The Project Gutenberg EBook of Whitman Mission National Historic Site, by

Erwin N. Thompson

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Whitman Mission National Historic Site

National Park Service Historical Handbook Series No. 37

Author: Erwin N. Thompson

Release Date: November 22, 2019 [EBook #60756]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WHITMAN MISSION NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE ***

Produced by Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

Stewart L. Udall, Secretary

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

George B. Hartzog, Jr., Director

HISTORICAL HANDBOOK NUMBER 37

This publication is one of a series of handbooks describing the historical and archeological areas in the National Park System administered by the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. It is printed by the Government Printing Office and can be purchased from the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D.C., 20402. Price 45 cents.

By Erwin N. Thompson

National Park Service Historical Handbook Series No. 37

Washington, D.C.: 1964

here they labored among the Cayuse Indians

It is a distinct pleasure to acknowledge my indebtedness to Jack Farr, formerly with the National Park Service, and Robert L. Whitner, Whitman College, Walla Walla, Wash., who prepared the material on which most of this manuscript was based.

E. N. T.

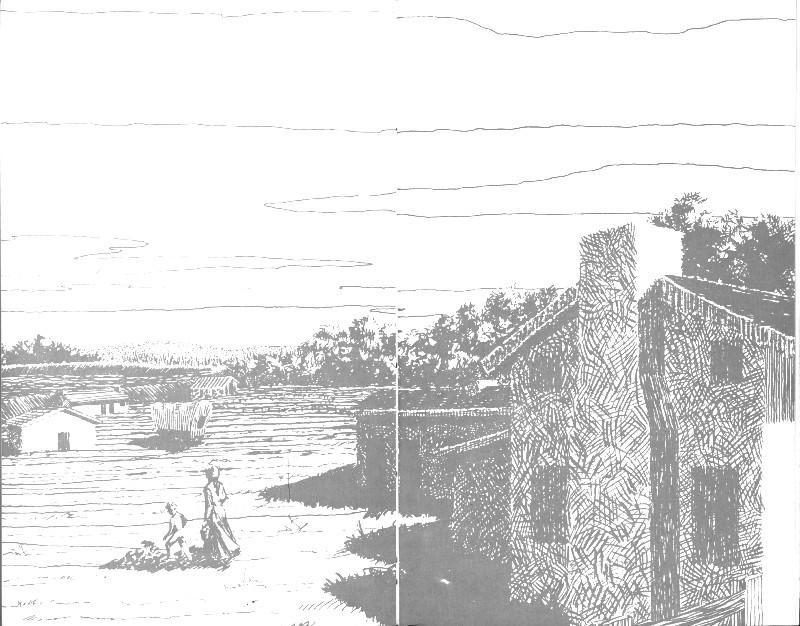

Waiilatpu is the site of the mission founded among the Cayuse Indians in 1836 by Marcus and Narcissa Whitman. After 11 years of ministering to the Indians and assisting emigrants on the Oregon Trail, these missionaries were killed and their mission destroyed by the Indians whom they sought to help. The Whitmans’ story of devotion, nobility, and courage places them high among the pioneers who settled the Far West.

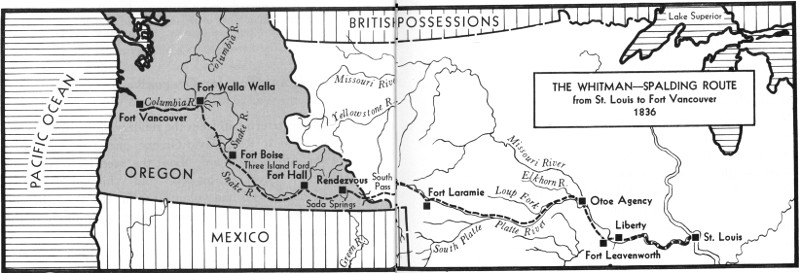

In 1836 five people—Dr. Marcus and Narcissa Whitman, the Reverend Henry and Eliza Spalding, and William H. Gray—successfully crossed the North American continent from New York State to the largely unknown land called Oregon. At Waiilatpu and Lapwai, among the Cayuse and Nez Percé Indians, they founded the first two missions on the Columbia Plateau. The trail they followed, established by Indians and fur traders, was later to be called the Oregon Trail.

Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spalding were the first white women to cross the continent; the Whitmans’ baby, Alice Clarissa, was the first child born of United States citizens in the Pacific Northwest. These two events inspired many families to follow, for they proved that homes could be successfully established in Oregon, a land not yet belonging to the United States.

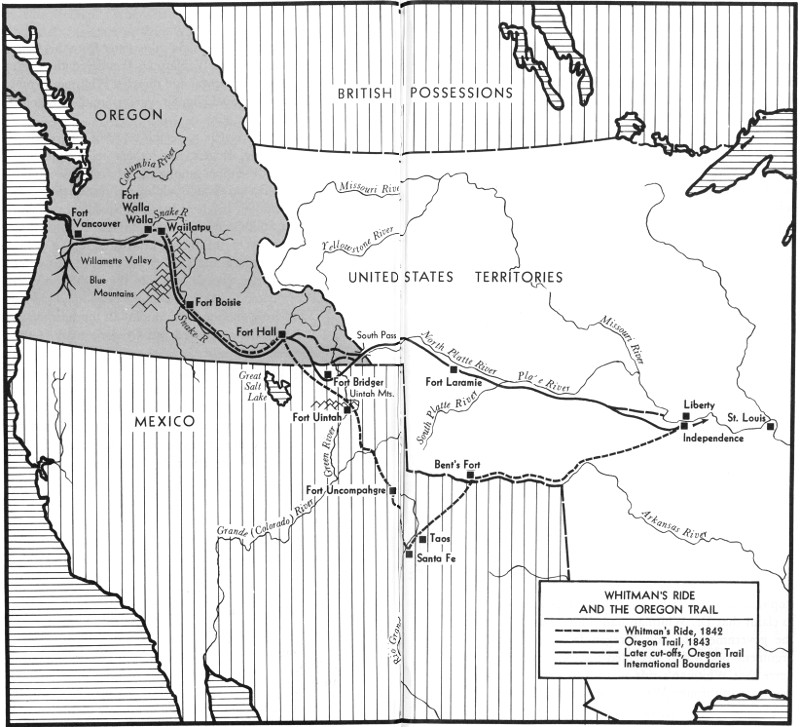

In the winter of 1842-43, Dr. Whitman rode across the Rocky Mountains in a desperate journey to the East to save the missions from closure. On his return to Oregon, another chapter in the western expansion of this Nation was added when he successfully encouraged and helped to guide the first great wagon train of emigrants to the Columbia River. The Whitmans’ mission 10 throughout its existence was a haven for the overland traveler. Medical care, rest, and supplies were available to all who came that way.

For 11 years, the Whitmans worked among the Cayuse Indians, bringing them the principles of Christianity, teaching them the rudiments of agriculture and letters, and treating their diseases. Then, in a time of troubles when two opposing forces failed to understand each other, the mission effort ended in violence. In the tragic conclusion, the lives of the Whitmans were an example of selflessness, perseverance, and dedication to a cause. Their story is symbolic of the great effort made by Protestant and Catholic missionaries to Christianize and civilize the Indians in the first half of the 19th century. The missions represented one aspect of American expansion into the vast, unknown lands of the Pacific Northwest.

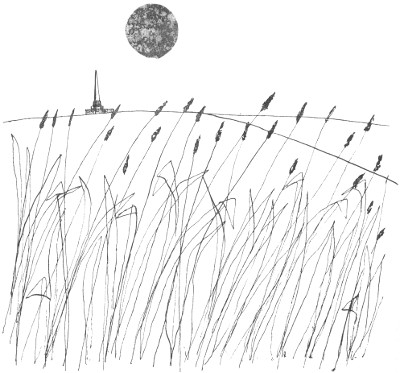

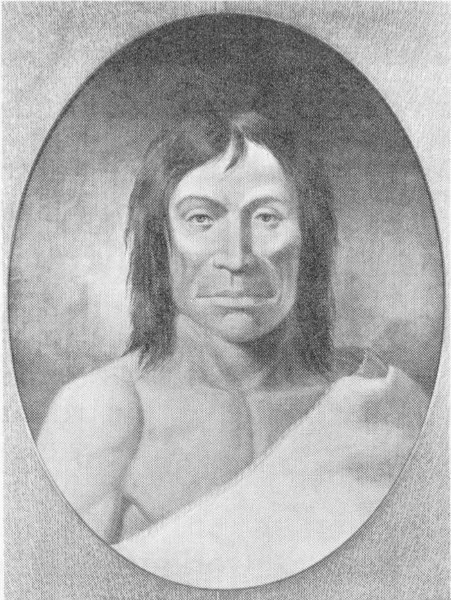

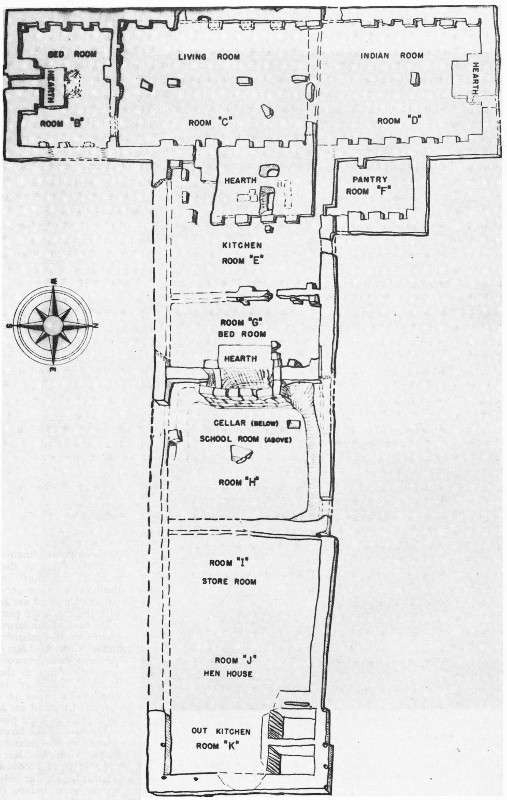

No-horns-on-his-head and Rabbit-skin-leggings, both Nez Percé Indians, were members of the 1831 delegation to St. Louis. Paintings by George Catlin. SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION

In 1831 two neighboring tribes west of the Rocky Mountains, the Nez Percé and the Flathead, sent a delegation of their tribesmen to St. Louis, Mo., to seek the white man’s religion.

Although their understanding of Christianity was slight and confused, they were interested in learning about it. Their own religion was associated with nature, and they assigned power to natural objects. Their spiritual goal was to attune themselves with nature so that they might acquire power that would make them successful in war or hunting. They sought this white man’s religion because, to their minds, it explained the great power possessed by the whites; if they could acquire Christianity, it would increase the power they already had.

In St. Louis the 4-man delegation visited William Clark, superintendent of Indian Affairs, who had passed through their country more than 25 years earlier as one of the co-leaders of the memorable Lewis and Clark Expedition. Myths and legends surround this visit to St. Louis, and the complete story will probably never be 11 known. Yet, it seems probable that they sought the white man’s “Book of Heaven” and teachers to show them how to read and write.

Their visit probably would have passed unnoticed had not a man named William Walker become aware of it. While visiting St. Louis in November 1832, he heard from William Clark the story of the Indian visitors. Becoming enthusiastic about helping the Indians of the far Northwest to become Christians, Walker wrote to a New York friend, G. P. Disoway, giving him a rather unusual version of the facts.

He told how Clark had held a weighty theological discussion with the Indians, despite the fact that they could not speak English and no interpreter could be found at the time. He claimed also to have seen the Indians in the city, though two of the delegation had died and the remaining pair had apparently departed 8 months before Walker’s arrival. He described them as “small in size, delicately formed, small limbed,” and having flat heads. This description hardly fits the stocky, well-built Flathead and Nez Percé, who did not flatten their heads. The famous painter of the West, George Catlin, claimed to have painted portraits of the two survivors of the delegation, and these likenesses indicate the Indians were normally developed. Disoway further flavored the story, and it was printed in New York in the Christian Advocate and Journal, a publication of the Methodist Episcopal Church.

Jason Lee. ANGELUS COLLECTION. UNIVERSITY OF OREGON LIBRARY

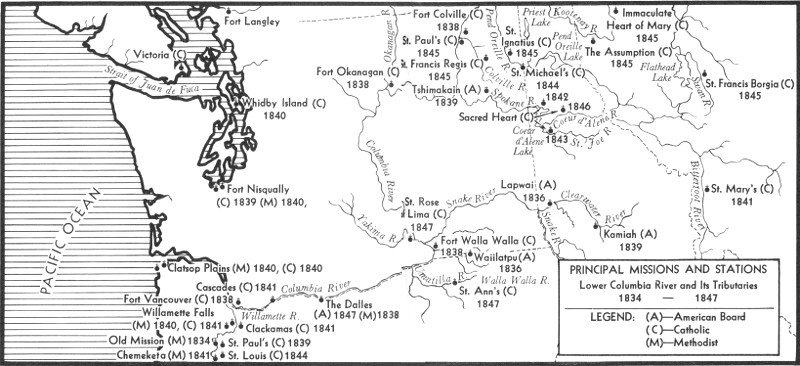

This call from the West was immediately heard by various churches in the United States. Several missionary organizations became active in finding men and women to send to the Pacific Northwest as missionaries. Among them were the Mission Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church; the Roman Catholic Order of the Society of Jesus; and the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, then supported by the Presbyterian, Congregational, and Dutch Reformed Churches.

The first to respond was the Methodists’ Mission Society. In 1834 Jason Lee and four associates joined the Wyeth Expedition and headed for the Northwest. Lee 12 did not stop in Flathead or Nez Percé country but went on to the lower Columbia and selected a site in the beautiful Willamette Valley. The Methodists established their mission near a small French Canadian farming settlement close to present-day Salem, Oreg. These settlers, who originally were trappers for the Hudson’s Bay Company, had turned to farming when the fur trade declined.

Reinforced with 13 new workers in 1836 and 50 additional persons in 1838, the Methodists began missions at The Dalles, the Clatsop Plains, Fort Nisqually, the Falls of the Willamette, and Chemeketa—now Salem.

Samuel Parker. WHITMAN COLLEGE

Their work among the coastal Indians was not very successful. New diseases brought by the whites were fatal to these tribes, and the number of Indians along the Willamette and lower valleys was rapidly declining. 13 Also, they simply were not interested in the “Book of Heaven.” Those who attended services wanted to be paid for coming, for it was not these people who had asked for missionaries. Although Jason Lee was the first missionary, the Nez Percé and the Flatheads were still awaiting a response to their call. The answer was soon to be supplied by another group of missionaries.

“I have had an interview with the Rev. Samuel Parker upon the subject of Missions and have determined to offer myself to the A. M. Board to accompany him on his mission or beyond the Rocky Mountains.” Marcus Whitman, Dec. 2, 1834.

Another man influenced by the Indians’ call was the Reverend Samuel Parker, pastor of the Congregational Church in Middlefield, Mass. Though 54 years of age, married, and the father of three children, Parker volunteered to the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions to go to the Flathead country. Turned down by the Board, Parker moved to Ithaca, N.Y. Early in 1834, he spoke at a special meeting in the Ithaca Presbyterian Church and aroused the congregation to such a high pitch that it was proposed that Parker go to Oregon to select mission sites. This time Parker was able to get the support of the American Board for the undertaking.

Knowing little more about the Pacific Northwest than its general direction, Parker set out in the spring of 1834; but he and two companions arrived at St. Louis too late to accompany the fur-traders’ annual caravan to the Rockies. It was risky to undertake the trip alone, so Parker returned to New York to raise money and recruits for the next year. In December 1834 he reported to the 14 American Board that a Dr. Marcus Whitman had volunteered to serve as a medical missionary.

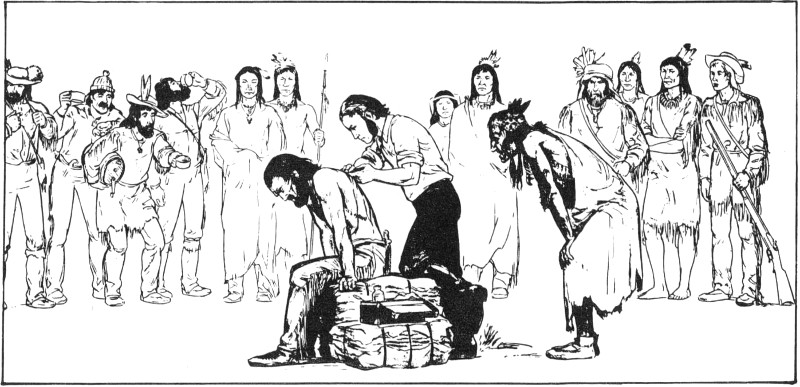

In 1835 Parker and his new recruit, Marcus Whitman, joined the fur-traders’ caravan and headed westward. Not until cholera had broken out and Dr. Whitman’s medical skill had prevented disaster in the caravan did the unholy traders appreciate having the missionaries in their group. On August 12 the party reached the fur-trading rendezvous, which was held that year near the junction of Horse Creek and the Green River in Wyoming. There, once again Whitman was able to display his medical skill. He successfully removed a 3-inch iron arrowhead from the back of the famous mountain man, Jim Bridger, under the watchful eyes of traders, mountain men, and Indians. This exhibition of competence was not lost on the Nez Percé and Flathead. Parker and Whitman talked to them and found that they were indeed anxious to have missions.

To get the missions established by the next year, Whitman decided to return East and organize volunteers for the new field. Parker was to continue on to Oregon, explore for mission locations, and meet Whitman’s party when it reached the rendezvous the next summer.

Parker, traveling with the Nez Percé, reached their homeland on the Clearwater River in present Idaho late in September. Thence he went down the Columbia River to Fort Vancouver, where he spent most of the winter with the Hudson’s Bay Company traders. During the winter and the next spring, he made several trips of exploration in the country between the Clearwater and the Willamette. In the spring of 1836, he learned that the Nez Percé were returning to the rendezvous by a northerly, rugged route. Parker, feeling his years at last, decided to return to the United States by sea. Before the Indians’ departure, he wrote letters for them to carry to the rendezvous. Although Whitman received these letters, it is doubtful if they contained any information of value to the 1836 American Board party. While Parker was at Fort Vancouver, Marcus Whitman, back in New York, had been busy gathering men and money in order to establish the missions in the Oregon country.

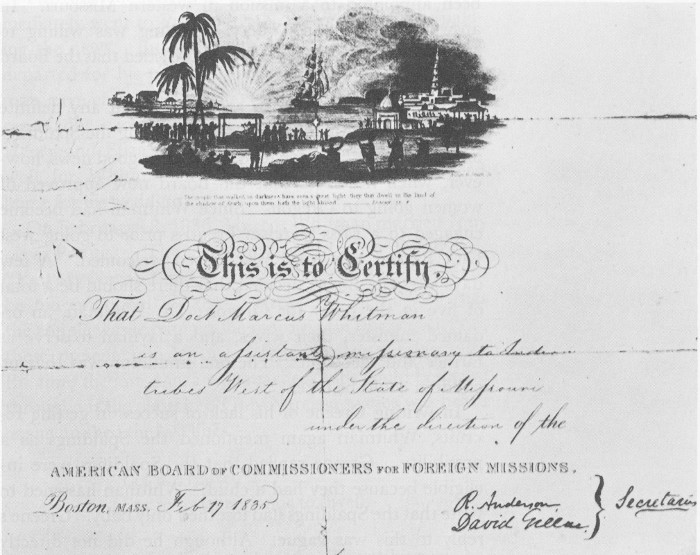

Marcus Whitman’s certificate appointed him “an assistant missionary to Indian tribes West of the State of Missouri.” It was also necessary for the missionaries to get permission from the Secretary of War to visit the Indian lands of western United States.

On his return trip from the rendezvous in 1835, Whitman wrote to Rev. David Greene, one of the secretaries of the American Board, about the need for recruits for Oregon. Greene in his reply told Whitman about two missionaries who had volunteered for the West; he also cautioned Whitman against taking a bride into the wilderness.

As it turned out, neither of the two ministers was able to go to Oregon. But when he arrived home, Whitman learned of a third minister, Henry Spalding, who had just 16 been appointed to a mission in western Missouri. In answer to Whitman’s query, Spalding was willing to change his destination to Oregon, provided that the Board approved.

The year 1835 came to an end without any definite word from the American Board concerning the Spaldings or anyone else. Greene forwarded some good news, however, when he wrote that the Board now approved of women going to Oregon. Since Whitman had become engaged to a Miss Narcissa Prentiss prior to going west with Parker, this word was indeed welcomed. A few days later the Board decided that there should be a total of five in the party for Oregon: Dr. Whitman, an ordained minister, their wives, and a layman to serve as farmer and mechanic. The one limitation was that no children could be taken.

In writing Greene of his lack of success in getting recruits, Whitman again mentioned the Spaldings as a possibility. Greene replied that the Spaldings were ineligible because they had a child. Whitman hastened to write that the Spaldings had lost their only baby. Greene’s reply to this was vague. Although he did not directly state that the Spaldings could go, he noted that he did not know who else would be available.

THE WHITMAN-SPALDING ROUTE

from St. Louis to Fort Vancouver

1836

This was enough for Whitman to act upon. He immediately went to Prattsburg, N. Y., to tell Henry Spalding the news. But he was too late. Spalding had just departed for his post in Missouri. Undismayed, Whitman gave chase and overtook the Spaldings on the road, reportedly exclaiming, “We want you for Oregon.” Henry and Eliza accepted the call and continued on to wait for Whitman in Cincinnati. Whitman returned home for his wedding.

On February 18, 1836, Marcus Whitman married Narcissa Prentiss. The ceremony closed with the hymn, “Yes, My Native Land! I Love Thee.” This proved to be too emotional for the congregation. Knowing that the couple was leaving in the morning for distant Oregon, those present, one by one, faltered in the singing. By the time the last stanza was reached, sobs could be heard throughout the church. Only Narcissa’s voice was heard as she finished the last lines:

Let me hasten

Far in heathen lands to dwell.

The call had finally been heard. The Whitmans began the long trip to the land beyond the Rockies.

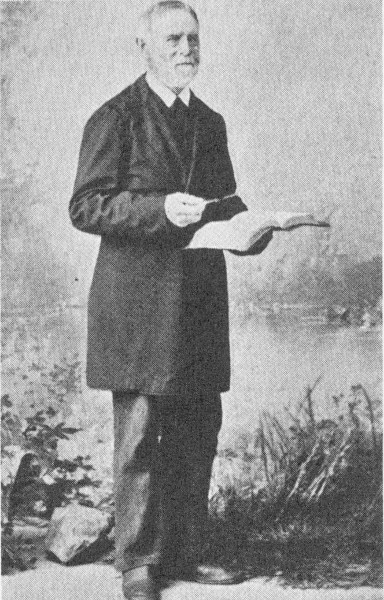

Henry Harmon Spalding, from a photograph taken several years after the massacre. WHITMAN COLLEGE

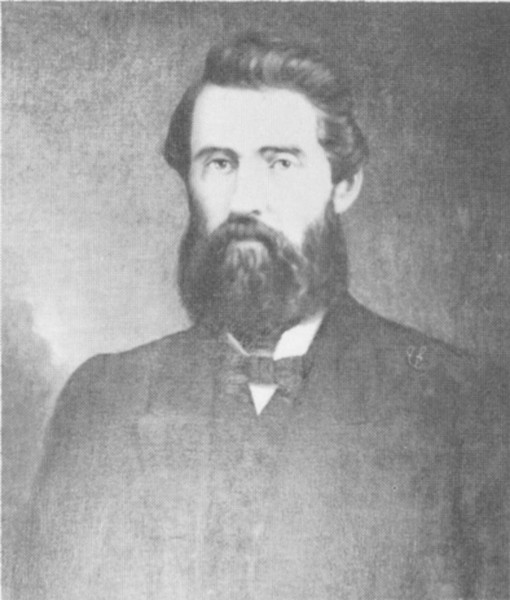

William Henry Gray. WHITMAN COLLEGE

On March 31, 1836, the Whitmans and Spaldings left St. Louis aboard the Chariton for Liberty, Mo., the jumping-off place for the West. In Liberty they were joined by the fifth member of the party, William H. Gray.

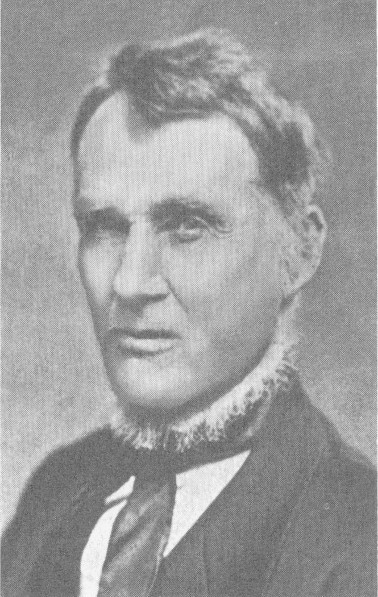

Marcus Whitman’s experience, gained in the preceding year on his trip to the Rockies, together with his dedication to the purpose of the trip, made him the natural leader of the little group. Born in 1802 in Rushville, N.Y., Marcus was 8 when his father died, and the boy then went to live with an uncle. Following classical school, he had hoped to prepare for the ministry. But a lack of money and his family’s disinterest in this career caused him to turn to medicine.

Whitman began riding with the local doctor, and in 1825 he entered a medical school in Fairfield, N.Y. Following practice in New York and Canada, Whitman settled in the town of Wheeler, N.Y. Before long, he became interested in medical missionary work. He concluded that his medical training and religious interests could be well combined in this field. His first application to the American Board for a mission assignment was turned down because of poor health. But after Dr. Samuel Parker interviewed him in 1835, the Board reconsidered and selected Marcus as a medical missionary.

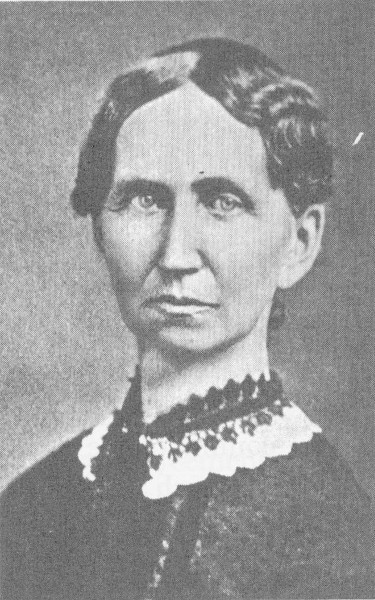

Narcissa Whitman was in many ways a contrast to her husband. Though he was sober and serious, Narcissa was animated and vivacious. Attractive in face and figure, endowed with a fine voice, she was a person of confidence and poise. Born in Prattsburg, N.Y., in 1808, Narcissa Prentiss attended Emma Willard’s “Female Seminary” in Troy and afterwards Franklin Academy in Prattsburg. She taught school for several years and then applied for the mission field. In her first attempt she too was turned down by the Board. It did not want single women for missionary work. But after her engagement to Marcus, the Board approved her application. The trip to Oregon was her honeymoon.

Riding with Marcus and Narcissa was a man whose marriage proposal Mrs. Whitman is said to have once 19 turned down, the Reverend Henry Harmon Spalding. Spalding was born at Bath, N.Y., in 1803, the child of an unwed mother. Bound out to foster parents at 14 months, he endured an unhappy childhood. The jeers and name-calling to which he was subjected by his stepfather and others left a bitter memory. By nature he was shy, quick tempered, and impatient with those who disagreed with him.

Spalding attended Franklin Academy, where he first met Narcissa Prentiss. After Franklin, he attended Western Reserve College in Hudson, Ohio and Lane Theological Seminary in Cincinnati. Upon completion of his studies, he was ordained in the Presbyterian Church. In 1831 he met Eliza Hart of Holland Patent, N.Y., and they were soon married.

Born in 1807 in Kensington, Conn., Eliza Hart grew into a studious and deeply religious person. In appearance she was tall, dark, and coarse of feature and voice; but she had a quiet charm that endeared her to those who knew her. Of them all, Eliza was best fitted by temperament to work among the Indians, but even she did not realize that the Indians’ first loyalty was to themselves and not to the whites and their ways.

William H. Gray, appointed to the Oregon mission as mechanic and carpenter, was born in Fairfield, N.Y., in 1810. His father died when William was 16, and he was apprenticed to a cabinetmaker. His best talents were in the use of his hands, but his ambitions always exceeded ordinary callings. His manual skills were to be of value to the missionaries, but his undependable temper and habit of complaining were to lead to serious complications for the missions of Oregon.

At Liberty, Mo., these five now made their final preparations for the trip across the Great Plains and over the Rockies to the still-strange land called Oregon in order to bring their faith to the Indians.

The camera had not made its appearance in the Pacific Northwest before the deaths of Marcus and Narcissa Whitman. Though artists visited the mission before the massacre, no known likenesses of the Whitmans have ever been found. Thus the few sketches that have been made of Marcus and his wife are conjectural drawings, the better ones based on descriptions written by those who knew them.

The tide of European adventurers and explorers had long pressed upon the Pacific Northwest coast. Britain, 20 France, Russia, Spain, and that fledgling nation, the United States, made claims along the rock-strewn shores as they searched for the elusive Northwest Passage between the two oceans and grasped for the wealth offered by the pelts of the sea otter.

Early in the 19th century overland explorers from Britain and the United States began mapping the vast area that stretched from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific and from the Russian settlements in the north to Spanish California. This was the Oregon Country. Alexander Mackenzie, Simon Fraser, and David Thompson made their way overland for the British crown. In 1804 President Thomas Jefferson sent an expedition led by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to find a route to the Pacific.

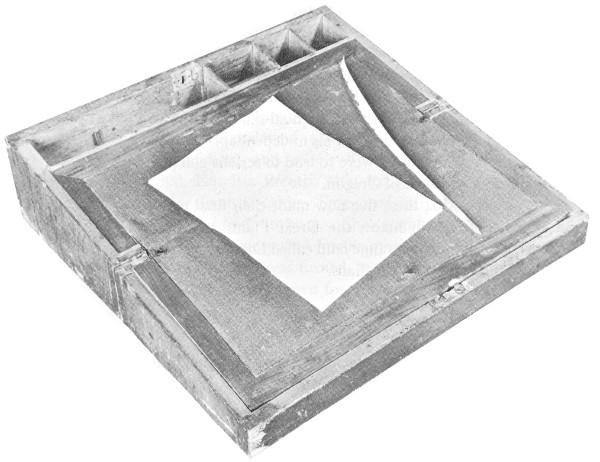

Narcissa Whitman’s portable writing desk and quill pen. OREGON HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Soon came the fur-trading companies, competing furiously for beaver pelts and thereby exploring much of the Northwest and strengthening national claims. Working its way down the Columbia River, the Canadian-based North West Company dominated the area between 1807 and 1821. John Jacob Astor challenged it briefly when his Pacific Fur Company established Fort Astoria at the mouth of the Columbia. In the American Rockies another company organized by Astor, the American Fur Company, obtained a virtual monopoly in that region by 1835.

text continued on page 24

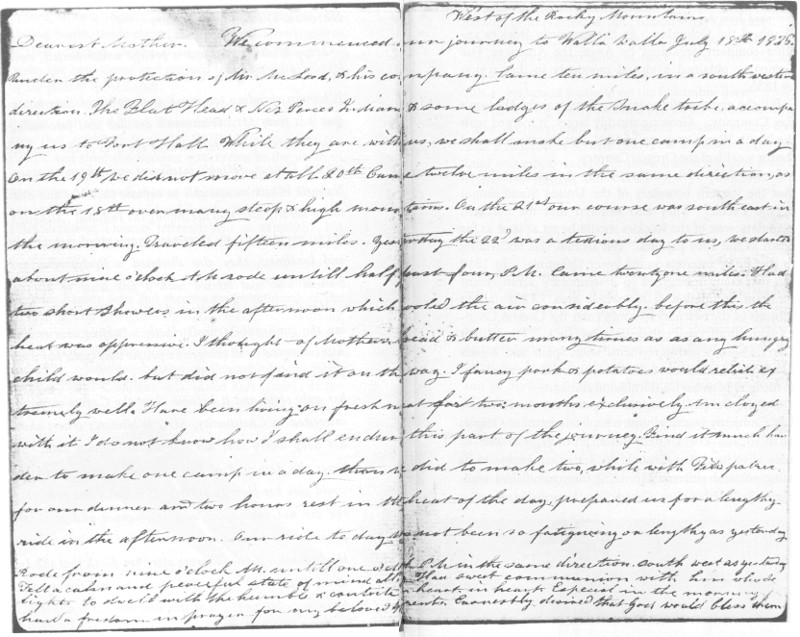

Narcissa Whitman’s Letters

Mary Walker, who was a prolific writer herself, once recorded in her diary a cutting remark about Narcissa Whitman spending too much time writing letters home. But it is from Mrs. Whitman’s detailed and fascinating letters that we get a close view of the lives of the missionaries in Oregon. Highly intelligent and a keen observer, Narcissa Whitman was able to capture the color and drama of her trip west and life among the Indians. Although her letters increasingly recounted moments of melancholy and loneliness, they also disclosed a lively, vivacious woman who was blessed with a fine sense of humor.

Her diary—really a series of letters written while crossing the continent—reveals clearly a lady of charm who was interested in all things and people who came her way. Later, in the Pacific Northwest, when death had taken her only child and it became clear the Cayuse were not interested in Christianity, Mrs. Whitman’s letters show her deep worry over her role in the mission field. At times she despaired of her own worth and wished she could give her place to others. It is likely, however, that she did not realize her own intelligence and relatively sophisticated personality were a barrier between her and the Indians. A friend wrote after her death that the Indians considered Mrs. Whitman to be remote and haughty. He added that this was not her fault; it was her misfortune.

A page from one of Narcissa Whitman’s letters written to her

family while crossing the continent. It was this series of long, detailed

letters that became famous as her diary.

747-534 O-64-2

WHITMAN COLLEGE

West of the Rocky Mountains.

Dearest Mother. We commenced our journey to Walla Walla July 18th 1825. Under the protection of Mr. McLeod, & his company. Came ten miles, in a southwestern direction. The Flat Head or Nez Perce Indians & some lodges of the Snake tribe, accompanying us to Port Half White—they are with us, we shall make but one camp in a day. On the 19th we did not move at all. 20th Came twelve miles in the same direction, as on the 18th over many steep & high mountains. On the 21st our course was southeast in the morning. Traveled fifteen miles. Yesterday the 22d was a tedious day to us, we started about nine o’clock And rode untill half past four, PM. Came twenty one miles. Had two short showers in the afternoon which cooled the air considerably, before this, the heat was oppressive. I thought of Mother’s bread & butter many times are as any hungry child would, but did not find it on the way. I fancy pork & potatoes would relish extremely well. Have been living on fresh meat for two months exclusively. Am cloyed with it. I do not know how I shall endure this part of the journey. Find it much harder to make one camp in the day, than we did to make two, while with Fish for our dinner and two hours rest in the heat of the day, prepared us for a lengthy ride in the afternoon. Our ride to day has not been so fatiguing or lengthy as yesterday. Rode from nine o’clock AM. until one o’clock PM in the same direction, south west as yesterday. Felt a calm and peaceful state of mind all day. How sweet communion with him who delights to dwell with the humble & contrite heart, in heart. Especial in the morning I had a freedom in prayer for my beloved parents. Earnestly desired that God would bless them

continued from page 20

But the giant of all the trading firms was the Hudson’s Bay Company. Growing steadily larger, it merged with the North West Company in 1821 and thereby inherited the fur wealth of the Oregon Country.

In the early 19th century, many Americans believed that the western boundary of the United States should be the Pacific. They also believed that the northern boundary west of the Rockies should be set at least as far north as the 49th parallel. But Britain was not willing to give up its interests on the lower Columbia. In 1818 the two countries agreed to a temporary arrangement for joint occupation of the whole area. Citizens and subjects of the two nations could enter the Oregon Country without affecting either nation’s claims. The United States also reached agreements with Spain and Russia that resulted in these two countries surrendering all claims to the land between California and Alaska.

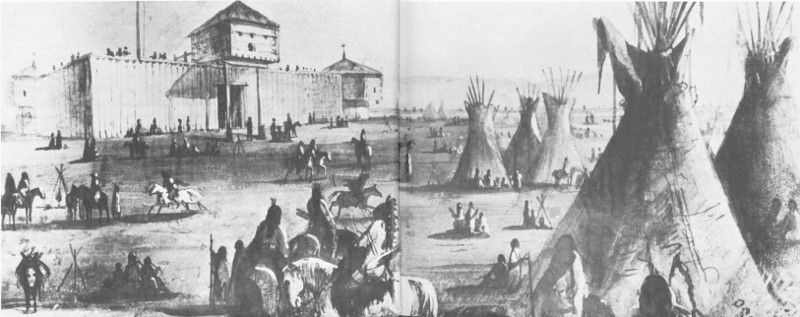

Alfred Jacob Miller’s painting of the first Fort Laramie. In 1836 it was still called Fort William.

Despite the joint-occupation agreement, the Hudson’s Bay Company was in almost complete control of Oregon after 1821. The United States, however, was able to keep alive its claims through the activities of some of its more colorful citizens. In 1828 the magnificent trailblazer Jedediah Smith visited Fort Vancouver, the Columbia 25 headquarters of the Hudson’s Bay Company. A few years later Capt. Benjamin Bonneville explored and trapped the western slopes of the Rockies. In 1832 and 1834 Nathaniel Wyeth attempted unsuccessfully to establish a permanent foothold on the Columbia River.

This was the Oregon Country to which the missionaries came. Other than the scattered Hudson’s Bay forts and a handful of settlers near Fort Vancouver, the vast land was empty except for the transient trappers and, of course, the Indians.

Spalding and Gray, driving the livestock overland, set out from Liberty on April 28, 1836. Whitman and the two wives waited for a steamer to take them to the assembly point of the American Fur Company caravan farther upriver. But the steamboat failed to stop, and Whitman had to hire a wagon and make a hurried pursuit of Spalding. Reunited, the missionaries caught up with the caravan near the junction of the Platte River and the Loup Fork in Nebraska on May 26.

Traveling 15 to 20 miles a day, the caravan crossed the dusty plains toward Fort Laramie. There the missionaries left the heavy wagon and, discarding excess baggage, repacked their goods on animals. They decided to take 26 Spalding’s light wagon as far as they possibly could.

On July 4 the caravan crossed the Continental Divide at South Pass and, 2 days later, reached that year’s fur-trapper rendezvous on the Green River, near Daniel, Wyo. While Narcissa enjoyed the excitement and tumult of the colorful affair, the quieter Eliza concentrated on learning the Indians’ languages.

Dismayed by Parker’s failure to return to the rendezvous, the missionaries were relieved by the unexpected arrival of two Hudson’s Bay Company traders, John McLeod and Thomas McKay. Guided by these two experienced men, the missionaries set out on the 700-mile journey through sagebrush, desert, canyons, and mountains to the Columbia. Stopping at Nathaniel Wyeth’s Fort Hall only overnight, the party moved westward along the south bank of the Snake River. The wagon finally broke down, and the men had to convert it into a two-wheeled cart. Two weeks later on August 19, they reached Fort Boise, a Hudson’s Bay Company post on the Snake River.

No wagon or cart had ever come this far west before, but here Whitman and Spalding were finally forced to abandon their cart. After a few days’ rest, the party moved on. Following the Powder River and crossing the beautiful Grande Ronde Valley, the missionaries reached the rugged, twisted Blue Mountains. Riding ahead to the crest, the Whitmans had their first view of the Columbia valley with majestic Mount Hood on the far horizon.

On the morning of September 1, the Whitmans excitedly galloped up to the gate of Fort Walla Walla, the Hudson’s Bay Company post on the Columbia. They were met by Pierre Pambrun, the chief trader, who was to be their near and good neighbor for the next few years. Two days later the Spaldings arrived with the livestock.

Needing household goods and wanting to meet the Chief Factor, Dr. John McLoughlin, the party decided to go to the Hudson’s Bay Company western headquarters at Fort Vancouver, more than 200 miles down the Columbia. Reaching the fort by boat on September 12, the missionaries completed their long journey 207 days 27 after their departure from Angelica, N. Y. On the move for more than 6 months, and traveling more than 3,000 miles, Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spalding had crossed the North American Continent—the first white women to do so.

The stern but kindly Dr. McLoughlin gave the missionaries a warm welcome. He appreciated the significance of the ladies’ successful journey across the continent. While complimenting them on this, he must have thought to himself that they were but the vanguard of many American families to follow.

Dr. John McLoughlin, Chief Factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company in Oregon, exercised vast sway over an area extending from British Columbia to western Montana. Physically a giant and of an imperious nature, he was to the Indians “The White Eagle.” On their arrival at Fort Vancouver Narcissa wrote: “I feel I have come to a father’s house indeed, even in a strange land has the Lord raised up friends.” OREGON HISTORICAL SOCIETY

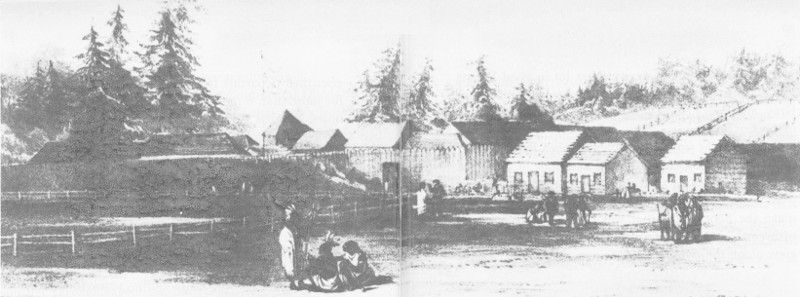

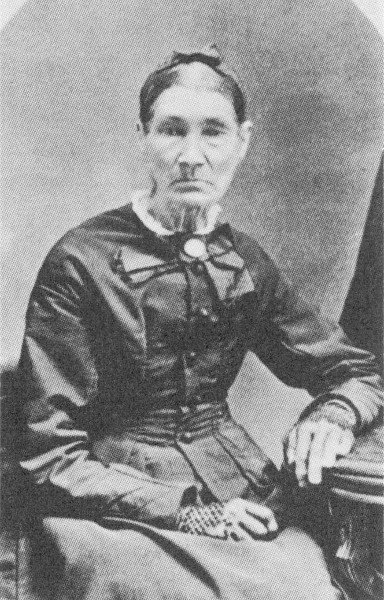

Fort Vancouver, sketched by Henry J. Warre in 1845. WASHINGTON STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

To the surprise of the party, McLoughlin’s stores contained most of the articles needed to establish the missions: household furniture, clothing, building supplies, books and provisions; all were for sale. Narcissa wrote home that it was not necessary to bring anything from the East, for everything could be found at Fort Vancouver, “the New York of the Pacific Ocean.”

While the ladies enjoyed the hospitality of the fort, Whitman, Gray, and Spalding went back up the Columbia to select their mission sites. With their husbands away, the two women caught up on their correspondence, sewed clothing, and picked out the household utensils they would need. Narcissa spent her evenings singing to the children at the fort school. On November 3 Spalding returned to escort Narcissa and Eliza to their new homes in the interior.

If McLoughlin had been cool toward the missionaries, such behavior could have been justified. The influx of Americans that was bound to follow would inevitably change Oregon. British control would then be threatened and fur trade profits reduced. Nevertheless, McLoughlin, Pambrun, and other Hudson’s Bay Company people extended a helping hand to the missionaries. Such success as the missions had in the Pacific Northwest was due, in good part, to the assistance they received from the company.

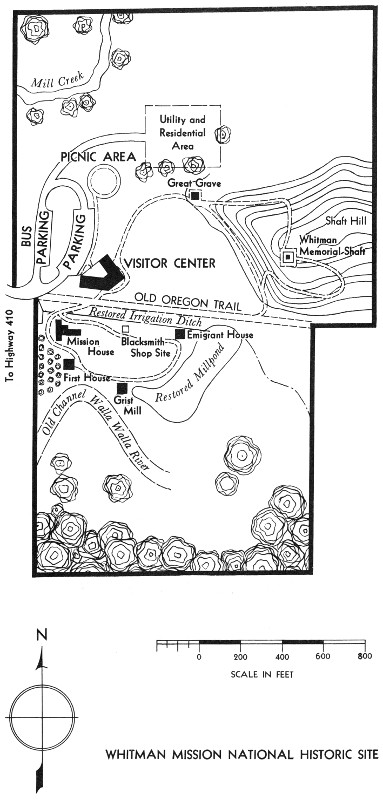

On the north bank of the Walla Walla River, 22 miles upstream from its junction with the Columbia, Marcus Whitman selected the site of his mission on the lands of the Cayuse Indians. Henry Spalding picked a site 110 miles to the east on Lapwai Creek, 2 miles from its confluence with the Clearwater; the Nez Percé tribe at last had a missionary.

Whitman selected Wai-i-lat-pu, “the place of the rye grass,” for several reasons. Close to Fort Walla Walla at the mouth of the river, Waiilatpu was near both a source of supply and the main travel route between Canada and Fort Vancouver. Whitman must have realized, too, that its location was on the line of march between South Pass in the Rockies and the Columbia, the trail that Americans would surely follow. In addition, it was the home of the Cayuse Indians, a “heathen” tribe that in the minds of the missionaries needed to be saved as much as any.

For his wife’s arrival from Fort Vancouver, Whitman built a crude log lean-to as a shelter against the oncoming winter. When Narcissa arrived at Waiilatpu on December 10, she found that the little structure had two bedrooms, a kitchen, a pantry, and a fireplace, but was still without windows and doors. Narcissa, though expecting 30 her first child, accepted her lot in good humor and set out to make a home. Meanwhile, Whitman, Gray, and their helpers worked steadily on the main part of this first house.

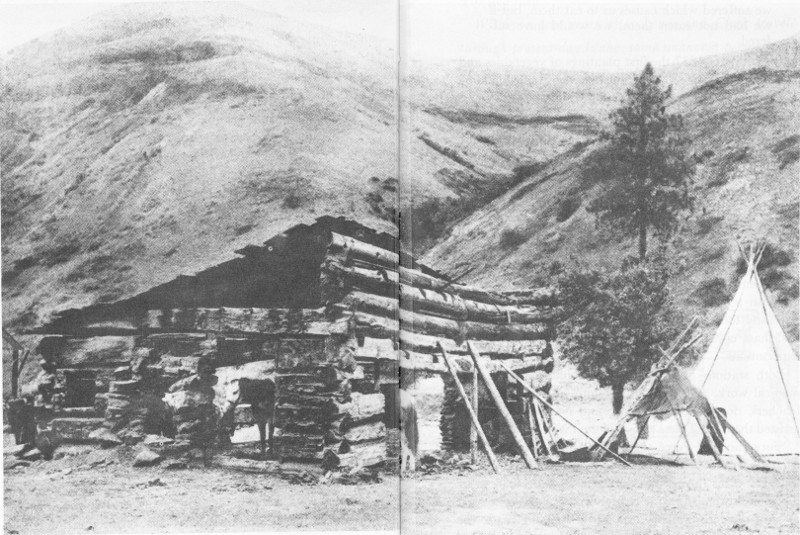

This photograph of the Spalding mission cabin at Lapwai—now called Spalding—was taken in 1900.

Because of the scarcity of suitable timber, the main part of the one-and-a-half story house was made of sun-dried adobe bricks. With great difficulty, enough pine boards were whipsawed in the Blue Mountains 20 miles away to make the floor. The roof was made of poles covered with earth and rye grass. From the cottonwoods that grew along the river, some furniture was made. Pierre Pambrun contributed by sending a small heating stove and a rocking chair from Fort Walla Walla. Bedsteads were boards nailed to walls, and, except for a feather tick Narcissa had acquired at Fort Vancouver, corn husks and blankets served as mattresses.

But even before it was finished, the first house was flooded by the Walla Walla River, just a few feet away. After a second flood, Whitman reluctantly decided that it would be necessary to build again on higher ground. Work was begun on the new T-shaped mission house in 1838. A few years later, the abandoned first house was 32 torn down, and its adobe bricks were used to build a blacksmith shop.

During the first year, the missionaries depended on the Hudson’s Bay Company for provisions to tide them over to their first harvest. From Fort Vancouver, Fort Walla Walla, and Fort Colville (in northeastern Washington), they bought pork, flour, butter, corn, and potatoes. Occasionally the Indians sold them fish and venison.

Horses purchased from the Cayuse provided steaks and stews. As Dr. Whitman put it:

we have killed and eaten twenty-three or four horses since we have been here, not that we suffered which causes us to eat them, but if we had not eaten them, we would have suffered....

In the spring of 1837 the first plantings of vegetables and grains were made. Also in that first year, both Spalding and Whitman planted apple orchards.

At the same time, the missionaries began their efforts among the Indians. Both men encouraged the Cayuse and Nez Percé to start cultivation of the soil. Although the Cayuse had an epidemic of sickness at this time, some of the families did plant crops before departing for the hill valleys to dig camas bulbs in the early summer of 1837. Whitman was greatly encouraged by this hesitant start. He wrote: “When they have plenty of food they will be little disposed to wander.” He greatly desired to lead them from their nomadic ways and to have them establish settled communities. But the Indians lacked skills and tools, and the results of their farming were far less than either their enthusiasm or the missionaries’ expectations.

Both stations also began educational, spiritual, and medical work. Spalding and Whitman were preachers, teachers, doctors, and farmers; and Narcissa and Eliza assisted them in all these phases of their work.

Since the Nez Percé tongue was understood by both tribes, it was used as the language of instruction at both stations. This meant that only one alphabet had to be devised and that the same written material could be used at both missions. Henry and Eliza Spalding made the most progress in mastering the difficult Indian tongue, and they took the lead in forming the alphabet and translating material. However, by the autumn of 1837 Marcus and Narcissa had learned enough Nez Percé to begin their school.

text continued on page 34

Nez Percé

The Nez Percé Indians called themselves the Nimipu, “The People.” Lewis and Clark, the first whites to travel through the Nez Percé country, called them by two names, the Chopunnish and the Pierced Nose Indians. But available records indicate that very few, if any, of these Indians pierced their noses. Such a custom was common with the Pacific Coast tribes who decorated their noses with sea shells.

Within a few years after Lewis and Clark traveled through present-day Idaho, some unknown person, probably a French-Canadian trapper, changed Pierced Nose to Nez Percé and so the name has come down to us today. The accent over the final “e” is no longer pronounced; Nez is pronounced as it looks, Percé is pronounced “purse.” Though some writers no longer use the accent, its usage is considered to be correct by most.

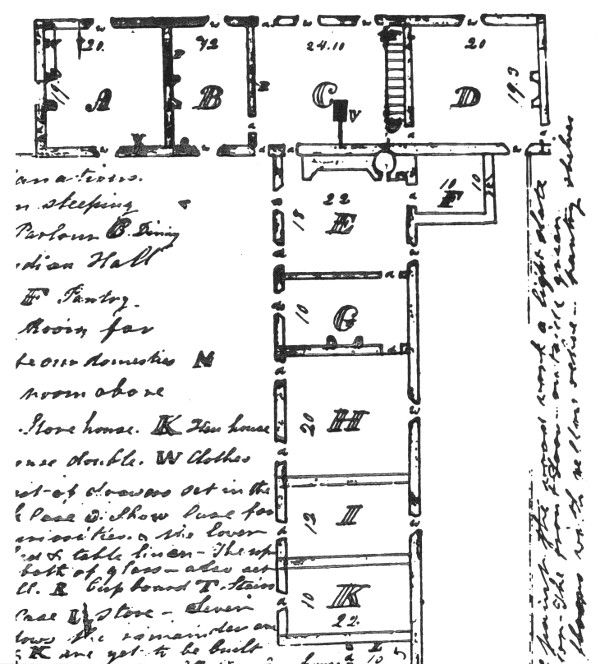

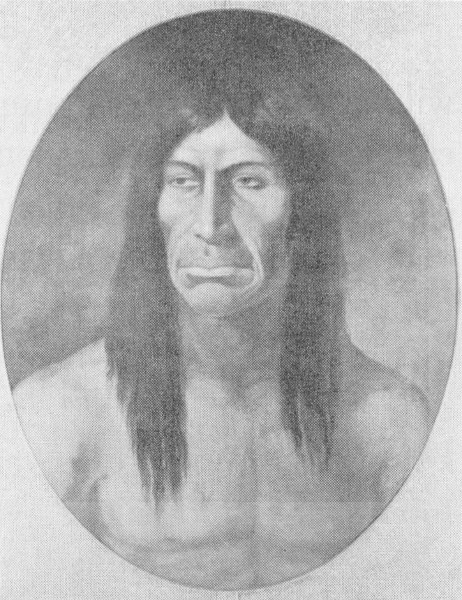

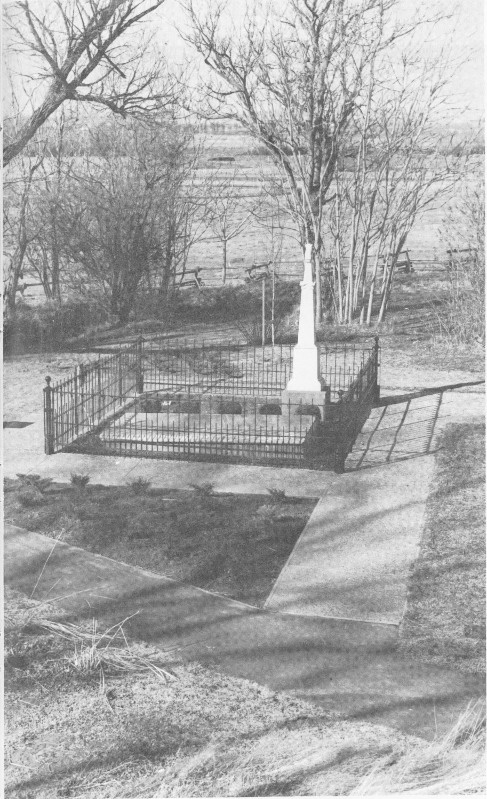

Narcissa sent this floor plan of the mission house to her mother while the house was still being built. Room A, which was to be her bedroom, was not constructed. Instead, room B was used for that purpose.

continued from page 32

Religious instruction was commenced promptly at both Waiilatpu and Lapwai. The Spaldings held daily prayers and conducted worship on Sundays. Handicapped by their slowness at learning the language, the Whitmans resorted mainly to encouraging the Indians to continue their daily prayer meetings, which some of them, inspired by fur traders, had been attending before the missionaries arrived.

Although Whitman was the trained doctor, Spalding also administered to the sick. At first, the Indians were receptive to white medicine; but it was medicine that was later to become a major issue of contention between the Indians and the missionaries. For the time being, however, an encouraging start had been made. The Nez Percé seemed truly happy to have the Spaldings in their midst, while the Cayuse, though less enthusiastic, accepted the Whitmans at Waiilatpu. What were these people like, whom man and wife had come 3,000 miles to convert and civilize?

The Cayuse tribe numbered little more than 400 when the Whitmans settled among them. Located principally on the upper Walla Walla and Umatilla Rivers, they had many contacts with their neighbors, the Nez Percé, Walla Walla, and Umatilla Indians. They were related to these tribes through marriage and through a common culture. Originally of a different language family than the surrounding tribes, the Cayuse were by 1836 an integrated part of the Columbia plateau culture.

The social organization of the tribe was a loose one. The basic unit was the family, which was headed by an autocratic father whose decisions were final and whose authority was independent of the chiefs or elders. 35 Several families formed a band, and several of these bands made the tribe. There was no head chief for the whole tribe; rather, each band had its own chief who held his position by inheritance, merit, or wealth, or by a combination of these. A chief was an influential person, but he was not a dictator over the actions of his band. For hunts or warfare, a chief would often turn over his leadership to the most experienced hunters or warriors. In addition, each band had a group of elders who offered advice and, to some extent, managed the common affairs of the band under the direction of the chief.

Like the Nez Percé, the Cayuse were adept at selective horse breeding. Large horse herds enriched the tribe and gave it power that far exceeded its small size. The horses also gave these Indians great mobility. In the appropriate seasons, they crossed the mountains to the east to hunt and rode down the Columbia to fish at Celilo Falls.

Hunts were composed of organized parties which pursued deer, American elk, pronghorn, bison, and smaller animals. Meat that was not eaten fresh was made into a highly concentrated, nutritious pemmican. During the salmon runs, nets, weirs, spears, hooks, and baskets were all used to catch the big fish. The Cayuse women roasted the fresh salmon on sticks or sun-dried, pulverized, and packed the fish in baskets for winter use. In addition, the Cayuse collected berries and roots in the mountains. Berries were preserved by being pressed into dry cakes or by being mixed with pemmican. Camas bulbs were dug in large quantities, steamed in pits, and formed into cakes that were dried in the sun. These cakes were eaten as bread, boiled into mush, or cooked with meat.

The Plateau Indians, though excellent hunters, were not as warlike as those on the Great Plains. Nonetheless, they fought with skill and bravery when forced to do so. The one traditional enemy of the Cayuse was the Snake tribe, which lived to the southeast. According to the Cayuse, the Snake people had forbidden them to hunt in the Blue Mountains. In retaliation, the Cayuse attempted to keep the Snakes from the fisheries and trading places along the Columbia.

For generations the Northwest Indians had traded among themselves. The Cayuse, with their wealth of horses, played an active role in this trade. They exchanged horses, robes, and reed mats for the shells, trinkets, and root foods of the coastal Indians. After the fur trade started, the Cayuse bartered their goods for blankets, guns, and ammunition.

Early observers saw the Cayuse from different points of view. Some considered them to be haughty, restless, and perhaps undependable. Others were favorably impressed by them. One such was Joel Palmer who wrote in his journal in 1845:

These Indians have decidedly a better appearance than any I have met; tall and athletic in form, and of great symmetry of person; they are generally well clad, and observe pride in personal cleanliness....

In dress, the Cayuse were similar to all the Columbia Indians. Lightly clad during the hot summer, they dressed in the skins of deer, elk, and bighorn in the winter. They protected their feet with moccasins, and Cayuse men wore leather leggings. Clothing was commonly decorated with fringes, feathers, quills, beads, shells, and colored cloth. Some of these garments were elaborate and extremely colorful. Following contacts with the white traders, the Indians often supplemented their costumes with articles of European manufacture.

Their homes were usually oblong lodges, from 15 to 60 feet in length. The larger lodges were multi-family dwellings. Within the lodge, each family had its own fire and a modicum of privacy. They also lived in tepees of a style borrowed from the Plains Indians. The frames of both lodge and tepee were covered with well-woven reed mats or buffalo hides.

Since it was their wives who put up and took down the lodges and tepees, and who did most of the work in the village, the men were interested in finding a healthy, strong wife. A man bought his wife, or wives, the price often depending on her capacity for work. Should a marriage not work out, it was a simple matter for either 37 the husband or wife to dissolve the marriage and go separate ways. Prostitution was rare, and wives were generally more faithful than those of the coast Indians.

Mary Walker.

Elkanah Walker.

Cushing Eells.

Myra Eells.

747-534 O-64-3 ALL: WHITMAN COLLEGE

The Cayuse and other tribes of the Columbia Plateau made their first contact with Christianity through fur traders. Many of the employees of the Hudson’s Bay Company were Roman Catholics—French Canadians 38 and Iroquois. Although the company did not at first bring priests into Oregon for its employees, the Indians learned a little about the new faith from these Hudson’s Bay men. Also, the Hudson’s Bay Company sent a few Indian boys to an Anglican mission school at the Red River Settlement in Canada.

These were the Indians among whom the Whitmans settled. Proud of their heritage, the Cayuse were yet interested in new things and the new ideas that the Whitmans introduced. Because of their age-old beliefs, they were not willing to completely surrender their own way of life.

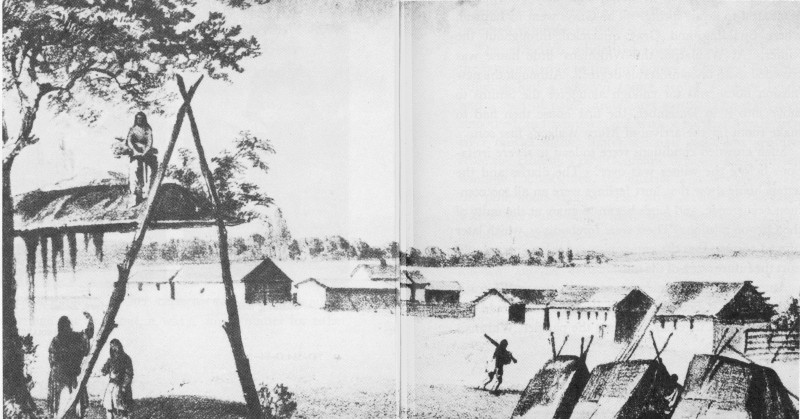

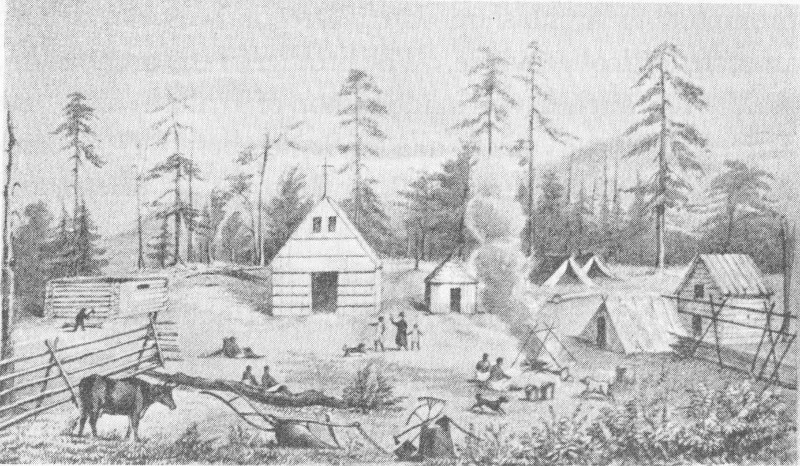

J. M. Stanley sketched this view of the Tshimakain mission in 1853. In the left foreground is an Indian burial on poles.

The arrival of the missionaries resulted in new stresses and emotions among the Cayuse. Problems were created which neither the Indians nor the whites fully understood. Previously the Cayuse had been able to survive the challenges of their environment. But the old ways were to prove inadequate in surmounting the new difficulties, real or imagined, that arose with the coming of the white man. The missionaries, too, found much that was 39 strange in their new surroundings and strove to adjust themselves to the primitive land.

Their first, short winter at Waiilatpu passed swiftly for the missionaries. But by summer a dissatisfied and restless William Gray left Oregon, without Whitman’s knowledge but with Spalding’s approval, to visit the East. Gray was unhappy with his position of mechanic and helper to the mission. He was ambitious to become a missionary in his own right, but neither Whitman nor Spalding felt he was qualified for such work. In Boston, Gray was coolly received by the American Board, but the trip gained him two things: he attended medical college briefly, and he married Mary Augusta Dix.

At this time the American Board was recruiting the only reinforcements it was to send to Oregon. In March 1838 Gray and his wife joined this group, and the party 40 headed overland for Oregon. Besides the Grays there were tall, shy Elkanah Walker and his cheerful wife, Mary; serious-minded Cushing Eells and his frail-looking wife, Myra; and fault-finding but intelligent Asa Bowen Smith and his sickly Sarah. Before they reached St. Louis, they were joined by Cornelius Rogers, a bachelor. In addition to the usual hazards, the journey was complicated by a clashing of strong personalities. One thing the new missionaries agreed upon, however, was that none of them wished to be assigned to the same station as William Gray.

Upon the new missionaries’ arrival at Waiilatpu, a meeting was held to decide a course for the future. Agreement was soon reached on the composition of the stations. The Grays were to join the Spaldings at Lapwai. The Smiths and Cornelius Rogers were to stay with the Whitmans. The Walkers and Eellses, the two couples among the newcomers who got along best, were to open a new station to the north among the Spokan Indians near Fort Colville. But these plans were to be changed in part.

Walker and Eells visited the Spokan tribe that autumn and selected a site at Tshimakain (“the place of springs”). But winter was close at hand, and they returned to Waiilatpu to await spring. The Grays went to Lapwai, where Spalding and Gray quarreled throughout the winter. At Waiilatpu, the Whitmans’ little house was crowded to an uncomfortable degree. Although the new mission house was far enough along for the Smiths to move into it in December, the first house then had to make room for the arrival of Mary Walker’s first son.

Such crowded conditions were to lead to severe irritations before the winter was over. The diaries and the letters home show that hurt feelings were an all too common occurrence, and feuds began to gnaw at the unity of the Oregon mission. There were forebodings, which later proved correct, that the antagonisms of that winter would hurt the future work of the missionaries.

Among the disagreements was one between Whitman and Smith. It became evident that the two would not be able to work together. Always the pacifier, Whitman 41 took the initiative by offering to leave Waiilatpu and begin a new station. But the arrival of spring brought a new spirit of cooperation. The Walkers and Eellses left for Tshimakain, and Whitman and Smith patched up their relations. Nevertheless, they did separate; but it was the Smiths who left. Asa and his wife moved to Kamiah, 50 miles up the Clearwater from Spalding, where they began a new mission among the Nez Percé. By the summer of 1839 there were four American Board stations in Oregon: Waiilatpu among the Cayuse; Lapwai and Kamiah among the Nez Percé, and Tshimakain in the country of the Spokan. Of these, the one most fully developed and the one destined to be the center for the Oregon field was Waiilatpu.

The number of people at Waiilatpu in the winter of 1838-39 convinced Whitman that work on the new mission house had to be speeded up. Fortunately, he was able to hire Asahel Munger, who was a skilled carpenter. Munger had come out to Oregon as an independent missionary only to find that a person could not be independent in that vast, unsettled country. He eagerly accepted Whitman’s offer.

The attractive, substantial mission house was built of the same materials as the first house. The new, T-shaped building had a wooden frame, walls of adobe bricks, and a roof of poles, straw, and earth. The walls were smoothed and whitewashed with a solution made from river mussel shells. Later, enough paint was acquired from the Hudson’s Bay Company to paint the doors and window frames green, the interior woodwork gray, and the pine floors yellow. The main section of the house was a story-and-a-half high with three rooms on the ground floor and space for bedrooms above. From it extended a long, single-story wing which contained a kitchen, another bedroom, and a classroom. An out-kitchen, storeroom, and other facilities were later added to the wing.

text continued on page 48

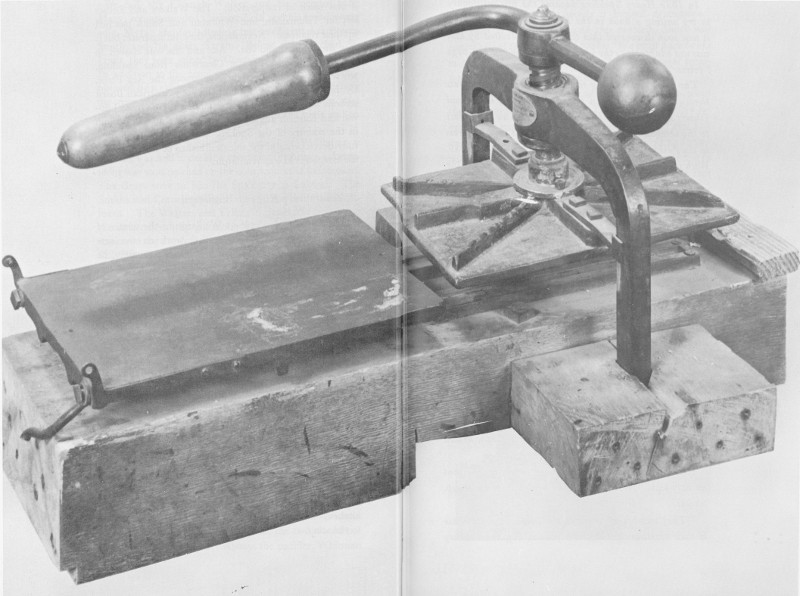

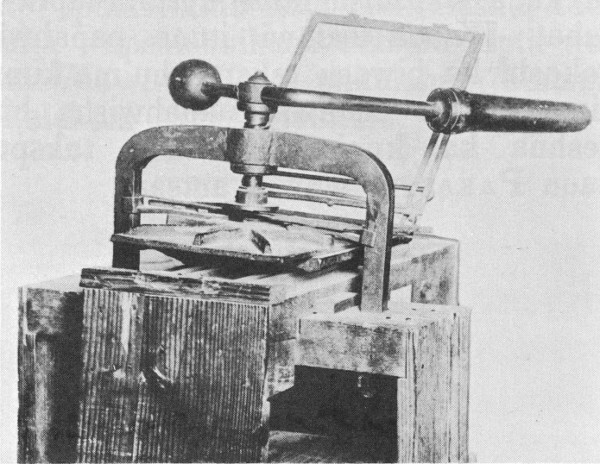

The press that printed the first books in the Pacific Northwest now reposes in the museum of the Oregon Historical Society, Portland.

The Mission Press

In 1837 Henry Spalding became the first missionary to try writing a book in the Nez Percé language. But it was soon discovered that the alphabet devised by him was not adaptable to the Indians’ tongue and this 72-page “primer” was never printed.

The next year, having received a new printing press themselves, the American Board missionaries in Hawaii (then called the Sandwich Islands) offered an older press to the Oregon missionaries. This, the first printing press in the Pacific Northwest, arrived at Lapwai in May 1839. With it came Edwin Hall who was to assist in starting the operation.

Eight days after setting up the press, the missionaries had proudly produced 400 copies of the first book printed in old Oregon. The authors, using an adaption of the alphabet employed in Hawaii, were Henry and Eliza Spalding and Cornelius Rogers. The significance of this achievement is not lessened by the fact that this book had only eight pages.

Between 1839 and 1845 a total of nine books were printed. The most elaborate of these was the Gospel according to St. Matthew turned out in Nez Percé by Spalding. All but one of the books were printed in the Nez Percé language; that one was a 16-page primer in Spokan translated by Elkanah Walker, the copies being stitched, pressed, and bound by his wife, Mary. All these imprints are now quite rare, and of one only a single copy is known to exist. This is the Nez Percé Laws, drawn up by Indian Agent Elijah White in 1842.

Reducing the Nez Percé language to writing was not an easy task. Asa Smith, the best linguist in the group, wrote:

“[The] number of words in the language is immense & their variations are almost beyond description. Every word is limited & definite in its meaning & the great difficulty is to find terms sufficiently general. Again the power of compounding words is beyond description.” But even as he struggled with this problem, Smith was convinced of the necessity of books: “We must have books in the native language, schools, & the Scriptures translated, or we are but beating the air....”

By 1846 the missionaries had become pessimistic about their progress in publishing. The amount of effort required for just a few pages was tremendous. Their best linguists—Smith and Cornelius Rogers—were no longer with the mission. The Indians were not as receptive to the printed word as the missionaries had hoped. In that year the press was moved from Lapwai to The Dalles, and this first publishing venture came to a close. After the Whitman massacre, the press was used in the Williamette Valley by some men who were among the first newspaper publishers in the Pacific Northwest.

The immensity of this undertaking can be grasped only if one remembers the primitiveness of the land in 1839 when the missionaries distributed the first pages ever printed in the Oregon Country.

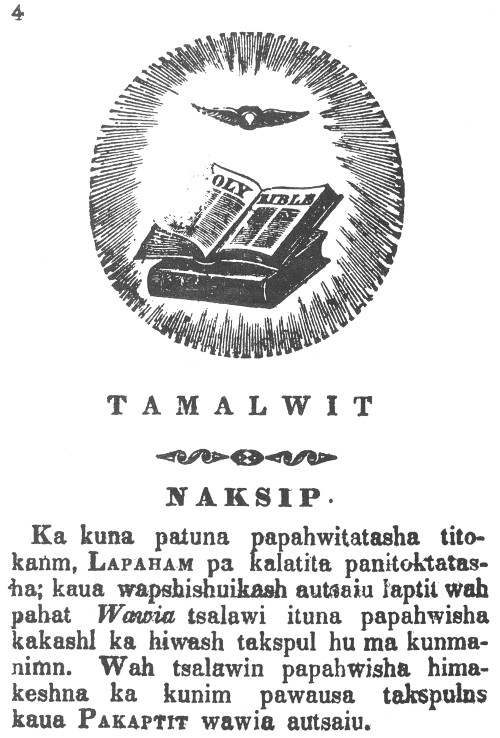

Page from Nez Percé Laws printed by Henry Spalding on the mission press. WHITMAN COLLEGE

TAMALWIT

NAKSIP.

Ka kuna patuna papahwitatasha titokanm, Lapaham pa kalatita panitoktatasha; kaua wapshishuikash autaaiu laptit wah pahat Wawia tsalawi ituna papahwisha kakashl ka hiwash takspul hu ma kunmanimn. Wah tsalawin papahwisha himakeshna ka kunim pawausa takspulns kaua Pakaptit wawia autsaiu.

LAPITIP.

Ka ipnim panpaitataisha ishina shikam inata, kaua kunia pusatatasha, miph panahnatatasha; hu ita mina inata hinptatasha, wawianash, hu itu uiikala ka hiwash hanitash patuain: ka kuna ioh pai hikutatasha, kaua kunapki hitamatkuitatasha ka kush wamshitp hiwash tamatkuit; kaua autsaiu laptit Wawia wapshishuikash, hu ma mitaptit, pilaptit, mas pakaptit, ka kale miohat hitimiunu.

MITATIP.

Ka ipnim passoaitataisha ishina tamanikash kaua kuna tamanikina popsiaunu; hu mu ipalkalikina pawiskilktatasha kaua kunapki kokalh haasu, tamanikina popsiaunu; kunapki kaua hiwasatitatasha tamanikitp, ipalkalikina taks panitatasha, kaua hanaka wapshishuikash autsaiu laptit wah pahat Wawia. Kush uiikalaham hiutsaiu ka kalaham kush hiuiakiu.

continued from page 41

William Gray, who had moved back to Waiilatpu from Lapwai, built a third house in 1840-41. Situated 400 feet east of the mission house, it was a neat, rectangular adobe building. Gray and his wife lived in it only a short time. In 1842 he decided that his future lay elsewhere than in the mission field. The Grays moved to western Oregon where they began an active life as settlers.

Although a blacksmith shop and a gristmill had been erected at Lapwai to serve all the stations, it became evident to Whitman that the central location of Waiilatpu required similar facilities there. In 1841 the blacksmith equipment was moved from Lapwai, and a small, adobe shop, 16 by 30 feet, was built half-way between the mission house and Gray’s residence. Its adobe bricks were taken from the first house, which was torn down at this time. A corral was also built near this shop.

A small, improvised gristmill was built on the south side of the mission grounds in 1839. A second, more efficient mill soon replaced it. With this mill, Whitman was able to produce enough flour to supply the other stations and to sell to the emigrants of 1842. In addition, some of the Cayuse began to bring their grain to the mill. After Whitman had departed for the United States in the autumn of 1842, fire destroyed the mill. Not until 1844 did Whitman find the opportunity to build his third mill. Much larger than the others, the new gristmill had grinding stones 40 inches in diameter. Later, a threshing machine and a turning lathe were built on the mill platform. For waterpower to operate the mill, a ditch was dug from the Walla Walla River to a millpond formed by two long earthen dikes.

Although some pine timber had been handsawed in the Blue Mountains and dragged to the mission by horses, Whitman felt a dire need for a waterpowered sawmill. Among other things, he wanted to replace his leaky, earthen roofs with boards. He picked a spot on a stream in the foothills about 20 miles from the station and, by 1846, had the mill ready for operation. In 1847 a small cabin was built at the sawmill to house two emigrant families whom Whitman hired that autumn for a season of sawing. Physically, Waiilatpu was fast becoming the 49 most substantial and comfortable of all the stations. From time to time, the other missionaries were just a shade envious of the Whitmans.

As the missionaries carried their work into the 1840’s, they continued their efforts among the Indians. Whitman had his greatest success in teaching them the rudiments of agriculture. In 1843 he wrote that about 50 Indians had started farms, each cultivating from a quarter of an acre to three or four. The Cayuse also became interested in acquiring cattle, and by 1845 nearly all possessed the beginnings of a herd.

Much slower progress was made in education and religious instruction. To the Whitmans’ disappointment, the Cayuse became less and less interested in learning the principles of Christianity. The demands made of them were too great for their simple and seminomadic way of life. Then, too, the Whitmans found they had less and less time to devote to Indian affairs. In addition to the multitude of details involved in the everyday job of acquiring food and shelter, the arrival of the annual emigrant trains from the United States demanded much time and energy from the Whitmans. Waiilatpu became not only an Indian mission but also an important station on the Oregon Trail.

At Lapwai, Spalding was having greater success among the Nez Percé and was able to convert several important Indian leaders. In 1839 he obtained a printing press from the American Board mission in Hawaii and printed parts of the Bible in the Nez Percé language. Both he and Asa Smith had difficulty in devising a workable alphabet. But on the second attempt, they contrived one that captured the sounds of the Nez Percé tongue. At Tshimakain and Kamiah the work of teaching and converting Indians proved a laborious and slow task. Although they recognized the difficulties facing them, the missionaries clung tenaciously to the idea of preparing the Indians for the day when white settlers would pour into the fertile lands of the Far West.

Meanwhile, the signs of white migration were becoming more plentiful at Waiilatpu, situated as it was on the main route of travel from the East. One of the ways in 50 which this movement was making itself apparent was in the increasing number of white children who were to be seen at Whitman’s station.

On her 29th birthday, March 14, 1837, Narcissa Whitman gave birth to her only child, a baby girl who was named Alice Clarissa after her two grandmothers. Alice was the first child born of United States citizens in the Pacific Northwest. Her arrival was a great joy not only to her parents but to the Cayuse as well. The Indians had been aware of the baby’s coming, and after her birth all the chiefs and elders of the tribe visited the house to see the temi or “Cayuse girl,” as they promptly named her because she was born on their lands.

That autumn the Whitmans took 8-month-old Alice Clarissa on a visit to the Spaldings at Lapwai. It was time for Eliza Spalding’s first confinement, and Dr. Whitman had come to officiate. On November 15, the baby arrived. The Spaldings named their daughter Eliza, after her mother. Back home again, little Alice Clarissa provided her parents with untold happiness. But that happiness was to be tragically short lived. On a fine Sunday afternoon, June 23, 1839, Alice Clarissa Whitman met death by drowning. Unattended for a few minutes, she had wandered down to the steep bank of the nearby Walla Walla River and had fallen in. Though her body was found but a short time later, all attempts to revive her failed. Her heartbroken parents tried to console themselves with the thought that her demise was the will of God. Yet their loneliness was immense. Before long, however, the Whitmans once again had children in their home to care for and to raise.

The first of these was Helen Mar, the half-breed daughter of the famous mountain man, Joe Meek. Helen Mar’s Nez Percé mother had deserted Meek, and when he journeyed to Waiilatpu in 1840, he persuaded Mrs. Whitman to accept the care of the child. The next year, 51 another little part-Indian girl was added to the Whitman household when another famous mountain man, Jim Bridger, sent his 6-year-old Mary Ann to the Whitmans.

In 1842 two Indian women brought a “miserable-looking child, a boy between three and four years old,” to Narcissa and asked her to take him in. This boy was also half-Indian; his Spanish father had once been an employee of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Narcissa tried to decline the responsibility, but her pity was too great. Taking the child, she named him after an old friend back home, David Malin. Then, when Marcus returned to Oregon in 1843 from his trip East, he brought with him his 13-year-old nephew, Perrin Whitman. Thus the Whitmans acquired their fourth youngster.

The next seven children to be added to the household were all of one family. In 1844 Henry and Naomi Sager left Missouri with six children. On the trail to Oregon, Mrs. Sager gave birth to her seventh child. But tragedy rode with the Sagers. Henry died when the family reached the Green River; a month later, Mrs. Sager died near what is now Twin Falls, Idaho. The children, benumbed by the loss of both parents, were brought on by the wagon train. The women of the train took turns caring for the baby, while Dr. Dagan, a German immigrant, drove the Sager cart with the other six children toward the Whitmans’ mission.

For many days, the emigrants’ wagons had been passing through Waiilatpu. Just before the seven orphans came, Narcissa had written home: “Here we are, one family alone, a way mark, as it were, or center post, about which multitudes will or must gather this winter.” On the morning the children arrived Mrs. Whitman was called to the yard to greet them. There she witnessed a poignant scene.

Before the cart stood the four barefoot girls in their tattered dresses. Afraid of the unknown, they huddled speechlessly, first looking at Mrs. Whitman then at one another, not knowing what to expect. John, the older boy, still sat in the cart. Exhausted but relieved, he bent his head to his knees and sobbed aloud. His brother, 52 Francis, leaned on a wheel and also began to cry. Dr. Dagan, who had been both father and mother to the orphans, stood to one side and, filled with emotion, watched Narcissa murmur a compassionate welcome. She then took the children into the mission house.

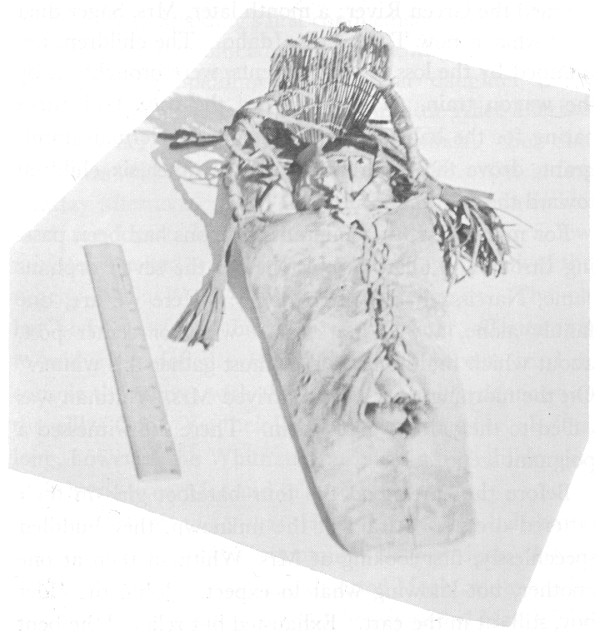

An Indian woman made this doll for young Elizabeth Sager.

At that time Narcissa’s health was not good, and she and Marcus debated that evening whether or not to take all seven orphans into their family. But the plight of the children resolved all doubts. The Whitmans now found themselves directly responsible for a family of 11 children.

In addition to this family, the children of the emigrant families stopped at the mission each autumn and often stayed for the winter. Also present were the children whom the Whitmans took into their school as boarders—such as the young lady whom Dr. Whitman had brought into the world, Eliza Spalding—and the two Manson 53 boys, the half-breed sons of a Hudson’s Bay employee at Fort Walla Walla. Thus, following the death of Alice Clarissa, there was always a large number of youthful voices at Waiilatpu, as indeed there was, to a lesser degree, at the other missions.

During the 11 years they operated in Oregon, the American Board stations continually sent home requests for lay assistants to help convert the Indian tribes. Despite these pleas, no additional reinforcements were sent to Oregon after 1838. On the contrary, the mission stations were reduced from four to three. Discouraged, lonely, and increasingly concerned over his wife’s health, Asa Smith left Kamiah in 1841 and sailed for the Hawaiian Islands. From then until 1847 only Waiilatpu, Lapwai, and Tshimakain remained in operation.

In western Oregon the Methodist missions, established with the arrival of Jason Lee in 1834, were suffering difficulties of their own. Faced with a rapidly diminishing number of Indians, the Methodists began to concentrate in the early 1840’s on establishing churches among the new white settlements that were rapidly filling the Willamette Valley. In 1847 the Methodists offered to sell their remaining Indian mission, Waskopum at The Dalles, to the American Board. Whitman, worried that Catholic missionaries would take over the area if the American Board did not, agreed to purchase it. Lacking a missionary to send there, he hired Alanson Hinman and his wife, from the Willamette Valley, to take charge of secular affairs and sent his nephew, Perrin, to live with them.

As early as 1834 French Canadian employees and ex-employees of the Hudson’s Bay Company in Oregon had petitioned the Catholic bishop at Red River in western Canada for priests. At first the Hudson’s Bay Company refused to help priests come to Oregon, but in 1838 it agreed to transport Catholic missionaries across the Rockies provided that no missions were established south of the Columbia River.

The Bishop of Quebec accepted responsibility for sending Catholic missionaries to the Pacific Northwest. As soon as the Hudson’s Bay Company agreed to help with transportation, the bishop sent the Reverend Francis N. Blanchet to be vicar-general of the new area. Joined at Red River by Father Modeste Demers, Blanchet arrived at Fort Vancouver late in 1838.

Because of the company’s restriction, Blanchet was careful not to establish mission stations south of the Columbia. Before long, however, the restriction was removed, and a Catholic mission was established at French Prairie in the Willamette Valley.

PRINCIPAL MISSIONS AND STATIONS

Lower Columbia River and Its Tributaries

1834-1847

During 1839 both Blanchet and Demers made extensive tours throughout Puget Sound and on the upper Columbia. While at Fort Colville, near the American Board station at Tshimakain, Demers learned that an American priest, Father Peter DeSmet, was in the Flathead country to the east. Father DeSmet had been sent out to Oregon by the Bishop of St. Louis in answer to a call similar to that which had stimulated the Protestant missions. In 1841 DeSmet founded St. Mary’s mission in the Bitter Root Valley in present-day Montana and, in the next year, the Sacred Heart mission among the Coeur d’Alene Indians, in what is now Idaho.

By 1842 the Canadian and American Catholic missions in Oregon were united under the authority of Blanchet. Soon reinforcements were received from Canada, the United States, and Europe. In 1844 Francis Blanchet was designated as bishop and 2 years later was promoted to archbishop when Oregon was elevated to an ecclesiastical province. The brother of the archbishop, A. M. A. Blanchet, was made bishop of Walla Walla. He arrived at Fort Walla Walla in September 1847, accompanied by Vicar-General J. B. A. Brouillet, six priests, and two lay brothers.

The 1830’s and 1840’s were years of strong antagonisms between the Protestant and Catholic churches in 56 the United States. The missionaries in Oregon shared in this feeling. When Marcus Whitman met Bishop A. M. A. Blanchet at Fort Walla Walla, he was greatly disturbed by the presence of the Catholic missionaries.

Peter John DeSmet, apostle to the Indians.

DeSmet founded Sacred Heart mission among the Coeur d’Alene Indians in 1842. From Thwaites, Early Western Travels.

Bishop Blanchet proceeded to establish St. Ann’s mission among the Cayuse on the Umatilla River and St. Rose of Lima near the mouth of the Yakima River. The Catholic missionaries unwittingly had chosen a most unpropitious time for establishing these missions. Their beginning was to coincide with the disaster at “the place of the rye grass.”

With the outbreak of violence at Waiilatpu in November 1847, strong anti-Catholic feeling flared up in Oregon that was to color many minds for years to come. The troubles at Waiilatpu, however, were not the result of religious rivalry, and the Catholic missionaries could in no way be rightfully blamed. The tragedy at the Whitman station would have occurred had there been no Catholics in eastern Oregon.

Besides the real and imagined troubles of rival churches during this decade, the American Board missionaries were experiencing difficulties within their own ranks. Out of this dissension came one of the most remarkable cross-country journeys in American history.

In September 1842 an alarming letter from the American Board arrived at Waiilatpu. It ordered the closing of Waiilatpu and Lapwai and directed Whitman to move to Tshimakain. Spalding, Gray, and Smith were told to return home.

These drastic orders were the result of letters written by Smith, Gray, Rogers, and others, telling the Board of the many dissensions among the missionaries. Reports were sent to Boston about Spalding’s bitterness toward the Whitmans, about the feud between Spalding and Gray, and about Smith’s constant faultfinding. They told, too, of the inability of the missionaries to agree on policies toward the Indians and toward the independent Protestant missionaries who strayed into the Northwest. The letters recounted in painful detail the petty squabbles that had risen from time to time among all the missionaries.

But before the orders reached Oregon, many of these problems had already been solved. The missionaries, realizing the harm coming from dissension, had agreed to patch up their differences and had had some success in doing so. The Smiths had long since left the mission, and the Grays were about to go. Meeting at Waiilatpu to discuss the orders, the missionaries first decided not to put the directive into effect until the Board should hear of the improvements that had been made. This would take time, for it was not unusual to wait a year or more for an answer to a letter. Deeply concerned over the matter, Whitman made the sudden decision that he should go at once to Boston to talk to the Board’s Prudential Committee. Reluctantly, the other missionaries agreed.

On October 3 Whitman set out on his remarkable ride across the continent in the height of winter. Accompanied by a newly arrived emigrant, Asa Lovejoy, and an Indian guide, Whitman reached Fort Hall on the upper Snake River after 15 days of travel. Persuaded to detour to the south because of rumors of Indian wars east of the Rockies, the tiny party crossed the Uintah Mountains to Fort Uintah, in Utah. The hazardous trip was made through deep snow and in bitter cold.

WHITMAN’S RIDE AND THE OREGON TRAIL

Following the Uintah, Colorado, and Gunnison Rivers, Whitman reached Fort Uncompahgre, Colo. From there, he set out for Taos in northern New Mexico, but had to return when his guide became lost. Severe winter storms continued to harass Whitman and Lovejoy, but by mid-December they reached Taos. On the trail to Bent’s Old Fort on the Arkansas River, they learned that a group of mountain men were leaving the fort for St. Louis. Whitman pushed on ahead to catch this party before it left.

Later when Lovejoy reached the fort, he discovered that Whitman had not yet arrived. Sending word to the mountain men to wait, Lovejoy turned back and found Whitman, who in his haste had become lost. Exhausted, Lovejoy stayed at Bent’s Old Fort until summer, when he joined Whitman at Fort Laramie for the return trip to Oregon. On February 15 Whitman reached Westport, Mo. By March 9 he was in St. Louis, and about March 23 he arrived in Washington, D.C.

Even after he reached Boston, Whitman left no written record of his overland journey. Although Lovejoy did write about it in later years, his account includes only the western part of the trip. For the last half of the journey, we must rely on the accounts of those who saw Whitman as he traveled toward the American Board headquarters at Boston. On reaching civilization at St. Louis, it is probable that he gave up the saddle gladly and traveled to Washington by steamer and stagecoach.

In Washington, Whitman visited Secretary of the Treasury J. C. Spencer, an old friend. It is possible, too, that he was introduced to President John Tyler. This stopover in Washington caused many people years later to claim that Dr. Whitman had ridden East to persuade the government to save Oregon from the British, an argument not widely accepted today. Most historians agree that Whitman’s ride was to save the missions and that the trip through Washington was secondary.

The great weakness in the “save Oregon” theory was that it failed to distinguish between the reasons for the 61 trip and the results that came of it. This theory also tended to link the causes of the journey with the results of all Whitman’s later efforts in Oregon, including assistance to the American emigrants and the development of Waiilatpu as an important way station on the Oregon Trail.

When Marcus Whitman arrived at New York City about March 25, he was interviewed by Horace Greeley, the famed editor of the Tribune. At New York the doctor boarded the Narragansett and sailed to Boston, where he arrived March 30. Despite the rough seas of the Atlantic coast, this part of the extraordinary trip must have seemed calm to Whitman after the hundreds of miles on horseback through the winter snows of the Rocky Mountains and the western prairie—a journey of hardships rarely paralleled in American history.

In the office of the American Board Whitman was greeted with coldness, but the Board agreed to listen to his reports and arguments in favor of the Oregon field. In all respects, Whitman’s visit was a successful one. The Board rescinded the unfavorable orders and agreed to send reinforcements to Oregon if suitable persons could be found.

His task accomplished and a hasty visit paid to his home, Whitman began his return trip to Oregon in April 1843. At Independence, Mo., he joined that year’s migration of almost 1,000 people who were preparing to follow the Oregon Trail.

The wagon train of 1843 was the largest yet to assemble for the trip to Oregon. Its way had been paved by the triumphs and failures of the fur traders, adventurers, missionaries, and settlers who had gone before. Back in 1832, Capt. Benjamin Bonneville had taken 20 wagons beyond the Continental Divide. However, he did not attempt to take them to the Columbia River, which he visited in 1834 and again in 1835. In 1836 Whitman and Spalding set a new milestone by taking a light wagon, 62 by then converted to a two-wheeled cart, as far west as Fort Boise.

The first wagons reached the Columbia in 1840. They were brought from Fort Hall, where earlier travelers had abandoned them, by a group of mountain men who were on their way to settle in the Willamette Valley. The trail was so rough that the men finally stripped the wagons down to their bare frames to get through the sagebrush. The next year an emigrant train of more than 100 people, led by Dr. Elijah White, reached the Columbia, but their wagons were taken only as far west as Fort Hall. It was the caravan of 1843 that brought all these efforts to fulfillment by taking its wagons intact to the Columbia. One of the reasons for this success was Dr. Whitman.

In May 1843 the emigrants held a general meeting at Independence to plan the organization of the wagons. For better control, it was eventually decided to divide the train into two parts: an advance group unencumbered by livestock, and a slower group that would take the cattle. Beyond Fort Hall, where the danger from Indian attack was much less, the train was to split into smaller units, each to proceed at its own speed. The emigrants also appointed a committee to talk to Dr. Whitman to obtain advice on the journey. From his own experiences, Whitman was in a position to offer many sound suggestions.

While the caravan crossed the prairie during June and July, Marcus Whitman remained behind with the cow column. But when the lead wagons reached the mountains in the first week of August, he moved up to the advance party. From then on Whitman was active in helping to guide the train westward. He assisted in finding the easiest fords and in crossing the rivers. He pushed on ahead to locate and mark the best routes. Whenever necessary, he treated the sick and the lame. Above all, he constantly urged the emigrants, some of whom were experiencing great discouragement, to keep on pushing westward so that they would reach Oregon before winter set in. At Fort Hall, the Hudson’s Bay Company trader, Richard Grant, in good faith advised the emigrants to 63 leave their wagons there. But Whitman insisted that the wagons could be taken to the Columbia. Catching his enthusiasm, the emigrants formally hired the doctor to lead them the rest of the way. From Fort Hall to the Grande Ronde Valley, he went ahead of the train marking the route for the wagons to follow.

Just before the difficult crossing of the Blue Mountains, Whitman received word by messenger to hurry to Lapwai where both Henry and Eliza Spalding were seriously ill. To help the emigrants in crossing the mountains, he persuaded them to accept as a guide an outstanding Cayuse leader named Stickus. This chief faithfully and carefully guided the wagons across the timber-covered range and on to the mission station.

After a fast ride to Lapwai, Whitman treated the Spaldings, then hurried on to Waiilatpu. He arrived home on September 28, just 5 days short of a year since he had started on his trip. Stopping only long enough to notice that the first of the emigrant wagons had already arrived, the doctor mounted his horse once more in answer to another summons and rode to the Tshimakain mission to deliver Myra Eells of a son.

By the time Whitman again returned to Waiilatpu, most of the emigrants had already stopped at the mission and had gone on to the Columbia. From the mission’s storerooms, the travelers had refurnished their supplies with wheat, corn, potatoes, beef, and pork raised at Waiilatpu.