar and the rise of the principal seasons and days of observance have chiefly attracted the interest of the writer. Later developments are not wholly neglected, but they occupy a subordinate place.

The enactments of civil legislation under the Christian Emperors and other rulers, in respect to the observance of Sunday and other Christian holy days, is an interesting field of study; but it has been impossible to enter upon it here in view of the limits of space at our disposal.

The study of Kalendars brings one into constant contact with hagiology, the acts of martyrs, and the lives of saints. It would however have been obviously vain to deal seriously in the present volume with so vast a subject, even in broadest outline.

A short Bibliography of some important or serviceable works dealing with various branches of the subject before us is prefixed.

Achelis, H. Die Martyrologien, ihre Geschichte und ihr Werth. (Berlin, 1900.)

ACTA SANCTORVM. [Of the Bollandists. This vast collection, of which the first volume appeared in 1643, had attained by the middle of the nineteenth century, after various interruptions in the labours of the compilers, to 55 volumes, folio, and the work is still in process, having now reached the early days of November. Various Kalendars and Martyrologies have been printed in the work. The Martyrology of Venerable Bede, with the additions of Florus and others, will be found in the second volume for March; the metrical Ephemerides of the Greeks and Russians in the first volume for May; Usuard’s Martyrology in the sixth and seventh volumes for June, and also an abbreviated form of the Hieronymian. The second volume for November contains the Syriac Martyrology of Dr Wright edited afresh by R. Graffin with a translation into Greek by Duchesne. The same volume contains the Hieronymian Martyrology edited by De Rossi and Duchesne.]

Assemanus, Josephus Simon. Kalendaria Ecclesiae Universae, in quibus tum ex vetustis marmoribus, tum ex codicibus, tabulis, parietinis, pictis, scriptis scalptisve Sanctorum nomina, imagines, et festi per annum dies Ecclesiarum Orientis et Occidentis, praemissis uniuscujusque[xxii] Ecclesiae originibus, recensentur, describuntur, notisque illustrantur. 4to, 6 tom. Romae, 1755. The title raises hopes which are not verified. [This work of the learned Syrian, who for his services to sacred erudition was made Prefect of the Library of the Vatican, was planned on a colossal scale, but it was never completed, and indeed we may truly say only begun. The six volumes which alone remain are wholly concerned with the Slavonic Church. The first four volumes, together with a large part of the fifth, are devoted mainly to the history of Slavonic Christianity. The concluding part of the fifth and the whole of the sixth volume deal with a Russian Kalendar, commencing the year, as in the Greek Church, with 1 September. This is treated very fully, but the work ends here.]

Baillet, Adrien. Les Vies des Saints. 2nd Ed. 10 vols. 4to. 1739. [The ninth volume on the moveable feasts abounds in valuable information; and, generally, this work may be consulted on the history of the festivals with much profit.]

Bingham, Joseph. Origines Ecclesiasticae, or the Antiquities of the Christian Church, etc. [Of the numerous editions of this important work, which has been by no means superseded, the most serviceable is the edition to be found in Bingham’s Works, 9 vols. 8vo. (1840) ‘with the quotations at length in the original languages.’ The editor is J. R. Pitman. Volume 7 contains most of what is pertinent to the antiquities of the feasts and fasts of the early Church.]

Binterim, A. J. Die vorzüglichsten Denkwürdigkeiten der Christ-Kathol. Kirche. Vol. V. (Mainz, 1829.)

Cabrol, Fernand. Dictionnaire d’archéologie chrétienne et de liturgie. Paris, 1907 (in process of publication).

D’Achery, Lucas. Spicilegium. Tom. II. fol. Paris, 1723. [This contains the Hieronymian Martyrology; the metrical Martyrology attributed to Bede; the Martyrology known as Gellonense (from the monastery at Gellone, on the borders of the diocese of Lodève in the province of Narbonne), assigned to about A.D. 804; the metrical Martyrology of Wandalbert the deacon, of the diocese of Trèves, about A.D. 850; and an old Kalendar (A.D. 826) from a manuscript of Corbie.]

Duchesne, L. Origines du Culte chrétien. 3rd Ed. 8vo. Paris, 1902. [There is an English translation by M. L. McClure, London (S.P.C.K.), 1903. The merits of Duchesne are so generally recognised that it is unnecessary to speak of them here.]

Grotefend, H. Zeitrechnung des deutschen Mittelalters und der Neuzeit. 4to. 2 vols. Hanover, 1891, 1892-8. [Besides exhibiting in full a large collection of Kalendars of Dioceses and Monastic Orders, not only of Germany, but also of Denmark, Scandinavia, and Switzerland, this work contains an index of Saints marking their days in various Kalendars, including certain Kalendars of England. There is also a Glossary, explaining both technical terms and the words of popular speech and folk-lore in connexion with days and seasons.]

Hampson, R. T. Medii Ævi Kalendarium, or dates, charters, and customs of the middle ages, with Kalendars from the tenth to the fifteenth century; and an alphabetical digest of obsolete names of days: forming a Glossary of the dates of the middle ages, with Tables and other aids for ascertaining dates. 8vo. 2 vols. London, 1841. [The first volume is mainly occupied with ‘popular customs and superstitions’; but it also contains reprints of various Anglo-Saxon[xxiv] and early English Kalendars. The second volume is given over wholly to a useful, though occasionally somewhat uncritical glossary.]

Hospinian, Rudolph. Festa Christianorum, hoc est, De origine, progressu, ceremoniis et ritibus festorum dierum Christianorum Liber unus (folio). Tiguri, 1593. [This is a work of considerable learning for its day, written from the standpoint of a Swiss Protestant. A second edition, in which replies are made to the criticisms of Cardinal Bellarmine and Gretser, appeared, also at Zurich, and in folio, in 1612.]

Ideler, Ludwig. Handbuch der mathematischen und technischen Chronologie. 8vo. 2 vols. Berlin, 1825-26. [Ideler was Royal Astronomer and Professor in the University of Berlin. His discussion of the Easter cycles cannot be dispensed with. This and his account of the computation of time in the Christian Church will be found in Vol. 2 (pp. 175-470). The Gregorian reform is well dealt with.]

Kellner, K. A. Heinrich. Heortology: a history of the Christian Festivals from their origin to the present day. Translated from the second German edition. 8vo. London, 1908. [Dr Kellner is Professor of Catholic Theology in the University of Bonn. An interesting and useful volume, though occasionally exhibiting, as is not unnatural, marked ecclesiastical predilections. It contains prefixed a useful bibliography.]

Lietzmann, H. Die drei ältesten Martyrologien. E. tr. 8vo. Cambridge, 1904. [This little pamphlet of 16 pages exhibits conveniently the texts of (1) what is variously known as the Bucherian, or Liberian, or Philocalian Martyrology, (2) The Martyrology of Carthage, and (3) Wright’s Syrian Martyrology.]

Maclean, Arthur John (Bishop of Moray). The article[xxv] ‘Calendar, the Christian’ in Hastings’ Dictionary of Christ and the Gospels [admirable, generally, for the early period.]

Maclean, Arthur John (Bishop of Moray). East Syrian Daily Offices. London, 8vo., 1894. [An appendix deals with the Kalendar of the modern Nestorians (Assyrian Christians).]

Neale, John Mason. A History of the Holy Eastern Church. General Introduction. London, 8vo., 1850. [Vol. II. gives information at considerable length on the Kalendars of the Byzantine, Russian, Armenian, and Ethiopic Churches.]

Nilles, Nicolaus. Kalendarium Manuale utriusque Ecclesiae Orientalis et Occidentalis, academiis clericorum accommodatum. 2 tom. 8vo. Oeniponte, 1896, 1897. [N. Nilles, S.J., Professor in the University of Innsbruck, deals mainly in these volumes with the ecclesiastical year in Eastern Churches.]

Quentin, Henri. Les Martyrologes historiques du moyen age, étude sur la formation du Martyrologe romain. 8vo. Paris, 1907.

Saxony, Maximilian, Prince of. Praelectiones de Liturgiis Orientalibus. Tom. I. 8vo. Friburgi Brisgoviae, 1908. [This volume is mainly concerned with the Kalendars and Liturgical Year of the Greek and Slavonic Churches. It is lucid and interesting.]

Seabury, Samuel, D.D. The Theory and Use of the Church Calendar in the measurement and distribution of Time; being an account of the origin and use of the Calendar; of its reformation from the Old to the New Style; and of its adaptation to the use of the English Church by the British Parliament under George II. 8vo. New York, 1872. [Excellent on the restricted subject with which it deals. It does not deal with[xxvi] Christian Festivals beyond the question of the determination of Easter, but is largely concerned with matters of technical chronology, the ancient cycles, golden numbers, epacts, etc.]

Smith, William, and Cheetham, Samuel. A Dictionary of Christian Antiquities. 2 vols. London, 1875, 1880. [The articles contributed by various scholars, as was inevitable, vary much in merit. Those on the festivals by the Rev. Robert Sinker are particularly valuable. This work is cited in the following pages as D. C. A.]

Wordsworth, John, Bishop of Salisbury. The Ministry of Grace. London, 8vo., 1901. [This learned work, under a not very illuminative title, discusses, inter alia, with a thorough knowledge of the best and most recent literature of the subject, the development of the Church’s fasts and festivals. It stands pre-eminent among English works dealing with the subject.]

[Gasquet, Abbot, and Bishop, Edmund. The Bosworth Psalter. London, 1908. Contains valuable information about some Mediaeval Kalendars, with discussions of them. Edd.]

The Church of Christ, founded in Judaea by Him who, after the flesh, was of the family of David, and advanced and guided in its earlier years by leaders of Jewish descent, could not fail to bear traces of its Hebrew origin. The attitude and trend of minds that had been long familiar with the religious polity of the Hebrews, and with the worship of the Temple and the Synagogue, showed themselves in the institutions and worship of the early Church. This truth is observable to some extent in the Church’s polity and scheme of government, and even more clearly in the methods and forms of its liturgical worship. It is not then to be wondered at that the same influences were at work in the ordering of the times and seasons, the fasts and festivals, of the Church’s year.

Most potent in affecting the whole daily life of Christendom in all ages was the passing on from Judaism of the Week of seven days. Inwoven, as it is, with the history of our lives, and taken very much[2] as matter of course, as if it were something like a law of nature, the dominating influence and far reaching effects of this seven-day division of time are seldom fully realised.

The Week, known in the Roman world at the time of our Lord only in connexion with the obscure speculations of Eastern astrology, or as a feature, in its Sabbath, of the lives of the widely-spread Jewish settlers in the great cities of the Empire, had been from remote times accepted among various oriental peoples. It would be outside our province to enquire into its origin, though much can be said in favour of the view that it took its rise out of a rough division into four of the lunar month. But, so far as Christianity is concerned, it is enough to know that it was beyond all doubt taken over from the religion of the Hebrews.

It is not improbable that at the outset some of the Christian converts from Judaism may have continued to observe the Jewish Sabbath, the seventh or last day of the week: and that attempts were made to fasten its obligations upon Gentile converts is evident from St Paul’s Epistle to the Colossians (ii. 16). But it is certain that at an early date among Christians the first day of the week was marked by special religious observances. The testimony of the Acts of the Apostles and the Epistles of St Paul shows us the first day of the week as a time for the assembling of Christians for instruction and for worship, when ‘the breaking of bread’ formed part of the service, and when offerings for charitable and religious purposes[3] might be laid up in store[2]. The name ‘the Lord’s day,’ applied to the first day of the week, may probably be traced to New Testament times. The occurrence of the expression in the Revelation of St John (i. 10) has been commonly regarded as a testimony to this application[3].

In the Epistle of Barnabas (tentatively assigned by Bishop Lightfoot to between A.D. 70 and 79, and by others to about A.D. 130-131) we find the passage (c. 15), ‘We keep the eighth day for rejoicing, in the which also Jesus rose from the dead.’ The date of the Teaching of the Apostles is still reckoned by some scholars as sub judice. But, if it is rightly assigned to the first century, its testimony may be cited here. In it is the following passage:—‘On the Lord’s own day (κατὰ κυριακὴν δὲ Κυρίον) gather yourselves together and break bread, and give thanks, first confessing your transgressions, that your sacrifice may be pure’ (c. 14).

The next evidence, in point of time, is a passage in the Epistle of Ignatius to the Magnesians (cc. 8, 9, 10), in which the writer dissuades those to whom he wrote from observing sabbaths (μηκέτι σαββατίζοντες) and urges them to live ‘according to the Lord’s day (κατὰ κυριακὴν) on which our life also rose through[4] Him.’ It is impossible to suppose that in early times the Lord’s day was held to be a day of rest. The work of the servant and labouring class had to be done; and it has been reasonably conjectured that the assemblies of Christians before dawn were to meet the necessities of the situation. Lastly, the passage from the Apology of Justin Martyr (Ap. i. 67) is too well known to be cited in full. He describes to the Emperor the character and procedure of the Christian assemblies on ‘the day of the sun,’ which we know from other sources to have been the first day of the week. Writings of the Apostles or of the Prophets were read: the President of the assembly instructed and exhorted: bread, and wine and water were consecrated and distributed to those present and sent by the Deacons to the absent: alms were collected and deposited with the President for the relief of widows and orphans, the sick and the poor, prisoners and strangers. Later than Justin we need not go, as the evidence from all quarters pours in abundantly to establish the universal observance of ‘the first day of the week,’ ‘Sunday,’ ‘the Lord’s day,’ as a day for worship and religious instruction[4].

Lack of positive evidence prevents us from speaking with any certainty as to whether there was among[5] Christians any recognised and approved observance of Saturday (the Sabbath) in the first, second and third centuries. There is no hint of such observance in early Christian literature; and there are passages which rather go to discountenance the notion[5].

Duchesne, whose opinion deservedly carries much weight, comes to the conclusion that the observance of Saturday in the fourth century was not a survival of an attempt of primitive times to effect a conciliation between Jewish and Christian practices, but an institution of comparatively late date[6]. Certainly one cannot speak confidently of the existence of Saturday as a day of religious observance among Christians before the fourth century.

Epiphanius[7], in the second half of the fourth century, speaks of synaxes being held in some places on the Sabbath; from which it may probably be inferred that it was not so in his time in Cyprus.

In the Canons of the Council of Laodicea (which can hardly be placed earlier than about the middle of the fourth century, and is probably later) we find it enjoined that ‘on the Sabbath the Gospels with other Scriptures shall be read’ (16); that ‘in Lent bread ought not to be offered, save only on the Sabbath and the Lord’s day’ (49); and that ‘in Lent the feasts of martyrs should not be kept, but that a commemoration of the holy martyrs should be made on Sabbaths and Lord’s days’ (50). Yet it was[6] forbidden ‘to Judaize and be idle on the Sabbath,’ while, ‘if they can,’ Christians are directed to rest on the Lord’s day. The Apostolic Constitutions go further; and, under the names of St Peter and St Paul, it is enjoined that servants should work only five days in the week, and be free from labour on the Sabbath and the Lord’s day ‘with a view to the teaching of godliness’ (viii. 33). Uncertain as are the date and origin of the Constitutions they may be regarded as in some measure reflecting the general sentiment in the East in the fifth, or possibly the close of the fourth century[8]. From these testimonies it appears that the Sabbath was a day of special religious observance, and that in the East it partook of a festal character. Falling in with this way of regarding Saturday we find Canon 64 of the so-called Apostolic Canons (of uncertain date, but possibly early in the fifth century[9]) declaring, ‘If any cleric be found fasting on the Lord’s day, or on the Sabbath, except one only [that is, doubtless “the Great Sabbath,” or Easter Eve], let him be deprived, and, if he be a layman, let him be segregated[10].’ The Apostolic Constitutions emphasise the position of the Sabbath by the exhortation that Christians should ‘gather together especially on the Sabbath, and on the Lord’s day, the day of the Resurrection’ (ii. 59); and again, ‘Keep the Sabbath[7] and the Lord’s day as feasts, for the one is the commemoration of the Creation, the other of the Resurrection’ (vii. 23³). We find also that one of the canons of Laodicea referred to above is in substance re-enacted at a much later date by the Council in Trullo (A.D. 692) in this form, that except on the Sabbath, the Lord’s day, and the Feast of the Annunciation, the Liturgy of the Pre-sanctified should be said on all days in Lent (c. 52).

In the city of Alexandria in the time of the historian Socrates the Eucharist was not celebrated on Saturday; but other parts of Egypt followed the general practice of the East. Socrates says that Rome agreed with Alexandria in this respect[11].

It is certain that very commonly, though not universally, in the East the Sabbath was regarded as possessing the features of a weekly festival (with a eucharistic celebration) second in importance only to the Lord’s day. And Gregory of Nyssa says, ‘If thou hast despised the Sabbath, with what face wilt thou dare to behold the Lord’s day.... They are sister days’ (de Castigatione, Migne, P.G. xlvi. 309).

In the West we find also that the Sabbath was a day of special religious observance; but there was a variety of local usage in regard to the mode of its observance. At Rome the Sabbath was a fast-day in the time of St Augustine[12]; and the same is true of some other places; but the majority of the Western Churches, like the East, did not so regard it. In North Africa there was a variety of practice, some[8] places observed the day as a fast, others as a feast. At Milan the day was not treated as a fast; and St Ambrose, in reply to a question put by Augustine at the instance of his mother Monnica, stated that he regarded the matter as one of local discipline, and gave the sensible rule to do in such matters at Rome as the Romans do[13]. In the early part of the fourth century the Spanish Council of Elvira corrected the error that every Sabbath should be observed as a fast[14].

As to the origin of the Saturday fast we are left almost wholly to conjecture. It has been supposed by some to be an exhibition of antagonism to Judaism, which regarded the Sabbath as a festival; while others consider that it is a continuation of the Friday fast, as a kind of preparatory vigil of the Lord’s day. It is outside our scope to go into this question.

A relic of the ancient position of distinction occupied by Saturday may perhaps be found in the persistence of the name ‘Sabbatum’ in the Western service-books. Abstinence (from flesh) continued, ‘de mandate ecclesiae,’ on Saturdays in the Roman Church. For Roman Catholics in England it ceased in 1830 by authority of Pope Pius VIII.

This seems a convenient place for saying something as to the use of the word Feria in ecclesiastical language to[9] designate an ordinary week-day. The names most commonly given to the days of the week in the service-books and other ecclesiastical records are ‘Dies Dominica’ (rarely ‘Dominicus’) for the Lord’s Day, or Sunday; ‘Feria II’ for Monday; ‘Feria III’ for Tuesday, and so on to Saturday which (with rare exceptions) is not Feria VII but ‘Sabbatum.’

Why the ordinary week-day is called ‘Feria,’ when in classical Latin ‘feriae’ was used for ‘days of rest,’ ‘holidays,’ ‘festivals,’ is a question that cannot be answered with any confidence. A conjecture which seems open to various objections, though it has found supporters, is as follows: all the days of Easter week were holidays, ‘feriatae’; and, this being the first week of the ecclesiastical year, the other weeks followed the mode of naming the days which had been used in regard to the first week. A fatal objection to this theory, for which the authority of St Jerome has been claimed, is that we find ‘feria’ used, as in Tertullian, for an ordinary week-day long before we have any reason to think that there was any ordinance for the observance of the whole of Easter week by a cessation from labour[15].

Another conjecture, presented however with too much confidence, is that put forward on the authority of Isidore of Seville[16] by the learned Henri de Valois (Valesius). He alleges that the ancient Christians, receiving, as they did, the week of seven days from the Jews, imitated the Jewish practice, which used the expression ‘the second of the Sabbath,’ ‘the third of the Sabbath,’ and so on for the days of the week: that ‘Feria’ means a day of rest, in effect the same as ‘Sabbath,’ and that in this way the ‘second Feria’ and ‘third Feria,’ etc., came to be used for the second and third days of the week[17].

The astrological names for the days of the week, as of the Sun, of the Moon, of Mars, of Mercury, etc., were generally avoided by Christians; but they are not wholly unknown in Christian writers, and sometimes appear even in Christian epitaphs.

In the ecclesiastical records of the Greeks the first day of the week is ‘the Lord’s day’; and the seventh, the Sabbath, as in the West. But Friday is Parasceve (παρασκευή), a name which in the Latin Church is confined to one Friday in the year, the Friday of the Lord’s Passion, which day in the Eastern Church is known as ‘the Great Parasceve.’ With these exceptions the days of the week are ‘the second,’ ‘the third,’ ‘the fourth,’ etc., the word ‘day’ being understood.

It is worth recording that among the Portuguese the current names for the week-days are: segunda feira, terça feira, etc.

Long prior to any clear evidence for the special observance among Christians of the last day of the week we find testimonies to a religious character attaching to the fourth and sixth days.

The devout Jews were accustomed to observe a fast twice a week, on the second and fifth days, Monday and Thursday[18]; and these days, together with the Christian fasts substituted for them, are referred to in the Teaching of the Apostles (8), ‘Let not your fastings be with the hypocrites, for they fast on the second and fifth day of the week; but do ye keep your fast on the fourth and parasceve (the sixth).’ In the Shepherd of Hermas we find the writer relating that he was fasting and holding a[11] station[19]. And this peculiar term is applied by Tertullian to fasts (whether partial or entire we need not here discuss) observed on the fourth and sixth days of the week[20]. Clement of Alexandria, though not using the word station, speaks of fasts being held on the fourth day of the week and on the parasceve[21].

At a much later date than the authorities cited above we find the Apostolic Canons decreeing under severe penalties that, unless for reasons of bodily infirmity, not only the clergy but the laity must fast on the fourth day of the week and on the sixth (parasceve). And the rule of fasting on Wednesdays and Fridays still obtains in the Eastern Church[22].

These two days were marked by the assembling of Christians for worship. But the character of the service was not everywhere the same. Duchesne[23] has exhibited the facts thus: In Africa in the time of Tertullian the Eucharist was celebrated, and it was so at Jerusalem towards the close of the fourth century. In the Church of Alexandria the Eucharist was not celebrated on these days; but the Scriptures were read and interpreted. And in this matter, as in many others, the Church at Rome probably agreed with Alexandria. It is certain, at least as regards Friday, that the mysteries were not publicly celebrated on these days at Rome about the beginning of the fifth century. The observance of Friday as a day of abstinence is still of obligation in the West.

We now pass from features of every week to days and seasons of yearly occurrence.

In point of time the celebrations connected with the Pascha are the earliest to emerge of sacred days observed annually by the whole Church. But for reasons of convenience it has been thought better to defer the consideration of the difficult questions relating to the Easter controversies till the origin of the days of Martyrs and Saints has been dealt with.

The Kalendar in some of its later stages exhibits a highly artificial elaboration. But in its beginnings it was, to a large extent, the outcome of a natural and spontaneous feeling which could not fail to remember in various localities the cruel deaths of men and women who had suffered for the Faith with courage and constancy in such places, or their neighbourhoods. The origins of the Kalendar show in various churches, widely separated, the natural desire to commemorate their own local martyrs on the days on which they had actually suffered.

As regards the order of time there is ample reason to convince us that the commemorations of martyrs[13] were features of Church life much earlier than those of St Mary the Virgin, of most of the Apostles, and even of many of the festivals of the Lord Himself.

The marks of antiquity that characterise generally the older Kalendars and Martyrologies are (1) the comparative paucity of entries, (2) the fewness of festivals of the Virgin, (3) the fewness of saints who were not martyrs, (4) the absence of the title ‘saint,’ and (5) the absence of feasts in Lent.

Again, the local character of the observance of the days of martyrs is a marked feature of the earlier records which illustrate the subject. Now and then the name of some martyr of pre-eminent distinction in other lands finds its way into the lists; but it remains generally true that in each place the martyrs and saints of that place and its neighbourhood form the great body of those commemorated. And in addition to the natural feeling that prompted the remembrance of those more particularly associated with a particular place, the fact that the commemorations were originally observed by religious services in cemeteries, at the tombs or burial places of the martyrs, tended at first to discountenance the commemoration of the martyrs of other places whose story was known only by report, whether written or oral.

The day of a martyr’s death was by an exercise of the triumphant faith of the Church known as his birthday (natale, or dies natalis, or natalitia). It was regarded as the day of his entrance into a new and better world. The expression occurs in its[14] Greek form as early as the letter of the Church of Smyrna concerning the martyrdom of Polycarp (c. 18).

There can be no doubt that at an early date records were kept of the day of the death of martyrs. Cyprian required that even the death-days of those who died in prison for the faith should be communicated to him with a view to his offering an oblation on that day (Ep. xii. (xxxvii.) 2). It is in this way probably that the earliest Kalendars of the Church originated.

Ancient Syriac Martyrology, written A D. 412

(Brit. Mus. Or. Add. 12150, fol. 252 v, ll. 1-20, col. 1.) The plate shows the entries from St Stephen’s Day to Epiphany.

We purpose dealing more particularly with the early Roman Kalendars. The earliest martyrology that has survived is contained in a Roman record transcribed in A.D. 354. It is known, sometimes as the Liberian Martyrology (from the name of Liberius, who was bishop of Rome at the time), sometimes as the Bucherian Martyrology, from the name of the scholar who first made it known to the learned world[24], and not uncommonly as the Philocalian, from the name of the scribe. It presents many interesting, and some perplexing features, which cannot be dealt with here. We must content ourselves with noticing that, besides recording, as in a serviceable almanack, several pagan festivals, it marks the days of the month of the burials (depositiones) of the bishops of Rome from A.D. 254 to A.D. 354, and also the burial-days of martyrs, twenty-five in number. In both lists the cemeteries at Rome where the burials took place are noted. But there are also entered three ecclesiastical[15] commemorations which do not mark entombments, (1) ‘viij Kal. Jan. (Dec. 25) Natus Christus in Bethleem Judeae’; (2) ‘viij Kal. Mart. (Feb. 22) Natale (sic) Petri de Cathedra’; (3) ‘Nonis Martii (March 7) Perpetuae et Felicitatis Africae[25].’ The appearance of St Perpetua and St Felicitas in a characteristically Roman document is a striking testimony to the fame of these two African sufferers for the Faith[26]. The use of the word natale in connexion with St Peter’s chair not improbably marks the dedication of a church; and, at all events at a later period, the word seems sometimes used as equivalent simply to a festival, or perhaps a festival marking an origin or beginning—as, for example, Natale Calicis, of which something will be said hereafter (p. 40). Easter could not appear in the Kalendar properly so-called; but the document contains cycles for the calculation of Easter, and a list of the days on which it would fall from A.D. 312 to A.D. 412.

Early Kalendars would be of much value in our enquiries; but they are few in number. The following three deserve notice. (1) The Syrian Martyrology first published by Dr W. Wright in the Journal of Sacred Literature (Oct. 1866). It was written in A.D. 411-12, but represents an original of perhaps about A.D. 380. It is Arian in origin, and has elements that show connexions with Alexandria,[16] Antioch, and Nicomedia; and its range of martyrs is much wider than that of other early documents of the kind. Yet of Western martyrs we find only in Africa Perpetua and Satornilos and ten other martyrs[27] (March 7) and ‘Akistus (?Xystus II) bishop of Rome’ (Aug. 1). We find St Peter and St Paul on Dec. 28; St John and St James on Dec. 27; and ‘St Stephen, apostle’ on the 26th[28]. (2) The Kalendar of Polemius Silvius, bishop of Sedunum, in the upper valley of the Rhone (A.D. 448). It contains the birthdays of the Emperors and some of the more eminent of the heathen festivals, such as the Lupercalia and Caristia, but with a view, apparently, of supplanting them by Christian commemorations. The Christian festivals recorded are few in number, those of our Lord being Christmas, Epiphany, and the fixed dates, March 25 for the Crucifixion, and March 27 for the Resurrection. There are only six saints’ days. The depositio of Peter and Paul on Feb. 22; Vincent, Lawrence, Hippolytus, Stephen, and the Maccabees on their usual days. Other features of interest must be passed over[29]. (3) The Carthaginian Kalendar[30] has been assigned as probably about A.D. 500[31]. It[17] is thus described by Bishop J. Wordsworth, ‘It has, in the Eastern manner, no entries between February 16 and April 19, i.e. during Lent. Its Saints are mostly local, but some twenty are Roman, and a few other Italian, Sicilian, and Spanish. It also marks SS. John Baptist (June 24), Maccabees, Luke [Oct. 13], Andrew, Christmas, Stephen [Dec. 26], John Baptist [probably an error of the pen for John the Evangelist] and James (Dec. 27) [‘the Apostle whom Herod slew’], Infants [Dec. 28] and Epiphany [sanctum Epefania][32].’ It may be added that this Kalendar marks the depositiones of seven bishops of Carthage, not martyrs, whose anniversaries were kept.

In one of the African Councils of the fourth century it was enacted that the Acts of the martyrs should be read in the church on their anniversaries. But Rome was slow in adopting this practice[33].

It will be seen that as time went on the strictly local character of the martyrs commemorated was invaded by a desire to record the famous sufferers of other parts of the Christian world. Rome, with its characteristic conservatism in matters liturgical, seems to have been slower than other places to yield to this impulse. At Hippo we find Augustine commemorating, beside local martyrs, the Roman Lawrence and Agnes, the Spanish Vincent and Fructuosus, and the Milanese Protasius and Gervasius whose bones (as was believed) had been recently discovered. He also commemorated the Maccabees, St Stephen, and both[18] the Nativity and Decollation of the Baptist. On the other hand in the laudatory sermons that have come down to us we find Chrysostom at Antioch commemorating only the saints of Antioch, and Basil, at Caesarea in Cappadocia, only those of his own country.

The Sacramentary, which is called after Pope Leo (A.D. 440-461), shows signs of a somewhat later date; but it is unquestionably a Roman book; and the Kalendar which we can construct from it represents the Kalendar of Rome as it was not later than about the middle of the sixth century. It gives us the following days; but it must be observed that the months of January, February, March, and part of April are unfortunately missing[34].

The first is April 14, Tiburtius (a Roman martyr). There follow ‘Paschal time’: April 23, George (Eastern)[?][35]; Dedication of the Basilica of St Peter, the Apostle; the Ascension of the Lord; the day before Pentecost; the Sunday of Pentecost; the fast of the fourth month; June 24, natale of St John Baptist; June 26, natale of SS. John and Paul (two Romans, brothers, martyrs under Julian); June 29, natale of the Apostles Peter and Paul (at Rome); July 10, natale of seven martyrs who are named (all at Rome; and the cemeteries where their bodies rest are named); Aug. 3[36], natale of St Stephen[19] (bishop of Rome and martyr, more commonly commemorated on Aug. 2); Aug. 6, natale of St Xystus and of Felicissimus and Agapitus (all martyrs at Rome); Aug. 10, natale of St Lawrence (Rome); Aug. 13, natale of SS. Hippolytus and Pontianus (Romans); Aug. 30, natale of Adauctus and Felix (at Rome); Sept. 14, natale of SS. Cornelius and Cyprian (the former bishop of Rome, the latter bishop of Carthage, his contemporary); Sept. 16, natale of St Euphemia (at Rome); Fast of the seventh month; Sept. 30, natale (sic) of the basilica of the Angel in Salaria (on the Via Salaria: evidently for the foundation or the dedication of a church at Rome, probably under the name of St Michael); Depositio of St Silvester (bishop of Rome, no date: in the Bucherian Martyrology it is at Dec. 31); Nov. 8 (or 9), natale of the four crowned saints (all at Rome); Nov. 22, natale of St Caecilia (Roman martyr); Nov. 23, natale of SS. Clement and Felicitas (both Roman martyrs); Nov. 24, natale of SS. Chrysogonus and Gregorius (the first, a Roman martyr, the second, uncertain[37]); Nov. 30, natale of St Andrew, Apostle; Dec. 25, natale of the Lord; and of the martyrs, Pastor, Basilius, Jovianus, Victorinus, Eugenia, Felicitas, and Anastasia (Eugenia was perhaps the Roman lady martyred with Agape; Anastasia was of Roman origin, though she suffered death in Illyria: her name appears in the canon of the Roman mass. The persons intended by the other names are more uncertain); Dec. 27, natale of St John, Evangelist; Dec. 28, natale of the Innocents.

It has been thought well to give in full this list, defective though it is (as lacking the opening months of the year). It exhibits indeed a large preponderance[20] of celebrations of local interest; but there are clear indications that already the martyrs of other places than Rome are securing themselves positions in the Roman Kalendar.

The collection of masses and other liturgical offices known as the Gelasian Sacramentary are not without interest in illustrating the development of the Kalendar, more particularly among the Franks. But we pass on to consider the features of the distinctively Roman service book, which, by a somewhat misleading name, has been called the Gregorian Sacramentary. In its present form (though it contains many ancient elements) it is probably not earlier than the close of the eighth century. Omitting notices of moveable days, and exhibiting the dates by the days of the month in our modern fashion, the Kalendar runs as follows[38], some remarks being added within marks of parenthesis.

January. 1. Octava Domini (the octave of Christmas). 6. Epiphania (called in the older Roman Kalendar ‘Theophania,’ as by the Greeks). 14. St Felix ‘in Pincis’ (on the Pincian). 16. St Marcellus, Pope. 18. St Prisca (at Rome). 20. SS. Fabian and Sebastian (both at Rome). 21. St Agnes (at Rome)[39]. 22. St Vincent (Spain). 28. Second of St Agnes (Octave).

February. 2. Ypapante, or Purification of St Mary. 5. St Agatha (Sicily: a church at Rome dedicated to her). 14. St Valentine (presbyter at Rome).

March. 12. St Gregory, Pope. 25. Annunciation of St Mary.

April. 14. SS. Tiburtius and Valerian (at Rome). 23. St George (Eastern: church ‘in Velabro’ at Rome). 28. St Vitalis (of Ravenna: a church at Rome).

May. 1. SS. Philip and James, Apostles. 3. SS. Alexander, Eventius and Theodulus (Pope, and two presbyters at Rome). 6. Natale of St John before the Latin gate (Rome). 10. SS. Gordian and Epimachus (both at Rome). 12. St Pancratius (at Rome, where a church was dedicated to him). 13. Natale of St Mary ‘ad Martyres’ (dedication of the Pantheon at Rome by Boniface IV). 25. St Urban, Pope.

June. 1. Dedication of the Basilica of St Nicomedes (at Rome). 2. SS. Marcellinus and Peter (at Rome: a church in their honour is said to have been erected by the Emperor Constantine on the Via Lavicana). 18. SS. Marcus and Marcellianus (both at Rome). 19. SS. Protasius and Gervasius (Milan). 24. Natale of St John Baptist. 26. SS. John and Paul (two brothers at Rome). 28. St Leo, Pope. 29. Natale of SS. Peter and Paul, Apostles (Rome). 30. Natale of St Paul (the Apostle).

July. 2. SS. Processus and Martinianus (legendary soldier-martyrs at Rome). 10. Natale of the Seven Brethren (at Rome). 29. SS. Felix, Simplicius, Faustinus and Beatrix (Pope Felix II; the others commemorated at Rome on the Via Portuensis). 30. SS. Abdon and Sennen (martyrs at Rome).

August. 1. St Peter ‘in Vincula’ (more commonly ‘ad Vincula’: it is probable that the date marks the dedication of a church at Rome). 2. St Stephen, bishop (of Rome). 5. SS. Xystus, bishop, Felicissimus and Agapitus (all of Rome). 8. St Cyriacus (deacon, at Rome: perhaps marks the date of his translation by Pope Marcellus). 10.[22] Natale of St Lawrence (Rome). 11. St Tiburtius (martyred outside Rome on the Via Lavicana). 13. St Hippolytus (martyr according to the legend at Rome). 14. St Eusebius, presbyter (at Rome). 15. Assumption of St Mary. 17. St Agapitus (at Praeneste). 22. St Timotheus (martyr at Rome). 28. St Hermes (at Rome). 29. St Sabina (virgin-martyr at Rome). 30. SS. Felix and Adauctus (both at Rome).

September. 8. Nativity of St Mary. 11. SS. Protus and Hyacinthus (both at Rome). 14. SS. Cornelius and Cyprian: also Exaltation of Holy Cross (Cornelius, Pope, Cyprian of Carthage). 15. Natale of St Nicomedes (presbyter martyr at Rome). 16. Natale of St Euphemia, and of SS. Lucia and Geminianus (all at Rome). 27. SS. Cosmas and Damian (Eastern). 29. Dedication of the Basilica of the Holy Angel Michael.

October. 7. Natale of St Marcus, Pope. 14. Natale of St Callistus, Pope.

November. 1. St Caesarius (an African deacon martyred in Campania). 8. The four crowned saints (at Rome). 9. Natale of St Theodorus (Asia Minor). 11. Natale of St Menna: likewise St Martin, bishop (Menna, Asia Minor: Martin of Tours). 22. St Caecilia (Roman). 23. St Clement: likewise St Felicitas (both Roman). 24. St Chrysogonus (Roman). 29. St Saturninus (a Roman, martyred at Toulouse). 30. St Andrew, Apostle.

December. 13. St Lucia (Syracuse). 25. Nativity of the Lord. 26. Natale of St Stephen. 27. St John, Evangelist. 28. Holy Innocents. 31. St Silvester, Pope.

When we examine these lists we find (1) the principal festivals of the Lord, of His Mother, and of His Apostles placed as they are still noted in the Kalendar. It may be observed that Jan. 1 is not[23] styled the Circumcision; and there is no reference to the Circumcision in the collect. In the mass for the Epiphany the leading of the Gentiles by a star and the gifts of the Magi are the prominent features. The use of the name Ypapante as the first name for the Purification (Feb. 2) suggests the Eastern origin of the festival. We find (2) the great majority of the saints recorded to be Roman martyrs—or of martyrs connected with Rome, either in fact or by legend; but (3) there are a few famous martyrs from other regions of the world, as St George, St Vincent, SS. Cosmas and Damian, and St Lucy, of Dec. 13. And Martin of Tours has a place. We also find that some of the obscurer saints of the earlier list disappear. Frequent pilgrimages to the East, together with the interchange of literary correspondence between the churches, are sufficient to account for the appearance of the Oriental martyrs. The leading features of the Western Kalendar, as it prevailed in the mediaeval period, and has subsisted to the present day, are already apparent.

It will be seen that All Saints does not appear on Nov. 1; and yet it was certainly observed in many churches in England, France, and Germany during the eighth century. It is placed at Nov. 1 in the Metrical Martyrology attributed to Bede, who died in A.D. 735. Though therefore this Martyrology, as we now possess it, shows signs of having been re-handled, it seems hazardous to attribute the origin of the festival, as is done by some, to the dedication of a church at Rome ‘in honorem Omnium Sanctorum’ by Pope Gregory III (A.D. 731-741).

Much obscurity attends the origin of All Souls’ Day. It would seem that Amalarius of Metz, early in the ninth century, had inserted in his Kalendar an anniversary commemoration of all the departed, and this was probably (as the context suggests) immediately after All Saints’ Day; but the practice of observing the day did not at once become general, and the earliest clear testimony to Nov. 2 does not emerge till the end of the tenth century, when Odilo, abbot of Clugny, stimulated by a vision of the sufferings of souls in purgatory, reported to him by a pilgrim returning from Jerusalem, enjoined on the monastic churches subject to Clugny the observance of Nov. 2. The practice rapidly spread.

The dominant influence of the Roman Church in Europe carried eventually the main features of the Roman Kalendar into all regions of the West. In early times at Rome the anniversary of a martyr was ordinarily kept, not in the various churches of the city and suburbs, but at the particular cemetery or catacomb where he was buried, or at the tomb within some church which had been erected over the place where his remains rested. Outside the walls, and at various distances along the great roads that led from the city, most of these commemorations were celebrated. As M. Batiffol has put it, with substantial correctness, ‘the old Roman Sanctorale is the Sanctorale of the cemeteries[40].’ It is a striking and impressive illustration of the looking of the Western peoples to Rome for guidance in matters of religion[25] that even obscure saints buried in the cemeteries of the neighbourhood of the Apostolic See now have places in the religious commemorations of all the remotest Churches of the Roman obedience.

The study of the origins of the Kalendar of the city of Rome illustrates the general proposition that the martyrdoms of a particular city or district form the main feature of each local Kalendar. To enter into detail in respect to the early Kalendars of the other provinces and dioceses of Europe, even when the scanty evidence surviving makes the enquiry possible, is too large a task to be attempted here.

The account of the commemorations of the early martyrs may be brought to a close by calling attention to a festival of general and perhaps universal observance before the fifth century—the festival of the pre-Christian martyrs, the seven Maccabees, on Aug. 1. It was not unnatural in the age of persecution, or when the memories of the great persecutions were still fresh, to fasten upon the Old Testament story of heroic constancy. After the Feast of St Peter’s Chains in the West, and the Procession of the Holy Cross in the East had displaced it from a position of primary importance, it was not wholly forgotten; and even now in both East and West in a subsidiary manner the memory of the Maccabees is still preserved in the services of the Church on Aug. 1. Chrysostom speaks of the celebration being attended in his day by a great concourse of the faithful, and we possess three homilies of his for the festival. Augustine shows us that the festival was observed in[26] Africa in his time, and mentions that there was a church called after the Maccabees at Antioch, a city named, he makes a point to inform us, after their persecutor, Antiochus Epiphanes. There are still extant sermons for the festival preached by Gregory Nazianzen, and, at a later date, by Pope Leo the Great.

It is certain that the assigning of the birth of the Lord to Dec. 25 appears first in the West; and it is not till the last quarter of the fourth century that we find it becoming established in some parts of the East. St Chrysostom in a homily delivered in A.D. 386 distinctly relates that it was about ten years earlier the festival of Dec. 25 came to be observed at Antioch, and that the festival had been observed in the West from early times (ἄνωθεν)[41]. At Constantinople the festival was kept on Dec. 25, apparently for the first time, in A.D. 379 or 380; and about the same time it appears in Cappadocia, as we learn from the funeral oration on Basil the Great pronounced by his brother, Gregory of Nyssa. At Alexandria this date was adopted before A.D. 432. At Jerusalem, however, the Nativity was observed on Jan. 6 not only in the time of the Pilgrimage of ‘Silvia,’ but, if we may credit the Egyptian monk Cosmas Indicopleustes,[28] even as late as at the middle of the sixth century. This writer relates that the people of Jerusalem, arguing from Luke iii. 23 (where, as he interprets the passage, Jesus is said to be beginning to be thirty years of age at His baptism) celebrated the Nativity together with the Baptism on Jan. 6[42].

But when did the observance of Dec. 25 make its appearance in the West? It must have been a well-marked festival at Rome when it appeared in the Bucherian Kalendar in A.D. 336 (see p. 15). And about one hundred years earlier (as we learn from his commentaries on Daniel) Hippolytus was led to infer, partly from a belief (however it originated) that the Incarnation took place at the Passover, and partly by a process of calculation with the help of his cycle, that the actual Incarnation took place on March 25 in the year of the world 5500 (or B.C. 3), and consequently the Nativity on Dec. 25[43].

The Bishop of Salisbury (J. Wordsworth) offers an ingenious conjecture which may possibly point to the early Eastern practice of commemorating the Nativity on Jan. 6 having originated in a similar way. Sozomen, the historian, writing in the fifth century, states that the Montanists always celebrated the pascha on the eighth day before the Ides of April (i.e. April 6), if it fell on a Sunday, otherwise on the[29] following Sunday (H.E. vii. 18). The Bishop thinks that the belief that April 6 was the proper day of the pascha ‘may probably have been an opinion quite unconnected with their [the Montanists’] sect.’ But he rightly admits that ‘actual facts are not yet forthcoming[44].’

Conjectures of this kind, though at present unsupported, are well worth remembering, if for no other reason, because students of early Christian literature are thus put on the alert to note any testimonies which make for, or else go to invalidate, the suggestion offered. I may add that the Montanist notion, as recorded by Sozomen, that the creation of the sun in the heavens took place on April 6, is of a kind that would well fall in, among fanciful speculators, with the notion that the Incarnation also took place on the same day[45].

Why this time of the year, late in December or early in January, was assigned for the Nativity is a question which it is not possible to answer with confidence. It is conceivable that the insecure and blundering argument alleged, among others, by Chrysostom may have had weight. He supposes that Zacharias, the father of the Baptist, was the High[30] Priest, and that he had entered the Holy of Holies on the day of Atonement when the angel appeared to him. The day of Atonement was in September. Six months later (Luke i. 26) the Annunciation was made to St Mary; and after nine months the Saviour was born.

By others it has been suggested that the festival of Christmas on Dec. 25 did not originate in any such calculations; but was suggested by the pagan festival Natalis Solis Invicti marked at that day. The solstice was passed. The sun was entering on its new increases. ‘The Light of the world,’ ‘the Sun of righteousness’ was to take the place of the sun-god in the heavens[46].

The Theophany, or Epiphany (Jan. 6), is, like its name, as characteristically Eastern in its origin as the feast of the Nativity (Dec. 25) is Western; but when it passed into the West it was in thought, either at the outset or certainly soon, separated from the Nativity; and eventually, while the baptism of Christ was not ignored, the main stress of liturgical allusion was on the visit of the Magi, so that the festival is not uncommonly designated simply as the feast of the Three Kings. In the East the dominant thought is the manifestation of Christ’s divinity at his baptism: and in the Basilian Menology the day is simply named ‘The Baptism of our Lord Jesus Christ.’ And it is to this connexion, baptism among the Greeks being known as ‘illumination,’ that has[31] been attributed another name for the day, ‘the lights’ (τὰ φῶτα)[47].

It is not improbable that the feast of the Epiphany made its way to the West, through the churches of Southern Gaul, whose affinities with the East are recognised facts of history. At all events it is in connexion with Gaul that we find the first reference to the Epiphany in the West. The pagan historian Ammianus Marcellinus, in his account of the Emperor Julian in A.D. 361 visiting a Christian church at Vienne, says that it happened on the day in the month of January which Christians call ‘Epiphania’ (Hist. xxi. 2).

The Epiphany was observed in the African Church by the orthodox in the time of Augustine, but he tells us that the Donatists did not observe it, ‘because they love not unity, nor do they communicate with the Eastern Church.’ The latter expression falls in with the supposition that the West derived the festival from the East. In the ancient Kalendar called the Kalendar of Carthage (unfortunately of uncertain date) we find at Jan. 6 the entry ‘Sanctum Epefania’ (sic). In Spain, as we learn from the canons of the Council of Saragossa (can. 4), the festival was recognised as a considerable commemoration before A.D. 380. For Rome, we have to note the silence of the Bucherian Kalendar; but for the fifth century we have the testimony of Pope Leo, and we possess no fewer than[32] eight sermons of his upon the festival of the Epiphany; in these the manifestation of Christ to the Magi is the truth upon which he chiefly enlarges. Elsewhere in the West we have references to other manifestations of the Deity of Christ, as at His baptism, and His first miracle at Cana. But generally, as in the East the baptism, so in the West the manifestation to the Gentiles is the leading note of preachers or theologians[48].

Among the Armenians the Epiphany is reckoned one of the five chief festivals: it is preceded by a week’s fast, and is followed by an octave. It is by them still reckoned as the day of the Nativity.

We see that in the Gregorian Kalendar the commemorations of St Stephen (Dec. 26), St John the Evangelist (Dec. 27), and Holy Innocents (Dec. 28), in the order with which we are familiar, were already established in the West. And long before the period of the Gregorian Kalendar we have evidence that in some parts of the East before the close of the fourth century a group of festivals commemorating eminent saints of the New Testament were celebrated between the feast of the Nativity and the first of January. Basil the Great died on Jan. 1 A.D. 379; and his brother Gregory of Nyssa delivered the funeral oration at his burial. In this discourse the preacher speaks of a group of feasts preceding the first of January, namely of St Stephen, St Peter, St James and St John, and St Paul. It may with some reason be believed that the dates of these festivals had no relation, real or fancied, to the days of the deaths of these saints of the Church’s beginnings.

As regards St James we know that he was killed at the time of the Passover, so that the Hieronymian Martyrology makes the day in December to be the day of his consecration to the episcopate. Liturgists have said it was becoming that the King of glory should come into the world accompanied by the chiefs of his court. And it is not a wholly baseless fancy that already there was a desire (of which at a later period we have many illustrations) to connect a great festival with one or more other commemorations[34] associated with it in thought. The memories of the age of the martyrs would naturally suggest the name of the protomartyr; while the relations of the Lord to St James, St John, and St Peter, and the eminence of St Paul may perhaps sufficiently account for their appearance here.

There is little doubt that at the close of the fourth century the churches of Asia Minor had festivals of St Stephen on Dec. 26, St James and St John on Dec. 27, and St Peter and St Paul on Dec. 28[49]. And in the West our earliest information shows us St Stephen on Dec. 26; but there are variations as regards the other festivals. The ancient Kalendar of Carthage shows us on Dec. 27 ‘St John the Baptist and James the Apostle, whom Herod slew,’ and Holy Innocents on Dec. 28[50].

The earliest Roman service-books show us only St John on Dec. 27, and he is St John the Evangelist[51]. Yet in the so-called Martyrology of St Jerome (which, though interpolated, contains many ancient features), we find at this day, together with ‘the Assumption of St John at Ephesus,’ ‘the ordination to the episcopate of James, the Lord’s brother, who was crowned with martyrdom at the paschal time[52].’ The Holy Innocents (Dec. 28) is[35] known in the Latin books since the sixth century, and may well have been earlier; but Peter and Paul are found together on another day (June 29), the day of their martyrdom at Rome, as was generally assumed. Though we are not able to determine with precision on what day the Innocents of Bethlehem were commemorated in early times, there can be little doubt that there was some commemoration of those whom, as St Augustine says, ‘the Church has received to the honour of the martyrs.’

There are some reasons for conjecturing that the commemoration of the Innocents was at first in association with the Epiphany. In the second half of the fourth century the poet Prudentius has some pretty lines on the Holy Innocents as martyrs in his hymn on the Epiphany[53]. And Leo the Great in more than one of his sermons on the Epiphany has laudatory passages on the martyrdom of the Innocents. Yet in estimating the weight that should attach to such references it should be remembered that Herod’s slaughter of the children at Bethlehem is in the Gospel narrative so closely connected with the visit of the Magi that it would not be unnatural for both poet and preacher to touch on that striking story, although there were no intentional commemoration of the Innocents attached by the Church to that day. In the Byzantine Kalendar the Fourteen Thousand[36] Holy Infants are commemorated on Dec. 29. In the Armenian Kalendar the Fourteen Thousand Innocent Martyrs are commemorated on June 10. It deserves notice that in the Mozarabic Kalendars we find ‘St James the Lord’s Brother’ at Dec. 28; ‘St John Evangelist’ at Dec. 29; and ‘St James the Brother of John’ at Dec. 30.

The commemoration of the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ was in the nature of things a natural and inevitable outcome of the religious beliefs and feelings of the infant Church. The fixing of days for the commemoration of other events in the life of our Lord came with thought and reflection; they belong to the period of constructiveness, and we have no evidence to show that their appearance was very early. Tertullian is silent about other days than Sunday (the Lord’s Day), the Pasch (including the Passion and the Resurrection), and Pentecost[54]; and Origen particularises the Lord’s Day, the Parasceve (perhaps in the sense of the weekly Friday ‘station’), the Pasch, and Pentecost, as being days specially observed by Christians[55].