The Project Gutenberg EBook of Life of J. E. B. Stuart, by Mary L. Williamson This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Life of J. E. B. Stuart Author: Mary L. Williamson Release Date: December 6, 2019 [EBook #60857] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LIFE OF J. E. B. STUART *** Produced by Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

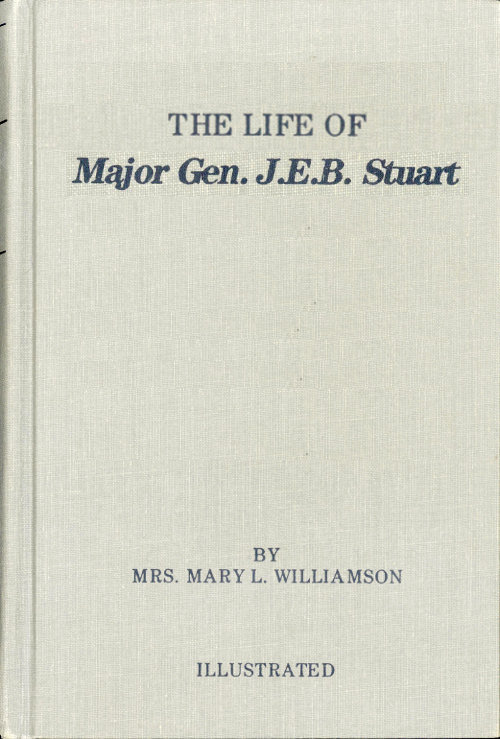

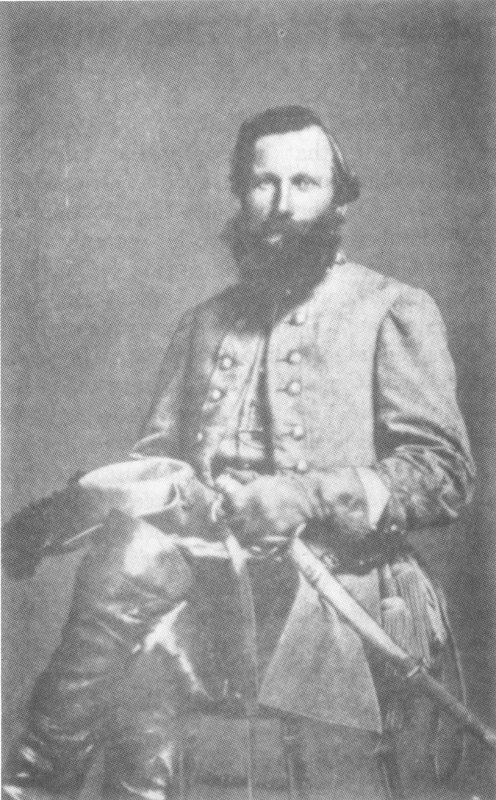

Copyright, 1914, by Mrs. J. E. B. Stuart General Stuart in 1854, from an ambrotype owned by Mrs. J. E. B. Stuart, which is here reproduced for the first time.

BY

MARY L. WILLIAMSON

Author of Life of Lee, Life of Jackson, and Life of Washington

EDITED AND ARRANGED FOR SCHOOL USE

BY

E. O. WIGGINS

English Department, Lynchburg High School, Virginia

Harrisonburg, Virginia

SPRINKLE PUBLICATIONS

1989

BOOKS

by Mary L. Williamson

For Third Grade

Life of Lee

183 pages, cloth. Price, 35 cents

For Fourth Grade

Life of Jackson

248 pages, cloth. Price, 40 cents

For Fifth Grade

Life of Washington

211 pages cloth. Price, 40 cents

For Fifth Grade

Life of Stuart

215 pages cloth. Price, 40 cents

Sprinkle Publications

P. O. Box 1094

Harrisonburg, Virginia 22801

Copyright, 1914

BY

B. F. JOHNSON PUBLISHING COMPANY

Some years ago, to fill what appeared to me a need in our literature for children, I made a study of the lives and campaigns of General R. E. Lee and of General Stonewall Jackson and prepared, for very young readers, histories of those great commanders.

In performing these tasks, I became interested in the combats and maneuvers of General Lee’s chief of cavalry, Major-General J. E. B. Stuart, who has been justly called “the eyes and ears of Lee.” As the years go by, I find no book in print recounting to children his wonderful feats and valorous service, or explaining to them the part played in the battles of Lee and Jackson by the Stuart Cavalry Corps and Horse Artillery whose exploits hold a brilliant place in modern military tactics.

To make good this omission, I have prepared this little life of Stuart, in the hope that it will not only pass on the story of military deeds as captivating as any in history, but warm the hearts of rising generations to lives of courage and devotion.

In the later stages of my work, Miss Evelina O. Wiggins has been associated, contributing various materials, obtaining three pictures and several interesting letters of General Stuart’s, and making available Mrs. J. E. B. Stuart’s criticism of the manuscript. Miss Wiggins has also rendered the aid of adapting the book to the practical needs of the schoolroom. Her experience and position as a teacher make the latter service highly valuable.

MARY LYNN WILLIAMSON

New Market, Virginia

September 1, 1914

The publishers wish to acknowledge their obligations to Mrs. H. B. McClellan for permission to use material from her husband’s book, Life and Campaigns of General J. E. B. Stuart; to General T. T. Munford and to Judge Theodore S. Garnett for information and pictures; to Mr. J. E. B. Stuart and the Confederate Museum, Richmond, Va., for permission to make photographic copies of the personal relics of General Stuart in the Museum; and to Mrs. J. E. B. Stuart for the ambrotype and letters of General Stuart which she allowed to be copied for use in this book and for the invaluable aid of her careful critical reading of the manuscript.

Henry of Navarre was a famous French king who led his forces to a glorious victory in a civil war. An English writer, Lord Macaulay, wrote a stirring poem in which a French soldier is represented as describing this battle. Here is his picture of the great, beloved king:—

“The King is come to marshal us, in all his armor drest,

And he has bound a snow-white plume upon his gallant crest.

He looked upon his people and a tear was in his eye,

He looked upon the traitors and his glance was stern and high;

Right graciously he smiled on us, as rolled from wing to wing,

Down all our line a deafening shout, ‘God save our lord, the King!’

“‘And if my standard bearer fall,—as fall full well he may,

For never saw I promise yet of such a bloody fray—

Press where you see my white plume shine amidst the ranks of war,

And be your oriflamme to-day the helmet of Navarre.’

“A thousand spurs are striking deep, a thousand spears in rest,

A thousand knights are pressing close behind the snow-white crest;

And in they burst and on they rushed, while like a guiding star,

Amidst the thickest carnage blazed the helmet of Navarre.”

These lines about the French king of the sixteenth century are often quoted in describing a gallant cavalry leader of our own country. As we read them, we see the Confederate general, “Jeb” Stuart, his cavalry hat looped back on one side with a long black ostrich plume which his troopers always saw in the forefront of the charge. His men would follow that plume anywhere, at any time, and when you read this story of his life, you will not wonder that he inspired their absolute devotion.

You have read about the lives of the peerless commander, General Robert E. Lee, and his great lieutenant, General Stonewall Jackson. In these you have learned something about the movements of the great body of our army, the infantry; but the infantry, even with such able commanders as Lee and Jackson, needed the aid of the cavalry and the artillery. It is with these two latter divisions of the army that we deal in studying the life of General Stuart. As chief of cavalry and commander of the famous Stuart Horse Artillery, he served as eyes and ears to the commanding generals. He kept them informed about the location and movements of the Federals, screened the location of the Confederate troops, felt the way, protected the flank and rear when the army was on the march, and made quick raids into the Federal territory or around their army to secure supplies and information as well as to mislead them concerning the proposed movements of Confederate forces. A heavy responsibility rested on the cavalry, and General Stuart and his men were engaged in many small but severe battles and skirmishes in which the army as a whole did not take part.

“To horse, to horse! the sabers gleam,

High sounds our bugle call,

Combined by honor’s sacred tie,

Our watchword, ‘laws and liberty!’

Forward to do or die.”

—Sir Walter Scott

James Ewell Brown Stuart, commonly known as “Jeb” Stuart from the first three initials of his name, was born in Patrick county, Virginia, February 6, 1833. On each side of his family, he could point to a line of ancestors who had served their country well in war and peace and from whom he inherited his high ideals of duty, patriotism, and religion.

He was of Scotch descent and his ancestors belonged to a clan of note in the history of Scotland. From Scotland a member of this clan went to Ireland.

About the year 1726, Jeb Stuart’s great-great-grandfather, Archibald Stuart, fled from Londonderry, Ireland, to the wilds of Pennsylvania, in order to escape religious persecution. Eleven years later, he removed from Pennsylvania to Augusta county, Virginia, where he became a large land-holder. At Tinkling Spring Church, the graves of the immigrant and his wife may still be seen.

Archibald Stuart’s second son, Alexander, joined the Continental army and fought with signal bravery during the whole of the War of the Revolution. After the war, he practiced law. He showed his interest in education by becoming one of the founders of Liberty Hall, at Lexington, Virginia, a school which afterwards became Washington College and has now grown into Washington and Lee University.

RUINS OF LIBERTY HALL ACADEMY, AT LEXINGTON, VA.

His youngest son who bore his name, was also a lawyer; he held positions of trust in his native State, Virginia, as well as in Illinois and Missouri where he held the responsible and honored position of a United States judge.

Our general’s father, Archibald Stuart, the son of Judge Stuart, after a brief military career in the War of 1812, became a successful lawyer. His wit and eloquence soon won him distinction, and his district sent him as representative to the Congress of the United States where he served four years.

There is an interesting story told about General Stuart’s mother’s grandfather, William Letcher. He had enraged the Loyalists, or Tories, on the North Carolina border, by a defeat that he and a little company of volunteers had inflicted on them in the War of the Revolution. One day in June, 1780, as Mrs. Letcher was alone at home with her baby girl, only six weeks old, a stranger, dressed as a hunter and carrying a gun in his hand, appeared at the door and asked for Letcher. While his wife was explaining that he would be at home in a short time, he entered and asked the man to be seated.

The latter, however, raised his gun, saying: “I demand you in the name of the king.”

When Letcher tried to seize the gun, the Tory fired and the patriot fell mortally wounded, in the presence of his young wife and babe.

Bethenia Letcher, the tiny fatherless babe, grew to womanhood and married David Pannill; and her daughter, Elizabeth Letcher Pannill, married Archibald Stuart, the father of our hero.

Mrs. Archibald Stuart inherited from her grandfather, William Letcher, a large estate in Patrick county. The place, commanding fine views of the Blue Ridge mountains, was called Laurel Hill, and here in a comfortable old mansion set amid a grove of oak trees, Jeb Stuart was born and spent the earlier years of his boyhood.

Mrs. Stuart was a great lover of flowers and surrounding the house was a beautiful old-fashioned flower garden, where Jeb, who loved flowers as much as his mother did, spent many happy days. He always loved this boyhood home and often thought of it during the hard and stirring years of war. Once near the close of the war, he told his brother that he would like nothing better, when the long struggle was at an end, than to go back to the old home and live a quiet, peaceful life.

When Jeb was fourteen years old, he was sent to school in Wytheville, and in 1848 he entered Emory and Henry College. Here, under the influence of a religious revival, he joined the Methodist church, but about ten years later he became a member of the Episcopal church of which his wife was a member.

Though always gay and high-spirited, Stuart even as a boy possessed a deep religious sentiment which grew in strength as he grew in years and kept his heart pure and his hands clean through the many temptations that beset him in the freedom and conviviality of army life. A promise that he made his mother never to taste strong drink was kept faithfully to his death, and none of his soldiers ever heard him use an oath even in the heat of battle. His gallantry, boldness, and continual gayety and good nature, coupled with his high Christian virtues, caused all who came in contact with him not only to love but to respect and admire him.

EMORY AND HENRY COLLEGE ABOUT 1850

He left Emory and Henry College in 1850 and entered the United States Military Academy at West Point where he had received an appointment.

At this time, Colonel Robert E. Lee was superintendent at West Point. Young Stuart spent many pleasant hours at the home of the superintendent where he was a great favorite with the ladies of the family. Custis Lee, the eldest son of Colonel Lee, was Stuart’s best friend while he was a student at the Academy.

An interesting incident is told about Stuart while he was on a vacation from West Point. Mr. Benjamin B. Minor of Richmond, had a case to be tried at Williamsburg, and when he arrived at the hotel it was so crowded that he was put in an “omnibus” room, so called because it contained three double beds.

Late in the afternoon when the stage drove up, he saw three young cadets step from it and he soon found that they were to share with him the “omnibus” room.

He went to bed early, but put a lamp on the table by the head of his bed and got out his papers to go over his case. After awhile the three cadets came in laughing and singing, and soon they were all three piled into one bed where they continued to laugh and joke in uproarious spirits.

Finally one of them said, “See here, fellows, we have had our fun long enough and we are disturbing that gentleman over there; let us hush up and go to sleep.”

“No need for that, boys,” said Mr. Minor, “I have just finished.”

Then as he tells us he ‘pitched in’ and had a good time with them.

The cadet who had shown such thoughtfulness and courtesy was young Jeb Stuart who as Mr. Minor discovered was one of his wife’s cousins. He was very much pleased with the boy and invited him to come to Richmond. Stuart accepted the invitation and called several times at the Minor home.

From daguerreotype Confederate Museum, Richmond, Va.

J. E. B. STUART

When a student at West Point

He explained to Mr. Minor his plan for an invention which was to be called “Stuart’s lightning horse-hitcher” and to be used in Indian raids. He excited Mr. Minor’s admiration because he had such gallant and genial courtesy and professional pride. He wanted even then to accomplish something useful and important to his country and himself.

General Fitzhugh Lee, who was at West Point with Stuart, and who later served under General Stuart as a trusted commander, tells us that as a cadet he was remarkable for “strict attendance to military duties, and erect, soldierly bearing, an immediate and almost thankful acceptance of a challenge to fight any cadet who might in any way feel himself aggrieved, and a clear, metallic, ringing voice.”

Although the boys called him a “Bible class man” and “Beauty Stuart,” it was in good-natured boyish teasing; where he felt it to be intended differently or where his high standards of conduct seemed to be sneered at, he was well able with his quick temper and superb physical strength to teach the offender a lesson.

BADGE OF WEST POINT GRADUATES

The arms of the United States

Academy, suspended by a ribbon

of black, gray, and gold from a

bar bearing the date of the graduate’s

class

As ‘Fitz’ Lee tells us, Stuart was always ready to accept a challenge, but he did not fight without good cause, and his father, a fair-minded and intelligent man, approved of his son’s course in these fisticuff encounters. Between his father and himself there was the best kind of comradeship and sympathy, and young Stuart was always ready to consult his father before taking any important step in life. The decision as to what he should do when he left West Point, however, was left to him, and just after his graduation he wrote home that he had decided to enter the regular army instead of becoming a lawyer.

“Each profession has its labors and rewards,” he wrote, “and in making the selection I shall rely upon Him whose judgment cannot err, for it is not with the man that walketh to direct his steps.”

Meanwhile, by his daring and skill in horsemanship, his diligence in his studies, and his ability to command, he had risen rapidly from the position of corporal to that of captain, and then to the rank of cavalry sergeant which is the highest rank in that arm of the service at West Point. He graduated thirteenth in a class of forty-six, and started his brief but brilliant military career well equipped with youth, courage, skill, and a firm reliance on the love and wisdom of God.

Most of Stuart’s time from his graduation at West Point until the outbreak of the War of Secession was spent in military service along the southern and western borders of our country. During this period, there was almost constant warfare between Indians and frontier settlers. Stuart had many interesting adventures in helping to protect the settlers and to drive the Indians back into their own territory. The training that he received at this time helped to develop him into a great cavalry and artillery leader.

The autumn after he left West Point, Stuart was commissioned second lieutenant in a regiment of mounted riflemen on duty in western Texas. He reached Fort Clark in December, just in time to join an expedition against the Apache Indians who had been giving the settlers a great deal of trouble. The small force to which he was attached pushed boldly into the Indian country north of the Rio Grande.

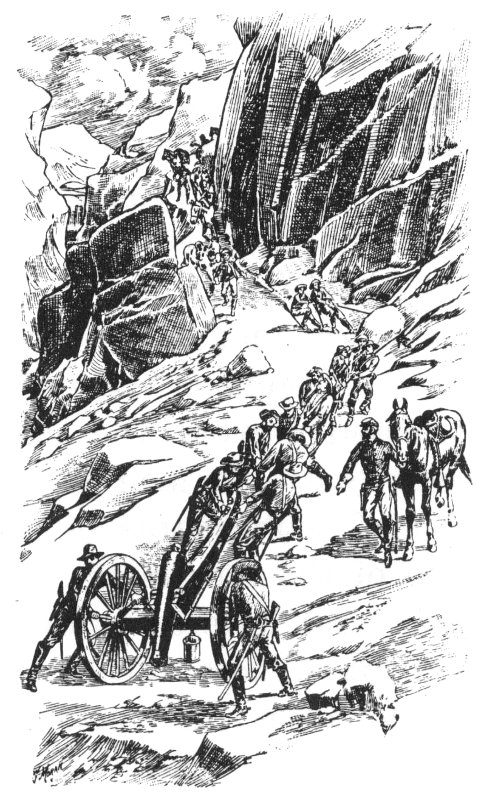

CARRYING THE GUN DOWN THE ‘MULEPATH’

It was not long before the young officer’s skill and determination received a severe test. The trail that the expedition followed led to the top of a steep and rugged ridge which to the troopers’ astonishment dropped abruptly two thousand feet to an extensive valley. The precipice formed of huge columns of vertical rock, at first seemed impassable, but they soon found a narrow and dangerous Indian trail—the kind that is called a ‘mulepath’—winding to the base of the mighty cliff. The officers and advance guard dismounted and led their horses down the steep path that scarcely afforded footing for a man and passed on to choose a bivouac for the night. A little later, Lieutenant Stuart, with a rear guard of fifty rangers detailed to assist him, reached the top of the ridge, with their single piece of artillery. Stuart worked his way down the trail alone, hoping that when he reached the foot he would find that the major in charge of the expedition had left word that the gun was to be abandoned as it seemed impossible to carry it down the precipice. No such order awaited him, however, and the young officer determined to get the gun down in spite of all difficulties. He noted well the dangers of the way as he regained the top and, having had the mules unhitched and led down by some of the men, he unlimbered the gun and started the captain of the rangers and twenty-five men down with the limber. He himself took charge of the gun and, with the help of the remaining men, lifted it over huge rocks and lowered it by lariat ropes over impassable places until it was finally brought safely to the valley below.

The major had taken it for granted that Stuart would leave the gun at the top of the precipice and was amazed when just at supper time it was brought safely into camp. Such ingenuity, grit, and determination were qualities which promised that the young officer would develop into a skillful and reliable leader.

A few days later, the command encamped for the night in a narrow valley between high ridges. The camp fires were burning brightly and the cooks were preparing supper when a sudden violent gust of wind swept through the valley and scattering the fire set the whole prairie into a moving flame. With such rapidity did the fire sweep over the camp that the men were unable to save anything except their horses, and in a deplorable condition the expedition was forced to return to the camp in Texas.

In May, 1855, Stuart was transferred to the First Regiment of cavalry, with the rank of second lieutenant. In July, this regiment was ordered to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas; and in September, it went on a raid, under the leadership of Colonel E. V. Sumner, against some Indians who had disturbed the white settlers. The savages retreated to their mountain strongholds and the regiment returned to the fort without fighting.

While on this expedition, Stuart learned with deep distress of the death of his wise and affectionate father. It had been only a few weeks before that Mr. Stuart had written to approve his son’s marriage to Miss Flora Cooke, daughter of Colonel Philip St. George Cooke who was commandant at Fort Riley. The marriage was celebrated at that place, November 14, 1855.

At this time, there was serious trouble in Kansas between the two political parties that were fighting to decide whether Kansas should become a free or a slave state. Stuart, who had been promoted to the rank of first lieutenant, was stationed at Fort Leavenworth in 1856-’57. Here he was involved in many skirmishes and local raids. It was at this time that he encountered the outlaw “Ossawatomie” Brown of whom we shall hear again a little later.

Stuart passed uninjured through the Kansas contest, and in 1857 entered upon another Indian war against the Cheyenne warriors who were attacking the western settlers. In the chief battle of this campaign, the Indians were routed, but Lieutenant Stuart was wounded while rescuing a brother officer who was attacked by an Indian.

Here is Stuart’s own account of the fight as given in a letter to his wife, which she has kindly allowed us to copy:

“Very few of the company horses were fleet enough after the march, besides my own Brave Dan, to keep in reach of the Indians mounted on fresh ponies.... As long as Dan held out I was foremost, but after a chase of five miles he failed and I had to mount a private’s horse and continue the pursuit.

“When I overtook the rear of the enemy again, I found Lomax in imminent danger from an Indian who was on foot and in the act of shooting him. I rushed to the rescue, and succeeded in firing at him in time, wounding him in his thigh. He fired at me in return with an Allen’s revolver, but missed. My shots were now exhausted, and I called on some men approaching to rush up with their pistols and kill him. They rushed up, but fired without hitting.

“About this time I observed Stanley and McIntyre close by; the former said, ‘Wait, I’ll fetch him,’ and dismounted from his horse so as to aim deliberately, but in dismounting, his pistol accidentally discharged the last load he had. He began, however, to snap the empty barrels at the Indian who was walking deliberately up to him with his revolver pointed.

“I could not stand that, but drawing my saber rushed on the monster, inflicting a severe wound across his head, that I think would have severed any other man’s, but simultaneous with that he fired his last barrel within a foot of me, the ball taking effect in the breast, but by the mercy of God glancing to the left and lodging so far inside that it cannot be felt. I rejoice to inform you that it is not regarded as at all fatal or dangerous, though I may be confined to my bed for weeks.”

After this battle, all of the force pursued the Indians, except a small detachment under Captain Foote, which was left behind to guard the wounded for whom the surgeon established rough hospital quarters on the banks of a beautiful, winding creek. Here Stuart spent nearly a week confined to his cot, and as he wrote his wife at the time, the only books that he had to read during the long, weary days were his Prayer Book which was not neglected—and his Army Regulations. A few pages of Harper’s Weekly that some one happened to have were considered quite a treasure.

At the end of about ten days, some Pawnee guides who had been attached to the expedition brought orders for this little detachment to leave the camp where it was exposed to attacks from the wandering bands of Cheyenne Indians and go back to Fort Kearny a hundred miles away.

Stuart was just able to sit on his horse again, yet we shall see that in spite of his wound he was the life and salvation of the little party. The Pawnees said they were only four days distant from the fort, but the second day these unreliable guides deserted and the soldiers were lost in a heavy fog, without a compass. They were forced to depend on a Cheyenne prisoner for information. After four days’ fruitless and difficult marching through the forest, Stuart, who believed that the guard was willfully misleading them, volunteered to go ahead with a small force, find the fort, and send back help for those who were still suffering too seriously from their wounds to keep up on a rapid and uncertain march.

From McClure’s Magazine

INDIANS OF THE PLAINS

After many dangers and deep anxiety on his part, taking his course by the stars when the fog lifted at night and working his way through it as best he could by day, he finally reached Fort Kearny. The Pawnees had come in three days before, and scouting parties had been searching for Captain Foote’s command about which much anxiety was felt. Help was immediately sent them, and as a result of Stuart’s indomitable will and able services, the little party was rescued and brought safely to the fort.

From the autumn of 1857 until the summer of 1860, Stuart was stationed at Fort Riley. During these three years, there were few skirmishes with the Indians and Stuart had leisure to perfect the invention of a saber attachment that he had been thinking of ever since his student days at West Point. This invention was bought and patented by the government in October, 1859, while the inventor was on leave of absence in Virginia, visiting his mother and his friends.

It was on the night of the sixteenth of this same October that a band of twenty men, under the leadership of John Brown, seized the United States arsenal at Harper’s Ferry. Brown was a fanatic who believed that all slaves should be set free and who had taken an active part in the recent disturbances in Kansas. After seizing the arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, he sent out his followers during the night to arrest certain citizens and to call to arms the slaves on the surrounding plantations. About sixty citizens were arrested and imprisoned in the engine house, within the confines of the armory, but the slaves, either through fear or through distrust of Brown and his schemes, refused to obey his summons.

ARSENAL AT HARPER’S FERRY

The next morning as soon as news of the seizure of Harper’s Ferry spread over the country, armed men came against Brown from all directions. Before night he and his followers took refuge in the engine house, but it was so crowded that he was obliged to release all but ten of his prisoners.

When the news of Brown’s raid was telegraphed to Washington, Lieutenant Stuart, who was at the capital attending to the sale of his patent saber attachment, was requested to bear a secret order to Lieutenant-Colonel Robert E. Lee, his old superintendent at West Point, who was then at his home, Arlington, near Washington city. Stuart learned that Colonel Lee had been ordered to command the marines who were being sent to suppress the insurrection at Harper’s Ferry, and he at once offered to act as aid-de-camp. Colonel Lee, who remembered Stuart well as a cadet, immediately accepted his offer of service.

Upon arriving at Harper’s Ferry on the night of October 17, they found that John Brown and his men were still in the engine house, defying the citizen soldiers who surrounded the building. Colonel Lee proceeded to surround the engine house with the marines; at daylight, wishing to avoid bloodshed, he sent Lieutenant Stuart to demand the surrender of the fanatical men, promising to protect them from the fury of the citizens until he could give them up to the United States government.

When Lieutenant Stuart advanced to the parley, Brown, who had assumed the name of Smith, opened the door four or five inches only, placed his body against it, and held a loaded carbine in such a position that, as he stated afterward, he might have “wiped Stuart out like a mosquito.” Immediately the young officer recognized in the so-called Smith the identical John, or “Ossawatomie,” Brown who had caused so much trouble in Kansas. Brown refused Colonel Lee’s terms and demanded permission to march out with his men and prisoners and proceed as far as the second tollgate. Here, he declared, he would free his prisoners and if Colonel Lee wished to pursue he would fight to the bitter end.

Stuart said that these terms could not be accepted and urged him to surrender at once. When Brown refused, Stuart waved his cap, the signal agreed upon, and the marines advanced, battered down the doors, and engaged in a hand-to-hand fight with the insurgents. Ten of Brown’s men were killed by the marines and all the rest, including Brown himself, were wounded.

That same day, Lieutenant Stuart, under Colonel Lee’s orders, went to a farm about four miles and a half away that Brown had rented and brought back a number of pikes with which Brown had intended to arm the negroes. Colonel Lee was then ordered back to Washington and Stuart went with him. John Brown and seven of his men were tried, were found guilty of treason, and were hanged.

The John Brown Raid cast a great gloom over the country. While many people in the North regarded Brown as a martyr to the cause of emancipation, the southern people were justly indignant at the thought that their lives and property were no longer safe from the plots of the Abolition party which Brown had represented. The bitter feelings aroused by this affair culminated, in 1861, in the bloody War of Secession.

There seems to have been no doubt in the mind of Lieutenant Stuart as to what he should do in the event of Virginia’s withdrawal from the Union. As soon as he heard that the Old Dominion had seceded, he forwarded to the War Department his resignation as an officer in the United States army, and hastening to Richmond, he enlisted in the militia of his native state. Like most other southerners, he preferred poverty and hardships in defense of the South to all the honors and wealth which the United States government could bestow.

On May 10, 1861, Stuart was commissioned as lieutenant colonel of infantry, and was ordered to report to Colonel T. J. Jackson at Harper’s Ferry. While he was at Harper’s Ferry, Stuart organized several troops of cavalry to assist the infantry and he was soon transferred to this branch of the service.

On May 15, General Joseph E. Johnston was sent by the Confederate government to take command of all the forces at Harper’s Ferry; while Colonel Jackson, who had previously been in command of the place, was assigned charge of the Virginia regiments afterwards famous as the “Stonewall Brigade.” General Johnston found that he was unable to hold the town against the advancing Federal force; so he destroyed the railway bridge and retired with his guns and stores to Bunker Hill, twelve miles from Winchester, where he offered battle to the Federals. They declined to fight and withdrew to the north bank of the Potomac river.

When the Federals under General Patterson again crossed the river, General Jackson with his brigade was sent forward to support the cavalry under Stuart and to destroy the railway engines and cars at Martinsburg. Jackson then remained with his brigade near Martinsburg, while his front was protected by Colonel Stuart with a regiment of cavalry.

On July 1, General Patterson advanced toward General Jackson, who went forward to meet him, with only the Fifth Regiment, several companies of cavalry, and one piece of artillery. The Confederate general posted his men behind a farm house and barn, and held back Patterson so well that he threw forward an entire division to overpower the small force of Jackson. The latter then fell back slowly to the main body of his troops, with the trifling loss of two men wounded and nine missing.

While supporting Jackson in this first battle in the Shenandoah valley, known as the battle of Haines’ Farm or Falling Waters, Colonel Stuart had a remarkable adventure. Riding alone in advance of his men, he came suddenly out of a piece of woods at a point where he could see a force of Federal infantry on the other side of the fence. Without a moment’s hesitation, he rode boldly forward and ordered the Federal soldiers to pull down the bars.

They obeyed and he immediately rode through to the other side, and in peremptory tones said, “Throw down your arms or you are dead men.”

The raw troops were so overcome by Stuart’s boldness and commanding tones that they obeyed at once and then marched as he directed through the gap in the fence. Before they recovered from their astonishment, Stuart had them surrounded by his own force which had come up in the meantime, thus capturing over forty men—almost an entire company.

After some marching backward and forward, General Johnston retired to Winchester; while General Patterson moved farther south to Smithfield as if he intended to attack in that direction. Stuart with his small force was now compelled to watch a front of over fifty miles, in order to report promptly the movements of the Federals, yet he did this so efficiently that later on when General Johnston was ordered west, he wrote to Stuart:

“How can I eat, sleep, or rest in peace, without you upon the outpost?”

General Johnston now received a call for help from General Beauregard who commanded a Confederate army of twenty thousand men at Manassas Junction. Beauregard was confronted by a Federal army of thirty-five thousand men, including nearly all of the United States regulars east of the Rocky Mountains. This army, commanded by General McDowell, was equipped with improved firearms and had fine uniforms, good tents, and everything that money could buy to make good soldiers. The North was very proud of this fine army and fully expected it to crush Beauregard and to sweep on to Richmond.

Beauregard was indeed in danger. He had a smaller army and his infantry was armed, for the most part, with old-fashioned smooth-bore muskets, and his cavalry with sabers and shotguns. One company of cavalry was armed only with the pikes of John Brown, which had been stored at Harper’s Ferry. Beauregard stationed his forces in line of battle along the banks of Bull Run from the Stone Bridge to Union Mills, a distance of eight miles. On July 18, the Federals tried to force Blackburn’s Ford on Bull Run, but were repulsed with heavy loss. Beauregard, knowing that the attack would be renewed the next day, sent a message to Johnston at Winchester, sixty miles away.

“If you are going to help me, now is the time,” was Beauregard’s message.

Two days before, Stuart had been transferred to the cavalry, with a commission as colonel, and he entered at once upon his arduous labors. At first he had in his command only twenty-one officers and three hundred and thirteen men, raw to military discipline and poorly armed with the guns they had used in hunting, but all were fine horsemen and good shots.

General Johnston, leaving Stuart with a little band of troopers to conceal his movements, immediately commenced his march from Winchester to Manassas. So skillfully did Colonel Stuart do his work that General Patterson was not aware of General Johnston’s departure until Sunday, July 21, when the great battle of Manassas was fought. Owing to a collision which had blocked the railway, some of the infantry did not reach Manassas until near the close of the battle, but the cavalry and the artillery marched all the way and arrived in time to render effective service during the entire battle.

It was at Manassas that General Jackson won his name of “Stonewall” because of the wonderful stand that his brigade made, just when it seemed that the Federals were about to overcome the Confederates. But we are concerned particularly with the movements of the cavalry which rendered fine service, protecting each flank of the army. Colonel Stuart, with only two companies of cavalry, protected the left flank from assault after assault. At one time Stuart boldly charged the Federal right and drove back a company of Zouaves resplendent in their blue and scarlet uniforms and white turbans.

General Early, who arrived on the field about three o’clock in the afternoon and assisted in holding the left flank, said, “But for Stuart’s presence there, I am of the opinion that my brigade would have arrived too late to be of any use. Stuart did as much toward saving the First Manassas as any subordinate who participated in it.”

General Jackson, in his report of the battle, said: “Apprehensive lest my flanks be turned, I sent orders to Colonels Stuart and Radford of the cavalry to secure them. Colonel Stuart and that part of his command with him deserve great praise for the promptness with which they moved to my left and secured my flank from the enemy, and by driving them back.”

Thus we see at the very crisis of the battle, Stuart with only a small force aided largely in gaining the great victory. When he saw the Federals fleeing from all parts of the field, he pursued them for twelve miles, taking many prisoners and securing much booty.

After the battle of First Manassas, the main armies were inactive for many months; but the Confederate cavalry was kept busy in frequent skirmishes with the Federal pickets and in raids toward the Potomac river. Stuart took possession of Munson’s Hill, near Washington, and for several weeks sent out his pickets within sight of the dome of the Capitol.

In a letter from General F. E. Paxton, of the Stonewall Brigade, we find this interesting mention of Colonel Stuart and his life at the outpost: “Yesterday I was down the road about ten miles, and, from a hill in the possession of our troops, had a good view of the dome of the Capitol, some five or six miles distant. The city was not visible, because of the woods coming between. I saw the sentinel of the enemy in the field below me, and about half a mile off and not far on this side, our own sentinels. They fire sometimes at each other. Mrs. Stuart, wife of the colonel who has charge of our outpost, visits him occasionally—having a room with friends a few miles inside the outpost. Whilst there looking at the Capitol, I saw two of his little children playing as carelessly as if they were at home. A dangerous place, you will think, for women and children.”

PICKETED CAVALRY HORSE

Mrs. Stuart, however, was a soldier’s daughter and a soldier’s wife, and she took advantage of every opportunity to be with her husband at his headquarters. During the beginning of the war, before the engagements with the Federals became frequent, she was often able to be with her husband or to board at some home near which he was stationed. Although he was a favorite with women, there was no woman who, in General Stuart’s eyes, could compare with his wife, and he was never happier than when with her and his children. When the general’s duties compelled him to be away from her, two days seldom passed that Mrs. Stuart did not hear from him by letter or telegram.

On September 11, Stuart’s forces encountered a raiding party which was forced to retire with a loss of two killed and thirteen wounded, while Stuart lost neither man nor horse.

During the summer, Stuart had been ordered to report to General James Longstreet who commanded the advance of the Confederate army.

General Longstreet in a letter to President Davis said of Stuart: “He is a rare man, wonderfully endowed by nature with the qualities necessary for an officer of light cavalry. Calm, firm, acute, active, and enterprising, I know no one more competent than he to estimate events at their true value. If you add a brigade of cavalry to this army, you will find no better brigadier general to command it.”

On September 24, 1861, Stuart received his promotion as brigadier general. His brigade included four Virginia regiments, one North Carolina regiment, and the Jeff Davis Legion of Cavalry. These regiments were composed of high-spirited, brave young men who could ride dashingly and shoot with the skill of backwoodsmen, but who were for the most part untrained in military affairs. Stuart, however, was an untiring drillmaster and by his personal efforts he developed his brigade into a command of capable and devoted soldiers.

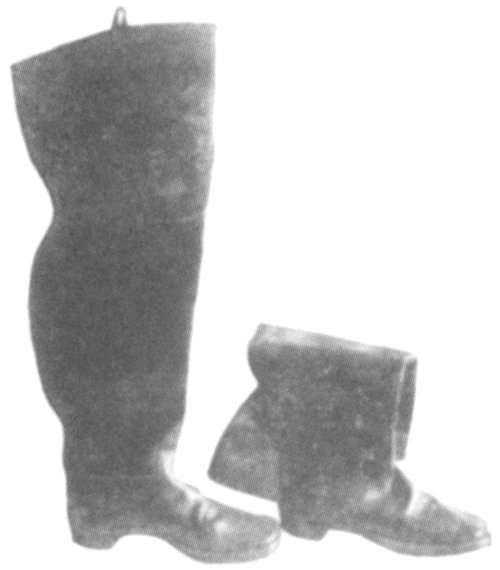

STUART’S GAUNTLETS

From originals in Confederate Museum, Richmond, Va.

The young general was not yet twenty-nine years old. He was of medium height, had winning blue eyes, long silken bronze beard and mustache, and a musical voice. He usually wore gauntlets, high cavalry boots, a broad-brimmed felt hat caught up on one side by a black ostrich plume, and a tight-fitting cavalry coat that he called his “fighting jacket.” He rode as if he had been born in the saddle.

Fitz Lee, who served under him, said: “His strong figure, his big brown beard, his piercing, laughing blue eyes, the drooping hat and black feather, the ‘fighting jacket’ as he termed it, the tall cavalry boots, formed one of the most jubilant and striking pictures in the war.”

STUART’S CAVALRY BOOTS

From originals in Confederate Museum, Richmond, Va.

Later on, John Esten Cooke described Stuart thus: “His ‘fighting jacket’ shone with dazzling buttons, and was covered with gold braid; his hat was looped up with a golden star and decorated with a black ostrich plume; his fine buff gauntlets reached to the elbow; around his waist was tied a splendid yellow sash and his spurs were of pure gold.”

One who formed an opinion of him from a casual glance might have thought that he was merely a gay young fop, fond of handsome and even showy dress. But his friends and his enemies knew better. Gay and even boyish as he was when off duty, loving music and good cheer, his men knew that the instant the bugles called him he would become the calm, daring, farsighted commander, leading them to glorious deeds. No leader of the southern army was more feared by the Federal troops or more admired by the commanders of the Federal cavalry—Sheridan, Pleasanton, Buford, and others—than Stuart whom they nicknamed “the Yellow Jacket.” He seemed to fly from place to place, guarding the Confederate line and charging the Federals at the most unexpected times and places; gayly dressed as that brilliant-colored insect, he was as sharp and sudden in attack.

Possessing the daring courage that is necessary for a great cavalry leader, he was so wary and farsighted that he won the respect of conservative leaders as well as the confidence of his men. And in victory or defeat he was the soul of good cheer. His mellow musical voice could be heard above the din of battle singing,

“If you want to have a good time

Jine the cavalry.”

Once General Longstreet laughingly ordered General Stuart to leave camp, saying he made the cavalrymen’s life seem so attractive that all the infantrymen wanted to desert and “jine the cavalry.”

On December 20, 1861, while the army was in winter quarters at Manassas, Stuart was placed in command of about 1,500 infantry, a battery of artillery, and a small body of cavalry, for the purpose of covering the movements of General J. E. Johnston’s wagon train which had been sent to procure forage for the Confederate troops. It was most important that this wagon train should be protected and the pickets had advanced to Dranesville with the cavalry following closely, when a Federal force of nearly 4,000 men, supported by two other brigades, attacked the pickets. The pickets were driven back, and the Federal artillery and infantry occupied the town, where they posted themselves in a favorable position.

Stuart, when informed that the Federals held the town, sent at once to recall the wagons and advanced as quickly as possible with the rest of his force to engage the Federals while the wagons were gaining a place of safety. The Federals had a much larger force of infantry and had a good position for their artillery; so Stuart, after two hours of unequal combat, was forced to retire with heavy loss in killed and wounded. The wagons, however, were saved from capture; and the next morning when Stuart returned to renew the attack, he found that the Federals had retired.

In this battle of Dranesville, the Confederate loss was nearly 200 and that of the Federals was only 68. This was the first serious check that Stuart had received, but he had displayed so much prudence and skill in extricating the wagons and his small force from the sudden danger that he retained the entire confidence of his men.

Writing about this battle to his wife, Stuart said, “The enemy’s force was at least four times larger than mine. Never was I in greater personal danger. Horses and men fell about me like tenpins, but thanks to God neither I nor my horse was touched.”

In the meanwhile, the Federal commander, General McClellan, had been organizing his forces and by March, 1862, he had under him in front of Washington a large army splendidly armed and equipped. General Johnston had too small an army to engage the Federal hosts; and so late in March he fell back from Manassas and encamped on the south side of the Rappahannock river.

General McClellan moved his large army to Fortress Monroe, and it was then seen that he intended to advance to Richmond by way of the Peninsula,—that is, the portion of tidewater Virginia lying between the James and York rivers.

The brave Confederate general, Magruder, stationed at Yorktown, was joined by General Johnston with his whole army. They saw, however, that it would be impossible to hold that position against McClellan, and so the Confederates gave up the town and retired toward Richmond.

The cavalry under Stuart skillfully guarded the rear of the army and concealed its movements from the Federals. At Williamsburg a stubborn and brilliant battle was fought, in which Johnston’s rear guard repelled the Federals. After the battle, the cavalry and the Stuart Horse Artillery protected the rear of the Confederate army as it withdrew toward Richmond and screened the infantry as it took position along the southern bank of the Chickahominy river.

McClellan placed his army on the north bank of the same river, and on May 31 and June 1, he threw a large force across the river and engaged the army of Johnston in the battle of Seven Pines. This battle was only a partial victory for the Confederates, and as the river was bordered by wide marshes and dense woods, neither side could make use of cavalry in the conflict. General Stuart, however, was actively engaged in giving personal assistance to General Longstreet on the field.

In his report of the battle, General Longstreet said: “Brigadier J. E. B. Stuart, in the absence of any opportunity to use his cavalry, was of material service by his presence with me on the field.”

In this battle of Seven Pines, General Johnston was severely wounded and gave place to General R. E. Lee, who was thus put in command of the army defending Richmond and of all of the other Confederate forces in Virginia. McClellan’s magnificent army, now numbering 115,000 men, stretched from Meadow Bridge on the right to the Williamsburg Road on the left, having in front the marshes of the Chickahominy as natural barriers. By entrenching his army behind positions which he secured from time to time, he advanced until at one point he was only five miles from Richmond and could see the spires of the churches and hear the bells ringing for services.

General Lee had a much smaller army with which to repel this large entrenched army and he withdrew to the south side of the Chickahominy. It was very important to him to learn the position and strength of the Union forces, so that he might be able to attack them at the weakest point. In order to gain this information, he resolved to send General Stuart with 1,200 cavalry to make a raid toward the White House on the Pamunkey river, which was the base of supplies for the Federal troops. General Lee wrote to General Stuart, giving definite instructions about this scouting expedition.

The letter said: “You are desired to make a scout movement, to the rear of the enemy now posted on the Chickahominy river, with a view of gaining intelligence of his operations, communications, etc., of driving in his foraging parties, and securing such grain and cattle for ourselves as you can make arrangements to have driven in.

“Another object is to destroy his wagon trains said to be daily passing from the Piping-Tree road to his camp on the Chickahominy. The utmost vigilance on your part will be necessary to prevent any surprise to yourself, and the greatest caution must be practiced in keeping well in your front and flanks reliable scouts to give you information.

“You will return as soon as the object of your expedition is accomplished, and you must bear in mind while endeavoring to execute the general purpose of your mission, not to hazard unnecessarily your command. Be content to accomplish all the good you can, without feeling it necessary to obtain all that might be desired.”

Such a raid demanded great daring and skill, coupled with cool judgment, and General Lee knew that these qualities were possessed by the man to whom he entrusted this responsible and dangerous undertaking. As we are to see, Stuart carried out his instructions in an able and brilliant manner and accomplished even more than was hoped by General Lee.

In the first place, Stuart chose for the enterprise men and horses picked to stand the strain of rapid movement. Colonel Fitzhugh Lee, Colonel W. H. F. Lee, and Colonel W. T. Martin were in command of the cavalry and Colonel James Breathed commanded the one battery of artillery.

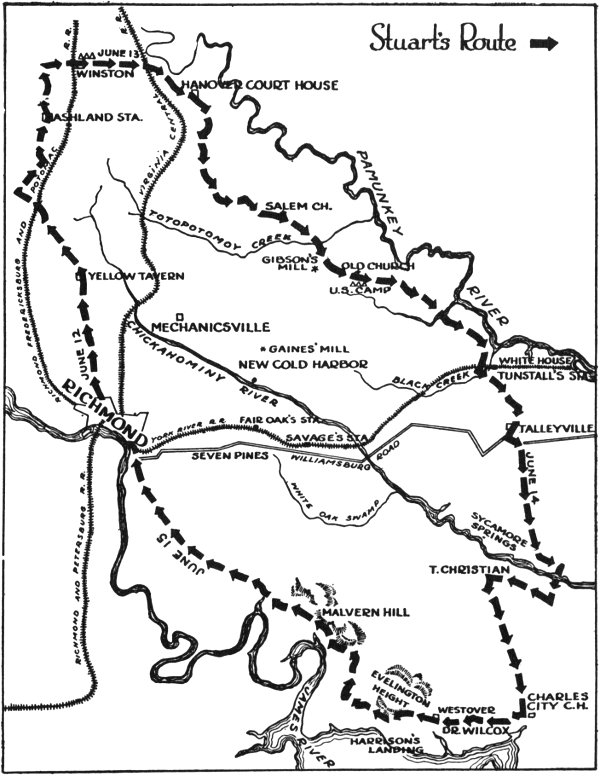

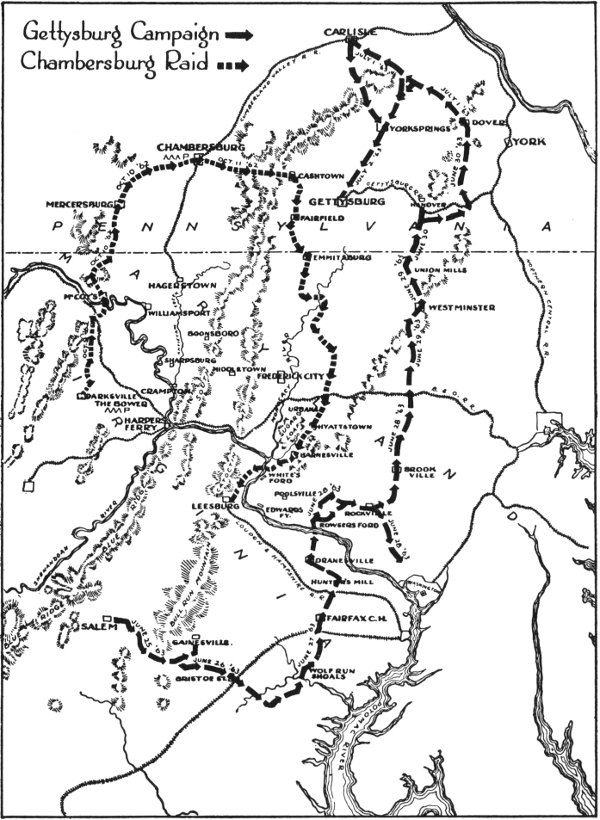

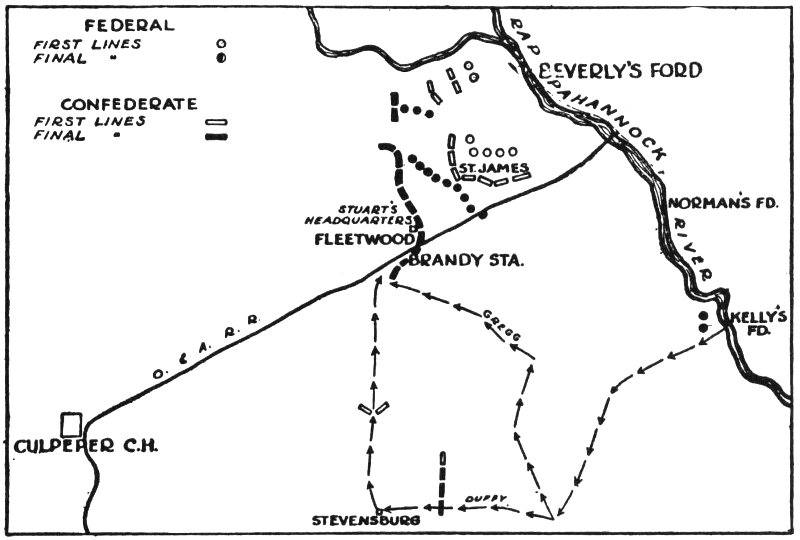

MAP OF THE CHICKAHOMINY RAID

Early on the morning of June 12, Stuart and his chosen troopers started on the famous “Chickahominy Raid,” or “Pamunkey Expedition” as it is sometimes called. In order to mask his real purpose, Stuart marched directly northward twenty-two miles. At sunrise the next morning, the little band of horsemen mounted and turned abruptly eastward toward Hanover Courthouse. They found the town in possession of a body of Federal cavalry that retired as the Confederate troopers advanced. The Confederates then passed on without serious trouble as far as Totopotomy Creek. Here, however, Stuart’s advance guard was attacked by a company of Federal troopers. Finding themselves outnumbered and almost surrounded, these troopers retired to the main body of Federal troops commanded by Captain Royall, who at once drew up his forces to receive the attack. Stuart immediately ordered a squadron to charge with sabers, in columns of fours. Captain Latané, a gallant young officer who was that day commanding the squadron, met Captain Royall in a hand-to-hand encounter. Royall was seriously wounded by a thrust from Latané’s saber. Latané fell dead, pierced by a bullet from Royall’s pistol. The Federals fled in dismay, but soon rallied and returned to the charge, only to be again repulsed, whereupon they retired to the Union lines.

Fitz Lee learned from some of the prisoners that the Federal camp was not far away and, having obtained from Stuart permission to pursue the Union troops, he pushed onto Old Church, repelled the cavalry, and destroyed the camp.

From a painting by W. D. Washington

THE BURIAL OF LATANÉ

General Stuart had now carried out the chief order given by General Lee,—that is, he had ridden to the rear of McClellan’s army and had discovered that the Federal right wing did not extend toward the railway and Hanover Courthouse—but it was a vexing problem how to bring this valuable information to his commanding general. The route the young officer had just passed was doubtless by this time swarming with Federals. The best way to return to Richmond would probably be to ride quickly around the entire Federal army and cross the Chickahominy river to the left of McClellan, before troops were sent to cut him off. Without halting or consulting with any of his officers, Stuart decided that there was less risk in following this circuitous route, especially as he had with him for a guide Lieutenant James Christian whose home was on the Chickahominy and who said that the command could safely cross a private ford on his farm.

The Federals were under the impression that there was a very large force of Confederates on the raid; and so they were collecting infantry and cavalry at Totopotomy Bridge to cut off the return of the raiders. Stuart, however, passed on toward Tunstall’s Station, on the York River Railroad, four miles from the White House which was the principal supply station of the Federal army.

He now proceeded to carry out the second part of Lee’s instructions,—namely, to destroy whatever supplies he might find on the way. As he passed on, numbers of wagons fell into his hands. He sent two squadrons to Putney’s Ferry and burned two large transports and numbers of wagons laden with supplies. Approaching Tunstall’s Station, one of the supply depots of the Federals, he sent forward a body of picked men to cut the telegraph wires and obstruct the railroad. Before they could perform the latter task, a train approached bearing soldiers and supplies to McClellan’s army. The Confederates fired on it, but instead of stopping the brave engineer stood at his post and carried the train by at full speed. He was struck by a shot and fell dying at his post, while the Confederates gave a cheer for his courage in risking his life to save his charge from their hands.

Vast quantities of Federal stores were destroyed by the Confederates whose men and horses reveled in an unusual supply of good rations and provender. It was now nearly dark and Stuart’s position was exceedingly dangerous. Behind him were regiments of cavalry in hot pursuit. Not more than four or five miles distant were the entrenchments of McClellan, whence in a short time troops could be sent by rail to cut off his progress to the James river. Before him was the Chickahominy, now a raging torrent from the spring rains. His chief guides through this maze of swamps and forest roads were Private Richard Frayser and Lieutenant Christian whose homes were near and who knew every part of the country through which they were passing. Stuart had the advantage also of knowing from his scouts just where the enemy was located.

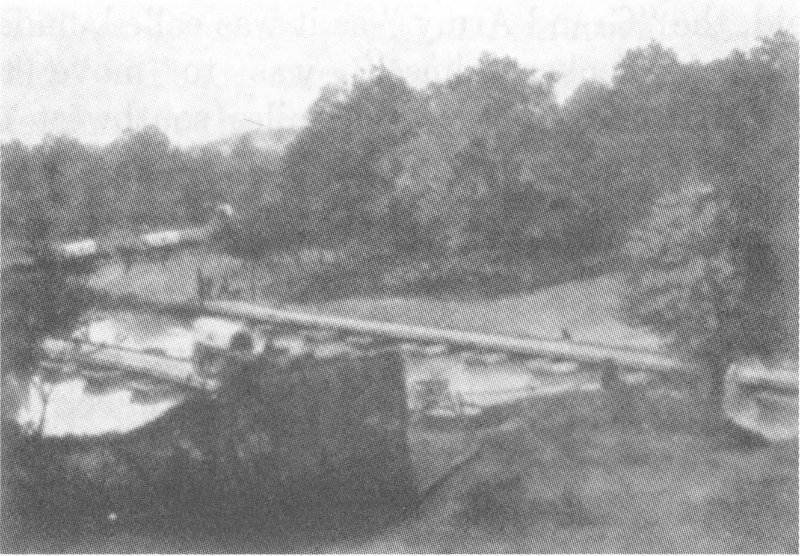

From a war-time photograph

THE CHICKAHOMINY RIVER

Having formed his plans, swiftness and boldness were his watchwords. After he had destroyed the Federal supplies at Tunstall’s Station and burned the railroad bridge over Black Creek, he set out about dark for Talleysville, four miles distant, where he halted for three hours and a half, in order to allow men and horses to rest and scattered troopers to come up.

Colonel John S. Mosby, later one of Stuart’s chief scouts, was at that time his aide. In describing the raid, Mosby said that one who had never taken part in such an expedition could form no idea of the careless gayety of the men that night. When they had set out the day before, they did not know where they were going. Now they were aware they were riding around McClellan and the boldness of the movement fired their imaginations, quickened their pulses, and roused their courage to any deed of daring. Therefore, in the midst of danger, they sang and laughed and feasted; and at midnight when the bugle sounded “Boots and Saddles,” every horseman was ready for whatever might come.

At daybreak on June 14, the Confederates reached the ford on Sycamore Springs, Christian’s farm,—a ford no longer for the river swollen by the heavy rains had overflowed its banks and become a raging torrent. Colonel Lee and a few men swam their horses across the stream and back again; but it was evident that the weaker horses and the artillery could not cross at that point. The Confederates then cut down trees tall enough to span the stream, and attempted to build a rough bridge, but the trees were swept down the rapid current as soon as they touched the water.

Stuart rode up and sat on his horse, calmly stroking his long silken beard as he watched his cavalrymen’s bootless efforts. Every other face betrayed keen anxiety. Learning there was the remains of an old bridge a few miles below, he moved the command thither with all speed. A deserted warehouse was near the old bridge, and a large force of men was set at work to tear down the house in order to secure material to rebuild the bridge. While the work was going on, Stuart laughed and jested with his officers.

The men worked with such swiftness that within three hours the bridge was ready for the cavalry and artillery to pass over; and at one o’clock that afternoon, the whole command had crossed. During those hours of anxiety, Fitz Lee, in command of the rear guard, had driven off several parties of Federal cavalry. After all the Confederates gained the southern shore—Fitz Lee being the last man to cross—, the bridge was burned to prevent pursuit. The men were exultant and happy at having crossed the river, but they were by no means out of danger, being thirty-five miles from Richmond and still far within the lines of McClellan. Stuart, who knew that every moment was precious to General Lee, hastened on at sunset with only one courier and his trusty guide Frayser and arrived at Richmond about sunrise on the morning of June 15. The men rested several hours and then were led by Colonel Fitz Lee safely back to their own camp where they were greeted with enthusiastic cheers by their comrades.

As soon as General Stuart reached Richmond, he sent Frayser to inform Mrs. Stuart of his safe return, while he himself rode to General Lee’s headquarters with his wonderful report.

He had been sent to find out the position of the right wing of McClellan’s army. He had not only located that, but he had destroyed a large amount of United States property, brought off one hundred and sixty-five prisoners and two hundred and sixty horses and mules. With only twelve hundred men, he had ridden around the great Federal army—a distance of about ninety miles in about fifty-six hours—with the loss of only one man, the lamented young Latané. By that dashing ride, Stuart gained for himself world-wide fame and an honorable place among the great cavalry leaders of all time. The Chickahominy Raid was one of the most brilliant cavalry achievements in history, and it inspired the Confederates with fresh courage and excited Federal dread of the bold cavalrymen who attempted and accomplished seemingly impossible things.

The information gained was invaluable for it made it possible for General Lee to send Jackson against the right flank of McClellan and to defeat the Federals at Cold Harbor.

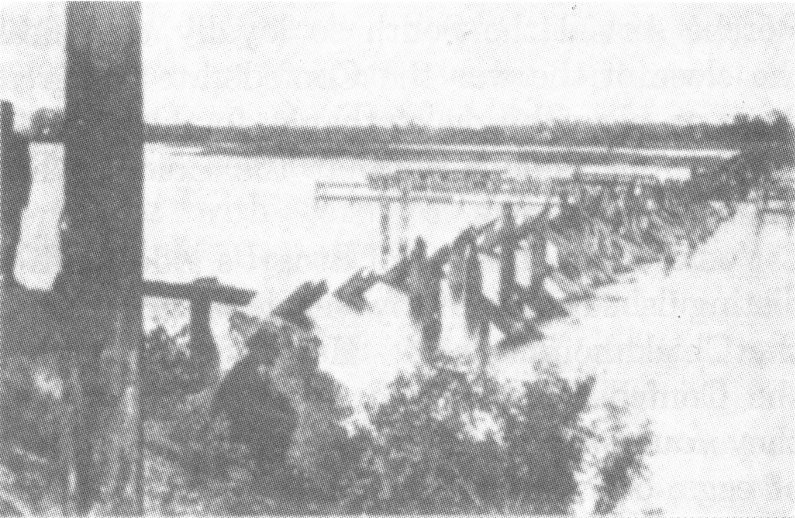

In the Seven Days’ Battle around Richmond, which began on June 26, Stuart at first guarded the left of Jackson’s march. In the battle of Gaines’s Mill, he found a suitable position for the artillery. He sent forward two guns under Pelham, a gallant young gunner from Alabama, who kept up an unequal combat for hours with two Federal batteries. When the Federal lines had been forced at Gaines’s Mill and Cold Harbor, Stuart advanced three miles to the left; but finding no trace of the Federals, he returned that night to Cold Harbor. On June 28, he proceeded toward the White House on the Pamunkey river, which the Federals had abandoned and burned. They had also set fire to many valuable stores and munitions of war. The illustration on this page is from a war-time photograph, showing the railroad bridge across the Pamunkey river which was destroyed in order to render the road useless to the Confederates. When McClellan changed his base from the White House to James river, he had two trains loaded with food and ammunition run at full speed off the embankment in the left foreground into the river, in order to keep these stores from falling into the hands of the southern troops.

From a war-time photograph

RUINS OF RAILROAD BRIDGE ACROSS PAMUNKEY RIVER

An interesting account of this campaign is given by Heros Von Borcke. Von Borcke was a noble young Prussian officer who gave his services as a volunteer to the Confederacy, just as LaFayette had given his services to the Colonies in the War of the Revolution; Von Borcke served the South so loyally that near the close of the war the Confederate Congress drew up a resolution of thanks for his services in just the same form that the Colonies had thanked LaFayette.

Von Borcke was one of Stuart’s aides and he distinguished himself by his gallantry during the Chickahominy raid. He tells us that when the Confederates arrived at the White House they found burning pyramids built of barrels of eggs, bacon and hams, and barrels of sugar. There were also boxes of oranges and lemons and other luxuries. Many of these luxuries were rescued by the Confederates, and when Von Borcke reached the plantation, shortly after it had been taken, he found General Stuart seated under a tree drinking a big glass of iced lemonade, an unusual treat for a Confederate soldier. All of Stuart’s troops had such a feast as was seldom enjoyed during the war, and large quantities of supplies and equipments were forwarded to the Confederate quartermaster at Richmond.

The Federal gunboat, Marblehead, was still in sight on the river. The soldiers at that period had an almost superstitious fear of the bombs thrown by the big guns of the gunboats, which made an awful whizzing noise and burst into many fragments. Stuart decided that he would teach his troopers a lesson and show them how little harm the dreaded shells did at short range. He selected seventy-five men whom he armed with carbines and placed under command of Colonel W. H. F. Lee who led them down to the landing. They fired at the boat and skirmishers were sent ashore from the boat to meet them. A brisk skirmish followed, during which Stuart brought up one gun of Pelham’s battery. This threw shells upon the decks of the Marblehead, while the screeching bombs of the big guns of the boat went over the heads of Pelham’s battery, far away into the depths of the swamps. The skirmishers hurried back to the Marblehead, and it steamed away down the river, pursued as far as possible by shells from Pelham’s plucky little howitzer.

Stuart sent General Lee the important news that McClellan was seeking a base upon the James river, and then stayed the remainder of the day at the White House, where he found enough undestroyed provisions to satisfy the hunger of the men and horses of his command.

After severe engagements with the Confederates at Savage Station and Frayser’s Farm, the Union forces were forced to retreat, closely followed by Jackson and Stuart. On the evening of July 1, was fought the bloody battle of Malvern Hill, after which McClellan retreated by night down the James to Harrison’s Landing where he was protected by the gunboats.

Early on the morning of July 2, Stuart started in pursuit and found the Federals in position at Westover. The next day he took possession of Evelington Heights, a tableland overlooking McClellan’s encampment and protecting his line of retreat. Here Stuart expected to be supported by Longstreet and Jackson, and he opened fire with Pelham’s howitzer.

The Federal infantry and artillery at once moved forward to storm the heights. Jackson and Longstreet were delayed by terrific storms, and Stuart unsupported held his position until two o’clock in the afternoon when his ammunition gave out. He then retired and joined the main body of the infantry, which did not arrive until after the Federals had taken possession of Evelington Heights and were fortifying it strongly.

The two armies now had a breathing spell of about one month. McClellan’s defeated hosts remained in their protected position at Harrison’s Landing until the middle of August, when they were recalled to join General Pope at Manassas. General Lee’s army was withdrawn nearer to Richmond which was saved from immediate danger.

As a reward for his faithful and efficient services in the Peninsular Campaign, Stuart received his commission as major general of cavalry on July 25, 1862. His forces were now organized into two brigades, with Brigadier-General Wade Hampton in command of the first and Brigadier-General Fitzhugh Lee in command of the second. During the month following the defeat of McClellan, these two brigades were placed by turns on picket duty on the Charles City road to guard Richmond and in the camp of instruction at Hanover Courthouse.

While conducting this camp of instruction where he drilled his men in the cavalry tactics that were later to win them such honor, Stuart and his staff were often pleasantly entertained at neighboring plantations. Mrs. Stuart with her two little children, Flora, five years of age, and “Jimmy,” aged two, was able to be near the general once more. The time passed pleasantly, enlivened by cavalry drills, visits from the young officers to the ladies of the vicinity, serenades and dances, and visits from the ladies to the general’s headquarters.

One Sunday evening as the general and most of his staff were visiting at Dundee, the plantation near which their camp was situated, a stable in the yard caught fire and the visitors proved themselves as good firemen as they were soldiers. The young Prussian officer, Von Borcke, an unusually large and heavily-built man, was so energetic in his efforts, that after the fire was out, the general, who was always fond of a joke, insisted that he had seen the young officer rush from the burning building with a mule under one arm and two little pigs under the other.

Stuart was soon called away from this pleasant life to make an inspection of all the Confederate cavalry forces. It was evident that General Lee’s army would soon be engaged against a new Federal commander, General Pope, who was concentrating a large army on the Rapidan river. General Jackson, who had been sent to hold General Pope in check, had his headquarters at Gordonsville.

Major Von Borcke tells us that the cars carrying the Confederate troops to Gordonsville were so crowded that General Stuart rode on the tender of the engine, rather than take a seat away from one of the soldiers. It was a hot night in July and there was a dense smoke from the engine, but it was so dark that it was not until they reached Gordonsville that the general discovered that both Von Borcke and himself were so black with soot that their best friends would not have recognized them. Indeed, it took a great deal of soap and water to make them presentable once more.

Stuart reached Jackson’s headquarters on August 10, the day after the Federal advance guard had been defeated in the battle of Cedar Run. At Jackson’s request, Stuart took command of a reconnaissance to find out the position and strength of the enemy. Upon hearing his report, Jackson decided to remain for the present on the defensive.

In the meantime, General Lee, who was watching General McClellan’s army still encamped at Harrison’s Landing, received information that the latter had been ordered to withdraw his forces and join General Pope at Manassas.

Leaving a small force in front of Richmond, Lee hastened to join Jackson so that they could engage Pope before his already large army was reenforced by McClellan. The cavalry was kept very busy at this time as it was necessary to defend the Central Road, now the Chesapeake and Ohio, from Federal raids.

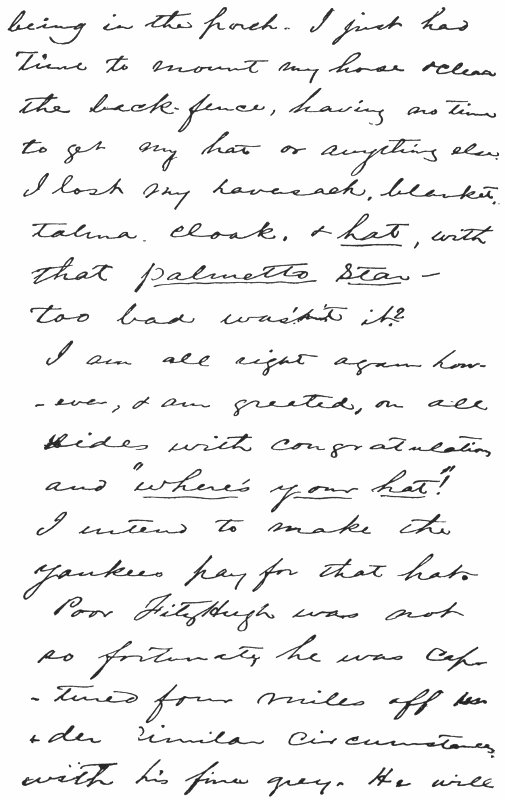

On the night of August 17, Stuart himself barely escaped capture. He wrote an interesting account of this adventure to his wife, and Mrs. Stuart has kindly allowed us to use the letter in this book. Here it is:

Rapidan Valley, August 19, 1862.

My Dear Wife—I had a very narrow escape yesterday morning. I had made arrangement for Lee’s Brigade to move across from Davenport’s bridge to Raccoon ford where I was to meet it, but Lee went by Louisa Court House. His dispatch informing me of the fact did not reach me, consequently I went down the Plank road to the place of rendezvous.

Hearing nothing of him, I stopped for the night and sent Major Fitzhugh with a guide across to meet General Lee. At sunrise yesterday a large body of cavalry from the very direction from which Lee was expected, approached crossing the Plank road just below me and going directly towards Raccoon ford. Of course I thought it was Lee—as no Yankees had been seen about for a month, but as a measure of prudence I sent down two men to ascertain. They had not gone 100 yards before they were fired on and pursued rapidly by a squadron.

FACSIMILE OF PAGE OF LETTER FROM GENERAL STUART TO HIS WIFE

I was in the yard bareheaded, my hat being in the porch. I just had time to mount my horse and clear the back fence, having no time to get my hat or anything else. I lost my haversack, blanket, talma, cloak, and hat, with that palmetto star—too bad, wasn’t it? I am all right again, however, and I am greeted, on all sides with congratulations and “where’s your hat!” I intend to make the Yankees pay for that hat.

Poor Fitzhugh was not so fortunate. He was captured four miles off under similar circumstances, with his fine grey. He will be exchanged in ten days, however. Von Borcke and Dabney were with me (five altogether) and their escape was equally miraculous. Dundee is the best place for you at present. We will have hot work I think to-morrow. My cavalry has an important part to play.

Love to all, my two sweethearts included.

God bless you. J. E. B. Stuart.

A few days later, as you will hear, General Stuart collected payment for his lost hat from General Pope himself. But before this took place, the Confederate cavalry was engaged in several skirmishes with the Federals. There was a severe encounter at Brandy Station on August 20 when sixty-five prisoners were captured. The regiments which had fought under Ashby, a gallant young officer who had been killed in the Valley, were now added to Stuart’s division as Robertson’s Brigade. At Brandy Station, these troopers fought under Stuart for the first time and he was much pleased at their dash and bravery.

While Lee, who had now joined Jackson, was waiting a favorable opportunity to attack the Federals, Stuart begged permission to pass to the rear of Pope’s army and cut his line of communication at Catlett’s Station where there was a large depot of supplies. General Lee gave his consent, and on the morning of August 22, General Stuart crossed the Rappahannock at Waterloo Bridge, to make a second raid to the rear of the Federal army.

By nightfall the Confederates reached Auburn near Catlett’s Station, where they captured the Federal pickets. Just as they reached the station, however, a violent storm arose; and amid the wind and the rain and the darkness, it seemed impossible to find their way. Fortunately, they captured a negro who knew Stuart and who offered to show them the way to Pope’s headquarters. They accepted his guidance and soon the Confederate cavalry surprised the unsuspecting enemy, attacked the camp, and captured a number of officers belonging to Pope’s staff, as well as his horses, baggage, a large sum of money, and his dispatch book which contained copies of the letters he had written to the government, telling the location and plans of his army. But for the fact that General Pope was out on a tour of inspection, he himself would have been captured.

From a war-time sketch by Harper’s Artist

CATLETT’S STATION

Catlett’s Station where Stuart made a raid and captured Pope’s baggage, Au-R. Ward

In the meantime, two of Stuart’s regiments had gained another part of the camp, and an attempt was made to destroy the railroad bridge over Cedar Run. But on account of the heavy rain it was impossible to fire it, and, in the dense darkness, it was equally hard to cut asunder the heavy timbers with the few axes which they found. Therefore, with more than three hundred prisoners and valuable spoils, Stuart retired before daybreak and regained in safety the Confederate lines.

Major Von Borcke gives an interesting incident of their return march. As the troops—wet, cold, and hungry—passed through Warrenton, coffee was served them by a number of young girls. One of the girls recognized among the prisoners General Pope’s quartermaster. He had boasted several days before, when at her father’s house, that he would enter Richmond within a month. She had promptly bet him a bottle of wine that he would not be able to do it, but as he was now a prisoner he would be obliged to enter the city even earlier than he had hoped. She, therefore, asked General Stuart’s permission to offer the quartermaster a bottle of wine from his own captured supplies. The general readily granted her request, and the Yankee prisoner entered good-naturedly into the jest, saying that he would always be willing to drink the health of so charming a person.

In retaliation for the loss of his hat and cloak, General Stuart sent General Pope’s uniform to Richmond where for some days it hung in one of the shop windows, to the delight of the populace who especially disliked Pope on account of his bombast and cruelty. He had boasted that he had come from the West where his soldiers always saw the backs of their enemies, and he had authorized his soldiers to take whatever they wished from the citizens of Virginia, whom he held responsible for damage done by raiding parties of the Confederate army.

Two weeks later, General Stuart wrote his wife that Parson Landstreet, a member of his staff who had been captured by the Federals, brought him a message from General Pope. Pope said that he would send back Stuart’s hat if Stuart would return his coat.

“But,” wrote Stuart, “I have got to see my hat first.”

It was against General Pope that the second Battle of Manassas was fought, August 28, 29, and 30, 1862. General Stuart and his cavalry in the maneuvers preceding the battle, screened the flank march of Jackson’s troops to Grovetown, by which movement they placed themselves between the Federal rear and Washington. It took two days for Jackson’s “foot cavalry” to make this march, and so perfectly did Stuart do his work that as late as August 28, Pope did not know to what place Jackson had marched from Manassas.

In the three days’ battle that followed, the cavalry was ever on the flank of the army, observing the Federals and guarding against attacks. On the morning of August 29, after a sharp skirmish, Stuart met Lee and Longstreet and opened the way for them to advance to the support of Jackson whose forces on the right wing were engaged in unequal and critical combat. Later on the same day, Stuart saw that the Federals were massing in front of Jackson, and with a small detachment of cavalry aided by Pelham and his guns, he gallantly held large forces in check and protected Jackson’s captured wagon train of supplies. On the afternoon of August 30, the cavalry did most effectual service, following the retreating Federals and protecting the exposed Confederate flank against heavy cavalry attacks. During the engagements, the Confederate infantry could not have held its position but for the assistance of the cavalry under the able direction of Stuart.

In these battles, Pope had forces largely superior in number and equipment to Lee’s, but Pope’s losses in killed and wounded were much the heavier. Finally he was forced to retreat toward Washington, leaving in the hands of the Confederates many prisoners as well as captured artillery, arms, and a large amount of stores. The North seemed panic-stricken, as Washington was now directly exposed to the attacks of the Confederates.

General Lee knew, however, that he did not have men enough to take by assault the strong fortifications around Washington, and he, therefore, planned to cross over into Maryland before the Federal army had recovered from its defeat, when its commanders were least expecting him. In order that he might completely mislead them and make it appear that he was beginning a general attack on Washington, he ordered Stuart and his troops to advance toward that city.

In their advance, they engaged in several sharp skirmishes with the Federals, finally driving them from Fairfax Courthouse, where, amid the cheers of the inhabitants, Major Von Borcke planted the beloved Confederate flag on a little common in the center of the village.

The people of this section had been under Federal control for several months and their joy at seeing Stuart and his troops was unbounded. They flocked to the roadside to get a glimpse of the great cavalry leader.

One lady, who had lost two sons in battle, came forward as the troops passed her home and asked permission to kiss the general’s battle flag. She held by the hand her only surviving son, a lad of fifteen years, and declared herself ready if it were needed to give his life too for her country.

On September 5, General Stuart and his forces crossed the Potomac. Four days later, General Lee moved his entire army across the river, encamped at Frederick, Maryland, and sent General Jackson to capture the strongly fortified Federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry.

Major Von Borcke, from whose Memoirs of the Confederate War for Independence we shall borrow several interesting incidents of this Maryland campaign, tells us that the crossing of the cavalry at White’s Ford was one of the most picturesque scenes of the war. The river is very wide at this point, and its steep banks, rising to the height of sixty feet, are overshadowed by large trees that trail from their branches a perfect network of graceful and luxuriant vines. A sandy island about midstream broke the passage of the horsemen and artillery, and as a column of a thousand troops passed over, the rays of the setting sun made the water look like burnished gold. The hearts of the soldiers crossing the river thrilled at the sound of the familiar and inspiring strains of “Maryland, my Maryland,” which greeted them from the northern bank.

Copyright, 1914, by E. O. Wiggins

From photograph owned by Gen. T. T. Munford

MAJOR HEROS VON BORCKE

The enthusiasm of the Maryland people at Poolesville, where Stuart first stopped, was boundless. Two young merchants of the village suddenly resolved to enlist in the cavalry and they put up all their goods at auction. The soldiers with the eagerness and carelessness of children cleared out both establishments in less than an hour. Many other recruits were made in this village, all the young men seeming to feel the inspiration of General Stuart’s favorite song,

“If you want to have a good time

Jine the cavalry.”