Copyright, 1897, by Harper & Brothers. All Rights Reserved.

| published weekly. | NEW YORK, TUESDAY, MARCH 2, 1897. | five cents a copy. |

| vol. xviii.—no. 905. | two dollars a year. |

General Sheridan, despite the reputation he had gained for dashing, reckless bravery, was withal a cautious commander. He did not believe in making long forced marches and hurling tired troops at an intrenched enemy. The success of a charge, in his mind, was due entirely to the freshness of the men, the fierceness of the onslaught, and the surprise occasioned to the enemy by sudden and unexpected movement.

Early in the month of September, 1864, Sheridan's army was encamped in the hills looking down into the little valley of the Opequan, a small, crooked stream about four miles from the town of Winchester. On the opposite side of the creek the Confederate army under General Early was intrenched in a strong position. The banks of the stream were steep and the crossings deep, requiring much care in fording.

For more than ten days the two armies fronted each other without sign of an advance on either part. But Early was on the defensive, and Sheridan was preparing a plan of attack that it was hoped would rout him completely; and if everything had worked to his entire satisfaction, it might have resulted in the capture of the whole Confederate army before the forces had time to fall back upon Winchester. By the afternoon of the 18th these plans had[Pg 426] been perfected; the commanders of divisions and the cavalry leaders had received their orders. The privates knew from the hurrying of orderlies and the sending of despatches that they would soon be on the move. There was little sleep that night for the blue-clad men. Ammunition was dealt out, tents were struck, and troopers and infantry lay down with their arms beside them. At 2 a.m. word was passed for the regiment to fall in line, and the great advance was begun. General Merritt's cavalry was ordered to proceed to the Opequan and cross at the fords near the bridge of the Winchester and Potomac Railroad. Merritt was ordered to cross at daylight, to turn to the left and attack the Confederate flank.

General Wilson's division, followed by the infantry, was to clear the crossings of the Opequan on the road leading from Berryville to Winchester. South of the town was Abraham's Creek; it emptied into the Opequan and flanked the line of the Confederate intrenchments. On the north was a similar creek, named the Red Bud, which served the same purpose. Along these natural fortifications, and spreading across the rise of ground on the farther side of the Opequan, lay the whole force of Early's army. It was Sheridan's intention to take the centre first and overthrow it before the rest of the Confederate army, which was somewhat scattered, could come up to its assistance.

As it is of the cavalry's work in this fight that this short paper treats, it is best to move at once to the right of the Union line, where the mounted forces were expected to ford the creek.

It was almost pitch dark, and a few minutes after two in the morning, when the Second United States Cavalry, under the command of Captain T. F. Rodenbough, moved with the reserve brigade of the First Cavalry Division down the sloping ground toward the valley of the stream. Early's outposts and pickets were met some time before the ford was reached. There were a few hasty shots exchanged in the darkness, without any damage being done, and then the mounted pickets crossed to the safety of their own lines on the farther side.

A small force of the Union cavalry was dismounted on the road, and the outbuildings of a farm-house were occupied by a reserve force; while the regiment was deployed, mounted, in the fields to the right and left of the ruins of the old railroad bridge. Nothing was standing of this structure but the stone abutments. The bridge that crossed the creek diagonally to the roadway had been destroyed, but the water was fordable on either side. Now the forces waited for daylight. Long before the sun rose, as the dim light spread and widened, the enemy's infantry pickets could be seen hurriedly making preparations to resist any attempt at crossing on the part of the waiting cavalry.

The bank of the creek was very steep and thickly wooded. The leaves were yet on the trees, and the dark masses of armed men could be seen distinctly here and there in the few clearings. The railroad entered the hill-side through a deep cut, forming a ready-made intrenchment for the enemy's infantry and riflemen. One of the stone abutments and the adjoining pier were close to the entrance of the cut, and formed an angle with a wooded bluff directly in line with it.

Despite the fact that the men had been in the saddle almost the whole night, they were keen to move; and before sunrise General Merritt, in command of the First Division, ordered Colonel Lowell, who led the reserve brigade, to carry the ford and effect a lodgement on the farther bank. At once Colonel Lowell dismounted a portion of his command, and with a cheer the men dashed into the water, and holding their carbines high above their heads, plashed through the stream, many standing waist-deep and replying to the fire that was poured into them. The Fifth United States Cavalry and a portion of the Second Massachusetts infantry followed at once.

Rodenbough, who had been waiting with his men in one of the fields on the hill-side, received his orders to move. With a loud shout the regiment charged down the side of the hill to one side of the slowly advancing men on foot, dashed pell-mell through the ford, and, in the face of a terrible fire from the enemy's infantry, swept up the opposite incline on a dead run, making for the railway cut, where the Confederates were completely hidden from the Union fire.

The Second had by this time made the solid ground, and charged also, without firing a shot until it gained the crest of the cut. The Confederates, who had not expected such an onslaught, threw down their arms as the mounted men poured over the sides of the embankment down upon them. Many started to run, but were taken prisoners, and it was a joyful sight for the commander of the cavalry to notice, as he reformed his line, that there were but few saddles empty. But in the early advance, before Rodenbough's cavalry had reached the crossing, the musket fire concentrated upon the ford was simply terrific.

Colonel W. H. Harrison, late Captain of the Second Cavalry, describes an experience through which no man would like to pass a second time.

"Lieutenant Wells, myself, and two orderlies, mounted, were unfortunately imprisoned in the archway between the abutment and adjacent pier on the enemy's side, the bullets, hot from the muzzles of their guns, striking the abutment, pier, and water like leaden hail. We were face to face with the enemy, yet powerless to harm him. Our only salvation was to hug the abutment until that portion of the regiment immediately on our left had gained the crest of the cut. Minutes were long drawn out, and in a fit of impatience Lieutenant Wells rashly attempted to take a peep beyond the corner of the abutment, thus exposing his horse, which instantly received a serious wound in the shoulder. The writer, with equal rashness, attempted to recross the creek, and when in the middle of it heartily wished himself under the protection of his good friend the abutment, the bullets being so neighborly and so fresh from the musket as to have that peculiar sound incident to dropping water on a very hot stove. Suddenly the cheers of our men apprised us that the crest of the cut had been gained and a portion of the enemy's infantry captured."

By the time the sun was up above the trees, the reserve brigade had gained the coveted position across the Opequan, connecting with Custer's forces on the left, which had gallantly carried the ford three-quarters of a mile below.

And now the roll of musketry and the thunder of cannon let every one know that the main infantry line under General Sheridan had commenced action. It was a cheerful sound to those on the flank, who had no inkling of how matters were going on either side of them. The advance was made at an eager pace, and confidence and determination were evident from the looks and actions of the officers and men. But the enemy fell back a few miles toward Winchester, and it was not until almost noon that any resistance was met with, except for the occasional shots of the pickets and rear-guard.

It was about this hour that Sheridan's forces were ready to advance along the entire line. Early had gathered all his strength and met them with a terrific fire. The battle raged with the greatest fury. Both sides were now fighting in open sight of each other, and the slaughter was dreadful, especially at the centre. General Merritt, whose cavalry had been following the Confederate General Breckenridge, charged again, and drove their broken cavalry through the infantry line, which he struck first in the rear, and afterwards face to face as it charged front to meet him. General Devin charged with his brigade, and turning, sought the shelter of the main force, bringing with him three battle flags and more than three hundred prisoners.

A line of the enemy's infantry was perceived at the edge of the heavy belt of timber, protected by rail barricades which they had hastily constructed on their front. Here they had evidently determined upon making a stand, for they waved their battle flags and showed in such considerable numbers that the cavalry line halted before them. As a critic of this battle has said, it seemed almost foolhardy to charge a line of infantry so well posted and protected, but the First Brigade and the Second United States Cavalry, at the word "Forward! Charge!" dashed across an open field and through a tangle of underbrush, and in[Pg 427] the face of a fearful fire poured into them, rode straight up to the barricade. But, alas! it was but a brilliant display of courage and determination. None of the flaunting battle flags was captured, and the broken remnant was obliged to retire hastily and in some disorder to their comrades who had watched their gallant effort.

A thrilling little incident happened in this charge, although it had lasted but a few minutes. When within a few yards of the barricades, Captain Rodenbough, who was well in advance, had his horse shot under him, killed almost in his tracks. His men swept by him full tilt to the line of wooden breastworks, and as they turned to ride back over the same ground, Orderly Sergeant Schmidt of Company K, mounted on a powerful gray horse, noticed his commander disentangling himself from his fallen mount. The sergeant rode up, reining in with difficulty, helped Captain Rodenbough to clamber up behind him, and, carrying double, the good charger crossed the open space in safety. But let an eye-witness tell the story of the last charge of the day, when the entire division was formed, and rode together knee to knee at the well-intrenched barrier and the double line of the enemy, who certainly had the advantage of position.

"It was well towards four o'clock, and though the sun was warm, the air was cool and bracing. The ground to our front was open and level, in some places as smooth as a well-cut lawn. Not an obstacle intervened between us and the enemy's line, which was distinctly seen nervously awaiting our attack. The brigade was in column of squadrons, the Second United States Cavalry in front.

"At the sound of the bugle we took the trot, the gallop, and then the charge. As we neared their line we were welcomed by a fearful musketry fire, which temporarily confused the leading squadron, and caused the entire brigade to oblique slightly to the right. Instantly officers cried out, 'Forward! Forward!' The men raised their sabres, and responded to the command with deafening cheers. Within a hundred yards of the enemy's line we struck a blind ditch, but crossed it without breaking our front. In a moment we were face to face with the enemy. They stood as if awed by the heroism of the brigade, and in an instant broke in complete rout, our men sabring them as they vainly sought safety in flight. In this charge the battery and many prisoners were captured. Our own loss was severe, and of the officers of the Second, Captain Rodenbough lost an arm and Lieutenant Harrison wag taken prisoner.

"It was the writer's misfortune to be captured, but not until six hundred yards beyond where the enemy was first struck, and when dismounted in front of their second line by his horse falling. Nor did he suffer the humiliation of a surrender of his sabre, for as he fell to the ground with stunning force its point entered the sod several inches, wellnigh doubling the blade, which, in its recoil, tore the knot from his wrist, flying many feet through the air.

"Instantly a crowd of cavalry and infantry officers and men surrounded him, vindictive and threatening in their actions, but unable to repress such expressions as these: 'Great heavens! what a fearful charge!' 'How grandly you sailed in!' 'What brigade?' 'What regiment?' As the reply proudly came, 'Reserve Brigade, Second United States Cavalry,' they fairly tore his clothing off, taking his gold watch and chain, pocket-book, cap, and even spurs, and then turned him over to four infantrymen. What a translation—yea, transformation! The confusion, disorder, and actual rout produced by the successive charges of Merritt's First Cavalry Division would appear incredible did not the writer actually witness them. To the right, a battery, with guns disabled and caissons shattered, was trying to make to the rear, the men and horses impeded by broken regiments of cavalry and infantry. To the left, the dead and wounded in confused masses around their field hospitals—many of the wounded, in great excitement, seeking shelter in Winchester. Directly in front an ambulance, the driver nervously clutching the reins, while six men, in great alarm, were carrying to it the body of General Rhodes. Not being able to account for the bullets which kept whizzing past, the writer turned and faced our own lines to discover the cause and, if possible, to catch a last sight of the stars and stripes.

"The sun was well down in the west, mellowing everything with that peculiar golden hue which is the charm of our autumn days. To the left, our cavalry were forming for another and final charge. To the right front, our infantry, in unbroken line, in the face of the enemy's deadly musketry, with banners unfurled, now enveloped in smoke, now bathed in the golden glory of the setting sun, were seen slowly but steadily pressing forward. Suddenly, above the almost deafening din and tumult of the conflict, an exultant shout broke forth, and simultaneously our cavalry and infantry line charged. As he stood on tiptoe to see the lines crash together, himself and guards were suddenly caught in the confused tide of a thoroughly beaten army—cavalry, artillery, and infantry—broken, demoralized, and routed, hurrying through Winchester."

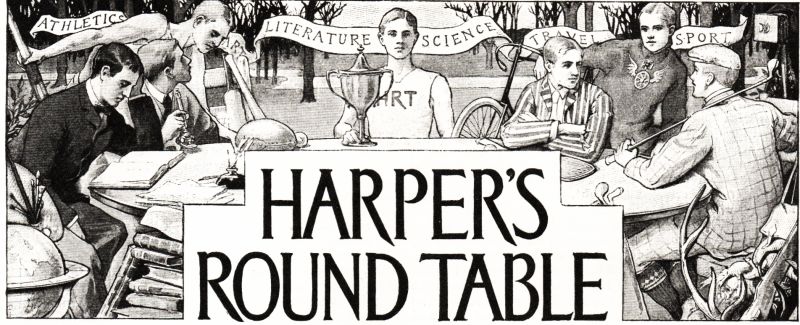

Jack was sitting quietly by the fire the other day, doing no harm to anybody, when a young person who thought well of himself rushed in and attacked him with the assertion, "You can't do that!"

The boy held out a card, upon which was drawn a dot in the centre of a circle, and repeated his challenge:

"You can't draw that figure without taking your pencil off the paper!"

Jack looked up and smiled. He bent one end of the card over, made a dot with his pencil on the face of it just at the margin of the part folded over, after which he moved the pencil across the overlying paper to the point where he wished to begin his circle; then he let the line slip off on to the face of the card, allowed the bent-over portion to fly back, and finished the "ring around the rosy" without once taking his pencil off the paper. This done, he handed the card to his friend, and went on studying the fire, without a word. It is great to be great!

It is reported of the late William H. Vanderbilt that his father, the Commodore, did not give his son, when a young man, much credit for business ability. Absolute verification of this is doubtful, but a good story is told of an incident wherein the son proved that he too carried in his head some of the astuteness in commercial intercourse that his father possessed. The Commodore presented him with a farm on Staten Island, informing him that he might live there, and to make the land pay, as that was all he cared to contribute towards the lad's support. A short time later the Commodore inquired of his son how he was getting along.

"Not very good, father," the young man replied. "What I need badly is some means of improving the earth."

"Well, suppose you go up to my stables and get a load of refuse; but mind, I shall only give you one load."

"All right," replied the son, and he took one load; but, to the astonishment of the Commodore, when he went to the stables they had been entirely cleaned.

"How many loads did that boy of mine cart away from here?" he inquired of the stableman.

"One, sir," replied that functionary; "but he carried the stuff away in a barge, sir."

Once in every four years one lady in the land is called upon to undertake the most onerous of its social duties—those of mistress of the White House—duties which, though attended by fewer formalities, are scarcely less exacting than those of crowned Queen or Princess Royal in a foreign court. Indeed, one may safely affirm that they are far more fatiguing, since the lady of the White House must be equally courteous, attentive, and considerate to all with whom she comes in contact, her doorway excluding only the ragged or disorderly, Betsey Brown, from the remotest village in Maine, enjoying the same right to call upon the President's wife which belongs to the leading society belle of the day, the male members of the two families having shared in electing their President to his office of ruler of the nation. Simple, however, as the etiquette of the White House may be, it is governed by certain rules and customs handed down from one ruler to the next—modified or changed according to the times, but in the main suggested by a spirit of republican simplicity and cosmopolitan good-breeding.

THE WHITE HOUSE.

THE WHITE HOUSE.

The President's family occupy a suite of rooms as secluded as possible from public view. They have their own staff of servants under a trained steward and housekeeper; their own personal friends are received and entertained with as much privacy as though the dwelling were not, in part, an official residence. The "state apartments," open to the public at fixed days and hours, include the Red Room, Blue Room, the galleries, etc., about which is a romantic as well as historic interest; and in turn various people are entertained therein as a matter of prescribed formality. All Senators, Congressmen, and their wives and families, foreign diplomats, visitors of any distinction, above and beyond all, the "army and navy," are not only to be received, but during the short winter season specially entertained, a series of dinners and receptions being planned for this purpose.

THE NURSERY.

THE NURSERY.

And meanwhile, is there time, one asks, for much home life in the White House? As a matter of fact, few home circles are more comfortably and agreeably managed than that of the President's family, provided, of course, the "all-ruling spirit"—the mother—has within herself that gracious gift which makes the fireside of home a radiant centre. "Mrs. President's" day can be very closely outlined, excepting, of course, such incidents as may occur at any time to alter the programme or such plans as result from her own personality, and unless she elects to add to her domestic cares, she need have nothing whatever to do with housekeeping matters.

Breakfast in the White House from time immemorial has been a social family gathering, and generally takes place about nine o'clock. After this the President's wife usually goes for a drive, during which she attends to any personal shopping, either visiting the shops herself or sending in her maid with orders, and it is one of the unwritten laws, closely adhered to, that every item purchased shall be scrupulously and promptly paid for—the system of "patronage" so extensively adopted in many foreign countries not holding good, thank fortune, in our republican government. Unless she especially desires to do so, the President's wife makes no calls, one rule of the administration being the blessed one which prohibits her returning any visits. She is therefore free from the terrible social bore and strain—a round of formal calls. Returning from her morning drive, she may be called upon to receive some guest who is invited to luncheon.

The methods of approaching the mistress of the White House or its ladies are pre-eminently simple. If the visitor has a special introduction, he or she can send this by messenger, receiving an answer through one of the President's secretaries. Generally a day and hour will be fixed for the guest to call at the White House, when he or she will be received as in any other mansion, the degree of formality being regulated by that of the introduction. An invitation to luncheon or dinner may follow—possibly to some afternoon drive or theatre party. On levee days some of the ladies of the cabinet, or it may be wives of special members of the Senate or Congress, the army or navy, etc., receive with the President's wife, relieving her in part of the fatigue of these weekly ceremonials. However, it is all so smoothly and agreeably managed that in the[Pg 429] course of many administrations the complaints of lack of courtesy have been very few.

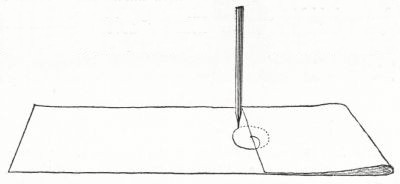

MRS. CLEVELAND'S DRAWING-ROOM.

MRS. CLEVELAND'S DRAWING-ROOM.

As I have said, the White House is replete with historic and romantic interest. On October 13, 1792, its cornerstone was laid with Masonic ceremonies, and seven years passed before its completion. The original plan called for three stories, but the public raised the cry of economy, and it was cut down to two stories and basement. The entire expense of building the White House, including furnishings, repairs, etc., up to the year 1814, amounted to the small sum of $334,000.

It was first occupied just ninety-six years ago by President John Adams, and various were the struggles to keep it in even ordinary repair. Mrs. Adams, its first mistress, was dissatisfied with the place, and her complaints were varied and numerous. She wrote that "the rooms were large and barren, and that it took a great deal of money to keep them in proper order. Everything is on too grand a scale." It is amusing to know that this lady used what is now called the great state drawing-room to dry the family linen in, stretching the clothes-lines from one wall to another.

A RECEPTION IN THE WHITE HOUSE.

A RECEPTION IN THE WHITE HOUSE.

After the decisive battle fought at Bladensburg, Maryland, in the war of 1812, the British advanced upon Washington. President Madison was in the rear of the American lines, and seeing that the city was lost, he sent word to his wife to escape. That noble lady's first thought was to save Stuart's celebrated oil portrait of George Washington, which hung in the White House. Hastening to the room, she had it taken from the wall and carried to the retreating ranks of the American army, thus saving for the republic one of its greatest art treasures. It was during this invasion that the White House obtained its name from the coat of white paint applied to its surface after the burning of its main building. Numberless suggestions have been made to enlarge the official residence, but the public objected. Its present occupation, doubtless, will end with the close of the century and its hundred years of life, since the needs and demands of the President's family and the public have outgrown its proportions and capacity. But it will forever be associated with all that has made our nation important. Tragedy has gone hand in hand with festivity within its walls more than once. The great men of the country have sat in its rooms in grimmest council, when the fate of the nation hung in the balance of a decision that sent a messenger at daybreak flying from the White House gates. Twice its doors have opened to receive a murdered President, and again the joy bells have rung to honor a bride, and a child born in its "purple," yet who lived to toil for her daily bread far from friends and home. It cannot be parted with or even altered carelessly, yet unquestionably its fate is sealed. With the close of the century its story of a hundred years will be told.

Author of "Rick Dale," "The Fur-Seal's Tooth," "Snow-Shoes and Sledges," "The Mate Series," etc.

illed with a determination not to become rattled by the perils surrounding him, our young hunter at once proceeded to select a camping-place and make his scanty preparations for passing the long hours of darkness. With neither wood, water, nor grass to be seen in any direction, and all places looking alike uninviting, the task was not difficult. Dismounting, and leading his horse to a little recessed gully at the foot of a steep bluff, which would at least afford a shelter from the wind, Todd unsaddled, fastened the free end of the picket-rope to a bowlder, cleared away the rocky fragments from a small space of level sand, and unrolled his blankets.

Thus the sorry camp was made; and as the poor boy contrasted it with the one he had occupied but the night before—a camp of cheerful fires, merry talk, an abundance of food, and an atmosphere of perfect security—the horrors of his present position crowded upon him like black forms, from which he recoiled with a shiver of apprehension. He found in one of his pockets half a hard biscuit that remained from his lunch of that day, and this, with a sup of lukewarm water from the scanty supply still remaining in his canteen, formed his evening meal. Then, with the saddle for a pillow and rifle by his side, he rolled himself in his blankets and tried to sleep.

For a long time he could not, and when he finally stepped into the land of dreams they were of such an unhappy nature that he was thankful to awake from them and find a faint dawn stealing over the weird landscape. Both he and his pony were shivering with the chill of early morning when he once more mounted and attempted to retrace his course of the previous day. This, however, was soon given up as a fruitless task, for in that region every prominent feature was reproduced over and over again with a bewildering sameness. Then he sought for some one among the many inaccessible sandstone bluffs by which he was surrounded that might be climbed. Before he found such a one and gained its summit the sun was high overhead, and blazing down with a pitiless heat. Still, on attaining the desired elevation, the lad felt amply repaid, for not many miles away he could plainly see a regular range of bluffs and the trees that indicated a river. He could even catch glimpses here and there of flashing waters. To be sure, these things did not lie in what he believed to be the right direction; but recalling that lost persons generally become turned about, he decided that this must have happened in his case. Carefully noting the bearings of intervening objects, the boy hastened down from his observatory, remounted, and began to urge his unwilling steed over the new course thus laid out.

For hours he travelled, wondering at the distance with each succeeding mile, until finally, at the crest of a long and toilsome ascent, he gained a point from which he again commanded a broad view of the outlying country. Casting an eager glance in the direction he supposed the river to be, the poor lad rubbed his eyes and looked again. Then, as he realized the bitter truth that there was no river, and that he had been the victim of a fleeting mirage, all his strength and energy seemed to leave him, and he sank down on a fragment of rock as weak as a babe. For some time he sat oblivious to his surroundings. He did not note the wonderful scenery outspread as far as the eye could reach on all sides, and upon which every other boy in the country would have considered it a rare privilege to gaze. He had no thought save for his crushing disappointment and his own melancholy condition. He was weak in body from hunger, thirst, and fatigue, and heart-sick at remembrance of the folly and disobedience that had brought him to such a pass.

After a while a pull on the bridle-rein hanging across his arm roused him and caused him to look up. His pony was pulling away, as though impatient to be off.

"I want to go as much as you do, old fellow," said the boy, sadly; "but which way shall we turn?"

Just then his eye lighted on a cluster of slender blue pinnacles rising above a distant horizon, and appearing so different from all that intervened as to seem like signs of friendly promise. At the same time he saw, lying between him and them, a lovely rock-rimmed valley filled with green grass and waving trees, and threaded by a sparkling stream of water.

The boy gazed eagerly at the beautiful picture; and then, as it became blurred by dancing heat-waves, he closed his eyes wearily, muttering that it was only an effect of imagination. In a minute he opened them again, and saw the lovely valley as distinctly as before.

"It may be real, and we'll make a try for it, at any rate," he said, aloud, rising from the rock on which he had been sitting, and climbing very slowly into the saddle.

This time he was determined to gain frequent assurance that he was on the right course. So, within half an hour after leaving the place from which he had discovered the lovely valley, he fastened his pony by the picket-rope to a miniature spire of sandstone, and clambered on foot to the top of another elevated outlook. He hardly dared glance abroad, for fear that all the things he had seen before would have vanished. No. There at least were the slender blue peaks, looking as cool and refreshing, but, alas! quite as distant as before. But where was the green valley? It had disappeared, and in its place rose a range of tall cliffs, like a great white wall, miles in length.

It was a very cruel disappointment; but either the lad's senses were becoming numbed by his sufferings or he had expected it, for he only sighed wearily as he turned away.

"The blue peaks are there, at any rate," he said to himself, as he descended to the plain, "and I will make toward them. If I can reach them, I know I shall be all right; and if I can't—well, I will die as near to them as possible."

When he regained the place where he had left his pony he had been absent from it nearly, if not quite, an hour. Now it seemed as though he must have made some mistake in retracing his steps, for the animal was nowhere to be seen. There were his tracks, though, and there was the slender shaft of rotten sandstone to which he had been fastened, freshly broken off, and lying there upon the ground.

"Oh, what a fool I am! What a poor blind fool!" groaned the boy, as the full extent of this fresh disaster was made plain to him. "If I had only let the brute have his head in the first place, he would have carried me to the nearest water. I have often heard Mort say that a horse has a better knowledge of such things than a man; and of course he knows, for Mort knows everything. He knew that I was no more fit to take care of myself than a child, and he knew I would get lost. Oh, why didn't he send me back home, or tie me up, or do something to save me from my own foolish self? The dear old fellow won't be bothered with me any more, though, for we shall never meet again in this world. Poor Mort, how he must be suffering! But I can't die here. I can't! It is too horrible! If I could only reach those blue mountains. I wonder if there is the slightest chance of it? I wonder[Pg 431] how long a fellow can live and travel without food or water?

"Water! Oh, for a long cool drink of it! How gladly would I give the wealth of the world to lie beside one of those springs that we passed a day or two ago, and drink and drink and drink! Or the well at grandfather's. Or the trout brook up in the Alleghanies. Or— But I mustn't think of such things or I shall go crazy, and that will be the end of everything. I will make a try, though, for those blue mountains, for I am sure there are springs and lovely streams in their dark cool valley. If I can only reach them! Oh, what joy! And if I don't— Well, I will have done my best. Which way are they? Yes, I know—they are over there, and if I walk all night and all day to-morrow I will surely come to them by to-morrow night. Only twenty-four hours more, and I believe I can hold out that long."

So the poor lad started, and walked with uncertain steps through the yielding sands in a direction that he believed would lead him to the wished-for mountains. He could no longer see them, but he knew their slender pinnacles were steadfastly uplifted like taper fingers beckoning to him and promising pleasant things.

Just before sunset he came to a broad opening between the clustering mesas, through which he caught another glimpse of them, now tinged with a rosy flush, and seeming more beautiful than before, but in a few minutes the light faded and they were gone. Then, trembling with weakness, the lad sat down and watched until a star rose where he had last seen them, when, with it as a guide, he resumed his weary way. He often stumbled, and sometimes he fell, but still he pushed on, until at length his glittering beacon was obscured by black clouds. Then he sank to the ground, without heart to rise again.

For a long time he lay asleep or in a stupor, from which he might never have awakened but for a shower of rain, that, falling on his upturned face, roused him to consciousness. Eagerly sucking the precious fluid from his saturated garments, and gaining fresh strength with every life-giving drop, he waited for the dawn, and with the first hazy glimpse of the far-away blue peaks he again staggered toward them.

The sun rose and scorched him with its pitiless heat, until he seemed to be treading coals of fire. Mirage after mirage danced before his bewildered vision, with pictures of all things shady and cool and refreshing, until his eye-sight failed him, and he groped his way amid a darkness shot by glowing sparks. The last thing of which he was conscious was a great white wall that seemed to rise to the sky before him, and stretch to infinity on either side. It seemed to shut him off completely from the blue peaks he had striven so bravely to gain, and apparently presented an effectual barrier to any further progress.

In that last moment his head was splitting, his brain was on fire, his mouth and throat were like molten brass, his whole body was racked with pain, and his feet were like leaden weights. Then all sense of suffering was lost in a delicious laughter, and he seemed to be floating through infinite space that was filled with the music of rippling waters.

For many hours Todd Chalmers slept heavily and dreamlessly, like one who will never again awaken. He had wandered blindly with reeling steps for some time after losing a consciousness of his surroundings, and had thus unwittingly penetrated a deep cleft of the great white wall that was the last thing upon which his despairing gaze had rested. At the inner end of this recess he stumbled and fell over a fragment of rock. There he lay through the long night in what was, to all appearance, his last sleep.

That it was not was owing wholly to his youth and the wonderful vitality of a splendid constitution. Not more than one person in a thousand would have lived to see another daylight under the circumstances; but our lad was that one, and at length he began to show signs of returning life. He moaned, shivered, and finally opened his eyes. For many minutes he lay motionless, striving to remember what had happened and where he was.

At length he slowly and painfully sat up. His head ached as though it would split, his eyes were blurred, his lips and tongue were swollen, and his limbs were heavy as lead. Still, his long rest, together with the chill of the night just passed, had restored him to life and to a certain degree of strength.

Now, with the encouragement of even a slight amount of hope, he would be ready to renew his struggle against the death that had so nearly overpowered him.

Thus thinking, Todd withdrew his eyes from the picture of glistening desolation disclosed through the narrow entrance of the cavern, and began listlessly to examine his more immediate surroundings. Slowly his gaze roved over the hopeless walls of rock, that rose so high as to be lost in gloom, and it was not until he had turned so as to look squarely behind him that he found anything to arrest his attention. Then his curiosity was aroused by a gleam of reflected light coming from beyond and over a rocky barrier that formed a rear wall of the cavern. This barrier did not appear to be more than ten or twelve feet high, while above it was an open space of a few feet more, through which streamed the light that indicated an opening of some kind beyond.

Whatever might lie in that direction, it could not be worse than the desert over which he had come, and it might be better. Of course that was not at all likely, for he did not believe there was anything but desert in that country. Still, it was worth investigating, and as Todd did not feel strong enough to stand, he crawled painfully to the barrier and up its easy slope.

HE GAZED LONG BEFORE HE COULD BELIEVE.

HE GAZED LONG BEFORE HE COULD BELIEVE.

Arrived at the top, and looking through the opening, he was greeted by a sight so amazing that he gazed at it for nearly a minute in breathless incredulity before he could believe in its reality. Instead of the desert that he had expected, it seemed as though the very gates of heaven had been suddenly opened to him.

Outspread before his astonished eyes was one of the loveliest valleys in the world, filled with flowers, green grass, and waving trees. It was not more than half a mile in width, and was bounded on the further side by another lofty wall of white rock, similar to the one he had just penetrated. The same wall extended entirely around the upper end of the valley, which Todd could see on his left, though to the right it stretched away beyond his range of vision, still enclosed by parallel walls of sheer cliffs. Though most of it still lay in cool shadow, certain portions of the verdant landscape were already sparkling in the morning sunlight, and from all sides came the joyous song of birds. No smoke rose from any part of the valley that he could see, neither was there any sign of human habitation nor sound of voices. All was as fresh and peaceful as though it were a new creation; but even if he had been confronted by opposing ranks of enemies, Todd would not have hesitated to scramble down the opposite slope and enter what still seemed to him the vale of enchantment. Its abounding verdure indicated the presence of water, for which our poor lad was longing so desperately that he would have thrown away life itself in an effort to obtain it.

He had already regained the use of his limbs, and after a minute of gazing, amazed and incredulous, he started in search of the life-giving fluid, instantly forgetful of feebleness, aches, pains, and everything else save the awful thirst by which he was choked. So concentrated were his thoughts upon this one subject that he failed to realize that he was following a distinctly marked pathway. Such was the fact, however, and after a hundred yards it led him to the edge of that most beautiful thing in all the world, especially when found in a land of deserts, a spring of pure cool water. It bubbled up from a bed of exquisitely colored sand, and was neatly walled about with rock.

It was fortunate that Todd plunged his whole head into the spring in his frantic eagerness to drink of its water, for he was compelled to withdraw it, gasping for breath before he had drunk a tenth part of what he craved. Much as he longed to drink, and drink until he could hold no more, he had sense enough to realize the danger of such[Pg 432] a proceeding, and the strength of will to restrain himself. So he only lay beside the delicious spring, bathing his face and dabbling his hands in it, taking moderate drinks at half-minute intervals, and feeling with each one a new life coursing through his veins.

For an hour he remained thus in perfect contentment, devoutly thankful for his wonderful deliverance from an awful death, and gaining strength with every minute. Then the sensation of thirst gave way to that of hunger. He had not thought of it before, but now he knew that he was starving, and must eat something, even if it were only grass. So he stood up and looked about him, recognizing for the first time that he had followed a trail which still extended beyond the spring, beside a stream that rippled merrily from it toward the centre of the valley. Looking in that direction, Todd caught glimpses through the trees of a pool or pond fed by the stream, and toward it he now made his way.

Although in the desperation of thirst he had rushed recklessly forward in search of water, he now proceeded with all the caution that his hunger would permit. The path that he was following and the artificial walling of the spring indicated so plainly the presence of human beings in the valley that he could not neglect the warning thus conveyed. "Of course," he argued to himself, "none but Indians could live in so isolated and out-of-the-world place as this, and while they might prove friendly, the chances are that they might shoot in the flurry of a sudden discovery. So I'll try and see them before giving them a chance to see me."

Advancing thus slowly, and peering eagerly ahead, he had gone but a short distance, when he was startled by the sight of a house, or rather a stone hut, only a short distance in front of him, and near the pool he had already noticed. For several minutes he stood motionless, regarding it closely; then, as it presented no sign of being occupied, he moved cautiously forward until he could command a view of its doorway, which was closed by a curtain of skins. The walls of the hut were low, and a stone chimney projected from its roof of coarse thatch.

It did not look to our lad exactly like an abode of Indians, nor yet like that of a white man, and he wondered what race of people would greet him when his presence should be discovered. He called twice, "Hello the house!" but receiving no answer, stepped softly to the door and looked in. The hut was empty, and Todd drew the curtain well back, so as to obtain plenty of light for an examination of its interior.

A fireplace, a rude table, two equally rude stools, a bunk filled with skins, and also a few earthenware vessels of crude design constituted its sole furniture. The young explorer examined these things carefully, in the hope of discovering something to eat; but, to his intense disappointment, he did not find so much as a kernel of corn. Nor could he learn anything concerning those to whom the hut belonged. Everything was sufficiently primitive to be the work of Indians, and yet he had seen equally rude furnishings in the cabins of certain white men whom he had remembered.

That the hut had been recently occupied was shown by fresh ashes in the fireplace, and by a jug of water that stood on the table. Who could its owners be? What had become of them? How would they treat him when they discovered his invasion of their premises? And where did they store all their provisions?—were questions that the boy asked himself over and over again. Above all, what was he to do for something to eat? For he was now suffering almost as much from hunger as he had from thirst an hour before. As he gazed moodily at the cold embers of the fireplace, deliberating these questions, he was startled by the sound of feet just outside the hut, and a voice, apparently that of a child, calling plaintively for its mother.

"The folks have come home," he said to himself, "and in another minute my fate will be decided." At the same time he stepped resolutely to the doorway and looked out.

A few months ago one of the youngest of the group of eccentric writers who call themselves "Symbolists" was paying a visit to London. The conversation in a drawing-room happened to run on the province of the Franche-Comté, and the guest remarked, as a curious circumstance, that no poet had ever come from that part of France. Somebody ventured to murmur the name of Victor Hugo. "Ah! sir," replied the young Symbolist, with a charming air of deprecation, "but we don't consider Victor Hugo a poet!" It is obvious that, for the present at least, this particular expression of opinion will remain rare; it was conceived in the very foppery of paradox, of course. But it is quite conceivable that such a judgment might spread, might become common, might become authoritative and universal. To our generation, at all events, Victor Hugo has appeared to be the typical poet; he and Tennyson have been named side by side as the very types of the imaginative creator, as purveyors of inexhaustible poetic pleasure. That is what we have all thought; but suppose that our grandchildren determine to think the opposite, what is to be done? Manifestly we shall be too old to whip them and too weary to argue with them. If they decide that Victor Hugo was not a poet, that Dickens was not amusing, that Hawthorne wrote bad novels, we shall have to go, indignant, to our tombs, but our indignation will not convert the younger generation.

So far as the history of the world has yet proceeded, the standards in literature have not been overturned in this rapid and revolutionary manner. But nowadays, if things once begin to move, they move fast, and we must be prepared for changes. In the parallel art of painting we have seen the most violent and apparently the most final reversals of the standards. It is very difficult to believe that various schools of art which have enjoyed great popularity in the course of the present century, and have fallen, will ever be revived. I had an uncle who purchased the works of Mr. Frost, R.A., and a very bad bargain it has proved to his family. Nothing is so deathly cold as the public interest to-day in Frost; his brown satyrs and his wax-white nymphs, with floating pink scarfs insufficiently concealing them, are not worth sixpence now. We do not, as I have said, see these violent upheavals in literature yet. No author who was praised and valued when Hilton or Frost or George Jones were thought to be great masters of painting has passed so utterly out of repute as they have. Hitherto, if a man of letters has contrived to secure a certain amount of respect, the public interest in him may dwindle, but it never quite disappears. Every now and then somebody "revives" him, his poems are reprinted and praised, his correspondence is published, he is respectfully admitted to have been "somebody."

The first standard in literary matters is, obviously, excellence in execution. In other words, to write singularly well, and to be recognized as doing so, is to achieve fame, though not necessarily popularity. But in using the word "standard" we accept the idea, not merely of individual excellence, but of comparison with others. In coinage, for instance, that is called the standard which unites in what is practically found to be the most useful combination the elements of precise weight and fineness. Again, there is a technical sense in which a "standard" is a type of which all other measures or instruments of the same kind must be exact copies. In yet another signification a standard is an ensign or flag carried on high in front of a marching army for its encouragement and stimulus. We have to consider in what degree, and how, without forcing language, we can form a conception of a literary standard of excellence in style which shall unite these various definitions.

The precision of the eighteenth century offers us a very clear example of the way in which the first of these ideas can be adapted to literary illustration. When it was determined by universal consent to bind all poetical writing down to set laws, and what was supposed to be the precept of Aristotle, there was at first no modern standard of style. The great object was to emulate the Latin poets; but as these writers had used not merely another language, but other prosodical effects, a different order of moral ideas, and totally distinct imagery, it was necessary to find a modern substitute for imitation. Various English poets wrote with force, but they lacked delicacy; others had fineness, but with an insufficiency of weight. At length Pope came, who accepted the theories of style which were current in his day, and acted upon them with a more perfect balance of the qualities they demanded than any one had done before him or has done since. The best parts of Pope's writings, therefore, created a standard, and one which was of paramount influence for nearly a century.

Again, those who invent forms of writing which are accepted by the world of letters as valuable additions to what we may call the tools of the author's trade, create standards in the second sense of the word. There does not appear to be an indefinite degree to which these forms can be created, and when once perfected they often remain for centuries unaltered. For instance, when an early Tuscan poet, of the age of Dante, invented the sonnet as we now possess it, he made a thing which has been proved to be the best possible of its sort. Ingenious people, in various languages, for centuries past, have tried to alter the form of the sonnet, to add to it, to retrench it; all their suggestions have proved vain, and it remains, in the best hands, exactly what its old Italian maker devised it in a moment of inspiration. In a lesser degree, the forms of prose are the result of invention and adaptation, and can be referred back, more or less indefinitely, to a standard or type. Thus the short story has certain limitations of length and character which distinguish it from a novel or a play or a lecture, and in discussing the merits of an example of this species of literature, we unconsciously hold before our minds a norm or ideal of what a short story should be. If we speak of it as highly successful, we think of it as a close copy in form of a typical short story which should be universally acknowledged as the best in every technical respect.

The third definition of a standard is one which may without difficulty be applied to literature, but which is really a little more dangerous to deal with than the preceding. If the standard is to be an ensign or flag carried at the head of an army, we are confronted with an idea[Pg 434] which is less durable than those which we have considered. For if the army marches with drums and trumpets, and all flags flying, it may not only march to defeat instead of victory, but it may alter its direction, and march back with no less pomp and noise than it marched forward. In these conditions, its ensigns, instead of representing a fixed purpose, may be the standards of irresolution and vacillation. We can find an exact literary parallel for this in European taste in the seventeenth century. The cleverness and fancy of writers, in prose and verse, and almost in every country, led them to adopt methods of writing which strained to the utmost the powers of language. Poetry, instead of being content to walk and run, turned somersaults on the trapeze. As long as this was done by very graceful and nimble intellectual athletes it gave great pleasure, and the world of letters seemed marching to victory under this ensign of imaginative acrobatism. But it speedily proved to have been a mistake; the graceful athletes gave place to grotesque contortionists, and the army of writers retreated in confusion, but slowly, doggedly, and under the same standards of taste. There was no other way back to health but to discard the existing ideals altogether; they were too obstinately fixed in men's minds to make it possible to modify them.

If we are to form any opinion with regard to that question of the literary standard, which democratic habits of thought tend to make every day a more dangerous one, it is manifest that we must regard it from these three points of view, or from a combination of them. The taste of the public is a floating, a vague impression of an amateur body with regard to a matter which is more precisely and sharply defined by a consensus of experts. But the experts themselves are not united, and the precision of their views only tends to darken counsel and reduce opinion to chaos. Unhappily a piece of literature cannot be assayed mechanically like a piece of coinage. Under the strictest rules that ever were enacted and a régime the most academic conceivable, there will never be anything like unanimity regarding the excellence of a literary product. All we can hope to reach is a general agreement of the best-trained minds, recurrent for so many generations as to become practically durable.

Even in the most ancient cases, where it would be supposed that opinion would finally have crystallized, we observe curious oscillations. Homer, it is true, is accepted by all critics, in all nations, as the final standard of what is admirable in heroic narrative poetry, and has for centuries been so accepted. But what is the standard of Greek tragedy? The study of classic criticism will show us that the standard has been incessantly shifting from Æschylus to Sophocles and on to Euripides and back again to Æschylus. If we wish to point to an authoritative type, we must consider this triad as one, since no two generations agree as to their comparative, though all to their positive merit. In like manner, the relative value of Virgil and Theocritus, of Horace and Catullus, is always shifting, according as the quality of the one or of the other happens to appeal to one or to another habit of modern thought. Yet antiquity obviously provides us with a standard of bucolic poetry, and another of subjective and semi-social lyric, each of them settled now beyond any probability of decay. People will go on preferring Theocritus to Virgil, or Virgil to Theocritus, but no rational person is likely to question again the excellence of the species of art of which these two are the leading exponents. So there are those who prefer Dryden to Pope, or Coleridge to Wordsworth, and to whom neither seem to present the complete practitioner of a system. Yet no one denies, and it grows increasingly probable that no one will ever deny, the authority of the Pope-Dryden or of the Wordsworth-Coleridge standard of excellence, final and unquestionable, in a particular department. Opinion, that is to say, wavers as to the individual long after it has irrevocably accepted the type.

In all consideration of the past we find ourselves securely guided by the test of technical excellence. Nothing else has preserved the principal writers of antiquity in esteem. Mr. Lowell called style "the great antiseptic"; good writing, in other words, is the only chemical product which can prevent literature from corrupting and fading away. In the days of Shakespeare there were a dozen writers who had a just right to consider themselves more "serious seekers after truth" than the playwright of Stratford, for they discussed graver subjects and brought forward a weightier array of facts. Their very names are now forgotten, while his pages grow more brilliantly vital as the years pass on. The fancy and tenderness of Shakespeare, the wit of Molière, the sublimity of Milton, the wisdom of Goethe, are revealed to us and preserved for us by their style, and without it would have sunk long ago in the ocean of oblivion. Such phrases as "the matter is the important thing, not the manner," "never mind how he says it, but find out what he has to say"—which are common enough on the tongues and pens of those who have secured no grace of delivery—are pure fallacies. Style is the atmosphere without which what is written cannot continue to breathe; it is the indispensable medium for rendering what a man has got to say continuously audible to the world. These are truths which we might suppose too obvious to need repetition, since the whole history of literature proclaims them, yet so great is the natural love of slovenly writing and vague thinking that this heresy about the matter being far more important than the manner is incessantly recurring. It is needful, once more, therefore, to say as plainly as possible that without a distinguished and appropriate manner, that is to say, without style, no "matter" will ever have the chance to reach posterity.

If once we resign this position as to the pre-eminent importance of style we lose all means of measuring the standards of literature. As long as excellence in writing is recognized as the main factor in the formation of judgment, we are not likely to go very far wrong. We have seen that those who permit themselves no other lamp than this may differ as to the relative value of figures in a single group, but they unite in their appreciation of that group itself. This is the case in the criticism of ancient writers, and what other means have we of forming a judgment about the moderns? As long as we are content to measure them as we do their noble predecessors, we may make mistakes, but they will be mistakes, not of principle, but only of detail. The moment that we allow ourselves to believe that modern writing, the authorship of to-day, is distinct in kind from that of the old masters, and can be measured by different standards, we have resigned ourselves to a heresy, and are in imminent peril of encouraging literary anarchy.

It is a mistake to be too yielding and shy in expressing a conviction which has been gravely formed on serious grounds. Those who love the more austere and splendid parts of literature will always find themselves in a minority in every collection of persons. It is probable that if the prestige of Paradise Lost had to depend upon popular suffrage, no majority of citizens in any part of the English-speaking world would be willing honestly to admit that they admired it or could read it with pleasure. That does not prevent it from being one of the most glorious, most enviable and unique possessions of the race. On questions of the literary standard it is the majority which is always wrong. The majority likes a warm easy book, without pretension, unambitiously written, on a level with the experience of the vast semi-educated classes of our society. "One man, one vote," extended to the domain of literary taste, would mean the absolute and final extinction of all distinguished masterpieces.

But in every generation there is a remnant which occupies itself with beauty and distinction. The individuals of this little group fight among themselves about the details of excellence, but they guard, as in a pyx or shrine, the primal idea of that excellence and a general sense of its formal character. Outside this small class of experts there is a large body of the public which recognizes its authority and is docile to its directions. Again, outside is the vast concourse of persons competent to read and write, but no more capable of forming an opinion than is the dog that barks at their shadow or the discreeter cat that curls at their fireside and says nothing. It has often occurred[Pg 435] to me as a grave speculation how long this vast dumb force of untrained readers will be content to be silent. How long will they have the good nature to pretend to respect the things which they cannot enjoy? Flattered as the average man or woman is in these days, accustomed to hear the voice of democracy praying for votes on every subject, how soon will the average reader pluck up courage to say to himself, "I do not like the novels of Thackeray nearly so much as I do those of E. P. Roe, and I do not intend to allow anybody to persuade me that they are better?" Questioning the standards of taste, refusing to bow to traditional canons of criticism—this is the Red Spectre which I dread to see arise in the midst of our millions of half-trained readers.

But the cure will probably come from the very nature of the disease. If we put a dangerous power in the hands of the crowd by the infinite facilities given nowadays to reading and the discussion of books, we support the traditions of literature by giving unprecedented opportunities to persons of native capacity to fortify themselves in the truth. No boy, nowadays, in the whole English-speaking world, can wholly refrain from indulgence in literary pleasures, if an appetite for such enjoyments have been born in him. In some newspaper, in some cheap reprint, that which is exquisite and final, that which is assimilated to the inviolable standards of excellence, must meet his eye and be accepted by him. The enemies of literature may become extremely numerous; they will remain languid and blundering; its friends will be always few, perhaps, but they will be ardent and active. That the good tradition may be swamped for a time in some Commune of the intellect seems to me very possible, but that it should be lost, that it should go down altogether into the deeps of anarchical vulgarity, that, happily, is not to be believed.

Meanwhile, every one who, however humbly, is devoted to what is nobly and purely said in prose and verse, may do his or her part to prevent even a temporary descent into barbarism. The only way to become sensitive to what literary excellence is, is to study and re-study those books which have stood the assaults of time, and are as fresh to-day as when they were written. It is not to be expected that to any one taste all these books, in their various classes, will appear equally delightful. But it is from a wide acquaintance with these, and a reverent and affectionate wish to discover their charm, that literary appreciation grows. If once we are convinced that there is a standard, that a well-written book is distinguishable from a dull and slovenly one, that style is not a vain ornament, but as essential to literary life as oxygen is to a human being, then, without affectation or priggishness, every man may become a sober lover of the best, and may feel that though certain specimens of literary work may go up and down in public esteem, the central standards are firm and the laws of intellectual beauty immutable.

Ho, for the Laughy-Man! laughing all day,

Laughing the sunshiny hours away,

Laughing and kicking his little pink heels

Just to impress us with how good he feels!

Hey, for the Laughy-Man!

Ho, for his smiles!

Hail to the angels who taught him such wiles!

Ho, for the Laughy-Man! waking to play,

Waking to laugh at the first peep o' day,

Waking to churn up the blanket and sheet,

Like waves of the sea, with his fists and his feet!

Hey, for the Laughy-Man!

Ho, for his smiles!

Hail to the angels who taught him such wiles!

Ho, for the Laughy-Man! lying abed,

Lying there wagging his cherubin head,

Lying there, merry, a bundle of love

Sent to our home by the seraphs above!

Hey, for the Laughy-Man!

Ho, for his smiles!

Hail to the angels who taught him such wiles!

There were seven kinds of Indians at the back of the largest hotel of the Western town—dirty and dirtier, which is two; young and old, which is four; male and female, making six; and one little clean pappoose. This latter tiny bit of aboriginal humanity was a chubby, round-faced, bright-eyed little tike, with the blackest of hair and the most bronze of complexions. He was playing around alone inside a close high board fence at the rear of the large hotel, his only shirt cut off at the knees, displaying a fat brownish pair of dimpled legs that were warm enough in spite of the fact of their bareness in the chilling air.

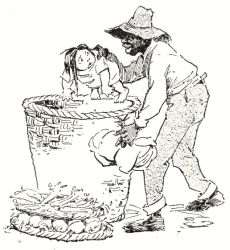

Presently around the corner came a trotting, smiling Chinaman, a vender of vegetables. A long slender pole, carved flat and tapering toward the ends, was balanced on his shoulder, and from either end, suspended by a bridle composed of four strings, hung a huge bamboo basket.

As he halted within the gate of the high board fence he lightly swung the receptacles to earth, rested his polished pole conveniently near, lifted a mat containing the day's supplies for the cook within, and carried it off to the kitchen.

Now it not very strangely befell that the vender of vegetables lingered a time in the kitchen, for that exceedingly tempting and savory seat of government was under the personal direction of another little yellow man, who called his countryman "Wong," and gave him to drink of tea. While the two engaged each other with inharmonious gutturals, a dusky cranium and equally dusky countenance came poking out from another door. Its owner was the negro porter, a grinning fellow, whose mania for jokes of the "practical" description was developed to a degree positively unhealthy. No sooner had he made himself certain that the yard was free of observers, and occupied alone by the wee pappoose, than he stealthily slipped from his place, and grabbed the scared little fellow by the tail of his wholly inadequate shirt.

The eyes of the miniature savage were apparently frozen wide open in an instant, while paralysis made him utterly stoic and dumb. The Chinaman's basket had a shallow tray in the top filled with beets; then an inside receptacle, also shallow, filled with celery. Below this last were cabbages, down in the bottom. These extra insides the negro quickly lifted out with his unemployed hand; then a couple of the cabbages, as large together as the wee pappoose, came forth with a jerk. In a second more the silent Indian baby had been dropped within the basket, the various trays had been properly replaced, and the darky had rapidly hopped through the open door with his cabbages, doubling himself like a nut-cracker and stretching his face in violent but silent laughter.

Out came Wong, beaming with the radiance of tea well swallowed. He rearranged his pole, bent his stout Mongolian back, straightened up, lifting his baskets, balanced them neatly, and trotted away with the frightened baby Indian, but quite oblivious that such a lively vegetable ever was grown.

Wong went singing up the street, or rather humming away about a "feast of lanterns," and he thought on how soon he would be enabled to purchase a wagon.

"Good-molling," he said, as he stopped at last at the rear of one of the most imposing houses. "Velly fine molling."

"Good-morning, Wong. It's a little bit chilly," said a gray-haired woman wearing glasses, rubbing her hands.

"Oh yeh, him feel lill bit chilly."

"What you got this morning?" she inquired.

"Oh, for callot, for cell'ly—velly nice for cell'ly—for turnip, for squash, any kine." Then, as she hesitated, "potatoe?—for ahple?—for cabbagee? Oh, lots um good kine, I tink."

She took a squash. "Did you say cabbage, Wong?"

"Oh yeh." He began at once to lift the tray. Next he hoisted forth the shallow inside basket and reached for a cabbage.

"Ki! yi!" he yelled. "Sumin—ah—got, yu nee mah! Kow long hop ti! Ha! What you call um? Hi! for Injun debbil!" And he lapsed again into awful Chinese exclamation points, and danced a fan-tan dango in a wonderful state of excitement. "Hi! What you call um? Sumin-ah-got, no belong for Wong! Huh!" Nerving himself for the fearful ordeal, he lifted the squirming baby forth and dropped it quickly to the ground. No sooner did the wild little thing find itself released than it scrambled to its feet and ran at the skirts of the elderly lady—the only thing it recognized—and clung there like a prickly burr.

"Mercy!" shrieked the lady. "Mercy! Where— Wong, where did you get this child—this savage child?" she demanded.

"Sumin-ah-got, no sabbee," said the terrified Wong, gathering baskets and mats in a desperate haste. "Plitty click for whole lots um for Injun come for nis one. Wong no takee. No see some nis one for baby befloh. Somebody makee for tlick—you sabbee?—makee velly much tlouble. Kow long hop ti! Yu nee mah!"

"But, Wong, you must take it back! I don't know anything about the trick! I don't wan't the Indians coming here. Mercy!"

Wong, however, had rapidly fixed his pole in its place, and swung his baskets clear of the ground, still jabbering wildly in his native tongue, and trotted away with a double-quick motion.

"Wong! Wong!" called the agitated woman. "I can't throw him away! You must take him back! Wong!" But the vender of vegetables, thoroughly alarmed, had fled.

"Did yez call, Miss Hoobart?" said a voice from the door.

"Oh, Maggie! Oh dear! Oh! Oh! What shall we do?" cried the woman. She was trying to shake her skirts of the brown little Indian, but he merely clung the harder, and buried his face in the folds.

"Ach, wurra, wurra!" said Maggie. "Oi wudden't a t'o't ut. Phere did yez git um?"

"Hush, you silly girl. It's an Indian baby, and Wong brought him—and he ran away frightened—and somebody played it as a trick—and the wild, infuriated Indian population may be down upon us at any moment to recover the child!"

"Ach!" screamed the girl, jumping high in the air and glancing quickly about. "Phy don't yez l'ave um in the sthrate, the turrible varmint?"

"What, a tiny child, Maggie? Suppose it should freeze to death? It hasn't any clothing to speak of. Oh dear! I do wish Charles were home!"

"Phat yez goin' to do?" whispered Maggie.

"I don't know. Oh, I don't know! We've got to take him in, I suppose, and wait for Charles." Accordingly she walked very gingerly in, while the very diminutive savage continued to cling to the dress and hide his face. "I don't see," she said, breathing easier when the door was closed, "how I'm going to get him away from my skirt. Don't you think you could take him away, Maggie?"

"Oi wudden' touch um for tin dollars!" cried the girl.

"What shall we do? He will never let go."

"Yez c'u'd l'ave um the skirt—take ut aff, an' put an anither wan, ye moind."

"Yes, I can; that is just the thing." She slipped the outside garment in a jiffy, and the baby sat down on the floor in the midst of the pile.

The warrior sat perfectly still, his big brown eyes and his wee red mouth wide open, his chubby hands playing at random with the skirt.

"Oi moight go out an' infarm Misther Patrick Murphy, the gintleman policemon, mum," ventured Maggie at length.

"Don't you dare to go and leave me an instant," said the woman. "There is nothing in the whole wide world to do but to watch him every minute and lock all the doors and wait for Charles. Oh dear! that I should live to see such a terrible day!"

So the barricades were placed on the doors, and the women brought their chairs to sit and watch their very unwelcome prisoner. As the day grew old it occurred to the lady that perhaps the child was hungry. She prepared a piece of bread with molasses, and handed it out with the tongs. With this the child emulated his parents, for he painted his face from chin to eyes. This continued till the curtain lashes of the bright brown eyes came drooping down; his chubby little face, with molasses adornment, sank slowly to rest on the skirt. The women continued to watch.

As the evening came on Miss Hobart paced the room impatiently. "Charles! Charles, my brother!" she would say, "why don't you come? You ought to know what a terrible, terrible trial it is!"

But the sound of his knock on the door, when he came at his usual time, nearly made the women faint. A thin little man was Mr. Hobart, but sensible, and not to be alarmed. He declared that the morning would be time enough in which to clear the matter up.

"Oh, but it won't," said his elderly sister. "Suppose there should be a night attack? They are very, very frequent—it's the Indian way of proceeding!"

"Well," said he, "I'll go and tell the sheriff. He can hunt the parents up and settle the whole thing in a minute."

"But," she protested, "the Indians are gone to their tents—campoodies—out in the sage-brush long before this—that is, providing they are not lurking around this neighborhood. And just fancy a poor mother deprived of her child all night!"

"Well, what shall I do?"

"Suppose—suppose you take a lantern and go out to the wigwams. You are not afraid?"

"No, of course I'm not; but what's the use?"

In the end he found himself muffled, mittened, provided with the lantern, packing the child—all wrapped in a blanket and fastened loosely in with a shawl-strap—out in the sage-brush, floundering aimlessly about in search of the Indian campoodies. Mile after mile he trudged about in the night, shifting baby and lantern from hand to hand as his arms grew weary, and growing more and more disgusted as it dawned on his mind that all he knew of the way to find campoodies was to wander toward the west in the brush, he shouldered the sleeping warrior and made some lively tracks for home.

"There," said he, as he tossed the wee pappoose, blanket and all, on the lounge, "you can leave it to snooze where you please, for I am going right straight to bed."

His sister sat in a chair all night, dressed, and she waked a hundred times from a dream of hideous Indian depredations. She was wearily sleeping when her brother ate his breakfast and went. An hour later the head of an old and silently whistling Indian appeared at the open window.

"Ketchum pappoose?" said this awful warrior, and his voice was barely audible. She whirled around, saw the face, tried to scream, and failed.

"Injun Jim h-e-a-p sick," drawled the chieftain, who had satisfied himself that his son and heir was present, the youngster being seated on the floor—"h-e-a-p sick, heap likum biscuit-lah-pooh."

Miss Hobart rallied. "Perhaps," she thought, "Charles has pacified the tribe." Then she said, "Oh, Mr. Indian Jim—James, is this your son—your little boy?"

"Yesh, h-e-a-p my boy. Injun Jim heap likum biscuit-lah-pooh, h-e-a-p sick."

"Are you sick? Poor man! you shall have all the biscuit you want. Here," she said, in a timid voice, as he tucked away a package of food, "is your son—your nice little boy—very nice little boy; and I'm very sorry—"

"Yesh, h-e-a-p nice—all same Injun Jim. You like buy um? Two dollar hap, you buy um, h-e-a-p goot!"

"Mercy! Oh, oh!" she gasped. "He would sell it! Two dollars and a half—and after such a night! Oh no—no, Jim—James—take him to his yearning mother, please!"

As the warrior slowly shuffled away to the gate, leading his son and heir by the hand, the bright little face was turned toward the woman who was standing in the door.

"It is a beautiful child," she said. "I wish I had noticed before."

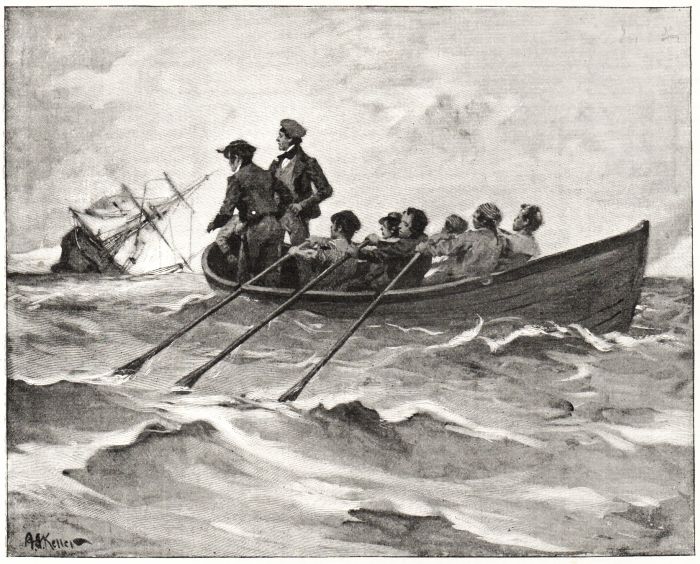

was almost stunned at the news the carpenter brought, but I knew of the only thing to do, of course.

"Rig the pumps and get to work at them," I squeaked faintly, fearing to try to talk loud.

"Ay, ay, sir," he answered, "but it will do no good. Lord Harry! she's opened up like a sieve, sir!"

Soon we had the water from below pouring on to the deck and running into the scuppers and mingling with that that came on board of us over the rail. But the wind increased in strength until it seemed that it would take the aged masts out of the brig, and it actually threatened to blow the clothes from off our backs.

Chips had gone below again to sound the well, and I was holding on to a belaying-pin, and trying not to show how weak and sick I was. I noticed that one of the men, a narrow-headed fellow with an ugly gash of a mouth, was not putting all of the beef he might into his stroke on the pump handles. So I slid over to him and laid hold myself; but the man endeavored to push me to one side.

"Hands off, Captain Jonah," he said, "it might stop working! We had plenty of good luck until you came aboard of us. Hands off, I say!" he cried, "or we'll feed you to the whales."

I could have struck the man for his insolence, as his words had been heard by two of the men opposite; but I saw that the result might be bad for me, so I replied nothing, but taking a firmer hold of the beam, I wedged him out of his position, ready at any moment to fell him if he attempted violence. I was the stronger, and at last I broke his hold. Where the force I now felt command of came from I cannot tell. The man would have slid over against the bulwarks if I had not caught him by the shoulder.

"Go over on the other side and work, you shirker," I cried, and, to my surprise, my voice roared out the words in tones like those of a bull.

I gave the man a push up the slope of the deck, and began heaving up and down with all my might and main, but I had made a discovery.

It was only my lower tones, my demi-voix, that were gone. For three days afterwards this phenomenon continued. If I wished to talk, I had to use the full lung-power that I possessed, and the result was a sound that would do credit to a boatswain's mate in a typhoon. It was as unlike my former voice as a broadside to a pistol-shot. But I am wandering.

The effect of my treatment of the insolent sailor had been marvellous. Not a disrespectful glance was cast at me thereafter. Soon the carpenter came up from below.

"We may have gained some three or four inches, Captain, but no more," he panted, laying hold alongside of me. "I think the water is getting in forward too, sir," he added.

"Get out four of the prisoners and man the forecastle pump," I roared at him.

He jumped at the odd sound of my voice, but made no remarks, and scrambled to the hatch in a jiffy.

"Four of you up out of that!" he cried through the hole, at the same time battering away at the fastenings with a belaying-pin. The hatch was flung open, and instead of four, all ten of the Britishers came rushing to the deck. They probably had been dying of terror down below, and one glance at us working away for dear life told them the condition of affairs.

Without a word they set to work, under the direction of their own officers, to get the spare gear out of the way and start the forecastle pump going.

The carpenter soon reported from the hold that we had gained some four inches, and were now holding our own. This was at the end of an hour's work by all hands.

I perceived, however, that it would be foolishness to work all the men to death at the outset, and that the sensible way would be to divide them into relays, even if the water gained a little on us.