This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Steam-Shovel Man

Author: Ralph Delahaye Paine

Release Date: November 19, 2019 [eBook #60740]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE STEAM-SHOVEL MAN***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/steamshovelman00painiala |

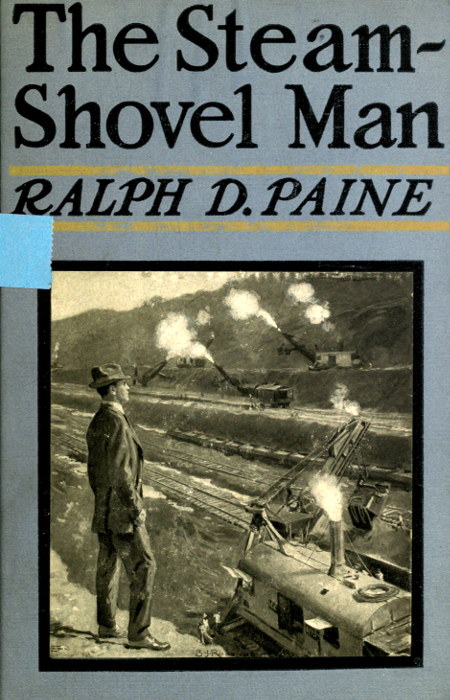

He stood at the brink of this tremendous chasm

THE

STEAM-SHOVEL MAN

By

RALPH D. PAINE

Author of "A Cadet of the Black Star Line," "The Wrecking Master," etc.

ILLUSTRATED BY

B. J. ROSENMEYER

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

1913

Copyright, 1913, by

Charles Scribner's Sons

——

Published September, 1913

| Chapter | Page | |

| I. | Walter Goodwin's Quest | 3 |

| II. | The Parrot and the Broomstick | 24 |

| III. | With the Dynamite Gang | 44 |

| IV. | A Landslide in the Cut | 66 |

| V. | Trapped in Old Panama | 91 |

| VI. | Jack Devlin in Action | 112 |

| VII. | A Fat Rascal Comes to Grief | 132 |

| VIII. | Walter Squares an Account | 152 |

| IX. | A Parent's Anxious Pilgrimage | 172 |

| X. | Base-Ball and a Happy Family | 193 |

| He stood at the brink of this tremendous chasm | Frontispiece |

| Facing Page |

|

| Lifting his feet very high and setting them down with the greatest caution | 50 |

| "Viva Panama! Pobre Colombia! Ha! Ha! Ha!" | 108 |

| "Report to me as soon as you come back. And bring Goodwin with you" | 144 |

THE STEAM-SHOVEL MAN

THE STEAM-SHOVEL MAN

A stout, elderly man stepped from a streetcar on the water-front of New York and hastened toward the nearest wharf at a lumbering trot. He held in one hand a large suit-case which must have been insecurely fastened, for, as he dodged to avoid collision with other wayfarers, the lid flew open and all sorts of things began to spill out.

The weather-beaten gentleman was in such a violent hurry and his mind was so preoccupied that he failed to notice the disaster, and was leaving in his wake a trail of slippers, shirts, hair-brushes, underwear, collars, and what not, that suggested a game of hare-and-hounds. In fact, the treacherous suit-case had almost emptied itself before he paid heed to the shouts of uproarious laughter from the delighted teamsters, roustabouts, and idlers. With a[Pg 4] snort, he fetched up to glare behind him, and his expression conveyed wrath and dismay.

This kind of misfortune, like the case of the man who sits down on his own hat, excites boundless mirth but no sympathy whatever. The victim stood stock-still and continued to glare and sputter as if here was a situation totally beyond him.

A tall lad, passing that way, jumped to the rescue and began to gather up the scattered wreckage. He was laughing as heartily as the rest of them—for the life of him he couldn't help it—but the instincts of a gentleman prompted him to undertake the work of salvage. As fast as an armful was collected, the owner savagely rammed it into the suit-case, and when this young friend in need, Walter Goodwin by name, came running up with the last consignment he growled, after fumbling in his pockets:

"Not a blessed cent of change left! Come aboard my ship and I'll square it with you. If I had time, I'd punch the heads of a few of those loafing swabs who stood and laughed at me."

"But I don't want to be paid for doing a little favor like that," said Goodwin. "And I[Pg 5] am afraid I laughed, too. It did look funny, honestly."

"You come along and do as I tell you," rumbled the heated mariner, who had paid not the least attention to these remarks. "Do you mind shouldering this confounded bag? I am getting short-winded, and it may fly open again. Had two nights ashore with my family in Baltimore—train held up by a wreck last night—must have had a poor navigator—made me six hours late—ought to have been aboard ship this morning—I sail at five this afternoon."

He appeared to be talking to himself rather than to Walter Goodwin, who could not refuse further aid. His burly captor was heading in the direction of a black-hulled ocean-steamer which flew the bluepeter at her mast-head. Even the wit of a landsman could not go wrong in surmising that this domineering person was her commander. And for all his blustering manner, Captain Martin Bradshaw had a trick of pulling down one corner of his mouth in a half smile as if he had a genial heart and, given time to cool off and reflect, could perceive the humor of a situation.

He charged full-tilt along the wharf, and Walter Goodwin meekly followed with the sensation of being yanked at the end of a tow-rope. At the gangway a uniformed officer sang out for a steward, who touched his cap and took charge of the troublesome piece of luggage. Walter hesitated, but as the skipper pounded along the deck toward the bridge he called back:

"Make yourself at home and look about the ship, my lad. I'll see you as soon as I overhaul my papers."

The tall youth had no intention of waiting to be paid for his services, but he lived in an inland town and the deck of a ship was a strange and fascinating place. The Saragossa was almost ready to sail, bound out to the Spanish Main. Many passengers were on board. Among them were several tanned, robust men who looked as if they were used to hard work out-of-doors. As Goodwin lingered to watch the pleasant stir and bustle, one of these rugged voyagers was saying to a friend who had come to bid him good-by:

"It's sure the great place for a husky young[Pg 7] fellow with the right stuff in him. There are five thousand of us Americans on the job, and you bet we're making the dirt fly. I was glad to get back to God's country for my six weeks' leave, but I won't be a bit sorry to see the Big Ditch again."

The other man replied with a shrug and a careless laugh:

"The United States is plenty good enough for me, Jack. I don't yearn to work in any pest-hole of a tropical climate with yellow-fever and all that. It's no place for a white man."

"Oh, you make me tired," good-naturedly retorted the sunburnt giant of a fellow. "You are just plain ignorant. Do I look like a fever-stricken wreck? High wages? Well, I guess. We are picked men. I am a steam-shovel man, as you know, and Uncle Sam pays me two hundred gold a month and gives me living quarters."

"You are welcome to it, Jack. It may look good to you, but you will have to dig the Panama Canal without me."

Walter Goodwin had pricked up his ears. The Panama Canal had seemed so remote that[Pg 8] it might have belonged in another world, but here were men who were actually helping to dig it. And this steam-shovel man looked so self-reliant and capable and proud of his task that he made one feel proud of his breed of Americans in exile. And that was a most alluring phrase of his, "a great place for a husky young fellow."

After some hesitation the lad timidly accosted him:

"I overheard enough to make me very much interested in what you are doing. Do you think I would stand any show of getting a job on the Panama Canal?"

The stranger's eyes twinkled as he scanned Goodwin and amiably answered:

"As a rule, they don't catch 'em quite as young as you are, my son. What makes you think of taking such a long jump from home?"

"I need the money," firmly announced the youth. "And when it comes to size and strength I'm not exactly a light-weight."

"I'll not dispute it," cheerily returned the steam-shovel man. "I am a man of peace except when I'm hunting trouble. But they[Pg 9] don't hire Americans on the Isthmus for their muscle. The Colonel—he's the big boss—has thirty thousand West Indian negroes and Spaniards on the pay-rolls to sweat with the picks and shovels. Are you really looking for a job, my boy? Tell me about it."

Walter blushed and felt reluctant to tell his troubles to a stranger. All he could bring himself to say was:

"Well, you see, I simply must pitch in and give my father a lift somehow."

"And you're not old enough to vote!" heartily exclaimed the other. "There's many a grown man that thinks himself lucky if he can buy his own meal-ticket, much less give his father a lift."

"I don't mean to talk big—" began Walter.

"It does you credit, my son. I like to see a lad carry a full head of steam. You look good to me. I size you up as our kind of folks. Yes, there are various jobs down there you might get away with. And the lowest wages paid an American employee is seventy-five dollars a month. But remember, it's a long, wet walk back from the Isthmus for a man that goes broke."

"Oh, I don't even know how I could get there. I am just dreaming about it," smiled Goodwin.

"If you do ever drift down that way, be sure to look me up, understand—Jack Devlin, engineer of steam-shovel 'Twenty-six' in Culebra Cut, and she broke all records for excavating last month."

He crossed the deck with a jaunty swagger, as if there was no finer thing in the world than to command a monster of a steam-shovel eating its way into the slope of Culebra Cut. Walter Goodwin concluded that he had been forgotten by the busy captain of the Saragossa, but just then the steward came with a summons to the breezy quarters abaft the wheel-house and chart-room. That august personage, Captain Martin Bradshaw, had removed his coat and collar, and a pair of gold-rimmed spectacles adorned his ruddy beak of a nose. Running his hands through his mop of iron-gray hair, he swung round in his chair and said, with the twist of the mouth that was like an unfinished smile:

"I think I owe you an apology. I failed to take a square look at you until we came aboard.[Pg 11] You are not the kind of a youngster who expects a tip for doing a man a good turn. I was so flustered and stood on my beam-ends that I made a mistake."

That this seasoned old mariner could have been in such a helpless state of mind over a mishap so trifling as the emptied suit-case made Walter grin in spite of himself. At this Captain Bradshaw beamed through his spectacles and explained:

"I am afraid of my life every minute I'm ashore—what with the infernal fleets of automobiles and trolley-cars and wagons, and the crowds of people in the fairway. A ship at sea is the only safe place for a man, after all. Have a cup of tea or a bottle of ginger-ale?"

"No, thank you, sir. All I want is some information," boldly declared Walter Goodwin, turning very red, but determined to strike while the iron was hot. "Is there any way, if a fellow can't afford to pay his passage, for him to get to the Isthmus of Panama?"

"And for what?" was the surprised query. "You look as if you had a good home and a mother to sew on your buttons. Have you[Pg 12] been reading sea-stories, or are you a young muck-raker in disguise, with orders to show the American people that the Canal is being dug all wrong?"

"No, I am thinking of trying to find a good job down there," Walter gravely declared. "I can't eat my folks out of house and home any longer. The Isthmus is a great place for a husky young fellow with the right stuff in him. I got it straight from a man who knows."

Captain Martin Bradshaw, who was a shrewd judge of manhood, replied in singularly gentle tones, as if he were thinking aloud:

"I did pretty much the same thing when I was in my teens. And I had the same reasons. I suppose if you broke the news to the folks they wouldn't be exactly enthusiastic."

"I am afraid it would take a lot of argument to convince them that I am sane and sensible," dubiously agreed Walter. "My father isn't used to taking chances, and—well, you know what mothers are, sir. Does it sound crazy to you?"

"No; just a trifle rash," and the wise skipper shook his head. "How old are you?"

"Seventeen and big for my age."

"I thought you were a year or two older. Well, you are as bold and foolish as a strapping lad of seventeen ought to be, if he has red blood in him. I'll not encourage you to run away from home. Maybe you can find a paying berth on the Isthmus, and maybe not. But it will do you no harm to try. Talk it over at home. If the bee is still in your bonnet a month from now, come to the ship and I'll give you a chance to work your passage to Colon on my next voyage."

Walter stammered his thanks, but the captain turned to rummage among the papers on his desk, as if he could give no more time to the interview. As the youth walked away from the ship, his thoughts were buzzing and his pulse beat faster than usual. The unexpected visit aboard the Saragossa had thrilled him like the song of bugles. It awakened a spirit of adventurous enterprise which had hitherto been dormant. It was calling him away to the world's frontier. Jack Devlin, the steam-shovel man, and the captain of the Saragossa had whirled him out of his accustomed orbit with a velocity[Pg 14] that made him dizzy. They were men of action, trained in a rough school, and if Walter wished to follow the same road they were ready to lend him a hand.

He had spent three days in New York, seeking a situation at living wages. His father had given him letters to several business acquaintances, besides which he had investigated such advertisements in the newspapers as sounded promising. He discovered that boys in their teens, no matter how tall and manly they might be, were expected to sell their brains and muscle for so few dollars a week that his boyish hopes of supporting himself were clouded. The city was overcrowded, underpaid.

From the ship he went to the house in which he had lodged, and then straightway to the railroad station to return to his home town of Wolverton. His high-hearted pilgrimage to New York had been a failure in one way, but he was braced and comforted by the bright dream of winning his fortune on the far-away Isthmus. It all sounded too good to be true.

Mr. Horatio Goodwin, the father of this young knight-errant, was a book-keeper who[Pg 15] had toiled at the same desk for twenty years in the offices of the Wolverton Mills. When a trust gained control of the plant it was promptly closed and dismantled in order to keep up prices by cutting down production. This modern instance of knocking competition on the head was satisfactory to the stockholders, but it brought desolation to the small city of Wolverton, of which the vast mills had been the industrial blood and sinews. The operatives drifted elsewhere, hopeful of finding work, but a middle-aged book-keeper, grown gray and round-shouldered before his time, is likely to find himself stranded in a business age which demands hustling young men of the brand known as "live-wires."

The Goodwins' cottage was pleasantly situated on a slope overlooking the town, but, alas, the streets no longer swarmed with tired, noisy people during the leisure hour after supper; many of the stores were untenanted behind their shuttered fronts; and the myriad windows of the mills stared blank and dead instead of twinkling like rows of jewels to greet the industrious army of the night shift. [Pg 16]Discouragement was in the very aspect of the stagnant town, and it had begun to grip the heart of anxious Mr. Goodwin. For the present, or until he might find something better, he had taken a small position with a coal-dealer in Wolverton.

He had great possessions, however, which were not to be measured in terms of hard cash—to wit, a wife who thought him the finest, bravest gentleman in the world, and a son and daughter who held the same opinion and were desperately in earnest about trying to mend the family fortunes. Walter was half-way through his senior year in high-school and was chiefly notable for a rugged physique, a brilliant record as a base-ball pitcher, and an alarming appetite which threatened to sweep the cupboard bare. His sister Eleanor, three years younger, was inclined to be absent-minded and wrote reams of what she called poetry, a form of industry which could hardly be considered useful in a tight financial pinch.

It was in the evening of a winter's day when Walter came homing back from New York. The other Goodwins were holding a family conference, and it was like Eleanor to kiss her[Pg 17] father's bald head and pat his cheek with such a protecting, comforting air that her mother found a glimmer of fond amusement in the midst of her worry. The affectionate lass dwelt in a world of romance and her father was a true knight daily faring forth on a quest in which she was serenely confident that he would conquer all the dragons of misfortune.

Walter had wisely concluded that the rash scheme of working his way to the Isthmus should be explained to the family with a good deal of care and tact. To break it to them suddenly would be too much like an explosion. When he tramped into the sitting-room, the welcome was as ardent as if he had been absent for months instead of days. Eleanor and her mother fluttered about him. Supper had been kept warm for him. Was he quite sure the melting snow had not wet his feet?

His father asked, when the excitement had subsided: "Well, what luck, my son?"

Assuming his best bass voice, as man to man, Walter answered: "New York is chuck-full of strong and willing lads anxious to run their legs off for four or five dollars a week. [Pg 18]Without throwing any bouquets at myself, I think I ought to be worth more than that to somebody. You see, I couldn't pay for my board and washing, much less give the family income a boost."

"Did my letters help you?"

"Yes, I had an offer of four per from the hardware man. I told him I should have to think it over. Wolverton is as dead as a doornail, but I can do better than that as a day laborer."

"I hate to think of your quitting school," sighed his father; "but perhaps you can graduate next year." He tried to hide his anxiety by adding quite briskly: "We have a great deal to be thankful for, and this—er—this period of business depression is only temporary, I am sure."

"I seem to be so perfectly useless," pensively murmured Eleanor. "Poetry doesn't pay at all well, even if you are a genius, and then you are supposed to starve to death in a garret."

Walter grinned and pulled her flaxen braid as a token of his high esteem.

"You are mother's little bunch of sunshine,"[Pg 19] said he, "and as first assistant house-keeper you play an errorless game."

With what was meant to be a careless manner, Walter turned to his father and exclaimed:

"Oh, by the way, I heard of something that sounded pretty good. It isn't in New York——"

"I certainly hope it is no farther away," broke in Mrs. Goodwin. "I can't bear to think of your leaving home at all."

Walter coughed rather nervously and assured her:

"Oh, I should take good care of myself and brush my teeth twice a day and say my prayers ditto, so you wouldn't have the slightest reason to worry about me. And I'd write home every week, sure."

"But couldn't you come home every week?" asked Eleanor.

"Well, hardly, sis. I have heard of the greatest place in the world for a husky young fellow with the right stuff in him. Seventy-five dollars a month, and there are various jobs I am capable of filling——"

"Is this a fairy story?" and Mr. Goodwin[Pg 20] gazed over his glasses with a perplexed expression.

"No, sir, and the climate is healthy nowadays, and the men on the job look as fit as can be, and they are just the bulliest-looking lot you ever saw and——"

"Oh, Walter, tell us the answer. What is it all about?" implored Eleanor.

"I'll send you a monkey and a string of pearls, Sis. Say, father, we Americans ought to be proud of the Panama Canal, don't you think?"

"The Panama Canal!" and Mr. Horatio Goodwin fairly jumped from his chair. "Is this what you have been leading up to?"

"Yes, I want to go there."

"Dear me, why did we let him make the trip to New York alone?" lamented Mrs. Goodwin. "He wants to go to the Panama Canal! Why, it is thousands of miles from home!"

Her agitation might have led one to suppose that Walter had announced his intention of taking up his residence in the moon. But Mr. Goodwin was regarding the ruddy, eager face of his son with a certain wistfulness. Walter[Pg 21] was undismayed, unscarred by the rough world. Ah, youth might win where plodding middle age had failed. The opportunities were for those who were not old enough to be afraid.

"Tell me about it, Walt," said he, and his voice was kindly and interested.

With bright eyes and animated gestures Walter told them of his acquaintance with Jack Devlin and the master of the Saragossa, and how the Panama Canal had been made to seem so near and real. Eleanor promptly soared on rosy wings of fancy and breathlessly interrupted:

"It is of such stuff that heroes are made! I shall never call life humdrum again. Gracious, to think of my big brother actually sailing away to help build the Panama Canal! I have a great deal of confidence in you, Walt, and I'm sure you will succeed, though you are inclined to be careless and you never would keep your bureau drawers in order. I suppose I shall have to write a poem, 'Lines to a Wandering Brother.' It must not be mournful, must it? I will cling to the lofty idea that you have gone to serve your country in peace instead of war."

"That will do for you," was Walter's laughing comment. "Please let mother and father have the floor."

"It sounds fantastic, but—" doubtfully began Mr. Goodwin.

"But it is utterly out of the question," his wife emphatically concluded. "Why, this working his way in a ship sounds dreadfully rough and dangerous. The captain may intend to kidnap him. What is it they do to sailors, Horatio? Something horrid and Chinese—shanghai or hong-kong them, or whatever it is."

Not in the least perturbed by this harrowing suggestion, Eleanor excitedly announced:

"I have seven dollars of my own saved up, Walt. I was planning to take a correspondence course in the art of writing perfectly good poetry, but I'd rather invest it in you. We women must arm our heroes for the fray."

"I am afraid I could not give you the funds you would need," soberly observed Mr. Goodwin. "You must not find yourself adrift in a strange land."

Walter walked across the room, a fine, [Pg 23]athletic figure, almost a six-footer. He felt sure that he could fight his way on the wonderful Isthmus, where there were quick promotion and high wages and a square deal for every man.

"If I can work my passage down there, I can work it home again," he cried. "But I'm not worrying about that."

"Wolverton is no place for you," declared his father. "Mother and I will talk it over, Walter, and I shall find out what I can. You have made us feel rather dizzy. We can't realize that you are no longer a little boy."

"My Salem great-grandfather went to sea when he was fourteen and was mate of an East-Indiaman at my age, and captain of her at twenty-one," stoutly quoth Walter.

"And be sure to write just how the Southern Cross looks to you," earnestly put in Eleanor.

The steamer Saragossa was sliding across a tropic sea where the trade-wind blew cool and steady to temper the blazing sun, the flying-fish skittered from the lazy swells like flights of silver arrows, and the stars by night seemed very bright and near. On the shady side of the promenade deck a boyish-looking member of the crew was scrubbing rust spots from the planking with a certain gusto which distinguished him from the so-called seamen, who were a sorry lot. The rough company and bullying usages of the forecastle had not dismayed Walter Goodwin, who forgot discomfort in the thought that, day by day, he was nearing the magical Isthmus. His parents' consent had been won and this was his great chance.

By far the most interesting passenger was the soldierly gentleman with the close-cropped white hair, the quiet voice, and pleasant smile[Pg 25] who walked the deck with the vigor of youth. This was actually Colonel Gunther himself, chief engineer of the Canal, chairman of the Isthmian Commission, master of forty thousand workers, the man who had made a success of the gigantic task after others had failed.

"We folks think he is the biggest man in the world," a quarter-master's clerk told Walter. "He just holds the whole job together. You can feel him from one end of the Zone to the other. Whenever he goes to the States, it seems as if the organization began to wobble a mite."

"But he is as courteous and kind to everybody on board as if he didn't amount to shucks," was Walter's comment. "Why, he even says 'Good-morning' to me!"

It happened on this day that Colonel Gunther halted near the industrious Walter and his scrubbing-brush. Several children tagged after him, and he was telling them a most fascinating story about a giant so enormous that he could dig a Panama Canal with a poke of his finger and then drink it dry at one gulp. Presently the audience scampered off to view a distant ship, and Colonel Gunther conversed[Pg 26] with one of his staff. They discussed problems of their work, and Walter was guilty of dawdling, but, alas, what he overheard came as a shock that filled him with uneasy forebodings.

"The organization has been at last recruited to its full working strength," said the Colonel. "It begins to look as if the hardest part of the job had been accomplished—to get enough good men and keep them."

"I presume the news will be published in the States," observed the other. "It would be a pity to have any more Americans coming down on the chance of finding places."

"Yes, notification was to be sent out from Washington this week. There are plenty of tropical tramps and beach-combers in Colon and Panama without adding to the number."

With a most melancholy demeanor, Walter Goodwin, ordinary seaman, went forward as eight bells struck the dinner-hour. His excellent appetite had vanished. The opportunity for a "husky young fellow" seemed to have been knocked into a cocked hat. Because he was such a very young man, his emotions were apt to veer from one extreme to the other. He was[Pg 27] ready to believe the worst, nor did he dream of accosting Colonel Gunther and pleading his own special case. A fellow couldn't help standing in awe of one whom the whole Isthmus regarded as "the biggest man in the world." The enchanted land of Panama had suddenly become unfriendly and forbidding. He feared that he was about to become that dismal derelict, a "tropical tramp."

"This is the toughest kind of luck," he said to himself. "They are actually warning Americans away from the place."

Captain Bradshaw, strolling through the ship on a tour of inspection, noticed the gloomy young seaman and kindly inquired:

"Lost anything? You can't be sea-sick in weather like this."

"I have lost my job," mournfully answered Walter.

"Lost it before you found it, eh? What kind of a riddle is that?"

Walter briefly and bitterly explained, at which Captain Bradshaw was moved to suggest:

"If I could shove Colonel Gunther overboard, accidentally on purpose, and you hopped[Pg 28] after him and saved him from a watery grave, what? He would simply have to offer you a good position."

"But I can't swim well enough. You will have to think of something else."

"Well, you can stay in the ship, and I will try to make an able seaman of you."

With a flash of his former determination Walter flung back: "Thank you, sir, but if I don't go ashore and try my luck, I shall feel like a yellow pup, whipped before I start."

At the boyish bravado of this speech Captain Bradshaw replied, with an air of fatherly pride:

"I should think less of you if you decided to stick in the ship, my lad. But if you find yourself flying distress signals, you are welcome to work your passage home with me."

Walter nodded and swallowed hard. He saw that if he whimpered or hung back he would lose the respect of this indomitable old sea-dog. Homesickness afflicted him for the first time, and now and then he regretted having met the persuasive Jack Devlin.

Perhaps because he was unhappy himself Walter felt sympathy for the young man from[Pg 29] the republic of Colombia whose name was on the passenger list as Señor Fernandez Garcia Alfaro. He had often lingered near the forecastle, as if disliking the company of his fellow-voyagers, and seemed to enjoy chatting with Walter, who found him rather puzzling. The South-American temperament was new to the sturdy young Anglo-Saxon from Wolverton, who had been trained to hide his feelings.

Señor Fernandez Garcia Alfaro wore his emotions on his sleeve. He was easily excited and his outbursts of temper seemed childish, although he had been to school and college in the United States and was now in the diplomatic service of Colombia, attached to the legation at Washington. To Walter he seemed much younger than his years. He had found much to annoy him during the voyage of the Saragossa, but Walter refused to take his troubles seriously until matters suddenly came to a head.

It was early in the morning, and Walter had finished his share of washing down decks under the critical eye of the Norwegian boatswain. Alfaro came out of his state-room and paced the wide promenade. His demeanor was [Pg 30]cheerful and he appeared to have forgotten his irritation.

As he halted to greet Walter, there came from an open window near by the harsh, screaming accents of a parrot which cried jeeringly:

"Viva Roosevelt! Viva Panama! Pobre Colombia! Pobre Colombia! Ha! Ha! Ha!"

Fernandez Garcia Alfaro spun round to glare at the disreputable bunch of green feathers which, from its gilded cage, continued to cackle its sentiments concerning "Poor Colombia" with diabolical energy. The young man's black eyes flashed astonishing wrath and hatred, and Walter Goodwin, watching the tableau with a perplexed air, said laughingly:

"Anything personal in the parrot's remarks?"

Alfaro shook both fists at the offending bird and passionately answered in his fluent English:

"It is an insult to me and my country. It is meant to be the worst kind of an insult. I will kill the cursed parrot before I leave this ship. I am a Colombian, as you know. My father is a minister of the government. Panama was stolen from my country to be made into a republic. It was a revolution? Bah! [Pg 31]Nonsense! The soldiers of Colombia could have stopped that little revolution, quick. It was your Teddy Roosevelt, it was your Uncle Sam with the Big Stick that prevented us. Colombia weeps, she is disgraced, when she thinks of Panama."

"But you ought not to be sore on the silly parrot," sagely replied Walter, trying to fathom what appeared to him as an absurd situation. "I never happened to read much about Colombia's side of the story, but the Panama Canal had to be built, you know, and I guess your country was like the grasshopper that sat on the railroad track."

"Grasshopper!" and Alfaro was in more violent eruption than ever as he strode hastily aft to get away from the parrot. "You do not understand, Goodwin. You Yankees can never, never understand. That parrot belongs to a Panamanian—to General Quesada, the big, yellow, fat man whom you have seen on deck. He made himself prominent in the revolution against Colombia, but he is no good. He is a tin soldier. He had taught his parrot to insult my country, to have fun with my honor. He has[Pg 32] laughed at me all the voyage. He had made the others laugh at me. It is dangerous to make me so mad."

Walter began to comprehend. He had heartily disliked General Quesada on sight, and he had heard something of the coarse teasing to which Alfaro had been subjected.

"I suppose that is why you have flocked by yourself," he replied. "But you ought not to be so touchy."

At this moment General Quesada himself came waddling on deck, parrot-cage in hand, evidently intending to give his accomplished pet an early morning airing. He was a gross, ungainly man, heavy of countenance. At sight of the indignant Alfaro he shook with laughter and prodded the bird with his finger, which prompted it to screech:

"Viva Panama! Pobre Colombia! Ha! Ha! Ha!"

The young man whom he had enjoyed taunting as a diversion of the voyage retorted with fiery Spanish abuse, which made the Panamanian scowl as if he had been stung by something sharp enough to penetrate his thick hide.[Pg 33] He uttered a volley of guttural maledictions in his turn, and was echoed by the blackguardly parrot. For Fernandez Garcia Alfaro this was the last straw. His inflammable temper was ablaze. He rushed at the corpulent general and let his fists fly against the full moon of a countenance.

Before Walter Goodwin could interfere, the Panamanian had found room to jerk a small automatic revolver from a pocket of his trousers. Alfaro caught a glimpse of the weapon and tried to grip the arm that flourished it. The decks were otherwise deserted at this early hour and duty called Walter to attempt the rôle of peacemaker. This was a difficult undertaking, for Alfaro, active as an angry jaguar, persisted in fighting at close range with hands and feet, while the bulky Panamanian twisted and wrenched him this way and that, and vainly tried to use his weapon.

There was no pulling them apart, and the swaying revolver was a menace which made Walter dive for a deck-broom left against the rail. The heavy handle was of hickory. Swinging it with all his might, Walter brought it down with a terrific thump across the knuckles[Pg 34] of General Quesada, who instantly dropped the revolver. Walter's blood was up and he intended to deal thoroughly with this would-be murderer. Whacking him with the broom-handle, he drove him, bellowing, toward the nearest saloon entrance, while Alfaro danced behind them, shouting approval.

By now the first mate came charging down from the bridge. Captain Bradshaw arrived a moment later, clad in sky-blue pajamas, his bare feet pattering along the deck. He picked up the revolver, eyed Walter and the broom-handle with a comical air of surprise, and inquired:

"Who started this circus? Is it a revolution? I shall have to put a few of you fire-eaters in irons."

The parrot had rolled into the scuppers, cage and all, and its nerves were so shaken that it twisted its favorite oration wrong end to, and dolefully and quite appropriately chanted at intervals:

"Viva Colombia! Pobre Panama!"

Captain Bradshaw aimed an accusing finger at the bird and exclaimed:

"Shut up! You talk too much."

"That was the whole trouble, sir," said Walter, wondering whether he was to be punished or commended. "General Quesada brought this—this broom-handle on himself. He was trying to shoot Señor Alfaro."

"I need no diagrams to tell me that Señor Alfaro sailed into him first," said the captain. "This had been brewing for some time. I shall have to investigate after breakfast."

A little later Walter discovered Fernandez Garcia Alfaro seated upon a hatch-cover forward. At sight of his Anglo-Saxon ally the impulsive Colombian sprang to his feet and cried, with outstretched hands:

"You have saved my life! I shall never forget it, mi amigo. I have hated the North Americans, but my heart is full of affection for you."

Rather taken aback by this tribute, Walter said in a matter-of-fact manner:

"You surely piled into that fat general like a West India hurricane. I'm glad I spoiled his programme."

Alfaro's expressive face was vindictive as he exclaimed: "I have not finished with him and his infernal parrot!"

"Pooh, forget him," carelessly advised Walter, to whom this threat of vengeance sounded theatrical. "Better steer clear of this Quesada person. He looks to me like an ugly customer."

Alfaro smiled rather sheepishly as he remarked:

"It was not very diplomatic? You must think I am a funny diplomat, Goodwin."

"Well, I never happened to meet one before," confessed Walter, returning the smile, "and I had an idea that diplomats were not quite so violent and sudden in their methods."

"It was that beastly parrot," began Alfaro in a quick gust of anger; but he checked himself with a shrug and asked a question which led Walter to reply:

"Oh, no, I am not a real sailor. I am going to the Isthmus to work in the Canal Zone."

Boyish pride made him reluctant to confess how dubious he was of finding work. Alfaro was so full of affectionate admiration that he was ready to believe great things of Walter, and he exclaimed:

"I am sure you will have a fine position. I knew you were not a common sailor. You are[Pg 37] working your passage as a lark? I have been wishing landslides and yellow-fever and all kinds of bad luck to the Yankees so they could never finish the canal. But now, for your sake, my feelings are different."

Walter had begun to be fond of the fiery Colombian who was so quick to express his likes and dislikes.

"Thank you," he replied. "I hope we shall run across each other on shore."

"I must wait a week for my steamer from Panama down the west coast," said Alfaro. "I am going home on leave of absence from the legation to see my father and mother. I will say nothing about the row with General Quesada. My father would not think it diplomatic. I will find you at your office in the Zone?"

"I certainly hope so," gravely answered Walter, but for reasons known to himself he failed to mention his address.

The interview was cut short by a summons from Captain Bradshaw, who wished to see Goodwin at once. He climbed to the bridge-deck and entered the captain's room, cap in hand.

"Don't look so scared, young man. I'm not going to eat you alive," was the good-humored reassurance. "General Quesada came boiling up here just now and demanded that I lock you up and turn you over to the Panamanian police when we dock at Colon. Of course I told him that the deck of this ship is American territory and he was talking foolishness."

"But he is the man who ought to be locked up," protested Walter. "What about his trying to shoot Señor Alfaro?"

"I said as much, but he didn't listen. He swore he pulled the revolver merely to frighten the Colombian. And then he says you whanged daylight out of him with a club. I had to talk Spanish with him and I missed some of his red-hot language."

"Yes, sir, I whanged him good and plenty," declared Walter, "and he yelled and ran for all he was worth."

"The ship's doctor had to bandage his knuckles," resumed Captain Bradshaw with a chuckle, "and there is a welt on his jaw, and he is marked in various other places. What hurts him worst is that a common sailor, and a boy[Pg 39] at that, chased him from the deck with a broomstick and battered him all up. This Quesada poses as a military hero in Panama, you understand, and plays a strong hand in the politics of that funny little republic."

"Perhaps I ought not to have hit him so hard," and Walter looked solemn.

"You were a bit overzealous, but he deserved a drubbing. I just want to give you a bit of friendly advice. Don't let this General Quesada catch you up a dark alley. His vanity is mortally wounded, and he carries a deck-load of it. A Spanish-American might as well be dead as ridiculous. And it makes Quesada squirm to think how he will be laughed at if this story gets afloat in Panama. He doesn't love you, Goodwin."

"But the Canal Zone is part of the United States. He can't do anything to me," said Walter.

"Not in the Zone, but it is the easiest thing in the world to drift across the line into Colon or Panama before you know it. And the Spiggoty police, as they call 'em, like nothing better than an excuse to put a Yankee in jail."

Elated that Captain Bradshaw's attitude[Pg 40] should be so friendly, and flattering himself that with so humble a weapon as a broomstick he had vanquished a real live general, Walter was inclined to make light of the warning. In fact, he forgot all about the humiliated warrior a day or so later when far ahead of the Saragossa a broken line of hills lifted blue and misty. Yonder was the Isthmus which Balboa had crossed to gaze upon the unknown Pacific, where Drake and Morgan had raided and plundered the Spanish treasure towns, and where in a later century thousands of brave Frenchmen had perished in their futile tragedy of an attempt to dig a canal between the two oceans.

Soon the low-roofed city of Colon was revealed behind the flashing surf, the white ribbon of beach, and the clusters of tall palms. From the opposite shore of the bay stretched the immensely long arm of the new breakwater, on top of which crawled toy-like engines and work-trains. What looked like a spacious, sluggish river extended straight inland toward the distant ramparts of the hills. On its surface were noisy dredges, deep-laden steamers, and tow-boats dragging seaward strings of barges heaped high with rock and dirt. This was part of the[Pg 41] Panama Canal itself, the finished section leading from the Atlantic, and where the hills began to rise a great cloud of smoke indicated the activities of steam-shovels, locomotives, and construction plants.

Walter Goodwin, no longer brooding over his fear of becoming a "tropical tramp," was impatient to see the wonderful spectacle at close range. After the steamer had been moored at one end of the government docks of Cristobal, he was assigned to duty at the gangway while the passengers filed ashore. Conspicuous among them was General Quesada, his right hand bandaged, his surly face partly eclipsed by strips of plaster, his gait that of one who was stiff and sore.

He balked at sight of the steep runway from the deck to the wharf, and Walter offered him a helping hand. The general angrily waved him aside and muttered something in Spanish which sounded venomously hostile. Fernandez Garcia Alfaro, who was within ear-shot, explained to Walter:

"He says he will find you again, and he swears it in very bad language."

"Pooh! I'm not afraid of the fat rascal," carelessly returned Walter. "I guess Uncle Sam is strong enough to look after me."

Before noon he found himself in the modern American settlement of Cristobal, among clean, paved streets whose palm-shaded houses, with wide, screened porches, were of uniform color and design. Boys and girls were coming home from school, as happy and noisy as Walter was used to meeting them in Wolverton. As he wisely observed to himself, this agreeable place was where the Americans lived, not where they worked, and a fellow had to find work before he could live anywhere. He was among his own countrymen, but where was there any place for him? He felt friendless and forlorn.

Strolling at random, he was unaware that he had crossed the boundary line into the Panamanian city of Colon until the streets became a wonderfully picturesque jumble of Spanish-speaking natives clad in white duck and linen, chattering West India negroes, idling Americans in khaki, and sailors from every clime.

Passing the city market, he thriftily bought his supper—bananas, mangoes, and peppery[Pg 43] tamales—at cost of a few cents, and pursued his entertaining tour of sight-seeing. It was all strange and fascinating and romantic to his untutored eyes. His wanderings were cut short at sight of General Quesada, who was seated at a table in front of a café with several friends. Two of these were in uniform adorned with gold lace and buttons.

Walter wasted no time in wondering whether these were officers of the army or the police. The battered general was pointing him out to them with a gesture of his bandaged hand. The officers stared as if to be sure they would know him again. Hastily deciding that the climate of Cristobal might be healthier, Walter retreated toward the Canal Zone and the shelter of the stars and stripes. As he glanced over his shoulder, the three men at the café table appeared to be discussing him with a lively interest which made him feel uneasier than ever. Perhaps the warning of Captain Bradshaw had not been all moonshine. It looked as if General Quesada were still thinking about that terrible broom-handle which had bruised his pompous pride as severely as his knuckles.

What he had heard Colonel Gunther say on shipboard made Walter think it useless to apply for one of those wonderful positions at seventy-five dollars a month on the "gold roll," which the steam-shovel man, Jack Devlin, had painted in such glowing colors. He must try to get a foothold somewhere, no matter how humble it might be, and hope to win promotion. It was really a case of jumping at the first chance to earn a dollar. Without employment what money he had would soon be spent, and then he must slink home in the Saragossa.

He picked his way through a net-work of tracks, switches, and sidings among the busy wharves and warehouses of Cristobal. This was the nearest scene of activity, although it seemed to have very little to do with digging the Panama Canal. There were railroad yards at home, reflected Walter, and he had seen[Pg 45] miles of warehouses and wharves along the water-front of New York. He walked rather aimlessly beyond the crowded part of Cristobal, hoping to find steam-shovels and construction gangs.

At length his progress was blocked by the wreckage of several freight-cars which were strewn across the tracks in shattered fragments. Negro laborers were clearing away this amazing disorder, which could have been caused by no ordinary collision. In answer to Walter's questions one of them said:

"Dynamite, boss. A car got afire down by de ship, sah, an' de mens tuk all de dynamite out 'cept two boxes. An' when dey was runnin' de car up here in de yard to fotch it away from de wharf, she done 'splode herself to glory."

"Anybody killed?"

"Two mens, sah, an' some more is in de hospitubble."

"Too bad, but there is something doing here," said Walter to himself. "This is a hurry-up job, and perhaps they can use another man."

Climbing over the débris, he accosted a lean,[Pg 46] brick-red American with a fighting jaw who was driving the wrecking-crews at top speed.

"I am not the superintendent," was the impatient reply, "but I'll save you the trouble of looking him up. He is taking no more men on the gold roll. The railroad has been laying people off."

"But I am not looking for a job on the gold roll," stubbornly returned Walter. "I am ready to pitch in with your laborers. Can't you take me on to help clear this mess?"

"For twenty cents an hour? You're joking," snapped the foreman. "White men don't do this kind of work down here."

Walter was for continuing the argument, but the other jumped to adjust the chains of a wrecking-crane. Just then there appeared a man of such a calm, unhurried manner that he seemed oddly out of place in this noisy, perspiring throng. As Walter brushed past him the placid stranger drawled:

"These tracks will be cleared by night. The job won't last long enough for you to make a start at it. Are you really looking for hard work at silver wages?"

"Please lead me to it," gratefully cried Walter. "I guess I can live on twenty cents an hour until something better turns up."

"Good for you," said the unruffled gentleman. "I am Mr. Naughton, in charge of the dynamite. We use eight hundred thousand pounds a month on the canal. I have a ship to unload, and the negroes have been panicky since the explosion this morning. Several of them quit me, and I guess they are running yet."

Walter shied like a frightened colt, and stammered with sudden loss of enthusiasm:

"A whole s-ship-load of d-dynamite? You w-want me to help handle it?" Then he grinned as his sense of humor overtook his fright. He had just fled from Colon at sight of General Quesada and his friends. This was hopping from the frying-pan into the fire with a vengeance.

"What if I drop a box of it?" he asked.

"I am not hiring you to drop it," was the pensive answer of Mr. Naughton, as he flicked a bit of soot from his white serge coat and caressed his neatly trimmed brown beard. "I[Pg 48] wish I had something better to offer you. I like your pluck."

"I am not showing any pluck so far," confessed Walter. "You have scared me out of a year's growth. But I'm willing to take a chance if you are."

"Then come along with me to the Mount Hope wharf, and I'll put you on my pay-roll."

The weather was wiltingly hot for one fresh from a northern winter, but as Walter followed his imperturbable employer he felt the chills run up and down his spine. The sight of the havoc wrought by two boxes of dynamite was not in the least reassuring.

"Here is where I get scattered all over the tropical landscape," he said to himself. "A greenhorn like me is sure to do something foolish, and if I stub my toe just once, I vanish with a large bang."

He might have taken to his heels but for the soothing companionship of Mr. Naughton, who was humming the air of a popular song and seemed to have not a care in the world. Ahead of them lay a rusty tramp steamer flying a red powder-flag in her rigging. A few laborers[Pg 49] and sailors were loafing in the shade of the warehouse. At a word from Mr. Naughton they filed on board, some to climb down into the hold, others to range themselves between an open hatch and the empty freight-cars on the wharf.

Walter pulled off his shirt, gingerly tightened his belt, and took the station assigned him on deck. Presently the men below began to pass up the heavy wooden boxes from one to another until the dangerous packages came to Walter, who was instructed to help carry them to the ship's side.

He eyed the first of them dubiously for a moment, took a long breath, and clasped the box to his breast, squeezing it so tightly that he was red in the face. Lifting his feet very high and setting them down with the greatest caution, he advanced with the knee action of a blue-ribbon winner in a horse-show. Quaking lest he trip or stumble, he delivered the box to the man at the gangway. The seasoned handlers chuckled, and Mr. Naughton said to the American who was checking the cargo:

"I took no risks in picking up that youngster,[Pg 50] even if he is a new hand with the powder. His nerves haven't been spoiled by rum or cigarettes. Nice, clean-built chap, isn't he? What do you think of him?"

Lifting his feet very high and setting them down with the greatest caution

"He is no stranded loafer or he would sponge on the Americans in Colon sooner than work on the silver roll."

"I shall ask him a few questions when we knock off," returned Naughton.

After Walter had safely handled a score of boxes, he gained confidence and worried less about "'splodin' himself to glory," as he toiled to keep pace with the other men. The humid heat was exhausting, but as the afternoon wore on his efficiency steadily increased. When the quitting hour came, Mr. Naughton told him:

"I'll be glad to keep you on until the cargo is out. Where are you living?"

"Nowhere at present. I can't afford to go to a hotel, and even if I had the price I am afraid Colon might disagree with me."

"Oh, it is a healthy town nowadays. Our people have cleaned it up like a new parlor."

"I mean the police—" began Walter, but this sounded so suspicious that he blushed,[Pg 51] thought it hardly worth while explaining, and concluded, "I guess I can find a bed somewhere."

Mr. Naughton whistled, cocked a scrutinizing eye, and observed:

"So you got into trouble with the Spiggoty police? Anything serious? I won't give you away."

"Nothing against my morals," smiled Walter. "My manners were disliked."

"I'll take your word for it. One of my minor ambitions has been to punch the head of a Panamanian policeman. The chesty little beggars!" drawled Mr. Naughton. "You don't belong with the laborers, Goodwin, and you wouldn't like their quarters. I can find you a place to sleep at our bachelor hotel, and you can get commissary meals at thirty cents each. Uncle Sam is a pretty good landlord."

Cordially thanking him, Walter exclaimed as he straightened his aching back:

"I haven't been as lame and tired since I pitched a twelve-inning game for the high-school championship of the State. Phew! I must have moved enough dynamite already to[Pg 52] blow Colon off the map. But I'll be glad to report in the morning, sir."

This casual reference to base-ball had a most surprising effect upon the placid Mr. Naughton, who had seemed proof against excitement. He jumped as if he had been shot at, grasped Walter by the arm, and shouted eagerly:

"Say that again. Can you pitch? Are you a real ball-player? Man alive, tell me all about it!"

Walter stared at the "powder man" as if suspecting him of mild insanity.

"We have a crack nine in Wolverton for a high-school," he replied. "It is a mill town, you see, and most of the fellows begin playing ball on the open lots as soon as they can walk. We were good enough last season to beat two or three of the smaller college teams."

"And you were the regular pitcher?" breathlessly demanded Mr. Naughton, as he backed away and surveyed the broad-shouldered youth from head to foot.

"Yes, I pitched in all the games."

"Well, you handle yourself like a ball-player, and I believe you are one. You come along to supper with me."

"But what in the world—" began the bewildered Walter.

"Leave it to me. Your destiny is in my hands," was the mysterious utterance of Mr. Naughton.

In the cool of the evening they sat and ate at their leisure on the breezy piazza of the "gold employees'" hotel. From other small tables near by several men called out greetings to Naughton, who beckoned them over to be presented to his protégé. No sooner had they learned that the tall lad was a base-ball pitcher of proven prowess than they became effusively, admiringly cordial. In fact, Walter held a sort of court.

"Goodwin is one of my unloading gang on the dynamite steamer," explained Naughton.

At this there arose a fiercely protesting chorus. One might have thought they were about to mob the "powder man."

"How careless, Naughton! It makes no difference about you, but we can't afford to risk having a ball-player blown up."

"A real pitcher is worth his weight in gold just now."

"It won't do, Naughton, old man. If you permit this valuable person to be destroyed, the Cristobal Baseball Association will hold you responsible."

"Don't you dare let him go near your confounded dynamite ship again."

Thanks to the magic of base-ball, although he could not understand the why and wherefore of it, Walter found himself no longer a friendless waif of fortune, but regarded as something too rare and precious to be risked with a dynamite gang. It seemed rather absurd that these transplanted Americans should have any surplus energy for athletics after the day's work in the steaming climate of the Isthmus. But his new friends proceeded to enlighten him, led by Naughton, who exclaimed with much gusto:

"My son, we eat base-ball. The Isthmian League is beginning its third season, and you have alighted among the choicest collection of fans, cranks, and rooters that ever adorned the bleachers. Mr. Harrison here is captain of the Cristobal nine. Our best pitcher went back to the States last week."

"But I'm afraid I shall have no time to play,"[Pg 55] said Walter. "I didn't come down here for base-ball."

"Oh, we all work for a living. Don't get a wrong impression of us," put in Harrison, a young man of chunky, bow-legged type of architecture whom nature had obviously designed for a short-stop. "I am a civil engineer, Atlantic Division. I used to play at Cornell. We can't practise much, but if you want to see some snappy games——"

"I would rather handle the dynamite than umpire when you play Culebra or Ancon," broke in Naughton, who showed signs of renewed excitement as he went on to say to Harrison:

"If I bring Goodwin to the field at five o'clock to-morrow afternoon, will you furnish a catcher and give him a chance to limber up? Better lay off and take it easy for the day, hadn't you?" he added, turning to Walter.

"No, the hard work will take the kinks out of my muscles, and I can't afford to lose any time on my first job."

"Oh, hang his tuppenny job!" spoke up one[Pg 56] of the company. "He doesn't understand how important he is. Enlighten him, Harrison."

"This frenzied person on my right means to convey that a young man with a first-class pitching arm will have the inside track with the powers that be," explained the Cristobal captain. "There is Major Glendinning, for instance——"

"He is head of the Department of Commissary and Subsistence," chimed in Naughton. "He feeds and clothes the whole Canal Zone. When Cristobal makes a three-bagger he jumps up and down and yells himself hoarse."

"But I heard Colonel Gunther himself say that no more Americans were needed down here," said Walter.

"That doesn't mean there is to be no more weeding out of undesirables," Naughton explained. "There is still room on our happy little Isthmus for a man who can deliver the goods. I don't want you to infer that the government is hiring ball-players. But as an introduction, Goodwin, you couldn't beat it if you brought letters from eleven United States senators."

"Now let's talk base-ball," impatiently interjected a lathy individual in riding breeches and puttees, who had come in from a construction camp somewhere off in the jungle.

"We ought to tuck our prize package in bed very early," objected Naughton. "He is as sleepy as a tree full of owls."

"Juggling dynamite is no picnic!" and Walter struggled with a yawn. His friends good-naturedly escorted him to the bachelor quarters, where he speedily rolled into his cot and dreamed of fighting a duel with General Quesada, the weapons being base-ball bats.

When he reported on board the dynamite ship next morning, Naughton greeted him with a slightly worried air and declared:

"I have been thinking it over and perhaps those chaps were right. We have very few accidents with the stuff, but we ought not to run the slightest risk of losing the league championship to Culebra or Ancon."

Walter laughed and replied:

"This is the best kind of practice for me. If I can keep my nerve and make no errors, I am not likely to be rattled when the bases are full."

This argument had weight, although Naughton was still anxious as he strolled to his office. By noon the stiffness had been sweated out of Walter's back and shoulders, and the supple vigor was returning to his good right arm. Shortly before five o'clock the inconsistent Naughton, who lived in daily peril of his life with all the composure in the world, was fairly fidgeting to be off to the base-ball field. A battered victoria and a rat of a Panama pony hurried them thither, and they found Harrison and several other players busy at practice against a background of cocoanut palms and bread-fruit trees.

The Cristobal catcher trotted up looking immensely pleased:

"Hello, Goodwin, you don't know me," said he, "but my kid brother was on that Elmsford freshman team that you trounced so unmercifully last season. I saw the game. Brewster is my name. When Harrison told me he had been lucky enough to discover you, I chortled for joy."

This was a cheering indorsement for the others to hear and it gave Walter the confidence[Pg 59] of which he stood in need. A great deal appeared to depend on his pitching ability, and this test was more trying to the nerves than handling dynamite or dodging General Quesada.

The catcher tossed him a ball and they moved to one side of the field. At first Walter pitched with caution, but as he warmed to his work the ball sped into Brewster's glove with a wicked thud.

"Send 'em along easy to-day. Better not overdo it," the catcher warned him. Walter smiled and swung his arm with a trifle more steam in the delivery. He felt that he must show these friendly critics what he had in him, wherefore the solid Brewster withstood a bombardment that made him grunt and perspire. The other players looked and whispered among themselves with evident approval.

"What did I tell you?" proudly exclaimed Naughton. "Am I a good scout? I unearthed this boy phenomenon."

The battery had paused to cool off when a big-boned American saddle-horse came across the field at an easy canter. The rider sat as erect as a cavalryman, although he was old[Pg 60] enough to be Walter's grandfather. Halting beside the group, he said:

"I rode out this way on the chance of seeing a bit of practice. Do you expect to whip those hard-hitting rascals from Culebra?"

"Good afternoon, Major Glendinning," replied Naughton, with a wink at the others. "Harrison has been feeling very gloomy over the prospects. We lost our only first-class pitcher, you know."

"What an outrageous shame it was!" earnestly ejaculated the head of the Department of Commissary and Subsistence.

Harrison nudged Naughton. Major Glendinning had come upon the scene at precisely the right moment. Here was the employer who, above all others, must be made to take an interest in Goodwin's welfare if these amiable conspirators could bring it about. Noting that Walter was beyond ear-shot, Harrison spoke up.

"Sorry you couldn't arrive a little sooner, Major. We are inclined to think we have found a better pitcher, though I'm not at all sure that we can keep him at Cristobal."

The elderly gentleman leaned forward in the saddle and eagerly inquired:

"Bless me, is that true? I swear you don't look at all gloomy, Harrison. Who is he? Where is he? And you think he can pitch winning ball for Cristobal?"

"Yes, sir. Brewster has seen him play at home. He is one of your born pitchers. He is a wonder."

"What do you mean by saying we can't keep him?" demanded the major.

"He is working for me—on the silver roll," vouchsafed Naughton, with a hopeless kind of sigh. "He hasn't been able to find anything better to do. But I can't hold him, of course. He is a first-class man in every way. He is likely to quit almost any day and drift over to Culebra or Ancon, where he will be sure to land a position on the gold roll, as foreman, clerk, or time-keeper. And then he will be pitching for our hated rivals."

"Um-m, he will, will he?" and Major Glendinning fairly bristled. "I am not letting any good men get away from my department. Show him to me."

Naughton nodded in the direction of Walter, who was deep in a discussion of signals with his catcher. Then the "powder man," with Harrison as fluent ally, paid tribute to the manly qualities of the young pitcher, nor were their motives wholly selfish. The major listened attentively, chewing his gray mustache, and now and then glancing at Walter with keen appraisement. At length he exclaimed:

"You chaps know how to get on my blind side. I have had my eye on a cheerful young loafer in the Cristobal commissary who is not earning his salary. If he should—er—resign, there might be a vacancy. I like Goodwin's looks. Fetch him over here, if you please."

Naughton and Harrison grinned at each other as they marched to the side of the field and escorted Walter with great pomp of manner. The abashed pitcher wiped his dripping face and heard Major Glendinning say to him:

"You had better not think of leaving Cristobal just now. It is the best place in the Zone. When you are through with Naughton and his infernal cargo, come and see me in my office, if he doesn't blow you sky-high in the [Pg 63]meantime. And don't forget that I expect you to win that next game against Culebra."

He wheeled his horse sharply and trotted from the field, leaving Walter to gaze after him with a dazed, foolish smile. Harrison thumped him on the back and jubilantly shouted:

"Wasn't that easy? What did we tell you?"

"But do you honestly think he has any intention of giving me a job on the gold roll?" tremulously implored Walter, whose emotions were in a state of tumult.

"Sure thing," said Naughton. "He can always find a place for a young fellow with the right stuff in him."

"'A husky young fellow with the right stuff in him,'" echoed Walter. The familiar words had come home to roost.

"He will start you in at seventy-five per month"—this was from Harrison—"and you will have to earn it. Base-ball cuts no figure with the major in business hours."

"Your conscience can rest easy on that score," added Naughton. "No danger of your cheating Uncle Sam."

"An honest pull is the noblest work of man,"[Pg 64] declaimed Harrison, and this seemed to sum up the whole matter.

When Walter returned to his quarters, his first impulse was to write a letter home. This proved more difficult than might seem. To report to his anxious parents and his adoring sister that he was employed on board a dynamite ship would not tend to ease their minds. He could imagine this bit of news landing in the cottage at Wolverton with the effect of a full-sized explosion. Eleanor would probably take her pen in hand to compose a metrical companion piece of "The Boy Stood on the Burning Deck."

"I must be tactful," frowningly reflected Walter. "I don't want to make them nervous. Perhaps I had better not go into details. I will simply say that I have a fairly lucrative position. Twenty cents an hour isn't much down here, but it sounds big alongside that four-dollar-a-week job in the hardware store."

Then he discovered that to discuss the better position which he had not yet secured was to raise hopes that sounded fantastic. Those rival ball-players from Culebra might knock[Pg 65] him out of the box in the first inning. This would mean good-by to Major Glendinning's favor. Base-ball cranks were fickle and uncertain persons. Walter therefore merely informed the family that the climate agreed with him and he was sure his judgment had been sound in coming to the Isthmus.

"Between unloading dynamite and worrying about this base-ball proposition," he soliloquized, "not to mention the fact that General Quesada is camping on my trail, I expect to be gray-headed in about one more week."

The dynamite ship had been almost emptied of cargo, when Naughton suggested:

"I won't need you on this job after to-day, Goodwin. Why not go to Culebra with me to-morrow morning and see some of the canal work? I shall have to inspect the dynamite stored in the magazines."

Walter jumped at the chance of a holiday before venturing to interview Major Glendinning. He was eager to behold the famous cut where they were "making the dirt fly," and to find his friend Jack Devlin, the steam-shovel man who had beguiled him to the Isthmus.

It was with a sense of wonderment as keen as that of the early explorers that Walter was whisked in a passenger train, as if on a magic carpet, into the heart of the jungle, past palm-thatched native huts perched upon lush green hill-sides, by trimly kept American settlements,[Pg 67] by vine-draped rusty rows of engines, cars, and dredges long ago abandoned by the French.

Soon there appeared the mighty Gatun dam and locks flung majestically across a wide valley, resembling not so much man's handiwork as an integral part of the landscape, made to endure as long as the hills themselves. Upon and around them moved in ceaseless, orderly activity a multitude of men and battalions of machines, piling up rock and concrete.

Walter drew a long breath and exclaimed, his face aglow:

"It makes me sit up and blink. Is there anything bigger to see?"

"The Gatun locks alone will cost twenty-five million, not to mention the dam," replied the practical Naughton, "but Culebra Cut is the heftiest job of them all. It broke the poor Frenchmen's hearts and their pocket-books."

They came at length to this far-famed range of lofty hills which link the Andes of South and Central America. Leaving the train, Naughton tramped ahead toward the gigantic gash dug in the continental divide. Clouds of gray smoke spurted from far below, and the earth trembled[Pg 68] to one booming shock after another. Dynamite was rending the rock and clay, and Walter realized, with a little thrill of pride, that he had been really helping to build the Panama Canal.

Presently he stood at the brink of this tremendous chasm. It seemed inadequate to call it a "cut." He gazed down with absorbed fascination at the maze of railroad tracks, scores of them abreast, which covered the unfinished bed of the canal. Along the opposite side, clinging to excavated shelves which resembled titanic stairs, ran more tracks. Beside them toiled the steam-shovels loading the processions of waiting trains.

No wonder Jack Devlin, engineer of "Number Twenty-six," had swaggered across the deck of the Saragossa. He knew that he was doing a man's work. To tame and guide one of these panting, hungry monsters was like being the master of a dragon of the fairy stories. There could be no Panama Canal without them. Intelligent, docile, tireless, they could literally remove mountains.

Walter sat upon a rock and watched one of them nudge and nose a huge bowlder this way[Pg 69] and that with its great steel dipper, exactly as if it were getting ready to make a meal of it. Then the mass was picked up, swung over a flat-car, swiftly, delicately, precisely, and the huge jaws opened to lay down the heavy morsel. Walter decided that he wanted to be a steam-shovel man. Naughton had to speak twice before the interested lad heard him say:

"I shall be busy for some time, and may have to jump on a work-train as far as Pedro Miguel station. Go down into the Cut, if you like, and look around."

"Thanks. Say, Mr. Naughton, how old must a man be to run a steam-shovel?"

"They break them in as firemen. Are you tough enough to shovel coal all day? Don't let these Culebra tarriers coax you away from us. You are scheduled to play ball for Cristobal, understand?"

By means of several sections of steep wooden stairs Walter clambered to the bottom of the cut, and dodged across the muddy area of trackage to gain the nearest bank upon which the steam-shovels were at work. Fascinated, he halted to watch one of them at closer range.

A noise of shouting came from several laborers who were running along a track further up the steep slope. The nearest steam-shovels blew their whistles furiously. The shrill blasts were sounding some kind of warning and Walter said to himself:

"Naughton's men must be ready to set off a blast. I guess I had better move on."

He started to follow the fleeing laborers when a mass of muddy earth came slipping down a dozen yards in front of him. It blocked the shelf upon which he had climbed, and he checked himself, gazing confusedly up the slope. A large part of the overhanging hill-side appeared to be in sluggish motion. The wet, red soil far up toward the top of the cut had begun to slide as if it were being pushed into the bed of the canal by some unseen force. Dislodged fragments of rock rolled down the surface of the slide and clattered in advance of it, but so deliberate was the movement of the mass that there seemed to be time enough to escape it.

Walter ran along the ties and began to plough knee-deep through the impeding heap of muddy[Pg 71] tenacious clay on the track. He glanced upward again, halted irresolutely, and gasped aloud:

"Great Scott, here comes a whole train of cars falling downhill."

The landslide had started just beneath the uppermost shelf of excavated rock, and the line of track supported thereupon was almost instantly undermined. The rails tilted and slipped with their weight of rock-laden cars before the engine could drag them clear. The train crew jumped and managed to crawl to the firm ground at the crest of the slope a moment before the flat-cars toppled over and broke loose from their couplings. Then the cars hung for an instant, spilled their burden of rock, which made a little avalanche of its own, and rolled down the slope with a prodigious clatter.

At this new peril, Walter knew not which way to turn. He could not be blamed for losing his presence of mind. The cars parted company, taking erratic courses, tumbling end over end. One of them bounded off at a slant to fall in front of him, while another was booming down to menace his retreat. All this was a matter of[Pg 72] seconds, precious time that was wasted for lack of decision.

Instead of making a wild dash in one direction or the other, Walter danced up and down in the same spot, his eyes fairly popping from his head. The result was that, by a miracle of good fortune, the flat-cars roared and rattled past on either side and left him unscathed.

Then the huge, loosened layer of earth, moving with lazy momentum, filled the ledge on which he stood, brushed him off, and carried him down the slope. To his amazement he was not wholly buried, but rolled over and over, now on the surface, now struggling in a sticky smother of stuff that held him like a fly in a bed of mortar. A projecting stratum of rock, not yet blasted away, checked the leisurely progress of the mass before it reached the bottom of the cut.

Plastered with mud from his hair to his heels, bleeding from a dozen scratches, his clothes in rags, Walter was quite astonished to find himself alive. He was stuck fast in clay almost to the waist and so dazed and breathless that he was unable to call for help.

Glancing stupidly up the slope, he beheld a[Pg 73] steam-shovel sway and totter. Nothing could surprise him now. With languid interest he watched the towering machine turn over on its side in a leisurely manner and then come slipping down to the next shelf. It resembled some prehistoric monster with a prodigiously long neck, which had lost its footing.

It came to rest on its side and out of one of the cab windows spilled a large man in overalls who tobogganed down the miry slope with extraordinary velocity, arms and legs flying.

He fetched up within a few yards of Walter, sat up, wiped the mud from his eyes, and sputtered:

"Poor old Twenty-six! She's sure in a mess this time."

Recognizing Jack Devlin, Walter managed to find his voice and called feebly:

"Is this what you call a great place for a husky young fellow?"

The steam-shovel man scrambled to his feet, active and apparently unhurt, as if such incidents were all in the day's work. Plunging through the débris of the slide, he peered into Walter's besmeared and bleeding countenance.[Pg 74] The voice and the words had sounded familiar and assisted identification.

"Well, I'll be scuppered!" roared Jack Devlin. "Goodwin is your name. You took my advice and beat it to the Isthmus. I'll have you out of this in a jiffy."

A gang of laborers arrived a moment later, and with Devlin shouting stentorian orders, their shovels speedily and carefully dug out the hapless Walter. They were about to carry him to the nearest switch-tender's shelter when he groaned protestingly:

"Ouch! Don't grab my right arm. It hurts."

Battered and sore as he was, all other damage was forgotten as he tried to raise the precious right arm, his pitching arm, the mainstay of his fortunes on the Isthmus. An acute pain stabbed him between wrist and elbow. He murmured sorrowfully:

"It is broken or badly sprained. I'm not dead, but I certainly am unfortunate."

"Those that try to stop a landslide in the Cut are generally lugged out feet first," cheerfully remarked Devlin. "The landscape isn't[Pg 75] fastened down very tight. Were you looking for me?"

"Yes. And I found you, didn't I?" Walter grinned as he added: "We were thrown together, all right."

They made him as comfortable as possible, while Devlin forgot his sorrow over the plight of his beloved "Twenty-six."

"I feel sort of responsible for you, Goodwin," said he. "I'm going to put you in the hospital car of the next train to Ancon, where they'll give you the best of everything. I can't go with you, but I'll try to see you to-night. I must boss a first-aid-to-the-injured job on that poor old steam-shovel of mine. She looks perfectly ridiculous, doesn't she? Now, cheer up."

The American hospital buildings at Ancon are magnificently equipped, and their situation along the windy hill-side commands a memorable view of the gray old city of Panama, the wide blue bay adorned with islands, and the rolling Pacific. To Walter Goodwin the place seemed like a prison, and he awaited the surgeon's verdict with the dismal face of a man about to be sentenced. The sundry cuts and[Pg 76] contusions were of small account. A few days would mend them. But his aching, disabled arm was quite a different matter.

"You were born lucky or you would be in the morgue," said the genial young surgeon of the accident ward.

"I am damaged enough," sighed Walter. "What about this arm?"

"No fracture. A severe wrench that will make it pretty sore for a month or so."

"A month or so!" and Walter winked to hold back the tears. "Why, I have to pitch a game of ball with this arm next week."

"Nothing doing," decreed the surgeon. "You had better stay here for two or three days and we'll try our best to patch you up in record time. Do you want to notify any friends?"

"Yes, indeed," cried Walter. "Please send word to Mr. Harrison, captain of the Cristobal nine."

"'Bucky' Harrison?" The surgeon showed lively interest. "Then you must be the new pitcher for Cristobal. We heard about you. You are in the enemy's camp, but we will treat you kindly."

Having been tucked in bed, Walter felt that he was a perfectly useless member of society. The landslide had wiped out his bright expectations. Major Glendinning could have no possible interest in a pitcher with a crippled arm. When dismissed from the hospital he would be unable to earn his food and lodging even as a laborer. As for his brave plan of helping the dear household in Wolverton, he might have to beg aid from them.

Jack Devlin appeared after supper. His manner was contrite and subdued as he sat down by the cot and strongly gripped Walter's sound hand.

"You and I were sort of disorganized there in the Cut," said he. "I had no chance to find out how things have been breaking for you. Have you landed a job? What about it?"